Federal Court of Australia

Munkara v Santos NA Barossa Pty Ltd (No 2) [2023] FCA 1421

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The order with injunction made on 2 November 2023, as varied on 13 November 2023, is revoked.

2. The respondent is restrained from undertaking any activity as described in the Barossa Gas Export Pipeline Installation Environment Plan (BAA-100 0329) (Revision 3, February 2020) in any place south of the point referred to in submissions as Kilometre Point (KP) 86 on the pipeline route, being the location situated at coordinates Latitude: 10° 31’ 31.9” S, Longitude: 130° 17’ 4.7” E, or alternatively described as Geocentric Datum of Australia 1994 (GDA 94), MGA Zone 52, being:

1. Easting: 640, 568

2. Northing: 8,836,194

3. The restraint in paragraph 2 is to remain in force until 15 January 2024, or such alternate date as the trial judge may determine.

4. Members of the public are granted permission to take a recording of the oral reasons given today, such recording to be used solely for the purpose of preparing a fair and accurate report of the proceedings.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

CHARLESWORTH J

1 This is a record of oral reasons for judgment pronounced on 15 November 2023 revised from the transcript.

2 On 2 November 2023, the Court granted an interim injunction restraining the respondent, Santos NA Barossa Pty Ltd from undertaking works for the construction of a gas export pipeline in the Timor Sea: Munkara v Santos NA Barossa Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1348 (Munkara No 1). The injunction followed an urgent hearing and was expressed to remain in force until 13 November 2023. The injunction was granted on the evidence then before the Court.

3 On 13 November 2023, the Court heard argument on whether the injunction should be extended so as to remain in force until judgment on the originating application. The restraint was extended for a short period to enable the preparation of oral reasons.

4 For the reasons that follow, I am satisfied that there should be a further order restraining works on the pipeline, although not in the whole of the area forming the subject of the applicant’s claim.

5 There will be orders to the following effect:

(1) The order with injunction made on 2 November 2023, as varied on 13 November 2023, is revoked.

(2) The respondent is restrained from undertaking any activity as described in the Barossa Gas Export Pipeline Installation Environment Plan (BAA-100 0329) (Revision 3, February 2020) in any place south of the point marked KP86 on the pipeline route;

(3) The restraint in paragraph 2 is to remain in force until 15 January 2024, or such alternative date as the trial judge may determine.

6 I will now give reasons for those orders.

7 The reasons in Munkara No 1 set out some of the background against which this proceeding was commenced. Given the time restraints, these reasons may repeat much of what was said there verbatim.

8 The applicant, Mr Simon Munkara, is an Aboriginal man from the Tiwi Islands. He is a member of the Jikilaruwu clan and a traditional owner of the land in and around Cape Fourcroy. Other traditional owners of the Tiwi Islands include members of the nearby Malawu and Munupi clans. There is presently an application before the Court for two further applicants to be joined. Those applicants are members of the Malawu and Munupi clans.

9 Mr Munkara commenced this proceeding by an originating application on 30 October 2023. The first order he seeks is expressed as follows:

1. An injunction under s 39B(1A)(c) of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) and s 23 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), prohibiting or restraining on a final basis the Respondent from undertaking the Activity until:

a. it submits a proposed revision to the Pipeline EP in accordance with reg 17(6) of the Environment Regulations; and

b. that revision is accepted by NOPSEMA in accordance with reg 21.

CRITERIA FOR AN INTERLOCUTORY INJUNCTION

10 As explained in Munkara No 1, the criteria for an interlocutory injunction are well established. In Australian Broadcasting Corporation v O’Neill (2006) 227 CLR 57, Gleeson CJ and Crennan J said (at [19]):

… in all applications for an interlocutory injunction, a court will ask whether the plaintiff has shown that there is a serious question to be tried as to the plaintiff’s entitlement to relief, has shown that the plaintiff is likely to suffer injury for which damages will not be an adequate remedy, and has shown that the balance of convenience favours the granting of an injunction. These are the organising principles, to be applied having regard to the nature and circumstances of the case, under which issues of justice and convenience are addressed. …

11 On such an application, the Court will ask whether the applicant has shown that there is a serious question to be tried as to his or her entitlement to relief, has shown that he or she is likely to suffer injury for which damages would not be an adequate remedy, and has shown that the balance of convenience favours the granting of the injunction.

12 Further, as Weinberg J said in Mobileworld Operating Pty Ltd v Telstra Corporation Ltd [2005] FCA 1365 (at [23]):

Sometimes, on an application for interlocutory relief, a court is sufficiently able, on the evidence before it, to reach a conclusion as to particular facts or matters in dispute. However, it must be remembered that any such conclusion will be provisional, and by no means necessarily the same as that which is subsequently reached at the final hearing. The degree to which a court is prepared to investigate disputes of fact depends on their difficulty and on the other circumstances in question, and particularly on the extent of urgency or prospective hardship involved: ICF Spry, The Principles of Equitable Remedies (6th ed, 2001) (‘Spry’) at 466.

13 As to the balance of convenience, the Court must assess and compare the prejudice likely to be suffered by each party if an injunction is granted with that which is likely to be suffered if one is not granted: Lucisano v Westpac Banking Corporation [2015] FCA 243, Gordon J (at [7]).

14 In O’Neill, Gummow and Hayne JJ said (at [65]), that an applicant for an interlocutory injunction must show a “sufficient likelihood” of success to justify the preservation of the status quo for the duration of the restraint. The sufficiency of the likelihood depends upon the nature of the rights the applicant asserts and the consequences that are likely to flow from the order: see Beecham Group Limited v Bristol Laboratories Pty Ltd (1968) 118 CLR 618, Kitto, Taylor, Menzies and Owen JJ (at 622); Samsung Electronics Company Ltd v Apple Inc (2011) 217 FCR 238, Dowsett, Foster and Yates JJ (at [59]). That aspect of the principles looms large on the application presently before this Court.

15 The two criteria of “serious question to be tried” and “balance of convenience” interrelate, and the extent to which it is appropriate to examine the merits of an applicant’s claim for relief will always depend on the circumstances of the case: Australian Broadcasting Corporation v Lenah Game Meats Pty Limited (2001) 208 CLR 199, Gleeson CJ (at [18]).

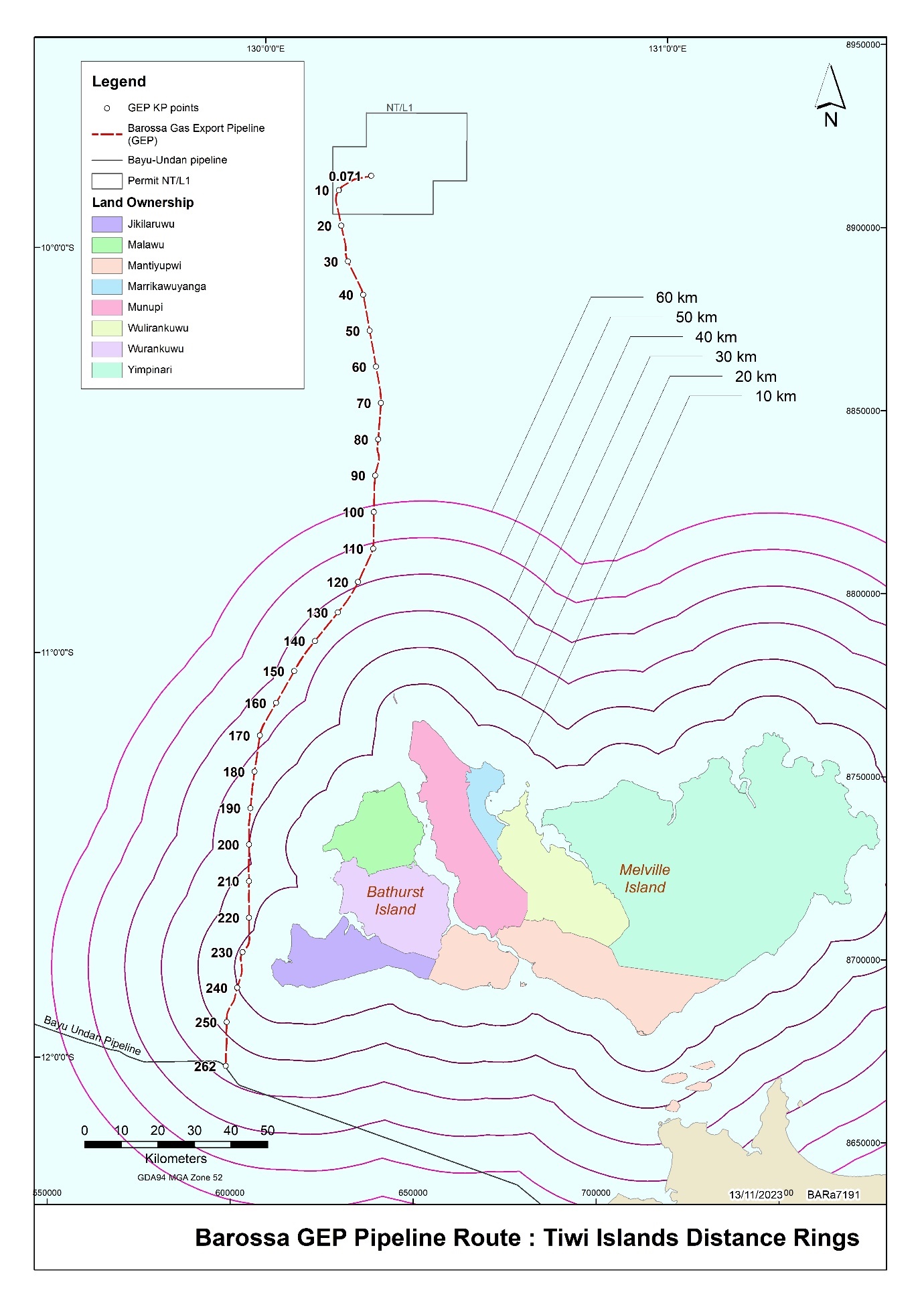

THE ACT AND REGULATIONS

16 The case falls to be decided by reference to the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage (Environment) Regulations 2009 (Cth), being regulations made under the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006 (Cth). Regulation 3 sets out the objects of the Regulations. It states:

The object of these Regulations is to ensure that any petroleum activity or greenhouse gas activity carried out in an offshore area is:

(a) carried out in a manner consistent with the principles of ecologically sustainable development set out in section 3A of the EPBC Act; and

(b) carried out in a manner by which the environmental impacts and risks of the activity will be reduced to as low as reasonably practicable; and

(c) carried out in a manner by which the environmental impacts and risks of the activity will be of an acceptable level.

17 Section 3A of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (referred to in reg 3(a) above) sets out “principles of ecologically sustainable development”. They include:

(b) if there are threats of serious or irreversible environmental damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation;

(c) the principle of inter-generational equity-that the present generation should ensure that the health, diversity and productivity of the environment is maintained or enhanced for the benefit of future generations;

18 The word “environment” is defined in reg 4 to mean:

(a) ecosystems and their constituent parts, including people and communities; and

(b) natural and physical resources; and

(c) the qualities and characteristics of locations, places and areas; and

(d) the heritage value of places;

and includes

(e) the social, economic and cultural features of the matters mentioned in paragraphs (a), (b), (c) and (d).

19 The expression “environmental impact” is defined to mean any change to the environment, whether adverse or beneficial, that wholly or partially results from an activity: reg 4.

20 It is an offence for a titleholder to undertake an “activity” if there is no environment plan in force for the activity: reg 6. It is also an offence for a titleholder to undertake an activity in a way that is contrary to an environment plan in force for the activity, or contrary to any limitation or condition applying to operations for the activity under the Regulations: reg 7.

21 Regulation 8(1) creates an offence that assumes some significance in the proceeding. It provides:

Operations must not continue if new or increased environmental risk identified

(1) A titleholder commits an offence if:

(a) the titleholder undertakes an activity after the occurrence of:

(i) any significant new environmental impact or risk arising from the activity; or

(ii) any significant increase in an existing environmental impact or risk arising from the activity; and

(b) the new impact or risk, or increase in the impact or risk, is not provided for in the environment plan in force for the activity.

22 The words “occurrence”, “significant”, “new” and “risk” are not defined.

23 Division 2.2 of Pt 2 of the Regulations establishes a scheme for the submission and acceptance of environment plans.

24 Before commencing an activity, the titleholder must submit an environment plan for the activity to the National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (NOPSEMA), defined as the “Regulator”: reg 9. The criteria for an environment plan are set out in reg 10A. It provides:

Criteria for acceptance of environment plan

For regulation 10, the criteria for acceptance of an environment plan are that the plan:

(a) is appropriate for the nature and scale of the activity; and

(b) demonstrates that the environmental impacts and risks of the activity will be reduced to as low as reasonably practicable; and

(c) demonstrates that the environmental impacts and risks of the activity will be of an acceptable level; and

(d) provides for appropriate environmental performance outcomes, environmental performance standards and measurement criteria; and

(e) includes an appropriate implementation strategy and monitoring, recording and reporting arrangements; and

(f) does not involve the activity or part of the activity, other than arrangements for environmental monitoring or for responding to an emergency, being undertaken in any part of a declared World Heritage property within the meaning of the EPBC Act; and

(g) demonstrates that:

(i) the titleholder has carried out the consultations required by Division 2.2A; and

(ii) the measures (if any) that the titleholder has adopted, or proposes to adopt, because of the consultations are appropriate; and

(h) complies with the Act and the regulations.

25 The Regulations confer functions and powers on NOPSEMA with respect to an environment plan submitted to it, including obligations of publication and a discretion to request the provision of further information. Regulation 10 relevantly provides that if the Regulator is reasonably satisfied that the environment plan meets the criteria set out in reg 10A, the Regulator must accept the plan. If not reasonably satisfied, it must provide the titleholder with an opportunity to resubmit the environment plan, and then accept the resubmitted plan if satisfied that the criteria in reg 10A are fulfilled in respect of it.

26 For the purposes of reg 10A(g)(i), reg 11A imposes obligations of consultation on a titleholder in respect of the preparation of an environment plan, and those obligations extend to the preparation of a revised environment plan. It provides:

Consultation with relevant authorities, persons and organisations, etc

(1) In the course of preparing an environment plan, or a revision of an environment plan, a titleholder must consult each of the following (a relevant person):

(a) each Department or agency of the Commonwealth to which the activities to be carried out under the environment plan, or the revision of the environment plan, may be relevant;

(b) each Department or agency of a State or the Northern Territory to which the activities to be carried out under the environment plan, or the revision of the environment plan, may be relevant;

(c) the Department of the responsible State Minister, or the responsible Northern Territory Minister;

(d) a person or organisation whose functions, interests or activities may be affected by the activities to be carried out under the environment plan, or the revision of the environment plan;

(e) any other person or organisation that the titleholder considers relevant.

(2) For the purpose of the consultation, the titleholder must give each relevant person sufficient information to allow the relevant person to make an informed assessment of the possible consequences of the activity on the functions, interests or activities of the relevant person.

(3) The titleholder must allow a relevant person a reasonable period for the consultation.

(4) The titleholder must tell each relevant person the titleholder consults that:

(a) the relevant person may request that particular information the relevant person provides in the consultation not be published; and

(b) information subject to such a request is not to be published under this Part.

27 For the purposes of the preparation of the Barossa Gas Export Pipeline Installation Environment Plan (BAA-100 0329) (Pipeline EP) presently in force, there is no dispute that Mr Munkara was a “relevant person” within the meaning of that provision, including because he is a person whose interests or activities may be affected by the activities to be carried out pursuant to it.

28 Division 2.3 of the Regulations prescribes the content of an environment plan. It contains the following requirements (reg 13):

Description of the environment

(2) The environment plan must:

(a) describe the existing environment that may be affected by the activity; and

(b) include details of the particular relevant values and sensitivities (if any) of that environment.

…

Evaluation of environmental impacts and risks

(5) The environment plan must include:

(a) details of the environmental impacts and risks for the activity; and

(b) an evaluation of all the impacts and risks, appropriate to the nature and scale of each impact or risk; and

(c) details of the control measures that will be used to reduce the impacts and risks of the activity to as low as reasonably practicable and an acceptable level.

(6) To avoid doubt, the evaluation mentioned in paragraph (5)(b) must evaluate all the environmental impacts and risks arising directly or indirectly from:

(a) all operations of the activity; and

(b) potential emergency conditions, whether resulting from accident or any other reason.

29 Division 2.4 of the Regulations is titled “Revision of an environment plan”. The powers of NOPSEMA to accept a revised environment plan are co-extant with those that apply to an original environment plan. Regulation 17(6) provides:

New or increased environmental impact or risk

(6) A titleholder must submit a proposed revision of the environment plan for an activity before, or as soon as practicable after:

(a) the occurrence of any significant new environmental impact or risk, or significant increase in an existing environmental impact or risk, not provided for in the environment plan in force for the activity; or

(b) the occurrence of a series of new environmental impacts or risks, or a series of increases in existing environmental impacts or risks, which, taken together, amount to the occurrence of:

(i) a significant new environmental impact or risk; or

(ii) a significant increase in an existing environmental impact or risk;

that is not provided for in the environment plan in force for the activity.

30 Regulation 18(1) provides that a titleholder must submit to NOPSEMA a proposed revision of the environment plan for an activity if NOPSEMA requests the titleholder to do so. Such a request must set out the matters to be addressed by the revision, the proposed date of effect of the revision and the grounds for the request: reg 18(2).

31 Regulation 21 relevantly provides that regs 10, 10A and 11A apply to the proposed revision as they do to an environment plan. More specifically, in the preparation of a revised environment plan, the titleholder must undertake the consultations required under reg 11A and NOPSEMA must not accept the revised environment plan unless satisfied that the criteria relating to consultation are fulfilled: Cooper v National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (No 2) [2023] FCA 1158, Colvin J (at [4]).

32 Regulation 22 provides:

Effect of non-acceptance of proposed revision

If a proposed revision is not accepted, the provisions of the environment plan in force for the activity existing immediately before the proposed revision was submitted remain in force, subject to the Act and these Regulations, (in particular, the provisions of Division 2.5), as if the revision had not been proposed.

33 Subject to procedural requirements, NOPSEMA may withdraw the acceptance of an environment plan if it has refused to accept a proposed revision of it: reg 23(2)(c). NOPSEMA may also withdraw an environment plan if a titleholder has not complied with (relevantly) reg 17 or reg 18.

34 Section 574 of the Act confers upon NOPSEMA the discretion to issue a direction to a titleholder in relation to any matter in which regulations may be made. It is an offence to engage in conduct in breach of such a direction: Act, s 576(1).

MR MUNKARA’S CASE

35 Mr Munkara alleges that Santos is presently obliged to submit a revised environment plan in accordance with reg 17(6). He claims that the obligation arises because there has been an occurrence of a significant new environmental impact or risk that is not provided for in the Pipeline EP (the environment plan that he asserts is presently in force for the pipeline activity) within the meaning of reg 17(6)(a). He relies in the alternative on reg 17(6)(b).

36 There is no dispute that environmental impacts may encompass impacts on cultural heritage both in an intangible and tangible sense. Mr Munkara alleges that in the circumstances, Santos cannot undertake any of the works described in the Pipeline EP without first submitting a revised environment plan because to do so would constitute an offence under reg 8. He submits that relief in the nature of a final injunction in terms set out in the originating application is directed to ensuring that Santos positively complies with its obligation under reg 17(6), a provision that he says is inextricably linked to the offence created by reg 8.

The Gas Export Pipeline

37 Santos is the holder of a Petroleum Licence and a Pipeline Licence issued under the Act. It is a titleholder for the purposes of the Regulations. It is, as I presently understand it, the vehicle for a joint venture undertaking the project for the construction of the pipeline, known broadly as the Barossa Project. The 263km long gas export pipeline forms one part of the Barossa Project. It is comprised of carbon steel and is coated with concrete. Works for the laying of the pipeline include the installation of foundations at each terminating end as well as “span correction” and “buckle correction” mattresses fixed to the sea bed. The pipeline is expected to settle into the sea bed at depths that will vary along its length. Its diameter varies, according to the depth at which it will be laid.

38 On 9 March 2020, a delegate of NOPSEMA accepted the Pipeline EP pursuant to reg 10(1)(a) of the Regulations. The Pipeline EP relates to the installation of the pipeline as well as all other activities necessary or incidental to its installation.

39 The location of the pipeline relative to the Tiwi Islands may be described by reference to a map marked BD4.04, forming Schedule A to these reasons.

40 As discussed in Munkara No 1, places along the length of the pipeline may be described in terms of their distance in kilometres from its northernmost commencement point. The descriptor KP0 represents the commencement point, and each kilometre along the length may be described with the initials KP followed by the distance from the point of commencement. On a direct route without deviation KP0 is situated about 220km from Cape Fourcroy and approximately 160km from Cape Helvetius (the northern-most point of the Tiwi Islands).

41 In practical terms, the interim injunction granted in Munkara No 1 restrained Santos from undertaking those works that had been scheduled to commence on 2 November 2023 and to continue to 13 November 2023, namely the laying of the pipeline between KP86 and KP121. As explained in Munkara No 1, KP121 is approximately 40km from the nearest land mass on the Tiwi Islands. It appears to be common ground that works for the construction of the pipeline would in the ordinary course proceed at rate of 3km per day.

42 Also in evidence is a map prepared by Dr Michael O’Leary, an Associate Professor in climate geoscience. I will refer to that as the O’Leary Map. It is comprised of a satellite image depicting the Tiwi Islands to the east and topographical features of the sea bed to the west. Those features include a submerged freshwater lake. The O’Leary Map depicts an oval shaped area bordered by a broken pink line in the vicinity of the freshwater lake, spanning approximately 20kms in length and 10kms in width. That area is said by Aboriginal informants to be the resting place of Ampitji, a creation being of considerable spiritual and cultural significance to them. A portion of the pipeline route passes between the Tiwi Islands about 7km to the east (at the closest point) and the Ampitji resting place about 2km to the west (also at the closest point). That portion commences at approximately KP218 and ends at approximately KP236. All of that is said with an appreciation that the O’Leary Map is not intended to depict any particular aspect of Aboriginal traditional law, custom or beliefs with geographical precision. But it is nonetheless relevant context for understanding the evidence of the lay witnesses to be called on Mr Munkara’s case and to understand some part of their case based on feared damage to intangible cultural heritage in the area of the pipeline.

43 The O’Leary Map also depicts, in a green broken line, a song line related to Jirakupai, the Crocodile Man. That intersection occurs at approximately KP233. The map depicts areas referred to as “Burial Grounds” in the same vicinity.

JURISDICTION AND STANDING

44 In Munkara No 1, I addressed arguments previously advanced by Santos as to whether there was before the Court a “matter” arising under a law of the Commonwealth and the closely related question of whether Mr Munkara had standing to sue for the final relief, namely a final injunction in the terms sought on the originating application: Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth), s 39B(1A)(c).

45 Santos has raised an additional argument with respect to that issue and invites the Court to revisit the questions of jurisdiction and standing to that limited extent.

46 Before turning to the additional argument, it is convenient to repeat what I said in Munkara No 1 on the topic:

JURISDICTION AND STANDING

39 On its terms, the originating application invokes the Court’s jurisdiction under s 39B(1A)(c) of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). It confers original jurisdiction on this Court in any matter ‘arising under any laws made by the Parliament, other than a matter in respect of which a criminal prosecution is instituted or any other criminal matter’.

40 The originating application does not invoke the Court’s supervisory jurisdiction to review any decision or conduct of NOPSEMA, nor is NOPSEMA joined as a respondent.

41 For present purposes Santos makes no submissions with respect to whether the qualification in s 39B(1A)(c) of the Judiciary Act with respect of criminal prosecutions ‘or any other criminal matter’ applies, but reserves it position with respect to that issue. Its primary submission is that the Court does not have before it a ‘matter’ within the meaning of s 39B(1A)(c) of the Judiciary Act.

42 As Kiefel, Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ observed in Palmer v Ayres (2017) 259 CLR 478:

26 A ‘matter’, as a justiciable controversy, is not co-extensive with a legal proceeding, but rather means the subject matter for determination in a legal proceeding – ‘controversies which might come before a Court of Justice’ (emphasis added). It is identifiable independently of proceedings brought for its determination and encompasses all claims made within the scope of the controversy. What comprises a ‘single justiciable controversy’ must be capable of identification, but it is not capable of exhaustive definition. ‘What is and what is not part of the one controversy depends on what the parties have done, the relationships between or among them and the laws which attach rights or liabilities to their conduct and relationships’.

27 The requirement that, for there to be a ‘matter’, there must be an ‘immediate right, duty or liability to be established by the determination of the Court’ reinforces that the controversy that the court is being asked to determine is genuine, and not an advisory opinion divorced from a controversy, and, further, that only a claim is necessary. A matter can exist even though a right, duty or liability has not been, and may never be, established.

(original emphasis, footnotes omitted)

43 The existence of a ‘matter’ cannot be separated from the existence of a remedy to enforce the substantive right, duty or liability: Abebe v Commonwealth (1999) 197 CLR 510, Gleeson CJ and McHugh J (at [32]). It is therefore necessary to have close regard to the relief sought in the proceeding: Australia Bay Seafoods Pty Ltd v Northern Territory (2022) 295 FCR 443, Besanko, Charlesworth and O’Bryan JJ (at [148]).

44 There plainly exists a controversy between Mr Munkara and Santos. The subject matter of their dispute is whether Santos presently has a duty under reg 17(6) of the Regulations (a law of the Commonwealth) to submit a revised environment plan. That is the question that Mr Munkara asks the Court to determine. If it be the case that Santos presently has an immediate duty to submit a revised environment plan, then it would follow that Mr Munkara, as a ‘relevant person’, has a present right to be consulted in the course of its preparation. In addition, it is not disputed that as an Aboriginal man he has an interest of the kind that the Act and the Regulations are designed to protect, at least insofar as the Act is concerned with the protection of cultural heritage as an aspect of the environment. That aspect of his interest is not wholly protected by the creation of the criminal offence in reg 8 of the Regulations. The answer to the question arising under reg 17(6) has very real and immediate consequences both for Santos and for Mr Munkara: cf Australia Bay Seafoods. There is nothing hypothetical about the question. I do not understand Santos to submit otherwise.

45 Rather, Santos’ position is that there can be no ‘matter’ because the injunctive relief claimed on the originating application is not relief that the Court can grant, at least on Mr Munkara’s application. The present case, Santos submitted, must be distinguished from cases in which an application for judicial review has been made in respect of a decision of NOPSEMA, and in which orders are sought against titleholders to preserve the subject matter of the judicial review proceeding: see for example Cooper.

46 Santos submitted that a person in the position of Mr Munkara may remonstrate to NOPSEMA for the exercise of its regulatory powers and then, if dissatisfied with the decision (or failure to make a decision as the case may be) he should commence an application for judicial review. It submitted that the present proceeding was ‘unorthodox’ because Mr Munkara did not invoke the Court’s supervisory jurisdiction vis a vis NOPSEMA. It submitted that the suite of powers conferred on NOPSEMA were such as to give rise to an implication that it was for NOPSEMA to supervise the discharge by Santos of its obligations under the Act, and that Mr Mankara’s rights to sue were therefore confined.

47 Whilst reference was made to a provision of the Act which relates to injunctions (namely s 611J), the Court was not given an explanation as to how it should be construed, nor as to how it supported the implication contended for, whether alone or in conjunction with other provisions.

48 On the basis of the submissions and material presently before me, I am not satisfied that the Act and Regulations should be construed so as to preclude Mr Munkara from seeking a final injunction to secure the performance by Santos of a duty that Mr Munkara submits has arisen on the facts and the law. There are three reasons for that conclusion.

49 First, on its terms reg 17(6) imposes an obligation in either of the events referred to in paragraphs (a) or (b). Whether the obligation has arisen turns on an objective assessment that is not premised on the formation of a state of mind of NOPSEMA as the Regulator or any other person. There is no express provision conferring exclusively on NOPSEMA the power to determine whether Santos is presently in breach of the obligation. It is true that the Regulations make provision for NOPSEMA to make a request under reg 18. However, the circumstance that it has not done so does not mean that Santos is not presently in breach of any discrete obligation presently arising under reg 17(6). Similarly, NOPSEMA has the power to issue a direction to Santos under s 574 of the Act including in respect of matters concerned with the protection of Mr Munkara’s asserted interests and concerns. Indeed it has already done so, albeit not to the extent of requiring that Santos submit a revised Pipeline EP. I do not consider that the fact or scope of NOPSEMA’s power to issue a direction supports a construction that precludes a person in Mr Munkara's position from seeking an injunction with a view to enforcing any obligation that arises under reg 17(6). To the extent that Santos submitted that the originating application involves an usurpation of NOPSEMA's functions, I do not accept the submission.

50 Second, in the absence of an express provision precluding the grant of relief sought (should the obligation be proven), the Court should be slow to identify any such preclusion by way of implication, in light of the objects stated in reg 3. On the construction preferred by Santos, a ‘relevant person’ who became aware that a titleholder was in breach of reg 17(6), would be limited to remonstrating his or her concern to NOPSEMA, no matter how imminent the threatened harm. He or she would be required to seek redress for non observance with the statute (and hence the protection of their relevant interest) by indirect rather than direct means. The objects of the Act tend against such a construction, because they are directed to the prevention of environmental harm.

51 Third, the structure of the environment plan regime is that a ‘relevant person’ has a right to be consulted by the titleholder, not by NOPSEMA. In that respect the Act itself establishes an obligation and coextensive right as between the titleholder and the relevant person. It would frustrate the objects of the Regulations if the titleholder avoided the obligation to submit the revised environment plan and so avoided the consultation obligations under reg 11A by incorrectly concluding that the obligation had not been triggered. In that sense, the controversy is one that directly arises between Mr Munkara and Santos, and concerns rights and duties as between them. The circumstance that NOPSEMA may impose other consequences on a titleholder for non-compliance with reg 17 (including the withdrawal of acceptance of the environment plan) does not foreclose, by necessary implication or otherwise, other avenues of relief for (at least) persons who meet the description of relevant persons.

52 Santos drew the Court’s attention to the voluminous correspondence passing between Mr Munkara’s solicitors, Santos and NOPSEMA since December 2022 in which Mr Munkara asserted the very interest sought to be protected in this proceeding and urged NOPSEMA to exercise its powers, including its discretion under reg 18 to request Santos to submit a revised Pipeline EP. Those remonstrations may be relevant in the exercise of the Court’s discretion to grant relief on the present application. However, I do not consider they inform the question of jurisdiction and standing. The evidence goes no further than to demonstrate that Mr Munkara (correctly) comprehends that there may exist alternate legal avenues to achieve the same object.

53 Finally, it should be observed that the arguments as to the availability of relief are closely related to the question of standing. I accept that a real question arises as to the geographical extent of Mr Munkara’s ‘interests’ as that word is employed in reg 11A of the Regulations. However, whether the claim for relief is cast too broadly depends on facts that cannot be substantively determined on an urgent application such as the present. The extent of his interests in the area affected by the pipeline is properly a matter for the trial judge. It is neither possible nor appropriate to substantively determine it as a preliminary issue.

54 As to the test for standing more generally, the best guidance is that given by Gibbs CJ in Onus v Alcoa of Australia Limited (1981) 149 CLR 27 (at 35 - 36):

The case is therefore one in which two private citizens who cannot show that any right of their own has been infringed bring an action for the purpose of restraining another private citizen (Alcoa) from breaking the criminal law by acting in contravention of s.21 of the Relics Act. The question is whether they have standing to bring the action. If an attempt were made to frame an ideal law governing the standing of a private person to sue for such a purpose, it would be necessary to give weight to conflicting considerations. On the one hand it may be thought that in a community which professes to live by the rule of law the courts should be open to anyone who genuinely seeks to prevent the law from being ignored or violated. On the other hand, if standing is accorded to any citizen to sue to prevent breaches of the law by another, there exists the possibility, not only that the processes of the law will be abused by busybodies and cranks and persons actuated by malice, but also that persons or groups who feel strongly enough about an issue will be prepared to put some other citizen, with whom they have had no relationship, and whose actions have not affected them except by causing them intellectual or emotional concern, to very great cost and inconvenience in defending the legality of his actions. Moreover, ideal rules as to standing would not fail to take account of the fact that it is desirable, in an adversary system, that the courts should decide only a real controversy between parties each of whom has a direct stake in the outcome of the proceedings. The principle which has been settled by the courts does attempt a reconciliation between these considerations. That principle was recently stated in Australian Conservation Foundation Inc. v. The Commonwealth. A plaintiff has no standing to bring an action to prevent the violation of a public right if he has no interest in the subject matter beyond that of any other member of the public; if no private right of his is interfered with he has standing to sue only if he has a special interest in the subject matter of the action. The rule is obviously a flexible one since, as was pointed out in that case, the question what is a sufficient interest will vary according to the nature of the subject matter of the litigation.

(footnotes omitted)

55 In the present case there can be no suggestion that Mr Munkara is abusing the processes of the law, nor that he is a busybody, crank, or actuated by malice. His concerns are not merely intellectual or emotional. He has a direct stake in the outcome of the proceeding. His interest in the underlying subject matter is beyond that of an ordinary member of the public. The same considerations affect my consideration as to whether there exists a matter arising under a law of the Commonwealth within the meaning of s 39B(1A)(c) of the Judiciary Act. For the purposes of considering the limited application before me, I proceed on the basis that there is such a matter and that the relief is of a kind for which Mr Munkara has standing to sue.

The additional argument

47 The final injunction sought on the originating application is one that seeks to enforce a legal duty under reg 17(6) to submit a revised environment plan before engaging in the activity described in the existing environment plan (and see reg 8). Santos submitted that a regulation creating such a duty that is enforceable at the suit of any person (other than NOPSEMA) would be ultra vires the regulation-making powers contained in the Act. It submitted that the regulations must be construed in conformity with the regulation-making powers and so must be understood to exclude any jurisdiction the Court may otherwise have to grant injunctive relief on the suit of any person other than NOPSEMA. The regulation-making powers, it was submitted, were to be understood as facilitating the performance of NOPSEMA’s functions and the exercise of its powers, and the regulations must therefore be narrowly construed in that context. The effect of the submission was that, properly construed, the general law with respect to standing in proceedings of the present kind (as explained in Onus v Alcoa of Australia Limited (1981) 149 CLR 27) is, by necessary implication, displaced. The necessary implication is one that is said to arise as a matter of statutory construction, given the “slender” regulation-making powers contained in the Act and the limited purpose of those powers.

48 As discussed below, the argument is one of substance going to the Court’s jurisdiction to grant the final relief, a question that in the present case cannot be extricated from the question of Mr Munkara’s standing: cf Hobart International Airport Pty Ltd v Clarence City Council [2022] HCA 5; 399 ALR 214. The challenge to standing in this respect equates to a challenge to the competency of the whole of the action. Given that an injunction will be granted, I therefore consider it necessary to be positively satisfied that a final injunction may be granted at the suit of Mr Munkara, assuming that he is successful in establishing that Santos’ legal obligation under reg 17(6) exists.

49 Counsel for Santos submitted that the Act did not make express provision for the promulgation of regulations providing for the creation and supervision of environment plans. It was submitted that to the extent that regulation-making powers contained in the Act referred to environment plans, they were narrow and discrete in their subject matter. For example, s 571 of the Act makes provision for a titleholder to give financial assurances, and it authorises the making of regulations permitting NOPSEMA to refuse to accept an environment plan in the event that financial assurances are not given. In addition, s 688C relates to the payment of levies in connection with environment plans. In both instances, the expression “environment plan” is defined in to mean:

environment plan for a petroleum activity means an environment plan for the activity under prescribed regulations, or a prescribed provision of regulations, made under this Act.

50 Counsel for Santos referred to a more general regulation-making power contained in s 781 of the Act. Among other things, it authorises the making of regulations as follows:

781 Regulations

The Governor-General may make regulations prescribing matters:

(a) required or permitted by this Act to be prescribed; or

(b) necessary or convenient to be prescribed for carrying out or giving effect to this Act.

51 In addition, Item 4 of the provision authorises the making of regulations in relation to the construction of a pipeline for the conveyance of petroleum.

52 The Act also contains provisions expressly authorising the making of regulations creating criminal offences or civil penalty provisions: Act, s 790A to s 790D. The latter provisions make reference to the Regulatory Powers (Standard Provisions) Act 2014 (Cth). However, neither party has referred to the regime established under that legislation and, for present purposes at least, I have had no regard to it.

53 There can be no doubt that the Act authorises the making of regulations that impose legal obligations on a titleholder, including legal obligations that relate to the preparation and submission of environment plans, and including obligations attracting criminal sanction or civil penalties for breach. The Act plainly authorises the making of regulations conferring powers on NOPSEMA in relation to the same subject matter. However, as explained in Munkara No 1, the circumstance that NOPSEMA may be authorised to commence an action for the enforcement of a titleholder’s legal obligations (whether arising under the Act or the Regulations) does not preclude the application of the general law of standing as it relates to suits of the present kind. Ordinarily, those principles apply in proceedings for the enforcement of legal obligations arising under a law of the Commonwealth, irrespective of whether the law is one contained in an Act or in subordinate legislation. They are, of course, subject to modification or abrogation. However, the empowering provisions in the Act are not such as to support a conclusion that Parliament intended to alter or abrogate them in connection with rights or obligations owing their existence to the Regulations. There is nothing “slender” about the empowering provisions. The Act itself presupposes that the Regulations will contain provisions for the making and enforcement of environment plans. Whether a person in Mr Munkara’s position may commence a suit for an injunction to enforce any legal obligation owing its existence to reg 17(6) is to be decided under a well established body of law. That law was applied in Munkara No 1 and the additional argument provides no basis to depart from what was said there.

54 The Court was otherwise taken to cases concerned with the question of whether a statute or legislative instrument should be construed so as to confer upon an individual a “private right”. However, no such question arises in the present case because Mr Munkara does not rely upon a private right or cause of action as the legal basis for his standing. He falls within the second class of case discussed by the High Court in Onus v Alcoa and his standing to sue turns on an orthodox application of the principles discussed in that case. For the purpose of granting interlocutory relief I am not satisfied that those principles are displaced expressly or by necessary implication drawn from the statutory regime.

ISSUES TO BE TRIED

55 It is necessary to assess whether Mr Munkara’s claim for final relief enjoys a sufficient likelihood of success and the related question of where the balance of convenience lies by reference to the evidence that is now before the Court. Both parties have filed further affidavits and it is reasonable to infer that the evidence of Mr Munkara now more closely resembles that which will be adduced from lay witnesses at the trial.

Extent of sea country

56 An ongoing interlocutory injunction in the form sought is one that would restrain all works on the pipeline no matter where they are situated within the pipeline corridor.

57 It is necessary to assess the seriousness of the questions to be tried as they relate to places proximate to the Tiwi Islands as well as to places more distant. That is because the relief sought in the present case has a tangible geographical component. The pipeline is linear. Its length is measurable in kilometres as is its distance from the land mass of the Tiwi Islands. Place is also relevant because the definition of “environment” in the Regulations makes it so.

58 In Munkara No 1 I observed that the evidence of Mr Munkara and other Aboriginal witnesses was expressed at a level of generality with respect to the geographic extent of their connection with sea country. The witnesses themselves have stated that they do not conceive of those connections in terms of physical boundaries. An example of that is the affidavit of Ms Carol Puruntatameri, affirmed on 7 November 2023, where she says:

We don’t think in the way of boundaries. Our connection goes out all the way in the Timor Sea.

59 As Counsel for Mr Munkara acknowledged, it is nonetheless necessary to consider their evidence in context so as to understand how it is that there exists a “significant environmental impact or risk” within the meaning of reg 17(6) that is not already provided for in any environment plan presently in force relating to the pipeline corridor. The claimed impact is one upon cultural heritage, and so depends on a proper understanding of the traditional law and custom to which Mr Munkara refers. It is reasonable to infer that the evidence filed since the order on 2 November 2023 more closely resembles that which is intended to be adduced by Mr Munkara at the trial.

60 On that topic, I have not overlooked that Santos may submit at trial that Mr Munkara’s evidence on critical topics may not coincide with the opinions or beliefs of other Tiwi Islanders, including other members of the Jikilaruwu, Munupi and Malawu clans. The position Santos may adopt on that question at trial is of course relevant, but for present purposes I express no concluded view about it. There is a serious case to be tried on the facts asserted by Mr Munkara and other Aboriginal witnesses as to the traditional law and custom upon which the concerns of some Tiwi Islanders are based, as well as their cultural authority to speak on those subjects. I am presently concerned with the geographical reach of those assertions so as to understand why it is said that there should be no works at all at any point on the pipeline.

61 On the evidence now before me, I have concluded that the evidentiary case is stronger insofar as it relates to places in the sea more proximate to the Tiwi Islands, relative to places that are more distant. There are a number of reasons for that conclusion, in connection with both intangible and tangible cultural heritage.

Intangible cultural heritage

62 Whilst it is not limited to these topics, Mr Munkara’s case places particular emphasis on Dreamings related to Ampitji and the Crocodile Man. The evidence suggests that the Crocodile Man songline has a geographical locale, that is capable of being described, albeit without precision. The same may be said of the resting place of Ampitji. The O’Leary Map is instructive on these questions but I accept that it is not determinative. In her affidavit affirmed on 7 November 2023, Ms Puruntatameri said:

We don’t want the pipeline to be put there. It will disconnect us from Mother Ampiji, and they can't separate us from that sacred site. That is our Mother Ampiji there, that is our sacred site. It’s got to go on the other side of that area. Not through the burial sites, but on the other side of where the freshwater source is so that it doesn’t disconnect us from Mother Ampiji.

63 The impact described by the witness is one caused by the severing of area between the Tiwi Islands and the Ampitji resting pace depicted on the O’Learly Map. However, the witness does not in terms speak of that particular concern persisting in the waters to the north-east of the Ampitji resting pace.

64 There is other evidence about the wider travels of Ampitji and the case of Mr Munkara must be understood as asserting a connection to sea country in that wider sense related at least in part to the unspecified extent of those travels. However, I do not consider that the evidence should be understood as asserting a connection to all areas of the sea no matter how far distant from the Tiwi Islands. It may be that the expertise of an anthropologist is required to assist the Court at trial to understand the nature and extent of asserted spiritual connection to sea country beyond the waters more proximate to the islands. At present, howsoever, it is not currently clear how Mr Munkara’s case will be presented on that point so as to demonstrate at trial that the feared impacts on cultural heritage exist at, for example, the northernmost point of the pipeline, that is, at KP0.

65 I have not overlooked that in Santos NA Barossa Pty Ltd v Tipakalippa (2022) 296 FCR 124, the Full Court referred to the applicant in that case (a member of the Munupi clan) having an interest of the kind that made him a “relevant person” for the purposes of the reg 11A in respect of an environment plan relating to drilling activities within the same Barossa Project. That observation related to materials that were before NOPSEMA containing information to the effect that some of the area that may be affected by the drilling included a part of the sea in which the applicant in that case asserted a spiritual connection. However, the remarks of the Full Court in that case must be understood in their legal context, and the reasons for judgment are not evidence in this proceeding of the facts recorded in them.

66 As I mentioned in Munkara No 1, the Court has before it affidavits that were filed for the purpose of the judicial review proceedings culminating in the appeal in Tipakalippa, however, it is not yet clear that those deponents will be called to give evidence at the trial of this action. I remain of the view that those affidavits should be afforded little weight because the evidence was given in a different context and does not concern the cultural heritage impacts of the different activities described in the Pipeline EP.

67 A further feature of the evidence relating to intangible cultural heritage values relates to the totemic significance of animal species. There is, for example, some evidence concerning the spiritual significance of the dolphin and turtle. However, beyond identifying those totems and their spiritual significance, it is unclear whether, and if so how, that spiritual belief relates to places a considerable distance from the land. The evidence may relate to the deponents’ responsibilities to care for totem animals, but on the material presently before me I did not consider that evidence could be understood to attach significance to those species in all areas of the sea, no matter how distant from the Tiwi Islands. Moreover, the Pipeline EP accepted on 9 March 2020 contains information concerning the risks to marine fauna from the pipeline activities. It is unclear whether the witnesses who refer to impacts upon their cultural heritage relating to totem species are aware of those provisions and, if so, why it is that they fear an impact on their cultural heritage in connection with them. I stress that these are preliminary observations, but they inform my assessment as to the strength of the applicant’s case in respect of areas of the sea that are further distant from the Tiwi Islands, so far as it can be assessed on the current state of evidence.

Tangible cultural heritage

68 The intangible cultural heritage values referred to in the evidence are closely related to expert archaeological evidence concerning human occupation of the land before its submersion. The intended witnesses speak of concerns to ensure the preservation of tangible cultural heritage, including a desire to ensure that further investigations of archaeological potential take place before the pipeline works are permitted to continue.

69 Submissions on the archaeological and anthropological values of the sea (particularly the sea bed) focused principally on Wessex Archaeology’s July 2023 report, titled “Barossa Gas Export Pipeline, Submerged Palaeolandscapes Archaeological Assessment Technical Report, Ref: 275911” (Wessex Report).

70 For present purposes it is sufficient to make three observations with respect to the Wessex Report.

71 The first is that the authors of the report were retained for purposes relating to the archaeological potential of the sea bed insofar as it pertains to Aboriginal cultural heritage. The whole of the Wessex Report is to be understood in that context. In particular, where it is said that a location has archaeological potential, that potential is to be understood as relating to Aboriginal cultural heritage and not some other archaeological field of interest or enquiry. Again, for present purposes, it is reasonable to infer that Aboriginal cultural heritage in the sea adjacent to the Tiwi Islands is cultural heritage relating to past Aboriginal occupation of land previously forming a part of the Tiwi Islands.

72 The second is that the Wessex Report categorises features as having archaeological potential described either as “P1” or “P2”. P1 denotes a feature of probable archaeological potential, either because of its palaeogeography or because of its likelihood for producing palaeoenvitonmental material. P2 denotes a feature of possible archaeological potential.

73 The third observation is that the occurrence of features categorised as both P1 and P2 become more concentrated the closer the location of the features to the Tiwi Islands. The case with respect to the asserted risk to tangible cultural heritage is considerably stronger in relation to areas in the sea closer to the Tiwi Islands, relative to areas that are more distant. More specifically, the Wessex Report identifies no features falling within categories P1 or P2 at all in the area of the pipeline works between KP0 and KP65. No P1 features exist before KP86. Less than 7% of the features categorised as P1 (totalling four) fall within the area between KP66 and KP120 (about 40km from the nearest land mass). The remainder of them (totalling 54) fall within KP120 and KP262.

74 There are only three P2 features occurring between KP65 and KP86. That is not to diminish the significance of that potential to Mr Munkara. However it does reinforce that cultural heritage is a human centred concern, and to the extent that the present claim is founded on a risk of impact on tangible cultural heritage located in the geographical location of the pipeline, the evidence of the risk of impact to tangible cultural heritage in the northernmost portion of the pipeline is, of itself, insufficient to justify the cessation of works on the whole of the pipeline. The relative strengthening of the case in connection with the sea more proximate to the Tiwi Islands coincides with my observations of the evidence concerning the asserted risks to intangible cultural heritage. All of that is said in the context of the very significant prejudice to Santos that may flow from an absolute restraint, as discussed later in these reasons.

75 As explained in Munkara No 1, an injunction is sought in respect of the whole of the pipeline corridor in circumstances where Mr Munkara is unable to provide an undertaking as to damages. The absence of the undertaking weighs heavily in the Court’s discretion, because the consequence of the injunction is that Santos may suffer significant uncompensated loss should the case be unsuccessful. As discussed later in these reasons, the likely losses are considerably higher if there is an absolute prohibition on any works.

Questions of law

76 Argument on the present application centred on two questions of law. It is neither necessary nor appropriate to provide answers to them. That is because the position of neither party is so compelling as to be determinative of the issues arising on the injunction application. I will briefly explain why that is so.

77 Both parties accept that the word “occurrence” in reg 17(6) refers to the happening of an event. Counsel for Santos acknowledged that the event may be the discovery of a thing not previously known or the appreciation of a risk or increased risk not previously appreciated. For Mr Munkara it is submitted that an “occurrence” occurs when information about a new risk is brought to the attention of the relevant titleholder. He contends that the occurrence in the present case happened (at the latest) when Santos was provided with a report of Dr O’Leary. Either construction is arguable. The question falls among the multitude of serious questions to be tried.

78 The second question of law relates to the identification of the environment plan that is currently “in force” within the meaning of reg 17(6). Santos submitted that on the proper construction of the Regulations, a titleholder may extend or modify an environment plan in circumstances where the occurrences in reg 17(6)(a) or (b) have not arisen. It submitted that such modifications and extensions may be “accepted” by NOPSEMA by processes other than the process established under Div 2.4 relating to revised environment plans.

79 To illustrate the point at a factual level Santos put before the Court an updated version of the Pipeline EP referred to as Revision 3.4. To avoid confusion I will refer to it as the Updated Pipeline EP.

80 The Updated Pipeline EP came into existence after Santos determined through its internal Management of Change Processes, that there had been no occurrence of a new significant environment impact or risk within the meaning of reg 17(6). The Updated Pipeline EP contains an “update” that was required to be made by NOPSEMA in the context of its assessment as to whether Santos has complied with the Direction referred to in Munkara No 1. The reasons in Munkara No 1 make no reference to the Updated Pipeline EP because its existence was not brought to the Court’s attention and nor was its existence made known to Mr Munkara.

81 The question of construction turns on the meaning of the words “environment plan”, “revise” and “in force” as defined reg 4. To “revise” includes to extend or modify.

82 It is arguable that an environment plan may be lawfully modified and extended and then be in “force”, if the modifications are “accepted” by NOPSEMA by some process outside of Div 2.4 of the Regulations. However, it is quite another thing to say that a titleholder can make “modifications” to an environment plan after a relevant “occurrence” under reg 17(6), other than by way of a revision made in accordance with Div 2.4. The evidence in the present case is that the “modifications” were made against a factual assumption that there had been no “occurrence” of the kind to which reg 17(6) refers. That is the heart of the dispute between Mr Munkara and Santos. If Mr Munkara is correct in respect of that occurrence then it is arguable that a titleholder could not adopt any other procedure to modify the environment plan in respect of the relevant impact or risk and so avoid the requirements of Div 2.4 of the Regulations. It would be equally arguable that NOPSEMA could not “accept” a modified environment plan in circumstances other than in the exercise of the power conferred under reg 21.

83 Again, the question of construction is a question for the trial. There are sound counter arguments against Santos’ preferred construction. If Santos were to succeed on the question of construction, it would then be necessary to establish the factual proposition that the Updated Pipeline EP was in fact “accepted” by NOPSEMA in a way contemplated by the Regulations, and that it deals with the particular cultural heritage risks that are the subject matter of this action. None of that can be determined at this preliminary stage.

BALANCE OF CONVENIENCE

84 The balance of convenience must be assessed with careful attention to both time and place.

85 The duration of the restraint sought by Mr Munkara would depend upon the expedition with which the matter may progress to trial and judgment. It is necessary to have regard to the Court’s own judicial and administrative resources. Having conferred with the parties it is reasonable to adopt an assumption that the trial may take place in mid December 2023 and that, in that event, judgment may be delivered by mid January 2024. It is not possible to be more exact or certain than that. The timeframes are approximate and subject to many contingencies.

Prejudice to Mr Munkara

86 In assessing the likely prejudice to Mr Munkara should an injunction not be granted it is necessary to consider not only the nature of the interest he seeks to protect, but also the statutory regime that regulates activities for the construction of the pipeline. I remain satisfied that there is a risk that there may be irreparable harm to the cultural heritage forming the subject matter of the claim should an injunction not be granted. However, it must also be emphasised that the legislative scheme does not, on its terms, prohibit all activities that may have an environmental impact (broadly defined). It remains that if a revised environment plan were required to be prepared and submitted, NOPSEMA may then accept the revisions even if they do not establish processes that entirely eliminate the risk. If Mr Munkara were to establish that the obligation under reg 17(6) exists, then the injunction sought by him may prevent the unlawful destruction of cultural heritage, that is, destruction that is not authorised by the Act or the Regulations. It is the risk of unlawful and irreparable damage to the cultural heritage that is to be weighed in the balance.

87 In light of the evidence referred to earlier in these reasons, I consider that risk to diminish in the northern regions of the pipeline corridor at least in respect of tangible cultural heritage. I have also made observations about the evidentiary case concerning intangible cultural heritage in that more distant region.

Prejudice to Santos

88 The evidence of prejudice to Santos is that contained in an affidavit of Santos’ solicitor. The whole of it is based on information provided to the solicitor by the Barossa Project director Mr Bamford. The circumstance that the evidence is hearsay does not affect its admissibility. However, it is unclear whether the information relayed to the solicitor was sourced from Mr Bamford’s own knowledge. In addition, the findings that may be supported by evidence are in some respects dependent on qualifications that are neither fully explored nor explained. The evidence is not sufficient to establish that delay in the completion of the gas export pipeline would cause the whole of the Barossa Project to be terminated. The evidence as to Santos’ prejudice flowing from the Court’s orders should be more robust and direct, if it is to support such a finding.

89 As briefly explained in Munkara No 1, the pipelaying works are to be undertaken by a contractor (Allseas) principally by a Primary Installation Vessel. The contract between Allseas and Santos is now in evidence. It provides that in the event that the works are suspended for a period of 60 consecutive days, there exists a contractual right in Allseas to terminate the contract. Whether that would in fact occur depends on Allseas’ discretion. There is evidence to suggest that the exercise of that contractual right might depend on whether Santos could be certain about a new start date.

90 The evidence of the solicitor (given on the basis of information provided by Mr Bamford) is expressed in part as follows:

I am informed by Mr Bamford that booking specialist pipelaying vessels requires long lead times because of the scarcity of these vessels that operate around the world. Organising a vessel depends on availability as they are for the most part booked many months or as is more likely, years in advance.

91 That evidence is expressed in general terms in that it deals with what occurs “for the most part”. What is missing is direct evidence as to what in fact would occur.

92 I nonetheless conclude that there is a real risk that a suspension of works for a period of more than 60 days may create a circumstance in which the works cannot commence for a considerably longer period of time. The degree of that risk cannot be reliably assessed on the basis of the evidence before me.

93 The affidavit contains evidence of costs incurred by Santos in connection with previous suspensions and variations of the works. Those prior suspensions were not in response to any order of this Court but appear to be the costs related to Santos’ obligations to comply with Act and the Regulations thus far. For example, they include the costs of complying with the Direction issued by NOPSEMA. On the evidence now before me it appears that NOPSEMA itself did not communicate its satisfaction as to compliance with the Direction until 29 October, 2023 the day before this action was commenced. It seems to me that that is a consequence of Santos conducting its business in an arena of legal uncertainty more generally.

94 I have previously found that NOPSEMA’s view as to compliance with the Direction does not supply the answer to the question as to whether Santos presently has an obligation to submit a revised environment plan.

95 In addition to the contractual risks of prolonged delay that might be occasioned by a cessation of works for more than 60 days, I am satisfied that Santos will occur significant holding costs as a consequence of maintaining a workforce and infrastructure during the suspension so that works may recommence soon after the suspension is lifted. The solicitor asserts (on the basis of information provided by Mr Bamford) that the holding costs will exceed $1million per day. The evidence is lacking in supporting detail and is unable to be tested given the time constraints. However, for the purposes of the order presently under contemplation I will proceed on the basis that the daily holding costs are stated in the affidavit. To my mind, little would turn in the result if the holding costs were half that figure. The holding costs, in any event, are very significant indeed. The holding costs will not be incurred for so long as the Primary Installation Vessel is able to carry out works in accordance the Allseas contract or some variation of it.

96 Santos otherwise asserts prejudice with respect to the uncertainty of its workforce, including staff situated at its DLNG plant in Darwin. However, the uncertainty referred to relates to whether the plant may receive gas from the pipeline from the expected completion date in May 2024. The evidence before me is not sufficient to support a finding that the grant of an injunction for the period presently under contemplation (to mid January) would cause the completion date to extend beyond May 2024.

97 It is otherwise submitted that the grant of an ongoing injunction is harmful to the commercial reputation of Santos. That evidence is lacking in sufficient detail and support for the Court to reliably form a conclusion about it. It is to be considered in a context in which Santos’ activities in the Timor Sea are only permitted by reason of its status as a titleholder and, in accordance with reg 8, its activities are not lawful if it is presently obliged to prepare and submit a revised environment plan. At present there is a real question to be tried as to whether the planned activities are in accordance with that regime. Of itself, that is not harmful to Santos’ reputation if the Court’s processes are properly understood. At the most, the evidence as to reputation may be understood as referring to a sense of frustration in connection with delay and expense affecting profitability of a significant investment. That is a relevant consideration and I take it into account.

98 The evidence is otherwise to the effect that if Santos were restrained from undertaking works south of the point where the works were due to commence (that is at KP86), then there would be costs involved in offloading from the Primary Installation Vessel pipe that is designed to be laid in that region, and loading pipe designed to be laid in regions that may be at a greater depth. Whilst unquantified, it may be inferred that that expense would also be significant, given the scale of the project.

99 A significant proportion of the losses that may be suffered by Santos may be avoided if works were permitted to proceed in the northern portion of the pipeline area some distance from the Tiwi Islands. To be clear, I am satisfied that there is a serious question to be tried with respect to the whole area, especially because it would be sufficient at trial to show that the circumstances referred to in reg 17(6) exist only in respect of intangible cultural heritage. But that consequence is only one aspect of the criteria for the grant of an interlocutory injunction.

100 I have observed that the strength of Mr Munkara’s case diminishes in the northern region of the pipeline, particularly between KP0 to KP86. I have already observed that the Wessex Report records no P1 archaeological features north of that point. There are three P2 features in that area upon which Mr Munkara relies and I have taken them into account. Using the scale provided to the Court in map BD4.04, the area at KP86 appears to be approximately 100kms from the northern most point of the Tiwi Islands and approximately 150kms – 200kms north of Cape Fourcray at the westernmost point of the Tiwi Islands. Beyond that region, the evidence as to intangible cultural heritage does not obviously relate to the Crocodile Man songline and the Ampitji resting place. I assess the sufficiency of the likelihood of that aspect of Mr Munkara’s case against the considerable exacerbation in Santos’ losses should works on the pipeline be suspended altogether.

101 All of that leads me to the conclusion that there should not be a restraint operating in the area north of KP86, notwithstanding that some part of Mr Munkara’s claim relates to at least intangible cultural heritage concerns in that area, and notwithstanding the nature of the interests sought to be protected by the relief and the potential for irreparable harm to them. In summary, that conclusion is based on my observations concerning the generalised evidence of the lay witnesses with respect to their connection to the sea in places beyond the waters surrounding the Tiwi Islands, the circumstance that there has been more time to develop the applicant’s evidentiary case in closer proximity to the expedited trial, the circumstance that suspension of the pipelay works for more than 60 days would, on the evidence now before me, give rise to a contractual right in Allseas to terminate the contract for the works, the circumstance that it is unlikely that judgment could be delivered within 60 days from the original restraint granted on 2 November 2023 and the important circumstance that there is no undertaking as to damages.

102 I have taken into account the risk of irreparable harm asserted on Mr Munkara’s case but consider that risk to be diminished in that area, and otherwise outweighed in the balance of convenience and by discretionary considerations.

103 I am however satisfied that the requirements for an injunction are satisfied, if the restraint were expressed in a way that prohibited works south of KP86. That assessment is based on my conclusion that the claim enjoys a sufficient likelihood of success to justify that particular form of relief. The balance of convenience with respect to an injunction in those terms is significantly different to that which would be made if an injunction were to apply to the whole of the area. The order would not prevent Santos from incurring holding costs (given the expected pace of works) but those losses would be substantially reduced. In addition, Santos would incur significant costs associated with a variation in the program of the works. On the assumption that judgment may be delivered early in 2024, I do not consider that the grant of interlocutory relief would give rise to a real risk that the completion of the project would be delayed beyond May 2024 and I am not satisfied that the grant of relief would give rise to a real risk that the Barossa Project as a whole would be terminated. Whether the project is delayed by any final grant of relief at the conclusion of the trial is of course a different question.

104 In the course of the hearing, Counsel for Santos confirmed that it was prepared to give an undertaking to the Court not to proceed with works beyond KP175 earlier than 12 January 2024. The Court’s orders do not coincide with the undertaking in the terms offered, but rather reflect my assessment of the materials against the criteria for the grant of injunctive relief.

105 For Mr Munkara it was submitted that performing pipelaying works at any place on the pipeline route would be futile in the event that he were to succeed at the trial. To my mind, whether Santos should proceed with works north of a defined point in the face of the present uncertainty is a decision for Santos to make, albeit that it remains subject to the operation of the law, including the prospect of criminal sanction for any breach of reg 8. The Court’s order will not authorise Santos to do any act that would constitute a breach of the law.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and five (105) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Charlesworth. |

Associate:

SCHEDULE A