FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

MSA 4x4 Accessories Pty Ltd v Clearview Towing Mirrors Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 24

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: | 24 JANUARY 2024 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to confer and provide to the chambers of Downes J an agreed form of order giving effect to the reasons for judgment and proposed directions as to the further conduct of this proceeding by 12.00 pm on 2 February 2024.

2. If the parties are unable to agree upon a form of order and proposed directions, the parties shall each provide their proposed draft of same to the chambers of Downes J by 12.00 pm on 6 February 2024 accompanied by any written submissions not exceeding three (3) pages.

3. The matter be listed for a case management hearing at 9.45 am on 7 February 2024.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[13] | |

[13] | |

[17] | |

[22] | |

[23] | |

[25] | |

[25] | |

[47] | |

[54] | |

[54] | |

[56] | |

[58] | |

[58] | |

[61] | |

[76] | |

[84] | |

[84] | |

[88] | |

[98] | |

[112] | |

[112] | |

[116] | |

[126] | |

[141] | |

[141] | |

[145] | |

[147] | |

[147] | |

[148] | |

[155] | |

[155] | |

[156] | |

[156] | |

[165] | |

[170] | |

[184] | |

[185] | |

[185] | |

[188] | |

[192] | |

[204] | |

[205] | |

[205] | |

[208] | |

[216] | |

[222] | |

[223] | |

[223] | |

[229] | |

[236] | |

[246] | |

7.5 Whether invention obvious in light of common general knowledge and Lutkus | [251] |

[255] | |

[261] | |

[270] | |

[276] | |

[277] | |

[277] | |

[282] | |

[285] | |

[293] | |

[307] | |

[307] | |

[309] | |

[309] | |

[317] | |

[331] | |

[333] | |

[336] | |

[337] | |

[337] | |

[342] | |

[342] | |

[345] | |

[346] | |

[352] | |

[362] | |

[367] | |

[374] | |

[383] | |

[383] | |

[387] | |

[387] | |

11.3.2.2 Whether representations were misleading or deceptive | [401] |

[403] | |

[404] | |

[405] |

DOWNES J:

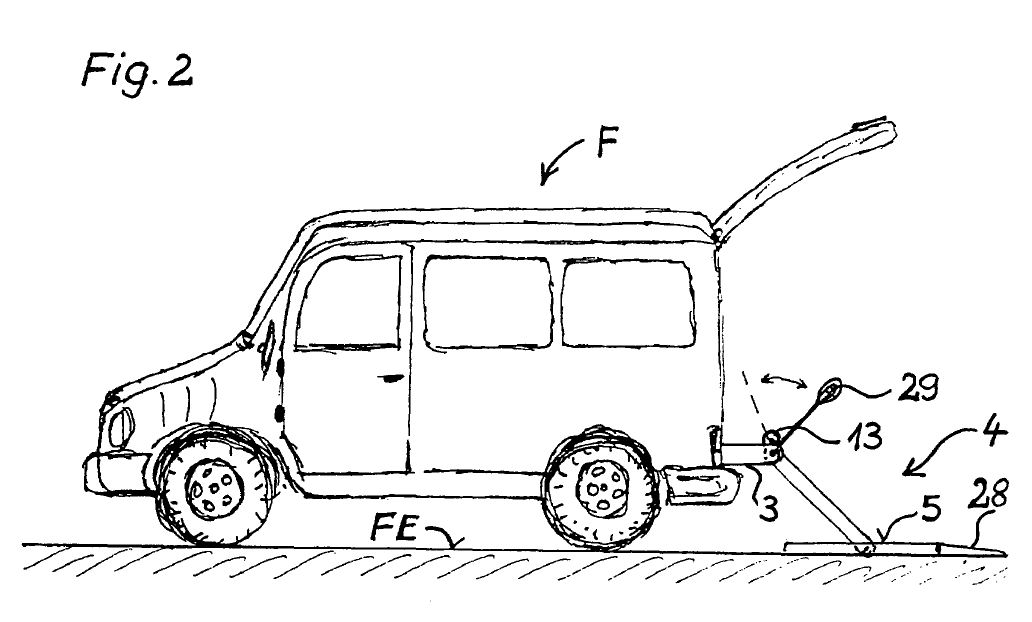

1 This proceeding concerns Australian Patent No. 2009245888, which is directed to an apparatus for storing or holding items, particularly in vehicles and more particularly, for storing accessories typically used by off-road enthusiasts and tradesmen. Mr Shane Miles is the owner of the Patent, and the first applicant (MSA) is the exclusive licensee. On the first day of trial, Mr Miles was removed as the second respondent and joined as the second applicant on certain conditions.

2 The Patent claims an earliest priority date of 22 October 2007 (priority date). The application for the Patent was a divisional application of Australian Standard Patent Application No. 2007229415 filed on 22 October 2007. The version of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) that applies to the Patent is that which appears in the compilation prepared on 27 March 2007.

3 Construction issues arise in relation to three terms in the claims of the Patent. These are: (a) “pivotally connected”, (b) “offset lever” and (c) “connected to” (disputed terms).

4 If MSA’s construction of “connected to” in the claims is accepted, then Clearview contends that the relevant claims are not fairly based because they travel beyond the invention disclosed in the Patent.

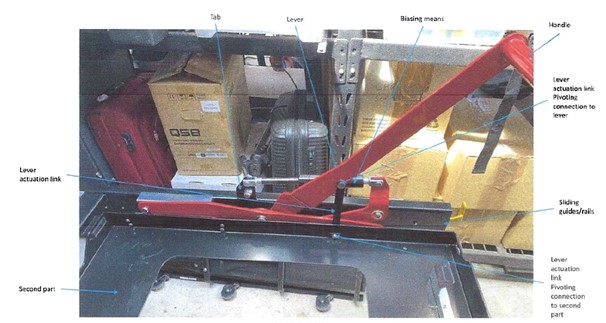

5 MSA alleges that the supply by the respondent/cross-claimant (Clearview) of its product infringes claims 1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 15 of the Patent (the relevant claims). That product is called the Clearview Easy Slide.

6 Clearview denies infringement and alleges that claims 1, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 15 are invalid for want of novelty, contending that:

(1) these claims lack novelty in light of United States Patent 6,019,567 (Lutkus);

(2) (if the construction of the disputed terms is found to be as posited by MSA), then these claims lack novelty in light of:

(a) German Patent Application Publication DE19606196A1 (Thomas);

(b) German Patent Application Publication DE19938727A1 (Dieter).

7 Clearview also contends that claims 1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 15 lack an inventive step in light of the common general knowledge, or the common general knowledge together with Lutkus.

8 Clearview also alleges that Mr Miles and MSA have made unjustified threats in contravention of s 128 of the Patents Act and engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law, being Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL).

9 For the reasons which follow, the claim for infringement has failed which has the consequence that the claim brought by MSA should be dismissed.

10 As to the cross-claim brought by Clearview, the attacks on the validity of the Patent have failed but I have accepted that MSA and Mr Miles made unjustified threats within the meaning of s 128 of the Patents Act in relation to a letter from their solicitors, and that MSA made an unjustified threat in contravention of that section in relation to an announcement. I have also accepted that MSA engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 18 of the ACL, and that Mr Miles was knowingly involved in such conduct. Declaratory and injunctive relief will be the subject of orders to be made shortly after these reasons are published and after conferral by the parties. However, by reason of an order of Greenwood J dated 5 March 2021, issues concerning the quantum of any damages award will require determination at a further hearing. The cross-claim should otherwise be dismissed.

11 I will order the parties to confer with a view to drafting a form of order giving effect to my findings and draft directions in relation to the further hearing.

12 Additionally, the parties should have leave to appeal and, if necessary, leave to cross-appeal.

2. WITNESSES CALLED BY THE PARTIES

13 Dr Bruce William Field is a mechanical engineer, consultant and retired academic in the field of mechanical engineering, a subject in which he has a PhD. Since before 1990, Dr Field has worked primarily as a full-time academic. Between this time and the priority date, his role also included teaching with some research work and consulting work. Dr Field affirmed four affidavits in the proceeding dated 17 November 2021, 23 March 2022, 6 May 2022 and 9 June 2022.

14 My general perception was that Dr Field’s evidence was heavily influenced by his academic experience, and by reliance on abstract and theoretical concepts. I expand on this further below.

15 Mr Michael Simonetti was (and remains) an expert in digital marketing and advertising as at the priority date. Mr Simonetti is the founder of AndMine, a digital agency assisting clients with online marketing and advertising. Mr Simonetti swore two affidavits dated 23 March 2022 and 12 May 2023.

16 Ms Suzanne Madar, solicitor at King & Wood Mallesons, affirmed three affidavits in this proceeding, dated 17 November 2021, 22 March 2022 and 5 May 2023. Ms Madar was not cross-examined.

2.2 Witnesses called by Clearview

17 Mr William Hunter is a consulting engineer with Masters level qualifications in mechanical engineering. Mr Hunter has more than 30 years of experience in developing and designing industrial products. Mr Hunter affirmed three affidavits in the proceeding dated 17 November 2021, 22 March 2022 and 13 May 2022.

18 Mr Rodney Cruise is a patent attorney, with more than 33 years of experience in patent searching. As at the priority date, and for at least seven years prior to 2007, the majority of Mr Cruise’s work related to patent and literature searching. Mr Cruise affirmed three affidavits in the proceeding dated 17 November 2021, 13 May 2022 and 9 May 2023.

19 Mr Graeme Chapman, Project Engineer for Clearview, affirmed one affidavit dated 19 November 2021, regarding the development of the Clearview Easy Slide from the Black Widow Easy Slide. Mr Chapman was not cross-examined.

20 Ms Robynne Sanders, solicitor at DLA Piper, affirmed three affidavits dated 17 November 2021, 8 May 2023 and 9 May 2023. Ms Sanders was not cross-examined.

21 Mr Kenneth Stewart is a German to English translator who affirmed one affidavit dated 12 October 2021 annexing his translation of Dieter and Thomas from the original German documents. Mr Stewart was not cross-examined and MSA did not dispute the accuracy of these translations.

22 Dr Field and Mr Hunter prepared a joint expert report which was filed on 9 March 2023 (JER).

23 The person skilled in the art is the hypothetical person to whom the patent specification is addressed and who, generally speaking, works in the art or science with which the invention is connected: see, e.g., Root Quality Pty Ltd v Root Control Technologies Pty Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 225; [2000] FCA 980 (Finkelstein J) at [70]–[71]. It is not a reference to a specific person but is a legal construct or notional person who may have an interest in using the products or methods of the invention, making the products of the invention, or making products used to carry out the methods of the invention either alone or in collaboration with others having such an interest: Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Konami Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 114 IPR 28; [2015] FCA 735 (Nicholas J) at [26]; Hanwha Solutions Corporation v REC Solar Pte Ltd [2023] FCA 1017 (Burley J) at [86].

24 In this case, the person skilled in the art is someone with expertise in and knowledge of mechanical engineering. There was no dispute in this case that both experts had such expertise.

25 The title of the Patent is “Apparatus for Storing or Holding Items”.

26 The Field of the Invention states that “[t]he present invention relates to an apparatus for storing or holding one or more items.”

27 The Background to the Invention describes known storage systems used in four-wheel drives and commercial vehicles, such as sliding drawers or other sliding arrangements, as follows:

Four-wheel drive and off-road enthusiasts frequently undertake lengthy journeys into wilderness areas. In order to provide for the necessities of life during such journeys, it is common for four [sic] drives and off-road enthusiasts to fit their vehicles with appropriate storage systems and refrigerators. Tradesmen often have to carry many tools in their vehicles and frequently use large tool boxes.

One common storage system fitted to four wheel drive and commercial vehicles includes sliding drawers mounted to the luggage compartment of four wheel drive vehicles. The sliding drawers typically have a common top surface that provides a further surface for storing further items. It will be understood that the top surface is positioned at a height above the height of the floor of the luggage compartment of the vehicle.

Refrigerators and tool boxes that are used by four-wheel-drive and off-road enthusiasts (which are typically called "car refrigerators" or “car fridges”) or tradesmen typically have a lid that pivots upwardly about a top edge thereof. In order to provide access to such refrigerators or tool boxes, they may be mounted on a sliding arrangement that itself is mounted to the common top surface of the storage drawers. In order to store the fridge or tool box, the sliding arrangement is slid into the vehicle such that the refrigerator or tool box sits over the top surface of the storage drawers. In order to access the refrigerator or tool box, it is slid outwardly so that the sliding arrangement is extended and the refrigerator or tool box extends out of the luggage compartment of the vehicle.

28 It also states that, throughout the specification, the term “comprising” and its grammatical equivalents shall be taken to have any inclusive meaning unless the context of use clearly indicates otherwise.

29 The specification then provides a Brief Description of the Invention, and states that it is an object of the present invention to provide an apparatus that provides an improvement over the prior art devices mentioned above, or at least provides a commercial alternative.

30 The specification goes on to describe aspects of the invention commencing at page 2 line 5. It states that:

In a first aspect, the present invention provides an apparatus for storing one or more items, the apparatus comprising a first part adapted to be mounted to a surface or a wall and a second part mounted to the first part, the second part adapted to store or hold one or more items, wherein the second part is movable relative to the first part such that the second part can be moved from a storage position to a first access position at which the second part is at one level, the second part being movable from the first access position to a second access position, the second access position being located at a lower level than the first access position.

31 The specification then progressively informs the reader of the componentry to be used in performing the invention.

32 For example, on page 2, the specification states:

In one embodiment, the second part slidably moves from the storage position to the first access position (and vice versa). When in the storage position, the second part may at least partially overlie the first part. In some embodiments, when in the storage position, the second part may be positioned at essentially the same level as the first part.

33 The concepts of “sliding mechanism” and “linkage arrangement” or “linkage mechanism” are introduced from page 2 line 17 as follows:

In some embodiments, the apparatus is provided with a sliding mechanism that can slidably move relative to the first part, the apparatus further including a linkage arrangement mounted to the sliding mechanism, the linkage mechanism mounting the second part to the sliding mechanism, the linkage mechanism operative to move the second part between the first access position and the second access position.

34 On page 2 commencing at line 23, the specification identifies that the first part, in one embodiment, may comprise opposed rails or sliding guides which are mounted to a surface or wall. One alternative which is stated is that “the opposed rails or sliding guides may be provided with attachment means for mounting to a surface. For example, the attachment means may comprise a strip of adhesive or adhesive tape”.

35 On page 3 commencing at line 3, by reference to another embodiment, it is stated that:

The second part may comprise a support frame. Alternatively, the second part may comprise a platform. In either case, the second part is adapted to support one or more items are thereon. For example, the second part may support a small refrigerator, such as a refrigerator commonly used in four-wheel-drive vehicles. It will be appreciated that the second part may provide support for a number of other items and that the present invention should not be considered to be limited solely to use in supporting small refrigerators.

36 The specification also refers to “actuating means”, “offset lever”, “biasing means” and “pivotally connected”. Such references appear in the specification commencing at page 3 line 10 as follows:

The apparatus may further comprise actuating means for moving the second part from the first access position to the second access position. The actuating means may comprise, for example, an offset lever connected to one or more linkages. Moving the lever, such as by rotating the lever upwardly or downwardly, causes the linkages to rotate and causes the second part to move between the first and second access positions. A biasing means, such as a spring, hydraulic cylinder, gas strut or the like, may be used to assist in moving the second part between the first access position and the second access position. A handle may be pivotally connected to the offset lever to facilitate movement of the offset lever.

Preferably movement from the first access position to the second access position comprises simultaneous vertical and horizontal movement. Even more preferably the second part extends further from the first part as it is lowered. Preferably the one or more items are maintained substantially level (i.e. not tilted or angled) when being moved from the storage position to the first access position, and also from the first access position to the second access position. The second part, or at least a portion of the second part, may by [sic] extendable in the second access position.

Preferably the second part is mounted to a mechanism that is adapted to lower the second part from the first access position to the second access position. The mechanism preferably moves/slides with the second part from the storage position to the first access position, and is actuated to move the second part from the first access position to the second access position…

37 Reference is made to the storage position commencing at page 4 line 3 as follows:

In the storage position the first part, second part, and mechanism are preferably adjacent and, even more preferably generally flat. If the second part is holding one or more items, it preferably holds those items from below, or at least at or near a lower region of the item.

38 A second embodiment is described at page 4 of the specification commencing at line 12:

In a second embodiment, the present invention provides an apparatus for storing a car fridge or a tool box in or on a vehicle, the apparatus comprising a base or frame adapted to be mounted in or on the vehicle, a sliding arrangement fixed to the base or frame, the sliding arrangement being slidably movable between a retracted position and an extended position, and a support platform being mounted to the sliding arrangement wherein the support platform is mounted to the sliding arrangement such that when the sliding arrangement is in the extended position, the support platform is movable between a first height that is at essentially the same height as the sliding arrangement and a second height that is lower than a height of the sliding arrangement. Preferably, the second height is lower than the level of the base or frame.

In another aspect, the present invention provides a storage device in which the first access position is lower than the second access position. This provides for easier access in situations where the first part is mounted at a low level.

There may be provided an apparatus for storing a car fridge or a tool box in a vehicle, the apparatus comprising a base or frame mounted in the vehicle, a sliding arrangement fixed to the base or frame, the sliding arrangement being slidably movable between a retracted position and an extended position, and a support platform being mounted to the sliding arrangement wherein the support platform is mounted to the sliding arrangement such that when the sliding arrangement is in the extended position, the support platform is movable between a first height that is at essentially the same height as the sliding arrangement and a second height that is higher than a height of the sliding arrangement.

In a further aspect, the present invention provides an apparatus for storing one or more items, the apparatus comprising a first part adapted to be mounted to a surface or a wall and a second part mounted to the first part, the second part adapted to store or hold one or more items, wherein the second part is movable relative to the first part such that the second part can be moved from a storage position to a first access position at which the second part is at one level, the second part being movable from the first access position to a second access position, the second access position being located at a higher level than the first access position.

39 On page 5, lines 11–25, there is described “another aspect” of the invention, in identical terms to claim 1 (being the first independent claim).

40 The specification then contains a further consistory clause commencing on page 5 at line 27, which is in the same terms as claim 15 (being the second independent claim):

In another aspect, the present invention provides an apparatus for storing a car fridge or a tool box in or on a vehicle, the apparatus comprising a base or frame adapted to be mounted in or on the vehicle, a sliding arrangement fixed to the base or frame, the sliding arrangement being slidably movable between a retracted position and an extended position, and a support platform being mounted to the sliding arrangement wherein the support platform is mounted to the sliding arrangement by a linkage arrangement including at least one arm pivotally connected at or near one end to the sliding mechanism and pivotally connected at or near another end to the support platform, and an offset lever connected to at least one of the at least one arm such that when the sliding arrangement is in the extended position, the support platform is movable between a first height that is at essentially the same height as the sliding arrangement and a second height that is lower than a height of the sliding arrangement by moving the offset lever.

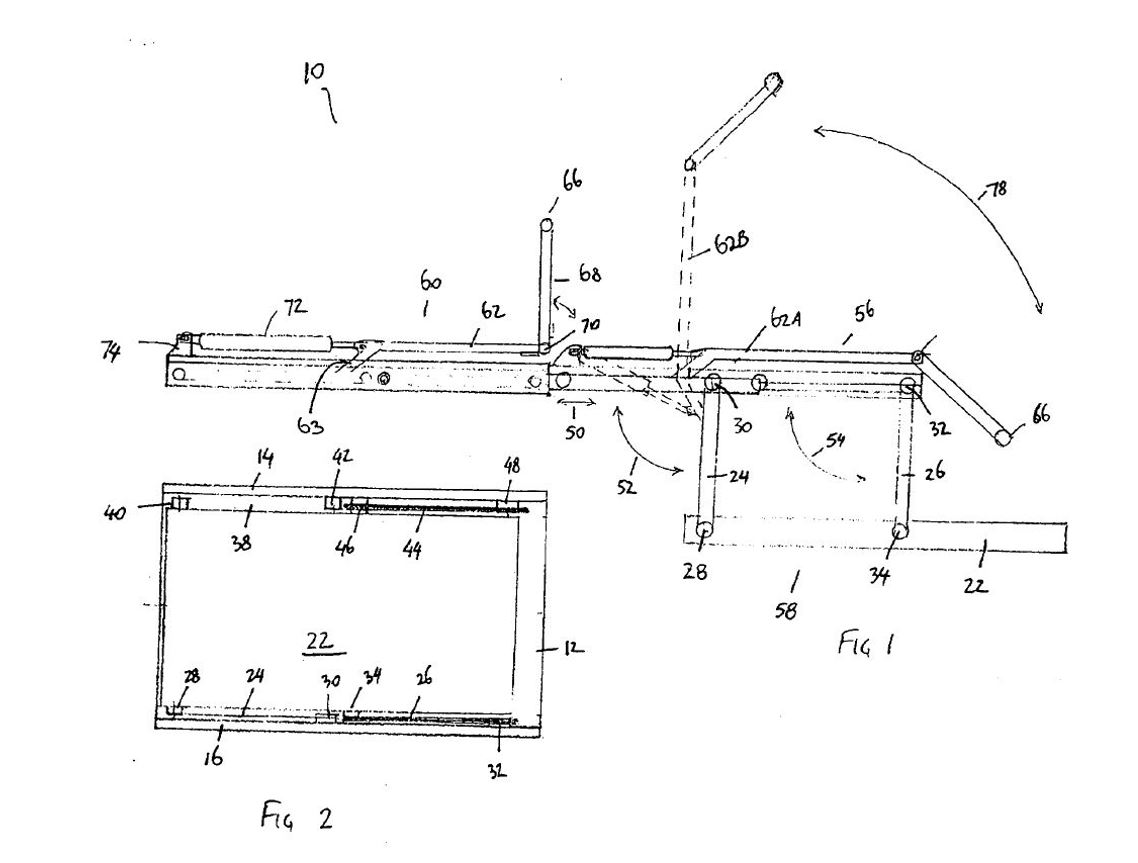

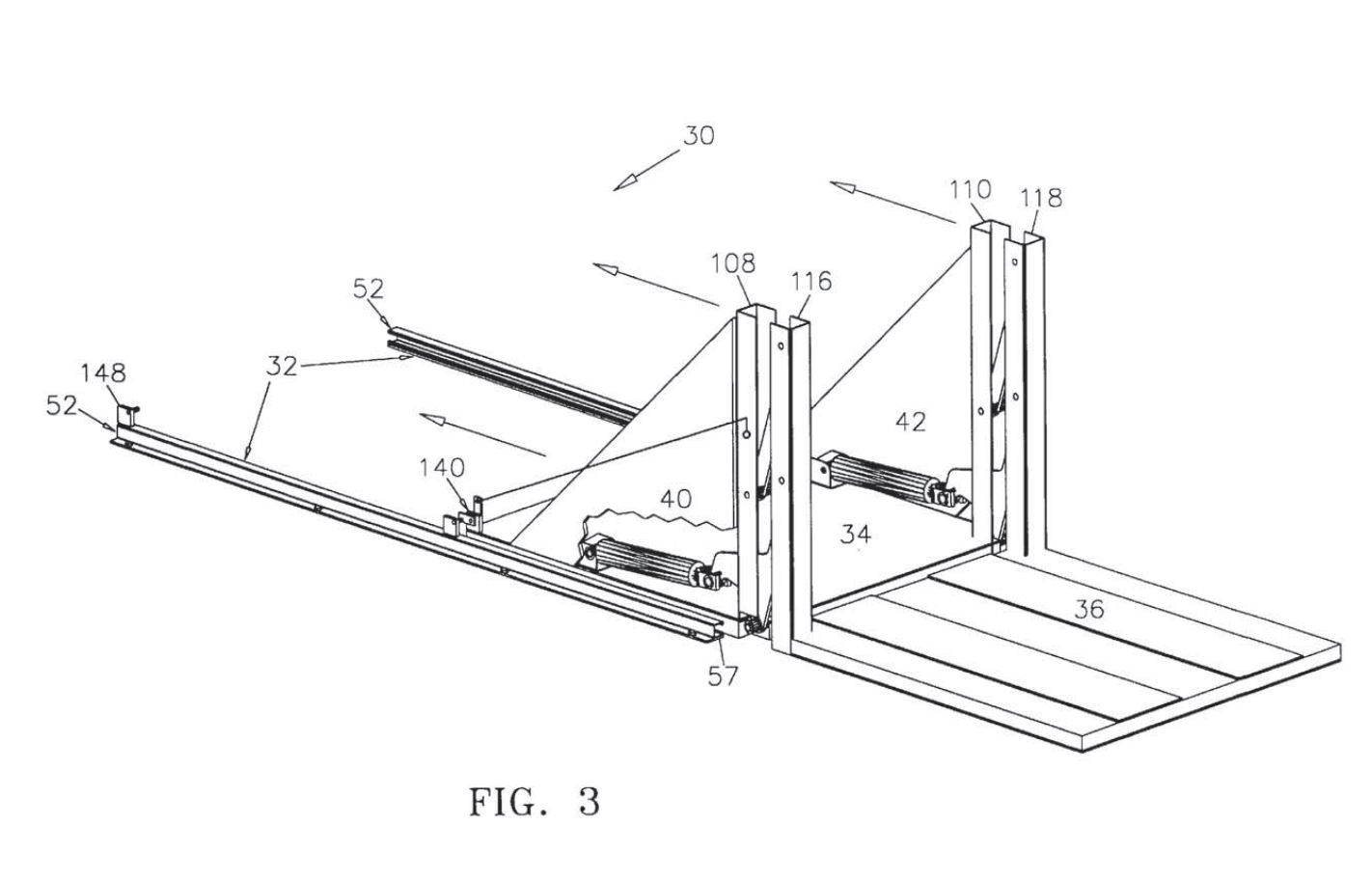

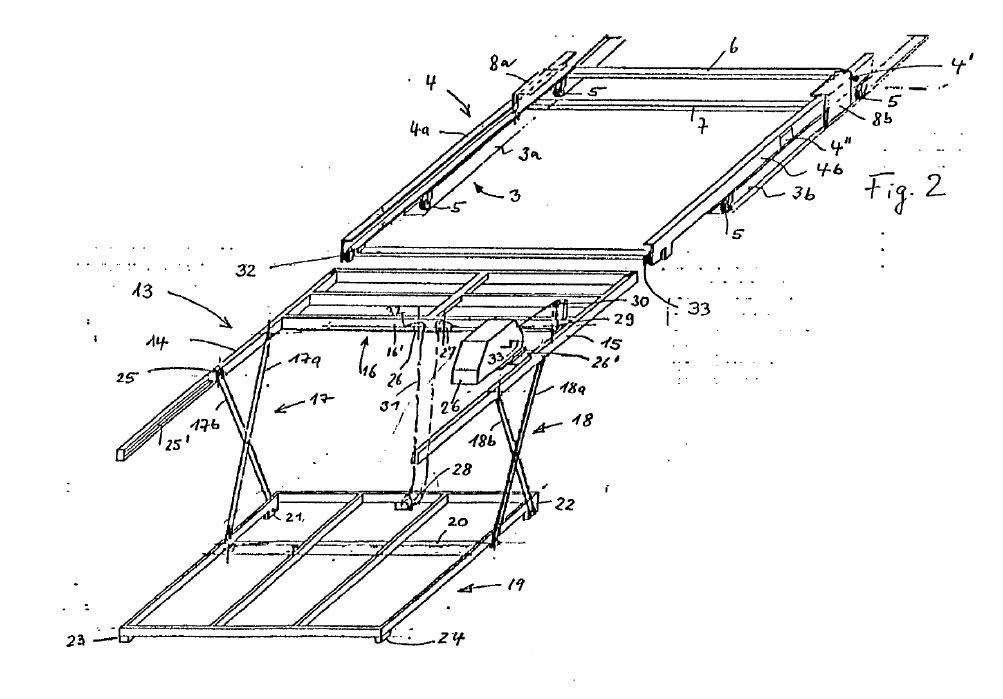

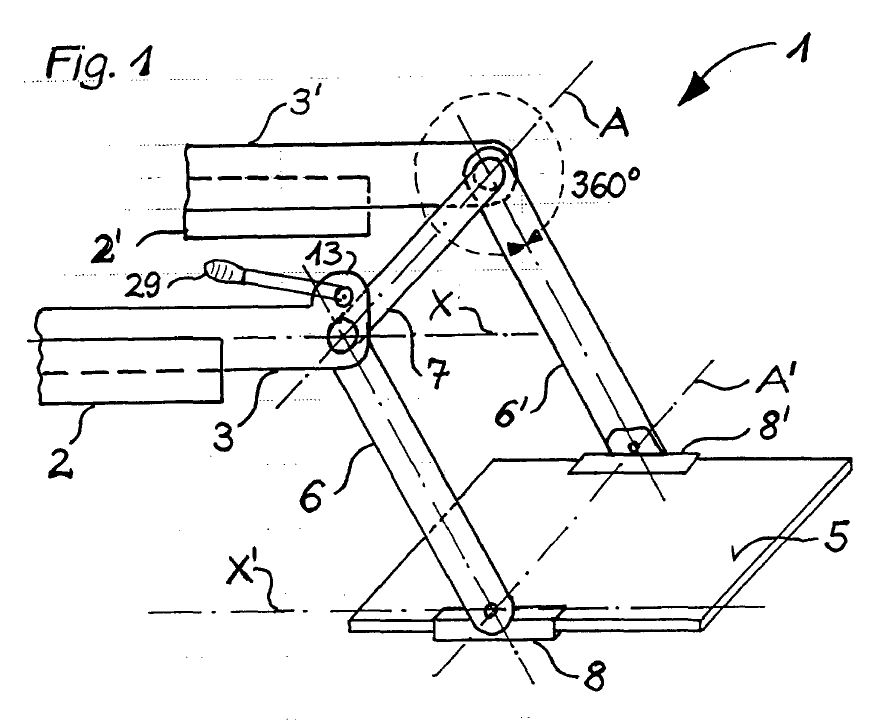

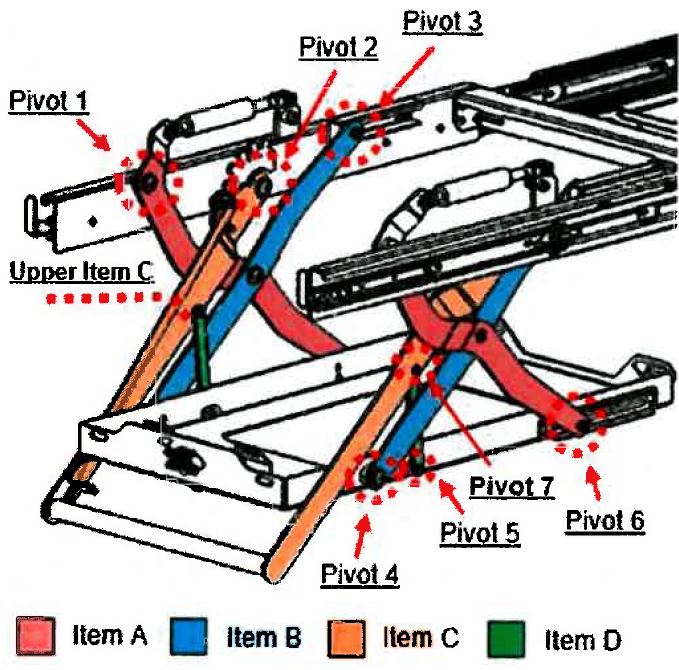

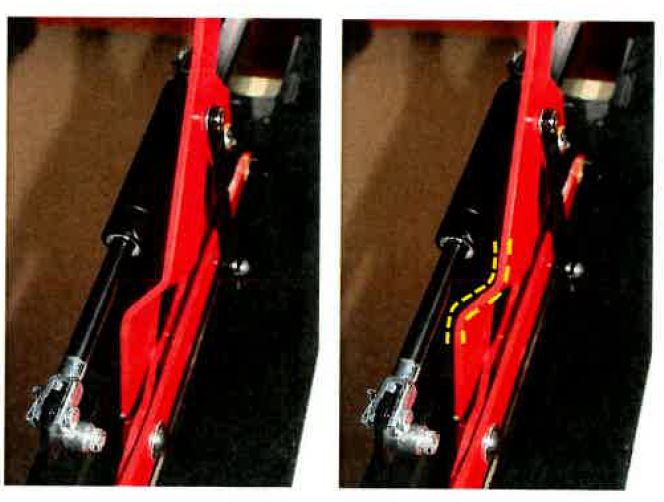

41 There is then a brief description of the drawings, which includes five drawings of the same embodiment of the invention (Figures 1 to 5). Figures 1 and 2 are reproduced below:

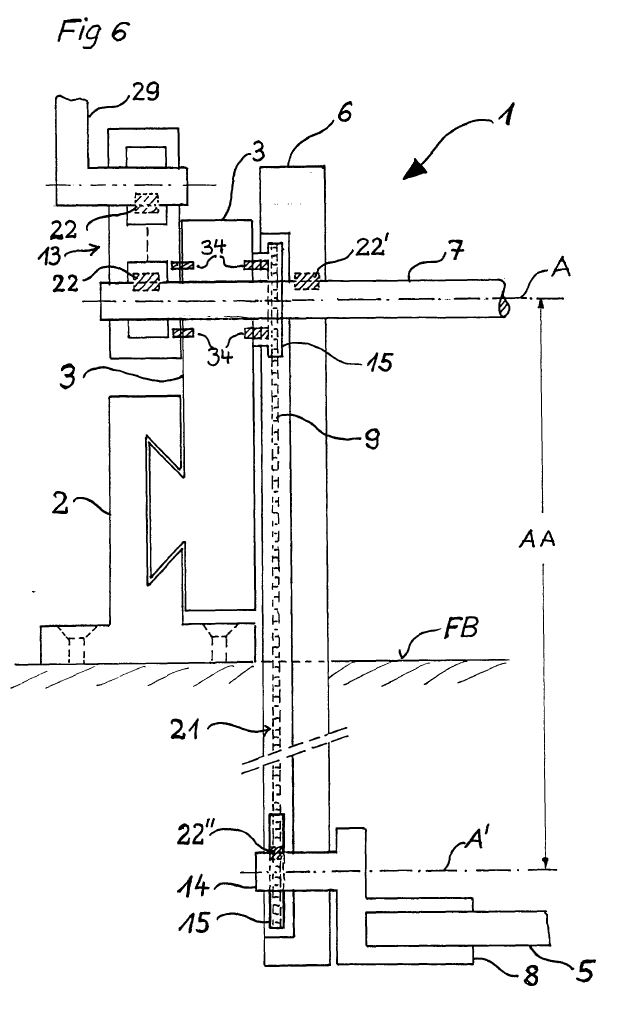

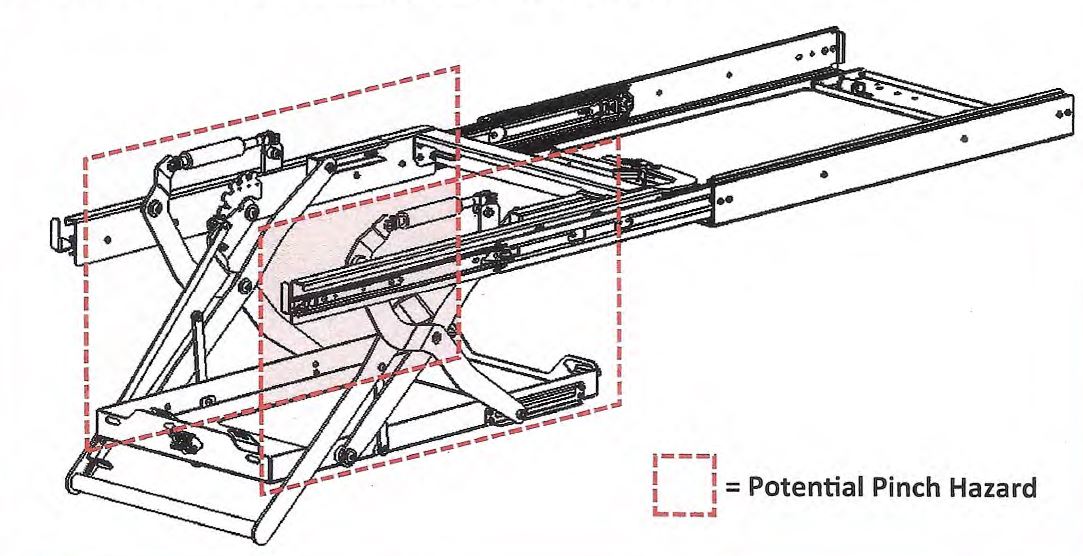

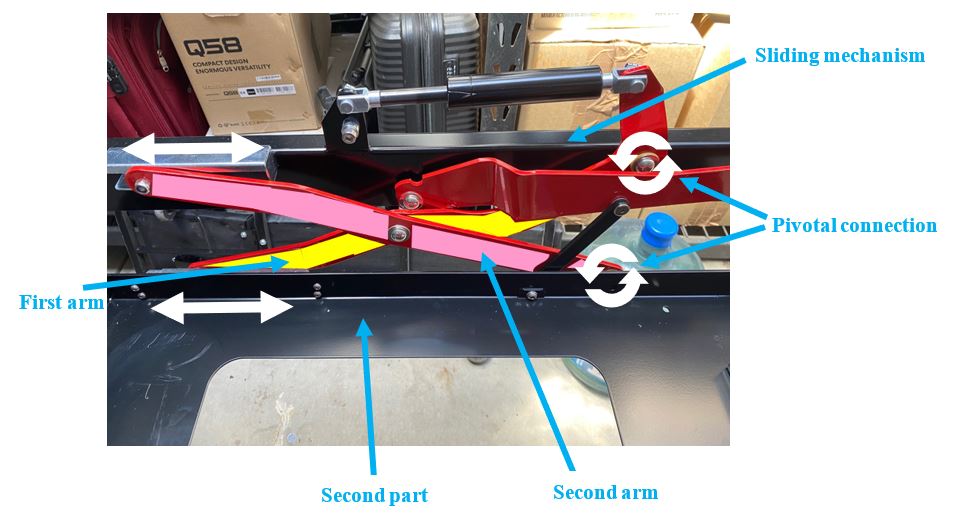

42 Figures 6 to 10 are photographs of the apparatus shown in Figure 1 moving from the first access position to the second access position.

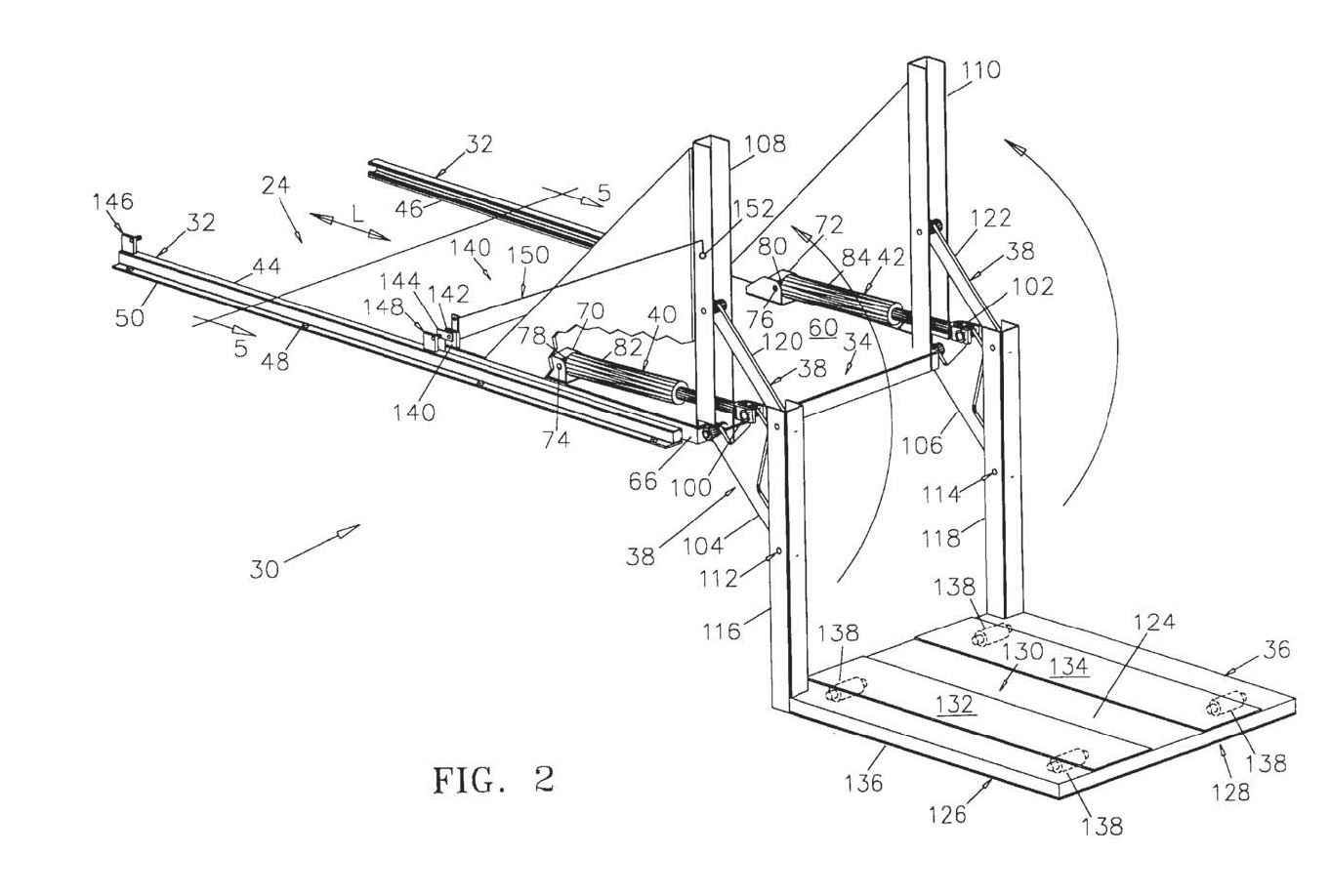

43 At page 8, lines 10–25, the linkage arrangement of the invention is described as follows:

As shown in figures 1 to 5, the support platform 22 is mounted to the sliding arrangement by use of two pivoted linkage arms on either side of the support platform. For example, referring to figure 1, linkage arms 24, 26 are mounted to one side of the platform. Similarly, two other linkage arms are mounted to the other side of the support platform 22. As best shown in figure 5, linkage arm 24 is pivotally mounted as one end to a pin 28. Pin 28, in turn, is mounted to the support platform 22. The linkage arm 24 is pivotally mounted at its other end to a pin 30. Pin 30 is, in turn, mounted to the innermost sliding member 20.

The other linkage arms are mounted to the platform and sliding arrangement in a similar fashion. For example, as shown in figure 1, linkage arm 26 is mounted to the sliding arrangement via pin 32. The other end of linkage 26 is pivotally mounted to the support frame 22 by pin 34. Similarly, on the other side of support platform 22, linkage arm 38 is pivotally mounted at one end to the platform by pin 40 and is pivotally mounted at the other end to the sliding arrangement by pin 42. Linkage arm 44 is pivotally mounted at one end to platform [sic] by pin 46 and pivotally mounted at the other end to the sliding arrangement by pin 48.

44 At page 9, lines 4–23, there is a description of how the platform is moved between the first and second access position in the following terms:

…the apparatus is further provided with an actuating means 60. The actuating means 60 comprises an offset lever 62 having an offset portion 63 that is mounted to linkage arm 24. This may be achieved, for example, by welding the end of offset portion 63 to the linkage arm 24. A handle 66 is connected via pivoting arm 68 to the offset lever 62. A pin 70 is used to connect the pivoting arm 68 to the offset lever 62. A gas strut 72 is also provided. Gas strut 72 is connected at one end via bracket 74 to the sliding mechanism to which the platform 22 is connected. The other end of gas strut 72 is connected to the offset lever 62. As is shown in figure 1, as the platform 22 moves between the first access position 56 and the second access position 58, the gas strut extends to thereby ease lowering and raising of the platform 22.

…

In order to lower the platform 22 from the first access position 56 to the second access position 58, the handle 66 is grasped by a user and swung upwardly. This causes the offset lever 62 to move from the position 62A (see figure 1) to the position 62B (shown in figure 1 in dotted outline). As the end of the offset portion 63 of offset lever 62 is mounted to the linkage arm 24, moving the offset lever as described above (and as shown by reference to arrow 78) causes the linkage arm 24 to pivot downwardly. This also causes the linkage arm 26 to pivot downwardly. The support platform also moved downwardly.

45 At page 11, lines 1–9, it is stated that:

The present invention provides an apparatus that allows for storage of one or more items in the storage position. For ease of access, the apparatus allows the second part to be moved to a first access position. The first access position is normally located outwardly from the storage position so that easier access is provided. The first access position is normally at essentially the same vertical height as the storage position. If the first access position is inconveniently or uncomfortably high, the second part of the apparatus can be moved from the first access position to the second access position. As the second access position is located at a lower level than the first access position, easier access may be obtained.

46 At page 11, lines 10 to 19, the specification states that the invention may be susceptible to variations and modifications other than those specifically described and then provides several examples of modifications but does not suggest any modification to the linkage arrangement, the arrangement of the offset lever, or the way in which the offset lever is positioned and interacts with other components of the apparatus. This passage includes the statement that, “Although a support platform is shown in the embodiments…, it will be appreciated that an item to be stored or held by the apparatus may be directly connected to the linkage arms”.

47 The Patent concludes with 20 claims, of which the relevant claims are asserted to be infringed.

48 The relevant claims are set out below, with claims 1, 5, 6 and 15 broken down into their integers for convenience.

49 As to Claim 1:

50 As to Claim 5:

|

|

|

|

51 As to Claim 6:

|

|

|

|

|

|

52 Claims 7 to 12 are set out below:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

53 As to Claim 15:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

54 As already observed, the disputed terms appear in claims 1 and 15, and are: (a) “pivotally connected”, (b) “offset lever” and (c) “offset lever connected to at least one of the at least one or more arms” (claim 1) or “offset lever connected to at least one of the at least one arm” (claim 15) (emphasis added).

55 A further issue arose following the preparation of the JER in connection with the construction of integers 1.6 and 1.7 which, in combination, state that “one or more arms pivotally connected at or near one end to the sliding mechanism and pivotally connected at or near another end to the second part”. That issue will also be addressed.

5.2 Principles on construction

56 The principles applicable to patent claim construction are well-settled and were not in dispute. In Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd (2005) 65 IPR 86; [2005] FCAFC 90 (Hill, Finn and Gyles JJ) at [67], the Full Court summarised the principles for the construction of patents as follows:

(1) the proper construction of a patent specification is a matter of law: Décor Corporation Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc (1988) 13 IPR 385 (Sheppard J) at page 400;

(2) a patent specification should be given a purposive, not a purely literal, construction: Flexible Steel Lacing Company v Beltreco Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 331; [2000] FCA 890 (Hely J) at [81]; and it is not to be read in the abstract but is to be construed in the light of the common general knowledge and the art before the priority date: Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Limited v Arico Trading International Pty Limited (2001) 207 CLR 1; [2001] HCA 8 (Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ) at [24];

(3) the words used in a specification are to be given the meaning which a normal person skilled in the art would attach to them, having regard to his or her own general knowledge and to what is disclosed in the body of the specification: Décor Corporation at page 391;

(4) while the claims are to be construed in the context of the specification as a whole, it is not legitimate to narrow or expand the boundaries of monopoly as fixed by the words of a claim by adding to those words glosses drawn from other parts of the specification, although terms in the claim which are unclear may be defined by reference to the body of the specification: Kimberly-Clark at [15]; Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 (Dixon CJ, Kitto and Windeyer JJ) at page 610;

(5) the body of a specification cannot be used to change a clear claim for one subject matter into a claim for another and different subject matter: Electric & Musical Industries Ltd v Lissen Ltd [1938] 4 All ER 221; (1939) 56 RPC 23 at page 39;

(6) experts can give evidence on the meaning which those skilled in the art would give to technical or scientific terms and phrases and on unusual or special meanings to be given by skilled addressees to words which might otherwise bear their ordinary meaning: Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd v Koukourou & Partners Pty Ltd (1994) 30 IPR 479 (Gummow J) at pages 485–486;

(7) the Court is to place itself in the position of some person acquainted with the surrounding circumstances as to the state of the art and manufacture at the time: Kimberly-Clark at [24]; and

(8) it is for the Court, not for any witness however expert, to construe the specification: Sartas No 1 at pages 485–486.

57 This decision, and these principles, were cited with approval in Reflex Instruments Asia Pacific Pty Ltd v Globaltech Corporation Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 158 (Moshinsky, Burley and Kennett JJ) at [75].

5.3 Issue 1: meaning of “pivotally connected”

5.3.1 The competing contentions

58 The first disputed term appears in integer 1.6 and integer 15.7, namely “one or more arms pivotally connected at or near one end to the sliding mechanism” (emphasis added). It also appears in integers 1.7 and 15.8.

59 MSA submits that a pivotal connection is one in which the connection between components is rotational so as to allow one component to rotate with respect to the other around a point or axis, and that the point of rotation does not need to be fixed.

60 Clearview submits that “pivotally connected” refers to a connection between two components that permits only rotational movement of the components relative to one another.

61 The expert evidence indicated that the term “pivotally connected” has (and had as at the priority date) a technical meaning for skilled addressees. It is therefore necessary to have regard to this technical meaning: see Product Management Group Pty Ltd v Blue Gentian LLC (2015) 240 FCR 85; [2015] FCAFC 179 (Kenny and Beach JJ) at [36].

62 The experts were asked by senior counsel for MSA to explain their understanding of this term during the concurrent evidence session.

63 Dr Field’s response was as follows:

DR FIELD: Pivotally connected, to me, means connected as in not able to come apart in a way that has a rotation that is either a pivot or a rotation that could be or is equivalent to having a pivot. Rotations can occur around a pivot, such as the hinge pin in an ordinary door hinge. But rotations can occur because of the way mechanisms are arranged to cause a rotation or to allow a rotation about a point which isn’t an actual object. For example, a train going around a curve is pivotally connected to the ground, even though there is no pivot in the middle of the curve. It’s - - -

HER HONOUR: Sorry. It’s connected to the ground? Is that what you said?

DR FIELD: Yes. Pivoted relative to the ground.

HER HONOUR: Relative.

DR FIELD: Everything is relative. Kitchen cabinet doors open and shut without having a hinge pin. They have a mechanism which makes it pivot, but not on a pin or on an axle. So that’s what I mean by pivotally connected. Literally, with a pin, an axle, or as if on a pin as created by the mechanism design itself.

64 Mr Hunter’s response was as follows:

MR HUNTER: … So, in my view, pivotally connected simply means that, at the connection point, one component can only rotate with respect to the other component. So only rotate. And that’s consistent with the way in which the term “pivotally connected” is used in patent specification. In each and every instance, the way in which pivotally connected is described is that a pivot occurs at a pinned connection, and that pinned connection is a location at which only rotation is possible. So, for example, page 8, lines 15 to 17 of the patent:

The linkage arm 24 is pivotally mounted at its other end to pin 30. Pin 30 is, in turn, mounted to the inner most lighting member.

So that’s an example of that type of connection.

(Emphasis original.)

65 While Mr Hunter accepted that there are other ways of creating pivotal connections which did not involve a pinned connection (that is, the pivot point fixed at a particular location), he maintained that “pivotally connected” as explained in the specification of the Patent is, in all cases, a pinned connection and that a pinned connection is a connection where only rotation can occur. Mr Hunter further explained during the hearing:

[I have] from my engineering training an understanding of what a revolute joint is, which is a joint which is – allows – is a pivotal connection that allows one degree of motion only, which is rotation, and I read a patent specification and I’m trying to understand pivotal connection from claim 1 in the context of the patent specification, and in every instance, the patent specification provides me with examples of pivotal connection which confirm my understanding of what a pivotal connection is, ie, one degree of freedom, meaning rotation, why would I be taken to some other idea for pivotal connection in claim 1?

66 As to this, Dr Field said that a pivot point did not need to be fixed at a particular location – that broader view, he said, arose from specific teaching and design experience he had with various components including hidden hinges, linkages that have a rotational point that is not a hinge pin, ligamentous type joints, flexure joints, and a reclining mechanism in a wheelchair, which had a “virtual pivot”.

67 However, it was also Dr Field’s evidence that there was nothing in the Patent which suggested “directly” to him that the pivot (in the context of “pivotally connected”) was of the kind that did not need to be fixed at a particular location. I can find no such suggestion either. This tends to support the construction posited by Mr Hunter.

68 Leaving aside the issue of whether a fixed or pinned connection is required, Dr Field maintained the view that “pivotally connected” encompassed a connection which allowed rotation as well as other degrees of motion, such as a sliding motion.

69 Mr Hunter distinguished a pivotal connection from a sliding connection (which he considered to be a different type of connection), such that, even if the sliding connection had rotational movement, the connection would no longer (in engineering terms) be referred to as a pivotal connection.

70 Dr Field did not like the expression “sliding connection” as used by Mr Hunter and expressed the view that it was “confusing” and “not useful” to use the same word, being “sliding”, for a connection that allowed for both rotation and sliding movement, because it would involve the same word being used for two types of connection.

71 It is difficult to reconcile this stance with Dr Field’s view as to the meaning of “pivotally connected” which, on his evidence, requires the same word “pivotally” to encompass both a pivotal connection, and a pivotal and sliding connection. This is especially as, during the view of the Clearview Easy Slide (which occurred in the court room with these experts and was filmed), Dr Field again emphasised the importance of precision in names:

I accept that Mr Hunter and I have different backgrounds and therefore have different ways of approaching the terminology. I have, I think, more background than he – I’m not trying to one-up – about design of mechanisms. So I would tend to use more specific descriptions than perhaps he. So it’s not a matter of right or wrong. But, as far as I’m concerned, if this has got dual movement, sliding and pivoting, it doesn’t help to describe it as a sliding connector because over here we have another sliding connector when the device moves in and out, so if that’s a sliding connector, this is sliding and pivoting, it deserves a separate name. So I call it a sliding pivot to distinguish it from a straight slider. I think Mr Hunter is calling them both sliders and that, to me, isn’t useful.

(Emphasis added.)

72 Self-evidently, the descriptor “sliding pivot”, which encompasses both pivotal and sliding movements, is more precise than describing a connection as “pivotally connected” or as a pivotal connection, if the latter is intended to encompass a sliding movement as well.

73 Yet the claims do not use the term “sliding pivot”. They use the term “pivotally connected” and there is no disclosure or even suggestion in the claims or the specification of a connection which involves a sliding pivot. Based on Dr Field’s evidence that precision in names is important (which evidence makes sense in the context of the type of skilled addressee in this case to whom the Patent is addressed), this tends against a construction of “pivotally connected” as encompassing a sliding movement (for example) or any movement other than rotation.

74 This is supported by the fact that Dr Field accepted (quite correctly) that the consequence of his approach to “pivotally connected” would allow for what he referred to as a “sliding pivot” (being a term not used in the Patent) to be placed at all four pivot points of the parallelogram linkage arrangement in the Patent, that is, at points 28, 30, 32 and 34 as seen in Figure 1. He conceded that if this occurred, there would be too many degrees of freedom to maintain the platform substantially level, as referred to at page 3 of the specification, unless other links were added. The addition of such further links is not addressed anywhere in the Patent, but they would be required. These matters also tend against the construction of “pivotally connected” in the claims as encompassing a sliding movement (for example) or any movement other than rotation.

75 Dr Field also accepted (and I agree) that the invention in the Patent is a relatively simple mechanical invention. Yet, on occasion, he appeared to take an overly complicated and technical approach to construction of the claims. This was demonstrated by (for example) his view that the relevant axis of rotation in a pivotal connection could be a “virtual centre of rotation” or an “instantaneous centre” (which required an understanding of complex vector mechanics). By contrast, Mr Hunter explained that the concept of “instantaneous centre” was not widely understood or practised in mechanical engineering, and that he would have to resort to textbooks to understand what an “instantaneous centre” was, and how it was calculated. These matters tend to support a conclusion that a person skilled in the art as at the priority date would approach the construction of the term “pivotally connected” in the claims in the way that Mr Hunter did, without the need to resort to complex engineering concepts which require resort to be had to academic texts. This is especially having regard to the nature of the invention and the content of the specification (which includes hand-drawn figures and a reference to using adhesive tape as an attachment at page 2, line 31 of the specification).

76 I have indicated above that, for various reasons, I prefer Mr Hunter’s construction in preference to Dr Field’s construction although that is not, of course, decisive. I turn then to the arguments advanced by the parties, in particular those of MSA.

77 Both sides relied upon the dictionary definition of “pivot”, and MSA also relied upon the dictionary definition of “pivotally”. That was so even though they also called experts who were united that the meaning to be ascribed to “pivotally connected” would be interpreted by mechanical engineers in a way which went beyond the English meaning of the words. It follows that the dictionary definitions proffered by the parties do not provide much, if any, assistance in a determination of the meaning that a skilled addressee would give to “pivotally connected” in the claims as at the priority date, having regard to his or her own general knowledge and to what is disclosed in the body of the specification.

78 MSA’s posited construction, relying upon aspects of Dr Field’s evidence, appeared to be focused on an abstract debate about the meaning of the words “pivotally connected”, rather than the meaning of those words in the claims. Further, my impression was that its arguments tended to move away from the manner in which the term would be understood by a skilled addressee and were more focused on ensuring that the term would be construed in a way which had the consequence that the Clearview Easy Slide (which has a sliding pivot) would be regarded as having infringed the Patent.

79 Further, MSA’s submissions did not grapple with the following, each of which told against MSA’s contended construction:

(1) the lack of any disclosure in the Patent of a pivotal connection between the components identified in the integers in question and which included any kind of movement other than, or in addition to, a rotational one;

(2) the fact that the claims use the term “pivotally connected” and not “sliding pivot”, remembering that (according to Dr Field) the use of the precise term is important. That precision is required makes sense – the Patent is addressed to a person skilled in the art, the term “pivotally connected” has a technical meaning to those skilled in the art and the invention is for a mechanical device;

(3) the fact that, if a sliding pivot was used at each of the four “pivotal connections” in the device, this would render the device uncontrollable in the absence of other links or constraints in the device to control motion. However, such arrangements are not contemplated in the Patent. As to this, a construction according to which the invention will work is to be preferred to one in which it may not: see Blue Gentian at [39];

(4) the fact that the invention in the Patent is for a relatively simple mechanical device such that it would not be expected that a skilled addressee would be required to have an understanding of complex vector mechanics.

80 By contrast to the inconsistencies in Dr Field’s evidence, Mr Hunter’s evidence remained consistent that a pivotal connection (which he also referred to as a revolute joint) was a connection that had only one degree of freedom, that is, it allowed only rotational motion. As submitted by Clearview, that construction is also consistent with: (a) the manner in which a skilled person would understand the term in the context of a mechanical apparatus, and (b) the way that the term is used throughout the Patent.

81 It is therefore not correct to say, as MSA does, that Mr Hunter or Clearview are impermissibly restricting the meaning to be given to the term “pivotally connected” in the claims because of what is disclosed in the specification. That is because Mr Hunter’s position was that “pivotally connected” has a particular meaning which a normal person skilled in the art would attach to that term apart from the disclosure in the specification and that there is no disclosure in the Patent of anything which indicates to him that a different meaning should be given to that term. In other words, the meaning given by Mr Hunter to the term is not narrowed by the disclosure in the specification – rather, it is confirmed by what is disclosed in the specification.

82 When one looks at the specification, it is apparent that Mr Hunter is correct in terms of his description of what is disclosed in the Patent. That is because the specification refers repeatedly and in simple terms to a sliding movement when that is intended (such as “sliding mechanism that can slidably move” or “mechanism preferably moves/slides with the second part”) whereas in the case of connections in the linkage arrangement of the kind described in integers 1.6/1.7 and 15.7/15.8, there is no suggestion that these connections have anything other than a pivotal (i.e. rotational) movement. In particular, notwithstanding that the apparatus in claims 1 and 15 are defined by what they “comprise” and that this term is defined as being inclusive, the specification does not disclose the construction of an apparatus which has pivotal connections of a type which is something other than that which would be understood by the notional skilled addressee by reference to that term (i.e. rotational).

83 For these reasons, I accept Clearview’s construction as to the meaning of “pivotally connected” in claims 1 and 15. That is, I find that “pivotally connected” in the claims refers to a connection between two components that permits only rotational movement of the components relative to one another.

5.4 Issue 2: meaning of “offset lever”

5.4.1 The competing contentions

84 The second disputed term “offset lever” appears in integers 1.8, 1.11, 15.9 and 15.10.

85 Both experts agreed that the term “offset lever” is not a term of art in mechanical engineering.

86 MSA submits that:

(1) an offset lever is a lever that is modified by a geometric offset in its shape, which construction is based on the ordinary meaning of its two components, both being ordinary English words: “offset” and “lever”;

(2) in the context of “Machinery”, the word “offset” is defined in the Macquarie Dictionary (8th ed, 2020) as “a more or less abrupt bend in a pipe, bar, rod, or the like, to serve some particular purpose” and in the Concise Oxford English Dictionary (12th ed, 2011) as “a bend in a pipe etc. to carry it past an obstacle”;

(3) a lever is “a bar or rigid piece acted upon at different points by two forces, as a voluntarily applied force (the power) and a resisting force (the weight), which generally tend to rotate it in opposite directions about a fixed axis or support (the fulcrum)”: Macquarie Dictionary (8th ed, 2020);

(4) its construction is consistent with the specification and points to the exemplary embodiment, in which the offset portion (63) is a bend in the offset lever.

87 Clearview submits that:

(1) the term “offset” in a mechanical device means that one component is spaced apart from, or set to the side of, another component (relying upon Mr Hunter’s evidence);

(2) the term “lever” means a solid component which has a rotational point and is capable of transmitting torque or leverage (relying upon Dr Field’s evidence, with which Mr Hunter agreed);

(3) by itself, the term “offset lever” does not identify what the lever is offset from, and its meaning is not apparent from the claims alone. It submits that, as such, a skilled person would look to the specification to assist their understanding of the term in the context of the Patent and would not attempt to understand the term “offset lever” by hybridising one dictionary definition of “offset” and one dictionary definition of “lever”;

(4) an offset lever in the claims is a lever having a centre line that is offset (that is, spaced apart) in the plane of operation of the mechanism from the centre line of one of the linkage arms to which it is connected.

88 In his first affidavit, Mr Hunter stated at [48]–[53]:

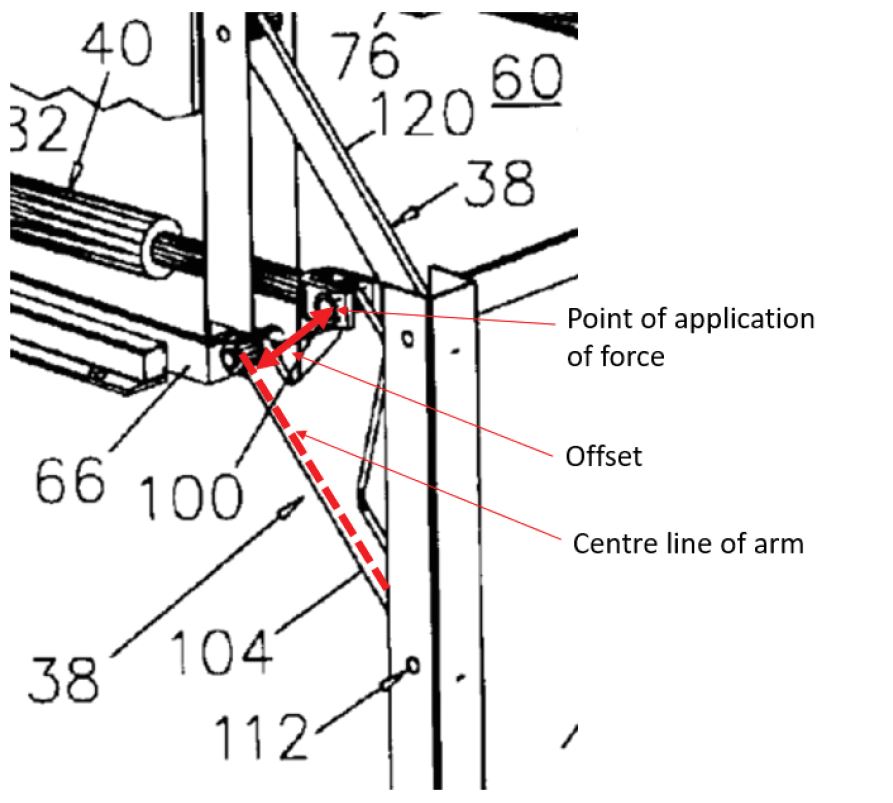

I am familiar with the term “offset” as this is used in mechanical devices. When used in relation to a mechanical device I understand the term “offset” to mean that the item that is offset is spaced apart, or set to the side, from another component. Therefore, I understand an “offset lever” to mean a lever that is set off to one side or spaced apart from another component. However, the term “offset lever” alone does not tell me what the lever is offset from. Without this information, the term is not clear to me. Therefore, in order to understand this term, I have looked at the remaining language of claim 1 and references to “offset lever” that appear in the specification.

Neither the claims nor the remainder of the specification explain what is meant by an offset lever. The specification also does not explain the purpose of the lever being offset.

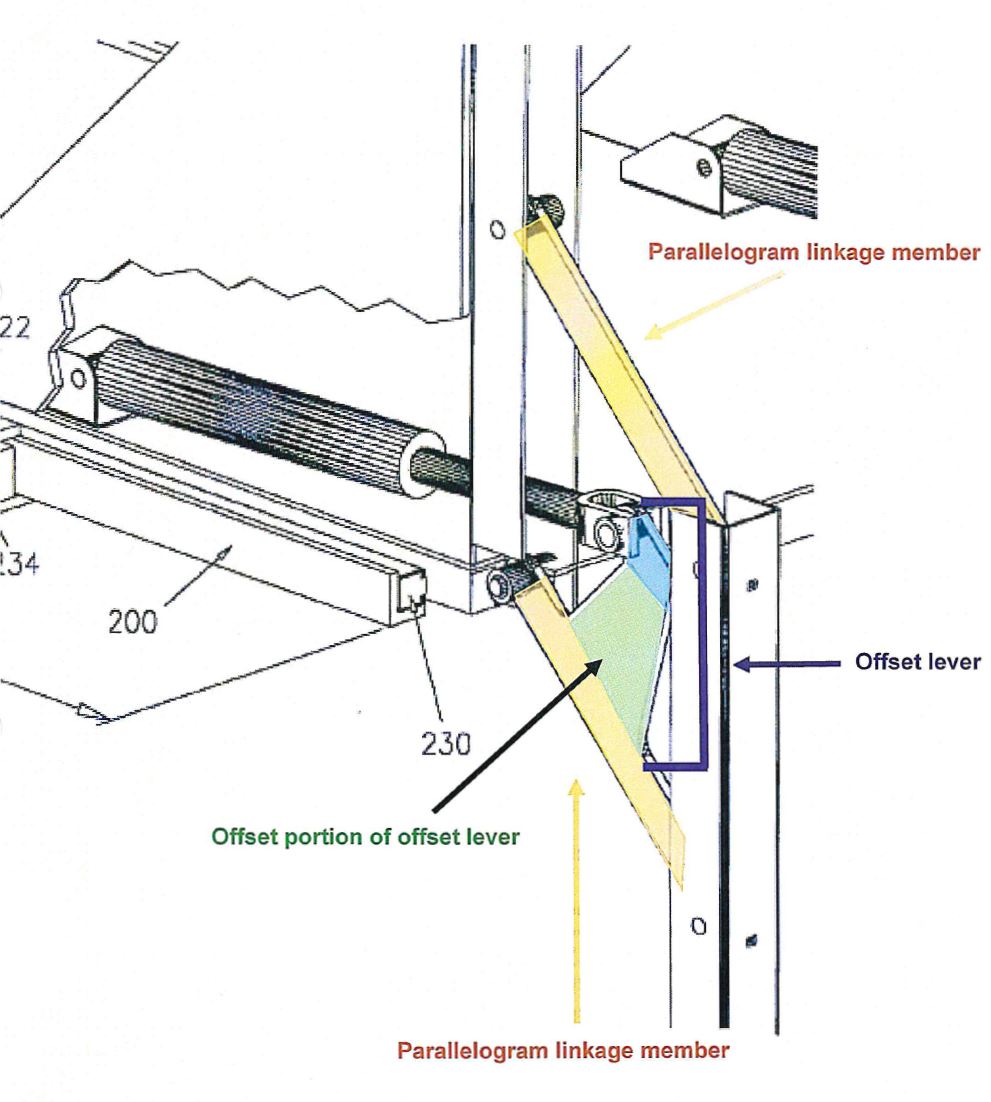

Claim 1 states that the “offset lever” is “connected to at least one of the one or more arms”. This suggest [sic] to me that the “offset” in “offset lever” is an offset between the lever and the arm to which it is connected. This understanding of “offset lever” is consistent with the single example of an “offset lever” that is given in the specification. This is described at page 9 lines 5 – 7 of the Patent, which refer to an offset lever 62 having an offset portion 63 which is mounted to linkage arm 24. From this, I understand that it is the offset portion 63 that is responsible for creating the offset in the offset lever 62.

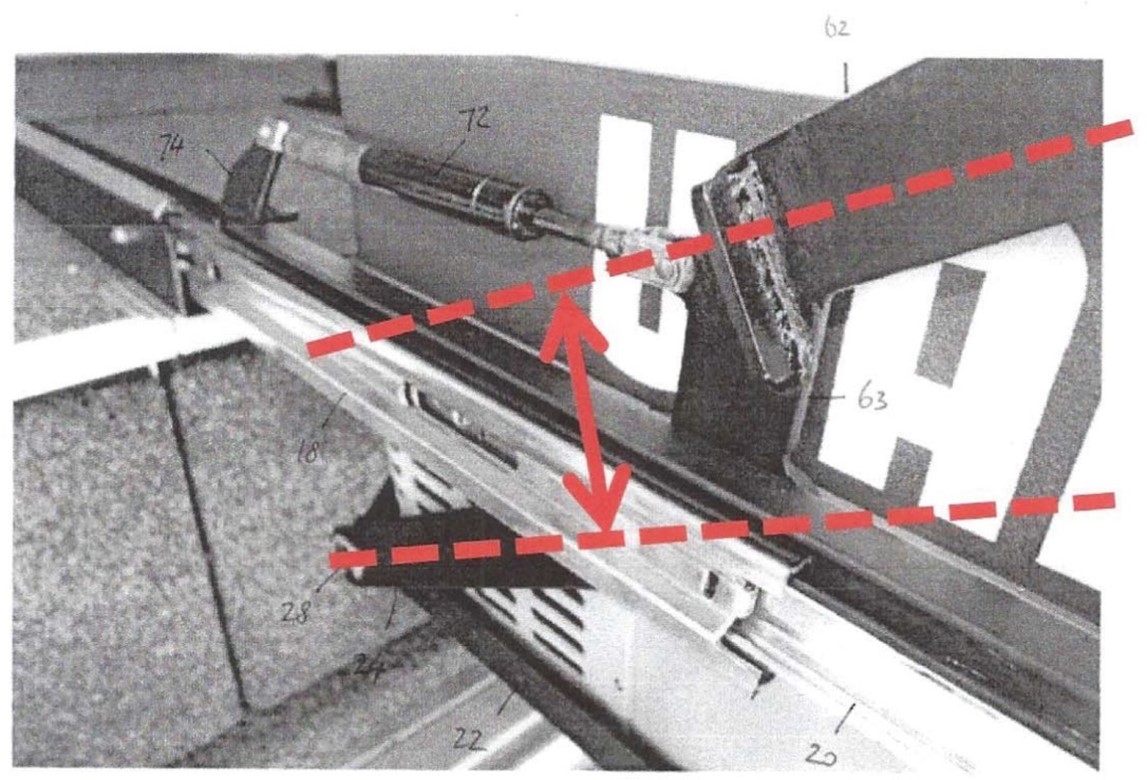

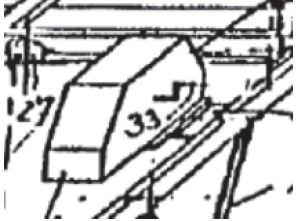

Referring to Figure 1 of the Patent, I can see an offset between offset lever 62 and the linkage arm 24. This is most clearly seen when the offset lever is in its raised position (indicated as item 62B). If I was to draw a centre line through linkage arm 24 and a centre line through the lever arm 62B, those centre lines would be parallel and spaced apart, or set aside, from each other. This relationship between the lever and the linkage arm is consistent with my understanding of an “offset” in a mechanical device.

Similarly, in Figure 7 (extracted below), I see that offset portion 63 causes the centre line of lever 62 (which is marked by a red dashed line) to be spaced apart or set aside from the centre line of linkage arm 24 (also marked by a red dashed line) [sic] The red arrow shows the offset created between these two components.

I therefore understand the term “offset lever” as it is used in the claims to be referring to an active lever that is offset (i.e. set to one side or spaced away) from the component to which it is connected (i.e. the linkage arm).

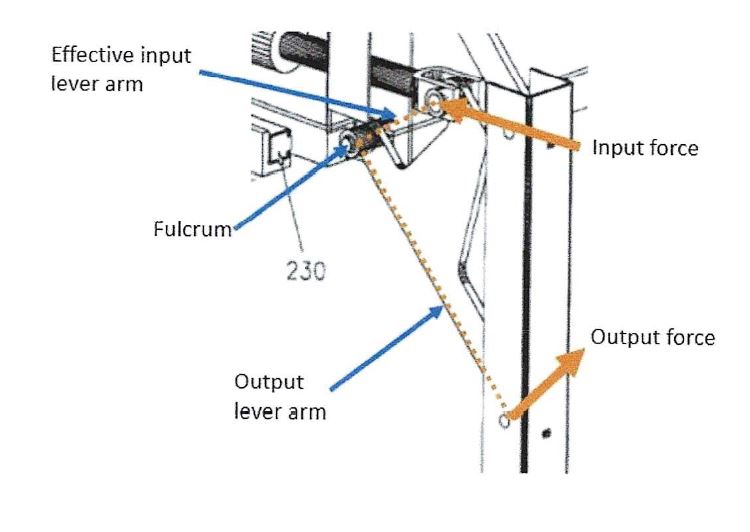

89 In his second affidavit, Mr Hunter stated at [35]–[39] that:

… [I]n the context of the Patent, I understand that the “offset” refers to something that has a configuration and orientation that is not in line with another thing in the plane of motion of the device, so that it has functional significance in the way in which the device operates.

By way of explanation, a mechanism such as the one disclosed in the Patent can be understood in a two-dimensional plane (notwithstanding that the device itself is three dimensional). This is because the motion of the device only occurs in two dimensions.

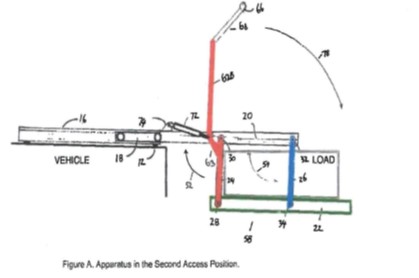

The motion of the device described in the Patent is illustrated by reference to drawings such as that shown in Dr Field’s Figure A, which is extracted below. In this drawing, there is no motion of the device in or out of the page. All the motion takes place in the plane of the page. The relevant “offset” in the offset lever is between the lever 62 and the linkage arm 24, which are parallel and offset to each other in the plane of the page.

Handle 66 also has a configuration and orientation that is not in line with the lever 62 (as it extends into the page). However, this is not described by the Patent as being “offset”, and nor do I regard it as being any type of offset that is relevant to the way the device moves and operates. In contrast, the “offset” in the offset lever is between the lever 62 and the linkage arm 24, and provides the function I described in paragraph 35 above.

The function of the offset lever as providing a point of attachment for the gas strut is described at page 9 lines 9 – 13 of the Patent: “A gas strut 72 is also provided. Gas strut 72 is connected at one end via bracket 74 to the sliding mechanism to which the platform 22 is connected. The other end of gas strut 72 is connected to the offset lever 62. As is shown in figure 1, as the platform 22 moves between the first access position 56 and the second access position 58, the gas strut extends to thereby ease lowering and raising of the platform 22.”

(Emphasis original.)

90 In the JER, Mr Hunter reiterated that he interprets “offset lever” to mean a lever which has an offset portion which is spaced apart (in the plane of the mechanism’s operation) from the longitudinal centreline of the lever.

91 Mr Hunter is criticised by MSA for adding the words “in the plane of motion of the device” in his construction of the term in his second affidavit, and for his opinion given in the JER, when those words were not part of his initial definition. Mr Hunter explained his reasons for this during the hearing, which included that Dr Field had a different interpretation (to which he was responding) which “takes us into a different plane other than the two-dimensional plane of operation of the mechanism”. He also explained that he had not volunteered it initially because he considered it to be self-explanatory “because all of the explanation of the way in which the mechanism worked in diagrams was in a two-dimensional sense, as mechanisms are often explained in engineering terms in a 2D planar sense”. Mr Hunter’s explanations for the modification to his initial construction are satisfactory, and MSA’s criticism is misplaced.

92 Mr Hunter also gave the following oral evidence during the concurrent evidence session:

MR FRANKLIN: And I’m suggesting to you that it need not be in a vertical orientation. It could be in a different orientation and still operate.

MR HUNTER: Yes, but the difficulty there, Mr Franklin, is that as a person skilled in the art I’m reading the patent and I’m trying to interpret a term, offset lever, which doesn’t have a general meaning in engineering terms. So the only way I can understand that term is to go into the patent specification and see how the patentee uses that term. Now, [the] patentee uses the term precisely in the manner that you’ve just described, which is that the offset is in the plane of operation of the mechanism. So if that’s what the patentee says that an offset lever is, then that’s what I take the meaning to be. The only – the only explanation which helps is the one embodiment that’s described in the patent. There are no others. So I have no other way of understanding what an offset lever is, other than by referring to that embodiment.

93 Mr Hunter also explained that it was entirely “inappropriate” to construct the meaning of offset lever from a dictionary and said that “engineers reading patent specifications don’t look at every term and look at dictionary definitions. We look at the specification to make sense of things”. When it was pressed upon him that he should have “simply” gone to the dictionary to understand what offset meant, Mr Hunter said this:

Well, you can suggest that to me, but that’s not what I did and that [sic] not what I do when I read patents. If I’m doing things the wrong way, perhaps I should be looking at the dictionary more often. I don’t know, but there are terms which, obviously, when they’re used in patent claims have a common sense easy to understand definition. You don’t need the dictionary even to look them up. But there are also terms which we come across, or I come across in patents which do need to be understood with the specification in mind. This is one of those cases.

94 In his first affidavit, Dr Field identified that a lever is a solid component which has a rotational point and is capable of transmitting torque or leverage. Mr Hunter agreed with this definition.

95 Dr Field’s definition of lever became more expansive in his second affidavit, when he was asked to consider novelty issues relating to prior art. Dr Field described a “lever” to have the following features:

(1) (pivoting about a fulcrum) pivoting movement about an axis (a fulcrum) to provide a force or torque. The fulcrum is located on or near the longitudinal axis of the lever;

(2) (arc of motion) an arc of motion that is less than a full revolution. That is, in engineering, a lever is generally understood to rotate about a fulcrum less than 360 degrees;

(3) (perpendicular force) force components are applied in directions that are perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the lever; and

(4) (elongation) levers are ordinarily rigid beams elongated in the direction of the axis of the lever.

96 In the JER, Dr Field stated that he interpreted “offset lever” as being one of the formally recognised lever types that has a portion or portions not parallel to the remaining portion, with the apparent principal purpose in the Patent of facilitating compact storage of the device.

97 Dr Field also gave oral evidence that:

…Offset in an engineering context is a physical dimensional measurement. Something is offset from something else... It has a measurement that you can measure in millimetres or metres or kilometres…And when applied to [the lever] it implies a physical distance associated with a lever. The word lever has a technical meaning which, in simple terms, is described as a beam with two forces perpendicular to the beam and [a] fulcrum, a seesaw is a lever in a simple form, or one form.

…As far as I’m concerned, there [are] dual meanings of the – the word offset and the one is that the lever is offset from something else, which is not the lever. It is using the word offset to mean a parallel displacement. A distance from something, is an offset. And the second meaning is the lever isn’t a classic lever, it contains offsets, so it’s no longer, for example, a straight beam, it’s a beam with – with zigzags or folds within it.

…

…That is, offset lever might be a lever with its own offset and offset from something else and still be an offset lever. I can’t exclude the possibility that both offset types apply in any one circumstance.

…

…When I now look at the 888 patent, I can ask does the patent say whether the offset lever is a lever which is offset from something, or is the lever a lever which has offsets in its shape.

And what I see most readily, is a lever with offsets in its shape, in the preferred embodiment. I don’t see anywhere in the general description and the specification, that it is one type or the other. In fact, I think lever or even offset lever are not generally mentioned in the overall. It’s – it’s the offset lever in the specification is used as a preferred way of causing the mechanism to work. So in the preferred embodiment that I see, I do see something which is very close to a first order lever, except that it has a an offset along its length. The two portions of the lever, like the seesaw, has one portion parallel to but not in line with the other, and that is clearly an offset.

98 Claims 1 and 15 do not describe the term “offset lever”. According to Dr Field, there are two possible meanings to be given to the term; however, which of those meanings is to be given to the term is unclear from the claims themselves.

99 As already observed, the claims must be construed in the context of the specification as a whole. As the meaning of the term “offset lever” in the claims is unclear, it is appropriate and indeed necessary to have resort to the specification to obtain an understanding of the meaning of “offset lever” in the claims. Contrary to MSA’s submission, such a course of action does not involve an impermissible use of the embodiment to define or restrict the claim; rather, it involves defining a term in a claim which is unclear by reference to the body of the specification.

100 Turning then to the specification, and other than in the consistory clauses or in the Detailed Description of the Drawings, the only references to “offset lever” appear at page 3 in a passage which commences at line 10:

The apparatus may further comprise actuating means for moving the second part from the first access position to the second access position. The actuating means may comprise, for example, an offset lever connected to one or more linkages. Moving the lever, such as by rotating the lever upwardly or downwardly, causes the linkages to rotate and causes the second part to move between the first and second access positions. A biasing means, such as a spring, hydraulic cylinder, gas strut or the like, may be used to assist in moving the second part between the first access position and the second access position. A handle may be pivotally connected to the offset lever to facilitate movement of the offset lever.

(Emphasis added.)

101 This passage tells the reader very little about why the word “offset” has been added before the word lever, rather than having the word “lever” appear on its own.

102 Because of this, it is necessary to have regard to the Figures in the specification, and to consider how they would be interpreted by the notional skilled addressee.

103 As to this, MSA is critical of an approach which is based on interpreting the apparatus in the Figures in a “2D planar sense” (as Mr Hunter did) but, again, its criticism is misplaced because it fails to grapple with the evidence of Mr Hunter (which Dr Field did not contradict) that mechanisms are often explained in engineering terms in a 2D planar sense. When asked by senior counsel for MSA why the offset portion must be spaced apart in the plane of the mechanisms operation, Mr Hunter gave this evidence:

Because that’s how I understand the mechanism is to be interpreted. That’s how all 2D planar mechanisms like this are interpreted in terms of how they function.

104 As the Patent is directed to a person with expertise in and knowledge of mechanical engineering, I will adopt the same approach (and, indeed, it is necessary that I do so).

105 Further, as Mr Hunter states in the JER, there is no description in the Patent of the offset being applied in any other plane.

106 The Figures depict that the “offset lever” has a centre line that is offset (ie. spaced apart) in the plane of operation of the mechanism from the centre line of one of the linkage arms to which it is connected. This is shown, for example, in the annotated version of Figure 7 prepared by Mr Hunter (see above at [88]), with 62 being the offset lever and 63 being the offset portion, which appears in his first affidavit. In this image, the red double-headed arrow is the offset of the centre line of the offset lever 62 from the linkage arm 24 to which it is connected.

107 If one uses the annotated Figure A from Dr Field’s affidavit, which Mr Hunter discussed in his second affidavit (see above at [89]), it is apparent that the offset lever 62 (when it is moved to position 62B) is offset (that is, spaced apart) from the centre line of the linkage arm 24 in the plane of motion of the device.

108 That offset occurs because of the displacement created by the offset portion 63. In the specification at page 9, lines 5–6, it is stated that, “The actuating means 60 comprises an offset lever 62 having an offset portion 63 that is mounted to linkage arm 24” (emphasis added). At page 9, lines 19–20, reference is made to “the offset portion 63 of offset lever 62 [which] is mounted to the linkage arm 24” (emphasis added). These sentences indicate that offset portion 63 forms part of the offset lever 62, and that offset portion 63 is the part of the lever which causes or creates the displacement referred to above.

109 Further, although the offset lever (including the offset portion) is depicted as a bent lever in the Figures, Mr Hunter’s evidence, which I accept, is that the bend has no functional significance in terms of how the mechanism works in a 2D planar sense. While Dr Field’s view was that the bend in the offset lever enabled the device to operate without the lever “snagging” on one of the arms, I did not understand this evidence was given by reference to the Figures and their interpretation in a 2D planar sense. This is confirmed by Dr Field’s evidence in the JER concerning the purpose of the offset by reference to page 4 of the specification.

110 For these reasons, I prefer Clearview’s construction to MSA’s construction as to the meaning of “offset lever” in integer 1.8, 1.11, 15.9 and 15.10. That is, I find that an “offset lever” in these integers is a lever having a centre line that is offset (that is, spaced apart and not in line with) in the plane of operation of the mechanism from the centre line of one of the linkage arms to which it is connected.

111 In reaching this view, I did not consider it to be necessary to decide the purpose of the offset lever which was the subject of a minor debate by the experts.

5.5 Issue 3: meaning of “connected to”

5.5.1 The competing contentions

112 The third disputed term appears in integer 1.8, namely “offset lever connected to at least one of the one or more arms” (emphasis added). It also appears in integer 15.9.

113 The dispute between the parties in relation to this term largely centres on whether the term “connected to” requires a direct or indirect connection.

114 MSA submits that the proper construction of “connected to” is that it connotes a relationship by which the link between the two parts can be effected by an indefinite number and type of intermediate components. It submits that, more particularly, “connected to” refers to a functional connection such that when Item X (in this case, the offset lever) is moved, so too is Item Y (such as, in the case of claim 1, the at least one of the one or more arms) and that there must necessarily be physical mechanical connections, albeit through intermediate components. MSA submits that whether the offset lever is “connected” to the arm(s) depends on whether, if the offset lever moves, the arm also moves.

115 Clearview submits that, in the context of the Patent, the term “connected to” requires a direct connection between the offset lever and the linkage arm (or arms) such that the offset lever acts directly on the linkage arm.

116 Dr Field contends that the term “connected” describes the functional (causal) interaction between the relevant parts (offset lever and one or more arms) so as to achieve the stated kinematic outcome in the claim, namely, “the second part being movable from the first access position to the second access position by moving the offset lever”). He stated in the JER that:

My interpretation acknowledges that the offset lever is to cause the motion of any of the separate arms, such as (26), either directly, or via routine alternative linkages and structure, whether part 60 has been constructed from separate pieces or not.

117 Dr Field expanded upon this in his oral evidence:

…[W]hat does connected to mean in the context of the patent? The term “connected to” is used through both the descriptions earlier in the specification and in the claims. In the claims, there is the use of the word “connected to” without qualifying the word “connected.” To an engineer, connected could mean several things. It could be welded to, or it could be functionally dependent on. That is, for example, the light switch is connected to the lights. But they actually are not in contact; they’re connected via electrical wiring.

So what connected means is contextual. And so in the context of the claims, we need to say what is the connection for in order to understand what the connection is. And, in a mechanical device, in a machine associated with movements, such as these products are, it’s called a kinematic connection. Kinematic meaning movement. So whereas a light switch and a light is an electrical type of machine, here we have a mechanical machine, and the use of the word “connected” means causing a corresponding movement in. That’s probably the simplest and shortest way to introduce it. It’s a functional causation of movement or [not].

118 Dr Field also gave this oral evidence by reference to [104] of his first affidavit, where he set out his views on each integer including integer 1.8:

MR FOX: Connected to, this is the last paragraph:

I understand connected to, to mean that items are joined together. Things can be connected to each other through any number of intermediary items joined together.

… So that raises the point that Mr Hunter raises about any number could be infinite; correct?

DR FIELD: Yes.

MR FOX: Right. And that’s the difficulty he has, conceptually, with it, you understand that?

DR FIELD: Yes, I understand that.

MR FOX: Yes. And then you give an example.

For example, one item, such as a fishhook, can be connected to another item such as a rod by a third item such as a fishing line.

Just dealing with that example alone, and I put this question to you, just to ventilate with you, what might be regarded as ordinary English use of the phrase “connected to”. So I’m not intending this as any offence, but I want to suggest to you that it’s just not normal use of the English language, to say that the hook is connected to the rod. Rather, what’s ordinary English language is to say that the hook is connected to the fishing line. Do you agree with that?

DR FIELD: Yes, I would agree that is – is normal English.

MR FOX: And by the same logic, that a person is not connected to the fish by the rod by the fishing line, by the fishing hook; do you agree with that? That’s not an ordinary use of English language to say that a person is connected to the fish?

DR FIELD: That’s not the way you use language; no.

119 Both Dr Field and Mr Hunter agreed that, if Dr Field’s interpretation was accepted, there would be redundant words in claim 15 (being the words “connected to at least one of the at least one arm”). Mr Hunter said that the term “connected to” has no work to do if the only purpose is to achieve a kinematic outcome.

120 In the JER, Mr Hunter agreed with Dr Field that “connected to” is not limited to “fixedly connected to” although that is one possibility. He also stated in the JER that:

Although the term “connected to” may mean directly or indirectly connected, I consider that “connected to” in the Patent means “directly connected”. If in the Patent mechanism I took connected to mean either directly or indirectly connected then every component in the mechanism is connected (either directly or indirectly) to every other component. This means that the skilled reader cannot make sense of the Patent when it is describing how the mechanism works via direct connections between linkage members. If “connected to” meant indirect connection there would be no point in the Patentee using the term “connected to” at all, since that would teach the skilled reader nothing about how the mechanism was intended to work.

…

[The term] “connected to” can also clearly include a pivoting (direct) connection. For example, page 8 lines 15-17: “The linkage arm 24 is pivotally mounted at its other end to a pin 30. Pin 30 is, in turn, mounted to the innermost sliding member 20.” Clearly this is a direct connection which is a pivotal (non-fixed) connection. Sliding connections are also expressly cited in the Patent (eg page 7, line 24:26) – “The sliding members may be in the form of sliding members that carry one or more bearings to facilitate sliding movement.”

121 During oral evidence, Mr Hunter summarised his position as follows:

… I think the dispute is, really, around the term “connected to,” whether it means something is directly or indirectly connected to another object. And, in a general sense, “connected to” could mean either of those two scenarios…. [I]f I think of something that’s indirectly connected, I can’t make sense of the mechanism, because any part of a mechanism could be said to be indirectly connected to any other part of the mechanism. So that doesn’t tell me anything. So to make sense of the mechanism, I need to interpret “connected to” as meaning directly connected to. And in every instance in the patent where the term – in the specification where the term “connected to” is used, it’s referring to a direct connection. So that then teaches me how the mechanism is connected together, and, therefore, works.

122 The debate about “connected to” in these integers and whether that encompassed “direct” and “indirect” connections, and what is an “indirect” connection, became what can only be described as a lawyer’s picnic or perhaps an engineer’s one.

123 It evolved into a debate as to whether a pivotal connection which involved a pin would be a “direct” connection (Mr Hunter) or an “indirect” connection (Dr Field). As to this, Mr Hunter gave oral evidence concerning the reference in the specification to Figure 5 which states “linkage arm 24 is pivotally mounted [at] one end to a pin 28. Pin 28, in turn, is mounted to the support platform 22. The linkage arm 24 is pivotally mounted at its other end to a pin 30. Pin 30 is, in turn, mounted to the innermost sliding member 20”. Mr Hunter explained:

MR HUNTER: So I understand what you’re saying, that – that it could be said that there – there is – there is an intermediary component, being the pin, between the linkage arm 24 and the support platform 22. I – I understand that. But it would be – I – I still think this is really a direct rotational connection. It would be laborious, when we were describing direct rotational connections, to go through the components which were actually involved in making the pivotal connection itself. For example, if I was saying that – using the example, again, of a wheel, and we might talk about a wheel being connected to an axle. I think most people would – would agree that a wheel was directly connected to an axle. In fact, what we have – we would have, strictly speaking, if we were to speak – speak through it as a chain of components, we would say the wheel was connected to the outer race with a bearing, which was connected to some rollers or – or spheres or balls, which were connected to the inner race of the bearing, which was connected to the axle. That would be laborious if we had to explain that – that chain every time we met a direct rotational connection. So I think the same applies here, that even though that – that pin – the pin – I – I take the pin in this case to essentially be a part of the support platform.

MR FRANKLIN: And - - -

MR HUNTER: Because it’s mounted to it.

MR FRANKLIN: - - - with reference to your wheel and the axle, you’ve just given her Honour a description of a number of intermediary connections between the wheel and the axle, but you - - -

MR HUNTER: Yes.

MR FRANKLIN: - - - never there say - - -

MR HUNTER: It - - -

MR FRANKLIN: - - - that the two are connected.

MR HUNTER: Yes. Directly. We would use a direct connection, and I think most people would use the term that way.

MR FRANKLIN: Notwithstanding the fact that there are, in that case, a large number of intermediary components.

MR HUNTER: I’ve explained the reason why we use - - -

MR FRANKLIN: Yes.

MR HUNTER: - - - that – that term for simplicity.

HER HONOUR: When you say we, who do you mean? Who do you say – who’s we?

MR HUNTER: The engineering community.

124 Mr Hunter expanded upon this during his oral evidence:

MR FRANKLIN: Well, if you have one – if you have an offset lever and one intermediary component, such as a line connected to an arm…You move the offset lever…And that moves the arm…And because moving the offset lever causes movement of the arm …they must be connected; do you agree with it?

MR HUNTER: They are. They’re indirectly connected, but that doesn’t help me to understand how the patent works. For instance, if I was trying to understand page 3 lines 11 to 14 of the patent. The only way that I can understand that – the – that working in the context of the patent is via direct connection. Otherwise, if it was indirect connection, you’re basically saying to me that any mechanism with a lever in it that raises a platform up and down, no matter how many components are in between the lever and the platform, or what the linkage mechanism or arrangement is would conform with the claims of the patent. So in my view, that would make the claims of the patent so broad that it would be meaningless…

125 Mr Hunter explained how he approached the interpretation of the term by reference to the specification:

MR HUNTER: I – I didn’t see any use of the term “connected to” in the specification which contemplated an indirect connection.

…

…An offset lever connected to at least one offset of the at least one arm. So let’s say I was puzzled by that. I would go to the specification there and then I would see in the specification, if I can just find that, on page 995. It starts at line 5, which says that:

The actuating means comprises an offset lever having an offset portion that is mounted to linkage arm 24.

So there’s an offset lever with an offset portion. And then it goes on to say:

This may be achieved, for example, by welding the end of offset portion 63 to the linkage arm.

So how could that be anything other than a direct connection.

MR FRANKLIN: Yes. And that is one preferred embodiment, is it not, Mr Hunter?

MR HUNTER: Yes. It’s the only preferred – it’s the only embodiment.

(Emphasis original.)

126 In my view and for the following reasons, the term “connected to” in integers 1.8 and 15.9 requires a direct connection between the offset lever and the linkage arm (or arms) such that the offset lever acts directly on the linkage arm. That is, the words “connected to” require that the relevant parts are immediately conjoined.