FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Munkara v Santos NA Barossa Pty Ltd (No 3) [2024] FCA 9

[34] Line 9: “Marie” amended to “Maria” | |

[59] Line 3: “18m each year” amended to “18mm each year” | |

[254] Line 6” “Eulalia” amended to “Eulalie” | |

[302] Line 3: “at [466]” amended to “at [1075]” | |

Heading above [396] “Marie” amended to “Maria” | |

[396] – [402], [403], [405], [406], [407], [408], [409], [411], [412] “Marie” amended to “Maria” | |

[417] Line 5: Wiaprali” amended to “Wiyapurali” | |

[436] Line 6: Wiaprali” amended to “Wiyapurali” | |

[453] Line 2, Line 7: Wiaprali” amended to “Wiyapurali” | |

[466] Line 3: Wiaprali” amended to “Wiyapurali” | |

[474] Line 2: “southwest coast of” amended to “southwest of” | |

[475] Line 3: Wiaprali” amended to “Wiyapurali” | |

[540] Line 1: “Wiaprali” amended to “Wiarprali” | |

[561] Line 2: “AAPA” amended to “Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority (AAPA)” | |

[651] Line 2: “30 – 440” amended to “30 – 40” | |

[697] Lines 3 and 5: “Hadlee” amended to “Tungatalum” | |

[713] Line 2: “skin tribe is” amended to “skin group is” | |

[797] Line 4: “they ever” amended to “they never” | |

[819] Line 1: “that in March 2023 he” amended to “that he” | |

[859] Line 1: “Marie Purtaninga” amended to “Maria” | |

[877] (1) Line 1: “Wiaprali” amended to “Wiyapurali” | |

[879] Line 3: “Wiaprali” amended to “Wiyapurali” | |

[882] Line 3: “Wiaprali” amended to “Wiyapurali” | |

[932] (4), (5), (6) “Marie” amended to “Maria” | |

[977] (7) and (8) Line 1: “Jonathan” amended to “Jonathon” | |

[989] Line 16: “be against” amended to “be in favour of” | |

[994] Lines 2 and 4: “May Corrigan Meeting” amended to “May Lewis Meeting” | |

[1006] Line 3: “Wiaprali” amended to “Wiarprali” | |

[1007] Line 3: “Wiaprali” amended to “Wiyapurali” | |

[1114] Line 2: “read both” amended to “read the” | |

[1145] Line 2: “Arnhem Land” amended to “the Dampier region” | |

[1180] Line 7: “does assuage” amended to “does not assuage” | |

[1187] Line 4: “that the” inserted after “He recognises” | |

[1268] Line 3: “that did” amended to “that did not” |

ORDERS

First Applicant CAROL MARIA PURUNTATAMERI Second Applicant MARIA SIMPLICIA PURTANINGA TIPUAMANTUMIRRI Third Applicant | ||

AND: | SANTOS NA BAROSSA PTY LTD ACN 109 974 932 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The originating application is dismissed.

2. The order with injunction granted on 15 November 2023 is discharged.

3. Subject to these orders, the applicants are to pay the respondent’s costs, such costs to be assessed by a Registrar of the Court on a lump sum basis.

4. Any application to vary or substitute the order in paragraph 3 is to be filed and served on or before 29 January 2024, such application to be accompanied by:

(a) an affidavit in support; and

(b) written submissions not exceeding five pages.

5. In the event that an application is filed and served in accordance with paragraph 4, on or before 14 February 2024 the person served is, if so advised, to file and serve:

(a) an affidavit in opposition; and

(b) written submissions not exceeding five pages.

6. In the event that an application is filed and served in accordance with paragraph 4, the application is to be set down for hearing on a date to be fixed, not before 19 February 2024.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

INTRODUCTION | [1] |

The applicants’ case | [9] |

The relief sought | [23] |

The role of the Court | [25] |

Summary of outcome | [26] |

THE TRIAL AND EVIDENCE | [27] |

Lay evidence | [34] |

Expert evidence | [38] |

Dr Brendan Corrigan | [40] |

Dr Jodie Benton | [41] |

Ms Stephanie Rusden | [42] |

Mr Harrison Rochford | [43] |

Mr Gareth Lewis | [44] |

Dr Amanda Kearney | [45] |

Dr Andrew McWilliam | [46] |

Dr Henry W Posamentier | [47] |

Dr Mick O’Leary | [48] |

Wessex Archaeology | [49] |

Joint reports | [50] |

Video evidence | [52] |

Documents | [54] |

THE TIWI ISLANDS | [57] |

TIWI SOCIETY | [61] |

Estates and boundaries | [68] |

Registration of sacred sites | [69] |

Cultural authority and the right to speak for country | [70] |

Spiritual beliefs, Dreamings and song lines | [71] |

Mudungkala | [73] |

Yiminga | [75] |

Ampiji | [78] |

Crocodile Man | [82] |

Totemic species | [88] |

THE PIPELINE EP | [89] |

EVENTS PRIOR TO THE LITIGATION | [110] |

Tipakalippa proceedings | [116] |

PART II | [131] |

THE PROPER CONSTRUCTION OF REG 17(6) | [131] |

Express objects | [144] |

The factual and legal landscape in which reg 17(6) resides | [155] |

Revised environment plans | [168] |

“Occurrence” and knowledge | [176] |

“Occurrence” of a risk | [186] |

Environmental impact | [192] |

Distribution of the adjectives “significant” and “new” | [211] |

Meaning of significant risk | [214] |

Standard or proof in respect of a risk | [220] |

“New” | [222] |

SOURCES OF TIWI EVIDENCE | [239] |

TIWI TESTIMONY | [253] |

Applicants’ witnesses | [261] |

Pirrawayingi “Marius” Puruntatameri | [261] |

Cross-examination of Pirrawayingi “Marius” Puruntatameri | [280] |

Tony Majirliyanga Pilakui | [303] |

Cross-examination of Tony Majirliyanga Pilakui | [315] |

Dennis Murphy Tipakalippa | [319] |

Cross-examination of Dennis Murphy Tipakalippa | [335] |

Therese Wokai Bourke | [340] |

Cross-examination of Therese Wokai Bourke | [357] |

Carol Maria Puruntatameri | [368] |

Cross-examination of Carol Maria Puruntatameri | [381] |

Maria Simplicia Purtaninga Tipuamantumirri | [396] |

Cross-examination of Maria Simplicia Purtaninga Tipuamantumirri | [403] |

Molly Munkara | [413] |

Cross-examination of Molly Munkara | [433] |

Ancilla Warlapikimayuwu Kurrupuwu | [450] |

Cross-examination of Ancilla Warlapikimayuwu Kurrupuwu | [458] |

Marie Frances Tipiloura | [472] |

Cross-examination of Marie Frances Tipiloura | [478] |

Magdalen “Maggie” Kelantumama | [487] |

Cross-examination of Magdalen “Maggie” Kelantumama | [496] |

Simon Munkara | [500] |

Cross-examination of Simon Munkara | [513] |

Valentine Intalui | [536] |

Cross-examination of Valentine Intalui | [551] |

Respondent’s witnesses | [561] |

Walter Kerinauia | [561] |

Cross-examination of Walter Kerinauia | [570] |

Kaitline Kerinauia | [582] |

Cross-examination of Kaitline Kerinauia | [588] |

Theresa “Amy” Munkara | [596] |

Cross-examination of Theresa “Amy” Munkara | [602] |

Eulalie Munkara | [619] |

Cross-examination of Eulalie Munkara | [625] |

Brian Dixon Tipungwuti | [631] |

Cross-examination of Brian Dixon Tipungwuti | [643] |

Wesley Kerinaiua | [658] |

Cross-examination of Wesley Kerinaiua | [672] |

Stanley Tipiloura | [676] |

Cross-examination of Stanley Tipiloura | [690] |

Jonathon “Jono” Munkara | [712] |

Cross-examination of Jonathon “Jono” Munkara | [720] |

John-Louis “JL” Munkara | [727] |

Cross-examination of John-Louis “JL” Munkara | [735] |

Mario Joseph Munkara | [746] |

Cross-examination of Mario Joseph Munkara | [753] |

Richard “Hadlee” Hyacinth Tungatalum | [767] |

Cross-examination of Richard “Hadlee” Hyacinth Tungatalum | [778] |

PART III | [826] |

SPIRITUAL CONNECTION TO SEA COUNTRY | [826] |

The nature of “sea country” | [830] |

“Sea country” and the asserted risks | [839] |

PART IV | [870] |

TRADITIONAL ACCOUNTS OF AMPIJI AND THE CROCODILE MAN | [870] |

Common ground and controversy | [871] |

The anthropologists | [885] |

Methodology | [890] |

Cultural protocol | [892] |

Reliance on anthropologists more generally | [895] |

Cultural authority and the relevance of dissent | [898] |

Expert evidence concerning cultural authority | [906] |

The Court’s task and the applicants’ onus | [919] |

Additional evidence concerning Ampiji | [926] |

Tiwi evidence | [932] |

Yiminga | [940] |

The evidence of Carol Puruntatameri | [947] |

Diverging accounts | [961] |

Additional evidence concerning the Crocodile Man | [963] |

Consideration of the competing testimony | [978] |

Conclusions in relation to Ampiji | [1001] |

Prior non-disclosure | [1015] |

PART V | [1016] |

THE ADAPTED AMPIJI ACCOUNT AND BURIAL GROUNDS | [1016] |

What is meant by “adapted” account? | [1018] |

Expert reports | [1029] |

O’Leary 1 | [1029] |

Synthesised narratives | [1039] |

Literature Review | [1053] |

2023 Marie Munkara Narratives | [1059] |

Dr O’Leary’s answers to questions 2 to 4 | [1067] |

Lewis 1 | [1088] |

Posamentier 2 | [1111] |

O’Leary 3 | [1113] |

O’Leary 4 | [1114] |

Further reports | [1115] |

Flaws in the cultural mapping process | [1116] |

May Lewis Meeting | [1117] |

Conclusions on Lewis 1 and Lewis 2 | [1136] |

Dr O’Leary’s maps | [1140] |

Events at the June O’Leary Workshop | [1143] |

Video evidence | [1154] |

2023 Marie Munkara Narratives | [1171] |

Synthesised narratives | [1178] |

Opinions beyond expertise | [1184] |

The alleged Ancient Lake and burial grounds as landforms | [1191] |

The Ancient Lake | [1192] |

Burial sites | [1199] |

PART VI | [1213] |

SUBMERGED TANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE | [1213] |

Admission into evidence of Wessex Reports and related testimony | [1219] |

General geological principles | [1238] |

Wessex 1: Methodology and Conclusions | [1250] |

Dr Henry Posamentier | [1255] |

Wessex 2 | [1258] |

Wessex 3 | [1259] |

Dr Posamentier’s instructions and expertise | [1261] |

General Areas of Disagreement | [1265] |

Fluvial channels | [1267] |

Anabranching channels | [1272] |

Sand dunes | [1274] |

Tidal currents | [1276] |

A parallel river | [1286] |

The significance of beheading | [1290] |

Other issues affecting weight of the evidence | [1295] |

The alleged significant risk arising from the activity | [1298] |

PART VII | [1311] |

THE RISKS ARE NOT NEW | [1311] |

OTHER MATTERS | [1315] |

ORDERS | [1321] |

CHARLESWORTH J

1 The applicants, Simon Munkara, Carol Puruntatameri and Maria Purtaninga Tipuamantumirri are Aboriginal people from the Tiwi Islands. They assert that they have cultural and spiritual connections to the sea forming part of their clan country.

2 The Tiwi Islands are located about 80km north of Darwin in the Timor and Arafura Seas. Parts of those waters are offshore areas within the meaning of the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006 (Cth). The Act establishes a regulatory framework for petroleum exploration and recovery in offshore areas extending seaward to the outer limits of the continental shelf.

3 The respondent, Santos NA Barossa Pty Ltd ACN 109 974 932 is the proponent of a project for the extraction and export of gas from the Bonaparte Basin in the Timor Sea, known as the Barossa Project. It is the holder of a number of licences issued under the Act authorising certain activities for the construction of infrastructure for the extraction and conveyance of gas in offshore areas. One of those activities involves the construction of a 262km gas export pipeline (referred to at times as the GEP), commencing in the Barossa Field and joining the existing Bayu-Undan pipeline in the south. The pipeline route passes to the west of the Tiwi Islands, past Cape Helvetius and within 7km of Cape Fourcroy. When completed, the pipeline will be used to supply gas to a liquified natural gas processing plant in Darwin.

4 The applicants alleged that there is a risk that the construction of the pipeline, and its existence on the sea bed, will significantly impact their cultural heritage.

5 The Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage (Environment) Regulations 2023 (Cth) (2023 Regulations) came into force on 10 January 2024, less than a week before the publication of these reasons. They repealed and substituted the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage (Environment) Regulations 2009 (Cth) to which the parties referred throughout the proceedings. The provisions of the now repealed Regulations have been re-numbered or organised differently in the 2023 Regulations, but in substance they are left unchanged. An explanatory memorandum to the 2023 Regulations confirms that changes in language are not intended to alter the meaning of the law as previously in force. In these reasons I will refer to the Regulations as numbered and in force when this action commenced, as they are relevantly unchanged by the 2023 Regulations. Neither party has suggested that the outcome would differ under the law now in force and I am independently satisfied that is so.

6 The Regulations establish a regime for the preparation by a titleholder of an environment plan for an “activity”, and acceptance of the environment plan by the National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (NOPSEMA). On 9 March 2020 NOPSEMA accepted an environment plan relating to the construction of the pipeline, titled “Barossa Gas Export Pipeline Installation Environment Plan (BAA-100 0329) (Revision 3, February 2020)” (Pipeline EP). That is the environment plan that is “in force for the activity” for the purposes of reg 17(6) of the Regulations. It provides:

New or increased environmental impact or risk

(6) A titleholder must submit a proposed revision of the environment plan for an activity before, or as soon as practicable after:

(a) the occurrence of any significant new environmental impact or risk, or significant increase in an existing environmental impact or risk, not provided for in the environment plan in force for the activity; or

(b) the occurrence of a series of new environmental impacts or risks, or a series of increases in existing environmental impacts or risks, which, taken together, amount to the occurrence of:

(i) a significant new environmental impact or risk; or

(ii) a significant increase in an existing environmental impact or risk;

that is not provided for in the environment plan in force for the activity.

7 Regulation 8 provides that a titleholder commits an offence if the titleholder undertakes an activity after the occurrence of (relevantly) any significant new environmental impact or risk arising from the activity which is not provided for in the environment plan in force for the activity.

8 Multiple questions of construction arise, including the intended meaning of the words “occurrence”, “significant”, “new” and “risk”, which are not defined in the Regulations. As will be explained later in these reasons, the word “environment” is broadly defined in the Regulations to include (among other things) “cultural features” of places, locations, areas and ecosystems. The phrase “cultural features” is not defined.

9 The first applicant, Simon Munkara, commenced this action on 30 October 2023, two days before works for the construction of the pipeline were then scheduled to commence. Carol Puruntatameri and Maria Tipuamantumirri were later joined as the second and third applicants. The applicants are respectively members of the Jikilaruwu, Munupi and Malawu clan groups.

10 The applicants alleged that Santos presently has an obligation under reg 17(6) to submit a revised environment plan, that obligation having been triggered by an “occurrence”. They alleged that the construction of the pipeline gives rise to a significant new environmental impact or risk, or a significant increase in an existing environmental impact or risk, that is not provided for in the Pipeline EP, within the meaning of reg 17(6). They alleged that commencement of the works for the construction of the pipeline would constitute an offence under reg 8.

11 Numerous risks were relied upon, referred to at trial as relating to both “intangible cultural heritage” and “tangible cultural heritage”.

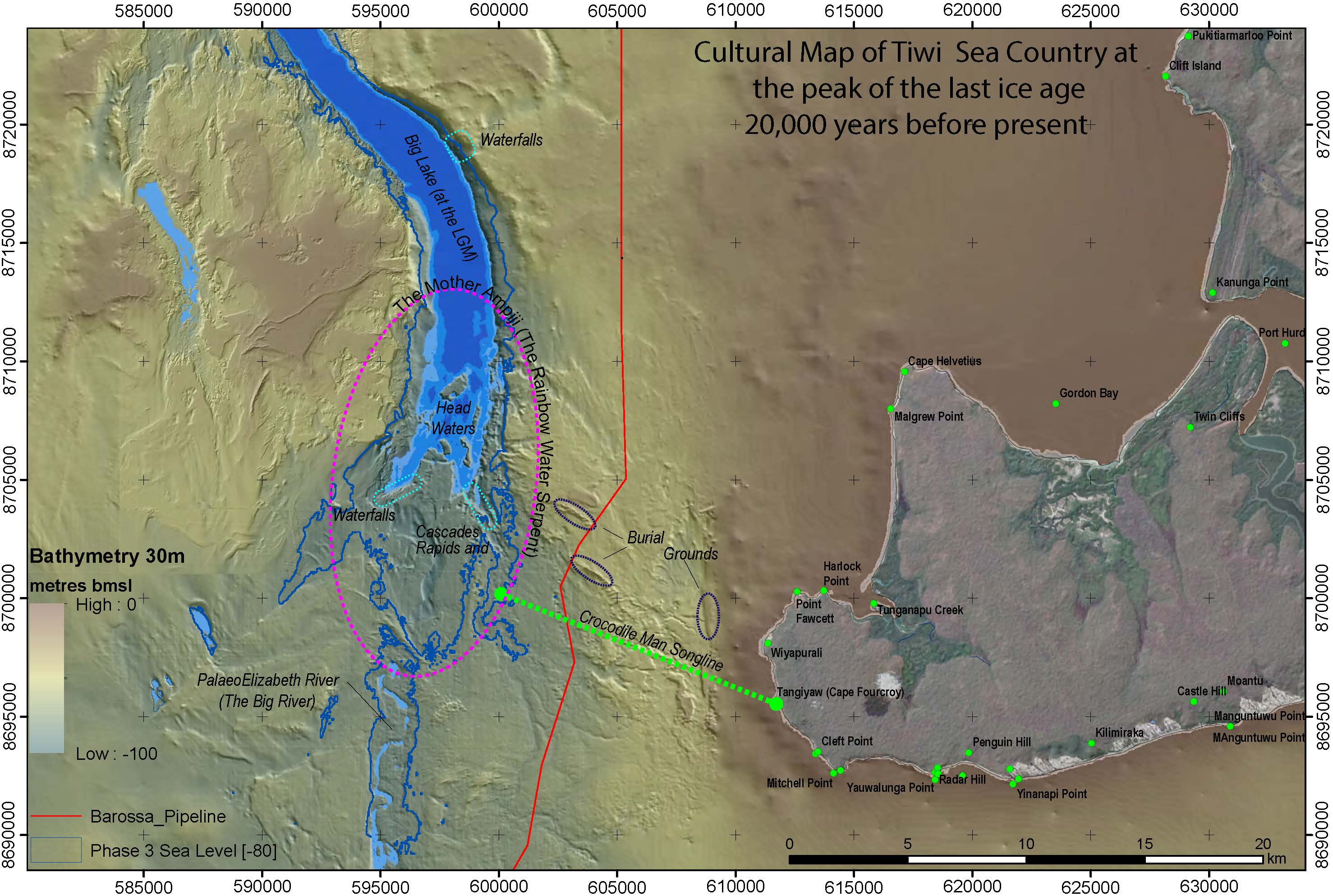

12 The case concerning intangible cultural heritage was based in part on two Dreaming stories said to form a part of the applicants’ cultural life relating to two ancestral or spiritual beings: a rainbow serpent or serpents known as Ampiji, and the Crocodile Man, known as Jirakupai.

13 There are two aspects to the intangible cultural heritage case.

14 The first aspect is one founded on ancient oral tradition, involving song lines told by certain clans of the Tiwi Islanders both in words and in their songs, dances and ceremonies over many generations. Reduced to its briefest expression, the allegation is that:

(1) There are one or more rainbow serpents named Ampiji, one of which resides in Lake Mungatuwu, a freshwater lake in the southwest of Bathurst Island. Ampiji is a caretaker of the land and the sea. She patrols the coastline around the Tiwi Islands and also travels into the deep sea and thus into the vicinity of the pipeline. The risk arising from the activity was alleged to include a fear that the construction and presence of the pipeline would disturb Ampiji and that she may cause calamities, such as cyclones or illness that would harm (at least) the people of certain clans. The applicants allege that the pipeline will thereby damage the spiritual connection of the Jikilaruwu, Munupi and Malawu people to areas of sea country through which the pipeline will pass.

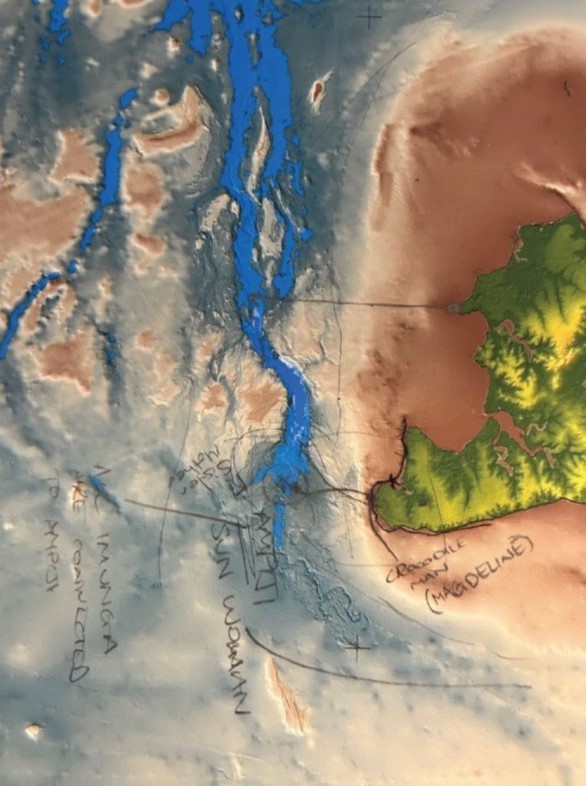

(2) The Crocodile Man song line is connected with a place in the sea in the vicinity of the pipeline. The applicants allege there is a risk that the activity will disturb the Crocodile Man in his travels and thereby damage the spiritual connection of the Jikilaruwu people to areas of sea country through which the pipeline will pass.

15 The second aspect of the intangible cultural heritage case relied upon what was referred to in closing submissions (but not before then) as “potentially adapted beliefs”. It involves an account of Ampiji said by the applicants to have been recently adapted in response to new information Tiwi Islanders have obtained about their sea country, presented to them by a geoscientist in June 2023. The new information, on the applicants’ case, is that in ancient times when the land now forming the sea bed was subaerially exposed, there existed a very large and deep freshwater lake in the area situated about 10km from what is now the western most point of Bathurst Island at or around Cape Fourcroy. At the mouth of the lake, the applicants allege, was an embayment (a recess in the landscape). Whether those features ever existed is an issue in dispute. I will refer to them as the Ancient Lake and the Ancient Embayment without suggesting any finding that they ever existed in fact.

16 The pipeline route lies between Cape Fourcroy and the place where the Ancient Lake and the Ancient Embayment are allegedly situated. The Ancient Lake is referred to in some materials as a “sacred freshwater source”.

17 The “potentially adapted beliefs” proceed from the premise that culture is ever changing, that matters of traditional cultural significance may evolve and adapt to new situations and circumstances, including new information and knowledge. The alleged adapted belief is that there exists a Mother Ampiji who lives in the Ancient Lake. The Mother Ampiji travels around the sea, including around the Tiwi Islands. The applicants assert a spiritual belief that the pipeline will pass between the Ancient Lake and the Tiwi Islands, that it will “disconnect” the Jikilaruwu, Munupi and Malawu clans from the Ampiji who lives in the Ancient Lake and thereby damage the spiritual connection of the Jikilaruwu, Munupi and Malawu people to the areas of their sea country through which the pipeline will pass.

18 The claims relating to Mother Ampiji and the Ancient Lake are also alleged to form a part of ancient Tiwi traditional knowledge and belief passed to Carol Puruntatameri by older generations.

19 The case founded on tangible cultural heritage alleged that there may be an archaeological record on and under the sea bed in the area to be affected by the activity, specifically objects and artefacts evidencing human occupation and activity from tens of thousands of years ago when the sea bed was subaerially exposed. The applicants alleged that there is a risk that the activity of constructing the pipeline and its embedment into the sea bed will cause the loss, destruction or relocation of some of that archaeological record and so presents a risk to Aboriginal cultural heritage having significance to the Jikilaruwu, Munupi and Malawu people. In addition, the applicants allege that the activity creates a risk of disturbance or destruction of a series of burial grounds that are said to be located between the pipeline route and the west coast of Bathurst Island.

20 Each of the alleged risks were described as involving a “real chance” of there being “notable” consequences, language that reflected the applicants’ preferred construction of reg 17(6).

21 The applicants allege that, for the purposes of reg 17(6), the risks asserted by them are “new” because they were not previously assessed by NOPSEMA and that they are not provided for in the Pipeline EP that is presently in force. They alleged that there was an “occurrence” of the risks within the meaning of the provision when the risks were first brought to Santos’ attention in late 2022 and throughout 2023, including by the commencement of these proceedings. They submitted that the conditions to trigger the obligation in reg 17(6) exist, and that Santos is therefore obliged to submit a revised environment plan to NOPSEMA for assessment. Upon the submission of such a plan, it would be for NOPSEMA to determine whether or not it should be accepted in accordance with conditions on its powers identified elsewhere in these reasons.

22 The above paragraphs give only a crude summary of the applicants’ case. They are intended to provide a sketch of broad issues so that the lengthy summaries of evidence that are soon to follow can be read with some framework of the allegations in mind. The case as finally articulated in closing submissions is detailed at [847] below.

23 The relief sought on the amended originating application filed 22 November 2023 included a declaration under s 39B(1A)(c) of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) and s 23 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) that:

1A. … the Respondent must submit a proposed revision to the Pipeline EP that provides for the risk posed by the Activity to submerged Tiwi cultural heritage, in accordance with reg 17(6) of the Environment Regulations.

24 In addition, the applicants sought a permanent injunction restraining Santos from undertaking the activity of laying the pipeline until it submits a proposed revision of the Pipeline EP in accordance with reg 17(6) and that revision is accepted by NOPSEMA.

25 This not an application for judicial review of any prior decision of NOPSEMA, and NOPSEMA is not joined as a party. The case articulated by the applicants was confined to an allegation that Santos has a present obligation to submit a revised environment plan. Even if that allegation were to be proven to the requisite standard, it would form no part of the Court’s function to decide what consultation must then take place between Santos and any person. Nor would it form any part of the Court’s function to determine what the content of any revised environment plan should be, nor to determine whether such a plan could or should be accepted by NOPSEMA.

26 For the reasons that follow the evidence does not establish that the obligation under reg 17(6) (properly construed) has been triggered. It follows that the amended originating application must be dismissed.

27 This action was commenced by originating application filed on 30 October 2023, accompanied by an interlocutory application seeking urgent injunctive relief. Simon Munkara was at that time the sole applicant. Argument on his application for interim relief extended into the evening of 1 November 2023. On the following day, the Court granted a short term injunction to restrain all work on the pipeline until 13 November 2023. Orders were made setting the matter down for more detailed argument on the question of whether there should be an ongoing injunction pending final judgment in the case. Oral reasons were given and written reasons followed: Munkara v Santos NA Barossa Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1348 (Munkara No 1).

28 In Munkara No 1, I explained why I was satisfied that the Court had jurisdiction to grant the relief then sought by Simon Munkara, and why I was satisfied at that time that he was a person who had standing to apply for it (at [39] – [55]).

29 The interim injunction remained in force until 15 November 2023. On that day, the Court granted an interlocutory injunction of a more limited kind. The order had the effect of restraining Santos from undertaking works on all but the northernmost 86km of the pipeline route and was expressed to remain in force until 15 January 2024, or such later date as the trial judge may determine: Munkara v Santos NA Barossa Pty Ltd (No 2) [2023] FCA 1421 (Munkara No 2). At the time of those orders, the final relief sought on the originating application was confined to an injunction. The claim for declaratory relief was later added by amendment.

30 In Munkara No 2, I addressed again the questions of jurisdiction and standing, including by rejecting a new argument raised by Santos on those questions. Questions of jurisdiction and standing have not been re-agitated and I remain of the views expressed in Munkara No 1 and Munkara No 2 on those interrelated topics.

31 An important feature of these proceedings is that the application for the interlocutory injunction was unsupported by any undertaking as to damages given by Simon Munkara or any person on his behalf. I concluded that it was in the interests of justice to proceed expeditiously to trial and judgment. That is principally because of conclusions I had previously drawn as to where the balance of convenience lay with respect to the injunctive relief, considered in light of the absence of the usual undertaking, and having regard to an earlier indication from Simon Munkara’s Counsel that he and other likely applicants were ready to proceed to trial. In addition, contractual terms relating to the pipeline’s construction were such that Santos’s losses were likely to significantly increase if the restraint were to remain in force for a longer period of time.

32 In the circumstances just described, the Court’s practice and procedure provisions have been applied in a way to best achieve the objective of making final orders on or before 15 January 2024, being the earliest date on which the Court could conceivably deliver judgment, having regard to the number and nature of issues in dispute. The matter was made ready for trial within a tight timeframe given its factual and legal complexity. The trial proceeded over 10 days in tranches between 4 and 22 December 2023, including oral closing submissions. The Court then received written closing submissions on 4, 5 and 7 January 2024.

33 The matter proceeded by way of a concise statement and a concise response in lieu of formal pleadings, although as will be seen, over the course of the proceedings the applicants reframed some aspects of their case and abandoned others.

34 The Court received written and oral evidence from 23 Aboriginal witnesses from the Tiwi Islands (in roughly even numbers from both sides of the dispute). The focus of the applicants’ case is on the people of three clan groups having land and sea country on and to the west of the Tiwi Islands, namely the Jikilaruwu, Munupi and Malawu clans. The 23 witnesses were from six clans, namely the Jikilaruwu (Simon Munkara, Ancilla Warlapikimayuwu Kurrupuwu, Molly Munkara, Valentine Intalui, Magdalen Kelantumama, Marie Frances Tipiloura, Eulalie Munkara, John-Louis Munkara, Jonathon Munkara, Mario Munkara and Theresa Munkara), the Munupi clan (Dennis Murphy Tipakalippa, Pirrawayingi Puruntatameri, Richard Tungatalum and Carol Puruntatameri), the Malawu clan (Therese Wokai Bourke and Maria Tipuamantumirri), the Wurankuwu clan (Tony Majirliyanga Pilakui and Brian Dixon Tipungwuti), the Mantiyupwi clan (Kaitline Kerinauia, Wesley Kerinaiua and Walter Kerinauia) and the Wulirankuwu clan (Stanley Tipiloura).

35 Given the common surnames, I will refer to the Tiwi witnesses by their full names throughout these reasons.

36 The first tranche of the trial was conducted in Darwin over four days, it being the most proximate place to the Tiwi Islands, the place of residence of nearly all of the lay witnesses. The applicants’ early suggestions for an on-country sitting were rejected as unrealistic.

37 The Court made orders for lay evidence-in-chief to be adduced by way of affidavit or by adoption of written witness statements. The parties had liberty to apply to adduce evidence-in-chief viva voce. However, that liberty was not exercised, other than the applicants making an application to give song and dance evidence by way of demonstration under s 136 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). That application was disallowed principally because the time available for the sitting in Darwin was already too compressed, but also because there would be an insufficient opportunity for Santos to obtain advice and give instructions to enable the applicants’ witnesses to be cross-examined in respect of some disputed matters that were expected to arise from it. The applicants ultimately tendered video recordings of the songs and dances. The Court made a ruling limiting their use, to avoid unfairness arising from their late provision.

38 The Court has before it 26 expert reports prepared by multiple experts, many of them responsive or counter-responsive. It is convenient at this juncture to name the experts and to give shorthand descriptions for their reports. The shorthand descriptions will be used throughout these reasons without referring again to the report titles. Some of the earlier reports were commissioned and produced before the proceedings were commenced and for purposes relating to a General Direction issued by NOPSEMA, discussed below. Consequently, some of the instructions put to the experts do not align entirely with the subject matter of the litigation. Each report is to be understood in the context in which it was sought and prepared. For the most part the experts themselves have acknowledged that limitation.

39 For convenience I will use the title “Dr” in connection with most experts, meaning no disrespect to those with higher titles.

40 Dr Brendan Corrigan is a Consultant Anthropologist. He holds a PhD in Anthropology (University of Western Australia) and an Honours degree in Anthropology and Archaeology (Australian National University). He has consulted on anthropological and traditional owner issues in relation to native title, environment and resource matters. Dr Corrigan authored three reports:

(1) “Assessment to identify any underwater cultural heritage places along the Barossa pipeline route to the west and northwest of the Tiwi Islands, Northern Australia”, dated 15 September 2023 (prepared with the assistance of others) (Corrigan 1);

(2) “Report in response to Lewis Supplementary Report and two supplementary reports by Associate Professor Michael O’Leary”, dated 27 November 2023 (Corrigan 2); and

(3) “Supplementary Report, Dr Brendan Corrigan, 13 December 2023”, dated 13 December 2023 (Corrigan 3).

41 Dr Jodie Benton is a Director and Principal Consulting Archaeologist at OzArk Environment & Heritage. She has a PhD in Burial Archaeology, Bachelor of Arts First Class Honours (Archaeology) and Bachelor of Arts (Archaeology and English) (University of Sydney). Dr Benton has 35 years’ experience in managing archaeological projects, including Aboriginal and historic heritage assessments and community consultation. Dr Benton assisted in the preparation of Corrigan 1 and provided one further report, titled “Report of Dr Jodie Benton 27 November 2023”, dated 27 November 2023 (Benton 1).

42 Ms Stephanie Rusden is a Senior Archaeologist at OzArk Environment & Heritage. She holds a Bachelor of Science (Land and Heritage Management) (University of Wollongong), Bachelor of Arts (Archaeology) (University of New England), and a MicroMasters in Evidence-Based Management (Australian National University). Ms Rusden assisted in the preparation of Corrigan 1, but did not give evidence in the proceedings.

43 Mr Harrison Rochford is an Archaeologist at OzArk Environment & Heritage. He holds a Masters of Philosophy (Arts and Social Sciences), and a Bachelor of Liberal Studies (Advanced) (Psychology/Ancient History) (Hons) (University of Sydney). Mr Rochford assisted in the preparation of Corrigan 1, but did not give evidence in the proceedings.

44 Mr Gareth Lewis is a consultant anthropologist and member of the Australian Anthropological Society. He holds a Bachelor of Arts (Social Sciences) with majors in Anthropology and Asian Area Studies (Curtin University of Technology) and has published papers on anthropological issues related to the environment and resources. Mr Lewis authored two reports:

(1) “Barossa Gas Export Pipeline Installation Cultural Heritage Assessment” Anthropologist’s Report prepared for Simon Munkara, Dennis Tipakalippa, Pirrawayingi Puruntatameri, Therese Bourke, Lynette De Santis, Valentine Intalui and Edward Puruntatameri (clients of the Environmental Defenders Office)”, dated 21 July 2023 (Lewis 1); and

(2) “Barossa Gas Export Pipeline Installation Cultural Heritage Assessment: Anthropologist’s Supplementary report in response to Dr Corrigan’s report of 15 September 2023”, dated 24 October 2023 (Lewis 2).

45 Dr Amanda Kearney is an Anthropologist and Professor at San Diego State University and the University of Melbourne. She holds a PhD in Anthropology (University of Melbourne) and Bachelor of Arts with Honours (Anthropology) (University of Queensland) and has served as a consultant and expert advisor to NOPSEMA. Dr Kearney provided one report titled “A Report to the Environmental Defenders Office, in regard to Munkara v Santos (VID907/2023) – Barossa Development Drilling and Completions Environment Plan”, dated 27 November 2023 (Kearney 1).

46 Dr Andrew McWilliam is an Anthropologist and Professor of Anthropology at Western Sydney University. He is a Fellow of the Australian Anthropological Society and member of the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Dr McWilliam holds a PhD in Anthropology (Timor Ethnography) (Australian National University) and provided one report titled “Review of the methodologies adopted by Dr Brendan Corrigan and Mr Gareth Lewis”, dated 27 November 2023 (McWilliam 1).

47 Dr Henry W Posamentier is a Geological and Geophysical consultant and Adjunct Professor of Geology at the University of Western Australia. He holds a PhD in Geology, a Master of Arts (Geology) (Syracuse University) and Bachelor of Science (Geology) (City College of New York). Dr Posamentier works as a consultant in the petroleum exploration and development sector with a focus on depositional settings. Dr Posamentier authored seven reports:

(1) “Barossa Field Seafloor Late Pleistocene/Holocene Depositional Environment”, dated 11 July 2023 (Posamentier 1);

(2) “Comments on the Report of Wessex Archaeology LTD”, dated 11 August 2023 (Posamentier 2);

(3) “Comments on the Barossa Gas Export Pipeline Underwater Cultural Heritage Assessment Report”, dated 21 August 2023 (Posamentier 3);

(4) “Schedule of my Analysis of the Features identified in Wessex Archaeology LTD Report”, dated 2 September 2023 (Posamentier 4);

(5) “Response to Supplementary Report to the Barossa Gas Export Pipeline Installation Underwater Cultural Heritage Assessment by Associate Professor Mick O’Leary”, dated 4 October 2023 (Posamentier 5);

(6) “Additional Observations Regarding Barossa Field Pipeline Seafloor”, dated 27 November 2023 (Posamentier 6); and

(7) “Report Summarizing my Response to O’Leary Report of November 30, 2023, and to Wessex Archaeology Report of December 11, 2023”, dated 14 December 2023 (Posamentier 7).

48 Dr Mick O’Leary is an Associate Professor at the School of Earth Sciences and the University of Western Australia Oceans Institute. He holds a PhD in Marine Sciences (James Cook University). Dr O’Leary has consulted on resource project assessments and conducts research with a focus on geomorphology and archaeology. Dr O’Leary provided five reports:

(1) “Barossa Gas Export Pipeline Installation Underwater Cultural Heritage Assessment”, dated July 2023 (O’Leary 1);

(2) “Supplementary report to the Barossa Gas Export Pipeline Installation Underwater Cultural Heritage Assessment”, dated 11 September 2023 (O’Leary 2);

(3) “Further supplementary report responding to matters arising from a report authored by Dr Brendan Corrigan titled Assessment to identify any underwater cultural heritage places along the Barossa pipeline route to the west and northwest of the Tiwi Islands, Northern Australia”, dated 7 October 2023 (O’Leary 3);

(4) “Supplementary Report #3 Assessing uncertainty arising from findings in the Wessex and Posamentier underwater cultural heritage (UCH) assessments”, dated 27 October 2023 (O’Leary 4); and

(5) “Supplementary report #4 responding to matters arising from a report authored by Prof Henry Posamentier titled Comments on the Barossa Gas Export Pipeline Underwater Cultural Heritage Assessment Report”, dated 30 November 2023 (O’Leary 5).

49 Wessex Archaeology Ltd and its subcontractor Extent Heritage were commissioned by Santos, in response to NOPSEMA’s General Direction to undertake a targeted scientific archaeological assessment of the proposed route of the pipeline. Multiple specialists from different disciplines assisted in the preparation of two reports under engagement by Santos. When Santos informed the Court that it would not be calling any of those authors as part of its case, the applicants sought leave to issue subpoenas to six of them. Three of the subpoenas were later recalled. The remaining three addressees (Dr Hanna Steyne, Dr Andrew Emery and Dr Andrew Bicket) appeared in response to subpoenas and participated in a concurrent session with Dr Posamentier. In advance of that session, the three witnesses prepared a third report. The three reports are as follows:

(1) “Barossa Gas Export Pipeline Submerged Palaeolandscapes Archaeological Assessment Technical Report”, dated July 2023 (Wessex 1);

(2) “Barossa Gas Export Pipeline Submerged Palaeolandscapes Archaeological Assessment Recommendations”, dated July 2023 (Wessex 2); and

(3) “Independent Expert report”, dated 11 December 2023, (Wessex 3).

50 The experts were cross-examined in various concurrent sessions.

51 Prior to those sessions there were two pre-trial conclaves helpfully facilitated by a former Justice of this Court, the Hon Neil McKerracher KC. The following three joint reports were produced following the conclaves:

(1) “Anthropology report (Methodology)” of Benton, Corrigan, Kearney, Lewis and McWilliam (conclave 9 December 2023 report dated 11 December 2023) (Methodology Joint Report);

(2) “Geoscience report of O’Leary and Posamentier” (report dated 13 December 2023) (Geoscience Joint Report); and

(3) “Anthropology report of Corrigan, Lewis and Benton” (conclave 9 December 2023 report dated 14 December 2023) (Anthropology Joint Report).

52 The Court has before it video evidence falling within two categories. There are 10 video recordings of traditional dances performed by the applicants and other Tiwi Islanders evidencing their traditional connection to the sea and their song lines. There are a further 41 video recordings of some events that occurred at a workshop on 19 June 2023 with Dr O’Leary (June O’Leary Workshop).

53 I have personally viewed all of the videos.

54 There are two tender books before me, totalling more than 14,000 pages. Some of the more critical documents have been read in full. I have otherwise confined my attention to those documents or parts of documents to which the parties have specifically drawn my attention, whether during the course of the trial or in their oral and written closing submissions.

55 Some evidentiary material has been received subject to rulings under s 136 of the Evidence Act limiting their use. It is not necessary to repeat the reasons for those rulings here. The parties are aware of them and should approach these reasons on the basis that my consideration of the documents has been limited by them.

56 Before proceeding further, it is necessary to set out some background facts and findings on preliminary issues. Unless stated otherwise, the background that follows may be understood as based on unchallenged evidence or uncontroversial facts.

57 The shoreline of the present day Tiwi Islands has remained largely unchanged for about 8,000 years. However, about 18,000 years ago, much of what today constitutes the continental shelf was subaerially exposed. The period between about 26,000 and 20,000 years ago is referred to as the last glacial maximum (LGM), being the most recent time during the last glacial period that ice sheets were at their greatest extent. At that time, the shoreline lay well seaward of where it is today. The land masses now known as the Tiwi Islands did not exist as islands but rather formed a part of the mainland. The shoreline was located well north of the modern mainland shoreline, approximately 60km south of the centre of what is now the Barossa Field. That is referred to in the evidence as lowstand shoreline, lowstand being a time during which sea levels are at their lowest, typically during glacial periods in the Earth’s history.

58 Between about 20,000 to 18,000 years ago, the sea level was about 120m lower than it is today. From between 18,000 to 12,000 years ago, the sea level rose slowly. The rise in sea level accelerated between 12,000 to 10,000 years ago before reaching its present position about 8,000 years ago.

59 The more rapid flooding of the continental shelf and the associated movement of the shoreline are known as shoreline transgression. In the period of more rapid sea rise, the flooding proceeded at a rate of about 18mm each year. The shoreline transgression resulted in a landward shift of the shoreline by approximately 150km to 200km.

60 The present day Tiwi Islands are comprised of two large and several smaller islands. Bathurst Island (in the west) and Melville Island (in the east) are separated by the narrow Aspley Strait. To the south of Melville Island are the three smaller Vernon Islands. Clarence Strait lies between the Tiwi Islands and the mainland.

61 Under their traditional laws and customs, the people of the Tiwi Islands have a system of social and territorial organisation described by anthropologists as a manifestation of the creation era and ordained by their creation ancestors. As Dr Corrigan expressed it (Corrigan 1, [93]):

In common with other Australian indigenous societies … the Tiwi have a normative system of laws and customs which provides a format for appropriate social life, including marriage practices, economic practices, ceremonial matters and concepts of discipline and punishment for transgressions of the same. …

62 Santos accepts that the normative system is what defines Tiwi people as a society.

63 According to their laws and customs, Tiwi Islanders are members of clan groups and skin groups.

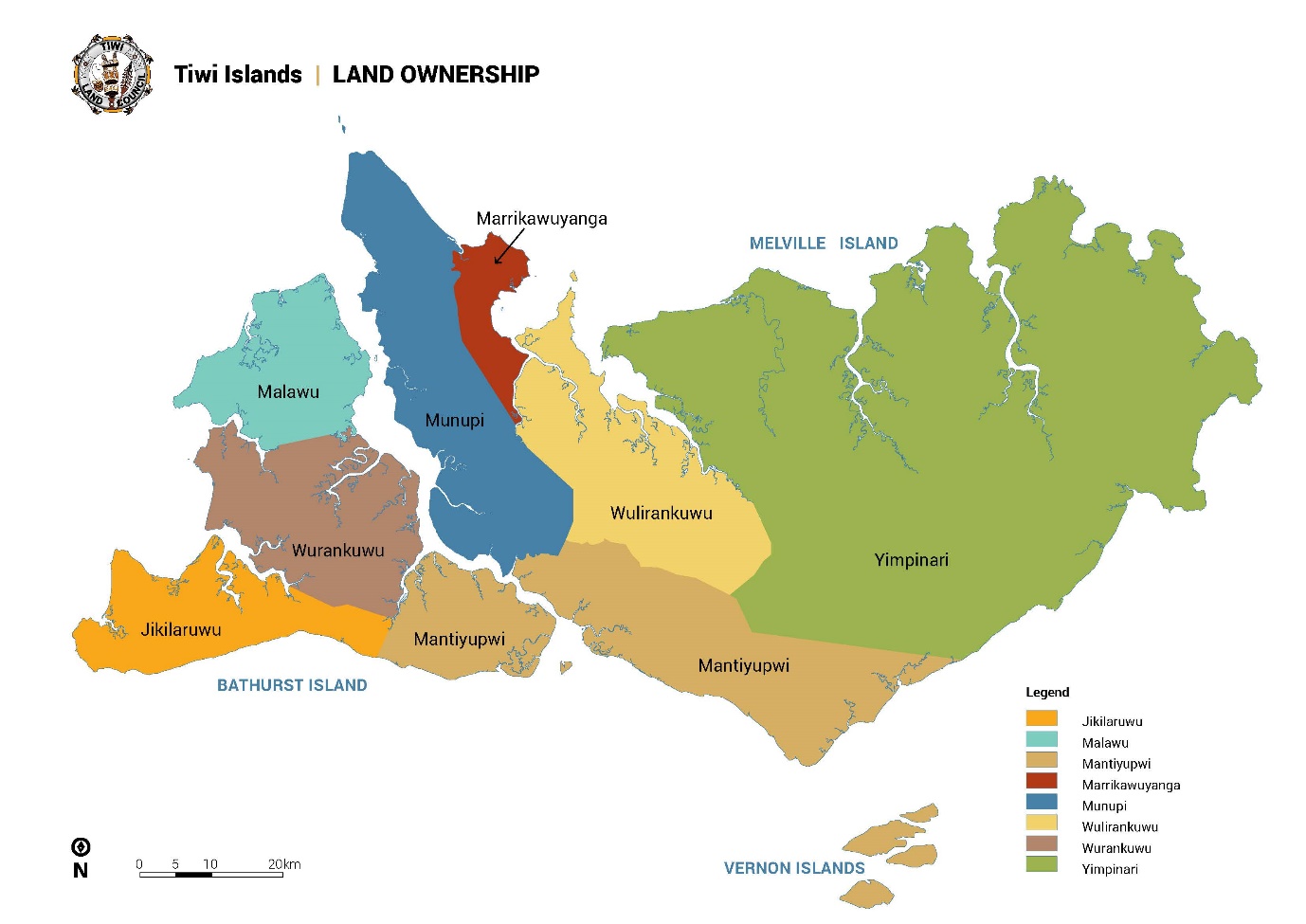

64 Clans are local descent groups, comprised of one or more lineages or families. The anthropologists described clan groups as the patrilineal or patrifocal territorial unit of Tiwi society. Clan membership is ordinarily determined by descendance through the father, although there may be interests in land or waters within a clan’s estate that are derived by adoptions, maternal lines or burials of certain ancestors at a place. There are eight clan groups: Jikilaruwu, Munupi, Wurankuwu, Malawu, Yimpinari, Mantiyupwi, Wulirankuwu and Marrikawuyanga.

65 Under modern law, the land that comprises the Tiwi Islands is controlled by the Tiwi Land Council under and in accordance with the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) (Aboriginal Land Rights Act). The Tiwi Land Council has responsibilities as a trustee of the interests of the Tiwi people as the traditional owners of the land and waters to which the statute relates. As I understand it, membership of the Tiwi Land Council is representative in nature, with each clan group having at least one person representing the interests of their clan estates.

66 The territorial locations of each clan are depicted on this map, prepared by the Tiwi Land Council (Map 1):

67 Membership of a skin group is acquired through the mother. The skin groups are non-territorial. They are manifestations of a kinship system which regulates marital and social relationships between clans and across the whole of Tiwi society. An aspect of that system is the avoidance relationship, prohibiting communications between certain individuals. Continued adherence to that customary practice was apparent throughout the course of the proceedings with witnesses at times declining to mention the names of others, explaining why they had not had dealings with another on the topic of the pipeline, or using the word “poison” to describe the relationship.

68 It was sometimes said by Tiwi witnesses that they did not speak in western concepts of boundaries. Those statements are to be understood in their proper context. The weight of the evidence is that there was a very strong sense among all witnesses that there existed such a thing as clan country. Map 1 demonstrates that the clan estates can and have been represented by the Tiwi Islanders themselves in a cartographic way, at least for some purposes. A good portion of the evidence focussed on the topic of who might have authority to speak for “Jikilaruwu country” or “Malawu country” or “Munupi country”, no witness questioning that such distinct places existed. That is hardly surprising given the territorial focus of the clans within the Tiwi social structure described by Dr Corrigan. Understood in their proper context, and at least when applied to land, assertions such as “we don’t speak in boundaries” may usually be understood as a reluctance to speak in terms of hard lines, absolute terms, modern measurements or two dimensions. But there is plainly such a thing as clan country: the Court was invited to assume the boundaries as depicted on Map 1 and to draw inferences about their natural extension into the sea.

69 The Northern Territory Aboriginal Sacred Site Act 1989 (NT) applies to the dry areas of the Tiwi Islands and the Northern Territory seas (extending about 2km from the shoreline). The Tiwi Land Council has been instrumental in recording and registering sacred sites under that regime, resulting in a map depicting many sacred sites on the land including around the coast. I accept that is an ongoing process. At present, the registered sacred sites do not include any place beyond the coast and into the vicinity of the pipeline, but that is no doubt explained by the territorial limit of the legislation.

Cultural authority and the right to speak for country

70 The topic of cultural authority was all pervasive during the course of the trial. It arises in part because the Court has before it conflicting accounts about what constitutes “culture” in light of differing views among Tiwi people as to whether the pipeline will have the impact the applicants assert. The applicants in particular sought to address that issue by inviting the Court to identify those who could, in accordance with Tiwi custom, speak authoritatively on a topic and to afford little or no weight to those who did not. The topic of cultural authority at times was equated with the question of which person had a right to speak for which country. The issue most often arose in the form of questions in cross-examination, putting the proposition that only Jikilaruwu can speak for Jikilaruwu country or song lines. Those questions did not get to the nub of the matter. They belied some complexity as to who could have an interest in (for example) Jikilaruwu country other than by way of patrilineal descent. They did not assist the Court to identify what song lines were exclusive to any particular clan. They were peculiar in a sense because the applicants themselves sought to draw on evidence of less senior Jikilaruwu people in preference over the evidence of those more senior, and to some extent draw on the evidence of non-Jikilaruwu people in relation to song lines that they say are exclusively Jikilaruwu. Perhaps most importantly, they do not assist the Court to grapple with the stark reality in the evidence that there were conflicting accounts given by Jikilaruwu clan members (including senior members of the same family group) about the content of song lines and the impact of the pipeline upon them. It will be necessary to return to the question of cultural authority and the related question of dissent. It is an issue infiltrating nearly all of the broader issues in dispute.

Spiritual beliefs, Dreamings and song lines

71 In these proceedings it is necessary to avoid language that labels “a thing” without carefully examining it for its essential meaning and features. As the Anthropology Joint Report stated:

We note that the term ‘Songline’ is a popular gloss for complex social phenomena akin to other glosses such as ‘Dreamings’ and ‘the Dreamtime’. We caution that such terms often hold contextually variable meaning(s) amongst Tiwi people which can be misleading. The following answer seeks to provide a best effort summary of how the term is used on the Tiwi Islands.

Songlines are sung narratives which recall and maintain the actions, journeys and behaviours of the creation ancestors. Songlines serve as a mnemonic device for maintaining and transmitting narrative across generations. They also serve to identify and justify cultural knowledge and proof of ownership of country. They act as a form of charter connecting the creation ancestors to the present bridging the gap between ancestral past and present. Ownership and performance of songlines emphasises connections both within clans to a specific segment of a songline relevant to their clan estate, as well as between clans and individuals who may share knowledge of all or parts of a songline for and beyond their own estate. Songlines are not physical features of the landscape or fresh water or the sea but they typically name and describe the actions of creation ancestors often with reference to particular sites and/or places.

72 Dr Corrigan added that he did not use the phrase “song line” in his reports or notes, that it did not appear to be a Tiwi word nor to have a Tiwi equivalent. He preferred the more nuanced phrase “traditional songs and any associated places therein mentioned”. In these reasons I will use the phrase “song line” to convey that same nuanced idea, subject to all of the qualifications to which I have just referred. So qualified, there are three song lines that should be briefly identified by way of background.

73 In Corrigan 1, Dr Corrigan extracted passages from a 2008 report of Mr Graham written for the purpose of supporting a land claim by the Mantiyupwi clan relating to the Vernon Islands. Mr Graham explained the creation story on the basis of information drawn from his Mantiyupwi informants as follows:

99 The Tiwi myth begins at the place known as Murupianga, on the Melville Island coast north east from Cape Gambier. From here an ‘Old Woman’ known as Mudungkala (Murtutakala), the ‘creation lady’ as one Tiwi described her, emerged from the ground. She had been living underground and broke to the surface by digging upwards with her wooden digging stick. She had three children, two girls and a boy (who are in turn major elements of Tiwi mythology, particularly her son Purrukuparli whose later story underlies the pukumani story). Mudungkala travelled widely in the area and created the islands, her journey forming the coasts of Bathurst and Melville Islands by extensive digging of the land’s surface with her stick. Water from the sea flowed into her depressions and created all of the waters and coastlines including the Clarence Strait. The claim area was described to the author by Tiwi informants as having been created by her. Mudungkala and her children’s story is one of the main Tiwi Dreamtime narratives and is to be found in a number of the published works on the Tiwi. Morris’ map number 5, (2001: 19) illustrates the ‘Creative Travels of Mudungkala (Murtankala)’. She formed the strait separating Bathurst and Melville Islands, as well as the Clarence Strait. Mudungkala and her children are shown in a painting exhibited at the Tiwi museum at Nguiu (copied below). [images not copied]

100 The various versions of this mythology are all essentially similar, Morris for example says that:

... the Tiwi hold that their islands were created by a woman, in this case an old, blind lady named Murtankala (also spelt by various researchers as Murdankala, Mudangkla and Mudungkala). Briefly, in the distant past the land was covered in darkness and contained no geographical features, animals or humans. Below the earth there lived some spirit people, including Murtankala and her three children. One day she dug her way up to the land’s surface. As she crawled about searching for food for herself and her infant children she gradually carved out the outlines of the Tiwi Islands. During her arduous journey she carried the children in a bark basket or tunga. Water flowed in behind Murtankala to surround the islands. The Creator Being began and ended her slow journey at Murupianga, on what is now the coast of Yimpinari (Impinari). Here she placed her children on the beach. With a bark torch she lit up the world, making day and night. Before disappearing forever, Murtankala clothed the islands with vegetation and introduced animal life to provide food for her children, Purrukuparli (Purukuparli) and his sisters Wurupurungala and Murupiyankala, the ancestors of the Tiwi. In his last hours on Melville Island, Purrukuparli performed the first Pukumani mortuary ritual near Cape Keith (Eeparli), declaring that thereafter all Tiwi were duty bound to carry out this ritual whenever an Islander passed away (Morris, 2001: 14-16).

101 It is Mudungkala's creativity, among other things of course, that is celebrated in Tiwi ritual. The most significant of these rituals are the kulama and mirringilaja initiations and pukumani funerary and mourning rituals. Again detailed accounts of them all can be found in the various ethnographic works referred to above: (Mountford, (1958), Hart and Pilling, (1960), Goodale, (1971) and Brandl, (1971). Of these, the Pukumani rituals are the most well known, involving the spectacular painted poles. While carried out as part of the last rites for deceased persons, these rituals have many other aspects as well.

(footnotes omitted)

74 The Anthropology Joint Report confirms that Mudungkala and her children are foundational creation narratives which are Tiwi wide. They explain the existence of the Tiwi Islands and the identity of the Tiwi people as islanders.

75 Yiminga (sometimes spelt Yimunga, Imunga or Imunka) was described in various ways by the Tiwi witnesses, most often as a spiritual force or presence. There is Yiminga present at sacred sites (especially but not only at burial sites). The word was used to refer to the real presence of ancestors in the here and now. Another witness said that the word meant “heart”. In Charles Mountford’s early ethnography (Mountford, C.P., The Tiwi: their art, myth and ceremony (Phoenix House, 1958)), Charles Mountford described it as “a universal life essence which permeates all living things, the plants, the creatures and man”.

76 In their concise statement the applicants originally referred to there being Yiminga in the whole of the sea. They alleged, as a discrete aspect of their claims, that the pipeline would disturb that Yiminga. Yiminga is now relied upon in the more narrow context of the claim relating to the travels of Ampiji, discussed below.

77 On a boat trip on 9 June 2023, Valentine Intalui explained Yiminga to Dr Corrigan as meaning a life force, something that gave Tiwi people their strength. He said “That’s how we have become”. Dr Corrigan asked Valentine Intalui if Yiminga was a life force in relation to everything, how was it that a house could be built near the place that they were then discussing. In cross-examination, Dr Corrigan paraphrased Valentine Intalui’s response: “Houses can be there because we know the right place, if there’s no sacred site or burial”.

78 Beliefs about Ampiji (sometimes spelt Ampitji) among Tiwi Islanders are varied in several respects, particularly on the question of the extent of her travels and the related question as to whether the pipeline would cause her to become disturbed. There are also differing accounts as to whether there is more than one Ampiji, and as to whether there exists a Mother Ampiji. Some of those differences are more significant than others.

79 The differences in account were as apparent in the evidence given in these proceedings, as they were at the time that Dr Corrigan obtained informant accounts for the purposes of preparing Corrigan 1. Dr Corrigan said that locations where Ampiji was said to reside on Bathurst Island, were Lake Mungatuwu (a freshwater lake on Jikilaruwu country on the southwest coast) and Rocky Point (a protrusion on the northwest coast of Malawu country). Some informants told Dr Corrigan that the Ampiji believed to inhabit Rocky Point and Lake Mungatuwu were one and the same, others said they were different. Dr Corrigan said that when passing those places on various boat trips, “relevant Tiwi Islanders” would call out to the spirits of ancestors and Ampiji to assure them that correct people were taking visitors to look around in the proper manner” (Corrigan 1, [110]). He said that he was advised that was the best way of taking people around and introducing them to the country and the spirits within it, to ensure the visitors’ physical and spiritual wellbeing.

80 Dr Corrigan reported that there were different accounts as to whether Ampiji went into the sea. In a passage relied upon heavily by the applicants, he said (Corrigan 1, [3]):

A consistent theme which has emerged among some informants is that a spirit being (or spirit beings) called Ampitji (sometimes known as a rainbow serpent, sometimes said to be plural, and sometime male or female in various versions) routinely traverses all of the sea in the vicinity of the islands and the GEP and that Ampitji might become disturbed by the laying of the GEP and cause spiritual and physical harm to the Tiwi Islanders and others. In some instances, people who believe this also believe that preventative measures, such as having relevant Tiwi people ‘introduce the pipeline and its work to the rainbow serpent’ would ameliorate any risk. Others have put the view that Ampitji remains fairly local to known geographic sites on the islands and does not travel in the sea around the Tiwi Islands.

(footnote omitted)

81 Fundamentally, it does not appear to be disputed that the spiritual belief in one or more Ampiji is a feature of Tiwi Islanders’ spiritual life, but is not exclusive to the Jikilaruwu, Malawu and Munupi clans. References to one or more Ampiji in earlier ethnographic materials confirm that the narratives about Ampiji are a long-standing feature of Tiwi spiritual life and that Ampiji may also have a role to play in ensuring compliance with Tiwi law. So much is not disputed by Santos.

82 Prior to this litigation there were several accounts of the Crocodile Man story recorded in writing by or with the assistance of Tiwi Islanders. Some of those accounts will be extracted here. The first comes from a book titled “Murli la: Songs and Stories of the Tiwi Islands”:

Song titled “Tini Ngini Yirrikapayi Yima Kapi Wiyapurali”

The crocodile man is sitting down making a spear

He was at this Country/home Wiyapurali on the beach

His people [of the tribe] Jikilawula did not like him

Because he did not share the land

Lying low down in the mud

When he crawled away and he changed into the crocodile

He crawled towards the sea with the spear in his back

At Wiyapurali they saw him - he was running very fast

The sharp pointed spear went through its back

Crocodile goes out with the sea

His people [of the tribe] Jikilawula did not like him

They all said you will be, from now on, the crocodile wuwu!

83 In the same text there is a reference to a heavy ceremonial spear known as the “Arawanakiri” with a broad spearhead at both ends resembling the tail of the Crocodile Man.

84 The story of the Crocodile Man is told in relatively the same terms in a picture book created in 1991, with a notation that it was sung by Beatrice Kerinaiui.

85 The following is an extract of the Crocodile Man story from a display at the Patakijiyali Museum, which some witnesses said accorded with the story told to them by their Elders:

Then Yirrikipayi ran and jumped. Hanging from his back were the spears that the people had thrown in him. Then he crawled along the beach cried out in pain and dived into the sea. After diving into the sea, he then surfaced for air far out in the deep water.

Then all the people came to watch him. ‘You are now the crocodile,’ they all shouted. ‘Your name will be crocodile,’ they said. So that is what we call him. His mother, Pawunga, cried for her son. Then she was transformed into Pied heron.

Pawunga sang this song for her son: ‘He was speared in the back so he ran into the sea at Wiyapurali. Then they called him ‘crocodile’.’

86 With only minor exceptions, the Tiwi Islander witnesses referred to a beach near Cape Fourcroy as the place where the Crocodile Man entered the sea. That aligns with the accounts given to Dr Corrigan, as summarised in Corrigan 1:

130. In the various instances where people raised details of the very well-known and routinely quoted story of the Crocodile Man, it was stated that he patrolled the various waters in the vicinity of a cave on the sea water edge on Cape Fourcroy, known as Wiya Pureli. When we visited that cave on boat trip #2 (16 March 2023), I was advised by the various Tiwi male delegates that the Crocodile Man lived in that cave and would patrol the waters up and down the coast in the general area, keeping an eye on things.

131. It is also the case that some Tiwi informants advised me about other spirit crocodile beings, who inhabit the seas in other parts of the Tiwi Islands, including one at Karlslake (to the northwest of Milli). Based on my interviews, there are no specific ‘underwater cultural heritage places’ that were identified in relation to the Crocodile Man along the GEP corridor.

87 Dr Corrigan reported accounts of the Crocodile Man travelling “in a range of locations”. He went on to note that it was apparent that the significance of a pipeline on the sea bed “to the movements of the Crocodile Man” was the subject of considerable disagreement amongst relevant Tiwi Islanders.

88 Individual Tiwi Islanders spoke of having a totem, often a plant or animal having special spiritual significance to them, and an attendant sense of responsibility to care for the environment in which their totem species lived or moved. Concerns about the environmental impact or risks of the pipeline were in some instances expressed as a concern about risks to a particular totemic species, such as the turtle or dugong. Although that is not articulated as a discrete risk upon which the applicants’ claims were based, they may inform the question of whether there exists a spiritual connection to areas in the sea through which the pipeline will pass.

89 As I have mentioned, the Pipeline EP is the environment plan that is “in force” for the relevant activity concerning the pipeline. Its preparation followed the acceptance by NOPSEMA of the Barossa Area Development Project Proposal in March 2018. The objective of the Barossa Project is to develop a “gas and light condensate field using a Floating Production Storage and Offloading (FPSO) facility, subsea production system, supporting subsea infrastructure and the pipeline.”

90 The Pipeline EP is one of several environment plans relating to the Barossa Project. It is structured in a way so as to address the detailed requirements for an environment plan prescribed in the Regulations. The following description of the pipeline and the environment that may be affected by it is drawn from the Pipeline EP itself.

91 The Barossa Field is located in the Bonaparte Basin in 210 – 2275m of water. Australia’s northwest continental shelf edge lies approximately 60km south of the centre of the Barossa Field. The pipeline extends from the Barossa Field approximately 227km north of the Northern Territory mainland, to a tie-in location at the existing Bayu-Undan to Darwin pipeline approximately 100km north of the mainland.

92 Water depths along the pipeline route range from between 33m to 254m and the pipeline traverses three geomorphic regions:

(1) continental outer shelf/slope (KP0 – KP73) comprising the shelf break and slopes of the Arafura Shelf characterised by gentle slopes (up to 0.2°);

(2) continental middle slope (KP73 – KP106) comprising a carbonate bank and terrace system of the Van Diemen Rise with intersecting valleys between banks; and the

(3) continental inner shelf (KP106 – KP262.39) comprising variable sediment types, including sub-aerially exposed cemented materials and significant terrestrial sediments especially in shallower water depths.

93 The “activity” consists of the installation of a 262km long 26-inch diameter carbon steel, concrete coated rigid pipeline. It encompasses installation of “pipeline end terminators” (PLET) including foundations and concrete mattresses to control flex and movement. The mattresses are to be made of blocks of dense material (typically concrete) bound together by flexible cables. The mattresses are 6m x 3m in area. Some scour protection may be added to the mattresses adding a further 3m around the structures. In addition, wedge-shaped support structures will be used, each having a sea bed footprint of 4m x 4m, with up to 3m of surrounding scour protection.

94 The total sea bed footprint (including the pipeline itself) is estimated to be 28.7ha.

95 The outside diameter of the pipeline varies according to the depth of water along its route, but it will not exceed 661mm in any one place. Once installed, the pipeline is expected to embed itself on the sea bed, at varying depths, not exceeding 65cm.

96 Places along the pipeline route are referred to by reference to their distance in kilometres from its northern most PLET (K0) to its tie-in point at the southern end (around K262). The distances from places on the Tiwi Islands are apparent in the map forming Schedule A to Munkara No 2.

97 The “operational area” is the area in which vessels constructing the pipeline will operate. It consists of a 3000m radius around each PLET and a 2000m buffer along each side of the pipeline route, reduced in some sections to remain within a proposed route presented in the accepted proposal.

98 The pipeline route passes over an existing fibre optic cable system located at KP257.3. Concrete mattresses are to be installed at that crossing point.

99 The pipeline route is said in the Pipeline EP to minimise the installation of the pipeline over areas of sea bed that are associated with certain features and values, including the shelf break and slope of the Arafura Shelf, and a carbonate bank and terrace system of what is known as Van Diemen Rise. The route crosses that bank and terrace system at two instances; between about KP70 and KP110 and in the south between about KP250 and KP255.

100 The Pipeline EP refers to a process known as “Mass Flow Excavation”, a method of “Span Rectification”, that involves:

… both pre-laying (i.e. by creating a trench for the pipeline) or post-laying (i.e. by facilitating burial) of a pipeline if a given span cannot be effectively rectified using mattresses or grout bags. Mass flow excavation reduces span heights at the span shoulders and assists pipeline stability by facilitating partial or complete burial of the pipeline in unconsolidated sediments. Mass flow excavation may be achieved by localised suction or jetting of water, with resuspended sediments being moved away from the pipeline. This process results in localised lowering of the pipeline into the sediment, with subsequent partial or complete burial of the pipeline providing stabilisation and therefore removal of a pipeline span. The direct disturbance footprint of mass flow excavation is dependent on the depth of excavation required. Use of mass flow excavation will be limited and any associated seabed disturbance has been included in the footprint estimations for span rectification in Table 3-6.

101 There is a dispute between the parties as to whether mass flow excavation would or could lawfully be employed, Santos having informed NOPSEMA of an intention not to carry it out. As will be explained, I have not considered it necessary to resolve that issue.

102 Once installed, the pipeline will be cleaned using chemically treated sea water, including a dye, up to 15,000 cubic metres of which will then discharge at the termination end.

103 In accordance with the Regulations, the Pipeline EP defines the “environment that may be affected” (EMBA) by the activity. Its spatial extent was identified using modelling technology assuming a spill scenario resulting from a vessel-to-vessel collision, as that represented the largest geographic extent of the EMBA. That is a much larger area than the 4km wide operational area along the pipeline route, and extends to the Tiwi Island shores.

104 The Pipeline EP contains an assessment of the environmental features and values of the operational area and the EMBA, by reference to the very broad statutory definition of the word “environment” discussed later in these reasons. It identifies biologically important areas, such as habits for marine life, for example turtles and dugongs.

105 Under the heading “Aboriginal Heritage” there are statements that “There are no recorded Indigenous heritage sites within the Operational Area” and “The Tiwi Islands are a declared Aboriginal reserve and comprise a number of protected sacred sites”. There are references to studies undertaken, among them a study titled “Tiwi Islands sensitivity mapping study” described as:

Collection of data on environmental, social, cultural and economic sensitivities for the Tiwi Islands. A desktop review of available data (spatial datasets) was followed by workshops with Traditional Owners to identify cultural and environmental sensitivities along the coast of the Tiwi Islands.

106 Part 4.6 of the Pipeline EP is titled “Socio-Economic and Cultural Environment”. It contains the following:

4.6.6 Aboriginal Heritage

There are no recorded Indigenous heritage sites within the Operational Area. The Tiwi Islands are a declared Aboriginal reserve and comprise a number of protected sacred sites under the Northern Territory Aboriginal Sacred Sites Act. Traditional practices (including fishing, which is addressed in Section 4.6.8) continue to take place on the islands. Most traditional fishing occurs within 3 nm of the shoreline.

ConocoPhillips undertook a mapping exercise with the Tiwi Island Land Council to identify environmental and socioeconomic values along the Tiwi Islands coastline (ConocoPhillips, 2019). The mapping exercise focussed on the northern, western and southern coastlines of the Tiwi Islands (within the EMBA). It included an initial desktop exercise to identify publicly available environmental, social, cultural and economic data sets. Preliminary maps were developed based on these datasets, and these maps were used during stakeholder engagement workshops held with Tiwi Islanders.

Two workshops were held, the objectives of which were to verify the preliminary maps and to gain a more thorough understanding of the environmental, social, cultural and economic sensitivities of the coastlines. Final maps were then developed and presented to the Tiwi Island Land Council.

The sensitivity mapping identified Aboriginal heritage sites along the northern, western and southern coastlines of the Tiwi Islands, including areas used for food collection, sacred sites, camping sites and a dreaming site. These coastlines are within the EMBA but outside the Operational Area.

107 The Pipeline EP also contains information about traditional fishing activities which need not be elaborated upon here.

108 Part 7.6.5 of the Pipeline EP contains processes for the “Management of Change”. That portion of the Pipeline EP states that a revised environment plan will be submitted if the obligation under reg 17 is triggered. As such, the Management of Change processes are not to be regarded as a mechanism for avoiding the obligation under reg 17(6), should it arise. The Pipeline EP also states that it may also be revised in line with the Management of Change process, but may not be resubmitted to NOPSEMA if reg 17(6) does not require it.

109 Part 8 of the Pipeline EP contains information about stakeholder consultation, including consultation with Indigenous groups. I will return to the question of consultation at the conclusion of these reasons.

EVENTS PRIOR TO THE LITIGATION

110 The applicants are legally represented by the Environment Defenders Office (EDO). The identity of a party’s lawyer is not ordinarily relevant, however in this case the EDO has undertaken work that forms a part of the factual background against which the issues are to be decided. In correspondence preceding the litigation (directed to both Santos and NOPSEMA) the EDO stated that it represented five clients, including Simon Munkara and three other witnesses in these proceedings.

111 The proponents of the Barossa Project originally included ConocoPhillips Australia Exploration Pty Ltd. In 2018, ConocoPhillips submitted the Barossa Area Development Offshore Project Proposal (Barossa OPP) to NOPSEMA in relation to a potential offshore development area approximately 100km north of the Tiwi Islands and 300km north of Darwin.

112 Acceptance by NOPSEMA of the Barossa OPP relating to the whole of the Barossa Project was necessary to enable ConocoPhillips to submit environment plans to NOPSEMA for assessment of future project activities. NOPSEMA accepted the Barossa OPP in March 2018.

113 Preparation of the Pipeline EP then occurred between March 2018 and March 2020. The process involved (among other things) the preparation of geophysical surveys, geotechnical site investigations and environmental mapping processes. ConocoPhillips engaged Jacobs Group (Australia) Pty Ltd to consult with the Tiwi Islands community in relation to the impact of the project. The scope of that engagement is in dispute.

114 Proposed environment plans relating to the pipeline were published on 29 July 2019 (Revision 0), 6 August 2019 (Revision 1), 30 October 2019 (Revision 2) and 6 February 2020 (Revision 3). The various revisions were prepared as NOPSEMA provided Santos with opportunities to provide additional information, including additional information concerning its consultation processes.

115 The Pipeline EP (being Revision 3) was accepted by NOPSEMA on 9 March 2020. In its written statement of reasons NOPSEMA stated that it had considered the description of the environment that may be affected by the activity “including relevant values and sensitivities” and found that “[s]ocial, economic and cultural features of the environment relating to the Commonwealth marine area, Australian Marine Parks (in this case, the Oceanic Shoals Marine Park), reef protection areas, cultural and heritage values, defence areas, tourism and recreational activities, commercial shipping, Commonwealth and Territory managed commercial fisheries and petroleum industry activities” had been identified and described. NOPSEMA recorded its finding that (relevantly) “[c]ultural and heritage environment features and values have been identified and described”. When applying the criteria for acceptance of an environment plan, NOPSEMA recorded that it was reasonably satisfied that Santos had carried out the required consultations and that the measures they proposed to adopt because of the consultations were appropriate. NOPSEMA recorded its satisfaction that all other criteria for acceptance had been complied with and so accepted the Pipeline EP. There has been no application for judicial review of that decision.

116 On 14 March 2022 NOPSEMA approved an environment plan relating to offshore gas drilling in the Barossa Field (Drilling EP). The Drilling EP is one of five environment plans which together cover the various activities of the Barossa Project. It is not the same as the Pipeline EP.

117 By orders made by Bromberg J on 21 September 2022, NOPSEMA’s decision to approve the Drilling EP was set aside on judicial review: Tipakalippa v National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (No 2) [2022] FCA 1121; 406 ALR 41 (Tipakalippa No 2). Those proceedings were commenced by Dennis Tipakalippa, an Elder and traditional owner of the Munupi clan (and a witness in the present proceedings). The judicial review proceedings were confined to a challenge to the Drilling EP, and did not impugn NOPSEMA’s decision to approve the Pipeline EP, which had occurred about two years earlier. Mr Tipakalippa was represented in those proceedings by the EDO. A number of Tiwi Islanders provided affidavits in the proceedings which have been tendered in evidence before me. They included Dennis Tipakalippa, Pirrawayingi Puruntatameri and Carol Puruntatameri.