FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

McFarlane as Trustee for the S McFarlane Superannuation Fund v Insignia Financial Ltd [2023] FCA 1628

ORDERS

JOHN DOUGLAS MCFARLANE ATF THE S MCFARLANE SUPERANNUATION FUND Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The originating application be dismissed.

2. Costs reserved.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ANDERSON J

1 The applicant (Mr McFarlane) claims that during the period from 1 March 2014 to 7 July 2015 (Relevant Period), the respondent contravened its obligation of continuous disclosure pursuant to s 674 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act) and, or alternatively, engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 1041H of the Corporations Act and analogous provisions in the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act) and Australian Consumer Law (ACL) as identified in his originating application.

2 The respondent has now re-named itself as “Insignia”. During the Relevant Period it was known by its former name, “IOOF”.

3 Throughout the Relevant Period IOOF operated a substantial Australian financial services business. This business involved providing wealth management services and financial advice to clients. From 2008 and through the Relevant Period, IOOF was operating a “roll up” model, meaning it was acquiring other financial services businesses to build scale and then use its existing infrastructure – including its Research team (referred to in these reasons as the Research team) – to service that increased scale. IOOF’s Research team provided advice and general recommendations to advisers across the IOOF network.

4 Mr McFarlane claims that IOOF failed to disclose to the market material information of which IOOF was or ought to have been aware during the Relevant Period about problems with that existing infrastructure, particularly the Research team, and therefore with the rolled-up businesses of IOOF. Mr McFarlane claims that the problems went to the heart of the adequacy of IOOF’s systems, processes and culture, including for governance and compliance.

5 Mr McFarlane claims that there were problems with IOOF’s Buy-model Portfolio. This purportedly measured the performance of a model investment portfolio put together by reference to the Research team’s “Buy” recommendations. The portfolio was marketed internally and externally to financial planners. Mr McFarlane claims that IOOF had materially overstated the Buy-model’s performance from 2010 to 2014. Mr McFarlane claims that in three of the four financial years during that period, IOOF had said the Buy-model Portfolio beat the relevant index, but the true position was that it had performed worse than the index. After an investigation, IOOF discovered that the Buy-model Portfolio had been incorrectly calculated since 2001.

6 The problem with the Buy-model Portfolio was one of a number of issues expressly brought to IOOF’s attention by a whistle blower on 4 March 2014 as part of the “March 2014 complaint” pleaded in paragraph 17 of Mr McFarlane’s Amended Statement of Claim filed on 23 November 2021 (ASOC).

7 Mr McFarlane claims that IOOF investigated the March 2014 complaint and was or ought to have been aware during the Relevant Period of the “Historical Information”, the “March 2014 Information” and the “Compromised Model Information” that Mr McFarlane pleads and particularises at ASOC paragraphs 20, 22 and 24. Taken together, that information is defined in the ASOC as the “Alleged Material Information”.

8 The Alleged Material Information was disclosed publicly to the market via a series of Fairfax media articles and statements by the Managing Director of IOOF, Chris Kelaher, to the Senate of the Federal Parliament between 20 June 2015 and 7 July 2015. The source of the revelations is identified by Mr McFarlane in Annexure B to the ASOC. Mr McFarlane alleges that this disclosure of the Alleged Material Information at the end of the Relevant Period, caused abnormal downward movements in IOOF’s share price.

9 Mr McFarlane brings this representative proceeding under Part IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) on behalf of himself and group members who acquired an interest in ordinary shares in IOOF during the Relevant Period, or who acquired a long exposure to ordinary shares in IOOF by entering into an equity swap confirmation in respect of such shares during the Relevant Period.

10 By his originating application, Mr McFarlane seeks orders that Insignia pay compensation to Mr McFarlane and group members for the market-based losses suffered by them as a result of its share price being artificially inflated during the Relevant Period by reason of its breach of its continuous disclosure obligation and, or alternatively, its misleading or deceptive conduct (prayers 1 and 2). Mr McFarlane also seeks orders that Insignia pay interest and costs (prayers 3 and 4).

11 The trial of the common issues in this representative proceeding was conducted on the basis of the questions identified in the document styled “List of Common Issues and Questions” that was filed by consent of the parties on 28 April 2023, which provides as follows:

I. Continuous disclosure case

1 During the Relevant Period, was Insignia “aware” (within the meaning of ASX Listing Rule 19.12) of any of the following information:

1.1 the Historical Information;

1.2 the March 2014 Information; and/or

1.3 Compromised Model Information?

(Alleged Material Information)

2 If the answer to any part of question 1 is “yes”, when during the Relevant Period was Insignia aware of the Alleged Material Information?

3 Was Insignia, at any time during the Relevant Period, obliged pursuant to ASX Listing Rule 3.1 to tell the ASX of the Alleged Material Information (or any part thereof)?

4 Did Insignia contravene section 674(2) of the Corporations Act during the Relevant Period?

II Misleading or deceptive conduct case

5 During the Relevant Period, did Insignia engage in misleading or deceptive conduct, in contravention of s 1041H of the Corporations Act, s 12DA of the ASIC Act and/or s 18 of the ACL by:

5.1 failing to disclose the:

5.1.1 Historical Information;

5.1.2 March 2014 Information; and/or

5.1.3 Compromised Model Information;

5.2 further or alternatively, making the statements that it did to the ASX as set out in Annexure A to the ASOC, unqualified by the:

5.2.1 Historical Information;

5.2.2 March 2014 Information; and/or

5.2.3 Compromised Model Information?

6 If the answer to question 5 is “yes”, when during the Relevant Period did Insignia engage in that misleading or deceptive conduct?

7 Did Insignia make statements to the ASX on:

7.1 22 June 2015; and/or

7.2 24 June 2015;

that were:

7.3 false; and/or

7.4 without reasonable basis;

in contravention of s 1041H of the Corporations Act, s 12DA of the ASIC Act and/or s 18 of the ACL, as pleaded in paragraph 41 of the ASOC?

III Causation, loss and damage

8. During the Relevant Period, did any of the alleged contravening conduct by Insignia cause the market price for ordinary shares in Insignia to be greater than:

8.1 their true value; and/or

8.2 the market price that would have prevailed but for the alleged contravening conduct (or any part of it)?

9 If the answer to question 8 is “yes”, by how much was the market price for ordinary shares in Insignia greater than their true value and/or the market price that would have prevailed during the Relevant Period?

12 The following background facts were summarised by the parties in their chronologies and written submissions and from my review of the documents jointly tendered by the parties.

13 IOOF has been listed on the ASX since 5 December 2003. In May 2009, Australian Wealth Management (AWM) merged with, and became a wholly owned subsidiary of, IOOF. At the time, both AWM and IOOF were listed financial service entities which provided a wide range of wealth management services. At the time of the merger:

(1) AWM operated through five divisions, including “Wealth Management” which provided financial advisory and stockbroking services through various subsidiary businesses. Those subsidiary businesses included Bridges Financial Services Pty Ltd (Bridges). Bridges provided financial advisory and stockbroking services through a network of financial planners. The Bridges business had a dedicated equities Research team which provided investment research services to its planner network. The head of the Bridges Research team was Mr Hilton;

(2) IOOF operated through four business units, one of which was Consultum, which provided financial advice through a network of authorised financial planners. Consultum’s business included its own equities research division that provided investment research services to its network of planners.

14 Following the AWM merger and until May 2013, Bridges and Consultum continued to operate independently within the merged group’s Financial Advice and Distribution division. That division was one of four divisions in the merged IOOF group structure, the others being: Platform Management and Administration; Investment Management; and Trustee Services.

15 In May 2013, the research functions of the group were combined to form a single IOOF Research team, which serviced both the Bridges and Consultum businesses. The Research team was headed by Mr Hilton, and continued to sit within the Financial Advice and Distribution division of the IOOF business.

16 The role of the Research team was set out in a document styled “IOOF Research Policy” dated June 2014. The document explained:

Research provides advice and general recommendations to advisers across the IOOF network (the network). The IOOF Advice Research objective is to disseminate well-articulated recommendations and opinions such that the network can provide a basis of opinion for client recommendations. Research recommendations are formulated through top down macro-economic analysis and bottom up investment selection in both direct assets and managed funds.

IOOF Advice provides services to four Dealer Groups within the IOOF Group. They are Bridges, Consultum, Plan B and My Adviser. Advice maintains APLs for Bridges, Consultum and Plan B. The APL’s are approved by the Dealer Group Investment Committees of which the Head of Research is a member.

Research is responsible for recommending approvals and removals from IOOF Platform Investment Menus. These recommendations are approved by the Product Investment Committee (PIC) of which the Head of Research is a member. The IOOF product offering also includes Australian Executor Trustees (AET) Small APRA Funds (SAFs). Research is tasked with providing risk ratings on these assets and with managing the Wholesale Access Fund menu which is the approved list for the SAF investors.

The Research Team comprises the Head of Research, six managed fund analysts, two equity analysts and an administration assistant.

17 The IOOF Research Policy went on to state that the Research team was delegated roles by the Boards of two entities – “Questor” and IOOF Investment Management Limited (IIML). The policy stated:

To ensure Questor and IIML perform duties in accordance with the obligations set out by law and regulation, the Board has established the Product Investment Committee (PIC) which delegates responsibilities to the Head of Research.

Specifically the role of Head of Research includes the following:

– Review and make recommendations to the Board on Investment Objectives and Strategies for all Products

– Report to the PIC on performance of appointed MIS funds to investment objectives and benchmarks and advise on any corrective actions

– Recommend to the PIC appointment and termination of MIS funds

– Review liquidity analysis of Products (data provided by Investment & Accounting Manager) and provide recommendations to the PIC

– Review stress testing analysis on Products (data provided by Investment & Accounting Manager) and provide recommendations to the PIC

18 In August 2014, IOOF acquired SFG Australia Ltd (SFGA), a financial advice and wealth management business. In February 2015, various changes were implemented across IOOF’s advice and shared services divisions. One of those changes was to appoint Matthew Drennan (who was formerly the Chief Investment Officer of SFGA) as the Group Head of Research and Portfolio Construction, reporting to the head of IOOF’s advice division, Michael Farrell. Mr Hilton’s title was changed to Head of Advice Research, reporting to Mr Drennan.

19 IOOF derives most of its earnings from fees and charges based on the level of funds under management, administration, advice and supervision (FUMAS). The level of FUMAS is impacted principally by net inflows (that is, the inflow of new client funds less withdrawals) and market performance (i.e., returns achieved on the investment of its FUMAS). Profits on IOOF’s FUMAS are generated principally from the Platform Management and Administration division and the Investment Management division.

20 On 24 December 2008, Rob Urwin, who was at the time AWM’s Head of Investigations, was informed by a member of the Bridges stockbroking team, that Mr Hilton had placed an order seeking to sell stock held by his wife in the ING Office Fund (IOF) in circumstances where Bridges had issued a buy recommendation in relation to the stock. Mr Urwin interviewed the Research team analyst who prepared the Bridges report on IOF. The analyst reiterated to Mr Urwin that he still considered IOF to be a strong buy. Mr Urwin then authorised the execution of Mr Hilton’s requested trade.

21 The matter prompted Mr Urwin to investigate Mr Hilton and his wife’s share trading activity (2009 AWM Investigation). The investigation included the trades which are the subject of Mr McFarlane’s allegations in this proceeding, being the IOF trade in December 2008, a purchase of Macquarie Convertible Preference Shares in July 2008, a purchase of stock in Toll Holdings Limited in August 2008, and the allocation of shares in a Platinum Asset Management placement to Mr Hilton’s wife in May 2007. On 13 May 2009, Mr Urwin sent an email to Gary Riordan, IOOF’s General Counsel, setting out his conclusions from his investigation and recommendations in relation to, amongst others, Mr Hilton (13 May 2009 Email).

22 The 13 May 2009 Email recorded that Mr Urwin had found that “[i]t has not been proved that [Mr Hilton] was [front running] trades placed on behalf of his wife Shirlene, however, some of the execution was close or coincided with dissemination of Research”. The 13 May 2009 Email contained no finding that Mr Hilton had engaged in any illegal activity. However, Mr Urwin recommended that, going forward, Mr Hilton should provide AWM with a current register of interests for himself and his wife on a quarterly basis, and that he should obtain approval from his manager or the company secretary for all future share or investment transactions. Mr Hilton agreed to do so, and he was issued with a letter recording these outcomes (2009 First and Final Warning Letter).

23 At the time of the investigation, a separate report was received by Mr Urwin in relation to a possible insider trading incident involving an AWM fund accountant, Edward Youds, and a trade he placed in Electronic Media and Telecoms Company (ETC). Mr Urwin investigated the matter. The 13 May 2009 Email recorded that Mr Urwin found that it had not been proved that Mr Youds had price-sensitive information in relation to the ETC trade. The 13 May 2009 Email nonetheless noted that, due to his “position and involvement in the transaction”, Mr Youds “should have due regard to the risks and consequences of his actions”.

24 Notwithstanding the conclusions in the 13 May 2009 Email, during an interview with Mr Youds on 4 May 2009, Mr Urwin advised Mr Youds that, to make controls more rigorous and transparent, AWM was going to require Mr Youds to provide a register of interests including all his trusts, superannuation funds and individual holdings; require that all of his trades be approved by his immediate manager effective immediately; and require Mr Youds to attend further training.

25 In early May 2009, another employee in AWM’s fund accounting team, Amit Malguri approached Mr Urwin and disclosed that he had on previous occasions up until October 2008 made personal trades through a CommSec account. At the time, AWM had in place a staff trading policy which required that any staff trades must take place through Bridges stockbroking. Mr Malguri disclosed that he had not been aware of that policy and the requirement to only trade through Bridges stockbroking, and that since October 2008 he had traded only through Bridges stockbroking. Mr Urwin investigated the matter. The 13 May 2009 Email recorded that Mr Urwin had determined that the trades which he had reviewed were “outside embargo parameters”. Mr Urwin recommended that going forward all of Mr Malguri’s trades needed to be approved by his immediate manager and that Mr Malguri should be required to attend further training.

26 As a result of the 2009 investigation, Mr Urwin determined that none of the matters involving Mr Hilton, Mr Youds or Mr Malguri involved front running or insider trading, or were required to be reported to regulators. Mr Urwin considered but dismissed the notion that the matters indicated any “systemic” issue.

27 On 2 March 2014, Mr Hilton sent an email to Max Riaz, an analyst in the IOOF Research team, in which he raised concerns about some aspects of Max Riaz’s performance. He indicated to Max Riaz that he wished to discuss those matters with him that week.

28 The email prompted a response from Max Riaz on 3 March 2014 in which he noted his distress at having received such an email, and proceeded to make various criticisms about the IOOF Research team, including that IOOF plagiarised research reports from JP Morgan. The email relevantly stated:

I have produced 37 reports in the month of February. Every report I produce I give due consideration to what I am putting in the report even then the report are highly compromised in the areas of snatching material from other sources without mentioning proper sources. The financials are plagiarised from JP Morgan without sourcing mentioned. And you approve these. Furthermore, ASIC prescribes adequate time must be given to analysts to produce a report. You had one equities analyst in the office last week fielding planner calls and queries at the same time. Much of what we produce and distribute to the network and the lack of sufficient resourcing for equities directly contravenes ASIC’s requirements. The easy option for me will be to re-badge the JP Morgan report and there will be no delays but then please be informed that I will have very updated knowledge of what I am reporting on and it further compromises my professional integrity. Are you willing to simply re-badge and distribute JPM reports and send to the network. I have had planners calling me last week and appreciating my work that I have produced.

29 Mr Hilton forwarded Max Riaz’s 3 March 2014 email to IOOF’s head of human resources, Danielle Corcoran. He also sent her a draft proposed response to Max Riaz. The draft made clear that he did not agree with Max Riaz’s criticisms of the Research team, however, on Ms Corcoran’s recommendation, the draft was not sent.

30 On 4 March 2014, Ms Corcoran had a meeting with Max Riaz, in which Max Riaz made the March 2014 complaint orally. Ms Corcoran discussed the complaint with Mr Farrell on the same day. When making the March 2014 complaint, Max Riaz used as notes for his discussion with Ms Corcoran an email that he had sent to his brother, Zach Riaz, the day before on 3 March 2014. On 2 April 2014, Max Riaz forwarded the text of that email to Mr Urwin and wrote that the forwarded text “is what I communicated initially with Danielle”.

31 In his ASOC, Mr McFarlane alleges that, taken together, the March 2014 complaint comprised the following allegations:

(1) that Mr Hilton gave selective and preferential treatment to some of his particular planners and clients by providing them with price-sensitive information whilst leaving other planners and/or clients to face known risks (ASOC [17(a)]);

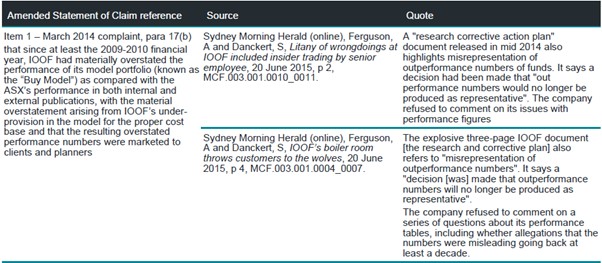

(2) that since at least the 2009-2010 financial year, IOOF had materially overstated the performance of its Buy-model Portfolio as compared with the ASX’s performance in both internal and external publications, with the material overstatement arising from IOOF’s under-provision in the model for the proper cost base and that the resulting overstated performance numbers were marketed to clients and planners (ASOC [17(b)]);

(3) that there had been breaches of password security to and within the Research team, including that Mr Hilton ordered Max Riaz to use the Head of Research’s network password to sign off on non-disclosure forms for capital transactions (ASOC [17(c)]);

(4) that IOOF plagiarised third party research reports and distributed that research without attribution or taking the time to verify that the research was accurate and/or had a reasonable basis (ASOC [17(d)]);

(5) that the Research team was inadequately resourced, leading to shortcuts being taken such as the alleged plagiarism, with only two analysts in the department:

(a) covering all of the ASX200 stocks plus other equities which might come onto that index; and

(b) during reporting season being expected to produce reports on approximately 300 companies over a three-week period, equating to approximately 14 stock reports per day (ASOC [17(e)]);

(6) that there had been bullying, intimidation and isolation of subordinate employees in the Research team by the Head of Research, Peter Hilton (ASOC [17(f)]);

(7) that Mr Hilton had since at least in or about 2010 instructed staff to complete his online Kaplan and eLearning modules for him (ASOC [17(g)]);

(8) that Mr Hilton imposed impractical deadlines for research reports during reporting seasons which placed client investments at risk by not giving due consideration to the results, a practice which the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC) explicitly warned against and then became a source of intimidation and harassment (ASOC [17(h)]); and

(9) that bonus payments had been withheld for improper / bullying reasons (ASOC [17(i)]).

32 Insignia admits that the March 2014 complaint comprised allegations at ASOC paragraphs 17(b)-(i) but says that the allegation in paragraph 17(a) was a more limited allegation made on 2 April 2014 by Max Riaz in relation to the Templeton Growth Fund.

IOOF’s 2014 Investigation of Max Riaz’s complaints

33 Between March and April 2014, Ms Corcoran and Mr Urwin investigated the various complaints Max Riaz had raised against Mr Hilton.

34 By early April 2014, IOOF had concluded its investigation in relation to the matters arising from Max Riaz’s complaint, and a “Summary & Action Plan” was prepared by Ms Corcoran and Mr Urwin which recorded the findings and actions to be taken in relation to the matters which had been investigated (Summary & Action Plan). Although the date of the final form of the Summary & Action Plan is not disclosed on the face of the document, it is apparent that the document was last amended by Mr Urwin on 8 April 2014.

35 The Summary & Action Plan recorded the following findings and proposed actions:

(1) In relation to “Bullying, harassment and isolation”, that there was no evidence to support these allegations, but the Research team, including Mr Hilton, would be required to attend a training session on bullying, harassment and discrimination.

(2) In relation to “Breach of password access”, that Mr Hilton had shared his password with staff for the purposes of enabling them to use risk management software on his computer (“SWORD”) and that this matter had in fact previously been disclosed to the risk department (prior to Max Riaz’s complaint). It was decided that Mr Hilton was to receive a warning letter in relation to this matter; that he was to be required to assure that he had read and accepted IOOF’s password management policies; and that he was to complete online IT competency training. IOOF also determined that warnings should be given to the staff members with whom Mr Hilton had shared his password.

(3) In relation to “Instructing a direct report to complete Kaplan and eLearning training”, that Mr Hilton had allowed his direct reports to complete his training requirements. It was decided that the letter to be sent to Mr Hilton would also advise him of this finding; that he would be required to complete 12 hours of supervised training; that his responsible manager status would be removed immediately as he “no longer qualifies as fit and proper” and that he would be required to re-sit all his eLearning modules.

(4) In relation to “Plagiarism”, that the manner in which the Research team utilised JP Morgan research was not plagiarism in circumstances where a contract was in place with JP Morgan which permitted IOOF to utilise JP Morgan research on condition that IOOF did not refer to JP Morgan. However, it was found that there were a number of research presentations which were not correctly sourced or did not have a disclaimer attached. It was determined that various actions would be taken in response to these findings, including that a policy in relation to plagiarism would be established and rolled out to the Research team; that the IOOF marketing team would review all presentations to ensure they are adequately sourced; and that Mr Hilton would be required positively to assure that each presentation or research report had the appropriate disclaimer attached.

(5) In relation to “Misrepresented outperformance data”, that: the Buy-model data “ha[d] been wrong i.e. not usual practice since 2001”; the model ought to have been tested more regularly; Mr Hilton should have escalated the matter at the time he was made aware of it; and the matter “is not fraud rather inaccurate”.

(6) In relation to “Bonus payment”, that Max Riaz received a rating in his online performance review that would not ordinarily warrant a bonus under IOOF’s policy. IOOF determined that Mr Hilton should implement a structure for setting KPIs, reviewing these with his staff and communicating bonus decisions.

36 The Summary & Action Plan also relevantly recorded the following under the heading “Other comment”:

Favourable clients – Research must not have different recommendations for the same security throughout the network e.g. Goodman Plus Jan 2014.

37 On 1 May 2014, IOOF issued Mr Hilton the warning letter contemplated in the Summary & Action Plan (2014 Final Warning Letter). The letter stated as follows:

This letter confirms the numerous formal discussions with either Danielle Corcoran or myself that commenced on 10 March 2014 and have continued over the last few weeks regarding a number of allegations that had been brought to our attention Issues outlined during our last discussion are highlighted below

1 Claims of bullying harassment and isolation within the Research team

2 Sharing passwords for SWORD and the e-learning system

3 Instructing a direct report to complete Kaplan and e-learning training on your behalf

4 Plagiarising and incorrect sourcing of research data received from JP Morgan

5 Misrepresenting outperformance data

I have considered your responses to each of the matters above and have found that your actions warrant a final warning with respect to items 2 and 3

As discussed the expectation going forward is that you ensure completion of all items of the attached corrective action plan

All other items have been dismissed however there are some process improvements required for the division

Please be aware that failure to improve and maintain adequate improvement in the above areas may result in termination of your employment.

38 IOOF’s human resources team also prepared a spreadsheet, entitled “Research Corrective Action Plan” (Research Corrective Action Plan). The last dated version of the Research Corrective Action Plan was emailed by Mr Urwin to Ms Corcoran and Mr Farrell on 24 April 2014. The Research Corrective Action Plan set out action items, with corresponding estimated dates for completion, under the following headings:

(1) “Bullying, harassment and isolation”;

(2) “Breach of password access”;

(3) “Instructing a direct report to complete Kaplan and eLearning training”;

(4) “Plagiarism”;

(5) “Misrepresentation of outperformance numbers”;

(6) “Bonus payment”; and

(7) “Research structure – question if adequate”.

39 Approximately a year later, a copy of the Research Corrective Action Plan was obtained by Fairfax, who described the spreadsheet in a newspaper article as an “explosive three-page IOOF document” which revealed a “scandal” at IOOF.

40 On 12 May 2014, IOOF hired a new analyst in the Research team, Chhai Ung.

41 On 26 November 2014, Mr Hilton informed Mr Ung that a new manager in the Research team had been hired. Mr Hilton advised Mr Ung that changes would be made to some of the titles and reporting structures within the team. On 27 November 2014, Mr Ung sent an email to Ms Abercromby which stated:

I believe this is the wrong path and structure to take–- I raise the following concerns:

…

In regards to myself,

Just as with Morgan Stanley, Aberdeen Asset Management, I am glad Peter has entrusted me with the equities function. I am extremely delighted to be part of the team and stress I do want a long term career within IOOF

I have long held in high regard yourself, Peter and Chris–- and I have seen a lot over my last 10 years. A lot as a fund manager with Aberdeen.

- When Peter Hilton notified me yesterday of the new hire, I did not initially contemplate why “Merrium” sounded so familiar. Overnight I recalled that she had applied for one of the junior fund manager roles at Aberdeen to report to myself – I recalled her CV on my desk. From memory, she had approximately 2 years equity analyst experience and more performance analyst-based experience, had been made redundant from Pengana and had moved from Henderson. Performance analysis is not relevant to equities or managed funds research. Performance analysts are well suited to conduct the daily rebalancing for a market neutral strategy – not the research.

At Aberdeen, we went for the younger candidate. We felt Merrium amongst others were talented but had changed jobs too often (5 or 6 (?) jobs in as many years in as many years) – should this not have been picked up by IOOF HR?

- What does this signal to myself, Zach, Robbie, Brad to report to someone who has less relevant experience than we do?

- This signals to myself that there is no progression within this firm and to look elsewhere.

- This new team structure casts me aside from what I was hired to do–- research managed funds. This area was my next level of development.

- With the managed funds component being outsourced, what will this new hire be doing?

We should look to promote and train internally. This new structure and new job description/shift in responsibilities is a morale killer.

I am keen to hear thoughts before considering my future elsewhere (emphasis original).

42 In around November 2014, Mr Ung obtained Mr Urwin’s hardcopy files in relation to the 2009 and 2014 investigations. In about December 2014, Mr Ung commenced using Mr Urwin’s files to prepare a dossier accusing Mr Hilton and IOOF of all manner of wrongdoing. Mr Ung’s allegations were set out in a letter from Mr Ung addressed to Fair Work Commissioner Hampton, copied to Ms Corcoran and Mr Urwin dated 22 December 2014 (December 2014 complaint). The most serious allegation made by Mr Ung in the December 2014 complaint was that Mr Hilton had engaged in “repeated, systemic and ongoing insider trading/front running of research which demonstrates a culture of constant breaches of fiduciary duty and market manipulation designed to profit at client’s expense”. Mr Ung further alleged that IOOF had known about but had not acted upon Mr Hilton’s insider trading. Mr Ung also purported to describe a conversation he had with Mr Urwin. Mr Ung alleged Mr Urwin told him that he had “a stack of files” on Mr Hilton; that IOOF had known about Mr Hilton’s trading behaviour; that Mr Urwin said to him “next time [Hilton] tells you to do front running, just tell him its insider trading and illegal, he’ll stop”; and that Mr Urwin asked Mr Ung not to discuss the matter with IOOF’s human resources team.

Mr Ung provides his insider trading dossier to IOOF

43 On 29 January 2015, Mr Ung commenced an anti-bullying application before the Fair Work Commission. Mr Ung repeated allegations of insider trading against Mr Hilton, although on this occasion it was said that Mr Hilton had, on multiple occasions, asked Mr Ung to commit “insider trading (front running of research)”.

44 On 2 March 2015, Mr Ung sent to Ms Corcoran, Mr Urwin and Mr Hilton, as well as the Fair Work Commission, a copy of the December 2014 complaint.

45 On 4 March 2015, Ms Corcoran sent an email to Mr Ung. She indicated that IOOF intended to investigate the matters he had raised. Ms Corcoran noted that, in relation to Mr Hilton’s alleged insider trading, Mr Ung had indicated in his March 2015 document that “I have yet to go through 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014 and 2015 YTD”. Ms Corcoran asked that Mr Ung provide the further information he had foreshadowed. No further information was forthcoming.

IOOF’s investigation of insider trading allegations post 2009

46 On 30 March 2015, PwC was engaged to investigate Mr Ung’s complaint. Its scope of work was defined as being to investigate and determine whether “there is any evidence from the past six years that Mr Hilton had engaged in insider trading or “front running” [or] plagiarised material with respect to research reports he has produced”.

47 On 11 May 2015, IOOF terminated Mr Ung’s employment.

48 On 15 May 2015, PwC issued its report to IOOF (PwC Insider Trading Report). PwC did not identify any evidence indicating Mr Hilton had engaged in front running from 22 December 2008 to March 2015 through research reports released by IOOF/Bridges. PwC noted that it had identified “no instances of Mr Hilton buying securities through either his or his wife’s accounts ahead of issuing a favourable research report in relation to the same security, or issuing a negative report and buying securities shortly after the price had moved”.

Publication of Fairfax articles

49 By 15 June 2015, Fairfax had obtained a copy of Mr Urwin’s investigation files.

50 On Saturday, 20 June 2015, and over the course of that weekend, a series of articles about IOOF appeared in Fairfax print and online publications variously under the headlines “Boiler room throws customers to the wolves”, “Insider trading – wrongdoings uncovered – planner hid dodgy trades” and “Litany of wrongdoings at IOOF included insider trading by senior employee”.

51 Following these disclosures, on 22 June 2015, being the first trading day after the first of the revelations in the Fairfax articles, there was an abnormal downward price movement in IOOF’s shares of 13.6%.

52 Over the course of ensuing days and weeks, a number of further articles would be published about the “scandal” at IOOF.

53 On 24 June 2015, Senator John Williams made a speech in the Senate concerning IOOF. The speech set out details of the alleged incidents of misconduct at IOOF previously reported by Fairfax, and disclosed that IOOF’s research processes were not ASIC compliant, it had no conflict-of-interest policy for research reports and no share trading policy.

54 On 7 July 2015, Mr Kelaher appeared before the Senate Economic References Committee (Senate Committee). The Committee was chaired by Senator Dastyari. Senator Williams was also in attendance. During a hearing before the Committee, Mr Kelaher relevantly stated that:

[IOOF’s] acquisition strategy over the years … has opened up tremendous long-term opportunities to our customers and our shareholders, but – candidly – it has also thrown up many challenges in respect of: merging IT systems; internal policies and protocols; and, most importantly, creating a single culture among staff coming from often diverse and formerly competitive organisations.

55 On 7 July 2015, there was an abnormal downward price movement in IOOF’s shares of 5.2%.

56 In July 2015, IOOF also engaged PwC to review its regulatory breach reporting policy and procedures for all regulated entities within the IOOF Group, being IOOF Holdings Limited and its subsidiaries, excluding Ord Minnett and Perennial. PwC was also to consider the current control environment of the Research Advice division. On 28 August 2015, PwC issued to IOOF an interim report setting out findings and recommendations arising from its review of the design of systems, processes and controls (PwC Interim Report).

57 Between 20 July 2015 and January 2016, ASIC conducted an investigation in connection with the Fairfax allegations.

58 On 25 November 2015, ASIC informed IOOF of the outcome of its investigation. An email from Mr Riordan to, amongst others, Mr Kelaher on that day stated that ASIC had informed him that its market surveillance team had investigated Mr Hilton’s trading activities, had not found sufficient evidence to warrant any further investigation into Mr Hilton, that there would be no formal investigation and that the matter was considered closed. ASIC confirmed the outcome of its investigation in a letter to IOOF dated 25 January 2016.

59 A representative of ASIC attended a meeting of the Board of Directors of IOOF on 27 May 2016. Minutes of that meeting record him as having communicated that:

The insider trading and front running allegations were examined with priority and there was no action for ASIC to take. This was because there was no price sensitive information being misused, noting that some trading was in breach of IOOF policies.

60 On 30 August 2016, IOOF issued its annual report for FY16. The report noted that ASIC had finalised its inquiries into allegations against IOOF, and that ASIC had announced that no further action would be taken. It stated that IOOF had “always maintained that the company had thoroughly investigated the concerns and, where appropriate, took decisive action”.

61 Mr McFarlane’ lay evidence is limited to his affidavit affirmed on 27 January 2021 (McFarlane Affidavit). Mr McFarlane deposed to having bought shares in IOOF during the Relevant Period on 2 June 2015. Mr McFarlane recalled reading media articles about IOOF in late June 2015 or early July 2015, which referred to a range of alleged corporate misconduct within IOOF. Mr McFarlane was unaware of the alleged corporate misconduct concerning IOOF referred to in those articles before reading them, nor of any other information to similar effect. Mr McFarlane was not cross-examined on his affidavit.

62 Insignia’s lay evidence is limited to the affidavit of Norika Kalember, the Payroll and Governance Manager in the Payroll Team at Insignia, affirmed on 7 June 2023. Ms Kalember deposed to the start and finish date of 24 individuals who were former employees of Insignia or its subsidiaries. Ms Kalember was not cross-examined on the content of her affidavit (Kalember Affidavit).

63 Mr McFarlane relies upon the expert reports of Mr Houston dated 26 September 2022 (Houston Report 1) and a reply report of Mr Houston dated 3 May 2023 (Houston Report 2).

64 Insignia relies upon the expert report of Dr Prowse dated 23 March 2023 (Prowse Report).

65 The parties also tendered in evidence a joint report of Mr Houston and Dr Prowse, dated 2 June 2023, which was prepared following a series of conferences facilitated by a Registrar of the Court (Joint Expert Report).

66 In overview, Mr Houston opined that the Alleged Material Information was disclosed to the market by the end of the Relevant Period which caused abnormal movements in IOOF’s share price on 22 June 2015 and 7 July 2015. Mr Houston calculated this movement and used it, in turn, to estimate the amount of inflation in IOOF’s share price during the Relevant Period resulting from IOOF’s failure to disclose the Alleged Material Information to the market. Mr Houston’s conclusions were based on an event study. An event study is an empirical technique that seeks to measure the extent to which observed movements in the share price of a company can be attributed to the release of particular information of interest.

67 Dr Prowse and Mr Houston agreed on the appropriate framework for assessing the price effect of information, the use of an event study and the magnitude of the abnormal price movements on 22 June 2015 and 7 July 2015. The principal disagreement between Mr Houston and Dr Prowse was the extent, if any, to which the language of the various disclosures may itself have affected Mr Houston’s estimate of the price effect of the disclosure of the information of interest on these two “event days”. I summarise the expert evidence at [157]-[327] below.

68 The parties tendered in evidence a substantial number of documents to which I was taken in opening and closing addresses as well as documents referred to in the parties’ written submissions. These documents were tendered jointly by the parties and marked Exhibit AR-3. In circumstances where the majority of documents sought to be tendered were IOOF’s internal business records, Insignia only objected to the tender of eight documents, as set out below:

(1) Insignia objected to the tender of a table titled “IOOF and ASIC Review Report dated 25 January 2016”. That table, which is referred to at [368] below, recorded concerns raised by ASIC in a letter to IOOF dated 25 January 2016, as well as IOOF’s responses to those concerns. During the trial, I ruled that I would receive the table into evidence together with an accompanying covering letter from IOOF to ASIC dated 5 February 2016: T 459.6-8. The covering letter confirmed that, although IOOF did not necessarily agree with some of ASIC’s observations in its letter of 25 January 2016, IOOF was keen to ensure that everything was done to satisfy ASIC that IOOF had responded to and dealt with the matter.

(2) Insignia objected to the tender of the correspondence comprising the December 2014 complaint. Ultimately, the parties agreed that the December 2014 complaint would be admitted subject to a limitation that it could not be used for a hearsay purpose other in relation to proof of asserted facts as to the timing and nature of the trades and research reports referred to in the complaint in items 1 to 57: Agreed Ruling on Respondent’s Outstanding Objections dated 27 June 2023, Item 1.

(3) Insignia objected to the tender of a memorandum titled “Insider Trading/Front Running of Research”. Ultimately, the parties agreed that the memorandum would be admitted subject to a limitation that the document could not be used for a hearsay purpose: Agreed Ruling on Respondent’s Outstanding Objections dated 27 June 2023, Item 2. In any case, Mr McFarlane’s closing submissions did not seek to rely on this document.

(4) Insignia objected to the tender of a memorandum titled “Unit Pricing Issues”. Ultimately, the parties agreed that the memorandum would be admitted subject to a limitation that the document could not be used for a hearsay purpose: Agreed Ruling on Respondent’s Outstanding Objections dated 27 June 2023, Item 3. In any case, Mr McFarlane’s closing submissions did not seek to rely on this document.

(5) Insignia objected to the tender of a memorandum titled “Non-ASIC RG79 Compliant Research Report”. Ultimately, the parties agreed that the memorandum would be admitted subject to a limitation that the document could not be used for a hearsay purpose: Agreed Ruling on Respondent’s Outstanding Objections dated 27 June 2023, Item 4. In any case, Mr McFarlane’s closing submissions did not seek to rely on this document.

(6) Insignia objected to the tender of the PwC Interim Report referred to at [56] above, and the final PwC report on the same matters dated 26 February 2016 (PwC Final Report). Insignia contended that neither document was admissible to prove opinions expressed by the author in relation to the adequacy of IOOF’s compliance arrangements. Further Insignia contended that the PwC Final Report could not be used to prove the content of IOOF’s register of interests. During the trial, I ruled that I would receive into evidence the PwC Interim Report and Final Report without limitation: T 459.8-12.

(7) Insignia objected to the tender of a newspaper article titled “Litany of wrongdoings at IOOF included insider trading by senior employee” dated 20 June 2015. Ultimately, the parties agreed that the article would be admitted subject to a limitation that the document could not be used for a hearsay purpose: Agreed Ruling on Respondent’s Outstanding Objections dated 27 June 2023, Item 5.

OVERVIEW OF MR MCFARLANE’S CASE

69 The Alleged Material Information comprises the “Historical Information”, the “March 2014 Information” and the “Compromised Model Information”.

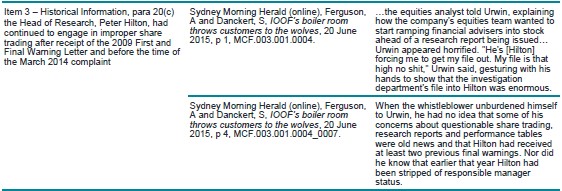

70 The Historical Information is comprised of a number of allegations of “incidents” which are alleged to have occurred within AWM and IOOF over the period 1995 to 2014. IOOF is alleged to have been aware of these matters between 25 March 2014 and 16 April 2014, whilst investigating the March 2014 complaint. The allegations fall into the following five broad categories.

71 Firstly, the share trades by Mr Hilton and his wife, Shirlene Hilton, Mr Youds and Mr Malguri that was considered as part of the AWM 2009 Investigation discussed above: ASOC [20(a)], [20(b)], and [20(c2)]-[20(c9)]. Specifically, it is alleged that:

(1) Mr Hilton “had engaged in improper share trading before 19 May 2009 which resulted in him receiving a First and Final Warning Letter” from AWM: ASOC [20(a)] and [20(b)];

(2) Mrs Hilton bought and sold shares between 1995 and 2014 where purchases preceded positive research and sales followed, and sales preceded negative research released by AWM, in particular in Toll Holdings and IOF in 2009 and in a Platinum Asset Management float in 2008: ASOC [20(c2)];

(3) Mrs Hilton: (i) made a profit selling shares in Platinum Asset Management and the Challenger Infrastructure Fund, which shares were obtained from an allocation for AWM’s customers; and (ii) bought and sold Macquarie Convertible Preference Shares in circumstances where Mr Hilton had published two positive reports on those shares, in each case where Mr Hilton “did not disclose a conflict of interest”: ASOC [20(c3)];

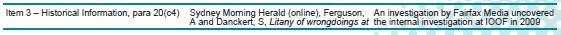

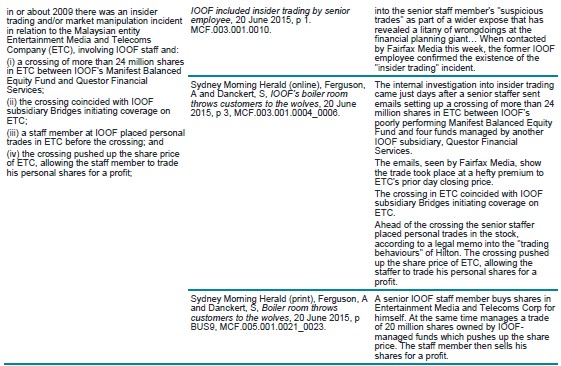

(4) there was an “insider trading or market manipulation incident”, being a reference to the ETC trade by Mr Youds referred to at [23] above, which ASIC was not notified of in breach of ASIC Regulatory Guide 238 “which required the reporting of suspicious activity”: ASOC [20(c4)]-[20(c8)];

(5) AWM investigated Mr Malguri for insider trading in 2009, concluded that Mr Malguri’s trades were outside embargo parameters, and did not notify ASIC of the investigation or outcome: ASOC [20(c9)].

72 Secondly, it is alleged that, on 16 December 2013, a Bridges financial planner sent an email questioning recommendations made by the Research team and stating that “I can’t help but feel our Research team has finally been compromised!!”: ASOC [20(c10)].

73 Thirdly, it is alleged that, since 2009, IOOF financial planning subsidiary companies (including Consultum) had been the subject of regulatory action by ASIC, with a number of planners banned and at least one planner sentenced to prison: ASOC [20(c11)].

74 Fourthly, it is alleged that, in the period 2012-2013, IOOF had at least 16 breaches of its own risk policies: ASOC [20(d)].

75 Fifthly, it is alleged that:

in and since 2009, there had been multiple incidents within IOOF of impropriety or possible impropriety which arose from one of the following:

(b) information barrier breaches (or “Chinese wall” breaches);

(ii) non-compliance with IOOF’s staff trading policy;

(iii) IOOF staff taking placement allocations ahead clients;

(iv) failure to manage conflicts of interest;

(v) data integrity and cybersecurity failures;

(vi) failures of compliance oversight,

and are recorded in one or more of the IOOF breach registers; documents passing between IOOF and ASIC during the course of inquiries undertaken by ASIC that commenced in or about July 2015; documents passing between IOOF and PWC during the course of investigations undertaken by PWC that commenced in or about March 2015 and July 2015. (ASOC [20(c1)])

76 Insignia, in its Further Amended Defence filed on 22 December 2021 (FAD), largely denies the substance of these allegations and says that it was not aware of any misconduct or wrongdoing such as insider trading, improper share trading and failures of compliance oversight. Insignia admits some of the allegations, such as the fact that it received the email on 16 December 2013 and that it knew that two Bridges planners were banned by ASIC and that one of those two was also sentenced to a term of imprisonment but says that this information was generally available: FAD [20].

77 The March 2014 Information comprises allegations of various unrelated matters that IOOF is alleged to have been aware of between 25 March 2014 and 16 April 2014.

78 Firstly, it is alleged that IOOF was aware that the allegations comprising the March 2014 complaint were true, namely, the allegations of preferential treatment; Buy-model errors; password sharing; inadequate resourcing of the Research team leading to plagiarism; impractical deadlines for research reports; that Mr Hilton had instructed staff to complete his online Kaplan and eLearning modules for him; bullying, intimidation and isolation; and that bonus payments had been withheld for improper/bullying reasons: ASOC [17] and [22(a)].

79 Insignia admits that as a result of the investigation of the March 2014 complaint IOOF concluded that some of the allegations were substantially true – namely, overstating the performance of the hypothetical Buy-model, breach of password access, failure to properly attribute third party research reports in research presentations and instructing direct reports to complete training: FAD [22(a)(i)].

80 Insignia pleads a number of additional factual matters relevant to those allegations which Insignia contends need to be considered in order to properly understand the “full picture” in relation to those matters: FAD [22(d)], [22(e)] and [22(g)]. Insignia otherwise denies that the allegations in the March 2014 complaint were true or substantially true: FAD [22(a)(ii)].

81 Secondly, a number of other allegations form part of the March 2014 Information including:

(1) that Mr Hilton had failed to comply with the 2009 First and Final Warning Letter, but had not been dismissed or disciplined (ASOC [20(b)]);

(2) that there was inadequate resourcing (technological and human) of the Research team (ASOC [20(c)]);

(3) that IOOF had failed to identify, record and control conflicts of interest [ASOC [20(h)];

(4) that IOOF had inadequate internal controls to monitor and mitigate compliance risks arising as a result within the Research team, having regard to the Research team’s role ([ASOC [20(i)]);

(5) IOOF employed manual or other work arounds or temporary patches to resolve incompatibility between legacy IT systems of its various businesses and IOOF’s IT infrastructure ([ASOC [20(j)]);

(6) that the Research team was the subject of a review and restructure by IOOF’s executive management team ([ASOC [20(k)]).

82 Insignia denies these allegations: FAD [22].

83 The Compromised Model Information is that the “implementation of the Roll Up Model was compromised in a material way”: ASOC [24].

84 The “Roll Up Model” is defined in the ASOC as IOOF’s strategy of seeking to grow in size and value by combining organic growth with acquisitions and using existing IOOF infrastructure (including IOOF’s Research team) to service both the pre-existing and newly acquired businesses: ASOC [9].

85 IOOF is alleged to have been aware of the Compromised Model Information “[b]ecause of its awareness of the Historical Information and the March 2014 Information”: ASOC [24].

86 The Compromised Model Information is premised on the existence and IOOF’s alleged awareness of the Historical Information and the March 2014 Information. Insignia denies these allegations.

Insignia’s awareness of the Alleged Material Information

87 Mr McFarlane contends that Insignia was aware of the Alleged Material Information because:

(1) firstly, Insignia received and investigated the March 2014 complaint;

(2) secondly, during the Relevant Period, Insignia was aware of the facts comprising the Historical Information, March 2014 Information and Compromised Model Information; and

(3) thirdly, officers of Insignia either did, or should have, drawn those facts of which they were aware together for the purposes of ensuring that Insignia complied with its obligation of continuous disclosure and, or alternatively, did not engage in misleading or deceptive conduct.

88 McFarlane relies upon an email from Mr Urwin to Paul Vine, IOOF’s General Manager of Legal, Risk and Compliance, on 30 March 2015 in relation to the investigations conducted in 2014 and noted his and Ms Corcoran’s awareness in 2014, of issues from 2009. Mr Urwin wrote (emphasis added):

As per my file note in the email attached I raised the previous matters with Danielle Corcoran as the behaviours of Peter Hilton were systemic and Peter was not exercising skill or diligence in his role. I needed to point out he should have been on a first and final warning previous and these examples should be taken into account with previous matters. (emphasis added)

89 Mr McFarlane submits that the documentary evidence establishes that most of the matters constituting the Alleged Material Information are true. In addition, he submits that the Court can conclude that those matters that are true, at least in combination, had a material consequence for the market’s view about IOOF such that (a) they were material and (b) in the absence of their disclosure, IOOF was misleading the market having regard to other representations it had made to the market. Mr McFarlane contends that the most logical inference is that the Alleged Material Information that is true was material to IOOF’s share price because of three matters:

(1) IOOF’s value was dependent upon its reputation and important aspects of its reputation were its integrity (because it needed clients and planners to trust it with their money) and the effectiveness of its Roll Up Model;

(2) the matters constituting the Alleged Material Information were contrary to IOOF’s reputation, integrity, and the effectiveness of its Roll Up Model;

(3) when information that substantially corresponded to the Alleged Material Information was revealed to the public by Fairfax reports and Mr Kelaher’s senate testimony, IOOF’s share price fell substantially.

90 Insignia disputes that, even if the matters are true, they were material to the value of IOOF.

91 Mr McFarlane also invokes Insignia’s constructive awareness, citing Crowley v Worley Ltd (2022) 293 FCR 438 (Crowley) at [5] (Perram J) and [160(4)], [166] (Jagot and Murphy JJ).

92 Mr McFarlane submits that, on any view, IOOF must have known that it had an undisclosed cultural problem that affected the effectiveness of its systems, governance and compliance.

93 Mr McFarlane submits that during the Relevant Period, the market was unaware of the matters in the March 2014 complaint, the December 2014 complaint, and the other matters comprising the Alleged Material Information. From the market’s perspective, there was no reason to doubt IOOF’s statements concerning its value and growth based in each case upon its model, as pleaded and admitted (ASOC [10], [14] and Annexure A; FAD [10] and [14]).

94 Mr McFarlane submits that in the circumstances, during the Relevant Period, IOOF ought reasonably to have formed the opinion that:

(1) the Historical Information and the March 2014 Information, or a summary of that information, ought to have been disclosed to the market; and/or alternatively

(2) IOOF’s implementation of its business model was compromised in a material way (i.e., the Compromised Model Information), which ought to have been disclosed to the market.

95 Mr McFarlane submits that the expert evidence of Mr Houston establishes that the Alleged Material Information was disclosed in June and July 2015 and caused material abnormal price movements in IOOF’s share price.

96 Mr McFarlane submits that the documentary evidence tendered makes it clear that IOOF was aware of the Alleged Material Information but failed to disclose it.

97 Mr McFarlane submits that during the Relevant Period, s 674(2) of the Corporations Act and ASX Rule 3.1 required Insignia to make immediate disclosure of information of which it was aware which was not generally available and a reasonable person would expect, if the information were generally available, to have a material effect on the price or value of Insignia’s shares.

98 Mr McFarlane submits that the Alleged Material Information satisfied those criteria. IOOF was required to disclose the Alleged Material Information to the market during the Relevant Period. It did not. As a consequence, IOOF breached s 674 of the Corporations Act.

99 In the alternative, Mr McFarlane claims that IOOF engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct by silence or, alternatively, that IOOF made statements which were false or without a reasonable basis in response to the Fairfax articles.

100 Mr McFarlane relies on indirect market-based causation. If an applicant shareholder can prove that a company’s conduct contravened a statutory norm such that its share price was inflated, then provided that the shareholder was not otherwise aware of the true position, the shareholder has established both loss and a causative link between the company’s conduct and the shareholder’s loss (TPT Patrol Pty Ltd v Myer Holdings Ltd (2019) 293 FCR 29 (Myer) at [1654], [1663].

101 Mr McFarlane deposes to not being aware of the true position: McFarlane Affidavit [11].

102 Mr McFarlane submits that the result of the Alleged Material Information being withheld from the market during the Relevant Period was that IOOF’s share price was inflated as compared with its true value.

103 Mr McFarlane alleges that the failure of IOOF to disclose the pleaded information caused the decline in IOOF’s share price between 19 June 2015 and 7 July 2015: ASOC [35]-[36]. Mr McFarlane alleges that the failure of IOOF to disclose the pleaded information caused loss and damage to Mr McFarlane and group members: ASOC [39].

104 Mr McFarlane’s case on quantum relies solely on Mr Houston’s expert reports and analysis. Mr Houston presented his opinion of the estimate of the inflation of IOOF’s share price during the Relevant Period, compared with the true value of those shares had IOOF made a corrective disclosure from 4 March 2014: Houston Report 1, pp 105-115.

Mr McFarlane’s submissions on the List of Common Issues and Questions

105 Mr McFarlane submits that the “List of Common Issues and Questions” filed by consent of the parties on 28 April 2023, and set out at [11] above, hinge on the Court’s determination of six key questions:

(1) whether certain pleaded information about the operations, systems and culture of IOOF was substantively true;

(2) whether IOOF was aware of the pleaded information that was substantively true during the Relevant Period;

(3) if so, whether IOOF was required to disclose some or all of that information to the market in accordance with its obligation of continuous disclosure;

(4) whether in the absence of public disclosure by IOOF of the substantively true information about the operations, systems and culture of IOOF, IOOF engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct having regard to the public statements that it did make;

(5) whether the contraventions of either the obligation of continuous disclosure or the prohibition on misleading or deceptive conduct caused any loss to Mr McFarlane and other persons who acquired shares in IOOF during the Relevant Period; and

(6) if the contraventions did cause loss, what the quantum of that loss is or how it should be determined.

106 Mr McFarlane submits that in answering these questions the Court will need to consider the effect of information on IOOF’s reputation. Mr McFarlane has pleaded that during the Relevant Period, the market value of IOOF’s shares was based on and/or materially affected by its good standing and reputation: ASOC [16(a)].

Allegations not pressed by Mr McFarlane

107 By letter dated 19 June 2023 (after the commencement of the trial on 5 June 2023), Mr McFarlane’s solicitors advised that there were three matters that were no longer pressed:

(1) firstly, in relation to ASOC paragraphs 17(f), 17(i) and 22(a) – Mr McFarlane maintains that the allegations in paragraphs 17(f) and 17(i) regarding bullying were made, but Mr McFarlane accepts for the purposes of ASOC paragraph 22(a) that they were not found to be true by IOOF at the time and cannot otherwise be substantiated on the evidence;

(2) secondly, in relation to ASOC paragraph 20(c2) – Mr McFarlane does not press sub-subparagraphs (iv) or (v) which relate to the IOF and Platinum allocations and are covered by other pleadings; and

(3) thirdly, in relation to ASOC paragraph 20(c4) – the only part of the allegation that Mr McFarlane presses is “that in or about 2009 there was an incident in relation to [ETC], involving IOOF staff” and thus does not press sub-subparagraphs (i)-(iv) or seek to establish that there was an “insider trading and/or market manipulation incident” (as referred to in the chapeau).

IOOF’s Defence – No Positive Defence Pleaded

108 An initial issue that emerges is whether it is permissible for the Court to consider whether information in the Fairfax articles and Senate testimony of Mr Kelaher other than the pleaded Alleged Material Information may have caused the decline of IOOF’s share price on the relevant event days. Mr McFarlane’s contention is that Insignia is precluded from advancing such a contention by reason of its articulation of its case in the FAD.

109 In overview, Mr McFarlane pleads at ASOC paragraph 35 that the Historical Information, March 2014 Information and Compromised Model Information (that is, the Alleged Material Information) were disclosed, or discernible from public disclosures, referable to the Fairfax articles and the Senate testimony of Mr Kelaher. In response to this plea, Insignia relevantly pleads at FAD paragraph 35, as follows:

(1) subject to limited exceptions, Insignia says that the allegations said to comprise the Historical Information, the March 2014 Information, and the Compromised Model Information were not substantiated: FAD [35(a)];

(2) Insignia denies that the allegations in the Fairfax articles or the statements made by Mr Kelaher in his Senate testimony amounted to the disclosure of the Historical Information, the March 2014 Information, and the Compromised Model Information “for the reasons stated above in sub-paragraph (a)”: FAD [35(b)]-[35(c)];

(3) Insignia otherwise denies the allegations: FAD [35(d)].

110 At ASOC paragraph 36, Mr McFarlane pleads that the revelations pleaded in ASOC paragraph 35 (that is, the disclosure of the Alleged Material Information) caused a decline in IOOF’s share price between 19 June and 7 July 2015. Insignia pleads that it does not know, and therefore cannot admit this allegation: FAD [36].

111 Mr McFarlane submits that Insignia at no point expressly pleads that the fall in IOOF’s share price was due to information in the Fairfax articles and statements by Mr Kelaher other than the Alleged Material Information. On Mr McFarlane’s submissions, having made the choice not to plead a positive case that it was the disclosure of other information that caused the fall in IOOF’s share price, Insignia cannot now submit to the Court that this in fact occurred.

112 I reject Mr McFarlane’s submissions. Mr McFarlane has pleaded, at ASOC paragraph 36, a positive case that the disclosure of the Alleged Material Information in the Fairfax articles and Mr Kelaher’s Senate testimony caused IOOF’s share price decline. Insignia has, at FAD paragraph 36, not admitted that plea. The practical effect of an express non-admission is the same as that of an express denial – that is, the opposing party is put to proof on the issue that is not admitted: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Craftmatic Australia Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 972 at [31]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cabcharge Australia Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 837 at [7]; Warner v Sampson [1959] 1 QB 297 at 311 (Lord Denning), 319 (Hodson LJ), 324-5 (Ormerod LJ). Insignia has therefore put Mr McFarlane to proof on the causal link between the disclosure of the Alleged Material Information and the decline in IOOF’s share price.

113 In the present case, Mr McFarlane seeks to prove this causal link by relying on the expert evidence of Mr Houston: see Mr McFarlane’s closing written submissions at [21], [280], [388]. The substance of Mr Houston’s evidence was that, as a result of the Alleged Material Information being withheld from the market during the Relevant Period, Insignia’s share price was inflated as compared with its true value. That conclusion was based on his event study, which measured the extent to which the movement in IOOF’s share price on 22 June 2015 and 7 July 2015 could be attributed to the disclosure of the Alleged Material Information (or “information of interest”) As will be discussed further below, Mr Houston’s opinion was that a condition for the performance of any event study was the ability to isolate the effect of confounding news, defined as price-relevant information that becomes known at around the same time as the information of interest.

114 It follows from the above that the probative value of Mr Houston’s evidence will depend on an assessment of whether his event study properly accounts for any confounding news which became known at the time of the disclosure to the market of the Alleged Material Information. Such confounding news would encompass price-sensitive allegations in the Fairfax articles and Mr Kelaher’s Senate testimony other than, or different to, the pleaded information constituting the Alleged Material Information.

115 It cannot be said that Mr McFarlane was not on notice that Insignia’s case would rely in part on a contention that there were material differences between the Fairfax articles and the Alleged Material Information, notwithstanding that Insignia had not specifically pleaded as to these differences in the FAD. Dr Prowse’s opinion, as stated in the Prowse Report, was that the entire IOOF share price reaction on 22 June 2015 could not be attributed to the information of interest – that is, the Alleged Material Information – because the corrective disclosures in the Fairfax articles in June 2015 contained “value-relevant negative information that was not included in the information of interest”: see Prowse Report, Pt IV(B). The value-relevant negative information to which Dr Prowse was referring in the Prowse Report was, in overview, the sensationalist language of the Fairfax articles. That is, of course, different to the value-relevant negative information in the Fairfax articles on which Insignia now seeks to place emphasis, namely, substantive allegations in the Fairfax articles other than, or different to, the Alleged Material Information. However, in my opinion, having put Mr McFarlane to proof on the causal link between the disclosure of the Alleged Material Information and the decline in IOOF’s share price by FAD paragraph 36, it is open to Insignia to test, in cross-examination, Mr Houston’s evidence to determine if it adequately accounts for the effect of any confounding news. Such cross-examination can permissibly extend to testing if Mr Houston’s event study accounted for confounding news in the form of price-sensitive allegations in the Fairfax articles and Mr Kelaher’s Senate testimony other than, or different to, the Alleged Material Information as pleaded in the ASOC. Similarly, I consider that it is open to Insignia to submit to the Court that Mr McFarlane has failed to establish a causal link between the disclosure of the Alleged Material Information and IOOF’s share price decline, because the evidence of Mr Houston has failed to account for confounding news in the form of price-sensitive allegations in the Fairfax articles and Mr Kelaher’s Senate testimony other than, or different to, the Alleged Material Information.

Mr McFarlane’s reliance upon the principle in Jones v Dunkel

116 As set out above, Insignia does not rely on any lay evidence in support of its case other than the Kalember Affidavit, which merely deposed to the start and finish date of numerous former employees. In these circumstances, Mr McFarlane makes, in substance, two submissions.

117 Firstly, Mr McFarlane submits that Insignia’s case relies on the Court impermissibly drawing a series of “reverse Jones v Dunkel” inferences, referring to Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298 (Jones v Dunkel) – that is, inferences in favour of Insignia in circumstances where Insignia has not called a witness to adduce evidence in support of its case. Mr McFarlane identifies the following examples of Insignia’s alleged invitation to the Court to draw a “reverse Jones v Dunkel” inference:

(1) Insignia’s attempts, according to Mr McFarlane, to downplay inferences arising from internal IOOF documents which refer to the important and centralised role of the Research team in the IOOF Group by referring to IOOF’s practical operations, the size of its business, its number of employees, and so on (Mr McFarlane’s closing written submissions at [38]);

(2) Insignia’s submission that any problems in its advice business had a de minimus effect on the value of IOOF’s business overall (Mr McFarlane’s closing written submissions at [39]);

(3) Insignia’s submission that the reason IOOF did not investigate the December 2014 complaint was because IOOF decided the allegations were nonsensical (Mr McFarlane’s closing written submission at [40]);

(4) Insignia’s submission that IOOF had properly investigated complaints (Mr Hodge KC, T 435.6-7);

(5) Insignia’s submission that there was another explanation for the problems with IOOF’s Buy-model apart from the issue identified by Max Riaz (Mr Hodge KC, T 435.7-8);

(6) Insignia’s submission that the unit pricing errors relied on by Mr McFarlane at ASOC paragraph 20(d) were insignificant (Mr Hodge KC, T 435.9);

(7) Insignia’s submission that the restructure of the Research team was due to the acquisition of SFGA (Mr Hodge KC, T 435.9-10);

(8) Insignia’s submission that the operation of the Research team was “in general okay” (Mr Hodge KC, T 435.10-11); and

(9) Insignia’s submission that there was not an under-resourcing issue at IOOF (Mr Hodge KC, T 435.11-12).

118 Secondly, Mr McFarlane also relies upon the principle expounded by Lord Mansfield CJ in Blatch v Archer (1774) 1 Cowp 63 at 65; 98 ER 969 (Blatch) at 970:

It is certainly a maxim that all evidence is to be weighed according to the proof which it was in the power of one side to have produced, and in the power of the other to have contradicted.

119 Mr McFarlane submits that consistently with the principle in Blatch and Jones v Dunkel at 308 (Kitto J), 321-2 (Menzies J), the Court can more comfortably draw inferences that are open on the contemporaneous documents against Insignia as a result of Insignia’s unexplained failure to adduce evidence from anyone other than Ms Kalember involved with Insignia. I understand the effect of Mr McFarlane’s submissions to be that the Court can more comfortably draw an inference in favour of Mr McFarlane in respect of each of the topics identified at [117] above: Mr Hodge KC, T 435.6-15. Mr McFarlane’s closing written submissions also identify two further inferences the Court may more comfortably reach given Insignia’s failure to call a witness:

(1) Mr McFarlane submits that the Court can infer that observations made by PwC in the PwC Interim Report about IOOF’s use of processes requiring manual data inputs, and multiple registers capturing different information, were matters that were observable more than a year earlier when IOOF received the March 2014 complaint (Mr McFarlane’s closing written submissions at [233]);

(2) Mr McFarlane submits that the Court can infer that the allegations contained in an email from a Bridges financial planner on 16 December 2013 alleging that the Research team had been “compromised” – an email which is identified at ASOC paragraph 20(c10) as forming part of the Historical Information – were regarded as serious given the email was forwarded to Mr Kelaher, the then Managing Director of IOOF, and Mr Mota, the current CEO of Insignia (Mr McFarlane’s closing written submissions at [168]).

120 It is convenient to address Mr McFarlane’s first and second submissions together.

121 The rule in Jones v Dunkel was summarised by Heydon, Crennan and Bell JJ in Kuhl v Zurich Financial Services Australia Ltd (2011) 243 CLR 361 at [63]-[64] as follows:

The rule in Jones v Dunkel is that the unexplained failure by a party to call a witness may in appropriate circumstances support an inference that the uncalled evidence would not have assisted the party’s case. … The failure to call a witness may also permit the court to draw, with greater confidence, any inference unfavourable to the party that failed to call the witness, if that uncalled witness appears to be in a position to cast light on whether the inference should be drawn …

The rule in Jones v Dunkel permits an inference, not that evidence not called by a party would have been adverse to the party, but that it would not have assisted the party.

122 In Coshott v Prentice (2014) 221 FCR 450 at [80], the Full Court (Siopis, Katzmann and Perry JJ) endorsed the following articulation of the relevant principles by Hodgson JA (with whom Beazley JA agreed) in Ho v Powell (2001) 51 NSWLR 572 at [14]-[15]:

[I]n deciding facts according to the civil standard of proof, the court is dealing with two questions: not just what are the probabilities on the limited material which the court has, but also whether that limited material is an appropriate basis on which to reach a reasonable decision.

In considering the second question, it is important to have regard to the ability of parties, particularly parties bearing the onus of proof, to lead evidence on a particular matter, and the extent to which they have in fact done so.

123 It must be borne in mind that Mr McFarlane bears the onus of proof in this matter. That onus cannot be discharged by using a Jones v Dunkel inference to “fill evidentiary gaps or convert conjecture into inference”: Chetcuti v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2019) 270 FCR 335 (Chetcuti) at [91] (Murphy and Rangiah JJ). That is to say, the absence of a particular witness cannot be used to make up any deficiency of evidence – any inference must be founded in evidence: Commonwealth v Fernando (2012) 200 FCR 1 at [117] quoting Lek v Minister for Immigration, Local Government and Ethnic Affairs (1993) 43 FCR 100 at 124. Further, the facts proved must give rise to a reasonable and definite inference, not merely to conflicting inferences of equal degree of probability so that the choice between them is a mere matter of conjecture: Chetcuti at [95].

124 The principles set out at [123] above supply a sufficient basis for refusing to draw a Jones v Dunkel inference on many of the topics set out at [117] and [119] above. It also explains why Mr McFarlane’s characterisation of Insignia as inviting the Court to draw a “reverse Jones v Dunkel” inference is, in many cases, misconceived. Taking the relevant topics in turn:

(1) Mr McFarlane seeks to rely on IOOF documents to establish the importance of the role of the Research team in IOOF. Such evidence is relevant to an assessment of the materiality of the issues identified in the ASOC relating to IOOF’s Research team and, in particular, IOOF’s Head of Research, Mr Hilton. However, evidence disclosed in IOOF’s internal documents about IOOF’s practical operations and the size of its business is also relevant to an assessment of the materiality of the issues identified in the ASOC. Insignia is entitled to rely on such documentary records to contradict Mr McFarlane’s case on materiality. Doing so, without calling a witness from within Insignia, does not amount to an invitation to the Court to draw a “reverse Jones v Dunkel inference” in favour of Insignia. It is to be remembered that Mr McFarlane bears the onus of establishing, on the balance of probabilities, the materiality of the Alleged Material Information. Mr McFarlane has not called expert evidence in support of his case on this issue. In these circumstances, the Court must assess the materiality of the Alleged Material Information on the documentary record available to it. For the reasons set out below in this judgment, on the basis of my review of the documents, I am not satisfied that Mr McFarlane has discharged his onus of proof. Mr McFarlane submits that the Court should draw a Jones v Dunkel inference which, in substance, would result in the Court disregarding Insignia’s evidence of IOOF’s practical operations and its business on the basis that it has not called a witness to give oral evidence about those topics. I decline to do so. In circumstances where Mr McFarlane has not satisfied his onus of proof on the materiality of the Alleged Material Information, drawing the inference pressed by Mr McFarlane would be to impermissibly permit Mr McFarlane to fill evidentiary gaps in his case on this issue.