FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Energy Regulator v Pelican Point Power Ltd [2023] FCA 1110

Table of Corrections | |

In paragraph 56, “foreign country” had been replaced with “foreign company” |

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | PELICAN POINT POWER LTD (ARBN 086 411 814) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicant prepare draft minutes of order reflecting the conclusions in these reasons and/or the orders sought as to the future progress of this proceeding and serve on the respondent and lodge with the Court such draft minutes of order within seven days.

2. The proceeding be adjourned to a date to be fixed after consultation with the parties.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BESANKO J:

INTRODUCTION

1 This is an application by the Australian Energy Regulator (the AER) for declaratory relief under s 44AAG(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the CCA) to the effect that Pelican Point Power Ltd (PPPL) is in breach of a State energy law as defined in s 4 of the CCA. A State energy law includes the National Electricity Law (NEL) which has been enacted in South Australia as a Schedule to the National Electricity (South Australia) Act 1996 (SA) (s 6) and the National Electricity Rules (NER) which have the force of law by reason of s 9 of the NEL.

2 The AER seeks three declarations. First, the AER seeks a declaration that in relation to each of its 27 short term PASA submissions submitted on or after 30 January 2017 for each trading interval during the 8 February 2017 trading day (but not including any trading interval that had concluded when the submission was made), PPPL contravened cl 3.7.3(e)(2) of the NER by failing to submit its short term PASA availability so as to reflect the true physical plant capability of the Pelican Point Power Station (Pelican Point PS) that could be made available on 24 hours’ notice and further, or in the alternative, by failing to submit its short term PASA availability to reflect its current intentions and best estimates as to the physical plant capability of the Pelican Point PS that could be made available on 24 hours’ notice. PASA is an acronym for Projected Assessment of System Adequacy. It is described in cl 3.7.1 of the NER as involving processes that are administered by the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO). Further details of the concept and the relevant Rules are set out below.

3 Secondly, the AER seeks a declaration that in relation to PPPL’s medium term PASA submissions for the day 8 February 2017, PPPL contravened cl 3.7.2(d)(1) of the NER in relation to each of its 10 medium term PASA submissions made after 11 November 2016, by failing to submit medium term PASA availability so as to reflect the physical plant capability of the Pelican Point PS that could be made available on 24 hours’ notice after the gas turbine known as GT12 was brought from dry to wet storage on 11 November 2016.

4 Thirdly, the AER seeks further, or in the alternative to the second declaration, a declaration that PPPL contravened cl 3.13.2(h) of the NER by failing to notify AEMO promptly on or after 11 November 2016 of the increased medium term PASA availability of the Pelican Point PS after GT12 was brought from dry to wet storage on 11 November 2016. On the AER’s case, that contravention continued for a period of in the order of 86 days.

5 The AER also seeks the imposition of civil penalties on PPPL in respect of the contraventions. The relevant Rules referred to in the declarations (i.e., cll 3.7.2(d)(1), 3.7.3(e)(2) and 3.13.2(h) of the NER) are each designated as a civil penalty provision: the NEL s 2AA; the National Electricity (South Australia) Regulations, reg 6(1) and Schedule 1.

6 At an early stage in these proceedings, the Court made an order that the issue of whether PPPL contravened the NER be tried separately from, and in advance of, the determination of what relief (including civil penalty) should be granted.

7 In the course of the proceeding, two major procedural issues arose. The case proceeded by way of a Concise Statement and a Concise Response. The proceedings were fixed for trial and before the trial, the parties filed and served lengthy and detailed opening submissions. As a result of that process, an issue arose between the parties about the scope of their respective cases. That led to an Interlocutory application by the AER and an issue as to whether each party proposed to run a case that went beyond the scope of its “pleadings”. I rejected PPPL’s submission that the AER proposed to run a case beyond the scope of its pleaded case and I refused PPPL’s subsequent application for an adjournment of the trial. At a later point in the trial, I rejected the AER’s objection to evidence about the physical condition of one of the gas turbines as being beyond the scope of PPPL’s pleaded case. The AER did not seek an adjournment following this ruling.

8 The trial commenced and proceeded for a number of days before it had to be adjourned for a number of months because the time allocated for the trial (based on the parties’ estimates) proved to be insufficient. Before the resumption, PPPL issued an Interlocutory application seeking leave to rely on a further report from its expert (Mr Andrew O’Farrell) and a further affidavit from one of its proposed witnesses (Mr Michael Weatherly). Leave was required because an order had been made for each party to file and serve its evidence in written form prior to the commencement of the trial. I granted that leave subject to conditions that would enable the AER to file responding evidence which it subsequently did.

9 Complaints by PPPL about the scope of the AER’s case and the notice it was given of the case lingered until the end of the trial. It is convenient for me to describe briefly how the case was pleaded and the issues identified.

THE CASE AS PLEADED

10 The AER issued a Concise Statement in support of its Originating application and an order was made that PPPL file and serve a Concise Response.

11 The AER’s case as pleaded was that PPPL was the operator of the Pelican Point PS and contravened cll 3.7.2(d), 3.7.3(e) and 3.13.2(h) of the NER by failing to disclose to AEMO all of the physical plant capability that could be made available on 24 hours’ notice for 8 February 2017 by the Pelican Point PS, as part of its PASA availability for that day.

12 The relevant version of the NER is version 88 and the directly relevant rules are as follows:

3.7.2 Medium term PASA

(d) The following medium term PASA inputs must be submitted by each relevant Scheduled Generator or Market Participant in accordance with the timetable:

(1) PASA availability of each scheduled generating unit, scheduled load or scheduled network service for each day taking into account the ambient weather conditions forecast at the time of the 10% probability of exceedence peak load (in the manner described in the procedure prepared under paragraph (g)); and

(2) weekly energy constraints applying to each scheduled generating unit or scheduled load.

Note

This clause is classified as a civil penalty provision under the National Electricity (South Australia) Regulations. (See clause 6(1) and Schedule 1 of the National Electricity (South Australia) Regulations.)

3.7.3 Short term PASA

(e) The following short term PASA inputs must be submitted by each relevant Scheduled Generator and Market Participant in accordance with the timetable and must represent the Scheduled Generator’s or Market Participant’s current intentions and best estimates:

(1) available capacity of each scheduled generating unit, scheduled load or scheduled network service for each trading interval under expected market conditions;

(2) PASA availability of each scheduled generating unit, scheduled load or scheduled network service for each trading interval; and

(3) [Deleted]

(4) projected daily energy availability for energy constrained scheduled generating units and energy constrained scheduled loads.

Note

This clause is classified as a civil penalty provision under the National Electricity (South Australia) Regulations. (See clause 6(1) and Schedule 1 of the National Electricity (South Australia) Regulations.)

3.13.2 Systems and procedures

(h) A Scheduled Generator, Semi-Scheduled Generator or Market Participant must notify AEMO of, and AEMO must publish, any changes to submitted information within the times prescribed in the timetable.

Note

This clause is classified as a civil penalty provision under the National Electricity (South Australia) Regulations. (See clause 6(1) and Schedule 1 of the National Electricity (South Australia) Regulations.)

13 Chapter 10 of the NER contains a glossary of terms.

Available capacity is defined as follows:

The total MW capacity available for dispatch by a scheduled generating unit, semi-scheduled generating unit or scheduled load (i.e. maximum plant availability) or, in relation to a specified price band, the MW capacity within that price band available for dispatch (i.e. availability at each price band).

Physical plant capability is defined as follows:

The maximum MW output or consumption which an item of electrical equipment is capable of achieving for a given period.

PASA availability is defined as follows:

The physical plant capability (taking ambient weather conditions into account in the manner described in the procedure prepared under clause 3.7.2(g)) of a scheduled generating unit, scheduled load or scheduled network service available in a particular period, including any physical plant capability that can be made available during that period, on 24 hours’ notice.

A scheduled generating unit is defined as follows:

(a) A generating unit so classified in accordance with Chapter 2.

(b) For the purposes of Chapter 3 (except clause 3.8.3A(b)(1)(iv)) and rule 4.9, two or more generating units referred to in paragraph (a) that have been aggregated in accordance with clause 3.8.3.

A generating unit is defined as follows:

The plant used in the production of electricity and all related equipment essential to its functioning as a single entity.

The word change is defined as follows:

Includes amendment, alteration, addition or deletion.

14 The definition of PASA availability is of central importance in this case and particularly that part of the definition that refers to “any physical plant capability that can be made available [during a particular period] on 24 hours’ notice”.

15 The AER alleges in its Concise Statement that the Pelican Point PS is an aggregated scheduled generating unit with a registered capacity of 478 megawatts (MW). It consists of two 160 MW gas turbines (designated GT11 and GT12 respectively) and a 158 MW steam turbine. The steam turbine is required to operate in conjunction with one or both gas turbines so that the Pelican Point PS can operate with a maximum capacity of 239 MW if only one gas turbine is operated, and a maximum capacity of 478 MW if both gas turbines are operated.

16 In its Concise Response, PPPL admits the description of the gas and steam turbines and the nameplate capacity of the Pelican Point PS.

