Federal Court of Australia

McD Asia Pacific LLC v Hungry Jack’s Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1412

ORDERS

First Applicant MCDONALD'S AUSTRALIA LIMITED Second Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | Cross-Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and supply to the chambers of Justice Burley by 4pm on 7 December 2023 draft short minutes of order giving effect to these reasons and a proposed timetable for the resolution of any further matters for determination, including costs.

2. Insofar as the parties are unable to agree to the terms of the draft short minutes of order referred to in Order 1, the areas of disagreement be set out in mark-up.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[1] | |

[8] | |

[11] | |

[13] | |

[13] | |

[19] | |

[23] | |

[23] | |

[31] | |

[60] | |

[71] | |

[83] | |

[93] | |

[93] | |

[95] | |

[109] | |

[118] | |

[128] | |

[128] | |

[134] | |

[139] | |

[149] | |

4.5 Conclusion in relation to the challenge to the BIG JACK registration | [151] |

[152] | |

[152] | |

[158] | |

[173] | |

[182] | |

[182] | |

[189] | |

[189] | |

[192] | |

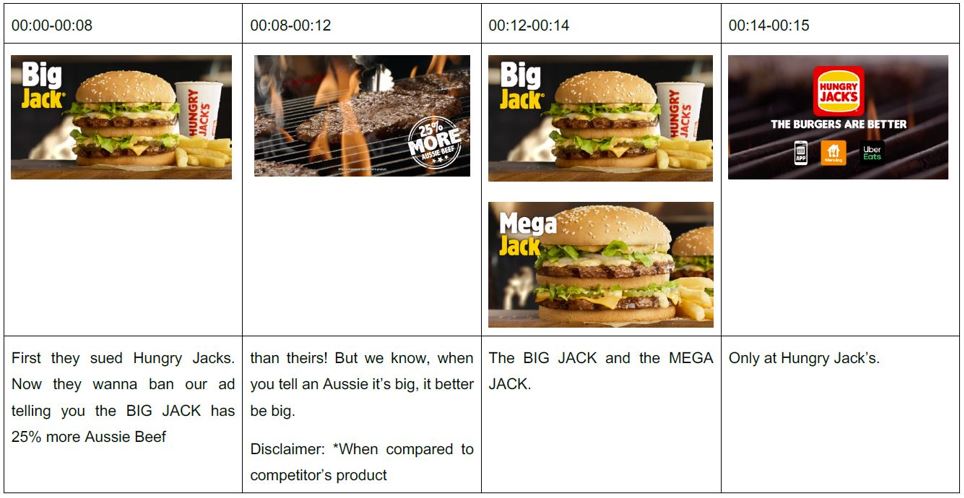

6.2.3 Consideration of the 25% more Aussie beef representation | [198] |

[208] | |

[218] |

BURLEY J:

1 This is a dispute about trade marks, misleading or deceptive conduct and hamburgers.

2 The applicants are McD Asia Pacific LLC and McDonald’s Australia Limited (collectively, McDonald’s). They are respectively the licensor and authorised user of the branding associated with the McDonald’s chain of quick service restaurants which first opened in Australia in 1971 and by 2020 had over 890 outlets operating in Australia. As at 2020, McDonald’s and its various affiliated franchisees and licensees operated over 35,000 McDonald’s restaurants in over 100 countries and territories around the world. The BIG MAC hamburger was first sold in the United States of America in 1968 and has been sold in Australia since operations commenced here. McD Asia is the registered owner of trade marks for the words BIG MAC and MEGA MAC.

3 The respondent is Hungry Jack’s Pty Ltd. It is a franchisee of Burger King Corporation, a United States entity, and trades under the name HUNGRY JACK’S and associated branding. It is a competitor of McDonald’s in the quick service restaurant business, in Australia and worldwide, and has also operated in Australia since 1971. In early 2020, Hungry Jack’s began to sell hamburgers by reference to the names BIG JACK and MEGA JACK.

4 McDonald’s contends that:

(a) Hungry Jack’s has infringed its BIG MAC and MEGA MAC trade marks in breach of s 120 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) by using the signs BIG JACK and MEGA JACK in relation to its hamburgers;

(b) orders should be made for the removal from the Trade Marks Register of Hungry Jack’s BIG JACK trade mark; and

(c) Hungry Jack’s has misrepresented to consumers that its BIG JACK hamburger contains 25% more Aussie beef than the BIG MAC hamburger (the 25% more Aussie beef representation) in breach of the provisions of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) (Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL claim).

5 Hungry Jack’s denies that it has infringed McDonald’s’ trade marks and contends that its BIG JACK mark should remain on the Register, the consequence of which is that it has a complete defence to the infringement allegation pursuant to s 122(1)(e) of the Trade Marks Act. Hungry Jack’s contends in its cross-claim that McDonald’s’ MEGA MAC trade mark should be removed from the Register for non-use pursuant to s 92(4)(b) of the Trade Marks Act. It also contends that the 25% more Aussie beef representation is correct and that the ACL claim must be dismissed.

6 A significant issue in the case is whether or not the impugned Hungry Jack’s trade marks are deceptively similar to the McDonald’s trade marks as prescribed by ss 10 and 120 of the Trade Marks Act. At the time of the hearing, one relevant issue was the extent to which the reputation is relevant to such an enquiry. That question was then pending for decision by the High Court and the parties submitted that the decision in the present case should await that decision. Judgment in Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd [2023] HCA 8; (2023) 408 ALR 195 was later delivered and the parties have subsequently made written submissions as to its effect, which I have taken into account in these reasons.

7 By orders made on 19 March 2021, issues of loss and damage and quantum of the pecuniary relief sought were to be heard and determined after and separately from all other issues in the proceeding. Accordingly, this judgment addresses only questions of liability.

1.2 The Registered Trade Marks

8 McD Asia is the registered owner of two registrations for the words BIG MAC, being trade mark Nos 271329 and 271330, both of which were filed on 14 August 1973. The first is in respect of goods in class 29 and the second is in respect of goods in class 30. The goods relevant to the infringement case are emphasised in bold:

Class 29: Meat, poultry and game, including hamburger patties, meat extracts; preserved, dried and cooked fruits and vegetables, eggs, milk and other dairy products; edible oils and fats, preserves, pickles

Class 30: Hamburgers; coffee, tea, cocoa, rice, coffee substitutes; flour and preparations made from cereals; bread, biscuits; yeast, baking powder; salt, mustard, pepper, vinegar, sauces, spices

9 McD Asia is also the owner of trade mark No 1539657 for the words MEGA MAC filed on 7 February 2013 in class 30 for:

Edible sandwiches, meat sandwiches, pork sandwiches, fish sandwiches, chicken sandwiches, biscuits, bread, cakes, cookies, chocolate, coffee, coffee substitutes, tea, mustard, oatmeal, pastries, sauces, seasonings, sugar

10 Hungry Jack’s is the registered owner of trade mark No 2050899 for BIG JACK, filed on 14 November 2019, in respect of the following goods:

Class 29: Hamburgers and burgers; meat burgers; vegetable burgers; cheese burgers; hamburger patties; meat, poultry, fish and game; meat extracts; sausages; meat products; chicken products; prepared vegetable products; chicken nuggets; fried chicken; grilled meat; sandwich fillings, being meat or cheese based; preserved, frozen, dried and cooked fruits and vegetables; potato chips; vegetable salads; fruit chips; fruit salads; pickles prepared from fruits and vegetables; potato and onion products included in this class; vegetable patties; eggs, milk and milk products including milk shakes and malted milks; beverages having a milk base; beverages made from yoghurt; fruit flavoured beverages having a milk base; preserves, pickles and relishes; jams, jellies

Class 30: Hamburgers and burgers (sandwich with filling); steak sandwiches and sandwiches; preparations made from bread; sandwiches containing meat including steak and hamburgers; steaks and burgers contained in bread rolls; hamburgers in buns; bread buns; foodstuffs made from cereals, corn, dough, farinaceous products, maize, oats, rice, sugar or flour; beverages made from cereals, chocolate, cocoa, coffee or tea; bread; biscuits; pastries; cakes; confectionery; prepared desserts (chocolate based); prepared desserts (confectionery); prepared desserts (pastries); flavoured toppings for desserts; salts included in this class, pepper, mustard, sauces, spices, vinegar, sauces (condiments); baking powder, yeast; salad dressings; fruit sauces, relishes; coffee, tea, cocoa, coffee substitutes; sugar; ices; sandwiches containing cheese

11 For the reasons set out below, I have concluded that:

(a) BIG JACK is not deceptively similar to BIG MAC within s 120 of the Trade Marks Act;

(b) MEGA JACK is not deceptively similar to MEGA MAC within s 120 of the Trade Marks Act;

(c) As a consequence of (a) and (b), McDonald’s has not established that the impugned use of the Hungry Jack’s trade marks infringes its registered trade marks;

(d) The Hungry Jack’s BIG JACK mark is not liable to be removed from the Register pursuant to any of ss 44, 60 or 88 of the Trade Marks Act, as a result of which Hungry Jack’s has an additional defence to the infringement allegation pursuant to s 122(1)(e) of the Trade Marks Act;

(e) The McDonald’s MEGA MAC mark is not liable to be removed from the Register for non-use, save that the registration should be amended to remove the following goods: biscuits, cakes, cookies, chocolate, coffee, coffee substitutes, tea, mustard, oatmeal, pastries, sauces, seasonings, sugar;

(f) Hungry Jack’s has engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in breach of s 18 of the ACL by making the 25% more Aussie Beef representation.

12 I will make orders requiring the parties to provide short minutes of order giving effect to these reasons and addressing any residual issues, including costs.

13 Tim Kenward has been Marketing Manager of McDonald’s Australia since July 2017. He has been associated with McDonald’s Australia since 2011, when he worked as a marketing consultant to the company from January 2011 until November 2012. He was then appointed National Brand Manager and, in 2015, Senior Brand Manager before being appointed to his present position.

14 Mr Kenward provided three affidavits. In his first he gives evidence about: McDonald’s business and trade marks; the BIG MAC hamburger; the BIG MAC Tagline “two all-beef patties, special sauce, lettuce, cheese, pickles, onions – on a sesame seed bun”; the BIG MAC build, being the club sandwich styled three tiered sesame seed bun with two beef patties; the MEGA MAC hamburger; and Hungry Jack’s activities which led to the commencement of these proceedings. In his second affidavit he responds to the affidavit of Scott Baird. In his third affidavit he provides supplementary evidence to his first affidavit in response to some objections taken to his first affidavit concerning the use by McDonald’s of the BIG MAC and MEGA MAC marks. Mr Kenward was cross examined.

15 Amandeep Dhanju has since January 2022 been Head of Business Insights and Analytics at McDonald’s Australia. She has a Bachelor of Science degree majoring in mathematics and computer sciences and has worked in the field of data analytics since 2007. Her current role is to lead a team providing advice on sales information about the performance of McDonald’s products, including providing regular reports and campaign analysis, including historical data analysis to management. Ms Dhanju explained the process of extracting data from McDonald’s’ records for the preparation of spreadsheets relied upon for the purpose of demonstrating use of the MEGA MAC mark. She was not cross examined.

16 Scott Balshaw is Systems Co-ordinator of Agrifood Technology in Victoria, a position he has held since 2013. He commenced working for Agrifood in 1992 as an analyst in the food safety laboratory. Mr Balshaw was provided with a test protocol for use in the conduct of tests to weigh BIG MAC and BIG JACK hamburger meat patties and conducted tests on 14 July 2021 in support of the ACL claim. He describes the testing that he carried out on patties acquired from 10 Hungry Jack’s restaurants and 10 McDonald’s restaurants located in Melbourne and reports on the results. Mr Balshaw was cross examined.

17 Ruma Prestney is Team Leader at Agrifood. She holds a PhD in analytical chemistry. Dr Prestney provided two affidavits. In her first affidavit, she gives evidence of testing that she conducted on various BIG MAC and BIG JACK hamburgers acquired from 20 locations in Brisbane to ascertain their weight. She reports on her results. In her second affidavit, Dr Prestney gives evidence of further testing that she conducted on 13 June 2021 in accordance with a protocol emailed to her by the solicitors engaged by McDonald’s, Spruson & Ferguson Lawyers Pty Ltd (SFL), and reports on the results. Dr Prestney was cross examined.

18 Lucy Hartland is a solicitor in the employ of SFL. Ms Hartland provided two affidavits. In her first affidavit, she exhibits correspondence with the solicitors representing Hungry Jack’s (Addisons), the trade marks in suit, and screen shots and reproductions of the impugned advertisements released by Hungry Jack’s. In her second affidavit, she annexes the results of searches of the Register for certain trade marks. Ms Hartland was not cross examined.

19 Scott Baird has since January 2015 been the Chief Marketing Officer of the respondent. He reports to the Chief Executive Officer of Hungry Jack’s. He gives evidence of the history of Hungry Jack’s in Australia and its position as a franchisee of Burger King. He explains that when Hungry Jack’s commenced operations in Australia it could not adopt the name BURGER KING because of trade mark issues with a third party and so elected to trade under the HUNGRY JACK’S trade mark, which had been registered in Australia since 1963. He gives evidence about the Hungry Jack’s outlets in Australia and the development of the BIG JACK and MEGA JACK hamburgers. Mr Baird was cross-examined.

20 Jennifer Jin is a primary school teacher who had been employed at McDonald’s on a casual basis from 2014 until 2016. She gives evidence about her experience of cooking hamburgers at McDonald’s and aspects of nomenclature. She was not cross examined.

21 Justine Munsie is a solicitor in the employ of Addisons, who represent Hungry Jack’s. She exhibits the results of various trade mark searches and gives evidence about how various restaurants promote the sale of meat products by reference to weight. She was not cross examined.

22 Brodie Campbell is a solicitor in the employ of Addisons. He gives evidence of the steps he took to make online purchases of Hungry Jack’s and McDonald’s hamburgers and exhibits screenshots from various websites and packaging. He was not cross examined.

3. TRADE MARK INFRINGEMENT CASE

23 Although its pleaded case is broader, in closing submissions McDonald’s infringement case was confined to reliance on s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act.

24 Section 120(1) and (2) provide (notes omitted):

120 When is a registered trade mark infringed?

(1) A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered.

(2) A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to:

(a) goods of the same description as that of goods (registered goods) in respect of which the trade mark is registered; or

(b) services that are closely related to registered goods; or

(c) services of the same description as that of services (registered services) in respect of which the trade mark is registered; or

(d) goods that are closely related to registered services.

However, the person is not taken to have infringed the trade mark if the person establishes that using the sign as the person did is not likely to deceive or cause confusion.

25 McDonald’s alleges that its trade marks have been infringed in two ways.

26 First, it contends that Hungry Jack’s’ use of the words BIG JACK involves infringement of its registered trade marks for BIG MAC. In refining its case in its closing submissions, McDonald’s submits that its registered trade mark No 271330 for BIG MAC for “hamburgers” in class 30 has been infringed by Hungry Jack’s’ use of the BIG JACK name because it is a sign that is deceptively similar to the BIG MAC mark.

27 Secondly, it contends that Hungry Jack’s’ use of the words MEGA JACK involves infringement of its registered trade mark No 1539657 for MEGA MAC for “edible sandwiches, meat sandwiches” in class 30 because it is a sign that is deceptively similar to the MEGA MAC mark.

28 McDonald’s pleads that Hungry Jack’s deliberately adopted the BIG JACK and MEGA JACK marks for the purpose of promoting in the mind of consumers a connection or affiliation between BIG MAC and MEGA MAC hamburgers and those (respectively) marked BIG JACK and MEGA MAC. Hungry Jack’s denies this allegation.

29 Hungry Jack’s does not dispute that its use of the impugned marks is use “as a trade mark” in relation to the sale of hamburgers or that those goods are “goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered” within s 120(1). As a consequence, the only relevant issue for determination is whether or not the impugned signs are deceptively similar to the McDonald’s trade marks.

30 The term “deceptively similar” is defined in section 10 of the Trade Marks Act:

For the purposes of this Act, a trade mark is taken to be deceptively similar to another trade mark if it so nearly resembles that other trade mark that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion.

3.2 Law regarding deceptive similarity

31 In Australian Woollen Mills Limited v FS Walton & Co Ltd [1937] HCA 51; (1937) 58 CLR 641 at 658, Dixon and McTiernan JJ described the test for deceptive similarity as follows:

But, in the end, it becomes a question of fact for the court to decide whether in fact there is such a reasonable probability of deception or confusion that the use of the new mark and title should be restrained.

In deciding this question, the marks ought not, of course, to be compared side by side. An attempt should be made to estimate the effect or impression produced on the mind of potential customers by the mark or device for which the protection of an injunction is sought. The impression or recollection which is carried away and retained is necessarily the basis of any mistaken belief that the challenged mark or device is the same. The effect of spoken description must be considered. If a mark is in fact or from its nature likely to be the source of some name or verbal description by which buyers will express their desire to have the goods, then similarities both of sound and of meaning play an important part. The usual manner in which ordinary people behave must be the test of what confusion or deception may be expected. Potential buyers of goods are not to be credited with any high perception or habitual caution. On the other hand, exceptional carelessness or stupidity may be disregarded. The course of business and the way in which the particular class of goods are sold gives, it may be said, the setting, and the habits and observation of men considered in the mass affords the standard. Evidence of actual cases of deception, if forthcoming, is of great weight.

32 Their Honours emphasised that the determination for the court is one of estimation and evaluation (at 659):

The main issue in the present case is a question never susceptible of much discussion. It depends on a combination of visual impression and judicial estimation of the effect likely to be produced in the course of the ordinary conduct of affairs.

33 The summary provided by Windeyer J in The Shell Company of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd [1963] HCA 66; (1963) 109 CLR 407 at 415 (Shell Oil) also encapsulates the approach required by s 120(1):

On the question of deceptive similarity a different comparison must be made from that which is necessary when substantial identity is in question. The marks are not now to be looked at side by side. The issue is not abstract similarity, but deceptive similarity. Therefore the comparison is the familiar one of trade mark law. It is between, on the one hand, the impression based on recollection of the plaintiff’s mark that persons of ordinary intelligence and memory would have; and, on the other hand, the impressions that such persons would get from the defendant’s television exhibitions.

34 In Hashtag Burgers Pty Ltd v In-N-Out Burgers, Inc [2020] FCAFC 235; (2020) 385 ALR 514 (Nicholas, Yates and Burley JJ), the Full Court noted at [64] that the distinction between consideration of whether one mark is deceptively similar to another, rather than substantially identical, lies in the point of emphasis on the impression or recollection which is carried away and retained of the registered mark, when conducting the comparison. In this context, the Full Court said:

…allowance must be made for the human frailty of imperfect recollection. In New South Wales Dairy Corporation v Murray Goulburn Co-operative Company Ltd [1989] FCA 124; 86 ALR 549, in a passage in his judgment not affected by the proceedings on appeal, Gummow J said at 589:

In determining whether MOO is deceptively similar to MOOVE, the impression based on recollection (which may be imperfect) of the mark MOOVE that persons of ordinary intelligence and memory would have, is compared with the impression such persons would get from MOO; the deceptiveness flows not only from the degree of similarity itself between the marks, but also from the effect of that similarity considered in relation to the circumstances of the goods, the prospective purchasers and the market covered by the monopoly attached to the registered trade mark: Shell Co of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407 at 414–15; Polaroid Corp v Sole N Pty Ltd [1981] 1 NSWLR 491 at 498. The latter case is also authority (at 497) for the proposition that the essential comparison in an infringement suit remains one between the marks involved, and that the court is not looking to the totality of the conduct of the defendant in the same way as in a passing off suit.

This passage was approved by the Full Court in C A Henschke & Co v Rosemount Estates Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 1539; 52 IPR 42 (Ryan, Branson, Lehane JJ) at [44].

35 In Self Care, the High Court summarised the position as follows (citations omitted):

[28] The question to be asked under s 120(1) is artificial – it is an objective question based on a construct. The focus is upon the effect or impression produced on the mind of potential customers. The buyer posited by the test is notional (or hypothetical), although having characteristics of an actual group of people. The notional buyer is understood by reference to the nature and kind of customer who would be likely to buy the goods covered by the registration. However, the notional buyer is a person with no knowledge about any actual use of the registered mark, the actual business of the owner of the registered mark, the goods the owner produces, any acquired distinctiveness arising from the use of the mark prior to filing or, as will be seen, any reputation associated with the registered mark.

[29] The issue is not abstract similarity, but deceptive similarity. The marks are not to be looked at side by side. Instead, the notional buyer's imperfect recollection of the registered mark lies at the centre of the test for deceptive similarity. The test assumes that the notional buyer has an imperfect recollection of the mark as registered. The notional buyer is assumed to have seen the registered mark used in relation to the full range of goods to which the registration extends. The correct approach is to compare the impression (allowing for imperfect recollection) that the notional buyer would have of the registered mark (as notionally used on all of the goods covered by the registration), with the impression that the notional buyer would have of the alleged infringer's mark (as actually used). As has been explained by the Full Federal Court, "[t]hat degree of artificiality can be justified on the ground that it is necessary in order to provide protection to the proprietor's statutory monopoly to its full extent".

(Emphasis added.)

36 Deceptive similarity must be assessed on the basis of whether there is a real, tangible danger of deception or confusion occurring. It is enough if the notional buyer would entertain a reasonable doubt as to whether, due to the resemblance between the marks, the two products come from the same source; Southern Cross Refrigerating Company v Toowoomba Foundry Pty Ltd [1954] HCA 82; (1953) 91 CLR 592 at 595; Registrar of Trade Marks v Woolworths Ltd [1999] FCA 1020; (1999) 93 FCR 365 at [50]; Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Ltd [2000] HCA 12; (2000) 202 CLR 45 at [83]. As the High Court noted in Self Care at [32], there must be “a real likelihood that some people will wonder or be left in doubt about whether the two sets of products… come from the same source”.

37 The question of intention to deceive or cause confusion is material to the present case. In this regard, the leading authority is again the decision of Dixon and McTiernan JJ in Australian Woollen Mills at 657:

The rule that if a mark or get-up for goods is adopted for the purpose of appropriating part of the trade or reputation of a rival, it should be presumed to be fitted for the purpose and therefore likely to deceive or confuse, no doubt, is as just in principle as it is wholesome in tendency. In a question how possible or prospective buyers will be impressed by a given picture, word or appearance, the instinct and judgment of traders is not to be lightly rejected, and when a dishonest trader fashions an implement or weapon for the purpose of misleading potential customers he at least provides a reliable and expert opinion on the question whether what he has done is in fact likely to deceive.

38 As this passage makes clear, the question of whether or not an infringing use was intentional is but one factor for the court to take into account in determining whether there is a reasonable probability of deception or confusion; Self Care [30]; Hashtag Burgers at [67] – [68].

39 In resolving a long-standing controversy on the subject, the High Court determined in Self Care that reputation based on actual use of the registered trade mark should not be taken into account when assessing deceptive similarity under s 120(1); Self Care at [3], [36], [46], [47], [51]. That conclusion was explained by reference to the fact that it is the registration of a mark in respect of particular goods or services that confers monopoly rights on the registered owner, and the scope of that right is not to be varied by reference to inherently uncertain notions concerning whether or not the user of the mark has developed a reputation in it, which notions were antithetical to the type of certainty that the Register was designed to nurture; Self Care [37] – [40], [48]. For that reason, the Court explained at [49] that it is impermissible to attribute to the notional buyer any familiarity with the actual use of a registered trade mark:

…The inquiry under s 120(1) is directed to avoiding deception and confusion between trade marks, and protecting the registered owner's trade mark rights in relation to the particular goods covered by the registration. It is not concerned with and does not seek to protect "the commercial value or 'selling power' of a mark"

40 However, the reasoning in Self Care has ignited a further dispute between the parties concerning what the High Court meant in the passage at [29], as emphasised above at [35], (and elsewhere) by its reference to “actual use” on the part of the alleged infringer.

41 In its supplementary submissions, Hungry Jack’s contends that the High Court made it clear that deceptive similarity for the purpose of s 120(1) infringement analysis is to be assessed in the context of the respondent’s actual use of the accused mark, including usage of other aspects of packaging. It disputes the submission advanced by McDonald’s to the effect that particular or idiosyncratic circumstances surrounding the alleged infringer’s use are not relevant. By emphasizing “actual use”, Hungry Jack’s submits that the High Court conveyed that idiosyncratic circumstances of a particular respondent’s use are to be taken into account. Hungry Jack’s submits that the Court should now consider such matters as the presence of the Hungry Jack’s trade marks and livery on its restaurants. In this regard, it submits that Self Care has the effect of expanding the inquiry beyond that envisaged in earlier authority, because not only are generalised trade circumstances to be taken into account, what were previously considered to be (and Hungry Jack’s accepted were, prior to the decision in Self Care) extraneous and irrelevant matters such as the presence of other trade marks used on or in relation to the goods, are now to be taken into account. It relies in this respect on the High Court’s treatment of the facts in Self Care to demonstrate how the comparison should be made.

42 For the following reasons, I am unable to accept that submission.

43 In Self Care at [29], [33] it is apparent that the Court was referring to the actual use of the impugned trade mark in the sense of the use of the impugned sign alone, rather than the broader context of use. The Court was contrasting that use in fact (of the impugned mark) with the notional use of the registered mark on goods within the class of registration. That is the comparison that has long been established by the authorities. Several matters lead me to this view.

44 First, the focal point of the High Court’s consideration was on the relevance of reputation within the statutory test for deceptive similarity under s 120(1). In reaching its conclusions on that subject, the Court provided a succinct review of about a century of law on the subject of deceptive similarity, addressing briefly topics that have been the subject of detailed consideration by other Courts. It would be surprising if the Court intended to overrule or change well-established principle in the manner contended without addressing it squarely and in such short form. The better view is that it did not do so.

45 Secondly, the three cases cited in support of the proposition made in [29] were Shell Oil at 415, Wingate Marketing Pty Ltd v Levi Strauss & Co [1994] FCA 163; (1994) 49 FCR 89 at 128 and MID Sydney Pty Ltd v Australian Tourism Co Ltd [1998] FCA 1616; (1998) 90 FCR 236 at 245. Examination of those cases, and the passages cited, demonstrate the context of the reference to “actual use”.

46 A passage from Shell Oil (Windeyer J) at 415 is set out above. That familiar case concerned a dispute between two well-known companies that sold petrol and oils about whether Shell had infringed Esso’s trade mark for a “humanized oil drop” (described as the “Esso oil-drop man”) in a television commercial. The novelty of the case at the time arose because before that date (1961), moving images in a film had not been found to constitute trade mark infringement. The two short commercials displayed an animated oil drop man. Windeyer J found the man not to be substantially identical with the Esso oil drop man mark but that he was deceptively similar to it, reciting the legal test at 415 which is set out above at [33]. Significantly, in both of the impugned animations it was clear from the voiceover and the word SHELL appearing on the animated oil drop that the oil drop man was associated with Shell, not Esso. Nevertheless, the comparison of the “actual use” of the mark led Windeyer J to the conclusion that the impugned Shell oil drop man was deceptively similar to Esso’s trade mark. The presence of what might be said to amount to disclaimers of any connection with Esso was not relevant.

47 It is in this context that reference to the comparison of the impression based on recollection of the registered trade mark and “the impressions that such persons would get from the defendant’s television exhibitions” must be understood. Windeyer J was not, in referring to use of the impugned mark, implicitly including the application by the defendant of the word “SHELL” in connection with the animated figure. The only “actual use” was the use of the impugned mark.

48 In MID Sydney, Burchett, Sackville and Lehane JJ similarly observed at 245 that it is irrelevant that the respondent may “by means other than its use of the mark, make it clear that there is no connection between its business and that of MID”, citing the established position set out in Mark Foy’s v Davies Co-op Ltd [1956] HCA 41; (1956) 95 CLR 190 at 205 where Williams J (Dixon CJ agreeing) adopted the following statement of Lord Greene MR in Saville Perfumery Ltd v June Perfect Ltd (1939) 58 RPC 141 at 161:

In an infringement action, once it is found that the defendants mark is used as a trade mark, the fact that he makes it clear that the commercial origin of the goods indicated by the trade mark is some business other than that of the plaintiff avails him nothing, since infringement consists in using the mark as a trade mark, that is, as indicating origin.

49 In Wingate Marketing at 128, Gummow J addressed the comparison for the purposes of deceptive similarity, noting that it must be between the mark registered on the one hand “and the mark as used by the defendant on the other”. However, this cannot be taken to refer to aspects of the defendant’s use beyond the impugned mark itself. The reason for this was explained by his Honour in the passage that followed at pages 128 – 129:

(i) The comparison is between any normal use of the plaintiff’s mark comprised within the registration and that which the defendant actually does in the advertisements or on the goods in respect of which there is the alleged infringement, but ignoring any matter added to the allegedly infringing trade mark; for this reason disclaimers are to be disregarded,…(ii) However, evidence of trade usage in the sense discussed above, is admissible but not so as to cut across the central importance of proposition (i)…

(Emphasis added.)

50 Thirdly, the approach taken by Hungry Jack’s, in my view, is contrary to a correct reading of Self Care, where the Court said at [33] (footnotes included):

In considering the likelihood of confusion or deception, "the court is not looking to the totality of the conduct of the defendant in the same way as in a passing off suit"81. In addition to the degree of similarity between the marks, the assessment takes account of the effect of that similarity considered in relation to the alleged infringer's actual use of the mark82, as well as the circumstances of the goods, the character of the likely customers, and the market covered by the monopoly attached to the registered trade mark83. Consideration of the context of those surrounding circumstances does not "open the door" for examination of the actual use of the registered mark, or, as will be explained, any consideration of the reputation associated with the mark84.

(Italics in original. Emboldening added.)

51 The reference in the second sentence to “actual use of the mark” is again a limited reference to the impugned mark itself, not surrounding marks or disclaimers. This is apparent from the first sentence which in footnote 81 refers to the passage in New South Wales Dairy Corporation v Murray Goulburn Co-operative Company Ltd [1989] FCA 124; (1989) 86 ALR 549 at 589, which I have set out above at [34]. It is clear that the Court is here reciting long-established authority that the whole of the conduct of the respondent is not taken into account when considering deceptive similarity. Footnote 82 repeats the citations identified in [29] which I have reviewed in relation to the second point above. It is plain that the High Court continues to focus on the “actual use” only of the respondent’s mark, not on the actual surrounding circumstances, which may include disclaimers or other marks. The relevant “surrounding circumstances” are confined to consideration of the way in which goods of the relevant kind are typically bought and sold.

52 Fourthly, Hungry Jack’s relies on passages in the High Court’s reasoning where it applies the facts. In that case the relevant question was whether PROTOX was deceptively similar to the registered trade mark BOTOX.

53 The Court said:

[69] Allergan was correct to submit that, as the Full Court accepted, there are visual and aural similarities between the two marks. The word PROTOX uses two short consonants, "p" and "r", to make the syllable "pro", which is visually and aurally similar to "bo"; both "pro" and "bo" are "sounded through the lips together"; and the word "otox" is "distinctive and identical" between PROTOX and BOTOX and is an "identical rhyme". But, as the Full Court correctly said, "[c]onsumers would not have confused PROTOX for BOTOX". The words are sufficiently different that the notional buyer, allowing for an imperfect recollection of BOTOX, would not confuse the marks or the products they denote. The visual and aural similarities were just one part of the inquiry.

[70] The question, then, was whether these similarities "imply an association" so that the notional buyer would be caused to wonder whether it might not be the case that the products come from the same source. The alleged deceptiveness was said to flow not only from the degree of similarity itself, but also from its effect considered in relation to the circumstances of the goods and the prospective purchaser and the market covered by the monopoly – anti-wrinkle creams in class 3. It is to be assumed that the products would be sold in similar trade outlets, including pharmacies, as well as through websites. The notional buyer has a recollection of the BOTOX mark being used on anti-wrinkle creams in class 3 in that context. The notional buyer sees the PROTOX mark used on a similar product – a serum which is advertised on its packaging and website to "prolong the look of Botox®". While the reputation of BOTOX cannot be considered, the relevant context includes the circumstances of the actual use of PROTOX by Self Care. "[P]rolong the look of Botox®" may suggest that Protox is a complementary product. However, as was observed by the primary judge, "it will be the common experience of consumers that one trader's product can be used to enhance another trader's product without there being any suggestion of affiliation".136 In this case, the back of the packaging stated in small font that "Botox is a registered trademark of Allergan Inc" and, although the assumption is that Botox is an anti-wrinkle cream, the website stated that "PROTOX has no association with any anti-wrinkle injection brand".

[71] Applying the applicable principles,137 there is no real risk of confusion or deception such that the notional buyer will be caused to wonder whether it might be that the products come from the same source. What is required is a "real, tangible danger" of confusion or deception occurring.138 As explained, the marks are sufficiently distinctive such that there is no real danger that the notional buyer would confuse the marks or products. The similarities between the marks, considered in the circumstances, are not such that the notional buyer nevertheless is likely to wonder whether the products come from the same trade source. That conclusion is reinforced by the fact that the PROTOX mark was "almost always used in proximity to the FREEZEFRAME mark" and that there was "no evidence of actual confusion".

54 Hungry Jacks relies on these paragraphs to support the contention that Self Care should be read to endorse the concept that in considering deceptive similarity under s 120(1) it is relevant to take into account disclaimers and other features of the packaging of the defendant’s use. I do not consider that, taken in the context of the whole of the judgment, this is the correct conclusion.

55 The analysis at [69] is consistent with the statements of principle to which the Court earlier referred and adopted, the Court noting that the correct approach was to consider the notional use of BOTOX against the actual use of the PROTOX mark. Paragraph [70] includes parts that might suggest that the Court took into account factors that went beyond a comparison of the marks and had regard to extraneous features of the packaging. However, [71] commences with the statement that the Court is applying the “applicable principles”, cross-referencing (as footnote 137 identifies) to [26] – [33] which endorse the long-established principles identified above. In those circumstances, it appears to me that the relevant reasoning on the facts is to be found in third and fourth sentences of [71] as follows:

…As explained, the marks are sufficiently distinctive such that there is no real danger that the notional buyer would confuse the marks or products. The similarities between the marks, considered in the circumstances, are not such that the notional buyer nevertheless is likely to wonder whether the products come from the same trade source….

56 That conclusion picks up the comparison of the marks identified in [69]. Having reached that conclusion, the statement that the conclusion is “reinforced” by the proximity of the impugned use to the FREEZEFRAME mark may be regarded as obiter dicta, the legal conclusion having already been provided to the effect that regardless of the presence of the FREEZEFRAME mark, the impugned mark was not deceptively similar to BOTOX. To take a different view would render significant parts of the earlier reasoning in Self Care otiose in circumstances where it is apparent that no argument before the High Court involved the contention that any of the prior cases referring to the subject were incorrectly decided, and the High Court expressly adopted those authorities.

57 To the extent that passages in [70] might be taken to indicate a broader view of context as part of the ratio decidendi, the aspects of packaging on the Self Care product that were emphasised in that paragraph are concerned with the proximity of the impugned PROTOX mark to the registered BOTOX® mark. That is not the situation in the present case, which may be distinguished from the conclusions reached in Self Care for that reason.

58 Accordingly, I do not consider that the decision of the High Court in Self Care leads to the conclusion for which Hungry Jack’s contends.

59 I note that in The Agency Group Australia Limited v H.A.S. Real Estate Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 482, Jackman J addressed the interpretation of Self Care. For the reasons set out above, I respectfully agree with his Honour’s observations at [56] – [59].

3.3 The use of BIG JACK and MEGA JACK

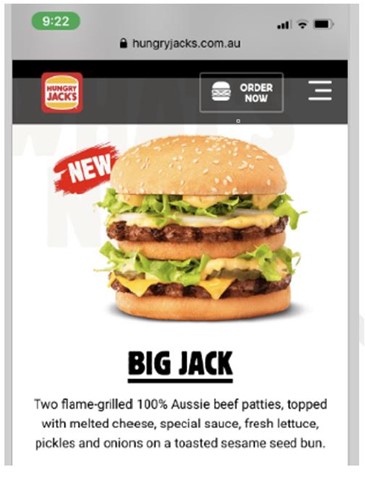

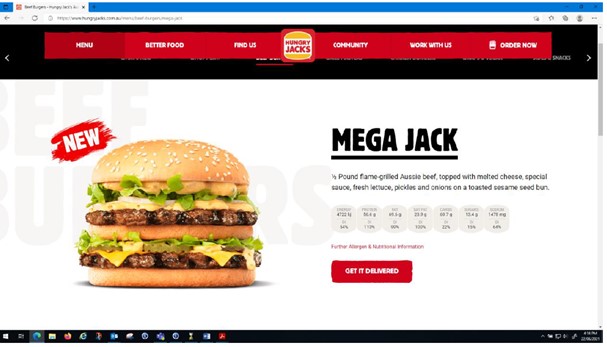

60 Hungry Jack’s accepts that since March 2020 it has promoted and offered for sale hamburgers under and by reference to the words BIG JACK and at about the same time started to use the words MEGA JACK in relation to a different hamburger offering. Examples of such use are set out in the evidence and appear in similar forms on the Hungry Jack’s website, in print advertising, social media platforms and television advertising:

|

|

61 The BIG JACK and MEGA JACK marks have been applied in Hungry Jack’s quick service restaurants. The meals offered at Hungry Jack’s outlets are comparatively low cost and service at physical outlets is swift. The purchaser selects the meal or menu item of interest and orders it at the counter. The meal is likely to be eaten more or less immediately.

62 The evidence indicates that Hungry Jack’s has operated such restaurants in Australia since 1971 under the brand name HUNGRY JACK’S and that there are over 400 such restaurants in Australia. The Hungry Jack’s quick service restaurants are located within food courts in shopping centres, in drive-through sites which offer eat in or take away drive-through facilities, in stand-alone stores which offer sit down service only and in co-branded sites, which are located within premises that have other branding, such as service stations (including BP, United Ampol and Shell service stations).

63 An example of a food court store frontage is set out below:

64 An example of the shop frontage of a drive-through store is as follows:

65 An example of a co-branded store is as follows:

66 Hungry Jack’s products can also be purchased through the Hungry Jack’s website and app. They can also be purchased using third party apps such as Uber Eats, Menulog and Deliveroo. Included within the options are the hamburgers identified by reference to the words BIG JACK and MEGA JACK. A typical version of the home page for the Hungry Jack’s website is as follows:

67 In the case of the UberEats, Menulog and Deliveroo apps the user must first select from a list of cuisines and restaurants and then select Hungry Jack’s as an option. An example is as follows:

68 Consumers then click through various menu options presented. Below, on the left, is an example of what appears on the Hungry Jack’s website. On the right is an example of an available selection from a third-party app, being an UberEats menu:

|

|

69 Various prompts are then followed to complete the transaction. Similar processes, and similar displays, appear in the various other online purchasing options available.

70 Whether a consumer acquires hamburgers from a restaurant (in person) or online, they are all supplied in cooked form.

71 The evidence of Mr Baird was relied upon by McDonald’s to support the case that Hungry Jack’s deliberately adopted the impugned trade marks for the purpose of appropriating McDonald’s’ reputation.

72 In his affidavit, Mr Baird gave evidence that he and those reporting to him in the Hungry Jack’s marketing team decided to offer a club-style sandwich – being a hamburger with an extra layer of bread to separate two hamburger patties – as a direct competitor product to McDonald’s’ BIG MAC, which would meet a gap in Hungry Jack’s offering. In around July 2019, he instructed Andrew McCallum, Marketing Director, and Andrew Cheong, New Product Development Manager, to develop a product in a trial market which was to adopt a 5”, club-style sandwich form, being a 5” club BIG KING hamburger. The BIG KING is a hamburger sold in Burger King outlets overseas, but not available in Australia. He gave evidence that adopting the club style made the product more distinctive within the Hungry Jack’s product range whilst the addition of two patties sandwiched between three pieces of bread mirrored other ingredients and the design of the Big King hamburger offered internationally, namely cheese melted on top of the patties, lettuce, pickles, sliced onions and a new sauce called “King Sauce”.

73 Mr Baird gave evidence that he did not consider that any of the trade marks available to Hungry Jack’s in Australia were suitable, and the name BIG KING as used elsewhere internationally was not, as he understood it, relevant in Australia where the HUNGRY JACK’S brand, not BURGER KING, is used. Instead, he considered that the name JACK or JACK’S would be suitable, as it would in part be a reference to the corporate branding and the name of the Hungry Jack’s founder, Jack Cowan and in part a flow-on from the chain of cafés that Hungry Jack’s had launched (attached to Hungry Jack’s restaurants) called JACK’S CAFÉ, of which there are now about 246 outlets (with 200 more planned). He gave evidence of other references to “Jack’s” or “Jacks” in limited promotional offers and internal training.

74 In his affidavit Mr Baird said:

I was aware that there was an element of cheekiness in naming the product BIG JACK, due to the rhyming of “Jack” and “Mac” in BIG MAC. I was aware that the name would likely be perceived as a deliberate taunt of McDonald’s. The use of cheeky “taunts” is common in overseas markets where McDonald’s and Burger King compete… Given the well-established level of competition between Hungry Jack’s and McDonald’s, together with the use of distinctive branding by both outlets, the separate trade channels operated by each of them, the common use of BIG and MEGA (as discussed below) together with Hungry Jack’s association with the name Jack, I did not consider there to be any risk that consumers would confuse the trade source of the Big Jack Hamburger with the source of the Big Mac Hamburger.

75 Prior to the launch of the BIG JACK hamburger, Hungry Jack’s secured a trade mark registration for the BIG JACK trade mark. Mr Baird noted that McDonald’s did not oppose that registration.

76 In relation to the MEGA JACK, as part of the same limited time offering of the BIG JACK, Hungry Jack’s trialled a larger sized variant of the BIG JACK with two larger (4oz) meat patties and a bigger (5”) bun which was named MEGA JACK. Hungry Jack’s had previously used the word MEGA for its two products MEGA MILKSHAKES and MEGA MEALS for promotional deals. Mr Baird gave evidence that the MEGA JACK hamburger was designed to provide a much bigger burger alternative to the BIG JACK hamburger. At that time, he was not aware that McDonald’s had registered the trade mark MEGA MAC and had never heard of a product of that name being sold or promoted by McDonald’s. Indeed, he first learned of that trade mark when Hungry Jack’s received a letter before action from Spruson & Ferguson dated 21 August 2020.

77 In cross examination, Mr Baird accepted that in adopting a club style hamburger form, Hungry Jack’s was following a BURGER KING strategy, in terms of how BURGER KING intentionally competes against the BIG MAC by having a type of hamburger that is similar to the BIG MAC. He gave evidence that this choice of name was part of the naming convention, following the international use of BIG KING, but adapting it for the Australian market where there was no recognition of KING, but recognition of HUNGRY JACK’S. He resisted the proposition that the name BIG JACK was chosen because of its similarity with BIG MAC, instead saying that it was coincidental that the names were similar (particularly in that they rhyme) and that the choice of JACK came about because the word JACK is a “property” of Hungry Jack’s. I take this to mean that as far as Hungry Jack’s is concerned, JACK is part of its recognised brand, which I find is plainly correct. Having said that, Mr Baird readily accepted that there are “obvious links between the two name[s], you can’t move away from that”, a point that he and other decision makers at Hungry Jack’s recognised. It was this that he considered gave the choice “an element of cheekiness”.

78 As developed in cross examination, Mr Baird’s evidence was:

And so the element of cheekiness was something that you were aware of at the time you were considering what to call the Big Jack?---Correct.

And it was something that you took into account in naming the product Big Jack, wasn’t it?---Moving – as we moved forward, correct.

And the cheekiness that you refer to in paragraph 40 was entirely intentional, wasn’t it, Mr Baird?---I think there was – I think there – we had gone through due process and we were looking for how we could actually leverage the name. And, as I said, it was – there was obviously – we understood that there would be some – that there would be that element of cheekiness between the two names.

So the element of cheekiness was deliberate in your choice, so far as you were concerned - - -?---Correct.

- - - of the name Big Jack, correct?---Correct.

And you also intended that consumers, seeing the name Big Jack or encountering it as the name of a hamburger, would call to mind the Big Mac because of that similarity, correct?---Correct.

79 Mr Baird did not accept that the absence of use of the apostrophe “s” at the end of JACK in the BIG JACK mark made any relevant difference, because the “naming convention” (and, I interpolate, the “leverage” mentioned in the above passage) was based on what he considered to be Hungry Jack’s “ownership” of the word “Jack”. He resisted the proposition that Hungry Jack’s wanted to leverage off consumer recognition of the BIG MAC brand, giving evidence that it was not his intention to do so, saying “[w]e wanted to ensure that we were trying to get people to buy the BIG JACK product”. Mr Baird accepted that he and those at Hungry Jack’s wanted there to be a recollection of the BIG MAC brand when they saw BIG JACK.

80 Mr Baird confirmed in his oral evidence that his view that there would be no consumer confusion as a result of the choice of BIG JACK was for several reasons: that there was an established level of competition between McDonald’s and Hungry Jack’s; that both businesses use distinctive branding, such as their logos and names; and the differences in the word marks.

81 Mr Baird was directly challenged on the question of intention as follows:

Now, Mr Baird, in proceeding with the launch of the product using the name Big Jack you knew, didn’t you, that there was a possibility that some consumers who encountered the words Big Jack as the name of hamburger might wonder whether it came from the source as the Big Mac?---No.

…

In particular, you knew that there was a possibility that consumers of that kind, that is, consumers who were only occasional consumers of QSR products, and had a limited familiarity with the Big Mac, might be cause to wonder whether a hamburger called the Big Jack came from the same source as the Big Mac?---In – I can’t see how that’s – how that’s conceivable.

And I suggest that in adopting the name Big Jack, so far as you were concerned, you intended to take advantage of that possibility in using that name for a Hungry Jack’s hamburger?---No. Incorrect. The research, as part of the discovery documents, showed that switchers, who were – who we were actually targeting as the core target – and there’s a reference there – were looking for variety, and variety and adding to our burger range would actually attract those consumers.

82 I consider that Mr Baird gave honest evidence and that the answers given in this passage represent his genuinely held view.

3.5 The deceptive similarity arguments

83 McDonald’s submits: that there are significant visual and aural similarities between the BIG MAC and BIG JACK; that the “idea” conveyed by the respective marks is similar with the word BIG being coupled with the name of a person with the latter being strong and colloquial or familiar names leading to the idea being that it is a large burger, perhaps personified or referable to a person, citing Cooper Engineering Co Pty Ltd v Sigmund Pumps Ltd [1952] HCA 15; (1952) 86 CLR 536 at 539; and that the “surrounding circumstances” which are relevant are that the goods are ready-to-eat and relatively low-priced food and that this increases the prospect that consumers will not subject the marks to detailed analysis and may be caused to wonder as to their origin by reason of their imperfect recollection. McDonald’s submits that there is at least a real, tangible danger of confusion, or of consumers being caused to wonder whether it might not be the case that the two products come from the same source, in the surrounding circumstances that the authorities permit to be taken into account in the infringement analysis, emphasising that the authorities do not permit consideration to be taken of Hungry Jack’s’ use of its HUNGRY JACK’S house mark and other distinguishing indicia.

84 McDonald’s submits that the question of deceptive similarity of MEGA JACK when compared to MEGA MAC should be determined in a manner analogous to the assessment of the BIG MAC and BIG JACK marks. It submits that the visual and oral similarities are striking, with the two marks again including an identical first word and otherwise being very similar phonetically and conveying a similar overall impression.

85 McDonald’s submits that the evidence establishes that Hungry Jack’s deliberately chose a visually and phonetically similar trade mark, BIG JACK, in respect of a “copycat” product which directly competes with its BIG MAC hamburger. It submits that this evinces an intention to adopt a significant part of the BIG MAC trade mark to take advantage of the similarity in the minds of consumers. It emphasises evidence given by Mr Baird to the effect that the BIG JACK hamburger was specifically designed to target and compete with the BIG MAC hamburger and that Hungry Jack’s went to considerable lengths to provide a burger with a similar “build” and similar taste profile to the BIG MAC. It submits that the choice of name was with full knowledge of the similarity of BIG JACK to BIG MAC and that this was deliberate, Mr Baird acknowledging that there was an “element of cheekiness” in choosing BIG JACK, knowing that that Hungry Jack’s could “leverage the name” and consumers’ recollection of the BIG MAC brand by using the similar name for a hamburger product.

86 McDonald’s submits that Hungry Jack’s failed to call evidence from the persons actually responsible for the decision to use the BIG JACK trade mark, as the decision to proceed with the BIG JACK hamburger (and name) was made by the board of directors of Hungry Jack’s. It submits that an inference may be drawn that evidence of Mr Jack Cowin or the other members of the board would not have assisted Hungry Jack’s; citing, inter alia, Jones v Dunkel [1959] HCA 9; (1959) 101 CLR 298 at 308, 312, 320-321. It submits that a similar inference may be drawn from the failure of Hungry Jack’s to call Andrew McCallum, Marketing Director, to give evidence.

87 McDonald’s submits that the suggestion that the name BIG JACK was part of an established “naming convention” should be rejected, and that the evidence showed that Hungry Jack’s uses “JACK’S” in its product names and promotions, not the word JACK simpliciter. In this regard, McDonald’s submits that the fact that the founder of Hungry Jack’s is a person whose forename is “Jack” is irrelevant from a branding perspective. Finally, McDonald’s submits that the evidence of Mr Baird in his affidavit to the effect that he did not consider there to be any risk that consumers would confuse the trade source of the BIG JACK hamburger with the BIG MAC hamburger is not to the point, because the reason for that view included his knowledge of the well-established level of competition between the parties and the distinctive use of branding by both outlets which were the main reasons why he thought that there would be no confusion. Those matters, McDonald’s submits, are irrelevant to the deceptive similarity enquiry, which depends fundamentally on a comparison between the trade marks, without regard to such considerations.

88 Hungry Jack’s disputes that the marks are visually and aurally similar and contends that aural similarities are less important in the present case where goods are bought in a manner that relies on predominantly visual cues, whether in takeaway restaurants or online. It submits that the ideas of the marks differ with BIG being a classically descriptive word which is common to the trade and is accordingly to be afforded less weight; citing Cooper Engineering at 539 (Dixon, Williams and Kitto J) and Pham Global Pty Ltd v Insight Clinical Imaging Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 83; (2017) 251 FCR 379 at [52] (Greenwood, Jagot and Beach JJ). Hungry Jack’s emphasises the differences between MAC and JACK and contests that the idea of each mark is similar and points to differences between the “look” of each mark.

89 Hungry Jack’s submits that as consumers can only purchase products from a dedicated site, whether physical or online, the context tells away from the likelihood of deception or confusion. Hungry Jack’s submits, relying on aspects of Self Care to which I have referred, that there is no likelihood that a consumer would be caused to wonder whether the goods sold in an Hungry Jack’s outlet by reference to BIG JACK would come from the same source as a BIG MAC because of the consistent use of the Hungry Jack’s branding. Hungry Jack’s submits that it is artificial to approach the question of likelihood of deception and confusion absent consideration of the fact that the marks in the present case will be used in conjunction with other trade marks (for instance, the MCDONALD’S mark, the golden arches or other trade livery on the one hand and the BURGER KING trade mark and livery on the other) by which the different sources of food will be readily identified. The quick service restaurants that are the outlets of the food are “single source” places, where there is no real prospect that a consumer will be caused to wonder.

90 Hungry Jack’s submits that it is relevant that McDonald’s has put forward no evidence of actual deception or confusion on the part of consumers and disputes that McDonald’s has established that there was a relevant intention on the part of Hungry Jack’s in the sense contemplated in Australian Woollen Mills at 657.

91 In relation to intention, Hungry Jack’s submits that McDonald’s has failed to establish that the impugned marks were fashioned “as an implement or weapon for the purpose of misleading customers” as required by Australian Woollen Mills at 657. It submits that McDonald’s has no monopoly on a particular form of hamburger build or the tagline used and that Hungry Jack’s’ decision to introduce a club-style burger was to encourage consumers directly to compare the BIG JACK with the BIG MAC, not to confuse customers as to the origin of the BIG JACK burger, as Mr Baird explained in his evidence. Hungry Jack’s submits that Mr Baird gave honest evidence of his view that the BIG JACK mark would not cause confusion, which was not challenged in cross-examination and should be accepted. It submits that even if the full get-up of Hungry Jack’s restaurants, website and advertising is not relevant for the s 10 comparison, that get-up makes it clear that the source of goods is different from McDonald’s. In such a circumstance in the real world, the choice of name cannot rationally have been intended to confuse or deceive, as Mr Baird’s evidence demonstrates.

92 In relation to the alleged infringement of the MEGA MAC mark by MEGA JACK, Hungry Jack’s, like McDonald’s, argues that by analogy the same arguments apply as for the BIG MAC and BIG JACK marks.

3.6 Consideration of deceptive similarity

93 The trade mark registrations for BIG MAC and MEGA MAC relevantly concern hamburgers. In the present case, the notional buyer is a person interested in acquiring a product from a quick service restaurant, purchased in store, from a drive-through outlet, or online. In such quick service restaurants, the hamburgers may be taken to be lower cost items that are cooked and sold for the convenience of consumers who are either cost conscious or short of time or both. As Mr Baird said in his evidence, the market for quick service hamburgers is driven by “convenience, taste and value”. It may also be taken that because people will eat hamburgers, they are likely to pay some attention to make sure that they get the right product. Unlike other relatively inexpensive items, persons consuming food will want to know what they are getting. They are not likely to be particularly careless or inattentive. The goods the subject of the registration appeal to a broad range of consumers, from the youthful to the elderly and everyone in-between. They are general consumer goods. The evidence indicates that Hungry Jack’s target market is people aged between 18 to 39 years of age and includes people who prefer Hungry Jack’s products (“preferers”), those who swap between brands (“switchers”) and those who may occasionally visit a quick service restaurant (“light users”). The evidence indicates that in 2020 the price of a BIG JACK hamburger was about $8 and a BIG MAC was around $7.

94 The decision in Self Care confirms that the reputation that McDonald’s has garnered in its trade marks is irrelevant as is any reputation that Hungry Jack’s has in its trade marks. This is important. It means the notional consumer would not approach either of the trade marks with preconceptions based on their experience with either McDonald’s or Hungry Jack’s or any of their branding. Each mark must be considered afresh, shorn of knowledge of the reputation of both. There is, of course, a degree of artificiality in the approach, but that is for the good reasons set out in the case law.

95 I start with the registered trade mark BIG MAC, considered by the hypothetical purchaser of hamburgers who has never heard of the famous chain of quick service restaurants called MCDONALD’S or anything related to that chain.

96 The trade mark is of two words of one syllable each. The word BIG is descriptive. A person unfamiliar with McDonald’s and any reputation residing in it would understand the word to convey something about the product promoted for sale, namely, having regard to the relevant registration, a hamburger that is large (big) as opposed to a small one. The word BIG may be regarded as both laudatory as well as descriptive, it being perhaps a good thing to have a larger hamburger. One may take judicial notice that it is a common adjective. Unsurprisingly, the evidence indicates that other sellers of hamburgers and fast food deploy the word BIG in association with their hamburgers and other products from quick service restaurants. Examples include BIG CARL, BIG QUEENSLANDER, BIG BUNZ, BIG BOY and THE BIG GRILL.

97 MAC is a one syllable word. It has a soft beginning (“m” sound) and a hard end, most likely pronounced “ack”.

98 The Macquarie Dictionary indicates that MAC may mean a prefix found in many family names of Irish or Scottish Gaelic origin, a colloquial abbreviation of “mackintosh” which is a type of raincoat, or, in a chiefly United States colloquial usage, a man (Macquarie Dictionary, 3rd edition, 1997). McDonald’s submits that many would see the word as the familiar or colloquial abbreviation of a person’s name. However, that is by no means clear. I consider it more likely that to the notional consumer, “Mac” may be understood to be a coined or unusual forename or surname, which may be Scottish or Irish, an abbreviation of a longer name or a word conveying no particular meaning, noting that for present purposes one must ignore the reputation of McDonald’s and the prospect that consumers would view it to be an abbreviation of “McDonald’s”.

99 Considering BIG MAC as a whole, it is a short, snappy, two-word mark, the idea of which draws attention to something that is large, namely a large “Mac”, “Mac” being the name of the product. The words together would be separately pronounced and read with the strong “b” providing a point of contrast to the softer “m” of the second word.

100 Turning to the BIG JACK mark, the word “big” will of course have the same descriptive and laudatory connotations. The word “big” will be understood to identify a characteristic of the word that follows.

101 Unlike MAC, the word JACK is an easily recognised forename and would be understood as such by most consumers. It could also have other meanings which are unlikely to be considered. Dictionary evidence indicates that it could refer to a tool for lifting things (such as a car to repair a tyre), the name of a playing card, a game or an ensign, as in “Union Jack”. More likely, consumers will consider BIG JACK to be some sort of personified hamburger that is large.

102 The word Jack has a strong “j” sound and finishes with a hard “ack”.

103 BIG JACK must be compared with BIG MAC. This comparison is not side by side but based on the typical consumer’s imperfect recollection. As I have noted, consumers of hamburgers within the class of goods of McDonald’s trade mark registration are likely to pay reasonable attention to a sign that denotes what it is that they will be eating. At a restaurant or drive-through they may order the goods orally. Online, they will order by reference to the name and description of the product, most likely by clicking on an option.

104 In so doing, in my view, the notional consumer will recognise that BIG is a descriptive and possibly laudatory term that is commonly used and likely give this lesser emphasis as a point of recollection than the word MAC. It is likely that the imperfect recollection of the consumer will call the word MAC to mind readily and identify it as an important and distinctive part of the mark. They will do the same when they see BIG JACK. Again, they are less likely to consider the word BIG as a point of distinction. They are likely to note several similarities: both contain two short monosyllabic words, both begin with BIG, both finish with an “ack” sound.

105 However, allowing for imperfect recollection, I do not think it likely that the typical consumers will confuse JACK for MAC or BIG JACK for BIG MAC or be caused to wonder whether hamburger products sold under and by reference to BIG JACK come from the same source or are affiliated with the trader who sells the BIG MAC. Jack is a very recognisable forename that will be known by most, if not all consumers. MAC is an unusual name or abbreviation. Although both are BIG, the idea conveyed by JACK and MAC is different. The words look and sound different, the “j” being quite distinctive of “m” both visually and phonetically. Whilst there is a similar rhyme to the conclusion of the two marks when said aloud, there is a phonetic difference between the spoken aspect of “mac” and “Jack”. In my view, people are likely to be attuned to noticing differences in forenames (Harry is not Barry, Pat is not Matt, Ryan is not Brian, Ronald is not Donald) and they are more likely to remember the different look and sound of the words MAC and JACK as points of distinction.

106 Taken together, these matters lead me to the conclusion that BIG JACK is not deceptively similar to BIG MAC.

107 Further, whilst neither is likely to be determinative, I separately note that McDonald’s has adduced no evidence of deception or confusion. Nor, as I note in a little detail below, am I persuaded that McDonald’s has established that Hungry Jack’s selected the BIG JACK mark for the purpose of misleading customers.

108 In reaching this conclusion, and contrary to the submission of Hungry Jack’s, I have not taken into account the use of any particular livery or trade marks in conjunction with the BIG JACK mark. For the reasons that I have set out in section 3.2 above, in my view the decision in Self Care does not mandate that approach. If I am incorrect in that conclusion and, contrary to my view, one is obliged to take into account the fact that the BIG JACK hamburger is sold exclusively at Hungry Jack’s outlets which use Hungry Jack’s trade livery and the HUNGRY JACK’S trade mark, my conclusion would be further reinforced. That is because the evidence indicates that the vast preponderance of the use of the BIG JACK mark is in conjunction with that trade livery and signage, all of which would indicate to a consumer that the trade origin of the hamburger being sold is Hungry Jack’s.

109 In Australian Woollen Mills at 657, the Court noted that in considering how prospective buyers will be impressed by a given word, the judgment of traders is not to be lightly rejected, and when a trader fashions an implement or weapon for the purpose of misleading potential customers, they at least provide a reliable and expert opinion on the question of whether what they have done is in fact likely to deceive. The rationale for this is based on the supposition that a trader will be well placed, as an expert in the field, to have an opinion as to the likely reaction of consumers. It will be sufficient for the trader to intend to adopt some or all of a trade mark so that consumers may be caused to wonder that one is the trade source of the other; Hashtag Burgers at [103], [104].

110 In the present case, I am not persuaded that Hungry Jack’s fashioned the name BIG JACK for the purpose of misleading consumers as required.

111 First, it is credible that BIG JACK was selected for the purpose of drawing attention to the JACK component of HUNGRY JACK’S, which is the widely promoted name of the respondent’s business. As Mr Baird accepted, the addition of “BIG” to JACK was likely to lead consumers to draw comparisons with the BIG MAC, but that was a conscious comparison of one product with another from a different trade source. I accept that in the process of decision-making, Mr Baird did not consider that a consumer would think that a BIG JACK was, or may be, a BIG MAC or that a BIG JACK could be purchased from McDonald’s. I do not consider that the absence of the apostrophe and “s” is indicative of purpose, but rather a grammatical choice.

112 Secondly, the question of whether a trader fashions a weapon for the purpose of misleading potential customers is a question of fact based on the workings of the mind of the trader in question. This is perhaps a rare case where both parties are able to claim a significant reputation in their businesses. McDonald’s in (at least) the names BIG MAC and MCDONALD’S and Hungry Jack’s (at least) in the name HUNGRY JACK’S. In these circumstances, it is unrealistic to postulate the highly theoretical circumstance, of the type that trade mark lawyers routinely engage, but normal people do not, where neither trader has any reputation. Mr Baird’s view that there would be no confusion was in part because it was inconceivable to him that a consumer who saw an advertisement or sought to purchase a BIG JACK hamburger in a Hungry Jack’s outlet or online could miss the fact that the trade origin of the product was Hungry Jack’s based on the livery of the store and/or the use of Hungry Jack’s’ other trade marks (including the name HUNGRY JACKS) and that the trade origin was not the well-known McDonald’s, with its quite different trade livery and trade marks. Based on the evidence in this case, that was an entirely credible view.

113 Of course, it would be unrealistic for Mr Baird to have formed any intention absent these matters. The circumstances of this case mean that the likelihood of obtaining evidence of the sort contemplated in Australian Woollen Mills is low. It is not possible to postulate what Mr Baird might have thought, absent knowledge of the reputation of McDonald’s and Hungry Jack’s, about the impression BIG JACK might have on persons with an imperfect recollection of BIG MAC. While reputation is not relevant to the assessment of whether two marks are deceptively similar, a trader’s knowledge or perception of reputation may be relevant to the assessment of whether they had an intention to mislead or deceive in using a particular trade mark. Here, Mr Baird’s knowledge or perception led him to the view that it was inconceivable that consumers would be confused at all. In such circumstances, I am not prepared to draw any inferences as to what Mr Baird’s state of mind may have been had he not taken reputation into account. Nor, quite properly, have I been asked to do so.

114 Thirdly, the fact that Hungry Jack’s set out to compete with the BIG MAC by producing a similar club sandwich style hamburger that seeks to emulate the taste of the BIG MAC, including by use of a particular tagline, does not of itself aid McDonald’s argument unless there was an intention to confuse consumers by the choice of the impugned trade mark.

115 Fourthly, I accept Mr Baird’s evidence that Hungry Jack’s was content for there to be an element of what he termed cheekiness in adopting the BIG JACK name. That evidence was reflected in Hungry Jack’s internal documents, which indicated a desire on the part of Hungry Jack’s to invite the comparison. As one internal document said:

It will be very hard for customers to resist the temptation to compare…

The Big Jack naming says it all and gets attention. Its cheeky [sic] and will generate trial through curiosity especially with brand switchers and lighter users generating trial. It will also generate PR as its news worthy…thus further amplifying media.

116 In other words, as Mr Baird said, Hungry Jack’s wished to compete with McDonald’s’ BIG MAC for the sale of a similar hamburger, and the use of BIG JACK was likely to draw attention to that fact for consumers familiar with the McDonald’s product. Both trade marks use the word “big” and have other similarities as noted above. However, the desire was to compete by a choice of name that had echoes of the BIG MAC name but was nonetheless recognisably different to it. I consider that the purpose was not to mislead but to invite a comparison and contrast. Other internal documents reflect that purpose.

117 Fifthly, I am not prepared to draw the inferences in accordance with the principles in Jones at 308, 312, 320 – 321 sought by McDonald’s. Mr Baird was the Chief Marketing Officer of Hungry Jack’s at the time. Although the ultimate decision as to whether to proceed was up to the Board of Directors, it is apparent that it was his reasoning that led to the point of adoption of the BIG JACK name upon recommendation being made to the board. Although the board of directors of Hungry Jack’s made the final decision, he was the person responsible for developing and implementing the strategy adopted by the Board. In my view, his reasoning was credible. I am not satisfied from the failure to call Mr Cowin or Mr McCallum that it may be inferred an alternative version of facts, namely that Hungry Jack’s selected BIG JACK for the purpose of misleading potential consumers, may be drawn.

118 The MEGA MAC mark must also be considered by the hypothetical consumer who has never heard of McDonald’s. It is of two words, the first of two syllables, the second of one. The commencement of each word provides a point of emphasis with the repeated “m” sound.

119 The word “mega” is descriptive. By its Macquarie Dictionary definition (3rd ed, 1997) it may mean a prefix denoting 106 of a given unit, as in megawatt; a prefix meaning ‘great’ or “huge” as in megalith; or colloquially to mean “to a very great degree” as in megatrendy. It is most likely that a consumer would understand the word to convey the second or third of these meanings, being something about the product promoted for sale, namely, a hamburger that is huge or giant (mega) as opposed to one that is smaller or simply large. As with “big”, it may be regarded to be laudatory as well as a descriptive term. In my view, it has a common adjectival meaning, whether used as a prefix or as separate words. The evidence indicates that the word “mega” has been used by a number of sellers of hamburgers and fast food to denote their products, including MEGA BURGER, MEGA BURGERS and BELLA’S MEGA BREKKY BURGER.

120 I have described aspects of the word MAC above at [98].

121 I have also reviewed the characteristics and likely meaning to be attributed to JACK above at [101].

122 Taken together, the ordinary consumer is likely to understand MEGA JACK to be a huge or giant Jack, a personified hamburger.