FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Palmanova Pty Ltd v Commonwealth of Australia [2023] FCA 1391

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to confer and provide a short minute of order giving effect to these reasons within 7 days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRAM J:

1. INTRODUCTION

1 This case concerns the provenance of an archaeological artefact (‘the Artefact’). The Artefact, which is made from black basalt, was purchased online on or around 5 June 2020 by the Applicant, an Australian company, for USD$17,340.00 from the Artemis Gallery in Colorado. It was shipped by FedEx to Melbourne on or about 24 June 2020. Upon its entry into Australia it was intercepted by officials acting under the Customs Act 1901 (Cth) (‘Customs Act’) and retained by them. Documentation accompanying the Artefact suggested that it was pre-Columbian in origin and came from Tiwanaku, an ancient city the monumental ruins of which lie in Bolivia near Lake Titicaca. There followed after its interception a period during which the Commonwealth Office for the Arts considered whether it should be seized under the provisions of the Protection of Movable Cultural Heritage Act 1986 (Cth) (‘the Act’). This period of reflection appears to have involved consultation through diplomatic channels with the government of Bolivia.

2 The Artefact is undoubtedly a fine piece:

3 Section 34 of the Act authorises an inspector appointed under it to seize ‘a protected object that the inspector believes on reasonable grounds to be forfeited’ which by s 27(1) includes being liable to forfeiture. On 17 May 2021, an official acting under s 203T of the Customs Act delivered the Artefact to an inspector appointed under the Act. By s 27(2) this was taken to have involved the seizure of the Artefact by the inspector. At the time of this deemed seizure it is not in dispute that within the meaning of s 34 the inspector held reasonable grounds for believing the Artefact to be a ‘protected object’. Section 37 authorises the owner of an object which has been seized by an inspector to apply to a court of competent jurisdiction for an order against the Commonwealth that the object is not liable to be forfeited. On 16 June 2021 the Applicant commenced the present proceeding pursuant to s 37.

4 The outcome of the proceeding turns on whether the Artefact is liable to forfeiture because of the operation of s 14(1) of the Act. Section 14 provides:

(1) Where:

(a) a protected object of a foreign country has been exported from that country;

(b) the export was prohibited by a law of that country relating to cultural property; and

(c) the object is imported;

the object is liable to forfeiture.

(2) Where a person imports an object, knowing that:

(a) the object is a protected object of a foreign country that has been exported from that country; and

(b) the export was prohibited by a law of that country relating to cultural property;

the person commits an offence.

Penalty:

(a) if the person is a natural person—imprisonment for a period not exceeding 5 years or a fine not exceeding 1,000 penalty units, or both; or

(b) if the person is a body corporate—a fine not exceeding 2,000 penalty units.

(3) This section does not apply in relation to the importation of an object if:

(a) the importation takes place under an agreement between:

(i) the Commonwealth, a State, a Territory, a principal collecting institution or an exhibition co-ordinator; and

(ii) any other person or body (including a government); and

(b) the agreement provides for the object to be loaned, for a period not exceeding 2 years, to the Commonwealth, State, Territory, principal collecting institution or exhibition co-ordinator, as the case may be, for the purpose of its public exhibition within Australia.

(4) In subsection (3):

exhibition co-ordinator means a body that arranges for the conducting in Australia of public exhibitions of objects from collections outside Australia, and that achieves this by, from time to time:

(a) entering into an agreement with a person or body (including a government) for the importation of such objects on loan; and

(b) entering into an agreement with the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory under which the Commonwealth, State or Territory agrees to compensate the person or body referred to in paragraph (a) for any loss of or damage to the objects arising from, or connected with, the carrying out of the agreement referred to in that paragraph or the public exhibition of the objects in Australia.

5 The parties agree that the Commonwealth bears the legal onus of proving on the balance of probabilities that s 14(1) is enlivened. The Commonwealth seeks to discharge its legal onus by demonstrating that: (a) the Artefact is part of the movable cultural heritage of Bolivia and hence, by s 3, a ‘protected object of a foreign country’; and (b) it was removed unlawfully from Bolivia. The parties also agree two facts: first, that the Artefact must have been removed from Bolivia prior to 1960; and second, under Bolivian law it only became unlawful to remove objects from the ruins at Tiwanaku (or the islands in the Bolivian part of Lake Titicaca) from Bolivia after 3 October 1906.

6 There are three issues between the parties, two factual and one legal. The first factual question is whether the Commonwealth can prove on the balance of probabilities that the Artefact is part of the movable cultural heritage of Bolivia. To prove this the Commonwealth seeks to demonstrate that the Artefact was made by the Tiwanaku at or near the ancient city of Tiwanaku.

7 The second factual question, which proceeds on the assumption that the Artefact was made by the Tiwanaku at Tiwanaku, is whether the Commonwealth has succeeded in demonstrating that it was removed from Bolivia after 1906 when it became illegal to do so. The third issue, which is legal in nature, arises from the Applicant’s contention that s 14(1) is only enlivened when the object to which it refers was removed from the foreign country after the commencement of the Act; in this case, 1 July 1987. If this be correct, then the Applicant is entitled to succeed because the object was removed from Bolivia before 1960.

2. THE STANDARD OF PROOF IN CIVIL LITIGATION

8 It is useful to begin by framing the nature of the inquiry at hand and, in particular, to identify what must be proved and by whom in a civil case such as the present. Section 37(3)(b) of the Act requires the Court to determine ‘on a balance of probabilities’ whether the Artefact is liable to forfeiture under s 14(1). In turn, this requires the Court to determine at the same civil standard whether the Artefact is a ‘protected object of a foreign country’ which, by s 3, means that the Court must determine whether it forms ‘part of the movable cultural heritage of a foreign country’. Because this is a civil trial in which the issues are framed by the parties, the Court’s function is to determine whether it accepts the case on that question which has been advanced by the Commonwealth. That case is that the Artefact: (a) was made by the Tiwanaku; (b) forms part of the movable cultural heritage of Bolivia; (c) originates from or near the monumental ruins at Tiwanaku; and (d) was removed from Bolivia contrary to Bolivian laws relating to cultural property.

9 If the Commonwealth establishes that the Artefact was made by the Tiwanaku at or near the ruins of Tiwanaku then the Applicant accepts that it is part of the movable cultural heritage of Bolivia. Thus, although there was a body of evidence at trial concerned with the cultural significance of the Artefact to modern day Bolivia this was not ultimately contested and other than to note this evidence it is not necessary to traverse it. As I have already noted, the parties also agreed that a Bolivian statute entitled ‘Law of Property of the Nation, Ruins of Tiahuanaco and Lake Titicaca’ of 3 October 1906 enacted a prohibition on the export from Bolivia of cultural objects originating from the ruins of Tiwanaku or Lake Titicaca. The reference to Lake Titicaca is of some importance because there was a suggestion in the evidence that the Artefact may have come from the Island of the Sun which is in the Bolivian portion of the lake and governed by the statute. This topic was related to a more general exploration of other islands in the lake which lie in Peru, specifically the island of Tikonata and, more tangentially, the Isla Esteves. I will return to this topic later in these reasons.

10 The Commonwealth’s case that the Artefact was made by the Tiwanaku at or near Tiwanaku and exported from Bolivia after 1906 involves indirect and circumstantial evidence. As to whether the Artefact was made by the Tiwanaku the Commonwealth relies on its age, its apparent method of manufacture and certain of its iconographic and morphological features which it says are typical of the Tiwanaku. The iconographic features of the Artefact consist of the artistic depictions it bears whilst the issue of morphology is concerned with its shape and form.

11 As to whether the Artefact was manufactured at Tiwanaku the Commonwealth relies on: the degree to which fine stonework was carried out by the Tiwanaku at the city of Tiwanaku rather than at other Tiwanaku sites in Peru and Chile; the fact that the Artefact is made from black basalt; the propinquity of Tiwanaku to two basalt quarries; and the fact that no other basalt object made by the Tiwanaku has ever been recovered from any other Tiwanaku site apart from Tiwanaku and certainly not from sites lying outside the present territorial confines of Bolivia.