17 The AER alleges and PPPL admits, subject to some qualifications which I will identify, that when the gas turbines are not operating, they are either in wet storage, from which they can be returned to operation relatively quickly, that is to say, in approximately four hours or less, or they are in dry storage from which they can be returned to operation in approximately four days. On 11 November 2016, GT12 was moved from dry to wet storage and that meant that from that date to at least 8 February 2017, GT11 and GT12 were in either operation or in wet storage, and were used interchangeably as the operational gas turbine at the Pelican Point PS and, to the extent that one of those gas turbines was not already in service, it could have been returned to operation in approximately four hours or less.

18 PPPL’s admissions as to these matters are qualified to the following extent. The first qualification is that the ability to return a gas turbine to operation is subject to PPPL having rights to gas supply and transport to operate one or both of those gas turbines. The second qualification is that the ability to return a gas turbine to operation is subject to contingencies, namely, GT11 remaining in operation and not having been removed from operation for repair or being in intermittent dry storage and GT12 being able to be used in a continuous manner in circumstances where (on PPPL’s case) it required significant overhaul works. Those qualifications are set out in PPPL’s Concise Response.

19 The AER’s case as to the nature of the PASA Disclosure Regime and the requirements of the regime is as follows. PPPL is a Scheduled Generator (a generator in respect of which a generating unit is classified as a scheduled generating unit in accordance with Chapter 2 of the NER) and is required to submit medium term PASA (MT PASA) inputs to AEMO under cl 3.7.2(d), and short term PASA (ST PASA) inputs under cl 3.7.3(e).

20 MT PASA inputs are defined as the inputs to be prepared in accordance with cll 3.7.2(c) and (d) and ST PASA inputs are defined as the inputs to be prepared in accordance with cll 3.7.3(d) and (e).

21 The AER alleges and PPPL admits that these inputs are important to AEMO’s ability to maintain power system security which is a defined term in the NER as follows:

The safe scheduling, operation and control of the power system on a continuous basis in accordance with the principles set out in clause 4.2.6.

22 Power system is defined in the NER as follows:

The electricity power system of the national grid including associated generation and transmission and distribution networks for the supply of electricity, operated as an integrated arrangement.

23 MT PASA inputs must be submitted to AEMO for each day over a 24 month forecast period, in accordance with the timetable published by AEMO, at least weekly or as changes occur. These inputs include the PASA availability of each scheduled generating unit for each day (MT PASA availability) (cl 3.7.2(d)(1)).

24 Timetable is defined in the NER as follows:

The timetable published by AEMO under clause 3.4.3 for the operation of the spot market and the provision of market information.

25 ST PASA inputs must be submitted to AEMO for each 30 minute trading interval over a forecast period of six trading days, in accordance with the timetable published by AEMO, at least daily or as changes occur. Unlike the clause dealing with MT PASA which contains no express statement as to what they must represent, the clause dealing with ST PASA inputs provides that they must represent the Scheduled Generator’s current intentions and best estimates. These inputs include the PASA availability of each scheduled generating unit for each trading interval (ST PASA availability) (cl 3.7.3(e)(2)).

26 Trading interval is defined in the NER as follows:

A 30 minute period ending on the hour (EST) or on the half hour and, where identified by a time, means the 30 minute period ending at that time.

Trading day is defined in the NER as follows:

The 24 hour period commencing at 4.00 am and finishing at 4.00 am on the following day.

27 A Scheduled Generator must notify AEMO of any changes to submitted information as changes occur (cl 3.13.2(h) and the timetable).

28 Subject to a number of significant differences about what the PASA Disclosure Regime requires in particular circumstances and the raising of some additional matters, PPPL in its Concise Response largely admitted with what is set out above.

29 The additional matters alleged by PPPL in its Concise Response are as follows. PPPL alleges that the Pelican Point PS is a “mid-merit” power station, that is to say, that it does not produce “base-load” power. PPPL alleges that in June 2014, it made a commercial and operational decision to “mothball” (i.e., retire or withdraw or place in reserve) half of Pelican Point PS’s generating capacity indefinitely for the following reasons. First, PPPL made this decision because it had incurred financial losses in the period leading up to the decision because of sustained periods of unfavourable market conditions and a view which it held that these conditions would continue indefinitely. Secondly, PPPL made this decision because of the physical condition of GT12 which it alleges required significant overhaul works and a capital commitment in order to be used in a continuous manner.

30 PPPL implemented its decision on 1 April 2015. PPPL alleges in its Concise Response that from that time to at least 8 February 2017, its rights under its gas supply and transport contracts only provided enough gas to make available a maximum of 239 MW, rather than the registered total capacity of the Pelican Point PS of 478 MW. It further alleges that it revised its MT PASA and ST PASA inputs “to reflect the portion of the Physical Plant Capability of Pelican Point PS that was available (including that portion of the Physical Plant Capability that ‘can be made available’) in the relevant period”.

31 PPPL alleges in its Concise Response that Mr Darren Foulds is the Origination Manager at International Power (Australia) Pty Ltd trading as ENGIE which is the owner of PPPL. ENGIE trades in the energy generated by those assets in the National Electricity Market (NEM). Mr Peter Adams is the General Manager of Wholesale Markets at AEMO and Mr Joe Spurio is the Acting Chief Operating Officer at AEMO. PPPL alleges that in a conversation with Mr Adams in June 2014 and in a subsequent email to Mr Spurio on 27 June 2014, Mr Foulds communicated to AEMO that PPPL intended to mothball half of its generation capacity at the Pelican Point PS from 1 April 2015 and its intention to revise its MT PASA inputs to reflect the reduction in its gas supply and transport contracts and the consequential reduction of generation capacity.

32 PPPL alleges that from 1 April 2015 to at least 8 February 2017, its MT PASA inputs and its ST PASA inputs for the Pelican Point PS had halved to a maximum of 239 MW reflecting the portion of the physical plant capability of the Pelican Point PS that was available in the relevant periods. PPPL asserts that neither AEMO nor the AER took issue with PPPL’s approach.

33 PPPL alleges that from 1 April 2015 to at least 8 February 2017, it operated its gas turbines in the following way. At certain times, PPPL moved its two gas turbines at the Pelican Point PS into dry storage (generally during the winter months) and into wet storage (generally during the summer months). The physical condition of GT12 meant that it was operated as a “back-up” unit and was moved into wet storage at certain times so that if GT11 failed or needed maintenance, the period during which the Pelican Point PS may have been off-line altogether was minimised or avoided. The operation was conducted in this way to ensure PPPL could continue to make available that portion of the physical plant capability notified in its PASA submissions. In the period from 1 April 2015 to at least 8 February 2017, and despite the fact that GT12 was moved into wet storage on occasions, PPPL did not amend its current gas supply and transport contracts or enter into new contracts so as to enable the Pelican Point PS to make available generation capacity in excess of a maximum of 239 MW and nor, on its case, did it estimate or intend that the Pelican Point PS would make available generation capacity in excess of a maximum of 239 MW.

34 A key issue in this case concerns the precise nature of the requirements of the PASA Disclosure Regime. I have already referred to the importance of the definition of PASA availability.

35 An important aspect of PPPL’s case as set out in its Concise Response and relevant to that issue is its allegation the PASA Disclosure Regime did not require disclosure of a portion of the physical plant capability of the Pelican Point PS that is not available and is not estimated or intended by the operator to be made available in the relevant period and could be said to be no more than theoretically available after a period of ramp up and subject to contingencies, including the following contingencies: (1) GT11 remaining in operation and not having been removed from operation for repair or being in intermittent dry storage; (2) GT12 being able to be used in a continuous manner in circumstances where it required significant overhaul works; and (3) the availability of gas supply and transport to enable the Pelican Point PS to make available generation capacity in excess of a maximum of 239 MW.

36 PPPL further alleges that the moving of GT12 from dry storage to wet storage, or from wet storage to dry storage, did not result in a change in the portion of physical plant capability of the Pelican Point PS for the purposes of cll 3.7.3(e)(2), 3.7.2(d)(1) or 3.13.2(h) of the NER and there was no requirement for PPPL to notify AEMO of any change to its PASA inputs.

37 As I will explain, the AER disputes these propositions or, at least, disputes them to the extent that it is said they provide the answers to the issues in this case.

38 The AER alleges and PPPL admits that on 9 February 2015, PPPL first submitted to AEMO that its MT PASA availability for 8 February 2017 was 224 MW and that between 9 February 2015 and 8 February 2017, PPPL submitted to AEMO on numerous further occasions, including on 10 occasions from 11 November 2016, that its MT PASA availability for 8 February 2017 was 224 MW (MT PASA submissions). The AER contends that PPPL was under an obligation which it did not discharge, to notify AEMO of the change to its MT PASA submissions after 11 November 2016 to reflect the fact that GT12 had been brought from dry storage to wet storage and nor did its subsequent MT PASA submissions reflect the fact that GT12 had been brought into wet storage. PPPL admits the absence of notification to AEMO, but denies that the NER required it to provide notification.

39 The AER alleges and PPPL admits that PPPL first submitted ST PASA availability for each trading interval in the 8 February 2017 trading day on 15 January 2017, and subsequently submitted its ST PASA availability for trading intervals in the 8 February 2017 trading day on 27 further occasions (ST PASA submissions). The highest ST PASA availability value that PPPL submitted for any of the trading intervals for the 8 February 2017 trading day was 235 MW. The submissions did not reflect the fact that GT12 had been brought from dry to wet storage. PPPL contends that it was not required to notify any greater PASA availability and that to have done so “would have been inaccurate and misleading to AEMO and to participants in the energy trading, derivatives and financial markets generally”.

40 I come then to the AER’s case as to events on 8 February 2017 as set out in its Concise Statement. The AER alleges that it was on that day at 17.39 that AEMO first became aware that GT12 was potentially available to return to operation within 24 hours’ notice. On that day, Adelaide recorded a maximum temperature of 42.4oC. During the afternoon, AEMO notified the market of forecast lack of reserve (LOR) with a forecast LOR1 issued at 15.18.

41 A lack of reserve level 1 (LOR1) is defined in cl 4.8.4 of the NER as follows:

(b) Lack of reserve level 1 (LOR1) – when AEMO considers that there is insufficient capacity reserves available in an operational forecasting timeframe to provide complete replacement of the contingency capacity reserve on the occurrence of the credible contingency event which has the potential for the most significant impact on the power system for the period nominated. This would generally be the instantaneous loss of the largest generating unit on the power system. Alternatively, it might be the loss of any interconnection under abnormal conditions.

42 An actual LOR1 was issued at 16.31. At 17.13 an actual LOR2 was issued. A lack of reserve level 2 (LOR2) is defined in cl 4.8.4 of the NER as follows:

(c) Lack of reserve level 2 (LOR2) – when AEMO considers that the occurrence of the credible contingency event which has the potential for the most significant impact on the power system is likely to require involuntary load shedding. This would generally be the instantaneous loss of the largest generating unit on the power system. Alternatively, it might be the loss of any interconnection under abnormal conditions.

43 At 17.25, electricity import flows across the Murraylink interconnector between South Australia and Victoria increased above its import limit, which resulted in the power system no longer being in a secure operating state in the South Australian region. As a consequence, AEMO was obliged under cll 4.2.6(b)(1) and 4.8.7 to take all reasonable steps to return the power system to a secure operating state, including by issuing directions, including, as a last resort, a direction to initiate load shedding. Load shedding is reducing or disconnecting from the power system and, speaking broadly, load is the electrical power at a connection point.

44 At 17.39, while the power system was not in a secure operating state, AEMO contacted PPPL to enquire whether GT12 was available to respond to a direction. PPPL responded that it did not have gas available to run GT12, but that if gas was available, GT12 could be made available on a minimum lead time of four hours. The AER alleges that this was the first time that AEMO was made aware that GT12 was potentially available to return to operation within 24 hours’ notice.

45 At 18.01, PPPL advised AEMO that GT12 could be made available, if necessary, within one hour.

46 At 18.03, AEMO issued a direction to ElectraNet (the operator of the transmission network in South Australia) to shed 100 MW of electrical load. This caused localised load shedding, that is, a loss of supply of electricity to customers in affected localities in South Australia. However, it also resulted in the power system being returned to a secure operating state.

47 PPPL’s response to these allegations by the AER about events on 8 February 2017 is an admission that it advised AEMO at about 17.39 (ACDT) that it did not have gas available to run GT12 concurrently with GT11 and an allegation by PPPL that the fact that GT12 was in wet storage and able to be returned to operation in four hours or less, subject to the availability of, and PPPL being able to negotiate contracts for, gas supply and transport during or at the end of that period, is irrelevant to the ST PASA availability of the Pelican Point PS in circumstances where PPPL did not have arrangements in place for gas supply or transport to run GT12 concurrently with GT11. PPPL further alleges that as at 17.39 on 8 February 2017, the ST PASA availability of Pelican Point PS still did not exceed 239 MW.

48 I have referred to conversations between representatives of AEMO and representatives of PPPL on 8 February 2017. Those conversations were recorded and aspects of the conversations are relied on by each party.

49 The AER alleges in its Concise Statement that events on 9 February 2017 are relevant to the MT PASA and ST PASA submissions that PPPL should have made for 8 February 2017. The AER’s case as to relevant events on 9 February 2017 is as follows. The forecast weather conditions for 9 February 2017 in South Australia were to the effect that heatwave conditions and high electricity demand would continue. Prior to 8 February 2017, PPPL had submitted that its MT PASA availability was 224 MW for each day in the week of 5 to 11 February 2017. By reason of AEMO becoming aware on 8 February 2017 that GT12 was capable of being returned to operation within one hour, AEMO was able to issue a direction to PPPL on 9 February 2017 to synchronise and dispatch GT12 in response to further forecast LOR2 conditions that afternoon. PPPL complied with that direction and that enabled AEMO to maintain power system security on 9 February 2017 without the need for load shedding.

50 PPPL alleges that its MT PASA availability was 224 MW for each day in the week of 5 to 11 February 2017. It admits that it was able to comply with the direction given by AEMO on 9 February 2017 to synchronise and dispatch GT12. It alleges that it was able to do that because after 17.39 on 8 February 2017, it had been able to arrange for gas supply and transport over and above its existing contractual rights. It alleges that the additional gas supply and transport that it arranged only in response to AEMO’s direction and the availability of both GT11 and GT12 on 8 February 2017 are, for reasons in its Concise Response, not relevant to the MT PASA and ST PASA submissions it made.

51 The way in which the AER put its case in its Concise Statement as to PPPL’s obligations with respect to ST PASA availability, MT PASA availability and the obligation in cl 3.13.2(h) may be summarised as follows.

52 PPPL, in relation to its 28 (amended now to 27) ST PASA submissions for each trading interval during the 8 February 2017 trading day, had an obligation (which it failed to discharge) to submit its ST PASA availability so as to reflect the true physical plant capability of the Pelican Point PS that could be made available on 24 hours’ notice. In addition, or in the alternative, PPPL, in relation to each of its 27 ST PASA submissions for each trading interval during the 8 February 2017 trading day, had an obligation (which it failed to discharge) to submit its ST PASA availability so as to reflect its current intentions and best estimates as to the physical plant capability of the Pelican Point PS that could be made available on 24 hours’ notice. PPPL denied these allegations for reasons previously given, including that it had gas and gas transport rights to generate no more than 239 MW in the relevant period.

53 By amendment to its Concise Response, PPPL introduced the following further response to the AER’s plea in relation to ST PASA submissions:

22A. In further answer to paragraph 16 of the CS, PPPL says that:

(a) clause 3.7.3(2)(e):

(i) only required that PPPL make PASA availability submissions in respect of a trading interval where that interval was during the 6 trading days from the end of the trading day covered by the most recent pre-dispatch schedule issued by AEMO; and

(ii) further, and in any event, did not require that PPPL make PASA availability submissions in respect of a trading interval that had already passed;

(b) PPPL could not and did not contravene clause 3.7.3(2)(e) by reason of PASA availability submissions not required to be made in respect of the trading interval; and

(c) PPPL could not and did not contravene clause 3.7.3(2)(e) in so far as any PASA availability submission related to a trading interval that had passed at the time of the submission to AEMO.

54 The AER alleges that PPPL had an obligation (which it failed to discharge) in relation to its MT PASA submissions for 8 February 2017 and in relation to each of its 10 MT PASA submissions made after 11 November 2016 to submit MT PASA availability so as to reflect the physical plant capability of the Pelican Point PS that could be made available on 24 hours’ notice after GT12 was brought from dry to wet storage. PPPL, in relation to its MT PASA submissions for 11 February 2017, had an obligation (which it failed to discharge) to notify AEMO promptly on or after 11 November 2016 of the increased MT PASA availability of the Pelican Point PS after GT12 was brought from dry to wet storage on 11 November 2016.

FACTS WHICH ARE NOT IN DISPUTE

55 The following facts are taken from the Statement of Agreed Facts signed by both parties.

56 The AER is a body corporate established pursuant to s 44E of the CCA, and has the functions and powers referred to in s 15 of the NEL. PPPL is a company incorporated in England and Wales and is registered in Australia as a foreign company under s 601CE of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). It is wholly owned by International Power (Australia) Pty Ltd trading as ENGIE and previously known as GDF Suez. PPPL is the operator of the Pelican Point PS and is a Registered Participant and a Scheduled Generator within the NER.

57 Pelican Point PS is and was at all material times an aggregated scheduled generating unit under cl 3.8.3 of the NER comprising two gas turbines with designated identifiers GT11 and GT12 and one steam turbine, and scheduled plant within the NER to which AEMO may issue a direction to PPPL under cl 4.8.9(a) and (a1)(1). At all relevant times, Pelican Point PS had a registered capacity of 478 MW. The ability of PPPL to operate the Pelican Point PS at its registered capacity is directly affected by certain operating conditions, including but not limited to, the ambient air temperature, the physical condition of the gas turbines and the steam turbine, the availability of gas supply and the availability of gas transport (operating conditions). Subject to the operating conditions, at all relevant times each gas turbine was capable of generating up to approximately 160 MW. Subject to the operating conditions and subject to one or both of the gas turbines operating, at all relevant times the steam turbine was capable of being operated in conjunction with one or both of the gas turbines to generate up to approximately 79 MW, if only one of the gas turbines was in operation, and up to approximately 158 MW if both of the gas turbines were in operation. Again, subject to the operating conditions, at all relevant times, Pelican Point PS was capable of generating up to approximately 478 MW, if both of the gas turbines were operating in combination with the steam turbine, or up to approximately 239 MW, if only one of the gas turbines was operating in conjunction with the steam turbine. Again, subject to the operating conditions, at all relevant times, Pelican Point PS was capable of a minimum generating capacity of approximately 160–170 MW, if only one gas turbine was operating in conjunction with the steam turbine, or approximately 320–335 MW, if both gas turbines were operating in conjunction with the steam turbine. PPPL does not agree that minimum generating capacity is relevant to whether it has breached any of cl 3.7.2(d)(1), cl 3.7.3(e)(2) and/or cl 3.13.2(h). As I will explain, the 320 MW minimum generating capacity is significant because it is this figure which is relevant to “the basic 320 MW scenario” or, as PPPL referred to it, “the 320 MW, 4 hour ‘benchmark scenario’”.

58 Each of the gas turbines when not actively generating was kept in either wet storage or dry storage. In each case, assuming sufficient availability of gas supply, availability of gas transport and operational staff on duty to operate the turbine (among other matters), the parties agree that wet storage is the state from which the gas turbine could ordinarily be returned to service relatively quickly, that is to say, in approximately four hours or less. Dry storage is a state from which the gas turbine could be returned to service in up to four days, if the entire power station is in dry storage, or in 60 hours or less, if only one gas turbine and the associated steam turbine is in dry storage.

59 The parties agree that on 8 February 2017, the net (sent-out) Heat Rate for Pelican Point PS was 8.31GJ/MWh. The volume of gas required to operate either of the gas turbines at a given level of active power output is calculated by using the following formula: Gas Requirement (TJ) = run-time (hrs) x power output (MW) x Heat rate (GJ/MWh)/1000.

60 During the relevant period between 11 November 2016 and 9 February 2017, the relevant timetable was version 1.3 of the AEMO Spot Market Operations Timetable published on 28 October 2016. During the relevant period, for the purposes of cl 3.7.2(d)(a) and AEMO’s Medium Term PASA Process Description, the reference temperature published by AEMO as reflecting a 10% probability of exceedance peak load in South Australia was 43oC (as published in AEMO’s Generation information data for South Australia, the relevant versions of which were published on 11 August 2016 and 18 November 2016).

61 The parties agree that on about 25 June 2014, in the course of a meeting between Mr Foulds and Mr Stephen Orr of GDZ Suez and Mr Spurio of AEMO (which was followed up by an email from Mr Foulds to Mr Spurio sent on 27 June 2014 confirming the same), PPPL’s parent company, GDF Suez, notified AEMO of the following: (1) that from 1 April 2015, PPPL would have firm gas arrangements to support the operation of only half of the Pelican Point PS (240 MW); (2) PPPL had updated its MT PASA inputs to reduce the capacity of Pelican Point PS to 240 MW from that date; and (3) Pelican Point PS “poses no ability to deliver generation on the remaining capacity”.

62 On 9 February 2015, PPPL first submitted its MT PASA inputs for 8 February 2017. In each submission of its MT PASA inputs between 9 February 2015 and 11 November 2016, PPPL submitted that its PASA availability for Pelican Point PS on 8 February 2017 was 224 MW.

63 The parties agree that from 1 April 2015 until 11 November 2016, both of the gas turbines GT11 and GT12 were kept in dry storage substantially throughout the period from 1 April 2015 until 2 October 2015; GT11 was brought into wet storage from 2 October 2015 until 28 April 2016 when it was returned to dry storage; GT12 was brought into wet storage from 26 November 2015 until 22 January 2016 when it was returned to dry storage; both GT11 and GT12 were kept in dry storage from 18 April 2016 to 13 July 2016; and GT11 was brought from dry storage to wet storage on 14 July 2016, and PPPL thereafter operated GT11 (in conjunction with the steam turbine) from time to time to supply power in the NEM.

64 The parties agree that on 11 November 2016, PPPL brought GT12 from dry storage to wet storage. At all relevant times from 11 November 2016 until at least 8 February 2017, each of GT11 and GT12 was either in operation or in wet storage; and only one or the other of them was used as the operational gas turbine at any time. At all relevant times from 11 November 2016 until 8 February 2017, to the extent that one of those gas turbines was not already in operation, and subject to it not having been removed from operation for repair, it could have been returned to operation in approximately four hours or less if PPPL had access to, or could procure, sufficient gas supply and transportation to operate the gas turbine.

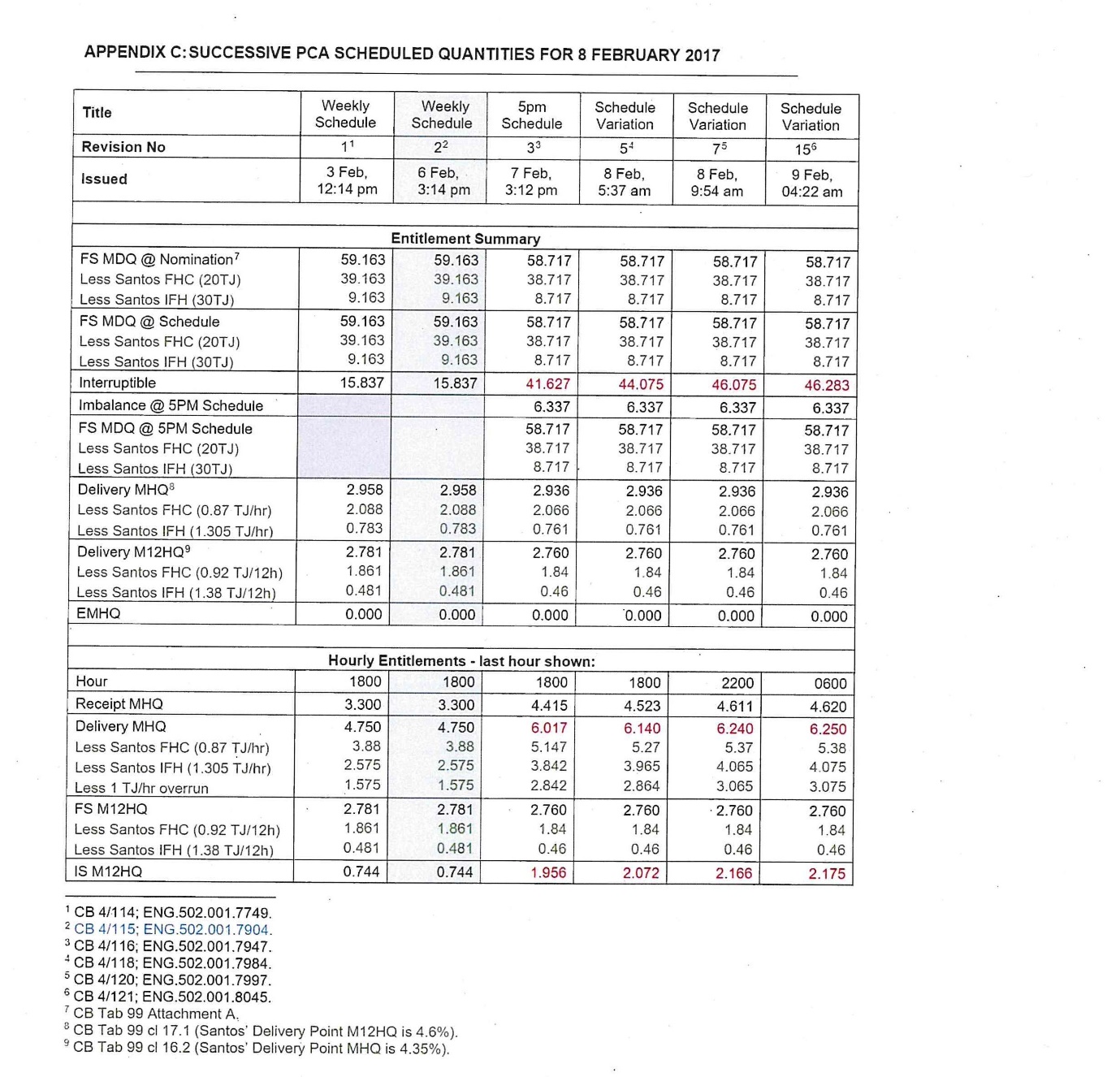

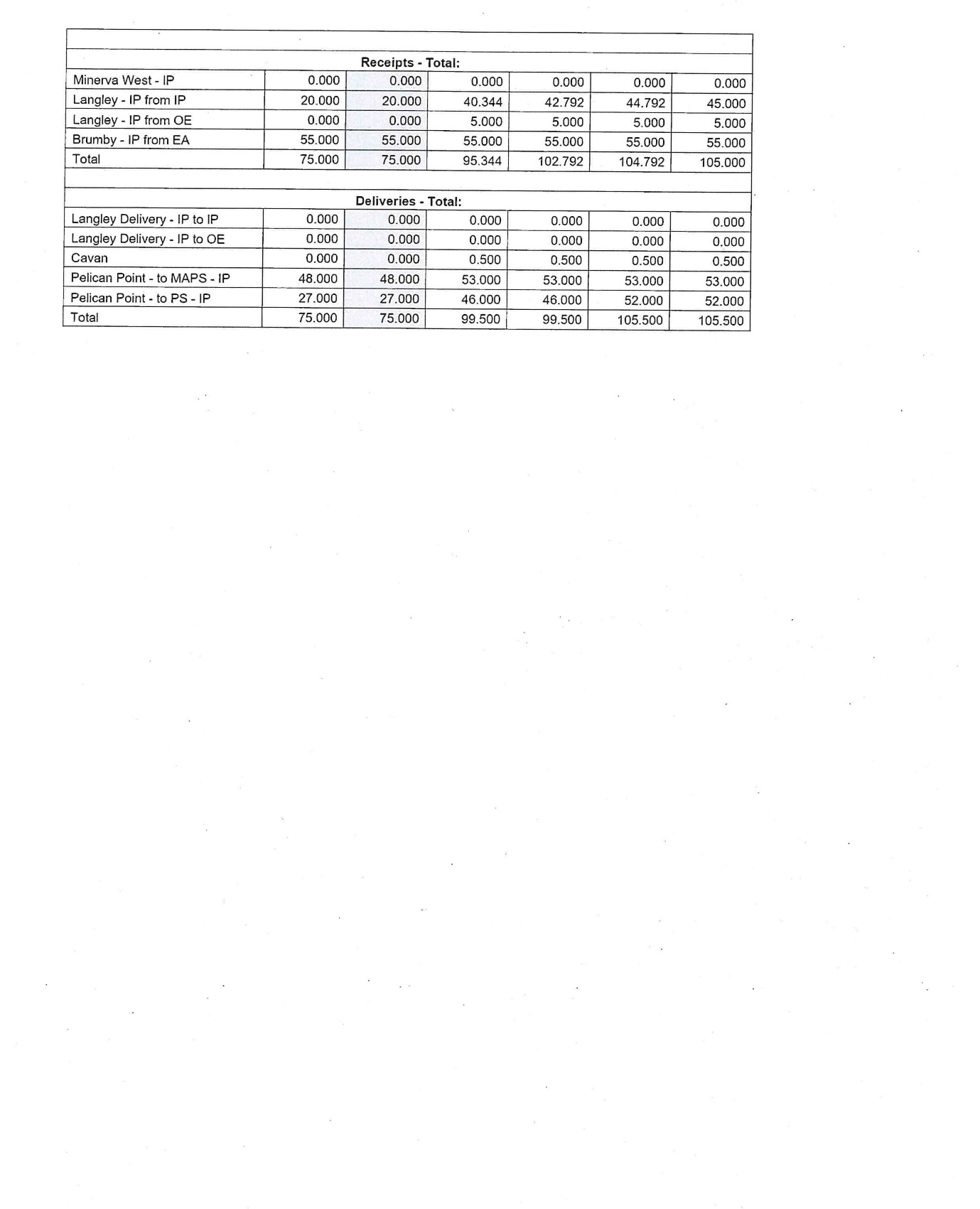

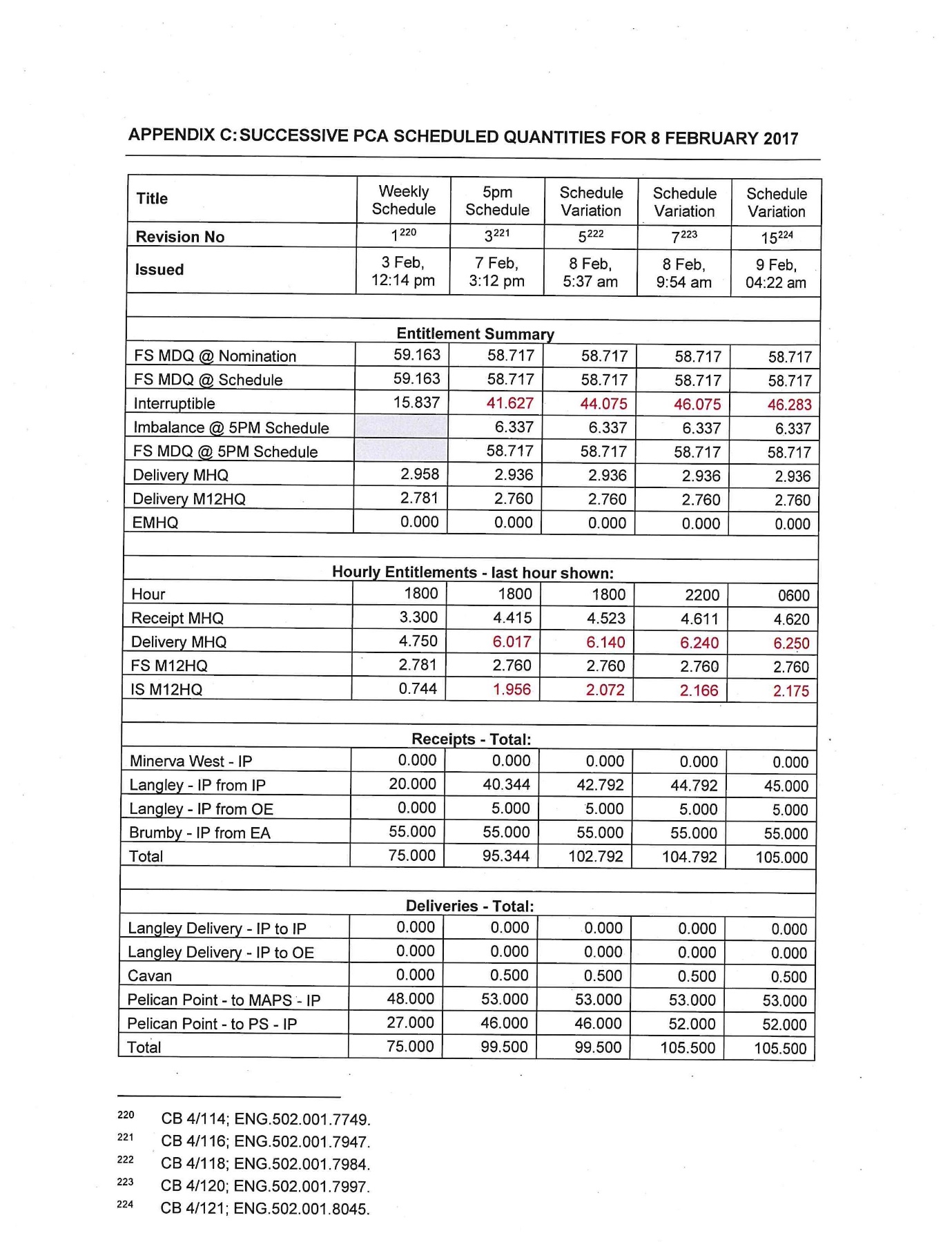

65 The parties agree that between 7 November 2016 and 8 February 2017, PPPL submitted its MT PASA inputs to AEMO on 11 occasions, in each case submitting that the PASA availability for Pelican Point PS on 8 February 2017 was 224 MW, with a value of 999999 for its weekly energy constraints, as set out in the following table:

Date of Submission | PASA availability (MW) | weekly energy constraints |

7/11/2016 | 224 | 999999 |

16/11/2016 | 224 | 999999 |

22/11/2016 | 224 | 999999 |

3/12/2016 | 224 | 999999 |

13/12/2016 | 224 | 999999 |

19/12/2016 | 224 | 999999 |

26/12/2016 | 224 | 999999 |

2/01/2017 | 224 | 999999 |

11/01/2017 | 224 | 999999 |

23/01/2017 | 224 | 999999 |

27/01/2017 | 224 | 999999 |

66 PPPL did not change its MT PASA inputs at or around 11 November 2016, or at any time between 11 November 2016 and 8 February 2017.

67 The parties agree that on 15 January 2017, PPPL submitted its first ST PASA inputs for the 8 February 2017 trading day. The dates of PPPL’s submissions to AEMO of its ST PASA inputs for Pelican Point PS for the 8 February 2017 trading day, and the values submitted for available capacity, PASA availability and projected daily energy availability, in respect of each trading interval are set out in an exhibit before the Court. It is sufficient at this point to say that in each of those submissions, PPPL’s ST PASA inputs for Pelican Point PS for each trading interval for the 8 February 2017 trading day, the highest value of PASA availability submitted by PPPL was 235 MW.

OPERATING SCENARIOS

68 The PASA submissions, whether they be medium term or short term, involve a forecast or prediction or prognostication, or to use one of the terms in the Rules, an estimate of physical plant capability available, or that can be made available, on 24 hours’ notice. After GT12 was brought out of dry storage, it was operated from time to time and, in fact, it was operated for a substantial period of time on 7 February 2017. It was operated in the alternative to GT11. They were not operated concurrently before 9 February 2017 when AEMO issued its direction under cl 4.8.9 of the NER.

69 In order to run a second turbine, there is a need for a supply of gas and gas transport. There is no dispute that to be able to be made available for the purposes of the definition of PASA availability means not just in wet storage, but there and able to be turned on and run for a period of time and thereby generate a maximum MW output. That assumes a quantity of gas and a quantity of gas transport. None of the definitions specify a particular time the turbine must run for the purposes of assessing availability. In other words, it is not to be assumed that an item of physical plant only meets the description of “can be made available” if it can be operated for the full day. There is nothing in the definitions to that effect. On the other hand, a certain amount of gas and gas transport must form an assessment of whether physical plant can be made available.

70 In order to prove its case, the AER needed to establish that the PASA submissions were too low and that PPPL should have reasonably expected (and I will come to address the precise formulation of the relevant standard) that it could have, on 24 hours’ notice, made GT12 available by switching it on and running it with GT11 to produce a greater amount of megawatts than those set out in the PASA submissions. The AER put forward two operating scenarios which it contends a reasonable generator would have had in mind when making PASA submissions.

71 The first operating scenario is what the AER referred to as the basic 320 MW scenario. This scenario involved both GT11 and GT12 operating for four hours concurrently and producing 320 MW. The second operating scenario is what the AER referred to as the 8 February counterfactual. This scenario involved GT11 operating on 8 February 2017 as it in fact did and GT12 operating on 8 February 2017 as it in fact operated on 9 February 2017. On 8 February 2017, GT11 operated for most of the day, but not always at the maximum amount specified in its PASA submissions. On 9 February 2017, GT12 was run concurrently with GT11 for about four hours.

72 Both these operating scenarios are, of course, hypothetical. However, they frame the issues concerning reasonable expectations as to the availability of gas supply and gas transport. No other operating scenarios were advanced by the AER.

THE EVIDENCE

73 The AER called four witnesses as follows:

(1) Mr Tjaart Nicolaas Van Der Walt who is employed by AEMO as Group Manager, NEM Real Time Operations;

(2) Ms Philippa Jean Eastgate who is employed by the AER as Assistant Director in its Compliance and Enforcement Branch;

(3) Mr Michael Nicholas Sanders who is employed by AEMO as Principal Analyst, Electricity Market Monitoring; and

(4) Mr James Arthur Snow, an expert who has extensive experience in the energy industry, including gas with both practical experience and experience as an adviser, reviewer and consultant.

74 PPPL called four witnesses as follows:

(1) Mr Darren Foulds who is employed by ENGIE as Head of Trading and Portfolio Management;

(2) Mr Debasis Baksi who was employed by ENGIE and was General Manager – South Australian Assets between 2012 to 2020;

(3) Mr Michael Weatherly who was employed by ENGIE (International Power), and was Origination Manager between 2015 and 2018; and

(4) Mr Andrew O’Farrell, an expert who has spent many years in the energy industry and between 2011 and 2018 was Gas Portfolio Manager for Origin Energy.

75 Each party also tendered a number of documents in support of its case. Without being exhaustive at this stage, the AER placed reliance on the transcripts of conversations between representatives of PPPL and representatives of AEMO on 8 and again on 9 February 2017, the events of 9 February 2017 and, in particular, the fact that PPPL was able to operate the two gas turbines concurrently on that day for about four hours and certain answers International Power (Australia) Holdings Pty Ltd (ENGIE) gave to a notice issued by the AER under s 28(2)(a) and (b) of the NEL and dated 15 June 2018. I will refer to this as the Section 28 Notice.

76 For its part, and again without being exhaustive, PPPL took the Court to a complex and detailed array of provisions in various gas supply and gas transport agreements and submitted that the uncertainties attending the market for gas and gas transport were such that its approach to the PASA submissions was appropriate and not in contravention of the NER. A further matter which was the subject of evidence and relied on by PPPL was the physical condition of GT12 and PPPL submitted that that was relevant to the issue of whether the PASA submissions complied with the NER.

77 Before addressing the evidence and the factual issues, it is necessary to address a number of construction issues concerning the relevant Rules. The parties made extensive and detailed submissions about these issues.

CONSTRUCTION ISSUES

The issues identified

78 The AER put forward a list of what it contended were the construction issues as follows:

(1) What is the proper construction of the defined term “PASA availability” in cll 3.7.2(d)(1) and 3.7.3(e)(2) when read in context and having regard to the meaning of the defined terms “physical plant capability” and “available capacity”?

(2) Is the commercial intention of a Scheduled Generator as to the amount it proposes to generate relevant to the submission it makes as to that aspect of PASA inputs which is PASA availability?

(3) In determining the availability of a scheduled generating unit within the definition of PASA availability, which includes a scheduled generating unit that can be made available on 24 hours’ notice, is the generator in making its PASA submissions limited to firm sources of gas and gas transport, or must it also take into account gas and gas transfers it ought reasonably expect that it would practically be able to procure on 24 hours’ notice if required to do so? “Firm” in this context refers to a term which is well understood in the gas industry in connection with the supply of gas and gas transport. It means contractually obliged to supply with a failure to do so attended by penalties and other contractual remedies. There is no binding obligation in the case of non-firm or “as available” gas or gas transport, although a firm obligation will arise on the execution of a Formal Transaction Notice or Confirmation. This was the evidence of Mr Snow which was not disputed and which I accept.

(4) What is the nature and extent of the generator’s obligation to submit estimates or forecasts of MT PASA and ST PASA?

(5) How is PASA availability for MT PASA affected by a practical limit on how long a generating unit can run for within a day?

(6) How is PASA availability for ST PASA affected by how long a generating unit can run for within a day?

79 The AER’s list of issues is a convenient way of identifying areas of dispute between the parties. I will deal with them in a different order and, as will become clear, there is a substantial overlap between a number of the issues.

General principles of statutory construction including the use of extrinsic material

80 In the section which follows, I do not intend to cover the whole field, but only those areas which are relevant having regard to the submissions of one or both of the parties.

81 The general principles of statutory construction, including the importance of text, context and the general purpose and policy of a provision, including the mischief sought to be remedied are well known and, with respect, are conveniently summarised by French CJ and Hayne J in Certain Lloyd’s Underwriters v Cross [2012] HCA 56; (2012) 248 CLR 378 at [23]–[26].

82 Section 8(2) of the National Electricity (South Australia) Act 1996 provides that the Acts Interpretation Act 1915 (SA) does not apply to the National Electricity Law (South Australia) or the National Electricity (South Australia) Regulations.

83 Section 3 of the NEL provides that Schedule 2 to the NEL (Miscellaneous provisions relating to interpretation) applies to the Law, the Regulations and the Rules.

84 Section 7 of the NEL provides that the objective of the Law is to promote efficient investment in, and efficient operation and use of, electricity services for the long-term interests of consumers of electricity with respect to:

(a) price, quality, safety, reliability and security of supply of electricity; and

(b) the reliability, safety and security of the national electricity system.

85 Clause 7 in Schedule 2 is equivalent to s 15AA of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) and it provides that in the interpretation of a provision of the NEL, the interpretation that will best achieve the purpose or object of the Law is to be preferred to any other interpretation and that is the case whether or not the purpose is expressly stated in the Law.

86 Clause 41 of Schedule 2 provides that the Schedule applies to the Rules notwithstanding that the provision refers to this Law.

87 In its submissions, the AER pointed out that at common law, there may be reasons to adopt what in one respect may be a different approach to the interpretation of subordinate legislation than that adopted in the case of Acts of Parliament. It referred to the following observations of Lord Reid in Gill v Donald Humberstone & Co Ltd [1963] 1 WLR 929 at 933–934, a case concerning regulations made under the Factories Act 1937 (UK) relating to the use of scaffolding, ladders, etc. Lord Reid said the following:

… I find it necessary to make some general observations about the interpretation of regulations of this kind. They are addressed to practical people skilled in the particular trade or industry, and their primary purpose is to prevent accidents by prescribing appropriate precautions … They have often evolved by stages as in the present case, and as a result they often exhibit minor inconsistencies, overlapping and gaps. So they ought to be construed in light of practical considerations, rather than by a meticulous comparison of the language of their various provisions, such as might be appropriate in construing sections of an Act of Parliament … difficulties cannot always be foreseen and it may happen that in a particular case the requirements of a regulation are unreasonable or impracticable. But if the language is capable of more than one interpretation, we ought to discard the more natural meaning if it leads to an unreasonable result, and adopt that interpretation which leads to a reasonably practicable result.

This decision was followed by the Full Court of this Court in Melbourne City Council v Telstra Corporation Limited [2020] FCAFC 200; (2020) 281 FCR 379 at [154] per O’Bryan J (with whom Gleeson J agreed). That case concerned the Telecommunications Act 1997 (Cth) and the Telecommunications (Low-Impact Facilities) Determination 2018 (Cth). The Court held that the Determination in issue was directed to practical people with particular skills and ought to be construed having regard to practical considerations. This case, it seems to me, calls for the same approach, but subject, of course, to the provisions of Schedule 2.

88 The AER seeks to rely on extrinsic material in support of its interpretation of the Rules.

89 Schedule 2 of the NEL addresses the use of extrinsic material in the interpretation of the Law and the Rules. In cl 8, two categories of extrinsic material are identified, namely Law extrinsic material and Rule extrinsic material.

90 The term “Rule extrinsic material” is defined in cl 8 to mean any of the following:

(a) a draft Rule determination; or

(b) a final Rule determination; or

(c) any document (however described)—

(i) relied on by the AEMC in making a draft Rule determination or final Rule determination; or

(ii) adopted by the AEMC in making a draft Rule determination or final Rule determination.

91 The AEMC is defined in s 2 of the NEL as the Australian Energy Market Commission established by s 5 of the Australian Energy Market Commission Establishment Act 2004 of South Australia.

92 Clause 8(2), (2a) and (3) in Schedule 2 provide for the circumstances in which Law extrinsic material or Rule extrinsic material may be taken into consideration in interpreting a provision of the Law or the Rules. Clause 8(2a) and (3) are relevant as far as the interpretation of a provision of the Rules is concerned and they are as follows:

(2a) Subject to subclause (3), in the interpretation of a provision of the Rules, consideration may be given to Law extrinsic material or Rules extrinsic material capable of assisting in the interpretation—

(a) if the provision is ambiguous or obscure, to provide an interpretation of it; or

(b) if the ordinary meaning of the provision leads to a result that is manifestly absurd or is unreasonable, to provide an interpretation that avoids such a result; or

(c) in any other case, to confirm the interpretation conveyed by the ordinary meaning of the provision.

(3) In determining whether consideration should be given to Law extrinsic material or Rule extrinsic material, and in determining the weight to be given to Law extrinsic material or Rule extrinsic material, regard is to be had to—

(a) the desirability of a provision being interpreted as having its ordinary meaning; and

(b) the undesirability of prolonging proceedings without compensating advantage; and

(c) other relevant matters.

93 For the purposes of cl 8, “ordinary meaning” is defined as the ordinary meaning conveyed by a provision having regard to its context in this Law and to the purpose of this Law.

94 PPPL contended that these sections worked a designedly limited variation to the ordinary modern rules of construction to the effect that a legislative instrument which is amended and the amending legislative instrument are to be read together as a combined statement of the will of the legislature with the consequence that the effect of the amending legislative instrument may be to alter the meaning which remaining provisions of the amended legislative provision bore before the amendment (Commissioner of Stamps (SA) v Telegraph Investment Co Pty Ltd [1995] HCA 44; (1995) 184 CLR 453 at 463 per Brennan CJ, Dawson and Toohey JJ and at 479 per McHugh and Gummow JJ; see also, by way of example, s 11 of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901). That may be accepted, but it is what follows which is significant.

95 In this respect, PPPL sought to rely on the unfairness of using Rule extrinsic material to interpret provisions that are civil penalty provisions. I will deal later with the significance of these provisions being civil penalty provisions. As far as the unfairness argument is concerned, this case is different from the case PPPL relied on — Australian Energy Regulator v Stanwell Corporation Ltd [2011] FCA 991; (2011) 197 FCR 429 at [325]–[331] — because in this case, the extrinsic material supports the ordinary meaning.

96 Before leaving the principles relevant to the use of extrinsic material, I note that one item of extrinsic material in this case is not Rule extrinsic material for reasons I will explain. That does not necessarily prevent me from considering it.

97 In CIC Insurance Ltd v Bankstown Football Club Ltd [1997] HCA 2; (1997) 187 CLR 384, Brennan CJ, Dawson, Toohey and Gummow JJ said (at 408):

It is well settled that at common law, apart from any reliance upon s 15AB of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth), the court may have regard to reports of law reform bodies to ascertain the mischief which a statute is intended to cure. Moreover, the modern approach to statutory interpretation (a) insists that the context be considered in the first instance, not merely at some later stage when ambiguity might be thought to arise, and (b) uses “context” in its widest sense to include such things as the existing state of the law and the mischief which, by legitimate means such as those just mentioned, one may discern the statute was intended to remedy.

(Footnote references omitted.)

98 The AER submitted that the proper construction of the PASA obligations is informed by the legislative history of modifications which were made to the MT PASA and ST PASA inputs with a view to clarifying their content. The AER referred to two amendments being first, what it referred to as the 2001 Code change and secondly, the 2010 Rule change.

99 The National Electricity Code (the Code or NEC) commenced operation in December 1998 and preceded the NER. Both legislative instruments contained requirements for generators and other Market Participants to submit information to AEMO, which prior to 1 July 2009 was known as NEMMCO, and for AEMO to prepare and publish outputs of MT PASA and ST PASA.

100 Prior to certain amendments to the Code in 2001, cll 3.7.2 and 3.7.3 only called for generators to provide forecasts of “availability” and for NEMMCO to publish information as to aggregate generating unit “availability” for the purposes of both MT PASA and ST PASA. The 2001 amendments did the following. With respect to MT PASA, the changes in 2001 substituted “PASA availability” for “availability” in cll 3.7.2(d)(1) and 3.7.2(f)(3). With respect to ST PASA, they inserted an additional requirement that Market Participants submit “PASA availability” and for NEMMCO to publish aggregate information about “aggregate generating unit PASA availability” for each region in cll 3.7.3(e)(1A) and 3.7.3(h)(4A). The amendments also made it clear that the availability input was, in the case of ST PASA, to be that “under expected market conditions” (cl 3.7.3(e)(1)). The amendments included a definition of “PASA availability” as follows:

The physical plant capability of a Scheduled Generator, scheduled load or scheduled network service, including any capability that can be made available within 24 hours.

101 The Code Change Panel prepared a report titled “Improvements to the projected assessment of system adequacy” in November 2000 which preceded the amendments and identified the mischief to which they were directed. The AER relies on the following passages in the report of the Code Change Panel:

The projected assessment of system adequacy (PASA) arrangements within the market are intended to provide short (up to a week ahead) and medium-term (up to two years ahead) forecasts of energy and reserve availability which also take account of planned transmission network outages. Such forecasts are essential to a properly functioning market, including to the ability of the demand side to participate fully and actively in the market. The existing PASA arrangements generally work well but there is scope to improve their operation overall by:

Clarifying and enhancing the information generators provide to NEMMCO by removing the existing ambiguity in the Code and drawing a distinction between the capacity they intend to make available and the capacity they could make available in extreme conditions. This is the purpose of these proposed Code changes;

…

The Code requires market participants to provide medium-term forecasts of the expected availability of each scheduled generating unit. Expected availability is, however, not defined and is ambiguous. It could be interpreted as the capacity generators intend to bid into the market based on their commercial decisions or the capacity which could physically be made available. As a result, at times the medium-term PASA forecast therefore provides an optimistic view of available capacity, ie that more capacity is available than will in fact be presented. At other times, there is more capacity available than the forecast suggests. It is not clear to the market whether the inaccuracy of the forecast is due to a change in the physical capability of the plant or a legitimate commercial decision to present less capacity. NEMMCO can, and does, seek informal advice to clarify its understanding but this is neither transparent nor available to the market.

The primary role of the medium-term PASA is to provide transparent reserve forecasts so that market participants can plan and adjust their operations, particularly plant outages, to maximise the value of market trading. The information also assists NEMMCO in its reserve trader contracting and to determine the need for directions. For these purposes, the relevant definition of available capacity in the medium term is that which could be presented at short notice under worst case conditions. The actual capacity presented to the market will normally be less than the maximum potentially available due to conditions at the time and commercial decisions about commitment. Timing is crucial to whether capacity can be made available in extreme conditions since planned maintenance outages can be deferred if sufficient notice is available, but closer to the event they are usually beyond practical recall. The current provisions do not recognise this.

The Panel published a consultation paper on 21 September on draft changes to the Code to remove the ambiguity surrounding the definition of expected availability and acknowledge the crucial role of timing in relation to commitment decisions. The changes would require scheduled generators to provide information, within both the short and medium-term PASA timeframes, about the capacity that could be made physically available at twenty four hours’ notice in response to extreme conditions. This new information is defined as PASA availability. In the short term, however, reliability will also depend on participants’ discretionary decisions. The proposed changes would also therefore require scheduled generators to provide a forecast of market availability, which is defined as the capability they intend to make available under normal anticipated market conditions, within the short-term PASA timeframe.

…

The Panel recommends that the Code changes, as amended, be forwarded to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission for authorisation.

102 In its submissions, the AER emphasised the change to cl 3.7.2(d)(1) from “expected availability” to “PASA availability” and the reference in the report of the Code Change Panel to the need to draw a distinction between the capacity which generators intend to make available and the capacity which they could make available in extreme conditions and the ambiguity surrounding the use of the expression, “expected availability”. The AER also referred to the “relevant definition” of available capacity in the medium term as that which could be presented at short notice under worst case conditions. The AER also referred to the amendment to cl 3.7.3(e) dealing with ST PASA to add to the element of the Market Participant’s current intentions and best estimates of availability under expected market conditions, the element of PASA availability for each trading interval and the statement that the changes would require Scheduled Generators to provide information within both the ST and MT PASA timeframes about the capacity that could be made physically available at 24 hours’ notice in response to extreme conditions and the statement in the report that as availability in the short term will also depend on participants discretionary decisions, Scheduled Generators would be required, in the case of ST PASA, to provide a forecast of market availability defined as the capability they intend to make available under normal anticipated market conditions.

103 What emerges from the passage from the report of the Code Change Panel set out above is clear recognition of the distinction between capacity a generator intends to make available and the capacity that could be made available under extreme conditions, that is, that could be made physically available at 24 hours’ notice in extreme conditions. There is, or can be, a difference between the capacity generators intend to bid into the market based on their commercial decisions and the capacity which could physically be made available. There is reason to require the latter in the case of MT PASA and to require both in the case of ST PASA. That is how the amendments to the NEC are framed.

104 The Code Change Panel said in response to a concern raised by a Market Participant that it was satisfied that the draft changes would not be construed as creating a legally binding commitment to deliver capacity. The AER submitted that the report of the Code Change Panel is not consistent with a construction of PASA availability based on an approach of business as usual in the sense of no special measures on 24 hours’ notice.

105 The definition of Rule extrinsic material includes determinations made by the AEMC. There appears to be a lacuna in the legislation because when the National Electricity Rules were initially made in 2005, what they did was to enact the former provisions of the NEC in statutory form under s 9 of the National Electricity Law. The AEM was established in 2004 and it did not have the function of making or recommending changes to the National Electricity Code. The AER submitted that on a “strict reading” of the definition of Rule extrinsic material, the report of the Code Change Panel is not within the definition because it was not material that was relied upon by the AEMC which was not in existence in 2000/2001. The AER submitted that this leaves a gap in how the Court may determine the purpose or objects of the Rules which were originally made as provisions of the Code and, therefore, were not made by the AEMC. The AER submitted that the provisions of cl 8 of Schedule 2 should not be read as a comprehensive code so that it excludes extrinsic material that is relevant to the meaning of its provisions when they were part of the National Electricity Code. It submitted that that could not have been the intention of cl 8 of Schedule 2 because that would mean that all of the extrinsic material that shed light on the proper interpretation of the provisions of the Code became redundant in 2005 notwithstanding their obvious relevance to interpreting the provisions of the NER when they were then enacted. Such an approach would not be consistent with s 7 of the NEL which sets out the objective of the Law. In summary, the AER submitted that in the particular setting involving the National Electricity Code being enacted in statutory form as the NER in 2005, the Court should have regard to “pertinent extrinsic material” associated with the 2001 Code change in the same way as the Court would, at common law, determine the mischief for a legislative change, in this case the insertion of the definition of “PASA availability”.

106 For the reasons given by the AER, I consider that I may have regard to this material. However, I would note that I would reach the same conclusion as to the proper construction of the relevant rules even if I exclude consideration of the extrinsic material.

107 The AER also referred to, and relied upon, statements made in the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s determination on an application for authorisation of the amendments to the National Electricity Code. The particular statements relied upon were the record of the submission made to the ACCC by NEMMCO as follows:

The Commission received one submission. The submission, from NEMMCO, states that it supports the proposed Code changes in principle, since they increase the clarity of participant obligations and provides additional resolution and transparency of the information used to forecast reserve levels.

The submission by NEMMCO was as follows:

These Code changes will now require Market Participants to advise NEMMCO of two different availability levels for scheduled plant in short term time frame. In addition NEMMCO will be required to report on two different levels of availability in the short term time frame. NEMMCO supports these proposed Code changes in principle, as they provide some increase in clarity of participant obligations, and additional resolution and transparency of the information used to manage forecast reserve levels.

108 In 2010, AEMO proposed a suite of amendments to the PASA provisions. A number of amendments to the Rules were made. The primary purpose of the amendments was, according to the AER, to “loosen the former requirement that AEMO should calculate a separate reserve requirement for each region, by allowing AEMO instead to calculate ‘dynamic joint regional reserve requirements’”. A number of other amendments were made at the same time which, according to the AER, were designed “to improve clarity of the PASA rules and to address various minor issues identified through a review of the PASA processes that had been undertaken in 2009”.

109 The AER submitted that for present purposes, the most important amendment was that made to the description of “availability” in the case of ST PASA. In place of the undefined word “availability” in cl 3.7.3(e)(1), the defined term “available capacity” was substituted. The substitution of “available capacity” in place of “availability” was recommended by AEMO because it considered that:

“availability” in amended clause 3.7.3(e)(1) is equivalent to the existing glossary definition “available capacity” and the clause should instead refer to the existing definition.

110 The AEMC agreed with the position advanced by AEMO “in order to improve clarity of the Rules”. The amendments in 2010 also included amendments to change the existing definition of “PASA availability” (see [100] above) to the following:

The physical plant capability of a scheduled generating unit, scheduled load or scheduled network service available in a particular period, including any physical plant capability that can be made available in that period given 24 hours’ notice of a requirement that the relevant scheduled generating unit, scheduled load or scheduled network service be made available.

111 The amendment actually made was to change the definition of “PASA availability” so that it read as follows:

The physical plant capability (taking ambient weather conditions into account in the manner described in the procedure prepared under clause 3.7.2(g)) of a scheduled generating unit, scheduled load or scheduled network service available in a particular period, including any capability that can be made available during that period, on 24 hours’ notice.

112 PPPL submitted that the relevant rules are civil penalty provisions and that any doubt or ambiguity about meaning should be resolved in its favour. It referred to the observations of Franki J in Trade Practices Commission v TNT Management Pty Ltd (1985) 6 FCR 1 (at 47–48):

It is, in my opinion, now necessary to look at certain aspects of the correct approach to be adopted in the construction of a statute such as Pt IV of the Act. It is clear that, although the criminal onus of proof does not have to be satisfied, it is necessary to have regard to the penal nature of the contravention alleged and the extent of the penalty, both financial and probably to trade reputation, which is involved in a finding of contravention. I have in mind that the legislation is of a highly penal nature and in TPC v Legion Cabs (Trading) Co-operative Society Ltd (1978) 35 FLR 372 at 382 … I said in relation to s 47 of the Act:

I consider that such a section should be construed in a similar way to a section imposing a criminal liability. As to the interpretation of statutes creating offences, see Beckwith v The Queen (1976) 135 CLR 569 per Gibbs J at 576.

The passage of Gibbs J, as he then was, to which I referred reads:

The rule formerly accepted, that statutes creating offences are to be strictly construed, has lost much of its importance in modern times. In determining the meaning of a penal statute the ordinary rules of construction must be applied, but if the language of the statute remains ambiguous or doubtful the ambiguity or doubt may be resolved in favour of the subject by refusing to extend the category of criminal offences: see R v Adams (1935) 53 CLR 563 at 567-568; Craies on Statute Law (7th ed, 1971), pp 529-534. The rule is perhaps one of last resort.

… In my opinion, if the language of the Act after the ordinary rules of construction have been applied remains ambiguous or doubtful, it is appropriate to remove or resolve that ambiguity or doubt in favour of a defendant, at least, where the proceedings are for a penalty.

113 The rules of construction in relation to civil penalty provisions are similar to those that apply in the case of criminal offences (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; (2018) 262 FCR 243 at [68]).

114 In R v A2 [2019] HCA 35; (2019) 269 CLR 507, Kiefel CJ and Keane J said (at [52]):

A statutory offence provision is to be construed by reference to the ordinary rules of construction. The old rule, that statutes creating offences should be strictly construed, has lost much of its importance. It is nevertheless accepted that offence provisions may have serious consequences. This suggests the need for caution in accepting any “loose” construction of an offence provision. The language of a penal provision should not be unduly stretched or extended. Any real ambiguity as to meaning is to be resolved in favour of an accused. An ambiguity which calls for such resolution is, however, one which persists after the application of the ordinary rules of construction.

(Footnotes omitted.)

115 I also refer to the following observations of Leeming JA in Grajewski v Director of Public Prosecutions (NSW) [2017] NSWCCA 251; (2017) 270 A Crim R 33 at [55]):

Although it was at the forefront of his written submissions, the principle invoked by Mr Grajewski does not exclude the ordinary rules of construction: Waugh v Kippen (1986) 160 CLR 156 at 164; [1986] HCA 12. Indeed, Gibbs J’s qualified observation in Beckwith v The Queen (1976) 135 CLR 569 at 576 that the “rule is perhaps one of last resort” has much more recently been reiterated in unequivocal terms: by Nettle and Gordon JJ in Re Day [No 2] [2017] HCA 14; 91 ALJR 518 at [276] and in the joint judgment in Aubrey v The Queen [2017] HCA 18; 91 ALJR 601 at [39]. I do not for a moment understand the High Court, by referring to “rules” and “last resort”, to be implying that the task of ascertaining the legal meaning of a statute is mechanistic, to be determined by the application of rules, amongst which the penal character of the statute is the last to be invoked. The process is considerably more nuanced, reflecting as it does the constitutional relationship between the various arms of government: Zheng v Cai (2009) 239 CLR 446; [2009] HCA 52 at [28]. As was express in the passage from Stevens v Kabushiki Kaisha Sony Computer Entertainment reproduced above – a statute’s penal character is to be regarded as a very minor consideration to be taken into account in ascertaining its legal meaning in light of its text, context and purpose.

116 Finally, it is relevant to note the principles relevant to when a word or words may be read into a legislative provision. A prior question is whether that exercise is necessary. For example, in Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner (Bay Street Appeal) [2020] FCAFC 192; (2020) 282 FCR 1 (the Bay Street Appeal case), Flick J discussed the difference between reading words into a legislative provisions and, to use the words of his Honour (at [62]), “to construe a legislative phrase by reference to the context in which the phrase appears and to read that phrase in a matter which gives effect to its presumed legislative object and purpose”.

117 Assuming it is a true case of reading words into the legislative provision, then the relevant principles are as follows.

118 In Wentworth Securities Ltd v Jones [1980] AC 74 at 105–106, Lord Diplock identified three conditions which must be satisfied before words are read into a statutory provision or the Court reads a provision in a way which modifies the words of an Act. His Lordship said:

First, the court must know the mischief with which the Act was dealing. Secondly, the court must be satisfied that by inadvertence Parliament has overlooked an eventuality which must be dealt with if the purpose of the Act is to be achieved. Thirdly, the court must be able to state with certainty what words Parliament would have used to overcome the omission if its attention had been drawn to the defect.

119 The High Court addressed this issue in Taylor v Owners – Strata Plan No 11564 [2014] HCA 9; (2014) 253 CLR 531. French CJ, Crennan and Bell JJ said the following (at [37]–[39]):

37 Consistently with this Court’s rejection of the adoption of rigid rules in statutory construction, it should not be accepted that purposive construction may never allow of reading a provision as if it contained additional words (or omitted words) with the effect of expanding its field of operation. As the review of the authorities in Leys demonstrates, it is possible to point to decisions in which courts have adopted a purposive construction having that effect …

38 The question whether the court is justified in reading a statutory provision as if it contained additional words or omitted words involves a judgment of matters of degree …