Federal Court of Australia

Babet v Electoral Commissioner [2023] FCA 1126

ORDERS

First Applicant CLIVE FREDERICK PALMER Second Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 20 September 2023 |

1. The application be dismissed.

2. The applicants pay the respondent’s costs.

3. The time within which a notice of appeal from these orders must be filed as provided in r 36.03 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 be abridged from 28 days to 27 September 2023.

4. The respondent file and serve an affidavit containing the responses of the Attorneys-General to his notice of a constitutional matter filed under s 78B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) on or before 21 September 2023.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

RARES J:

1 The applicants, Senator Ralph Babet and Clive Palmer, seek declarations as to how the respondent, the Electoral Commissioner, should cause assistant returning officers (under s 90(1)(e)(iv) of the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984 (Cth) (RMP Act)), for the purposes of determining whether or not it constitutes a formal or an informal ballot paper, to count a cross, or, alternatively, not count a tick that an elector marks on his or her ballot paper at the referendum to amend the Constitution to provide for an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to be held on 14 October 2023.

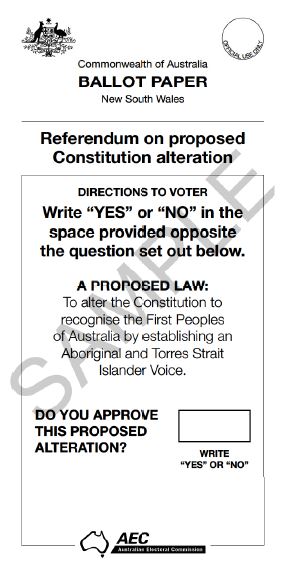

2 The ballot paper for the referendum poses a single question in the following form, being form B in Sch 1 of the RMP Act and prescribed by force of s 25(1)(a) (except for variations of the name of the applicable State or Territory in which it will be issued):

Issues

3 Relevantly, the applicants contend that instructions in both the Ballot Paper Formality Guidelines, the Scrutineers Handbook, and the Static Polling Place Election Procedures Handbook, that the Commissioner has published, wrongly state that a vote should be counted as informal, if a cross is used, but counted as formal, if a tick is used. Each of those documents states:

[T]icks () are ... capable of clearly demonstrating the voter’s intention.

...

A vote at a referendum will be informal if any of the following apply .... a cross () is used on a referendum ballot paper which has only one question, since a cross on its own may mean either ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

4 A similar statement is made in the Officer-in-charge Referendum Static Return, which the Commissioner has also published.

5 The applicants say that a cross signifies a ‘no’ vote but that, if this not be correct, a tick ought not be counted as conveying a ‘yes’ vote because the use of each symbol is equally ambiguous or unclear.

6 The Commissioner has questioned the applicants’ standing to seek relief and, on 13 September 2023, lodged a notice under s 78B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) which, on acceptance by the Registrar of the Court, he immediately served on 14 September 2023. No Attorney-General has sought to intervene under s 78B.

Agreed facts

7 The parties agreed the following facts:

each applicant is an Australian citizen, is enrolled on the Electoral Roll made under the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) and is an elector for the purposes of the RMP Act and s 128 of the Constitution;

Senator Babet was elected to the Senate for Victoria at the 2022 general election, has held office since then and was a member of the Senate at the time it passed the Constitutional Alteration (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice) 2023 (Cth);

the United Australia Party is not a registered political party for the purposes of the Electoral Act or the RMP Act and, on 8 September 2022, was deregistered as a political party under s 135(1) of the Electoral Act; and

on 11 September 2023, his Excellency the Governor-General issued a writ for the submission of the proposed constitutional amendment to the electors pursuant to s 7 of the RMP Act and appointed 14 October 2023 as the date for the referendum.

The legislative scheme

8 Relevantly, the RMP Act provides:

The voting at a referendum shall be by ballot and each elector shall indicate his or her vote:

(a) if the elector approves the proposed law—by writing the word “Yes” in the space provided on the ballot paper; or

(b) if the elector does not approve the proposed law—by writing the word “No” in the space so provided.

Note: See also subsection 93(9) for when votes are formal.

9 Under s 27, each of the Governor-General, the Governor of each State, the Chief Minister of the Australian Capital Territory, the Administrator of the Northern Territory, or a person authorised by him or her, may appoint one person to act as a scrutineer during voting at a referendum at each voting place in respectively the Commonwealth, State or Territory, and the registered officer of a registered political party may appoint persons to act as scrutineers at each polling place.

10 A person voting at a polling booth at a referendum must be given a ballot paper by the presiding officer under s 33(1), and unless otherwise prescribed, shall on receiving a ballot paper retire alone to a voting compartment there “and mark, in private, his or her vote on the ballot paper”, fold the paper to conceal the vote and place it in the ballot box (s 35). Every elector has a duty to vote at a referendum by force of s 45(1).

11 Part VI of the RMP Act is headed ‘Scrutiny of a referendum’. Importantly, s 89(1) provides:

The result of a referendum shall be ascertained by scrutiny.

12 Mirroring s 27, under s 89(2)-(4A), each of the Governor-General, Governors of the States, Chief Minister and Administrator or a person authorised by him or her and the registered officer of a registered political party may appoint, in the approved form, persons to act as scrutineers at each counting centre.

13 The conduct of the scrutiny is prescribed in s 90(1), which relevantly provides in respect of all ballot papers in s 90(1)(e)(iv):

90 Conduct of scrutiny

(1) The scrutiny of votes at a referendum shall be conducted in accordance with the following provisions:

…

(e) each Assistant Returning Officer shall, in the presence of a polling official and any scrutineers who attend, do the following:

…

(iv) count the number of ballot papers with votes given in favour of the proposed law, the number of ballot papers with votes given not in favour of the proposed law, and the number of informal ballot papers;

14 Under s 91(1), the action at the scrutiny is prescribed, including in s 91(1)(e):

91 Action at scrutiny

(1) At the scrutiny, the following things shall be done:

...

(e) each Divisional Returning Officer shall, forthwith after completing the scrutiny of the ballot papers taken from the ballot-boxes opened by the Officer and making those ballot papers into bundles, prepare a statement showing, in relation to those ballot papers:

(i) the number of votes given in favour of the proposed law;

(ii) the number of votes given not in favour of the proposed law; and

(iii) the number of ballot papers rejected as informal;

15 After completing the scrutiny prescribed in s 91(1)(e), each assistant returning officer must place bundles of the ballot papers that have votes for, against and informal into separate secure containers, together with a statement showing the respective numbers of those votes (s 91(1)(f)). A scrutineer appointed under s 89 can object to a ballot paper being counted as informal under s 92. The officer conducting the scrutiny must make a decision, then mark the ballot paper accordingly as ‘admitted’ or ‘rejected’, but the officer can reject any ballot paper as informal without there being any objection.

16 Critically, s 93(1)(b), (8) and (9) provide:

93 Informal ballot papers

(1) A ballot paper is informal if:

...

(b) it has no vote marked on it or the voter’s intention is not clear;

…

(8) Effect shall be given to a ballot paper of a voter according to the voter’s intention, so far as that intention is clear.

(9) For the purposes of subsection (8):

(a) a voter who writes the letter “Y” in the space provided on the ballot paper is presumed to have intended to approve the proposed law; and

(b) a voter who writes the letter “N” in the space provided on the ballot paper is presumed to have intended to not approve the proposed law.

(emphasis added)

17 Under s 96(3), if the validity of a referendum is disputed after a recount, the High Court may consider any ballot papers that the officer conducting the recount, at the request of a scrutineer, has reserved for the decision of the Australian Electoral Officer of the State or Territory concerned who decided that any reserved ballot paper should have been admitted or rejected. However, the High Court must not order a recount of the whole or any part of the ballot papers unless satisfied that a recount is justified.

18 Part VIII of the RMP Act deals with disputed returns. Under s 100, only the Commonwealth, a State, the Australian Capital Territory or Northern Territory can petition the High Court to dispute the validity of any return or statement showing the voting at a referendum. In addition, s 102 gives the Electoral Commission the right to file a petition. The requirements for a valid petition are set out in s 101. Under s 103, the jurisdiction and powers of the High Court are:

103 Jurisdiction and powers of High Court

(1) The High Court has jurisdiction with respect to matters arising under this Part.

(2) Following the hearing of a petition in relation to a referendum, the High Court may:

(a) declare the referendum to be void;

(b) uphold the petition in whole or in part; or

(c) dismiss the petition.

(3) The High Court may exercise all or any of its powers under this section on such grounds as the Court in its discretion thinks just and sufficient.

(4) Without limiting the generality of this section, the High Court may exercise its powers to declare a referendum void on the ground that contraventions of this Act or the regulations were engaged in in connection with the referendum.

19 The High Court must make its decision on a petition as quickly as is reasonable in the circumstances (s 107AA) and can have regard to rejected ballot papers (s 107A), but, importantly, s 108(1) provides:

108 Immaterial errors not to invalidate referendum

(1) A referendum or a return or statement showing the voting at a referendum shall not be declared void on account of:

(a) any delay in relation to:

(i) the taking of the votes of the electors; or

(ii) the making of any statement or return; or

(b) the absence of any officer or any error of, or omission by, an officer;

that did not affect the result of the referendum.

20 Under Pt XI, headed ‘Miscellaneous’, s 139 confers jurisdiction on the Federal Court, on the application of the Electoral Commission, to grant an injunction in respect of actual or apprehended contraventions of the RMP Act or any other law of the Commonwealth in its application to referendums. However, s 139(10) provides that the powers conferred on this Court by s 139 are in addition to, and not in derogation of, any other of its powers however conferred.

The parties’ submissions

The applicants’ submissions on the merits

21 The applicants drew attention to the following statement of principles that the Commissioner has set out in the Election Procedures Handbook:

Principle one

Start from the assumption that the voter has intended to vote formally

The assumption needs to be made that a voter who has marked a ballot paper has done so with the intention to cast a formal vote.

Principle two

Establish the intention of the voter and give effect to this intention

When interpreting markings on the ballot paper, these must be considered in line with the intention of the voter.

Principle three

Err in favour of the franchise

In the situation where the voter has tried to submit a formal vote (i.e. the ballot paper is not blank or defaced), the concept of reasonableness should be applied to questions of formality and wherever possible be resolved in the voter’s favour.

Principle four

Only have regard to what is written on the ballot paper

The intention of the voter must be unmistakable, i.e. do not assume what the voter was trying to do if it’s not clear – only consider what is written on the ballot paper.

Principle five

The ballot paper should be construed as a whole

By considering the number in each box as one in a series, not as an isolated number, a poorly formed number may be recognisable as the one missing from the series.

(emphasis in original)

22 They contended that the issue was what the voter intended to convey, rather than being concerned solely with the use of a tick or a cross. They accepted that the reference to a voter’s intention was what a reasonable person would understand whatever the marking on the ballot paper conveyed. They submitted that the test did not involve identifying what a reasonable voter would have intended, but required consideration of only the marking on the ballot paper in its context. The applicants referred to the reasoning of Tracey J in Mitchell v Bailey (No 2) (2008) 169 FCR 529 as identifying the relevant principles. They argued that his Honour (at 550 [53]) had stated what is now reflected in Principle 1 in the Election Procedures Handbook (“start from the assumption that the voter has intended to vote formally”), but they said this was inconsistent with its Principle 3 (“err in favour of the franchise”).

23 The applicants’ essential contention was that a cross marked on a ballot paper was a clear indication that a voter intended to vote ‘no’, and therefore it should be counted as a formal vote.

24 They submitted, however, that if the test the High Court formulated in Kane v McClelland (1962) 111 CLR 518 at 527 were applied stringently, so that a vote would be informal where there was a possibility of a different interpretation of the voter’s marking, with the result that they lost on their argument that a cross was unambiguous and signified a ‘no’ vote, then necessarily a tick is equally ambiguous and should count as informal. They argued that because voting is mandatory, an elector has to express his or her vote, so that it is possible that in ticking the box, he or she will do so as a mechanical exercise. Accordingly, they contended that it was possible to interpret a tick as not being a signification of assent to the question on the ballot paper.

The parties’ submissions on standing

25 Both parties urged that the determination of the issues which the applicants have raised as to the way in which the Commissioner proposes that his officers assess the formality of a tick or a cross marked on the ballot paper at the referendum would be utile and resolve important questions.

26 The applicants argued that they had standing by reason of, first, their status as electors pursuant to s 128 of the Constitution and therefore being persons necessarily affected by the way in which the votes were counted and, secondly, Senator Babet being a member of the Parliament.

27 The Commissioner argued that it would not be necessary to resolve the issue of standing were I of the view that the proceeding should be dismissed, for then, on any view, whether the applicants had standing or not, their claim would fail. The Commissioner contended, correctly, that the applicants’ argument raised unresolved issues of considerable public importance, which, because of their constitutional implications, it was not desirable for the Court to adjudicate if the proceeding could otherwise be determined on the merits. He submitted that what McHugh and Kirby JJ had said, in dissent, in Combet v Commonwealth (2005) 224 CLR 494 (at 556 [96] and 618-619 [304] respectively) about the standing of a member of the Parliament to challenge a law was distinguishable in the present circumstances.

Principles

28 Despite the terms of s 24 of the RMP Act, s 93(1)(b), (8) and (9) make clear that the Parliament intended that a vote in which the elector marks something on the ballot paper would only be informal if the voter’s intention is not clear. In Kane 111 CLR at 527, Dixon CJ, McTiernan, Kitto, Taylor, Menzies, Windeyer and Owen JJ construed an analogue of s 93(1)(b) and (8) that required a ballot paper to be “given effect to according to the voter’s intention so far as his intention is clear”. They held that a vote is not necessarily informal if it satisfies this requirement “by a clear, that is unmistakeable, indication of the voter’s intention”. Their Honours continued:

But what is clear is that the intention must be indicated so that it is not left to inference, still less conjecture, that it is expressed or indicated in a way that leaves it indisputable.

29 They held that a “shrewd guess” or other plausible hypothesis or inference was insufficient if the intention was not manifest “with sufficient certainty”, concluding: “[t]o state or investigate the imaginary hypotheses which may explain such errors is not to the point. It is enough to say that it is an inference and not a clear expression or ‘indication’ of the voter’s intention” (at 528). Conjectures and guesses as to how a marking on a ballot paper might be understood are not enough to avoid it being counted as an informal vote, where certainty is lacking. Critically, certainty as to the voter’s intention is essential.

30 There is nothing in either the Scrutineers Handbook, the Guidelines, the Officer-in-charge Return, or the Election Procedures Handbook that would mislead or incorrectly inform voters as to the manner of voting, unless the applicants’ argument about the use of a cross or tick is correct. What appears on the ballot paper itself correctly explains how the voter should mark his or her vote to indicate clearly the voter’s choice: cf Evans v Crichton-Browne (1981) 147 CLR 169 at 204-205 per Gibbs CJ, Stephen, Mason, Murphy, Aickin, Wilson and Brennan JJ.

31 Early in the Federation, the use of a cross to signify a voter’s choice was common, as appeared in Chanter v Blackwood (No 1) (1904) 1 CLR 39. There, s 151 of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1902 (Cth) required a voter to place a cross in the square opposite the name of the candidate for whom he intended to vote (see at 51). Griffith CJ (at 53) and Barton J (at 61) relied on s 199, which required the Court to be guided by the substantial merits and good conscience of each case, regardless of technical legal form. Griffith CJ formulated a principle (at 55) that “if we are called upon to use the extremest technicality in construction, I think we ought to use it in favor of the franchise rather than against it”. The Chief Justice used this principle to find formal a vote that perfectly clearly indicated the elector’s intention. Barton J reasoned similarly (at 60-61). Both Griffith CJ and Barton J applied Woodward v Sarsons (1875) LR 10 CP 733 as correctly expressing the common law of elections, which has consistently been applied since.

32 In In re Raglan Election Petition (No 4) [1948] NZLR 65 at 78 (the Raglan case), O’Leary CJ and Blair J, sitting as the Electoral Court, discussed whether a tick alongside a candidate’s name clearly indicated the elector’s intention to record a vote. Under s 136(1) of the then New Zealand Electoral Act 1927 (NZ), each voter had to cross out the names of all candidates on the ballot paper other than the one for whom he or she wished to vote. It was in that context that the question arose as to whether a voter who had not crossed out any names on the ballot paper, but had placed a tick against one candidate’s name, had cast a valid vote. O’Leary CJ and Blair J held that “the tick did not clearly indicate the intention of the voter”. They disagreed with the magistrate’s view that “a tick is universally regarded as a mark of approbation” and disallowed the vote.

33 However, as the Raglan case [1948] NZLR at 78 demonstrates, the voting context is critical to formation of an understanding whether, by using a particular form of communication when the elector marks a ballot paper, he or she conveys a clear and unmistakeable intention as to what the vote is that he or she has cast.

34 That also seems to be the position in New Zealand now, as decided in Wybrow v Chief Electoral Officer [1980] 1 NZLR 147 at 153. There, Richmond P, giving the decision of himself and Woodhouse, Cooke, Richardson and McMullin JJ, said that the New Zealand Parliament had set “the only test of the validity of a vote so far as the intention of the voter ... is concerned is whether that intention is clearly indicated”. The Court of Appeal said that uniformity of voting methods was not an end in itself. They held that if a voter failed to understand the voting instructions but “does succeed in making his or her intention clear, we would be very slow to attribute to Parliament the pedantry of insisting on rejection of the vote” (at 154). They held that the Raglan case [1948] NZLR at 78 was “yet another instance of a decision based on the clear indication test”, noting that a tick is very often used as a form of selection (at 160). Their Honours also referred to Kane 111 CLR 518 as supporting their construction.

35 In Benwell v Gray, Electoral Commissioner [1999] FCA 1532, Sackville J refused an interlocutory mandatory injunction on the eve of voting on the referendum on whether Australia should become a republic that would have required the Commissioner to segregate at the scrutiny ballot papers that had particular markings other than ‘yes’ or ‘no’. In that referendum, the ballot papers had two questions. The Commissioner had published in the then version of the Scrutineers Handbook numerous examples of voting indications that he said should be counted as formal or informal.

36 Sackville J held (at [26]) that s 24 did not provide for the only method by which a formal vote could be cast, because such a construction would deny any effect at all to the language of s 93(8). His Honour applied (at [29]) the reasoning in Kane 111 CLR at 527 and found that s 93(8) preserved as formal a vote in a ballot paper that conveyed the elector’s clear intention.

37 In Mitchell 169 FCR at 545-550 [44]-[55], Tracey J examined the principles applicable to determining whether a mark on a ballot paper indicated the voter’s intention. He said (at 549 [52]):

In my view the two cardinal principles are those identified by Gummow J in Langer v Commonwealth 186 CLR 302 namely “that the ballot, being a means of protecting the franchise, should not be made an instrument to defeat it and that, in particular, doubtful questions of form should be resolved in favour of the franchise where there is no doubt as to the real intention of the voter.” These principles are given statutory force by s 268(3) of the [Commonwealth Electoral Act]. Other, subordinate, principles may be identified which assist in giving effect to the two cardinal principles. These are:

• When seeking to determine the voter’s intention resort must be had, exclusively, to what the voter has written on the ballot-paper.

• The ballot-paper should be read and construed as whole.

• A voter’s intention will not be expressed with the necessary clarity unless the intention is unmistakeable and can be ascertained with certainty. A Court of Disputed Returns must not resort to conjecture or the drawing of inferences in order to ascertain a voter’s intention.

Consideration

38 I reject the applicants’ submission that the Commissioner’s statement of principles 1 and 3 in the Electoral Procedures Handbook and other publications, set out at [21] above, are inconsistent. The first principle reflects what Tracey J said in Mitchell 169 FCR at 550 [53]. That principle is correct. It does no more than require the officer to approach the task of ruling on whether a mark on a ballot paper expresses the voter’s intention clearly, that is, unmistakeably, by assuming that this was his or her intention in placing that mark as it appears. Of course, the nature of the marking might reveal immediately that it was not a vote at all but a rejection of the elector’s obligation to cast his or her vote. But, once the officer uses principle 1 to guide the approach, principles 2 to 5 require him or her to discern whether something that at least, at first blush, appears to be the elector’s attempt to exercise the franchise succeeded in creating a formal vote. Principle 3 does no more than require an objective evaluation of whether or not the mark is a clear communication of the voter’s intention, in conformity with Griffith CJ’s reasoning in Chanter 1 CLR at 55 that, where possible, a mere technicality should be resolved in favour of the franchise rather than against it, but not so as to allow the returning officer to draw an inference where there is not a manifestly clear statement of intention.

Whether a cross manifests a clear intention to vote ‘no’

39 A cross is used in daily life both as a means of selecting one of two or more choices and as indicating a negative choice. Often one is asked to select a choice with a cross and, as I have noted, this was an early form of voting after Federation. The use of a cross placed in the answer to the single question on the ballot paper for the referendum (namely, “Do you approve this proposed alteration?”) is inherently ambiguous as to the intention that the voter is intending to convey as to the proposal. One must guess whether it means, first, as the applicants reasonably assert, that the elector indicates that he or she is voting ‘no’ or, secondly, whether he or she is intending to vote ‘yes’ because that is one alternative in the question and the voter, carelessly, is responding as he or she is used to doing with other forms that he or she has had to complete, by placing a cross there to signify approval or, thirdly, whether the voter is intending the cross to mean that he or she does not want to engage with or answer the question at all.

Whether a tick manifests a clear intention to vote ‘yes’

40 I reject the applicants’ submission that this characterisation for the use of a cross in answering the ballot paper question applies equally when the voter uses a tick instead. The context for the evaluation, under s 93(8), of whether a tick manifests a clear intention is that it will be placed by the voter against the open question “Do you approve this proposed alteration?”. Unlike a cross, which has more than one signification as either a disapproval or a selection of an answer, being approval, the tick both approves or selects the affirmative as the voter’s answer.

41 A tick signifies assent or approval. It is not a symbol that conveys a negative response. I agree with what Sackville J said in Benwell [1999] FCA 1532 at [29]: “[i]t is difficult to see, for example, what other intention could lie behind a voter’s use of a tick (with or without the word “NO” crossed out)”.

42 For the reasons I have given, it follows that the application must be dismissed.

Whether it is necessary to decide if the applicants have standing

43 Given the conclusion at which I have arrived, it is unnecessary to resolve the somewhat vexed issue of whether the applicants have standing, either because both are electors or because Senator Babet is a member of the Parliament.

44 In Combet 224 CLR 494, Gleeson CJ at 531 [31] and Gummow, Hayne, Callinan and Heydon JJ at 578 [164], and in Wilkie v Commonwealth (2017) 263 CLR 487, Kiefel CJ, Bell, Gageler, Keane, Nettle, Gordon and Edelman JJ at 521-522 [56]-[57], held that the resolution of the issue of standing is not always a threshold question, and, in an appropriate case, the court has a discretion to deal with the merits without resolving that issue. In Phong v Attorney-General (Cth) (2001) 114 FCR 75, Black CJ at 76 [4], Beaumont J at 85 [43] and Hely J at 87 [59] and 89 [70]-[71] also proceeded to dismiss the appeal on its merits without deciding the issue of standing that had been raised.

45 Here, this proceeding involved important issues that are required to be resolved urgently in the context that a deal of preparation still needs to be undertaken by the Commissioner before the voting occurs at the referendum, including settling voting instructions beforehand. The evidence also disclosed that there is a vigorous public debate as to the meaning of a cross being placed on the ballot paper. Both parties wanted a resolution of that debate on the merits, albeit that the Commissioner properly raised the constitutional issue as to whether the applicants had standing.

46 As I have explained, there are practical reasons for deciding the merits of the application which warrant the Court proceeding to do so without first determining the issue of standing: see also Ansett Australia Ground Staff Superannuation Fund Pty Ltd v Ansett Australia Ltd (2003) 176 FLR 393 at 401 [15] per Ormiston JA, with whom Callaway JA at 405 [27] and Batt JA at 407 [34] agreed.

47 The issue of standing raises a constitutional question that, ordinarily, ought not be resolved unless it is necessary to do so. Since I have decided to dismiss the proceeding on the merits, I do not consider it necessary or appropriate to engage with the question of whether the applicants have standing to maintain this proceeding. The question of standing is difficult, complex and raises important issues of principle that have not necessarily been fully explored in the limited time available both to the parties and the Attorneys-General. Moreover, if I have erred in resolving the questions that I have decided and that error has, or is alleged to have, some impact on the outcome of the voting at the referendum, the High Court will have jurisdiction to deal with all those issues and resolve them authoritatively on any petition presented to it.

Disposition

48 Accordingly, I am of opinion that the application must be dismissed with costs.

49 The Commissioner also sought an order abridging the time to file a notice of appeal under s 36.03 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 from 28 days, so that, if the applicants wish to appeal this decision, they be required to do so promptly. I agree and will order that any notice of appeal be filed on or before 27 September 2023.

I certify that the preceding forty-nine (49) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justices Rares. |

Associate: