FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

MMD Design and Consultancy Limited v Camco Engineering Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 827

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and, within 21 days of these orders, submit to the Associate to Justice Rofe an agreed minute of orders giving effect to these reasons, alternatively if no agreement each party submit a proposed minute of order.

2. Orders 1 and 2 made 14 September 2022 be extended until further order of the Court.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[6] | |

[31] | |

[33] | |

[49] | |

[69] | |

[70] | |

[75] | |

[86] | |

[87] | |

[92] | |

[98] | |

[108] | |

[110] | |

[115] | |

[120] | |

[132] | |

7.5.1 Weldingly secured to and seated in face to face contact with the front face (or rear face) of the support body | [133] |

[141] | |

[153] | |

[160] | |

[167] | |

[179] | |

[182] | |

[185] | |

[188] | |

[190] | |

[199] | |

[204] | |

[206] | |

[206] | |

[208] | |

[216] | |

9.4 Parties’ submissions on terms where there was no expert agreement | [218] |

[239] | |

[281] | |

[282] | |

[287] | |

[296] | |

[299] | |

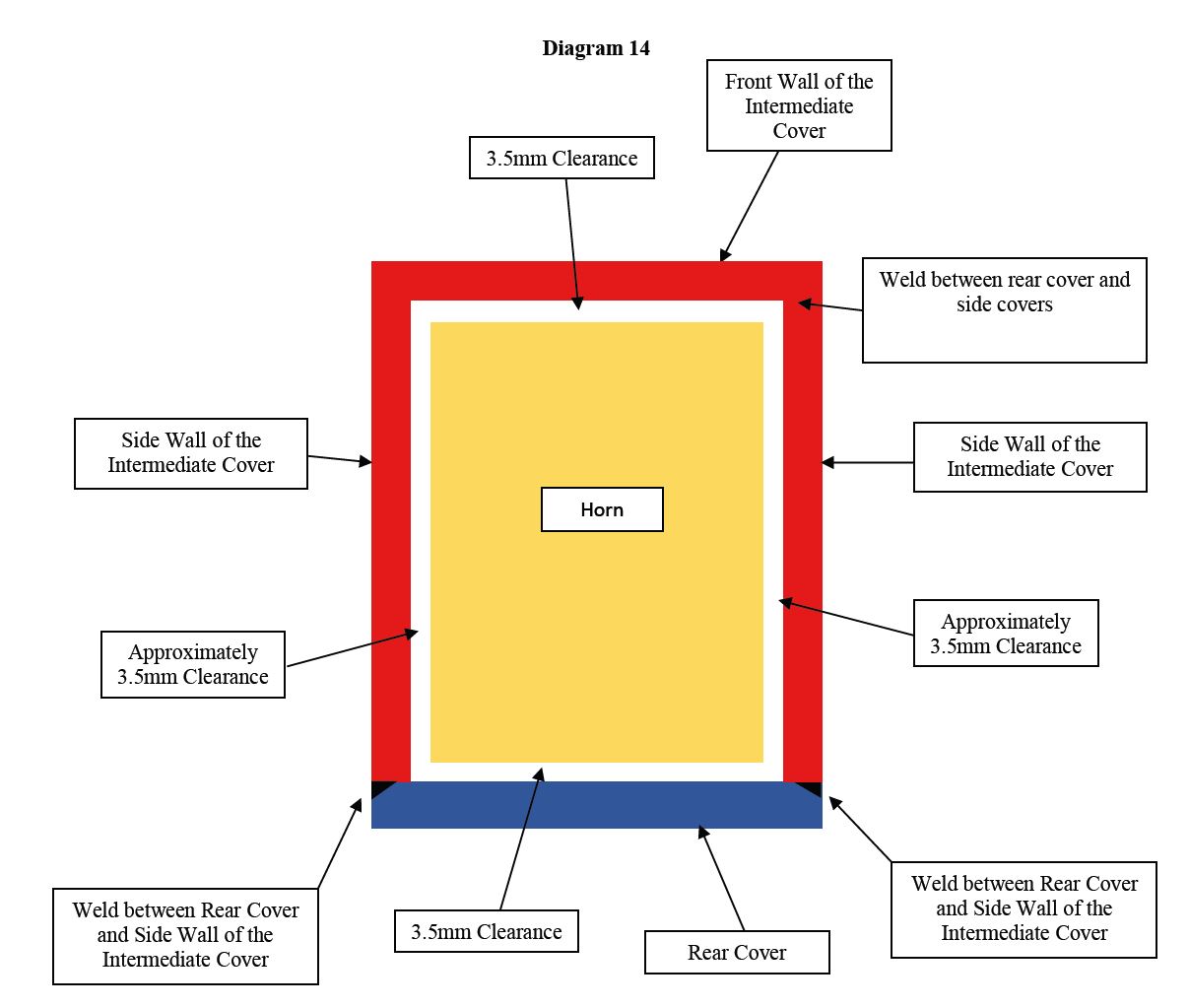

10.3 Front/rear cover in face to face contact with the front/rear face of the support body | [301] |

[303] | |

[307] | |

[308] | |

[330] | |

[336] | |

[338] | |

[341] | |

[354] | |

[367] | |

[381] | |

[384] | |

[389] | |

[395] | |

[396] | |

[397] | |

[408] | |

[427] | |

[440] | |

[444] | |

[460] | |

[466] | |

[486] | |

[496] | |

[498] | |

[502] | |

[513] | |

[514] | |

[526] | |

[538] | |

[550] | |

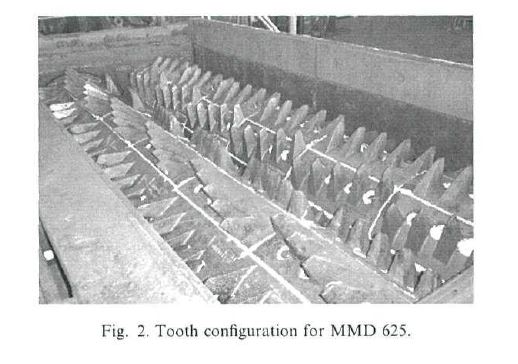

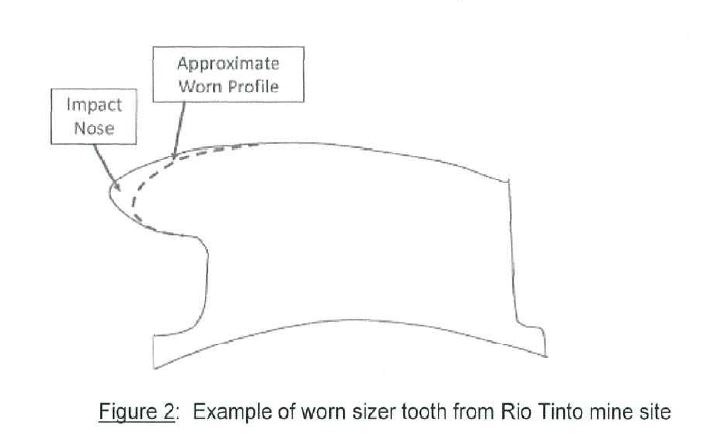

15.5 Dr Huggett’s evidence as to methods of protection of sizer teeth | [555] |

[559] | |

[560] | |

[564] | |

[594] | |

[606] | |

[607] | |

[613] | |

[624] | |

[624] | |

[639] | |

[653] | |

[665] | |

[669] | |

[672] | |

[678] | |

[686] | |

ROFE J:

1 MMD Design and Consultancy Limited is the patentee of Australian Patent No. 2004289510 entitled “A tooth construction for a mineral breaker” (the Patent). MMD and MMD Australia Pty Ltd (together are referred to as MMD) contend that Camco Engineering Pty Ltd has infringed claims 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 17 of the Patent (the Asserted Claims) by the unauthorised supply of five tooth constructions for mineral sizers (Camco Constructions) to particular mine sites in Western Australia.

2 MMD seeks injunctive, declaratory and monetary relief (including additional damages) against Camco for infringement of the Asserted Claims.

3 Camco denies infringement of the Asserted Claims and cross-claims for revocation of those claims. Camco denies that its sizers take all the integers of the Asserted Claims and also contends that the Camco Constructions are used to repair MMD sizers and thus do not constitute infringement. Camco’s cross-claim raises four grounds of invalidity: manner of manufacture, novelty, inventive step and s 40 issues (fair basis and clarity).

4 MMD also contends that Camco has engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct under s 18(1) of the Australian Consumer Law in Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL) by failing to warn its customers of the existence of the Patent, that the exploitation of the respective Camco Constructions infringed the relevant claims of the Patent, and that Camco is not entitled without the authority or consent of MMD to supply the Camco Constructions. MMD alleges that Camco’s failure to warn of these matters occurred in circumstances where each of Camco’s customers reasonably expected Camco to provide each of these warnings.

5 For the reasons set out below, I consider that the Camco Constructions do not infringe the Asserted Claims, and that the Patent is valid.

6 The Patent was filed on 5 November 2004 and claims a priority date of 8 November 2003. The priority date is not in dispute in these proceedings. The Patent is due to expire on 5 November 2024.

7 The Patent concerns a tooth construction for a mineral breaker. Mineral breakers are also known as mineral sizers. As “mineral sizers” was the description used by the parties throughout the trial and in their submissions, I will use that term.

8 Mineral sizers are large pieces of equipment used predominantly on mine sites to break mineral ore into smaller sizes so that the rocks are a suitable size for processing. Mineral sizers typically comprise two counter-rotating parallel shafts, with each shaft having a series of adjacent drums with radially projecting teeth, the teeth from each shaft being offset so as to be interlaced.

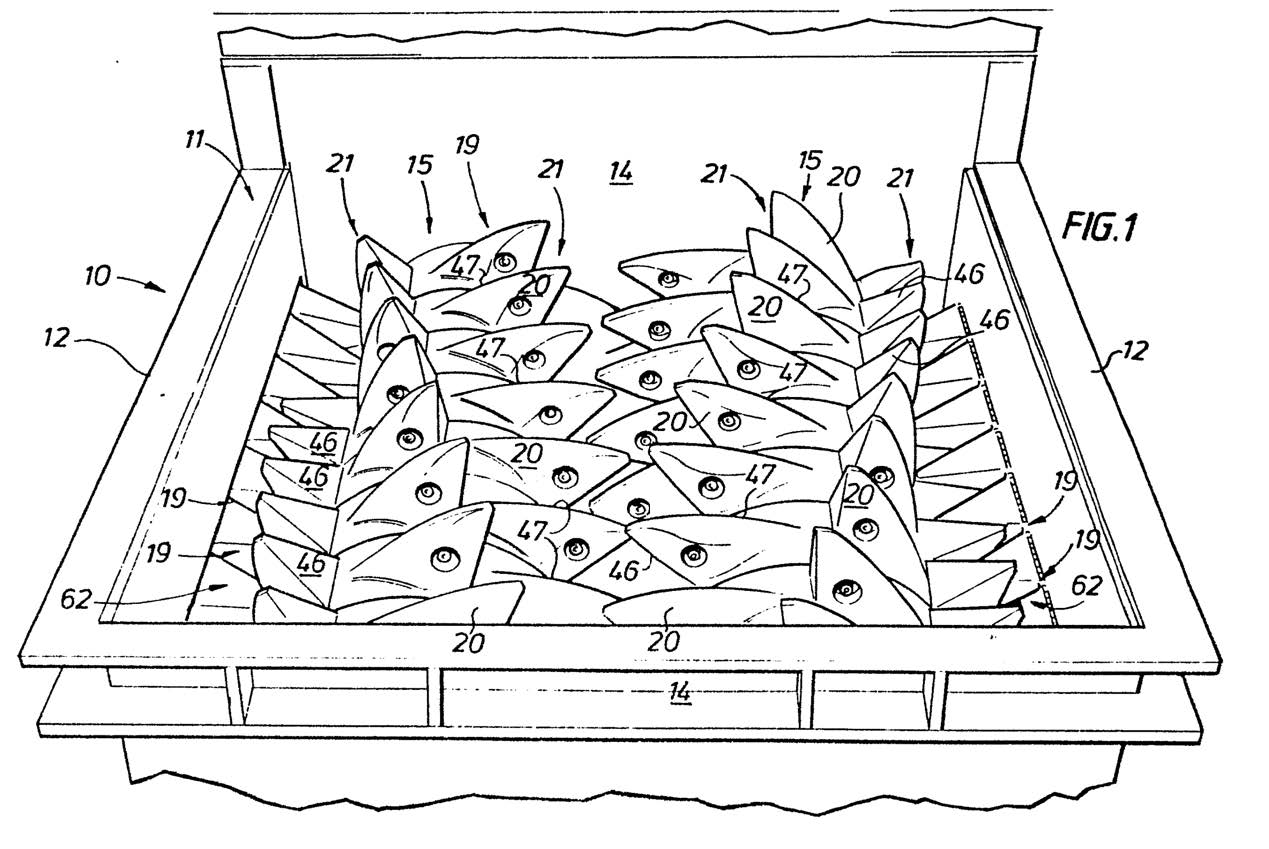

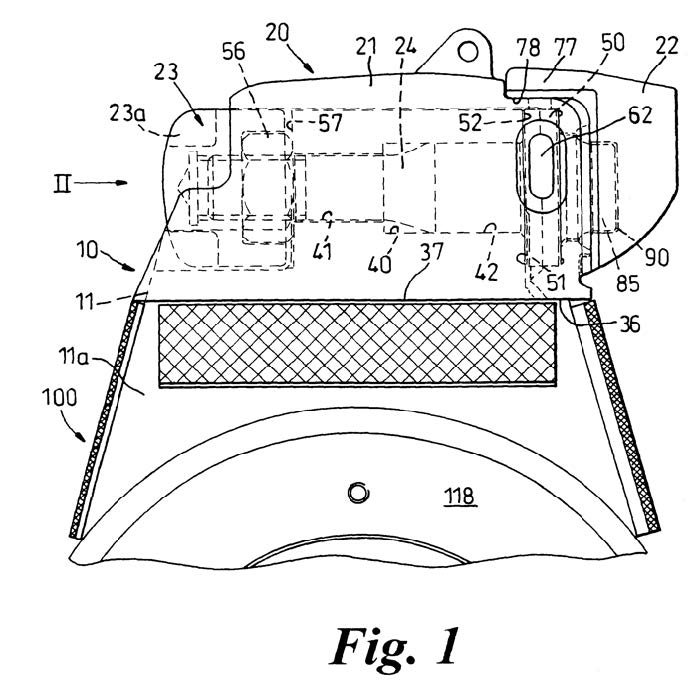

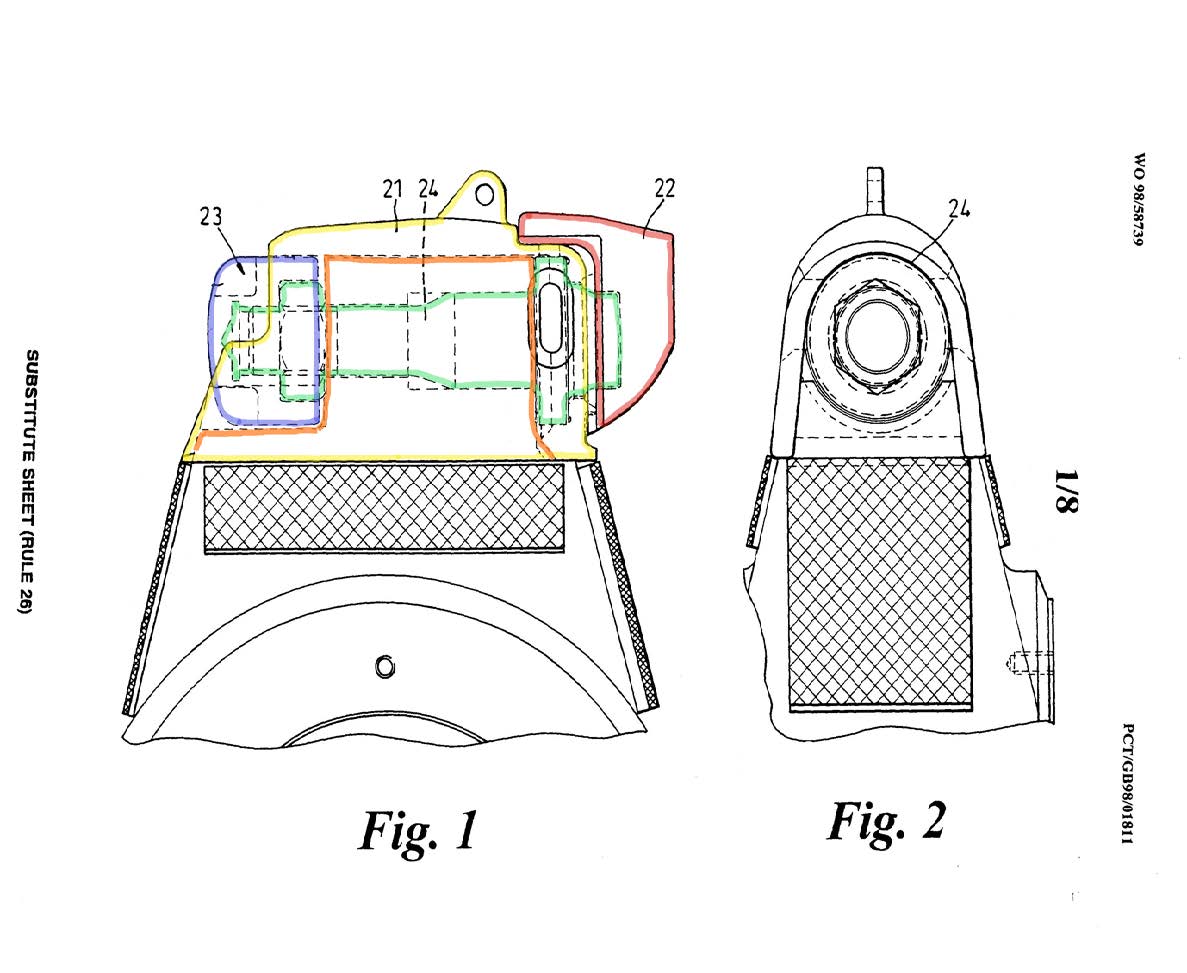

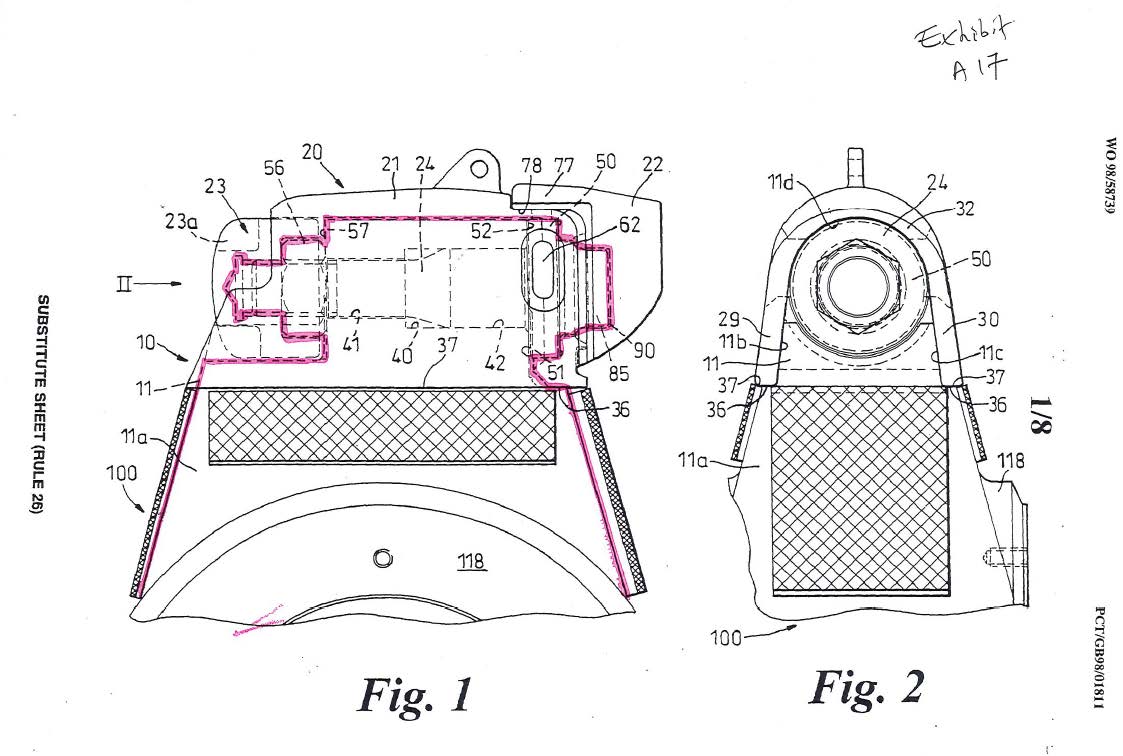

9 The Patent states that the present invention is primarily concerned, but not exclusively, with the type of mineral breaker disclosed in an earlier MMD European patent 0167178. The illustration below is Figure 1 from that European patent:

10 With a sizer of the kind depicted above, mineral lumps are broken down by gripping the lumps and applying tensile forces to cause the lump to break by a snapping action. Each tooth is exposed to large breaking forces applied, on the one hand, onto the front of the tooth and then, on the other hand, onto the rear of the tooth.

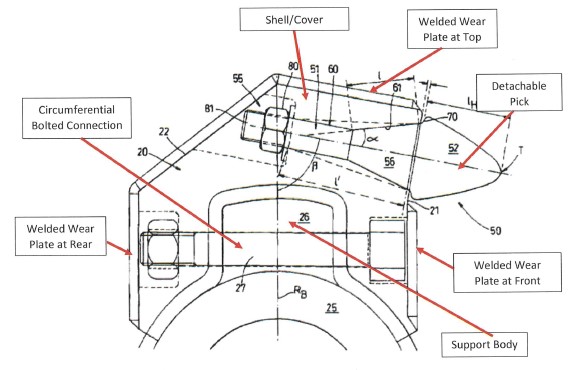

11 A tooth construction is the combination of a support body (also known as a “horn”) covered by a shell so as to protect the horn.

12 The Patent sets out the purpose of the invention on page 1, lines 19–27:

In order to enable each tooth to withstand the breaking forces without snapping it is desirable to construct each tooth so as to have a core formed of ductile metal which is covered with a tooth shell of a wear resistant material, which in itself can be relatively brittle. In order to be capable of breaking particularly hard minerals, such as for example granite, it is necessary to be able to transmit, from the drive shaft, relatively large forces. These large forces, in turn, exacerbate the securance of a tooth shell on the tooth core or horn and also require the core or horn construction to be robust enough to transmit the relatively high forces required.

13 At the foot of the first page, the Patent sets out the first consistory clause in language which mirrors claim 1:

According to one aspect of the present invention there is provided a tooth construction for a mineral breaker, the tooth construction including a tooth shaped support body covered by a shell which defines the outer shape of the tooth construction, the shell being composed of a plurality of covers which are fixedly secured to one another and/or to the support body by welding to define a unitary tooth construction the support body having a front face and an opposed rear face and the plurality of covers including at least a front cover weldingly secured to and seated in face to face contact with the front face of the support body and a separate rear cover weldingly secured to and seated in face to face contact with the rear face of the support body.

14 The second consistory clause which commences at page 2, line 10, is to a “drum construction for a mineral breaker”, and mirrors claim 12, which is not one of the Asserted Claims.

15 The Patent includes 12 figures which relate to two embodiments of the invention. Various aspects of the invention are described in the following section of the Patent by reference to the figures:

Figure 1 is a part perspective view of a drum annulus according to an embodiment of the present invention;

Figures 2 to 6 illustrate a sequence of construction steps, according to a first embodiment, for creating a toothed annulus for a mineral breaker using the drum annulus of Figure 1;

Figures 7 to 11 illustrate a sequence of construction steps, according to a second embodiment, for creating a tooth annulus for a mineral breaker using the drum annulus of Figure 1; and

Figure 12 is a part side view of a tooth construction according to a further embodiment of the invention.

(Emphasis added.)

16 Figures 2 to 6 are said to illustrate the method of construction to produce a breaker tooth of a given height (the first embodiment). The method of construction of a breaker tooth illustrated in figures 7 to 11 enable a breaker tooth of a height greater than that of the first embodiment to be produced whilst using the same size of drum annulus (the second embodiment).

17 The “two methods of construction” are said to be illustrative of the principle that the same drum annulus may be used to produce breaker teeth of different heights. The Patent notes that this is particularly advantageous since it enables the same size of drive shaft and drum annulus to be used for the construction of mineral breakers having different sizes of teeth. The Patent also notes that “these two methods of construction” are also illustrative of different ways of securing covers to each horn to define the outer, exposed faces of breaker teeth.

18 The Patent describes a series of steps (or method of construction) to assemble two embodiments of a tooth construction of the invention.

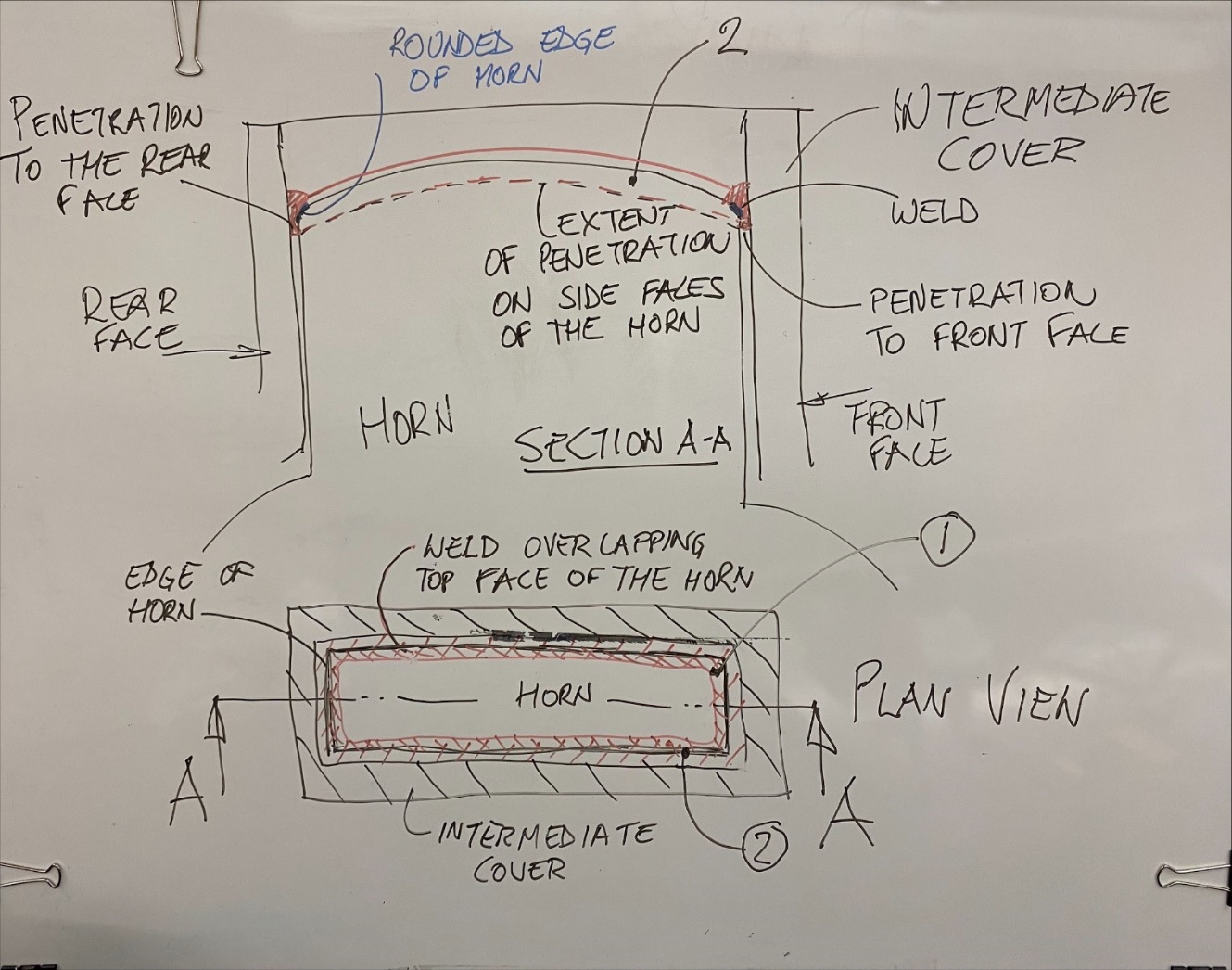

19 The method of construction according to the first embodiment is described at pages 4 to 6 (inclusive) as follows:

As shown in Figure 2, the axial side faces 33, 34 of the horn 12 are partially covered by a pair of side covers 36, 37.

Each side cover 36, 37 include a plate-like body 38 and an arcuate flange 39 located at the lower edge of body 38.

Preferably the side faces 33, 34 are planar and bodies 38 are preferably formed from a metal plate which is also planar.

The front and rear edges 40, 41 of body 38 are preferably co-planar with the front and rear faces 44, 45 respectively of the horn 12. The upper edge 47 of each body 38 is preferably rectilinear and extends from the upper part of the front face 33 to the upper part of the rear face 34 of the horn 12. Accordingly the upper portions of side faces 33, 34 are left exposed to define a crown portion 50.

The side covers 36, 37 are secured to the horn 12 preferably by welding. Preferably this is achieved by providing welding along the front, upper and rear edges 40, 47, 41 respectively to produce a welded seam 55. Accordingly the side covers 36, 37 are securely bonded to the horn 12.

The arcuate flange 39 is seated upon a portion of the annular shoulder 20 and serves to cover that part of the shoulder 20.

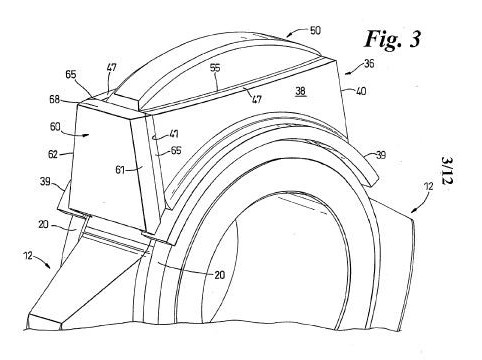

As shown in Figure 3, a rear cover 60 is then provided which is seated in face to face contact with the rear face 31 of horn 12. The cover 60 has side edges 61, 62 which are co-planar with the outer face of bodies 38 and so covers the rear edges 41 of both side covers 36, 37. The rear cover 60 is preferably formed from a metal plate.

The rear cover 60 is secured to the horn 12 and side covers 36, 37 preferably by welding. Preferably this is achieved by welding along the side edges 61, 62 to produce welded seams 65. Whilst it is preferred that the cover 60 is directly welded to the horn 12 it is envisaged that it may be indirectly welded to the horn 12 by being welded to side covers 36, 37 only (which in tum are weldingly connected to the horn).

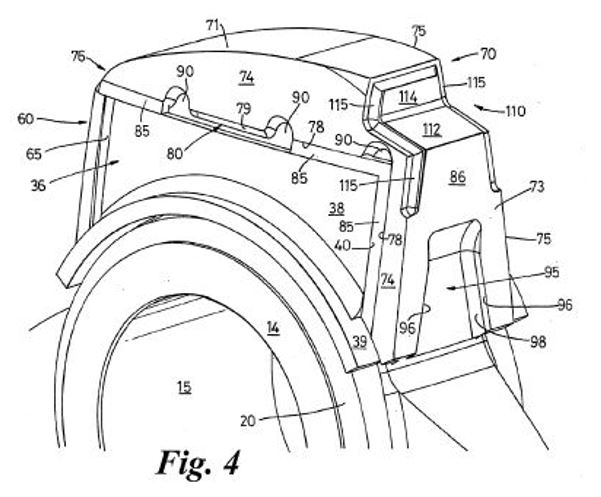

As shown in Figure 4, the horn 12 is then provided with a front and top cover 70.

Cover 70 includes a top portion 71 which has an inner groove (not shown) of complementary shape and size to the exposed crown 50 of the horn 12 which is left exposed after securance of side covers 36, 37 and rear cover 60. Cover 70 further includes a depending front wall portion 73 which has an internal face (not shown) which is seated in face to face contact with the front face 32 of the horn 12. The front wall portion 73 has an upper front face 86 which is preferably planar. The lower portion 87 of the front wall portion 73 preferably includes a window 95. Side walls 96 of the window 95 are preferably secured to the exposed front face of the horn 12 by welded seams 98 in order to directly weldingly secure the front wall portion 73 to the horn 12.

The cover 70 has outer side faces 74, 75 which lie in the same plane as the outer face of side plates 38 and so have inner faces 78, 79 respectively which face and overlie edges 40, 47 of the side plates 38. Preferably a rear end portion 76 of the cover 70 overlies the upper edge 68 of cover 60.

Preferably the side edges of top portion 71 which define faces 78 are spaced from opposed edges 47 to form a gap 80 extending along the edge 47 (only a portion of gap 80 is shown). This enables the inner surface of the top portion 71 to seat upon the upper portion of crown 50.

The cover 70 is then secured to the horn 12 preferably by welding so as to join the opposed faces between cover 70 and plates 38 to one another via a welded seam 85.

A further welded seam 86 is preferably provided to weldingly join the upper edge 68 of cover 60 to the end portion 76.

The weld seam 85, where it extends along the upper edge 47 of each plate 38, also fills the gap 80 and so is weldingly joined to that part of the horn 12 which is exposed by gap 80. Preferably recess windows 90 are provided to enable a gouging tool to be inserted for removal of the weld seam 85 to thereby enable the cover 70 to be removed in the event of a replacement cover 70 being necessary due to wear.

(Emphasis added.)

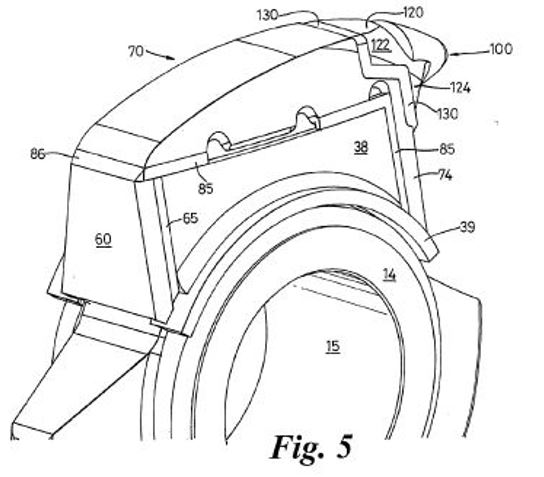

20 Figures 3, 4 and 5 of the Patent are as follows:

21 There is a description of the mounting of the breaking tip member at page 7, lines 13–19:

The tip member 100 preferably has a mounting body 120 in which is secured a pick-like tip 121. The mounting body 120 has an upper part 122 which seats in rebate 110 and a lower depending part 124 which has an inner face which lies in face to face contact with the upper front face 86 of wall portion 73. The body 120 has outer edges which overlie the peripheral groove 115 and is preferably secured to the cover 70 by a welded seam 130 extending along groove 115.

(Emphasis added.)

22 The Patent notes at page 7, line 20 to page 8 line 12, that:

The above arrangement produces a breaker tooth in which a horn 12 is provided which is completely enclosed by a fabricated shell-like tooth cap defined by covers 36, 37, 60 and 70. The tooth cap is fabricated in-situ on the horn 12, preferably by welding covers 36, 37, 60, 70 to one another and/or the horn 12. This provides a very strong tooth construction having a shell-like construction which is securely fixed to the horn 12.

In this construction, the front of the tooth is fully seated on the horn front face 32 at the time of assembly and so is highly resistant to loosening during operation by being exposed to impacts on the front of the tooth. Similarly, the rear of the tooth shell (as defined by plate 60) is fully seated on the rear face 31 of the horn during assembly and is fixed in position independently of the front of the tooth. This means that the rear plate 60 of the shell is highly resistant to loosening by impacts on the rear of the tooth. It follows therefore that the fabricated shell is highly resistant to loosening by repeated alternate impacts to the front and rear of the tooth.

As wear takes place, in use, replacement covers can be simply installed by removal of the worn cover and insertion of a new one. Removal is easily achieved by first removing the relevant welded seam.

(Emphasis added.)

