Federal Court of Australia

Elanor Funds Management Ltd v Alceon Group Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1291

ORDERS

ELANOR FUNDS MANAGEMENT LIMITED (ACN 125 903 031) Applicant | ||

AND: | ALCEON GROUP PTY LTD (ACN 122 365 986) First Respondent CPRAM INVESTMENTS PTY LTD (ACN 120 836 839) Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The proceeding is dismissed.

2. Any application for costs is to be made in writing, within 14 days of the publication of these reasons, limited to no more than five pages.

3. Any response to an application for costs is to be made in writing within 7 days thereafter, limited to no more than five pages.

4. Subject to any further order of the Court, the question of costs will be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MCELWAINE J:

[1] | |

[9] | |

[26] | |

[49] | |

[114] | |

[114] | |

[121] | |

[153] | |

[169] | |

Did the respondents engage in misleading conduct by non-disclosure? | [172] |

[182] | |

[183] | |

[220] | |

[239] | |

[247] | |

[273] | |

[274] | |

[315] | |

[351] | |

[359] |

1 This proceeding concerns the sale of a shopping centre where the purchaser contends that the vendor and its agent engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct prior to completion of the sale. It is a no transaction case: if the conduct had not been engaged in, the purchaser would not have contracted to buy the asset. The purchaser is Elanor Funds Management Ltd (applicant or Elanor). The vendor is Alceon Group Pty Ltd (Alceon) and its agent is CPRAM Investments Pty Ltd (CPRAM). At times in this judgment it is convenient to simply refer to Alceon and CPRAM as the respondents.

2 The Bluewater Square Shopping Centre (Centre) is situated at Redcliffe in Queensland, approximately 30 kilometres north of Brisbane. It is proximate to the coast. The Centre was constructed in 2008 as a neighbourhood shopping complex comprising 49 tenancies with a Woolworths Supermarket as the anchor tenant, two mini-major tenants, 28 specialty shops, five kiosks, three ATMs, eight upper level commercial tenants and two basement tenants with an aggregate gross lettable area of 10,000 m2. The site comprises 1.356 ha with an underground car park for 311 vehicles plus adjoining car parks offering an additional 339 spaces.

3 In May 2017, Alceon sought expressions of interest from persons to participate in a sale of the Centre closing on 30 May 2017. In that process it prepared and issued an Information Memorandum and provided it to Elanor on 2 May 2017 (Information Memorandum). On or about 30 May 2017, Elanor submitted an expression of interest to Alceon to purchase the Centre for $54.75 million. Alceon did not accept that expression of interest and, after the sale to an alternative purchaser failed to complete, invited Elanor to submit a further proposal.

4 On 18 August 2017, Alceon and Elanor entered into a Heads of Agreement in relation to a potential sale of the Centre. The Heads of Agreement was expressed so as not to create any binding legal relationship between the parties, save as to an exclusive dealing period and confidentiality. The purchase price was $55.25 million as a going concern. An exclusive dealing period of 20 business days was agreed, commencing on 21 August 2017 and concluding on 15 September 2017 during which period, Elanor would conduct due diligence. Amongst other things, the Heads of Agreement contained a number of special conditions including that the fully leased income and passing net operating income of the Centre as at 1 December 2017, was $4,266,720 and $3,907,170 respectively. Elanor conducted due diligence, including by reference to material made available by Alceon and CPRAM in an electronic data room. Elanor also engaged Mr Alexander Hamilton of the firm CBRE Pty Ltd (CBRE) to undertake due diligence on its behalf. On being satisfied as to the extent of due diligence undertaken, in early September 2017, the directors of Elanor executed a circulating resolution, the effect of which was to authorise officers of Elanor to enter into a Put and Call Option Agreement to purchase the property dated 15 September 2017 (Option Agreement). On or about 23 October 2017, Elanor exercised the call option in the Option Agreement and as a consequence Elanor and Alceon became contracting parties for the sale of the Centre pursuant to a Sale Contract dated 23 October 2017 (Sale Contract) for a price of $55,250,000, less certain adjustments at settlement.

5 The Sale Contract settled on 1 November 2017, when Elanor became the registered proprietor by transfer. In this proceeding, as finally resolved in closing submissions, Elanor contends that Alceon and CPRAM made various representations to it concerning incentives that had been provided to a number of Food Court Tenants (as defined at paragraph 27 below), the correctness of tenancy arrears reports for the Food Court Tenants and that the rent that Elanor should expect to receive from all of the tenants was in accordance with a rental return representation equivalent to the net operating passing income of $3,870,759 per annum. Elanor contends that these representations were misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive within the meaning of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law, which is schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL and Act). Elanor also contends that Alceon and CPRAM engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in failing to disclose the true position of rental arrears, actual incentives and deferrals of the lease commencement dates of certain of the Food Court Tenants.

6 Elanor pleaded a substantial claim for damages calculated by reference to the difference between the purchase price paid by it and the true value of the Centre at the time of purchase. In accordance with the valuation evidence that it relies upon, the true value of the Centre was $49 million and therefore the primary claim for damages is in the order of $6 million.

7 At trial, Mr A Fernon SC appeared with Ms E Keynes for Elanor, Mr M Henry SC appeared with Mr D Delaney for Alceon and Mr P McQuade KC appeared with Mr S Monks and Ms K Boomer for CPRAM. Despite the number of issues and large quantity of documentary evidence, the trial was conducted efficiently and sensible agreement was reached on a number of matters between counsel.

8 For the detailed reasons that follow, I have concluded that Elanor has failed to prove to the civil standard the misleading and deceptive conduct that it relies upon and that in any event if I am wrong in that conclusion, then Elanor has failed to establish that it relied upon that misleading or deceptive conduct and further, has failed to prove that it suffered damage because of that conduct and the claimed reliance. Accordingly, the proceeding must be dismissed.

Parties, documentary evidence and witnesses

9 I commence with the applicant.

10 Elanor is the responsible entity of the Elanor Investment Fund which is a registered managed investment scheme operated pursuant to a trust. Units in the trust form part of stapled securities that are listed on the Australian Stock Exchange. It is a corporation within the Elanor Investors Group which conducts an investment and funds management business.

11 Mr Blake McNaughton since July 2019 has been employed by Elanor as an executive director within the office of the chief executive officer. Mr McNaughton holds a Bachelor of Commerce with majors in information systems management and management. As at August 2017, he had in excess of five years’ experience in analysing potential investments and in determining investment yields in order to identify investment opportunities for Elanor.

12 Mr Michael Baliva is employed by Elanor as its co-head of real estate, a position he has held since 2014. Mr McNaughton reported to Mr Baliva as to the outcome of the assessments that he made concerning a prospective acquisition of the Centre by Elanor. Mr Baliva’s primary role was to report to Elanor’s board in relation to the proposed acquisition, and following the board resolution, his role was to negotiate the purchase terms, including the purchase price. He performed this work in conjunction with Mr McNaughton.

13 Mr Alexander (Sandy) Hamilton in August 2017 was employed as the regional director for investment advisory services by CBRE. He is experienced in performing due diligence investigations for investors buying or selling multi-tenanted properties, including regional and sub-regional shopping centres in Australia. In August 2017, he was engaged by Mr McNaughton to undertake a due diligence assessment in relation to the Centre for Elanor.

14 Ms Anna-Maree Coco has extensive experience in managing shopping centres in Queensland. Between May 2016 and November 2017, she was employed by Savills (QLD) Pty Ltd (Savills) as the on-site property manager at the Centre. Savills in turn was engaged by Alceon as manager of the Centre pursuant to an agreement dated 19 December 2015.

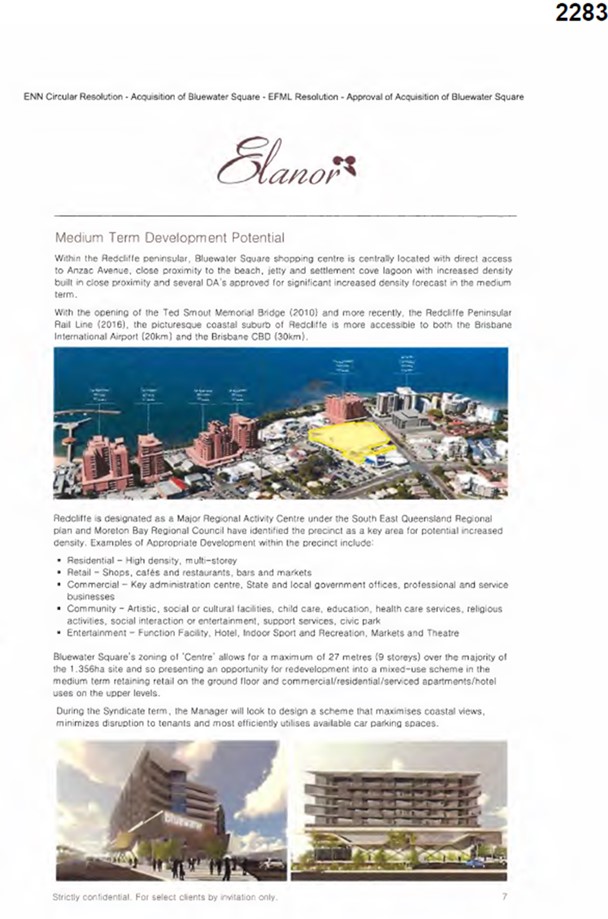

15 Mr Paul Kwan is a registered valuer and is the head of valuation and advisory at Knight Frank Valuation and Advisory, Queensland. He was first engaged by Mr McNaughton on 21 August 2017 to prepare a valuation of the Centre for mortgagee purposes. Pursuant to that engagement, and a letter of instruction from the Bank of Queensland, he produced a market valuation report dated 6 September 2017 pursuant to which he calculated the market value of the Centre at $55.25 million exclusive of GST assuming a capitalisation rate of 7%. He was again engaged by Mr McNaughton on 2 September 2021 to prepare a “retrospective indicative valuation” of the Centre on the assumption that nine of the food court tenancies were vacant at a total gross annual rental loss of $701,448. Pursuant to that engagement, Mr Kwan on 15 September 2021, provided some “draft calculations” which valued the Centre at $52.5 million assuming a capitalisation rate of 7% and which he later revised on 17 September 2021, following correspondence with Mr McNaughton, to $51 million assuming a capitalisation rate of 7.75%.

16 Later on 12 December 2022, Mr Kwan was engaged as an independent expert witness for Elanor by its solicitor and in that capacity authored his expert report dated 22 December 2022. In it he expresses the opinion that the market value of the Centre as at 1 November 2017 was $49 million exclusive of GST assuming a capitalisation rate of 7.25%.

17 Mr Matthew Gwynne is a chartered accountant who was engaged by Elanor’s solicitors to undertake a review of the respondents’ expert accounting report prepared by Mr Bradley Hellen, who in turn undertook a financial reconciliation of rental charges paid and received by each of the Food Court Tenants together with a reconciliation of incentives, abatements and security deposits. Mr Gwynne prepared an expert report dated 21 June 2023.

18 I deal next with the respondents’ witnesses.

19 Mr Frenil Shah is a director of CPRAM and holds degrees in management studies and financial management. Alceon engaged CPRAM pursuant to the terms of an investment management agreement dated 13 December 2012, pursuant to which CPRAM acted on behalf of Alceon as an asset manager in the day-to-day management and administration of the Centre. In 2017 he acted as the portfolio manager for CPRAM in relation to four shopping centres, including the Centre. Mr Shah’s responsibilities extended to supervising centre managers and liaising with external contractors and consultants. In particular, as portfolio manager he was responsible for the oversight of day-to-day management and administration of the Centre, financial analysis and reporting as well as direct liaison with the tenants. Specifically in relation to the Centre, Mr Shah supervised a leasing manager, Mr Carrigan, an analyst, Mr Song and a junior analyst, his brother, Mr Neil Shah. It was on his recommendation that Alceon engaged Savills as the property manager for the Centre.

20 Mr Oliver Sicouri is the founding director of CPRAM. He holds a law degree, is admitted as a solicitor and barrister and is also a licensed real estate agent.

21 Ms Fiona Hansen is a qualified chartered accountant and a senior managing director for the valuation practice FTI Consulting. She was jointly engaged by the solicitors for the respondents as an expert witness in relation to the undertaking of financial due diligence investigations. Pursuant to that engagement, she prepared an expert opinion report dated 28 April 2023.

22 Mr Bradley Hellen, as I have noted, was engaged by the respondents’ solicitors to undertake accounting reconciliations of rental charged to and paid by the Food Court Tenants between December 2016 and October 2017. In addition, his engagement extended to a reconciliation of security deposits and bank guarantees, tenancy arrears reports, the commencement date of relevant leases and a reconciliation of various incentives as provided to the Food Court Tenants. Mr Hellen prepared an expert witness report dated 3 May 2023.

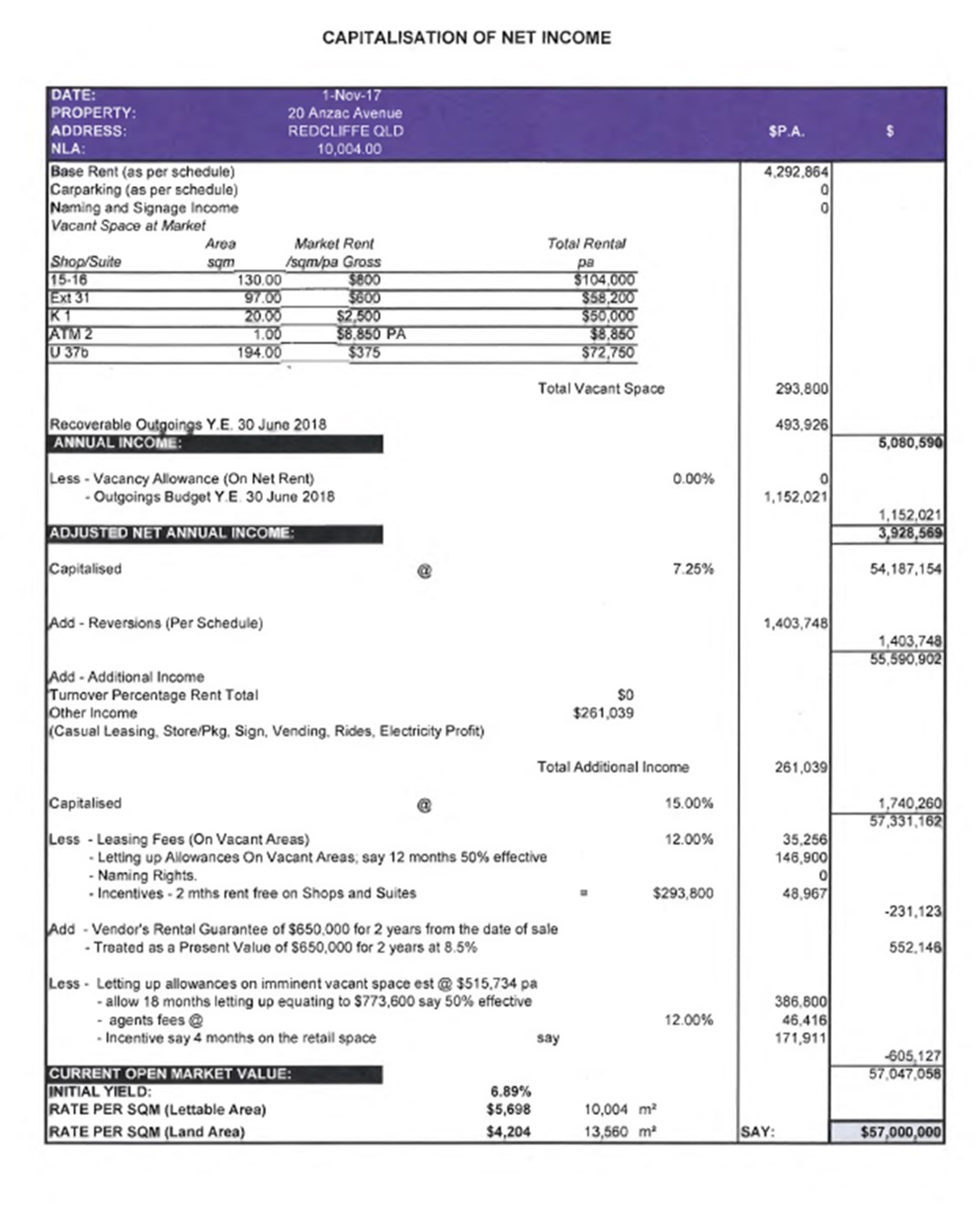

23 Mr Michael Goran is a qualified and registered valuer and a senior valuer of the firm Field & Kaye. He was jointly engaged, together with another valuer Mr Field, to prepare a market valuation of the Centre as at 1 November 2017. He is one of the authors of the report prepared in consequence dated 26 May 2023. Based on the assumptions contained in the report, Mr Goran and Mr Field concluded that the market value of the Centre was $57 million exclusive of an added development potential value of $1,700,000 assuming a capitalisation rate of 7.25%. Ultimately, only Mr Goran gave evidence before me.

24 The expert accountants and valuers, pursuant to case management orders, attended a conference before a Registrar of the Court for the purpose of conferring and producing joint expert reports as set out at Pt 7 of the Expert Evidence Practice Note (GPN-EXPT). Mr Hellen and Mr Gwynne produced a joint report dated 30 June 2023 and Mr Kwan and Mr Goran produced a joint report dated 28 June 2023. Save for separate cross-examination of Mr Kwan on issues relating to his independence, the accounting and valuation expert evidence was given concurrently.

25 In addition, the parties prepared an extensive court book of documents, initially comprising approximately 5,300 pages, which was then supplemented with hundreds of pages of further documentation during the course of the trial. Faced with such a large amount of documentation, I required each counsel to prepare a tender list, limited only to the documents relied on by each party. At the commencement of each oral closing submission, the tender list of each party was received as identifying and comprising only the documents relied upon, which I then received into evidence. In proceeding in this way, I made it clear to all counsel that I would not refer to any document in the court book, or the separate tender bundles, that is not referred to in the tender lists.

26 Elanor opened its case in accordance with the issues as framed in its Amended Statement of Claim dated 19 June 2023. By the conclusion of the trial, it abandoned a number of contentions there pleaded. As I explain in these reasons, how the applicant’s case evolved is important in resolving the issues. The claim essentially concerns nine Food Court Tenants at the Centre and whether they were in rental arrears, the commencement dates of the leases for those tenants, the expected passing base rent of the Centre and the extent to which individual Food Court Tenants had received incentives that were not disclosed in documents produced to Elanor during the due diligence period.

27 The Food Court Tenants in issue are:

(1) Dizzy Dukes, an American style bar and grill;

(2) Burrito Bar, a Mexican restaurant;

(3) Bel Cibo, an Italian restaurant;

(4) Mass Nutrition, a supplier of fitness supplements;

(5) Kebab Express, a fast food outlet;

(6) Sushi Kuni, a Japanese style fast food outlet;

(7) Mumbai Blues, referred to as Mumbai Blue in some documents, an Indian restaurant;

(8) Thai Me Down, a Thai restaurant; and

(9) Redcliffe Noodle Kitchen, an Asian noodle restaurant.

28 These were not the only food tenancies in the Centre at the time, but each was situated in the Centre’s casual dining precinct and were proximate to each other. Some of these tenancies had external access. The tenancy occupation percentages at the Centre were:

Component | Area (sqm)* | % of Total |

Woolworths | 3,941 | 39% |

Mini-Majors (2) | 1,646 | 16% |

Specialty Shops (28) | 2,831 | 29% |

Kiosks (5) | 107 | 1% |

ATMs (3) | 3 | 0% |

Basement Tenants (8) | 134 | 1% |

Office & Legal (8) | 1,342 | 13% |

Total (approximate) | 10,004 | 100% |

29 The Information Memorandum depicted the location of each Food Court Tenant within the Centre and expressly stated the Centre net operating income (fully leased) at $4,230,309 and the net operating income (passing) at $3,870,759 each per annum. Net passing income is a term of art amongst valuers. It is an annualised calculation based on the net rental that is received at a point in time. In this case the Information Memorandum expressly stated that the passing income “reflects the tenancy information forecast to 30 June 2017 and is based upon estimated expenditure as shown in the FY17 Budget. A detailed tenancy schedule is available in the online data room.”

30 Elanor contends that the data room contained copies of leases for each of the Food Court Tenants, Incentive deeds for seven of those tenants (excluding Bel Cibo and Sushi Kuni) and a document for each month between December 2016 and July 2017 in the form of a Tenant Arrears Report. As will become apparent from these reasons, many more documents were contained in the data room. However, a primary contention of Elanor (opened on its case), is that the Tenant Arrears Reports “did not identify any of the [Food Court Tenants] as being in arrears for any amount” and further that no other arrears report nor any other documents were provided which recorded tenancy arrears between December 2016 and July 2017, save for the report of July 2017 which recorded total arrears in that month of $2,957.05 for five tenancies that are not the subject of complaint by Elanor.

31 Elanor also relies on the content of a discussion between Mr Hamilton and two employees from his office, and Mr Shah on 30 August 2017 (the 30 August Meeting) during which, and in answer to questions put to him, it is said Mr Shah did not identify any of the Food Court Tenants as having outstanding arrears, or being in receipt of abatements or incentives beyond those disclosed in the relevant Incentive deeds or otherwise as having any adverse issues in relation to sales, the ability to pay rent or to satisfy other obligations under their leases. There is significant dispute as to the content of the discussion at that meeting.

32 Based on the disclosed information, Elanor pleads that the passing base rent per annum and the outstanding abatements as set out in the tenancy schedule and the outstanding incentive schedules was:

Tenant | Passing Base Rent $p.a. | Outstanding Incentives/Abatements - Outstanding Incentive Schedule | Outstanding Incentives/Abatements - October Incentive Schedule |

Dizzy Dukes | $119,191.00 | $24,957 comprising an abatement of $4,991.31 per month until 14 February 2018 | $17,470 comprising an abatement of $4,991.31 per month until 14 February 2018 |

Burrito Bar | $80,618.00 | ||

Bel Cibo | $71,939.70 | ||

Mass Nutrition | $46,385.64 | ||

Kebab Express | $40,000.00 | $2,500 comprising an abatement of $1,667.67 per month until 31 October 2017 | |

Sushi Kuni | $90,956.25 | ||

Mumbai Blues | $48,529.50 | $8,088 comprising an abatement of $2,022.06 per month until 14 January 2018 | $4,957 comprising an abatement of $2,022.06 per month until 14 January 2018 |

Thai Me Down | $54,600.00 | $6,825 comprising an abatement of $2,275 per month until 14 December 2017 | $3,302 comprising an abatement of $2,275 per month until 14 December 2017 |

Redcliffe Noodle Kitchen | $43,262.00 |

33 The Elanor pleading then moves to the central allegations of falsity that each of the Food Court Tenants between December 2016 and 1 November 2017 at various times were in arrears in paying the rent and in discharging other obligations under their leases and further, had received incentives and other benefits that were not disclosed in the leases and incentive deeds. The pleading in this respect is very detailed and is a matter that I focus on when finding the material facts.

34 The misleading conduct claim is pleaded by reference to a number of express and implied representations together with a misleading conduct case anchored by a failure to disclose relevant matters. The pleading is quite complex and detailed. Parts of it were abandoned by the time of closing submissions. With due deference to the pleading ability of Mr Fernon for Elanor, the claim as framed in opening the case may be reduced to the following contentions of express or implied misleading conduct. Representations that:

(1) The passing base rent per annum for each tenant listed in the tenancy schedule was correct (Passing Base Rent representation);

(2) The amount of rent actually payable to Alceon between May and 1 November 2017 was the rent specified in each lease less any adjustment under an incentive deed (Rent Representation);

(3) The outstanding incentive schedules were correct (Outstanding Incentive Schedule Representation);

(4) The Incentive deeds were a correct and complete record of all abatements and incentives (Incentive Representations);

(5) The Food Court Tenants with Incentive deeds had been invoiced for rent and other charges since the rent commencement date in each incentive deed and had paid those amounts (Commencement Date Representation);

(6) The Tenant Arrears Reports, including a further arrears report for October 2017, were correct and complete statements of all amounts not paid by each of the Food Court Tenants in the month corresponding to the report period and that all other invoiced amounts had been paid in full (Arrears Representations); and

(7) The rent that Elanor should expect to receive from tenants was in accordance with the passing Base Rent Representation and or the Rent Representation (Rental Return Representation).

35 Elanor’s case shifted at the point of closing submissions. It abandoned the claims of undisclosed rental arrears for Kebab Express, Thai Me Down and Mass Nutrition; abandoned the Commencement Date Representation claims in relation to Bel Cibo, Sushi Kuni and Mass Nutrition and abandoned the express representation misleading conduct claims relating to: (1) the Passing Base Rent Representation, (2) the Rent Representation, (3) the Outstanding Incentive Schedule Representation and (4) the Incentive Representations.

36 In consequence, that leaves for determination as issues on the pleading that the express or implied representations were misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in three respects being claims (5), (6) and (7). The pleading of these claims received significant attention in the respondents’ closing submissions and for that reason I set them out.

37 First, at [44] of the Further Amended Statement of Claim (FASOC):

(e) the Food Court Tenants subject to an incentive deed had been invoiced for rent and other charges since the rent commencement date listed in their respective incentive deed and had paid rent and other charges since the rent commencement date listed in their respective incentive deed (Commencement Date Representation);

Particulars

The Commencement Date Representation is partly express and partly implied.

(i) In so far as it is express, it arises from the content of the Leases in respect of the rent commencement dates and rent due subject to the incentive deeds and Tenants Arrears Reports.

(ii) In so far as it is implied, it arises from the circumstances in which such documents were provided in the absence of any other document or information to advise the commencement dates had not been deferred.

(iii) In so far as it was oral, it arises from the matters and conversations pleaded in paragraphs 25 and 26 above.

38 Second:

(f) The Tenant Arrears Reports and the October Arrears Report were correct and complete statements of all amounts which had not been paid by the Food Outlet tenants in the corresponding month for that report from all previously rendered invoices and that all amounts in invoices rendered in the months prior to the month of the respective report had otherwise been paid in full by the tenants of the respective Food Outlets (Arrears Representations);

Particulars

The Arrears Representations are partly express, partly implied and partly oral.

(i) In so far as they are express, they are contained in the Tenant Arrears reports and the October Arrears Report.

(ii) In so far as they are implied, they arises from the circumstances in which the Tenant Arrears Reports and the October Arrears Report were provided and absence of any other document or information of a similar nature for different periods or difference [sic] tenants being provided.

(iii) In so far as they are oral, they arise from the matters and conversations pleaded in 25 and 26 above.

39 Third:

(g) the rent that Elanor should expect to receive from tenants was in accordance with the Passing Base Rent Representation and/or the Rent Representation (Rental Return Representation);

Particulars

The Rental Return Representation is implied and arises from the content of the Passing Base Rent Representation and the Rent Representation together with the content of each of the representations referred to in 44 of this claim.

40 By the time of closing submissions, Elanor’s case as to why it is said that each of the remaining representations were incorrect, contained material omissions or understated the true quantum of arrears for the Food Court Tenants, reduced to three subparagraphs in the FASOC at [46]:

(e) The Commencement Date Representation was incorrect and contained material omissions in respect of the Food Court Tenants.

Particulars

(i) Dizzy Dukes’ rent commencement date was allegedly deferred from 14 May 2017 to 1 June 2017 and it did not pay rent and other charges due from July 2017 (see paragraph 42 (h) in relation to Dizzy Dukes).

(ii) Burrito Bar’s rent commencement date was allegedly deferred from 1 March 2017 to 14 May 2017 and it did not pay rent and other charges from the date of rent commencement set out in its incentive deed (see paragraph 42 (d) and (e) in relation to Burrito Bar).

(iii) Mass Nutrition’s rent commencement date was allegedly deferred from 1 April 2017 to 1 May 2017 and it did not pay rent and other charges from the date of rent commencement set out in its incentive deed (see paragraph 42 (d) and (e) in relation to Mass Nutrition.

(iv) Kebab Express’ rent commencement date was allegedly deferred from 30 April 2017 to 1 June 2017 and it did not pay rent and other charges from the date of rent commencement set out in its incentive deed (see paragraph 42 (d) and (e) in relation to Kebab Express).

(v) Mumbai Blues’ rent commencement date was alleged [sic] deferred from 14 April 2017 to 1 May 2017 and it did not pay rent and other charges from the date of rent commencement set out in its incentive deed (see paragraph 42 (d) and (e) in relation to Mumbai Blues).

(vi) Thai Me Down’s rent commencement date was allegedly deferred from 14 June 2017 to 1 July 2017 and it did not pay rent and other charges from the date of rent commencement set out in its incentive deed (see paragraph 42 (d) and (e) in relation to Thai Me Down).

(vii) Red Noodle Kitchen’s rent commencement date was allegedly deferred from 14 May 2017 to 25 June 2017 and it did not pay rent and other charges from the date of rent commencement set out in its incentive deed (see paragraph 42 (d) and (e) in relation to Red Noodle Kitchen).

(f) Further, or in the alternatively, the Arrears Representations were incorrect and understated in respect of the Food Outlets;

Particulars

(i) See paragraph 42.

The Food Court Tenants subject to incentive deeds were not paying rent until deferred dates which had the effect that the Tenants Arrears Reports did not provide evidence of those tenants paying rent by the date it was due and not being in arrears (see the particulars to paragraph 46 (e)).

(g) by reason of the matters pleaded in sub-paragraphs in (a) to (f) above, the Rental Return Representation was incorrect and overstated in respect of the Food Outlets.

Particulars

See paragraph 42.

41 Turning next to the misleading conduct by omission case, it has two remaining elements. First, Elanor contends that it had a reasonable expectation that the respondents would have disclosed any arrears of more than 30 days owed by any of the Food Court Tenants within the period December 2016 to October 2017 and that the failure to do so gave rise to a reasonable expectation by Elanor that none of the Food Court Tenants were in arrears for more than 30 days during that period. This aspect of the case is labelled in the pleading as the Conduct. Secondly, in relation to Dizzy Dukes, Burrito Bar, Mass Nutrition, Kebab Express, Mumbai Blues, Thai Me Down and Red Noodle Kitchen, Elanor had a reasonable expectation that if the rent commencement date was later than that set out in each incentive deed, the respondents would have disclosed to it that fact and that if there were rental arrears for August, September or October 2017 that fact would also have been disclosed. The failure to disclose these matters was, in the particular circumstances, misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive Elanor. This is labelled in the pleading as the Deferral Conduct.

42 In reliance on each and every one of the three remaining representations, the Conduct and the Deferral Conduct, Elanor contends that it entered into the Option Agreement, exercised the call option and entered into and ultimately performed the Sale Contract. In the event that Elanor had known that the impugned representations and or conduct was incorrect or “omitted material information” then Elanor would have paid less than the purchase price to acquire the Centre or, if that had not “been possible” it would not have entered into the Sale Contract and would not have purchased the Centre. By the time of closing submissions, however, Elanor did not press the alternative price (alternative transaction) case. Mr Fernon for Elanor assented to a proposition that I put to him that, on the evidence, if Elanor had known the true position that would have materially affected the purchase price calculation that Mr McNaughton undertook with the result that Alceon would not have accepted a price less than $55.25 million. Thus, this is a no transaction case: Hughes-Holland v BPE Solicitors [2018] AC 599; Wyzenbeek v Australasian Marine Imports Pty Ltd (in liq) [2019] FCAFC 167; 272 FCR 373 at [105]-[109] (Rares, Burley and Anastassiou JJ).

43 To establish that the representations, Conduct and Deferral Conduct were misleading or deceptive, Elanor pleads in detail what it contends was the true position, primarily by reference to business records made available to it after settlement of the sale and which are set out in detail in an affidavit of Mr McNaughton made on 9 December 2022. That portion of his affidavit was admitted into evidence not as proof of the facts there summarised, but as limited to his understanding of the records. The records are in evidence. What those records establish is the subject of detailed evidence from the accountants and submissions from counsel that I resolve later in these reasons.

44 Finally on the loss or damage question (s 236 of the ACL), Mr Fernon accepts that in order to succeed, Elanor must prove that the price paid for the Centre was more than its true value at the time of purchase and reliance is placed on the expert evidence of Mr Kwan. He also accepts that the principle in Potts v Miller (1940) 64 CLR 282 guides the approach to the assessment of damages, but of course is not to be regarded as the test pursuant to s 236. The correct approach is to award an amount for damages which best accords with the remedial purpose of the ACL: Murphy v Overton Investments Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 3; 216 CLR 388; Henville v Walker [2001] HCA 52; 206 CLR 459 (Henville). Elanor does not contend that it suffered detriment in a more general way: cf Harvard Nominees Pty Ltd v Tiller [2020] FCAFC 229; 282 FCR 530 at [72]-[76] (Lee, Anastassiou and Stewart JJ).

45 The respondents join issue in their pleadings on the material questions of misleading or deceptive conduct, reliance, damage and damages. They also rely on positive defences. Alceon draws attention to several of the express statements in the Information Memorandum including that no representation or warranty was made as to the accuracy of the net operating income (fully leased) or net operating income (passing) representations. Alceon accepts that there were construction delays in undertaking the project to remodel the casual dining precinct, which delays consequentially impacted on the ability to provide possession to six of the Food Court Tenants in accordance with the lease commencement dates. As a result, Alceon agreed to defer the rent commencement dates, corresponding with the respective periods of delay. On its case, this fact was known to Elanor during the due diligence period. In a detailed way, Alceon pleads to each of the rental arrears, lease commencement and incentive contentions of Elanor by way of positive assertion. In particular, and in answer to Elanor’s claim that the Tenancy Arrears Reports did not relevantly disclose any arrears for Food Court Tenants, Alceon pleads that the arrears reports “represented that the rental arrears of the tenants referred to in those reports were as stated in the reports as at the date upon which the reports were printed” and in consequence do not bear the objective construction of Elanor.

46 Alceon pleads in the alternative that if it engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct, then CPRAM is a concurrent wrongdoer within the meaning of ss 87CB and 87CD of the Act. Recognising the difficulty of how that could be so when CPRAM was Alceon’s agent, Mr Henry abandoned this defence by the time of his closing submission.

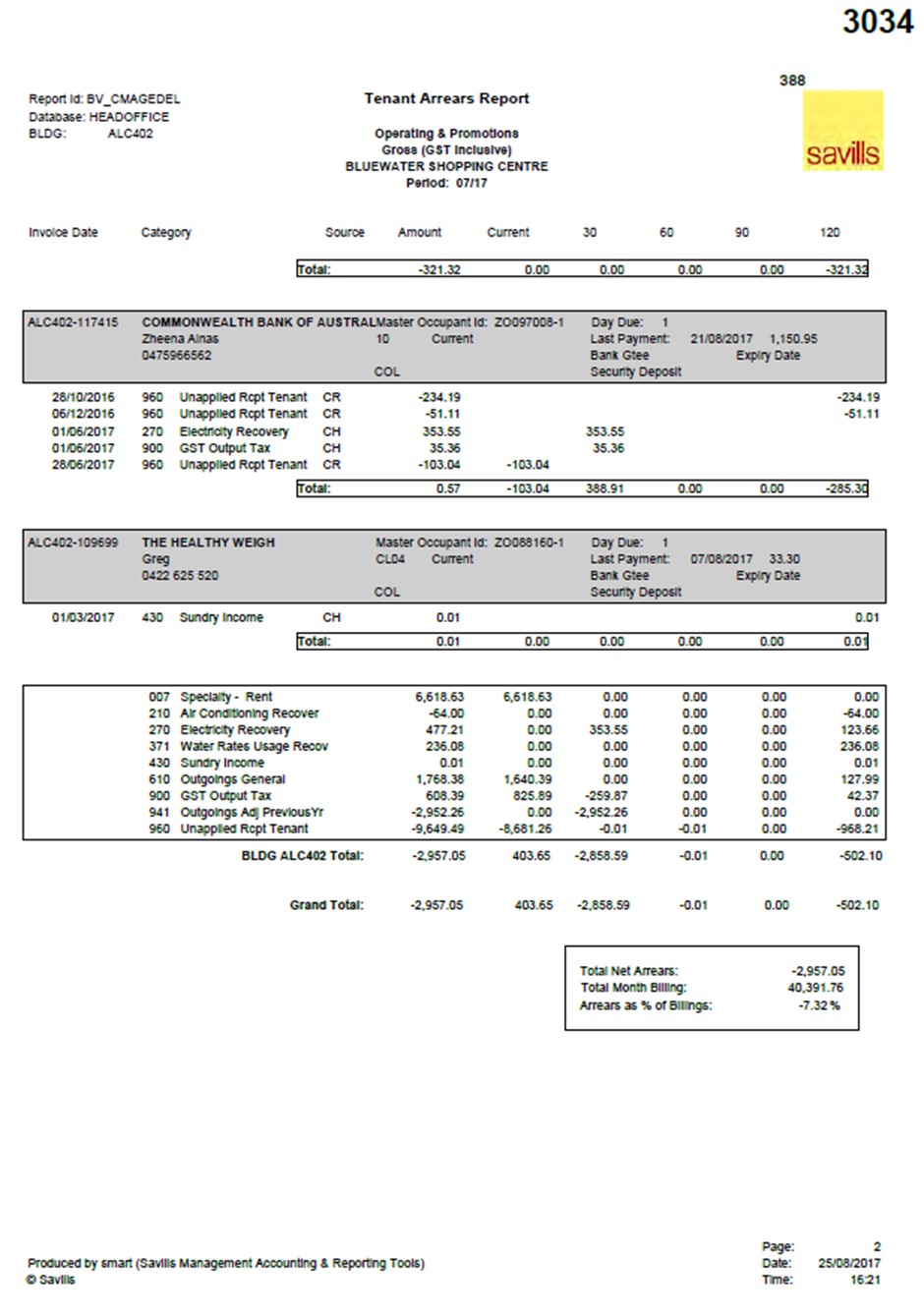

47 In material respects CPRAM’s defence corresponds with that of Alceon where issue is joined with the claims made by Elanor, although, and in considerably more detail, CPRAM responds to each of the contentions made by Elanor in relation to the arrears position, the lease commencement dates and the incentives provided to each of the Food Court Tenants. On the reliance question, CPRAM pleads that Elanor had access to the data room and the ability to undertake its own due diligence, did so by itself and by retaining Mr Hamilton as a consultant, was experienced in undertaking due diligence of commercial properties (in particular shopping centres) and places reliance upon the terms of the Sale Contract to the effect that the due diligence material may include estimates and projections which may not be correct and that Elanor had examined for itself and had satisfied itself of all relevant matters during the due diligence period. Further, CPRAM contends that a motivating factor for Elanor was the development potential of the Centre in the form of a mixed residential and commercial use. In that context, CPRAM contends that if the representations were made and the conduct engaged in was misleading or deceptive then they were immaterial in the context of the Centre’s overall value, including its anticipated value as a result of its development potential.

48 CPRAM relies on two proportionate liability defences. One, that Alceon is a concurrent wrongdoer by reason of the matters pleaded by Elanor against it and the other, that CBRE is a concurrent wrongdoer in that it failed to make sufficient inquiries during the due diligence in breach of its duty to exercise reasonable care pursuant to its engagement with Elanor. Finally, CPRAM pleads that if Elanor suffered loss and damage, then it contributed to that damage within the meaning of s 137B of the Act by failing to undertake and/or investigate matters which a reasonable person in the position of Elanor would have undertaken in the circumstances. In this regard, CPRAM places particular reliance upon the expert evidence of Ms Hansen.

49 The parties managed to agree a somewhat narrow and limited set of facts in the form of the Statement of Agreed Facts dated 6 July 2023. Regrettably a large number of facts which ultimately were not in issue between the parties were not referred to in that document, despite case management orders that I made and which required the legal representatives for the parties to attend before a registrar of the Court in order to agree uncontentious facts. However, by the time of the trial, and the involvement of counsel, the territory of factual dispute narrowed considerably. To the extent that the Statement of Agreed Facts remains of utility in resolving the issues, I record the following.

50 On 13 December 2012, Alceon and CPRAM entered into an investment management agreement. By it, establishment of the unregistered managed investment scheme known as the Bluewater Trust is recorded. CPRAM accepted appointment as one of the joint managers of the trust. Its duties included identification of intended trust acquisitions, management of trust assets (including asset level strategy), budgeting, forecasting, reporting and oversight of day-to-day asset management and administration of trust assets. It was also tasked with identification of opportunities for the disposal of trust assets.

51 Alceon was registered as proprietor of the Centre by transfer on 3 April 2013 for a consideration of $41,750,000. Alceon entered into a property management agreement with Savills on 19 November 2015. By it, Savills accepted an appointment to provide each of the services in respect of the Centre as set out at schedule 2 to the agreement. The scope of services included the general administration of each of the tenancies by collecting rent, holding security deposits, ensuring compliance with tenant obligations, maintaining a tenancy schedule, maintaining tenancy files and financial management. In particular, the financial management obligation extended to the preparation of a monthly statement of monies received and expenses incurred, the issue of monthly invoices to tenants for rental payable and other charges, the collection of rent and charges and review of rental arrears. Savills also accepted an obligation to provide monthly financial management reports for the Centre. Savills operated a reporting system known as the MRI Management System (MRI) in order to comply with its financial management and reporting obligations to Alceon. Importantly, Alceon and CPRAM did not have the ability to make changes within MRI, but CPRAM could generate reports from it.

52 For the nine Food Court Tenants, leases were entered into between May 2017 and 1 November 2017 as follows:

(a) a lease of shop T02-03 which, according to the lease terms, commenced on 1 April 2017. This lease was granted to TGS Kuber Pty Ltd trading as Dizzy Dukes Bar and Grill;

(b) a lease of shop T04 which, according to the lease terms, commenced on 1 March 2017 granted to Kailash Corporation Pty Ltd trading as Burrito Bar;

(c) a lease of shop T05 commencing on 1 May 2016 granted to Tushaan Enterprises Pty Limited trading as Bel Cibo;

(d) a lease of shop T07A which, according to the lease terms, commenced on 1 April 2017 granted to Mass Nutrition Chermside Pty Ltd;

(e) a lease of shop T07C which, according to the lease terms, commenced 1 April 2017 granted to Queensland Employment Services Pty Ltd trading as Kebab Express;

(f) a lease of shop T28A commencing on 15 February 2015 assigned to Gorani Pty Ltd trading as Sushi Kuni pursuant to an assignment of lease with effect from 30 April 2017;

(g) a lease of shop T29 which, according to the lease terms, commenced on 1 March 2017 granted to TGS Kuber Pty Ltd, trading as Mumbai Blues;

(h) a lease of shop T30 which, according to the lease terms, commenced on 1 May 2017 granted to Thai Me Down Pty Ltd;

(i) a lease of shop T32 which, according to the lease terms, commenced on 1 April 2017 granted to Ms Jie Liu trading as Redcliffe Noodle Kitchen.

53 In August 2017, Elanor engaged CBRE to undertake financial due diligence in relation to the Centre. Between 18 August 2017 and 15 September 2017, Alceon and CPRAM provided Elanor and its representatives, including CBRE, with access to the data room for that purpose. The data room was electronically maintained. Within it were contained copies of (amongst other things):

(a) leases for the Food Court Tenants;

(b) the Incentive deeds; and

(c) the Tenant Arrears Reports.

54 CBRE and Elanor were each able to make inquiries regarding the tenants and the financial position of the Centre through a question-and-answer facility in the data room. The Tenant Arrears Reports did not identify any of the Food Court Tenants as being in arrears for any amount. In addition to the material contained in the data room, on 27 October 2017, Minter Ellison lawyers on Alceon’s behalf provided to Elanor’s solicitor a Tenant Arrears Report for the month of October 2017 (October Arrears Report) and a document comprising an outstanding incentive schedule as at 31 October 2017. These documents did not disclose any arrears for the Food Court Tenants.

55 I now record my findings on material facts based on the evidence. In late 2016, CPRAM recommended to Alceon that the casual dining precinct of the Centre be upgraded to create a new restaurant precinct in the expectation of securing new food tenants. This project formed a portion of a broader strategy for the Centre, designed to attract a range of new tenants. The recommendation was accepted and work commenced in late 2016. Progress was delayed. The works did not complete until late June 2017. The evidence does not permit a more precise finding. Certainly, the works were complete by the date of commencement of the last deferred tenancy commencement, which was Thai Me Down on 1 July 2017.

56 Alceon appointed the real estate firms Stonebridge Property Group and CBRE to market the Centre for sale. By no later than 2 May 2017, the Information Memorandum had been prepared for that purpose. It invited expressions of interest by 30 May 2017. The Information Memorandum was sent to Mr McNaughton by email on 2 May 2017. Seven summary points were made in the email, including “significant future mixed-use potential”, a matter that was prominently emphasised in the content of the document. The Information Memorandum references the availability of leases and associated documents in the data room. Mr McNaughton was provided with access to the data room on 10 May 2017. He commenced inspecting documents in it on 11 May 2017. There is a data room log which records who accessed the data, when, for how long and what was viewed. Documents could be downloaded and printed, either individually or in bulk. Initially, the data room comprised folders of information, indexed as follows:

(1) Key Campaign Documents: including the Information Memorandum, trade area analysis reports and financial reports including a tenancy schedule;

(2) Title and Transaction Documents: including draft sale contract with schedules and statutory reports;

(3) Leases and Security: including copies of leases and lease variation documents, bank guarantees, security deposit register, disclosure statements and Incentive deeds;

(4) Income information: including the Tenancy Arrears Reports, information concerning other income, for example licenses and signage income, monthly rental invoices for the period January to May 2017 and a detailed income & expenditure budget for the Centre for the 2018 financial year;

(5) Outgoings information: including audited outgoings statements, budgets, rate notices, recovery letters for the 2017 and 2018 financial years and audited promotional fund statements;

(6) Plans and Surveys: including miscellaneous contractual documents, survey plans and as built construction drawings, architectural drawings and mechanical and electrical drawings;

(7) Building: including development approvals, certificates and a fitout guide;

(8) Turnover: including monthly turnover data for various tenancies between March to July 2017, with separate audited turnover statements for Woolworths for the 2014, 2015 and 2016 financial years;

(9) Insurance: including certificates of currency and claims history;

(10) Value Add Potential: including a mixed-use development assessment report prepared by Urbis, a development approval for commercial spaces, a development approval for the casual dining precinct and a set of mixed use development schemes prepared by the architectural firm Bureau Proberts; and

(11) Leases, Tenancy & Security: including further incentive deeds.

57 The data room log records that Mr McNaughton performed a bulk download of all of the documents in the data room on 18 May 2017 comprising 484 documents totalling 786.2 MB and another bulk download on 23 May 2017 comprising 486 documents totalling 786.3 MB. Mr McNaughton did not thereafter access the data room until 21 August 2017 when he undertook a further bulk download of 628 documents totalling 1 GB. Thereafter, on various days, he accessed the data room to view specific documents until 2 November 2017. Just what he viewed and for what purpose was the subject of considerable cross-examination which I return to when addressing the issues of misleading or deceptive conduct and reliance.

58 Elanor first submitted an expression of interest to purchase the Centre on 30 May 2017 for $54.75 million in the form of a letter signed by Mr Baliva. Expressly it assumed the annual fully leased and passing net operating income as $4,230,309 and $3,870,759 respectively “per the information provided” which is a reference to each of those figures in the Information Memorandum. It required Alceon to grant a rental income guarantee equivalent to 2 years’ gross market rent for any tenancy that was vacant as at the settlement date. It requested the grant of an exclusive dealing period of 20 business days during which Elanor would conduct due diligence to its satisfaction and negotiate in good faith to agree and execute a contract of sale. This expression of interest was stated to expire on 2 June 2017. Little evidence was given in chief as to how Elanor calculated this purchase price. Mr McNaughton mentions the submission of this expression of interest in his affidavit of 9 December 2022, but does not explain the process of calculation of the purchase price, in contrast with the particularity with which he deals with how he calculated the price in the second expression of interest that Elanor submitted.

59 In cross-examination Mr McNaughton accepted, and I find accordingly, that when the expression of interest was submitted on 30 May 2017 he knew that the Food Court Tenants in the casual dining precinct had not commenced to trade, that this area was “a work in progress” and that he made no inquiries as to whether any of the Food Court Tenants outside of the casual dining precinct had commenced to trade. He accepted that he knew at that time that Food Court Tenants in the casual dining precinct may or may not have commenced trading and may or may not fall into rental arrears. He accepted that he did not know whether any of the Food Court Tenants outside of the casual dining precinct were or were not in arrears at that time. It was then put to Mr McNaughton that, in submitting the first expression of interest, Elanor was prepared to pay $54.75 million and assume the risk that the Food Court Tenants may fall into rental arrears. Although Mr McNaughton did not accept that proposition for the reason that the offer was subject to due diligence, I find that it was the case that in calculating the price of $54.75 million, Elanor did so without interrogating the risk that one or more of the Food Court Tenants may subsequently fall into rental arrears. That finding logically flows from the sequence of events and that Mr McNaughton did not consider this question before 30 May 2017. Whether the arrears position would have been the subject of investigation, had the expression of interest been accepted, is another matter.

60 Sometime between 30 May and early August 2017, Alceon entered into a conditional contract with another prospective purchaser for a price of $57 million, which contract failed to complete, which facts are summarised in the valuation report of Mr Kwan dated 6 September 2017. Thereafter, Mr McNaughton and Mr Baliva met with Mr Gartland of Stonebridge at which time Elanor was invited to submit a further expression of interest to purchase the Centre. Either immediately following the meeting or shortly thereafter, Mr Baliva inspected the Centre with Mr Gartland, although his evidence did not describe what he observed.

61 Following his inspection of the property, Mr Baliva reviewed the Information Memorandum with Mr McNaughton. Mr McNaughton then undertook certain calculations in order to derive a purchase price for the Centre. At that time Mr McNaughton had more than five years’ experience in analysing potential investments and in determining an appropriate investment yield. He derived a yield of 7%, in part based upon yield information disclosed for comparable sales in a database that he had access to. There is a difference in those comparable sales between initial yield and core market yield. As explained by Mr McNaughton, initial yield is based on the passing rent and core market yield is based on the fully leased market rent. In those comparable sales the initial yield is within the range of 5.57% at the lower end and 8.97% at the upper end. On the assessment undertaken by Mr McNaughton, the majority of comparable sales revealed initial yields of 6.5% or less. Despite that comparable sales information, Mr McNaughton considered that the Centre should be purchased at a higher yield for a number of reasons: the reported sales for Woolworths were less than what might be expected, the Centre faced an increased risk of competition, the Woolworths lease was due to expire (subject to the exercise of any options) in 2028, the catchment area for the Centre was limited by its proximity to the coast and was relatively small in comparison with other centres and the purchase price that Alceon wanted (in excess of $50 million) was comparatively high with a corresponding increased risk of investment.

62 Having derived the yield figure, Mr McNaughton applied it to the net operating passing income. He used a figure of $3,907,170 which differs from the figure in the Information Memorandum of $3,870,759. Mr McNaughton could not recall why he used a different figure in his evidence-in-chief. What is now clear is that this is the same as the figure for total passing net operating income disclosed in a revised statement of financial figures for the Centre that was emailed to Mr McNaughton on 2 August 2017. As expressly recorded in that document the figure, indeed each of the figures contained therein, are based on a financial summary and projection as at 1 December 2017. In order to calculate the purchase price, Mr McNaughton divided $3,907,170 by 7 and then multiplied by 100 to calculate an amount of $55,816,714. From that figure he then subtracted $500,000 on account of his estimate of the expected future capital expenditure, based on 1% of the purchase price, as was his practice. Having deducted that sum, the price reduced to $55,316,714 which he then rounded down to $55.25 million.

63 Something more needs to be said about the revised financial figures that were provided on 2 August 2017. The covering email to Mr McNaughton attached an Excel spreadsheet with a series of tabs. One was labelled “Bluewater Square turnover figures” divided as between the various tenants which included information about whether a tenant had reported trading data and if so, the month of the first report. Some comments were also recorded in relation to relevant tenants.

64 The effect of that data is accurately summarised in a table contained in the closing submissions of Alceon:

Food court Tenant | Trading data reported? | Month commenced reporting trading | Comments? |

Sushi Kuni | Yes | July 2015 | N/A |

Bel Cibo | Yes | June 2016 | N/A |

Dizzy Dukes | Yes | June 2017 | Yes, “14 days of actual trading converted to full month” |

Burrito Bar | Yes | May 2017 | Yes, “Disruption in trade as Dizzy Dukes fitting out” |

Mumbai Blues | Yes | June 2017 | Yes, “12 days of actual trading converted to full month” |

Mass Nutrition | No | N/A | N/A |

Kebab Express | No | N/A | N/A |

Thai Me Down | No | N/A | N/A |

Redcliffe Noodle Kitchen | No | N/A | N/A |

65 Mr McNaughton recalled the spreadsheet when cross-examined as to its content but disputed it as a reliable record as to when those tenants commenced trading. On his evidence it is the tenancy schedule, being that tab on the Excel spreadsheet, which is the reliable source of that information. Similar turnover reports for March 2017 were available in the data room and were viewed by Mr McNaughton. Mr McNaughton gave similar evidence to that effect in answer to a number of questions put to him in cross-examination. On his evidence the turnover data is not a reliable indicator of the commencement of a tenancy because it depends upon the accuracy of the reporting of the tenant, which accuracy cannot be assumed in the case of small operators. He described these as “mum and dad operators” who sometimes prefer cash sales which are not subsequently disclosed.

66 Whilst that fact may impact on the quantum of the reported turnover, I do not find Mr McNaughton’s explanation to be satisfactory. The Food Court Tenant leases were in standard form. By cl 3.2 each tenant was obliged to “keep complete and accurate accounting records” of all transactions relating to the leased premises including data relevant to gross sales. Not later than seven days after the end of each calendar month, the tenant was obliged to give to Alceon a statement in reasonable detail of the gross sales for the previous month. By cl 3.3, Alceon had the right to inspect and have audited the tenant’s records. I find that the turnover data was a reliable indicator as to whether tenants had or had not commenced to trade because it was provided in satisfaction of a lease obligation. Logically the commencement of trading would be reflected in a monthly gross sales amount reported by each of the Food Court Tenants to Alceon. Correspondingly, the absence of a reported amount points strongly to the conclusion that a tenant had not commenced trading or at least should have invited further inquiry.

67 It is also of note that when Mr Baliva provided the revised financial figures to Mr McNaughton by email of 9 August 2017 he said: “Could you run this asset as a new syndicate at 50% LVR. Price indicated is $57.5m with 2-year income guarantee.” Mr McNaughton accepted in cross-examination that he understood that he was being requested to calculate a price of around $57.5 million in order to submit a competitive expression of interest.

68 I return to the methodology of Mr McNaughton’s calculation. He was aware that there were five vacant tenancies at the time, which he accounted for by including a condition in the letter of offer requiring Alceon to provide a rental income guarantee equivalent to two years’ gross market rent for any vacant tenancy as at the settlement date. Having completed his calculations, he discussed them with Mr Baliva. Apart from stating in his evidence-in-chief that “we reviewed” the calculations, he did not say what was done or discussed. Mr Baliva in his evidence-in-chief provides some detail of what was discussed with Mr McNaughton. In substance, Mr McNaughton advised that he had been through the Information Memorandum and had reviewed comparable sales. Based on those inquiries he had determined that a 7% investment yield was appropriate. Mr Baliva accepted that assessment and agreed with Mr McNaughton’s methodology. The result of this meeting was that Mr Baliva signed and caused to be delivered an expression of interest addressed to Mr Gartland at Stonebridge dated 16 August 2017. The letter reads:

Dear Philip,

Bluewater Square

Offer

Elanor Investors Group (ENN) is pleased to submit an Offer to acquire the below Property in accordance with the terms outlined below:

Property: Bluewater Square Shopping Centre (Shopping Centre) Anzac Avenue, Redcliffe QLD 4020

Vendor: Alceon Group ATF Bluewater Trust

Purchaser: Elanor Funds Management Limited (or nominee)

Purchase Price: $55,250,000

(Fifty five million, two hundred and fifty thousand dollars)

Offer Assumptions: The offer assumes:

1. The annual Fully Leased and Passing Net Operating Income is $4,266,720 and $3,907,170 respectively per the information provided

2. The Vendor will grant the Purchaser a rental income guarantee equivalent to two (2) years gross market rent (as assessed by the Purchaser) for any tenancies which are not subject to a lease at the date of settlement. This guarantee will be held in a trust account managed by the Purchasers solicitor

3. Budgeted Outgoings are appropriate to operate and maintain the Property to a competitive standard and are consistent with operating cost benchmarks for similar properties

4. Plant & Equipment has been maintained to a high standard and no material capital expenditure will be required to either replace or extend its useful life

5. All outstanding leasing incentives, fit-out contributions, rental abatements, and other capital commitments, will remain the responsibility of the Vendor and be adjusted in the Purchaser's favour at settlement

6. All bank guarantees and or security deposits required under the leases will be in place at Settlement and novated across to the Purchaser. There will be an adjustment in favour of the Purchaser for any outstanding bank guarantees or security deposits not provided at Settlement

Exclusivity Period: The Vendor will grant the Purchaser an exclusive dealing period of 20 business days, during which period the Purchaser will:

1. conduct Due Diligence to its satisfaction, with the Vendor providing full co-operation and access to the Purchaser and or its consultants; and

2. negotiate in good faith to agree and execute contracts and other relevant agreements.

Deposit: 5% of Purchase Price at exchange of contracts.

Settlement: 30 business days following exchange of contracts, or earlier subject to the Purchaser providing 10 business days’ written notice to the Vendor.

Offer Expiry: This Offer will expire on Friday 25 August 2017

Acceptance: Please confirm the Vendors' acceptance of the terms outlined in this letter by signing below and returning a copy to the Purchaser

General Terms: This Offer is not intended to and does not create legally binding or enforceable obligations between the parties.

We look forward to the vendor's acceptance and proceeding with the acquisition of the Property in accordance with the terms outlined in this Offer.

69 Alceon accepted those terms, and on 18 August 2017 the parties entered into the Heads of Agreement which relevantly provided as follows:

(1) A purchase price of $55.25 million “as a going concern”;

(2) The annual fully leased and passing net operating income was $4,266,720 (as at 1 December 2017) and $3,907,170 (as at 1 December 2017) respectively per the information provided.

(3) The vendor would grant to the purchaser a rental income guarantee equivalent to two (2) years’ gross market rent (as per financials provided as at 1 December 2017) for any tenancies which are not subject to a lease at the date of settlement. This guarantee would be held in a trust account managed by the purchaser’s solicitor.

(4) All outstanding leasing incentives, fit-out contributions, rental abatements, and other capital commitments would remain the responsibility of the vendor and be adjusted in the purchaser’s favour at settlement.

(5) All bank guarantees and or security deposits required under the leases would be in place at settlement and novated across to the purchaser. There would be an adjustment in favour of the purchaser for any outstanding bank guarantees or security deposits not provided at settlement.

(6) Alceon granted to Elanor an exclusive dealing period of 20 business days commencing on 21 August 2017 and expiring on Friday, 15 September 2017 during which the purchaser would:

(a) Conduct due diligence to its satisfaction, with the vendors providing full cooperation and access to the purchaser and or its consultants; and

(b) Negotiate in good faith to agree and execute contracts and other relevant agreements.

70 Expressly, the Heads of Agreement did not create a binding legal relationship between the parties, save as to the exclusive dealing period and a clause concerned with confidentiality.

71 Each of Mr McNaughton and Mr Baliva had access to the data room throughout the due diligence period. Although he described his role following the signing of the Heads of Agreement as limited to coordinating consultants to undertake due diligence, the data room log records that Mr McNaughton very extensively accessed documentation in the data room during the entirety of the due diligence period and thereafter until 1 November 2017, which was the date of settlement of the Sale Contract. It is notable that within the due diligence period his access included viewing documents relating to the mixed-use development potential of the site, the Urbis town planning assessment for redevelopment, including the favourable mixed use zoning pursuant to the local council planning scheme, several architectural montages of a compliant mixed-use development, the monthly turnover data for July 2017 and a tenancy arrears schedule for July 2017 (July Arrears Report) which he viewed on 28 August and 30 October 2017. Following expiry of the due diligence, Mr McNaughton did review other tenancy arrears schedules for May and June 2017, but not until 30 October 2017.

72 In mid-August 2017, Mr McNaughton spoke with Mr Hamilton with the purpose of retaining him to undertake a due diligence assessment. He requested the submission of a written proposal with a fee estimate, which he received on 21 August 2017. Amongst other matters, Mr Hamilton offered a “financial and tenancy due diligence service” which included “comparison of the net income provided by the vendor with our revised estimate of the sustainable net income”. Pursuant to the scope of works, Mr Hamilton advised that he would undertake “a critical review of all income and expenditure” to cover a number of issues including: a review of the commercial aspects of the lease agreements and audit of the tenancy schedule, the identification of any clause in the lease “that may have an impact on the income stream”, review of the trading performance of the property including the major tenants and each individual tenant, review and comment “upon the current arrears report”, the undertaking of a SWOT analysis, the identification of “‘problem’ tenants” by analysis of arrears reports and the undertaking of a check of rental and other charges due under each lease with the charges depicted on monthly invoices. CBRE offered to do all of this work for a fee of $50,000 plus GST. Mr McNaughton accepted the proposal. On 21 August 2017, he sent an email to Mr Hamilton attaching a financial pack of relevant information.

73 Mr McNaughton also contacted Mr Kwan on 21 August 2017, first by telephone and then by confirming email. He provided the financial information received from Stonebridge and the Information Memorandum and requested a valuation proposal. The email continued:

Could you kindly provide a valuation proposal.

Because we will be buying in a standalone syndicate (as opposed to ERF), we will probably be casting the net a little wider than usual on the debt sourcing, so do let me know if there are any banks who you are not on the panel of.

74 Mr McNaughton explained the acronym ERF is a reference to a listed real estate trust on the Australian Stock Exchange. Mr McNaughton received a fee proposal from Mr Kwan later that day, which he accepted.

75 The engagement of Mr Hamilton did not conclude the inquiries that Mr McNaughton undertook. The Information Memorandum referenced the existence of a report from Bureau Proberts Architects, comprising a site analysis and montages of a range of mixed-use development schemes that may be approved on the site. This report was included in the data room within a folder marked “Value Add Potential”. This report is in the form of a site analysis, its context, the extent of surrounding development and use together with an analysis of the development potential, particularly having regard to the views towards the ocean obtainable from a multilevel residential development constructed above the Centre. The report contained a number of residential options for development by reference to setbacks and heights, each being compliant with the provisions of the planning scheme. The data room log records that Mr McNaughton first viewed this report on 21 August 2017, before viewing it again on 23 and 24 August, 4 and 13 September and 13 October 2017. On the same day he also viewed another report in the same folder in the data room authored by the town planning firm Urbis. That report is in the form of a letter addressed to Alceon dated 27 April 2017. It contains a site analysis, identifies the relevant zoning and planning controls, examines the use and development requirements of the planning scheme for acceptable outcomes (i.e. not involving the exercise of the discretion to grant or to refuse approval) and provides an analysis of one of the options for development identified in the Bureau Roberts report. The conclusion is that ‘Option 3’ complied with the provisions of the planning scheme for a development of a total of 85 residential units over five levels whilst retaining the existing commercial aspects of the Centre. The maximum height of 25.5m complied with the planning scheme. In the summary to that report the author said:

The recently endorsed Moreton Bay Regional Planning Scheme 2016 offers the owner of Bluewater Square the opportunity to implement a Code Assessable mixed-use development for 85 units.

A review of the mixed-use Option 3 scheme prepared by Bureau Proberts indicates the scheme having a maximum height of 25.5m, would be subject to Code Assessment. Option 3 also meets the relevant provisions for setbacks, car parking and site cover.

76 On 23 August 2017, Mr McNaughton emailed the author of the Urbis report, Ms Sophie Lam. He stated: “I would like to have a call please to discuss, as we too believe there is good medium to long term potential to develop the site into a mixed use [sic] scheme.” On the same day, Mr McNaughton sent an email to Mr Stewart Pentland at the Moreton Bay Regional Council. Omitting formal parts, he said:

Confidentially we are in exclusive due diligence to acquire the Bluewater Square shopping centre in Redcliffe.

From the current zoning, Bluewater Square would appear to have strong medium to long term prospects to be redeveloped into a mixed-use project.

I understand that Moreton Bay Regional Council is undergoing some strategic planning when it comes to zoning and development.

Given your role as Head of Planning at Moreton Bay Regional Council, would we be able to have a phone call to learn more about how the strategic planning may effect [sic] Bluewater Square in the future.

77 Mr McNaughton received a response from Ms Amy White of the Council on 24 August 2017. Further emails were exchanged and ultimately Mr McNaughton and Mr Baliva attended a pre-lodgement meeting with Ms White on 5 September 2017, by telephone. Ms White prepared a comprehensive note of the matters discussed. It discloses that she summarised the planning scheme controls, pointed out the relevant development and use clauses relevant to the “Option 3” referred to in the Bureau Proberts and Urbis reports, highlighted the strategic development intent provisions of the zoning overlay and relevantly commented as follows:

The proposal is generally consistent with the intended role of the Seaside Village precinct as a higher order centre. In its current form the proposal reflects a mixed use, high density residential development.

Further information is required to determine how the proposed streetscape treatment ensures Sutton Street is provided as a vibrant main street for the centre’s shopping business, commercial and community uses.

78 Ms White also provided advice as to what documentation would be required in order to lodge a development application and the fees applicable. Mr McNaughton and Mr Baliva also met with Ms Lam on 25 August 2017, but what was discussed at that meeting was not explored in the evidence, save for an email that Ms Lam sent to Mr McNaughton and Mr Baliva at 5.06 pm that day, where she explained the car parking ratio requirements for short term accommodation. Mr McNaughton had further external correspondence on 25 August 2017, this time to Mr Greg Malempre at the firm Location IQ and relevantly said:

As part of your research on Bluewater Square, can you report on the number of hotels/hotel rooms/occupancy etc. on the peninsula?

If we build above the shopping centre it may make more sense to build some resi [sic] and some service apartments.

Given car park ratios this may also be what we need to do.

79 Subsequently, on 8 September 2017, Mr McNaughton received the report from Mr Malempre. It is an independent centre and market review with analysis arranged as:

(1) review of the regional and local context of the site;

(2) a benchmarked summary of the Centre’s composition and performance;

(3) definition of the trade area and review of current and projected population and retail spending levels;

(4) review of the socio-economic profile of the Centre trade area;

(5) identification of customer segments;

(6) review of the current and future competitive environment;

(7) analysis of current estimated market share; and

(8) a detailed analysis of projected sales for the Woolworths tenancy.

80 Within the report there is a section dealing with estimated sales for various tenancies, including estimates of sales for seven of the Food Court Tenants based on information provided by Elanor, where sales data was not available. In addressing the “ultimate potential assessment” the report identifies a number of key issues including: “the specialty component of the shopping centre currently includes a high proportion of independent traders which perform moderately”. A recommendation is made that Elanor should “consider greater promotion and more national brands for the food catering offer”, by reference to a number of well-known national retailers.

81 I pause at this point to observe that Mr McNaughton in his evidence-in-chief did not disclose the inquiries that he made in relation to the Bureau Proberts report, the Urbis report or his contact with the Moreton Bay Regional Council. This is surprising in light of the fact that CPRAM pleaded in its defence that if the impugned representations were made, they were immaterial in the context of the overall value of the property including the development potential of the site by reference to the Urbis and Bureau Proberts reports. Further on the question of reliance, CPRAM pleaded that Elanor was motivated to acquire the Centre because of its potential for re-development, in particular as emphasised in the Information Memorandum. I return to this point in my analysis and findings relating to the issues of misleading or deceptive conduct and reliance.

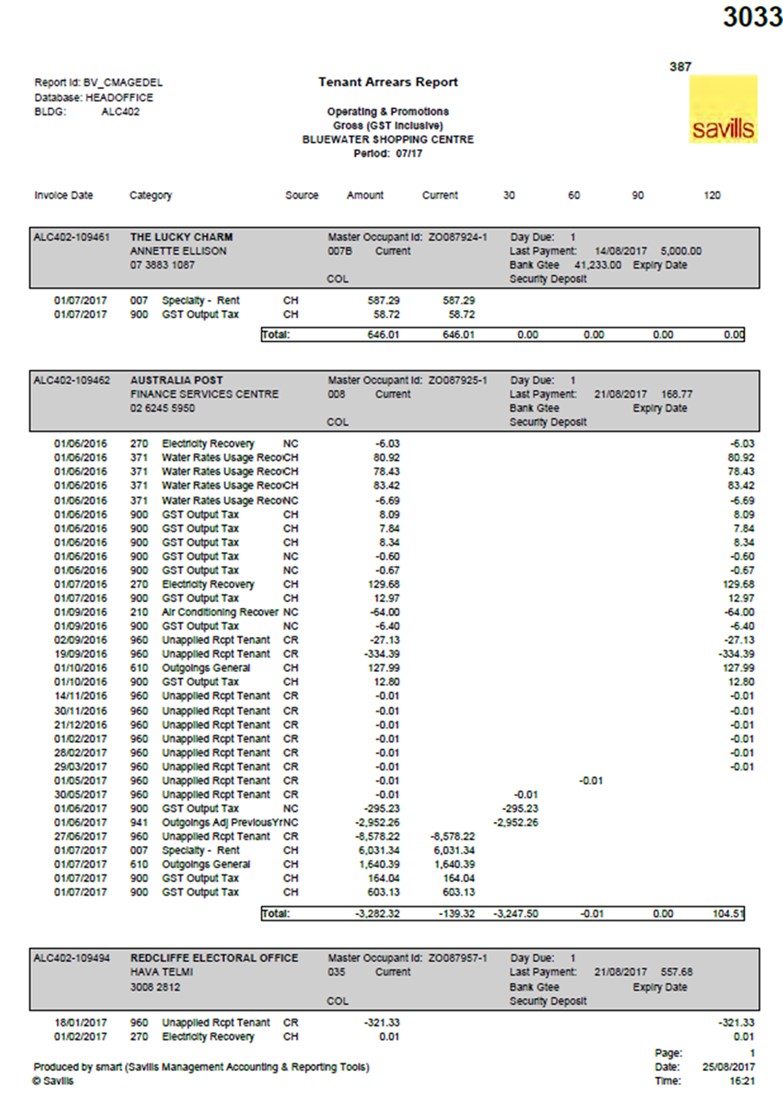

82 Resuming the sequence of material events, the July Arrears Reports was produced and printed on 25 August 2017 and was then made available in the dataroom. This, on the case of Elanor is a very significant document.

83 I reproduce it:

84 According to the data room log, Mr Hamilton viewed this report on 27 August 2017 and again on 29 August 2017, when he printed it. Mr McNaughton viewed the document on 28 August and 30 October 2017. Just what objective meaning was conveyed by this report in context is a central issue in this proceeding which I address in my analysis of the misleading conduct claim.

85 On 28 August 2017, Mr Kwan requested a copy of the Heads of Agreement and received it from Mr McNaughton. Much was made, at least initially, in the cross-examination of Mr Kwan to the effect that by receiving this information he knew the valuation figure that was required by Alceon in order to support the purchase of the Centre. However, it subsequently emerged (and I accept) that the standard form instructions from the Bank of Queensland to his firm required that he sight and have regard to any relevant sales contract, and I accept Mr Fernon’s submission that this component of the cross-examination proceeded on a false basis.

86 At some time prior to 28 August 2017, Mr McNaughton contacted Mr Stephen Schneider of the firm Colliers by way of inquiry as to whether Colliers would, in the event of the acquisition proceeding, manage the Centre for Elanor. Without being prompted, Mr Schneider visited the Centre on 28 August 2017 at 3.40 pm and provided a report by email to Mr McNaughton at 4.16 pm. Under the heading “Retailer and Performance” he observed:

At 3:40 the Centre is very quiet, would think with school pick up the Centre would be busier

Woolworths looks fresh with new fitout - not very busy

Internal common area retailers - one vacancy next to What's Hot

Donut King and lean green kitchen extremely quiet - no customers for 20 minutes

Sushi kiosk closing at 4pm

Juice kiosk closed - possible vacancy.

Level 1 commercial looks to be ok with traffic flow to that level

Good mix of food and services internally

External tenancies mainly food retailers.

All food retailers extremely quiet with a vacancy next to Thai restaurant

Restaurants not all trading - only opening for lunch and dinner

Potentially too much food - not enough traffic / customers to support the two precincts

Australia Post should be internal to pull traffic - post boxes could remain in current location.

87 Mr McNaughton accepted in cross-examination that based on this information he was aware, during the due diligence period, that the Food Court Tenants were quiet, at least on the day and at the time of the inspection and that there were insufficient customers to support the two food precincts at the Centre.

88 On 30 August 2017, Mr Hamilton and two of his colleagues Ms Brunninghausen and Ms Levene, met with Mr Shah at the Centre for the 30 August Meeting. Only Mr Hamilton gave evidence as to what was discussed, by reference to a contemporaneous file note. Mr Shah disputes Mr Hamilton’s recollection. This evidence is very controversial and forms a material component of the misleading conduct claim. I return to it in more detail later in these reasons.

89 On 7 September 2017, Mr Kwan sent an email to Mr McNaughton and Mr Baliva and attached draft calculations “based on the information provided to date for your review”. The calculations adopted an adjusted net annual income of $3,801,936 and to it applied alternative yields of 6.50%, 6.75% and 7% which, after further “below the line adjustments” respectively valued the Centre at $57,713,832, $55,547,486 and $53,535,880. In that analysis Mr Kwan adopted a value of $55.25 million. A point which that analysis demonstrates is that relatively minor alterations to the yield assumption has the effect of producing very large differences in the value of the Centre. For example, at a yield of 6.5%, the capitalised value is $58,491,329. At a yield of 6.75% the capitalised value is $56,324,984, a difference of $2,166,345 before the application of the below the line adjustments, by reason of only a 0.25% alteration to the capitalisation rate. In each case the adjustments applied by Mr Kwan are the same. Mr McNaughton responded to Mr Kwan’s draft calculations approximately one hour after receipt. He said:

Thanks Paul.

Will take a detailed look tomorrow.

On a quick pass, we’d rather the cap rate be higher and have less below the line adjustments (e.g. CapEx).

90 A few minutes later, Mr Kwan responded to the effect that he noted the comment and would “look at what rates we might be able to adjust. I’ve got a few negative reversions in there and might have another look at the outgoings.” Mr McNaughton did not wait to receive revised figures from Mr Kwan before meeting with Mr Baliva on 8 September 2017. In his evidence-in-chief, he said:

On or about 8 September 2017 I attended a meeting with Mr Baliva. We reviewed the documentation provided through the Due Diligence, including the Due Diligence Reporting documents and the Valuation Figures from Mr Kwan. From those documents together we prepared the transaction approval checklist (Approval Checklist) and the investment overview (Investment Overview). The Approval Checklist included a checklist of the due diligence for the Centre including the structure of the purchase, legal checklist as to the sale contract, fund and asset level financial forecasts, financial due diligence, valuation outcome and property management proposals. The Investment Overview included details about the Centre, its valuation, income, size and turnover. The Approval Checklist and the Investment Overview made up the report to be provided to the Board (Report).