FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Allied Pumps Pty Ltd v LAA Industries Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1457

Table of Corrections | |

In paragraph 122, in the last sentence, the words “referred to this integer as” have been amended to “referred to this disputed term as” | |

4 December 2023 | In paragraph 178, subparagraph 2, in the last sentence, the words “against them such they were” have been amended to “against them such that they were” |

4 December 2023 | In paragraphs 577, 578, 580 and 581, the words “Southern Cross 1” have been amended to “Southern Cross” |

4 December 2023 | In paragraph 587, the words “Roy Hill Acts amount to secret use” have been amended to “Roy Hill Acts amounts to secret use” |

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | LAA INDUSTRIES PTY LTD (and another named in the Schedule) First Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | Cross-Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 24 november 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to ss 37AF(1)(b) and 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), until further order of the Court, and subject to any restrictions imposed by the Order dated 7 June 2023, access to and disclosure (by publication or otherwise) of the unredacted text of the reasons for judgment delivered today be restricted to the parties and their legal representatives, and those persons to whom access is allowed under the terms of the confidentiality regime agreed by the parties.

2. Nothing in Order 1 or any earlier order of the Court prevents any party from publishing the covering pages of these reasons for judgment up to paragraph 15 of the reasons, including these orders, along with the final paragraph of the reasons and the associate’s certificate.

3. By 4.00 pm AEDT on 4 December 2023, the legal representatives for the parties confer on redactions to be proposed, agree on the proposed redactions, and provide to the chambers of Downes J an agreed form of the reasons for judgment with the proposed redactions highlighted, together with an agreed redacted form of the reasons for judgment that is suitable for publication.

4. The parties are to otherwise confer and provide to the chambers of Downes J an agreed form of order giving effect to the reasons for judgment by 4.00 pm AEDT on 8 December 2023.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[16] | |

[16] | |

[23] | |

[28] | |

[31] | |

[43] | |

3.1 Whether known that dewatering lowers the local water table | [60] |

3.2 Whether known that pressure sensors were used to measure level | [71] |

[86] | |

[94] | |

[95] | |

[118] | |

[119] | |

[119] | |

[120] | |

[122] | |

[123] | |

[127] | |

[136] | |

[137] | |

[150] | |

[156] | |

[156] | |

[163] | |

[184] | |

[186] | |

[194] | |

[200] | |

[200] | |

[203] | |

[206] | |

[207] | |

8.3.5 Whether the Roy Hill Systems could be controlled on level | [215] |

[216] | |

[237] | |

[250] | |

[251] | |

[269] | |

[276] | |

[289] | |

[298] | |

[331] | |

[338] | |

[361] | |

[363] | |

[364] | |

[379] | |

[390] | |

[390] | |

[392] | |

[395] | |

[404] | |

[404] | |

[412] | |

[413] | |

[413] | |

[425] | |

[441] | |

[442] | |

[456] | |

[457] | |

[457] | |

[463] | |

[464] | |

[464] | |

Whether disclosure of level sensor integer in Boot and Elizondo | [474] |

[483] | |

[484] | |

[495] | |

[496] | |

[496] | |

[505] | |

[506] | |

[511] | |

[513] | |

[528] | |

[538] | |

[539] | |

[541] | |

[548] | |

[553] | |

[557] | |

[569] | |

[570] | |

[570] | |

[573] | |

[583] | |

[588] | |

[589] | |

[594] | |

[598] | |

[599] | |

[603] | |

[613] | |

[614] | |

[617] | |

[621] | |

[623] | |

[625] | |

[631] | |

[633] | |

[638] | |

[642] | |

[647] | |

[653] | |

[657] | |

[661] | |

[674] | |

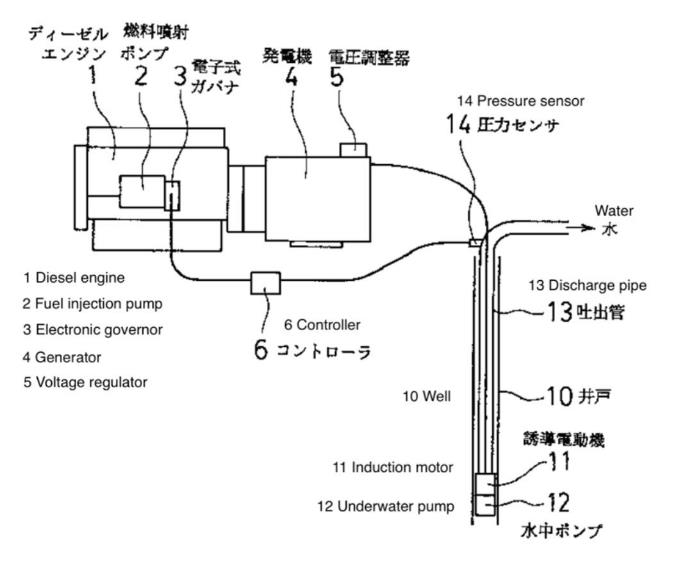

13.6.8 Dewatering Generator Trailer Package Operation & Maintenance Manual | [683] |

[693] | |

[696] | |

[715] | |

[715] | |

[718] |

DOWNES J:

1 This case concerns Australian Innovation Patent No. 2020103197, which is directed to a “power and control system” for a “dewatering submersible pump”, and a means of controlling the frequency and voltage of the electricity from a generator provided to the pump based on the water level in a bore. This generator is called a variable speed generator (VSG) or variable frequency generator (VFG) and provides a variable electrical output to the pump as compared to a fixed speed generator which would generally provide a fixed electrical output.

2 The main characteristic of an electric submersible pump or “ESP” is the design of the electric motor such that it can be operated submersed in fluid without affecting its electrical integrity. ESPs are commonly placed in a borehole and used to lift water from underground.

3 The application for the Patent was a divisional application of Australian Standard Patent Application No. 2019203740 (740 Application) filed on 28 May 2019. The 740 Application is in turn a divisional application of Australian Standard Patent Application No. 2017210650 (650 Application), which claims priority from Australian Provisional Patent Application No. 2016903254 (254 Provisional) filed on 16 August 2016. The expiry date of the Patent is 5 August 2025.

4 The earliest priority date of the claims of the Patent is therefore 16 August 2016. The applicant, Allied Pumps Pty Ltd, asserts that the Patent is not entitled to a priority date that is earlier than 3 November 2020 or, alternatively, 28 May 2019 (the deferred priority dates). It is not in dispute that the Patent is invalid for lack of novelty in light of Australian Patent Application number AU 2017213531 (Taranis) if the deferred priority dates apply to the Patent claims.

5 The respondent and first cross-claimant, LAA Industries Pty Ltd, is the patentee of the Patent. LAA exclusively licences the Patent to the second cross-claimant, UON Pty Ltd, which manufactures, hires and sells its “GMC Pro Power” VSGs according to the claims of the Patent. It is generally convenient to refer to LAA and UON together as UON, unless the context requires both to be identified.

6 Allied Pumps is a competitor of UON. The device supplied by Allied Pumps is referred to by the parties as the “Allied Pumps System”, and further divided into what were described as Category A Systems and Category B Systems. The Category A Systems have two sub-categories, being those supplied to BHP Billiton Iron Ore Pty Limited (BHP Category A Systems) and those supplied to Rio Tinto (Rio Tinto Category A Systems).

7 UON asserts that Allied Pumps has infringed the Patent. Allied Pumps admits that it has manufactured, kept for the purposes of sale and supply, offered for sale, sold and supplied the Category A Systems and the Category B Systems, but generally denies infringement on the basis that the Patent is invalid.

8 Allied Pumps also denies that the BHP Category A Systems possess each of the integers of the claims of the Patent as alleged by UON; and denies that indirect infringement has been established pursuant to s 117(2)(b) and s 117(2)(c) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (being the allegations pressed by UON in relation to these systems).

9 While Allied Pumps maintains that the Rio Tinto Category A Systems do not possess each of the integers of the claims of the Patent, Allied Pumps admitted, for the purposes of this proceeding only, that the alleged acts of exploitation with respect to the Rio Tinto Category A Systems constitute infringement of the Patent, if the Patent is held to be valid. Allied Pumps also admitted, for the purposes of this proceeding only, that the Category B Systems possessed each of the integers of the claims of the Patent. Allied Pumps has ceased exploiting the Category B Systems and offered an undertaking not to exploit the Category B Systems in the future, while the Patent remains enforceable in its current form.

10 As part of its invalidity case (by the conclusion of the trial), Allied Pumps alleges that:

(1) the Patent is invalid for want of novelty in light of prior public disclosure by the act of UON hiring out two of its GMC Pro Power VSGs to Roy Hill Iron Ore Pty Ltd before the earliest priority date (the Roy Hill Systems);

(2) the Patent is invalid for want of novelty in light of each of the following prior art documents: International Patent publication number WO2015/041805 (Torrey); Patent Application JP H08270594 (Komatsu); US Patent application number 2014/0209289 (Boot) in combination with US Patent number 8,347,953 (Elizondo), which is incorporated by reference in Boot; the Canadian Advanced ESP Inc. manual entitled “Variable Frequency Generator Operator’s Manual” (CA Manual, also referred to in the evidence in some instances as the VFG Operation Manual);

(3) the Patent is invalid for want of novelty because of two combinations of acts concerning Canadian Advanced’s supply of two of its VFGs to Lihir Gold Ltd for dewatering in about 2012 (CA Lihir Systems);

(4) there has been secret use of the invention (by reference to the commissioning and testing of the GMC Pro Power VSGs at Roy Hill) (in the alternative to (1));

(5) the invention does not involve an innovative step within the meaning of s 18(1A)(b)(ii) of the Patents Act.

11 UON disputes that its GMC Pro Power VSGs had capacity to control by reference to level prior to the earliest priority date but, if they were so capable, also disputed that they were configured to control by level when commissioned at Roy Hill. Finally, UON contends that, if they were so capable and were so commissioned, then that occurred in the course of a reasonable trial within the meaning of s 24(1)(a) of the Patents Act and reg 2.2B of the Patents Regulations 1991 (Cth).

12 The hearing on liability only was held over 11 days in March and April 2023, with a separate hearing to be held on the issues of election and quantification of pecuniary relief.

13 For the reasons which follow, my primary conclusion is that the Patent is invalid for want of novelty. I have also found that, in any event, there was no infringement as alleged in the cross-claim and the cross-claim should be dismissed. I will order that the parties confer with a view to drafting a form of order giving effect to the conclusions I have reached.

14 These reasons were published to the parties on 24 November 2023 in an unredacted form but, conscious that there were confidential affidavits, exhibits and submissions filed in this proceeding, only the first 15 paragraphs and the final paragraph will be publicly available. The full reasons for judgment, if necessary subject to some redactions, will be published once the parties have had an opportunity to consider whether any redaction is necessary. Accordingly, I will also order that the parties confer with a view to drafting a form of order which reflects their agreement as to any redactions to be applied to these reasons.

15 Additionally, both parties should have leave to appeal and, if necessary, leave to cross-appeal.

2. WITNESSES CALLED BY THE PARTIES

2.1 Witnesses called by Allied Pumps

16 Mr Richard Pilson is a civil/mechanical engineer with 25 years’ experience in water, wastewater, civil and mechanical engineering and project delivery. He is currently employed by Roy Hill as a Senior Engineer, in its Water Division. From 2014 to 2018, he was employed by Roy Hill as a Water Engineer and Project Manager and was responsible for procuring all of Roy Hill’s dewatering equipment. During that period, Roy Hill had approximately 90 dewatering bores in operation; and Mr Pilson was responsible for designing and supervising approximately 30–60 dewatering boreholes in the Pilbara Region. Mr Pilson affirmed four affidavits in this proceeding dated 24 February 2022, 31 October 2022, 27 January 2023 and 10 February 2023.

17 Mr Patrick Murphy is an Engineer in Water Projects at Roy Hill, a role that he has held since March 2015. This role involves supervising the installation of water infrastructure on the Roy Hill mine site. Mr Murphy swore two affidavits in this proceeding dated 27 January 2023 and 10 February 2023.

18 Professor Donald Holmes is an electrical engineer, a retired Professor of Smart Energy Systems and an Honorary Professor at RMIT University, Melbourne. Prof. Holmes has significant experience in electrical motors; the digital control of power electronic systems; and the conversion of electrical energy from one form to another using this technology. Prof. Holmes affirmed five affidavits in this proceeding dated 23 February 2022, 11 July 2022, 26 August 2022, 28 October 2022 and 31 October 2022.

19 Mr Gerard Baarslag is a dewatering engineer with 26 years’ experience in dewatering systems, including consulting, design, project management, supervision, installation and commissioning activities, including for mining and civil applications. Mr Baarslag’s experience includes six and a half years spent managing the dewatering systems at Lihir Gold’s mine, located in Papua New Guinea. Mr Baarslag affirmed two affidavits in this proceeding dated 23 February 2022 and 8 July 2022.

20 Mr Zoran Vukadin is a mechanical engineer and the Manager of Engineering and Operations at Canadian Advanced, which specialises in the manufacture of pumps and power supply equipment. Mr Vukadin’s work has focused on ESPs for 23 years and his experience includes the design, installation and commissioning of ESPs across a range of activities including mining activities. Mr Vukadin affirmed three affidavits in this proceeding dated 10 July 2022, 21 July 2022 and 30 October 2022.

21 Mr Craig Meredith is a control systems engineer with over 20 years’ experience providing control system engineering solutions to the mining industry, approximately 10 years of which have been dedicated to dewatering. Mr Meredith affirmed one affidavit in this proceeding dated 2 June 2022.

22 Mr Troy Walters is an electrician who worked for Allied Pumps between 2015 and 2021. His role included factory acceptance testing of Allied Pumps’ products, including VSGs to be supplied to BHP. Mr Walters affirmed one affidavit in this proceeding dated 30 May 2022.

23 Mr Duncan Quick is an electrical engineer, who has, for the last 36 years, worked as a consulting engineer in the engineering design and project management of automation, control and instrumentation projects in the mining, coal, power generation water and wastewater and transportation sectors. His experience includes the design and programming of power and control systems including pumps. He has experience in the oil and gas industry, having worked on oil wells (including designing power management systems for an oil rig), as well as downstream oil and gas facilities. He also has experience with emergency water supply equipment, including fire pumps. Mr Quick affirmed three affidavits in this proceeding dated 13 April 2022, 2 June 2022 and 30 September 2022.

24 Mr Jose Bernedo is a mechanical engineer with around 30 years’ experience working with pumps, around 25 years of which have been focused on ESPs. Mr Bernedo affirmed one affidavit in this proceeding dated 30 September 2022.

25 Mr Anthony Reid, a licensed electrician, is a Technical Support Technician at UON and a named co-inventor on the Patent. Mr Reid affirmed two affidavits in this proceeding dated 11 August 2022 and 19 December 2022.

26 Mr Geoffrey Smith is a Product Manager at UON, where he has worked since 2011. Mr Smith affirmed one affidavit in this proceeding dated 19 December 2022.

27 Mr Sebastianus Meys is a Project Manager – Products at UON, where he has worked in various roles since 2011. Mr Meys affirmed one affidavit in this proceeding dated 15 July 2022.

28 Two joint expert reports were prepared with the helpful assistance of a judicial registrar of this Court.

29 The first report involved three separate conclaves: (a) Mr Quick, Prof. Holmes and Mr Baarslag on questions common to electrical engineering and dewatering; (b) Mr Quick and Prof. Holmes on questions relevant to electrical engineering; and (c) Mr Quick and Mr Baarslag on questions relevant to dewatering. The first report was filed on 10 February 2023 (Electrical/Dewatering JER).

30 The second report addressed the conclave between Mr Bernedo and Mr Vukadin, and was filed on 9 February 2023.

2.4 Observations about the experts

31 For the following reasons, I do not accept Mr Quick’s evidence to the extent that it differs from any of the evidence of Mr Baarslag, Mr Vukadin and Mr Bernedo in connection with topics relating to dewatering.

32 That is because Mr Quick has no direct experience in dewatering. Indeed, the evidence advanced by UON in support of its contention that Mr Quick has the relevant expertise emphasises that Mr Quick has only ever indirectly engaged with dewatering and is only familiar with concepts related to dewatering. Relevantly, he has never been involved in the construction or maintenance of a below ground submersible pump in a borehole; never seen one removed from a borehole; never had to understand the mechanical aspects of those pumps; never had to understand the workings of ground water or the relationship between the borehole and ground water; and never seen a pressure sensor in a borehole.

33 The opinions that Mr Quick expressed were often in direct contrast to the three other experts (Messrs Baarslag, Vukadin and Bernedo) who do have direct experience in dewatering. For example, Mr Quick was adamant that an inlet/intake pressure sensor had to be positioned at the inlet of the pump (even though he had never seen one located at such a position). This was contradicted by each of Mr Vukadin, Mr Bernedo and Mr Baarslag, all of whom had direct experience with these types of sensors.

34 Mr Quick’s direct lack of experience in dewatering was also apparent from his evidence concerning the Patent itself.

35 The specification of the Patent discusses:

(1) a mode of operation described as the constant flow rate mode, as part of which a sensor measures the flow rate through the transport pipe and the controller operates a feedback loop between the engine speed and the measured water flow until a steady state is reached;

(2) a mode of operation described as the constant pressure mode, as part of which a sensor measures the pressure in the transport pipe and the controller operates a feedback loop between the engine speed and the measured water pressure until a steady state is reached.

36 In his first affidavit, Mr Quick stated that, based upon his experience and his reading of the Patent, he sees “limited use” for these modes, and that, in dewatering, “the primary objective is to remove water from the bore to maintain the level of groundwater below a certain level”. He also stated that it is not apparent why these modes would be used in dewatering operations.

37 However, the Patent specification itself explains the purposes of these modes:

(1) As to the constant flow rate mode, it is stated at [0051] that water being extracted from the bore can be used in many applications, some of which (for instance, use as process water within ore processing operations) require a constant rate of water;

(2) As to the constant pressure mode, it is stated at [0055] that water being extracted from the bore can be used in many applications, some of which (for instance, dust suppression and tank filling via a pressure valve) may require a constant water pressure.

38 Further, it is UON’s case in relation to the Roy Hill Systems supplied in 2016 for dewatering that the VSGs could control by reference to flow and pressure (but not level). That UON developed such modes of control (i.e. flow and pressure) as at 2016 illustrates the perceived utility of these modes when dewatering, being something which Mr Quick was not familiar with, either in 2016 or as at the time of preparing his first affidavit.

39 Otherwise, I generally treat the evidence of Mr Quick with significant caution to the extent that it differs from the evidence of the other experts.

40 That is because Mr Quick generally appeared intent on assisting UON when answering questions asked of him during the concurrent session (such as by, for example, giving lengthy and unresponsive answers to questions).

41 By contrast, Mr Baarslag gave careful and considered answers to questions asked of him during the hearing, appeared to be attempting to assist the Court and, by his answers and general demeanour, did not appear to be favouring any party or outcome in the dispute. Prof. Holmes, Mr Vukadin and Mr Bernedo behaved in the same manner during the hearing, and I found their evidence (and that of Mr Baarslag) to be very helpful.

42 In addition, Mr Quick was not provided with significant parts of Prof. Holmes and Mr Baarslag’s evidence (despite preparing a joint expert report with them). Relevantly, Mr Quick was not provided with and did not give written evidence in response to Mr Baarslag’s analysis of the Patent or the prior art; or the affidavits of Prof. Holmes dated 11 July 2022, 28 October 2022 and 31 October 2022 which included Prof. Holmes’ analysis of the testing data that was produced during Roy Hill’s testing of the Roy Hill Systems. This has the consequence that Mr Quick’s reasons for his opinions in relation to these issues were either set out in truncated form in the Electrical/Dewatering JER or were the subject of oral explanation during the hearing (with the attendant problems identified above). It also has the consequence that Mr Quick did not possess all relevant information about the opinions of the other experts when he expressed his own.

43 Common general knowledge is the background knowledge and experience which is available to all in the trade in considering the making of new products, or the making of improvements in old, and it must be treated as being used by an individual as a general body of knowledge. It is not limited to what is specifically memorised or in the mind of the skilled addressee but includes material which is habitually consulted as a matter of course by him, her or them as part of their role, including publications of detailed and technical information: ICI Chemicals & Polymers Ltd v Lubrizol Corporation Inc (1999) 45 IPR 577; [1999] FCA 345 (Emmett J) at [111]–[112]; Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Co v Beiersdorf (Australia) Ltd (1980) 144 CLR 253 (Aickin J) at page 292; Aktiebolaget Hässle v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2000) 51 IPR 375; [2000] FCA 1303 (Wilcox, Merkel and Emmett JJ) at [73].

44 The parties were not in serious dispute about the majority of what follows. To the extent that there was any controversy, I have accepted the evidence of Mr Baarslag to that of Mr Quick, for the reasons already explained, or I have addressed those matters separately.

45 Standalone generator sets (referred to as gensets) were commonly used for dewatering operations where an electrical supply grid was not available. Gensets were usually located near the system it was to supply. The standard components of a genset included a prime mover (or engine), an alternator that converts mechanical rotation to electrical power, a controller and human machine interface (HMI) (sometimes called an HMI screen), an engine control unit (ECU) to control the speed of the engine, and an automatic voltage regulator (AVR) to control the output voltage of the genset.

46 In mining operations, it was common to artificially draw down the ground water level to allow for minerals to be extracted when relatively dry. To achieve this, a borehole (or well) was drilled into the earth’s subsurface, which filled with water as a result of underground aquifers. The terms borehole and well were interchangeable (and were understood to be so) by persons skilled in the art.

47 To remove the water from a borehole, it was common to place an ESP into the borehole to lift fluid from underground (this being an example of artificially pumping fluid from a well or “artificial lift”). The ESP would typically be a component of an “artificial lift system”.

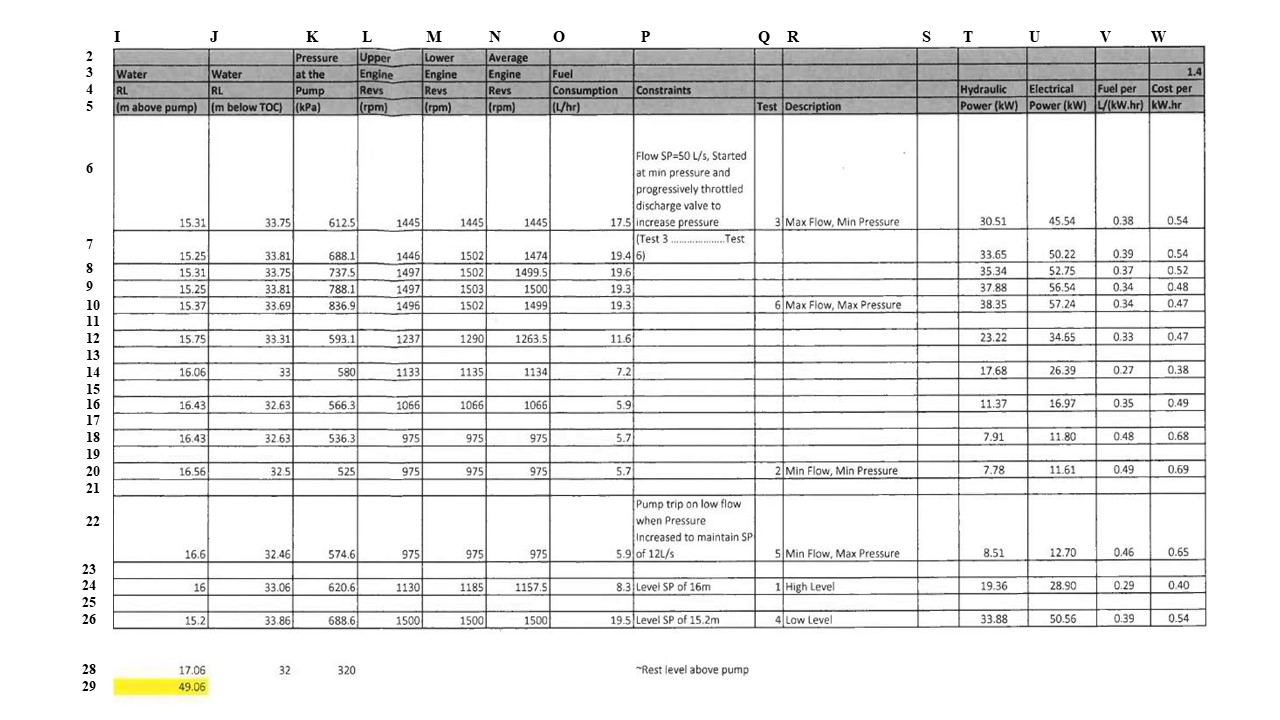

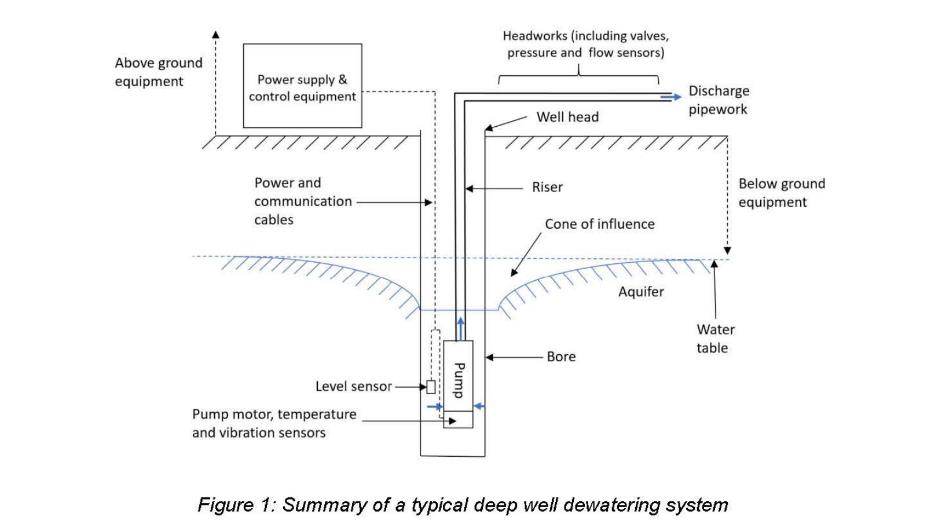

48 A typical artificial lift system, such as was used for dewatering purposes in mining applications, included “downhole equipment” and “above ground equipment” (see Figure 1 below, which was extracted from Mr Baarslag’s first affidavit). As at the earliest priority date, the “downhole equipment” typically included an ESP; power and communication cables that supplied power and instructions to the ESP; sensors that monitored the operation of the ESP and well conditions; as well as rising main pipework (known as a riser) that allowed the ESP to pump fluid out of the well.

49 The “above ground” equipment typically included a power supply system (e.g. a genset with a separate variable speed drive to allow the speed of the ESP to be controlled) and headworks, which typically included control valves and sensors to measure, for example, flow and discharge pressure of the fluid produced from the pump.

50 The speed of the ESP was automatically controlled using three main parameters: pressure, level, or flow. Automatic control of the ESP was based on information received from a pressure sensor that usually formed part of the headworks (measuring discharge pressure), a level sensor that formed part of the downhole equipment (measuring level of fluid above the ESP), or a flow sensor that typically formed part of the headworks (measuring the flow rate of fluid from the ESP).

51 There were different types of sensors that could be used to monitor the level of fluid in the well, including:

(1) capillary tubes (which expand and contract as a result of pressure in the well and provide a pressure reading in bars);

(2) floats (mechanical devices where the float rests on the fluid surface);

(3) cox whistles (which operate on air pressure);

(4) pressure sensors (which measure level by determining the pressure of fluid on the pressure sensor);

(5) vibrating wires (electric devices);

(6) ultrasonic sensors (which measure level using ultrasonic sound pulses).

52 It was industry practice to maximise production from a water well by obtaining the highest flow rate possible, whilst maintaining the water level within the recommended safe limits, just above the suction requirement.

53 It was also common to control the speed of an ESP using certain setpoints (i.e. the number in the controller which is used as a target for the closed loop control). The most common setpoints used to control the speed of the pump in a well were fluid level, flow rate of fluid from the pump and discharge pressure of the pump.

54 Whether to control the pump based on fluid level, flow rate and/or discharge pressure depended on the system components and well characteristics. For all wells, it was common to control the speed of the pump via fluid level, so that the pump could be run at high speed and produce a high output flow rate without causing damage to the pump.

55 When an automatic control mechanism was used, a proportional integral derivative (PID) control was the primary type of control used for controlling a variable to achieve a setpoint, and setpoints were typically entered via an HMI, but could also be entered remotely, hard-coded into the controller or dynamically operated by another layer of control which adjusted the setpoint for that particular controller to achieve some functional objective.

56 Submersible pumps were designed to automatically shut down in circumstances where the level, pressure, flow, temperature and/or vibration parameters fell outside of a certain range, in order to protect the pump.

57 The fluids which could be lifted from underground using an artificial lift system included, for example: salt and fresh water; water with entrained solids or sediment; oil; and mixtures of oil and water.

58 ESPs were not characterised by the application in which they were used, or the fluid that was moved by the pump. Such pumps were selected based on the characteristics of the relevant well, and were suitable for multiple applications, including in oil and gas, and mining applications. As Mr Vukadin and Mr Bernedo agreed during their concurrent evidence session:

(1) a pump is designed to displace a liquid from A to B, whatever its design;

(2) the purpose to which that pump is being put is irrelevant; and

(3) the design of the pump will not change depending on whether you are, for example, using that pump to lower the local water table or, for example, supplying water to a mining site.

59 In general terms, “dewatering” referred to removing water from solids from above or below the ground. An example of above ground removal of water from solids was the removal of water from tailings dams. An example of below ground removal of water occurred in mining applications; that is, water was commonly extracted from underground aquifers to create a dry environment to allow material to be excavated, for use as a water supply source or both of these purposes.

3.1 Whether known that dewatering lowers the local water table

60 There is a dispute between the parties as to whether below ground dewatering necessarily results in the lowering of the local water table, and whether this formed part of the common general knowledge as at the earliest priority date. Unless otherwise indicated, all further references to dewatering in these reasons is to below ground dewatering.

61 Allied Pumps submits that the level of a borehole prior to removing any ground water is more or less the level of the local water table and that, as water is removed, that level is lowered, and that this is the case irrespective of the purpose for removing the water. It submits that the water in the borehole is then replenished, at least in part, by the surrounding water table. Allied Pumps relied on the evidence of Mr Baarslag and Prof. Holmes.

62 Mr Baarslag was asked to identify the information that he knew and regarded to be well known and generally accepted by dewatering engineers by 16 August 2016. In response, he gave this evidence in his first affidavit:

Dewatering has many different meanings depending on the context in which it is used. Generally speaking, “dewatering” refers to removing water, and potentially other fluids, from solids. This can involve removing ground water to temporarily lower the ground water table or removing surface water out of the working area.

For example, in mining applications, water is commonly extracted from underground aquifers to allow for material to be excavated from areas that would otherwise be submersed in water. In civil applications, water is commonly extracted from underground reservoirs to allow for piping installations to occur in a dry environment that would otherwise be submersed in water. In construction applications, water is commonly extracted from underground reservoirs to allow for building works to take place in a dry environment that would otherwise be submersed in water. In oil and gas applications, water is commonly extracted from underground aquifers during the extraction of oil and gas from underground reservoirs. In each case, the ground water is lowered.

…

In mining projects, it was common to artificially lower the ground water table. Drawing down the ground water level, by extracting water via pump, allows for minerals to be extracted when relatively dry. Both diesel and electrical pumps are used for dewatering applications. When a diesel pump is used, it is located on the surface. When an electric pump is used, it is typically submersed in fluid. This is referred to as an electric submersible pump. For mining dewatering applications, it is most common to use an electric submersible pump.

As part of a dewatering drilling operation, a bore hole (also referred to as a well) is drilled into the earth’s subsurface. The bore hole fills with water as a result of underground aquifers. In order to remove water from the bore hole and to reduce the underground water level around the bore hole, it is common to locate an Electric Submersible Pump (Pump) into the bore hole. This is an example of “deep well artificial lift” (i.e. artificially pumping fluid from a deep well).

In deep well artificial lift applications, extracting water from below the ground causes a “cone of influence” on the underground aquifer around the well. This is shown in Figure [1]. The height and width of the cone of influence depends on many factors...

63 The “cone of influence” appears in Figure 1 above (depicted by the curved lines), being the figure which was extracted from Mr Baarslag’s first affidavit.

64 Mr Baarslag expanded upon his affidavit evidence in the concurrent evidence session:

MR BAARSLAG: It is my view that, when you’re pulling water out of a borehole, you’re dewatering. In my opinion, there is no soil that doesn’t have any hydraulic resistance. Therefore, there will always be a cone of influence of some description.

…

MR BAARSLAG: So it draws the water table down. Whether that’s a big cone or a small cone, it will draw it down somewhat and Mr Quick is right. It depends on the permeability, on how fast it gets, I guess, back to the previous level of where it was before you start[ed] pumping, but as soon as you start pumping, it will draw down.

MR BANNON: And those considerations in relation to permeability, do they apply equally to a dewatering exercise for a mining operation?

MR BAARSLAG: Yes. Yes. There – there is – there is no difference between drawing water out of a – a bore for the purpose of dewatering or for the purpose of water supply in terms of what it does in the ground.

…

MR BAARSLAG: For instance, in Mount Tamborine, Coca Cola is pulling water out of the aquifer for the supply and – and to make fizzy drinks. Mount Tamborine doesn’t have town water, and most people either rely on tank water that comes in trucks, or they have a bore. Coca Cola is not intending to lower the water table, but they are because they [dry] all these other people’s bores out because theirs is not as deep, and they simply take too much, and it’s a big dispute there, right there, at the moment, so that’s – it’s an unintended consequence.

65 Prof. Holmes gave this evidence during the same session:

PROF HOLMES: It seems to me, from just general engineering principles, if you need to get water out, you have to lower the surrounding water table from the borehole because, otherwise, you won’t get inflow because if the borehole water level is at the level of the ground table, there’s no water flow. You actually have to have a lowering of the localised water table around the borehole to let the water from the wider area flow in to where you want it to go. Now, whether it’s a minimal lowering or a significant lowering, it’s still lowering because, otherwise, you don’t get the differential pressure that will get you the flow, so the two are interrelated. If you take water out of a borehole, you – just to get a replenishment of the water, you must have a lowering in and around the hole to let the water flow in.

Now, Mr Quick says that might be minimal. It might be. If the water table is huge, it might be substantial. If the water table is not so huge – you just have to read documentaries about people draining aquifers to realise that, within Australia, with limited water, there’s constraints on how much water you can take out of a borehole for the use of taking water out so that you don’t lower the water table too much – suggest that, by definition, taking water out of a hole, for any purpose, is lowering the water table. If your intent is to lower it for the purposes of lowering it, or your intent is to take water, it’s the same engineering process. It’s the same result.

66 UON submits that the proposition that dewatering necessarily results in the lowering of the local water table is not agreed to be factually correct, and therefore disputes that it formed part of the common general knowledge. It says that that is because whether the local water table is lowered by dewatering will depend in any given case on factors including the permeability of surrounding rock, and the ability of ground water to flow into the reservoir to replace the fluid that is extracted.

67 By his second affidavit, Mr Quick gave evidence that, when oil is lifted from an oil reservoir, it will not necessarily lower the level of the surrounding ground water and that, whether it does will depend on factors including the permeability of the surrounding rock, and the ability of ground water to flow into the reservoir to replace fluid that is extracted.

68 During the hearing, Mr Quick applied the same reasoning to a dewatering operation on a mine. His evidence was somewhat confusing and illogical, and culminated in a claim that he was qualified to comment on the issue because he had been dux of earth science at high school:

MR BANNON: No, and so that – well, you would agree that, if your only purpose is to use a bore for water supply, you want that bore to be replenished from the water table as you pour water out, don’t you?

MR QUICK: Yes, that’s true.

MR BANNON: And it’s your intention that it be – when you use it for a water supply only, it’s your intention that it be replenished from the water table.

MR QUICK: Yes.

MR BANNON: And reducing – replenishing it from the water table reduces the level of the local water table, doesn’t it?

MR QUICK: Generally, it will. That’s right. It depends on the permeability and the supply of where that aquifer is being fed from.

…

MR BANNON: Well, do you understand, in mining applications – and I’ve heard your answer previously is through experience, but nevertheless, do you understand that, in mining applications, if you are dewatering in anticipation of digging, it’s a continuing continuous process? The pumps run all the time. Did you understand that?

MR QUICK: Yes, so dewatering is a different application from water supply. In dewatering, you’re deliberately attempting to lower the water table, which means you need enough withdrawal capacity to affect that water table. So you have to have enough bores to do it and big enough pumps to do it to substantially affect that water table and bring it down so that it’s clear of underground shafts or open cut pits or whatever you’re trying to remove the water – lower the water table to protect so that you don’t get ingress of water into those workings. So that’s a different purpose. If you’re intending on simply supplying water, then the last thing you want to do is drain your aquifer. So you don’t want to lower the water table. It’s a different objection.

MR BANNON: But do you understand that, in a mining application, when you are using bores for a dewatering purpose, the pumps run all the time because, if they don’t, the water table just goes back up again? Did you understand that?

MR QUICK: Yes, that’s true.

MR BANNON: So in a mining application, a dewatering purpose, the lowering of the water table is a temporary thing, isn’t it?

MR QUICK: While the pumps run, yes.

MR BANNON: Yes.

MR QUICK: That’s – yes, it is a temporary thing. If the dewatering pumps were to stop for some reason, for any period of time, then the water table will seep back up.

…

MR BANNON: But what I’m suggesting to you is you read the claims. You satisfy the claims if you’ve got one pump down one borehole which has the relevant elements. Correct? Right. So understanding that, the impact of one pump in one borehole for a dewatering purpose of lowering the water table, firstly, is only effective while the pump is running, while you’re pulling water out. You agree?

MR QUICK: Yes, that’s right. I agree on that.

MR BANNON: And it’s a lowering, a temporary lowering of the water table in the immediate vicinity of that individual borehole.

MR QUICK: That’s right. Yes.

MR BANNON: Right. Now, tell me, if you can, the difference between that circumstance and pumping water out of a well for water supply in terms of the impact on the immediately surrounding water table. Can you tell me that?

MR QUICK: Yes. The difference between a supply and a dewatering application is supply is trying not to deplete the well because, eventually, you’re going to run out of supply. So you would locate that where you have plenty of water flowing into the – from the aquifer into the well and you would draw it off at a rate that’s less than the inflow rate. Otherwise, you’re going to suck air. So it’s a different objective and you would locate it in a different place.

…

MR BANNON: With your background, your experience, you’re not in a position to actually dispute the proposition, are you, that, no matter where you put this borehole, if you’re pulling water out, it will, necessarily, lower, to some degree, the water table. You’re not qualified to resist that proposition, are you?

MR QUICK: I’m not a qualified hydrologist, but I’m a well-experienced engineer. I’ve had – worked on many different sites around this country and overseas, and several of those sites that I’ve worked on have had bore fields and dewatering systems that I’ve had to review, and, yes, I’m qualified enough to speak on - - -

MR BANNON: Sorry. When you say you’ve had to review the dewatering system, I thought you said your involvement was just in electrical componentry and that sort of thing. Are you wanting to expand on that?

MR QUICK: No. I’m not claiming to be a hydrologist or a - - -

MR BANNON: Right.

MR QUICK: Although I’m familiar with the sciences and geology. I was dux of earth science in high school. I am quite familiar with how these things work, and you do need some appreciation of the mechanics and the hydraulics in doing any kind of electrical and instrument-control design and software and – and functional arrangements. So yes, I would say I’m qualified to comment.

69 I find that dewatering necessarily results in the lowering of the local water table, and that this formed part of the common general knowledge as at the earliest priority date. If water finds its way into a borehole or well from the local water table (whether quickly or slowly, depending on the permeability of the walls of the borehole and other factors) and then that water is removed by the artificial lift system, the physical dislocation of the water from the water table into the borehole and then out of the borehole must necessarily result in a reduction of water in the local water table (and therefore a lowering of that water table), however temporary or insignificant the reduction in the level might be. That is because the water from the water table will enter the borehole and replace the water which has been removed by the artificial lift system.

70 In making this finding, I rely upon and accept the evidence of Mr Baarslag and Prof. Holmes, whose evidence I prefer over that of Mr Quick for the reasons explained above and because, as already observed, I found Mr Quick’s evidence on this issue to be confusing and illogical, and occasionally self-contradictory. For example, he appeared to conflate what could or would be done to avoid diminishing the water table substantially in a water supply situation with the physical consequences of dewatering on the water table irrespective of the purpose of the removal of the water.

3.2 Whether known that pressure sensors were used to measure level

71 There is limited divergence between the parties about whether and the extent to which it was common general knowledge that pressure sensors were used to measure the level of the fluid in the borehole or well (and how that was done) as at the earliest priority date. As this is an important issue in this case, however, I will address it separately.

72 It was common general knowledge at the earliest priority date that an artificial lift system needed to be designed and configured so as to ensure that the level of fluid did not fall below the minimum required fluid level over the pump because this would result in cavitation, which could damage the pump. This requirement was understood both in the context of water level and pressure, in which case it was referred to as the net positive suction head required (NPSHR). The NPSHR for each pump was provided by the pump manufacturer, so that users could ensure that the pump was operated within safe operating ranges so as not to damage the pump. Despite being described as a measure of pressure, NPSHR was in fact identified as a measure of the height (typically metres) of fluid required above the inlet of the pump.

73 Further, in his first affidavit, Mr Baarslag explained that, for dewatering applications, the “rule of thumb” to ensure that the pump is operating at, or close to, its best efficiency point is that the NPSHA (or net positive suction head available) is at least one metre above NPSHR. He explained that when the pump is operating within its preferred operating range, vibration is minimised, a high output flow rate is achieved, and the pump motor operates efficiently.

74 It was also common general knowledge that downhole pressure sensors (known as inlet pressure sensors or intake pressure sensors) were commonly used to measure the level of fluid in a borehole or well.

75 By his first affidavit, even Mr Quick accepted that it was common general knowledge as at the earliest priority date that, “In applications where access is difficult and an ultrasonic level sensor cannot be used (such as dewatering), a pressure-based sensor may be used to determine the water level based on the water pressure”.

76 The following passage of oral evidence is also instructive in this regard (with the reference to paragraph 19 being a reference to [0019] of Boot):

MR BANNON: So, coming back to my question, a pressure-based sensor in water will give you a reliable – or can give you a reliable sense of level in a water bore, subject to your issue with whether you put it over the inlet or in – or accounting for flow?

MR QUICK: The pressure sensor can be used to sense level in a bore, yes.

MR BANNON: Okay. And, looking at paragraph 19, would you agree, understanding that this particular can apply to a water well, that the reference to a pressure sensor is telling you that this system can be operated to vary speed based on the reading of a pressure sensor in a water well?

MR QUICK: Yes, it can be – that’s right. It could be varied – it could be using one of those operational characteristics, including pressure, to vary the speed; that’s true.

MR BANNON: Do you – do you agree with that?

MR BAARSLAG: Yes.

…

MR BANNON: And would you agree that one of the most common uses of a pressure sensor in a water bore as in 2016 was to measure level?

MR QUICK: Yes, certainly.

MR BAARSLAG: Yes.

(emphasis added.)

77 Such sensors worked by measuring the pressure exerted by the fluid on the sensor, which has a correlation (or mathematical relationship) with the fluid level. As explained by Mr Bernedo, who was called by UON:

Pressure at the pump intake is correlated with the fluid level, and because of this these terms are sometimes used interchangeably. However, the two are not identical.

In general terms, the pressure at the pump intake can be given by the equation:

Pip = ρ * g * h + Pcsg

[where Pip is pump intake pressure, ρ is the density of the fluid, g is a gravitational constant, h is the height of the fluid above the pump intake and Pcsg is the casing pressure]

As the height of the fluid above the pump increases, the pump intake pressure will increase. In this way, changes in pump intake pressure can indicate a rise or fall in the fluid level. However, pump intake pressure alone does not tell you the level of the fluid. In order to calculate the fluid level above the pump intake from the pump intake pressure you also need to know the density of the fluid, and the casing pressure.

…When pump intake pressure remains constant and there is no change in the density of the fluid or the casing pressure, it can be inferred that there has been no change in the fluid level. If the pump intake pressure changes, and there is no change in the density of the fluid or the casing pressure, then you can infer that the fluid level has changed. However, to calculate the exact amount by which it has changed you would need to carry out the calculations above.

78 In summary, then, if one takes the equation Pip = ρ * g * h + Pcsg, and assumes that each of ρ, g and Pcsg are constant, or relatively so, then an increase or decrease in Pip will typically mean that there has been a corresponding increase or decrease in h. That is (and was as at the earliest priority date) the known manner in which pressure sensors were used to measure level in the typical dewatering scenario.

79 This is because, in the case of dewatering:

(1) the density of fluid is typically relatively constant, and any changes in density because of changes in temperature, salinity or sediment are not sufficient to materially affect the accuracy of the sensor measurement for the purposes of determining level;

(2) the gravitational constant does not change;

(3) the boreholes are almost always open to the atmosphere, so there is no casing pressure. Even where there is a casing pressure (e.g. in a “closed system”), then, unless the casing pressure changes materially over time, it also will have no overall practical effect on the accuracy of the sensor measurement for the purposes of determining water level.

80 It was also common general knowledge that inlet/intake pressure sensors were positioned either above or below the pump inlet to ensure that the pressure reading was not affected by the disturbance and flow of fluid by the pump impeller at the inlet. The only expert who disputed this was Mr Quick, whose evidence was to the effect that inlet/intake pressure sensors were positioned directly at the pump intake/inlet, with the consequence that the flow at the intake/inlet prevents the sensor from accurately determining the level.

81 However, Mr Quick’s evidence was refuted by each of Mr Baarslag, Mr Vukadin and Mr Bernedo. Their evidence was that an intake/inlet pressure sensor is not placed directly at the intake, but rather either above the pump or below the motor. Indeed, neither Mr Vukadin and Mr Bernedo had ever seen an intake pressure sensor located directly at the inlet and considered that such placement would be “impractical”. Rather, the intake/inlet pressure sensor would be placed away from the inlet itself and any necessary adjustments to the calculation made by reference to the distance of the sensor from the intake.

82 At one stage, Mr Quick appeared to accept, if a pressure sensor was used to measure level, the sensor would need to be positioned away from the pump inlet. This acceptance occurred during the following exchange relating to [0058] and [0059] of the Patent specification:

MR BANNON: ...And you accept that would be a pressure sensor - - -

MR QUICK: Yes.

MR BANNON: - - - or pressure-based sensor which could measure that bore water level sufficiently above the pump; that’s right?

MR QUICK: Well, it would need to be – as Mr Baarslag and I agree, it would need to be some distance from the intake of the pump in order to accurately indicate level, but we need the level in order to produce the pressure on the intake of the pump.

(emphasis added.)

83 The evidence of Mr Baarslag, Mr Vukadin and Mr Bernedo, who were qualified to give evidence about this issue, is preferred to the evidence of Mr Quick, for the reasons already given and because Mr Quick had no direct experience with installing intake/inlet pressure sensors for submersible pumps in a borehole and had never seen a pressure sensor installed in a borehole.

84 It was also common general knowledge that electronic pressure sensors included a transmitter that communicated a signal, typically in milliamps, to a controller, which typically converted the milliamp signal and, where required, displayed some unit of measurement in pressure (e.g. kPA, head pressure) or depth (e.g. metres of fluid column) or in some instances both. If required, the system controller or the sensor device itself could convert the pressure signal to depth so that it could be displayed to the user via an HMI screen. It was, however, not necessary for the system controller to convert the milliamp signal into a unit of measurement for it to control the operation of the pump by such a signal. Instead, the system controller could be set to ensure that the ESP did not run in a manner which drew down the water level below the NPSHR.

85 Finally, in the case of dewatering, it was industry practice to maximise production from a water well by obtaining the highest flow rate possible, whilst maintaining the water level within the recommended safe limits, just above the NPSHR, and this could be done using an inlet/intake pressure sensor to control the pump. This was common ground between Mr Bernedo and Mr Vukadin through their evidence during the concurrent evidence session.

86 UON submits that the notional skilled addressee in this case is a person with practical experience in pump systems used in dewatering and the means of powering such pumps, who may be an electrician or electrical engineer. It also submits that, while there may be occasions where the person skilled in the art is a composite team, such as where no single person has the necessary range of knowledge, this is not such a case because Mr Quick has the skill and knowledge of such a person. UON also complains that Allied Pumps has provided no detail as to why a team is the necessary, or appropriate, way to characterise the relevant person skilled in the art, but, notwithstanding these submissions, did not object to the admission of the evidence of the experts called by Allied Pumps.

87 However, as French CJ explained in AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd (2015) 257 CLR 356; [2015] HCA 30 (AstraZeneca HC) at [23], the skilled addressee is not:

…an avatar for expert witnesses whose testimony is accepted by the court. It is a pale shadow of a real person – a tool of analysis which guides the court in determining, by reference to expert and other evidence, whether an invention as claimed does not involve an inventive step.

88 In other words, the skilled addressee is not a reference to a specific person but is a legal construct who may have an interest in using the products or methods of the invention, making the products of the invention, or making products used to carry out the methods of the invention either alone or in collaboration with others having such an interest: Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Konami Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 114 IPR 28; [2015] FCA 735 (Nicholas J) at [26]; Root Quality Pty Ltd v Root Control Technologies Pty Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 225; [2000] FCA 980 (Finkelstein J) at [71]; see also AstraZeneca HC at [23].

89 As observed by Burley J in Hanwha Solutions Corporation v REC Solar Pte Ltd [2023] FCA 1017 at [86]:

Skilled addressees are those likely to have a practical interest in the subject matter of the invention: Catnic Components v Hill & Smith Ltd [1982] RPC 183 at 242 (Diplock LJ). There may be more than a single person with such an interest, and the notional skilled reader to whom the document is addressed may not be a single person but a team, whose combined skills would normally be employed in that art in interpreting and carrying into effect instructions such as those which are contained in the document to be construed: General Tire & Rubber Co v Firestone Tyre & Rubber Co Ltd [1971] 7 WLUK 130; [1972] RPC 457 at 485 (Sachs LJ). Put another way, the skilled addressee is a notional person who may have an interest in using the products or methods of the invention, making the products of the invention, or making products used to carry out the methods of the invention either alone or in collaboration with others having such an interest: Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Limited v Konami Australia Pty Limited [2015] FCA 735; 114 IPR 28 at [26] (Nicholas J); Pharmacia LLC v Juno Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 92; 165 IPR 200 at [111] (Burley J).

(emphasis omitted.)

90 Evidence from multiple experts can be relied upon in identifying the background knowledge and experience of the single skilled addressee, particularly where a patent traverses multiple technical disciplines: see, for example, Aristocrat Technologies at [26]–[27]; see also Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd (2005) 65 IPR 86; [2005] FCAFC 90 (Hill, Finn and Gyles JJ) at [154].

91 That the Patent traverses more than one discipline, such that evidence from multiple experts can be relied upon, accords with the practical experience of Mr Baarslag that he had resort to electrical engineers in his role as a dewatering engineer.

92 In this case, the skilled addressee is someone with expertise in and knowledge of both electrical engineering and dewatering. This may be a single person, or a team with the collective expertise and knowledge. Having regard to their qualifications and experience, the evidence of the experts called by Allied Pumps can be taken to reflect the knowledge and expertise of the skilled addressee.

93 Further, for the reasons given above relating to his lack of experience, I do not accept that Mr Quick (alone) has the skill and knowledge of the skilled addressee in this case. Thus, to the extent that UON contends that Allied Pumps has failed to explain why a team with the collective expertise and knowledge may represent the skilled addressee because a single person has the necessary range of knowledge (and that person is Mr Quick), that contention fails.

94 The Patent relates to submersible pumps used in dewatering applications, and, in particular, to the powering of such pumps when mains power supply is not available. The specification is to be understood in the light of the common general knowledge of the persons skilled in the art.

95 The title of the Patent is “Power and control of a submersible pump”.

96 The Background to the Invention in the specification includes the following statements:

Mining operations frequently occur below the local water table. In such operations, it is necessary to remove local ground water by an operation known as dewatering. Dewatering is achieved by drilling a bore; locating a submersible pump within the bore; and operating the pump to remove water from the vicinity of the pump.

Submersible pumps used in dewatering are typically driven by an electrically powered motor…

Where mains power is not available, the electrical power for the motor must be generated on the surface. This is typically achieved by use of a generator having an internal combustion engine which drives an alternator.

In a typical installation, electrical power and voltage produced by the generator is supplied to an electrical control unit [which], in turn, provides electrical power to the pump motor. Such an electrical control unit may weigh up to four tonnes, and cost up to $300,000.

In order to maintain the motor condition the pump must be operated within a range of interdependent parameters. For a given pump speed, such as 40Hz, the pump curve for that pump will show the flow rate of the pump for a given pressure head. In a downhole operation, both the pressure head and a desired flow rate are subject to change. Such changes can be accommodated by a change in the pump speed, within safe pump operating limits. This is typically achieved by the use of a variable speed drive within the electrical control unit.

The present invention seeks to avoid the use of a variable speed drive by instead providing direct control of the generator. In a preferred embodiment, this may eliminate the need for a separate electrical control unit.

97 At [0008] of the specification, the following statement is made (which paragraph received significant attention during the trial):

For the avoidance of doubt, the term ‘dewatering’ as used herein is defined as the removal of groundwater from a borehole in order to lower the level of the local water table.

98 The specification then contains a Summary of the Invention, which describes the various aspects and embodiments of the invention.

99 The specification describes one aspect of the invention as providing a power and control system for a dewatering submersible pump, the system including a generator comprising an engine and an alternator, the engine having an ECU, the alternator having a voltage regulator, the generator supplying electrical power to the pump; at least one sensor arranged to provide information regarding pump operation and/or surrounding conditions; and a system controller, the system controller being arranged to receive information from the sensor and to control the voltage regulator and the ECU, wherein the voltage regulator is an AVR. It states in relation to this aspect that the sensor may be arranged to monitor the operation of a motor controlling the pump; to monitor the operation of the pump; to monitor the condition of fluid within a system connected to the pump; or to monitor external conditions. It states that the voltage regulator preferably provides an excitation voltage to the alternator in order to regulate output voltage of the alternator; and that the excitation voltage is arranged to vary in response to a comparison of measured output voltage of the alternator and a desired output voltage indicated by the system controller. It states that the sensor may be arranged to monitor the operation of a motor controlling the pump; to monitor the operation of the pump; to monitor the condition of fluid within a system connected to the pump; or to monitor external conditions.

100 The specification then provides that, in a preferred embodiment, at least one sensor is arranged to measure borehole water level; it is also preferred that at least one sensor is arranged to measure a fluid flow rate within a pipe connected to an outlet of the pump; and it is further preferred that at least one sensor is arranged to measure fluid pressure within a pipe connected to an outlet of the pump.

101 The specification then describes a second aspect of the invention as providing a power and control system for a dewatering submersible pump, the system including a generator comprising an engine and an alternator, the engine having an ECU, the alternator having a voltage regulator, the generator supplying electrical power to the pump; at least one sensor arranged to provide information regarding pump operation and/or surrounding conditions; and a system controller, the system controller being arranged to receive information from the sensor and to control the voltage regulator and the ECU, wherein the system controller is arranged to compare the information from the sensor to an input setpoint, and to control the voltage regulator and the ECU in response to deviation of the sensed information from the setpoint.

102 The specification states that the setpoint may be one of the set of desired water level in a bore; desired fluid flow rate within a pipe connected to an outlet of the pump; and desired pressure within a pipe connected to an outlet of the pump.

103 The specification then describes a third aspect of the invention as providing a method of controlling a dewatering submersible pump, the pump being powered by a generator having an engine and an alternator, the method including monitoring at least one condition using a sensor; using a system controller to receive information from the sensor; using the system controller to control an ECU to in turn control an output frequency of the generator in response to information from the sensor; and using the “system control [sic]” to control an AVR to in turn control an output voltage of the generator in response to the sensed condition. It states that the condition(s) being monitored may be borehole water level and/or fluid conditions in a pipe connected to an outlet of the pump. These fluid conditions include fluid flow rate and fluid pressure. It states that the ECU and AVR are “preferred operated to maintain pump speed within a recommended range”.

104 The specification then discusses certain pieces of prior art. The specification states at [0020] that “[t]he applicant is not aware of similar power and control systems and methods used in dewatering” but acknowledges that other power and control systems exist “for submersible oil pumps”.

105 The specification first discusses US Patent Number 7170262 (Pettigrew) which was initially relied upon by Allied Pumps as part of its novelty case, but which was then not pressed at trial. The specification states that Pettigrew describes such a submersible oil pump, and that, rather than an AVR, Pettigrew uses an excitation controller which adjusts voltage according to the frequency of the engine-generator combination. The specification states that Pettigrew does not suggest the use of sensors in order to inform the operation of the excitation controller, or to control for a desired setpoint.

106 The specification then discusses Torrey at [0022] in these terms:

International patent publication number WO2015/051805 (Torrey) describes another submersible oil pump, with a control system arranged to regulate pump inlet pressure. Torrey also describes the use of pump sensors such as temperature and vibration. In one embodiment, Torrey describes the use of an exciter commanded by a system controller, however Torrey does not describe the use of an automatic voltage regulator. Torrey does not suggest the use of sensors monitoring either well level or conditions in connected piping, or the control for associated setpoints.

107 The specification next discusses Boot at [0023] in these terms:

US Patent application publication 2014/0209289 (Boot) describes yet another submersible oil pump. As in Torrey, Boot suggests sensing operational characteristics within the pump, but not within connected piping. There is no suggestion of monitoring well level. Boot does not suggest the maintenance of setpoints.

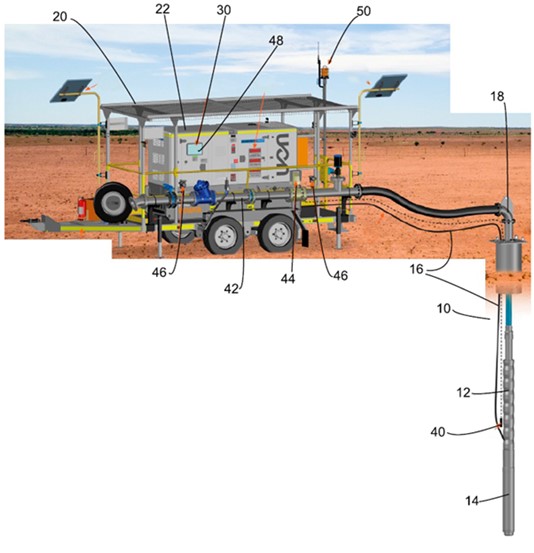

108 There is then a brief description of the drawings and a Detailed Description of the Preferred Embodiments of the invention by reference to Figures 1, 2 and 3. Figure 1, which is a schematic view of a power and control system for a submersible pump in accordance with the invention, is reproduced below.

109 The specification states, by reference to the figures, that:

(1) there is shown a water bore 10 in which a submersible pump 12 has been lowered. The submersible pump 12 is powered by an electrical motor 14. A primary electrical cable 16 provides electrical power to the motor 14. An outlet pipe 18 carries water from the pump 12 to the surface;

(2) a power and control unit 20 is located on the surface. The power and control unit 20 includes outer casing 22 which houses a generator 24 comprising an internal combustion engine 26 and an alternator 28. The generator 24 supplies electrical power to the primary electrical cable 16;

(3) the power and control unit 20 includes a controller 30. The controller 30 is arranged to manage an ECU 32 and an AVR 34;

(4) the AVR 34 regulates the voltage supplied via the primary electrical cable 16 to the motor 14. It achieves this by applying an excitation voltage to the alternator 28, and varying the excitation voltage in response to measured output of the alternator 28. The arrangement is such that the controller 30 provides an indication of desired output voltage to the AVR 34, and the AVR 34 constantly manages the excitation voltage in order to achieve the desired output voltage by means of a feedback loop;

(5) the ECU 32 controls the speed and power of the engine 26, primarily through control of electronic fuel injectors. The controller 30 provides the ECU with a desired speed (i.e. frequency) and load for operation of the alternator 28 under the relevant conditions. The ECU 32 acts to maintain efficiency of the engine 26 through changing conditions. The ECU 32 actively controls the volume of fuel delivered per engine stroke by the fuel injectors to provide the required engine speed and torque;

(6) a circuit breaker 36 is located electrically between the generator 24 and the primary electrical cable 16;

(7) the controller 30 is connected to a plurality of sensors. A first sensor 40 is located within the bore 10, and extends down to the pump 12. The first sensor 40 is arranged to detect and monitor the level of ground water within the bore 10;

(8) the outlet pipe 18 is fluidly connected to a transport pipe 42. A second sensor 44 is mounted on the transport pipe 42. The second sensor is a flow meter, arranged to detect the flow rate of water passing through the transport pipe 42;

(9) two third sensors 46 are mounted at spaced locations along the transport pipe 42. The third sensors 46 are pressure sensors, arranged to detect pressure within the transport pipe 42;

(10) a temperature sensor (not shown) is attached to the motor 14;

(11) operation of the controller 30 may be done directly via a HMI 48, or may be done remotely via a network interface 50, arranged to communicate with an electronic network 52 and to be operated from a remote control centre 54;

(12) the present invention operates on the understanding that pump speed, flow rate, and pressure head together provide an interrelated threedimensional operation range for the pump 12.

110 At [0063] of the specification, the HMI is described in this way:

The HMI 48 is a physical interface electronically coupled to the controller 30. The HMI 48 includes output means, such as a display, speaker and/or printer; and input means, such as a keypad, keyboard, touch screen, touch pad and the like. The HMI 48 provides the ability to control the system controller 30 locally, that is, by a user physically located in the vicinity of the power and control unit 20.

111 The specification then describes three modes, being water-level maintenance mode, constant flow rate mode and constant pressure mode.

112 The water-level maintenance mode is described at [0048]–[0050]:

In this mode the key sensor is the first sensor 40, measuring the level of water in the bore 10. The level of ground water surrounding a bore 10 can be calculated using the baseline aquifer level, the porosity of the surrounding medium, the distance from the bore, and the level within the bore. As such, maintaining an appropriate level within the bore 10 provides certainty that the water level in the surrounding area will be below the required level. This appropriate level is input into the controller 30 as a setpoint.

In water-level maintenance mode, the pump 12 is operated at its full speed (e.g. 50Hz) to achieve maximum possible flow rate until the water level in the bore reaches the setpoint. Once the setpoint has been reached, the controller 30 operates a feedback loop between the engine speed governed by the ECU 32 (operated in conjunction with excitation voltage of the AVR 34) and the measured water level of the first sensor 40 until a steady state is reached. It will be appreciated that the steady state must be within the system capacity (including within safe pump speeds and system pressures) otherwise an alarm will activate and the pump 12 will be shut down. In a preferred embodiment, the feedback loop employs Proportional Integral Derivative (PID) control.

The controller 30 will continue to operate the feedback loop in the event that there is a change in surrounding conditions.

113 The constant flow rate mode is described in these terms at [0051]–[0054]:

In this mode the key sensor is the second sensor 44, measuring the flow rate through the transport pipe 42. Water being extracted from the bore 10 can be used in many applications, some of which (for instance, use as process water within ore processing operations) require a constant flow rate of water. This flow rate is input into the controller 30 as a set point.

In constant flow rate mode, the controller 30 operates a feedback loop between the engine speed governed by the ECU 32 (operated in conjunction with excitation voltage of the AVR 34) and the measured water flow past the second sensor 44 until a steady state is reached. In a preferred embodiment, the feedback loop employs PID control. It will be appreciated that the steady state must be within the system capacity (including within safe pump speeds and systems pressures temps) otherwise an alarm will activate and the pump 12 will be shut down.

The controller 30 will continue to operate the feedback loop in the event that there is a change in surrounding conditions.

Figure 3 shows usage of the pump curve diagram in constant flowrate mode. As head pressure changes from 230m to 90m (for instance, different valves are opened or closed downstream, or in response to changes in bore water level), the pump speed is changed from 50Hz to 35Hz while maintaining a flow rate of 30I/s.

114 The constant pressure mode is described in these terms at [0055]–[0057]:

In this mode the key sensors are the third sensors 46, measuring the pressure in the transport pipe 42. Water being extracted from the bore 10 can be used in many applications, some of which (for instance, dust suppression and tank filling via a pressure valve) may require a constant water pressure. This pressure is input into the controller 30 as a set point.

In constant pressure mode, the controller 30 operates a feedback loop between the engine speed governed by the ECU 32 (operated in conjunction with excitation voltage of the AVR 34) and the measured water pressure at the third sensors 46 until a steady state is reached. In a preferred embodiment, the feedback loop employs PID control. It will be appreciated that the steady state must be within the system capacity (including within safe pump speeds) otherwise an alarm will activate and the pump 12 will be shut down.

The controller 30 will continue to operate the feedback loop in the event that there is a change in surrounding conditions.

115 There is then a description of the system operating safeguards. In particular, the specification states at [0058] and [0059] that:

The controller 30 includes a plurality of thresholds within which the system must operate, including current draw, pump speed, system pressure, bore water level, motor temperature, and minimum flow rate. The controller 30 is arranged to activate an alarm and, if necessary, shut down the system should any of the thresholds be breached.

Typical thresholds include a motor speed of 30Hz to 50Hz or 60Hz, a bore water level sufficiently above the pump 12, and a motor temperature below 65°C or 70°C. Thresholds such as minimum flow rate are specific to particular pump/motor combinations.

116 At [0066] of the specification, the following is stated:

It will be appreciated that the methods described above essentially allow the power and control unit 20 to provide the function of a variable speed drive (VSD), thereby removing the need for a dedicated VSD and hence the additional capital and operating expenditures associated with having a VSD coupled to a fixed speed generator.

117 Relevantly to the issues in this case, I observe that:

(1) The Detailed Description does not indicate that the system that is the subject of the claimed invention must be used for the express purpose of lowering the local water table.

(2) By reference to the water-level maintenance mode, the specification does not confine the “first sensor 40” to any particular type of sensor which measures the level of water in the bore; does not identify any particular unit of measurement that must be used (for example, metres); does not require any display of the measured level; does not detail where the sensor is placed in the borehole; does not identify how level is calculated or where such calculation is to take place; or stipulate against what the measurements should be made (for example, distance below ground level or level above the pump).

(3) The description of the pumping system in the Detailed Description is not limited to a pump which can only be used to pump water and it does not exclude pumps which can pump water but also other fluids, or which have other additional features.

118 Below are the claims of the invention:

1. A power and control system when used for a dewatering submersible pump, the system including:

a generator comprising an engine and an alternator, the engine having an Engine Control Unit (ECU), the alternator having a voltage regulator, the generator supplying electrical power to the pump;

at least one sensor arranged to provide information regarding pump operation and/or surrounding conditions; and

a system controller, the system controller being arranged to receive information from the sensor and to control the voltage regulator and the ECU based on the received information,

wherein the voltage regulator is an automatic voltage regulator,

wherein the ECU is controlled to govern the speed of the engine and thus the frequency of the electrical power supplied to the pump, and the voltage regulator is controlled to govern the voltage of the electrical power supplied to the pump,

and wherein the sensor is arranged to measure borehole water level.

2. A power and control system when used for a dewatering submissible pump, the system including:

a generator comprising an engine and an alternator, the engine having an ECU, the alternator having a voltage regulator, the generator supplying electrical power to the pump;

at least one sensor arranged to measure borehole water level; and

a system controller, the system controller being arranged to receive information from the sensor and to control the voltage regulator and the ECU,

wherein the system controller is arranged to compare the information from the sensor to an input setpoint, and to control the voltage regulator and the ECU in response to deviation of the sensed information from the setpoint.