FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

PepsiCo, Inc v Commissioner of Taxation [2023] FCA 1490

Table of Corrections

1 December 2023 In paragraph 7(e), the words “to PepsiCo and SVC” have been replaced with “to PBS”.

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days, the parties provide to the Court any agreed minute of proposed orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons for judgment, and in relation to costs.

2. If the parties cannot agree, then within 21 days each party file and serve a minute of proposed orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons for judgment, and in relation to costs, together with a short submission.

3. The Court’s reasons for judgment be published, in the first instance, on a confidential basis to the parties and to Asahi Beverages Pty Ltd and Asahi Holdings (Australia) Pty Ltd (Asahi), to enable them to consider whether to seek confidentiality orders with respect to any part of the judgment. Within two business days, the parties and Asahi provide the Court with any submission on proposed confidentiality orders.

4. Subject to further order, the Court’s reasons for judgment otherwise be and remain confidential for a period of seven days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

VID 55 of 2022 | ||

BETWEEN: | PEPSICO, INC Applicant | |

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION Respondent | |

order made by: | MOSHINSKY J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 30 NOVEMBER 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days, the parties provide to the Court any agreed minute of proposed orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons for judgment, and in relation to costs.

2. If the parties cannot agree, then within 21 days each party file and serve a minute of proposed orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons for judgment, and in relation to costs, together with a short submission.

3. The Court’s reasons for judgment be published, in the first instance, on a confidential basis to the parties and to Asahi Beverages Pty Ltd and Asahi Holdings (Australia) Pty Ltd (Asahi), to enable them to consider whether to seek confidentiality orders with respect to any part of the judgment. Within two business days, the parties and Asahi provide the Court with any submission on proposed confidentiality orders.

4. Subject to further order, the Court’s reasons for judgment otherwise be and remain confidential for a period of seven days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

VID 56 of 2022 | ||

BETWEEN: | STOKELY-VAN CAMP, INC Applicant | |

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION Respondent | |

order made by: | moshinsky j |

DATE OF ORDER: | 30 NOVEMBER 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days, the parties provide to the Court any agreed minute of proposed orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons for judgment, and in relation to costs.

2. If the parties cannot agree, then within 21 days each party file and serve a minute of proposed orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons for judgment, and in relation to costs, together with a short submission.

3. The Court’s reasons for judgment be published, in the first instance, on a confidential basis to the parties and to Asahi Beverages Pty Ltd and Asahi Holdings (Australia) Pty Ltd (Asahi), to enable them to consider whether to seek confidentiality orders with respect to any part of the judgment. Within two business days, the parties and Asahi provide the Court with any submission on proposed confidentiality orders.

4. Subject to further order, the Court’s reasons for judgment otherwise be and remain confidential for a period of seven days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

VID 57 of 2022 | ||

BETWEEN: | STOKELY-VAN CAMP, INC Applicant | |

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION Respondent | |

order made by: | MOSHINSKY J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 30 NOVEMBER 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days, the parties provide to the Court any agreed minute of proposed orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons for judgment, and in relation to costs.

2. If the parties cannot agree, then within 21 days each party file and serve a minute of proposed orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons for judgment, and in relation to costs, together with a short submission.

3. The Court’s reasons for judgment be published, in the first instance, on a confidential basis to the parties and to Asahi Beverages Pty Ltd and Asahi Holdings (Australia) Pty Ltd (Asahi), to enable them to consider whether to seek confidentiality orders with respect to any part of the judgment. Within two business days, the parties and Asahi provide the Court with any submission on proposed confidentiality orders.

4. Subject to further order, the Court’s reasons for judgment otherwise be and remain confidential for a period of seven days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

VID 74 of 2022 | ||

BETWEEN: | PEPSICO, INC Applicant | |

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION Respondent | |

order made by: | MOSHINSKY J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 30 NOVEMBER 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days, the parties provide to the Court any agreed minute of proposed orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons for judgment, and in relation to costs.

2. If the parties cannot agree, then within 21 days each party file and serve a minute of proposed orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons for judgment, and in relation to costs, together with a short submission.

3. The Court’s reasons for judgment be published, in the first instance, on a confidential basis to the parties and to Asahi Beverages Pty Ltd and Asahi Holdings (Australia) Pty Ltd (Asahi), to enable them to consider whether to seek confidentiality orders with respect to any part of the judgment. Within two business days, the parties and Asahi provide the Court with any submission on proposed confidentiality orders.

4. Subject to further order, the Court’s reasons for judgment otherwise be and remain confidential for a period of seven days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

VID 82 of 2022 | ||

BETWEEN: | STOKELY-VAN CAMP, INC Applicant | |

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION Respondent | |

order made by: | MOSHINSKY J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 30 NOVEMBER 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days, the parties provide to the Court any agreed minute of proposed orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons for judgment, and in relation to costs.

2. If the parties cannot agree, then within 21 days each party file and serve a minute of proposed orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons for judgment, and in relation to costs, together with a short submission.

3. The Court’s reasons for judgment be published, in the first instance, on a confidential basis to the parties and to Asahi Beverages Pty Ltd and Asahi Holdings (Australia) Pty Ltd (Asahi), to enable them to consider whether to seek confidentiality orders with respect to any part of the judgment. Within two business days, the parties and Asahi provide the Court with any submission on proposed confidentiality orders.

4. Subject to further order, the Court’s reasons for judgment otherwise be and remain confidential for a period of seven days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

MOSHINSKY J:

1 PepsiCo, Inc (PepsiCo), a United States company, and Stokely-Van Camp, Inc (SVC), also a United States company, have commenced these proceedings to challenge royalty withholding tax notices, and diverted profits tax assessments, issued to them by the Commissioner of Taxation (the Commissioner) in respect of the years of income ended 30 June 2018 and 30 June 2019 (the relevant years).

2 In brief outline, the background facts are as follows.

3 At all relevant times, the PepsiCo group of companies (the PepsiCo Group) operated a global beverage business. PepsiCo was the owner of a world-wide portfolio of trademarks, designs and other rights and assets relating to the Pepsi and Mountain Dew brands, and SVC was the owner of a world-wide portfolio of trademarks, designs and other rights and assets relating to the Gatorade brand.

4 On or about 3 April 2009, each of PepsiCo and SVC entered into an agreement with Schweppes Australia Pty Ltd (SAPL), an Australian company that was owned by Asahi Breweries, in relation to the Australian market. The two agreements were:

(a) a Restated and Amended Exclusive Bottling Appointment between PepsiCo, the Concentrate Manufacturing Company of Ireland (CMCI) and SAPL (the PepsiCo EBA); this agreement relates to carbonated soft drinks (CSDs); and

(b) a Restated and Amended Exclusive Bottling Agreement between SVC and SAPL (the SVC EBA); this agreement relates to non-carbonated beverages (NCBs),

(together, the EBAs).

5 Under the EBAs:

(a) PepsiCo or SVC (as the case may be) agreed to sell, or cause a related entity to sell, beverage concentrate (concentrate) to SAPL; the concentrate was to be mixed by SAPL with other ingredients in accordance with formulas, specifications and other information provided by the PepsiCo Group to produce finished beverages for retail sale in Australia; and

(b) PepsiCo or SVC (as the case may be) granted SAPL the right to use in Australia trademarks and other intellectual property to enable SAPL to manufacture, bottle, sell and distribute the finished beverages in branded PepsiCo Group packaging.

6 The EBAs provided for SAPL to pay for the concentrate. They did not expressly provide for the payment of a royalty for the right to use the intellectual property.

7 During the relevant years:

(a) Concentrate Manufacturing (Singapore) Pte Ltd (CMSPL), a member of the PepsiCo Group incorporated in Singapore, produced concentrate according to a recipe or formula provided by, and with flavour keys supplied by, PepsiCo and SVC;

(b) CMSPL supplied the concentrate to PepsiCo Beverage Singapore Pty Ltd (PBS), a member of the PepsiCo Group that was (despite its name) incorporated in Australia;

(c) PBS was nominated as the “Seller” by PepsiCo under the PepsiCo EBA and as the “Seller” by SVC under the SVC EBA;

(d) PBS supplied concentrate to SAPL and invoiced SAPL for the concentrate that had been supplied;

(e) SAPL paid PBS for the concentrate in accordance with those invoices. In total, SAPL made payments of approximately A$240 million to PBS during the relevant years; and

(f) PBS transferred almost all of the money received from SAPL to CMSPL, retaining only a small margin.

8 The Commissioner relies on two alternative contentions in relation to the facts and matters outlined above:

(a) The Commissioner’s primary contention is that each of PepsiCo and SVC is liable for royalty withholding tax pursuant to s 128B of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (ITAA 1936) and Art 12 of the Convention between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of Australia for the Avoidance of Double Taxation and the Prevention of Fiscal Evasion with respect to Taxes on Income, signed at Sydney on 6 August 1982 (as amended) (US DTA).

(b) The Commissioner’s alternative contention (which only arises if PepsiCo and SVC are not liable for royalty withholding tax) is that the diverted profits tax provisions of Pt IVA of the ITAA 1936 apply.

9 PepsiCo and SVC (the PepsiCo parties) have commenced two proceedings under s 39B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) (VID 74 of 2022 and VID 82 of 2022) seeking declaratory relief to the effect that they are not liable to pay royalty withholding tax in relation to the relevant years in the amounts determined by the Commissioner, or at all.

10 The PepsiCo parties have also commenced four proceedings pursuant to Pt IVC of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) in relation to diverted profits tax assessments made by the Commissioner in relation to the relevant years. The proceedings are:

(a) VID 53 of 2022 – brought by PepsiCo in relation to the year ended 30 June 2018;

(b) VID 55 of 2022 – brought by PepsiCo in relation to the year ended 30 June 2019;

(c) VID 56 of 2022 – brought by SVC in relation to the year ended 30 June 2018; and

(d) VID 57 of 2022 – brought by SVC in relation to the year ended 30 June 2019.

11 The six proceedings were heard together, and evidence in one proceeding was evidence in the other proceedings.

12 The key issues to be determined in relation to royalty withholding tax are as follows:

(a) whether the payments made by SAPL under the EBAs were, to any extent, consideration for the use of, or the right to use, the items set out in paragraphs (4)(a) and (b) of Art 12 of the US DTA and the items set out in paragraphs (a) to (d) of the definition of “royalty” in s 6(1) of the ITAA 1936;

(b) if so, whether the relevant portions of the payments were income derived by PepsiCo or SVC (as applicable) for the purposes of s 128B(2B)(a) of the ITAA 1936 and amounts to which they were beneficially entitled for the purposes of Art 12 of the US DTA; and

(c) if so, whether the relevant portions of the payments were paid, or taken to have been paid, to PepsiCo or SVC (as applicable) for the purposes of s 128B(2B)(b)(i) as affected by s 128A(2).

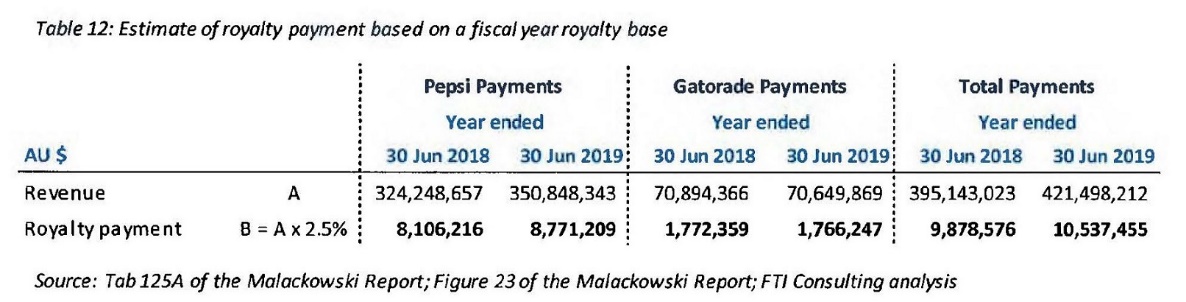

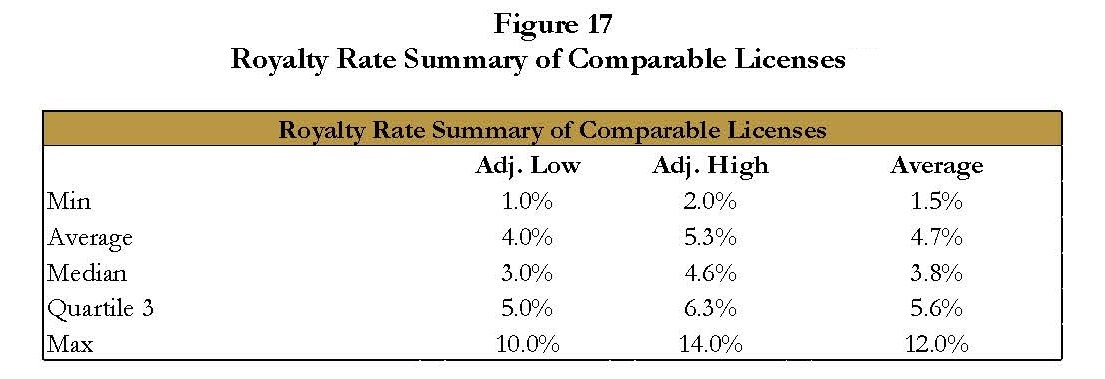

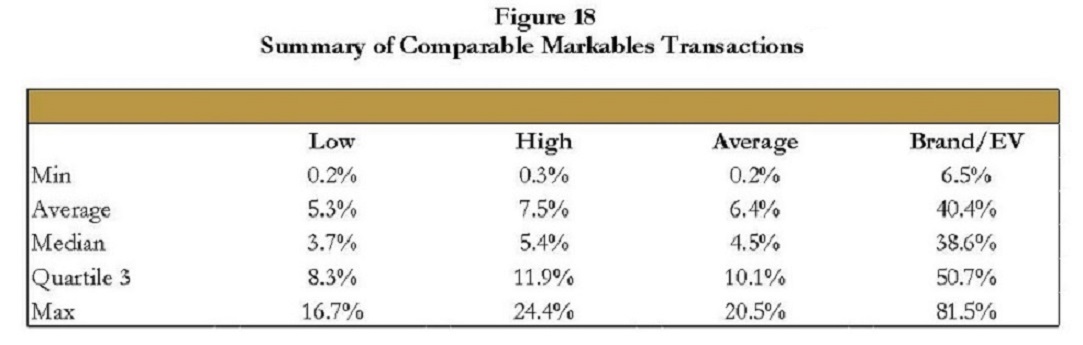

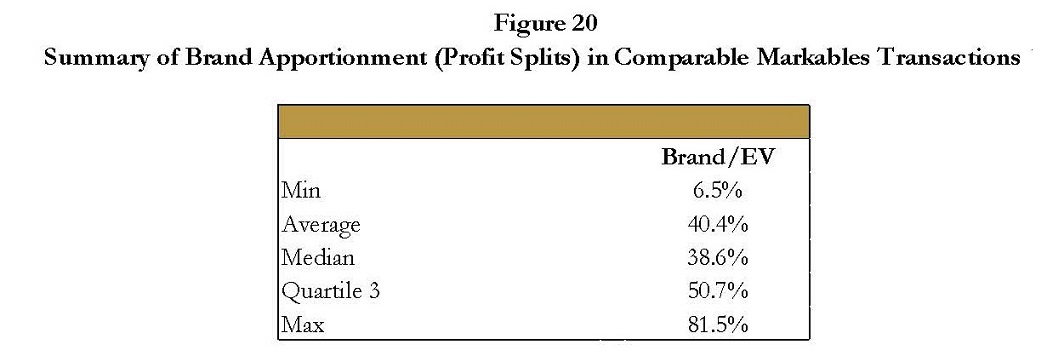

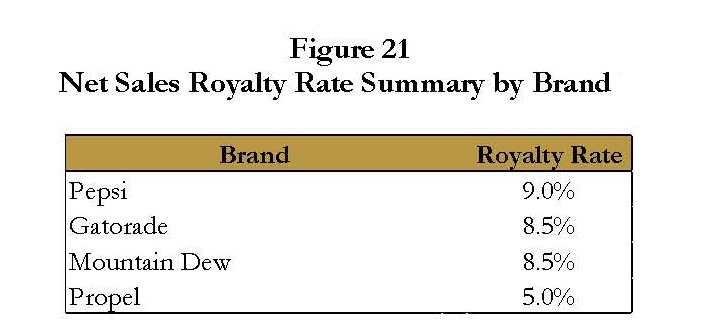

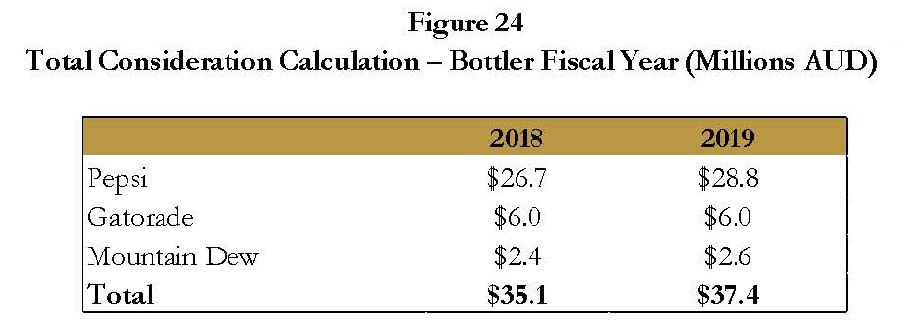

13 If it is concluded that portions of the payments made by SAPL under the EBAs constitute “royalties” for the purposes of the royalty withholding tax provisions, the next issue is the amount of the royalties (upon which royalty withholding tax is payable). The parties have each filed expert evidence in relation to this issue. In summary, the expert evidence filed by the Commissioner states that the royalties are to be calculated by applying rates of 9.0% or 8.5% (depending on the brand) to SAPL’s net revenue from sales of the relevant products. The expert evidence filed by the PepsiCo parties is to the effect that the royalties are to be calculated by applying a rate of 2.5% to SAPL’s net revenue from sales of the relevant products.

14 The Commissioner’s contentions in relation to diverted profits tax are predicated on royalty withholding tax not applying. The Commissioner’s alleged scheme is, in summary, entry into the relevant EBA on terms whereby no royalty was paid for the use of intellectual property, technical knowledge and/or assistance. There is no real issue about the identification of the scheme. The key issues to be determined in relation to diverted profits tax are:

(a) whether PepsiCo or SVC (as applicable) obtained a tax benefit in connection with the scheme for the purposes of s 177J(1)(a) of the ITAA 1936; and

(b) whether it would be concluded, having regard to the matters in s 177J(2) of the ITAA 1936, that the person, or one of the persons, who entered into or carried out the scheme or any part of the scheme did so for a principal purpose of, or for more than one principal purpose that includes a purpose of:

(i) enabling the relevant taxpayer (here, PepsiCo or SVC, as applicable) to obtain a tax benefit, or both obtain a tax benefit and to reduce one or more of the relevant taxpayer’s liabilities to tax under a foreign law, in connection with the scheme; or

(ii) enabling the relevant taxpayer and another taxpayer (or other taxpayers) each to obtain a tax benefit, or both to obtain a tax benefit and to reduce one or more of their liabilities to tax under a foreign law, in connection with the scheme.

15 The Commissioner initially calculated royalty withholding tax and (in the alternative) diverted profits tax on the basis of certain figures for royalties. However, following the filing of expert evidence in this proceeding, the Commissioner amended (downwards) the royalty withholding tax notices and the diverted profits tax assessments to accord with the opinions expressed in the expert evidence he had filed.

16 Under the amended notices of royalty withholding tax (dated 6 March 2023), the liabilities of the two companies for royalty withholding tax for the relevant years (calculated at a rate of 5% of the royalties) are:

(a) for PepsiCo: $3,023,148; and

(b) for SVC: $601,413.

17 Under the amended diverted profits tax assessments (dated 6 March 2023), the liabilities of the two companies for diverted profits tax for the relevant years (calculated at a rate of 40% of the royalties) are approximately:

FY 2018 | FY 2019 | Total: | |

PepsiCo | $11.6 million | $12.5 million | $24.1 million |

SVC | $2.4 million | $2.4 million | $4.8 million |

Total: | $14 million | $14.9 million | $28.9 million |

As is apparent from the figures set out above, the tax in issue on the Commissioner’s alternative case is greater than the tax in issue on his primary case.

18 The following is a summary of my conclusions:

(a) In relation to the royalty withholding tax issue, I have concluded that:

(i) the payments made by SAPL under the EBAs were, to some extent, consideration for the use of, or the right to use, the relevant trademarks and other intellectual property;

(ii) the relevant portions of the payments were income derived by PepsiCo or SVC (as applicable) for the purposes of s 128B(2B)(a) of the ITAA 1936 and amounts to which they were beneficially entitled for the purposes of Art 12 of the US DTA; and

(iii) the relevant portions of the payments are deemed to have been paid by SAPL to PepsiCo or SVC (as applicable) by virtue of s 128A(2) of the ITAA 1936.

It follows from the above that the payments made by SAPL under the EBAs in the relevant years were, to an extent, “royalties” and PepsiCo and SVC are liable to pay royalty withholding tax at the rate of 5% on those royalties.

(b) In relation to the amount of the royalties, subject to one matter, I have concluded that the amount of the royalties is 5.88% of SAPL’s net revenue from sales of the relevant products during the relevant years. The one matter is that I consider that one licence agreement (contained in the set of comparable transactions) that was treated as non-exclusive (and therefore the subject of an adjustment) should have been treated as exclusive. Accordingly, I consider that that agreement should not have been the subject of an adjustment. I conclude that the figure of 5.88% needs to be revised (downwards) in light of that matter. This would appear to be a mathematical exercise based on material already in evidence.

(c) In light of the above conclusions, it is unnecessary to consider the diverted profits tax issue. However, I consider this issue for the sake of completeness. The Commissioner's diverted profits tax case is predicated on the royalty withholding tax provisions not applying. Therefore, in dealing with the diverted profits tax issue, I proceed on the assumption that (contrary to the conclusion I have reached above), the royalty withholding tax provisions do not apply. On that assumption, I have concluded that:

(i) each of PepsiCo and SVC obtained a tax benefit in connection with the relevant scheme; and

(ii) having regard to the matters in s 177J(2) of the ITAA 1936, it would be concluded that one of the principal purposes of each of PepsiCo and SVC in entering into or carrying out the relevant scheme was to obtain a tax benefit (namely not being liable to pay Australian royalty withholding tax) and to reduce foreign tax (namely, US tax on their income).

It follows that, had I not concluded that the royalty withholding tax provisions applied, I would have concluded that the diverted profits tax provisions apply.

19 The PepsiCo parties called the following lay witnesses:

(a) Lillian Dent, General Counsel for the Australia and New Zealand business unit of the PepsiCo Group; Ms Dent has worked in the PepsiCo Group in legal roles for over nine years; on 27 June 2018, she was appointed as a director of PBS; she ceased acting as director on 16 October 2019; she was reappointed as a director on 11 July 2022 and remains a director of PBS;

(b) Andrew Williams, who worked for the PepsiCo Group in marketing and bottling franchise-related roles for over 35 years; in about 2012, he took on the role of establishing the franchise function across PepsiCo International; in 2019, that role was consolidated with the PepsiCo Group’s global beverage marketing role, so he became the President of the PepsiCo Group’s Global Beverage Group and the Franchise Team; in that capacity, he was responsible for setting marketing and bottling franchise-system strategies to be implemented in approximately 115 countries worldwide;

(c) Randall Lovorn, the General Manager of PepsiCo Global Concentrate Solutions (PGCS), which is a division of the PepsiCo Group; he has held that role since 2019; he is responsible for all of the functions performed by PGCS related to the manufacture of concentrate, namely manufacturing, planning, logistics, finance, information technology and human resources; and

(d) Myles O’Donnell, the Vice-President of the Coded Materials function and the lead Flavour Trustee within PGCS; he commenced in that role in January 2020; he has worked within PGCS for the last 25 years; Mr O’Donnell was appointed as a Flavour Trustee (described later in these reasons) in 2015; his roles at the PepsiCo Group relate to the manufacture and supply of concentrate, in particular, in recent years, the Coded Keys (described below).

20 Each of these witnesses gave evidence-in-chief by affidavit and was cross-examined.

21 Ms Dent was somewhat tentative in her answers to certain questions and it perhaps appeared that she was not answering some questions directly. In any event, I have no doubt that she gave evidence honestly and was intending to assist the Court, and I generally accept her evidence.

22 Mr Williams answered questions in a clear and straightforward way. It should be noted that he did not have personal knowledge of several matters that are relevant in these proceedings. He was not familiar with the company, Stokely-Van Camp, Inc; he thought (incorrectly) that PepsiCo owned the Gatorade trademark (in fact it is SVC); he was not familiar with the PepsiCo EBA (one of the key documents in the case), and he said that he had not gone through an exclusive bottling agreement in any detail for many years. As discussed later in these reasons, while I accept many parts of Mr Williams’s evidence, there are some aspects that I have difficulty in accepting.

23 Mr Lovorn evinced a very good command of the subject-matter. He answered questions in a clear and straightforward way. I generally accept his evidence.

24 The cross-examination of Mr O’Donnell was brief. I generally accept his evidence.

25 The Commissioner did not call any lay witnesses.

26 Each party called one expert witness in relation to the quantification issue; that is, the issue of what proportion of the amounts paid by SAPL constituted a royalty, on the assumption that (contrary to the PepsiCo parties’ position) part of those amounts did constitute a royalty. The experts called by the parties were:

(a) the PepsiCo parties called Dawna Wright, a forensic accountant at FTI Consulting based in Melbourne; and

(b) the Commissioner called James Malackowski, an intellectual property consultant at Ocean Tomo, LLC (a part of JS Held) based in Chicago, Illinois, United States of America.

27 The experts prepared reports: Ms Wright prepared an initial report dated 19 September 2022; Mr Malackowski prepared a report dated 22 December 2022; and Ms Wright prepared a reply report dated 3 February 2023.

28 As detailed later in these reasons, the experts updated their calculations following the preparation of their reports, with the updated calculations set out in certain letters.

29 The experts were cross-examined separately (rather than giving evidence concurrently). I discuss and make observations about their evidence later in these reasons.

30 The parties also tendered a number of documents. These were contained in an electronic revised Court Book (CB) and an electronic Supplementary Court Book (SCB). Following the trial, the parties provided an annotated version of the index to the CB that indicated which documents had gone into evidence.

The pleadings or equivalent documents

31 In relation to the royalty withholding tax proceedings (VID 74 of 2022 and VID 82 of 2022), PepsiCo or SVC (as applicable) have filed an amended originating application and an amended statement of claim, and the Commissioner has filed an amended defence. These documents were filed in March 2023 and reflect the updated figures relied on by the Commissioner in the notices dated 6 March 2023.

32 In relation to the diverted profits tax proceedings, in each proceeding, PepsiCo or SVC (as applicable) has filed a notice of appeal. In each proceeding, the Commissioner has filed an amended appeal statement (albeit the title omits the word “amended”) and PepsiCo or SVC has filed an amended appeal statement. The amended appeal statements were filed in March 2023 and reflect the amended diverted profits tax assessments of 6 March 2023. In each proceeding, the Commissioner’s amended appeal statement sets out the “scheme” and the counterfactuals (relevant for the “tax benefit” issue). For example, the Commissioner’s amended appeal statement in VID 53 of 2022 states:

67. [The] Commissioner contends that PepsiCo entered into a scheme comprising some or all of the following (the Scheme):

67.1. effective from 3 April 2009, PepsiCo entered into the [PepsiCo] EBA with SAPL whereby:

(a) SAPL was appointed as the sole and exclusive licensee to bottle, sell and distribute trademarked PepsiCo Group carbonated soft drink beverages. (The beverage brands the subject of the [PepsiCo] EBA, apart from the Seven Up brands, are referred to below as the Pepsi Beverages);

(b) SAPL agreed to purchase concentrate for the manufacture of the Pepsi Beverages from PepsiCo or one of its appointed subsidiaries; and

(c) SAPL obtained, under the [PepsiCo] EBA and/or the agreements referred to within it, including the Co-op A&M Agreements:

i. the use of, or rights to use, certain intellectual property owned by PepsiCo in the bottling, sale and distribution of the Pepsi Beverages;

ii. technical, industrial or commercial knowledge or information in relation to the Pepsi Beverages; and/or

iii. assistance ancillary to and furnished as a means of enabling the application or enjoyment of such intellectual property or knowledge or information.

(d) no royalty was paid for the items set out at (c) above.

68. Had the Scheme not been entered into or carried out:

68.1. the [PepsiCo] EBA would or might reasonably be expected to have:

(a) expressed the EBA Payments to be for all of the property provided by (and promises made by) the PepsiCo group entities (rather than for concentrate only); or

(b) expressly provided for the EBA Payments to include a royalty for the provision to SAPL of the rights, knowledge and assistance referred to above at [67.1(c)] (whether or not the amount of the royalty was specified); and

68.2. consequently, a royalty would or might reasonably be expected to have been paid by SAPL to PepsiCo or to another entity on PepsiCo’s behalf or as PepsiCo directed (the Counterfactual).

33 Contentions in substantially the same form appear in the Commissioner’s appeal statements in the other diverted profits tax proceedings.

34 In these reasons, I will refer to the counterfactuals set out in paragraphs (a) and (b) of paragraph 68.1 (read with paragraph 68.2) (and the corresponding paragraphs in the other amended appeal statements) as the Commissioner’s Counterfactuals.

Overview of the PepsiCo Group business model

35 The PepsiCo Group beverages each have (and had during the relevant years) a “brand owner”, namely PepsiCo or CMCI (and later Portfolio Concentrate Solutions UC (PCS)) for CSBs, and SVC for NCBs (being mostly sports drinks under the Gatorade brand).

36 The recipe or formula for the manufacture of concentrate for a particular beverage is (and was during the relevant years) highly secret.

37 During the relevant years, the PepsiCo Group had a number of concentrate manufacturing facilities around the world. The concentrate manufacturer either sold the concentrate directly or through a concentrate distributor that derived a small margin on the sales. The local bottler converted the concentrate into finished beverages and was responsible for distributing the beverages in the local market.

38 Under the model, the brand owner (PepsiCo, CMCI (or PCS) or SVC) has (and had during the relevant years) a direct relationship with the bottler. The brand owner controls and protects how the brand is used by the bottler and also has an ability to enforce quality requirements and consistency of how the brand is used.

39 During the relevant years, the concentrate manufacturer bore responsibility for manufacturing the concentrate so as to ensure that each beverage had its distinctive taste, and for getting the concentrate to the bottler. The concentrate manufacturer, or the concentrate distributor, also had responsibility for contributing some of the proceeds it received from the sale of concentrate towards marketing activities and payments to the bottler if it met certain targets.

Exclusive bottling agreements (2000 to 2008)

40 On 6 October 2000, PepsiCo, Seven-Up International (a division of CMCI) and Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd (as bottler) entered into an exclusive bottling appointment in relation to Australia.

41 On or about 16 May 2001, SVC entered into an exclusive bottling agreement with Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd (as bottler) in relation to Australia.

42 On or about 16 August 2006, SVC and Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd entered into a Restated and Amended Exclusive Bottling Agreement.

43 On 24 December 2008, Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd, Associated Home Delivery Pty Ltd (as SAPL was then known), PepsiCo, CMCI and SVC entered into a Deed of consent and novation.

44 In 2009, the Cadbury group of companies that controlled the beverage business was acquired by the Asahi group of companies and new exclusive bottling agreements, namely the PepsiCo EBA and the SVC EBA, were entered into. These are described below.

45 On 3 April 2009, PepsiCo, CMCI and SAPL entered into the PepsiCo EBA. I note that PBS was not a party to this agreement. The PepsiCo EBA (as amended) was in place during the relevant years.

46 The “Bottler” for the purposes of the agreement was SAPL. The term “Company” was defined as follows:

When used herein with respect to any matter concerning PEPSI, PEPSI MAX, PEPSI LIGHT, PEPSI LIGHT CAFFEINE FREE or MOUNTAIN DEW, the term ‘Company’ refers to PepsiCo, when used herein with respect to any matter concerning SEVEN-UP, the term ‘Company’ refers to CMCI; when used herein generally without regard to any particular trademark or beverage, the term ‘Company’ means both and each of PepsiCo and CMCI collectively. When used in clauses 24, 26, 29, 32 and 36 hereof, PepsiCo and CMCI shall collectively be regarded as one party;

47 The recitals noted that the Bottler and the Company were parties to an exclusive bottling agreement dated 6 October 2000 in respect of beverages known as and sold under the trademarks “Pepsi”, “Pepsi Max”, “Pepsi Light”, “Pepsi Light Caffeine Free”, “Mountain Dew” and “Seven-Up” (referred to as the “EBA”). The recitals also stated that the Bottler and the Company wished to restate and amend the EBA in accordance with this agreement.

48 Clause 2 stated that the EBA was amended and restated by being replaced wholly with this agreement with effect from the Commencement Date (which was 3 April 2009).

49 Clause 3 dealt with the appointment of the bottler as follows:

3 Appointment

(a) Subject to the terms of this Agreement, PepsiCo hereby appoints Bottler, to bottle, sell and distribute the beverages known as and sold under the trade marks PEPSI, PEPSI MAX, PEPSI LIGHT, PEPSI LIGHT CAFFEINE FREE and MOUNTAIN DEW; and CMCI hereby appoints Bottler, to bottle, sell and distribute the beverages known as and sold under the trade mark SEVEN-UP, in each case as its sole and exclusive licensee within the Commonwealth of Australia (‘Territory’) and nowhere else.

All the above beverages are hereinafter referred to as the ‘Beverages’ and all the above trade marks are hereinafter referred to as the ‘Trade marks’.

(b) The term of this Agreement shall be from the Commencement Date until 6 October 2020 (‘Original Term’). This Agreement will be automatically extended for a term of 20 years, unless either Bottler or Company shall give notice in writing to the other party of its intention not to renew this Agreement, said notice to be given at least one year in advance of the expiration of the Original Term.

(c) Bottler accepts this appointment upon the terms herein contained and will bottle, sell and distribute the Beverages only for ultimate resale to consumers in the Territory and will not bottle, sell or distribute the Beverages to any person or entity whom bottler knows, or has reason to know, will export the Beverages, whether directly or indirectly, outside the Territory.

(d) Further, Company grants to Bottler a right of first refusal in relation to any other offer of bottling and/or distribution appointment in the Territory which Company or its affiliate wishes to make for any beverage which has not been previously licensed to Bottler. If Bottler declines any such offer or if no written acceptance of the offer is received from Bottler within 30 days of Company’s written offer being sent to Bottler, Company reserves such right for itself and for third parties, on terms and conditions no more favourable than those offered to Bottler.

(Emphasis added.)

50 Insofar as the appointment clause, set out above, involved CMCI appointing SAPL in respect of Seven-Up, this can be put to one side for the purposes of the present proceedings, as they do not raise any issues concerning Seven-Up.

51 Clause 4 dealt with supply of concentrate and included:

4 Supply of Concentrate

(a) Company will sell or cause to be sold by one of its subsidiaries (Company and/or such subsidiary hereinafter both called ‘Seller’) to Bottler, and Bottler will buy only from Seller, all units of concentrate (hereinafter called ‘Units’) required for the manufacture of the Beverages by Bottler, at the following prices for the calendar year 2009.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(b) The above prices per Unit shall be adjusted on January 1 of each year during the term of this Agreement based on the official Australia Consumer Price Index (all groups) (‘CPI’) as published from time to time by the relevant government majority measured over the 12 month period ended on the immediate preceding June 30 or such other comparable index as the parties will agree if the CPI is suspended or discontinued or its method of calculation is substantially altered.

(c) All Units shall be delivered to Bottler’s plant, with freight, insurance and handling charges to be prepaid by Seller and charged to Bottler. Bottler shall be responsible for paying customs duty and GST. Bottler will at its own cost and expense, and without any cost or expense to Seller, obtain all import licenses and permits in relation to the Units. Company is responsible for ensuring the Units comply with all applicable laws and regulations in the Territory necessary to obtain all import licenses and permits. Title to all Units shipped by Seller to Bottler shall remain in Seller until the Units are paid by Bottler according to the provisions hereof. Payment in full for each order of Units shall be made by Bottler within 7 days of delivery.

(d) Bottler agrees that it shall carry an inventory of Units equal to 45 days’ projected usage, but not less than the previous financial year’s average 45 days’ actual usage.

(Emphasis added.)

The Commissioner draws attention to the fact that the clause provides for sale of concentrate “at” certain prices; it does not state that the payments are made “as consideration for” the concentrate or that the payments are made “only” for the concentrate.

52 Clause 5 dealt with the trademarks:

5 Trade Marks

(a) Company represents and warrants that it is (and will remain during the term of this Agreement) the registered proprietor in the Territory of the Trade marks and that the use of each of the Trade marks by Bottler according to the provisions of this Agreement will not infringe the rights of any other party.

(b) The decision of Company on all matters concerning the Trade marks shall be final and conclusive on, and not subject to question by, Bottler. Company will protect and defend the Trade marks at its sole cost and expense, but, subject to the indemnity provided by Company under clause 22 hereof, Company shall not be liable to Bottler for any loss or damage suffered by Bottler by Bottler’s use of the Trade marks or as a result of any litigation or proceeding involving the Trade marks. Bottler will cooperate fully with Company in the defence and protection of the Trade marks and will promptly and fully advise Company of any use in the Territory of any mark infringing the Trade marks. Company agrees to be responsible for any reasonable third-party costs incurred by Bottler in defending and protecting the Trade marks at the request of Company.

(c) Bottler recognises Company’s ownership of the Trade marks and will not take any action which will prejudice or harm the Trade marks, or Company’s ownership thereof, in any way.

(d) Nothing herein contained shall be construed as conferring upon Bottler any right or interest in the Trade marks, or in their registrations or in any designs, copyrights, patents, trade names, signs, emblems, insignia, symbols and slogans, or other marks, used in connection with the Beverages.

(Emphasis added.)

I note that the expression “Trade marks” was earlier defined in clause 3(a).

53 Clause 6 dealt with manufacturing directions. Clause 7 dealt with manufacturing materials. Clause 8 dealt with bottling plants and clause 9 dealt with bottling plant standards.

54 Clause 11 related to selling activities:

11 Selling activities

(a) Bottler will sell Beverages in the Territory in agreed packages and proprietary packages as Company may from time to time specify.

(b) Company anticipates that Bottler will sell Beverages in the Territory at prevailing competitive market prices.

(c) Bottler will sell and distribute beverages in accordance with all national, state municipal, local and other governmental laws, decrees, ordinances, rules, orders, regulations and charges.

(d) As may be agreed between the parties from time to time, Bottler will test market and introduce new packages and new package sizes for the Beverages in all or part of the Territory, and provide the bottling, selling and distribution facilities for such purposes.

(e) Bottler will use its reasonable endeavours to maximise the sale of Beverages throughout the Territory. Without in any way limiting bottler’s obligations under this clause 11, Bottler must use its reasonable endeavours to fully meet and increase the demand and share of market for Beverages throughout the Territory and secure full distribution up to the maximum sales potential therein through all distribution channels or outlets available to soft drinks, using any and all equipment reasonably necessary to secure such distribution, must fully exploit new packages, new package sizes and new Beverages opportunities; must serve all accounts with frequency adequate to keep them at all times fully supplied with Beverages; must use its own salesmen and trucks (or salesmen and trucks of independent distributors, of whom Bottler shall notify Company), in quantity adequate for all reasons; must cooperate in Company’s cooperative advertising and sales promotion programs and campaigns for the Territory.

(Emphasis added.)

55 Clause 12 required SAPL to maintain sufficient inventory. Clause 13 required SAPL to provide samples to the Company on a monthly basis. Clause 14 allowed the Company to conduct inspections of SAPL’s plant or plants. Clause 15 required SAPL to keep records of tests. Clause 16 required SAPL to provide certain information and reports to the Company.

56 Clause 17 dealt with permitted activities of SAPL and provided in part:

17 Permitted activities

(a) Bottler will sell and distribute Beverages under the Trade marks and will make only such representations concerning Beverages as shall have been previously authorised in writing by Company.

Neither Bottler nor any affiliated or related entity or one under common ownership or control or one in which Bottler has an interest or participation will, in the Territory, bottle, distribute or sell, directly or indirectly:

(i) any other cola drink or any drink or beverage similar to a cola beverage having the word ‘cola’ as part of its name, or

(ii) any clear carbonated lemon and/or lime drink which imitates or can reasonably be confused with SEVEN-UP or DIET SEVEN-UP (including get-up, trade mark or logo). For the avoidance of doubt, the following are excluded …

(iii) any carbonated beverage which imitates or can reasonably be confused with MOUNTAIN DEW, and

(b) Bottler will not use in connection with any beverage any trade mark, designation or trade dress which imitates or is likely to be confused with Company’s Trade marks, designations or trade dress.

(c) Notwithstanding the foregoing, Company recognises that bottler is involved in co-packaging certain house brand private label supermarket beverages. With the exception of co-packaging of private label cola beverages or beverages similar to a cola beverage, Company agrees that Bottler may continue co-packaging such beverages, provided that the total volume of such co-packed beverages shall not exceed [redacted]% of the total volume of all of the beverages (including Beverages) produced by Bottler in any calendar year. In that regard, Bottler shall provide to Company a certificate signed by a director of Bottler certifying compliance with such volume number.

(d) For the avoidance of doubt, nothing herein shall prohibit Bottler from co-packing any alcoholic pre-mixed beverage with an alcohol content greater than 1%.

(Emphasis added.)

57 Although the agreement did not expressly licence SAPL to use the relevant trademarks and other intellectual property, it is common ground that the agreement contained an implied licence to this effect, having regard to clause 17 and the agreement generally; the agreement could not operate otherwise.

58 Clause 18 dealt with entry into a co-operative advertising and marketing agreement in relation to the beverages in the Territory (defined in clause 3(a) as Australia). Clause 19 related to a performance agreement entered into by Pepsi-Cola International, Cork (PCIC), a subsidiary of PepsiCo based in Ireland, and SAPL on the same day as the agreement.

59 Clause 20 dealt with permitted advertising:

20 Permitted advertising

In order to ensure consistency of image Bottler will use only such advertising strategies for Beverages as Company may develop for that market. In that connection, Bottler will use only advertising and promotion materials furnished or caused to be furnished by Company or approved by it in writing which comply with the laws in the Territory and to the extent any of Company’s Trade marks is used, will not advertise the Beverages in or through media or engage in promotions of the Beverages, not approved by Company in writing (which approval will not be unreasonably withheld or delayed). Company reserves the right to contract with, control and administer national and local media and reserves the right to appoint advertising, sales promotion and public relations and research agencies with respect to Beverages and to be the client of record of these agencies.

(Emphasis added.)

60 Clause 24 dealt with rights of termination and included:

24 Rights of termination

(a) Upon the happening of any one or more of the following events to a party, in addition to all other rights and remedies, the other party shall have the right to cancel and terminate this Agreement by one month’s written notice to such party:

(i) The failure of a party to perform or comply with any one or more of the material terms or conditions of this Agreement and such failure (if capable of remedy) is not remedied by such party within 60 days after it has been served with a written notice specifying such failure PROVIDED HOWEVER the right to cancel and terminate and all other rights and remedies under this clause 24(a)(i) will not apply if such failure is not capable of remedy within such 60-day period and such party has demonstrated that it has diligently pursued all necessary steps to cure such failure.

61 Clause 27 dealt with matters arising on termination and stated in part:

27 Matters arising on termination

Should this Agreement be terminated:

(a) Bottler will not after the date of termination use in any manner whatsoever any of the Trade marks, marks, names, symbols, slogans, emblems, insignia or other designs; and …

62 Clause 28 dealt with compliance by distributors and provided:

28 Compliance by distributors

In the event Bottler utilizes distributors, to the extent permissible by law, Bottler will use reasonable endeavours to ensure that distributors comply fully with all of the terms and conditions of this Agreement relative to the sale and distribution of Beverages.

63 Clause 36 provided:

36 Confidential information

Each of the parties has been advised by the other that the information provided by each party to the other hereunder and the provisions hereof (collectively the ‘information’) which is non-public, confidential and proprietary information and of the possible damage which could result if any of the information is disclosed to a third party. Accordingly both Bottler and Company agree to use the information solely for the purposes contemplated by this Agreement, disclose the information only to its respective directors, officers and employees on a need-to-know basis and keep the information strictly confidential and not disclose any of the information to any third party, without the express prior written approval of the other party.

64 The PepsiCo EBA was varied on a number of occasions.

65 The evidence includes an undated variation agreement that took effect on and from 1 June 2012. The agreement deleted and replaced clause 3(a) with the following:

Subject to the terms of this Agreement, PepsiCo hereby appoints Bottler, to bottle, sell and distribute the beverages known as, and/or sold under the trade marks PEPSI, PEPSI MAX, PEPSI LIGHT, PEPSI LIGHT CAFFEINE FREE, MOUNTAIN DEW, MOUNTAIN DEW ENERGISED WITH CAFFEINE, DIET PEPSI, DIET PEPSI CAFFEINE FREE, PEPSI NEXT AND PEPSI MAX KICK and CMCI hereby appoints Bottler, to bottle, sell and distribute the beverages known as and sold under the trade mark SEVEN-UP, in each case as its ‘sole and exclusive licensee within the Commonwealth of Australia (‘Territory’) and nowhere else.

All of the above beverages are hereinafter referred to as the ‘Beverages’ and all of the above trade marks are hereinafter referred to as the ‘Trade Marks’.

66 On 16 September 2015, the parties signed a letter agreement varying the PepsiCo EBA by including additional terms relating to the “Say it With Pepsi” campaign and, in particular, the use of certain “Artwork” by the Bottler. The additional terms included the following licence (expressed to be royalty free):

2. Licence and IPR

2.1 In consideration for the Bottler complying with its obligations under the EBA (including this letter), PepsiCo grants to the Bottler an exclusive, irrevocable, royalty free licence (including a right to sublicense) for the Term to use the Artwork or part of the Artwork (and any Intellectual Property Rights in the Artwork) in the Territory in the exercise of its rights under the EBA, including this letter (hereinafter, the Licence).

2.2 The Bottler acknowledges that all right, title and interest in the Artwork (and any Intellectual Property Rights in the Artwork) remains vested in PepsiCo at all times.

2.3 The Bottler must comply with PepsiCo’s reasonable directions relating to the use and application of the Artwork (and any Intellectual Property Rights in the Artwork).

The letter agreement also included warranties, indemnities, general terms and definitions of “Artwork” and “Intellectual Property Rights”.

67 On 20 March 2018, the parties signed a letter agreement varying the PepsiCo EBA by including additional terms relating to the bottling, sale and distribution of Pepsi and Pepsi Max branded beverages in a new bottle, known as the AXL Bottle. The letter agreement was broadly similar to that set out above.

68 On 16 May 2018, the parties signed a letter agreement varying the PepsiCo EBA by including additional terms relating to the bottling, sale and distribution of PepsiCo’s Pepsi Max Raspberry product. The additional terms were similar to those in the previous two letter agreements.

69 On 23 November 2018, the parties signed a letter agreement varying the PepsiCo EBA by including additional terms relating to the bottling, sale and distribution of PepsiCo’s 1893 Pepsi Cola product. The additional terms were similar to those in the letter agreements described above.

Agreements related to the PepsiCo EBA

2009 CSD Performance Agreement

70 On or about 3 April 2009, PCIC and SAPL entered into a performance agreement (the 2009 CSD Performance Agreement) that deals, broadly, with minimum sales volumes, quality standards, and advertising and marketing. I infer that, at this time, PCIC was the designated seller under the PepsiCo EBA. (In Ms Dent’s affidavit, at paragraph 45, she stated that PCIC was the designated seller of concentrate to SAPL as at 2015.) I also infer that the 2009 CSD Performance Agreement remained in place during the relevant years. (The term of the agreement is the same as that of the PepsiCo EBA and there is no indication in Ms Dent’s affidavit that the agreement ceased to be in effect or was replaced.) The evidence does not seem to include any agreement by which PCIC was replaced by PBS when it became the designated seller under the PepsiCo EBA. Ms Dent’s affidavit does not refer to any such agreement in the part of her affidavit dealing with this subject-matter (paragraphs 40-41). I will proceed on the basis that PCIC remained a party to this agreement during the relevant years. Nothing turns on whether the PepsiCo Group company that was party to this agreement was PCIC or PBS.

71 The Introduction to the 2009 CSD Performance Agreement stated that the purpose of the agreement was to record the agreement of PCIC and SAPL (referred to as the “Bottler”) in relation to certain aspects of the operation of the bottler under the PepsiCo EBA in relation to the beverages sold under the trademarks specified in Sch 1 (defined as “Beverages”). Schedule 1 listed the following trademarks: Pepsi, Pepsi Max, Seven-Up, Mountain Dew, Pepsi Light and Pepsi Light Caffeine Free. The agreement stated that it was the performance agreement referred to in the PepsiCo EBA. It was stated that: definitions and expressions in the PepsiCo EBA applied in this agreement; in the event of any inconsistency, the PepsiCo EBA would prevail; and this agreement, the PepsiCo EBA and the annual Co-operative Advertising and Marketing Agreement (Co-op A&M Agreement) contained the entire agreement between the parties with respect to its subject-matter.

72 Clause 3 dealt with minimum annual sales volumes and the setting of sales volume targets. The clause set out agreed total minimum annual sales volumes for the Beverages for each of the calendar years 2009, 2010, 2011 and 2012. It stated that, for each of the subsequent calendar years 2013 to 2020, PCIC and Bottler would discuss in good faith and seek to agree on minimum sales volumes for Beverages for each calendar year, and that these discussions would take place as part of the development of the annual Co-op A&M Agreement.

73 Clause 5 dealt with distribution targets and investments. Clause 6 dealt with quality standards.

74 Clause 7 dealt with marketing and advertising, referring to Above-the-Line (ATL) and Below-the-Line (BTL) marketing and promotional activities. These expressions were explained in the affidavit of Mr Williams. Mr Williams stated that marketing programs are commonly split into two areas, referred to as “pull” and “push”. He explained that: “pull” refers to enticing consumers to go and pull the PepsiCo Group’s brands off the shelf; it covers communication and sponsorship; “push” refers to the strategies directed to getting PepsiCo Group beverage brands on the shelves in the right stores and pushing it to the consumers by appropriate pricing and store placement strategies. He stated that the ATL and BTL references in the 2009 CSD Performance Agreement corresponded to the pull and push activities described earlier in his affidavit; the PepsiCo Group was primarily responsible for ATL activities while the bottler (here, SAPL) was primarily responsible for BTL activities. I accept this evidence.

75 Mr Williams gave evidence in his affidavit (which I accept) that: “ATL” also relates to building brand equity; there are various measures of brand equity, which the PepsiCo Group uses largely to monitor performance against its competitors; for example, taste, frequency of consumption, and whether the brand is top of mind for a consumer; Schedule 3 of the 2009 CSD Performance Agreement describes this as a PepsiCo Group responsibility; brand equity initiatives are typically included in Performance Agreements such as in Schedule 3 because, if too much of a marketing budget is spent on push, this might lead to selling product, but brand equity in the mind of the consumer is not being built; and the PepsiCo Group needs that brand equity to gain pricing power so that higher prices may be charged for its beverages.

76 Clause 7.1 stated that the advertising, marketing and promotional guidelines in Schedule 3 set out the respective roles of PCIC and the Bottler to undertake advertising, marketing and promotional activities.

77 Clause 7.2 stated that, for the calendar years 2009 to 2012, PCIC and SAPL would discuss in good faith, with the intention of entering into, by no later than the end of the second business week in December, a Co-op A&M Agreement to apply for the following calendar year; each Co-op A&M Agreement would outline an annual advertising and marketing expenditure program designed to sustain and grow the volume of Beverages.

78 Clause 7.3 set out a series of principles and terms relating to advertising and marketing. Clause 7.4 provided:

For each calendar year 2013 to 2020, Bottler and PCIC will negotiate in good faith as part of the annual Co-op A&M an annual advertising and marketing expenditure program designed to sustain and grow the volume of Beverages and for each annual period will provide for and record:

(a) minimum annual sales volumes;

(b) annual sales volume targets;

(c) specific innovation commitments, and

(d) the amount of the PCIC’s Fixed Controlled Expenditure, and the allocation of such expenditure as between ATL activities, PCIC BTL, and the amount to be provided for as the Bottler Volume Incentive.

In the event that a Co-op A&M agreement is entered into for a calendar year, the principles and terms set out in clause 7.3 will apply to it.

79 The 2009 CSD Performance Agreement was amended twice, by a letter agreement dated 25 February 2010 and a letter agreement dated March 2011 (effective 1 January 2011).

80 For each calendar year during the period 2009 to 2019, a Co-op A&M Agreement was entered into between a company or companies in the PepsiCo Group and SAPL.

81 For example, PBS and SAPL entered into a Co-op A&M Agreement for the 2017 calendar year (the 2017 CSD Co-op A&M Agreement). The agreement stated that definitions referred to in the PepsiCo EBA would apply to the agreement, and those definitions would prevail in the event of inconsistency.

82 Clause 2 of the agreement provided that the parties would contribute financially towards the advertising and marketing of the Beverages in the Territory to the extent and in the manner set out in the agreement.

83 Clause 3 dealt with (among other things) the target amount to be spent on advertising and marketing of the Beverages during the year, and the amount to be contributed by each of the Seller and the Bottler. The clause also provided some detail as to how that expenditure was to be allocated, with a breakdown between ATL and BTL activities. Appendix C contained details of the calculations.

84 Clause 7 stated that the agreed allocation of the expenditure to specified advertising and marketing programs was set out in Appendix A. Clause 8 stated that the current proposed allocation of expenditure by the Bottler towards BTL activities was set out in Appendix B. Clause 9 provided in part that the Bottler would not use any art work depicting images of PepsiCo brands in any program that had not been approved by the Seller.

85 Clause 16 provided that the bottler acknowledged that its contribution to the expenditure was for the purposes of improving its sales of Beverages, “not to build the brands of the Beverages”.

86 On or about 3 April 2009, SVC and SAPL entered into the SVC EBA. I note that PBS was not a party to this agreement. The SVC EBA (as amended) was in place during the relevant years.

87 The recitals stated that: SVC (referred to as the “Company”) and SAPL were parties to an exclusive bottling agreement (referred to as the “EBA”) dated 16 May 2001 in respect of Gatorade products (which were described in Schedules 1A and 1B); the parties wished to wholly restate and amend the EBA in accordance with the agreement; the parties intended the agreement to take effect upon the Commencement Date (defined as 3 April 2009); the parties also agreed to enter into the agreement in respect of the Propel products; and, subject to the terms and conditions of the agreement, SVC appointed SAPL to manufacture, package, distribute and sell the Gatorade products and the Propel products “under the respective Trade Marks … as its exclusive licensee of the Intellectual Property within the Territory”. Thus, unlike the PepsiCo EBA, the SVC EBA contained an express licence. I note that the present proceedings do not raise any issue concerning the Propel products; that aspect of the agreement can therefore be put to one side.

88 Clause 1.1 included the following definitions (which are relevant to clauses set out below):

Company Affiliate means any company, partnership, joint venture, branch or other corporate entity under the Control of or majority owned by Company.

…

Information means data, instructions, plans, specifications, formulae, technology, know-how, technical data, computer software, drawings, process descriptions, reports, developments, results, technical advice and trade secrets, whether in documentary, visual, oral, machine readable or other form and samples, equipment, and other tangible items.

Intellectual property means all intellectual property rights in, or in respect of, the Products, Powder Products and SMP including without limitation:

(a) copyright, design rights, Trade Marks, Works, Packaging Specifications, Product Specifications and Artwork;

(b) any registration, application for or right to apply for registration of, any of those rights owned by or licensed to Company; and

(c) Company’s information,

but excludes all Intellectual property rights owned by [SAPL] or its Related Corporations.

…

Licence means the licence of Intellectual Property granted pursuant to clause 4.

…

Packaging means all packaging, containers, bottles, labels (including for the avoidance of doubt promotional labels), closures and other similar items used in relation to the Products and Powder Products.

…

Products means the products to be manufactured by [SAPL] in the Territory in accordance with this Agreement, as described in schedules 1A, and 1C and any other products agreed during the Term.

…

Registrations means the Australian trade mark registrations described in Part 2 of schedule 3.

Related Corporation has the meaning given to related body corporate in the Corporations Act.

…

Seller has the meaning given to that term in clause 7.1.

…

SMP means in respect of Gatorade Products and PROPEL products their respective proprietary beverage base which is an essential ingredient of the Products but does not include liquid sucrose or citric acid.

…

Territory means Australia and includes such other geographical areas that may be agreed to by the parties from time to time to form part of the Territory, such agreement being evidenced in writing and signed by both parties.

Trade Marks means the trade marks the subject of the Registrations and the trade marks the subject of the Applications listed in schedule 3 and all other trade marks as agreed in writing and signed by the parties.

89 Clause 2(a) stated that the EBA was amended and restated by being replaced wholly by this agreement with effect from the Commencement Date.

90 Clause 3(a) dealt with the appointment of SAPL and provided:

3 Exclusivity

(a) Subject to the terms of this Agreement, Company appoints [SAPL] as the exclusive manufacturer, packager, seller and distributor of the Gatorade and PROPEL Products, and the exclusive seller and distributor of the Powder Products, in the Territory.

91 Clause 4.1 contained an express, royalty-free licence of the Intellectual Property:

4 Intellectual Property licence

4.1 Licence

Subject to clause 3, Company grants to [SAPL], for the duration of the Term, an exclusive royalty-free licence to use the Intellectual Property within the Territory in relation to:

(a) the production, manufacture, packaging, distribution and sale of Products (including the production and manufacture of Packaging for the Products);

(b) the distribution and sale of Powder Products; and

(c) the display, marketing, promotion and advertisement of Products and Powder Products,

subject to [SAPL] complying with the terms and conditions of this Agreement. For the avoidance of doubt, nothing in this Agreement permits [SAPL] to distribute or sell the Large Sachets.

(Emphasis added.)

Insofar as the above clause referred to Large Sachets, that can be put to one side for present purposes.

92 Clause 5 dealt with manufacturing and quality control.

93 Clause 6 dealt with Intellectual Property and included:

6 Intellectual Property

6.1 Ownership of Intellectual Property

[SAPL] for the Term and the Extended Term (if any):

(a) acknowledges that, as between the parties, all rights and interests in the Intellectual Property are and will remain owned absolutely by Company or a Related Corporation of Company and all goodwill accruing in relation to the Intellectual Property after the Commencement Date shall insure to the exclusive benefit of Company; and

(b) will not do anything directly or indirectly, that would or might:

(i) infringe Company’s Intellectual Property or the Intellectual Property of a Related Corporation of Company;

(ii) invalidate or put into dispute Company’s (or its licensor’s) title or the title of a Related Corporation of Company to the Intellectual Property; or

(iii) without limiting clause 6.1(b)(ii), oppose any application for registration of any of the Intellectual Property or support any application to limit, remove, cancel or expunge any of the Intellectual Property.

94 Clause 6.3 contained warranties and an indemnity. These included the Company representing and warranting to SAPL that the Company or a related corporation was the registered proprietor of the Registrations (i.e. the Australian trademark registrations described in Part 2 of schedule 3) and the sole legal and beneficial owner of all common law and other rights attaching to the Intellectual Property. It was also represented and warranted that each of the Registrations was valid and subsisting and, to the Company’s knowledge, there was no matter, fact or circumstance that would render any of the Registrations void or voidable.

95 Clause 7 dealt with SMP and Powder Products. As noted above, “SMP” was defined as meaning the proprietary beverage base in respect of Gatorade products and Propel products. Clause 7 provided in part:

7 SMP and Powder Products

7.1 Supply of SMP

(a) During the Term, Company agrees to sell or cause to be sold by a Related Corporation of Company or a designated Company Affiliate acting as agent of Company (“Company and/or such subsidiary hereinafter both called “Seller”), and [SAPL] will buy only from Seller, all of [SAPL’s] requirements for SMP. [SAPL] shall use the SMP only for, and in connection with, production of the Products and in strict compliance with the Product Specifications and the terms and conditions of this Agreement and shall not export from the Territory the SMP or any Products containing the SMP.

(b) If the SMP is supplied by a Related Corporation of Company or a Company Affiliate, the terms of this Agreement, to the extent that they are relevant, apply to transactions between [SAPL] and the Related Corporation of Company or Company Affiliate as if they were direct parties to this Agreement.

(c) Company warrants that all SMP supplied to [SAPL] will:

(i) be of good and merchantable quality;

(ii) be fit for their intended purpose;

(iii) be free from any defects; and

(iv) comply with all applicable Laws.

(d) Neither Company nor any Company Affiliate or Supplier of Company shall be required under this Agreement to disclose to [SAPL] or any other person the secret and unique formula comprising the SMP. In the event that a governmental authority requires [SAPL] to provide the SMP ingredients or formula information, Company must provide the required information to [SAPL] solely for the purpose of remitting such information to the relevant governmental authority. [SAPL] must not use such information for any other purpose or make copies of, record in any way or make note in any manner of such information. Company may require [SAPL] or any of its agents or employees to enter into a separate confidentiality agreement covering the provision of the SMP ingredients and/or formula information under this clause. If a disclosure of the SMP formula or any of its ingredients is required by a governmental authority in order to sell the Products in the Territory, Company must provide in a timely manner the SMP ingredients and/or formula information directly to the governmental authority requiring such information.

7.2 Price of SMP

(a) The price of each unit of SMP necessary to produce one single strength litre of the relevant Product sold to [SAPL] (Price) as at the Commencement Date for the Annual Period of 2009 shall be $[redacted] to be increased at each Review Date during the Term and Extended Term (if any) in accordance with clause 7.2(c).

(b) The price of SMP is CIF Australia port of entry (as defined in the 2000 edition of Incoterms). [SAPL] will reimburse Company for all port charges, customs service fees and delivery costs from the Australian Port to Company’s Warehouse. Company shall be responsible for any import duty on the SMP. [SAPL] will bear all costs and expenses incurred in taking delivery of the Products at Company’s Warehouse and subsequent transportation to [SAPL’s] Facilities.

(c) Effective upon each Review Date, the Price will increase to an amount equal to the Current Price multiplied by [redacted] in instances only where CPI is positive.

…

7.4 Delivery and payment

(a) To assist Company in its production schedule, [SAPL] must:

(i) on or before the Review Date, provide to Company a written estimate of the volume of SMP and Powder Product which [SAPL] will require for the following 12 month period (Annual Schedule); and

(ii) on or before the 15th day of each Month, provide Company a written estimate of the volume of SMP and Powder Products which [SAPL] will require for the following 12 week period (Rolling Schedule).

(b) The Initial Annual Schedule and Rolling Schedule are annexed to this Agreement as annexure A.

(c) Each Annual Schedule and Rolling Schedule must be in substantially the same format as that specified in annexure A (or as otherwise agreed between the parties at any time).

(d) A fixed purchase order (Order) will be deemed to have been placed by [SAPL] and accepted by Company (for supply in accordance with the Order subject to clause 7.4(e)) for any SMP or Powder Products specified in the first 8 weeks of each Rolling Schedule but only after written acknowledgment of such Order is given by Company to [SAPL] which will be provided promptly after receipt of the Order. In the event that more than one Order applies to any specific period, the Order in the Rolling Schedule first received by Company will be deemed to be the Order for that period.

(e) If an Order exceeds a written estimate previously provided under clause 7.4(a) for a 12 week period, Company will use its reasonable efforts to meet that Order from [SAPL] but may refuse or reduce it.

(f) [SAPL] must pay the Price for the SMP and Powder Products supplied by Company, a Related Corporation of Company or a Company Affiliate within 28 days after the invoice, which shall be issued on the date of delivery of the SMP or Powder Products. Unless the parties agree otherwise, payment shall be made by telegraphic transfer to such bank account in the U.S.A. as may be specified by Company or a Company Affiliate at any time.

(g) Any failure by [SAPL] to make any payment required under this Agreement when due shall be a breach of this Agreement and without limiting Company’s other remedies:

(i) Company may at its option require immediate payment to Company, a Related Corporation of Company or a Company Affiliate of all [SAPL’s] liabilities and other indebtedness outstanding to Company, a Related Corporation of Company or a Company Affiliate regardless of previously agreed-upon terms of payment;

(ii) [SAPL] shall owe and pay to Company, a Related Corporation of Company or a Company Affiliate as the case may be interest on such overdue payment at the rate of 2% over the prime lending rate of National Australia Bank.

7.5 Passing of Property and Risk

Property and risk in the SMP and Powder Products will pass to [SAPL] on completion of delivery to [SAPL] which shall occur upon [SAPL] or its agent or nominee taking custody of the goods at Company’s Warehouse.

(Emphasis added.)

96 Clause 9 dealt with selling and distributing the Products and the Powder Products. Clause 10 dealt with marketing and the allocation of responsibility for aspects of marketing as between the parties. Broadly, the Seller or a Related Corporation of the Seller would be responsible for the Marketing Program (being the program set out in item 1 of schedule 6, being the ATL marketing) and SAPL would be responsible for the BTL marketing.

97 Clause 12 dealt with inspections, samples and reports.

98 Clause 18 dealt with the term of the agreement and termination. The agreement continued until 31 December 2012, but could be extended. It is common ground that the agreement was in place during the relevant years.

99 Clause 18.2(a) provided:

18.2 Termination

Either party may terminate this Agreement immediately by notice to the other party if:

(a) the other party commits a material breach (it being agreed that any non-payment is considered a material breach) of this Agreement (unless the breach is capable of remedy, in which case if the other party fails to remedy the breach within 30 days after being required in writing to do so); or …

100 Clause 18.5 dealt with the effect of termination and included:

18.5 Effect of termination

…

(b) On termination of this Agreement or in the case of any Holding-over Period at the end of the Holding-over Period and subject to any provisions of this Agreement that apply only during such Holding-over Period:

…

(ii) [SAPL’s] rights and licences under this Agreement will cease. Without limitation, [SAPL] must not do anything that might lead any person to believe that it is still licensed to use the Trade Marks or is in any way connected with Company;

101 Clause 19 dealt with confidentiality and included:

19.3 Permitted use

Each party may use the information of the other party only for the purpose of performing its obligations under this Agreement.

102 Clause 30 dealt with taxes and duties and included:

30 Taxes and duties

…

(b) Company indemnifies [SAPL] against any Liabilities arising from any withholding tax which may be found to be applicable in respect of the Licence. In the event that withholding tax is imposed, [SAPL] will take such actions as are reasonably required by Company, at Company’s cost, to legally challenge such imposition.

103 The SVC EBA was amended by the parties a number of times. The amending agreements are listed in paragraph 33 of Ms Dent’s affidavit and are set out at CB tabs 24.12 to 24.19. Some of these involved adding additional products to the agreement. The amendments are not material for the purposes of the issues raised by these proceedings.

Change to the manufacturer of concentrate

104 In 2015, CMSPL was in the process of constructing a new concentrate manufacturing facility in Singapore, which was intended to become the supplier of concentrate to Australia as well as other countries in the region.

Change to the seller under the EBAs

105 As at 2015, the designated seller of concentrate to SAPL under the PepsiCo EBA and the SVC EBA was PCIC.

106 On 25 November 2015, PBS was incorporated.

107 On 8 December 2015, letters were sent by PepsiCo and SVC to SAPL pursuant to the EBAs. The letters are set out below. I note that the Commissioner relies on these letters as constituting a direction to pay for the purposes of the royalty withholding tax provisions.

108 On 8 December 2015, PepsiCo sent a letter to SAPL that stated:

I refer to the Restated and Amended Exclusive Bottling Appointment between PepsiCo, Inc. (“PepsiCo”), The Concentrate Manufacturing Company of Ireland (“CMCI”) and Schweppes Australia Pty Limited (“SAPL”), as amended and restated from time to time (the “Amended EBA”). Unless otherwise specified, capitalised terms in this letter have the meaning given to them in the Amended EBA.

PepsiCo notifies you that, from 1 January 2016, the Seller of Units will change to:

PepsiCo Beverage Singapore Pty Ltd

ABN: 609 497 832

[address redacted]

Contact:

[email and telephone number redacted]

From 1 January 2016, all purchase orders should be sent to PepsiCo Beverage Singapore Pty Ltd

109 On 8 December 2015, SVC sent a similar letter to SAPL as follows:

I refer to the Restated and Exclusive Bottling Appointment between Stokely-Van Camp, Inc. (“SVC”) and Schweppes Australia Pty Limited (“SAPL”), as amended and restated from time to time (the “Amended EBA”). Unless otherwise specified, capitalised terms in this letter have the meaning given to them in the Amended EBA.

SVC notifies you that, from 1 January 2016, the Seller of SMP and Powder Products will change to:

PepsiCo Beverage Singapore Pty Ltd

ABN: 609 497 832

[address redacted]

Contact:

[email and telephone number redacted]

From 1 January 2016, all purchase orders should be sent to PepsiCo Beverage Singapore Pty Ltd

110 On 11 January 2016, a letter on PepsiCo letterhead, but signed by PBS, was sent to SAPL as follows:

I refer to the letter from PepsiCo, Inc. to Schweppes Australia Pty Ltd dated 8 December 2015, notifying you that PepsiCo Beverage Singapore Pty Ltd will be the Seller of Units from 1 January 2016.

The bank account details for PepsiCo Beverage Singapore Pty Ltd are:

|

|

111 On 11 January 2016, a further letter on PepsiCo letterhead, but signed by PBS, was sent to SAPL as follows:

I refer to the letter from Stokely Van Camp, Inc. to Schweppes Australia Pty Ltd dated 8 December 2015, notifying you that PepsiCo Beverage Singapore Pty Ltd will be the Seller of SMP and Powder Products from 1 January 2016.

The bank account details for PepsiCo Beverage Singapore Pty Ltd are:

|

|

Concentrate Distribution Agreement

112 On or about 1 January 2018, CMSPL and PBS entered into a Concentrate Distribution Agreement. The recitals to the agreement noted that CMSPL was in the business of producing Concentrate (as defined) used in the Beverages (as defined) within the Territory (as defined) and that PBS was in the business of distributing Concentrate for use in the production of the Beverages within the Territory.

113 Article 1 of the agreement defined “Beverages” as meaning all CSDs and NCBs that were owned or licensed by CMSPL and sold in the Territory. “Concentrate” was defined as the concentrated essence, salts, acidulants, and any other components that were used in making Beverages for sale in the Territory.

114 Article 2 dealt with distribution of Concentrate. Broadly, Section 2.1 provided that PBS would distribute Concentrate to Bottlers and Approved Resellers in the Territory in such annual volumes as PBS and CMSPL agreed.

115 By section 2.4, PBS agreed to perform all necessary activities to fulfil its obligations under Section 2.1 for the benefit of CMSPL.