FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

North East Forest Alliance Inc v Commonwealth of Australia [2024] FCA 5

ORDERS

NORTH EAST FOREST ALLIANCE INC Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent | |

STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Second Respondent | ||

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application is dismissed.

2. On or before 4:00pm on Wednesday, 31 January 2024, the parties are to indicate to the Court whether they wish to be heard separately on costs.

3. In the event that agreement between the parties as to the appropriate orders for costs is not reached:

(a) the parties are to agree a timetable by 4:00pm on Wednesday, 7 February 2024 in which short submissions on, and any evidence with respect to, costs are to be filed and served; and

(b) subject to further order of the Court, any issue as to costs is to be determined on the papers.

4. Liberty to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRY J:

[1] | |

[7] | |

[9] | |

[10] | |

[15] | |

[28] | |

[37] | |

[47] | |

[50] | |

7 ISSUE 1: WERE FURTHER “ASSESSMENTS” REQUIRED BEFORE EXTENDING THE NE RFA | [53] |

[53] | |

[59] | |

8 ISSUE 2: DOES AN “ASSESSMENT” NEED TO BE EVALUATIVE AND REASONABLY CONTEMPORANEOUS TO SATISFY THE DEFINITION OF AN RFA? | [85] |

[85] | |

[89] | |

[106] | |

[106] | |

[112] | |

[134] | |

[153] | |

[153] | |

[163] | |

[175] |

1. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS

1 On 31 March 2000, the first respondent, the Commonwealth, and the second respondent, the State of New South Wales (NSW or the State), entered into an intergovernmental agreement being the Regional Forest Agreement for North East New South Wales (Upper North East and Lower North East) (the NE RFA). The purpose of the NE RFA included establishing “the framework for the management of the forests of the Upper North East and Lower North East regions”: recital 1A of the NE RFA. The NE RFA provided that it was to remain in force for 20 years from 31 March 2000, unless terminated earlier or extended in accordance with its provisions: clause 6 of the NE RFA. Subsequently, the Commonwealth Parliament enacted the Regional Forest Agreements Act 2002 (Cth) (RFA Act). A primary purpose of the RFA Act is to reinforce the certainty which the NE RFA and other RFAs between the Commonwealth and States were intended to provide for regional forestry management by “giv[ing] effect to certain obligations of the Commonwealth under Regional Forest Agreements”: s 3(a) of the RFA Act.

2 Shortly before the expiry of the 20 year period for the NE RFA, on 28 November 2019 the respondents executed the “Deed of variation in relation to the Regional Forest Agreement for the North East Region” (the Variation Deed). The Variation Deed stated that it “amend[ed] the Regional Forest Agreement on the terms and conditions contained in this deed”: Variation Deed, Preamble B. As described in further detail below, one effect of the Variation Deed was to extend the NE RFA at least by a further 20 years.

3 The applicant, North East Forest Alliance Incorporated, seeks a declaration pursuant to s 39B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) that the NE RFA as amended by the Variation Deed (the Varied NE RFA) is not a “regional forest agreement” within the meaning of s 4 of the RFA Act. The consequence of so holding would not be that the Varied NE RFA is invalid, as the applicant accepts. Rather, the consequence relevantly would be that neither s 38 of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act) nor s 6(4) of the RFA Act would apply so as to exempt forestry operations undertaken in accordance with the Varied NE RFA from the approval processes under Part 3 of the EPBC Act.

4 In essence, the applicant contends that the Varied NE RFA is not an RFA for the purposes of the RFA Act because, in amending the NE RFA, regard was not had to an “assessment” of “environmental values” and “principles of ecologically sustainable management” as required by paragraph (a) of the definition of an RFA in s 4 of the RFA Act. This is because, in the applicant’s submission, of the failure in the materials before the Prime Minister, who executed the Variation Deed on behalf of the Commonwealth, to sufficiently evaluate those matters and to do so on the basis of reasonably contemporaneous information.

5 Those submissions are rejected for the reasons which I develop below. First, properly construed, there is no requirement that regard must be had to an assessment before an RFA is amended, including by extending its term, in order that the intergovernmental agreement continue to meet the definition of an RFA. That requirement applies only where the parties enter into an RFA. Secondly and in any event, there is no implicit requirement that an assessment must be sufficiently evaluative and reasonably contemporaneous in order to satisfy the condition in paragraph (a) of the RFA definition. Rather, the question is whether, objectively speaking, regard was had to assessments of the values and principles referred to in paragraph (a) of the definition of an RFA. Thirdly, applying that test, the evidence establishes that the materials before the Prime Minister, and in particular the “Assessment of matters pertaining to renewal of Regional Forest Agreements” (Assessment Report), addressed each of the values and principles referred to in paragraph (a) of the definition of an RFA. That being so and there being no issue that the Prime Minister had regard to the materials attached to the Prime Minister’s brief, the applicant has not established that the Varied NE RFA is no longer an RFA for the purposes of the RFA Act, even if an assessment was required before the RFA was amended. It follows that the application for relief must be dismissed.

6 Finally, it is important to stress that the effect of an RFA is not to leave a regulatory void with respect to the forest regions covered by the NE RFA. Rather, as I explain below, an RFA provides an alternative mechanism by which the objects of the EPBC Act can be achieved by way of an intergovernmental agreement allocating responsibility to a State for regulation of environmental matters of national environmental significance within an agreed framework. As such, the question of whether or not to enter into or vary an intergovernmental agreement of this nature is essentially a political one, the merits of which are matters for the government parties, and not the Courts, to determine.

7 The applicant is an incorporated association, whose primary purpose is to protect the public native forests of north east NSW including threatened species and their habitat and old growth forests. Since 1989, it has been actively engaged in activities in pursuit of its objects including:

(1) conducting forest audits and reporting to the NSW Environment Protection Authority on potential contraventions of the applicable forest laws arising from the audits;

(2) advocacy in local and State media and public education;

(3) making submissions in response to State and Commonwealth government public consultation opportunities relating to native forest management and forestry operations in north east NSW;

(4) preparing and publishing reports concerning native forest management, forestry operations, and threatened species and ecological communities in forests in north east NSW; and

(5) participation, by invitation, in State and Commonwealth government committees concerning the management and regulation of forests in north east NSW and species that are found therein, including for the purposes of the Comprehensive Regional Assessment.

(Statement of Agreed Facts (SAF) at [1].)

8 It was rightly accepted by the respondents that the applicant has standing to seek declaratory relief and that there is, therefore, a justiciable controversy for the purposes of Chapter III of the Constitution and s 39B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth).

9 The relevant facts were largely not in dispute, being the subject of the SAF.

3.1 The National Forest Policy Statement

10 Together with the other regional forest agreements, the NE RFA was a product of the National Forest Policy Statement (NF Policy Statement or NFPS) signed by the Commonwealth and mainland State and Territory governments in 1992. Further, as I shortly explain, one of the objects of the RFA Act is to give effect to certain aspects of the NF Policy Statement. The purpose of the NF Policy Statement was to outline “agreed objectives and policies for the future of Australia’s public and private forests”: NF Policy Statement, p 1.

11 The adoption of the NF Policy Statement was a response to “the task of balancing competing interests of environment/conservation, industry and recreation regarding the use, management and conservation of native forests and forest resources”: Explanatory Memorandum to the Regional Forest Agreement Bill 2002 (Cth) (RFA Bill) p 3. This “had established a climate of uncertainty for investors and contributed to community uncertainty that environmental values were being adequately protected”: ibid. As such, the NF Policy Statement was intended to provide “a framework agreed by Commonwealth and all State Governments for a long-term and lasting resolution of conservation, forest industry and community interests and expectations concerning Australian forests”: ibid (emphasis added).

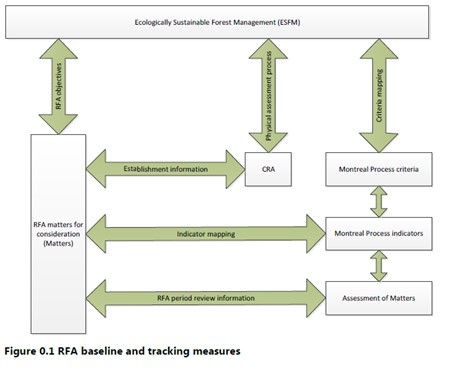

12 In furtherance of this objective, the NF Policy Statement required the Commonwealth and State or Territory Government to conduct joint comprehensive regional assessments (CRAs) of environmental, heritage, economic and social values relating to forests in certain regions. The essential features of those CRAs were explained as follows in the NF Policy Statement at pp 21–22:

The Governments have identified a single, comprehensive regional assessment process whereby the States can invite the Commonwealth to participate in undertaking all assessments necessary to meet Commonwealth and State obligations for forested areas of a region.

Comprehensive regional assessments will involve the collection and evaluation of information on environmental and heritage aspects of forests in the region. The Commonwealth will ensure that its evaluation of information is efficient, avoiding duplication and delays wherever possible and taking into account the analyses of other Commonwealth agencies where appropriate.

13 The CRAs were designed to provide the basis for “enabling the Commonwealth and the States to reach a single agreement relating to their obligations for forests in a region”: NF Policy Statement p 22. Those Commonwealth obligations were limited and said to include:

assessment of national estate values, World Heritage values, Aboriginal heritage values, environmental impacts, and obligations relating to international conventions, including those for protecting endangered species and biological diversity.

14 Subsequently, between 1999 and 2001, NSW and the Commonwealth entered into three RFAs, being the Eden RFA, the Southern RFA and the NE RFA. Those RFAs were executed following CRAs of the Eden, Upper North East, Lower North East, and Southern regions as I explain below. A further seven RFAs were signed between the Commonwealth, Tasmania, Victoria and Western Australia between 1997 and 2001. The purpose of the RFAs was, as the Full Court summarised in Vicforests v Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc [2021] FCAFC 66; (2021) 389 ALR 552 (Leadbeater’s FCAFC) at [29]:

to establish between the Commonwealth and the States a framework for the management and use of native forests. RFAs were intended to provide for the conservation of forests, and the flora and fauna found in them, while allowing for ecologically sustainable management and use of those forests. RFAs were concluded after a process of environmental assessment conducted by the Commonwealth to determine that State forest management systems would provide adequate protection to the environment. This included implementation of a Comprehensive Adequate Representative (CAR) Reserve System, and implementation of ecologically sustainable forest management (ESFM).

15 In January 1996, NSW and the Commonwealth entered into a Scoping Agreement for New South Wales Forest Agreements (the Scoping Agreement). By that agreement, the Commonwealth and the State stated their mutual intention “to proceed to the negotiation of Regional Forest Agreements (RFAs) for several regions of New South Wales, and to establish processes and timetables for their completion”. Amongst other things, the Scoping Agreement provided (at clause 23) that:

Both Governments aim to develop RFAs that will operate for up to 20 years. The Commonwealth and New South Wales agree to identify appropriate performance indicators to measure RFA outcomes and to develop monitoring arrangements and to report on those indicators and the performance of each RFA every 5 years. Both Governments also agree prior to the signing of each RFA, to identify exceptional circumstances which could influence those RFA outcomes significantly and which would require a reassessment and amendment of the RFA before its due expiry date.

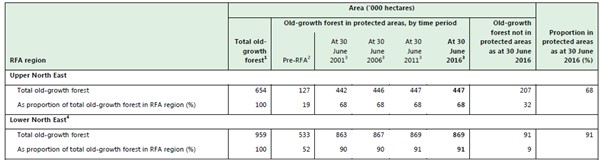

16 Furthermore, as envisaged by the NF Policy Statement, during 1997 and 1998 the Commonwealth and NSW undertook a comprehensive regional assessment in the Upper North East and Lower North East regions of NSW (the North East Region). The comprehensive regional assessment was summarised in the “North East CRA/RFA Project Summaries” published by the NSW and Commonwealth governments in 1999 and covered biodiversity, old growth, wilderness, endangered species, National Estate values, World Heritage values, Indigenous Heritage, social values, economic values and industry development opportunities in forested areas, and ecologically sustainable management.

17 On 31 March 2000, the Commonwealth and State entered into the NE RFA. The NE RFA established the “framework for the management of the forests of the Upper North East and Lower North East regions”. Recital B to the agreement provides that:

This Agreement is a Regional Forest Agreement … [T]he Agreement;

(a) identifies areas in the region or regions that the parties believe are required for the purposes of a Comprehensive, Adequate and Representative Reserve System, and provides for the conservation of those areas; and

(b) provides for the ecologically sustainable management and use of forested areas in the regions; and

(c) is for the purpose of providing long-term stability of forests and forest industries; and

(d) has regard to studies and projects carried out in relation to all of the following matters that are relevant to the regions:

(i) environmental values, including Old Growth, Wilderness, endangered species, National Estate Values and World Heritage Values;

(ii) Indigenous Heritage Values;

(iii) economic values of forested areas and forested industries;

(iv) social values (including community needs); and

(v) principles of Ecologically Sustainable Forest Management.

18 Clause 7 of the Agreement, contained in Part 1, confirmed the parties’ “commitment to the goals, objectives and implementation of the National Forest Policy Statement (NFPS)”. That goal was to be achieved, amongst other things, by “[d]eveloping and implementing Ecologically Sustainable Forrest Management” and “[e]stablishing a Comprehensive, Adequate and Representative (CAR) Reserve System”.

19 The NE RFA referred to a number of additional documents, agreed copies of which were attached to the SAF, namely:

(1) the Scoping Agreement;

(2) the assessment process carried out pursuant to Attachment 1 of the Scoping Agreement, being the “Comprehensive Regional Assessment” or “CRA”; and

(3) the “report by the Joint Australian and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council (ANZECC) / Ministerial Council on Forestry, Fisheries and Aquaculture (MCFFA) National Forests Policy Statement Implementation Sub-committee titled Nationally Agreed Criteria for the Establishment of a Comprehensive, Adequate and Representative Reserve System for Forests in Australia, published by the Commonwealth of Australia in 1997” (the JANIS Report).

(SAF at [5]–[6].)

20 Importantly for reasons I shortly explain, under the heading, “Duration of Agreement”, contained in Part 1, the NE RFA provides that:

5 This Agreement takes effect upon signing by both Parties and, unless earlier terminated in accordance with clauses 112, 113, 114 or 115, will remain in force for 20 years.

6 The process for extending the Agreement for a further period will be determined jointly by the Parties as part of the third five-yearly review.

21 It will be recalled that the Scoping Agreement, at clause 23, also contemplated the development of RFAs that would operate for 20 years.

22 Part 2 of the NE RFA is comprised of clauses 16 to 106 inclusive and deals with a wide range of subject matters including:

(1) annual reporting for the first five years by the parties on the achievement of milestones given in Attachment 5 (clause 39);

(2) five yearly reviews (clause 40);

(3) the parties’ agreement that ecologically sustainable forest management (ESFM) requires a long-term commitment to continuous improvement (clause 44);

(4) that key elements for achieving ESFM are the establishment of a CAR Reserve System, the development of internationally competitive forest products industries, and “integrated, complementary and strategic forest management systems capable of responding to new information” (clause 44);

(5) monitoring, reporting and consultative mechanisms (clauses 49–51); and

(6) the management of threatened flora and fauna (clauses 60–64), the CAR reserve system (clauses 65–72) and indigenous heritage (clauses 92–93).

23 However, clause 16 of Part 2 of the NE RFA provided that the Part was not intended to create legally binding obligations; similarly, the provisions of Part 1, “in so far as they relate to Part 2 are also not binding”: see also Recital B to the NE RFA. In this regard, the Full Court in Bob Brown Foundation Inc v Commonwealth [2021] FCAFC 5; (2021) 283 FCR 225 at [80] held that there was no requirement that an RFA must impose legally enforceable obligations in order to constitute an RFA for the purposes of the RFA Act.

24 As earlier mentioned, clauses 40–43 of the NE RFA establish a mechanism for five yearly reviews of the performance of the Agreement. Specifically, clause 40 of the Agreement relevantly provides:

40 Within each five year period a review of the performance of the Agreement will be undertaken. The purpose of the five-yearly review is to provide an assessment of progress of the Agreement against the established milestones, and will include:

(a) The extent to which milestones and obligations have been met, including management of the National Estate;

(b) The results of monitoring of Sustainability Indicators; and

(c) Invited public comment on the performance of the Agreement.

25 In contrast to Part 2, clause 107 provides that it is the parties’ intention that Part 3 (comprising clauses 107–115) creates legally enforceable rights and obligations. Among other provisions, clause 110.1 relevantly provides that the parties agree that:

110.1 If to protect the Environment and Heritage Values in native forests and in connection therewith the protection of:

(a) CAR Values;

(b) National Estate Values; or

(c) World Heritage Values; or

(d) Wild Rivers

the Commonwealth takes any Action during the period of this Agreement which is inconsistent with any provision of this Agreement and a foreseeable and probable consequence of which is to prevent or substantially limit: [certain uses of land outside the CAR Reserve System, selling or commercial use of Forest Products sourced from land not included within the CAR Reserve System, or constructing on land outside the CAR Reserve System]

…

the Commonwealth will pay compensation to the State in accordance with the remaining provisions of clauses 110.2 to 110.20.

26 Clause 2 defines “CAR Values” to mean the conservation values as described in the JANIS Reserve Criteria for establishing the CAR Reserve System, being criteria which address Biodiversity, Old Growth forest and Wilderness, taking account of reserve design and management and social and economic considerations. “Action” in turn is defined in clause 110.20(a) to relevantly mean the commencement of legislation (including subordinate legislation) and administrative action taken pursuant to or in accordance with legislation.

27 Clauses 110.2 to 110.20 set out the details of the compensation scheme. Specifically, under clause 110.1 the Commonwealth accepted liability to pay compensation for certain future acts, including passing legislation or subordinate legislation, which are inconsistent with the NE RFA: clause 110.20 of the NE RFA. The effect of clause 110.2, in-turn, is to extend the remit of debt compensation not only to the State Government, but to private persons as well.

28 On 28 November 2018, the Commonwealth and State executed the NE RFA Variation Deed, which amended the NE RFA. Importantly, the recitals to the Variation Deed under the heading “Context”, state that:

This deed is made in the following context:

A. The parties entered into the Regional Forest Agreement to establish a framework for the management of certain forests.

B. The parties have agreed to amend the Regional Forest Agreement on the terms and conditions contained in this deed.

C. Except as amended by this deed, the Regional Forest Agreement continues in full force and effect without amendment.

29 In line with the recitals, clause 3 of the operative provisions headed “Confirmations” provides that the parties confirm and acknowledge that:

a. this deed varies the Regional Forest Agreement, and does not terminate, discharge, rescind or replace the Regional Forest Agreement.

b. except as expressly agreed in this deed, its obligations and covenants under, and the provisions of, the Regional Forest Agreement continue and remain in full force and effect;

c. nothing in this deed:

i. prejudices or adversely affects any right, power, authority, discretion or remedy which arose under or in connection with the Regional Forest Agreement before the date of this deed; or

ii. discharges, releases or otherwise affects any liability or obligation which arose under or in connection with the Regional Forest Agreement before the date of this deed; and

d. notwithstanding anything in this deed, nothing in this deed is intended to make legally binding any obligations in the Regional Forest Agreement that the parties have expressed an intent to be non-binding.

(Emphasis added.)

30 The Varied NE RFA is at annexure 1 to the NE RFA Variation Deed, while a clean copy of the Varied NE RFA is at annexure 2 to the Variation Deed. Clause 5 of the Varied NE RFA provides that the agreement “takes effect on 31 March 2000, and unless earlier terminated in accordance with clauses 112, 113, 114 or 115, will remain in force until 26 August 2039, or until a later date pursuant to clauses 6A and 6B”. Clauses 40–43 of Part 2 of the NE RFA creating a non-binding requirement to undertake five yearly reviews are omitted in the Varied RFA. In their stead, clauses 6A and 6B of Part 1 of the Varied RFA provide for the automatic extension of the agreement for a further five years on the “satisfactory completion” of each five-yearly review in accordance with clause 8M. Furthermore, in contrast to the original NE RFA, the requirement to undertake five yearly reviews is no longer included in Part 2 of the agreement which, it will be recalled, states that it is not intended to create legally binding relations. In light of these amendments, the applicant correctly submits that the purported effect of the Variation Deed was to extend the NE RFA at least by a further 20 years, and possibly indefinitely.

31 The Variation Deed was executed on behalf of the Commonwealth by then Commonwealth Prime Minister, the Hon Scott Morrison MP, and then NSW Premier, the Hon Gladys Berejiklian MP. When executing the Variation Deed, the Prime Minister had before him a briefing note entitled “Extension of Eden, North East New South Wales (NSW) and Southern New South Wales Regional Forest Agreements (RFA)” and various attachments (the Prime Minister’s Brief) (Annexure 8 to the SAF). In the briefing note, the Prime Minister was expressly directed to consider the Assessment Report at Attachment E. The purpose of the Assessment Report is explained (at p 12) as follows:

to provide an update on the matters listed in para (a) of the definition of the RFA in order to support the decision by the parties to enter into the proposed renewal of the RFA. This assessment considers the likely applicability of the findings of the CRAs to the proposed term of the renewed RFAs, the current status of the values based on additional information derived from various sources published since the governments entered into the agreement, and the likely impact on those values of the proposed renewal of the NSW RFAs. This document summarises the above consideration by reference to each of the listed matters.

32 With respect to the then proposed Varied NSW RFAs, the Assessment Report (at pp 14–15) explained that:

The Australian and NSW governments have committed to:

• Renewing each of the NSW RFAs for a further term of 20 years

• establishing a ‘rolling’ life for each Regional Forest Agreement by including a provision to extend its term for a further five years based upon successful completion and implementation of each independent five-yearly review of the Regional Forest Agreement.

…

In renewing the NSW RFAs, the Australian and NSW governments seek to maintain the objectives of the agreement. The governments are also seeking to negotiate a range of other minor improvements to the NSW RFAs to address some of the issues raised by various consultative reviews, consistent with continual improvement.

These improvements include:

• Streamlined and strengthened review and reporting arrangements

• Graduated dispute resolution

• Better handling of forest management complaints

• Improved communication and consultation between the Australian and NSW governments.

33 The Assessment Report concluded that the extension of the NE RFA and the Eden and Southern NSW RFAs, to 26 August 2039 will enable continued protection and sustainable management of RFA values. Specifically, the Assessment Report found (at p 378) that:

This report has demonstrated that the Australian and NSW governments have, through a comprehensive and diverse range of processes, formally had ongoing regard to the matters listed in para (a) of the definition of ‘RFA’ in the RFA Act relevant to the NSW RFA regions. Given the commitments of both governments to continue implementing the ongoing obligations and commitments of the NSW RFAs, while allowing for the forest management framework and implementation mechanisms to be responsive to new information consistent with adaptive management and continual improvement principles, it could be expected that the management of NSW forests in RFA regions would continue within this framework.

34 The Assessment Report relied among other things upon published data from various sources which postdate the original North East CRA in 1999 and the execution of the NSW RFAs, and are described in the Assessment Report as “the latest available information”: at p 13. These included NSW RFA annual reports, the formal five-yearly reviews of the NSW RFAs undertaken jointly by the Commonwealth and NSW, the (then) most recent joint government response to the latest independent five-yearly review of the NSW RFAs, and the NSW Forest Management Framework: see the Assessment Report at p 16. The Assessment Report also notes that reliance was placed on the Montréal Process Criteria and Indicators as a framework for reporting on and assessing sustainable forest management. The Montréal Process Criteria and Indicators are described later in this judgment.

35 In line with its purposes, however, the Assessment Report further explained (at p 13) that:

It is not a replacement for other reviews that have been done relating to NSW RFAs or which have included the Montréal Process indicators. Rather, it draws on these sources to illuminate the state of the matters and indicators as they have changed over the life of the current NSW RFAs.

36 Thus, it is common ground that no new comprehensive regional assessments were undertaken before the Variation Deed was executed.

37 The RFA Act was enacted in 2002. It was common ground that the RFA Act applied to RFAs already in force when the legislation was enacted, including the NE RFA. It follows that the parties correctly accepted that “in enacting the RFA Act, the Commonwealth proceeded on the basis that each of the existing Regional Forest Agreements … constituted an ‘RFA’ as defined”: Bob Brown Foundation at [72] (the Court).

38 Section 3 of the RFA Act outlines three “main objects of this Act”, namely:

(a) to give effect to certain obligations under Regional Forest Agreements;

(b) to give effect to certain aspects of the National Forest Policy Statement;

(c) to provide for the existence of the Forest and Wood Products Council.

39 These objects need to be understood in context. Specifically, given the conflict and uncertainty with respect to the use of native forests which led to the original NF Policy Statement, the Explanatory Memorandum explained that the RFA Bill was intended to provide “a high degree of certainty for conservation and environmental interest, forests and forest products industry operators, recreational users of forest and the broader community in that significant commitments made under the RFAs will be supported by legislation.” Thus, the Explanatory Memorandum stated that:

Since February 1997, ten Regional Forest Agreements (RFAs) have been concluded between the Commonwealth and the Victorian, Tasmanian, New South Wales and State Governments. As a key feature of the National Forest Policy Statement of 1992, the RFAs have a 20-year life and have delivered:

…

• 20-year certainty in resource supply;

…

• Participation of local community and stakeholder groups in the assessment of environmental, social and economic values and the development of options for sustainable development of RFA regions.

40 The Explanatory Memorandum explained that the RFA Act would “underpin” the RPAs by:

• precluding the application of controls under the Export Control Act 1982, and other Commonwealth laws which have the effect of prohibiting or restricting exports of wood from a region where an RFA is in force (supporting the current Export Control Regulations which have removed export controls where RFAs are in place);

• preventing application of Commonwealth environmental and heritage legislation as they relate to the effect of forestry operations where an RFA, based on comprehensive regional assessments, is in place (reflecting provisions already in the EPBC Act);

• ensuring that the Commonwealth is bound to the termination and compensation provisions in RFAs and cannot effectively change these provisions in the future without legislative action; and

• binding future executive governments to consider advice from the Forest and Wood Products Council on the implementation of the Forest and Wood Products Action.

41 Thus, as the Full Court explained in Bob Brown Foundation at [59]:

the purpose of the RFA Bill is to enshrine certain obligations of the Commonwealth: “The benefits of the RFAs flow from stability in forest management, access and use over 20 years. The RFA Bill reinforces those benefits by ensuring that Commonwealth governments will not materially alter the conditions negotiated in the RFAs.”

(Emphasis in the original; quoting the Explanatory Memorandum at p 1.)

42 An “RFA or Regional Forest Agreement” is defined in s 4 of the RFA Act as follows:

"RFA or Regional Forest Agreement" means an agreement that is in force between the Commonwealth and a State in respect of a region or regions, being an agreement that satisfies all the following conditions:

(a) the agreement was entered into having regard to assessments of the following matters that are relevant to the region or regions:

(i) environmental values, including old growth, wilderness, endangered species, national estate values and world heritage values;

(ii) indigenous heritage values;

(iii) economic values of forested areas and forested industries;

(iv) social values (including community needs); and

(v) principles of ecologically sustainable management.

(b) the agreement provides for a comprehensive, adequate and representative reserve system;

(c) the agreement provides for the ecologically sustainable management and use of forested areas in the region or regions;

(d) the agreement is expressed to be for the purpose of providing long-term stability of forests and forest industries;

(e) the agreement is expressed to be a Regional Forest Agreement.

43 The proper construction of paragraph (a) of this definition lies at the heart of this application. It is convenient to refer to paragraph (a) of the definition of an RFA as Condition (a).

44 In turn, an “RFA forestry operation” is defined in s 4 as meaning, relevantly, “forestry operations (as defined by an RFA as in force on 1 September 2001 between the Commonwealth and New South Wales) that are conducted in relation to land in a region covered by the RFA (being land where those operations not prohibited by the RFA)”.

45 Section 6(4) of the RFA Act provides that “Part 3 of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 does not apply to an RFA forestry operation that is undertaken in accordance with an RFA”. This means (as explained in the Explanatory Memorandum) that approval is not required under the EPBC Act for an RFA forestry operation undertaken in accordance with an RFA: see also s 38(1) of the EPBC Act to the same effect. In other words, the EPBC Act “does not apply to forestry operations in RFA regions, and the way in which the objects of the Act will be met in relation to those operations is to be ascertained by the relevant RFA”: Forestry Tasmania v Brown [2007] FCAFC 186; (2007) 167 FCR 34 at [61] (the Court). As a consequence, the applicant submits that (Applicant’s Written Submissions in Chief (AS) at [25]):

The great practical significance of [an agreement falling within the definition of an RFA in s 4 of the Act] is illustrated by the recent decision in Leadbeater’s FFC, in which the Full Court upheld findings that VicForests had engaged in numerous breaches of Victorian legal requirements, but these did not result in the exemption from EPBC Act requirements falling away (contrary to the primary judge’s finding). The Full Court held that if forestry operations are conducted in the geographic area covered by an RFA, then only State law requirements apply, and the EPBC Act does not.

46 Furthermore, s 6(1) of the RFA Act at the relevant time provided that RFA wood, being wood sourced from a region covered by an RFA, is not “prescribed goods” for the purposes of the Export Control Act 1982 (Cth). The Export Control Act regulated the export of “prescribed goods”. Section 6(2) of the RFA Act exempt RFA wood generally from other export control laws unless that legislation expressly referred to RFA wood.

47 In essence, the applicant’s case is that the Variation Deed was not entered into having regard to assessments in relation to climate change, endangered species and old growth values, and ecologically sustainable management as required by Condition (a) of the definition of RFA. As a result, the applicant contends that the Varied NE RFA is not an RFA for the purposes of the RFA Act.

48 At the risk of oversimplification, the issues as they ultimately emerged through the parties’ submissions can be summarised as follows.

(1) Before an RFA is varied so as to substantially extend its term, are further “assessments” required in order for the agreement to continue to meet Condition (a) of the definition of an RFA in s 4 of the RFA Act?

(2) If so, in order to satisfy Condition (a) of the RFA definition, what do those assessments require? Specifically, was it necessary when entering into the Variation Deed for regard to be had to assessments of the matters in Condition (a) which were “evaluative, based on the gathering of relevant information, reasonably contemporaneous to the date the relevant decision is made, and addressing risks to the identified environmental values known to be relevant to the region/s in question” (AS at [40])?

(3) If the answer to issue (2) is “yes”, was Condition (a) of the RFA definition complied with before the Variation Deed was entered into? In particular, in entering into the Variation Deed, was regard had to:

(a) projected impacts or effects of climate change on old growth, endangered species, world heritage values and wilderness (Ground 1, statement of claim); and/or

(b) environmental values as regards endangered species and the principles of ecologically sustainable management insofar as the harvesting of native forests envisaged by the Varied NE RFA would impact on endangered species (Ground 2, statement of claim); and/or

(c) environmental values as regards old growth forests and the principles of ecologically sustainable management insofar as the harvesting of native forests envisaged by the Varied NE RFA would impact upon existing and/or potential future old growth within the North East region (Ground 3, statement of claim);

in a manner which was sufficiently evaluative and reasonably contemporaneous.

(4) In the event that the applicant is successful in establishing that the NE RFA is not an RFA within the meaning of the RFA Act, is it in the interests of justice to grant declaratory relief?

49 For the reasons that follow, I consider that the first issue must be answered “no”. With respect, the construction for which the applicant contends on this issue is simply not open on the text of the relevant provisions. In those circumstances, the remaining issues do not strictly arise. However, in line with the role of a primary judge, I have considered issues 2 and 3 on the alternative assumption that issue 1 is determined in the applicant’s favour. Given that in my view, the applicant must fail on each of issues 1, 2 and 3, it is unnecessary to consider whether relief should be granted in the exercise of discretion.

6. RELEVANT PRINCIPLES OF STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION

50 The first and second issues turn on questions of statutory construction. The relevant principles are well-established and were not in issue. As McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ explained in Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority [1998] HCA 28; (1998) 194 CLR 335 (at [69]):

The primary object of statutory construction is to construe the relevant provision so that it is consistent with the language and purpose of all the provisions of the statute. The meaning of the provision must be determined “by reference to the language of the instrument viewed as a whole”. In Commissioner for Railways (NSW) v Agalianos [(1955) 92 CLR 390 at 397], Dixon CJ pointed out that “the context, the general purpose and policy of a provision and its consistency and fairness are surer guides to its meaning than the logic with which it is constructed”. Thus, the process of construction must always begin by examining the context of the provision that is being construed.

51 The importance of commencing with the text in its statutory context was also emphasised by Kiefel CJ, Nettle and Gordon JJ in SZTAL v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2017] HCA 34; (2017) 262 CLR 362 in the following passage (at [14]):

The starting point for the ascertainment of the meaning of a statutory provision is the text of the statute whilst, at the same time, regard is had to its context and purpose [citing Project Blue Sky with approval]. Context should be regarded at this first stage and not at some later stage and it should be regarded in its widest sense. This is not to deny the importance of the natural and ordinary meaning of a word, namely how it is ordinarily understood in discourse, to the process of construction. Considerations of context and purpose simply recognise that, understood in its statutory, historical or other context, some other meaning of a word may be suggested, and so too, if its ordinary meaning is not consistent with the statutory purpose, that meaning must be rejected.

52 Context “in its widest sense”, as referred to in this passage, includes “such things as the existing state of the law and the mischief which … one may discern the statute was intended to remedy” CIC Insurance Ltd v Bankstown Football Club Ltd [1997] HCA 2; (1997) 187 CLR 384 at 408 (Brennan CJ, Dawson, Toohey and Gummow JJ) (cited with approach in SZTAL at [14]). To have regard to context in this sense, as integral to the process of statutory construction irrespective of whether ambiguity or inconsistency exists in the literal text, accords with the mandate in s 15AA of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) that the interpretation which best gives effect to the legislative purpose must be preferred to any other interpretation: Mills v Meeking [1990] HCA 6; (1990) 169 CLR 214 at 235 (Dawson J). As a result, as Dawson J also explained, the approach required by interpretive provisions of this kind “allows a court to consider the purposes of an Act in determining whether there is more than one possible construction” (ibid); see also the discussion in Pearce D, Statutory Interpretation in Australia (9th ed, LexisNexis Butterworths, 2019) at [2.17]–[2.20]; Herzfeld P and Prince T, Interpretation (2nd ed, LawBook, 2020) at [7.20]–[7.30].

7. ISSUE 1: WERE FURTHER “ASSESSMENTS” REQUIRED BEFORE EXTENDING THE NE RFA

7.1 Overview of the parties’ submissions

53 The first issue is whether further “assessments” of the specified “matters” in Condition (a) of the RFA definition are required before substantially extending the term of an existing RFA, if that agreement is still to meet the RFA definition. In this regard, it will be recalled that the RFA definition provides that an RFA agreement is an agreement that “satisfies all the following conditions”, including under paragraph (a), that:

(a) the agreement was entered into having regard to assessments of the following matters that are relevant to the region or regions:

(i) environmental values, including old growth, wilderness, endangered species, national estate values and world heritage values; …

(v) principles of ecologically sustainable management…

54 It is common ground that paragraphs (a) to (e) of the definition of an RFA turn upon the existence of objective facts and that they do not require the establishment of a state of satisfaction by a decision-maker. There was also no question of whether the Varied RFA complied with paragraphs (b) to (e) of the definition of an RFA. The constructional issues in dispute pertain to:

(1) whether it was necessary for the Deed varying the NE RFA to be entered into in compliance with Condition (a) in order that the Varied RFA remain an RFA under the Act; and if so,

(2) what constitutes an “assessment” for the purposes of Condition (a).

55 Initially the applicant submitted that where, as in this case, there had been a material extension to the term of an RFA under the RFA Act, “then what is at issue is in substance a new RFA. Consideration of entry into such a substantially new RFA requires having regards [sic] to the assessments spelt out in s 4”: AS at [39]. However, in oral submissions, the applicant expressly disavowed any argument that the Varied RFA involved the creation of a substantially new agreement: Transcript (T)20.29–31. Rather, in essence the applicant submits that for any substantial extension of an RFA, regard must be had to further “assessments” of the matters specified in Condition (a) of the RFA definition in order that the agreement may remain an RFA for the purposes of the RFA Act.

56 In support of its submission, the applicant relies upon the purpose of the RFA Act. Referring to the various extrinsic materials (as discussed shortly below), the applicant contends that the purpose of the RFA Act was to ensure that RFAs were based on a comprehensive assessment of the particular regions in question. As the applicant submits, “[t]he purpose of these requirements [to perform assessments prior to entry into an RFA] is obvious: to inform consideration of whether the particular RFA should be entered [into]”: AS at [32]. On the applicant’s submission, to allow the Commonwealth to extend an RFA indefinitely based on environmental assessments from the 1990s, without the need for further assessments, would therefore undermine the clear purpose of the RFA Act.

57 The applicant also submits that the respondents’ construction of the Act would elevate form over substance. By way of illustration, the applicant submits that, if an RFA ended and was shortly thereafter replaced by a new RFA, the requirements in s 4 would apply to the entry into the new agreement. By contrast, the applicant observed that on the respondent’s construction, if the form of the change was instead to amend the existing RFA, the requirements in s 4 would not apply. This, in the applicant’s submission, would enable the conditions in paragraph (a) of the statutory definition to be circumvented with the result that historic assessments need never be revisited when extending an RFA. The applicant submits that this is particularly problematic in the context of forest agreements, given that forests “like all parts of the environment, are dynamic parts of nature. They change, for better and for worse”: AS at [34].

58 In the respondents’ construction, however, s 4 of the RFA imposes a requirement for certain assessments to be conducted upon entry only into an RFA. In their submission, the RFA Act imposes no requirement to conduct assessments before agreeing to extend the term of an RFA. In support of this construction, the respondents rely upon the ordinary and natural meaning of Condition (a) imposing a requirement to have regard to specified matters only on “enter[ing] into” an RFA despite the RFA Act expressly contemplating that amendments might be made to an RFA.

59 In my view, the respondents’ construction of s 4 of the RFA Act must be accepted. Properly construed, Condition (a) of the definition of an RFA does not impose any requirement to have regard to new “assessments” of the specified matters relevant to the region(s) in circumstances where an RFA is being amended by way of an extension, substantial or otherwise, to its duration in order that the agreement continue to meet the definition of an RFA.

60 First, in terms of the general approach to construction, I note that this issue focuses on what is described in the legislation as a “definition”. In this regard, it is generally accepted that “a legislative definition should not be framed as a substantive enactment”: Vincentia MC Pharmacy Pty Ltd v Australian Community Pharmacy Authority [2020] FCAFC 163; (2020) 280 FCR 397 at [51] (Perry and Stewart JJ), citing Gibb v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [1966] HCA 74; (1966) 118 CLR 628 at 635 (Barwick CJ, McTiernan and Taylor JJ). However, a statutory definition may, upon its proper construction, impose substantive requirements or criteria. As Pearce explains, “Drafters do occasionally include substantive material in a definition. This is poor drafting and can lead to error in the interpretation of the legislation because of the approach set out in Gibb’s case”: Pearce D, Statutory Interpretation in Australia at [6.14]; see also Herzfeld P and Prince T, Interpretation at [3.10].

61 Despite being described as a definition, the so-called definition of an “RFA” in s 4 is an example in point. It plainly has a substantive operation because it prescribes “conditions” (i.e. substantive criteria) with which an agreement must comply in order to be an RFA for the purposes of the RFA Act and thereby attract the prescribed statutory consequences: see, e.g., by analogy, San v Rumble (No 2) [2007] NSWCA 259; (2007) 48 MVR 492 at [52] (Campbell JA, Beazley and Ipp JJA agreeing); ACCC v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; (2018) 262 FCR 243 at [113]–[114] (the Court); and Vincentia at [50]–[51]. As in Vincentia, to so construe the definition in issue here best gives effect to the purpose of the RFA Act and does not give rise to the kinds of difficulties which might arise where a so-called definition applies potentially to a number of different statutory provisions: see by analogy Rumble at [55]; and Yazaki Corporation at [113]–[114] (the Court). Nonetheless, it is convenient, given the location of the “definition” of RFA in s 4 headed “Definition”, to refer to it as such.

62 Secondly, applying the principles explained above, the task of construction must commence and end with a consideration of the statutory text: see also Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Consolidated Media Holdings Ltd [2012] HCA 55; (2012) 250 CLR 503 at [39] (the Court). In this case, paragraph (a) of the statutory definition expressly requires that the agreement only be “entered into” having regard to assessments of the matters specified in subparagraphs (i) to (v). In its natural and ordinary meaning, those words are apt only to cover the execution of an RFA; they are not apt to encompass variations or amendments to an existing RFA, including extensions to the term of the intergovernmental agreement. As such, bearing in mind that the text of the provision is the surest guide to its purpose, the evident purpose of paragraph (a) is to require that regard be had to assessments of specified values and principles in order to inform the decision as to whether an intergovernmental agreement intended to be an RFA should be “entered into”.

63 Thirdly, that Parliament intended to distinguish between entering into an RFA and amending an RFA is supported by s 10 of the RFA Act. That section relevantly provides that:

(1) The Minister must cause a copy of an RFA to be tabled in each House of the Parliament within 15 sitting days of that House after:

(a) the commencement of this section; or

(b) the RFA is entered into;

whichever is later.

…

(3) The Minister must cause a copy of an amendment of an RFA to be tabled in each House of the Parliament within 15 sitting days of that House after:

(a) the commencement of this section; or

(b) the amendment is made;

whichever is later

(Emphasis added.)

64 Hence, s 10 distinguishes between “enter[ing] into” an RFA, on the one hand, under s 10(1)(b), and the “mak[ing]” of “an amendment” to an RFA, on the other hand, under s 10(3)(b)). That distinction, in turn, accords with the ordinary meaning of entering into an agreement as distinct from subsequent amendments to that agreement.

65 Furthermore, that Parliament intended the phrase “entered into” an RFA in Condition (a) of the definition of an RFA and in s 10(1) to bear the same meaning is apparent from the relationship between the two provisions. Specifically, once an RFA is “entered into” in accordance with Condition (a), the obligation in s 10(1), as opposed to s 10(3), is triggered. By contrast, where an amendment is made to an agreement, it is the obligation in s 10(3) which is enlivened. That relationship between the conditions for entering an RFA Agreement and the obligation in s 10(1) militates, in my view, a consistent construction of words “entered into" in both provisions. This approach accords with the principles of statutory construction requiring that the meaning of a provision must be determined by reference to the language of the instrument as a whole and on the prima facie basis that its provisions are intended to give effect to harmonious goals: Project Blue Sky at [69]–[70]. The applicant’s construction, however, would create a conflict between Condition (a) of the definition of an RFA on the one hand, and the operation of ss 10(1) and (3), on the other hand, despite their obvious interrelationship.

66 Understood in this light, with respect, the applicant asks the Court to “make an insertion which is ‘too big, or too much at variance with the language in fact used by the legislature’”: Taylor v Owners — Strata Plan No 1564 [2014] HCA 9; 253 CLR 531 at [38] (French CJ, Crennan and Bell JJ). As the second respondent submits:

Neither the text nor the context of s 4 of the RFA Act should be construed as providing that [as the applicant submits]:

an RFA that was in force when the RFA Act was enacted ceases to be an RFA for the purposes of the Act after expiry of the original terms of the RFA, unless any agreement that materially extends the term of the RFA (or alternatively extends the term by at least 20 years and potentially in perpetuity) was entered into having regard to assessments of the matters identified in paragraph (a) of the definition that are relevant to the region or regions.

(Second Respondent’s Written Submissions (R2S) at [2].)

67 There is nothing in the text of the RFA Act to suggest that the Parliament intended to impose any requirement for new “assessments” to be undertaken in order for an RFA to remain an RFA for the purposes of the Act where it is proposed to extend the term of the RFA or otherwise to amend it. Had the Parliament intended to impose any such limitations, it would have been a simple matter for it to have so provided expressly.

68 Fourthly, the applicant placed considerable weight on extrinsic materials, and the purpose of the RFA, as supporting its construction. The following two contextual features, in particular, were said to support the applicant’s construction:

(1) the legislation was enacted with an expectation that assessments would cover a twenty-year period only; and

(2) the legislation was designed to ensure that RFAs were based on comprehensive assessments of the particular regions in question.

69 However, with respect, those extrinsic considerations provide no warrant for departing from the language actually used in the provision.

70 With respect to the first point, it is true that the secondary materials refer to the ordinary duration of RFA Agreements being twenty years. Hence, the Explanatory Memorandum to the RFA Bill described the RFAs as having “a 20-year life”, and they were said to have delivered “20-year certainty in resource supply”: at p 2; see also pp 3 and 6. Those references reflect the original lifespan of the ten RFAs in existence when the RFA Act was enacted, all of which were said to “remain in force for 20 years”: see, e.g., NE RFA clauses 6 and 40.

71 However, those extrinsic materials do not necessarily support the applicant’s construction. As the respondents submit, whilst the NE RFA had an initial lifespan of 20 years, clause 8 of the NE RFA expressly envisaged that the RFA could be amended with the written consent of the parties and, in particular, provided in clause 6 that the parties were to determine the process for extending the agreement for a further period as part of the third five yearly review. While the Eden and Southern RFAs were not in evidence before me, the clear inference from the materials before the Minister, including the Assessment Report, is that each of these RFAs included essentially the same mechanisms for amendments to be made them, including extensions to their term.

72 In line with this, in enacting the RFA Act, the Parliament recognised in s 10(3) of the RFA Act that RFAs could be amended, but did not expressly limit the amendments which could be made (save for certain express limits imposed on the Commonwealth concerning compensation in s 8 of the RFA Act, and also by implication that the amendments could not have the consequence that the amended agreement no longer met the definition of an RFA in s 4 of the RFA Act). In particular, the RFA Act did not make it a condition that an RFA be in force for a specified or maximum duration only; nor did it otherwise exclude amendments to the duration of an RFA. To the contrary, the capacity to extend the agreements is consistent with and promotes the purpose of the RFA Act in reinforcing the long-term certainty which the RFAs were intended to provide for forestry management in the RFA regions as against a historical background of conflict between industry and environmental and conservation interests. The absence of any constraints on the capacity to amend and extend such agreements, therefore, must be taken to manifest the purpose of the Act: Certain Lloyd’s Underwriters v Cross [2012] HCA 56; 248 CLR 378 at [25] (French CJ and Hayne J).

73 This is particularly so given that the RFA Act is concerned with attaching certain legal consequences to intergovernmental agreements which may and do contain unenforceable obligations, and are intended to further the broadly expressed objectives stated in paragraphs (b), (c) and (d) of the RFA definition. The balancing of those objectives must occur, furthermore, having regard to the potentially conflicting, broadly expressed values in paragraph (a). In that sense, the RFAs of their nature represent a compromise or balancing of the competing interests of conservation and the environment on the one hand, and “forest and forest products industry operators and their workforces [and] recreational forest users” on the other hand, regarding the use, management and conservation of forests and forest resources: Explanatory Memorandum at 4.

74 Those contextual matters render highly unlikely any implied intention by the Parliament to fetter the means by which the Commonwealth and other federal entities might seek to resolve the potentially conflicting values and interests over time through the negotiation of amendments to existing RFAs. In line with this view, the Full Court in Bob Brown Foundation held at [49] that:

As paras (a) to (e) of the definition of “RFA” indicate, an RFA is concerned with matters of environmental and economic policy. While such matters could be the subject of legally enforceable obligations, they could also be (and perhaps would more readily be) matters of a political nature, often involving compromise between competing policy considerations and interests, not intended to be the subject of adjudication by the courts.

75 Similarly, in endorsing the NF Policy Statement, the Commonwealth, State and Territory governments stated that they committed their respective governments “to implement, as a matter of priority, the policies in it for the benefit of present and future generations of Australians”. However, at the same time they acknowledged that “implementation of policies requiring funding will be subject to budgetary priorities and constraints in individual jurisdictions”.

76 Furthermore, as the Full Court accepted in Bob Brown Foundation at [52], the NF Policy Statement was also cognisant of the likely need to accommodate future changes in forest management and the need for adaptive processes, stating that:

Managing Australia's forests in a sustainable manner calls for policies, by both governments and landowners, that can be adapted to accommodate change. Pressures for change may result from new information about forest ecology and community attitudes, new management strategies and techniques (such as those that incorporate land care and integrated catchment management principles), and new commercial and non-commercial opportunities for forest use. These pressures may affect the forests themselves.

77 In short, therefore, as the Full Court in Bob Brown Foundation at [53] held:

Consideration of the [National Forest Policy Statement] assists with understanding that an RFA, as referred to in the RFA Act, is likely to contain provisions which “essentially depend on matters of principle or policy into which obviously financial and economic considerations must enter” (South Australia v Commonwealth (1962) 108 CLR 130], per Dixon CJ at 147) and that the legislative scheme contemplates the revision and development of codes of practice and management plans as knowledge changes.

78 These contextual considerations lend strong support to the view that the Parliament intended to leave open the possibility that the Commonwealth and State or Territory parties to an RFA could negotiate amendments to existing RFAs, including to extend their duration, without imposing constraints upon that process, save relevantly that an RFA must continue to meet the definition of an RFA. The fact that the RFAs were originally negotiated on the basis that they would endure for a period of 20 years, subject to agreed extensions, affords in my view no basis for inferring that the Parliament intended to fetter the process by which they might be extended.

79 Similar issues affect the applicant’s reliance on the second contextual factor, namely, that the legislation was designed to ensure that RFAs were based on comprehensive assessments of the particular regions in question. As the applicant submits, the purpose of paragraph (a) of the definition of RFA in s 4 is plainly to ensure that a decision of government parties to enter into an RFA is made on an informed basis insofar as the necessary assessments must address the values and principles specified in paragraph (a). However, that does not provide any support for effectively reading into the text a requirement for such assessments to be undertaken again, in whole or in part, where it is proposed materially to extend the duration of an RFA or otherwise to amend it. Instead the implication is that the Parliament left it to the government parties to decide what assessments, if any, might be undertaken before agreeing to amend an RFA.

80 In the fifth place, the applicant contends that the effect of construing the term “entered into” according to its ordinary meaning would be to give precedence to form over substance, because it would open the possibility that the government parties could avoid undertaking new assessments if the form of a change is to extend an existing RFA, rather than entering a new RFA altogether. That submission should not be accepted.

81 It is clear that if an RFA were amended so that it no longer met the conditions in the statutory definition of an RFA, it would no longer constitute an RFA for the purposes of the RFA Act. Approvals for forestry actions impacting on matters of national environmental significance would therefore have to be obtained in accordance with the EPBC Act and relevant export control laws. Furthermore, while it is unnecessary to decide the issue, an argument might be made that the amendments to an RFA are so extensive that, as a matter of substance, the agreement is plainly a new RFA. However, that was not the contention put in this case, and indeed the applicant expressly disavowed the making of that case: T20.29–31.

82 Absent these possibilities, however, to recognise a distinction between entering an agreement and varying an agreement for the purposes of s 4 of the RFA Act does not prioritise form over substance but gives effect to Parliament’s clear intention to impose conditions upon the entry into an RFA which it has not seen fit to impose when an RFA is amended.

83 Finally, the NE RFA and other RFAs in place when the RFA Act was enacted form part of the context against which the RFA Act falls to be construed. That is so given, as I have earlier explained, that the purpose of the RFA Act was to give effect to certain obligations of the Commonwealth under the RFAs and to preclude the Commonwealth from terminating an RFA otherwise than “in accordance with the termination provisions of the RFA”: s 7 of the RFA Act. It is therefore significant that, for example, clause 6 of the NE RFA provides that “the process for extending the Agreement for a further period will be determined jointly by the parties as part of the third five-yearly review” (emphasis added). The fact therefore that the RFA Act did not require that any amendment to extend the duration of an RFA have regard to fresh assessments of the kind referred to in Condition (a) in order to continue to be an RFA for the purposes of the RFA Act therefore assumes significance. It can be assumed that the Parliament was aware of these terms, and the possibility that RFAs might be substantially extended, but intentionally chose not to impose limits on the government parties’ ability to make those extensions.

84 For all of these reasons, the applicant’s construction of the RFA Act must be rejected. Given that the applicant’s case depended on its success on this first issue, this conclusion is sufficient to dispose of the application for declaratory relief. The remainder of these reasons address issues 2 and 3 on the alternative basis that the applicant correctly submits that an assessment was required.

8. ISSUE 2: DOES AN “ASSESSMENT” NEED TO BE EVALUATIVE AND REASONABLY CONTEMPORANEOUS TO SATISFY THE DEFINITION OF AN RFA?

8.1 Overview of the parties’ submissions

85 The applicant contends for “similar reasons” to those advanced with respect to issue one above (AS at [40]), that for an agreement to meet the RFA definition, the assessment of the matters in Condition (a) must be:

evaluative, based on the gathering of relevant information, reasonably contemporaneous to the date the relevant decision is made, and addressing risks to the identified environmental values known to be relevant to the region/s in question. Again, were it otherwise the purpose of the provision – to inform the decision – would not be fulfilled.

In the applicant’s submission, any failure to meet these conditions means that the intergovernmental agreement will not, or, if amended, will not continue to, meet the definition of an RFA for the purposes of the RFA Act.

86 The applicant’s submissions principally rely on the requirement in Condition (a) that, to meet the RFA definition, the parties to the RFA must “hav[e] regard to assessments of the following matters that are relevant to the region or regions” (emphasis added). The applicant contends that “the notion of ‘assessment’ refers to an opinion or evaluation which has measured or evaluated the five matters” in Condition (a) and that this “involves a process of acquiring (measuring) and considering (evaluating) relevant information” (AS at [41]). The applicant further contends that the requirement for reasonable contemporaneity “is implicit in the textual requirement that there are ‘assessments of the following matters that are relevant to the region or regions’” (emphasis added). In this regard, the applicant submits that:

(1) to be relevant, the information must be directed to the five identified subject matters in Condition (a) of the statutory definition; and

(2) to be relevant to the regions, they must be reasonably up to date, given that it is in the nature of the five subject matters, such as the state of old growth and wilderness, that they will change over time.

(AS at [42].)

87 The applicant contends that this construction again best aligns with the purpose of the RFA definition, being to ensure that the Commonwealth is able to make an informed decision about changing matters of environmental significance before entering an RFA.

88 On the other hand, whilst accepting that the Commonwealth and the State were required to conduct assessments of the matters in Condition (a) when entering into an agreement for that agreement to fall within the definition of an RFA, the respondents submit that the sufficiency of those assessments is not a matter subject to judicial scrutiny. In the respondents’ submission, neither the text nor context of the RFA Act indicate that Parliament specified any particular content or standard with which assessments of the matters listed in Condition (a) must comply.

89 Applying the principles of statutory construction outlined above, and on the assumption that the applicants’ construction on the first issue is correct contrary to my earlier findings, the applicant’s construction of the RFA definition with respect to issue two must be rejected. In my view, there is no implicit requirement in the text that an assessment must be sufficiently evaluative and contemporaneous in order to satisfy Condition (a) of the RFA definition.

90 Three preliminary points should be made at the outset.

91 First, the question of whether the agreement is an RFA for the purposes of the RFA Act, including whether the matters in Condition (a) are met, is not a question in respect of which the RFA Act has vested a power and/or conferred a duty on a specific officer of the Commonwealth to determine. There is no decision which is the subject of a challenge by way of judicial review. References at various points in the applicant’s submissions to “the relevant decision” are, therefore, with respect misconceived. Rather, as the State submits, the present proceeding (R2S at [20]):

is a challenge to the effectiveness of an intergovernmental agreement by which the Commonwealth intended to disapply certain of its regulatory requirements on the basis of a political judgment that matters of Commonwealth concern are capable of being sufficiently advanced through a forest management framework agreed with the State.

92 Secondly, that notwithstanding, it was not in issue that it is within the jurisdiction of the Court to determine whether an intergovernmental agreement in fact satisfies the conditions in the RFA definition, given that the RFA Act attaches legal consequences to an RFA which meets those conditions, including Condition (a).

93 Thirdly, as the parties accept, in its ordinary meaning the phrase “to assess” means to measure or evaluate. That the word “assessments” in Condition (a) accords with this meaning is also common ground between the parties and rightly so in my view. However, that does not answer the question of whether, as the applicant contends, the legal effectiveness of the RFA under the RFA Act depends upon the quality and sufficiency of the assessments to which regard must be had under Condition (a).

94 In my view, when the question posed by Condition (a) is considered in context, it is clear that the quality and sufficiency of the assessments, as opposed to the fact of assessments on the matters specified by Condition (a), are intended to be matters for political judgment only. That is so for essentially three reasons.

95 First, the context in which an RFA is entered, and particularly the regulatory framework which governs an RFA region, must be appreciated in construing the RFA definition. In this regard, as the Full Court held in Bob Brown Foundation at [60], [t]he purpose of the RFA Act was never to be the sole source, or even the primary source, of measures to protect [State’s] native forests, nor threatened species. … there is a broader suite of protective measures in force in Tasmania”. The same applies with respect to NSW. Thus, within the complex international, national and state regulatory framework applying in NSW with respect to forestry management, the State is the principal regulator with respect to areas subject to an RFA. The State performs that function pursuant to the NSW Forest Management Framework which is comprised of legislation, policy, regulatory instruments, and programs directed to regulating and supporting sustainable forest management in the State. The NSW Forest Management Framework was explained in detail in the Overview of the New South Wales Forest Management Framework August 2018 (NSW Framework Overview) which was attachment J to the Prime Minister’s Brief. Key legislation underpinning the NSW Forest Management Framework included (at the time of entry into the Variation Deed): the Forestry Act 2012 (NSW); the Plantations and Reafforestation Act 1999 (NSW); the Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997 (NSW); the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (NSW); the Local Land Services Act 2013 (NSW); the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (NSW); the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW); and the Heritage Act 1977 (NSW).

96 In turn, as the State submits, several Commonwealth laws, including the EPBC Act, the Export Control Act and the RFA Act, may affect the management of forests in NSW, notably those laws are directed to matters of national environmental significance such as compliance with Australia’s international obligations concerning the environment. They do not purport to provide a comprehensive regulatory framework in relation to forest management or to duplicate the requirements of State law. Thus, for example, s 3 of the EPBC Act provides that in order to achieve the objects of the Act, among other things the Act:

(a) recognises an appropriate role for the Commonwealth in relation to the environment by focussing on Commonwealth involvement on matters of national environmental significance and on Commonwealth actions and Commonwealth areas; and

(b) strengthens intergovernmental co-operation, and minimises duplication, through bilateral agreements; and

(c) provides for the intergovernmental accreditation of environmental assessment and approval processes; and

….

(g) promotes a partnership approach to environmental protection and biodiversity conservation through:

(i) bilateral agreements with States and Territories; …

97 In line with these objects, the operative provisions of the EPBC Act require Commonwealth environmental approvals for actions likely to have a significant impact relevantly on matters of national environmental significance (see s 11 and Part 3 of the EPBC Act) save where alternative means have been adopted in pursuit of the objects of the EPBC Act, such as through:

(1) bilateral agreements between the Commonwealth and a State or Territory (Part 4, Division 1; Part 5); or, more relevantly,

(2) the entry into a Regional Forest Agreement (Part 4, Division 4).

98 It follows, as the Full Court explained in Forestry Tasmania v Brown [2007] FCAFC 186; (2007) 167 FCR 34 at [61] and as the Explanatory Memorandum accompanying the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Bill 1999 indicates, that “the way in which the objects of the Act will be met in relation to [forestry operations in RFA regions] is to be ascertained by reference to the relevant RFA.” In other words, an RFA provides an alternative mechanism by which the objects of the EPBC Act can be achieved by way of an intergovernmental agreement allocating responsibility to a State for regulation of environmental matters of Commonwealth concern within an agreed framework. It is important therefore to reiterate that entry into an RFA does not result in a regulatory void with respect to any particular forestry region on matters of national environmental significance.

99 It also follows that neither a bilateral agreement nor an RFA authorise the taking of any specific action that may impact on the environment or exempt any specific actions from being regulated. As such, this proceeding is not akin to an administrative law challenge to an approval authorising a person to perform an action which would be unlawful absent that authorisation in contrast, for example, to the approvals regime in Part 3 of Chapter 2 of the EPBC Act.

100 Secondly, it is against these important contextual considerations that the conditions imposed by the RFA definition fall to be construed. These considerations explain why the requirement in Condition (a) is to have regard to environmental, indigenous heritage, economic and social “values” and “principles” of ecologically sustainable management relevant to the particular region (emphasis added). The potential for conflict between these broadly expressed values and principles—the economic and the environmental in particular—is obvious, and the balancing of them is inevitably political, indicating that the requirement to have regard to the assessments is intended to be “an open-textured one” and policy driven: First Respondent’s Written Submissions (R1S) at [42]. As the Full Court held in Bob Brown Foundation at [49] (and it bears repeating):

As paras (a) to (e) of the definition of “RFA” indicate, an RFA is concerned with matters of environmental and economic policy. While such matters could be the subject of legally enforceable obligations, they could also be (and perhaps would more readily be) matters of a political nature, often involving compromise between competing policy considerations and interests, not intended to be the subject of adjudication by the courts.

101 Thus Condition (a) does not require that environmental impacts be assessed, consistently with the purpose for which the assessments are being undertaken. Nor does it identify any particular requirements with which assessments of the values and principles in subparagraphs (i) to (v) must comply, the content of those assessments (save for requiring that they assess the specified values and principles relevant to the region), or any standard by which the Court could determine the adequacy or sufficiency of the assessments. Yet, as the Commonwealth submits, it was open to the Parliament to have expressly specified the content of the assessments required to meet Condition (a) by reference, for example, to the assessment methodology adopted in the Comprehensive Regional Assessments, if it had intended to impose requirements to that effect; equally it was open to the Commonwealth to have imposed procedures to be followed in the preparation of assessments, such as expert or public consultation, but it elected to impose no such requirements.