FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Phoenix Institute of Australia Pty Ltd (Subject to Deed of Company Arrangement) (No 3) [2023] FCA 859

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The first respondent is to pay to the Commonwealth of Australia pecuniary penalties of:

(a) $100,000,000.00 in respect of the conduct in contravention of s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law (the ACL) by the Phoenix Marketing System (as defined by paragraph [73] of the Amended Statement of Claim);

(b) $300,000,000.00 in respect of the conduct in contravention of s 21 of the ACL by the Phoenix Enrolment System (as defined by paragraph [86] of the Amended Statement of Claim);

being penalties cumulatively totalling $400,000,000.00 for the said contraventions.

2. The second respondent is to pay to the Commonwealth of Australia pecuniary penalties of:

(a) $7,000,000.00 in respect of the conduct in contravention of s 21 of the ACL by the Phoenix Marketing System (as defined by paragraph [73] of the Amended Statement of Claim);

(b) $30,000,000.00 in respect of the conduct in contravention of s 21 of the ACL by the Phoenix Enrolment System (as defined by paragraph [86] of the Amended Statement of Claim);

being penalties cumulatively totalling $37,000,000.00 for the said contraventions.

3. The first respondent is to pay to the Commonwealth of Australia pecuniary penalties of:

(a) $180,000.00 in respect of the conduct in contravention of ss 21 and 29 of the ACL with respect to Consumer A;

(b) $285,000.00 in respect of the conduct in contravention of ss 21 and 29 of the ACL with respect to Consumer B;

(c) $285,000.00 in respect of the conduct in contravention of ss 21 and 29 of the ACL with respect to Consumer C;

(d) $250,000.00 in respect of the conduct in contravention of ss 21 and 29 of the ACL with respect to Consumer D;

being penalties cumulatively totalling $1,000,000.00 for the said contraventions with respect to Consumers A, B, C and D.

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

4. Pursuant to s 239 of the ACL and s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), in respect of each consumer:

(a) who was enrolled in a Phoenix course BSB50207 Diploma of Business, BSB50215 Diploma of Business, BSB51107 Diploma of Management, BSB51915 Diploma of Leadership and Management, CHC50113 Diploma of Early Childhood Education and Care, and CHC50612 Diploma of Community Services Work, between 13 January 2015 to 23 November 2015 inclusive; and

(b) by whom, or in whose name, a request for VET FEE-HELP Assistance from the Commonwealth in respect of that enrolment was made; and

(c) has completed one or more units of study in the course in which they were enrolled (Completion Student);

that:

(d) any enrolment agreement between the Completion Student and Phoenix in respect of the course or any unit of study within the course is void ab initio; and

(e) the Completion Student’s liability to pay a VET tuition fee to Phoenix for the unit of study or course (VET liability) is annulled; and

(f) any associated liability of the Completion Student to the Commonwealth in relation to VET FEE- HELP assistance and the loan fee in respect of that VET FEE- HELP assistance is annulled.

THE COURT FURTHER ORDERS THAT:

5. Pursuant to s 237 of the ACL, any liability of the Second Applicant to pay the amount of the loan made to any consumer falling with the description at paragraphs 4(a) and (b) above (Phoenix Student) to Phoenix in discharge of the Phoenix Student’s VET liability is annulled.

6. The respondents are to pay the applicants’ costs as agreed or assessed.

7. In the absence of agreement as to the orders otherwise required to give effect to these reasons:

(a) on or before 4pm on Monday 21 August 2023 the applicants, and the respondents if so advised, are to file and serve an outline of written submissions not exceeding 5 pages in length in support of their respective proposed orders and attaching their proposed orders; and

(b) final orders will be determined on the papers without a further oral hearing, unless the Court otherwise orders.

8. There be liberty to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRY J:

1. INTRODUCTION

1 By these proceedings, the applicants, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (the ACCC) and the Commonwealth, seek declarations, pecuniary penalties, compensation orders, orders for non-party redress, and costs, against the respondents, Phoenix Institute of Australia Pty Ltd (Subject to Deed of Company Arrangement) (Phoenix) and Community Training Initiatives Pty Ltd (Subject to Deed of Company Arrangement) (CTI). Those orders are variously sought under the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), contained in Sch 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the CCA), and the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

2 The ACCC is the statutory authority responsible for enforcing the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the CCA). At all relevant times, Phoenix was a registered training organisation (RTO) approved to offer VET FEE-HELP loans in relation to its vocational education training (VET), and was therefore a VET Approved Provider. From 12 January 2015, Phoenix was a wholly owned subsidiary of a publicly listed company, Australian Careers Network Limited (ACN). CTI (renamed VIA Network in October 2015) was also a wholly-owned subsidiary of ACN. CTI operated as the marketing arm for the eleven registered training organisations (RTOs) owned and operated by ACN, including Phoenix.

3 On 13 August 2021, I made declarations that each of the Respondents had engaged in conduct in connection with the supply of online VET courses to consumers that was unconscionable in contravention of s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) during the period 13 January 2015 to 23 November 2015 (Relevant Period): Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Phoenix Institute of Australia Pty Ltd (Subject to Deed of Company Arrangement) (No. 4) [2021] FCA 956 (Phoenix (Liability) or J).

4 In so finding, I held that the business model adopted by Phoenix with respect to its online courses was “pursued ruthlessly” through marketing and enrolment systems which “were the product of calculated design born out of sheer avariciousness … and callous disregard” for the interests of many thousands of consumers enrolled in Phoenix’s online courses (J[1271] and [1352] respectively). That conduct exploited reforms made to the Commonwealth’s VFH loan scheme which were designed to benefit disadvantaged and vulnerable Australians, for massive financial gain. Specifically, Phoenix received payments of $106 million in VFH payments from the Commonwealth over the relevant period, and asserted an entitlement to a further amount of approximately $250 million in VFH payments from the Commonwealth. The $106 million received by Phoenix has never been repaid.

5 Furthermore, as the ACCC submits (at Applicants’ submissions (AS), [3]):

The damage caused to 11,393 consumers [who enrolled in Phoenix’s online courses] was immense. For a significant period of time, each of these consumers carried substantial debts (often over $43,000 in loans and fees) in their personal taxation records, towards which they were required to make payments if they reached certain income thresholds. The total student debts – in terms of both loan amounts and loan fees – exceeded $428 million. They also suffered the humiliation of being taken advantage of, the stress of undertaking courses to which they were not suited and which were not suited to them, and the obvious loss of opportunity to undertake other courses which would have given them vocational skills and qualifications suited to their needs.

6 It is not surprising that I concluded that the conduct of both respondents was “grossly exploitative and at times dishonest, and … lacking in any respect for the dignity and autonomy of the vulnerable consumers who were targeted” (J[1352]).

7 I also declared in Phoenix (Liability) that during the relevant period Phoenix, by the conduct of its Brokers and Agents, engaged in conduct with respect to four consumers (Consumers A, B, C and D) that was false or misleading or deceptive in breach of ss 18 and 29(1)(i) of the ACL, and in conduct that was unconscionable, thereby contravening s 21 of the ACL.

8 The ACCC seeks penalties under s 224 of the ACL against Phoenix and CTI in respect of the two systems employed by Phoenix and CTI which I held to be unconscionable in Phoenix (Liability), namely: the Phoenix Marketing System and the Phoenix Enrolment System. The systemic unconscionability across these two systems was on an extraordinary scale. Specifically in Phoenix (Liability), I held at [1353] that the ACCC had established 22,786 contraventions of s 21 of the ACL, being two contraventions in respect of each of the 11,393 enrolled consumers for whom VET FEE-HELP payments were made. As such, the maximum penalties in respect of the contraventions available against each Respondent under the ACL as at the relevant time would exceed $25 billion. In this regard, I note that a new penalty regime was introduced with effect from 1 September 2018 by the Treasury Laws Amendment (2018 Measures No 3) Act 2018 (Cth). That new regime does not apply in this case.

9 Given the gravity of unconscionable conduct in this case, the ACCC submits that penalties producing a very high level of deterrence are required. As the ACCC accepts (at AS [48]), specific deterrence is not a relevant consideration in the present case, given that both respondents are in liquidation and that the ACCC will not be able to prove any penalties imposed against Phoenix and CTI in their respective liquidations: see Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 553B; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Get Qualified Australia Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (No 3) [2017] FCA 1018 at [78] (Beach J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cornerstone Investment Aust Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 5) [2019] FCA 1544 at [31] (Gleeson J). Nonetheless, the ACCC submits that the public interest will be served by the imposition of very substantial penalties, given the egregious nature of the contravening conduct, so as to operate as a strong general deterrent against similar conduct: cf Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; (2022) 96 ALJR 426 at [106] (Edelman J); Cornerstone at [32]. As Beach J pertinently observed in Get Qualified (at [1]):

In recent years, the education sector has been infected by the parasitic practices of operators preying upon the vulnerable and the unwary. They have taken unconscientious advantage of those who commendably have sought to improve themselves and their qualifications. It is to be expected that when such practices are exposed to judicial scrutiny, the Court will grant the relief necessary to eradicate such behaviour. Specific [where relevant] and general deterrence are the primary objectives of such relief, with the Court's protective jurisdiction a necessary adjunct.

10 The ACCC submits that when the various factors relevant to calculating penalties are considered, it is apparent that this case of systemic unconscionability is of the gravest kind, and that there are no mitigating factors. As such, the ACCC submits that the highest penalties ever imposed under the former penalty regime by way of general deterrence are warranted for the unconscionable systems in the range of $330 to $400 million against Phoenix, and in the range of $29 to $35 million against CTI.

11 In this regard, and acknowledging the magnitude of the penalties sought, the ACCC submitted (at AS [7]) that:

penalties of this order can be seen to be necessary when settled penalty principles are applied to the disturbing facts of this case – the astonishing scale of the unconscionable conduct of both Phoenix and CTI and the immense financial gains and losses against which deterrence falls to be assessed. The ACCC submits that the scale of the payments which Phoenix and CTI claimed for their unlawful conduct is such that lower penalties would not have appropriate deterrent value. Accordingly, to impose lower penalties simply because penalties of this magnitude have not previously been imposed would be to avoid, not apply, settled principles. Such an approach would have the perverse effect that the very scale of the unconscionable conduct in issue may serve to “cap” the penalty that will be imposed, and would thereby undermine the necessary deterrent message. Future wrongdoers should be on notice that misconduct on an epic scale will be sanctioned by a commensurate pecuniary penalty.

12 In addition, the ACCC seeks penalties in the following ranges against Phoenix in respect of the contraventions in relation to each of the four individual consumers:

(1) Consumer A – $150,000 to $200,000

(2) Consumers B and C – $250,000 to $300,000

(3) Consumer D – $200,000 to $250,000

13 The applicants also seek declaratory relief pursuant to s 239 of the ACL for a limited number of students who had completed one or more units of study in a Phoenix online course (Completion Student). By that declaratory relief, the applicants seek (amongst other things) an annulment of any liability by the Completion Student to the Commonwealth in relation to the VET FEE-HELP assistance and the loan fee. The applicants also seek compensation orders and costs.

2. OVERVIEW OF CIVIL PENALTIES IMPOSED AND OTHER RELIEF GRANTED

14 For the reasons set out below, I have awarded the following penalties by way of general deterrence:

(1) against Phoenix in the following amounts:

(a) $100 million in respect of its conduct in contravention of s 21 of the ACL by the Phoenix Marketing System as defined in [73] of the Second Further Amended Originating Application (SFAOA);

(b) $300 million in respect of its conduct in contravention of s 21 of the ACL by the Phoenix Enrolment System as defined in [86] of the SFAOA; and

(2) against CTI in the following amounts:

(a) $7 million in respect of its conduct in contravention of s 21 of the ACL by the Phoenix Marketing System as defined in [73] of the SFAOA;

(b) $30 million in respect of its conduct in contravention of s 21 of the ACL by the Phoenix Enrolment System as defined in [86] of the SFAOA.

15 In concluding that penalties in these amounts are appropriate, I agree with Bromwich J that “[s]ubstantial penalties are called for when a commercial enterprise systematically predates on both a government education support scheme designed to help disadvantaged members of the Australian community, and consequently, upon those consumers”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Institute of Professional Education Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 5) [2021] FCA 1516; (2021) 397 ALR 208 (AIPE (No 5)) at [1]. A penalty of $150 million was awarded in that case in relation to the overall system of unconscionable conduct. The greater penalties which I have decided should be imposed in this case reflect the fact that the conduct by the respondents in this case is even more egregious, and the associated benefits to the respondents and loss to consumers and the Commonwealth, even more serious. Indeed, as counsel for the applicants submitted at the hearing, it is difficult to think of a more serious case of unconscionability that has come before this Court.

16 I have also awarded penalties against Phoenix for the contraventions of ss 21 and 29 of the ACL with respect to the individual consumers by way of general deterrence:

(1) $180,000.00 for the contraventions with respect to Consumer A;

(2) $285,000.00 for the contraventions with respect to Consumer B;

(3) $285,000.00 for the contraventions with respect to Consumer C; and

(4) $250,000.00 for the contraventions with respect to Consumer D;

17 In addition, I have made consumer redress orders under s 239 of the ACL effectively voiding any enrolment and annulling any VFH liability and loan owed by any student who was enrolled in a Phoenix Online Course and completed one or more units of study in the course in which they were enrolled. I further agree that orders should be made under s 237 of the ACL for the payment of compensation to the Commonwealth in the sum of $104,138,195.00 in reliance upon my findings in Phoenix (Liability) as to the unconscionable conduct engaged in by Phoenix in respect of all 11,393 students enrolled in Phoenix Online Courses. In my view, the Commonwealth is entitled to compensation in this amount on the basis that the Commonwealth is unable to recover any payments for VFH debts from the 11,393 consumers who were enrolled in the Phoenix Online Courses, because each of the enrolled consumers is presumed to be entitled to relief, and is not required to pay their VET tuition fees, in light of the Court’s finding in Phoenix (Liability) at [1353]-[1354].

18 Finally, subject to hearing from the respondents, I consider that an order should be made providing (to the extent necessary), that the applicants may seek to prove Phoenix’s and CTI’s liability to pay the amounts awarded by way of compensation and costs in the liquidations of Phoenix and CTI, as unsecured creditors.

19 The key aspects of my decision in Phoenix (Liability) were summarised at J[8]-[18] and are conveniently repeated here.

8 Phoenix was an approved VET provider with 378 enrolled students in face-to-face courses before it was purchased by the Australian Careers Network (ACN) Group in January 2015.

9 Following its acquisition, the key officers of Phoenix and CTI (and the parent company, ACN), Mr Ivan Robert Brown and Mr Harry Kochhar (also known as Harpreet Singh), acted swiftly to radically reorientate Phoenix’s operating model so as to offer for the first time, online diplomas nationally to many thousands of consumers under the banner of “myTime Learning”. Central to the respondents’ plans for rapid growth was the deployment of hundreds of Agents across the country through contracts with Brokers, who primarily employed high-pressure sales tactics, including the offer of inducements and the making of misrepresentations, so as to persuade thousands of consumers to sign up to Phoenix’s Online Courses largely through door-to-door sales. The consumers targeted included Indigenous Australians, people from non-English speaking backgrounds, with a disability, from regional and remote areas, from low socio-economic backgrounds and/or who were unemployed at the relevant time.

10 It is no coincidence that consumers from these target groups also fell within the demographic groups to which reforms to the Commonwealth’s VET FEE-HELP loan scheme were directed. These reforms had liberalised the scheme so as to make VET an end in itself as opposed to a pathway to higher education, in order to increase participation in VET by people from these demographic groups. As such, while in itself the targeting of consumers from these groups was not necessarily unconscionable, a not insignificant proportion of such consumers were likely to be vulnerable. Conscionable marketing and enrolment systems therefore needed to incorporate measures to mitigate the inherently higher risk that members of these demographic groups may be unsuitable for an online diploma, or require additional support in order to have a reasonable opportunity of successfully completing an online diploma.

11 Provided that a student was entitled to VET FEE-HELP assistance under cl 43 of Sch 1A of the Higher Education Support Act 2003 (Cth) (the HES Act) (an Eligible Student), the fees for these courses were paid directly to the VET provider by the Commonwealth. In return, the Eligible Student would incur a debt to the Commonwealth via a loan scheme for the cost of the course, together with a loan fee. However, the debt would become repayable through the tax system by the students concerned once they began to earn more than a minimum amount. Safeguards existed under the scheme which the VET provider was required to observe in order to ensure that students were fully informed about their rights and liabilities under the VET FEE-HELP loan scheme before embarking upon a course and incurring the liability. This included ensuring that no liability for a debt to the Commonwealth would arise until the census date had passed. This key element of the scheme was intended to afford each student a “cooling off” period within which to ensure that she or he wished to pursue the unit of study or course and that it was suitable for them.

12 However, once the census date had passed, neither the student’s liability for the debt nor the making of payments to the VET provider depended upon the student actually embarking on the course in which they were enrolled. Furthermore, if approved by the Department of Education and Training (the Department or DET), VET FEE-HELP payments could be made to the VET provider in advance on the basis of the VET provider’s estimate of the amount of VET FEE-HELP to which it expected to be entitled during the calendar year. These features of the VET FEE-HELP scheme in particular rendered it ripe for ruthless exploitation by unscrupulous agents and brokers and VET providers, as Mr Brown candidly explained in a radio interview in April 2016. Hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue under the scheme were potentially available to a VET provider, without the provider actually affording any meaningful educational service to its “students”.

13 That is precisely what occurred in this case. The figures are telling.

(1) Between mid-January and mid-November 2015, at least 11,393 consumers were enrolled in 21,413 online courses with Phoenix, with most being enrolled in two diplomas concurrently despite each diploma involving a full-time study load.

(2) Phoenix was paid over $106 million by the Commonwealth under the VET FEE-HELP assistance scheme in advance payments pursuant to cl 61(1) of Sch 1A to the HES Act, and claimed to be entitled to a further amount of approximately $250 million in payments from the Commonwealth.

(3) Only nine of the 11,393 enrolled consumers formally completed an online course with Phoenix. Indeed, only a very small number of the 11,393 enrolled consumers even attempted a unit of study of their courses, while some were unaware that they were enrolled at all and many remained enrolled even after requesting cancellation.

14 This was achieved first by the deployment without any effective training, monitoring or control, of a veritable army of at least 548 Agents engaged by the Brokers with whom the respondents contracted to market Phoenix’s Online Courses. The Brokers and Agents were highly incentivised by substantial commissions payable only after the census date to prey on vulnerable consumers likely to sign up unaware that an offer presented to them as a great deal to obtain a free laptop or other inducement, was in fact a very bad deal under which they would incur substantial debts. In particular, the Agents and Brokers (and respondents on whose behalf they acted) targeted vulnerable consumers whose general attributes meant they were less likely to understand their rights and obligations under the VET FEE-HELP scheme, to interrogate the misinformation they were given, and to resist the inducements offered to them for signing up. Far from reining in the unethical conduct of the Brokers and Agents or responding with a “root and branch” reappraisal of their operating model, among other things, the respondents actively sought and rewarded the submission of hundreds and even thousands of enrolment forms weekly by Brokers and increased the commission payable to the worst offending Broker.

15 Secondly, despite being aware from the outset of the risks (duly realised) of ineligible and unsuitable candidates applying for enrolment by deploying this marketing system, the respondents engaged in conduct which included enrolling consumers without verifying their eligibility or suitability for the course, their capacity to speak English, or even whether they intended to undertake the course. Directions were regularly given by Mr Brown and Mr Kochhar to bypass measures intended to protect against such risks, such as instructing staff not to undertake telephone verifications of enrolment applications, to overlook “red flags” when telephone verifications were in fact conducted, and not to check for suspicious patterns in enrolment forms indicating that they may have been forged. Moreover, a significant number of consumers were enrolled after the commencement date of their online course(s) without any extension to the relevant census date, or were enrolled on, shortly before, or after the census date so as to deprive consumers of the statutorily mandated “cooling off” period. Furthermore, staff who repeatedly raised concerns with Mr Brown and Mr Kochhar about these and other issues, including suspected Broker and Agent misconduct, and endeavoured to address them, were undermined, sidelined, bullied, subjected to verbal abuse, and directed to ignore the problems and to act against their conscience.

16 Not surprisingly, the flow of complaints by consumers and consumer advocates throughout the relevant period was unrelenting. Furthermore, as the respondents’ conduct increasingly came to the attention of the regulators, they sought to conceal what was truly occurring by, among other measures, statements of compliant policies which they knew were not in fact observed (“guff” as such statements were described in internal correspondence), the impersonation of student activity on Phoenix’s learning management system, and the backdating and falsification of student records on an industrial scale.

17 This conduct, together with other evidence, established that the focus of key officers of Phoenix and CTI was upon attaining the highest possible levels of enrolment so as to generate and retain revenue derived from VET FEE-HELP payments, rather than genuinely attempting to provide education and training to those ostensibly enrolled in online courses offered by Phoenix. As such, the respondents’ focus was upon presenting the appearance of compliance with precisely the kinds of measures required to protect and support consumers, but not upon implementing such measures in circumstances where to have done so would have undermined their business model and significantly impacted upon revenue. As Bromwich J found in AIPE (No 3) at [688], equally in this case it was both an accepted and anticipated part of the respondents’ business model that a very high proportion of students would pass the census date and incur a VET FEE-HELP debt in circumstances where it was predictable that they would never require training and support. This was a highly profitable outcome for the respondents who therefore were not required to, and did not, invest in the staff and resources which would have been required to train and support over 11,000 genuine students enrolled in over 21,000 full-time diplomas.

18 I have concluded that in all of the circumstances, the respondents engaged in a marketing system and an enrolment system which were separately “unconscionable” within the meaning of s 21 of the ACL. Both systems were informed by the desire to maximise profit over even modest levels of engagement by consumers with their courses, and by a callous indifference, among other things, to the suitability and eligibility of consumers to undertake the courses in which they enrolled. I also find that Phoenix has, by the conduct of its Brokers and Agents, engaged in conduct with respect to Consumers A, B, C, and D that was false or misleading or deceptive in breach of ss 18 and 29(1)(i) of the ACL and in conduct that was unconscionable, thereby contravening s 21 of the ACL.

4. PRINCIPLES GOVERNING THE IMPOSITION OF PECUNIARY PENALTIES UNDER THE ACL

4.1 Power to impose a penalty and relevant matters to be considered in imposing the penalty: s 224, ACL

20 The power to impose a pecuniary penalty is governed by s 224 in Part 5-2 of the ACL entitled “Remedies”. Under ss 224(1)(a)(i) and (ii), the Court may order a person who has contravened, relevantly, ss 21 (which concerns unconscionable conduct) and 29 (which concerns false or misleading representations about goods or services) to pay such pecuniary penalties, in respect of each act or omission by the person, as the Court determines to be appropriate.

21 Section 224(2) of the ACL provides that in determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty the Court “must have regard to all relevant matters including”:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by a Court in proceedings under Chapter 4 or this Part to have engaged in any similar conduct.

22 Section 224(2) therefore sets out certain mandatory factors to be considered in determining the appropriate penalty. Without endeavouring to be exhaustive, the following considerations are also potentially relevant:

(1) the size of the contravening company and its financial position;

(2) the degree of market power that the contravening company has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market;

(3) the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended;

(4) whether the conduct was systematic or covert;

(5) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level;

(6) whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the CCA including the ACL as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention; and

(7) whether the company has shown a disposition to cooperate with the ACCC.

(See e.g. Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd (No 4) [2011] FCA 761; 282 (2011) ALR 246 at [11] (Perram J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Limited [2015] FCA 330; (2015) 327 ALR 540 (Allsop CJ) at [8]-[9].)

23 As Allsop CJ observed in Coles Supermarkets at [9], there is a degree of overlap between these factors and the statutory mandatory considerations in s 224(2). However, as his Honour further explained, “These factors do not necessarily exhaust potentially relevant considerations; nor do they regiment the discretionary sentencing function”: ibid. Nor should the Court address its consideration of relevant matters in a regimented or formulaic way. As Wigney J stated in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Visa Inc [2015] FCA 1020; (2015) 339 ALR 413 at [83], “to do that would impermissibly constrain or formalise what is, at the end of the day, a broad evaluative judgment”: see also e.g. Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Homeopathy Plus! Australia Pty Limited (No 2) [2015] FCA 1090 at [22] (Perry J).

4.2 Each respondent should be separately penalised

24 The first issue raised by the applicant’s submissions is whether each respondent should be separately penalised. I accept the applicants’ submission that the penalties must take account of the fact that there were two active respondents with different levels of responsibility for each of the systems found to be unconscionable in Phoenix (Liability).

25 First, while members of the same corporate group (J[39]-[40] and [88]), Phoenix and CTI performed distinct roles in the overall scheme giving rise to the contraventions, and it was only through these distinct actions that the Phoenix marketing and enrolment systems operated. Specifically in Phoenix (Liability), I held that:

(1) During the Relevant Period, Phoenix was an RTO and VET Approved Provider which offered diplomas nationally in online full-time courses, trading under the banner of “myTime Learning”: J[9] and [247]-[250]. Following its acquisition by ACN on 12 January 2015 and the immediate and radical reorientation in Phoenix’s operating model thereafter, ACN derived its primary revenue from Phoenix’s operations: J[39] and [88].

(2) On the other hand, CTI “operated as the marketing arm” for Phoenix and ten other RTO’s owned and operated by ACN: J[40]. Specifically, over the relevant period, CTI “managed relationships with Brokers and Agents and enrolments into Phoenix’s Online Courses on behalf of Phoenix via CTI’s Client Relationship Management Team (CRM Team), Data and Quality Team, Telephone Verification Team, as well as the course trainers”: J[40]. That arrangement between CTI and Phoenix was formalized in an agreement dated 1 July 2015: ibid.

26 Secondly, Phoenix separately contravened s 21(1) of the ACL in relation to each and every enrolled online diploma student in respect of both the Phoenix Marketing System and the Phoenix Enrolment System over the relevant period: declarations [1] and [2]. In addition, Phoenix contravened ss, 18, 21(1) and 29(1)(i) in relation to Consumers A, B, C and D: declarations [3] and [4].

27 On the other hand, CTI aided, abetted, counselled or procured Phoenix’s contraventions of s 21 of the ACL, in relation to the Phoenix Marketing System: declaration [5]. For that reason CTI is liable to separate pecuniary penalties for that conduct. CTI also directly contravened s 21(1) of the ACL in relation to each enrolled student in relation to the Phoenix Enrolment System: declaration [6].

28 Thirdly, the fact that a deliberate choice was made by the ACN group to arrange its affairs such that separate subsidiaries had different roles in the marketing and enrolment of “students” in Phoenix’s online courses does not involve any element of double punishment for the same or substantially similar conduct: see by analogy, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Origin Energy Limited [2015] FCA 55 at [62]-[64] (White J); cf Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dimmeys Stores Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 1175 at [39] (Weinberg J). It can be inferred, as in Origin Energy, that this structure was deliberately adopted because it was considered advantageous to ACN’s and the respondents’ business model. Thus, having taken the benefits of that structure, it is (as the applicants contend at AS [17]) appropriate that the respondents also assume the burden of that structure, including the imposition of separate penalties. In other words, as White J held in Origin Energy at [64], having adopted that structure presumably to their advantage, “it does not seem appropriate to ignore their separate status” in imposing a penalty. Furthermore and importantly, the imposition of separate penalties in this case is intended to reflect the different culpability of Phoenix and CTI: ibid.

29 Thus, as the applicants submit, this is not a case where it is appropriate for the Court to apportion responsibility by asking who was the “lead” contravener. As the Full Court relevantly held in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 159; (2017) 258 FCR 312 at [391]:

the one principle to be discerned [from the case law] is that each contravenor must be separately responsible for its own course of conduct. This is not just a discretionary factor. The legislature has indicated that the contravenor should be subject to the “appropriate” pecuniary penalty — the “appropriateness” is to be determined by reference to the contravenor’s own conduct and the acts and omissions of that person.

30 Accordingly, I agree that it is both appropriate and necessary to impose separate penalties on CTI and Phoenix so as to reflect their respective involvement in the contraventions, and the benefits gained and the losses occasioned by their conduct. In so doing, I am mindful that the imposition of separate penalties is required in the present case in order to appropriately tailor the penalty to each respondent’s degree of culpability for its contraventions.

4.3 The primary objective of deterrence

31 The purpose of civil penalties “is primarily if not wholly protective in promoting the public interest in compliance”: Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; (2015) 258 CLR 482 at [55] (French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ (with whose reasons Keane J agreed at [79])); see also Pattinson at [9] and [15] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ). In civil penalty matters, retribution has no part to play: Pattinson at [39].

32 Thus as Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ explained in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2018] HCA 3; (2018) 262 CLR 157 (ABCC) at [116] (with whose reasons Kiefel CJ agreed at [50]):

Other things being equal, it is assumed that the greater the sting or burden of the penalty … the more potent will be the example that the penalty sets for other would-be contraveners and therefore the greater the penalty's general deterrent effect. Conversely, the less the sting or burden that a penalty imposes on a contravener, the less likely it will be that the contravener is deterred from further contraventions and the less the general deterrent effect of the penalty. Ultimately, if a penalty is devoid of sting or burden, it may not have much, if any, specific or general deterrent effect, and so it will be unlikely, or at least less likely, to achieve the specific and general deterrent effects that are the raison d'être of its imposition.

33 Such considerations are especially relevant where the benefit in contemplation is, as in this case, profit or other material gain: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; (2016) 340 ALR 25 at [151] (the Court). As the Full Court held in Reckitt, “the greater the prospect of gain to the contravener, the greater the sanction required, so as to make the risk/benefit equation less palatable to a potential wrongdoer and the deterrence sufficiently effective”: ibid.

34 It follows that the statutorily prescribed and other penalty factors to which I later refer fall to be considered in the context of setting a penalty of appropriate deterrent value so as to ensure that the penalty is not regarded relevantly by others as an acceptable cost of doing business: see e.g. Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [66] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ); Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work at [110] (Keane J); Pattinson at [17] and [66] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ). As, for example, the Court held in Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; (2012) 287 ALR 249 (Singtel Optus (FCAFC)) at [62]-[63]:

There may be room for debate as to the proper place of deterrence in the punishment of some kinds of offences, such as crimes of passion; but in relation to offences of calculation by a corporation where the only punishment is a fine, the punishment must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not such as to be regarded by that offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business. The primary judge was right to proceed on the basis that the claims of deterrence in this case were so strong as to warrant a penalty that would upset any calculations of profitability. …

Generally speaking, those engaged in trade and commerce must be deterred from the cynical calculation involved in weighing up the risk of penalty against the profits to be made from contravention.

35 These principles have been emphasised also in other matters imposing penalties for unconscionable conduct in other VFH provider cases: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Acquire Learning and Careers Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 602 [51]–[53] (Murphy J); Get Qualified at [31] and [61] (Beach J); Cornerstone at [41] (Gleeson J); AIPE (No 5) [19(d)] and [20] (Bromwich J).

36 It follows from these principle that where “deterrence is the object, the penalty should not be greater than is necessary to achieve this object; severity beyond that would be oppression”: NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [1996] FCA 1134; (1996) 71 FCR 285 at 293 (Burchett and Kiefel JJ). As Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ recently held in Pattinson at [10]:

What is required is that there be “some reasonable relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty imposed”. That relationship is established where the maximum penalty does not exceed what is reasonably necessary to achieve the purpose of s 546 [of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) conferring power to impose civil pecuniary penalties]: the deterrence of future contraventions of a like kind by the contravenor and by others.

(Footnotes omitted.)

37 Thus the High Court in Pattinson held that the penalties imposed by the primary judge were appropriate “because they were no more than might be considered to be reasonably necessary to deter further contraventions of a like kind by [the contravenors] or others. They represented a reasonable assessment of what was necessary to make the continuation of the CFMMEU’s non-compliance with the law, amply demonstrated by the history of its contraventions, too expensive to maintain” (at [9] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ); see also at [40]). However, as their Honours then proceeded to explain, there is no place for the notion that a civil penalty must be proportionate to the seriousness of the conduct comprising the contravention or that the maximum penalty should be reserved for the most serious examples of offending (at [40] and [49]-[55]).

38 The High Court further explained with respect to types of considerations that may be taken into account in the setting of an appropriate civil penalty at [46]-[48] that:

an “appropriate” penalty is one that strikes a reasonable balance between oppressive severity and the need for deterrence in respect of the particular case. A contravention may be a “one off” result of inadvertence by the contravener rather than the latest instance of the contravener’s pursuit of a strategy of deliberate recalcitrance in order to have its way. There may also be cases, for example, where a contravention has occurred through ignorance of the law on the part of a union official, or where the official responsible for a deliberate breach has been disciplined by the union. In such cases, a modest penalty, if any, may reasonably be thought to be sufficient to provide effective deterrence against further contraventions.

The penalty that is appropriate to protect the public interest by determine future contraventions of the Act may also be moderated by taking into account other factors of the kind adverted to buy French J in CSR. For example, where those responsible for a contravention of the Act express genuine remorse for the contravention, it might be considered appropriate to impose only a moderate penalty because no more would be necessary to incentivise the contravener is to remain mindful of their remorse and their public expressions of that remorse to the court. …

It is not necessary to multiply examples further. It is sufficient to say that a court empowered by s 546 [of the Fair Work Act] to impose an “appropriate” penalty must act fairly and reasonably for the purpose of protecting the public interest by deterring future contraventions of the Act.

39 Whilst Pattinson arose in the context of industrial penalties, the reasoning of the plurality is equally apt to apply with respect to civil penalties which arise under s 224 of the ACL: viagogo AG v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2022] FCAFC 87 at [129]–[131] (Yates, Abraham and Cheeseman JJ).

4.4 General deterrence considerations in the present case

40 First, as I have stated, given that Phoenix and CTI are now in liquidation, there is no role for specific deterrence. However, general deterrence considerations continue to apply and for this reason it is appropriate to impose a meaningful penalty even though there is no prospect that Phoenix and CTI will pay the penalties. For example, as I held in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Birubi Art Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 3) [2019] FCA 996:

22 Given that Birubi is in liquidation, it is unlikely that Birubi would be able to pay any pecuniary penalty in any event. However, even if Birubi were not already in liquidation, it follows from this and other authorities to like effect that the fact that the penalties proposed would have significantly exceeded Birubi’s annual income … and may have caused it to become insolvent, would not have constituted a mitigating factor that might have justified a lesser penalty if the Court were satisfied that penalties at the level proposed were necessary in order to have the appropriate deterrent effect.

23 Nor, as the ACCC submits, should the fact that Birubi is now in liquidation dissuade the Court from assessing appropriate penalties because they may still have an important general deterrent effect even though they may not be recovered. For reasons I develop below, that deterrent effect is of particular importance in the present context given the economic, social and cultural harms to Indigenous Australians which may flow from businesses misrepresenting the provenance of art and souvenirs as Australian Indigenous art and artefacts. Thus, as the Full Court explained in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dataline.Net.Au Pty Ltd (in liq) [2007] FCAFC 146; (2007) 161 FCR 513:

20. … a court may impose a penalty on a company in liquidation if, to do so, would clearly and unambiguously signify to, for example, companies or traders in a discrete industry that a penalty of a particular magnitude was appropriate (and was of a magnitude which might be imposed in the future) if others in the industry sector engaged in the same or similar conduct. …

24 By way of illustration, the Full Court referred to the decision of O’Loughlin J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v The Vales Wine Company Pty Ltd (1996) ATPR 41-528 (Vales Wine) in which his Honour observed that even though the company was in liquidation and there would be no hope of recovering any penalties or costs, that should not dissuade the Court from assessing appropriate penalties to “serve as a warning throughout the wine industry and elsewhere of the attitude of the Court to offences of this nature” (at 42,776).

(See also Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v SIP Australia Pty Limited [2003] FCA 336; (2003) ATPR 41-937 at [59] (Goldberg J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v SensaSlim Australia Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 7) [2016] FCA 484 at [20]-[28] (Yates J); and Australian Communications and Media Authority v Limni Enterprises Pty Ltd (formerly known as Red Telecom Pty Ltd) [2022] FCA 795 at [62] (Perry J).)

41 Secondly, while the particular government program exploited by Phoenix and CTI has been replaced by a different type of student loan program for the skill sector, a strong message of general deterrence is still appropriate. As the applicants submit, quite apart from this particular program, the fundamental point remains that it is critical that businesses do not regard programs involving large government expenditure directed to achieving important social purposes “as an invitation to engage in cynical profiteering and exploitation” (AS [25]).

42 Thus, the applicants contended that the penalties which the ACCC seeks in this case (AS [27]):

achieve the primary and fundamental goal of general deterrence, having regard to the scale and nature of the contravening conduct in issue and, in particular, the value of the vast gains that the conduct was designed to generate and the vast harms that it was liable to cause. The significant penalties sought against both Phoenix and CTI will serve to operate as a meaningful deterrent for other businesses that may be similarly tempted by gains of this magnitude to target vulnerable consumers and exploit them via government funded programs. Although the VFH scheme under which the conduct took place has ceased, there always remains an ongoing risk that unscrupulous actors may engage in similar conduct, especially in relation to large-scale government-funded schemes.

43 As I have noted, civil penalties require “some reasonable relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty imposed”: Pattinson at [10]. It is therefore necessary, in assessing the appropriate penalty, to identify the maximum penalty. In this case the maximum penalty for each contravention by a corporation of a provision in Parts 2-2 and 3-1 of the ACL was, at the time of Phoenix and CTI’s contraventions, $1.1million: see item 2 of s 224(3), ACL.

44 As the Phoenix Marketing and Enrolment Systems touched and operated upon all of the consumers enrolled in Phoenix Online Courses and in respect of whom Phoenix claimed VET FEE-HELP payments (J[1353]), the number of contraventions here is such that, as the applicants submit, “the theoretical maximum penalties … are staggering” (AS [39]). Specifically, Phoenix contravened s 21 of the ACL on 11,363 occasions as a result of the Phoenix Marketing System and on 11,363 occasions as a result of the Phoenix Enrolment System, giving a total of 22,786 contraventions: J[1353]. This means that the theoretical maximum penalty in respect of Phoenix’s contraventions exceeds $25 billion. For the same reasons, CTI’s contraventions are also subject to a theoretical maximum penalty in excess of $25 billion. In this regard, the ACCC accepted that “by reason of the sheer number of contraventions, the theoretical maximum is vastly greater than would be necessary to secure deterrence, even on the appalling facts of this case, and so is of little assistance in setting penalty” (AS [29]). There is therefore no meaningful maximum penalty to be applied in this case. The assessment of the appropriate range for penalty is best assessed by reference to other factors (see e.g. Reckitt at [157] by analogy) including:

(1) the payments in fact made by the Commonwealth to Phoenix which totalled $106m, bearing in mind that this sum has not been repaid and that there is no realistic prospect that it will be repaid;

(2) the gross benefits to which Phoenix asserted an entitlement including the $106m which was in fact paid to Phoenix, totalling approximately $360m; and

(3) the losses to enrolled consumers who were exposed for a significant period to total debts exceeding $428m (see the affidavit of Byron Vickers, data analyst, Skills Programs Compliance Branch (previously the VFH Compliance Branch) Skills and Training Group of the Department, affirmed 3 March 2022 (Vickers affidavit) at [20]).

45 As to the last of these propositions, I note that the Commonwealth has now re-credited the Non-Completion Students’ HELP balances with the amount of VFH assistance and remitted their VET FEE-HELP debts. The third party redress orders which I have made will have the consequence that this will be true for all enrolled consumers, i.e., including the Completion Students, being those who completed a unit of study in a Phoenix Online Course in which they were enrolled.

4.6 The same conduct cannot be penalised twice

46 Section 224(4)(b) of the ACL provides that:

If conduct constitutes a contravention of 2 or more provisions referred to in subsection (1)(a):

(b) a person is not liable to more than one pecuniary penalty under this section in respect of the same conduct.

(Emphasis added.)

47 Section 224(4)(b) is directed to preventing multiple, and therefore cumulative, penalties being imposed on one contravener for the same conduct that constitutes a contravention of two or more provisions of the Act. As a unanimous Full Court explained Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; (2018) 262 FCR 243 at [219] with respect to s 76(3) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (which is an analogue of s 224(4)):

For the purposes of the application of s 76(3) the actual conduct that constitutes a contravention of one provision must be the “same conduct” that constitutes the contravention of the other provision [for that provision to be enlivened].

(See also Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Jetstar Airways Pty Limited (No 2) [2017] FCA 205 at [13]-[17] (Foster J).)

48 In applying these principles, I agree with the applicants’ submission that, in this case:

it is perfectly orthodox to impose separate penalties for the contraventions of s 21 (and s 29) relating to the four identified consumers and for the contraventions of s 21 relating to the unconscionable systems. This is because the “conduct” relied upon in the contraventions relating to the individuals was different to the conduct relied upon which established the systemic unconscionability (which was also conduct that differed as between the affected 11,393 consumers) (that is, it is not, and cannot be characterised as, the “same conduct” as required by s 224(4)).

(AS [34]; emphasis added.)

4.7 The course of conduct analysis

49 In Pattinson, six members of the High Court explained that, while concepts of retribution are immaterial in the context of fixing an appropriate civil penalty (at [45]):

some concepts familiar from criminal sentencing may be usefully deployed in the enforcement of the civil penalty regime. In this regard, concepts such as totality, parity and course of conduct may assist in the assessment of what may be considered reasonably necessary to deter further contraventions of the [Fair Work] Act. On behalf of the CFMMEU, the rhetorical question was asked, on several occasions, how it was that proportionality as a principle of sentencing did not translate to the civil penalty regime when other concepts familiar in criminal sentencing such as totality, parity and course of conduct have been accepted as relevant. A compelling answer to that rhetorical question was provided by the Commissioner’s counsel. Proportionality in this context has a normative character foreign to the purpose of the power, whereas concepts such as totality, parity and course of conduct are analytical tools which assist in the determination of a reasonable application of the law. Although these analytical concepts have been developed in the context of the punishment of crime, unlike proportionality, they are not so closely tied to retribution as to be incompatible with a civil penalty regime focused on deterrence.

50 The course of conduct principle has frequently been applied in imposing penalties for breaches of the ACL, particularly where, as here, the number of legally distinct breaches is large: see e.g. Reckitt at [139]-[145] (the Court); and Singtel Optus (FCAFC) at [51]-[55]. This principle was explained by the Full Court in Yazaki as follows:

The course of conduct or one transaction principle means that consideration should be given to whether the contraventions arise out of the same course of conduct or the one transaction, to determine whether it is appropriate that a “concurrent” or single penalty should be imposed for the contraventions. The principle was explained by Middleton and Gordon JJ in Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; 194 IR 461 at [41]:

the principle recognises that where there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of two or more offences for which an offender has been charged, care must be taken to ensure that the offender is not punished twice for what is essentially the same criminality. That requires careful identification of what is the same criminality and that is necessarily a factually specific enquiry.

51 As I explained in Birubi, the course of conduct principle is a “tool of analysis” (at [66]). In civil penalty proceedings this analytical tool can, but need not necessarily, be used in the particular case: Cement Australia at [424] (the Court).

52 It is plain from my findings in Phoenix (Liability) that the Phoenix Marketing System and the Phoenix Enrolment System should not be treated together as comprising a single course of conduct because they do not involve the same conduct. As the applicants submit, the Phoenix Marketing System was directed to eliciting signed enrolment application forms from consumers via the deployment of a veritable army of marketing brokers and agents “operat[ing] much like a dragnet, hauling in manipulated and unsuspecting consumers and enticing them to lodge enrolment applications for VET courses" (AS at [39]). This conduct was anterior to the Phoenix Enrolment System which was deployed at a later stage with respect to each consumer and involved different conduct.

53 Under the VET-FEE-HELP scheme and under Phoenix’s own policy manual (with which Phoenix never in fact intended to comply (J at Section 10.12.5)), the process of enrolment was intended to operate as a safeguard. In particular, among other things, the enrolling officer was required to confirm that the consumer understood that they were enrolling to undertake an online course and would assume a debt to the Commonwealth by reason of that enrolment, satisfied eligibility requirements, that the consumer was equipped to undertake the course, and that the course was suitable for the particular consumer.

54 However, in furtherance of their insatiable quest for profit, the respondents deliberately disregarded and circumvented this safeguard through the Phoenix Enrolment System including (as I found in Phoenix (Liability)) by:

(1) enrolling consumers without verifying them (at [1280]-[1285]);

(2) enrolling consumers without adequate verification (at [1286]-[1290]);

(3) failing to confirm consumers’ Language, Literacy and Numeracy (LLN) test results (at [1291]-[1294]);

(4) failing to ensure consumers were within the target cohorts and satisfied eligibility criteria (at [1295]-[1298]);

(5) failing to consider work placements (at [1297]-[1298]);

(6) extensively enrolling consumers in more than one course (at [1299]);

(7) extensively charging students for unnecessary units of study (at [1300]-[1302]);

(8) enrolling students too close to the census date at [1303]-[1308]; and

(9) providing log-in details or laptops to consumers shortly before or after the census dates (at [1309]-[1318]).

Considered cumulatively, in Phoenix (Liability), I considered these features of the enrolment system to be unconscionable, independently of Phoenix’s Marketing System.

55 Furthermore, the respondents’ respective levels of culpability with respect to the Phoenix Marketing System and the Phoenix Enrolment System were different. Accordingly, as the applicants submit, if the two systems were grouped together as a single course of conduct, this would fail to reflect the differing levels of responsibility and culpability attributable to Phoenix and CTI with respect to each system (AS at [41]).

56 Applying this course of conduct analysis, in my view it is correct to characterise:

(1) the 11,363 contraventions of section 21 of the ACL by each respondent relating to the Phoenix Marketing System as constituting one course of conduct for each respondent; and

(2) the 11,363 contraventions of section 21 of the ACL relating to the Phoenix Enrolment System as constituting another course of conduct for each respondent.

57 In this regard I would emphasise that applying the course of conduct analysis in this way does not convert many separate contraventions into a single contravention; nor does it impose a “de facto limit” upon the available maximum penalty: see Yazaki at [231]-[232]. Rather, it reflects the fact that the 11,363 contraventions with respect to the Phoenix Marketing System represent “essentially the same criminality”: Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; 194 IR 461 at [41]. So too for the 11,363 contraventions occasioned by the Phoenix Enrolment System. Ultimately, in so holding, I recognise that the object remains to ensure that the penalties imposed are of appropriate deterrent value: Cement Australia at [424] (the Court); Pattinson at [10].

58 Finally, I agree with the submission by the ACCC that separate penalties should be levied for each of the four individual consumers. Those contraventions were separately pleaded and proved, and my findings that the contraventions were established were based on the particular circumstances pertaining to each consumer (see especially Chapter 12 of Phoenix (Liability)). As the applicant submitted, that wrongdoing was “proved by reference to different consumers being affected in different ways, at different times and in different places” (AS at [44]). There is no basis in my view for treating these four contraventions as a single course of conduct.

4.8 The effect of compensation orders and the penalty calculation

59 As Bromwich J held in AIPE (No 5) at [19(e)], compensation orders “serve a fundamentally different function, being redress, rather than prevention or deterrence: see [Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work] at [24], where compensation was described as a ‘competing consideration’ of prevention and deterrence”.

60 Compensation may and should be taken into account in determining the quantum of a penalty where compensation ameliorates the loss or damage caused by the contravening conduct and reduces the wrongdoer’s unlawful gains: AIPE (No 5) at [19(e)]. However, those considerations have no relevance here. That is because in reality neither respondent will be able to pay any compensation even though the applicants press the prayer for compensation.

4.9 Approach to considering the relevant considerations to arrive at an appropriate penalty

61 The manner in which the various considerations are to be considered and weighed in the ultimate setting of an appropriate penalty is well settled. As I explained in Birubi:

78 … in common with criminal sentencing, the process of arriving at the appropriate civil penalty under the ACL (and its predecessor, the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth)) involves an intuitive or instinctive synthesis of all of the relevant factors rather than a sequential mathematical process: [Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v] Coles Supermarkets [[2015] FCA 330; (2015) 327 ALR 540] at [6] (Allsop CJ). This does not of course mean that all of the considerations which are relevant to criminal sentencing are also relevant to assessing an appropriate civil penalty. Rather it is the process itself which is the same. Instinctive synthesis in this sense was helpfully described by McHugh J in Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; (2005) 228 CLR 357 as meaning:

51. … the method of sentencing by which the judge identifies all the factors that are relevant to the sentence, discusses their significance and then makes a value judgment as to what is the appropriate sentence given all the factors of the case” (at [51])

(See also by analogy Barbaro v The Queen [2014] HCA 2; (2014) 253 CLR 58 (Barbaro) at [34]-[35] (French CJ, Hayne, Kiefel and Bell JJ).)

79 This does not mean that the final result is a “gut reaction”, as the Full Court explained in Reckitt at [175]. Rather, it must be the outcome of a reasoned and transparent process.

(Emphasis added.)

62 Finally, as I held in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Jetstar Airways Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 797; (2019) 136 ACSR 603 with respect to the totality principle:

59 … the Court must consider all of the contravening conduct and determine whether the total penalty for each offence aggregated together exceeds that which is proper for the entire contravening conduct involved (the totality principle): Mill v The Queen (1988) 166 CLR 59 (Mill) at 63 (the Court) (by analogy). As such, the totality principle operates as a final check of the penalties to be imposed on the respondent, considered as a whole. As Goldberg J explained in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd (1997) 145 ALR 36 (Safeway Stores) at 53:

The totality principle is designed to ensure that overall an appropriate sentence or penalty is [imposed] and that the sum of the penalties imposed for several contraventions does not result in the total of the penalties exceeding what is proper having regard to the totality of the contravening conduct involved.

60 The application of the totality principle will not necessarily result in a reduction in the penalty. Rather, as the parties submit, in cases where the Court considers that the cumulative total of the penalties to be imposed would be too high or too low, it should alter the final penalties to ensure that they are “just and appropriate”: Safeway Stores at 53 (quoting Mill at 63).

(See further Pattinson at [45]).

5. CONSIDERATION OF RECOGNISED PENALTY FACTORS IN RELATION TO THE UNCONSCIONABLE SYSTEMS

5.1 Mandatory factors relevant to penalty

5.1.1 The nature and extent of the acts or omissions and any loss or damage suffered (subs 224(2)(a))

5.1.1.1 The nature and extent of the acts or omissions

63 There are a number of key points as to the nature and extent of the conduct and the loss and damage suffered.

64 First, the Phoenix Marketing and Enrolment Systems “were the product of calculated design born out of sheer avariciousness…”: (Phoenix (Liability) at [1352]).

65 Secondly, the ACCC submits (at AS [53]), and I accept, that:

the scale of the rort was vast. This is the largest VET provider case – in terms of the number of students affected by the unconscionable conduct, the volume of courses in which they were enrolled and the sum of money in question – to ever move through this Court. The unit of study completion rates by Phoenix was the equal worst amongst VET Providers at that time and it had the highest average of enrolments per student for VET Providers enrolling students in the same period.

(Citing the affidavit of Haylee Marlene Jones, affirmed on 29 June 2018 at [11]-[16], and the affidavit of Geoffrey Koochew, affirmed on 23 August 2019 at [11]-[14]).

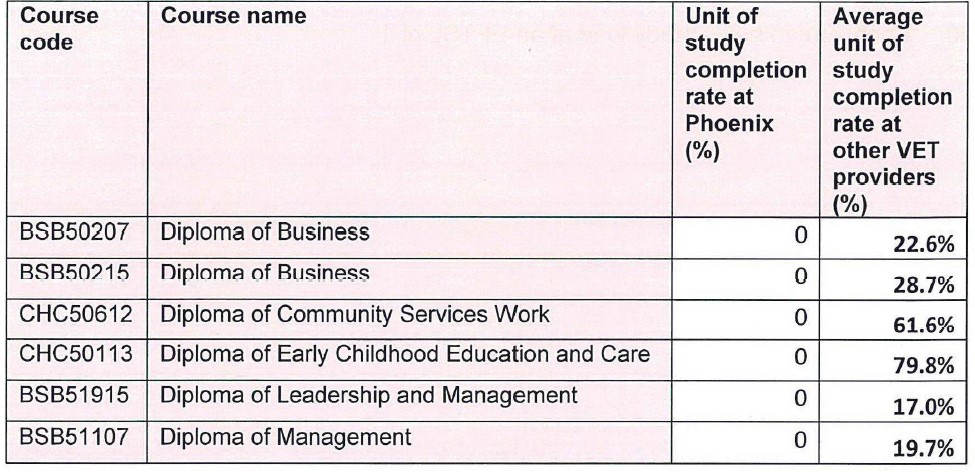

66 Thus, in her affidavit affirmed on 29 June 2018 at [30], Hayley Marlene-Jones, Director, Data and IT Section, VET Student Loans Branch (VETSL Branch), Commonwealth Department of Education and Training, included a table, prepared by her, which compared the unit of study completion rates for students enrolled in the Phoenix online courses and the average unit of study completion rates for students enrolled in the same courses with other VET providers at the time. That table provided as follows:

67 By way of further explanation, as I found in Phoenix (Liability) at [1192]-[1193]:

the data analysis evidence highlights the incredibly poor educational outcomes achieved by all but a handful of the many thousands of consumers enrolled in Phoenix’s Online Courses, This is itself indicative of callous indifference by Phoenix and CTI to each of the pleaded Callous Indifference components. At the risk of repetition, the evidence establishes that:

(1) of the 21,413 Online Courses in which 11,393 VET FEE-HELP consumers were enrolled, only 9 consumers completed the courses;

(2) 8,944 of 11,393 consumers (ie 78.5%) showed no evidence of any activity [by students] in FinPa [the Phoenix online learning platform], while in the case of 16,956 courses out of 21,413 courses (ie 79%), there was no evidence of activity in FinPa; and

(3) there was evidence of activity in FinPa in only 1.77% of all of the units of study in which the 11,393 consumers were enrolled.

…

As the applicants submit, these results are even more stark when it is considered that much of the evidence of consumer activity in FinPa was falsely generated by staff and agents of Phoenix and CTI at the direction of the respondents, as opposed to the consumers themselves…

(See also Phoenix (Liability) at [1141].)

68 Furthermore, in his affidavit affirmed on 23 August 2019 at [14], Geoffrey Koochew, Director, Data and Reporting Section, VETSL Branch, Department (Koochew Affidavit), gave evidence based on his analysis of data extracted from the relevant databases that:

(1) Phoenix had an average of 1.86 enrolments per student, which was the highest average of all VET providers recorded in the relevant databases for the period 13 January 2015 to 22 March 2016; and

(2) 85.8% of all students recorded in the relevant databases as enrolled with Phoenix were enrolled in more than one course with Phoenix, that is, as I found in Phoenix (Liability) (at [1128]):

(a) 10,013 students out of a total of 11,678 students were enrolled with Phoenix in two courses;

(b) three students were enrolled in three courses; and

(c) four students were enrolled in four courses.

69 Indeed, the fact that the consumers enrolled in Phoenix online courses were set up not only to fail, but largely not to engage with their courses, was an essential aspect of Phoenix’s business model in its merciless pursuit of profit. As I found at J[17], in comments which bear repeating:

it was both an accepted and anticipated part of the respondents’ business model that a very high proportion of students would pass the census date and incur a VET FEE-HELP debt in circumstances where it was predictable that they would never require training and support. This was a highly profitable outcome for the respondents who therefore were not required to, and did not, invest in the staff and resources which would have been required to train and support over 11,000 genuine students enrolled in over 21,000 full-time diplomas.

70 Thirdly, the contravening conduct occurred for close to a year from 13 January 2015 to 23 November 2015, the number of people affected by the unconscionable conduct was substantial, and the conduct was deliberate and systemic in character.

71 Fourthly, I explained the Phoenix Marketing System and the Phoenix Enrolment System in Phoenix (Liability) at [1321]-[1322] as follows:

On the one hand, the Phoenix Marketing System focused upon the direct, unsolicited approaches made by Agents to consumers to elicit enrolment forms from them for enrolment in Phoenix Online Courses in furtherance of the Profit Maximising purpose, with a Callous Indifference to their suitability for the courses, on the basis of misleading representations, and using high pressure and unfair tactics. In effect, this first aspect of the applicants’ systems case might loosely be described as focused upon “recruiting students” and “capturing them in the [Phoenix] net”. In respect of the Phoenix Marketing System, the conduct of the Agents and of the Brokers who engaged them is attributed to Phoenix, which contracted with the Brokers initially through CLI acting on its behalf and subsequently directly. The applicants also allege that CTI was directly or indirectly knowingly concerned in that system and/or aided, abetted, counselled or procured the contraventions by Phoenix.

On the other hand, while also pursued in furtherance of the Profit Maximising Purpose and with the Callous Indifference, the Phoenix Enrolment System was concerned with what happened after submission of the enrolment forms by the Brokers to CTI. This aspect of the applicants’ systems case focused upon the processing of the enrolment forms and enrolling of consumers in Phoenix’s Online Courses, including in multiple full-time courses, in circumstances where, among other things there was systemic non-compliance with the safeguards mandated by the VET FEE-HELP legislative scheme and by Phoenix’s policies for ensuring that students had an opportunity to make informed decisions about whether courses were suitable for them, for vetting unsuitable candidates, and for ensuring that consumers who were enrolled would have the support they required to undertake the courses. This system also included charging enrolled consumers duplicated and unnecessary fees for particular units of study. The applicants’ primary case is that Phoenix and CTI (which acted on behalf of Phoenix in enrolling consumers) contravened s 21 of the ACL.

72 By way of explanation, the “Profit Maximising Purpose” is a reference to Phoenix and CTI’s purpose of maximising the number of consumers who received VET FEE-HELP so as to maximise Phoenix’s revenue from the Commonwealth through the VET FEE-HELP assistance scheme (Phoenix (Liability) at [1175]). In turn, the reference to the “Callous Indifference” refers to the fact that, in eliciting enrolment from consumers and then enrolling them in the Phoenix Online Courses, Phoenix and CTI were callously indifferent as to whether:

(a) the consumers were in the target cohorts of the online courses;

(b) the consumers satisfied the eligibility criteria for those courses;

(c) the online courses were suitable for the consumers and the consumers were suited to the courses, having regard to their formal education, previous work experience, and literacy, numeracy and computer skills;

(d) the consumers had reasonable prospects of successfully completing the online courses in respect of which they applied to be enrolled;

(e) the consumers meaningfully participated in the Online Courses, including any assessments;

(f) Phoenix had appropriate trainer to student ratios;

(g) there was a reasonable prospect that a consumer enrolled in an online course which required a work placement could secure a work placement; and

(h) Phoenix was capable of inspecting those work placement venues

(Phoenix (Liability) at [94].)

73 I found that both the Profit Maximising Purpose and the Callous Indifference were “overwhelmingly" established by the evidence: Phoenix (Liability) at [1175] and [1191] respectively.

74 While both the Phoenix Marketing System and the Phoenix Enrolment System were highly egregious, the ACCC sought larger penalties for the Phoenix Enrolment System for the reasons that (at AS[55]):

The conduct underpinning the Phoenix Enrolment System was that which most directly led to the losses incurred and the benefits gained – it crystalised the effects set in motion by the marketing system. It calls for larger penalties than the Phoenix Marketing System. The very purpose of the separate enrolment step was to act as a final check that the courses were suitable for the consumers and the consumers were willing to and were capable of undertaking the courses, and yet in practice the enrolment system operated to compound the unconscionability already enacted towards the consumers. While the trial judge held at J[1320] that the two systems “worked in tandem” and involved “overlap”, it was the enrolment system that perfected the contravening conduct in the sense of crystallising the harm to consumers and reaping the benefits for the contraveners: see J[1322]; see also J[97]. The ongoing and repetitive nature of this conduct in the face of effectively negligible completion rates compounded the aggravating nature of the conduct.

75 I agree with the ACCC that for these reasons it is appropriate to award larger penalties against Phoenix and CTI with respect to the Phoenix Enrolment System.

5.1.1.2 Loss to the Commonwealth

76 The loss to the Commonwealth is substantial, with the Commonwealth having paid over $106m to Phoenix in VET FEE-HELP payments, none of which has been (and most probably will never be) recovered.

77 This occurred through the respondents’ ruthless exploitation of a central feature (now shown to be a vulnerability) in the VFH scheme, being the census date. In effect, the census date feature of the scheme was intended to afford a consumer a “cooling off” period after enrolling in a VET course. The duration of that period, which was set by the VET provider, was required to be equivalent to at least 20% of the course duration: Phoenix (Liability) at [198]. However, “[o]nce the census date was passed, the consumer incurred a debt amounting to 120% of the loan regardless of whether or not the student completed or indeed even commenced the unit of study in which she or he was enrolled…” (Phoenix (Liability) at [199]; emphasis in the original). Key features of the manner in which the respondents exploited this aspect of the VFH scheme were that:

(1) the Phoenix Marketing and Phoenix Enrolment systems “worked in tandem with the apparent intention of maximising Phoenix’s profit by ensuring the enrolment of as many customers as possible who were unlikely to engage with the Online Courses and unlikely to appreciate the consequences of their enrolment such that they would withdraw prior to the census date” (Phoenix (Liability) at [1320]);

(2) the vast majority of students were enrolled into two diploma courses, thereby doubling Phoenix’s entitlement in respect of each student recruited (see above); and

(3) Phoenix claimed VET FEE-HELP payments for subsequent VET units of study without the students having first completed (or indeed even logged into) earlier VET units of study in their courses (Koochew affidavit at [26]-[27]).

5.1.1.3 Economic loss and damage suffered by enrolled consumers

78 Each of the 11,393 consumers enrolled in one or more of the Phoenix online diploma courses are aptly described as victims of the Phoenix Marketing and Phoenix Enrolment systems. Phoenix charged fees of between $18,000-$21,000 for each course. As I have noted, most students were enrolled in two diplomas (described as “doubles” by officers of the respondents, Mr Brown and Mr Kochhar), despite each diploma involving a full-time load. It is therefore no exaggeration to say, as does the ACCC, that the students were “set up to fail” by the respondents’ conduct (AS at [62]). Yet this deliberate tactic of enrolling students in “doubles” not only had consequences for the VET FEE-HELP payments sought by Phoenix from the Commonwealth; it also doubled the level of debt in fact owed by the students to the Commonwealth once the census date in relation to each course (being each course component of the diploma) had passed.

79 The evidence establishes that these debts have now largely been re-credited by the Commonwealth under a legislative redress scheme so as to remedy the economic losses suffered by consumers as a result of the respondents’ misconduct (Vickers affidavit). However, as the ACCC submits, this re-dress is in no way attributable to the respondents and therefore does not mitigate the penalties which might otherwise be imposed.

5.1.1.4 Non-economic loss and damage suffered by enrolled consumers