Federal Court of Australia

StarTrack Express Pty Ltd v TMA Australia Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1271

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

UPON THE RESPONDENT, BY ITS COUNSEL, UNDERTAKING:

1. until trial or further order, and whether by itself, its directors, servants, agents, employees or howsoever, to cease and forever refrain from:

(a) using the words "Australia Post" or "StarTrack", or imagery bearing the logos of those businesses (“ST signs”), in the TMA Online Store (as defined in paragraph 30 of the affidavit of Rhys Kneepkens affirmed herein on 6 October 2023), other than in the URL https://startrackgalaxy.tmagroup.com.au/ and as set out in the “Important Notice” as appearing on the current TMA Online Store (as shown at paragraph 32 of the affidavit of Rhys Kneepkens affirmed herein on 11 October 2023) (the “Important Notice”); and

(b) offering for sale or selling any consumable products marked with the ST signs;

2. to provide to StarTrack, within seven days of these orders, print-outs of the packing slips for sales made for products offered through the ST Portal which were processed by TMA during the period 21 August 2023 to 12 September 2023; and

3. until further order of the Court, to retain the Important Notice so that consumers will need to actively close the pop-up window before they can purchase any product from the TMA Online Store.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application for interlocutory relief be dismissed.

2. Pursuant to s 37AF(1)(b) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and until further order, there be no publication or disclosure of the following documents to any person other than the parties to the proceeding, their legal representatives and officers of the court, namely:

(a) the exhibit marked “Confidential RA-2” to the affidavit of Rebecca Louise Arsenoulis sworn on 4 October 2023;

(b) the exhibit marked “Confidential RA-3” to the affidavit of Rebecca Louise Arsenoulis sworn on 4 October 2023;

(c) the exhibit marked “Confidential RK-4” to the affidavit of Rhys Andre Kneepkens affirmed on 6 October 2023;

(d) the exhibit marked “Confidential RK-5” to the affidavit of Rhys Andre Kneepkens affirmed on 6 October 2023; and

(e) the annexures marked “RK-8”, “RK-10”, “RK-11”, “RK-21”, “RK-23” and “RK-28” to the affidavit of Rhys Andre Kneepkens affirmed on 11 October 2023.

3. Order 2 is made on the ground specified in s 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

PENAL NOTICE

TO: TMA AUSTRALIA PTY LTD IF YOU (BEING THE PERSONS BOUND BY THIS ORDER): (A) REFUSE OR NEGLECT TO DO ANY ACT WITHIN THE TIME SPECIFIED IN THIS ORDER FOR THE DOING OF THE ACT; OR (B) DISOBEY THE ORDER BY DOING AN ACT WHICH THE ORDER REQUIRES YOU NOT TO DO, YOU WILL BE LIABLE TO IMPRISONMENT, SEQUESTRATION OF PROPERTY OR OTHER PUNISHMENT. ANY OTHER PERSON WHO KNOWS OF THIS ORDER AND DOES ANYTHING WHICH HELPS OR PERMITS YOU TO BREACH THE TERMS OF THIS ORDER MAY BE SIMILARLY PUNISHED. |

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

SNADEN J:

1 The applicant (“StarTrack”) provides parcel, freight and logistics services to businesses in and outside of Australia. In the course of doing so, it has occasion to supply to its clients packaging “consumables” (such as envelopes, satchels and the like).

2 In approximately mid-2012, StarTrack entered into a contract (known as “Contract STA0005”) with the respondent (“TMA”), pursuant to which TMA provided various services associated with its consumables business. The precise scope of those services is the subject of dispute; but, at the least, they included the manufacture and warehousing of consumable freight products.

3 In 2017, TMA developed an online e-commerce platform, by which customers were able to purchase StarTrack’s products via an internet website. That facility (the “ST Portal”) operated via the use of a customer identifier that TMA generated for customers which had received a StarTrack customer account number. The ST Portal was accessible from a website hosted on TMA’s internet domain: https://startrackgalaxy.tmagroup.com.au.

4 The ST Portal was used exclusively for the sale of StarTrack products to customers that StarTrack pre-authorised. StarTrack also used it for administrative purposes, including to generate reports for the purposes of billing customers for the goods purchased through it, as well as inventory management and financial record keeping.

5 In May 2023, StarTrack gave notice to TMA of its intention to terminate Contract STA0005. Since then, a dispute has arisen between the parties about the continued operation of the ST Portal (or of a successor facility, which TMA has put in its place). In effect, TMA has repurposed the ST Portal for the sale of its own consumable products, which it has sold to customers who have been able to access it at the same internet location via unchanged login credentials. Additionally, StarTrack’s ability to generate reports from the ST Portal has ceased. TMA has claimed ownership of the ST Portal (in the form that it now assumes) and has invited StarTrack to buy it for a sum of $25 million.

6 By an originating application dated 5 October 2023, StarTrack moves the court for urgent interlocutory relief to, amongst other things, restrain TMA from continuing to operate the ST Portal (in its present form) or otherwise “dealing with” nominated customers. StarTrack accuses TMA of appropriating confidential information provided to it for the purposes of Contract ST0005, of soliciting custom in breach of a contractual restraint, and of engaging in misleading or deceptive (or analogously tortious) conduct.

7 The application was the subject of a brief hearing on Friday, 6 October 2023. It was supported by two affidavits, namely one affirmed by Mr Antonio Citera on 4 October 2023, and another sworn on the same day by Ms Rebecca Louise Arsenoulis. At that brief hearing, senior counsel for TMA applied for an adjournment to permit some assimilation of the material upon which StarTrack relied, some of which had been served after business hours the evening prior. That application was granted over appropriately muted objection. With input from the parties, it was ultimately agreed that an adjournment of one week should be accommodated and it was.

8 StarTrack’s application for interlocutory relief was, thus, the subject of a more fulsome hearing on Friday, 13 October 2023. TMA relied upon two affidavits of Mr Rhys Andre Kneepkens: one affirmed on 6 October 2023 and another on 11 October 2023. StarTrack relied upon a further affidavit of Ms Arsenoulis sworn on 12 October 2023.

9 Some of the affidavit material was the subject of rulings under pt VAA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (hereafter, the “FCA Act”); specifically, parts that contained commercially sensitive client information. Those rulings are the subject of expansion and further analysis below.

10 For the reasons that follow, the interlocutory relief for which StarTrack moves should (and will) be declined.

Principles to be applied

11 The court’s power to grant interlocutory relief of the kind that StarTrack seeks is not to be doubted. It is conferred at the least by s 23 of the FCA Act.

12 Similarly, the principles that govern the court’s discretion to grant interlocutory injunctive relief are well settled and not in dispute. In Metro Trains Melbourne Pty Ltd v Australian Rail, Tram and Bus Union Industry [2019] FCA 1265, I set them out as follows (at [38]-[41]):

…In order to qualify for the relief that it seeks, [an applicant for injunctive relief] must demonstrate that it has a prima facie case and that the balance of convenience favours the grant of an injunction: Australian Broadcasting Corporation v O’Neill (2006) 227 CLR 57, 81-84 (Gummow and Hayne JJ, with whom Gleeson CJ and Crennan J agreed).

When considering the grant of an interlocutory injunction, the issue of whether an applicant has established a prima facie case and whether the balance of convenience favours injunctive relief are related inquiries. Whether there is a prima facie case is to be considered together with the balance of convenience: Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd v Apple Inc. (2011) 217 FCR 238, 261 [67] (Dowsett, Foster and Yates JJ).

In Bullock v FFTSA (1985) 5 FCR 464, Woodward J (with whom Smithers and Sweeney JJ relevantly agreed) stated (at 472):

…an apparently strong claim may lead a court more readily to grant an injunction when the balance of convenience is fairly even. A more doubtful claim (which nevertheless raises “a serious question to be tried”) may still attract interlocutory relief if there is a marked balance of convenience in favour of it.

An applicant for interlocutory injunctive relief must, in showing that the balance of convenience favours that outcome, point to inconvenience for which an award of damages at trial would not be a sufficient remedy: Castlemaine Tooheys Ltd v South Australia (1986) 161 CLR 148, 153 (Mason ACJ); Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v Blue Star Pacific (2009) 184 IR 333, 339 (Greenwood J).

13 Lest there be any doubt, the adequacy of an award of damages is not a third consideration that guides the court’s discretion to grant or not grant interlocutory injunctive relief. Rather, it forms “…part of the broader balance of convenience question”: Liberty Financial Pty Ltd v Jugovic [2021] FCA 607, [283] (Beach J; hereafter “Liberty Financial”).

14 It is convenient to address the central issues separately.

Prima facie case

15 StarTrack submits that there is a strong prima facie case for the relief that is sought. Several causes of action are pressed to that end, specifically that TMA has:

(1) acted in breach of the terms of Contract ST0005;

(2) engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct in contravention of ss 18 and 29(1) of the Australian Consumer Law (comprising Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), the “ACL”);

(3) committed the tort of passing off; and

(4) engaged in unconscionable conduct in breach of s 21(1) of the ACL.

16 It is convenient to address each in turn.

Breach of contractual restraints

17 It must be acknowledged at the outset that there is at least some dispute about the application or scope of Contract ST0005. Specifically, there is room to doubt that it was pursuant to the terms of that instrument that TMA developed and maintained the ST Portal. By its terms, Contract ST0005 expired several years ago; and, perhaps, terminated upon that expiry rather than by the notice described earlier. At trial, TMA intends to submit that Contract ST0005 has limited or no application to the present dispute and, on the as-yet un-tested evidence furnished for interlocutory purposes, that submission could not entirely be discounted.

18 Nonetheless, I consider that there is at least a prima facie case basis for holding that Contract ST0005 should serve as a sound contractual foundation for present purposes. TMA did not seriously contend otherwise and rightly so. By Contract ST0005, TMA was engaged to provide various services to StarTrack. Key among them were what the contract described as “Print management services”, which were described to include (errors original):

• Centralised management of image library, proofing and version control;

• Integrated IT platform with automated reporting and end-to-end data capture.

• Specialised project team to manage the integration process;

• Online ordering tool providing easy order access, visibility of current stock levels and previous order history;

19 The “Print management services” were provided for an agreed monthly fee of $12,500.00. They complemented other services, including warehousing services.

20 Contract ST0005 commenced with effect in August 2012. It had an initial term of one year, which could be extended for a further 12 months. At present, there is no evidence as to what, if anything, was expressly agreed thereafter. Nonetheless, there appears to be little if any doubt that TMA continued, until 1 September 2023, to provide print management services to StarTrack; and to invoice and receive in return monthly sums approximating the $12,500.00 to which Contract ST0005 expressly referred.

21 Furthermore, there is reason to conclude—at least on an interlocutory basis—that the development and/or maintenance of the ST Portal fell within what was contemplated by those print management services. As much appears to have been acknowledged in email correspondence that TMA, via its chief executive officer, Mr Anthony Karam, sent in April 2017, in response to some concerns that StarTrack had raised about the provision of print management services.

22 Satisfied, then, that there is at least a prima facie case for supposing that Contract ST0005 should assume some significance to the present dispute, attention should turn to its terms.

23 Clause 8 of Contract ST0005 is headed, “Conflict of interest and Restraint”. Clause 8.4 is of particular significance:

8.4 No Solicitation and No Poaching

(a) The Contractor shall not at any time during the Term and for a period of 1 year after the expiry of the Term (Restraint Period) for any reason, whether or not on its own accord or as agent, representative or employee of any person, firm or company:

(1) directly or indirectly approach, solicit or persuade any person or corporation which is a customer or client of StarTrack or any of its Related Bodies Corporate, to cease doing business with StarTrack or any of its Related Bodies Corporate or to otherwise reduce the amount of business which the customer or client would normally do with StarTrack or any of its Related Bodies Corporate; or

…

…

(c) The undertakings contained in this clause 8.4 are provided for the benefit of StarTrack and its Related Bodies Corporate and shall be regarded as separate and distinct and severable each from the other so that the unenforceability of an undertaking shall in no way affect the enforceability of the other undertakings.

(d) If there is a breach by the Contractor of its obligations under this clause 8.4 then, in addition and without prejudice to any other remedies which StarTrack or its Related Bodies Corporate may have, StarTrack and its Related Bodies Corporate shall be entitled to seek injunctive relief in any court of competent jurisdiction.

(e) If a court of competent jurisdiction determines that, in respect of any of the severable undertakings in this clause, the Restraint Period is unreasonably long but that a shorter period would be lawful and reasonable, then such undertakings shall be read down so as to refer to such shorter period as the court considers valid in respect of such restraints.

24 Clause 11 of Contract ST0005 is headed, “Confidentiality and privacy”. Relevantly, it provides as follows:

11. Confidentiality and privacy

11.1 Confidential Information

All Confidential Information of a party ("Disclosing Party") which comes into the possession of the other party its employees, directors, officers, agents or contractors ("Receiving Party") pursuant to these Terms and Conditions or otherwise must be treated as confidential and will not be used or disclosed by the Receiving Party except as is absolutely necessary for the purposes of performing its obligations under these Terms and Conditions or otherwise as expressly authorised in writing by the Disclosing Party or under these Terms and Conditions. The Receiving Party must:

(a) protect and maintain the confidentiality of the Confidential Information;

(b) implement all reasonable procedures and safeguards to ensure that the Confidential Information is identified and protected; and

(c) ensure that all of its employees, directors, officers, agents and subcontractors (including, but not limited, to the Contractor's Employee where the Recipient is the Contractor) having access to the Confidential Information are under obligations of confidentiality in relation to the Confidential Information which are no less stringent than the obligations set out in these Terms and Conditions.

11.2 Exclusions to the Obligation of Confidentiality

These obligations of confidentiality imposed on the Receiving Party under this clause 11 do not apply to information:

(a) disclosed to the Receiving Party by a third party having a right to disclose the Confidential Information without any obligation of confidentiality attached;

(b) independently developed by the Receiving Party as evidenced by written record;

(c) in the public domain otherwise than as a result of a breach by the Receiving Party of this clause 11.

11.3 Injunctive Relief

The parties acknowledge that damages are an insufficient remedy and that a party will be entitled to injunctive relief in the event of a breach of this clause 11.

…

11.6 Period of obligation

The obligations of confidentiality contained in this clause 11 continue to bind each party after termination of these Terms and Conditions.

…

11.8 Privacy

Each party must:

…

(f) upon completion of its obligations under these Terms and Conditions, return to the Disclosing Party, all copies of the Personal Information or any record of the Personal Information or in accordance with the Disclosing Party's directions in writing, destroy the Personal Information (and any copies thereof) and any record of the Personal Information other than copies which it is required to retain by law; …

…

25 It is not clear what is contemplated by the capitalised term, “Personal Information”.

26 “Confidential Information” is defined at cl 1.1 as follows:

1.1 Definitions

…

Confidential Information means any accounts, statements, marketing plans, research, product concepts, design concepts, customer details, contractor details, contracts, agreements (including these Terms and Conditions), briefing documents, business interests and methodologies, drawings, reports, technical information and all other knowledge or information at any time disclosed (whether in writing, electronic or orally) by one party to the other unless it was:

(a) acquired from a third party having the right to disclose the information; or

(b) in the public domain,

other than through a breach of these Terms and Conditions.

27 Clause 16 of Contract ST0005 is headed, “Termination”. Of present relevance is cl 16.5, which provides:

16.5 Consequences of termination

On the expiration of the Term or earlier termination of these Terms and Conditions:

(a) the Contractor will deliver to StarTrack as soon as practicable and in any event no later than 5 Business Days after the date of termination, all identification passes issued by StarTrack or any of its customers, any goods belonging to StarTrack or any of its customers, all StarTrack Equipment, all StarTrack Material, StarTrack’s Confidential Information and any other property, equipment, documents and materials and freight belonging to StarTrack or its customers (StarTrack Property) in the Contractor's control or possession;

(b) in the event that the Contractor fails to comply with paragraph (a), StarTrack may without notice enter the Contractor's premises and inspect any Contractor's Equipment for the purposes of retrieving the StarTrack Property;

(c) the Contractor must observe its obligations in relation to confidentiality and privacy under clause 11; and

(d) any provision of these Terms and Conditions which are expressly stated to survive termination will continue to apply after termination.

28 Two propositions are central to StarTrack’s claim for interlocutory relief: first, that, by continuing to operate the ST Portal (in its present form) and, thereby, engaging with customers that previously used it to purchase consumable goods from StarTrack, TMA is acting in contravention of cl 8.4(a)(1) of Contract ST0005; and second, that TMA is doing so in a way that involves the continuing use of “Confidential Information” (as defined), which in turn sets it in breach of cl 11.1 of Contract ST0005.

29 It is convenient to address the second proposition first. There doesn’t appear to be much room for doubting that, during the currency of Contract ST0005, TMA received information from StarTrack that should qualify as “Confidential Information” (as defined). It is apparent that StarTrack furnished TMA with information about its customers, specifically for the purposes of enabling them to use the ST Portal. That information included, at the least, customer contact details. It appears that it might also have included information about order histories.

30 Similarly, there appears little reason to doubt that TMA had occasion to use some—and probably all—of that information in connection with its provision of the print management services for which it was contracted; and, more specifically, in connection with the ST Portal (in its historical form). At the least, it (or some of it) was used to create login credentials so that StarTrack’s customers could access the ST Portal and make such orders they required from time to time.

31 StarTrack complains that, since the termination of Contract ST0005 (and despite request), TMA has not returned any confidential information. That might or might not put TMA in contravention of cll 16.5(a) or 11.8(f) of Contract ST0005; but, for present purposes, it is clear enough that StarTrack’s claim for interlocutory injunctive relief turns upon whether or not TMA should be understood to be conducting itself in contravention of cl 11.1. In other words, is TMA continuing to use StarTrack’s Confidential Information—and, more specifically, failing thereby to protect and maintain such confidence as might otherwise and properly inhere in it? Perhaps more specifically still, the question for consideration presently is whether there is a prima facie case that such use is occurring.

32 Some preliminary observations are appropriate. It is inherent in the provision of third-party logistics services that a business such as TMA will find itself privy to information about its client’s customers. To the extent that that information is supplied by the client, it would ordinarily be supplied in confidence; and, upon the cessation of the relationship, the service provider could expect to labour under an obligation to return and refrain from using it. But so to observe is not to require that, in the absence of some express contractual requirement, it should also have to relieve itself of other information that it has independently generated about those customers in the usual course of supplying its services.

33 Although the possibility cannot be discounted, I am not persuaded that StarTrack has a strong prima facie case that any of its Confidential Information (as defined) continues to be used in contravention of cl 11.1 of Contract ST0005. Indeed, it is not clear precisely what information is said to have been improperly retained and used. During oral submissions, senior counsel for StarTrack noted that his client was “still waiting” for the return of its confidential information. That prompted the following exchange:

HIS HONOUR: But how – what are you waiting for?

MR HEATH: Give back the documents.

HIS HONOUR: In what form? Well

MR HEATH: I don’t know in what

HIS HONOUR: So documents.

MR HEATH: I don’t know in what form they’ve been kept, but we want to understand, and we want to have back, copies of that personal information. And that’s, again, another part of trying to work out what is being done. Again, it fits in and complements 8.4(a)(i) and 16.5, which I will turn to in a moment.

HIS HONOUR: But these sorts of provisions are usually engaged when – let’s take the solicitor example again. On the second last day of their engagement, they print out a client list with names and phone numbers and courts can, and do, step in and say, “Well, that’s – that information in the form that you’ve acquired it, namely, a list, is quite clearly confidential and you must give the list back.”

MR HEATH: Yes.

HIS HONOUR: “But to the extent that you know who people are and you can operate a phone book, have at it.” So I’m not quite sure – I’m not – don’t take this as alarming in any way, but what is it that you want?

MR HEATH: Give back copies of documents recording the personal information and then we will understand what we’re dealing with in terms of 8.4(a)(i). It’s just another obligation with which compliance should occur. And your Honour, of course, if they’ve got in their minds Dan Murphy as a client, then subject to compliance with clause 8.4(a)(i), they can go and do business with Dan Murphy. But 8.4(a)(i) says, if you’ve had that one in the records, that’s a client dealing with ST. You can’t deal

HIS HONOUR: Yes, that’s a different – that’s a non-solicitation

MR HEATH: Yes.

HIS HONOUR: That is a restraint of

MR HEATH: But my point is, your Honour, they’re interlocking. So that one is not to be viewed in isolation. That’s going to work in conjunction with 8.4(a)(i). It must, in my respectful submission, your Honour, because

HIS HONOUR: Well, it would certainly inform the boundaries of reasonableness as to what is enforceable and what is not.

MR HEATH: Correct.

34 StarTrack’s primary complaint—perhaps understandably so—appears to be not so much that TMA continues to use information that is properly described as confidential; but that it continues to solicit business from customers in whom StarTrack asserts some measure of proprietary interest. It seems clear enough that it is the ST Portal (in its current form) that serves as the means by which TMA has done (and continues to do) so. TMA has maintained the same login credentials by which access to that portal is (and has long been) gained. It would appear (if, indeed, it is not plain) that, in the case of customers who used the portal previously to acquire StarTrack’s consumable products, TMA established those credentials in consequence of StarTrack’s telling it certain details about them. But should the credentials themselves—which StarTrack did not provide—fall within the contractual contemplation of “Confidential Information”? It is not apparent to me how they might.

35 By its proposed orders, StarTrack hopes to compel TMA to deliver up to it “…all versions and forms of information and material relating to [identifiable StarTrack customers], including Personal Information relating to [each of them]”. It seeks to qualify as “Personal Information” information that was “…provided by [each of the identifiable StarTrack customers] in relation to their registration as a StarTrack Customer or in the course of using the [ST Portal], including their identity, contact details, and billing and other financial details (including bank account number, credit card number, and order history).”

36 Two observations spring immediately for noting. First, information given to TMA by third parties does not obviously qualify as “Confidential Information” within the meaning that Contract ST0005 attributes to that phrase. Second—and perhaps to the extent that, for the purposes of Contract ST0005, “Personal Information” is apt to extend beyond “Confidential Information” (as defined)—it is not clear what part of Contract ST0005 might be thought to oblige TMA to deliver any such information up to StarTrack.

37 Those observations understood, I do not consider that StarTrack has established a prima facie case that TMA has used and continues to use its confidential information in breach of Contract ST0005.

38 I turn, then, to consider the significance of cl 8.4(a)(1) of Contract ST0005. On any view, it stands as the primary contractual hook upon which StarTrack’s interlocutory application hangs.

39 There was no material dispute between the parties about the principles that regulate the enforcement of contractual provisions that purport to operate in restraint of trade. As a general proposition, clauses in restraint of trade are presumed void on public policy grounds; but that presumption may be rebutted where it might be said that circumstances render a particular clause reasonable as between the parties and not unreasonably contrary to the public interest: Just Group Ltd v Peck (2016) 344 ALR 162, 173-175 [30]-[36] (Beach and Ferguson JJA and Riordan AJA; hereafter “Just Group”); Liberty Financial, [194] (Beach J).

40 In Just Group, the Victorian Court of Appeal (albeit in the slightly different context of post-employment restraints) made the following relevant observations (at 174 [33]-[35]):

A restraint clause in favour of an employer will be reasonable as between the parties, if at the date of a contract:

(a) the restraint clause is imposed to protect a legitimate interest of the employer; and

(b) the restraint clause does no more than is reasonably necessary to protect that legitimate interest in its:

(i) duration; or

(ii) extent.

It is well established that employers do have a legitimate interest in protecting:

(a) confidential information and trade secrets; and

(b) the employer’s customer connections.

For the legitimate purpose of protecting the employer’[s] confidential information, a restraint clause does not need to be limited to a covenant against disclosing confidential information. It may restrain the employee from being involved with a competitive business that could use the confidential information.

(references omitted)

41 It has been said that “…covenants in employment contracts are viewed more jealously than in other more commercial contracts”: Safetynet Security Ltd v Coppage [2013] EWCA Civ 1176, [9]. Regardless, the task for the court is to construe cl 8.4(a)(1) and to assess whether there is a prima facie case that it might operate to restrain TMA from doing what StarTrack hopes to stop it from doing.

42 In Findex Group Ltd v McKay [2020] FCAFC 182, [76]-[87] (Markovic, Banks-Smith and Anderson JJ) the full Federal Court made the following observations about that task:

The exercise of construction is undertaken for the purpose of ascertaining the real meaning of the restraint, independently of the rules proscribing tests of reasonableness for the purpose of ascertaining its validity: Butt v Long (1953) 88 CLR 476, 487 per Dixon CJ.

The Court should approach the task of construction on the basis that the parties intended to produce a commercial result, and one which makes commercial sense: Electricity Generation Corporation v Woodside Energy Ltd [2014] HCA 7; 251 CLR 640 (Woodside Energy), [35]; Ecosse Property Holdings Pty Ltd v Gee Dee Nominees Pty Ltd [2017] HCA 12; 261 CLR 544 (Ecosse Property), [17].

A commercial contract is to be construed so as to avoid it making commercial nonsense or working commercial inconvenience: Woodside Energy, [35]; Zhu v Treasurer (NSW) [2004] HCA 56; 218 CLR 530, [83]; Hide & Skin Trading Pty Ltd v Oceanic Meat Traders Ltd (1990) 20 NSWLR 310, 313-314.

Commercial contracts must be interpreted fairly and broadly, without being too astute or subtle in finding defects: Pan Foods Company Importers and Distributors Pty Ltd v Australia and New Zealand Banking [2000] HCA 20; 170 ALR 579, [14]; Australasian Performing Right Association, 109-110.

A construction that avoids unreasonable results is to be preferred to one that does not, even though it may not be the most obvious, or the most grammatically accurate: Australasian Performing Right Association, 109-110.

Determining the meaning of a contractual term normally requires consideration not only of the text, but also of the surrounding circumstances known to the parties, and the purpose and object of the transaction: Toll (FGCT) Pty Ltd v Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 52; 219 CLR 165, [40] (Toll); Codelfa Construction Pty Ltd v State Rail Authority (NSW) (1982) 149 CLR 337, 350; Pacific Carriers Ltd v BNP Paribas [2004] HCA 35; 218 CLR 451 (Pacific Carriers), [22]; Woodside Energy, [35]; Mount Bruce Mining Pty Ltd v Wright Prospecting Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 37; 256 CLR 104 (Mount Bruce Mining), [47] and [49]-[50]; Ecosse Property, [17].

Words may generally be supplied, omitted or corrected, in an instrument, where it is clearly necessary in order to avoid absurdity or inconsistency: Fitzgerald v Masters (1956) 95 CLR 420, 426-427.

In deciding whether there are special circumstances justifying a restraint of trade, the Court should be wary of placing weight upon “improbable and extravagant contingencies as indicating the restraint to be unreasonable”: Adamson v NSW Rugby League Ltd (1991) 31 FCR 242, 286 per Gummow J citing Haynes v Doman [1899] 2 Ch 13, 26.

Agreements in restraint of trade, like other agreements, must be construed with reference to the object sought to be attained by them. The object is the protection of one of the parties against rivalry in trade. Such agreements cannot be properly held to apply to cases which, although covered by the words of the agreement, cannot reasonably be supposed ever to have been contemplated by the parties, and which, on a rational view of the agreement, are excluded from its operation by falling, in truth, outside and not within its real scope: Haynes v Doman [1899] 2 Ch 13, 26.

If a clause is valid in all ordinary circumstances which have been contemplated by the parties, it is equally valid notwithstanding that it might cover circumstances which are so ‘extravagant’, ‘fantastic’, ‘unlikely or improbable’ that they must have been entirely outside the contemplation of the parties: Home Counties Dairies Ltd v Skilton [1970] 1 WLR 526, 536 endorsed in Rentokil, 304 (Doyle CJ), 320-321 (Matheson J) and 339 (Debelle J). See also Marion White Ltd v Frances [1972] 1 WLR 1423; Littlewoods Organisation Ltd v Harris [1978] 1 All ER 1026; Clarke v Newland [1991] 1 All ER 397.

The preferred approach is to have regard to the object and intent of the parties and read down a restraint of trade to give effect to that object and intent: Rentokil, 339; Koops Martin v Dean Reeves [2006] NSWSC 449, [40]; cf. Geraghty v Minter (1979) 142 CLR 177, 180.

A construction which will preserve the validity of the contract is to be preferred to one which will make it void: Pearson v HRX Holdings Pty Ltd [2012] FCAFC 111; 205 FCR 187, [45].

43 There are a number of features of cl 8.4(a)(1) of Contract ST0005 that warrant comment. The first is that it does not (at least not in terms) prevent TMA from operating in competition with StarTrack. Rather, it prohibits attempts to have StarTrack’s “customer[s] or client[s]” cease to do business with StarTrack or reduce what business they might otherwise so do. Although plainly it might, TMA’s maintenance of the ST Portal (in its current form) would not necessarily visit either consequence. To the extent that it might be made the subject of restraint, orders would need to be fashioned in such a way as to recognise that reality.

44 Second—and assuming, for the moment, that TMA is engaging in conduct that does visit one or both of those proscribed outcomes—it is apparent that the clause is one of very wide application. By its terms, it purports to restrain, for the term of the contract and a year thereafter, conduct that diverts any form of business (including not just the purchase of freight consumables) from any customer of StarTrack (including those with whom TMA has not hitherto interacted). Indeed, it is not limited to customers of StarTrack. It extends to customers or clients of StarTrack’s Related Bodies Corporate, one of which would surely be its parent, Australian Postal Corporation.

45 As with most debates about what is or is not reasonable, it would seem difficult to foreclose entirely upon the possibility that the court might ultimately be persuaded that cl 8.4(a)(1) of Contract ST0005 should serve validly to restrain TMA from operating the ST Portal (in its current form). I accept, then, that StarTrack has established a prima facie case that the ST Portal is currently being maintained in contravention of a valid contractual restraint.

46 Nonetheless, such case as has been established does not strike me as inherently strong. On the contrary, there appears to be a compelling argument that cl 8.4(a)(1) is irredeemably broad in what it purports to restrain; and, to that extent, travels beyond (if not well beyond) what might be justified as reasonable (and, therefore, enforceable). Perhaps the court will accept that the clause was never intended to prohibit (and should be construed so as not to prevent) TMA from selling a satchel or envelope to anybody who has ever purchased satchels or envelopes from Australia Post. It seems, however, more likely that it will not; if only because it is difficult to see how the words that are employed might fairly be construed in any other way.

47 A provision that purports to operate in restraint of trade is not enforceable to the extent that it is reasonable as between the parties and not unreasonably contrary to the public interest. Rather, it is enforceable if it satisfies those conditions. It is not open to the court to redraw the bargain that the parties struck so as to afford a measure of protection that is reasonable: Just Group, 182 [50].

48 In my view, cl 8.4(a)(1) of Contract ST0005 is ripe for rejection as an impermissible attempt to restrain TMA’s freedom to trade. The argument to the contrary, whilst open, does not strike me as strong.

Misleading and deceptive conduct and passing off

49 It is convenient to address StarTrack’s second and third causes of action together. The complaint is that, by continuing to operate the ST Portal (in the form that it now assumes), TMA may be understood to be luring customers on the false premise that it has some association with StarTrack.

50 Before considering that submission, some exploration of the evidence is appropriate. The ST Portal has, since its inception, operated from the same web address (or uniform resource locator, or “URL”): https://startrackgalaxy.tmagroup.com.au. Prior to 1 September 2023, it was adorned with imagery and prose that unambiguously associated it with StarTrack.

51 Access to the ST Portal is gained from a web browser. Historically, in order that one might place an order for the consumable products that it offered, one needed to enter login credentials supplied for that purpose. When credentials were created, TMA sent to the customer for whom they were created a “welcome email”, which directed customers to StarTrack’s “packaging” webpage (http://www.startrack.com.au/packaging). On that page, StarTrack placed an “Order Now” button, which, when clicked upon, redirected users to the ST Portal, whereupon they were invited to enter their login credentials.

52 Since the termination of Contract ST0005—and for obvious reasons—the StarTrack “packaging” webpage no longer has an “Order Now” button that links to the ST Portal.

53 On 19 and 20 September 2023, TMA sent emails to each of the registered users of the ST Portal (of which there were approximately 25,700). In each case, the email originated from the email address “Customer.Service@tmagroup.au” (which may or may not have been intended to be “Customer.Service@tmagroup.com.au”—nothing turns upon that presently). The email began with a virtual “button” that read “click here to order”, below which appeared a graphic of some packaging consumables next to the following:

Important Notice: There’s a change coming for StarTrack Users New TMA Online Shop available now

54 There then followed some email text, namely:

Dear Valued Customer,

We have heard your frustration and feedback and moving forward you will now be able to deal with TMA free from the frustrations and roadblocks as we now provide a direct offering free from any association with StarTrack.

This means better service, and cheaper pricing than you have currently been paying.

We are pleased to announce we will soon be launching our new TMA Online Shop – where you can order products such as satchel, cartons, printers, thermal labels, and much more, with free delivery and discounted prices.

What does this mean for me?

The new TMA Online Shop will provide an upgraded online ordering experience, replacing your old ordering platform.

What do I need to do?

It’s simple, just click the link and use your current login.

What are the benefits of the new TMA Online Shop?

• You’re already registered, use your current login

• Orders are charged direct to you

• Your choice, receive an Invoice, or make it simple with a discounted Credit Card payment

• Free Freight

• Deal direct, no third parties

• Talk to TMA about putting your logo and details on your Satchels and Boxes

…

55 The email concluded with some contact information and another virtual “click here to order” button identical to the earlier one. The two “click here to order” buttons linked to the ST Portal. Although there is an obvious similarity, the ST Portal now assumes a form that is different to that which it previously assumed. The most obvious change is that references to StarTrack have been removed (although, as will shortly be addressed, perhaps not removed as fulsomely as TMA would have preferred).

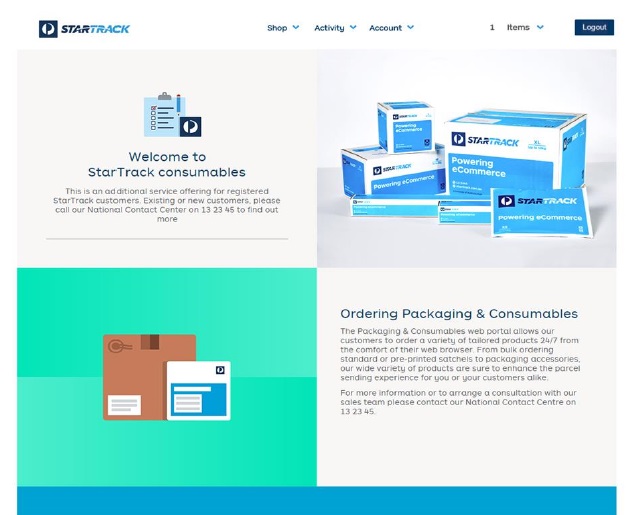

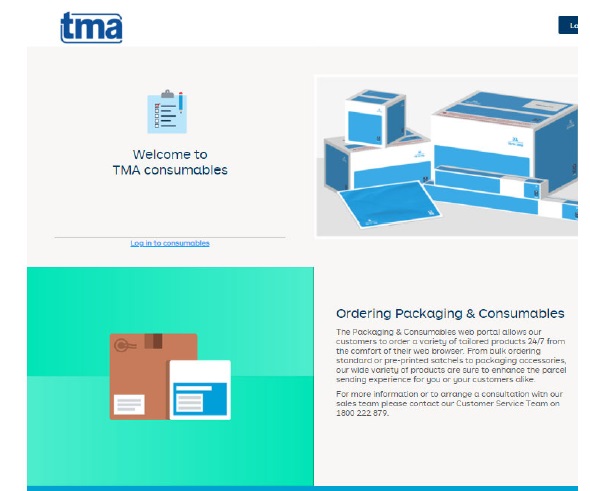

56 In its former state, the ST Portal’s home page bore the following appearance:

57 Since 19 September 2023, it has appeared as follows:

58 Although there was no evidence (certainly not anything properly admissible) as to how users typically access the ST Portal, there was evidence about what occurs when attempts are made to “bookmark” it (that is, when a user has occasion to add its URL to a suite of “favourite” or “bookmarked” websites stored for ease of access in or by his or her web browser). Specifically, the evidence was that users who attempt to “bookmark” the link are prompted to assign it a name and to identify where they wish it to be stored within the folder hierarchy by which their “bookmarked” websites are catalogued. The default name for any such “bookmark” is “Home” and there is a small “TMA” icon associated with the newly- or soon-to-be-created “bookmark”. The web address of the portal itself is not identified.

59 It would seem that users now access the ST Portal in one of four ways, namely: one, by entering the URL directly into their web browsers; two, by using a search engine to locate the URL and then clicking on it when (or if) it appears in relevant search results; three, by accessing the URL via a “bookmark” created for that purpose (either before or after TMA rebadged the ST Portal); or four, by opening the “welcome email” described above and clicking directly on one of the virtual “click here to order” buttons. It is only by means of the first two options that a user would gain any appreciation as to the content of the site’s URL.

60 Since approximately 10 October 2023—and, I would infer, in response to StarTrack’s having commenced this proceeding—TMA has added a “pop-up” notice to the ST Portal, which features the following, red text:

TMA no longer has any commercial relationship with StarTrack and TMA now offers its own consumable products to all customers from the TMA online shop, which can be accessed via your current link.

61 In total, 32 products are now offered for sale on the ST Portal. That compares to the many hundreds that were offered prior to 1 September 2023. The prices have been determined directly by TMA and apply universally to all users.

62 I accept that there is a prima facie case that, by continuing to operate the ST Portal in a form that bears at least some resemblance to how it appeared prior to 1 September 2023 and from a URL that contains reference to “StarTrack”, TMA is engaging in misleading or deceptive (or potentially tortious) conduct. It bears noting that conduct of that kind may inhere not merely in the inducement of a person to transact upon a false premise; but also in conduct that induces negotiations or offers to contract. That may be so even if steps are taken to correct false impressions before any resultant transaction is concluded: Verrocchi v Direct Chemist Outlet Pty Ltd (2015) 112 IPR 200, 212 [60] (Middleton J; cited with approval on appeal in Verrocchi v Direct Chemist Outlet Pty Ltd (2016) 247 FCR 570, 581 [68] (Nicholas, Murphy and Beach JJ)).

63 Thus, although not unimportant, TMA’s efforts to make clear to customers of the ST Portal that it no longer has any association with StarTrack (above, [53]-[54] and [60]) are not sufficient to inoculate it altogether against a charge that it is engaging in misleading and deceptive (or analogously tortious) conduct. I accept that, insofar as it continues to engage in online commerce with customers who are accustomed to purchasing StarTrack products from a website that contains StarTrack’s name and an appearance not dissimilar to that which it currently sports, it is at least arguably liable to the charges now levelled against it.

64 Nonetheless, I do not consider that such prima facie case as has been established is especially strong. For reasons already alluded to, there is good cause for thinking that many—and perhaps most or all—of the customers who, since 1 September 2023, have continued to transact via the ST Portal have done so unaware that its URL contains any reference to “StarTrack” (if, indeed, they ever had such an awareness). Further, although the appearance that the portal now assumes bears more than a passing similarity to that which it has historically borne, it remains the case that it has been unambiguously rebranded. Although not non-existent, the risk that present day users might arrive at the ST Portal thinking that they have accessed a StarTrack website (or a website otherwise associated in some way with it) seems very low.

65 Such risk as might exist (despite the rebranding of the portal and despite the unambiguous emails of 19 and 20 September 2023) is then quite effectively addressed by the pop-up notification described earlier (above, [60]). It appears very much to be the case that no user of the ST Portal could now reasonably labour under the impression that any consumable products purchased from it are products of StarTrack’s, nor that any such transactions are transactions entered into with StarTrack or with a business associated with it.

66 Something should be said about TMA’s ongoing use of the ST Portal URL. That, I think, is StarTrack’s most persuasive angle of attack: that the continued use of a URL that contains its name is apt to mislead users into assuming an association that does not exist. Clearly, it could be (and I have accepted as much). An obvious solution to at least part of the dispute that has arisen between the parties would be for TMA to migrate the ST Portal to a new URL that does not include reference to “StarTrack”. The evidence demonstrates that that possibility has been explored. There appear to be highly technical considerations that render it uncommercial or impossible (or both) in the short term. Nothing turns upon that but I note it lest it be thought that that obvious solution has, thus far, gone unconsidered.

67 In all of the circumstances, I do not consider that there is a strong prima facie case that TMA’s continued operation of the ST Portal is such as might mislead or deceive customers into thinking that they are transacting—or even being invited to transact—with StarTrack or a business associated with it. Such case as there is in that regard appears to me to be weak.

Unconscionable conduct

68 StarTrack submits that, since Contract ST0005 came to an end (and, possibly, in the timeline leading up to that point), TMA has engaged in unconscionable conduct. I regret to confess some difficulty in following what, precisely, that conduct has comprised; and how or why it should sound in the grant of interlocutory relief. That observation should not be mistaken for criticism. On the contrary, it seems more likely than not that StarTrack’s unconscionable conduct cause of action, to the extent that it is not subsumed in its other causes, is ancillary to its more immediate and primary submissions about TMA’s ongoing operation of the ST Portal.

69 Regardless, it is said that TMA has acted unconscionably by disabling (or not otherwise maintaining) StarTrack’s ability to generate reports about transactions undertaken via the portal prior to 1 September 2023, by asserting ownership in or an ongoing ability to continue operating the ST Portal, and by continuing so to operate it after offering to sell it to StarTrack for $25 million.

70 Unconscionability is, by nature, fact- and context-specific: Unique International College Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2018) 266 FCR 631, 654 [104] (Allsop CJ, Middleton and Mortimer JJ). To qualify as unconscionable, a respondent’s conduct must bespeak a “high level of moral obloquy” or otherwise be “so far outside societal norms of acceptable commercial behaviour as to warrant condemnation as conduct that is offensive to conscience”: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Kobelt (2019) 267 CLR 1, 40 [92] (Gageler J).

71 Insofar as StarTrack’s unconscionable conduct allegations are subsumed in the causes of action already addressed, I am led to equivalent conclusions: namely, that any prima facie case for relief (principally in the form of an injunction or injunctions to restrain TMA from continuing to operate the ST Portal) that StarTrack has established is not strong. I do not consider that StarTrack has established anything more than a weak prima facie case that, by continuing to operate the ST Portal in the way and circumstances that it has, TMA has offended against accepted standards of commercial conscience.

72 Insofar as it extends to other conduct with which those other causes of action do not engage, some further background should be noted.

73 TMA’s evidence was that the reporting architecture of which StarTrack was unable to avail itself prior to September 2023 was not deliberately disabled. Mr Kneepkens deposed to that functionality being dependent upon a “separate server” and that the information generated by it was “not produced from the Portal directly”. The software that is (or was) used to produce that of which StarTrack complains that it has been deprived “…needs a software patch or upgrade in order to produce th[o]se reports”. The evidence suggests that it would take 14 days and cost a minimum of $35,000.00 (ex GST) to correct the problem.

74 As a workaround, TMA has offered to provide StarTrack with packing slips, which record what TMA dispatched in response to orders placed via the ST Portal prior to 1 September 2023. Those packing slips, it is said, would enable StarTrack to generate invoices related to those sales (which it complains it is currently unable to generate for want of information about what was sold).

75 StarTrack offered no explanation as to why the production of packing slips would be insufficient to address the problems that have animated its application for urgent interlocutory injunctive relief. In light of what little evidence there is about the content of those records and what might be done with it, there is no reason to reject what TMA says.

76 Insofar as StarTrack’s unconscionable conduct allegations extend beyond what has already been addressed in connection with its other causes of action—and, in particular, to the disabling or non-maintenance of StarTrack’s ability to generate reports concerning transactions undertaken via the ST Portal prior to 1 September 2023—I accept that there is at least a prospect that StarTrack will establish, at trial, an entitlement to relief. Nonetheless, such prima facie case as there might be does not strike me as inherently strong. In the interim, TMA should provide packing slips as it has undertaken to.

Balance of convenience

77 The grant of interlocutory injunctive relief necessarily involves what TMA described as “…an indulgence in circumstances where the full matter has not been heard”. That being so, the court is concerned to “…take the course that appears to carry the lower risk of injustice if it should turn out to have been wrong, in the sense of granting an injunction to a party who fails to establish the asserted right at trial, or failing to grant an injunction to a party who succeeds at trial”: Yimiao Australia v Cyber Intelligence [2023] VSCA 21, [29] (McLeish, Walker and Macaulay JJA), citing Bradto Pty Ltd v State of Victoria (2006) 15 VR 65, 73 [35] (Maxwell P and Charles JA); CIP Group Pty Ltd v So (No 3) [2023] FCA 518 [32] (Derrington J).

78 StarTrack submits that, unless the court intervenes to restrain TMA from operating the ST Portal, it stands to suffer irreparable damage to its freight consumables business. It is said that that damage will likely spill over into its primary parcel, freight and logistics business as well.

79 As concerns the damage that interlocutory injunctive relief will visit upon TMA, StarTrack contends that it should be assessed bearing in mind that (reference to authority omitted):

(a) TMA has only recently launched the new TMA Online Shop. In contrast, StarTrack spent over a decade acquiring its customers and building a relationship with them;

(b) the new TMA Online Shop operates from a URL that has StarTrack’s name in it, and that name is a registered trademark;

(c) the new TMA Online Shop appears to only be accessible by StarTrack customers such that its sole purpose is to divert StarTrack’s customers and their business to TMA;

(d) the new TMA Online Shop uses photographs, images, fonts, product codes and product descriptions and specifications provided by StarTrack to TMA (including some which show the StarTrack trademarked name, and StarTrack and AusPost logos);

(e) having regard to the matters in (b)-(d) above, TMA launched the new TMA Online Shop with its “eyes wide open” to its use of StarTrack’s confidential customer information and StarTrack Property – TMA did not accidentally use StarTrack’s confidential customer information and intellectual property; and

(f) in relation to StarTrack’s application for injunctions to restrain TMA from dealing with StarTrack’s customers, using StarTrack’s confidential customer information and StarTrack’s Property, StarTrack has identified the information and property with sufficient particularity…

80 StarTrack further acknowledged the possibility that a grant of interlocutory relief now might, in effect, approximate the granting of final relief, in that there is at least some risk that the court would not be able to hear and determine its substantive originating application before the expiry of the one-year restraint that it seeks to enforce. It is acknowledged that, in such circumstances, the court might give additional attention to the prospect that StarTrack’s case might not succeed at trial: Wilson Pateras Accounting Pty Ltd v Farmer [2020] FCA 1763, [116] (Wheelahan J); Liberty Financial, [278] (Beach J).

81 It is appropriate, at this juncture, to say something about StarTrack’s contention that TMA has continued to use StarTrack or Australia Post-branded imagery in the ST Portal, and has continued to offer StarTrack products for sale. There is evidence to support both propositions (untested though it obviously is at this interlocutory stage). It is apparent that that evidence has come as something of a surprise to TMA (and that, in the absence of being able to test it, TMA is unable to explain how those occurrences have transpired, assuming that they have).

82 Regardless, TMA has offered undertakings to the court that it will refrain from featuring on the ST Portal (other than on the pop-up notice described earlier) any references to or imagery associated with Australia Post or StarTrack, and from offering for sale or selling any consumable products bearing StarTrack attire. Those undertakings appear to reflect its broader commercial intentions and should be accepted. Leaving aside concerns about the ST Portal’s URL momentarily, those undertakings quite plainly address StarTrack’s legitimate concerns about any unauthorised use of its name, imagery or products.

83 That leaves for consideration TMA’s ongoing operation of the ST Portal and the relief that StarTrack seeks in connection with the provision of reporting information. As to the former, it appears to be the case that, absent injunctive relief, the damage that StarTrack stands to endure from the continued operation of the ST Portal inheres primarily in damage to its goodwill and market share. Damage of that kind is notoriously difficult to quantify and it is only in rare cases that an order for damages would be considered adequate to address it: Ricegrowers' Co-Operative Limited v Howling Success Australia Pty Limited (1987) ATPR 40-778, 48,494 (Gummow J, citing Turner v General Motors (Australia) Pty Ltd (1929) 42 CLR 352, 362-363 (Isaacs J), 368 (Dixon J)); Nintendo Co Ltd v Care (2000) 52 IPR 34, [18] (Goldberg J).

84 I pause to repeat that it appears to be the case that the inconvenience to StarTrack in TMA’s ongoing operation of the ST Portal will or might inhere (at least principally) in damage to goodwill and loss of market share. TMA submits—not without justification—that that cannot be accepted with unwavering confidence. As much is that so in that the evidence does not disclose how (or even if) it is that StarTrack now markets the consumables that were once purchased via the ST Portal.

85 It is, then, difficult for the court to make much of an assessment about the impact that TMA’s continued operation of the ST Portal is likely to visit upon StarTrack. It is not apparent on such evidence as there is at the moment how StarTrack now markets its consumable products, what revenues it generates from those efforts or what portion of its overall income those revenues represent. Indeed, the evidence suggests—albeit in the usual, untested way, at this interlocutory stage—that supplying freight consumables is not StarTrack’s core business.

86 StarTrack submits that TMA’s continued operation of the ST Portal threatens to divert freight business that would otherwise fall to it. It is suggested that the sale of StarTrack consumable products is one of the ways in which customers are moved to engage StarTrack to oversee the shipping of their own goods. StarTrack’s concern is that if TMA continues to sell its own consumable products via the ST Portal, customers who purchase them might not have occasion to engage StarTrack to undertake the deliveries for which they are subsequently used. In other words, StarTrack’s value proposition as a “one-stop shop” might be undermined.

87 It is fair to say, without criticism, that the evidence on that front is thin. The high point of it appears to be a confirmation from one of StarTrack’s freight competitors, Border Express, concerning the delivery of goods purchased from TMA. It would appear—perhaps without much in the way of surprise—that TMA has engaged a different freight provider to deliver the consumable goods that are purchased from it via the ST Portal. Whether the customers to whom those goods are delivered have, thereafter, continued to use (or, indeed, whether they ever used) StarTrack for their own delivery purposes is unknown.

88 In those circumstances, I do not consider that I could determine with confidence that—nor the extent to which—TMA’s ongoing operation of the ST Portal presents as a threat to StarTrack’s freight business. I would be prepared to assume that it, insofar as it continues to market its consumable products, StarTrack stands to endure at least some damage to its goodwill and market share; and that that damage would be difficult to quantify in dollar terms. How significant it might be, however, remains unclear.

89 Against those observations, there are compelling reasons to think that a grant of interlocutory injunctive relief to restrain TMA from continuing to operate the ST Portal (and otherwise transacting with “StarTrack customers”) would visit significant prejudice against it. That prejudice would extend beyond the revenue that the ST Portal (in its present form) has generated since its rebadging (which the evidence suggests is somewhere in the order of $36,500 per week). Further, the evidence suggests that some of the customers that purchased StarTrack goods via the ST Portal prior to 1 September 2023 are customers with whom it has independently transacted via other means.

90 Additionally, TMA has led evidence that suggests that, if it is restrained (temporarily or otherwise) from operating the ST Portal, it will likely have to make a number of employees redundant. Although that might not sound as prejudice that the grant of injunctive relief would visit upon TMA, it is nonetheless a species of prejudice that is apt to guide the exercise of the court’s discretion: Patrick Stevedores Operations No 2 Pty Ltd v Maritime Union of Australia (1998) 195 CLR 1, 42 [65] (Brennan CJ, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ).

91 All told, I am not persuaded that the balance of convenience here tends strongly in favour of or against the grant of interlocutory relief to restrain TMA from continuing to operate the ST Portal or otherwise transacting with “StarTrack customers”. On the contrary, it appears that the prejudice inherent in either eventuality is balanced. It might well tend against what StarTrack proposes.

Disposition

92 Given the conclusions that I have drawn about the apparent weaknesses inherent in the causes of action that StarTrack pursues—and, in particular, its attempt to enforce the contractual restraint that cl 8.4(a)(1) of Contract ST0005 purports to establish—I am not persuaded that the balance of convenience here calls for an exercise of the court’s discretion to grant interlocutory injunctive relief to restrain TMA from operating the ST Portal or otherwise transacting as it proposes to.

93 I turn, then, to consider the provision of reporting information. It bears repeating that TMA has offered to supply StarTrack with packing slips relating to transactions that were completed before it took over operation of (or repurposed) the ST Portal. It was explained that information in that form would afford StarTrack a means of particularising those transactions, and of invoicing relevant customers in respect of what was purchased.

94 As has been noted, StarTrack has not explained why, at an interlocutory level, relief in that form should not suffice. TMA has volunteered it by means of an undertaking to the court. That should be accepted (and, for now at least, acceptable).

95 I shall refrain from making any order for costs at this juncture. Instead, the parties should have an opportunity to reflect upon these reasons and, if possible, to agree upon what, if any, costs order ought to be made. In the absence of agreement, the parties can notify my chambers and the issue can be taken from there.

Suppression

96 At the hearing of the application for interlocutory relief, related applications were made (without opposition) for orders to maintain aspects of commercial confidentiality that was said to attach to several documents annexed to the affidavit material that was relied upon. Unable to rule upon those applications at the time (and in the absence of opposition), I made interim orders pursuant to s 37AI of the FCA Act. For the reasons below, I intend to confirm those orders on an ongoing basis under s 37AF.

97 The interim orders pertain to two documents annexed to the affidavit sworn by Ms Arsenoulis on 4 October, two documents annexed to the affidavit affirmed by Mr Kneepkens on 6 October 2023 and six documents annexed to the affidavit affirmed by Mr Kneepkens on 11 October 2023.

98 All of the documents that are the subject of the interim orders contain information about StarTrack’s and TMA’s customers. That information assumes various forms, including contact information, order histories, pricing profiles, and customer-specific screenshots and reports.

99 Section 37AF of the FCA Act provides as follows:

37AF Power to make orders

(1) The Court may, by making a suppression order or non‑publication order on grounds permitted by this Part, prohibit or restrict the publication or other disclosure of:

(a) information tending to reveal the identity of or otherwise concerning any party to or witness in a proceeding before the Court or any person who is related to or otherwise associated with any party to or witness in a proceeding before the Court; or

(b) information that relates to a proceeding before the Court and is:

(i) information that comprises evidence or information about evidence; or

(ii) information obtained by the process of discovery; or

(iii) information produced under a subpoena; or

(iv) information lodged with or filed in the Court.

(2) The Court may make such orders as it thinks appropriate to give effect to an order under subsection (1).

100 A “suppression order” is an order that prohibits or restricts the disclosure of information, whether by publication or otherwise: FCA Act, s 37AA.

101 The grounds upon which the court might make a suppression order are the subject of s 37AG, which provides as follows:

37AG Grounds for making an order

(1) The Court may make a suppression order or non‑publication order on one or more of the following grounds:

(a) the order is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice;

(b) the order is necessary to prevent prejudice to the interests of the Commonwealth or a State or Territory in relation to national or international security;

(c) the order is necessary to protect the safety of any person;

(d) the order is necessary to avoid causing undue distress or embarrassment to a party to or witness in a criminal proceeding involving an offence of a sexual nature (including an act of indecency).

(2) A suppression order or non‑publication order must specify the ground or grounds on which the order is made.

102 In deciding whether to make a suppression order, the court is obliged to take into account that a primary objective of the administration of justice is to safeguard the public interest in open justice: FCA Act, s 37AE.

103 In Naude v DRA Global Limited [2023] FCA 493, I had occasion to survey the principles that guide applications under pt VAA of the FCA Act. I made the following observations (at [13]-[15]), which are presently apt:

In R v Davis (1995) 57 FCR 512 (Wilcox, Burchett and Hill JJ), this court observed (at 514):

Whatever their motives in reporting, [the media’s] opportunity to do so arises out of a principle that is fundamental to our society and method of government: except in extraordinary circumstances, the courts of the land are open to the public. This principle arises out of the belief that exposure to public scrutiny is the surest safeguard against any risk of the courts abusing their considerable powers. As few members of the public have the time, or even the inclination, to attend courts in person, in a practical sense this principle demands that the media be free to report what goes on in them.

The exclusion of public access to the processes with which a court deals is only to be effected in exceptional cases: The Country Care Group Pty Ltd v Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) (No 2) (2020) 275 FCR 377, 379 [8] (Allsop CJ, Wigney and Abraham JJ; hereafter “Country Care Group”); David Syme & Co v General Motors-Holden’s Ltd [1984] 2 NSWLR 294, 299 (Street CJ), 307 (Hutley AP, Samuels JA agreeing). In John Fairfax Group Pty Ltd (Receivers and Managers Appointed) v Local Court (NSW) (1991) 26 NSWLR 131, Kirby P (in dissent but not on this issue) said (at 142-143):

It has often been acknowledged that an unfortunate incident of the open administration of justice is that embarrassing, damaging and even dangerous facts occasionally come to light. Such considerations have never been regarded as a reason for the closure of courts, or the issue of suppression orders in their various alternative forms… A significant reason for adhering to a stringent principle, despite sympathy for those who suffer embarrassment, invasions of privacy or even damage by publicity of their proceedings is that such interests must be sacrificed to the greater public interest in adhering to an open system of justice. Otherwise, powerful litigants may come to think that they can extract from courts or prosecuting authorities protection greater than that enjoyed by ordinary parties whose problems come before the courts and may be openly reported.

It is well accepted that “…mere embarrassment, inconvenience or annoyance will not suffice to ground an application for suppression or non-publication”: Keyzer v La Trobe University (2019) 165 ALD 93, 99 [29] (Anastassiou J). It is a feature of open justice that those to whom court processes refer may thereby suffer embarrassment or distress; but “…that is a price the community has to pay for the undoubted benefit of court proceedings being, except in very exceptional circumstances, conducted in public”: Williams v Forgie (2003) 54 ATR 236, 239 [14] (Heerey J).

104 A suppression order may be made only if it is necessary to achieve one of the objects listed in s 37AG(1) of the FCA Act. For present purposes, only s 37AG(1)(a) is relevant. The word “necessary” in s 37AG(1)(a) is a strong one: The Country Care Group Pty Ltd v Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) (No 2) (2020) 275 FCR 377, 379 [9] (Allsop CJ, Wigney and Abraham JJ). That an order might be convenient, reasonable or sensible, or otherwise might serve some notion of public interest is not enough: Hogan v Australian Crime Commission (2010) 240 CLR 651, 664 [31] (French CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Heydon and Kiefel JJ); Australian Rail, Tram and Bus Industry Union v Busways Northern Beaches Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 188, [8] (Bromberg, Wheelahan and Snaden JJ).

105 The authorities recognise that there is a risk that prospective litigants might feel deterred from taking legal action to vindicate their rights if doing so should require that they disclose information that is commercially sensitive (or, indeed, sensitive in some other way). It is accepted that that deterrence can qualify as a form of prejudice to the proper administration of justice: Huikeshoven v Secretary, Department of Education, Skills and Employment [2021] FCA 1359, [57]-[58] (Jackson J) and the authorities to which his Honour there refers.

106 In Porter v Australian Broadcasting Corporation [2021] FCA 863, Jagot J observed (at [84]):

…The administration of justice may be prejudiced in a variety of ways. If, for example, people cannot come to a court confident that some kinds of information can be protected from disclosure if necessary (such as commercially confidential information valuable to a person or a third party, or sensitive information about a person’s health, or personal information about parties or third parties of no more than prurient interest to others) then public confidence in and access to justice may itself be undermined.

107 Specifically in the context of information that is commercially sensitive, it has been observed that:

It is in the interests of the proper administration of justice that the value of confidential information not be destroyed or diminished. Otherwise, the parties and members of the public might lose confidence in the Court and the Court’s processes “might open the way to abuse”…

Australian Competition & Consumer Commission v Origin Energy Electricity Ltd [2015] FCA 278, [148] (Katzmann J); see also Clark v Digital Wallet Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 877, [21] (Abraham J).

108 There is, in my view, no doubt that the information that the parties here seek to maintain as confidential between themselves is commercially sensitive information of the kind that the court should protect by means of orders under s 37AF(1) of the FCA Act. There shall be relief accordingly.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and eight (108) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Snaden. |

Associate: