Federal Court of Australia

Northern Territory of Australia v Aboriginal Land Commissioner [2023] FCA 1183

ORDERS

NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent MINISTER FOR INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIANS Second Respondent NORTHERN LAND COUNCIL (and another named in the Schedule) Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The Applicant’s Originating Application is dismissed.

2. Unless an application is made by the Applicant on or before 12 October 2023 seeking a different order as to costs, the Applicant pay the Third Respondent’s costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BROMBERG J:

Introduction

1 To my great delight, proceedings in this Court often raise fascinating issues. This proceeding is no exception. The critical question is where does the sea end and the land begin? That engaging question is raised on the judicial review application of the Northern Territory of Australia (NT).

2 The NT seeks judicial review of decisions made by an Aboriginal Land Commissioner (ALC) appointed under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) (Act) recommending that there be a number of grants of land to persons whom the ALC determined were the Aboriginal traditional owners of the land. The asserted jurisdictional error relied upon by the NT is, broadly speaking, that the ALC misconstrued the Act. In the context of the ALC’s function being limited to recommending a grant of “land in the Northern Territory”, each of the impugned recommendations included an estuary or part thereof. The NT contends that the ALC thereby misconstrued the Act’s conception of “land” and exceeded his jurisdiction.

3 The word “land” can be used in a broad or a narrow sense and, like most words, its intended meaning usually depends upon the context in which it is used. At its narrowest, “land” may be a reference to dry land, thus excluding the beds of a lake, a river, an estuary or the sea. At its broadest, “land” can connote the crust of the Earth including the land under the sea or any body of water or water course: see in relation to seabed, Goldsworthy Mining Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) [1973] HCA 7; (1973) 128 CLR 199. The sea is a body of salt water but the word “sea” is capable of being used to include the seabed upon which salt waters sit.

4 It is not in contest in this proceeding that the Act’s conception of “land” is not confined to dry land and includes the bed of a river, a stream or a creek and, I would presume, the bed of a lake. Nor is it in dispute that the bed under the sea is not land within the Act’s conception of what constitutes “land”. What is in contest is where the Act’s conception of “land” ends and its conception of the sea begins in relation to an area occupied by an estuary.

5 As to that question, the parties are literally miles apart. Broadly stated, the NT contends that the land ends where the estuary begins at what it calls “the mouth of the river” located at the low water mark of the estuary into which the river flows. The third respondent, the Northern Territory Land Council, contends that, for the purposes of the Act, the coastal low water mark is the boundary of the sea and thus where the “land” begins. Therefore, it contends that the bed of an estuary landward of the coastal low water mark is “land” and not sea.

6 The Land Council’s contention is consistent with the conclusion arrived at by the ALC. For the reasons that follow, I am not persuaded that the ALC’s recommendations are tainted by the jurisdictional errors for which the NT contends.

Statutory framework

7 By its long title, the Act is described as “[a]n Act providing for the granting of Traditional Aboriginal Land in the Northern Territory for the benefit of Aboriginals, and for other purposes”. There are two relevant schemes in the Act for the grant of land. First, in relation to areas of land described in Sch 1 of the Act (s 10 and s 12) and, second, in relation to areas of land the subject of a “traditional land claim”, report and recommendation made by an ALC (s 11 and s 12). Under each scheme the land in question is Crown land, a term defined in s 3(1) as:

Crown Land means land in the Northern Territory that has not been alienated from the Crown by a grant of an estate in fee simple in the land, or land that has been so alienated but has been resumed by, or has reverted to or been acquired by, the Crown, but does not include:

(a) land set apart for, or dedicated to, a public purpose under an Act; or

(b) land the subject of a deed of grant held in escrow by a Land Council.

(Emphasis added).

8 Under each scheme, where a grant of land is made, it is made to an Aboriginal Land Trust. Section 4(1) provides for the responsible Minister to “establish Aboriginal Land Trusts to hold title to land in the Northern Territory for the benefit of Aboriginals entitled by Aboriginal tradition to the use or occupation of the land concerned”.

9 A Land Trust exercises its powers as an owner of the land vested in it in accordance with the Act, “for the benefit of the Aboriginals concerned”: s 5(1)(a) and (b).

10 In relation to the second scheme engaged by the making of a “traditional land claim”, s 50(1) of the Act relevantly provides for the following function of the ALC:

50 Functions of Commissioner

(1) The functions of a Commissioner are:

(a) on an application being made to the Commissioner by or on behalf of Aboriginals claiming to have a traditional land claim to an area of land, being unalienated Crown land or alienated Crown land in which all estates and interests not held by the Crown are held by, or on behalf of, Aboriginals:

(i) to ascertain whether those Aboriginals or any other Aboriginals are the traditional Aboriginal owners of the land; and

(ii) to report his or her findings to the Minister and to the Administrator of the Northern Territory, and, where the Commissioner finds that there are Aboriginals who are the traditional Aboriginal owners of the land, to make recommendations to the Minister for the granting of the land or any part of the land in accordance with sections 11 and 12;

11 A “traditional land claim” means “in relation to land … a claim by or on behalf of the traditional Aboriginal owners of the land arising out of their traditional ownership”: s 3(1). “Traditional Aboriginal owners” means “in relation to land … a local descent group of Aboriginals who: (a) have common spiritual affiliations to a site on the land, being affiliations that place the group under a primary spiritual responsibility for that site and for the land; and (b) are entitled by Aboriginal tradition to forage as of right over that land”: s 3(1). “Aboriginal tradition” means “the body of traditions, observances, customs and beliefs of Aboriginals or of a community or group of Aboriginals, and includes those traditions, observances, customs and beliefs as applied in relation to particular persons, sites, areas of land, things or relationships”: s 3(1).

12 As in this case, if the ALC makes a recommendation to the Minister for an area of Crown land to be granted to a Land Trust, subject to certain requirements being met, the Minister is obliged to “recommend to the Governor-General that a grant of an estate in fee simple in that land or part be made to that Land Trust” (s 11(1)(d)).

13 There are two further observations about the Act which are relevant and conveniently addressed now. First, some of the areas referred to and described in Sch 1 of the Act abut the coast and include rivers that enter the sea at the coast, some parts of which would be inundated permanently. That observation about the Act was made by Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Kirby and Hayne JJ in Risk v Northern Territory of Australia [2002] HCA 23; (2002) 210 CLR 392 at [8]. The observation may, relevantly, be supplemented by the Northern Territory’s acceptance in this proceeding that beds of some rivers, streams and estuaries are included in areas described by Sch 1 and fall within the Act’s conception of “land”.

14 Second, s 73(1)(d) of the Act provides:

73 Reciprocal legislation of the Northern Territory

(1) The power of the Legislative Assembly of the Northern Territory under the Northern Territory (Self‑Government) Act 1978 in relation to the making of laws extends to the making of:

…

(d) laws regulating or prohibiting the entry of persons into, or controlling fishing or other activities in, waters of the sea, including waters of the territorial sea of Australia, adjoining, and within 2 kilometres of, Aboriginal land, but so that any such laws shall provide for the right of Aboriginals to enter, and use the resources of, those waters in accordance with Aboriginal tradition;

but any such law has effect to the extent only that it is capable of operating concurrently with the laws of the Commonwealth, and, in particular, with this Act, Division 4 of Part 15 of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 and any regulations made, schemes or programs formulated or things done, under this Act, or under or for the purposes of that Division.

(emphasis added)

15 As the plurality stated at [20] of Risk:

Apart from the references in Sch 1 to the low water mark of the coast, in cases where the land is described by metes and bounds, the provisions of s 73(1)(d) were the only explicit reference in [the Act], at the time of its enactment, to the sea or to waters of the sea.

Background

16 In 1997, the Land Council relevantly made two traditional land claim applications under s 50(1)(a) of the Act on behalf of Aboriginal groups claiming to be the traditional Aboriginal owners of the following areas of unalienated Crown land in the Northern Territory:

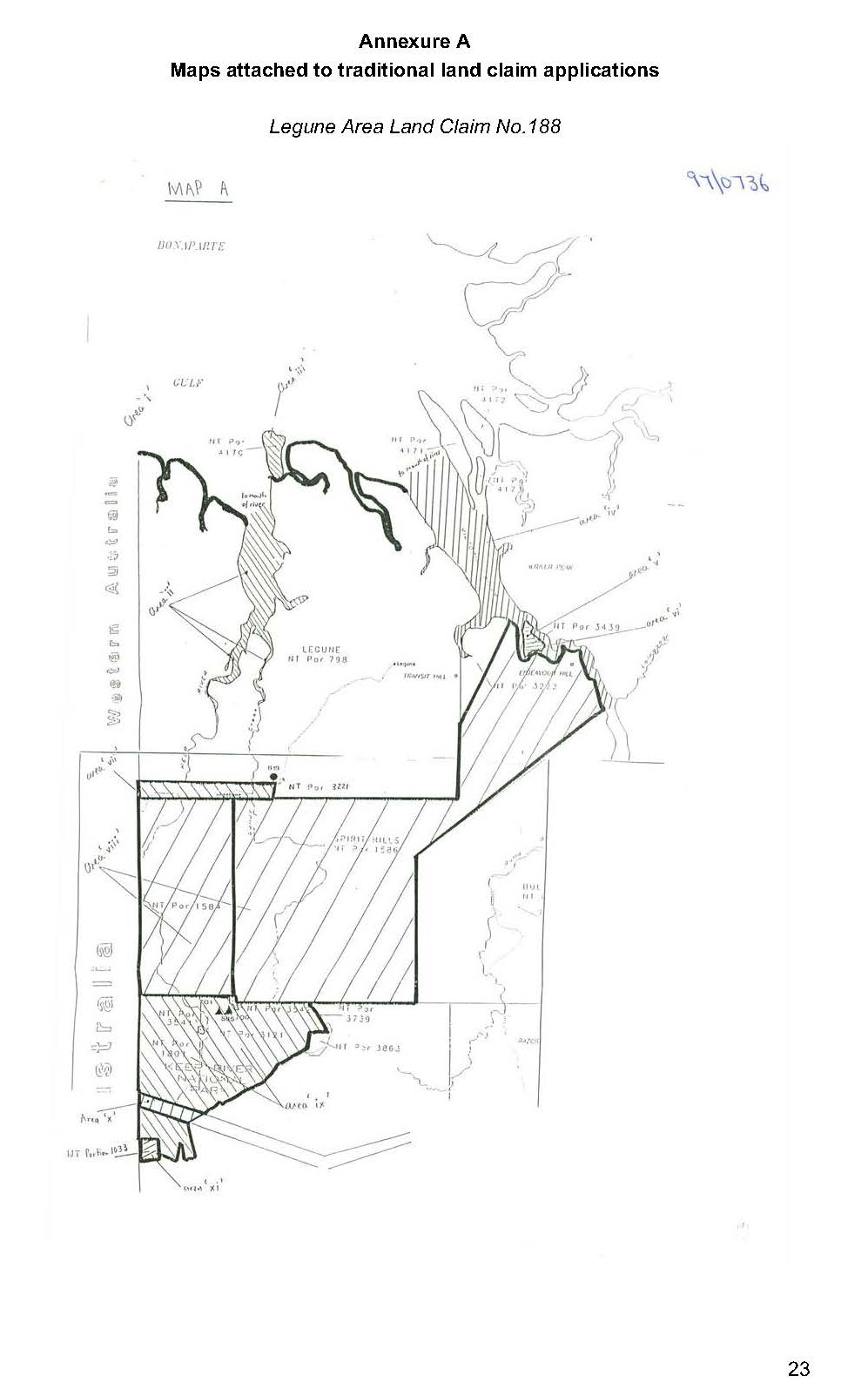

(i) The area covered by the Legune Area Land Claim No 188, which includes the estuary of each of the Keep River and the Victoria River; and

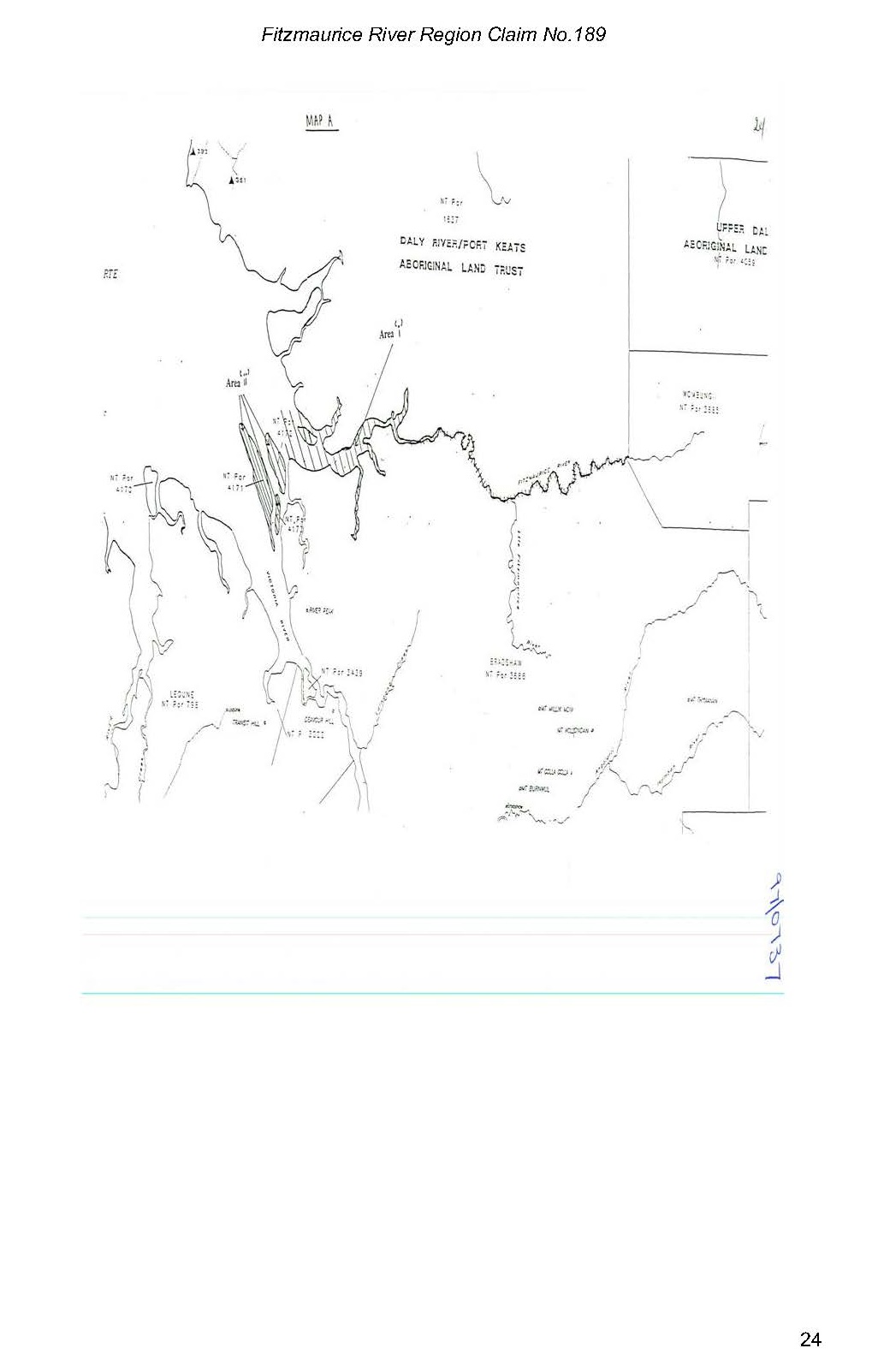

(ii) The area covered by the Fitzmaurice River Region Claim No 189, which includes the estuary of the Fitzmaurice River.

17 As the ALC described it, each claimed area is in the northern western section of the Northern Territory, near the border of Western Australia, around where each of the Keep River, Victoria River and Fitzmaurice River flow into the south-eastern section of the Josephine Bonaparte Gulf.

18 It is not necessary to set out the terms of each of the two claims in question. For present purposes, it is sufficient that the areas claimed be broadly described by reference to the descriptors utilized by those applications. The Legune Claim included what was described as the beds and banks of the Victoria River and the Keep River, in each case commencing from the mouth of the river (marked “mouth of river”) and extending landward as shown by hatching on a map attached to the application. The Fitzmaurice Claim similarly included what was described as the beds and banks of the Fitzmaurice River, commencing from what hatching on an attached map sought to identify as the mouth of that river and, by further hatching, extending landward. In each case, what was said to be the “mouth of the river” was located by a line drawn between the nearby headlands of the coast of the Josephine Bonaparte Gulf. The maps attached to each of the Legune Claim and the Fitzmaurice Claim are shown at Annexure A to these reasons.

19 The inquiry conducted by the ALC in relation to the Legune Claim was described by the ALC as “a relatively straightforward process, with one major qualification”. After the close of final submissions, the Northern Territory sought, and was granted leave, to raise the issue the subject of this application for judicial review). The Northern Territory contended that the mouths of the Keep River and the Victoria River were not, as contended for by the Land Council, at the low water mark of the coastline and at a line drawn across the two adjoining headlands where the river flowed into the Josephine Bonaparte Gulf, but were much further inland and located at the mean low water mark of the tidal waters of the sea.

20 The same contention was made by the Northern Territory in the Fitzmaurice Claim in relation to the mouth of the Fitzmaurice River.

21 In broad terms, what divided the parties was whether the sea ended and the land began at the seaward or landward end of the estuary. In other words, was each of the estuaries in question land or sea?

22 After conducting its inquiries into the two claims, the ALC issued reports which recommended that the whole of the land claimed in the Legune Claim Legune Report at [307]) and most of the land claimed in the Fitzmaurice Claim (Fitzmaurice Report at [223]) be granted to a Land Trust for the benefit of the Aboriginal traditional owners. Although not germane to the issues here raised, the reasons for not all of the land claimed being granted in the Fitzmaurice Claim was that the applicants were unable to established traditional ownership over the whole of the area and not because the area claimed was not “land”: Fitzmaurice Report at [211]-[223].

23 At the time the Originating Application was first filed, the Northern Territory sought judicial review of the ALC’s decision in relation to the Legune Claim and what was referred to as the proposed decision to be made by the ALC in relation to the Fitzmaurice Claim. On 22 June 2022, subsequent to the filing of the Originating Application, the ALC made a recommendation in relation to the Fitzmaurice Claim. Accordingly, and with the Court’s leave, the Originating Application was amended and the Northern Territory now seeks judicial review of the decision of the ALC in relation to the Legune Claim made on 25 June 2021 and the decision of the ALC in relation to the Fitzmaurice Claim made on 22 June 2022. The Northern Territory’s application for judicial review is made pursuant to s 39B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) and s 5 the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth).

24 The Northern Territory did not dispute, either during the relevant inquiries before the ALC or in this proceeding, that the Aboriginal claimants were the traditional owners of the area claimed (Legune Report at [66]). The key issue is whether some of the area in the two claims is not “land in the Northern Territory” within the meaning of s 3(1) of the Act and therefore not within the jurisdiction of the ALC to make a recommendation to the Minister to issue a grant for that area.

25 Annexure D of the Legune Report and Annexure F of the Fitzmaurice Report deal with whether, in each case, the area claimed is land which may properly be the subject of an application under s 50(1)(a) of the Act. The reasons within these relevant annexures are, for practical purposes, identical and I will hereafter refer to them both as Annexure D.

The critical determinations made by the ALC

26 The NT (supported by the Commonwealth) made two submissions to the ALC in relation to whether the areas claimed were available to be claimed under the Act. The first is described by the ALC at [3] of Annexure D. This contention sought to confine the claims made to the way in which they were described by the land claim application. It was contended that the expression there used – “mouth of the river” – should be understood as the landward low water mark of the estuary (where the river may be said to meet the estuary) rather than at the seaward end of the estuary (where it may be said the river meets the sea). There is no challenge to the ALC’s rejection of that first submission.

27 The second submission is set out by the ALC at [9] of Annexure D as follows:

The second issue was that each of the land claims, to the extent that they covered river waters seaward of the lines said to represent the mouths of the three rivers as identified by the three witness’ evidence (excluding Mr Willis), could not succeed because each of the claims was not to that extent made over unalienated Crown land in the Northern Territory. In short, it was said, such waters in the three rivers were beyond the jurisdiction of the Aboriginal Land Commissioner (the Commissioner) to recommend a grant of that part of the claim areas because the waters in each of those three watercourses – using a neutral term – downstream from the defined and identified ‘mouth’ of each river was not over unalienated Crown land, and was not Crown Land, as those terms are defined in section 3 of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) (ALRA). Relevantly, section 50(1)(a)(i) of the ALRA requires an application to have been made by Aboriginals claiming to have a traditional land claim to an area of land being unalienated Crown land, and the inquiry and report of the Commissioner to the Minister must be in relation to that land.

28 As the ALC noted, the second submission was propounded on the basis of the High Court’s decision in Risk. At [14] of Annexure D the ALC said:

The decision in Risk HC was said by the Commonwealth and by the Northern Territory to be a decision which effectively concludes the current issue in their favour. It is said that Risk HC must be taken as prohibiting claims ‘to seabed in estuaries, inlets or arms of the sea regardless of whether or not the seabed is within a bay or gulf or can be said to be “landward of the low water mark of the coast” [a passage from the submission of the claimants] (i.e. the estuary mouth)’: see [62] of the written submission of the Commonwealth of 29 May 2018.

29 Having set out the second submission and noted the reliance placed by the NT on the decision in Risk, the ALC then considered Risk. The ALC identified the central question and the focus of the judgment in Risk as being whether the seabed of the bays and gulfs within the territorial limit of the Northern Territory can be the subject of a traditional land claim under the Act (at [16] of Annexure D). The ALC further observed that the focus of the High Court in Risk was not upon the issue raised by the Northern Territory and the Commonwealth before the ALC but, more generally, upon whether a claim could be made in relation to land seaward of the low water mark of the coastline (at [20] of Annexure D). The ALC again reiterated (at [27] of Annexure D) that the “present issue” was not a matter considered or decided by Risk. Consequently, the ALC said at [31] of Annexure D:

I do not accept the primary contention of the Commonwealth and of the Northern Territory that the decision in Risk HC necessarily determines that the ‘land in the Northern Territory’ available for claim does not include the waters of the three rivers landward of the coastal low tide line. In particular, I reject the proposition that the waters and beds and banks of the three rivers where they are seaward of the point where the ‘mouth’ of each river has been fixed (by the evidence adduced by the Northern Territory referred to above) is excluded from ‘land in the Northern Territory’ as that term is used in the ALRA. The extent of the proposed exclusion includes waters in the three rivers which ultimately run into the sea and which are landward of the coastal low water line and the line drawn across headlands, including the exclusion of estuarine waters.

30 In relation to an estuary, the ALC essentially construed the boundary of “land within the Northern Territory” to be landward of the coastal low water mark and at a point determined by reference to the coastline and the character of the estuarine and like waters. This is evident from the ALC’s observations at [40] of Annexure D:

In short, in my view, the meaning of the term ‘land in the Northern Territory’ used in the definition of ‘Crown land’, in the context of the ALRA as a whole is not limited by the imposition of a definition of ‘river mouth’ or ‘mouth of a river’ by that evidence, and does not necessarily exclude waters, including estuarine waters, landward of the low water mark along the coast where the waters of a river flow into the sea. It then becomes a matter of evidence in each case as to whether estuarine waters and waters adjacent to tidal and mangrove flats within the low water mark of the coastline and across facing headlands or other physical features delineating the coastline are shown to be part of the land in the Northern Territory which has traditional Aboriginal owners. Obviously, the character of the estuarine and like waters, including whether they are always underwater at low tide and the character of the water flow in the vicinity will be relevant to whether the necessary ownership is established.

The Application for review

31 There are five grounds of review set out in the Amended Originating Application. However, the Northern Territory accepted during the hearing that the asserted jurisdictional errors for which it contends is encapsulated at [8] of its reply submission as follows:

The jurisdictional error is that the Commissioner failed to ask the right question — whether on Risk principles beds [subjacent] to internal waters of the sea and below the low water mark [of those internal waters] may be the subject of a claim (cf Ruling [10], [31], [40], [66], [69], [71]) — and ignored or failed to appreciate the significance of the evidence that the claim area included such beds.

32 Further clarified by the submissions made by the Northern Territory, there are two broad questions raised by the application for review as follows:

(a) Did the ALC fail to apply the decision or the principles stated in Risk, by not determining that the beds of the relevant estuaries seaward of the low water mark of those internal waters were not “land” claimable under the Act; and

(b) ignored or failed to appreciate the significance of the evidence that the claim area included seabeds.

The Northern Territory’s construction of “land”

33 The Northern Territory’s contention in a nutshell is that, applying Risk principles, the right question to be asked is whether “beds [subjacent] to internal waters of the sea and below the low water mark” of those internal waters may be the subject of a claim under s 50(1)(a) of the Act. It was contended that Risk stood for three relevant propositions. First, that under the Act, “land” means that part of the Northern Territory that is bounded, as a general rule, by the low water mark of the sea. Second, that the low water mark of the sea extended (beyond the coastal low water mark) to the low water mark of the “internal waters of the sea”. Third, the “internal waters of the sea” are not confined to bays and gulfs and extend to any waters of the sea landward of the territorial sea baseline. On the Northern Territory’s argument, Risk holds that beds and banks below the low water mark of the internal waters of the sea are sea and not “land” claimable under the Act. The Northern Territory relied on [31] and [40] of the ALC’s decision in Annexure D to contend that the ALC wrongly construed the principles in Risk by confining “the internal waters of the sea” to bays and gulfs and by wrongly focussing on the coastal low water mark.

34 It is important to appreciate that the NT’s submission about Risk is premised upon two contentions about how the reasoning in Risk is to be construed. First, that the reference made in Risk at [24] to the “low water mark”, is an intended reference to the low water mark of the coastal mainland as well as the low water mark of what the NT calls the “internal waters of the sea”. Relying on Risk at [24], the Northern Territory asserted that Risk “defines ‘land in the Northern Territory’ capable of being the subject of a claim under s 50(1)(a) of [the Act] to exclude seabed below the low water mark of the territorial sea at the geographical limits of the mainland and seabed below the low water mark of internal waters within the geographical limits of the mainland” (emphasis in original). It is on that basis that the NT contended that it was held in Risk that “the seabed below the low water mark of bays and gulfs” was not “land” for the purposes of the Act.

35 Second, the NT contended that what was in issue in Risk was whether seabed in the “internal waters of the sea” was land within the meaning of the Act and not merely whether the seabeds of bays and gulfs were land. In support of that proposition the NT contended that the expression “waters of the sea” in s 73(1)(d) of the Act is and was understood in Risk as a reference to all the “internal waters of the sea” on the landward side of the base line of the territorial sea. Relevantly, the NT contended that:

The expression “territorial sea” is not defined in the Land Rights Act. Section 2B of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) provides that in any Act, a reference to the “territorial sea” has the same meaning as in the Seas and Submerged Lands Act 1973 (Cth). That Act defines the expression as having the same meaning as in Arts 3 and 4 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea: ss 3(1), 5, Sch 1. Section 10 declares sovereignty in respect of the “internal waters” of Australia, being “any waters of the sea on the landward side of the baseline of the territorial sea”. The baseline may be determined by the Governor-General in accordance with the Convention (s 7(2)), which provides in Art 7 that in areas where the coastline is deeply indented or cut into, straight baselines may be adopted joining appropriate points “selected along the furthest seaward extent of the low-water line”. The expression “internal waters” refers to waters on the landward side of the baseline of the territorial sea: Art 8.

Did the ALC fail to apply the reasoning in Risk?

36 For the following reasons, the NT’s reliance on Risk and its contention that the ALC misapplied the reasoning in Risk is unpersuasive.

37 First, as the ALC correctly determined (at [25]-[32] of Annexure D), the holding in Risk was confined to the seabed of bays and gulfs within the limits of the NT. So much is apparent from the judgment of the plurality (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Kirby and Hayne JJ) at [1] where their Honours identified the central question on the appeal as being “whether the seabed of bays or gulfs within the limits of the Northern Territory can be the subject of claim under [the Act]”. The holding in Risk was then identified as follows:

The seabed of bays and gulfs within the limits of the Northern Territory cannot be subject to a claim under [the Act].

38 Next, and in order to address what I apprehend the NT to be contending, it is necessary to consider whether that holding in Risk is based on the plurality’s reasoning that the seabeds of bays and gulfs were not “land” because the seabeds of all internal waters of the sea are not “land”. In this respect, it is necessary to note that if the plurality so reasoned they did not do so expressly. Accordingly, it becomes necessary to consider whether that reasoning is implicit from the stated reasons of the plurality and in particular those parts of the reasons for judgment of the plurality relied upon by the NT.

39 It is necessary therefore to set out the plurality’s reasons at [24] upon which the NT relied. The subject of that paragraph was introduced at [22] by the plurality’s expression of a desire to “say something about the limits of the Northern Territory” and preceded at [23] by a reference to s 4 of the Northern Territory Acceptance Act 1910 (Cth). That section defined the Northern Territory as “that part of Australia which lies to the northward of the twenty-sixth parallel of South Latitude and between the one hundred and twenty-ninth and one hundred and thirty-eighth degrees of East Longitude, together with the bays and gulfs therein, and all and every the islands adjacent to any part of the mainland within such limits as aforesaid, with their rights, members, and appurtenances”. At [24], the plurality then said:

For present purposes, what is notable is that, but for whatever may be the consequence of the inclusion within the geographic limits of the Northern Territory of “the bays and gulfs therein, and all and every the islands adjacent to any part of the mainland . . . with their rights, members, and appurtenances”, the geographical limits of the Territory ordinarily end at low water mark. Of course, within those limits there will be areas that are permanently inundated, but apart from the bays and gulfs in the mainland, there is no seabed within the areas of the Northern Territory, only the inter-tidal zone on the coast. With that in mind, how is the expression “land in the Northern Territory” to be understood when it is read in the definition of “Crown Land” in the Land Rights Act?

(Emphasis added)

40 The Northern Territory’s submission that “land in the Northern Territory” does not include “seabed below the low water mark of internal waters within the geographical limits of the mainland” relied on [24] of Risk. It would appear that what was being contended was that, in relation to internal waters, the reference in the first sentence of [24] to the “low water mark” is an intended reference to the low water mark of internal waters within the limits of the Northern Territory. In other words, that the plurality used the expression “low water mark” in the way that the Northern Territory used it in its submission, as the coastal low water mark extended to the low water mark of all internal waters.

41 The plurality described the geographical limits of the Northern Territory as ordinarily ending at the low water mark “but for” the inclusion of bays and gulfs within those limits by s 4 of the Northern Territory Acceptance Act. What was here being said in the first sentence of [24] was that, putting aside bays and gulfs, the low water mark along the coast of the Northern Territory was ordinarily the geographical limit of the Northern Territory. The low water mark referred to could only have been the low water mark along the coast of the Northern Territory. There is no intended reference to the low water mark of waters internal to that coast such as the waters of an estuary or a river. In so far as the Northern Territory’s submission sought to suggest otherwise, that contention is clearly wrong.

42 Furthermore, it is relevant to consider the second sentence of [24]. In that sentence, the plurality continued their observations about the limits of the Northern Territory, but here those observations were made on those geographical limits including bays and gulfs. Their Honours referred to areas within the geographical limits which are “permanently inundated”. They clearly had in mind bays and gulfs. However, by reference to the recognition made at [8] that rivers abut the coast and that therefore “some parts of those areas … would be inundated permanently” and also by reason of the reference made in the second sentence of [24] to the “inter-tidal zone on the coast”, their Honours’ reference to areas “permanently inundated” was a reference to both waters (bays and gulfs) seaward of the coast and waters internal of the coast. In relation to that dichotomy, the plurality observed that it was only bays and gulfs that have a seabed. In other words, of the waters internal to the geographical limits of the Northern Territory, seabed only exists in the internal waters seaward of the coastline and do not exist in the internal waters of the Northern Territory which abut, but are internal to, the coastline.

43 This observation of the plurality is consistent with, and reflective of, the reasoning of French and Kiefel JJ in the decision below in Risk v Northern Territory of Australia [2000] FCA 1779; (2000) 105 FCR 109 where their Honours said at [34] “the ordinary and ordinary legal meaning of ‘land’ does not extend to the seabed of coastal waters beyond the low water mark”. That observation itself is reflective of the fact that the boundary between the land and the sea is ordinarily at the coast. Land ordinarily meets the sea at the coastline.

44 The coastline of the Northern Territory, including the coastline along bays and gulfs, was clearly of importance to the reasoning of the plurality in Risk. So much was understood by the ALC. As the ALC stated at [45] of Annexure D, “[t]he reasoning in [Risk] is based on factors that relate to waters seaward of the low water mark along the coast”. At [66], the ALC described the decision in Risk as restricting “land in the Northern Territory … to the low water line along the coast”. Furthermore, at [38]-[39] and [71]-[72], the ALC rejected the proposition that the reasoning in Risk supported the NT’s distinction between beds seaward of where the Northern Territory asserted the “mouth” of a river is located and those beds landward of that asserted boundary between the land and the sea. The ALC was correct to so determine and was also correct to reject that the reference made to “bays and gulfs” in Risk was intended to extend to a “bay, gulf, inlet, estuary or watercourse” (at [71]).

45 Furthermore, contrary to the implicit reasoning from Risk for which the NT contends, at [94] of Risk Gummow J said this:

It should be added that nothing decided by this litigation denies the efficacy of grants under the Act in respect of areas including rivers and estuaries. The determination by the Commissioner was not directed to such matters.

46 The next matter to consider is the Northern Territory’s reliance on the plurality’s reasoning about s 73(1)(d) of the Act. To restate that provision, section 73(1)(d) empowers the Northern Territory Parliament to make:

laws regulating or prohibiting the entry of persons into, or controlling fishing or other activities in, waters of the sea, including waters of the territorial sea of Australia, adjoining, and within 2 kilometres of, Aboriginal land, but so that any such laws shall provide for the right of Aboriginals to enter, and use the resources of, those waters in accordance with Aboriginal tradition[.]

47 The plurality in Risk considered that the effect of this provision was that the Act clearly intended that the 2 km zone of sea adjoining Aboriginal Land is not “land”. There were two reasons for reaching that conclusion. The first being textual and the second based on legislative history. The plurality at [29] considered that s 73(1)(d) assumes that the 2 km “buffer zone” which the provision empowered the legislature to regulate is not “land”, because if it were claimable land under the Act, s 73(1)(d) “would have little if any useful work to do”.

48 Turning later to the legislative history of s 73(1)(d), the plurality noted the recommendation made to Parliament in 1973 by the then ALC, Justice Woodward, that “the definition of Aboriginal land where a coastline is involved should include both offshore islands and waters within two kilometres of the low tide line”: Risk at [35] (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Kirby and Hayne JJ). This recommendation was ultimately not adopted and, instead, what is now s 73(1)(d) was enacted (at [35]). In the plurality’s view, this history clearly indicated that, contrary to the applicant’s claims in Risk for areas “seaward of the low water mark of the seacoast of the mainland”, areas such as the beds of bays or gulfs seaward of the low water mark of the coast were not “land”.

49 The NT’s submission proceeded on the basis that the reasoning of the plurality about s 73(1)(d) was implicitly based on an acceptance that the expression “waters of the sea” in s 73(1)(d) was a reference to all of the intended waters of the sea on the landward side of the territorial base line and that therefore, according to Risk, any bed of the internal waters of the sea should be regarded as seabed and not “land”.

50 The only basis given for that contention seems to be a simple assertion that the reasoning of the plurality about s 73(1)(d) in relation to bays and gulfs would be equally applicable in respect of any seabed in the internal waters of the Northern Territory. However, that contention is not based on anything stated by the plurality. The plurality did not discuss the concept of the internal waters of the sea nor the meaning of the expression “waters of the sea”. The NT’s contention seems to be based on an assumption that the expression “waters of the sea” was understood by the plurality to refer to all internal waters of the Northern Territory. However, why I should conclude that that assumption was made was not explained.

51 In any event, given that the plurality drew an important distinction between those internal waters of the Northern Territory that have seabed (i.e. bays and gulfs) and those internal waters of the Northern Territory that abut the coast but are internal to the coastline and do not have seabeds (rivers and estuaries), it does not follow that the reasoning of the plurality about s 73(1)(d) in relation to bays and gulfs would be equally applicable in respect of the waters internal of the coast of the Northern Territory.

52 Contrary to the NT’s core contentions, Risk does not stand for the proposition that all “beds [subjacent] to the internal waters of the sea” may not be the subject of a claim under the Act. The reasoning in Risk is consistent with the ALC’s concentration upon the line of the coast constituting the demarcation between land and sea. Accordingly, the first question raised by the NT’s application (see [32(a)] above) must be answered “No” and the NT’s grounds for its application encompassed by that question should be dismissed.

Did the ALC ignore or fail to appreciate the significance of the evidence?

53 The second way in which jurisdictional error is asserted by the NT is really no more than a re-expression of its first basis; namely, that the ALC misconstrued the Act by failing to apply the reasoning in Risk.

54 The NT asserted that the ALC “ignored or failed to appreciate the significance of the evidence that the claimed area included [seabeds]”. Reliance was here placed on the observations of the High Court in Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v SZJSS [2010] HCA 48; (2010) 243 CLR 164 at [27] “that jurisdictional error may include ignoring relevant material in a way that affects the exercise of a power”.

55 The evidence said to have been ignored was that provided by three experts, namely, Professor Stuart Kaye, Mark Alcock and Simon Watkinson. It is evidence which the NT submitted identified that the boundary (or mouth) of the rivers in questions was where the river flowed into the sea at the landward end of the estuary and thus demonstrative of the fact that the estuary was part of the internal waters of the sea.

56 The material said to have been “ignored” is not material that the NT contends was not considered. It certainly was considered as the reasons of the ALC show at [49]-[68] of Annexure D. The NT contended, however, that the ALC failed to appreciate the significance of the evidence to the statutory question – namely, whether the estuaries in question were “land” within the meaning of the Act. However, the NT accepted that the alleged failure of the ALC to appreciate the significance of the evidence was entirely a product of the ALC’s misconstruction of the Act.

57 Therefore, this asserted jurisdictional error is dependent upon and travels no further than the first asserted error dealt with above and already dismissed. As the NT has not succeeded in demonstrating that the ALC erred by failing to apply the reasoning in Risk and thus misconstrued the Act, it has necessarily failed to demonstrate that the evidence in question had significance to the correct statutory question and was thus improperly ignored in a way which affected the ALC’s jurisdiction.

Conclusion

58 Accordingly, the NT’s application for judicial review should be dismissed. There is no need to determine other contentions raised by the Land Council which addressed issues not directly raised by the particular jurisdictional errors asserted by the NT.

59 I will also make a conditional order that the NT pay the costs of the Land Council, but preserve the NT’s ability to contend that the usual order for costs ought not be made. If the NT seeks to make that contention it should file and serve a submission (limited to 2 pages) on or before 12 October 2023. Any responding submission (again limited to 2 pages) should then be filed and served on or before 19 October 2023. Any issue as to costs will then be determined on the papers.

I certify that the preceding fifty-nine (59) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Bromberg. |

Associate:

Annexure A

NTD 19 of 2021 | |

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENCE |