Federal Court of Australia

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Meta Platforms Inc [2023] FCA 842

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION & CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent ONAVO INC Second Respondent FACEBOOK ISRAEL LTD Third Respondent | |

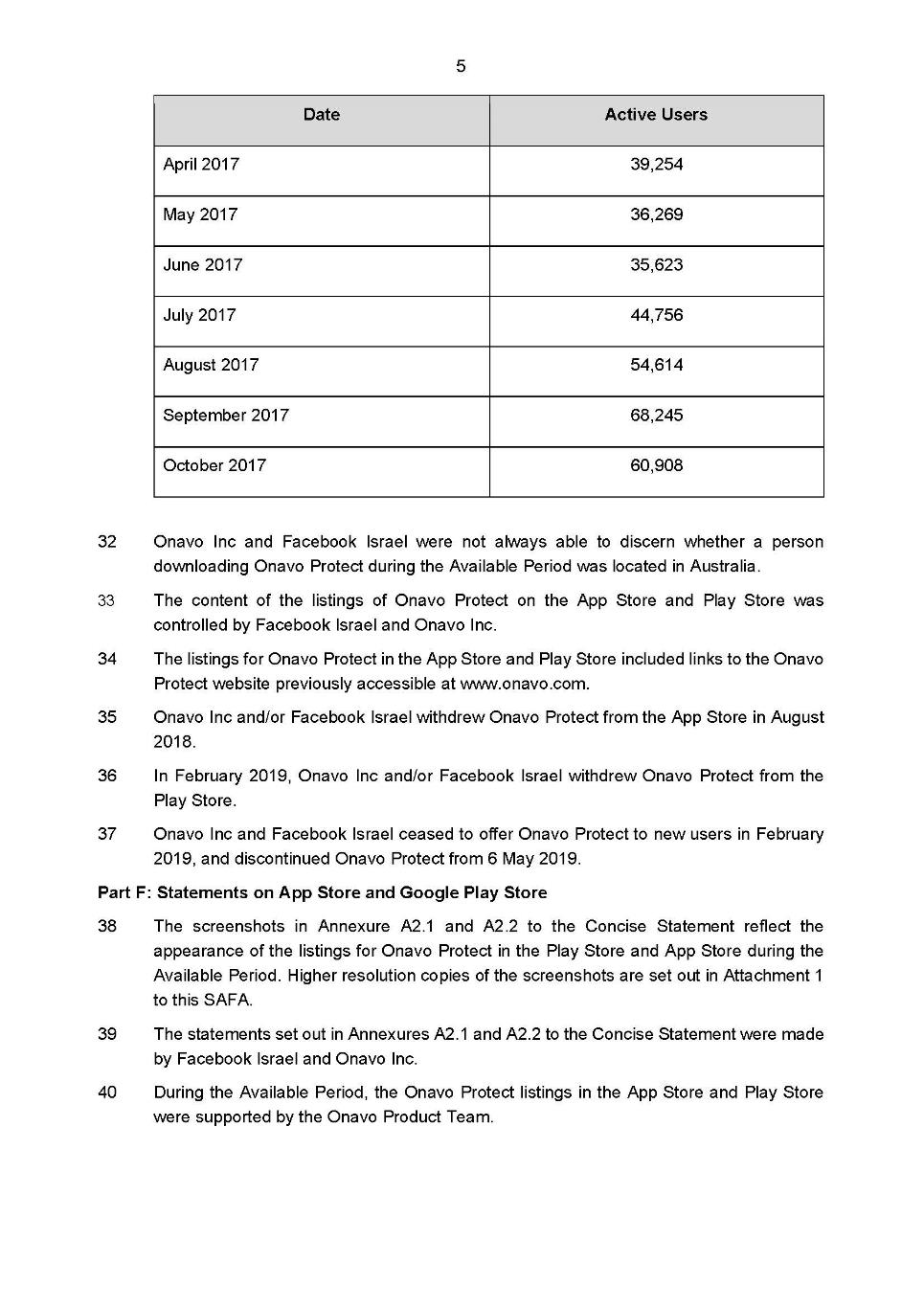

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

In these declarations and orders, terms have the following effect:

(a) ACL means the Australian Consumer Law contained in Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth).

(b) Onavo Protect means the free, downloadable software application for mobile devices known as Onavo Protect.

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. Facebook Israel Ltd. did, in trade or commerce, in the period between 1 February 2016 and 31 October 2017 contravene ss 18 and 33 of the ACL by advertising and promoting Onavo Protect in the listings for the Google Play Store and Apple App Store in the form set out in Schedule A to these orders without making disclosures to Australian consumers that were sufficiently prominent and proximate to those listings that users’ data would be used for purposes other than providing Onavo Protect.

2. Onavo, Inc. did, in trade or commerce, in the period between 1 February 2016 and 31 October 2017 contravene ss 18 and 33 of the ACL by advertising and promoting Onavo Protect in the listings for the Google Play Store and Apple App Store in the form set out in Schedule A to these orders without making disclosures to Australian consumers that were sufficiently prominent and proximate to those listings that users’ data would be used for purposes other than providing Onavo Protect.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 224(1) of the ACL, within 30 days of the date of this order, Facebook Israel Ltd. pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty of $10,000,000 in respect of the conduct of Facebook Israel Ltd. in the declaration in paragraph 1 declared to be a contravention of s 33 of the ACL.

2. Pursuant to s 224(1) of the ACL, within 30 days of the date of this order, Onavo, Inc. pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty of $10,000,000 in respect of the conduct of Onavo, Inc. in the declaration in paragraph 2 declared to be a contravention of s 33 of the ACL.

3. Pursuant to s 43 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), within 30 days of the date of this order, Facebook Israel Ltd. and Onavo, Inc. pay a contribution of $400,000 to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s costs of and incidental to the proceeding.

4. The proceeding otherwise be dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

SCHEDULE A

ABRAHAM J:

1 The first and second respondents, Onavo Inc (Onavo) and Facebook Israel Limited (Facebook Israel), offered a free, downloadable software application (or app) for mobile devices, known as “Onavo Protect” on the Google Play Store (Play Store) and the Apple App Store (App Store) in Australia.

2 Onavo and Facebook Israel admit contraventions of ss 18 and 33 of the Australian Consumer Law, contained in Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA). The contraventions occurred during the period from 1 February 2016 to 31 October 2017 (Available Period), when Onavo and Facebook Israel advertised and promoted Onavo Protect on the Play Store and App Store in Australia (in the form set out in Schedule A to the orders) (the Listings), without making disclosures to Australian consumers that were sufficiently prominent and proximate to those Listings that data collected from users of Onavo Protect would be used for purposes other than providing Onavo Protect. While Onavo Protect was advertised and promoted as protecting users’ personal information and keeping their data safe, in fact, Facebook Israel and Onavo used the app to collect an extensive variety of data about users’ mobile device usage. An anonymised and aggregated form of that data was provided to their parent company, Meta Platforms Inc (Meta), and used by Meta for a range of commercial purposes.

3 This hearing proceeded by way of a Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions (SAFA) agreed between the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) and the respondents, reproduced at Annexure A, and joint submissions on penalty. The summary that follows is taken from those agreed documents. The parties have agreed proposed declarations and orders, which include pecuniary penalty orders of $10 million each against Facebook Israel and Onavo in relation to their contraventions of s 33 of the ACL.

4 For the reasons below, declarations are made in the terms sought and the proposed pecuniary penalty totalling $20 million is imposed.

The Contravening Conduct

5 Facebook Israel and Onavo admit that they offered, advertised and promoted Onavo Protect and made the app available to download by users in Australia via the App Store (for iOS users) and the Play Store (for Android users) during the Available Period: SAFA [18], [22] and [67]. Onavo Protect was only available for download and installation by people using mobile devices: SAFA [25].

6 During the period from December 2016 to 31 October 2017, once installed on a device, Onavo Protect provided all Australian users a VPN service, and users of the Android version data management services that allowed a user to track and block data usage, limit specific apps to use only Wi-Fi, and set data limits: SAFA [11]. A VPN service uses encryption and other security mechanisms designed to provide secure transmission, across a public or private network, of a user’s app and web traffic. Features of a VPN service may be used to protect the user’s privacy and anonymity: SAFA [12]-[13].

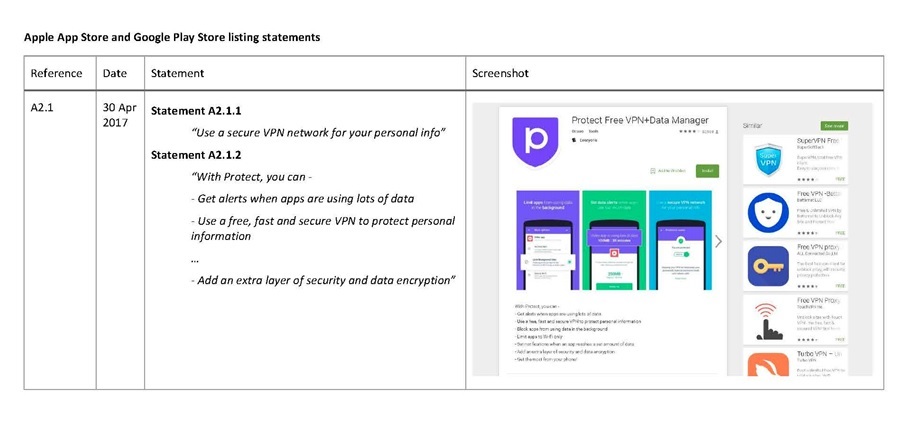

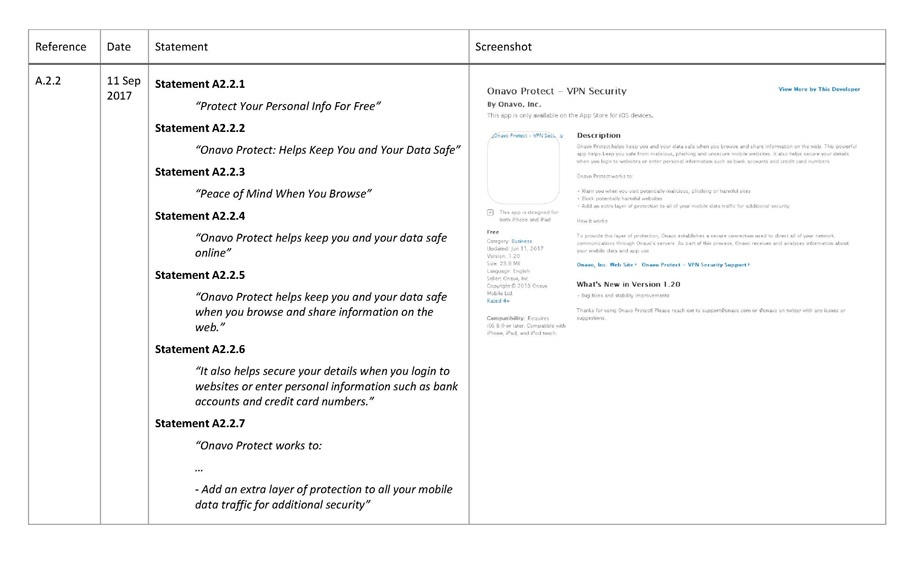

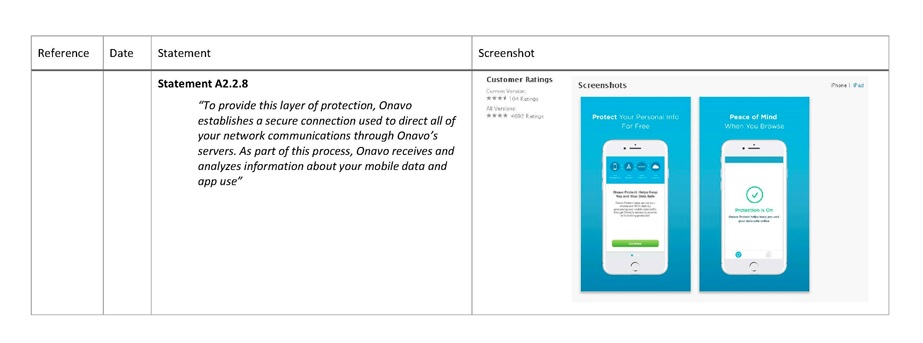

7 Facebook Israel and Onavo further admit that the Listings contained each of the following statements made by Facebook Israel and Onavo during the Available Period (together, the Statements): SAFA [38]-[39].

(a) In the Play Store listing:

(i) “Use a secure VPN network for your personal info”

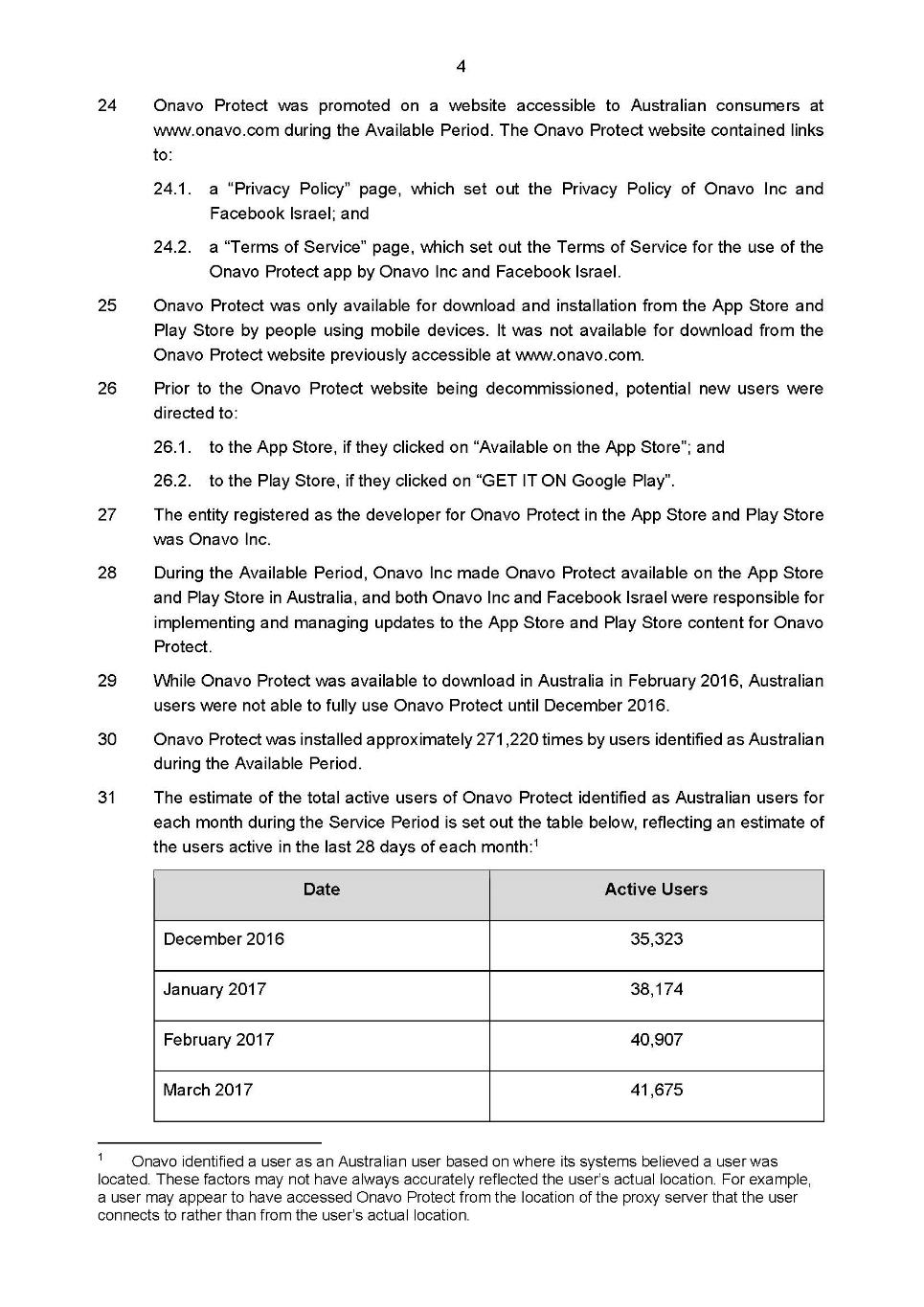

(ii) “With Protect, you can - - Get alerts when apps are using lots of data - Use a free, fast and secure VPN to protect personal information … - Add an extra layer of security and data encryption”

(b) In the App Store listing:

(i) “Protect Your Personal Info For Free”

(ii) “Onavo Protect: Helps Keep You and Your Data Safe”’

(iii) “Peace of Mind When You Browse”

(iv) “Onavo Protect helps keep you and your data safe online”

(v) “Onavo Protect helps keep you and your data safe when you browse and share information on the web.”

(vi) “It also helps secure your details when you login to websites or enter personal information such as bank accounts and credit card numbers.”

(vii) “Onavo Protect works to: … - Add an extra layer of protection to all your mobile data traffic for additional security”

(viii) “To provide this layer of protection, Onavo establishes a secure connection used to direct all of your network communications through Onavo’s servers. As part of this process, Onavo receives and analyzes information about your mobile data and app use”.

8 As well as providing a VPN service to Onavo Protect users, Facebook Israel and Onavo collected a range of data from users through the app and provided that data to Meta: SAFA [47], [53]. Once a user had downloaded Onavo Protect and activated its VPN functionality, a secure connection was established between the user and the servers operated for Onavo Protect (Onavo Protect Servers), and the user’s online activity (app use and web traffic) on the relevant mobile device could be transmitted through the Onavo Protect Servers: SAFA [15]-[16]. The Onavo Protect Servers also received a variety of information about the user’s app usage. I return to address the types of data collected by the app below at [36], (collectively, the Onavo Protect Data). If an Australian user of Onavo Protect had a Facebook account, Meta was also able to combine that user’s Onavo Protect Data with information that Meta maintained about the user’s Facebook account, using an algorithm: SAFA [56].

9 Meta and Facebook Israel’s internal documents state that Onavo Protect was “a business intelligence tool” for Meta, which provided Meta with “a sample of users who we are able to know nearly everything they are doing on their mobile device” (which was in the form of anonymised, aggregated data): SAFA [53]. Meta then used anonymised and aggregated data derived from sets of the Onavo Protect Data (in the form of statistical information) for a range of purposes, including in relation to its advertising and marketing activities, improving its products and services and developing commercial strategies: SAFA [54].

10 Disclosures concerning how Australian consumers’ data would be used for purposes other than providing Onavo Protect were contained in the Terms of Service and Privacy Policy for Onavo Protect: SAFA [43]-[46]. However, these disclosures were not sufficiently prominent or proximate to the Listings. The Terms of Service and Privacy Policy were available to Australian Consumers during the Available Period via links on a website promoting Onavo Protect: SAFA [24]. Users were also taken through a page containing a link to those documents when opening Onavo Protect for the first time: SAFA [43]. For four months of the Available Period, iOS users of Onavo Protect would see text in addition to the links, as set out at SAFA [46].

11 Facebook Israel and Onavo admit that, given the above facts, the Listings that contained the Statements were likely to mislead or deceive (within the meaning of s 18 of the ACL), and liable to mislead the public (within the meaning of s 33 of the ACL), in the absence of sufficient disclosures to Australian consumers (which they admit were not made in those Listings) of the fact that Australian users’ data would be used for purposes other than providing Onavo Protect: SAFA [67].

12 As indicated above, the parties jointly submitted the Court should make declarations in the form they proposed, and impose a pecuniary penalty against Facebook Israel and Onavo. For the reasons below, I make the orders sought.

Legal principles

13 I recently summarised the principles relevant to imposing a pecuniary penalty in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Insurance Australia Limited, in the matter of Insurance Australia Limited [2023] FCA 724. I rely on that summary in large part below.

Pecuniary penalty

14 The purpose of a civil penalty is primarily protective, in promoting the public interest in compliance by deterring further contravening conduct: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson (Pattinson) [2022] HCA 13; (2022) 399 ALR 599 at [15]-[16], [43] and [45]. A penalty of appropriate deterrent effect “must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not such as to be regarded by [the] offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business”: Pattinson at [17] citing Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; (2012) 287 ALR 249 at [62].

15 Section 224(2) of the ACL provides that in determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the Court must have regard to all relevant matters. Those matters include: the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and whether the person has previously been found by the court in proceedings under Chapter 4 or Part 5-2 (in which s 224(2) is located) to have engaged in any similar conduct. The Court is to decide what penalty is “appropriate” in all the circumstances.

16 In addition, there are a number of factors identified in the authorities, relevant to this task. For example, the assessment of penalty of appropriate deterrent value will have regard to: (1) the nature and extent of the contravening conduct; (2) the amount of loss or damage caused; (3) the circumstances in which the conduct took place; (4) the size of the contravening company; (5) the degree of power it has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market; (6) the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended; (7) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level; (8) whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance, as evidenced by educational programs or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention; and (9) whether the company has shown a disposition to co-operate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to contravention: Pattinson at [18]. These are not to be considered to be a rigid list of factors to be ticked off: Pattinson at [19]. Rather, they are to inform a multifactorial investigation that leads to a result arrived at by a process of “instinctive synthesis” addressing the relevant considerations: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; (2016) 340 ALR 25 (Reckitt Benckiser) at [44].

17 The maximum penalty is also one of the relevant factors. In this regard, in Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; (2005) 228 CLR 357, the majority observed at [31]:

…careful attention to maximum penalties will almost always be required, first because the legislature has legislated for them; secondly, because they invite comparison between the worst possible case and the case before the court at the time; and thirdly, because in that regard they do provide, taken and balanced with all of the other relevant factors, a yardstick.

18 In a civil penalty context, the relevance of a prescribed maximum penalty as a yardstick was explained by the Full Court of the Federal Court in Reckitt Benckiser at [155]-[156] as follows:

The reasoning in Markarian about the need to have regard to the maximum penalty when considering the quantum of a penalty has been accepted to apply to civil penalties in numerous decisions of this Court both at first instance and on appeal (Director of Consumer Affairs, Victoria v Alpha Flight Services Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 118 at [43]; Australian, Competition and Consumer Commission v BAJV Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 52; (2014) ATPR 42-470 at [50]-[52]; Setka v Gregor (No 2) [2011] FCAFC 90; (2011) 195 FCR 203 at [46]; McDonald v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner [2011] FCAFC 29; (2011) 202 IR 467 at [28]-[29]). As Markarian makes clear, the maximum penalty, while important, is but one yardstick that ordinarily must be applied.

Care must be taken to ensure that the maximum penalty is not applied mechanically, instead of it being treated as one of a number of relevant factors, albeit an important one. Put another way, a contravention that is objectively in the mid-range of objective seriousness may not, for that reason alone, transpose into a penalty range somewhere in the middle between zero and the maximum penalty. Similarly, just because a contravention is towards either end of the spectrum of contraventions of its kind does not mean that the penalty must be towards the bottom or top of the range respectively. However, ordinarily there must be some reasonable relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty imposed.

19 This passage was more recently cited with approval in Pattinson at [53].

20 Where the theoretical maximum penalty is in the billions or trillions of dollars, the overall maximum penalty will not be a meaningful factor in the court’s assessment. In these circumstances, the appropriate range is best assessed by reference to factors other than where the conduct falls in the range of seriousness of offending in relation to the maximum penalty: Reckitt Benckiser at [157].

21 Ordinarily separate contraventions arising from separate acts should attract separate penalties. However, where separate acts give rise to separate contraventions which are inextricably interrelated, they may be regarded as a “course of conduct” for penalty purposes: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; (2018) 262 FCR 243 (Yazaki) at [234]. This avoids double-punishment for those parts of the legally distinct contraventions that involve overlap in wrongdoing: see for example, Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; (2010) 269 ALR 1 at [39] and [41]. However, “[i]t is not appropriate or permissible to treat multiple contraventions as just one contravention for the purposes of determining the maximum limit dictated by the relevant legislation”: Yazaki at [227]. “It cannot in itself operate as a de facto limit on the penalty to be imposed for contraventions”: Reckitt Benckiser at [141] quoting Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Hillside (Australia New Media) Pty Ltd (t/as Bet365) (No 2) [2016] FCA 698 at [24]–[25].

22 The principle of totality requires the Court to make a “final check” of the penalties to be imposed on a wrongdoer, considered as a whole, to ensure that the total penalty does not exceed what is proper for the entire contravening conduct: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd [1997] FCA 450; (1997) 145 ALR 36 at 53, citing Mill v The Queen [1988] HCA 70; (1988) 166 CLR 59.

23 An appropriate penalty is therefore one that is fashioned by reference to the facts of the particular case before the Court, in order to arrive at a penalty that is sufficient to deter the conduct in question, without being overly oppressive: Pattinson at [46].

24 The principles to be applied in considering a jointly proposed penalty were considered in Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; (2015) 258 CLR 482 (DFWBII), where the majority observed at [46]:

[T]here is an important public policy involved in promoting predictability of outcome in civil penalty proceedings and that the practice of receiving and, if appropriate, accepting agreed penalty submissions increases the predictability of outcome for regulators and wrongdoers. As was recognised in Allied Mills and authoritatively determined in NW Frozen Foods, such predictability of outcome encourages corporations to acknowledge contraventions, which, in turn, assists in avoiding lengthy and complex litigation and thus tends to free the courts to deal with other matters and to free investigating officers to turn to other areas of investigation that await their attention.

25 Further, their Honours said at [58]:

... Subject to the court being sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the penalty which the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances thus revealed, it is consistent with principle and ... highly desirable in practice for the court to accept the parties’ proposal and therefore impose the proposed penalty.

(emphasis added)

26 Those observations about the desirability of acting upon agreed penalty submissions were made in the context of a broader recognition that as a civil litigant in civil proceedings, civil penalties are but one of numerous forms of relief which regulators can pursue, and it is entirely orthodox for regulators to make submissions as to that relief: see DFWBII at [24], [57]-[59], [63], [103], [107]. Those principles to be applied in considering a jointly proposed penalty were recently considered in Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2021] FCAFC 49; (2021) 284 FCR 24 (Volkswagen) at [124]-[131], referring to DFWBII, NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition Commission [1996] FCA 1134; (1996) 71 FCR 285 and Minister for Industry, Tourism and Resources v Mobil Oil Australia Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 72; (2004) ATPR 41-993. A number of points were highlighted, including: first, the Court must be satisfied that the penalty proposed by the parties is appropriate: at [125]; second, if persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and that the proposed penalty is an appropriate remedy, it is highly desirable for the Court to accept the proposal: at [126]; third, in considering whether the proposed penalty is appropriate, it is necessary to bear in mind that there is no single appropriate penalty, but rather a permissible range. The proposed penalty may be “an” appropriate penalty if it falls within that range: at [127]; fourth, the Court should generally recognise that the proposed penalty was most likely a result of compromise and pragmatism on the part of the regulator, and while the regulator must estimate the penalty necessary to achieve deterrence, the Court must assess the proposed penalty on its merits, being wary of the possibility that the regulator may have been too pragmatic: at [129]; fifth, the Court’s task is not limited to simply determining whether the jointly proposed penalty is within the permissible range, though that might be expected to be a highly relevant and perhaps determinative consideration. The overriding statutory directive is for the Court to impose a penalty that is determined to be appropriate having regard to all relevant matters: at [131].

Declaration

27 The power to grant declaratory relief pursuant to s 21 of Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) "is a very wide one" and the court is "limited only by its discretion": Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd [2009] FCAFC 166; (2009) 182 FCR 160 at [1016], citing Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd [1972] HCA 61; (1972) 127 CLR 421 (Forster) at 435. Three requirements need to be satisfied before making declarations: (1) the question must be a real and not a hypothetical or theoretical one; (2) the applicant must have a real interest in raising it; and (3) there must be a proper contradictor: Forster at 437-438. That a party has chosen not to oppose a grant of particular declaratory relief is not an impediment to such relief being granted by the Court: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd [2012] FCAFC 56; (2012) 201 FCR 378 at [14], [30]-[33]. Other factors relevant to the exercise of the discretion include: (a) whether the declaration will have any utility; (b) whether the proceeding involves a matter of public interest; and (c) whether the circumstances call for the marking of the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct: ASIC v Pegasus Leveraged Options Group Pty Ltd [2002] NSWSC 310; (2002) 41 ACSR 561 at 571; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Monarch FX Group Pty Ltd, in the matter of Monarch FX Group Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1387; (2014) 103 ACSR 453 at [63]; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Stone Assets Management Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 630; (2012) 205 FCR 120 at [42].

28 Even where there is agreement between the parties in respect of proposed declarations, it remains for the Court to decide whether declaratory relief is appropriate: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v MLC Nominees [2020] FCA 1306; (2020) 147 ACSR 266 at [109].

Consideration

29 Given the agreement between the parties it is unnecessary to recite the submissions in detail.

30 That said, I make the following observations, taken in large part from the submissions.

31 First, under item 3 of s 224(3) of the ACL, the maximum pecuniary penalty for each contravention of s 33 of the ACL during the Available Period was $1.1 million. Pursuant to s 224(1)(a)(ii), if satisfied a person has contravened a relevant provision of the ACL (including s 33), the Court may order a person to pay a pecuniary penalty in respect of each contravening act or omission by the person. A contravention of s 33 occurred each time an Australian consumer accessed the Listings containing one or more of the Statements and read the Statements: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v La Trobe Financial Asset Management Ltd [2021] FCA 1417; (2021) 158 ACSR 363 at [91].

32 Although the precise number of occasions on which an Australian consumer viewed the Listings for Onavo Protect is unknown, during the Available Period, it was installed by Australian users on 271,220 separate occasions: SAFA [30]. Even if only half of the total downloads were made by separate Australian consumers, it still implies a maximum penalty of more than $145 billion. As raised above, the maximum penalty, while important, is “but one yardstick that ordinarily must be applied” and must be treated “as one of a number of relevant factors”: Pattinson at [54]. That said, although the theoretical maximum remains relevant, it is so vast as to make precise calculation unnecessary and unhelpful, if it were even possible, and the penalty is best assessed by reference to other factors: Reckitt Benckiser at [157].

33 Second, I accept the contraventions can be characterised as a single course of conduct. Although Onavo Protect was made available on two different platforms (the App Store to iOS users and the Play Store to Android users), the Listings on each of those platforms contained similar Statements made by Facebook Israel and Onavo that are the basis for the admitted contraventions.. The statements were present in the Listings over many months. Onavo was registered as the developer for Onavo Protect in the App Store and Play Store and made it available on both platforms: SAFA [27]-[28]. The Onavo Product Team, mostly employed by Facebook Israel, was responsible for the development of Onavo Protect and writing the content of the Listings: SAFA [21], [43]. Facebook Israel and Onavo were both responsible for Onavo Protect, and for controlling and updating the content of the Listings: SAFA [28], [33].

34 Third, the nature and circumstances of the contraventions are undoubtedly serious. The Listings for Onavo Protect conveyed that Onavo Protect users’ data would only be used for purposes of providing the Onavo Protect VPN and data management services, but did not mention that Onavo Protect also collected and supplied data about Australian users’ online activities to the respondents for other purposes. The failure to make sufficient disclosures in the Listings for Onavo Protect may have deprived tens of thousands of Australian consumers of the opportunity to make an informed choice about the collection and use of their data before downloading and/or using Onavo Protect. Significantly, data about the online activities of those Australian consumers was able to be obtained and used (albeit, on an anonymised and aggregated basis) for purposes other than for the VPN and data management functions and services offered by Onavo Protect, without adequate disclosure that this was occurring. This is in the context where consumers had expected to download an app that would “protect [their] personal information” and “keep [their] data safe” (as promoted in the Listings). The conduct that was liable to mislead the public went to the heart of the nature and characteristics of Onavo Protect, given the purpose for which it was promoted in the Listings. The conduct occurred as part of Facebook Israel and Onavo’s efforts to advertise and promote Onavo Protect, with a view to encouraging Australian consumers to download and activate the app.

35 The ACCC submitted that it is significant that users of Onavo Protect were only asked to accept the Terms of Service having already been induced to download the app. The ACCC noted the Terms of Service were 12 pages long and had no summary. Moreover, the Terms of Service themselves did not disclose that users’ data would be provided to Meta, rather, consumers were required to follow a separate link to the Privacy Policy to understand how their data would be used. The Privacy Policy was itself 10 pages long. I accept those submissions. Plainly the conditions contained in the Terms of Service and Privacy Policy, when considered together with the statements in the Listings, were not sufficient to modify the contravening conduct: Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Limited [2004] HCA 60; (2004) 218 CLR 592 at [151].

36 Fourth, the seriousness and impact of the contraventions is readily apparent from the detail of what actually occurred. Facebook Israel and Onavo collected the following types of data from Onavo Protect users through the Onavo Protect app and provided that data to their parent company, Meta (SAFA [47]):

(1) information about the user's device, including the type of device, its operating system, the mobile carrier or network, IP address, location information (such as the user's country or region), and unique device identifiers (for example, the Android device identifier available to developers and the iOS advertiser ID);

(2) information about the user's mobile applications and data usage, including the names and details of the applications installed on the user's device, the user's use of those applications (for example, information relating to the frequency with which users accessed applications, the time spent in those applications, and the actions taken by the user within those applications), the websites visited by the user (for example, domain names and uniform resource locators (URL)), and the amount of data the user used;

(3) log information and other data from the user's device, such as each webpage address visited (i.e., the exact URL and the different parameters attached to it) and data fields (i.e., the fields in the URL of the webpage address such as referral URL and ad network);

(4) metadata about the volume of traffic, user agent and domain when mobile data was transferred through the Onavo Protect servers; and

(5) location-related information when the user accessed location-based services, or based on IP addresses.

It is plain from that summary and the summary at [9] that Onavo Protect operated to collect extensive data about its Australian users for use by Meta in a wide range of commercial applications. The breadth and depth of the data and the purposes for which it was collected reinforce the seriousness of the admitted contraventions.

37 Fifth, during the Available Period, Onavo Protect was installed by Australian users on approximately 271,220 separate occasions. Although Australian consumers suffered no financial loss given Onavo Protect was free to download, financial loss is not the only measure of harm that is relevant. I accept, as submitted by the ACCC, that a consumer who was interested to download Onavo Protect was a consumer that was concerned about their online privacy. The ability of Australian consumers to make fully informed choices about the collection and use of their data by apps downloaded from App Store and Play Store listings is a “serious matter” which ought to be recognised by the Court in imposing a pecuniary penalty under the ACL: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Google LLC (No 4) [2022] FCA 942 at [40]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Uber B.V. [2022] FCA 1466 at [14]-[15]. It has been accepted that in general terms, the maintenance of a fair, reliable and efficient market depends upon consumers having confidence that they are being given reliable and accurate information. If misrepresentations to consumers are not seen to attract appropriate penalties, consumer confidence will be undermined: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Birubi Art Pty Ltd (in liq) [2019] FCA 996; (2019) 374 ALR 776 at [29].

38 Sixth, neither Facebook Israel, nor Onavo has previously been found to have contravened the ACL: SAFA [66].

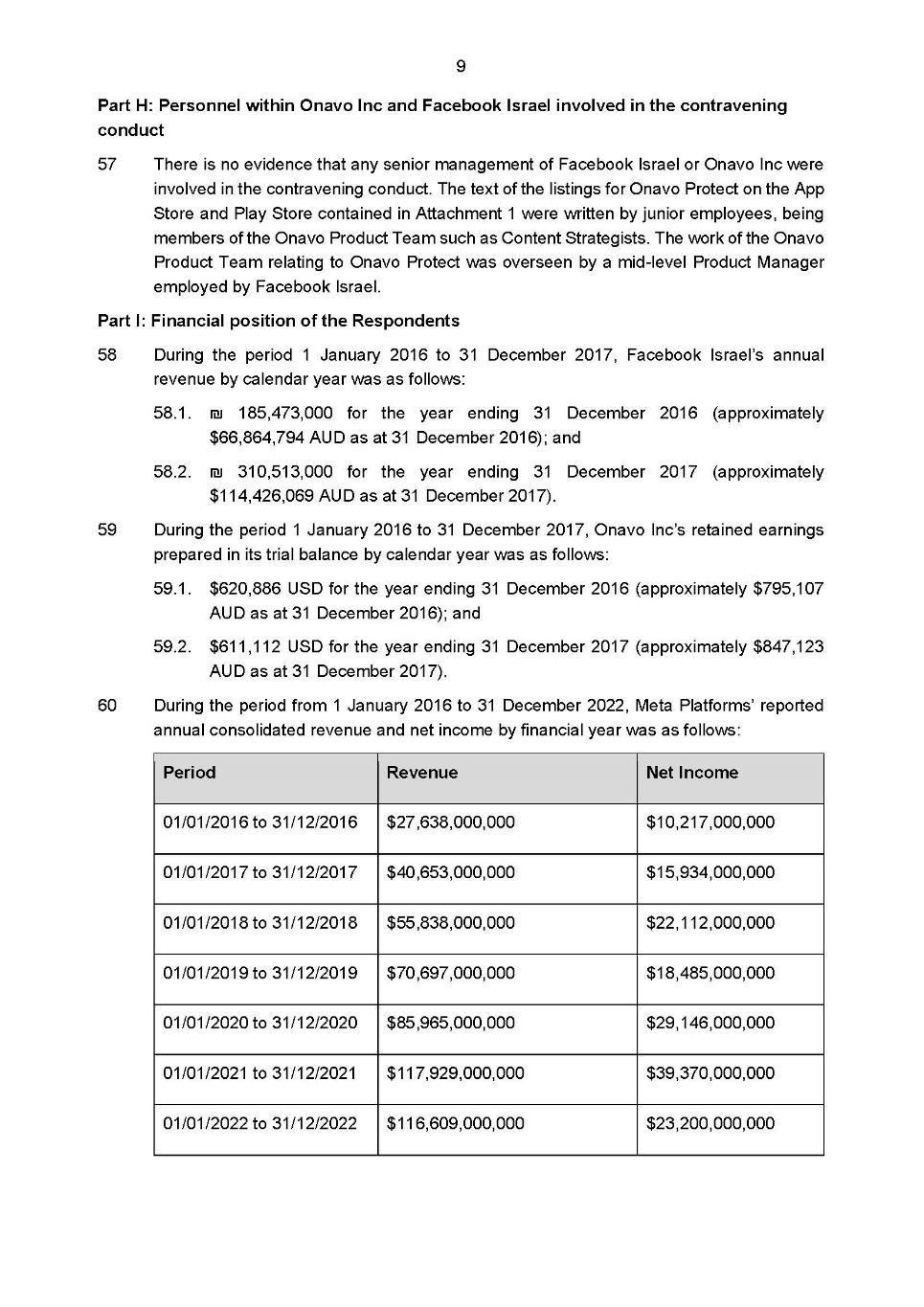

39 Seventh, the size and financial position of the contravening companies is set out in some detail at SAFA [58]-[60]. I accept, as the respondents submitted, that the proposed penalties are significant when regard is had to the size of the contraveners. Facebook Israel and Onavo are both indirect wholly owned subsidiaries of Meta: SAFA [8]-[9]. During the period from 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2022, Meta’s reported annual consolidated revenue and net income by financial year is also detailed in the SAFA. I note that although Meta was involved in the use of the aggregated and anonymised data, it is agreed that it was not involved in the contravening conduct. That said, as the parties submitted, as deterrence necessitates that the penalty imposed carry a sufficient sting or burden, so as not to be seen as a mere cost of doing business, it is important that the penalty in the present case has regard to Meta’s substantial resources: Australian Competition Consumer Competition v GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2020] FCA 724 at [50]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Oakmoore Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCA 1170 at [105].

40 Eighth, although the Listings for Onavo Protect containing the Statements were deliberately made available to the public, it is agreed that they were not deliberately misleading.

41 Ninth, there is no evidence that any senior management of Facebook Israel or Onavo were involved in the contravening conduct: SAFA [57]

42 Tenth, Facebook Israel and Onavo admitted contravening the ACL, and agreed to the proposed orders and to make joint submissions on penalty. Prior to that, Onavo and Facebook Israel cooperated and engaged with the ACCC in relation to the investigation and subsequent litigation, including that they: provided information to the ACCC on a voluntary basis and responded to three notices issued by the ACCC under s 155 of the CCA; after the proceeding began (and issues relating to service of the proceeding had been resolved), worked collaboratively with the ACCC on case management issues such that only one case management hearing was held in the course of the proceeding; and engaged in settlement discussions with the ACCC and reached agreement to resolve the proceeding on the basis of the proposed relief, without the need for a contested hearing or a court-ordered mediation. It was accepted that this resulted in meaningful cost and time savings to the ACCC and the Court, despite the admissions of contravention having not been made until immediately prior to trial.

43 Eleventh, the Onavo Protect app is no longer available for download or available for use, nor is it advertised or promoted to consumers.

Conclusion

44 Having considered the facts as agreed, the joint submissions of the parties, the evidence relied on, the contraventions and relevant principles, I am satisfied that it is appropriate to order the pecuniary penalty in the amount agreed and make the declarations sought.

45 The ACCC emphasised that the proposed cumulative penalty reflects its pragmatic assessment that the public interest is best served by bringing this proceeding to a conclusion on the agreed terms, citing the observations of Keane J in DFWBII at [108]-[109] as being particularly pertinent:

… In determining whether to commence, continue or compromise proceedings in pursuit of that task, the Commissioner may be expected to weigh broad considerations of cost and benefit in order to maximise the impact of the performance of the Commissioner’s functions given the relative scarcity of resources available for that purpose.

… the willingness of the Commissioner to accept a particular sum by way of civil penalty in discharge of the Commissioner’s claim against the defendant can be expected to reflect a considered estimation that, given the hazards and expense of litigation, satisfaction of the Commissioner’s claim against the defendant on such terms is apt to advance the public interest in the enforcement of the regulatory regime more effectively and efficiently than the continued prosecution of the claim. Those considerations may include the cost of proceeding to a judgment against a defendant who is willing to acknowledge its contravention upon terms, and the risk of failure involved in pursuing the case to a successful conclusion if a compromise cannot be reached. Modest successes may be regarded by the Commissioner as of greater value to the public interest in general deterrence of wrongdoing than the exhaustion of its resources upon an egregious but isolated example of wrongdoing. The Commissioner’s stance can be expected to reflect a pragmatic assessment by the authority charged by the legislature with the effective investigation and enforcement of the regulatory regime that the public interest is best served by bringing the proceedings to a conclusion on agreed terms as to penalty. That course may be informed by a perceived need to conserve resources for the pursuit of other wrongdoing and wrongdoers, and to avoid the risks and uncertainties usually associated with litigation.

46 In that context, I am also conscious of the approach outlined in Volkswagen at [26] above, namely that the Court must assess the proposed penalty on its merits, being wary of the possibility that the regulator may have been too pragmatic: Volkswagen at [129].

47 It is readily apparent from the submissions of the ACCC and Facebook Israel and Onavo, that they have given close and careful consideration to the relevant issues, appropriate declarations, orders and pecuniary penalties, noting also that that the ACCC is a specialist regulator. In that context, in DFWBII, the High Court at [60]-[61], noted the relevance of the fact that submissions were being advanced by a specialist regulator able to offer “informed submissions as to the effects of contravention on the industry and the level of penalty necessary to achieve compliance”, albeit that such submissions will be considered on the merits in the ordinary way. As expressed above, where the Court is persuaded that the agreed penalty proposed is an appropriate remedy in all the circumstances, as in this case, it is highly desirable in practice for the Court to accept the parties’ proposal and therefore impose the proposed penalty: Volkswagen at [126].

48 This Court must impose a penalty that is appropriate in all the circumstances. The principal object of deterrence is achieved if the pecuniary penalty has the necessary “sting or burden” to secure “the specific and general deterrent effects that are the raison d’être of its imposition”: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2018] HCA 3; (2018) 262 CLR 157 at [116]. A consideration of totality does not lead me to alter the penalty that I would otherwise impose. I am satisfied the agreed penalty of $20 million, in the circumstances, satisfies the significant element of deterrence required in this proceeding. It carries with it a sufficient sting to ensure that the penalty amount is not such as to be regarded by the parties or others as simply an acceptable cost of doing business: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [66]. Weighing all the relevant factors, bearing in mind the protective and deterrent purpose of a pecuniary penalty, as applied to the facts of this case, I am satisfied that agreed penalty is appropriate.

49 These proceedings are a matter of public interest, and the circumstances of the contraventions call for marking of the Court’s disapproval of the conduct. Consequently, the declarations sought have significant utility. I am satisfied that it is in the interests of justice to make the declarations sought.

50 The parties have agreed that Facebook Israel and Onavo will make a contribution to the ACCC’s costs of the proceeding, fixed in the sum of $400,000. I make that order.

51 Finally, the parties seek that the proceeding be otherwise dismissed, the effect of which is to dismiss the claim against Meta. I also make that order.

I certify that the preceding fifty-one (51) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Abraham. |

Associate:

ANNEXURE A – Statement of agreed facts and admissions