Federal Court of Australia

Deripaska v Minister for Foreign Affairs [2024] FCA 62

ORDERS

WAD 15 of 2023 | ||

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

KENNETT J | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

2. The applicant pay the respondent’s costs as agreed or assessed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

KENNETT J:

introduction

1 The applicant challenges a decision made by the Minister for Foreign Affairs (the Minister) on 17 March 2022 to designate him for targeted financial sanctions and declare him for travel bans under the Autonomous Sanctions Act 2011 (Cth) (the Act). The applicant is a Russian national, described in the material that was before the Minister as an oligarch and prominent businessman with close personal ties to President Putin.

2 The decision of the Minister is embodied in, and purported to be given legal effect by, a statutory instrument entitled the Autonomous Sanctions (Designated Persons and Entities and Declared Persons — Russia and Ukraine) Amendment (No 7) Instrument 2022 (Cth) (the Amending Instrument), which amended an earlier instrument so as to include the applicant’s name in a list of persons and entities in that instrument. It will be necessary to consider these instruments in more detail below.

3 The Minister at the time, who made the decision, was Senator the Hon Marise Payne. She is no longer a member of the Government or indeed a Senator. Appropriately, orders are not sought against Ms Payne in a personal capacity, but against the current Minister in her capacity as an officer of the Commonwealth. It will be necessary to refer briefly to Ms Payne in a personal capacity later in these reasons. References to “the Minister” in these reasons are references to the office holder at relevant times: ie, the decision-maker, in her capacity as such, and the respondent in these proceedings.

4 The applicant pressed six arguments. They are, in summary (and in the order presented in written submissions):

(a) the regulations under which the instruments were made are wholly invalid by reason of inconsistency with principles entrenched in Ch III of the Constitution;

(b) the regulations are wholly invalid because they infringe the implied freedom of political communication;

(c) the regulations are wholly invalid because they are inconsistent with fundamental common law principles;

(d) the Amending Instrument fails to perform the statutory function of “designating” or “declaring” the applicant;

(e) the Minister misunderstood the nature of the power that she purported to exercise; and

(f) the Minister’s satisfaction that a relevant criterion was met was not supported by any probative material.

5 The arguments will be addressed in this order. Before doing so, it is necessary to note the relevant aspects of the statutory scheme and the decision-making process in the present case.

relevant aspects of the statutory scheme

6 The Act provides for the imposition and enforcement of “autonomous sanctions” which are, broadly, sanctions that:

(a) are intended to influence foreign governments, persons or entities outside Australia in accordance with Australian Government policy; or

(b) involve the prohibition of conduct in or connected with Australia that facilitates the engagement by a person or entity in conduct outside Australia that is contrary to Australian Government Policy.

7 The objects of the Act, set out in s 3, make clear that such sanctions may be country-specific or may be thematic (in that they may be directed at identified international problems such as the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, malicious cyber activity or serious violations of human rights).

8 The Act operates principally by authorising the making of regulations which impose sanctions of the kinds contemplated. Section 28 of the Act is a general power to make regulations prescribing matters required or permitted to be prescribed or necessary or convenient to be prescribed for carrying the Act into effect. Section 10 expressly provides for the regulations to apply sanctions, as follows.

10 Regulations may apply sanctions

(1) The regulations may make provision relating to any or all of the following:

(a) proscription of persons or entities (for specified purposes or more generally);

(b) restriction or prevention of uses of, dealings with, and making available of, assets;

(c) restriction or prevention of the supply, sale or transfer of goods or services;

(d) restriction or prevention of the procurement of goods or services;

(e) provision for indemnities for acting in compliance or purported compliance with the regulations;

(f) provision for compensation for owners of assets that are affected by regulations relating to a restriction or prevention described in paragraph (b).

(2) Before the Governor-General makes regulations for the purposes of subsection (1), the Minister must be satisfied that the proposed regulations:

(a) will facilitate the conduct of Australia’s relations with other countries or with entities or persons outside Australia; or

(b) will otherwise deal with matters, things or relationships outside Australia.

…

9 Regulations may have extraterritorial effect (s 11). They are to have effect despite any other laws including pre-existing Acts of the Commonwealth (s 12). Later Commonwealth Acts are not to be interpreted as amending or repealing the regulations (or authorising the making of any instrument affecting their operation) except to the extent that they do so expressly (s 13).

10 The Act provides for enforcement of the regulations by an injunction granted by a court on the application of the Attorney-General (s 14). The Act also creates the following offences:

(a) contravening a “sanction law” (ie a law specified under s 6 as a sanction law) (s 16); and

(b) giving false or misleading information to the Commonwealth in connection with the administration of a sanction law (s 17).

11 The Autonomous Sanctions Regulations 2011 (Cth) (the Regulations) provide for the imposition of sanctions. Relevantly for present purposes, reg 6 provides as follows:

6 Country-specific designation of persons or entities or declaration of persons

For paragraph 10(1)(a) of the Act, the Minister may, by legislative instrument, do either or both of the following:

(a) designate a person or entity mentioned in an item of the table as a designated person or entity for the country mentioned in the item;

(b) declare a person mentioned in an item of the table for the purpose of preventing the person from travelling to, entering or remaining in Australia.

Item | Country | Activity | |||

6A | Russia | (a) A person or entity that the Minister is satisfied is, or has been, engaging in an activity or performing a function that is of economic or strategic significance to Russia. (b) A current or former Minister or senior official of the Russian Government. (c) An immediate family member of a person mentioned in paragraph (a) or (b). | |||

12 Item 6A was inserted into the table in reg 6 by the Autonomous Sanctions Amendment (Russia) Regulations 2022 (Cth) (the Russia Regulations), which commenced on 25 February 2022 (shortly before the Minister’s decision in the present case was made).

13 Where a person is declared under reg 6(b), provisions in the Migration Regulations 1994 (Cth) make that declaration a ground for refusal of a visa (PIC 4003 in Schedule 4) or for cancellation of an existing visa (reg 2.43(1)(aa)(i)).

14 Where a person or an entity is designated under reg 6(a), later provisions of the Regulations come into play. Regulations 14 and 15 provide as follows.

14 Prohibition of dealing with designated persons or entities

(1) A person contravenes this regulation if:

(a) the person directly or indirectly makes an asset available to, or for the benefit of, a designated person or entity; and

(b) the making available of the asset is not authorised by a permit granted under regulation 18.

(1A) Strict liability applies to the circumstance that the making available of the asset is not in accordance with a permit under regulation 18.

Note 1: For strict liability, see section 6.1 of the Criminal Code.

Note 2: Strict liability is not imposed on an individual for any other element of an offence under section 16 of the Act that relates to a contravention of this regulation.

(2) Section 15.1 of the Criminal Code applies to an offence under section 16 of the Act that relates to a contravention of this regulation.

Note 1: This has the effect that the offence has extraterritorial operation.

Note 2: This regulation may be specified as a sanction law by the Minister under section 6 of the Act.

15 Prohibition of dealing with controlled assets

(1) A person contravenes this regulation if:

(a) the person holds a controlled asset; and

(b) the person:

(i) uses or deals with the asset; or

(ii) allows the asset to be used or dealt with; or

(iii) facilitates the use of the asset or dealing with the asset; and

(c) the use or dealing is not authorised by a permit granted under regulation 18.

(1A) Strict liability applies to the circumstance that the use or dealing with the asset is not in accordance with a permit under regulation 18.

Note 1: For strict liability, see section 6.1 of the Criminal Code.

Note 2: Strict liability is not imposed on an individual for any other element of an offence under section 16 of the Act that relates to a contravention of this regulation.

(2) Section 15.1 of the Criminal Code applies to an offence under section 16 of the Act that relates to a contravention of this regulation.

Note 1: This has the effect that the offence has extraterritorial operation.

Note 2: This regulation may be specified as a sanction law by the Minister under section 6 of the Act.

15 “Controlled asset” is defined in reg 3 to mean an asset “owned or controlled by a designated person or entity”. “Asset” is defined in s 4 of the Act, as follows:

asset means:

(a) an asset of any kind or property of any kind, whether tangible or intangible, movable or immovable, however acquired; and

(b) a legal document or instrument in any form (including electronic or digital) evidencing title to, or interest in, such an asset or such property.

Note: Some examples of documents and instruments described in paragraph (b) are bank credits, travellers cheques, bank cheques, money orders, shares, securities, bonds, debt instruments, drafts and letters of credit.

16 Regulation 15 is thus contravened by a very wide range of dealings involving “assets” (which is also a wide concept, including intangible property and documents) owned or controlled by a designated person or entity.

17 Regulations 14 and 15 are declared to be “sanction laws”, for the purposes of s 6 of the Act, by the Autonomous Sanctions (Sanction Law) Declaration 2012 (Cth). That means that contravention of reg 14 or 15 is (subject to proof of the relevant fault elements) an offence under s 16 of the Act.

18 The effect of regs 14 and 15 can be mitigated by the grant of a permit by the Minister under reg 18. Regulation 18(1) authorises (inter alia) the grant of a permit authorising the making available of an asset that would otherwise contravene reg 14, or the use of or dealing with a controlled asset (paras (e), (f)). The regime for granting permits is discussed further below.

Designation of persons and entities and declaration of persons in respect of Russia

19 On 19 June 2014 the Minister made an instrument under reg 6 of the Regulations entitled the Autonomous Sanctions (Designated Persons and Entities and Declared Persons – Russia and Ukraine) List 2014 (Cth) (the 2014 Instrument). Section 3A of that Instrument, which was inserted by the Autonomous Sanctions (Designated Persons and Entities and Declared Persons – Ukraine) Amendment (No 4) Instrument 2022 (Cth) (the No 4 Instrument) with effect from 26 February 2022, is as follows.

3A Designated persons and entities and declared persons—Russia

(1) For the purposes of paragraph 6(a) of the Autonomous Sanctions Regulations 2011, each person or entity mentioned in an item of a table in Schedule 2 is designated as a designated person or entity for Russia.

(2) For the purposes of paragraph 6(b) of the Autonomous Sanctions Regulations 2011, each person mentioned in an item of the table in Part 1 of Schedule 2 is declared for the purpose of preventing the person from travelling to, entering or remaining in Australia.

20 Schedule 2 to the 2014 Instrument comprises two tables. The table in Part 1 of the Schedule lists individuals who, as a result of their inclusion, are declared for the purposes of reg 6(b) (by s 3A(2)) and designated for the purposes of reg 6(a) (by s 3A(1)). Part 2 of Schedule 2 lists entities which are designated (by s 3A(1)) but which are not within the scope of reg 6(b).

21 The 2014 Instrument is the Instrument which was amended by the Amending Instrument signed by the Minister on 17 March 2022. The Amending Instrument added the applicant’s name to the table in Part 1 of Schedule 2.

the present case

22 Pursuant to proposed consent orders drawn up by the parties (which were ultimately not made by the Court, but implemented by agreement), the Minister’s solicitors were, subject to any claims for public interest immunity, to file and serve “a book comprising copies of all documents relating to the respondent’s decision in relation to the applicant made on 17 March 2022 that were before the respondent at the time of making that decision”. They filed and served a book of documents in compliance with that proposed order, which is now in evidence. I proceed on the basis (no party having suggested otherwise) that these documents comprise everything relevant to the decision that was before the Minister at the time she made the decision.

What the Minister received

23 The Minister was provided with a “Ministerial Submission” prepared by officers in her Department. The submission itself is undated, but other evidence indicates that it was sent to her office on the morning of 16 March 2022 (the day before the Minister made the decision under review). The Ministerial Submission dealt with the applicant and one other person, and the discussion of that other person (which is irrelevant) has been redacted. In what follows I omit references to the other person.

24 The Ministerial Submission was headed “Russia: Autonomous sanctions against Russian oligarchs Deripaska and [redacted]”. Its first page set out what it described as “Key Issues” and its “Recommendation”. The “Key Issues” section said:

This submission seeks your (Minister Payne’s) agreement to list Oleg Deripaska, founder of United Company Rusal, and [redacted] for targeted financial sanctions and travel bans. Statements of case are at Attachment A. Deripaska and [redacted] have interests in Queensland Alumina Limited (QAL), which Rio Tinto controls. [Redacted]. Any impact on QAL [redacted] would depend on the detail of the relevant commercial arrangements. Deripaska and [redacted] have been listed by the United States and the United Kingdom. Deripaska has also been listed by Canada.

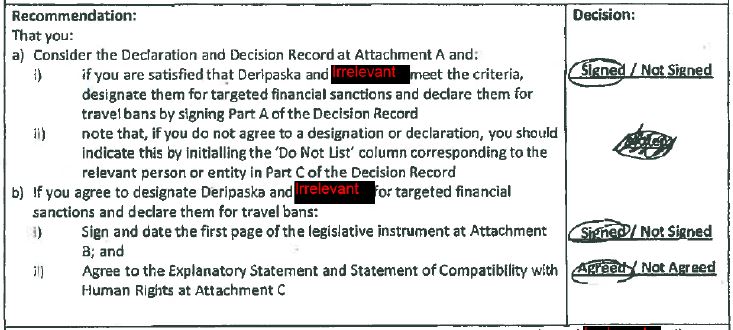

25 The “Recommendation” set out the Department’s recommendations, with a facility opposite each recommendation for the Minister to indicate her decision thereon. The following is an image of this part of the document, including the Minister’s annotations. (The “decision” next to para (a)(ii), which the Minister has circled and then crossed out, appears to read “Noted”.)

26 On the next page, under the heading “Background”, came a brief discussion of the applicant’s case.

You (Minister Payne) decided on 13 March to list 11 Russian oligarchs for targeted financial sanctions and travel bans (see MS22-000360). They did not include Oleg Vladimirovick Deripaska and [redacted] pending further analysis of their Australian business interests. Now that we have undertaken that analysis, we recommend that you list Deripaska and [redacted].

Imposing targeted financial sanctions against Deripaska and [redacted] would prohibit Australians from using or dealing with any asset that is owned or controlled by either of them; and prohibit Australians from providing any asset directly or indirectly to, or for the benefit of, either of them. The Autonomous Sanctions Act 2011 defines ‘asset’ for these purposes broadly to include an asset or property of any kind, whether tangible or intangible, movable or immovable.

Both Deripaska and [redacted] have interests in United Company Rusal, a state-owned Russian company. Rusal owns a 20 per cent share of Queensland Alumina Limited (QAL), which operates an alumina refinery in Gladstone. Rio Tinto owns the remaining 80 per cent. Rio issued statement on 10 March that it would sever all business links with Rusal. Separately, Rio informed DFAT in-confidence on 16 March that it had planned for the possible listings of Deripaska and [redacted] which Rio indicated would not affect QAL’s operations.

[Redacted].

Listing Deripaska and [redacted] would further align us with like-minded partners. Both have been listed by the United States and the United Kingdom. Deripaska has also been listed by Canada. Neither has been listed by the EU. Beyond merely aligning with like-minded partners, listing Deripaska and [redacted] would demonstrate that we are committed to imposing severe sanctions on Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine, even where that may have an impact on our economic interests and those of Australian businesses. To the contrary, not listing Deripaska and [redacted] may attract domestic criticism questioning our commitment to sanctions that actually bite. Largely because of their greater exposure to Russia, our like-minded partners have already suffered direct economic damage, whereas we have not.

On balance, we consider that our prevailing interest is in aligning with like-minded partners to demonstrate our commitment to strong sanctions against Russia. Should you agree to list Deripaska and [redacted] we would register the legislative instrument on the same day. The listings would take effect at 12.01 am on the following day.

27 The next section of the Ministerial Submission was headed “Decision Record”. It was evidently prepared for the Minister to sign if she agreed with its contents, so that there would be a record of what the Minister had decided and on what basis (even though the Minister was under no legal obligation to give reasons for her decision). The Decision Record was divided into four parts.

28 Part A was headed “Designation and Direction”. Underneath was a space for the Minister to sign. The text of this section was as follows.

I am satisfied that the persons identified in Part C meet the criteria for designation and declaration (if applicable), outlined in Part B below, unless I have initialled the ‘Do Not List’ column in respect of a person.

I confirm that I considered the statements of case supporting designation for targeted sanctions and declaration for travel bans in respect of each person in Part D in reaching my decision.

29 Part B was headed “criteria for listing” and set out the relevant text of item 6A of reg 6 (set out at [11] above).

30 Part C was headed “Decision on designation and declaration”. It began with a table listing the name and some other details of the applicant, including the “Do Not List” column referred to in the Recommendation. Under the heading “Context”, there was some further text describing the applicant’s role and interests. There was then a brief reference to the sanctions imposed on the applicant by the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada.

31 Part D was headed “Statements of Case supporting designation and direction” It set out information which it said was, “to the Australian Government’s knowledge, accurate and reliable”. In relation to the applicant, that information was as follows.

Name: Oleg Vladimirovich Deripaska

Nationality: Russian Federation, Cyprus

Oleg Vladimirovich DERIPASKA is a prominent Russian businessman (oligarch) and public reports state he has particularly close personal tied to President Putin.4

DERIPASKA is the founder of UC Rusal which has a 20 percent interest in Queensland Alumina.5 On 10 March 2022, Rio Tinto, which owns the remaining 80 percent, announced that it would sever all business links with Russia.6

DERIPASKA has said that he does not separate himself from the Russian state. He has also acknowledged possessing a Russian diplomatic passport and claims to have represented the Russian government in other countries.7

DERIPASKA has been subject to US sanctions since 20188 and Canadian sanctions since 6 March 2022.9 The UK imposed sanctions on DERIPASKA on 10 March 2022.10

In March 2019, DERIPASKA sued the US, alleging that it had overstepped its legal bounds in imposing sanctions on him and made him the “latest victim” in the US probe into Moscow’s election interference. The lawsuit was dismissed in June 2021, as lacking merit.11

DERIPASKA is or has been involved in obtaining benefit from or supporting the Government of Russia, by carrying on business in, and owning or controlling and working as a director or equivalent in businesses in the Russian extractives and energy sectors, sectors of strategic significance to the Government of Russia.12

Given his business interests and close personal ties to Putin, it is open for the Minister to be satisfied that Oleg Vladimirovich DERIPASKA is, or has been, engaging in an activity or performing a function that is of economic or strategic significance to Russia.

32 I have retained the footnote references in this extract to indicate which of the assertions in this part of the Ministerial Submission were supported by reference to sources, but I have not reproduced the footnotes themselves. The Minister’s legal representatives did not include the footnoted material in the bundle of documents that was filed and served. It was submitted that I should infer that that material was available to the Minister if she wanted to see it, and I see no reason not to draw that inference. However, it was not submitted that I should infer that the Minister had physically in front of her, or read, any of that material.

33 Two further documents were included with the Ministerial Submission. One was a draft of what ultimately became the Amending Instrument (the draft Instrument). The other was a draft Explanatory Statement for the Amending Instrument (the draft Explanatory Statement), which had annexed to it a draft Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights (the Compatibility Statement). The draft Explanatory Statement included, immediately under its main heading, the words “Issued by the Authority of the Minister for Foreign Affairs”.

What the Minister did

34 It is not in contest that the markings and signatures on the documents that are in evidence are those of the Minister.

35 First, the Minister signed Part A of the Decision Record and inserted the date. She thereby indicated that she was satisfied that the applicant met the criteria for designation and declaration in item 6A of reg 6, and said that she had considered the “statement of case” appearing in the Decision Record in respect of him. The qualification in the first paragraph of Part A, referring to the “Do Not List” column, did not apply because the Minister did not make any mark in that column.

36 Secondly, the Minister signed and dated the draft Instrument. This was the legally operative aspect of what she did.

37 Thirdly, the Minister marked the first page of the Ministerial Submission to indicate what she had done, and signed and dated that page.

(a) As to para (a)(i) of the Recommendation, which recommended that she sign Part A of the Decision Record, she circled “Signed”.

(b) As to para (a)(ii), which invited her to initial the “Do Not List” column if she did not agree to a designation or declaration, she appears to have initially circled “Noted” but then struck it through.

(c) As to para (b)(i), which invited her to sign the draft Instrument if she agreed to designate and declare the applicant, she circled “Signed”.

(d) Paragraph (b)(ii) of the Recommendation asked the Minister to indicate whether she agreed to the draft Explanatory Statement and the Compatibility Statement. The Minister circled “Agreed”.

38 The operative provision of the Amending Instrument is s 4, which provides:

Each instrument that is specified in a Schedule to this instrument is amended or repealed as set out in the applicable items in the Schedule concerned, and any other item in a Schedule to this instrument has effect according to its terms.

39 Schedule 1 to the Amending Instrument refers to the 2014 Instrument as the instrument being amended, and provides that the name of the applicant and his date and place of birth are to be inserted into the table in Part 1 of Schedule 2 to that Instrument.

40 The other exercise of statutory power that should be noted is that, on 7 November 2022, the Assistant Minister for Foreign Affairs issued a permit under reg 18 of the Regulations (“the permit”). The permit applied to any “designated person or entity” as described in reg 3 of the Regulations. In general terms, it allowed dealings with assets that would otherwise be prohibited by the Regulations for the purpose of providing legal advice, legal representation and ancillary services to designated persons or entities in relation to matters arising under or related to Australian law. It is discussed further below.

The validity of the regulations

41 The arguments concerning the validity of the regulations focus on the effect that regs 14 and 15 have, absent a permit, on the provision of legal advice and representation to a designated person or entity. These effects were carefully explained in the submissions but can be noted fairly briefly. The substance was not in dispute. First, a designated person or entity is prevented from remunerating an Australian lawyer who works for them. Secondly, it will very likely be impossible for a lawyer effectively to advise or represent a designated person or entity without dealing with “controlled assets” (which include legal documents or instruments belonging to the person or entity, including documents brought into existence by the lawyer on the client’s instructions). Thirdly, any “asset” in the lawyer’s possession, including intellectual property (and likely including the lawyer’s own notes) would not be able to be made available “to, or for the benefit of” a designated person or entity who was the lawyer’s client.

42 The permit referred to at [40] above largely if not wholly avoids these effects. However, the applicant’s point is that the Regulations cannot validly make access to legal representation a matter for executive discretion. This is also uncontroversial, up to a point.

43 The applicant submits that, because of the effects of regs 14 and 15 on the ability to obtain legal representation, the Regulations as a whole:

(a) are inconsistent with principles embedded in Ch III of the Constitution;

(b) infringe the implied freedom of political communication; and

(c) are inconsistent with fundamental common law rights.

Chapter III

44 It is necessary, under this heading, to give separate consideration to three levels of particularity at which the argument is pitched. They are:

(a) challenges to the validity of the particular instrument designating the person or entity, or other things done under the Act itself;

(b) all proceedings brought by the designated person or entity in the jurisdiction conferred on the High Court by s 75(v) of the Constitution (and the analogous jurisdiction of this Court under s 39B(1) of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) (Judiciary Act)); and

(c) all proceedings in federal jurisdiction to which the designated person or entity is a party.

