Federal Court of Australia

Selkirk v Hocking (No 2) [2023] FCA 1085

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent NAMEBRIGHT.COM INC Second Respondent NATHAN HOWARD (and others named in the Schedule) Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The proceeding be dismissed.

2. The fifth and sixth respondents file submissions on costs, not exceeding three pages, by no later than 4:00pm on 20 September 2023.

3. The applicant file submissions on costs in reply, not exceeding three pages, by no later than 4:00pm on 27 September 2023.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

O’CALLAGHAN J

Introduction

1 By her amended statement of claim dated 5 December 2022, the applicant, Ms Selkirk, alleges that the fifth and sixth respondents published, including in the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory, an online article entitled “Simone Selkirk appeals ruling after being found guilty of David Jones scam” on the website at www.MyLocalPages.com.au that was defamatory of her.

2 The fifth respondent, Mr Martin Wyatt, is the sole director of the sixth respondent, Real Estate Online Pty Ltd, which owns the “MyLocalPages” website. Ms Selkirk pleaded, and it was agreed, that Mr Wyatt is the controlling mind of the sixth respondent, which owns the MyLocalPages website. (I understand that the proceeding has otherwise resolved against the other named respondents).

3 Following publication of my reasons in Selkirk v Hocking [2023] FCA 432, on 20 June 2023, Senior National Judicial Registrar Legge made the following order:

1. A hearing for the determination of the following preliminary questions be set down for 4-5 September 2023 (Preliminary Questions Hearing):

a. Whether the article entitled “Simone Selkirk appeals ruling after being found guilty of David Jones scam” that appeared on the website at www.mylocalpages.com.au and is identified in Annexure F to the Amended Statement of Claim in this proceeding (MyLocalPages Article) conveyed in its natural and ordinary meaning any one or more of the imputations pleaded in paragraph 30 of the Amended Statement of Claim (Carried Imputations).

b. What is the extent of the publication of the MyLocalPages Article?

c. Whether publication of the MyLocalPages Article has caused or is likely to cause serious harm to the applicant’s reputation.

4 For reasons which I will explain, the first question is unnecessary to decide. These reasons address the second and third questions.

5 The evidence was that the MyLocalPages article was “translated” from the original, which had appeared in the mainstream press (News Corp), by some unidentified tool of artificial intelligence, in the process of “feeding” it into what was described as the “filler section” containing some 60,000 articles on the MyLocalPages website. The translation was in parts quite curious. To understand why I say that, I set out below the original article (annexed to the first statement of claim) and the article about which complaint is made in this proceeding (which I will refer to in these reasons as the article).

6 The original article as it appeared on the news.com.au website was in these terms:

Simone Selkirk appeals ruling after being found guilty of $16k David Jones scam

A high-flying consultant found guilty of scamming David Jones stores to the tune of $16,000 will now appeal the decision in the Supreme Court.

Consulting firm director Simone Selkirk used false invoices to persuade staff at David Jones to refund her a total of $16,000 over two years.

A once high-flying lawyer and consultant found guilty of using a fake name and receipts to swindle David Jones stores out of thousands of dollars has taken her case the NSW Supreme Court.

Simone Olivia Selkirk’s sentencing for multiple counts of dishonestly obtaining financial advantage by deception has been delayed as a result.

In a decision at Sydney’s Downing Centre Local Court in December, the Darling Point woman was found to have raked in $16,000 in refunds for clothes and bedding she returned 10 several David Jones outlets between July 2016 and August 2018.

The court previously heard the 45-year-old produced fake online receipts, under the name of “Samantha Ellison”, in the form of emails to dupe staff at David Jones stores in Elizabeth St, Barangaroo, Bondi Junction and Chatswood.

She returned goods including Country Road clothes and expensive bed sheets, with refunds being made to her personal credit card.

Simone Olivia will appeal after being found guilty.

Where the items originated from remains a mystery, with the court hearing last year there were no records of the clothes and bedding ever being bought from the department stores.

But before her first slated sentence date in February, Selkirk lodged an appeal over Magistrate Lisa Viney’s decision in the NSW Supreme Court.

She did not appear before the Downing Centre on Monday, which heard the matter would be adjourned until August 3 to allow time for her appeal heard on June 11 to be decided.

Justice Stephen Campbell has reserved his judgment.

Selkirk is the former director of consulting firm Marc1 and ran her own style and lifestyle blog as editor of MARC Fashion.

The eastern suburbs woman was arrested in October 2018 and was later charged with dozens of offences, including 34 counts of dishonestly obtain financial advantage by deception.

She was also hit with 15 counts of dealing with the proceeds of crime, which were later withdrawn.

Selkirk entered a late guilty plea to four counts of dishonestly obtaining a financial advantage by deception before reneging and unsuccessfully defending the charges at hearing.

7 (On 29 August 2020, Ms Selkirk commenced a defamation proceeding against News Corp, the owner of news.com.au, and subsequently resolved it, on the basis that News Corp remove the article’s URL).

8 The article the subject of this proceeding was in these terms:

Simone Selkirk appeals ruling after being found guilty of David Jones scam

Consulting company director Simone Selkirk employed fake invoices to persuade staff members at David Jones to refund her a complete of $16,000 more than two years.

A at the time significant-traveling law firm and advisor observed guilty of using a faux identity and receipts to swindle David Jones stores out of thousands of dollars has taken her circumstance to the NSW Supreme Courtroom.

Simone Olivia Selkirk’s sentencing for multiple counts of dishonestly obtaining monetary advantage by deception has been delayed as result.

In a choice at Sydney’s Downing Centre Local Courtroom in December, the Darling Stage woman was observed to have raked in $16,000 in refunds for dresses and bedding she returned to a number of David Jones outlets amongst July 2016 and August 2018.

The court earlier heard the 45-year-outdated manufactured fake on the internet receipts, beneath the title of “Samantha Ellison”, in the variety of email messages to dupe personnel at David Jones stores in Elizabeth Street, Barangaroo, Bondi Junction and Chatswood.

She returned products together with Country Highway apparel and high priced mattress sheets, with refunds becoming made to her private credit card.

Simone Olivia will attraction soon after remaining uncovered responsible.

In which the objects originated from stays a thriller, with the court docket hearing last 12 months there were being no records of the apparel and bedding ever staying acquired from the office merchants.

But before her first slated sentence date in February, Selkirk lodged an attraction above Magistrate Lisa Viney’s final decision in the NSW Supreme Courtroom.

Selkirk is the former director of consulting agency Marc1 and ran her very own design and life-style weblog as editor of MARC Manner.

The eastern suburbs female was arrested in October 2018 and was later billed with dozens of offences including 34 counts of dishonestly receive fiscal edge by deception.

She was also hit with 15 counts of dealing with the proceeds of criminal offense, which were being later on withdrawn.

Selkirk entered a late guilty plea to 4 counts of dishonestly getting a monetary gain by deception ahead of reneging and unsuccessfully defending the prices at hearing.

9 That which was “lost in translation” is obvious enough. “Simone Olivia will appeal after being found guilty” became “Simone Olivia will attraction soon after remaining uncovered responsible”. “Where the items originated from remains a mystery, with the court hearing last year there were no records of the clothes and bedding ever being bought from the department stores” became “In which the objects originated from stays a thriller, with the court docket hearing last 12 months there were being no records of the apparel and bedding ever staying acquired from the office merchants”. “Selkirk lodged an appeal” became “Selkirk lodged an attraction”. “[D]ishonestly obtain financial advantage by deception” became “dishonestly receive fiscal edge by deception”. And so on.

10 The particulars of “serious harm” alleged by Ms Selkirk in her amended statement of claim were:

The publication of the matters complained of were (sic) to a mass media audience.

Further, those who searched “Simone Selkirk” will have been confronted with links to the MyLocalPages Article.

The imputations are serious, the Applicant’s professional reputation depends on her integrity as an admitted member of the legal profession and to have an unblemished reputation. The imputations as alleged pose a serious risk to the Applicant’s ability to obtain gainful employment in a legal or executive role. The matters complained of are likely to prejudice the Applicants ability to obtain such employment.

The MyLocalPages Article associates the Applicant with serious crimes.

Following the publication of the MyLocalPages Article, the Applicant has been questioned about the crimes.

(Errors in original).

11 Ms Selkirk alleged that in its natural and ordinary meaning, the article was defamatory of her and carried the following defamatory meanings, viz that she:

(a) is a fraudster;

(b) is a scammer;

(c) is guilty of defrauding David Jones;

(d) is a criminal in that she dishonestly sought to deceive David Jones to obtain a financial advantage by returning goods without genuine receipts;

(e) is a criminal in that she dishonestly sought to deceive David Jones to obtain a financial advantage by returning goods using fake receipts;

(f) produced fake receipts when returning goods to David Jones so she could claim refunds;

(g) is a criminal in that she falsified records of proof of purchase of goods she returned so that she could obtain a financial advantage by receiving refunds for those goods;

(h) is guilty of dishonestly deceiving David Jones to obtain a financial advantage by obtaining refunds for goods returned using fake receipts;

(i) is guilty of scamming David Jones by providing fraudulent proofs of purchase to obtain refunds for goods;

(j) dishonestly deceived David Jones by providing fraudulent proofs of purchase to obtain refunds for those goods;

(k) produced fraudulent proofs of purchase when returning goods to David Jones so she could claim refunds;

(l) committed the crime of dishonestly obtaining financial advantage by deception;

(m) is untrustworthy; and

(n) is untrustworthy in that she sought to profit from dishonest conduct.

12 In their defences, the fifth and sixth respondents, among other things, pleaded defences of fair reporting of proceedings of public concern under s 29 of the Defamation Act 2005 (Vic) (Defamation Act), publication of a matter concerning an issue of public interest under s 29A of the Defamation Act and statutory qualified privilege under s 30 of the Defamation Act.

13 Before turning to the three questions, I will set out the relevant legal principles governing the question of “serious harm”. I do so because those principles are relevant to both the serious harm and extent of publication questions.

Serious harm

14 Nowadays, in all jurisdictions in Australia except the Northern Territory and Western Australia, a statement is defamatory only if and to the extent that its publication causes serious harm to the reputation of the claimant or is likely to do so.

15 This proceeding was brought in the Victoria District Registry, and this hearing was conducted in Victoria. The parties correctly agreed that s 10A(1) of the Defamation Act applied. See s 79 of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth).

16 Sub-section 10A(1) of the Defamation Act provides: “It is an element (the serious harm element) of a cause of action for defamation that the publication of defamatory matter about a person has caused, or is likely to cause, serious harm to the reputation of the person”.

17 Section 1 of the Defamation Act 2013 (UK) is similar and relevantly provides: “A statement is not defamatory unless its publication has caused or is likely to cause serious harm to the reputation of the claimant”. A number of the English cases are useful in interpreting our Act, as will be apparent.

18 Section 10A(1) of the Defamation Act places the onus upon the applicant, Ms Selkirk, to prove as a necessary element of the cause of action that the relevant publication has caused or is likely to cause serious harm to her reputation. See Newman v Whittington [2022] NSWSC 249 at [47] (Sackar J). As his Honour also said at [69], “s 10A … has the effect of abolishing the common law rule that upon publication of a defamation, damage is to be presumed. The plaintiff is therefore obliged to prove serious harm as a fact in every case.”

19 As Lord Sumption (with whom Lords Kerr, Wilson, Hodge and Briggs JJSC agreed) explained in Lachaux v Independent Print Ltd [2020] AC 612 at 623-24 [14]:

Secondly, section 1 necessarily means that a statement which would previously have been regarded as defamatory, because of its inherent tendency to cause some harm to reputation, is not to be so regarded unless it “has caused or is likely to cause” harm which is “serious”. The reference to a situation where the statement “has caused” serious harm is to the consequences of the publication, and not the publication itself. It points to some historic harm, which is shown to have actually occurred. This is a proposition of fact which can be established only by reference to the impact which the statement is shown actually to have had. It depends on a combination of the inherent tendency of the words and their actual impact on those to whom they were communicated. The same must be true of the reference to harm which is “likely” to be caused. In this context, the phrase naturally refers to probable future harm. Ms Page QC, who argued Mr Lachaux’s case with conspicuous skill and learning, challenged this. She submitted that “likely to cause” was a synonym for the inherent tendency which gives rise to the presumption of damage at common law. It meant, she said, harm which was liable to be caused given the tendency of the words. That argument was accepted in the Court of Appeal. She also submitted, by way of alternative, that if the phrase referred to the factual probabilities, it must have been directed to applications for pre-publication injunctions quia timet. Both of these suggestions seem to me to be rather artificial in a context which indicates that both past and future harm are being treated on the same footing, as functional equivalents. If past harm may be established as a fact, the legislator must have assumed that “likely” harm could be also …

20 Many of the English cases, however, correctly say that “it is not a numbers game”, because, for example, very serious harm to a person’s reputation can be caused by limited publication of a defamatory statement. See, by way of example only, Ames v Spamhaus Project Ltd [2015] 1 WLR 3409 at 3418-19 [33] (Warby J).

21 On the other hand, as Davis LJ (with whom Sharp and McFarlane LJJ agreed) said in Lachaux v Independent Print Ltd [2018] QB 594 at 620 [79] (consistently with what Lord Sumption said on appeal):

Whether in any given case the imputation is of sufficient gravity as of itself to connote serious reputational harm (quite apart from the question of consequential or special damage) should therefore normally be capable—where the question of serious harm is in issue and is not appropriately to be left to trial—of being relatively speedily assessed at the meaning hearing. If it is, nevertheless, desired by a defendant to put in evidence at an interlocutory stage designed to show that there is no viable claim of serious harm the summary judgment procedure under CPR Pt 24 is available if the circumstances so justify. There may, for instance, be cases where the evidence shows that no serious reputational harm has been caused or is likely for reasons unrelated to the meaning conveyed by the defamatory statement complained of. One example could, for instance, perhaps be where the defendant considers that he has irrefutable evidence that the number of publishees was very limited, that there has been no grapevine percolation and that there is firm evidence that no one thought any the less of the claimant by reason of the publication.

(Emphasis added).

22 Evidence that a claimant had no reputation to lose is admissible on the question of serious harm. As Lord Sumption said in Lachaux v Independent Print Ltd [2020] AC 612 at 624 [16]:

Suppose that the words amount to a grave allegation against the claimant, but they are published … to people among whom the claimant had no reputation to be harmed. The law’s traditional answer is that these matters may mitigate damages but do not affect the defamatory character of the words. Yet it is plain that section 1 was intended to make them part of the test of the defamatory character of the statement.

