Federal Court of Australia

Energy Beverages LLC v Kangaroo Mother Australia Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 999

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | KANGAROO MOTHER AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Respondent

| |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The respondent’s application pursuant to s 197 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) that its Australian Trade Mark Application No. 1989429 for KANGAROO MOTHER be amended in accordance with the minute of proposed order dated 14 June 2023 be refused.

2. The appeal be allowed.

3. The decision of the Delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks dated 5 July 2021, refusing the appellant’s opposition to the application by the respondent for registration of KANGAROO MOTHER (Australian trade mark number 1989429) in respect of goods in classes 5, 29, 30, 31 and 32 (the KANGAROO MOTHER Mark) be set aside.

4. The respondent’s application for registration of the KANGAROO MOTHER Mark be refused.

5. The respondent pay the appellant’s costs of the proceeding and of the proceeding before the Delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

O’CALLAGHAN J:

Introduction

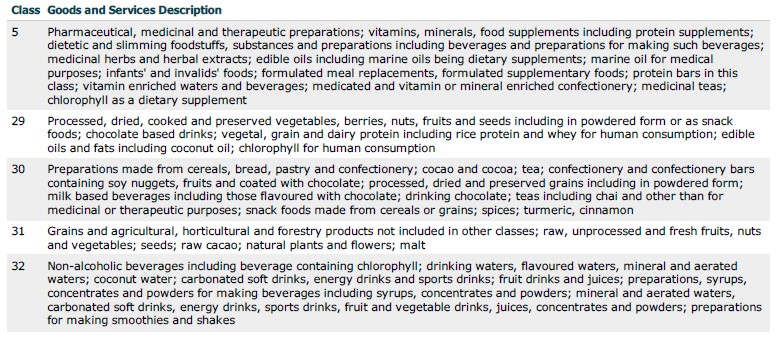

1 Energy Beverages LLC (EB) appeals from a decision of a Delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks (the Delegate) dated 5 July 2021, refusing its opposition to the application by Kangaroo Mother Australia Pty Ltd (KMA), the respondent, for registration of KANGAROO MOTHER (Australian trade mark number 1989429) in respect of goods in Classes 5, 29, 30, 31, and 32 (the KANGAROO MOTHER Mark). Attached to these reasons marked annexure A is complete list of the Designated Goods.

2 EB is a subsidiary of Monster Beverage Corporation, whose shares are listed on the NASDAQ Stock Market. It is a supplier in Australia of energy drinks. Its MOTHER energy drink was launched by the Coca-Cola Company in 2007 and acquired by EB in June 2015.

3 EB owns a number of Australian trade mark registrations incorporating the word MOTHER for goods in Classes 5 and 32. Two MOTHER marks are of particular relevance for the purpose of this proceeding, namely:

NO. | MARK | FILING DATE | GOODS |

1230388 [(388 Mark)] | MOTHER | 17 Mar 2008 | Class 32: Non-alcoholic beverages; drinking waters, flavoured waters, mineral and aerated waters; carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks and sports drinks; fruit drinks and juices; syrups, concentrates and powders for making beverages including syrups, concentrates and powders for making mineral and aerated waters, carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks, sports drinks, fruit drinks and juices |

1320799 [(799 Mark)] |

| 14 Sep 2009 | Class 5: Pharmaceutical and veterinary preparations; dietetic substances and preparations adapted for medical use; food and beverages for babies; medicated and dietary beverages; liquid vitamin preparations and tonics; health food supplements; nutritional and food supplements; liquid nutritional and vitamin supplements; syrups, concentrates and powders for making all of the aforesaid Class 32: Non-alcoholic beverages; drinking waters, flavoured waters, mineral and aerated waters; carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks and sports drinks; fruit drinks and juices; syrups, concentrates and powders for making beverages including syrups, concentrates and powders for making mineral and aerated waters, carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks, sports drinks, fruit drinks and juices; low-calorie beverages |

(I will refer to the 388 Mark and the 799 Mark collectively as EB’s Marks).

4 KMA is an Australian corporation. It was incorporated in July 2019. It has never traded.

5 Erbaviva Natural Care (New Zealand) Limited (Erbaviva) assigned its application for registration of the KANGAROO MOTHER Mark to KMA on 10 March 2020.

6 Erbaviva is a New Zealand company. It was incorporated in March 2014. Its sole director and shareholder, Mr Zheng, is also a director and secretary of KMA.

7 On 7 August 2020, Erbaviva changed its name to Dodwell & Co Limited. Like KMA, it has never traded.

The decision of the delegate

8 EB opposed the registration of the KANGAROOO MOTHER Mark before the Delegate under ss 42(b), 44, and 60 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth). See Energy Beverages LLC v Kangaroo Mother Australia Pty Ltd [2021] ATMO 62; (2021) 166 IPR 371.

9 The Delegate commenced (at [11]) by noting that “[t]here is nothing before me from which I might provide a background of [KMA]”.

10 The Delegate’s reasons were relatively brief. He found that EB failed to establish any of the grounds of opposition it contended for, and registered KANGAROOO MOTHER Mark in respect of all of the goods specified in the application.

11 As to s 44, the Delegate was not satisfied that any of EB’s Marks relied upon were deceptively similar to the KANGAROOO MOTHER Mark. As to s 60, the Delegate found that EB had not established that because of the reputation acquired by one or more of its marks (including MOTHER rendered in a Gothic-style script) that use of the KANGAROOO MOTHER Mark would be likely to deceive or cause confusion. As to s 42(b), for essentially the same reasons, the Delegate found that he was not satisfied that use of the KANGAROOO MOTHER Mark would be contrary to law. Each ground of opposition therefore failed.

The notice of appeal

12 EB relied on the following three grounds in its notice of appeal filed on 27 July 2021:

1. The Delegate erred in concluding at [30] that the ground of opposition under s 44 of the Act was not established.

Particulars

a. The Delegate erred in concluding that the Opposed Mark was not deceptively similar to the Appellant’s Trade Marks outlined at [10] (including its Mother Trade Mark the subject of Australian Trade Mark registrations 1230388 and 1364858).

b. The Delegate ought to have concluded that the Opposed Mark was deceptively similar to the Mother Trade Mark, and the remainder of the Appellant’s Trade Marks.

2. The Delegate erred in concluding at [47] that the ground of opposition under s 60 of the Act was not established.

Particulars

a. The Delegate erred in concluding that, having regard to the reputation of the Appellant in the Mother Trade Mark in Australia, the use of the Opposed Mark was not likely to deceive or cause confusion.

b. The Delegate ought to have found that, because of the prior reputation in the Appellant’s Trade Marks in Australia, including the Mother Trade Mark, the use of the Opposed Mark would be likely to deceive or cause confusion, with the result that the ground of opposition under s 60 of the Act was established.

…

5. The Opposed Mark should be refused registration pursuant to the ground of opposition under s 59 of the Act.

Particulars

a. In light of the matters referred to in the particulars to paragraph 4 above, the Respondent and/or Erbaviva did not as at the filing date of the Application (and do not) intend to use, or authorise the use of, the Opposed Mark in Australia or assign the Opposed Mark to a body corporate for use by the body corporate in Australia.

13 In so far as they are relevant, the particulars to paragraph 4 (which ground of appeal was not pressed) that were picked up in the particulars to paragraph 5 were as follows:

The Respondent was not the applicant for registration of the Opposed Mark as at the filing date of the Application and the applicant for registration of the Opposed Mark as at that date, Erbaviva … was not using or authorising the use of the Opposed Mark and did not intend to use or authorise the use of the Opposed Mark or assign the Opposed Mark to a body corporate that was about to be constituted with a view to the use by the body corporate of the Opposed Mark in relation to the [Designated Goods].

14 The issues for determination on the appeal are thus:

(1) Under s 59 of the Trade Marks Act: whether, as at the priority date, Erbaviva intended to use or authorise the use of the KANGAROO MOTHER Mark in Australia in respect of the Designated Goods.

(2) Under s 44 of the Trade Marks Act: (a) whether the KANGAROO MOTHER Mark is deceptively similar to EB’s Marks; and (b) whether the Designated Goods are the same as, or of the same description as, goods in respect of which EB’s Marks are registered.

(3) Under s 60 of the Trade Marks Act: (a) whether, as at the priority date the trade mark MOTHER had acquired a reputation in Australia; and (b) if so whether, because of that reputation, the use of the KANGAROO MOTHER Mark in respect of any of the Designated Goods in Australia was likely to deceive or cause confusion.

The nature of the appeal

15 This appeal is brought pursuant to s 56 of the Trade Marks Act, which relevantly provides that “… the opponent may appeal to the Federal Court … from a decision of the Registrar under section 55”.

16 Justice Yates summarised the nature of an appeal under the cognate appeal provision in s 35 (which is the appeal provision applicable when the Registrar accepts an application subject to conditions or limitations or rejects it) in Apple Inc v Registrar of Trade Marks (2014) 227 FCR 511 at 516 [22]-[25] by reference to the authorities, as follows:

Although styled an “appeal”, this proceeding involves the exercise of the original jurisdiction of the court: Registrar of Trade Marks v Woolworths Ltd (1999) 93 FCR 365 at [32]. The court is to determine judicially whether the application should succeed on its merits, not whether the registrar has lawfully discharged her duties: Jafferjee v Scarlett (1937) 57 CLR 115 at 126.

What is required in that regard is a hearing de novo in which the court approaches the matter “afresh and without undue concern as to the ratio decidendi of the Registrar”: Rowntree Plc v Rollbits Pty Ltd (1988) 90 FLR 398 at 403. That said, weight should be given to the Registrar’s opinion as “a skilled and experienced person”: Jafferjee at CLR 126; ALR 408–9. On some occasions, it has been said that “due weight” should be given to the Registrar’s opinion: Eclipse Sleep Products Incorporated v Registrar of Trade Marks (1957) 99 CLR 300 at 308. On other occasions, it has been said that “great weight” (Eclipse at 321; Registrar of Trade Marks v Muller (1980) 144 CLR 37 at 41) or “very considerable importance” (Joseph Bancroft & Sons Co v Registrar of Trade Marks (1957) 99 CLR 453 at 457) should be given to the registrar’s opinion.

I do not think that, by using these varying expressions, the cases intend to convey different notions of deference. Nevertheless, the degree to which weight should be given to the Registrar’s opinion will, no doubt, depend on the circumstances of each case and the particular question involved. For example, in the present case, both parties accepted that the weight to be given to the Registrar’s opinion may be affected by the fact that evidence has been adduced in the appeal which was not before the delegate.

In Woolworths, French J observed (at 377):

… Weight can be given to the Registrar’s opinion without compromising the duty of the Court to construe the relevant legal criteria. When the proper principles are applied to the manner in which a judgment is to be made about an issue such as “deceptive similarity” there is room for a degree of deference to the evaluative judgment actually made by the Registrar. That does not mean that the Court is bound to accept the Registrar’s factual judgment. Rather it can be treated as a factor relevant to the Court’s own evaluation.

17 As to onus, it lies on EB to establish the grounds of opposition upon which it relied. The standard of proof is on the balance of probabilities. See Telstra Corporation Ltd v Phone Directories Company Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 237 FCR 388 at 420 [132]-[133] (Besanko, Jagot and Edelman JJ).

18 In this case, the weight to be given to the Delegate’s decision is limited, because his reasons were brief, additional evidence was adduced on appeal, and the ground of opposition under s 59 was not relied on before him.

The witnesses

19 EB read the following affidavits:

(1) An affidavit of Mr Samuel Thiele sworn 1 December 2021. Mr Thiele is the Vice President – Oceania for Energy Beverages Australia Pty Ltd, a wholly owned subsidiary of EB; and Monster Energy AU Pty Ltd, a wholly owned subsidiary of Monster Energy Company. He gave evidence about the acquisition of EB; the range of products sold under various of EB’s Marks; and the advertising, marketing and promotion of the products under or by reference to them.

(2) An affidavit of Ms Lucy Robinson affirmed on 1 December 2021. Ms Robinson is a solicitor employed by EB’s solicitors. She produced various online searches relating to EB’s Marks, other energy drink and beverage companies, and photographs of product refrigerators in eight supermarkets and petrol stations in Victoria; trade mark searches relating to certain energy drink and coffee companies; some podcasts relating to EB’s Mother products; and some newspaper articles relating to EB’s Mother products.

(3) An affidavit of Ms Emma Drinkwater affirmed on 1 December 2021. Ms Drinkwater is a solicitor employed by EB’s solicitors. She gave evidence of visiting two hotels, one Woolworths store, and one 7-Eleven store in Melbourne, where she purchased some of EB’s Mother products. She gave evidence of visiting one further hotel which was out of stock of EB’s Mother products.

20 Mr Thiele was cross-examined by Ms E Whitby of counsel, who appeared for KMA, mainly in relation to questions related to EB’s evidence of reputation.

21 KMA read the following affidavits:

(1) An affidavit of Mr Antony Zheng affirmed 13 April 2022. He gave evidence as to Erbaviva’s intention to use the mark as at the priority date.

(2) An affidavit of Mr Onur Saygin affirmed 13 April 2022. Mr Saygin is a solicitor employed by KMA’s solicitors. He produced a trade mark search of the Australian Trade Mark database for applications and registrations incorporating the word “Mother” in the various classes of the Designated Goods and images of the website situated at https://www.motherenergydrink.com/en-au, being EB’s website for its MOTHER energy drink.

22 KMA also produced MFI Ex R2, comprising a selection business records, which were said to “relate to the trade mark prosecution history of the Kangaroo Mother marks and email communications between Mr Zheng and the Shanghai Urganic ‘conglomerate’ in relation to the Kangaroo Mother brand and trade marks”. Other than that observation about the document, KMA did not place any particular reliance on it in its closing submission.

23 Mr Zheng was cross-examined at length by senior counsel for EB, Mr TD Cordiner KC (who appeared with Mr SM Rebikoff of counsel).

Application by KMA to amend the trade mark application

24 On the penultimate day of the trial (14 June 2023), KMA handed up a short minute, asking that I make an order “[p]ursuant to s 197 of the of the Trade Marks Act … [that] the Respondent’s Australian Trade Mark Application No. 1989429 for KANGAROO MOTHER in the name of Kangaroo Mother Australia Pty Ltd be amended by deleting those specification of goods struck-out in Annexure A”.

25 If the (extensive) strikethroughs were made, the following goods would remain:

(a) Class 5: (including) Pharmaceutical, medicinal and therapeutic preparations; vitamins, minerals and food supplements including protein supplements; dietetic beverages adapted for medical purposes.

(b) Class 29: (including) milk based beverages; milk-based beverages flavoured with coffee, cocoa, chocolate or tea; preserved, dried, frozen, processed and cooked fruits and vegetables;

(c) Class 30: (including) Breakfast cereal; cereal preparations; cereal-based energy bars and snack foods; tea; tea-based beverages; tea substitutes; artificial tea; cocoa; cocoa-based beverages; chocolate-based beverages; cocoa substitutes; artificial cocoa; chocolate-based beverages [sic].

(d) Class 31: (including) grains (cereals); raw, unprocessed and fresh fruits, nuts and vegetables; raw and unprocessed grains and seeds.

(e) Class 32: (including) Mineral and aerated waters; non-alcoholic drinks, fruit drinks and fruit juices; vegetable juices, soy based beverages, smoothies.

26 The application was made orally. There was no interlocutory application, and no affidavit. And it was made, as I said, on the penultimate day of the trial.

27 The only explanation proffered by counsel for making the application was that it was designed “to narrow the issues in dispute” and was done “simply [to] inform[] the Court that it does not press the specifications indicated in strikethrough as a matter of efficiency”.

28 The application was opposed, including on the ground that KMA had not provided full and frank disclosure of the reason for the amendment, or for the delay in making it, and that it is to be inferred that the real reason for it was to do an end run around EB’s contention that if part of the KANGAROO MOTHER Mark failed, then the whole mark would fail. See Apple Inc v Registrar of Trade Marks [2014] FCA 1304; (2014) 322 ALR 1 at 41 [232] (Yates J) (“There is but one application covering registration of the mark for all the services that have been specified. If the application fails in one respect, it fails as a whole”). (For reasons that are not obvious, the authorised version of his Honour’s reasons in volume 227 of the Federal Court Reports stops at [59]). See too Dr August Wolff GmbH & Co KG Arzneimittel v Combe International Ltd [2020] FCA 39; (2020) 149 IPR 1 at 9 [39] (Stewart J); Henley Arch Pty Ltd v Henley Constructions Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 1369; (2021) 163 IPR 1 at 182 [790] (Anderson J).

29 Section 197 of the Trade Marks Act provides that the court, on hearing an appeal against a decision or direction of the Registrar, “may … (e) give any judgment, or make any order, that, in all the circumstances, it thinks fit.”

30 That power is discretionary, obviously enough.

31 There is no doubt, and EB accepted, that the court has power to amend the specification of a trade mark application pursuant to s 197 while seized of an appeal from a decision of the Delegate from an opposition to the trade mark application.

32 As Yates J said in Frucor Beverages Ltd v Coca-Cola Company [2018] FCA 993; (2018) 358 ALR 336 at 372 [195]:

I do not see how an appeal to this Court from a decision of the Registrar in opposition to registration proceedings under the Trade Marks Act differs materially from an appeal to this Court from a decision of the Commissioner in opposition to grant proceedings under the Patents Act. Whilst I acknowledge that, in the present case, an application under s 63 of the Trade Marks Act was not before the Registrar, the registrability of the mark the subject of the application was in contest. In the proceedings below, the Registrar had the power to permit the application to be amended subject to the constraints placed upon the exercise of that power by the Act. Given the nature of the “appeal” to this Court, the Court’s power to quell the controversy as to the registrability of the mark — the subject matter of the appeal — cannot be more limited than the Registrar’s power. Further, it cannot matter that the Registrar was not asked to exercise the power of amendment, just as it cannot matter that an opponent might seek to raise additional or new grounds of opposition, or that the parties might seek to adduce different evidence to the evidence that was before the Registrar or raise new or different arguments. The opposition proceeds afresh before the Court on the subject matter that was before the Registrar and is adjudicated upon accordingly.

33 A similar power to the power to amend in s 197 of the Trade Marks Act is contained in s 105 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth).

34 As Kenny and Stone JJ said in Les Laboratoires Servier v Apotex Pty Ltd [2010] FCAFC 131; (2010) 273 ALR 630 at 647-48 [76]-78] about that provision:

The discretion to grant or deny leave to amend under s 105 is, on the face of the statute (and save for s 105(4)), unfettered. However, various cases have set forth guidelines to assist judges in the exercise of this discretion: see Novartis AG v Bausch & Lomb (Aust) Pty Ltd (2004) 62 IPR 71; [2004] FCA 835 at [67]-[68] and authorities cited therein, especially Smith Kline & French Laboratories Ltd v Evans Medical Ltd [1989] 1 FSR 561 (Smith Kline & French). The guidelines provided in the latter case have often been relied on. In that case (at 569) Aldous J stated:

The discretion as to whether or not to allow amendment is a wide one and the cases illustrate some principles which are applicable to the present case. First, the onus to establish that amendment should be allowed is upon the patentee and full disclosure must be made of all relevant matters. If there is a failure to disclose all the relevant matters, amendment will be refused. Secondly, amendment will be allowed provided the amendments are permitted under the Act and no circumstances arise which would lead the court to refuse the amendment. Thirdly, it is in the public interest that amendment is sought promptly. Thus, in cases where a patentee delays for an unreasonable period before seeking amendment, it will not be allowed unless the patentee shows reasonable grounds for his delay. Such includes cases where a patentee believed that amendment was not necessary and had reasonable grounds for that belief. Fourthly, a patentee who seeks to obtain an unfair advantage from a patent, which he knows or should have known should be amended, will not be allowed to amend. Such a case is where a patentee threatens an infringer with his unamended patent after he knows or should have known of the need to amend. Fifthly, the court is concerned with the conduct of the patentee and not with the merit of the invention.

The primary judge summarised these guidelines at [87] of her reasons: see Apotex Pty Ltd v Les Laboratoires Servier (No 2) 83 IPR 42; [2009] FCA 1019 at [87]. Citing Bodkin, Patent Law in Australia (Lawbook Co, 2008) at [13510], the primary judge listed the following matters as relevant to the exercise of discretion under s 105:

• whether there has been a full disclosure of all relevant matters;

• whether the patentee has sought to obtain an unfair advantage from the unamended patent;

• whether there has been any unreasonable delay in seeking amendment; and

• whether any circumstances arise that would lead the Court to refuse the amendment.

Her Honour continued (at [88]):

The court does not approach the exercise of its discretion in a manner hostile or antipathetic to amendment. However, the onus is on the patentee to satisfy the court that the amendments should be allowed. The court is concerned with the conduct of the patentee and not with the merit of the invention: Smith Kline at 569. Bodkin, 2008, at [13520] and following conveniently summarises some of the matters that have been considered relevant. They include:

• Mere delay does not warrant refusal although the patentee must explain any delay, which should be reasonable.

• If a patentee becomes aware of the undue breadth of its claims, it must act to amend them without undue delay.

Both parties accepted the formulation of the guidelines in the primary judge’s reasons as correct. Both acknowledged also that they are merely guidelines and not fixed rules of law and that “[t]he discretion under s 105, like any other discretion, is to be exercised in the light of all relevant factors”: Wimmera Industrial Minerals Pty Ltd v RGC Mineral Sands Ltd (No 3) (1997) AIPC 91-366 at 39,790 per Sundberg J.

35 In my opinion, their Honours’ approach to the exercise of the discretion provided for in s 105 of the Patents Act is applicable to the exercise of the discretion provided for in s 197 of the Trade Marks Act, and each of the matters they mentioned above, when and if they arise, may be taken into account when exercising the discretion whether to permit an amendment pursuant to s 197. It is true, as Ms Whitby submitted, that an application under s 105 of the Patents Act arises in a different context, but that is not a reason that considerations of the type summarised by Kenny and Stone JJ in Les Laboratoires Servier may not be taken into account under s 197 of the Trade Marks Act. As Yates J said in Frucor Beverages Ltd v Coca-Cola Company [2018] FCA 993; (2018) 358 ALR 336 at 372 [195], “… an appeal to this Court from a decision of the Registrar in opposition to registration proceedings under the Trade Marks Act [does not] differs[] materially from an appeal to this Court from a decision of the Commissioner in opposition to grant proceedings under the Patents Act”. It seems to me, therefore, that there is no reason of substance why the same discretionary considerations should not apply in both instances when a party to an appeal seeks to amend its case in running.

36 EB made a number of compelling submissions in opposition to KMA’s application to amend. Without doing disservice to them, they may be summarised as follows:

(1) In its opening submissions, counsel for EB contended that, if the KANGAROO MOTHER Mark failed in one respect, it would fail as a whole, citing Apple Inc v Registrar of Trade Marks [2014] FCA 1304; (2014) 322 ALR 1 at 41 [232], and pointed out that no application to amend the specification had been made.

(2) Absent any explanation, it is to be inferred that the amendment application seeks to avoid the consequence of that principle, and is therefore not made with the full and frank disclosure required of such applications.

(3) KMA did not identify why it intended to delete some goods but not others from the specification, and thus failed to identify any principled basis to distinguish between the Designated Goods, and why some should remain but others should be removed.

(4) At the time of the making of the trade mark application, KMA made it clear to their lawyers (in evidence that is set out later in these reasons) that it wanted to obtain the “widest scope of protection” by accepting their lawyers’ recommendation to prepare a specification that would encompass “a broad range of goods in those classes” that were plainly well beyond any possible intention to use.

(5) KMA has had the benefit of a diverse scope of the Designated Goods sitting on the Register, blocking other applications pursuant to s 44 of the Trade Marks Act, for over four years, which is an unfair advantage for which no explanation has been proffered.

37 In my view, each of those submissions is compelling.

38 And KMA had no answer to any of them, other than submit that EB’s opposition was “strategic”. I do not agree. That is a criticism that is, on the contrary, properly levelled at the apparent motivation for the amendment application.

39 In those circumstances, the application will be refused.

Ground of opposition under section 59 of the Trade Marks Act

40 I turn first to the ground of opposition raised under s 59 of the Trade Marks Act because, for the reasons set out below, it is dispositive of the appeal in favour of EB.

The governing principles

41 Sub-section 27(1) of the Trade Marks Act is contained in Part 4—Application for Registration and it provides:

(1) A person may apply for the registration of a trade mark in respect of goods and/or services if:

(a) the person claims to be the owner of the trade mark; and

(b) one of the following applies:

(i) the person is using or intends to use the trade mark in relation to the goods and/or services;

(ii) the person has authorised or intends to authorise another person to use the trade mark in relation to the goods and/or services;

(iii) the person intends to assign the trade mark to a body corporate that is about to be constituted with a view to the use by the body corporate of the trade mark in relation to the goods and/or services.

42 Section 59 is contained in Part 5 – Opposition to Registration. It provides:

Applicant not intending to use trade mark

The registration of a trade mark may be opposed on the ground that the applicant does not intend:

(a) to use, or authorise the use of, the trade mark in Australia;

(b) to assign the trade mark to a body corporate for use by the body corporate in Australia;

in relation to the goods and/or services specified in the application.

43 As Burley J (with whom Greenwood J agreed on this point) explained in Bauer Consumer Media Ltd v Evergreen Television Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 71; (2019) 367 ALR 393 at 455 [247]:

The requirement under s 27(1)(b) that the applicant for a trade mark is using or intends to use the trade mark in relation to the goods and/or services (or authorise another or assign to a body corporate to do so) is matched by the ground of opposition under s 59 and ground for rectification under s 92(4)(a). Nothing in the [Trade Marks] Act or the Trade Marks Regulations 1995 (Cth) requires an applicant to state its intention, and the making of the application itself has long been regarded as prima facie evidence of intention to use; Aston v Harlee Manufacturing Co (1960) 103 CLR 391 at 401; [1960] ALR 605 (Aston). The burden falls upon an opponent to registration (or an applicant under s 92(4)(a)) to establish a relevant lack of intention on the part of the trade mark applicant a the filing date. This may involve the consideration of the intention of the applicant having regard to any of his or her statements of intent, prior uses consistent or otherwise with that intention, and uses shortly after the filing date. The scope of the inquiry may be broad, but commences from the prima facie position set out in Aston.

44 The passage in Aston v Harlee Manufacturing Co (1960) 103 CLR 391 to which Burley J referred was from the judgment of Fullagar J and is as follows:

There is another element mentioned by Dixon J in the Shell Co’s Case, which is stated as essential to the proprietorship of an unused trade mark. That element is the intention of the applicant for registration to use it upon or in connexion with goods. As to this I need only say that I do not regard his Honour as meaning that an applicant is required, in order to obtain registration, to establish affirmatively that he intends to use it. There is nothing in the Act or the Regulations which requires him to state such an intention at the time of application, and the making of the application itself is, I think, to be regarded as prima facie evidence of intention to use. I cannot think that the Registrar is called upon to institute an inquiry as to the intention of any applicant, and I think that, on an opposition or on a motion to expunge, the burden must rest on the opponent or the person aggrieved, of proving the absence of intention.

45 In other words, when an opponent has made out a prima facie case of lack of intention to use the mark, the onus shifts to the applicant for registration to establish intention to use. See Goodman Fielder Pte Ltd v Conga Foods Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1808; (2020) 158 IPR 9 at 43 [151] (Burley J); Health World Limited v Shin-Sun Australia Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 100; (2008) 75 IPR 478 at 497 [163] (Jacobson J). See also Food Channel Network Pty Ltd v Television Food Network GP (2010) 185 FCR 9 at 29 [72] (Keane CJ, Stone and Jagot JJ).

46 In order to demonstrate the requisite intention, it must be shown that the applicant for registration had “a real intention to use, not a mere problematical intention, not an uncertain or indeterminate possibility, but a resolve or settled purpose which has been reached at the time when the mark is to be registered”. See Ducker’s Trade Mark [1929] 1 Ch 113 at 121 (Lord Hanworth MR, Lawrence and Sankey LJJ agreeing).

47 It is not sufficient if the intention to use is “a speculative possibility” or “a general intention to use the mark at some future but unascertained time”. See Optical 88 Ltd v Optical 88 Pty Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 1380; (2010) 275 ALR 526 (Yates J), upheld on appeal in Optical 88 Ltd v Optical 88 Pty Ltd (2011) 197 FCR 67 at 93-94 [87]-[88] (Cowdroy, Middleton and Jagot JJ).

48 It was common ground that the time at which the intention to use referred to in s 59 must exist is the date of application (here, 15 February 2019) (the priority date).

Background to the s 59 ground of opposition

49 In this case, as I have already said, the s 59 ground of opposition was not raised before the Delegate.

50 EB raised the ground by way of its notice of appeal filed on 27 July 2021.

51 On 8 September 2021, and following up on the fact that the s 59 ground was now being raised, EB’s solicitors (King & Wood Mallesons (KWM)) wrote a letter to KMA’s solicitors (Spruson & Ferguson Lawyers Pty Limited (SFL)) relevantly as follows:

As you will have seen from our client’s notice of appeal in the proceedings, our client considers that, based on the material available to it to date, when the application for registration of Australian trade mark application no. 1989429 (Application) was filed, there was no intention to use, or authorise the use of, the trade mark KANGAROO MOTHER in Australia.

To enable our client to consider that ground further, we are instructed to request details surrounding your client’s use or intended use (if any) of the KANGAROO MOTHER trade mark, particularly in relation to goods in classes 29, 30 and 32, including but not limited to beverages.

Our client has found no evidence that your client is using, or has at any time used (including as at the 15 February 2019 Priority Date of the Application), the KANGAROO MOTHER trade mark in Australia in relation to any goods.

Our client has further found no evidence of any use or intended use (including as at the filing date) by the originally named applicant being Erbaviva Natural Care (New Zealand Limited), now known as Dodwell & Co Limited.

Dodwell & Co Limited appears to be in the cosmetics industry. We have also found an Erbaviva brand used in respect of what are ostensibly class 3 goods, but no such use on goods in classes 29, 30 and 32. Given that there is no natural connection between (for example) cosmetics and the class 29, 30 and 32 goods the subject of the Application, it seems quite clear that there was lack of any use or intended use of the KANGAROO MOTHER trade mark in any material sense in respect of (at least) such goods as at the Priority Date.

52 There was no response to that letter, so on 26 October 2021, KWM again wrote to SFL, relevantly as follows:

We refer to our client’s grounds of appeal based on sections 58 and 59 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) as set out in paragraphs 4 and 5 of its Notice of Appeal.

We also refer to our letter dated 8 September 2021, to which we have not received any response.

As you know, the inquiry necessitated by the grounds of opposition in sections 58 and 59 concerns the intention of the applicant for registration of trade mark application no. 1989429 (Application) as at the filing date of that Application (15 February 2019). Our client bears the legal onus in relation to those grounds.

As discussed in our 8 September letter, the preliminary searches undertaken by our client disclose no evidence of any use or intended use of the KANGAROO MOTHER trade mark in Australia by either your client or the applicant for registration of the trade mark as at the filing date, Erbaviva Natural Care (New Zealand) Limited (Erbaviva).

However, our client only has access to records in the public domain and does not have access to documents that may be in your client’s possession concerning any intention on the part of your client or Erbaviva as at the filing date to use the KANGAROO MOTHER trade mark. Those documents would clearly be relevant to the sections 58 and 59 grounds (should they exist) and our client ought be entitled to inspect those documents and adduce evidence as to their existence or non-existence as part of its evidence in chief.

Accordingly, the purpose of this letter is to request you to produce documents in your client’s possession which are relevant to the section 58 and 59 grounds of opposition, being:

Copies of any documents created between January 2018 and June 2019, which record or evidence an intention by Kangaroo Mother Australia Pty Ltd or Erbaviva Natural Care (New Zealand) Limited:

(a) to use, or authorise the use of, the KANGAROO MOTHER trade mark in Australia; or

(b) to assign the KANGAROO MOTHER trade mark to a body corporate for use by the body corporate in Australia, in respect of the goods specified in the application for registration of the KANGAROO MOTHER trade mark (as amended).

We ask that your client provide copies of these documents by 5 November 2021. If there are no such documents in your client’s possession, we ask that you confirm this in writing so that this letter, and your client’s response, can form part of our client’s evidence in chief.

If you do not agree to provide the documents sought by 5 November 2021, we reserve the right to make an application for orders requiring your client to make discovery of the documents. If such an application is necessary, we also reserve the right to rely on this letter in relation to the question of costs.

53 There was no response to that letter either.

54 Instead, KMA caused to be filed Mr Zheng’s 13 April 2022 affidavit, pursuant to the orders made for the filing of evidence for the trial of the proceeding. Relevantly, Mr Zheng deposed as follows:

1. Unless indicated to the contrary, the contents of this declaration are based upon my own knowledge acquired from my experience and from the examination of the books and business records of Respondent and/or Erbaviva, which are made and kept in the normal course and for the purpose of their respective businesses, to which I have full access.

2. Unless indicated to the contrary, the contents of this declaration are based upon my own knowledge acquired from my experience and from the examination of the books and business records of Respondent and/or Erbaviva, which are made and kept in the normal course and for the purpose of their respective businesses, to which I have full access.

3. Trade Mark Application No. 1989429 KANGAROO MOTHER the subject of this proceeding (Application) was initially filed on 15 February 2019 by Erbaviva. At the time of filing the Application an 15 February 2019, I confirm that it was the intention of Erbaviva to use, or authorise the use, in Australia of the trade mark KANGAROO MOTHER in respect of the following the [sic] goods in Classes 5, 29, 30, 31 and 32 the subject of the Application, details of which are set out in the print-out of that Application from the Australian Trade Marks Office database attached and marked Annexure AFZ-1.

55 Annexure AFZ-1 is in the same terms as annexure A to these reasons.

Production of documents by KMA in relation to s 59 ground of opposition and adjournment of trial

56 On 19 August 2022, I ordered KMA to give discovery of documents recording an intention by it or Erbaviva to use or authorise the use of the KANGAROO MOTHER Mark in Australia. I also gave leave to EB to issue a subpoena to Erbaviva, seeking production of the same category of documents.

57 On 27 September 2022, Erbaviva answered the subpoena by producing for inspection five documents and claiming legal professional privilege over six other documents.

58 On 5 October 2022, Mr Zheng made, and SFL filed and served, an affidavit identifying the same five non-privileged documents produced by Erbaviva, an unspecified number of documents in respect of which privilege was claimed.

59 On 17 October 2022, Mr Zheng made, and SFL filed and served, a further affidavit on behalf of Erbaviva in which he set out the grounds for Erbaviva’s privilege claim.

60 Two business days before the trial commenced, SFL told KWM that their client intended to rely on documents over which a claim of privilege had previously been made, as well as a number of additional documents.

61 In the course of the trial, and before he was to be cross-examined, Mr Zheng produced what counsel for EB correctly described as a “further, extensive, tranche of documents which ought to have been produced in answer to the order for discovery or the subpoena”.

6 April 2023 ruling

62 KMA then sought leave to rely on some of those documents, but I refused the application in an ex tempore ruling on 6 April 2023. The reasons that I gave for doing so were not published publicly, so I will set them out here:

This is an oral application by the respondent that it be granted leave to tender late served documents. The precise form of the order sought is as follows:

The respondent be granted leave to tender the documents highlighted in yellow in the respondent’s list of tender bundle documents from discovery dated 6 April 2023 as set out in annexure A to these orders (such documents being produced in the respondent’s second further supplemental list of documents dated 31 March 2023 and sworn and filed on 1 April 2023).

These reasons are not as extensive as they may otherwise be because it is highly desirable, if not essential, to resolve this application today for reasons which I trust are self-evident in light of the fact that the trial is to resume on 13 June. The circumstances giving rise to the application may briefly be described as follows: the hearing of this proceeding commenced before me on Monday 27 March 2023. On the second day of the hearing, the respondent produced newly discovered documents. As a result of that production, the parties accepted that it was necessary for the hearing of the proceeding to be adjourned and, as I say, a trial is scheduled to resume and will resume on 13 June.

On 28 March 2023, the second day of the hearing, I made an order in substance requiring Mr Zheng, a director of the respondent, to file and serve and affidavit setting out in detail the steps he took to comply with previous orders for discovery. Mr Zheng subsequently produced an 83-paragraph affidavit sworn on 31 March by which he produced four volumes of newly discovered documents. On that day I gave the respondent leave to make an application to tender or rely on those documents or some of them. At the hearing this morning, counsel for the respondent handed to me the folder of documents referred to in the order that I read. The respondent seeks to tender and rely upon – I think it is 30 documents as a subset of the larger discovered volume.

The appellant objects. It says in substance that the respondent should not be permitted to adduce any further evidence for these reasons: first, it submits that the respondent made a deliberate forensic choice over a year ago that it would – and putting the matter in the broad and in substance – not adduce evidence on the question of use under section 59 of the Trade Marks Act, but instead put the appellant to its proof to prove non-use. The appellant says that the respondent should now – not now be permitted to depart from that forensic choice. The second reason that the appellant says that the respondent should not be granted the relief it seeks is that nowhere in Mr Zheng’s affidavit does he provide any or any sufficient explanation as to why the documents now sought to be relied on were not produced in the ordinary course of discovery a long time ago.

In that regard, counsel for the appellant relied on what Perram J said in Capic v Ford Motor Company of Australia Limited [2020] FCA 1117 at [22], namely that in cases of this sought, when it comes to the question of an explanation for delay, the explanation …:

Must lay bare both why it is only now that the action is sought to be taken, but also why it was not taken when it should have been.

The respondent pointed to paragraphs 19 and 20 of Mr Zheng’s 31 March affidavit as providing a sufficient explanation. Those paragraphs are in these terms:

(19) Secondly, on or about 20 March 2023 in preparation for the hearing with my solicitors and counsel, I became aware that:

(a) documents that I received from Shanghai Urganic or NZ Skin Care relating to Kangaroo Mother could fall within the scope of the discovery categories and subpoena categories.

(b) documents relating to steps taken by myself and employees of Shanghai Urganic to develop the Kangaroo Mother brand and its products could fall within the scope of the discovery categories and subpoena categories.

(20) At the time of my initial searches, I was not aware and did not understand that the discovery categories and subpoena could capture such correspondence. I realise now that this was incorrect.

As I understood the submissions advanced on behalf of the respondent, that is the high point of their explanation as to why the documents sought now to be tendered were not produced by way of discovery over a year ago. The third point that the appellant advances is that it would be – is that it would be unfairly prejudicial to require it now to issue subpoenas and potentially prepare a different form of cross-examination of Mr Zheng than would otherwise have been the case.

Counsel for the respondent submitted that I should grant the leave sought because the explanation was sufficient, the documents are relevant to the question of use, and it would be artificial not to have regard to them in circumstances where many of them are related to documents that are already in evidence. Examples included such matters as chains of emails and the like. The applicable principles were not disputed. The starting point is, of course, the decision of the High Court in Aon Risk Services Australia Limited v Australia National University (2009) 239 CLR 175. Counsel for the appellant handed me a copy of the decision of Rofe J in Bed Bath ‘N’ Table [2022] FCA 1380 not because it says anything different by way of a statement of principle, but because it contains a convenient summary of the applicable principles and references to some recent decisions.

The passages in her Honour’s reasons concern stressing the importance of an explanation by the parties seeking to support the exercise of the court’s discretion of delay and also the obvious enough proposition that the party seeking the indulgence has the onus of showing that the interests of justice favour the granting of the leave necessary. Her Honour also set out a checklist of factors which may, in certain circumstances – I will withdraw that – her Honour also set out a checklist of factors, but obviously enough this is not a - the exercise of the court’s discretion is not a box ticking exercise. In my view, it would not be an appropriate exercise of my discretion to permit the tender of the relevant documents – when I say relevant, I mean the documents sought to be tendered.

In my view, there is no satisfactory explanation given by the respondent for the delay. Specifically, there was no explanation at all given by the witness as to why it only occurred to him recently to conduct the further and different searches set out in his affidavit. He does not say that he misunderstood any directions given to him by his solicitors, for example. He does not, to give another example, say that he only acquired the – only recently acquired the requisite knowledge to be able to conduct the new searches. Instead, the reader of his affidavit is left entirely in the dark as to why that which was done recently could not and should not have been done more than a year ago.

The cases make clear that the need to a satisfactory explanation is of critical importance in the exercise of the court’s discretion. Secondly, the point made by the appellant as to the forensic choice made by the respondent is also a compelling one. I see no good reason why the court should, effectively, permit the respondent now to depart from that choice. The point about prejudice, on the other hand, in the scheme of things seem to me to be less critical for reasons advanced by counsel for the respondent. It is prejudice, to be sure, to require a party to issue subpoenas and prepare a different line of cross-examination, but, as I say, in the scheme of things it does not seem to me to weigh heavily, in this case at least, in the exercise of the discretion.

If I may say so, with respect, counsel for the respondent said everything that could be said as persuasively as it could be put in support of the contention that I should make the orders sought. For the reasons I have given, I am not persuaded that it is appropriate to make the order. I should, though, in deference to those submissions, also say that I am not persuaded that there is anything in the point that much of the new documents serve to put other documents that are in evidence in some form of context. In my view, even accepting that that might be so, it is not a separate reason to permit tender of late served documents when no explanation is provided for the delay and where to admit them would fly in the face of the forensic choice made.

Further, the difficulty that counsel envisaged about cross-examination will not arise because, as I was reminded, the documents have been discovered and will be in the possession of counsel and their instructors. In my view, in circumstances where the forensic choice was made and where no sufficient explanation of delay is given, then in light of the admonitions contained in cases like Aon, including that the court’s discretion should not be approached on the basis that the party is entitled to proffer new evidence or make a new claim, subject to paying costs, I should refuse the respondent’s application to tender the documents.

I will accordingly order that the application which was made orally be refused [with costs].

63 I turn now to the evidence of particular relevance to the s 59 ground of opposition.

Respondent “group” companies

NZ Skin Care Company Limited

64 NZ Skin Care Company Limited (NZ Skin Care) was incorporated in New Zealand in March 2000. Mr Zheng was appointed as its “Assistant to Group Chairman” in July 2013. He remained in that role until May 2014. Mr Zheng said that in that position he acted as the assistant to Mr Xiaokun (or Aaron) Liu, the Chairman of a Chinese company called Shanghai Urganic Biotechnology Co Ltd (Shanghai Urganic). As at the priority date, it was wholly unrelated to NZ Skin Care or Erbaviva.

65 When Mr Zheng was appointed to that position, there were three directors of the company: Ms Xiang Zhang, Mr Wen Chen and Ms Penny Vergeest. They were also the shareholders of the company, and remained so until 22 August 2019, when Mr Zheng (through his trust) and Urganic New Zealand Ltd became the shareholders.

66 At that time, NZ Skin Care sold a range of skincare products for babies and toddlers, as well as for adults. It also sold a range of home cleaning products. Mr Zheng agreed in cross-examination that NZ Skin Care did not and does not have “Good Manufacturing Process” certification for any goods, including pharmaceuticals. It was also not disputed that it has never sold foodstuffs, beverages or pharmaceutics under its own brands.

67 Mr Zheng was appointed “General Manager New Zealand” of NZ Skin Care in May 2014, and became a director on 13 April 2016, together with Mr Wen.

US Erbaviva Natural Care (New Zealand) Limited

68 Mr Zheng incorporated Erbaviva in New Zealand under the name “US Erbaviva Natural Care (New Zealand) Limited” on 21 March 2014, and he was and remains its sole director and shareholder. It was established to sell Erbaviva-branded skincare products in New Zealand. On 25 August 2015, it changed its name to “Erbaviva Natural Care (New Zealand) Limited”.

Shanghai Urganic Biotechnology Co Ltd

69 Shanghai Urganic is the holding company for a group of other unrelated companies which sell consumer products. It employed Ms Emily Deng as a brand manager and Ms Emily Yin as an “International Business Director”. She was not an employee of NZ Skin Care, but for some reason NZ Skin Care allowed her to use a NZ Skin Care email signature for business development purposes, describing her as its “International Business Director”. Mr Zheng conceded in cross-examination, however, that “[i]t’s not ideal that she [was] calling herself … a director”.

The facts

70 On 18 August 2017, Mr Zheng wrote to Ms Jessica Tye of AJ Park, a firm of trade mark attorneys, attaching a draft trade mark in the form of a logo incorporating the words KANGAROO MOTHER. He asked Ms Tye: “Do you think we can get this mark registered in Australia for classes 3, 5 and 21?” (The email exchanges between Mr Zheng and Emily Yin set out below were in the Mandarin language and were translated by NAATI qualified translators. Mr Zheng is, however, fluent in English).

71 On 4 September 2017, Ms Tye replied, suggesting that one option Mr Zheng should consider was filing a Headstart application with IP Australia.

72 Mr Zheng agreed by return email that such a filing was a good idea, and that it should be done “as soon as possible”. He also said that “for commercial reasons we would like to use one of our NZ companies”, namely Erbaviva, as the applicant, and that “[o]nce the mark is successfully registered we will incorporate an Australian entity to hold the mark”.

73 Ms Tye responded that she would prepare specifications of goods in Classes 3, 5, and 21 “in accordance with IP Australia’s accepted classifications” and send them to Mr Zheng for review.

74 On 12 September 2017, Ms Tye lodged an application for registration of the KANGAROO MOTHER logo in respect of goods in Classes 3, 5, and 21, viz Australian trade mark no. 1871805 (Device) in Class 3 (cosmetics and skincare), Class 5 (soaps) and Class 21 (toothbrushes and accessories).

75 The 1871805 (Device) shown below was registered in the name of Erbaviva on 16 April 2018:

76 On 30 July 2018, Mr Zheng asked Ms Tye to prepare a further application for the word mark KANGAROO MOTHER in respect of the same goods as the KANGAROO MOTHER logo.

77 On 7 August 2018, Ms Tye lodged an application for registration of the KANGAROO MOTHER word mark in Classes 3, 5 and 21.

78 On 7 November 2018, that application was accepted and the mark was also subsequently entered on the Register in the name of Erbaviva.

79 Early the next year, on 12 February 2019, Mr Zheng received an email from a Ms Emily Yin at 7.02pm. (At that point, Shanghai Urganic had no formal corporate relationship with NZ Skin Care or Erbaviva, although it later became the ultimate holding company of NZ Skin Care). Ms Yin’s email was in these terms:

During today’s meeting, Director Liu mentioned that we should at the same time apply for a food trademark with Kangaroo Mother, and in the future, we may focus on designing nutritional supplements such as DHA/folic acid. Please refer to the attached information of the New Zealand OEM factory for your reference. Let’s discuss if you have any questions. Thank you.

80 The reference to “Director Liu” was a reference to Mr Liu, the Chairman of Shanghai Urganic.

81 The “attached information” to which Ms Yin referred in her email was a product catalogue from an unrelated New Zealand company called Unipharm Healthy Manufacturing Co Ltd (Unipharm). The catalogue said that Unipharm “has established long-term and close partnerships with renowned Chinese brands for mothers and children”.

82 The catalogue contained information on Unipharm’s product range, including “gel candies” “pressed candies”, “drops”, “powdered dairy products”, “solid beverages” and “capsules”.

83 Mr Zheng said in cross-examination that the email was “relaying a meeting that happened in China to me, but I don’t [sic] take that as an instruction from Mr Liu to develop DHA – to me personally”.

84 Mr Zheng responded to Ms Yin’s email about 15 minutes later, asking Ms Yin: “Have the classes and items of trademark registration been confirmed?”

85 A little less than 25 minutes later, Ms Yin replied: “Please refer to the attached picture: pressed candies, gel candies, solid beverages and drops.” The attachment was an image taken from the index to the catalogue Ms Yin had sent earlier.

86 Mr Zheng responded to Ms Yin in an email sent about 35 minutes later with the question, “Planning to register the following classes and items, anything need to be added?” Mr Zheng attached the following list of goods to his email:

87 This list of products across five classes (with one minor exception in Class 30 – “chocolate flavoured cola drinks”) was identical to an existing trade mark registration on the Intellectual Property Office of New Zealand (IPONZ) website, being the BIOGLAN mark registered in May 2015 to a third party, Natural Bio Pty Limited.

88 Under cross-examination, Mr Zheng initially suggested that he compiled the list of products in Classes 5, 29, 30, 31 and 32 himself, but he ultimately accepted that he copied the list from the BIOGLAN registration on the IPONZ website. His evidence in that regard included the following response to a question from Mr Cordiner about the provenance of the list:

To me it was simply that, you know, I’ve done similar things, and, you know, essentially we’re trying to extend our product offering to the same target audience that we’ve been offering to – you know, for skincare products. So, you know, with that information in the background, now it looks like, you know, I just went onto the register and somehow found this company [Natural Bio Pty Limited] and, you know, decided that, you know, that’s the direction that we want to go to and those are the products that we want to make. … There was not a – at least when I put together that list I did not have a clear picture of when. Also, I did not – 100 per cent sure that these are the products in the mind of Emily [Yin] and Aaron [Liu], therefore I send them to check if, you know, we’re on the same picture.

(Emphasis added).

89 On 13 February 2019, Ms Yin replied to the question in Mr Zheng’s email from the previous day (“Planning to register the following classes and items, anything need to be added?”) as follows: “Yes, I think the 5, 30, 32 class will be used first.”

90 The next day, Mr Zheng emailed Mr Ben Sullivan of AJ Park at 5.01pm (New Zealand time). (Mr Sullivan had by this time taken over carriage of the matter from Ms Tye). In his email, Mr Zheng stated:

Hi Ben

We are looking to expand our registration of KANGAROO MOTHER mark in Australia to the following classes and goods. Would you be able to provide us with a quote? The new mark will also be owned by Erbaviva Natural Care New Zealand Limited.

91 Mr Zheng attached to his email the same list of goods sent to Ms Yin in his email on 12 February 2019.

92 After receiving a quote for an application in an email sent by Mr Sullivan at 5.29pm, Mr Zheng confirmed in his reply at 5.35pm that “we would like to proceed to apply for the word mark Kangaroo Mother in Australia under the new classes.”

93 Mr Sullivan replied to Mr Zheng in an email sent at 5.40pm, as follows:

Thanks Tony. I understand you would like the mark to cover the goods listed below. Would you like the specification to cover those explicit goods? Alternatively, I can prepare a specification that will encompass a broad range of goods in those classes (including those listed below) to ensure you have the widest scope of protection in those classes.

94 Mr Zheng replied to Mr Sullivan at 5.41pm, stating: “The widest scope of protection would be preferable.”

95 Mr Sullivan proceeded to file Mr Zheng’s application with IP Australia the next day, without further giving him an opportunity to review the final specifications before filing. As it happened, the application was significantly broader in scope than the list proposed by Mr Zheng. It is self-evident that the classes of goods in annexure A are greater in scope than those set out at paragraph [86] above.

96 In the course of cross-examination, Mr Zheng was asked a number of questions about how that came to be, and about his evidence in paragraph [3] of his 13 April 2022 affidavit that “that it was the intention of Erbaviva to use, or authorise the use, in Australia of the … KANGAROO MOTHER [Mark] in respect of the following the [sic] goods in Classes 5, 29, 30, 31 and 32 the subject of the Application”, as follows:

Mr Zheng, go back to paragraph 3 of your affidavit in April last year? Yes.

Yes. Paragraph 3, you say:

At the time of filing the application on 15 February 2019, I confirm it was the intention of Erbaviva to use –

and you’ve confirmed with me? Yes.

that that means it was your intention to have Erbaviva use or authorise the use in Australia of the trademark “Kangaroo Mother” in respect of the following goods and classes 5, 29, 30, 31 and 32, and then you refer to AZF1. Right? So when you wrote this affidavit, did you even bother looking at the specification and confirming that as at 15 February 2019, you had an intention of Erbaviva to use or authorise the use of every good in class 5 identified there? I did look at the list of goods and services; however, my understanding was that they aligned with the instruction that I gave to Mr Sullivan of AJ Park, which covers five classes in that copy and paste email that we saw.

Yes. And that was an email – that was one of the five documents that you discovered – yes – and you didn’t claim privilege over? Correct.

That email? That instruction. Yes.

Yes. So you had that? And that was the only instruction that I gave AJ Park.

That was the only instruction that you gave. You had that to hand when you were making this affidavit. And are you truly telling me when you made this affidavit, looking at that instruction you gave to Mr Sullivan, you said to yourself, “Yes. It is correct for me to say to this court that on 15 April 2019 – February 2019, I had an intention for Erbaviva to use and authorise the use of Kangaroo Mother in respect of, for example, adhesive tapes for medical purposes.” It’s just not true, is it? I mean, again

Mr Zheng, is it true or not? Did you have an intention on 15 February 2019 for Erbaviva to use the mark “Kangaroo Mother” in respect of adhesive tapes for medical purposes? I mean, if you just pick that one term out of the – the – the whole list of goods, you know, we – we – at the time I instruct AJ Park, it wasn’t the goods in our mind; however

No, Mr Zheng. Do you agree with me that the statement you made in your affidavit is false insofar as you assert that there was an intention to use or authorise the use by Erbaviva of Kangaroo Mother in respect of adhesive tapes for medical purposes? Is that a false statement? I made a statement based on my knowledge that the list of goods that I instructed AJ Park to file was the goods that we wanted to make. Whether that list is exactly the same as what Mr Sullivan drafted – I mean, it looked – it certainly looked different, in terms of the wording that he used, but in my mind, they are – the difference or technical drafting differences … to give us better protection.

Did you have an intention for Erbaviva to use the mark “Kangaroo Mother” on 15 April before – 15 February 2019 in respect of adhesive tapes for medical purposes? I’m just picking one. There’s many. I’m just picking one. Did you have an intention for Erbaviva to use that mark in respect of those goods? It was not included in the instruction that I sent to AJ Park.

Put aside the instruction for the moment? No.

No. Okay. That’s one. What about sanitary preparations for medical purposes? Yes or no? To us, it sounds like – well, to me, it sounds like a sanitiser – hand sanitiser, so that was something that we wanted to do.

What about plasters? Again, like, I – I – I don’t know what those specific – you know, what’s the legal definition – what’s the trademark definition of those goods. You know, what I’m confident about is that we’re going to make – or we want to make everything that I send to AJ Park, and if you’re asking me, like, you know, there are a lot of words that I – you know, I’m not sure how I should be interpreting them, and – and we were just relying on the advice of AJ Park to offer good protection based on what we wanted to do.

97 On 6 March 2019, Ms Yin, on behalf of NZ Skin Care, wrote to Mr Zheng as follows:

We are looking for a factory for Australian Kangaroo Mother. Delta Lab seems to have been recommended to [Ms] Liu Dong by you before. Because the formula is specified by us, an NDA needs to be signed, I will use NZ SKINCARE as the counterpart first and attach the contract in the attachments.

98 During the course of his cross-examination, Mr Zheng agreed that neither Erbaviva nor the respondent had used the KANGAROO MOTHER Mark in any capacity in respect of the Designated Goods. In re-examination, Mr Zheng suggested that this was due to the ongoing dispute with EB, in this exchange:

MS WHITBY: Thank you, Mr Zheng. One more question? Yes.

Mr Cordiner asked you in cross-examination – you agreed with Mr Cordiner in cross-examination that you have not used or authorised the use of Kangaroo Mother in respect of the class 5 goods in your 2019 registration. Can you explain to the court why it is that Kangaroo Mother has not used or authorised the use?

MR CORDINER: Your Honour, I don’t know how that rises from – directly from my question.

HIS HONOUR: … I will allow the question.

THE WITNESS: … The biggest reason was that the trade mark was in dispute or the application was in dispute very soon after we filed it and, you know, we were in dispute. We are still in dispute with a pretty large company from the US [this proceeding] and, because of that, we placed a hold on our internal efforts to further develop the brand Kangaroo Mother until this dispute has finally settled down. You know, there could be resources wasted or even possible damages claimed by the other side as we understand. Add to that – it’s – you know, we don’t have a physical presence in Australia by personnel or otherwise; therefore, our business development is largely based on the partners that we can work with in Australia. And given the dispute that we are resolving now, it’s extremely difficult to find partners who are willing to work with us on this brand; therefore, you know, we haven’t and we’re not planning on making any further investment or make further decisions on how we’re going to use Kangaroo Mother as a brand regardless, you know, it’s about cosmetics or supplements or food or otherwise.

Consideration

99 In the end, KMA’s case rested on the proposition that I should accept – essentially at face value – Mr Zheng’s assertion in paragraph [3] of his 13 April 2022 affidavit that “it was the intention of Erbaviva to use, or authorise the use, in Australia of the … KANGAROO MOTHER [Mark] in respect of the following the [sic] goods in Classes 5, 29, 30, 31 and 32 the subject of the Application, details of which are set out in the print-out of that Application from the Australian Trade Marks Office database attached and marked Annexure AFZ-1”.

100 I say “in the end” because KMA produced on discovery and put in its tender bundle a number of documents that were said to be relevant to Erbaviva’s intention to use or authorise the use of the KANGAROO MOTHER Mark in relation to the relevant classes of goods. One such document was an unsigned non-disclosure agreement between NZ Skin Care and a company called Delta Laboratories Pty Ltd, bearing the date 6 March 2019. Leaving aside the obvious enough difficulty that the agreement was entered into by NZ Skin Care, not Erbaviva, the list of products included within the scope of the non-disclosure agreement concerned cosmetics – not foodstuffs, beverages or supplements, or any of the Designated Goods, a point accepted by Mr Zheng in this passage of cross-examination:

Now, you remember you discovered this document as a document relevant to whether Erbaviva had an intention to use or authorise the use of the Kangaroo Mother mark in relation to the classes of goods we’ve seen before, yes? Yes.

Yes. Let’s go to page 10. These are the products that Ms Yin had put on the NDA. First, we see cleansing? Yes.

Toning water? Yes.

Lotion? That’s right.

Cream, essence, eye cream, face masks and massage oil? Yes.

It’s pretty clear, isn’t it, that these are all personal care products? Yes.

Skin care products, aren’t they? Yes.

They don’t fit within any of the classes we’ve been talking about, do they? For some of products – some of the products, they may be classified as class 5, if they’re medical or for medical purposes. But, again, like, I wasn’t part of the discussion between Emily Yin and this manufacturer, so I – I wasn’t sure, you know, what the discussion was about. But I agree with you in principle. Like, most of them – they were personal care and, you know, preparations for – for cosmetics.

101 The evidence that KMA ultimately sought to rely on in support of the proposition that it was Erbaviva’s intention to use, or authorise the use, in Australia of the trade mark KANGAROO MOTHER in respect of the goods in the list which Mr Zheng provided to Mr Sullivan on 14 February 2019, alternatively all of the Designated Goods, is this:

(1) On 12 February 2019, at 7.02pm, Ms Yin emailed Mr Zheng saying that Mr Liu “mentioned” that “we” should “apply for a food trade mark with Kangaroo Mother, and in the future we may focus on designing nutritional supplements such as DHA/folic acid”.

(2) The brochure attached for Mr Zheng’s “reference” contained information about product ranges that included “gel candies”, “pressed candies”, “drops”, “powdered dairy products”, “solid beverages” and “capsules”.

(3) By 8.19pm the same day – just a little more than an hour after Mr Yin’s first email – and having “cut and pasted” lengthy descriptions of different goods in classes 5, 29, 30, 31 and 32 from the IPONZ website, Mr Zheng told Ms Yin that he planned to register them all.

102 KMA also made these brief submissions in its written closing submission:

In respect of the Class 3 goods, the evidence demonstrated advanced plans in respect of skincare range, ingredients, negotiations with Delta Laboratories and also, preparation of draft packaging: Exhibits AXB-42 - 46.

In respect of the Class 5 goods, the evidence demonstrated consideration of a Unipharm Brochure for supplements and/or health food products: Exhibit AXB-27 and Exhibit AXB-28.

Other preparatory steps were taken, such as the establishment of KMA itself, an email account (Exhibit R3, Exhibit R4); and account with GS1 for obtaining product barcodes: Exhibit R10.

103 There a number of difficulties with KMA’s submission that I should accept at face value Mr Zheng’s assertion in paragraph [3] of his 13 April 2022 affidavit. In particular, as the correspondence shows, and as Mr Zheng had to concede, Mr Sullivan filed the application with IP Australia with a significantly broader range of goods than the list he instructed be filed. So to the extent that Mr Zheng asserted in his affidavit and insisted in cross-examination (see the passage from his cross-examination at paragraph [96] above) that he and therefore Erbaviva intended to use, or authorise the use, in Australia of the KANGAROO MOTHER Mark in respect of goods he had not instructed be included in the application, the assertion must be rejected because it is nonsensical.

104 But even if one were to accept KMA’s submission that Mr Zheng’s assertion in his affidavit should be read instead as an assertion that it was Erbaviva’s intention to use, or authorise the use, in Australia of the KANGAROO MOTHER MARK in respect of the goods in the list which he provided to Mr Sullivan, all of the relevant evidence is to the contrary.

105 First, Mr Zheng agreed in cross-examination that he did not take the email from Ms Lin about DHA/folic acid as an instruction from Mr Liu to develop DHA.

106 Secondly, there was no evidence of any documentation, plan or proposal for any intended use that went beyond the gel candies, pressed candies, drops, powdered dairy products, solid beverages or capsules mentioned in the brochure attached to Ms Yin’s email.

107 Thirdly, Mr Zheng’s proposal for an application for registration of the KANGAROO MOTHER Mark was, on his own evidence, conjured in a matter of minutes by cutting and pasting from the IPONZ website. As EB submitted, it was obviously speculative and went beyond anything that could even remotely be said to have been the subject of an intention to use of any kind, let alone a “real and definite intention” of the type necessary. See Goodman Fielder Pte Ltd v Conga Foods Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1808; (2020) 158 IPR 9 at 37 [119] (Burley J); Health World Limited v Shin-Sun Australia Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 100; 75 IPR 478 at 497 [160].

108 Fourthly, it is also relevant that since filing the application for the KANGAROO MOTHER Mark well over four years ago, neither Erbaviva nor KMA has manufactured or attempted to have manufactured any of the Designated Goods. Compare Goodman Fielder Pte Ltd v Conga Foods Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1808; (2020) 158 IPR 9 at 38 [125] (“a failure to use after the filing date may enable a Court to infer that there was a lack of intention”).

109 In re-examination, in the passage set out at paragraph [98] above, Mr Zheng said that was because of the dispute the subject of this proceeding. Mr Zheng’s newly minted reason in re-examination was unconvincing, and I do not accept it. Among other things, as EB submitted in closing:

[The trade mark] dispute did not commence until 16 December 2019, and did not stop Ms Yin or Ms Deng from making preparations to commence using “Kangaroo Mother” or the like in respect of cosmetics, even before the registration of that mark had been granted.

110 KMA’s next contention was that Shanghai Urganic, Erbaviva and Mr Zheng operated as a “conglomerate” in relation to the so-called the KANGAROO MOTHER brand and trade marks generally, and that in some way the actions of other entities and entities were relevant to the question of intention to use under s 59.

111 The submission was put this way in KMA’s written submissions:

The Conglomerate or “Group” of Shanghai Urganic are companies that within the group had direct ownership, a shareholding relationship, the same senior management and/or the same investors. Companies in the Group included various entities including KMA, Erbaviva, NZ Skin Care and Urganic New Zealand.

Given that the companies in the Group are in the consumer product industry and deal with the same target audience, they often work together and share resources including channels, suppliers, personnel, investors and skillsets.

112 It was never explained what any of that amounted to as a matter of legal principle.

113 And the only evidence cited in closing in support of the “conglomerate” submission was the following passage from Mr Zheng’s re-examination:

In a number of your answers, Mr Zheng, you referred to “the conglomerate” or “the group”? Yes.

What are the companies that you consider to form part of the conglomerate, or group? They are companies that within the group had direct ownership or a shareholding relationship. For example, Shanghai Urganic, Urganic New Zealand, New Zealand Skin Care. But there are other groups – group companies that are slightly more remote but have the same senior management or same investors behind. So, you know, we don’t formally call ourselves a group because of various reasons, you know, and to avoid, for example, conflicts between the investors behind. But, you know, because we are all in this consumer product industry and we are dealing with the same target audience. So we often work together and share resources, you know, channels, suppliers, etcetera. Sometimes even personnel or investors, you know. So that’s what I meant by … the group.

114 I must confess, and intending no disrespect to Mr Zheng, that answer is incomprehensible.

115 As to KMA’s submissions set out at paragraph [102] above, they are also to no avail, because the exhibits there cited have nothing to do with Erbaviva. They are emails from Ms Yin to Mr Zheng from NZ Skin Care and NZ Skin Care (AXB 27 and AXB 28); emails between Mr Zheng and Ms Deng and others (AXB 42 and AXB 43) and emails from Ms Deng to Mr Zheng using the email address emilydeng2011@foxmail.com (AXB 44 and 45). Further, the emails are dated between February and August 2020, over a year after KMA’s application was filed.

116 And AXB 46 is a List of Documents, so that is of no use.

117 And “the establishment of KMA itself, an email account (Exhibit R3, Exhibit R4); and account with GS1 for obtaining product barcodes (Exhibit R10)” self-evidently do not evidence an intention to use the KANGAROO MOTHER Mark.

118 The relevant intention as to use for s 59 purposes can only be ascribed, in a case such as this, to the entity that made the application for the mark – here, Erbaviva and its sole guiding mind, Mr Zheng.

119 If it is sought to contend that beliefs or opinions or states of mind of others are to be attributed to that guiding mind and thus the applicant corporate entity, “it is necessary to specify some person or persons so closely and relevantly connected with the company that the state of mind of that person or those persons can be treated as being identified with the company so that their state of mind can be treated as being the state of mind of the company”. See Brambles Holdings Ltd v Carey (1976) 15 SASR 270 at 279 (Bright J), cited with approval in Krakowski v Eurolynx Properties Ltd (1995) 183 CLR 563 at 582-3 (Brennan, Deane, Gaudron and McHugh JJ).

120 There is not a skerrick of evidence to suggest that the state of mind of KMA, NZ Skin Care, Urganic New Zealand, or Mr Liu, Ms Deng or Ms Lin, “can be treated as the state of mind” of Erbaviva.

121 As EB submitted, and I agree:

In the case of a single director company, owned by that director, with no employees other than the director, that director must hold the intent to use or authorise the use of the trade mark. That company’s intention cannot be evidenced by a third party’s intention, or activity, which has not itself been adopted, or directed by, respectively, the director.