FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Bed Bath ‘N’ Table Pty Ltd v Global Retail Brands Australia Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1587

Note | |

Paragraph numbering between [202]–[217] has been skipped inadvertently due to a Word Processing issue. |

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | GLOBAL RETAIL BRANDS AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 14 December 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. If the parties agree on the appropriate orders to be made by the Court reflecting these reasons for judgment, including as to relief and costs, the parties file a minute of proposed orders by 4.00 pm on 9 February 2024.

2. If the parties are unable to agree on the orders which should be made, each of the parties file and serve by 4.00 pm on 9 February 2024:

(a) A minute of the orders that the party proposes; and

(b) Any outline of submissions in support of the proposed orders (not exceeding five pages in length).

3. In the event the parties are unable to agree on the orders which should be made, the matter be listed for hearing at 10.15 am on 15 February 2024.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ROFE J:

[1] | |

[15] | |

[15] | |

[21] | |

[24] | |

[24] | |

[26] | |

[36] | |

[43] | |

[48] | |

[52] | |

[56] | |

3.3.2 GRBA’s earlier attempt to enter the soft homewares market | [64] |

[69] | |

[73] | |

[76] | |

[78] | |

[82] | |

[88] | |

3.10 Use of “bed” and “bath” as category or navigational descriptors | [92] |

[99] | |

[111] | |

[125] | |

[128] | |

[169] | |

[189] | |

[219] | |

[226] | |

[232] | |

[234] | |

[243] | |

[243] | |

[253] | |

[259] | |

[286] | |

[286] | |

[290] | |

[292] | |

[297] | |

[299] | |

[300] | |

[302] | |

[307] | |

[309] | |

[313] | |

[316] | |

[317] | |

[317] | |

[319] | |

[321] | |

[323] | |

[324] | |

[329] | |

[333] | |

[341] | |

[342] | |

[345] | |

[347] | |

[353] | |

[365] | |

[374] | |

[389] | |

[389] | |

[399] | |

[406] | |

[409] | |

[415] | |

[432] | |

[443] | |

[451] | |

[454] | |

[463] | |

[482] | |

[484] | |

[486] | |

[493] | |

[496] | |

[504] | |

[504] | |

[506] | |

8.5.3 Whether conduct misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive | [507] |

[523] | |

[525] | |

[530] | |

[534] | |

[535] | |

[538] |

1 For over three decades, the parties, both substantial retailers, each with descriptive words in their names, have managed to co-exist in distinct spaces in the broader homewares sector. Over time, each has built up a substantial reputation in its brand, until one day one decides to open a sub-brand in the domain of the other, using a name that incorporates words from the brand of the other.

2 Since 1976, Bed Bath N’ Table Pty Ltd (BBNT) has conducted a business operating a network of stores selling soft homewares under the trade mark “BED BATH N’ TABLE”.

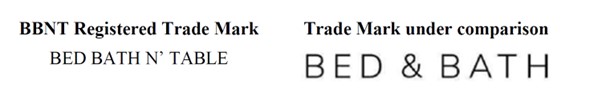

3 BBNT is the owner of Australian Trade Mark Registration Numbers:

(a) 654780 for the sign BED BATH ‘N’ TABLE, registered in class 24 (780 TM);

(b) 654781 for the sign BED BATH ‘N’ TABLE, registered in class 42 (781 TM); and

(c) 1878972 for the sign BED BATH N’ TABLE, registered in class 24 and class 35 (972 TM).

(collectively, the BBNT marks)

4 There is no challenge to the validity of the BBNT marks. They are taken as being distinctive and valid across the full scope of their registration.

5 Global Retail Brands Australia Pty Ltd (GRBA) is the owner of a business selling kitchenware and hard homewares under a trade mark incorporating the word “House”.

6 In addition, GRBA owns and operates retail stores under the following House sub-brands: “House WAREHOUSE”, “House OUTLET”, “House POP UP”, “House CASA | MAISON | HOME”, and “House Superstore” (as well as other brands, including “The Custom Chef”, “Robins Kitchen” and “MyHouse”).

7 In May 2021, GRBA began operating a new soft homewares business selling products for the bedroom and bathroom, using the following logo/mark:

(House B&B logo or House B&B mark)

8 The first House BED & BATH (House B&B) store was opened in the Doncaster shopping centre in Victoria. Since May 2021, GRBA has launched a number of other stores under the House B&B logo including at Chadstone shopping centre.

9 BBNT alleges that by launching House B&B, GRBA has:

(a) infringed the BBNT marks under s 120 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth);

(b) contravened s 18(1) and s 29(1)(a), (g) and (h) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) as contained in Sch 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth); and

(c) engaged in the tort of passing off.

10 GRBA’s alleged infringing conduct commenced in May 2021 when it opened its first House B&B store, trading under the House B&B logo. Therefore, that is the critical date to assess the reputation enjoyed by BBNT and the state of the soft homewares market in Australia.

11 GRBA denies each of the above allegations. It contends that its use of the words “bed” and “bath” is purely descriptive, the words are used as category or navigational descriptors to describe categories of soft homewares, and therefore the words do no work in designating commercial origin when read in conjunction with the well-known House trade mark.

12 Initially, GRBA sought to challenge various registered trade marks owned by BBNT through a cross-claim filed on 4 August 2021. By consent orders dated 8 November 2022, GRBA’s cross-claim was dismissed.

13 This hearing was on the issue of liability only. BBNT sought to be heard separately on relief if it was successful.

14 For the reasons given below, I am not satisfied that GRBA has infringed BBNT’s marks. However, I have found that GRBA has contravened s 18(1) and s 29(1)(g)–(h) of the ACL, and engaged in passing off.

15 BBNT called the following lay witnesses, each of whom were cross-examined (aside from Mr Cruise):

(a) Mr Jonathan Dempsey, who made three affidavits dated 25 January 2022, 19 April 2022 and 27 September 2022. Mr Dempsey is the Managing Director and sole director of BBNT.

(b) Ms Kate Mackie, who made one affidavit dated 11 February 2022. Ms Mackie is the Head of Buying and Product Development at BBNT.

(c) Mr Rodney Cruise, who made one affidavit dated 24 December 2021. Mr Cruise is an expert intellectual property researcher and patent attorney.

16 BBNT also filed three affidavits from its solicitor, Mr David Longmuir, dated 4 February 2022, 28 September 2022 and 8 November 2022. Mr Longmuir was not cross-examined.

17 BBNT sought to rely on affidavits from 36 witnesses — who were either store managers, assistant store managers or sales staff — deposing to instances of alleged confusion. Early on the first day of the trial, I directed that BBNT select its best 10 “confusion” witnesses.

18 Following my direction, BBNT called the following “confusion” witnesses, each of whom were cross-examined:

(1) Ms Maria Michelle D’Alessio, a former assistant store manager at BBNT in Doncaster, Victoria. Ms D’Alessio made one affidavit in these proceedings dated 5 May 2022.

(2) Ms Natalie Anna Erdossy, an assistant store manager at BBNT in Chadstone, Victoria. Ms Erdossy made one affidavit in these proceedings dated 4 February 2022.

(3) Ms Elizabeth Rita Dimopoulos, a sales assistant at BBNT in Chadstone, Victoria. Ms Dimopoulos made one affidavit in these proceedings dated 16 May 2022.

(4) Ms Nicole Louise Harry, a former assistant store manager and current store manager at BBNT in Woodgrove, Victoria. Ms Harry made one affidavit in these proceedings dated 6 May 2022.

(5) Ms Giulia Lea Downes, a sales assistant at BBNT in Doncaster, Victoria. Ms Downes made one affidavit in these proceedings dated 4 May 2022.

(6) Ms Karis Rae Chatfield, a store manager at BBNT in Busselton, Western Australia. Ms Chatfield made one affidavit in these proceedings dated 23 February 2022.

(7) Ms Shelley Grace Timms, an assistant store manager at BBNT at DFO Perth, Western Australia. Ms Timms made one affidavit in these proceedings dated 14 February 2022.

(8) Ms Honor Bettina van der Plight, a store manager at BBNT in Doncaster, Victoria. Ms van der Plight made one affidavit in these proceedings dated 10 February 2022.

(9) Mr Mitchell John Andrew Tabe, an assistant store manager at BBNT in Doncaster, Victoria. Mr Tabe made one affidavit in these proceedings dated 4 May 2022.

(10) Ms Tori Vigors, an assistant store manager at BBNT in Busselton, Western Australia. Ms Vigors made one affidavit in these proceedings dated 3 May 2022.

19 GRBA called the following lay witnesses, each of whom was cross-examined (aside from Mr Butler):

(1) Mr Steven Lew, the founder, Executive Chairman and a director of GRBA, who made three affidavits dated 6 May 2022, 22 August 2022 and 19 October 2022. He is also a director of Global Retail Brands Pty Ltd, the parent company of GRBA, and the Executive Chairman of several companies, including:

(i) House, which his website (<www.stevenlew.com.au>) describes as “Australia’s #1 largest specialty kitchenware retailer”;

(ii) Robins Kitchen, which his website describes as “Australia’s #2 largest specialty kitchenware retailer”; and

(iii) the Playcorp Group of Companies, which distributes apparel to third-party customers.

(2) Ms Ashleigh Cameron, GRBA’s Head of Design, who made one affidavit dated 6 May 2022.

(3) Ms Meghan Jane McGann, GRBA’s Head of Brand and Media, who made one affidavit dated 6 May 2022.

(4) Mr Darron Gary Kupshik, a director and the Chief Operating Officer of GRBA, who made two affidavits dated 6 May 2022 and 19 October 2022.

(5) Ms Kylee Ann Brodrick, a regional sales manager at GRBA, who made one affidavit dated 5 August 2022.

(6) Mr Bernard Bartholomew Caruana, GRBA’s Store Development Manager, who made one affidavit dated 6 May 2022.

(7) Ms Janice Nicola Mary Turner, shop manager at House B&B in Halls Head, Western Australia, who made one affidavit dated 4 August 2022. She was previously employed by BBNT as a store manager for eight years.

(8) Ms Jennifer Powell, a store manager at House B&B in Chadstone, Victoria, who made one affidavit dated 10 August 2022.

(9) Ms Louise Mary Sevenich, a sales consultant at House B&B in Chadstone, Victoria, who made on affidavit dated 5 August 2022.

(10) Mr Christopher Butler, the Office Manager at the Internet Archive in San Francisco, United States, who made two affidavits dated 21 December 2021 and 24 October 2022.

20 GRBA also filed four affidavits from two of its lawyers (neither of whom were cross-examined):

(a) Three affidavits of Ms Robynne Sanders dated 17 December 2021, 5 August 2022 and 19 October 2022; and

(b) One affidavit of Mr Ben Mawby dated 6 May 2022.

21 BBNT called independent marketing expert evidence from Professor Don O’Sullivan who made one affidavit dated 14 February 2022. Professor O’Sullivan is a professor of marketing at the Melbourne Business School, University of Melbourne, and has held various academic roles since 1992.

22 GRBA called independent expert evidence from Associate Professor Gergely (Greg) Nyilasy who made one affidavit dated 6 May 2022. Associate Professor Nyilasy is a professor of marketing and entrepreneurship at the Melbourne Business School, University of Melbourne, and has held various academic roles since 2010.

23 The experts prepared a joint expert report and gave evidence in person by way of a concurrent evidence session.

24 The term “soft homewares” encompasses textile goods, such as bedding and bed linen (for example, sheet sets, pillowcases and quilt covers), bathroom products (bath linen, such as towels, and bathroom accessories, such as soap dishes and shower caddies), household linen (for example, table cloths, table runners, napkins, teas towels and place mats), kitchenware (for example, cutlery, plates and bowls, serving ware and glasses, cups and mugs) and other homewares (for example, cushions, throws, vases and candles).

25 The parties adopted the term “soft homewares” to refer to bedroom and bathroom products as described above, to be contrasted with “hard homewares” such as pots, pans, plates, knives and cutlery. I have adopted that definition in these reasons.

26 BBNT has continuously traded in Australia under, and in respect of, the trade mark comprising the words “BED BATH N’ TABLE” since 1976. The BBNT business operates throughout Australia and retails soft homewares in both physical stores and online. It has retailed a vast range of soft homewares products, including textile goods, such as bedding and bed linen, bathroom products, household linen, kitchenware, and other homewares. BBNT does not sell beds, baths or tables.

27 BBNT has approximately 30% of the Australian market share of the speciality homewares and allied products market based on store numbers. Mr Dempsey considered that BBNT’s main specialty competitors (that is, businesses that specialise in bed linen, bathroom products and household linen) were Adairs, MyHouse, Pillow Talk, Linen House and Sheridan. Other notable competitors selling bed linen and bathroom products are Myer, Kmart, Target, Domayne, Canningvale (online only), Spotlight, Westelm, Pottery Barn, Big W, Best & Less, Freedom, Temple & Webster (online only), Harris Scarfe and David Jones. As at December 2021, Adairs operated about 159 physical stores, and Sheridan operated around 57. BBNT operated 167 physical stores at that time. Mr Dempsey stated in his first affidavit that “Adairs is our closest competitor, in my opinion, both in terms of market share and look and feel”.

28 Confidential sales data showed that as at 2021, BBNT had annual sales in the hundreds of millions of Australian dollars. BBNT is evidently a significant business and occupies a dominant position in the speciality soft homewares sector.

29 On the basis of BBNT loyalty and customer information, Mr Dempsey’s evidence was that the main BBNT customer demographic is predominantly female and in the 25–65 age bracket.

30 BBNT’s branding is carefully managed through regimented “brand guidelines” and has consistently, since at least the mid-1990s, been presented in block capital letters on a plain background, as shown below:

31 Store signage typically appears with illuminated white letters, with green on the inside of the letters and no background, and also in frosted white writing on the front glass of the store.

32 BBNT has used its branding in full and without alteration on a dark green background in respect of its clearance outlets and rewards program, as shown below:

33 The BBNT mark has appeared on packaging of some of BBNT’s goods and on ancillary point of sale and related materials, such as invoices, bags and catalogues.

34 BBNT has made very substantial sales of products from BBNT stores for decades and has also spent considerable funds on advertising featuring the BBNT mark, including the distribution of many millions of catalogues and the sending of many millions of promotional emails each year to the members of its loyalty scheme. BBNT has also advertised extensively in magazines such as Better Homes & Gardens, Australian Style, Home Beautiful, Vogue Living and Australian Country Style, and newspaper lift out supplements and weekend magazines. BBNT’s business has also been featured on television programs including Channel 7’s “Postcards” and Channel 7’s “House Rules”. More recently, BBNT has shifted its advertising focus more towards online advertising on its website, social media and email.

35 Mr Dempsey accepted that BBNT did not shorten the BBNT name on the internal or external signage of its store, in any advertising or on the BBNT website.

36 BBNT stores generally operate in prime retail locations with high consumer traffic, such as major shopping centres like Westfield Doncaster shopping centre where the first House B&B store opened.

37 According to BBNT’s statement of claim, each BBNT store front typically has:

(a) a prominent store front appearance including an open glass store front displaying homewares;

(b) prominent display signage bearing the BBNT mark appearing above the entryway to the store;

(c) the BBNT mark in frosted writing on the front glass of the store; and

(d) BBNT signage visible through the front windows and/store entryway.

(the BBNT Get-up)

38 Mr Dempsey gave evidence in his first affidavit and during cross-examination of more factors of get-up than are listed in the statement of claim, including the finishes of the store floors, the point of sale signage and the product signage.

39 Mr Dempsey’s evidence was that BBNT stores are carefully designed to create a home/boutique feel, with a bed or beds and linen/pillows displayed in the front windows, which he said was consistent with conveying a sense of quality and trust to consumers. He considered the store’s design to be a key element of consumer association with the BBNT brand, as being able to feel and experience the product was important to BBNT customers. The design is meant to approximate what you find in a good home. The presentation of a typical BBNT store is shown below:

40 BBNT accepts that a store front including an open glass display of homewares and made-up beds is not unique to BBNT. BBNT claims that what is unique about the BBNT store presentation was the Get-up in combination with the store name. As depicted above, the BBNT store front also includes prominent display signage with “BED BATH N’ TABLE” (see above left on the vertical blade sign). BBNT contends that this display signage is a common feature to all its BBNT stores. The words “BED BATH N’ TABLE” also appear prominently above the doorway in white illuminated writing.

41 BBNT stores promote exclusive lines of products, such as Morgan & Finch and Sleeping Beauty. It also promotes some third party branded products such as Sanderson, Harlequin and Morris & Co, which are produced under licence and a related company is the exclusive distributor in Australia. Products under those brands, and other house brands such as “Cotton House” are only available through BBNT stores or, for select products, are supplied to David Jones by BBNT.

42 In around 2016, BBNT launched a customer rewards scheme called “HOMEstyle — BED BATH N’ TABLE”. This was promoted in-store through printed flyers encouraging customers to join. The BBNT customer rewards scheme rewards loyal customers and offers exclusive everyday savings, along with access to special offers and VIP events throughout the year. Customers can join the program in-store or online. Loyalty scheme members receive regular emails from BBNT. As at May 2021, the BBNT customer loyalty scheme had almost 3 million members in Australia.

3.2.2 BBNT online and social media presence

43 BBNT launched its online store in November 2013 (<www.bedbathntable.com.au>). BBNT products are offered for sale through the BBNT online store.

44 Since August 2017, BBNT has operated a Facebook page at <www.facebook.com/bedbathntablehome/>. As at January 2022, the BBNT Facebook page had been liked approximately 130,000 times.

45 BBNT operates an Instagram account at <www.instagram.com/bedbathntable>. As at July 2021, the BBNT Instagram page had 285,000 followers.

46 BBNT also operates a Pinterest account at <www.pinterest.com.au/bedbathntable>. As at December 2021, the BBNT Pinterest page had 7,100 followers.

47 BBNT undertakes digital display advertising which includes advertising via publisher websites such as Google or Facebook, and Google search advertising.

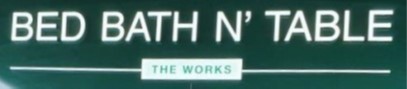

48 BBNT has also launched a number of concept stores, each of which included the use of “BED BATH N’ TABLE” in full and without alteration, on a dark green background, with other trade marks such as “THE WORKS”, as shown below:

49 BBNT holds a trade mark registration for “THE WORKS”. However, Mr Dempsey accepted that “BED BATH N’ TABLE THE WORKS” (THE WORKS) was a single brand, which leverages off the parent brand.

50 THE WORKS stores are larger in size than traditional BBNT stores and offer a wider variety of products, including cookware, dinnerware, home fragrances, handbags, gift cards, stationery and home décor items. However, THE WORKS stores still carry all the products carried by traditional BBNT stores, such as bed linen and towels.

51 For a few years in the mid-2010’s, BBNT also operated two stores in Chatswood Chase in Sydney and Chadstone shopping centre in Victoria as HOMEWORKS. As shown in the images below, the BBNT mark on the dark green background was underneath the word HOMEWORKS. Mr Dempsey considered that it was important that the other BBNT stores retained the BBNT brand identity and endorsement, which was maintained via the BBNT mark still featuring in the store branding.

52 As well as House, GRBA owns several other brands, including The Custom Chef, Robins Kitchen, MyHouse and PetHouse Superstore.

53 In 2014, GRBA acquired the assets of Lineville Pty Ltd, which had gone into liquidation and traded as Robins Kitchen. Robins Kitchen was a hard homewares retailer, which Mr Lew described as being similar to House. GRBA reopened the Robins Kitchen stores and, as at 2022, there were around 60 Robins Kitchen physical retail stores and an online store. Robins Kitchen stores sell essentially the same products as House branded stores.

54 House stores are located in areas with high foot traffic, and often near supermarkets. GRBA follows the same strategy for Robins Kitchen stores, but GRBA prefers to place Robins Kitchen stores at the opposite end of the shopping centre to the House store. As a result, generally if a Robins Kitchen store is located near a Woolworths, Coles or Aldi, the House store will be at the other end of the shopping centre, near the other supermarket/s present in the shopping centre. Mr Lew said that the co-location strategy with House and Robins Kitchen has been successful for GRBA.

55 According to Mr Lew, it was GRBA’s practice to apply for trade marks when it made a foray into a business outside of what the customer would deem the traditional House area of kitchenware and cookware. Examples were PetHouse SUPERSTORE and House CASA | MAISON | HOME.

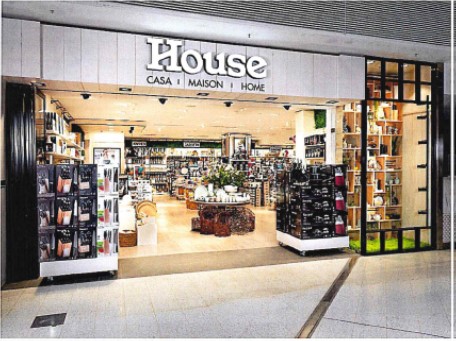

56 Since at least 1978, GRBA’s predecessors operated retail stores in Australia under the brand “House”. GRBA acquired that business in July 2007 and, as at May 2021, there were approximately 100 physical “House” branded stores open throughout Australia, selling kitchenware and hard homewares. The House stores are generally located in major shopping centres or retail precincts, often near supermarkets, and prominently feature the House mark. GRBA has a substantial reputation in House as a retail brand throughout Australia. In May 2021, the House brand was well-established in the hard homeware market.

57 House stores typically feature discount marketing in crowded displays with discount signage, typically in yellow and red. The signs display phrases such as “UP TO 80% OFF” and “CLEARANCE CLEARANCE CLEARANCE”. The signs are prominent, often covering most of the shopfront windows and are hung as bunting across the tops of store doorways. House stores are in an open format and, consistent with selling hard homewares not soft homewares, do not have beds in the window. Each House store has between 1,500 and 2,000 sales tickets on products and shelves, the majority of which feature the House mark. The presentation of typical House stores is shown in the two images below:

58 Mr Lew’s evidence was that House currently has seven sub-brand stores that it trades under and that 30% of House stores are sub-branded. GRBA owns and operates, or has operated, retail stores under the following House sub-brands: House WAREHOUSE, House OUTLET, House POP UP, House CASA ׀ MAISON ׀ HOME, and House Superstore.

59 GRBA commenced use of the trade mark “House WAREHOUSE” in 2014 for stores located in homemaker or outlet centres, not shopping centres. Mr Lew’s evidence was that the word “warehouse” was selected to inform consumers that the stores were selling higher volumes of product at cheaper prices. The House WAREHOUSE logo is shown below:

60 GRBA commenced use of the trade mark “House Superstore” in 2021. GRBA uses that mark on stores with a large footprint that sell a wide range of products. House Superstores are located in Ballina, Kalgoorlie and Warrnambool and sell everything for every room in the house. These stores therefore sell products from both traditional House stores (hard homewares) and from House B&B stores (soft homewares). The House Superstore logo is shown below:

61 GRBA operates an online House store at <www.house.com.au/> that is visited by “many millions of users”. The House B&B website can be accessed from a tab on the House online store.

62 GRBA sells a large range of products in its House branded retail stores. Around 95% of all the products sold in House stores are supplied to GRBA by a related company, Playcorp. Playcorp sources its products from supplier factories and then resells them to GRBA. Only about 5% of products sold in physical House stores is supplied by independent third-party suppliers, with the balance supplied by Playcorp. The figure is approximately 25% for the House website. The products supplied by Playcorp are not branded House. All products sold through House branded retail stores are branded with other trade marks.

63 GRBA has 15 registered trade marks which incorporate “House”, including multiple trade marks with the words “for home and kitchen”. All trade marks for the House logo (except for one) use the same capitalisation and font as the logo shown below:

3.3.2 GRBA’s earlier attempt to enter the soft homewares market

64 Despite House branded stores focussing on hard homewares, House has always sold some soft homewares that are associated with kitchenware, such as napkins, placemats, aprons and tea towels. However, in 2008, GRBA tried (unsuccessfully) to enter the soft homewares market under the brand “House CASA | MAISON | HOME”. In addition to selling hard homewares, these stores also sold bedroom and bathroom products, and other home decorations products.

65 GRBA has several trade mark registrations for the words “CASA | MAISON | HOME” in a large number of classes. GRBA has a trade mark registration for the House CASA ׀ MAISON ׀ HOME logo as depicted below:

66 Mr Lew referred to CASA ׀ MAISON ׀ HOME as a “sub-brand”. Mr Lew’s evidence was that the tag line “CASA MAISON HOME” was added to the House trade mark to differentiate these stores from traditional House stores, whilst still using the House brand to take advantage of existing customer brand recognition.

67 According to Mr Lew, the inclusion of “CASA MAISON HOME” in the brand was unsuccessful in differentiating these stores from traditional House stores as consumers did not recognise the difference. Nor did they associate House CASA | MAISON | HOME stores with bedroom, bathroom and home decoration products. This is evident from the picture of a House CASA | MAISON | HOME store front below, as these stores looked far more like the traditional House stores selling kitchenware than a soft homewares store.

68 After about two years, GRBA discontinued bedroom, bathroom and home decoration products from these stores.

69 Both BBNT and GRBA accept that the other has a substantial and independent reputation in their respective marks: BED BATH N’ TABLE and House.

70 The experts agree that the BBNT mark appears prominently on stores and that BBNT is a well-established brand in the soft homewares category with which many consumers are likely to be familiar. As GRBA’s witness Ms Turner observed: “Everybody loves Bed Bath ‘N’ Table. Who doesn’t love Bed Bath ‘N’ Table? You know, it’s a great store.”

71 BBNT says that, despite its name, it is not engaged in selling beds, baths or tables and therefore “BED BATH N’ TABLE” is an arbitrary combination of words.

72 The experts made similar comments regarding the House brand being featured prominently on stores, well-established and recognised by consumers in its particular category — hard homewares. Mr Lew agreed that the mark House was itself inherently descriptive, but that GRBA had established reputation in that mark through extensive usage in over 140 stores, trading over four decades.

3.5 Other retailers in the soft homewares market

73 The major retailers in the soft homewares market in Australia may be classified broadly into department stores, speciality linen stores and discount department stores. The retailers include Adairs and Sheridan (specialty linen stores), Myer and David Jones (department stores), and Kmart, Big W, Target and Harris Scarfe (discount department stores). There were also a range of other smaller specialty retailers selling soft homeware products, including Pillow Talk and Linen House. Mr Dempsey gave evidence that increasingly bed linen, bathroom products and household linen are sold through retailers which operate predominantly online (such as Temple & Webster) and through the online stores of retailers which have physical stores. Both Adairs and Sheridan were well known as specialty linen retailers. Mr Dempsey agreed that Adairs was BBNT’s closest competitor. Mr Lew also considered that the leading specialty competitors of House B&B, in addition to BBNT, were Adairs and Sheridan.

74 The experts and relevant lay witnesses all agreed that it is common for speciality retail linen stores to have similar store designs which comprises large shopfront glass windows with a made-up display bed visible through the windows near entrance and the store name over the entrance. This “Hamptons” style look with white walls, wooden floorboards and no discount signage is intended to convey “a quality image” and a home feel that is luxurious and upmarket. This differentiates these stores from those with a strong discount focus, such as House, JB-HIFI or Chemist Warehouse, which tend to use yellow markdown signage.

75 None of BBNT’s existing competitors use “bed” or “bath” in their name. Until GRBA’s launch of House B&B, BBNT had been the only retailer in Australia that used the words “bed” and “bath” in its name for over 40 years.

76 Cross-promotion with other brands or related brands is a common practice in the soft homewares sector. For example, Adairs has had cross-promotions with Urban Home Republic, and Pottery Barn has had cross-promotions with its related brands West Elm and William Sonoma.

77 As noted above, BBNT sells exclusive lines such as Morgan & Finch and Sleeping Beauty as well as some third party branded products such as Sanderson, Harlequin and Morris & Co, which are produced under licence and a related company is the exclusive distributor in Australia.

3.7 Co-location of soft homewares stores

78 Partly as a result of shopping centres tending to group like stores together, specialty soft homeware retailers like Adairs, Sheridan and BBNT are often clustered together in “precincts” in shopping centres. As a result, House B&B is in close proximity to BBNT in many shopping centres, such as Doncaster where the first House B&B store was opened.

79 Ms Chatfield, in the course of giving confusion evidence, asserted that the geographic proximity between BBNT and House B&B stores, some often 100 metres apart, and the fact they both displayed bedding products in the store window, contributed to customer confusion.

80 Ms Turner gave evidence that in Western Australia “you will always find that Bed Bath N’ Table was beside Adairs or House was beside us”.

81 House and BBNT were often found in the same shopping centres, but not necessarily in close proximity to each other in the same centre as they sold different goods.

82 Both parties accepted that the relevant class of consumer shopping for soft homewares is the general public or the “ordinary reasonable consumer”.

83 One thing to emerge from the “confusion” evidence (discussed below) was how little attention many customers appeared to pay to the store that they were entering. Many appeared unconcerned as to the particular shop that they were in until they were seeking to use a voucher or scan their loyalty card. According to Ms Turner, “a lot of people come in and they don’t know where they are”.

84 Ms Turner gave evidence that when she worked at BBNT, sometimes customers would pull out an Adairs loyalty card when at the BBNT register. According to Ms Turner, there were “hardcore” Adairs, BBNT and Sheridan customers and then there were the general customers that were looking for a particular item who were not concerned which shop they bought it from.

85 There was a wide spectrum of consumer involvement in the decision to enter a soft homewares store. At one end, some consumers would be browsing between stores in the soft homewares precinct, whilst at the other end, a consumer might be seeking a particular item such as a quilt cover from a particular retailer.

86 One group of consumers was undoubtedly focussed on what store they were entering. These were the consumers that had purchased a product online via “Click and Collect” and were attending the store to collect the product that they had purchased. For these consumers, it was important to be attending the correct store.

87 As I will discuss further below, the witnesses who gave evidence regarding confusion at shopping centres, where customers were either confused about which store they were in or simply did not know where they were, often had imperfect recollections about these interactions and therefore such evidence must be treated with some caution.

88 Professor O’Sullivan’s evidence was that it is common for companies to market a product or service using two brands — a family brand (a brand that sits across multiple products or services) and a sub-brand (a product or service-specific brand). He considered that consumers were highly accustomed to this multi-brand approach to marketing. He gave as examples:

(a) Nestlé using both Nescafé and Gold Blend together to market a range of soluble coffee; and

(b) Woolworths using its apple peeling logo in the logo for its Metro stores.

89 According to Professor O’Sullivan, sub-branding is commonly used in retail settings where a company wishes to signal that it is introducing a new range or retail format (either through organic growth or acquisition), or that it is collaborating with another brand or has integrated (acquired) another brand. Associate Professor Nyilassy in the joint session did not disagree with this aspect of Professor O’Sullivan’s evidence.

90 Other sub-brand examples from Professor O’Sullivan’s evidence, included by GRBA in its submissions, included:

(a) Adairs launching “Adairs Kids” for retailing homeware products relating to children;

(b) Cotton:On launching “Cotton:On KIDS” for retailing children’s clothing;

(c) Toys R Us launching “Babies R Us” for retailing baby-related products; and

(d) Coles launching “Coles Express” in relation to a range of convenience stores.

91 Adairs also has “adairs HOMEMAKER” and “adairs OUTLET”, and Cotton:On also has “Cotton:On BODY”. GRBA itself, of course, also has several House sub-brands as outlined above.

3.10 Use of “bed” and “bath” as category or navigational descriptors

92 There was evidence of substantial use by third party sellers of soft homewares in Australia of “bed” and “bath” as navigational or category descriptors both inside their physical stores or on their online stores. GRBA contends that such use is ubiquitous in relation to the retailing of bedroom and bathroom products. To take some examples:

(a) in the stores of major retailers and BBNT competitors:

(i) “BED & BATH”, and “Bed” and separately “Bath” in Big W stores;

(ii) “bed & bath”, “bath & bed”, “bedding” and separately “bath” in Kmart stores;

(iii) “Bath & Bed Linen” in David Jones stores;

(b) and on their (and other retailers’) websites:

(i) “BED & BATH” and “Bed and Bath” on the David Jones website;

(ii) “BED & BATH” on the Myer website;

(iii) “BED & BATH” on the Temple & Webster website;

(iv) “BED & BATH” on the Freedom website;

(v) “bed, bath & home” on the Harris Scarfe website;

(vi) “Bed, Bath and Kitchen” and “Bed, Bath & Kitchen” on the Kmart website;

(vii) “BED” and separately “BATH” on the Spotlight website;

(viii) “Bed” and separately “Bath” on the MyHouse website;

(ix) “Bath” and separately “Bedding” on the BIG W website; and

(x) “Bath & Beach” on the Sheridan website.

93 According to Mr Lew, “bed and “bath” are also used as category descriptors in catalogues.

94 Each of these examples of the use of the words “bed” and “bath” are navigational aids on websites or general category descriptors found inside shops and are seen by the consumer after they enter the physical store or enter the website. None of the examples in evidence were the use of the words “bed” and “bath” on store exteriors or external store branding. None of these uses is the use of the words “bed” and/or “bath” as a trade mark. As noted above, GRBA accepted that no retailer in Australia other than BBNT used “bed” or “bath” in its name.

95 Mr Dempsey accepted, albeit reluctantly, that “bed” and “bath” were commonly used in the industry for their descriptive nature to navigate customers to bedroom or bathroom products. BBNT itself has used “bed” and “bath” (and also “table) as navigational aids for consumers and as category descriptors on its own website from at least November 2013 until May 2021.

96 However, as can be seen from the examples extracted above where “bed” and “bath” are used as part of a composite phrase rather than used separately, the order of the two words is typically, but not always, “bed” and then “bath”. For example, in some Kmart stores and on David Jones’ website, “bath” precedes “bed”. Further, when used together and not separately, “bed” and “bath” are generally used in a composite phrase including “and” (or “&)” but in some cases, such as Kmart and Harris Scarfe’s websites, “bed” and “bath” are separated by commas in a composite phrase with a third category (“bed, bath & home” in the case of Harris Scarfe and “Bed, Bath and Kitchen” in the case of Kmart). These examples highlight that BBNT is far from the only retailer to use “bed and bath” or even “bed, bath and [other]” as a composite phrase to describe categories of products, even if they are the only retailer to use that combination of words in their name and in trade marks. Professor O’Sullivan explained that “[c]onsumers who visit [BBNT’s] website would learn that bed is a shorthand for bedroom ware, and bath is a shorthand for bathroom ware”.

97 Associate Professor Nyilasy’s evidence was that “almost every one of BBNT’s ‘most significant competitors’ uses similar terms to the words bed and bath to categorise their products” and that “therefore the category of bed and bath products in general will come to mind when [consumers] see the words bed and bath”. Associate Professor Nyilasy explained that bed and bath are “generic words that are overlearned and overused in everyday language”, there is “no amount of marketing that could erase those generic associations”, because “it’s impossible to erase the generic associations in people’s heads from these Anglo-Saxon words”.

98 GRBA therefore submits that the extremely generic nature of the words “bed” and “bath” is a core fact to be taken into account in the determination of the issues in this proceeding.

99 Mr Dempsey annexed a two-page report prepared by the BBNT marketing department from the Google Analytics data available to BBNT. The table was annexed to support his proposition that the terms “bed and bath” and “bed n bath” were frequently used by customers to locate BBNT’s website and online store.

100 The Google Analytics data records the terms searched by internet users on the Google search engine during the period January to October 2021, before those users then clicked onto the BBNT website. The table prepared by the BBNT marketing department displays results from the Google Analytics data in columns under headings including “search query”, “clicks”, “impressions” and “CTR”.

101 The number of “clicks” is the measure of the number of clicks on the <www.bedbathntable.com.au> website from a Google Search results page, not including clicks on paid AdWords search results. The number of “impressions” refers to the number of times any URL from the <www.bedbathntable.com.au> website appeared in search results viewed by a user, not including paid AdWords search impressions. The CTR or “click through rate” provides an indication of the extent to which users considered or treated any listing on Google as responsive to their Google search. The CTR was calculated as a percentage of the impressions which ultimately result in clicks to the BBNT website (CTR = clicks/impressions x 100).

102 The data in the table is arranged from the search term with the highest clicks to the term with the lowest clicks. BBNT claimed that the search results are confidential, and therefore I will refer to them in broad terms without using actual figures.

103 The top three search terms used by internet users before navigating to the BBNT website were:

(1) “bed bath and table” (by far the largest number of clicks and impressions, by an order of 10 times larger than the next most clicked search term);

(2) “bed bath n table”; and

(3) “bed bath table”.

104 All of these top three search terms had a CTR in the low 70%.

105 The term with the fourth highest amount of clicks, “bed and bath”, had a similar number of impressions to the second and third terms, but around half the clicks, with a corresponding CTR of around half that of the second and third terms.

106 Many of the other search terms listed on the first page of the Google Analytics data as generating clicks on the BBNT website also featured the BBNT brand as a composite whole, including: “bedbathntable”, “bedbath and table”, “bed bath & table”, “bed bath and table sale”, “bed bath and table outlet”, “bed bath and table nz”, “bath bed and table”, “bed bath and table christmas”, “bed bath and table cushions”, “bed bath and table quilt covers”, “Bed and bath table”, “bedbathandtable”, and “bedbathtable”.

107 It appeared from the results that when internet users searched for the BBNT brand as a composite whole and were presented with a hyperlink to the BBNT website, they generally visited the BBNT website. Namely, the CTR to the BBNT website was high when internet users searched for the BBNT brand by using some combination of the words “bed”, “bath” and “table”. In contrast, it was rare for internet users to visit the BBNT site after searching for “bed” and/or “bath”. Mr Dempsey accepted in cross-examination that the Google Analytics data demonstrated that approximately 95% of the clicks on the URL <www.bedbathntable.com.au> followed the entry of search terms other than “bed” and “bath” simpliciter.

108 GRBA sought to highlight the disparity by observing that a higher percentage of internet users clicked through to the BBNT website after searching for “silk face mask” than those who searched for “bed bath” or “bed & bath”. More than 80% of users who searched those two terms did not click through to the BBNT website.

109 Mr Dempsey conceded that it is not possible to tell from the Google Analytics data whether when an internet user typed the words “bed bath” into Google, they were searching for BBNT or using the words “bed bath” as a category descriptor.

110 Every reported occasion in the table where a Google search was undertaken for a BBNT store at a specific location in Australia, each of the words “bed” “bath” and “table” were used, together with the location. For example, internet searches for “bed bath and table hobart”, “bed bath and table adelaide”, “bed bath and table perth”, “bed bath and table ballarat”, “bed bath and table canberra”, “bed bath and table hawthorn”, “bed bath and table bendigo”, “bed bath and table geelong”, and “bed bath and table townsville”, were all reported as generating clicks on the BBNT website. In contrast, there were not any reported searches for “bed bath” or “BED & BATH” linked to any location in Australia.

111 BBNT contends that there is evidence of consumers and others dealings with BBNT to refer to the store as “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH”. The tendency of consumers to truncate, shorten and abbreviate store or other names is well-known and entirely natural, as was recognised in London Lubricants (1920) Limited’s Application (1924) 42 RPC 264 at 279 (per Sargant LJ).

112 BBNT primarily relied on the evidence of its store managers and employees to support the existence of this tendency to shorten. Each of Ms Erdossy, Ms D’Alessio, Ms Dimopoulos, Ms Harry, Ms Downes, Ms Chatfield, Ms Timms, Ms van de Plight, Mr Tabe and Ms Vigors gave evidence that they experienced customers shortening the BBNT name to “BED BATH”. However, these witnesses provided significantly varying estimates of how often they experienced customers shortening the BBNT name. The estimates ranged from only “a few occasions”, to “once every two months”, to “a few times a month”, to “about once a week”, to “once or twice a day”, to 50%, to 60%, to 80%, and even 95%.

113 The evidence from store employees is essentially survey evidence. However, the survey evidence presented by BBNT is of a very low quality because it is not randomised or representative and derives from highly generalised, subjective recollections. BBNT did not undertake any properly controlled consumer survey to establish the extent to which consumers might abbreviate the BBNT name, or adduce evidence from a single consumer as to their own practice in abbreviating the BBNT name. The evidence derives purely from BBNT’s handpicked “10 best” store witnesses (and some of the other store witnesses who were not called). This Court has rejected the utility of survey evidence of this kind (not randomised, representative or properly conducted) on numerous occasions: Telstra Corp Ltd v Phone Directories Co Pty Ltd (2014) 107 IPR 333 at [332] (per Murphy J); Samsung Electronics Australia Pty Ltd v LG Electronics Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 113 IPR 11 at [346] (per Nicholas J); Australian Postal Corp v Digital Post Australia Pty Ltd (2013) 105 IPR 1 at [49] (per North, Middleton and Barker JJ); Adidas AG v Pacific Brands Footwear Pty Ltd (No 3) (2013) 103 IPR 521 at [180]–[212] (per Robertson J); Apple Inc v Registrar of Trade Marks (2014) 109 IPR 187 at [219]–[231] (per Yates J).

114 I therefore give the evidence of BBNT’s store employees some weight as it showed that a reasonable number of consumers have a tendency to shorten BBNT to “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH”, but I do not think it is conclusive of establishing that tendency.

115 BBNT also relied on some further evidence of shortening.

116 Ms Mackie provided evidence of third parties emailing BBNT and shortening the name of BBNT to “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH”. However, each of the seven examples provided by Ms Mackie were from overseas correspondents and therefore I give this evidence very little weight as it does not reflect the tendency of ordinary consumers in the Australian market. Ms Mackie did not provide any examples of local customers, staff or suppliers shortening the name of BBNT in email correspondence. Nor did any other BBNT witness provide such evidence.

117 Mr Dempsey gave the following examples of shortening by the media and general public:

(a) A news reporter said “Bed and Bath” on the Today Show on Channel 9 on 24 October 2021 in reference to BBNT hiring staff post-Covid lockdown.

(b) A disgruntled customer said “Bed and Bath” in a Facebook livestream on 19 November 2021 when she complained that she was denied entry into a BBNT store due to vaccination requirements.

118 Again, these examples have no representative weight to establish a tendency among the ordinary consumer.

119 Finally, BBNT pointed to evidence of GRBA staff shortening the name of BBNT. Ms Kuzmanovich, GRBA’s state manager of Western Australia, referred to a BBNT store as the “Bed Bath store”. Further, both Ms Turner and Ms McGann referred to BBNT as “Bed Bath” in cross-examination. These are all one-off examples of shortening and not necessarily supportive of a general tendency among GRBA staff, let alone consumers, to shorten the BBNT name. Notably, BBNT did not point to any documentary evidence, such as internal email correspondence, of BBNT staff shortening the name.

120 Even if I was wholly satisfied that consumers have a tendency to shorten the BBNT name, I do not consider that, in any event, BBNT has established that it has any independent reputation in “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH” alone.

121 As Associate Professor Nyilasy explained, there is “a difference between the informal and formal use of Bed and Bath”. The mere fact that consumers might, in certain contexts such as instore, contract the BBNT name, does not mean that consumers will expect the contracted words “BED BATH” to be “institutionally applied” (ie used by BBNT as a badge of origin). Associate Professor Nyilasy said that consumers will not “form that expectancy” unless there has been institutional use of that contraction.

122 In this case, the evidence was clear that BBNT had not made any institutional use of “BED BATH”. To the contrary, BBNT strictly followed its brand guidelines at all times, which required use of the brand only as a composite whole. Mr Dempsey accepted that BBNT had not contracted its brand to “BED BATH” in any advertising or promotion prior to May 2021. He agreed that BBNT used the BBNT mark in full (not contracted) on social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, and on its online store. Further, in its history of brand extensions and sub-brands, BBNT has always used the whole of the BBNT name in unaltered form, in combination with the dark green colour background. In so doing, BBNT has further reinforced to consumers that it is the composite phrase “BED BATH N’ TABLE” which indicates a commercial connection with BBNT, and not simply “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH”.

123 The Google Analytics data reflects that BBNT’s institutional consistency in using the composite whole of the name has been digested by consumers. As discussed above, the Google Analytics data clearly recorded that when internet users searched for BBNT, they overwhelmingly did so by searching for the BBNT brand as a composite whole, and when they searched for specific BBNT stores, they exclusively did so by reference to the BBNT name as a composite whole. I give this objective evidence more weight than the subjective recollections of the BBNT store witnesses.

124 I therefore consider that, although consumers may have a tendency to occasionally shorten the BBNT name in informal settings such as in store or on the phone, BBNT has not established that it has a reputation, in any formal or institutional sense, in “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH” alone.

3.13 Instances of use of the House B&B mark

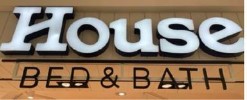

125 In an appendix to its submissions, BBNT listed 15 different instances of the use of the House B&B mark. These included examples of House B&B store signs (some of which are below) with and without the horizontal line between “House” and “BED & BATH”, where “House” was illuminated, where “House” was in solid black font, and where the “BED & BATH” was cut out from a solid block.

126 There were also examples of where “House BED & BATH” appeared on a single line on printed receipts, or on social media.

127 Finally, there were examples of use on gift cards, advertising, employee name badges, signage directories at shopping centres, store windows, domain names (such as <www.housebedbath.com.au>) and various websites (such as <www.house.com.au>). The image below shows one such example of frosted glass window decals:

4. ADOPTION OF THE HOUSE B&B NAME

128 In a very short timeframe and at the last minute before the launch of its new store in Westfield Doncaster shopping centre, GRBA resolved that House B&B would be a better brand than MyHouse, even though the MyHouse brand incorporated the word “House” and was a long-established business in NSW.

129 GRBA contends that the intention (and the effect) of GRBA adopting House B&B was to send a message that the well-known retailer House had moved away from its core activities, kitchenware and cookware, and extended its activities into bedroom and bathroom products.

130 BBNT contends that GRBA’s intention behind the adoption of the House B&B mark is relevant to the following issues:

(a) the ACL case;

(b) trade mark infringement;

(c) the question of deceptive similarity; and

(d) the good faith defence under s 122(1)(b)(i) of the Trade Marks Act if GRBA is found to have infringed the BBNT marks.

131 The events which led to GRBA’s last minute change from MyHouse to the House B&B mark and the layout of the House B&B stores were the subject of a significant amount of evidence and cross-examination.

132 The chronology of events leading up to the adoption of the House B&B mark is as follows.

133 In around June 2020, GRBA acquired the MyHouse business from administrators. MyHouse sold predominantly soft homewares (as opposed to the hard homewares predominantly sold through GRBA’s House and Robins Kitchen stores). The MyHouse stores consisted of a network of 26 stores in NSW and one in Victoria which closed shortly before the acquisition. After the acquisition, one MyHouse store re-opened in Victoria and two new stores were opened in Queensland.

134 GRBA initially planned to open over 50 MyHouse stores, and the set-up costs of the new soft homewares stores was substantial — in the many millions of dollars. Ms McGann agreed that the MyHouse acquisition and the intention to open another 35 stores was a very big investment for GRBA and one would expect great care to be exercised in thinking of branding options if the brand was to change.

135 As at around June 2020, House had little or no trading reputation in the soft homewares market. In fact, GRBA’s attempts to enter that market (as House CASA ׀ MAISON ׀ HOME) had largely failed, and therefore the entrance into this market was a new category for GRBA.

136 Mr Caruana, GRBA’s Store Development Manager, was instructed by Mr Lew to design a new fit out for the MyHouse stores. Mr Lew was looking for a fit out that was “more modern and consistent with how GRBA fitted out its other retail stores, but appropriate for a store that sold ‘soft’ furnishings”. Mr Caruana had not previously designed a fit out for a store that sold mainly soft homewares. His evidence was that his first step was to become familiar with the products sold in the MyHouse stores, as this would determine the types of product displays required. Mr Caruana also took external and internal photographs of a BBNT store (amongst others) as part of his research. As part of this process, Mr Caruana determined that, as the MyHouse stores had done prior to the acquisition by GRBA, at least one bed needed to be displayed at the front of each MyHouse store to ensure that customers could see the products (in particular, quilt covers) available for sale, including from outside the store.

137 Mr Lew also instructed Mr Caruana to include the concept of a “linen press” shelving located prominently close to a bed in store with quilt covers and pillow cases out of their packages to enable them to be placed on the bed so that customers could see how they looked and felt. At the instruction of Mr Lew, Mr Caruana designed the display bays for new MyHouse stores to display sheets and quilt covers in portrait, as opposed to landscape, orientation, the latter being the orientation generally used in most soft homewares stores.

138 According to Mr Caruana, the new design for the fit out of MyHouse stores needed to be consistent with GRBA’s design ethos for its other stores. In particular:

(a) it needed to have as much product as possible in the store, not kept in the back room;

(b) the design needed to be modular, to allow elements of the fit out to be used regardless of the dimensions of the store (for example, using six wall bays rather than eight); and

(c) the elements of the fit out had to be capable of being used in all stores operating under the MyHouse brand, to benefit from economies of scale on the cost of design and manufacturing.

139 In about June 2020, Mr Caruana met with Mr Lew and his wife in their home to discuss store features they wanted to integrate into the MyHouse store design concept. Mr Caruana presented the first store fit out sketches and they discussed and agreed upon colours, fastenings and finishes.

140 Due to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, GRBA did not open any new MyHouse stores in 2020. The first opportunity to do so arose in early 2021 when GRBA leased a store in Westfield Doncaster. This was to be the first new MyHouse store opened by GRBA since its acquisition of the MyHouse business. Mr Caruana described the Westfield store as a “warm shell”, meaning the previous tenants had left some of their fit out behind, including the flooring and wall treatments. The store was one floor above a BBNT store. Mr Lew visited the Doncaster site prior to May 2021.

141 Mr Lew informed Mr Caruana of the new Doncaster store by email on 13 April 2021. By this time, Mr Caruana had completed his design of the new MyHouse fit out, and so he started making arrangements to use the modular fit out components he had designed in this new MyHouse store.

142 As the new Doncaster store was large and square, Mr Caruana created a layout that had two beds in the windows promoting the products displayed, and a third bed on the main floor with the linen press nearby. Mr Caruana located the cash register where it had been for the previous tenant so that the existing electrical wiring and cabling would not need to be relocated.

143 On 28 April 2021, Mr Caruana emailed Mr Lew and Ms McGann, GRBA’s Head of Brand and Media, three layout options that he had prepared for the MyHouse store in Doncaster.

144 On the afternoon or evening of 3 May 2021 — at the “very last minute”, only days before the first MyHouse store was scheduled to open on 14 May 2021 in Westfield Doncaster — Ms McGann queried during a telephone call with Mr Lew whether it was “too late to consider rebranding and calling this a HOUSE branded store?”. Mr Lew’s initial reaction was that this was “a good idea”, as it would “allow GRBA to leverage off the goodwill associated with the HOUSE brand”.

145 On further reflection, Mr Lew considered that if the new store was branded House, GRBA could also use the House customer database and potentially negotiate better leases with shopping centres. It would also give customers more confidence in this new store as they were familiar with the House brand and, after only a year of trading, there was little awareness of the MyHouse brand outside NSW.

146 Later that day at 9.10 pm, Ms McGann emailed Mr Lew, stating:

Thanks for calling

We WILL make this work and more than that — SOAR.

Just on our chat

Something to mull over

SHE KNOWS WHAT WE DO WELL

WE OFFER EXCELLENT PRODUCT WITH A GREAT VALUE PRICE TAG

WHY DOES A [ROBINS KITCHEN] AND A [HOUSE] IN THE SAME CENTRE ALWAYS FAVOUR HOUSE IN SALES? — SHE KNOWS AND TRUSTS THE BRAND.

We have all this BRAND LOYALTY TO LEVERAGE

Just something to think about? Not 100% there myself but there is something in it??

Before we roll out too many MYHOUSE — One could be [HOUSE] — we could try?

Aim to always open in the SAME centre so can push them either which way for deals — double our audience.

Will have Bed bath and table running scared.

HOUSE bed & bath.

HOUSE BATH AND BED

HOUSE BEDWORKS

(the running scared email or 3 May 2021 email)

147 In cross-examination, Ms McGann described the second option of potential brand names (“HOUSE BATH AND BED”) as “playful”.

148 Mr Lew’s evidence was that the 3 May 2021 email was the first he had heard of “House BED & BATH” as a potential brand. Mr Lew’s evidence was that despite the reference to BBNT in the 3 May 2021 email, he and Ms McGann had never had a discussion about BBNT. Mr Lew rejected the proposition that the proposed name was derived from BBNT, saying “I never thought about Bed Bath ’N’ Table”, adding, what became a common refrain from Mr Lew and Ms McGann, “the words bed and bath are common descriptors in the category of all soft furnishings”. He also rejected the idea that the words “BED & BATH” triggered an association with the only competitor identified in the running scared email, BBNT, responding that “the terminology ‘Bed & Bath’ in that combination and usage of words is highly used by a lot of retailers, and it’s very highly understood by the consumer”.

149 Mr Caruana spoke with Mr Lew on 4 May 2021. During that conversation, Mr Lew said that he was thinking of changing the MyHouse store name.

150 In a text message to Ms McGann at 7.03 am on 5 May 2021, Mr Lew sent the House B&B logo from Ms McGann’s email of 3 May 2021 with the comment “I think you could be right”. Ms McGann’s text in response stated: “We start at 80% instead of 0% re roll outs with a customer base”. Ms McGann agreed that these figures were in relation to House entering the soft homewares market, and that she saw a significant advantage in being branded House B&B as opposed to MyHouse. Ms McGann considered “BED & BATH” to be a “callout to what categories we sell in that store”, to indicate to the customer that the shop would not be selling cookware. Ms McGann’s evidence was that House was the advantage — it had the customer database, the credibility, the trust and the recognition. Ms McGann described House B&B as the “same brand” with a completely different product offer.

151 At 7.32 am on 6 May 2021, Ms Cameron sent 12 House B&B logo concepts to Mr Lew, copied to Ms McGann. Each featured the House® mark with variations of “BED & BATH” in different fonts and all in upper case. For each version, there was a mock-up of how it would appear over a store entrance. Ms McGann and Ms Cameron were unable to explain the change to all upper case from the lower case version in her 3 May 2021 email.

152 At 7.40 am on 6 May 2021, Ms McGann responded to Ms Cameron’s email copying in Mr Lew, stating “I like 8 then 11”. At 9.56 am, Ms Cameron sent three sets of mocked up pairs of store fronts with House and House B&B on them, with “BED & BATH” scaled differently on each.

153 On 6 May 2021, Mr Lew made the final decision to proceed with the now House B&B logo as his preferred option. Following a request from Mr Lew’s executive assistant at 3.25 pm on 6 May 2021 to “fast track the registration of the HB&B logo in Australia in class 35 only”, Mr Kenmar, GRBA’s corporate lawyer, lodged a Headstart application with IP Australia for the House B&B logo at 5.03 pm that same day.

154 In an email to Mr Lew sent at 5.10 pm on 6 May 2021, Ms McGann commented “we need to do due diligence on some ‘house keeping’”. She then set out a number of queries (in bold) to which Mr Lew responded 20 minutes later by filling in the answer next to Ms McGann’s questions, including the following:

1. CHECK WITH LEGAL?

HOUSE Bed & Bath

BEING FAST TRACKED ….. NOT A BIG CONCERN FROM LAWYERS.

Check we can proceed — no objections

Send logo off to register

155 When asked why it was necessary to check with legal, given the brand was “House”, Ms McGann responded that she was not sure whether there were any legal implications with the name change on the lease that GRBA had signed for the Doncaster store and whether GRBA could change its lease agreement with the centre. Ms McGann refused to concede that the “check with legal?” query related to a concern about using “BED & BATH” as a brand. She added after further questioning that she suggested they check with legal because “it is protocol in our company to check with Legal on almost everything we do in terms of brand, regardless of what the brand is”.

156 Ms McGann’s evidence on this issue was frankly unbelievable. Despite the email saying “send logo off to register”, Ms McGann said that she did not have trade mark issues in mind when saying check with legal. However, given that Mr Lew’s response referred to “being fast tracked”, which was the language used to request that Mr Kenmar “fast track the registration”, Ms McGann’s reference to concerns about the name on the lease is clearly not what Mr Lew took “check with legal?” to mean. Mr Lew’s evidence was that he understood “check with legal?” to mean “to check if the marks are available for registration” — that is, to see if GRBA could get the House B&B mark registered. It is therefore highly unlikely that Ms McGann intended to refer to the lease when she said “check with legal?”. This conclusion is supported by the fact that no one else at GRBA referred to seeking legal advice about the lease and there is no record of any such advice being sought. In my view, and for further reasons explained below regarding Ms McGann’s credibility as a witness, her explanation regarding the lease was likely a subsequent invention to avoid conceding that there might have been a concern about “BED & BATH” being used as a trade mark.

157 According to Mr Lew, the “fast tracking” related to the speed at which a response would be received in respect of the Headstart application. Mr Lew’s evidence was that a Headstart application gives a picture within around five days of whether there are any marks cited against the mark. Mr Lew’s evidence was that he understood the “check we can proceed — no objections” comment to be a reference to no objections coming from the trade marks office. In his comment about “not a big concern from lawyers”, the “concern” was as to the speed of response to the Headstart application. Mr Lew made no mention about seeking legal advice about the store lease.

158 On 6 May 2021, Mr Lew met Mr Caruana at the Doncaster store. Mr Lew asked Mr Caruana if he could get signage for the new brand made and put up in time for the launch of the store in four days. Mr Caruana agreed that he could get the signage made up in time as long as Mr Lew was happy for “House” to be illuminated like the other House stores, but not the other words, as Mr Caruana could use an already fabricated “House”. Mr Caruana gave evidence that the Doncaster shopping centre management imposes limitations on storefront signage, including that only one sign on the same façade is allowed to be illuminated in the store’s signage.

159 On 10 May 2021, Ms McGann sent an email to Mr Lew, copied to Mr Caruana, which discussed the possibility of an “additional semi transparent pull down screen behind the print banner so that the content in the bays doesn’t interfere with the visual on the beds”. The email noted that “Bed bath and table do it”.

160 On 11 May 2021, GRBA received an assessment from IP Australia which raised a single citation (unrelated to BBNT). According to Mr Lew, as GRBA had successfully overcome this citation in relation to other uses of its trade marks incorporating House in the past, he expected it would also be overcome in relation to House B&B. Mr Lew accepted that the Headstart application expressly noted that “Headstart cannot provide legal business advice such as … whether you will be infringing another trader’s common law rights”. Mr Lew’s evidence was that he understood that in order to be confident that GRBA was not infringing another trader’s common law rights he needed to get proper legal advice.

161 GRBA applied for the registration of the House B&B logo on 12 May 2021:

being trade mark application number 2176694. The application was accepted on 5 July 2021 but was opposed by BBNT, and the opposition is presently on hold.

162 On 13 May 2021, the new signage with the House B&B logo was installed at the Westfield Doncaster store. Mr Caruana’s evidence was that, other than the signage, the layout and fit out of the Westfield Doncaster store did not change from the original plans he had prepared when it was intended to be a MyHouse store.

163 On 14 May 2021, GRBA launched the House B&B store in Westfield Doncaster using the signage shown below:

164 Also on 14 May 2021, Inside Retail published an article titled “Full House: Steven Lew’s GRB unveils new homewares brand” which reported on GRBA’s launch of a new brand “House — Bed & Bath”. That same day, GRBA registered a number of domain names incorporating Housebedbath (.com, .com.au, .com.nz and .co.uk).

165 On 25 May 2021, BBNT’s solicitors sent a letter to GRBA, noting the existence of the BBNT marks, and BBNT’s “extremely high level of brand recognition throughout Australia, in the name BED BATH N’ TABLE”, and requesting that GRBA rename the new store at Westfield Doncaster. The letter noted that GRBA’s conduct in choosing to name its new store “House BED & BATH” was conduct which constituted misleading and deceptive conduct contrary to s 18 and s 29 of the ACL, passing off and trade mark infringement.

166 GRBA’s lawyers responded to this letter on 1 June 2021. The letter set out the trade mark registrations held by GRBA and noted that the House brand and trade marks were well known in Australia in the homewares sector. The letter noted that House B&B was a “clear brand extension” of the iconic House brand, and said that the mark was not deceptively similar to the BBNT marks. There was no mention of the concept of “bed” and “bath” being category descriptors or navigational aids. The letter appended a list of four registered trade marks which contained the words “bed” and “bath”.

167 GRBA opened a House B&B store in Knox shopping centre about a month after the Doncaster store opened. At the time that BBNT commenced these proceedings on 11 June 2021, there were two House B&B stores in operation. The Doncaster store closed in January 2022 as the lease on the store was only for seven months. Since May 2021, GRBA has launched a number of retail stores, each featuring either the use of the House B&B Logo or one of the other instances of the use of the House mark set out at [125] and [127] above.

168 On 13 October 2021, GRBA was advised by IP Australia that its trade mark application for House B&B was accepted. Mr Lew agreed that he knew that acceptance of a trade mark did not equate to registration of the mark.

169 Mr Lew has extensive business experience, including in retailing hard homewares. He publicly promotes himself as the founder and executive chairman of GRBA, Australia’s number one largest specialty kitchen retailer. The businesses under Mr Lew’s control have very significant annual revenue.

170 Mr Lew gave evidence that “brand” is very important to his business and in the home furnishing sector.

171 Mr Lew had been aware of BBNT since at least 2004 and, as at May 2021, he knew that BBNT was a leading competitor in the soft homewares market, and that it was the kind of brand that had trust amongst consumers. He agreed that BBNT had a “very prominent and successful brand” and that it was “very well established in the market”. Mr Lew’s evidence was that he regularly attended shopping centres and kept an eye on all competitors in the soft furnishings business.

172 Mr Lew was not aware of any other retailer using the term “bed and bath” as part of its store name in Australia: “I have not seen it — had not seen the words ‘bed and bath’ in a store branding aside from Bed Bath N’ Table in Australia”.

173 Mr Lew rejected the proposition that he looked closely at what BBNT stores were doing. His evidence was that he was no more aware of BBNT than he was of Adairs, Pillow Talk, Sheridan, Myer, David Jones or Harris Scarfe.

174 Mr Lew agreed that he was very hands-on in relation to the opening of the new Doncaster store. At the time of opening that store, Mr Lew said that the competitor he was most cognisant of was Adairs, “and their sub-brand … Adairs Kids” as they were across the hallway from the new store.

175 Mr Lew’s evidence was that he selected the name “House BED & BATH” because he considered that consumers were already very familiar with the House brand. He wanted to capitalise on the House brand, but wanted to differentiate its existing House kitchenware and cookware stores from the new stores that GRBA was planning to open (such as the Westfield Doncaster store) that would sell soft furnishings for the bedroom and bathroom. He preferred the suffix “BED & BATH” because he considered that:

(a) it was a category descriptor that clearly indicated to consumers that the new store sold different products to those of the traditional House store;

(b) “BED & BATH” “rolls off the tongue” more easily than “Bath & Bed”; and

(c) it was important to use generic category words to describe the difference between the new store and the other House stores, particularly as they could be co-located in the same shopping centre.

176 Mr Lew agreed in cross-examination that GRBA could have picked “bedroom and bathroom” instead of “BED & BATH” but said:

the words “bed” and “bath”, even as opposed to “bedroom” and “bathroom” allow the main mark of House to stand out and be prominent. And the — potentially the shorter your sub-brands, the more emphasis is given on the prominent mark and the logo.

177 It was put to Mr Lew in cross-examination that the idea for the change of name to “House BED & BATH” suggested by Ms McGann came from, or was associated with, BBNT. His response was: “Not at all. I never thought about Bed Bath ‘N’ Table”.

178 Mr Lew accepted that BBNT was the only retailer using “bed” and “bath” in their name and store signage prior to House B&B, and that the public knew BBNT by reference to the words “bed” and “bath”. Mr Lew rejected that there was any distinction between the use of the words “bed” and “bath” as part of external store branding and their use inside stores as category or navigational descriptors because those words are “a commonly accepted term that people use in the industry and the general public”. He explained that the public:

may very well know the words “bed” and “bath” from Bed Bath ‘N’ Table , but if they walked into any other store — or many other stores that sold soft furnishings for the bedroom and bathroom or most of the competitors that I mentioned before, then they would see the words “bed” and “bath” and, particularly, online, the words “bed” or “bedroom and “bathroom” are used extensively.

179 In cross-examination, Mr Lew repeatedly observed (and did not miss an opportunity to observe) that the words “bed” and “bath” are common descriptors in the category of soft homewares and furnishings.

180 Mr Lew’s evidence was that it never crossed his mind that there might be a potential problem with any to similarity, or confusion with, BBNT. At no point did he think that House B&B was infringing the BBNT marks. His evidence was that he could not see an association between the names House BED & BATH and BED BATH N’ TABLE — even when it was raised in the context of the running scared email:

I didn’t pay too much attention to her line about running scared because we are in the market to take market share from all of our competitors. I went to straight to have a look at the logo that was being presented.

181 Despite Ms McGann’s references to BBNT in the running scared email and the email regarding the layout of the new Doncaster store, Mr Lew’s evidence was that he had never had a discussion with Ms McGann about BBNT.

182 Mr Lew selected the new name without reference to any lawyer. By the time the Headstart application was commenced, Mr Caruana had been instructed to prepare the new sign to put over the entrance to the shop which was to open on 14 May 2021. The decision had been made.

183 Mr Lew’s evidence was that it never occurred to him to check with lawyers whether there might be a problem with the use of House B&B because of the presence of BBNT. The only checking with lawyers that was done was to check whether GRBA could register the House B&B mark. According to Mr Lew, it was customary every time GRBA created a logo or brand in its business to check if the marks were available for registration. He said that if GRBA was not successful in registering the House B&B mark, it would have continued with the plan to open as MyHouse.

184 In response to a question in cross-examination regarding the usage of the House B&B mark, Mr Lew said “on the advice I had I was happy to continue”. GRBA accepted that there had been a waiver as to any documents containing such advice. However, no documents relating to that advice were produced in response to a notice to produce from BBNT following the hearing. There has also been no disclosure by GRBA of any legal advice in this period concerning the adoption of the House B&B name.

185 There was an absence of any comprehensive consideration accompanying the adoption of the new name in Mr Lew’s evidence (and, for that matter, the evidence of every other GRBA witness). The evidence suggests that the decision to adopt House B&B as the name for the new soft homeware’s business occurred within a matter of three days via a flurry of phone calls and emails, a week before the first store opened and without any input from external or internal lawyers. It also apparently occurred without the key decision-makers, Mr Lew and Ms McGann, having even the slightest inkling that the new name might bear even a passing similarity to the name of the dominant, or at least one of the dominant, players in the soft homewares market.

186 The resistance of Mr Lew to acknowledge his awareness of BBNT was particularly telling when he was asked whether he perceived any similarity between the store names BED BATH N’ TABLE and House BED & BATH, to which he answered “no”:

You can’t see it? — No.

That’s your honest answer? — Honest answer.

You can’t pick the fact that you’ve got two words in your store name that are two words in the name of Bed bath N’ Table. That never occurred to you? — No.