23 As Warby LJ (with whom Singh LJ and Dame Victoria Sharp P agreed) said in Banks v Cadwalladr [2023] 3 WLR 167 at 184 [58]:

Proof that the relevant sector of the claimant’s reputation is bad among those to whom the statement complained of was published can reduce damages, perhaps very substantially. A claimant is only entitled to recover compensation for injury to the reputation he actually has. By the same token proof of an existing bad reputation in the relevant sector must be relevant to the question of whether the publication of a statement caused serious harm to the claimant’s reputation.

24 An example of a case decided before the introduction of s 10A and its equivalents where a defendant sought to mitigate damage for its defamatory statement that was “other things being equal … an extremely grave libel” is O’Hagan v Nationwide News Pty Ltd (2001) 53 NSWLR 89. In that case, the imputation conveyed in the newspaper article the subject of the proceeding was that the plaintiff, a detective senior sergeant in the NSW police force, “had arranged with another person, for the price of $10,000.00 to have a third person murdered”. The plaintiff’s case at trial was conducted on the basis of his good reputation as a police officer. The defendant contended in its defence that the plaintiff’s reputation as a policeman had always been so bad that he had virtually no reputation to lose and sought to mitigate damages by leading evidence in furtherance of this plea:

The plaintiff had at the time of publication of the matter complained of a reputation in the New South Wales Police Service, the National Crime Authority and the Australian Federal Police as:

(i) A policeman who had pleaded guilty to two NSW Police Service departmental charges of misconduct;

(ii) A policeman who had been suspended from duty in 1988 after being charged with conspiracy to pervert the course of justice;

(iii) A person who fabricated evidence against persons who had been charged with criminal offences; and

(iv) A person who was generally dishonest and corrupt.

25 The primary judge substantially upheld the respondent’s plea. Justice Meagher, with whom Stein JA agreed, dismissed the appeal from the primary judge’s orders, and in the course of his reasons said the following at 91-2 [4]-[5]:

The question of the admissibility of evidence of reputation is of some importance, although, unlike some other aspects of defamation, not overburdened by authority. The starting point is that expressed by Devlin LJ in Plato Films Ltd v Speidel [1961] AC 1090 at 1100:

“The action of libel is an action for loss of reputation. On the issue of damage, what has to be investigated is not whether in truth the plaintiff is a good or bad man, but whether he is reputed to be a good or bad man. If a man’s reputation is already so bad that it cannot be made worse, the man who defames him will, in fact, have done him no further damage …”

One would therefore have suspected that a plaintiff would always be at liberty to lead evidence about the excellence of his reputation, and a defendant would always be at liberty to lead evidence about the evil reputation of the plaintiff. However, things are not as simple as that. Despite earlier doubts on the matter, it is now clear that evidence may be led by a plaintiff of his good reputation, either by his own testimony or from the evidence of witnesses; Anderson v Mirror Newspapers (No 2) (1986) 5 NSWLR 735 per Hunt J; and it has always been held that the defendant may lead evidence to the contrary; but, in either case, the reputation evidence is subject to two fundamental rules. The first is that the evidence must relate to “the relevant sector” of the plaintiff’s reputation. Thus if a plaintiff sues on a libel that he is a dishonest solicitor, it is not to the point that he has a reputation as a good golfer. Similarly if the libel is that he is dishonest, it is not to the point for the defendant to demonstrate that he is a reckless motorist. (See Plato Films per Lord Denning).

26 Justice Stein said in that case at 93 [14], “[t]he law of libel operates to protect a person’s reputation and therefore it follows that what is to be protected is a person’s actual reputation”. He then cited the following passage from the judgment of Cave J in Scott v Sampson (1882) 8 QBD 491 at 503:

Speaking generally the law recognizes in every man a right to have the estimation in which he stands in the opinion of others unaffected by false statements to his discredit; and if such false statements are made without lawful excuse, and damage results to the person of whom they are made, he has a right of action. The damage, however, which he has sustained must depend almost entirely on the estimation in which he was previously held. He complains of an injury to his reputation and seeks to recover damages for that injury; and it seems most material that the jury who have to award those damages should know if the fact is so that he is a man of no reputation. “To deny this would,” as observed in Starkie on Evidence, “be to decide that a man of the worst character is entitled to the same measure of damages with one of unsullied and unblemished reputation. A reputed thief would be placed on the same footing with the most honourable merchant...”

…

On principle, therefore, it would seem that general evidence of reputation should be admitted …

27 The cases also say that “a relevant and potentially significant factor when deciding whether publication has caused serious harm to reputation is the scale of publication or, putting it another way, the total number of publications”. See, by way of example only, Banks v Cadwalladr [2023] 3 WLR 167 at 182 [52] (Warby LJ).

28 I should also say something about the phrase “serious harm to the reputation of the person” used in s 10A(1). In Rader v Haines [2022] NSWCA 198 at [27], Brereton JA, with whom Macfarlan JA agreed, said:

Courts appear so far to have avoided endeavouring to explain the word “serious”. Indeed, it has been said that “serious” is an ordinary word in common usage. But in my view there is utility in giving some further explanation of its content. It is used in the sense third mentioned in the Oxford Dictionary definition, namely “significant or worrying because of possible danger or risk; not slight or negligible”, for which the example given is “she escaped serious injury”, and the synonyms include “severe” and “grave”. In Lachaux, whereas the Court of Appeal had considered that the new statutory test was the same as the common law “tendency to cause substantial harm” test, in Thornton v Telegraph Media Group, albeit raised to the level of “serious harm”, the Supreme Court confirmed that it “raises the threshold of seriousness above that envisaged in Jameel (Yousef) and Thornton”. At least, this shows that “serious” involves more than merely “substantial”. In Monroe v Hopkins, Warby J concluded that “whilst the claimant may not have proved that her reputation suffered gravely, I am satisfied that she has established that the publications complained of caused serious harm to her reputation and met the threshold set by s 1 of the 2013 Act”. In my opinion, “serious” harm sits on the spectrum above “substantial” but below “grave”. Importantly, there can be harm which, though substantial, does not reach the level of serious harm.

(Citations to the cases omitted).

29 The third member of the Court, Basten AJA, agreed with the orders proposed by Brereton JA, with this reservation (at [91]):

The reservation relates to the exegesis on the meaning of “serious” in s 1 of the Defamation Act 2013 (UK). There is a risk in seeking synonyms, which may later be treated as valid replacements for the ordinary English word adopted by the Parliament. There is also a risk in seeking to place the term on a scale, between other terms of equal imprecision. The critical concept is “serious harm to the reputation of the claimant”; it is that to which the court is required to attend by reference to the evidence of a range of matters. Analysis of individual component words is apt to distract from that inherently impressionistic exercise.

30 I agree, with great respect, with Basten AJA that there is a risk in seeking synonyms and “[t]he critical concept is ‘serious harm to the reputation of the claimant’”.

31 It seems to me that judges risk leading themselves into error by positing alternative taxonomies to ordinary and well-understood English phrases used in legislation.

32 As Ormiston JA said in Mobilio v Balliotis [1998] 3 VR 833 at 854-58, as to why the phrase “serious injury” within the meaning of s 93(4) of the Transport Accident Act 1986 (Vic) should not be subject to any gloss, including by adopting as a synonym the words “very considerable”:

There remains for consideration the meaning of the word “serious” itself, where it appears in paras (a) and (b) of the definition. In the first place I should make clear that I agree with Brooking JA that the test in Humphries v Poljak at 140 should continue in its totality to be considered as providing appropriate “guidance”, as the majority described it (ibid), as to the meaning of the terms in the definition.

The difficulty I perceived in Cropp v Transport Accident Commission [1998] 3 VR 357 was that one of the expressions used in Humphries v Poljak, namely “very considerable”, had been taken by the trial judge outside its context and used by him as if it were a substitute for the definition and for the whole of the judicial exposition in the latter case. So in Cropp it was used by the judge as the basis for concluding that the test was so “stringent” that Parliament had “intended the category of eligible claimants to be a very restricted one”: cf Cropp at 362. That narrow approach is what I there said was “not what the majority in Humphries said, nor, having regard to the observations of the High Court [in Fleming], should they be taken to have implied.” In consequence the appeal was allowed.

The danger, then and now is that judges will seek to apply the supposed synonym, “very considerable”, for the words of the section. “It is the text, and not the gloss, that we are called upon to interpret”: Coates v National Trustees Executors & Agency Co Ltd (1955) 95 CLR 494 at 523 per Fullagar J. (dissenting). Compare Kavanagh v Commonwealth (1960) 103 CLR 547 at 578. As it was expressed by the Privy Council in Ogden Industries Pty Ltd v Lucas [1970] AC 113 at 127, in terms approved by Gummow J as a member of the Federal Court in Brennan v Comcare (1994) 50 FCR 555 at 572:

It is quite clear that judicial statements as to the construction and intention of an Act must never be allowed to supplant or supersede its proper construction and courts must be aware of falling into the error of treating the law to be that laid down by the judge in construing the Act rather than found in the words of the Act itself.

What was the extent of the publication of the article?

Meaning of publication

33 Publication is a “bilateral act”, in which the publisher makes material available and a third party has it available for his or her comprehension. See Dow Jones & Co Inc v Gutnick (2002) 210 CLR 575 at 600 [26] (Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow and Hayne JJ).

34 As the New South Wales Court of Appeal said in Stoltenberg v Bolton [2020] NSWCA 45 at [28] (Gleeson JA, with whom each of Macfarlan JA and Brereton JA agreed):

In an action for defamation involving online material, publication is established through evidence that a third party downloaded and read the material. Publication, in the legal sense, may be established by pleading and proving a platform of facts from which an inference that material has been downloaded can properly be drawn. The mere fact of posting material online does not lead to an inference that is has been downloaded.

(Internal citations omitted).

35 Determining the extent of publication thus requires, in a case such as this, proof by an applicant of when the publisher made the relevant article available, and how many third parties downloaded and read it.

When was the Article available to be searched online?

36 Mr Wyatt deposed that the article was first uploaded on to the MyLocalPages website on 29 June 2020.

37 The article did not become publicly available, however, via a search engine like Google until some date in June 2021, and counsel for Ms Selkirk, Mr TJ Sowden, apparently accepted as much.

38 Mr Sowden put to Mr Wyatt in cross-examination that the article had not been removed from the MyLocalPages on 11 April 2022 (when Mr Wyatt swore that he did remove it), but that it continued to be accessible until 18 May 2022, some five weeks later.

39 Mr Wyatt deposed in his 14 August 2023 affidavit as follows:

I was not aware of the MyLocalPages Article until on or about 11 April 2022, when I received a telephone call from a female person who identified herself as Ms Selkirk. The substance of that telephone call was as follows:

Ms Selkirk: Hello, my name is Simone Selkirk. There is an article on your website relating to me that needs to be removed. I just want it to be removed. When will this be done?

Me: What is the article about? What is the title of the article?”

Ms Selkirk: It’s about me, Simone Selkirk and a court case involving David Jones, which was now out of date as I had won an appeal that overturned the original finding. I cannot believe how poorly the article is written, how could anyone even read it, it’s barely readable. I just want it to be removed. When will this be done?

Me I will action it immediately once I’m off the call with you.

Ms Selkirk: Good. (Ms Selkirk then terminated the call).

40 Mr Wyatt also deposed in that affidavit that “[w]ithin 5 minutes after and as a result of, the telephone call … I removed the article from the MyLocalPages Website and put it into the trash” and that “then any link to the [article] that may have appeared on a Google search result would have led a reader to an ‘error 404’ message”.

41 In his evidence in chief, Mr Wyatt further explained that:

What is your belief as to what happens to an article once you remove it from the filler section? Well, once it’s removed from the website – you go into the back of a – what we call a cPanel which is an administrative panel which gives us access to the rear end of the website. We then take the given article and we place that into trash. And we then do the update. And then we do the check to verify that that article is no longer viewable. And that’s – that what I did in this situation, as well.

What happens to the article after you’ve put it into trash? It is no longer viewable and on that given page – if someone saw that page link, that’s when the page 404 comes up which means that, basically, a search engine has gone to do a search from where it knew an original URL was – so the original address. And it knows that that was the address. But when you click through, the same information will come up in the search engine. So the search engine – until the search engine catches up – because search engines rarely do full spider crawls and everything else. Logistically, they simply can’t do that every single time you do a search. That would be impossible. So what they want to do is they want to have the search engines and the spiders and the crawlers actually do that crawl through. And if an article is already there and already established, they don’t need to go back to that instantly every time. They know that there’s an article there. So under Google, you would still see in a search result – in a search result – that page showing with the brief summary. But when you click through, there would be nothing there. There would be the 404 page. Because it has been completely removed from the website administrative panel.

Which is your website? Correct.

Okay? For any website. The admin panel is where you remove an article or a post

HIS HONOUR: And when do you say you removed this article? On 11 April. I got the phone call about 1.40-ish – 1.45 in the afternoon. Because we’ve never had anyone ever call. So I would know. And the phone number came through my 1300 number – the business number – to – and transferred on to me. …

So you say after that was done, if you had done a Google search you would have maybe found a reference to the article but if you tried to access it, you would get an error 404 message? Correct – correct. It was just not there. Because I – I personally took the call. And – and the – because that was the first point in contact that we had had in regards to this article or we had even had from Simone.

42 On 20 May 2022, Macpherson Kelley (solicitors then representing for Ms Selkirk) sent a Concerns Notice by way of letter to Mr Wyatt. Annexure A to that letter was a version of the Article with a date and timestamp “18/05/2022, 09:32”.

43 Ms Selkirk contended that the date and timestamp meant that the article was available for downloading by the public after 11 April 2022, contrary to Mr Wyatt’s sworn evidence.

44 Mr Wyatt gave evidence that the article could only have been available to Ms Selkirk on 18 May 2022 via a “cached version” on her computer or device, which he explained in the following way:

[A] cached version is basically because our computers store the memory of what was on a page. So that if we go through and we’ve got the same link, that it can be there on your computer.

You’ve probably heard the term “having to clear your cache” or – which is a computer term. It’s – what it’s asking you to do is on your computer clear the memory of all the sites that you’ve been to, because otherwise you’re seeing the historical page up there and maybe not a current page. We have this happen time to time when we’re doing development work, if we’re seeking a cached version and someone is saying, “No, but I updated that. Okay, I will have to clear my cache” and we have to clear the memory so we can see the current, new – today’s version of the page. So it’s based on the memory of the computer and what it has there.

MR CASTELAN: … What is the significance of [the 18 May 2022 date, which was five weeks after Mr Wyatt deposed he took down the Article]? It is the cached version. So … that means it’s still in the memory on the computer that

HIS HONOUR: Of the person who generated the document? Correct.

So does that mean – I’m sorry to interrupt, but does that mean if you search something on your iPhone – so you go to the newspaper – you search the Guardian or the Age or something, and you – you read the headline article, and you click it so you read it? Yes.

And then, you close it? I’ve got two of them stuck on my iPhone at the moment, and I’ve got one

Why do some – why do some of them get stuck and some not? Because I know? You’ve – you’ve got to clear the cache. It’s just a case of some phones – it can be turning them on and off, and that can clear it, but I’ve got one stuck from the AFL. I’ve got the – Richmond losing to Port Adelaide by 10 points each time I go back to there, and I’ve got a news.com.au story that pops up every time as soon as I go back into there, and I’ve just got to refresh on each of those.

And is that – I see. So it’s? And it happens to me.

It’s just a kind of happenstance or? It’s just one of those things. I will get round to clearing it and clearing the cache but – but I’ve – I generally don’t have a lot of time to sit down and just muck around doing that sort of thing. So I just hit refresh and know that I’m back onto a live website.

But you – you say that the only explanation for someone using a computer to generate a copy of the article on 18 May 2022 in circumstances where you swear that you took it down from the website on 11 April 2022? Correct.

Is that – that version that had been on your website before 11 April 2022 was cached on that individual’s … device from which they generated the document? Correct. They’ve viewed it prior to that time and day.

And it has been – through the magic of something, it’s? Just memory.

Memory? Computer memory because – look. Electronic devices are designed to minimise your work and your output. So if there is something that you’re going to that you’ve already been to, they will pull up that cache version unless you want to go back to a live version. So if they had gone through that process

(Emphasis added).

45 Mr Sowden, counsel for Ms Selkirk, challenged Mr Wyatt on this during cross-examination:

MR SOWDEN: … It was possible to access that article independently of having it cached on your computer on – in May 2022. It’s possible, is it not? No.

…

And I want to suggest to you ... that that article could still be access[ed] from MyLocal[Pages] post 12 April 2022 up until around June 2022 independently of whether the article was cached on your system or not. Yes or no? Not at all.

Okay? Zero chance.

46 Mr Wyatt was, as his evidence shows, emphatic that (i) the article was not capable of being searched anywhere online until June 2021; (ii) he deleted it on 11 April 2022, within minutes of Ms Selkirk asking him to do so, which meant that the article was not publicly available on the MyLocalPages Website after 11 April 2022; and (iii) the only explanation for Ms Selkirk being able to produce to her lawyers a version of the article date stamped 18 May 2022 annexed to the Concerns Notice and to the statement of claim was that the article must have been “cached” on Ms Selkirk’s relevant electronic device.

47 Mr Wyatt was very familiar with how the MyLocalPages website worked and his responses to the cross-examination were persuasive. I accept the truth of what he said in each of those respects.

What was the extent of the publication?

48 The onus is on an applicant in a defamation case to adduce evidence to establish that the material complained of has been viewed by someone.

49 Ms Selkirk sought to tender unsigned witness statements from “professional and[ ]acquaintance contacts”, who she says had “actively identified the MyLocalPages Article from a Google name search of ‘Simone Selkirk’ in and around early 2022”.

50 I ruled this evidence inadmissible because it was irrelevant and, as I said to Mr Sowden, “it would be a strange way of conducting litigation” to proffer unsigned witness statements, attach them as an exhibit to someone else’s affidavit, and obviate the need to call the witnesses and test their evidence.

51 After I ruled those statements inadmissible, as they obviously were, Mr Sowden sought leave to call three of the statement-makers to give evidence via video-link.

52 I refused that leave in circumstances where Senior National Judicial Registrar Legge made an order on 20 June 2023 that the applicant file and serve all affidavit material by 1 August 2023. In such circumstances, it would be inconsistent with the principles of s 37M of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) to permit the late calling of such evidence. My ruling was in these terms:

I have before me an application by counsel for the applicant to adduce viva voce evidence from three witnesses in circumstances where the application was first foreshadowed after I had made rulings this morning excising considerable parts of the proposed testimony to be given by Ms Selkirk, the applicant. That material excised on the basis of relevance and the like included three unsigned statements given by three different individuals that are said to relate to the issue of publication and the issue of serious harm. The application is opposed by the fifth and sixth respondents, for whom Mr Castelan appears.

On 20 June 2023, Registrar Legge made orders setting down the preliminary questions, which is not necessary for me to recite now, and made orders for the filing of affidavit material. Her orders included that the applicant file and serve all of the affidavit material that she intends to rely on at the hearing of the preliminary questions by 1 August 2023, which I observe is more than a month ago. Mr Sowden, who appears for the applicant, contended that it was in the interests of justice to permit the last minute calling of three individual witnesses, which would necessarily entail the evidence being given by video link.

In my view, it is simply too late now to seek to rely on additional evidence in circumstances where the very first notice that the fifth and sixth respondents have had of that application was a few minutes ago, that is to say, at the end of the first half of the first day of the two days that have been allocated to hear this proceeding. In my view, it would not be consistent with the well-known principles which lie behind section 37M of the Federal Court of Australia Act (Cth) to permit the late calling of such evidence in all the circumstances. For those reasons, the application to adduce oral evidence from the three named individuals is refused.

53 I return now to the evidence.

54 Ms Selkirk deposed as follows:

From late 2021 and early 2022, when the NewsCorp Articles were beginning to be URL removed by NewsCorp, as part of the settlement arrangements, I engaged at considerable expense an Online Reputation Management and Search Engine Optimisation (SEO) group, Spotcodes Technologies (via Upworks) (Spotcodes), to create SEO optimised and Google cached online content attached to a Google name search result linked to searches of (Simone Selkirk; Simone Selkirk and David Jones; Simone Selkirk and Appeal; Simone Selkirk and Fraud; Simone Selkirk and Scam/ Scammer; Simone Selkirk and Crime), which efforts were intended to suppress the MyLocalPages Article[.]

55 She also sought to adduce evidence that she undertook these efforts at a time when the article appeared as the first result from a Google search of her name. I ruled that evidence inadmissible because it was hearsay and irrelevant, but gave counsel leave to ask the witness about the general subject matter in her evidence in chief.

56 In closing submissions, Mr Sowden sought to rely on Ms Selkirk’s oral evidence about her dealings with Spotcodes, as follows:

MR SOWDEN: Just – can you just explain how and why you engaged Spotcodes? I engaged Spotcodes because when I discovered that there were republications not authorised by Fairfax and News Corp and they couldn’t remove them under the terms of my settlement with them I had – we had tried to communicate with those – or we tried to get News Corp and Fairfax to communicate with those republishes to remove them and the ones that weren’t removed after that conversation remained online and I, therefore, had to try and get rid of them and get them – pushed down the first hits of my names and the only way I could do that was to engage a Search Engine Optimisation group called Spotcodes to create online content that would, ideally, be produced as a – as return name searches above the legacy article such as MyLocalPages which was coming in at the first article on the first page of a name search of my name. So Spotcodes … was engaged so that they … could create online content to push the MyLocalPages article down, hopefully, off page 1 onto page 4, 5, 6, 7, 8. But that wasn’t successful.

Okay. So you? That’s why I engaged Spotcodes.

…

Your evidence is that you engaged Spotcodes in about February 2022. Is that right? That – that’s right. We started to create online content around February 2022 so that when the first report that Spotcodes produced as to what the return on investment, if you will, of that online content – how that had pushed down the MyLocalPages article and a handful of others. We could then see, you know, what was happening or, at least, benchmark what the online content was doing to the MyLocalPages article returning as the first article on Google.

Now, you said that the MyLocalPages article was returning as the number 1 hit on a Google search. Just explain what you mean by that and when? Okay. So the MyLocalPages article was returning as number 1 on a Google search of my name because when I had Googled my name to double-check what was left on the internet after the News Corp and Fairfax articles had been removed I was, obviously, interested to – thank you – I was interested to know what was left. Where it was – where it was standing and how and how to contact the republishes that were left online to try and get the information removed and that’s how I came to see the MyLocalPages article as the very first article. It was also very prominent because it had photos of – two photos of me. So it was very, obviously, in your face. So I also became aware of that article as being the first article on Google because, also, my lawyers emailed and identified the article to my attention as well.

…

… How often would you Google your name in – after November 2021? I would Google my name at least once a week to – you know, and I had to do that because I had to identify what articles were online, what articles were removed, what articles remained and what articles I needed to identify to Spotcodes to link metadata so that they could then follow, track and – and target those leftover articles so that the articles could – the work they did could suppress what was left on – on the internet

57 Mr Sowden said that “pretty powerful inferences arise from that [evidence]”. It was not clear to me what those inferences were, and in the absence of any further explanation about what the Spotcodes evidence amounted to, I cannot take the matter any further.

58 Ms Selkirk sought to adduce evidence in her affidavit that:

I am aware of the following classes of persons (which total 22 classes), which is not an exhaustive list but represent the classes of persons presently aware to me, who had access to and viewed the MyLocalPages Article up to the end of May 2022:

(a) Persons who told me about the presence of the MyLocalPages returning against a Google Name Search of my name

(b) Persons who I had submitted an application for employment

(c) Persons who knew I was a lawyer in Sydney and/ or identified me by the photo attached to the MyLocalPages Article

(d) Persons from my social circle who identified me from the photo attached to the MyLocalPages Article

(e) Former employers and legal colleagues

(f) Former clients

(g) Legal representatives who I engaged for defamation legal advice

(h) Barrister who I engaged for other legal matters

(i) Persons I approached to be a referee for employment purposes

(j) Persons who had read the MyLocalPages Article

(k) Persons who identified me from Google Search results and by the two photos’ attached to the MyLocalPages Article arising from administrative or personal affairs engagements with me, including my tax accountant

(l) Persons who shortly after reading the MyLocalPages Article identified me from their own investigations and/ or identified me by the photo attached to the MyLocalPages Article

(m) Persons who I engaged to perform the SEO Reputation Management service, and their extended employees and sub-contractors

(n) My family and extended family

(o) My friends in Sydney and in Perth, Western Australia and internationally

(p) My partner

(q) Persons my partner discussed the MyLocalPages Article with, including his friends in Sydney and his extended family internationally in Chile

(r) Persons to whom the MyLocalPages Article website link was on forwarded to others

(s) Persons who were told by people in all of the above classes of people

(t) Persons, including international persons, who were following the outcomes of the criminal proceedings against me and who were interested to independently publish their own coverage of the criminal allegations against me

(u) Persons who are engaged in the care of my disabled sister, and their extended works, including the Public Guardian Government department

(v) LinkedIn Viewers of the Simone Selkirk LinkedIn profile

(Errors in original).

59 Mr JA Castalen, counsel for the fifth and sixth respondents, objected to the evidence on the grounds that it was without foundation, speculation, conclusion, hearsay and irrelevant. And Mr Sowden made no real attempt to explain why one or more of those objections was not valid. So I declined to receive it.

60 The fifth and sixth respondents were not strictly speaking obliged to proffer evidence of the extent of publication, but they did.

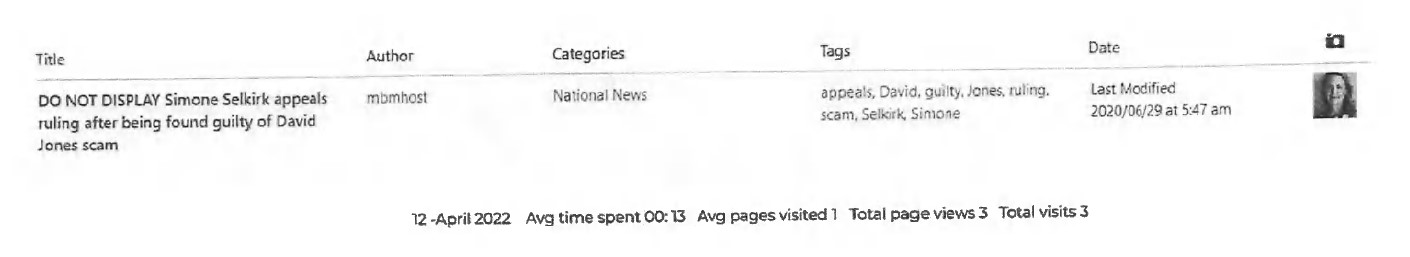

61 Mr Wyatt produced Exhibit R1, being this screenshot:

62 Mr Wyatt swore that this is a “unique page viewer’s report” taken from the website’s administrative panel, and that he took the screenshot on the day he made the search (12 April 2022).

63 He deposed that the “Total page views: 3” refers to the number of unique views of the article between July 2021 and 11 April 2022, and that one “unique” view is from one device.

64 I accept Mr Wyatt’s evidence that, at most, the article was published from the MyLocalPages website to three people within that time period.

Did publication of the Article cause or is it likely to cause serious harm to the applicant’s reputation?

The facts

65 Ms Selkirk was tried before a Magistrate in the New South Wales Downing Centre Local Court in November 2019 on various counts of dishonestly obtaining a financial advantage by deception, one count of using a false document to attempt to obtain financial advantage and seven counts of dealing with property the proceeds of crime.

66 The case against her was that on 17 occasions (including an attempt) between July 2016 and August 2018 she had “returned” various goods to David Jones stores, presenting a falsified online purchase invoice email.

67 The false details were:

• the proof of payment number;

• credit card details purportedly used for payment of the goods; and

• the name of the purchaser.

68 The allegation was that Ms Selkirk received a “refund” of the price of the items she “returned” specified on the invoice which was credited to one of her three credit cards. None of her cards was the card nominated on the invoice as used for the online purchase. The deception specifically relied on was the falsified proof of purchase number which was derived from Ms Selkirk’s mobile phone number.

69 The matter proceeded (including) by way of a statement of agreed facts under s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW).

70 The facts to which Ms Selkirk agreed included the following (in substance):

(a) she attended in person at David Jones stores on 17 occasions between 7 July 2016 and 26 August 2018 to obtain a refund for “returned goods”;

(b) on each occasion she presented a false online purchase invoice email as proof of purchase (using numbers which were a derivative of her mobile phone number);

(c) she knew that the proof of purchase numbers in each document were false; and

(d) she had not used either of the credit cards to which refunds were credited for the purchase of the goods in question.

71 Ms Selkirk was convicted of 16 counts of dishonestly obtaining a financial advantage by deception contrary to s 192E of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW), one count of using a false document to attempt to obtain financial advantage contrary to s 254(b)(ii) of the Crimes Act and seven counts of dealing with property the proceeds of crime contrary to s 193C(2) of the Crimes Act.

72 Ms Selkirk appealed all of the convictions. See Selkirk v Director of Public Prosecutions [2020] NSWSC 1590 (Campbell J).

73 The appeal was allowed, essentially (and at the risk of putting the point too simply) because the Crown had not proved where Ms Selkirk had obtained the goods in the first place, it had not proved an essential element of each of the charges.

74 In the course of his reasons, Campbell J said:

[46] There was no issue [before the Magistrate] about deception. It was constituted by the presentation of the false proof of payment document. Nor was there any causation issue that by its presentation the refund was received as her Honour found. However, her Honour’s conclusion which I have set out above made no mention of the separate element of dishonesty, particularly in circumstances where the prosecution admitted that it could not establish the provenance of the goods returned and the possibility that they had been purchased in a cash transaction, by use of a different credit card or by someone else on Ms Selkirk’s behalf, perhaps as a gift. As I have said, her Honour found that the financial advantage is the sum of money that was returned to Ms Selkirk’s credit card. Apart from recording the submission on behalf of Ms Selkirk that the prosecution had conceded that there was no evidence of the provenance of the goods, her Honour did not refer to that consideration again and, as I have said, made no explicit finding about the separate element of dishonesty. This also is of some importance because absent a finding of dishonesty excluding a claim of right to return the goods for a refund the charge of financial advantage by deception is not made out.

…

[59] It seems to me, as Mr Stratton [senior counsel who appeared for Ms Selkirk] argued, that the evidence established that the provision of the refund to Ms Selkirk was caused not only by the presentation of the false POP but also by the “return” of the goods themselves. And that these circumstances together were some evidence of a representation by conduct of an entitlement to the refund sought. Absent evidence of the providence of the goods, more specifically absent evidence that they were not lawfully obtained from David Jones, these matters were sufficient to require consideration of claim of right given that that matter was central to the question of whether the Crown had proved the mental element of an intent to defraud, dishonestly, beyond reasonable doubt. The acceptance of the concession contained in the agreed facts and other evidence tending to prove, that none of Ms Selkirk’s credit cards identified in the agreed facts were used to purchase any of the goods does not of itself exclude a claim of right.

…

[65] For these reasons I am satisfied that Ms Selkirk has established Ground 1. While this is sufficient to dispose of the appeal, I will deal with the other grounds as they were fully argued. To be clear, I am satisfied that with respect, her Honour did not deal separately with the element of dishonesty bound up as it was with the issue of claim of right.

[66] Ground 2 is really put in the alternative to Ground 1 and given that I have upheld Ground 1, it does not arise. However, to the extent to which it asserts that her Honour reversed the onus of proof in relation to the element of dishonesty, and the available “defence” of “claim of right”, I am not satisfied that her Honour made this fundamental error.

[67] Mr Stratton sought leave to amend ground 3 to: “Ground three: her Honour erred in finding that the Plaintiff obtained a financial advantage, when there was no evidence that the Plaintiff received such an advantage.”

…

[79] Focusing solely and separately upon the element of financial advantage, clearly if the element of dishonesty were proved, or to put it another way, the related “defence” of claim of right were negatived, which may amount to the same thing, there was evidence, as her Honour found, that Ms Selkirk received a financial advantage. That evidence was the agreed fact that the amount of each refund shown in Exhibit 5 was transferred to one or other of her identified credit cards. For the reasons I have already given, Exhibit 4 is not evidence that Ms Selkirk received a financial advantage over and above the amount a person with a genuine entitlement to a refund in respect of the various items listed would receive. If the prosecution established dishonesty beyond reasonable doubt, claim of right would have been negatived, and Ms Selkirk would not have been entitled to any refund. Thus the receipt of the agreed electronic financial transfer applicable to the individual charge in her credit card account would have been a financial advantage.

Disposition

[80] It follows from my decision that the conviction for each of the fraud offences must be set aside. This includes the “attempt” offence of using a false document to obtain a financial advantage, an intention to defraud applies equally to that charge. It also follows that the convictions for each of the proceeds offences likewise must be set aside. Each of them was wholly dependent upon the refund being the proceeds of a charged fraud offence of which Ms Selkirk was convicted.

[81] Given that there was evidence supporting the charges before her Honour and that the error I have found consists of omitting to deal with the issue of dishonesty and the related matter of claim of right, which I have found fairly arose on the evidence, it will be necessary to remit the matters to the local court to be dealt with in accordance with these reasons.

75 In the course of her cross-examination, Ms Selkirk gave the following evidence in relation to the charges:

So we’re going to the New South Wales local court. And it proceeded by a statement of agreed facts, facts that you agreed to. That’s correct? They are facts that I agreed to, not offences that I agreed to. That’s correct.

So you agreed to a fact that you attended in person at each of these David Jones stores on 17 occasions to get a refund? You agreed to that? That’s correct. I would have agreed to them saying that it was purple in the sky at that day.

And that each of those occasions you attended you presented a proof of purchase document that had a false number that was a derivative of your phone number; that’s correct? That’s correct. That’s an admission to a fact; not an admission to an offence.

And you admitted that you knew that the proof of purchase numbers in each document were false; that’s correct? That’s correct.

And you conceded that you used a fraudulent receipt to obtain a refund of goods on 17 occasions; that’s correct? That is – that is not correct.

Well, 16 occasions; that’s correct? That is not correct. I did not at any stage concede to fraud – ever – ever – ever.

So on your view, you conceded deception? That’s correct, isn’t it? I conceded deception.

But you didn’t concede dishonesty? No, I did not. And I did – still do not. And I have maintained all along – I’ve – absolutely did not engage in dishonest conduct insofar as it is classed under that – those charges. And that is a very important distinction that needs to be understood which is exactly what was borne out under the appeal.

76 As is clear from that passage of cross-examination, Ms Selkirk did not (nor could she) deny the proposition that, despite the fact that her appeal was allowed and the charges ultimately withdrawn, on 17 occasions (including one attempt) she had committed those acts referred to in paragraph [70] above and that such conduct constituted what she admitted was “deception”.

77 The second important factual matter concerns the (limited) extent of the publication of the article.

78 The evidence was about publication is set out above. In substance, the evidence goes no higher than that three people, one of whom must have been Ms Selkirk, read the article on the MyLocalPages website.

79 The final factual matter concerns Ms Selkirk’s evidence about what she says was the serious harm to her reputation caused by the publication of the article.

80 I ruled significant parts of her 1 August 2023 affidavit to be inadmissible.

81 Her evidence that survived objection included the following:

32 I was admitted as a Barrister and Solicitor of the Supreme Court of Western Australia on 13 July 2003 and as a solicitor of the Supreme Court of New South Wales in June 2008 …

33. From about February 2014, I commenced working as a Consultant, primarily in the mining and resources sector, under my Incorporated Legal Practice MARC1 Consulting Pty Ltd, which was suspended from practice in 2019 and which has subsequently recently been re-instated as an Incorporated Legal Practice.

34. From February 2022, after the settlement of the News Corp Proceedings and removal of all of the NewsCorp and Fairfax source and licenced republished articles, I urgently commenced a significant legal employment application process, which included but was not limited to applications for the following jobs:

(a) a role for Head of Legal with &Legal, a law firm based in Double Bay New South Wales;

(b) a Senior Associate role with Resolve Litigation lawyers, a law firm based in Sydney New South Wales;

(c) a General Counsel role with Viva leisure, a company which operates health clubs in Australia;

(d) a role with Star Casino as in-house counsel for Domestic and International Governance

(e) an In-house Counsel role at Hoyts Group

(f) a General Counsel role at Meritos

(g) a head of legal role at Maple-Brown Abbott Private Investment Managers

(h) an numerous other Seek Executive Board and In-House General Counsel and Special Counsel/ Senior Associate/ Partner level roles.

35. The legal employment roles that I had progressed from February 2022 up to and including June 2022, which had active indications for reference check, due diligence and offer stage, but which employment offers and employment opportunities subsequently went cold … included:

(a) a role for Head of Legal with &Legal – I was invited to submit my referees … after asking my salary package expectations, however over the due diligence stage of this interview the opportunity went cold …;

(b) Senior Associate role with Resolve Litigation Lawyers – I was requested to provide referees for a reference check …;

(c) …

36. In or about late February/ March 2022, I had lunch with Chloe Noel deKerbrech (Chloe) who is a General Manager at Misfits Media. … Over lunch Chloe and I discussed the consulting opportunity and Chloe casually raised with me some reservations she had around any online articles referring to my criminal legal proceedings, that her management might be able to search my name and find. I told Chloe that all of the source NewsCorp and Fairfax articles, and their licenced republished articles, had been removed from the Google search platform under settlement agreements. This conversation prompted Chloe to do a Google search of my name and the Google search results returned the MyLocalPages Article …

37. In and around February 2022 to the end of May 2022, the specific times and dates I am not able to recall … nor had I been contacted to inform me that the offer and reference check process had been suspended … I suspended applying and interviewing for legal roles in around June 2022, at the time I engaged legal representation to issue the Concerns Notice to the Fifth and Sixth Respondents.

(a) On or around April 2022 I called Chloe and asked her to act as my referee. I said to Chloe, in words to the effect, that I had interviewed for a few roles, they had gone well and I had been asked to provide referees … She said further that she was concerned about having to respond to questions that potential employers may ask about the criminal proceedings. Ultimately, Chloe agreed to act as my referee …

(b) On or around April/ May 2022 I called Cliff Royle … and asked him to act as my referee. He agreed to act as my referee for the &Legal and Resolve Litigation and Viva Leisure roles …

(c) …

38. Maple-Brown Abbott Private Investment Managers

(i) On or around April/ May 2022, a friend of mine, Dale Herbert … called me and told me that I should apply for the head of legal role at Maple Brown Abbott Private Investment Managers. He said that I should send him my Curriculum Vitae so he could recommend me to the HR Manager. I told Dale that I was concerned about applying for the role as a Google search of my name still returned a few articles about the Convictions. After this conversation I sent my CV to Dale to give to his HR manager.

(j) …

39. I was not able to secure employment in my legal field until September 2022.

(Errors in original).

82 I should also add that Ms Selkirk filed written submissions which she prepared herself, but they were not referred to by her counsel in his closing submissions (or at all). I therefore put them to one side. Her counsel also made no particular reference to Ms Selkirk’s affidavit evidence either, other than to make this submission:

So the serious harm, your Honour – there is some evidence as to impact on the applicant herself. She gives evidence that she was shunned in terms of applying for jobs. Some of that is still left in. Some of it is out. I think it would be open for your Honour to draw an inference that, as a professional, as a solicitor and given the importance of honesty and integrity in the profession, that it would have a deleterious impact on her reputation and a serious one at that. I don’t – in my submission, direct evidence that people, for example, shunned her is not needed, although, there’s some evidence of that left in her affidavit …

Consideration

83 The only particular or serious harm alleged by Ms Selkirk about which any evidence was led was that her “professional reputation depends on her integrity as an admitted member of the legal profession and to have an unblemished reputation”; that the “imputations as alleged pose a serious risk to [her] ability to obtain gainful employment in a legal or executive role” and are matters which are “likely to prejudice [her] ability to obtain such employment”. See paragraph [10] above.

84 The immediate difficulty with the plea, and with the evidence led in support of it, is that neither address the critical question of whether the publication of the article caused any, let alone any serious, harm to Ms Selkirk. As Lord Sumption said in Lachaux v Independent Print Ltd [2020] AC 612 at [14]: “… [t]he reference to a situation where the statement ‘has caused’ serious harm is to the consequences of the publication, and not the publication itself. It points to some historic harm, which is shown to have actually occurred. This is a proposition of fact which can be established only by reference to the impact which the statement is shown actually to have had. The same must be true of the reference to harm which is ‘likely’ to be caused”.

85 Here, the evidence goes no further than vague assertions by Ms Selkirk that between February 2022 and September 2022, when she obtained employment in her field, the process of finding a job did not go very well, offers went cold and a number of referees were not contacted. Even if those things were attributable to the publication of the article – and I emphasise, there is no evidence of that whatsoever – I do not accept that those things constitute “serious harm” within the meaning of s 10A(1) of the Defamation Act, in any event.

86 Further, Ms Selkirk has admitted through her counsel, before the Magistrate and on appeal, and in the witness box before me, that on 17 separate occasions over a very significant period of time (more than two years), she engaged in the acts of deception set out at paragraph [70] above. In those circumstances, I do not accept that even widespread publication of the article telling the tale of her convictions and of her intention to appeal them, could have caused her reputation to be made worse. It is true that the convictions were quashed on grounds that included that the Crown had not proven “dishonesty” within the meaning of the statute, but where Ms Selkirk conceded that what she did was nonetheless deceitful, in my view she proffered a distinction without a relevant difference.

87 Put another way, and to adopt what Davis LJ said in Lachaux v Independent Print Ltd [2018] QB 594 at 620 [79], there is no evidence that anyone “thought any the less of [her] by reason of the publication”.

88 I should add that in her 1 August 2023 affidavit, Ms Selkirk deposed as follows:

I estimate that the lost opportunities of imminent offers of employment, over the period from January 2022 to well after June 2022 (up to end of September 2022), cost me a financial earning capacity in the vicinity of $25,000.00(+)/ month (plus Super) (before tax). This economic cost represents lost earning income …

89 I ruled that (and like) evidence to be inadmissible, because it was, among other things, conclusory and without evidentiary foundation. But in any event, it leads nowhere because no evidence was sought to be adduced to prove that the salary “lost” was caused by the publication of the article.

90 Lastly, there is the fact that the number of persons to whom the article was published was, on any view of the mater, very limited. As Davis LJ also said in Lachaux v Independent Print Ltd [2018] QB 594 at 620 [79], “[t]here may … be cases where the evidence shows that no serious reputational harm has been caused or is likely for reasons unrelated to the meaning conveyed by the defamatory statement complained of. One example could … be where the defendant considers that he has irrefutable evidence that the number of publishees was very limited”. This case is one such instance.

91 For each of those reasons – and each is sufficient on its own – in my view, Ms Selkirk has not proven that the publication of the article has caused, or is likely to cause, serious harm to her reputation.

Did the article convey one or more of the pleaded imputations?

92 This question is unnecessary to decide (and I therefore do not decide it) because the proceeding must be dismissed in any event.

93 I have not gone on to consider the question also because, on reflection, I was wrong to have proposed that it be set down for hearing as a separate question, untethered from the defences of fair report of proceedings of public concern, publication of matter concerning an issue of public interest and statutory qualified privilege.

94 The advantages of hearing separate questions can often end up being be more ephemeral than real, and so it is here with the imputations question.

Disposition

95 The proceeding must therefore be dismissed.

96 I will hear the parties about costs.

I certify that the preceding ninety-six (96) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice O’Callaghan. |

VID 429 of 2022 | |

GRIPEO LLC | |

Fifth Respondent: | MARTIN WYATT |

Sixth Respondent: | REAL ESTATE ONLINE PTY LTD |