FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Electoral Commissioner of the Australian Electoral Commission v Laming (No 2) [2023] FCA 917

ORDERS

ELECTORAL COMMISSIONER OF THE AUSTRALIAN ELECTORAL COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The respondent contravened s 321D(5) of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) by posting electoral matter on the “Redland Hospital: Let’s fight for fair funding” Facebook page on 24 December 2018, 7 February 2019 and 5 May 2019 without ensuring that his name and the town or city in which he lives were notified in accordance with the requirements of the Commonwealth Electoral (Authorisation of Voter Communication) Determination 2018.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The respondent pay the following pecuniary penalties to the Commonwealth of Australia within 28 days:

(a) in respect of his contravention arising from the Facebook post of 24 December 2018, $10,000;

(b) in respect of his contravention arising from the Facebook post of 7 February 2019, $5,000;

(c) in respect of his contravention arising from the Facebook post of 5 May 2019, $5,000.

3. The parties file and serve submissions as to costs (not exceeding five pages) by 4.30 pm on the following dates:

(a) the applicant, 23 August 2023;

(b) the respondent, 6 September 2023;

(c) the applicant in reply, 20 September 2023.

4. The question of costs will be decided on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[9] | |

The legislative scheme | [12] |

The submissions | [28] |

The evidence | [54] |

Application to withdraw admissions | [68] |

Consideration | [93] |

Whether the First, Third and Fourth Posts are “electoral matter” within s 4AA(1) of the Electoral Act | [104] |

The First Post: 24 December 2018 | [128] |

The Third Post: 13 February 2019 (stating Mr Laming had “ripped Labor a new one”) | [162] |

The Fourth Post: 13 February 2019 (containing an extract from Hansard) | [162] |

Whether the Fourth and Fifth Posts are excepted from the definition of “electoral matter” under s 4AA(5)(a) of the Electoral Act | [176] |

Whether Mr Laming’s name and town or city was disclosed in the “About” section of the Facebook Page | [192] |

Whether s 321D does not apply by reason of the “meeting” exception under s 321D(4)(f) of the Electoral Act | [200] |

The number of contraventions | [213] |

Relief | [236] |

RANGIAH J:

1 The applicant (the Commissioner) alleges that the respondent, Andrew Laming, contravened s 321D(5) of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) (the Electoral Act). The Commissioner seeks declarations and the imposition of pecuniary penalties.

2 Although the respondent is a medical doctor, he has indicated his preference for the title “Mr”.

3 Mr Laming was elected as a member of the House of Representatives for the electoral division of Bowman in 2016. He was also a candidate in the federal election held on 18 May 2019.

4 In the six months prior to the 2019 federal election, Mr Laming published a series of posts on a Facebook page entitled, “Redland Hospital: Let’s fight for fair funding”. The Commissioner alleges that five of the posts were “electoral matter” and that Mr Laming failed, in contravention of s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act, to disclose his name and relevant town or city. Mr Laming denies any such contravention.

5 The matter has a lengthy and somewhat tortuous procedural history, but, by the time the trial commenced, Mr Laming had made a number of admissions which operated to reduce the scope of the dispute.

6 The substantive issues remaining in dispute are:

(1) Whether three of the Facebook posts are “electoral matter” within s 4AA(1) of the Electoral Act.

(2) Whether two of the Facebook posts are excluded from the definition of “electoral matter” under the “reporting of news” or “presenting of current affairs” exceptions in s 4AA(5)(a) of the Electoral Act.

(3) Whether the “meeting” exception in s 321D(4)(f) of the Electoral Act applies to the Facebook Posts.

(4) If Mr Laming contravened s 321D(5), how many contraventions occurred and what penalties should be imposed.

7 After the first day of the hearing, Mr Laming terminated his lawyers’ retainers and chose to represent himself. On the second day, Mr Laming sought to withdraw an admission he had made, but I refused him leave to do so. It will be necessary to provide my reasons for that ruling. There are also questions of the admissibility of evidence that must be determined.

8 I will describe the factual background and admissions made before proceeding to consider the procedural, evidentiary and substantive issues.

9 The parties tendered an Amended Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions which states, relevantly:

PART II THE PARTIES

3. By s 82 of the Regulatory Powers (Standard Provisions) Act 2014 (Cth) (Regulatory Powers Act), an “authorised applicant” may apply, within six years of an alleged contravention, for an order that a person alleged to have contravened a “civil penalty provision” pay a “pecuniary penalty”. By s 384A(2) of the Electoral Act, the Applicant is an “authorised applicant”. Section 321 D is a “civil penalty provision”.

4. Mr Laming is, and between 6 December 2018 and 18 May 2019 (Relevant Period) was, a member of the House of Representatives in the Australian Federal Parliament. He was a candidate in the federal election held on 18 May 2019.

5. During the Relevant Period, Mr Laming was a “disclosure entity” within the meaning of s 321 B of the Electoral Act.

6. Mr Laming has engaged constructively with the AEC since the commencement of these Proceedings, including by agreeing facts as set out in this document.

PART III AGREED FACTS

A. BACKGROUND FACTS

7. During the Relevant Period, as noted above at paragraph 4, Mr Laming was a member of the House of Representatives in the Australian Federal Parliament, representing the division of Bowman.

8. Bowman is an electoral division which encompasses part of the Redland City and part of the Brisbane City within Queensland, including the suburbs of Wellington Point, Cleveland, Victoria Point and Redland Bay.

9. A federal election was held on 18 May 2019 (Election).

10. Mr Laming was a candidate for the Liberal National Party of Queensland (LNP) in the Election.

11. The Liberal Party of Australia (Liberal Party), the LNP and the Australian Labor Party (ALP) were each at all material times a registered political party, and thereby a political entity, for the purposes of the Electoral Act.

B. REDLAND HOSPITAL: LET’S FIGHT FOR FAIR FUNDING FACEBOOK PAGE

12. During the Relevant Period, Mr Laming was the administrator of a public Facebook page titled “Redland Hospital: Let’s fight for fair funding” (Page).

13. On the following occasions Mr Laming posted (or in the words of the Act, communicated) content to the Page (separately and together, the Posts):

13.1. On 24 December 2018 he wrote a post, referring to himself in the third person, stating that he had “boosted” funding of the Redland Hospital by $77 million.

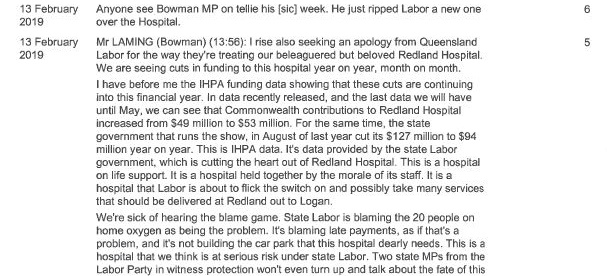

13.2. On 7 February 2019 he posted an image, and wrote an accompanying caption, comparing the federal funding for “Metro South Health” provided under the LNP with that provided under the ALP.

13.3. On 13 February 2019 he wrote a post, referring again to himself in the third person, stating that he had “ripped Labor a new one over the Hospital”.

13.4. On 13 February 2019 he posted an extract from Hansard in which he told the federal House of Representatives that the Commonwealth Government (Liberal Party/LNP) had increased contributions to Redland Hospital.

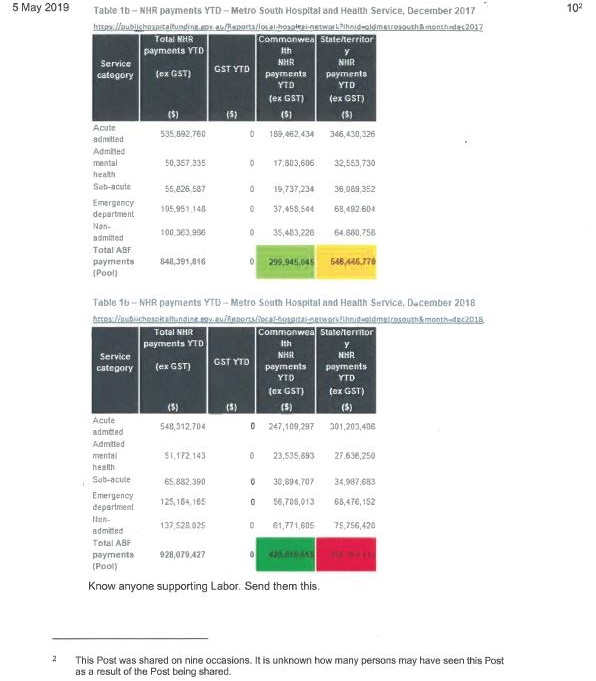

13.5. On 5 May 2019 he posted a table setting out National Health Reform payments to Metro South Hospital and Health Service, between 2017 and 2018, by both the Commonwealth Government and the Queensland Government. He also wrote the accompanying caption: “Know anyone supporting Labor. Send them this”.

14. Each Post and the occasions on which each post was viewed are set out at Schedule 1.

…

16. Each of the Posts was:

16.1. available to be viewed on the internet throughout the Relevant Period because the Facebook setting of the Page was “public”;

16.2. communicated to the public;

16.3. made by a political entity; and

16.4. viewed by a number of persons.

17. The Posts did not communicate matter which:

17.1. was an electoral advertisement falling within the terms of s 321 D(1)(a) of the Electoral Act;

17.2. was part of a sticker, fridge magnet, leaflet, flyer, pamphlet, notice, poster or how-to-vote card falling within the terms of s 321 D(1)(b) of the Electoral Act; or

17.3. fell within the terms of ss 4AA(5)(c), (d), (e) or (f), 321D(3) or 321D(4)(c), (d), (e), (g), (h) or (i) of the Electoral Act.

18. Mr Laming did not notify his name or relevant town or city in respect of any of the Posts, as required by s 321D(5), item 4 of the Electoral Act.

C. OTHER MATTERS

19. The “about” section of the Page stated: “This page supports Andrew Laming’s efforts to reveal funding for Redlands Hospital. Do you support the push for honesty?” The about section also included “Cleveland, QLD, Australia 4163”, being Mr Laming’s suburb. The Page was established as a Facebook category, “politician – political organisation”.

20. The majority of the posts made by Mr Laming to the Page did not communicate electoral matter within the meaning of the Electoral Act. Those posts generally related to the political issue of funding the Redland Hospital, including criticism of the Queensland Labor government.

D. HARM

21. The authorisation of electoral matters promotes, in compliance with the Electoral Act:

21.1. the transparency of the electoral system, by allowing voters to know who is communicating electoral matter; and

21.2. the accountability of those persons participating in public debate relating to electoral matter, by making those persons responsible for their communications.

22. As set out in Schedule 1, the Posts were viewed on at least 28 occasions by 25 persons. The Post dated 5 May 2019 was shared by nine persons and it is unknown how many persons may have viewed this Post as a result of the Post being shared.

PART IV ADMISSIONS

23. Mr Laming admits that:

23.1. he was a “disclosure entity” within the meaning of s 321D of the Electoral Act during the whole of the Relevant Period;

23.2. he was a “political entity” for the purposes of s 4AA(4)(b) of the Electoral Act during the whole of the Relevant Period.

(Interlineations, deletions and underlining omitted.)

10 Schedule 1 of the Amended Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions sets out the Facebook posts relied on by the Commissioner as follows:

11 It is convenient to describe the five Facebook posts the subject of the Commissioner’s allegations collectively as “the Five Posts”, and individually in the following way:

24 December 2018: the First Post;

7 February 2019: the Second Post;

13 February 2019 (stating Mr Laming had “ripped Labor a new one”): the Third Post;

13 February 2019 (posting an extract from Hansard): the Fourth Post;

5 May 2019: the Fifth Post.

12 It may be noted that the figures in the final row of the Fifth Post are indecipherable. However, that does not matter in view of an admission made by Mr Laming that the Fifth Post is “electoral matter” within s 4AA of the Electoral Act.

The legislative scheme

13 It is necessary to consider the Electoral Act in its form at the date each of the Five Posts was made. At the date of the First Post, the applicable version was Compilation No. 66. At the dates of the Second, Third and Fourth Posts, the applicable version was Compilation No. 67. At the date of the Fifth Post, the applicable version was Compilation No. 68. I will set out the relevant provisions from Compilation No. 68. The only relevant amendment was to Item 4 of s 321D(5).

14 Part XXA of the Electoral Act (ss 321B-321H) is entitled, “Authorisation of electoral matter”.

15 Section 321C sets out the objects of Pt XXA as follows:

321C Objects of this Part

(1) The objects of this Part are to promote free and informed voting at elections by enhancing the following:

(a) the transparency of the electoral system, by allowing voters to know who is communicating electoral matter;

(b) the accountability of those persons participating in public debate relating to electoral matter, by making those persons responsible for their communications;

(c) the traceability of communications of electoral matter, by ensuring that obligations imposed by this Part in relation to those communications can be enforced.

(2) This Part aims to achieve these objects by doing the following:

(a) requiring the particulars of the person who authorised the communication of electoral matter to be notified if:

(i) the matter is an electoral advertisement, all or part of whose distribution or production is paid for; or

(ii) the matter forms part of a specified printed communication; or

(iii) the matter is communicated by, or on behalf of, a disclosure entity;

(b) ensuring that the particulars are clearly identifiable, irrespective of how the matter is communicated.

(3) This Part is not intended to detract from:

(a) the ability of electoral matters to be communicated to voters; and

(b) voters’ ability to communicate with each other on electoral matters.

16 Section 321D(5) of the Electoral Act requires that a notifying entity must ensure that certain “electoral matter” discloses the prescribed particulars. Subsections 321D(1), (4)(f) and (5) and the definition of “electoral matter” in s 4(1) and (5) are of particular significance in this case.

17 Section 321D provides, relevantly:

321D Authorisation of certain electoral matter

(1) This section applies in relation to electoral matter that is communicated to a person if:

…

(c) the matter is communicated by, or on behalf of, a disclosure entity (the notifying entity) (and the matter is not an advertisement covered by paragraph (a), nor does the matter form part of a sticker, fridge magnet, leaflet, flyer, pamphlet, notice, poster or how-to-vote card).

…

Exceptions

…

(4) This section also does not apply in relation to electoral matter referred to in paragraphs (1)(b) and (c) if the matter forms part of:

(c) an opinion poll or research relating to voting intentions at an election or by-election; or

(d) a communication communicated for personal purposes; or

(e) an internal communication of a notifying entity; or

(f) a communication at a meeting of 2 or more persons if the identity of the person (the speaker) communicating at the meeting, and any disclosure entity on whose behalf the speaker is communicating, can reasonably be identified by the person or persons to whom the speaker is speaking; or

(g) a live communication of a meeting covered by paragraph (f), but not any later communication of that meeting; or

(h) a communication communicated solely for the purpose of announcing a meeting; or

(i) a letter or card that contains the name and address of the notifying entity.

Notifying particulars

(5) The notifying entity must ensure that the particulars set out in the following table, and any other particulars determined under subsection (7) for the purposes of this subsection, are notified in accordance with any requirements determined under that subsection.

Required particulars | ||

Item | If … | the following particulars are required … |

… | ||

4 | the communication is any other communication authorised by a disclosure entity who is a natural person | (a) the name of the person; (b) the relevant town or city of the person |

… | ||

Note 1: This provision is a civil penalty provision which is enforceable under the Regulatory Powers Act (see section 384A of this Act).

Note 2: A person may contravene this subsection if the person fails to ensure that particulars are notified or if the particulars notified are incorrect.

…

Civil penalty: 120 penalty units.

...

Legislative instrument

(7) The Electoral Commissioner may, by legislative instrument, determine:

…

(b) requirements or particulars for the purposes of any one or more of the following:

(i) subsection (5) of this section;

…

18 The Commissioner relies on s 321D(1)(c) and Item 4 of s 321D(5). The expression “relevant town or city” is defined in s 321B to mean, relevantly, “the town or city in which the natural person who was responsible for giving effect to the authorisation lives”.

19 In Compilation No. 66, in force at the time the First Post was made, Item 4 of s 321D(5) required notification of “the town or city in which the person lives”. The amendment is inconsequential for present purposes.

20 The application of s 321D depends upon the matter communicated being “electoral matter”. The expression “electoral matter” is defined in s 4AA of the Electoral Act as follows:

4AA Meaning of electoral matter

(1) Electoral matter means matter communicated or intended to be communicated for the dominant purpose of influencing the way electors vote in an election (a federal election) of a member of the House of Representatives or of Senators for a State or Territory, including by promoting or opposing:

(a) a political entity, to the extent that the matter relates to a federal election; or

(b) a member of the House of Representatives or a Senator.

Note: Communications whose dominant purpose is to educate their audience on a public policy issue, or to raise awareness of, or encourage debate on, a public policy issue, are not for the dominant purpose of influencing the way electors vote in an election (as there can be only one dominant purpose for any given communication).

(2) For the purposes of subsection (1), each creation, recreation, communication or recommunication of matter is to be treated separately for the purposes of determining whether matter is electoral matter.

…

Rebuttable presumption for matter that expressly promotes or opposes political entities etc.

(3) Without limiting subsection (1), the dominant purpose of the communication or intended communication of matter that expressly promotes or opposes:

(a) a political entity, to the extent that the matter relates to a federal election; or

(b) a member of the House of Representatives or a Senator, to the extent that the matter relates to a federal election;

is presumed to be the purpose referred to in subsection (1), unless the contrary is proved.

Matters to be taken into account

(4) Without limiting subsection (1), the following matters must be taken into account in determining the dominant purpose of the communication or intended communication of matter:

(a) whether the communication or intended communication is or would be to the public or a section of the public;

(b) whether the communication or intended communication is or would be by a political entity or political campaigner (within the meaning of Part XX);

(c) whether the matter contains an express or implicit comment on a political entity, a member of the House of Representatives or a Senator;

(d) whether the communication or intended communication is or would be received by electors near a polling place;

(e) how soon a federal election is to be held after the creation or communication of the matter;

(f) whether the communication or intended communication is or would be unsolicited.

Exceptions

(5) Despite subsections (1) and (3), matter is not electoral matter if the communication or intended communication of the matter:

(a) forms or would form part of the reporting of news, the presenting of current affairs or any genuine editorial content in news media; or

…

Note: A person who wishes to rely on this subsection bears an evidential burden in relation to the matters in this subsection (see subsection 13.3(3) of the Criminal Code and section 96 of the Regulatory Powers Act).

21 The expression “political entity” is defined in s 4(1) to mean any of the following:

(a) a registered political party;

(b) a State branch (within the meaning of Part XX) of a registered political party;

(c) a candidate (within the meaning of that Part) in an election (including a by-election);

(d) a member of a group (within the meaning of that Part).

22 Section 321B defines “election” to mean a general election or an election of Senators for a State or Territory.

23 Section 321B provides that a person “authorises” the communication of electoral matter if, relevantly, the person communicates the matter.

24 Section 321D(5) requires the notifying entity to ensure that the relevant particulars are notified in accordance with any requirements determined under s 321D(7). At the time of the Five Posts, the relevant determination was the Commonwealth Electoral (Authorisation of Voter Communication) Determination 2018 (the 2018 Determination).

25 Section 9(1)(a) of the 2018 Determination contained a table which set out requirements for notifying particulars for the purposes of s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act. Item 4 provided that if the communication is by social media, the particulars must be notified:

(a) at the end of the communication; or

(b) if the particulars are too long to be included in the communication – in:

(i) a website that can be accessed by a URL included in the communication; or

(ii) a photo included in the communication.

26 The note to s 321D(5) states that it is a civil penalty provision. The section sets out at its foot, the words, “Civil penalty: 120 penalty units”.

27 Section 384A of the Electoral Act provides, relevantly:

384A Application of Regulatory Powers Act

Application of Parts 4 and 6

(1) Section 321D is enforceable under Parts 4 and 6 of the Regulatory Powers Act.

Note: Part 4 of the Regulatory Powers Act allows a civil penalty provision to be enforced by obtaining an order for a person to pay a pecuniary penalty for the contravention of the provision….

Authorised applicant and relevant court

(2) For the purposes of Parts 4 and 6 of the Regulatory Powers Act:

(a) for Part 4—the Electoral Commissioner is an authorised applicant; and

…

(c) for Parts 4 and 6—the Federal Court of Australia is a relevant court;

in relation to section 321D of this Act.

28 Section 79(2)(a)(i) of the Regulatory Powers (Standard Provisions) Act 2014 (Cth) (the Regulatory Powers Act) provides, relevantly, that a provision of an Act instrument is a “civil penalty provision” if the provision sets out at its foot a pecuniary penalty, or penalties, indicated by the words “Civil penalty”.

29 The hearing commenced on 7 September 2022. It did not finish within the one day allocated, and was adjourned to 21 September 2022. Shortly before the resumption, Mr Laming decided to terminate his lawyers’ retainer and represent himself. He applied for an adjournment, which was refused. My reasons were provided in Electoral Commissioner of the Australian Electoral Commission v Laming [2022] FCA 1175.

30 Before Mr Laming terminated his lawyers’ retainer, they had prepared written submissions and his counsel had made oral submissions on the first day of the hearing. Mr Laming continues to rely substantially upon those submissions. In these circumstances, I consider it appropriate and fair to acknowledge that the submissions made by his lawyers were considered, thorough and skilled. Where these reasons refer to Mr Laming’s submissions, they generally refer to submissions made by his lawyers on behalf of Mr Laming, except where identified as being made by Mr Laming personally.

31 The Commissioner alleges that Mr Laming contravened s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act by:

(1) communicating an electoral matter;

(2) to a person;

(3) as a disclosure entity;

(4) without disclosing his name and relevant town or city.

32 Initially, Mr Laming admitted the second, third and fourth of these matters in respect of the Five Posts, but disputed that the First, Third and Fourth Posts were “electoral matter”. During the resumed hearing, he sought to withdraw his admission of the fourth matter, but I ruled that Mr Laming would not be permitted to withdraw his admission.

33 Mr Laming’s contention that the Commissioner has not proved that the First, Third and Fourth Posts were not “electoral matter” relies upon three propositions:

(1) the posts were not communicated for the dominant purpose of influencing electors in a federal election;

(2) the posts did not relate to a federal election;

(3) the posts fall within the exception in s 4AA(5)(a).

34 As to the first of these matters, the Commissioner submits that the First, Third and Fourth Posts attract the rebuttable presumption in s 4AA(3) of the Electoral Act. The Commissioner submits that, even if they do not, the application of the mandatory considerations in s 4AA(4) confirms that they had the dominant purpose of influencing the way voters vote in a federal election. The Commissioner argues that each post was made in a period leading up to the May 2019 election in which Mr Laming was a candidate; they expressly promoted Mr Laming or his party, or criticised an opposing party; and were made on a public platform created to advocate upon a political issue, namely government funding of Redland Hospital. The Commissioner also submits that none of the posts contain any hints that Mr Laming was the author of the post and, in fact, two of the posts promoting Mr Laming convey the impression that the author is someone else.

35 As to the second of Mr Laming’s arguments, the Commissioner submits that it is unnecessary to show that the posts directly referred to the election, or had a direct relationship with the election, for them to, “relate to a federal election”. It is submitted that the fact that three of the posts appear to relate to the State branch of the Labor Party does not preclude them from relating to a federal election, consistently with the definition of s 4 of “political entity”, which includes a State branch of a registered political party.

36 As to the third matter, the Commissioner submits that the exception in s 4AA(5)(a) of the Electoral Act (“the reporting of news, presenting of current affairs or any genuine editorial content in news media”), is only for the benefit of news media, and that neither Mr Laming nor the Facebook Page were part of the news media.

37 Mr Laming submits that the exception in s 321D(4)(f) (where, relevantly, the identity of a speaker communicating at a meeting can reasonably be identified) is engaged. The Commissioner submits that “meeting” in its ordinary usage refers to a gathering either in-person or through other mediums, but that the Facebook Posts do not resemble a meeting as they could be viewed by anyone as long as the Posts remained. It is also submitted that there was no mechanism to identify the author of the Posts.

38 In support of his contention that the First, Third and Fourth Facebook Posts were not “electoral matter”, Mr Laming submits that the rebuttable presumption does not apply and that the Commissioner retains the onus of proof. He argues that the phrase in s 4AA(3), “expressly promotes or opposes ... to the extent that the matter relates to a federal election”, means that the presumption only operates if a communication details who a person should or should not vote for. He relies on the Explanatory Memorandum which, it is said, makes it clear that “expressly promotes or opposes” requires specific communication and sets a high threshold. He submits that the First, Third and Fourth Posts do not meet this high threshold since they do not make any reference to how to vote, or to a federal election.

39 Mr Laming submits that to prove the requisite “dominant purpose”, the Commissioner must show that the Posts were made:

(1) for the ruling, prevailing or most influential purpose of;

(2) influencing voters’ formation of political judgement;

(3) in relation to the act of voting in a federal election.

40 Mr Laming submits that the overall context of the communications is important. He argues that the ruling, prevailing or most influential purpose of the Posts was to address the Queensland Government’s reduction in funding of the Redland Hospital, not to influence voting in a federal election. Mr Laming contends this is made clear by the Page’s title, the “About” section of the Facebook Page and the First, Third and Fourth Posts themselves. He submits that to the extent that the Page was political, it expressly related to Queensland politics, not federal politics. He also submits that, usually, only followers of the Facebook Page would see the Posts, so they were not unsolicited.

41 Mr Laming submits that the fact the Facebook Page operated well before and after May 2019 Federal election shows that the Page was not related to the election. He argues that the starting premise must be that he posted policy information about Redland Hospital funding, not that it posted electoral matters.

42 Mr Laming submits that the Commissioner’s focus on the date of the May 2019 federal election ignores the important temporal circumstance that the election was not called until 11 April 2019, and until then, no one was actively campaigning for an upcoming election. Mr Laming submits that the First, Third, and Fourth posts were made two or more months before the election was called, and well before the public knew there was an upcoming election.

43 Mr Laming submits that the First Post does not contain any reference to a political party, a federal election, voting, or any express support or opposition of a political entity, or any information that relates to a federal election. Rather, to prove the communication was an electoral matter, the Commissioner relies on an allegation that the First Post promoted Mr Laming. While the First Post states, “[Mr Laming] boosted funding by $77 million”, it is only part of a single sentence in a long post that focuses on funding for the Redland Hospital. It is submitted that the First Post, when read in its entirety and in the context of the other posts on the Facebook Page, was made for the dominant purpose of sharing information about funding the Redland Hospital, and is not about promoting Mr Laming.

44 Mr Laming also submits that, in any event, there is no connection between any promotion of him and a federal election and, accordingly, the First Post cannot have contained electoral matter.

45 Mr Laming submits that the Third and Fourth Posts are related as they address the same issue, namely the Queensland Government’s funding of the Redland Hospital. He argues that the Third and Fourth Posts contain no reference to a federal election, voting, or the federal Labor Party. At their highest, they contain implied support for Mr Laming and implied opposition of the Queensland Labor government. He submits that their main purpose was to criticise the Queensland Labor government in relation to Redland Hospital funding.

46 Mr Laming also submits that the Electoral Act is not concerned with State elections, but only federal elections. The Commissioner’s submission that Mr Laming’s criticism of the Queensland Labor government is transferable to the federal Labor party, is said to invite the Court to concern itself with State politics.

47 Mr Laming submits that “news” for the purposes of s 4AA(5)(a) of the Electoral Act refers to the reporting of a recent event, or situation, and “current affairs” means presenting commentary, analysis and editorial content in relation to recent events and occurrences. He submits that the provision does not require that such reporting or presentation be done by professional news media.

48 Mr Laming submits that the Fourth Post does nothing more than replicate a statement he made in the House of Representatives and the Fifth Post simply excerpts two tables from two reports on Metro South Hospital funding and reports the data.

49 Mr Laming also relies on the exception from disclosure requirements under s 321D(4)(f) of the Electoral Act in respect of communications created during a meeting if the identity of the person communicating can reasonably be identified. He points to the Explanatory Memorandum, which states that the expression “meeting” is intended to refer to, “any assembly or gathering, including in-person, by telephone or using other mediums”. He argues that “other mediums” can include communications on a Facebook page. He submits that any viewer of the Page would have been able to reasonably identify him as the author of the Posts.

50 On the second day of the hearing, when Mr Laming was self-represented, he sought to rely on s 12(2)(d) of the Commonwealth Electoral (Authorisation of Voter Communication) Determination 2021 (the 2021 Determination), which requires that the particulars required under s 321D(5) be notified in one or more of the following ways:

(i) at the end of the communication;

(ii) on a webpage that can be accessed by a URL that is included, either in whole or as a hyperlink, at the end of the communication;

(iii) if the communication is on a webpage—in the footer of the webpage;

(iv) if the communication is communicated on or using a social media service and the notifying entity for the communications is an individual—in the “About Us” or “Contact Us” section (however described) that relates to the individual and that is directly linked to, or can be accessed by clicking a link in, the communication.

51 Mr Laming submits that the Five Posts complied with the requirements in (ii) and (iv).

52 The Commissioner submits that the 2021 Determination did not apply at the relevant time, not having come into force until 7 July 2021. The Commissioner submits that, in any event, the Five Posts did not satisfy the requirements of (ii) or (iv) as there was no URL allowing access to a webpage containing the particulars and the “About” section of the Facebook Page did not provide the relevant particulars.

53 As I have indicated, Mr Laming also sought to withdraw his admission that he did not notify his name and the town or city in which he lived in respect of any of the Five Posts.

54 Mr Laming elaborated upon the admissions already made by his counsel. He focussed, in particular, upon an assertion that the viewers of the Posts were all his “Facebook friends” who must have been able to identify him as the person making the Five Posts.

The evidence

55 The applicant relied on two affidavits of Matthew Blunn, a solicitor. His first affidavit annexed a copy of all 232 posts and comments on the Facebook Page produced by Mr Laming in response to a notice to produce information.

56 The parties tendered the Amended Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions.

57 On the first day of the hearing, Mr Laming sought to rely on three affidavits of Ron Pennekamp (affirmed on 10 May 2022, 27 June 2022 and 24 August 2022 respectively), each annexing a report he had prepared. Mr Pennekamp runs a digital marketing agency. Mr Pennekamp answered a series of questions he was asked concerning the Facebook application generally and the Five Posts specifically.

58 The Commissioner objected to the whole of Mr Pennekamp’s three affidavits on the basis of s 56 (relevance) and s 135 (unfairly prejudicial or cause or result in undue waste of time) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (the Evidence Act). The Commissioner also objected to paras 11-24 of Mr Pennekamp’s first report, paras 8-14 of his second report and pages 3 and 31-36 of his third report on the basis that the factual basis for his opinions were not stated or proved.

59 I consider that a number of the answers Mr Pennekamp gave are relevant and useful in providing an understanding about how Facebook operates and giving context to the Five Posts. There may be some questions and answers that are not relevant, but the Commissioner’s objection on the basis of relevance and waste of time was to the whole of the reports, not to particular paragraphs. When viewed as a whole, I consider the reports to be relevant and useful. I reject the Commissioner’s objections to the whole of the reports.

60 I also reject the Commissioner’s objections to specific paragraphs of Mr Pennekamp reports on the basis that the factual basis for his opinions are not stated or proved. It is apparent from Mr Pennekamp’s reports that he interrogated the Facebook application in order to produce the statistics and other information he considers. His expertise has not been challenged. I reject the Commissioner’s objections to the specific paragraphs.

61 On the second day of the hearing, Mr Laming produced two further affidavits of Mr Pennekamp, each annexing a further report. I rejected the tender of those affidavits, principally on the basis of the lateness of their production and consequent prejudice to the Commissioner.

62 Mr Laming did not give evidence.

63 Mr Pennekamp explains that a Facebook page is linked to a business, product, service or cause. Facebook users can interact, discuss, comment and share posts on a Facebook page. Unlike a Facebook group, a Facebook page cannot have a “private” mode.

64 A person needs a Facebook profile in order to interact with other users, pages and groups on Facebook. A Facebook profile is an individual account belonging to a user. All Facebook profiles can view the content on a Facebook page.

65 A Facebook user can like or follow a Facebook page in order to receive updates in their feed. Users may also receive updates in their feeds by way of promoted posts (paid advertisements) or suggested posts, based on what Facebook’s algorithm has determined the user may be interested in.

66 Mr Pennekamp explains that if a user clicks a link onto a Facebook page, they will see all the recent posts published in chronological order.

67 Mr Pennekamp describes the “reach” of a post as the number of unique (individual) views a post has received. He gives the example that if 10 people see a post, the reach is 10; if one of the same viewers sees the post again, the reach remains at 10. He indicates that the reach of the First Post was six; the Second Post was eight; the Third Post was nine; the Fourth Post was eight; and the Fifth Post was 14.

68 Mr Pennekamp states that most of the profiles that engaged with the Five Posts are “friends” with Mr Laming’s personal profile, and 12 of those users have Facebook messenger chat history with Mr Laming prior to the First Post. He indicates that there were only two profiles, “which are not affiliated with [Mr Laming’s] personal profile”. He indicates that those two users do, however, share a large number of mutual “friends” with Mr Laming.

Application to withdraw admissions

69 On the second day, Mr Laming sought to withdraw the admission he had made in para 18 of the Amended Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions that:

Mr Laming did not notify his name or relevant town or city in respect of any of the Posts, as required by s 321D(5), item 4 of the Electoral Act.

70 Mr Laming also sought to withdraw the admission in his Further Amended Concise Statement in Response of the allegation that, “Mr Laming did not notify his name or relevant town or city in respect of any of the Posts”, and an admission in his Outline of Submissions that the Five Posts, “did not disclose his name or relevant city”.

71 Mr Laming proposed to argue that his name and town were in fact disclosed in the “About” section of the Facebook Page. That was inconsistent with his Outline of Submissions. It was also inconsistent with his counsel’s identification of the relevant issues in oral submissions on the first day of the hearing.

72 After hearing argument, I ruled that Mr Laming would not be permitted to withdraw his admissions and indicated that my reasons would be provided in due course. These are my reasons.

73 Mr Laming asserted that it was only through hearing the submissions on the first day of the hearing that he came to realise that the “About” section of the Facebook Page contained his name and relevant city. He argued that para 18 of the Amended Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions is inconsistent with para 19 of the same document, which states:

The “about” section of the Page stated: “This page supports Andrew Laming’s efforts to reveal funding for Redlands Hospital. Do you support the push for honesty?”

74 Mr Laming also argued that the “About” section also referred to, “Cleveland, QLD, Australia 4163”, which he asserted was his suburb.

75 The Commissioner relied on s 191 of the Evidence Act, which provides:

Agreements as to facts

(1) In this section:

“agreed fact” means a fact that the parties to a proceeding have agreed is not, for the purposes of the proceeding, to be disputed.

(2) In a proceeding:

(a) evidence is not required to prove the existence of an agreed fact; and

(b) evidence may not be adduced to contradict or qualify an agreed fact;

unless the court gives leave.

(3) Subsection (2) does not apply unless the agreed fact:

(a) is stated in an agreement in writing signed by the parties or by Australian legal practitioners, legal counsel or prosecutors representing the parties and adduced in evidence in the proceeding; or

(b) with the leave of the court, is stated by a party before the court with the agreement of all other parties.

76 An application to withdraw an agreed fact does not fall within s 191(2)(b) of the Evidence Act. Section 191(2) distinguishes between “evidence” and “an agreed fact”, so that agreed facts are not themselves evidence. Mr Laming seeks to withdraw an agreed fact and, once withdrawn, seeks to make submissions that place a different complexion on another agreed fact. He does not seek to adduce “evidence” to, “contradict or qualify an agreed fact”. Section 191(2) is not applicable to the present circumstances.

77 However, the necessity for a party to obtain leave to withdraw an admission is not confined to circumstances where such leave is required under legislation or the rules of a court. So, for example, in Coopers Brewery Ltd v Panfida Foods Ltd (1992) 26 NSWLR 738, the defendant was refused leave to withdraw admissions made in a letter from its former solicitors and repeated in court by its former counsel in circumstances where a consent order providing for the making of admissions had been made. In that case, Rogers CJ Comm D rejected the view expressed in H Clark (Doncaster) Ltd v Wilkinson [1965] Ch 694 (H Clark) at 703 that an admission made by counsel can be withdrawn unless the circumstances are such as to give rise to an estoppel. The Full Court of the Federal Court in Jeans v Commonwealth Bank of Australia Ltd (2003) 204 ALR 327 (Jeans) at [17] also rejected the position taken in H Clark.

78 In Jeans, the Full Court held at [18] that in an application to withdraw an admission, the Court has a broad discretion, the overall aim being to ensure that there is a fair trial. The Full Court cited with approval the following summary of principles given by Santow J in Drabsch v Switzerland General Insurance Co Ltd (unreported, New South Wales Supreme Court, 16 October 1996) at 7–8:

1. Where a party under no apparent disability makes a clear and distinct admission which is accepted by its opponent and acted upon, for reasons of policy and the due conduct of the business of the court, an application to withdraw the admission, especially at appeal, should not be freely granted …

2. The question is one for the reviewing judge to consider in the context of each particular appeal, with the general guidelines being that the person seeking on a review to withdraw a concession made should provide some good reason why the judge should disturb what was previously common ground or conceded …

3. Where a court is satisfied that admissions have been made after consideration and advice such as from the parties’ expert and after full opportunity to consider its case and whether the admission should be made, admissions so made with deliberateness and formality would ordinarily not be permitted to be withdrawn …

4. It will usually be appropriate to grant leave to withdraw an admission where it is shown that the admission is contrary to the actual facts. Leave may also be appropriate where circumstances show that the admission was made inadvertently or without due consideration of material matters. Irrespective of whether the admission has or has not been formally made, leave may be refused if the other party has changed its position in reliance upon the admission …

5. Following Cohen v McWilliam (1995) 38 NSWLR 476, a court is not obliged to give decisive weight to court efficiency, such that a party who wishes to defend its claim is entitled to a hearing on the merits, with costs orders being available as a means of compensating the other party for any costs thereby unnecessarily incurred or not fairly visited on the other party.

79 In considering the exercise of the discretion, it is relevant to set out some of the lengthy procedural history of the matter.

80 The Originating Application was filed on 21 December 2021. On 31 January 2022, I ordered, by consent, that the Commissioner file and serve a Statement of Agreed Facts in a form agreed by the parties. Mr Laming was self-represented at that time.

81 On 1 February 2022, the parties filed a Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions. The admissions made by Mr Laming included that he had not notified his name or relevant town or city in respect of any of the Posts as required under s 321B(5); and that he had contravened s 321D on each occasion on which the content in the Five Posts was communicated to a person.

82 By the time the next case management hearing was held on 10 March 2022, Mr Laming had obtained legal representation. At a further case management hearing on 28 March 2022, Mr Laming’s lawyers sought, and he was granted, leave to withdraw his admissions. The matter was to proceed to hearing on the questions of contravention and penalty. The matter was set down for hearing on 16 June 2022.

83 On 10 May 2022, Mr Laming’s lawyers filed his Concise Statement, which indicated that he wished to withdraw a number of other admissions in the Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions.

84 At a case management hearing on 24 May 2022, I ordered that Mr Laming file an application seeking leave to withdraw his admissions and, on 1 June 2022, that application was filed. The final hearing listed for 16 June 2022 was vacated and the interlocutory application was to be heard instead on that day.

85 On 9 June 2022, an order was made by consent, allowing further amendment of the Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions. The matter was set down for a final hearing on 9 September 2022.

86 On 15 June 2022, the Amended Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions was filed. On 19 July 2022, Mr Laming filed his Further Amended Concise Statement.

87 On 9 September 2023, the hearing commenced. Mr Laming was represented by counsel and solicitors. On 13 September 2022, Mr Laming terminated his lawyer’s retainer.

88 Mr Laming’s admission that he did not notify his name or relevant town or city in respect of any of the Posts was maintained until 21 September 2022, the second day of the hearing. It is apparent that his admissions of that matter in his Further Amended Concise Statement, the Amended Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions and his Outline of Submissions were made with the opportunity for full consideration and advice from his lawyers and with deliberateness and formality. His counsel’s submissions at the hearing were consistent with maintaining that admission.

89 Mr Laming was the administrator of the Facebook Page. He was obviously familiar with its content and operation. Mr Laming failed to provide any adequate explanation for why he only came to the realisation during the hearing that the “About” section of the Facebook Page contained his name and relevant city and why he only sought to withdraw the admission at such a late stage.

90 While leave to withdraw the admission was capable of being granted with an adjournment and an award of costs in favour of the Commissioner, it was also necessary to take into account the public interest in the finalisation of the matter, bearing in mind its lengthy procedural history.

91 I was not satisfied, contrary to Mr Laming’s submission, that there was any necessary inconsistency between his admission that he had not notified his name or relevant town or city, and the statement on the Facebook Page that, “This page supports Andrew Laming’s efforts to reveal funding for Redlands Hospital”, and the reference to, “Cleveland, QLD, Australia 4163”. As I will discuss later in these reasons, the “About” section of the Facebook Page does not in fact disclose the particulars required by s 321D(5).

92 For these reasons, I refused Mr Laming’s application for leave to withdraw his admission that he did not notify his name or relevant town or city in respect of any of the Five Posts as required by s 321D(5) of Item 4 of the Electoral Act.

93 I note that in supplementary submissions made after the hearing, Mr Laming asserted that due to the Commissioner replacing the 2018 Determination with the 2021 Determination on their website, he was unable to locate the earlier Determination and remained unaware of its existence. Mr Laming claims that as a result of his ignorance of the 2018 Determination, he agreed to make admissions which he otherwise would not have made. Even if this submission had been made before I ruled that Mr Laming could not withdraw his admissions, it would have made no difference. That is because, as I will discuss, the “About” section of the Facebook Page made no disclosure of the required particulars, so having earlier knowledge of the 2018 Determination could have made no difference to his case or the outcome.

94 The objects of Part XXA of the Electoral Act are to promote free and informed voting at elections by enhancing the transparency of the electoral system, the accountability of persons participating in public debate relating to electoral matter, and the traceability of communications of electoral matter. It does so by requiring, under s 321D(5), notification of the particulars of the person who authorised the communication of electoral matter.

95 It has long been recognised that transparency of the identity of persons publishing electoral matter is important to the integrity of the Australian electoral system. In Australian Electoral Commission v Kelly [2023] FCA 854, Rares J observed:

81 The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1902 (Cth) (the 1902 Act), when first enacted, provided in s 180 that the publication or printing of an electoral advertisement, hand-bill or pamphlet, or the issue of an electoral notice, would be an illegal practice if it did not include “at the end thereof” the name and address of the person authorising it.

82 Indeed, from at least the mid-nineteenth century, it was not uncommon, as Griffith CJ recognised in Smith v Oldham (1912) 15 CLR 355 at 358, for electoral laws in the United Kingdom and the Australian Colonies to require “advertisements, pamphlets and other election literature to bear the name of the printer and of the person by whose authority it is issued”. That case concerned the then s 181AA of the 1902 Act, which required every “article, report, letter, or other matter commenting upon any candidate or political party, or the issues being submitted to the electors” that was “published in any newspaper, circular, pamphlet, or ‘dodger’” to be signed at its end by its author with his or her true name and address, and made a contravention an offence. Griffith CJ continued:

It is a notorious fact that many persons rely upon others for their guidance, especially in forming their opinions. It is obvious, therefore, that the freedom of choice of the electors at elections may be influenced by the weight attributed by the electors to printed articles, which weight may be greater or less than would be attributed to those articles if the electors knew the real authors. It was contended that the electors should be allowed to form their own opinions from the abstract arguments addressed to them, irrespective of the persons by whom those arguments are put forward. But it is notorious, again, that many electors are unable to do so; and rely upon authority; and they may be less likely to be misled or unduly influenced if they know the authority upon which they are asked to rely. Parliament may, therefore, think that no one should be allowed by concealing his name to exercise a greater influence than he could command if his personality were known. It is impossible to say that an enactment to that effect is not an enactment regulating the conduct of persons in regard to elections.

(emphasis added)

…

86 The requirement for authorisation of electoral matter in s 321D addressed the importance of deterring anonymous dissemination of electoral matter…

96 The Commissioner alleges that Mr Laming communicated electoral matter, namely the Five Posts, in contravention of s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act, by failing to ensure that the particulars required under Item 4 of the table in s 321D(5) (his name and relevant town or city), were notified in accordance with the requirements determined under s 321D(7).

97 Item 4 of s 9(1) of the 2018 Determination required that if the communication was by social media, the particulars must be notified at the end of the communication; or if the particulars were too long to be included in the communication, in a website that could be accessed by a URL included in the communication, or a photo included in the communication.

98 Section 321D(1) provides that s 321D applies, relevantly, to, “electoral matter that is communicated to a person if…the matter is communicated by…a disclosure entity.” Accordingly, the requirement under s 321D(5) to notify the requisite particulars does not arise unless the matter communicated is “electoral matter”, is communicated to a person and is communicated by a “disclosure entity”.

99 The Commissioner carries the onus of proving a contravention of s 321D(5). Section 140(1) of the Evidence Act requires the Court to be satisfied on the balance of probabilities that the contravention occurred.

100 However, for the definition of “electoral matter” under s 4AA(1), s 4AA(3) creates a rebuttable presumption concerning the purpose of communication of certain matter. In addition, by operation of s 96 of the Regulatory Powers Act, a person relying on the exceptions to “electoral matter” in s 4AA(5) bears an evidential burden, as does a person relying on the “meeting” exception in s 321D(4)(f).

101 Under s 140(2) of the Evidence Act, the Court must take into account the nature of the cause of action or defence, the nature of the subject matter of the proceeding and the gravity of the matters alleged. Those matters reflect Dixon J’s exposition of the operation of the civil standard of proof in Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 (Briginshaw) at 361-363: see Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2007) 162 FCR 466 at [31].

102 An allegation that a person has contravened s 321D(5) exposes the person to a civil penalty. The Commissioner’s case will not be made out by inexact proofs, indefinite testimony or indirect references: cf Briginshaw at 362.

103 Mr Laming has admitted that that he made the Five Posts, that they were communicated to persons, and that he was a “disclosure entity”. However, he contends that:

(1) No presumption as to his purpose in making the First, Third and Fourth Posts arises under s 4AA(3) because the Posts did not expressly promote him or oppose a political entity, and did not relate to a federal election.

(2) The First, Third and Fourth Posts were not “electoral matter” within the meaning of s 4AA(1) of the Electoral Act because they were not communicated for the dominant purpose of influencing the way electors vote in an election of a member of the House of Representatives or a Senator.

(3) The Fourth and Fifth Posts fall within the “reporting of news” or “presenting of current affairs” exceptions under s 4AA(5)(a).

(4) All five Posts fall within the “meeting” exception under s 321D(4)(f).

104 I will proceed to consider each of these contentions.

Whether the First, Third and Fourth Posts are “electoral matter” within s 4AA(1) of the Electoral Act

105 Section 321D of the Electoral Act has no application unless there is, relevantly, communication of “electoral matter”.

106 Mr Laming has admitted that the Second and Fifth Posts fall within the definition of “electoral matter” in s 4AA(1). That is, he admits that the Second and Fifth Posts were matter communicated for the dominant purpose of influencing the way electors vote in an election of a member of the House of Representatives.

107 However, Mr Laming disputes that the First, Third and Fourth Posts fall within the definition of “electoral matter” in s 4AA(1).

108 The expression “electoral matter” is defined in s 4AA(1) to mean, relevantly:

…matter communicated...for the dominant purpose of influencing the way electors vote in an election (a federal election) of a member of the House of Representatives or of Senators for a State or Territory, including by promoting or opposing:

(a) a political entity, to the extent that the matter relates to a federal election; or

(b) a member of the House of Representatives or a Senator.

109 Section 4AA(2) provides that, “each creation, recreation, communication or recommunication of matter is to be treated separately for the purposes of determining whether matter is electoral matter”.

110 Section 4AA(3) creates a rebuttable presumption that the dominant purpose of a communication is to influence the way electors vote in a federal election of a member of the House of Representatives or of Senators for a State or Territory, if the communication, “expressly promotes or opposes…a political entity…or a member of the House of Representatives or a Senator, to the extent that the matter relates to a federal election”.

111 Section 4AA(4) identifies various matters that must be taken into account in determining the dominant purpose of the communication of matter.

112 In order to understand these provisions, it is necessary to consider the meaning of some of the expressions used within them.

113 The expression “dominant purpose” in s 4AA(1) is not defined in the Electoral Act and should be understood according to its ordinary meaning. In Commissioner of Taxation of the Commonwealth of Australia v Spotless Services Ltd (1996) 186 CLR 404, the High Court held at 416, “[i]n its ordinary meaning, dominant indicates that purpose which was the ruling, prevailing or most influential purpose”. The “purpose” of conduct is, “the end sought to be accomplished”: News Ltd v South Sydney District Rugby League Football Club (2003) 215 CLR 563 at [18] (Gleeson CJ). There can only be one dominant purpose.

114 Section 4AA(1) uses the expression, “matter communicated”. The definitions in the Macquarie Dictionary which most closely convey the meaning of “matter” in this context are, “the material or substance of a discourse, book, etc…”, and, “things written or printed”. However, neither of those definitions fully captures the breadth of the use of the word in the phrase, “matter communicated”. The noun “matter” describes that which is “communicated”. The phrase is apt to encompass words and images in any form communicated by any means (subject to the exceptions under the definition of “communication” in s 321B and in s 321D(3) and (4)). It is capable of encompassing words and images communicated via social media platforms such as Facebook.

115 When the expression “matter communicated” is understood as a single phrase, the definition in s 4AA(1) is concerned with the dominant purpose of the particular communication of the particular matter. Accordingly, the nature of the communication and the content of the matter communicated must be considered together in determining the dominant purpose.

116 The phrase “for the dominant purpose of” in s 4AA(1) raises the question of why the relevant person communicated the matter. The Commissioner submits that the question is to be determined objectively, apparently meaning that it is to be determined by reference to what a reasonable person would understand the purpose to be. Although the Commissioner did not refer to authority in support of that proposition, in the context of legal profession privilege, it has been held that whether a purpose is a dominant purpose is objectively determined, but that subjective purpose is relevant and often decisive: Esso Australia Resources Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation of the Commonwealth of Australia (1999) 201 CLR 49 at [172] (Callinan J); Sydney Airports Corp Ltd v Singapore Airlines Ltd [2005] NSWCA 47 at [6] (Spigelman CJ).

117 However, the present context does not suggest that an objective test is intended. Section 4AA(3) creates a presumption that, in the circumstances specified, the dominant purpose of the matter communicated is the purpose referred to in s 4AA(1), unless the contrary is proved. The presumption throws onto the person communicating the matter, the onus of proving that which lies peculiarly within their own knowledge: cf General Motors-Holdens Pty Ltd v Bowling (1976) 51 ALJR 235; 12 ALR 605 at 617 (Mason J). There would be no need for the presumption if it were unnecessary for the Commissioner to prove the subjective, or actual, purpose of the relevant person. The presumption is consistent with the inquiry being as to the relevant person’s actual purpose or purposes: cf Board of Bendigo Regional Institute of Technical and Further Education v Barclay (2012) 248 CLR 500 at [44].

118 Determining whether the presumption under s 4AA(3) applies requires consideration of whether the communication of matter, “expressly promotes or opposes…a political entity…or a member of the House of Representatives or a Senator, to the extent that the matter relates to a federal election”.

119 Mr Laming argues that the word, “expressly”, extends to qualify the phrase, “to the extent that the matter relates to a federal election”. The phrase, “to the extent that the matter relates a federal election”, is intended to indicate that the content of the matter communicated must relate to a federal election to at least some extent for the presumption to operate. While the matter communicated must expressly promote or oppose a political entity, or a member of the House of Representatives, or a Senator, it need not expressly relate to a federal election. This view is consistent with the language of the provision and the insertion of the comma after “Senator” to separate the phrases used.

120 There are three requirements of s 4AA(3): first, there must be communication of matter; second, the matter communicated must expressly promote or oppose a political entity, or member of the House of Representatives, or a Senator; and, third, the matter communicated must relate a federal election to at least some extent. It is not enough that the matter communicated expressly promotes or opposes a political entity or a member of the House of Representatives or a Senator if it does not relate to a federal election. Nor is it enough that the matter communicated relates to a federal election if it does not expressly promote or oppose a political entity or a member of the House of Representatives or a Senator.

121 It may be observed that para (b) of s 4AA(3) applies only to persons who are members or Senators at the time of the communication and does not extend to promotion or opposition of candidates. However, para (a) uses the expression “political entity”, and the definition of that expression in s 4(1) extends to candidates for election.

122 Another question of construction concerns whether the requirement of para (b) that the communication of matter, expressly “promotes or opposes… a member of the House of Representatives or a Senator…”, requires promotion or opposition of a person as a member of the House of Representatives, a Senator or a candidate. In other words, must the express promotion or opposition be (to at least some extent) of a person in their capacity as a member of the House of Representatives or Senator or candidate? In my opinion, that question should be answered in the negative because, first, the terms of s 4AA(3) do not expressly incorporate any such requirement, and, secondly, the phrase, “relates to a federal election”, brings into account whether the promotion or opposition of a member of the House of Representatives, Senator or candidate is in that capacity.

123 The word “promotes” is defined in the Macquarie Dictionary as, “to advance in rank, dignity, position, etc”. In ordinary usage, it encompasses praising or lauding the deeds or virtues of a person in order to cause others to think well of that person.

124 The expression, “relates to” a federal election, is used in s 4AA(3)(b) (as well as s 4AA(1)(a)). In Tooheys Ltd v Commissioner of Stamp Duties (NSW) (1961) 105 CLR 602, Taylor J observed at 620:

… [T]he expression “relating to” is extremely wide but it is also vague and indefinite. Clearly enough it predicates the existence of some kind of relationship but it leaves unspecified the plane upon which the relationship is to be sought and identified. That being so all that a court can do is to endeavour to seek some precision in the context in which the expression is used.

125 This observation was approved in Bull v R (2000) 201 CLR 443 at 462, [65].

126 In PMT Partners Pty Ltd (in liq) v Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service (1995) 184 CLR 301 at 313, Brennan CJ, Gaudron, and McHugh JJ stated:

Inevitably, the closeness of the relationship required by the expression “in or in relation to” in s 48 of the Act — indeed, in any instrument — must be ascertained by reference to the nature and purpose of the provision in question and the context in which it appears.

[See also Toohey and Gummow JJ at 331.]

127 While the expression “relates to” is a capable of having substantial width, the closeness of the relationship required depends on the statutory context, including the nature and purpose of the provision in question. The objects of s 321D of the Electoral Act, as set out in s 321C, are stated to be to ensure the transparency of the electoral system, the accountability of those participating in public debate in relation to electoral matter, and the traceability of communications. Section 15AA of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) requires that in interpreting a provision of an Act, the interpretation that would best achieve the purpose or object of the Act is to be preferred to each other interpretation. The objects of the Electoral Act are best achieved by giving the expression, “relates to a federal election”, a meaning encompassing both a direct and indirect relationship between the matter communicated and a federal election. The matter communicated may “relate to” a federal election without expressly referring to it.

128 In contrast to s 4AA(1), the issues arising under s 4AA(3) do not depend upon the purpose of the person making the communication and must be determined objectively.

The First Post: 24 December 2018

129 Before directly considering the First Post, it is relevant to consider the Facebook Page as a whole.

130 The Facebook Page was entitled, “Redland Hospital: Let’s fight for fair funding”. The “About” section of the Facebook Page stated, “This page supports Andrew Laming’s efforts to reveal funding for Redlands Hospital. Do you support the push for honesty?”. The language suggests that government funding of the Redland Hospital was unfair, in the sense of being inadequate, and that the underfunding was being hidden by government. The aim was said to be to support Mr Laming’s efforts to reveal the underfunding. On its face, that was the purpose of the Facebook Page.

131 Mr Laming admits that he was the “administrator” of the Facebook Page, and that he made the Five Posts. The Facebook Page did not disclose that Mr Laming was its administrator.

132 The Facebook Page was accessible to the public. Anyone with a Facebook account could choose to view or follow the Page. The posts made on the Facebook Page were also accessible to followers and other members of the public with Facebook profiles.

133 Mr Laming was elected as a member of the House of Representatives at the federal election held in 2016. He represented the electoral division of Bowman, which encompasses part of Redland City and part of the Brisbane City within Queensland, including the suburbs of Wellington Point, Cleveland, Victoria Point and Redland Bay.

134 The Facebook Page operated from 14 August 2018 to 9 March 2022. I infer that Mr Laming understood that many of the persons who accessed or followed the Facebook Page, or who were likely to do so, would have an interest in the Redland Hospital as local residents. As Mr Laming’s counsel accepted, “people who have an interest in their local hospital, in a local area, are always concerned…that it’s being funded properly”. Mr Laming must also have understood that many such people were likely to be electors in the electoral division of Bowman, which encompassed part of Redland City.

135 Mr Laming became a candidate for the Liberal National Party of Queensland in the federal election held on 18 May 2019. The election was not announced until April 2019, well after the first four Posts had been made.

136 Under s 28 of the Constitution, the House of Representatives has a maximum term of three years. I infer that at the times the Five Posts were made, it was well known amongst the public that a federal election had been held in 2016 and another had to be held during 2019. I also infer that Mr Laming knew that a federal election was to be held during 2019.

137 A total of 232 posts were made on the Facebook Page between 14 August 2018 to 9 March 2022, so that some posts were made before and some after the May 2019 federal election. It is evident from their content that some of the posts on the Page were made by Mr Laming. For example, a post made on 19 December 2018, contains a letter to a journalist signed “Andrew” and is identifiable as having been written by Mr Laming, and he commented on another comment under his own name on 26 December 2018. A post made on 14 January 2019 (after the First Post, but before the remainder of the Five Posts), stated:

Labor in a lather, calling this a fake page. Apparently none of us are real. Read the “About” tab which make it clear that Andrew Laming was involved in establishing this page and maintaining it. So what! We just want our $39 million back.

138 It is an agreed fact that the majority of the posts made by Mr Laming to the Facebook Page did not communicate “electoral matter”, and that those posts generally related to the “political issue” of funding the Redland Hospital, including criticism of the Queensland Labor government.

139 The First Post was made on 24 December 2018. It stated:

We are working so hard to sort out Redland Hospital funding, and we were delighted when Andrew Laming announced an $83million dollar funding boost to our local hospital service in the latest financial year (17/18). Well let’s FACT CHECK. Turns out he wasn’t entirely correct. One of our spies found Queensland National Health Reform Funding – and it tells a different story. We cant reproduce it, but the statewide table shows that indeed 7.8% of the 2017/18 money was from previous years. So Laming is 92.2% accurate if State data reflects Redlands and he boosted funding by $77million.

140 Although Mr Laming wrote and posted the First Post, it does not identify him as the writer and publisher. In fact, it is evident from the Post that Mr Laming was pretending it was posted by someone else. That is made plain by Mr Laming’s use of the words “we” and “our” in reference to the author of the post, and his reference to “Andrew Laming” in the third person. That is consistent with the “About” page, which also refers to Mr Laming in the third person and failed to reveal that he was in fact the administrator of the Facebook Page.

141 The First Post indicates that its author was delighted by Mr Laming’s announcement of an $83 million funding boost in funding for the local hospital service, presumably Redland Hospital, in the latest financial year. The author then purports to “fact check” that announcement, concluding that Mr Laming was, “92.2% accurate”, in the sense that, “he boosted funding by $77 million”. It seems to be a case of praising through faint criticism. In effect, Mr Laming, while pretending the post was made by someone else, purports to check the accuracy of his own claim, and concludes that while he did not boost funding by $83 million, he did boost funding by $77 million. His conduct brings to mind the observation of Griffith CJ in Smith v Oldham (Chief Electoral Officer for the Commonwealth) (1912) 15 CLR 355 at 358 that the weight attributed by the electors to printed articles, “may be greater or less than would be attributed to those articles if the electors knew the real authors”. I infer Mr Laming thought that by pretending the post was written by someone else, his self-flattery is more likely to be accepted by viewers as true and his achievement admirable.

142 I will begin by considering whether the First Post attracts the presumption under s 4AA(3).

143 There is no doubt that Mr Laming’s making of the First Post involved the communication of “matter”.

144 Through the deception practiced by Mr Laming, the First Post, on its face, seems to carry faint criticism, as well as praise of him. While the First Post certainly operates to promote Mr Laming, it does so principally by implication. When the First Post is considered as a whole, I find that it does not expressly promote Mr Laming. Therefore, the presumption provided for in s 4AA(3) does not apply to the First Post.

145 In case I am wrong, I will consider the requirement that the First Post “relates to” a federal election, namely the May 2019 election. That issue must be considered objectively, and not by reference to Mr Laming’s subjective purpose.

146 It is well known that many politicians intending to stand for re-election engage in self-promotion or promotion of their political party aimed at persuading electors to vote for them. However, s 4AA(3) does not treat every act of every promotion or self-promotion of a member of the House of Representatives or a Senator as one that “relates to” an election. Otherwise, there would have been no need to specifically include that requirement.

147 The Commissioner submits that s 4AA(4) requires the Court to take into account the factors set out in that provision in determining whether, for the purposes of s 4AA(3), “the matter relates to a federal election”. That submission cannot be accepted since the language of s 4AA(4) plainly indicates that it applies to the determination of the dominant purpose under s 4AA(1). It does not apply in determining whether the presumption under s 4AA(3) arises. However, it can be accepted that, in a particular case, factors set out in s 4AA(4) may well be relevant to determining whether the matter communicated relates to a federal election.

148 The First Post does not mention any election. It was made on 24 December 2018, at a time when the May 2019 election had not yet been announced, and when an election was not in distinct prospect in the near future. I accept that the stated aim of the Facebook Page, namely to support Mr Laming’s efforts to reveal the underfunding of the Redland Hospital by government, concerned a political issue. The substantial content of the Page, namely criticisms of the Queensland Labor government’s funding of the Hospital, also involved political issues. While the First Post must be understood in the context of that setting, I do not consider that every communication of political nature can necessarily be regarded as one that “relates to” an election.

149 The most that can be said is that the First Post was made at a time when an election was in prospect within a period of some months, it concerned a political issue and promoted a member of the House of Representatives. In my opinion, those matters do not allow it to be concluded that the communication of the First Post, objectively, “relates to a federal election”.

150 In these circumstances, the presumption under s 4AA(3) is not engaged in respect of the First Post. It is necessary to determine whether the First Post is “electoral matter” within s 4AA(1) without the aid of the presumption.

151 Section 4AA(1) defines “electoral matter” as, relevantly, “matter communicated...for the dominant purpose of influencing the way electors vote in an election…of a member of the House of Representatives or of Senators for a State or Territory”. The provision includes the promotion or opposition of a political entity to the extent that the matter relates to a federal election or a member of the House of Representatives or a Senator.

152 In contradistinction to s 4AA(3), s 4AA(1) does not require any promotion or opposition, or the influencing of electors, to be express. That is made abundantly clear by s 4AA(4)(c) which requires consideration of whether the matter contains, “an express or implicit comment”. The matters specified in s 4AA(4) must be taken into account.

153 The Commissioner’s case is that Mr Laming’s dominant purpose in making the First Post was to influence electors to vote for him in the federal election anticipated to be held in 2019.