Federal Court of Australia

Coleman v Veale [2023] FCA 1023

File number: | NSD 333 of 2023 |

Judgment of: | KENNETT J |

Date of judgment: | |

Catchwords: | BANKRUPTCY AND INSOLVENCY – application to set aside bankruptcy notice under s 30 of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (the Act) – whether failure to note and make allowance for a costs order adverse to respondent vitiated bankruptcy notice – consideration of whether invalidity flows automatically from misstatement – consideration of meaning of “amount in fact due” BANKRUPTCY AND INSOLVENCY – where bankruptcy notice includes a final judgment expressed in a foreign currency – error in publication date of exchange rate used – exchange rate expressed to two decimal places and equivalent amount understated due to rounding – whether bankruptcy notice complied with s 12 of the Bankruptcy Regulations 2021 (Cth) – whether non-compliance is merely formal PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE – where application lodged prior to, but not accepted for filing until after, expiration of the period in s 41(6A) of the Act – consideration of whether Court’s jurisdiction in bankruptcy properly invoked in light of Lamb v Sherman [2023] FCAFC 85 |

Legislation: | Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) ss 30, 40, 41, 306 Bankruptcy Regulations 2021 (Cth) s 12 Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) r 2.25 |

Cases cited: | Coleman v Gannaway [2023] FCA 224 Croker v Commissioner of Taxation [2005] FCA 127; 145 FCR 150 Duarte v Coshott [2017] FCA 1238 Farah Constructions Pty Ltd v Say-Dee Pty Ltd [2007] HCA 22; 230 CLR 89 Grant v Green & Associates Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 934 Herat v McLean Holdaway Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 816 Kleinwort Benson Australia Ltd v Crowl (1988) 165 CLR 71 Lamb v Sherman [2023] FCAFC 85 N & M Martin Holdings Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation [2020] FCA 1186 Nugawela v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation [2016] FCAFC 164 Parianos v Lymlind Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 684; 93 FCR 191 Re Emerson; Ex parte Wreckair Pty Ltd (1991) 101 ALR 315 Re Greenhill; Ex parte Myer (NSW) Ltd (1984) 5 FCR 84 Re Prossimo; Ex parte De Marco (1952) 16 ABC 86 Re Walsh (1982) 65 FLR 87 Seovic Civil Engineering v Groeneveld [1999] FCA 255; 87 FCR 120 Skououlis v St George Bank [2008] FCA 1765; 173 FCR 236 Walsh v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (1984) 156 CLR 337 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | General and Personal Insolvency |

Number of paragraphs: | |

27 June 2023 | |

Counsel for the applicant: | T Smartt |

Solicitor for the applicant: | Shiff & Company Lawyers |

Counsel for the respondent: | J Mee |

Solicitor for the respondent: | Campbell Paton and Taylor Solicitors |

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 30 of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth), bankruptcy notice BN 259365 issued on 23 March 2023 be set aside.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

KENNETT J

introduction

1 The applicant applies under s 30 of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (the Act) to set aside a bankruptcy notice (the notice) issued on 23 March 2023 at the request of the respondent.

2 On 28 June 2021 the respondent succeeded in obtaining a judgment against the applicant, in the District Court of the Republic of Singapore, in the amount of USD 150,000 plus interest at 5.33 percent per annum from the date of the writ of summons (which was 25 January 2018) to the date of payment (the Singapore trial judgment). The applicant appealed. The High Court of Singapore dismissed the appeal on 18 January 2022 (the Singapore appeal judgment). In doing so, the appellate court ordered that the costs of the proceedings be fixed at SGD 15,000 and ordered the release to the respondent of an amount of SGD 3,000 which the applicant had been ordered to pay as security for costs.

3 These two judgments were registered by the Supreme Court of New South Wales on 16 August 2022 (the NSW judgment). The NSW judgment is for the following amounts:

(a) USD 186,471.25, being the principal amount of the Singapore trial judgment plus accrued interest;

(b) AUD 12,396.64, being the AUD equivalent of the SGD 12,000 remaining to be paid by way of costs under the Singapore appeal judgment; and

(c) AUD 7,964.18, being the respondent’s costs of applying for registration.

4 The respondent obtained the issue of a bankruptcy notice in respect of the NSW judgment on 20 February 2023. That notice was set aside by this Court, by consent, on 21 March 2023. It has no further relevance, except that the respondent was ordered to pay the applicant’s costs fixed in the sum of $3,700 (the costs order).

5 On 21 March 2023 the respondent’s solicitor made a fresh application to the Official Receiver for the issue of a bankruptcy notice to the applicant. The notice with which the Court is presently concerned was issued, in response to that application, on 23 March 2023.

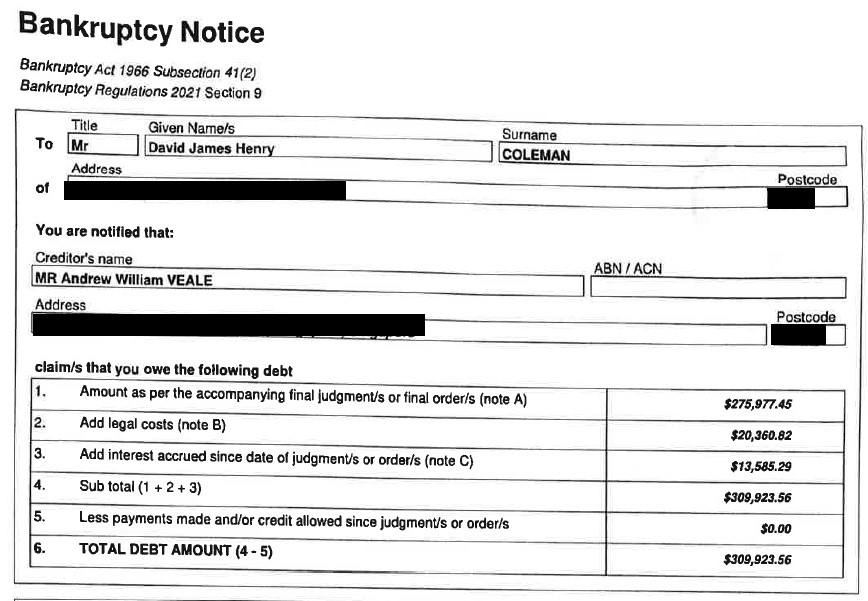

6 The notice asserts a total debt amount of $309,923.56, which it explains as follows:

7 Complaint is made about two aspects of the notice:

(a) the absence of allowance for the $3,700 payable by the respondent to the applicant pursuant to the cost order (ground 1 in the application); and

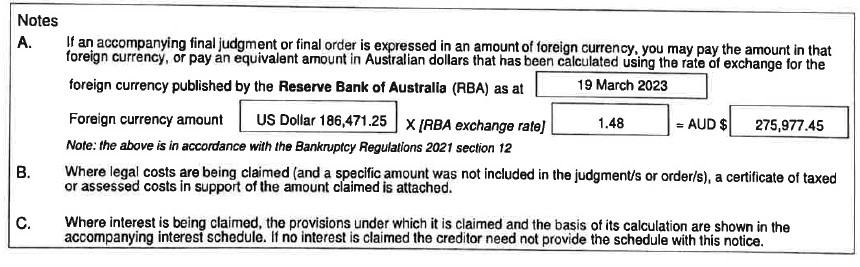

(b) an alleged error in note A of the notice, where it is said that the principal amount has been converted from USD to AUD using the rate of exchange published by the Reserve Bank of Australia (the RBA) “as at 19 March 2023” which was said to be 1.48 (ground 2 in the application).

relevant provisions

8 The substantive issues involve s 41 of the Act which, relevantly, provides as follows:

(1) An Official Receiver may issue a bankruptcy notice on the application of a creditor who has obtained against a debtor:

(a) a final judgment or final order that:

(i) is of the kind described in paragraph 40(1)(g); and

(ii) is for an amount of at least the statutory minimum; or

(b) 2 or more final judgments or final orders that:

(i) are of the kind described in paragraph 40(1)(g); and

(ii) taken together are for an amount of at least the statutory minimum.

(2) The notice must be in accordance with the form prescribed by the regulations.

(2A) The notice must specify a period for compliance with the notice. That period must be:

(a) if the notice is to be served in Australia—the statutory period after the debtor is served with the notice; or

(b) ...

(3) A bankruptcy notice shall not be issued in relation to a debtor:

(a) except on the application of a creditor who has obtained against the debtor a final judgment or final order within the meaning of paragraph 40(1)(g) or a person who, by virtue of paragraph 40(3)(d), is to be deemed to be such a creditor;

(b) if, at the time of the application for the issue of the bankruptcy notice, execution of a judgment or order to which it relates has been stayed; or

(c) in respect of a judgment or order for the payment of money if:

(i) a period of more than 6 years has elapsed since the judgment was given or the order was made; or

(ii) the operation of the judgment or order is suspended under section 37.

(5) A bankruptcy notice is not invalidated by reason only that the sum specified in the notice as the amount due to the creditor exceeds the amount in fact due, unless the debtor, within the time fixed for compliance with the notice, gives notice to the creditor that he or she disputes the validity of the notice on the ground of the misstatement.

(6) Where the amount specified in a bankruptcy notice exceeds the amount in fact due and the debtor does not give notice to the creditor in accordance with subsection (5), he or she shall be deemed to have complied with the notice if, within the time fixed for compliance with the notice, he or she takes such action as would have constituted compliance with the notice if the amount due had been correctly specified in it.

(6A) Where, before the expiration of the time fixed for compliance with a bankruptcy notice:

(a) proceedings to set aside a judgment or order in respect of which the bankruptcy notice was issued have been instituted by the debtor; or

(b) an application has been made to the Court to set aside the bankruptcy notice;

the Court may, subject to subsection (6C), extend the time for compliance with the bankruptcy notice.

(6C) …

(7) Where, before the expiration of the time fixed for compliance with a bankruptcy notice, the debtor has applied to the Court for an order setting aside the bankruptcy notice on the ground that the debtor has such a counter-claim, set-off or cross demand as is referred to in paragraph 40(1)(g), and the Court has not, before the expiration of that time, determined whether it is satisfied that the debtor has such a counter-claim, set-off or cross demand, that time shall be deemed to have been extended, immediately before its expiration, until and including the day on which the Court determines whether it is so satisfied.

9 Failure to comply with a bankruptcy notice within the time specified for compliance is (subject to certain other conditions being satisfied) an act of bankruptcy. Section 40(1)(g) provides:

(1) A debtor commits an act of bankruptcy in each of the following cases:

…

(g) if a creditor who has obtained against the debtor a final judgment or final order, being a judgment or order the execution of which has not been stayed, has served on the debtor in Australia or, by leave of the Court, elsewhere, a bankruptcy notice under this Act and the debtor does not:

(i) where the notice was served in Australia—within the time fixed for compliance with the notice; or

(ii) where the notice was served elsewhere—within the time specified by the order giving leave to effect the service;

comply with the requirements of the notice or satisfy the Court that he or she has a counter-claim, set-off or cross demand equal to or exceeding the amount of the judgment debt or sum payable under the final order, as the case may be, being a counter-claim, set-off or cross demand that he or she could not have set up in the action or proceeding in which the judgment or order was obtained;

…

10 In the present case, the “time fixed for compliance with the notice” has been extended by orders made under s 41(6A).

11 It is useful also to mention s 30, which defines the powers of the Court exercising jurisdiction in bankruptcy (which is conferred by s 27). Section 30(1) provides:

(1) The Court:

(a) has full power to decide all questions, whether of law or of fact, in any case of bankruptcy or any matter under Part IX, X or XI coming within the cognizance of the Court; and

(b) may make such orders (including declaratory orders and orders granting injunctions or other equitable remedies) as the Court considers necessary for the purposes of carrying out or giving effect to this Act in any such case or matter.

preliminary issue

12 A question was raised by the registry as to whether the Court’s jurisdiction in bankruptcy had been properly invoked, in the light of Lamb v Sherman [2023] FCAFC 85 (Lamb). The respondent did not take a position on this point.

13 Lamb involved an issue as to whether the appellant had made an application to set aside a bankruptcy notice within the time permitted by s 41(6A) of the Act. Her application had been lodged electronically using the Court’s electronic filing system at 4:37 pm on the last day of the relevant period and accepted for filing at 2:44 pm the following day. The Full Court noted at [54] that, in order for the Court’s jurisdiction to be invoked, an application must be not only lodged but accepted for filing by the registry. However, in the same paragraph, the Full Court noted the effect of r 2.25(3) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), which is that:

(a) a document that is received by electronic communication by 4:30 pm on a business day is “taken to have been filed” on that day; and

(b) otherwise, the document is taken to have been filed the next day.

14 The problem for Ms Lamb was that her application was transmitted after 4:30 pm. The application was not “made” at the moment of lodgement. There was nothing before the Court until it was accepted for filing; and once accepted, the date when it was taken to have been filed was dictated by r 2.25(3). It was thus taken to have been filed on the day after transmission (which was too late). Acceptance for filing also occurred on the day after the transmission, but that was not determinative given the deeming effect of r 2.25(3).

15 The application in the present case was lodged electronically on 12 April 2023, five days before the period in s 41(6A) expired, at 2:05 pm. For reasons which are not clear, it was not accepted for filing until 18 April 2023, the day after the period expired. However, pursuant to r 2.25(3), it is taken to have been filed on the day it was lodged (and thus within time). Nothing in Lamb suggests to the contrary.

Ground 1

16 Ground 1 raises the issue whether the notice is vitiated by the failure to note, and make allowance for, the $3,700 which the respondent was required to pay the applicant as a result of the costs order.

17 On 11 April 2023, after the notice had been served, the applicant’s solicitors gave notice in accordance with s 41(5) of the Act disputing the validity of the notice on the ground of misstatement and pointing to the amount that was payable pursuant to the costs order. The respondent’s solicitors replied on the same day agreeing to pay that amount to the applicant, and payment was made on 13 April 2023. The applicant nevertheless maintains that the notice was invalid because it overstated the amount due.

18 In this regard the applicant relies on an implication drawn from s 41(5). That subsection (which is set out above) begins with a general proposition that a bankruptcy notice is not invalidated by having overstated the amount due, but then states a qualification which excludes that proposition in a case where notice of a dispute has been given. On one view, the qualification may be taken as implying that overstating the amount due does invalidate the bankruptcy notice in a case where such notice is given.

19 The Full Court in Nugawela v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation [2016] FCAFC 164 at [24] (Nugawela) observed that s 41(5) “is not the source of the power to set aside bankruptcy notices for misdescription”. The Court expressed agreement with observations by Lockhart J in Re Walsh (1982) 65 FLR 87 at 91–92 (Re Walsh), noting that ss 41(5) and (6) were derived from provisions in earlier bankruptcy legislation whose intention and effect was to save certain bankruptcy notices from invalidity if the relevant notice had not been given.

20 This does not mean that there is no power to set aside a bankruptcy notice for overstatement. Section 41(5) clearly assumes that such power exists, and s 30(1)(b) of the Act is broad enough to contain such a power. However, the conclusion in Nugawela, that the power is not found in s 41(5), means that the qualifying words in that subsection cannot be taken to confer the power or define its extent. Those words therefore do not sustain a conclusion that any misdescription leads to invalidity so long as the necessary notice is given by the debtor. Rather, they identify the circumstance in which a question as to whether the bankruptcy notice should be set aside for misdescription can properly arise.

21 In part of the passage quoted with approval in Nugawela, Lockhart J said of ss 41(5) and (6) (Re Walsh at 91–92):

They are ameliorating provisions. They do not either in terms or in substance themselves invalidate anything. They save some bankruptcy notices from what otherwise would be invalidity, but the subsections are not based on an assumption that overstatement necessarily leads in every case to invalidity of the bankruptcy notice

22 Lockhart J held at 91 that, under the earlier law (which was not displaced by s 41(5)), misstatement of the amount due would lead to invalidity only if it had the consequence that the notice could reasonably mislead the debtor on whom it was served.

23 Morling J in Re Greenhill; Ex parte Myer (NSW) Ltd (1984) 5 FCR 84 (Re Greenhill) and Pincus J in Re Emerson; Ex parte Wreckair Pty Ltd (1991) 101 ALR 315 (Re Emerson) disagreed with the reasoning of Lockhart J in Re Walsh. The Full Court in Seovic Civil Engineering v Groeneveld [1999] FCA 255; 87 FCR 120 (Seovic) at [51] assumed (without needing to decide) that Re Greenhill and Re Emerson correctly stated the law. Flick J proceeded similarly in Herat v McLean Holdaway Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 816 at [19].

24 Both Morling J and Pincus J were influenced by a statement by Gibbs CJ in Walsh v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (1984) 156 CLR 337 at 339 (the ultimate appeal from the decision of Lockhart J (Walsh HCA)) that:

There is no doubt that a bankruptcy notice will be invalid if the sum specified in the notice as to the amount due to the creditor exceeds the amount for which the creditor is entitled to issue execution.

25 The observation of Gibbs CJ was also relied upon in one post-Seovic decision that clearly supports an understanding of s 41(5) in which invalidity flows automatically from overstatement, so long as a notice of dispute is served: Skoudoulis v St George Bank [2008] FCA 1765; 173 FCR 236 (Skoudoulis) at [22]–[27] (Edmonds J). (Skoudoulis is distinguishable from the present case on its facts, as the bankruptcy notice in that case had failed to reflect payments made by the debtor in respect of the relevant judgment debt itself.)

26 The observation of Gibbs CJ, however, merely served to introduce the actual issue that remained to be decided by the High Court in Walsh HCA, namely the date at which any misstatement was to be identified. No disagreement was expressed with the aspects of Lockhart J’s reasoning referred to above; indeed, no reference was made to it. I do not consider that this single sentence comes within the category of “seriously considered dicta” (cf Farah Constructions Pty Ltd v Say-Dee Pty Ltd [2007] HCA 22; 230 CLR 89 at [134]).

27 Be that as it may, the endorsement of Lockhart J’s position by the Full Court in Nugawela appears to decide the point so far as a single judge is concerned. In Tu v Chang (No 2) [2016] FCA 1568 at [29], Nugawela was cited by Bromwich J for the proposition that:

The words in s 41(5) are capable of being given too much weight or too little. They neither protect all misstatements, nor operate on the presumption that all misstatements are fatal.

28 The following year, in Duarte v Coshott [2017] FCA 1238 at [41], his Honour said (after again citing Nugawela):

It is true that a valid s 41(5) notice does not automatically lead to invalidity. That provision is not the source of any power to set aside a bankruptcy notice, as opposed to s 30, which bestows a broad discretion. Further, it falls for consideration whether the relevant misstatement was material, such that it is beyond the purview of s 306(1) of the Bankruptcy Act.

29 In my view, this represents the correct approach. Although Wigney J in Grant v Green & Associates Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 934 at [19] expressed a position consistent with Re Greenhill, Re Emerson and Skoudoulis, his Honour does not appear to have been referred to Nugawela or the subsequent statements by Bromwich J. Wigney J referred in that paragraph to Seovic and Skouloudis (which are discussed above) and to Croker v Commissioner of Taxation [2005] FCA 127; 145 FCR 150; at [16] (Hely J) (which, in my respectful opinion, does not take matters far). All of these cases predate Nugawela.

30 A construction of s 41(5) that allows an unscrupulous debtor to take advantage of immaterial errors in a bankruptcy notice by having the notice set aside is, in the light of the purposes of bankruptcy legislation, to be avoided. Section 41(5) should be understood as foreclosing any question of invalidity on the ground of overstatement where notice of a dispute has not been given within the specified time (with the debtor in such a case having the benefit of s 41(6)) and, in the case of a dispute, leaving the question whether the bankruptcy notice should be set aside to be decided in the exercise of discretion under s 30(1)(b). Because the power is discretionary, it may be that the categories of case in which a bankruptcy notice should be set aside are not closed (as the reasoning in Re Walsh at 91–92 possibly suggests). However, it is difficult to envisage a case, other than one in which the overstatement “could reasonably mislead the debtor on whom [the bankruptcy notice] is served”, where overstatement alone would justify setting aside a bankruptcy notice.

31 In the present case, the overstatement that is alleged is the absence of any allowance for the sum of $3,700 which the respondent owed to the applicant pursuant to the costs order. In this respect, the notice was very clear. The notice (the relevant part of which is set out above) recites the respondent’s claim “that you owe the following debt”, followed by six lines in which amounts have been inserted leading to the “TOTAL DEBT AMOUNT (4 - 5)”. Line 4 is the total of the relevant judgment debt, legal costs and interest. Line 5 reads “Less payments made and/or credit allowed since judgment/s or order/s”. The amount entered in line 5 was $0.00. It was therefore obvious that the respondent was claiming the entire amount that he asserted he was owed by the applicant, rather than that amount minus the amount of the costs order.

32 The applicant could not realistically have been misled by this aspect of the notice as to what was claimed by the respondent. It was clear from the time he received the notice that he could:

(a) pay the entire amount claimed and pursue the respondent separately for the $3,700 that the respondent owed him;

(b) pay the entire amount minus $3,700, and rely on s 41(6) in support of an argument that that was sufficient to comply with the notice; or

(c) decline to pay anything, knowing that in doing so he was likely committing an act of bankruptcy.

33 In my view the failure to deduct $3,700 from the amount claimed in the notice, even if it results in overstatement of the relevant debt, does not justify an order invalidating the notice.

34 There was some debate in the parties’ submissions as to whether the failure to deduct $3,700 resulted in overstatement. The debate focused on the expression “the amount in fact due” in s 41(5). That emphasis may be misplaced in the light of the point made in Nugawela: s 41(5) defines a class of case in which a bankruptcy notice is protected from attack on the ground of overstatement, but does not define the class of cases in which a bankruptcy notice must be (or may be) set aside on that ground. However, against the possibility that my reasoning above is incorrect, I have considered whether the failure to deduct $3,700 resulted in the notice in the present case overstating “the amount in fact due” in the sense in which that expression is used in s 41(5).

35 Section 41(1) sets out the conditions that must exist before a bankruptcy notice can be issued. The debtor must have obtained one or more “final judgments or final orders” which, alone or together, are (inter alia) “for an amount” that exceeds the statutory minimum. Section 41(3) stipulates further requirements in relation to the “final judgment or final order” which the creditor who makes the application must have obtained against the debtor.

36 The need for a “final judgment or order” as the basis for a bankruptcy notice is also reflected in s 40(1)(g), which is set out above. That paragraph provides that, to avoid committing an act of bankruptcy, the debtor must either comply with the bankruptcy notice or satisfy the Court that they have “a counter-claim, set-off or cross demand equal to or exceeding the amount of the judgment debt or sum payable under the final order”. A debt owed by the creditor to the debtor is thus irrelevant, at that stage, unless it exceeds the amount of the judgment debt that formed the basis for the bankruptcy notice.

37 These provisions indicate that a bankruptcy notice, and its statutory consequences, are based on the debts specifically attributable to one or more identified “final judgments or orders”. They are a means by which payment of judgment debts can be enforced, rather than a vehicle for the adding up and balancing out of all current obligations as between the creditor and the debtor. This is consistent with the relatively streamlined procedure for the issuing of bankruptcy notices under the Act. If the “amount in fact due” (being the amount which can properly be claimed) referred to a calculation of the overall position as between creditor and debtor, the creditor (in applying for the issue of a notice) and the Official Receiver (in issuing the notice) would in some cases have to digest a significant amount of information and resolve potentially contestable questions as to the availability of set-off. Instead, references to an “amount” or the “amount in fact due” should be taken to refer to the amount due pursuant to the identified judgment debt.

38 For these reasons, I do not think a bankruptcy notice that claims the amount of an identified judgment debt plus associated legal costs and interest is liable to be invalidated for overstatement, subject to making an appropriate deduction having been made for any part of that debt that has been paid or forgiven (cf Re Prossimo; Ex parte De Marco (1952) 16 ABC 86 at 89 (Clyne J); Skoudoulis). If the question turns on the construction of the expression “the amount in fact due” in s 41(5), I would construe it accordingly. Legal and equitable doctrines of set-off, which might be available in other contexts, have no purchase here.

39 Ground 1 is therefore rejected.

Ground 2

40 Ground 2 alleges non-compliance with ss 12(2)(a)(ii) and (b) of the Bankruptcy Regulations 2021 (Cth) (the Regulations). Section 12 is as follows:

12 Judgment or order in foreign currency

(1) This section applies in relation to a bankruptcy notice issued by the Official Receiver in relation to a debtor if the notice includes a final judgment, or final order, that is expressed in an amount of foreign currency (whether or not the judgment or order is also expressed in an amount of Australian currency).

(2) The bankruptcy notice must include the following:

(a) a statement to the effect that the debtor must pay:

(i) the amount of foreign currency; or

(ii) the equivalent amount of Australian currency;

(b) the conversion calculation for the equivalent amount of Australian currency;

(c) a statement to the effect that the conversion of the amount of foreign currency into the equivalent amount of Australian currency has been made in accordance with this section.

(3) For the purposes of subparagraph (2)(a)(ii), the equivalent amount of Australian currency is the amount worked out using the rate of exchange for the foreign currency published by the Reserve Bank of Australia in relation to the day that is 2 business days before the day on which the application for the notice is made.

Note: The Reserve Bank of Australia exchange rates could in 2021 be viewed on the Reserve Bank of Australia’s website (http://www.rba.gov.au).

41 The requirements set out in s 12 are aspects of the “form” with which a bankruptcy notice must comply, by force of s 41(2) of the Act. Section 12 applies to the notice in the present case, because the NSW judgment (upon which the notice relied) was expressed in US dollars.

42 Note A to the notice in the present case includes a statement of the kind required by s 12(2)(a). Note A is framed as a footnote to the first line in the calculation set out above at [6]. It says:

43 The text of Note A quoted above is that of the standard form for bankruptcy notices. I was informed (and this does not appear controversial) that it is the form in which a notice issues after relevant details have been submitted through the website of the Australian Financial Security Authority (AFSA). The information contained in the boxes in the image above is the information inserted by the respondent in the process of applying for issue of the notice.

44 The applicant argues that the notice:

(a) fails to comply with s 12(2)(a)(ii), because it does not contain a statement to the effect that the debtor must pay “the equivalent amount of Australian currency” as that term is defined by s 12(3); and

(b) fails to comply with s 12(2)(b), because the “conversion calculation” that it sets out is not a calculation for “the equivalent amount of Australian currency” as defined.

45 As to the first argument, what is required by s 12(2)(a) is a statement to the effect that the debtor must pay either the amount of the judgment as expressed in foreign currency or the equivalent amount of Australian currency. A statement in those terms (without further elaboration of what “the equivalent amount of Australian currency” is) would meet the requirement. However, the text of Note A does not take that approach. It says that the debtor must pay either the foreign currency amount or “an equivalent amount in Australian dollars that has been calculated” in the manner that the Note sets out. If the product of that calculation is not “the equivalent amount of Australian currency” as defined by s 12(3), it will follow that the Note fails to set out the alternatives identified by s 12(2)(a).

46 As to the second argument, what is required by s 12(2)(b) is a setting out of the conversion calculation “for the equivalent amount of Australian currency”. The calculation that is set out must be one that leads to “the equivalent amount of Australian currency” as defined.

47 The important point for both arguments, therefore, is whether the calculation set out in Note A of the notice aligns with s 12(3).

48 The first problem with the calculation set out in the notice is that it refers to an exchange rate published by the RBA “as at 19 March 2023”. That day was a Sunday and was two calendar days, rather than business days, before the application for the notice was made. The exchange rate that Mr Bennett, the respondent’s solicitor, actually used to make the calculation was that published by the RBA on Friday 17 March 2023, which was the correct rate for the purposes of s 12(3). However, because the incorrect date was inserted into the form, the notice failed to set out a calculation of “the equivalent amount of Australian currency” as defined by s 12(3).

49 The second problem with the calculation arises in connection with the fact that the relevant exchange rate was expressed to two decimal places. Because the RBA does not actually publish rates for converting foreign currency into Australian dollars, it was necessary to use the inverse of the published rate. The published RBA rates are expressed to four decimal places. In materially similar circumstances in Coleman v Gannaway [2023] FCA 224 (Gannaway) at [39], Jackman J said:

It has not been necessary for me to deal with the question of how many decimal places should be used when adopting a foreign currency exchange rate which is not in fact published expressly by the RBA, but which is the inverse of the rates published by the RBA. Regulation 12(3) does not stipulate in those circumstances how many decimal places should be used. Given that the RBA publishes rates to four decimal places, in my view a sensible reading of reg 12(3) is that, when calculating the inverse of those published rates, one should use at least four decimal places.

50 This observation was not necessary to his Honour’s decision. Similarly, I do not think it is necessary for me to express a concluded view as to how many decimal places should be used. The true problem lies elsewhere.

51 In converting an amount expressed in US dollars into Australian dollars, it was necessary for Mr Bennett to find the relevant exchange rate published by the RBA and then multiply the relevant US dollar amount by the inverse of that rate. The published rate was 0.6714. Unimpeded by the demands of a prescribed form, a sensible person would simply divide the US dollar amount (186,471.25) by 0.6714, using their mobile phone or a pocket calculator, and obtain an answer of $277,734.96. However, the form used in the present case (which is the online form on the AFSA website) requires the foreign currency amount to be multiplied by the relevant exchange rate and therefore demands that the inverse of the RBA rate be set out in decimal form. That immediately introduces inaccuracy or confusion (or both), because expressing the inverse of the RBA rate in decimal form is highly likely to require rounding. The problem is exacerbated because the form only allows a figure with two decimal places to be inserted in the relevant space.

52 In Gannaway, the creditor’s solicitor derived a multiplier of 1.11495 from the published RBA rate, which he applied to the relevant foreign currency amount. His calculation was not criticised, and he had inserted the product of that calculation in the space provided for the “AUD” amount in Note A. However, being limited to two decimal places in expressing the relevant rate, he inserted “1.11” in that space. Jackman J said (at [30]):

In my opinion, the error in Note A in the Bankruptcy Notice constitutes a non-compliance with reg 12(2)(b), which requires that the bankruptcy notice “must” include “the conversion calculation for the equivalent amount of Australian currency”. The bankruptcy notice referred to the multiplier as being 1.11, rather than the calculation which was actually performed using 1.11495. Accordingly, the stated product AUD923,614.07 was wrong as a matter of arithmetic, based on the figures that were adopted in Note A, even though it was in fact the product which was produced by the calculation that was in fact performed. Accordingly, Note A did not set out the conversion calculation which was actually performed, and nor did it set out, as a result of the calculation expressed in Note A, the “equivalent” amount of Australian currency.

53 Mr Bennett, the respondent’s solicitor in the present case, was aware of what had been said in Gannaway and attempted to accommodate it. He calculated the inverse of 0.6714, to four decimal places, as 1.4894. With Gannaway in mind, he sought to avoid setting out a calculation that was wrong on its face, and therefore rounded the inverse figure to two decimal places before performing the calculation. If rounded in a conventional manner, the multiplier would be 1.49, which would overstate the amount due. He therefore rounded the multiplier down to 1.48, which produced an Australian dollar amount of $275,977.45. The calculation thus expressed is correct, but the answer understates “the equivalent in Australian currency” by (by my calculation) $1,757.51.

54 In Gannaway at [38] Jackman J expressed sympathy for the respondent, whose solicitor had diligently sought to comply with the statutory requirements. The same can be said here. Mr Bennett did the best that could be done, in the light of the reasoning in Gannaway, to comply with the requirements of s 12(2) while using the AFSA website. The evidence in Gannaway did not show whether AFSA’s online portal was the only means available to apply for a bankruptcy notice. Here, it is possible to infer from Mr Bennett’s affidavit that that is the case, and if necessary I would do so. However, the dictates of the website cannot override the requirements of s 12 or avoid the consequences of their breach.

55 Section 12(3) defines “the equivalent amount of Australian currency” in a way that means that, for any foreign currency amount on any given day, there is a single correct answer (at least if the RBA publishes an exchange rate for that currency). The “rate of exchange for the foreign currency published by the Reserve Bank of Australia” means the rate published on the relevant day, expressed to however many decimal places the RBA expresses it. Dividing the relevant amount by that number (or multiplying by its inverse, which is the same thing) can as a matter of arithmetic produce only one answer, which is then to be rounded to the nearest cent. There is no scope for discretion or judgment in the process. Rounding the inverse of the published rate to two (or any particular number of) decimal places before doing the calculation produces, except in the exceedingly rare cases where the rounding makes no difference, an answer that is not “the equivalent amount of Australian currency”. The consequence, for reasons set out above, is that the notice in the present case did not comply with ss 12(2)(a) or (b).

56 The next issue that arises is whether that non-compliance is fatal to the notice. Section 306(1) of the Act provides that a “formal defect or irregularity” does not invalidate things done under the Act unless the Court considers that the irregularity causes “substantial injustice”. However, Mason CJ, Wilson, Brennan and Gaudron JJ observed in Kleinwort Benson Australia Ltd v Crowl (1988) 165 CLR 71 (Crowl) at 79–80 that, according to the authorities, “a Bankruptcy Notice is a nullity if it fails to meet a requirement made essential by the Act, or if it could reasonably mislead a debtor as to what is necessary to comply with the notice … In such cases the notice is a nullity whether or not the debtor in fact is misled”.

57 The actual decision in Crowl was that an understatement of the interest due on the judgment debt (by some $23,000) was a formal defect which attracted s 306(1). Because the notice was clear as to what had to be done to comply with it, it was not capable of misleading and therefore not a nullity (at 80–81). However it appears to have been a necessary step in this reasoning that interest on a judgment debt need not be included in a bankruptcy notice (see at 77), so that an accurate statement of the interest was not “a requirement made essential by the Act”.

58 The formulation in Crowl at 79–80 was extended in Parianos v Lymlind Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 684; 93 FCR 191 (Parianos) at [15] (Sackville J) to a requirement “rendered essential by a valid regulation made pursuant to [the Act]”. The regulation in question in that case, held to have erected “essential” requirements (at [16]–[19]), was a predecessor of s 12. Jackman J accordingly regarded Parianos as indistinguishable in Gannaway, a conclusion with which I agree.

59 For my own part, I have some reservations concerning the reasoning in Parianos. Arguably, the regulation making power that sustains s 12 and sustained its predecessors is s 315(1)(a) (matters “required or permitted by this Act to be prescribed”), in combination with s 41(2) (which requires a notice to be “in accordance with the form prescribed by the regulations”). There is something to be said for the view that non-compliance with a requirement as to the “form” of a bankruptcy notice constitutes a defect or irregularity that is “formal” (the term used in s 306(1)) and, consequently, should be regarded as invalidating a bankruptcy notice only if it leads to substantial injustice. That would have the potential to avoid the obvious injustice of invalidation of a bankruptcy notice in a case such as the present, where the Australian dollar amount sought by the notice is understated to the advantage of the debtor and what must be done in order to comply with the notice is tolerably clear. However, Parianos has stood as authority for more than 20 years and I do not think it can be said to be plainly wrong (cf, eg, N & M Martin Holdings Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation [2020] FCA 1186 at [43]–[46] (Steward J)).

60 On this basis, I am driven to conclude that the defects in compliance with s 12(2) in the present case lead to the invalidity of the notice.

disposition

61 The order sought by the applicant, setting aside the notice, should be made.

62 I will hear the parties as to costs. Counsel for the respondent foreshadowed a costs application at the hearing. I also have the preliminary view that the respondent should not bear the costs incurred by the applicant in relation to the jurisdictional issue, which he did not raise.

I certify that the preceding sixty-two (62) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Kennett. |

Associate: