Federal Court of Australia

Australian Electoral Commission v Kelly [2023] FCA 854

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN ELECTORAL COMMISSION First Applicant ELECTORAL COMMISIONER Second Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

ATTORNEY-GENERAL OF THE COMMONWEALTH Intervener | ||

DATE OF ORDER: | 27 July 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The proceeding be dismissed.

2. The applicants pay the respondent’s costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

RARES J:

Introduction

1 The Australian Electoral Commission and the Electoral Commissioner (the applicants) seek a declaration against Craig Kelly that he contravened s 321D(5) of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) during the election campaign period for the general election held on 21 May 2022 (the 2022 election), from 28 April 2022 up to and including 20 May 2022. From 2010 until the 2022 election, Mr Kelly had been elected as the member in the House of Representatives for Hughes, a seat in Southern Sydney.

2 The applicants allege that Mr Kelly contravened s 321D(5) because, when notifying particulars of his authorisation in 8pt font (the 8pt authorisation) on two forms of election posters, being portrait and landscape size corflutes that he caused to be printed and displayed throughout Hughes, those particulars were not, first, “reasonably prominent” and or, secondly, “legible at a distance at which the communication [of electoral matter in the posters] is intended to be read”, as required respectively by cl 11(3)(a) and (b) of the Commonwealth Electoral (Authorisation of Voter Communication) Determination 2021 (Cth) (the Determination) that the Commissioner had made on 30 June 2021 under s 321D(7) of the Electoral Act.

3 The applicants also seek an order imposing pecuniary penalties on Mr Kelly for the alleged contraventions pursuant to s 82 of the Regulatory Powers (Standard Provisions) Act 2014 (Cth) (the Regulatory Powers Act), which s 384A of the Electoral Act applied to contraventions of its civil penalty provisions, including s 321D(5).

4 Mr Kelly denies that the notification of particulars of his authorisation of the posters contravened s 321D(5). But, he asserts that if it did, he was not liable to a civil penalty by force of s 95(1) of the Regulatory Powers Act because he acted under a mistaken but reasonable belief of fact or, alternatively, each of s 321D(5) and (7) of the Electoral Act or cl 11(3)(a) and (b) of the Determination is invalid because it impermissibly allows infringement of, or infringes, the implied constitutional freedom of communication on government and political matter. The Attorney-General of the Commonwealth intervened to seek to uphold the constitutional validity of each of s 321D(5) and (7) of the Electoral Act and cl 11(3)(a) and (b) of the Determination.

The legislative scheme

5 Relevantly, ss 31 (that mirrors s 10 in respect of the election of senators) and 51(xxxvi) of the Constitution provide:

31. Application of State Laws

Until the Parliament otherwise provides, but subject to this Constitution, the laws in force in each State for the time being relating to elections for the more numerous House of the Parliament of the State shall, as nearly as practicable, apply to elections in the State of members of the House of Representatives.

51. Legislative Powers of the Parliament

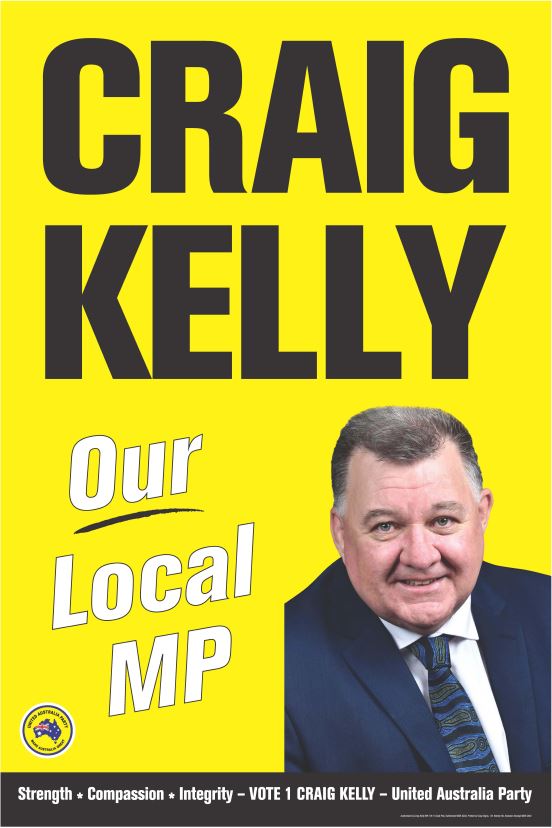

The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to:

…

(xxxvi) matters in respect of which this Constitution makes provision until the Parliament otherwise provides;

(emphasis added)

6 The objects of Pt XXA of the Electoral Act, in which s 321D appeared, were in s 321C, which provided:

321C Objects of this Part

(1) The objects of this Part are to promote free and informed voting at elections by enhancing the following:

(a) the transparency of the electoral system, by allowing voters to know who is communicating electoral matter;

(b) the accountability of those persons participating in public debate relating to electoral matter, by making those persons responsible for their communications;

(c) the traceability of communications of electoral matter, by ensuring that obligations imposed by this Part in relation to those communications can be enforced;

(d) the integrity of the electoral system, by ensuring that only those with a legitimate connection to Australia are able to influence Australian elections.

(2) This Part aims to achieve these objects by doing the following:

(a) requiring the particulars of the person who authorised the communication of electoral matter to be notified if:

(i) the matter is an electoral advertisement, all or part of whose distribution or production is paid for; or

(ii) the matter forms part of a specified printed communication; or

(iii) the matter is communicated by, or on behalf of, a disclosure entity;

(b) ensuring that the particulars are clearly identifiable, irrespective of how the matter is communicated;

(c) restricting the communication of electoral matter authorised by foreign campaigners.

(3) This Part is not intended to detract from:

(a) the ability of Australians to communicate electoral matters to voters; and

(b) voters’ ability to communicate with each other on electoral matters.

(emphasis added)

7 Importantly, s 4AA(1) defined “electoral matter” to mean “matter communicated or intended to be communicated for the dominant purpose of influencing the way electors vote in an election” for a member or senator of one of the Houses of the Parliament and s 4AA(2) provided:

4AA Meaning of electoral matter

…

(2) For the purposes of subsection (1), each creation, recreation, communication or recommunication of matter is to be treated separately for the purposes of determining whether matter is electoral matter.

8 Relevantly, s 321D(1)(b) provided that s 321D applied in relation to electoral matter that was communicated to a person if it formed part of a poster and its content was approved by a person, called a notifying entity. Next, s 321D(5) and item 3 in the table to it relevantly provided:

321D Authorisation of certain electoral matter

…

Notifying particulars

(5) The notifying entity must ensure that the particulars set out in the following table, and any other particulars determined under subsection (7) for the purposes of this subsection, are notified in accordance with any requirements determined under that subsection.

Required particulars | ||

Item | If … | the following particulars are required … |

3 | the communication is a sticker, fridge magnet, leaflet, flyer, pamphlet, notice, poster or how-to-vote card authorised by a disclosure entity who is a natural person | (a) the name of the person; (b) the address of the person |

Note 1: This provision is a civil penalty provision which is enforceable under the Regulatory Powers Act (see section 384A of this Act).

Note 2: A person may contravene this subsection if the person fails to ensure that particulars are notified or if the particulars notified are incorrect.

Civil penalty: 120 penalty units.

(emphasis added)

9 The Commissioner had power, by force of s 321D(7)(b)(i), to determine by legislative instrument requirements and further particulars for the purpose of s 321D(5). This was the source of the Commissioner’s power to make the Determination.

10 The Determination provided the requirements for notifying particulars for the purposes of s 321D(5) in the case of a printed communication (cll 10(1) and 11(1)). The particulars had to “be notified … at the end of the communication” (if it were not published in a journal: cl 11(2)(b). Relevantly, cl 11(3) provided:

11 Requirements relating to notifying particulars for printed communications

…

Formatting and placement of particulars

(3) The particulars must:

(a) be reasonably prominent; and

(b) be legible at a distance at which the communication is intended to be read; and

(c) not be placed over complex pictorial or multicoloured backgrounds; and

(d) be in a text that contrasts with the background on which the text appears; and

(e) be printed in a way that cannot be removed or erased under normal conditions or use; and

(f) be printed in a way that the particulars will not fade, run or rub off.

(emphasis added)

11 The Regulatory Powers Act, when read with s 384A(2)(a) and (c) of the Electoral Act, permits the Commissioner to apply to this Court for an order that a person, who is alleged to have contravened a civil penalty provision, pay to the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty that, in the case of an individual, was no more than the civil penalty specified for such contraventions (here, 120 penalty units, fixed at the time of the alleged contraventions at $222 each, or a maximum of $26,640) (s 82(1) and (5)(b)). The civil rules of evidence and procedure apply to such applications (s 87). The Court can impose such a civil penalty order under s 82(3). Relevantly, s 95 of the Regulatory Powers Act provided:

(1) A person is not liable to have a civil penalty order made against the person for a contravention of a civil penalty provision if:

(a) at or before the time of the conduct constituting the contravention, the person:

(i) considered whether or not facts existed; and

(ii) was under a mistaken but reasonable belief about those facts; and

(b) had those facts existed, the conduct would not have constituted a contravention of the civil penalty provision.

(2) For the purposes of subsection (1), a person may be regarded as having considered whether or not facts existed if:

(a) the person had considered, on a previous occasion, whether those facts existed in the circumstances surrounding that occasion; and

(b) the person honestly and reasonably believed that the circumstances surrounding the present occasion were the same, or substantially the same, as those surrounding the previous occasion.

(3) A person who wishes to rely on subsection (1) or (2) in proceedings for a civil penalty order bears an evidential burden in relation to that matter.

(emphasis added)

The issues

12 The parties did not seek to separate the issues of liability and, if it arises, relief, including penalties. They raised potentially five issues for decision, namely:

(1) What is the meaning of cl 11(3)(a) and (b) of the Determination? (the requirements issue)

(2) Did Mr Kelly fail to comply with s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act (because he failed to comply with cl 11(3)(a) and or (b) of the Determination) by displaying with an 8pt authorisation:

(a) at least 11 portrait posters and one landscape poster at Holsworthy Train Station on about 28 April 2022 (the Holsworthy communication);

(b) one landscape poster at a pedestrian crossing at Sutherland Train Station on about 18 May 2022 (the Sutherland communication);

(c) one portrait poster near the Engadine Pre Poll Voting Centre (the Engadine PPVC) on about 19 May 2022 (the first Engadine communication);

(d) at least six portrait posters within 50 metres of the Engadine PPVC on about 20 May 2022 (the second Engadine communication); and

(e) at least seven portrait posters at the front of the Wattle Grove Pre Poll Voting Centre (the Wattle Grove PPVC) on about 20 May 2022 (the Wattle Grove communication)?

(the compliance issue)

(3) If the answer to any part of issue 2 is yes, did Mr Kelly, at or before the time of his failure so to comply, consider whether or not facts existed that the 8pt authorisation was able to be, or was, used on the poster or posters, and was he also under a mistaken but reasonable belief about those facts, so that, had those facts existed, his conduct would not have constituted a contravention of s 321D(5) and cl 11(3)(a) and or (b) of the Determination, within the meaning of s 95(1) of the Regulatory Powers Act? (the mistake of fact issue)

(4) If the answer to issue 3 is no, did the discretion conferred on the Commissioner by s 321D(7) to make a determination authorise the making of requirements that unjustifiably infringe the implied freedom, and if so, is s 321D(7) a valid law? (the implied freedom constitutional issue)

(5) If the answer to issue 4 is no, did cl 11(3)(a) and (b) of the Determination unjustifiably infringe the implied freedom and so were invalid? (the validity issue)

13 The implied freedom constitutional and the validity issues only would arise if I had found Mr Kelly liable to a civil penalty order. For the reasons below, I have decided he is not.

Factual background

14 Each witness who gave oral evidence was credible and honest.

Mr Kelly’s state of mind

15 When Mr Kelly was first elected as member for Hughes in 2010, he had stood as a candidate for the Liberal Party of Australia. He remained a member of that party when successfully recontesting his seat in the 2013, 2016 and 2019 general elections. However, in the lead up to the 2022 election, Mr Kelly joined and became the leader of the United Australia Party (UAP). He was preparing to recontest his seat from the standpoint of being a sitting member, albeit standing for a new party different from that for which he had succeeded in being elected in the four previous campaigns.

16 Mr Kelly knew of the amendments to the Electoral Act dealing with authorisations (scil: the introduction of Pt XXA in 2017) because he was a member of the Parliament at that time and read about those matters in his official capacity. He understood that the intention of the amendments was to ensure that authorisation of electoral communications was traceable and accessible.

17 I accept Mr Kelly’s evidence that he believed that, in respect of electoral communications, “[a]uthorisatio[n] was always an important matter … [w]e were basically told from my first days at the Liberal Party … if in doubt, authorise it”. He understood that authorisation involved him, as the person responsible for a communication of electoral matter, including in a written communication stating in it that he had authorised its making by the insertion of his name and address, printed legibly and in a text and colour that contrasted with its background.

18 In particular, I accept Mr Kelly’s evidence that he sought to, and believed that he did, comply with whatever requirements were in force to place his name and address on all copies of the posters with 8pt authorisation in a way that complied with the law. In other words, I am satisfied that his intention, at all times relevant to this proceeding, was to ensure that his communications complied fully with all legal requirements under the Electoral Act.

How the posters came to be printed

19 On 30 March 2022, Mr Kelly emailed Amanda Goyen of A1 Design & Print, with whom, over the preceding 12 years, he had previously arranged the design and printing of election and political campaign material. He wrote that he was interested in getting quotes for portrait and landscape style corflutes based on a design that he included in the email. He had adapted that design from the standard format that the UAP was using in its 2022 election campaign. He wanted to remind voters in Hughes that he was their sitting member by adapting the standard UAP designs for corflutes or posters so that these promoted him in his capacity as their member together with his connection to the UAP.

20 Over the next few days, Mr Kelly and Ms Goyen exchanged numerous emails discussing and settling on the designs, sizes and content of the proposed corflutes. He discussed printing 900mm x 600mm portrait corflutes and 1200mm x 900mm landscape corflutes. On 2 April 2022, Ms Goyen emailed him with mock-ups of the latest designs, saying “I have added the Authorised line on the portraits and will add to your landscape as well. Should [it] be your office address or same as previous corflutes … ?”. She also told him that the printer, Easy Signs, had sent him quotes for printing the corflutes. Mr Kelly told Ms Goyen that the address used in the authorisation should be that of his Parliamentary electorate office in Sutherland.

21 On 3 April 2022, during the email exchanges to settle the designs for the corflutes, he told Ms Goyen that he wanted his name to appear on them “as large as possible, and have this dominating the sign” with the UAP logo “a bit smaller”, as represented in the mock-ups that he attached to an email, and he reminded her “Don’t forget the authorisation”.

22 Late on 4 April 2022, Mr Kelly emailed Ms Goyen confirming the design for the corflutes. He ordered 500 each of two types of portrait corflute, both 900mm x 600mm, with one type to be 3mm thick and printed only on one side and the other 5mm thick and printed on both sides, together with 300 landscape corflutes of 1200mm x 900mm. Reduced pictures of the corflutes appear below:

23 The authorisation on all of these corflutes appeared in the bottom right hand corner in 8pt font. The 8pt authorisation read:

Authorised by Craig Kelly, MP, 1/9-15 East Pde, Sutherland NSW 2232. Printed by Easy Signs, 144 Hartley Rd, Smeaton Grange NSW 2567.

24 The actual size of the 8pt authorisation as it appeared on the posters was:

![]()

25 Before giving his final approval to the design of the posters so that they could be printed, Mr Kelly considered how Ms Goyen had included the 8pt authorisation. He did not talk to anyone about whether the 8pt authorisation was large enough. However, he had not read the Determination. He said, and I accept, that:

That [design] was emailed through to me in a very high resolution file. I looked at it and I inspected it and I saw the authorisations were there. They were correctly worded. I believed the size was adequate, and I approved it to be printed … I believed that they were correct.

(emphasis added)

26 Mr Kelly had worked with A1 Design for over the preceding 12 years to prepare his electoral material and assumed that:

[W]hen I asked them to do the authorisation, that they would do it [in accordance with] the requirement … any requirement by the law, in the required size, font, placement and such.

27 He left this to A1 Design as “professional … designers of signs for elections” and relied on their professional experience.

28 After they were printed and delivered to his office, Mr Kelly and his campaign workers began to use and display the portrait and landscape corflutes with the 8pt authorisation (the 8pt authorisation posters) in campaigning for his re-election.

29 Mr Kelly’s design intention for the posters was to “emphasise my name as the sitting member of Parliament rather than the party’s name” whereas, he understood, other candidates’ signs had very large party logos and their names were in smaller print. He said that the posters were designed for as many people as possible to see and read them from all distances near and far, but (perhaps with a degree of exaggeration) “you wouldn’t have been able to read the graphics of the United Australia Party logo on the bottom of the sign” from further than a metre’s distance. Mr Kelly said that “a lot of people, I think, sometimes become oblivious to … election signs from a distance” and “I’ve generally found that the average person pays very little attention to an election sign”. He intended that the posters would be used principally for election day so that they could be put on the standard school fences, that all but one school in his electorate had, by weaving the poster between railings. He wanted people to be able to read the posters from close up, but recognised that, of course, people view signs from multiple distances.

The Holsworthy communication

30 On 28 April 2022, at about 5:00am, Mr Kelly, with his chief of staff, Frank Zumbo, set up both his portrait and landscape corflutes with the 8pt authorisation (collectively, the posters) at the entrance to Holsworthy Train Station. Mr Zumbo took photographs of the scene, before commuters started to arrive. Mr Kelly had been travelling around Australia as leader of the UAP and campaigning since mid-2021, but this was the first train station at which he campaigned in the 2022 election. He agreed that there were at least 12 of the 8pt authorisation posters shown in the picture below, that depicts him among the posters that he and Mr Zumbo had set up at Holsworthy Train Station that morning. He proudly posted it to his social media accounts.

31 This led to a complaint to the Commission that it received on Facebook. On 29 April 2022, the Commission wrote to the UAP asserting that the 8pt authorisation on the posters in the above picture at Holsworthy Train Station did not comply with cl 11(3)(a) and (b) of the Determination. The UAP immediately forwarded the Commission’s email to Mr Kelly. The Commission had required Mr Kelly and the UAP to remove all copies of the posters by close of business on 3 May 2022.

32 On 30 April 2022 Mr Kelly replied to the Commission enquiring what font size it considered acceptable for a standard election corflute so as to comply with the law. He also attached the photograph below, that he took that morning, of corflutes displayed by three other candidates for Hughes opposite his electorate office that, he wrote, appeared to have authorisations that were not legible at a distance at which the communication was intended to be read. He made a formal complaint about those corflutes.

Mr Kelly redesigns the authorisation

33 Later, on 30 April 2022, Mr Kelly emailed Ms Goyen informing her of the Commission’s complaint about the size of the 8pt authorisation. He ordered 1000 stickers in black with the authorisation contrasting on them in white print, originally, in 20pt font that could be stuck over the existing 8pt authorisations on the posters, together with 500 more 3mm thick one-sided portrait corflutes with two changes, first, to increase the authorisation to 20pt font, and, secondly, to substantially increase the weight of the black outline for the words ‘Our Local MP’.

34 Mr Kelly also spoke to Ms Goyen on 30 April 2022. She told him that the 8pt authorisation was in “the font size we’ve always used to print a lot of election signs over the years”. She said “I know from everything I’ve done recently and over the years that 8pt font is the minimum … I’m … lawfully allowed to print” (emphasis added). Ms Goyen did not tell him about the requirements in the Determination or the applicable provisions in the Electoral Act. He then went onto the internet and researched recommended font sizes. He found, among other things, an American document setting out what, it claimed, were the smallest sizes that could be used at various viewing distances, giving 8pt for a distance of one metre or 3.3 feet.

35 Mr Kelly decided to place the order for 1000 stickers based on the information that his staff and volunteers in the campaign office gave him about the inventory that they had taken of posters available for display which would need the new authorisation. As he said, because “you’re talking about cents each”, “it’s not as though you would try and save some money … by not getting another few stickers done”. Mr Kelly explained that he did not order more than 1000 stickers because by then, unlike his experience of previous campaigns, many of his posters in the 2022 election campaign had been either vandalised or removed overnight after his campaign workers had affixed them to fences or used other means of display, and so thought he did not need more stickers to make the remaining 8pt authorisation posters compliant. He said that he believed that all or “pretty much” all of the posters that had been put on display through the electorate had been stolen and that “as soon as we would put a sign out, it would be stolen and taken down”. He said that his volunteers had told him this, saying (for example):

[W]hen the requirement was that we had to change them, firstly I said, “Hold off. Don’t put any more signs out until we get this sorted out. All right. And then if there’s any you can see, let us know.” That was over a couple of days maybe or a week maybe while we were waiting for the new signs to be printed up. And in that period … there was basically nothing left around. As I said … it was strip mining of our signs basically every single day. You just had to keep on putting them out.

(emphasis added)

36 When challenged about that, he gave this evidence in relation to the period before he received the Commission’s letter of 29 April 2022, that I accept:

And is it your evidence to the court that all of the posters that put out prior to the notification to the AEC were stolen? --- … I’m going on what my staff are telling me, what my volunteers were telling me. …I don’t have a log of every place that everyone was put and went round and inspected them myself whether they were there or not, but … I can tell you that ...my volunteers were putting signs out, would come back to me the next day and said, basically, “Everything we put out overnight has been taken down”.

HIS HONOUR: How big was your electorate in size, approximately? --- It goes from Wattle Grove/Holsworthy in the west across to Bundeena, down to Waterfall in the national park, up to the Menai/Alfords Point area. I think it’s one of … – the largest … Sydney based electorates by size.

MR TRAN: And so when you tell the court that all of these posters were stolen, you’re really just basing that off what your staff told you? --- Correct.

You don’t personally know yourself? --- … I remember seeing some of the signs they had put up in certain places and then driving back the next day and … seeing them not there.

Seeing some? --- That was a very regular … occurrence.

And the volunteers who had a stock of the pre-existing corflutes, did you tell them to make sure that they put the new stickers onto those corflutes? --- No, … because … I told them [the volunteers] to bring them back, and all the stickers were put on by … my staff in my office.

(emphasis added)

37 On 4 May 2022, Mr Kelly replied to the Commission’s email of 29 April 2022. He said that he had done an inventory of the posters in question for their recall “and it appears that the few that have been put on public display have been stolen”. He said that he was printing new signage and would ensure compliance with the Electoral Act.

38 On 11 May 2022, the Commission emailed Mr Kelly concerning a complaint about photos of two portrait 8pt authorisation corflutes attached to telegraph poles at undisclosed locations. The Commission reminded Mr Kelly of the terms of cl 11(3) of the Determination and required him to “remove the pictured campaign signage and any other invalidly or unauthorised signage” by close of business on 13 May 2022.

39 Later on 11 May 2022, Mr Kelly emailed Ms Goyen enquiring about whether and when 300 more landscape corflutes could be printed, adding “Also – we’d just need to increase the font size for the authorisations”.

40 On 12 May 2022, Mr Kelly emailed Ms Goyen to correct the proof for the proposed new run of landscape corflutes, saying “Can you double the font size of the authorisation”, which she subsequently arranged.

41 In the event, the stickers and the form of authorisation printed at the end of the second order for posters that Mr Kelly placed on 30 April 2022 were in 24pt font (the 24pt authorisation) and not the 20pt font to which he had referred initially in his 30 April 2022 email to Ms Goyen.

42 When the stickers arrived at his office, soon after 12 May 2022, Mr Kelly was pleased with how they looked and put some of them onto the 8pt authorisation posters to test their efficacy, adhesion and where to put them on each corflute. He then told his chief of staff to make sure that the stickers were put onto every one of the supply of posters in the office. He later checked with Mr Zumbo who confirmed to him that the stickers had been put out on all of the original 8pt authorisation posters and Mr Kelly also saw evidence that this had occurred.

43 After Mr Zumbo told him that his staff had put the stickers onto the remaining stock of original 8pt authorisation posters, Mr Kelly believed that all of the posters that would be displayed in his electorate thereafter and on election day would have the 24pt authorisation and “thought that would be the end of the matter”.

The events immediately before the 2022 election

The correspondence on 17 May 2022

44 On 17 May 2022, the Australian Government Solicitor (AGS), on behalf of the Commission, wrote to Mr Kelly. The applicants relied on this letter only on the issue of penalty. The letter complained of noncompliance with the Commission’s demand of 11 May 2022 to remove the two pictured signs.

45 Quite how Mr Kelly could have dealt with the demand to remove or amend the two signs without being told where they were in a large electorate was not explained in any correspondence by or on behalf of the Commission or in argument at the trial. As I said in the course of argument, given the seriousness of Mr Kelly’s alleged contraventions which the Commission was asserting, it is difficult to understand why it did not tell him fairly and precisely where the allegedly infringing signs were. Of course, it could also have added that he had also to ensure that the rest of his posters all complied with the law. The Commission would be aware of the realities and the various campaign tasks performed by a candidate, his or her staff and volunteers, when involved in any candidate’s election campaign, including the widespread dissemination and use of corflutes and other signs over the geographic spread of an electorate. Not informing a candidate or party of the location of allegedly contravening conduct was unjustifiable and unreasonable. Yet this appeared to have been a deliberate position that the Commission took in its dealings with Mr Kelly in May 2022 in the lead up to polling day.

46 In his role as the leader of the UAP, Mr Kelly was travelling and campaigning extensively throughout the country during the election campaign period. He said that he was in his electorate in the days immediately preceding polling day but “it was an incredibly busy period” and that he had authorised his solicitor, Sam Iskander, to represent him in dealings with the Commission and the AGS, including, as will appear below, to seek details of the locations of 8pt authorisation posters that the Commission alleged were noncompliant (which information it only provided on Friday, 20 May 2022).

The Commission’s next steps

47 Three electoral officers, Warren Lane, Roy Beer and Dennis McCroary, gave evidence of the display of the 8pt authorisation posters the subject of the Commission’s allegations of contravention, comprising the Sutherland, the first and second Engadine and the Wattle Grove communications. At the time of the trial, each of them was a retiree.

48 Mr Lane was an early voting liaison officer at PPVCs at Engadine, Wattle Grove (both in Hughes), Miranda and Carringbah South (both in the neighbouring seat of Cook) (collectively, the four PPVCs) from 4 to 20 May 2022. He had worked for the Commission during the 2016 general election, first, as an election officer in the mobile pre-poll team (institutions) visiting aged care homes and hospitals to assist residents and patients to vote and, secondly, as a polling place liaison officer on polling day.

49 At about 6:00pm on 18 May 2022, Sandra McIntyre, the Commission’s divisional returning officer for the division of Hughes, asked Mr Lane to take a photograph of any of Mr Kelly’s posters that he came across. On his rounds, Mr Lane routinely checked, up to three times daily, authorisations on posters and how-to-vote cards for all the candidates at the four PPVCs for which he had responsibilities and which he travelled between as part of his role. He told Ms McIntyre that all the posters of all candidates that he had sighted previously in visiting each of the four PPVCs were in order, including on Mr Kelly’s posters that he had seen at the Wattle Grove PPVC. He was clear in his evidence that Mr Kelly’s posters at the Wattle Grove PPVC, being the 8t authorisation posters complained of, had been authorised by Mr Kelly.

The Sutherland communication

50 After Ms McIntyre’s call, Mr Lane visited the Engadine PPVC, but it was closed for the evening and all the posters were packed away. Later that evening, Mr Lane drove through Sutherland where he recalled having seen Mr Kelly’s posters displayed. He stopped at Sutherland Train Station on the western side close to the entrance at the top of East Parade. He was familiar with the station because, about once a month, he drove to it and parked there so that he could take a direct train to the city. Mr Lane saw two of Mr Kelly’s landscape corflutes attached to a telegraph pole on the opposite side of the road facing a pedestrian crossing that led from one of the station’s entries and exits. He said that, when he visited the station, he commonly saw exiting commuters cross the road using this crossing and walk north where they would pass the telegraph pole that displayed the two landscape corflutes, on a route that led to a bus terminal and a car park. He said that, in this area, there is no footpath on the other side of East Parade.

51 Mr Lane said that, at 6:56pm, he stood about one to two metres away from the telegraph pole in the gutter on the same side of the road and, with a clear, uninterrupted view, photographed one of the landscape corflutes. At the time, it was dark and about six people walked past him while he took the photographs. In those conditions, Mr Lane did not see any authorisation on the landscape corflute. However, he also could not see the 8pt authorisation in the witness box on exhibit A (being a copy of the landscape 8pt authorisation corflute) when shown it. I infer that, based on the expert evidence of Fabian Mammarella, an optometrist, the night-time conditions and less than perfect lighting in the witness box inhibited Mr Lane’s vision whereas, when he visited the PPVCs and checked the posters of all candidates, he was able to see, and actually saw, the 8pt authorisation on Mr Kelly’s posters in broad daylight. Mr Mammarella said that natural sunlight was many times stronger than artificial light “so it gives you a hell of a lot more information; so people can see a lot more outdoors”. He said that a lot of his patients tell him that they can read outdoors but not with a bed lamp.

The first and second Engadine communications

52 Mr Beer was the officer in charge of the Engadine PPVC between 4 and 20 May 2022 and worked there every day except 11, 13 and 15 May 2022. He said that the PPVC was at 51 Station Street, Engadine, a short walk down the street from Engadine Train Station. It was a busy street. Mr Beer said that, between 9 and 20 May 2022, the area directly around the PPVC became busiest at about lunchtime and the early evening, around 5:00pm, when people attended to vote after work. He observed that most of the campaign workers for candidates had sandwich board posters that they put out on Station Street in the same locations each morning, six metres or more away from the PPVC entrance, and collected each night, placing them inside the PPVC before Mr Beer locked them away till the next day. He said that some of Mr Kelly’s posters were not displayed on sandwich boards but were set up standing in a garden bed in front of a tree in Court Lane, at around 64 Station Street, and that those posters were not kept inside the PPVC overnight, but remained in place.

53 In the early afternoon of 19 May 2022, Ms McIntyre phoned Mr Beer and asked him to photograph Mr Kelly’s posters near the Engadine PPVC. He did not recall why she wanted the photographs. He went outside soon after and tried to take the photos discretely with his phone. He did not know how to use the zoom function on the phone. The first of Mr Kelly’s portrait corflutes that Mr Beer photographed appears creased in the picture. Mr Beer said that, to his observation, this poster “had been torn up” as had a few of Mr Kelly’s posters. Mr Beer photographed, from about five metres away, two of Mr Kelly’s portrait corflutes in a garden bed adjacent to a paved footpath, each with the base on the ground, leaning against a tree. Mr Beer said that about three to five people walked past him when he took this photograph.

54 Next, Mr Beer photographed another portrait corflute on a street that appeared, from the angle at which the photo was taken, with the seat of the bench facing the photographer, to obscure the bottom half of Mr Kelly’s face and the matter below it. Mr Beer also took two photographs of various candidates’ corflutes displayed on sandwich boards on both sides of a wide footpath that included Mr Kelly’s that were on a sandwich board at about 10 to 20 metres away from him. He also took another photo of sandwich board posters, including Mr Kelly’s, at a different part of the footpath. Mr Beer saw the larger writing on the portrait corflutes, including the lower line ‘Strength, Compassion, Integrity – Vote 1 CRAIG KELLY – United Australia Party’, but he “did not take notice of whether the posters contained authorisation details”.

The Wattle Grove communication

55 Mr McCroary was the officer in charge of the Wattle Grove PPVC from 6 to 20 May 2022, which was open for pre-poll voting from 9 May 2022. He worked there every day except 15 May 2022. He had worked in the same role in the 2019 general election and for the Commission in the 2010, 2013 and 2016 general elections as well as for the New South Wales Electoral Commission.

56 The Wattle Grove PPVC was in the main function room of the Wattle Grove Community Centre at 8 Village Way, Wattle Grove. Mr McCroary said that Village Way was a reasonably busy street that ran through the shopping centre and there was also a nearby early childhood centre. As a result, he observed, parking in the vicinity was usually quite congested, including in the car park located directly outside the Community Centre which serviced it, the shopping and early childhood centres.

57 In the afternoon of 20 May 2022, Mr McCroary received a call from Ms McIntyre. She told him that there were some issues with the legality of Mr Kelly’s posters. He did not think that she said anything to him about authorisations on the posters. She asked him to go outside the PPVC, photograph Mr Kelly’s posters and send the photographs to her.

58 Soon after the call, at 2:47pm, Mr McCroary took two photographs of Mr Kelly’s portrait corflutes, one from a distance of two to three metres, the other from about five metres. He said that Mr Kelly’s posters were located within 10 to 15 metres of the front of the Wattle Grove PPVC. The photos showed them placed upright on grass. He said that those posters had been displayed continuously during voting hours outside the PPVC since 9 May 2022. Mr McCroary said that the campaign workers of all candidates would put their posters inside the Community Centre after the PPVC closed for the day, he would lock the centre and the next morning, when it opened, they would set their respective candidate’s posters up again outside. However, Mr McCroary did not check to see if every poster had been brought in each night.

59 He could not recall seeing any authorisation on Mr Kelly’s posters but said that he was not focussed on that topic. In cross-examination, he agreed that the photo taken from about five metres away also showed a poster of another candidate for Hughes, Jane Seymour, and that he could not see any authorisation on any of those posters in the photo. Indeed, the quality of the photo and the distance from the camera meant that even the words in the black band at the foot of Mr Kelly’s portrait corflutes were not legible in it. Mr McCroary said that he did not know whether Mr Kelly’s posters, that he photographed, contained an authorisation. But, he knew that they were Mr Kelly’s posters.

Voting statistics at the Engadine and Wattle Grove PPVCs

60 The applicants led unchallenged evidence from Dale Emery, the Commission’s director, national event management, of votes cast at the four PPVCs before election day in May 2022. The Commission had an electronic election management system (ELMS) that, among other functions, recorded votes cast at each PPVC for each division (or seat) in an ELMS report of pre-poll voting activity (an ELMS report).

61 The ELMS report in respect of the Engadine PPVC on 19 May 2022 recorded 1,490 votes cast for Hughes as well as votes cast there for the two neighbouring seats, namely 41 for Cook and 164 for Cunningham, totalling 1,695 votes. The ELMS report in respect of the Engadine PPVC on 20 May 2022 recorded 1,825 votes cast for Hughes, 60 for Cook and 165 for Cunningham, totalling 2,050 votes. The total votes cast between 9 and 20 May 2022 recorded in the ELMS report for the Engadine PPVC were 11,161 for Hughes, 318 for Cook and 916 for Cunningham.

62 The ELMS report for the Wattle Grove PPVC recorded 1,591 votes cast for Hughes on 20 May 2022 and a total of 9,629 for the whole pre-poll voting period.

The correspondence on 19 and 20 May 2022

63 In the meantime, on 19 May 2022, Mr Iskander, through his firm, Alexander Law, responded to the AGS’ letter of 17 May 2022. He said that Mr Kelly had had the 24pt stickers printed and was complying with the Electoral Act. He wrote that the Commission had failed to identify the location of the two allegedly infringing posters on telegraph poles, saying that the complaint that it had received must have listed those locations. He asked for the location of each of those signs “so that our client may inspect them and take appropriate action without further delay”.

64 Later, at 5:52pm on 19 May 2022, the AGS responded to Mr Iskander noting that, as he had advised, Mr Kelly had done an inventory of posters. The AGS noted that Mr Iskander had asked for the location of the signs complained of so that Mr Kelly could address any problem. However, not only did the AGS’ letter not identify those locations, it said that since its 17 May 2022 letter, it had “identified further examples of signs in the electorate of Hughes both yesterday evening (18 May 2022) and today, which do not comply with the authorisation requirements” and attached photos of the alleged further contraventions, but also gave no locations for them. The evidence revealed that these were photos that Mr Lane had taken at Sutherland Train Station on 18 May 2022 and Mr Beer had taken at the Engadine PPVC on 19 May 2022. The AGS required Mr Kelly to give an undertaking by 8:00am the next day that, by 12 noon on that day, he would review all electoral material communicated on his behalf and rectify any noncompliance, as well as ensure that future signage was compliant.

65 At 10:50am on 20 May 2022, the AGS emailed Mr Iskander noting that Mr Kelly had not given an undertaking or otherwise responded to its letter sent at 5:52pm the previous night. The letter notified Mr Kelly that the Commission would be applying to this Court for urgent injunctive relief under s 383 of the Electoral Act to address “your client’s continued and ongoing use of the non-compliant signage including as at 19 May 2022”.

66 At 11:44am on 20 May 2022, Mr Iskander replied to the AGS’ letter of 19 May 2022. He complained, again, of the failures of the Commission and AGS to identify the locations of the allegedly noncompliant posters in their photographs. His letter reiterated previous assertions that “the subject signs were stolen from Mr Kelly and are not under his control”, but if he were informed of their locations in the electorate of Hughes, he was “willing to reclaim and have them removed” and asked, yet again, for their locations.

67 At 12:57pm on 20 May 2022, Mr Iskander emailed the AGS saying that Mr Kelly was heavily involved in campaigning and, unless told of the locations of the posters complained of, could not remove them.

68 At 2:35pm on 20 May 2022, the AGS replied seeking further undertakings about allegedly noncompliant posters, but stated that “[w]e have obtained instructions on the locations of the signs identified yesterday” and told Mr Iskander that they were at a Sutherland Train Station footpath crossing and near the Engadine PPVC. The letter said that the Commission intended to commence proceedings as soon as possible later that day.

69 At 3:17pm on 20 May 2022, Mr Iskander replied. His letter engaged in the by now entrenched positions of both parties. However, he thanked the AGS for identifying posters at Sutherland Train Station and the Engadine PPVC and said that they were attending to remove them.

70 At 5:02pm on 20 May 2022, the AGS replied attaching, among others, one of the photos taken by Mr McCroary earlier that afternoon showing Mr Kelly’s and one of Ms Seymour’s portrait corflutes on a grass dividing strip in front of a car park and asserting that their location was “in the vicinity of the Engadine and Wattle Grove PPVCs”. The letter asserted that it appeared that Mr Kelly had “made no effort to remedy the authorisation particulars on these signs” and that they were displayed as part of his electoral campaign.

71 At 5:57pm on 20 May 2022, Mr Iskander replied saying that stickers would be applied to the posters in the most recent photo or the posters would be removed, as would be the case at any other location of allegedly noncompliant signage of which the Commission or AGS notified Mr Kelly.

72 Late at night on 20 May 2022, Jagot J heard the Commission’s application for an interlocutory injunction under s 383 of the Electoral Act. After finding that it had established a prima facie case, her Honour refused relief on the ground that it was not appropriate, at 10:30pm on the night before election day, to order Mr Kelly to procure removal of the posters in the vicinity of the Engadine and Wattle Grove PPVCs: Australian Electoral Commission v Kelly [2022] FCA 628 at [25].

The requirements issue

The applicants’ submissions

73 The applicants argued that cl 11(3)(a) meant that an authorisation had to “stand out so as to strike the attention”, “be conspicuous”, “be easily seen” or “be very noticeable”, relying on the definition of ‘prominent’ in the Macquarie Dictionary and the decisions in Australian Consumer and Competition Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2011) ATPR 42-383 at 44-699–44-700 [124] and [126] per Murphy J, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v viagogo AG [2019] FCA 544 at [186] per Burley J and National Australia Bank Ltd v Rose [2016] VSCA 169 at [76] per Warren CJ and McLeish JA, [123] per Ferguson JA. They contended that the word “reasonably” as used in cl 11(3)(a) did not attenuate that meaning of prominent, but rather emphasised that the authorisation’s prominence had to be assessed in the context of the printed communication as a whole. They submitted that the relevant context included the size of the other printed text in the communication, asserting “the larger the other text, the larger the particulars [of authorisation]”, and the likely distance at which it will be read, again asserting that the greater that distance, the larger the particulars had to be. They argued that the legislative regime’s beneficial purpose was to ensure that voters be informed about who has authorised electoral matter and this required that they be able to read the particulars easily and “should not have to approach a poster, crouch down, and get out a magnifying glass in order to do so”. They submitted that it is not enough that one can identify the particulars of authorisation as being distinct from the electoral matter in the communication. Rather, the applicants relied on the word “identifiable” in s 321C(2)(b), and argued that, had cl 11(3)(a) merely intended that it would suffice if one could identify the particulars, the Determination would have said so, rather than be expressed more amply.

74 The applicants submitted that the word “legible” in cl 11(3)(b) required the particulars to be clear and large enough so that voters could read them “at the relevant distance” and, once again asserted that the “greater the distance, the larger the particulars”. They argued that “legible” within the meaning of cl 11(3)(b) meant more than that the particulars of authorisation merely be accessible. Rather, they contended, by requiring that the particulars “be legible at a distance at which the communication is intended to be read”, as a matter of common-sense, cl 11(3)(b) is incapable of being satisfied by an authorisation in “tiny font, tucked away in the corner of a large poster”, even if it be accessible there. They submitted that the focus of cl 11(3)(b) was on the particulars being readable by a person at a distance at which the communication was intended to be read, which was more than one metre away from the posters given the very large size of the font they used to convey the electoral matters in them.

75 They argued that the 8pt authorisation on the posters was so “impossibly small” to read from the distance at which most people would be expected to view the posters that it did not comply with cl 11(3)(a) or (b). They contended that the 8pt authorisation was very difficult to read even at a close distance. They submitted that the 8pt authorisation, first, was in text that was miniscule compared with the rest of the posters in which it appeared and, secondly, was not visible at all, or barely so, in each of the photographs that Mr Lane, Mr Beer and Mr McCroary had taken, being photographs that were taken from distances at which voters may have been expected to view the posters.

76 The applicants asserted that the Commissioner’s explanatory statement for cl 11(3) (which I set out at [108] below) was not subordinate legislation or binding on them, but rather had to be laid before both Houses of the Parliament to explain the Determination, because, as s 321D(7) provided, it was a legislative instrument. The applicants said that the font size of the authorisation did not have to be the same as used elsewhere in the communication, but that the 8pt authorisation, on any view, was too small to comply with cl 11(3)(a) or (b).

Consideration

77 If a communication of electoral matter (as defined in s 4AA of the Electoral Act) is a printed communication, cl 11(1) of the Determination provides that the balance of cl 11 applies to it. The meaning of cl 11(3)(a) and (b) is not immediately self-evident. These requirements apply to particulars that, in the case of a poster, cl 11(2)(b) stipulates be notified “at the end of the communication”. The particulars that s 321D(5) requires a notifying entity (here, Mr Kelly) to ensure be notified in accordance with s 321D appear, relevantly, in item 3 in the table to s 321D(5), as being his name and address, together with any other particulars, which must be notified in accordance with any additional requirements that the Commissioner determined under s 321D(7)(b)(i).

78 Part XXA of the Electoral Act was enacted to give effect to recommendations in “The 2016 Federal Election: Interim Report on the authorisation of voter communication” by the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, as stated in both the Revised Explanatory Memorandum circulated to the Senate by the Special Minister of State on the Electoral and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2017 (Cth) and by the Minister for the Environment and Energy in moving the second reading speech for the Bill in the House of Representatives (Hansard: House of Representatives, 30 March 2017 at 3792). The Explanatory Memorandum stated:

10. The authorising requirements amount to restrictions on anonymous political speech in limited circumstances, and, in doing so, engage the rights specified above. The restrictions are objective, legitimate and proportional because they:

• are provided for by law

• serve a genuine public interest by protecting free, fair and informed voting, which is essential to Australia’s system of representative government

• support the right to protection against unlawful attacks on reputation

• apply to an objectively defined group of entities who freely choose to play a prominent role in political debate.

11. There is a strong public interest in ensuring that voters are aware of who is communicating to them without adversely impacting public debate. These authorisation requirements facilitate transparency and public confidence in Australia’s electoral processes. They allow voters to assess the credibility of the information they rely on when forming their political judgment and selecting their representatives in the Parliament.

12. Ultimately, this Bill facilitates free and informed voting at elections, an object which is essential to Australia’s system of representative democracy. The strong public interest in achieving these objectives outweighs the rights to privacy of those covered by the authorisation regime who might wish to communicate anonymously.

…

46. Subsection 321C(3) notes that new Part XXA is not intended to detract from the ability of electoral matters to be communicated to voters, and voters’ ability to communicate with each other on electoral matters. This highlights that, when applying the requirements in new section 321D, public debate should be enhanced through increased transparency and accountability, and not stilted by red tape that does not contribute to the objects specified in new section 321C.

(emphasis added)

79 I am of opinion that the Commissioner’s delegated power under s 321D(7), to determine particulars that a nominating entity must notify, and that notification be done in accordance with any other requirements that the Commissioner determines, cannot be at large. Importantly, the Parliament set out the objects of Pt XXA in s 321C to address the reality that, while that Part of the Electoral Act is intended to burden the implied freedom, the burden will be limited and apply only to the extent that the Parliament sought to justify in s 321C. The enactment of Pt XXA necessarily created an interaction between the Constitution’s conferral of legislative power on the Parliament, that it made expressly “subject to this Constitution” as provided in ss 10 and 31, to make laws that relate to the elections of senators and members of the House of Representatives and the additional powers to make laws about, and incidental to, that subject matter in s 51(xxxvi) and (xxxix).

80 The Commission, Mr Kelly and the Attorney-General acknowledged in argument that Pt XXA and the Determination could be construed as imposing a burden on the implied freedom. Such provisions must be construed having regard to the matters to which I have referred in [78] and [79] above and the principles that Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ identified in Residual Assco Group Ltd v Spalvins (2000) 202 CLR 629 at 644 [28], namely:

Moreover, legislation “must not be read in a spirit of mutilating narrowness” (United States v Hutcheson (1941) 312 US 219 at 235, per Frankfurter J). If the choice is between reading a statutory provision in a way that will invalidate it and reading it in a way that will not, a court must always choose the latter course when it is reasonably open. Courts in a federation should approach issues of statutory construction on the basis that it is a fundamental rule of construction that the legislatures of the federation intend to enact legislation that is valid and not legislation that is invalid (Davies and Jones v Western Australia (1904) 2 CLR 29 at 43; Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Munro; British Imperial Oil Co Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1926) 38 CLR 153 at 180; Attorney-General (Vict) v The Commonwealth (the Pharmaceutical Benefits Case) (1945) 71 CLR 237 at 267; Chu Kheng Lim v Minister for Immigration, Local Government and Ethnic Affairs (1992) 176 CLR 1 at 14). Here there are two competing constructions — one spells invalidity, one does not. That being so, we should adopt the construction that saves the section and reject the construction upon which the defendants rely.

(emphasis added)

81 The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1902 (Cth) (the 1902 Act), when first enacted, provided in s 180 that the publication or printing of an electoral advertisement, hand-bill or pamphlet, or the issue of an electoral notice, would be an illegal practice if it did not include “at the end thereof” the name and address of the person authorising it.

82 Indeed, from at least the mid-nineteenth century, it was not uncommon, as Griffith CJ recognised in Smith v Oldham (1912) 15 CLR 355 at 358, for electoral laws in the United Kingdom and the Australian Colonies to require “advertisements, pamphlets and other election literature to bear the name of the printer and of the person by whose authority it is issued”. That case concerned the then s 181AA of the 1902 Act, which required every “article, report, letter, or other matter commenting upon any candidate or political party, or the issues being submitted to the electors” that was “published in any newspaper, circular, pamphlet, or ‘dodger’” to be signed at its end by its author with his or her true name and address, and made a contravention an offence. Griffith CJ continued:

It is a notorious fact that many persons rely upon others for their guidance, especially in forming their opinions. It is obvious, therefore, that the freedom of choice of the electors at elections may be influenced by the weight attributed by the electors to printed articles, which weight may be greater or less than would be attributed to those articles if the electors knew the real authors. It was contended that the electors should be allowed to form their own opinions from the abstract arguments addressed to them, irrespective of the persons by whom those arguments are put forward. But it is notorious, again, that many electors are unable to do so; and rely upon authority; and they may be less likely to be misled or unduly influenced if they know the authority upon which they are asked to rely. Parliament may, therefore, think that no one should be allowed by concealing his name to exercise a greater influence than he could command if his personality were known. It is impossible to say that an enactment to that effect is not an enactment regulating the conduct of persons in regard to elections.

(emphasis added)

83 Barton J explained (Smith 15 CLR at 360) that the expression in s 31 of the Constitution (which also appears in s 10) “relating to elections” in the phrase “the laws in force in each State, for the time being, relating to elections” included laws regulating not only the conduct of elections “in its official aspect only” but also “their conduct in respect of the prevention and punishment of misconduct of one kind or another in connection with elections”. His Honour also held that the Parliament had validly enacted the then s 181AA.

84 Isaacs J, too, recognised (at 363) that knowing the identity of a person making a communication to voters about electoral matter can also be of importance and that the then s 181AA was a valid law.

85 The objects of Pt XXA in s 321C(1) express the intention of the Parliament to promote free and informed voting at elections. The Parliament chose to ensure this by seeking to use Pt XXA to enhance, first, transparency (by allowing voters to know who is communicating with them), secondly, accountability (by making persons responsible for their communications), thirdly, traceability of communications of electoral matter (to aid enforcement of obligations imposed in Pt XXA) and, fourthly, the integrity of the electoral system (by ensuring that only those with a legitimate connection to Australia can influence its elections).

86 The requirement for authorisation of electoral matter in s 321D addressed the importance of deterring anonymous dissemination of electoral matter. This section was the principal means that the Parliament contemplated in s 321C(2) would achieve its objects, that it enacted recognising in s 321C(3) the constraint that the implied freedom imposed on its legislative power. For present purposes, the legislative aim in s 321C(2)(b) is particularly relevant. That aim was to ensure that particulars of the person who authorised the communication of electoral matter “are clearly identifiable, irrespective of how the matter is communicated”.

87 The power to prescribe requirements or particulars for the purposes of s 321D(5) (in a determination made under s 321D(7)(b)) must be understood as intended to achieve the complex balancing of the objects, aims and constitutional constraints on its powers that the Parliament expressed and acknowledged in s 321C and in regulating and promoting free and informed voting in elections. The Parliament’s purpose of requiring relevant communications to voters on electoral matter to disclose the name and address of the person who authorised it was to promote the ability of voters to know who was making the communication and how to contact, or serve process on, that person and ensure that there was no interference in Australian elections by persons who had no legitimate right to seek to influence voters in their participation in the constitutionally prescribed system of representative and responsible government and the procedure prescribed by s 128 for submitting to them a proposed amendment to the Constitution.

88 In this context, s 321D(5) requires that any determination made under s 321D(7) can only “prescribe particulars” for the purposes of s 321D(5) and make requirements that are conformable with the objects and aims stated in s 321C and within the legislative constraints imposed by the implied freedom, in order to regulate the communication of electoral matter.

89 The nature of the communications in s 321D(1)(b)(i) and item 3 in the table to s 321D(5) varies from physical items that an individual can, and usually will, hold in his or her hand (such as a leaflet, flyer, pamphlet, notice or how-to-vote card) to ones that he or she can display to others (such as a fridge magnet, sticker or poster) either domestically or publicly. Each of those eight media of communication ordinarily has a size distinct from the others and will be likely to convey its message differently, yet must include somewhere on its visible surface, as a part of and at the end of that communication, the particulars of at least the name and address of the notifying entity.

90 The purpose of requiring that a communication of electoral matter include particulars of the person who authorised it in a manner that is “clearly identifiable irrespective of how the matter is communicated” (s 321C(2)(b)) is to ensure that voters can know that, first, the communication is not anonymous and, secondly, the communication, regardless of its medium, will enable them clearly to identify who authorised it and what that person’s address is. Such a notification may alter the character and context of the communication in and to the limited extent that it reveals the specific particulars required in the table to s 321D(5) so as to achieve the objects of Pt XXA of the Electoral Act.

91 The above considerations inform the construction of cl 11 of the Determination: Spalvins 202 CLR at 644 [28]. Each of the media referred to in s 321D(1)(b)(i) and at item 3 in the table to s 321D(5) is a printed communication in which the particulars of authorisation must be notified at the end of the relevant medium of communication pursuant to cl 11(1) and (2)(b). The particulars comprising the authorisation must meet the requirements, relevantly, in cl 11(3)(a) and (b), namely they must be “reasonably prominent” and “legible at a distance at which the communication is intended to be read”. Moreover, cl 11(3)(a) and (b) must be read in the context of cl 11(3) as a whole since each of its six subclauses is joined by the “and” to each of the others. Thus, the particulars must also meet the requirements in cl 11(3)(c)-(f), which, in substance, require that they be indelible and not be obscured in or among the background in which they appear (by placement over backgrounds that make them hard to read or lack contrast). It follows that cl 11(3) required that a communication of electoral matter notify particulars of its authorisation, in a cognate way, by complying with all of its provisions.

The construction of “reasonably prominent” in cl 11(3)(a)

92 The Oxford English Dictionary online defines ‘prominent’ as meaning, among others, “that stands out so as to catch the attention”, “that catches the eye; conspicuous” (senses 2a and b). The Macquarie Dictionary online defines ‘prominent’ as meaning, among others, “standing out so as to be easily seen; conspicuous; very noticeable” (sense 1).

93 However, the word ‘prominent’ as used in cl 11(3)(a) is qualified by “reasonably” and must be read having regard to the considerations to which I have referred above. In enacting Pt XXA, the Parliament did not intend to detract from the ability of Australians and voters to communicate with each other on electoral matter, as s 321C(3) made manifest. Rather, the Parliament’s purpose in requiring the notification of the name and address of the person who authorised a communication of electoral matter was to achieve the objects in s 321C(1) by the mechanisms that it described in s 321C(2). Those mechanisms included, importantly for present purposes, that the particulars of authorisation be “clearly identifiable, irrespective of how the matter is communicated” (s 321C(2)(b)).

94 Thus to be “reasonably prominent” within the meaning of cl 11(3)(a) of the Determination, the particulars must be conspicuous in the sense of standing out so as to be easily recognised by a voter to be notifying the communication’s authorisation. That is, when a voter is seeking to ascertain who authorised a printed communication of electoral matter, he or she should be able clearly to identify the particulars of authorisation on that printed medium, regardless of how that medium communicates the electoral matter. The purpose that the notification serves is not to alter or impede the character or context of the communication itself, but, rather, to include the particulars of authorisation in it so that they appear to be clearly identifiable and be conveyed in a manner calculated to achieved the objects in s 321C(1).

95 If a fridge magnet were the medium under consideration, and reasonable prominence of the particulars meant that the particulars had to stand out on it independently of the context, there would be no, or very little, room for communication of any electoral matter on the rest of the magnet. Likewise, a pamphlet may consist of more than one page and the dominant message may appear on its first page, with the authorisation appearing only at the end (as cl 11(2)(b) requires). In such a case, reasonable prominence of the particulars on the back or final page may have no impact on the dominance or content of the message on the reverse page or first several pages of the pamphlet.

96 Thus, the requirement in cl 11(3)(a) for the particulars to be “reasonably prominent” must relate to their being prominent in signifying their function as particulars of the authorisation at the end of the communication, not in their overall appearance or conspicuousness in, or as part of, the communication. While the Parliament intended that the particulars, necessarily, had to form part of the overall communication of printed electoral matter, it did so in the context of seeking to achieve the objects in s 321C(1).

97 I reject the applicants’ argument that the word “prominent” as used in cl 11(3)(a) should be understood in the same way as it was used in s 53C(1)(c) of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) and s 48(1) of the Australian Consumer Law in Sch 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), being the legislative provisions discussed in TPG Internet (2011) ATPR 42-383 and viagogo [2019] FCA 544. Those decisions dealt with consumer protection legislation that provided that a person who made a representation with respect to the amount that, if paid, would constitute a part of the consideration for the supply of goods or services, contravened the Act unless the person also “specifies, in a prominent way, and as a single figure, the single price for the goods or services”. Likewise, in Rose [2016] VSCA 169, the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of Victoria considered the operation of cl 28.4(a)(i)-(iv) of the Code of Banking Practice published by the Australian Bankers’ Association in May 2004 which required a bank to give to a prospective guarantor “a prominent notice” of the matters required by those provisions.

98 Each of the three above decisions, on which the applicants relied, was dealing with provisions intended to protect a consumer or guarantor who may have been induced to enter into potentially a disadvantageous contract unless the specific matters prescribed were drawn to the attention of the consumer or guarantor by a “prominent” statement in the document conveying the representations about the prospective dealing. None of the legislation considered there qualified the word ‘prominent’ with an adverb such as ‘reasonably’. In that context, it is unsurprising that the Courts found that the purpose for which the provision concerned required the representor to give the prescribed information to the prospective consumer or guarantor in “a prominent way” or by “a prominent notice” was so that he or she could be expected to use, or have regard to, that information in deciding whether to proceed.

99 For the same reasons, I also reject the applicants’ argument in respect of both cl 11(3)(a) that “the larger the other text, the larger the particulars” of authorisation should be, for the reasons I have given above.

100 The context and purpose of Pt XXA of the Electoral Act and a determination made under s 321D(7) is to ensure the achievement of the Parliament’s objectives in s 321C(1), mindful of the constraints on its legislative power imposed by the implied freedom, that, first, a voter can know who authorised the communication of electoral matter, secondly, if he or she wants to, a voter can find the particulars of its author’s name and address at the end of the communication, where it is required to be placed (by cl 11(2)(b)), and thirdly, the requirement for the inclusion in a communication of electoral matter be done in a manner that does not alter the character of the communication itself by the notification of that information. As I have explained, the word “reasonably” as used in cl 11(3)(a) attenuates the meaning of “prominent” by respecting the balance that the Parliament intended to strike in Pt XXA in a way that would ensure that the burden on the implied freedom remains no more than is reasonable and proportionate.

101 Accordingly, I am of opinion that the requirement in cl 11(3)(a) that the particulars be “reasonably prominent” must be read in the context of the available space on the medium concerned and the fact that it must be effective to communicate the electoral matter which it is intended to convey, while including in a distinct way the particulars of authorisation as well as complying with the other requirements in cl 11(3). The purpose of requiring particulars to be “reasonably prominent” is to enable them to be found on the medium in a reasonable way so that the objects in s 321C of promoting free and informed voting will be enhanced: that is, so that they can be “clearly identifiable” as the notification, in the communication, of its authorisation by a notifying entity (as s 321C(2)(b) sought). The word “reasonably” in cl 11(3)(a) must be understood as intended to ensure that the prominence of the particulars will be of the character that enables a voter to find the particulars of authorisation without difficulty where they should be (as required by cl 11(2)(b)) at the end of the communication, that is, that they be identifiable to a voter who is interested to find them, as the particulars notifying the authorisation.

The construction of “legible at a distance at which the communication is intended to be read” in cl 11(3)(b)

102 The requirement in cl 11(3)(b) is at first glance capable of appearing confusing. Each of the applicants, Mr Kelly and the Attorney-General said that it could not be read to impose an obligation to use the same font size as the largest lettering on the posters the subject of this proceeding. As I have noted above, the applicants contended that the larger the size of the font in the communication, the larger the particulars of authorisation had to be, without, however, suggesting any objective standard to create a relationship between the two, or what size would suffice.

103 The requirements in cl 11(3) apply distributively to the particular medium comprising a printed communication, and obviously must be adapted to that medium. The nature of the medium of communication of electoral matter must affect the font and size of any authorisation appearing on it. The size of the font used on a fridge magnet to notify an authorisation must be adapted to respect the surface area of the fridge magnet itself and the fact that the remaining surface area is intended to carry the communication of the electoral material. Obviously, a fridge magnet could be expected to be small and affixed to a magnetic surface. The authorisation, comprising an individual’s name and address, necessarily will be no less than the words “authorised by” together with an initial or first name, a surname, a street number, the name of the street (being at least two words), the city or suburb and possibly the State or Territory, all of which have varying lengths. For example, I have set out Mr Kelly’s authorisation particulars at [23]-[24] above.

104 A sticker could be affixed to a motor vehicle. A how-to-vote leaflet, card, flyer or pamphlet can be expected to be held in one’s hand. And, a poster, such as Mr Kelly’s, can be put up in a variety of locations, viewed by various audiences and from various distances. For example, the poster erected on a telegraph pole near Sutherland Train Station was able to be viewed from the street, either by pedestrians or persons driving past in their cars. No one would expect that particulars of an authorisation of the length needed to comply with item 3 in the table to s 321D(5) that must appear on a sticker placed on a car’s rear window or bumper bar would be legible to other road users while the car was in motion, stationary in traffic or parked, even though its communication of electoral matter would be legible to other road users. Yet, such particulars of an authorisation should readily be legible if a voter approached the car when parked and looked at close range for it at the end of the sticker, provided that the other requirements of cl 11(3) were met, including that, in its position at the end of the sticker, it was reasonably prominent.

105 The expression “legible at a distance” (emphasis added) used in cl 11(3)(b) appears to recognise that there may, and often will, be more than one distance at which the communication of electoral matter is intended to be read. A large corflute or a billboard with both big and smaller writing may be expected to be legible or read differently at different distances. Here, some of the writing on Mr Kelly’s 8pt authorisation posters was very large and could be seen from quite a distance, while the black band of material written on it in white towards the base of the portrait corflutes or the top of the landscape ones would only be legible as the voter moved closer. And, the 8pt authorisation would only be legible if the voter moved much closer still. However, it would not be realistic to think that one size fits all so that the proportionate size of an authorisation on a poster could satisfy cl 11(3)(b) by appearing in the same way as one on a fridge magnet or a sticker might. A voter may have to pick up or walk very close to a fridge magnet or a sticker and look closely at it to see the authorisation, or for that matter, its communication of electoral matter, both of which may have a different proportionate relationship to the medium.

106 If the electoral matter is intended to be read at a close distance, regardless of whether it, or parts of it, is also intended to be read further away, cl 11(3)(b) will be satisfied if the authorisation is legible only at the close distance. That is because s 321C(2)(b) specifies the legislative purpose of “ensuring that the particulars are clearly identifiable, irrespective of how the matter is communicated”. The Parliament’s concern was to ensure that one could clearly identify the authorisation, in its character as giving particulars of the notifying party, included in the medium used for the communication of electoral matter, but not that the particulars became part, or altered the character, of the communication itself, although at some distance it may do so.

107 It is necessary to read cl 11(3) as a whole, in the context that it was intended to give effect to the objects of Pt XXA of the Electoral Act as the Parliament expressed in s 321C, and to determine how a natural person would “notify” particulars set out in item 3 of the table to s 321D(5) in accordance with the requirements that cl 11(3) specified, pursuant to s 321D(5) and (7)(b)(i). The Parliament chose the word “notify” to describe the function of the authorisation as being different from the function of the communication of electoral matter of which it must form part. The notification is intended to ensure that the person authorising that communication is clearly identifiable in it and that the author was not anonymous. But the Parliament did not intend that every possible communication on any medium always had to convey the authorisation itself to a voter seeing or reading only part of it from any specific distance. Rather, it intended that notification of an authorisation would be sufficient so long as the medium of the communication included that notification in a clearly identifiable manner to enable a voter, who wished, to ascertain the particulars from looking at the end of that medium.

108 In his explanatory statement, the Commissioner set out his understanding of how and why cl 11(3) was intended to operate as follows: