Federal Court of Australia

UIL (Singapore) Pte Ltd v Wollongong Coal Limited [2023] FCA 1578

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | WOLLONGONG COAL LIMITED (ACN 111 244 896) First Respondent WONGAWILLI COAL PTY LTD (ACN 111 928 762) Second Respondent JINDAL STEEL AND POWER LIMITED Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 7 days of the date hereof, the parties file and serve draft minutes of orders to give effect to these reasons including on the question of costs, together with any necessary written submissions (limited to 3 pages each).

2. Liberty to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BEACH J:

1 UIL (Singapore) Pte Ltd (UIL) has brought proceedings against Wollongong Coal Limited (WCL), Wongawilli Coal Pty Ltd (Wongawilli) and Jindal Steel and Power Limited (JSPL) concerning the non-supply to UIL of coking or metallurgical coal.

2 The present issue before me concerns whether there was a waiver of legal professional privilege concerning various documents discovered by WCL, Wongawilli and JSPL. There is also a related question as to whether common interest privilege exists. But before turning to those questions I should say something more about the present proceedings.

3 UIL has advanced four principal claims against the respondents.

4 First, there is a claim for damages invoking various articles of the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (the Vienna Convention) which is brought against WCL for breach of a sale agreement entered into on 9 May 2014 between UIL and WCL under which WCL agreed to supply UIL with 500,000 metric tonnes of high ash, unwashed coking coal per annum.

5 Second, there is a claim for damages against Wongawilli for breach of a sale agreement between UIL and Wongawilli under which Wongawilli was also to supply UIL with 500,000 metric tonnes of high ash, unwashed coking coal per annum.

6 Third, there are claims against WCL, Wongawilli and JSPL for misleading or deceptive conduct relating to the negotiations which culminated in the parties’ entry into of a suite of agreements in May 2014.

7 Fourth, there are claims against JSPL and WCL for misleading or deceptive conduct in relation to the price and value of 150 million shares in WCL that were transferred to UIL (the relevant WCL shares) in connection with UIL’s entry into of a deed of settlement and release in May 2014 (the settlement deed).

8 Now these claims have given rise to various factual and legal issues.

9 Did the sale agreements give rise to enforceable obligations on the part of WCL and Wongawilli or did they amount to agreements to agree or were otherwise affected by uncertainty?

10 Did the respondents breach their respective sale agreements in the manner alleged by UIL? Did the breaches cause UIL to suffer any loss? And what was the nature, likelihood and value of the commercial opportunities that UIL lost as a result of such breaches?

11 Were the sale agreements representations, supply representations and settlement deed representations made in trade or commerce and with the necessary territorial nexus? Were the representations misleading or deceptive? Did UIL rely on the representations? Did it suffer any damage by reason of such misleading or deceptive conduct?

12 And did JSPL or WCL make any misleading or deceptive representations as to the share price or value of the relevant WCL shares? Did UIL rely on such representations concerning the share price and value of those shares? And did UIL suffer any damage by reason of such conduct?

13 Now before proceeding further it is also appropriate to note the following in terms of the corporate structure and ownership of the various parties and entities as such matters relate to the waiver questions before me.

14 At the relevant time JSPL, an Indian company, owned 100% of the issued capital of Jindal Steel & Power (Mauritius) Ltd (JSPML), a Mauritian entity. At the relevant time, JSPML owned more than 50% of the issued capital of WCL, an Australian entity. I should note that WCL was never a wholly owned subsidiary of JSPML. Further, at the relevant time, WCL owned or controlled 100% of the issued capital of Wongawilli.

15 So, in terms of the time frame relevant to the waiver questions, JSPL ultimate controlled or had the capacity to control both WCL and Wongawilli through JSPML. JSPL was the ultimate holding company in the Jindal Group. Moreover, for most purposes there is no reason to distinguish between JSPML and JSPL. The former at all times was a wholly owned subsidiary of the latter. More generally, and as a consequence thereof, it is convenient from time to time to refer to the Jindal Group.

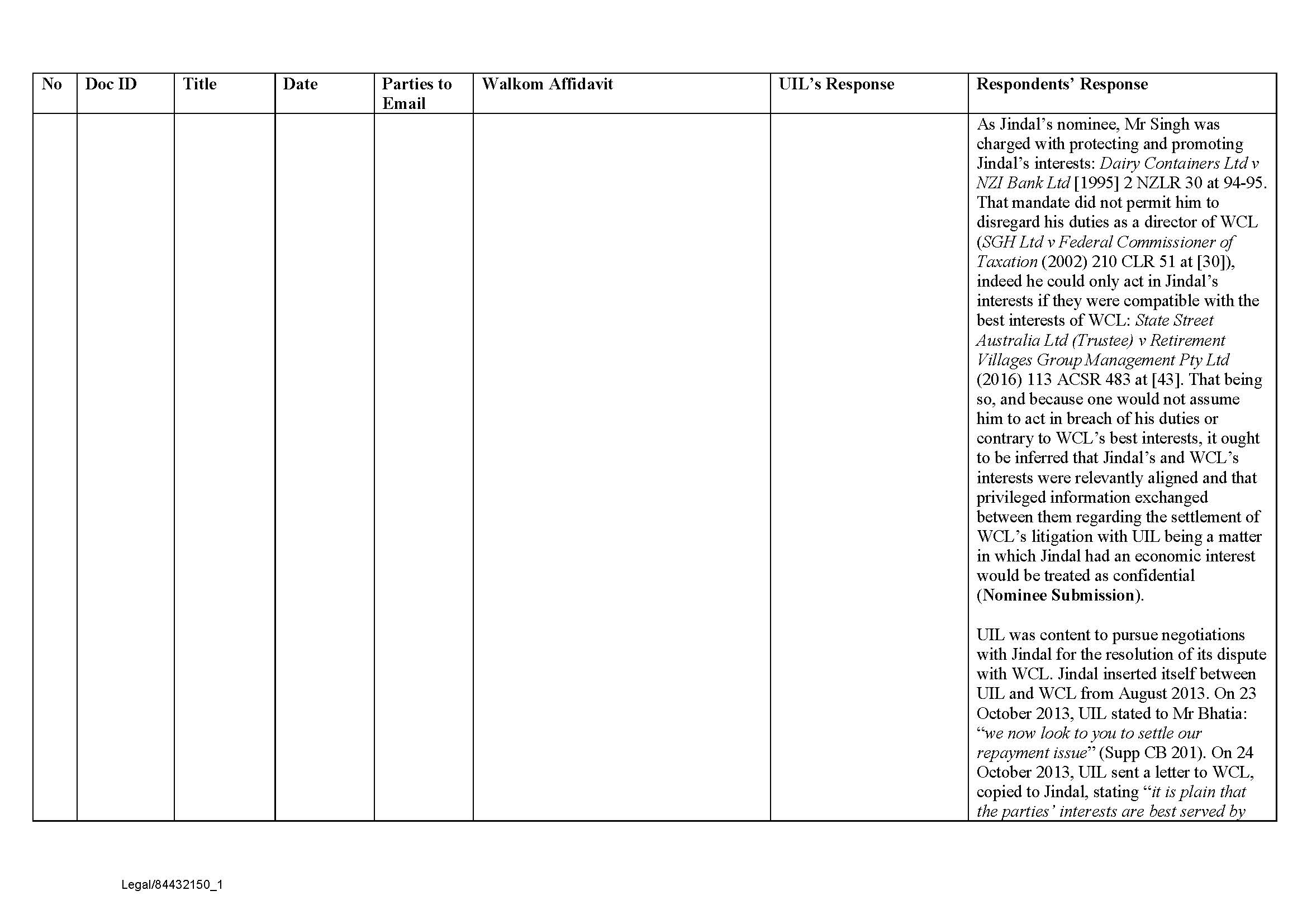

16 I should also note that at the relevant time Mr Rajesh Bhatia was a director of JSPL and JSPML. He left the Jindal Group in all capacities on 30 June 2017.

17 Further, at the relevant time, Mr Jasbir Singh was the chairman and CEO of WCL, being a nominee of the Jindal Group or JSPML specifically. Mr Singh left WCL in May 2015.

18 Further, Mr Milind Oza was a director of WCL and Wongawilli from 5 December 2016 to May 2022. He was also a nominee of the Jindal Group or JSPML specifically.

19 Further, Mr Sanjay Shama is the company secretary of WCL and Wongawilli and has been since November 2004. He is also a director of WCL and was appointed to this position on 6 May 2022. He had previously held the position of director of Wongawilli from 24 November 2004 to 20 October 2005. Further, from 6 May 2022 he was re-appointed and has been a director of Wongawilli. He has provided instructions to the respondents’ solicitors in the present case concerning the privilege claims.

20 I have set all of this out as one issue that arises is whether JSPL and WCL shared a common interest privilege in the settlement at the relevant time of WCL’s dispute with UIL, as ultimately embodied in the settlement deed.

21 Now before I turn to the various legal arguments concerning waiver and common interest privilege, it is necessary to say something more about the background to the relevant communications the subject of the privilege claims as disclosed by the documentary evidence before me.

Some relevant background

22 Prior to January 2013 WCL had been controlled by the Gujarat Group, the parent of which was Gujarat NRE Coke Limited, a listed public company in India.

23 On 31 January 2013, the Jindal Group announced an on-market takeover bid of WCL. As at the offer date, the Jindal Group, which then relevantly included Jindal Steel and Power (Australia) Pty Ltd, a wholly owned subsidiary of JSPML, which in turn was a wholly owned subsidiary of JSPL, held in the aggregate 268,072,803 shares in WCL. At the time, that holding represented a relevant interest of 19.48% in WCL.

24 Now although the on-market takeover bid failed, the Jindal Group through JSPML increased their holding in WCL to 31.49% by 28 March 2013. Nevertheless, the Gujarat Group retained control, holding in aggregate 63.95% of the issued shares in WCL at that time.

25 Now throughout this period, WCL was in a difficult if not parlous financial state.

26 As at 31 March 2013, WCL and its controlled entities had made a loss (after tax) of $76.59 million over the relevant financial year, and had a liquidity deficiency of current liabilities exceeding current assets by more than $400 million. It would appear from the accounts that were in evidence that a substantial amount of its current liabilities were the result of a re-classification on account of breaches of financial covenants with its lenders.

27 In May 2013, WCL attempted to raise $69 million through a partially underwritten rights issue. But this attempt failed, raising only $35,135.

28 On 3 July 2013 the WCL Board resolved to accept and to put to its shareholders a recapitalisation proposal from the Jindal Group. The Jindal Group had offered funding of $15 million on terms which contemplated the parties entering into an off-take agreement for 60% of WCL’s “run of mine” coal and a convertible note deed and agreeing to the appointment of a nominee of the Jindal Group to the Board of WCL.

29 On 8 July 2013 JSPML advanced $15 million to WCL.

30 On 25 July 2013, WCL and UIL entered into an override deed, following WCL’s earlier default under a coal purchase agreement with UIL entered into on 25 March 2013. Under the override deed, WCL agreed that it would repay UIL $20 million plus interest in instalments. The final repayment date was 31 August 2013.

31 On 29 July 2013, WCL and JSPML executed a binding terms sheet which contained the key commercial terms of the deal contemplated in the 3 July 2013 WCL Board resolution. The terms sheet obliged WCL to apply the $15 million, and any further tranche up to $10 million, towards payment of WCL’s creditors. Further, there was to be a convertible note deed which was to be secured by a charge over all the assets and undertaking of WCL. Further, it was contemplated that there would be a placement of 328.5 million shares and an agreement by the Jindal Group to subscribe for those shares for a total consideration of $68,824,765.80. As part of this arrangement, WCL was required to apply US$2.5 million from the placement proceeds towards the payment of another creditor.

32 The terms sheet also made provision for the WCL Board to be reconstituted with one nominee from the Gujarat Group, one nominee from the Jindal Group, and for the existing two non-executive directors to resign should they be requested to do so by the Jindal Group, for replacement with two further Jindal Group nominees. Mr Singh, as the Jindal Group’s nominee, was appointed to the WCL Board on 29 July 2013.

33 On 1 August 2013, WCL lodged an announcement with the ASX as to the entry into of the binding terms sheet. The announcement described the transaction and noted that “the Board has been restructured to accommodate Mr. Jasbir Singh being the nominee director of the Jindal Group, following the resignation of Mrs. Mona Jagatramka.”

34 On 5 September 2013, WCL’s solicitors wrote to the ATO, in response to two statutory demands that the ATO had served on WCL and Wongawilli for debts totalling $8,683,005.41. The letter stated:

…

In order to overcome significant cash flow issues and to reframe the ongoing operations of [WCL], the significant shareholders, Jindal Steel & Power (“JSPL”) has agreed to contribute further capital up to $66 million to increase its stake in [WCL], from 31.5% to 44%. That increase in share ownership will see JSPL become the largest single shareholder in [WCL] and, it will see substantial reframing and reshaping of [WCL]’s operations and in particular, secure its financial success.

…

As a sign of good faith, JSPL has already paid $34 million to [WCL] in last 8 weeks mainly to support ongoing weekly cost including salaries/wages, PAYG and other ongoing obligations.

…

JSPL has indicated informally that it will be agreeable to releasing further funds upon the ASX and ASIC agreeing to the form of notice to shareholders for the anticipated shareholders meeting.

Our client hopes that it will be in a position to issue the notice of the meeting to shareholders in the next few days and this will hopefully see formal approval being given to the proposed acquisition by JSPL in the early weeks of October this year.

[WCL] with JSPL have seen also that there is an ongoing need to ensure that the future expansion and operations of the Collieries are properly funded. With JSPL, [WCL] has received sanctions for a bank loan of $76 million US as a total refinancing package of some $200 million. The present terms of the refinancing of $200 million is being undertaken with a consortium of banks which are under advanced further negotiation.

…

We request that you indicate by return that the ATO will not proceed to file proceedings seeking the winding up of [WCL] and that it will give a further period of grace to permit our client to complete the reorganisation of its share structure with JSPL and seek the utilisation of further funds which will be received in the coming weeks.

…

35 So, there was to be an intimate relationship between WCL and the Jindal Group.

36 Earlier, on 30 August 2013, the eve of the final repayment date under the override deed, WCL provided UIL with a letter signed by JSPML. The letter stated:

…

As you are aware, we have executed a term sheet with [WCL], pursuant to which we have agreed to inject an amount of AUD 65 Mn approx. by way of issue of Convertible Note and the placement of shares. Out of said amount, we can advance an amount equivalent of USD 15 Mn to [WCL] to enable [WCL] to repay the balance outstanding advance of 15 Mn.

…

37 The Jindal Group and WCL thereafter jointly pursued negotiations with UIL for the repayment of its debt.

38 On 23 October 2013, there was an exchange of emails between UIL and the Jindal Group, where it was stated:

Spoke to Rajesh Bhatia yesterday after his return from Australia. Have made our claim for this repayment to him but his contention was that he is still in the process of taking over the control from Arun and therefore not in a position to decide.

…

Will talk to Mr. Bhatia again today to find out any other avenue for this repayment including some cargo. There could also be a meeting with Navin Jindal around Diwali with you.

…

39 This then led to an email from UIL to the Jindal Group on the same day:

Thank you for returning my call yesterday. As discussed, we now look to you to settle our repayment issue in NRE at the earliest. …

40 By 24 October 2013, the debt remained outstanding. UIL wrote to JSPML, WCL (then known as Gujarat NRE Coking Coal Limited) and Gujarat NRE India Pty Ltd, which was the owner of shares in WCL which had been pledged to UIL as security for WCL’s obligations under the override deed. The letter took the form of a demand, and provided:

Override Deed dated 25 July 2013 and related matters

We refer to our previous discussions and correspondence in relation to amounts owing to UIL (Singapore) Pte Ltd (UIL) under the Override Deed dated 25 July 2013 (Override Deed) between UIL, Gujarat NRE India Pty Limited (Gujarat India), Gujarat NRE Coking Coal Limited (GNM) and Argonaut Securities Pty Ltd (Argonaut).

1. As you are aware:

(a) UIL has exercised its rights under the Override Deed and related Specific Security Deed (Shares) dated 26 March 2013 (Specific Security Deed) between Gurajat India and UIL, and has taken possession of 150 million GNM shares owned by Gujarat India;

(b) Jindal Steel & Power (Mauritius) Limited (Jindal) has put a re-capitalisation proposal to GNM and the same has been approved in the general meeting of GNM on Wednesday, 16 October 2013;

(c) Jindal has previously offered to commit an amount equivalent to USD15 million to GNM to enable GNM to repay the amounts outstanding to UIL under the Override Deed out of the amounts Jindal will commit to GNM as part of the re-capitalisation proposal; and

(d) UIL has made a number of demands for payment of the amount outstanding under the Override Deed, and maintains its demands for repayment.

2. In the event UIL is paid the amount outstanding under the Override Deed in full, it is willing to return the shares it has taken possession of under the Override Deed and Specific Security Deed.

3. It is plain that the parties’ interests are best served by Jindal’s re-capitalisation proposal going ahead, and arrangements being made for immediate repayment of the amounts outstanding under the Override Deed.

4. The current amount outstanding under the Override Deed is US$ 14,136,624.00 calculated as follows:

…

5. To facilitate a ready resolution of this matter, please indicate, by 5pm on Friday, 25 October 2013, that you will make immediate arrangements for repayment of the total amount outstanding under the Override Deed to UIL by 31st October 2013. In the event you give that indication, UIL is prepared for that payment, plus any additional interest accruing between now and the date of payment, to be subject to an appropriate escrow arrangement whereby the money paid to UIL would not be released until UIL had delivered documents to effect the re-transfer of the GNM shares to Gujarat India.

6. Once that indication is given, we will arrange for documentation to be prepared to effect the repayment and re-transfer of the shares to the mortgagor Gujarat India. Once prepared, that documentation can also be held in an appropriate escrow arrangement.

7. If you do not provide the indication sought in paragraph 5 above by 5pm on Friday, UIL reserves its rights under the Override Deed, Specific Security Deed and related documents, including to take any step UIL considers necessary or appropriate to recover the amounts owed to it under the Override Deed.

We look forward to your response.

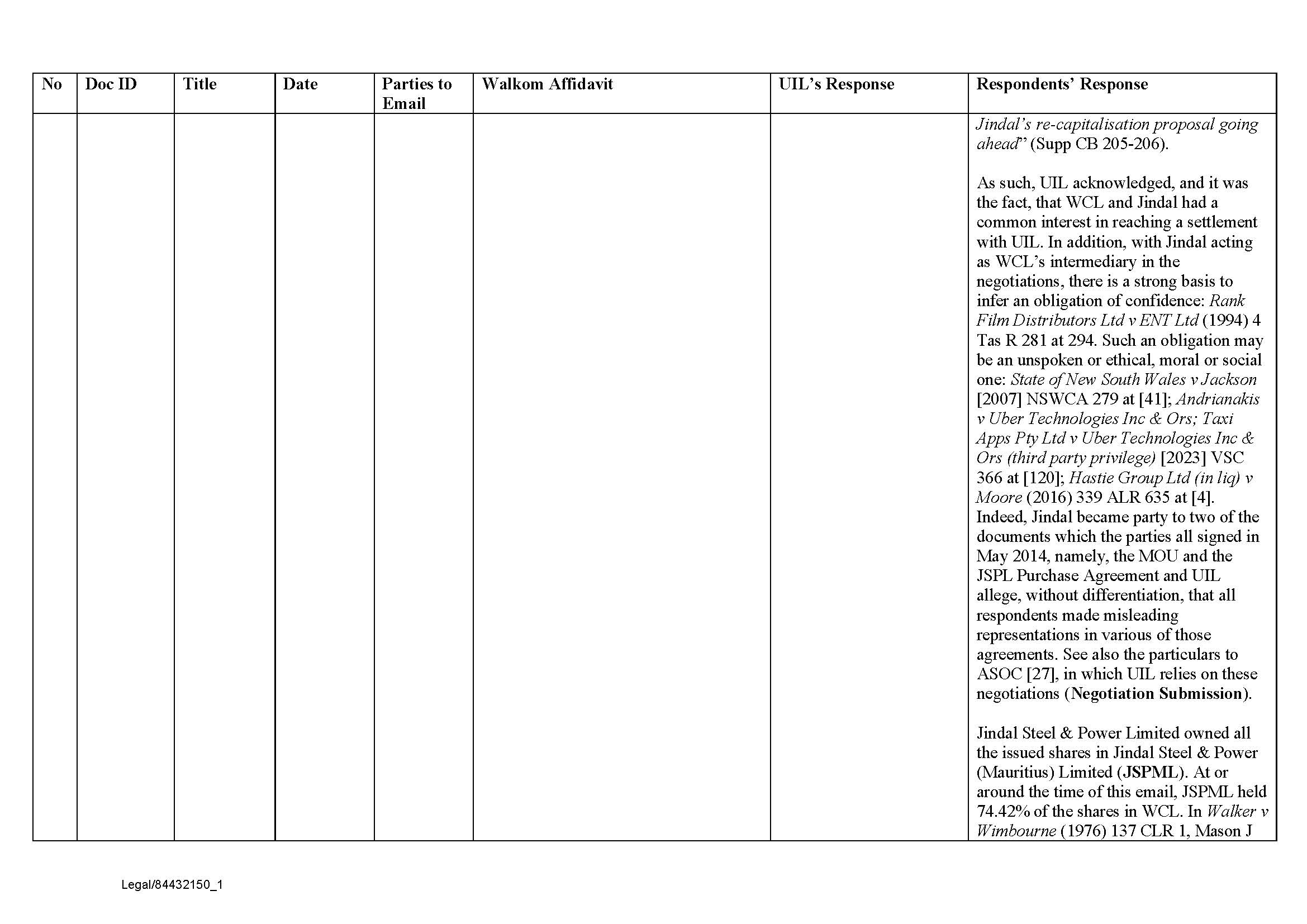

41 On 28 October 2013, WCL released an ASX announcement that Mr Singh had been appointed as chairman and interim chief executive officer, effective 26 October 2013. The letter went on to state that “Mr Singh heads Jindal operations in Australia”.

42 On 20 December 2013, WCL released its half yearly report for the period 1 April 2013 to 30 September 2013. The report acknowledged that the Jindal Group had advanced $42 million to WCL by 30 September 2013. In a note to the accounts, it was observed that JSPL had acquired majority control on 15 November 2013, holding a relevant interest of 53.63% in WCL, and that since that date, it had invested a further $58 million and increased its holding to 65.84% by 2 December 2013. In another note to the accounts it was stated that the directors were of the view that WCL remained a going concern, including because JSPL had “injected over $110 million into the company over the past three months”.

43 In summary, throughout 2013 the Jindal Group pursued and implemented a significant recapitalisation strategy concerning WCL. As part of that strategy, the Jindal Group appointed its nominee to the WCL Board, who subsequently became chairman and CEO, acquired majority control, injected over $110 million into WCL’s coffers and assisted WCL in its negotiations with creditors, including UIL.

44 Moreover, it is readily apparent from the evidence that UIL considered it expedient to involve the Jindal Group in its negotiations with WCL.

45 Further, in terms of the relationship between WCL, JSPML and JSPL, and communications between UIL and JSPL, the respondents’ solicitor also gave the following evidence:

[There] are the following two documents dated 31 January 2013 and downloaded from the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) website (respectively, HopgoodGanim First Letter and HopgoodGanim Second Letter). [T]he HopgoodGanim First Letter states in part that Mr Rajesh Bhatia is a director of Jindal Steel & Power (Mauritius) Ltd (JSPML) and the HopgoodGanim First Letter states in part that JSPML is a wholly owned subsidiary of JSPL.

…

[There] is an internal email dated 22 October 2013 between personnel of UIL (Singapore) Pte Ltd (UIL), the plaintiff in these proceedings, which has been discovered by UIL in these proceedings … The UIL October 2013 Email states in part:

Spoke to Rajesh Bhatia yesterday after his return from Australia. Have made our claim for this repayment to him but his contention was that he is still in the process of taking over the control from Arun and therefore not in a position to decide...Will talk to Bhatia again today to find out any other avenue for this repayment including some cargo. There could also be a meeting with Navin Jindal around Diwali with you...

[There] is an email dated 23 October 2013, whereby Mr Arvind Prasad of UIL emailed Mr Rajesh Bhatia of JSPL. … The Second October 2013 Email records in part:

Thank you for returning my call yesterday. As discussed, we now look to you to settle our repayment issue in NRE at the earliest. As you know, it is already seven months since we paid this amount and helped the company at a very crucial time in March end but that good gesture has now become a nightmare for our business.

…

On 30 October 2013, UIL issued a letter of demand to:

(a) WCL;

(b) Jindal Steel & Power (Mauritius) Limited (JSPML);

(c) Gujarat NRE India Pty Limited,

(October 2013 Demand).

…

The October 2013 Demand records, in part:

…

(b) Jindal Steel & Power (Mauritius) Limited (Jindal) has put a re-capitalisation proposal to GNM and the same has been approved in the general meeting of GNM on Wednesday, 16 October 2013;

(c) Jindal has previously offered to commit an amount equivalent to USD15 million to GNM to enable GNM to repay the amounts outstanding to UIL under the Override Deed out of the amounts Jindal will commit to GNM as part of the re capitalisation proposal ...

The final paragraph of the October 2013 Demand, includes a reservation of rights to “take any step UIL considers necessary or appropriate to recover the amounts owed to it under the Override Deed.”

On 6 March 2017, UIL sent a letter of demand to WCL and JSPL. …

…

[There is] the 2013-14 Annual Report prepared for JSPL for the year ended 31 March 2014 which state(s) that JSPML is a 100% owned subsidiary of JSP.

46 Clearly there were relevant interactions between UIL and JSPL in 2013 and involving WCL.

47 Let me now turn to the waiver questions.

Waiver of privilege

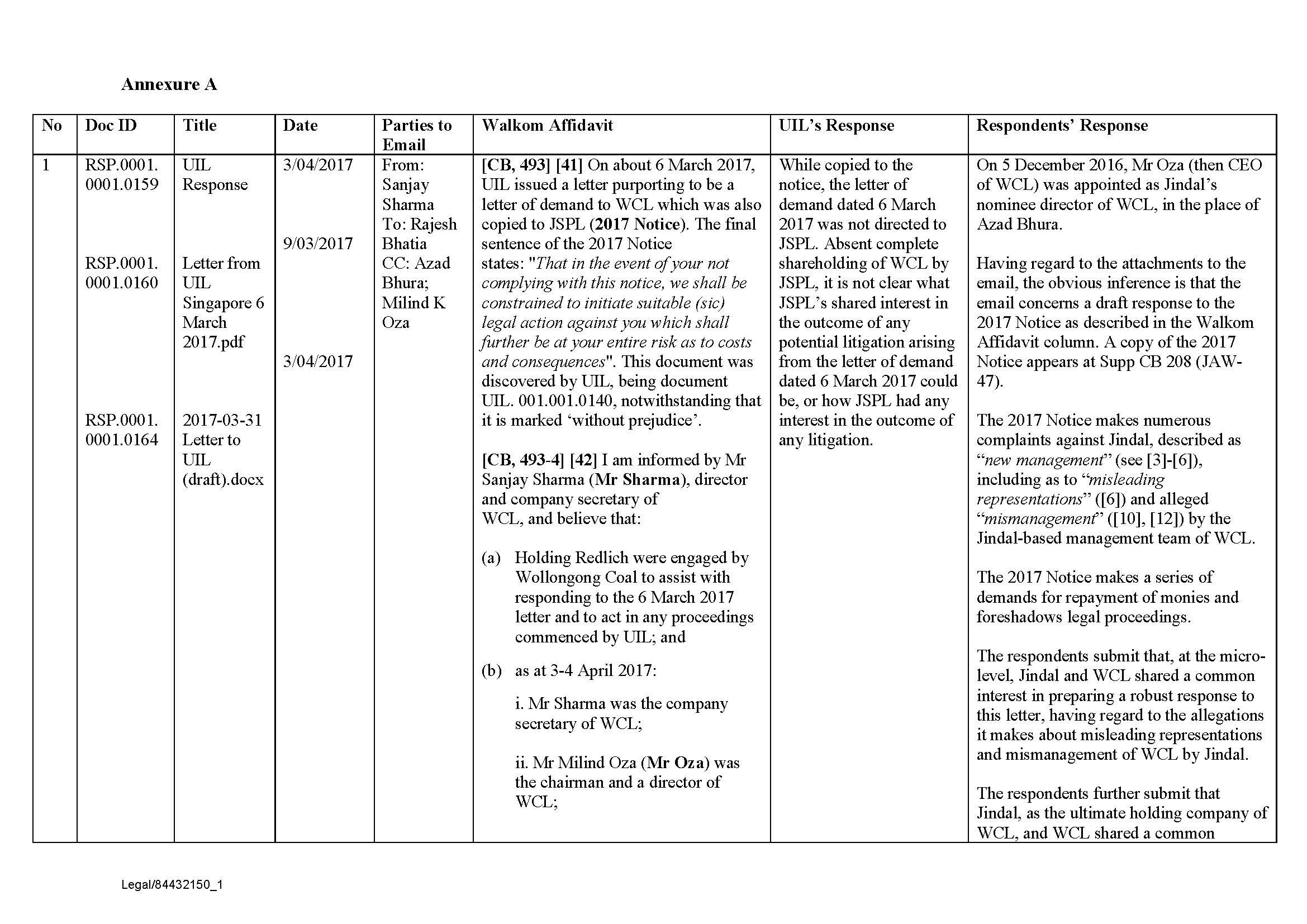

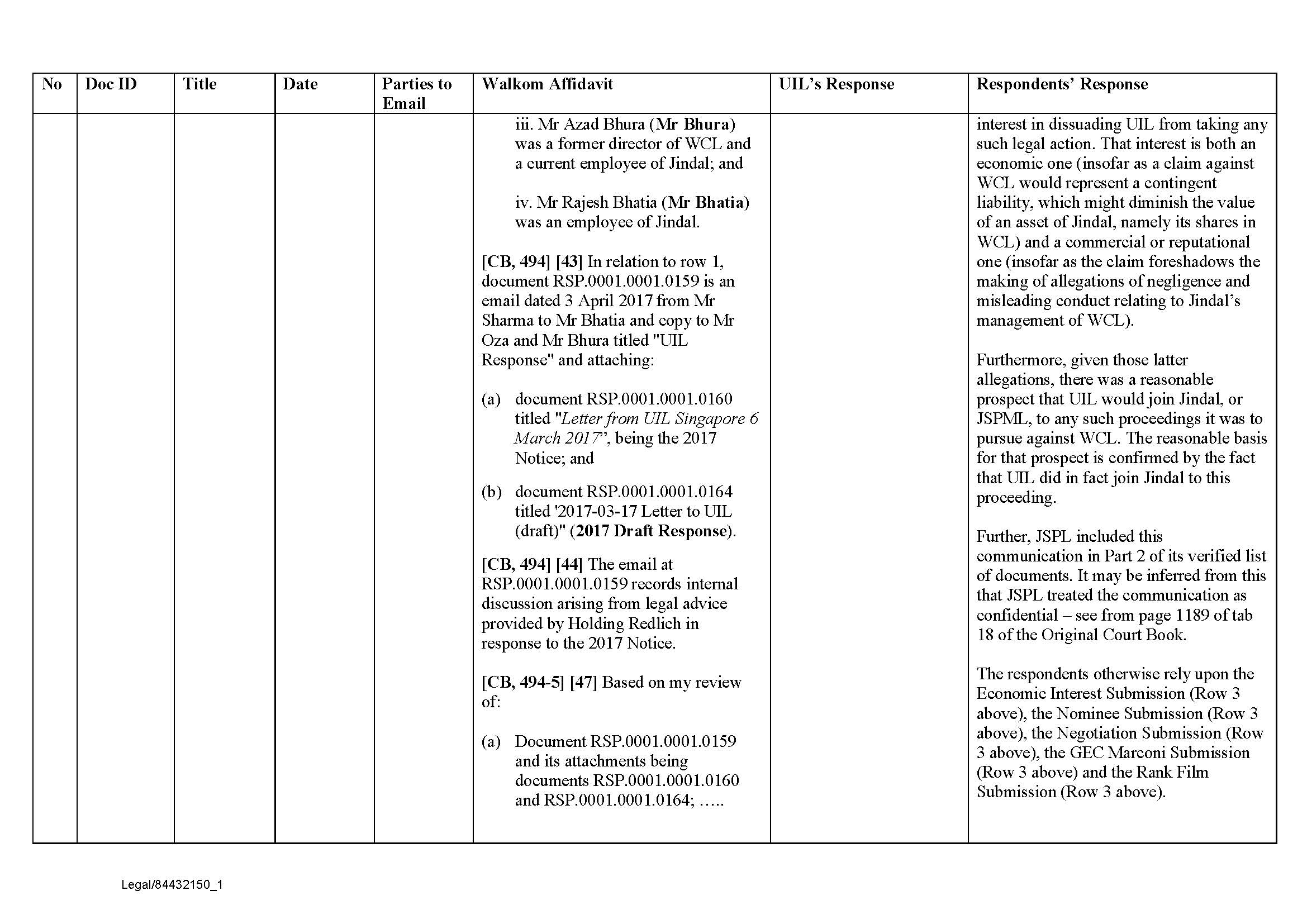

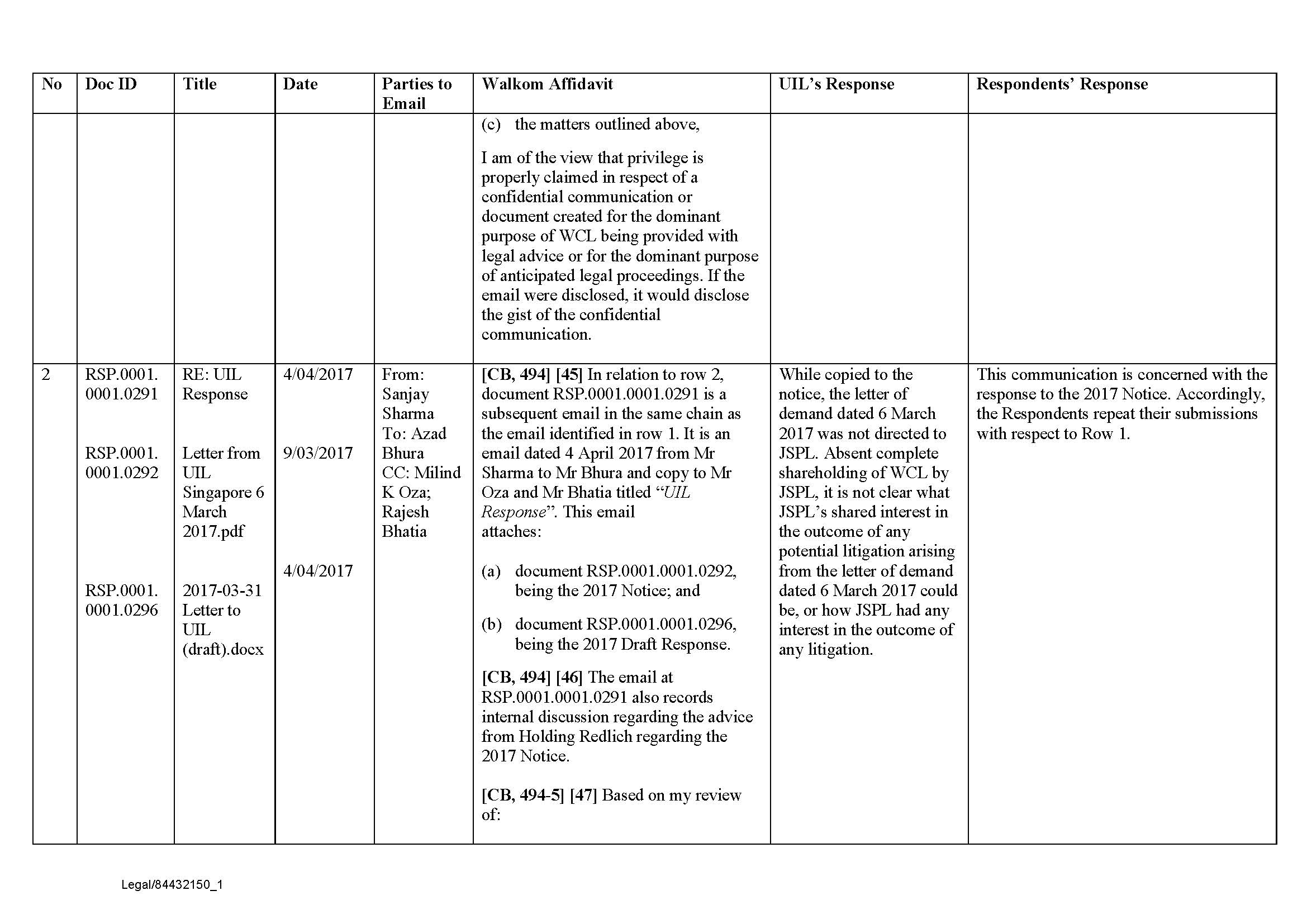

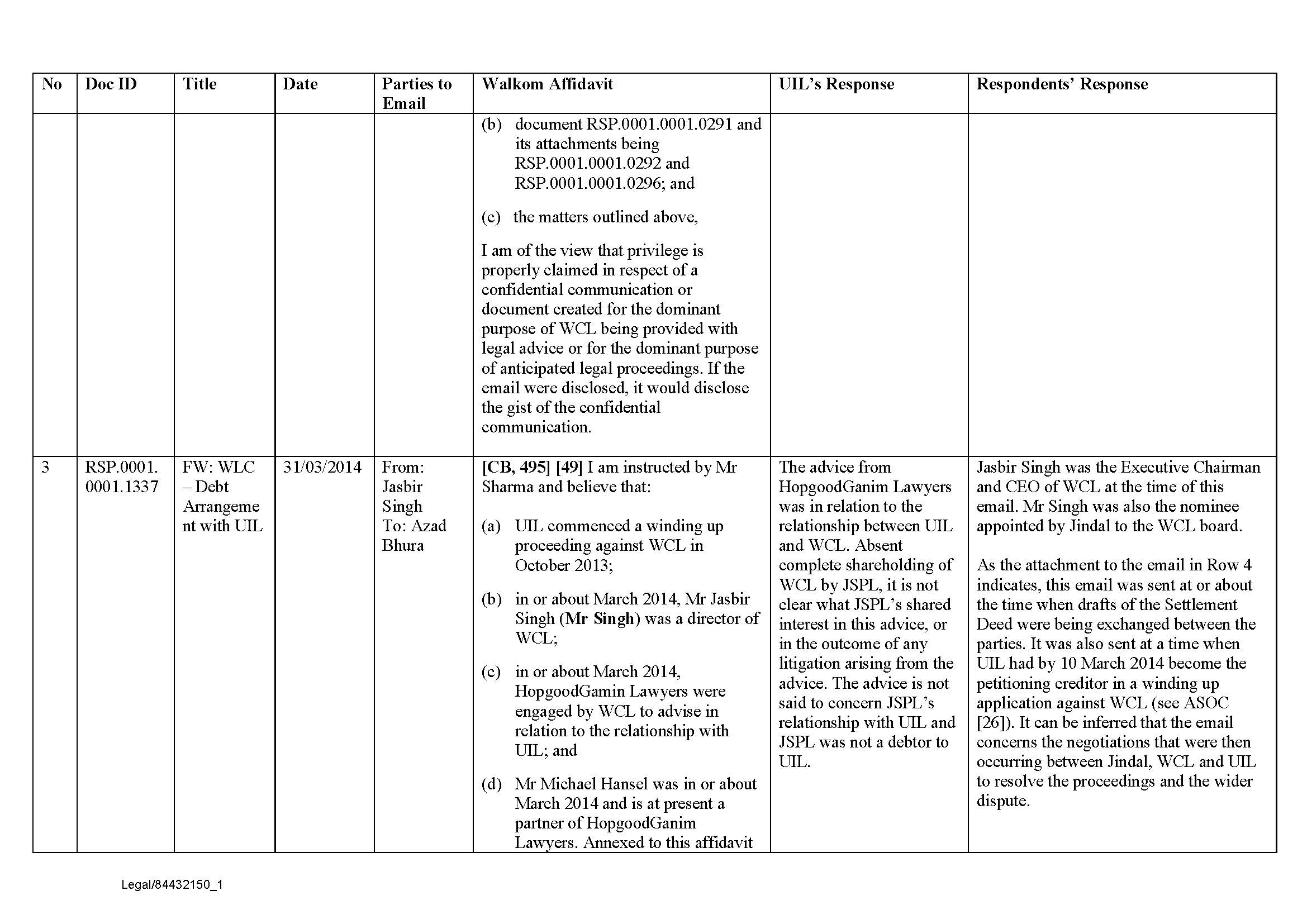

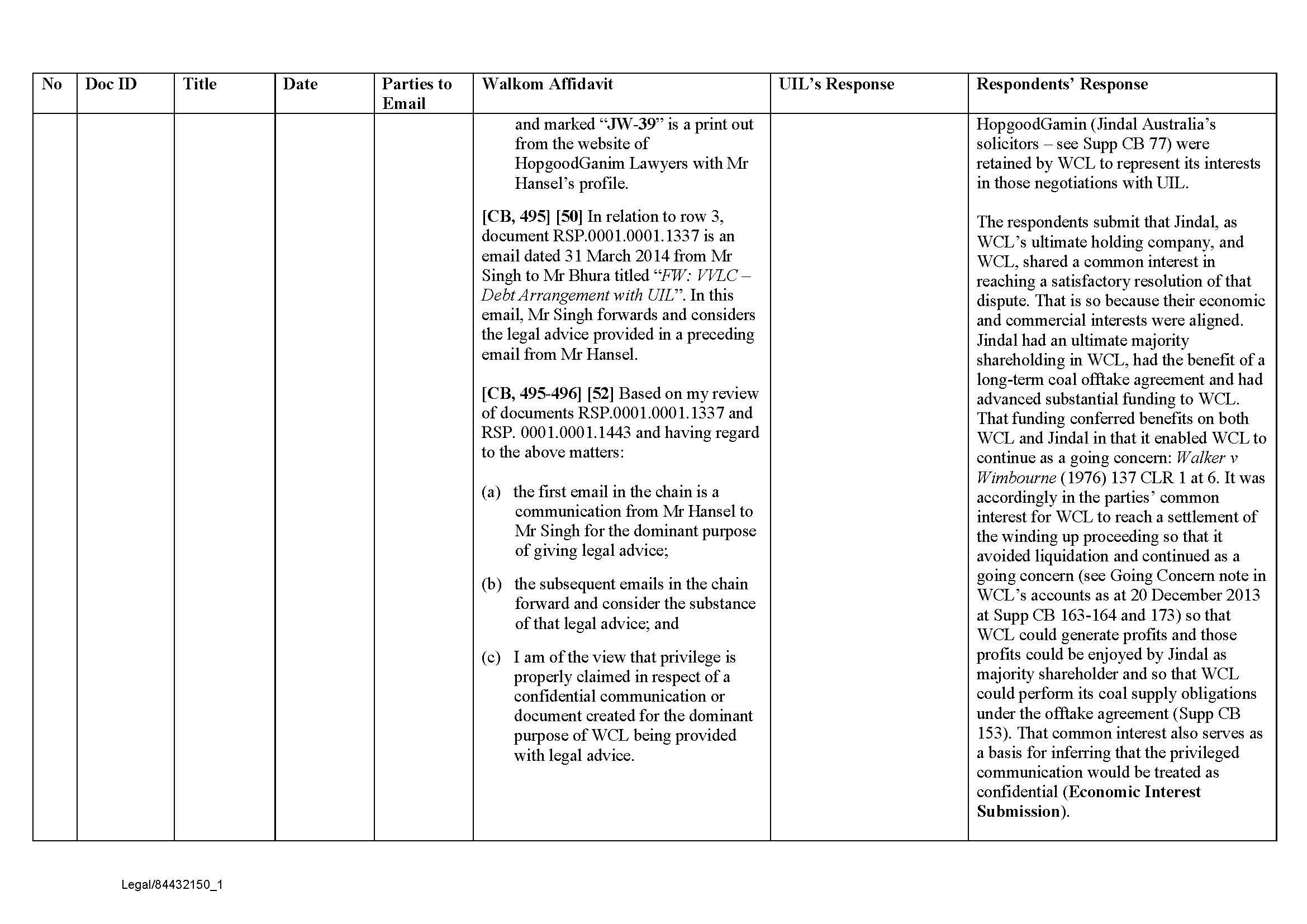

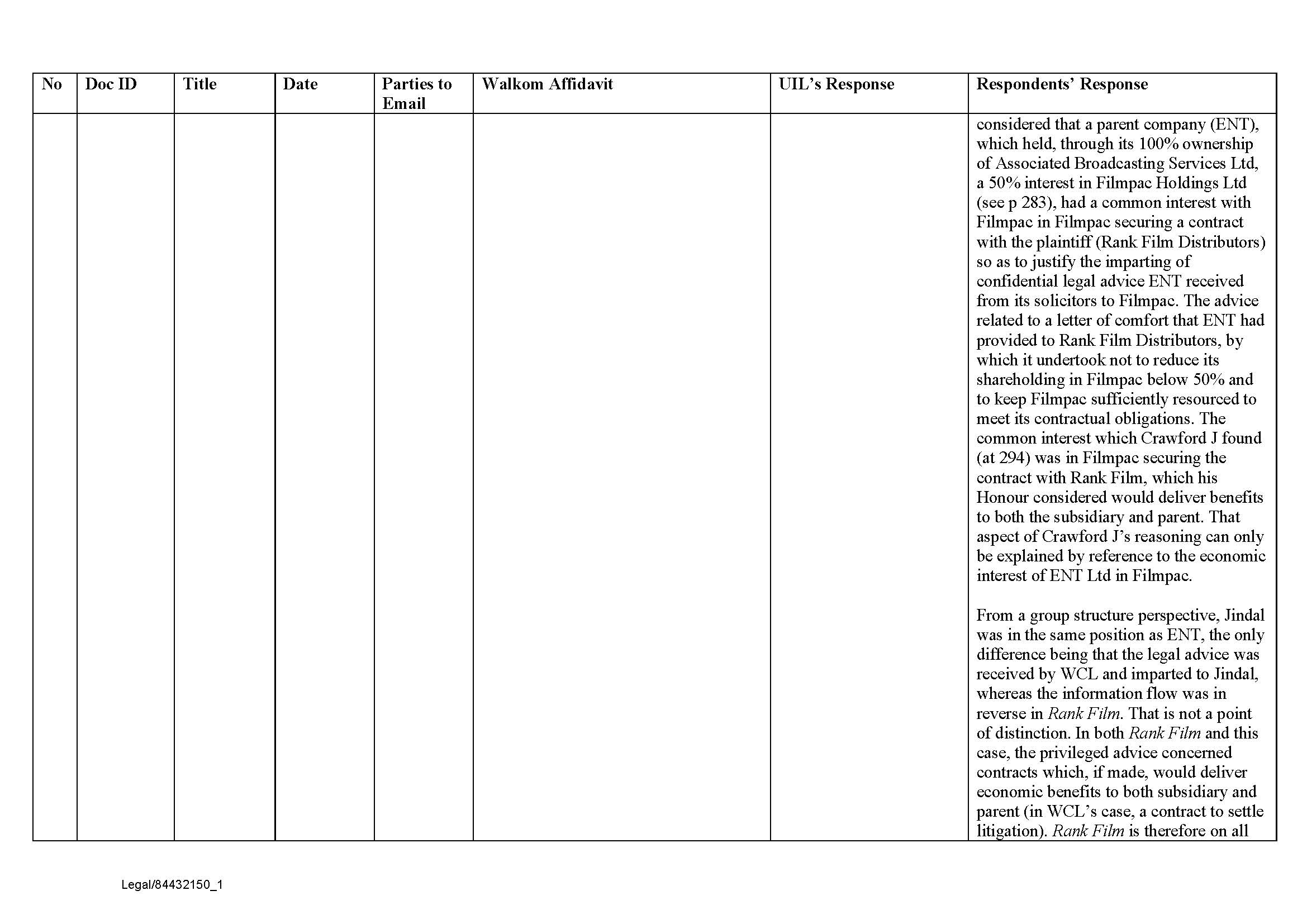

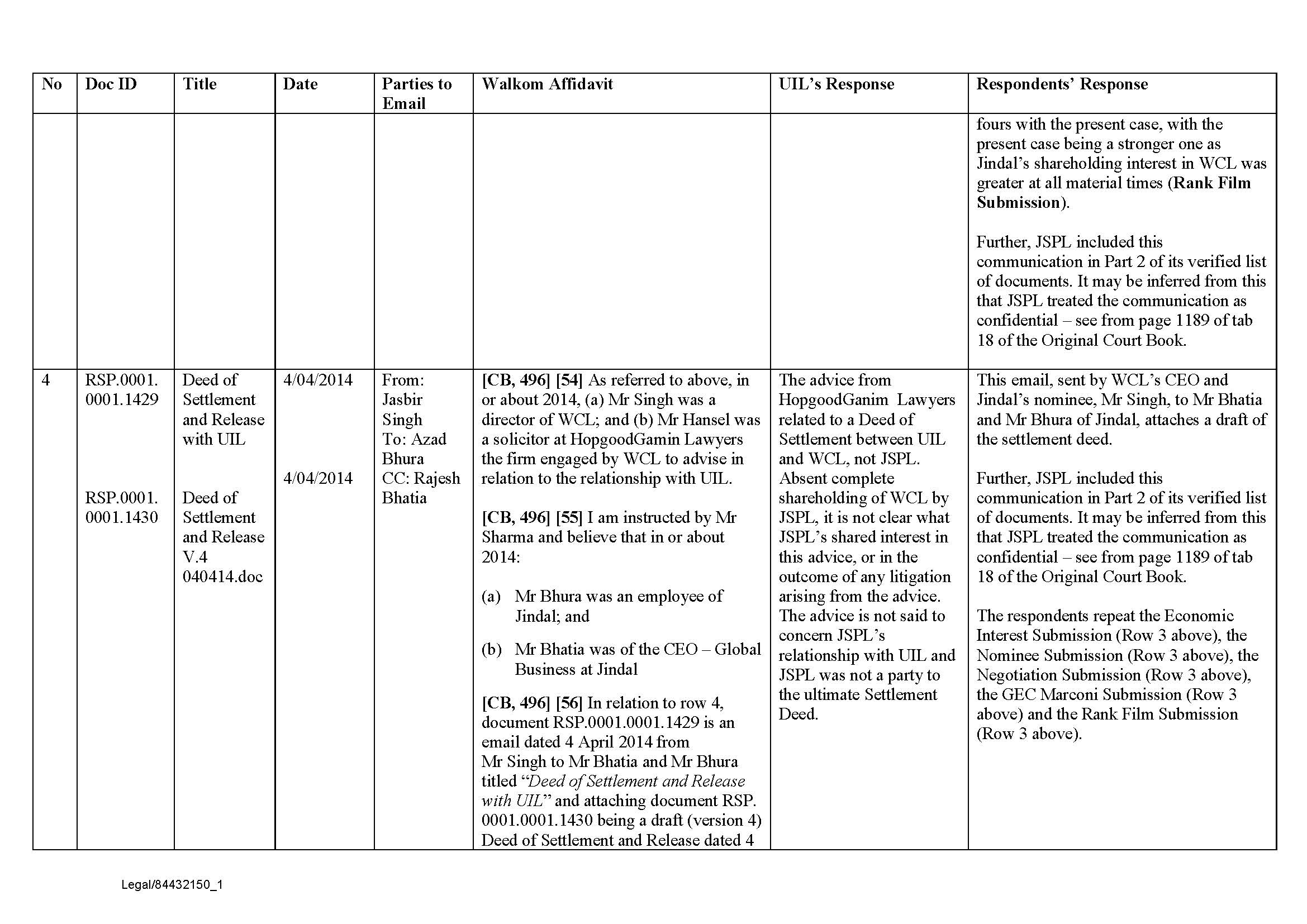

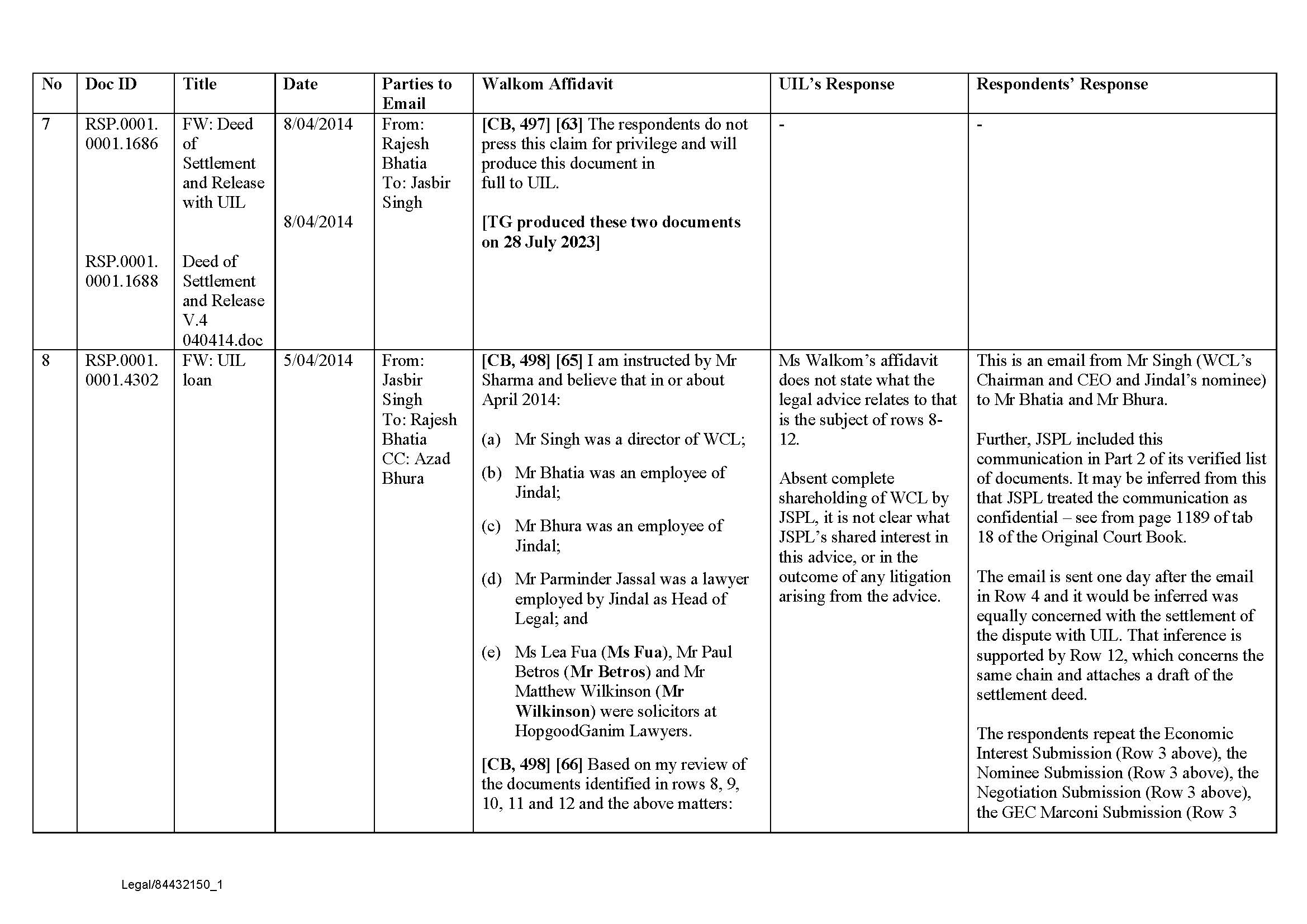

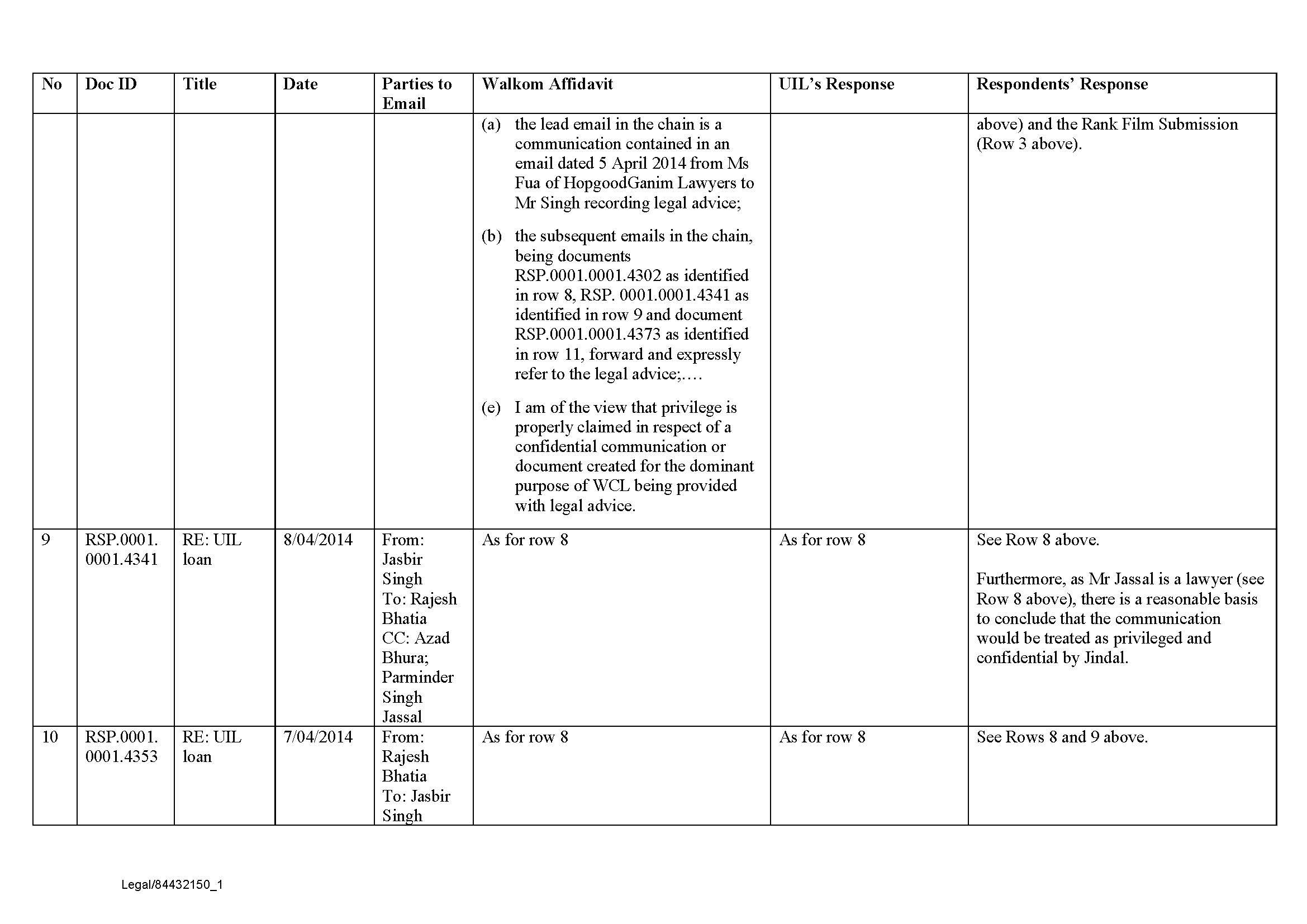

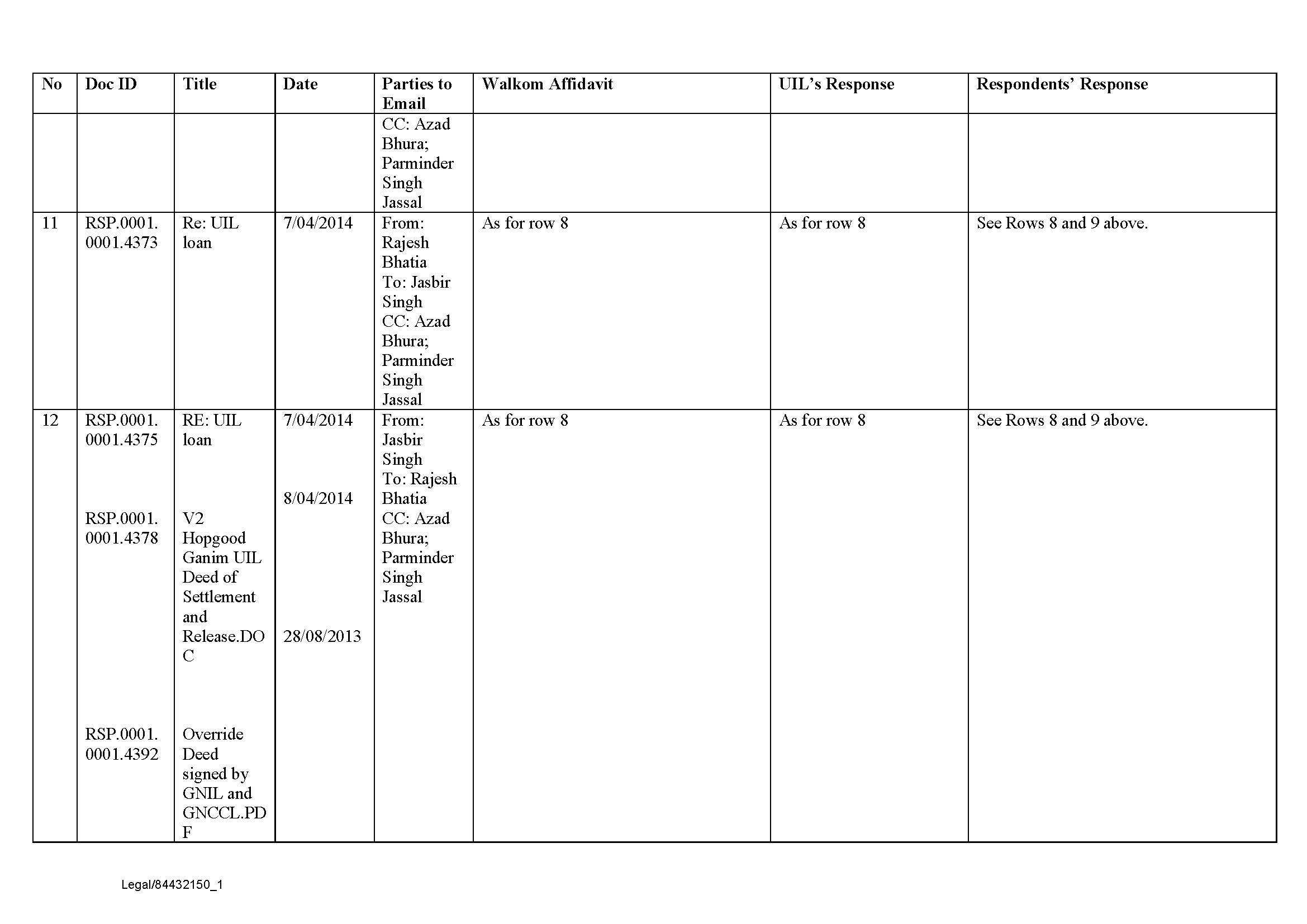

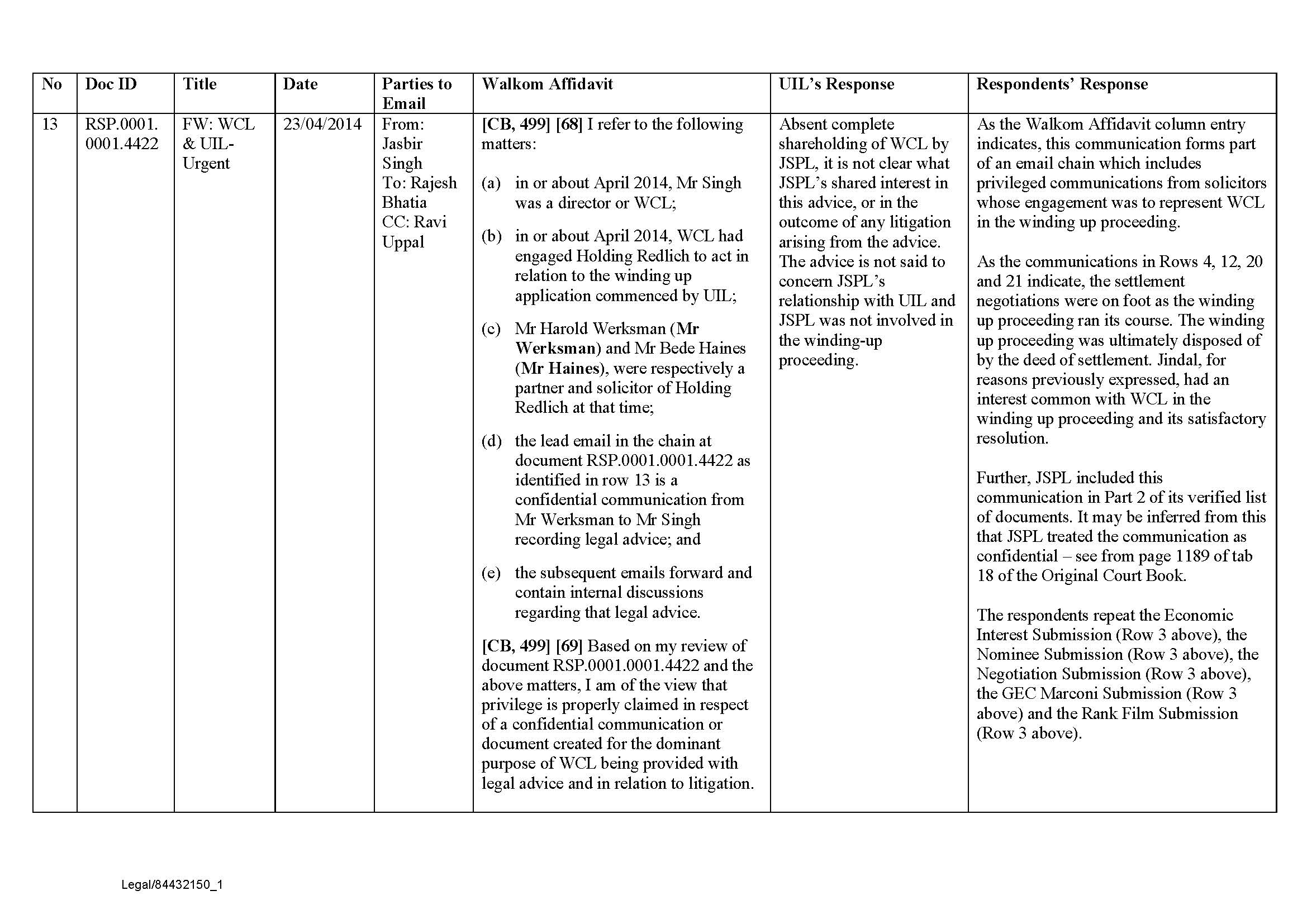

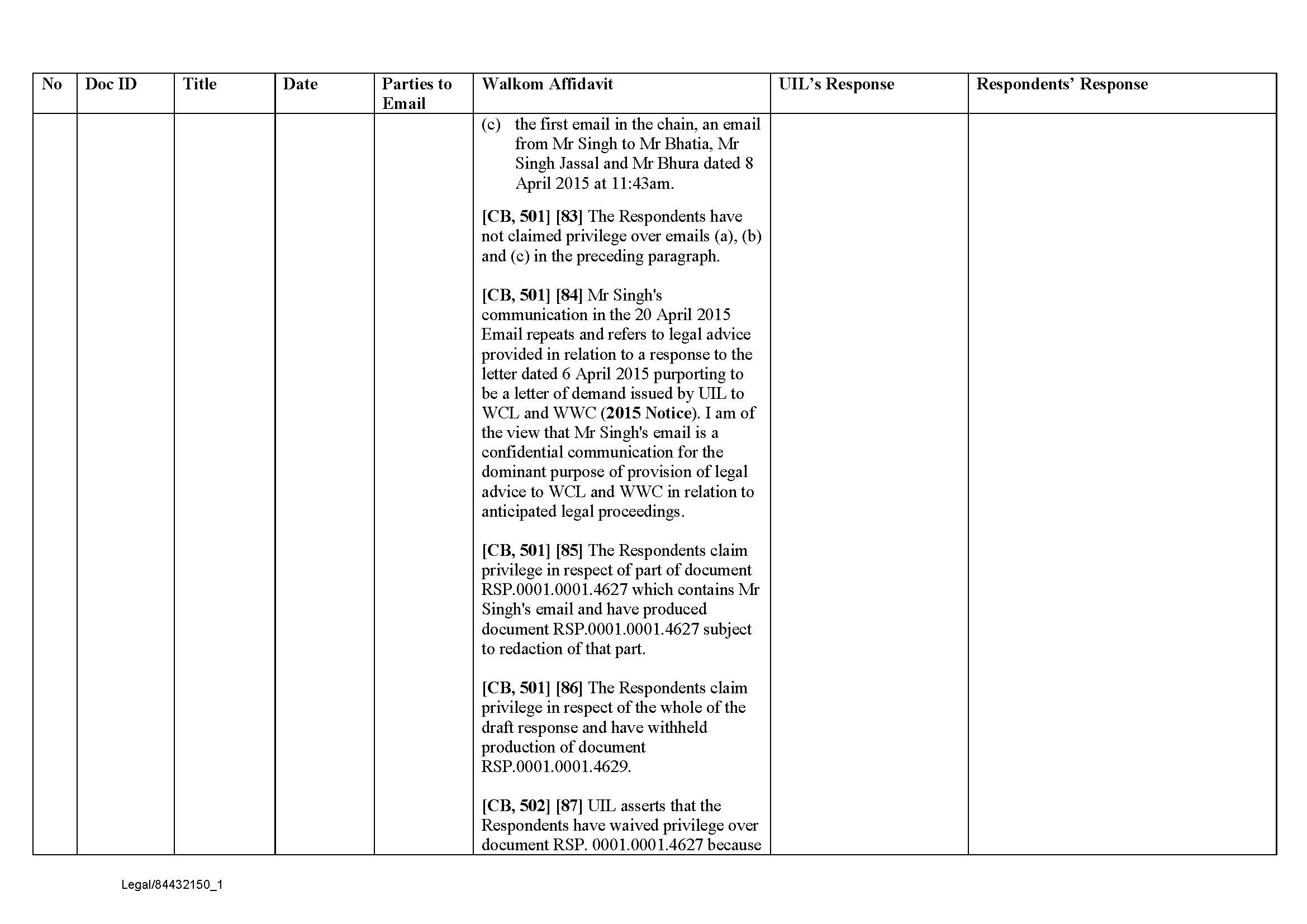

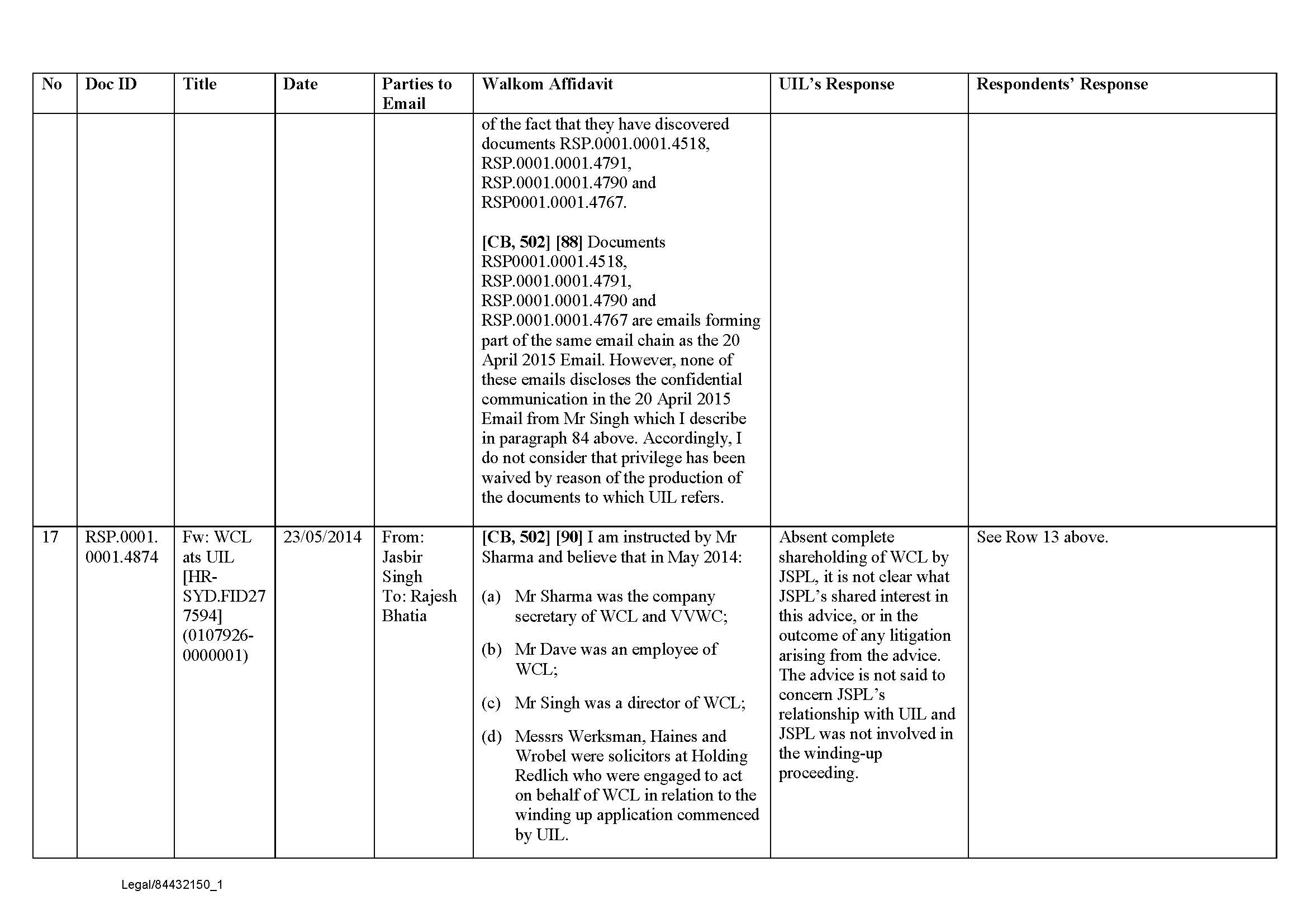

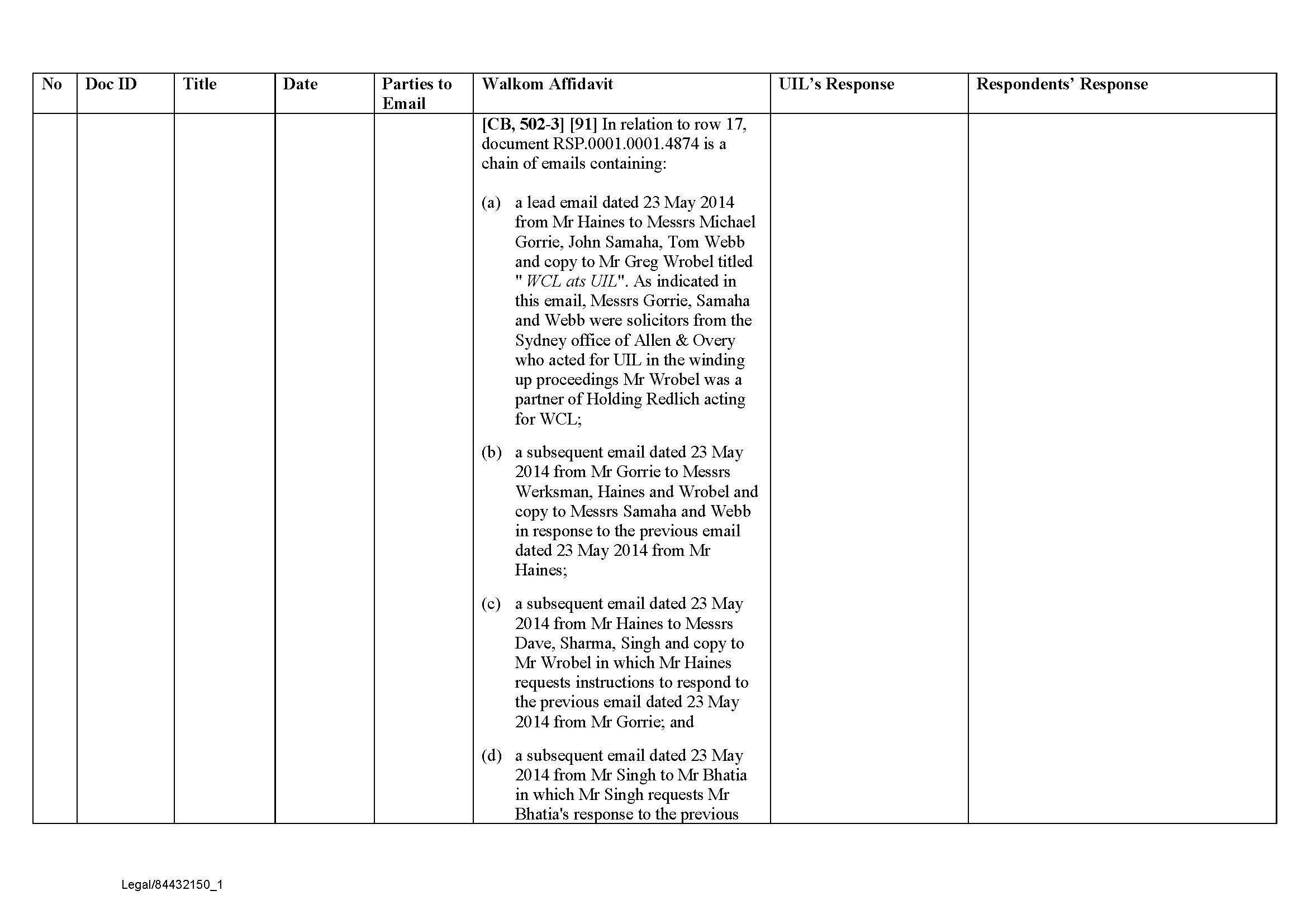

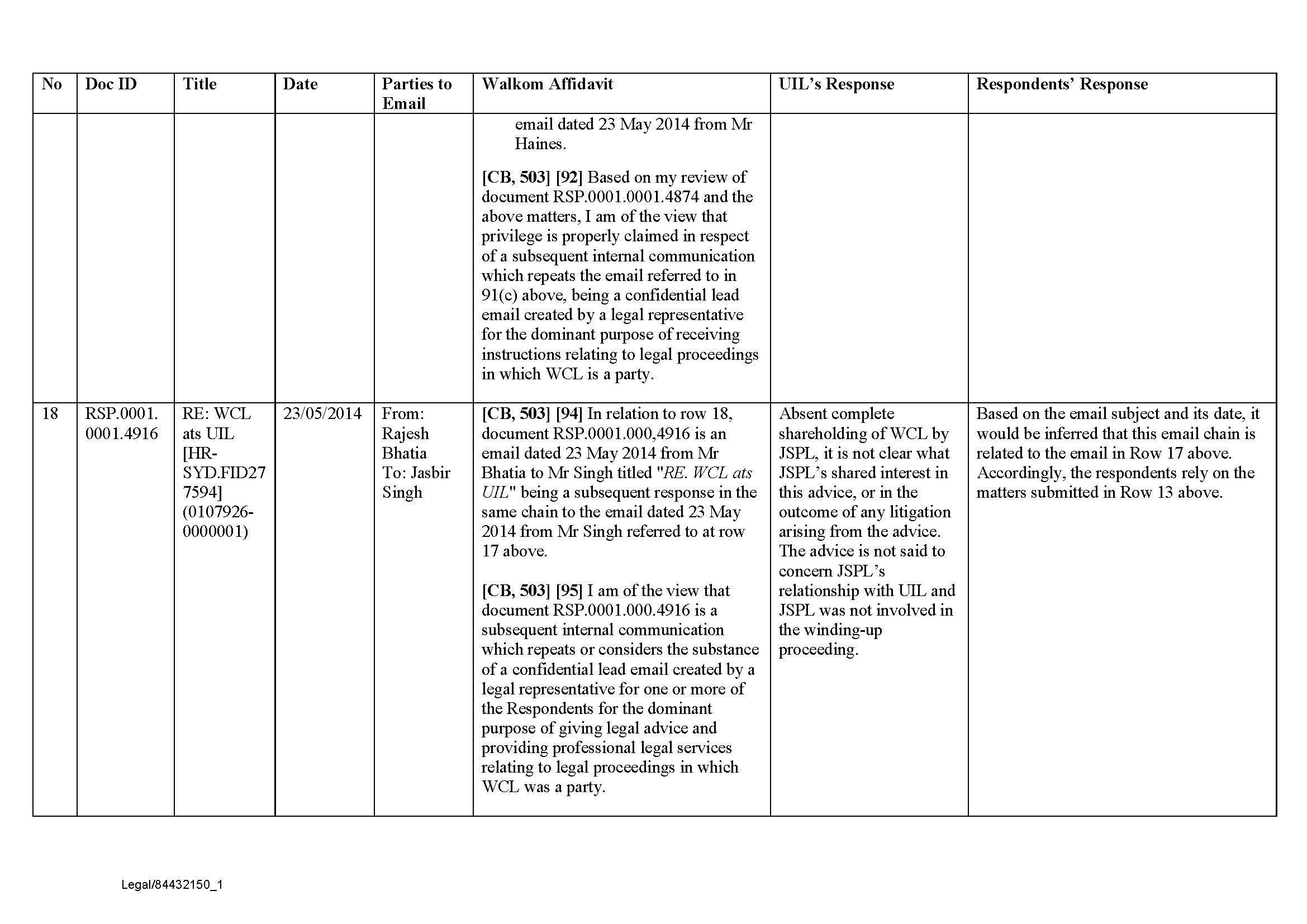

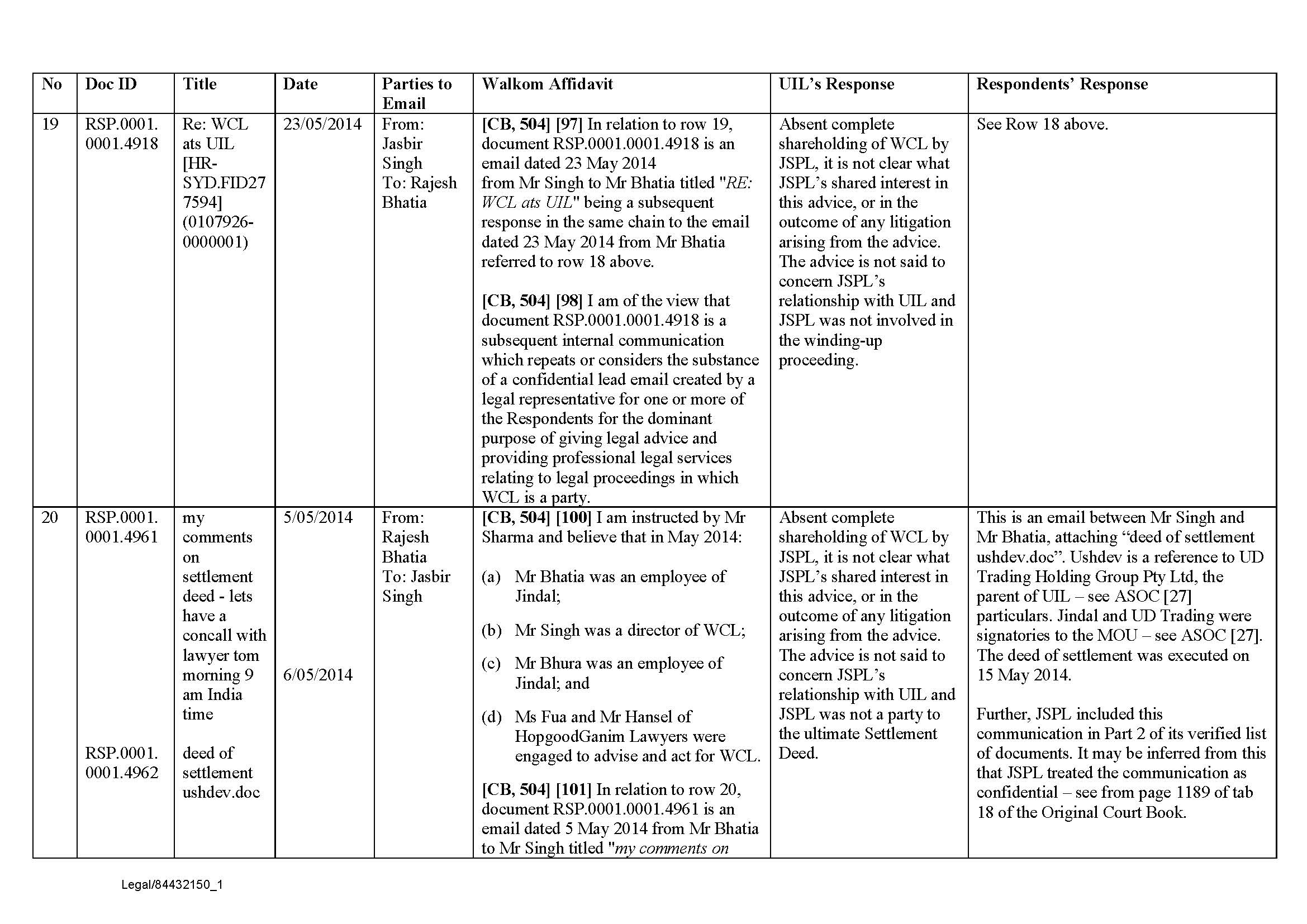

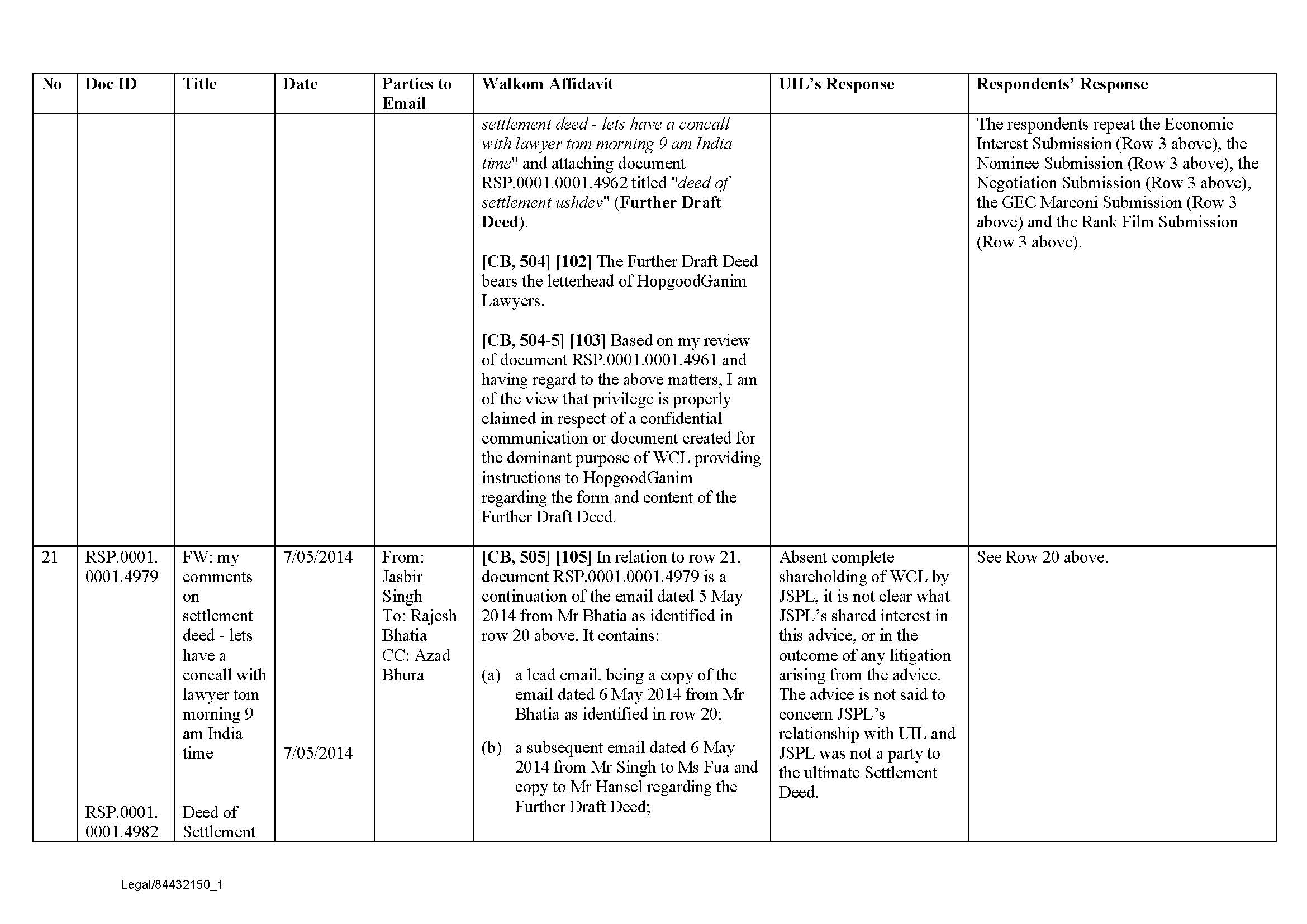

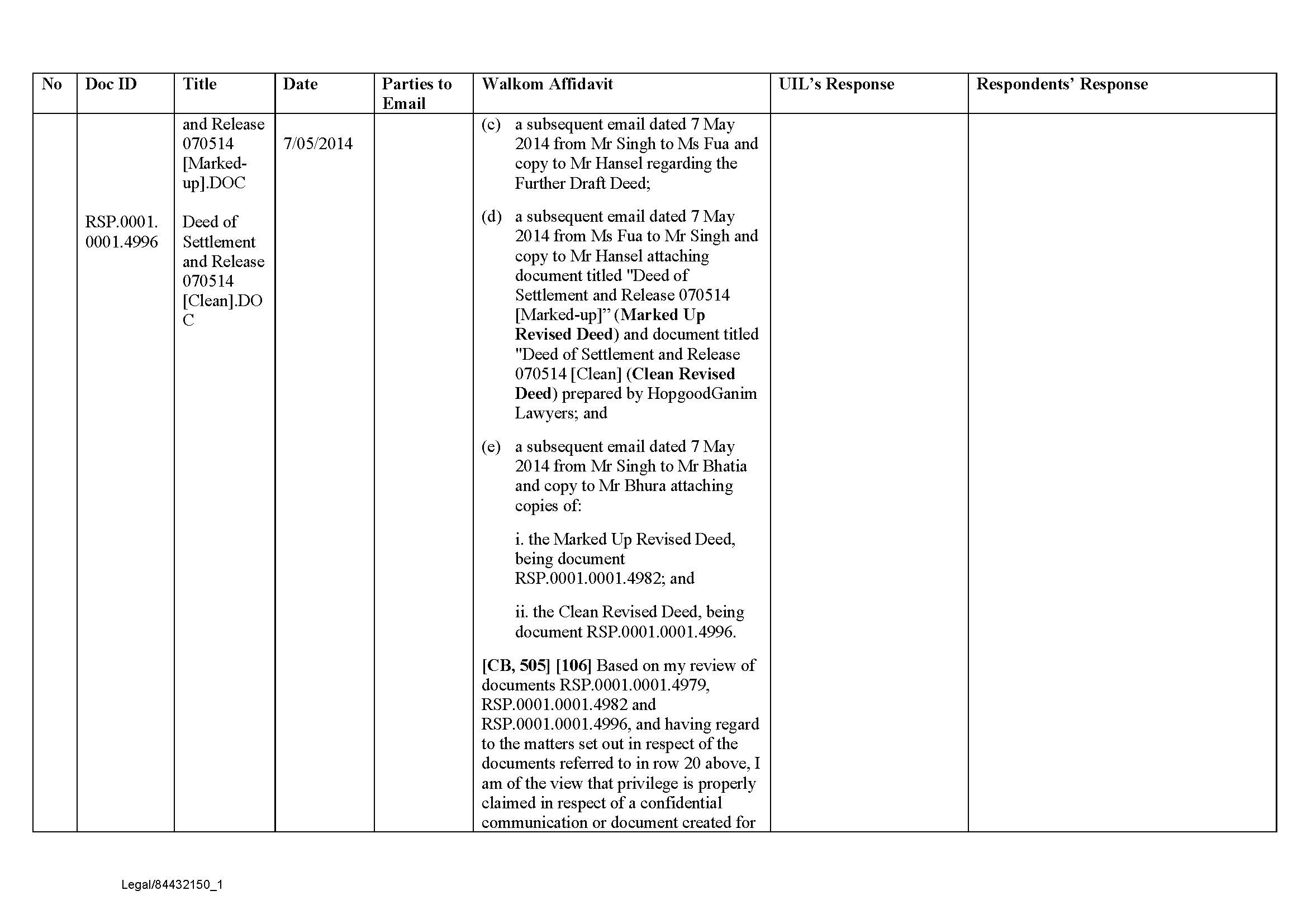

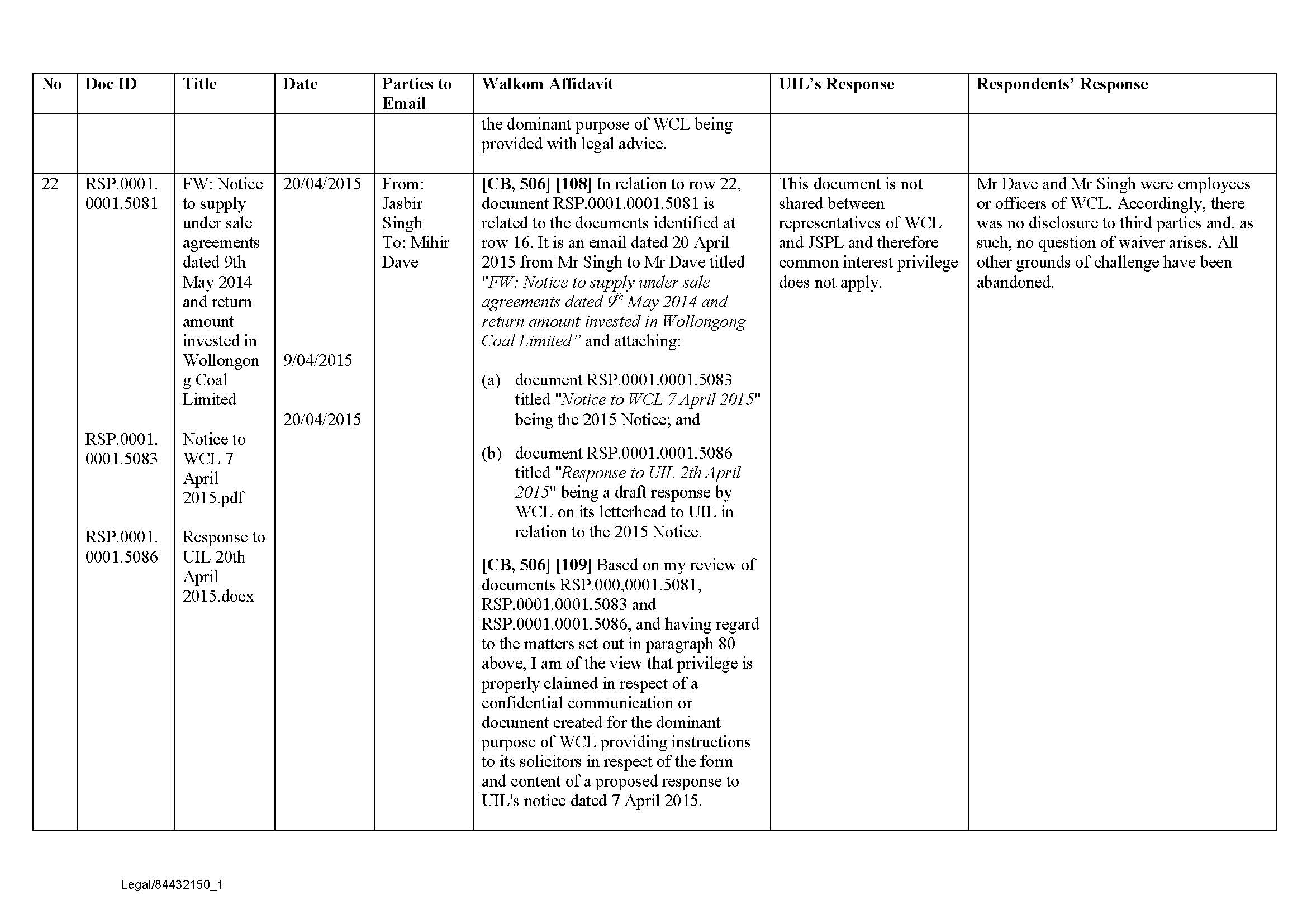

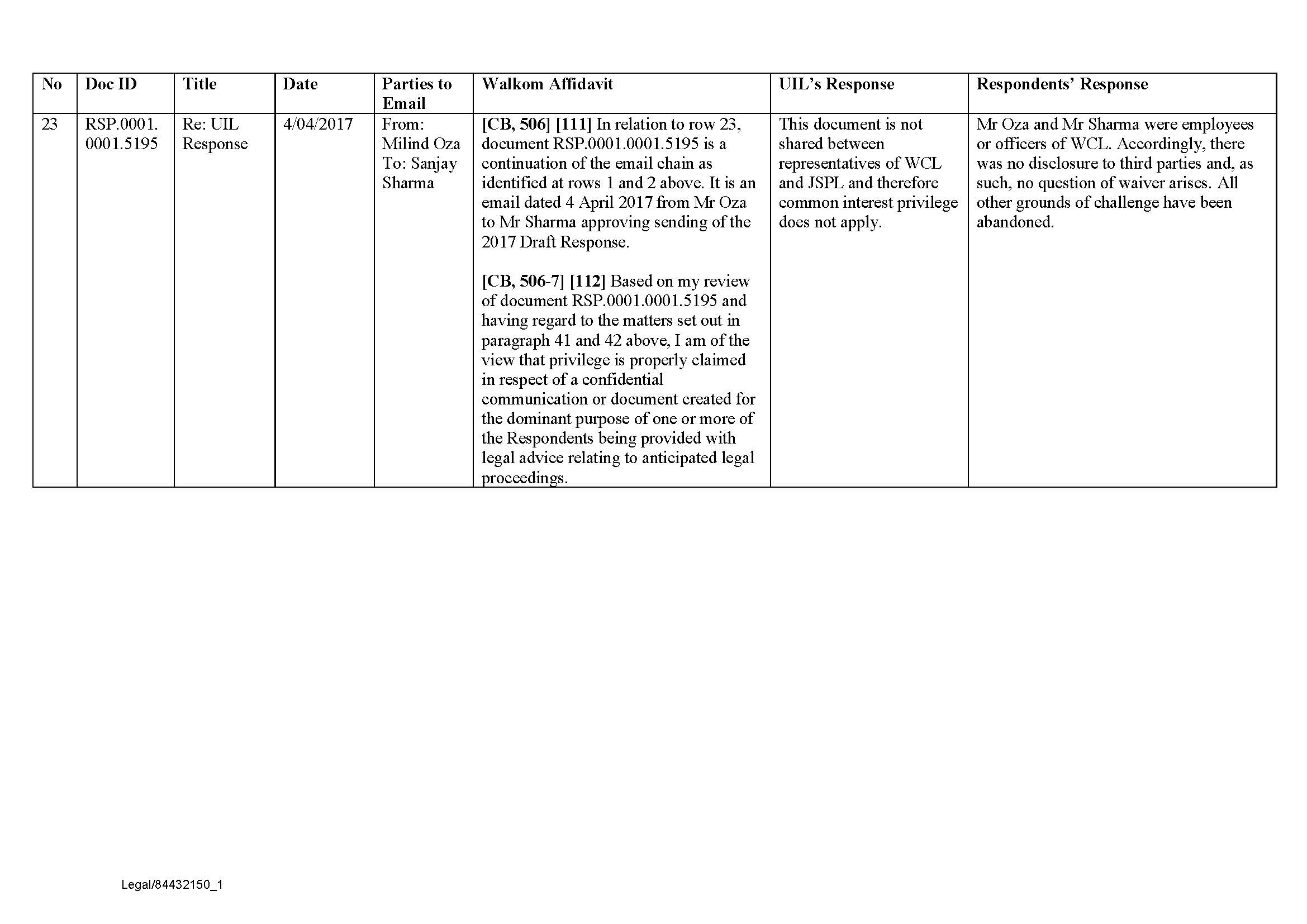

48 UIL challenges the respondents’ assertion of privilege over 35 of the 37 documents discovered by the respondents and listed in annexure A to these reasons. Originally UIL challenged whether privilege ever existed in these documents, but now only presses the waiver question.

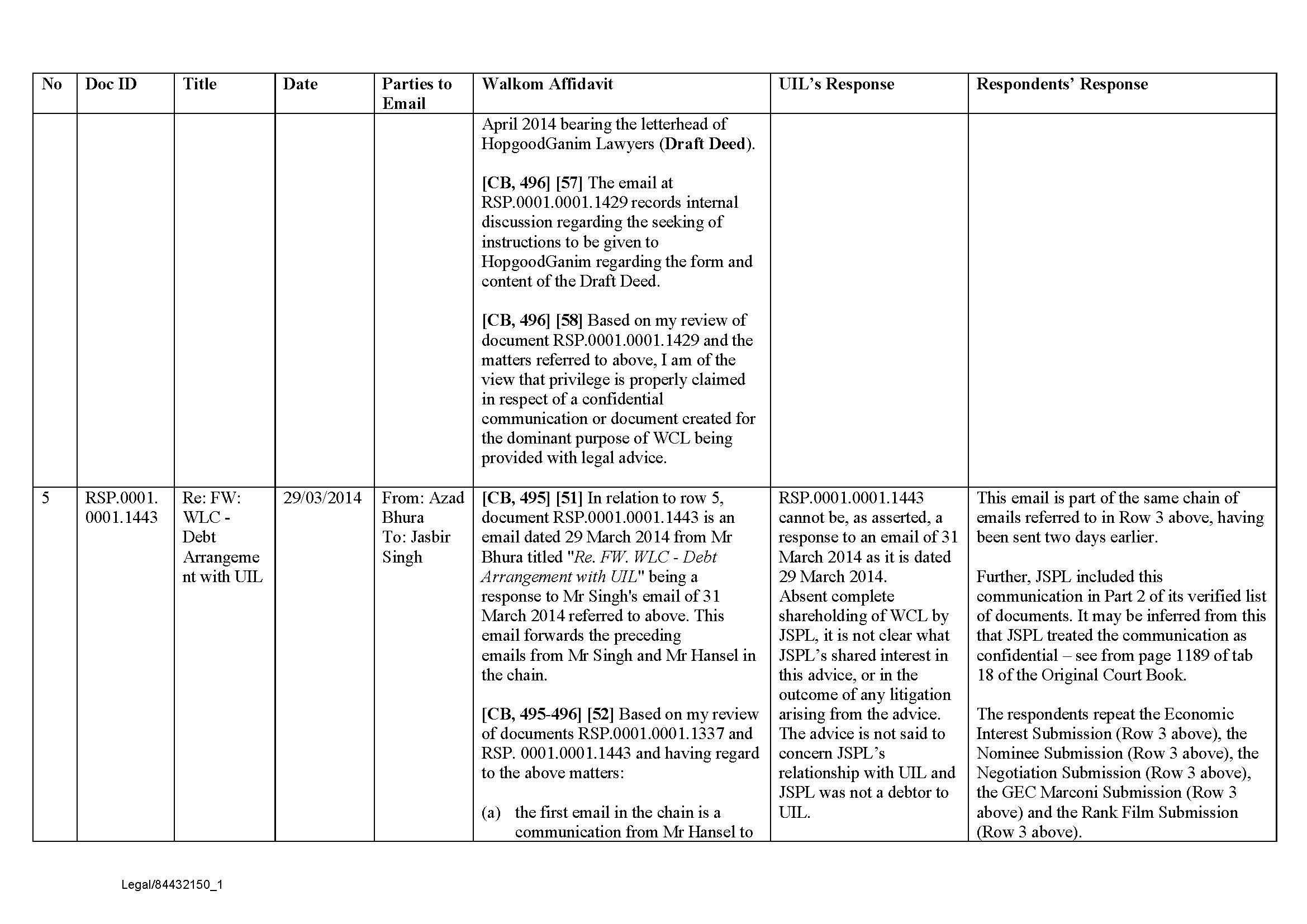

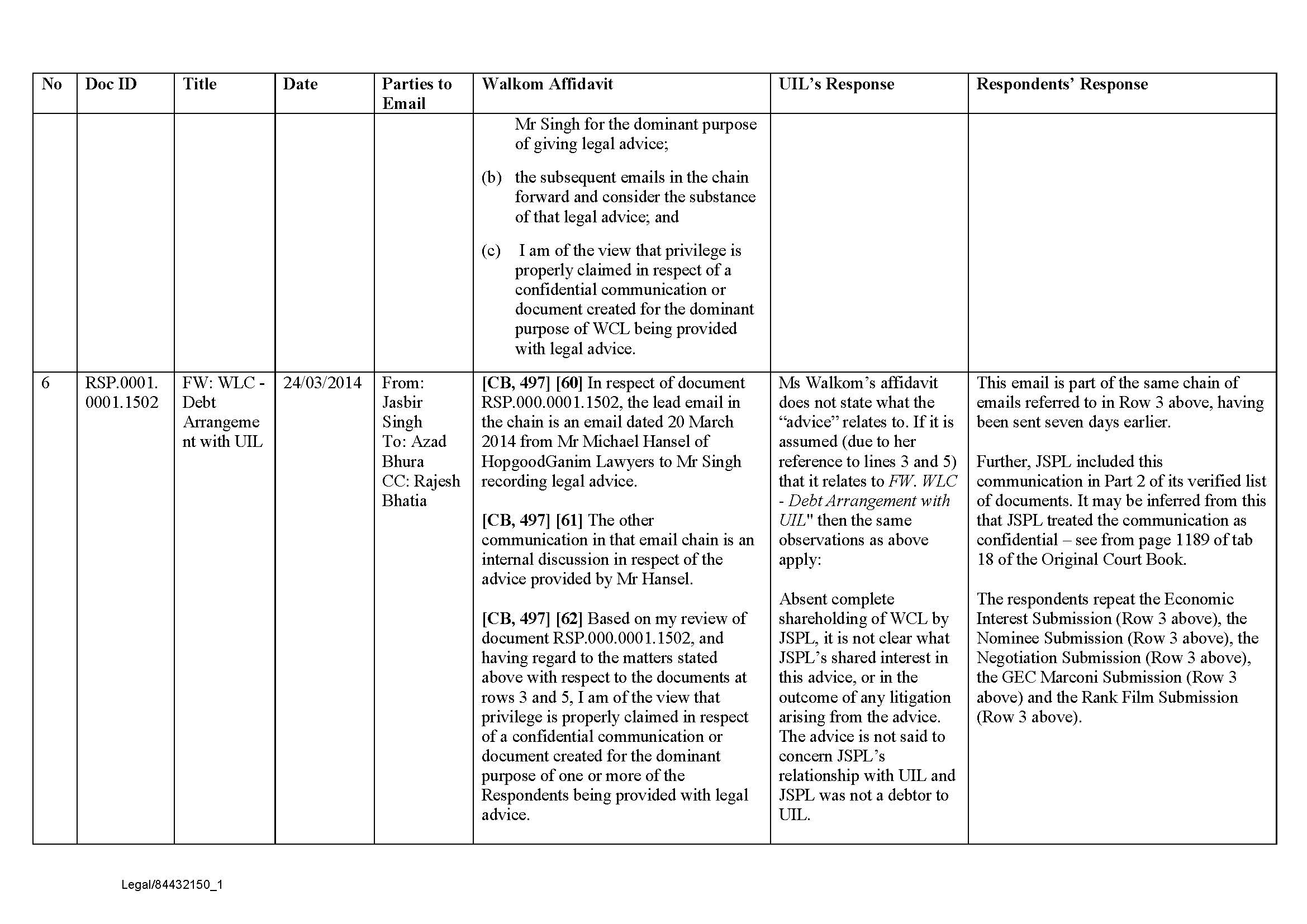

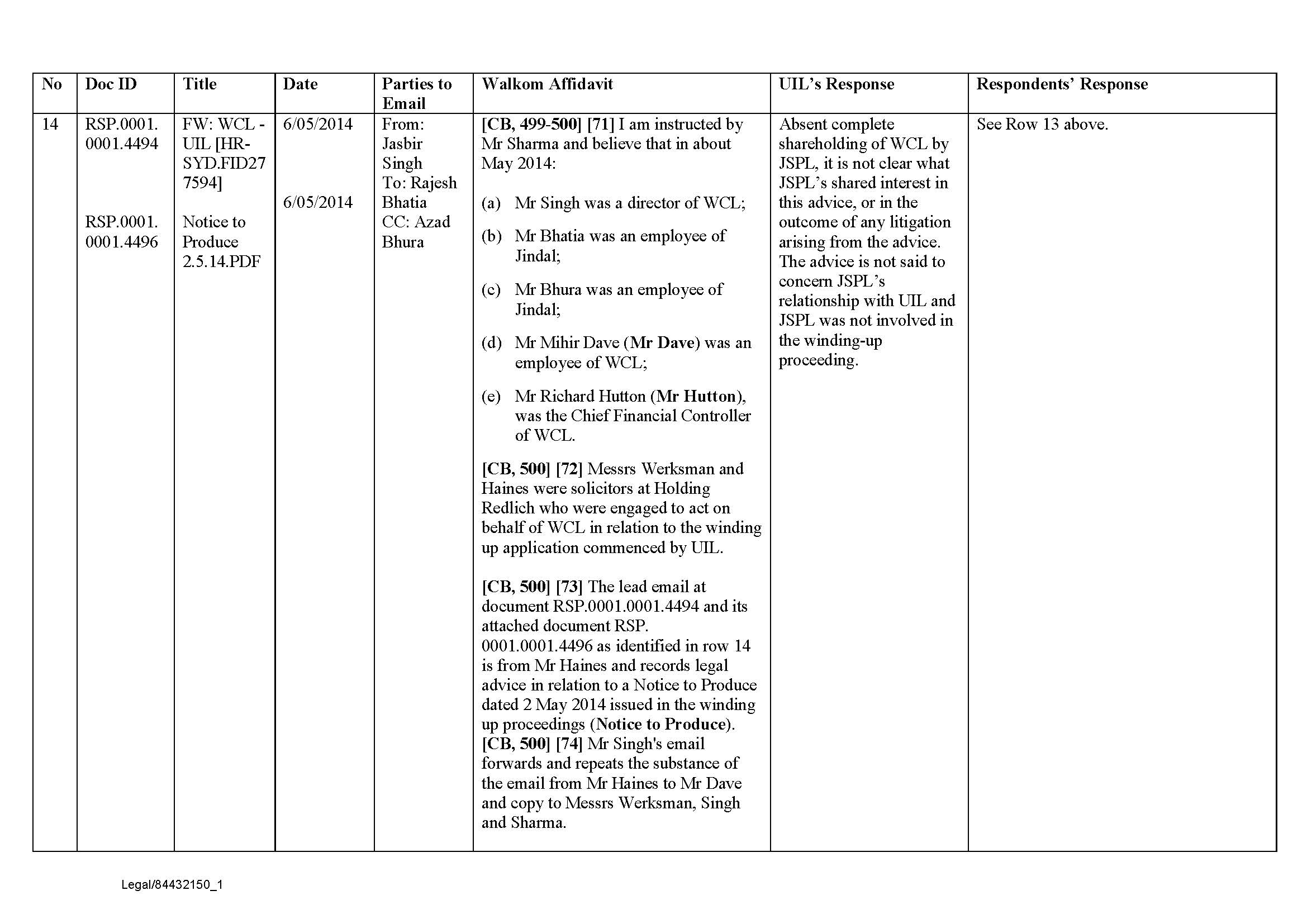

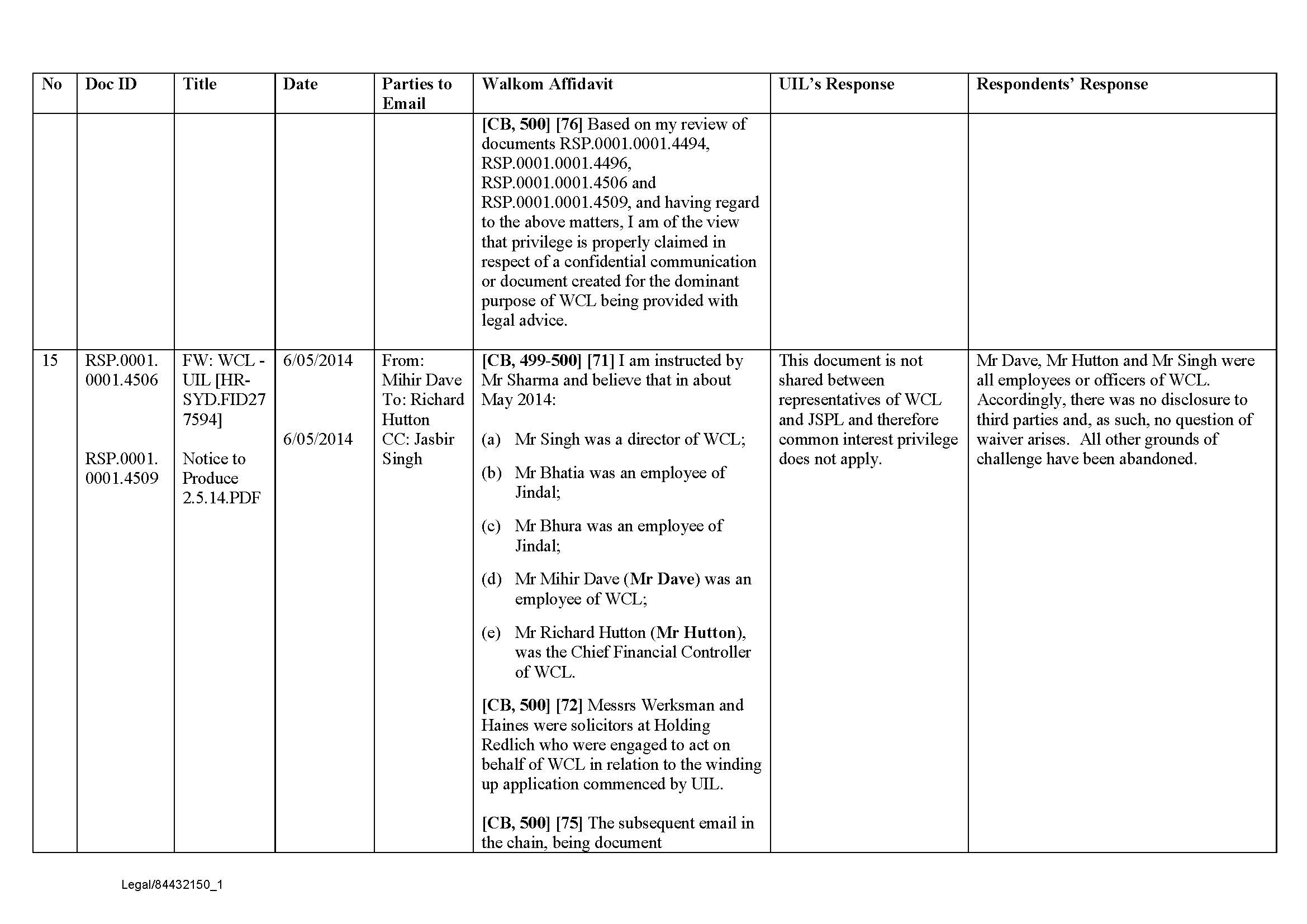

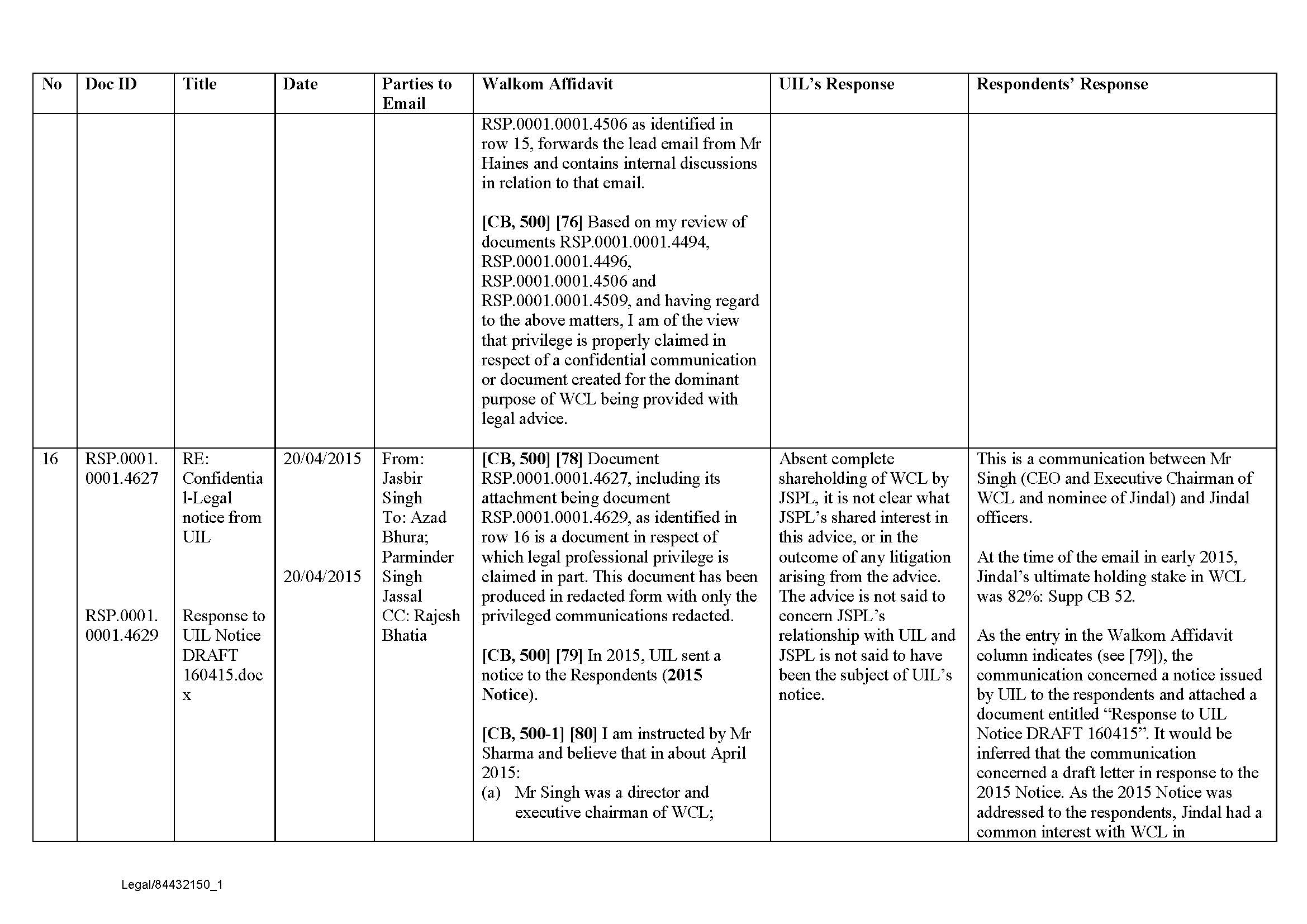

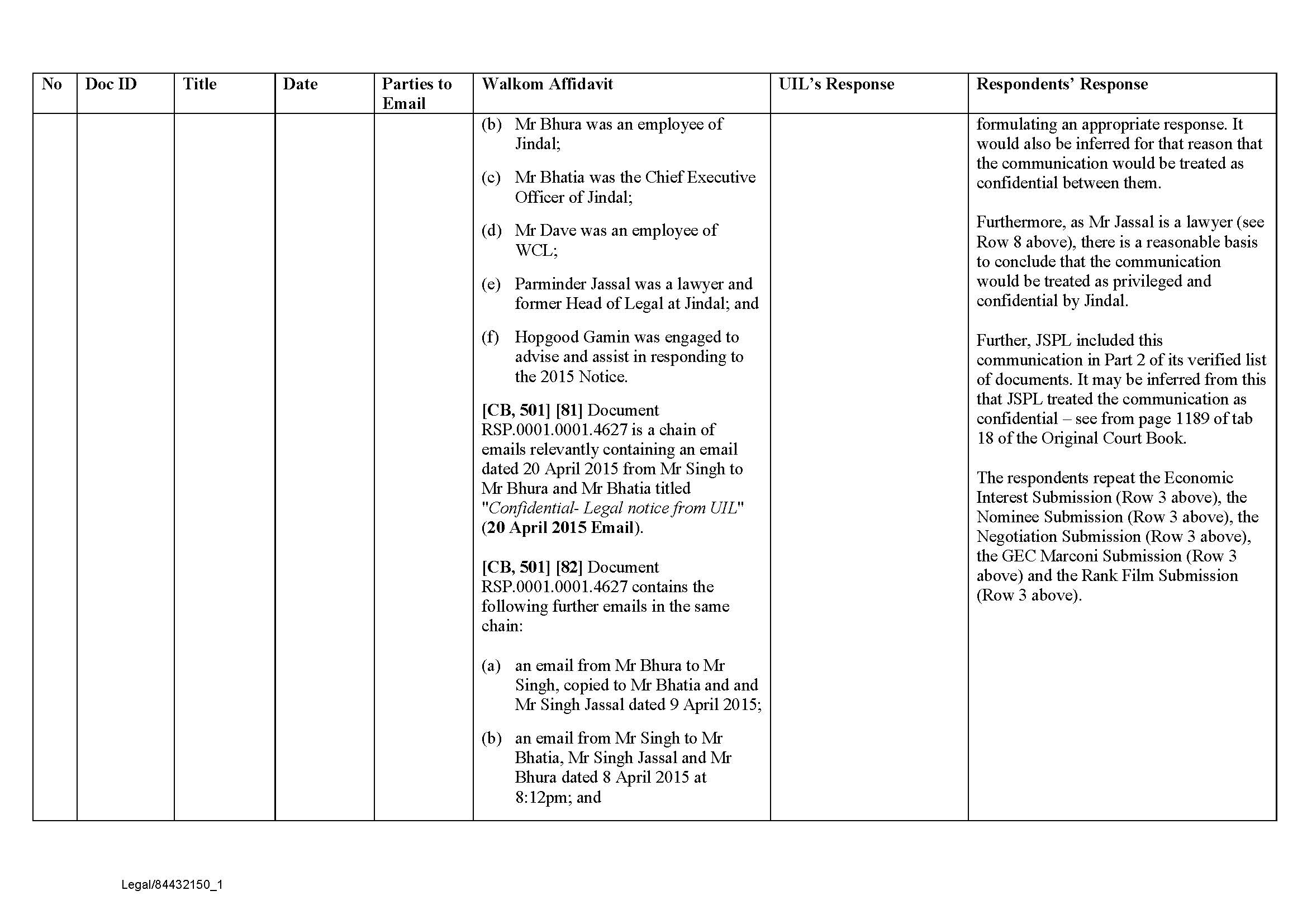

49 Now the relevant documents are all emails either attaching or discussing legal advice. The emails cover various issues facing WCL from 24 March 2014 to 4 April 2017. WCL repeatedly copied employees of JSPL into these emails. UIL says that the evidence does not reveal any limited or specific purpose for WCL copying JSPL into these emails.

50 UIL submits that the relevant documents are not protected from production by privilege. It says that in the circumstances, by copying JSPL into the emails, WCL impliedly waived the privilege in those documents by acting inconsistently with the maintenance of confidentiality of those documents.

51 Moreover, it says that WCL cannot establish common interest privilege for both its and JSPL’s benefit over the emails. I will return to the common interest privilege question later, although of course it is related to the waiver question and can provide a separate answer to waiver. Disclosure of a communication by the privilege holder to a third party cannot amount to a waiver of the privilege if the third party has a common interest privilege relevant to that communication and its disclosure.

52 Now it is not in doubt that waiver of privilege occurs when a party claiming privilege acts inconsistently with the maintenance of the confidentiality which the privilege is intended to protect; see Mann v Carnell (1999) 201 CLR 1 at [28] and [29] per Gleeson CJ et al and Expense Reduction Analysts Group Pty Ltd v Armstrong Strategic Management and Marketing Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 303 at [30] and [31] per French CJ et al.

53 In Osland v Secretary, Department of Justice (2008) 234 CLR 275 it was said at [45] and [49] by Gleeson CJ et al:

Waiver of the kind presently in question is sometimes described as implied waiver, and sometimes as waiver “imputed by operation of law”. It reflects a judgment that the conduct of the party entitled to the privilege is inconsistent with the maintenance of the confidentiality which the privilege is intended to protect. Such a judgment is to be made in the context and circumstances of the case, and in the light of any considerations of fairness arising from that context or those circumstances. …

…

Whether, in a given context, a limited disclosure of the existence, and the effect, of legal advice is inconsistent with maintaining confidentiality in the terms of advice will depend upon the circumstances of the case. As Tamberlin J said in Nine Films and Television Pty Ltd v Ninox Television Ltd, questions of waiver are matters of fact and degree. It should be added that we are here concerned with the common law principle of waiver, not with the application of s 122 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) which, as was said in Mann v Carnell, has the effect that privilege may be lost in circumstances which are not identical to the circumstances in which privilege may be lost at common law.

(footnotes omitted)

54 Now as to the documents identified in annexure A and save for some exceptions, representatives of both WCL and JSPL were parties to the communications, all of which were said to involve the forwarding and/or “internal discussion” of legal advice. The representatives of JSPL identified were Mr Bhatia and Mr Azad Bhura.

55 But UIL says that no evidence has been given regarding the purpose for which the privileged communications were shared and nor of the conditions pursuant to which they were shared.

56 Further, although UIL accepts that disclosure of legal advice or the substance thereof by officers of one corporation to officers of other corporations within the same group will not result in a loss of privilege, it says that the communications in question do not fall within this characterisation.

57 Now the communications in question span the period from 24 March 2014 until 4 April 2017. But UIL says that within this period, JSPL was not a direct shareholder of WCL. JSPL was a shareholder of JSPML. But of course JSPML itself was at the relevant time a shareholder of WCL.

58 JSPML’s shareholding in WCL was as follows across the relevant periods: for the financial year ending 31 March 2014, between 68.39% and 74.42%; for the financial year ending 31 March 2015, 82.04%; for the financial year ending 31 March 2016, between 60.385% and 72.92%; for the financial year ending 31 March 2017, 60.38%; and for the financial year ending 31 March 2018, 60.38%.

59 UIL submits that the disclosure of the existence and contents of legal advice on such a scale to a third party, notwithstanding that JSPL was a shareholder of JSPML and JSPML was a shareholder of WCL, constitutes conduct inconsistent with the maintenance of the privilege.

60 Moreover, UIL says that the respondents have failed to establish that there was at the relevant time an implied obligation of confidentiality and/or a sufficient common interest between WCL and JSPL.

61 Now the respondents say that it should be inferred that JSPL was under an implied obligation to maintain confidentiality in the privileged communications. But UIL says that the basis for this inference is not apparent from the facts and there is no evidence to indicate why JSPL would be under such an obligation.

62 UIL says that JSPML became the majority shareholder of WCL on 15 November 2013 and provided funds to WCL in the last three months of 2013. UIL says that whilst this may explain why WCL chose to disclose privileged communications regarding legal advice and proceedings to JSPL, it does not explain why JSPL would have been under an obligation to maintain confidentiality in the documents in its capacity as a shareholder and investor in WCL.

63 Further, UIL says that it is incorrect for the respondents to assert that the interests of JSPL and WCL were closely aligned because both were facing litigation from UIL. At the relevant time, UIL’s claim was against WCL only. That claim arose from WCL’s failure to perform its obligations and repay the advance payment made by UIL under the coal purchase agreement made on 25 March 2013 between UIL and WCL. UIL had no claim against JSPL prior to the commencement of these proceedings. Accordingly, UIL says that the respondents’ assertion that WCL and JSPL shared a common opponent prior to the entry of the May 2014 agreements is flawed.

64 UIL says that in order to determine whether there was any implied obligation of confidentiality, one must consider the terms under which the privileged material was communicated, including whether it was marked confidential or stated to be subject to a requirement to keep it confidential. I should say that I have no difficulty with the generality of that proposition.

65 More generally, I also agree that matters relevant to assessing whether a confidential obligation is implied include conduct and conversations surrounding the communications in question, the nature of the documents and the purpose and context of their communication.

66 UIL says that there is no evidence as to any conversation or context in relation to the communications concerning maintaining confidentiality including any restriction being placed on the use of the materials communicated between WCL and JSPL.

67 Further, UIL says that no present or former officer or employee of WCL, JSPML or JSPL has given evidence in relation to any implied obligation of confidentiality or the circumstances in which JSPL and WCL are said to have shared a common interest in the relevant communications.

68 Now the respondents refer to the principle that the disclosure of legal advice between corporations within the same corporate group will not result in a loss of the privilege. But UIL says that the respondents have conflated the concepts of majority shareholding and the existence of a corporate group.

69 Now in GEC Marconi Systems Pty Ltd v BHP Information Technology Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 593, Lehane J (at [6] to [9] and [12]) made reference to corporations being part of the same corporate group, but did not define “corporate group”. The respondents have treated “corporate group” as embracing the concept of companies that are related to each other as a “holding company” and a “subsidiary” under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

70 But according to UIL, “corporate group” within the context of the principle expressed in GEC Marconi refers to parent companies and their wholly-owned subsidiaries. In other words, a parent company, being a company having full ownership of a wholly-owned subsidiary, may share privileged material with its subsidiary, and vice versa, without resulting in the loss of privilege.

71 But in the present case, UIL says that the corporate group argument breaks down in the respondents’ case because although JSPML is a wholly-owned subsidiary of JSPL, WCL was not at any of the relevant times a wholly-owned subsidiary of JSPML.

72 UIL accepts that the basis for the principle that privilege is not waived where privileged material is shared within a corporate group is that companies within the group have aligned interests. That is true in respect of a parent company and its wholly-owned subsidiary. But UIL says that the same cannot be said for a holding company that owns a majority but not all of the shares in its subsidiary.

73 UIL says that as there are other shareholding interests in the subsidiary that need to be accounted for by directors acting in the best interests of the subsidiary, the interests of the subsidiary and its holding company may not necessarily align.

Analysis

74 In Hastie Group Ltd (in liq) v Moore (2016) 339 ALR 635, which concerned the disclosure of a litigation funding agreement, Beazley P and Macfarlan JA rejected the assertion of waiver, stating (at [60]):

Thus it is sufficient if the person to whom the communication was made was under an express or implied obligation not to disclose its contents, the concept of obligation in this context being capable of extending to an unspoken obligation, and to an ethical, moral or social obligation. By reason of the parties’ knowledge of the proposed litigation and the Report’s function of providing expert assistance in relation to it, the proper funder would, in our view, have clearly been under an obligation of confidentiality. As a result, the provision of the report to it for a purpose connected with the litigation did not give rise to a waiver of privilege.

(emphasis in original)

75 Similarly, in the present case the communications in question are concerned with legal advice relating to the dispute with UIL and the negotiations which led to the entry into of the May 2014 agreements. In my view it was implicit in the parties’ dealings that the communications would be treated as confidential. JSPL was in the same camp as WCL relevantly to the context and substance of these communications.

76 As such, the acts of WCL in disclosing its legal advice relating to these negotiations to JSPL was not conduct of WCL that was inconsistent with the maintenance of the confidentiality in those privileged communications which the privilege was intended to protect.

77 Let me say something more concerning the relevant principles.

78 A party who asserts waiver bears the onus of establishing that the privilege holder’s conduct is inconsistent with the maintenance of the confidentiality which the privilege is intended to protect.

79 But the conduct will not be inconsistent where the disclosure is subject to an express or implied obligation on the other party to maintain confidentiality. And one may infer such an obligation despite there being no direct evidence. There is little doubt that an implied obligation of confidence, being unspoken or unwritten, can be implied from the context or the circumstances under which the disclosure was made or from the relationship between the parties or the characteristics or status of either the disclosing party or the party to whom the disclosure was made, which characteristics or status were known or ought to have been known by each of them.

80 Now sometimes it is said that an implied obligation of confidence can arise from an “ethical, moral or social obligation”. But I would prefer not to use such a phrase, the elements of which are pregnant with imprecision and also substantially overlap each other.

81 Let me at this point make reference to two further authorities.

82 In Hamilton v State of New South Wales [2016] NSWSC 1213, there was no direct evidence before Beech-Jones J of an obligation of confidentiality. But his Honour accepted that the matters relevant in assessing the presence of such an obligation include the nature of the relationship in question, the circumstances, including conduct and conversations, surrounding the communications or documents in question, the nature of the documents in question and the purpose and context of their communication. He said (at [37]):

Nevertheless, an obligation of the kind referred to in the definition of confidential communication can be implied. In Jackson, Giles JA noted that the obligation can “extend to an unspoken obligation and to an ethical, moral or social obligation”. At [46] his Honour approved a statement by Bergin J (as her Honour then was) in Rickard Constructions Pty Ltd v Rickard Hails Moretti Pty Ltd [2006] NSWSC 234 (“Rickard”) to the effect that the “matters relevant in assessing whether a confidential obligation is implied in relationships or circumstances outside that of solicitor/client include the nature of the relationship in question and the circumstances, including conduct and/or conversations, surrounding the communications or documents in question” as well as it “is also permissible to have regard to the nature of the documents in question and the purpose and context of their communication”.

83 In Rickard Constructions Pty Ltd v Rickard Hails Moretti Pty Ltd [2006] NSWSC 234, Bergin J said (at [29], [33] and [43]):

There was no evidence of any express statement or agreement that the funder would undertake to keep confidential the communications (or any record thereof) that it heard or observed at the regular meetings. Similarly there is no evidence of any request made of the funder, or any undertaking given by the funder, to keep confidential the contents of the documents forwarded to it. The only basis upon which the communications could be confidential in the presence of the funder and/or the contents of the documents could be confidential, is if the funder was under an implied obligation to keep the communications and/or contents of the documents confidential (the confidentiality obligation).

…

Assuming the correctness of the analysis by the Full Federal Court, it seems to me that matters relevant in assessing whether a confidential obligation is implied in relationships or circumstances outside that of solicitor/client include the nature of the relationship in question and the circumstances, including conduct and/or conversations, surrounding the communications or documents in question. It is also permissible to have regard to the nature of the documents in question and the purpose and context of their communication: see Bulk Materials (Coal Handling) Services Pty Ltd v Coal and Allied Operations Pty Ltd [1998] 13 NSWLR 689 at 695E.

…

It seems to me, having regard to the obviously privileged material that was provided to the funder, that the plaintiff, through Mr Quigley, was seeking to provide the material to the funder so that the litigation could be properly funded and continued and so that the plaintiff could retain its legal representation. I am satisfied that the collaborative and supportive aspects of the relationship between the funder and the plaintiff, the nature of the meetings attended, the documents provided and the abovementioned purpose are matters from which it is appropriate to imply that when the information at the meetings and the contents of the documents were disclosed to the funder it had an obligation not to disclose their contents. In those circumstances, I am satisfied that the communications with the funder were confidential communications within the meaning of that term in s 117 of the Act.

84 So, in determining whether there is an implied obligation of confidentiality, a broad range of matters may be considered.

85 Moreover, disclosures of legal advice between corporations within the same group will not result in the loss of the privilege, generally speaking.

86 Now UIL says that the communications in the present case fall outside the scope of that principle because JSPL was not a direct shareholder in WCL; its shareholding was held through JSPML. But such a distinction does not grapple with the relevant underlying rationale.

87 The reason that such disclosures to related entities do not result in a loss of privilege is because there is no inconsistency with the maintenance of the confidentiality of the communication. That absence of inconsistency arises because companies within a corporate group usually have aligned interests or at least aligned interests relevant to the substance and communication of legal advice as between them concerning claims made against an entity in the group by an outside party. Indeed, unsurprisingly, a parallel may be drawn with common interest privilege.

88 Once that is appreciated, the principle can apply whether the interest is held directly or through a subsidiary and whether wholly owned or majority owned. But in any event, Mr Bhatia, who was the primary recipient on behalf of the Jindal Group of the communications the subject of UIL’s challenge was a director of JSPML as well.

89 Further, it is unsurprising that WCL from time to time shared with its majority shareholder (or the ultimate holding company thereof) legal advice it had received in relation to the dispute with UIL. Both were facing litigation from UIL. Further, the Jindal Group had recently acquired a controlling interest in WCL through one of its related entities, JSPML, and was the principal funder of its operations. Moreover, in accordance with those change of control arrangements, the Jindal Group had appointed Mr Singh as its nominee on the WCL Board. Indeed, from 26 October 2013, Mr Singh acted as WCL’s chairman and CEO.

90 Moreover, UIL embraced the Jindal Group, as the incoming majority shareholder of WCL and its funder, as a necessary participant in its settlement negotiations. In the light of that acceptance of the Jindal Group prior to any of the disclosures now in question, there is no inconsistency in the Jindal Group being made privy to advice received by WCL relating to those negotiations.

91 Now I do accept that it is a fair criticism made by UIL that the respondents’ evidence in some respects is general and vague. But there are various points to make.

92 First, many of the individual officers or employees of the respondents have left their employ.

93 Second, the respondents have put into evidence relevant contemporaneous documents concerning the key events from which appropriate inferences can be drawn as business records.

94 Third, it is to be recalled that the solicitor for the respondents had a relevant prior background and gave the following evidence concerning her prior involvement in matters involving WCL:

I was involved from January 2014 in acting for WCL including in relation to claims made by shipping companies (British Marine PLC, Ultrabulk A/S, PCL (Singapore) Pte Limited). I was also involved, in respect of claims against the former chairman and in respect of a significant claim (valued at approximately US$59 million) that these companies brought against the former major shareholder, Gujarat NRE Coke Ltd, which was precipitated by events in 2013 when the Jindal Steel & Power group became the majority shareholder in WCL in the place of the Gujarat Group. I was also aware of the winding up application that UIL brought against WCL because this winding up application had the prospect of impacting upon the ability of WCL and WWC to maintain their claims against Gujarat NRE Coke Ltd. Mr Werksman and Mr Wrobel were responsible for WCL’s opposition to that application.

95 Fourth and as I have already noted, the solicitor for the respondents took instructions in the matter from Mr Sharma who in May 2014 was the company secretary of WCL and Wongawilli.

96 As I have indicated, the respondents do not rely on affidavit evidence given by any officer of WCL or the Jindal Group to support a finding that the disclosures occurred in a context which imported an obligation of confidence. But the relevant emails were exchanged more than ten years ago, and were primarily between officers such as Mr Singh and Mr Bhatia who have long since left their positions with WCL and the Jindal Group/JSPML respectively. But the business records and circumstances surrounding the relevant disclosures enable me to infer an obligation of confidence.

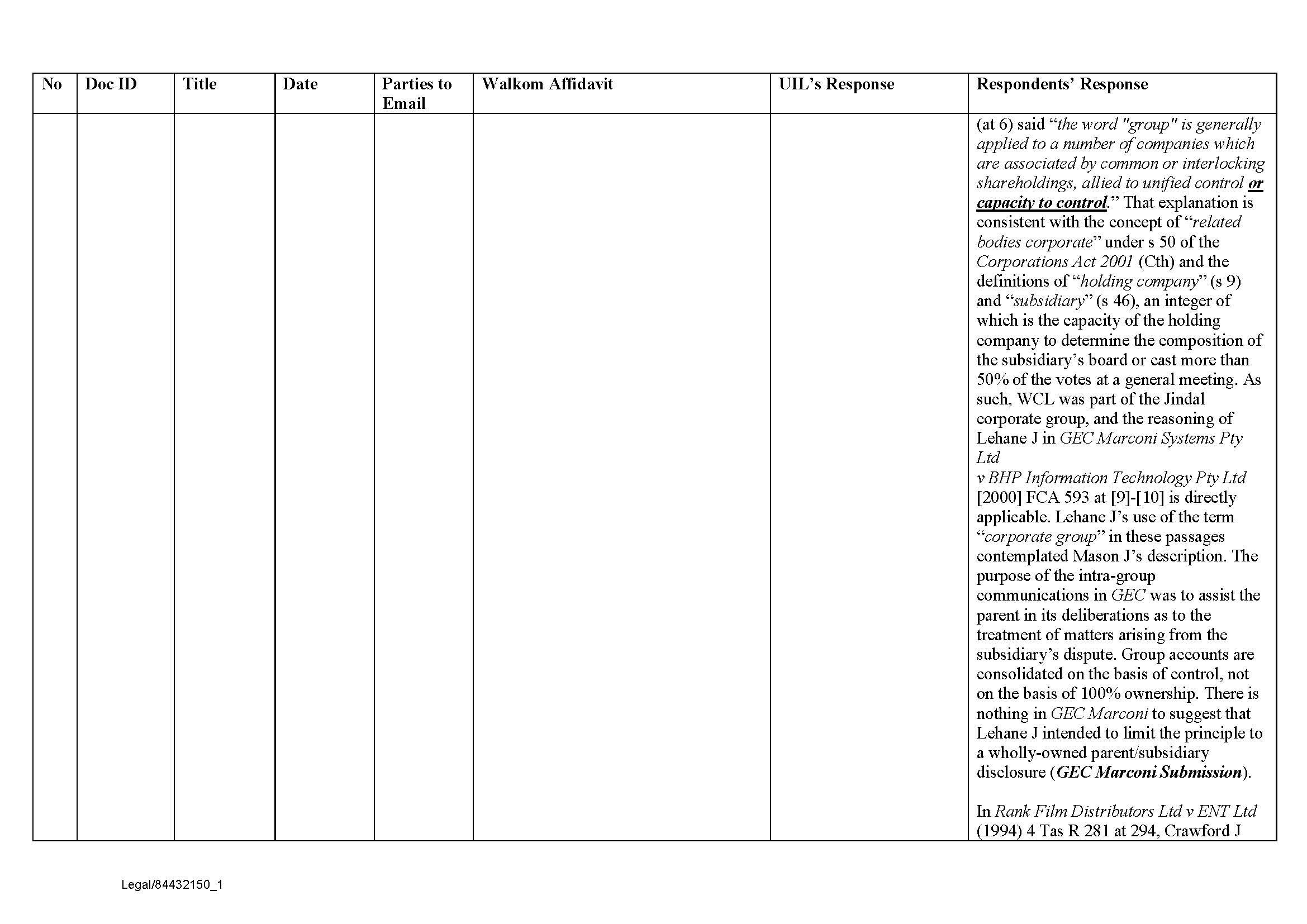

97 Let me say something further concerning GEC Marconi. The reasoning in GEC Marconi is not limited to relationships between a parent and a wholly owned subsidiary. Lehane J’s use of “group” in the phrase “corporate group” was used in the generally accepted sense described by Mason J in Walker v Wimborne (1976) 137 CLR 1 at 6 as describing “a number of companies which are associated by common or interlocking shareholdings, allied to unified control or capacity to control”.

98 There is no reason why his Honour’s reasoning ought not to apply in the context of majority ownership, where the disclosure is to the majority shareholder about matters in which both the subsidiary and shareholder share a common interest.

99 As the respondents contended, to the ordinary businessperson there would be no relevant difference between the interests of a company and a shareholder who owns 99% of that company’s shares versus the interests of a company and a shareholder who owns 100% of the shares, yet according to UIL, for the purposes of privilege, the former scenario would give rise to the risk of waiver but the latter would not.

100 Clearly, the Jindal Group had a capacity to control WCL through JSPML’s majority interest. JSPML was of course wholly owned by JSPL. There were, as Mason J described it, “common or interlocking shareholdings”.

101 Let me dispose of one other point. On 23 September 2013 UIL exercised security rights, as pledgee, over Gujarat NRE India Pty Ltd’s shares in WCL. UIL only became the outright owner of those shares upon execution of the settlement deed on 15 May 2014. It promptly on-sold them to UD Mining Group Holding Pte Ltd in June 2014. By 28 August 2015, those shares appear to have been on-sold again having regard to the list of substantial shareholders. But UIL’s brief status as a member has no impact on the application of the GEC Marconi principle in the present context.

102 In summary, I would reject UIL’s waiver argument. Confidentiality was not lost by reason of the disclosure of the privileged communications. I readily infer that there was an implied obligation on JSPL and/or entities within the Jindal Group to keep the relevant communications confidential. Moreover, the making of the disclosure was not inconsistent with the maintenance of the privilege. Let me now say something more on the common interest privilege question as a separate but related answer to the question of waiver.

Common interest privilege

103 A useful description of common interest privilege at common law was given by Giles J in Network Ten Ltd v Capital Television Holdings Ltd (1995) 36 NSWLR 275 at 279 in the following terms:

If two parties with a common interest exchange information and advice relating to that interest, the documents or copy documents containing that information will be privileged from production in the hands of each; thus, if one of the parties obtains a letter of advice attracting legal professional privilege and provides it to the other, the other can also claim legal professional privilege.

104 So, for common interest privilege to apply the relevant communication must be subject to legal professional privilege, the interest said to be common must be identified, and the exchange of the information or advice subject to legal professional privilege must relate to that interest.

105 Now the types of relationships and communications made between the parties thereto in which common interest privilege has been held to exist include insurer and insured, liquidator and creditor, trustee and beneficiary, and neighbours opposing a proposed development in their area.

106 Now UIL says that it is not sufficient for the respondents to assert a generalised common interest between WCL and JSPL. It is necessary to show a common interest that relates to the particular privileged communication being exchanged or discussed.

107 UIL complains that the subject of legal advice contained in the relevant emails is not disclosed in respect of various rows of annexure A. And where it is disclosed, UIL says that there is a paucity of evidence as to how the exchange of information relates to any common interest between WCL and JSPL.

108 It is convenient to refer to an instantiation of the perceived problem by reference to an email which included:

(a) a notice regarding possible legal action by UIL against WCL sent to WCL (Rows 1, 2 and 23);

(b) a notice to produce sent by UIL to WCL (Rows 14 and 15);

(c) a debt owed by WCL to UIL (Rows 3, 5 and 6);

(d) winding up proceedings by UIL against WCL (Rows 13, 14, 15, 17, 18 and 19);

(e) the settlement deed between UIL and WCL (Rows 4, 20 and 21).

109 Now as to (d) and (e), UIL says that JSPL was not a party to the winding up proceedings and nor was it a party to the settlement deed executed between WCL and UIL. Further, as to (b) and (c), JSPL was not a debtor of UIL and the notice to produce was not directed to JSPL.

110 UIL says that absent evidence of JSPL’s interest in any of these matters, any asserted common interest between WCL and JSPL is not sufficient to constitute a claim for common interest privilege sufficient to negate a finding that privilege has been waived.

111 Now Rickard Constructions at [50] cites Rank Film Distributors Ltd v ENT Ltd (1994) 4 Tas R 281 in support of the proposition that a commonality of interest may arise in cases that include “a company and parent (being the beneficial holder of a 50% interest) (sic)”; of course the reference should have been to a more than 50% interest.

112 But UIL says that the basis for the commonality of interest in Rank Film Distributors did not arise by reason of the shareholding per se. Rather, there was a common interest that the defendant and the subsidiary had in the legal advice received, which was for both their benefit. In that case, legal advice was provided in circumstances where the subsidiary acted as an intermediary and agent for the holding company in negotiations with the plaintiff. It was arguable that on that basis alone there was no waiver of privilege.

113 In Rank Film Distributors, significantly, the party that obtained the legal advice (ENT) and shared the advice with its subsidiary, had provided a letter of comfort to Rank Film Distributors, undertaking to not reduce its shareholding in Filmpac and to keep Filmpac sufficiently resourced to meet its contractual obligations. Crawford J (at 294) referred to:

the common interest the defendant [ENT] and Filmpac [its subsidiary] had in the advice received by the defendant from its solicitors … in securing for Filmpac, for the perceived benefit of Filmpac and the defendant, a distribution agreement with the plaintiff upon such terms and conditions, and subject to such undertakings from the defendant to the plaintiff, as might be negotiated with the plaintiff by Filmpac on its own behalf and on behalf of the defendant.

114 But in the present context, no such letter or guarantee of any kind had been provided by JSPL to UIL at the time of the relevant communications.

115 Further, UIL says that the situation of liquidator and creditors referred to in Southern Cross Airlines Holdings Ltd (in liq) v Arthur Andersen & Co (1998) 84 FCR 472 bears significant differences from the common interest relied upon by the respondents in the present case. A liquidator must exercise its powers for the benefit of creditors, is required to keep them informed of the progress of the liquidation and can be subject to general oversight by the creditors. But it is said that none of these factors apply in relation to the relationship between WCL and JSPL.

116 UIL says that the fact that JSPL became a majority shareholder and provided funds to WCL does not constitute a commonality of interest. UIL accepts that as a creditor of WCL, JSPL may have been interested in the outcome of UIL’s dispute with WCL. But UIL says that that is not the same as a commonality of interest.

117 UIL relies on Spotless Group Ltd v Premier Building & Consulting Pty Ltd (2006) 16 VR 1 where it was held (at [34]) that the interests of a funder and of the funded party were different. It was said that the respondent had a direct interest in the outcome of the litigation as plaintiff whereas the financier’s interest was indirect, being that of a creditor. I should say that the analysis on this topic was superficial and does not assist me. Moreover, Chernov JA’s analysis is incorrect if it is to be taken as indicating that litigation funders cannot be brought under the umbrella of common interest privilege, indeed joint privilege in many cases. Of course interests may diverge. But the question is whether they diverge concerning the subject matter or substance of the privileged communication. If they converge, as they must for common interest privilege to apply, any other extraneous divergence is an irrelevance to the context being considered.

118 Further, UIL says that the fact that the winding up of WCL would significantly impact the Jindal Group, as its investment in WCL was substantial, is not a sufficient basis on which to establish a common interest.

119 Further, UIL says that the interests of a wholly owned subsidiary and its parent align in a way that the interests of a company and a majority shareholder do not. In particular, the company must act in the interests of all shareholders, which will include minority shareholders, such as UIL. JSPL was, indirectly, one of several shareholders in WCL. So, it says that common interest privilege cannot arise between a majority shareholder and the company by reason of that holding alone.

Analysis

120 In my view the respondents have established the existence of the relevant common interest privilege.

121 The concept of common interest is not rigidly defined and is a question of fact in each case; see Farrow Mortgage Services Pty Ltd (in liq) v Webb (1996) 39 NSWLR 601 at 609 per Sheller JA. And as Sheller JA said (at 608), the “shared or similar interest may be the product of the particular situation in which a group of people find themselves”. There are no hard and fast rules. The context and circumstances of the particular case are what drive the appropriate analysis.

122 Further, the fact that there is the potential for disputes on other matters between the parties with the common interest does not necessarily negate the common interest privilege. For example, an insured and an insurer may have a common interest in the best defence being put forward by an insured to a claim against the insured with disclosures between them of relevant legal advice concerning the defence, even though the question of whether indemnity is to be given by the insurer is up in the air and may potentially be adverse to the insured.

123 The question is whether as to the privileged communications concerning a particular issue, the parties have a common interest in that issue. If they only have selfish and potentially adverse interests to each other on that issue, then there will be no common interest privilege.

124 Moreover, categories of relationship in which a sufficient commonality of interest is likely to arise are not closed, but relevantly include a parent and a non-wholly owned subsidiary; see Rickard Constructions at [50], citing Rank Film Distributors. This case falls within that category, treating JSPL and JSPML as part of the one group.

125 Further, in Southern Cross Airlines, Drummond J (at 481) considered that a liquidator and the creditors of the company had a shared interest in the proper administration of the company, including the successful outcome of litigation brought by the liquidator in the company’s name. That was because the litigation was intended to augment the funds available for the purposes of paying the liquidator’s fees and increasing the return to creditors. As such, Drummond J concluded that the communication of privileged advice by the liquidators to creditors did not destroy the privilege.

126 By analogy, albeit a loose one, JSPL had a shared interest with WCL in dealing with UIL in such a manner as to promote the best commercial outcome available to WCL, a company in which it made a very considerable financial investment. JSPL assisted WCL in managing WCL’s creditors. JSPML was the principal shareholder of WCL. The Jindal Group was the principal funder of WCL. And the Jindal Group, because of its investment in WCL, had a common interest with WCL in dealing with the winding up proceedings. Moreover, JSPL and WCL shared a common interest in the settlement of WCL’s dispute with UIL.

127 Now UIL identifies five broad categories which describe the 35 communications the subject of its challenge and which I have set out earlier. UIL asserts that it was necessary for WCL to advance evidence as to the interest held by JSPL and WCL in the subject matter of each communication.

128 But as to category (a), both WCL and JSPL had a shared interest in managing and co-ordinating any response to any potential legal action by UIL against WCL. And as to categories (b), (c), (d) and (e), all relate to the negotiations which culminated in the suite of agreements in May 2014.

129 In my view JSPL and WCL shared a common interest in the settlement of the dispute with UIL, which is the topic with which the legal advice was obviously concerned.

130 As the respondents point out, the Jindal Group was the majority shareholder and principal funder of WCL. It had been actively assisting WCL with the management of its creditors (including the ATO, Ultrabulk A/S and, relevantly, UIL). Its nominee, Mr Singh, was the chairman and CEO of WCL. Both parties had a keen interest in resolving those disputes, especially with UIL, given that it was the then petitioning creditor in winding up proceedings against WCL. Plainly, the winding up of WCL would significantly impact the Jindal Group, as its investment in WCL exceeded $110 million.

131 The legal advice was concerned with the settlement of the dispute with UIL, and WCL and JSPL shared a common interest in the advice. In my view JSPL and WCL had a common interest because their economic and commercial interests were aligned.

132 Now UIL has made various points concerning specific rows in annexure A which I have considered. But none of these points negate the force of what I have said.

133 Finally, UIL says that it has not been shown how the interests of JSPL aligned with those of JSPML, notwithstanding the different shareholding arrangements. UIL says that JSPML had no agreements with WCL. UIL says that the interests of JSPML in WCL’s affairs were no greater than the interests of a range of stakeholders in WCL, including employees, other shareholders, and lenders. But with respect, there is an air of uncommerciality if not unreality in focusing on JSPML in such a fashion as I have endeavoured to explain. The correct focus is to consider JSPL and the Jindal Group including within it JSPML.

Conclusion

134 In summary, there was no waiver of privilege by UIL. Moreover, if I need to say it, the respondents have established common interest privilege concerning the relevant communications.

135 I will hear further from the parties as to the necessary orders to give effect to these reasons, including on the question of costs.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and thirty-five (135) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Beach. |

Associate: