Federal Court of Australia

Taylor v August and Pemberton Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1313

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | AUGUST AND PEMBERTON PTY LTD (ACN 150 962 315) First Respondent SIMON GREW Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Judgment be entered in favour of the applicant.

2. By 4:00pm on 21 November 2023 the parties bring in short minutes of order giving effect to the judgment.

3. In the event that the applicant presses her claim for remedies other than damages (as sought in her amended originating application):

(a) the parties confer with a view to reaching agreement;

(b) if no agreement is reached:

(i) the applicant file submissions, not exceeding 5 pages, by 4:00pm on 28 November 2023;

(ii) the respondents file and serve submissions in response, not exceeding 5 pages, by 4:00pm on 5 December 2023;

(iii) the applicant file and serve submissions in reply, not exceeding 3 pages, by 4:00 pm on 12 December 2023; and

(iv) unless the court otherwise orders, any claim for additional relief be determined on the papers.

4. The respondents pay the applicant’s costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

[1] | |

[2] | |

[26] | |

[28] | |

[35] | |

[35] | |

[37] | |

[54] | |

[54] | |

[61] | |

[61] | |

[62] | |

[70] | |

[70] | |

[73] | |

[82] | |

The white gold hammered band ring and the 5 mm and 10 mm silver rings | [86] |

[91] | |

[91] | |

[97] | |

[107] | |

[118] | |

[126] | |

[133] | |

[145] | |

[148] | |

[161] | |

[164] | |

[164] | |

[168] | |

[175] | |

The comments | [185] |

[186] | |

[187] | |

[194] | |

[199] | |

[206] | |

[209] | |

[219] | |

[239] | |

[243] | |

[246] | |

[253] | |

Ms Taylor’s condition in March 2020 | [254] |

[255] | |

[280] | |

[282] | |

[291] | |

[297] | |

[302] | |

[303] | |

[311] | |

[312] | |

[313] | |

[313] | |

[317] | |

Did Mr Grew slap Ms Taylor on her buttock(s) on 23 July 2019? | [326] |

Did Mr Grew make unsolicited comments to Ms Taylor about her appearance between October and December 2019 as alleged? | [337] |

Did Mr Grew say to Ms Taylor the things she attributed to him in the conversations in the office on 6 January 2020 and in the car on 1 June 2020? | [342] |

Which, if any, of the alleged conduct was of a sexual nature and/or a sexual advance and unwelcome? | [350] |

[350] | |

[352] | |

[376] | |

[377] | |

[378] | |

Were the circumstances in which the relevant conduct occurred such that a reasonable person would have anticipated the possibility that Ms Taylor would be offended, humiliated or intimidated? | [387] |

[394] | |

[395] | |

[396] | |

[396] | |

[403] | |

[404] | |

Ms Taylor complains of sexual harassment and foreshadows the making of a complaint to the AHRC (the 28 August letter) | [407] |

The response to the 28 August letter (the 4 September letter) | [409] |

[421] | |

The respondents press their claim for the return of company property and add a new allegation (the 15 October letter) | [422] |

[424] | |

The respondents file their response to the AHRC complaint accusing Ms Taylor of theft and threaten to report her to the police | [427] |

[431] | |

The respondents request the return of confidential information (the 19 March letter) | [432] |

[439] | |

[441] | |

[449] | |

[455] | |

[455] | |

[457] | |

[458] | |

[459] | |

[472] | |

[488] | |

[501] | |

[523] | |

[541] | |

[549] | |

[554] | |

[558] | |

[559] | |

[560] |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

KATZMANN J:

1 Fiona Taylor complains that she was sexually harassed by Simon Grew over a period of about 22 months while she was employed by his company, August and Pemberton Pty Ltd t/as Grew & Co, and claims that Mr Grew victimised her after she complained. She alleges that Mr Grew’s conduct breached her contract of employment and was unlawful under the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth) (SDA) and the Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 (Cth) (AHRC Act). She seeks various forms of relief from Grew & Co and Mr Grew himself. The claims were vigorously contested and the credit of the two protagonists is squarely in issue.

2 Nonetheless many of the facts were uncontroversial. The following account is derived from an agreed statement, the documentary evidence, and undisputed testimony.

3 Grew & Co is a small business which manufactures and sells fine jewellery. It was established in 2007 by Mr Grew, who is a jeweller, designer, the manager of the business, and the sole director of the company.

4 Ms Taylor accepted an offer of employment from Grew & Co on 30 November 2017. At the time she was employed by Larsen Jewellery. The previous day Mr Grew sent her an email stating, among other things:

I think you will be an asset to our company and I also think you will have creative opportunities and professional growth within Grew & Co that will far exceed your available potential within the structure and management of Larsen Jewellery. Often new opportunities come with the element of risk which in this case for both of us is now financial, by meeting you in the middle we both have the incentive to make the opportunity work and be profitable in the future.

Think it over, let me know how you feel. I want to make G&Co the most forward thinking and performing brand with[in] the Australian jewellery industry, it would be great to have you on board with that.

5 Ms Taylor was employed by Grew & Co from 18 January 2018 until 6 April 2022, reporting directly to Mr Grew. Ms Taylor was born on 14 September 1988, which means that when she began working for Grew & Co she was 29 and ceased when she was 34. Mr Grew is 10 years her senior.

6 The terms of her contract included those set out in an email from Mr Grew on 9 December 2017:

As we discussed your position will be full time, from Tuesday to Saturday and we have agreed to $65k + super commencing on January 18, 2018. Your role will involve managing client enquiries and project management, liaising with suppliers and diamond & gemstone sourcing as well as managing consignments. Your role will also involve working with clients as a creative representation of Grew & Co.

The title on your business cards will be “Couturier of fine jewellery” however we can work on your title within the business which will be a mix of project management and creative.

7 It was an implied term of the employment contract that Grew & Co would take reasonable care to provide her with a safe place of work.

8 Ms Taylor was educated to year 12 level. She enrolled in a Bachelor of Fine Arts at the University of New South Wales, majoring in jewellery design, but discontinued after two years. Her previous job as a “studio assistant” with Larsen Jewellery lasted about 18 months. Before that she worked in the music industry as a “booker” for bands.

9 When she started working for Grew & Co, Ms Taylor was one of six employees, all of whom reported directly to Mr Grew. Mr Grew, Ms Taylor and two other employees — Andrew Snow and Mai Vu — worked from the Sydney premises of Grew & Co at 350 George Street Sydney. Three employed jewellers worked in an off-site workshop. There was no human resources (HR) department and “no HR person” on the staff. Anyone who had an issue had to raise it directly with Mr Grew.

10 Ms Taylor was excited to join Grew & Co. She considered the culture was friendly and welcoming. She enjoyed the company of those with whom she worked. She felt that she “finally” had a boss who recognised her talents and championed them. Mr Grew told her “constantly” how valuable she was to the business and that she did “an amazing job”. He also told her she was a “superstar”. She felt like she had found her dream job.

11 Ms Taylor began as a sales consultant or, as she put it, in a “customer service sales role”. But over time she took on more responsibilities and by late 2018 she became “production manager”. Around this time, Grew & Co relocated to premises at 161 Clarence Street Sydney. From then on she shared an office with Mr Grew.

12 As Mr Grew put it, in her role as production manager Ms Taylor “fundamentally manag[ed] the entire stages of the production of jewellery within the workshop”. That involved liaising with sales staff and designers, sourcing gemstones and diamonds, creating job packets, responsibility for quality control, and, for a time, managing Grew & Co’s Instagram account. It is common ground that she performed very well. Mr Grew said she was “organised, consistent and … motivated”, and “really efficient”. He described her as “a trusted and great asset to the company”.

13 Ms Taylor and Mr Grew often worked in close proximity to each other. Their conversations were not confined to work-related matters. Mr Grew was aware that Ms Taylor was in a relationship when she started working at Grew & Co and during the course of her employment they spoke about the problems she was having in the relationship.

14 At the time Ms Taylor joined the staff of Grew & Co, Mr Grew was married. In about August 2018 he and his wife separated. He informed Ms Taylor first before telling all the other employees individually.

15 From about this time, Mr Grew gave Ms Taylor numerous gifts, which she alleges were unwelcome. Mr Grew was also generous to other members of staff, although not to the same extent.

16 Ms Taylor gave Mr Grew a birthday present in 2019 and Christmas presents in 2018 and 2019. She also organised a group gift for Mr Grew’s birthday in 2018.

17 Ms Taylor and Mr Grew often communicated by text. The text messages reproduced in these reasons appear in their original form, without correction for errors in spelling or punctuation. Many of the texts were personal in nature and in at least one of them Mr Grew praised her appearance. He also admitted to telling Ms Taylor that she had a beautiful body.

18 In January 2020 Mr Grew revealed to Ms Taylor that he had developed “feelings” for her. She was overwhelmed by the revelation. Ms Taylor made it clear to him that she was not interested in a romantic relationship with him. There was a dispute about whether she did so at the time, but for present purposes at least it does not matter.

19 The following month Ms Taylor and Mr Grew were due to take a business trip to attend an international gem and mineral exhibition (the Gem and Mineral Show) in Tucson, Arizona. Before they left Ms Taylor informed Mr Grew, via text, that she was feeling anxious about the trip and wanted to put down some boundaries.

20 In mid-March 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Mr Grew directed all employees to work from home except for Asato Tanaka, another jeweller, and Ms Taylor. Mr Grew offered to reimburse his employees for parking costs and tolls incurred by driving into work during this time.

21 On 1 June 2020, after driving Ms Taylor home from work, Mr Grew and Ms Taylor had a conversation in which he revived the subject of his January 2020 revelation which caused Ms Taylor considerable distress.

22 Ms Taylor did not attend work from 2 June 2020 until 8 June 2020 and last attended work for Grew & Co on 7 August 2020. Psychiatrists retained for both parties to the litigation consider she has a psychiatric disorder to which, if her history is accepted, the events she described substantially contributed.

23 On 28 August 2020 Ms Taylor, through her lawyers, complained that Mr Grew had sexually harassed her. The letter generated a combative response.

24 On 23 September 2020 she lodged a complaint with the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC). The complaint was terminated in accordance with s 46PH(1B)(b) of the AHRC Act because the President, through her delegate, was not satisfied there were reasonable prospects of the matter being settled by conciliation.

25 Ms Taylor resigned from Grew & Co on 6 April 2022. She found other, less rewarding, work in Queensland.

26 As Ms Taylor is the moving party, she bears the onus of proof. As this is a civil case, the standard of proof is the balance of probabilities. The question of whether the standard is met and the onus discharged is informed by the nature of the cause of action, the nature of the subject-matter of the proceeding, and the gravity of the allegations: Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), s 140. Section 140 is effectively an enactment of the principle described by Dixon J in Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 at 361–2:

Except upon criminal issues to be proved by the prosecution, it is enough that the affirmative of an allegation is made out to the reasonable satisfaction of the tribunal. But reasonable satisfaction is not a state of mind that is attained or established independently of the nature and consequence of the fact or facts to be proved. The seriousness of an allegation made, the inherent unlikelihood of an occurrence of a given description, or the gravity of the consequences flowing from a particular finding are considerations which must affect the answer to the question whether the issue has been proved to the reasonable satisfaction of the tribunal. In such matters “reasonable satisfaction” should not be produced by inexact proofs, indefinite testimony, or indirect inferences.

27 In considering whether Ms Taylor’s allegations have been made out, I have applied this standard, mindful of the principle in Briginshaw.

28 Six lay witnesses gave evidence, including Ms Taylor and Mr Grew.

29 Ms Taylor was the only witness in her case. Although she had foreshadowed through her counsel that her sister, Sonia, would also be called, Sonia was not called. But the respondents made nothing of that. In particular, they did not submit that the Court should infer from her absence that nothing she could say would assist Ms Taylor’s case: see Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298. And I draw no such inference.

30 Mr Grew submitted that Ms Taylor was “far from a satisfactory witness”. He claimed that her evidence changed, was embellished in parts, was self-serving, and at times incredible. I put to one side the submission that the evidence was self-serving. That could be said of the evidence of any party to any proceeding. It is true that there were some inconsistencies in her accounts. But inconsistencies are not necessarily the product of dishonesty. They may be the product of faulty recollection. Ms Taylor was cross-examined at length. By and large I found her to be an impressive witness. She was never defensive, evasive or aggressive. She appeared to answer the questions honestly. While some aspects of her evidence appeared to be reconstructions of events, rather than genuine recollections, and some of her answers appeared, as the respondents submitted, rather formulaic, I do not consider that she was dissembling. She made reasonable concessions and did not appear to exaggerate her claims. There were few inconsistencies and much of her evidence was supported by contemporaneous documents.

31 Mr Grew gave evidence, together with four of his current and former employees: Andrew Snow, Asato Tanaka, Mai Vu, and Ayesha Nicholson-Black.

32 Mr Grew presented well in examination in chief. But in several respects his evidence was inconsistent and when that was pointed out to him in cross-examination he became defensive. Unlike Ms Taylor, he failed to make reasonable concessions. At times he was aggressive in his responses and often evasive. When he was obviously uncomfortable with the line of cross-examination he appeared unwilling to give direct answers to simple questions. Aspects of his account strained credibility.

33 Mr Snow came across as honest, sincere and genuine. I also formed a favourable impression of Ms Nicholson-Black and Mr Tanaka. There is no reason not to accept their evidence and Ms Taylor made no submission to this effect.

34 On the other hand, Ms Vu appeared rehearsed in examination in chief and defensive under cross-examination. She struggled to give direct answers and did not make reasonable concessions. I consider that her evidence was affected by her obvious loyalty to Mr Grew, for whom she continues to work.

35 Ms Taylor alleges that Mr Grew contravened s 28B(2) of the SDA by engaging in various acts constituting unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature in relation to her and/or making unwelcome sexual advances to her. The acts fall into relatively discrete categories: the provision of numerous gifts; the making of certain comments and “declarations of feelings”.

36 Mr Grew conceded that some, but by no means all, of the gifts were unsolicited. The fact that Mr Grew made some of the comments upon which Ms Taylor relies was not in dispute but Mr Grew sought to provide an innocent explanation for them. As I have already indicated, Mr Grew admitted that he was attracted to Ms Taylor and that he told her as much, but he denied that he engaged in conduct of a sexual nature, made sexual advances to her or that any of his conduct was unwelcome.

37 The prohibition against sexual harassment appears in Pt II Div 3 of the SDA.

38 Section 28B(2) relevantly provides that it is unlawful for one employee to sexually harass another. Ms Taylor’s pleading contains no allegation that Mr Grew was an employee of Grew & Co although that was plainly a material fact that should have been pleaded. Nevertheless, the case was defended on the basis that, if Mr Grew were found to have contravened the SDA, Grew & Co is liable. The respondents admitted as much in the statement of agreed facts. I infer that it is common ground that Mr Grew was an employee of Grew & Co as well as its sole director and manager.

39 In any case, s 28B(1) relevantly provides that it is unlawful for a person to sexually harass an employee of the person. References to a person in any Commonwealth statute include both corporations and individuals: Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth), s 2C. Thus Grew & Co is a person for the purpose of s 28B(1).

40 Section 106 of the SDA renders a person vicariously liable for unlawful discrimination and sexual harassment committed by its employee or agent unless the employer took all reasonable steps to prevent conduct of that kind. It provides:

(1) Subject to subsection (2), where an employee or agent of a person does, in connection with the employment of the employee or with the duties of the agent as an agent:

(a) an act that would, if it were done by the person, be unlawful under Division 1 or 2 of Part II (whether or not the act done by the employee or agent is unlawful under Division 1 or 2 of Part II); or

(b) an act that is unlawful under Division 3 of Part II;

this Act applies in relation to that person as if that person had also done the act.

(2) Subsection (1) does not apply in relation to an act of a kind referred to in paragraph (1)(a) or (b) done by an employee or agent of a person if it is established that the person took all reasonable steps to prevent the employee or agent from doing acts of the kind referred to in that paragraph.

41 If Mr Grew was not an employee of Grew & Co, he was its agent.

42 Section 28B is a remedial provision in legislation intended to protect human rights and should therefore be broadly construed: Ewin v Vergara (No 3) [2013] FCA 1311; 307 ALR 576; 238 IR 118 (Bromberg J) at [32] (appeal dismissed: Vergara v Ewin (2014) 223 FCR 151 per North, Pagone and White JJ). Further, as Bromberg J observed in Ewin v Vergara at [37], “temporal considerations”, such as whether the conduct in question occurred during working hours or while the people in question were working, are not mentioned and the legislation was not intended to be limited by considerations of that kind.

43 “Sexual harassment” is defined in s 28A of the SDA. At all relevant times it read as follows:

Meaning of sexual harassment

(1) For the purposes of this Division, a person sexually harasses another person (the person harassed) if:

(a) the person makes an unwelcome sexual advance, or an unwelcome request for sexual favours, to the person harassed; or

(b) engages in other unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature in relation to the person harassed;

in circumstances in which a reasonable person, having regard to all the circumstances, would have anticipated the possibility that the person harassed would be offended, humiliated or intimidated.

(1A) For the purposes of subsection (1), the circumstances to be taken into account include, but are not limited to, the following:

(a) the sex, age, sexual orientation, gender identity, intersex status, marital or relationship status, religious belief, race, colour, or national or ethnic origin, of the person harassed;

(b) the relationship between the person harassed and the person who made the advance or request or who engaged in the conduct;

(c) any disability of the person harassed;

(d) any other relevant circumstance.

(2) In this section:

conduct of a sexual nature includes making a statement of a sexual nature to a person, or in the presence of a person, whether the statement is made orally or in writing.

44 In Ewin v Vergara at [27] Bromberg J explained the meaning of “unwelcome” for the purposes of s 28A:

In the context of conduct which is directed (intentionally or not) by one person to another or others, “unwelcome” simply means conduct that is disagreeable to the person to whom it was directed. In Aldridge v Booth (1988) 80 ALR 1 at 5; 15 ALD 540, Spender J described unwelcome conduct as conduct that was not solicited or invited and was regarded as undesirable or offensive by the person to whom it was directed. That understanding was adopted by Wilcox J in Hall v A & A Sheiban Pty Ltd (1989) 20 FCR 217 at 247; 85 ALR 503 at 531 (Hall) and by Mansfield J in Poniatowska v Hickinbotham [2009] FCA 680 at [289] (Poniatowska).

45 In Spencer v Dowling [1997] 2 VR 127 at 156, Hayne JA considered the meaning of “sexual advance”. His Honour observed that “[i]n ordinary usage, “advance” may mean (as the Oxford English Dictionary 2nd ed. tells us) “a personal approach, a movement towards closer acquaintance and understanding; an overture” including an amorous overture or approach. Whether or not in a particular case an approach or overture amounts to a “sexual advance” may involve difficult questions of fact and degree. Not every proposal for social contact will be a sexual advance.

46 As Bell P and Payne JA observed of the phrase “other unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature” in the analogue of s 28A in the Anti-Discrimination Act 1977 (NSW), it is “of broad import” and “should not be read down or confined by limits or restrictions which do not appear in the statute”: Vitality Works Australia Pty Ltd v Yelda (No 2) (2021) 105 NSWLR 403 at [97]. Over a decade earlier, in Poniatowska v Hickinbotham [2009] FCA 680 at [294], Mansfield J acknowledged that s 28A(1)(b) and (2) were intended to extend the circumstances of sexual harassment beyond the scope of s 28A(1)(a) but said that he thought “it involves some conduct which invites or otherwise explores the prospect of the object of such conduct participating or engaging in some form of sexual behaviour or which suggests that the object of such conduct may have done so or may do so, or is a person of a character empathetic to such behaviour”. That said, his Honour added that it is neither necessary nor appropriate to set the outer bounds of “conduct of a sexual nature”. And in Vitality Works at [105] Bell P and Payne J agreed.

47 As Perram J observed in Hughes (t/as Beesley and Hughes Lawyers) v Hill (2020) 277 FCR 511 at [21]–[25] (Collier and Reeves JJ agreeing at [1] and [2] respectively), there are essentially three elements to the definition in s 28A. First, the Court is required to determine whether any of the forms of conduct mentioned in subs (1) have occurred. Obviously enough, that is a question of fact. Second, if such conduct occurred, it must have been unwelcome to the person harassed, whom I shall call the complainant. That, too, is a question of fact. But it is a subjective question, the answer to which turns only on the attitude of the complainant at the time the conduct took place. Third, even if these two elements are satisfied, the ambit of the section is limited by an objective criterion, namely that the unwelcome conduct occurred in circumstances in which a reasonable person would have anticipated the possibility that the complainant would be “offended, humiliated or intimidated” by it.

48 In other words, it is not enough that the conduct was unwelcome. Nor is it enough that the complainant was offended, humiliated or intimidated by it. If the circumstances were such that a reasonable person would not have anticipated that was a possibility, the definition is not satisfied and the case must fail.

49 In Hughes at [26], Perram J explained that for the purposes of determining whether the objective criterion is satisfied:

[T]he reasonable person is assumed by the provision to have some knowledge of the personal qualities of the person harassed. The extent of the knowledge imputed to the reasonable person is a function of the ‘circumstances’ which the provision requires be taken into account. Mention has already been made of the nature of the relationship between the harasser and the harassed … The canvas is broad.

50 The intention of the alleged harasser is entirely irrelevant. Bell P and Payne JA remarked in Vitality Works at [98]:

As to the subject matter, scope and purpose of the Anti-Discrimination Act, it cannot seriously be suggested that the subjective intention of the alleged perpetrator has anything to do with proof of the statutory prohibition. If it were otherwise, an important societal norm would rest on the subjective opinions of the putative sexual harasser. In effect, the greater the subjective tolerance of sexually inappropriate conduct on the part of the sexual harasser, the more difficult sexual harassment would be to prove. That conclusion needs only to be stated to be rejected.

51 Moreover “conduct of a sexual nature” may be explicit or implicit, as the Court of Appeal recognised in Vitality Works. And conduct which, when considered in isolation, appears to have no sexual connotation may still amount to “conduct of a sexual nature” or, for that matter, a “sexual advance”. The conduct in question must always be assessed in its context: see, for example, Kraus v Menzie [2012] FCA 3 at [45] (Mansfield J). Indeed, as Bell P and Payne JA said in Vitality Works at [101], in determining whether particular conduct meets the description of “other unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature”, “context is everything”. In Kraus, with respect to the presentation of a gift by an employer to an employee, Mansfield J concluded that, having regard to the nature of the gift (a jacket) and the fact that “the occasion took place overtly”, his Honour was not persuaded that the conduct had “sexual undertones”. He acknowledged, however, that:

The conclusion would or might be different if there were repeated unsolicited gifts, which in fact were unwelcome, even if the gifts were not patently sexual in nature, as their character may be determined from all the circumstances.

52 I respectfully agree with the observation of McCallum JA in Vitality Works at [125] that:

The sexualisation of women in the workplace often isn’t [explicit]. Innuendo, insulation, implication, overtone, undertone, horseplay, a hint, a wink or a nod; these are all devices capable of being deployed to sexualise conduct in ways that may be unwelcome … The suggestion that conduct cannot amount to sexual harassment unless it is sexually explicit overlooks the infinite subtlety of human interaction and the historical forces that have shaped the subordinate place of women in the workplace for centuries. The scope of the term “conduct of a sexual nature” in s 22A of the Anti-Discrimination Act is properly construed with an understanding of those matters.

The same must be said of the identical expression in s 28A of the SDA.

53 Furthermore, the failure to make a contemporaneous complaint or to inform the alleged harasser at the time that the conduct in question is unwelcome does not (at least without more) signify the converse.

Mr Grew’s feelings for Ms Taylor

54 It is common ground that in early January 2020 Mr Grew declared his feelings for Ms Taylor. I will come to that in due course. But that was not a sudden development.

55 In his evidence in chief Mr Grew testified that he started to develop some feelings for Ms Taylor over December 2019. In cross-examination, however, he clarified that that was the time he realised he had feelings for her. The two are not necessarily synonymous.

56 It is entirely possible, if not likely, that Mr Grew’s feelings for Ms Taylor had developed earlier, perhaps much earlier, whether or not he recognised it at the time. In cross-examination, he accepted that Ms Taylor was an attractive woman, describing her as “a pretty person”. They worked in close proximity to each other and, it seems, quickly developed a close working relationship that was pleasurable to both of them, at least for a period of time. They discussed all manner of things during working hours, some work-related, some not.

57 It was put to Ms Taylor in cross-examination that it would not be unusual for her to seek Mr Grew’s attention by touching his shoulder or squeezing his arm. She accepted that she would tap him on the shoulder but denied squeezing his arm. In cross-examination Ms Taylor revealed that, when she would place finished products on her hand to see how they looked, Mr Grew would come over and touch her hand, without being invited to do so. Before she knew he had feelings for her, she had had no difficulty with that. Afterwards, however, it made her feel uncomfortable.

58 On 10 August 2019, four months before Mr Grew says he started to develop feelings for Ms Taylor, Ms Vu sent the following text to Ms Taylor:

59 Ms Taylor agreed she would not tell Mr Grew.

60 Ms Vu conceded in cross-examination that she believed Mr Grew had feelings for Ms Taylor at this time. While this matter was not explored further, for reasons which will become apparent I have no doubt that, by this time, or indeed earlier than then, Mr Grew had feelings for Ms Taylor in that he was attracted to her and that some of the gifts were, at least in part, an expression of those feelings.

The allegations

61 Ms Taylor alleged that between September 2018 and March 2020 Mr Grew gave Ms Taylor a total of 19 gifts, which were both unsolicited and unwelcome:

(1) a quilted black Chanel coin purse;

(2) a platinum ring with emeralds and diamonds (emerald and diamond platinum ring);

(3) an 18-carat white gold bezel set (Hydra) ring incorporating a sapphire she had purchased (Hydra ring);

(4) a 14-carat gold six stone diamond necklace (six stone diamond necklace);

(5) a small round cut peach sapphire he purchased at an overseas gem fair (peach sapphire);

(6) a 14-carat diamond cluster necklace incorporating the peach sapphire (diamond cluster necklace);

(7) a jade bangle;

(8) $2,000 in cash which he described as an early Christmas bonus to assist with her savings for purchasing a property;

(9) a massage at a local shop during work hours;

(10) a pair of diamond “Gemini” stud earrings (Gemini stud earrings);

(11) a silver pinkie signet ring (silver signet ring);

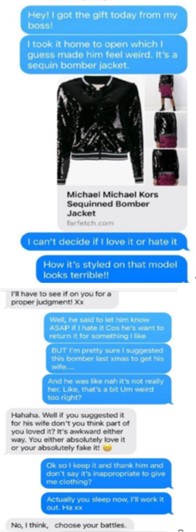

(12) a black sequinned Michael Kors bomber jacket, which retailed for $548 (Michael Kors bomber jacket);

(13) a $200 MECCA gift card (MECCA gift card);

(14) a 14-carat white gold hammered band ring (white gold hammered band ring);

(15) a plain 5 mm silver ring (5 mm silver ring);

(16) a plain 10 mm silver ring (10 mm silver ring);

(17) a pair of Stuller gold hoop earrings (Stuller gold earrings);

(18) a 14-carat gold pinkie signet ring (gold signet ring); and

(19) a channel set diamond ring.

62 The respondents accepted that the Chanel coin purse, the jade bangle, and the silver signet ring were gifts but put in issue the allegations that Mr Grew gave Ms Taylor any of the following items: the gold signet ring; the channel set diamond ring (a stock item he had seen her wear from time to time); the white gold hammered band ring; the 5 mm silver ring; and the 10 mm silver ring.

63 The respondents accepted that Mr Grew gave the other items to Ms Taylor but denied that they were unsolicited and/or gifts.

64 The respondents also disputed that statements allegedly made, and text messages sent to, Ms Taylor, praising her and her appearance were unsolicited.

65 In the event that the items and remarks are found to have been unsolicited, the remaining questions are first, whether the conduct was “unwelcome conduct”, “conduct of a sexual nature”, and/or a “sexual advance”; second, whether the conduct took place in circumstances in which, having regard to all the circumstances, a reasonable person would have anticipated the possibility that Ms Taylor would be “offended, humiliated or intimidated”; and third, whether Mr Grew contravened s 28B(2) of the SDA.

66 Ms Taylor gave evidence to support the allegations relating to all the alleged gifts except for the channel set diamond ring.

67 Despite the absence from Ms Taylor’s evidence of any mention of Mr Grew giving her a channel set diamond ring, it was put to Mr Grew in cross-examination (without objection) that, having seen her wear the ring, he told her she could have it if she liked. Mr Grew rejected the proposition. Consequently, there is no evidence to support the allegation in the pleading that the channel set diamond ring was a gift.

68 In evidence, Mr Grew agreed that he gave Ms Taylor all these things, except for the gold signet ring, the channel set diamond ring, the white gold hammered band ring, the 5 mm silver ring and the 10 mm silver ring.

69 He also agreed that many of these items were gifts. He sought to explain them, however, by reference to a reciprocal culture of generosity at the workplace and by pointing to gifts he had made to other employees as well. He also claimed that Ms Taylor had asked for many of them.

70 The first gift Ms Taylor received from Mr Grew was the Chanel coin purse. She testified that one day in September 2018 Mr Grew approached her in the office holding a Chanel bag (which I take to be a cloth bag featuring the Chanel logo which contained the purse), saying: “Hey. This is for you. Happy birthday. You bring so much value to the company and this is just a token of that”. Ms Taylor said that she was “quite shocked to see a Chanel bag”, “caught off guard”, and “quite put on the spot because it seemed quite extravagant”. She said it made her feel “a bit overwhelmed” but she accepted the gift because she did not want to seem rude or ungrateful. In cross-examination she rejected the proposition that, by accepting the purse, thanking Mr Grew and holding on to it, she welcomed its receipt.

71 In examination in chief Mr Grew was asked whether he was able to provide any context for the gift. This was his answer:

I have a – a leather business card holder that I used and she mentioned that she really liked it, and it was around her birthday, I was looking up leather business card holders for women, and came across this one which is on – from memory, it was on eBay, but it could have been on, like, Gumtree or some classified thing. And it was located in the city, and it was about $130 or something, and I went to pick it up from a lady that lived in an apartment building on the corner of Kent Street and King Street, there’s a couple of apartment buildings there. She was selling a number of, kind of, designer label things of various types.

72 He went on to say that he gave her the purse as a birthday gift. He was asked whether she said anything at the time. His reply was not entirely responsive. It was that she was “very happy” and “really grateful”. He said she did not display any discomfort or embarrassment.

The emerald and diamond platinum ring

73 This was a ring consisting of a platinum band, with a large emerald bordered by two smaller emeralds and two diamonds.

74 Ms Taylor gave evidence that, in around September 2018, Mr Grew asked her to start “designing pieces and creating some layouts for pieces”. She came across some emeralds in the safe at work and created a layout which appealed to her. She then approached Mr Grew and asked whether it would be “okay” if she created a ring for herself. He readily agreed. Mr Grew’s evidence was to the same effect.

75 She testified that he then informed her “[w]e do it at a wholesale cost for staff”. She said she asked him to get back to her with “some pricing” but, while he agreed to do so, he never did.

76 After the ring was made, Mr Grew approached her and asked to see the ring on her hand. She obliged and inquired: “How much do I owe you for this?” Mr Grew replied: “I don’t want any payment. It’s a gift. You bring so much value to the company”. Ms Taylor was “quite shocked and overwhelmed” as this was the second gift she had received from Mr Grew within a couple of weeks. Again, she thanked him because she did not want to offend him or appear ungrateful. It was put to her in cross-examination that she did not indicate any hesitation in accepting the gift. She rejected the proposition. She said she paused to think about it before thanking him.

77 Ms Taylor estimated that the value of the ring was around $4,000 to $5,000 and that the cost price was around $1,500 to $2,000. In cross-examination, however, it was put to her that the materials were relatively inexpensive (about $390). Ms Taylor did not recall whether Mr Grew had told her that the emeralds were “old stock”. She said she did not know whether the cost of the platinum would have been $180, the main emerald $90 and the small emeralds $30 each, as suggested, and she disagreed with the proposition that the diamonds would have cost $30 each.

78 Mr Grew was not invited to comment on much of Ms Taylor’s evidence. Mr Grew said that he did not recall asking to be paid or receiving any offer of payment. Importantly, however, he agreed that the ring was a gift.

79 Otherwise, his evidence was broadly, though not entirely, consistent with what was foreshadowed by the cross-examination of Ms Taylor. He testified that the two diamonds and two smaller emeralds were worth around $30, that the larger emerald was worth around $100 and the platinum would cost around $180. He did not provide an estimate of the cost of labour or an indication of its retail value. Indeed, the same is true in relation to all the jewellery items in question.

80 When asked why he did not seek payment for the ring he said:

The stone had been sitting in the safe for some time. It hadn’t been used. I didn’t really see it being used in the foreseeable future. It was of fairly little consequence to me and if it was an item that Ms Taylor in this instance or a member of staff wanted, from my point of view it’s an item of the company which also advertises the company. It’s beneficial for the company for them to be wearing it, and I would prefer that they asked me about these kind of items if it’s something that they want because then I know that they’re not stealing, and these sort of items are overall fairly inconsequential.

81 In cross-examination Ms Taylor accepted that in around June 2020 she asked Mr Grew to remake the ring in yellow gold. She did not recall whether Mr Grew said that he would take the old platinum metal in exchange for the yellow gold such that no payment was required. Mr Grew testified that he told her that they could remake the rings and then exchange the original metal in lieu of payment.

82 Ms Taylor said she received the ring in about September or October 2018 in the following circumstances.

83 Ms Taylor had designed a ring for the Grew & Co stock designs, called the Hydra, and she had also recently purchased a sapphire for herself. She asked Mr Grew whether it would be alright if she made (by which she meant designed) a Hydra for herself. He readily agreed. Again she asked him to “get back to [her] with pricing”. Again he did not.

84 After the ring was made, Mr Grew approached her and asked to see it on her hand. She asked how much she owed him. He replied that he did not want any payment and she should “consider it a gift for doing such good work”. She testified that she felt “uncomfortable and overwhelmed” as “it started to feel a little bit like special treatment at that point”. As she had “never been in a situation like that before”, she “didn’t really know what to do” and “didn’t want to jeopardise [her] working relationship with him”. In cross-examination she maintained that she did not know “how [Mr Grew] would have reacted” such that she was “scared” he would react in a way that would be “awkward and uncomfortable”. She did accept however that he had not done anything to give her that indication.

85 Mr Grew testified that there was “never any request for payment and never any offer made” in relation to this ring. He said that he did not request payment because it was “around the time of [Ms Taylor’s] birthday”, was made using a stone she had purchased; and because the “overall costs of the materials [was] fairly inconsequential”. He estimated that the white gold was worth around $180, the two baguette diamonds around $60 each, the two trillion cut diamonds around $120 or $140 for both of them (that is to say the materials cost a total of $420 to $440). He said that, at the time Ms Taylor was an employee, his practice was not to charge staff for making items of jewellery.

The white gold hammered band ring and the 5 mm and 10 mm silver rings

86 Ms Taylor testified that in December 2018 she received from Mr Grew a white gold hammered band ring, a 5 mm silver ring and a 10 mm silver ring. She said that she wanted to hide some recent tattoos from her parents and mentioned to Mr Grew that she was worried about her father seeing them. After the conversation they exchanged text messages that indicate that Mr Grew told her that Mr Tanaka could “knock up some wide silver ones before Christmas”. She testified that “some time after these text messages” they “discussed payment at a wholesale cost in the office”.

87 Ms Taylor testified that, after the rings were made Mr Grew approached her and asked to “see them on”. She obliged. She asked him how much they would cost and he told her not to worry about payment. She adhered to this evidence in cross-examination and denied that it was merely an assumption on her part that Mr Grew “gifted” her the rings.

88 Mr Grew testified that, after the exchange of texts on 16 December, they had no further conversations about the rings. Nonetheless, he admitted it was “likely” that he would not have required Ms Taylor to pay for them.

89 Mr Tanaka testified that he made “a couple of silver rings” for Ms Taylor to cover up some tattoos on her hand. He said he did not have a discussion with Mr Grew about the making of those rings; rather, Ms Taylor asked him to “make her some rings to hide her tattoos”. He said that “straight after” he made the rings he gave them to Ms Taylor, who was “really happy” to receive them. In cross-examination he disagreed with the proposition that his recollection might be wrong.

90 Mr Tanaka had a recollection of the 14-carat white gold hammered band ring but did not recall that it was included in the same job packet.

The six stone diamond necklace

91 On 28 March 2019, Ms Taylor sent the following text to Mr Grew:

“Hey I still need to buy a chain for my little diamond necklace right???

92 Ms Taylor testified that she had designed a “14-carat yellow gold diamond necklace” that she “wanted to get made up at a wholesale cost” and this text message referred to the “chain that was to go with it”. She explained that in early 2019 she had approached Mr Grew and told him that she would like to make a delicate diamond necklace for herself “at a wholesale cost”. She said she asked him to “let [her] know how much that will come to” to which he replied: “Of course”.

93 On 18 April 2019 Mr Grew informed Ms Taylor, via text, that he had finished her chain. In the text conversation that followed, she wrote: “Let me know what I owe you for the necklaces!”. She testified that she used the plural “necklaces” because she was also referring to another necklace that had “joined the production line while the first necklace was being made”, namely, the diamond cluster necklace (discussed below).

94 In cross-examination Ms Taylor accepted that Mr Grew obtained the chain after she had indicated she needed one and after she asked him to obtain one from the supplier.

95 Mr Grew testified that he did not request payment for the six stone diamond necklace or the diamond cluster necklace because “they were for staff and items that Fiona indicated that she wanted” and he was “happy to offer items to staff members”.

96 He estimated the value of the six small diamonds was about $7 to $15 each, the chain $60 and the housings that hold the diamonds around $18 in toto, making the total cost of the materials $120 to $168.

The peach sapphire and the diamond cluster necklace

97 In December 2018 Ms Taylor gave Mr Grew “a session with [her] healer” as a Christmas present. On 29 December 2018, presumably in response to an inquiry from Mr Grew about how she was feeling, Ms Taylor informed Mr Grew that she was feeling fine and that her “healer” told her she needed an orange stone like carnelian (a semiprecious stone) and she should make a necklace to wear for “protection”. He replied: “Carnelians cool. What do you need protection from?”. Ms Taylor answered that she had “an entity attached to [her] from [her] brother”, who was suffering from depression, which the healer “cleared” but that the healer told her that her throat was her “creative self-expression” and it needed to be kept open and protected. Mr Grew responded: “Wow, ok well better [get] that sorted out pronto”. In cross-examination she said that she shared this with Mr Grew because they “had developed a nice friendship, and [they] would often talk about what [they] did on the weekend”.

98 Ms Taylor testified that, after returning from a gem and mineral fair overseas, Mr Grew “presented” her with a round peach sapphire. Ms Taylor recalled that he approached her and said:

I found a stone for you overseas at the gem fair. I would really like you to make this up into a necklace. I know your healer told you [that] you needed an orange stone.

99 Ms Taylor testified that she was “quite shocked” that he had remembered their conversation and that he had “personally selected a stone” for her. She said that she did not want to “seem ungrateful because “he ha[d] gone out of his way to get it for [her]” so she thanked him. She testified that in comparison to carnelian, the stone she mentioned in their text message exchange on 29 December 2018, a sapphire is “much more desirable” and a “more expensive and hardwearing precious stone”.

100 On 9 May 2019, Mr Grew sent her this text message:

Hey also about your pendants, I dont want any money for them I want you to have them. I appreciate everything you do and maybe it just a small sign of that. I wanted to tell you but haven’t had the chance. Enjoy your break, it sounds amazing[.]

101 She replied:

Aww man, thank you so much! I had every intention to pay for them but that’s really amazing of you, thank you[.]

102 Ms Taylor testified that she “felt a little awkward”, “uncomfortable” and “overwhelmed at the same time” as “it was definitely starting to feel like special treatment” since they had “got into a weird cycle” and “a pattern of behaviour” of “crossing boundaries”. She estimated that the sapphire would have cost “a couple of hundred dollars” and that, once made up, the necklace could have cost upwards of $2,500.

103 In cross-examination she accepted that, in her text, she was showing her appreciation, exhibited no reluctance in accepting the necklaces as gifts, and that she did not insist on paying. She also agreed that she did not return the necklaces at any stage. In re-examination she maintained that she felt “uncomfortable and a bit awkward”.

104 Mr Grew confirmed in his evidence that he had bought the stone at a jewellery fair and that he “gifted” the necklace to Ms Taylor. He estimated the cost of the stone at between $100 and $200, with the chain costing around $60 and the gold holding the stones at about $90 to $100. He said that Ms Taylor had added other stones on each side but he was unable to recall the value of them.

105 He testified that he did not request payment for the stone because “Ms Taylor intended it for herself” and the stone was “part of a parcel of stones that [he] had purchased” and the value was “fairly inconsequential” from his point of view. He said that Ms Taylor had seen the stone and liked it. He was not asked why he did not request payment for the other components of the necklace.

106 In cross-examination Mr Grew accepted that Ms Taylor had not asked for a sapphire, that carnelian was “a much cheaper stone”, and that she had not asked him to “get anything for free”. He conceded that he “took it upon [himself] to … gift [it] to Ms Taylor”. Despite this, he maintained that it was not inaccurate to say (as pleaded in para 9(f) of the defence) that the gift was unsolicited. He claimed that the sapphire was not unsolicited because she had specifically asked him to find one in a conversation they had before he attended the fair.

107 On 2 July 2019 Ms Taylor received a jade bangle from Mr Grew. As I mentioned earlier, it is an agreed fact that this was a gift.

108 Ms Taylor gave the following account of the circumstances in which she received the gift.

109 Mr Grew came into their shared office, shut the door and told her that he had a jade bangle for her that he acquired at an overseas gem fair. He said to her, “jade is all about luck, you should look up the properties of it”. She recalled that at the time she was “quite caught off guard”. The gift was unexpected, especially since it was not something she would even like. Nonetheless, she thanked him because she did not want to seem rude or ungrateful.

110 At short time later, Mr Grew’s ex-wife, Gabrielle, walked into the office, saw the bangle, and told her that Mr Grew had given her “that same bangle”. Ms Taylor recalled feeling “extremely uncomfortable” and “extremely awkward”. Ms Taylor spoke to Mr Grew about her conversation with Gabrielle and testified that he seemed surprised. While she could not remember exactly what he said, her impression was that he seemed “caught out”.

111 In cross-examination, Ms Taylor was referred to a text she sent later that day to Mr Grew:

Hey, thanks so much for my jade bracelet! It’s very thoughtful. ![]()

112 She accepted that the unicorn emoji was her way of showing appreciation to Mr Grew for the gift.

113 When it was put to her that he never said that he got the bangle for her she did not agree. She said that she did not recall seeing a pouch with a jade bangle in it on Mr Grew’s desk for five months, denied that she had told Mr Grew she was feeling down that day, and that he said “[h]ere you go. You can have this” when he gave her the bangle. She accepted that she did not attempt to refuse the bangle and did not return it at any point.

114 This was Mr Grew’s account.

115 At an international gem fair in Hong Kong in February 2019 he purchased a number of stones from a supplier who he had worked with over the years. As this occurred around the time of Chinese New Year, the supplier’s wife gave him the jade bangle and explained that it was to bring luck and offer protection.

116 On the day he gave the bangle to Ms Taylor, she had been telling him that she was “feeling exhausted” and had “low vibrational energy”. He recalled the conversation he had in February 2019 and showed Ms Taylor the bangle, explaining that it was “meant to absorb all the negative energy”. He recalled that she was grateful and he told her that she could have it. He testified that their later text conversation followed on from their conversation in which he told her to look into the properties of jade because “it sounded similar to what she was saying”.

117 He testified that he had previously bought a lavender jade bangle for Gabrielle in around 2007, that he had not had a conversation with Ms Taylor about that gift, and that Ms Taylor did not tell him about a conversation she had with Gabrielle about hers. He maintained this position in cross-examination.

118 In early September 2019, in conversation with Mr Grew in the office, Ms Taylor expressed frustration about the fact that she attended several auctions and “it seemed as though [she] needed to save about $25,000 more to be in with a chance for the type of apartment [she] would like to buy”. She said that Mr Grew replied in words to the following effect: “Yes, that’s really difficult. I’d like to give you some money towards your savings for your first property”. She said she declined, saying “No. That’s not your problem”.

119 In his evidence Mr Grew said he had had a conversation with Ms Taylor in which she showed him the types of apartments she could afford to buy and those she would like to buy but would require an increase in her deposit by $25,000.

120 After that conversation, in about the middle of the month, Mr Grew raised the subject again in a text message. Again, Ms Taylor pushed back. This is the contemporaneous exchange:

MR GREW: I’ll give you something towards that extra that you need

MS TAYLOR: Woah. No way!

You have so much going on as it is!

MR GREW: I want to see you achieve your goal

MS TAYLOR: I really appreciate that, but it’s so not your problem!

MR GREW: Take it as a sign of appreciation for who you are and everything you do[.]

121 The next day Mr Grew came into the office with an envelope containing $2,000. He insisted she take it. She said she could not accept it. He replied: “Consider it an early Christmas bonus”. Ms Taylor testified that in response she thought she said something like: “If it’s a Christmas bonus then okay, thank you”. She said she was “a bit tired of saying no” and felt like she had to accept it as she did not want to seem rude or ungrateful. When asked about whether she had any concerns about her employment at Grew & Co at this time, she answered:

I was definitely starting to feel anxious. I felt kind of trapped. I didn’t know how to – well, really, what to do. I – he always presented it in a way where I couldn’t say no or it would be quite rude to say no. So, yes, I felt like I was in a really difficult position, that I had to placate my boss to keep my job.

122 Mr Grew confirmed in his evidence that he gave her $2,000. He said “she was really grateful” and did not indicate any hesitation in accepting the money. He recalled encouraging her to do her best to achieve her goal.

123 In cross-examination Ms Taylor admitted that she did not return any of the money at any stage. She also accepted that there was nothing inherently improbable about Mr Grew wanting to reward her for doing a good job when she was, as she believed herself, doing a good job.

124 Later that year, Ms Taylor also received a Christmas bonus of $1,000.

125 Mr Grew gave evidence about giving cash to other employees, a subject I deal with below.

126 Ms Taylor testified that, on 6 September 2019, following a conversation with Mr Grew about a colleague and at a time when she felt “quite stressed out at work”, he “randomly” called to say he had booked a massage for her. He told her to take some cash from the envelope in his “workshop box”. She thanked him. She said she felt “a bit shocked” because it seemed to come out of nowhere. Since he had already made the booking, she felt obliged to go.

127 Mr Grew then sent her a text message with the name of the masseuse, the address and phone numbers of the business, directions about how to find it, and a photograph of the entrance. Ms Taylor replied: “That’s very thoughtful, thank you!!!” She took the money and attended the appointment. Later that day Ms Taylor sent Mr Grew a text message saying: “I fully look like I’ve had a massage hah” and “[s]he’s was super cute! I needed that- thanks again!”

128 It was put to Ms Taylor in cross-examination that she had had a telephone conversation with Mr Grew in which she told him that she needed to leave work early because she was getting “neck and jaw tightening” as a result of “a situation regarding a colleague” that had arisen at work. She accepted that her text message reply reflected that she was grateful for the massage. But she explained that when she wrote that she “needed” the massage, she did not mean that “he had to provide it for [her]”. In re-examination, she said that she felt “a bit weirded out and uncomfortable”, despite what she had said in the text message.

129 If Mr Grew’s evidence is to be accepted, his call was not, or at least not entirely, “random”. On his account, earlier that day Ms Taylor had been “venting” about “the frustration that she was feeling from [a] colleague”, and that she told him it had caused her neck and jaw pain. He said she mentioned that she might leave work early. He said that put him in a difficult position because he was moving house and could not lock up the store himself. In the hope that it might alleviate her symptoms, he said he booked her in for a half hour massage (as he recalled it) at a place only a block away from the store and told her to take the money out of petty cash.

130 It is common ground that at no time did Ms Taylor communicate to Mr Grew that she felt any embarrassment or discomfort by him paying for a massage.

131 Mr Grew’s unchallenged evidence was that he had suggested to another employee that she see a chiropractor during business hours because she could not move her neck and paid for the consultation after she told him she was unable to afford it. He paid for three-month gym memberships for Mr Tanaka and Mr Snow who were experiencing “difficult” times and he believed it would be good for both of them to “have an outlet”. And during the COVID-19 lockdown he paid for four visits to a psychologist for Ms Nicholson-Black, who was in Melbourne away from work and feeling “quite isolated”.

132 While he accepted that a massage could be “a personal thing”, Mr Grew rejected the suggestion put to him in cross-examination that the massage was “simply [his] way of showing his affection towards Ms Taylor”.

133 The Gemini stud earrings were a stock item which Grew & Co sold to customers. They were earrings consisting of two small diamonds positioned side by side. Mr Grew estimated their “cost value” at around $200.

134 Ms Taylor testified that in or around November 2019 she and Ms Vu would chat about how they quite liked “these new earrings that had come into stock” and that “Mr Grew knew this”. One day he presented them with a pair each and said something like, “here’s a pair of Gemini studs for each of you”. She testified that she was “shocked” as it was “out of the blue” and thanked him because Ms Vu was there.

135 Ms Taylor testified that she had a conversation with Mr Grew later that day in which she asked him how much the earrings cost. She recalled that he replied: “I don’t want any payment for them”. Again she felt “shocked”. To avoid appearing ungrateful, she thanked him.

136 Later, Ms Vu asked Ms Taylor whether Mr Grew had asked her to pay for the earrings. She recalled that Ms Vu told her that he requested “around $200 cash for [hers]”. She testified that she felt “extremely awkward” because Ms Vu “seemed quite frustrated” or “even jealous” and it was “clear” that Ms Taylor was receiving special treatment. In cross-examination she accepted that after this conversation she knew the cost price for the earrings and did not attempt to pay Mr Grew for the earrings or return them.

137 In cross-examination Ms Taylor’s attention was drawn to a text message she sent to Mr Grew on 20 November 2019 in which she wrote: “ThAaaaank you for the studs!!!” followed by a unicorn emoji. She accepted that this was an indication of her “appreciation and gratitude” at the time.

138 In her evidence in chief Ms Vu denied that she was there when Mr Grew presented Ms Taylor with her earrings. She said she became aware of the gift when she saw Ms Taylor wearing them. She decided she wanted a pair too so asked Ms Taylor how much she paid for hers. Ms Taylor told her that she did not pay for them; Mr Grew gave them to her. Ms Vu said she placed an order for a rose gold pair and paid Mr Grew $280 for them. She was not cross-examined on this evidence.

139 On 28 November 2019 Mr Grew sent Ms Taylor a text in which he wrote:

Hey I didn’t get to see your Gemini earrings on. Can you wear them tmw? Unless your planning on wearing something else that is[.]

140 Ms Taylor replied::

Haha sure! I love them thank you!!

141 Ms Taylor denied that this conversation occurred because she had asked to pick another pair of earrings since her pair was mismatched.

142 Mr Grew’s account was as follows.

143 Ms Taylor tried on a pair of the Gemini stud earrings. She told him she loved them and that she really wanted a pair of diamond earrings. Not long afterwards, he was working on several pairs of the earrings in a mixture of coloured golds. When he finished them, he offered a white gold pair to Ms Taylor and told her that, if she wanted them, she could have them. He said he gave Ms Vu a rose gold pair at the same time (“she wanted a rose gold pair”). He added that he offered to give them to her but she insisted on paying. When asked in chief why he did not request payment from Ms Taylor he replied:

[I]t’s not a huge issue for me. From my personal point of view I think that – from an employment point of view I get better results from people by being good to them and if staff or Ms Taylor or anybody else wants to wear an item that we make, more often than not the value is fairly insignificant in the overall scheme. So I’m happy for them to have it.

144 In cross-examination, after initially maintaining that the earrings were solicited because “she told [him] that she wanted a pair”, Mr Grew accepted that he approached Ms Taylor with the Gemini stud earrings and “gave them to her as a gift”; that she did not ask him to give them to her; that he volunteered them; and that his conduct in making and offering of the earrings to Ms Taylor was unsolicited.

145 It is an agreed fact that in about November or December 2019 Mr Grew gifted Ms Taylor a silver signet ring.

146 Ms Taylor’s account was that she was sitting in her office with Mr Grew when “out of the blue” he said to her: “Hey, I found this silver signet in the safe. Can you try it on?” Ms Taylor obliged and, when he saw that it fit, he replied: “You can keep this as a gift”. She felt “a bit awkward” and “a bit shocked” as the gift “came out of nowhere”. Nevertheless, she thanked him. In cross-examination she accepted that she did not indicate to Mr Grew that the gift was unwanted and did not return it at any time.

147 Mr Grew did not dispute the substance of the conversation as recounted by Ms Taylor and his evidence was essentially consistent with it. His explanation was that he had discussed with Ms Taylor incorporating signet rings into Grew & Co’s inventory and remembered that he had a “silver sample” that had been sitting in the safe for around 12 years. He said that at the time he wondered whether the size of a signet ring would be comfortable on a woman’s hand and asked Ms Taylor whether, if he sized the ring down, she would wear it and give him feedback on how it felt. He recalled that she later told him that it fit well and he told her that she could keep it as it was sized to fit her. He said that silver is “pretty inexpensive”. He estimated that the cost of the material “might be somewhere around $60”.

148 Mr Grew purchased this gift in early December 2019.

149 December 2019, it will be recalled, was the time Mr Grew said he first realised he had developed feelings for Ms Taylor. The parcel containing the jacket arrived in the store on 6 December.

150 Mr Grew said that he paid $296.65 for the jacket and produced a receipt to support his evidence. While the receipt appears to indicate that the price was in fact $380.93 for the jacket alone (that is, excluding shipping), nothing was made of the apparent discrepancy.

151 Ms Taylor testified that when the package arrived she “felt a bit anxious”. She sent a text message to Mr Grew saying “Ps, can I take the box home” and later “how can I not be curious”. She accepted, in cross-examination, that this reflected that she was excited to open the present.

152 On 10 December 2019 he gave her the gift. She told him that she would prefer to take it home to open it. Ms Taylor testified that “it felt really personal” for him to have bought her clothing and that he had “obviously … assessed [her] body in some way and purchased an item for it”. She felt like they “had crossed a boundary at this point” and this made her feel “really uncomfortable”.

153 Her evidence was supported by a series of text messages she sent to a friend (Leanne) that evening:

154 Similarly, in a text to her sister, Sonia, she wrote of the jacket:

No, this is where it gets weird. Simon got it for me for xmas…

And I didn’t know if I should keep it or not

It’s Michael kors[.]

155 In her reply Sonia agreed it was weird. Ms Taylor also texted her saying:

Buying clothing is super person so o was slightly weirded out about it but being a bomber jacket I was like wel he just knows me well kinda thing. Don’t wanna look into it too much. Plus I think he did it Cos I mentioned getting him something but mai and I bought his a joint gift which is a backpack…

156 Ms Taylor explained that “it was an uncomfortable thing to look deeper into because [she] had to continue to work with Mr Grew in close quarters” and that “it was easier to kind of try to ignore the meaning behind it”.

157 Later that evening, she sent a text message to Mr Grew that said “[s]o, I love it” and “[t]hank you so much! Very cool”. In cross-examination, she accepted that this message indicated that she had considered her options and had decided to keep the gift. She said that she sent this message because she did not want to “acknowledge it at the office” and did not “want to seem ungrateful”. When it was put to her that this message was unprompted, unsolicited and that she reached out to Mr Grew, she maintained that she sent him this message because she was “worried” about appearing rude or offending him.

158 The next day Mr Grew closed the door of their shared office and asked her to try the jacket on in front of him. When “he saw that it was a bit fitted” he “suggested that we go up a size”. She then “awkwardly said yes”.

159 Mr Grew testified that the day after she took the jacket home, Ms Taylor told him that she loved it but thought it was too small, put the jacket on and asked for his opinion, and then asked him to exchange it for another size. He denied asking Ms Taylor to try the jacket on for him and denied closing the door to their office during this conversation. He said that Ms Taylor did not indicate any discomfort or embarrassment by the receipt of this gift.

160 In cross-examination he denied that in late 2018 he had a conversation with Ms Taylor about buying a bomber jacket for his wife. Mr Grew testified that Ms Taylor had mentioned in October 2019 that she wanted to get a sequinned bomber jacket (a proposition Ms Taylor denied in cross-examination) and that he bought it for her after she told him that she had bought him a Christmas present.

161 The gift card was for $200. MECCA is a retailer of numerous brands of beauty and personal care products for men and women. Mr Grew gave Ms Taylor the gift card at the end of December 2019, after Christmas. It is common ground that he had purchased it for his ex-wife and decided not to give it to her when he learned she had no intention of buying him a present. It is also common ground that he told Ms Taylor that and she suggested he use the voucher on himself. Contemporaneous Instagram messages confirm this.

162 In cross-examination, Ms Taylor denied telling Mr Grew that, if he did not use it, she would. But Mr Grew testified that he had a conversation with Ms Taylor in which she did say that and it was her offer to use it that accounted for his action:

I said I don’t know what to do with it and she said they do men’s things as well, and I said, like, I wouldn’t know where to start and there’s nothing that I need. And she said, “Well, I’ll use it if you don’t”, and I said okay and you can have it. I had lost the receipt. It got thrown out with the kids’ toy wrapping. So it really wasn’t any use to me. So I didn’t mind giving it to her.

163 Mr Grew also testified that Ms Taylor never indicated any discomfort or embarrassment in accepting this gift card.

164 Ms Taylor testified that in March 2020, following Mr Grew’s confession of feelings and their trip to the USA (which I will come to), he approached her at work and presented her with the gold signet ring, based on the silver signet ring he had previously given her and in the same size, and asked her to try it on. She said he also told her he would “really like [her] to get something engraved on the face of the ring”, although Mr Grew denied this. According to a letter from the respondents’ lawyers relied upon in the victimisation case, the recommended retail price for this ring is $1,900.

165 Mr Grew denied ever “gifting” the gold signet ring to Ms Taylor. In response to her claim, he testified:

[F]rom that point, we made the similar version signet rings for men and women. They’re now currently featured on our website. And Ms Taylor would wear one of the gold ones from time to time, and it’s a – you know, it’s a fairly regular practice that staff members can take something from stock and – and wear it, and wear it that day or sometimes they might wear it, you know, semi-regularly. And it’s – it’s better for them to be – if a client comes in, it’s better for them to be wearing an item of our jewellery rather than someone else’s. So I’m happy for them to do that.

166 This evidence is at odds with the contemporaneous text messages.

167 On 4 March 2020 Ms Taylor sent Mr Grew a text message in the following terms: “Thank you so much for the signet, I really love it!” Mr Grew replied: “No problem. I feel like it needs something on it tho”. Although he admitted that he had started to develop the gold signet ring series in early 2020, Mr Grew claimed that his response related to the silver signet ring. Mr Grew admitted the messages were sent in March 2020, which was three or four months after he had given her the silver signet ring. In these circumstances I consider it to be highly unlikely that Ms Taylor’s message related to the silver signet ring and more likely than not it related to the gold signet ring.

168 Stuller is a business based in the US which supplied jewellery to Grew & Co.

169 Ms Taylor testified that one day in March 2020, when they were both in the office, Mr Grew presented her with a pair of gold hoop earrings supplied by Stuller in the following context:

[I]t was pretty normal to talk about jewellery in the office and things that we liked, and I had mentioned that I was looking for a pair of hoop earrings in a particular thickness. And Mr Grew purchased a pair and presented them to me out of the blue one day, when he had – he was unpacking a Stuller order.

170 Mr Grew said to her: “Hey, I got you those hoop earrings”. She replied: “Oh, you didn’t have to do that. How much were they?” He told her not to worry about payment.

171 Later Ms Taylor sent a text message to Mr Grew saying “I hope those hoops weren’t too expensive!” to which he replied “[n]ah they weren’t”. She then responded: “Haha ok, well, thank you!”. He wrote back: “You’re welcome:) Is the size ok?” She replied: “The size is perfect ![]() I should’ve checked stuller all along!”

I should’ve checked stuller all along!”

172 Nonetheless, Ms Taylor testified that his purchase “came as a shock” and made her feel “a bit awkward and uncomfortable”. In cross-examination she said she accepted the gift because “he wouldn’t let [her] pay and [she] hoped he hadn’t spent too much money on [her]”. She acknowledged that she did not offer to pay in the text message exchange or in a verbal conversation afterwards but maintained that she offered to pay before the texts when he handed her the earrings. She admitted that she had not offered to return the earrings.

173 Mr Grew’s evidence was that he was prompted to purchase the earrings for Ms Taylor by a text message she sent him on 29 December 2019. On that day, Ms Taylor wrote: “Hey, do you think these are a good price $300usd for 14ct white gold hoops?”. She attached a link to an American jeweller’s website. Mr Grew replied to the text: “For you? We coukd probably get them cheaper if they are”. Ms Taylor confirmed they were for her but said: “I don’t need 14ct white gold, silver or 9ct is fine but I just wondered if it’d be cheaper or not! But I’m searching for the right thickness which seems to be 2mm”. Mr Grew then texted: “It should’ve too hard to find otherwise we can make them”.

174 Mr Grew testified that he did not seek payment because the earrings were of “very little value”, at around $60. He said that at no time did Ms Taylor indicate any discomfort or embarrassment about receiving any of the gifts, “only gratitude”. He noted that Ms Taylor chose the hoops and selected the size she wanted.

175 Ms Taylor was cross-examined about a “culture” of generosity in the business and about gifts she gave Mr Grew.

176 Ms Taylor accepted that she was able to, and did, purchase items for friends at cost price while working at Grew & Co and that this was “something he offered to all staff members”. She also accepted that it was a benefit that staff could obtain jewellery or other items sold in-store at a “reduced wholesale cost” but denied it was a benefit of her employment. In addition, she accepted that another “perk” of working in the jewellery industry was that from time to time she could wear stock items while at work.

177 In cross-examination, Ms Taylor was asked about gifts she had purchased for Mr Grew. Apart from the group gift for his birthday in 2018, there were three. The first was for Christmas 2018, when she presented him with a session with her healer. The second was for his birthday in November 2019 when she gave him a turquoise inlaid pocketknife after first checking with him that he liked turquoise. The third was for Christmas 2019, when she and Ms Vu presented him with a backpack, which Ms Taylor had sourced, sharing the cost equally with Ms Vu.

178 Mr Grew testified that he gave jewellery to three other members of staff. They were:

(1) a titanium signet ring inlaid with gold and earrings to Mr Snow for his wife, for which he received no payment;

(2) a diamond pendant necklace with a gold chain, which was made for Ms Nicholson-Black and which she insisted on paying for but for which she paid below the cost price, and a gold diamond ring as a “going-away present” when she left Grew & Co;

(3) matching pendants for Ms Vu as well as her sister and her mother, which he had offered as a gift but for which she insisted on paying and for which he charged cost price; a pair of rose gold “Gemini” stud earrings, for which she also insisted on paying but for which she paid cost price; and not charging Ms Vu for remaking her mother’s engagement ring and setting diamonds into it.

179 Mr Grew also testified that he had given cash, not only to Ms Taylor, but to other employees as well. He said that on several occasions he had “gifted” Mr Tanaka money to assist with the care of his son, who has cerebral palsy, or the purchase of items he needed, such as new walking frames or bicycles. He also said that he had given Mr Tanaka various amounts of money between $1,000 and $2,000 on multiple occasions as donations to charities supported by Mr Tanaka or for which his son’s school was raising funds.

180 Mr Snow testified that the titanium signet ring was a 40th birthday gift from Mr Grew and Mr Tanaka. He said the materials were not very expensive but the gold inlay was 24-carat and the ring was both unique and “ludicrously hard to make”. He estimated the retail price at between $3,500 and $5,000. He said that the earrings he gave to his wife for Christmas 2019 consisted of three small diamonds on each earring. He said that the cost value would have been “relatively low” and estimated that it was “around the 150, $200 mark”, and that the retail price was around $990. He testified to receiving cash bonuses throughout the time he worked for Grew & Co and in the period during which Ms Taylor worked there the bonus was “around $3,000 to $5,000”. In addition, towards the end of his employment Mr Grew gave him a $5,000 cash bonus to help towards the purchase of a “family car”.

181 Mr Tanaka testified that during the period in which Ms Taylor worked for the business Mr Grew gave him a Bunnings gift card (that he recalled being worth about $200), a Garmin watch, and a massage coupon, and that he had paid for a CrossFit gym membership for him and Mr Snow. He made no mention of receiving cash for the benefit of his son or for charities associated with his son’s disability. Nevertheless, Mr Grew was not challenged on his evidence on these matters and in those circumstances I accept it.