Federal Court of Australia

Greentree v Jaguar Land Rover Australia Pty Ltd (Carriage Application) [2023] FCA 1209

ORDERS

First Applicant ADAM GREENTREE Second Applicant | ||

AND: | JAGUAR LAND ROVER AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 004 352 238) Respondent | |

NSD 85 of 2023 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | MICHELLE JENNINGS Applicant | |

AND: | JAGUAR LAND ROVER AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 004 352 238) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to rule 9.12(1) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), the applicants in proceeding NSD 1010 of 2022 (Greentree proceeding) be granted leave to intervene in proceeding NSD 85 of 2022 (Jennings proceeding).

2. In the event the applicants in the Greentree proceeding (Greentree applicants), Gilbert + Tobin and Balance Legal Capital II UK Ltd (Balance) provide to the Associate to Justice Lee an undertaking to the Court within 28 days of these Orders that the Greentree applicants, Gilbert + Tobin and Balance will not seek to recover a total amount upon any settlement or judgment representing all legal costs, and other fees and expenses of more than 25 per cent (proposed undertaking) then, upon the receipt and acceptance by the Court of the proposed undertaking as an undertaking to the Court, the Jennings proceeding be permanently stayed.

3. A copy of the proposed undertaking is to be served on the applicants in the Jennings proceeding immediately upon its delivery to the Associate to Justice Lee.

4. In the event the proposed undertaking is not provided in accordance with Order 2 above or is thereafter not accepted by the Court, the Greentree proceeding be declassed pursuant to s 33N of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and then be temporarily stayed pending a mediation of the Jennings proceeding and the Greentree proceeding (with the intention that if the mediation does not result in a s 33V application in the Jennings proceeding, the Greentree proceeding then be the subject of a further stay until after the initial trial and determination of common questions in the Jennings proceeding).

5. Liberty to any party in the Greentree proceeding or Jennings proceeding to relist the proceeding immediately upon delivery of any proposed undertaking to the Associate to Justice Lee.

6. Costs be reserved.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

LEE J:

A INTRODUCTION

1 This is a multiplicity dispute between two competing, duplicative, open class actions brought against Jaguar Land Rover Australia (Jaguar). The proceedings concern claims under the Australian Consumer Law (as contained in Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) (ACL) in respect of alleged defects in models of diesel motor cars sold under the “Jaguar” or “Land Rover” brand. The relevant proceedings are as follows:

(1) Leah Maree Greentree v Jaguar Land Rover Australia Pty Ltd (ACN 004 352 238) (NSD 1010 of 2022) (Greentree proceeding); and

(2) Michelle Jennings v Jaguar Land Rover Australia Pty Ltd (ACN 004 352 238) (NSD 85 of 2023) (Jennings proceeding).

2 The applicants in the Greentree proceeding (Greentree applicants) seek an order that the Jennings proceeding be permanently stayed. The applicant in the Jennings proceeding (Jennings applicant), on the other hand, seeks an order that the Greentree proceeding be permanently stayed or, alternatively, declassed pursuant to s 33N of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act) and temporarily stayed, pending the determination of common questions in the Jennings proceeding.

3 I have written at length elsewhere about the appropriate remedial response to multiplicity disputes: see, for example, Klemweb Nominees Pty Ltd (as trustee for the Klemweb Superannuation Fund) v BHP Group Ltd [2019] FCAFC 107; (2019) 369 ALR 583 (at 593 [48]–[49]). It is a matter of case management involving an evaluation, and not a calculus; it involves weighing up incommensurable and sometimes conflicting considerations and it is inevitable that different judges may weigh the relevant considerations differently. It is also a decision made in the context of there being a range of potential solutions and there being no uniquely “correct” answer. The decision involves an appraisal informed by diverse factors, and the ultimate judgment is one upon which reasonable minds might, and often will, differ.

4 More fundamentally, as I explained in Perera v GetSwift Ltd [2018] FCA 732; (2018) 263 FCR 1 (at 83–84 [345]–[349]), multiplicity is not to be encouraged and the continuation of competing open class actions can be inimical to the administration of justice: see Wigmans v AMP Limited [2021] HCA 7; (2021) 270 CLR 623 (at 666 [106] per Gageler, Gordon and Edelman JJ). Although, by virtue of both s 33C of the FCA Act (which allows class actions to be commenced on behalf of some potential claimants) and the opt out mechanism, Pt IVA does contemplate some multiplicity, ordinarily the maintenance of substantially duplicative open class actions is contrary to the just resolution of disputed claims in a quick, inexpensive and efficient manner.

5 In the ordinary course, I would have proceeded to deal with this multiplicity contest by delivering judgment ex tempore or as promptly as possible, to resolve such issues with a minimum of cost and a maximum of expedition. The present difficulty is that these applications coincided with the referral of a question to the Full Court in a different case concerning the question as to whether the Court has power pursuant to s 33V of the FCA Act to make an order distributing amounts considered by the Court to be “just” from an approved settlement fund, known commonly as a “settlement CFO”.

6 The funding proposals of both parties involve seeking a settlement or judgment CFO from the Court. This was overlaid with the complication that the Jennings applicant (putting to one side the question of the Court’s power to make a CFO simpliciter) seeks what has been described as a “solicitors’ common fund order”, which incorporates a payment to solicitors of an amount, in addition to legal costs, out of any settlement or judgment sum.

7 Several judges, including me, have remarked on the difficulty of jargon and labels in this area. What is contemplated by the Jennings applicant is a form of order under s 33V(2) providing that following an approved settlement (or under ss 33Z, 33ZA or s 33ZJ(3) or otherwise upon judgment) a proposed “just” distribution is made to third-parties, including a solicitor corporation, which have borne the risks of funding the costs of the litigation and securing the creation of the fund or the judgment sum for the benefit of the group members or a group member.

8 An order of this type was contemplated in Klemweb where, leaving aside the question of discretion, it was suggested that power existed under s 33V to make an order which resulted in a payment to a solicitor (at 587–588 [16]–[23] per Middleton and Beach JJ).

9 I considered that when one has regard to the equitable roots and restitutionary basis of common fund orders, which assist in informing a characterisation of what is just in all the circumstances, far from apparent why a CFO incorporating some payment to a solicitor is heterodox (at 612–613 [139]–[141]); see also R&B Investments Pty Ltd (Trustee) v Blue Sky Alternative Investments Limited (Administrators Appointed) (in liq) (Carriage Application No 2) [2023] FCA 142 (at [18]). I will return to this issue (at [41]–[45]) below.

10 Accordingly, as noted above, it was appropriate to defer consideration of any multiplicity issues until after the Full Court had delivered judgment today in Elliott-Carde v McDonald’s Australia Limited [2023] FCAFC 162, where the Full Court held it is licit for the Court to make a settlement CFO pursuant to s 33V.

11 I have organised the balance of these reasons under the following headings:

B BACKGROUND TO THE PROCEEDINGS

C THE RELEVANT LAW

D CONSIDERATION OF RELEVANT FACTORS

E THE APPROPRIATE REMEDY

F THE POSSIBLE WAYS FORWARD

G CONCLUSION AND ORDERS

B BACKGROUND TO THE PROCEEDINGS

B.1 The Greentree Proceeding

12 The Greentree proceeding was commenced on 23 November 2022. It is being conducted by the firm of solicitors, Gilbert + Tobin, and is funded by Balance Legal Capital II UK Ltd, being a fund managed by Balance Legal Capital LLP (collectively, Balance).

13 For reasons that will assume some importance, Gilbert + Tobin successfully conducted almost identical claims the subject of these proceedings on behalf of applicants in a class action against Toyota Motor Corporation Australia Limited (Toyota proceeding) concerning allegedly defective diesel particulate filter (DPF) systems in motor vehicles sold to Australian consumers (see Williams v Toyota Motor Corporation Australia Limited (Initial Trial) [2022] FCA 344).

14 Mr Mackenzie and Ms Spigelman, partners of Gilbert + Tobin, have had carriage of the Toyota proceeding since April 2019. Mr Mackenzie gave evidence in his affidavit sworn 26 February 2023 (Mackenzie Affidavit) that Gilbert + Tobin began investigating matters the subject of the Greentree proceeding in around April 2022.

15 The investigation conducted by Gilbert + Tobin was thorough. It has involved three stages, the first of which comprised of searches and reviews of information relating to DPF systems in diesel vehicles distributed by Jaguar in Australia and issues consumers reported experiencing with the DPF systems.

16 The second stage involved Gilbert + Tobin negotiating the provision of “seed funding” with Balance to enable Mr Smithers (a technical expert engaged by the Greentree applicants) to investigate technical matters, and to enable Gilbert + Tobin counsel to identify a suitable representative applicant (or applicants) and prepare an originating application and statement of claim. In May 2022, Gilbert + Tobin and Balance entered into an agreement pursuant to which Balance agreed to provide the seed feeding to facilitate the investigation.

17 The third stage involved Mr Smithers and solicitors from Gilbert + Tobin between May and October 2022 investigating various technical matters, including, among other things:

(1) reviewing public information collated by Gilbert + Tobin for the purpose of designing a detailed plan for inspecting and testing certain models of diesel motor vehicles distributed by Jaguar in Australia;

(2) physically inspecting and testing 14 diesel motor vehicles which featured a Jaguar “D8” or “D7U” vehicle platform, which included Mr Smithers and Mr Schenk (an employee of Mr Smithers’ company, 44 Energy Technologies) travelling from the United States to Australia to inspect, inter alia:

(a) the physical design, layout, geometry, components and operation of DPF systems in the relevant vehicles;

(b) the servicing records of the relevant vehicles; and

(c) oil samples from the relevant vehicles;

(3) conducting a programme of logging data recorded by on-board computers of 11 diesel motor vehicles distributed by Jaguar in Australia, including calibrating “HEM data loggers” which collected real-time data about the performance of the vehicles while they were being driven, including:

(d) the frequency and duration of regeneration experienced by the vehicles;

(e) the temperature of the exhaust produced by the vehicles’ engines measured at different locations in the DPF systems; and

(f) the speeds at which the vehicles were being driven; and

(4) Mr Smithers and Mr Schenk participating in video conferences with counsel and solicitors from Gilbert + Tobin with respect to the results of tests on the operation of DPF Systems.

18 Mr Mackenzie estimates that he participated in around a dozen video conferences with Mr Smithers and his team, and more than 20 telephone calls with Mr Smithers in relation to the investigation. Further, the Greentree applicants’ originating application and statement of claim were prepared in parallel with the investigation conducted by Mr Smithers, and Mr Mackenzie estimates that between September and November 2022, he participated in an additional three video conferences and half a dozen telephone calls with Mr Smithers.

19 The Greentree proceeding was allocated to my docket in late January 2023, and I listed the matter for a first case management hearing shortly thereafter on 3 February 2023.

B.2 The Jennings Proceeding

20 The Jennings proceeding is the later of the two proceedings and is being conducted by Maurice Blackburn, which began investigating the matters subject of the proceedings in or around July 2022. The Jennings proceeding is “co-funded” by Maurice Blackburn and a litigation funder, CF FLA Australia Investments 3 Pty Ltd, being an entity within the Vannin Capital group (collectively, Vannin).

21 Mr Watson, a principal of Maurice Blackburn, and one of Australia’s most experienced class action lawyers, provided evidence in his affidavit of 26 February 2023 (Watson Affidavit) in which he deposed to Maurice Blackburn’s work in conducting consumer and product liability class actions, including the Volkswagen, Audi and Skoda class actions in 2015 (VW class actions). The VW class actions involved similar consumer protection claims to the present proceedings arising out of the fitting of “defeat devices” to certain diesel vehicles which caused the vehicles to emit lower levels of nitrogen oxide when being tested for emissions standards.

22 Mr Watson also gave evidence identifying the work Maurice Blackburn has conducted to advance the Jennings applicant’s claim to date:

19.1 Identifying and considering potential causes of action against Jaguar Land Rover;

19.2 Briefing and conferring with senior and junior counsel in relation to the factual and technical background to the claims, potential causes of action, remedies and class definition;

19.3 Reviewing and analysing a large amount of publicly available information in relation to various Jaguar Land Rover models, including design specifications and performance issues;

19.4 Reviewing consumer complaints in relation to DPF issues in a wide range of Jaguar and Land Rover models;

19.5 Exploring potential funding arrangements with Vannin;

19.6 Launching an online webpage and registration portal for registrants, for the purpose of:

(a) Identifying a lead applicant;

(b) Collecting vehicle data from potential group members;

(c) Registering expressions of interest in the proposed claim (at this stage potential group members have not been asked to enter into any costs agreements or litigation funding agreements);

(d) Providing further information about the investigation to prospective group members;

19.7 Corresponding with registrants in relation to queries about eligibility for the proposed class action;

19.8 Preliminary discussions with a technical expert;

19.9 Preparation of pleadings.

23 As I expressed to the parties during the hearing, the matters above are outlined at what might be described as a relatively high level of generality.

24 In any event, in December 2022, Maurice Blackburn publicly announced its investigation and commenced a registration process for prospective group members. As of February 2023, there were 329 potential group members registered for the class action.

25 On 2 February 2023, the Jennings proceeding was commenced by way of originating application, with funding secured from Vannin shortly thereafter.

C THE RELEVANT LAW

26 There was no dispute as to the relevant principles. My summary in CJMcG Pty Ltd as Trustee for the CJMcG Superannuation Fund v Boral Limited (No 2) [2021] FCA 350; (2021) 389 ALR 699 (at 703–704 [9]–[13]) remains apposite:

9. First, in determining the appropriate remedial response, the focus of the Court is on what “would be in the best interests of group members”: at [52]. This is a task directed to ensuring that justice is done in the competing proceedings: at [116]. In this way, the approach mandated by Wigmans is entirely consonant with the Court’s statutory requirement contained in Pt VB of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (Act) to facilitate the overarching purpose.

10. Secondly, there is no race to the courthouse. The High Court has decisively rejected that there be a presumption that the “first in time” rule applies: at [52] and [94]. In and of itself, it is not vexatious, oppressive or an abuse of process to commence a subsequent bona fide class action prior to the Court giving substantial directions in existing but overlapping proceedings: at [107], citing Getswift (at [150]). Although the time of filing may remain a relevant consideration, as I will explain below, it is a less relevant consideration in cases such as the present where the competing proceedings have been commenced within a relatively short time of each other: at [107], citing Wigmans v AMP Ltd (2019) 103 NSWLR 543; 373 ALR 323; [2019] NSWCA 243 (at [83] per Bell P, with whom [Macfarlan], Meagher, Payne and White JJA agreed).

11. Thirdly, as is to be expected in a multifactorial inquiry, the factors relevant to the determination of applications such as the present will vary from case to case: at [109], citing Getswift First Instance (at [169]) and Getswift (at [195]). The point made by the High Court is that it is necessary for a court to determine, by reference to all relevant considerations, which proceeding going ahead would be in the best interests of group members: at [109].

12. Fourthly, the litigation funding arrangements adopted by the competing applicants are not irrelevant, and there is nothing foreign to the judicial process for a court to take into account likely success in proceedings or quantum of recovery, both of which may be affected by the litigation funding arrangements in place: at [111]–[112].

13. It follows from the above that the factors that will be relevant in conducting a multifactorial analysis for the purposes of staying one or more of the duplicative proceedings cannot be exhaustively stated. Having said that, previous cases, for example, Wigmans v AMP Ltd [2019] NSWSC 603 (at [121]–[126] per Ward CJ in Eq) (Wigmans First Instance), McKay Super Solutions Pty Ltd (as trustee for the McKay Super Solutions Fund) v Bellamy’s Australia Ltd [2017] FCA 947 (at [71] per Beach J) and GetSwift First Instance (at [169] per Lee J), have identified at least the following factors, which all participants have suggested are relevant considerations to a greater or lesser extent (summarised in Wigmans (at [6])):

(1) the competing funding proposals, cost estimates and net hypothetical return to group members;

(2) proposals for security;

(3) the nature and scope of the causes of action advanced (and relevant case theories);

(4) the size of the respective classes;

(5) the extent of any book build;

(6) the experience of the legal practitioners (and funders) and availability of resources;

(7) the state of progress of the proceedings; and

(8) the conduct of the representative applicants to date.

27 As I explain below, two of these factors loom large in the circumstances of the case. The first factor concerns the differences between the funding arrangement proposed by the Jennings applicant and the more common model proposed in the Greentree proceeding; and the second is the comparative subject-matter experience of the solicitors for the Greentree applicants in conducting the Toyota class action. While there are additional relevant considerations, some of which do not fall squarely within the eight categories above, these other factors are relatively neutral.

28 I should stress that I have had the opportunity of reading the affidavit material and the submissions filed by the applicants in both proceedings and, to the extent that I do not refer to any of the material filed, it does not mean that I have not had regard to it. These applications are not to be equated to mini-hearings. Indeed, at some risk of repetition, it is inimical to the overarching purpose in Pt VB to allow applications such as the present to give rise to lengthy judgment and delay the pursuit of the substantive underlying claims. The only reason why the resolution of this dispute has been delayed is because of the necessity to await the Full Court’s decision as to common fund orders.

D CONSIDERATION OF RELEVANT FACTORS

29 I now turn to consider each of the factors relevant in the circumstances of this case dealing initially with the two most prominent factors I have identified.

D.1 Competing Funding Proposals

30 Two competing funding proposals are in evidence, and it is necessary to descend into the detail of each proposal.

D.1.1 The Greentree proposal

31 This funding proposal is reflected in the funding agreement dated 15 November 2022 (Greentree LFA). Also relevant are the retainer and conditional costs agreement between the Greentree applicants and Gilbert + Tobin dated 14 November 2022 (Greentree Retainer) and the coordination agreement between Gilbert + Tobin and Balance dated 15 November 2022 (Greentree Coordination Agreement).

32 In summary, pursuant to those agreements, Balance is to fund Gilbert + Tobin’s legal fees and disbursements, adverse costs awards, the costs of any “after-the-event” (ATE) insurance and the costs of any insurance or deed of indemnity providing for security for costs: Greentree LFA, cl 5.1. As consideration, subject to the Court’s approval, Balance is entitled to recover a commission on the resolution sum of:

(1) 20 per cent if the proceeding is resolved within 12 months of its commencement (that is, by 23 November 2023);

(2) 25 per cent from 23 November 2023 until six weeks before the trial; or

(3) 30 per cent thereafter.

33 In the event of any appeal (or further appeal), Balance is entitled to recover a further five per cent per appeal, including all legal costs and any adverse costs liability: Greentree LFA, cll 5.1, 8.1. ATE insurance costs are also said to be recoverable notwithstanding the fact that several judges of this Court, experienced in class actions, have pointed to the inappropriateness of such an impost to be recovered by a funder which, in substance, is a cost incurred to defray the very risk to be run by the funder in exchange for its funding commission. If a traditional funding fee is sought, it is generally unfair that the cost of this prudential protection for the funder should be visited upon group members. Put bluntly, the exposure to risk is what the funder is being paid for. As I recently said in J & J Richards Super Pty Ltd v Linchpin Capital Group Limited (Settlement Approval) [2023] FCA 656 (at [54]): “[t]here is a limit to how much a funder should be allowed to wet its beak”.

34 In any event, notwithstanding the funding terms above, Balance, through the Greentree applicants’ instructing solicitors, has undertaken to make improvements to its funding proposal if the Greentree proceeding is awarded carriage of the matter and the Jennings proceeding is stayed, as follows: first, Balance will not seek to recover the costs of any ATE insurance from the resolution sum in the event of a settlement or judgment; secondly, Balance will seek a funding commission of 20 per cent if the proceeding is resolved within 18 months (rather than 12 months) of filing but more than six weeks before any trial of the common questions; and thirdly, Balance will otherwise seek a funding commission of no more than 25 per cent of the resolution sum if the proceeding is resolved within six weeks of any trial of the common questions or any time thereafter: Mackenzie Affidavit (at [62]).

D.1.2 The Jennings proposal

35 This funding proposal is primarily reflected in the litigation management and funding agreement dated 13 February 2023 (Jennings LFA), to which is attached, as Schedule 1, and adopting the Americanism, a “law firm relationship agreement” (Jennings Relationship Agreement). Also relevant is the retainer and conditional costs agreement between the Jennings applicants and Maurice Blackburn dated 13 February 2023 (Jennings Retainer).

36 In summary, Maurice Blackburn and Vannin are responsible for the entirety of the costs of the Jennings proceeding and the arrangements provide that Maurice Blackburn acts on a “no win, no fee” basis, such that if the proceeding is successful, the Jennings applicant will seek a CFO (or other order for the equitable distribution of costs, fees and expenses) whereby Vannin will be paid a commission on the resolution sum of (Jennings Relationship Agreement, cl 6):

(1) 20 per cent if the proceeding is resolved before 1 March 2024; or

(2) 25 per cent thereafter.

37 I note that Vannin has agreed to extend the period for which the proposed funding commission is capped at 20 per cent for the Jennings proceeding from 1 March to 23 May 2024, provided the date of resolution is more than six weeks before the commencement of the trial of common issues. But needless to say, because of procedural delays, the prospect of resolution prior to 24 May 2024 is now remote and it is safe to proceed on the basis that the commission will be 25 per cent.

38 As to the commission itself, subject to the approval of the Court, half of that fee is shared with Maurice Blackburn, and, in that event, there is no further payment to Maurice Blackburn (Jennings Relationship Agreement, cl 9). It follows that under the arrangements struck, if there is not a successful resolution of the proceeding, neither the Jennings applicant nor the group members will be charged any amount, but if there is a successful resolution of the proceeding (whether by way of judgment or settlement), the CFO sought will provide for a certain amount to be paid to Vannin at the Court’s discretion, but in no case would exceed 25 per cent of any claim proceeds.

39 The net effect of this arrangement is that group members will always receive at least 75 per cent of any resolution sum. As I explained in CJMcG (No 2) (at 711 [48]), this funding model offers real benefits for group members because it avoids a problem which has arisen in many class actions by removing any uncertainty as to the power of the Court to vary the terms of the commission arrangements agreed.

40 More particularly, it allows the Court to determine the appropriate level of remuneration that is to be provided to Vannin and Maurice Blackburn at the conclusion of the proceeding, having regard to the way in which the proceeding develops. This protects group members from downside risk in the event that significant legal expenses are incurred but the resolution sum is relatively modest.

41 There was some suggestion by senior counsel for the Greentree applicants that such an approach may be contrary to the prohibition in all Australian jurisdictions on solicitors entering into costs agreements which provide for a contingency fee (see, for example, s 183(1) of the Legal Profession Law Application Act 2014 (Vic)). But there is no suggestion such an agreement has been, or is proposed to be, struck: we are dealing here with a proposed order made by a Court.

42 In Klemweb, Middleton and Beach JJ observed some salient differences between the general statutory prohibition on solicitors entering into contingency fee arrangements and the payment of a contingency fee out of any settlement proceeds under Pt IVA, suggesting that if power was available to make a CFO, power would be available under s 33V to make a solicitors’ CFO (at 587–588 [16]–[23]).

43 Further, as I noted in McDonald’s (at [380]), the distribution of monies paid under a settlement to a third-party to a class action who has acted in such a way to facilitate the realisation of the fund, and to whom a payment is “just” within the meaning of s 33V(2) by reference to all the circumstances, need not necessarily be a commercial funder. What matters, at least in the context of any settlement fund, is whether a proposed payment out of the realised fund can be characterised as being just.

44 In characterising what might be considered just depending upon all the circumstances, it is relevant that a settlement CFO can be seen as being consistent with the notion that a person who benefits from another’s efforts in producing a fund is obliged to provide appropriate value in return, as is reflected in the underlying principle that it would be inequitable for the person who has created or realised a valuable asset, in which others claim an interest, not to have the costs, expenses and fees incurred in producing the asset paid out of the fund or property created. As I said in Klemweb (at 612–613 [139]–[141]):

Focussing on the context of Pt IVA proceedings, it is not apparent to me why a properly formulated common fund order that relates, in its operation to a common fund and involves a contingency payment to a solicitor could not, in some cases, be appropriate to ensure justice in some Pt IVA proceedings. …

In circumstances where there is real doubt about the ability to intervene with contractual promises given to funders absent any complaint by the contractual counterparty … the practical benefit of common fund orders has been to maintain control over disproportionate deductions from modest settlements, prevent windfalls, and ensure the Court’s protective and supervisory role in relation to group members is given effect. …

Subject to being properly framed…, I do not consider it unlikely that a common fund order incorporating a contingency payment could be made. When one has regard to the equitable roots and restitutionary basis of common fund orders, it is not apparent why a common fund order incorporating a contingency component is antithetical to doing justice in a Pt IVA proceeding in an appropriate case.

45 For these reasons, and those I have explained in McDonald’s, there is no substance in the argument that Pt IVA precludes, as a matter of power, the possibility of a settlement CFO which incorporates the payment of a fee to solicitors in an appropriate case. The same considerations apply mutatis mutandis to a CFO being sought upon a judgment obtained because solicitors ran the risk of funding the claim or claims that merged in the judgment.

46 On the current state of the authorities, I do not consider the fact that the Jennings funding proposal contemplates a form of payment to solicitors as a reason to prefer staying the Jennings proceeding in favour of the Greentree proceeding. Indeed, the Jennings funding model preserves the Court maximum flexibility and discretion in setting the amount payable to the funder and the solicitors: see CJMcG (No 2) (at 711 [50]).

D.2 Costs Estimates

47 It is necessary to say something briefly about the professional fees proposed to be charged. The table below compares Maurice Blackburn’s professional fees (Jennings Retainer, Annexure A) and Gilbert + Tobin’s professional fees (Greentree Retainer, cl 3.5) (all amounts are exclusive of GST):

Maurice Blackburn | Gilbert + Tobin | ||

Professional | Hourly Rate | Professional | Hourly Rate |

Principal/Special Counsel > 15 years’ experience | $905 | Senior Partner | $830 |

Principal/Special Counsel < 15 years’ experience | $850 | Junior Partner | $720–$770 |

Senior Associate | $720 | Special Counsel | $720 |

Associate | $630 | Senior Associate | $510–$690 |

Lawyer | $520 | Associate | $420–$500 |

Trainee Lawyer/Law Graduate | $410 | Graduate/Junior Associate | $300–$410 |

Law Clerk/Paralegal | $380 | Lech tech support specialists | $290–$650 |

Litigation Technology Consultant | $285 | Review specialists and managers | $200–$400 |

Client Services Officer | $190 | Paralegal | $200 |

48 To someone who became a solicitor in the 1980s and recalls the hourly rates charged by large firms in those times and up until the end of the last century, it might be intuitively surprising that partners at some firms are now charging in excess of $1,000 per hour inclusive of GST, but things have changed. There is no reason to doubt they reflect the market, albeit the top end of the market.

49 More relevantly for present purposes, there are some differences, which, taken as a whole, indicate that the charge-out rates of Gilbert + Tobin are somewhat less expensive than the rates charged by Maurice Blackburn. Paralegals, for example (putting to one side whether such costs are allowable pursuant to Sch 3 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (FCR)) are charged-out at $380 per hour on the Jennings Retainer, whereas on the Greentree Retainer, paralegals garner a rate of $200 per hour.

50 I was entreated by senior counsel for the Jennings applicant, Mr Moore SC, not to be distracted by any comparison because no matter the scale of professional fees incurred by Maurice Blackburn, group members in the Jennings proceeding will never be exposed a settlement or judgment CFO which awards an amount more than 25 per cent of the claim proceeds.

51 There is significant force in this submission.

52 I have already referred to the fact that a feature of the Jennings funding proposal is that it protects group members from the risk of spiralling legal costs, even if the resolution sum is relatively modest. Bearing this in mind, and doing the best I can at this stage, any difference between the charge-out rates of Maurice Blackburn and Gilbert + Tobin will be offset by the funding arrangement proposed in the Jennings proceeding and the appointment of a costs referee.

53 The Greentree Retainer (cl 6.1) and the Jennings retainer (cl 10) also contain detailed budgets, which are unnecessary to set out here. I have previously remarked that the prognostications of solicitors in this regard are likely to be of dubious utility, but, to the extent the budgets do differ between the proceedings, Maurice Blackburn’s estimate is slightly lower than the estimate put forward by Gilbert + Tobin. This, however, is a neutral consideration in the circumstances of this case.

D.3 Net Hypothetical Returns to Group Members

54 Subject to a matter to which I will return, I should preface any comparison of the net hypothetical returns to group members by noting that because the proposals in both proceedings contemplate seeking a form of settlement or judgment CFO, any differences in the rates or method of calculation under the respective arrangements may not be particularly significant at the end of the day. The reason for this is obvious: at the conclusion of the proceeding, it is contemplated the Court will fix the amount to be distributed. Those circumstances will include the net returns to group members, and what it regards as a reasonable return for the risk undertaken, assessed ex ante: see Money Max Int Pty Ltd v QBE Insurance Group Ltd [2016] FCAFC 148; (2016) 245 FCR 191 (at 210 [82] per Murphy, Gleeson and Beach JJ).

55 With that said, it seems to me tolerably clear that in the vast majority of conceivable scenarios, the likely net return to group members on the “all-in” Jennings funding model is superior to the model proposed in the Greentree proceeding.

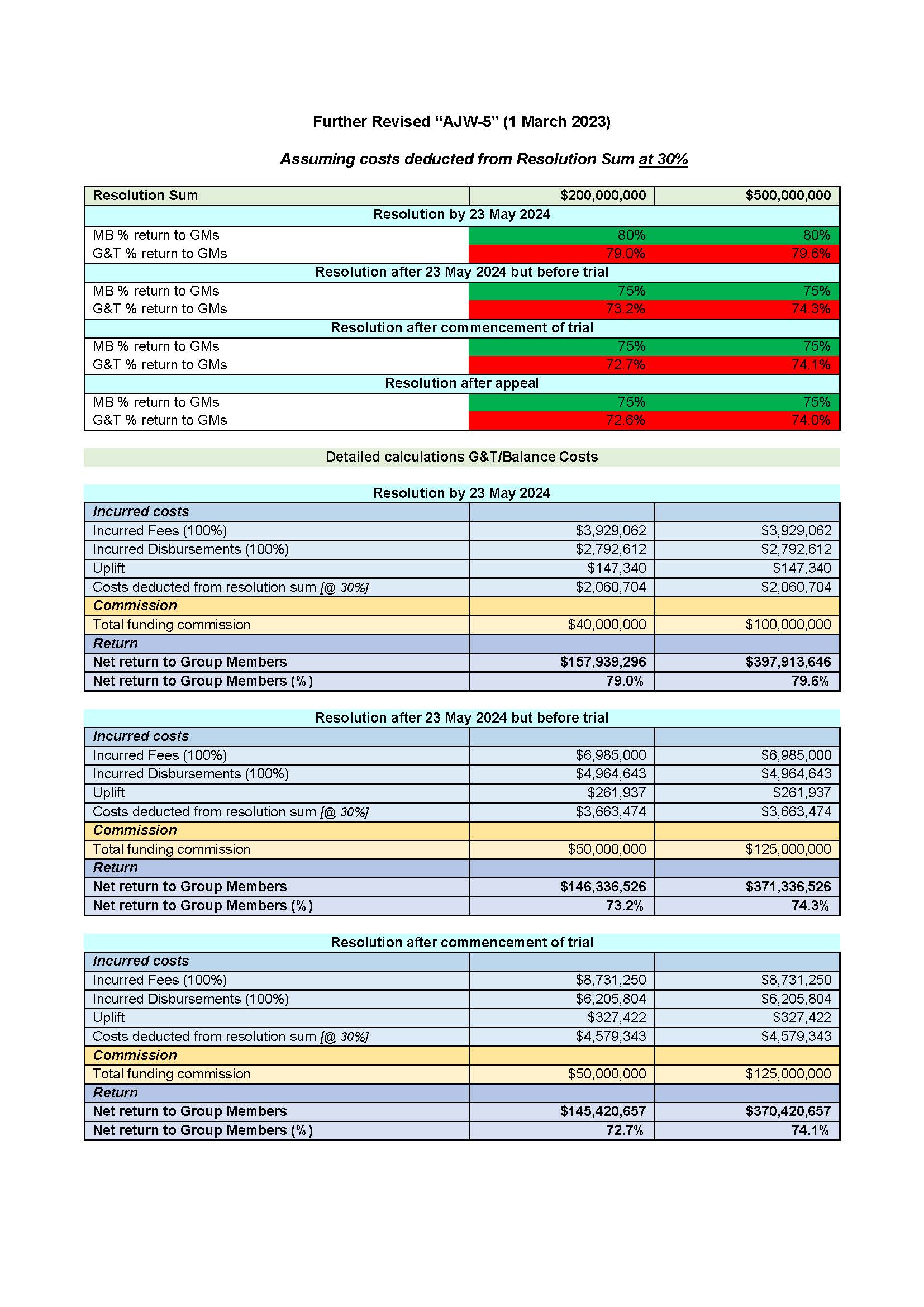

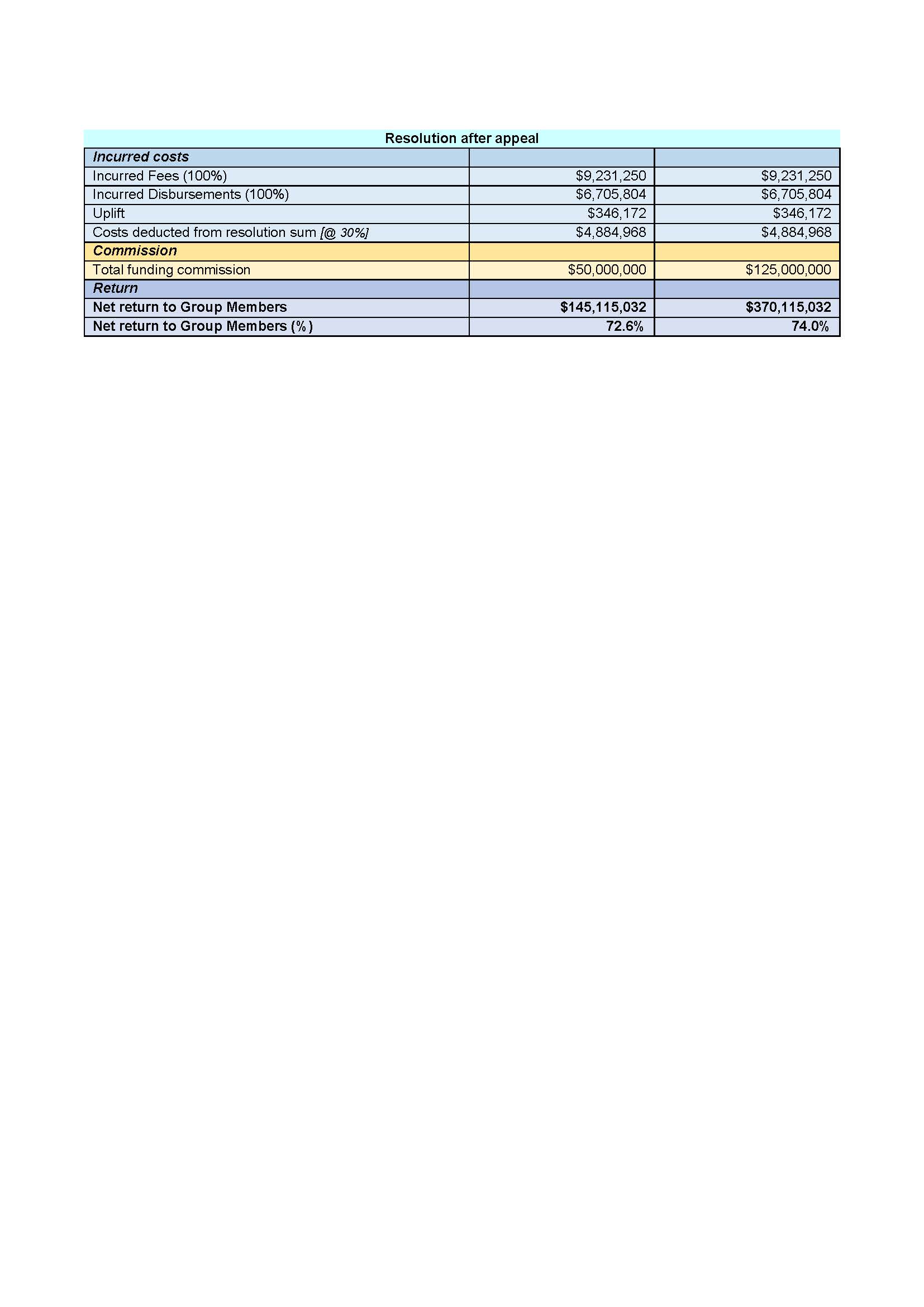

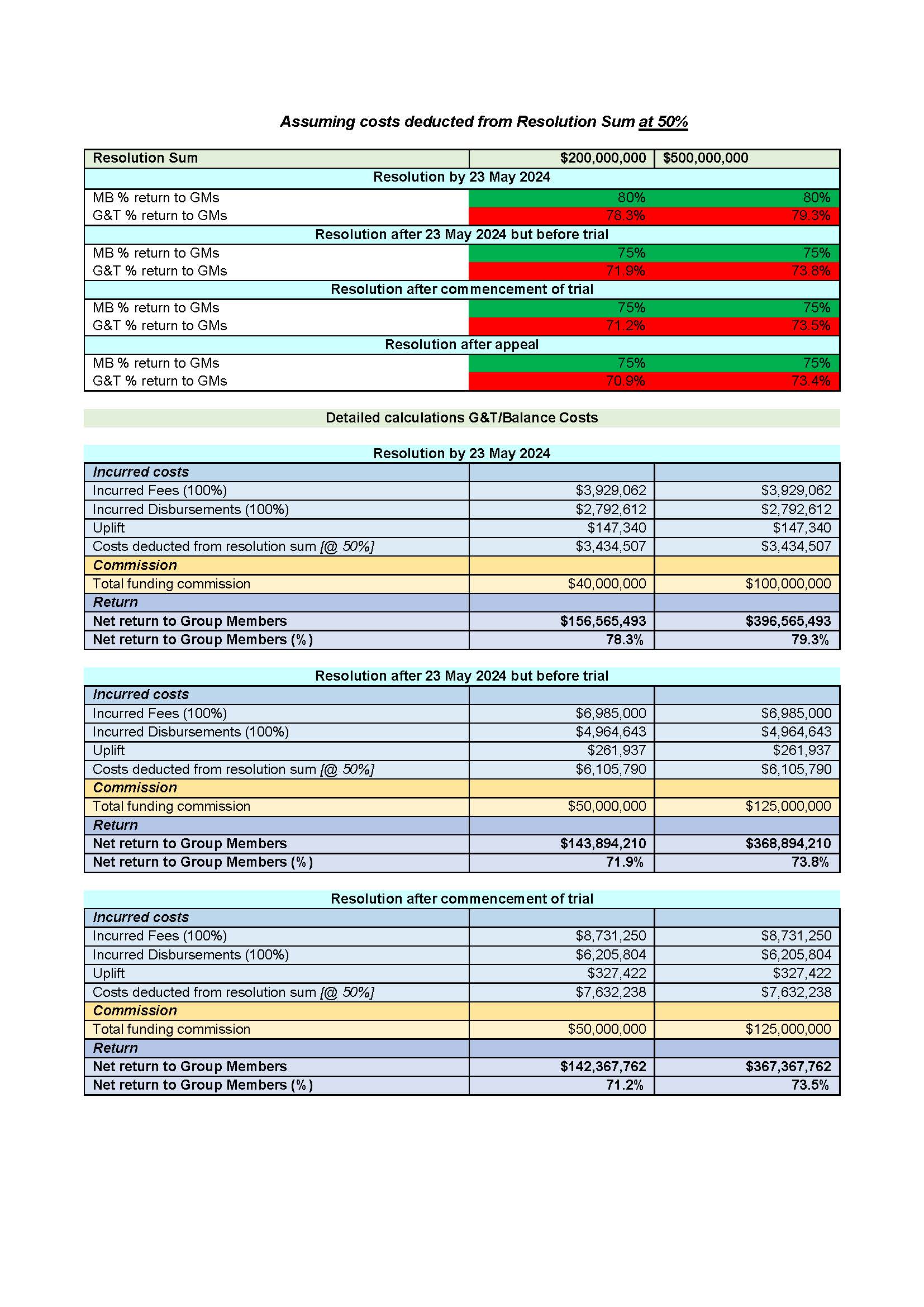

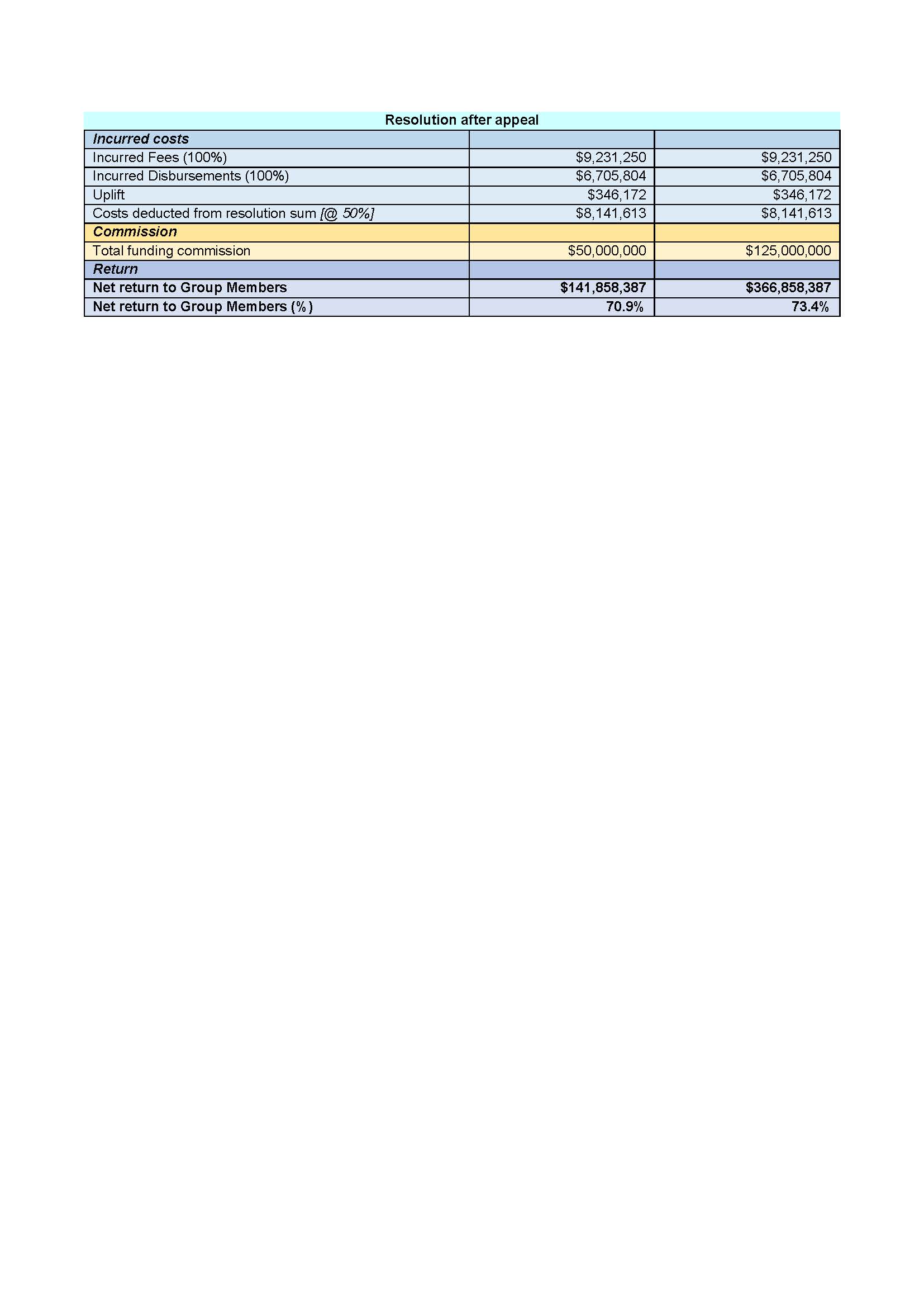

56 The Annexure to these reasons is a copy of a document marked “AJW-5” which, in its final form, contrasts the funding terms in the Greentree proceeding against the terms in the Jennings proceeding first on the assumption that 30 per cent of the Greentree applicants’ costs are deducted from the resolution sum; and secondly, on the assumption that 50 per cent of the Greentree applicants’ costs are deducted.

57 Before going further, I should note that there was somewhat of a moveable feast in relation to the assumptions in AJW-5 and the appropriate discount to be applied to the professional fees and disbursements in the Greentree proceeding. The first iteration of AJW-5 annexed to the Watson Affidavit worked on the assumption that in the event of a settlement or judgment CFO, 100 per cent of the costs incurred in the Greentree proceeding would be deducted from the resolution sum. At the case management hearing, the Greentree applicants tendered a revised version of AJW-5 which, among other things, applied a 70 per cent discount to the costs to be deducted from the resolution sum. This had the effect of attenuating the differences between the net hypothetical returns to group members in both proceedings; the rationale being that a 70 per cent discount more accurately reflects the costs recoverable from the respondent on a party-party basis (whether by way of Court ordered costs or allowance in a settlement), thereby leaving the remaining 30 per cent to be deducted from the resolution sum.

58 To anyone experienced in class actions, the notion that 70 per cent represents an accurate approximation of the costs that would likely be recoverable on a party-party basis might seem bullish. I invited the Greentree applicants to provide a further revised version of AJW-5 (now the Annexure) which incorporates two models: one applying a 70 per cent discount, and the other applying a 50 per cent discount. Further, I received supplementary submissions from Greentree applicants and the Jennings applicant as to why it is appropriate that AJW-5 take into account a 70 per cent discount, as opposed to an assumption that 100 per cent of the professional fees and disbursements incurred in the Greentree proceeding would be deducted from the resolution sum.

59 The Greentree applicants’ submissions may be summarised as follows. First, in the event judgment is delivered in favour of the Greentree applicants, the amount likely to be deducted from the resolution sum would not be 100 per cent of the applicants’ professional fees and disbursements, but an amount equal to the difference between the costs recovered on a party-party basis and the applicants’ costs assessed by a referee. Secondly, if the proceeding settles on terms which justify a CFO, even if the settlement amount is inclusive of costs, it is reasonable to expect that that amount will be influenced by the quantum of professional fees and disbursements incurred to that point. Thirdly, the Greentree applicants estimate of 70 per cent represents a fair discount on the costs to be deducted from the resolution sum in the light of the professional judgment and experience of Gilbert + Tobin in conducting the Toyota class action, a matter to which I will return below.

60 Whether or not one accepts that the discount contended for by the Greentree applicants represents a fair estimation of the costs recoverable on a party-party basis, these submissions obscure the reality that the Jennings funding model provides greater net returns to group members in most, if not all, realistic scenarios.

61 Taking the Greentree applicants’ submission at its highest, if a resolution sum of $200 million is achieved after the commencement of the trial, then, on the Greentree applicants’ modelling (applying a 70 per cent discount), approximately $146,336,526 (or 73.2 per cent) will be paid to group members, whereas group members would always receive $150,000,000 (or 75 per cent) on the Jennings applicant’s modelling. The differences, however, become more pronounced in the lower range of resolution sums as legal costs consume a greater proportion of any settlement or judgment proceeds. On a “worst case” scenario, for example, using the modelling from the original AJW-5, a resolution sum of $80,000,000 following an appeal would leave approximately $43,716,774.40 (or 54.6 per cent) for group members in the Greentree proceeding, whereas group members would always receive $60,000,000 (or 75 per cent) in the Jennings proceeding. This demonstrates one of the important structural advantages of the Jennings funding proposal, namely that it shifts the risk of a low resolution sum that is disproportionate to the costs incurred in the proceeding from group members onto Maurice Blackburn and Vannin.

62 I cannot leave this topic without making a further comment. The Greentree applicants fastened upon a point I made earlier that to the extent the modelling indicates differences in the net hypothetical returns to group members, such differences may be “ironed out” at the settlement approval stage when the Court comes to fixing a deduction that is just in all the circumstances.

63 That may be accepted to a point, but the analysis of what is just is informed by a wide variety of matters, including what group members have been told during the proceeding.

64 If group members in the Jennings proceeding, for example, are told that the funding commission rate is a total cap of 25 per cent inclusive of costs, the fact that the group members have been apprised of that information and, in turn, have made an election whether to opt out of the proceeding is a relevant consideration for the Court in fixing a CFO rate. On the other hand, if group members in the Greentree proceeding are told that the commission rate is capped between 20 and 30 per cent, plus costs, the Court may take the view that proposed 30 per cent plus costs deductions are just because there was no ambiguity as to what had been communicated to group members. As Mr Moore SC submitted, this may contribute to disparities between the net hypothetical returns to group members which cannot be ignored simply because the Court retains a discretion under s 33V(2).

65 At the end of the day, I need not trouble myself unduly with this matter because for reasons I have explained, I find the Jennings funding proposal offers superior returns to group members in all realistic scenarios.

D.4 Experience of the Legal Practitioners

66 This was a matter relied upon heavily by the Greentree applicants.

67 There can be little doubt that if carriage was awarded to either of the experienced and well-regarded firms of solicitors (who have, in turn, briefed highly competent and experienced barristers), then the interests of group members would be appropriately advanced in accordance with the overarching purpose. As I have noted above, as one of Australia’s leading plaintiff and class action firms, Maurice Blackburn has an established track record of successfully conducting product liability group proceedings to settlement, including the VW class actions which, while not on all fours with the present claims, advanced similar claims under the ACL concerning use of a defeat device.

68 But to the extent this factor bears upon the relevant assessment, I consider that it militates in favour of the Greentree applicants, for the following reasons.

69 First, the Toyota proceeding, like the present proceedings, was concerned with allegedly defective DPF systems in motor vehicles sold to Australian consumers. The causes of action advanced in that case were almost identical to the causes of action advanced in these proceedings. There was some reliance placed by the Jennings applicant on the fact that the defect in the Toyota proceeding involved the emission of white smoke when the vehicles were driven at high speeds, as opposed to low speeds the subject of the defect in these proceedings, but I do not think this diminishes the specific accumulated experience of the Greentree applicants’ legal representatives in conducting the Toyota proceeding. The Toyota class action involved a defect in the same component of a diesel engine vehicle and, accordingly, many of the same legal, factual and evidentiary issues that arose in the Toyota proceeding are bound to arise in these competing class actions, including many of the same forensic challenges.

70 Secondly, and as a result, group members will have the benefit of engaging solicitors with significant technical expertise. The relevant subject-matter concerning defective DPF systems in diesel engine vehicles is, to say the least, highly technical. The relative experience of the solicitors in the Greentree proceeding in advancing claims in respect of those systems in the Toyota proceeding will allow the Greentree proceeding to be conducted with comparative efficiency, and work to offset any advantage that Jaguar would otherwise enjoy by dint of its subject-matter experience.

71 Thirdly, and relatedly, the relative subject-matter expertise of the solicitors in the Greentree proceeding is apparent from the conduct of the proceeding to date. As already noted above, the accumulated experience has enabled those practitioners to first, identify and engage an expert from the United States, Mr Smithers, who specialises in analysing defective DPF systems; secondly, conduct, with the assistance of Mr Smithers, a detailed and technical expert analysis of the relevant vehicles, which has involved Mr Smithers and his team travelling to Australia to conduct testing on the relevant vehicles, including collecting “HEM data” from relevant vehicles; thirdly, prepare a pleading that contains detailed and technical allegations about the nature of the alleged defects in the relevant vehicles; fourthly, commence proceedings earlier than the Jennings proceedings; and fifthly, engage with Jaguar in relation to categories of initial discovery and the provision of key information that will be necessary in order to progress group members’ claims.

72 For these reasons, and despite the high reputation and experience of Maurice Blackburn, I do not think this is a neutral factor. The relative experience of the solicitors in the Greentree proceeding in conducting near identical claims in the Toyota proceeding offers real benefits to group members. Without any intended disrespect, the barristers do not really matter when it comes to differentiation. This is not because barristers are fungible (heaven forfend), but because it would be open to either firm to instruct the junior and senior counsel who appeared in the Toyota proceeding.

D.5 Size of Classes, Scope of Claims and Nature of the Representative Applicants

73 These matters can be addressed together.

74 The applicants in both proceedings advance the same causes of action, namely a claim for damages under ss 271 and 272 of the ACL for non-compliance with the guarantee of acceptable quality under s 54, and a claim for loss and damage based on misleading or deceptive conduct. As such, neither proceeding confers a juridical advantage over the other.

75 With that said, to the extent that these factors tend to favour any proceeding, the following differences were identified.

76 First, the class in the Jennings proceeding is slightly larger. It includes purchasers of Jaguar vehicles with the “D2a” vehicle platform, whereas the Greentree proceeding does not. The “D2a” platform was used to manufacture the Jaguar XJ model between the years 2016 to 2019. The Jennings applicant contends that those cars are affected by the alleged defect for the same reason as the other models the subject of the claim. The Jennings proceeding also does not carve out group members who may fall within s 33E(2), being governments or government officials who may have purchased the relevant vehicles and who may choose to opt in. However, this adds a relatively small number of Jaguar XJ cars to the claim (namely, 41 vehicles). In any event, I am told that the Greentree applicants expect to include those vehicles in the Greentree proceeding: Mackenzie Affidavit at [82].

77 It is necessary to pause here to note that the Jennings applicant contended that the group member definition in the Jennings proceeding also includes any person who acquired an interest in a “relevant vehicle”, even someone who purchased a vehicle second-hand from a private seller who themselves purchased their vehicle in a private sale. It was said that on its proper construction, such persons are “affected persons” within the meaning of s 2(1) of the ACL, and therefore have a claim under ss 271 or 272 because the subsection defines “affected person” to mean, in relation to goods, a consumer who acquires the goods. It does not relevantly circumscribe whether a “consumer” must be a person who acquires the goods, or a person who acquires the goods from the consumer. That construction may be correct, but it is unnecessary for me to form any view about it presently.

78 Secondly, the Jennings applicant identifies the “Core Defect” as being the manifestation of two basic issues with the vehicles, namely: (1) the oil dilution and fuel issues; and (2) the DPF blockage issues. The first category of issue concerns the excess fuel consumption and dilution of engine oil that arises from the repeated active regeneration of the DPF in the subject vehicles. The second category of issues is the result of the failure of the regeneration mechanism to effectively clear the DPF in most cases, thereby leading to blockages and associated issues. It is these two sets of issues that are alleged to have made the vehicles “not fit for purpose” in contravention of s 54 of the ACL. By contrast, the applicants in the Greentree proceeding have pleaded the design and performance of the DPF in detail and have defined the “Vehicle Defects” as a list of specific problems, with detailed technical particulars appended. The Jennings applicant submits this detail is supererogation for the purpose of proving that the relevant cars were not “fit for all purposes for which goods of that kind are commonly supplied”, but is justified by the Greentree applicants on the basis that a greater degree of specificity is conducive to issues being joined, and the identification of technical questions for the purposes of any referral.

79 Thirdly, there are some differences in the loss claimed. The Greentree applicants confine their claim for reduction in value of the vehicles under s 272(1)(a) of the ACL together with “excess” fees and charges incurred because of the purchase at an overvalue under s 272(1)(b). The Jennings proceeding also claims the reduction in value under s 272(1)(a) in accordance with the statutory formula. However, it also particularises the s 272(1)(b) losses by reference to the counterfactual situation where the vehicle was not bought at the inflated price (or at all). The Jennings applicant contends that this allows for the possibility for advancing a “no transaction” case that seeks compensation for more than the incremental costs of the acquisition of the vehicle. The Greentree applicants submit that this difference is immaterial given that a “no transaction” case is encompassed within its claim under s 236 of the ACL.

80 Fourthly, there is a difference between the two representative applicants. The Greentree applicants acquired their relevant vehicle new and have not sold it. By contrast, the Jennings applicant’s car was purchased in a used condition as a demonstrator, and subsequently has been sold. That is, Ms Jennings would be a “Partial Period Group Member”. As I explained in Williams v Toyota (at [432]), this can have the effect of complicating the assessment under s 54 of the ACL because it may be difficult to determine on a principled basis how compensation for the owners of the relevant vehicles ought to be assessed and distributed. The Greentree applicants submit that the Greentree proceeding would be a better vehicle for resolving common questions concerning non-compliance with s 54 and reduction in value damages under s 272(1)(a).

81 I am satisfied that the size of the respective classes, the causes of action advanced, and the nature of the representative applicants between the proceedings are relatively neutral factors. It is common ground that the claims in both proceedings arise from common factual substrata and concern the same causes of action. Accordingly, although one cannot identify with precision at this stage the full extent of the differences between the two proceedings, they are largely immaterial.

82 As I have noted in a different context, for those experienced in class actions, any concerns relating to distinctions between the factors above at the commencement of proceedings can amount to splitting hairs and conjuring difficulties which will likely never arise. If upon careful reflection it is thought that a claim exists that should be advanced or refinements made, I have little doubt that the practitioners with carriage of these proceedings will conscientiously consider the interests of group members and advance the optimal case.

83 As such, as already noted, I see these factors as essentially neutral.

D.6 Progress of Proceedings and Conduct of the Representative Applicants

84 I have canvassed the relevant chronology in Section B and it does not need to be repeated, save to reiterate that on any view, significant work has been undertaken in the Greentree proceeding to progress investigations into technical matters the subject of the proceedings.

85 As a consequence, in the event that carriage was awarded to the Jennings applicant, the amount of sunk costs would, in the overall context, be relatively significant. This is not a case where the steps taken by one applicant could be undertaken very quickly by another applicant. As I have noted earlier, in contrast to the Jennings proceeding, the accumulated experience of Gilbert + Tobin in conducting the Toyota class action has enabled it to take steps early to progress the Greentree proceeding by conducting, in three stages, detailed investigatory work into various technical matters canvassed above (at [15]–[17]).

86 Further, notwithstanding my comments in Klemweb (at 593 [45]) that any prejudice to funders occasioned by the issue of sunk costs might arguably be thought to be part of the “rough and tumble” of conducting the business of commercial litigation, the work conducted to date in the Greentree proceeding relative to the Jennings proceeding is a relevant consideration as a prejudice that would be occasioned to Balance in the event that carriage was awarded to the Jennings applicant.

87 The Greentree proceeding therefore has an advantage in this respect.

E THE APPROPRIATE REMEDY

88 This is an unusually challenging multiplicity dispute. As I have explained above, the difficulty arises primarily due to two factors which loom large in the exercise of the discretion, and which point in different directions: namely the benefits of the funding arrangement proposed by the Jennings applicant and the comparative subject-matter expertise of the legal representatives engaged in the Greentree proceeding.

89 Before turning to the appropriate remedial response in all the circumstances, it should be reiterated that the proper approach requires me to fasten upon what I think is in the best interests of group members. As Gageler, Gordon and Edelman JJ explained in Wigmans (at 649 [52]):

In matters involving competing open class representative proceedings with several firms of solicitors and different funding models, where the interests of the defendant are not differentially affected, it is necessary for the court to determine which proceeding going ahead would be in the best interests of group members. The factors that might be relevant cannot be exhaustively listed and will vary from case to case.

90 It is often the case that the proceeding which estimates a greater net hypothetical return to group members is a powerful factor which bears heavily upon the discretion to allow that proceeding to go ahead. But it is not always the case. The comparison of class action proceedings and common fund models necessitates more than a mere matter of arithmetic, and the exercise of the discretion is more nuanced than simply comparing likely financial outcomes. No matter how attractive a particular funding proposal may be, for example, a funder may not have the financial wherewithal to sustain the litigation to its conclusion. It is not a race to the bottom. Each case turns on its own circumstances and what must be undertaken in the comparative analysis is a broad evaluative assessment and synthesis of the factors to which I have referred.

91 In the end, I think I should try to fashion a remedy response which recognises and accommodates each of these two most important factors. It is worth recording some further observations as to why.

92 First, and importantly, I have a protective role towards group members and, all other things being equal, they are likely to be impacted adversely financially if I was simply to stay the Jennings proceeding and allow the Greentree proceeding to proceed as initially contemplated.

93 Secondly, without seeking to diminish the quality and experience of Maurice Blackburn in conducting product liability class actions, I suspect Gilbert + Tobin are experiencing a sense of déjà vu. This is not the usual case of legal practitioners being experienced in conducting claims of a similar kind in a familiar area of law: there is a remarkable similarity between the claims advanced in these proceedings and the Toyota class action.

94 It is therefore inevitable that the legal representatives in the Greentree proceeding will be faced with having to prove similar facts to those proved in the Toyota class action, namely, inter alia: (a) that the alleged defects were present in the vehicles at the time they were supplied; (b) that the respondent engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct in connexion with the advertising, marketing and distribution of the relevant vehicles; (c) that the value of the relevant vehicles were reduced at the time they were first supplied as a result of the alleged defects; and (d) that the applicants and group members suffered loss and damage as a result of these matters. Similar legal and evidentiary issues are also bound to arise, including with respect to: (a) the proper construction of ss 54, 271 and 272 of the ACL and the interaction between such provisions and Pt IVA of the FCA Act; (b) the nature of the evidence to be obtained and submitted to any referee; and (c) the expert evidence necessary to prove and quantify any loss or damage suffered by the applicants and/or group members and provide the Court with a sufficient evidentiary basis to make an award pursuant to s 33Z(1)(e) or (1)(f) of the FCA Act.

95 Thirdly, the Toyota class action was capable of being conducted in a highly efficient and professional manner due to the way in which the factual, legal and evidentiary issues canvassed above were distilled and presented to the Court by the parties, but relevantly for present purposes, the solicitors acting for the Greentree applicants. With the exception of some contested factual issues, the conduct of Gilbert + Tobin in that proceeding contributed to a large measure of agreement between the parties as to the common questions to be determined at the initial trial, following the adoption of two reports of a referee, the preparation of a statement of agreed facts and a supplementary statement of agreed facts (see Williams v Toyota (at [14])). I can see no reason why the accumulated experience of Gilbert + Tobin would not enable the claims of the group members to be advanced efficiently and effectively, and consistently with the overarching purpose.

96 Fourthly, it is significant that the expert briefed, Mr Smithers, was engaged by the applicants in the Toyota class action as a technical expert to assist with the analysis of the alleged defects associated with DPF systems. Mr Smithers work in that proceeding included, among other things: (a) conducting an investigation similar to that conducted to date in the Greentree proceeding (see above (at [17])); (b) assisting with the preparation of pleadings; and (c) reviewing technical documents and information disclosed by Toyota and assisting the applicants to participate in the reference process (see Williams v Toyota (at [14])). Group members will therefore not only have the benefit of solicitors who have successfully conducted almost identical claims on a previous occasion, but the benefit of the same technical expert who specialises in defective DPF systems.

F THE POSSIBLE WAYS FORWARD

97 The transcript will record that during oral submissions, I raised the prospect of consolidation. I put to senior counsel for the applicants in both proceedings whether it would be contrary to principle for the Court to make an order consolidating the proceedings with a litigation committee based on the Jennings funding proposal, provided the applicants in both proceedings agree to consolidation within a fortnight: T54.45.

98 It quickly became apparent, however, that neither the Greentree applicants nor the Jennings applicant had contemplated consolidation, let alone the terms upon which it might occur. While the absence of any cooperative agreement between the parties is not dispositive of the Court’s power to order the consolidation of two or more representative proceedings, forced consolidation often suffers from the same problems as orders for specific performance of personal services: that is, you cannot make people work together. As Beach J observed in McKay Super Solutions Pty Ltd (Trustee) v Bellamy’s Australia Ltd [2017] FCA 947 (at [12]) in similar circumstances:

The difficulty in the present case is not so much the existence of the power but rather its exercise. Here, I have no agreement between all parties in both proceedings as to consolidation. Further, there are different lawyers for the applicants and different litigation funders in each of the proceedings. Absent agreement by both sets of lawyers and funders, there are a number of difficulties in relation to consolidation. For example, what uniform funding model would operate for the consolidated proceedings given the different sets of signed up group members in each of the proceedings, when considered from the perspective of signed up group members, the unsigned group members or the funders? And, what uniform legal representation for the applicants would be used, absent leave being given for separate representation for each of the applicants?

99 Senior counsel for Jaguar, Mr Darke SC, noted that allied to these difficulties is that any consolidated proceeding would not include the broader class definition unless the legal representatives for the Greentree applicants agreed.

100 In these circumstances, it was suggested alternatively that if the Greentree applicants and other relevant parties were prepared to accept something like the funding terms proposed in the Jennings proceeding, it would render consolidation otiose because group members would have the benefit of the accumulated experience and work conducted by the solicitors engaged in the Greentree proceeding to date, coupled with the advantages of the bespoke funding arrangement proposed in the Jennings proceeding. In other words, group members would enjoy the best of both worlds.

101 It is difficult to gainsay this logic. For the reasons I have outlined above, I am satisfied that this is the appropriate course in all the circumstances. It gives proper weight to the two most important but conflicting considerations in assessing this multiplicity dispute.

102 In reaching this conclusion, I stress that I have had regard to all the factors that the applicants in both proceedings have identified as being relevant but in the end, as these reasons indicate, the real issues are the benefits of the accumulated subject-matter expertise of Gilbert + Tobin counterbalanced against the advantages for group members of the funding arrangement proposed in the Jennings proceeding.

103 I am conscious that this solution means that both the Greentree applicants, Gilbert + Tobin and Balance will need to assess whether they are prepared to continue to conduct the Greentree proceeding on a different commercial basis. Needless to say, they should be given sufficient time to assess whether such a course is acceptable. The orders that I propose provide a period of 28 days to see whether the Greentree applicants, Gilbert + Tobin and Balance are prepared to agree not to seek to recover upon settlement or judgment an amount, combining both legal costs and other fees and expenses, of more than 25 per cent.

104 It may be that an undertaking will not be provided or be provided in a form which is said to contain deficiencies. Accordingly, I will require the proposed undertaking to be provided to the Court and served on the solicitors for the Jennings proceeding, and I will give leave to any party to relist the matter for the purposes of further argument and, if there is no further argument, for receipt of the undertaking in open Court. If a proposed undertaking is not provided or the form is unacceptable, I do not consider it is consistent with my protective and supervisory role in relation to group members to allow the Greentree proceeding to be the vehicle in which the group members’ claims are determined.

105 Further, if an undertaking is not provided, it would be inappropriate to grant a permanent stay of the Greentree proceeding as no doubt significant costs have been incurred and there will be a necessity to deal with the individual claim. Accordingly, after a declassing, a temporary stay will be maintained until there is a mediation of both proceedings, which I will order in due course. If the mediation is unsuccessful and there is a necessity to determine common issues, then the Greentree proceeding will be further stayed until after the initial trial. Although if an undertaking is not provided, the adverse consequences of losing the benefit of the experience of Gilbert + Tobin could be somewhat mitigated by counsel previously instructed by Gilbert + Tobin, who have had extensive experience in the Toyota class action, being briefed in the Jennings proceeding, if it was thought appropriate that this course be adopted.

G CONCLUSION AND ORDERS

106 It would be remiss of me not to record the Court’s appreciation for the evident care and thought that has gone into the funding models in both proceedings. The competition engendered by competitive class actions places demands upon the Court and might be conducive of some delay. Counterbalanced against this, however, is the reality that the sort of funding proposals the Court has considered in this case are vast improvements on those pursuant to which class actions were conducted at an earlier stage in the development of Pt IVA.

107 Accordingly, I will make orders facilitating the course I have outlined above.

I certify that the preceding one-hundred and seven (107) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Lee. |

Associate:

ANNEXURE