Federal Court of Australia

AHG WA (2015) Pty Ltd v Mercedes-Benz Australia/Pacific Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1022

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties on or before 21 September 2023 file and serve proposed minutes of orders to give effect to these reasons.

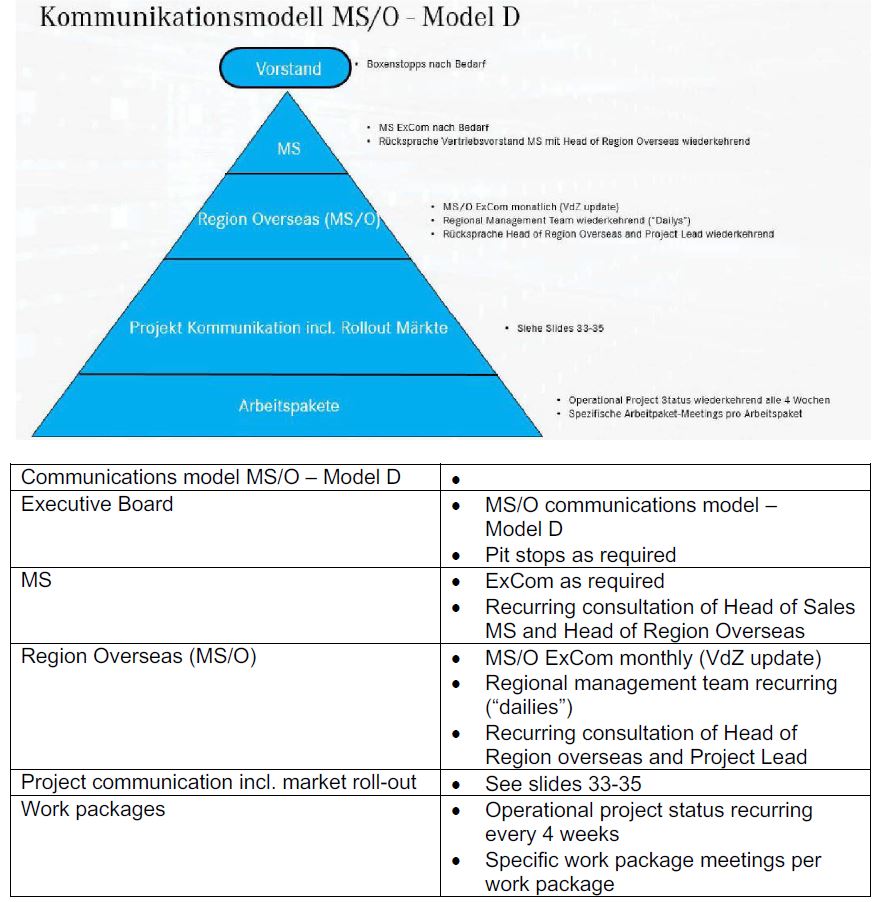

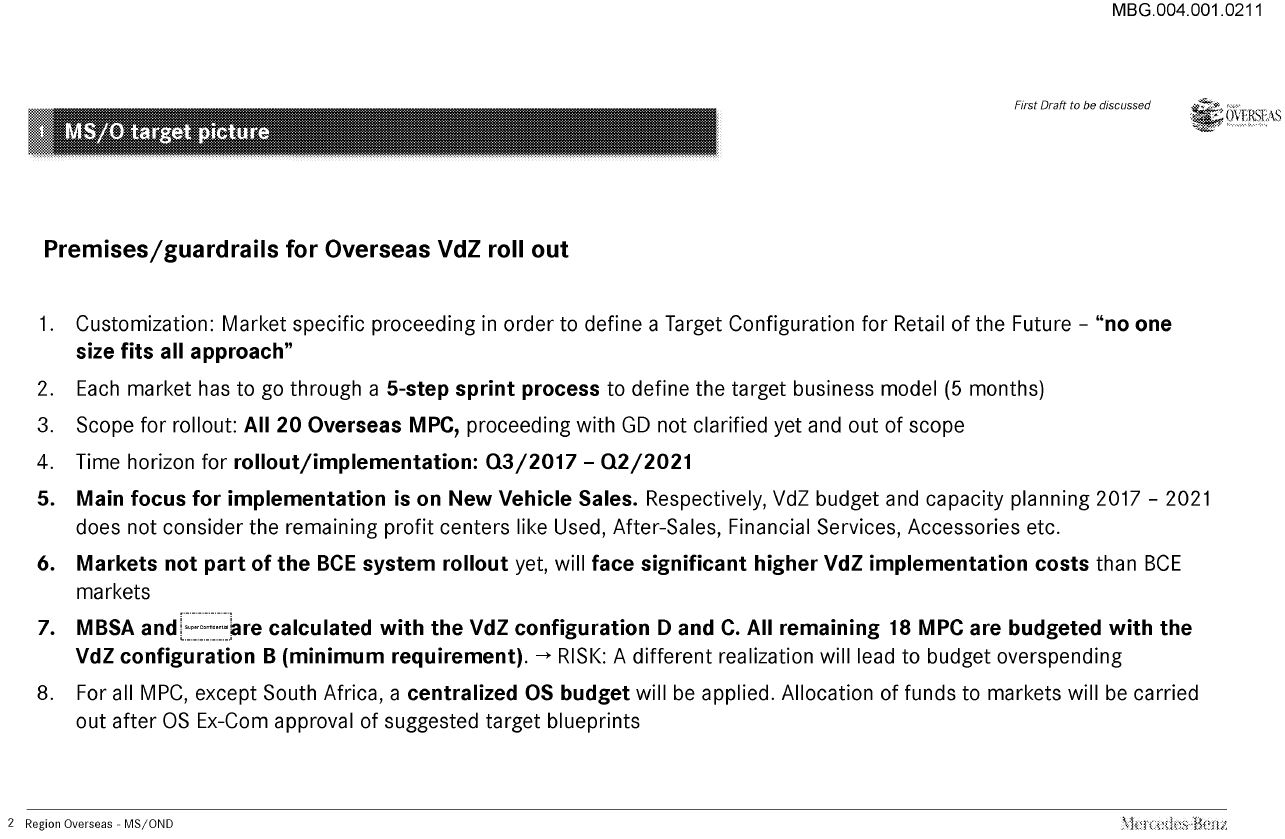

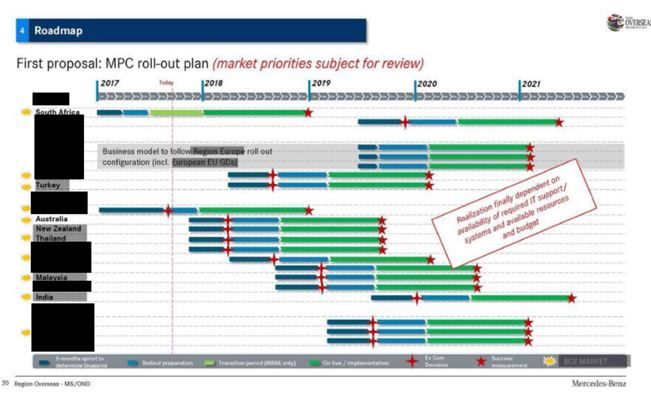

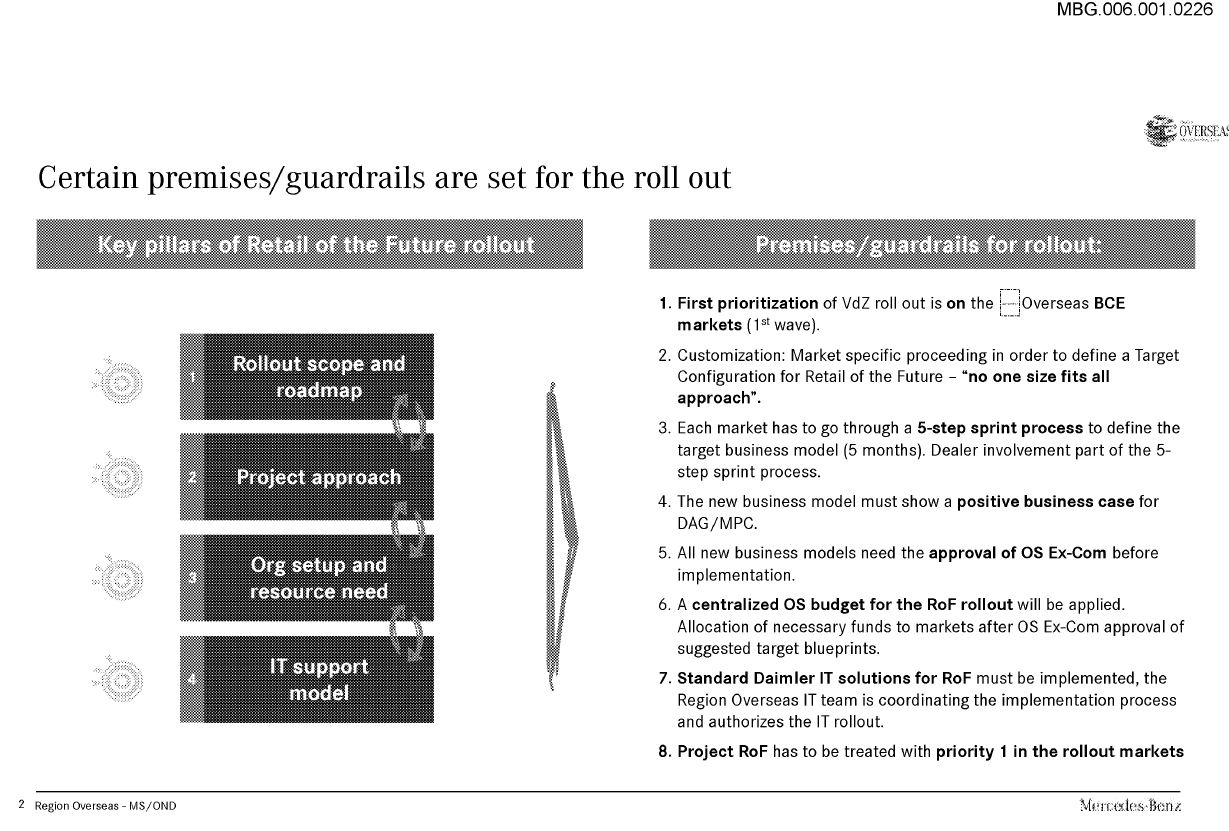

2. There be a further case management hearing on a date to be fixed to deal with confidentiality issues.

3. Liberty to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BEACH J:

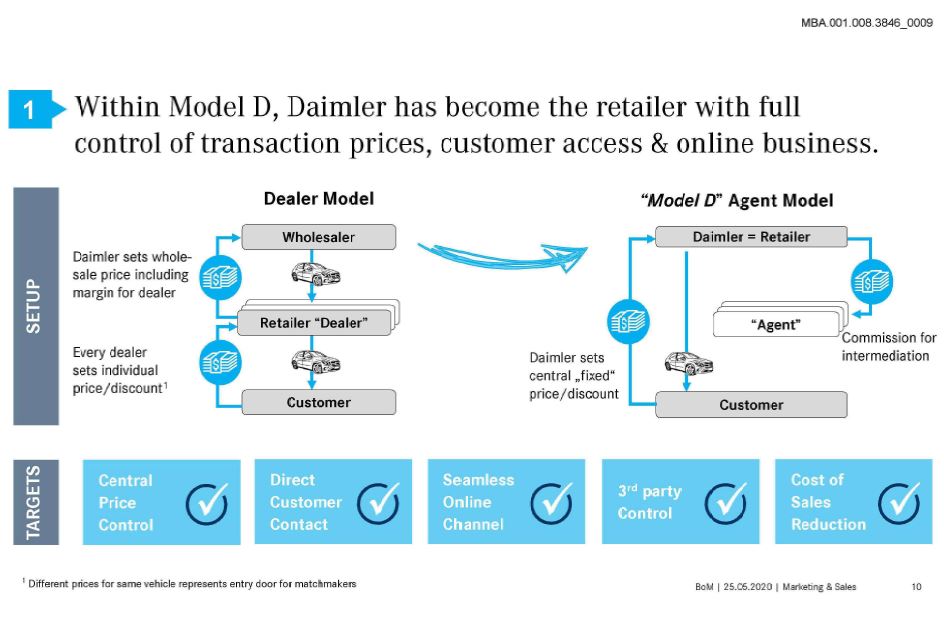

1 Mercedes-Benz dealers have brought the present proceeding asserting that the agency model as implemented in Australia by Mercedes-Benz Australia/Pacific Pty Ltd (MBAuP) has involved the appropriation of their goodwill and customer relationships for no or inadequate compensation. It is said that this agency model has provided a worse financial return to the dealers than existed under the prior dealership model.

2 Now from 2018 onwards the dealers consistently opposed the introduction by MBAuP of the agency model. It is said that they did so having endured years of misrepresentations by MBAuP, threats to their ongoing business relationship, and the refusal to genuinely negotiate the terms of the agency agreements. Such conduct was said to involve the spin and dissimulation of officers of MBAuP including Mr Horst von Sanden, Mr Florian Seidler and Mr Jason Nomikos in their dealings with the dealers.

3 It is said that the implementation of the agency model and the issuing of non-renewal notices bringing to an end their relationships under the prior dealer agreements were not the product of a genuinely conducted process, and were not conducted in good faith.

4 Further, it is said that there has been an appropriation of the dealers’ goodwill in the events which have occurred without compensation. Moreover, it is said that MBAuP knew or was recklessly indifferent to the fact that most if not all of the dealers would be worse off under the agency model. It is said that this model was imposed on the dealers in contumelious disregard of their interests.

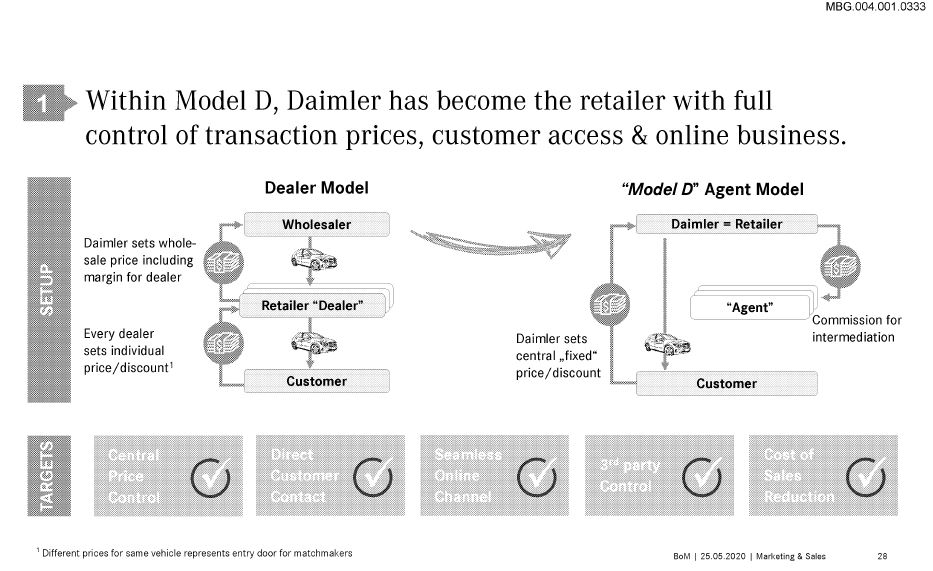

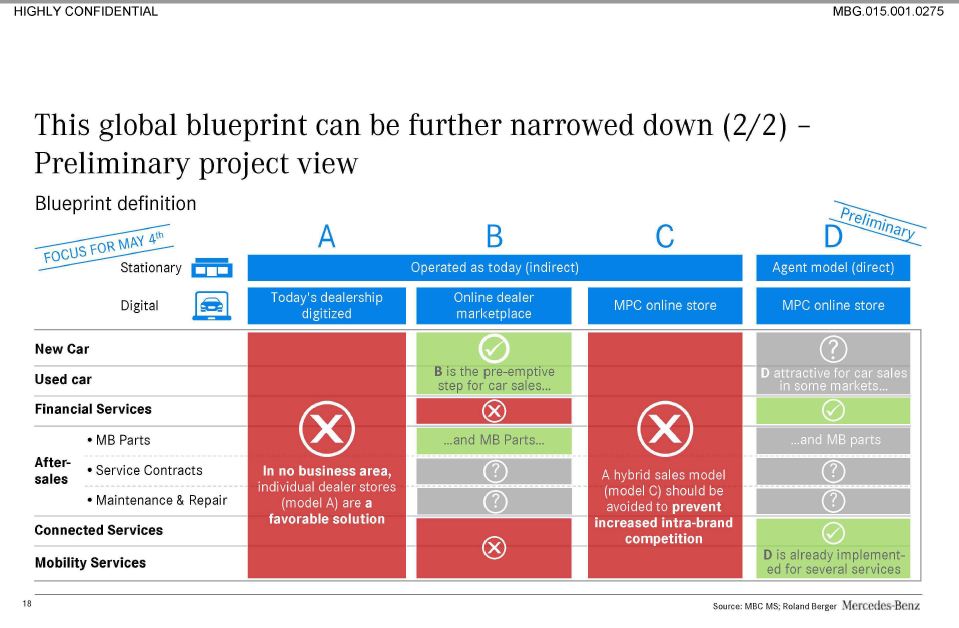

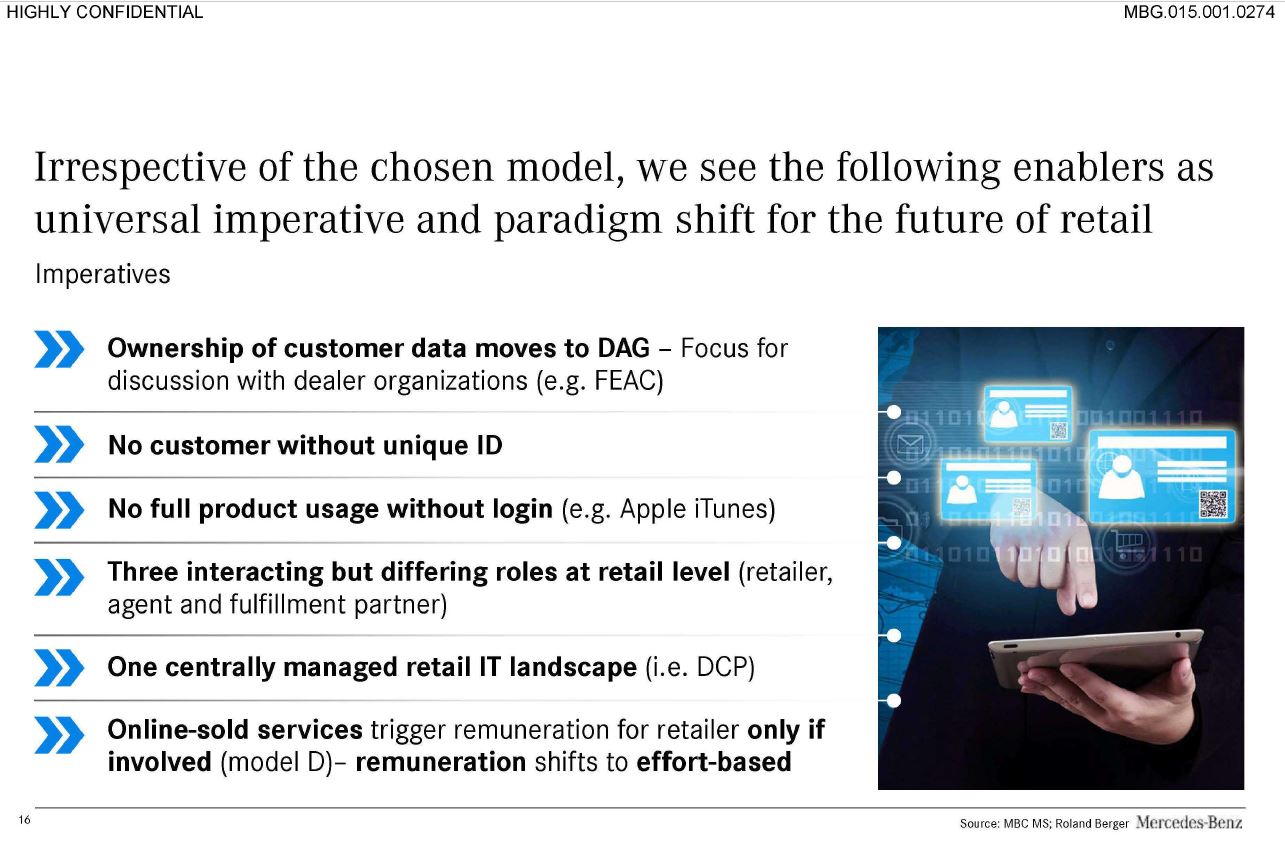

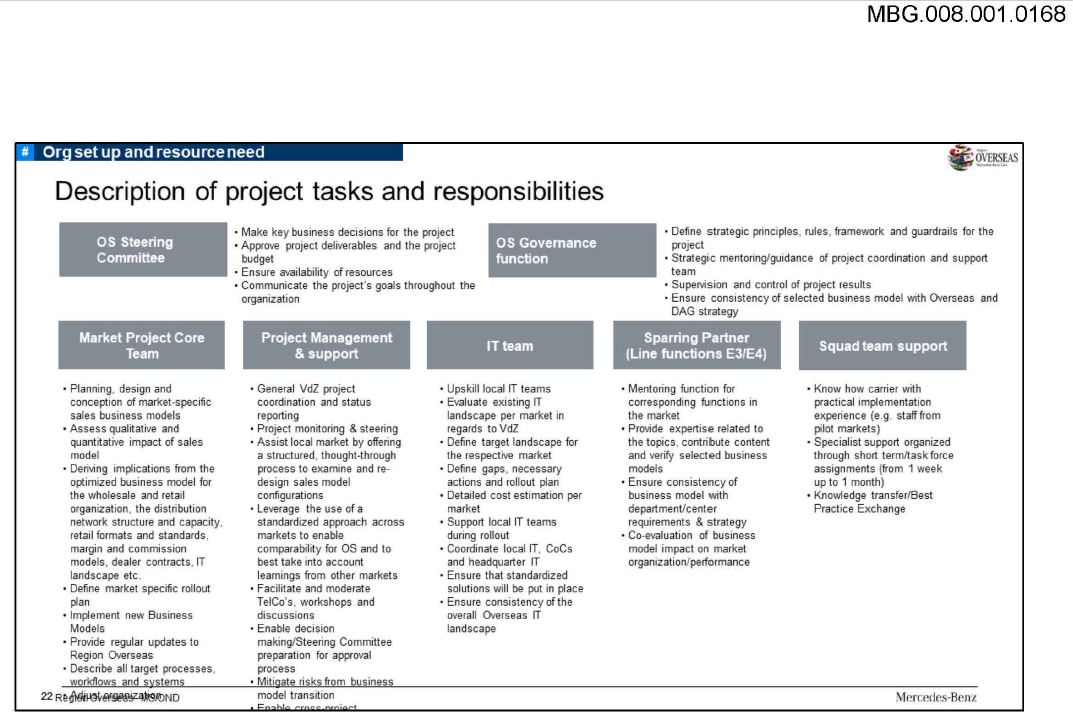

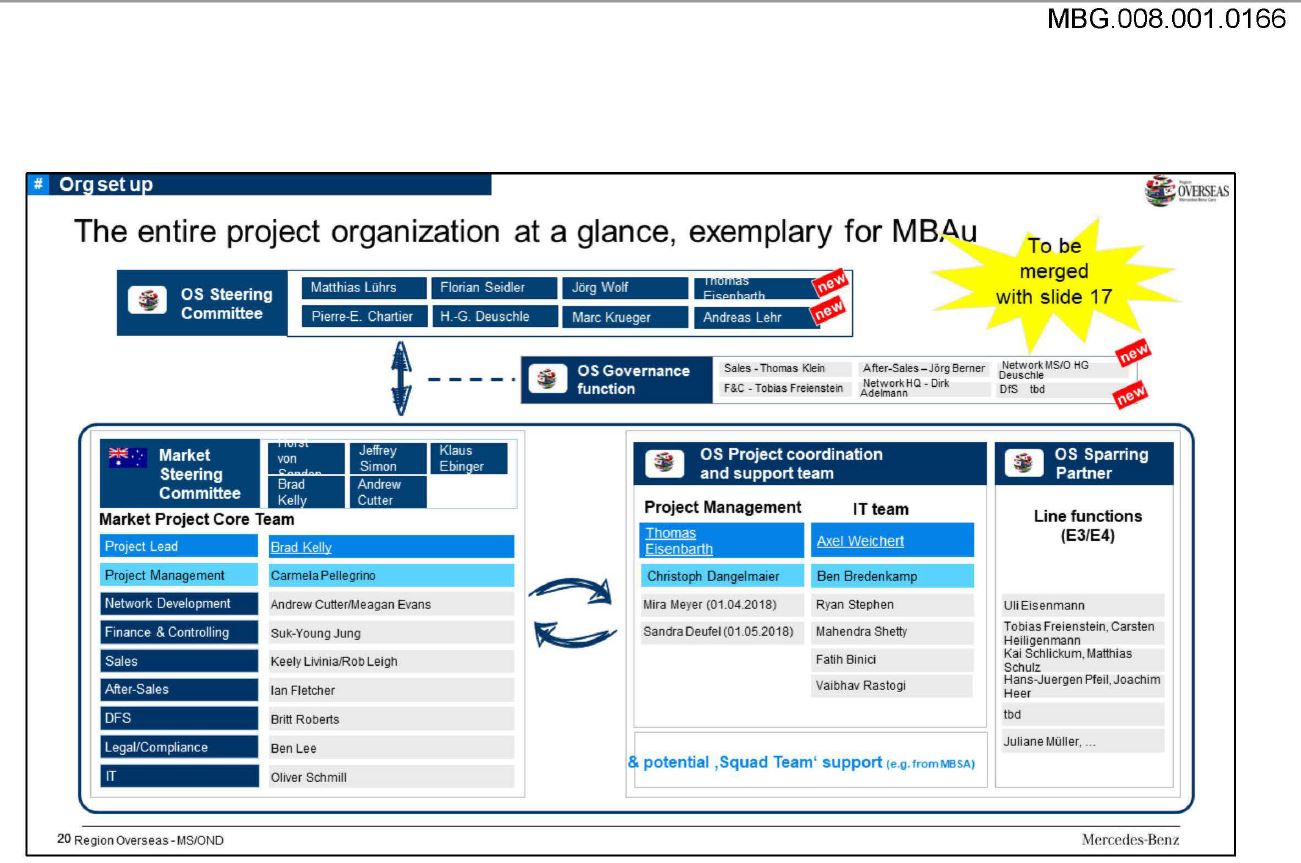

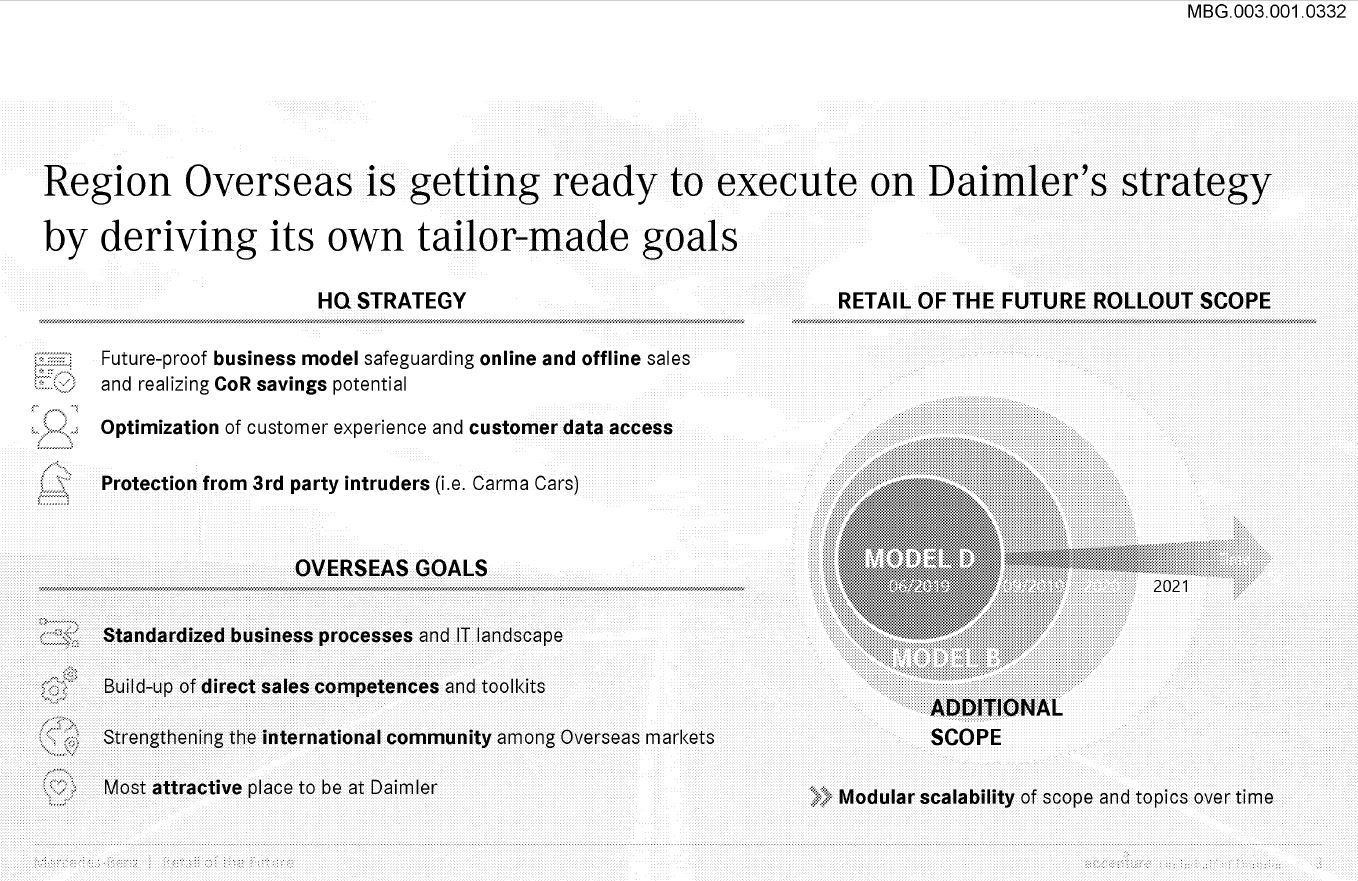

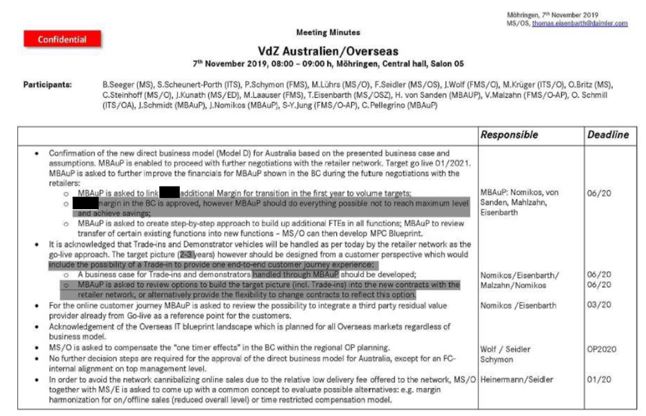

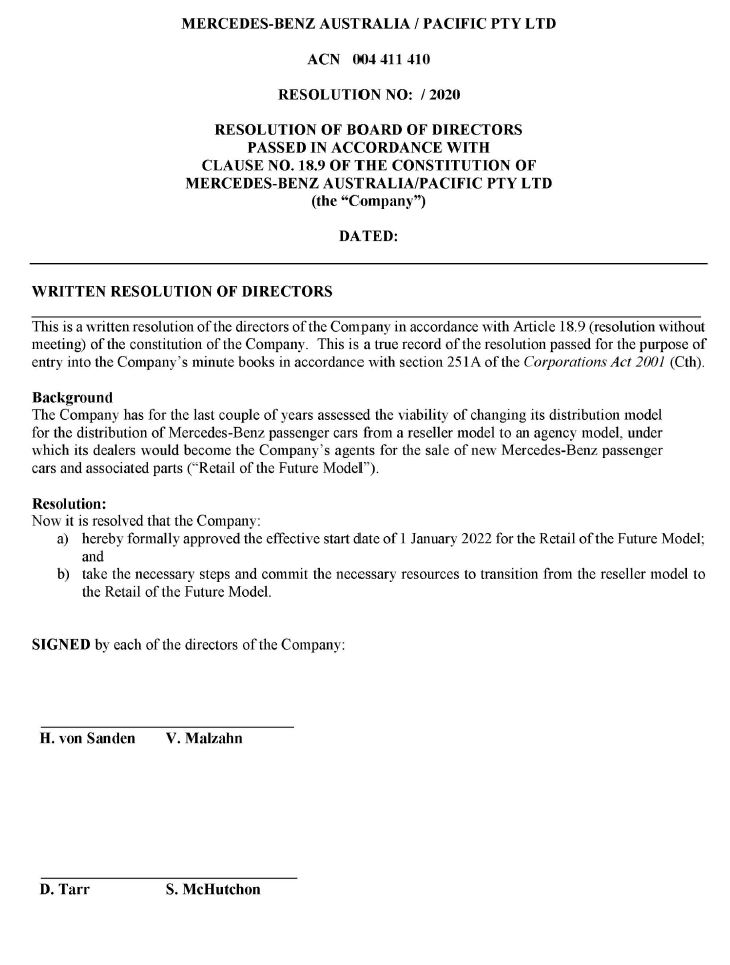

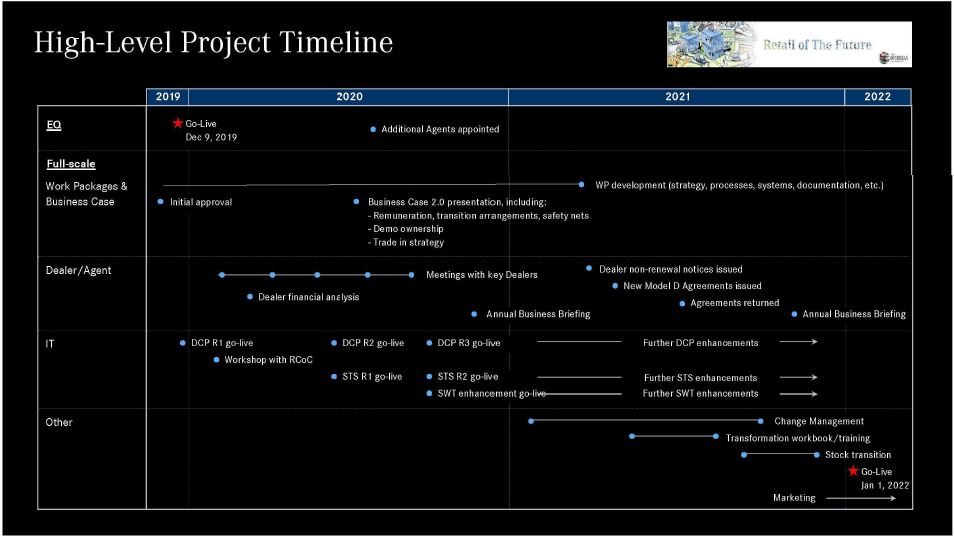

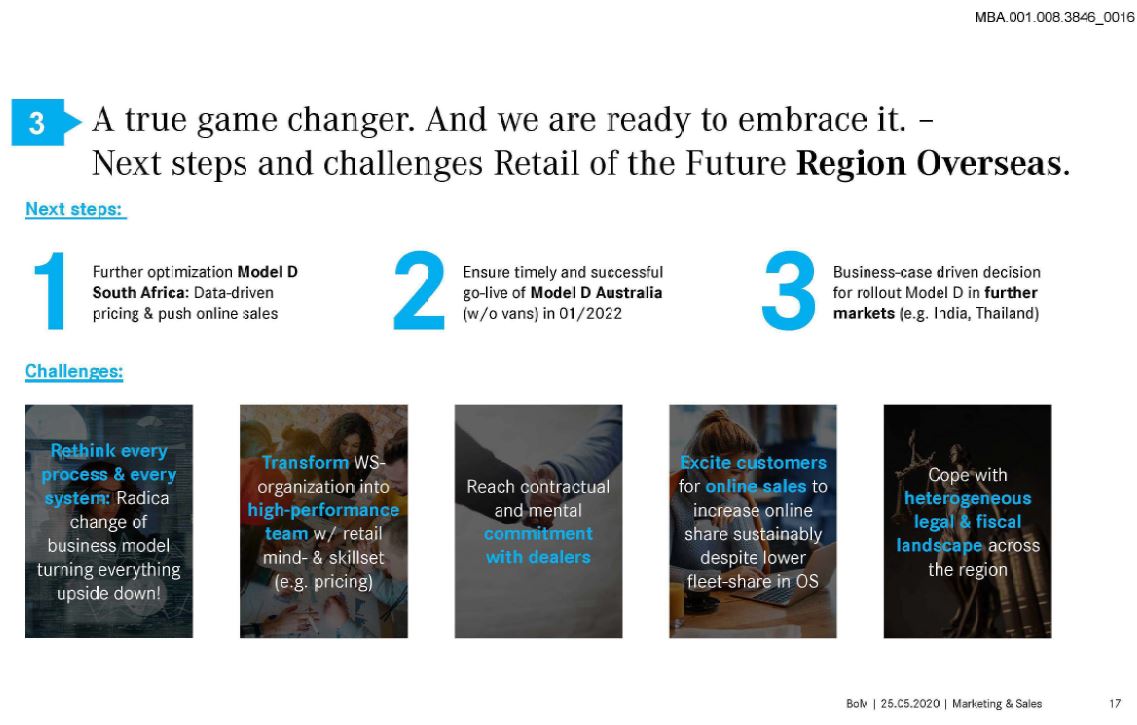

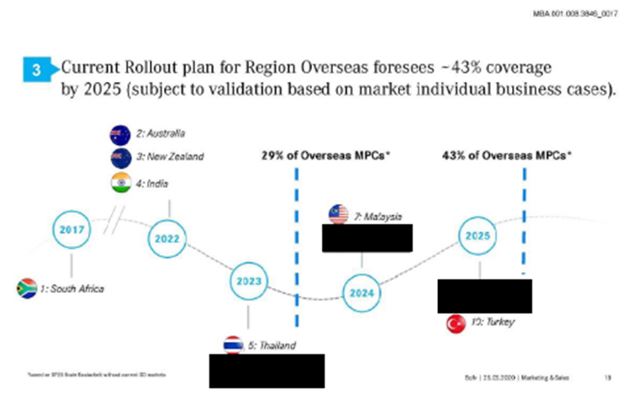

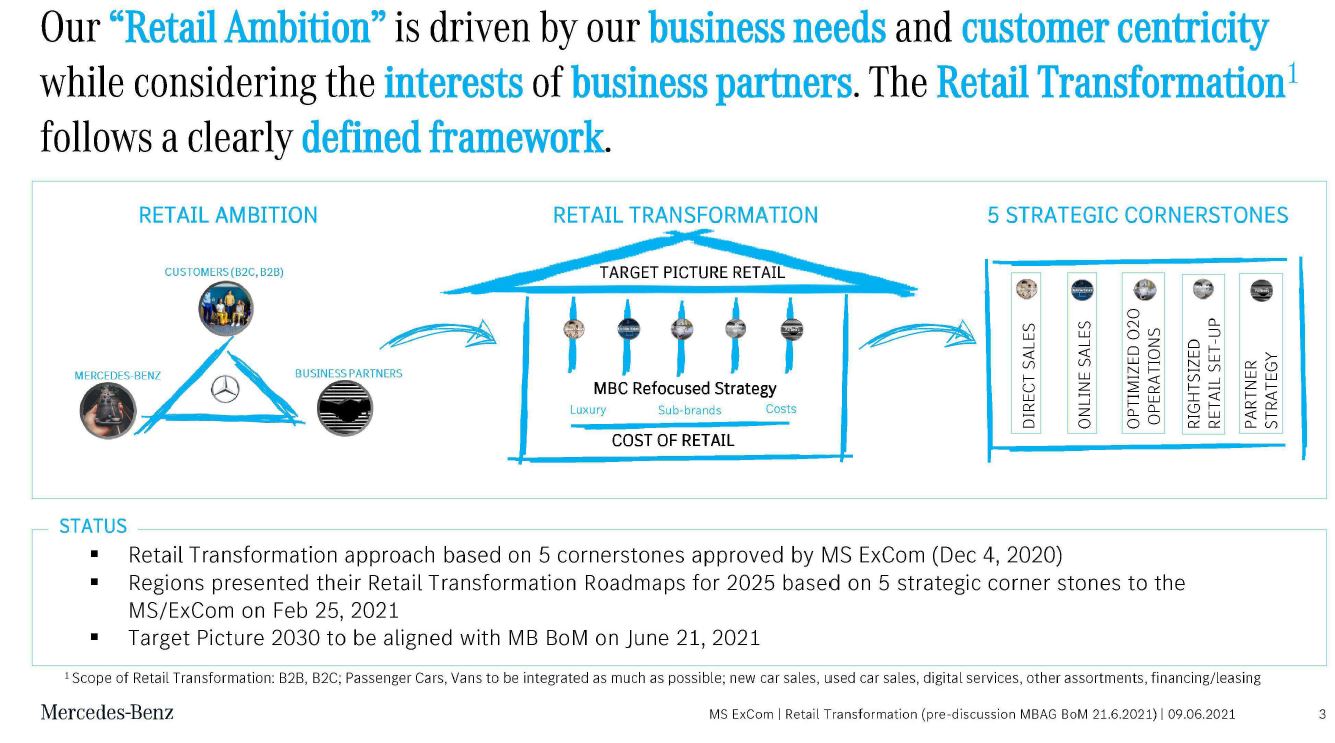

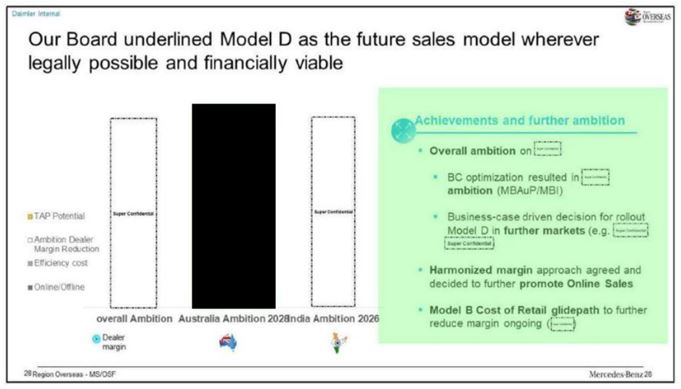

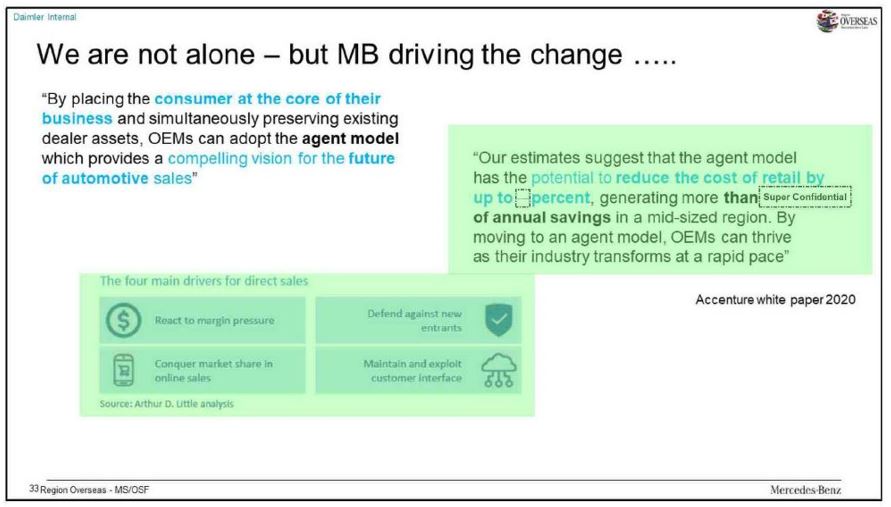

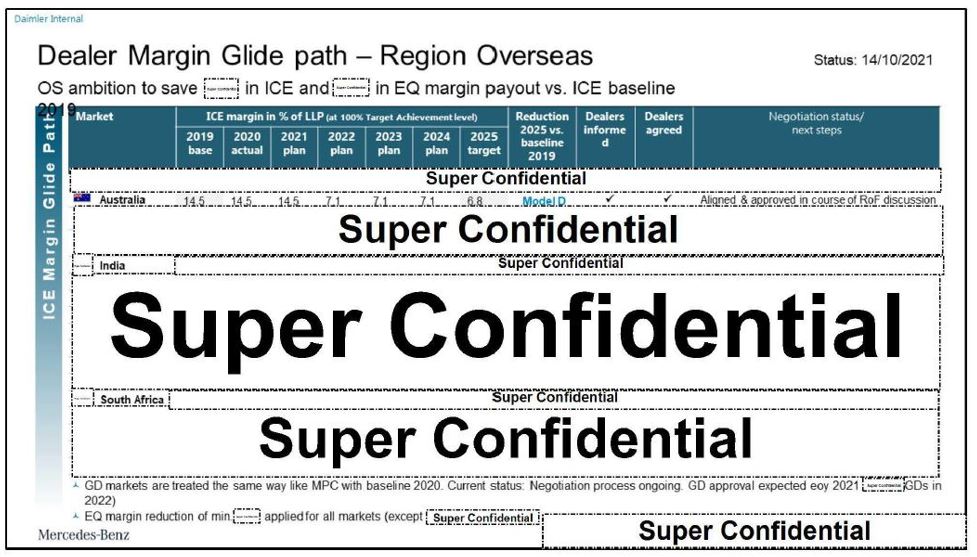

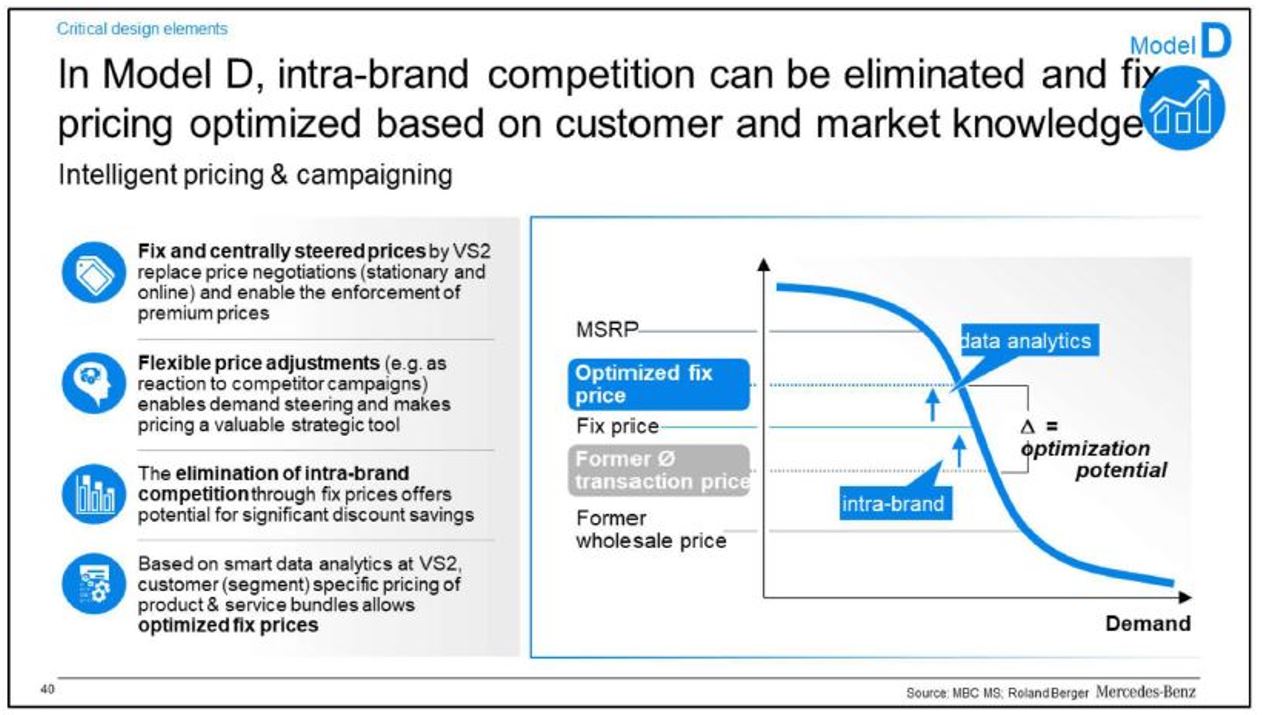

5 Further, in implementing the agency model the applicants say that MBAuP was little more than the cat’s paw of its ultimate holding company, Mercedes-Benz AG (MBAG). It is said that MBAuP acted in accordance with the directions of MBAG, through the latter’s formal decision-making structure with key decision-makers including Mr Matthias Lührs, Ms Britta Seeger, Mr Peter Schymon, Mr Harald Wilhelm and Mr Ola Källenius.

6 It is said that various reporting lines converged at the MBAG Board of Management level, which was the real decision-making body so far as the agency model in Australia was concerned. I will discuss these matters in detail later, including the role and conduct of Region Overseas (RO) personnel.

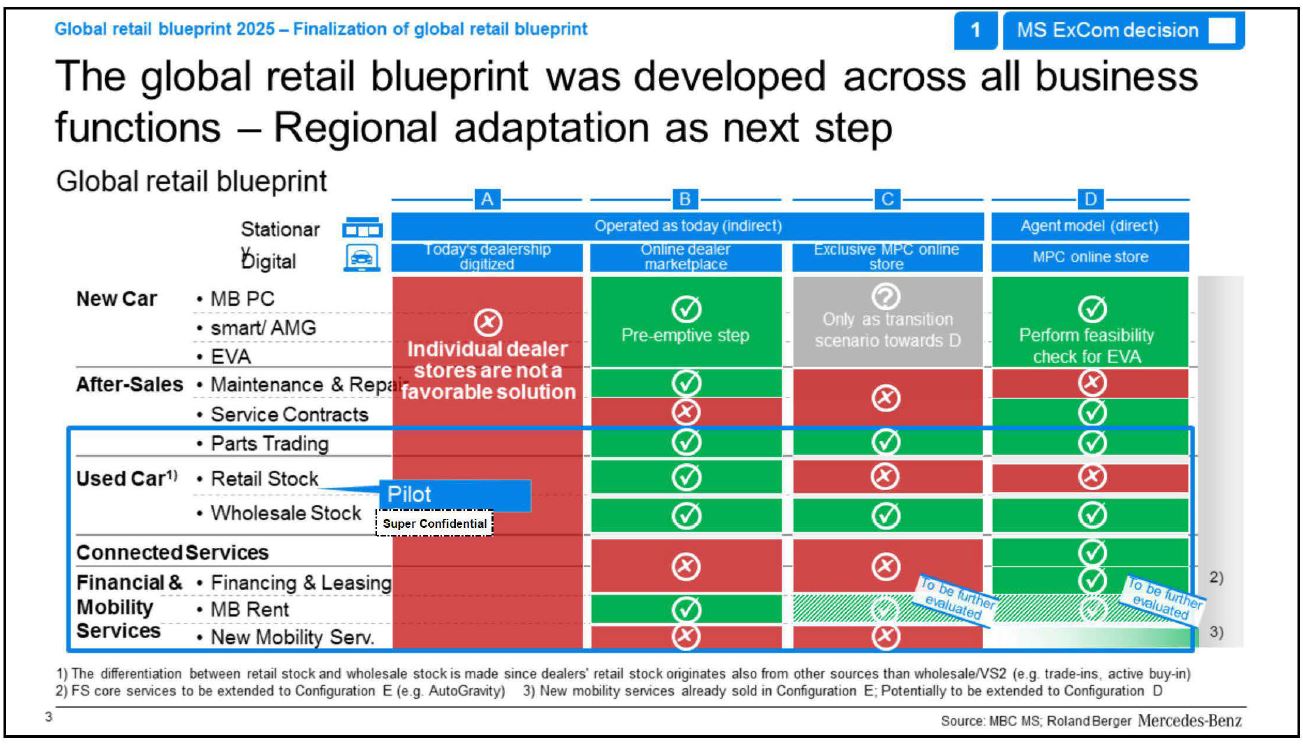

7 It is said that MBAG not only made all the critical strategic and timing decisions for the rollout of agency in Australia, but set the guardrails for the operational decisions. It is said that MBAG collaborated closely with the MBAuP project team in relation to operational issues, but that the Finance and Controlling staff including Messrs Wilhelm, Schymon, Jörg Wolf, and Tobias Freienstein had the final say in relation to the setting of dealer commissions.

8 More generally it is said that no decision of any significance about the agency model in Australia was made by MBAuP.

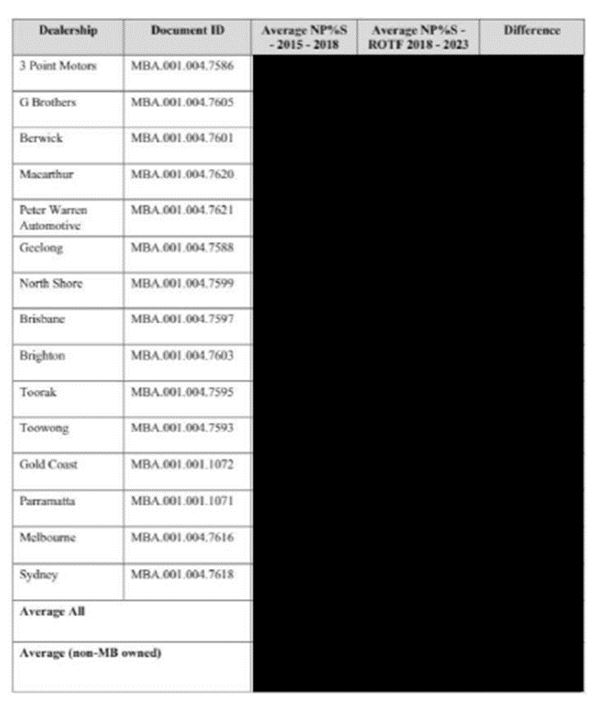

9 Now these proceedings were commenced on 18 October 2021 by 38 of the then 49 dealers operating Mercedes-Benz (MB) dealerships in Australia. I will refer to Mercedes-Benz and MB inter-changeably throughout these reasons.

10 On 12 November 2021 I ordered:

Subject to further order, the trial of the claims of the individual applicants identified by operation of orders 2 and 3 (other than the quantification of any monetary compensation) and any other issues that the Court directs, be fixed for hearing on 2 August 2022 at 10.15am on an estimate of 4 weeks.

11 So, orders were made setting down the matter for an expedited hearing commencing on 2 August 2022 with further orders concerning the selection of four of the applicants to serve as exemplars for the purpose of that hearing, such that each of their individual claims would be dealt with. Two exemplars were nominated by the applicants, being the fourth and twenty-first applicants, and two exemplars were nominated by MBAuP, being the twenty-eighth and thirty-sixth applicants. Between them, the four exemplars represented all of the 38 applicants in relation to their dealership agreements with MBAuP.

12 The trial occurred over August to October 2022 with further written material filed up to December 2022. In addition to more than 100 folders of witness statements, annexures and other exhibits, other evidence had to be filtered and synthesised from an electronic database. The case was forensically complex although legally straight-forward for a case of this type. Notwithstanding, I have had to say a little on the concepts involved in statutory unconscionable conduct as a counterpoint to what can be described as value-laden philosophising in some of the authorities. This is a characterisation not a criticism.

13 Let me now say something further about the case and the claims made.

14 The applicants challenge the non-renewal of their dealer agreements and the imposition on them of the agency model, which they say has involved the appropriation of their goodwill.

15 The applicants say that the dealer agreements were “evergreen”. By “evergreen”, the applicants mean that the non-renewal power was constrained such that MBAuP could exercise the power of non-renewal only if a dealer failed to meet their targets or make mutually agreed improvements.

16 On the applicants’ case, the parties made a permanent bargain. So, because a dealer made investments in their dealership, the dealer was entitled to continue to operate under the dealer model permanently, provided the dealer met their targets, made mutually agreed improvements and did not breach the agreement. They allege that by force of clause 1.2 of the dealer agreements, MBAuP gave away the right to operate any business model in Australia other than the dealer model. They say that in essence clause 1.2 was a renunciation of agency.

17 The applicants say that the non-renewal power, which could be exercised by MBAuP without cause, did not extend to permitting MBAuP to use that power to continue the existing relationship between MBAuP and each of the dealers on the basis of an agency relationship.

18 They say that the non-renewal notices (NRNs) given to them by MBAuP at the end of 2020 were invalidly issued. Now they advance such a case despite the express words of clause 8 of each dealer agreement and the fact that, correspondingly, a dealer could terminate the agreement without cause on 60 days’ notice. And they advance their case despite the fact that each dealer agreement did not grant a dealer an entitlement to any particular margin or any particular level of supply, if at all, of Mercedes-Benz vehicles and MBAuP could change the dealer’s prime marketing area (PMA) on three months’ notice.

19 Further, the applicants say that MBAuP has appropriated the dealers’ property being their goodwill. It is said that the agency model implemented in Australia involves the appropriation of the dealers’ goodwill and customer relationships for no or inadequate compensation. It is said that the purpose of issuing the NRNs was to terminate the dealer agreements and force the applicants to enter into the agency agreements to achieve the purpose and effect of transferring the goodwill in each applicant’s dealership to MBAuP.

20 Generally, the applicants contend that MBAuP’s conduct in issuing the NRNs was motivated by a purpose which was antithetical to the dealer relationships and dealer agreements, being to take the customer relationships and the profits to be earned from the unexpired lifetime value of their customers, without paying anything to the dealers for that taking.

21 Let me at this point say something more about the NRNs. The applicants allege that MBAuP had various improper purposes in issuing the NRNs and failed to consider certain matters in issuing the NRNs.

22 First, it was said that the purpose of the NRNs was to terminate the dealer agreements and introduce the agency model so as to transfer the goodwill in each applicant’s dealership to MBAuP. It was said that MBAuP misused a contractual mechanism intended for another purpose.

23 Second, it was said that the issuing of the NRNs was to give effect to directives issued by MBAG to MBAuP and to give effect to a global strategy or policy of MBAG to implement the agency model. So, it was said that MBAuP introduced a direct sales model at the behest of MBAG without exercising its own judgment.

24 The applicants allege that the proper purpose of the non-renewal power was to allow MBAuP to bring the relationship to an end where a dealer did not meet their performance targets or did not carry out mutually agreed improvements. Moreover, the applicants contend that the purpose of the power of non-renewal was to end the relationship between MBAuP and a dealer, not to continue the relationship on different terms unilaterally imposed by MBAuP.

25 The applicants allege that by engaging in the relevant conduct for an impugned purpose, each NRN was issued with the following characterisations.

26 First, the NRNs were issued in contravention of the good faith duty under clause 6 of the Franchising Code as set out in Schedule 1 to the Competition and Consumer (Industry Codes–Franchising) Regulation 2014 (Cth) and involved a contravention of s 51ACB of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA).

27 Second, the NRNs were issued in contravention of certain alleged implied duties owed by MBAuP to each of the applicants under their respective dealer agreements, such duties being a duty to cooperate to achieve the objects of each such dealer agreement and a duty to act reasonably and in good faith, having regard to the terms, purpose and object of each such dealer agreement.

28 Third, the NRNs were issued for a purpose foreign to the power of non-renewal contained in each of the three different forms of the dealer agreements, being the 2002 dealer agreement term provision, the 2015 dealer agreement term provision and the Wollongong dealer agreement term provision.

29 Fourth, in respect of applicants with a 2002 dealer agreement, it was said at the outset of the trial that the NRNs were not issued during 2021, and so were spent by automatic renewal of those dealer agreements on 1 January 2021 in accordance with the 2002 term provision. But by the end of the trial it appeared that the spent notices claim was no longer pressed by the applicants. But even if it had been persisted in, in my view it was meritless.

30 Now the applicants say that if one or more of these grounds are established, then each of the NRNs should be set aside or is void and of no effect. And the applicants say that if the NRNs are set aside or are void, then each of the applicants is entitled to have their dealer agreements automatically continued on and from 1 January 2022.

31 But I should say now that I have rejected the applicants’ case on this aspect.

32 The very purpose of the non-renewal power is to bring the existing contractual bargain to an end. And the content of MBAuP’s obligation pursuant to any duty of good faith and to act with fidelity to the bargain between the parties is necessarily informed by the nature of the power which is to bring that bargain to an end.

33 So, the proper inquiry is directed to MBAuP’s non-renewal of each dealer agreement and whether the non-renewal was faithful to that contractual bargain. It was. MBAuP exercised the non-renewal power for the purpose for which it was created, being to bring each dealer agreement to an end.

34 Moreover, the applicants’ position fails to recognise that it will be difficult to discern a want of good faith in the exercise of a power which can serve only the interests of the party upon whom the power is conferred.

35 Further, once it is appreciated that the commercial bargain struck by the dealer agreements was not a permanent bargain, the proper analysis of the NRNs claim is to evaluate whether the exercise of the non-renewal power was faithful to that bargain. On the NRNs claim, the inquiry is not whether the introduction of the agency model, at large, was in good faith or faithful to the bargain struck under the dealer agreements. However, and in any event, even if that were the proper inquiry, the evidence demonstrates that MBAuP introduced the agency model in good faith.

36 Let me turn to some other matters concerning the applicants’ case.

37 First, the applicants have brought a claim asserting that they were subject to economic duress. They say that they did not have the opportunity to give their consent freely to enter into any of the agency agreements, by reason of MBAuP’s pressure or threat to treat the dealers’ relationships with MBAuP and the MB brand as ceasing on 31 December 2021 if the applicants did not sign and return to MBAuP each of those agreements. They allege that the pressure exerted and the threats made upon each of the applicants to sign the agency agreements was illegitimate, thereby amounting to economic duress. They seek orders setting aside and/or rescinding the agreements. But for the reasons that I have set out later, such a claim is not made out.

38 Second, the applicants allege that other conduct of MBAuP was a contravention of its obligation of good faith under clause 6 of the Franchising Code. The applicants say that MBAuP contravened the good faith duty under the Franchising Code in relation to the negotiation of the agency agreements, the service and parts agreements and the agency related agreements, and also by imposing unfair terms. But again, such claims have not been made out.

39 Third, the applicants allege that MBAuP engaged in unconscionable conduct in contravention of s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), as set out in Schedule 2 to the CCA, in three principal respects.

40 The first principal respect was said to be by purporting to bring to an end the dealer model by not renewing each of the applicants’ dealer agreements.

41 The second principal respect was said to be by imposing the agency agreements, service and parts agreements, and agency related agreements on each of the applicants as the basis for continuing to operate their dealerships.

42 The third principal respect was said to be by failing to compensate each of the applicants for the value of their dealerships, including the loss of the value of their goodwill, as a result of the termination of the dealer model, and the implementation of the agency model under the agency agreements, service and parts agreements, and agency related agreements.

43 Generally, the applicants allege that MBAuP has engaged in the unjustifiable pursuit of its self-interest by appropriating the substantial value of the assets and/or goodwill of the Mercedes-Benz dealership businesses, undermining the basis of the commercial bargain and relationship between itself and the applicants under the dealer model, implementing terms in the agency agreements to allow MBAuP to rationalise its network and implementing a global directive, strategy or policy of MBAG.

44 But I agree with MBAuP that the applicants in essence seek to rewrite the contractual bargain struck by the dealer agreements into one which better suits their commercial interests. They seek to convert the commercial judgment they made when they entered into those agreements into a guarantee of permanent tenure (subject to certain qualifications that it is convenient for them to concede) and a fetter on the exercise by MBAuP of its legitimate business judgment as to how best to adapt to a changing marketplace concerning the Mercedes-Benz brand in Australia. In essence, the commercial judgment made by each dealer was that MBAuP would not issue a notice of non-renewal if the dealer performed well, because it was assumed that it would be in MBAuP’s commercial interest and the dealer’s interest for that agreement to continue. No doubt that was a sensible commercial assumption to make. But it was not the contractual bargain that was struck. The NRNs could be given without cause.

45 Moreover, the applicants do not allege that the agency agreements have not provided them with a reasonable opportunity to make a return on their investments during the term of those agreements, that being a statutory requirement under clause 46B of the Franchising Code which provides that:

A franchisor must not enter into a franchise agreement unless the agreement provides the franchisee with a reasonable opportunity to make a return, during the term of the agreement, on any investment required by the franchisor as part of entering into, or under, the agreement.

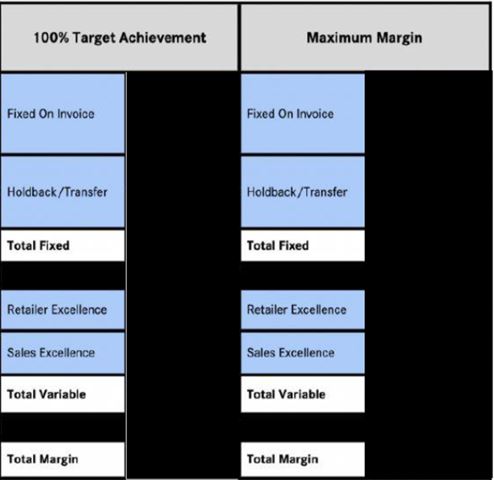

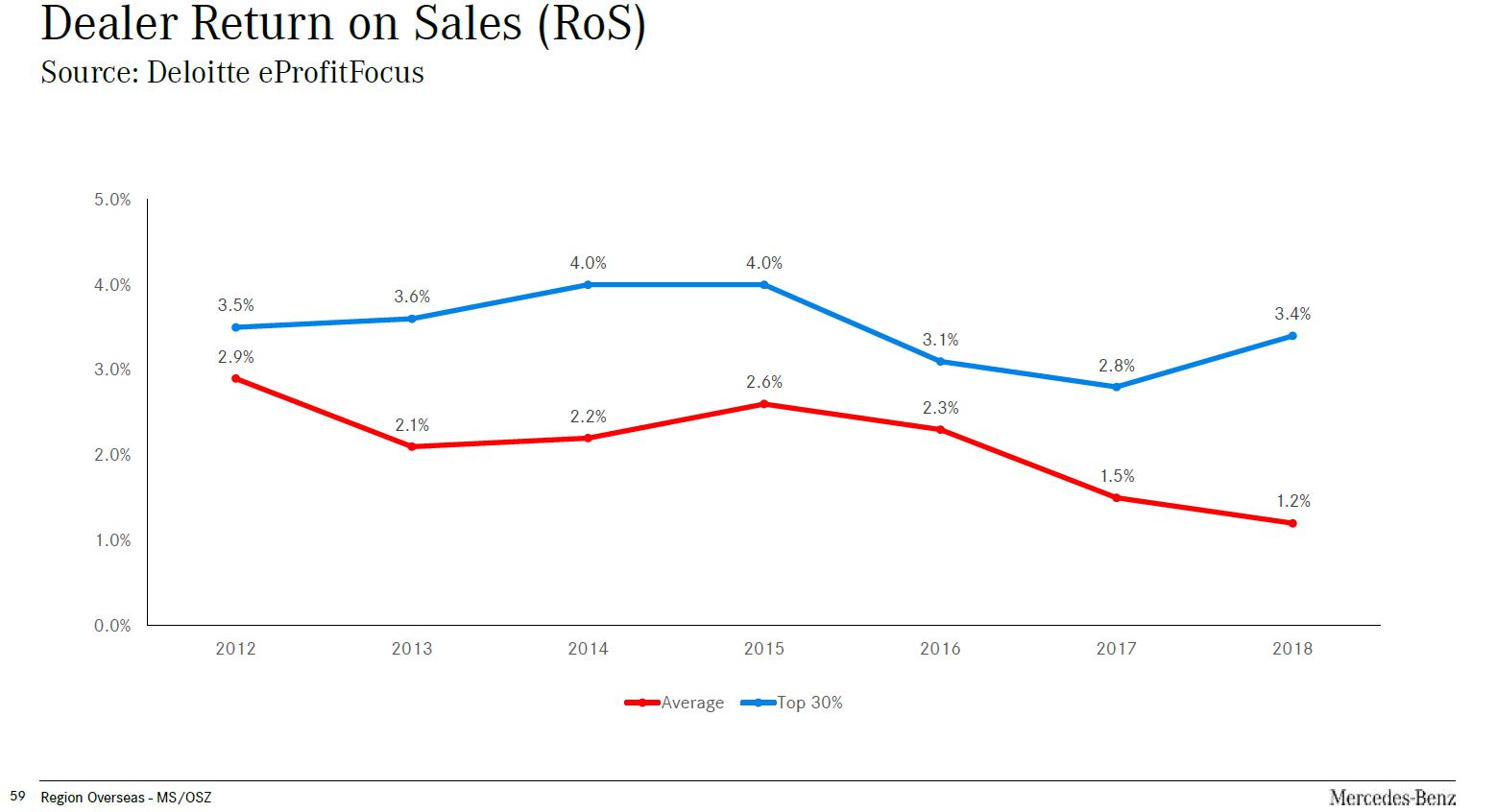

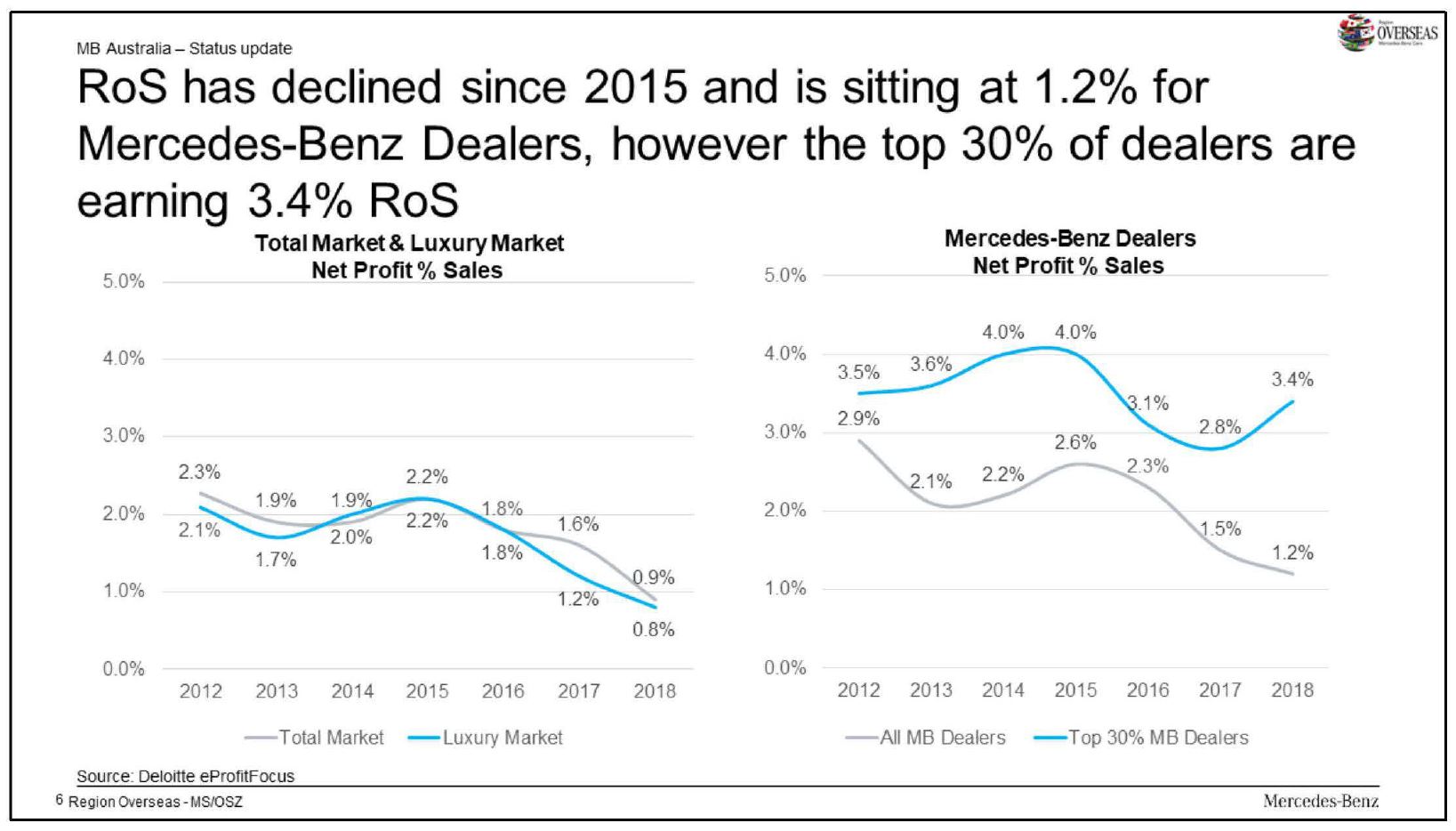

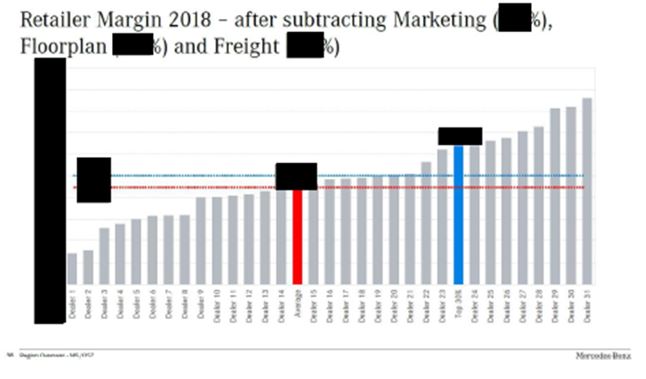

46 Instead, the applicants’ case proceeds on the basis of a “better off/worse off” analysis of Mr Terence Potter, the applicants’ financial expert witness. I will return to this later in my reasons. But in any event, it does not follow that MBAuP has acted unconscionably or failed to act in good faith because a dealer is financially worse off under the agency model as compared to the dealer model.

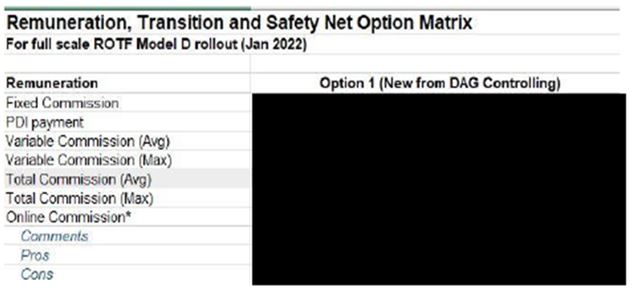

47 Moreover, the applicants have neither run a case nor sought to establish that the remuneration under the agency model ought to have been set at a particular level or to generate a particular return on sales (RoS).

48 In summary, I would reject the applicants’ unconscionable conduct case although I must say that it had greater merit than the applicants’ other claims and has involved a harder judgment call on my part.

49 Now the principal remedy sought by the applicants is the setting aside of the NRNs and damages for the losses suffered by the applicants as a result of the implementation of the agency model in 2022, with alternative or other relief.

50 The applicants’ relief is framed by reference to provisions of the CCA and the ACL as well as under the common law and in equity.

51 First, they seek declarations that MBAuP has contravened s 51ACB of the CCA by breaching clause 6 of the Franchising Code and engaging in conduct that was unconscionable in contravention of s 21 of the ACL. Section 51ACB, which is in Division 2 of Part IVB, provides that a corporation must not contravene an applicable industry code. Relevantly, the Franchising Code is an industry code prescribed by the regulations.

52 Second, they seek declarations pursuant to ss 80 and 87 of the CCA, ss 232 and 237 of the ACL and at law and in equity declaring the NRNs issued to the applicants to be void, declaring the agency agreements and the service and parts agreements entered into with the applicants to be void ab initio, and declaring that the dealership agreements of the applicants continue to have their full force and effect after 31 December 2021. They also seek orders that MBAuP specifically perform and carry into effect the dealer agreements of the applicants or other orders or relief as will restore the applicants to the full enjoyment of their rights under their respective dealer agreements as if they had continued to have full force and effect after 31 December 2021.

53 Third, alternatively, the applicants seek orders pursuant to ss 80 and 87 of the CCA and ss 232 and 237 of the ACL and at law and in equity declaring relevant terms of the agency agreements and/or the service and parts agreements of the applicants to be void ab initio either in whole or to the extent that those terms are not fair and reasonable, or varying such terms as and from the commencement of the agency agreements and/or the service and parts agreements.

54 Fourth, the applicants seek damages and/or orders for compensation pursuant to ss 82(1)(a) and 87(1) of the CCA, ss 236 and 237 of the ACL and at law or in equity.

55 In essence, the applicants seek orders that will put them in the position that they were in prior to MBAuP’s imposition, as they would describe it, of the agency model on them. In other words, the applicants seek orders which will restore the status quo ante.

56 Now MBAuP did not defer the implementation of the agency model. Instead, with knowledge of these proceedings and the nature of the relief sought by the dealers, MBAuP proceeded to implement the agency model to conform to a deadline for implementation on 1 January 2022.

57 Now the applicants have prayed in aid the philosophy manifested in Metz Holdings Pty Ltd v Simmac Pty Ltd (No 2) (2011) 216 IR 116 at [872] to [874]. The applicants say that I should take a similar approach in the present case. They say that to make an order for damages and not to grant relief setting aside the agency agreements would be to allow MBAuP to enjoy the fruits of its wrongful conduct and to condemn dealers to the servitude of a business arrangement to which they did not consent and had no alternative but to subject themselves to. They say that I should restore the status quo prior to the implementation of the agency model. And by restoring the applicants to their rights under the dealership model, including to their rights of automatic renewal, they say that MBAuP would be deprived of the benefits of its wrongdoing.

58 Now this is all very interesting, but it is only of hypothetical interest concerning the exemplar applicants’ claims. That is because I have found against the exemplar applicants.

59 Now although this trial was in relation to the exemplar applicants, the applicants say that various issues are likely to be determined that are of general application to similarly situated dealers, and potentially all dealers. The applicants’ statement of declarations and remedies, which was provided in accordance with my direction at the case management hearing on 3 June 2022, comprehensively sets out the issues arising on the claims of the applicants generally.

60 Further, the manner of disposition of the issues between the parties and the consequences for other dealers similarly situated to the exemplar applicants was the subject of an exchange with counsel at the commencement of trial. Perhaps potential extrapolation of some of my findings concerning the exemplar applicants to the broader field may be appropriate. I will hear further from the parties on these questions to the extent necessary.

61 Let me now turn to my detailed reasons for finding against the exemplar applicants.

62 It is convenient to divide my discussion into the following sections:

(a) The main themes litigated and key conclusions ([63] to [266]).

(b) The applicants generally and the exemplar applicants’ lay witnesses ([267] to [353]).

(c) The NDC, DAC and Mr Jennett ([354] to [380]).

(d) MBAuP and MBAG ([381] to [469]).

(e) MBAuP’s lay witnesses ([470] to [531]).

(f) The parties’ Jones v Dunkel points ([532] to [576]).

(g) The dealership model ([577] to [652]).

(h) The dealer agreements ([653] to [747]).

(i) The dealership businesses and investments ([748] to [834]).

(j) The agency model ([835] to [848]).

(k) The agency agreements and agency overview ([849] to [904]).

(l) Other agency related agreements ([905] to [970]).

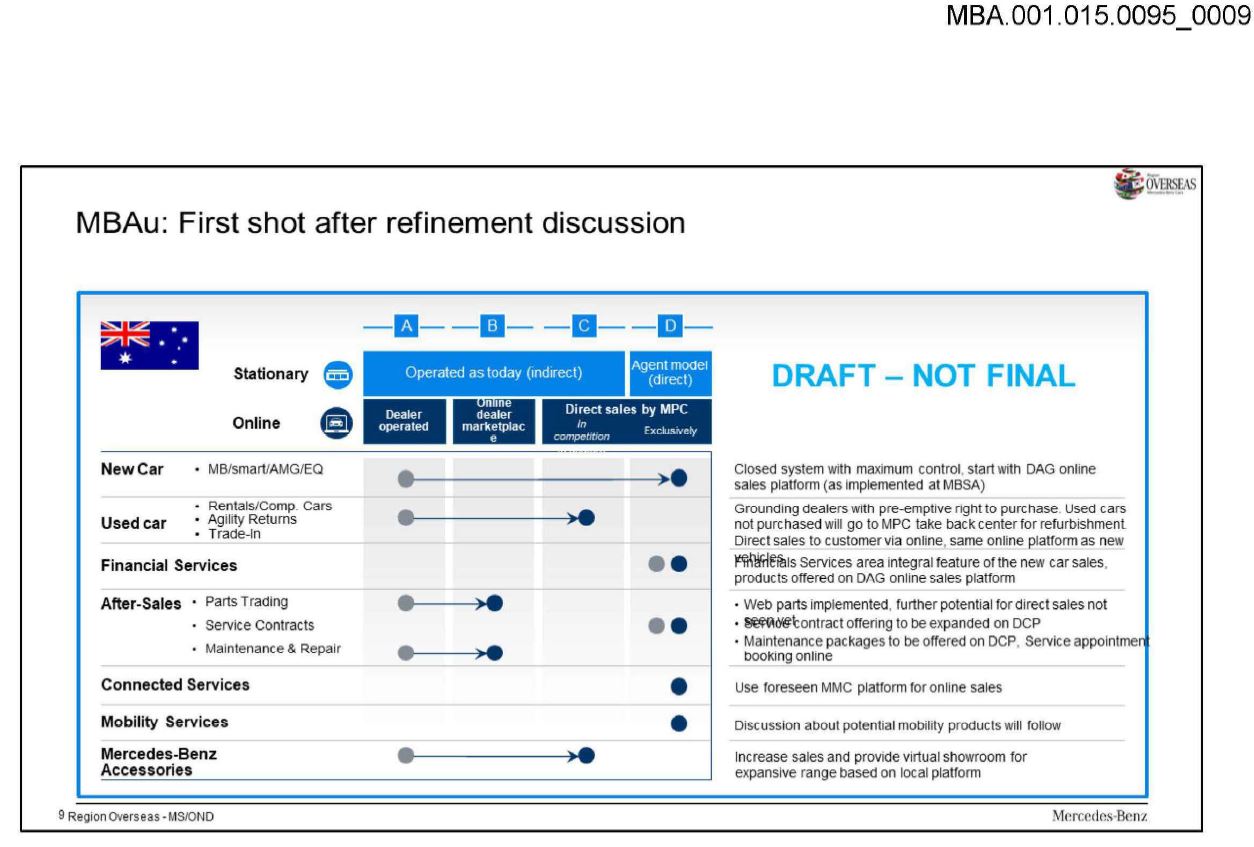

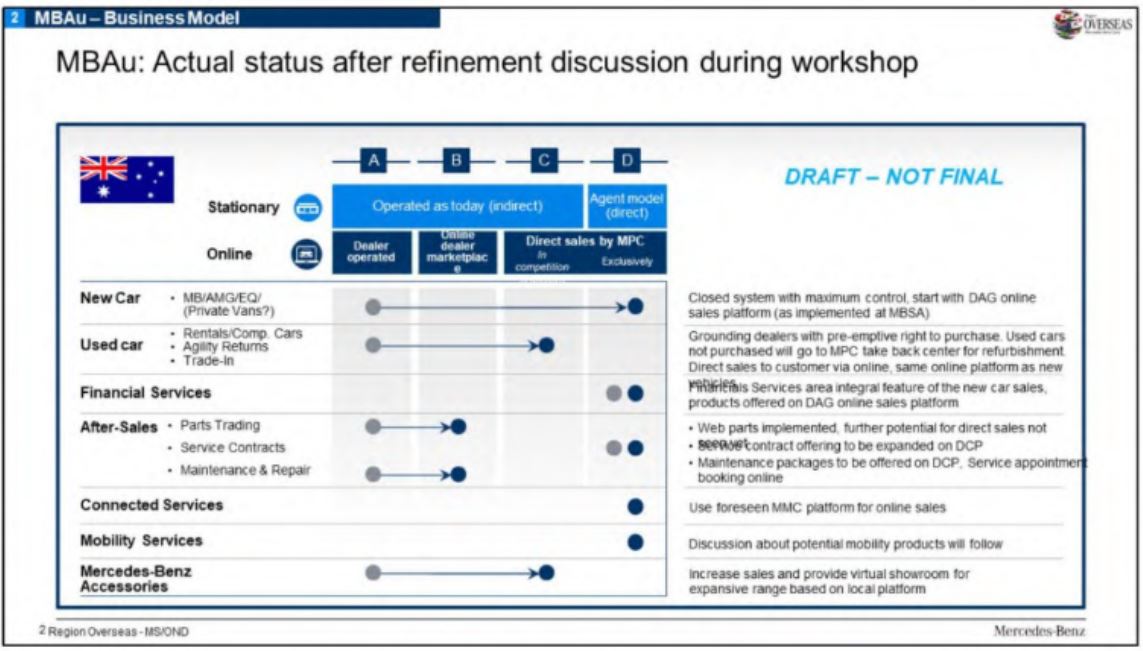

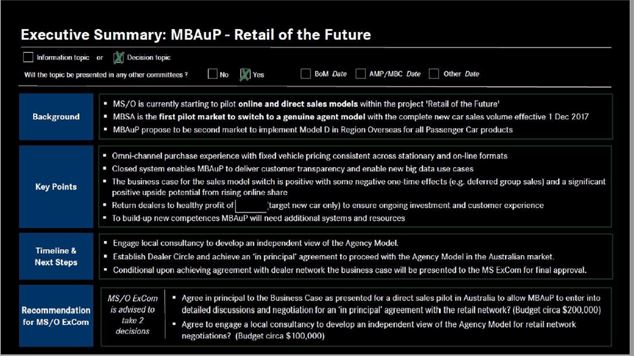

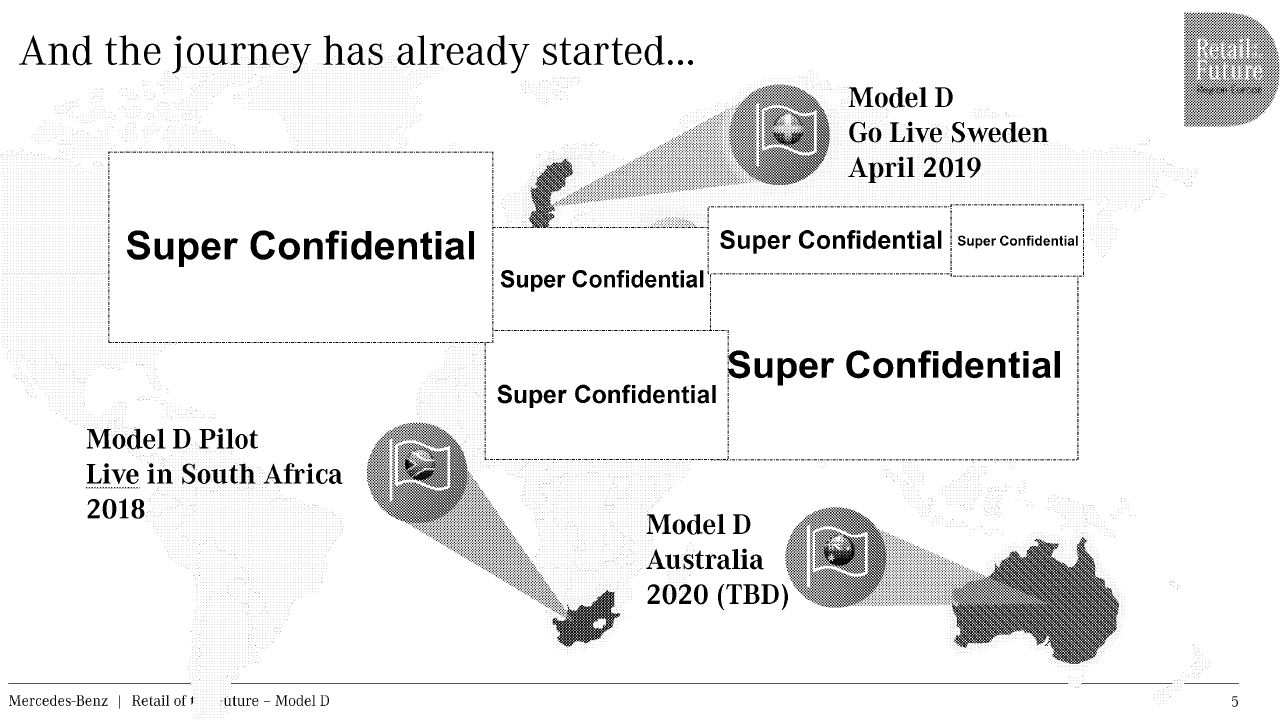

(m) Some relevant facts – the evolution and implementation of agency ([971] to [2207]).

(n) The economic expert evidence ([2208] to [2330]).

(o) The financial expert evidence ([2331] to [2375]).

(p) Business Case 2.1 update – a critique ([2376] to [2562]).

(q) The Deloitte modelling ([2563] to [2584]).

(r) Analysis of expert evidence – dealers worse off ([2585] to [2660]).

(s) Exemplar applicants – impact of agency model ([2661] to [2732]).

(t) Valuation evidence ([2733] to [2770]).

(u) Non-renewal notices and contractual claims ([2771] to [3043]).

(v) Statutory duty of good faith ([3044] to [3223]).

(w) Unfair and unreasonable terms ([3224] to [3361]).

(x) Economic duress ([3362] to [3453]).

(y) Statutory unconscionable conduct ([3454] to [3750]).

(z) Conclusion ([3751] to [3752]).

The main themes litigated and key conclusions

63 It is appropriate at this point to identify and address various sets of themes that permeated the parties’ dispute before I descend into the detail of the evidence. Perhaps this is an unusual course to take, but much of the later detail in my reasons concerning financial information and the global strategy of MBAG is likely to be redacted as a result of confidentiality claims and so it is advantageous at the outset to synthesise some of the highlights of these themes and how I have resolved them for ease of comprehension for those who may only have access to the redacted version of my reasons.

64 One set of themes raised by the applicants concerns the proper construction of the dealer agreements, including the object of the agreements and nature of the commercial bargain reflected in them, the duration of those agreements and the purpose of the power of non-renewal. Let me begin with this subject matter.

The scope and purpose of the contractual power of non-renewal

65 The determination of the NRNs claim principally turns on the proper construction of clause 8 of the dealer agreements, including the ascertainment of the proper purpose of that clause.

66 The applicants allege that the object of the dealer agreements was to encourage and facilitate the investment in, establishment, operation of and/or maintenance by the dealer of an MB dealership at the premises identified in the dealer agreement, and the taking of financial risks by the dealer in relation thereto.

67 The applicants plead that the commercial bargain that MBAuP struck with each dealer was that each dealer would invest time, money, effort and entrepreneurial skill, and take financial risks, to build their MB dealerships, from which they would enjoy ongoing profits and which they could sell to reap the benefits of the goodwill they had generated.

68 The applicants submit that determining a proper purpose is a matter to be assessed in conformity with the object of the contract, which they also refer to as the nature of the bargain. That object or bargain contemplates a particular form of relationship between MBAuP and the dealer, on the faith of which the dealer has invested in its dealership to make future profits and enhance the goodwill of its dealership.

69 On that case, it is alleged that because a dealer made investments in their dealership, the dealer was entitled to continue to operate that dealership under the dealer model permanently, provided the dealer met their targets and made mutually agreed improvements. Indeed, the applicants say that is the case regardless of the quantum and timing of the investments made by a dealer.

70 On the basis of that asserted permanence of the commercial bargain, the applicants assert that MBAuP could never exercise the power of non-renewal as a precursor to a change of business model, regardless of how much notice it gave to dealers and no matter what the financial terms of that new business model were.

71 Now the applicants characterise the power by reference to what it does not empower MBAuP to do. So, it is said that the power of non-renewal granted to MBAuP is not at large and that the power of non-renewal is limited by the bargain reached between MBAuP and the dealer, and cannot be used in a manner which is antithetical to that bargain or to destroy it.

72 The applicants contend that the non-renewal power in clause 8 did not extend to permitting MBAuP to use that power to continue the existing relationship between MBAuP and each of the dealers on the basis of an agency relationship, which was contrary to clause 1.2 of the dealer agreements.

73 The applicants’ case as to the purpose of the non-renewal power is that its purpose was to allow MBAuP to bring its relationship (cf the dealer agreement) with a given dealer to an end, in two circumstances.

74 The first circumstance was where that dealer had failed to meet its targets or make mutually agreed improvements.

75 The second circumstance was said to be some other purpose “consistent with the object of the dealer agreement” and relevant “business circumstances”. Now the facts described as the business circumstances that inform the exercise of the non-renewal power appear to be that the dealers operated as retailers and MBAuP as a wholesaler, each applicant had invested time, money, effort, entrepreneurial skill and took financial risks to acquire, establish, build and/or maintain the businesses comprising their MB dealerships, each applicant established relationships with customers such that they created a valuable asset of and/or goodwill in the business at their MB dealership, MBAuP encouraged the dealers to make those investments and take those risks, and MBAuP represented that the dealers could build a successful long-term relationship with MBAuP and/or the Mercedes-Benz brand provided that they achieved their targets and made any mutually agreed improvements. So, the business circumstances describe aspects of the dealer model under which MBAuP and the applicants had previously operated.

76 But there is no articulation as to the justification for the constraint effected by the words “consistent with the object of the dealer agreement” and the “relevant business circumstances”. I agree with MBAuP that the applicants have not explained why it would be unlawful for MBAuP to issue a non-renewal notice for some other good faith purpose, simpliciter.

77 But the applicants do accept that MBAG could decide in good faith to exit the Australian market and that the power of non-renewal could be exercised for this purpose. But in my view this also implies an acceptance that the power could be exercised by reference to broader network-wide considerations, rather than just individual circumstances concerning particular dealerships.

78 So in summary, the applicants allege that the proper purpose of the non-renewal power was to allow MBAuP to bring the relationship (cf the dealer agreement) to an end where a dealer did not meet their performance targets or did not carry out mutually agreed improvements, but not otherwise except in the circumstances that I have just indicated.

79 But in my view the purpose of clause 8 was to enable MBAuP to bring the term of a dealer agreement to an end. It was the only means by which MBAuP could bring a dealer agreement to an end, absent agreement of the parties or breach by the dealer. And it symmetrically matched a dealer’s right to terminate the dealer agreement without cause on 60 days’ notice. The only substantive constraint on its exercise was that it be exercised in good faith, which was, inter alia, an obligation imposed by clause 6 of the Franchising Code. Further, the applicants’ concept of a broader bargain superimposed on the contractual framework must be rejected.

80 Three other features of this case should be noted before proceeding further.

81 First, the applicants do not allege that they were or are in a fiduciary relationship with MBAuP, let alone that there has been any breach of any fiduciary duty. This is unsurprising as any attempt to erect such a relationship would have been at odds with the relevant express contractual provisions. But some of their arguments went close to seeking to implicitly raise such a relationship, particularly when they sought to superimpose over the applicable contractual framework the suggestion of a long-term relationship between MBAuP and the dealers and to suggest somehow that the bargain struck between MBAuP and the dealers under the dealer agreements was somehow broader than the bargain enshrined in the contractual framework and provisions. Of course, some dealers in fact had contractual relations with MBAuP over an extended period. But that is a different question.

82 Second, I have also rejected the applicants’ theme concerning relational contracts, except as used in the narrow sense by Finn J to which I will return later.

83 Third, the applicants have not run any broad estoppel case concerning representations that:

(a) dealer agreements would be renewed, alternatively expressed that NRNs would not be given;

(b) dealer agreements would be continued to be renewed, that is NRNs not given, until at least the capital investments of dealers was recouped;

(c) MBAuP would not over time reduce the foot-print of the dealers.

84 Now the applicants did run in the context of the Wollongong dealer agreement scenario and analogues, a narrow estoppel by convention case. But this was hopeless.

85 Let me turn then to another set of themes.

The concept of goodwill – confusion and conflation

86 Another set of themes concerns the nature of goodwill. How does the legal concept of goodwill differ from the accounting concept? What is the particular nature of goodwill under franchise agreements such as the dealer agreements? Has the change from the dealer model to the agency model effected an acquisition or appropriation of goodwill by MBAuP from the dealers generally and the exemplar applicants specifically?

87 The applicants’ case is that the change from the dealer agreements to the agency agreements involved a transfer of goodwill from the dealers to MBAuP. Goodwill was defined to mean a valuable asset of and/or goodwill in the business at the dealership as a result of attracting customers, establishing customer relationships and generating customer revenue. The applicants say that MBAuP has transferred that value to itself.

88 Contrastingly, MBAuP takes a narrow view of goodwill, which it says was tethered to the dealer agreements, and was lost when the dealer agreements ended. Consequently, MBAuP says that the applicants had no goodwill that survived termination, and so there was nothing taken or transferred.

89 In summary, I have taken MBAuP’s position which has the advantage of according with High Court authority. I will put to one side for the moment more informal concepts that I will discuss later. Let me turn to some of the authorities.

90 As was made plain in Commissioner of State Revenue (WA) v Placer Dome Inc (2018) 265 CLR 585, goodwill at law is not equivalent to a going concern valuation or an accountant’s concept of goodwill. So it was said by the plurality (at [97] to [99]):

Goodwill for legal purposes is different from, and is not to be confused with, the “going value” or the going concern value of a business. These terms are not separate methods of valuing the same intangible. The distinction between them is clear and, in the context of this appeal, important. As seen earlier, goodwill represents a pre-existing relationship arising from a continuous course of business – to which the “attractive force which brings in custom” is central. Without an established business, there is no goodwill because there is no custom. A collection of assets has no custom.

Going concern value, on the other hand, is the ability of a business to generate income without interruption even where there has been a change in ownership. It has been recognised as a property right by the Supreme Court of the United States. In general terms, in a number of US decisions, it has been described as what differentiates an established business from one just starting; and, importantly, is present even when there is no goodwill.

For present purposes, the difference is best understood in the terms identified and discussed in Murry. Goodwill is property in the nature of the right or privilege to conduct the business by “means which have attracted custom to the business”. The courts will protect that property – those means of attracting custom to the business – irrespective of the profitability or value of the business, so far as it is legally possible to do so. Going concern value is not of that nature: it is not the right or privilege to conduct the business by means which have attracted custom to the business and, thus, going concern value does not comprise the means of attracting custom to the business which the courts will or can protect.

(emphasis and footnotes removed)

91 In terms of the legally relevant context with which I am considering, a dealer holds goodwill constituting property only if the dealer holds the right or privilege that satisfies the definition of goodwill at law. As explained in Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Murry (1998) 193 CLR 605 at [23] by the majority:

From the viewpoint of the proprietors of a business and subsequent purchasers, goodwill is an asset of the business because it is the valuable right or privilege to use the other assets of the business as a business to produce income. It is the right or privilege to make use of all that constitutes “the attractive force which brings in custom”. Goodwill is correctly identified as property, therefore, because it is the legal right or privilege to conduct a business in substantially the same manner and by substantially the same means that have attracted custom to it. It is a right or privilege that is inseparable from the conduct of the business.

92 Further, it was said at [45]:

Once goodwill as property is recognised as the legal right or privilege to conduct a business in substantially the same manner and by substantially the same means which in the past have attracted custom to the business, it follows that a person acquires goodwill when he or she acquires that right or privilege. The sources of the goodwill of a business may change and the part that various sources play in maintaining the goodwill may vary during the life of the business. But, as long as the business remains the “same business”, the goodwill acquired or created by a taxpayer is the same asset as that which is disposed of when the goodwill of the business is sold or otherwise or transferred.

93 Now in a franchise context, the fact that the legal definition of goodwill is aligned with the legal right or privilege to conduct a business in substantially the same manner and by substantially the same means that have attracted custom to it is of significance.

94 As MBAuP correctly points out, the franchise business cannot be conducted in substantially the same manner and by substantially the same means absent the rights granted to the franchisee by the franchisor. In other words, in the context before me, the continued existence of goodwill as asserted by each of the dealers before me turned upon the continued existence of a dealer agreement, which was the source of the legal right or privilege to conduct the business in substantially the same manner and by substantially the same means that had attracted custom to the particular dealer(s).

95 Now a central pillar of the applicants’ case is their allegation that MBAuP has acquired or appropriated their property, being their goodwill.

96 On the NRNs claim, they allege that one purpose of MBAuP in issuing those notices was to appropriate the dealers’ goodwill. The unconscionable conduct case alleges that the agency model resulted in the transferral of the goodwill in their dealership businesses to MBAuP without compensation. It proceeds on the footing that dealers’ goodwill is property and that the appropriation of one person’s property is objectively dishonest.

97 The applicants’ case exhibits a misunderstanding of the meaning of goodwill at law. They routinely equate the accounting definition of goodwill with the legal definition of goodwill. The applicants refer to dealers having paid an amount of money described as goodwill as evidence that they have goodwill that meets the legal description of property. But as was stated in Placer Dome at [53], goodwill to accountants clearly means something different than goodwill to lawyers. Goodwill for accounting purposes is essentially subjective, reflecting the excess that a purchaser is willing to pay for a business or the discount a seller is willing to accept for the same. However, as a matter of law, the existence or otherwise of goodwill is objectively ascertained.

98 In Inland Revenue Commissioners v Muller & Co’s Margarine Ltd [1901] AC 217 at 235, Lord Lindley stated:

Goodwill regarded as property has no meaning except in connection with some trade, business, or calling. In that connection I understand the word to include whatever adds value to a business by reason of situation, name and reputation, connection, introduction to old customers, and agreed absence from competition, or any of these things, and there may be others which do not occur to me. In this wide sense, goodwill is inseparable from the business to which it adds value, and, in my opinion, exists where the business is carried on. Such business may be carried on in one place or country or in several, and if in several there may be several businesses, each having a goodwill of its own.

99 The plurality in Box v Commissioner of Taxation (1952) 86 CLR 387 at 397 recognised that different businesses derive their value from different considerations such as location or reputation.

100 Moreover, as Placer Dome discussed, goodwill may have different sources depending on the facts of the case. As was said at [63]:

…the notion of custom encompassed connections between a business identity and customers, however those connections were made. This expansion of the view of goodwill from being sourced in a place of business to recognising that there were other sources – such as the personality of those that ran the business or the way it was conducted – did not diverge from the idea that custom was central to goodwill. Custom was and remains central. What had occurred was that the law now recognised that custom could be generated by and from different sources.

101 Let me return to Murry. The issue was whether under the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth), by reason of an exempting provision, the capital gain from the disposal of a business or an interest in a business was deemed to be reduced by half because the disposal included the goodwill of the business. Goodwill was not defined in the legislation. The factual context was the disposal of a licence to operate a taxi.

102 The majority held that the taxpayer did not dispose of a business within the meaning of the exempting provision, nor did they dispose of an interest in a business which included the goodwill of the business. The majority considered the nature of goodwill, goodwill as property, the sources of goodwill, and then the value of goodwill.

103 First, they stated that the existence of goodwill (at [12]) depends upon proof that the business generates and is likely to continue to generate earnings from the use of the identifiable assets, locations, people, efficiencies, systems, processes and techniques of the business.

104 Second, they endorsed Lord Linley’s description of goodwill in Inland Revenue Commissioners v Muller at 235 as:

…whatever adds value to a business by reason of situation, name and reputation, connection, introduction to old customers, and agreed absence from competition, or any of these things, and there may be others…

105 Third, they stated that the attraction of custom still remained central to the legal concept of goodwill. Moreover, they stated that the legal concept of goodwill has three different aspects, namely, property, sources and value, and that what unites those aspects is the conduct of a business. But for each aspect identified in Murry, the attraction of custom remained the focus of and central to the legal conception of goodwill.

106 Now in seeking to identify the sources of goodwill, the starting point was custom. So it was said in Murry at [24] that the goodwill of a business is the product of combining and using the tangible, intangible and human assets of a business for such purposes and in such ways that custom is drawn to it. They went on to say that:

Much goodwill, for example, derives from the use of trade marks or a particular site or from selling at competitive prices. But it makes no sense to describe goodwill in such cases as composed of trade marks, land or price, as the case may be. Furthermore, many of the matters that assisted in creating the present goodwill of a business may no longer exist. It is therefore more accurate to refer to goodwill as having sources than it is to refer to it as being composed of elements. In Muller, Lord Lindley referred to goodwill as adding value to a business “by reason of” situation, name and reputation, and other matters and not because goodwill was composed of such elements.

107 Goodwill has sources which are typically those that motivate service or provide competitive prices that attract customers.

108 But patronage in the sense of customers through the door is no longer the sole means of generating or adding value or earnings to a business by attracting custom.

109 Further, the sources of goodwill for a business are not static. The sources of goodwill of a business may change. Indeed, the part that various sources play in maintaining goodwill may vary during the life of a business.

110 Moreover, in some businesses, price and service may have little effect on attracting custom. The goodwill may instead derive from custom being attracted because of location, statutory monopolies including patents and trademarks and expenditure such as advertising. It was said in Murry (at [27]):

Goodwill may also be the product of expenditures rather than the use of assets. Thus, money spent on advertising and promotions, although charged against annual earnings rather than capitalised, may generate brand, product or business name recognition that helps to generate revenue...

111 Further, Murry reinforced the idea that goodwill for legal purposes is property and that (at [29]):

[t]o the extent that the proprietor of a business has the right or privilege to conduct the business in the manner and by the means which have attracted custom to the business, the courts will protect the sources of the goodwill of the business, so far as it is legally possible to do so…

112 The Court observed that goodwill has no existence independently of the conduct of a business and goodwill cannot be severed from the business which created it.

113 The Court noted that whilst goodwill (at [4]):

…may derive from identifiable assets of a business … it is an indivisible item of property, and it is an asset that is legally distinct from the sources - including other assets of the business - that have created the goodwill. Because that is so, goodwill does not inhere in the identifiable assets of a business, and the sale of an asset which is a source of goodwill, separate from the business itself, does not involve any disposition of the goodwill of the business.

114 So, the sale of an asset of a business does not involve any sale of goodwill unless the asset sale is accompanied by or carries with it the right to conduct the business.

115 The Court stated that when viewed from the perspective of the proprietors of a business and subsequent purchasers, goodwill is an asset of the business because it is the valuable right or privilege to use the other assets of the business as a business to produce income. The Court stated (at [23]):

From the viewpoint of the proprietors of a business and subsequent purchasers, goodwill is an asset of the business because it is the valuable right or privilege to use the other assets of the business as a business to produce income. It is the right or privilege to make use of all that constitutes “the attractive force which brings in custom.” Goodwill is correctly identified as property, therefore, because it is the legal right or privilege to conduct a business in substantially the same manner and by substantially the same means that have attracted custom to it. It is a right or privilege that is inseparable from the conduct of the business.

(footnotes omitted)

116 The Court later stated (at [45]):

Once goodwill as property is recognised as the legal right or privilege to conduct a business in substantially the same manner and by substantially the same means which in the past have attracted custom to the business, it follows that a person acquires goodwill when he or she acquires that right or privilege. The sources of the goodwill of a business may change and the part that various sources play in maintaining the goodwill may vary during the life of the business. But, as long as the business remains the “same business”, the goodwill acquired or created by a taxpayer is the same asset as that which is disposed of when the goodwill of the business is sold or otherwise transferred.

117 As custom is central to the nature and sources of goodwill, the value of the goodwill of a business varies with the earning capacity of the business and the value of the other identifiable assets and liabilities.

118 Let me say something about the nature of goodwill under a franchise agreement.

119 As I have indicated, goodwill constitutes property because it is the legal right or privilege to conduct a business in substantially the same manner and by substantially the same means that have attracted custom to it. It is an asset of a business because it is the valuable right or privilege to use the other assets of the business as a business to produce income. It is only when a person holds that right or privilege that they hold goodwill constituting property.

120 In Murry, it was concluded that the taxi licence was merely an item of property the value of which was not dependent on the present existence of a business, and therefore the majority held that the taxi licence contained no element of goodwill.

121 Now the fact that the legal definition of goodwill is tethered to the legal right or privilege to conduct a business in substantially the same manner and by substantially the same means that have attracted custom to it takes on particular significance in a franchise context, because the franchise business cannot be conducted in substantially the same manner and by substantially the same means absent the rights granted to the franchisee by the franchisor.

122 In the present context there was no Mercedes-Benz dealership business without the rights granted to a dealer under a dealer agreement. So, the question is not, as the applicants would have it, who owns the customer?

123 Without access to supply of Mercedes-Benz vehicles and rights to use the Mercedes-Benz brand, a dealer could not generate any future profits from the sale of Mercedes-Benz vehicles, whether that be through customer relationships or otherwise. Absent that supply and those rights, there would exist no Mercedes-Benz dealership from which they could derive future profits, nor would there be such a dealership that an applicant could transfer to a third party.

124 Without that supply and those rights, a former Mercedes-Benz dealer might deploy its physical assets, personnel and customer relationships to generate profits by operating a business as, say, a used car dealer or a servicing business, or, subject to obtaining a grant of rights from another brand, as a new car dealer for that other brand. But that would be a different business, with a different goodwill. In that circumstance the goodwill would be the right or privilege to conduct that other business.

125 Further, the absence of any right at law for a franchisee to be compensated for goodwill on non-renewal of a franchise agreement has long been recognised.

126 As Ward CJ in Eq said in Favotto Family Restaurants Pty Ltd v Chief Commissioner of State Revenue (2020) 111 ATR 283 at [104]:

Second, as to the nature of the rights under a franchise agreement, reference was made to the decision of the Full Court of the Federal Court (Lockhart, Wilcox and Gummow JJ) in Ranoa Pty Ltd v BP Oil Distribution Ltd (1989) 91 ALR 251 (Ranoa), a matter involving a franchise governed by the Petroleum Retail Marketing Franchise Act 1980 (Cth). In Ranoa, it was held that, on the expiry or termination of a franchise agreement, the franchisee has no right to continue operating the business and no right (in the absence of specific provision in the agreement to the contrary) to any goodwill that may have accrued to the business whilst it was operated by the franchisee. Their Honours noted (at 256) that, under the general law, “the benefit of goodwill built up by reason of a tenant carrying on a business from the leased premises enures to the benefit of the landlord at the expiration of the term” (citing Lord Coleridge CJ in Llewellyn v Rutherford (1875) LR 10 CP 456 at 467 ) and that, “in the absence of any special covenant and any other applicable statute, upon the tenancy coming to an end, the benefit of any goodwill of that character would be lost to the tenant and would enure to the benefit of the lessor” (see at 257).

127 Similarly, Habersberger J stated in Foxeden Pty Ltd v IOOF Building Society Ltd [2003] VSC 356 that a franchise merely confers a licence to participate in the franchisor’s business system for a specified term. He said at [269]:

However, Mr Hayes recognised that, generally, a franchise merely confers a licence to participate in the franchisor’s business system for a specified term. During the term of the franchise, the franchisee owns the goodwill of the franchise in the relevant sense and is able to sell the goodwill (by assigning the franchise agreement). In the absence of a contractual provision providing for compensation for goodwill on expiry or termination of the franchise, the franchisee will forfeit the goodwill…

128 Habersberger J subsequently observed at [295], that:

Whether or not the relationship between the Taylors and IOOF is correctly described as a franchise is not strictly relevant. What is important is what was actually agreed between the parties, whatever label is given to the relationship…

129 The absence of any right to compensation for goodwill on non-renewal of a franchise agreement is an issue that has long attracted the attention of those seeking to change franchising laws in Australia.

130 The Trade Practices Act Review Committee, which released its report in 1976, considered the issue of compensation to franchisees for the loss of goodwill upon the termination or non-renewal of their franchise agreement by the franchisor. It recommended that franchisees be given the right to just and equitable compensation.

131 In 2013, the issue was also considered in the review of the Franchising Code; see Wein A, Review of the Franchising Code of Conduct: Report to the Hon Gary Gray AO MP, Minister for Small Business, and the Hon Bernie Ripoll MP, Parliamentary Secretary for Small Business, 30 April 2013. The report of that inquiry concluded (at p107):

Nonetheless, there should not be a general overarching right to compensation for franchisees at the end of a fixed term franchise agreement. Making such a recommendation would substantially and fundamentally change long established legal principles of property and contract law. There would also be a risk of greater cost and uncertainty in the industry and possible unintended consequences from any such change to contractual rights.

While appreciating the contribution made by franchisees to the development of their franchise site or territory, a franchisee should expect that the franchise period should be no longer than the negotiated terms of the contract. Any equitable right to compensation for a franchisee whose franchise is not renewed must lie with the courts and any statutory right that may exist under the ACL.

Arguably, adequate remedies already exist if a franchisor fails to renew a franchise agreement in a situation where the franchisee has complied with all the conditions for renewal. Unlawful refusal will amount to a breach of the agreement by repudiation or possibly unconscionable conduct. However, if the agreement does not provide for renewal, the franchisee knows before entering into the agreement that the franchisee’s rights under the agreement will terminate on the expiry of the term. In that situation the franchisee should not be entitled to compensation.

132 Following the Wein review, amendments were made to the Franchising Code in relation to the enforceability of restraint of trade provisions where a franchise agreement is not renewed and nominal or no compensation for goodwill is given to a franchisee. But no right to compensation for goodwill, and no right to renewal, has been included in the Franchising Code. Rather, a franchisor is required to disclose “the prospective franchisee’s rights relating to any goodwill generated by the franchisee (including, if the franchisee does not have a right to any goodwill, a statement to that effect)” (Franchising Code, Annexure 1 (Disclosure Document for franchisee or prospective franchisee), [18.1(fa)]).

133 Now both Ward CJ in Eq in Favotto and Habersberger J in Foxeden referred to Ranoa Pty Ltd v BP Oil Distribution Ltd (1989) 91 ALR 251. Let me elaborate on Ranoa.

134 The appellant in Ranoa had operated a BP service station franchise at Engadine in New South Wales for 9 years. On 30 March 1988, the second respondent (BP Australia Limited) wrote to the appellant advising that “BP intends to take back control of BP Engadine at the end of your current lease” and “BP is unable to offer renewal at that time”. The proceeding concerned the construction of s 23 of the Petroleum Retail Marketing Franchise Act 1980 (Cth). Section 23 provided that:

(1) Where, but for this section, the operation of a provision of this Act would result in the acquisition of property from a person by another person otherwise than on just terms, there is payable to the person by that other person such reasonable amount of compensation as is agreed upon between those persons or, failing agreement, as is determined by a court.

(2) In sub-section (1), ‘acquisition of property’ and ‘just terms’ have the same respective meanings as in paragraph 51(xxxi) of the Constitution”

135 The question as framed on the appeal assumed that the respondents acquired property, namely some species of goodwill from the appellant, and that such property was acquired otherwise than on just terms. The primary judge had answered in the negative a question which had been ordered to be decided separately from and before all other questions in the proceedings. The question was:

Upon the true construction of s.23 of the [Petroleum Retail Marketing Franchise Act 1980] in its setting in the Act, is the franchisee, upon the expiration of the period of nine years, provided for in ss.13 and 17B entitled to such reasonable amount of compensation as is determined by a Court upon the basis that the franchisor acquired property from the franchisee otherwise than on just terms by reason of the operation of this Act?.

136 The question before the Full Court was reformulated as:

Upon the basis of the following assumptions, namely, that for the purpose only of the determination of this separate question, on 18 September 1989:

(a) the respondents acquired property namely some species of goodwill from the Appellant and,

(b) such property was acquired otherwise than on just terms,

did the operation of some provision of the [Petroleum Retail Marketing Franchise Act 1980] result in the acquisition of this property so as to require the Respondents to pay to the Appellant compensation pursuant to s 23 of the said Act?

137 So, the issue that was posed was whether the operation of s 23 of that Act resulted in the acquisition of goodwill such as to require the respondents to pay compensation to the appellant. In passing, Lockhart, Wilcox and Gummow JJ opined on the position of a franchise under the common law and held that the legislation under consideration in that case did not alter the position at general law. So it was said (at 257):

Upon the expiry of the term of a franchise agreement in circumstances such as those in the present case, where the franchisor is not bound to renew the agreement and does not voluntarily do so, does the legislation bring about a result as regards the goodwill which differs from that under the general law?...

138 As to the specific question in that case, their Honours held that the:

…acquisition of goodwill upon the end of the term … was not the result of the operation of any provision of the Act so much as a consequence of what the Parliament did not provide, namely an entrenched tenure for a period greater than 9 years.

139 Their Honours noted that under the general law the benefit of goodwill built up by reason of a tenant carrying on a business from the leased premises enures to the benefit of the landlord at the expiration of the term and that in the absence of any special covenant and any other applicable statute, upon the tenancy coming to an end, the benefit of any goodwill of the relevant character would enure to the benefit of the lessor. Their Honours stated (at 257 and 258) that:

Where a franchisor elects to grant a new lease the franchisee has the benefit of continued exploitation of the goodwill of the site... But where a franchisor elects not to grant a new lease, the franchisee is turned from the site without compensation for any goodwill which it may have developed during its period of occupancy. A franchisee, such as the appellant, may regard this result as harsh, the harshness being exacerbated if it should be the case - we do not know whether it is so - that franchisors are more likely to decide themselves to operate sites to which substantial goodwill attaches…

140 So, the views expressed in Ranoa are consistent with the principle, recognised in Murry and Placer Dome, that goodwill is the legal right or privilege to conduct a business in substantially the same manner and by substantially the same means which in the past have attracted custom to the business. The continued existence of that goodwill turns on the continued existence of that right or privilege.

141 Now I accept though that Ranoa concerned the “taking back” by the franchisor from a franchisee tenant of a leased service station, by a notice of non-renewal of the lease. It was against that factual background, and a general law principle that goodwill built up by a tenant from leased premises enures to the benefit of the landlord at expiration, that the Court found there was no residual goodwill in the tenant franchisee’s business. The present case does not share that common factual and legal substratum.

142 But again, to use the present case as an example, a dealer whose term has expired cannot transfer to a purchaser the essential ingredient required to conduct a Mercedes-Benz franchise, being the rights granted under the dealer agreement, including access to supply of MB vehicles and use of MB intellectual property.

143 As Chesterman J observed in McDonald’s Australia Holdings Ltd v Commissioner of State Revenue (2004) 57 ATR 395 in discussing whether there had been a transfer of the goodwill of a McDonald’s franchise (at [61]):

It follows that the applicants cannot have become the transferee of the licensee’s goodwill, or have otherwise acquired the goodwill, unless it acquired those assets which the licensees held prior to 31 January 1994 and which allowed them to carry on the business, which is said to have given rise to the goodwill. In practical terms that means the licences, or rights, to use the McDonald’s System’s trademarks, trade names and service names. Without these licenses the licensees would not have conducted their businesses which were McDonald’s restaurants. They may have needed other things as well, but the licenses were the essential ingredient. Customers are attracted to a McDonald’s restaurant because of the reputation of the McDonald’s name and the fact that enforced compliance with the detail of the McDonald’s System means that on the occasion of every visit and in every McDonald’s restaurant the quality and choice of food and the quality of service and standard of fit-out will be the same. There is a uniformity of product, service and milieu in every McDonald’s restaurant. This uniformity, which the public confidently expects to experience at a McDonald’s restaurant, comes from the adherence by each restaurant proprietor to the McDonald’s System including the use of the trademarks, trade names and service names. It is the right to use these items of intangible property which generates goodwill…

144 Similar issues arose in relation to the sale of two McDonald’s restaurant businesses in Favotto concerning assessments for duty issued by the Chief Commissioner of State Revenue (NSW) in respect of transactions entered into by Favotto relating to those restaurants. The principal issue was whether there was dutiable property and, specifically, whether the transactions effected a transfer or agreement for the sale or transfer of the goodwill of the existing McDonald’s restaurant businesses to Favotto or merely the non-dutiable grant of new franchise rights to enable Favotto to continue the operation of the existing restaurant businesses.

145 Ward CJ in Eq considered that what was revealed on a consideration of the respective transaction documents was that Favotto acquired a limited licence to use the respective premises and the “McDonald’s System” for the purpose of running a McDonald’s restaurant (for a limited time and on strict conditions) at each of the premises. Her Honour considered it significant that on the termination of the licence arrangement, there was no goodwill that enured to the benefit of Favotto. Favotto had the temporary enjoyment of the goodwill of the businesses but there was no transfer as such to Favotto of the goodwill in the sense that it would be free to deal with or dispose of this at the end of the licence arrangements. As her Honour stated, “in effect, Favotto’s right to make use of that goodwill simply comes to an end” (at [170]). On the expiry or termination of a franchise agreement, a “franchisee has no right to continue operating the business and no right (in the absence of specific provision in the agreement to the contrary) to any goodwill that may have accrued to the business whilst it was operated by the franchisee” (at [104], citing Ranoa). Moreover, in the absence of a contractual stipulation to the contrary, no compensation for any so-called loss of goodwill is payable.

146 Let me say something about two other cases that the parties before me lingered on being Burger King Corporation v Hungry Jack’s Pty Ltd [2001] NSWCA 187; 69 NSWLR 558 and Bond Brewing (NSW) Pty Ltd v Refell Party Ice Supplies Pty Ltd (unreported, Supreme Court of NSW, Equity Division, 17 August 1987).

147 Let me deal first with Burger King and the scenario that it was dealing with.

148 Burger King Corp as franchisor and Hungry Jack’s as franchisee entered into four agreements, one of which was a development agreement. Those agreements, together with the individual franchises for each store, governed their contractual relationship, including Hungry Jack’s development rights in Australia.

149 The development agreement conferred upon Hungry Jack’s the non-exclusive right to develop and to be franchised to operate Burger King restaurants in Australia. Under clause 2.1, Hungry Jack’s was required either by itself or through a third-party franchisee to develop and open a minimum of four new Burger King restaurants per year in Western Australia, South Australia and Queensland. The agreement also provided for non-exclusive development rights in the other Australian states and territories. Further, there was a provision allowing termination for breach and a requirement that 30 days’ notice be given in respect of any breach that was capable of cure. Clause 4.1 required Hungry Jack’s to obtain individual franchises for each restaurant developed under the agreement. That required compliance with various procedures, including entering into a further agreement, which provided for conditional approval in respect of nominated sites and to have certain approvals at the time of application for a franchise agreement for a newly developed restaurant.

150 Now from 1993, Burger King Corp took a more active role in Australia with a view to reducing Hungry Jack’s role in the market. In 1995, Burger King Corp took three steps that restricted Hungry Jack’s ability to develop. First, it advised that it would no longer approve any further recruitment of third party franchisees. Second, it withdrew financial approval. Third, it withdrew operational approval. The effect of these actions was to impede Hungry Jack’s development of new outlets. The impact of this was significant as Hungry Jack’s was required under the development agreement to develop a minimum of four stores in Western Australia, South Australia and Queensland each year.

151 During 1994, the parties also entered into discussions with Shell about the feasibility of establishing Hungry Jack’s outlets in Shell service stations. A test site agreement was initially proposed to assess the viability of a long-term venture. The initial discussions were conducted on the basis that if the test sites were successful, the parties would enter into a long-term tripartite venture. During the course of these discussions, Burger King Corp then commenced dealing with Shell separately. Months after Burger King Corp had decided to proceed with Shell without Hungry Jack’s, Burger King Corp informed Hungry Jack’s of the position.

152 Now over the relevant period Hungry Jack’s was operating 148 Hungry Jack’s restaurants and operating another two restaurants controlled by Shell on service station sites. 18 Hungry Jack’s restaurants were operated by third party franchisees and Hungry Jack’s provided training and other services to those restaurants. From November 1990 to November 1996 Hungry Jack’s had paid royalties to Burger King Corp exceeding $20 million.

153 By two separate notices given in November 1996, Burger King Corp purported to terminate the development agreement for breach. The first notice particularised Hungry Jack’s failure to develop new restaurants as required by clause 2.1 as the breach giving rise to the right to terminate. The second alleged various breaches relating to a sunglass promotion campaign, advertising without approval and improper trademark use. A third notice was given in September 1997, after the commencement of proceedings, against the possibility that the earlier notices were held to be invalid.

154 Hungry Jack’s challenged the notices of termination and was substantially successful before the primary judge. Burger King Corp then pursued an appeal, but unsuccessfully.

155 Now it was common ground that there were implied terms of the development agreement that Burger King Corp would do all that was reasonably necessary to enable Hungry Jack’s to enjoy the benefits of that agreement, that Burger King Corp would act reasonably in exercising its powers under the agreement, and that Burger King Corp would act in good faith in the exercise of its contractual powers.

156 Now as to the steps taken by Burger King Corp to reduce Hungry Jack’s role in the Australian market, the Court of Appeal observed that Burger King Corp’s conduct and its intentions in respect of the Australian market were to be reviewed against the fact that under the development agreement, Hungry Jack’s had the prospect of expanding over a 20 year period and that the franchise agreements for each restaurant provided for a term of either 15 or 20 years with an option to renew for the same period. A detailed review of the facts is contained in a schedule to the judgment which has been omitted from the authorised report.

157 On the issue concerning the third party freeze by which Burger King Corp would not approve any further recruitment of third-party franchisees, the Court held that Burger King Corp did not seek to support the freeze on any contractual basis and that the freeze was imposed at a time when Burger King Corp had made a policy decision to, in some way, take back the Australian market. The Court was satisfied that it was clear that Burger King Corp was actively seeking ways to at least reduce Hungry Jack’s dominant role if it could not remove it from the market altogether. One of the means available to Hungry Jack’s to both satisfy the development schedule and to develop generally was through third party franchisee arrangements. But it was precluded from doing so from mid-May 1995 at a time when there was active interest by prospective franchisee applicants. The Court held that the continued imposition of the freeze was in breach of the implied terms of reasonableness and good faith.

158 On the issue concerning Burger King Corp’s financial disapproval of Hungry Jack’s which was the second step of a process whereby Hungry Jack’s ability to expand was affected, the Court stated (at [276]) that there was considerable force in the trial judge’s observation that the “odd thing about BKC’s approach, which, in my opinion, is only explicable because of the attitude BKC was taking to HJPL, is that the financial disapproval preceded the receipt of the various information [requested of Hungry Jack’s], rather than followed an analysis of it and the exercise of the discretion based on that analysis”.

159 The Court held that Burger King Corp’s conduct in this regard breached an implied term of good faith, stating (at [310]):

…the evidence clearly establishes that BKC’s conduct is properly characterised as being directed not to furthering its legitimate rights under the Development Agreement but to preventing HJPL from performing its obligations under the Development Agreement.

160 The Court reached the same view regarding the other issue concerning the withdrawal of operational approval. It accepted that Burger King Corp breached its obligations of good faith and reasonableness by its conduct in imposing the third party freeze, and in financially and operationally preventing Hungry Jack’s from further expansion.

161 Now the conduct of Burger King Corp was not in good faith because it was directed not to furthering its own legitimate interests but, rather, to preventing Hungry Jack’s from performing its obligations under the development agreement. Its conduct was directed to setting up a basis for terminating the development agreement and denying Hungry Jack’s the benefit of the contractual bargain. The long-term nature of the parties’ bargain in Burger King was clear on the contractual documents. Hungry Jack’s had the prospect of expanding over a 20-year period and the franchise agreements for each restaurant provided for a term of either 15 or 20 years, with an option to renew for the same period. As the Court said (at [185]), Burger King Corp’s conduct was wrongful because it sought to “thwart HJPL’s rights under the contract”.

162 In particular, the Court held (at [187]) that:

the discretion conferred in clause 4.1 was one which was required to be exercised reasonably, so that it could not be used for a purpose foreign to that for which it was granted, such as to thwart the respondent’s right to develop and ultimately to procure a situation where the Agreement could be terminated.

163 Burger King Corp did not withhold operational and financial approval under clause 4.1 of the development agreement out of any concern regarding the merits of applications for approval submitted by Hungry Jack’s under that clause, that being the purpose of the development procedure under that clause. It withheld approval because it wanted to thwart Hungry Jack’s right to develop and ultimately to procure a situation where the agreement could be terminated.

164 Let me now deal with Bond Brewing and the scenario that it was dealing with. Bond Brewing is an estoppel case.

165 In Bond Brewing, a notice to quit was served by the plaintiff, a brewery and the owner of the New Brighton Hotel at Manly, NSW, on the defendant, the tenant hotelkeeper, who was holding over as a monthly tenant after expiry of a one-year lease. In 1982, the tenant had, with the consent of the brewery, taken an assignment of an interest in the leasehold and had paid in consideration for the assignment an amount partly attributable to “goodwill”.

166 From 1976, the brewery had required incoming tenants to sign a so-called goodwill letter addressed to the brewery, a condition of which was that the brewery would not be obligated to compensate the tenant for loss of goodwill if the brewery decided not to renew the current or any subsequent lease or otherwise retake possession of the premises. During the period 1970 to 1985, which was both before and after the goodwill letter was required of the tenant, the brewery had a practice where on each occasion when it sought to gain possession of a hotel the subject of a brewery lease, it paid the particular tenant substantial compensation for giving up possession even though the tenant was holding over under a weekly or monthly tenancy. The evidence also showed that the person who had authority to state to the tenant in that case what the brewery’s policy was in relation to the goodwill letter had told the tenant before its signature was affixed that the letter was a mere formality.

167 The brewery decided not to renew the lease and did not offer to pay any compensation for loss of goodwill to the tenant. The tenant argued that when it took an assignment of the lease, it acted on a representation made by the landlord or relied upon an assumption, which the landlord did not correct, that the landlord would not terminate without paying to the tenant a reasonable sum for the goodwill. The landlord argued that the tenant was precluded from relying upon its understanding of the landlord’s practice because of the terms of the goodwill letter.

168 Waddell CJ in Eq upheld the tenant’s estoppel in pais argument.

169 Bond Brewing is not authority for the proposition for which the applicants have cited the case before me. In summary, neither Bond Brewing nor Burger King assist the applicants.

170 Now more generally the applicants say that the notion that goodwill as a matter of legal analysis ends when the underlying franchise agreement terminates is inconsistent with the analysis in Murry. But I disagree. Goodwill in terms of the legal concept did not transcend the non-renewal of the dealer agreements. Moreover, there was no acquisition or appropriation by MBAuP of the dealers’ goodwill at the time of the service of the NRNs or at any time thereafter.