Federal Court of Australia

Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA Inc v Zoetis Services LLC [2023] FCA 1119

ORDERS

BOEHRINGER INGELHEIM ANIMAL HEALTH USA INC. Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | Cross-Appellant | |

AND: | BOEHRINGER INGELHEIM ANIMAL HEALTH USA INC. Cross-Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 21 SEPTEMBER 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. If the parties agree on the appropriate orders to be made by the Court reflecting these reasons for judgment, the parties file a minute of proposed orders on or before 5 October 2023.

2. If the parties are unable to agree on the orders which should be made, each of the parties file and serve on or before 5 October 2023:

(a) A minute of the orders that the party proposes; and

(b) Any outline of submissions in support of the proposed orders (limited to three pages).

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ROFE J:

[1] | |

[10] | |

[11] | |

[28] | |

[81] | |

[85] | |

[88] | |

[90] | |

[95] | |

[99] | |

[103] | |

[110] | |

[112] | |

[118] | |

Regard to confidential information not part of common general knowledge | [130] |

Not representative of non-inventive person skilled in the art | [147] |

[154] | |

[158] | |

[175] | |

[184] | |

[189] | |

[211] | |

[224] | |

[235] | |

[259] | |

[261] | |

[263] | |

[267] | |

[277] | |

[284] | |

[292] | |

[294] | |

[306] | |

[320] | |

[345] | |

[360] | |

[370] | |

[372] | |

[378] | |

[384] | |

[389] | |

[393] | |

[409] | |

[417] | |

[421] | |

[425] | |

[425] | |

[437] | |

[447] | |

[455] | |

[472] | |

[476] | |

[477] | |

[489] | |

[494] | |

[496] | |

[519] | |

[525] | |

[532] | |

[556] | |

[584] | |

[599] | |

[610] | |

[612] | |

[618] | |

[618] | |

[636] | |

[647] | |

[650] | |

[656] | |

Dr Nordgren’s evidence as to the examples in the Applications | [656] |

[684] | |

[697] | |

[716] | |

[725] | |

[744] | |

[769] |

INTRODUCTION

1 These proceedings are an appeal pursuant to s 60(4) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Patents Act or Act) from a decision of a delegate of the Commissioner of Patents by the opponent, Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA Inc, and a cross-appeal by the patent applicant, Zoetis Services LLC, to the grant of three related patent applications: Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA Inc. v Zoetis Services LLC [2020] APO 40 (Delegate’s decision).

2 The three patent applications were each filed on 3 April 2013, and their claim of a priority date of 4 April 2012 was not challenged. The three Australian Patent applications are the:

(a) 535 Application, entitled “Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae vaccine”;

(b) 537 Application, entitled “PCV/Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae combination vaccine”; and

(c) 540 Application entitled “PCV/Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae/PRRS combination vaccine”.

3 The delegate found claims 1–2, 4–6, 9–10 and 12–18 of the 535 Application did not involve an inventive step. The oppositions to the 537 and 540 Applications were unsuccessful.

4 Boehringer filed a notice of appeal and notice of contention. Zoetis filed a notice of cross-appeal and a notice of contention.

5 Ultimately on appeal, the following grounds of opposition were pressed for each Application:

(1) That the invention claimed is not supported by the matter disclosed in the specification within s 40(3) of the Act;

(2) That the complete specification does not disclose the invention in a manner which is clear enough and complete enough for it to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art within s 40(2)(a) of the Act;

(3) That the complete specification does not disclose the best method known to Zoetis within the requirements of s 40(2)(aa) of the Act;

(4) That the invention claimed does not involve an inventive step because it was obvious in light of the common general knowledge considered together with information in any one or more of the Okada papers (defined later); and

(5) That the invention claimed in certain “kit” claims is not for a “manner of manufacture” within s 18(1)(a) of the Act.

6 Although styled as an appeal, the present proceeding is in the original jurisdiction of this Court and involves a hearing de novo on the grounds and evidence before the Court. As the opponent to the grant of a patent on each of the Applications, Boehringer bears the onus in relation to each ground of opposition raised.

7 Section 60(3A) of the Act, which was introduced with the passage of the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth) (RTB Act), provides that the Commissioner may refuse an application if satisfied, on the balance of probabilities, that a ground of opposition exists. That is the standard by which the present proceeding is to be judged.

8 The Patents Act that applies to the present dispute is in the form as amended by the introduction of the RTB Act.

9 For the reasons that follow, I have concluded that the opposition to the grant succeeds in respect of the following claims:

(a) 535 Application:

(i) Claims 1, 3, 7–8, 11–12, 16–17

(b) 537 Application:

(i) Claims 1 to 24

(c) 540 Application:

(i) Claims 1 to 25

10 Before going further, I will set out a brief background to vaccines, taken principally from uncontroversial parts of the first affidavits of Professor Chase and Dr Nordgren and supplemented with extracts from Professor Browning’s affidavit.

11 A pathogen is an organism that can infect and cause disease to a host such as a pig or a human. There are four main types of pathogens:

(a) bacteria;

(b) viruses;

(c) fungi; and

(d) parasites, such as protozoa and helminths (eg nematodes or roundworms).

12 The immune system protects its host from infection by pathogens. The immune system is a complex system comprised of different types of cells, tissues and chemotypic messengers, each of which have specific roles, and which work together to protect and heal the host from damage caused by foreign invading pathogens.

13 There are three main types of immunity:

(a) innate immunity (also known as the “innate immune system”, “innate immune response”, or “primary immune response”);

(b) adaptive immunity (also known as the “adaptive immune system”, “adaptive immune response”, or “secondary immune response”); and

(c) passive immunity (also known as the “passive immune system” or “passive immune response”).

14 Each pathogen has unique lifecycles and components, typically proteins or carbohydrates, which stimulate the immune response of a host. The components of pathogens which are capable of being recognised by the immune system and generating a response are known as “antigens”.

15 The innate immune response is the first line of defence against infection. Most components of innate immunity are present before the onset of infection and consist of a set of disease-resistant mechanisms that are not specific to a particular pathogen. These include physical barriers such as skin and the mucosal membranes, as well as phagocytic cells such as macrophages. The innate system is able to recognise a given class of molecules but does not change its response based on its previous exposure to the same pathogen.

16 Macrophages can engulf, or “phagocytize”, invading pathogens and foreign particles and expose them to other intracellular compounds involved in the innate immune response, such as lysozymes (enzymes which can cleave bacterial cell wall membranes). Macrophages, and other components of the innate immune response such as dendritic cells, also stimulate the adaptive immune response, by displaying antigens on their cell surface.

17 The adaptive immune response is typically triggered when there is a recognised antigenic challenge to a host organism. Adaptive immunity provides a second, specific and comprehensive line of defence that eliminates pathogens that evade the innate responses or persist in spite of them. An important consequence of adaptive immune response is memory. If the same pathogen infects the body a second time, memory cells provide the means for the adaptive immune system to make a rapid and often highly effective attack on the invading pathogen.

18 Two characteristics of the adaptive immune system that are crucial to a successful immune response are its antigenic specificity and its diversity. The antigenic specificity of the adaptive immune response enables it to recognise subtle differences among antigens, such as a difference of one amino acid in two otherwise identical proteins. The diversity of the adaptive immune response allows it to recognise billions of unique structures on foreign antigens.

19 The major agents of adaptive immunity are lymphocytes and the antibodies that they produce. Lymphocytes are a class of white blood cells that are produced in the bone marrow, and that produce and display antibodies. The two major types of lymphocytes are B lymphocytes (or B cells) and T lymphocytes (or T cells).

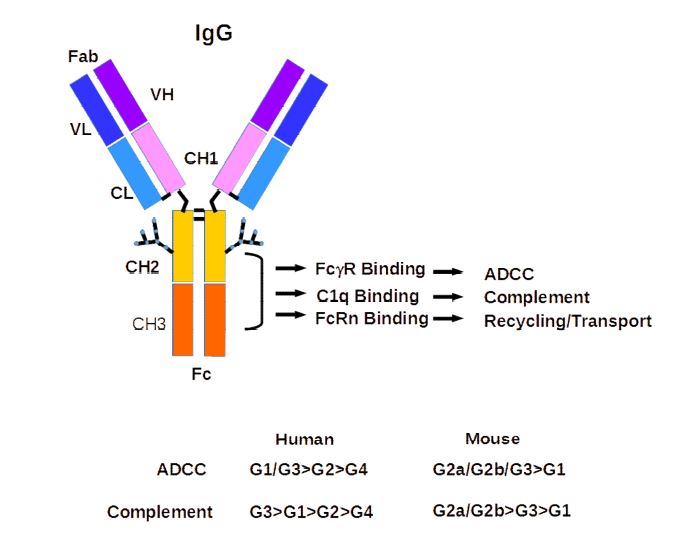

20 Antibodies, also known as immunoglobulins (or Ig), are proteins that mediate the humoral immune response by recognising and binding to antigens.

21 Antibodies bind to specific portions of an antigen. Each antibody-binding site of an antigen is called an “epitope”. The combined strength of the interactions between a single antigen-binding site on an antibody and a single epitope is referred to as the affinity of the antibody for that epitope.

22 There are five major antibody classes, or immunoglobulins: IgG, IgM, IgD, IgA and IgE, each of which plays a specific role in the immune response of a host.

23 Antibodies consist of “heavy” polypeptide chains and “light” polypeptide chains. Each chain comprises a “constant” region and a “variable” region. The constant region is common across all antibodies of a class, while the variable region of each antibody is specific to the antigen against which it was generated.

24 The most abundant immunoglobulin is immunoglobulin G (IgG), which is released by Plasma B cells. There are several sub-classes of IgG. IgG consists of two “heavy” polypeptide chains and two “light” polypeptide chains in a “Y” shape:

25 A vaccine is a preparation containing one or more antigens which is intended to trigger an adaptive immune response, but not cause disease, or at least not cause severe symptoms of disease, associated with that pathogen. The vaccine is intended to generate memory cells against a pathogen. This protects the host against the consequences of subsequent exposure to a pathogen bearing that antigen.

26 Vaccines involve presenting a killed or weakened version of a pathogen (or an antigen or antigens, or specific parts of an antigen or antigens of a pathogen) to the immune system, in a form suitable for the immune system to recognise the antigen or antigens and stimulate the body to produce antigen-specific antibodies and related memory cells in response. If the vaccinated individual is exposed to the pathogen again after vaccination, the immune system will be primed and able to rapidly produce antigen-specific antibodies in order to neutralize and prevent the pathogen from reproducing and the disease from developing.

27 Pathogens often have more than one antigen against which hosts will generate antibodies and memory cells that are capable of providing adaptive immunity. This means that, for a given pathogen, a number of different antigenic compositions may be able to confer acceptable levels of immunity.

28 There are three patent applications in issue.

29 The Applications have substantially the same specification, save for different introductory statements as to the field of the invention and consistory statements, and different examples being included in the 537 and 540 Applications.

30 The 535 Application is entitled “Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae vaccine” and the invention is said to relate to Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (M. hyo). More particularly, the invention relates to the soluble portion of an M. hyo whole cell preparation and its use in a vaccine for protecting pigs against enzootic pneumonia.

31 The 537 Application is entitled “PCV/Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae combination vaccine”, and the invention is said to relate to porcine circovirus and M. hyo. More particularly, the invention relates to a multivalent immunogenic composition including a soluble portion of an M. hyo whole cell preparation and a PCV-2 antigen and its use in a vaccine for protecting pigs against enzootic pneumonia and Post-weaning Multisystemic Wasting Syndrome (PMWS).

32 The 540 Application is entitled “PCV/Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae/PRRS combination vaccine” and the invention is said to relate to porcine circovirus, M. hyo and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus. More particularly, the invention relates to a trivalent immunogenic composition including a soluble portion of an M. hyo whole cell preparation, a PCV-2 antigen and a PRRS virus antigen and its use in a vaccine for protecting pigs against enzootic pneumonia and PMWS.

33 Relevant parts of the specification (of all three Applications), referred to throughout these reasons for judgment, include the following.

34 The background of the invention notes enzootic pneumonia in swine, also called mycoplasmal pneumonia, is caused by M. hyo. Whilst infected pigs show only mild cough and fever symptoms, the disease has significant economic impact due to reduced feed efficiency and reduced weight gain. The primary M. hyo infection may be followed by secondary infection by other mycoplasma species as well as other bacterial pathogens.

35 The specification describes M. hyo as a small, prokaryotic microbe capable of a free living existence, although it is often found in association with eukaryotic cells because it has absolute requirements for exogenous sterols and fatty acids. These requirements generally necessitate growth in serum-containing media. M. hyo is bounded by a cell membrane, but not a cell wall.

36 After describing in more detail the mechanism and effect of an M. hyo infection in a pig, and the characteristic lung lesions found in infected pigs, the specification observes (at page 1a, line 3) that there is a great need for effective preventative and treatment measures.

37 The specification continues (at page 2, lines 5–11):

Vaccines containing preparations of mycoplasmal organisms grown in serum-containing medium have been marketed, but raise concerns regarding adverse reactions induced by serum components (such as immunocomplexes or non-immunogenic specific proteins) present in the immunizing material. Other attempts to provide M. hyo vaccines have been successful, but the disease remains widespread.

38 The specification then explains that M. hyo and porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV-2) are the two most prevalent pathogens that are encountered in the pig industry. Swine infected with PCV-2 exhibit a syndrome commonly referred to as Post-weaning Multisystemic Wasting Syndrome (defined above as PMWS). In addition to PMWS, PCV-2 has been associated with several other infections, one of which is PRRS.

39 At page 2a, lines 1–2, the specification states that it is an object of the present invention to overcome or ameliorate at least one of the disadvantages of the prior art, or to provide a useful alternative. An example given is an improved vaccine against mycoplasma infection in swine.

40 The specification continues (at page 3, lines 1–4):

M. hyo vaccine will be compatible with other porcine antigens, such as PCV2 and PRRS virus, whether they are given concurrently as separate single vaccines or combined in a ready-to-use vaccine. It would be highly desirable to provide a ready-to-use, single-dose M. hyo/PCV2 combination vaccine.

41 Under the heading “summary of the invention”, the specification describes four aspects of the invention, the first aspect being (page 3, lines 7–11):

According to a first aspect, the present invention relates to an immunogenic composition comprising the supernatant of a Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (M.hyo) culture, wherein the supernatant of the M.hyo culture has been separated from insoluble cellular material by centrifugation, filtration, or precipitation and is substantially free of both (i) IgG and (ii) immunocomplexes comprised of antigen bound to immunoglobulin.

42 The second aspect of the invention relates to a kit for use in carrying out the invention, the third aspect, a method for preparing an immunogenic composition, and the fourth, a method for immunising a pig against M. hyo.

43 At page 3a, lines 10–12, the specification states that in one aspect, the soluble portion of the M. hyo whole cell preparation has been treated with Protein A or Protein G prior to being added to the immunogenic composition.

44 The specification then describes some embodiments of the invention (at page 3a, line 14–page 5, line 13):

In one embodiment, the soluble portion of the M. hyo preparation includes at least one M. hyo protein antigen. In another embodiment, the soluble portion of the M. hyo preparation includes two or more M. hyo protein antigens.

In some embodiments, the immunogenic composition of the present invention further includes at least one additional antigen. In one embodiment, the at least one additional antigen is protective against a microorganism that can cause disease in pigs.

In one embodiment, the microorganism includes bacteria, viruses, or protozoans. In another embodiment, the microorganism is selected from, but is not limited to, the following: porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2), porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), porcine parvovirus (PPV), Haemophilus parasuis, Pasteurella multocida, Streptococcum [sic] suis, Staphylococcus hyicus, Actinobacilllus [sic] pleuropneumoniae, Bordetella bronchiseptica, Salmonella choleraesuis, Salmonella enteritidis, Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, Mycoplama [sic] hyorhinis, Mycoplasma hyosynoviae, leptospira bacteria, Lawsonia intracellularis, swine influenza virus (SIV), Escherichia coli antigen, Brachyspira hyodysenteriae, porcine respiratory coronavirus, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea (PED) virus, rotavirus, Torque teno virus (TTV), Porcine Cytomegalovirus, Porcine enteroviruses, Encephalomyocarditis virus, a pathogen causative of Aujesky's [sic] Disease, Classical Swine fever (CSF) and a pathogen causative of Swine Transmissable [sic] Gastroenteritis, or combinations thereof.

In certain embodiments, the at least one additional antigen is a porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) antigen, a PRRS virus antigen or a combination thereof. In one embodiment, the composition elicits a protective immune response in a pig against both M. hyo and PCV2. In another embodiment, the composition elicits a protective immune response in a pig against M. hyo, PCV2 and PRRS virus.

In one embodiment, the PCV2 antigen is in the form of a chimeric type-1-type 2 [sic] circovirus, the chimeric virus including an inactivated recombinant porcine circovirus type 1 expressing the porcine circovirus type 2 ORF2 protein. In another embodiment, the PCV2 antigen is in the form of a recombinant ORF2 protein. In still another embodiment, the recombinant ORF2 protein is expressed from a baculovirus vector.

In some embodiments, the composition of the present invention further includes an adjuvant. In one embodiment, the adjuvant is selected from, but is not limited to, the following: an oil-in-water adjuvant, a polymer and water adjuvant, a water-in-oil adjuvant, an aluminum hydroxide adjuvant, a vitamin E adjuvant and combinations thereof. In another embodiment, the composition of the present invention further includes a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier.

In certain embodiments, the composition of the present invention elicits a protective immune response against M. hyo when administered as a single dose administration. In further embodiments, the composition elicits a protective immune response against M. hyo and at least one additional microorganism that can cause disease in pigs when administered as a single dose administration. In still further embodiments, a composition of the present invention elicits a protective response against both M. hyo and at least one additional microorganism that causes disease in pigs when administered as a two dose administration.

The present invention also provides a method of immunizing a pig against M. hyo. This method includes administering to the pig an immunogenic composition including a soluble portion of an M. hyo whole cell preparation, wherein the soluble portion of the M. hyo preparation is substantially free of both (i) IgG and (ii) immunocomplexes comprised of antigen bound to immunoglobulin. In one embodiment, the soluble portion of the M. hyo preparation of the administered composition includes at least one M. hyo protein antigen.

In one embodiment of the method of the present invention, the composition is administered intramuscularly, intradermally, transdermally, or subcutaneously. In another embodiment of the method of this invention, the composition is administered in a single dose. In yet another embodiment of the method of this invention, the composition is administered as two doses.

In a further embodiment of the method of the present invention, the composition is administered in conjunction with at least one additional antigen that is protective against a microorganism that can cause disease in pigs, such as one or more of the microorganisms described above. Such other antigens can be given concurrently with the M. hyo composition (i.e., as separate single vaccines) or combined in a ready-to-use vaccine.

45 There follows a brief description of the drawings and the sequences.

46 At page 8, lines 15–24, there is the following detailed description of the invention:

The present invention provides an immunogenic composition including a soluble portion of an M. hyo whole cell preparation, wherein the soluble portion of the M. hyo preparation is substantially free of both (i) IgG and (ii) antigen-bound immunocomplexes. Applicants have surprisingly discovered that the insoluble fraction of the M. hyo whole cell preparation is non-immunogenic. In contrast, the IgG-free M. hyo soluble preparation is immunogenic and can be effectively combined with antigens from other pathogens, such as PCV2, without analytical or immunological interference between the antigens. This makes the M. hyo soluble preparation of this invention an effective platform for multivalent vaccines, including one-bottle, ready-to-use formulations. Applicants have also surprisingly discovered that removing the immunoglobulin and the insoluble cell debris enhances the safety of the immunogenic composition.

47 The specification then includes (at page 8, line 26–page 13, line 4) a number of definitions of terms used in the specification, including “comprising” at page 8, lines 30–2:

As used herein, the term “comprising” is intended to mean that the compositions and methods include the recited elements, but do not exclude other elements.

48 At page 9, lines 1–9, the specification states that, as defined, a soluble portion of an M. hyo whole cell preparation refers to a soluble liquid fraction of an M. hyo whole cell preparation after separation of the insoluble material and substantial removal of IgG and antigen-bound immunocomplexes. The specification continues:

The M. hyo soluble portion may alternatively be referred to as the supernatant fraction, culture supernatant and the like. It includes M. hyo expressed soluble proteins (M. hyo protein antigens) that have been separated or isolated from insoluble proteins, whole bacteria, and other insoluble M. hyo cellular material by conventional means, such as centrifugation, filtration, or precipitation. In addition to including M. hyo-specific soluble proteins, the soluble portion of the M. hyo whole cell preparation also includes heterologous proteins, such as those contained in the culture medium used for M. hyo fermentation.

The term “antigen” as used in the specification refers to a compound, composition, or immunogenic substance that can stimulate the production of antibodies or a T-cell response, or both, in an animal, including compositions that are injected or absorbed into an animal. The immune response may be generated to the whole molecule, or to a portion of the molecule (e.g., an epitope or hapten).

49 The term an “immunogenic or immunological composition”, as used in the specification, refers to a composition of matter that comprises at least one antigen which elicits an immunological response in the host of a cellular and or antibody-mediated immune response to the composition or vaccine of interest.

50 At page 9, lines 20–30 the specification continues:

The term "immune response" as used in the specification refers to a response elicited in an animal. An immune response may refer to cellular immunity (CMI); humoral immunity or may involve both. The present invention also contemplates a response limited to a part of the immune system. Usually, an “immunological response” includes, but is not limited to, one or more of the following effects: the production or activation of antibodies, B cells, helper T cells, suppressor T cells, and/or cytotoxic T cells and/or yd T cells, directed specifically to an antigen or antigens included in the composition or vaccine of interest. Preferably, the host will display either a therapeutic or protective immunological response such that resistance to new infection will be enhanced and/or the clinical severity of the disease reduced. Such protection will be demonstrated by either a reduction or lack of symptoms normally displayed by an infected host, a quicker recovery time and/or a lowered viral titer in the infected host.

51 The term “adjuvant”, as used in the specification (at page 10, line 5), means:

[A] composition comprised of one or more substances that enhances the immune response to an antigen(s). The mechanism of how an adjuvant operates is not entirely known. Some adjuvants are believed to enhance the immune response by slowly releasing the antigen, while other adjuvants are strongly immunogenic in their own right and are believed to function synergistically.

52 The term “multivalent”, as used in the specification, means a vaccine containing more than one antigen whether from the same species (ie different isolates of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae), from a different species (ie isolates from both Pasteurella hemolytica and Pasteurella multocida), or a vaccine containing a combination of antigens from different genera (eg a vaccine comprising antigens from Pasteurella multocida, Salmonella, Escherichia coli, Haemophilus somnus and Clostridium).

53 The term “vaccine composition”, as used in the specification, includes at least one antigen or immunogen in a pharmaceutically acceptable vehicle useful for inducing an immune response in a host.

54 At page 13, lines 5–9, the specification states:

All currently available M. hyo vaccines are made from killed whole cell mycoplasma preparations (bacterins). In contrast, the present invention employs a soluble portion of a Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (M. hyo) whole cell preparation, wherein the soluble portion of the M. hyo preparation is substantially free of both (i) IgG and (ii) immunocomplexes comprised of antigen bound to immunoglobulin.

55 The specification then discusses the growth media requirements specific to M. hyo at page 13, lines 11–23:

M. hyo has absolute requirements for exogenous sterols and fatty acids. These requirements generally necessitate growth of M. hyo in serum-containing media, such as porcine serum. Separation of the insoluble material from the soluble portion of the M. hyo whole cell preparation (e.g., by centrifugation, filtration, or precipitation) does not remove the porcine IgG or immune complexes. In one embodiment of the present invention, the M. hyo soluble portion is treated with protein-A or protein-G in order to substantially remove the IgG and immune complexes contained in the culture supernatant. In this embodiment, it is understood that protein A treatment occurs post- M. hyo fermentation. This is alternatively referred to herein as downstream protein A treatment. In another embodiment, upstream protein A treatment of the growth media (i.e., before M. hyo fermentation) can be employed. Protein A binds to the Fc portion of IgG. Protein G binds preferentially to the Fc portion of IgG, but can also bind to the Fab region. Methods for purifying/removing total IgG from crude protein mixtures, such as tissue culture supernatant, serum and ascites fluid are known in the art.

56 At page 13, lines 25–27, the specification notes that in some embodiments, the soluble portion of the M. hyo preparation includes at least one M. hyo protein antigen. In other embodiments, the soluble portion of the M. hyo preparation includes two or more M. hyo protein antigens.

57 The specification discusses (at page 13, line 29–page 14, line 25) at least one M. hyo antigen included in the M. hyo soluble portion. In one embodiment, the M. hyo supernatant fraction is said to include one or more of the following M. hyo protein specific antigens: M. hyo proteins of approximately 46kD (p46), 64kD (p64) and 97kD (p97); kD being molecular weight expressed in kilo Daltons. In another embodiment, the M. hyo culture supernatant may include further M. hyo specific antigens such as, but not limited to, proteins of approximately 41 kD (p41), 42kD (p42), 89kD (p89), and 65kD (p65). The specification cites Okada et al, “Protective effect of Vaccination with Culture Supernate of M. hyopneumoniae against Experimental Infection in Pigs” (2000) Journal of Veterinary Medicine, Series B 47(7) 527–533 (Okada 2000a) following the list of specific protein antigens.

58 At page 15, lines 18–22, the specification details another embodiment:

In one embodiment, M. hyo soluble p46 antigen is included in the compositions of the invention at a final concentration of about 1.5 µg/ml to about 10 µg/ml, preferably at about 2 µg/ml to about 6 µg/ml. It is noted that p46 is the protein used for the M. hyo potency test (see example section below). In another embodiment, the M. hyo antigen can be included in the compositions at a final amount of about 5.5% to about 35% of the M. hyo whole culture protein A-treated supernatant.

59 At page 15, lines 24–30, the specification states that the M. hyo soluble preparation of the present invention is both safe and efficacious against M. hyo and is suitable for single dose administration. In addition, it is said that it has been surprisingly discovered that the M. hyo soluble preparation can be effectively combined with antigens from other pathogens without immunological interference between the antigens. That is said to make the M. hyo soluble preparation of the invention an effective platform for multivalent vaccines. The additional antigens may be given concurrently with the M. hyo composition (ie as separate single vaccines) or combined in a ready-to-use vaccine.

60 At page 16, the specification provides details of other embodiments, including where:

(a) The immunogenic composition includes at least one M. hyo soluble antigen and at least one additional antigen; or

(b) The immunogenic composition includes the combination of at least one M. hyo soluble antigen (eg two or more) and a PCV-2 antigen.

61 See also page 19, lines 23–26, which describes further embodiments, including a combination of at least one M. hyo soluble antigen (eg two or more), a porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV-2) antigen and a PRRS virus antigen.

62 Page 19, lines 9–21, includes the following examples of absolute concentration:

In one embodiment, a chimeric PCV1-2 virus is included in the compositions of the invention at a level of at least 1.0 < RP< 5.0, wherein RP is the Relative Potency unit determined by ELISA antigen quantification (in vitro potency test) compared to a reference vaccine. In another embodiment, a chimeric PCV1-2 virus is included in the composition of the invention at a final concentration of about 0.5% to about 5% of 20-times (20X) concentrated bulk PCV1-2 antigen.

In another embodiment, the PCV2 ORF2 recombinant protein is included in the compositions of the invention at a level of at least 0.2 µg antigen/ml of the final immunogenic composition (µg/ml). In a further embodiment, the PCV2 ORF2 recombinant protein inclusion level is from about 0.2 to about 400 µg/ml. In yet another embodiment, the PCV2 ORF2 recombinant protein inclusion level is from about 0.3 to about 200 µg/ml. In a still further embodiment, the PCV2 ORF2 recombinant protein inclusion level is from about 0.35 to about 100 µg/ml. In still another embodiment, the PCV2 ORF2 recombinant protein inclusion level is from about 0.4 to about 50 µg/ml.

63 Examples of suitable adjuvants for use in the compositions of the invention are listed at page 24.

64 The specification notes at page 26, lines 24–27 the methods used to separate the M. hyo whole cell preparation from the insoluble cellular material. These conventional methods include filtration, centrifugation and precipitation across various embodiments.

65 The 535 Application has 13 examples. Example 1 provides a high level description of a method by which an M. hyo cell culture is fermented and inactivated for the purposes of producing a PCV-2 combinable M. hyo antigen. Example 2 provides a description of methods by which chimeric porcine circovirus (cPCV)1-2 can be produced. Examples 1 and 2 are replicated in the 537 and 540 Applications.

66 Example 3 (in each of the Applications) is entitled “Down Stream Processing of M. hyo antigens and Analytical Testing of these Processed Antigens”. This example describes how a number of M. hyo preparations prepared as described in example 1 were treated and then analysed for M. hyo specific p46 antigen. The processed M. hyo antigens were then employed in example 4 (in each of the Applications) to prepare M. hyo vaccine formulations. Formulations relevant to BI’s validity case, which are discussed later, include:

T03: (10X UF (ultra filtration) concentrated) Concentrated by tangential flow filtration via a 100KDa molecular weight cut-off membrane (hollow fibre). Final volume reduction was equal to 10X.

T04 and T05: (10X UF concentrated and centrifuged) Concentrated mycoplasma cells (from T03) were collected and washed one time with PBS via centrifugation at ~20,000xg (Sorvall model RCB).

T06 and T07: (10X centrifuged) Inactivated fermentation fluid was centrifuged at ~20,000xg (Sorvall RC5B) and washed one time by resuspending the cells in PBS followed by additional centrifugation. Final volume reduction was equal to 10X.

T08: (10X centrifuged and heated) Mycoplasma cells were concentrated and washed per T06 and heated to 65°C for 10 minutes.

T09: (cell-free supernatant) Supernatant collected from the first centrifugation as described for T06 was filter sterilized through a 0.2 micron filter (Nalgene).

T10: (cell-free-supernatant-Protein-A treated) Sterile supernatant (prepared per T09) was mixed with Protein A resin (Protein A Sepharose, Pharmacia Inc) at a 10:1 volume ratio for 4 hours. Resin was removed and sterile filtration and filtered fluid was stored at 2-8˚C. This process uses post-fermentation “downstream” Protein A treatment to remove antibodies and immunocomplexes.

67 The specification notes (at page 32) that, although the present invention does not preclude upstream Protein A treatment, the present inventors have found that, in the case of M. hyo, upstream processing of the growth media led to P46 results which were lower and inconsistent as compared to untreated media.

68 The specification continues at page 33, line 13:

Since it is known in the art that Protein A binds IgG, it is understood by those of ordinary skill in the art that not only PCV2 antibody, but other swine antibodies, including PRRS antibody, HPS antibody, and SIV antibody will be effectively removed by the Protein-A treatment. This makes the Cell-free Protein-A treated M. hyo supernatant of this invention compatible not only with PCV2 antigen, but also with other porcine antigens due to the lack of immunological interference between the antigens. Additionally, the removal of the non-protective cell debris and removal of the immunoglobulin and antigen/immunoglobulin complexes is reasonably expected to make a safer vaccine.

69 The differences between the three specifications as far as the examples are concerned can be summarised as follows:

(a) Examples 12 and 13 of the 537 Application are not present in the 535 or 540 Applications. These examples describe two studies, the first designed to evaluate the efficacy of the PCV1-2 chimera, killed virus fraction of an experimental 1-bottle PCV-2/M. hyo combination vaccine, administered once to piglets, and the second to evaluate the efficacy of the M. hyo fraction of an experimental PCV1-2 chimera.

(b) Examples 14 and 15 of the 537 Application are labelled example 12 and 13, respectively, in the 535 and 540 Applications.

(c) The 540 Application contains three additional examples not present in the 535 or 537: examples 14 to 16. Examples 14 to 16 describe various further studies designed to evaluate the efficacy of the M. hyo, PCV-2 and PRRS components respectively of a trivalent vaccine of the invention.

70 The 535 Application’s specification ends with 18 claims. Claim 1 of the 535 Application claims:

An immunogenic composition comprising the supernatant of a Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (M. hyo) culture, wherein the supernatant of the M. hyo culture has been separated from insoluble cellular material by centrifugation, filtration, or precipitation and is substantially free of both (i) IgG and (ii) immunocomplexes comprised of antigen bound to immunoglobulin.

71 Claim 2 of the 535 Application is dependent upon claim 1, and adds “wherein the soluble portion has been treated with Protein A or Protein G prior to being added to the immunogenic composition”.

72 Claim 3 of the 535 Application is dependent upon claims 1 or 2, and claims:

The composition of claim 1 or claim 2, wherein the composition further comprises at least one additional antigen which is protective against a microorganism selected from the group consisting of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), porcine parvovirus (PPV), Haemophilus parasuis, Pasteurella multocida, Streptococcum [sic] suis, Staphylococcus hyicus, Actinobacilllus [sic] pleuropneumoniae, Bordetella bronchiseptica, Salmonella choleraesuis, Salmonella enteritidis, Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, Mycoplama [sic] hyorhinis, Mycoplasma hyosynoviae, leptospira bacteria, Lawsonia intracellularis, swine influenza vims (SIV), Escherichia coli antigen, Brachyspira hyodysenteriae, porcine respiratory coronaviruses, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea (PED) vims, rotavims, Torque teno virus (TTV), Porcine Cytomegalovirus, Porcine enterovimses, Encephalomyocarditis virus, a pathogen causative of Aujesky’s [sic] Disease, Classical Swine fever (CSF) and a pathogen causative of Swine Transmissable [sic] Gastroenteritis, or combinations thereof.

(Emphasis added.)

73 The bolded references above are to the “5 Pathogens” which were the subject of discussion by the experts and which are relevant to Boehringer’s validity case. Four of the 5 Pathogens are viruses, and one, Brachyspira hyodysenteriae, is a bacteria.

74 Claim 16 of the 535 Application is a “kit” claim, which claims:

A kit for use in carrying out the method of claim 9 comprising:

a bottle comprising an immunogenic composition including the supernatant of a Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (M. hyo) culture, wherein the supernatant of the M. hyo culture has been separated from insoluble cellular material by centrifugation, filtration, or precipitation and is substantially free of both (i) IgG and (ii) antigen/immunoglobulin immunocomplexes.

75 The 537 Application contains 24 claims, the broadest of which is claim 1, which claims:

A multivalent immunogenic composition comprising the supernatant of a Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (M. hyo) culture; and a porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) antigen, wherein the supernatant of the M. hyo culture has been separated from insoluble cellular material by centrifugation, filtration, or precipitation and is substantially free of both (i) IgG and (ii) immunocomplexes comprised of antigen bound to immunoglobulin.

(Emphasis added.)

76 Claim 2 of the 537 Application is dependent on claim 1 and claims where the soluble portion of the M. hyo preparation has been treated with Protein A or Protein G prior to being added to the immunogenic composition.

77 Claim 3 claims the composition of claim 1 or 2 wherein the composition is in the form of a ready-to-use liquid composition.

78 Dependent claim 8 of the 537 Application claims the composition of any one of claims 1 to 7, further comprising at least one additional antigen which is protective against a microorganism selected from the same group listed in claim 3 of the 535 Application with the exception of PRRSV which is in the list of antigens in claim 3 of the 535 Application but is not found in the list in claim 8 of the 537 Application.

79 The 540 Application contains 25 claims. Claim 1 of the 540 Application claims:

A trivalent immunogenic composition comprising the supernatant of a Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (M. hyo) culture; a porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) antigen; and a porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus antigen, wherein the supernatant of the M. hyo culture has been separated from insoluble cellular material by centrifugation, filtration, or precipitation and is substantially free of both (i) IgG and (ii) immunocomplexes comprised of antigen bound to immunoglobulin.

(Emphasis added.)

80 Claims 2 to 13 of the 540 Application are dependent claims that also define trivalent immunogenic compositions, adding various characteristics to claim 1. In particular, claim 3 defines a “ready-to-use” composition containing the M. hyo and PCV-2 antigens but not the PRRS virus antigen. Claims 24 and 25 are claims to methods of preparing an immunogenic composition comprising the M. hyo supernatant, and PCV-2 and PRRS antigens.

81 The invention described and claimed in the specification of each Application may be broadly summarised as the provision of an immunogenic composition being an M. hyo supernatant platform which may itself be used as a vaccine, or which can be combined with other vaccines to form a preferably single dose ready-to-use vaccine. Relevant to each application, the nature of the M. hyo supernatant platform is such that immunogenic interference when combined with other antigens is absent due to the removal of IgG and immunocomplexes comprised of antigen bound to immunoglobulin (immunocomplexes) in the production of the M. hyo supernatant.

82 The 535 Application claims an immunogenic composition being an M. hyo supernatant platform, which may itself be used as a vaccine, or which can be combined with other vaccines to form a preferably single dose ready-to-use vaccine.

83 The invention as claimed in the 537 Application is a multivalent immunogenic composition being an M. hyo supernatant platform combined with a PCV-2 antigen, which may be combined with other vaccines to form a preferably single dose ready-to-use vaccine.

84 The invention as claimed in the 540 Application is a trivalent immunogenic composition being an M. hyo supernatant platform combined with a PCV-2 antigen and a PRRS antigen.

85 The statutory provisions of particular relevance to this matter are as follows.

86 Section 7 of the Act states:

7 Novelty, inventive step and innovative step

Novelty

(1) For the purposes of this Act, an invention is to be taken to be novel when compared with the prior art base unless it is not novel in the light of any one of the following kinds of information, each of which must be considered separately:

(a) prior art information (other than that mentioned in paragraph (c)) made publicly available in a single document or through doing a single act;

(b) prior art information (other than that mentioned in paragraph (c)) made publicly available in 2 or more related documents, or through doing 2 or more related acts, if the relationship between the documents or acts is such that a person skilled in the relevant art would treat them as a single source of that information;

(c) prior art information contained in a single specification of the kind mentioned in subparagraph (b)(ii) of the definition of prior art base in Schedule 1.

Inventive step

(2) For the purposes of this Act, an invention is to be taken to involve an inventive step when compared with the prior art base unless the invention would have been obvious to a person skilled in the relevant art in the light of the common general knowledge as it existed (whether in or out of the patent area) before the priority date of the relevant claim, whether that knowledge is considered separately or together with the information mentioned in subsection (3).

(3) The information for the purposes of subsection (2) is:

(a) any single piece of prior art information; or

(b) a combination of any 2 or more pieces of prior art information that the skilled person mentioned in subsection (2) could, before the priority date of the relevant claim, be reasonably expected to have combined.

87 Section 40, which deals with sufficiency, support and best method, states:

…

Requirements relating to complete specifications

(2) A complete specification must:

(a) disclose the invention in a manner which is clear enough and complete enough for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art; and

(aa) disclose the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention; and

(b) where it relates to an application for a standard patent—end with a claim or claims defining the invention; and

(c) where it relates to an application for an innovation patent—end with at least one and no more than 5 claims defining the invention.

(3) The claim or claims must be clear and succinct and supported by matter disclosed in the specification.

(3A) The claim or claims must not rely on references to descriptions, drawings, graphics or photographs unless absolutely necessary to define the invention.

(4) The claim or claims must relate to one invention only.

88 Four expert witnesses gave evidence at trial. Boehringer engaged Dr Nordgren and Professor Chase, and Zoetis engaged Professor McVey and Professor Browning.

89 Prior to the trial, the experts prepared a Joint Expert Report (JER). They were each cross-examined in the course of a joint session over 3 days. Dr Nordgren was also cross-examined in a separate session which followed the completion of the joint session.

90 Dr Nordgren has more than 35 years of experience in vaccine development and formulation for animals and has been involved in the registration of over 80 animal health products. He has a Bachelor of Science, a Master of Science (Veterinary Parasitology) and a Doctorate of Philosophy in Veterinary Immunology.

91 Dr Nordgren has worked for leading animal healthcare companies, including Solvay Animal Health, Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica and Merial Ltd. Dr Nordgren has managed global teams which have been responsible for over 80 unique animal products, including vaccines. A significant number of the vaccines for which he was responsible were developed before 2012.

92 While working at BIV in approximately 1998, Dr Nordgren was involved in a vaccine development project which created a one-dose inactivated whole cell bacterin vaccine for M. hyo in pigs. During the joint expert session Dr Nordgren agreed with senior counsel for Zoetis, Mr Flynn, that bacterins were a state of the art product and the best available option by 1998.

93 While working at Merial from 1999, Dr Nordgren was responsible for reviewing patents, and on occasion gave evidence in patent proceedings for Merial. His role at Merial also required the surveillance of products entering the market and acquisition of innovative competitor products.

94 Zoetis strongly challenged Dr Nordgren’s independence and ability to give impartial and relevant expert evidence on four grounds which I consider at the end of the evidence section.

95 Professor Chase has over 30 years of experience in veterinary immunology, including experience developing and researching vaccines for the treatment of diseases in swine. He is currently a Professor in the Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Science at South Dakota University. He holds a professional doctorate degree in Veterinary Medicine and a Master of Science and PhD.

96 During the period before the priority date, Professor Chase was involved in swine and ruminant disease diagnostics while teaching virology and immunology and undertaking research in infectious disease and immunology. Since 1 June 1998, Professor Chase has also held the position of President at his contract research company that undertakes, amongst other research, swine vaccine studies.

97 No challenge was made to Professor Chase’s independence. Professor Chase answered questions directly and engaged with the views expressed by his colleagues on technical matters. I consider that Professor Chase was a helpful witness who did his best to assist the Court throughout his evidence.

98 Zoetis made a hindsight challenge in relation to some of Professor Chase’s evidence. This challenge was based on the manner in which Professor Chase was briefed with the prior art and the questions put to him in the preparation of his evidence for the opposition proceeding. I deal with this challenge later where it is relevant to the issue of inventive step.

99 Professor McVey has around 40 years’ experience in animal health and veterinary microbiology. He has worked with both academic institutions and pharmaceutical and animal health companies in the field of vaccine formulation and development. Professor McVey holds a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree and a PhD in Veterinary Microbiology. He also has experience in the field working as a veterinarian, including treating endemic diseases of commercial farm animals, and has been employed by Merial from 1995–1998, and Pfizer Animal Health from 1998–2006.

100 Professor McVey is currently a Professor and Director of the School and Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and the Associate Dean of the Nebraska/Iowa Program for Veterinary Medicine.

101 Professor McVey has particular expertise in the immunology of infectious diseases of livestock, including diseases associated with M. hyo, PCV-2 and PRRS, and associated control measures including vaccine development.

102 No challenge was made to Professor McVey’s independence as an expert witness and he gave helpful affidavit and oral evidence.

103 Professor Browning is a Professor of Veterinary Microbiology in the Faculty of Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences at the University of Melbourne and has been since 2003. He has more than 35 years’ experience in veterinary microbiology, including the pathogenesis and epidemiology of infectious diseases and related animal vaccines.

104 Professor Browning’s research focuses on vaccines to control bacterial and viral respiratory diseases in swine and other livestock. He has particular expertise in relation to mycoplasmas including M. hyo.

105 Professor Browning has some industry experience, having collaborated on research projects on vaccine development and diagnostics with a range of industry partners including Pfizer, Bioproperties Pty Ltd, Grange Laboratories and BioBest Laboratories.

106 From 1998 to 2017, Professor Browning advised the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority on the safety, efficacy, chemistry and manufacture of veterinary vaccines.

107 During oral evidence, Professor Browning described himself as “a bit pedantic”. This characteristic made him consider carefully all propositions put to him, or comments made by the other experts before accepting or rejecting them. Professor Browning was not afraid to depart from the comments of the other three expert witnesses where he felt it appropriate.

108 Boehringer pursued a line of questioning during the joint expert session which called Professor Browning’s independence into question. Professor Browning has worked on a number of projects that had received industry funding, including from Pfizer Animal Health (now Zoetis). As a result of these research projects, he is a named inventor on a number of patents co-owned by Zoetis and the University of Melbourne. The other named inventors on at least one of those patents are Zoetis employees. Professor Browning confirmed that he is entitled to a share of the royalties from this patent.

109 All of the research projects funded by Zoetis were declared in Professor Browning’s extensive CV, along with any patents on which he is a named inventor. I consider that Professor Browning was an independent, careful expert who gave considered and useful evidence.

110 Mr Eichmeyer is Boehringer’s Director of International Project Management – Vaccines. He has been employed by Boehringer, and its predecessors, since 2001, and is responsible for leading teams involved in vaccine registration across the world. Mr Eichmeyer was the head of a research project undertaken by Boehringer to develop a ready-to-use bivalent M. hyo/PCV-2 vaccine combination product. This project did not lead to the development of a bivalent, ready-to-use vaccine that was superior to Boehringer’s monovalent offerings.

111 Mr Eichmeyer swore one affidavit in the proceeding but was not called by either party. Zoetis tendered part of his affidavit

Zoetis’ challenge to Dr Nordgren

112 Zoetis challenged Dr Nordgren’s independence and ability to give impartial and relevant expert evidence on four grounds.

113 First, as a result of his lengthy and ongoing consulting arrangements with Boehringer and its predecessors, Zoetis contends that Dr Nordgren cannot be considered to be an independent witness.

114 Second, Zoetis submits that Dr Nordgren took into account significant non-common general knowledge in forming his opinions. Dr Nordgren failed to disclose his involvement in highly relevant confidential in-house M. hyo research work during his time at Merial. This, combined with a failure in his evidence to differentiate his use of the knowledge derived from his involvement with in-house research work from information generally known to all in the field in the formation of his opinions, means that the Court cannot disentangle the confidential in-house information and the common general knowledge used to form the basis of his opinions.

115 Third, Zoetis submits that Dr Nordgren is not representative of the hypothetical non-inventive person skilled in the art. Zoetis contends that Dr Nordgren’s inventorship on relevant patents and patent applications, and his participation in inventive research work relevant to the subject matter of the Applications, before the priority date, means that he is particularly ill-equipped to opine on the knowledge or approach of an uninventive person of ordinary skill in the field of swine vaccine development.

116 Fourth, Zoetis submits that Dr Nordgren’s role at Merial and Boehringer was not limited to undertaking research and experiments in the development of animal vaccine products. His ongoing consultancy role at Boehringer and its predecessors required him to review, and be involved in (including by providing expert witness testimony), challenges to competitors’ patents and patent applications relating to vaccine products. Zoetis submits that, in giving evidence in this proceeding, Dr Nordgren was acting under an obligation to act in the best interests of Boehringer and was not acting as an independent expert.

117 Accordingly, Zoetis submits that the Court should be reluctant to rely on Dr Nordgren’s evidence other than where it has been corroborated by the other experts.

Ongoing consulting role with Boehringer

118 Zoetis submits that Dr Nordgren’s relationship with Boehringer, its predecessor companies, and related entities is unique by reason of its longevity and, in particular, having regard to the fact that the services provided by Dr Nordgren relate not only to technical matters, but also to patent reviews, strategy and providing expert evidence.

119 Over a 20-year period from 1996 to 2016, Dr Nordgren held senior positions in Boehringer’s predecessor companies, including Vice President, Global Biologics Research & Development at Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica (1996-1999), Executive Director, Global Biologics Research & Development at Merial Ltd (1999-2001), Head of Research & Technology Acquisition at Merial Ltd (2001-2006), Vice President & Global Head of Biologics Research & Development at Merial Ltd (2006-2013) and Vice President & Global Head of External Innovation at Merial Ltd (2013-2016).

120 In his first affidavit, Dr Nordgren stated in paragraph 3 that “[a]part from my role as an expert witness, I have no direct relationship with either the Boehringer Ingelheim or Zoetis groups of companies”.

121 Dr Nordgren’s third affidavit was filed the day before the trial commenced. In his third affidavit, Dr Nordgren was asked to “describe in greater detail any work that I undertake for the Boehringer Ingelheim group of companies, referred to in paragraph 3 of my First Affidavit”. Dr Nordgren clarified that his reference in his first affidavit to his role as an expert witness was intended to encompass his role as an expert witness in this proceeding and other cases, and stated:

I undertake consulting work for the Boehringer Ingelheim group of companies on matters including contract disputes and patent litigation. This work includes acting as an independent expert witness for the Boehringer Ingelheim group of companies. However, the work is broader than being an expert witness. This is because, from time to time, I review and provide comments to the Boehringer Ingelheim group of companies on patents and patent applications in matters where I am not also asked to act as an expert witness. I wish to correct paragraph 3 of my First Affidavit to the extent it suggested that I am always formally engaged by the Boehringer Ingelheim group of companies as an expert witness in matters where I provide consulting services.

(Emphasis added.)

122 As revealed in his third affidavit, after ceasing his employment with Merial in 2016, Dr Nordgren was engaged by Merial as a consultant pursuant to a confidential agreement. Sometime later, Dr Nordgren entered into a “very similar” agreement pursuant to which he provides consulting services for the Boehringer Ingelheim group of companies (which includes Boehringer). The consultancy services provided by Dr Nordgren under the terms of that agreement do not relate to vaccine development, but rather to “contract disputes and patent litigation”.

123 Dr Nordgren agreed that part of his Boehringer consultancy role required him to review, and be involved in (including by providing expert witness testimony) challenges to competitors’ patents and patent applications relating to vaccine products. Since November 2015, Dr Nordgren has been called by Merial and Boehringer as an expert witness in eight domestic animal vaccine related patent proceedings, including in the European Patent Office, the US Patent Office, this Court and the Australian Patent Office. Dr Nordgren did not recall being aware of, or exposed to, the Applications prior to being asked about them in the course of preparing his evidence in this proceeding.

124 The existence of Dr Nordgren’s consulting agreements with Merial and Boehringer was disclosed for the first time in his third affidavit. In cross-examination, Dr Nordgren confirmed that his work for the Boehringer group of companies and their predecessors under those agreements is “wider than acting as an independent expert witness”.

125 The first approach to Dr Nordgren to act as an expert in this proceeding was made by Boehringer, rather than Boehringer’s instructing solicitors in this proceeding.

126 In the course of cross-examination, the following exchange took place between Zoetis’ senior counsel and Dr Nordgren:

[Counsel]: And under that contract [i.e., the Boehringer Consultancy Agreement], although we don’t have it, you tell us in paragraph 5 [of your third affidavit], that under that contract, you undertake consulting work from BI group of companies on matters including contract dispute and patent litigation; correct?

DR NORDGREN: That’s correct.

[Counsel]: And under that contract, you’re required to act in the best interests of BI; correct?

DR NORDGREN: On those cases that I’m working on; yes.

[Counsel]: And there’s no requirement in that contract that you act independently of BI if you’re acting as an expert witness; do you agree?

DR NORDGREN: I would agree.

[Counsel]: And in these proceedings, you are engaged, pursuant to that contract with BI, aren’t you?

DR NORDGREN: Yes, sir.

127 Zoetis submits that Dr Nordgren’s answers in the exchange set out above make clear that, in giving evidence in this proceeding, Dr Nordgren understood himself, first, to be under an obligation to act in the best interests of Boehringer and, secondly, to be under no obligation to act independently, an approach which is inconsistent with the Court’s Expert Evidence Practice Note and the Harmonised Expert Witness Code of Conduct.

128 Boehringer sought to explain the reason for Dr Nordgren’s third affidavit as being to clarify that Dr Nordgren’s reference to his “role as an expert witness” was intended to encompass his role as an expert witness in other proceedings in addition to the present. Boehringer says that it became apparent at a hearing before the Registrar that Zoetis had interpreted the words as only referring to this proceeding. However, the third affidavit goes beyond clarifying Dr Nordgren’s role as an expert witness.

129 Dr Nordgren’s third affidavit makes plain that his role with Boehringer is broader than his being engaged as an expert witness. His statement in his first affidavit: “Aside from my role as an expert witness, I have no direct relationship with either Boehringer Ingelheim or Zoetis groups of companies” (emphasis added), was not correct when the first affidavit was made. If Dr Nordgren’s third affidavit had not been filed on the eve of the trial, the Court would not have been informed of Dr Nordgren’s ongoing consulting role with Boehringer.

Regard to confidential information not part of common general knowledge

130 In his first affidavit Dr Nordgren mentioned two instances of experience with M. hyo: he oversaw or supervised the development of “an industry-first, one-dose inactivated whole cell vaccine, also known as a bacterin for M. hyo in pigs”, and whilst at Merial, his involvement in “the development of a significant number of vaccine products, including for the following diseases of swine: (a) M. hyo; (b) PRRS; and (c) Porcine circovirus 2 (PCV-2), including the first PCV-2 vaccine, which was released first in Europe and subsequently in other countries”. No further details of his prior experience with M. hyo were provided.

131 It emerged in the course of the concurrent evidence session that, before the priority date, in approximately 2008 or 2009, Dr Nordgren had led a team of researchers at Merial engaged in experimental work aimed at combining a PCV-2 vaccine with, amongst others, an M. hyo vaccine.

132 Dr Nordgren’s experimental M. hyo and PCV-2 work included efforts aimed at addressing impediments the M. hyo formulation may present to combining it with a PCV-2 antigen. Strategies investigated by Dr Nordgren and his colleagues at Merial included attempting to source serum with a reduced likelihood of containing anti-PCV-2 antibodies, as well as attempting to clarify serum of anti-PCV-2 antibodies. The research work was done in an effort to develop a process that would eliminate to a substantial degree the antibodies from the serum to enable Merial to formulate a vaccine (the in-house Merial M. hyo research work).

133 According to Dr Nordgren, the M. hyo experimental work was regarded by Merial as being highly confidential and a trade secret that Merial was concerned to ensure that its competitors did not find out. The confidential information obtained by Dr Nordgren as a result of the Merial M. hyo experimental work was not publicly disclosed. The confidential in-house knowledge gained by Dr Nordgren in the course of the Merial M. hyo experimental work did not form part of the common general knowledge of the person skilled in the art.

134 Boehringer submitted that it was “unsurprising” that Dr Nordgren did not expressly mention his prior work at Merial on combination vaccines, even after reviewing the Applications. According to Boehringer, the Applications concern the use of an M. hyo supernatant, whereas Dr Nordgren’s work at Merial involved its existing bacterin product and seeing if they could be improved with a goal to potentially combining them with PVC-2.

135 Boehringer also submitted that Dr Nordgren’s first affidavit “does impliedly” refer to his in-house M. hyo/PCV-2 research work. Boehringer explained that part of that work involved looking for PCV-2 antibody free serum, and that Dr Nordgren discussed his experience in trying to source PCV-2 antibody free serum in his affidavit, but was not taken to that in cross-examination.

136 However, in Dr Nordgren’s first affidavit, he stated that in April 2012 there was a need for bivalent M. hyo/PCV-2 and trivalent M. hyo/PCV-2/PRRS combination vaccines. There was no requirement or limitation that the M. hyo be in the form of a supernatant.

137 Dr Nordgren conceded that he did not refer to the in-house Merial M. hyo research work in any of his affidavits filed in the proceeding, including his third affidavit filed on the eve of the trial.

138 Dr Nordgren agreed that it would have been “highly relevant” and “important” to disclose this work to the Court. In particular, Dr Nordgren agreed that the fact he had engaged in the in-house Merial M. hyo research work was material to assessing the difference between his own knowledge and the knowledge of others in the field.

139 Dr Nordgren agreed in cross-examination that he took information from the confidential in-house Merial M. hyo research work into account in reaching the views he expressed in his affidavits in these proceedings.

[Counsel]: And to the extent that you had held any view as at April 2012 about the potential preparations based on the supernatant of M. hyo vaccines, that view was based on matters including your particular knowledge regarding experimental vaccines. Correct?

DR NORDGREN: That’s correct.

140 Zoetis submits that Dr Nordgren’s failure to disclose his involvement in the in-house Merial M. hyo research work, or the fact that he took this work into account when preparing his affidavits, presents insurmountable difficulties for the evaluation of Dr Nordgren’s evidence. According to Zoetis, it is impossible to determine which of the opinions expressed by Dr Nordgren in his affidavits and the joint expert session are based upon material which formed part of the common general knowledge of those skilled in the art, and those which are infected with the confidential in-house Merial information.

141 Zoetis contends that the effect of Dr Nordgren’s failure to disclose his involvement in the in-house Merial M. hyo research work is compounded by the absence of any instruction to Dr Nordgren in the course of preparing his affidavits to differentiate between his own particular knowledge (such as that obtained from confidential in-house research projects) and matters he considered to be generally well known and accepted by those skilled in the area.

142 Dr Nordgren was aware in April 2012 of studies demonstrating that specific enrichments of different culture fractions can improve the effectiveness of a vaccine response. He provided no details of the studies but observed that the exact compositions of commercially available M. hyo vaccines were most often kept confidential, as a trade secret.

143 Before the priority date, Dr Nordgren had collaborated with Professor Ross (the author of the Ross 1984 paper referred to in the Okada papers discussed below in the inventive step section) to research an experimental subunit vaccine against M. hyo using the 97kD antigen. The 97kD antigen research program was not pursued further as the 97kD antigen on its own did not produce sufficient protection. The collaborative work with Professor Ross was not published. Dr Nordgren agreed that he knew from the Ross paper and his teams’ own experiments that the combination of different antigens in supernatant based M. hyo vaccines were immunogenic and provided an adaptive immune response.

144 In addition, Dr Nordgren was involved, before the priority date, in the development of a first-in-class one-dose inactivated whole-cell (bacterin) vaccine against M. hyo that was commercially released around 1998, the first commercially available vaccine against PRRS virus, and the first PCV-2 vaccine to be released.

145 Before the priority date, Dr Nordgren worked with and tested experimental M. hyo vaccine preparations made from M. hyo cell culture supernatant fractions in the course of his work at Solvay and in the course of supervising the work of his team at Boehringer. In both cases, the project did not result in the launch of a commercial product and the information concerning those M. hyo supernatant was never made public.

146 I consider that the in-house work done by Dr Nordgren on a bivalent M. hyo/PCV-2 combination vaccine, the choices made by his research team and the reasons for those choices, and the success or failure of that work may well have had a role in the formation of the opinions which Dr Nordgren was being asked to give when addressing the development of a new or improved bivalent M. hyo/PCV-2 vaccine.

Not representative of non-inventive person skilled in the art

147 During the concurrent session, Dr Nordgren agreed that he is “inventive” in relation to M. hyo/PCV-2 combinations, and that he “knew more than most” people who participate in project teams associated with vaccines.

148 Dr Nordgren is named as an inventor on a number of patents and patent applications. Several examples were tendered during the hearing. That Dr Nordgren is listed as an inventor on patents and patent applications is not apparent from his first affidavit (or subsequent affidavits) as he did not annexe a curriculum vitae (CV) listing the patents and patent applications on which he is listed as an inventor.

149 Boehringer submits that Dr Nordgren’s CV was omitted from his affidavits simply because the information in his CV was already summarised at paragraphs 6 to 20 of his first affidavit, and that no inference can be drawn from his failure to do so as the Expert Evidence Practice Note does not require an expert to annexe a CV. Whilst that may be correct, the inference is not sought to be drawn from the absence of a CV per se, rather from the absence of detailed information that would usually be found in a CV, such as inventorship on patents and published papers.

150 Being listed as an inventor on a patent itself is unsurprising in an expert witness in a patent case. However, it is relevant when assessing the evidence of an expert, for the purpose of determining by reference to the non-inventive person skilled in the art whether an invention as claimed involves an inventive step, to know whether the expert is listed as an inventor on one or multiple patents and patent applications. It will also be relevant if the invention claimed in the patent or patent application is in the same or a related field to the patent in suit.

151 At least one family of Dr Nordgren’s patents and patent applications were directed to subject matter bearing a relationship to the subject matter of the Applications, including the WO 462 application in the name of Merial Limited (WO 2005/009462), filed on 26 July 2004 (and the Australian patent granted on the WO 462 application: AU 2004259034). Dr Nordgren’s inventorship on the WO 462 application or its Australian progeny was not disclosed in any of his affidavits.

152 The WO 462 application is entitled “Vaccine formulations comprising an oil-in-water emulsion”. Claims 26 and 27 of the WO 462 application are directed to a novel M. hyo/PCV-2 combination vaccine, including a one-dose regimen. Although Dr Nordgren initially sought to suggest that the claims directed to M. hyo/PCV-2 combination vaccines were not adequately supported by experimental work and may have been dropped after the application was filed, he subsequently accepted that those claims were retained in an Australian patent granted on the WO 462 application.

153 Dr Nordgren agreed that it would be relevant for the Court to take the WO 462 application into account in determining the difference between his knowledge and the knowledge of those of ordinary skill in the art.

154 Dr Nordgren’s first affidavit omitted relevant information including, in particular, his prior in-house experience with an M. hyo/PCV-2 vaccine and his ongoing consultancy with Boehringer. Details only emerged subsequently due to the tenacity of Zoetis’ legal team.

155 I do not consider that Dr Nordgren engaged in a deliberate practice to hide the extent of his prior knowledge of M. hyo by omitting his in-house Merial research experience from his affidavit. I consider that Dr Nordgren did his best to give independent evidence and answer the questions put to him by his instructors. However, the absence of a detailed description of that earlier confidential research work is unfortunate. That absence, combined with a lack of any explanation by Dr Nordgren as to how he was able to put any knowledge derived from that work aside in formulating his opinions, undermines the weight that would otherwise be given to his evidence as to what would be obvious to the non-inventive person skilled in the art, armed only with the common general knowledge and the Okada documents (separately or in combination) seeking to develop a new or improved M. hyo/PCV-2 vaccine, or trivalent M. hyo/PCV-2/PRRS vaccine.

156 Dr Nordgren agreed that he had used information that was not part of the common general knowledge in formulating his opinions. I am unable to disentangle the parts of Dr Nordgren’s evidence which are infected with information not generally known to others in the field of vaccine development from those that are based on solely common general knowledge. Where, particularly in matters relating to inventive step, Dr Nordgren’s evidence is not corroborated by the evidence of the other experts, particularly Professor Chase and Professor McVey, I will not accept that evidence. I note, however, that in large part, Dr Nordgren’s evidence was corroborated by the other experts.

157 Dr Nordgren’s evidence on the best method issue is in a different category. Dr Nordgren gives evidence as to what is disclosed in the examples of the Applications. This evidence was unchallenged, and I do not consider it to be undermined by his failure to disclose the information about his prior research and ongoing consultancy.

158 In Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1, Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ said at [24]:

It is well settled that the complete specification is not to be read in the abstract; here it is to be construed in the light of the common general knowledge and the art before 2 July 1984, the priority date; the court is to place itself “in the position of some person acquainted with the surrounding circumstances as to the state of [the] art and manufacture at the time”.

159 For the purposes of the Joint Expert Report, the parties defined the relevant field as relating to animal vaccine development.

160 Zoetis submits that the technical field of the invention described and claimed in the Applications is animal vaccine development, in particular, vaccines for swine. According to Zoetis, the notional skilled team to which the Applications are directed would include microbiologists (including bacteriology and virology) together with individuals having expertise in the development and evaluation of vaccine candidates.

161 Boehringer contends that the skilled person to whom the Applications are directed is a team with experience in the field of animal health. That team consists of a vaccinologist, with expertise in vaccine development and formulation for animals, and an expert in the field of immunology and the development of vaccines for swine.

162 Where the parties differ is that Zoetis submits that the Applications are directed to a team with specific expertise in, and a deep understanding of, M. hyo (or mycoplasmas generally), and that depending on the combination of antigens in the immunogenic composition, the skilled team would collaborate with, or consult, scientists with a deep understanding of each target pathogen or disease (the list in claim 3 of the 535 Application and claim 8 of the 537 Application). Boehringer disagrees.

163 Each of the Applications disclose immunological compositions (including vaccines) being M. hyo platforms which may be combined with other antigens such as PCV-2 and those listed in claim 3 of the 535 Application and claim 8 of the 537 Application. Zoetis submits that the team should be differently constituted for each combination of antigens to be included in the immunogenic composition, and that the team would collaborate with academics or specialists with a deep understanding of each of the target pathogens and who had familiarity with the state of research and the literature published in relation to their particular pathogen.