12 As to whether the Artefact was removed from Tiwanaku after 3 October 1906 the Commonwealth puts forward two alternate hypotheses which between them it says are more likely than not: first, that it was excavated by an archaeologist, Dr Eduardo Casanova, from one of 25 pits dug in the cemetery area of Tiwanaku in 1934 and conveyed by train to Buenos Aires; or, second, that it was removed from Bolivia in or around 1950, falling victim to the significant surge in the looting of Tiwanaku artefacts during the late 1940s and 1950s until this was brought under control by the Bolivian government. The surge in the demand for pre-Columbian artefacts that created this window of desecration was an international phenomenon which afflicted most of South America at the time and was caused by the popularisation of pre-Columbian art by artists such as Pablo Picasso and Henry Moore.

13 For its part, the Applicant puts in the Commonwealth’s path an array of alternate competing hypotheses. Whilst the Artefact displays some elements which may indicate that the person who manufactured it was familiar with Tiwanaku culture, the arrangement of these elements is unprecedented in the archaeological record and could on one view suggest that the person lacked an actual understanding of the canon of Tiwanaku art and tradition. The Applicant’s initial position was that the Artefact was a modern fake or pastiche crudely assembled from at least two pieces of basalt but this case was abandoned in the face of scientific evidence which showed that the Artefact was at least several hundred years old and made from a single piece of basalt.

14 The Applicant disputes the Commonwealth’s contention that basalt objects made by the Tiwanaku have only ever been recovered from the city of Tiwanaku and points particularly to a basalt object in the Ethnological Museum of Berlin which can be shown to have been purchased by a doctor in 1888 at the city of Puno on the Peruvian side of Lake Titicaca. This object was a recurrent subject of discussion in this litigation and I will refer to it as ‘the Berlin Object’, postponing more detailed discussion of it for now. The Applicant says that even if the Artefact was made by the Tiwanaku it could have been made at Tiwanaku sites in the Moquegua Valley in Peru or at the oasis town of San Pedro de Atacama which is in the Atacama Desert in Chile (and hence would not have been subject to removal from Bolivia at any point and could not therefore form part of the movable cultural heritage of Bolivia). Although not advanced in a very developed form, the Applicant also hints at the possibility that the Artefact may have been made by some other pre-Columbian civilisation.

15 In the event that the Court concludes that the Artefact was made by the Tiwanaku at Tiwanaku the Applicant also disputes the Commonwealth’s contention that it was removed from Bolivia after 1906. Whilst the Commonwealth advances the two hypotheses I have referred to above, the Applicant advances an array of hypotheses to demonstrate the opposite. Some of these were more developed than others. For example, the Applicant posits the possibility that the Artefact could have been: (a) transported by the Tiwanaku themselves by caravans of llama to the Tiwanaku sites in the Moquegua Valley or San Pedro de Atacama in the course of exchanges of ritual goods or trade; (b) transported by the Tiwanaku to the sites in the Moquegua Valley and there exchanged with another culture also dwelling in the Valley at that time, the Wari; (c) removed from Tiwanaku by some other culture such as the Inca or the Aztec; (d) looted by treasure hunters during the Colonial Period following the Spanish Conquest; or (e) removed by archaeologists or collectors during the 19th century. There are other lesser hypotheses, too.

16 It will thus be seen that the case calls for findings not only about conventional facts such as the material from which the Artefact is made and its age but also ancient and modern historical facts proved indirectly from circumstantial matters. These are undoubtedly unusual facts to be traversed in a court case but they are to be assessed in the same manner as in any other civil trial.

17 Where the fact is an historical fact the civil standard requires a court to feel actual persuasion that the occurrence of the fact is more likely than not. Thus a court will not be satisfied that a coin tossed on 1 January 1900 came up heads. This underscores the distinction between the unknown and unknowable truth of historical events and the end to which civil litigation is directed which is the quelling of disputes between parties about what happened in the past by reference to some standard which society at large views as legitimate. At one time the legitimacy of the civil standard was supplied by the ancient practices of the common law but it now finds legislative embodiment in s 140(1) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (‘Evidence Act’). It requires a fact to be found proved if a court ‘is satisfied that the case has been proved on the balance of probabilities’ and this standard is, of course, specifically recognised in forfeiture proceedings under the Act in s 37(3)(b).

18 Indeed, the Applicant explicitly draws attention to the fact that s 14(1) operates as a forfeiture provision and submits that this should be brought to account in the process of fact finding. It observes, with respect correctly, that s 140(2) of the Evidence Act provides that the Court may, in determining whether it is satisfied that a case has been proved on the balance of probabilities, take into account the nature of the action, the nature of the subject-matter of the proceeding and the gravity of the matters alleged. Two elements of this are relevant. First, the nature of the action is a civil forfeiture proceeding which has the potential to result in the confiscation of private property without compensation. Although a prosecution for knowing import under s 14(2) is penal, the liability to forfeiture under s 14(1) is not and its ends are not punitive. Secondly, the nature of the subject matter of the proceeding is an item of private property of significant value. By the end of the trial, the uncontested evidence was that the Artefact was at least several hundred years old and had cost the Applicant USD$17,340.00. Its forfeiture is therefore not a trivial matter. I accept the Applicant’s submission that reasonable satisfaction under s 140(1) in this case should not be produced by inexact proofs, indefinite testimony or indirect inferences: Applicant’s Closing Submissions (‘ACS’) [47], citing Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 at 362 per Dixon J.

19 Where, as here, there can be no direct evidence of an historical fact the Court may proceed by the drawing of inferences. But inference does not include pure speculation and the available inferences are confined by the necessity that they should be reasonably open on the evidence. Whether an inference which is reasonably open on the evidence will in fact be drawn turns on whether the Court feels actual persuasion that the occurrence of the fact to be inferred is more likely than not: see, e.g., Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing & Allied Services Union of Australia v Australian Competition & Consumer Commission [2007] FCAFC 132; 162 FCR 466 at [31] per Weinberg, Bennett and Rares JJ. In this case for example, the constellation of Tiwanaku motifs on the Artefact, its age and so forth must be such that it is reasonably open to infer that it was made by the Tiwanaku (so that the drawing of the inference that it is Tiwanaku would be lawful) and the Court must feel actual persuasion that it was made by the Tiwanaku.

20 In a civil case where a party seeks to prove a fact indirectly from other circumstances this will involve demonstrating that the hypothesis that the fact occurred is more likely than not. In such a case the Court does not ask whether each of the posited circumstances individually proves that the hypothesis of the occurrence of the fact is more likely than not but rather whether all of the circumstances when considered together do so. Thus one does not ask whether the mere fact of Dr Casanova’s archaeological expedition to Tiwanaku in 1934 shows that it is more likely than not that the Artefact was removed after 1906. Rather, one considers together all of the circumstances and asks whether it is more likely than not that the Artefact was removed from Bolivia after 1906. By way of example, these may include the circumstances that the Artefact was made by the Tiwanaku (if that be proved), that no Tiwanaku objects made from basalt have ever been found outside Tiwanaku, that there is no record of the Artefact before the 1950s and that it appears first to have surfaced in Buenos Aires, which was also the destination of the train transporting the objects excavated by Dr Casanova (this statement is by way of example; the actual circumstances are more detailed than this).

21 The multiple competing hypotheses which must be assessed in this case give rise to a need for special care. Where there are only two competing hypotheses that between them account for the universe of possibilities open on the evidence, a court’s satisfaction that one is more likely than the other will entail that the occurrence of the fact supported by the more likely hypothesis is proved on the civil standard. Whilst it is important not to approach the civil standard in an excessively arithmetical way in terms of numeric probabilities it can be useful to do so to illustrate some consequences in a circumstantial case where multiple hypotheses are in competition with each other. For example, where there are only two competing hypotheses and one is more probable than the other then it must follow that the more likely one is more likely than not. (More formally: if P(A)>P(B) then since P(A)+P(B)=1 then one may validly infer that P(A)>1/2.) But the logic of this breaks down where there are three or more competing hypotheses. If P(A)>P(B)>P(C) then the fact that P(A)+P(B)+P(C)=1 does not warrant the conclusion that P(A)>1/2 as will be seen if P(A)=45%, P(B)=30% and P(C)=25%. Thus the court will only be satisfied that a fact is established if the hypothesis supporting it is more likely than all of the others considered together (i.e. P(A)>(P(B)+P(C))). In particular, the mere fact that one of the hypotheses emerges as more likely than each of the others will not suffice, it must be more likely than all of them.

22 In this case, for example, the Commonwealth’s hypothesis is that the Artefact was removed from Bolivia after 1906 either because it was excavated in 1934 by Dr Casanova or because it was looted in or around 1950 as an unexpected consequence of Picasso’s Primitivism Period. It is not enough for the Commonwealth to show that the hypothesis that the Artefact was removed from Bolivia after 1906 is more likely than each of the hypotheses that the Artefact was taken from Bolivia before 1906 by the Tiwanaku themselves, or exchanged with the Wari or carried away by whatever means by the Incas, the Aztecs, treasure hunters, archaeologists or other collectors. It must show that the hypothesis of removal after 1906 is more likely than all of these other pre-1906 removal hypotheses raised by the evidence put together.

23 Another matter which may be relevant is the existence of other hypotheses not specifically mentioned in the evidence. Generally, in an ordinary case this will not be germane. However, as will be seen the hypotheses in this case range over 1500 years of human history. Across such a stretch of time almost anything is possible. My initial impression was that these unexplored hypotheses should be given no weight. However, in the course of preparing these reasons I have changed my mind about this and have concluded that this aspect of the ordinary course of human affairs must be brought to account: see, eg, Martin v Osborne (1936) 55 CLR 367 at 381 per Evatt J; Jones v Sutherland Shire Council [1979] 2 NSWLR 206 at 222 per Mahoney JA; Holloway v McFeeters (1956) 94 CLR 470 at 480-481 per Williams, Webb and Taylor JJ. The fact that the subject-matter of this case traverses 1500 years of human history is a relevant circumstance disclosed by the evidence. I will return later in these reasons to how this observation is to be brought to account in the fact finding process.

24 There is another implication of the civil standard of proof and the nature of a civil trial that should be noted. The question for a court conducting a civil trial without a jury is whether the fact has been proved to the requisite standard. In some cases, perhaps many, the court may find that a party has failed to prove fact A because the court is satisfied that not-A is the case. Thus in a case where a party bears the legal onus of proving that two people met and conspired to rig the widget market the court may find, as a fact, that the two people never met and hence could not have rigged that market. But this is not necessary and the court may simply declare itself not satisfied that the party bearing the onus of proof has discharged its burden without making any finding. The court is not bound always to accept the case of one or other of the parties: Kuligowski v Metrobus [2004] HCA 34; 220 CLR 363 at [60], quoting Rhesa Shipping Co SA v Edmunds [1985] 1 WLR 948 at 955; 2 All ER 712 at 718 per Lord Brandon of Oakbrook.

25 The immediate consequence of this observation is that where the evidence leaves a civil court without a sense of persuasion that a fact has been established, the default rule in civil litigation is that it is the party bearing the legal onus of proving that fact who bears the consequences. But this case involves a consideration of detailed archaeological evidence of an essentially academic kind. Academic debate about the origins of the Artefact differs from the nature of the question in this proceeding. The various fields of human knowledge are bent toward the end of finding the truth. On the other hand, whilst truth is an important value in civil litigation its ascertainment is not its sole end: see, eg, Stephen Gageler, ‘Evidence and Truth’ (2017) 13 The Judicial Review 1 at 4-5; J J Spigelman, ‘Truth and the Law’ in Nye Perram and Rachel Pepper (eds), The Byers Lectures: 2000-2012 (Federation Press, 2012) 232. The system of civil courts is a manifestation of the power of the State which is brought to bear to quell disputes between its subjects in a way which is perceived to be, and so far as possible is, just. Trials are conducted in accordance with specified rules of procedure and evidence and the parties are afforded an opportunity to adduce evidence and to make submissions about the significance of that evidence. The necessary function of quelling the dispute before it requires each court hearing a suit to resolve the case by reference to the evidence and submissions before it and the existence of a legal burden of proof on one of the parties guarantees that every case has an answer.

26 The point for present purposes is that academic debate is never definitively quelled and there is neither a person who corresponds with the function of a court to resolve debates definitively nor correlatively any such concept as the civil standard of proof to assist in that resolution. Thus merely because a court is not satisfied that a fact has been proven to the requisite civil standard does not necessarily entail the resolution of any corresponding academic disagreement about that fact. For example, were the Court to conclude that it was not satisfied that it had been demonstrated that the Artefact was removed from Bolivia after 1906 this would not entail the conclusion that it was not in fact so removed. It would simply record the outcome of a very formal public contest under specified rules between two parties. And, indeed, this is the origin of the word ‘trial’. Put another way, the present litigation gives rise to a contest not an inquiry.

27 With these broad principles in mind, the evidence may be divided into five topics. The first concerns the uncontroversial history of the Artefact since it perhaps first surfaced in Argentina in the 1950s. Most of the evidence on this topic is documentary in nature and it is simply a question of putting the material in order as best one can.

28 The second topic, which is also largely uncontroversial, is scientific in nature and is concerned with the age, composition and likely manner of manufacture of the Artefact. Most of the evidence about this was given by two witnesses: a geologist, Professor Mavrogenes, and a conservator, Ms McHugh, neither of whom were required for cross-examination.

29 The remaining three topics are controversial and concern matters of archaeology and cultural and art history. The evidence about them was given by four witnesses. The Commonwealth called Mr Julio Condori Amaru (who I shall refer to by his preferred appellation, Mr Condori) and Drs Vranich and Yates. The Applicant called Dr Young-Sánchez. It is convenient to refer to each of these witnesses as an archaeologist although, as will be seen, that does not quite capture their areas of expertise in the same way that the word ‘lawyer’ does not quite capture the range of professions which it encompasses. Each witness provided one or more written reports. Mr Condori gave his evidence virtually from Bolivia with the assistance of a Spanish interpreter on the first day of the trial and was cross-examined. Dr Vranich, Dr Yates and Dr Young-Sánchez gave their evidence during a concurrent session which extended over two non-sequential days and during which each was cross-examined closely.

30 Turning to the disputed topics, the third is whether the Artefact was made by the Tiwanaku. Each of the four witnesses gave evidence about this and each was examined extensively. The fourth topic, which assumes that the Tiwanaku made the Artefact, concerns whether it was made by them at Tiwanaku. The fifth topic, which assumes that the Artefact was made by the Tiwanaku at Tiwanaku concerns the circumstances and timing of its removal from the territorial confines of modern day Bolivia.

31 The determination of whether the Commonwealth has proved its case involves a consideration of a range of smaller topics relating to each of these issues. For example, whilst the parties agree that the Artefact has finely engraved animal figures on its sides they disagree as to whether these are felines, deer or birds and whether their arrangement is typical of Tiwanaku art or not. In relation to some matters there was a determined effort by both parties to discredit the testimony adduced by the other. I will deal with these challenges as they become pertinent.

3. THE KNOWN HISTORY OF THE ARTEFACT

32 The case was conducted on the probable basis that the Artefact derived from the private collection of a Mr Rafael Osona and had been acquired by him in Buenos Aires sometime between 1950 and 1960. The basis for this was an ‘Evidentiary Statement’ signed by Mr Raul Goler, a resident of Taos in New Mexico on 12 August 2010. The statement says that in 1970 Mr Osona, by that time at least also a resident of New Mexico, gave Mr Goler his private collection of ‘primitive’ art objects. A list of the objects given to Mr Goler by Mr Osona is attached to the statement.

33 The word ‘primitive’ sounds somewhat pejorative to the 21st century ear. Pre-Columbian cultures built large stone pyramids, smelted gold and killed each other in a variety of imaginative ways. Whether these activities are the necessary indicia for the presence of a civilisation is perhaps a bigger question but we do not call the ancient Egyptians, who made very similar lifestyle choices, primitive and it is clear that modern archaeologists altogether eschew the expression. Where possible, I too will avoid using the word ‘primitive’ and instead use the word ‘ancient’, although at some points the use of the word will be unavoidable.

34 Returning to Mr Goler’s list, there were a large number of items on it amongst which was item 7: ‘5 (five) stone cups with feline figures and engravings’. Mr Goler said that Mr Osona had assembled his collection from different private collectors in Buenos Aires and mainly from the Antigua Casa Pardo. The evidence does not disclose the nature of the Antigua Casa Pardo. Mr Osona had told Mr Goler that he should store the objects until further notice and eventually sell them since Mr Osona was no longer interested in them.

35 Mr Goler says that he sold a ‘large portion’ of the objects in the collection to Mr Hugo A Arias, a resident of Miami, and that this occurred sometime between 1965 and 1970. An affidavit sworn in 2009 by an Edma Nelly Esper reveals that both she and Mr Arias lived in Miami between 1971 and 1973 and that they were married at some point (although by the time of her affidavit it appears that Mr Arias had passed away and she lived in Buenos Aires). Although it is not entirely clear, the affidavit is consistent with Mr Arias having died in 1973 and Mr Arias’ collection having devolved upon her. She said that the collection included five stone cups between 10 and 30 cm in height with engraved decorations from Bolivia. She also said that she was keeping the entire collection in Denver.

36 The Artefact next appears to have surfaced at the Artemis Gallery and to have done so by no later than 18 October 2017. On that date, Stoetzer, Inc Fine Art Services provided the Artemis Gallery with a report which was signed by Mr Nicholas Stoetzer and Mr Robert Stoetzer. It was their opinion that the Artefact was consistent with a period of manufacture of 400-900 AD and was a fine example of the craftsmanship and artistry of the Tiwanaku.

37 The Artefact was then put up for sale by auction on a website, www.liveauctioneers.com, as lot 144 and entitled ‘Important Tihuanaco Stone Kero w/ Stoetzer Report’. The auction closed at midnight on 5 June 2020. The successful bidder was the Applicant and an invoice was issued by the Artemis Gallery dated 4 June 2020 in the amount of USD$17,340.00 which included a buyer’s premium of 24.5%. I am unable to account for why the invoice is dated the day before the sale. The Artemis Gallery itself appears to be located in Louisville, Colorado. The gallery provided a certificate of authenticity which described its provenance as being ‘private Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, USA collection acquired before 1995; acquired from private Argentina collection from the 1950s’. The certificate carried a guarantee by the gallery’s founder and executive director, a Mr Dodge, that ‘The above item is guaranteed to be of the time period and condition as described, has been exported legally and is legal to buy and sell under all international laws relating to cultural patrimony’.

38 The Artefact was then shipped by FedEx to Melbourne on or about 24 June 2020 in the manner already described and seized. This, then, is all that is directly known about the modern history of the Artefact.

39 There are, I think, some significant problems with this account. For example, there is nothing which directly links the Artefact to being one of the objects in Mr Osona’s collection. Although I would infer that the five stone vessels held by Ms Esper in Denver in 2009 were the same vessels mentioned by Mr Goler as being in Mr Osona’s collection, there is nothing which shows that the Artefact was one of those vessels because there are no photographs of any items in the collection. The best that can be said is that the Artefact matches the description on Mr Goler’s list of being a stone cup with feline figures and engravings.

40 Making the assumption that the Artefact is one of the vessels on Mr Goler’s list, there is also nothing which explains how it made its way from Ms Esper’s collection in Denver (where it certainly was on 20 March 2009 when she swore her affidavit) to the unidentified private collection in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Further, whilst the Artemis Gallery certificate states that the private collection in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania had acquired the Artefact before 1995, it is evident from Ms Esper’s affidavit that the collection now said to have included the Artefact had been owned by her or Mr Arias between 1973 and 2009 and before her by Mr Goler and Mr Osona. There is no space in that chronology for the private collection in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania to have acquired the Artefact prior to 1995. Of course, it might be that Ms Esper’s collection is the private collection in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. But Denver is not Pennsylvania and if Ms Esper or her estate were the holders of the private collection in Harrisburg then it is odd that no one appears to have thought it worthwhile to say so. It might be possible that Ms Esper disposed of the Artefact (or perhaps died) after 2009 and it was afterwards acquired by the interests in Harrisburg, whoever they are, but this is inconsistent with the assertion that those interests acquired the Artefact before 1995.

41 Were it necessary to decide therefore whether the Artefact was one of the stone vessels that had been acquired by Mr Osona in the 1950s in Argentina, I would not be satisfied that it was. However, this was not an issue between the parties (although Dr Yates was also understandably underwhelmed by the provenance documentation). The parties conducted the case on the basis that there was no evidence that the Artefact had been in circulation prior to the 1950s which is certainly true for there is no other evidence about its origins except for the history relating to Mr Osona.

42 Against that backdrop there was no reason for either party to contend that the Artefact in fact originated from somewhere else at some later time. As such, now to make a finding that the Artefact is not the object acquired by Mr Osona would give rise to two related problems. First, neither party has been heard on the proposition which would therefore be procedurally unfair. Secondly, not having heard from either party it is possible that other evidence might have been available which would have explained how the Artefact made its way from Denver to Harrisburg. In that circumstance, it is especially necessary to avoid reasoning that the evidence which has been adduced is the complete universe of evidence particularly where that evidence has not been assembled with a view to dealing with this issue. For example, if this had been known to be an issue the Applicant might well have called as a witness Mr Dodge to explain who the owners of the private collection in Harrisburg were.

43 In that situation, I conclude that the Artefact first surfaced in the 1950s in Buenos Aires in Mr Osona’s collection. The nature and significance of that conclusion may be weighed against the earlier observations I have made about the nature of fact finding in a civil trial.

4. THE SCIENTIFIC ANALYSIS OF THE ARTEFACT

44 Two witnesses gave the principal evidence about what could be gleaned from examining the Artefact. The first was Professor John Mavrogenes. He is a professor at the Research School of Earth Sciences at the Australian National University and produced a report dated 20 October 2021. In that report he said that he had inspected the Artefact and was certain that it was made from black basalt. Professor Mavrogenes has been a geologist for 35 years and has a PhD in geochemistry. I find that the Artefact is made from black basalt.

45 He also said that if it were possible to take a sample from the Artefact one might be able to determine the origin of the black basalt from which it had been carved. However, he had not been permitted to take a sample from the Artefact. I accept this evidence. During the course of the trial I suggested to the parties that it might be useful to take a sample from the Artefact and to test it in the manner suggested by Professor Mavrogenes so that the source of the basalt could be definitively identified. As will be seen, there is evidence that the Tiwanaku extracted basalt from ancient quarries near Tiwanaku and here the thinking was that if the chemical composition of the basalt from which the Artefact had been carved matched the chemical signature of the basalt in these quarries then this would assist in proving it had been made at Tiwanaku. By the conclusion of the trial, however, the Artefact had not been tested in this fashion.

46 Professor Mavrogenes inspected the Artefact a second time on 25 January 2022, which included a microscopic examination, as a result of which he produced two further short reports dated 2 February 2022 and 4 February 2022. In the first report, he expressed the opinion that the Artefact was made from a single piece of black basalt but had been broken at one point and repaired. The breakage and repair were on its main body on the side opposite to the animal head. I accept this evidence.

47 In the second report he explained that he was unable to determine the age of the Artefact without more involved analysis. However, he said that fresh basalt is glassy and does not have a patina. The Artefact has a patina which Professor Mavrogenes thought would have taken hundreds of years to develop. In relation to the portion which had been repaired he noted that the patina was less developed which led him to conclude that the Artefact was broken a long time after it had been initially made. He estimated the time between the initial manufacture of the Artefact and its breakage to be between tens of years to hundreds of years.

48 The second witness was Ms Sarah McHugh. She is the Senior Object Conservator at the National Gallery of Australia and holds a Master of Applied Science (Materials Conservation) from the University of Canberra. She has expertise in materials science, the chemistry of materials including their analysis, the conservation of works of art (and other objects) and the methods and techniques which exist for their restoration and preservation. She has worked as an object conservator since 2003. Ms McHugh examined the Artefact on 28 January 2022 at the National Gallery to which the object was brought for that purpose. The examination was conducted under ambient light, with magnification and under ultraviolet light. She also took x-rays of the Artefact.

49 From her examination Ms McHugh concluded that the Artefact been made without the use of modern methods of manufacture and that its surface was consistent with it being a pre-Columbian stone artefact. It was her view that the chipped uneven edges of the incising on the sides of the vessel and the absence of any striations from abrading within the incised grooves suggested that the incising was achieved by the percussive action of hitting a sharpened tool into the stone to chip it, rather than a modern engraving implement which abrades the lines away. She thought that the surface of the Artefact was consistent with it having been produced using non-mechanical hand tools. For completeness, the incising on the sides of the vessel to which Ms McHugh referred related to the figures and other motifs which appear around the Artefact’s body and about which there is a lively debate concerned with iconography. Ms McHugh’s point is that the figures and motifs were made by hitting a sharpened tool into the basalt (‘chipping’) rather than scraping the stone to make the lines with a modern engraving tool.

50 Like Professor Mavrogenes she thought that it had been repaired at some stage, most likely within the last 30 years, and that it had been carved from a single piece of stone. The 30-year estimate derived from her consideration of the nature of the repairs which she felt were modern in nature and not executed with a particularly high level of skill. She observed that evidence of restoration was consistent with an older object. Here the thinking was that it is unlikely that someone would bother seeking to restore to its original state an object which was not old. Ms McHugh was not required for cross-examination. Neither party suggested that Ms McHugh’s evidence raised the possibility that the Artefact had been excavated in the 1990s (and damaged during that process) and it is not open to consider such a hypothesis (although noting that it would fit with the difficulties presently associated with understanding how the Harrisburg interests acquired the Artefact prior to 1995).

51 In addition to these matters, the certificate issued by the Artemis Gallery states that the Artefact is 30.5 cm high and 21.9 cm wide. There is no reason to doubt this aspect of the certificate.

52 As I have said, by the end of the trial neither party had applied for an order that a sample should be taken so that an attempt might be made to match the Artefact to the basalt quarries located near Tiwanaku. The Applicant submitted that the Court should infer that such testing would not have assisted the Commonwealth. I do not accept this submission. Neither party had the ability to test the Artefact without the permission of the other. Prior to the making of a forfeiture order, the Applicant continues to own the Artefact and the Commonwealth, whilst having custody of it, has thereby no right to damage it by taking a sample from it. Correspondingly, the Applicant cannot test the Artefact because it does not have possession of it. The only way through this would be for both parties to co-operate or for one to apply to the Court for an order for testing. Neither of these paths were pursued. I do not think in that circumstance it would be appropriate to draw any inference about the failure of either party to arrange for testing.

53 The Applicant accepted the evidence of Professor Mavrogenes and Ms McHugh ‘so far as it goes’: ACS [20]. On the basis of the provenance evidence and the evidence of Professor Mavrogenes and Ms McHugh, I make these findings:

(a) the Artefact is made from a single piece of black basalt and is 30.5 cm high and 21.9 cm wide;

(b) the figures and motifs on the side of the vessel were incised with the percussive action of a sharpened tool rather than by engraving with a modern tool;

(c) the Artefact was manufactured not less than hundreds of years ago;

(d) its surface is consistent with it being of pre-Columbian origin;

(e) it was damaged long after it was manufactured (due to the different levels of patination on the damaged portion) with the damage occurring between tens and hundreds of years after it was manufactured;

(f) it was repaired at some stage in around the last 30 years in a manner which was not particularly expert; and

(g) it first surfaced in the 1950s in Buenos Aires.

5. WAS THE ARTEFACT MADE BY THE TIWANAKU?

54 It is necessary to deal with a number of matters:

(a) the witnesses: Mr Condori, Dr Young-Sánchez, Dr Vranich and Dr Yates;

(b) the general history of the Tiwanaku;

(c) whether the Artefact is an example of a ceremonial drinking vessel known as a kero; and

(d) the iconography and morphology of the Artefact.

(a) The witnesses

Mr Julio Condori Amaru

55 Mr Condori was the Executive General Director of the Centre for Archaeological Anthropological Research and Administration of Tiwanaku from 14 May 2015 to 11 January 2021. He is now a Registration and Assessment Expert of Archaeological Projects and Historical Sites within the Bolivian Ministry of Cultures, Decolonisation and Depatriarchalisation. His work has involved the management of museums and the ruins of Tiwanaku, where he has also carried out research projects.

56 Mr Condori was called by the Commonwealth and provided reports dated 15 September 2021 and 11 January 2022. These reports were prepared with Mr Erick Leonel Ovando Lopez but Mr Lopez did not give evidence and I proceed on the basis that the reports are to stand as the evidence of Mr Condori. In Mr Condori’s opinion the description, shape, style and type of manufacture of the Artefact indicated that it was most probably from the Tiwanaku ruins. He thought that the Artefact had been created between 300 and 800 AD.

57 Mr Condori gave his evidence on the first day of the trial from Bolivia by means of an imperfect video link and with the aid of a Spanish interpreter. He was extensively cross-examined. A number of specific challenges were made to Mr Condori’s evidence which I will deal with as the need arises. However, more generally Mr Lancaster SC for the Applicant submitted that Mr Condori was an employed representative of the Bolivian government and could not be regarded as a truly independent expert. I accept this submission although noting that in the case of culturally important objects the experts in the area are often likely to include employees of the government of the nation in question. To my observation, Mr Condori was an enthusiast for the return of the Artefact to Bolivia. I do not think this impacted on his expertise but I have taken it into account in assessing the use to which his evidence should be put.

Dr Donna Yates

58 Dr Yates is an associate professor of criminal law and criminology at Maastricht University in the Netherlands and prior to this was a senior lecturer in antiquities trafficking and art crime at the University of Glasgow’s Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research. She holds a bachelor’s degree in archaeology from the Boston University which focussed on Latin American archaeology; a master’s degree from the University of Cambridge which focussed on the international market for South American archaeological objects in response to changes in law and policy; and a PhD in archaeology also from the University of Cambridge. The subject matter of her thesis was 20th and 21st century Bolivian archaeological law and policy within the local and international context. She has published widely on Bolivian cultural objects and the trafficking of archaeological and historic objects out of Bolivia. In addition she spent two years in 2005 and 2006 working as an archaeologist at the monumental core of Tiwanaku. She has given expert commentary relating to Bolivian cultural objects to the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, the US State Department and the Bolivian Embassy in London. She also provides primary identifications of seized Bolivian cultural objects for the World Customs Organization.

59 Dr Yates was called by the Commonwealth and provided a report dated 22 October 2021 and a supplementary report dated 9 February 2022. In her opinion, the Artefact had been made at Tiwanaku by the Tiwanaku. She believed that it had been removed from Tiwanaku by looters around 1950. She gave her evidence by means of a virtual platform from the Netherlands during a concurrent session with Dr Vranich (who was in Warsaw) and Dr Young-Sánchez (who was in Auckland) and was examined extensively.

60 A number of specific challenges were made to Dr Yates’s evidence by the Applicant and I will deal with these as I come to each topic. However, a general challenge was made to her expertise with which it is convenient to deal at this point. It was submitted that Dr Yates did not have a significant depth of personal experience in the identification of Tiwanaku artefacts. I do not accept this submission. Whilst it is true that on a number of topics Dr Yates deferred to the views of Dr Vranich I do not think that this signifies that she lacked significant expertise herself. Thus for example, although she thought that Dr Vranich could say more on the general topic of the Tiwanaku culture she was happy to do so herself and indeed did so: T70.1-15. The same may be said in relation to her deferral to Dr Vranich on the topic of the relationship between the Tiwanaku and the Wari: T76.8-15. I do accept that she did defer to the expertise of Dr Vranich on the topic of the source of basalt for Tiwanaku objects: T81.1-9. I do not accept the submission that T99.22-23 shows that Dr Yates deferred to Dr Vranich on the topic of the design features of the Artefact – this appears to be evidence about an entirely different topic. Likewise, it does not seem to me that Dr Yates deferred to Dr Vranich on the topic of 19th century expeditions at T10.32-33 although I do accept that Dr Vranich was more expert on that topic than Dr Yates. The Applicant submitted that in relation to significant issues, Dr Yates in her report ‘simply adopted other analyses’ provided to her by the Commonwealth. However, this submission does not appear fairly to characterise Dr Yates’s consideration of those other analyses. I am satisfied that the sections of Dr Yates’s report to which I was directed by this submission (Court Book (‘CB’) 78 and 81) show that she has independently evaluated the claims in those other analyses before discussing their significance.

61 The Applicant also drew my attention to a portion of Dr Yates’s examination during the concurrent session at T114.1-4. The full passage is at T113.39-114.8:

MR LANCASTER: Dr Yates, can I ask you a similar question to one of my earlier questions to Dr Vranich. Do you accept that it’s a fair summary of your methodology that you came to an early first impression that this was a Tiwanaku object and after that point you were looking for conclusive proof that it was not a Tiwanaku object to dissuade you from that initial view?

DR YATES: I think that that’s a mischaracterisation in that, yes, being shown the piece, my initial reaction was that it was a Tiwanaku object. But my research methodology focused mostly on comparability. Not to disprove the Tiwanaku identification, but also to prove it. So this involved looking at comparable objects from archaeological excavations in museums. It involved reading academic papers and books. It involved finally getting around to reading a whole book on experimental archaeology related to the creation of Tiwanaku stonework. So I – I think that I approach this in a more holistic way than you’re describing. Yes, there was an element for looking for derivations from possibility, but there is also an element of looking at, you know, comparing it to pieces that we know about to – just to see – see how it compares, if that makes sense.

62 The submission was that this showed that Dr Yates’s expertise had been acquired quite recently rather than being the result of deep research and long-standing knowledge. I think there is little in this criticism. I do not see how a close examination of the iconography and provenance of the Artefact could not involve consulting other works and it would be implausible to think that any of the experts carried around in their heads the details both as to form and source of every Tiwanaku object. I do not think that this answer shows that Dr Yates was a Tiwanaku ingénue who had read up on the topic in order to give her evidence.

63 A part of Dr Yates’s evidence touched on the topic of the location of the nostrils on the feline of the Artefact which I deal with in detail later in these reasons. However, her cross-examination showed that in between the two days over which the concurrent session was conducted and after the completion of the first day during which the topic of the nostrils had been introduced, Dr Yates had resorted to Twitter, as it was then known. She had done so to see if she could find a feline head with its nostrils set back from its teeth (the curious relevance of the nature of this inquiry will later emerge). The Applicant submitted that she had thereby attempted to ‘crowd-source’ this information and, as I apprehended the submission, this too showed that she lacked expertise.

64 I do not accept this submission. Dr Yates was simply trying to track down an object with the requisite snout. It is true that Dr Young-Sánchez had indicated in her report that the location of the feline’s nostrils was anomalous, an observation which supported her predominant thesis that the Artefact was a modern fake or pastiche. No doubt, it would have been preferable if Dr Yates had endeavoured to find a feline whose nostrils were set back from its mouth when she prepared her report in reply. But I do not think it redounds on her credit either that she did not do so or when subsequently it became clear that she was being cross-examined closely about it, that she sought to redress this deficiency. That she chose to do so on Twitter is no doubt modern but I do not think that it shows that she is not an expert. An insinuation was made during her cross-examination that she had in fact been attempting to find an object with a particular provenance feature for the second day of the concurrent session. I record for completeness that I accept Dr Yates’s evidence that the reason she went looking for the object was related to the nature of its snout.

65 I therefore reject the Applicant’s challenges to Dr Yates’s expertise. There was also a general submission that she was extremely reluctant to concede obvious propositions that went against the Commonwealth’s case. I will deal with the individual criticisms on which the submission rests as they arise, however, as a general proposition I do accept that Dr Yates was, like Mr Condori, something of an enthusiast for the return of items of Bolivian cultural heritage. I do not agree with the Applicant that this means that her evidence is of no value but I do accept that in assessing her evidence one must filter out the reasoning on which her evidence rests (which is in my view valuable) from her background enthusiasm.

Dr Alexei Vranich

66 Dr Vranich is from the Archaeological Institute of Archaeology at the University of Warsaw. He received his PhD in 1999 for his dissertation entitled ‘Interpreting the Meaning of Ritual Spaces: The Temple Complex of Pumapunku, Tiwanaku, Bolivia’ and has held academic positions at several universities. The Pumapunku is the Gateway of the Puma at Tiwanaku and some of the evidence in the case turns on it. Dr Vranich has published widely on the Tiwanaku and has extensive archaeological experience in the field. This field experience included 10 years as the co-director and principal investigator of an archaeological project at Tiwanaku between 1996 and 2006. Having surveyed his curriculum vitae it is evident that he has devoted a significant portion of his professional life to Tiwanaku and the Tiwanaku culture.

67 Dr Vranich provided a report dated 17 May 2021 and a supplementary report dated 19 February 2022. His evidence dealt with three questions: (i) when was the Artefact made; (ii) where was the Artefact made; and (iii) in what circumstances was it removed from Bolivia? As to the question of when the Artefact was made, it was Dr Vranich’s opinion that the design of the Artefact indicated that it had been made during the pre-Tiwanaku Period or the Tiwanaku Period which collectively went from 100 BC to 950 AD. He thought it likely that the date of manufacture was towards the end of these two periods and narrowed the range to 500-1000 AD which he identified as the Middle Horizon Period.

68 As to the question of where the Artefact was made, it was Dr Vranich’s opinion that the Artefact came from the ruins at Tiwanaku. He accepted that the Tiwanaku culture was present in places other than Tiwanaku and that there were other sites in Chile and Peru. However, he did not think that the Artefact could have come from any site apart from Tiwanaku. The reason for this conclusion was that the Artefact was an advanced piece of stonework and advanced stonework in Tiwanaku culture had been found only at Tiwanaku itself. He accepted that it was true that a carved stone object had been found at the site of Lukurmata, one valley to the north of Tiwanaku (in Bolivia), but even that had been made at Tiwanaku and dragged over the low hills.

69 As to the question of how the Artefact came to leave Bolivia, Dr Vranich favoured the view that the Artefact had been removed from Tiwanaku during excavations conducted by the Argentinian archaeologist Dr Eduardo Casanova in 1934 and transported by train to Buenos Aires.

70 Dr Vranich gave his evidence by means of a virtual platform from Warsaw during the concurrent session with Dr Yates and Dr Young-Sánchez and, like Dr Yates, was examined extensively. A number of challenges were made to his evidence which I will deal with as the need arises. Like Mr Condori and Dr Yates, I do think that Dr Vranich was also an enthusiast for the return of the Artefact to Bolivia. However, as in their cases, I do not think that this requires the rejection of his evidence, just some care in its use.

Dr Margaret Young-Sánchez

71 Dr Young-Sánchez is presently the head of exhibitions and collection services at the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. She holds both a Bachelor and a Master of Arts in anthropology from Yale University and a PhD from Columbia University. Her PhD dissertation was on the art of Peru’s Central Coast from 800-1100 AD. She has extensive experience in pre-Columbian cultures generally and the Tiwanaku culture in particular having worked in her field for 40 years. For 30 years she served as a curator of pre-Columbian art at the Cleveland Museum and later the Denver Art Museum. In 2004, following years of research at Tiwanaku and at museums holding Tiwanaku artefacts, she organised an exhibition at Denver Art Museum entitled ‘Tiwanaku: Ancestors of the Inca’ which was (and remains) the most significant museum presentation of Tiwanaku art ever staged.

72 Dr Young-Sánchez was called by the Applicant and provided a report dated 21 December 2021. Her initial opinion was that the Artefact was a fake or pastiche but she had largely revised this opinion by the time of the hearing. In her view, the iconography of the Artefact had several elements which could not be found in other Tiwanaku objects. It was her view that the Artefact had been made by someone familiar with the Tiwanaku culture but inexpert in its application.

73 Dr Young-Sánchez gave her evidence by means of a virtual platform from Auckland during the concurrent session with Dr Yates and Dr Vranich. She was extensively examined. Both Dr Vranich and Dr Yates clearly respected the opinion of Dr Young-Sánchez although they differed from it. I accept the Applicant’s submission that this shows that they accepted her views, especially on the question of provenance, as legitimate, defensible and respectable. I think it may fairly be said that all three witnesses respected each other’s views. I do not think, however, this advances debate in either direction.

(b) The general history of the Tiwanaku

74 The experts were largely in agreement about the overarching facts of the Tiwanaku culture. Dr Yates described the Tiwanaku as an ancient culture that rose to prominence in the Andean Middle Horizon in the period from 600 to 1000 AD and which was based on the Bolivian high plain, or altiplano, in the Lake Titicaca basin. It appears to have been preceded by the Pucara civilisation. Dr Young-Sánchez said that Lake Titicaca and Tiwanaku had later been used by the Inca as sacred places of origin and pilgrimage until the Spanish conquest in the 16th century. The Inca capital, Cuzco, lies hundreds of miles north of Tiwanaku in Peru.

75 Dr Yates explained that the Tiwanaku culture was well-known for its masterful stonework which was particularly exemplified by the city of Tiwanaku. The city comprises monumental structures including temples and pyramids as well as large and small sculptural works. Dr Young-Sánchez thought that interest had long been focussed on Tiwanaku’s finely cut and fitted stone masonry, monumental stone gateways, lintels and statues, some of which were decorated with animals, supernatural beings and geometric motifs.

76 All parties accepted that Tiwanaku was the primary city of the Tiwanaku culture. Dr Young-Sánchez said that only a small part of Tiwanaku had been documented in detail. Fundamental questions still remained about important aspects of the city including its construction history and the functions of its major architectural structures.

77 Dr Vranich observed that the Tiwanaku civilisation extended across the modern-day Bolivian border into what are now Peru and Chile, a view with which Dr Yates, Dr Young-Sánchez and Mr Condori agreed. Dr Young-Sánchez added that at one time it was thought that Tiwanaku was the capital of a great empire which had controlled territories in Bolivia, Chile, Peru and Argentina. However, the present view was that its sphere of direct cultural influence was more limited, extending only into southern Peru and northern Chile. Dr Yates felt that the primary archaeological sites were nevertheless in the Bolivian heartland. Mr Condori thought that the Tiwanaku culture was located on the south-eastern side of Lake Titicaca and radiated from Tiwanaku towards inter-Andean valleys, reaching the coastline, although this latter claim was refuted by Dr Vranich, who said that no Tiwanaku sites have been found along the coast: T71.20-23.

78 According to Dr Yates, the nature of the relationship between the sites in Chile and Peru and the Bolivian heartland has been the subject of much discussion. The discussion had ranged from those sites being colonies of the Bolivian Tiwanaku people, possibly sent there for the purposes of trade, through to them being politically separate from Tiwanaku. In her supplementary report Dr Yates indicated that most scholars now assumed that the true position lay somewhere between these two poles. Dr Young-Sánchez thought that these settlements were linked to Tiwanaku by trade and kinship ties, with llama caravans transporting goods between the regions.

79 However, there was no real dispute between the witnesses that the sites in Peru and Chile were Tiwanaku. Dr Yates and Dr Vranich each volunteered the connection and Dr Young-Sánchez gave slightly more detailed evidence about it, noting the tomb excavations which had been carried out in the Moquegua Valley in southern Peru and the Atacama Desert in Chile. I will refer to these sites as being Tiwanaku sites for the sake of convenience but in doing so I do not mean to step into the debate as to whether the people within the Tiwanaku sphere of direct cultural influence were the same people as the Tiwanaku at Tiwanaku and, in particular, the question of whether they were ethnically the same. For the purposes of the Applicant’s case it is sufficient that they lie within the sphere of direct cultural influence.

80 It is open to infer, and I do, that the Tiwanaku culture rose to prominence roughly between 600 and 1000 AD and was centred around the ancient city of Tiwanaku on the south-eastern side of Lake Titicaca. The culture extended to sites in the Moquegua Valley and the Atacama Desert.

81 The difference between the witnesses about the Tiwanaku settlements in Chile and Peru lay in their differing views about the extent of the stonework carried out in those places. I will return to this topic when I come to deal with the important issue of basalt below.

82 A general point Dr Young-Sánchez made about the Tiwanaku culture was that the number of objects which were in museums and collections was small when compared to other Andean civilisations such as the Inca, Moche or Wari. She thought that this related not only to the export restrictions imposed by the Bolivian government in the 20th century but also the Tiwanaku’s limited manufacture of artworks which were in media durable enough to survive centuries of burial in the Andean altiplano’s harsh climate.

(c) Could the Artefact be a kero?

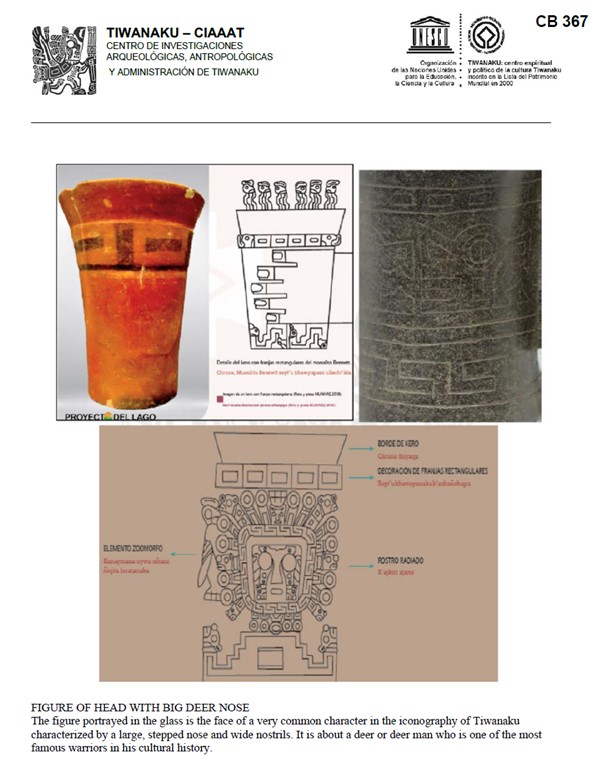

83 Dr Yates explained that a kero was a particular vessel shape common to the Andes typically consisting of a cylindrical cup without a handle and with a flaring upper edge. Here are some pictures of Tiwanaku ritual keros:

84 Dr Young-Sánchez added keros were used at Tiwanaku and elsewhere in the Andes for drinking corn beer which was an essential element in feasting and religious ritual. On the other hand, Mr Condori was of the view that kero ceremonial vessels were peculiar to and characteristic of the Tiwanaku culture. I do not accept Mr Condori’s evidence to the extent that it suggests that there are no keros in other ancient Andean civilisations. It is contradicted by the evidence of Dr Yates and Dr Young-Sánchez.

85 Dr Yates explained that whilst ceramic keros are common at Bolivian Tiwanaku sites, the Artefact was made from stone which made it extremely rare in the canon of known Tiwanaku sculptural works. In her report, Dr Young-Sánchez thought that basalt had been used at Tiwanaku for making vessels such as keros. This evidence may be reconciled by concluding that basalt keros at Tiwanaku were very rare although not unknown. On the other hand, it was also Dr Young-Sánchez’s evidence that basalt keros found at Tiwanaku were typically much smaller and had much thinner walls than the Artefact. She also made the point, which has the advantage of common sense, that the Artefact’s thick walls, large size and heavy weight made it completely impractical for use as a drinking vessel. It was her view that there were no comparable keros in Tiwanaku culture. I accept this evidence.

86 I therefore find that: (a) the use of basalt to make keros at Tiwanaku was relatively unusual but the extant basalt keros are smaller, have thinner walls and weigh less than the Artefact; (b) the Artefact is not practical for use as a kero in the sense that it is hard to imagine a person comfortably quaffing corn beer from it; and (c) its weight and size make it an especially rare find. The Applicant sought to muddy these waters at ACS [88(a)] by pointing out, correctly, that other Andean cultures also worked in basalt, instancing a winged figure currently held in the National Anthropological Museum of Peru at Lima. As I later explain, this object appears to have been made by the Pucara civilisation which preceded the Tiwanaku civilisation. However, in the absence of a suggestion from the Applicant that the Artefact was made by the Pucara civilisation (which there was not), I do not see that this has any relevance. More generally, whilst I am content to assume that there were other Andean civilisations which worked in basalt, in the absence of any evidence which suggests that the Artefact was made by such a civilisation, this likewise goes nowhere. For completeness, I note that the Applicant’s submission at ACS [88(a)] also references a ‘winged puma figure’ located at page 5 of Exhibit 3. This is the object that was purchased by the Peruvian doctor at Puno, now located at the Ethnological Museum of Berlin, and is believed to be a Tiwanaku object. I have proceeded here on the basis that it is the Pucara object being referred to as this submission would not make sense otherwise.

87 Returning to the task at hand, the conclusion that the Artefact is not actually likely to have been used as a kero does not negate the possibility that it is a sculptural depiction of a kero rather than an actual kero. It will be recalled Dr Young-Sánchez herself gave evidence that the kero was an essential element in feasting and religious ritual and Dr Yates expressed the opinion that the kero was significant in the Tiwanaku culture. It would therefore not be entirely surprising to find sculptural depictions which include keros. While this deductive observation would of course be purely speculative without more, it is borne out by the evidence of Dr Yates who provided an example of a large stone figural sculpture at Tiwanaku holding a kero. Dr Yates also said there were other examples at Tiwanaku and nearby Bolivian Tiwanaku sites of stone figures holding keros. This was consistent with the evidence of Mr Condori who said that keros could be found in the sculptural iconography of the Tiwanaku culture. In her report, I did not apprehend Dr Young-Sánchez to take issue with this proposition which I therefore accept.

88 Thus whilst Dr Yates accepted that generally keros were ceramic vessels she thought the Artefact appeared to be a stone rendering of a ceramic kero. Dr Vranich went somewhat further. It was his view that the Artefact was ritual in nature. First, he thought that the intact nature of the Artefact indicated that it had been buried (and therefore protected from the depredations of open exposure). Whereas Professor Mavrogenes had deduced from the Artefact’s patina that it was at least hundreds of years old, Dr Vranich saw evidence that the Artefact had been very often touched. In particular he thought that the surface of the protruding feline head had a gloss, an observation from which he was inclined to infer that it had been frequently touched and had therefore been an object of veneration. The burial of a venerated object suggested to Dr Vranich that it was ritually significant.

89 I would accept Dr Vranich’s evidence that the Artefact had been buried because it is difficult to see how an object at least hundreds of years old could be in such an intact condition otherwise. However, I do not think I could find on the state of the evidence that the Artefact had been venerated because of the patination pattern on the feline head which, at this stage, cannot be said to be more than admittedly informed speculation. As I have explained above, I do not mean by this to suggest that the Artefact was not venerated as Dr Vranich suggests, only that in the context of a civil trial I am not affirmatively persuaded that this is so.

90 However, I am satisfied that the Artefact was ritual in nature. Dr Vranich’s view that the Artefact was ritual is consistent with the following facts: (a) its fashioning from basalt was labour intensive and suggests that it was a prestigious object; (b) it is a depiction of a kero; (c) keros were used in ritual ceremonies involving the drinking of corn beer; and (d) the Artefact is not practically useful for drinking corn beer. This view is also supported by the evidence of Mr Condori who likewise thought that the Artefact was used for ceremonial or ritual purposes. The Applicant submitted that Mr Condori provided no evidentiary basis for his conclusion that the Artefact was ritual in nature (ACS [52(e)(i)]), which is correct. On the other hand, I do not accept the criticism made by the Applicant at ACS [52(e)(ii)] that there was a tension between Mr Condori’s evidence that ceremonial or ritual objects were not found outside Tiwanaku and the evidence he gave at T43.8-19 that ceremonial objects assumed to have been made at Tiwanaku were found in Chile and Peru. At T95.44-45 Dr Young-Sánchez thought that feline figures tended to get used in high-prestige objects which were sometimes religious. Further, when giving evidence about the rate of change of stylistic elements part of her reason for saying that variations would be slow was that the Artefact had a religious purpose (T107.12), a view with which Dr Yates agreed (‘Absolutely, I completely agree with that’): T107.17.

91 I am satisfied that the Artefact served a ritual purpose of some kind.

92 The evidence can reasonably sustain the drawing of an inference that the Tiwanaku culture included not only ceramic and occasionally smaller basalt keros which were used for ritual or feasting purposes but also sculptural depictions of keros in stone. I am affirmatively persuaded that this is the case and therefore draw this inference.

93 As such, I do not accept Dr Young-Sánchez’s point that the basalt Artefact’s cumbersome size and weight make it unprecedented in the Tiwanaku culture. No doubt this is true if attention is confined to actual drinking vessels but I do not think that Dr Young-Sánchez’s evidence dealt with the implications of the Artefact perhaps being a sculptural depiction of a kero rather than a functional kero. As Dr Vranich observed on this topic, many people wear crucifixes whose design features differ markedly from the real thing.

94 Of course, this does not mean that the Artefact is, in fact, a basalt depiction of a kero. Rather the point is that the fact that the Artefact is made from basalt and is too large and heavy for practical use as a kero does not negate the possibility that it is a sculptural depiction of a kero.

(d) The iconography and morphology of the Artefact

95 At this point it is helpful to provide an additional angle from which to view the Artefact:

96 Most of the evidence about iconography and morphology was given by Dr Yates, Dr Young-Sánchez and Mr Condori although Dr Vranich was also cross-examined about it. Dr Yates thought that the Artefact was decorated with incised geometric and faunal designs and was fronted with the projected head of a feline on a square base. I did not apprehend this evidence to be disputed by anyone. Rather, the debate centred around what the designs depicted actually were and the extent to which the designs and the projected feline head on a square base could be said to be within the canon of the Tiwanaku culture.

97 Thus what is required is a comparison between the Artefact on the one hand and, on the other, what is known from the archaeological record of the Tiwanaku about incised designs and feline heads projecting from square bases.

98 Dr Young-Sánchez opened the batting on this topic by pointing out the paucity of the archaeological record and the fact that the Tiwanaku culture had been understudied in relation to other pre-Columbian cultures. She observed that the study of the specialised art history of the Tiwanaku, including their stylistic conventions, had been hampered by the very limited number of trained researchers working in the field as well as the comparatively small body of well-preserved artworks. Whilst it was true that stone, ceramics, metal and bone were preserved in the archaeological record, other less durable materials had not endured at Tiwanaku and the vast majority of excavated artefacts were fragmentary in nature. The preservation of less durable artworks was, on the other hand, greater in extent in the more arid regions of Peru and Chile. It is also useful to recall her evidence that the documentation of the Tiwanaku site is not yet anywhere near complete. She also thought that there was only a tiny body of published art historical literature.

99 To my mind Dr Young-Sánchez’s observation does not perhaps go very far on this particular topic. As will be seen, the evidence of Dr Yates attempted to match the iconography of the Artefact to what is presently known about the iconography and morphology of the Tiwanaku culture. The fact that the available range of Tiwanaku objects is limited to what is available in stone, ceramics, metal or bone does not really detract from her point that the incisions on the Artefact and its protruding feline head correspond with what is apparent from the archaeological record which already exists.

100 The fact that less durable objects have not endured into modern times or that many of the durable items are fragmentary in nature does not detract from the point Dr Yates is making. In particular, in the counter-factual world in which what remains at Tiwanaku now includes in an intact state all the objects which are fragmentary and all of the objects made from less durable materials, this would not logically be capable of detracting from Dr Yates’s matching of the iconography of the Artefact to those objects which have in fact endured into modern times. For example, if, as Dr Yates thought, the use of a deer motif was distinctive of the Tiwanaku culture because a deer motif could be discerned in the existing archaeological record, this conclusion could not be dented merely because many objects may have been lost which might have proved the popularity amongst the Tiwanaku of, say, an eagle motif. Put another way, future finds will not be capable of extinguishing the fact that what has already been uncovered shows that the Tiwanaku used deer motifs. I do not think therefore that the limited nature of the archaeological record can rationally erode Dr Yates’s opinions on the Artefact’s iconography.

101 Further, whilst I accept that less durable objects have been retrieved from the sites in Chile and Peru, Dr Young-Sánchez did not point to any of these objects in her explanation of why the Artefact was not an example of the Tiwanaku culture. One reason for this may be the logic of the previous paragraph. At best, they might have shown other features not present on the Artefact but this would not have advanced the debate for the reasons I have given.

102 Having cleared that point away, the parties were in dispute about the correct interpretation of six stylistic elements of the Artefact. These were:

stylised figures which appear on the body of the vessel;

a pattern on the lower portion of the vessel referred to as a meander or Greek key;

a band around the top of the vessel which contains small rectangles;

the feline head which protrudes from the body of the vessel and is mounted on a square base (and the related question of whether the Artefact depicts a kero or an incensario);

the crossed canines of the feline and the number of its front teeth; and

the position of the nostrils on the protruding feline head.