FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Sandoz AG v Bayer Intellectual Property GmbH [2023] FCA 1321

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The Cross-Respondent has threatened to infringe claims 3 and 4 of Australian Patent AU2006208613 entitled “Prevention and treatment of thromboembolic disorders” (the 613 Patent).

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The First and Second Applicants’ application be dismissed.

2. The First and Second Cross-Claimants’ cross-claim be allowed in-part.

3. The Cross-Respondent, whether by itself, its directors, officers, servants, agents, Related Bodies Corporate (as defined in the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)), Associated Entities (as defined in the Corporations Act) or howsoever otherwise (together, Sandoz), during the term of the 613 Patent be restrained from infringing claims 3 and 4 of the 613 Patent, including (without limitation) by engaging in the following acts within the patent area (as that term is defined in the Patents Act 1990 (Cth)), without the licence or authority of the Cross-Claimant:

(a) importing, selling, supplying or otherwise disposing of the Sandoz Rivaroxaban Products;

(b) offering to sell, supply or otherwise dispose of the Sandoz Rivaroxaban Products;

(c) authorising other persons to use the Sandoz Rivaroxaban Products or engage in any of the acts described in subpara (a) and (b) above;

(d) procuring or inducing, whether by instructions or otherwise, any of the acts described in subpara (a) and (b) above; or

(e) otherwise infringing the 613 Patent.

4. The 613 Patent be amended in the manner described in the Annexure hereto.

5. The First Applicant and Second Applicant/Cross-Respondent pay the Respondent/Cross-Claimants’ costs of the application and the cross-claim with a 15% reduction for the Applicants succeeding on the meaning of “in hydrophilized form” issue. Such costs are to be taxed if not agreed.

6. The Cross-Claimants pay the costs of the amendment application.

7. If any party seeks a variation of the costs orders in paragraphs 5 and 6 above, it may, within seven days, file and serve a written submission (of no more than two pages) and any affidavit in support. In that event, the other party may file and serve a responding written submission (of no more than two pages) and any affidavit in support within a further seven days, and the issue of costs will be determined on the papers.

THE COURT CERTIFIES THAT:

8. Pursuant to s 19 of the Patents Act, the validity of each of the claims of the Australian Patent AU2004305226 entitled “Method for the production of a solid, orally applicable pharmaceutical composition” and the 613 Patent were questioned in this proceeding and found to be valid.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Insert the number “7” immediately after the incomplete PCT number PCT/04/01289 and insert

the country code "EP" before the application date code of "04" on page 10, line 13 of the 613 Patent, as shown below.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

ROFE J:

[1] | |

[8] | |

[13] | |

[69] | |

[93] | |

[104] | |

[104] | |

[125] | |

[143] | |

[143] | |

[144] | |

[149] | |

[163] | |

[183] | |

[184] | |

[194] | |

[199] | |

[219] | |

[237] | |

[238] | |

[241] | |

[244] | |

[244] | |

[261] | |

[273] | |

[280] | |

[289] | |

[301] | |

[302] | |

[306] | |

[311] | |

[314] | |

[321] | |

[328] | |

[335] | |

[341] | |

[352] | |

[358] | |

[361] | |

[367] | |

10.1.13 Unmet need for safe and effective new oral anticoagulant | [374] |

[383] | |

[417] | |

[423] | |

[431] | |

[443] | |

[449] | |

[467] | |

[472] | |

[497] | |

[516] | |

[524] | |

[529] | |

[540] | |

[579] | |

[591] | |

[624] | |

[627] | |

[628] | |

[631] | |

[638] | |

[653] | |

10.5.5.1 Evidence on the information disclosed in the Abstracts | [656] |

[666] | |

[672] | |

[680] | |

[688] | |

[693] | |

[707] | |

12.3 Patent prosecution history: Overseas equivalent patents and applications of the 613 Patent | [723] |

[724] | |

[730] | |

[735] | |

[738] | |

[741] | |

[748] | |

[752] | |

[756] | |

[767] | |

[773] | |

[774] | |

[787] | |

[789] | |

[792] | |

[799] |

1 Bayer Intellectual Property GmbH is the patentee of the two patents in suit:

(a) Australian Patent No. 2004305226 entitled “Method for the production of a solid, orally applicable pharmaceutical composition” (the 226 Patent); and

(b) Australian Patent No. 2006208613 entitled “Prevention and treatment of thromboembolic disorders” (the 613 Patent).

2 Bayer Australia Ltd is, and has been since 14 February 2023, the exclusive licensee of the 226 Patent and the 613 Patent in Australia. Bayer Australia markets and sells Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme listed products comprising rivaroxaban in Australia under the trade name XARELTO.

3 Sandoz AG and Sandoz Pty Ltd (Sandoz Australia) (together, Sandoz) seek to revoke the 226 and 613 Patents. It contends that the claims of each patent are invalid on several bases.

4 By way of cross-claim, Bayer seeks permanent injunctive relief against Sandoz Australia for threatened infringement of claims 8 to 22 of the 226 Patent and claims 3 and 4 of the 613 Patent (asserted claims).

5 Subject to the validity of the 613 Patent, Sandoz Australia admits infringement of the claims asserted against it. One issue remains for determination on the infringement of the 226 Patent: the construction of the term “in hydrophilized form”.

6 By an interlocutory application dated 27 June 2022, Bayer seeks to amend the 613 Patent to correct what it terms “a mistake”. The reference to “PCT/04/01289” on page 10, line 12, of the specification should read “PCT/EP04/012897” (the mistake). No amendments are sought to the claims. Sandoz opposes the amendment on a number of grounds.

7 In summary, and for the reasons that I explain in more detail below, I find that both the 226 Patent and the 613 Patent are valid. However, on my construction of “in hydrophilized form”, I do not consider that the Sandoz rivaroxaban products infringe the 226 Patent. Therefore, I only find that Sandoz has threatened to infringe claims 3 and 4 of the 613 Patent. I will also exercise my discretion to grant Bayer’s amendment to the 613 Patent.

8 The 226 Patent relevantly relates to orally administrable pharmaceutical compositions comprising rivaroxaban “in hydrophilized form” and the use of those pharmaceutical compositions for the prophylaxis and/or treatment of a thromboembolic disease.

9 The 613 Patent relates to a method of treatment of thromboembolic disorders by once daily administration of a rapid-release tablet comprising rivaroxaban.

10 Rivaroxaban itself had, as one of a class of factor Xa inhibitors, been disclosed and claimed in an earlier Bayer patent application, International Patent Publication No. WO 01/47919 (WO 919), which is a key piece of prior art in relation to each Patent. The validity of the Australian patent resulting from that application, Australian Patent No. 775126 (the Compound Patent), is not challenged by Sandoz in this proceeding. The Compound Patent, as extended, is due to expire on 24 November 2023.

11 Sandoz Australia is the sponsor on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods of the following pharmaceutical compositions, each comprising rivaroxaban (the Sandoz products):

(a) ARTG ID 335415: Rivaroxaban Sandoz rivaroxaban 10 mg film-coated tablet blister pack.

(b) ARTG ID 335420: Rivaroxaban Sandoz rivaroxaban 15 mg film-coated tablet blister pack.

(c) ARTG ID 335496: Rivaroxaban Sandoz rivaroxaban 20 mg film-coated tablet blister pack.

12 Sandoz Australia intends, without Bayer’s authorisation, to exploit the Sandoz products in Australia after 24 November 2023.

13 The parties filed an agreed glossary and technical primer prior to the commencement of the trial. This section includes extracts from the glossary of the agreed technical primer.

14 Absorption refers to the process by which an API (defined below) moves from the site of administration into a site in the body, usually the bloodstream. Absorption may be defined in terms of its rate and extent. For an orally administered API, the administration site is the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. In the case of a solid oral dosage form, the total extent of absorption may be determined by a number of factors, including the extent of release, solubility, permeability, local and pre-systemic metabolism, stability characteristics of the API in the GI tract and GI tract transit times. In the case of a solid oral dosage form, the rate of absorption may be determined by factors including the rate of release (including disintegration), dissolution rate, solubility, permeability, local and pre-systemic metabolism, rate of degradation (if any) of the API in the GI tract and the presence of food in the GI tract.

15 Absorption half-life is the time it takes for the absorption of 50% of the dose that was absorbed (eg that moved from the administration site into the blood stream) when absorption is a first-order process.

16 Absorption profile of an API refers to both its rate and extent of absorption.

17 Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (APTT or aPPT) is an assay used to monitor heparin treatment and is also known as PTT or Partial Thromboplastin Time. APPT is sensitive to the heparin-induced inhibition of factors IIa, IXa, Xa and XIa. It is performed on citrated plasma, which has been processed to remove the platelets, using an APTT reagent and a recalcification step.

18 Anticoagulants are a class of antithrombotic drugs that inhibit the formation and/or propagation of coagulation, and/or the formation of fibrin, and are used in the treatment of thromboembolic disorders. By inhibiting the formation or growth of a clot, the anticoagulant allows the body time to break down the clot. Anticoagulants are also used prophylactically and chronically to decrease the risk of a new clot forming.

19 API means active pharmaceutical ingredient. The words “API” and “drug” can be used interchangeably.

20 Atrial fibrillation is a disease in which the heart beats irregularly. The irregular heart beat can cause clots in the heart or arterial system because the blood flow is not smooth, and thus is subject to turbulence, which results in blood clotting in areas of slow flow (most frequently the left atrial appendage).

21 Arterial thromboembolism occurs where a blood clot forms in the arterial system. Generally, the most common pathologies are atrial fibrillation, peripheral vascular disease or coronary artery thrombosis. Clots formed due to atrial fibrillation and peripheral vascular disease can result in a stroke, whereas clots formed due to coronary artery thrombosis can result in heart attacks.

22 AUC, or area under the curve, refers to the area under the concentration versus time curve. The “concentration” refers to the concentration of a drug, biomarker or clotting factor. When measuring the concentration of a drug in plasma, AUC is a measure of the extent of absorption of a drug. AUC may be defined according to a particular time period.

23 Bioavailability refers to the extent and rate of absorption of the API from a dosage form into a body site. Bioavailability is determined by, among other things:

(a) the absorption profile of the API;

(b) the dosage form within which it is administered to the patient; and

(c) its first pass extraction (by metabolism or excretion).

The fraction of API absorbed from a dosage form is usually estimated by comparing AUC of the test dosage form or dosage amount, and a reference dosage form.

24 Clearance (CL) refers to a measure of the efficiency with which an API is eliminated from blood or plasma, and encompasses the API’s metabolism and excretion. Clearance is defined as the "volume of blood or plasma cleared of drug per unit time", and is thus expressed in units of volume per time (eg L/hr).

25 Clot or thrombus consists of a mesh of fibrin that embeds activated platelets and red and white blood cells.

26 Cmax is the peak concentration of the API, biomarker or a clotting factor(s) in a biological matrix after a treatment. In the case of an API, Cmax is the peak plasma concentration achieved following administration of a single dose of the API or during repeated dosing.

27 Cmin is the minimum concentration of the API, biomarker or a clotting factor(s) in a biological matrix after multiple treatments. In the case of an API, Cmin is the minimum plasma concentration achieved during the time interval between administration of two doses of an API during repeated dosing.

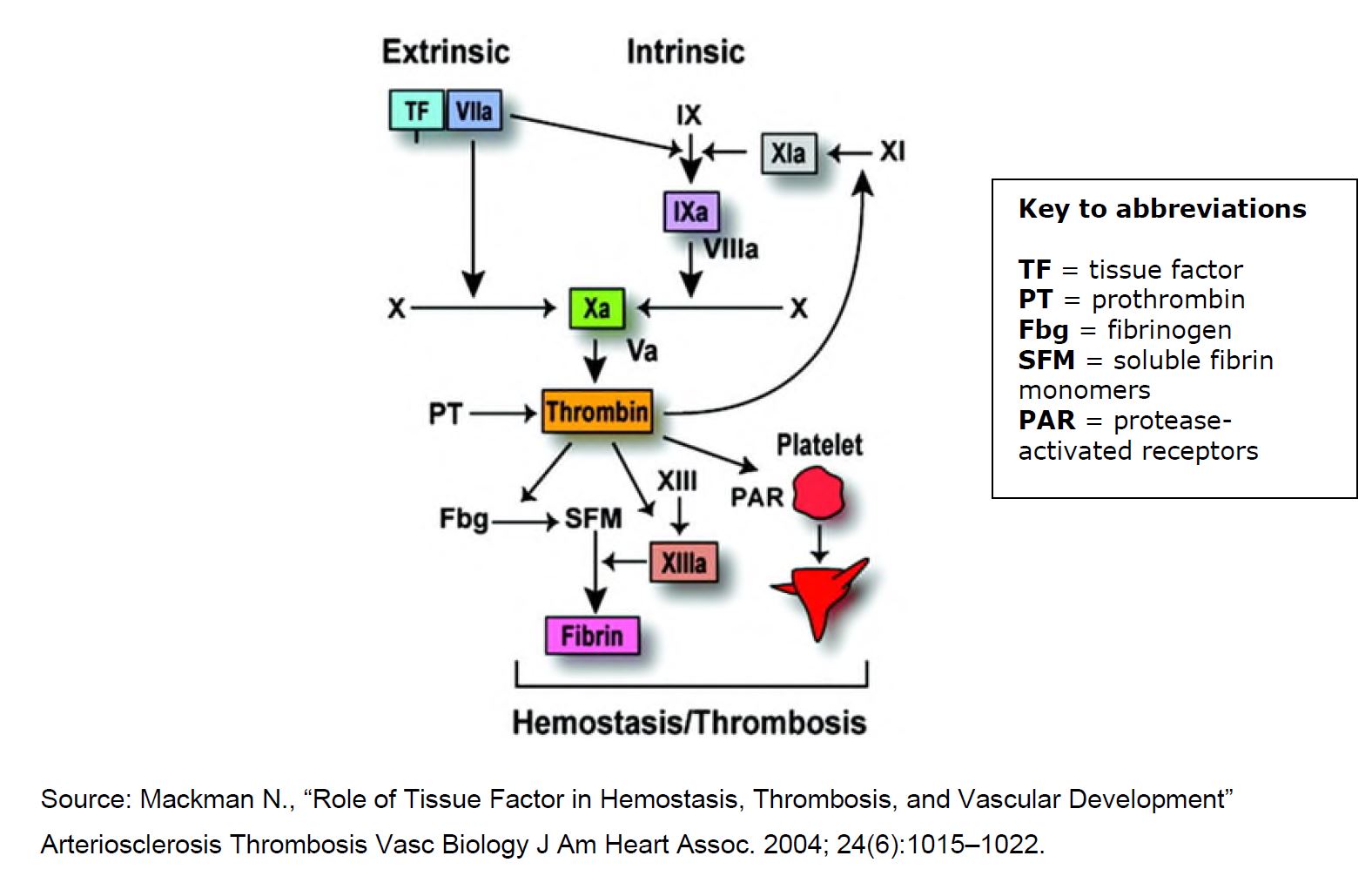

28 Coagulation cascade refers to a series of activation steps of various enzymes (factors) involved in coagulation. Under normal physiological conditions, it is only upon an injury that the coagulation system should rapidly and locally respond at an injured blood vessel wall to generate a clot.

29 Coronary artery thrombosis can occur where a clot is formed in a blood vessel in the heart.

30 Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) refers to the formation of a blood clot in a deep vein, usually in the leg. If DVT is left untreated, the blood clot can break off from the formation site and travel to the lungs causing PE. PE occurs where there is a blockage of the pulmonary artery in the lung and can be life-threatening.

31 Direct compression is a tablet manufacturing process in which the API is blended with excipients and compressed into finished tablets without modifying the physical nature of the blended material itself.

32 Dissolution rate refers to the rate at which a solid or liquid (eg a solid or liquid form of a drug) dissolves in a solvent.

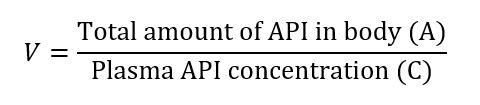

33 Distribution refers to both the rate and extent to which an API moves into, and out of, different body components, including movement between plasma and blood cells or between the bloodstream and tissues. For APIs that become systemically available via the blood, the extent of the API’s distribution can be quantified by the term “apparent volume of distribution” (V), which is a proportionality between the total amount of the API in the body and the concentration of the API in the plasma:

For example, if 100 mg of an API is in the body at a particular time and, at that same time, the plasma concentration is 5 mg/L, the volume of distribution will be 20 L.

34 Dosage form refers to the form in which the API is administered to the patient, such as tablets, capsules, solutions, suspensions, nasal sprays etc.

35 Dosage regimen refers to the regimen by which an API is administered, and includes the dose (quantity of API administered), dosage form, route (eg oral, intravenous, subcutaneous) and frequency of administration.

36 Elimination refers to the irreversible removal of an API from the body by metabolism (conversion to a different chemical species) and/or excretion.

37 Elimination half-life refers to the time taken for the concentration of the API in blood, plasma or serum to fall by half during the elimination phase of a pharmacokinetic profile.

38 Excretion refers to the removal of the API from the body via an excretory process, such as filtration across the kidneys and removal via the urine, breath, sweat and faeces.

39 Factors refers to the main enzymes involved in the coagulation cascade.

40 Fibrin is the fibrous protein that makes up a clot or thrombus.

41 First order elimination occurs where the rate of elimination of a drug is directly proportional to drug concentration.

42 Granulation involves the combination of powder particles, often with a binder, to form granules. Granules comprise multiple different particles. These granules are an intermediate product, which are compressed into a tablet or filled into a capsule. Granulation methods can be broken into two categories: wet and dry. Wet granulation involves the combination of drug particles with a binder and other excipients into granules in the presence of a solvent, typically water. The parties agreed that moist granulation and wet granulation refer to the same process. Dry granulation is a similar process conducted in the absence of the solvent.

43 In vitro refers to analysis, tests or evaluations conducted outside a living organisation (eg in a test tube).

44 In vivo refers to analysis, tests or evaluations conducted in a living organism.

45 International Normalized Ratio (INR) is a corrected ratio that expresses the patient’s prothrombin time (PT) over the mean normal PT, adjusted by the thromboplastin responsiveness value (known as the international sensitivity index (ISI), which is specific to each thromboplastin reagent).

46 Log P is the logarithm of the octanol-water coefficient of a molecule. That is, it is the logarithm of the ratio of a compound’s concentration in octanol (which is an organic solvent) and water.

47 Melting point is the temperature at which a compound will change from solid to liquid state.

48 Metabolism refers to the process by which enzymes in the body change the chemical structure of the API, thereby converting it into a different chemical form. Metabolism of an API occurs primarily in the liver, but can occur to varying extents in other organs. The extent of metabolism and the type of metabolism of an API depends on its interactions with the many metabolic enzymes in the body, and is thus highly dependent on the API’s chemical structure.

49 Metabolites are the products of metabolism. As metabolites have a different chemical structure to the parent API, they can have different pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties to the parent API. Metabolites can be inert, can contribute to the improvement in the condition (efficacy) or produce side effects.

50 Off-target side effects refers to the consequences that can occur when a drug affects targets or tissues other than targets with which the drug was meant to bind.

51 Parenteral administration refers to administration other than by the GI tract (eg mouth), generally injection or infusion.

52 Peripheral vascular disease refers to where the arteries develop atherosclerosis, which is the thickening or hardening of arteries caused by the build-up of plaque in the inner lining of an artery. Rupture of the plaque results in a highly thrombotic surface, resulting in blood clot formation.

53 Permeability refers to the ability of an API to move across cell membranes such as those lining the GI system. Permeability encompasses passive movement (eg through or between the cells of the GI lining) and active movement (eg via transporters within the GI lining). Permeability is also affected by efflux transporters which restrict movement across the GI lining.

54 Pharmacokinetics refers to the study of the time course of API in the body. The pharmacokinetic profile of an API depends on its:

(a) absorption;

(b) distribution;

(c) metabolism; and

(d) excretion.

“Elimination” is the combination of metabolism and excretion. Pharmacokinetics is sometimes referred to as PK or by using the acronym ADME.

55 Pharmacodynamics refers to the time course of the intensity of the pharmacological effect(s) that an API has in the body. Pharmacodynamics incorporates both (i) the therapeutic effect of the API (ie treating or improving the relevant condition) and (ii) any side effects caused by the API. Pharmacodynamics may be distinguished from pharmacokinetics in that pharmacodynamics describes how an API affects the body, whereas pharmacokinetics describes how the body affects an API. Pharmacodynamics is sometimes referred to as PD.

56 Plasma refers to the liquid component of blood after it has undergone centrifugation to separate the cellular components such as red and white blood cells and platelets.

57 Pre-formulation typically includes experimental, in vitro investigations into at least the stability, dissolution and solubility of the drug (in various potentially relevant biological and environmental conditions), its crystal form and polymorphism, as well as its compatibility with any excipients that might be selected for use in the formulations used in clinical trials. To assess such matters, particularly for potentially sold oral dosage forms, in vitro solubility and dissolution testing are often performed.

58 Prothrombin time (PT) test is a clotting test that was used to measure the effects of warfarin treatment before the priority dates. It was known to respond to reductions in factors II, VII, IX and X during warfarin therapy. It was performed by adding thromboplastin (generally a phospholipid-protein tissue extract) and calcium to plasma, which has been treated with citrate, to prevent it from clotting.

59 Pulmonary embolism occurs where there is a blockage of the pulmonary artery in the lung.

60 Solubility refers to the maximum amount of a compound that will dissolve in a given volume of specified fluid at a particular temperature and pH. Solubility is distinct from dissolution, which refers to the rate at which particles dissolve in solution.

61 Steady-state occurs during repeated (or constant) administration once there is no further accumulation of a drug. Once a drug reaches steady-state, values of Cmax and Cmin remain constant and plasma levels remain within what is defined as a “steady-state range”.

62 Stroke can be caused by clots occluding blood vessels or from bleeding outside blood vessels. Clots can be formed from atrial fibrillation (with the clot forming in the heart), or in cerebral blood supply vessels (both large and small calibre), or from thrombosis in the deep veins of the legs that crosses into the arterial system through a hole in the heart. Some clots may move further after they have detached from the initial location (eg embolized) and travelled to the brain.

63 Terminal half-life is the time taken for a drug concentration to decrease by half across the final portion of a drug concentration versus time profile.

64 Tmax is the time at which Cmax occurs.

65 Therapeutic index or therapeutic window in anticoagulants refers to the range of anticoagulant effect, spanning a lower limit where the risk of thrombosis is unacceptably increased, to an upper limit where unwanted bleeding occurs with unacceptable frequency. A narrow or low therapeutic index is to be distinguished from a high or wide therapeutic index. A higher or wider therapeutic index is one where a broader range of doses of the compound can be given to a person to achieve a desired effect without having adverse effects. A low therapeutic index will mean a risk of toxicity if levels are too high and therapeutic failure if levels are too low.

66 Thromboembolism is a general term describing the combined processes of thrombosis (where a vessel is occluded by clots in part, or in entirety), or embolism (when a clot breaks off from the formation site and lodges elsewhere in the body). Thrombotic or thromboembolic disorders involve thrombosis and/or thromboembolism, which may develop in the venous or arterial circulatory systems.

67 Thrombosis is a pathological clot formation resulting in the obstruction of blood flow through a blood vessel. The primary mechanisms for thrombosis are the improper regulation of the coagulation cascade, and/or excessive platelet activation.

68 Venous thromboembolism (VTE) refers to a clot that develops in the venous system. Common manifestations of VTE are DVT and pulmonary embolism.

69 Bayer relies on the evidence of Professor James Polli in support of its cross-claim for infringement. Professor Polli is a Professor and Ralph F. Shangraw/Noxell Endowed Chair in Industrial Pharmacy and Pharmaceutics at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. He obtained a PhD in pharmaceutics from the University of Michigan in 1993. Professor Polli made two affidavits dated 6 October 2022 and 29 January 2023.

70 Professor Polli has published approximately 100 scientific articles in the areas of dissolution, drug intestinal permeability, transporter substrate requirements, prodrug design, oral bioavailability, in vitro-in vivo correlation and bioequivalence. His two primary research interests are improving oral bioavailability of drugs through formulation and chemical approaches, and developing public quality standards for oral dosage forms.

71 Bayer relies on the evidence of Professor Polli, Professor Allan Evans and Professor Mark Crowther in relation to the validity of the 613 and 226 Patents.

72 Professor Evans is a pharmaceutical scientist and pharmacologist, with extensive teaching, research and industry experience in drug discovery and development. He is a Professor of Pharmaceutical Science at the University of South Australia. He obtained a PhD in pharmacokinetics at the University of Adelaide. Professor Evans made one affidavit dated 8 February 2023.

73 At the relevant dates, Professor Evans was Head of the School of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences at the University of South Australia. He was also lecturing in pharmacokinetics, biopharmaceutics, clinical pharmacology and pharmacy practice.

74 Professor Evans has acted as primary investigator, investigator or consultant in at least 50 clinical trials studying the pharmacokinetics, safety and/or efficacy of APIs. A focus of Professor Evans’ work was to understand whether doses were safe and therapeutically effective in humans and the relationship between safety and therapeutic effectiveness.

75 Professor Crowther is a haematologist specialising in the treatment of thromboembolic disorders with extensive clinical, research, teaching and industry experience. He is a Professor and Chair of the Department of Medicine and Leo Pharma Chair in thromboembolism research at McMaster University in Canada. Professor Crowther made one affidavit dated 7 February 2023.

76 Professor Crowther obtained a Doctor of Medicine from the University of Western Ontario in 1990 and completed a residency in internal medicine and haematology. He went on to become a research fellow in thromboembolism at McMaster University and the Medical Research Council of Canada, as well as a clinical fellow in internal medicine. Professor Crowther also completed a Master of Science in epidemiology and biostatistics from McMaster University in 1998. He is listed as an author on over 600 peer-reviewed articles.

77 Professor Crowther has consulted extensively with the pharmaceutical industry. He has training in clinical trial design and has been engaged in a number of clinical studies including as principal or co-principal investigator to determine the most appropriate dose to initiate and maintain the therapeutic effect of warfarin. Professor Crowther has also been engaged as the principal investigator of an international project for approximately 10–15 studies in the field of coagulation. Most of Professor Crowther’s clinical trial experience has been in Phase II and III clinical trials, but he has also been involved in the early phase discussions as a consultant when defining the therapeutic objectives of a trial program.

78 Bayer also relies on an affidavit from a patent analyst, Dr Louisa King, made on 30 January 2023.

79 Dr King is a director of IP searching and an IP analyst at Aperture Insight. Dr King gave evidence reflecting the results of searches she carried out to locate “PCT/04/01289” referred to on page 10 of the 613 Patent.

80 Sandoz relies on the evidence of Professor Michael Roberts. Professor Roberts is currently the Adjunct Professor of Therapeutics & Pharmaceutical Science at the University of South Australia, an Emeritus Professor of Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics and Director of Therapeutics Research Centre at the Diamantina Institute, University of Queensland.

81 Professor Roberts made three affidavits dated 3 October 2022 in support of Sandoz’s case on invalidity, 30 January 2023 in answer to Bayer’s evidence on infringement and 3 March 2023 in reply to Bayer’s evidence on validity.

82 Professor Roberts gave evidence of his active research in areas of pharmacology and toxicity. He has authored more than 578 peer reviewed articles and contributed chapters or other sections to more than 75 books.

83 Professor Roberts was involved in University of Tasmania projects from 1978–1984 developing a slow release oral dosage form of aspirin for use in the prevention of stroke and heart attacks. The teams on these projects conducted in vitro and human dose ranging studies on the antithrombotic effect of aspirin with enteric coating. From 1986–1989, in his capacity as head of the University of Otago Department of Pharmacy, Professor Roberts was involved in conducting clinical trials, including early-phase clinical trials or later stage comparative trials comparing innovator and generic products.

84 Bayer accepts that Professor Roberts is suitably qualified to express an opinion as to matters of formulation and clinical pharmacology in this proceeding.

85 Prior to the hearing, Professor Polli and Professor Roberts prepared a joint report for the Court in which they gave their responses to 11 questions posed by the parties, and indicated where they agreed or disagreed in their response (JER1). The two experts gave concurrent oral evidence at the hearing as a joint expert session (JES1). The parties rely on JER1 primarily in relation to the validity of the 226 Patent. During the course of JES1, it became clear that Professor Roberts had a broader experience in pharmaceutics than Professor Poli.

86 Sandoz also relies on the evidence of Professor Ross Baker, a senior consultant haematologist and clinician scientist, in support of its case of invalidity. Professor Baker made one affidavit dated 3 October 2022.

87 Professor Baker has over 30 years’ experience as a senior consultant haematologist, has published over 138 peer reviewed papers in journals and acted as principal investigator in over 133 international Phase II and Phase III clinical trials. He has worked as principal investigator and in an advisory capacity for pharmaceutical companies in the development of various anticoagulants (eg rivaroxaban, ximelagatran, fondaparinux, dabigatran and apixaban).

88 Professor Baker has also acted as a peer reviewer for scientific abstracts submitted to the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis Annual Congress.

89 Sandoz also relies on the evidence of a patent attorney, Mr Rodney Cruise, in support of its case in relation to best method and ascertainment. Mr Cruise made one affidavit in the proceeding on 30 September 2023.

90 Mr Cruise is a principal of the intellectual property firm, Phillips Ormonde Fitzpatrick, and the manager of the intellectual property research company, IP Organisers Pty Ltd. Mr Cruise’s evidence related to searches for patent and non-patent literature on the Chemical Abstracts database.

91 Prior to the hearing, Professors Roberts, Baker, Crowther and Evans prepared a second joint report for the Court in which they gave their responses to 10 questions posed by the parties, and indicated where they agreed or disagreed in their response (JER2).

92 The experts gave concurrent oral evidence in two groups at the hearing: Professors Polli and Roberts in the first session, and Professors Roberts, Baker, Crowther and Evans in the second session.

93 The person skilled in the art is not a reference to a specific person but is a legal construct drawn by reference to the available evidence. As French CJ explained in AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd (2015) 257 CLR 356 at [23] (AstraZeneca HC):

The notional person is not an avatar for expert witnesses whose testimony is accepted by the court. It is a pale shadow of a real person — a tool of analysis which guides the court in determining, by reference to expert and other evidence, whether an invention as claimed does not involve an inventive step.

94 The legal construct may not be a single person but may be a team of persons “whose combined skills would normally be employed in that art in interpreting and carrying into effect instructions such as those which are contained in the document to be construed”: General Tire & Rubber Co v Firestone Tyre & Rubber Co Ltd [1972] RPC 457 at 485 (per Sachs LJ, Buckley and Orr LJJ agreeing).

95 The person skilled in the art is likely to have a “practical interest in the subject matter … and may often work in the art in which the invention is connected”: KD Kanopy Australasia Pty Ltd v Insta Image Pty Ltd (2007) 711 IPR 615 at [16] (per Kiefel J). They are unimaginative and without inventive capacity.

96 In relation to the 226 Patent, Sandoz says that the skilled team includes a haematologist, a formulator and a pharmacologist.

97 Bayer considers the person skilled in the art possesses a mixture of attributes drawn from a team of skilled scientists, including a medicinal chemist, a clinician (being a haematologist), a formulator and a clinical pharmacologist.

98 The parties agreed that the question of construction for the 226 Patent is informed by the views of a formulator, and that Professors Roberts and Polli were appropriately qualified to give such evidence. However, Sandoz expressed some doubt regarding Professor Polli’s experience as a formulator and his expertise in pharmaceutics, pointing to the evidence he gave that he had only taught compounding and physical pharmacy, not tabletting, for the past 30 years.

99 The experts agreed that a drug company’s clinical trial program is very carefully constructed and will require the input of all team members, including pharmacologists and clinicians. The experts agreed that clinical trials involve a broad range of specialists for Phase I and II studies. A clinician will be involved in the conduct of clinical trials and will have input, with others, into their design, analysis and interpretation. Professor Baker considered that the input from a clinician would be particularly relevant in developing anticoagulant drugs given the complexity of the coagulation system. Other specialists that may be included in the team as required include pharmaceutical scientists, toxicologists, statisticians, analysts and database specialists, as well as experts in regulatory requirements as these studies will form a seminal component of a regulatory filing for the product. The roles of the various members of the skilled team and their involvement during the stages of the drug development process are discussed further below in section 10.1.14 “Stages of drug development”.

100 Professor Crowther noted that the term “clinician” is quite broad, which may help explain some of the differing views of the experts, particularly with respect to the role of a clinician in the early stages of drug discovery and development. Professors Evans and Crowther considered that the term applies to a health professional (a medical practitioner or specialist) providing day-to-day care (directly or indirectly) in a clinical setting such as a hospital. Professors Roberts and Baker took the view that the “clinician” was the person providing a clinical perspective, and that may be, for instance, in providing advice on an aspect of patient care or providing advice to other clinicians working directly with patients, as may arise for clinicians working in anatomical and chemical pathology, clinical pharmacology, public health and laboratory medicine. They gave as an example a haematologist specialising in laboratory medicine who will frequently have postgraduate fellowship and/or PhD qualifications and whose main responsibility is to supervise routine clinical, as well as translational, research laboratories. The haematologist’s duties may include laboratory and clinical research, pathology testing and/or patient care.

101 The experts agreed that there should be a clinical perspective in a drug development program. In this case, I consider that the “clinician” would be a practising haematologist with experience in treating patients with thromboembolic disorders and diseases, and who may also have some laboratory experience.

102 The clinician may be involved at the outset of a drug discovery program in terms of providing input as to desirable drug properties and, crucially, desirable improvements over current therapies (the existing standard of care). Clinicians are not generally involved in the drug discovery aspect of the program, or selecting the drug or defining the development program, but they play a critical part in the design, conduct and evaluation of the clinical studies themselves. A clinician’s involvement in design may be limited in the case of multi-centre clinical trials (usually Phase III) but there is usually at least one clinician who has a central role in leading the entire clinical trial program.

103 The roles of the various members of the skilled team and their involvement during the stages of the drug development process are discussed further below in section 10.1.14 “Stages of drug development”.

104 Sandoz alleges that the claims of the 226 Patent are invalid for lack of clarity, by reason of their use of the unfamiliar term “in hydrophilized form”. This term is not defined in the 226 Patent and neither Professor Polli nor Professor Roberts had heard of the term “hydrophilization” before.

105 The 226 Patent claims an earliest priority date of 27 November 2003 (First Priority Date).

106 The 226 Patent was amended on 18 May 2010 to introduce seven new consistory clauses on page 2a described as further aspects of the invention, to delete claim 21 and insert new claims 21 to 23. Bayer does not rely on the added consistory clauses to provide fair basis for the claimed invention.

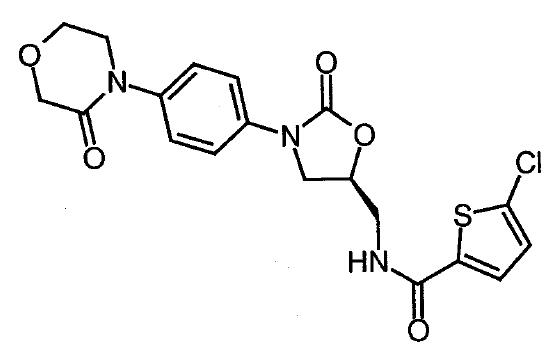

107 The invention described in the 226 Patent is said to relate to a process for the preparation of a solid, orally administrable pharmaceutical composition, comprising 5-chloro-N-({(5S)-2-oxo-3-[4-(3-oxo-4-morpholinyl)-phenyl]-1,3-oxazolidin-5-yl}-methyl)-2-thiophenecarboxamide (compound I) in hydrophilized form, and “its” use [ie use of the pharmaceutical composition comprising compound I in hydrophilized form] for the prophylaxis and/or treatment of diseases.

108 Compound I is now known as rivaroxaban. It is a direct factor Xa inhibitor.

109 The specification of the 226 Patent explains that rivaroxaban is a low molecular weight, orally administrable inhibitor of blood clotting factor Xa, which can be employed for the prophylaxis and/or treatment of various thromboembolic diseases.

110 The 226 Patent does not otherwise describe rivaroxaban in detail, instead referring the reader to WO 919 and incorporating the disclosure of WO 919 by reference (page 1, lines 6–12). More will be said about WO 919 later, as Sandoz relies on WO 919 in its inventive step challenge to both the 226 and 613 Patents.

111 The specification of the 226 Patent explains that rivaroxaban has a relatively poor water solubility and that, therefore, difficulties with oral bioavailability and an increased biological variability of the absorption rate can result. The specification observes that various concepts have been described in the past to increase oral bioavailability. Three concepts for increasing bioavailability are discussed. It is in relation to the third, “a process for hydrophilization”, that a reference is made to two papers (the Lerk papers) (at page 1, line 17 to page 2, line 4):

Thus, solutions of active compounds are frequently used which can be filled, for example, into soft gelatine capsules. On account of the poor solubility of the active compound (I) in the solvents used for this purpose, this option is not applicable, however, in the present case, since, in the necessary dose strength, capsule sizes would result which are no longer swallowable.

An alternative process is the amorphization of the active compound. Here, the solution method proves problematical, since the active compound (I) is also poorly soluble in pharmaceutically acceptable solvents such as ethanol or acetone. Amorphization of the active compound by means of the fusion method is also disadvantageous because of the high melting point of the active compound (about 230°C), since an undesirably high proportion of breakdown components is formed during the preparation.

Furthermore, a process for the hydrophilization of hydrophobic active compounds as exemplified by hexobarbital and phenytoin has been described (Lerk, Lagas, Fell, Nauta, Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Vol. 67, No. 7, July 1978, 935 – 939: “Effect of Hydrophilization of Hydrophobic Drugs on Release Rate from Capsules” [Lerk 1978]; Lerk, Lagas, Lie-A-Huen, Broersma, Zuurman, Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Vol. 68, No. 5, May 1979, 634-638: “In vitro and In vivo Availability of Hydrophilized Phenytoin from Capsules” [Lerk 1979]). The active compound particles are blended here in a mixer with a methyl- or hydroxyethylcellulose solution with extensive avoidance of an agglomeration step and then dried. The active compound thus obtained is subsequently filled into hard gelatine capsules without further treatment.

112 The Lerk papers are described in more detail below in section 6.5.

113 Immediately following the discussion of the three concepts the specification states:

Surprisingly, it has now been found that a special treatment of the surface of the active compound (I) in the course of the moist granulation brings about improved absorption behaviour. The use of the active compound (I) in hydrophilized form in the preparation of solid, orally administrable pharmaceutical compositions leads to a significant increase in the bioavailability of the formulation thus obtained.

114 The present invention is said at page 2, line 10, to relate to a process for the preparation of a solid, orally administrable pharmaceutical composition comprising rivaroxaban in hydrophilized form, in which:

(a) first granules comprising the active rivaroxaban in hydrophilized form are prepared by moist granulation; and

(b) the granules are then converted into the pharmaceutical composition, if appropriate with addition of pharmaceutically suitable additives.

115 The specification states that the moist granulation in step (a) can be carried out in a mixer (mixer granulation) or in a fluidized bed (fluidized bed granulation). Fluidized bed granulation is said to be preferred.

116 From page 2a, line 24, some preferred embodiments are described by reference to the particular form of the active compound (crystalline or micronized), and the specification then moves on at page 3 to a more detailed description of the process of the invention. The granulating liquid “used according to the invention” is said to contain a solvent, a hydrophilic binding agent and, if appropriate, a wetting agent. The hydrophilic binding agent is, in this case, dispersed in the granulating liquid or preferably dissolved therein.

117 From page 3, line 4 onwards, the specification discusses solvents used for the granulating liquid, hydrophilic binding agents employed for the granulating liquid, hydrophilic polymers (including hydroxypropylmethylcellulose (HPMC)) and optionally present wetting agents.

118 The specification describes that the granules obtained in process step (a) are subsequently converted into the pharmaceutical composition according to the invention in process step (b). At page 4, lines 20–22, a number of options are described for step (b) of the process, including tabletting, filling into capsules and filling as sachets.

119 At page 5, lines 3–12, the specification discusses the solid, orally administrable pharmaceutical composition of the invention:

The present invention further relates to a solid, orally administrable pharmaceutical composition, comprising 5-chloro-N-({(5S)-2-oxo-3-[4-(3-oxo-4-morpholinyl)-phenyl]-l,3-oxazolidin-5-yl}- methyl)-2-thiophenecarboxamide (I) in hydrophilized form.

The solid, orally administrable pharmaceutical composition according to the invention by way of example and preferably comprises granules, hard gelatine capsules or sachets filled with granules, and tablets releasing the active compound (I) rapidly or in a modified (delayed) manner. Tablets are preferred, in particular tablets rapidly releasing the active compound (I). In the context of the present invention, rapid-release tablets are in particular those which, according to the USP release method using apparatus 2 (paddle), such as described in the experimental section in chapter 5.2.2., have a Q value (30 minutes) of 75%.

120 The specification further describes at page 5, lines 28–32, that the invention relates to the use of the pharmaceutical composition according to the invention for the prophylaxis and/or treatment of various thromboembolic diseases such as cardiac infarct, angina pectoris (including unstable angina), reocclusions and restenoses after an angioplasty or aortocoronary bypass, cerebral infarct, transitory ischemic attacks, peripheral arterial occlusive diseases, pulmonary embolisms or deep venous thromboses.

121 The invention is illustrated by means of preferred exemplary embodiments, each of which involves wet granulation (page 6, line 1 to page 11, line 8). The specification notes at page 6 that the examples are “preferred exemplary embodiments” and non-limiting.

(a) Example 1 describes the preparation of a tablet comprising compound I in hydrophilized form by a fluidized bed granulation process (a type of wet granulation).

(b) Example 2 describes the preparation of a tablet comprising compound I in hydrophilized form via a “high speed granulation process”.

(c) Examples 3 and 4, respectively, describe preparation of sachets, and preparation of gelatine capsules, each containing compound I in hydrophilized form. In both cases, the drug is prepared using a method similar to Example 1.

(d) Example 5 compares the tablet properties and improved bioavailability of formulations comprising hydrophilized compound I prepared by the fluidised bed process described in Example 1, with a tablet comprising micronized compound I in non-hydrophilized form, prepared by direct tabletting without granulation.

122 The specification ends with 23 claims. Claims 1 to 7 claim a process for the preparation of a solid, orally administrable pharmaceutical composition comprising compound I in hydrophilized form, using the two-step process described above at [114].

123 Claims 8 to 22 claim a pharmaceutical composition of rivaroxaban “in hydrophilized form”, and methods involving the use of such a composition. These claims are asserted against Sandoz.

124 Claim 23 is an omnibus claim which is not asserted.

125 The 613 Patent relates to a method of treatment of thromboembolic disorders by once daily administration of a rapid-release tablet comprising rivaroxaban.

126 The 613 Patent claims an earliest priority date of 31 January 2005 (Second Priority Date).

127 The background of the invention identifies the blood coagulation mechanism, the blood coagulation cascade, the fact that there are numerous factors and intrinsic and extrinsic pathways, as well as the fact that activated serine protease Xa cleaves prothrombin to thrombin, allowing a further step in the cascade to occur. Following a discussion of haemostasis, coagulation and thromboembolic disorders, there is then a discussion of the existing anticoagulants (heparin, low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) and warfarin) and their “often severe disadvantages” which make the effective treatment of thromboembolic disorders “very difficult and unsatisfactory”.

128 Heparin is said to be administered parenterally (intravenously or subcutaneously) and to have a non-selective action as it inhibits a plurality of factors of the blood coagulation cascade at the same time. Warfarin is described as a vitamin K antagonist with a slow onset of action (latency to the onset of action 36 to 48 hours). Owing to the high risk of bleeding and the narrow therapeutic index, time-consuming individual adjustment and monitoring of the patient are said to be required.

129 The specification then describes at page 2, lines 20–29, a novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of thromboembolic disorders which aims to inhibit factor Xa.

130 The specification sets out that oral application is the preferable route of administration, and that once daily oral application is preferred for convenience and compliance. However, it says this can be “difficult to achieve depending on the specific behaviour and properties of the drug substances, especially its plasma concentration half-life”.

131 The 613 Patent then states at page 3, lines 5–10:

When the drug substance is applied in no more than a therapeutically effective amount, which is usually preferred in order to minimize the exposure of the patient with that drug substance in order to avoid potential side effects, the drug must be given approximately every half live [sic] (see for example: Malcolm Rowland, Thomas N. Tozer, in “Clinical Pharmacokinetics, Concepts and Applications”, 3rd edition, Lea and Febiger, Philadelphia 1995, pp 83).

132 Following this, at page 3, line 17, the invention in the 613 Patent is identified:

Surprisingly, it has now been found in patients at frequent medication that once daily oral administration of a direct factor Xa inhibitor with a plasma concentration half lifetime of 10 hours or less demonstrated efficacy when compared to standard therapy and at the same time was as effective as after twice daily (bid) administration.

133 From page 3a, line 18, a preferred embodiment of the invention is said to be:

In a preferred embodiment, the present invention relates to [rivaroxaban], a low molecular weight, orally administrable direct inhibitor of blood clotting factor Xa (see WO-A 01/47919, whose disclosure is hereby included by way of reference) as the active ingredient.

134 On page 4, lines 6–9, the plasma concentration half-life of rivaroxaban is described:

For [rivaroxaban] a plasma concentration half life of 4-6 hours has been demonstrated at steady state in humans in a multiple dose escalation study (D. Kubitza et al, … [Blood Abstract 3004]).

135 Page 4 of the 613 Patent discusses a clinical study, set out in greater detail on pages 11 to 14, that compared rivaroxaban administered once and twice daily with LMWH in patients undergoing orthopaedic surgery.

136 There is then discussion of various other (unclaimed) compounds which are said to be preferred embodiments of the invention, each of which appear to have been the subject of a publication. These are other factor Xa inhibitors, in addition to rivaroxaban. They are not within the scope of the claims (the claims having been amended to narrow them to rivaroxaban, after the application for the 613 Patent was filed). For example:

AX-1826 [S. Takehana et al. Japanese Journal of Pharmacology 2000, 82 (Suppl. 1), 213P; T. Kayahara et al. Japanese Journal of Pharmacology 2000, 82 (Suppl. 1), 213P]

HMR-2906 [XVIIth Congress of the International Society for Thrombosis and Haemostasis, Washington D.C., USA, 14-21 Aug 1999; Generating greater value from our products and pipeline. Aventis SA Company Presentation, 05 Feb 2004]

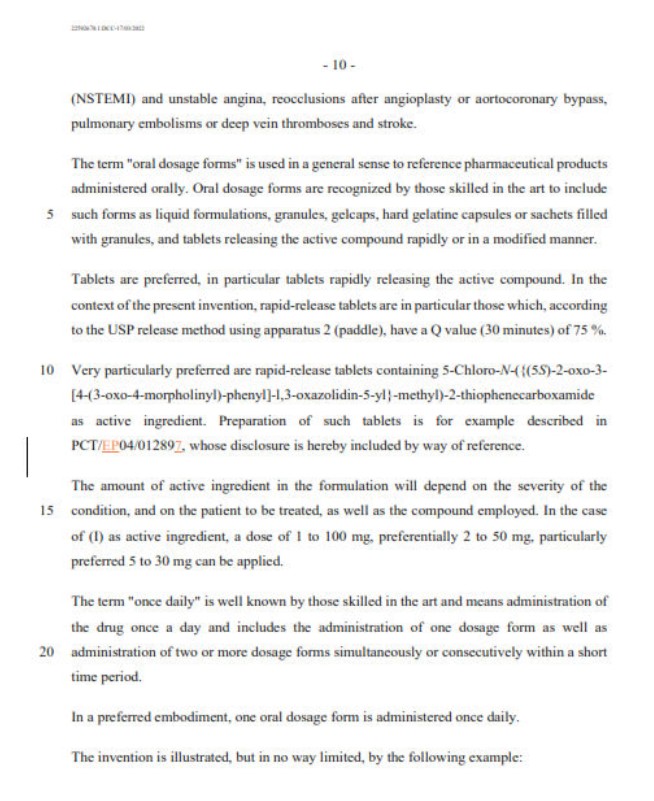

137 On page 10 of the 613 Patent, tablets rapidly releasing the active compound are said to be preferred, in particular those with a particular release rates defined by reference to a specified USP release method. Then follows the passage relevant to the best method case, which Bayer seeks to amend:

Very particularly preferred are rapid-release tablets containing 5-Chloro-N-({(5S)-2 oxo-3-[4-(3-oxo-4-morpholinyl)-phenyl]-1,3-oxazolidin-5-yl}-methyl)-2 thiophenecarboxamide as active ingredient. Preparation of such tablets is for example described in PCT/04/01289, whose disclosure is hereby included by way of reference.

138 The 613 Patent then discusses the clinical trial study (comprising 642 patients) that was referred to on page 4, which involved orally administering to different groups of patients different doses of rivaroxaban as rapid-release tablets — 2.5 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg, 20 mg and 30 mg twice daily, and 30 mg once a day. The data on page 14, lines 5–7, demonstrates the safety and efficacy of such once daily dosing of rivaroxaban.

139 The 613 Patent has four claims. Claims 1 and 3 are independent. Claim 1, a Swiss style claim to the use of rivaroxaban to manufacture a medicament, and claim 2, which claims the use of that medicament to treat thromboembolic disorders, were not pressed at the hearing.

140 Claim 3 provides:

A method for the treatment of a thromboembolic disorder in a patient said method comprising administration to the patient of a rapid-release tablet comprising 5-Chloro-N-({(5S)-2-oxo-3-[4-(3-oxo-4-morpholinyl)phenyl]-l,3-oxazolidin-5-yl}methyl)-2-thiophenecarboxamide once daily for at least five consecutive days, and wherein the 5-Chloro-N-({(5S)-2-oxo-3-[4-(3-oxo-4-morpholinyl)phenyl]-l,3-oxazolidin-5-yl}methyl)-2-thiophenecarboxamide has a plasma concentration half life of 10 hours or less when orally administered to a human patient.

141 Claim 4 is to the method of claim 3, wherein the thromboembolic disorder is selected from a specified group.

142 Claims 3 and 4 are asserted against Sandoz.

143 Subject to the validity of the 613 Patent, Sandoz Australia admits the direct and indirect infringement of each of the asserted claims of the 613 Patent.

144 The only issue for determination on infringement arises in respect to the 226 Patent. The term “in hydrophilized form” forms an essential part of the definition of the invention in all of the claims (either directly, or via dependency) of the 226 Patent. Bayer’s infringement case turns upon the construction of the term “in hydrophilized form” in each of the asserted claims of the 226 Patent.

145 Sandoz’s primary submission is that the term “in hydrophilized form” is unclear, such that the claims of the 226 Patent are unclear and are liable to be revoked on that basis. It follows that there can be no infringement. Sandoz submits that Bayer’s attempt to give meaning to “in hydrophilized form” by resorting to the Lerk papers — two prior art papers cited in the background section of the Patent, each dated more than 24 years before the asserted priority date — is both illegitimate, in that it is plainly wrong as a matter of construction, and unsuccessful, in that it fails to give any clear meaning to the term even if that impermissible process of construction is adopted.

146 If, contrary to that submission, the term “in hydrophilized form” can be given any meaning, Sandoz submits that it must refer to a composition that is produced using a wet granulation technique having regard to the disclosure of the 226 Patent. As Bayer concedes, Sandoz’s rivaroxaban products are not produced by such a process, and therefore it follows that there can be no infringement on that construction.

147 If, however, the term “in hydrophilized form” is given a broader meaning to encompass a composition made by a process not involving wet granulation, Sandoz submits the asserted claims of the 226 Patent are not fairly based, or not entitled to their claimed priority date, and are liable to be revoked as a result. It follows again that there can be no infringement. Sandoz also challenges the validity of the asserted claims on other bases, not related to the use of the term “in hydrophilized form”.

148 The parties came to an agreement on day one of the trial confining the scope of the 226 Patent infringement case as follows:

1. The Applicants/Cross-respondent (Sandoz) accept that, if, contrary to its submission, the Court finds that:

a. the asserted claims of the 226 Patent are valid;

b. the term "in hydrophilized form" in the asserted claims of the 226 Patent is clear; and

c. on its proper construction, that term encompasses a composition in which the surface of the hydrophobic active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) has been rendered hydrophilic as a result of close physical interactions between rivaroxaban and hydrophilic excipients without the use of any liquid,

then the Sandoz Rivaroxaban Products (as defined in the Amended Statement of Cross-claim) have the features of the asserted claims.

2. Bayer accepts that, if the term "in hydrophilized form" in the asserted claims of the 226 Patent, on its proper construction, only refers to a composition which has been made with the use of wet or moist granulation, or a liquid, then the Sandoz Rivaroxaban Products do not have the features of the asserted claims.

6.3 Principles of construction and clarity

149 A patent is construed through the eyes of the person skilled in the art: GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Investments (Ireland) (No 2) Limited v Generic Partners Pty Limited (2018) 131 IPR 384 at [106] (per Middleton, Nicholas and Burley JJ) (GSK FC).

150 The principles governing claim construction are well established and have been recently set out by Rares, Moshinsky and Burley JJ in Airco Fasteners Pty Ltd v Illinois Tool Works Inc [2023] FCAFC 7 at [48], citing Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd (2005) 65 IPR 86 at [67] (per Hill, Finn and Gyles JJ):

(i) the proper construction of a specification is a matter of law: Décor Corp Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc (1988) 13 IPR 385 at 400;

(ii) a patent specification should be given a purposive, not a purely literal, construction: Flexible Steel Lacing Company v Beltreco Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 331 at [81]; and it is not to be read in the abstract but is to be construed in the light of the common general knowledge and the art before the priority date: Kimberley-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1 at [24];

(iii) the words used in a specification are to be given the meaning which the normal person skilled in the art would attach to them, having regard to his or her own general knowledge and to what is disclosed in the body of the specification: Décor Corp Pty Ltd at 391;

(iv) while the claims are to be construed in the context of the specification as a whole, it is not legitimate to narrow or expand the boundaries of monopoly as fixed by the words of a claim by adding to those words glosses drawn from other parts of the specification, although terms in the claim which are unclear may be defined by reference to the body of the specification: Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [15]; Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 610; Interlego AG v Toltoys Pty Ltd (1973) 130 CLR 461 at 478; the body of a specification cannot be used to change a clear claim for one subject matter into a claim for another and different subject matter: Electric & Musical Industries Ltd v Lissen Ltd [1938] 56 RPC 23 at 39;

(v) experts can give evidence on the meaning which those skilled in the art would give to technical or scientific terms and phrases and on unusual or special meanings to be given by skilled addressees to words which might otherwise bear their ordinary meaning: Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd v Koukourou & Partners Pty Ltd (1994) 30 IPR 479 at 485-486; the Court is to place itself in the position of some person acquainted with the surrounding circumstances as to the state of the art and manufacture at the time (Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [24]); and

(vi) it is for the Court, not for any witness however expert, to construe the specification; Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd, at 485–486.

151 To those, I would also add:

(a) when construing claims, “a generous measure of common sense should be used”: Product Management Group Pty Ltd v Blue Gentian LLC (2015) 116 IPR 54 at [36] (per Kenny, Nicholas and Beach JJ); and

(b) a construction that would lead to an absurd result is to be avoided: NV Philips Gloeilampenfabrieken v Mirabella International Pty Ltd (1993) 26 IPR 513 at 559 (per Northrop, Lockhart and Burchett JJ).

152 It is impermissible for either the court or the witnesses to approach the issues of construction with any regard to the alleged infringing articles: Fresenius Medical Care Australia Pty Ltd v Gambro Pty Ltd (2005) 67 IPR 230 at [95] (per Wilcox, Branson and Bennett JJ). As observed by Heerey J in Welcome Real-Time SA v Catuity Inc (2001) 51 IPR 327 at [21]:

All that needs be added is the perhaps trite observation that the alleged infringement is to be ignored when construing the patent. Although the forensic contest will throw up the particular construction issues to be resolved, a patent must, as the saying goes, be construed as if the infringer had never been born.

153 Although it is preferred that claims should be construed in a manner that avoids redundancy, Full Courts of this Court have indicated that where the plain meaning of a claim has the effect that one or more dependent claims are redundant, then the consequence of redundancy would not drive the construction of the claim itself: Nichia Corporation v Arrow Electronics Australia Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 2 at [41] (per Jagot J, Besanko J agreeing at [1] and Nicholas J agreeing at [126]); Davies v Lazer Safe Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 65 at [65] (per Greenwood, White and Burley JJ).

154 Claims should be construed in the context of the specification, even where there is no ambiguity: Product Management at [37] (per Kenny, Nicholas and Beach JJ), cited in Esco Corporation v Ronneby Road Pty Ltd (2018) 131 IPR 1 at [144] (per Greenwood, Rares and Moshinsky JJ). Reference is made to the specification to understand the background and context of the claims and to ascertain the meaning of technical terms: Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Co v Beiersdorf (Aust) Ltd (1980) 144 CLR 253 at 271–287 (per Aickin J). Terms in the claim which are unclear may be clarified or defined by reference to the body of the specification: Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1 at [15] (per Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ). However, the plain and unambiguous meaning of a claim cannot be varied or qualified by reference to the body of the specification: Kimberly-Clark at [15].

155 The requirement of clarity is also well-established. Relevantly, s 40(3) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) requires that the claims of a patent specification be clear. In Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 610, Dixon CJ, Kitto and Windeyer JJ said:

It is, however, fitting that we remind ourselves of the criterion to be applied when it is said that a specification is ambiguous. For, as the Chief Justice pointed out in Martin v Scribal (1954) 92 CLR 17, at p 59 … we are not construing a written instrument operating inter partes, but a public instrument which must, if it is to be valid, define a monopoly in such a way that it is not reasonably capable of being misunderstood. Nevertheless, it is to be remembered that any purely verbal or grammatical question that can be resolved according to ordinary rules for the construction of written documents, does not, once it has been resolved, leave uncertain the ambit of the monopoly claimed (see Kauzal v Lee (1936) 58 CLR 670, at p 685).

156 Sandoz submits that given the unfamiliar and ambiguous nature of the term “in hydrophilized form”, this is not a case of a “purely verbal or grammatical question that can be resolved according to ordinary rules for the construction of written documents”.

157 As Bayer submits that it is legitimate to have regard to the disclosure in the Lerk papers in order to properly understand the term “in hydrophilized form”, it is also necessary to refer to the principles that bear upon the extent to which, if at all, a document cited in a patent specification may be treated as part of its disclosure for the purpose of resolving any issue of clarity or construction.

158 The specification is to be construed in the light of the common general knowledge before the priority date. However, the common general knowledge is limited to information which had entered the common stock of knowledge and was well known to, and generally accepted by, the bulk of those in the field at that time. Sandoz submits that documents, such as the Lerk papers, which do not form part of the common general knowledge cannot be taken into account via that route.

159 For a cited document which did not form part of the common general knowledge, it is necessary to have regard to the nature and purpose of the reference to the document in the specification in question. A cited document may, for example, be said to be incorporated by reference into the specification. In such a case, it may be legitimate to have regard to its contents. However, the authorities demonstrate that, even in such cases, it remains necessary to have regard to the nature and purpose of the reference to the document, and that it may be legitimate to use the contents of the document for some purposes but not others: Idenix Pharmaceuticals LLC v Gilead Sciences Pty Ltd (2017) 134 IPR 1 at [165] (per Nicholas, Beach and Burley JJ).

160 Sandoz submits that where (as in the 226 Patent) the cited document is not incorporated by reference, the prima facie position is that its contents cannot be referred to, or treated as part of the disclosure of the specification. Sandoz accepts that it is not strictly necessary to use the incantation of “incorporation by reference” in order to ensure that a document, or part of its contents, which is cited in the specification is incorporated into, or forms part of, the disclosure of the specification. However, regard must be had to the nature and purpose of the reference in considering whether or not the patentee intends to incorporate some or all of its contents as part of the disclosure. The citation of a document as prior art in the background section of the specification is unlikely to entail such an indication. Further, where the material details of the prior art process or the product are themselves described in the specification, Sandoz submits that it is likely that the reference is to be understood as providing background only, or further information, rather than evincing an intention to incorporate additional content into the disclosure of the specification.

161 Bayer submits that Sandoz’s approach to the Lerk papers is erroneous and should be rejected. Bayer submits that the correct approach is that, where the patentee demonstrates an intention that words used in the specification have a particular meaning, effect should be given to such a “dictionary”: see Austal Ships Sales Pty Ltd v Stena Rederi Aktiebolag (2008) 77 IPR 229 at [13] (per Heerey, Finn and Dowsett JJ) quoting Flexible Steel Lacing Co v Beltreco Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 331 at [76]–[77] (per Hely J).

162 Bayer submits that the correct approach to construction by reference to a document referred to in a specification is that described by Greenwood J in Uniline Australia Ltd v SBriggs Pty Ltd (2009) 81 IPR 42 at [73]–[75].

6.4 Meaning of “in hydrophilized form”

163 The term “in hydrophilized form” does not have an ordinary meaning. Neither of the very experienced formulation experts were familiar with the term “in hydrophilized form”. Both experts agreed that a formulator would probably not have heard the term before reading the 226 Patent.

164 As Sandoz points out, the Lerk papers are not said to be incorporated by reference, nor do they form part of the common general knowledge. That being so, the correct approach according to Sandoz is to not read them. Sandoz submits that if there is any permissible use to be made of the Lerk papers in construing the 226 Patent, which Sandoz disputes, that use is very limited. At best, they might give some context to the particular discussion of the Lerk papers by the authors of the 226 Patent: see Uniline at [75] (per Greenwood J). They are not put forward as, and do not stand as, a means of defining the term “in hydrophilized form”, which is unclear to the skilled reader. They are not referred to for that purpose, or as part of a definition of that term.

165 Sandoz submits that the construction of claims that use an unfamiliar term to describe an essential characteristic of the invention is not to be determined by “plumbing the depths” of the disclosure of papers cited as prior art in the background section of the patent and then adding common general knowledge. Relying on Welch Perrin at 610 (per Dixon CJ, Kitto and Windeyer JJ), Sandoz submits that a patent is a public instrument “which must, if it is to be valid, define a monopoly in such a way that it is not reasonably capable of being misunderstood”. Sandoz submits that the Lerk papers do not remedy the lack of definition in the 226 Patent.

166 If, contrary to its primary submission, the person skilled in the art would have regard to the Lerk papers, Sandoz submits that the term is still unclear as the Lerk papers do not purport to define the term and do not provide any clear disclosure of, or the boundaries of the concept of, “in hydrophilized form”.

167 If, contrary to those submissions, it is possible to discern any meaning of the term “in hydrophilized form”, Sandoz submits that it is not the all-encompassing meaning contended for by Bayer. The only process disclosed in the 226 Patent for preparing a composition comprising rivaroxaban “in hydrophilized form” involves wet granulation with a hydrophilic binder such as HPMC, a standard technique for formulating solid oral dosage forms before the priority date, and an excipient commonly used in wet granulation. Similarly, Sandoz submits that the only process disclosed in the Lerk papers for “hydrophilizing” a hydrophobic active compound involves blending particles of the compound in a mixer with a solution of a hydrophilic excipient. In both cases, the production of a compound “in hydrophilized form” requires the use of a liquid with a hydrophilic excipient. On this construction, Sandoz submits that there is no infringement because the Sandoz rivaroxaban products are not made using wet granulation or a liquid.

168 Sandoz submits that, following the joint session, there was no consensus between the experts on what was taught by the Lerk papers, rather the entire discussion tended to underscore the ambiguity in the term.

169 Bayer submits, employing the language in Uniline, that the person skilled in the art would read the Lerk papers to give context to, and to understand, the words “hydrophilization” and “in hydrophilized form” in light of the particular discussion in the 226 Patent of “hydrophilization” and “a process for the hydrophilization of hydrophobic active compounds” the subject of the Lerk papers.

170 Bayer contends that it does not seek to refer to the Lerk papers beyond that permitted context and understanding. In that context, Bayer submits that the person skilled in the art would read and understand the words “in hydrophilized form” in the context of the whole of the specification to describe the surface of a hydrophobic drug particle which has been rendered hydrophilic as a result of close physical interactions with a hydrophilic excipient.

171 Bayer contends that, consistent with the evidence of Professors Roberts and Polli, the Lerk papers would be understood by the person skilled in the art to disclose a principle for improving dissolution beyond the precise experiments conducted in those papers. Having read the Lerk papers, Bayer submits that the person skilled in the art would understand that “in hydrophilized form”, which requires achieving close physical interactions between a hydrophobic drug particle and a hydrophilic excipient, might be achieved in a number of different ways, including intensive mixing without the use of a liquid in a confined space or a lower energy process with water.

172 As I explain below, I consider that the person skilled in the art would have recourse to the Lerk papers. Thus, it is appropriate to briefly outline the manner in which the Lerk papers arise in the specification and their contents.

173 The reference to the Lerk papers arises in the section of the 226 Patent which discusses three concepts to increase oral bioavailability which have been discussed in the past.

174 The first involves solutions of active compounds being filled into gelatine capsules. That option is said to be unavailable in the present case as the capsule size required in order to provide the necessary dose would not be swallowable.

175 Second is a process of amorphization of the active compound which Professor Polli described as being a process wherein a crystalline drug is converted to a non-crystalline, amorphous drug form in the hope that the amorphous form will have higher solubility. The “solution method” of amorphization is said by the specification to be problematical as the active compound, as well as being relatively poorly soluble in water, is also poorly soluble in pharmaceutically acceptable solvents such as ethanol or acetone. The “fusion” method is also said to be disadvantageous due to the high melting point of the active compound, which would lead to an undesirably high proportion of breakdown components forming during the preparation.

176 Third is “a process for the hydrophilization of hydrophobic active compounds as exemplified by hexobarbital and phenytoin [which] has been described [in the Lerk papers]”. The specification describes how the active compound particles are blended in a mixer with methyl- or hydroxyethylcellulose solution with extensive avoidance of an agglomeration step and then dried. The active compound thus obtained is subsequently filled into hard gelatine capsules without further treatment.

177 Immediately following the discussion of the three past concepts for increasing oral bioavailability is the “surprisingly, it has now been found” paragraph (extracted above at [113]). This paragraph refers to a “special treatment of the surface of the active compound (I) in the course of the moist granulation [which] brings about improved absorption behaviour”. That special treatment results in the active compound (I) being “in hydrophilized form” and leads to a “significant increase in the bioavailability of the formulation thus obtained”.

178 Before considering the Lerk papers, it is useful to summarise the state of the common general knowledge about wet and dry granulation as at the First Priority Date. As at that date, there were two commonly used production methods for the manufacture of a solid oral dosage form, being:

(a) granulation (encompassing wet and dry granulation); and

(b) direct compression.

179 Granulation involves the combination of powder particles with a binder to form granules. The rationale for granulation includes: to increase the bulk density of the powder, to improve the flowability of the powder, to improve mixing homogeneity, and to affect the dissolution process for hydrophobic poorly soluble particles. The granules are compressed into a tablet or filled into a capsule.

180 Wet granulation involves the combination of drug particles with a binder and other excipients into granules in the presence of a granulating fluid, usually water. The granulation liquid may be used alone, or as a solvent containing a binding agent. Organic solvents, rather than water, may be used if the drug is water sensitive or rapid drying is required. At the First Priority Date, wet granulation was considered an effective means, in terms of production and cost, to prepare good-quality granulation.

181 Wet-granulation techniques were widely used in the pharmaceutical industry to make tablets to achieve a number of objectives, including homogeneity, improved flowability, compactibility and stability, and to cause the production of hydrophilic surfaces. Wet granulation is not suitable for drugs that are sensitive to moisture or heat.

182 Dry granulation is a similar process, but carried out in a dry environment in which no liquid is used (eg using a dry binder). Dry granulation is generally suitable for drugs that are sensitive to moisture and heat. It involves less processing steps than wet granulation but generally does not result in the advantages of wet granulation in terms of improved flowability and compactibility. Therefore, dry granulation can generally only be used where the tablet ingredients have sufficient inherent binding or cohesive properties.

183 The first thing to note is that, at the First Priority Date, the Lerk papers were over 24 years old. They are clearly not common general knowledge, nor had the term “hydrophilized” been embraced by formulators after the publication of the Lerk papers as neither expert had come across the term “hydrophilized” prior to reading the 226 Patent in 2022, over 40 years after publication of the Lerk papers.

184 Lerk 1978 is entitled “Effect of Hydrophilization of Hydrophobic Drugs on Release Rates from Capsules”.

185 The abstract states that the release of poorly soluble hydrophobic drugs from capsules can be improved significantly by the creation of a hydrophilic surface by intensive mixing of the hydrophobic drug with a small amount of a solution of a hydrophilic excipient. The abstract continues:

The data presented indicate that the hydrophilic material is mechanically distributed over the hydrophobic surface. The creation of hydrophilic capillaries in a capsule or tablet allowed the rapid penetration of the dissolution fluid, resulting in a dispersion of well-wetted particles, so that the maximum surface area of the powder was exposed to the dissolution medium.

186 The last sentence of the abstract concludes that “hydrophilization of hydrophobic drugs has the important benefit that the release rate from capsules is independent of the surface tension of the dissolution medium”. This is to be contrasted with non-hydrophilized, hydrophobic drug samples in which the release rate varied with the surface tension properties of the dissolution medium.

187 The body of the article begins by discussing several methods for increasing the dissolution rate of poorly water-soluble drugs, and the problems associated with those methods. The article continues: