FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Luke v Aveo Group Limited (No 3) [2023] FCA 1665

Table of Corrections | |

12 March 2024 | In the third sentence of the quote at paragraph 159, replacing “Frequently, class actions perform a public function by being employed to vindicate statutory policies such as disclosure to the securities market, approving cartels of posturing safe medical and pharmaceutical products: see Legg M, Class Actions, Litigation Funding and Access to Justice (Law Research Paper No 17-57, UNSW, 7 September 2017)” with “Frequently, class actions perform a public function by being employed to vindicate statutory policies such as disclosure to the securities market, prohibition of cartel conduct and the provision of safe medical and pharmaceutical products: see Legg M, Class Actions, Litigation Funding and Access to Justice (Law Research Paper No 17-57, UNSW, 7 September 2017)”. |

ORDERS

VID 996 of 2017 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | MICHAEL ROBERT LUKE (IN HIS CAPACITY AS THE CO-EXECUTOR OF THE ESTATE OF ROBERT COLIN LUKE, DECEASED) First Applicant MEREDITH ANNE LUKE (IN HER CAPACITY AS THE CO-EXECUTOR OF THE ESTATE OF ROBERT COLIN LUKE, DECEASED) Second Applicant ANN MARY STROUD (IN HER CAPACITY AS THE CO-EXECUTOR OF THE ESTATE OF JOAN MARY COLOMBARI, DECEASED) (and another named in the Schedule) Third Applicant | |

AND: | AVEO GROUP LIMITED (ACN 010 729 950) Respondent | |

order made by: | MURPHY J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 22 december 2023 |

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

A. Galactic Aveo LLC will not seek to recover a funding commission from the applicants and group members; and

UPON THE UNDERTAKINGS BY:

1. GALACTIC AVEO LLC THAT it will not seek to enforce any contractual rights it has in relation to recovery of legal costs and disbursements from group members who entered into a litigation funding agreement with it; and

2. STEWART LEVITT TRADING AS LEVITT ROBINSON SOLICITORS THAT Levitt Robinson Solicitors will not seek to enforce any contractual rights the firm has in relation to recovery of legal costs and disbursements from group members who retained the firm.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Costs

1. Pursuant to s 33V(2) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth);

(a) the Applicants’ legal costs and disbursements for the conduct of this proceeding up to the date of settlement be approved in the sum of $8,523,516;

(b) the Applicants’ legal costs of the settlement approval process be approved in the sum of $394,538; and

(c) the Administration Costs, as defined in the Settlement Scheme, be approved in the sum of $186,000 plus GST.

2. Stewart Levitt trading as Levitt Robinson pay the Contradictor’s reasonable fees within 21 days of receipt of an invoice.

Administration

3. Within seven (7) days after the distribution by the Administrator of the whole of the Settlement Sum, the Administrator is to apply to the Court for the proceeding to be dismissed with no further order as to costs.

4. The Administrator have liberty to apply with respect to any issues arising under the Administration.

5. The Applicants and the Respondent be excused from attendance in relation to any application brought by the Administrator pursuant to Order 4.

Confidentiality Application

6. Pursuant to ss 37AF and 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (the Act), on the ground that the order is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, the material set out in Annexure A (Confidential Material A) is, until further order or until after the expiry of all periods in which an appeal may be brought from this Court’s orders made on 22 November 2023 (as specified in Annexure A), not to be published or disclosed without prior leave of the Court to any person other than: (a) the Court; (b) the Applicants; (c) the Applicants’ legal representatives; (d) group members who have provided an appropriate acknowledgment of their obligations under this order; (e) counsel appointed as Contradictor; (f) counsel for Levitt Robinson; (g) Galactic Aveo LLC; and (h) Galactic Aveo LLC’s legal representatives, with such permitted disclosures to be on terms that none of those persons or entities disclose the Confidential Material A or any part of it to any person or entity other than those listed in this order.

7. Pursuant to ss 37AF and 37AG(1)(a) of the Act, on the ground that the order is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice and until further order, the material set out in Annexure B (Confidential Material B) is not to be published or disclosed without prior leave of the Court to any person other than: (a) the Court; (b) the Applicants; (c) the Applicants’ legal representatives; (d) counsel appointed as Contradictor; (e) counsel for Levitt Robinson; (f) Galactic Aveo LLC; and (g) Galactic Aveo LLC’s legal representatives, with such permitted disclosures to be on terms that none of those persons or entities disclose the Confidential Material B or any part of it to any person or entity other than those listed in this order.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Annexure A

# | CB tab | Evidence/ Submissions | Document /Section over which Confidentiality claimed | Time |

2. | 7 | Confidential Affidavit of Stewart Alan Levitt 29 September 2023 | Exhibit SAL-10 Confidential Opinion (whole) | Until further order |

3. | 11 | Contradictors’ Confidential Outline of Submissions dated 16 October 2023 | Parts specified below. | |

[23] | content of footnote 30. | Until expiry of appeal periods | ||

[25]-[27] | whole | Until further order | ||

[31] | whole | Until further order | ||

[43] | From “That abandonment” to end paragraph | Until further order | ||

[44] | whole | Until further order | ||

[48] | From “We address this below” to end paragraph | Until further order | ||

[49] | From “Having analysed” to end paragraph | Until further order | ||

[50] | Whole | Until further order | ||

[52-62] | Whole | Until further order | ||

[66] | The words in parentheses | Until further order | ||

[67] | Contents of footnote 45. | Until further order | ||

[69] | The words “it appears” in the first line to “the litigation funder” in the penultimate line | Until further order | ||

[70] | Whole | Until further order | ||

[74] | Whole | Until further order | ||

[79(a)] | The words “having regard … the evidence,” | Until further order | ||

[100]-[101] | Whole | Until further order | ||

[127] | Second sentence of chapeau (“With the benefit … the Court.”) | Until further order | ||

[127(a)] | Whole | Until further order | ||

[127(d)-(e)] | Whole | Until further order | ||

[128]-[129] | Whole | Until further order | ||

[132] | Second sentence (“That history”) to end paragraph | Until further order | ||

[136]-[137] | Whole | Until expiry of appeal periods | ||

[139] | From beginning up to the words “instructions from Adamson,” in the second sentence | Until expiry of appeal periods | ||

[142(d)] | The words “although it is … much,” | Until expiry of appeal periods | ||

[143] | Second sentence | Until further order | ||

[143] | Last sentence, the words “the claims here … reports, then” | Until further order | ||

4. | 10 | Applicants’ Confidential submissions in reply dated 31 October 2023 | Parts specified below. | |

[7]-[14] | Whole | Until further order | ||

5. | 18 | Confidential Affidavit of Stewart Alan Levitt sworn 2 November 2023 | Parts specified below. | |

[24]-[25] | Whole. | Until further order | ||

[26] | Whole. | Until expiry of appeal periods | ||

[29] | Fourth and fifth lines, the words “other than” to “Adam Bell SC”. | Until further order | ||

9. | 13 | Costs Referee’s first report dated 26 July 2023 | Parts specified below. | |

[20] | First sentence, the words “Whilst … applicant,” | Until further order | ||

[21]-[22] | Whole | Until further order | ||

[24] | Whole | Until further order | ||

[26] | Entries in chronology bearing the following dates: March 2016 May 2016 October 2016 August 2017 December 2017 July 2020 15 June 2022 (first sentence only) | Until further order | ||

[46]-[50] | Whole (including sub-heading F.1) | Until further order | ||

[75] | First sentence, the words “not to … fees and” | Until further order | ||

[77] | Whole | Until expiry of appeal periods | ||

[78] | Whole | Until further order | ||

[86]-[105] | Whole (including headings) | Until further order | ||

[110] | First two sentences | Until expiry of appeal periods | ||

[111] | Second and third sentences (“On a number … being incurred.”) | Until expiry of appeal periods | ||

[112] | Second sentence (“I assume…”) to end paragraph | Until expiry of appeal periods | ||

[113] | Whole | Until further order | ||

[114] | Second sentence (“An example…” to end paragraph | Until expiry of appeal periods | ||

[116] | Second sentence (“A March…”) to end paragraph | Until expiry of appeal periods | ||

[132] | Whole | Until further order | ||

[142]-[143] | Whole | Until further order | ||

[152] | Second sentence (“By late…”) to end paragraph | Until expiry of appeal periods | ||

[168] | Whole | Until further order | ||

[169] | Whole | Until expiry of appeal periods | ||

[170] | Whole | Until further order | ||

[215] | The third sentence (“However, I consider…”) | Until further order | ||

[218] | Third and fourth sentences (“The file … be successful.”) | Until further order |

Annexure B

# | CB tab reference | Evidence/ Submissions | Document /Section over which Confidentiality claimed | Claimant |

10. | 5 | Confidential Affidavit of Stewart Alan Levitt 28 September 2023 | [11]–[21], whole | Stewart Levitt |

MURPHY J:

INTRODUCTION

1 Before the Court is an interlocutory application dated 28 April 2023 in which the applicants in this class action, Michael Robert Luke and Meredith Ann Luke (in their capacities as co-executors of the estate of Robert Colin Luke, deceased) and Ann Mary Stroud and Neil Bernard Colombari (in their capacities as co-executors of the estate of Joan Mary Colombari, deceased), seek Court approval of a proposed settlement under s 33V of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (the Act).

2 The applicants bring the class action on their own behalf and on behalf of approximately 2,700 current and former owners of freehold or leasehold interests in units in retirement villages operated by the respondent, Aveo Group Limited, which is a major operator of retirement villages in Australia. The proceeding is funded by Galactic Aveo LLC pursuant to litigation funding agreements it entered into with the applicants and approximately 232 group members.

3 The applicants’ claims arise from Aveo’s introduction of the “Aveo Way Programme”, which it began implementing in about 2014 and 2015, and which it continues to implement today. The essence of the claims is that Aveo sold to the applicants and group members their rights to occupy a retirement village unit upon a certain set of contractual terms, commonly a freehold interest in the unit with lower deferred management fees and the prospect of a capital gain when leaving the unit, Aveo then altered the terms on which incoming residents were to be offered units. The central allegation is that under the Aveo Way, in practice, incoming residents could only acquire a leasehold interest, which meant that the applicants and group members were not able to sell as attractive a set of rights to incoming residents as the rights they had themselves originally purchased; that the value of their existing rights was therefore materially diminished; and that Aveo unconscionably took advantage of its bargaining power in order to shift the applicant and group members over to being required to sell their existing rights under the Aveo Way.

4 The applicants have reached an in-principle settlement with Aveo (the proposed settlement) under which, if approved, Aveo will pay the applicants and group members $11 million (settlement sum) inclusive of interest, legal costs and settlement administration costs in full and final settlement of the proceeding.

5 Mr Levitt’s evidence in the approval application shows that he knew that the settlement sum would be consumed by Levitt Robinson’s legal costs. In an affidavit in support of the approval application he said that the firm had incurred $10,999,558 in legal costs in conducting the case up to the date of settlement, and estimated the costs of the settlement approval application at $251,450. It must have been plain to Mr Levitt that the sum provided under the proposed settlement would mean that the applicants and group members would get nothing.

6 Group members might reasonably ask how the applicants and their lawyers could conscientiously put forward the proposed settlement for approval when the group members are to receive nothing under the settlement, yet the applicants’ lawyers seek payment in full for their work. A group member who objected to the proposed settlement complained that the “[t]he fees applied by Levitt Robinson appear to be unreasonable and what remains for the Group Members is an insult”. Group members might also reasonably ask how the Court could conclude that such a settlement is fair and reasonable in the group members’ interests. They might think that a settlement under which the only winners are the lawyers indicates that something is terribly amiss in the operation of the class action regime in Pt IVA of the Act.

7 The Court’s fundamental task in a settlement approval application under s 33V(1) of the Act is to determine whether the settlement is fair and reasonable and in the interests of the group members who will be bound by it, including as between the group members. There must be a good reason why a settlement could be considered fair and reasonable from the perspective of group members, when the lawyers and litigation funders get more out of the class action than the people for whom the proceeding is brought: Clarke v Sandhurst Trustees Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCA 511 at [29]; Petersen Superannuation Fund Pty Ltd v Bank of Queensland Ltd (No 3) [2018] FCA 1842; 132 ACSR 258 at [244].

8 However, the fact that a proposed settlement is reached on terms which are quite unfavourable to group members does not necessarily indicate that the settlement is not fair and reasonable having regard to their interests, nor does it necessarily indicate a failure in the operation of the Pt IVA regime. Every day, in courts around the country, litigants are forced to confront the reality that their claims or defences are not as strong as they thought, and are forced to the realisation that it is appropriate to settle the case on unfavourable terms, or even to entirely capitulate. That is what happened here.

9 The parties reached the proposed settlement after six days of trial. The evidence in the approval application tends to show that the applicants accepted the offer of $11 million inclusive of costs because they (or more accurately their lawyers) had come to the view that the applicants’ and group members’ claims were likely to fail if the trial continued to judgment. It is not the Court’s role in a settlement approval application to second guess the decisions or risk appetite of the applicants or their lawyers. Different applicants and different lawyers will have different risk settings, and the question is whether the proposed settlement falls within the range of reasonable outcomes: Kelly v Willmott Forests Ltd (in liquidation) (No 4) [2016] FCA 323; 335 ALR 439 at [74]. Even so, it is perhaps worth noting that the applicants’ assessment of their prospects of success had a sound basis. Having regard to the materials in the approval application, I consider that their claims were likely to have failed had the trial continued to judgment.

10 I was satisfied that the proposed settlement fell within the range of reasonable outcomes of the proceeding, and fair and reasonable in the interests of group members to be bound to it, including as between group members. On 22 November 2023 I made orders to approve the proposed settlement.

11 But there remained a question as to the reasonableness of Levitt Robinson’s legal costs and of Galactic’s litigation funding charges. The Court must decide whether it is ‘just’ under s 33V(2) of the Act to approve the payment of those amounts from the settlement fund.

12 Class actions are intended to be conducted for the benefit of the applicants and group members rather than for service providers such as lawyers and funders and the legal costs and litigation funding charges should be both reasonable and proportionate: Caason Investments Pty Limited v Cao (No 2) [2018] FCA 527 at [148]. The Court has a supervisory role in relation to the legal costs and litigation funding charges proposed to be deducted from a settlement, and it is appropriate to scrutinise those costs as part of the settlement approval process: Kelly at [11], [333] and [346]; Earglow Pty Ltd v Newcrest Mining Ltd [2016] FCA 1433 at [91].

13 In order to best protect the group members’ interests I made orders on 8 June 2023 to appoint:

(a) Elizabeth Harris, an experienced legal costs consultant, as a referee pursuant to s 54A of the Act (the Costs Referee) to inquire and report in relation to the reasonableness of the applicants’ legal costs for work done up to the hearing of the settlement approval application, including costs anticipated but yet to be incurred as at the date of her report. The Costs Referee concluded that the reasonable legal costs incurred by Levitt Robinson up to the date settlement was reached were not $11 million as Levitt Robinson initially claimed, but instead $9,664,594. That represented a reduction of $1,334,964 (the Disallowed Costs). Neither the applicants, Levitt Robinson nor Galactic opposed adoption of the Costs Referee’s reports, and I concluded that it was appropriate to adopt the reports and disallow those costs; and

(b) Lachlan Armstrong KC and Kane Loxley of counsel as contradictor (Contradictor), to assist the Court to perform its judicial function by representing group members’ interests in the settlement approval application. The Contradictor submitted that after taking account of the Disallowed Costs, the Court should further reduce Levitt Robinson’s approved costs by $1,141,078 which the Contradictor submitted resulted from Levitt Robinson’s lack of expedition and serious inefficiency (the Avoidable Costs).

If both the Disallowed Costs and the Avoidable Costs are taken into account Levitt Robinson’s reasonable legal costs will be reduced by $2,476,042, to a total $8,523,516.

14 The Contradictor contended that Levitt Robinson failed to act with due expedition and efficiency by failing to serve the applicants’ expert evidence in accordance with the Court ordered pre-trial timetable. On the Contradictor’s argument, had Levitt Robinson complied with the pre-trial timetable in relation to the service of its expert evidence the applicants would have had Aveo’s expert reports by late November/early December 2022; because of Levitt Robinson’s late service of its expert reports it did not receive Aveo’s expert reports until the eve of trial; that the parties’ expert evidence was pivotal to achieving a settlement and that the case would most likely have settled at a mediation in December 2022 had the expert evidence been on; and because the parties did not have their expert evidence, the case did not settle at the mediation and Levitt Robinson ran up $1.141 million in costs in the period immediately prior to trial which would have been avoided had the firm complied with its professional obligations.

15 Levitt Robinson denied any serious lack of expedition, inefficiency or delay, and said that any failure on its part that was found to exist did not cause the Avoidable Costs. It said, and I accept, that the Court should be cautious before requiring the firm to write off substantial costs when there is no suggestion that they were incurred other than in an honest endeavour to prosecute the applicants’ and group members’ claims. This was a large and complex case and it is appropriate to be cautious before reaching a conclusion, several years later, well removed from the heat of battle, and with the benefit of 20/20 hindsight, as to what could or should have been done by Levitt Robinson.

16 But for the reasons I explain I came to broadly accept the Contradictor’s submissions. I am persuaded that Levitt Robinson failed to act with due expedition and was seriously derelict in failing to serve the applicants’ expert evidence in accordance with the Court-ordered pre-trial timetables. It is more likely than not that the case would have settled earlier had the firm complied with its professional obligations, and the $1.141 million in costs which the firm ran up in the immediate lead up to trial were avoidable.

17 It is material to my view that the question of whether the applicants and group members had suffered any loss in the value of their freehold or leasehold interests in units in retirement village operated by Aveo was central to the case. Notwithstanding that centrality, Levitt Robinson ran the case for more than five and a quarter years before it obtained a report by an expert property valuer. Levitt Robinson did not serve its expert evidence until 16 January 2023, which was so late that the applicants could not realistically expect to receive Aveo’s expert reports in response until effectively the eve of trial.

18 When Aveo served its expert reports on 10 March 2023, three business days before trial, it should have been immediately apparent that Aveo’s expert evidence, coupled with the evidence of its sales managers, seriously damaged the prospects of the applicants being able to establish loss. It is sufficiently clear on the materials in the approval application that the difficulties the applicants faced in establishing loss were significant in the decision to accept the proposed settlement. Had Levitt Robinson complied with the pre-trial timetable so that Aveo was required by the pre-trial timetable to serve its expert evidence by late November 2022, it is likely that at the December 2022 mediation the applicants' lawyers would have understood the difficulties the applicants faced in establishing loss, and that the case would have settled at around that point. The applicants would thereby have avoided the $1.141 million in Avoidable Costs that Levitt Robinson ran up in 2023, in the immediate pre-trial period.

19 I do not, though, accept the Contradictor’s contention that after reducing Levitt Robinson’s approved costs by: (a) $1.335 million in Disallowed Costs; and (b) $1.141 million in Avoidable Costs; none of Levitt Robinson’s costs incurred in the settlement approval application should be approved. In the circumstances of the case a reduction of $2.476 million is sufficient, and Levitt Robinson’s reasonable costs incurred in the settlement approval application should be approved. Those costs are minor in the scheme of things and they would have been incurred regardless of whether Levitt Robinson complied with the pre-trial timetable for service of the applicants’ expert reports.

20 I have therefore approved Levitt Robinson’s reasonable and proportionate costs up to the date of settlement in the amount of $8,523,516, and also approved the firm's reasonable costs of the settlement approval process in the amount of $394,538, as assessed by the Costs Referee. I have ordered that Levitt Robinson pay the costs of the Contradictor. If not for the legal costs that Levitt Robinson sought to have deducted from the settlement fund the greater part of the Contradictor’s fees would not have been incurred.

21 When the settlement approval costs and the settlement administration costs (estimated at $186,000) are taken into account, there will be approximately $1,895,946 available for distribution to the applicants and group members, which represents approximately 17% of the settlement. That is a far from a happy result for them, but the unfortunate reality is that their case was weak and always likely to fail. The fact that this is a class action rather than ordinary inter partes litigation does not provide a proper basis for giving group members something for what turned out to be worth nothing or something beyond what the true value of their claims are worth: Kuterba v Sirtex Medical Limited (No 3) [2019] FCA 1374 at [18]-[19].

THE EVIDENCE

22 The applicants rely upon the following:

(a) affidavits of Stewart Levitt, senior partner of Levitt Robinson and the solicitor on the record in the proceeding, sworn 26 April 2023, 28 September 2023 and 29 September 2023;

(b) confidential affidavits of Stewart Levitt sworn 28 September 2023 and 29 September 2023;

(c) affidavits of Brett Imlay, special counsel with Levitt Robinson, sworn 26 April 2023, 30 October 2023 and 2 November 2023;

and the exhibits thereto;

(d) the applicants’ submissions in reply to the Contradictor’s submissions dated 31 October 2023.

23 The Contradictor relies upon submissions dated 16 October 2023 and reply submissions dated 10 November 2023, and claims confidentiality in respect of parts of them;

24 Mr Levitt, trading as Levitt Robinson, was given leave to file evidence and make submissions in relation to his own interests. He relies upon the following:

(a) the affidavit of Mr Levitt sworn 21 October 2022, made in support of the applicants’ application to vacate the trial date;

(b) a confidential affidavit of Mr Levitt sworn 2 November 2023;

and the exhibits thereto; and

(c) confidential submissions dated 2 November 2023.

25 Galactic relies upon:

(a) the affidavit of Fredrick Schulman, Galactic’s sole director, sworn 27 October 2023; and

(b) submissions dated 3 November 2023.

26 The Costs Referee’s reports dated 26 July 2023, 10 August 2023, 14 November 2023 and 21 November 2023 are also before the Court.

27 I have drawn directly and indirectly on the affidavits and written submissions in these reasons.

THE RELEVANT PRINCIPLES

28 The applicable principles in relation to settlement approval under s 33V of the Act are well-established and I recently set them out in Webb v GetSwift Limited (No 7) [2023] FCA 90 at [15]-[17]. The organising principle of s 33V(1) is whether the proposed settlement is fair and reasonable and in the interests of the group members to be bound by the settlement, including as between the group members. Upon the Court deciding to approve a proposed settlement, s 33V(2) empowers the Court to “make such orders as are just with respect to the distribution of any money paid under a settlement”.

29 There are three essential questions to be addressed in the approval application:

(a) whether the proposed settlement is fair and reasonable having regard to the interests of the group members considered as a whole, the inter partes question;

(b) whether the proposed arrangements for sharing any settlement fund between the applicants and group members are fair and reasonable, again having regard to the interests of the group members considered as a whole, the inter se question; and

(c) as an aspect of (b) above, whether the proposed deductions from the settlement fund before distribution to the group members, for example, legal costs, litigation funding charges, a reimbursement payment to the applicant and settlement administration costs are reasonable such that it is appropriate to approve them.

THE ROLE OF THE CONTRADICTOR

30 The precise role of a contradictor in any case will be defined by the terms of their appointment by the Court. Here, my orders specified that the Contradictor’s role was to represent the interests of group members and to assist the Court to perform its judicial function in deciding whether the proposed settlement of this proceeding is fair and reasonable having regard to the interests of group members who will be bound by the settlement (if approved), and as between group members.

31 Contradictors are regularly appointed in this context. In Bolitho v Banksia Securities Ltd (No 6) [2019] VSC 653 at [123] Justice John Dixon observed as follows:

The court appoints a contradictor on a s 33V application in order to more effectively discharge its judicial function. In doing so, a court does no more than refine its process to the task. In my view…a contradictor appointed by a court on a s 33V application has, on behalf of and for the benefit of group members, the rights and powers of a party to the dispute unless the scope and extent of such powers is expressly constrained by the appointing court or necessarily constrained by the context of the appointment.

32 The appointment of a contradictor to represent the interests of absent group members in a settlement approval application can provide real assistance to the Court in the discharge of its judicial function. Sometimes a contradictor’s submissions shine a light into the dark corners of a proposed settlement, in circumstances where the parties (both friends of the deal) fail to do so. Appointment of a contradictor can be a useful tool in ensuring “both that justice is done and is seen to be done”: J Kirk SC (as his Honour then was), “The Case for Contradictors in Approving Class Action Settlements” (2018) 92 Australian Law Journal 716, 729.

33 Here, the Contradictor accepted that its role was to act as counsel for the group members who are not otherwise directly represented before the Court. The Contradictor said, correctly in my view, that its role was not to take every arguable point that might be said to be in the group members’ interests, but rather to exercise the normal and proper forensic judgements of counsel in determining what submissions ought be made in the interests of those they represent, and to assist the Court to exercise its protective role under s 33V: Gill v Ethicon Sàrl (No 10) [2023] FCA 228 at [42] (Lee J). That includes, where appropriate, explaining to the Court why the contradictor chooses not to take a point, or to make a submission, that might be regarded as open. That is so because it is important that the Court be satisfied that its appointed contradictor has not overlooked something that the Court would expect to have been considered.

34 The Contradictor’s submissions in this case were helpful. They brought to light a concern in relation to the quantum of the legal costs proposed to be deducted from the settlement fund and paid to the applicants’ lawyers, which no other party brought to my attention.

OVERVIEW OF THE PROCEEDING

35 The essence of the applicants’ and group members’ claims is that Aveo, having sold to them rights to occupy their retirement village units upon a certain set of terms, then:

(a) altered the terms on which new residents might be offered units; and

(b) in practice tended to confine the existing residents to the terms of the Aveo Way.

Their central contention is to the effect that the changed terms meant that the claimants were not able to sell as attractive a set of rights as they had themselves originally purchased, that the value of their existing rights was therefore materially diminished, and that Aveo had unconscionably taken advantage of its bargaining power in order to shift residents over to the Aveo Way. The applicants relied heavily on the proposition not only that the applicants and group members suffered (or were likely to suffer) loss from the diminished value of the rights that they were able to sell, but also that Aveo arrogated to itself the benefit of all future capital appreciation on the units.

36 The applicants alleged four species of conduct said to give rise to Aveo’s liability, which can be summarised as follows.

37 First, the Unconscionable System claim. The gist of this claim is that Aveo had a multiplicity of “levers”, that is, existing and available aspects of its business and relationship with residents that it could use to move, by power or influence, residents of its retirement villages in their decision-making. Aveo knew that it had these “levers,” and in so knowing it designed the Aveo Way.

38 The object of the Aveo Way was to replace pre-Aveo Way interests in units in Aveo’s retirement villages (Pre-AWIs) with Aveo Way interests (AWIs). Aveo wished to do this because it expected that it could obtain a financial benefit from the replacement of Pre-AWIs with AWIs. Relevantly, the differences are that:

(a) the holders of Pre-AWIs were generally entitled to capital appreciation, whereas the holders of AWIs were not (with Aveo obtaining that entitlement under AWIs); and

(b) the holders of AWIs were exposed to a deferred management fee (DMF) either of a greater percentage, faster accrual, or both (with Aveo obtaining the benefit of those changes); and

(c) some holders of AWIs paid additional membership fees to Aveo.

39 The mechanism adopted by Aveo to implement the replacement of Pre-AWIs with AWIs was by ensuring that, upon the introduction of the Aveo Way, the price paid by the incoming resident for an AWI in a retirement unit would be the price paid by Aveo to the outgoing resident for or in respect of the Pre-AWI. If, as the applicants alleged, the Pre-AWIs were more valuable than AWIs (or were likely to be), then that meant that Aveo benefited, by avoiding having to pay that difference in value between what it bought (a Pre-AWI) and what it sold (an AWI). Without paying the outgoing interest holder anything more for the interest, Aveo acquired the additional value attributable to the superiority of the Pre-AWI over the AWI.

40 In this way Aveo was alleged to have converted a portfolio of interests in which residents were generally entitled to capital gains (and to a lower DMF), into a portfolio of interests in which Aveo was entitled to capital gains (and a higher DMF), without having to pay the outgoing resident anything for the greater value of the Pre-AWI that the resident held. That system is one of the crucial aspects of the conversion to Aveo Way on which the applicants’ case was focused. It worked against the outgoing interest holder in relation to capital gains and at a portfolio level resulted in a massive capital gain for Aveo.

41 The applicants contended that they are not just complaining about Aveo legitimately pursuing its own advantage. They allege that, using the levers available to it, Aveo took a number of steps to achieve its desired result, which were not necessary to protect its legitimate interests, which it did for the primary purpose of obtaining a benefit for itself, resulting in detriment (or the likelihood thereof) to the applicants and group members. The features that are alleged to support a finding that Aveo’s conduct was unconscionable include its superior knowledge and bargaining power, its purposes in introducing and effecting Aveo Way, the vulnerability of the applicants and group members, and the fact that ARE, Aveo’s “in-house” real estate agency, was used by Aveo to effect the system when ARE stood in a fiduciary relationship with the selling applicants and group members (who were its clients).

42 Second, the introduction and promotion of Aveo Way at a village-level by some village operators was unconscionable and caused damage to some group members. It is alleged that AWIs were (or were likely to be) less valuable than Pre-AWIs, and having regard to that and all of the circumstances of each sale, introducing and promoting Aveo Way in relevant Aveo villages involved statutory unconscionability by Aveo directly, and as an accessory to the village operators’ conduct.

43 Third, that Aveo and the village operators represented to the applicants and group members that disposing of Pre-AWIs pursuant to the Aveo Way would leave sellers of Pre-AWIs no worse off. That is alleged to constitute misleading or deceptive conduct, either because selling pursuant to the Aveo Way would or was likely to, in fact, leave sellers worse off, or (on the basis that the representation related to a future matter), because there were no reasonable grounds for the representation. This is alleged against Aveo directly and also as an accessory to the village operators’ conduct.

44 Fourth, the failure to disclose to the applicant and group members (in the presence of a reasonable expectation of disclosure) that there was no need for the holders of freehold Pre-AWIs to appoint ARE to sell their freehold interest constituted unconscionable conduct. It is alleged that there was no need for the holders of freehold Pre-AWIs to appoint ARE to sell their interests because, inter alia, the relevant village operator would inevitably be the purchaser of the Pre-AWI (so that there was no need to identify a buyer). This is alleged against Aveo directly and as an accessory to the failure to disclose by relevant village operators, and also as an accessory to ARE’s failure to disclose which includes an allegation that Aveo is accessorially liable for ARE’s unconscionable and misleading conduct and deceptive charging of commission on the sales.

The centrality of loss in the case

45 The essence of the applicants’ claims was that the introduction of the Aveo Way programme caused a reduction in the desirability of units in Aveo retirement villages, giving rise to: (a) a lower sale price for an outgoing resident’s unit than otherwise would have been achieved; and/or (b) a longer time on the market for the unit than would otherwise have been the case. The applicants’ case centrally turned upon evidence as to the value of units in Aveo’s retirement villages before the introduction of Aveo Way, compared to their value when resold or re-leased under the terms of the Aveo Way. Essentially, if the applicants and group members who held Pre-AWIs could not show that they had suffered, or were likely to suffer, a loss as a result of the introduction of the Aveo Way then it was not unconscionable for Aveo to introduce the Aveo Way and doing so did not involve misleading or deceptive conduct.

46 The centrality of loss in the case was obvious from early in the proceeding. Since almost everything in the proceeding turned on the Court’s acceptance that there has been a lower sale price for units or longer sale time since the Aveo Way programme was introduced, on 30 July 2019 Aveo submitted that a separate question as to loss should be heard.

47 That suggestion was opposed by the applicants. I was, however, attracted to the idea and I made orders on 30 July 2019 authorising National Judicial Registrar Gitsham to confer with the parties in the endeavour to have them agree, or to set, a separate question in relation to loss, and to make such directions as she considers appropriate, including by setting a timetable to a hearing of a separate question.

48 Unfortunately, that process became a lengthy one. The conferral process before Registrar Gitsham involved a series of case management hearings in the second half of 2019 and the first half of 2020. Aveo provided the applicants with the raw sales data in relation to freehold unit sales in July 2019 and it provided the raw sales data in relation to leasehold unit “sales” in September 2019. The applicants engaged two actuaries with expertise in the valuation of retirement village interests to review the sales and leasehold data with which it had been provided. Eventually the applicants proposed alternative separate questions in relation to loss but the parties could not agree on those.

49 Aveo eventually filed an interlocutory application dated 12 February 2021 in which it sought determination of separate questions pursuant to rule 30.01 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (the Separate Question Application). It proposed two separate questions, based on common questions drawn from the Further Amended Application, namely:

1. Whether upon the implementation of the Aveo Way Programme with respect to an outgoing resident with a Pre-AWFI [a pre-Aveo Way freehold interest]:

(a) the outgoing resident would, or would likely, receive less monies upon the sale of their interest than if the Aveo Way Programme had not been implemented;

(b) the period of time in which the unit was required to be marketed before sale to a new resident would likely be prolonged.

2. Whether upon the implementation of the Aveo Way Programme with respect to an outgoing resident with a Pre-AWLI [a pre-Aveo Way leasehold interest]:

(a) the outgoing resident would, or would likely, receive less monies upon the sale of their interest than if the Aveo Way Programme had not been implemented;

(b) the period of time in which the unit was required to be marketed before sale to a new resident would likely be prolonged

50 I heard that application on 31 August 2021 and made orders to dismiss the application on 2 September 2021.

KEY TERMS OF THE PROPOSED SETTLEMENT

51 The proposed settlement is recorded in a Deed of Settlement dated 27 March 2023 (Settlement Deed) to which the following are signatories:

(a) the applicants;

(b) Aveo;

(c) Mr Levitt, in his personal capacity and as the senior partner of Levitt Robinson;

(d) Class Marketing and Management Pty Ltd (which I understand to be a class action marketing company associated with Levitt Robinson); and

(e) Galactic Aveo LLC (which is the Galactic entity funding the proceeding) and

(f) Galactic Litigation Partners LLC (which is the Galactic parent company).

52 The key terms of the proposed settlement are that, upon final orders of the Court approving the proposed settlement (after expiry of all appeal periods) on the terms contained in the Settlement Deed or substantially on the terms of the Settlement Deed,

(a) Aveo will pay $11 million in full and final settlement of the proceeding into the Settlement Account, inclusive of interest, costs and settlement administration, to be distributed by the Administrator as directed by the Court;

(b) the applicants on behalf of themselves and on behalf of all group members will release Aveo, its related bodies corporate, its related entities and/or its related persons respectively from all of their Claims; and

(c) the applicants on behalf of themselves and on behalf of all group members, Mr Levitt by himself and his servants or and agents, and Galactic and its related entities, agree that they will not bring or pursue, or otherwise aid, abet, counsel, provide funding or procure that a third-party bring or pursue a Claim against Aveo, its related bodies corporate, its related entities and/or its related persons;

53 One unusual term of the proposed settlement is the requirement for Mr Levitt to provide to Aveo a signed copy of an agreed public statement on Levitt Robinson letterhead, the terms of which are as follows:

Levitt Robinson has today withdrawn the class action proceedings against Aveo.

Levitt Robinson acknowledges that the introduction and implementation by Aveo and its related entities of Aveo Way contracts were lawful, in accordance with industry standards and that we are now satisfied that the Federal Court is not likely to find that its introduction has caused current or former residents of Aveo to suffer any loss.

We express regret for any distress or anxiety which Aveo residents and staff have experienced as a result of or incidental to the Aveo class action litigation.

IS THE PROPOSED SETTLEMENT FAIR AND REASONABLE INTER PARTES?

Counsel’s Confidential Opinion

54 I have had the benefit of considering the Confidential Opinion of Nick Kidd SC and Daniel Meyerowitz-Katz of counsel dated 28 September 2023, who were briefed in the trial. Because the proposed settlement was reached after six days of trial, counsel had substantially more information regarding the parties’ respective cases and their prospects than is commonly the case in a settlement approval application. At the point settlement was reached the parties had put on detailed opening written submissions and had made oral openings, both sides had called their lay witnesses, both sides had filed and served their expert evidence, and the trial judge had made some remarks about aspects of the applicants’ case during the oral openings.

55 The Confidential Opinion is careful and comprehensive, and the level of candour is consistent with the expectations of the Court. Counsel did not endeavour to put a gloss on the proposed settlement. Because of its confidentiality I cannot go to the detail of the Confidential Opinion but it does not damage that confidentiality to note that it sets out some events in the lead up to the trial, including changes in the applicants’ counsel team, the applicants’ failure to comply with the pre-trial timetables for filing expert evidence and the asserted reasons for that failure, the applicants’ unsuccessful application to vacate the trial, the lateness of Aveo’s expert evidence, the applicants’ second unsuccessful application to vacate the trial, the trial judge’s remarks in the course of oral openings which the applicants saw as favourable to Aveo, and the trial judge’s ruling that the applicants’ claim that ARE acted in breach of its fiduciary duties to holders of pre-AWFIs was outside the scope of the pleading.

56 Counsel concluded that the proposed settlement is fair and reasonable in the interests of group members to be bound by it, and as between group members. It is appropriate to give substantial weight to their opinion.

The Contradictor’s submissions

57 The Contradictor put on detailed written and oral submissions. Insofar as the submissions go to the applicants’ prospects of success in the case they are confidential and I cannot go to the detail of them. It suffices to note that the Contradictor, who was charged with the obligation to represent the interests of absent group members, concluded that notwithstanding that the proposed settlement represents a very disappointing result for group members it could not responsibly be put that some feature of the proposed settlement inter partes ought be rejected by the Court.

58 The Contradictor also considered an argument as to whether, irrespective of the prospects of the applicants’ claims, it was in the interests of group members to have those claims prosecuted to their conclusion. On this argument, compared to a settlement under which they are to receive nothing, group members had nothing to lose by continuing the case. That risk fell entirely on Galactic, and it is a risk that Galactic assumed in financing the claim. On this argument the proposed settlement is not in the interests of group members to be bound to it.

59 But, the Contradictor noted, that argument is not tenable because:

(a) it ignores the terms of the litigation funding agreements (LFAs) with the applicants and the Terms of Engagement Levitt Robinson entered into with Galactic. Galactic did not agree to fund the case to judgment regardless of its own assessment of the prospects, and it had the right to terminate the LFA and the Terms of Engagement; and

(b) it proceeds on a false premise that Galactic would have continued to fund the litigation in the event the settlement offer was refused. The applicants and their lawyers were obliged to keep Galactic fully informed in relation to the prospects of the case, and it is appropriate to infer that they did so. It seems likely that the same concerns that lay behind the applicants’ decision to accept a costs-only settlement would have motivated Galactic to cease funding the proceeding if the applicants wanted to continue it. If funding ceased then there is nothing to show that Levitt Robinson would be prepared to continue to act in the case without litigation funding, and nothing to show that the applicants would have been prepared to assume the risk of an adverse costs order in the case.

60 The Contradictor’s submissions point strongly in favour of approving the proposed settlement inter partes.

The scope of the proposed releases

61 Clause 3.1.2 of the Settlement Deed provides that upon final settlement approval orders the applicants for and on behalf of themselves and on behalf of group members release Aveo, its related bodies corporate, its related entities and/or its related persons respectively from all of their “Claims” (as defined).

62 “Applicants’ and Group Members’ Claims” is defined in cl 1.1 to mean “any claim or cause of action in the Proceedings or any claim or cause of action arising out of, or in relation to, the subject matter of the Proceeding including any other potential or related Claim”.

63 “Claim” is broadly defined in cl.1.1 to mean:

any claim, demand, action, suit or proceeding for damages, debt, restitution, equitable compensation, account, injunctive relief, specific performance, declaratory relief or any other remedy, whether by original claim, cross-claim, claim for contribution or otherwise whether presently known or unknown and whether arising at common law, in equity, under statute or otherwise and whether involving a third party or party to this Deed and all liabilities, losses, damages, costs (including legal costs on a full indemnity basis), interest, fees, and penalties of whatever description (whether actual, contingent or prospective).

64 Thus, the applicants purport to release not only group members’ claims in the proceeding, but also “any claim” by a group member “in relation to the subject matter of the Proceeding”, including “any other potential or related Claim”, whether the Claim is known or unknown, and whether it involves someone other than a party to the Settlement Deed.

65 The phrases “in relation to the subject matter of the Proceeding” and “any other potential or related Claim” carry broad meanings, which include a group member’s claims “relating to” the subject matter of the proceeding and to related claims. That may extend to include a group member’s claim which is individual or idiosyncratic to the group member; that is, claims which are not common claims under s 33C of the Act. As I said in Ghee v BT Funds Management Limited [2023] FCA 1553 at [27]-[29], acting on own behalf the applicants can provide Aveo with whatever release they like, but there are limits to their capacity to release group members’ claims. The Full Court in Dyczynski v Gibson [2020] FCAFC 120; 280 FCR 583 at [250]-[251] (Murphy and Colvin JJ) and [395]-[396] (Lee J) held that the authority of the representative applicant in a class action does not extend to settling individual or idiosyncratic claims of group members (as opposed to ‘common claims’ recognised under s 33C of the Act), subject to the qualifications expressed by Lee J (at [398]).

66 I raised this difficulty in the settlement approval hearing and it was resolved by counsel for Aveo accepting that the releases cannot and are not intended to go beyond the common claims of the group members which are or could have been pleaded in the proceeding. Having regard to that concession in open Court, I concluded that the scope of the releases did not stand in the way of settlement approval.

Relevant factors under the Class Actions Practice Note (GPN-CA)

The stage of the proceeding at which settlement was achieved

67 There had been six days of trial at the point the parties reached the proposed settlement, and the applicants and their lawyers were therefore in a good position to make an informed assessment as to whether prospects of success of the applicants’ and sample group members’ claims were such that it was appropriate to effectively abandon their claims, and instead settle for legal costs only.

The complexity and likely duration of the litigation

68 The case is both factually and legally complex and had the proposed settlement not been reached the initial trial would have run for approximately 4 additional weeks. The proposed settlement avoids the uncertainty and delay associated with prosecuting the claims to judgment.

The risks of establishing liability and loss or damage

69 The applicants’ prospects of establishing that Aveo engaged in unconscionable conduct or misleading or deceptive conduct essentially turns on their ability to establish that the introduction of the Aveo Way Programme caused loss to the holders of pre-AWI interests. Having regard to the evidence in the approval application I am satisfied that the applicants’ and sample group members’ prospects of establishing loss were very low. In my view it is more likely than not that their claims would have failed. This points strongly in favour of approving the proposed settlement.

The range of reasonableness of the settlement in light of the best recovery

70 The proposed settlement represents a negligible percentage of the potential best-case outcome for the applicants and group members. Indeed, once the proposed deductions for legal costs are applied, they will receive nothing.

The reasonableness of the proposed settlement in light of the attendant litigation risks

71 The proposed settlement is a very disappointing result for the applicants and group members, and no doubt also for the applicants’ lawyers. But as I have said, the prospects of the applicants’ and sample group members’ succeeding in establishing loss were low. Based on the materials in the approval application it is more likely that than not that their claims would have failed had the initial trial continued to judgment. I therefore consider that the proposed settlement is reasonable in light of the attendant risks of litigation and that it falls within the range of reasonable outcomes in the case.

72 I note in this regard that Levitt Robinson’s evidence is redolent with complaint in relation to the trial judge’s refusal of the applicants’ two applications to vacate the trial (which had the result that the applicants did not receive Aveo’s expert evidence until the eve of trial) and his Honour’s finding that the applicants’ claim of breach of fiduciary duty by ARE, and of Aveo’s involvement in that breach fell outside the pleadings. Those matters are said to have been important to the decision to accept the proposed settlement.

73 Of course, instead of deciding to recommend acceptance of a costs-only settlement the applicants (or more accurately their lawyers) might have chosen to continue to judgment and, if unsuccessful, to then appeal the trial judge’s rulings and judgment. Different lawyers or a different funder, with different appetites for risk, might have made such a decision. But it is not my role in a settlement approval application to second-guess the applicants’ lawyers to such an extent. It is clear that the decision to settle was a reasonable option in light of all the circumstances. In any event Mr Shulman stated that Galactic would not have funded an appeal. There is nothing to show that Levitt Robinson would have been prepared to conduct an appeal without litigation funding, or that the applicants would have been prepared to take on the risk of an adverse costs order in any appeal.

The reaction of the class

74 Only one group member filed a notice of objection to the proposed settlement. Ms Jill Orr, the executor for Valda Rutledge (deceased), said:

The fees applied by Levitt Robinson appear to be unreasonable and what remains for the Group Members is an insult.

75 That is not an objection to the proposed settlement, but rather to the legal costs Levitt Robinson proposes to deduct from the settlement fund. I accept the broad thrust of this objection, but it does not stand in the way of approving the settlement. For the reasons I later turn to explain, I consider the legal costs that Levitt Robinson proposed be deducted from the settlement fund are not reasonable, and that the firm's costs should be approved in a reduced amount.

76 For the above reasons, notwithstanding that group members will receive very little from the proposed settlement, I am satisfied that it is fair and reasonable in the interests of group members inter partes.

IS THE PROPOSED SETTLEMENT FAIR AND REASONABLE INTER SE?

77 The revised Settlement Scheme (Scheme) is annexed to the 14 December 2023 orders. Under cl. 39 of the Scheme the settlement fund of $11 million is to be allocated as follows, and in this sequence:

(a) first, reimbursement of legal costs and disbursements paid by Galactic, in the amount approved by the Court;

(b) second, any unpaid or unbilled costs and disbursements of Levitt Robinson;

(c) third, the costs incurred by Levitt Robinson in the settlement approval application;

(d) fourth, the reasonable settlement administration costs incurred by the Administrator of the Scheme; and

(e) fifth, the residue remaining after payment under (a) to (d) above – the “Net Settlement Distribution Fund” - will be distributed amongst those eligible group members who registered to participate in the settlement (Registered Group Members or RGMs) in the same proportion as the “sale” price for each person’s freehold or leasehold interest bears to the total sale prices of the freehold and leasehold interest of Eligible Group Members.

78 The basic process contemplated by the proposed Scheme provided as follows:

(a) only Eligible Group Members (EGMs) (as defined) are eligible to claim against the settlement fund;

(b) the EGMs must register by a Court-approved deadline in order to be considered for a distribution from the settlement fund;

(c) Korda Mentha or such other suitable qualified person nominated by Aveo is appointed as the Administrator of the Scheme and will vet registrations by EGMs, and the data submitted by EGMs regarding the freehold or leasehold sale prices that form the basic integer in the calculation of their pro rata entitlements from the settlement fund;

(d) the Administrator may obtain from Aveo any necessary details to confirm the eligibility of any RGM;

(e) the Administrator will provide to each RGM a “Certificate of Claim Amount”; which the RGMs will have an opportunity to dispute;

(f) any dispute in relation to (e) above is to be arbitrated by the Administrator;

(g) the Certificates of Claim Amount as agreed or arbitrated will form the basis for the calculation of RGMs’ pro rata entitlements; and

(h) the Net Settlement Distribution Fund will be distributed according to those pro rata entitlements.

79 The Contradictor identified a small error in the proposed Scheme which Levitt Robinson then addressed, and also asserted a more substantive error which it ultimately withdrew.

80 Mr Levitt’s evidence addressed the quantum of administration costs. It shows that Korda Mentha’s estimated its settlement administration costs at $427,300 (excl. GST) for 2,700 claimants, reflecting full participation, and $402,500 (excl. GST) reflecting half participation, including a fixed component of $340,000 which appears to be payable irrespective of the rate of group member participation. However, Steven Nicols, the Court-appointed administrator in several other class action settlements schemes, provided a fee estimate of $186,000 (excl. GST) for full participation and $132,000 (excl. GST) for half participation. On 22 November 2023 I made orders to appoint Mr Nicols as the Administrator.

81 I had a concern that the Administrator should not be the arbiter of disputes in relation to any Certificate of Claim Amount, as it was the Administrator who had decided the amount in that Certificate in the first place. But, having regard to the fact that the Scheme does not require the Administrator to make “judgment calls”, and having regard to the small percentage of each RGMs loss that is likely to be paid under the Scheme, I concluded that the cost of providing an independent review was not justified by the benefit.

82 In my view the proposed settlement is fair and reasonable inter se.

WHETHER LEVITT ROBINSON’S COSTS ARE REASONABLE

The change in Levitt Robinson’s position

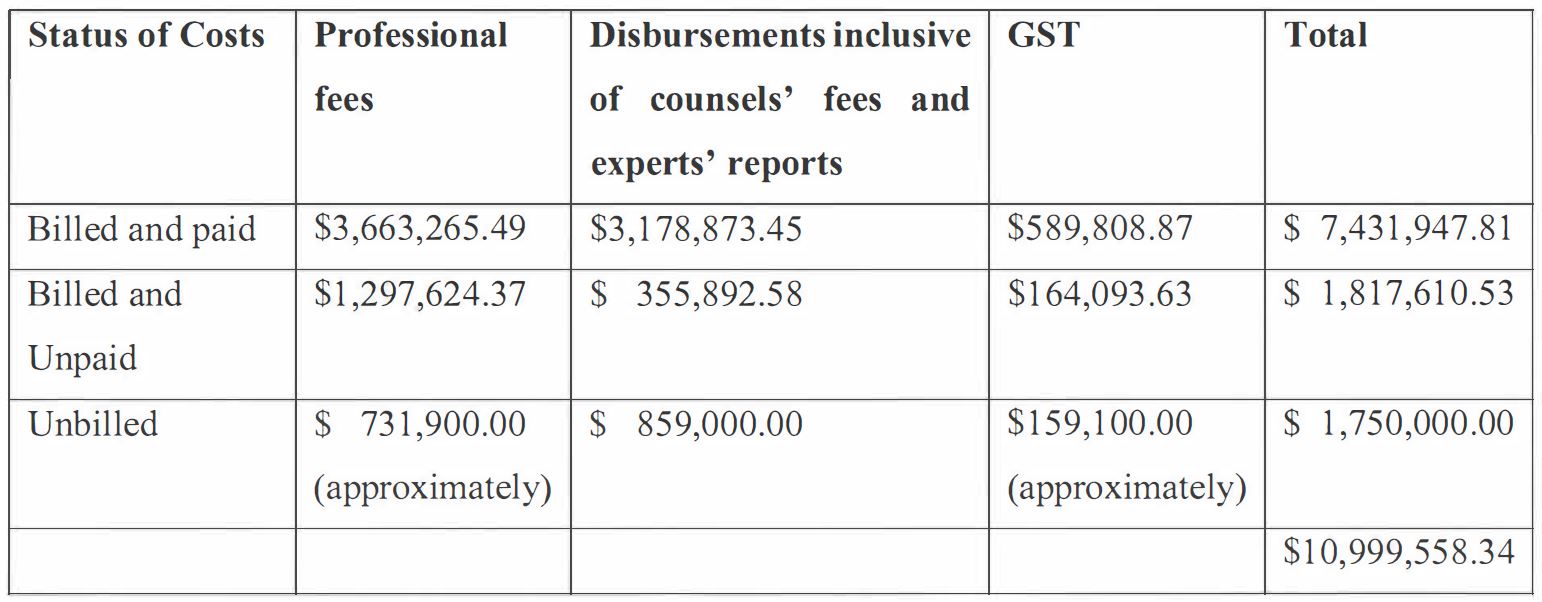

83 The quantum of the costs which Levitt Robinson sought to have deducted from the settlement fund reduced over time. In his first affidavit Mr Levitt stated that the firm had incurred $10,999,558 in legal costs (incl. disbursements and GST) in conducting the proceeding on behalf of the applicant up to the date of settlement, made up as follows:

He also estimated that Levitt Robinson would incur $251,450 in costs in the settlement approval application, assuming that no contradictor was appointed and that the approval hearing concluded within one day.

84 But by the time of the approval hearing on 22 November 2023 the Costs Referee had provided her reports. She did not accept that Levitt Robinson’s costs of approximately $11 million were reasonable. Instead, she concluded that the firm’s reasonable legal costs up to the date of settlement were $ $9,664,594; being a reduction of $1,335,406. Neither Levitt Robinson, nor any other party, opposed adoption of the Costs Referee’s Reports. I concluded that it was appropriate to adopt the Costs Referee’s Reports. Thus, at this point, Levitt Robinson sought approval to deduct approximately $9.665 million from the settlement fund.

Galactic’s position in relation to Levitt Robinson’s costs

85 Galactic’s position as to the reasonableness of Levitt Robinson’s costs also changed over time. At the time that settlement was reached Galactic had paid Levitt Robinson only $7.69 million of the approximately $11 million in legal costs that Levitt Robinson claimed to have incurred; which meant that there was approximately $3.31 million outstanding. At an early case management hearing in the approval application Galactic submitted through senior counsel that Levitt Robinson’s costs claim was not reasonable, and that costs should not be approved in any greater amount than $7.69 million. In his affidavit Mr Schulman stated that Levitt Robinson initially provided an estimate of $8.195 million to Galactic and the applicants, to run the proceeding from the start to the conclusion of the initial trial. Then, he said that less than two months before the trial was due to commence, Levitt Robinson sought to revise its estimate upwards to $11.639 million; an increase of $3.5 million.

86 But by the approval hearing on 22 November 2023 Galactic no longer contended that Levitt Robinson’s costs were unreasonable. Neither Galactic nor Levitt Robinson explained the reason for that change of position. In my view it is appropriate to infer that Levitt Robinson and Galactic have come to a private arrangement in regard to Levitt Robinson’s costs.

The salient procedural steps

87 To understand the Contradictor’s contentions in relation to Levitt Robinson’s alleged lack of expedition and its inefficiency, and also Levitt Robinson’s response, it is unfortunately necessary to descend to an extent into the minutiae of the firm’s conduct of the proceeding, at least in relation to the seven-month period from November 2021 to 2 July 2022, which the Contradictor focussed on.

88 By orders made 2 September 2021 I dismissed the application for a separate question, and listed the initial trial of the proceeding on 1 March 2023, on an estimate of five weeks. That allowed 18 months for the parties to complete the remaining pre-trial steps.

89 By the orders made to September 2021, the applicants were required to provide Aveo with a proposed timetable for the further steps in the litigation by 16 September 2021, including for:

(a) an express pleading of the applicants’ claim for “special value” loss articulated in the hearing on 31 August 2021;

(b) identification of the sample group members whose claims are proposed to be part of the initial trial of common issues and for filing points of claim and points of defence in regard to those persons, discovery including in relation to the sample group members;

(c) opt out;

(d) the filing of lay and expert evidence; and

(e) finalising the common issues for trial.

The orders provided for Aveo to respond to the proposed timetable by 30 September 2021, and for the parties to confer in an attempt to agree the timetable by 7 October 2021.

90 The parties reached an agreed timetable for the necessary interlocutory steps up to trial. On 11 October 2021 I made orders, by consent, setting out the timetable to trial (the first pre-trial timetable). The orders provided that:

(a) by 11 October 2021, the applicants file a proposed Third Further Amended Statement of Claim;

(b) by 24 December 2021, the applicants file points of claim in relation to sample group members’ claims, and by 25 March 2022 Aveo file points of defence;

(c) by 22 November 2021, the parties exchange proposed categories of documents to be discovered with respect to the claims of the third and fourth applicants and the unconscionable system claim, and by 6 December 2021 seek to agree on those categories. At this point there had already been substantial discovery but there had not yet been discovery in relation to the leasehold claims, or the unconscionable system claim;

(d) by 4 March 2022, the parties exchange proposed categories of documents to be discovered in respect of the sample group members, and by 25 March 2022 seek to agree on those categories;

(e) by 4 March 2022, the applicants provide a proposed form of the opt out notice to Aveo, and by 18 March 2022 the parties seek to agree on the form and content of that notice and accompanying orders for publication, responses and inspection; and

(f) by 1 April 2022, any party wishing to bring an interlocutory application in relation to discovery, the filing of proposed points of claim on behalf of sample group members, or the form and content of the opt out notice and accompanying orders file and serve such an application. Any such application was to be determined at a hearing listed on 21 April 2022.

91 Most importantly for the present application, the consent orders provided that:

(a) by 13 May 2022 the applicants serve their lay evidence; by 8 July 2022 Aveo serve its lay evidence; and by 29 July 2022 the applicants serve any lay evidence in reply,

(b) by 29 July 2022 the applicants serve their expert evidence; by 28 October 2022 Aveo serve its expert evidence; and by 25 November 2022 the applicants serve any expert evidence in reply; and

(c) there be a mediation by 16 December 2022.

92 On 5 October 2021 the applicants sought and were granted leave to serve seven subpoenas on retirement villages said to be in close proximity to the retirement village in which the property the subject of the Colombari applicants’ claim was located. The documents were said to be necessary for the preparation of the Colombari applicants’ evidence in relation to the value of their property. On 15 October 2021 the applicants sought and were granted leave to serve six further subpoenas.

93 The applicants did not comply with the order to file points of claim on behalf of sample group members by 24 December 2021, and they were substantially late in that regard.

94 On 14 April 2022 the applicants filed an interlocutory application seeking leave to file points of claim on behalf of sample group members, outside the timeframe in the first pre-trial timetable. The applicants also sought orders for further discovery by Aveo and for approval of the form, content and mode of distribution of an opt out notice. In an affidavit in support of the application sworn 14 April 2022 Mr Levitt stated that Levitt Robinson had been unable to comply with the timetable and it expected to serve the last sample group member’s points of claim before the end of April 2022. He said that preparing the points of claim had taken much longer than anticipated including because of: (a) the commitments of Mr Imlay and counsel arising from the rescheduling of the settlement approval application in the 7-Eleven class action; (b) difficulties in finding appropriate sample group members and investigating their claims; (c) deficiencies in the information discovered by Aveo relevant to sample group members’ claims; (d) the appointment of senior counsel in the proceeding as the counsel assisting the Star Casino Royal Commission, so that he was no longer available; and (e) that the delay in investigating sample group members’ claims meant that the time set aside in December 2021 by two other members of the counsel team could not be utilised.

95 Mr Levitt further stated that the parties had agreed on the categories of discovery in relation to the new Colombari applicants added in November 2021; that such discovery had largely been provided, and that all but one of the categories of further discovery by Aveo had been agreed. Levitt Robinson had provided a proposed opt out notice and orders to Aveo but the parties had been unable to agree on the form of the notice.

96 I heard the applicants’ application for variation of the first pre-trial timetable on 21 April 2022. By orders that day I revised some aspects of the first pre-trial timetable by extending the time for compliance (the second pre-trial timetable) so that:

(a) by 29 April 2022, the applicants serve the last of the sample group members’ points of claim. Aveo was directed to advise as to whether it consented to the points of claim provided to it by 6 May 2022. If there was no dispute Aveo was ordered to serve points of defence in relation to sample group members’ points of claim by 24 June 2022;

(b) for Aveo to provide discovery in respect to sample group members by 24 June 2022; and

(c) to extend the time for the parties to serve their lay and evidence, as follows:

(i) by 22 July 2022 the applicants serve their lay evidence; by 16 September 2022, Aveo serve its lay evidence; and by 7 October 2022, the applicants serve any lay evidence in reply; and

(ii) by 19 August 2022 the applicants serve their expert evidence; by 18 November 2022 Aveo serve its expert evidence; and by 9 December 2022 the applicants serve any expert evidence in reply.

97 In an affidavit by Danielle Gleeson, a solicitor at Levitt Robinson, dated 20 May 2022 she exhibited correspondence to show that the parties:

(a) had resolved all disputes regarding the further categories of documents to be discovered by Aveo; and

(b) had agreed the form of the proposed opt out orders but not the form of the proposed opt out notice or newspaper notice.

The correspondence showed that Aveo was not persuaded as to the utility of hearing the sample group member claims as part of the initial trial and it neither consented to nor opposed the filing of points of claim in relation to them.

98 The proceeding was then transferred to the docket of Justice Anderson (the trial judge). His Honour listed the proceeding for a case management hearing on 2 June 2022, and made orders that day:

(a) granting leave to the applicant to file and serve the proposed points of claim for five sample group members (which had already been provided to Aveo);

(b) for Aveo to file and serve points of defence by 24 June 2022; and

(c) to appoint an amicus curiae to represent the interests of group members who had not sold their units and had not entered into a LFA. The amicus was appointed because Aveo expressed concerns regarding the form of funding equalisation order that the applicants’ proposed opt out notice had said Galactic might seek in relation to unfunded group members.

99 On 4 July 2022, at the applicants’ request, the Court issued 29 subpoenas all of which were said to be to assist with the preparation of the applicants' expert evidence. 25 of the subpoenas were issued to retirement village operators seeking sales information to assist in the preparation of reports by the applicants’ expert valuer in relation to the claims of the sample group members, and five were issued to accounting firms and real estate agents seeking information requested by the applicants’ forensic accountant.

100 On 9 August 2022 the trial judge heard an interlocutory application in relation to the appropriate form of the opt out notice, in which the amicus curiae opposed the form of opt out notice proposed by Levitt Robinson. On 12 September 2022 his Honour made orders approving the form and content of the opt out notice in a revised form.

101 The applicants failed to serve their lay evidence in compliance with the second pre-trial timetable. Instead, they served 12 lay affidavits between 29 July and 19 August 2022, between about one week and one month later than that extended timetable. Aveo was required to serve its lay evidence by 16 September 2022 but given the delay in provision of the applicants’ lay evidence it could not be expected to file its lay evidence until approximately mid-October 2022.

102 There was then some delay by Aveo in providing the further discovery it was required to provide. The applicants also experienced some delay in obtaining some of the documents that they had subpoenaed.

103 The applicants also failed to serve their expert evidence by 19 August 2022 in compliance with the second pre-trial timetable. Instead, over two months later, the applicants filed an interlocutory application dated 24 October 2022 in which they sought to vacate the hearing. The application was supported by an affidavit made by Mr Levitt sworn 21 October 2022. He deposed that the trial date was no longer maintainable because of:

(a) delay in the process of identifying sample group members and preparing their points of claim;

(b) delay in the provision of further discovery by Aveo which was required by the applicant’s experts for their reports;

(c) delay in production of documents by various subpoena recipients, for various reasons;

(d) turnover in the applicants’ counsel team through no fault of the applicant; and

(e) limitations in the applicants’ resources.

Two months after the due date the applicants had not filed any expert evidence.

104 Mr Levitt proposed a revised timetable to the primary judge, which accommodated the vacation of the trial date, and then two distinct processes:

(a) an application for leave to file and serve a Fourth Further Amended Statement of Claim and Fourth Amended Application; and

(b) an application for leave file and serve points of claim for one or more further sample group members.

105 The trial judge heard the application to vacate the hearing on 17 November 2022 and refused the application. In his Honour’s view the applicants failed to adequately explain the delay, and there had been a lack of application, diligence and expedition by Levitt Robinson: see 17 November 2022 transcript of hearing at T30.1-21; T34.25-,T35.20; and T 38.3-11.

106 Rather than vacate the trial date his Honour made orders to again extend the pre-trial timetable (the third pre-trial timetable), and required the applicants to serve their expert evidence by 16 January 2023. By orders made on 2 December 2022, in accordance with what had been discussed at the 17 November 2022 hearing, the third pre-trial timetable provided that:

(a) by 5 December 2022 Aveo serve its lay evidence; by 19 December 2022 the applicants serve any further lay evidence; by 27 January 2023 Aveo serve its lay evidence in response; by 17 February 2023 the applicants serve any lay evidence in reply; and

(b) by 16 January 2023 the applicants serve their expert evidence, subject to a guillotine order; and by 24 February 2023 the respondents serve their expert evidence.

107 Under the third pre-trial timetable, the applicants would not receive Aveo’s expert evidence until a week before the trial was scheduled to commence. That was obviously tight, but that was no doubt informed by his Honour’s view (expressed in the hearing) that if the case was adjourned he could not hear it for the rest of the year. It was also informed by the fact that the case had been on foot for more than five years at that point.

108 The applicants complied with the third pre-trial timetable. They served three further lay affidavits on or before 19 December 2022 and their expert reports on 16 January 2023. Their expert evidence comprised:

(a) a report by Dennis Barton, an actuary; and

(b) seven reports by Nicole Adamson, a property valuer, in relation to the applicants and each of the sample group members.

As it eventuated, the applicants did not to rely on Mr Barton’s report.

109 Aveo, however, failed to comply with the third pre-trial timetable. It did not serve its lay evidence by 5 December 2022 and instead served a series of lay affidavits between 6 and 22 December 2022. Then, on 21 February 2023 Aveo informed the applicants that it would not be in a position to serve all of its expert evidence by 24 February 2023. It said that it anticipated doing so by 13 March 2023 (that is, two weeks into the hearing). It served one expert report on 24 February 2023, being a report of Laila Burnet, a property valuer.

110 In response to that news the applicants made another application to vacate the trial. The trial judge heard the application on 27 February 2023. His Honour declined to vacate the trial, and instead made orders again extending the timetable (the fourth pre-trial timetable). The orders required Aveo to serve its expert evidence by 10 March 2023, subject to a guillotine order, and pushed back the start of the trial to 14 March 2023, which ultimately became 16 March 2023.

111 There was a mediation in February 2023, which was held after the applicants’ lay and expert evidence had been served but before Aveo’s expert evidence. The case did not settle.

112 On the evening of Friday, 10 March 2023 Aveo served:

(a) a further report by Ms Burnet;

(b) a further affidavit by Keith Tang, a lay witness who had earlier provided an affidavit dated 20 December 2022;

(c) affidavits by two new lay witnesses;

(d) a report by Dawna Wright, a forensic accountant; and

(e) a report by Greg Houston, an economist.

113 The applicant did not receive any lay evidence from Aveo before 6 December 2022, received new lay evidence as late as 10 March 2023, and received the majority of Aveo’s expert evidence, including evidence on loss and damage, three business days before trial.

114 The trial commenced on 16 March 2023, and settled after six days, on very unfavourable terms for the applicants and group members.

The Contradictor’s submissions