Challenging the validity of the designating instrument

The potential invalidity

45 Section 75 of the Constitution provides:

In all matters:

(i) arising under any treaty;

(ii) affecting consuls or other representatives of other countries;

(iii) in which the Commonwealth, or a person suing or being sued on behalf of the Commonwealth, is a party;

(iv) between States, or between residents of different States, or between a State and a resident of another State;

(v) in which a writ of Mandamus or prohibition or an injunction is sought against an officer of the Commonwealth;

the High Court shall have original jurisdiction.

46 In these classes of matter, jurisdiction is conferred directly by the Constitution. That conferral cannot be interfered with or set at naught by legislation. This is to be contrasted with the classes of matter in s 76, in respect of which federal jurisdiction has long been (but in principle need not be) conferred on various Australian courts by statute.

47 Leaving aside s 75(i) (which may have no operation at all: see Re East; Ex parte Nguyen [1998] HCA 73; 196 CLR 354 at [16]-[18] (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ)), s 75(v) is the only head of entrenched jurisdiction that is defined by reference to legal remedies. Paragraphs (ii) to (iv) depend on who the parties are.

48 Because s 75(v) confers an entrenched jurisdiction to hear matters in which recognised remedies are sought — and hence to apply the legal principles relating to the grant of those remedies — it has been understood to introduce an “entrenched minimum provision of judicial review” (Plaintiff S157/2002 v Commonwealth [2003] HCA 2; 211 CLR 476 at [103] (Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ) (Plaintiff S157)). It thus serves the important purpose of making it “constitutionally certain that there would be a jurisdiction capable of restraining officers of the Commonwealth from exceeding Federal power” (Bank of New South Wales v Commonwealth (1948) 76 CLR 1 at 363 (Dixon J), cited in Bodruddaza v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs [2007] HCA 14; 228 CLR 651 at [45] (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Kirby, Hayne, Heydon and Crennan JJ) (Bodruddaza).

49 In Plaintiff S157, the centrality and protective purpose of s 75(v) was an important element of the reasoning leading to a narrow reading of a privative clause purporting to limit judicial review of decisions under the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (the Migration Act). It was observed that, while Parliament may define the scope of Commonwealth officers’ powers and the content of the laws to be obeyed, “it cannot deprive this Court of its constitutional jurisdiction to enforce the law so enacted” (at [5] (Gleeson CJ)). In Bodruddaza, a short and inflexible time limit for judicial review applications to the High Court in relation to migration decisions was held to be invalid on the basis that it “subverts the constitutional purpose of the remedy provided by s 75(v)” (at [58]).

50 The plurality in Graham v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2017] HCA 33; 263 CLR 1 (Kiefel CJ, Bell, Gageler, Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ) (Graham) took up the same theme at [38]-[49], and extended the analysis to the exercise of jurisdiction conferred by statute “by reference to s 75(v)”. At [48], their Honours said:

What Parliament cannot do under s 51(xxxix) or under any other source of legislative power is enact a law which denies to this Court when exercising jurisdiction under s 75(v), or to another court when exercising jurisdiction within the limits conferred on or invested in it under s 77(i) or (iii) by reference to s 75(v), the ability to enforce the legislated limits of an officer's power. The question whether or not a law transgresses that constitutional limitation is one of substance, and therefore of degree. To answer it requires an examination not only of the legal operation of the law but also of the practical impact of the law on the ability of a court, through the application of judicial process, to discern and declare whether or not the conditions of and constraints on the lawful exercise of the power conferred on an officer have been observed in a particular case.

51 The Minister therefore accepted, correctly, that regs 14 and 15 could not apply according to their terms to actions taken for the purpose of challenging the validity of decisions or actions under the Act pursuant to s 75(v) or s 39B(1) of the Judiciary Act. (“Purpose” was used here in an objective sense, to describe the end served by the actions referred to rather than the subjective intentions of the people involved.) There would be an obvious and compelling vice in the Regulations if they did operate in this way. The decision to designate a person or entity would effectively insulate itself against legal challenge.

The issue

52 The Minister submitted that the relevant expressions in regs 14 and 15 (“deal with”, “make available” and “use”) could, and therefore should, be read as excluding actions taken for this purpose. The applicant, however, submitted that such an exercise in reading down was not permissible.

53 Before turning to this question in more detail, it should be noted that issues of constitutional validity are to be assessed at the level of the Act. This may affect how the issue of construction in play here is conceptualised, but does not affect its resolution.

54 If a statute complies with constitutional limitations on its proper construction, the only issues remaining in relation to exercises of power under that statute are administrative law questions: Palmer v Western Australia [2021] HCA 5; 272 CLR 505 at [63]-[67] (Kiefel CJ and Keane J) (Palmer). In stating this proposition their Honours referred to Wotton v Queensland [2012] HCA 2; 246 CLR 1 (Wotton), where French CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Crennan and Bell JJ accepted a submission in relation to a parole order that (at [22]):

(i) where a putative burden on political communication has its source in statute, the issue presented is one of a limitation upon legislative power; (ii) whether a particular application of the statute, by the exercise or refusal to exercise a power or discretion conferred by the statute, is valid is not a question of constitutional law; (iii) rather, the question is whether the repository of the power has complied with the statutory limits; (iv) if, on its proper construction, the statute complies with the constitutional limitation, without any need to read it down to save its validity, any complaint respecting the exercise of power thereunder in a given case, such as that in this litigation concerning the conditions attached to the Parole Order, does not raise a constitutional question, as distinct from a question of the exercise of statutory power.

55 Step (iv) in that argument envisaged that the statute in question was compliant with the constitutional limitation “without any need to read it down to save its validity”. That may not be the case where the statute contains a broadly expressed regulation making power. A power of that kind may itself need to be construed in the light of the constitutional limitation. Thus, it is appropriate to proceed by formulating a “composite hypothetical question”: whether, if the regulations had been enacted as primary legislation, they would have been compliant with the relevant constitutional limitation (Palmer at [122]-[124] (Gageler J)). If the answer to that question is negative, it will likely follow that the regulation making power is to be read down so as not to permit the making of regulations in those terms.

56 It is well established that a construction of legislation that is consistent with the Constitution should be adopted if it is reasonably open: Wainohu v New South Wales [2011] HCA 24; 243 CLR 181 at [97] (Gummow, Hayne, Crennan and Bell JJ) (Wainohu); Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) s 15A (Acts Interpretation Act). Section 15A of the Acts Interpretation Act is made applicable to subordinate legislation by s 13(1)(a) of the Legislation Act 2003 (Cth) (Legislation Act). Section 13(1)(c) of that Act requires subordinate legislation to be read subject to the enabling Act and not to exceed power; and s 13(2) (perhaps repetitively) substantially reproduces, as a rule of construction for all legislative instruments, the terms of s 15A. Thus, in addressing the composite hypothetical question referred to in the previous paragraph in relation to a regulation, the regulation must be construed (as if it were an Act) subject to s 15A. Another way of framing the task is that the enabling provision must be construed so as not to exceed constitutional power if possible (pursuant to s 15A), and then the regulation must be read so as not to go beyond the enabling provision if possible (pursuant to s 13(1)(c) and (2)). Either way one arrives, in practice, at the issue posed by the competing submissions referred to at [52] above: can regs 14 and 15 be construed so as not to apply to actions undertaken for the purposes of challenging, under s 75(v) or s 39B(1), decisions or actions taken under the Act? The questions of what is the correct construction of the Regulations and whether they are valid are thus closely connected. Validity cannot be determined without identifying the correct construction; however, the correct construction cannot be finally settled without consideration of whether “reading down”, to preserve validity, is required by the constructional rule being referred to here.

57 Reference was made in argument to Zhang v Commissioner of the Australian Federal Police [2021] HCA 16; 273 CLR 216 at [25]-[27] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Edelman, Steward and Gleeson JJ) (Zhang), where the Court mentioned the problems that arise where a plaintiff seeking to invalidate a statute propounds an expansive, draconian construction (potentially contrary to their own interests if the statute is valid) while the party seeking to defend the statute urges a narrow construction (again, potentially against its own interests). Such circumstances lead to a lack of concreteness in the presentation of constitutional questions. In Zhang, these considerations led the High Court to answer the questions reserved in the special case in a minimalist way which avoided a binding determination of the constitutional issue.

58 The present case has this problem. The applicant is not relevantly affected in his acquisition of legal services by regs 14-15, having the benefit of the permit mentioned above. His argument relies on their potential effect in other cases and on other people. The issue concerning the extent to which expressions used in regs 14 and 15 need to be read down to avoid invalidity, and the effect of that exercise on the operation of the Regulations, therefore have a somewhat nebulous character.

59 While I agree (with respect) with what was said in Zhang, I do not have the leeway that was available to the High Court in that case. The applicant seeks orders setting aside the decision to designate and declare him under the Regulations and asserts the complete invalidity of the Regulations as a reason why there was no power to make that decision. Because I have not found the decision to be invalid on any other grounds (as will appear below), the argument that the Regulations are invalid must be dealt with.

Reading down of general expressions to avoid invalid operation

60 The application of s 15A in relation to general words and expressions was discussed in Victoria v Commonwealth (the Industrial Relations Act case) (1996) 187 CLR 416 at 502 (Brennan CJ, Toohey, Gaudron, McHugh and Gummow JJ). Their Honours there identified three considerations that may prevent s 15A (or an analogous provision) being applied so as to give a provision a valid partial operation. The applicant invokes each of these (albeit by reference to the later and briefer discussion, referring to s 31 of the Interpretation Act 1987 (NSW), in Wainohu at [102]) and ultimately makes five points.

61 First, s 15A cannot be implied to effect a partial validation unless “the operation of the remaining parts of the law remain unchanged”. Reference to the cases cited for this proposition (eg Pidoto v Victoria (1943) 68 CLR 87 at 108 (Latham CJ) (Pidoto) and Re Dingjan; Ex parte Wagner (1995) 183 CLR 323 at 347-348 (Dawson J)) indicates that s 15A is limited in this way because the Parliament, in enacting the impugned law, is assumed not to have intended to enact some other, different law. In other words s 15A, being an interpretation provision, is displaced by a contrary intention appearing from the Act that that is being interpreted. That is unsurprising, and consistent with s 2 of the Acts Interpretation Act in the form in which it stood at the time these cases were decided (and s 2(2) as it now stands). Section 13(2) of the Legislation Act is not subject to a similar qualification (although s 13(1) is expressed to be subject to a contrary intention, and so are the provisions of the Acts Interpretation Act that it imports). There may be a question whether a constructional rule imposed by an Act can be qualified or displaced by a contrary intention appearing in subordinate legislation. It may be, therefore, that s 13(2) can operate to save parts of a regulation even if that results in what is left having a different operation to that intended by the regulation maker.

62 That question does not need to be decided, because the operation of regs 14 and 15 following the “carve-out” proposed by the Minister would not be materially different from that which the provisions have if given their ordinary meaning. The consequence would be that circumstances would exist in which the prohibitions in regs 14 and 15 did not apply. That would not involve any change to the operation of the prohibitions in circumstances to which they did apply. It is true that the Minister’s construction would do some of the work presently done by the permit, and would to that extent make reg 18 unnecessary. However, the potential scope for permits is vastly broader than the exception that is created by the Minister’s construction. That is illustrated by the dealings that can be the subject of an application for a permit under reg 20 (which include, among many other things, “reasonable professional fees” (reg 20(3)(b)(vii)). The Minister also has power to grant a permit on their own initiative (reg 18(2)(a)), which may be for a purpose for which no application can be made under reg 20. The Minister’s construction does not leave reg 18 with no work to do.

63 Secondly, s 15A cannot apply “if it appears that ‘the law was intended to operate fully and completely according to its terms, or not at all’”. The quotation is from Pidoto at 108. Again, the reasoning appears to be that s 15A has to give way to an intention of the legislature that appears from the statute being interpreted. As noted above, there is scope for doubt as to whether the same is true of s 13(2) of the Legislation Act.

64 I do not discern in the Regulations an intention that they are not to have any operation at all if the prohibitions in regs 14 and 15 cannot apply to the full extent of their language.

(a) The provisions enact draconian prohibitions which were clearly intended to operate as broadly as they could. The carving out of cases in which the prohibitions cannot apply for constitutional reasons results in a slightly less comprehensive regime but does not in any way compromise what appears to be the policy rationale for the scheme of designating persons and entities. It is very unlikely that, if informed during the drafting process that a prohibition on people using their resources to challenge decisions made in respect of them under the Act could not validly be put into effect, the legislator would have given up on the project. It is much more likely that they would have included a form of words that avoided having that effect.

(b) The provision for declaring a person for travel bans in reg 6(b) is completely separate and has consequences under other legislation. There is no reason to think that this provision was not intended to operate if part of the designation regime could not validly be put into effect.

(c) The Regulations expressly contemplate that provisions of regs 14 and 15 will not apply in all cases, by providing for the issue of permits whose effect is to create exemptions from their effect. As noted above, the power to grant permits is broad. It is inconsistent with any suggestion that regs 14 and 15 were intended to operate completely or not at all.

65 Thirdly, there is an additional difficulty if the impugned law “can be reduced to validity by adopting any one or more of a number of several possible limitations”. The problem in such a case is not a legislative intention against reading down; it is the limits of the judicial function. It is not appropriate for the Court to choose for itself between two or more possible ways of limiting the operation of a law, as this would involve performing a legislative function. Thus, “if, in a case of that kind, ‘no reason based upon the law itself can be stated for selecting one limitation rather than another, the law should be held to be invalid’” (quoting Pidoto at 111). (This consideration covers the applicant’s third and fourth arguments against reading down, which are closely related.)

66 The applicant’s submissions emphasised this limitation. It was said that the reference to “purpose” in the Minister’s submissions introduced a controlling factor that had no basis in the legislation; however, this point fell away when it was confirmed that the Minister was not invoking any person’s subjective purpose as a limiting factor. The applicant nevertheless maintained that carving out things done for the purpose of challenging purported exercises of power under the Act was essentially a legislative choice, not based on anything in the language of the Regulations, which the Court was being asked to make.

67 The majority in the Industrial Relations Act case also said that, “where a law is intended to operate in an area where Parliament’s legislative power is subject to a clear limitation, it can be read as subject to that limitation” (at 502-503). Their Honours went on to hold that the section under consideration, which provided in completely general terms that the legislation bound the Crown in right of each of the States, could be read down so as not to infringe the implied limitation on power established earlier in Re Australian Education Union; Ex parte Victoria (1995) 184 CLR 188; that is,

as binding the States to the extent that the provisions of the Act do not prevent them from determining the number of persons they wish to employ, the term of their appointment, the number and identity of those they wish to dismiss on redundancy grounds and the terms and conditions of those employed at the higher levels of government.

68 The actual holding in the Industrial Relations Act case thus demonstrates that, in the case of a generally expressed provision, the constitutional limitation itself can supply the standard by which reading down is to be effected. General expressions (such as, in this case, “deal with”, “make available” and “use” in regs 14 and 15) can be read as referring to dealings that may validly be controlled or prohibited but not other dealings. To do so is to apply the constitutional limitation to the law, and does not involve choosing between equally effective modes of limitation. The entrenched jurisdiction under s 75(v), as outlined above, gives rise to a limitation on legislative power whose existence can be described as “clear” and whose boundaries are similarly well-understood to those of the limitation applied in the Industrial Relations Act case.

69 Pape v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2009] HCA 23; 238 CLR 1 at [247]-[251] (Gummow, Crennan and Bell JJ), which was relied on by the applicant, is an example of the different considerations that arise where, instead of giving general words a limited meaning, it is suggested that the impugned provision should be saved by inserting some qualifying words so as to create a different, valid, provision. Their Honours concluded at [251] that treating s 15A as permitting the introduction of a “foreign integer” would run the risk of construing it as “impermissibly entrusting legislative power to Ch III courts”.

70 The holding in the Industrial Relations Act case also illustrates that reading a provision down to accommodate a constitutional limitation is possible — and thus required — even if the boundaries of the limitation are imprecise or unsettled. Whether particular circumstances come within the legislation as read down may require detailed argument in future cases as those circumstances arise. Gageler J, as his Honour then was, made this point in Tajjour v New South Wales [2014] HCA 35; 254 CLR 508 at [171] (Tajjour):

That a severance clause operates only as a rule of construction, however, is no impediment to its application to read down a provision expressed in general words so as to have no application within an area in which legislative power is subject to a clear constitutional limitation. Such reading down can occur even if the constitutional limitation is incapable of precise definition, and even if an inquiry of fact is required to determine whether the constitutional limitation would or would not be engaged in so far as the law would apply to particular persons in particular circumstances. Where reading down can occur, the constructional imperative of a severance clause is that reading down must occur.

(Citations omitted.)

71 This paragraph was cited with apparent approval in Graham at [66] (Kiefel CJ, Bell, Gageler, Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ) in support of a conclusion that the word “court” must be read to exclude the High Court when exercising s 75(v) jurisdiction and this Court when exercising analogous statutory jurisdiction. Graham thus furnishes a further example, close to the circumstances of this case, of reading down of the kind contended for by the Minister.

72 The applicant’s fifth argument is not found in the Industrial Relations Act case, but draws on the more recent decision in BHP Group Ltd v Impiombato [2022] HCA 33; 96 ALJR 956 at [17] (Kiefel CJ and Gageler J). It is that a court should not read down a provision by inserting an exclusion that suffers from “inherent imprecision”. That language was used by Kiefel CJ and Gageler J, but in the context of an argument that the relevant provision should be given a particular construction consistently with the ordinary presumption that statutes are not intended to have extraterritorial effect. “Inherent imprecision” was one reason to reject the proposed reading down, but it is far from clear that it was the principal one. Their Honours also referred, in the same paragraph, to an aspect of the statutory scheme pointing strongly to an intention that the relevant class of persons could include persons overseas. In any event, this was not a case involving the “constructional imperative” (as Gageler J called it in Tajjour) of reading a statute down, if possible, to avoid invalidity. As the Industrial Relations Act case and his Honour’s reasons in Tajjour illustrate, some indeterminacy in the articulation of the relevant constitutional principle is not a barrier to reading down.

Conclusion

73 For these reasons, regs 14 and 15 are not to be understood to have applications that would subvert the exercise of jurisdiction under s 75(v) or s 39B(1). The Regulations are therefore not invalid by reason of inconsistency with the constitutional entrenchment of that jurisdiction.

74 This means, at least, that the Regulations do not prevent a person or entity who is the subject of a designation under reg 6 from being represented (including paying for relevant professional services) in order to challenge that designation, or other things purportedly done under the Act, in proceedings commenced under s 75(v) or s 39B(1). The scope of the relevant exclusion may go further than that. This does not need to be determined in the present case, as the actual application of regs 14 and 15 is not in issue.

Other proceedings under s 75(v)

75 Circumstances can be imagined in which a person or entity designated under the Regulations might be affected by a decision of an officer of the Commonwealth made under other legislation (or in the exercise of the non-statutory executive power) and seek to have that decision set aside in proceedings commenced under s 75(v). Regulations 14 and 15, if read according to their terms, would also make it extremely difficult if not practically impossible for those proceedings to be maintained. That would not have the obvious vice of making the designation decision self-insulating. However, there is much to be said for the view that a subversion of s 75(v) would nevertheless occur.

76 That question does not need to be pursued, in the light of the conclusion reached above concerning the construction of regs 14 and 15. Those provisions are inapplicable to the extent required in order to prevent subversion of the proper exercise of the jurisdiction in s 75(v) and its analogues.

77 It does not matter, for present purposes, that this conclusion leaves a wide field for argument in future cases concerning the scope of the constitutional limitation. It is useful to note what Gageler J said in this connection in Tajjour at [172]:

It is instructive in this respect to recall that severance clauses were routinely applied by this Court during the period between the Bank Nationalisation Case [(1948) 76 CLR 1] and Cole v Whitfield [(1988) 165 CLR 360], when the guarantee in s 92 of the Constitution that “trade, commerce, and intercourse among the States … shall be absolutely free” was understood to be infringed by a law which “burdened” trade, commerce or intercourse among the States in a manner which was not justified as “reasonable regulation”. Absent a severance clause, a provision of a law which had a distributive application to a range of persons, subject matters or circumstances was invalid in its entirety if the law imposed an unjustifiable burden on trade, commerce or intercourse among the States in any of those applications. The presence of a severance clause produced a markedly different result: such a provision was invalid only “in so far” as it “would apply” to burden conduct or transactions found to be the subject of trade, commerce or intercourse among the States within the meaning of s 92 of the Constitution. The imperative to read down the provision in the event of invalidity had the additional salutary consequence of removing the need for a court to consider hypothetical or speculative applications of the provision in order to determine the rights of the parties. Barwick CJ explained that consequence as follows:

“Where [a severance clause] is available, and the statute can be given a distributive operation, its commands or prohibitions will then be held inapplicable to the person whose inter-State trade would thus be impeded or burdened. Of course, the question of validity or applicability will only be dealt with at the instance of a person with a sufficient interest in the matter; and, in my opinion, in general, need only be dealt with to the extent necessary to dispose of the matter as far as the law affects that person.”

In a case where the particular conduct or transaction which the provision burdened was found not itself to be the subject of trade, commerce or intercourse among the States within the meaning of s 92 of the Constitution, the availability of severance meant that no further analysis was required in order to dismiss a challenge to the validity of the provision.

(Footnotes omitted.)

Federal jurisdiction

78 The applicant put a further and much broader argument relating to invalidity arising from Ch III. The argument, briefly stated, had two steps. First, the conferral of federal jurisdiction by s 75, and by statute as authorised by ss 76 and 77 of the Constitution, requires that the courts exercising that jurisdiction be able to do so effectively and fairly. Secondly, legislation which compromises that exercise of jurisdiction, including by preventing a party from using its resources to obtain legal representation, is invalid.

79 The applicant sought support for this argument in statements made by several Justices in APLA Ltd v Legal Services Commissioner (NSW) [2005] HCA 44; 224 CLR 322 (APLA). APLA involved a challenge, on several grounds, to a provision in a New South Wales statute that prevented lawyers from advertising services in relation to recovery of money for personal injury. It did not prevent communication with existing clients. One of the grounds advanced by the plaintiffs was that the law infringed the requirements of Ch III and the principle of the rule of law as given effect by the Constitution. This ground did not succeed.

80 Gleeson CJ and Heydon J said, at [30]:

The rule of law is one of the assumptions upon which the Constitution is based. It is an assumption upon which the Constitution depends for its efficacy. Chapter III of the Constitution, which confers and denies judicial power, in accordance with its express terms and its necessary implications, gives practical effect to that assumption. The effective exercise of judicial power, and the maintenance of the rule of law, depend upon the providing of professional legal services so that citizens may know their rights and obligations, and have the capacity to invoke judicial power. The regulations in question are not directed towards the providing by lawyers of services to their clients. They are directed towards the marketing of their services by lawyers to people who, by hypothesis, are not their clients.

(Footnotes omitted.)

81 McHugh J said at [84], [87]:

Communications between legal practitioner and client, between legal practitioners, and between judges and practitioners, are critical to the administration of justice in Australia. They make up part of the essential elements of judicial processes required under the Constitution, without which proceedings in federal jurisdiction would become a mockery of the judicial system contemplated by Ch III. And, without communications between legal practitioners and potential litigants, the number of actions brought in federal jurisdiction would be greatly reduced. It is impossible to accept therefore that Ch III raises no barrier to State legislation interfering with or impairing such communications. The argument of New South Wales and others appeared to accept that the States could not interfere with these communications. But they contended that the Regulation operated before any relationship of practitioner and client had formed and Ch III had been engaged.

…

In my opinion, the implications to be drawn from Ch III make it clear that the States have no power to interfere in federal jurisdiction by legislation that has the effect or the object of reducing litigation in that jurisdiction. For these reasons the Regulation cannot constitutionally apply to all advertisements that fall within its terms.

82 Gummow J said at [247]-[248]:

However, the effective exercise of the judicial power of the Commonwealth does not require an immunity of legal practitioners from legislative control (as exemplified in Pt 14) in promoting their availability to perform personal injury legal services. It is to be accepted that a law may not validly require or authorise the courts in which the judicial power of the Commonwealth is vested to exercise judicial power in a manner which is inconsistent with the essential character of a court or with the nature of judicial power. The extent to which this prohibition protects aspects of “due process” is a matter of debate. What is presently significant is that involved in these aspects of “due process” is the actual exercise of federal jurisdiction.

It is neither of the essential nature of a court nor an essential incident of the judicial process that lawyers advertise. Part 14 operates well in advance of the invocation of jurisdiction. It does not prevent prospective litigants from retaining lawyers, nor prevent lawyers or others from publishing information relating to personal injury legal services and the rights and benefits conferred by federal law.

83 Hayne J said at [390], [393]-[394]:

The implication alleged in this case concerns what is said to be a freedom to receive advice or information about the possible exercise of the judicial power of the Commonwealth; it is not an implication concerned with the invocation or exercise of that judicial power.

…

The plaintiffs point only to matters that may make the asserted freedom desirable. They point to no matter making it a necessary consequence of constitutional text or structure.

That is most easily demonstrated by pointing to what the impugned regulations do not do. The impugned regulations do not preclude the seeking of advice or information about whether to invoke the judicial power of the Commonwealth. They concern only a prior step of conveying information (which is either unsolicited or not addressed to any particular recipient) which may provoke a recipient to seek advice or information.

(Original emphasis.)

84 With the exception of McHugh J these statements are concerned with explaining what the impugned law did not do, and thus pointing to a constitutional issue that did not arise. They do not provide authority for a proposition that Ch III gives constitutional force to any general concept of the rule of law. Nor do they support the applicant’s argument that a law which compromises the exercise of federal jurisdiction, by impairing the procurement of legal advice and representation by a party or potential party to proceedings, is for that reason unconstitutional.

85 An argument in the broad terms put by the applicant (which is the only argument that can be canvassed, given the somewhat hypothetical nature of the point in the present proceeding) cannot be accepted. The following points should be noted in that regard.

(a) In Graham, the arguments for the plaintiff as to why the impugned provision was invalid included one relying on the proposition (drawn from Chu Kheng Lim v Minister for Immigration, Local Government and Ethnic Affairs (1992) 176 CLR 1 (Chu Kheng Lim)) that courts in which the judicial power of the Commonwealth is invested cannot be required to act inconsistently with the essential nature of a court (see 263 CLR 1 at 4-5). The majority evidently did not accept that argument. It held that the impugned provision could be read down so as to operate validly other than in proceedings under s 75(v) and its analogues (at [66]), and was on that basis valid.

(b) As noted earlier, s 75(v) stands in a special position among the heads of federal jurisdiction. That is so in two respects. One is the centrality, in the constitutional sense, of judicial review of the legality of things done by Commonwealth officers in purported exercise of their powers. The other is that the s 75(v) jurisdiction is conferred directly by the Constitution (and so cannot be abrogated) and brings with it a body of legal principle. While federal jurisdiction across the whole range of matters described in ss 75 and 76 has been part of Australia’s legal landscape since the enactment of the Judiciary Act in 1903, the existence of that jurisdiction (other than in s 75 matters) is not dictated by the Constitution. Thus, the federal jurisdiction exercised (for example) by the District Court of New South Wales in a contract case involving residents of different states can rightly be said not to be constitutionally entrenched. Federal jurisdiction may be (and in fact very often is) exercised by State courts, which as a general rule Parliament must take as it finds them (see, eg, Forge v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2006] HCA 44; 228 CLR 45 at [61] (Gummow, Hayne and Crennan JJ)). The fact that litigation (or potential litigation) is heard (or would be heard) in the exercise of federal jurisdiction is thus a problematic starting point for an implication, drawn from constitutional text or structure, protecting a person from the effect of financial sanctions on the ground that those sanctions inhibit the ability to obtain legal advice and representation.

86 These considerations do not deny that the principle drawn from Chu Kheng Lim (referred to above), that courts exercising federal jurisdiction cannot be required to act inconsistently with the essential character of a court, may have work to do in limiting the extent to which a litigant’s access to legal assistance can be foreclosed by statute. However, I do not accept the argument in the broad terms put by the applicant, and therefore do not accept that the Regulations are invalid in their application to the acquisition of legal services for the purpose of conducting litigation in federal jurisdiction.

87 In any event, the principles of construction discussed above are also an answer to this argument. The extent to which those principles require the general expressions in regs 14 and 15 to be confined in their denotation is directly related to the breadth of the relevant constitutional limitation. For reasons outlined above, the fact that the breadth of that limitation has not yet been fully articulated in the case law is not a barrier to accepting that the provisions can and must be read down to accommodate it. That full articulation is not necessary and would not be appropriate in this case, because the applicant does not claim that the operation of the Regulations in relation to him breaches any constitutional limit.

The implied freedom of political communication

88 The discussion in Wotton and Palmer, referred to above at [54], is also relevant to the frame of reference within which the issues concerning the implied freedom should be addressed. Wotton itself was a case concerning the implied freedom. For the reasons outlined above, the issue is best approached by way of the “composite hypothetical question” framed by GagelerJ in Palmer at [122]-[124]: whether, if the regulations had been enacted as primary legislation, they would have been compliant with the relevant constitutional limitation.

Burden on political communications

89 The parties agreed that the operation of regs 14 and 15 burdens the implied freedom, but differed as to how it does so. The nature and scope of that burden is relevant to whether it is “justified” (LibertyWorks Inc v Commonwealth [2021] HCA 18; 274 CLR 1 at [63] (Kiefel CJ, Keane and Gleeson JJ), [194] (Edelman J) (LibertyWorks)).

90 The applicant’s submissions focused on communications by lawyers. It was submitted that lawyers’ ability to communicate “meaningful advice or representations” concerning a designated person or entity was curtailed or eliminated, and that a lawyer could not communicate in written form to, or on behalf of, a designated person or entity. These submissions were based on the inhibitions, referred to briefly above, on lawyers being remunerated by a designated person or entity or having any dealings with their assets (including documents).

91 The applicant relied on Cunliffe v Commonwealth (1994) 182 CLR 272 (Cunliffe), where four members of the Court regarded laws regulating the provision of migration advice and assistance as placing a burden on political communication.

(a) Mason CJ observed that the freedom “necessarily extends to the working of the courts and tribunals which administer and enforce the laws of this country”, and hence that the “provision of advice and information, particularly by lawyers, to, and the receipt of that advice and information by, aliens in relation to matters and issues arising under the Act clearly falls within the potential scope of the freedom” (at 298-299).

