Federal Court of Australia

Fair Work Ombudsman v Foot & Thai Massage Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (No 7) [2023] FCA 1164

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | FOOT & THAI MASSAGE PTY LTD (ACN 147 134 272) (IN LIQUIDATION) First Respondent COLIN KENNETH ELVIN Second Respondent JUN MILLARD PUERTO Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The notice to produce lodged with the Court by the second respondent on 6 September 2023, and served on the applicant on 20 September 2023, be set aside.

2. The notice to admit lodged with the Court by the second respondent on 19 September 2023, and served on the applicant on 20 September 2023, be set aside.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

KATZMANN J:

Introduction

1 This proceeding relates to claims by the Fair Work Ombudsman of multiple contraventions of numerous civil penalty provisions of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act). The Ombudsman’s investigation began in April 2016. The proceeding commenced in 2018. On 13 August 2019 (about two months before the hearing on liability was due to start) liquidators were appointed to the first respondent, Foot & Thai Massage Pty Ltd (FTM). On 26 September 2019 I granted the Ombudsman leave to proceed against FTM: Fair Work Ombudsman v Foot & Thai Massage Pty Ltd (in liquidation) [2019] FCA 1601. The trial on liability started on 21 October 2019 and concluded on 11 December 2020. A number of witnesses who had been required for cross-examination in the first tranche of hearings were recalled for further cross-examination in the second tranche.

2 On 14 October 2021 I resolved the overwhelming majority of the Ombudsman’s claims in her favour and I referred the quantification of the underpayments of wages to a referee: Fair Work Ombudsman v Foot & Thai Massage Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (No 4) [2021] FCA 1242 (the liability judgment). Over the objection of the only active respondent, Colin Elvin, whom I found to be an accessory to the contraventions by FTM, I adopted the referee’s report: Fair Work Ombudsman v Foot & Thai Massage Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (No 6) [2023] FCA 1116.

3 The only outstanding matter is the question of relief, including the form of the declarations that should be made to reflect my reasons, whether an order should be made that the amount of the underpayments be paid to the Ombudsman for payment out to the relevant employees, and what penalties should be imposed. The hearing in relation to these matters was fixed on 6 April 2023 for 3 and 4 October 2023. The same day I ordered that the respondents file and serve any affidavit evidence on which they intend to rely at the penalty hearing by 10 August 2023 and their outlines of submissions on penalties by 21 September 2023. No application was made to adjourn the scheduled hearing dates or to extend the time for the filing of evidence.

4 Three days before he was due to file his evidence, however, Mr Elvin served a notice to produce on the Ombudsman seeking production of records and documents relating to six former employees of FTM, who were not employees covered by the Ombudsman’s pleading and who did not give evidence at the liability hearing (the August notice to produce). Documents were produced by the Ombudsman in response to that notice on two occasions. An objection to the production of four documents covered by the August notice to produce on the ground of legal professional privilege was upheld by the duty judge on 13 September 2023: Fair Work Ombudsman v Foot & Thai Massage Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (No 5) [2023] FCA 1098.

5 On 20 September 2023 Mr Elvin served on the Ombudsman another notice to produce (dated 6 September 2023) (the September notice to produce) together with a notice to admit facts and the authenticity of certain documents (dated 19 September 2023) (notice to admit). An unsealed copy of the September notice to produce was served on or around the date it was lodged with the Court.

The present application

6 On 22 September 2023, the Ombudsman filed an interlocutory application seeking orders setting aside both notices in their entirety under r 1.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (Rules). In the alternative, she sought orders under r 1.34 dispensing with the need to comply with the notices.

7 The interlocutory application is supported by two affidavits, both affirmed on 21 September 2023. The deponents are Luke Russell Thomas and Myles Douglas Vincent. Neither was required for cross-examination.

8 Mr Thomas is an Assistant Director of an enforcement team in the Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO). Mr Vincent is a Principal Lawyer in the FWO and the supervisor of the senior lawyer in the FWO who has had carriage of this proceeding since about December 2021.

9 Mr Elvin relied on an affidavit he filed on 27 September 2023.

10 For the reasons that follow, both the September notice to produce and the notice to admit should be set aside.

Background

11 One of the Ombudsman’s claims, which I found proved, was that in two discrete periods Mr Elvin and the second respondent, Jun Puerto required six employees of FTM to repay FTM $800 in cash each fortnight because of a decline in the fortunes of FTM. The Ombudsman alleged, and I found, that the requirements to repay the money were contraventions of s 325(1) of the FW Act which at the time of the contraventions provided that:

An employer must not directly or indirectly require an employee to spend any part of an amount payable to the employee in relation to the performance of work if the requirement is unreasonable in the circumstances.

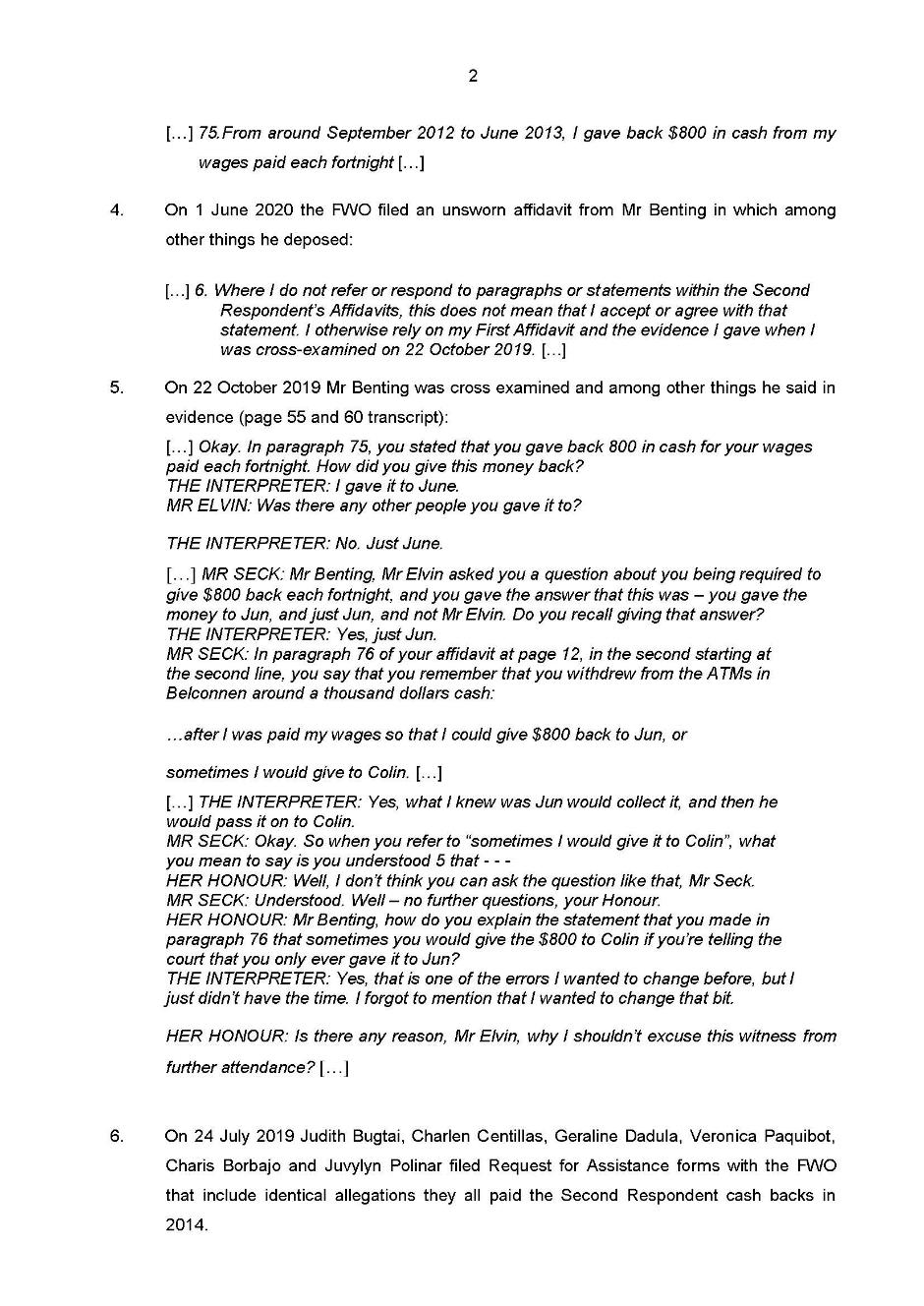

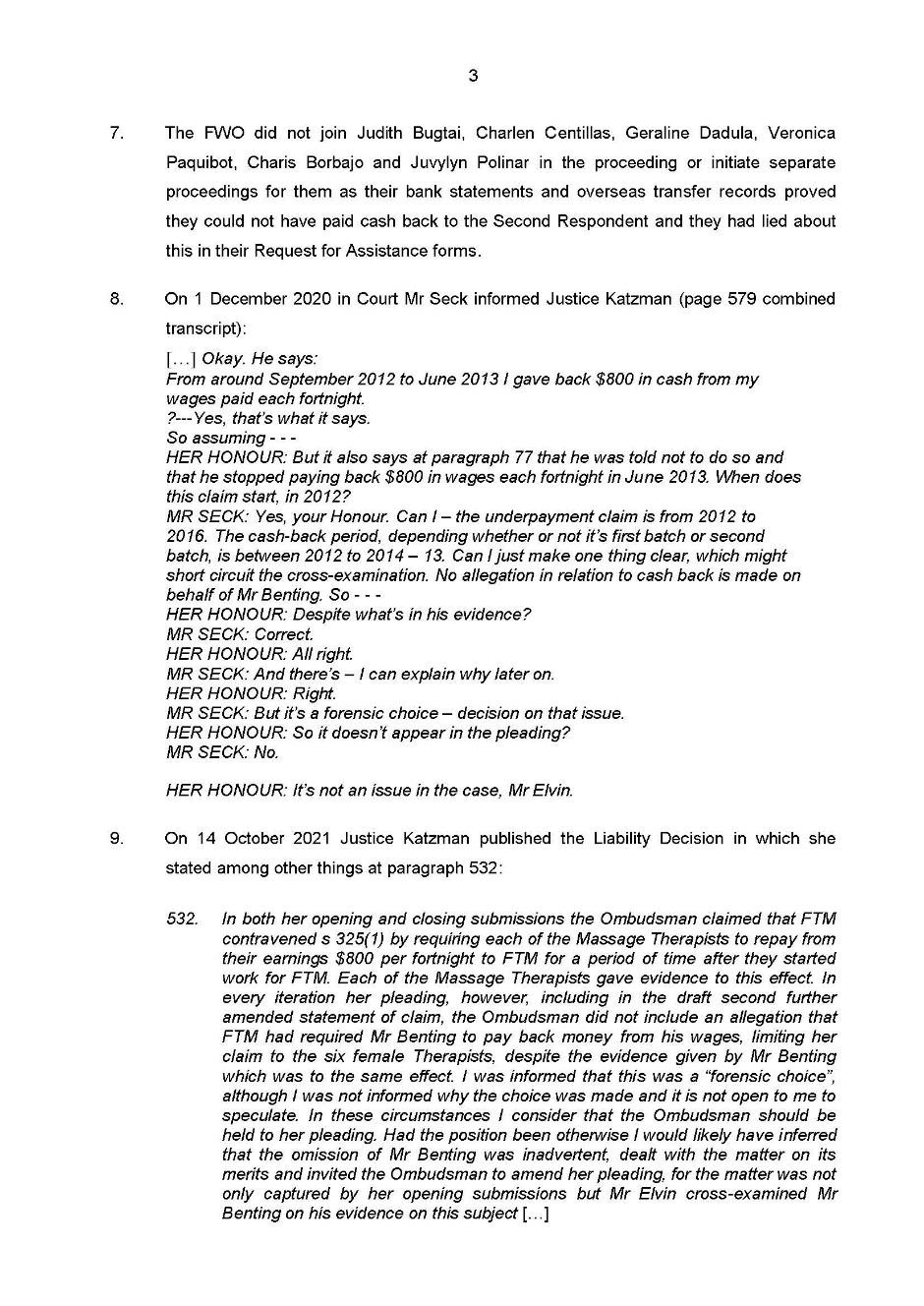

12 One of the witnesses who gave evidence in the Ombudsman’s case was Ruben Benting. He was one of the employees of FTM who was allegedly underpaid. He deposed that he was required to make similar payments to FTM. I queried with the Ombudsman’s counsel during the liability hearing why no claim had been made in relation to him and was told it was “a forensic choice”.

13 It appears from the material before the Court that Mr Elvin is vexed by the Ombudsman’s forensic decision. He has pressed the Ombudsman for detail and is dissatisfied with her responses to his queries. Equally, he is vexed by the Ombudsman’s decision not to pursue a case against the respondents based on allegations by other FTM employees who made similar allegations against them. He explained that this is the reason he issued the notices.

The competing positions

14 The Ombudsman’s position, in short, is that the documents sought by the September notice to produce and the answers sought by the notice to admit have no apparent relevance to the issues that remain to be determined and complying with the September notice to produce would be oppressive. In the circumstances, she submits that both notices are an abuse of process.

15 Mr Elvin contends that the purpose of both notices is to enable him to make factual submissions and to file affidavit evidence for the penalty hearing and that the purpose of the notice to admit is to enable him to make submissions about factual matters. In his affidavit, he submitted that there are “several salient issues” the Court “need[s]” to consider before any penalty orders are made. He said those “issues” are addressed in the outline of submissions he has filed for the forthcoming hearing. As described there, the alleged issues are:

(1) the Ombudsman’s “forensic choice” not to plead one particular contravention with respect to Mr Benting when Mr Benting gave evidence which would, if accepted, have supported a finding that FTM had committed that contravention with respect to him as well;

(2) the Ombudsman’s refusal to explain why she made that choice;

(3) the lengths to which the Ombudsman has gone to avoid explaining why she did not “join in the proceeding or initiate a separate proceeding in relation to” six other employees; and

(4) the fact that, after the liability decision was published, five of the employees the subject of the Ombudsman’s case applied to the ACT Magistrates Court for personal protection orders against him.

16 Mr Elvin has repeatedly questioned the Ombudsman about these matters and is dissatisfied with her responses. He accuses the Ombudsman of acting inconsistently with her obligations as a model litigant (contained in appendix B to the Legal Services Directions 2017 (Cth)) and her lawyers of acting inconsistently with their ethical obligations. In oral argument he went further, claiming that the Ombudsman’s lawyers have been “trying to hide their files” and “conspiring together to hide all this information”. No proper basis for any of these allegations was laid.

The relevant rules and principles

Notice to produce

17 Rule 30.28 enables a party to serve on another party a notice to produce a document or thing in the party’s control and, if the party upon whom it is served does not produce that document or thing, the party serving the notice may lead secondary evidence of its contents or nature. It provides:

Notice to produce

(1) A party may serve on another party a notice, in accordance with Form 61, requiring the party served to produce any document or thing in the party's control:

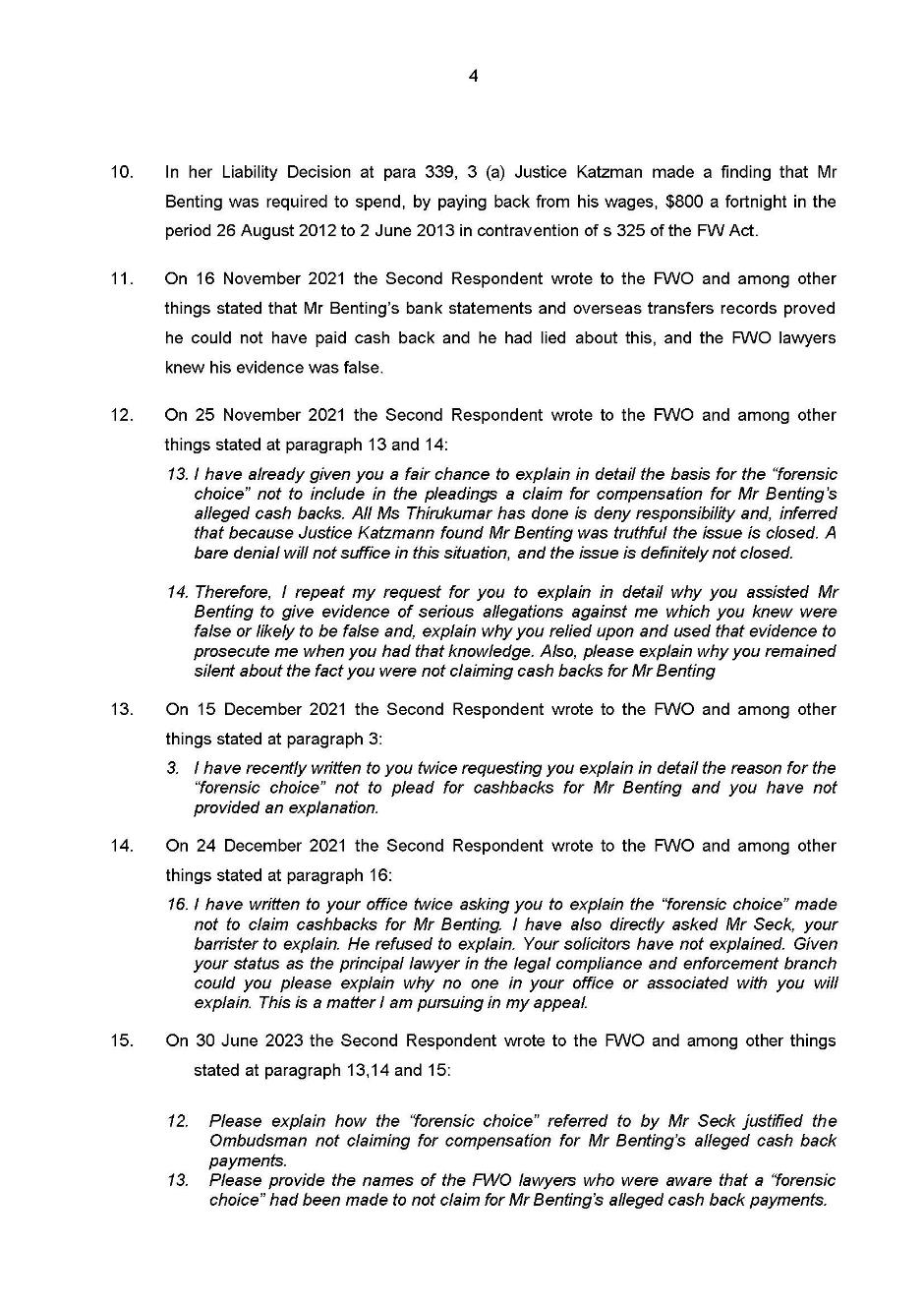

(a) at any trial or hearing in the proceeding; or

(b) at any hearing before a Registrar or any examiner or other person having authority to take evidence in the proceeding.

(2) If the document or thing required to be produced under subrule (1) is not produced, the party serving the notice may lead secondary evidence of the contents or nature of the document or thing.

(3) If a notice under subrule (1) specifies a date for production, and is served 5 days or more before that date, the party served with the notice must produce the document or thing in accordance with the notice, without the need for a subpoena for production.

Note: A party who fails to comply with a notice under subrule (1) may be liable to pay any costs incurred because of the failure.

18 A notice to produce has the same coercive effect as a subpoena to produce documents and the same or similar principles apply: Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd (No 5) [2005] FCA 510; 216 ALR 147 at [6] and [10] (Sackville J); Re Ox Operations Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 61 at [42] (Gordon J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v BlueScope Steel Limited (No 4) [2021] FCA 1162 at [19] (O’Bryan J). As O’Bryan J remarked in BlueScope, the authorities show that a subpoena or a notice to produce may be set aside for any one or more of a number of reasons, including:

where it is an abuse of process;

where it is oppressive; and

where the documents sought to be produced do not have apparent relevance to the issues in the proceeding in that the documents are reasonably likely to add, in the end, in some way or other, to the relevant evidence in the case.

19 With respect to the first matter, Yates J observed in Campaign Master (UK) Ltd v Forty Two International Pty Ltd (No 4) [2010] FCA 398; 269 ALR 76 at [37] that:

The power to control and supervise the court’s process is directed to preventing injustice. In this context, injustice is not simply a question of the true purpose for which the issue of the subpoena was procured, but also the effect or impact of the subpoena on the person to whom it was issued: Trade Practices Commission v Arnotts Ltd (No 2) (1989) 21 FCR 306; 88 ALR 90 at 102 (Arnotts); Hamilton v Oades (1989) 166 CLR 486 at 502; 85 ALR 1 at 10–11; 15 ACLR 123 at 131–2.

20 The burden of proving abuse of process or oppression rests with the person seeking to set aside a subpoena or notice to produce: see, for example, Campaign Master at [38]. However, the person issuing the notice to produce carries the burden of proving that the documents the subject of the notice are sufficiently relevant to require production: see, for example, Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd (No 11) [2006] FCA 174 at [7] (Sackville J).

21 On an application to set aside a notice to produce, the time the notice is issued and served is also relevant and “the potential disruption of a trial by unduly proximate service … may be a determinative factor”: Construction, Forestry, Mining, Maritime and Energy Union v BHP Coal Pty Ltd (No 3) [2012] FCA 61 at [7] (Collier J).

Notices to admit

22 Part 22 of the Rules deals with notices to admit facts or documents.

23 Rule 22.01 provides that one party may serve on another a notice, in accordance with Form 41, requiring the second party to admit, for the purposes of the proceeding only, the truth of any fact or the authenticity of any document. “Authenticity of a document” is defined in the Dictionary contained in Sch 1 to the Rules to mean, in the case of an original document, that “it was created, printed, written, signed and executed as it purports to have been” and, in the case of a copy, that “it is a true copy”.

24 Rule 22.02 enables the second party, within 14 days after service of the notice to admit, to serve on the issuing party a notice of dispute, in accordance with Form 42, disputing the truth of any fact or the authenticity of any document specified in the notice to admit.

The relevant rules

25 The Rules do not provide for the filing of an application to set aside a notice to produce or a notice to admit. Nor do they expressly provide for objections to be made to such a notice or for applications to set aside a notice. But it is beyond doubt that a party may take the course the Ombudsman has taken here.

26 The Court’s powers are contained in Pt 1 Div 1.3 of the Rules. Relevantly, they entitle the Court to “make any order that the Court considers appropriate in the interests of justice” (r 1.32); to dispense with compliance with any of the Rules either before or after the time for compliance arises (r 1.34); and even to make any order that is inconsistent with the Rules (r 1.35). The Court is under an obligation to exercise these powers in the way that best promotes the overarching purpose of the civil practice and procedure provisions, which include the Rules: Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act), s 37M(3). That purpose is “to facilitate the just resolution of disputes according to law and as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible”: FCA Act, s 37M(1). Section 37M(2) provides that:

Without limiting the generality of subsection (1), the overarching purpose includes the following objectives:

(a) the just determination of all proceedings before the Court;

(b) the efficient use of the judicial and administrative resources available for the purposes of the Court;

(c) the efficient disposal of the Court’s overall caseload;

(d) the disposal of all proceedings in a timely manner;

(e) the resolution of disputes at a cost that is proportionate to the importance and complexity of the matters in dispute.

27 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Valve Corporation [2015] FCA 721 the ACCC brought an application to set aside a notice to admit, relying on r 1.32. Edelman J acceded to the application. In the course of his reasons his Honour observed (at [12]) that “the ACCC could have made a forensic decision either (i) to serve a notice of dispute on these matters, or (ii) to reply saying that the matters are irrelevant but be deemed to have admitted the truth of them”. But his Honour considered that was inappropriate for various reasons.

28 Here, the Ombudsman submitted that it was inappropriate to take either course because the notice to admit is an abuse of process (and in any event the 14-day period after which the matters contained in the notice to admit would be deemed to have been admitted by the Ombudsman would not expire until after the penalty hearing had commenced).

The evidence

29 Mr Thomas’s affidavit was largely concerned with the time and effort likely to be required to comply with the notices. But he began by saying that, in response to requests for assistance lodged with the FWO in July 2019 by six former employees of FTM (the Group of Six), the FWO commenced a further investigation and that he supervised Fair Work Inspector, Adam Doe, in the conduct of that investigation. Mr Thomas deposed that approximately three weeks after its commencement, the FWO determined that the further investigation should be closed “based on a number of factors including the liquidation of [FTM]”.

30 Mr Thomas also deposed that, between approximately 7 and 11 August 2023, he conducted searches of an electronic database maintained by the FWO known as “Titan” in order to respond to the August notice to produce, which also sought production of documents relating to the Group of Six. Mr Thomas said that he provided various documents located during those searches to lawyers in the FWO’s Legal Group, that he was aware that another Fair Work Inspector conducted further searches of Titan on 21 August 2023 which yielded further documents which were provided to the Legal Group, and that on 28 August 2023 he conducted additional searches of Titan to locate documents responsive to the August notice to produce but did not locate any.

31 Mr Thomas described the nature, and estimated the duration, of the searches he anticipated would need to be conducted for the Ombudsman to comply with the September notice to produce. Mr Thomas explained that the FWO maintains four electronic databases in addition to Titan, not all of which can be electronically searched using keywords, and estimated that two of the databases would take one full business day each to search, that another database would require one to two hours, and that the final database (to which he did not presently have access but estimated that access could be arranged within two to three business days) would require a “few hours”. Mr Thomas also explained that the FWO maintains archives of physical material and hard copy documents at offsite locations and estimated that it would require about an hour to assess whether any archived material would be required to be recalled from an offsite location and approximately one to two business days to receive any recalled material and assess it.

32 Finally, Mr Thomas deposed that Mr Doe is no longer an employee of the FWO and estimated that it would take three to four business days to review Mr Doe’s email correspondence, given that it would take at least one day for the FWO’s IT department to arrange access to Mr Doe’s email inbox and it could be expected that Mr Doe’s would contain over 20,000 emails.

33 Mr Vincent’s affidavit is concerned with the circumstances in which the notices were served on the Ombudsman and the length of time required to complete searches of the FWO Legal Group’s records. Mr Vincent deposed that he received an email from Mr Elvin on 6 September 2023 which attached an unsealed copy of the September notice to produce, and that a sealed copy was attached to an email sent by Mr Elvin to the senior lawyer with carriage of the matter on 20 September 2023 which she forwarded to Mr Vincent later that day. On the same day, Mr Vincent deposed that the senior lawyer forwarded to him an email she received earlier that day from Mr Elvin which attached a sealed copy of the notice to admit.

34 Mr Vincent also deposed that the FWO’s Legal Group maintains its own legal record management system which is separate from the FWO’s databases and is accessible by the FWO’s in-house lawyers and support staff within the Legal Group.

35 He estimated that, to identify documents held by the Legal Group which are responsive to the September notice to produce, it would take one of the FWO’s in-house lawyers:

one to two days to search the legal record management system;

an additional day to search the archived emails of a lawyer previously employed by the FWO who provided advice during the investigation of the requests for assistance lodged by the Group of Six;

two to three hours to search physical files maintained by the Legal Group; and

one to two additional days to assess whether any documents located by the above searches are subject to legal professional privilege and to prepare a schedule setting out any such claims.

36 As the Ombudsman submitted, Mr Elvin’s affidavit was argumentative and largely consisted of irrelevant material, submissions and opinion. I indicated (without objection) that I would receive into evidence that which was evidence, by which I meant admissible evidence, and treat that which was a submission as a submission.

37 Mr Elvin’s evidence was that certain documents had been produced to him by the Ombudsman pursuant to the August notice to produce, that the documents provided to him were not in chronological order, that the documents did not contain any bank statements, overseas transfer records, emails or any other documentation from the Group of Six which related to him or FTM, and that the Ombudsman later provided some “incomplete historical bank statements” and "historical employment agreements” relating to the Group of Six which she said had been inadvertently omitted. He also spoke about some matters relating to the history of the employment of the Group of Six with FTM.

Consideration

The September notice to produce

38 The September notice to produce seeks:

Copies of letters, file notes, correspondence, interview transcripts, bank statements, overseas money transfer records and, any other documentation in relation to Judith Bugtai, Charlen Centillas, Geraline Dadula, Veronica Paquibot, Charis Borbajo and Juvylyn Polinar held by the Fair Work Ombudsman.

39 Although the sealed copy of the notice does not record the time, date or place of hearing, I was informed that the parties were notified by an email from the ACT Registry of the Court that the return of the documents was listed in courtroom 7 at 9.30 am on Friday 22 September 2023, that is to say two days after the sealed copy of the notice was served.

40 The persons mentioned in the notice were the employees in the so-called Group of Six. The effect of the notice is to require the Ombudsman to produce all the records or documents it holds relating to them, wherever they may be located.

41 None of the contraventions alleged or proved in the proceeding concerned any of the named persons. As I mentioned earlier, Mr Thomas deposed that in response to the requests for assistance received from the Group of Six, the Ombudsman began a second investigation into the respondents’ compliance with the FW Act but decided not to take further action and the second investigation was closed.

42 The Ombudsman submitted that none of these former employees of FTM were mentioned in her pleading and no claim was made or relief sought in relation to them. In these circumstances, she argued, any material that may be produced in answer to the notice could have no conceivable bearing on the issues which remain to be decided.

43 Mr Elvin reminded me that affidavits from three of the employees in the Group of Six were read in the hearing of the Ombudsman’s application for leave to proceed against FTM (the leave application). He claimed that the Ombudsman’s counsel had said their evidence would strengthen the Ombudsman’s case and that I decided the case should continue because “there were these new people who were being abused”. A perusal of those affidavits, the Ombudsman’s written submissions on the leave application, the transcript of the interlocutory hearing, and my reasons for granting leave (Fair Work Ombudsman v Foot & Thai Massage Pty Ltd (in liquidation) [2019] FCA 1601) demonstrates that that claim is fallacious.

44 On the leave application, the Ombudsman relied on the affidavits only to support “an inference that [Mr Elvin] remained involved in the running of [FTM] after he ceased to be a director of [FTM] on 11 April 2016” (at [50]), to suggest “the possibility that he may be found to be a ‘shadow director’ or ‘de facto director’ under s 9 of the Corporations Act” (at [50]) and to raise the prospect that there was an uncommercial transaction in the sale of FTM’s assets to a company owned by Mr Elvin’s then partner (at [51]).

45 The only reference to the argument in the judgment on the leave application is at [47]. It is abundantly clear that I did not decide that leave should be granted to the Ombudsman to continue the case because additional employees “were being abused”. This is what I said about the matter at [47]:

The Ombudsman also argued that the circumstances surrounding the voluntary liquidation suggest that Mr Elvin may have had a role in placing the company into liquidation and that the assets of the company were sold to a company owned by Mr Elvin’s partner, Khara Sanchez. Some of the evidence adduced on the application went to this issue. If that were so, the Ombudsman submitted, the liquidators might be able to apply to the Court under s 588FF of the Corporations Act which may result in additional funds being available to meet the claims and/or that there has been a contravention of s 596AB of the Corporations Act, which prohibits a person from entering into an agreement or transaction with the intention of preventing the recovery of employees’ entitlements or significantly reducing the amount that can be recovered. She submitted that conduct of this kind is a powerful factor weighing in favour of the grant of leave: see, for example, ACN 093 117 232 Pty Ltd (in liq) v Intelara Engineering Consultants Pty Ltd (in liq) [2019] FCA 1489 (Derrington J). But the Ombudsman only submits that the evidence raises a suspicion of an “uncommercial transaction” (see s 588FB) or an “unreasonable director-related transaction” (see s 588FDA). Having regard to the other considerations, it is unnecessary to deal with the relevant evidence or to decide whether it rises higher than a suspicion.

46 In his affidavit of 27 September 2023, Mr Elvin submitted that it was “very surprising” that the request for assistance forms lodged with the FWO by the employees in the Group of Six “contain identical historical complaints about FTM and [him] personally”. He tendered those forms at the liability hearing. Now he wants access to other documents he suspects are in the Ombudsman’s possession. He argued that the request for assistance forms were relied upon by the Ombudsman’s lawyers and “subsequently adopted by the Court to support the erroneous proposition that because they included similar claims to the massage therapists, they made the massage therapists claims more believable”. He submitted that the documents he now seeks “may show that the Group of 6’s claims were false and the FWO lawyers knew the claims were false”.

47 One evident purpose of the September notice to produce is to support a theory Mr Elvin advanced at the trial that the Group of Six were part of a conspiracy by certain massage therapists to harm him (see, for example, T1446–8). That was the reason he tendered the request for assistance forms. If there were evidence to support the theory, it could conceivably have affected the outcome of the trial. As I observed in the liability judgment, the request for assistance forms did not support his case theory (at [554]–[563]) and no evidence to support the theory was proffered at the trial. Before the time for filing his evidence or, for that matter, before the evidence closed, it was open to Mr Elvin to serve such a notice on the Ombudsman or to apply to the Court for an order for discovery. He did neither. While production of the documents the subject of the notice may alleviate Mr Elvin’s concerns, satisfy his curiosity or serve some other ulterior purpose, I fail to see how those documents have any apparent relevance to the determination of the outstanding issues.

48 In the circumstances it is strictly unnecessary to decide whether the notice of produce should be set aside as oppressive. Nevertheless, I am persuaded that it would be oppressive to require the Ombudsman to comply with the notice to produce at this time.

49 Mr Elvin described the Ombudsman’s estimates of the time the searches could take as “preposterous”. He pointed out that the Ombudsman was able to comply with the August notice to produce in a “timely” fashion. He submitted that he served the August notice to produce on 2 August 2023 and on 17 August 2023 the Ombudsman produced documents from the FWO Titan database “without any obvious issue about accessing the material”. He argued that, since he already has some of the documents relating to the Group of Six, “there can be no argument that [the September notice to produce] is not a fishing expedition” [sic]. He also submitted that FWI Doe was “the primary recipient of the material” and it would be an easy task for him to find the files.

50 But the August notice to produce only sought access to documents on the Titan database. And FWI Doe is no longer in the employed in the FWO.

51 Having regard to his experience, there is no reason to doubt Mr Thomas’s evidence that the FWO maintains other databases in addition to Titan, which would need to be searched, and that hard copy documents may need to be located and reviewed. Similarly, there is no reason to doubt Mr Vincent’s evidence as to the time that would be required to search the separate record keeping system maintained by the FWO’s Legal Group. After all, on Mr Elvin’s own evidence it took the Ombudsman some 15 days after the notice was served to produce documents from a single database.

52 As the Ombudsman submitted, if she were required to comply with the September notice to produce, the trial would have to be adjourned and new dates would have to be found to complete the matter which are convenient to the parties and the Court. Since this proceeding has been on foot now for over five years, any further delay is, as the Ombudsman put it, “to be assiduously avoided”. It would be antithetical to the overarching purpose of the civil practice and procedure provisions to insist on compliance in these circumstances.

The notice to admit

53 The notice to admit seeks information relating to the Ombudsman’s decision not to commence proceedings in relation to the Group of Six; the decision she took not to plead that FTM had contravened s 325 of the FW Act with respect to Mr Benting; about evidence at the hearing; and correspondence between Mr Elvin and the Ombudsman about these matters. A copy of the notice to admit is annexed to these reasons.

54 The Ombudsman urged the Court to take the approach adopted by Kunc J in FSS Trustee Corporation as Trustee of the First State Superannuation Scheme v Metlife Insurance Ltd [2014] NSWSC 369, which was to deal with the document as a whole “rather than attempting to investigate whether there is any individual part that may, if taken as such, be able to be salvaged from the shipwreck” (see, too, Kalgeracos v Bomba [2009] NSWC 1271 per Brereton J). Mr Elvin did not suggest that any other approach should be adopted.

55 Mr Elvin summarised the facts he asked the Ombudsman to admit in his affidavit as follows:

(a) Ruben Benting lied about paying him cash backs;

(b) the Ombudsman’s lawyers knew Mr Benting lied about paying him cash backs;

(c) Mr Benting's false evidence was extremely prejudicial to him; and

(d) the Group of Six lied to the Ombudsman in their request for assistance forms;

(e) the Ombudsman’s lawyers knew the Group of Six had lied;

(f) the Ombudsman’s lawyers know that on 22 October 2021 Delo be Isugan, Janice Castaneda, Mayet Ortega, Irene Amacio and Crisanta Bantilan [five former employees of FTM] applied to the ACT Magistrates Court for personal protection orders against him;

(g) the Ombudsman’s lawyers know the reason for the forensic choice they made not to claim that FTM contravened s 325(1) of the FW Act by requiring Mr Benting to pay cash backs and the reason they did not join in the proceeding or initiate a separate proceeding in relation to the Group of Six; and

(h) the Ombudsman’s lawyers know that Ms Isugan, Ms Castaneda, Ms Ortega, Ms Amacio and Ms Bantilan relied on the same historical allegations in the Magistrates Court as they used in this proceeding, and they were not believed.

56 In the submissions he has filed on the remaining issues Mr Elvin submitted:

19. The Applicant has gone to extraordinary lengths to avoid explaining the reason for the forensic choice, as Mr Seck called it. There are two associated issues.

20. The first issue is the Applicant has also gone to extraordinary lengths to avoid explaining why they did not join in the proceeding or initiate a separate proceeding in relation to Judith Bugtai, Charlen Centillas, Geraline Dadula, Veronica Paquibot, Charis Borbajo and Juvylyn Polinar (the Group of 6).

21. The second issue is that I made the Applicant aware that following publication of the Liability Decision, on 22 October 2021 Delo Be Isugan, Janice Castaneda, Mayet Ortega, Irene Amacio and Crisanta Bantilan applied to the ACT Magistrates Court for personal protection orders against me.

22. I submit these issues and other matters I will cover need to be addressed before the Court embarks on determining penalties.

23. There is a reasonable basis to infer that the Applicant has conducted the proceeding in an impermissible manner causing an obvious miscarriage of justice. The Court and the Respondents have been misled or deceived.

57 Later in those submissions he referred to the Ombudsman’s submission that the accounts about the cashback requirements in the request for assistance forms lodged by the employees in the Group of Six were “strikingly similar” to the accounts of the other employees.

58 The so-called issues are no more than assertions. They have no apparent relevance to any of the remaining issues. The real purpose of the notices is to mount a direct attack on certain of the Court’s factual findings and the conduct of the Ombudsman and her lawyers. That is a collateral or ulterior purpose. Although no final orders have been made, it is too late to revisit the matters which trouble Mr Elvin. If Mr Elvin wishes to challenge any of my findings, he may do so in the customary way by filing a notice of appeal after the question of relief is determined. If there is any substance to his conjecture, he may have other remedies available to him. But he may not do so by means of the notices the subject of the present application. To use the Court’s processes for this purpose amounts to an abuse of process.

59 Mr Elvin concedes that the “timing” of his notices “may be viewed as being late in the proceeding” but seeks to shift the blame to the Ombudsman. He submits that if the Ombudsman’s lawyers had acted as model litigants and disclosed all of the documents they hold in relation to the named persons and, either admitted or disputed the alleged facts, he may not have needed to issue them. He suggests that the process would not be arduous.

60 But the requests for the documents were not made until after the liability judgment was published and at the time the Ombudsman was preparing for hearing on relief. Mr Elvin offered no explanation for the delay. He had legal representation until two weeks before the liability hearing commenced. As Mr Elvin and Mr Puerto had raised the penalty privilege in their defences, they were given the opportunity to file amended defences after the Ombudsman’s witnesses were called and cross-examined. There was a long delay – over 12 months – before the trial resumed due to multiple requests Mr Elvin made for extra time to prepare which the Ombudsman did not resist. There is simply no excuse for the lateness of the requests. No blame for the delay can reasonably be attributed to the Ombudsman and the allegations of impropriety were made without any proper foundation.

61 The Ombudsman accepts that she is bound by the model litigant obligation. She points out, however, that s 55ZG of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) relevantly provides that:

(2) Compliance with a Legal Services Direction is not enforceable except by, or upon the application of, the Attorney-General.

(3) The issue of non-compliance with a Legal Services Direction may not be raised in any proceeding (whether in a court, tribunal or other body) except by, or on behalf of, the Commonwealth.

62 In any event, Mr Elvin has apparently overlooked note 4 to the model litigant obligation, namely:

The obligation does not prevent the Commonwealth and Commonwealth agencies from acting firmly and properly to protect their interests. It does not therefore preclude all legitimate steps being taken to pursue claims by the Commonwealth and Commonwealth agencies and testing or defending claims against them …

63 The purpose of the part of the notice to admit that calls for the Ombudsman to admit the authenticity of certain documents is obscure. The documents in question consist of unidentified FWO documents, various letters from Mr Elvin to the FWO, a sworn and an unsworn affidavit of Mr Benting, the liability judgment, two days of transcript, and a document entitled “Discovery – 2 August 2023 in response to Second Respondent’s Notice to Produce”. The description of the first item is too vague. There is no reason why the Ombudsman should be required to admit the authenticity of the transcript or the liability judgment. Mr Benting’s sworn affidavit is already in evidence. Without knowing what Mr Elvin intends to do with the other documents, it is difficult to know what relevance they may have to the remaining issues. It follows that Mr Elvin has not discharged the burden he bears to demonstrate their relevance. If his purpose is to use them to further his case theory and his attack on the integrity of the Ombudsman and her lawyers, then, for the reasons given above, that would be an abuse of process.

Conclusion

64 I am not satisfied that either the September notice to produce or the notice to admit has been issued for a legitimate forensic purpose. Neither the documents sought to be produced nor the admissions sought to be made have any apparent relevance to the issues which remain to be determined. Rather, they are an abuse of process. I also consider that the September notice to produce is oppressive having regard to the nature of the documents it seeks and the time it was served. Accordingly, both the notice to produce and the notice to admit should be set aside.

I certify that the preceding sixty-four (64) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Katzmann. |

Associate:

ANNEXURE