FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Secretary, Department of Health and Aged Care v Vapor Kings Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1297

ORDERS

SECRETARY, DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND AGED CARE Applicant | ||

AND: | VAPOR KINGS PTY LTD (ACN 615 112 877) First Respondent AMIR KANDAKJI Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 27 October 2023 |

PENAL NOTICE TO: VAPOR KINGS PTY LTD (ACN 615 112 877) AND AMIR KANDAKJI IF YOU (BEING THE PERSON BOUND BY THIS ORDER): (A) REFUSE OR NEGLECT TO DO ANY ACT WITHIN THE TIME SPECIFIED IN THE ORDER FOR THE DOING OF THE ACT; OR (B) DISOBEY THE ORDER BY DOING AN ACT WHICH THE ORDER REQUIRES YOU NOT TO DO, YOU WILL BE LIABLE TO IMPRISONMENT, SEQUESTRATION OF PROPERTY OR OTHER PUNISHMENT. ANY OTHER PERSON WHO KNOWS OF THIS ORDER AND DOES ANYTHING WHICH HELPS OR PERMITS YOU TO BREACH THE TERMS OF THIS ORDER MAY BE SIMILARLY PUNISHED. |

DECLARATIONS

1. The Court declares under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) that, at various points in time from at least 24 November 2021 to 15 June 2022:

Advertising goods not included in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods

(a) the first respondent, by advertising or causing the advertising of nicotine vaping products (NVPs) on its websites located at Uniform Resource Locator (URL) https://vaporkings.com.au/ (AU Website), in circumstances where s 42DLB(9) of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) (TG Act) applied because:

(i) the advertisements referred to NVPs that are, and were during the period the subject of this declaration:

A. “therapeutic goods” within the meaning of s 3(1) of the TG Act;

B. not entered in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods maintained by the applicant under s 9A of the TG Act (the Register); and

C. prescribed by reg 7(i) of the Therapeutic Goods Regulations 1990 (Cth) (TG Regulations), being therapeutic goods not the subject of an exemption, approval or authority under the TG Act nor an exemption, approval or authority under regulations under the TG Act; and

(ii) those references are not and were not authorised or required by a government or government authority (including a foreign government or foreign government authority),

in respect of each advertisement, contravened s 42DLB(1) of the TG Act;

(b) the second respondent, by advertising and/or causing the first respondent to advertise NVPs on the AU Website and on the website located at URL https://vaporkings.co.uk/ (UK Website), in the circumstances outlined in paragraph 1(a) above, contravened s 42DLB(1) of the TG Act;

(c) the second respondent aided, abetted, counselled or procured the first respondent’s contraventions of s 42DLB(1) of the TG Act referred to in paragraph 1(a) above and was therefore involved in those contraventions for the purposes of s 42YC of the TG Act;

(d) further, the second respondent, by failing to take all reasonable steps to prevent the first respondent’s contraventions of the TG Act described in paragraph 1(a) above, in circumstances where he knew that the contraventions would occur and was in a position to influence the conduct of the first respondent in relation to such contraventions, contravened s 54B(3) of the TG Act;

Advertising referring to substances included in Schedule 4 to the Poisons Standard

(e) the first respondent, by advertising or causing the advertising of NVPs on the AU Website in circumstances where s 42DLB(7) of the TG Act applied because:

(i) the advertisements contained references to a substance, being nicotine, or goods containing the substance nicotine, which is and was during the period the subject of this declaration, included in Schedule 4 to the current Poisons Standard (as defined in the TG Act) but not in Appendix H of the current Poisons Standard; and

(ii) those references are not and were not authorised or required by a government or government authority (not including a foreign government or foreign government authority),

in respect of each advertisement, contravened s 42DLB(1) of the TG Act;

(f) the second respondent, by advertising and/or causing the first respondent to advertise NVPs on the AU Website and the UK Website, in the circumstances outlined in paragraph 1(e) above, contravened s 42DLB(1) of the TG Act;

(g) the second respondent aided, abetted, counselled or procured the first respondent’s contraventions of s 42DLB(1) of the TG Act referred to in paragraph 1(e) above and was therefore involved in those contraventions for the purposes of s 42YC of the TG Act; and

(h) further, the second respondent, by failing to take all reasonable steps to prevent the first respondent’s contraventions of the TG Act described in paragraph 1(e) above, in circumstances where he knew that the contraventions would occur and was in a position to influence the conduct of the first respondent in relation to such contraventions, contravened s 54B(3) of the TG Act.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

INJUNCTIONS

2. Pursuant to s 42YN of the TG Act, the first respondent is restrained, for a period of ten years from the date of this order, whether by itself, its servants or agents, from advertising or causing to be advertised therapeutic goods if such advertisements refer to:

(a) therapeutic goods which are not entered in the Register, and are prescribed by reg 7(i) of the TG Regulations; and/or

(b) substances, or goods containing substances, included in Schedule 4 to the current Poisons Standard as in force at the relevant time,

unless s 42AA, s 42AB or s 42AC of the TG Act applies.

3. Pursuant to s 42YN of the TG Act, the second respondent is restrained, for a period of ten years from the date of this order, whether by himself, or by his servants or agents, from advertising or causing to be advertised therapeutic goods if such advertisements refer to:

(a) therapeutic goods which are not entered in the Register, and are prescribed by reg 7(i) of the TG Regulations; and/or

(b) substances, or goods containing substances, included in Schedule 4 to the current Poisons Standard as in force at the relevant time,

unless s 42AA, s 42AB or s 42AC of the TG Act applies.

PECUNIARY PENALTIES

4. Pursuant to s 42Y of the TG Act, the first respondent is to pay to the Commonwealth of Australia pecuniary penalties in the agreed sum of $4,900,000.00 in respect of its contraventions of the TG Act referred to in paragraph 1 above.

5. Pursuant to s 42Y of the TG Act, the second respondent is to pay to the Commonwealth of Australia pecuniary penalties in the agreed sum of $100,000.00 in respect of his contraventions of the TG Act referred to in paragraph 1 above, with 65% of that sum to be suspended on the condition that he commits no:

(a) breach of the injunction set out in paragraph 3 of these orders; and

(b) offence nor further civil penalty offence against any provision of the TG Act for a period of ten years.

OTHER ORDERS

6. The first respondent is to pay the applicant’s costs of and incidental to these proceedings in the fixed sum of $100,000.00.

7. The second respondent is to pay the applicant’s costs of and incidental to these proceedings in the fixed sum of $10,000.00.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ABRAHAM J:

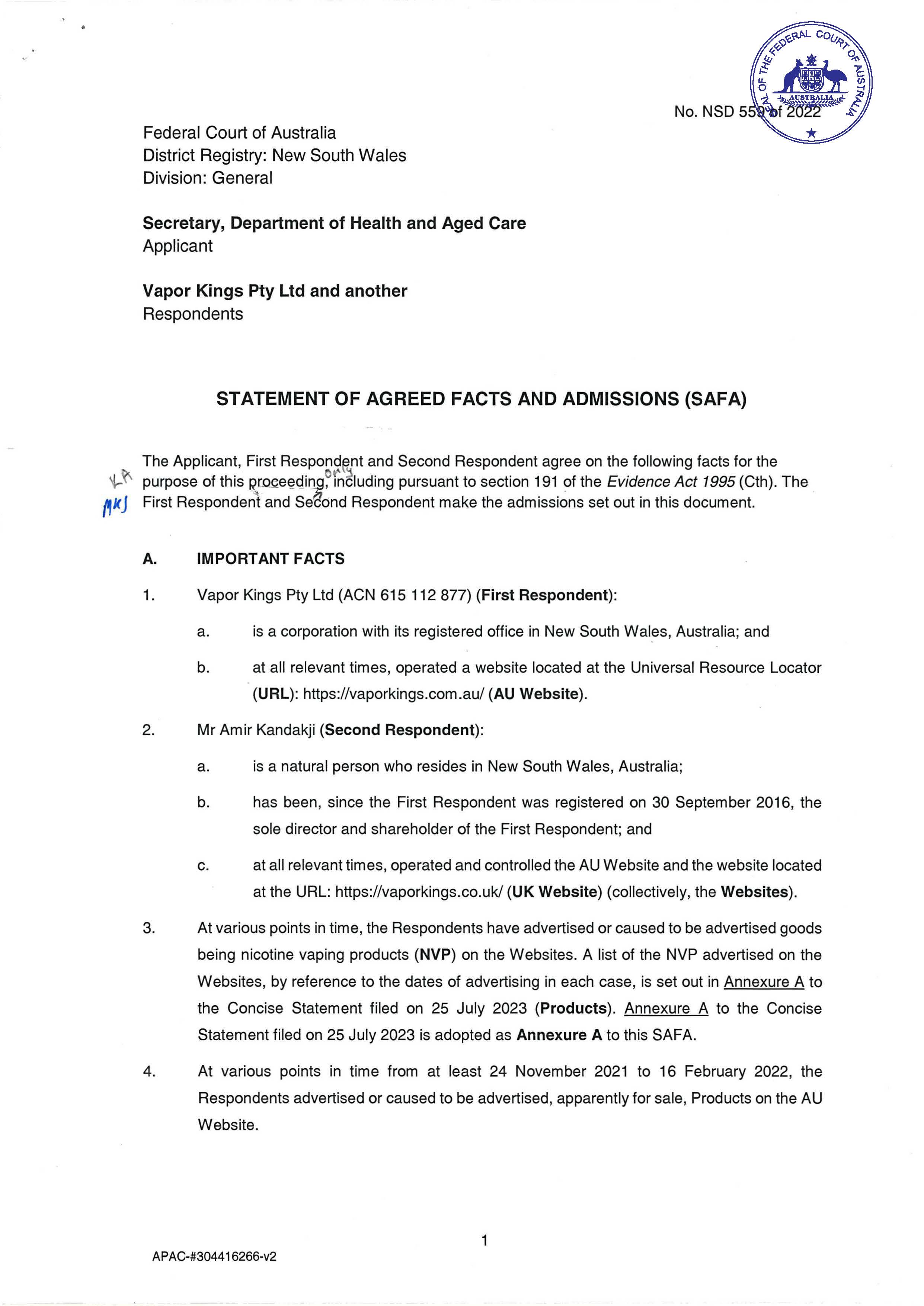

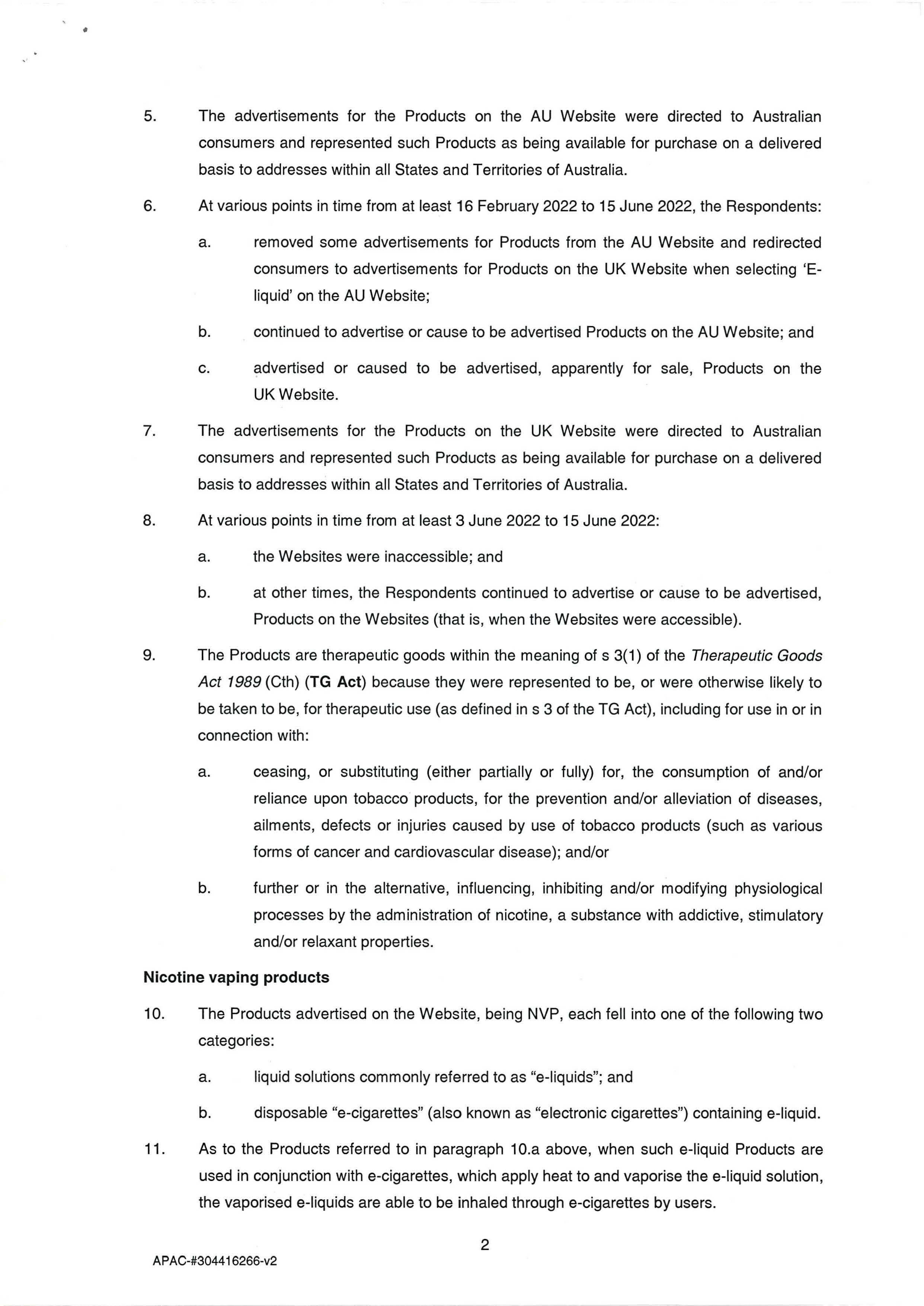

1 Vapor Kings Pty Ltd (Vapor Kings, the first respondent) and Amir Kandakji (Mr Kandakji, the second respondent) admit to contraventions of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) (TG Act) relating to the advertising of nicotine vaping products (NVPs) on websites they controlled and operated. Mr Kandakji was the sole director and shareholder of Vapor Kings at the relevant time.

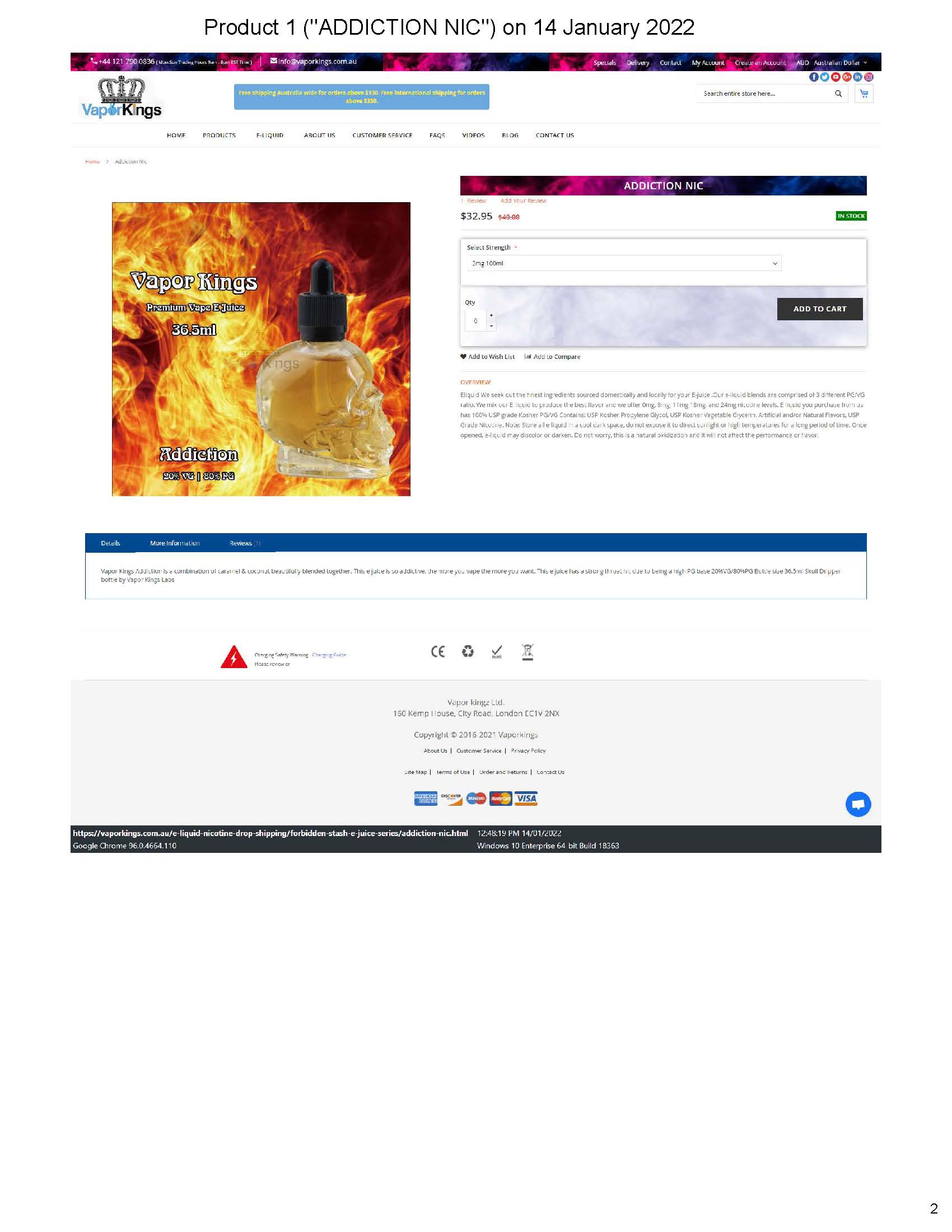

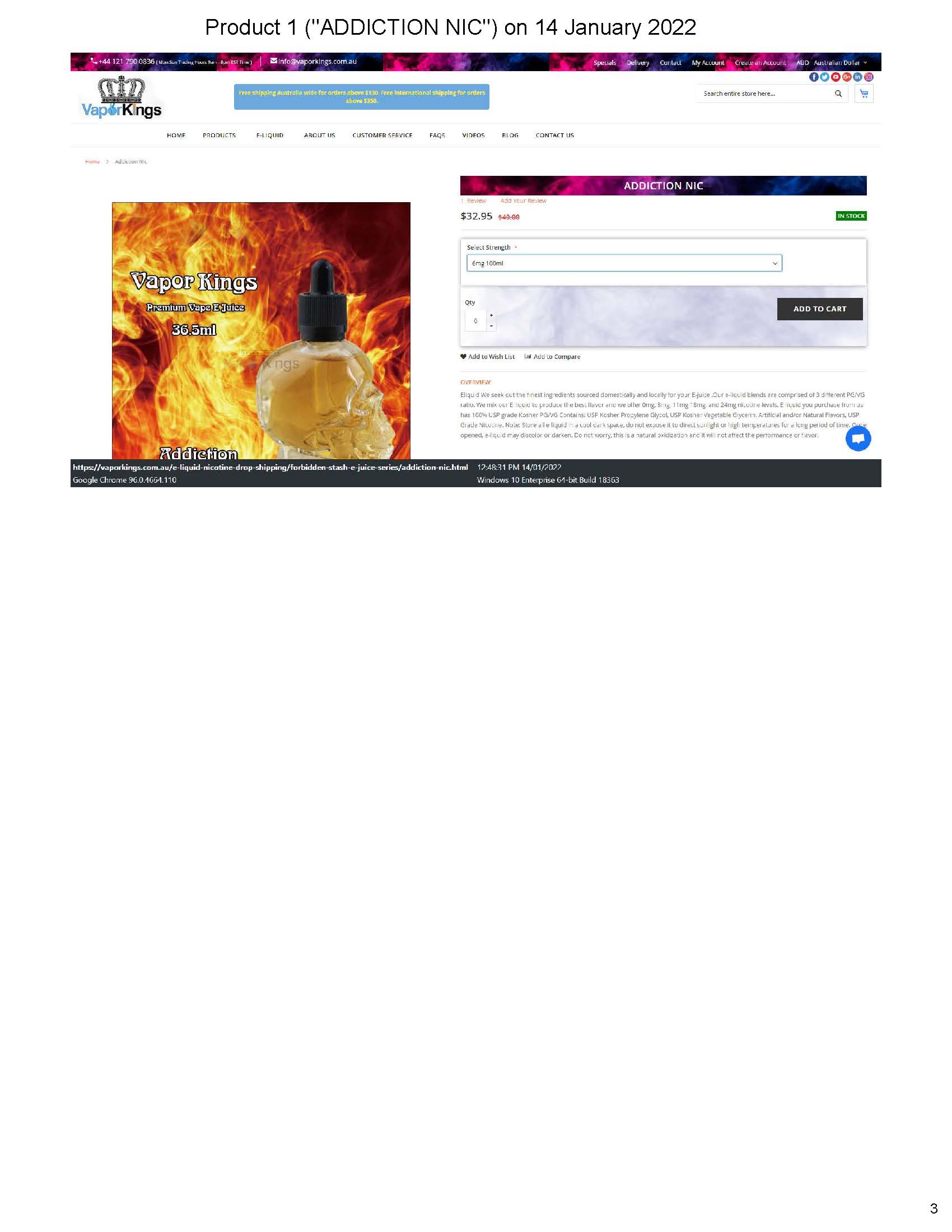

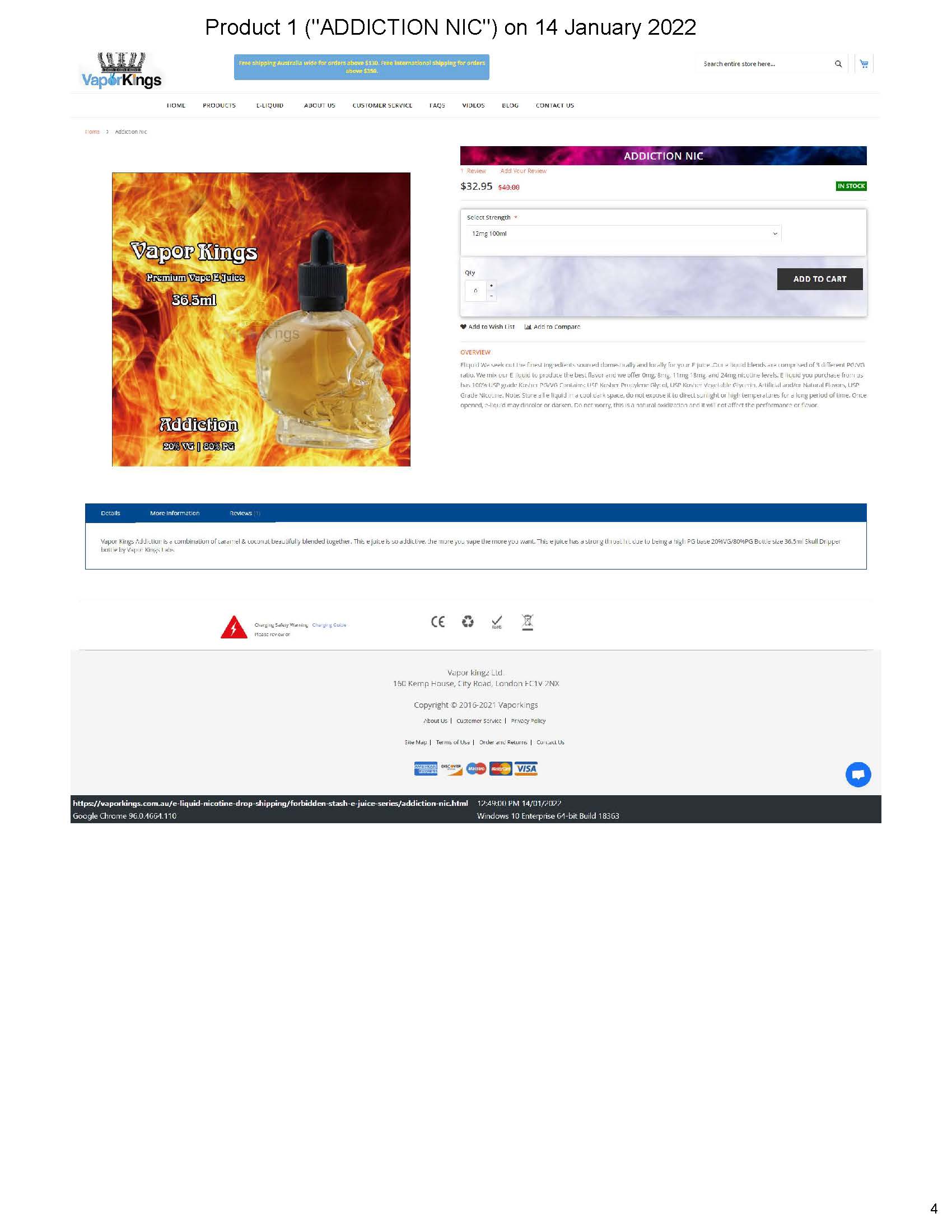

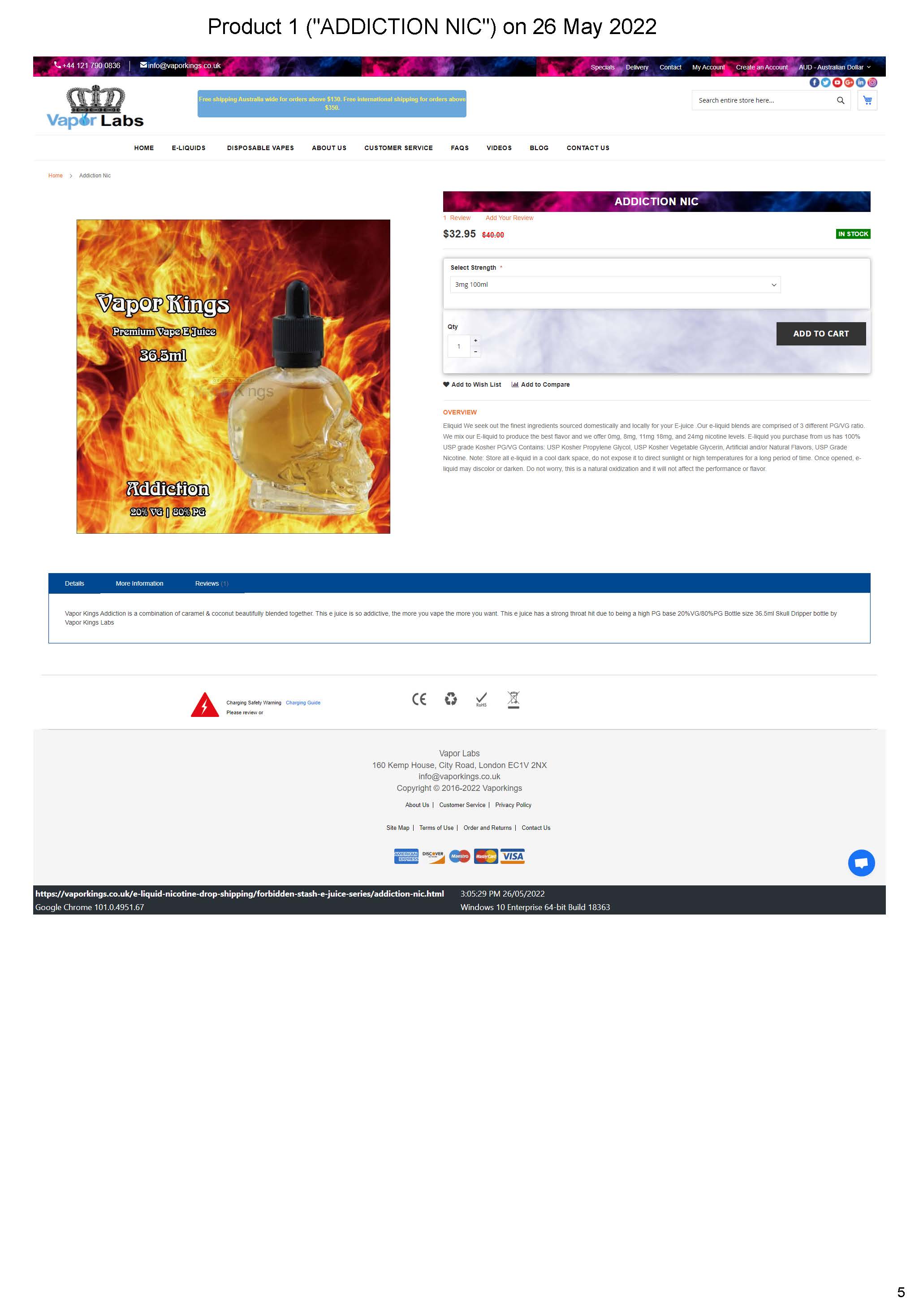

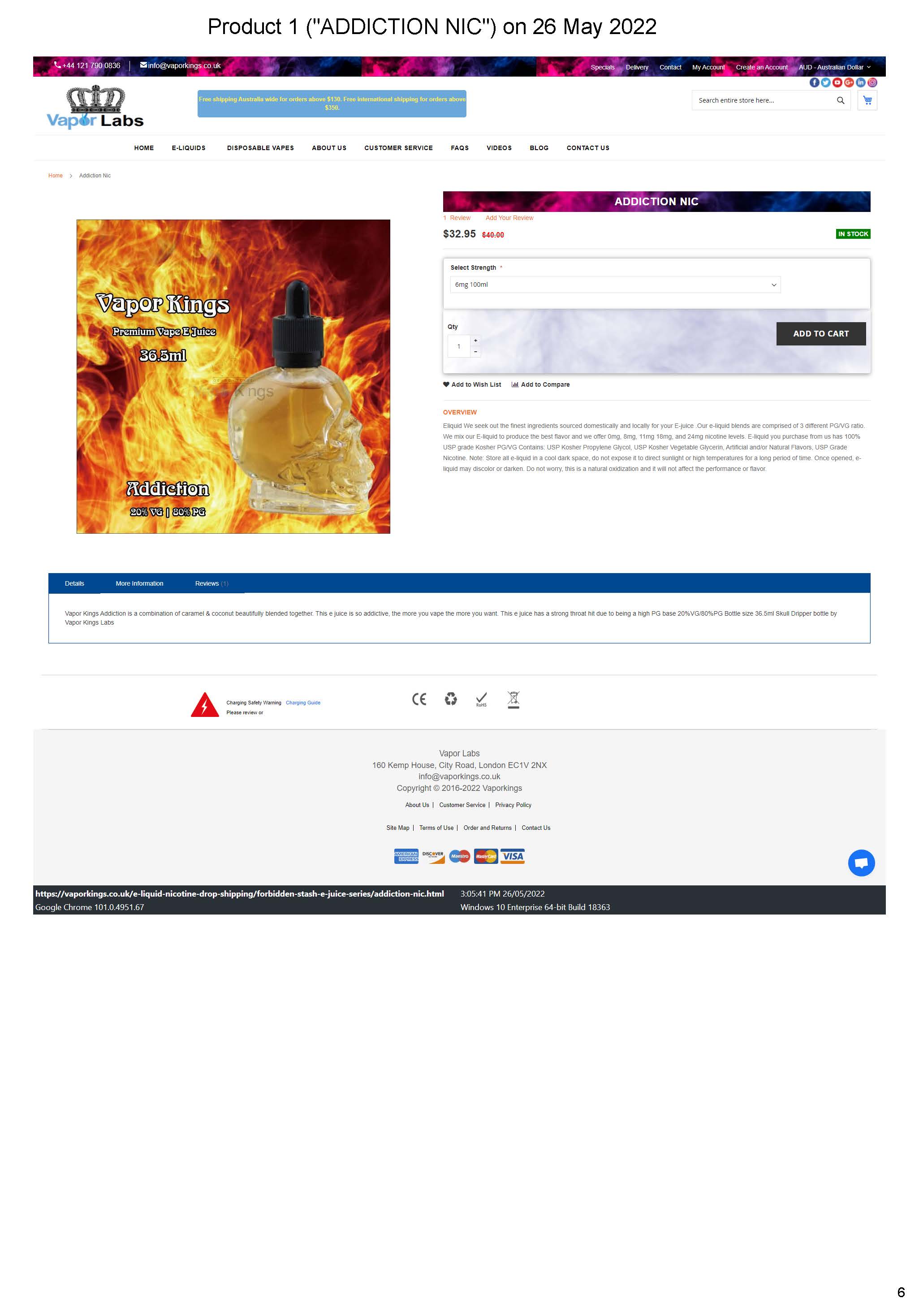

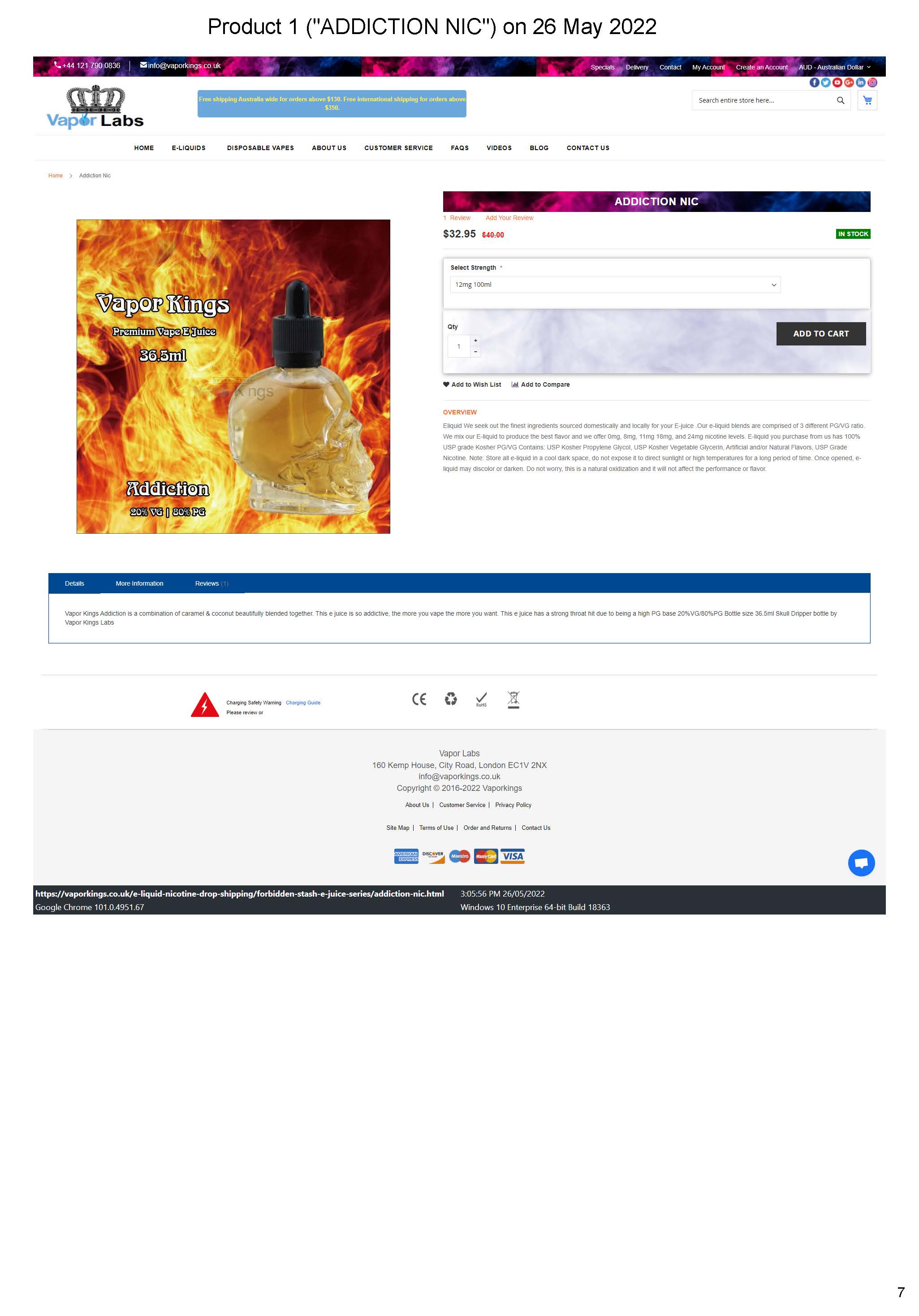

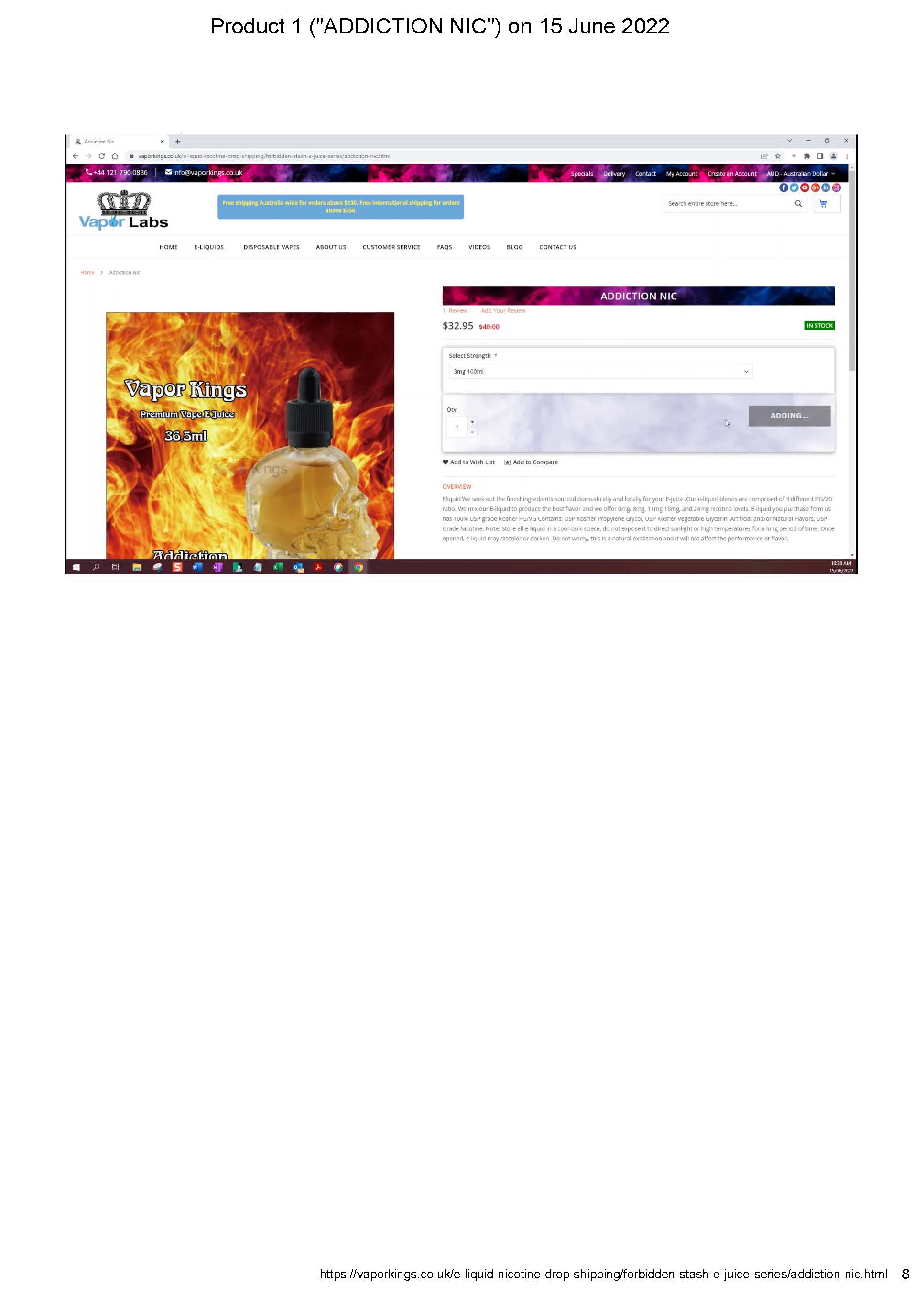

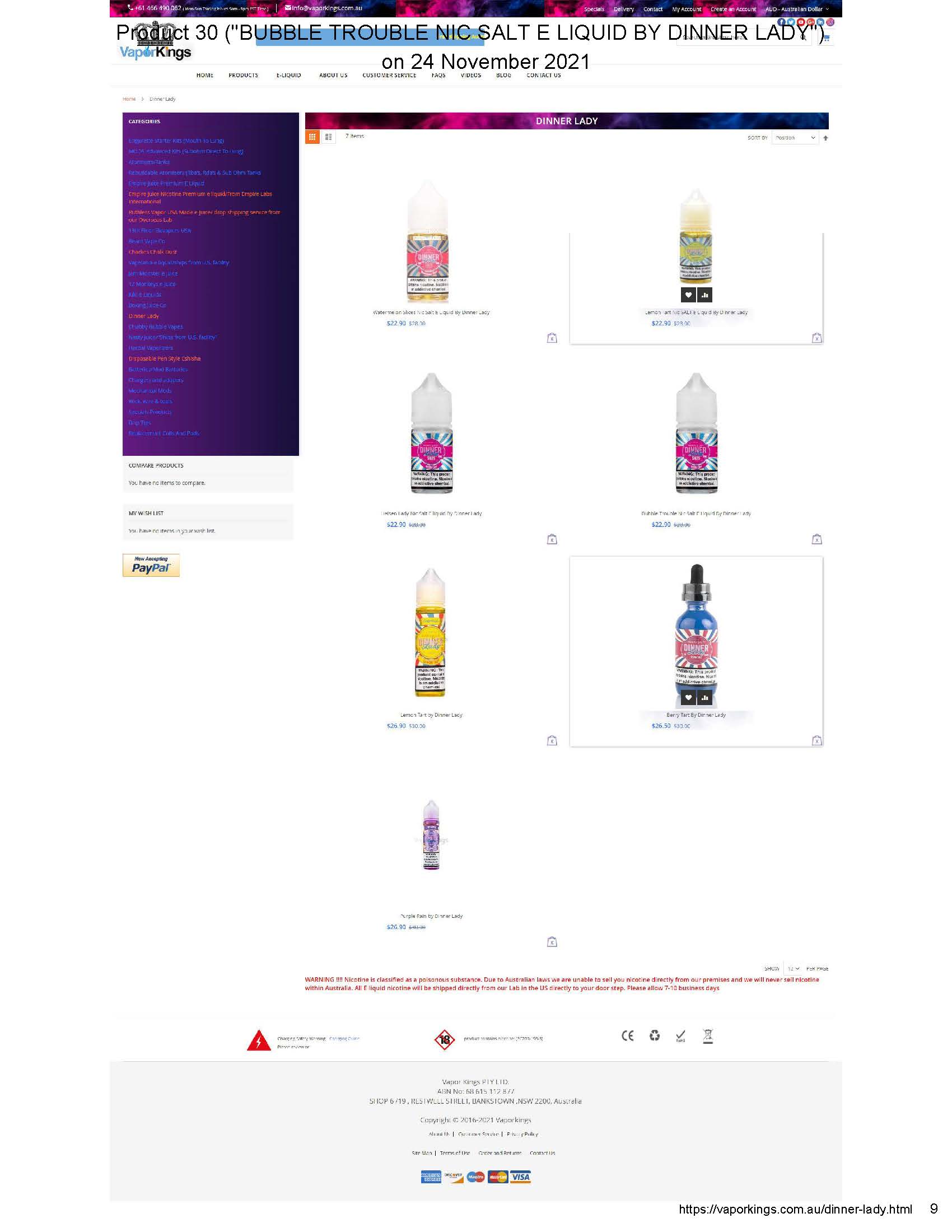

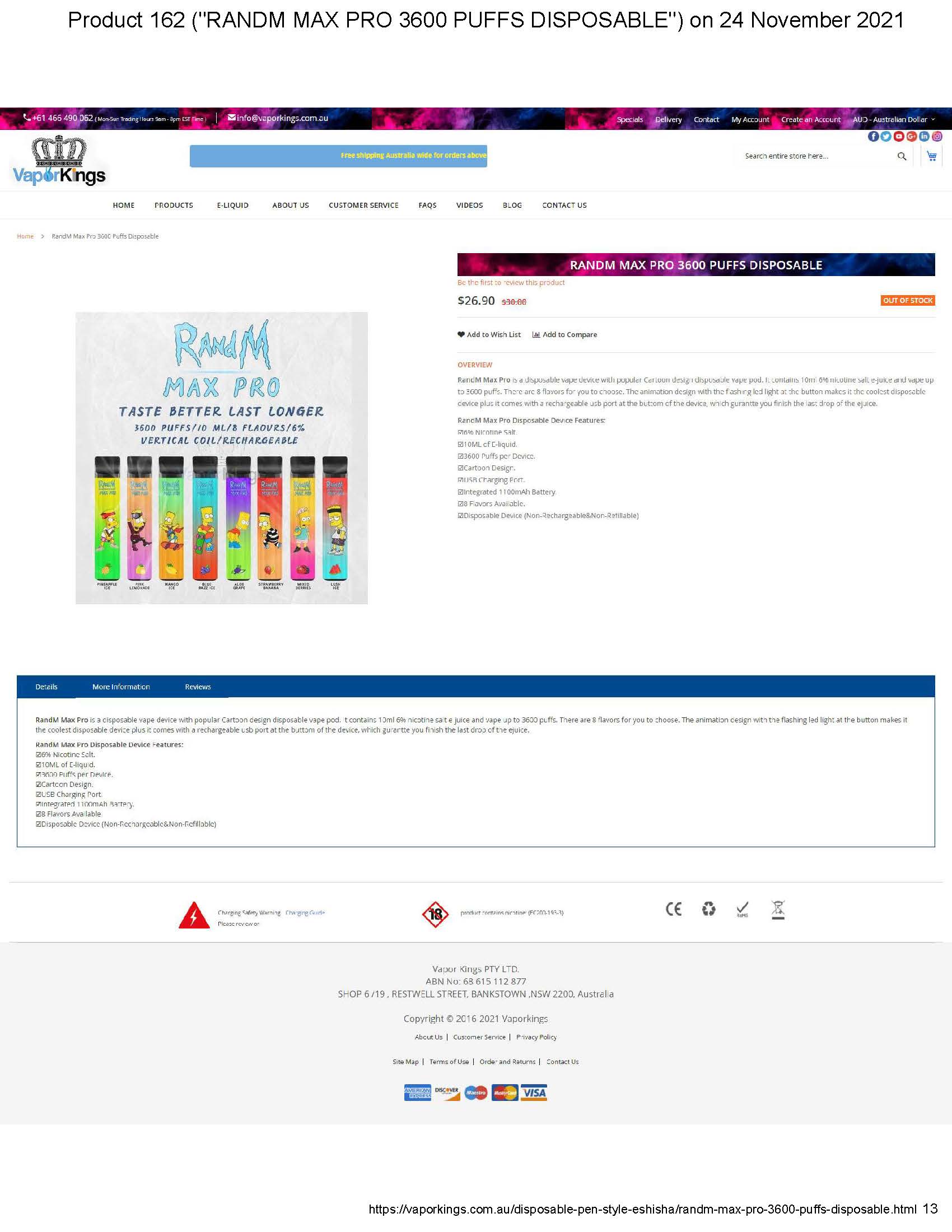

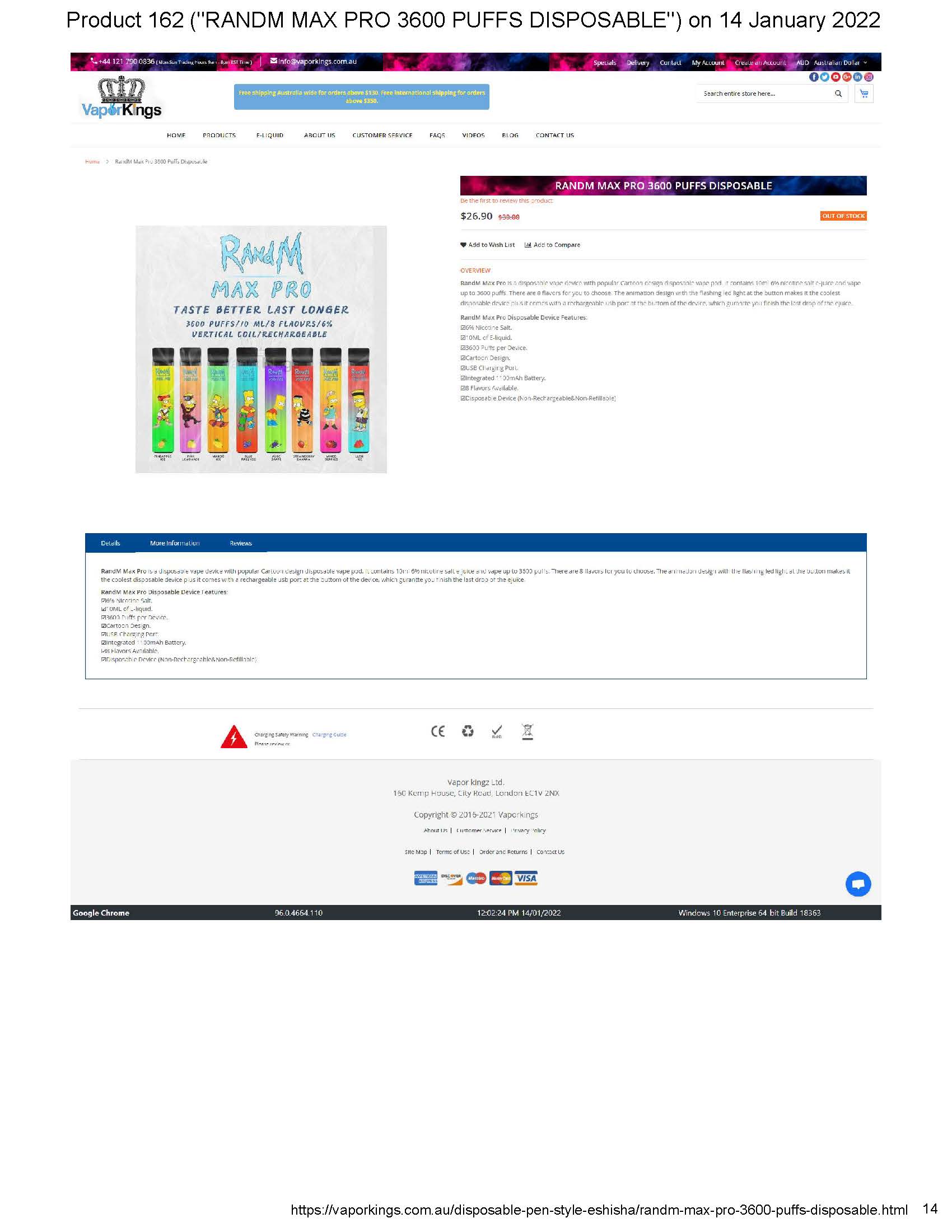

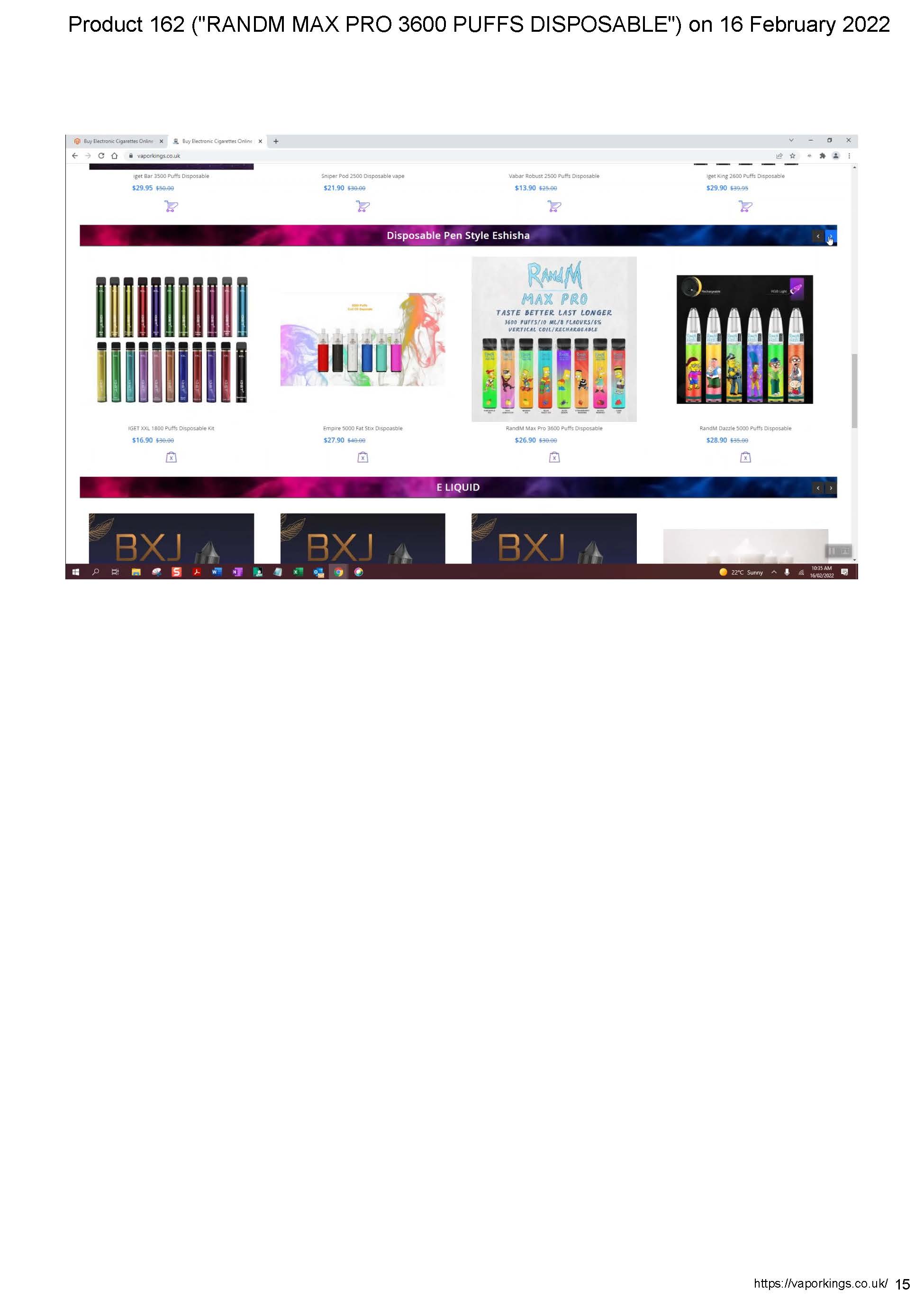

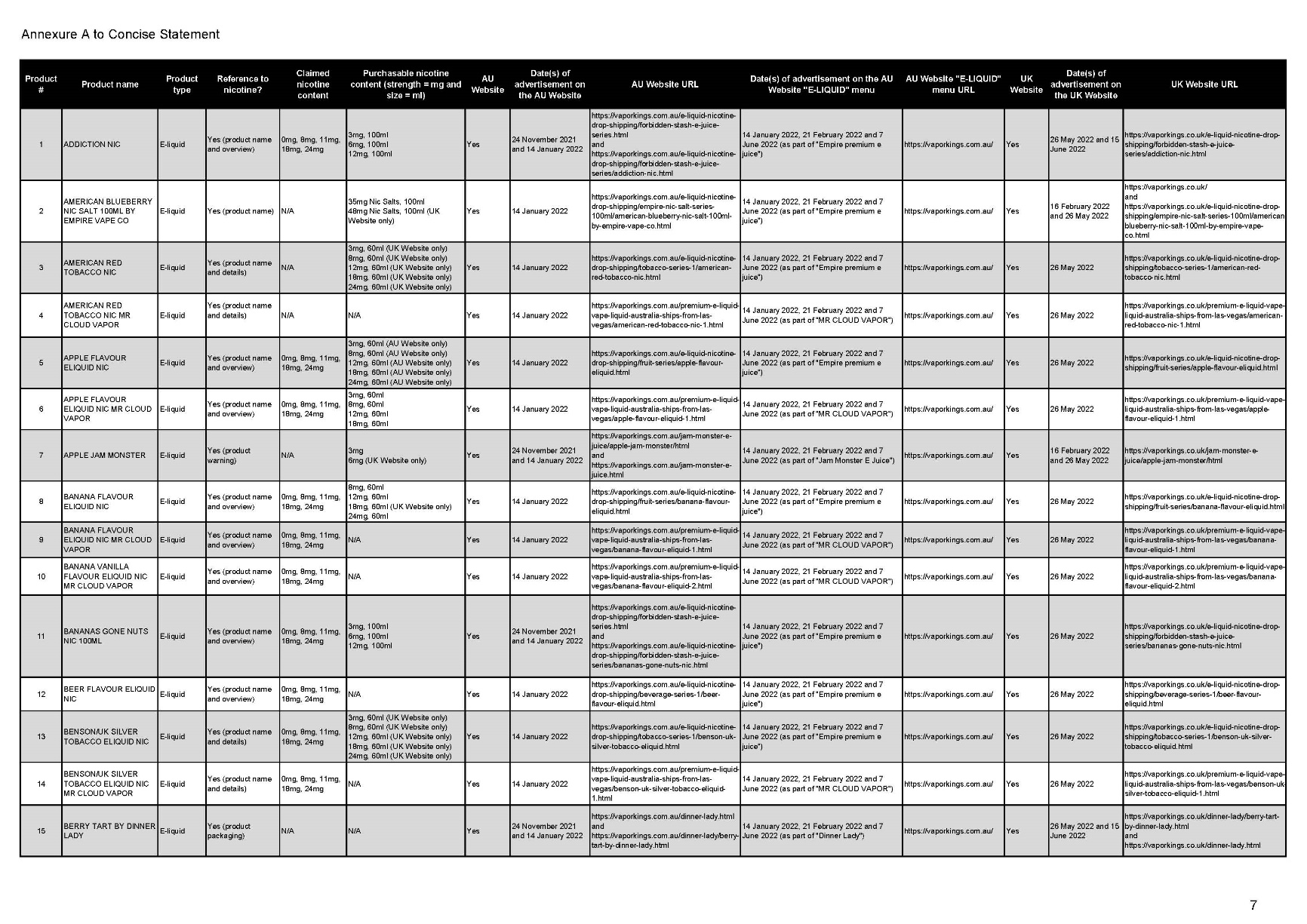

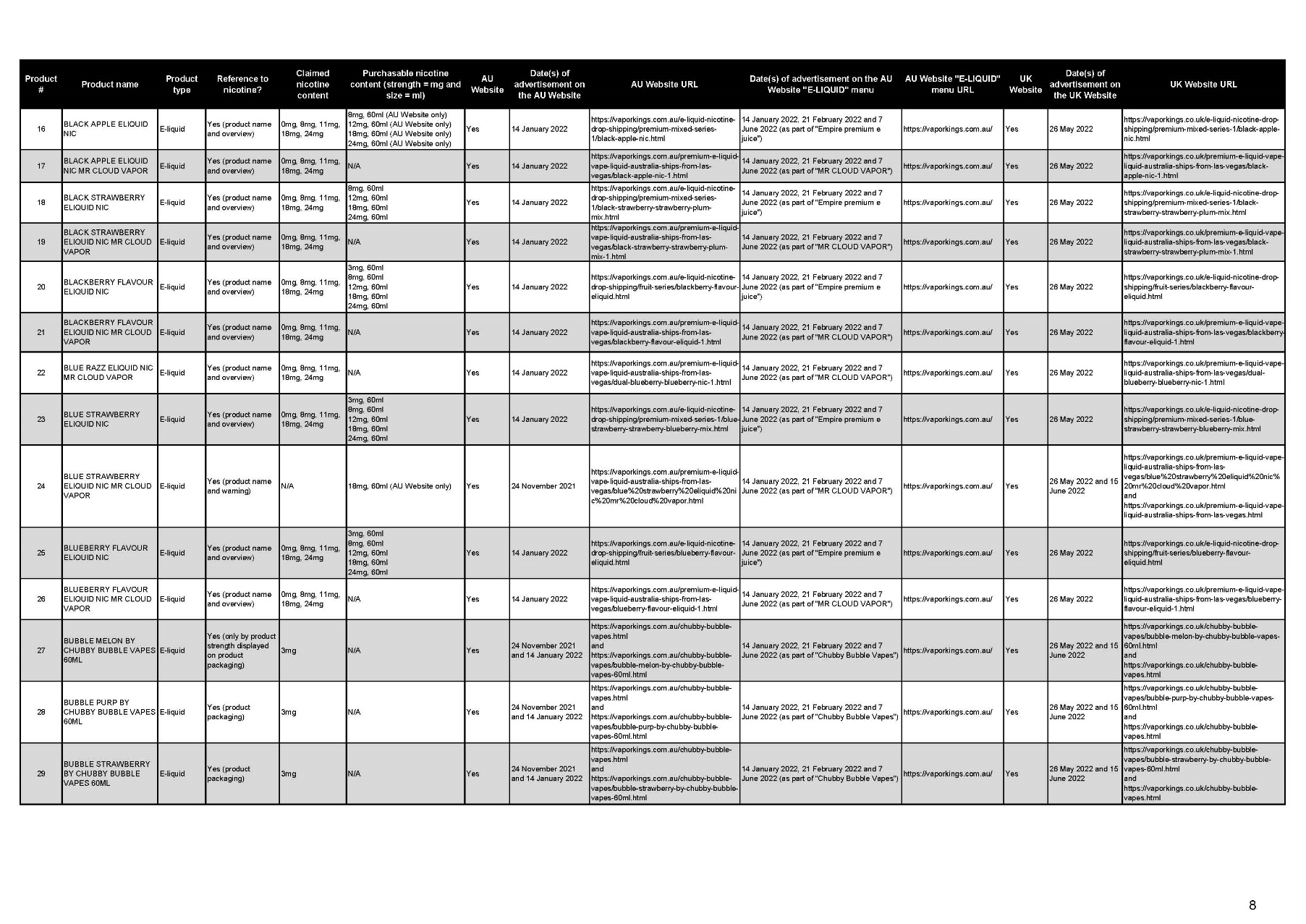

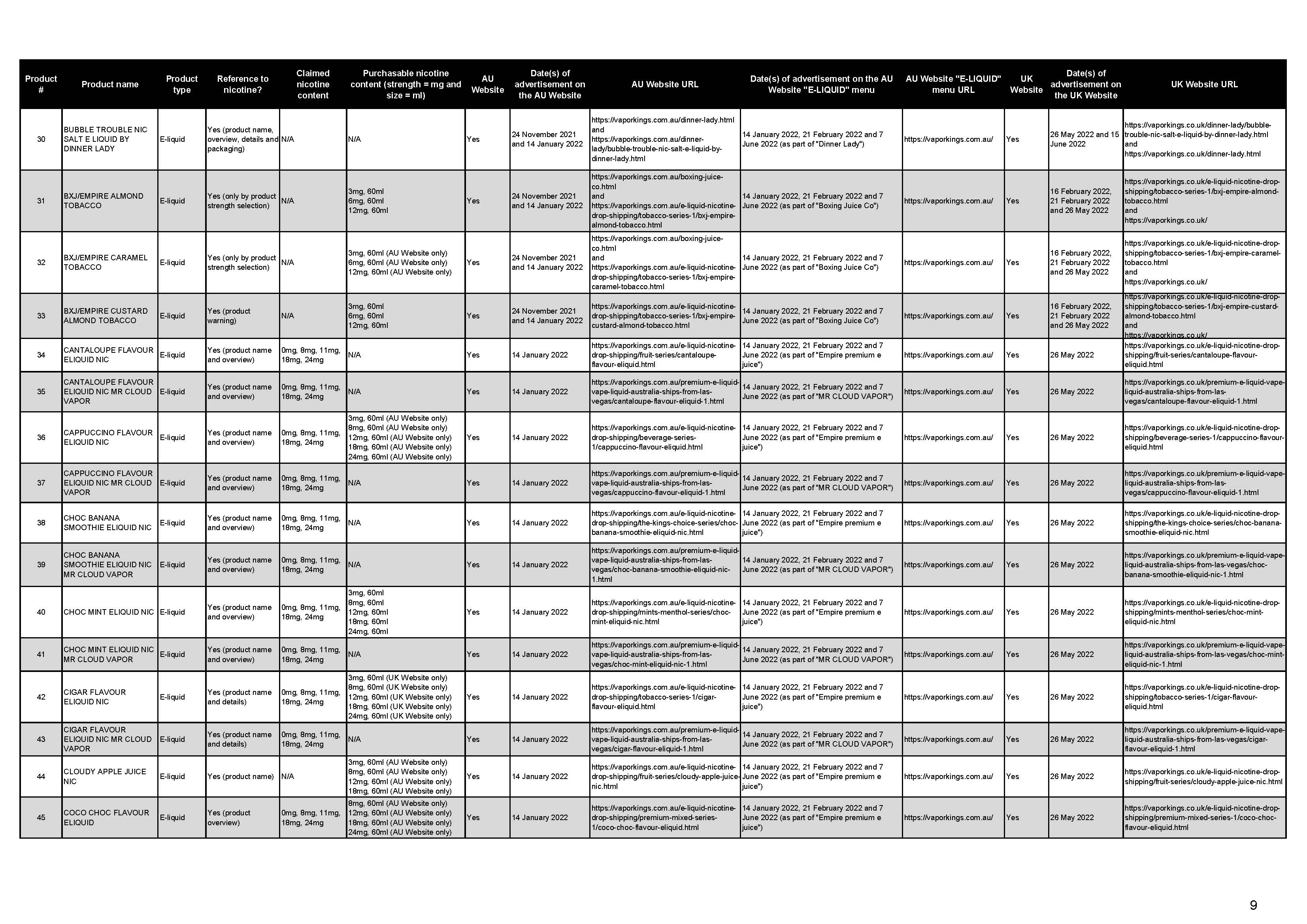

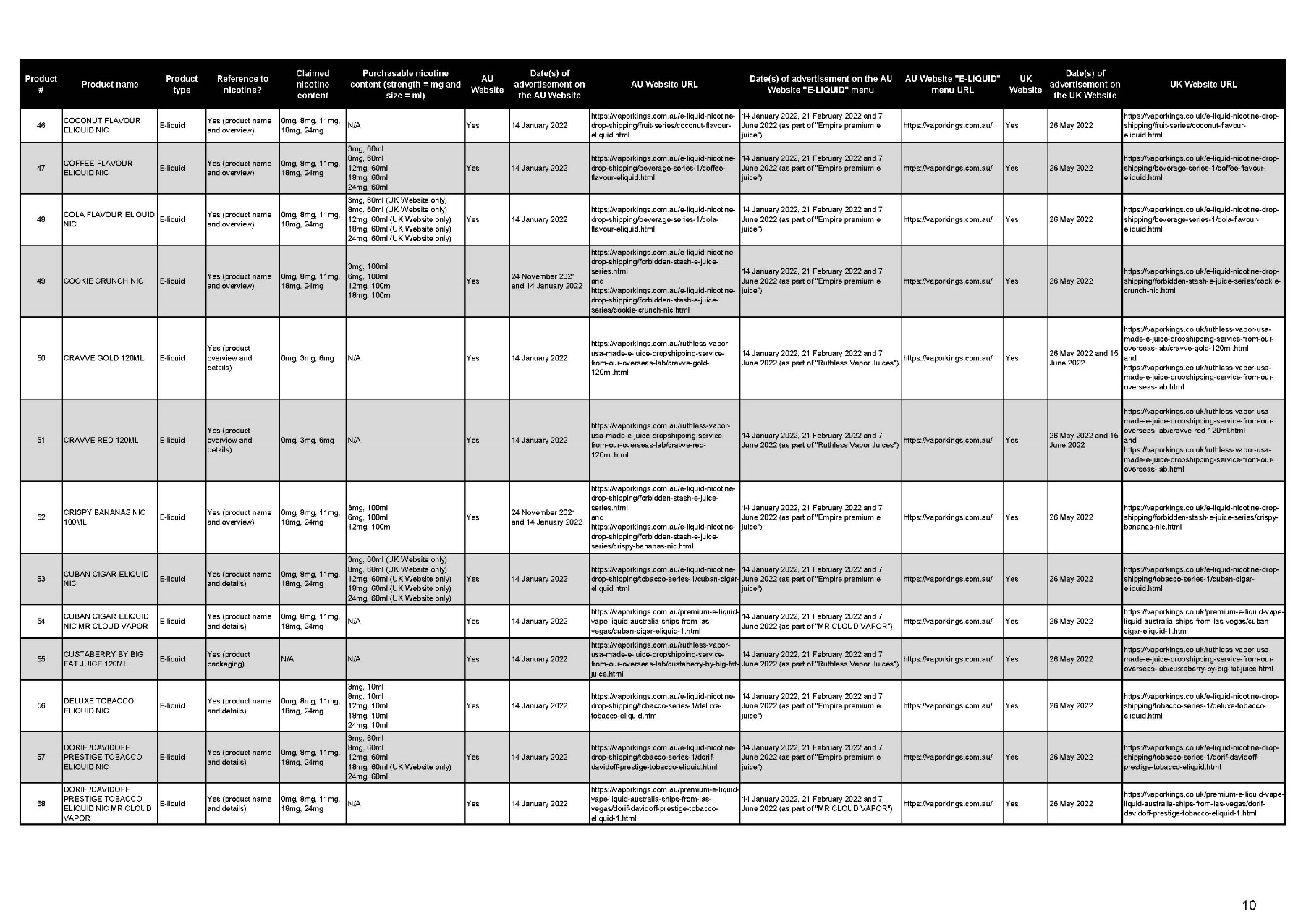

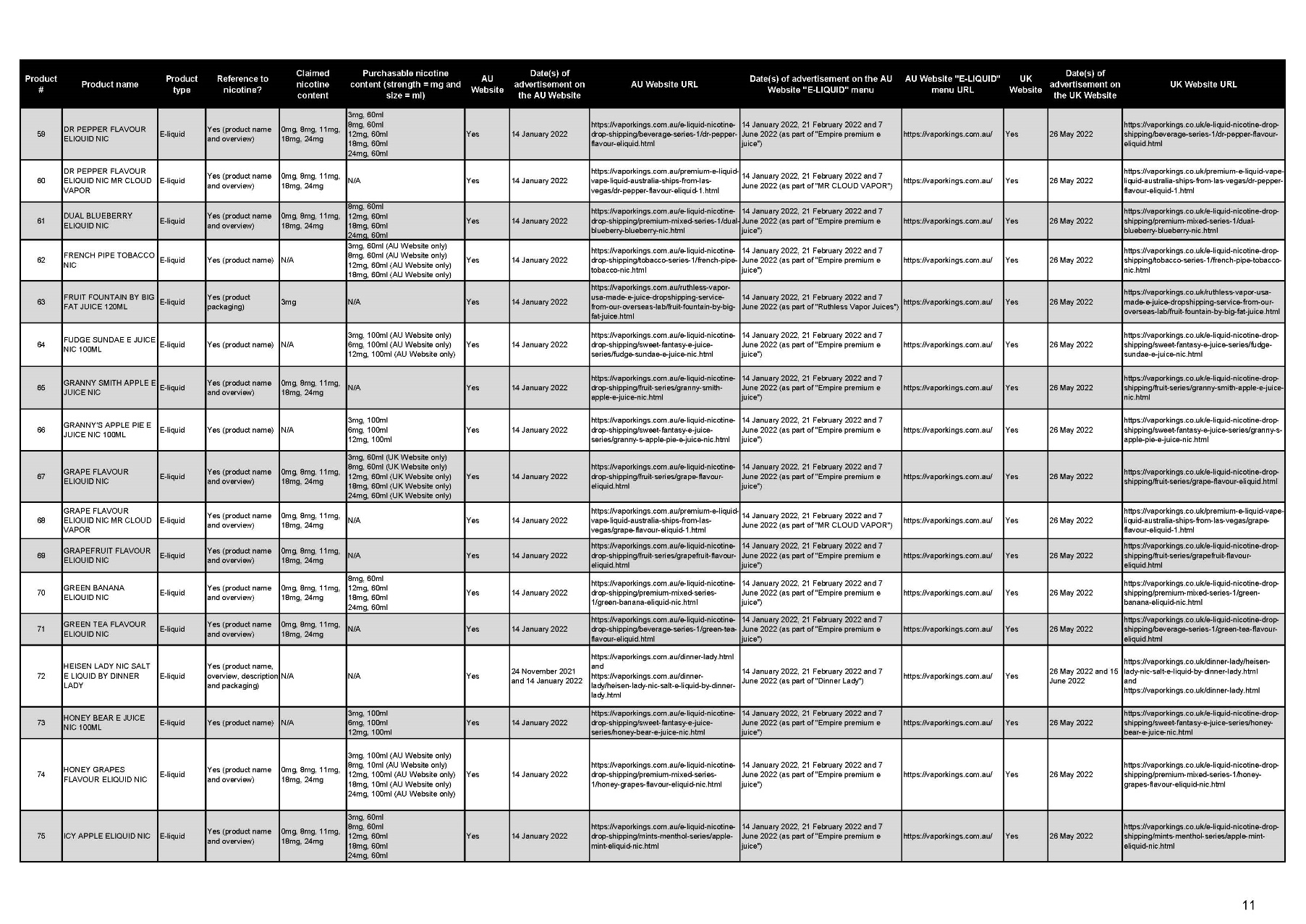

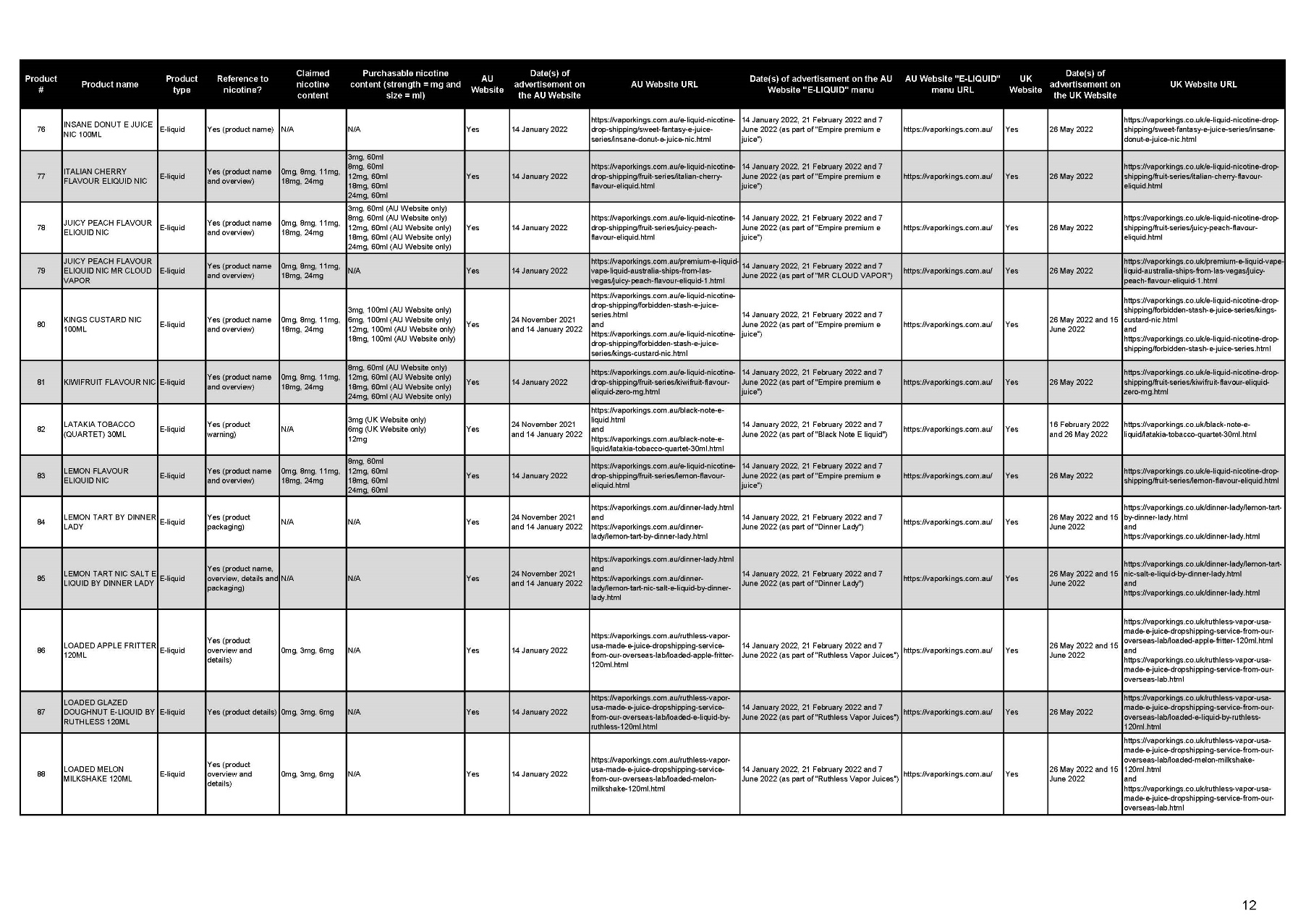

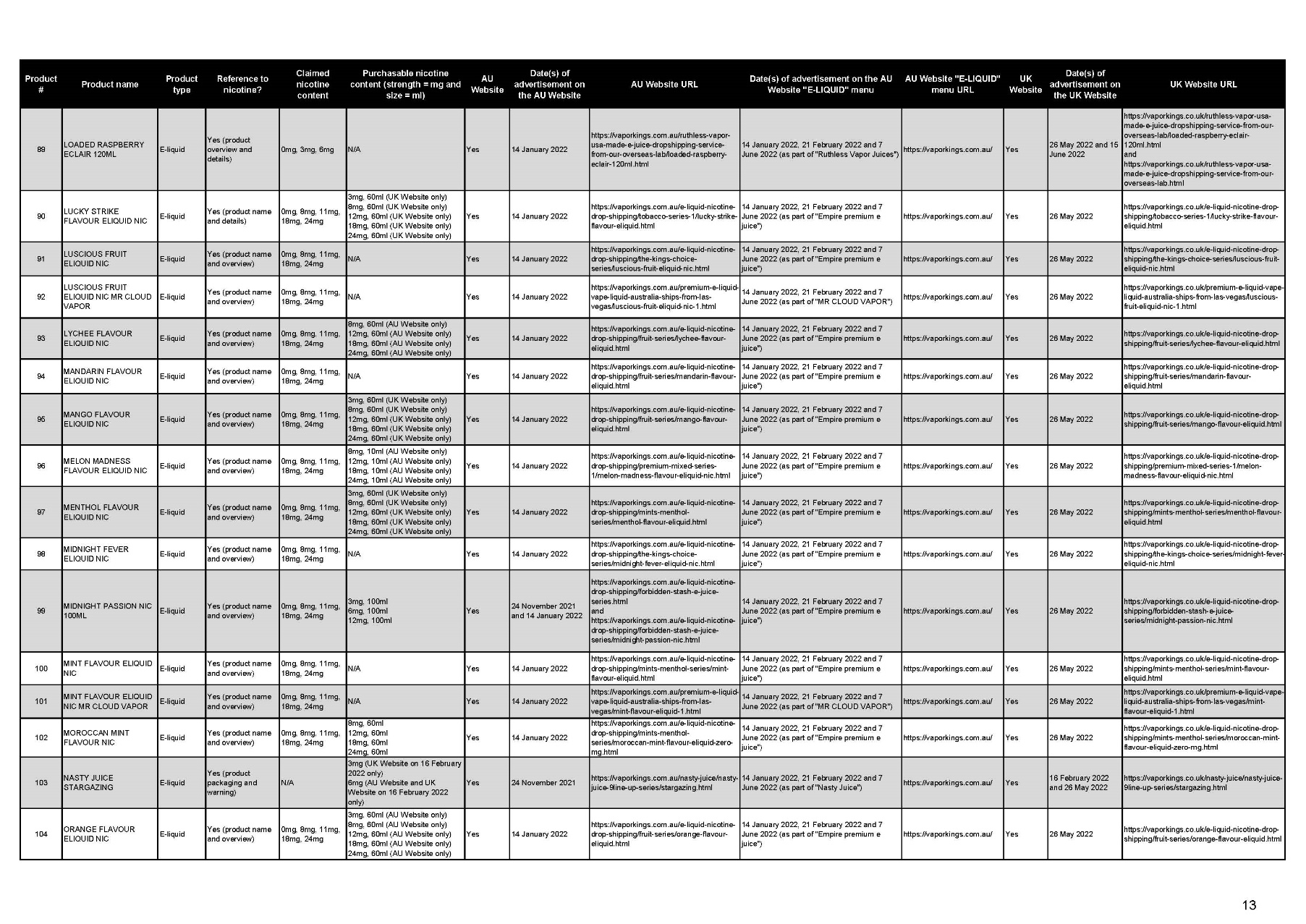

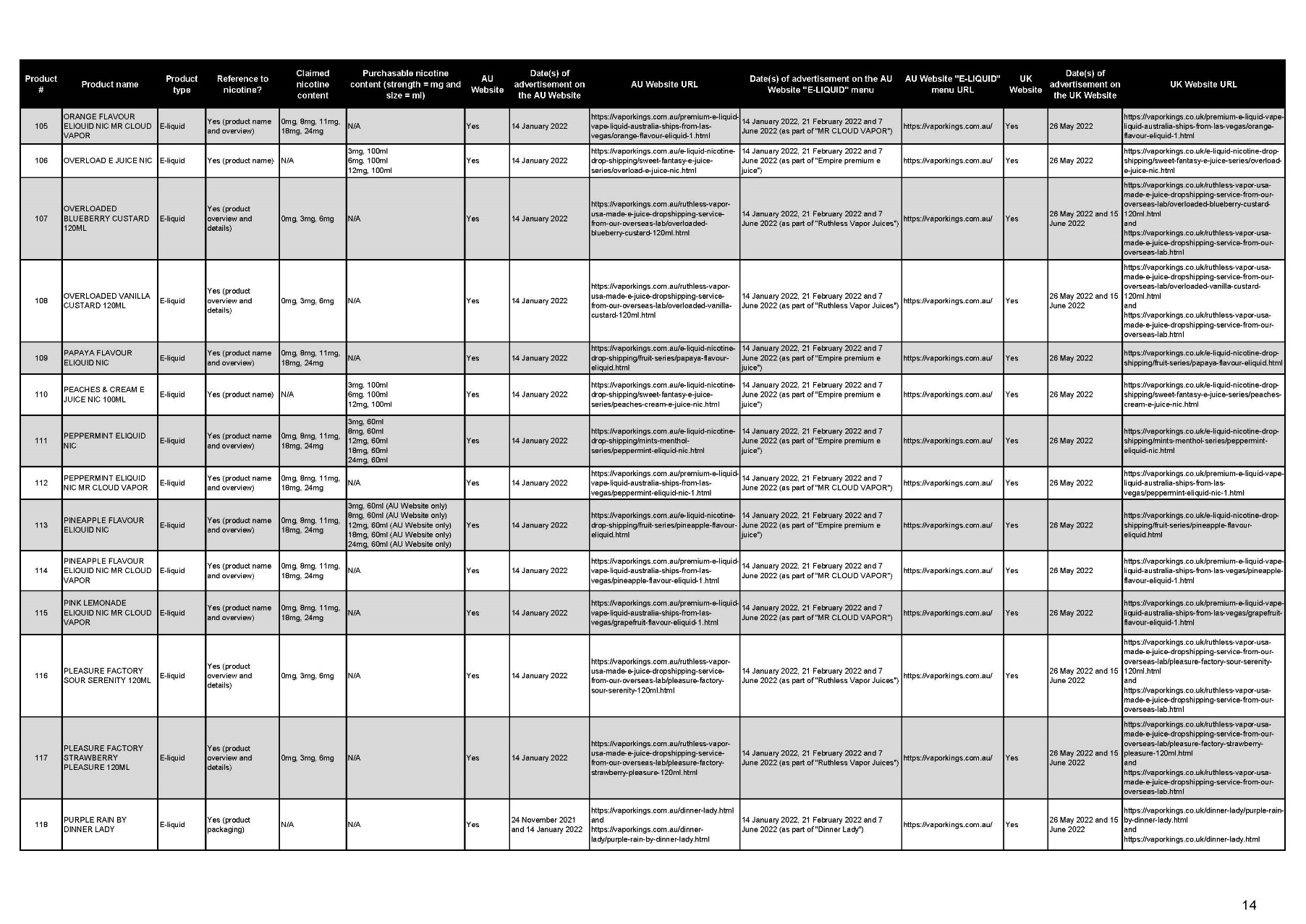

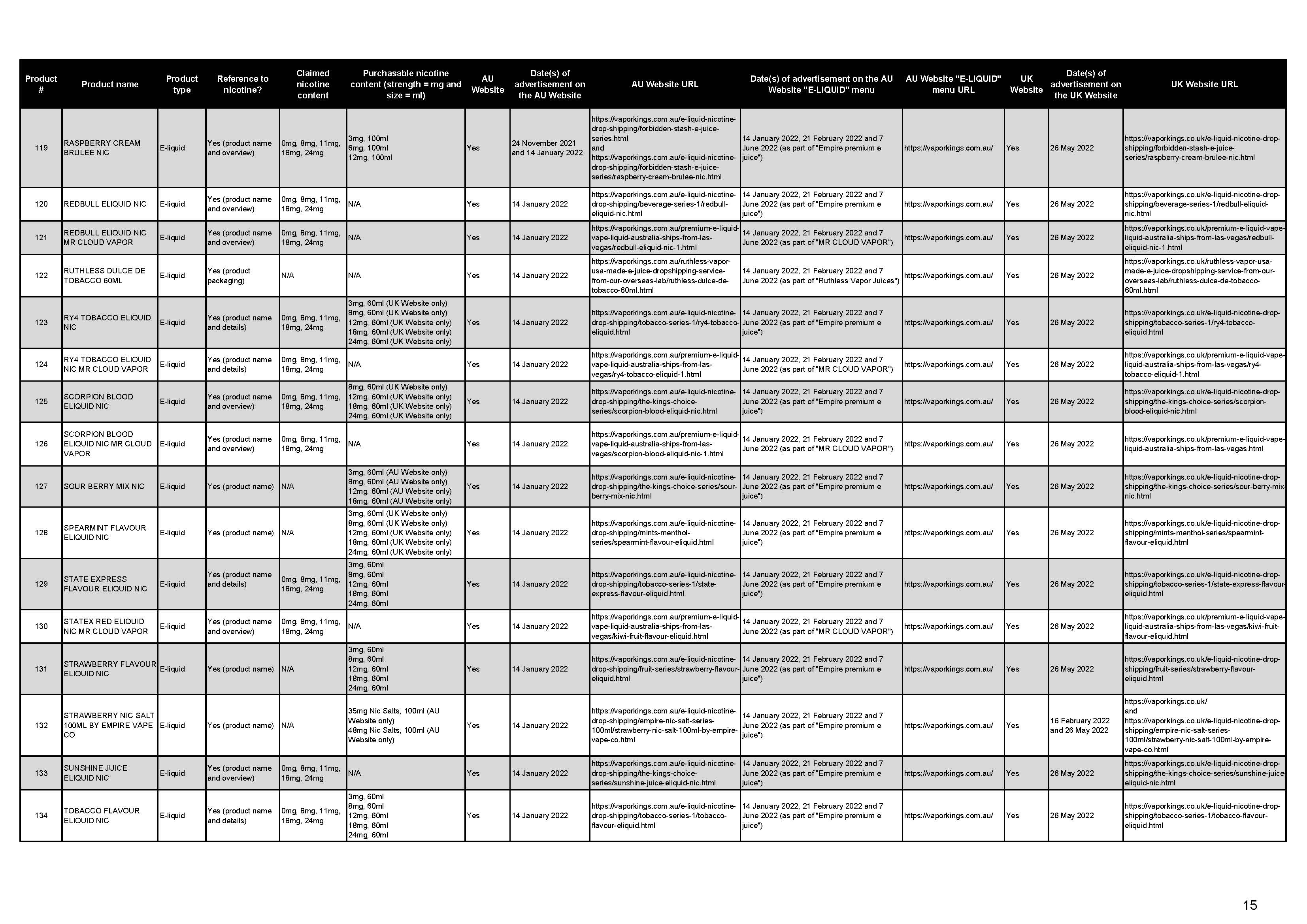

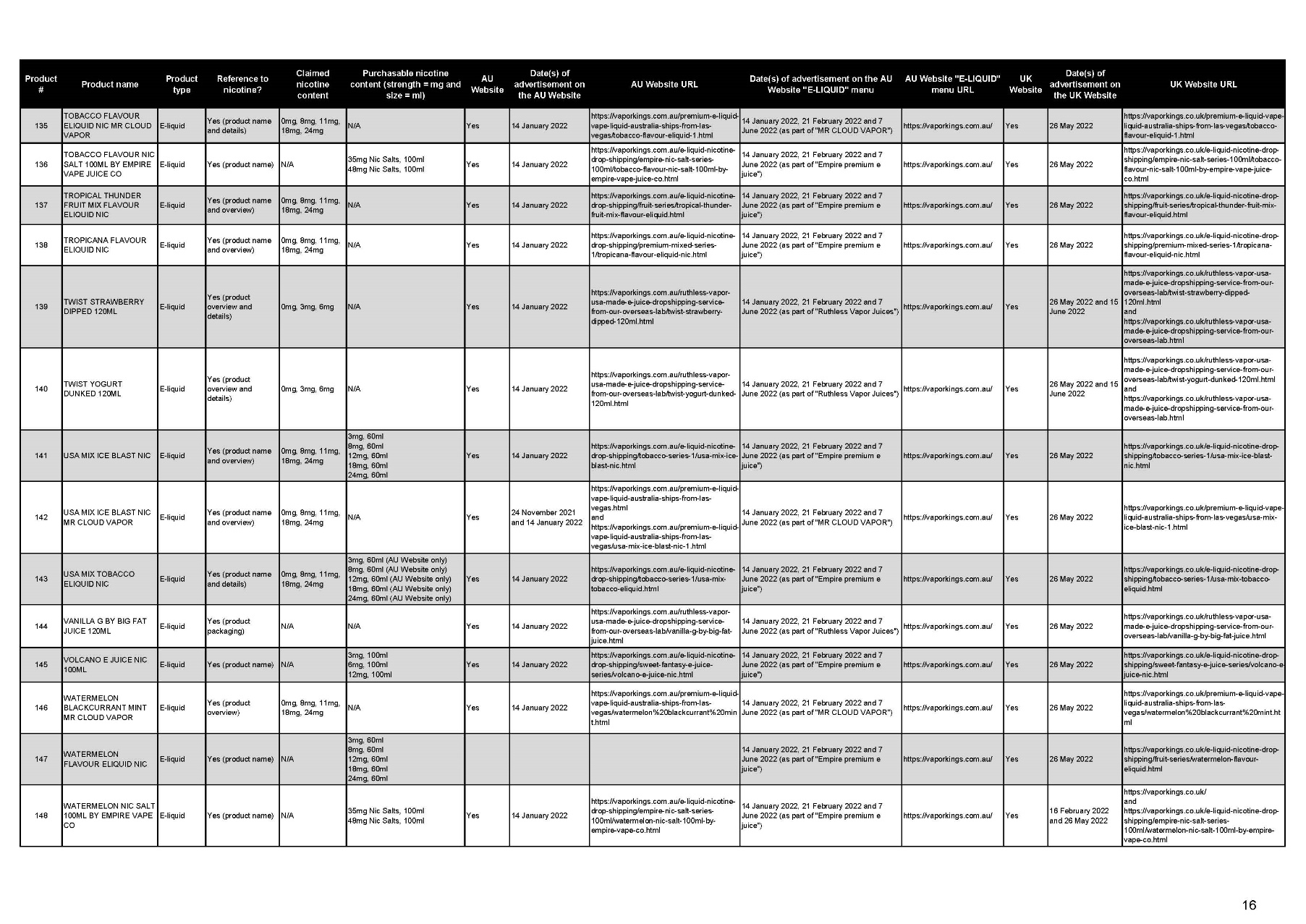

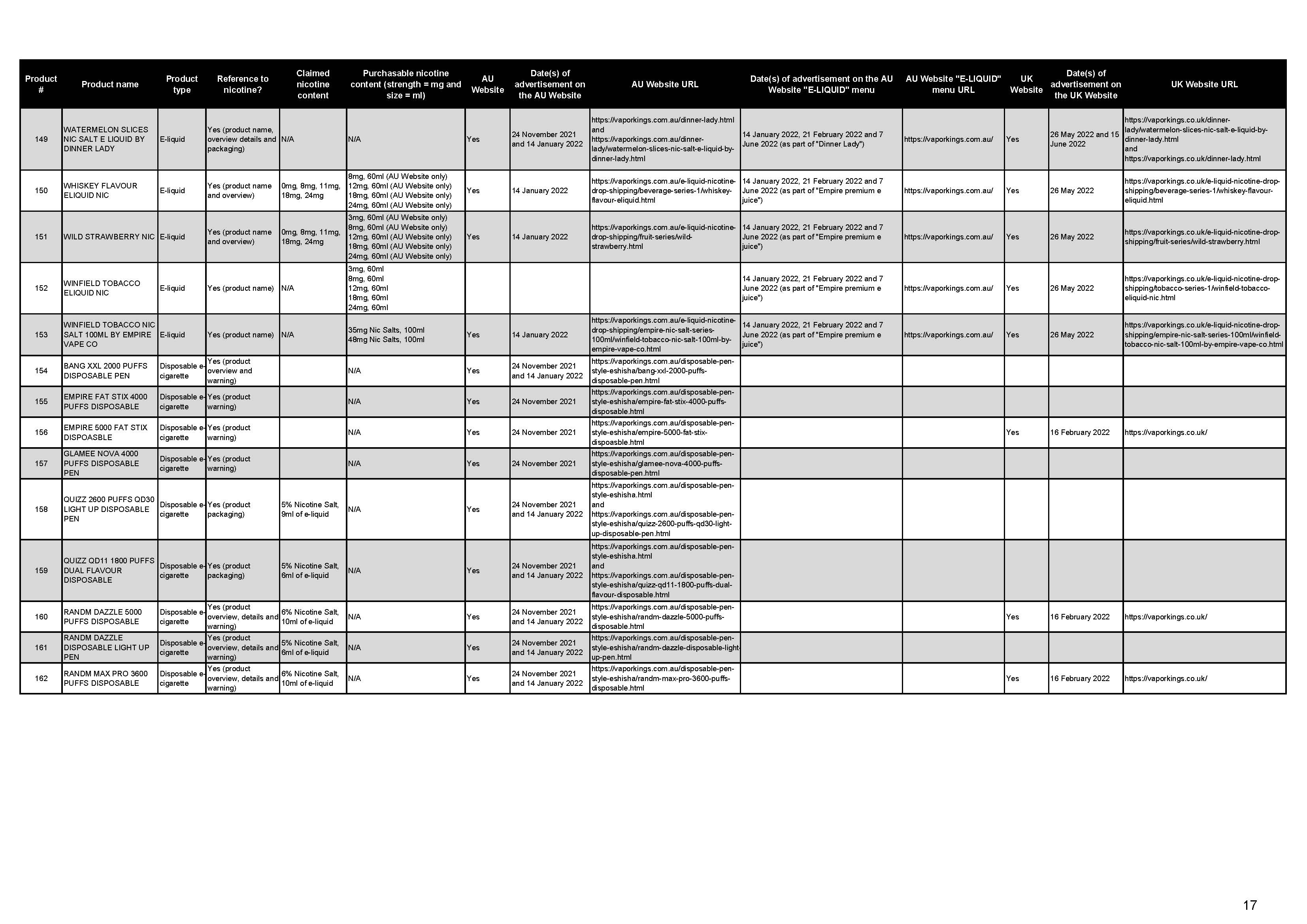

2 This hearing proceeded by way of a Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions (SAFA) agreed between the Secretary of the Department of Health and Aged Care (the Secretary, the applicant) and the respondents, reproduced at Annexure A. As referred to at [3] of the SAFA, a list of the NVPs advertised by the respondents on certain websites (Products) by reference to the dates of advertising was provided and is reproduced in these reasons at Annexure B. The parties filed joint written submissions, attached to which are screenshots providing examples of the contraventions, reproduced at Annexure C. The summary that follows is taken from those agreed documents.

3 The respondents admit that, at all relevant times, they operated and controlled the website located at the Universal Resource Locator (URL): https://vaporkings.com.au/ (AU Website), and the website located at the URL: https://vaporkings.co.uk/ (UK Website) (collectively, the Websites). It is agreed that advertising the Products on the Websites falls within the definition of “advertise” in s 3(1) of the TG Act.

4 The parties agree that the Products which the respondents advertised or caused to be advertised on the Websites fell into one of the following two categories: (1) liquid solutions commonly referred to as “e-liquids”; and (2) disposable “e-cigarettes” (also known as “electronic cigarettes”) containing e-liquid. E-liquids are used in conjunction with e-cigarettes, which apply heat to vaporise e-liquid solutions, enabling them to be inhaled through e-cigarettes by users. Examples of three Products are shown in the screenshots at Annexure C. The parties agree that the Products are “therapeutic goods” within the meaning of s 3(1) of the TG Act because they were represented to be, or were otherwise likely to be taken to be for “therapeutic use” (as defined in s 3(1) of the TG Act) in or in connection with ceasing, or substituting for, the consumption of and/or reliance upon tobacco products and/or influencing, inhibiting and/or modifying physiological processes by the administration of nicotine, a substance with addictive, stimulatory and/or relaxant properties.

5 Part 5-1 of the TG Act contains provisions regulating the advertising of therapeutic goods. Relevant to this case is s 42DLB.

6 It is agreed that the Products were not at any relevant time entered in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods maintained by the applicant pursuant to s 9A(1) of the TG Act (Register), and were not the subject of an exemption, approval or authority under the TG Act or the Therapeutic Goods Regulations 1990 (Cth) (TG Regulations). The Products were therefore prescribed by reg 7(i) of the TG Regulations for the purposes of s 42DLB(9) of the TG Act, and the parties agree that the advertising of the Products contravened s 42DLB(1) of the TG Act, where s 42DLB(9) applied.

7 Additionally, the advertisements for the Products referred to nicotine and/or Products containing nicotine. Those references were not authorised or required by a government or government authority. Nicotine was at all relevant times a substance included in Schedule 4 to the Poisons Standard within the meaning of s 52A of the TG Act (Poisons Standard), being a prescription-only substance, but not in Appendix H of the Poisons Standard. The parties therefore agree that advertising the Products contravened s 42DLB(1) of the TG Act, where s 42DLB(7) applied.

8 The parties have agreed to proposed orders, which include a pecuniary penalty pursuant to s 42Y of the TG Act against Vapor Kings in the amount of $4,900,000, and against Mr Kandakji in the amount of $100,000 (with 65% of that $100,000 suspended on the condition that he commits no breaches of the injunction; or offence; or further civil penalty offence against any provision of the TG Act for a period of 10 years). In addition, the parties agree to declarations that the respondents contravened the TG Act by advertising or causing the advertising of NVPs on the Websites; that the second respondent aided, abetted, counselled or procured the first respondent’s contraventions of the TG Act and was therefore involved in those contraventions; and that the second respondent contravened the TG Act by failing to take all reasonable steps to prevent the first respondent’s contraventions in circumstances where he knew that the contraventions would occur and was in a position to influence the conduct of the first respondent. The parties also agree to injunctions that the respondents be restrained for a period of 10 years from advertising or causing to be advertised therapeutic goods contrary to the TG Act; and to an order that the respondents pay costs of the proceedings to the applicant in the fixed sum of $100,000 and $10,000, respectively.

9 For the reasons below, I make the orders sought.

Legal principles

10 The principles applied in imposing civil penalties are well established and I have recently summarised them in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Insurance Australia Limited, in the matter of Insurance Australia Limited [2023] FCA 724 and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Meta Platforms Inc [2023] FCA 842. I rely on those summaries in large part below, supplemented and tailored to the contraventions of the TG Act.

11 For recent application of those principles to contraventions of the TG Act, I refer to Secretary, Department of Health v Oxymed Australia Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 1518; (2021) 397 ALR 241 (Oxymed) at [127]-[134]; Secretary, Department of Health v Evolution Supplements Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCA 872 (Evolution Supplements (No 2)) at [52]-[69] and Secretary, Department of Health v Peptide Clinics Australia Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 1107; (2019) 137 ASCR 494 (Peptide Clinics) at [28]-[34].

12 It is appropriate to observe at the outset that the objects of the TG Act include providing for “the establishment and maintenance of a national system of controls relating to the quality, safety, efficacy and timely availability of therapeutic goods that are used in Australia” and providing “a framework for the States and Territories to adopt a uniform approach to control the availability and accessibility, and ensure the safe handling, of poisons in Australia”: s 4 of the TG Act; Peptide Clinics at [28].

Pecuniary penalty

13 Section 42Y of the TG Act empowers the Court to order the payment of a pecuniary penalty to the Commonwealth in respect of a contravention of a “civil penalty provision”.

14 The purpose of a civil penalty is primarily protective, in promoting the public interest in compliance by deterring further contravening conduct: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; (2022) 274 CLR 450 (Pattinson) at [15]-[16], [43] and [45]. A penalty of appropriate deterrent effect “must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not such as to be regarded by [the] offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business”: Pattinson at [17] citing Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; (2012) 287 ALR 249 at [62].

15 Section 42Y(3) requires the Court, in determining a pecuniary penalty, to have regard to “all relevant factors” including: the nature and extent of the contravention; the nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the contravention; the circumstances in which the contravention took place; and whether the person has previously been found by the Court in proceedings under the TG Act to have engaged in any similar conduct.

16 In addition, there are a number of factors identified in the authorities, relevant to this task. For example, the assessment of a penalty of appropriate deterrent value will have regard to: (1) the nature and extent of the contravening conduct; (2) the amount of loss or damage caused; (3) the circumstances in which the conduct took place; (4) the size of the contravening company; (5) the degree of power it has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market; (6) the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended; (7) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level; (8) whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance, as evidenced by educational programs or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention; and (9) whether the company has shown a disposition to co-operate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to contravention: Pattinson at [18]. These are not to be considered as a rigid list of factors to be ticked off: Pattinson at [19]. Rather, they are to inform a multifactorial investigation that leads to a result arrived at by a process of “instinctive synthesis” addressing the relevant considerations: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; (2016) 340 ALR 25 (Reckitt Benckiser) at [44].

17 The maximum penalty is also one of the relevant factors. The maximum penalty for a contravention of s 42DLB by a body corporate (Vapor Kings) is 50,000 penalty units, and by an individual (Mr Kandakji) is 5,000 penalty units. At the times relevant to the contraventions admitted by the respondents, a penalty unit was $222.00: s 4AA of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) (for contraventions between 1 July 2020 and 31 December 2022).

18 In respect to the maximum penalty, the majority in Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; (2005) 228 CLR 357 observed at [31]:

…careful attention to maximum penalties will almost always be required, first because the legislature has legislated for them; secondly, because they invite comparison between the worst possible case and the case before the court at the time; and thirdly, because in that regard they do provide, taken and balanced with all of the other relevant factors, a yardstick.

19 In a civil penalty context, the relevance of a prescribed maximum penalty as a yardstick was explained by the Full Court of the Federal Court in Reckitt Benckiser at [155]-[156], a passage recently cited with approval in Pattinson at [53].

20 Each day on which an advertisement for one of the Products remained on the Websites amounts to a separate contravention of the TG Act: Peptide Clinics at [12] and [43].

21 Ordinarily, separate contraventions arising from separate acts should attract separate penalties. However, where separate acts give rise to separate contraventions which are inextricably interrelated, they may be regarded as a “course of conduct” for penalty purposes: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; (2018) 262 FCR 243 (Yazaki) at [234]. This avoids double punishment for those parts of the legally distinct contraventions that involve overlap in wrongdoing: see for example, Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; (2010) 269 ALR 1 at [39] and [41]. However, “[i]t is not appropriate or permissible to treat multiple contraventions as just one contravention for the purposes of determining the maximum limit dictated by the relevant legislation”: Yazaki at [227]. “It cannot of itself operate as a de facto limit on the penalty to be imposed for contraventions”: Reckitt Benckiser at [141] quoting Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Hillside (Australia New Media) Pty Ltd (t/as Bet365) (No 2) [2016] FCA 698 at [24]-[25].

22 The principle of totality requires the Court to make a “final check” of the penalties to be imposed on a wrongdoer, considered as a whole, to ensure that the total penalty does not exceed what is proper for the entire contravening conduct: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd [1997] FCA 450; (1997) 145 ALR 36 at 53, citing Mill v The Queen [1988] HCA 70; (1988) 166 CLR 59.

23 An appropriate penalty is therefore one that is fashioned by reference to the facts of the particular case before the Court, in order to arrive at a penalty that is sufficient to deter the conduct in question, without being overly oppressive: Pattinson at [46].

24 The principles to be applied in considering a jointly proposed penalty were addressed in Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; (2015) 258 CLR 482 (DFWBII), where the majority observed at [46]:

[T]here is an important public policy involved in promoting predictability of outcome in civil penalty proceedings and that the practice of receiving and, if appropriate, accepting agreed penalty submissions increases the predictability of outcome for regulators and wrongdoers. As was recognised in Allied Mills and authoritatively determined in NW Frozen Foods, such predictability of outcome encourages corporations to acknowledge contraventions, which, in turn, assists in avoiding lengthy and complex litigation and thus tends to free the courts to deal with other matters and to free investigating officers to turn to other areas of investigation that await their attention.

25 Further, their Honours said at [58] (emphasis added):

... Subject to the court being sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the penalty which the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances thus revealed, it is consistent with principle and ... highly desirable in practice for the court to accept the parties’ proposal and therefore impose the proposed penalty.

26 Those observations about the desirability of acting upon agreed penalty submissions were made in the context of a broader recognition that as a civil litigant in civil proceedings, civil penalties are but one of numerous forms of relief which regulators can pursue, and it is entirely orthodox for regulators to make submissions as to that relief: see DFWBII at [24], [57]-[59], [63], [103], [107]. Those principles were more recently considered in Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2021] FCAFC 49; (2021) 284 FCR 24 (Volkswagen) at [124]-[131], referring to DFWBII, NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [1996] FCA 1134; (1996) 71 FCR 285 and Minister for Industry, Tourism and Resources v Mobil Oil Australia Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 72; (2004) ATPR 41-993. A number of points were highlighted in Volkswagen, including: first, the Court must be satisfied that the penalty proposed by the parties is appropriate: at [125]; second, if persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and that the proposed penalty is an appropriate remedy, it is highly desirable for the Court to accept the proposal: at [126]; third, in considering whether the proposed penalty is appropriate, it is necessary to bear in mind that there is no single appropriate penalty, but rather a permissible range, and that the proposed penalty may be “an” appropriate penalty if it falls within that range: at [127]; fourth, the Court should generally recognise that the proposed penalty was most likely a result of compromise and pragmatism on the part of the regulator, and while the regulator must estimate the penalty necessary to achieve deterrence, the Court must assess the proposed penalty on its merits, being wary of the possibility that the regulator may have been too pragmatic: at [129]; fifth, the Court’s task is not limited to simply determining whether the jointly proposed penalty is within the permissible range, though that might be expected to be a highly relevant and perhaps determinative consideration: at [131].

27 The overriding statutory directive is for the Court to impose a penalty that is determined to be appropriate having regard to all relevant matters: Volkswagen at [131].

Declaration

28 The power to grant declaratory relief pursuant to s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) “is a very wide one” and the court is “limited only by its discretion”: Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd [2009] FCAFC 166; (2009) 182 FCR 160 at [1016], citing Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd [1972] HCA 61; (1972) 127 CLR 421 (Forster) at 435. Three requirements need to be satisfied before making declarations: (1) the question must be a real and not a hypothetical or theoretical one; (2) the applicant must have a real interest in raising it; and (3) there must be a proper contradictor: Forster at 437-438. That a party has chosen not to oppose a grant of particular declaratory relief is not an impediment to such relief being granted by the Court: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd [2012] FCAFC 56; (2012) 201 FCR 378 at [14], [30]-[33]. Other factors relevant to the exercise of the discretion include: whether the declaration will have any utility; whether the proceeding involves a matter of public interest; and whether the circumstances call for the marking of the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct: ASIC v Pegasus Leveraged Options Group Pty Ltd [2002] NSWSC 310; (2002) 41 ACSR 561 at 571; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Monarch FX Group Pty Ltd, in the matter of Monarch FX Group Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1387; (2014) 103 ACSR 453 at [63]; Australian Securities & Investments Commission v Stone Assets Management Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 630; (2012) 205 FCR 120 at [42].

29 Even where there is agreement between the parties in respect of proposed declarations, it remains for the Court to decide whether declaratory relief is appropriate: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v MLC Nominees Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1306; (2020) 147 ACSR 266 at [109].

Injunctions

30 Section 42YN of the TG Act empowers the Court to grant an injunction restraining a person from engaging or proposing to engage in conduct that is a contravention of the TG Act.

31 Relevant factors in the discretion include matters such as: whether the TG Act needs to be supplemented by the availability of sanctions applicable to contempt of court; the contraventions found; the risk of similar contraventions in the future and the utility of an injunction in minimising that risk; whether the conduct was intended, isolated and/or occurred many years before the enforcement proceedings; the clarity and specificity of the injunction; and the intended methods of enforcement of the injunction: see for example Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (No 2) [2012] FCA 629; [2012] ATPR 42-402 at [17]-[18].

Consideration

32 Given the agreement between the parties it is unnecessary to recite the submissions in detail.

33 That said, I make the following observations, taken in large part from the submissions.

34 First, the nature of the harm from the contraventions and the intent behind the prohibition on advertising NVPs is explained in the SAFA at [25]-[31]. The risks from the use of nicotine, as described in those paragraphs, is readily apparent. As a result, on 1 October 2021, the entry for nicotine in Schedule 4 to the Poisons Standard was amended such that it now captures all NVPs as prescription-only substances that may only be supplied by or on the order of persons authorised to prescribe medicines under State or Territory legislation. The advertising of NVPs is prohibited by the TG Act. This prohibition is intended to ensure that patients decide whether to use prescription-only medicines, such as NVPs, based on information from trusted sources such as their medical practitioner, rather than from commercial advertising. This reflects the importance of deterrence in the assessment of any relief to be imposed. The purpose of the prohibition informs the considerations relevant to the assessment of pecuniary penalties, and the declarations and injunctions sought in this case.

35 Second, the contraventions are serious; they involve numerous breaches of s 42DLB of the TG Act, which regulates the advertising of “therapeutic goods” and was introduced to promote the protection of public health. The respondents advertised or caused to be advertised goods being NVPs on two websites. Vapor Kings admits it operated the AU Website. Mr Kandakji admits that he operated and controlled the AU Website and the UK Website. In relation to the AU Website, the conduct took place between 24 November 2021 and 16 February 2022, being approximately 84 days. In relation to the UK Website, the conduct took place between 16 February 2022 and 15 June 2022, being approximately 119 days (accepting that, at some points, between 3 and 15 June 2022, the UK Website was inaccessible). It involved the advertising of 162 Products. Screenshots of the Websites are reproduced at Annexure C. The contravening conduct occurred on each day the advertising for a Product appeared on the Websites: see for example, Annexure B.

36 Third, as reflected in the SAFA, the advertisements for the Products on the AU Website were directed to Australian consumers and represented such Products as being available for purchase on a delivered basis to addresses within all States and Territories of Australia. At times, from at least 16 February 2022 to 15 June 2022, the respondents removed some advertisements for Products from the AU Website and redirected consumers to advertisements for Products on the UK Website when selecting “E-liquid” on the AU Website. The advertisements for the Products on the UK Website were directed to Australian consumers and represented such Products as being available for purchase on a delivered basis to addresses within all States and Territories of Australia.

37 Fourth, the conduct by the respondents, which involves numerous breaches of s 42DLB of the TG Act, can be properly considered as a course of conduct for the purposes of imposing penalty, as described above at [21]: and see for example Peptide Clinics at [44]; Evolution Supplements (No 2) at [63]-[64]; Oxymed at [178]-[179].

38 Fifth, although no specific harm is relied on, it is accepted that there is the significant risk of harm arising from the use of NVPs as reflected in the SAFA at [25]-[31]. It is appropriate to recite that passage in full:

[25] The risks associated with NVP vary depending on the composition of the relevant nicotine e-liquid solution. As the Products were advertised and supplied outside the TG Act framework, they were not subject to the appropriate regulatory controls required to ensure that they did not contain ingredients that presented an elevated risk to consumers and were otherwise suitable for prescription-based use for the purpose of smoking cessation.

[26] Even NVP that do not contain ingredients that are specifically known to be harmful are associated with serious risks that should be managed by a patient in consultation with their medical practitioner. Those risks include poisoning, toxicity from inhalation (including seizures) and lung injury. The long-term health risks of NVP are still unclear and evidence of their potential efficacy for smoking cessation is currently mixed.

[27] In some cases, users of NVP subsequently begin using tobacco products, such as tobacco (combustible) cigarettes, in circumstances where they have not been previously using tobacco cigarettes. Where this occurs, the user will be exposed to the serious adverse health effects that can be caused by such products, including cancer, cardiovascular disease and respiratory conditions. Tobacco use is a significant public health problem in Australia, and the promotion of NVP to persons not requiring those goods for smoking cessation may therefore increase the overall public health burden created by tobacco use.

[28] Nicotine is highly addictive, and therefore presents a risk of abuse for recreational purposes. Recreational users of NVP are likely to become addicted to nicotine. Persons addicted to nicotine have considerable difficulty ceasing the use of nicotine products if they attempt to do so and are exposed to the health risks referred to above.

[29] Due to these risks, the nicotine in NVP is included in Schedule 4 to the current Poisons Standard as a prescription-only substance and is not included in Appendix H to the current Poisons Standard as a substance that is permitted to be advertised. As a result, the advertising of NVP is prohibited by the TG Act. This prohibition is intended to ensure that patients decide whether to use prescription-only medicines such as NVP based on information from trusted sources such as their medical practitioner, rather than from commercial advertising.

[30] The prohibition on the advertising of products that are not entered in the Register and not otherwise subject to an exemption, approval or authority is intended to prevent the promotion of goods posing these kinds of risks to patients or consumers, and thereby reduce unsafe consumer use of such goods.

[31] The Websites advertised the Products to the public at large. While viewers were asked to self-certify that they were over 18 years of age, there were no meaningful measures in place to prevent the purchase and abuse of the NVP advertised and apparently sold through the Websites for recreational purposes, including by children. The nature of the Products advertised on the Websites, and in particular their high concentration of nicotine, brightly coloured presentation and range of flavours, had the potential to encourage purchase and/or abuse for recreational purposes, including by children and young people.

39 The sentiment in [31] of the SAFA as to the presentation of the advertisements is amply illustrated in the screenshots from the Websites reproduced in Annexure C.

40 Sixth, it is accepted that the respondents cooperated with the Secretary in resolving the proceedings. The proceedings resolved after mediation, before the matter was set down for hearing and prior to evidence being filed. There was utilitarian benefit to the administration of justice from the respondents’ cooperation: Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v Fair Work Ombudsman (Boggo Road Cross River Rail Case) [2023] FCA 507 at [52]-[54]; and see Fair Work Ombudsman v 85 Degrees Coffee Australia Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 1317 at [52]. It is also accepted that the admissions, consent to relief and cooperation with the Secretary manifest a subjective willingness on the part of the respondents to facilitate the course of justice.

41 Seventh, the Secretary accepts that Vapor Kings is no longer trading. Mr Kandakji was for a time unemployed. Those circumstances, including the Mr Kandakji’s financial position, are set out in an affidavit affirmed by him on 21 June 2023, read in these proceedings. In his affidavit affirmed 6 October 2023 also read in these proceedings, Mr Kandakji explains that Vapor Kings no longer operates, that he no longer operates any business concerning vaping products (including NVPs) and that he does not intend to do so in the future. Mr Kandakji explains the circumstances in which the contraventions occurred, accepts responsibility for them and expresses contrition. The evidence from Mr Kandakji was not challenged. I accept that evidence. This impacts on the question of the extent of the need for the penalty and reflects the consideration of specific deterrence. I note also that neither respondent has been found previously to have engaged in any similar conduct.

Conclusion

42 Having considered the facts as agreed, the joint submissions of the parties, the evidence relied on, the contraventions and relevant principles, I am satisfied that it is appropriate to order pecuniary penalties in the amounts agreed and to make the declarations and injunctions sought.

43 In reaching that conclusion, I am conscious of the approach outlined in Volkswagen, described at [26] above, including that the Court must assess the proposed penalty on its merits, being wary of the possibility that the regulator may have been too pragmatic: Volkswagen at [129].

44 It is readily apparent from the joint submissions of the Secretary and the respondents that they have given close and careful consideration to the relevant issues, appropriate declarations, injunctions, and pecuniary penalties. I note in this context that the Secretary is a specialist regulator. In DFWBII, the High Court noted (at [60]-[61]) the relevance of the fact that submissions were being advanced by a specialist regulator able to offer “informed submissions as to the effects of contravention on the industry and the level of penalty necessary to achieve compliance”, albeit that the merits of such submissions will be considered in the ordinary way. As expressed above, where the Court is persuaded that the agreed penalty proposed is an appropriate remedy in all the circumstances, as in this case, it is highly desirable in practice for the Court to accept the parties’ proposal and therefore impose the proposed penalty: Volkswagen at [126].

45 The principal object of deterrence is achieved if the pecuniary penalty has the necessary “sting or burden” to achieve “the specific and general deterrent effects that are the raison d’être of its imposition”: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2018] HCA 3; (2018) 262 CLR 157 (CFMEU) at [116]. The parties accepted that, having regard to the circumstances of the respondents, the agreed and jointly proposed penalties are not merely an “acceptable cost of doing business”: Chief Executive Officer of the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre v Crown Melbourne Limited [2023] FCA 782 at [95], citing Pattinson at [17] and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [66]. I am satisfied that is so. In the circumstances, the pecuniary penalties satisfy the significant element of deterrence required in this proceeding. They each carry with it a sufficient sting to ensure that the penalty amount is not such as to be regarded by the parties or others as simply an acceptable cost of doing business. Weighing all the relevant factors, bearing in mind the protective and deterrent purpose of a pecuniary penalty, as applied to the facts of this case, I am satisfied that the agreed penalty in respect to each respondent is appropriate.

46 I accept that the Court has the power to suspend a pecuniary penalty imposed, or any part thereof: CFMEU at [114], [118], and see [44]; see also Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (The Quest Apartments Case) (No 2) [2018] FCA 163; (2018) 358 ALR 725 at [66]. I also accept, given Mr Kandakji’s evidence including as to his financial position, acceptance of responsibility, contrition and co-operation, and that he no longer operates any business concerning vaping products and does not intend to do so in the future, that part of the penalty imposed on him be suspended, on the nominated conditions. Those conditions include compliance with the injunction, which is for a period of 10 years. The consequences of a breach of the conditions are significant.

47 These proceedings are a matter of public interest, and the circumstances of the contraventions call for marking of the Court’s disapproval of the conduct. Consequently, the declarations sought have significant utility. I am satisfied that it is in the interests of justice to make the declarations sought.

48 I am also satisfied that the injunctions are appropriate. They ensure that the respondents know what, as a matter of fact, is expected of them in the future.

49 The costs order, in the circumstances, ought also to be made.

50 Accordingly, I make the orders in the terms sought by the parties.

I certify that the preceding fifty (50) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Abraham. |

Associate:

ANNEXURE A

ANNEXURE B

ANNEXURE C