Federal Court of Australia

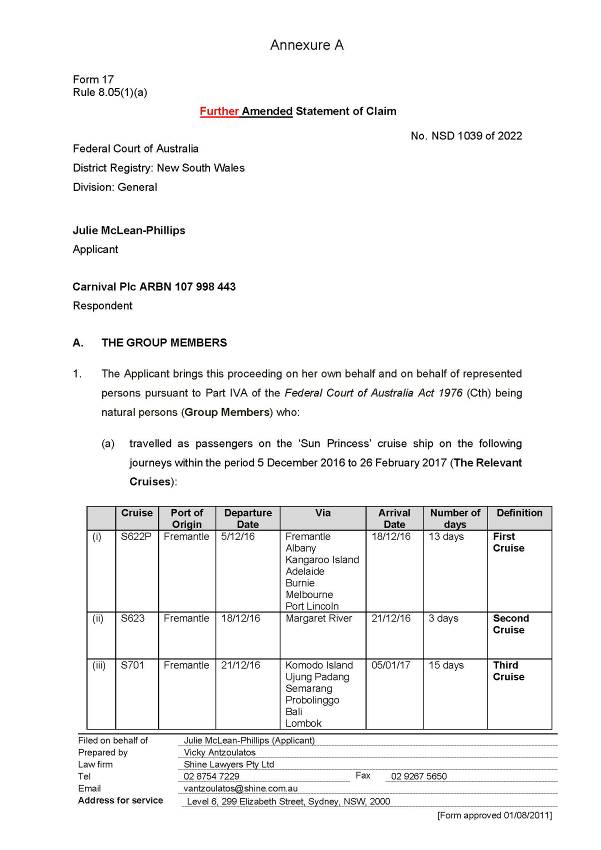

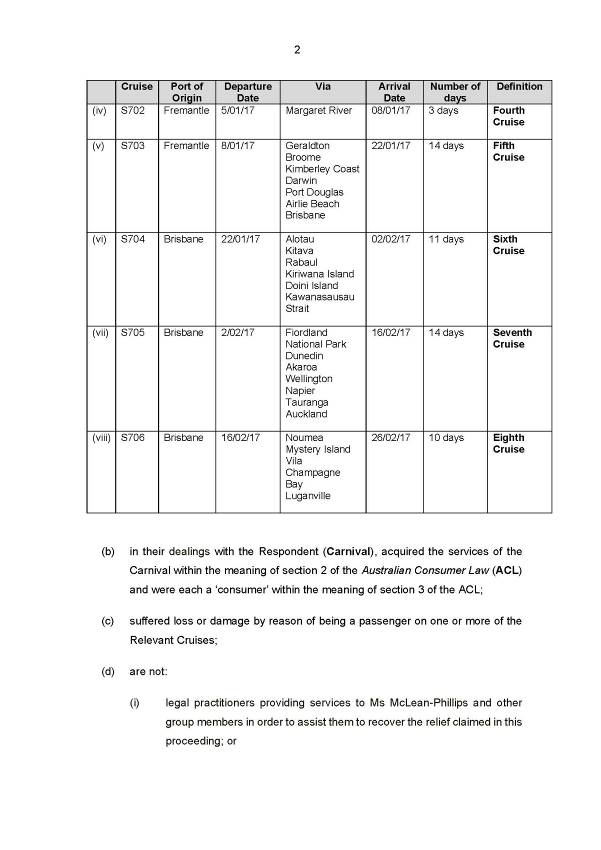

McLean-Phillips v Carnival plc t/as P&O Cruises Australia (No 3) [2023] FCA 985

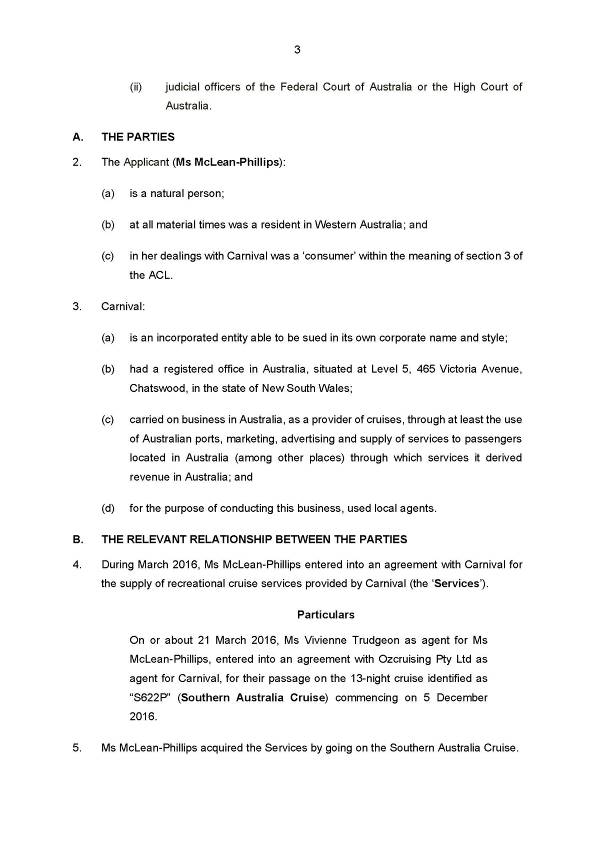

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | CARNIVAL PLC T/AS P&O CRUISES AUSTRALIA Respondent | |

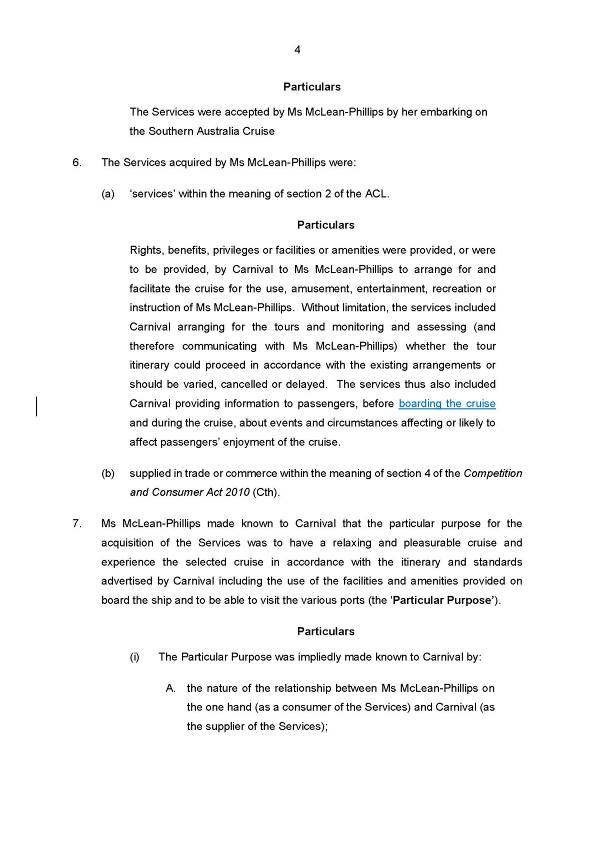

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Leave be granted to the applicant to file a further amended statement of claim in the form annexed and marked “A”.

2. The costs of the respondent’s Interlocutory Application dated 23 June 2023 be costs in the cause.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

JACKMAN J

1 In McLean-Phillips v Carnival plc t/as P&O Cruises Australia [2023] FCA 328 (the Initial Judgment), I struck out the statement of claim and granted leave to the applicant to file and serve an amended statement of claim. The applicant duly filed an amended statement of claim on 12 May 2023, and on 23 June 2023 the respondent filed an interlocutory application seeking summary judgment against the applicant pursuant to r 26.01(1) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (Rules), or alternatively an order that the amended statement of claim be struck out pursuant to r 16.21(1) of the Rules. The interlocutory application also sought security for costs, but that matter was disposed of consensually during argument before me.

2 On 28 July 2023, the applicant sent to the respondent a proposed further amended statement of claim (the FASC) and indicated in her written submissions dated 14 August 2023 that the applicant sought leave to file the FASC. Accordingly, the argument before me focused on the FASC, rather than the amended statement of claim dated 12 May 2023.

3 I indicated to the parties at the conclusion of the oral argument that I would grant leave to the applicant to file the FASC. The form of that pleading can be found as Annexure A to the orders which I have made, and I have not reproduced that pleading in these reasons. The following are my reasons for granting leave to file the FASC.

4 In the Initial Judgment, I expressed the following conclusions in relation to the operation of ss 61, 267 and 268 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). First, in assessing whether the guarantee in s 61(1) of the ACL (that services are reasonably fit for a purpose made known by the consumer) has been complied with, the analysis must deal with the services actually provided, and whether they were in fact reasonably fit for the particular purpose: [11]. The guarantee in s 61(2) of the ACL (that services are of such a nature, and quality, state or condition, that they might reasonably be expected to achieve the result made known by the consumer) focuses attention on the nature and quality, state or condition of the services actually provided, and tests those matters against a standard of reasonableness in achieving the desired result; a failure to comply with that guarantee must therefore be assessed according to the nature and quality, state or condition of the services actually provided: [12]. In order to obtain a remedy under s 267 of the ACL, the requirement in s 267(1)(b) (that the guarantees in s 61 are not complied with) involves an analysis directed to the services actually provided, and a shortcoming or deficiency in those services. It cannot be sufficient to say that a cruise ship operator promised a relaxing and enjoyable holiday, but the claimant has in fact had a miserable and stressful time; there would have to be some link between an identified deficiency in the services provided and the lack of relaxation and enjoyment which resulted from that: [13]. In order to establish that a failure to comply with the guarantees was a major failure within the meaning of s 268 by reason of any of ss 268(1)(a), (c) or (d), the claimant must identify some deficiency or shortcoming in the supply of the relevant services: [14]. In order to claim compensation for any reduction in the value of the services below the price paid or payable by the consumer for the services pursuant to s 267(3), the claimant must allege material facts as to how the services that were actually supplied to the applicant were of a value less than that which was paid by the applicant: [23]. In order to claim damages for loss and damage suffered “because of” the supplier’s failure to comply with a relevant guarantee, and to establish that such loss or damage was reasonably foreseeable as a result of the failure, as required by s 267(4), the claimant must plead a causal link between the relevant breach of the statutory guarantee and the loss and damage, which in turn requires that there be specific identification of the deficiency or shortcoming in the services actually provided so that the elements of causation and reasonable foreseeability can be analysed by reference to the specific failure which is complained of.

5 In the FASC, the applicant has accordingly sought to plead the services actually provided and required to be provided, the deficiencies in those services, and a causal link between those deficiencies and the claimed loss. As a matter of general principle, the applicant draws attention to the approval by Jagot and Murphy JJ in Crowley v Worley Limited [2022] FCAFC 33; (2022) 400 ALR 452 at [70] of the following observation of Beaumont J in Pancontinental Mining Limited v Posgold Investments Pty Ltd [1994] FCA 131; (1994) 121 ALR 405 at 414 that:

… under the modern system of pleading, the question is not whether the facts pleaded are in themselves sufficient to give rise to a cause of action. Rather, the question is whether it would be open to the applicant upon the pleadings to prove facts at the trial which would constitute a cause of action (see Mutual Life & Citizens’ Assurance Company Limited v Evatt (1970) 122 CLR 628 at 631).

The respondent does not challenge that statement of principle.

6 The respondent in its oral submissions began by criticising paragraphs 17 and 18 of the FASC, which make allegations concerning the implementation of effective cleaning protocols (including, if necessary, disembarking all passengers and changing the cruise ship to a new cruise ship) and the implementation of the respondent’s own policies and procedures to address the spread of the norovirus. First, the respondent submits that there is no reasonable prospect of the applicant establishing that the respondent contravened the statutory guarantees in s 61 by failing to transfer all the passengers on each cruise to a new cruise ship. This seems to me to raise questions to be resolved by reference to the evidence to be led at the trial, and I am not prepared to say in the abstract that the applicant has no reasonable prospect of successfully prosecuting that part of the proceeding, to adopt the language of s 31A(2)(b) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

7 Second, the respondent submits that the qualification in paragraph 17, that a new cruise ship should be substituted “if necessary”, is confusing and ambiguous. I do not accept that criticism in the context of the paragraph, which concerns the implementation of effective cleaning controls, of which the substitution of a new vessel is alleged to be one control available, and in my view the circumstances (if any) in which any such substitution would have been necessary is a matter for evidence.

8 Third, the respondent submits that the applicant should not be permitted to plead in conclusory terms in paragraph 25(d) that the respondent did not competently implement the 17 policies and procedures (which are particularised in paragraph 18) to address the spread of the norovirus, and the applicant must identify specific steps and link those to the specific requirements of the relevant policies and procedures in sufficient detail to assess whether the respondent complied with its policies and procedures. The respondent draws attention to the applicant’s concession in the past that she does not possess copies of the relevant policies and procedures set out in the particulars to paragraph 18. However, the case which the applicant seeks to propound, as I understand it, is based on an alleged inference of a broad kind to the effect that if proper processes had been implemented, then there would either have been no outbreak of the norovirus, or any such outbreak would have been contained. Whether that inference is open and should be drawn is a matter to be assessed on the balance of probabilities at the trial on the basis of the evidence adduced.

9 Fourth, the respondent submits that the allegations of causation in paragraph 46 of the FASC are rolled up in a way which does not make it clear whether all the matters referred to in that paragraph are relied on in the aggregate, or individually, or in various combinations. The same criticism is made of paragraph 77, in relation to the claims by Group Members. In my view, paragraphs 46 and 77 are sufficiently widely expressed to embrace all of those ways of the applicant putting her case, and the applicant is not required to establish the role of each of the alleged deficiencies in the alleged failure to comply with the relevant consumer guarantee.

10 Fifth, the respondent submits that it is not pleaded that the failure to implement effective cleaning protocols or implement the respondent’s own policies and procedures caused the norovirus outbreak, or contributed to its severity, or caused the applicant or her sister or specific Group Members to fall ill, or in some other way caused or contributed to the applicant’s failure to have an enjoyable voyage. In my view, those measures are sufficiently pleaded in paragraphs 46 and 77 as means to control the outbreak of the virus, and those paragraphs convey with sufficient clarity a case based on the proposition that if those steps had been taken then more effective control and containment of the norovirus would have occurred.

11 The respondent then turned to the allegations as to failures to warn by the respondent set out in paragraphs 13, 14 and 15 of the FASC. As a general matter, the respondent says that there is no allegation that the failures to warn constituted the breach of any separate legal or equitable duty, but correctly observes that the services alleged in paragraph 6(a) included the provision of information to passengers, both before boarding the cruise and during the cruise, about circumstances likely to affect passengers’ enjoyment of the cruise. The respondent submits (by reference to paragraph 5 of the FASC) that the applicant acquired the alleged services by going on the cruise, and therefore the services could not extend to the failure to provide information prior to the applicant boarding the vessel. In my view, that criticism misunderstands the pleading, in that paragraph 5 merely identifies one aspect of the conduct of the applicant amounting to the “acquisition” of services, but does not define the services or when they were (or were not, as the case may be) provided. Paragraphs 13 and 20 of the FASC make it clear that the applicant alleges that there was a deficiency in the services by reason of a failure to provide certain information prior to embarkation.

12 Further, the respondent submits that the fundamental problem with the failure to warn case is that no warning could have mitigated the outbreak or its effect on the applicant’s enjoyment of the voyage. The particulars provided in correspondence by the applicant (in relation to what is now paragraph 46 of the FASC) include the proposition that the relevant counterfactual is that if the applicant had been informed of the matters in paragraphs 13 and 14, or given the alternatives in paragraph 16, the applicant would not have taken this particular cruise and may have taken a different cruise which was capable of complying with the statutory guarantees with all the facilities available, or taken her refund. (It appears that no request for particulars was made in respect of paragraph 77, which deals with the claims by Group Members in similar terms to paragraph 46 pertaining to the applicant.) If those propositions are made good at the trial, then the applicant may well establish a course of decision-making which would have avoided the unpleasant experience of the cruise which the applicant actually went on. As to the Group Members, I assume that a similar counterfactual will be sought to be established by them at the stage when their individual cases are heard and determined.

13 The respondent then makes a further 8 criticisms of the failure to warn case as follows.

14 First, the respondent relies on the alleged inconsistency between paragraph 5 (as to the acquisition of the services upon the applicant embarking on the voyage) and the allegation in paragraphs 13 and 20 of a failure to give a warning before embarkation. In my view, there is no inconsistency, and the pleading clearly alleges that the services included the provision of relevant information prior to embarkation.

15 Second, the respondent submits that the allegation that the services included warning passengers of the likely effect of a norovirus outbreak cannot be made good absent a pleading that an outbreak was likely. However, it is alleged in paragraph 11(b) that there was “a real risk” of the virus spreading so as to cause an outbreak, and in paragraph 10(e) that norovirus was well-known for being susceptible to an outbreak on cruise ships. It will be a matter for evidence whether a warning was required (and if so, what warning) in the particular circumstances. Whether, as the respondent submits, a warning of the kind alleged would be so lengthy and detailed as to rob it of any utility is also a matter which depends on the evidence to be adduced at the trial.

16 Third, the respondent submits that even if the applicant were to allege that a norovirus outbreak on the voyage was likely, this would still merely be an ordinary risk inherent in activities where people congregate and there is no prospect the Court would find that any required warning would include detailing aspects of the norovirus. That is also a matter for evidence.

17 Fourth, the respondent submits that the allegation that giving the alleged warnings would have caused the applicant and Group Members not to proceed with their voyages is not tenable, because it is said that the implicit assumption is that no one who goes on a cruise is aware of the risks allegedly presented by norovirus. I do not see how those submissions could be accepted on a summary dismissal or strike-out application, and will depend on the evidence given at the trial.

18 Fifth, the respondent submits that the allegation that warnings should have been given once the voyage was under way and norovirus cases occurred, and the related allegation in paragraph 16 that the respondent should have offered the applicant and Group Members the opportunity not to proceed with their voyage upon identifying a case of norovirus on board, are not tenable, and there is no prospect the Court would find that the services contravened s 61 of the ACL unless the cruise operator offered every passenger the right to cancel their voyage and a full refund upon a single crew member or passenger contracting the norovirus. The respondent also submits that permitting or requiring passengers to disembark at the next scheduled stop would not have been feasible or conducive to an improved experience. These submissions also depend upon factual matters to be determined at the trial, and may well depend on evidence as to the degree of contagion and the severity of symptoms of the norovirus.

19 Sixth, the respondent submits that the allegation in paragraph 16 of the FASC that the respondent should have offered alternative opportunities for a subsequent journey is inconsistent with the allegations in paragraphs 43 and 76 that no passenger would travel on a cruise once told of the risk of norovirus. However, paragraphs 43 and 76 are directed to the particular cruises which the applicant and Group Members had booked to travel on, not cruises at some unspecified time in the future. The issue depends on evidence to be adduced at the trial.

20 Seventh, the respondent submits that even if the applicant establishes that the services included providing the pleaded warning about norovirus, causation will not be established because the applicant’s inability to enjoy her voyage was caused by her and her sister falling ill, not by the failure to give a warning. However, there is a pleading at paragraph 43, supported by paragraph 37 of the particulars provided in correspondence to which I have referred above, to the effect that if a warning had been given then the applicant would not have embarked on the cruise, and thus would not have fallen ill on that cruise. Whether that is established at the trial will depend on the evidence.

21 Eighth, the respondent submits that the applicant will not establish that it was reasonably foreseeable that failing to give the pleaded warnings would result in the applicant suffering the pleaded loss and damage as required by s 267(4), because it was not reasonably foreseeable that every passenger would refuse to embark on the voyage and demand a refund if given that warning, as the applicant pleads. However, the question of reasonable foreseeability is a matter for the final hearing in the light of the evidence adduced at the trial. A relevant circumstance will be the terms of the particular warnings (if any) which are found to have been required. Further, the applicant may be able to succeed without establishing the reasonable foreseeability of each and every passenger taking that course.

22 The respondent made a further submission in its oral address to the effect that the allegations in paragraphs 13 to 16 are incapable of falling within s 61 of the ACL. The respondent draws attention to the allegation in paragraph 7 as to the particular purpose for the acquisition of the services being to have a relaxing and pleasurable cruise, and experience the selected cruise in accordance with the itinerary and standards advertised by the respondent. Further, paragraph 8 alleges that the desired result which the applicant made known to the respondent that she wished to achieve from the acquisition of the services was a relaxing and pleasurable cruise and to experience the cruise in accordance with the itinerary and standards advertised by the respondent. The respondent submits that the applicant’s case is that if the services were provided consistently with s 61, then she would not have gone on the cruise, with the consequence that she could not have achieved the particular purpose and the desired result which are alleged.

23 I do not accept that argument. The case propounded by the applicant is to the effect that the services within the meaning of s 61 in the present case included the provision of appropriate information (before and after boarding), opportunities to disembark, the implementation of appropriate policies and procedures, and appropriate care for anyone who fell ill. An element of the applicant’s case, as I understand it, is that in light of the purpose and desired result identified in the pleading, the applicant required reasonable information concerning the risks and features of the services to be provided to ensure that, as a consumer, she would be comfortable with those services, and would not be confronted by adverse and unexpected experiences. In my view, such a case is open to be pleaded pursuant to ss 61 and 267. As the applicant submits, the cause of action is complete when, by virtue of the services not being of the appropriate standard, any loss or damage has been suffered by the consumer because of the failure to comply with the guarantee if it was reasonably foreseeable that the consumer would suffer such loss or damage as a result of such a failure: s 267(4). It is not necessary for the claimant to demonstrate, as an additional intermediate step, that the damage was caused because the purpose or desired result had not been realised.

24 Accordingly, I grant leave to the applicant to file the FASC. While the applicant has succeeded in obtaining that leave, the FASC is in materially different terms to the amended statement of claim which was the subject of the respondent’s interlocutory application. In those circumstances, in my view, the appropriate order as to costs in relation to the pleading dispute is that costs be costs in the cause.

25 As to the costs of the security for costs application, I have not decided that application on the merits, given the resolution which the parties arrived at during the course of oral submissions. Those costs will overlap to some extent with the costs incurred in relation to the pleading dispute, particularly in that both aspects of the interlocutory application were fixed for hearing on the same day, and were the subject of the same orders for the exchange of affidavits and written submissions. In those circumstances, the appropriate order for costs of the security for costs application is also that they be costs in the cause.

I certify that the preceding twenty-five (25) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Jackman. |

Associate: