Federal Court of Australia

Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd v Lavazza Australia Pty Ltd (No 3) [2023] FCA 1258

ORDERS

CANTARELLA BROS PTY LTD (ACN 000 095 607) Applicant | ||

AND: | LAVAZZA AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 605 275 107) First Respondent LAVAZZA AUSTRALIA OCS PTY LTD ACN 626 604 555 Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. By 30 November 2023, the parties bring in orders giving effect to these reasons.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[6] | |

[35] | |

[117] | |

[209] | |

[212] | |

[220] | |

[223] | |

[262] | |

[264] | |

[332] | |

[332] | |

[338] | |

[351] | |

[368] | |

[375] | |

[383] | |

[392] | |

[392] | |

[403] | |

[417] | |

[434] | |

[455] | |

[469] | |

[486] | |

[486] | |

[502] | |

[538] | |

[549] | |

[552] | |

[594] | |

[602] | |

[602] | |

[603] | |

[611] | |

[619] | |

[629] | |

[655] | |

YATES J:

1 The applicant, Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd (Cantarella), sues the respondents, Lavazza Australia Pty Ltd (Lavazza Australia) and Lavazza Australia OCS Pty Ltd (Lavazza OCS), for infringement of two registered trade marks—Trade Mark No. 829098 (the 098 mark) and Trade Mark No. 1583290 (the 290 mark)—each of which is the word mark ORO registered in class 30 for “Coffee; beverages made with a base of coffee, espresso; ready-to-drink coffee; coffee based beverages” (the ORO word mark). For ease of reference, I will refer to these goods as coffee or the registered goods. I will also refer to, and treat, the respondents as a single entity—Lavazza—unless it is necessary to distinguish between them.

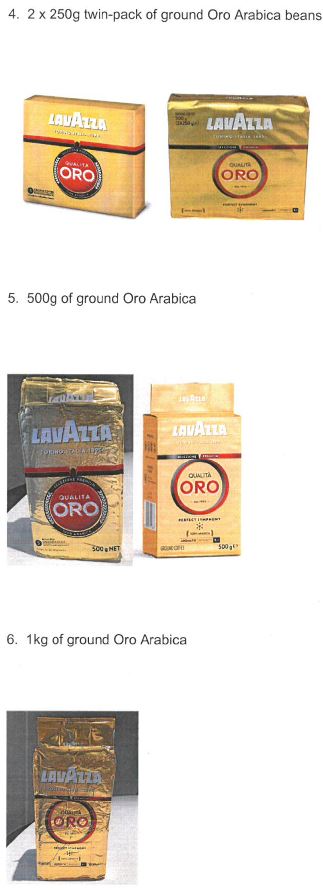

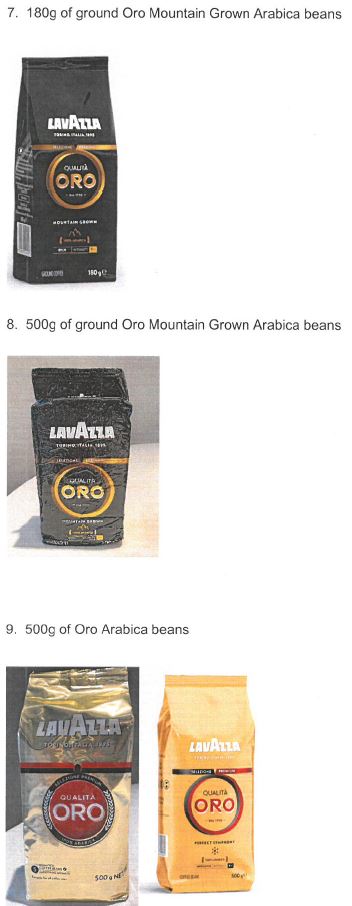

2 Cantarella’s case is based on s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (the Act). The goods, and the manner in which Lavazza has used the word “oro” on them, are shown in Schedule 1 to these reasons. Cantarella alleges that Lavazza Australia has supplied all the goods. It alleges that Lavazza OCS has supplied the goods shown as items 11 and 12 (coffee capsules). Cantarella also alleges that Lavazza has advertised the goods on websites.

3 Lavazza does not dispute that the goods shown in Schedule 1 have been supplied and advertised. Lavazza does dispute, however, that the 098 mark and the 290 mark have been infringed. Lavazza contends that, in undertaking these activities, the word “oro” has not been used as a trade mark. Lavazza also contends that, even if, in undertaking these activities, the word “oro” has been used as a trade mark, various defences to infringement exist, and have been established, in the particular circumstances of this case.

4 More fundamentally, Lavazza disputes that the two marks are validly registered. By a notice of cross-claim, now supported by a further amended statement of cross-claim, Lavazza seeks orders that the registrations of the two marks be cancelled for two independent reasons: first, each mark is not inherently adapted to distinguish Cantarella’s goods from the goods of other persons and, therefore, does not meet the requirements of s 41 of the Act as in force at the relevant time; and secondly, Cantarella is not, in any event, the owner in Australia of the ORO word mark in respect of coffee.

5 For the reasons that follow, I am satisfied that Lavazza’s supply of LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO coffee has involved use of the ORO word mark. However, Cantarella’s case on infringement cannot succeed because the registrations of the 098 mark and the 290 mark on which it relies are not valid. Given that conclusion, it has not been necessary for me to determine the defences that have been raised. I have, nonetheless, made a number of observations about the applicability of those defences.

6 At the outset, it is necessary for me to say something about the conduct of this case. Some of the history of the proceeding has been recorded in another published judgment of the Court: Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd v Lavazza Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCA 894 (Cantarella (No 2)). It is appropriate, however, that some of the matters referred to in that judgment be repeated in the following overview.

7 The proceeding was commenced on 23 August 2019 by the filing of an originating application and statement of claim. Lavazza filed its cross-claim on 11 October 2019 and its defence to the statement of claim on 14 October 2023.

8 On 11 December 2019, orders were made by consent setting down the proceeding for final hearing commencing on 7 December 2020, with an estimated duration of four days (to 10 December 2020). On 2 November 2020, an order was made that the hearing be extended by an additional day to 11 December 2020.

9 Early in the case management of the proceeding, a regime was put in place for the notification, and possible resolution, prior to the commencement of the hearing, of objections to evidence. An order was made on 2 November 2020 that the proceeding be listed on 1 December 2020 to determine any outstanding objections. That hearing took place, as appointed. A number of rulings were made. The determination of some objections was deferred on the basis that those objections might be overcome by further consultation between the parties’ legal advisers, or by the service of supplementary affidavits.

10 The hearing commenced on 7 December 2020. On 11 December 2020, the last day appointed for the hearing, a number of objections to affidavits (which Cantarella had progressively filed throughout the course of the hearing to overcome other objections to evidence that had been made) were still being argued. I was persuaded that rulings on those objections would best be made in the context of a voir dire. The hearing was therefore adjourned part heard.

11 On 15 January 2021, the proceeding was listed for further hearing on 8, 15 and 16 June 2021, with the final two days set aside for the parties’ closing submissions. A period of much earlier dates in March – April 2021 was offered to the parties, but the Court was informed that there were difficulties with the availability of counsel in that period.

12 On 19 May 2021, in the intervening period, Lavazza served copies of the affidavits of two employees of Caffè Molinari SpA (Molinari). The service of these affidavits (the Molinari affidavits) had not been foreshadowed. At the same time, Lavazza indicated that it also wished to make amendments to its defence and cross-claim. On 21 May 2021, Cantarella, through its solicitors, informed Lavazza’s solicitors that it opposed those amendments and also Lavazza’s reliance on the new affidavits.

13 On 1 June 2021, the proceeding was relisted at Lavazza’s request. On that day, I granted leave to Lavazza to file an interlocutory application (dated 21 May 2021) seeking leave to adduce and rely on the Molinari affidavits, and an affidavit by Mr Lee, a partner in the firm acting for Lavazza in this proceeding. The interlocutory application also sought leave to make the pleading amendments that Lavazza wished to make. I made other procedural directions at that time and set down the interlocutory application for hearing on 8 June 2021, the date to which the hearing had already been adjourned for the hearing of the voir dire and the possible cross-examination of the deponent whose affidavits were still under challenge.

14 At the resumed hearing on 8 June 2021, the outstanding objections to the affidavits on which Cantarella wished to rely were resolved by agreed rulings. The need for the voir dire, and subsequent cross-examination of the deponent involved, was thereby obviated.

15 Lavazza’s interlocutory application was heard on 8 June 2021. It was strenuously opposed. Nevertheless, at the conclusion of the hearing, I granted leave to Lavazza, on terms, to rely on the Molinari affidavits. I also granted leave to Lavazza to amend the pleading of its defence and cross-claim. This led to the vacation of the hearing dates appointed for 15 and 16 June 2021 because I acceded to the proposition that Cantarella should have the opportunity to respond to those affidavits.

16 Cantarella filed a further amended defence to Lavazza’s further amended cross-claim dated 10 June 2021. The further amended defence raised a substantial number of additional grounds on which Cantarella resisted Lavazza’s claim for cancellation of the registrations of the 098 mark and the 290 mark.

17 On 21 July 2021, Cantarella sought to revisit the grant of leave I made on 8 June 2021 to allow Lavazza to adduce and rely on the Molinari affidavits, by having further conditions imposed on the grant of leave that had been made. That application was refused: Cantarella (No 2).

18 On 4 August 2021, orders were made by consent setting down the resumed hearing for four days (and, if the court permitted, to continue on a fifth day) commencing on 6 December 2021.

19 The resumed hearing commenced on 6 December 2021 and concluded on 8 December 2021, at which time judgment was (initially) reserved.

20 By the conclusion of the two hearings, the Court had been provided with a large number of written submissions, which were of considerable length. When those submissions were reviewed in the non-sitting period in January 2022, following closing addresses in December 2021, it became clear that the sequence of the submissions was difficult to follow. The problem was exacerbated by the fact that the parties had used non-standardised terms in their cross-references to each other’s submissions.

21 I therefore listed the proceeding for a case management hearing on 14 February 2022 to discuss my concerns. The parties accepted that revision of the written submissions was required. They advanced a proposal whereby they would adopt uniform abbreviations for the various submissions; that the submissions be presented as a bundle in a given order with certain formatting; and that the submissions be updated with standardised cross-references to each other’s submissions and, where necessary, new transcript references.

22 Revised written submissions, which alleviated some of the problems involved with the sequence of the submissions, were prepared and provided to the Court in electronic form on 24 March 2022. At that time, I was informed that the parties’ written submissions were constituted by the following documents:

(a) Cantarella’s Opening Submissions on Infringement (16 November 2020);

(b) Cantarella’s Opening Submissions on the Cross-Claim (Validity) (30 November 2020);

(c) Cantarella’s Closing Submissions on Infringement (1 November 2021);

(d) Cantarella’s Closing Submissions on the Cross-Claim (Validity) (1 November 2021);

(e) Lavazza’s Closing Submissions on Infringement and on the Cross-Claim (Validity) (1 November 2021);

(f) Cantarella’s Closing Submissions in Answer on Infringement and on the Cross Clam (Validity) (12 November 2021);

(g) Lavazza’s Closing Submissions in Answer on Infringement and on the Cross-Claim (Validity) (15 November 2021);

(h) Lavazza’s Closing Submissions on the Molinari Issue (8 December 2021) (replacing submissions dated 22 November 2021);

(i) Cantarella’s Opening Submissions on the Molinari Issue (20 December 2021) (originally filed on 30 November 2021, but amended with cross-references to the submissions referred to at (h)); and

(j) Cantarella’s Closing Submissions on the Molinari Issue (20 December 2021) (originally filed on 8 December 2021, but containing a correction made orally by Senior Counsel).

23 On 27 April 2022, Cantarella filed an interlocutory application (dated 22 April 2022) seeking leave to further amend its statement of claim and to re-open its case to allege further infringements by Lavazza of the 098 mark and the 290 mark by the importation and supply of Lavazza coffee capsules in packaging which had not previously been raised in the proceeding. It appears that capsules in this packaging were put on supermarket shelves in Australia from 4 April 2022.

24 Despite Lavazza’s opposition, I was persuaded that leave should be granted to Cantarella to re-open its case on the basis that a determination of the issues raised by the new infringements might well influence the determination of some of the issues already before the Court.

25 On 15 June 2022, I made a number of timetabling orders for the filing of further amended pleadings, further affidavit evidence, and further written submissions. I then listed the proceeding for a case management hearing on 7 September 2022 in the expectation that, at that time, a further hearing date would be appointed.

26 The following further written submissions were filed in respect of the alleged new infringements:

(a) Cantarella’s submissions in chief dated 19 August 2022;

(b) Lavazza’s submissions in answer dated 26 August 2022; and

(c) Cantarella’s submissions in reply dated 2 September 2022.

27 On 5 September 2022, the Court was informed that the parties did not wish to be heard further. Judgment was then reserved from that date.

28 The hearing of the proceeding has been protracted because of the various twists and turns to which I have referred. At the time the hearing was adjourned part heard on 11 December 2020, these twists and turns were not, and could not have been, foreseen. Indeed, at the time of closing addresses on 8 December 2021, the events occurring after that date were not, and could not have been, foreseen.

29 By the time the Court was informed on 5 September 2022 that the parties did not wish to be heard further, other allocated hearings in my docket had, inevitably, intervened, with the consequence that the opportunity for full and complete deliberation of the issues raised in this proceeding has been delayed.

30 The parties have been granted leave to amend their pleadings numerous times. The final pleadings comprise:

(a) Cantarella’s second further amended statement of claim dated 30 May 2022;

(b) Lavazza’s third further amended defence dated 27 June 2022;

(c) Cantarella’s third further amended reply dated 11 July 2022;

(d) Lavazza’s further amended statement of cross-claim dated 10 June 2021;

(e) Cantarella’s further amended defence to cross-claim dated 9 July 2021; and

(f) Lavazza’s reply to further amended defence to cross-claim dated 23 July 2021.

31 A prodigious amount of evidence has been adduced, including through the tender of a large number of documents and a large number of physical exhibits. The documentary tenders are to be found largely, but not exclusively, in two electronic court books. The first court book (comprising 6904 pages) was prepared for the hearing in December 2020. The second court book (comprising 1319 pages) was prepared for the hearing in December 2021. Further evidence was adduced in respect of the alleged new infringements in 2022.

32 As I have noted, objections to evidence were dealt with prior to the commencement of the hearing on 7 December 2020. A number of remaining objections, and a number of new objections to evidence, either fell away during the course of the hearings in December 2020 and in December 2021 or were accommodated by agreed rulings. The affidavits read at those hearings, and the rulings made in respect of those affidavits, have been recorded in a document marked as Joint Exhibit 1. The documents tendered at those hearings (other than documents referred to as exhibits in affidavits which were taken to have been admitted into evidence) have been recorded in a document marked as Joint Exhibit 2.

33 My consideration of this matter has been considerably assisted by the written submissions which I have listed (in total, 498 pages). My consideration has also been assisted by recourse to a full transcript of the proceeding and the extensive notes I made during the course of the hearing.

34 A great many issues were raised and canvassed by the parties. Given the conclusions I have reached, it has not been necessary for me to decide all the issues that were raised.

The Lavazza business in Australia

35 Lavazza Australia is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Luigi Lavazza SpA (LL SpA). Lavazza OCS is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Lavazza Australia.

36 Since 2015, Lavazza Australia has distributed Lavazza products in Australia. Lavazza OCS was established in 2018 to acquire The Blue Pod Coffee Co Pty Ltd which, in the period 2008 to 2018, was the exclusive distributor of Lavazza products in Australia in the Office Coffee Service (OCS) sector.

37 These are relatively recent events. The evidence shows, however, that Lavazza products have been supplied in Australia over a much longer period of time. The history of that activity is relevant to a number of issues in this proceeding.

38 LL SpA was incorporated in Italy as a joint-stock company in 1927. However, the Lavazza business had its beginnings in 1895 when Luigi Lavazza founded a business selling a variety of goods, including soap, spirits, oil, candles, spices, and coffee.

39 LL SpA has its headquarters in Turin. The company has operated as a family business, with generations of the family holding key positions in the management of the company.

40 Following the Second World War, the company’s focus became the production and supply of coffee and related accessories. The business is operated under three principal divisions: Home, Food Service, and OCS.

41 In 1956, LL SpA developed a blend of coffee which it sold under the name TAZZA ORO LAVAZZA. In 1962, the name was changed to MISCELA LAVAZZA ORO. In about 1971, the name was changed again to LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO. The product is a premium full-bodied blend of Arabica beans sourced mainly from Central and South America and processed in Turin. The blend is described in the evidence as having a golden crema, a warm colour, and an aroma of fruit and flowers.

42 The graphics and logo for the product were developed in Italy in the 1960s. From at least the 1970s, the product has been packaged and sold in gold-coloured tins and vacuum-packed aluminium foil packets.

43 Early versions of the packaging included, on the front panel, a medallion which was registered as a trade mark in various jurisdictions. In Australia, the mark is Trade Mark No. 340868, which has been registered since 4 December 1979 in Class 30 for “Coffee and all other goods in this class”:

(the Lavazza device mark).

44 The registration in Australia was (and is) subject to an endorsement:

Registration of this trade mark shall give no right to the exclusive use of the Italian words ‘QUALITÀ ORO’, which may be translated into English as ‘GOLD QUALITY’.

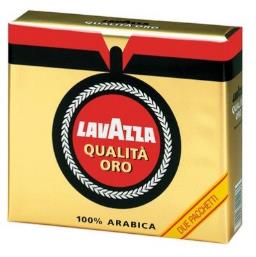

45 The packaging—referred to in the evidence as the Classic Packaging—is shown below.

46 It will be observed that the medallion device shown on the Classic Packaging is different to the Lavazza device mark in that the words QUALITÀ ORO appearing under the name LAVAZZA within the medallion are disposed over two lines, rather than one line. Also, the Lavazza device mark is not limited to any particular colour or colours. However, LL SpA has traditionally used red and black colours for the medallion and the ribbons at the top of the medallion. I will refer to the medallion and ribbons as shown on the Classic Packaging as the Classic medallion.

47 LL SpA first exported Lavazza coffee in around 1972. Lavazza products entered the Australian market as a result of a strong relationship between the Lavazza family and the Valmorbida family who, since the 1960s, have owned and operated a wholesale food and wine business generally known as Conga. There are various companies involved in conducting this enterprise. One of these is Valcorp Fine Foods Pty Ltd (Valcorp). Another is Conga Amalgamated Pty Ltd (Conga Amalgamated).

48 Conga commenced importing and distributing Lavazza coffee in about 1974. Initially, there was no written distribution agreement between LL SpA and Conga. The Lavazza products were produced and packaged in Italy under LL SpA’s management. Conga worked with LL SpA on the marketing and promotion of those products in Australia, but LL SpA had final approval over all marketing and communications concerning the products. LL SpA also contributed to the funding of some marketing initiatives which Conga undertook. The range of Lavazza products distributed by Conga included LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO.

49 John Valmorbida is a director of Valcorp. His evidence was that, from the beginning, LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO was “very much the ‘headline act’” within the range of Lavazza products that Conga imported and distributed. He said that, in terms of volume, LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO was “by far the leading blend” within the Lavazza range that Conga imported and sold.

50 Conga sold LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO in the Classic Packaging. The evidence establishes that, in the period 1987 to 1989, Conga sold 38,758 cartons of LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO in Australia.

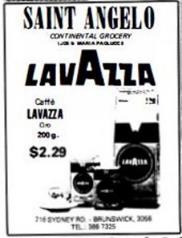

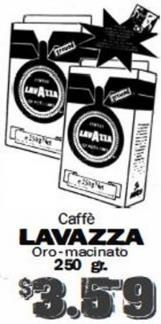

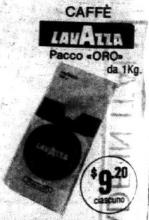

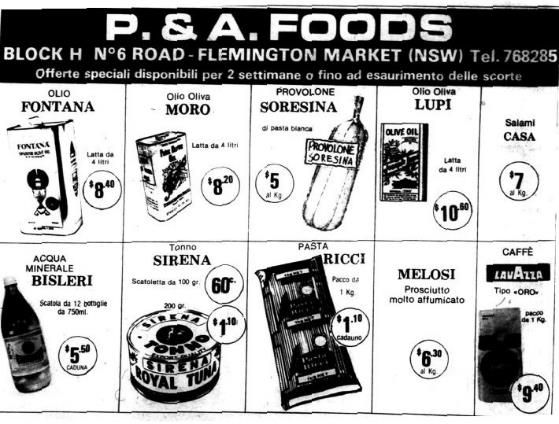

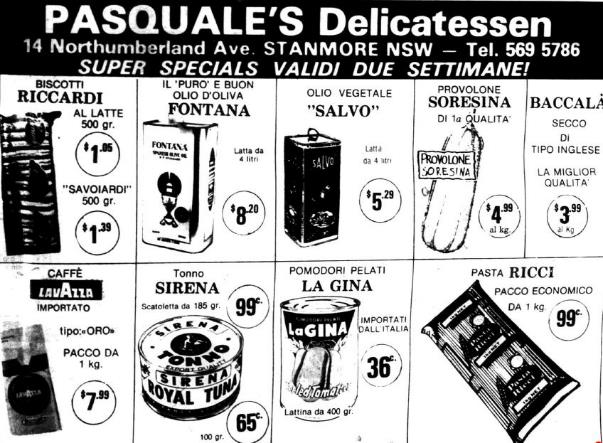

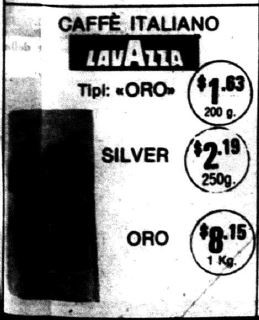

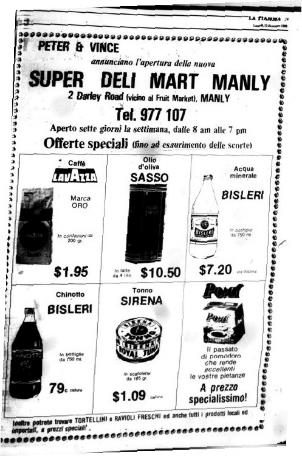

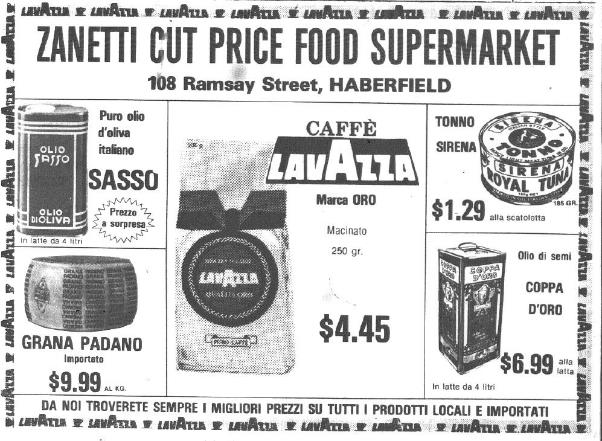

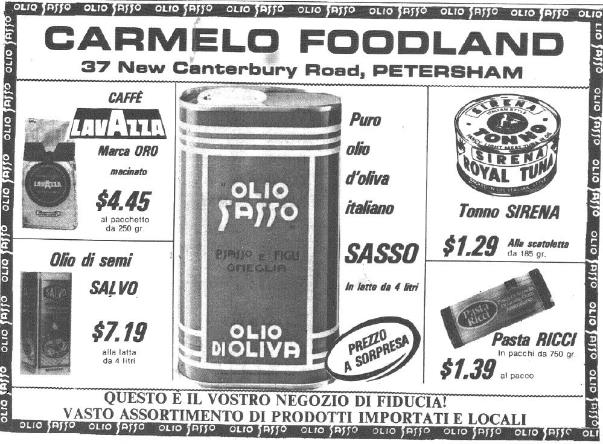

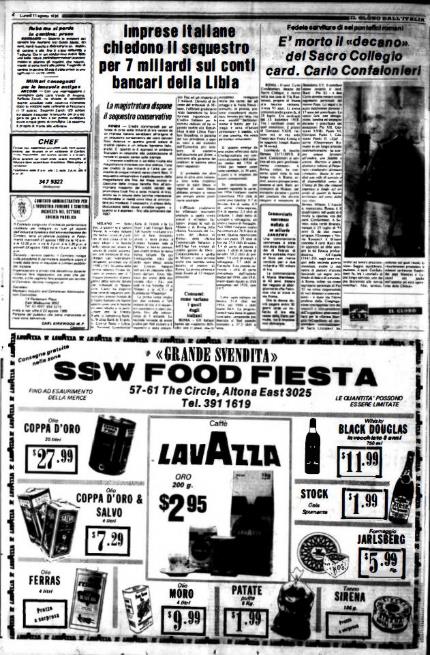

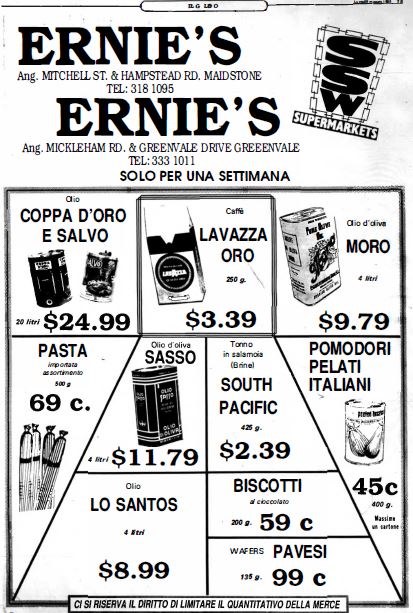

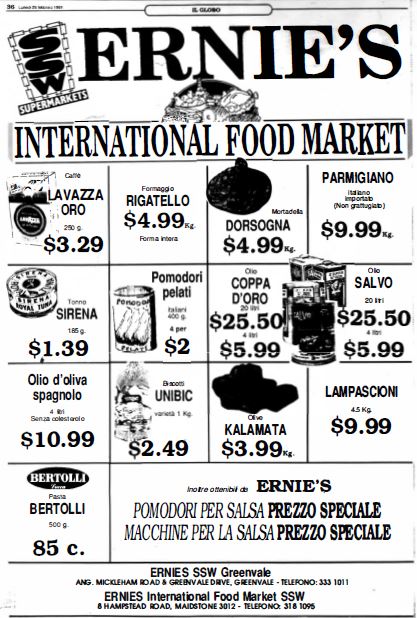

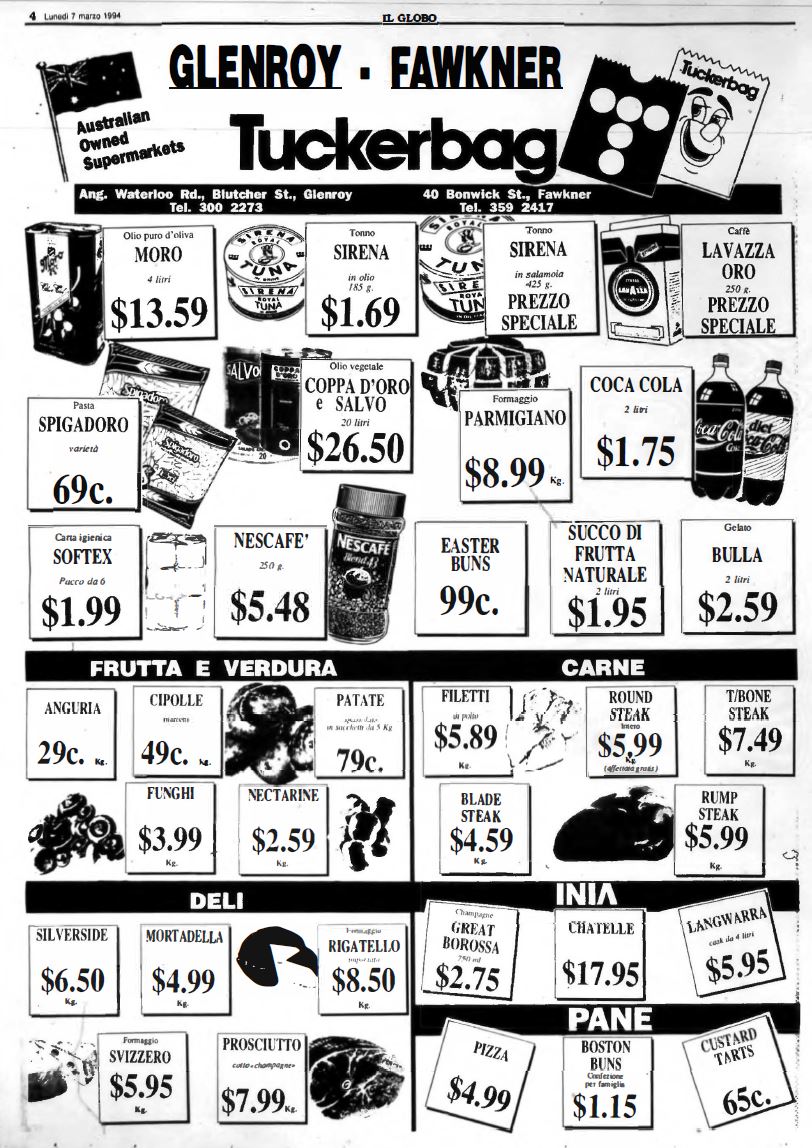

51 The evidence contains examples of the advertising and promotional activities undertaken in respect of the Lavazza products. In its closing submissions, Lavazza focused on particular newspaper advertising in La Fiamma newspaper (in New South Wales) and in Il Globo newspaper (in Victoria) for LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO. Over the years, the Valmorbida family has had an association with both newspapers, which service the Italian community. Lavazza drew attention to the appearance of the word “oro” in these advertisements. Many of the advertisements in evidence are display advertisements that were placed by independent retailers, not by Conga. Mr Valmorbida’s evidence is that Conga supplied images (provided by LL SpA) of Lavazza products for use by its retail customers to enable them to conduct Lavazza promotions.

52 In the account that follows, I have reproduced the display advertisements because they provide context in which the Lavazza products were promoted. It will be appreciated that these advertisements were but a part of the promotion that was undertaken.

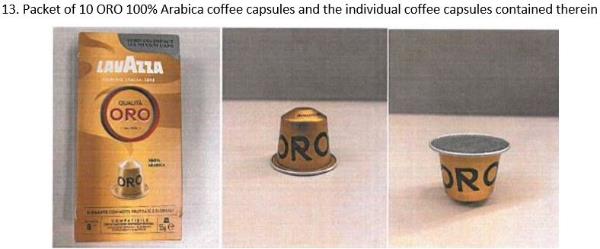

53 On 26 March 1981, the following display advertisement appeared in the La Fiamma newspaper:

54 The relevant part of the advertisement for the present case is:

55 In the period 30 March 1981 to 22 June 1981, the following six display advertisements appeared in La Fiamma:

56 The relevant parts of the advertisements for the present case are:

|

|

|

|

|

|

57 On 4 June 1981, the following display advertisement appeared in La Fiamma:

58 The relevant part of the advertisement for the present case is:

59 In the period 26 August 1982 to 16 May 1988, the following display advertisements appeared in La Fiamma.

60 The relevant parts of the advertisements for the present case are:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

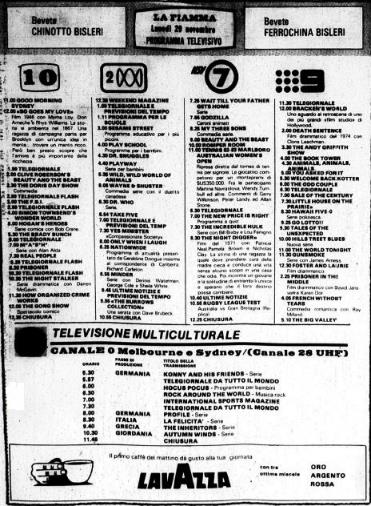

61 In the period 25 November 1982 to 6 December 1984, Conga placed a banner advertisement in La Fiamma for Lavazza coffee as part of a television guide, on 23 occasions. The following is an example:

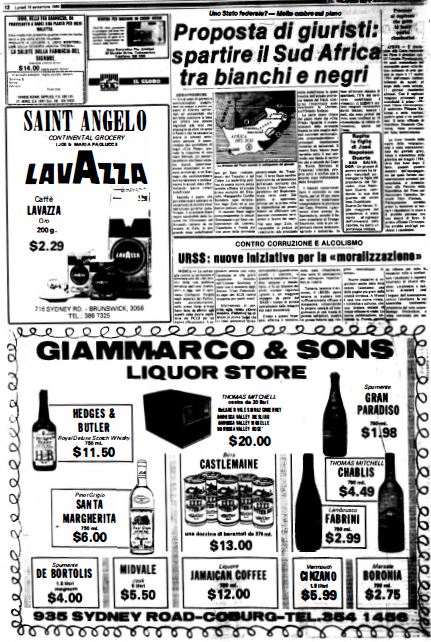

62 In the period 19 August 1985 to 18 February 2002, the following display advertisements appeared in Il Globo newspaper:

63 The relevant parts of the advertisements for the present case are:

|

|

| ||||

|

|

| ||||

|

|

| ||||

64 On 28 March 1988 and 6 June 1994, the following display advertisements appeared in La Fiamma.

65 The relevant parts of the advertisements for the present case are:

66 On 16 November 1990, LL SpA entered into an exclusive distributorship agreement for Australia and New Zealand with one of the companies in the Conga group, Conga Amalgamated. This agreement formalised the previous arrangements between LL SpA and Conga. Amongst other things, the agreement provided that Conga was to effectively and efficiently promote Lavazza products in Australia and New Zealand, subject to LL SpA’s specific prior approval of Conga Amalgamated’s advertising and publicity material. Conga Amalgamated was also granted the right to use some of LL SpA’s trade marks, subject to certain restrictions. The agreement commenced on 1 December 1990, and was for an indefinite period.

67 Following this agreement, advertising for LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO continued in the Il Globo and La Fiamma newspapers.

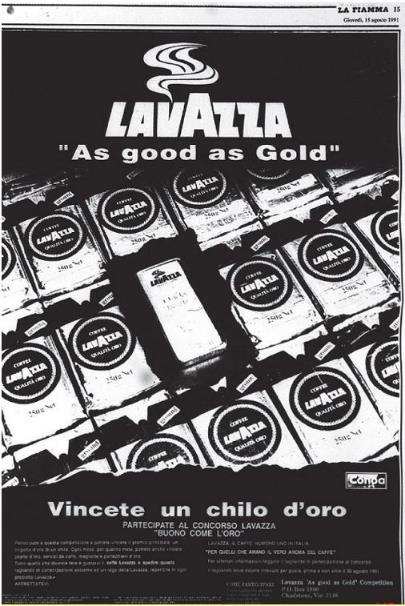

68 Between 27 May 1991 and 30 September 1991, Conga Amalgamated advertised LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO in Il Globo, La Fiamma, and also the trade magazine Retail World, by reference to the tagline: LAVAZZA “As good as Gold”. An example from La Fiamma newspaper on 15 August 1991 is:

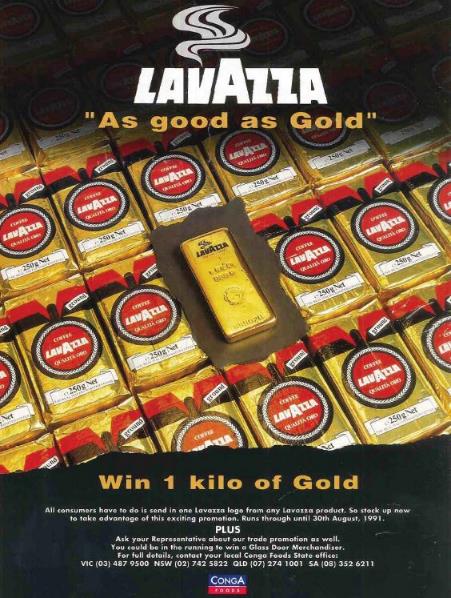

69 The following colour version of the advertisement appeared in Retail World on 24 July 1991:

70 Sometimes the advertisements included other Lavazza coffee products. Sometimes LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO was simply referred to as LAVAZZA ORO.

71 For example, the following advertisement was published in Il Globo on 16 March 1992. The same advertisement was published on 14 occasions between 24 February 1992 and 2 November 1992 in Il Globo and La Fiamma:

72 Another example is the following advertisement published in Il Globo on 1 June 1992:

73 The evidence includes other examples of where, in print media, LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO is referred to as “Lavazza Gold”, or where “gold” is used in conjunction with the words “qualità oro”.

74 The evidence also includes invoices issued by supermarkets (including Woolworths and Coles) to Conga for advertising Lavazza coffee, including coffee referred to as “Lavazza Gold”, which I accept is a reference to LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO. However, the supermarket catalogues in evidence, which include advertisements for LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO, do not use the word “gold” in connection with the product.

75 The evidence also includes a video clip from March 1993 of a Lavazza promotion on the Australian television program “What’s Cooking” in which Ennio Ranaboldo (then the Head of Marketing and Training in the Italian Foodservice Sector at LL SpA) promotes LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO and refers to it as “Lavazza Gold Quality”.

76 On 1 July 1994, LL SpA, Conga Amalgamated, and Valcorp (then called Valcorp Holdings Pty Ltd) entered into a Transfer of Distribution Agreement. The effect of this agreement was to transfer the rights and obligations of Conga Amalgamated under the exclusive distributorship agreement to Valcorp. This arrangement continued from 1994 to 2015.

77 A report prepared by Valcorp for LL SpA, dated September 1995 and titled “Australian Market Data Update Report”, included AC Nielsen data which recorded that the LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO “GOLD GRND BRICK 250g” had the highest ranking in national sales (excluding Tasmania) for ground coffee, with sales from October 1994 to 30 September 1995 totalling $3,291,104. In its report, Valcorp claimed that, in the period January to September 1995, Lavazza coffee products held 11.1% of the Australian market (excluding Tasmania) for ground coffee.

78 A report prepared by Valcorp for LL SpA dated 6 March 2000, titled “National Market Overview Roast Coffee Valcorp Fine Foods”, included AC Nielsen data which recorded that the LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO “GOLD GRND BRICK 250g” had the highest ranking in national sales with a 4.9% share of the market segment for ground coffee. The LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO “GOLD GRND BRICK 500g” was ranked fourth in national sales with a 3.1% share of the market segment for ground coffee.

79 In 2003, LL SpA commissioned Ipsos to conduct a brand awareness survey of the Lavazza brand, including in Australia. Amongst other things, the results showed that consumer awareness in Australia of the Lavazza brand increased from 25% in 1999 to 28% in 2003; that, from 2000 to 2003, 80% of consumers who were aware of the Lavazza brand associated it with high quality coffee and 84% associated it with being consumed at a bar or restaurant; and that, in 2003, 79% of consumers aware of the Lavazza brand associated it with Italian provenance, with 77% of consumers identifying it as a well-known brand.

80 In 2003, LL SpA commissioned AC Nielsen to prepare a report on the Australian market for coffee. The report, titled “The coffee market in Australian Families”, was dated 9 January 2003. Of the 17 Lavazza products listed, “Lavazza Gold Ground Coffee 500g” (which I take to be a reference to LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO) was shown as at 28 September 2002 to be the second most popular Lavazza product (equal with “Lavazza Black Ground Coffee 250g”). The most popular Lavazza product was “Lavazza Caffe Espresso 250g”. The fourth most popular product was “Lavazza Gold Ground Coffee 125g” (which I also take to be a reference to LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO).

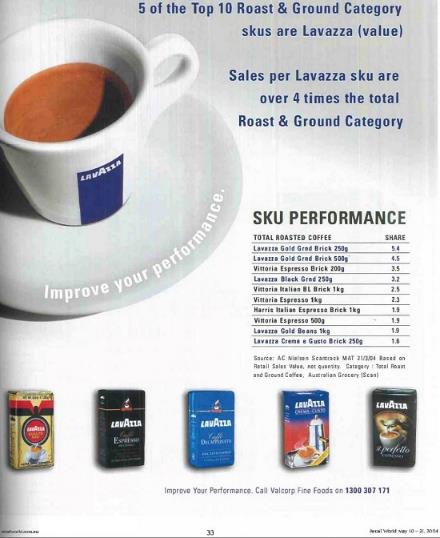

81 In May 2004, Valcorp placed the following advertisement for Lavazza coffee (including LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO) in Retail World magazine:

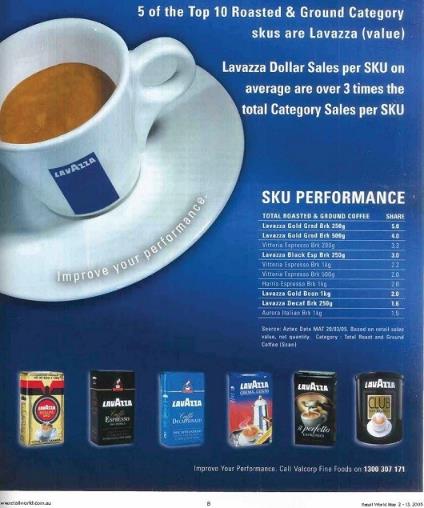

82 Valcorp placed a similar advertisement in Retail World in May 2005:

83 Lavazza draws attention to the description, in each advertisement, of LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO as “Lavazza Gold Grnd Brk” (250g and 500g) and “Lavazza Gold Bean”.

84 In 2007, Valcorp and LL SpA agreed to update the packaging of the Lavazza products destined for Australia. This was to distinguish the products sold by Valcorp as LL SpA’s exclusive distributor in Australia from genuine Lavazza products that were being imported into Australia by third parties.

85 The new packaging was more uniform in design. At the time, there were seven Lavazza retail products. All retained a medallion device, but each product was allocated a unique colour, with LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO retaining its gold-coloured packaging:

86 The medallion in the new packaging is different to the Classic medallion. The wreath is depicted outside the medallion; the black and red ribbons have been removed; the background colour of the medallion is blue, not LL SpA’s traditional red; and the word “Torino” and the date “1895” have been added. I will refer to the medallion in this form as the Blue medallion.

87 Exceptionally, new packaging was not developed for the LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO twin packs (2x250g). This product was packaged in accordance with LL SpA’s international (called ESTERO) packaging:

88 From at least around 2010, the ESTERO packaging for LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO included the following forms:

89 The medallion in this packaging is also different to the Classic medallion. The brand name LAVAZZA is not part of the medallion. Rather, it appears at the top of the packaging with the words “Italy’s favourite coffee” underlined by a strip bearing the colours of the Italian flag; and an image of a cup of coffee appears at the base of the medallion. The packaging depicted on the right above also uses a new font for the words “qualità oro”, which are depicted in gold with the word “oro” larger than the word “qualità”. For both packs, there is no associated ribbon device. I will refer to this as the ESTERO medallion. It is important to note, however, that other than for the twin packs, the packaging of LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO in Australia remained, at this time, the packaging with the Blue medallion. There were, however, parallel importations into Australia, in around 2010 or 2011, of products in the ESTERO packaging depicted above on the right.

90 Valcorp maintained websites from the early 2000s on which it advertised the Lavazza range of coffee products. Examples taken from the website on 19 September 2008 and 16 October 2011 include depictions of LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO, in the packaging with the Blue medallion, with the following description:

Qualita Oro or Lavazza Gold, as it is known in Australia, is the iconic product that made Lavazza famous worldwide and is also the first product to be imported to our shores by the founders of Valcorp Fine Foods back in 1955. Its classic Italian blend has been a favourite of Australian coffee connoisseurs for many years.

91 In 2013, LL SpA updated its Italian packaging for LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO. This packaging was launched in September 2013:

92 In 2014, LL SpA updated the ESTERO packaging for LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO to bring it into “harmony” with the updated Italian packaging:

93 In Australia, the update to the ESTERO packaging only applied to LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO twin packs:

94 The evidence establishes that there were substantial sales of this product in Australia for the 2015 year. The monetary value of these sales is given in a confidential exhibit. It is not clear whether the years referred to are calendar years or financial years, but nothing turns on this for present purposes. Apart from the twin packs, Valcorp continued to supply coffee in Australia in the packaging with the Blue medallion.

95 By 2015, the Lavazza business in Australia had grown to such a size that LL SpA decided to undertake direct distribution. As a consequence, the distribution agreement with Valcorp was brought to an end and Lavazza Australia commenced distribution of all the Lavazza products. In effect, the distribution of Lavazza products in Australia was brought “in-house”.

96 In June 2015, LL SpA issued guidelines for the LAVAZZA brand (the 2015 Brand Guidelines). The 2015 Brand Guidelines were designed to emphasise LAVAZZA as the “masterbrand” and the “central element” above all other promotional elements.

97 At around this time, LL SpA updated the Australian-specific packaging for LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO. This change reflected the changes introduced by the 2015 Brand Guidelines:

98 In 2015, LL SpA commenced a global packaging update—the “Perfect Pack” project. One of the main objectives of the project was to guarantee recognisability of the LAVAZZA brand across all countries, categories, and segments. Another objective was to create global consistency in the presentation of the packaging of LL SpA’s international range of products. The project involved 90 countries and 300 new packaging designs, including in respect of LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO.

99 There was concern within Lavazza Australia that the “Perfect Pack” project would affect the structural consistency that had been achieved for the LAVAZZA product range in Australia through use of the Australian packaging incorporating the Blue medallion. Lavazza Australia saw the proposed changes as posing a significant risk to the existing Australian “brand block”.

100 A draft of a Lavazza Australia internal “marketing update” expressed this concern as follows:

[T]he new pack structure is very different within the Autralian (sic) range and lacks structural consistency. As such, it look (sic) uncoordinated and undermines our premium brand image. We will lose the lovely brand block we have today with the recognisable (and consistent) flat colour and circle lockup.

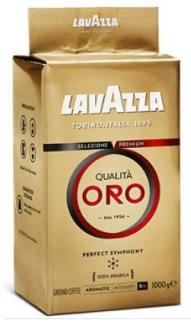

101 In 2017, LL SpA rolled out the “Perfect Pack” revision to LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO. This revision applied globally and extended to the packaging of LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO products sold in Australia, replacing the packaging with the Blue medallion, which LL SpA considered to be inconsistent with its global uniform packaging strategy:

102 The twin packs of LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO were supplied in Australia in the following packaging:

103 Cantarella contends that Lavazza’s supply in Australia of coffee in the “Perfect Pack” revisions referred to above infringes its registered marks.

104 As I have noted, in 2018 Lavazza OCS acquired the exclusive distributor in Australia of the Lavazza products in the OCS sector.

105 On 10 December 2018, LL SpA entered into separate distribution agreements with Lavazza Australia and Lavazza OCS, granting them exclusive distribution rights in respect of LAVAZZA products and the use of LL SpA’s trade marks.

106 In 2018, LL SpA conducted market research in Australia and Italy relating to updated packaging for LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO, including the possibility of introducing a “Mountain Grown” sub-blend.

107 As a result of this work, LL SpA introduced new packaging for LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO in 2019 which, at the same time, also introduced the “Mountain Grown” sub-blend. The new packaging for LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO was:

108 The new packaging of the twin packs of LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO was:

109 The packaging of the LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO “Mountain Grown” sub-blend was:

110 Cantarella contends that Lavazza’s supply in Australia of coffee in the new packaging introduced in 2019 infringes its registered trade marks.

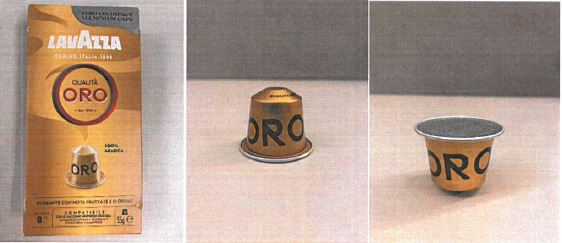

111 In more recent times, LL SpA has launched new aluminium packaged Nespresso-compatible coffee capsules (NCCCs), including for LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO. The packaging for these products is the same for all of LL SpA’s markets. The packaging for the LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO NCCCs is closely similar to the 2019 packaging referred to above, except for the fact that the capsules themselves prominently bear the word “oro” in stylised script and the front of the box, in which the capsules are contained, bears an image of such a capsule:

112 In 2021, Lavazza Australia showed the NCCCs to a number of main supermarket retailers in Australia as part of an annual review process.

113 Between 15 February and 11 April 2022, Lavazza Australia imported a large quantity of NCCCs which included LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO NCCCs. Between 4 and 12 March 2022, Lavazza Australia supplied LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO NCCCs, as well as other NCCCS, to Coles. These products were available for sale to the public from 4 April 2022.

114 Lavazza says that LL SpA supplied the LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO NCCCs to it by mistake—the mistake being that, while the present proceeding was on foot, LL SpA had determined that these NCCCs should not be supplied in Australia. However, because of oversight and communication mistakes within LL SpA, those products were supplied to Lavazza Australia.

115 From 11 April 2022, Lavazza Australia took steps to suspend the further sale and promotion of the LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO NCCCs. Nevertheless, the products that were already on shelves at Coles were sold and Lavazza Australia continued with its pre-planned promotional launch of those products. Lavazza Australia subsequently arranged a “clearance promotion” with Coles, commencing from around 4 May 2022, to have the products sold-down as quickly as possible so that they would, by that means, be “removed” from the market. In the course of that activity, some promotional materials for LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO NCCCs remained on display.

116 Before 9 April 2022 (when it learned of the mistake), Lavazza Australia had also provided samples of the LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO NCCCs to other retailers. One of these retailers was Amazon Australia, which subsequently placed orders for the product. Despite measures taken by Lavazza Australia to impede the receipt of such orders, orders from Amazon Australia were received and processed. Amazon Australia then supplied LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO NCCCs online for a limited time.

The use of “oro” by Molinari in Australia

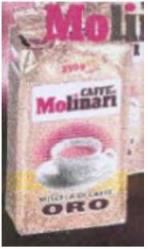

117 The use by Molinari of the word “oro” as a trade mark in Australia was a substantial topic in this proceeding. Its significance lies in Lavazza’s challenge to the validity of the registrations of the 098 mark and the 290 mark. Lavazza contends that Cantarella’s claim to ownership of the ORO word mark (registered as the 098 mark and the 290 mark) is defeated by the sale of coffee by Molinari to CMS Coffee Machine Services Pty Ltd (CMS, later called Saeco Australia Pty Ltd (Saeco)) in Australia from September 1995, which Lavazza says amounted to use of the word “oro” as a trade mark. This is before the first date on which Cantarella says it used the ORO word mark in respect of coffee. Hence the significance of this topic in the proceeding.

118 Lavazza’s case focuses critically on three shipments of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee which, it says, Molinari invoiced to CMS in September and October 1995 and in March 1996. The invoices for the shipments are no longer available because of changes to Molinari’s computer system in March 1996 and because archived documents have been destroyed over time. However, Maurizia Baraccani—the Head of Molinari’s Data Processing Centre who has worked for Molinari since 1994 and who assumed the role of Head of the Data Processing Centre in 1997—interrogated Molinari’s computer records and prepared two spreadsheets of sales data concerning Molinari coffee exported to Australia in the period 1995 to 2003.

119 CMS was the first Australian distributor of Molinari coffee. In Molinari’s sales records, CMS was given the client code 110103453 and Saeco was given the client code 110103878.

120 In her evidence in chief, Ms Baraccani explained that, before 1996, information relating to all Molinari coffee sales, both in Italy and abroad, was stored on a database managed by a computer system called “Olimpix”. Using that system, Molinari issued invoices to customers and recorded sales data in the system. The invoices were printed in hard copy and sent to customers by post or facsimile transmission. Molinari kept the hard copies in its archives. However, much of Molinari’s old paper records, including sales invoices, have now been destroyed.

121 Ms Baraccani participated in the migration of data from the Olimpix system to a new management system called “Kronos”. The migration occurred in March 1996. Because of limits on the type of information stored in the Olimpix database, only some information in relation to Molinari’s sales and products, existing before June 1996, was migrated to the Kronos system. The Kronos system can reproduce old sales invoices from 1996 onwards, but it cannot do so for sales before 1996 because the data transferred from the Olimpix system was only for “statistical purposes”. The Kronos system is still in operation at Molinari.

122 The spreadsheets prepared by Ms Baraccani contained data for client codes 110103453 (CMS) and 110103878 (Saeco). The spreadsheets also contain data for client codes 110106320 and 110107006: see [134] below.

123 Fabrizio Mengoli is the Sales, Marketing and Export Manager for Molinari. He was promoted to that position in 2008. He commenced his employment with Molinari on 18 March 1996 as an Export Manager. At that time, he was responsible for administering all exports of Molinari coffee, which included developing procedures for the sale and export of coffee, liaising with overseas clients, managing communications with export authorities, developing relationships with customers in global markets, and ensuring that orders placed with Molinari were fulfilled.

124 Mr Mengoli gave evidence concerning the Molinari coffee business, particularly with reference to the sales of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee to Australia.

125 When Mr Mengoli commenced working at Molinari in March 1996, CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee was packaged as follows:

126 Mr Mengoli (and others in his team) carried out an investigation of Molinari’s records to ascertain whether different packaging was used by Molinari for these products in 1995. The result of this investigation was that nothing was identified which suggested that there was different packaging for these products in 1995.

127 A sample of the 3 kg product is in evidence. The sample was packaged on 25 September 2007. However, I am satisfied that the sample exemplifies the packaging of the 3 kg product in 1995.

128 The use of the word “bar” on the packaging of the 1 kg product refers to the fact that it was sold as part of Molinari’s “bar range”. Products in the bar range are sold to “coffee bars” (the equivalent of cafes). The 3 kg product was also part of Molinari’s bar range. Mr Mengoli’s evidence was that the word “bar” does not appear on the packaging of the 3 kg product because, given the size of the product, it was obviously intended for the hotels, restaurants, and catering distribution line of Molinari’s business.

129 With reference to the first spreadsheet prepared by Ms Baraccani, Mr Mengoli identified that the first recorded shipment by Molinari of coffee to Australia was on 18 September 1995. The supply was to CMS for products having specified product codes. The product codes included code 6093 and code 6091.

130 Mr Mengoli’s evidence was that product codes beginning with “60” and “15” refer to products within (what he called) “Molinari’s Oro range”. The evidence before me includes extracts of records from the Kronos system of various product codes. The records confirm that product code 6093 (which is recorded as having been created on 13 March 1996) refers to the product described as “CAFFE’ ORO BAR GRANI 3000g” and product code 6091 (which is recorded as also having been created on 13 March 1996) refers to the product described as “CAFFE’ ORO BAR GRANI 1000g”. Mr Mengoli said, and I accept, that the word “grani” in Italian means, in English, “grains” or “beans” and that this is how “grani” is used in these descriptions.

131 I draw attention to the recorded dates of creation of the product codes because, on the evidence before me, these dates correspond to the date of migration of Molinari’s sales records into the Kronos system. Mr Mengoli’s evidence was that, throughout March 1996, existing product items were migrated across from the Olimpix system to the Kronos system. However, the product codes themselves existed before 13 March 1996. I accept that evidence.

132 With reference to the first spreadsheet prepared by Ms Baraccani, Mr Mengoli identified further shipments of coffee to CMS on 17 October 1995 and 26 March 1996 (approximately one week after Mr Mengoli commenced his employment with Molinari). Once again, the invoices for the shipments are no longer available, but the Kronos system records that the shipments included product codes 6093 (the 3 kg pack) and 6091 (the 1 kg pack). Mr Mengoli’s personal observation was that, as at 26 March 1996, these particular products were packaged as shown at [125] above.

133 Molinari’s first three shipments to CMS on 18 September 1995, 17 October 1995, and 26 March 1996 comprised 36 units of product code 6093 (the 3 kg pack) and 612 units of product code 6091 (the 1 kg pack), being (in total) 720 kg of CAFFÉ MOLINARI ORO coffee. Mr Mengoli estimated that this was enough product to make approximately 86,400 to 100,800 cups of coffee.

134 The evidence also includes copies of invoices (extracted from the Kronos system) issued by Molinari to CMS and Saeco in the period from 24 July 1996 to 16 April 2003, and to two other Australian customers of Molinari—namely, a business called Coffee Supplies Australia located in Perth, Western Australia (client code 110106320) and Russo Pty Limited located in Hurstville, New South Wales (client code 110107006).

135 The invoices issued by Molinari to CMS in the period from 24 July 1996 to 24 March 2000 (the priority date of the 098 mark) include CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee in the 250 g pack (packaged as shown at [125] above).

136 The invoices issued by Molinari to Coffee Supplies Australia are for the period 9 December 1999 to 4 April 2002. The only invoice that predates the priority date of the 098 mark is an invoice dated 9 December 1999 which includes CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee pods (packaged as shown at [125] above).

137 The invoice issued by Molinari to Russo Pty Limited is dated 26 October 2000. This is after the priority date of the 098 mark but before the priority date of the 298 mark. The invoice includes CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee in the 1 kg pack.

138 To complete the chain of evidence in relation to Molinari’s first supply of coffee to CMS, Lavazza called evidence from Giorgio Massimo Ubertini and Esther Toledano. Cantarella initially objected to the receipt of this evidence (in the form of Mr Ubertini’s and Ms Toledano’s respective affidavits) on the basis that the evidence was not in reply. However, Mr Ubertini’s and Ms Toledano’s affidavits were read (subject to agreed rulings) and both deponents were cross-examined.

139 Mr Ubertini was a director of CMS (and then Saeco) between June 1993 and June 2007. He set up CMS with three business partners—Antonio Petrolito, Vincenzo Nespeca, and Angelo Augello. He was one of CMS’s directors and oversaw all aspects of the operation and management of its business. This included travel to Italy to liaise with manufacturers and to source products for CMS’s business.

140 CMS’s primary business was the importation and distribution of a range of Italian commercial and domestic coffee machines and grinders. The business also offered after-sales servicing and training to its customers, who were mainly commercial coffee suppliers and coffee roasters. However, CMS also supplied non-commercial customers (Mr Ubertini referred to them as “ordinary customers”) who bought domestic coffee machines and grinders for home use.

141 CMS operated from various premises in Melbourne, firstly from 1/33 Acheson Place, Coburg and then, from about August 1996, from 86 Newlands Road, Reservoir. In the middle of 2002, after CMS changed its corporate name to Saeco Australia Pty Ltd, the premises moved “across the road” to 87 Newlands Road.

142 Mr Nespeca and Mr Augello were also coffee roasters. They operated a separate business distributing their own brand of coffee called MONTE COFFEE. For a time, CMS’s business operated next door to the MONTE COFFEE warehouse, which was located at 31 Acheson Place, Coburg.

143 In the first couple of years of its business, CMS provided promotional packs of MONTE COFFEE to purchasers of its coffee machines.

144 In mid-1995, Mr Ubertini and Mr Petrolito purchased Mr Nespeca’s and Mr Augello’s shares in CMS, after which Mr Nespeca and Mr Augello were no longer involved in CMS’s business. Corporate records show that Mr Nespeca and Mr Augello ceased being directors of CMS on 17 August 1995. It seems that the parting was not entirely amicable. There were, apparently, some bad feelings due to disagreements about the operation of the CMS business.

145 After Mr Nespeca and Mr Augello had left, CMS had the opportunity to offer other brands of coffee to its customers. Mr Ubertini took up that opportunity.

146 Mr Ubertini’s evidence was that, in around September 1995, while in Italy on a regular buying trip and in his home town of Modena, he visited Molinari’s headquarters and met Giuseppe Molinari for the purpose of securing supplies of Molinari coffee to replace the MONTE COFFEE that CMS had previously supplied.

147 Mr Ubertini fixed on the period “of around September 1995” for two principal reasons. First, his meeting with Mr Molinari was not long after Mr Nespeca and Mr Augello had left the CMS business. Secondly, Mr Ubertini recalled that his meeting took place during one of his regular trips to Italy to attend the HOST tradeshow. The HOST tradeshow is Italy’s leading trade fair for the catering and hospitality industry. It was where Mr Ubertini met the suppliers of the coffee machinery that CMS was selling. When Mr Ubertini attended the HOST tradeshow, his practice was to travel to Italy at the end of August or the start of September, attend the tradeshow in October, and then return home to Australia immediately thereafter.

148 Mr Ubertini’s evidence was that he placed an initial order with Molinari for CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO at his first meeting with Mr Molinari. Mr Ubertini was not able to recall precisely when the first shipment of the coffee arrived in Australia. He did recall, however, that the first shipment arrived shortly after he returned from the 1995 HOST tradeshow at the end of October 1995. He also said that, at the time, he was importing a lot of products from Italy which generally arrived by sea sometime between 3 to 6 weeks after orders were placed. This is broadly consistent with Mr Mengoli’s evidence as to the time taken for shipments by sea from Italy to Australia. Mr Mengoli’s evidence was that Molinari’s invoices are dated on the day that products leave its warehouse en route to its customers. Molinari’s shipments to Australia have always been by sea, with shipments generally taking between 25 to 50 days to arrive in Australia.

149 At the time that the first shipment arrived, CMS’s business was still located at 1/33 Acheson Place, Coburg, next door to the MONTE COFFEE warehouse. Mr Ubertini said that he covered the first pallet of the coffee received from Molinari when it arrived at CMS’s premises because he did not want to upset Mr Nespeca and Mr Augello by “showing off” the new brand of coffee he had imported. As I have noted, the circumstances in which Mr Nespeca and Mr Augello left the CMS business were not entirely amicable and Mr Ubertini did not want to increase the tensions between them by selling a competing brand of coffee in close proximity to the MONTE COFFEE warehouse. That said, Mr Ubertini’s evidence was that CMS continued to purchase the cheapest blend of MONTE COFFEE, which was used in the testing and servicing of the coffee machines supplied by CMS (as Mr Ubertini later explained, he did not want to use the more expensive CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO for this purpose).

150 Although Mr Ubertini could not recall specifically what was in the first shipment, he nevertheless remembered that it was CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO, which he described as the “top-quality Molinari coffee used in bars and restaurants in Italy, mainly in 1 kg bags”. He also remembered that CMS imported some larger 3 kg bags of the same blend.

151 Following the first shipment, Mr Ubertini remained the key contact within the CMS business for purchases of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee. This involved placing orders by telephone and facsimile, receiving invoices and overseeing the payment of the invoices, and other general correspondence with Molinari. After initially dealing with Mr Molinari directly, Mr Ubertini commenced to deal with Mr Mengoli several months later.

152 The evidence includes a copy of a letter dated 23 July 1996 from Molinari addressed to CMS at 1/33 Acheson Place, Coburg. The copy of the letter was found in Molinari’s archived records. It is written in Italian, but an English translation has been provided by an independent translator. The letter was written by Mr Mengoli. Mr Mengoli addressed the letter personally to “Mr Ubaldini”.

153 Mr Mengoli’s evidence was that the reference to “Mr Ubaldini” was a misspelling of Mr Ubertini’s name. Mr Mengoli says that, at the time, Mr Ubertini was the only person in Australia with whom he was dealing. I accept this explanation of the use of “Mr Ubaldini”.

154 The letter commences by thanking “Mr Ubaldini” for an order and for a “cordial telephone call [on] 18/06/96”. The letter then raises various propositions that Molinari was interested in pursuing with CMS—specifically, filters; “white label” coffee pod production; and developing Molinari coffee distribution in Australia.

155 Mr Ubertini’s evidence did not go so far as to acknowledge his receipt of this letter, although he did say that he recalled receiving “many communications of this sort throughout CMS’s trade relationship with Molinari”.

156 Cantarella submits that this letter is not consistent with “any relevant existing relationship” between Molinari and CMS and that, taken with Mr Mengoli’s cross-examination, indicates, amongst other things, that there was no actual or even potential supply of Molinari coffee to CMS prior to 18 September 1996 (i.e., one year later than the Molinari affidavits show).

157 In that connection, Cantarella draws attention to the fact that the letter refers to Mr Mengoli having included “some samples of pods which we hope may come close to those demanded by your market for a much longer extraction of coffee”. Cantarella submits that it is unlikely that there would have been a supply of sample pods if Mr Ubertini had already ordered them in a previous shipment. Cantarella submits that this makes the possibility of any transaction between Molinari and CMS before 23 July 1996 “improbable”.

158 I do not accept that submission. Molinari’s computer records show that, prior to 23 July 1996, the only shipment of pods to CMS was that covered by an invoice dated 26 March 1996. This was for only 5 units (with 25 pods to a unit). The identity of the pods to which the letter of 23 July 1996 refers has not been established. In other words, it is far from clear that the samples that Mr Mengoli provided were the same product as the relatively small quantity of pods that Molinari had shipped under the invoice. Indeed, there is good reason to think that they were not. In his letter, Mr Mengoli said that “… on the basis of your report, we have included some samples of pods …” (emphasis added). This suggests that Mr Ubertini had already reported to Mr Mengoli on pods and that Mr Mengoli was sending further pods, which had a “much longer extraction of coffee” for Mr Ubertini to try.

159 Mr Ubertini said that, from September 1995 to about 2003, CMS purchased CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO from Molinari. He said that when pallets arrived in Australia, he arranged for someone in the business to check that all the goods on the relevant invoice had arrived. He said that he did not recall any shipments that he had ordered not arriving or falling short of the orders that had been placed.

160 Mr Ubertini recalled that the packaging of the CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee that CMS received was that depicted above at [125].

161 Mr Ubertini’s evidence was that CMS imported the CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee to sell alongside its coffee machines direct from CMS’s premises, rather than the MONTE COFFEE. He said that, from about the end of October 1995 onwards, customers who purchased a domestic coffee machine from CMS were given a “promotional” 1 kg bag of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO in the packaging depicted above at [125]. He said that this form of promotion proved to be very successful because many of CMS’s domestic customers would return to purchase more packs. He said that, from the end of October 1995 onwards, he recalled selling CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee directly to customers “on many occasions”.

162 Mr Ubertini also gave evidence that, at the start of CMS’s importation of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee, he also sold 3 kg and 1 kg packs to Giancarlo Squillaciotti for use in the Italian restaurant called “Trattorante”, which operated on Church Street, South Brighton.

163 Mr Ubertini also gave evidence that staff and directors of CMS also used the CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee to make coffee beverages for themselves and customers at CMS’s premises to promote the coffee.

164 Mr Ubertini said that CMS’s sales of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee increased from about August 1997 when CMS moved to new premises at 86 Newlands Road, Reservoir. Mr Ubertini felt that CMS could more freely promote the coffee at the new premises without upsetting Mr Nespeca and Mr Augello. However, CMS only promoted and sold CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee on its premises. It did not actively promote or advertise the coffee because, although keen to sell it, the focus of CMS’s business was coffee machines and Mr Ubertini did not want to “cut across” CMS’s valued customers who were coffee suppliers or coffee roasters. Therefore, the CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee was only directly promoted to “domestic” customers and other customers who were not coffee suppliers or coffee roasters.

165 I did not find Mr Ubertini to be an entirely satisfactory witness under cross-examination. On some occasions he appeared to be unable to attend to the questions asked of him. On some occasions, he gave answers that were not entirely responsive. On some occasions, he attempted to offer information he was not asked to offer (he was loquacious).

166 In fairness, I should point out that Mr Ubertini gave his oral evidence by video-link from Italy at a difficult time (late evening/early morning). Mr Ubertini is elderly and giving evidence by this means at this time of the day was likely to have been challenging for him. I make allowance for that possibility in relation to his presentation as a witness. I do not think that Mr Ubertini was intending to be unhelpful. I do not think that he was attempting to evade answering questions. I consider him to be a truthful witness. Nevertheless, based on his presentation in cross-examination, I treat his evidence with circumspection.

167 Ms Toledano was employed by CMS (and then Saeco) between June 1993 and February 2007 as a Finance and Administration Manager. In that role, she was responsible for supervising and maintaining financial and administrative records, and monitoring CMS’s systems to account for and reconcile expenditures, sales, balances, and payments. This involved managing invoices, shipping costs, and data entry in relation to CMS’s imports and sales to ensure that all stock was accounted for.

168 Ms Toledano confirmed that CMS operated from different premises in Melbourne including, first, 1/33 Acheson Place, Coburg until CMS moved its warehouse premises to 86 Newlands Road Reservoir. Ms Toledano fixed the date of the move as (around) August 1996 by reference to the birth of her daughter (having previously deposed that the move occurred around August 1997). Ms Toledano said that CMS moved to 87 Newlands Road in the middle of 2002.

169 I do not think that anything turns on the date of the move to 86 Newlands Road. However, I mention these matters because Cantarella places much reliance on a company search of CMS which shows that the start date for the business address at 1/33 Acheson Place was 24 July 1996—the point being, apparently, that, if this was the actual start date, CMS could not have received supplies of Molinari coffee at 1/33 Acheson Place in 1995 or the early part of 1996.

170 I do not accept that contention. Whatever the corporate records with the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) show, I accept Ms Toledano’s evidence as to the actual location of CMS’s business in 1995 and the first half of 1996. I note, in this regard, that, curiously, the same company search also shows that CMS’s principal place of business in the period 30 June 1994 to 23 July 1996 was 31 Acheson Place.

171 The better view of the evidence is that before 24 July 1996 (including in 1995), CMS’s principal place of business was actually 1/33 Acheson Place. It is possible (although I do not need to find) that, because of the corporate and business relationship between the four founders of the CMS business, and bearing in mind that Mr Nespeca’s and Mr Augello’s other business (MONTE COFFEE) was next door to CMS at 31 Acheson Place, the 31 Acheson Place address was originally, but mistakenly, given to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission as CMS’s principal place of business. I am satisfied, however, that CMS did not trade, physically, from the MONTE COFFEE premises at 31 Acheson Place. I am satisfied that Molinari’s early shipments of coffee to CMS were received at 1/33 Acheson Place, which was CMS’s principal place of business before 24 July 1996.

172 I also note that Mr Mengoli’s letter to “Mr Ubaldini” was dated 23 July 1996, and addressed to CMS at 1/33 Acheson Place, indicating that that address was already known to Mr Mengoli (or, at least, Molinari). Cantarella suggests that, at the time of the conversation between Mr Mengoli and Mr Ubertini (to which the letter refers), Mr Ubertini must have given the 1/33 Acheson Place address as a “proposed new address” for CMS. I am not persuaded that this was the case. It is more likely that this address was already known to Molinari because, in fact, it had already made shipments of Molinari coffee to that address.

173 In Ms Toledano’s early years of employment at CMS, she was the only person physically working in the business (apart from Mr Ubertini and Mr Petrolito). This meant that she was responsible for taking orders (in person and over the telephone), packing orders, and selling machinery and coffee to walk-in customers when Mr Ubertini was not at the warehouse. CMS employed another person to assist with these tasks in around April or May 1996, when Ms Toledano was pregnant with her first daughter (who was born in September 1996).

174 Ms Toledano’s affidavit evidence was that, shortly after Mr Nespeca and Mr Augello left the CMS business, CMS began importing coffee from Molinari to supply to its customers. Ms Toledano placed the commencement of this activity at sometime after August 1995, but before the end of 1995. She said that, although not involved in arranging the purchases, she remembered shipments of Molinari coffee arriving at CMS’s warehouse at 1/33 Acheson Place. It was part of her job to take account of all imported goods to make sure they “aligned with the invoices”.

175 Ms Toledano’s evidence was that CMS mainly imported CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO beans in 1 kg packs. However, she said that, at the start, CMS also imported larger 3 kg packs of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO beans. Ms Toledano said that CMS later imported CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee pods (when CMS started to sell pod machines), and also some ground CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee in 250 g packets. She said that CMS’s preference was to import beans rather than ground coffee, so that the beans could be sold with CMS’s coffee machines and grinders. Ms Toledano confirmed that the Molinari coffee was packaged as depicted at [125] above.

176 Ms Toledano’s evidence was that the CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee was kept in CMS’s showroom at its warehouse at 1/33 Acheson Place, and that, in order to promote sales of the coffee, 1 kg packs were provided to customers when they purchased coffee machines. Ms Toledano recalled that customers who purchased domestic coffee making machines from CMS, and had received a “promotional” pack of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO, would often return to CMS’s warehouse to purchase more of the coffee. Her evidence was that some customers returned within a month of receiving the first pack. Ms Toledano said that she specifically recalled providing and selling bags of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee to several of these walk-in customers when she was alone in CMS’s showroom at 1/33 Acheson Place.

177 Ms Toledano’s evidence was that CMS continued to import and sell CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO after CMS moved its warehouse premises to 86 Newlands Place in around August 1996.

178 Ms Toledano said that CMS “did not ever widely advertise its distribution” of Molinari coffee. This was because selling coffee was only a small part of the CMS business and CMS did not want to be seen by its coffee supplier customer-base to be promoting and selling coffee that would be a rival brand to the coffee supplied by those customers. Nevertheless, Ms Toledano said that, before April/May 1996 (i.e., at a time when she was CMS’s only employee at the premises at 1/33 Acheson Place), she often made cups of coffee for walk-in customers using the 3 kg and 1 kg bags of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO. She said that these bags were displayed next to the coffee machines and grinders used in the warehouse, for customers to see and purchase.

179 Ms Toledano was not directly challenged in cross-examination on her affidavit evidence. She agreed that the first supply of Molinari coffee was to CMS’s premises at 1/33 Acheson Place. She said that CMS was at 1/33 Acheson Place from 1993. It was put to her that the ASIC records showed that CMS’s principal place of business did not become 1/33 Acheson Place until 24 July 1996. She responded by saying that she did not know what the ASIC records showed, but CMS was trading at 1/33 Acheson Place before 1996.

180 It was put to Ms Toledano that the first shipment of Molinari coffee did not arrive until after 24 July 1996. She gave this answer:

… Well, I know it arrived when we were still at 1/33 Acheson Place – yes – so July – no, it would have been before that, I think. Or maybe around that time. I can’t recall exactly when the shipment arrived.

And do you accept that the first arrival was at 1/33 Acheson Place?---Yes.

181 Ms Toledano later accepted that it was possible that the first shipment arrived after 24 July 1996. But, in the end, her oral evidence was no more definite than that (a) the first shipment would have arrived before 24 July 1996; (b) that it was at least possible that it arrived after 24 July 1996; and (c) that the first shipment arrived at 1/33 Acheson Place which CMS had occupied from 1993.

182 Ms Toledano’s affidavit gives a more focussed recollection—namely, that CMS commenced ordering Molinari coffee shortly after Mr Nespeca and Mr Augello had left the CMS business, and that the first two shipments from Molinari arrived before the end of 1995. Although Ms Toledano’s oral evidence throws some doubt on the reliability of this recollection, I do not take her to have resiled from what she had said in her affidavit. Moreover, her evidence must be considered as a whole and with the other evidence before the Court, which includes Mr Ubertini’s evidence as to his first order on Molinari and the timing of the arrival of that order at 1/33 Acheson Place, and Molinari’s available accounting records, which accord with Mr Ubertini’s evidence on this topic.

183 It is necessary for me to say something about an affidavit given by Mr Molinari in the Modena proceeding (to which I refer at [264] below). In that affidavit, which was tendered by Cantarella in this proceeding, Mr Molinari deposed that Molinari commenced exporting products to Australia “in or about July 1996”. He referred to CMS’s distribution of products in Australia in the period July 1996 to March 2001. He produced a number of invoices evidencing that supply. He also referred to Molinari’s supplies to Coffee Supplies Australia and to Russo Pty Ltd.

184 Mr Molinari’s evidence that Molinari commenced exporting products to Australia “in or about July 1996” is inconsistent with the evidence before me. Although Lavazza emphasises Mr Molinari’s use of the expression “in or about” (to suggest a degree of imprecision), I do not accept that the expression “in or about” has the plenitude which Lavazza seeks to attribute to it.

185 Cantarella submits that precedence should be given to the statements in, and evidence given through, Mr Molinari’s affidavit read in the Modena proceeding over the evidence given in this proceeding by, and through, Mr Mengoli, Ms Baraccani, Mr Ubertini, and Ms Toledano. Cantarella submits that the Court ought to presume that Mr Molinari, as a director of Molinari, interrogated all relevant electronic records and had “taken great care to produce the best evidence available and to present the best case possible in the Modena proceedings”. Cantarella also submits that if, in giving evidence in the Modena proceeding, Mr Molinari could advance a case that Molinari was the owner of the ORO word mark, then it can be expected that Mr Molinari would have done so. Cantarella argues that the fact that no such case was advanced in the Modena proceeding “must be a complete answer” to the case now advanced by Lavazza and “speaks to the inherent unreliability of the purported business records … which are asserted to evidence sales from Molinari to CMS” before 18 September 1996.

186 Cantarella also contends that the records on which Lavazza relies in respect of the supply of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee to CMS are “incomplete”—an apparent reference to the fact that certain invoices cannot be reproduced by Molinari notwithstanding the fact that evidence of the transactions in question is captured within Molinari’s Kronos system.

187 Cantarella points out that Lavazza has not adduced evidence that Molinari has searched its paper records in an attempt to locate invoices with respect to its early supplies of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee to Australia. I observe, however, that the supplies in question were, at the time of the hearing, some 25 years ago. Ms Baraccani’s evidence was that while Italian law requires companies to keep hard copies of invoices for a period of not less than five years, much of Molinari’s old paper documentation, including sales invoices, has been destroyed. Cantarella submits that, in the absence of evidence of search and destruction, “the Court must infer that such records exist and were not destroyed”.

188 Notwithstanding these submissions, I accept the evidence of Mr Mengoli, Ms Baraccani, and Ms Toledano. I consider their evidence to be credible and reliable. Despite some unsatisfactory aspects of Mr Ubertini’s oral evidence (to which I have referred), I accept his evidence as well. In particular, I accept his evidence that he first ordered Molinari coffee when he was in Modena in September 1995 and that the first shipment of Molinari coffee arrived at 1/33 Acheson Place by the end of October 1995.

189 Further, I am satisfied that reliance can, and should, be placed on Molinari’s computer records tendered in this proceeding through Ms Baraccani and Mr Mengoli. I do not accept Cantarella’s contention that these records should not be given weight.

190 I reach these findings fully cognisant of the significance that this evidence has to Cantarella’s present rights of ownership of the ORO word mark as a registered trade mark.

191 On the whole, the evidence adduced by Lavazza on this topic is comprehensive and detailed, and has been subjected to testing by Cantarella in the cross-examination of all the witnesses who contributed to the evidence on this topic. Subject to the comments I have made with respect to Mr Ubertini’s testimony, I have not found that evidence to be wanting.

192 I prefer this body of evidence to the statement made in Mr Molinari’s affidavit with respect to the time that Molinari began exporting products to Australia. Based on the other evidence before me, I am satisfied that Mr Molinari’s statement in this regard is mistaken and inaccurate. The statement was made some 16 years after the event. It appears to have been made on the basis of incomplete information provided to him. It may be, as Mr Mengoli suggested, that the change to Molinari’s computer system in the first half of 1996 explains why Mr Mengoli did not provide evidence of the supply of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee to Australia prior to July 1996 and why, in his affidavit, Mr Molinari proceeded on the basis that export to Australia only commenced “in or about July 1996”. I do not propose, however, to speculate about that matter.

193 Having regard to all the evidence before me on this issue, I am satisfied that Molinari supplied CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee to CMS in 1995 and in the first half of 1996. In particular, I am satisfied that:

(a) each shipment to CMS covered by the invoices dated 18 September 1995, 17 October 1995, and 26 March 1996 (as recorded in Molinari’s Kronos system) was made;

(b) the products identified by product codes 6091 and 6093 were included in the shipments in the quantities stated in Molinari’s Kronos system, and were packaged in the packaging depicted at [125] above;

(c) each shipment left Molinari’s warehouse in Italy on the date of the invoice corresponding to that shipment as recorded in Molinari’s Kronos system;

(d) each shipment was received at CMS’s warehouse premises, in accordance with the invoice corresponding to that shipment, at 1/33 Acheson Place, Coburg, approximately 4 to 7 weeks after the invoice date; and

(e) the CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee received by CMS was used, displayed for sale, and supplied by CMS, as described in Ms Toledano’s evidence.

194 For reasons that will become apparent, it is appropriate that I refer to other aspects of Molinari’s supply of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee to the Australian market.

195 Espresso Group Pty Ltd (Espresso Group) distributed Molinari products in Australia from about January 2001 until November 2009. It was appointed as Molinari’s exclusive Australian distributor in around March 2003.

196 Modena Trading Pty Ltd (Modena) is Molinari’s current Australian distributor. It was appointed as Molinari’s exclusive Australian distributor in around 2009.

197 I have already referred to copies of invoices (extracted from the Kronos system) that Molinari issued to CMS in the period 24 July 1996 to 16 April 2003 and to Coffee Supplies Australia in the period 9 December 1999 to 4 April 2002 in respect of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee. The supplies covered by these invoices included supply of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee in the 250 g pack (product code 1525E). These packs are directed to the retail sector of the market, for supermarkets and consumers.

198 There is also a spreadsheet in evidence which contains details of invoices of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee supplied to Espresso Group (for the period January 2001 to August 2009) and Modena (for the period October 2009 to September 2021). This spreadsheet evidences that CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee in the 250 g pack was also supplied to Espresso Group as late as 6 November 2007.

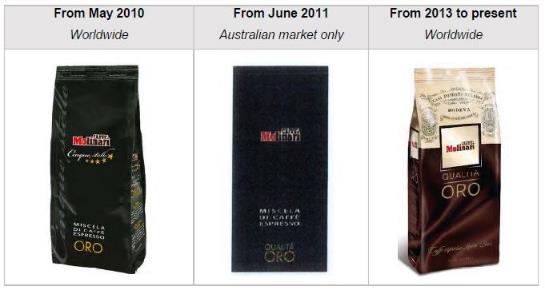

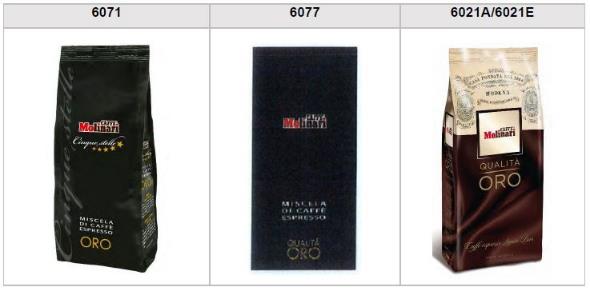

199 At some time before December 2003 (the evidence is no clearer than that) the packaging of the 250 g pack was updated to the following packaging:

200 I am satisfied that the 250 g packs of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee (product code 1525E) that Molinari supplied to CMS (invoice dated 25 September 1997) and Coffee Supplies Australia (invoices dated 26 July 2001 and 4 April 2002) were in the form of the packaging depicted at [125] above, and that the 250 g packs of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee that Molinari supplied to Espresso Group (invoices dated 11 September 2001, 17 January 2002, 19 February 2002, 18 April 2002, 18 December 2002, 25 March 2004, 12 April 2005, 21 November 2006, and 8 June 2007) were either in the form of the packaging depicted at [125] above or at [199] above.

201 The packaging of the 1 kg pack of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee (product code 6091) was also updated to the following:

202 The evidence is unclear as to when this packaging change occurred. The best evidence that Mr Mengoli could give was that the change occurred sometime after the similar change to the packaging of the 250 g pack of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee was made.

203 The spreadsheet records numerous supplies, in significant quantities, of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee in 1 kg packs to both Espresso Group and then to Modena in the period 22 January 2001 to 22 October 2009. I am satisfied these supplies in the period after December 2003 included supplies to Espresso Group of 1 kg packs (product code 6091) in the form of the packaging depicted at [201] above: see invoices dated 25 March 2004; 27 May 2004; and 15 July 2004 totalling 13,540 packs. (I note that the spreadsheet records numerous supplies, in significant quantities, of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO in 1 kg packs to both Espresso Group and then to Modena in the same period under product code 6091E. There is no direct evidence of the packaging for this product code.)

204 Mr Mengoli said that, to the best of his recollection, 1 kg packs of CAFFÈ MOLINARI ORO coffee in the packaging depicted at [201] above were exported to Molinari’s Australian distributors until the packaging was further updated, as follows: