FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Airbnb Ireland UC [2023] FCA 1633

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | AIRBNB IRELAND UC (IRELAND COMPANY REGISTRATION NUMBER 511825) First Respondent AIRBNB, INC (REGISTRATION NUMBER 4566980) Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

BY CONSENT, THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. Between 1 January 2018 and 30 August 2021, Airbnb Ireland UC displayed to some users of the Airbnb service who were located in Australia (Consumers) the total price for accommodation in Australia with a dollar sign without any, or any nearby indication of whether the amount was in Australian Dollars (AUD) or United States Dollars (USD) prior to the booking (checkout) page and thereby represented to some Consumers that the total price for the accommodation was the displayed amount in AUD, when in fact the displayed amount was in USD (AUD Representation).

2. By making the AUD Representation, Airbnb Ireland UC, in trade or commerce:

(a) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or was likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of section 18(1) of the Australian Consumer Law at Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL); and

(b) made a false or misleading representation with respect to the price of services, in contravention of section 29(1)(i) of the ACL.

3. Between 1 January 2018 and 30 August 2021, Airbnb Ireland UC represented to some users of the Airbnb service who were located in Australia and raised concerns with customer support personnel about having been charged in USD for accommodation in Australia (Complainant Consumers) that Airbnb had used amounts in USD for the Complainant Consumer’s booking because the Complainant Consumer had selected for Airbnb to do so, when in fact some Complainant Consumers had made no such selection (Selection Representation).

4. By making the Selection Representation, Airbnb Ireland UC, in trade or commerce, engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of section 18(1) of the ACL.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Pecuniary penalty

5. Pursuant to section 224(1) of the ACL, Airbnb Ireland UC pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty in the amount of $15,000,000 in respect of the contraventions of section 29(1)(i) of the ACL declared by the Court, within thirty (30) days of the date of this order.

Compliance orders

6. Pursuant to section 246(2)(b) of the ACL, Airbnb Ireland UC, at its own expense:

(a) establish and implement, within 90 days of the order, an ACL compliance program which meets the requirements set out in the Annexure to this order; and

(b) maintain the ACL compliance program referred to in subparagraph (a) for three (3) years from the date on which it is established.

7. Airbnb Ireland UC serve on the Applicant:

(a) an affidavit verifying that it has carried out its obligations under paragraph 6(a), to be served within 100 days of the date of the order; and

(b) an affidavit verifying that it has carried out its obligations under paragraph 6(b), to be served within 3 years and 10 days of the date of the order.

Other orders

8. Airbnb Ireland UC pay the Applicant’s costs of, and incidental to, this proceeding, fixed in the amount of $400,000, within thirty (30) days of the date of this order.

9. The proceedings against the Second Respondent, Airbnb, Inc, be dismissed.

10. Until further order or final completion of the compensation scheme required by the Undertaking given by Airbnb Ireland UC to the Applicant a redacted copy of which is at Annexure C to the reasons for judgment for making these orders (the Scheme) (whichever first occurs) and pursuant to section 37AF(1)(b) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), on the ground that it is necessary to prevent prejudice to the administration of justice, any disclosure (by publication or otherwise) of the redacted portions of that Annexure is prohibited save for disclosure to:

(a) the Court and its staff, and any person performing services for the Court, acting in the course of their duties;

(b) the Applicant, and its legal representatives and staff and any person performing services for the Applicant, in the course of their duties; and

(c) Airbnb Ireland UC and its legal representatives and staff and any person performing services for Airbnb Ireland UC, in the course of their duties.

ANNEXURE – CONSUMER LAW COMPLIANCE PROGRAM

1. Airbnb Ireland UC (Airbnb Ireland) will establish a Consumer Law Compliance Program (Compliance Program) that applies, where relevant, to Airbnb Ireland and its related entities and complies with each of the requirements below.

Appointments

2. Within ninety (90) days of the date of the Order, Airbnb Ireland will appoint a person with appropriate seniority with suitable qualifications or experience in corporate compliance as a Compliance Officer with responsibility for ensuring the Compliance Program is effectively designed, implemented and maintained (the Compliance Officer).

Compliance Policy

3. Airbnb Ireland will, within thirty (30) days of the Order, issue to its employees a policy statement outlining Airbnb Ireland’s commitment to compliance with the ACL (the Compliance Policy).

4. Airbnb Ireland will ensure that the Compliance Policy:

(a) contains a statement of commitment to compliance with the ACL;

(b) contains an outline of how commitment to ACL compliance will be realised within Airbnb Ireland; and

(c) contains a requirement for all employees of Airbnb Ireland to report any Compliance Program related issues and ACL violations to the Compliance Officer.

Complaints Handling System

5. Airbnb Ireland will ensure that the Compliance Program includes a consumer law complaints handling system which implements procedures to record and respond to consumer law complaints from Australian consumers who use the Airbnb platform (the Complaints Handling System).

6. Airbnb Ireland will ensure that staff whose responsibilities include communicating with Australian consumers who use the Airbnb platform or resolving complaints from Australian consumers are made aware of the Complaints Handling System.

Staff Training

7. Airbnb Ireland will ensure that the Compliance Program provides for regular (at least once a year) training for all directors, officers, employees, or representatives of Airbnb Ireland, whose duties could result in them being concerned with conduct in respect of Australian consumers that may contravene sections 18(1) and/or 29(1)(i) of the ACL, such training to be directed at ensuring price or other representations to Australian consumers comply with sections 18(1) and/or 29(1)(i) of the ACL.

8. Staff Training may be conducted either in-person, via an online or video communications platform, and/or by relevant employees viewing a pre-recorded video.

9. Airbnb Ireland must ensure that the training is conducted by a suitably qualified compliance professional or legal practitioner with expertise in competition and consumer law.

10. Airbnb Ireland will ensure that the Compliance Program includes a requirement that awareness of consumer compliance issues relating to sections 18 and/or 29(1)(i) of the ACL forms part of the induction of all new directors, officers, employees, representatives and agents, whose duties could result in them being concerned with conduct in respect of Australian consumers that may contravene sections 18 and/or 29(1)(i) of the ACL.

Reports to Board/Senior Management

11. Airbnb Ireland will ensure that the Compliance Officer reports to Airbnb Ireland’s Board or governing body every six (6) months on the continuing effectiveness of the Compliance Program.

Compliance Review

12. Airbnb Ireland will, at its own expense, cause an annual review of the Compliance Program (the Review) to be carried out in accordance with each of the following requirements:

(a) Scope of Review – the Review should be broad and rigorous enough to provide Airbnb Ireland and the ACCC with:

(i) a verification that Airbnb Ireland has in place a Compliance Program that complies with each of the requirements detailed in paragraphs 1 to 11 above; and

(ii) the Compliance Reports detailed at paragraph 13 below.

(b) Independent Reviewer – Airbnb Ireland will ensure that each Review is carried out by a suitably qualified, independent compliance professional with expertise in competition and consumer law (the Reviewer). The Reviewer will qualify as independent on the basis that he or she:

(i) did not design or implement the Compliance Program;

(ii) is not a present or past staff member or director of Airbnb Ireland;

(iii) has not acted and does not act for, and does not consult and has not consulted to, Airbnb Ireland in any competition and consumer law related matters, other than performing Reviews under this Order; and

(iv) has no significant shareholding or other interests in Airbnb Ireland.

(c) Evidence – Airbnb Ireland will use its best endeavours to ensure that each Review is conducted on the basis that the Reviewer has access to all relevant sources of information in Airbnb Ireland’s possession or control, including without limitation:

(i) the ability to make enquiries of any officers, employees, representatives and agents of Airbnb Ireland;

(ii) documents relating to Airbnb Ireland’s Compliance Program, including documents relevant to Airbnb Ireland’s Compliance Policy, Complaints Handling System, Staff Training and induction program; and

(iii) any reports made by the Compliance Officer to the Board or senior management regarding Airbnb Ireland’s Compliance Program.

(d) Airbnb Ireland will ensure that a Review is completed within one (1) year of the date of the Order, and that a subsequent Review is completed within each year for three (3) years.

Compliance Reports

13. Airbnb Ireland will use its reasonable endeavours to ensure that within thirty (30) days of the completion of a Review, the Reviewer includes the following findings of the Review in a report provided to Airbnb Ireland (the Compliance Report):

(a) whether the Compliance Program of Airbnb Ireland includes all the elements detailed in paragraphs 1 to 11 above, and if not, what elements need to be included or further developed;

(b) whether the Staff Training and induction is effective and if not, what aspects need to be further developed;

(c) whether Airbnb Ireland’s Complaints Handling System is effective and if not, what aspects need to be further developed;

(d) whether there are any material deficiencies in Airbnb Ireland’s Compliance Program, or whether there are or have been any instances of material non- compliance with the Compliance Program (Material Failure), and if so, recommendations for rectifying the Material Failure/s.1

Airbnb Ireland response to Compliance Reports

14. Airbnb Ireland will ensure that the Compliance Officer, within 30 days of receiving the Compliance Report:

(a) provides the Compliance Report to the Board or relevant governing body of Airbnb Ireland;

(b) where a Material Failure has been identified by the Reviewer in the Compliance Report, provides a report to the Board or relevant governing body identifying how Airbnb Ireland can implement any recommendations made by the Reviewer in the Compliance Report to rectify the Material Failure.

15. Airbnb Ireland will work with the Board to consider the recommendations made by the Reviewer in the Compliance Report to address a Material Failure and, if it deems appropriate, implement reasonable measures to address the Material Failure.

Reporting Material Failures to the ACCC

16. Where a Material Failure has been identified by the Reviewer in the Compliance Report, Airbnb Ireland will:

(a) provide a copy of that Compliance Report to the ACCC within thirty (30) days of the Board or relevant governing body receiving the Compliance Report; and

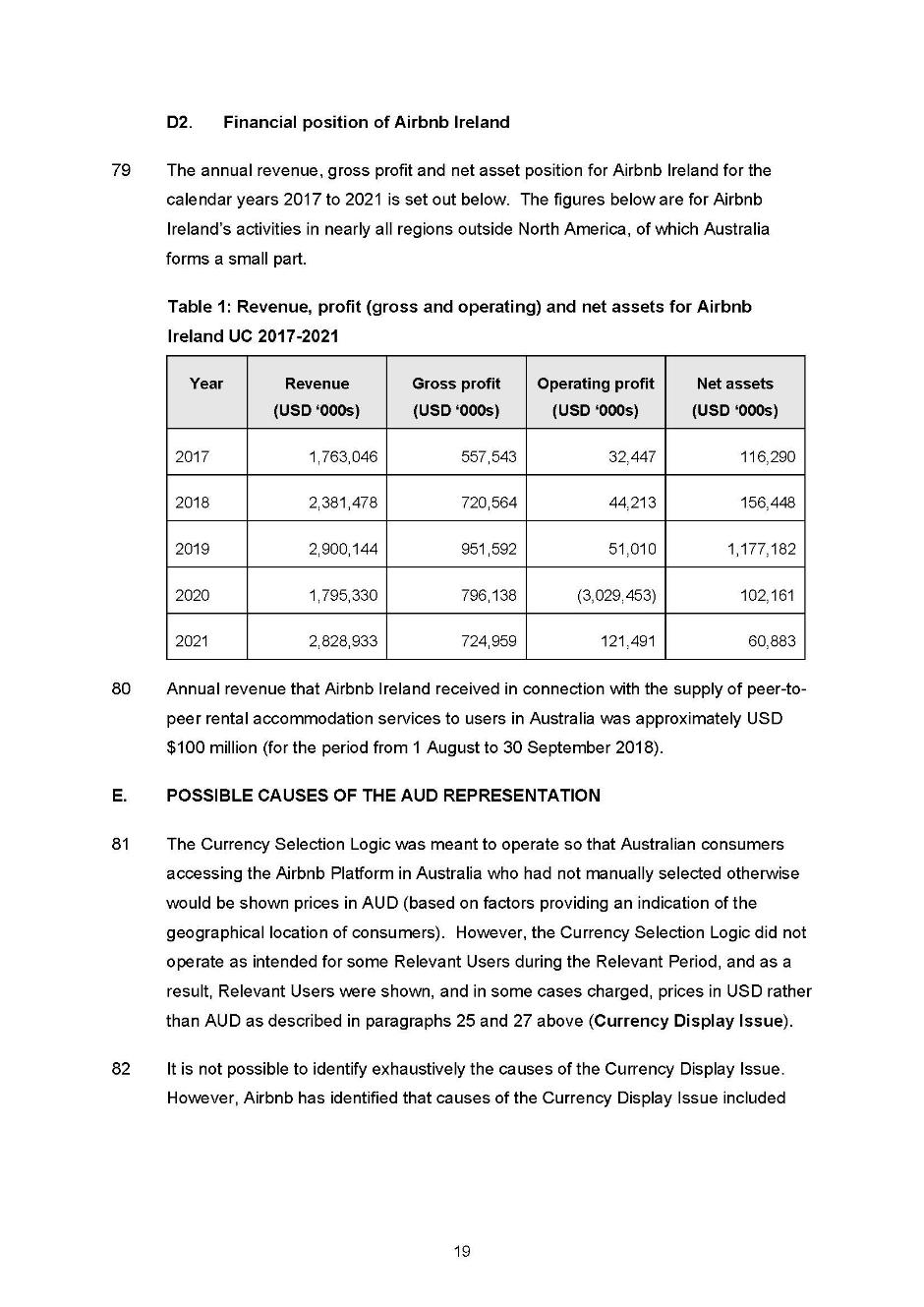

(b) inform the ACCC of any steps that have been taken to implement the recommendations made by the Reviewer in the Compliance Report; or

(c) otherwise outline the steps Airbnb Ireland proposes to take to implement the recommendations and will then inform the ACCC once those steps have been implemented.

Report to ACCC and maintenance of records

17. Airbnb Ireland will provide a confirmation in writing to the ACCC every 12 months from the date on which these orders are made as to whether Airbnb Ireland has implemented the Compliance Measures in accordance with these orders.

18. Airbnb Ireland will maintain a record of copies of compliance policies and training materials utilised in implementing the Compliance Measures for a period not less than 3 years.

19. If requested by the ACCC during the period of 3 years following the Undertaking coming into effect, Airbnb Ireland will, at its own expense, cause to be produced and provided to the ACCC copies of all documents constituting the Compliance Program, including:

(a) the Compliance Policy;

(b) an outline of the Complaints Handling System;

(c) Staff Training materials and induction materials;

(d) all Compliance Reports that have been completed at the time of the request;

(e) copies of the reports to the Board and/or senior management referred to in paragraph 11 and paragraph 14.

ACCC Recommendations

20. Airbnb Ireland will work with the Board to consider any reasonable recommendations made by the ACCC and, if it deems appropriate, implement reasonable measures.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MCELWAINE J:

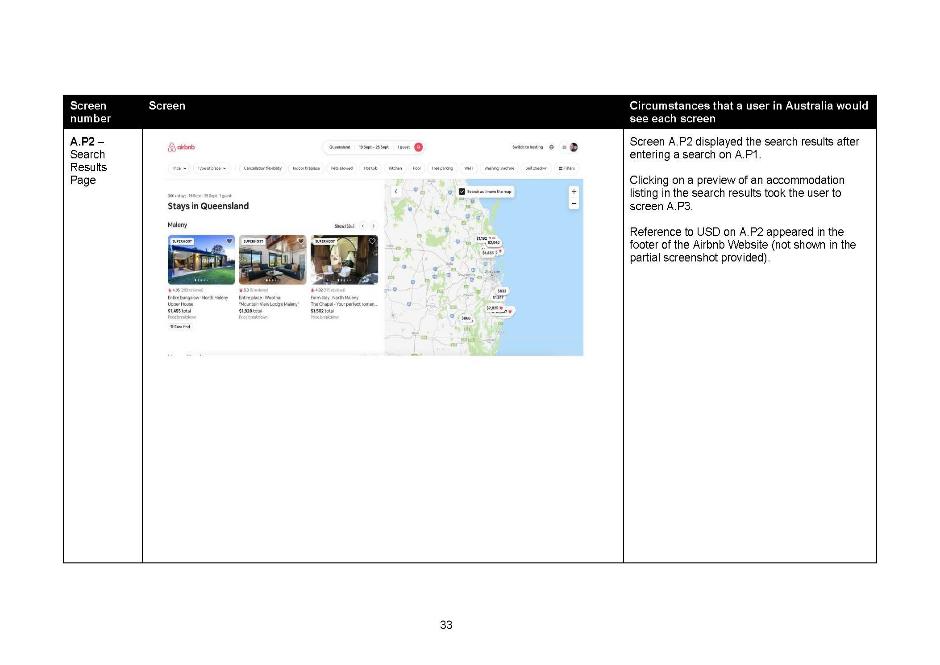

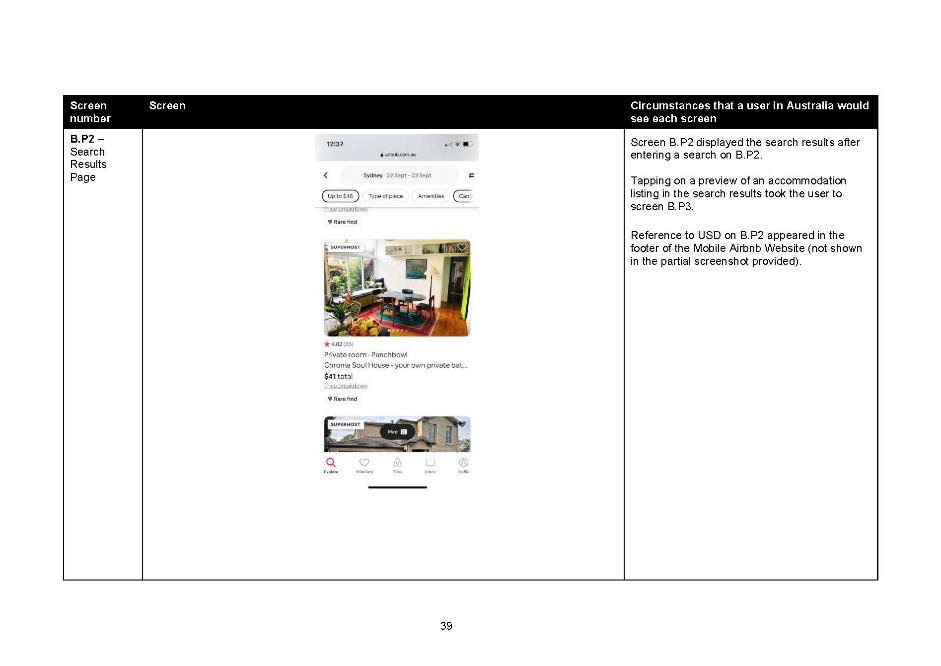

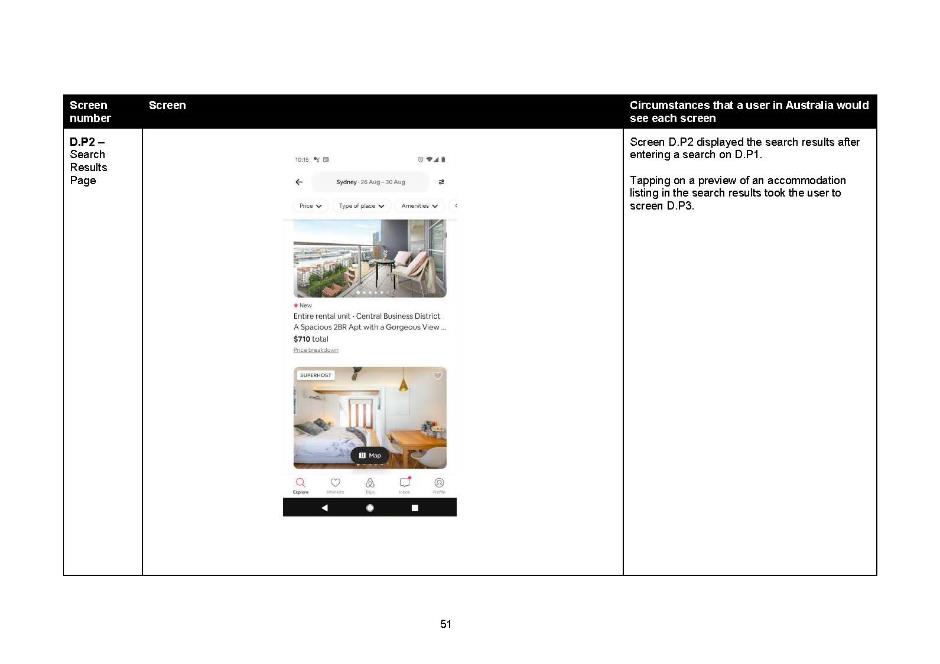

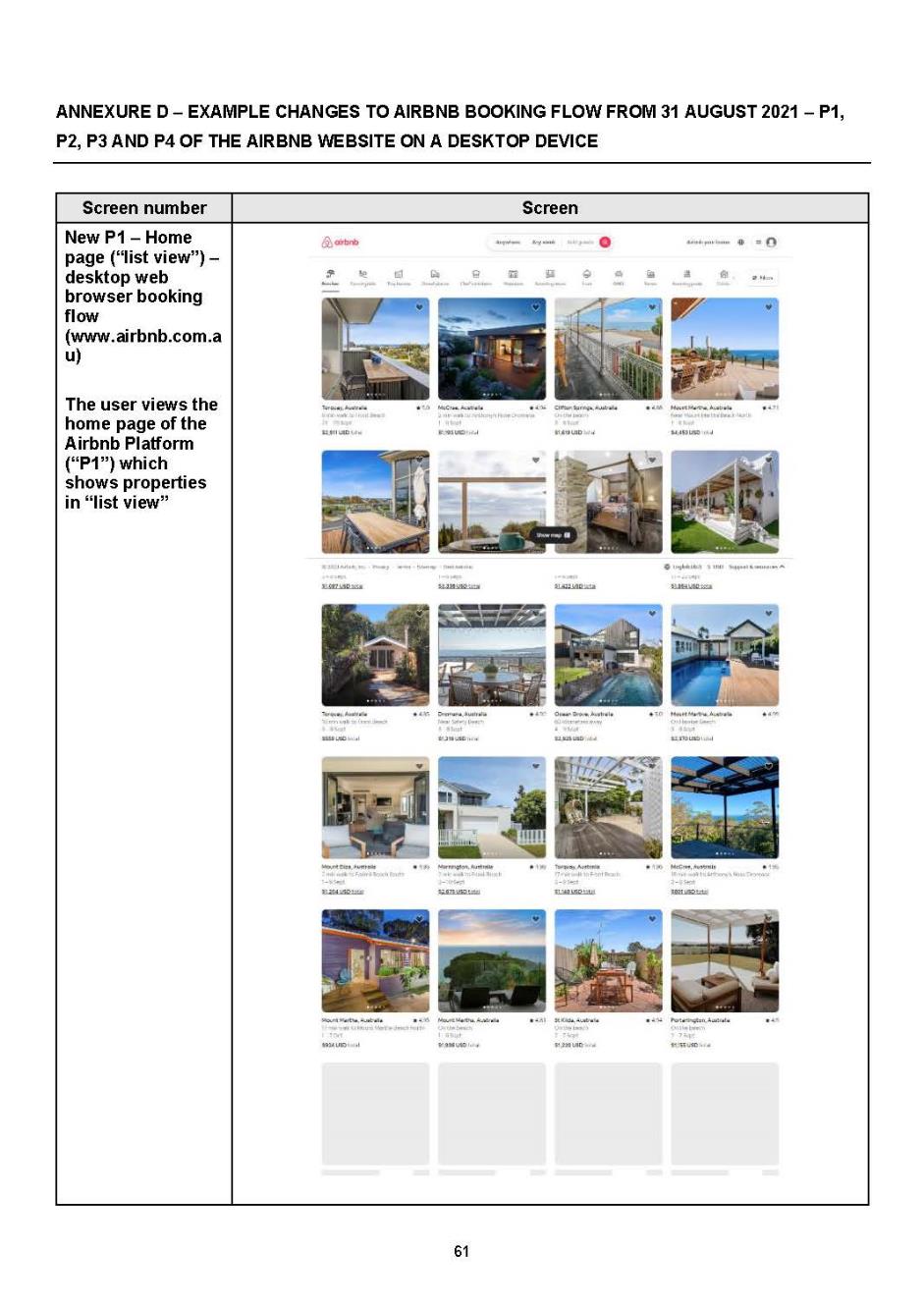

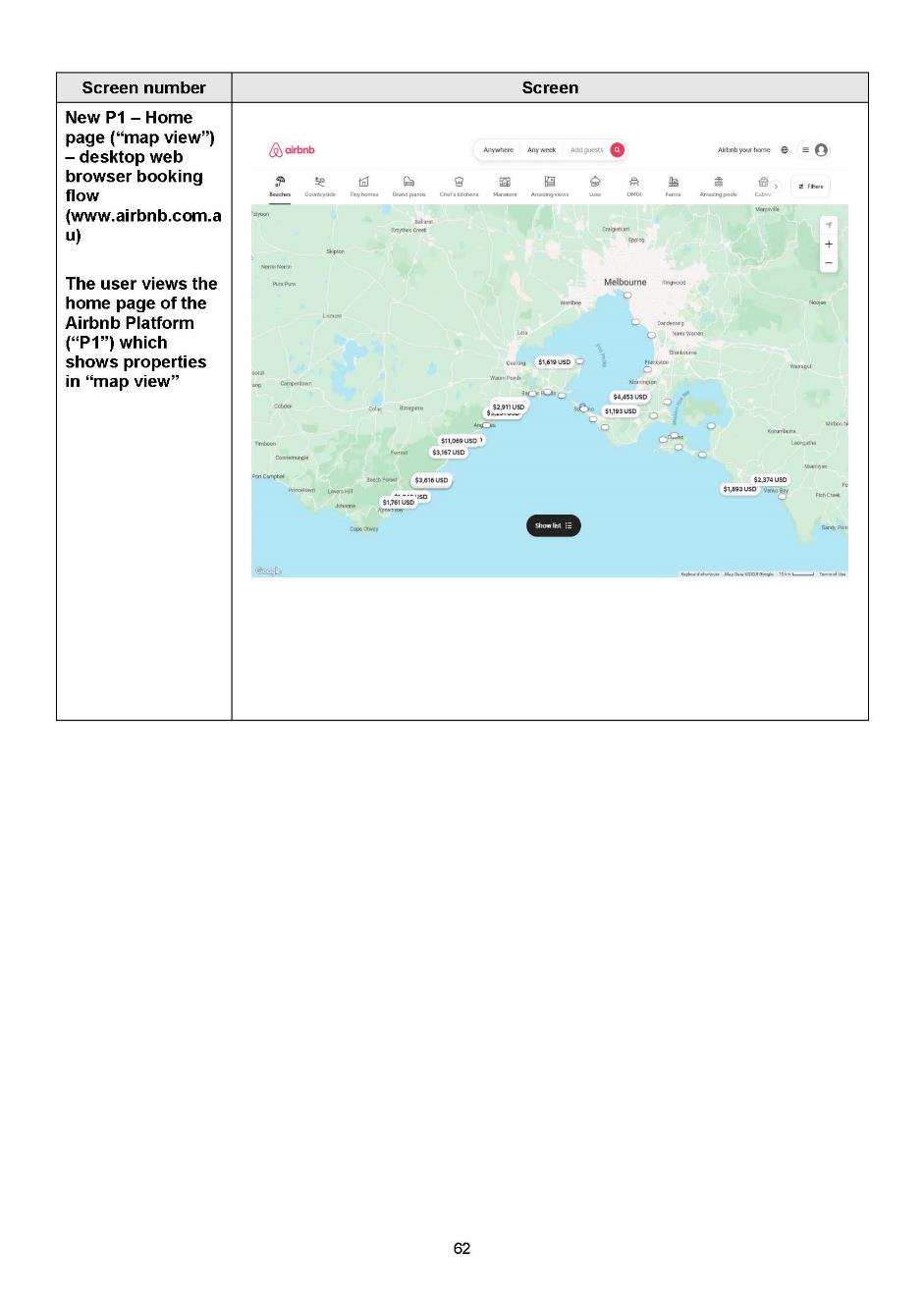

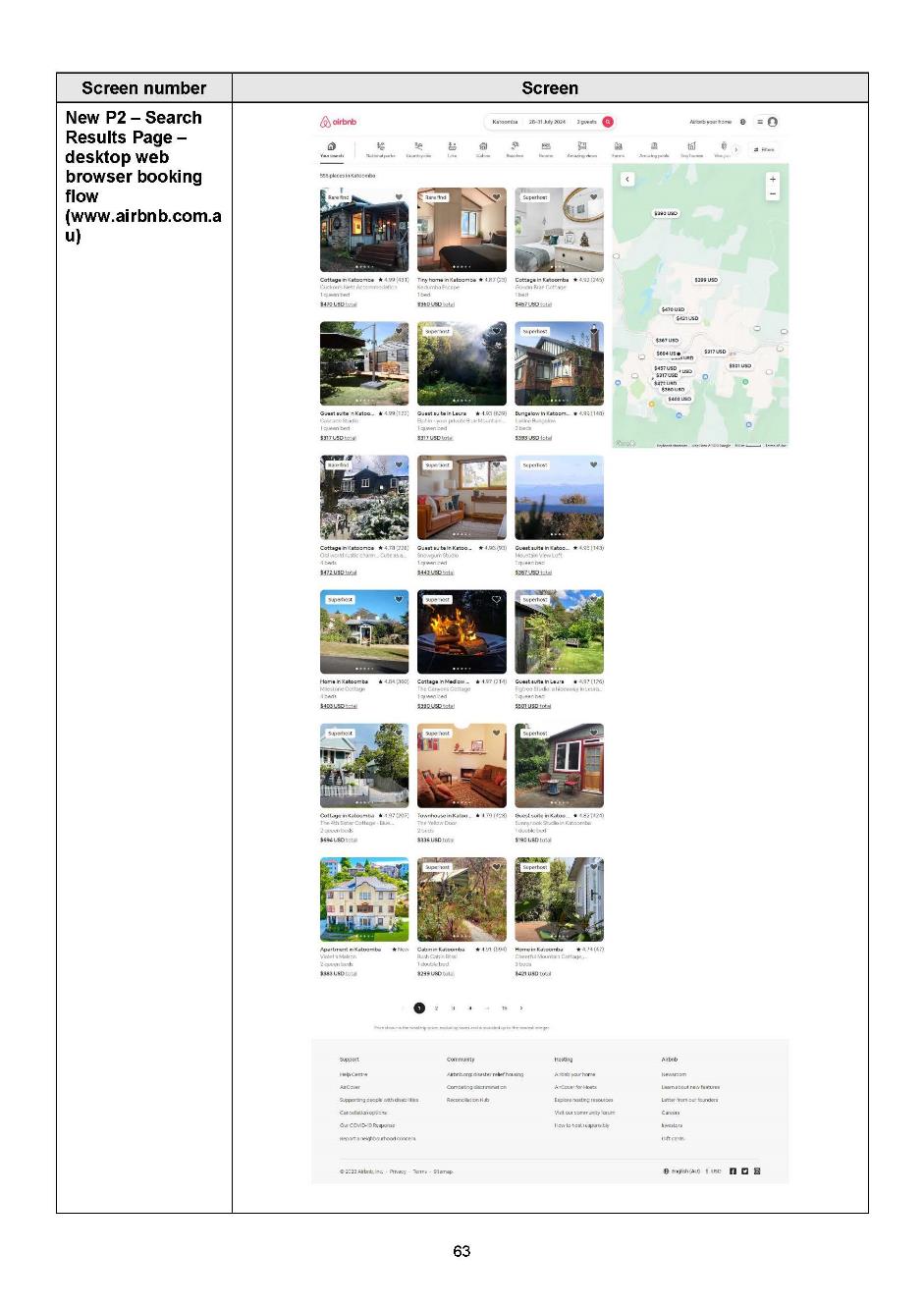

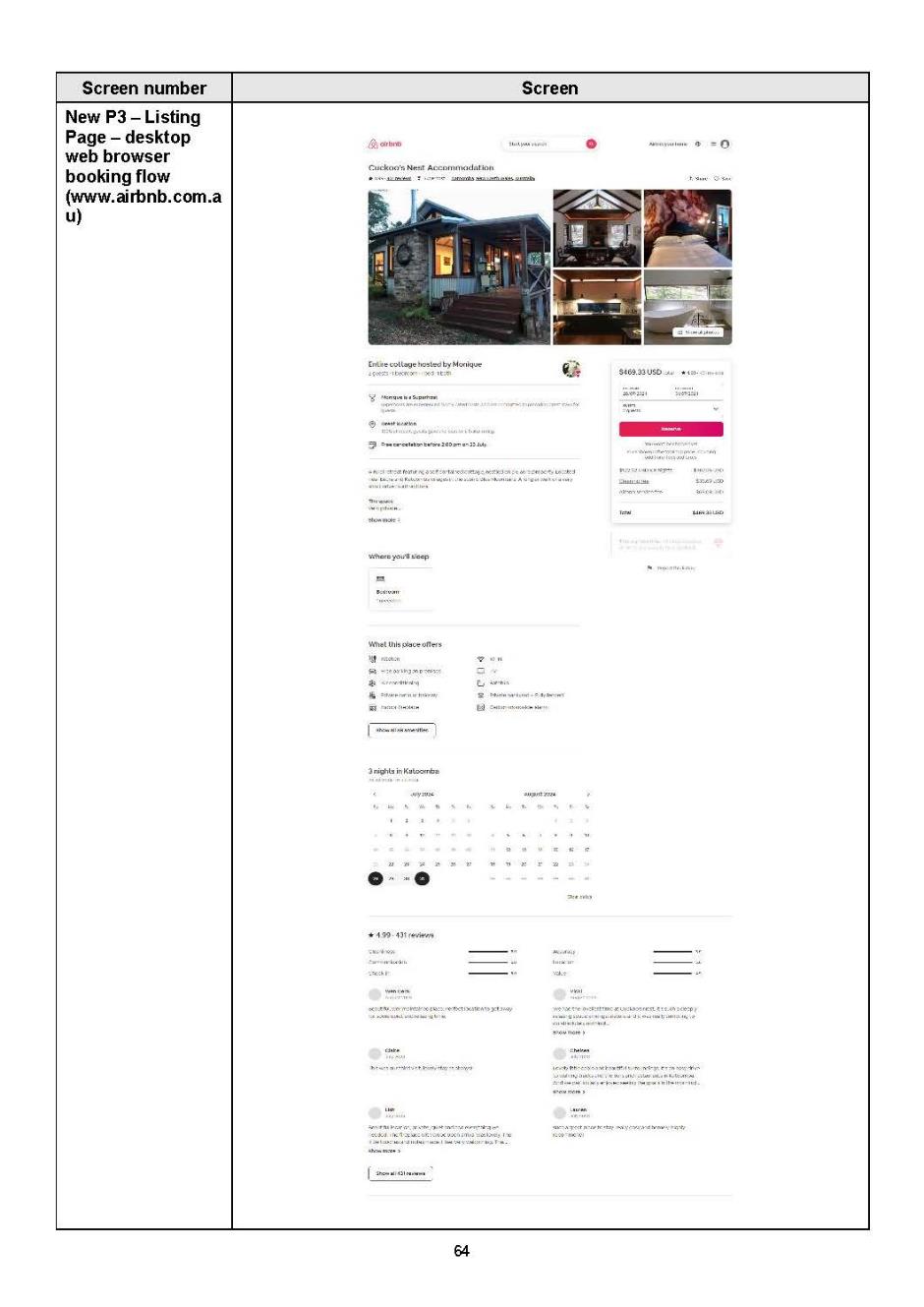

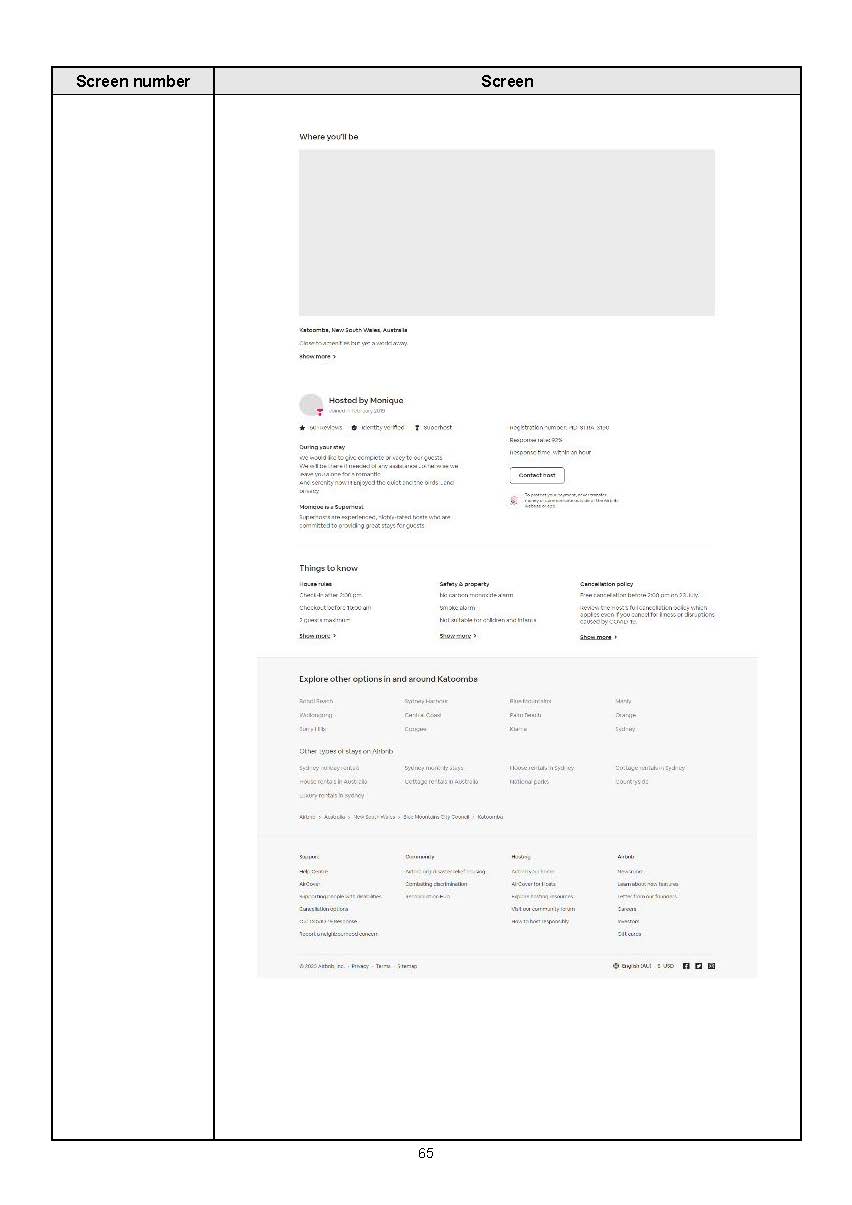

1 Airbnb Ireland UC is a well-known operator of an online peer-to-peer short-term rental accommodation service that operates globally. Its parent company, Airbnb Inc is incorporated in the United States of America. Relevant to this proceeding is that Airbnb provided services to Australian consumers through a website accessible by a desktop or laptop computer, a mobile version of the website accessible on mobile phones or tablets and an App available on Android or iOS devices, which together may be described as the Platform.

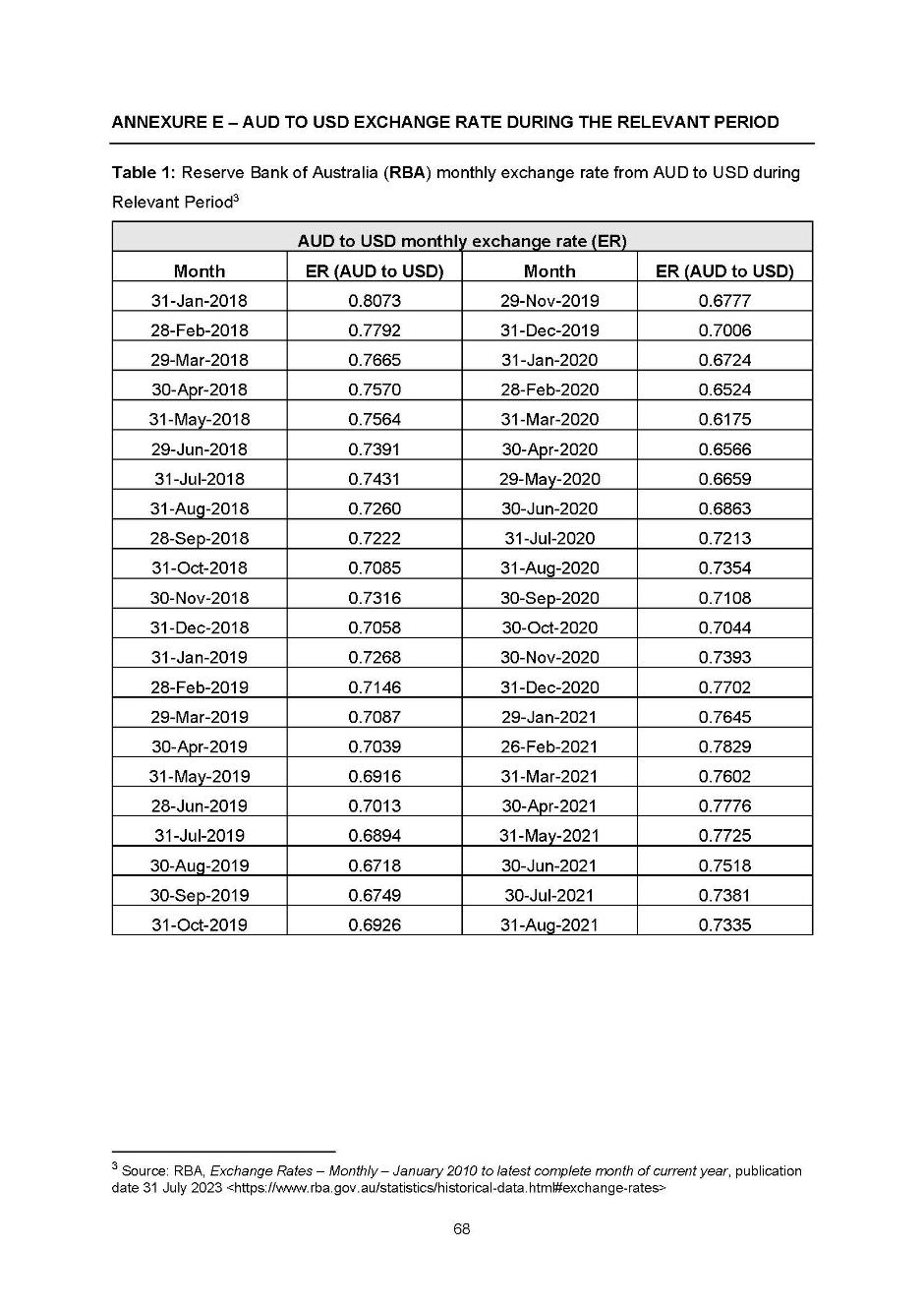

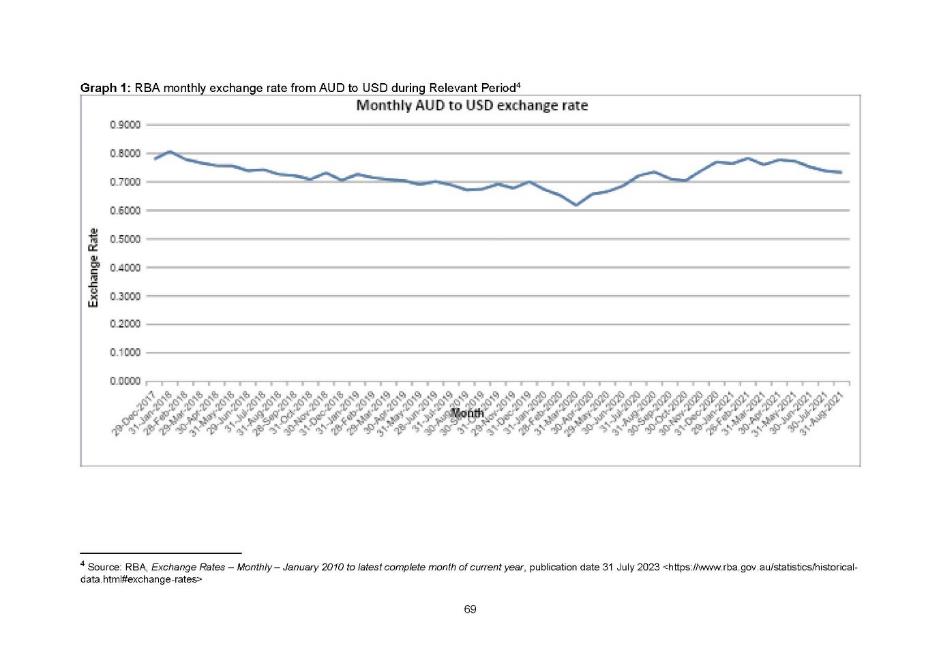

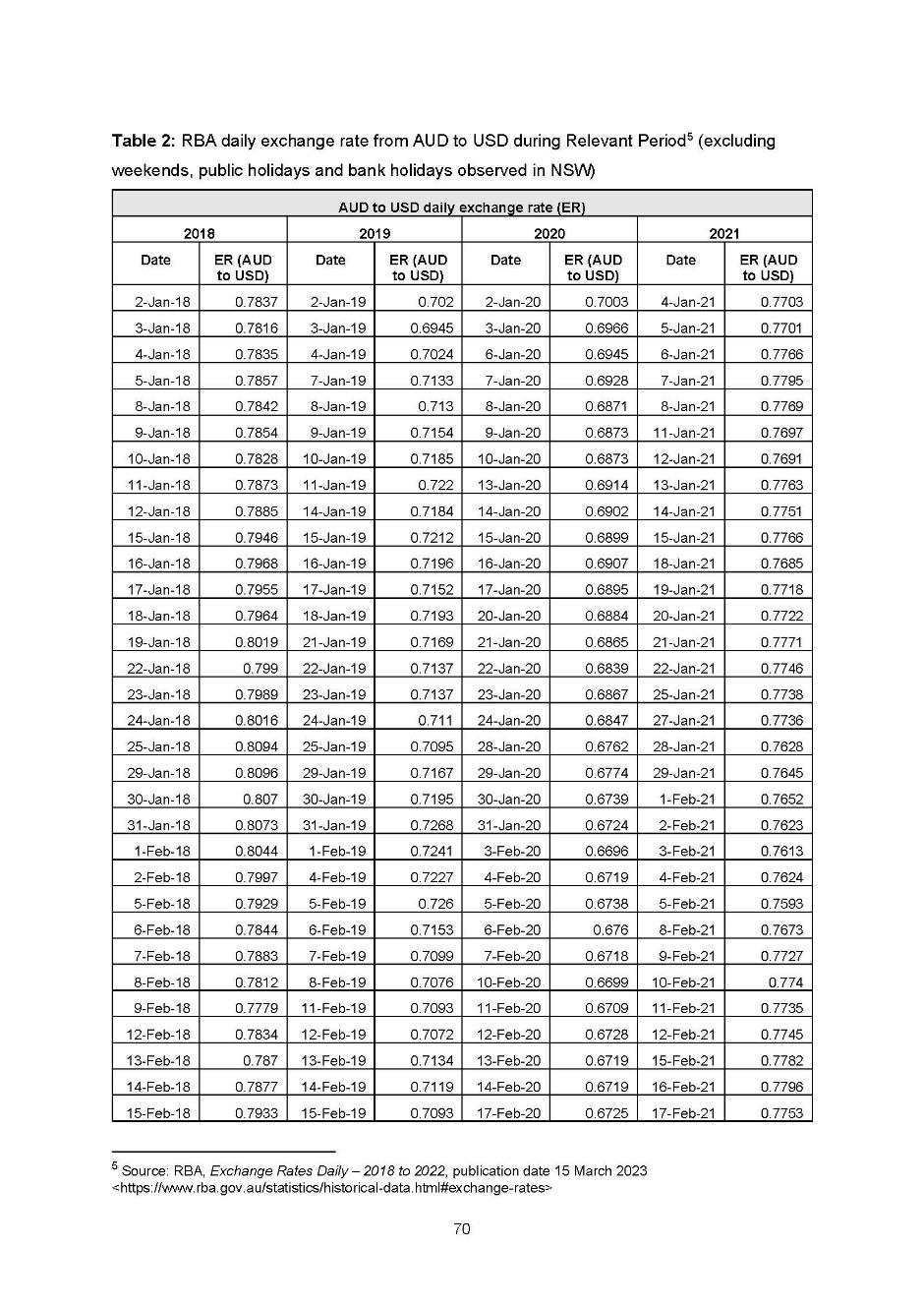

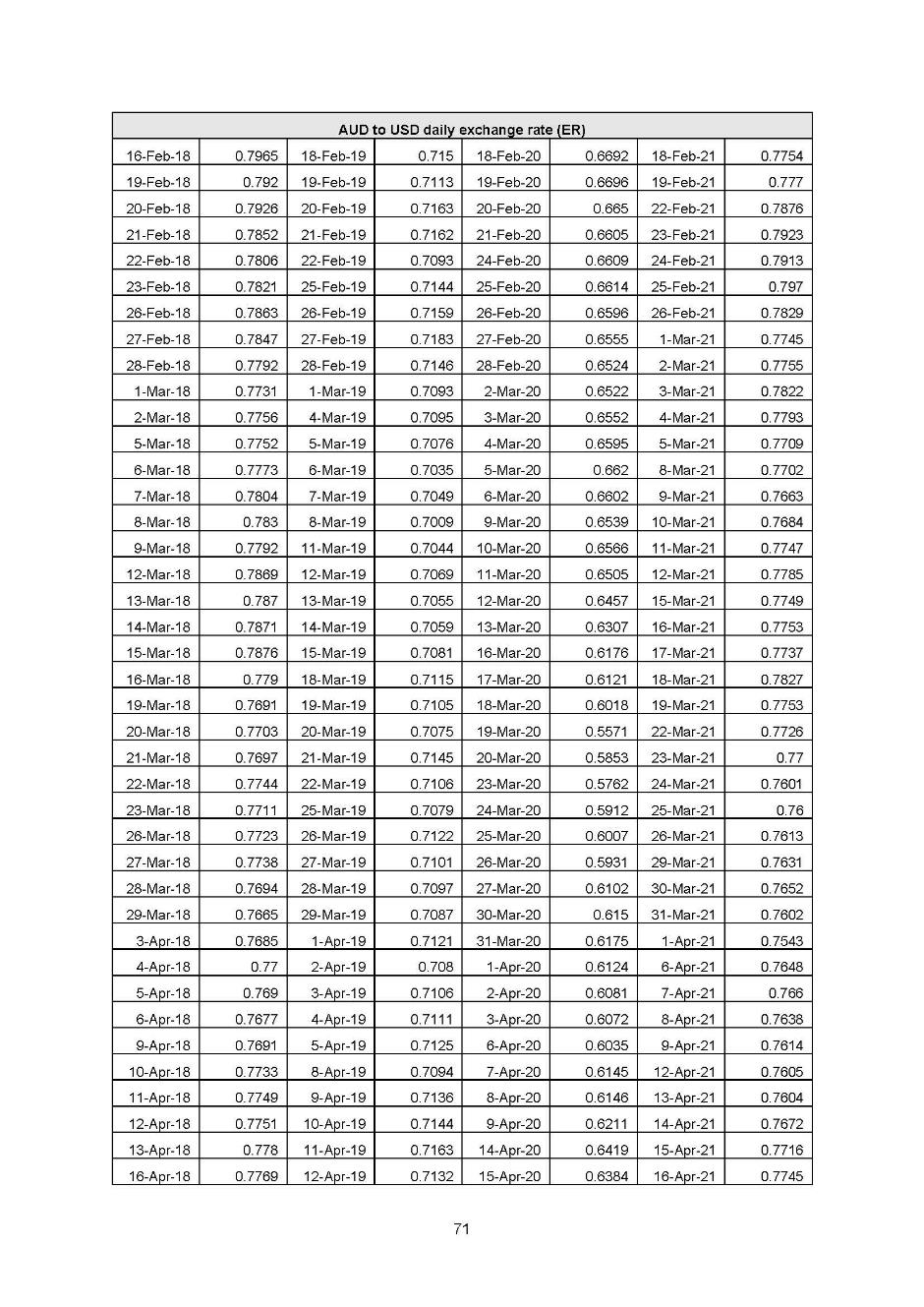

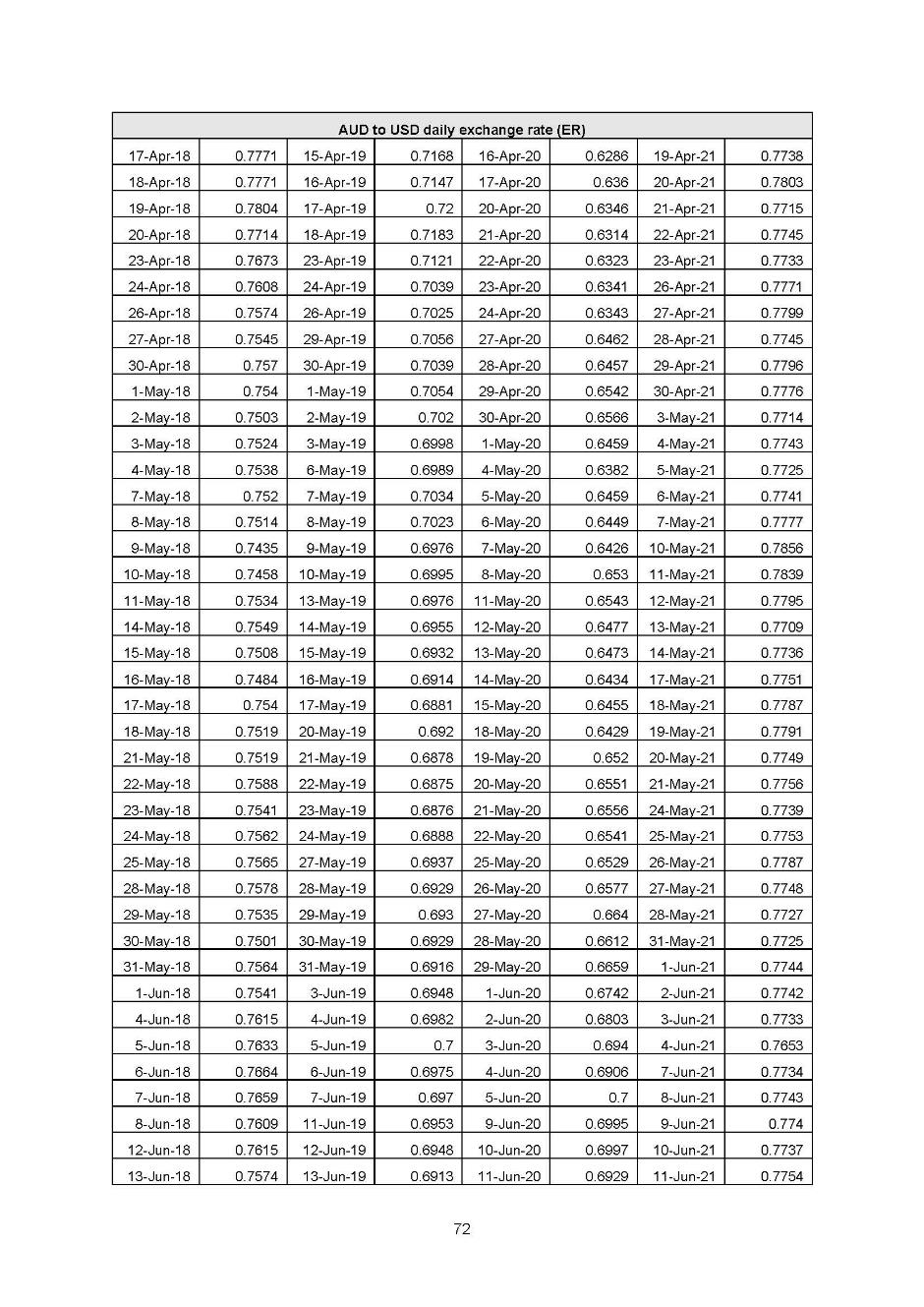

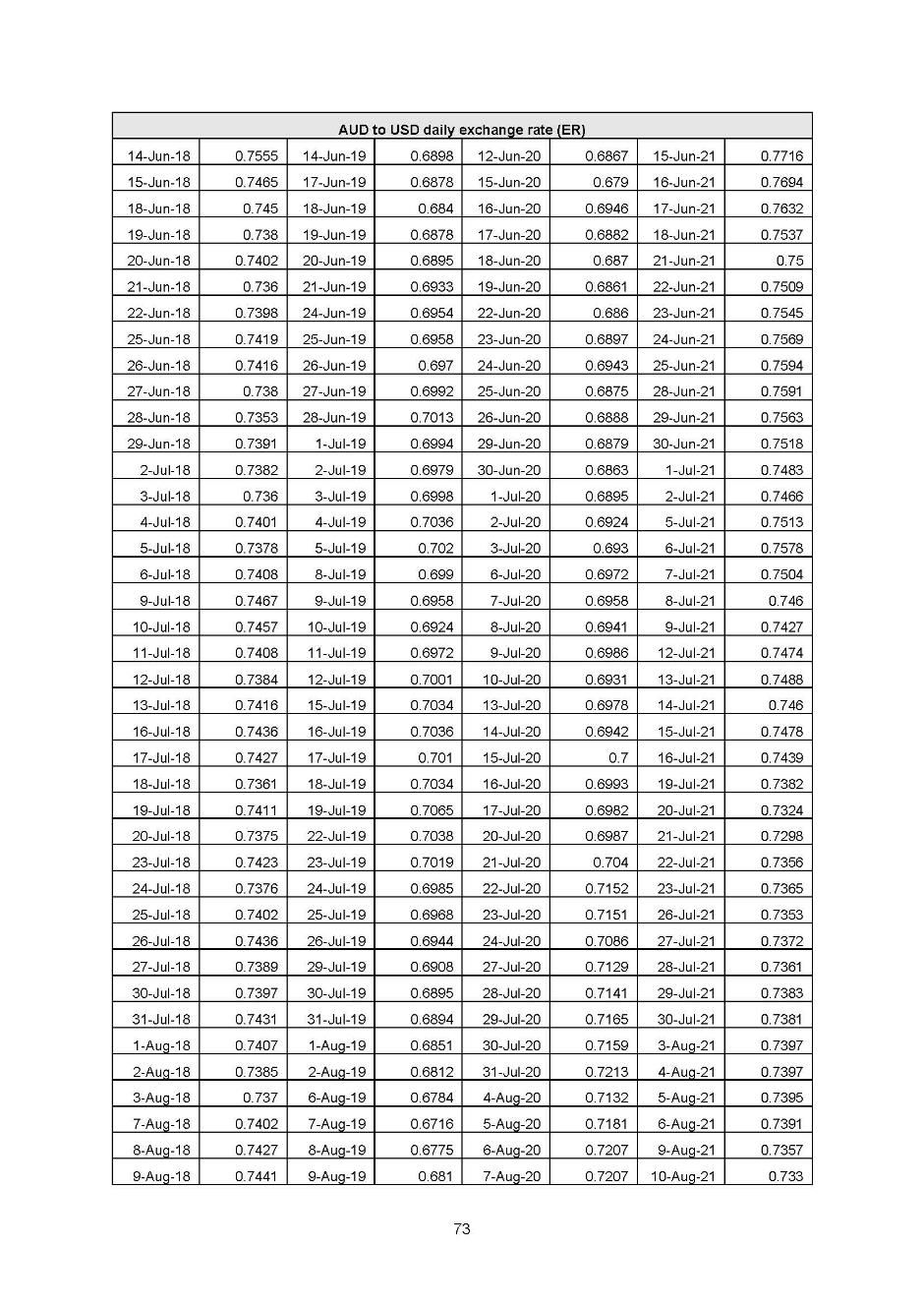

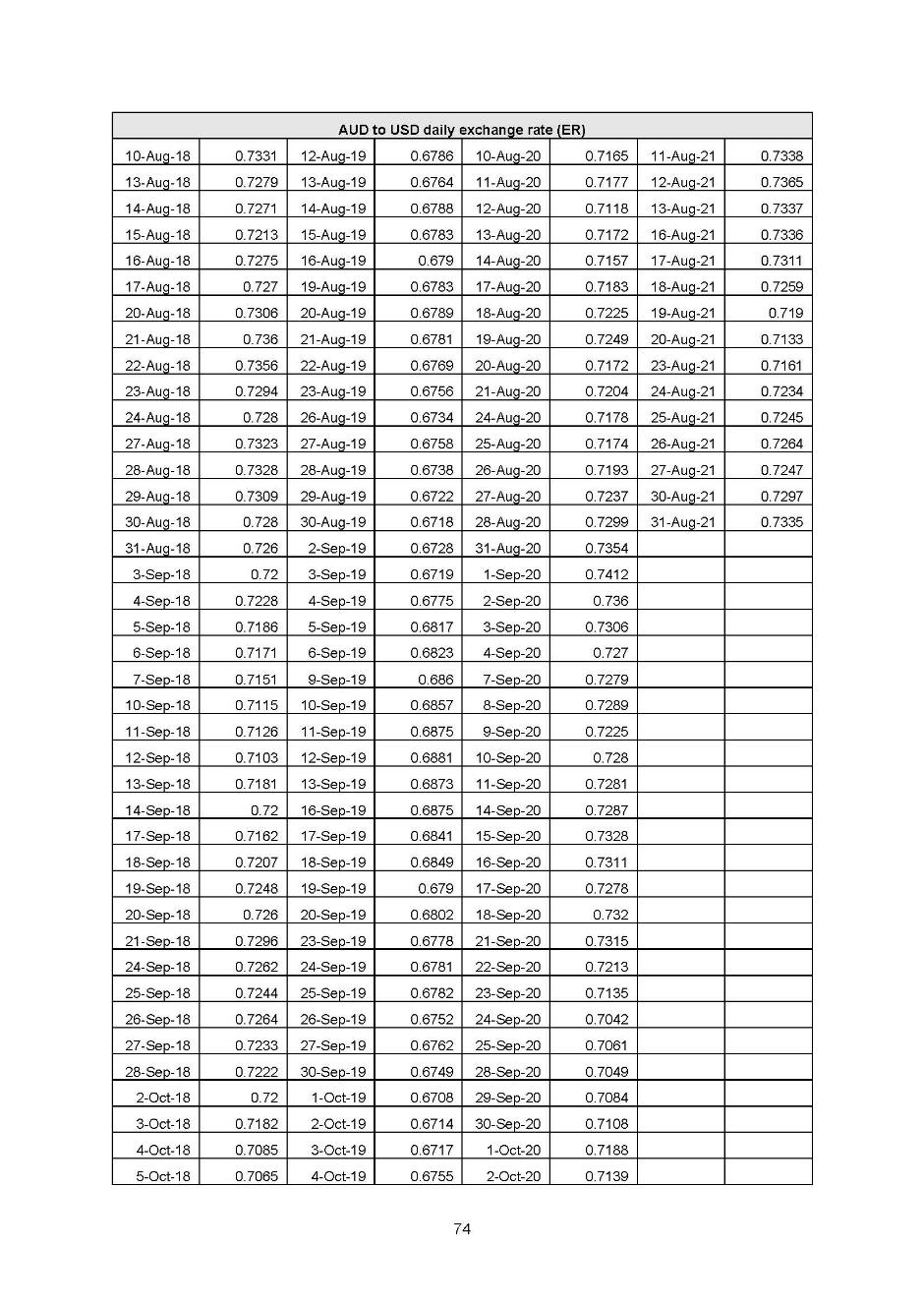

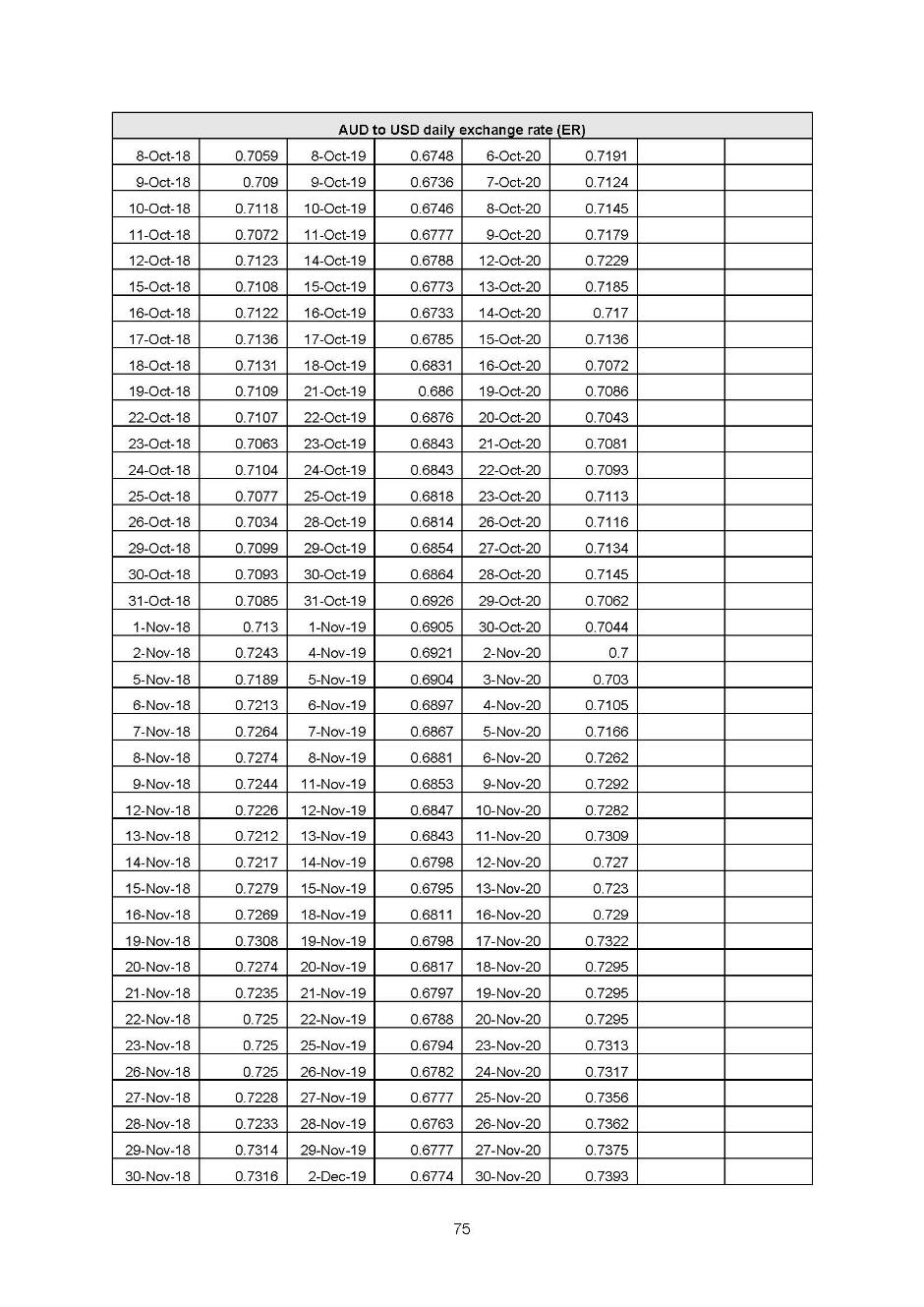

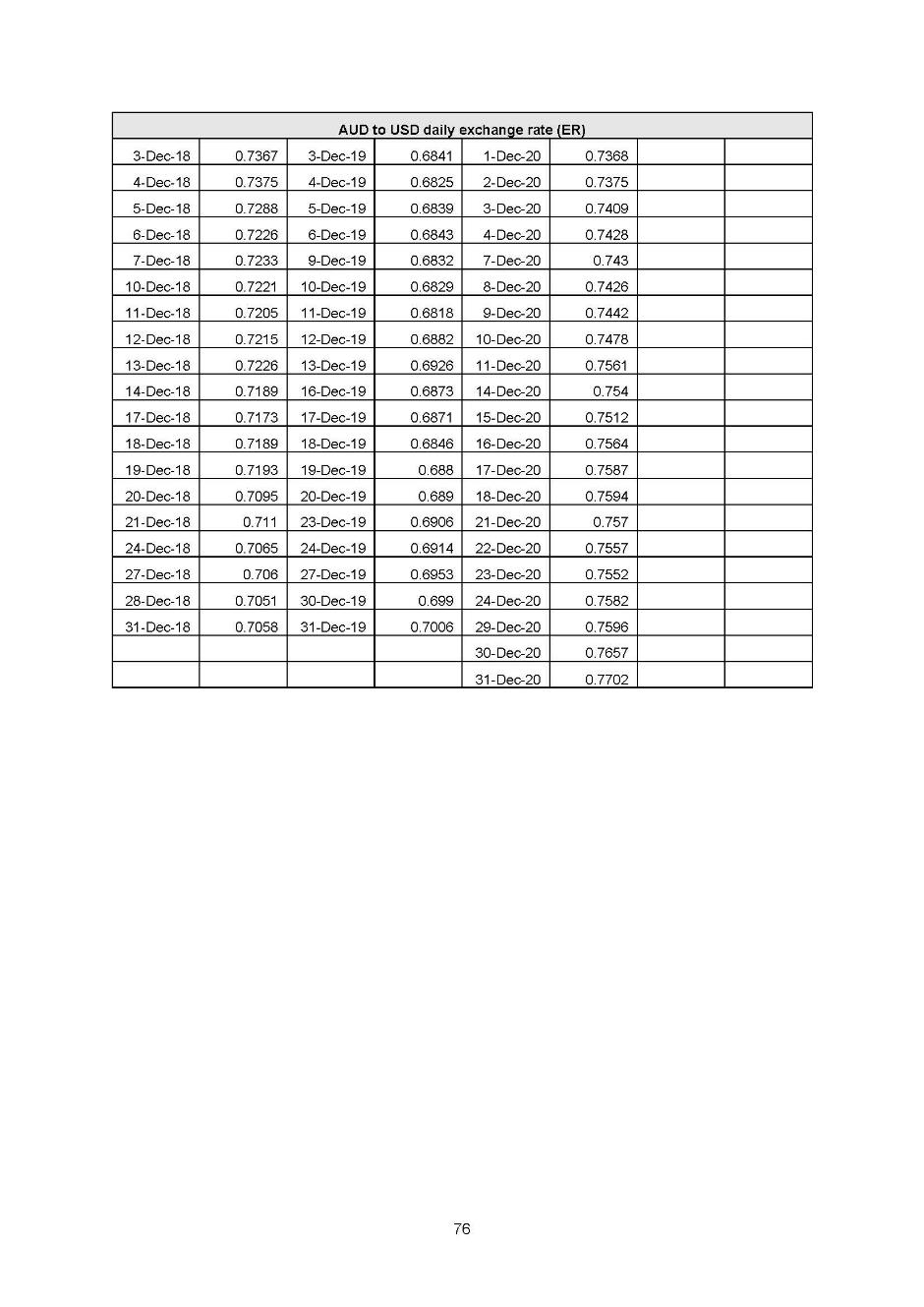

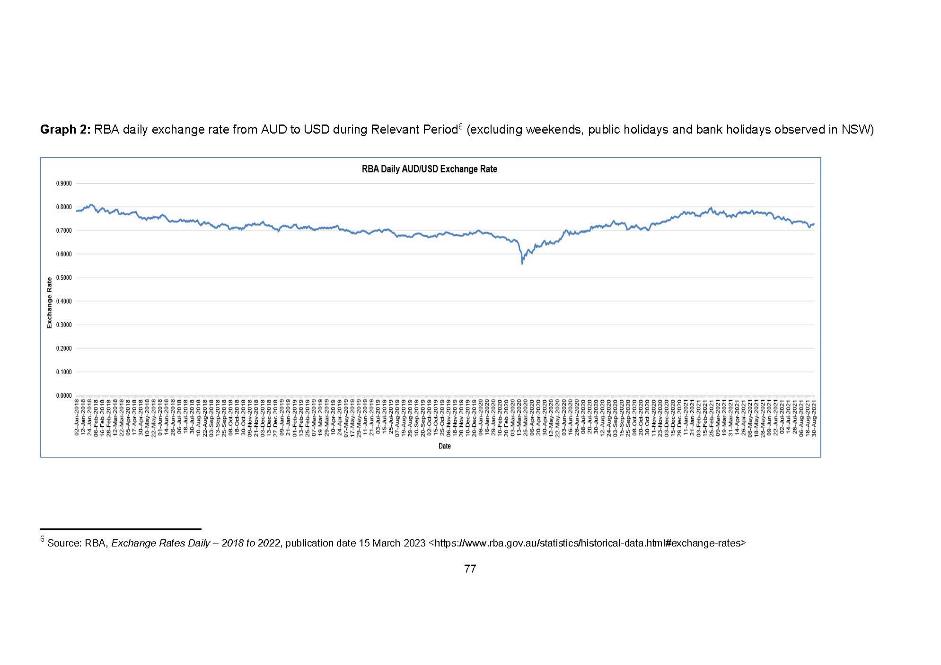

2 Between 1 January 2018 and 30 August 2021 (relevant period), Airbnb displayed to some Australian consumers the total price for accommodation in Australia without clearly disclosing that the price was in United States Dollars (USD). That conduct was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive within the meaning of ss 18(1) and 29(1)(i) and of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA) because in each case, Airbnb misrepresented to those consumers that the total price was the displayed amount in Australian Dollars (AUD). Within the relevant period there was at all times a material difference in the exchange rates. For example, on 30 April 2018 the rate from AUD to USD was 0.7570.

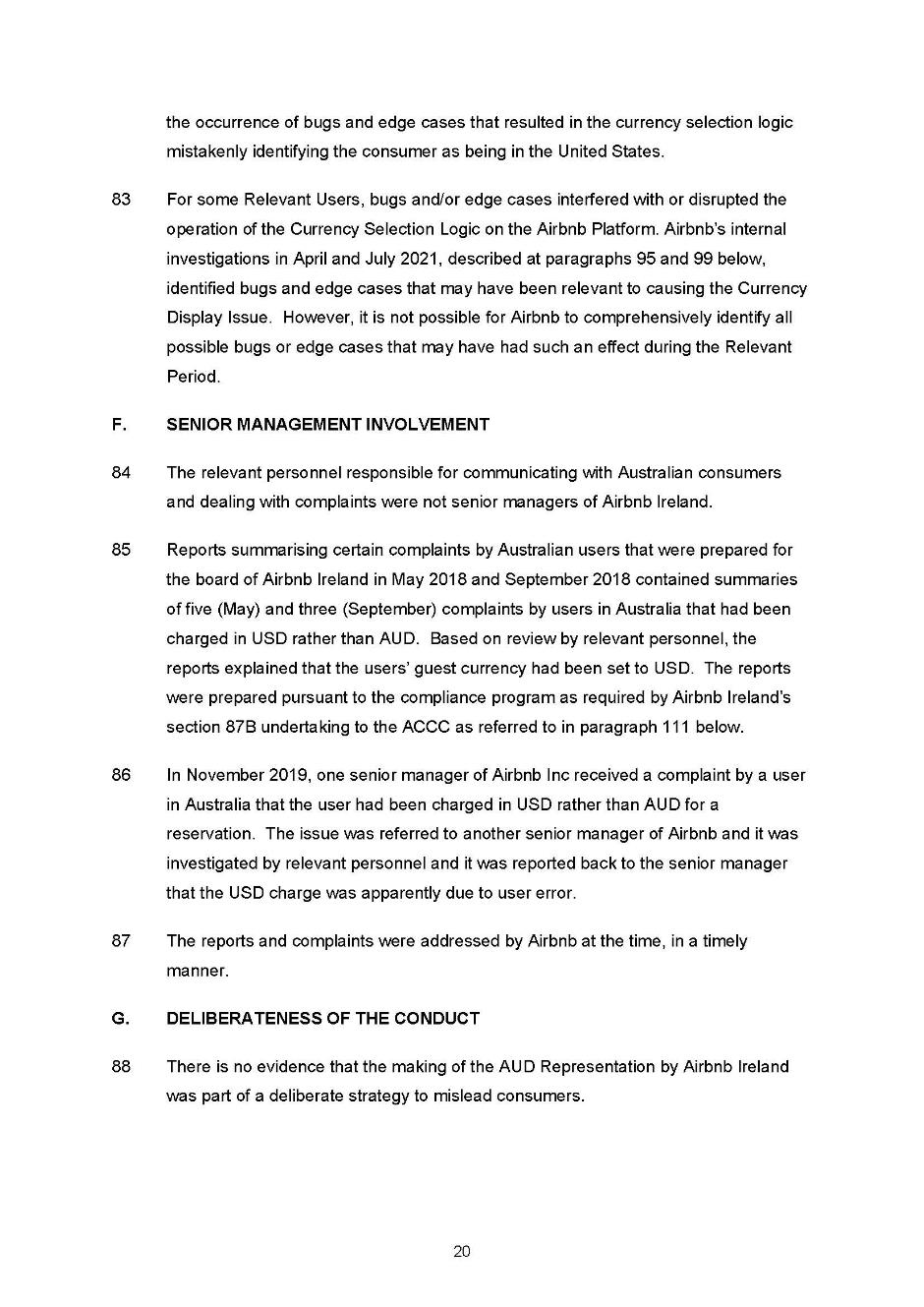

3 On 8 June 2022, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) commenced proceedings in this Court seeking various forms of relief including declarations of contravening conduct pursuant to s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act), pecuniary penalties under s 224 of the ACL, orders for redress for non-party consumers pursuant to s 239 of the ACL, compliance and publication orders pursuant to s 246 of the ACL and costs. Following the first case management hearing on 24 November 2022, Airbnb constructively engaged with the ACCC with the result that it admits it contravened the ACL and an agreed position has been reached as to the form and content of orders that are sought by consent. To this end, the Court has received and admitted into evidence a Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions (SAFA) pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). A copy is at Annexure A to this judgment. The parties have also provided a Joint Submission which is Annexure B to this judgment together with a proposed minute of consent orders, that align with the orders that I am persuaded should be made.

4 I have considered this material in detail, assisted by oral submissions from Mr M Borsky KC and Ms A Lord for the ACCC and Ms K Brazenor for the respondents. For the reasons that follow, I am satisfied that the SAFA is accurate, the breaches asserted are made out, and the remedies proposed, in particular the total penalty of AUD15 million, are appropriate in all of the circumstances. It is therefore consistent with the “important public policy involved in promoting predictability of outcome in civil penalty proceedings” to exercise my discretion consistently with the agreed position: Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; 258 CLR 482 (Agreed Penalties Case) at [46] (French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ).

AGREED FACTS AND CONDUCT

5 I make each finding of fact as set out in the SAFA. In broad summary, in the relevant period, Airbnb held the intellectual property rights to operate the Platform in Australia and was responsible for publishing the pages in the Platform available to users in Australia for the purpose of searching for accommodation within Australia. Consumers, in addition to accessing the Platform, could seek assistance by contacting customer support personnel, either through a chat function on the Platform or by telephone. Some of those personnel were employees of Airbnb, but others were engaged by third-party suppliers of this service and were agents of Airbnb.

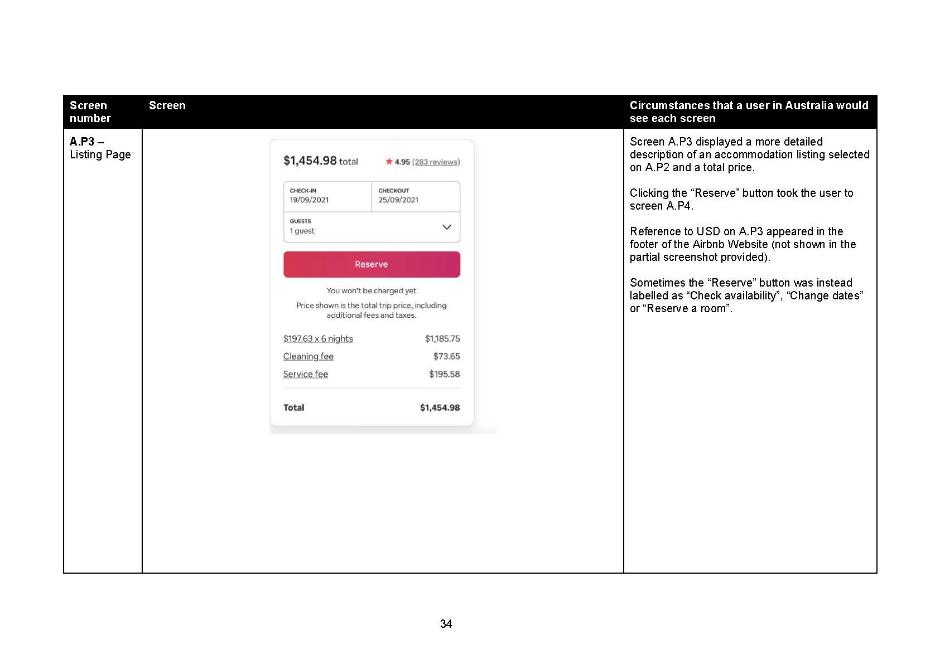

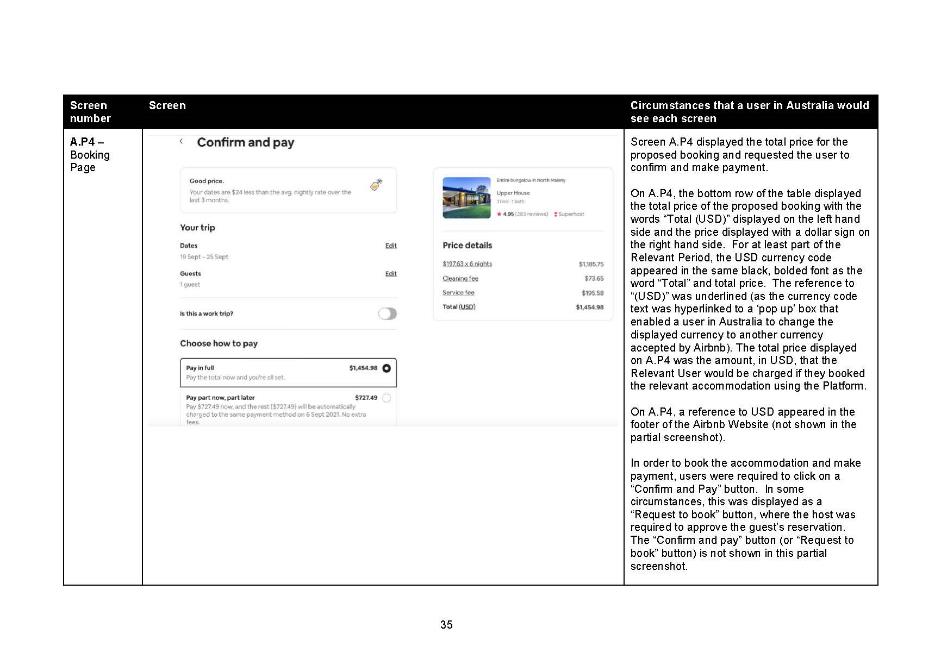

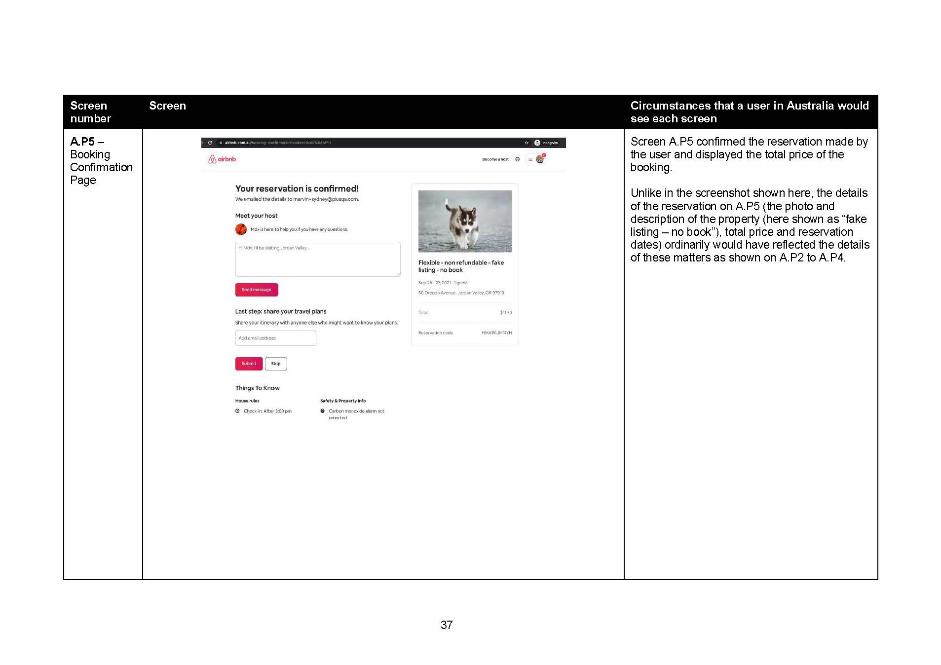

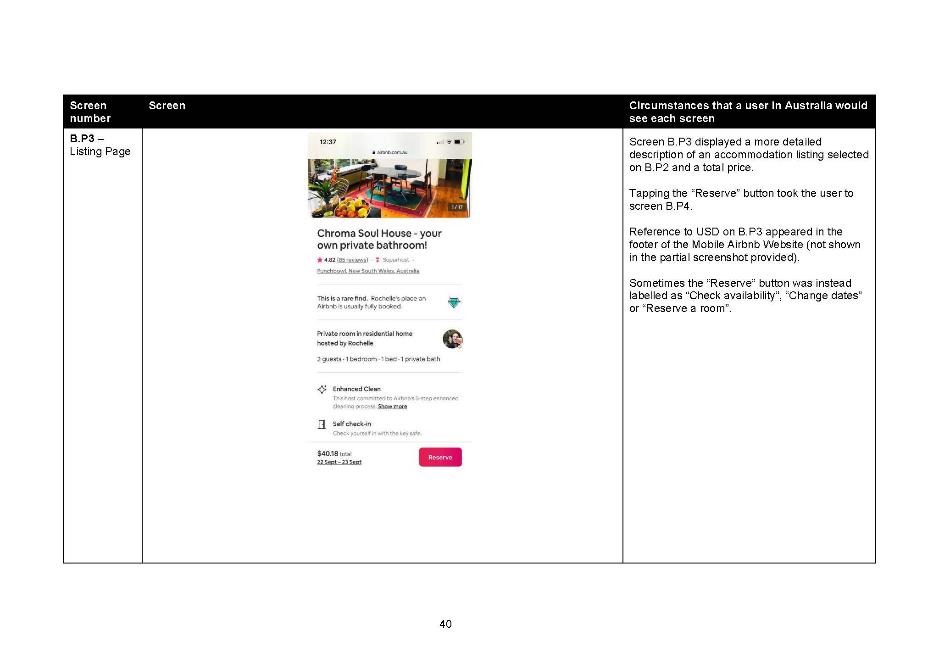

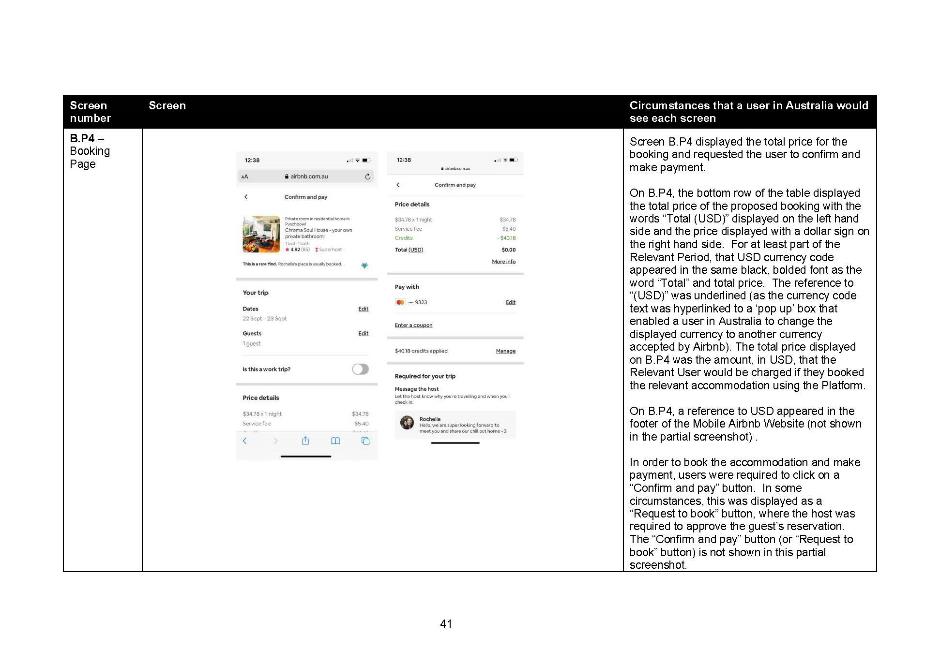

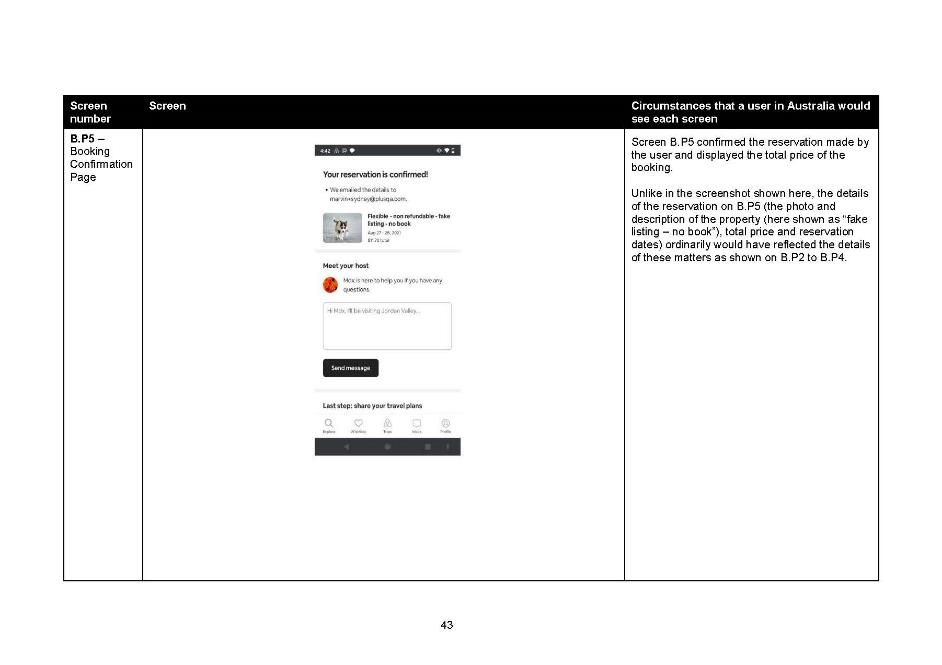

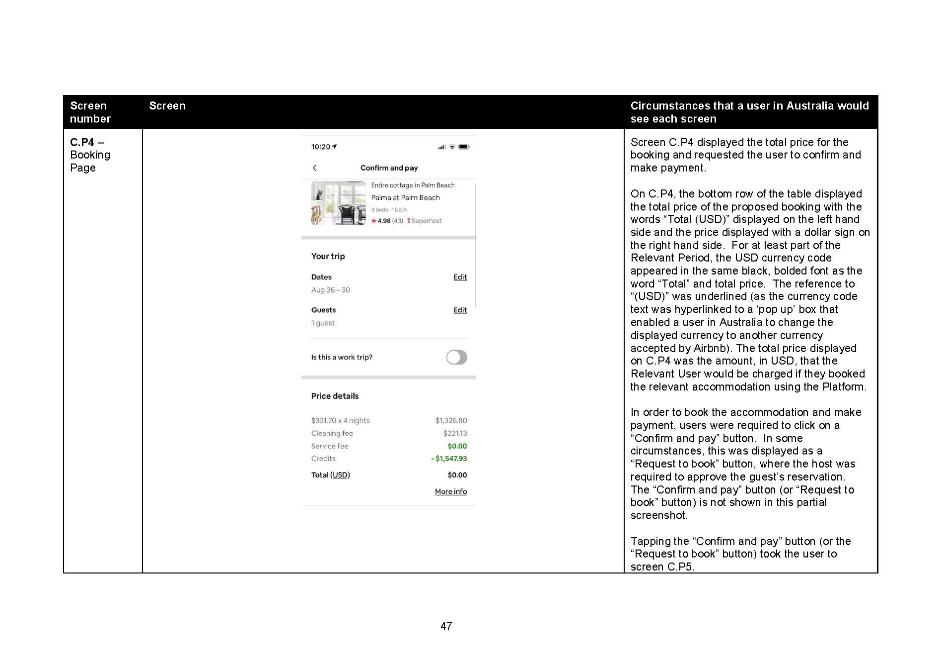

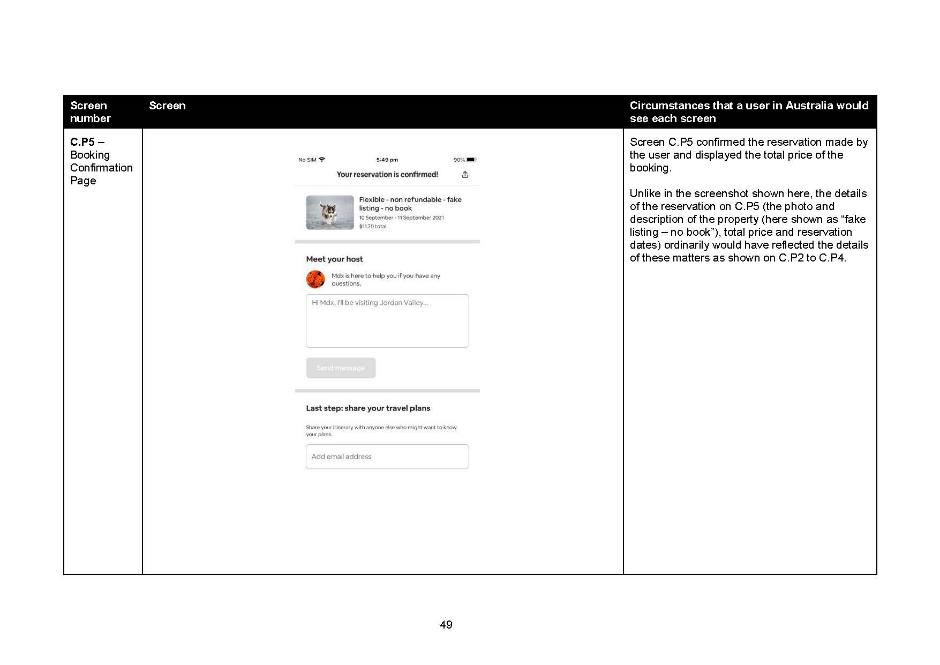

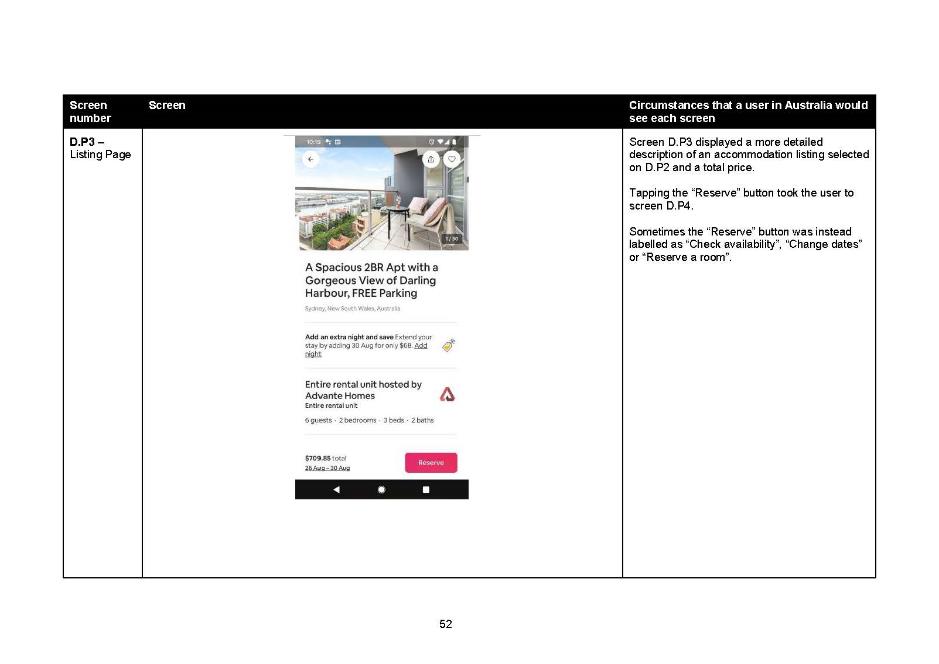

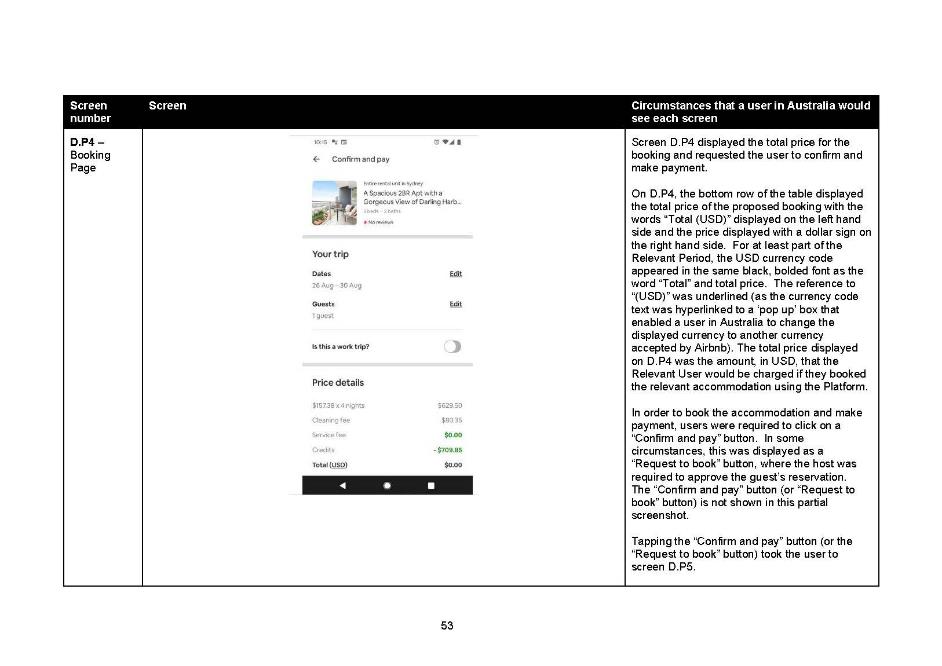

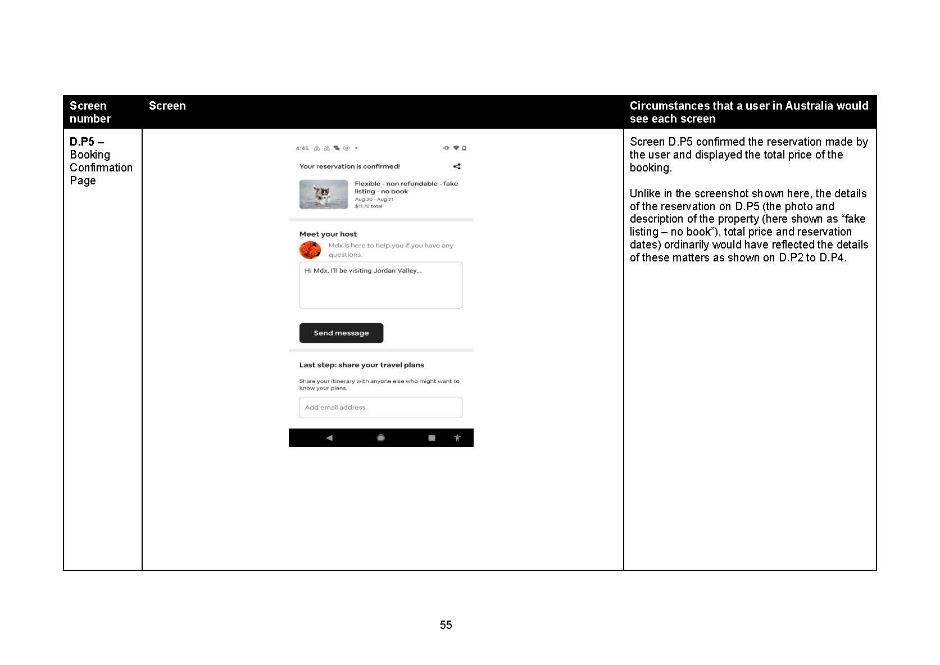

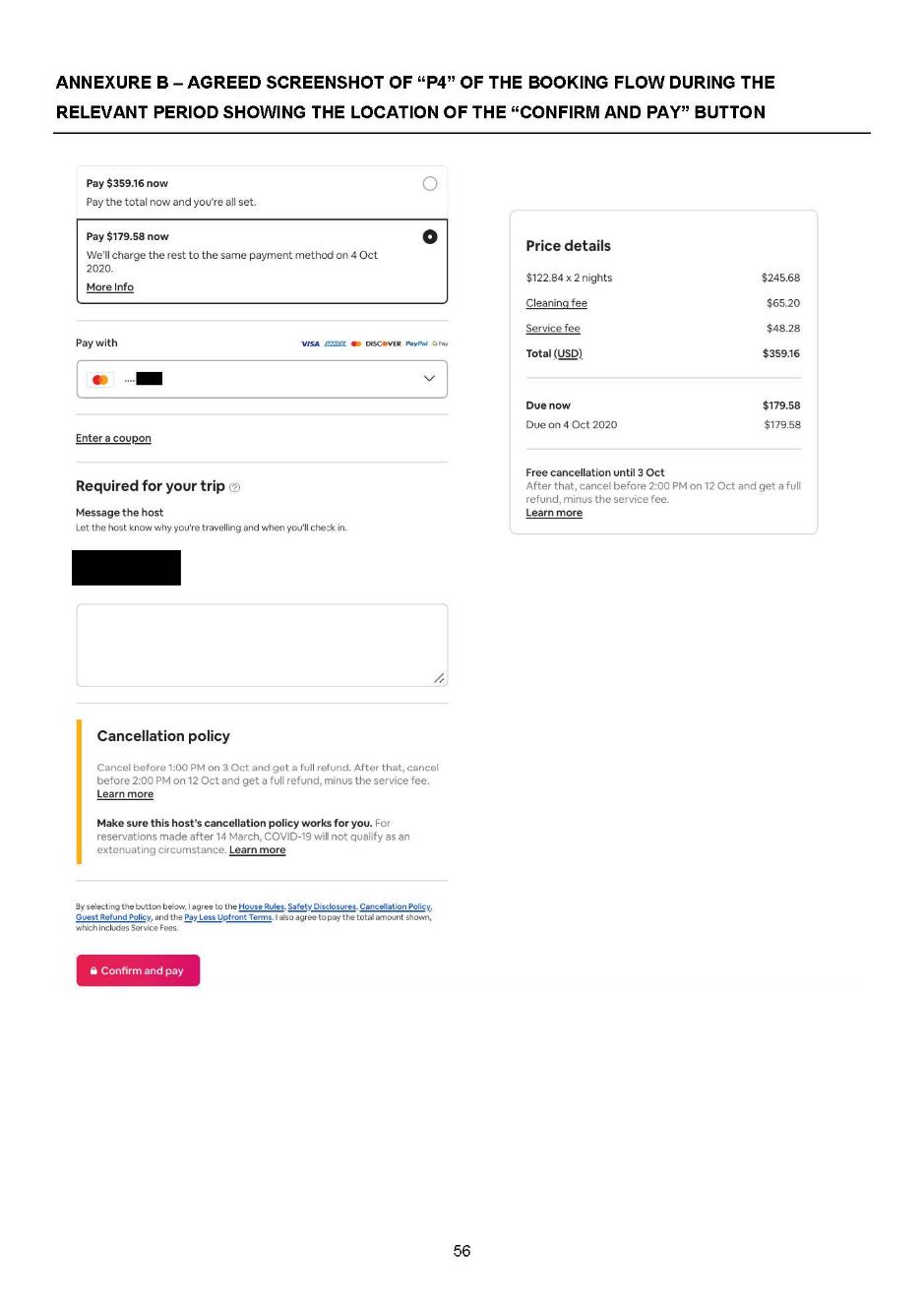

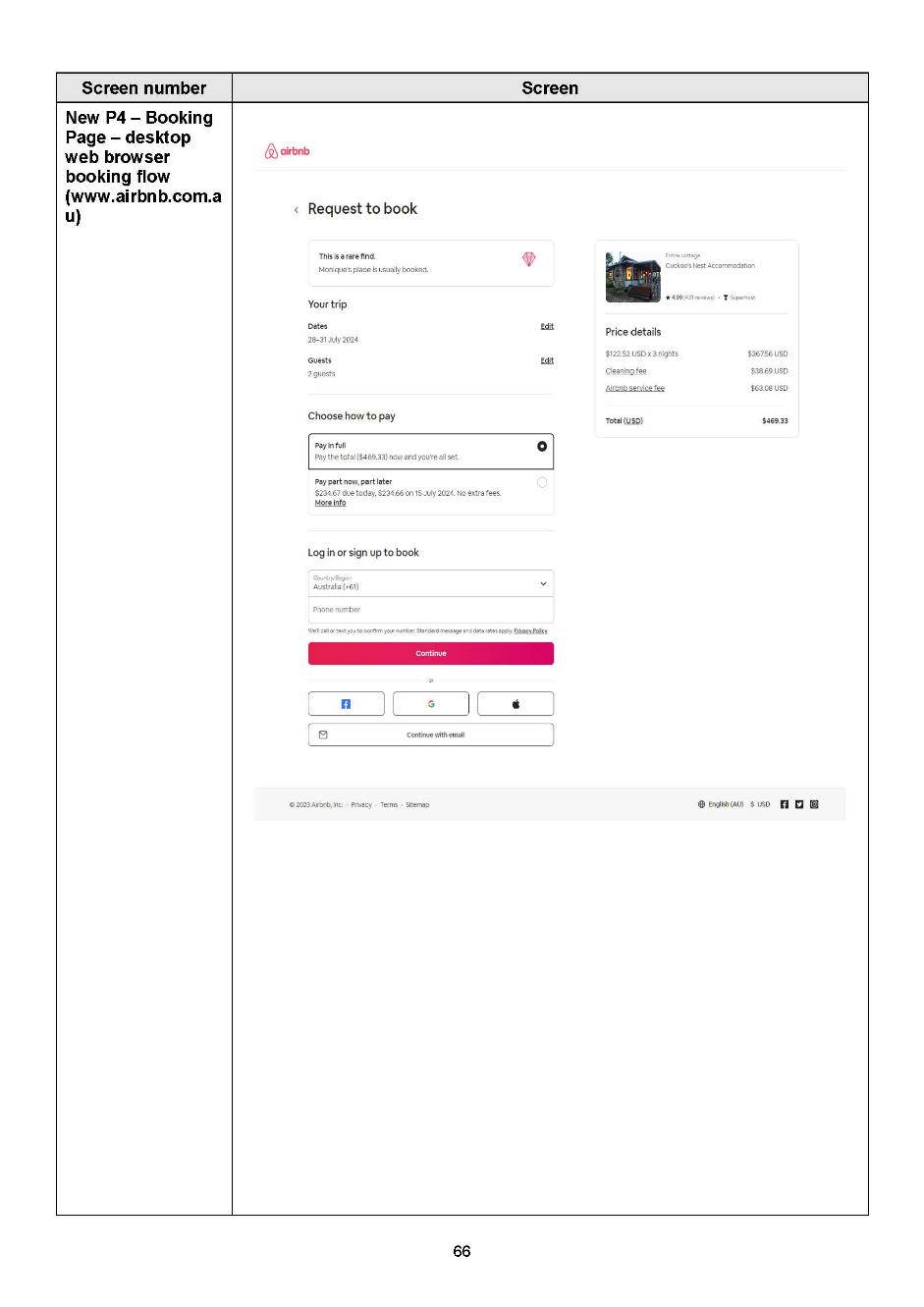

6 In the relevant period, approximately 9 million reservations were made by Australian consumers using the Platform for accommodation within Australia. Of that group, approximately 144,000 reservations were made in USD: that is approximately 1.6% of the total number of reservations. For that sub-group, the Platform displayed the price of properties available by the “$” sign denomination, without clearly disclosing that the price was in USD. I say clearly disclosing because, to the trained eye of an assiduous consumer, that fact was mentioned at the bottom of each of the first three pages of the Platform and then, somewhat more prominently, on the final fourth page where the user is requested to confirm the booking and pay the agreed price. Despite those disclosures, Airbnb accepts that overall and viewed objectively in context the Platform made representations that were misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive contrary to s 18 of the ACL. It further accepts that it engaged in conduct contrary to s 29(1)(i) of the ACL which prohibits a person in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services from making false or misleading representations about the price of a good or a service. This conduct as affecting relevant users is described in the SAFA as the AUD Representation.

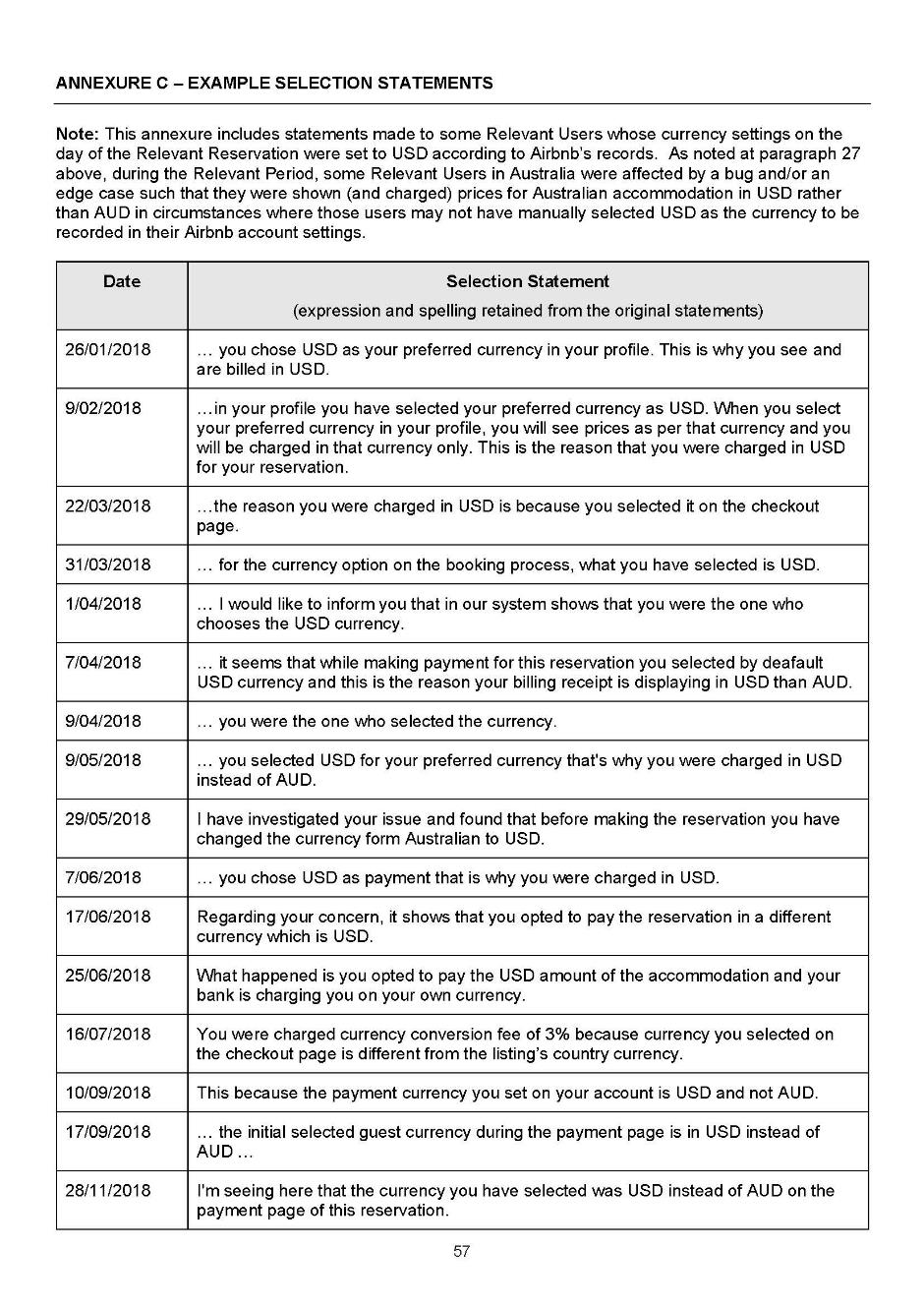

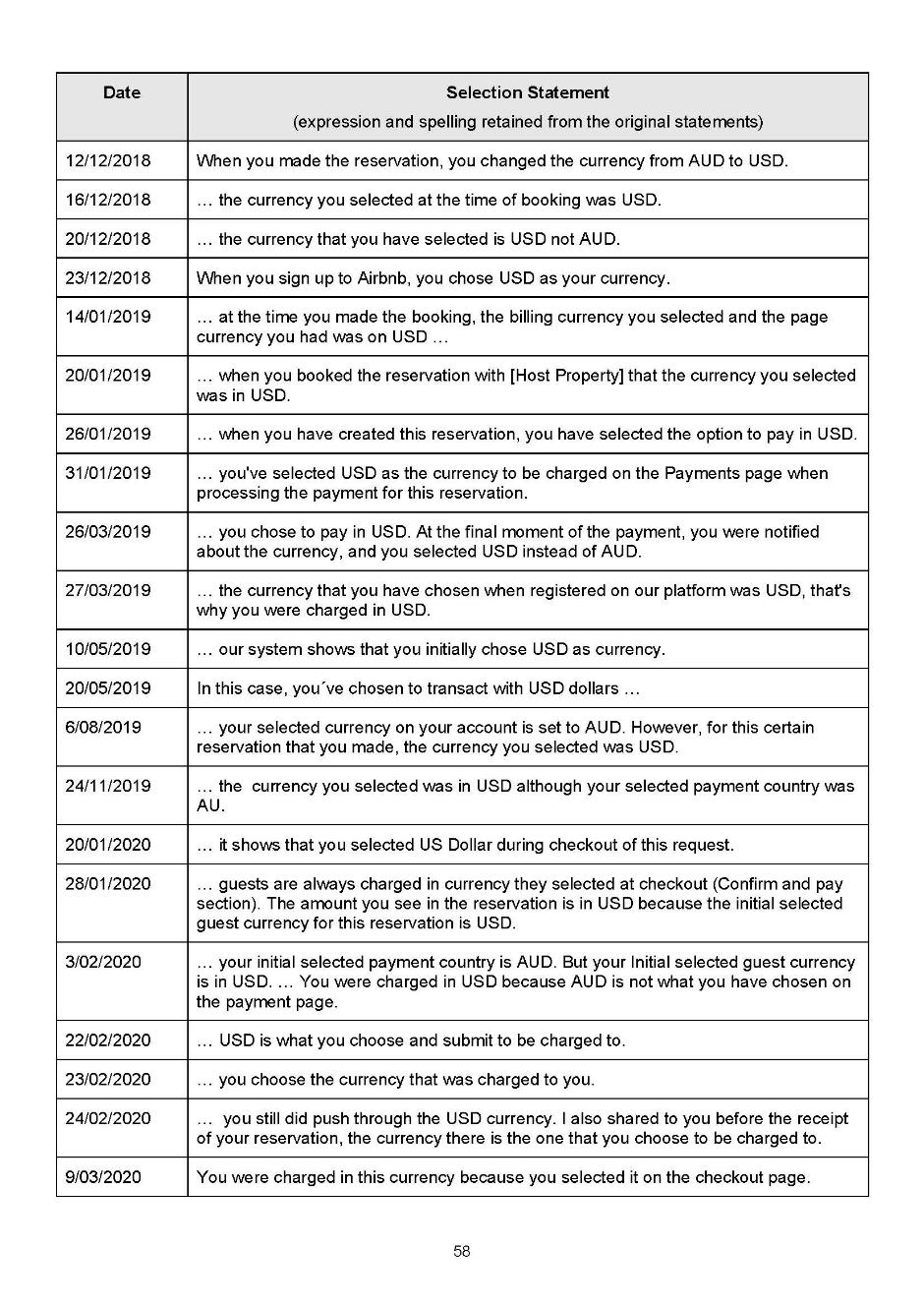

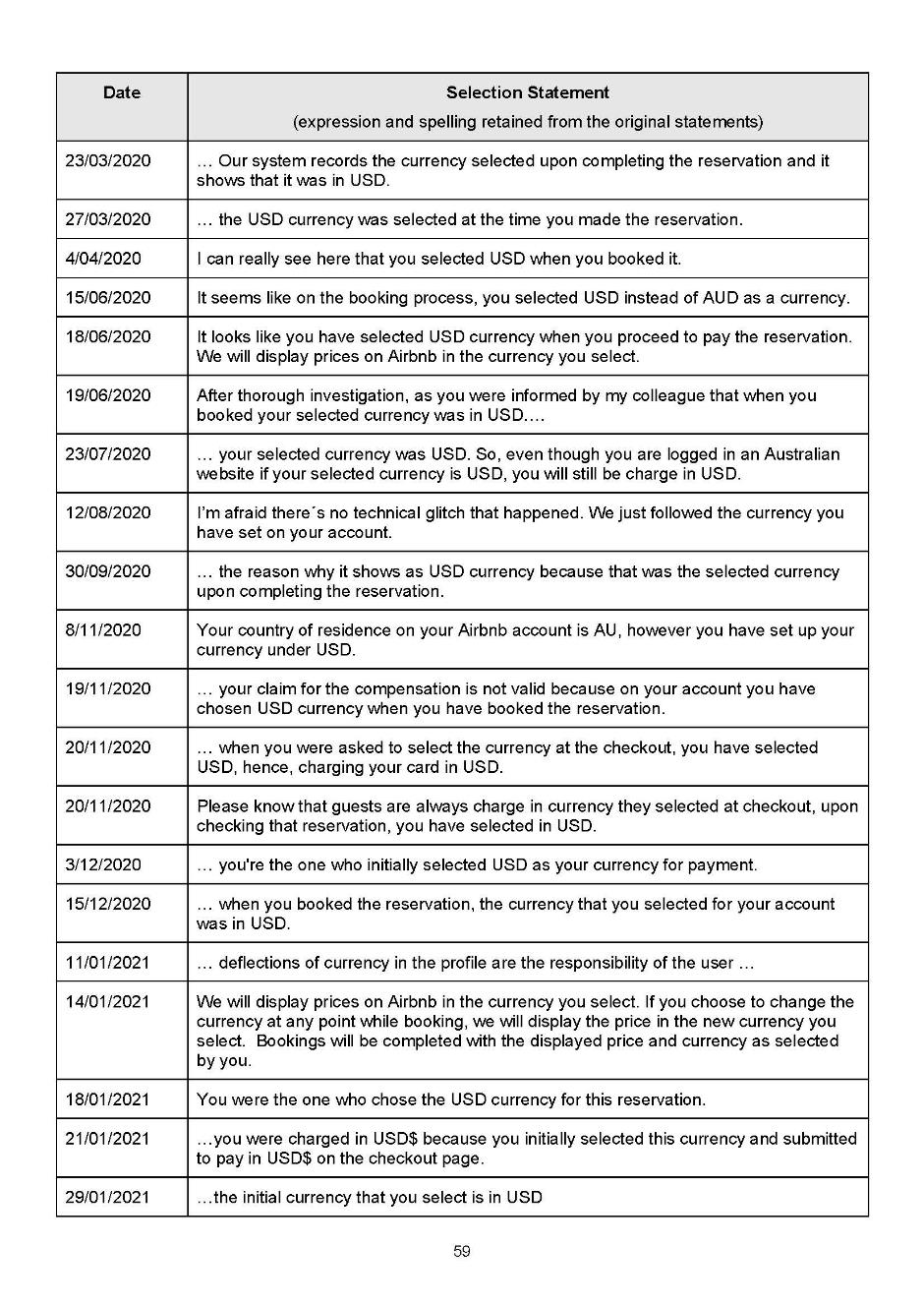

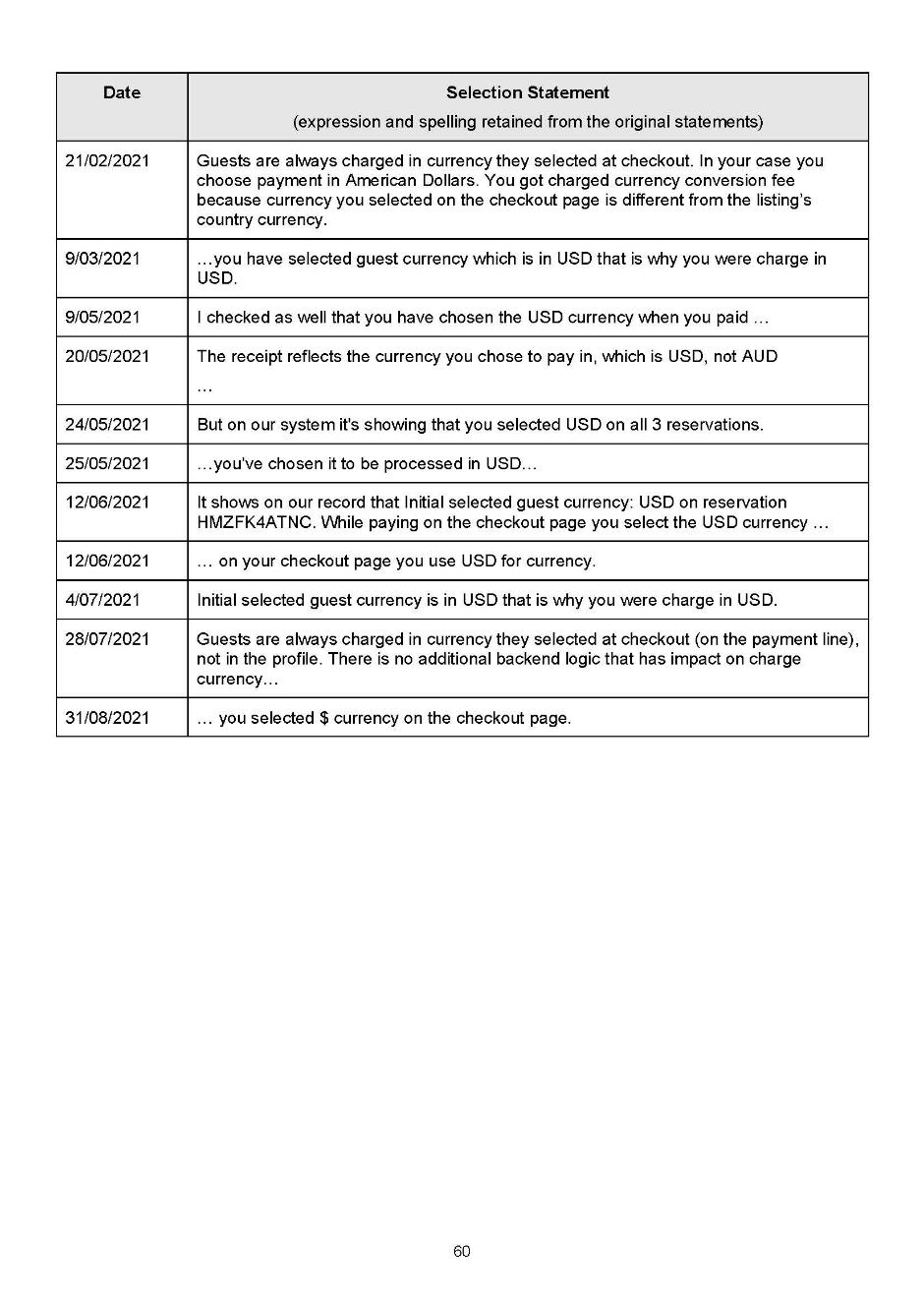

7 There is a second aspect of the admitted contravening conduct. Approximately 2,088 relevant users who booked accommodation in Australia in USD within the relevant period, raised complaints with the customer support personnel about having been charged in USD. Some of those complainants were informed by the personnel that they had been charged in USD because that is what had been selected on the Platform, which statement was false. This is referred to in the SAFA as the Selection Representation. Airbnb also admits that the Selection Representation was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive contrary to s 18 of the ACL.

8 It is not possible to determine how many times Airbnb made the AUD Representation in the relevant period. What is known is that there were approximately 77,000 reservations made by approximately 63,000 affected users. This group of 63,000 persons does not include approximately 8,000 users who have received a full refund of the price of the accommodation that was booked. The aggregate amount paid by Airbnb to those persons is approximately AUD9.4 million.

9 The affected users who were misled about the price of accommodation on the Platform suffered damage in several ways. First, they were deprived of the opportunity of making an informed choice of accommodation. Second, by reason of differences in the prevailing currency exchange rates throughout the relevant periods, all prices displayed in USD appeared lower than if they had been displayed in AUD. Thus, the relevant users paid more than they expected to pay for the accommodation selected. Some of the affected users also incurred charges to their financial institutions which would not have been imposed if the service had been transacted in AUD. For the consumers who made complaints, they suffered general harm and inconvenience to the extent to which they spent time and energy in pursuing the matter, and in some cases, they were informed that they were not entitled to a cash payment as compensation. This may have discouraged some complainants from taking the issue further.

10 Airbnb obtained commercial benefits because of the AUD Representation in that if the price had been displayed in AUD, consumers may not have made reservations. It is not possible to accurately quantify this amount. However, for the relevant reservations, the total value of the price difference was approximately AUD16.8 million. Airbnb received revenue, not profit, from the relevant reservations of approximately AUD9 million. Any benefit received by Airbnb is likely to be reduced by the quantum of refunds already provided, the cost incurred for merchant service fees associated with the USD transactions, the cost incurred for the handling of customer complaints and, perhaps more importantly, the consumer redress compensation scheme that is proposed may result in an additional amount of compensation being paid to relevant users of approximately AUD15 million.

11 How did this occur? The operating software of the Platform was designed to function so that Australian consumers accessing the Platform in Australia, who had not manually selected a currency, would default to AUD. The geographic location of the consumer was a determining factor. As humans well understand, sometimes computer programs do not function as designed. The precise cause of the software malfunction has not been identified, apart from the general statement that there were “bugs and/or edge cases” that caused the currency selection logic to mistakenly identify the consumer as present in the United States of America.

12 An important fact is that the AUD Representation was not the result of deliberate conduct, designed to intentionally mislead. Also, there is no evidence that the Selection Representation formed part of a deliberate strategy to mislead consumers. Rather, standard form responses were provided to complainants without proper investigation or understanding of the relevant facts and certainly no understanding of the software malfunction. For the purposes of my findings, I consider this as incompetence on the part of the customer service personnel and those responsible for their training and instruction.

13 In April 2021, Airbnb commenced an internal investigation prompted by complaints received from relevant users. Of the 2,088 complaints made, 22 were ‘escalated’ to the Airbnb Regulatory Response team. The currency issue was noticed, but not fully comprehended. Some steps were taken to address the format of the Platform, to clearly indicate the currency throughout the entire search and booking process. In July 2021, the ACCC commenced an investigation, which spurred Airbnb into further action. A more detailed investigation was undertaken. Finally, the software malfunction was identified and Airbnb promptly implemented remedial action including, on 13 August 2021, advising the ACCC that it intended to change the Platform to clearly denominate USD where USD was the applicable currency. These changes were effected from 31 August 2021. Consumers can now select as an option, the displayed prices in AUD or USD, with the currency code clearly displayed for either selection.

14 Airbnb has made significant improvements to its compliance programs and processes in response to the ACCC investigation and this proceeding. During the period of the investigation, that is from July 2021 to May 2022, Airbnb cooperated by providing information and documents to the ACCC voluntarily and in response to multiple requests. That cooperation has continued since commencement of this proceeding. It is of particular significance that Airbnb sought, at an early stage, to resolve this proceeding by admitting to the AUD Representation and the Selection Representation as conduct contrary to the ACL. The cooperation extended to agreement as to the facts set out in the SAFA and the Joint Submission as to the appropriate remedies. Absent this cooperation, the quantum of the appropriate pecuniary penalty is likely to have been somewhat larger.

RELEVANT STATUTORY PROVISIONS AND GENERAL PRINCIPLES

15 Section 18(1) of the ACL provides:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

16 Section 29(1) of the ACL relevantly provides:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

…

(i) make a false or misleading representation with respect to the price of goods or services;

…

17 Pecuniary penalties may be imposed for conduct contrary to s 29 (but not s 18) as provided for at s 224 where the Court is satisfied that a person has contravened a relevant provision by ordering the person to pay, relevantly, to the Commonwealth “such pecuniary penalty, in respect of each act or omission by the person… as the court determines to be appropriate.” A pecuniary penalty is not to exceed the amount worked out in accordance with the table at s 224(3). For each contravention in this case the maximum penalty varies:

(1) Until 1 September 2018, $1.1 million per contravention;

(2) From 1 September 2018, the greater of $10 million, three times the value of the benefit obtained from the contravention (if that can be determined) or 10% of the annual turnover of Airbnb during the 12-month period ending at the end of the month in which the act or omission first occurred.

18 It is not possible to determine precisely how many contraventions occurred before and after 1 September 2018, which precludes findings about the value of the benefit obtained.

19 Pecuniary penalties are imposed for the public purpose of promoting compliance with the CCA. Deterrence, specific and general, is the objective, not retribution or rehabilitation: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; 274 CLR 450 (Pattinson) at [14], [16], [39] [40], [43], [45] and [55] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ). Further, as those references in the plurality judgment make clear, proportionality as derived from the criminal law has no role to play but totality, parity and the course of the contravening conduct may assist in determining the appropriate penalty. Importantly the statutory maximum “does not constrain the exercise of the discretion… beyond requiring ‘some reasonable relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty imposed’”: at [55], quoting the Full Court in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; 340 ALR 25 at [156] (Jagot, Yates and Bromwich JJ).

20 Section 224(2) requires that:

In determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the court must have regard to all relevant matters including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by a court in proceedings under Chapter 4 or this Part to have engaged in any similar conduct.

21 It is usual to have regard to the list of factors identified by French J in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1991] ATPR 41-076 at 52,152-52,153. The Joint Submission addresses each factor that is relevant to the circumstances, as I explain later in these reasons.

22 Something should also be said about the ultimate quantum of the penalty that is proposed in this case. In Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; 287 ALR 249 at [62]-[63], Keane CJ, Finn and Gilmour JJ in part said:

[T]he punishment must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not such as to be regarded by that offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business. The primary judge was right to proceed on the basis that the claims of deterrence in this case were so strong as to warrant a penalty that would upset any calculations of profitability….

Generally speaking, those engaged in trade and commerce must be deterred from the cynical calculation involved in weighing up the risk of penalty against the profits to be made from contravention….

23 I note that Airbnb has provided an undertaking to the ACCC pursuant to s 87B of the CCA which provides for a compliance program and a redress compensation scheme for affected consumers. A redacted version of the undertaking is at Annexure C to this judgment. I am satisfied as required by s 37AG of the FCA Act that it is necessary to prevent prejudice to the administration of justice in this proceeding that a non-publication order should be made in respect of the redacted portions of the undertaking, because the clauses are central to the effective operation of the redress scheme and disclosure is likely to undermine its implementation. The orders proposed by the parties will be amended to that effect.

24 Orders are also sought pursuant to s 246(2)(b) of the ACL requiring Airbnb to implement a compliance program, that is an annexure to the proposed orders. Section 246 permits the making of non-punitive orders on the application of the ACCC, including:

(b) an order for the purpose of ensuring that the person does not engage in the conduct, similar conduct, or related conduct, during the period of the order (which must not be longer than 3 years) including:

(i) an order directing the person to establish a compliance program for employees or other persons involved in the person's business, being a program designed to ensure their awareness of the responsibilities and obligations in relation to such conduct; and

(ii) an order directing the person to establish an education and training program for employees or other persons involved in the person's business, being a program designed to ensure their awareness of the responsibilities and obligations in relation to such conduct; and

(iii) an order directing the person to revise the internal operations of the person's business which led to the person engaging in such conduct;

25 Declaratory relief is sought pursuant to s 21 of the FCA Act, to the effect that Airbnb contravened the ACL in making the AUD Representation and the Selection Representation. Declaratory relief of that type is of utility, even where pecuniary penalties are imposed, as serving the public purpose of expressing the Court’s disapproval of contravening conduct: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCAFC 113; 254 FCR 68 at [93] (Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ). For declaratory relief, the question must not be hypothetical, a contradictor is required, and the applicant must have a sufficient interest in the relief sought: Hobart International Airport Pty Ltd v Clarence City Council [2022] HCA 5; 96 ALJR 234 at [32] (Kiefel CJ, Keane and Gordon JJ). Those conditions are met in this case.

WHAT REMEDIES ARE APPROPRIATE?

26 I am satisfied that the Joint Submission proceeds upon a correct understanding of the facts and the applicable legal principles. There is no material issue that requires detailed consideration concerning the declaratory relief and the implementation of a compliance program. As to the former, this is an appropriate case for this Court to express its disapproval of the contravening conduct by making each of the declarations that are sought. This is a serious case involving multiple breaches affecting tens of thousands of consumers by a well-known and easily recognisable corporation. That relief also serves the purpose of publicly vindicating the decision of the ACCC to first investigate and then to commence this proceeding by alleging each aspect of the contravening conduct. It also serves as a public warning to other persons who may be minded to engage in the same or similar conduct.

27 An integral component of the Joint Submission is that a compliance program must be implemented for the purpose of ensuring awareness within Airbnb of its responsibilities in relation to the contravening conduct and the need to be diligent to avoid a repetition of the conduct, or similar or related conduct, in the future. There is in this case a clear relationship between the terms of the compliance program and the contravening conduct: see generally Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Sontax Australia (1988) Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 1202 at [36]-[38] (Gordon J). I am satisfied that implementation of the compliance program should be ordered pursuant to s 246 of the ACL.

28 The matter which requires more detailed consideration is whether I should accede to the joint position of the parties and impose an aggregate pecuniary penalty of AUD15 million as the appropriate penalty in the circumstances of this case. It should be emphasised that in this case I may only impose pecuniary penalties for the AUD Representation having been made contrary to s 29(1)(i) of the ACL: s 224(1)(ii). The case is not framed by a contention that the Selection Representation attracts a civil penalty. That said, as Ms Brazenor accepted in her oral submissions, I am entitled to take the Selection Representation into account as contextually relevant to the AUD Representation. Self-evidently, if the complaining consumers had not been dealt with dismissively, it is likely that the software malfunction which caused the AUD Representation would have been identified early on. Had that occurred, the scale of the AUD Representation is likely to have been significantly less.

29 Dealing first with the mandatory matters at s 224(2) of the ACL, the first consideration is the nature and extent of the conduct engaged in by Airbnb during the relevant period and any loss or damage suffered as a result. The SAFA in detail sets out the facts concerned with these matters in considerable detail. As noted, I have found in accordance with those facts. The relevant period is approximately 3½ years, commencing on 1 January 2018 and ending on 30 August 2021. That is by any measure a substantial period. The AUD Representation was made to approximately 63,000 affected consumers who used the Platform within that period. Approximately 77,000 reservations were made, though it is not possible to determine how many of those consumers were misled and or suffered financial harm as a result of the AUD Representation. Although the number of bookings made by affected users was approximately 1.6% of the total number of Australian reservations, that statistic tends to mask the scale of the contravening conduct. Rather, it reflects the vast size of the business of Airbnb in Australia in the relevant period.

30 I accept the submission of Mr Borsky for the ACCC that this is a serious case involving tens of thousands of individual contraventions which of itself warrants a substantial penalty. The estimated quantum of the currency differential is approximately AUD16.8 million, which is the best estimate of the total loss suffered by the 63,000 affected consumers. The contravening conduct was widespread, affected many unwitting consumers who were entitled to expect that they would not be misled by a corporation as large and well-known as Airbnb.

31 The seriousness of the AUD Representation was compounded by the Selection Representation made to the sub-group of 2,088 consumers who, upon raising concerns about being overcharged, were further misled by false statements the effect of which was to cast blame for the error onto the consumer. There are multiple examples of this egregious conduct referenced in the SAFA. By way of illustration (and without correcting for grammatical errors):

25 June 2018: What happened is you opted to pay the USD amount of the accommodation and your bank is charging you on your own currency.

28 November 2018: I’m seeing here that the currency you have selected was USD instead of AUD on the payment page of this reservation.

21 February 2021: Guests are always charged in currency they selected at check out. In your case you choose payment in American dollars. You got charged currency conversion fee because the currency you selected on the checkout page is different from the listing’s country currency.

32 These patently false statements should not have been made if proper and adequate steps had been taken to investigate the operation of the Platform. I emphasise, however, that the ACCC does not allege that the Selection Representation was a knowingly false statement on any of the individual occasions when made to consumers. Rather, as put by Mr Borsky in oral submissions, the answers provided to consumers were certainly deliberate, but those misrepresentations were not made with knowledge of the true state of affairs. However, as explained, the Selection Representation does not attract any civil penalty.

33 Despite that there is no element of deliberate conduct engaged in by Airbnb to mislead consumers, in my view the real culpability lies in the fact that insufficient procedures and controls were in place from the outset to monitor the Platform to detect technical computer programming glitches in a timely way and to rectify them. After all, Airbnb operates globally – across many countries where consumers do not usually transact business in USD. The culpability then extended to a failure to take adequate steps to investigate the issue once complaints had been received from affected consumers. And there were very many complaints, commencing with 711 between 1 January and 31 December 2018, approximately 610 in each of the calendar years 2019 and 2020 and 155 between 1 January and 30 August 2021.

34 Airbnb is a very substantial global business, with total revenue of USD1.7 billion in 2017, USD2.3 billion in 2018, USD2.9 billion in 2019, USD1.7 billion in 2020 and USD2.8 billion in 2021. The gross revenue received from Australian consumers in the relevant period was approximately USD100 million. Airbnb as a corporate entity of that scale, with the primary business of facilitating peer-to peer rental accommodation services via the Platform, quite clearly had the resources and capacity to implement robust monitoring services to ensure that consumers were not misled as happened in this case. Much more should have been done to ensure compliance with the ACL in the conduct of its business in Australia. What is now known, in consequence of the investigations undertaken primarily by the ACCC, is that the computer malfunction was able to be identified and addressed such that the Platform now clearly displays all prices for Australian accommodation, on all relevant pages, with a currency code that clearly indicates whether the prices are in AUD, USD, or such other currency as selected by the customer, so that informed choices may be made.

35 As to the nature and extent of loss or damage suffered by consumers, as I have explained precise findings cannot be made beyond a broad estimate of approximately 63,000 affected users, who made approximately 77,000 reservations and who may have been misled. Somewhat obviously, there may have been many affected users who realised that they were to be charged in USD, at least by the time that they reached the confirmation and payment page of the Platform. Those persons may have been perfectly content to continue, notwithstanding. What is agreed in the SAFA is that the total value of the price difference is approximately AUD16.8 million plus an unquantifiable potential further financial harm suffered by affected users who incurred transaction fees, that are commonly imposed by financial institutions where goods and services are purchased in Australia in a foreign currency.

36 Balanced against that, is the fact that Airbnb has thus far taken positive but incomplete steps to provide financial compensation to affected users by refunding the full price of the accommodation that they booked. There are approximately 8,000 consumers within this category and the aggregate amount of refunds paid is approximately AUD 9.4 million. For other consumers, there is the consumer redress compensation scheme that must be implemented pursuant to the undertaking given to the ACCC. There is also the question of opportunity loss, being the inability to make an informed purchasing choice.

37 Although there is no precise evidence, I infer it likely that Airbnb gained a financial advantage over its competitors because during the relevant period the exchange rate difference resulted in the appearance of cheaper rates for comparable accommodation through the Platform, when compared with other similar peer-to peer accommodation service providers who, cognisant of their obligations not to engage in misleading conduct, either displayed prices in AUD or, if not, made it clear to consumers that prices were displayed in USD, or some other currency. I infer that a significant number of consumers are likely to have booked accommodation through the Platform, ignorant of the actual price comparison which they were entitled to make if the contravening conduct had not been engaged in.

38 These findings also address the second mandatory consideration: the circumstances in which the contravening conduct occurred. An additional matter that is relevant at this point is the knowledge of senior management of Airbnb, when that knowledge was acquired and what steps were taken to address the contravening conduct. The agreed fact is that the board of Airbnb was aware of “a small number” of the complaints that were made in 2018, by reason of reports that were prepared for and submitted to it between May and September 2018. Quite wrongly, those reports represented to the board that the complaints by consumers resulted from the conduct of the consumers in setting the Platform currency to USD on their devices. The board was not aware of any wider issue until commencement of the ACCC investigation.

39 There had been an earlier compliance issue, the subject of an undertaking given by Airbnb to the ACCC on 12 October 2015 (2015 undertaking), relating to the display of additional cleaning and service fees that were added to the displayed price of a property at a later stage of the booking process. That undertaking required Airbnb to establish a compliance program to address that issue. It is accepted that the currency display issue the subject of this proceeding is not related to the conduct that was the subject of the 2015 undertaking.

40 However, it should not be overlooked that Airbnb simply failed to have in place adequate systems and processes to identify what might have been causing the substantial number of complaints that it received, commencing in 2018.

41 That said, I note that in response to the commencement of this proceeding steps have been taken to improve compliance processes, including the implementation of procedures to ‘escalate’ ACL consumer complaints to a specialist team, which works in the Asia-Pacific legal team.

42 The third mandatory consideration is whether Airbnb has previously been found to have engaged in any similar contravening conduct. It has not.

43 I next deal with several other discretionary considerations, largely in accordance with the sequence set out in the Joint Submission, which I accept is comprehensive and adequate.

44 Airbnb has not behaved as a recalcitrant in response to the ACCC investigation or this proceeding. As I have noted, documents were produced voluntarily in response to multiple requests from the ACCC and, following commencement of the proceeding, there was very significant cooperation which resulted in an early resolution on agreed facts with appropriate admissions. The result is a very significant saving in the resources of the ACCC, the costs of the proceeding and the resources of this Court. The early acknowledgement of misconduct by Airbnb has been commendable. I accept the submission put for Airbnb that these matters indicate a lower need for specific deterrence, particularly combined with the consumer redress undertaking and with it the scheme to refund affected consumers at an estimated cost of up to AUD15 million. This compensation, however, must not be viewed as some form of additional penalty: it is compensation that is properly payable by Airbnb to affected consumers for loss suffered by reason of the contravening conduct.

45 The need for deterrence is, as I have noted, the primary purpose of a civil penalty for breach of the ACL. This is the matter that I have given most anxious consideration to. The agreed penalty of AUD15 million does not bear a direct mathematical relationship with the USD100 million of gross revenue derived by Airbnb from the supply of peer-to-peer rental accommodation services to users in Australia in the relevant period, because it does not take account of the currency conversion difference. It is therefore necessary that I correct that error which arose in oral argument. Rather, I proceed on the basis that the agreed penalty must be the result of a process of synthesising all relevant considerations: Agreed Penalties Case at [72] (Gageler J).

46 The penalty must be sufficiently large to have a persuasive impact on Airbnb to comply with the ACL in all relevant aspects of the conduct of its business when offering its services to Australian consumers. The provisions in issue establish statutory moral standards that apply to all conduct in trade or commerce with respect to the price for the supply, or possible supply of goods or services. Airbnb must be made to understand that a failure to comply with the statutory norm has consequences, and in this case, they are very serious. As explained in Pattinson at [60]:

Indeed, in some cases, the circumstances of the contravenor may be more significant in terms of the extent of the necessity for deterrence than the circumstances of the contravention. In this regard, it is simply undeniable that, all other things being equal, a greater financial incentive will be necessary to persuade a well-resourced contravenor to abide by the law rather than to adhere to its preferred policy than will be necessary to persuade a poorly resourced contravenor that its unlawful policy preference is not sustainable.

47 The penalty must not be so significant as to be oppressive, which in this case is not an issue as Airbnb agrees to the penalty quantum.

48 As I have noted, steps have been taken to provide partial consumer redress in the form of the compensation payments made thus far and in the undertaking that has been given to the ACCC. This is evidence of contrition and demonstrates an understanding of the impact that the contravening conduct has had on consumers and mitigates the specific deterrence objective.

49 This is a case of multiple contraventions, involving misleading conduct, over an extended period and as I have noted, one cannot simply proceed by determination of an appropriate amount for each individual contravention. The interrelationship between the conduct, factually and legally, permits the contraventions to be grouped and regarded as a single course of conduct for the AUD Representation: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; 262 FCR 243 (Yazaki) at [226]-[236] (Allsop CJ, Middleton and Robertson JJ). As the Joint Submission correctly notes, it is then relevant to consider the course of conduct principle and the totality principle.

50 The course of conduct principle does not operate to group multiple contraventions and treat them as one. In this case, as I have explained, the contravening conduct for the AUD Representation involved many individual acts of contravention that affected a large number of Australian consumers, with significant financial consequences. The course of conduct principle provides support for and is reflected in the total agreed penalty which is not derived mathematically by aggregating the penalty for individual contraventions: Yazaki at [234]-[236].

51 The totality principle operates as a guide to ensure that the penalty is appropriate having regard to the entirety of the contravening conduct: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v AGL Sales Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 1030 at [62]-[63] (Middleton J). I am persuaded that the agreed penalty in the overall context of the admitted AUD Representation contravening conduct, balanced and weighed with each of the other factors that I have set out does not exceed what is proper.

52 Overall, I am satisfied in the exercise of my discretion to impose pecuniary penalties, that the amount of AUD15 million is appropriate in the circumstances of this case, and not simply because it is the sum agreed to by the ACCC and Airbnb. In isolation it is a very significant amount, and will not be simply regarded as a cost of doing business, but one which I am satisfied provides the appropriate “sting or burden” (Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2018] HCA 3; 262 CLR 157 at [116] (Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ)) which is appropriate to achieve the objectives of specific deterrence for Airbnb and general deterrence as a warning to other would-be contraveners who may consider engaging in similar conduct.

53 Finally, there is the question of costs. The agreed contribution of $400,000 to reimburse a portion of the costs incurred by the ACCC is entirely appropriate.

54 For these reasons, I make the orders set out above.

I certify that the preceding fifty-four (54) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice McElwaine. |

Associate:

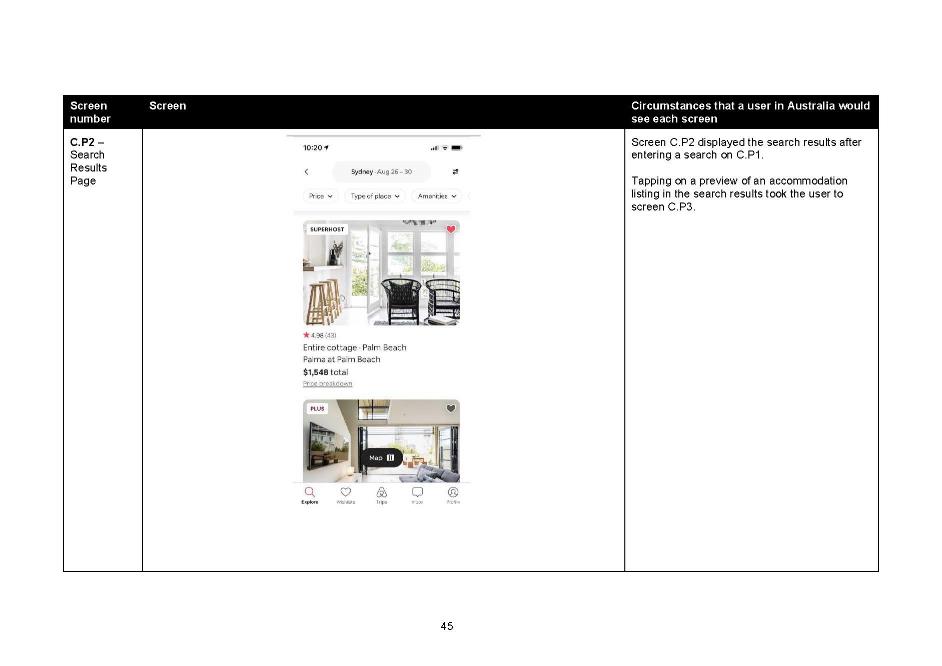

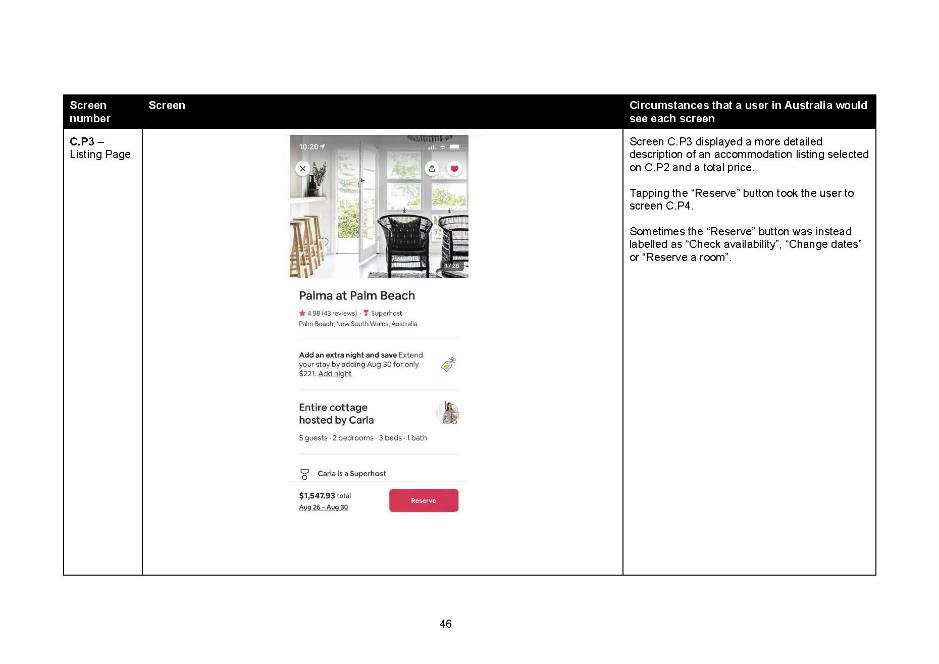

ANNEXURE A – STATEMENT OF AGREED FACTS AND ADMISSIONS

ANNEXURE B – JOINT SUBMISSIONS

ANNEXURE C – UNDERTAKING