(b) Deane J (with whom Gaudron J agreed on this point) noted that the provision of immigration assistance involved both communication between clients and advisers and representations to the relevant Minister, their staff and Department, and said that these activities “constitute communication and discussion about matters relating to the government of the Commonwealth, that is to say, political communication and discussion” (at 340-341).

(c) Toohey J (who ultimately held that the law did not place an undue restriction on the freedom) said that the freedom “must include the communication of information and the expression of opinions regarding matters that involve a minister of the Government” (at 380).

92 Of these formulations, it is only that of Mason CJ that contains any suggestion that communications involved in the presentation of arguments to a court are ipso facto political. What brought the provision of immigration advice and assistance within the scope of the freedom, in their Honours’ view, appears to be the direct connection between the relevant communications and the exercise of powers by an officer of the executive government.

93 Cunliffe therefore does not support a proposition that advancing a case to a court constitutes communication on government or political matters within the scope of the implied freedom, except possibly where the subject matter of the case is an exercise of power by an officer of the executive government of the Commonwealth, a State or Territory. So far as exercises of power by Commonwealth officers are concerned, there is a significant if not complete overlap with matters that come within the s 75(v) jurisdiction and its analogues, which, for reasons outlined above, are not caught by regs 14 and 15.

94 Further, their Honours did not speak with one voice. Mason CJ referred to advice or information passing between an adviser and an alien (who might or might not be one of the “people of the Commonwealth” referred to in s 24 of the Constitution) in relation to issues arising under the Migration Act. Deane J referred to that kind of communication and to representations made (on behalf of a client) to executive decision-makers. Toohey J referred in very general terms to communications in matters “regarding” a Minister. The only point of unanimity appears to be that communications between adviser and client, which concern a decision made (or to be made) by a Minister or other officer, are a form of political communication.

95 It should also be observed that, while this aspect of Cunliffe has not been revisited by the High Court, there was not majority support in that case for the view that the impugned law infringed the implied freedom. The statements referred to above sit somewhat uneasily with the explanation of the implied freedom and its foundations given in the unanimous judgment of the whole Court in Lange v Australian Broadcasting Commission (1997) 189 CLR 520 at 559-562. That explanation emphasises the importance of communications concerning “political or government matters” between electors and the elected representatives, between electors and candidates for election and between electors themselves to a system of representative government, and holds that “ss 7 and 24 and the related sections of the Constitution necessarily protect that freedom of communication between the people concerning political or government matters which enables the people to exercise a free and informed choice as electors” (at 560). The nature and foundation of the implied freedom was described in similar terms much more recently in Libertyworks at [44] (Kiefel CJ, Keane and Gleeson JJ). In the same case, referring to Cunliffe (but not to specific passages), Gageler J said (at [120]):

Conformably with the implied freedom’s centrally informing concern to protect the integrity of the processes of representative and responsible government, the permissible incidents of a scheme of registration directed to persons representing others in dealing with government can be expected to be more burdensome in practice than the permissible incidents of a scheme of registration directed to persons engaging in political communication with the public.

96 For these reasons, I do not think Cunliffe can be treated as authority that the making of representations to an executive decision-maker about an individual case (on one’s own behalf or on behalf of a client) is a form of political communication. Some communications in this class may be protected by a different principle (cf Cunliffe at 328 (Brennan J)), but that has not been raised here. However, statements by a majority of Justices in that case (which have not been disapproved) do support the view that discussions between an adviser and their client, which have as their subject matter actual or potential exercises of power by officers of the executive government, are a form of political communication. The operation of regs 14 and 15 with respect to a designated person or entity may be said to affect such communication, in that it makes it difficult if not impossible for the designated person or entity to pay for advice from a professional adviser. The restriction on an adviser dealing with the assets of a designated person or entity, including its documents, may also hamper such communications.

97 In addition, the Minister accepted that the Regulations burden the implied freedom in that they “prevent a designated person from hiring a lawyer (or any other person) to perform other activities which constitute communication on political topics, such as issuing of press releases, giving interviews or lobbying MPs”.

98 Of course, this identification of burdens on the implied freedom assumes that none of the effects of regs 14 and 15 have been mitigated by the grant of authorisations under reg 18. In fact, as things presently stand, the effect of the Regulations on the provision of legal services (and services ancillary thereto) is significantly reduced by the terms of the permit. It is therefore more accurate to describe the burden imposed on the implied freedom by the Regulations as making the ability to communicate freely with legal advisers, or obtain professional services for the purpose of engaging with the Australian public, contingent on a favourable exercise of discretion by the Minister.

99 Justification of a burden on the communications subject to the implied freedom depends on the relevant law having a legitimate purpose and being proportionate to the achievement of that purpose. The requirement of proportionality is satisfied if the law is “suitable, necessary and adequate in its balance”: LibertyWorks at [45]-[46] (Kiefel CJ, Keane and Gleeson JJ).

Legitimate purpose

100 The Minister submits, and the applicant does not appear to deny, that the Regulations serve a legitimate purpose. They allow the Australian government to pursue its foreign policy objectives by aiming sanctions at governments, individuals and entities who are considered to be responsible for or linked to matters of international concern. The “situations” referred to in the Replacement Explanatory Memorandum for the Autonomous Sanctions Bill 2010 (Cth) (the Bill for the Act) as matters to which sanctions might be directed were:

the grave repression of the human rights or democratic freedoms of a population by a government, or the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) or their means of delivery, or internal or international armed conflict.

101 To the extent that the legitimacy of objectives pursued by the executive government in the conduct of Australia’s foreign relations is a proper matter for determination by the courts (see, eg, Brodie v Singleton Shire Council [2001] HCA 29; 206 CLR 512 at [92] (Gaudron, McHugh and Gummow JJ) and XYZ v Commonwealth [2006] HCA 25; 227 CLR 532 at [135] (Kirby J)), I am satisfied that the imposition of sanctions on individuals and entities, directed at discouraging conduct of the kind referred to, is a legitimate objective. An alternative and perhaps more traditional understanding of the position is that, the conduct of foreign relations being a matter exclusively for the executive, the objective of facilitating the conduct of those relations by the executive is necessarily a legitimate one.

Proportionality

Suitability

102 Suitability entails a rational connection between the purpose of the statute in question and the measures that it adopts to achieve that purpose: LibertyWorks at [76]. The connection between the objective sought to be pursued by the Regulations and the measures that it adopts is manifest. No submission was made to the contrary.

Necessity

103 The issue of necessity involves consideration of whether there is an alternative measure available that is equally practicable but less restrictive of the freedom, and which is “obvious and compelling”: LibertyWorks at [78].

104 The applicant submits that the terms of a suitable alternative measure can be seen in the permit, with one section removed from it.

105 The permit authorises:

(a) “Class (a) Permit Holders” (being “Australian persons”) to make assets available to or for the benefit of a designated person or entity, or use or deal with (or facilitate the use or dealing with) controlled assets, “to the extent doing so is required to provide, to Class (b) or (c) Permit Holders, legal advice, legal representation, and Ancillary Services, in relation to matters arising under or related to Australian law”;

(b) “Class (b) Permit Holders” (being designated persons and entities) to use or deal with any assets that a Class (a) Permit Holder makes available to them (either directly or through a Class (d) Permit Holder), or use or deal with foreign assets which are “controlled assets”, “to the extent doing so is required to receive legal advice, legal representation, and Ancillary Services, in relation to matters arising under or related to Australian law”;

(c) “Class (c) Permit Holders” (being persons acting for or on behalf of designated persons or entities) to use or deal with any assets that a class (a) Permit Holder makes available to them (either directly or through a Class (d) Permit Holder, or use or deal with foreign assets which are “controlled assets”, “to the extent doing so is required to receive, in their capacity acting for, or on behalf of, a Class (b) Permit Holder, legal advice, legal representation, and Ancillary Services, in relation to matters arising under or related to Australian law”; and