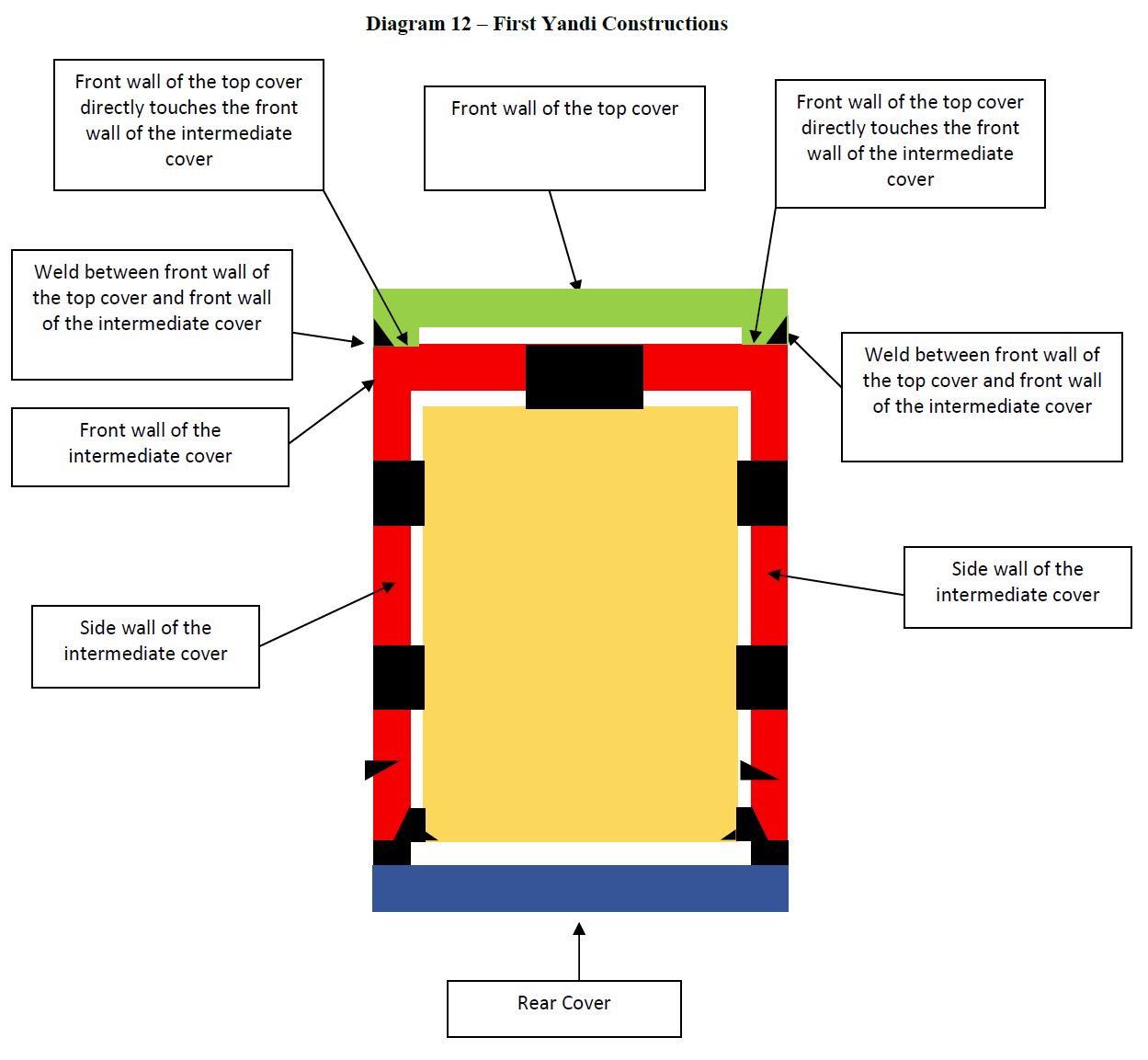

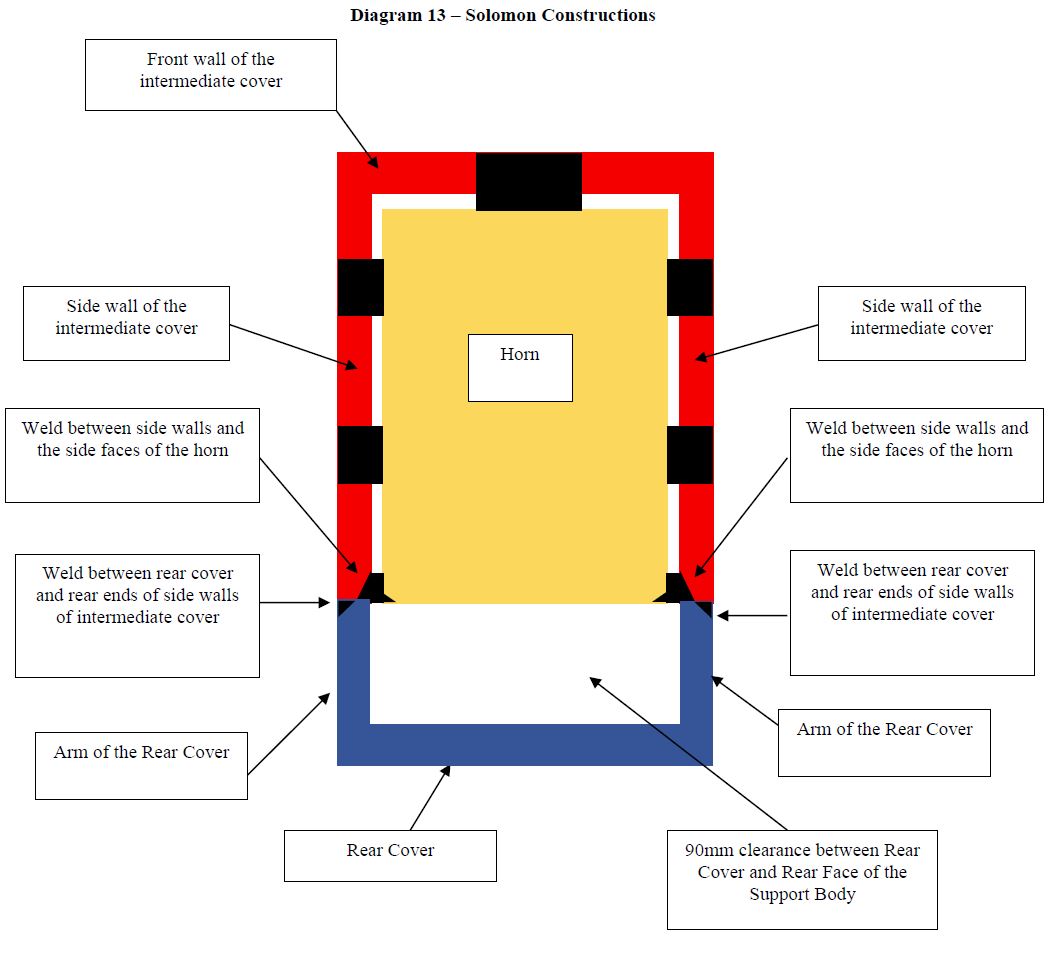

23 The second embodiment which is illustrated in figures 7 to 11 is said to be an example of a tooth construction which uses the same sized horn as the first embodiment but has a tooth height greater than that of the first embodiment as depicted in figure 6. This is achieved primarily by the provision of an intermediate cover.

24 The second embodiment is described on pages 8 to 9.

In embodiment 200, the horn 12 is first covered with a cover 210 which is preferably cast from a suitable metal. The cover 210 has a pair of opposed sides 212, 214, a front wall 216 and a top 215. The cover 210 has an open back (not shown).

The cover 210 defines an internal pocket which has faces which seat in face to face contact with faces 32, 33, 34 and 50 of the horn 12.

The side walls 212, 214 include at least one window or aperture 218 which exposes a portion of the underlying face 33 or 34 of the horn 12. The aperture 218 has side walls 219 which are secured to the exposed face 33 or 34 of the horn 12 by welding. Preferably the entire aperture 218 is filled with weld.

Similarly, the front wall 216 is provided with at least one window or aperture 225 which exposes a portion of face 32.

The aperture 225 has side walls 226 which are secured to the exposed portion of face 32 by welding.

The rear end faces 219 of the cover 210 are preferably co-planar with the rear face 31 of horn 12 and are secured to the horn 12 by a welded seam extending between the internal edges of faces 219 and the horn 12.

Accordingly the cover 210 is securely fixed to the horn 12 by welding located at the front, both sides and rear of the cover 210.

The top 215 of cover 210 defines an upper crown 250 of similar shape to crown 50.

As shown in Figure 8, a rear cover 60 is provided which overlies the rear face 31 and end faces 219 of the cover 210. The cover 60 is formed of a metal plate and is located in face to face contact with rear face 31. It is secured to the cover 210 and horn by a seam of weld 65 which extends along both sides of plate 60.

As shown in Figure 9, a cover 270 similar to cover 70 is located on the crown 250 and is secured in place by welded seams 85.

(Emphasis added.)

25 At page 10, the Patent notes that the construction of the breaker tooth, as exemplified in the two embodiments, provides a very strong breaker tooth since welding of the covers to the horn in effect adds strength to the horn. This means that the tooth construction of the invention can transmit relative high forces for breakage of very hard minerals with a reduced risk of snapping and in addition without a risk of the tooth shell or cover working loose.

26 The Patent notes that the strength of the tooth construction according to the invention is also enhanced by the fact that the horn is solid, eg does not contain through bores as is commonly required with prior art constructions.

27 The Patent has 19 claims.

28 Claim 1 claims:

A tooth construction for a mineral breaker, the tooth construction including a tooth shaped support body covered by a shell which defines the outer shape of the tooth construction, the shell being composed of a plurality of covers which are fixedly secured to one another and/or to the support body by welding to define a unitary tooth construction the support body having a front face and an opposed rear face and the plurality of covers including at least a front cover which is weldingly secured to and seated in face to face contact with the front face of the support body and a separate rear cover which is weldingly secured to and seated in face to face contact with the rear face of the support body.

(Emphasis added.)

29 The highlighted integers are where the primary dispute lies in construction of the claim and infringement.

30 Claims 2 to 9 are dependent on claim 1. Claims 10 and 17 are omnibus claims.

31 Much of the infringement evidence was the subject of claims to confidentiality. In particular, the drawings of the Camco Constructions at each of the mine sites at which MMD contends there is infringement of the Asserted Claims.

32 References to certain confidential manufacturing tolerances and evidence that is confidential to MMD are redacted in the public version of these reasons.

33 Before going further, it is necessary to address what I term “the ore fines issue”.

34 At trial MMD opened its case on the construction of a critical claim integer: “in face to face contact”, orally and in writing by reference to ore fines and corrosion.

35 At [32] of its written opening submissions on the construction of the “in face to face contact” integer, MMD submitted:

… seated in face to face contact with the front face of the support body: Consistent with Mr De Vos’ evidence, MMD submits that this integer requires that the front cover is positioned (whether when fitted or during use)71 so that the forces are transmitted from the front cover to the front face of the Support Body (horn), whether by the front cover directly touching the Support Body (horn), or indirectly through an intermediate component (such as an Intermediate Cover) or ore fines and/or corrosion present in the clearance between the cover and the Support Body (horn).72 In order for forces to be transmitted between two components, there must be a physical connection between them.73 “Seated in face to face contact” does not require that forces are transmitted across the entire face of the front cover.74

(Original emphasis, with bold emphasis added.)

36 Footnotes 71, 72, 73 and 74 are to Mr de Vos’ first affidavit. Footnote 72 additionally refers to the joint expert report.

37 Camco denied that the Camco Constructions infringed principally on the basis that there were gaps between the face of the horn and the cover, such that they were not in face to face contact.

38 As will be discussed further later, Mr de Vos considered that the invention described in the Patent is concerned with efficiently transmitting the large forces applied to the tooth construction in operation to the horn, because the covers may fall off the support body if those forces are not efficiently transmitted.

39 The ingress of ore fines into tooth constructions and their compaction (together with any corrosion) during operation to fill any gaps and thus provide an efficient transmission of force from the covers to the horn was a central part of Mr de Vos’ construction of the “in face to face contact” integer in his first affidavit. Interestingly, Mr de Vos had no prior experience with or knowledge of the ingress of ore fines and their compaction during operation until he was instructed to accept that ore fines would infiltrate into the tooth construction during operation and compact in any gaps, and asked how that would affect the transfer of forces.

40 Once instructed to accept the ingress of ore fines to fill gaps or clearances, Mr de Vos included ore fines as part of his consideration of the construction of the “in face to face contact” integer, and in his infringement analysis.

41 I note that Dr Huggett did not accept the compaction of ore fines as a solid intermediary component through which forces could be effectively transmitted. In his opinion the transfer of forces in a tooth construction that contained clearances would occur exclusively through the weld.

42 On day seven of the trial MMD informed the Court that “its position on ore fines is no longer pressed”. MMD’s fourth amended position statement on infringement was marked up to remove references to ore fines, however no mark up of the evidence was provided to show which parts, if any, were no longer relied on.

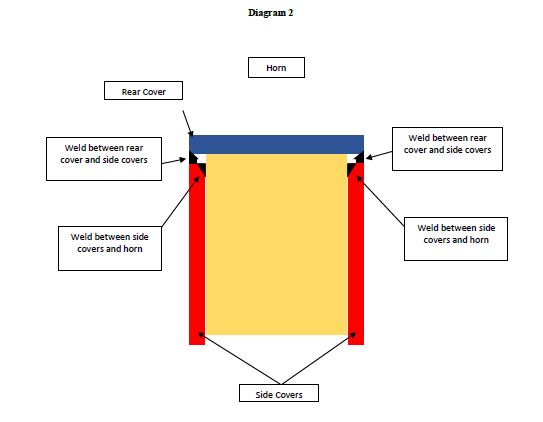

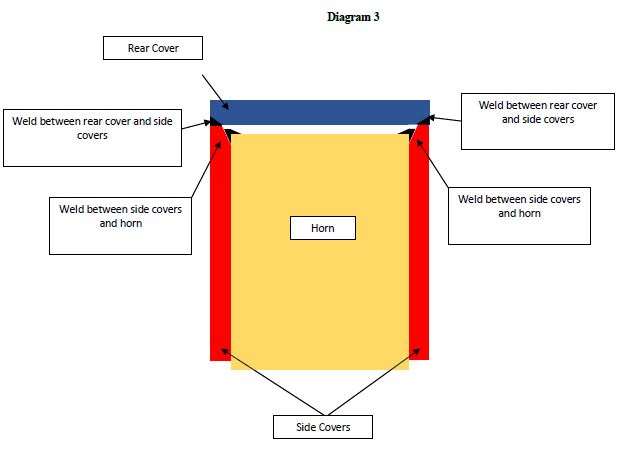

43 By closing, the MMD infringement argument had evolved to no longer rely on ore fines and corrosion filling the gaps during operation to enable efficient transmission of the forces. Instead, where the faces of the relevant covers were not in physical contact with the support body (eg there were gaps) MMD now relied on the presence of weld at the edges of the front or rear face for the transmission of force from the cover to the support body. The extreme point of this argument is illustrated by diagram 3 (discussed in detail below) where the weld is the sole means by which force can be transferred from the front/rear cover to the support body. Diagram 3 appeared for the first time in the joint expert session.

44 For reasons which I set out below, I do not consider that a tooth construction in which the transfer of force from the front/rear covers is solely via the weld connecting the edge of the front/rear covers to the ends of the side covers (as depicted in diagram 3) falls within claim 1 of the Patent.

45 Mr de Vos’ extensive written evidence on construction placed emphasis on the transmission of compressive force as the most efficient and effective means for the transfer of force from the faces of the front/rear covers to the front/rear faces of the support body. He observed that once the clearances are filled with ore fines or corrosion, forces are able to be transmitted to the support body in the same manner as occurs with front and rear covers that are placed against the front and rear faces of the support body, respectively.

46 Mr de Vos’ evidence in the joint expert report also referred to the transmission of force indirectly through ore fines and/or corrosion present in the clearance between the covers and the support body.

47 Despite abandoning the ore fines argument on day seven of the trial, MMD’s written closing submissions still contained a submission that the forces could be transmitted from the covers of the Camco Constructions to the support body via ore fines and/or corrosion present in the clearance between the covers and the support body. Whilst this reference may have been a relict from the opening submissions, overlooked in the preparation of a very extensive submissions document in a short space of time, it serves to illustrate the centrality of this argument to MMD’s infringement argument in opening, and to Mr de Vos’ reasoning in his evidence, and just how difficult it is to simply excise ore fines from the infringement case, where they had previously played a central role.

48 It is because I consider that the ore fines issue was integral to Mr de Vos’ reasoning on construction and infringement in his affidavit evidence such that it cannot be simply surgically excised, that I have discussed his written evidence at length in a following section.

49 MMD led evidence from three non-expert witnesses employed by MMD, and Andrew Mullane, one of MMD’s solicitors. Each of the MMD non-expert witnesses, other than Mr Mullane was cross-examined.

50 Darren Balmer, Production Director at MMD Australia, made five affidavits dated 27 January 2022, 2 February 2022, 11 May 2022, 10 June 2022 and 24 June 2022. Mr Balmer commenced with MMD Mineral Sizing (Europe) Ltd in 1993, and has been employed by various MMD companies since then, moving to MMD Australia’s Brisbane office in 2009.

51 Starting in about 1995, Mr Balmer began assisting in MMD Mineral Sizing’s service department in the United Kingdom and was involved in the installation of new equipment and the repair and changing of worn components for bolted tooth constructions.

52 According to Mr Balmer, MMD Australia has supplied mineral sizers to mine sites in Australia since the late 1980’s. For the majority of MMD Australia’s mineral sizers, the teeth are composed of a support body clad with covers. The covers are wear parts.

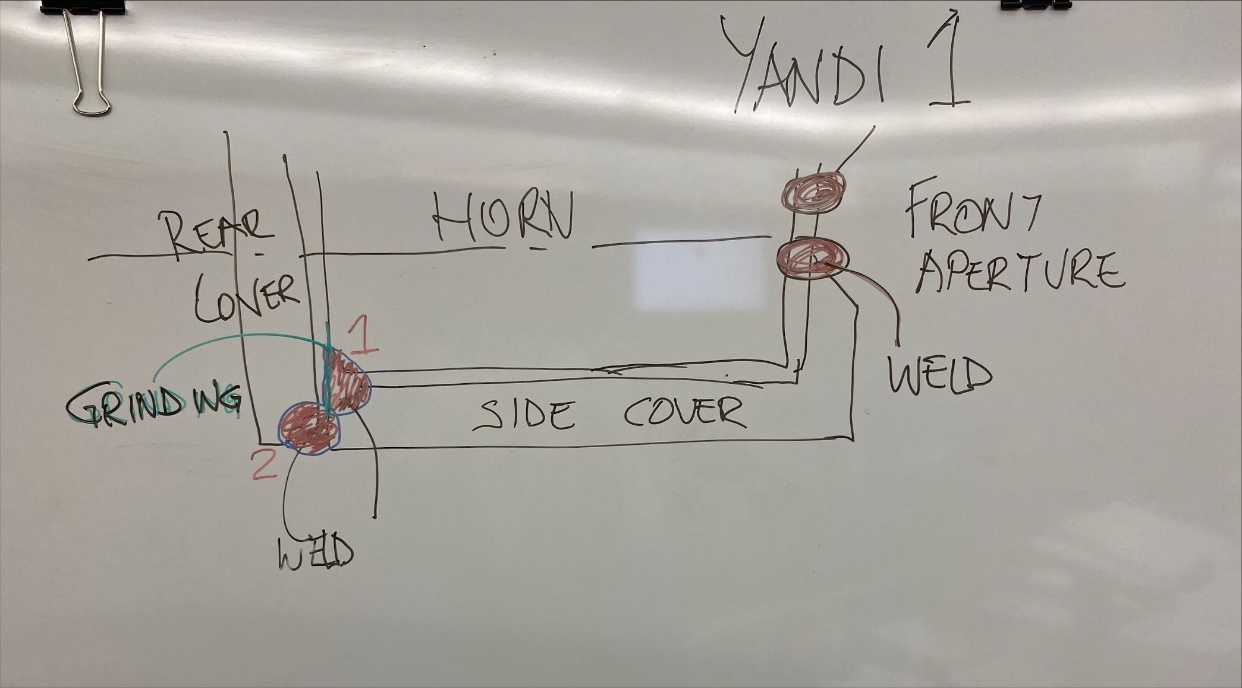

53 In a confidential annexure to his first affidavit, Mr Balmer gave post priority date evidence about the MMD tooth constructions at each of the Yandi, Solomon and Worsley Alumina sites at which MMD contends that Camco supplies infringing tooth constructions. According to Mr Balmer, the MMD intermediate, rear and top covers are made by casting which he describes as a “relatively imprecise fabrication technique”. He observes that there are manufacturing tolerances associated with the cast covers depending on the length of the component. MMD’s cast covers have a manufacturing tolerance of approximately [REDACTED].

54 The MMD covers also undulate across their inner and outer surfaces (another product of the casting process). As a result, the faces of the covers (both inner and outer) are not perfectly flat.

55 According to Mr Balmer, when fitting the intermediate cover of the MMD tooth construction to the support body [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED].

56 Mr Balmer gave extensive evidence relating to the ore fines issue. For example:

[REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED]. [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED]

(Emphasis added.)

57 The majority of the evidence in Mr Balmer’s affidavits was devoted to the ore fines argument. In a confidential section of his first affidavit Mr Balmer describes how he has observed ore fines and corrosion filling clearances in the MMD tooth constructions when they are being removed from a support body. He exhibits various photographs of MMD tooth construction components with corrosion or ore fines on their faces. Mr Balmer opines that the rotation of the tooth construction about the shaft generates centrifugal force that causes the ore fines to compact toward the outer portions of the covers and become solid. Once solid, the compacted ore fines are able to efficiently transmit forces.

58 Scott Harvey is employed as Service Manager at MMD Australia. Mr Harvey made two affidavits dated 19 July 2022 and 21 July 2022 in which he gave evidence as to the provenance of certain photographs (annexed to Mr Balmer’s first affidavit) of tooth constructions at sequential stages of removal during the MMD refurbishment process. Mr Harvey’s evidence was entirely relevant to the ore fines issue.

59 David Waring, the Operations Director of MMD, made one affidavit dated 18 July 2022. Mr Waring gave evidence as to MMD Australia’s exclusive licence to exploit the Patent. Mr Waring appeared by video from the United Kingdom.

60 Mr Mullane annexed to his two affidavits an extensive collection of correspondence between his firm, Wrays Lawyers, and Camco’s lawyers, Griffith Hack.

61 Camco led evidence from its director, Frank Fusco. Mr Fusco made two affidavits, dated 13 May 2022 and 10 June 2022. Mr Fusco’s current role at Camco is Executive Director of Operations and he oversees operational activities at Camco. He agreed in cross-examination that his original claim that he oversaw “all” operational activities was an overstatement. This includes overseeing the workshop repairs conducted by Camco for its customers. Mr Fusco did not have any engineering qualifications and was unable to comment on engineering issues such as the transmission of forces between covers.

62 Camco was incorporated on 4 November 1994 and commenced trading in June 1995 as a start-up business by Bruce Cameron, Victor Fusco, Alan Leese and Mr Fusco. Mr Fusco has been a part owner of Camco since it commenced trading. Mr Fusco and Mr Cameron are responsible for the day-to-day operation of the Camco business and both take a very “hands on” role in all aspects of the business. Mr Cameron, a mechanical engineer, took the lead in relation to negotiating supply contracts and attending meetings, and giving instructions (together with Mr Prasad, a Camco project engineer) including deciding which diagrams to provide to the expert, Dr Paul Huggett, in the course of the MMD litigation. Mr Fusco was generally aware of the negotiations and litigation but was more involved in overseeing the refurbishment operations of the business. Camco currently has over 300 full time equivalent employees.

63 Mr Fusco gave evidence as to Camco and MMD’s business history and he described the nature of Camco’s business as follows:

Camco is not an original equipment manufacturer (OEM) supplier. That is, Camco does not design and supply capital equipment and machinery to resource sector companies when those companies are expanding or developing a new mine site. Rather, Camco provides an after-market repair service (what I described above as ‘operational support’) to those companies. With particular reference to the current proceedings, Camco has repaired parts of mineral breakers (sizers) owned by mining companies and in particular Camco has repaired the breaker shaft assemblies which generally consist of a pair of shafts with drum annuli and wear covers welded around the horns of the drum annuli. Repair of mineral breaker teeth is required because the components forming the teeth are consumable parts worn away by the mineral breaking process and need replacing after a period of time in use. Over the years, Camco has repaired tooth structures as part of the overall repair of breaker shaft assemblies by using OEM parts provided by the mining companies, purchasing parts directly from the OEM, or by Camco manufacturing parts of its own, or by Camco using welding and other hard facing techniques that do not require spare parts.

64 Mr Fusco gave evidence as to the creation of various confidential Camco Fitment and Welding drawings for each of the Camco Constructions at the relevant mine sites alleged to infringe and which were the subject of discussion by the expert witnesses (Camco Drawings). According to Mr Fusco he gave instructions for the preparation of the drawings and supervised their creation. The Fitment and Welding drawings were created to depict the construction method but most importantly to emphasise to workshop staff the importance of particular aspects such as clearances or where welding should be minimised.

65 Mr Fusco said that he sometimes gave verbal variations to the instructions in the Fitment and Welding drawings directly to the workshop staff, and that not all these variations were recorded in the drawings. Modifications to the drawings might also arise during the casting process. The foundry might be asked to make a small modification to the initial casting and to do this they would make a relevant modification to the pattern. Mr Fusco said that these types of modifications, often as a result of verbal discussions, were not always reflected by a revision to the 3D model and creation of revised 2D drawings because he considered them to be so minor that he did not consider it necessary for revised modelling or drawings to be created.

66 Mr Fusco outlined the process by which Camco carried out the refurbishment of mineral sizers. Camco undertakes mineral sizer refurbishment projects in its workshops. The sizer shaft assemblies typically arrive at the Camco workshop by truck on transport frames and are delivered back to the mine site for reinstallation in the mineral sizer following refurbishment.

67 Mr Fusco also gave evidence on the ore fines issue. Mr Fusco’s second affidavit was primarily directed to responding to Mr Balmer’s evidence on the ore fines issue.

68 As a witness, Mr Fusco was at times pugnacious and combative, particularly when presented with a proposition he disliked. He was unable to recall whether he had seen certain emails relating to Camco’s tender negotiations to which he was copied, at the time they were sent. Mr Fusco also had memory lapses in relation to whether he had attended important meetings such as meetings with Watermark, or the 18 December 2018 meeting with MMD.

69 MMD and Camco each called an expert witness. Mr Jurrien de Vos was called by MMD and Dr Paul Huggett was called by Camco. Mr de Vos and Dr Huggett prepared a joint expert report (JER) prior to the hearing, and gave evidence at the hearing in a joint session.

70 Dr Huggett graduated with a Bachelor of Applied Science with honours in Materials Science from the NSW Institute of Technology in 1986. He obtained a Masters in Materials Science from the University of Technology Sydney in 1992. His PhD was conferred by the University of Technology Sydney in 2008 for his research on a novel manufacturing process for a composite wear material. He has been a certified Materials Professional with Materials Australia since about 2004. Dr Huggett is listed as an inventor on four Australian patents.

71 Dr Huggett has worked as a materials scientist in the manufacturing and mining industry for the past 30 years. He started his career as a materials scientist in the manufacturing of pumps, and then moved to earthmoving and mining equipment. From about 1998 Dr Huggett worked with mineral sizers and wear components for mineral sizers, amongst other mineral processing equipment such as crushers, mills, chutes, conveyors, screens and flotation units.

72 As at the priority date, Dr Huggett had worked for mining companies to prolong the life of various equipment including mineral sizers through making changes to their design and materials. His experience included materials failure analysis, wear materials, material testing, research and development, open cut and underground mining, construction, slurry and water pipeline design, project engineering and project management with the mining, manufacturing and oil and gas industries.

73 Dr Huggett had post priority date experience of working with mineral sizers, including MMD sizers for Fortescue Metals Group Ltd’s Solomon In-Pit crushing projects and at Rio Tinto’s Mesa A mine site, and failure analysis of sizer teeth.

74 As at the priority date, Dr Huggett’s evidence was that he stayed informed about mineral sizer design and materials by:

(a) maintaining close relationships with manufacturers;

(b) conducting his own research through internet searches;

(c) reading scientific journals and papers, such as Wear, Minerals Engineering, conference papers and patents, trade publications in the metallurgical field, and textbooks; and

(d) attending and presenting at conferences, including Materials Innovations in Surface Engineering conferences, and educational and networking events through Materials Australia and Australian Corrosion Association.

75 Jurrien de Vos is a mechanical engineer, who graduated with First Class Honours from Curtin University in 1989. Since then he has gained significant experience with respect to the general principles and process of engineering design, particularly in relation to equipment for the mining and heavy industries.

76 Mr de Vos had two periods of employment at Hofmann Engineering (1990–1993 and 1996–1998). During his second period of employment at Hofmann Engineering, as a Design Manager, he designed and improved a variety of different pieces of mining equipment, including the gearbox of an MMD mineral sizer and an ABON-designed mineral sizer, jaw crushers and cone crushers.

77 The ABON mineral sizer had a shaft with teeth that were an all-in-one casting (with no separate covers). Due to a combination of the heavy loading and abrasive ore applied to the mineral sizer during its use, the teeth had worn down significantly. Hofmann Engineering cast new tooth constructions for ABON’s mineral sizer using a harder material to increase their wear life. Mr de Vos, in collaboration with another employee of Hofmann, made the decision as to the materials from which the new tooth constructions would be cast. The ABON sizer did not include covers. The entire tooth was removed and replaced with a new tooth when it became too worn to perform its function.

78 In 2006, Mr de Vos started deVos Chater & Associates (dVCA) with another engineer. He was Director and Principal Design Engineer of dVCA. In 2009 dVCA was dissolved, and Mr de Vos started Deacon Engineers. Since 2009, Mr de Vos has been the Managing Director and Principal Design Engineer of Deacon Engineers.

79 As at the priority date, Mr de Vos had supervised the design of mechanical power transmissions, process equipment and ore crushing equipment. This included the design for a rock breaker for a jaw crusher, to improve the installation of a cone crusher, the investigation and redesign of a rolls crusher, and the design of a new tooth removal machine for mineral sizers.

80 Mr de Vos had not seen a mineral sizer in operation before the priority date.

81 Mr de Vos gave evidence as to his construction of the terms used in the Patent claims, his analysis of whether the Camco Constructions infringed the claims of the Patent and on invalidity.

82 When undertaking a new design task at the priority date, Mr de Vos’ approach was to rely substantially on his own experience gained through designing equipment. He also consulted formally and informally with colleagues, metallurgists and suppliers that he worked with to ask them about their experiences and new developments. He conducted internet searches to see the designs of similar equipment being manufactured and supplied to the market, and the materials available. At the priority date the information on the internet was more limited than it is today.

83 Mr de Vos also referred to textbooks, including the Machinery Handbook, Fundamentals of Machine Component Design, Applied Mechanical Design and the Procedure Handbook of Arc Welding and Design with Weldox and Hardox. He relied more on textbooks at the priority date than now because in his experience there is more, and more up to date, information available on the internet now.

84 Mr de Vos never undertook a patent search before beginning a new design task. It was his view that many patented designs were good ideas but which did not work in practice. In order to produce a design that he would be confident would work, he preferred to use designs and components that were commercially available as it was more likely that they would be useful.

85 Mr de Vos also referred to engineering design standards, such as the Australian Standards and British Standards and to supplier design handbooks and catalogues, such the Ajax Fastener Handbook and bearing catalogues, to obtain information about components that were commercially available.

86 The following background information is taken from Mr de Vos’ first, third and fourth affidavits.

87 Mineral sizers typically consist of two shafts housed within a rectangular enclosure with an open top side and open bottom side. The shafts have rows of teeth affixed to them that rotate in opposite directions to one another. The teeth are designed to crush rocks.

88 The teeth of the mineral sizer do the majority of the work reducing the size of rocks. The teeth break the rocks against other teeth. The teeth are typically shaped to have a pointed front (eg a pick or breaking tip) that allow the teeth to grip the rocks. Depending on the design of the mineral sizer, the teeth may have sacrificial covers.

89 Where a tooth consists of a tooth core (which Mr de Vos described as a “support body”) and sacrificial covers, the covers protect the support body from becoming damaged by the rocks. The covers wear during use and are replaced periodically. The support body may need to be replaced on occasion, but less frequently than the covers. Where a tooth does not include covers, the tooth itself is a sacrificial part, and will be replaced periodically due to wear from the rocks.

90 As a result of the action of the teeth, significant forces are imparted during use to the front, top and rear faces of the teeth. Smaller forces are imparted on the sides of the teeth. The front face of each tooth is subject to the greatest number of forces, though the magnitude of the forces imparted on the front and rear faces of the teeth is similar.

91 Tooth constructions are typically made from steel. Steels tend to be relatively malleable, meaning that it tends to deform, rather than fracture, when force is applied to it. Steel can be hardened to reduce its malleability, making it resistant to plastic deformation when a force is applied to it. Steel is an alloy of iron with a small amount of carbon. A common way of hardening steel is to create an alloy by introducing other elements (such as other metals). For example, manganese steel is a hardened form of steel. The inclusion of manganese makes the steel more resistant to plastic deformation when forces are applied to it.

92 According to Mr de Vos, the well-known principle: for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction, is critical to the operation of a mineral sizer tooth construction.

93 In a mineral sizer, there must be a physical connection between two components (according to Mr de Vos this can be directly or through an intermediary) in order for forces to be transferred between them. When a force is applied to Component A, that force can be transmitted to other components that are physically connected to Component A.

94 Mr de Vos described the transmission of forces between two components through a third, intermediate component. He referred to a situation where Component A touches Component B, and Component B touches Component C, but Component A does not touch Component C. A force applied to Component A may be transmitted to Component B, and then may be transmitted from Component B to Component C. In this way, the force is transmitted from Component A to Component C, even though Component A and Component C do not touch one another directly, because there is a physical connection between them.

95 Forces may be transmitted between components in several different ways. The most efficient way of transmitting force is a “compressive force”. Compressive forces involve pushing into, or compressing, a component. A compressive force occurs where, for example, Component A and Component B are touching and a force is imparted on Component A in the direction of Component B. The force is transmitted from Component A to Component B in a way that compresses Component B.

96 A “tensile force” relies on a fastening medium to transmit the force between components. Tensile forces involve pulling away from, or stretching, a component. A tensile force occurs where, for example, Component A and Component B are secured to one another (for example by a weld), and a force is imparted on Component A in the direction away from Component B. The tensile force will be transmitted from Component A to Component B in a way that stretches Component B and the bond between the two components. A tensile force can only be transmitted in this manner if the two components are secured to one another. If the two components are not secured to one another, a force that is applied to Component A in the direction away from Component B will not be transmitted to Component B.

97 “Shear forces” are another way that forces may be transmitted between components. A shear force is a transverse force, not an axial force. In comparison, compression and tensile forces are generally axial. A shear force relies on either a fastening medium or friction in order to transmit the force between two components.

98 There are different methods for manufacturing components made from steel, including forging, casting and machining.

99 Forging involves creating a desired shape through compressive forces that are applied to the metal whilst it is in a semi-solid state to plastically deform the metal. The semi-solid state is achieved through an elevated temperature. There are several different types of forging, including hammering, pressing and rolling.

100 Casting involves melting the metal, pouring the molten metal into a mould and allowing it to cool. Once the metal is cooled it is removed from the mould and keeps the shape of the mould.

101 There are different types of casting. There are advantages and disadvantages associated with each, including with respect to the precision (manufacturing tolerances), the size and complexity of the components that can be manufactured, the ability to re-use the die and cost. Three common forms of casting are: sand, die and investment casting.

102 Sand casting uses silica-based materials that are tightly packed together into a smooth moulding surface. The silica-casting reduces the potential for tearing or cracking by allowing some flexibility and shrinkage during the cooling phase of the process. The main advantages to sand casting include:

(a) relatively low production costs, particularly where a relatively small number of components are being produced; and

(b) the ability to cast large components.

103 Sand casting is not a high-precision production method. Sand casting involves relatively high manufacturing tolerances. Components that are produced using sand casting have relatively large manufacturing tolerances and relatively rough surfaces. The product from sand casting requires thicker walls than die and investment casting (discussed below), because the method relies on gravity, not pressure, to push the molten metal into the mould. In sand casting there is significant distortion because there is movement and cracking in the sand cast mould as the cast metal cools.

104 The various parts of the sand cast component will shrink to different degrees across the component and between different moulds, leading to differences in the dimensions of the manufactured component. The size of the manufacturing tolerances for a particular cast component depends on the quality and process of the casting.

105 Die casting involves injecting molten metal into a steel die under high pressure. The die is often coated with a lubricant to regulate the temperature of the die and assist with ejecting the cast metal part once it has cooled. Die casting provides greater precision but it is more expensive than sand casting.

106 Investment casting uses a disposable wax pattern for each cast part. The wax is injected into a die having the desired shape of the component. The wax pattern is removed from the die before the wax pattern is surrounded by a ceramic compound to create a mould (the “investment process”). The wax is then removed from the mould by heating it up. Molten metal is injected into the mould. Once the metal has cooled, the mould is broken to release the cast metal. Investment casting provides significantly greater precision and lower manufacturing tolerances than sand casting, and allows more complex geometrical shapes to be created. However, investment casting is more expensive than sand casting (unless the sand cast part is machined to increase its precision, as machining increases costs).

107 Machining involves cutting the part into the desired shape using a variety of different tools, and can produce a high degree of precision. It is possible to increase the precision of a cast component by machining it after it has been cast. Machining is a labour-intense process, and therefore adds substantially to the cost of producing the part, and so is usually only used when a high degree of precision is required.

7.4 The invention described in the Patent

108 Mr de Vos considered that the invention described in the Patent is concerned with efficiently transmitting the forces to the horn, because the covers may fall off the support body if those forces are not efficiently transmitted.

109 Dr Huggett considered that the essence of the patentee’s invention appeared to be to make discrete cover plates that are welded to the horn in face to face contact at assembly, thereby to allow the maximum amount of load to be transmitted to the horn without compromising the fatigue strength and subsequent breaking of (i) the cover plates which can otherwise occur when there are gaps between a plate and the underlying substrate (horn), and (ii) the horn which would otherwise occur where cover plates are not used.

110 Mr de Vos considered that it is important that tooth constructions have the properties of both malleable and hardened steel. This is consistent with the statement in the Patent at page 1, lines 19–22 that, “[i]n order to enable each tooth to withstand the breaking forces without snapping it is desirable to construct each tooth so as to have a core formed of a ductile metal which is covered with a tooth shell of a wear resistant material, which in itself can be relatively brittle”.

111 Mr de Vos explained that “ductility” describes the ability of a metal to be drawn into a thin wire. In the context of the Patent, Mr de Vos understood the reference to ductility as a reference to the core being formed of a “malleable” material.

112 According to Mr de Vos, if a tooth construction is made entirely from material that is too hard, it may be too brittle to withstand the forces imparted during use. It will have an increased likelihood of snapping at the juncture of the support body and shaft as large forces are imparted onto the tooth construction. This is because hardened steel will fracture more readily than malleable steel (which will more readily plastically deform) when large forces are applied to it. In comparison, a malleable metal will tend to plastically deform, rather than snap, when forces greater than its yield strength are applied to it.

113 If a tooth construction is too malleable, it may not be able to transmit the amount of force required to snap or crush the rocks. Instead, the tooth construction may deform and experience accelerated rates of wear. The tooth construction may quickly become so deformed or worn that it loses the shape required to reduce the size of rocks to the desired extent.

114 According to Mr de Vos, the Patent explains that it is possible to obtain the desirable properties of both malleable and hardened steel by using a malleable support body clad in hardened covers. This arrangement will only work if the forces applied to the tooth construction can be efficiently transmitted between the covers and support body. The transmission of those forces prevents the covers from deforming to the point where they fracture.

7.4.2 Efficient transmission of force

115 Mr de Vos considered that a critical element of a tooth construction is its capacity to transmit forces from the covers to the support body. According to Mr de Vos, the use of the word “contact” in the claims to imports the critical concept of the efficient transfer of forces into the claims.

116 According to Mr de Vos, a robust tooth construction that includes sacrificial covers to protect the support body must be capable of efficiently and effectively transmitting the forces imparted by the teeth breaking the rocks:

(a) from the rocks to the covers;

(b) from the covers to the support body; and

(c) from the support body to the shaft;

and back in the opposite direction.

117 As a result of the large forces that are imparted on the teeth, it is necessary for those forces to be efficiently transmitted to the support body and the shaft in order for the teeth to be sufficiently robust. Mr de Vos observed that this concept was described on page 1, lines 22–27 of the Patent:

In order to be capable of breaking particularly hard minerals, such as for example granite, it is necessary to be able to transmit, from the drive shaft, relatively large forces. These large forces, in turn, exacerbate the securance of a tooth shell on the tooth core or horn and also require the core of horn construction to be robust enough to transmit the relatively high forces required.

118 Tooth constructions are commonly composed of covers that are secured to a support body. As compressive forces do not rely on a fastening medium unlike tensile and shear forces, according to Mr de Vos it is preferable for the forces imparted on the covers during use to be transmitted to the support body through compressive forces.

119 Mr de Vos explained that where a tooth construction does not efficiently transmit forces from the covers to the support body, this places strain on the means of securing the covers to the support body. The large forces that are imparted onto the teeth during operation (particularly in hard rock mining) can cause the means of securing the covers to fail if those forces are not efficiently transmitted to the support body.

120 The ingress and compaction of the ore fines and corrosion was first raised by Mr de Vos in his discussion of the use of sand cast covers on mineral sizers.

121 In Mr de Vos’ experience, the covers of tooth constructions are most commonly sand cast. As the covers are sacrificial parts, and designed to be replaced periodically, there is an imperative to minimise manufacturing costs. The covers do not have a particularly intricate design, which in Mr de Vos’ opinion makes them suitable for sand casting.

122 Although sand cast parts have relatively large manufacturing tolerances, Mr de Vos considers that those tolerances are not functionally significant to the performance of the covers. This is because, in practice, the covers are secured in place (meaning that a perfectly neat fit is not required) and any gaps that are left between components as a result of the manufacturing tolerances will be filled with ore fines and corrosion once the tooth constructions are in use. In use, sand cast covers which have not been machined therefore effectively provide the same efficient and effective transmission of force between components as covers which had been machined to create a perfect fit from the outset.

123 Mr de Vos also considered ore fines and corrosion in the context of fitting an intermediate cover of the kind described as the second embodiment in the Patent, with a separate rear cover to the support body.

124 Due to the manufacturing tolerances associated with sand casting, it is common for a sand-cast component that will be installed over a second component, such as an intermediate cover with welded or integral front and rear covers over a support body, to be manufactured so that there are slight clearances between the two components. These clearances allow for an easier fitment.

125 If the intermediate cover is cast to the precise dimensions of the support body, with no clearances, the imprecision of the casting process will mean that the intermediate cover will likely not fit well to the support body at various places. The intermediate cover will need to be ground or machined at each place there is poor fit in order for the two components to fit together. This is a time-consuming and costly exercise.

126 A fitment clearance is of less importance if the rear cover is welded to the intermediate cover after the intermediate cover is installed on the support body. The front cover can be pressed up against the front face of the support body. Once the front cover is in position, the rear cover can be placed against the rear face of the support body (provided that the side covers of the intermediate cover do not extend beyond the rear face of the support body).

127 It was Mr de Vos’ evidence that in practice, there will still be some clearances between (a) the support body and (b) the front and/or rear covers due to the imprecision involved with sand casting. The front and/or rear covers will undulate across their surface, meaning part of the face will touch the support body and part will not. Mr de Vos observed that the clearances arising from the surface undulations of the cast cover will be smaller than those required to fit an intermediate cover with welded or integral front and rear covers.

128 In Mr de Vos’ opinion, the small clearances required for an intermediate cover with welded or integral front and rear covers are immaterial to the function of the tooth constructions. Mr de Vos’ evidence was that in use, these small clearances typically fill with ore fines and corrosion. Once the clearances are filled, forces are able to be transmitted to the support body in the same manner as occurs with front and rear covers that are placed against the front and rear faces of the support body, respectively. I understand Mr de Vos to be describing the transmission of compressive force.

129 Mr de Vos considered that there may be some advantages with effectively transmitting forces to the front and rear faces of the support body from the moment that the mineral sizer is first used, rather than waiting for the clearances to fill over time. However, in practice, Mr de Vos expected the welds to be strong enough to hold the tooth construction together until any clearances have been filled with weld. In his experience, weld may fail over time due to fatigue cracking resulting from repeated cycles (unless the tooth construction has been designed in such a way that the welds can transmit and withstand the forces over an extended period of time). Accordingly, in practice, having clearances that fill over time is unlikely to affect the longevity of the tooth construction, and fabricating a tooth construction with no clearances will be of marginal benefit.

130 Mr de Vos’ evidence as to the infiltration of ores and fines was based entirely on information provided to him from Mr Balmer’s affidavits. Mr de Vos accepted in cross-examination that he did not know about the possibility of an ingress of “ore fines and/or corrosion” until he was given instructions to consider them in them as part of his consideration of claim construction:

MR DE VOS: … The information that was provided to me from Mr Balmer’s affidavit related to the compaction of ore fines because I had no experience with that and that was a point of consideration: could that be possible. And I still – I don’t know. And that was the purpose of that affidavit – the disclosure of that affidavit was to confirm for me that ore fines would, in fact, make their way in between the covers and compact, and could that, in fact, be a way of transmission of force.

COUNSEL: And that information from Balmer was conveyed to you before you completed your construction exercise in section C. Correct?

MR DE VOS: I couldn’t say exact dates, but I do know that I was – I was instructed to accept that ore fines would get their way in there, and then I was asked, “If ore fines did get their way in there, would they affect ..... transfer?” And I said yes. …

131 Mr de Vos’ evidence was that forces can be transmitted between two components with a clearance between them (Component A and Component C) through ore fines and/or corrosion that are present within that clearance, provided that the ore fines and/or corrosion are sufficiently compacted between Component A and Component C to allow for the transmission of that force. In this situation, the ore fines and/or corrosion act as an intermediate component that provides a physical connection between Component A and Component C, allowing forces to be transmitted between them.

7.5 Experts’ evidence as to the construction of claim terms

132 Dr Huggett provided his understanding as at the priority date of the construction of the claim terms in his first affidavit. Mr de Vos gave evidence as to his construction of the terms of the claims of the Patent in his first, third and fourth affidavits. Dr Huggett and Mr de Vos agreed in the JER on the construction of a number of terms. The terms on which the construction was agreed are discussed separately in the JER section below.

7.5.1 Weldingly secured to and seated in face to face contact with the front face (or rear face) of the support body

133 Both Mr de Vos and Dr Huggett considered the “weldingly secured to …support body” integer to have the same meaning for the front and rear covers.

134 Mr de Vos understood the phrase “weldingly secured to and seated in face to face contact with the front face of the support body” to require that:

the front cover is:

(i) weldingly secured to; and

(ii) seated in face to face contact with the front face of;

the support body.

135 In other words, Mr de Vos understands that the front and rear covers must be welded to the support body. They may, but need not, be welded to the front and rear faces of the support body (respectively). They also may, but do not necessarily have to, be welded directly to the support body. They may instead be welded indirectly to the support body through an intermediary component, such as the side covers.

136 Dr Huggett considered that there were two equally possible ways to construe the “weldingly secured …support body” integer. The first, which he termed Meaning A, required that (taking the front cover as the example) the front cover be directly welded to the front face of the support body:

the front cover is:

(i) weldingly secured to; and

(ii) seated in face to face contact with,

the front face of the support body.

137 The second, which he termed Meaning B, accorded with Mr de Vos’ construction above.

138 Mr de Vos considered that passages from the specification, such as the one at page 5 lines 16–21, showed that the Patent contemplated indirect welding to the support body via an intermediate component, such as the side covers, which are themselves secured to the horn, preferably by welding (see page 5, lines 1–5 and fig 2 and page 9, lines 1–4). In addition, the front wall of the top cover of the second embodiment is welded to the support body indirectly through the intermediate cover. Mr de Vos expected that if it were a feature of the invention that the rear cover must be welded (directly or indirectly) to the rear face of the support body, was that the Patent would have said so. The Patent states only that the rear cover and side covers are welded to the side faces of the support body and to the “horn” (eg the support body).

139 Mr de Vos considered that a first cover can be indirectly welded to the support body if there is weld connecting the first cover to a second cover (an intermediary cover), and weld connecting that second cover to the support body. Mr de Vos considers that claim 1 requires an unbroken chain of welding between the front (or rear cover) and the support body. For example if a first cover is welded to a second cover but the second cover is bolted to the support body, Mr de Vos would not consider either cover to be weldingly secured to the support body.

140 Dr Huggett disagreed with Mr de Vos’ inclusion of indirect welding in the construction of “weldingly secured”. The disagreement was explored in the joint session.

7.5.2 Seated in face to face contact

141 Dr Huggett considered that the requirement that the front cover be “seated in face to face contact with the front face” means that the front cover and the front face are flush, in intimate contact across their surfaces, without any gaps.

142 Dr Huggett considered the language “seated in face to face contact”, in relation to a tooth construction for a mineral sizer, was not surprising because in his view mineral sizers have always been designed for the horn to take the loads rather than the covers and shells. Intimate contact and in a fixed (seated) position across the surface gives the maximum amount of strength to the horn for power transmission or loads and to minimise the risk of fatigue, movement or cracking in the shell. The large forces mean the tooth shell on the horn needs to be secured to withstand and transmit the high forces required.

143 Mr de Vos disagreed with Dr Huggett’s construction of the “seated in face to face contact” integer as meaning (in the context of the front cover) that the front cover and the front face are flush, in intimate contact across their surfaces without any gaps.

144 Mr de Vos did not see a practical reason why there was a need for the components to directly touch one another to satisfy the “contact” requirement. As noted earlier, Mr de Vos considered that the use of the word “contact” imports in the claim the critical concept of the efficient transfer of forces. Provided forces can be transmitted from one component to another, he considered they will obtain the benefit of being in “contact”, even if there is an intermediate component between them.

145 Mr de Vos considered that, if the claims were intended to be limited to front and rear covers that directly touch the support body (as is the case with the first embodiment), the claims would have used a phrase equivalent to “seated on the horn (or support body)”, as the Patent does at page 7, line 27 to page 8, line 2. In his opinion, if one component is “seated on” a second component, the two components are touching one another. In comparison, a component that is seated in “face-to-face contact” with a second component does not, in Mr de Vos’ opinion, need to touch the second component provided that forces can be transmitted between the two components including through an intermediary component.

146 Mr de Vos also noted that due to the manufacturing tolerances associated with sand casting, the covers described in the Patent (with the exception of the covers made from steel plate (the side covers of the tooth constructions described in the Patent and the rear cover)) would not be “flush, in intimate contact across their surfaces, [with the support body] without any gaps”.

147 In the course of explaining why the cover did not need to be in intimate contact with the horn across the entire surface without any gaps, Mr de Vos discussed further the transmission of force between two components. He observed that the same total force will be transmitted between two components, irrespective of whether they are “flush, in intimate contact across their surfaces, without any gaps” or there are some gaps between them.

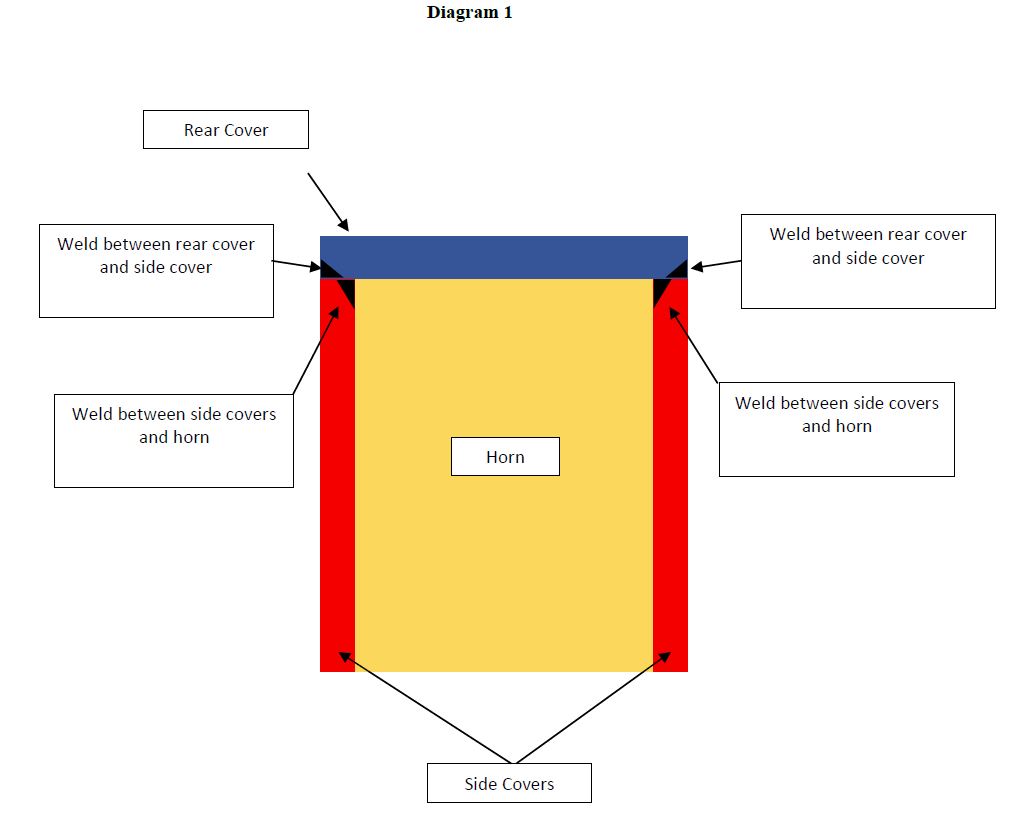

148 Provided that the front or rear cover is seated in face to face contact with the support body, Mr de Vos considered that the forces imparted on those covers during use will be transmitted efficiently to the support body. Mr de Vos discussed as an example where the rear cover is welded to the sides of the support body. According to Mr de Vos the forces will predominantly be transmitted through the face to face contact between the rear cover and the rear face of the support body. In this configuration, (which I consider to be as depicted in diagram 2 below) the weld is required primarily to secure the rear cover to the support body. Mr de Vos considered that a tooth construction in which the rear cover is in face to face contact with the rear face of the support body, and welded to a part of the support body that is not the rear face, is still a robust design within the principles described in the Patent.

149 Mr de Vos understands the phrase “face to face contact” to require that the forces are able to be transmitted from the face of one component to the face of a second component. A front cover will be seated in face to face contact with the front face of the support body if forces can be transmitted from the face of the front cover to the front face of the support body.

150 Mr de Vos saw no reason why a cover would not be seated in face to face contact with the support body if there is a clearance between the cover and the support body and that clearance is bridged by, for example:

(a) weld between the cover and the support body;

(b) an intermediary cover between the first cover and the support body; or

(c) ore fines and corrosion between the cover and the support body.

151 Mr de Vos explained further that where there is a clearance between a cover and a support body at the time of installation:

(a) those clearances may close as the cover deforms because of the forces imparted on it during use. The clearances may be permanently closed (plastic deformation), or closed only while the force is applied to the cover (elastic deformation); and

(b) clearances between two components can fill with ore fines and/or corrosion, allowing forces to be transmitted through the ore fines and/or corrosion.

152 In either case, as forces will be transmitted to between the cover and the support body, the cover and the weld are unlikely to fail. Mr de Vos considered that the weld securing the cover to the support body may crack over time if there was a permanent gap between the cover and support body.

153 According to Dr Huggett, the term “seated” when used in engineering applications, in particular in relation to valves, refers to two parts which have been wholly matched in shape so that the surface of one part is in intimate contact with the surface of the other part. Dr Huggett referred to the example of a valve, if the respective parts of a valve were not in intimate contact across their surfaces, the valves would leak.

154 Mr de Vos understands “seated” in the phrase “seated in face to face contact” to mean “positioned” or “in the position of”. He considers that claim 1 can be understood as requiring that the front cover is “positioned”, or “in the position of being”, in face to face contact with the front face of the support body. The requirement that the rear cover is seated in face to face contact with the rear face of the support body has an equivalent meaning. The front cover will be seated in face to face contact with the front face of the support body at any time that it is in face to face contact, irrespective of whether it was placed in face to face contact by the fitter at the time of assembly, or it came to be in face to face contact over time during use through the ingress and compaction of ore fines or corrosion. Mr de Vos did not consider that the claims were limited to tooth constructions in which the front and rear of the tooth shell touch the front and rear faces of the support body at the time of assembly.

155 Mr de Vos discussed further his understanding of the meaning of “seated” in his third affidavit. He said that his use of the term seated in contexts like a tooth construction is consistent with a Macquarie Dictionary definition of the term: “to fix firmly or accurately in a particular place”. In Mr de Vos’ experience, a component of an assembly or construction can “fix firmly or accurately in a particular place” without being “flush, in intimate contact across the surface, without any gaps”.

156 According to Mr de Vos, the Macquarie definition is consistent with the use of covers that have been manufactured via sand casting. As above, the surface of a cover that has been sand cast will not be perfectly flat; there will be gaps between the face of the cover and the corresponding face of the support body. These components will not be “flush, in intimate contact across their surfaces, without any gaps”.

157 Mr de Vos observed that aside from the broadest statement of the invention on pages 1–2, and claim 3, the Patent uses the phrase “face to face contact” on five occasions.

(a) Page 5, lines 10–11: “As shown in Figure 3, a rear cover 60 is then provided which is seated in face to face contact with the rear face 31 of horn 12”.

(b) Page 5, line 29 to page 6, line 1: “Cover 70 further includes a depending front wall portion 73 which has an internal face (not shown) which is seated in face to face contact with the front face 32 of the horn 12”.

(c) Page 7, lines 13–16: “The mounting body 120 has an upper part 122 which seats in rebate 110 and a lower depending part 124 which has an inner face which lies in face to face contact with the upper front face 86 of wall portion 73”.

(d) Page 8, lines 27–28: “The cover 210 defines an internal pocket which has faces which seat in face to face contact with faces 32, 33, 34 and 50 of the horn 12”.

(e) Page 9, lines 24–25: “The cover 60 is formed of a metal plate and is located in face to face contact with rear face 31”.

158 Mr de Vos observed that in each of the instances listed above, the two components that are described as being in face to face contact are also directly touching one another. Two components that are directly touching are in contact with one another because forces can be transmitted between them. They are therefore in “direct contact”. However, his observations did not cause Mr de Vos to consider that two components can only be in “contact” if they are directly touching one another. He considered that “contact” is a broad term that encompasses both direct and indirect transmission of force.

159 According to Mr de Vos, the phrase “face to face contact” does not require that forces can be transmitted across the entire faces of each component. In his opinion this is because the Figures of the Patent depict multiple covers that are said to be in face to face contact with the support body, yet the cover or support body remains partially exposed once the cover is secured to the support body.

160 Mr de Vos discussed weld failure in his third affidavit. He explained that weld is well suited to withstanding compression forces and is generally assumed as having similar strength to the components being joined together (eg the parent metal). However, when used in an application where forces are applied cyclically, resulting in fatigue (as is the case with tooth constructions in a mineral sizer), the welds have less fatigue strength than the parent metal. According to Mr de Vos weld failure would commonly occur where large shear forces or tensile forces are repetitively imparted on the weld.

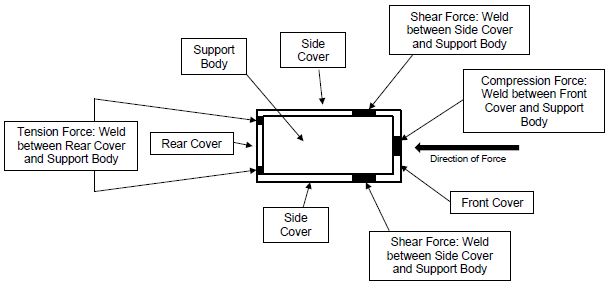

161 Mr de Vos then explained by reference to the diagram below, that on a welded tooth construction, even if there are clearances between a cover and the support body, there are limited circumstances in which shear and tensile forces imparted on the welds are large enough to cause the welds to fail.

162 Mr de Vos’ diagram illustrates the situation where there is weld between the front cover of the tooth construction and the front face of the support body. In that case, the majority of force imparted at the front of the tooth construction will be transmitted directly to the front face of the support body as a compression force. The same principle applies to the rear face of the tooth construction.

163 Mr de Vos identifies the force on the weld between:

(a) the side cover and the support body as a shear force; and

(b) the rear cover and the support body as tension force.

164 According to Mr de Vos in his third affidavit, in practice, it is possible to create a tooth construction with clearances between the covers and support body provided that:

(a) at the time of installation the cover touches the support body (whether directly or through weld) across enough of its face to transmit the forces without the cover deforming;

(b) clearances between the covers and the support body will fill with ore fines and/or corrosion during use, so that forces can be transmitted through the ore fines and/or corrosion;

(c) during use the cover is able to deform (plastically or elastically) to close the clearances between the cover and the support body, so that the cover is in contact with the support body during use;