Federal Court of Australia

Sherrin Rentals Pty Ltd, in the matter of Herbert v Herbert [2023] FCA 1323

ORDERS

IN THE MATTER OF RODNEY HERBERT | ||

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application for the review of the sequestration order made by the Registrar on 31 May 2023 be dismissed.

2. For the avoidance of doubt, the sequestration order made against the estate of RODNEY HERBERT by the Registrar on 31 May 2023 is affirmed.

3. The petitioning creditor’s costs of and incidental to the application filed on 20 June 2023 be taxed and paid in accordance with the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) on the footing that they form part of the petitioning creditor’s costs in respect of the creditor’s petition presented on 17 March 2023.

The Court notes that the date of the act of bankruptcy is 28 DECEMBER 2022.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

(REVISED FROM TRANSCRIPT)

LOGAN J:

1 On 31 May 2023, a registrar of the Federal Court of Australia (Court) made an order on the application of Sherrin Rentals Pty Ltd (Sherrin), as petitioning creditor that the estate of one Rodney Herbert be sequestrated pursuant to the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (Bankruptcy Act). The Court made an ancillary order in respect of costs and noted that the act of bankruptcy was 28 December 2022.

2 There was on file at the time, as there is today, a consent to act as trustee signed by Mr David Michael Stimpson and Ms Anne Meagher pursuant to s 156A of the Bankruptcy Act.

3 As is his right, Mr Herbert has sought the review by a judge of the sequestration order. The position in relation to such a review is that it is a hearing afresh – de novo, to use the Latin term – on the evidence and on the law at the time of the review hearing: see as to this, Bechara v Bates (2021) 286 FCR 166, at [17], and also, notably, the judgment of Emmett J in Totev v Sfar (2008) 167 FCR 193. The effect of these authorities is that it is for Sherrin to discharge the onus of proof in respect of the matters stated in the petition. It is also for Sherrin to prove service of the petition and the fact that the debt upon which it relies is still owing.

4 Even if such proofs are present, the court retains a discretion as to whether or not to make a sequestration order. In this regard, one but not the only relevant circumstance is whether the debtor has persuaded the court that he or she is solvent.

5 The background to the bankruptcy proceeding lies in the obtaining by Sherrin in the Queensland Magistrates Court on 29 October 2022 of a judgment against Mr Herbert in the sum of $104,660.17. I am satisfied on the evidence that this judgment debt remains owing in full to this day. In reliance upon the judgment debt, Sherrin obtained a bankruptcy notice. This notice, I am satisfied, was served upon Mr Herbert.

6 I am further satisfied that Mr Herbert failed, within the time allowed, to comply with the bankruptcy notice.

7 As it happened, it proved necessary for Sherrin to obtain an order for substituted service in respect of the petition. I am satisfied that the petition was served as required. Indeed, there is no contest by Mr Herbert that all of the necessary proofs in terms of s 52(1) of the Bankruptcy Act are present on the evidence relied upon by Sherrin at today’s hearing.

8 The principal question for determination is whether or not Mr Herbert has shown that he is solvent such that the court should, as a matter of discretion, dismiss the petition? There is also a question as to whether the petition is, in effect, being used by Sherrin just as a means of debt recovery? Another question is whether there is, in truth and reality, a debt in respect of which judgment was given in the Magistrates’ Court? A further question, even in the event that Mr Herbert fails on those earlier questions, is whether to exercise a discretion under s 52(3) of the Bankruptcy Act to stay the operation of the sequestration order?

9 As to solvency, ss 5(2) and (3) of the Bankruptcy Act provide:

(2) A person is solvent if, and only if, the person is able to pay all the person's debts, as and when they become due and payable.

(3) A person who is not solvent is insolvent.

10 Whether or not that test is met is inherently fact-specific to a particular case. It has been said of the current test in the Bankruptcy Act that it is a cashflow rather than balance sheet test. Acknowledging the inherently fact-specific nature of whether that test is met, there is nonetheless helpful guidance to be found in a summary, offered by Murphy J in Tarwala v Amirbeaggi as trustee for bankruptcy [2022] FCA 1593, at [18] – [23], of observations which have been made in particular cases, be they corporate insolvency or personal insolvency, as to proof of solvency. The focus is on liquidity.

11 Further, the prescription in s 5(2) “as and when they become due and payable” in relation to debts looks to the future beyond the day on which the question of solvency or insolvency is to be determined as much as it does to the present.

12 The proceedings are civil in character. That means that proof need only occur on the balance of probabilities: see s 140(1) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). That said, it behoves a person seeking to prove solvency to be candid both as to assets as well as liabilities.

13 Mr Herbert’s evidence is, with respect, rather thin on both the asset and debit sides of the ledger. As to assets, he states:

Assets

8. I:

8.1 do not have any real property assets;

8.2 have a work vehicle;

8.3 do not have shares in any listed entities;

8.4 have approximately $20,000 in superannuation.

14 As to expenses, he states:

Expenses

9. My share of monthly expenses are roughly $2,320.00 and comprise:

9.1 Food and groceries $1,000;

9.2 Health insurance $135.00;

9.3 Child Support/ School Fees $500.00;

9.4 Phone & Internet $100.00;

9.5 Life Insurance $335.00;

9.6 Entertainment $250.00

[emphasis in original]

15 In respect of outstanding liabilities, Mr Herbert states:

My Outstanding Liabilities

10. I have four outstanding liabilities totalling approximately $153,000.00, and comprise:

10.1 The debt upon which the Applicant relies, being a judgment of the OLD Magistrates Court dated 29 October 2022 in the sum of $104,660.17 (the Judgment).

10.2 The Judgment has accrued some post judgment interest, roughly $4,141.96 as at the date of swearing this affidavit; and

10.3 A debt of approximately $22,000.00 owed to Kennards Hire under a personal guarantee for a debt incurred by the Company prior to its liquidation (the Kennards Hire Debt).

10.3.1 My solicitors wrote to Kennards Hire on 5 July 2023 seeking confirmation of this debt and further confirmation as to whether the debt is pursued, however Kennards Hire have not responded within the time period requested, as such it is conceivable that this is not a current liability. If my solicitors receive a further update from Kennards Hire, I will instruct them to file a further affidavit to ensure my disclosures as to my liabilities are full and frank.

10.4 A debt of approximately $15,000.00 owed to Viva Energy under a personal guarantee for a debt incurred by the Company prior to its liquidation (the Viva Energy Debt). I am not aware of any circumstances to suggest this debt is not still pursued.

10.5 A debt of approximately $8,000.00 owed to MacRherson Kelley Lawyers under a personal guarantee for a debt incurred by the Company prior to its liquidation (the MacPherson Kelley Debt) Again, I am not aware of any circumstances to suggest this debt is not still pursued.

[emphasis in original – [sic]]

16 Mr Herbert states, and he confirmed in oral evidence, that he presently works for a company controlled by his wife, Ms Kirsty Elizabeth Webb, Bid Collective Australia Pty Ltd (Bid Collective). Mr Herbert stated at [6] of his affidavit that:

6. I am currently a business development manager for my wife’s company and earn an equivalent and approximate salary of $75,000 per annum.

17 No payslips or PAYG summary statements were annexed to his affidavit. It emerged in the course of cross-examination of Mr Herbert that the term “salary” was, perhaps, inapt in that it seems, in fact, that he is paid expenses by Bid Collective, as well as amounts of cash. It is uncertain as to whether PAYG deductions are made. Indeed, there is much that is uncertain about the operation, assets and liabilities of Bid Collective.

18 Mr Herbert annexed to his affidavit a credit report by Data Registries Pty Ltd. Whilst, on the face of this, it discloses an absence of credit defaults or what are termed “serious credit infringements”, the worth of this report is moot, given that it states “no judgments”, whereas the position in fact, of course, is that there has been since October last year a judgment against Mr Herbert by the Queensland Magistrates Court.

19 Mr Herbert asserts in his affidavit and notwithstanding the debts disclosed in that affidavit (as indicated) that he is solvent. There is no forensic accounting report based even on the evidence offered by Mr Herbert and Ms Webb that he is solvent. That, of course, is no barrier to the court reaching its own conclusions on that subject.

20 By his solicitors, Mr Herbert has caused particular inquiries to be made of creditors, both as disclosed in the affidavit, as well as a range of other creditors. The long and the short of that is that no creditor has waived a debt. At most, the upshot of the inquiries that have been made is that some creditors are not presently disposed to pursue Mr Herbert for debts.

21 In respect of a judgment debtor who owns apparently no real property and whose arrangement with a company controlled by his wife in respect of alleged salary is hardly precise, it is no great surprise that Sherrin has not sought to enforce the judgment either by seeking, on the basis of it, to execute against particular assets, or, for that matter, to seek to garnishee a wage. I am not at all satisfied that there is any substance in Mr Herbert’s assertion that the bankruptcy proceeding was just being used as a means of debt recovery by Sherrin. If anything, it looks to be a proceeding which Sherrin has instituted in order to participate according to bankruptcy law in whatever might be realised by a trustee in bankruptcy.

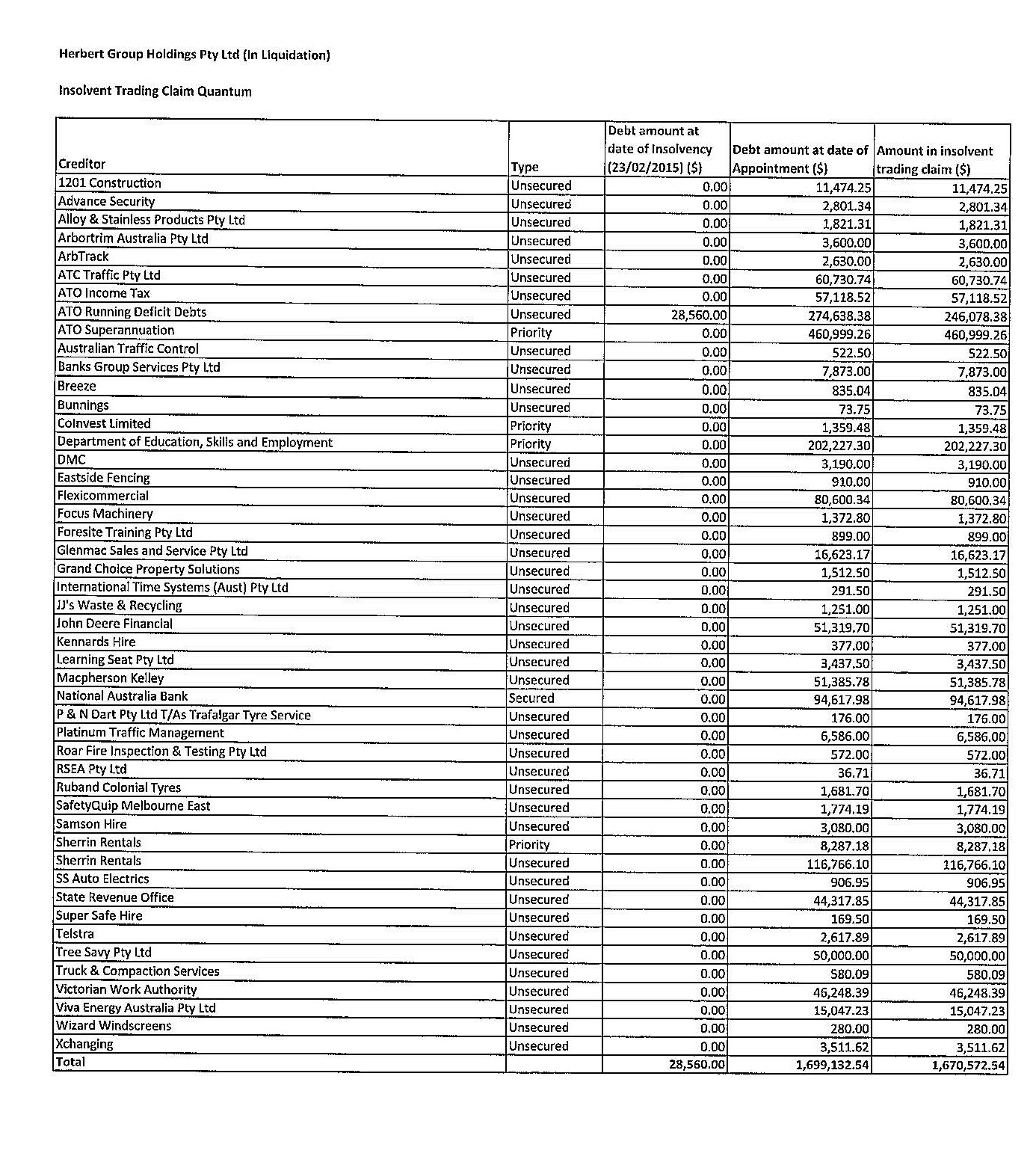

22 It is apparent on the face of his affidavit and other evidence in the proceeding that Mr Herbert has at least debts which total $392,015.78. These debts comprise the judgment debt mentioned, debts of $48,339.83 identified by Mr Herbert in his affidavit, and also debts owed to various creditors of another company, Herbert Group Holdings Pty Ltd, which total $293,015.78, as attested to by that company’s liquidator, Mr Morgan. These arise from personal guarantees provided by Mr Herbert in respect of various corporate liabilities of Herbert Group. Mr Herbert was once a director of that company.

23 I had the benefit of hearing evidence from Mr Morgan orally, as well as two affidavits made by him. As liquidator, he faces the difficult task of performing his duties against a background of a company which is apparently and spectacularly insolvent. Mr Morgan stated in evidence that potentially, there was, on behalf of Herbert Group, a claim against Mr Herbert in respect of insolvent trading. Mr Morgan did not disclose fully the factual foundation for the expression of that opinion. Whilst I respect the view of a liquidator as an officer of the court, I have not adversely taken that opinion into account, given the absence of a precise factual foundation for it. Nonetheless, it is, in my view, relevant in terms of discretion to take into account the size and range of corporate debts in the insolvency of Herbert Group as detailed by Mr Morgan. I attach as Annexure “A”, Mr Morgan’s table yielding the total of 1.6 odd million dollars.

24 I heard in evidence and a related submission on behalf of Mr Herbert that a basis for the conclusion of solvency should be found in a facility agreement entered into as between Bid Collective and Mr Herbert earlier this month. This provides for a facility accessible by Mr Herbert to a facility limit of $300,000 on terms set out in a written agreement entered into earlier this month. Bid Collective is controlled wholly by Ms Webb. A curious feature of the facility agreement is that one of the identified events of default in cl 1 is at para (c):

The Borrower becomes an insolvent under administration within the meaning of s 9 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

25 The agreement, of course, is as between Bid Collective and a natural person, Mr Herbert, not a corporation. Clause 3.2 provides that the facility is unsecured. Clause 3.3 provides that the borrower, Mr Herbert, may use proceeds of an advance of principal for any lawful purpose. Clause 3.4 provides that, at any time, the Borrower may volunteer repayment of the whole or any of principal outstanding, providing that subject to the provisions of this Deed such amount repaid may be readvanced.

26 One might, therefore, describe the facility, as subject to the limit mentioned, a come and go facility. Notably, clause 3.5 provides: –

3.5 the Borrower must pay interest if demanded on the Principal outstanding:

3.5.1 at the rate of 5% per annum (Higher Rate) except the Lender must accept interest at the rate of 3% per annum (Lower Rate) in lieu of the Higher Rate for any period in which the Borrower has observed and performed its obligations under this Deed (other than the Borrower's payment of interest at the Higher Rate) and the Borrower pays interest at the Lower Rate not later than the day on which interest ought to be paid (as to which time is of the essence) and provided that this provision for a Lower Rate ceases to apply while an Event of Default exists;

3.5.2 calculated daily for each day on and from the date the Principal is advanced until and including the date the whole of the Principal advanced is repaid; and

3.5.3 in arrears on the first day of each calendar month;

27 In the course of her oral evidence, Ms Webb stated that her disposition was that Bid Collective would charge Mr Herbert the specified lower rate of interest in respect of any sum advanced. As I have mentioned, judgment debt apart, there is no waiver by any creditor in respect of any of the other debts. At most, there is a disposition apparently not presently to institute proceedings in respect of the debt.

28 What necessarily follows from that is that the amount of the facility is insufficient to meet Mr Herbert’s total indebtedness. Further, as was highlighted in submissions on behalf of Sherrin, if the loan facility were to be drawn down in full at the specified three per cent per annum interest rate, that would create a liability in respect of interest alone of some $750 per month. When one looks at the differential between income and expenses as disclosed by Mr Herbert and in his affidavit, that would yield a deficiency in respect of payment of interest were the sum to be drawn down in full.

29 In her affidavit, Ms Webb stated in respect of the facility agreement:

3. On 10 July 2023, Bid Collective entered into a Facility Agreement by way of deed (the Facility Agreement), pursuant to which Bid Collective has agreed to, and have since, made available to the Respondent, in immediately available funds, (the Facility) the sum of AU$300,000 (the Facility Limit).

[emphasis added]

30 It emerged in the course of Ms Webb’s oral evidence that this statement was not accurate. As at the time that she made the affidavit on 11 July 2023, Bid Collective did not have the sum of $300,000 to make available to Mr Herbert immediately or even at all at that time. Indeed, it was only in the course of her oral evidence and after questioning about the accuracy of the Statement in [3] that it emerged that she expected that the sum would become available later today for on lending to Mr Herbert. Ms Webb’s evidence as to the source of the funds for provision of the facility was notably vague. She annexed no documents whatsoever concerning the application for these funds by Bid Collective. She had difficulty even recalling the name of the entity which was to provide the funds.

31 Given the inaccuracy which remained uncorrected by her until cross-examination, I am just not confident in the evidence given by Ms Webb as to the provision of funds today. It seems to me that there is a note of optimism in respect of which I can have no confidence. Indeed, the position of Bid Collective is also notably vague as to assets and liabilities. There is no profit and loss statement in evidence; there is no balance sheet in evidence. There is not even a bank statement as to its current position with its banker in evidence, although I was told that it does maintain a bank account.

32 Mr Herbert personally has not lodged a tax return since 2019. Bid Collective’s position with the Australian Taxation Office is similar. It has not lodged tax returns for the years ended 30 June 2021 or 30 June 2022. Its compliance with its business activity statement lodgement obligations and related remission of any goods and services tax or other amounts owed to the Tax Office is, to say the least, moot. I was left with a most uneasy feeling indeed upon hearing the evidence, or rather lack thereof, of adherence to obligations with the Tax Office that there may be an episode of history repeating itself with Bid Collective when I looked to the list of unsecured creditors annexed by Mr Morgan to his affidavit in respect of Herbert Group.

33 Ms Webb stated that she made as sole director, ultimate decisions in respect of the operations of Bid Collective. Nonetheless, it was apparent from Mr Herbert’s evidence and Ms Webb’s that Mr Herbert does play at least an advisory role to her in relation to the operations of Bid Collective.

34 Absent whatever might be the worth of the facility agreement, Mr Herbert is, in my view, on the evidence, hopelessly insolvent. I am not at all satisfied that there is any worth in the facility agreement.

35 The facility agreement is an exemplar of an associated party transaction. Of course, that does not in itself mean that it cannot provide evidence of solvency. Solvency can be found in an ability of a person to command funds from other sources to meet debts as and when they fall due. In the context of corporate insolvency, in Leveraged Equities Limited v Hilldale Australia Pty Ltd [2008] NSWSC 190, at [62], Hammerschlag J observed:

62 The principal reason why such contractual subordinations are unsatisfactory is that there is no barrier to their consensual rescission.

That same sentiment, in my view, can apply in the context of personal insolvency. On its face, the facility here terminates, and the borrower must pay to the lender the whole of the outstanding liability, on the earlier of three events: written demand made by the lender if an event of default exists or the maturity date; see cl 3.6. The maturity date is expressed to be 30 June 2035 or as the parties may agree in writing: see cl 1, Definition.

36 These are related parties par excellence a company controlled by a wife on the one hand and the husband on the other. There is nothing whatsoever to prevent some earlier maturity date being appointed. Indeed, even if I were satisfied that there was any worth in the facility agreement for the purpose of proving solvency, there would be nothing to prevent, assuming there are any funds to come to Bid Collective, those funds being round-robinned tomorrow back to whoever is the lender with a related consensual variation of the facility agreement to terminate it.

37 However, as I have indicated, I find the facility agreement as a source of funds the subject of shadowy evidence. I have, as I have indicated in light of the inaccuracy, uncorrected until cross-examination in the statement about immediately available as at earlier this month, no confidence that funds are available at all to Bid Collective for on-lending pursuant to the facility agreement.

38 Although Mr Herbert asserted that he contested the judgment debt, he offered no evidence upon which I might reach a conclusion that there was in truth no debt owed by him to Sherrin. Recently, in Thompson v Lane (Trustee) [2023] FCAFC 32, at [145], and with reference in particular to Ramsay Health Care Australia Pty Ltd v Compton (2017) 261 CLR 132 and Lowbeer v De Varda (2018) 264 FCR 228, Downes J observed:

145 Where a question is raised as to whether a judgment or order establishes the amount truly owing to the petitioning creditor, there are two separate questions: first, whether there is a proper basis to exercise the discretion to go behind the judgment, and second, if there is, whether there is in truth and reality no debt.

[citations omitted]

39 Her Honour added the following, at [146]:

146 The discretion may be exercised where the judgment or order which comprises the debt was reached with fraud, collusion or a miscarriage of justice. However, as also recognised by the primary judge at [69], the circumstances in which a court may go behind a judgment are not limited to fraud, collusion or miscarriage of justice. A bankruptcy court should go behind a judgment where sufficient reason is shown for questioning whether behind the judgment there is in truth and reality a debt to the petitioning creditor.

[citations omitted]

40 Mr Herbert has not sought to set aside the judgment upon which Sherrin obtained the bankruptcy notice. In itself, that is no barrier to the Court going behind the judgment, although it is relevant to take into account that he has not availed himself of any rights of challenge to that judgment in the Queensland State jurisdiction. The real difficulty is that, assertion apart, there is not, in my view, any basis to exercise a discretion to go behind the judgment much less for any conclusion that there is not in truth and reality any debt.

41 The position which obtains in my view is that Mr Herbert is indeed indebted to Sherrin. Further, he is, in my view, on the evidence, hopelessly insolvent. As I have indicated, I have no confidence at all that the facility agreement in any way changes that position, and that is so irrespective, I emphasise, of whatever may be the position in respect of any claim which Herbert Group in liquidation may have against him.

42 In terms of a discretion as to whether or not to sequestrate, quite apart from my conclusion as to insolvency, I bear in mind that proceedings in bankruptcy are not inter parties proceedings. They entail a public interest. That interest is one which, here, also tells in favour of the affirmation of a sequestration order. As I have indicated, I have an uneasy feeling in respect of this case that it is possible that history may repeat itself with Bid Collective in relation to the history with Herbert Group. The absence of affirmative evidence as to tax compliance is deeply concerning in respect of a company where Mr Herbert plays at least a managerial role. Also deeply concerning is the inaccuracy when one came to detail in oral evidence as to the nature of his arrangement with Bid Collective for reward. It is not in truth and reality a salary but rather a very loose form of remuneration, it seems. Further and also deeply concerning is the absence of any documentation at all, be they payslips or PAYG summaries, in respect of payments made to Mr Herbert.

43 Of course, the position is that great informality can attend the operation of private companies. I have made observations in that regard in the context of determining a tax appeal in Anglo American Investments Pty Ltd (Trustee) v Commissioner of Taxation [2022] FCA 971. But there is a certain minimum one might nonetheless expect and expect to be evidenced in the context of an endeavour to prove solvency. And that minimum, in my view, is at least some evidence which shows that there is, however informal arrangements may be, compliance with tax obligations as between an apparent employee and the apparent employer. Neither Mr Herbert nor Ms Webb offered any such evidence, and they were the two persons peculiarly placed so to do.

44 I was also asked to exercise a discretion to stay the operation of a sequestration order if I was disposed to affirm that made by the registrar. Were the case one where there was some finely balanced question either as to solvency or existence of a judgment debt such that one might see reasonable prospects on appeal, I would be disposed to grant a stay of the sequestration order. I would also be disposed to grant such a stay in the event that there was persuasive evidence that it was only a matter of a few days for funds to become available. Here, the absence of any evidence from the asserted lender to corroborate the availability of funds is again deeply concerning.

45 In light of the conclusions which I have reached, I do not consider the present to be a case where a stay pursuant to s 52(3) should be ordered. Instead, being satisfied that the act of bankruptcy alleged in the petition has been committed, that the petition was served, that the judgment debt remains owing and of other matters required to be proved under s 52, the orders that I make are as follows:

(1) The application for the review of the sequestration order made by a registrar on 31 May 2023 be dismissed. For the avoidance of doubt, the sequestration order made by a registrar on 31 May 2023 be affirmed.

(2) The petitioning creditor’s costs of and incidental to the application be taxed and paid in accordance with the Bankruptcy Act, on the footing that they pay part of the petitioning creditor’s costs in respect of the creditor’s petition presented on 17 March 2023.

I certify that the preceding forty-five (45) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Logan. |

Associate:

Dated: 31 October 2023

annexure “a”