Federal Court of Australia

Corbisieri v NM Superannuation Proprietary Limited [2023] FCA 1319

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal is allowed.

2. Pursuant to s 1057(4)(a) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), the determination of Australian Financial Complaints Authority Limited (AFCA) in case number 871726 is set aside.

3. Pursuant to s 1057(4)(b) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), the complaint made by the second respondent is remitted to AFCA to be determined again in accordance with these reasons.

4. The parties are to file submissions as to costs, not exceeding three pages, within seven days of the publication of these reasons, if the question of costs is not agreed.

5. If there is no agreement, the costs of the appeal will be determined on the papers.

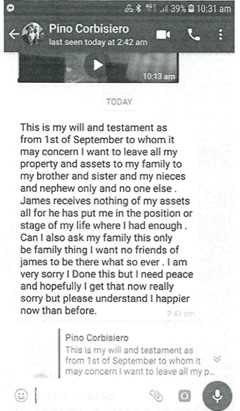

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

O’CALLAGHAN J

Introduction

1 This is an appeal on a question of law pursuant to s 1057 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) brought by Mrs Rosaria Corbisieri, as executrix of the Will of her late son, Pino Corbisiero, against a decision by the second respondent, the Australian Financial Complaints Authority Limited (AFCA), determining that the entire amount of a death benefit of $1.122m payable pursuant to the terms of a policy of insurance (the death benefit) between Mr Corbisiero and the first respondent (NM Super or the trustee) be paid to the second respondent (Mr Nguyen) who was in a de facto relationship with Mr Corbisiero, and in whose favour Mr Corbisiero had made a “Non-Lapsing Binding Nomination” dated 6 December 2018 to pay that sum to him.

2 NM Super is a body corporate and administers the AMP Super Fund (the Fund) as its trustee.

3 AFCA is the operator of the external dispute resolution scheme for which an authorisation is in force pursuant to part 7.10A of the Corporations Act.

4 Mrs Corbisieri contended that immediately before his death (by suicide) on 1 September 2019, her son expressed his intention to terminate his de facto relationship with Mr Nguyen in a message he sent to his sister via WhatsApp (which I will call the text); the Non-Lapsing Binding Nomination was thus invalid at the time of his death in accordance with the relevant Fund rules; AFCA erred as a matter of law in finding otherwise; and that the proceeding should therefore be remitted to AFCA to be determined again according to law.

5 NM Super and AFCA each filed a submitting notice. Mr Nguyen seeks to uphold AFCA’s decision.

The rules of the Fund and the Non-Lapsing Binding Nomination

6 Rule 7.10C of the relevant deed of trust (the AMP Superannuation Savings Trust Consolidated Trust Deed dated December 2017) provides:

Subject to rule 7.10D, if all the requirements of the Superannuation Law have been met, where:

(a) the Trustee is in receipt of a current, valid Non-Lapsing Nomination; and

(b) the Trustee has consented to the Non-Lapsing Nomination in accordance with rule 7.10B; and

(c) the Non-Lapsing Nomination complies with any terms and conditions determined by the Trustee pursuant to rule 7.10B,

the Trustee must pay the deceased Member’s Death Benefit to the person or persons listed in the Non-Lapsing Nomination.

7 Rule 7.10D(d) in turn provides that “[a] Non-Lapsing Nomination ceases to be valid and effective” upon “the date … the Member’s de-facto relationship (including with a person of the same sex) terminates”.

8 On appeal, counsel for Mrs Corbisieri accepted that Mr Corbisiero was in a de facto relationship with Mr Nguyen until shortly before his death.

9 On 6 December 2018, Mr Corbisiero completed a “Beneficiary Nomination Form” (exhibit 1) in which he nominated Mr Nguyen in his Non-Lapsing Binding Nomination as “partner”.

The text

10 On 1 September 2019, Mr Corbisiero wrote, and sent to his sister, the text. The following screenshot of the text from his sister’s mobile phone was in evidence:

11 Sometime shortly after the text was sent, Mr Corbisiero committed suicide.

The question of law posed

12 At the hearing, counsel for both Mrs Corbisieri and Mr Nguyen agreed that although multiple grounds of appeal were contained in the notice of appeal, the appeal turned on one question only, namely, whether the communication of the text by Mr Corbisiero to his sister shortly prior to his death was on its proper construction effective to terminate the de facto relationship between him and Mr Nguyen within the meaning of rule 7.10D(d) of the rules. If the answer to that question is yes, then the matter must be remitted to AFCA “to be determined again” according to law, pursuant to s 1057(4)(b) of the Corporations Act.

Procedural history

13 On 20 November 2019, Mr Nguyen lodged a “Death claim” form with the trustee claiming the death benefit.

14 On 25 November 2021, the trustee made its initial decision to the effect that it would pay 100% of the death benefit to Mr Corbisiero’s estate.

15 On 30 November 2021, Mr Nguyen lodged an objection with the trustee.

16 On 9 February 2022, the trustee made a decision to the effect that the death benefit was to be paid as 80% to Mr Corbisiero’s estate and 20% to Mr Nguyen.

The trustee’s decision

17 Mr Nguyen subsequently objected to that decision, but the trustee reaffirmed it, including for these reasons:

The Trustee further considered the deceased member’s Beneficiary nomination form dated and witnessed on 6 December 2018 where he nominates [Mr Nguyen] as his partner and non lapsing beneficiary (Non-Lapsing nomination) in light of the new information received.

Based on the new information, the Trustee has determined that it does not provide any reason to cause the Trustee to either change its decision of 9 February 2022 and/or validate the Non-Lapsing nomination. The new information confirms the information already reviewed by the Trustee up to its decision of 9 February 2022.

Therefore, the Trustee reaffirms that whilst the Non-Lapsing nomination includes [Mr Nguyen] as “partner” of the deceased member, the Trustee must be satisfied that a Non-Lapsing nomination is valid as at the date of death in terms of the relevant trust deed and superannuation law. In doing this, the Trustee considers all circumstances as at the date of death. The new information has not provided any reason for the Trustee to change its consideration of the circumstances at the date of the deceased member’s death.

…

It is argued that the Trustee has placed weight on the [text] left by the deceased member on 1 September 2019 at the time of his death. However, the Trustee reaffirms that this [text], as provided in the information reviewed prior to the objection, reflects the wishes of the deceased member at the time of his death.

The Trustee highlights the following trust deed rule in terms of the Non-Lapsing nomination,

7.10D A Non-Lapsing Nomination ceases to be valid and effective upon the earlier of the following events:

…

(d) the date the Member divorces or the Member’s de-facto relationship (including with a person of the same sex) terminates;

…

On that basis, the Trustee confirms the invalidation of the Non-Lapsing nomination based on the information received and considered to date. Therefore, the Trustee has discretion within the provisions of the trust deed to make a determination regarding the distribution of the deceased member’s death benefit to dependant/s and/or the LPR, and if none to other persons.

The Trustee within its discretion remains satisfied that an interdependency relationship did not exist between [Mr Nguyen] and the deceased member as at the date of death within the meaning of superannuation law. The reasons were provided in the letter of 9 February 2022 which the Trustee confirms, and the new information has not provided reason to change the Trustee’s view.

However, the Trustee confirms that it remains satisfied that the deceased member was providing some financial support to [Mr Nguyen] in the form of rent for the Richmond property where [Mr Nguyen] was residing, paying for [Mr Nguyen]’s mobile phone expenses and private health insurance.

The Trustee, within its discretion, determined that [Mr Nguyen] was a partial financial dependent on the deceased member as at the date of death. The Trustee has therefore reaffirmed to distribute to [Mr Nguyen] a portion of the death benefit proceeds. The portion of the distribution to [Mr Nguyen] is based on the level of financial support provided by the deceased member to [Mr Nguyen] for which [Mr Nguyen] has provided documentary evidence.

The new information does not give reason to the Trustee to change the proposed portion of 20% to [Mr Nguyen].

18 Mr Nguyen then lodged a complaint with AFCA. Mrs Corbisieri, in her capacity as the executrix of the estate, was later joined as a party.

AFCA’s decision

19 By decision dated 19 May 2023, AFCA determined that Mr Nguyen receive 100% of the death benefit.

20 It is not necessary to set out the bulk of AFCA’s reasons. There was a live issue before it as to whether and when Mr Corbisiero and Mr Nguyen were in a de facto relationship, that was the subject of detailed and often conflicting evidence, but most of that evidence and AFCA’s consideration of it is not relevant here.

21 In so far as AFCA’s reasons concern the text, it reasoned as follows:

2.2 Was the deceased’s [Non-Lapsing Binding Nomination (BN)] valid at the date of his death?

Yes, the panel found the BN was valid as it was satisfied the spousal relationship between the deceased and complainant was ongoing and had not terminated at the date of the deceased’s death.

The trust deed requires the trustee to pay a death benefit in accordance with a valid BN

On 6 December 2018 the deceased completed a BN, nominating the complainant to receive his death benefit in its entirety as his ‘partner’. This was a ‘Non-Lapsing Nomination’ for the purposes of the fund’s trust deed.

The fund’s trust deed sets out rules in relation to BNs and the circumstances under which a BN that is a Non-Lapsing Nomination ceases to be valid. At the time the deceased made his BN, Rule 7.10A of the trust deed gave the trustee power to allow a member to make a BN that was a Non-Lapsing Nomination.

The panel accepts the trustee had the ability to allow the deceased to make a BN and that it was governed by the relevant trust deed provisions.

…

Rule 7.10B of the trust deed explains that, where the trustee receives a BN and it satisfies the required terms and conditions, the trustee’s consent becomes effective from the time the nomination is processed by or on behalf of the trustee. While the deceased had died before he received his annual statement for the July 2018 to 30 June 2019 year, the panel noted it listed the complainant as the person nominated in the BN. The panel was satisfied the trustee had consented to the BN in the relevant sense and that it met the required terms and conditions.

The trustee in its submissions says the BN was not valid because the spousal relationship was no longer in existence at the date of death.

….

Common law factors assist in determining whether a spousal relationship exists

…

The panel considered the evidence as it relates to each of the following common law factors, indicative of when two people are living together on a genuine domestic basis in a relationship as a couple.

Duration of the relationship

…

Although the panel acknowledged the deceased’s message to his sister just prior to his death, it did not consider this terminated the relationship between him and the complainant. This is because relationships have their ups and downs and, while there may have been some disagreement just prior to the deceased’s death, the panel did not consider the relationship had been terminated. While the deceased may have had misgivings and vented his frustrations to his family and may have indicated to another party he wanted to leave the relationship, the evidence does not support he had actually taken steps to end his relationship with the complainant prior to his death. The panel considered the relationship was ongoing up to the date of death and therefore its duration was from 2006 until the date of the deceased’s passing, spanning some 13 years.

(Emphasis added).

22 The parties agreed that those emphasised words constituted the crux of AFCA’s reasons about the proper construction, meaning and effect of the text.

23 After considering each of the common law factors about whether a de facto relationship existed (not relevant here), AFCA’s reasons continued:

The panel considered the BN was valid

As the panel was satisfied the complainant was the deceased’s ‘spouse’ for the purposes of the trust deed, it was also satisfied the BN was valid at the date of the deceased’s death.

2.3 Is the trustee’s decision fair and reasonable?

No, the trustee should have recognised the spousal relationship between the complainant and deceased at the date of the deceased’s death and given effect to the BN. Therefore its decision to exercise discretion and pay the death benefit to the complainant and [Mrs Corbisieri as executrix] is not fair and reasonable in its operation in relation to the complainant and joined party in all the circumstances.

Trustee’s decision was not fair and reasonable

As the panel was satisfied the complainant was the deceased’s spouse and the BN was valid at the date of the deceased’s death (as outlined in the section 2.2 above), the trustee’s decision to pay the death benefit according to its discretion is not fair and reasonable in its operation in relation to the complainant and joined party in all the circumstances. This is because it is not in accordance with the requirement to pay the death benefit in accordance with the BN under Rule 7.10C of the trust deed.

AFCA has power to substitute its own decision

If AFCA finds a trustee’s decision to be unfair and unreasonable, it may exercise its determination-making powers to the extent necessary to remove the unfairness or unreasonableness found to exist. In doing so, AFCA has all of the powers, obligations and discretions of the trustee. AFCA may set aside the decision and substitute its own decision.

Therefore the panel considered it appropriate to set aside the trustee’s decision and substitute its own decision. This is because the trustee had a BN to which it was required to give effect.

2.4 Determination

The determination sets aside the trustee’s decision AFCA’s substituted decision is that the death benefit be paid to the complainant in accordance with the BN.

The competing submissions

24 Counsel for Mrs Corbisieri submitted as follows:

The message contained in the [text], in particular the statement that: “[Mr Nguyen] receives nothing of my assets all for he has put me in the position or stage of my life where I had enough” and his ultimate suicide is:

(a) evidence of conduct or behaviour by [Mr Nguyen] contrary to the interests of the deceased, which in itself can be sufficient to impute an intention to separate; and

(b) reflective of the breakdown of the relationship; and

(c) shows in the most tragic way that the deceased was not committed to a mutual shared life with [Mr Nguyen] from at least that moment in time.

The [text] is conclusive proof that the deceased had terminated his defacto relationship with [Mr Nguyen] by the time he transmitted [it] to his sister Teresa Corbisieri at 2.42 am on 1 September 2019 and subsequently ended his life later that morning. The deceased clearly did not intend to continue with having any form of relationship with [Mr Nguyen], including any financial arrangements. He clearly intended to and did end their relationship and subsequently his life.

Consequently, the [binding notification] was not binding on the trustee as the spousal relationship had ended prior to his death.

25 Counsel for Mrs Corbisieri submitted that analogous cases in the family law context make it clear that communication of an intention to sever a de facto relationship is not necessary, citing, among other cases, In the Marriage of Tye (1976) 9 ALR 529; [1976] 1 Fam LR 11,235; and Hibberson v George (1989) 12 Fam LR 725 at 740.

26 Counsel for Mr Nguyen submitted that:

(1) the text did not in terms terminate the de facto relationship;

(2) the text was sent not to Mr Nguyen, but to Mr Corbisiero’s sister;

(3) in any event, analogous cases require in addition to a communication of an intention to terminate a relationship some objective manifestation of that intention,

and that in those circumstances no error of law was disclosed.

Consideration

27 The jurisdiction of AFCA, and its relevant functions, were explained by Wheelahan J in Tratter v Aware Super [2023] FCA 491 at [13]-[21]. As his Honour explained at [15]-[16]:

The content of a complaint that may be made to AFCA in relation to a death benefit is constrained by s 1053(1)(j), which provides that a person may make a complaint in relation to a death benefit only if the complaint is that the decision was unfair or unreasonable. The powers of AFCA conferred by s 1055 of the Corporations Act are aligned with the authorised subject-matter of the complaint. In relation to death benefits, s 1055(3) mandates that AFCA must affirm the decision under review if it is satisfied that the decision, in its operation, was fair and reasonable in all the circumstances –

(3) AFCA must affirm a decision relating to the payment of a death benefit if AFCA is satisfied that the decision, in its operation in relation to:

(a) the complainant; and

(b) any other person joined under subsection 1056A(3) as a party to the complaint;

was fair and reasonable in all the circumstances.

Correspondingly, AFCA’s powers in s 1055(6) to vary, set aside, substitute, or remit a decision are conditioned by s 1055(5) on AFCA finding that the decision under review relating to the payment of a death benefit is, in its operation, unfair, or unreasonable, or both. The formation of this opinion by AFCA is a subjective jurisdictional fact –

(5) If AFCA is satisfied that a decision relating to the payment of a death benefit, in its operation in relation to:

(a) the complainant; and

(b) any other person joined under subsection 1056A(3) as a party to the complaint;

is unfair or unreasonable, or both, AFCA may take any one or more of the actions mentioned in subsection (6), but only for the purpose of placing the complainant (and any other person so joined as a party), as nearly as practicable, in such a position that the unfairness, unreasonableness, or both, no longer exists.

28 It is not necessary to rehearse the other matters to which his Honour drew attention, because no particular issue arises on this appeal about the role or jurisdiction of AFCA.

29 It is sufficient to note for present purposes two things. First, under s 1055A of the Corporations Act, AFCA is required to give reasons for its determination. That obligation is subject to the requirement in s 25D of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) that the reasons should set out the findings on material questions of fact and refer to the evidence or other material on which those findings were based. Secondly, AFCA is not a judicial body. Its obligation to give reasons for its determinations is statutory, and is subject to the standard of reasons established by the Acts Interpretation Act. It follows that in evaluating AFCA’s reasons for its determination, the reasons are to be read as a whole, and not in an over-zealous way with an eye keenly attuned to error.

30 In this case, in my view, AFCA did err as a matter of law in finding that the text was not effective to terminate the de facto relationship between Mr Corbisiero and Mr Nguyen within the meaning of rule 7.10D(d), because the only construction of the text reasonably open is that Mr Corbisiero intended by the writing and sending of it to terminate the relationship.

31 In terms, Mr Corbisiero said that the text was his “will and testament as from 1st of September”; that he “want[ed] to leave all [his] property and assets to [his] family to my brother and sister and [his] nieces”; and that Mr Nguyen put him in “the position or stage of [his] life where [he] had [had] enough”. He went on to ask that “this” (which it was accepted was a reference to his funeral) “only be [a] family thing” and that he “want[ed] no friends of [Mr Nguyen] to be there what so ever”.

32 It seems to me that, by those words, Mr Corbisiero made an unequivocal statement of his intention to terminate his de facto relationship with Mr Nguyen.

33 To say, as AFCA did, that the text instead conveyed that “relationships have their ups and downs” and that Mr Corbisiero “may have had misgivings and vented his frustrations” and “indicated to another party he wanted to leave the relationship” seems to me, with respect, to be an untenable reading of the text, and it was not reasonably open to AFCA to find as it did.

34 As McElwaine J said in Sharma v H.E.S.T. Australia Ltd [2022] FCA 536 at [35], “… if in determining a superannuation complaint, AFCA materially misdirects itself as to the legal rights or obligations of the parties in order to found the statutorily required state of satisfaction (that a decision in its operation in relation to the complainant was fair and reasonable in all of the circumstances), the determination is reviewable for legal error: Craig v South Australia (1995) 184 CLR 163 at 179”.

35 In my view, the cases decided in the family law jurisdiction about the meaning of the verb “to separate” upon which Mrs Corbisieri’s counsel relied are analogous in assessing the question whether Mr Corbisiero “terminated” his de facto relationship with Mr Nguyen in his text.

36 In In the Marriage of Tye (1976) 9 ALR 529; [1976] 1 Fam LR 11,235, the parties to a marriage lived together in Melbourne until the husband left for Singapore to live and work, leaving his wife in Melbourne. The husband on leaving Melbourne told his wife that, after he had settled in, he would “send for her”. The husband took all their ready money. Not long afterwards, the wife received a letter from the husband informing her that he would not resume cohabitation. The wife made an application under the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) for a decree of dissolution of the marriage. Justice Emery reasoned as follows (at ALR 531-32; Fam LR 11,237-8):

The question then arises as to whether or not, on those findings of fact, the consortium vitae was brought to an end by this unilateral act of one of the spouses before that act was communicated to the other spouse.

In my opinion the ground for dissolution is made out, namely that the marriage between the parties has broken down irretrievably, which ground is established by the fact that they have been separated for the necessary period of 12 months prior to the filing of the application for dissolution.

There is no element of guilt in the concept of separation in the Family Law Act 1975. Section 48(2) enacts that a decree shall be made, if, and only if, the court is satisfied that the parties separated and thereafter lived separately and apart for a continuous period of not less than 12 months immediately preceding the date of the filing of the application for dissolution of marriage.

Under the provisions of s 28(m) of the Matrimonial Causes Act 1959, from which ss 48 and 49 of the Family Law Act 1975 are derived, the requirement was that the parties “have separated and thereafter have lived separately and apart”. In Baily v Baily (1962) 3 FLR 476 …, it was held that separation within the meaning of s 28(m) may occur through the unilateral act of either spouse.

Looking at the desertion cases it is clear that desertion, a unilateral act, could commence without knowledge of the fact being communicated to the other spouse. A spouse may be deserted without being aware of the fact (see Pulford v Pulford [1923] P 18; [1922] All Rep 121; Sotherden v Sotherden [1940] P 73; [1940] 1 All ER 252, and a quite curious case Papadopoulos v Papadopoulos [1936] P 108, where the husband was held to be in desertion though both he and his wife imagined they were separated by agreement).

In McRostie v McRostie [1955] NZLR 631, Adams J held that in a separation case consortium can be terminated by the unilateral act of one spouse unknown to the other and that an animus deserendi supervening upon a de facto separation is sufficient, notwithstanding that the separation may have been brought about by circumstances beyond the control of the spouse, as by committal to a mental institution.

In Koufalakis v Koufalakis (1963) 4 FLR 31, Travers J held that, notwithstanding that the separation was brought about by the husband, the husband himself was entitled to a decree under s 28(m) of the Matrimonial Causes Act 1959. At (4 FLR) p 312; he said: “On reading s 28(m), my first impression of the words ‘that the parties … have separated’ was that they require some voluntary separation by the parties or at least one of which both parties were fully aware and conscious and in respect of which both parties were quite capable of doing what may be necessary to remedy the matrimonial breach.” His Honour then proceeds to say that s 36 of the Matrimonial Causes Act 1959 requires an artificial meaning to be given to “separated” as it enacts that separation may occur as a result of the act of one party only.

As stated by Lord Blackburn in Young & Co v Mayor etc of Leamington Spa (1883) 8 App Cas 517 at 526, the courts “ought in general, in construing an Act of Parliament, to assume that the legislature knows the existing state of law”. I can see no reason to depart from that principle and, therefore, on a comparison of ss 48(2) and 49(1) of the Family Law Act 1975 with ss 28(m) and 36 of the Matrimonial Causes Act 1959 there can be no doubt that the unilateral intention of one spouse, not communicated to the other spouse, can bring the consortium vitae to an end. “Separation” therefore means not only actual physical separation but a physical separation in such circumstances that the consortium vitae has been brought to an end.

(Emphasis added).

37 In Hibberson v George (1989) 12 Fam LR 725, one of the issues before the New South Wales Court of Appeal was whether a de facto relationship had been terminated before the commencement of the De Facto Relationships Act 1984 (NSW). Justice Mahoney (with whom Hope JA and McHugh JA each agreed on the point) reasoned as follows (at 739-40):

The Act came into effect on 1 July 1985. The learned judge held that it did not apply because, from May 1985, there did not exist the de facto relationship upon the basis of which the Act operated and it had no retrospective effect.

It was submitted to the learned judge, and the submission repeated here, that although the parties had lived apart from each other in separate homes from May 1985 onward, the relevant relationship had not ceased. The de facto relationship defined by s 3 of the Act is a relationship “of living or having lived together as husband and wife on a bona fide domestic basis”. The submission was, in effect, that a relationship existed between them; that they were apart only until they decided whether the relationship should end or continue; and that the decision to end it did not occur until after 1 July 1985.

The learned judge decided against Miss Hibberson in this regard. In my opinion, his conclusion was correct. What is involved is “living … together as husband and wife on a bona fide domestic basis”. It is correct, as Mr Hamilton QC has submitted, that the relevant relationship may continue notwithstanding that the parties are apart, for example on holidays. And he referred to the law which was developed in the context of marriage upon the distinct question, viz, whether physical separation constituted desertion.

There is, of course, more to the relevant relationship than living in the same house. But there is, I think, a significant distinction between the relationship of marriage and the instant relationship. The relationship of marriage, being based in law, continues notwithstanding that all of the things for which it was created have ceased. Parties will live in the relationship of marriage notwithstanding that they are separated, without children, and without the exchange of the incidents which the relationship normally involves. The essence of the present relationship lies, not in law, but in a de facto situation. I do not mean by this that cohabitation is essential to its continuance: holidays and the like show this. But where one party determines not to “live together” with the other and in that sense keeps apart, the relationship ceases, even though it be merely, as it was suggested in the present case, to enable the one party or the other to decide whether it should continue.

(Emphasis added).

38 That decision was applied by the Queensland Court of Appeal in S v B (No 2) [2005] 1 Qd R 537 by Dutney J (with whom McPherson and Williams JJA agreed), as follows at 549 [48]:

Applying the passage of Mahoney JA in Hibberson v George, which I set out earlier, a de facto relationship ends when one party decides he or she no longer wishes to live in the required degree of mutuality with the other but to live apart. It does not seem to me that it is necessary to communicate this intention to the other party providing the party that is desirous of ending the relationship acts on his or her decision. I do not think it is necessary that the other party agree with or accept the decision.

(Emphasis added).

39 In my view, by analogous reasoning, it is not necessary for a party to a de facto relationship to communicate their intention to the other party in order to “terminate” it within the meaning of rule 7.10D(d).

40 It follows that the fact that Mr Corbisiero communicated his intention to his sister, not Mr Nguyen, is not relevant.

41 Mr Nguyen’s counsel also argued that it is necessary for the termination to be effective that the party seeking to terminate engage in some conduct that turns a unilateral thought into termination – by way of example only, as in In the Marriage of Tye, by moving to Singapore.

42 I do not agree that an expression of intention to terminate a relationship (or “to separate”, as in the family law cases) in all cases requires some overt, physical act in addition to a statement of intention. Each case must be determined on its individual facts.

43 But in any event, in the tragic circumstances of this case, by taking his own life, Mr Corbisiero did exhibit by his actions such an act, or to adopt what Dutney J said in S v B (No 2), he “acted on his decision”.

44 Accordingly, I will make orders to this effect:

(1) The appeal be allowed.

(2) The determination of AFCA be set aside.

(3) The complaint made by the second respondent to AFCA be remitted to it to be determined again in accordance with these reasons.

45 I will also make directions about the question of costs.

46 I wish to add one other thing. Mr Corbisiero died in September 2019. It is now almost 2024. The matter should be determined again by AFCA as a matter of priority, for everyone’s sake.

I certify that the preceding forty-six (46) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice O’Callaghan. |

Associate: