FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Peck v Australian Automotive Group Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1413

ORDERS

First Applicant CARMEN ELIZABETH PECK Second Applicant | ||

AND: | AUSTRALIAN AUTOMOTIVE GROUP PTY LTD (ACN 088 817 912) First Respondent ATECO AUTOMOTIVE PTY LTD (ACN 000 486 706) Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 17 november 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The amended originating application dated 13 July 2021 be dismissed.

2. Subject to Order 3, the applicants pay the respondents’ costs as agreed or failing agreement as assessed by a Registrar in a lump sum.

3. The parties be granted leave to apply to vary Order 2 by filing and serving submissions (of no more than 3 pages) and any affidavit in support of the variation for which they contend by 4pm, 21 November 2023.

4. In the event that a party exercises the leave granted in accordance with Order 3 by filing and serving written submissions under Order 3 then:

(a) any party opposing the application to vary Order 2 is to file and serve submissions in response (of no more than 3 page) and any affidavit in support by 4pm, 23 November 2023; and

(b) any submissions in reply (of no more than 1 page) are to be filed and served by 4pm, 24 November 2023.

5. Any submissions filed and served under Orders 3 and 4 are to be emailed to the Associate to Cheeseman J at the same time as the submissions are served and the parties are to advise whether they consent to any application to vary Order 2 being heard on the papers.

6. By 4pm, 22 November 2023, the parties to the cross-claims are to submit to the Associate to Cheeseman J proposed consent orders disposing of the cross-claims.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

CHEESEMAN J:

INTRODUCTION

1 Mr and Mrs Peck claim in respect of fire damage to their home that they allege was caused by a fire that ignited in Mrs Peck’s Fiat 500 C two door soft top convertible car when the car was parked in the garage attached to the home as a result of a defect in the Fiat. These reasons relate to the hearing in relation to liability.

2 The fire occurred in the early hours of 24 January 2018. The Pecks and their adult son were at home and were awoken by one of their dogs barking. Upon investigation, Mr Peck discovered a fire in the garage. Mr Peck was an experienced firefighter but he was not able to extinguish the blaze. The Peck family escaped uninjured.

3 The respondents to the claim are Australian Automotive Group Pty Ltd (AAG) and Ateco Automotive Pty Ltd. AAG sold the Fiat to Mrs Peck in August 2010. Ateco imported the Fiat. Under Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL), Ateco is deemed to be the manufacturer of the Fiat.

4 Cross-claims brought by each of the respondents against, relevantly, the Italian company, Fiat Group Automobiles S.p.A (now known as Fiat Chrysler Automobiles FCA Italy S.p.A) have resolved. The respondents were jointly represented at the hearing. The Court was informed that Fiat Group had advised the applicants that it had taken over conduct of the proceedings on behalf of the respondents.

5 The applicants’ claim is for damages pursuant to Part 3-5 Division 1 and Part 5-4 Divisions 1 and 2 of the ACL and for damages for negligence. The applicants allege that the respondents are liable in damages as a result of their breach of the consumer guarantees provided by s 54(2) of the ACL (the Acceptable Quality Guarantee) and s 55(2) (the Fitness for Purpose Guarantee) and also in negligence. It is further alleged against Ateco, as manufacturer of the Fiat, that the vehicle had a safety defect within the meaning of s 9 of the ACL for which Ateco is liable to pay damages pursuant to ss 140 and 141 of the ACL.

6 Shortly after the fire, the Pecks lodged insurance claims in respect of the damage caused as a result of the fire to the house and its contents and to their two cars, one of which was the Fiat. The claim is being pursued by the Pecks’ insurer under its rights of subrogation. The Pecks sold the house that was the site of the fire in March 2019. The insurer acquired the Fiat under its rights of subrogation.

7 The contest between the parties centred on whether there was a defect in the Fiat and if so, whether it caused the fire. By the time of the fire, the Fiat had been owned and operated by Mrs Peck for over seven years without incident. It had been regularly serviced every six to nine months. During the first year she owned the vehicle, Mrs Peck recalls that the Fiat was subject to a product recall in relation to the airbags in the vehicle. Mrs Peck’s Fiat was not the subject of a 2014 Fiat product recall in relation to a wiring issue on the steering column. The opposing parties called witnesses as experts with differing areas of expertise. No party called evidence from an electrician or electrical engineer.

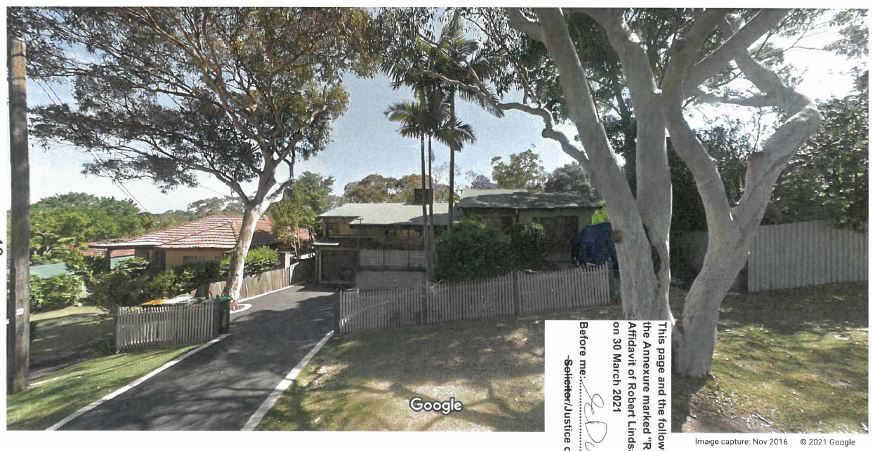

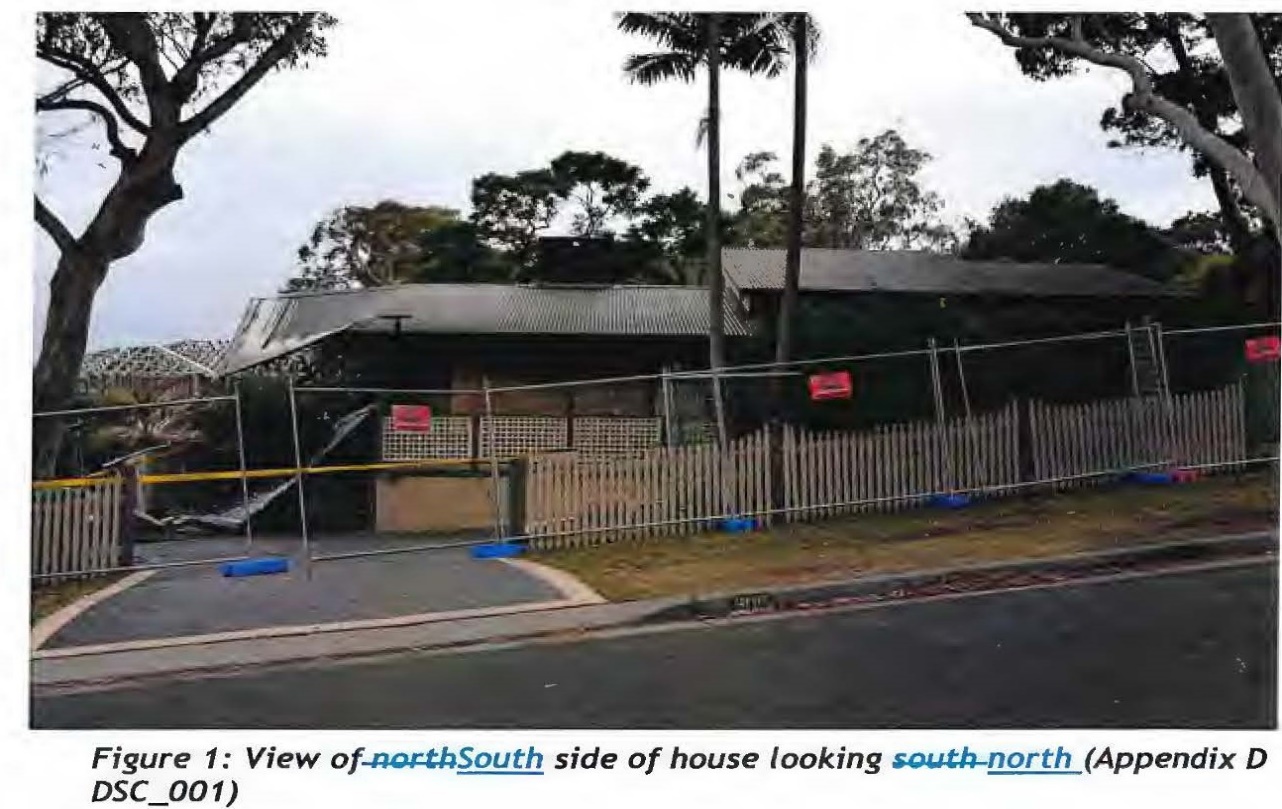

8 The applicants’ experts had access to the scene of the fire and to the Fiat shortly after the fire. The respondents’ expert did not. The key witness relied on by the applicants in relation to their contention that the fire originated in the Fiat due to a defect in the Fiat’s wiring did not inspect the Fiat until after the scene had been made safe, the Fiat had been excavated from the remains of the garage and relocated to the area in front of the house

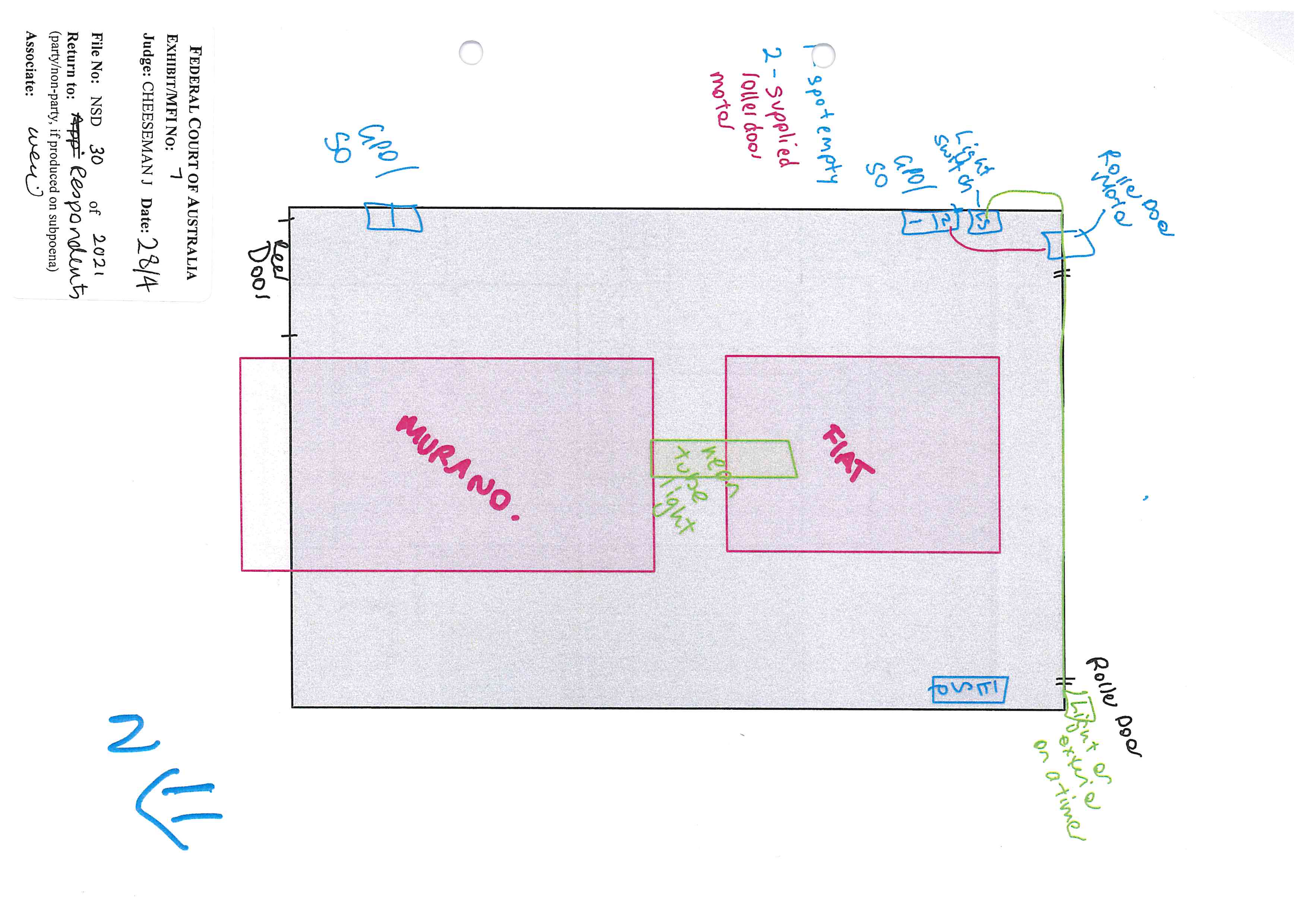

9 It was common ground that during the course of the fire, the mezzanine level which was situated over the garage was severely damaged and collapsed, impacting the garage below and the Fiat housed within. Even allowing for this, the Fiat was not preserved as a, if not the, critical piece of evidence, in the applicants’ case. By the time the respondents’ expert had access to the Fiat it was in a severely degraded and contaminated state. In addition, critical photographs taken by the applicants’ experts in the early period after the fire were out of focus. This is relevant because it is primarily on the basis of, inter alia, these photographs that the applicants’ expert opined that electrical arcing in a particular section of the wiring found near the steering column of the Fiat, evidences a defect which the applicants allege to be the cause of the initial ignition responsible for the fire.

10 Against this evidentiary canvas, the applicants contend that the Court should draw the inference that the fire started as a result of a wiring defect in the Fiat. They contend that the evidence establishes on the balance of probabilities that the Fiat was afflicted by the alleged defect and that the defect caused the fire. They submit that the competing hypotheses advanced by the respondents as to other possible causes of the fire are based on inferences that are not equally available. The applicants urge the Court to conclude that although the evidence may fall short of permitting the Court to be certain, the evidence is sufficient to establish to the requisite civil standard that the Fiat was affected by the defect as alleged and that the fire was caused by that defect.

11 By way of contrast, the respondents contend that the evidence does not establish, on the balance of probabilities, that there was a defect in the Fiat as alleged, and even if such a defect is proven, that the applicants have not discharged their onus in demonstrating that it caused the fire. The respondents submit that the applicants’ reliance on inferential reasoning is flawed in two critical respects. First, the applicants’ posited cause of the fire does not rise above being only one, of a number of possibilities. Importantly, the respondents contend that this is so regardless of whether it is established that the fire originated in the garage, and more particularly, in and or around the Fiat. Secondly, the applicants’ case on causation ignores key evidence as to the sequence of events which is critical, and which undermines the applicants’ reliance on inferential reasoning in relation to causation.

12 For the reasons that follow, and largely as a result of the applicants’ failure to establish on the civil standard that the Fiat was affected by the defect as alleged and that the fire was caused by such a defect, the application must be dismissed.

ISSUES TO BE DETERMINED

13 The parties agreed on the following joint list of issues to be determined:

Section 54 of the ACL – First and Second Respondents

1. Whether the Fiat Vehicle (Fiat) had the defect alleged, namely that the Fiat experienced an electrical and/or other malfunction within the electrical system of the Fiat Vehicle causing the ignition (the Defect).

2. If so, was the Defect present at the time of manufacture or supply?

3. If yes to 1 and 2 above, whether the Defect was such that the Fiat was not of acceptable quality at the time of manufacture or supply within the meaning of s 54(2) of the ACL.

4. If the answers to 1-3 above are yes, whether the Defect in the Fiat was the cause of the fire, involving the following sub-issues:

a. Whether the point of origin of the fire was within the Fiat.

b. Whether the Defect in the Fiat caused the fire including whether the fault identified by Renzo Alessi identified at paragraph 17, page 6 of his report dated 31 May 2018 caused the fire.

c. The possibility of some other cause of the fire.

d. How damage patterns assist in determining the origin of the fire.

e. Whether the Fiat’s wiring assists in determining the origin of the fire.

f. How Mr and Mrs Peck’s evidence assists in determining the cause of the fire.

Section 55 of the ACL – First Respondents

5. Was there a disclosed purpose for which the Fiat was acquired? If so, what was it?

6. Did the First Respondent represent that the Fiat was reasonably fit for any particular purpose? If so, what was that representation?

7. Do the circumstances demonstrate that the Applicants relied upon the skill or judgment of the First or Second Respondent?

8. If the answer to issue 7 is yes, whether it was unreasonable for the Applicants to rely upon the skill or judgment of the First or Second Respondent.

9. If yes to 5 or 6 and 7 and 8 above, whether the Fiat was reasonably fit for that purpose?

10. If the Fiat was not reasonably fit for any disclosed purpose, or for any particular purpose that the First Respondent represented that the Fiat was reasonably fit for, and section 55(3) of the ACL does not apply, whether there was any breach of a guarantee that caused the fire, involving the sub-issues at paragraph 4 above.

Section 9 of the ACL – Second Respondent

11. Whether the Fiat had a safety defect within the meaning of section 9 of the ACL, involving consideration of whether the Fiat had the Defect.

12. If yes to 11 above, was the safety defect present at the time of manufacture?

13. If the answers to 11 and 12 above are yes, whether the Defect in the vehicle was the cause of the fire, involving the sub-issues at paragraph 4 above.

General Law – First Respondent

14. What was the scope of the duty of care owed by the First Respondent to the Applicants?

15. What was the risk of harm for the purpose of 5B of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW) (CLA)?

16. What precautions under section 5B CLA should the First Respondent have taken to address the risk of harm?

17. Whether the First Respondent took those precautions.

18. Whether any failure by the First Respondent to take the precautions was a necessary condition of the occurrence of the harm for the purpose of section 5D CLA.

19. Whether it is appropriate for the liability to extend to the harm so caused pursuant to section 5D(1)(b) CLA.

General Law – Second Respondent

20. The same issues identified in paragraphs 14-19 above

14 As is clear from this distillation of the issues, the focal point, variously framed for each of the causes pursued by the applicants, was whether the Fiat had a defect at the time of manufacture or supply, and if so, whether that defect caused the fire. These two issues were at the heart of the claim. The way in which the case was conducted concentrated on these issues almost exclusively. The submissions on all other issues were cast in general terms and were not developed in any detail. This may have been problematic if the two critical issues were determined in favour of the applicants. However, in the result it did not matter, because the remaining issues only arose if the applicants succeeded in discharging their onus on these two issues, which they did not.

EVIDENCE

15 The applicants’ lay evidence comprised affidavits of Mr Peck and Mrs Peck. Both affidavits were read without objection. Mr and Mrs Peck were not required for cross-examination. Both parties relied on the unchallenged evidence of the Pecks, particularly the evidence of Mr Peck addressed to his observations on the night of the fire.

16 AAG relied on the affidavit of Michael Clements, Director of Operations at Automotive Group Pty Ltd, affirmed 12 July 2021. Mr Clements’ affidavit, inter alia, annexed copies of documents relating to the sale of the Fiat to Mrs Peck. The respondents also relied on the affidavit of Stefano Marchesani, EMEA – Integration Engineer at Fiat Chrysler Automobiles Italy S.p.A, affirmed 31 January 2022. Mr Marchesani’s affidavit, inter alia, annexed technical diagrams and documentation in respect of Mrs Peck’s Fiat vehicle.

17 The expert evidence comprised the following:

For the applicants:

(1) Ms Jones’ expertise is detailed below. In summary, she is a qualified fire investigator. Ms Jones completed an initial report on 18 March 2018, which was not tendered by the applicants. A heavily redacted version was tendered by the respondents following her cross-examination. Only those parts of the report on which Ms Jones was cross-examined were admitted into evidence. Ms Jones prepared a second report on 1 April 2021, which was tendered by the applicants following rulings on objections, including as to limitation on use. The applicants then tendered a corrected version of her 1 April 2021 report during the hearing, which corrected mistakes in the expression of the orientation of the house and garage — the corrected version of the report is dated 28 April 2022. The revised version of the report should have been marked in accordance with the rulings given on objections but was not. In its revised form, the report is subject to the same rulings given in respect of corresponding passages of the earlier iteration of the report. Ms Jones gave oral evidence and was cross-examined during the hearing.

(2) Mr Alessi’s expertise is addressed below. In summary, he is a motor vehicle mechanic and a qualified fire investigator. Mr Alessi completed an initial report on 31 May 2018, which was not tendered by the applicants. A heavily redacted version was tendered by the respondents following Mr Alessi’s cross-examination. Mr Alessi prepared a further report on 1 April 2021, which was tendered by the applicants. Mr Alessi gave concurrent oral evidence with Dr Casey during the hearing. They were each cross-examined.

For the respondents:

(3) Dr Casey is a mechanical engineer and academic. Dr Casey produced two reports, dated 19 July 2021 and 14 January 2022. Both reports were tendered by the respondents.

Joint report following conclave:

(4) A joint expert report between Mr Alessi and Dr Casey finalised on 17 March 2022 was in evidence. The report followed an expert conclave between Mr Alessi and Dr Casey facilitated by a Registrar of the Court. Ms Jones was released from participating in the expert conclave because the three experts agreed that there was insufficient overlap in her area of expertise with that of Mr Alessi and Dr Casey so as to make her participation useful.

18 Objection was taken to parts of the joint expert report on the basis that Mr Alessi introduced information and opinions based on new information that was not addressed in his earlier reports which had been served. I deferred ruling on that objection at the hearing. I am satisfied that that part of the joint report to which objection was taken should be admitted on the basis that it is relevant, and as the evidence unfolded, the respondents were not prejudiced by it. The particular issue had been alluded to in Ms Jones’ report in any event.

FACTUAL FINDINGS — UNCHALLENGED LAY EVIDENCE

19 As mentioned, the evidence of Mr and Mrs Peck was not challenged. Both parties relied on this evidence but contended that different inferences should be drawn from it. The Pecks’ son, who was also at home on the night of the fire did not provide an affidavit and was not called. The affidavits of Mr Clements and Mr Marchesani were read without objection and neither were required for cross-examination. The parties also relied on a short statement of agreed facts.

20 The following represents my findings of fact, based on the evidence of the lay witnesses and the documentary record.

Prior to the Fire

The House and the Cars

21 In January 2018, Mr and Mrs Peck lived in a house at Caringbah South with their adult son and two dogs. They had owned the house since August 1990. The house was a 1970s era fibro house that had its original wiring. The property was North-rear facing with the street frontage being on the South side of the property.

22 Mr Peck owned and primarily drove a Nissan Murano TI Z51 four door wagon.

23 In around August 2010, Mr and Mrs Peck attended a car dealership owned and operated by AAG. Mrs Peck purchased the Fiat, a relatively small two door convertible car with a soft top roof, which was then new. She was the primary driver of the Fiat. The Fiat was regularly serviced. During the first year she owned the vehicle, Mrs Peck recalls that the Fiat was subject to a product recall to which she responded. She believed the recall had something to do with the airbags in the vehicle. Mrs Peck had not experienced any issues when driving the vehicle. She described it as being in “perfect” condition having never being involved in a collision and that she had never experienced any issues whilst driving it. From the date the Fiat was purchased to the date of the fire, Mrs Peck believes the Fiat had not been modified and had not been in any accidents or otherwise damaged.

24 The house was a three-bedroom, split level house with an annexed garage on the Western side. Directly above the garage was a mezzanine living area, which was approximately three by eight metres, in which was housed a pool table, a desk, a chair, some computers and computer accessories and the usual assortment of treasures and artefacts generally stored in a room of that kind (the Pool Room). There were also two pet bearded dragons in the Pool Room, which Mr Peck valued. The ground level of the house comprised a living/dining room, kitchen and laundry. Three bedrooms and a bathroom were located above the living/dining room, accessible by a small staircase. There was a door at the bottom of the stairs which separated the stairs from the living/dining room.

25 A view of the house from the street before and after the fire is included in Annexure A. The “before” photograph was tendered in evidence through Mr Peck and is sourced from Google Maps Street View. The “after” photograph was taken by Ms Jones. The collapsed area on the left of the photograph is where the garage and mezzanine were located.

The garage

26 A rough diagram of the garage, which is not to scale, but which was tendered in evidence at the hearing, is included as Annexure B. The diagram was made by Ms Jones and has markings and annotations made by her in the course of giving evidence. I stress that Ms Jones’ diagram is not to scale and the positional size and distance relationship between the objects depicted is not consistent. At best, this diagram serves only as a rough indication of Ms Jones’ understanding of the general location of the labelled objects within the garage.

27 The evidence does not reveal the dimensions of the garage (the garage was located directly below the mezzanine area in which the Pool Room was located). The size of the mezzanine area above the garage was estimated by Mr Peck to be approximately three by eight metres but it was not clear if the garage was wholly aligned with the perimeter of the mezzanine area. The garage is described by Mr Peck as being a single car width (that is from East to West). The length (that is North to South) had been extended on the Northern side in the form of a concrete pad, an equal distance from the Western wall and the exterior door in the Northeast corner (the Northeastern Door), by an additional floor area of around two metres by two metres. The Eastern wall of the garage was a common wall with the house.

28 The Fiat and Nissan were both ordinarily housed in the garage. The Pecks, when using their cars, accessed the garage via a standard sized, remote-controlled roller door situated in the Southern wall of the garage which could be seen from the street front. The remote-controlled system which controlled the electric roller door was plugged into a powerpoint on the Southern side of the garage. The motor for the garage door was located at height on the Eastern side of the Southern wall of the garage.

29 As mentioned, the garage had been extended so that it could accommodate the two cars parked lengthwise, nose to rear, notwithstanding the enclosed space in the garage was too small to do so without modification. The single car width of garage was such that to fit both cars in, the cars had to be parked with one car directly in front of the other car. The combined length of the two cars when parked nose to rear was such that in order to fit both cars in the garage, a hole had been cut into the Northern wall of the garage, and the floor had been extended as described above. This allowed a car, typically the Nissan, to be parked with its nose protruding beyond the line of the Northern wall. The extra room created by this hole in the Northern wall meant that the second car, typically the Fiat, could be parked behind the Nissan, with sufficient clearance to close the roller door.

30 When parked in the garage together, the vehicles always faced the Northern wall of the garage, and the Fiat was typically parked directly behind the Nissan, with the rear of the Fiat being closest to the roller door, and the front of the Nissan protruding through the hole cut in the Northern Wall.

31 Mrs Peck started work early each day. It was Mr Peck’s practice when he returned home after Mrs Peck, to move the Fiat out of the garage if it was parked in the garage first, then park the Nissan in the garage, and then park the Fiat behind the Nissan in the garage. When in the garage together, the cars were parked with their noses facing to the North of the garage and with the Fiat’s nose facing the rear of the Nissan.

32 Mr Peck explains that he always preferred for the Nissan to be parked at the rear of the garage, that is to the North with the Fiat parked closest to the roller door, at the Southern end of the garage closest to the street, because it would allow Mrs Peck to leave for work in the morning without him needing to get up and move the Nissan out of the way for her.

33 In the Northeastern corner of the Northern wall of garage there was a standard exterior door. This was to the East of the hole made in the Northern wall of the garage to accommodate the length of both cars. This door was accessible by a pathway leading from a sliding door on the Northern side of the living/dining room.

34 On the Western wall of the garage, approximately one metre from the roller door, was an electrical switchboard that controlled the power to the property. This was the only switchboard in the house.

35 On the Eastern wall of the garage there were two power outlets, one close to the Northeastern Door, the other on the Southern side of the garage. The Southern powerpoint on the Eastern wall powered the remote-control roller door. The roller door was plugged into this outlet on the night of the fire. Mr Peck’s evidence was that the other power point was used intermittently for power tools or vacuum cleaners. He believed that nothing was plugged into this second power point on the night of the fire and the outlet was switched off. There was a small crawl space on the Eastern wall of the garage, from which the underneath the house could be accessed.

36 There was a window on the Western side of the garage, centrally located between the Northern and Southern sides of the garage, around 1.5 or 2 metres from each end. From within the garage, through this window one could see a Colorbond fence which separated the Pecks’ property and the neighbouring property.

37 To get to the garage from the house, Mr Peck would normally exit the house through the sliding door at the rear of the house, walk along the pathway leading towards the garage and then enter the garage through the Northeastern Door. Alternatively, Mr Peck would walk out the front door of the house, onto the porch, across the front lawn, and through the roller door.

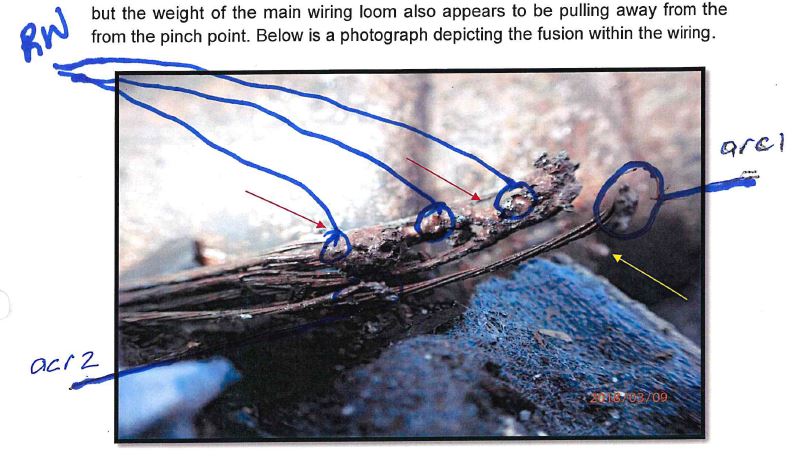

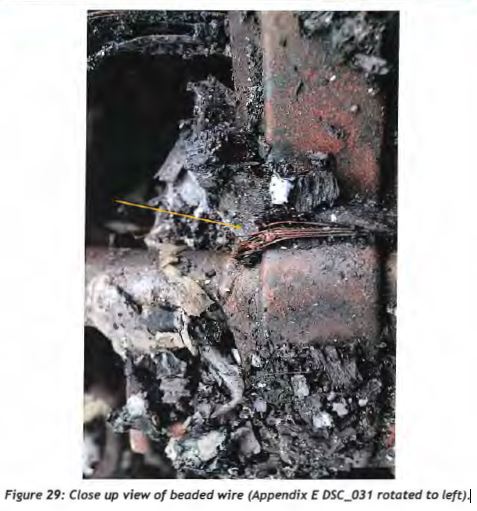

38 When the Fiat and the Nissan were both parked in the garage in the usual configuration, Mr Peck’s evidence was that:

(1) from the open roller door, a person would see the rear of the Fiat, and the rear of the Nissan behind it; and

(2) from the open Northeastern Door, a person would see the front of the Nissan, and the front of the Fiat behind it.

39 The garage was narrow. The gap between the sides of the vehicles and each of the Western and Eastern walls was about approximately 50cm.

40 To the best of Mr Peck’s recollection, the following items were usually kept inside the garage:

(1) On the Eastern wall (which as noted was a common wall between the house and the garage):

(a) two five litre fuel drums, one containing petrol and one containing two stroke fuel;

(b) shelving holding various items such as gym equipment, a small air compressor, car cleaning products and a small battery charger; and

(c) various tools such as two whipper snippers, a hedge trimmer, a bolt cutter, a sledgehammer and a crowbar.

(2) On the Western wall (which was an exterior wall of the garage) there were:

(a) two large ladders, leaning against the wall;

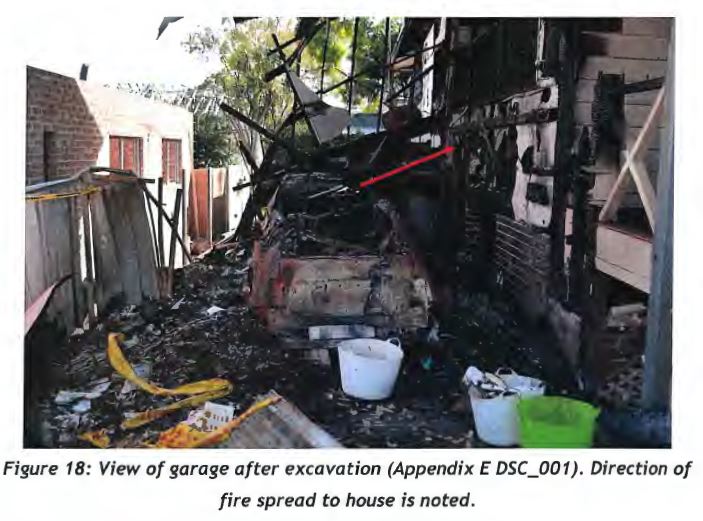

(b) two fishing rods and other fishing equipment such as a basket, nets and reels; and

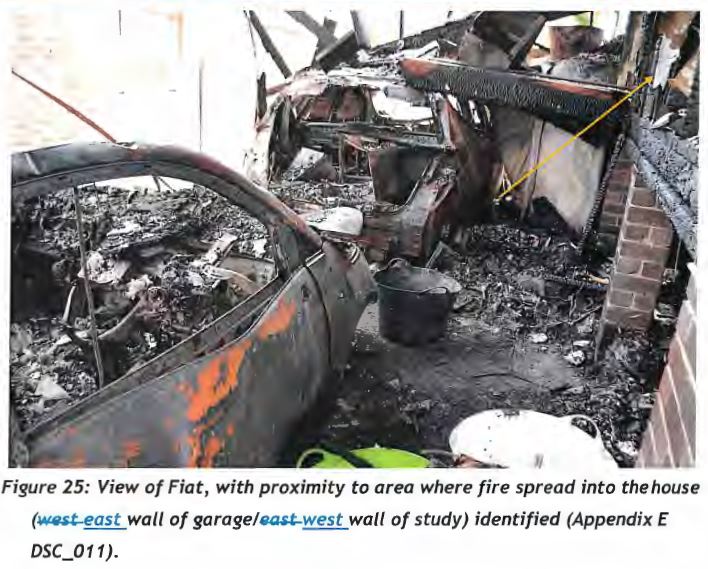

(c) a golf buggy and two golf bags, with several golf clubs and various golfing accessories.

41 Mr Peck did not recall how much fuel was in the fuel drums at the time of the fire.

Mr Peck’s prior experience as a firefighter

42 Mr Peck was a retired firefighter. He worked for 27 years with the NSW Rural Fire Services — from 1980 to 2007. Mr Peck’s work as a firefighter typically included identifying the source of residential and commercial fires and acting as part of a firefighting team to identify and extinguish fires, suppress fires and rescue people caught in fires. In his affidavit, he said that given his:

experience as a firefighter, [he had] knowledge, training and experience in:

(a) identifying fires;

(b) fire suppression including the use of equipment such as extinguishers and fire blankets;

(c) fire prevention;

(d) rescues including from residential and commercial fires, motor vehicles that have been in a collision and other emergencies; and

(e) emergency medical treatment.

43 Mr Peck retired in 2007 at the age of 57 years due to a range of heart and hearing problems. When he retired, he held the rank of Senior Firefighter. By the time of the fire, Mr Peck had been working for about four years as a cleaner.

The night of the fire

44 As mentioned, the fire occurred in the early hours of 24 January 2018. It was summer. It was a very hot evening. Bushfires had been burning in Sydney. The Australian Open Tennis Tournament was underway in Melbourne and was being broadcast in the evenings in other states, including New South Wales. The Peck family were at home.

Configuration of the vehicles on the night of the fire

45 At approximately 10.30 pm on 23 January 2018, Mr Peck returned home from work. He was driving the Nissan. The Fiat was already parked in the garage. Mrs Peck had parked it at around 7pm. Mr Peck moved the Fiat out of the garage and parked the Nissan in the garage. The front of the Nissan was protruding through the hole in the Northern wall of the garage. He then parked the Fiat directly behind the Nissan. The front of the Fiat was directly behind the rear of the Nissan. The rear of the Fiat was facing the roller door. This was the last time the Fiat’s engine was turned on prior to the fire. After Mr Peck parked the vehicles, he made sure that the car windows of both cars were closed to prevent spiders, particularly Huntsman spiders, getting into the vehicles. Mr Peck does not suggest that there was any issue that he observed in relation to the operation of the Fiat at this time. Mrs Peck does not suggest that when she parked the Fiat earlier that night that she noticed any issue with the way in which it was operating. As mentioned, she described the Fiat as being in perfect condition and that she did not have any issues while driving it.

46 I find that the last time the Fiat’s engine was turned on was very shortly after approximately 10.30pm on 23 January 2018 when Mr Peck parked it in the garage behind the Nissan. That was approximately three hours and 45 minutes before the Peck family first became aware of the fire.

Events alerting the Pecks to the fire

47 Mr Peck watched the Australian Open on TV with his son, before retiring to bed. He says he went to bed at about 1.30am on 24 January 2018. The power in the house was operating normally at this point in time. Mrs Peck was already asleep in their shared bed.

48 At around 2.15 am on 24 January 2018, Mr and Mrs Peck were awoken by one of their dogs barking.

49 Mrs Peck woke up first. She could hear popping noises through the open windows in the bedroom. She thought kids were throwing “throw downs”, a small fire cracker that makes popping noises, on the road.

50 Mrs Peck walked out of the bedroom and went to the bathroom down the hall. The light in the bathroom would not turn on. Mrs Peck heard her son say the power was out. Mrs Peck and her son headed downstairs. When the door to the living/dining room, situated at the foot of the stairs between the upper and lower levels of the house, was opened, Mrs Peck could smell smoke. She wondered if it was from recent bushfires in the area. She heard her son say words to the effect that the garage was on fire. Mrs Peck called the fire brigade. Mrs Peck left the house and held the family’s two dogs in the far Southeastern part of the property, at a point which is furthest away from the garage. She was standing behind a boat and did not have a good view of the fire.

51 Mr Peck awoke slightly after Mrs Peck. When he awoke, Mrs Peck was not in bed. He heard his son shouting at the dog and then saying that the power was out. Mr Peck noticed that the house was particularly dark. He thought there was a power outage. Mr Peck looked out the window and saw that other houses in his street had their lights on. He thought there was an issue with a fuse or the switchboard. He saw his wife in the hallway. He could smell smoke and hear “crackling noises”. Mr and Mrs Peck were heading downstairs. Their son was coming up the stairs. He said to them that something was on fire, and it was coming from the garage.

52 Pausing at this point, I find that the occupants of the house noticed that the power in the house was out before they noticed any sign of fire. I find that the evidence establishes that the power in the house was out at the time, or shortly before, smoke was detected in the house and that the power outage was confined to the Pecks’ house — it did not affect neighbouring properties. I further find that shortly before or when smoke was first detected in the house, “popping” or “crackling” noises could be heard from the upstairs bedroom.

53 Mr Peck immediately went to the garage to inspect the fire.

Mr Peck’s observations of the fire

54 Mr Peck entered the garage from the Northeastern Door. He gave the following account of what he saw (as written):

68. Once at the end of the path, I opened the NE Door and looked into the Garage.

69. I saw an orange flame over the rear of the Fiat.

70. The orange glow looked like it was both internal and external to the rear of the Fiat.

71. The glow looked particularly bright just above the rear tyre on the side of the Fiat closest to the eastern wall of the Garage, which was the side of the Garage directly in my eyeline at the NE Door. This was very close to the items stored against the eastern wall.

72. I estimate that the flames in the rear of the Fiat were approximately halfway from the bottom of the Fiat, to the roof of the Fiat and I did not see any flames in any other part of the Garage.

73. On seeing the flames, I grabbed a hose, which was located around 1 metre from the NE door, turned the hose on, and walked down towards the Fiat along the eastern wall. I stopped towards the rear of the Nissan, which was the safest position I could stand without getting too close to the flames.

74. I directed the hose towards the rear of the Fiat because that is where the flames were the most intense.

75. As soon as I started hosing water onto the flame, the Garage became thick with smoke and it became difficult to see.

76. Various items in the Garage started exploding, causing sparks to fly, further impairing my vision which I expect were the fuel cylinders stored along the eastern wall which were partially filled with fuel. I could not identify which items were exploding but I recall that it was a number of the items on the eastern wall, in the shelving unit. This is not unusual in my experience as a fire spreads to other materials.

77. In the time that I had been hosing the Fiat, which was only around 15 or 20 seconds, the flame in the Fiat had grown quickly:

(a) internally towards the roof of the Fiat so that the flames were almost touching the roof; and

(b) externally at the rear of the Fiat, so that I could now see larger flames outside the rear of the Fiat.

78. As a firefighter, I have seen many vehicles on fire and in my experience, once a fire has started in a vehicle it spreads rapidly. I expected that the flames in the Fiat would spread even more rapidly because the Fiat was a convertible, meaning most of the roof was made of fabric. I knew that it wouldn’t be long before the whole Fiat caught fire, and potentially caused the Nissan to ignite, which would be rapidly engulfed in flames too.

79. I had been hosing the Fiat standing at the rear of the Nissan for around 30 seconds when the smoke, the flames and the Garage items exploding around me became too much and I had to move backwards out of the Garage.

55 Mr Peck went back into the house to tell his wife and son to get out of the house. He says they were running around the house grabbing items. He told them to get out of the house now. Mr Peck then returned to the Northeastern door at the rear of the garage where he made the following observations (as written):

86. I estimate that there was only around 90 seconds between me first seeing the orange glow in the rear of the Fiat, running back into the House, and back out to the Garage, but in this short time, the flames had spread significantly.

87. The flames were no longer localised around the Fiat. The Nissan was engulfed in flames too. The flames were almost to the height of the ceiling of the Garage.

88. I picked up the hose and directed it towards the flames, causing more smoke to fill the Garage. I was not able to see exactly where the hose was reaching but given I was standing right outside the NE Door, the water was likely impacting the Nissan the most.

89. By this time, the Fiat and the Nissan’s ignition was the stage of a vehicle fire that I was most familiar with in my experience as a firefighter. They were at the point of ignition where the whole vehicle is ablaze and there is no prospect of saving the vehicle from being completely destroyed by flames.

90. I knew that the Fiat, the Nissan and the Garage would need more than a hose to be extinguished, and that every second I stood near the Garage, I was putting myself in more and more danger of being burnt.

91. I ran back up the stairs from the Garage and into the House.

92. The living/dining room was very smoky and hot. Given the heat I was feeling, I knew from my experience that it would catch completely alight soon.

93. I saw Austen running back up to his bedroom. We exchanged words to the following effect:

Me: What are you getting?

Austen: My laptop.

Me: That’s the last thing. Close the door on your way back through.

94. The door I was referring to was the door at the bottom of the stairs to the bedrooms. By telling Austen to close the door, I was trying to prevent the fire spreading to the bedrooms. Attempting to contain a house fire in a smaller area by closing doors is basic fire training. It was instinctive for me to tell Austen to close the door.

95. At around this time, the fire alarm in the House started going off.

96. I watched Austen run out of the House with his laptop.

56 When Mr Peck went to the mezzanine level, he grabbed his wallet and sunglasses from a cabinet in the corner of the Pool Room which he could access without walking across the section of the mezzanine above the garage. As he did this he observed that there were now flames inside the house in the living/dining room. He says he wanted to grab the two pet bearded dragons from the Pool Room but realised it was too dangerous, because the Pool Room was directly above the garage, and the garage was by then engulfed in flames. Mr Peck ran out the front door to the front lawn, where his wife and son were standing.

57 Mr Peck made further observations of the fire while waiting for the fire brigade to arrive. He took a hose from a neighbour and trained it on the roller door from outside the garage (as written):

102. …I was aiming the hose at a gap at the top of the Rolling Door, but I knew that the hose was not doing much.

103. It had only been a few minutes since I had first seen the glow in the rear of the Fiat, but the whole Garage was on fire, as was much of the Mezzanine and parts of the House. Whilst I could be wrong about the time, it is not unusual in my experience for a fire to spread that quickly.

104. I was hosing the Rolling Door for around 2 minutes when the fire brigade arrived.

105. When the fire brigade arrived, I stood back and let them take over.

58 The fire was extinguished at approximately 4.00 am.

59 In the police report of the fire, Mr Peck is recorded as having “entered the garage from the rear of the property and saw the external wall of the garage and one of the two vehicles parked in the garage alight and there was thick smoke”. In his affidavit, Mr Peck does not refer to what is attributed to him the police report. There is no evidence to suggest that he adopted the account attributed to him either by signing the police officer’s notebook or otherwise. The only relevant reference Mr Peck makes to his interaction with the police on the night of the fire is to the effect that he recalled answering some questions from the police together with Mrs Peck but that the police did not stay for very long. Mr Peck is unable to recall the specifics of the conversation he had with the police. I prefer the account given directly by him in his affidavit, which he has affirmed and on which all the parties relied.

60 The police report refers to Ausgrid attending and disconnecting the power from the home “as it began arcing and sparking while the fire burnt”. There was no other evidence in relation to the Ausgrid attendance at the property.

61 The conclusion in the police report is that the fire “is not suspicious and it is unclear if the fire ignition point was in the vehicle or at the fuse/electrical box on the garage wall”. The site was held as a crime scene until fire investigators and detectives attended later on 24 January 2018.

62 As mentioned, Mr Peck’s observations on the night of the fire were relied upon by both parties. As the homeowner, familiar with the house, the garage, and their contents, and as an experienced fire fighter of 27 years’ experience, Mr Peck was uniquely placed to make detailed observations about what he saw when he went to inspect the fire. That said, Mr Peck’s affidavit was made about three years after the fire and is based on his opportunity to make observations of the fire in the garage over a very short period of time in circumstances where his access was obstructed. His affidavit is detailed and dispassionate. Mr Peck’s evidence comprises evidence of matters of which he has personal knowledge — the layout and contents of his home and garage and matters going to the patterns of his daily living, for example, the routine in relation to shuffling the Nissan and the Fiat in and out of the garage. His evidence on these matters is largely consistent with, and confirmed by, that of Mrs Peck. Mr Peck’s evidence also goes to the particular chronology of events on the night of 23 January 2018 and the early hours of 24 January 2018. Finally, and critically, Mr Peck gives a detailed account of the observations he made of the fire during those brief occasions on which he went into the garage and observed the fire. There is an overlap between the evidence of Mr and Mrs Peck in terms of what they each observed and did after being woken at about 2.15am on 24 January 2018. Their evidence in this respect, while not identical, is broadly consistent. Their affidavits are factual and frank in what they recount. Mr Peck’s evidence of his personal observations of the fire are expressed in simple and direct language. The content and the tone of his affidavit do not suggest that he is embellishing his recount of what he saw. The parties did not submit that to be the case. As mentioned, they all relied on his evidence.

63 I make the following findings in relation to Mr Peck’s observations of the fire from his vantage point in the garage on the occasions on which he entered the garage prior to leaving the house for the final time.

64 Mr Peck’s first vantage point was looking into the garage from the Northeastern Door. He made his initial observation while “at the NE Door”. He had a clear view along the Eastern wall of the garage between the drivers’ side of the Nissan and the Fiat. The noses of each car were pointing North. The Nissan, the larger of the two cars, was parked to the North of the Fiat and was the car to which Mr Peck was closest.

65 His first visual observation of the fire was that there was “an orange flame over the rear of the Fiat”. Mr Peck uses the word “flame” and he situates the flame as being “over” the rear of the Fiat. From that I take that he saw a flame above, and external to, the Fiat. He elaborates by saying that the “orange glow looked like it was both internal and external to the rear of the Fiat”. He further adds that “the glow” was “particularly bright just above the rear tyre” on the driver’s side closest to the Eastern wall of the garage and that this was “very close to the items stored against the eastern wall”. The items stored against the Eastern wall included items that were highly flammable, liable to explode and which Mr Peck subsequently observed exploding.

66 Mr Peck in his choice of language in his affidavit distinguishes between his observation of “flames” and his observation of the “glow” which I take to be the area of illumination given off by a flame. Having regard to the fact that he is an experienced fire fighter and the purposes for which he provided his affidavit I take his choice of language to be both deliberate and precise. I find that Mr Peck could see an illumination or glow both inside and outside the Fiat. Further, that the glow was visible “to the rear of the Fiat”. The glow was brightest above the rear tyre on the driver’s side of the Fiat and was “very close to the items stored against the eastern wall of the garage.” While it is possible that the glow that Mr Peck describes as external to the Fiat emanated from flames within the Fiat which could be seen by the light passing through the windows of the Fiat, it is equally possible that the external glow emanated from flames outside and to the rear of the Fiat. Mr Peck’s description of the area where the glow was particularly bright as being above the rear tyre on the driver’s side is suggestive of there being flames inside and or under the Fiat in this area. The first flame that Mr Peck saw was a flame that was external to, and towards the rear of the Fiat. It was not touching the ceiling of the garage and the power was already out.

67 Mr Peck then moves to provide a description of the “flames” that he saw “in” the rear of the Fiat. It is useful to again extract this passage of Mr Peck’s affidavit out in full:

72. I estimate that the flames in the rear of the Fiat were approximately halfway from the bottom of the Fiat, to the roof of the Fiat and I did not see any flames in any other part of the Garage.

68 Noting the position in which Mr Peck was standing at the Northeastern Door when he made this observation, the description is perhaps a bit ambiguous. It may on the one hand, be understood as an account of seeing flames inside the rear passenger compartment of the Fiat. It may on the other hand be understood to convey that the flames were “in the rear of the Fiat” in the sense that the flames were “to the rear of the Fiat”, noting that Mr Peck recounts seeing a flame over the rear of the Fiat. To understand the description to the rear of the Fiat in that way makes sense of the final phrase of the sentence — “and I did not see any flames in any other part of the garage” — in a way that is consistent with Mr Peck’s earlier observation of “an orange flame over the rear of the Fiat”. Mr Peck was not called and so it was not possible to clarify precisely what Mr Peck meant.

69 Doing the best I can, reading Mr Peck’s observations in context and taking into account that Mr Peck had a limited opportunity to make observations and did not make a formal record of his recollections until some years later, I find that Mr Peck in his first visit to the garage saw flames both outside the Fiat and inside the Fiat. Further, that the presence of the flames was towards the rear of the Fiat, which was positioned against the roller door. I also find that Mr Peck could see a glow generated by the fire that was internal and external to the Fiat and which was brightest above the rear driver’s side wheel. The Southeastern corner of the garage was closely proximate to the area where Mr Peck observed the flames and the brightest glow generated by the fire from his initial vantage point. The Southeastern corner housed a power outlet, with two powerpoints, one of which powered the roller door motor. The roller door motor was located in an elevated spot on the Eastern side of the Southern wall. The flame that Mr Peck first recounted seeing was a flame over the rear of the Fiat. This is likely to have been in close proximity to the roller door motor which was affixed at height on the Eastern side of the Southern wall of the garage. The glow that Mr Peck saw was “very close” to the items stored against the Eastern wall.

70 Based on what Mr Peck could see from his position at the Northeastern Door, I find that he was able to see into the interior of the Fiat through the windows of the vehicle and to describe what he saw inside the Fiat.

71 The observations made by Mr Peck from his first vantage point described at paragraphs 68 to 72 of his affidavit (extracted above) were made quickly.

72 Mr Peck on seeing the flames, briefly exited the garage and quickly grabbed a hose, turned it on and re-entered the garage. He walked along the Eastern wall of the garage and stopped towards the rear of the Nissan. This was his second vantage point. He was considerably closer to the Fiat when he was in this position. He says that this was the safest position where he could stand without getting too close to the flames. He observed that the flames were most intense “towards the rear of the Fiat.” I find that at this point in time the flames were both internal and external to the Fiat and most intense towards the rear of the Fiat.

73 Mr Peck trained the hose on the flames causing the garage to fill with smoke “and it became difficult to see”. He makes no reference to any difficulty in seeing inside the garage or the Fiat prior to hosing the flames. The fire grew very quickly. In the 15 or 20 seconds in which he was hosing the flames he saw the fire grow internally within the Fiat so that the flames were almost touching the roof of the Fiat and externally at the rear of the Fiat he could see “larger flames outside the rear of the Fiat”. From this evidence, together with his observations from his first vantage point, I infer that Mr Peck had earlier seen smaller flames outside the rear of the Fiat. I infer that Mr Peck did not at this point see flames touching the ceiling of the garage. Had he done so he would have said so, given his subsequent reference to the flames being almost to the ceiling.

74 On his last visit to the garage via the Northeastern Door, he observed that the flames had spread significantly and were no longer localised around the Fiat. The Nissan was by then also engulfed in flames and the flames were almost to the height of the ceiling of the garage.

75 At about 8.30am, 24 January 2018, detectives and fire investigators from the Fire and Rescue Investigation Unit (FRIU) attended and examined the scene. The police report includes the following account of the conclusions drawn by the FRIU (as written):

About 12.45pm FRIU David O’Brien spoke to the Police and confirmed the fire as accidental. The cause has been determined a electrical fault in the wiring that caused the compromise and distribution for the mains power to the house. 2 of the ceramic fuses had blown out backwards (inside out) which indicates electrical fault also. One of the two vehicles parked in the garage was a “soft-top” which accelerates the fire as the make up of the vehicle fuels the fire without containment.

76 Mrs Peck lodged an insurance claim with the home and contents insurer on the morning after the fire. Sometime thereafter she lodged claims with the vehicle insurer of the Fiat and the Nissan.

Damage as a result of the fire

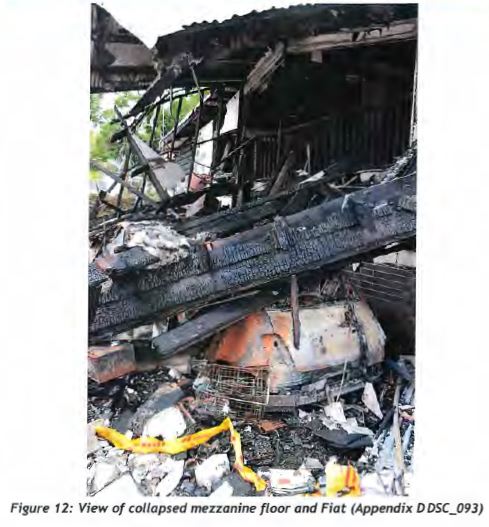

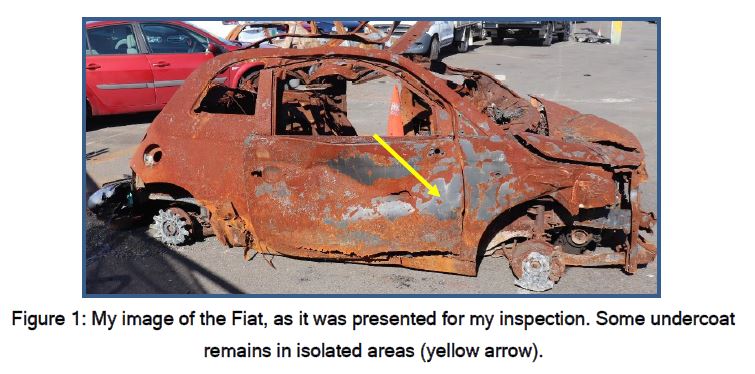

77 The fire caused substantial damage to house, especially to the garage and the mezzanine, and destroyed both cars. The mezzanine level above the garage collapsed into the garage and onto the two cars. Reproduced in Annexure C are a series of photographs taken by Ms Jones that depict the damage to the garage and mezzanine end of the house. The photographs taken by Ms Jones shows the collapsed mezzanine floor and Fiat before and after excavation of the debris occasioned by the fire and structural collapse.

Fiat documentation – service and product recall history

78 The logbook and service records for the Fiat were kept inside the glove compartment of the Fiat. They were destroyed in the fire.

79 As mentioned above, during the first year she owned the vehicle, Mrs Peck remembers responding to a product recall which she believed was to do with the airbags in the vehicle.

80 The wiring diagrams for the relevant Fiat model were produced by Fiat Group on discovery. Fiat’s records show that the Fiat had the chassis number 00523884 and instrument panel (IP) wiring harness identifier as 51853360. The IP wiring harness is the wiring behind the dashboard, instruments and steering column in the Fiat.

81 On 30 June 2014, Fiat issued a product recall, “CAMPAIGN 5839 – Recall Campaign Fiat 500 model, right-hand drive version – wiring under the dashboard”. The recall notice was in the following terms:

On 113,253 Fiat 500 vehicles with right-hand drive, whose chassis numbers range in the interval from 757836 to 997473 and from J000001 to J201532, due to a potential interference of the wiring under the dashboard with the steering column, the wiring might wear out in time.

Therefore, it is compulsory to make a pre-delivery intervention on vehicles still in stock. For vehicles which have already been delivered, customers must be contacted by registered letter (Annex 1) and the operating cycle described in the attachment (Annex 2) must be implemented to upgrade all vehicles.

82 The fault identified in the recall notice was in relation to wiring located “under the dashboard with the steering column”. This was in a “[d]ifferent area” to the area on the dash where the applicants’ expert, Mr Alessi, alleged the fault in Mrs Peck’s Fiat was situated.

83 The chassis number of the Fiat was not included in the list of vehicles that were subject to this recall.

84 The chassis number of the Fiat was not identified as being subject to any other relevant recall.

85 As mentioned, Mrs Peck’s evidence was that apart from airbag recall in the first year in which she owned the Fiat, there was no product recall of which she was aware in relation to her Fiat.

EXPERT EVIDENCE

86 Before moving to the detail of the experts’ opinions, it is useful to briefly address two topics. First, the debate between the experts in relation to what constitutes arc damage and whether the cause of arc damage can be determined by physical inspection. Secondly, the chronology of inspections undertaken by and photographs taken by the expert witnesses retained by the parties.

Detection of arc damage

87 The process of arcing in electrical wires assumes some significance in this matter because the applicants seek to establish by inferential reasoning that the fire was caused by the ignition of car wires in the Fiat that then spread to the garage, and from the garage to the house. The underlying premise of the applicants’ case being that the alleged arcing occurred as a result of a defect in the Fiat that was present at the time it was manufactured and or supplied. Notwithstanding that arcing in the Fiat’s wiring is the crux of the applicants’ case, the applicants did not call an expert electrician or electrical engineer. Given no expert evidence of this type was led against them, the respondents similarly did not call an electrician or electrical engineer. The evidence given on the topic of arc damage was given by Ms Jones, certified fire investigator, Mr Alessi, an automotive mechanic and certified fire investigator and Dr Casey, a mechanical engineer and academic.

88 The experts agreed that there was a distinction between a wire short circuiting as opposed to a wire arcing. The experts agreed that electrical wires that touch each other may short circuit but that a short circuit will not generate a spark. The experts also agreed that energised (“live”) electrical wires may arc and that arcing will generate a spark. Arcing will only occur where a wire is energised. The focus on arcing was because the experts agreed that arcing in electrical wires may ignite a fire whereas a short circuit would not.

89 The experts agreed that when arcing, the wire itself may fuse, and molten metal from the wire may be shed and form small beads — arc beads. These beads typically copper which has a lower melting temperature. The experts agreed that arc beads tend to form at the end of the wire that has shed the molten material. The molten metal shed from the wire may then cause “arc damage”, either directly or indirectly upon contact with surrounding materials.

90 The experts used the terms “cause arc beads” and “victim arc beads” to distinguish between arc beads which form before a fire occurs and which may be implicated as the cause of a fire (“cause arc beads”) and arc beads which form during a fire as a result of the fire damaging the insulation surrounding the energised wires and causing them to arc (“victim arc beads”).

91 The experts disagreed as to whether on examination it was possible to distinguish between cause arc beads and victim arc beads. By way of presage, Mr Alessi opined that it was possible to, and he could, identify by visual examination whether an arc bead is a cause arc bead or a victim arc bead. Dr Casey said that the differentiation between the two types of arc bead is simply temporal — when in time the arcing occurs relative to the fire and that there is no way to reliably differentiate between a cause arc bead and victim arc bead by inspection or examination. Ms Jones’ evidence was consistent with Dr Casey’s. The experts’ views on this issue are addressed in greater detail below.

Chronology of expert inspections and photographs

92 The experts’ observations are based on their respective inspections of the Fiat and their review of the collections of photographs taken of the Fiat. The chronology of the inspections and the time at which the photographs were taken forms part of the agreed facts, the relevant paragraphs of which are extracted below. It will be recalled that the fire occurred on 24 January 2018.

8. Ms Jones inspected the property on 31 January 2018 and 1 March 2018: CB 1484. Ms Jones conducted a limited inspection of the garage during her first inspection on 31 January 2018 due to safety concerns as the mezzanine level had severe fire damage and had collapsed directly down onto the garage, with the roof above also having partially collapsed down: Jones2 [2.1], [2.7] CB 1547-1548, 1551. The photos taken by Ms Jones during her first inspection on 31 January 2018 are at CB 190. When Ms Jones conducted her second inspection on 1 March 2018, builders were present and completed a staged excavation where the garage, mezzanine and roof structure was removed from on top of the garage and off the vehicles: Jones2 [2.12]-[2.13] CB 1564-1565. The photos taken by Ms Jones during her second inspection on 1 March 2018 are at CB 299.

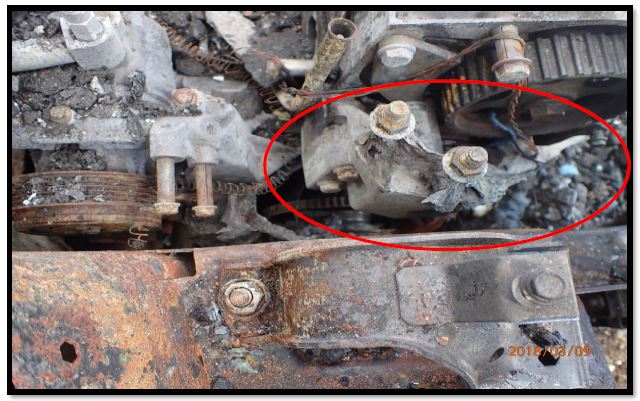

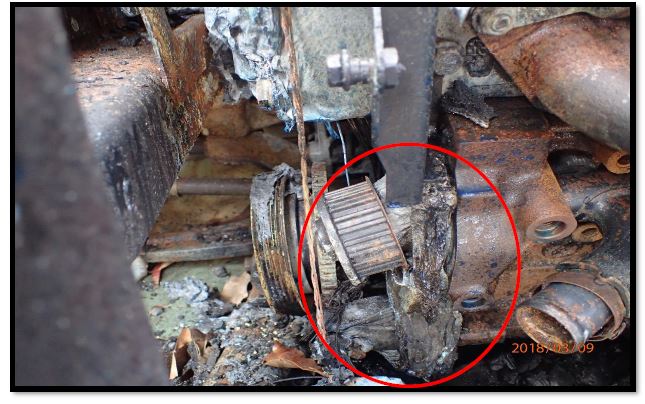

9. Mr Alessi inspected the Fiat at the property on 9 March 2018: CB 1505. Prior to Mr Alessi’s first inspection on 9 March 2018, the Fiat had been moved from the garage and was parked on the eastern side of the property covered with a tarp: Alessi2 [11], [16] CB 1522-1523. The photos Mr Alessi took on 9 March 2018 are at CB 388. Ms Jones was an observer during Mr Alessi’s inspection on 9 March 2018. The photos taken by Ms Jones on 9 March 2018 are at CB 381.

…

11. Mr Alessi conducted a second inspection of the Fiat on 15 March 2021: CB 1531. Dr Casey conducted an inspection of the Fiat on 16 June 2021: CB 1622. Prior to Mr Alessi’s second inspection on 15 March 2021 and Dr Casey’s first inspection on 16 June 2021, the Fiat had been removed from the property and was stored in an open air holding yard: Casey1 [27] CB 1603. At the time of Dr Casey’s inspection, he found a number of items in the rear of the Fiat that did not belong to the Fiat: Casey1 [28] CB 1603.

Ms Jones – certified fire investigator

93 Ms Jones holds an international qualification as a “Certified Fire Investigator’ conferred by the International Association of Arson Investigations. She says that there is no equivalent Australian certification at present and that she is one of only seven fire investigators in Australia who hold this qualification. Ms Jones also has a graduate diploma of Fire Investigation from Charles Sturt University and has a Bachelor of Science in Applied Chemistry with a Honours in Forensic Science on the topic of the development and validation of the canine accelerant detection program. Since 2007, Ms Jones has worked in various roles as a fire investigator and since 2018 as an adjunct lecturer in courses related to fire investigations and on the structure and effects of fire.

94 Ms Jones attended the scene on 30 or 31 January 2018, the references in her reports are inconsistent as the date of her first inspection, and 1 March 2018, on instructions from the insurer to investigate the origin and cause of the fire. She took photographs at each inspection. Nothing turns on whether her first inspection was on 30 or 31 January 2018, for consistency I will refer to the date of her first inspection as being on 31 January 2018, but it could have been the day before. At the time of her first attendance the scene was unsafe and Ms Jones was not able to inspect the area inside the garage. During her initial visit, she did not identify the Fiat as the likely point of origin in her view. At that time, she said that it was “not certain as a potential area or point of origin in the garage until the make safe was done. I examined the house and determined that the general area of origin was the garage.”

95 Her second attendance was on 1 March 2018. She was present during the make safe works. Ms Jones said that she “controlled the make safe to a point”. She was not asked to, and did not, do an “excavation-type forensic examination of all of the contents of the Fiat”.

96 On the basis of her cumulative observations on her first two attendances at the scene, Ms Jones opined that the “Probable ignition mechanism(s)” for the fire was “An electrical fault in the wiring around the steering column created a smouldering or slow burning fire in the dashboard of the Fiat 500C. This has then spread to the passenger compartment and, from this point, to the garage and house”. Mr Alessi was then instructed on behalf of the insurer to examine the Fiat for a potential fault. Ms Jones attended the property again with Mr Alessi on 9 March 2018 during which she took some further photographs.

97 In respect of her attendance on 9 March 2018, Ms Jones says:

The reason is because I was there to basically identify the vehicle for Mr Alessi, which was removed outside of the actual garage and covered in a tarpaulin and, basically, I left it to him. At that point it was outside my area. I was just there to be an observer and that’s why there are only seven photos and it was mainly just to show that the vehicle had been removed and covered in a tarp and that was the circumstances and context with which Mr Alessi saw the vehicle.

When asked whether her attendance on 9 March 2018 added to her observations about the Fiat and the house, she answered “No. That was outside my expertise.”

98 Ms Jones’ second report was first published on 1 April 2021. The stated purpose of the second report was that it had been amended “due to receipt of additional information requested in instructions received 10 March 2021 and NSW Police Report, received 23 March 2021”. Ms Jones’ second report was re-issued on 28 April 2022. It was re-issued to correct the orientation references throughout the report which misstated the directional orientation of the scene by inverting the points of the compass in the references that she gave. For example, Ms Jones identified the rear wall of the garage as being the Southern wall when in fact it was the Northern wall.

99 During her second examination and inspection of the Fiat on 1 March 2018, Ms Jones identified what she describes as three areas of beaded/arced wiring in the passenger compartment of the Fiat. She says that these were located on the passenger side (near side) of the dashboard, the driver’s side (off side) of the dashboard and around the steering column. In her second report, as revised, she included photographs of the beaded wire she identified in the area of the steering column. These photographs are included as Annexure D. She did not include photographs of the other areas of beading in the photographs embedded in her second report (revised).

100 Ms Jones opined that beading and arcing can result from either a fault whereby two energised wires contact each other, or where a fire in an area consumes the sheathing of the wires and energised wires touch and arc. She regarded the beaded wires as potential ignition sources. This was the impetus for her arranging for Mr Alessi to be retained.

101 In cross-examination, Ms Jones suggested that she had moved or may have moved the arced/beaded wires near the steering column in the course of inspecting them. Her evidence on this point was unclear. She did not appear to have a recollection on which she could draw and was attempting to speculate based on looking at the photographs she had taken. I find that it is possible that the relevant wires were moved by Ms Jones during the course of her examination on 1 March 2018. It is not necessary to resolve that issue because having regard to the scale of the excavation required to remove the debris generated by the collapse of the mezzanine from the Fiat, I find that it is likely that the wires as photographed by Ms Jones were disturbed from their original position by the impact of the fire, the collapse of mezzanine, the process of the make safe works and or the excavation of the Fiat. In addition, it is at the least possible that by the time of Mr Alessi’s inspection on 8 March 2018, the wires had been moved by Ms Jones in the course of examining and photographing them.

102 In her second report, Ms Jones summarised her views as follows:

Area of origin of fire: attached garage with mezzanine over the garage.

Point of origin of fire: the interior of the Fiat, the passenger compartment.

Most likely fuel source first ignited: wiring and electrical components in the dashboard area.

Potential ignition source(s) excluded: Murano, socket outlet, roller door motor, electrical service panel, cigarette ignition, deliberate ignition.

Potential ignition sources not excluded: NIL in garage.

Most likely ignition source: unspecified electrical fault.

Probable cause of fire: an unspecified fault.

Probable sequence of events and timings: that an unspecified electrical fault in the dashboard area has caused the surrounding wiring, plastic components and dashboard to ignite, causing a fire in the interior of the Fiat. The fire has then spread out of the vehicle to affect the garage and house.

Criminal activity indicators: none.

Any other relevant features: NIL.

103 Remarkably, the additional information supplied to Ms Jones for the purpose of her providing her second report on behalf of the applicants, did not include a copy of Mr and Mrs Pecks’ affidavits. This resulted in the unusual situation where the expert called on behalf of the applicants was not given the applicants’ lay evidence, or even a set of assumptions modelled on it, on which to inform their expert opinion.

104 No satisfactory explanation was given as to why the applicants did not attempt to integrate the lay evidence on which they relied with the expert evidence on which they relied, whether by way of providing accurate assumptions or by briefing the experts with copies of the Pecks’ affidavits. Counsel appearing for the applicants suggested that this was not possible because of the timetabling orders made by the previous docket judge. That suggestion is rejected. Given the elapse of time between the proceeding being commenced and the deadline for the filing and service of evidence there was more than ample opportunity to stage the preparation and finalisation of lay evidence prior to briefing expert witnesses. Instead of being instructed on the basis of the Pecks’ evidence, Ms Jones recites instructions she was given, by way of additional information, about what Mr Peck observed, as follows:

Additional information:

I have been instructed as follows:

1.5 Mr Peck had been up with his son in the early hours of the morning of the fire. He had parked the Murano in the garage, then moved the Fiat in behind it around 11pm. He watched tennis till around 1:30am with his son before going to bed. His son also went to his bedroom but was watching television.

1.6 Around 2.15am the dog barked waking his wife. His son called that the power had gone off. Mr Peck looked through his blinds to see his neighbour’s lights were on. He went to open the door closing off the bedrooms from the living area and smelt smoke. He also heard popping noises. He then went down to the garage from the back of the house and opened a door in the south-east north-west corner of the garage, adjacent to the front of the driver’s side/front of the Murano vehicle.

1.7 Mr Peck saw that the Fiat was on fire at the rear of the passenger compartment, not in the engine. He got a hose but was unsuccessful in fighting the fire, so he returned to the house and got his family out of the house. He attempted to use the hose again unsuccessfully and went back through the house to await the fire brigade. They arrived a few minutes later.

105 The letter of instruction which Ms Jones attached to her report does not include this additional information and it is not clear how it came to be supplied to Ms Jones. In cross-examination, Ms Jones said that she had conversations with Mr and Mrs Peck that she “recorded in my first report – like, notes, but not an official affidavit or transcript.” As already noted, Ms Jones’ first report was not tendered. The redacted version tendered by the respondents does not include an account of any conversations between Ms Jones and Mr or Mrs Peck.

106 As will be immediately apparent the instructions that Ms Jones refers to having received significantly conflate the details given in Mr Peck’s affidavit.

107 In her evidence-in-chief, Ms Jones was asked to read paragraphs 69 to 74 of Mr Peck’s affidavit, extracted at paragraph 54 above. She then said:

Okay. So in terms of the fire that was observed by Mr Peck, I would say it was small but growing. It was a room fire. It was – Mr Peck did not observe any issues with, like, glowing on the ceiling or any of the wiring or appliances in the room. So the glow that he saw was isolated or discrete around the actual Fiat and that the Fiat would provide, at that stage, enough heat generation just from the heat release rate of the tyres, which he notes was actually – as one of the items that he saw specifically on fire or around that area. So the heat given off would just, in terms of fire dynamics, create a room fire which would create a heat layer at the ceiling and could affect the wiring. I won’t say how but it could affect the wiring to cause – I won’t go any further. But it could affect the wiring just on based on room and fire growth and dynamics. In terms of the molten metal thrown off, I can comment in terms of ignition fuel load in the vehicle, because fuel load of vehicles, as well as household equipment, and so forth, is in my area. And as a fire investigator, I am required to actually understand the interaction of an ignition source with any fuel load and the form that takes. So I can comment on that. But I would then possibly – there are different timings around, and I don’t know if you want me to go that far. So in terms of what was observed by me being there, I identified through my fire investigation experience the area of origin being the garage. The point of origin I identified through burn patterns and so forth as the actual Fiat. And within the Fiat, I identified a specific piece of wiring which was outside my expertise to identify this specific cause. In terms of the garage itself as part of what I do, the methodology and process is that I have to have a working knowledge of all the wiring in the house and all of the appliances to then look at what was in the garage and either include or exclude them. Now, if I had thought the electrical service panel was at fault, like I identified something going on in the Fiat, that’s when I would step outside my expertise and get an electrical engineer in. It’s not practical to get an electrical engineer or an electrician to look at every fire. They just don’t have the expertise to, sort of, look at it in context. So my job is to look at all of this in context as part of the structure and have an understanding of how the wiring in house works. How short circuits work. I do understand that you don’t want me to comment about that in this case. But that is within my expertise. So I examine – well, I didn’t examine the wiring in the ceiling, but understanding how it works, I know how a fault would occur. I’m not going to comment on that. I understand the timings around such a molten metal causing a fire in the Fiat. And I can talk to that, but I won’t. And I do understand how and why, which I have alluded to, but I didn’t detail in specifics why I eliminated the wiring around the power point and the actual motor and the actual electrical service panel. … So in my conclusions, I eliminated them, but … I didn’t specifically state why.

108 Ms Jones did not resile from the view she had formed in her report as to the likely ignition source of the fire being inside the Fiat. She suspected that the point of ignition was a wire near the dashboard of the Fiat but recognised it was outside her expertise to test this hypothesis.

109 In reaching her conclusion that the ignition source was most likely in the wiring around the dashboard of the Fiat, Ms Jones relied on the fact that she had identified what she believed to be a potential ignition source in three areas of beaded wires she identified in the Fiat. Once Ms Jones had identified these wires, she did not proceed to undertake a comprehensive review of the contents of the Fiat to ascertain whether there were any other artefacts present that may have indicated other potential sources of ignition. Given the way in which the make safe and excavation of debris from the Fiat was managed, it may have been difficult to ascertain in any event how and when such artefacts, if present, came to be in the Fiat. Ms Jones also relied on her analysis of the directional spread of the fire and her satisfaction that she had excluded the electrical service panel (ESP) and the roller door motor as the other potential origins of the ignition.

Directional spread of fire

110 The pattern, location and extent of the damage to the house, led Ms Jones to the conclusion that the fire spread from the garage in an Easterly direction through the house. The fire damage to the garage was most severe. Burn patterns to the mezzanine structure indicated in Ms Jones’ view that the fire had burned up into the house from below to affect the floor. Further, that the fire had also moved into the study via the common wall between the garage and the study and the floor of the mezzanine junction point.

111 Within the garage, Ms Jones considered that the pattern, location and extent of the damage to the Nissan and the Fiat indicated the initial ignition was in wires in the area of the steering column and the dashboard of the Fiat.

112 As already mentioned, Ms Jones’ inspection of the garage with the cars in situ was limited on the first occasion on which she attended the scene due to safety concerns. On her second inspection, she took photographs of the garage, with the cars in situ, as well as of the house.

113 In her second report, as revised, she included a photograph, taken on her first inspection before the garage was excavated, which she has annotated to illustrate her conclusions about the direction of the fire spread emanating from the front of the Fiat to the rear of the Nissan. This photo is reproduced in Annexure E.

114 Ms Jones also included a further two photographs taken on 1 March 2018, after the garage had been excavated, but when the Fiat was still in situ, which she annotated to illustrate her conclusion as to the direction of fire spread to the house (reproduced in Annexure F). In cross-examination, Ms Jones agreed that this was not an investigation where she was asked to, or did, conduct a thorough excavation-type audit of everything that she could locate within the Fiat itself. Mr Alessi also eventually agreed in cross-examination that he did not, and was not asked to, conduct a forensic dig or excavation of the material situated in the Fiat or to keep a list or log of photographs of its contents.

115 Ms Jones opined that:

The Murano was examined and showed directional fire damage to the rear of the vehicle, around the boot area, with less fire damage to the house structure of the mezzanine on the right/ offside of the vehicle. Indicating that the fire had not spread/burnt as much on the side of the vehicle towards the house.

I understand Ms Jones to refer to the driver’s side of the vehicle when she says the “right / offside” of the vehicle.

116 Mr Peck’s affidavit, to which Ms Jones did not have access, confirms that various flammable and explosive materials were stored on the Eastern wall of the garage which was a common wall with the house. Based on Mr Peck’s account of those materials exploding I find that those materials were against the Eastern wall proximate to the Fiat. Ms Jones does not address this fact and whether it bears on her conclusions of fire spread direction informed by her observations as to burn patterns, although she makes a reference to there being “petrol cans and some WD40 stored on the eastern wall”.

117 One basis on which Ms Jones’ concluded that the initial point of ignition of the fire was in the vicinity of the dashboard of the Fiat was her observation of the directional spread of the fire. She summarises her views as follows (as written):

The first fuel ignited was in my opinion, components in the dashboard, around the steering column such as foam, wiring insulation etc. The basis of this conclusion was the fire damage in the passenger compartment of the vehicle and the directional fire damage from the Fiat upwards to affect the mezzanine floor above the vehicle. Also the fire damage to structure of the mezzanine and house adjacent to the front driver’s side area of the Fiat. The fire spread from the passenger compartment of the Fiat upwards and outwards.

Exclusion of the ESP as cause of ignition

118 The next strand of Ms Jones’ reasoning was directed to excluding the ESP as a potential source of ignition.