Federal Court of Australia

Holland v BT Securities Limited (No 2) [2023] FCA 822

ORDERS

First Plaintiff VIVIENNE LESLEIGH HOLLAND Second Plaintiff | ||

AND: | Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The plaintiffs’ claim is dismissed.

2. I will hear the parties as to costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

O’SULLIVAN J:

1 In 1997, the first plaintiff (Mr Holland) opened a Margin Loan Account (Facility) with the defendant (BT) for the purposes of trading in shares. The terms of the Facility, required the amount by which the Facility was drawn down to be secured.

2 Over the following 24 years, Mr Holland used the Facility to trade in shares. In so doing, Mr Holland used the services of a stockbroker, Mr Peter Bennett, initially with Barton Capital Securities Pty Ltd and then Centec Securities Pty Ltd.

3 The plaintiffs are self-represented although Mr Holland, who has a Law Degree and has been admitted to the Supreme Court of South Australia, presented the case on behalf of himself and the second plaintiff, to whom he is married (Mrs Holland).

4 The plaintiffs allege that from 1997, BT paid commission to Mr Holland’s stockbroker which they allege was contrary to legislation or otherwise wrongful.

5 There is no dispute that during the period 1 April 2013 to 30 November 2020, BT paid commission to Centec in the sum of $1,059.80.

6 During the period Mr Holland operated the Facility, BT made margin calls on it. To satisfy those margin calls, shares initially gifted to Mrs Holland by Mr Holland, were sold by Mrs Holland to Mr Holland and then to market with the proceeds used to reduce the balance of the Facility.

7 The plaintiffs allege that the margin calls would not have been necessary and that they have paid fees and interest since 1997 as a result of the commission paid by BT to Barton and Centec.

8 The plaintiffs in their statement of claim allege nine causes of action, although at trial they abandoned a cause of action in dishonesty. The remaining eight causes of action comprise:

(a) Non-disclosure of the payment of commission to Centec and the failure to provide a Product Disclosure Statement (PDS) to Mr Holland;

(b) Unconscionable conduct contrary to s 12CB of the Australian Securities Investment Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act);

(c) Misleading and deceptive conduct contrary to s 12DA of the ASIC Act;

(d) Breach of fiduciary duty; or knowingly assisting or receiving in breach of fiduciary duty;

(e) Breach of contract;

(f) Fraud; and

(g) Breach of duty of care and breach of fiduciary duty owed to Mrs Holland.

9 Arising out of these causes of action, the plaintiffs claim an entitlement to an award of damages in the sum of $27,488,230, together with exemplary damages totalling $174,242,081.

10 Notwithstanding the period of time involved, BT does not take any limitation point.

11 It is for the reasons which follow that the plaintiffs’ claim is dismissed.

The Witnesses

12 The plaintiffs relied upon eight affidavits which stood as their evidence in chief – six sworn by Mr Holland and two by Mrs Holland:

(a) The affidavit of Mark William Holland sworn 21 August 2021 (first Holland affidavit) Exhibit P1;

(b) The affidavit of Mark William Holland sworn 22 September 2021 (second Holland affidavit) Exhibit P2;

(c) The affidavit of Mark William Holland sworn 12 October 2021 (third Holland affidavit) Exhibit P3;

(d) The affidavit of Mark William Holland sworn 21 December 2021 (fourth Holland affidavit) Exhibit P4 – save that in item 9 in the index of annexures to this affidavit, the words commencing from “collected from BT in Adelaide” until the words “with additional copy” are deleted and to that extent do not form part of the exhibit;

(e) The affidavit of Mark William Holland sworn 23 March 2022 (fifth Holland affidavit) Exhibit P5;

(f) The affidavit of Mark William Holland sworn 29 April 2022 (sixth Holland affidavit) Exhibit P6;

(g) The first affidavit of Vivienne Lesleigh Holland sworn 21 August 2021 - Exhibit P10; and

(h) The second affidavit of Vivienne Lesleigh Holland sworn 27 April 2022 - Exhibit P11.

Mark William Holland

13 Mr Holland is a chartered accountant and is legally qualified: See the footer to the letter dated 24 February 2021 in the first Holland affidavit, Exhibit P1, Annexure MWH-4, p 20; Exhibit 13, p 29. There is no evidence as to when he obtained those qualifications nor as to whether he holds or has held a practising certificate in the past in order to practise as a legal practitioner. In his closing submissions, he described himself as a lawyer.

14 I gained the strong impression from his evidence that he is obsessed by the notion he and Mrs Holland have been the subject of a grievous wrong. In cross-examination he was reluctant to answer questions directly, often engaging in argument with the cross-examiner. His evidence was, at times, confusing and he focussed on irrelevant points. The events in question commenced some 25 years ago, yet Mr Holland was on occasion adamant as to his recollection of events occurring at or about that time, notwithstanding contemporaneous documents and records did not support his recollection. Further, documents which he relied upon to support the plaintiffs’ case did not do so. Having said that, to his credit, on some occasions he accepted propositions notwithstanding those propositions were contrary to the plaintiffs’ case. Overall, Mr Holland reconstructed significant portions of his evidence and I consider him unreliable as a witness. I approach his evidence with a great deal of caution.

Vivienne Lesleigh Holland

15 Mrs Holland was cross-examined. Her claims in this proceeding rely on both a breach of duty of care and a breach of fiduciary duty. Mrs Holland was largely ignorant of the proceedings, such that she did not know anything about the statement of claim, did not know the quantum of her claim, and was unable to say how the damages she claimed had been calculated. Mrs Holland was an honest witness but I have concerns about her reliability as a witness. Her evidence is of little to no assistance and in cross-examination, she accepted she did not claim any damages other than for her claim in breach of duty of care/breach of fiduciary duty. Overall I treat her evidence with caution.

David Michael Morrissey

16 David Michael Morrissey was the sole witness called by BT. His affidavit sworn 14 February 2022 was received in evidence as Exhibit D12 (Morrissey affidavit).

17 Mr Morrissey is the Head of Margin Lending and Online Products for BT. He was cross-examined by Mr Holland.

18 Mr Morrissey was an impressive witness, answering questions directly and concisely, explaining when necessary. That was so notwithstanding that in cross-examination the questions were often prolix, confusing and argumentative. In saying that, I intend no criticism of Mr Holland who, as I have noted, appeared for himself and is not trained in the skills of cross-examination. Mrs Holland did not cross-examine Mr Morrissey. I have no hesitation in accepting Mr Morrissey’s evidence.

The Causes of Actions - an overview

19 The Facility was taken out by Mr Holland with BT in 1997.

20 Whereas there are a number of different aspects to the case advanced by the plaintiffs, there are three central features of the claims:

(a) The operation of the relevant legislation as it applied over the 24 years the Facility was in place;

(b) The alleged failure by BT to provide a PDS to the plaintiffs which disclosed commission payable to Mr Holland’s stockbrokers - initially Barton and then Centec; and

(c) As to the latter, the plaintiffs allege that payment of commission by BT to Centec over the period of the Facility from 1997 was wrongful because Centec provided no financial advice or sold financial products to Mr Holland.

21 It is these allegations which found, in large part, the basis for the eight causes of action.

Legislation

Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)

22 The plaintiffs rely on the Corporations Act and the amendments to that Act over a number of years in relation to the obligation to provide a PDS. No specific sections are identified by the plaintiffs, which is a common theme in the plaintiffs’ statement of claim, but BT submits and I accept, that Mr Holland appeared to rely upon ss 1012B in relation to the requirement for a PDS and its content; s 1017B of the Act in relation to a supplementary PDS and its requirements; s 963K of the Act in relation to conflicted remuneration; and s 1022B in relation to a claim arising from a failure to provide a PDS.

23 The Act commenced on 15 July 2001. It was not until 11 March 2002 that a PDS was required for a “financial product” as it was defined in s 763A of the Act at that time. Section 765A set out specific things which are not financial products. Section 765A(1)(h)(i) provided that a credit facility within the meaning of the Corporations Regulations 2001 (Cth) is not a financial product.

24 Regulation 7.1.06(1)(a) defined a “credit facility” for the purposes of s 765A(1)(h)(i) as including the provision of credit, “with or without prior agreement between the credit provider and the debtor; and whether or not both credit and debit facilities are available”. That includes the Facility such that the Facility did not come within the definition of what constituted a financial product at the time the Act commenced.

25 There was no change to s 765A(1)(h)(i) between 11 March 2002 and 1 January 2010. On 1 January 2010, the Corporations Legislation Amendment (Financial Services Modernisation) Act 2009 (Cth) came into operation. That Act amended s 765A by inserting after the words “a credit facility within the meaning of the regulations” the words “(other than a margin lending facility)”, thus bringing a margin loan facility (and here the Facility) within the meaning of a “financial product” for the purposes of the Act.

26 The obligation to provide a PDS in relation to a financial product is found in s 1012B(3)(a)(i) and (b) of the Act. That section was incorporated into the Act by the Financial Services Reform Act 2001 (Cth) which came into effect on 11 March 2002. As I have noted above, the Facility did not come within the definition of a “financial product” until 1 January 2010.

27 Section 1022B of the Act, which also came into effect on 11 March 2002, provides that if a person is required to give another person a PDS or a supplementary PDS and fails to do so then a person may recover the amount of any loss or damage by action as a result of that failure from a “liable person”. A “liable person” is somewhat cryptically defined but may be summarised as being a person who is obliged to give a PDS to a retail client but fails to do so. Self-evidently, it is only if there is a requirement to give another person a PDS in the circumstances prescribed by s 1022B and a person suffers loss as a result, there is a right to recover against a liable person.

28 The Reform Act also amended s 1017B of the Act, which concerns the requirement to provide ongoing disclosure of material changes and significant events. The provision came into effect on 11 March 2002. It is a civil penalty provision and insofar as is relevant, provided at that time:

1017B Ongoing disclosure of material changes and significant events

Responsible person must notify holders

(1) If:

(a) a person (the holder) acquired a financial product as a retail client; and

(b) either:

(i) the financial product was offered in this jurisdiction; or

(ii) the holder applied for the financial product in this jurisdiction; and

(c) the product is not specified in regulations made for the purposes of this paragraph; and

(d) a Product Disclosure Statement was, or should have been, produced for the product;

the person who is the responsible person for the Product Disclosure Statement for the financial product under Division 2 must, in accordance with subsections (3) to (8), notify the holder of:

(e) any material change to any of the matters specified, or that should have been specified, in the Statement that occurs while the holder holds the product; or

(f) any significant event that affects any of the matters specified, or that should have been specified, in the Statement and that occurs while the holder holds the product.

Note 1: Information in a Supplementary Product Disclosure Statement is taken to be contained in the Product Disclosure Statement it supplements (see section 1014D).

Note 2: Failure to comply with this subsection is an offence (see subsection 1311(1)).

…

(8) In any proceedings against the responsible person for an offence based on subsection (1), it is a defence if the responsible person took reasonable steps to ensure that the other person would be notified of the matters required by subsection (1) in accordance with subsections (3) to (8).

Note: A defendant bears an evidential burden in relation to the matters in subsection (8). See subsection 13.3(3) of the Criminal Code.

(9) In this section:

fees or charges does not include fees or charges payable under a law of the Commonwealth or of a State or Territory.

29 The relevant provisions of the Financial Services Reform Amendment Act 2003 (Cth) came into effect on 18 December 2003. Amongst other things, it amended s 1017B of the Act by repealing s 1017B(1) and replacing it with the following:

79 Subsection 1017B(1)

Repeal the subsection, substitute:

Issuer to notify holders of changes and events

(1) If:

(a) a person (the holder) acquired a financial product as a retail client (whether or not it was acquired from the issuer); and

(b) either:

(i) the financial product was offered in this jurisdiction; or

(ii) the holder applied for the financial product in this jurisdiction; and

(c) the product is not specified in regulations made for the purposes of this paragraph; and

(d) the circumstances in which the product was acquired are not specified in regulations made for the purposes of this paragraph;

the issuer must, in accordance with subsections (3) to (8), notify the holder of changes and events referred to in subsection (1A).

Note: Failure to comply with this subsection is an offence (see subsection 1311(1)).

The changes and events that must be notified

(1A) The changes and events that must be notified are:

(a) any material change to a matter, or significant event that affects a matter, being a matter that would have been required to be specified in a Product Disclosure Statement for the financial product prepared on the day before the change or event occurs; and

(b) any other change, event or other matter of a kind specified in regulations made for the purposes of this paragraph.

Note: Paragraph (a) applies whether or not a Product Disclosure Statement for the financial product was in fact prepared (or required to be prepared) on the day before the change or event occurs.

30 In 2012, the Corporations Amendment (Further Future of Financial Advice Measures) Act 2012 (Cth) (FoFA Act) was introduced. The FoFA Act introduced s 963K into the Act which banned conflicted remuneration, in turn defined by s 963A of the Act as:

Conflicted remuneration means any benefit, whether monetary or non-monetary, given to a financial services licensee, or a representative of a financial services licensee, who provides financial product advice to persons as retail clients that, because of the nature of the benefit or the circumstances in which it is given:

(a) could reasonably be expected to influence the choice of financial product recommended by the licensee or representative to retail clients; or

(b) could reasonably be expected to influence the financial product advice given to retail clients by the licensee or representative.

31 Section 963K did not apply to a benefit given to a financial services licensee or its representative if it was given prior to the application day: s 1528(1) of the Act. Section 1528(4) prescribed the application day as 1 July 2013. Section 1528(1) was repealed by the Treasury Laws Amendment (Ending Grandfathered Conflicted Remuneration) Act 2019 (Cth), Schedule 1, s 1 as from 1 January 2021.

Australian Securities Investment Commission Act 2001 (Cth)

32 The plaintiffs plead unconscionability under the ASIC Act in the statement of claim at [42]-[45], however the plaintiffs do not plead any sections of the ASIC Act. It seems the plaintiffs rely on ss 12CA and 12CB as they seek damages under the ASIC Act: see s 12GF(1).

33 Section 12CA is directed to the prohibition of a person in trade and commerce engaging in conduct in relation to financial services that is unconscionable within the meaning of the unwritten law, from time-to-time, of the States and Territories. It does not apply to conduct prohibited by s 12CB.

34 Section 12CB is directed to the supply or possible supply of financial services to a person or the acquisition or possible acquisition of financial services from a person.

35 The definition of financial services in s 5 of the ASIC Act cross-refers to s 12BAB. Section 12BAB(1) provides that for the purposes of Division 2 of the ASIC Act (in which s 12CB appears) a person provides a financial service if they engage in the matters set out in s 12BAB(1) which refers to a “financial product”. The definition of “financial product” is found in s 12BAA. Section 12BAA(7) identifies specific financial products for the purposes of Division 2 and concludes in s 12BAA(7)(m) “anything declared by the regulations to be a financial product for the purposes of this subsection”. Although s 12BAA(7)(m) is subject to s 12BAA(8), which excludes various things as financial products for the purposes of Division 2, nothing turns on that in the circumstances of this matter.

36 It was not until 1 January 2011, when the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Amendment Regulations 2010 (No. 2) (Cth) (ASIC Amendment Regulations) came into force that a margin lending facility became a “financial product” for the purposes of s 12BAA(7).

37 The ASIC Act does not define “unconscionable conduct” for the purposes of s 12CB of the ASIC Act although in s 12CC the legislation sets out a number of matters to which a court may have regard for the purposes of s 12CB. I deal with those matters when considering this cause of action.

Factual Findings

38 Given the length of time since the Facility was opened, documents cannot now be located and memories are unreliable. Further, it is not easy to untangle Mr Holland’s evidence and much of it was intermingled with submissions. In the sections that follow, I consider each of the pleaded causes of action, however prior to doing so I set out by way of narrative my factual findings. Most of the facts are not in dispute, however where there is a dispute over facts, I deal with that dispute. To the extent a particular cause of action involves factual matters not dealt with in this section of the reasons, I deal with those further facts, as necessary, when considering that particular cause of action.

39 In general terms, margin lending involves an institution making finance available to that institution’s clients, with which the purchase of approved shares or investment in managed funds may be effected. The funds drawn down are secured both against the investments as well as other security. Since the value of investments can change, so the amount of security required can also change. If the security drops below a pre-set limit, the borrower may be required either to provide additional security or sell some of the existing security (for example shares) in order to reduce the indebtedness and bring the facility within its predetermined parameters (a “margin call”).

40 BT holds an Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL), number 233722, and is an Australian Financial Services Licensee.

41 In 2002, BT became part of the Westpac Banking Corporation Group and since that time BT’s margin lending business has been conducted within a number of different divisions within the Westpac group.

Mr Holland’s stockbroker

42 Mr Holland used the services of Barton as his stockbroker with Mr Peter Bennett as the individual with whom he dealt, although there is an issue as to when he first started using Barton. There is no issue that in or about late 2003, Mr Bennett moved from Barton to Centec and Mr Holland followed him, using Centec’s services as stockbrokers with Mr Bennett remaining as Mr Holland’s contact.

43 In the first Holland affidavit, Exhibit P1, Mr Holland was not able to say when he opened his stockbroking account with Barton, only that it was before 28 May 1997: at [3]. He corrected that position in the fourth Holland affidavit, Exhibit P4, deposing that his account with Barton had an account number 11530, Mr Bennett was his stockbroker, and the account was opened on or about 12 November 1997. Prior to that time, he did not know Mr Bennett: at [14].

44 Annexure MWH-13 to the fourth Holland affidavit, Exhibit P4, is a statement of transactions with Barton during the period 1 July 1996 to 19 March 1997. The statement of transactions gives an account number 7069 and identifies Mr Guiseppe Rocca as Mr Holland’s “advisor”.

45 Also on the statement of transactions is a handwritten reference “CHQ No 3 SENT 2/6/97”. There is no evidence about the entry.

46 Following the statement of transactions are copies of some “Buy” and “Sell” contract slips. The first two Sell contract slips in that annexure following the statement of transactions, are a reversal of Sell contract 110176. That occurred on 6 October 1997 and refer to Mr Holland’s account number 7069 and Mr Rocca: Annexure MWH-13 pp 116-117. The following Buy and Sell contract slips in that same annexure reveal that as at 12 November 1997, Mr Bennett was Mr Holland’s “advisor” and that his account number had changed to 11530. That is consistent with Mr Holland saying that Mr Bennett was his stockbroker from about 12 November 1997.

47 However, those contract slips are inconsistent with a letter from Mr Holland to BT dated 27 May 1997 in which Mr Holland advised BT that Mr Bennett was his stockbroker: Morrissey Affidavit, Exhibit D12, Annexure DMM-3. That letter makes no reference to Mr Rocca as Mr Holland’s then stockbroker. Had that been the case, I would have expected the letter to have advised that Mr Rocca was then Mr Holland’s stockbroker rather than Mr Bennett. Instead, the letter advised:

Pleas (sic) be advised that my stockbroker is:

Mr Peter Bennett

(address given)

You are authorised to supply any information Mr Bennett may require. He requires settlement on some shares purchased in connection with my margin lending facility. It would be excellent of this matter could be attended to expediently.

…

48 Although there was a transaction on 6 October 1997, in which Mr Rocca was named as Mr Holland’s advisor, that transaction was reversed. There is no evidence as to how that sequence of events came about and in view of the letter to which I have referred above, I find it was an error on the part of Barton.

49 Further, Mr Holland deposes in the first Holland affidavit, Exhibit P1, that from on or about 28 May 1997 until 23 March 2009, he bought and sold shares with Mr Bennett, by telephone instruction using the Facility with consideration for and proceeds of all trades applied to or from the Facility. I accept that Mr Holland corrected his evidence in his fourth affidavit but the evidence he gave in his first affidavit is inconsistent with Mr Holland using Mr Bennett from 12 November 1997 but consistent with Mr Holland opening another account with Barton on or about 27 May 1997.

50 There is no evidence that covers the period 19 March 1997 to 27 May 1997. In the circumstances, I consider it is unlikely that Mr Holland was using his Barton account 7069 with Mr Rocca as his stockbroker (or “advisor”) after 19 March 1997 at which time Annexure MWH-13 to the fourth Holland affidavit, Exhibit P4, shows the account had a balance of $143.95.

51 Given the passage of time, I prefer the documentary evidence to what is almost certainly incomplete or faulty recollection. When Mr Holland deposed in the fourth Holland affidavit, Exhibit P4, at [14] that his account with Barton with account number 11530, with Mr Bennett as his stockbroker, was opened on or about 12 November 1997 and that prior to that, he did not know Mr Bennett, he was reconstructing his evidence and I do not accept it.

52 Accordingly, I find that Mr Holland had no stockbroker from on or about 19 March 1997 until 27 May 1997 when he opened a new account with Barton with Mr Bennett as the individual with whom he dealt from that time and that Mr Holland then advised BT accordingly.

The Facility is opened - the relevant forms

53 It is common ground that Mr Holland opened the Facility in 1997 with the designated account number HOLLM12973-6.

54 There is a difference between the parties as to the date Mr Holland opened the Facility. Mr Holland pleads he did so on 28 May 1997, whereas the defendant pleads on or about 28 April 1997. In his affidavit, Exhibit D12, Mr Morrissey deposes at [15] that he took a screenshot of BT’s electronic records which show Mr Holland opened the Facility on 28 April 1997. Given these events occurred some 25 years ago, I prefer documentary evidence over recollection and I find that Mr Holland opened the Facility on or about 28 April 1997.

55 There was an issue at trial as to the forms Mr Holland used when he opened the Facility.

56 Mr Holland deposed that to open the Facility, he completed forms which were contained in a bundle of documents obtained from BT including a document titled “How to Establish Your Loan”. He obtained a bundle of documents from BT on two separate occasions. The first occasion was in August/September 1996 when he collected them from BT’s Customer Service Office in Grenfell Street, Adelaide (Adelaide documents). He described the package as a green folder and identified two specific documents: a “BT Margin Loan” “flyer” and a document titled “How to Establish Your Loan” together with 11 other documents (fourth Holland affidavit [7]). Mr Holland did not complete the Adelaide documents.

57 In October 1996, the plaintiffs relocated to London, England. Mr Holland again received from BT the documents required to open a margin loan account which he received, in London, under cover of a letter dated 10 March 1997 (London documents). The package of documents he received at that time contained a “BT Margin Loan” brochure and what he described as “another complete application package in its green folder”. He said the London documents were identical to the Adelaide documents. It is for the reasons I explain below that I do not accept the London documents were identical to the Adelaide documents.

58 Mr Holland annexed copies of the Adelaide documents to his fourth affidavit, Exhibit P4, as Annexures MWH-4 – MWH-9 inclusive. At the footer of some of the documents are figures in the form 5/95 and 5/96. Ultimately, after prevaricating somewhat, Mr Holland agreed it was likely that the figures referred to the month and year such that 5/96 meant May 1996. Mr Morrissey confirmed in his evidence that was the case.

59 Mr Holland deposed in [7] of his fourth affidavit, Exhibit P4, that a document described as a Loan Agreement with a footer 5/96 was included in the Adelaide documents. He annexed a copy to Exhibit P4 as Annexure MWH-8. In cross-examination he produced what he described as the original of that document save that it had his signature and other of his handwriting upon it. A copy of that document is annexed to the fifth Holland affidavit, Exhibit P5 at Annexure MWH-2. He agreed that the original Loan Agreement he produced was identical to the document at Annexure MWH-8 save for his hand writing and signature. He said that he did not send the “original” Loan Agreement to BT after he signed it because he had made an error in filling it out in the sense that he signed in the wrong place.

60 In the fifth Holland affidavit, Exhibit P5, Mr Holland deposed that the London documents were, save for the documents he signed and returned to BT, annexed as Annexure MWH-2 to that affidavit.

61 Mr Morrissey joined the Westpac Banking Group, which now includes BT, approximately 12 years ago and has worked in BT’s margin lending, online share trading and equity-related businesses since that time. He has been in his current role as Head of Margin Lending and Online Products for approximately the last seven years. He has conducted and co-ordinated searches for documents relating to the Facility in BT’s physical records as well as its electronic records. The records are not complete for the full duration of the Facility given that it commenced in 1997. He has reviewed the available records for the Facility located by the searches.

62 Mr Morrissey deposed that BT’s records show that the Facility was opened in Mr Holland’s name on about 28 April 1997. He has been unable to locate a copy of any document signed by Mr Holland for the purpose of opening the Facility.

63 Mr Morrissey deposed further that BT makes available documents to potential customers for the purposes of opening a margin lending facility but they are updated from time-to-time with many of the documents marked with their month of issue for example “5/96” was used in May 1996. Notwithstanding he did not work for BT or Westpac at the time, based on his knowledge of BT’s records, in about 1996 and 1997 the documents provided to potential customers for a margin loan application comprised a sequentially numbered set of documents including a “Borrower Details Form”, a “Risk Disclosure Statement” and a “Loan Agreement” as well as other documents. He continued that documents within the application bundle were updated occasionally with the most up-to-date version of each document being included in the bundle provided to margin loan applicants. He annexed to his affidavit at Annexure DMM-1 a bundle of BT margin loan application documents with various dates from in about 1995 and 1996.

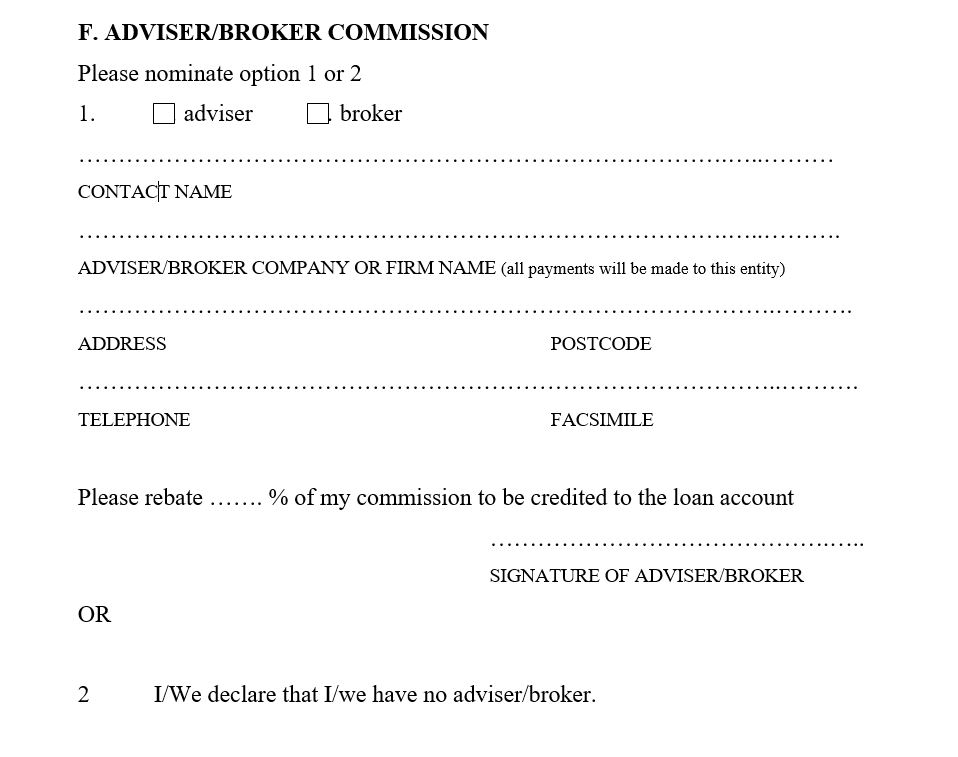

64 Included within Annexure DMM-1 is a document titled “Borrower Details Form” with the footer 9/96. That document includes Section F in which the person completing the form is to identify either an advisor or a broker: Exhibit D12, Annexure DMM-1, p 21; Exhibit P13, p 295.

65 Section F is important. It comprises two sections, one to be completed by the advisor/broker or, in the absence of there being an advisor/broker, by the client.

66 Consistent with that statement, cl 18 of the “Risk Disclosure Statement”, Annexure DMM-1, p 24 (Exhibit P13, p 298) states:

If you have completed details of an Adviser/Broker in the Borrower Details Form, that person may be entitled to receive commission from BTS during the term of the loan. BTS does not, in any circumstances, accept any responsibility for any statement, act or omission of your Adviser/Broker and the payment of any commission is not an endorsement of them by BTS.

67 The reference in cl 18 to an adviser/broker as “… may be entitled to receive commission” is consistent with the first option in Section F.

68 Section F of the “Borrower Details Form” and cl 18 of the “Risk Disclosure Statement” in Annexure DMM-1, pp 21 and 24 respectively, both have a reference date 9/96.

69 Mr Morrissey annexes at Annexure DMM-2, BT’s “Loan Facility Standard Terms” used from in or about May 1997.

70 The first and second pages of Annexure DMM-2 appeared to be what may be described as a cover sheet and first page of a “flyer”. The third page of Annexure DMM-2 contains details to be completed by the applicant with the following pages setting out what it described as “Standard Terms”. Within those standard terms is cl 48 (Annexure DMM-2, p 83; Exhibit P13 p 357) which reads:

If on the application form you filled out when entering into this transaction (entitled “Borrower application form”) you complete the details for a financial advisor or broker, that person, or a person connected to that financial advisor or broker, may be entitled to receive commission from BTS during the term of this agreement. Payment of any such commission is not an endorsement of that financial advisor or broker by BTS.

71 The italicised “broker” is defined in cl 52 of the document. Nothing turns on the definition.

72 There is no reference date in the footer of this document, however given Mr Morrissey’s evidence that the documents he annexed at DMM-2 were in use as from May 1997 and I have found the Facility was opened on 28 April 1997, I find that this document was not provided to Mr Holland by BT in or about March 1997 as part of the London documents.

73 Mr Morrissey deposes that based on his review of BT’s records and the application documents made available to customers by BT in or about August or September 1996 and March 1997 the documents sent to Mr Holland were most likely either the documents he annexes at DMM-1, alternatively the documents annexed to the fourth Holland affidavit, Exhibit P4 as Annexures MWH-4 – MWH-9 or a combination of them, however he cannot be certain about which version of the application documents BT provided to Mr Holland were used to open the Facility.

74 If Mr Holland had the Adelaide documents with him in London, there would be no need for him to request further copies, although I accept he may have been sent them gratuitously when in or about March 1997 he asked BT for updated indicative lending ratios for shares he might buy if using a loan from BT: Fourth Holland affidavit, Exhibit P4 [7].

75 Mr Holland did not accept that documents with a 9/96 footer were the ones he signed and sent back to BT from London in 1997. He said in cross-examination that he had never seen cl 18 of the “Risk Disclosure Statement” before and is adamant that the Adelaide documents did not have a footer 9/96.

76 I accept Mr Holland’s evidence that the Adelaide documents did not have a footer 9/96. That is because it seems to me that if new versions of the documents were provided no earlier than September 1996, which seems most likely given the footer 9/96, Mr Holland did not receive documents with that footer when he collected them in August 1996 and in the event he collected them in September 1996 perhaps not at that time either given that is the month and year those versions began to be distributed by BT.

77 Mr Holland is adamant that he did not see a “Borrower Details Form” with Section F or a “Risk Disclosure Statement” with cl 18 when he completed the application for the Facility in or about March 1997. However, the London documents, in particular the documents with the footer 9/96 in Annexure DMM-1 including Section F of the “Borrower Details Form” and cl 18 of the “Risk Disclosure Statement”, are likely to have been in circulation for some six months.

78 Mr Holland also said in cross-examination that he could not have completed Section F of the “Borrower Details Form” which had an option to complete indicating he did not have a stockbroker, because in fact, Mr Bennett was his stockbroker at the time he completed the “Borrower Details Form”. However, I have found that the terms in which Mr Holland wrote his letter to BT dated 27 May 1997, Exhibit D12, Annexure DMM-3 to which I have referred above, are consistent with Mr Holland not having a stockbroker until on or about 27 May 1997, which was after the Facility was opened.

79 Further, Mr Holland is relying on his memory from some 25 years ago. The provisions relating to commission are inconsistent with the case the plaintiffs put at trial and the plaintiffs, in particular Mr Holland, have an interest in disclaiming the “Borrower Details Form” and the “Risk Disclosure Statement”, such that it calls into question his dogmatic position in relation to the completion of the forms when he opened the Facility in April 1997.

80 Whereas Mr Holland disagreed that what documents he signed and sent back to the defendant are those Mr Morrissey has produced at Annexures DMM-1 and was certain that the documents he completed did not contain the commission clause to which I have referred, I do not accept that evidence and consider it is another example of Mr Holland reconstructing his evidence.

81 Whereas I am conscious that Mr Morrissey cannot be sure which documents Mr Holland received in March 1997, it is for the same reasons as I have set out above, in particular the time which has passed since Mr Holland completed the forms and his tendency to reconstruct his evidence, that I do not accept Mr Holland’s evidence.

82 On balance, I accept Mr Morrissey’s evidence that the London documents sent to Mr Holland contained at least to those documents he annexes at DMM-1 as the “Borrower Details Form” containing Section F and the “Risk Disclosure Statement” containing cl 18, both of which have a footer 9/96, as well the documents annexed to the fourth Holland affidavit, Exhibit P4 as annexures MWH-4 – MWH-9 or a combination of them. It seems to me that given some of the documents have footers with 5/95 and 5/96, as well as 9/96, it is more likely than not that the London documents in these annexures were a combination of documents with various footer dates, each representing the latest version of the document in question being distributed by BT.

83 Accordingly, I find that Mr Holland collected the Adelaide documents in or about August or September 1996. I find that those documents in DMM-1 which have footer dates of 5/95 and 5/96 were in the Adelaide documents. I do not accept that any of the Adelaide documents had the footer 9/96.

84 I find that the London documents comprised at least the documents listed below which form either Annexures to Mr Holland’s fourth affidavit, Exhibit P4, or Annexure DMM-1 to Mr Morrissey’s affidavit, Exhibit D12:

(a) A covering letter from BT to Mr Holland at an address in the United Kingdom dated 10 March 1997 - Annexure MWH-4;

(b) A BT Margin Loan brochure - Annexure MWH-6;

(c) A document titled “How to Establish Your Loan” - Annexure MWH-7, also part of DMM-1 pp 30, 31;

(d) A single document with sections titled: (Annexure DMM-1)

(i) “1. Borrower Details Form” with a footer 9/96 and containing Section F;

(ii) “2. Risk Disclosure Statement” with a footer 9/96 and containing clause 18;

(iii) “3. Power of Attorney” with a footer 5/95;

(iv) “4. Declaration of purpose for which credit is provided under the BT Margin Loan” with a footer 9/96;

(v) “5. Loan Agreement” with a footer 5/96. This document comprises eight pages. A single page of the document occurs earlier in annexure DMM-1 at p 28, however this appears to be a collating error;

(vi) “6. Deed of Mortgage” with a footer 5/95;

(vii) “7. Nominee Deed” with a footer 5/95;

(viii) “8. Chess Sponsorship Agreement” with a footer 5/96; and

(ix) “9. Sample of Accountant’s Letter” with a footer 5/95.

85 I find that Mr Holland completed the “Borrower Details Form”, “Risk Disclosure Statement”, “Power of Attorney”, “Loan Agreement” and “Declaration of Purpose” and returned them to BT shortly prior to 28 April 1997.

86 Mr Holland said he opened the Facility, without the involvement of Mr Bennett or anyone at Barton, whom I have found was Mr Holland’s stockbroker as from on or about 27 May 1997. I accept that evidence.

87 I find that when completing the “Borrower Details Form”, Mr Holland completed Section F as him having no stockbroker for the reasons I have set out above, in particular that as at April 1997, Mr Holland did not, in fact, have a stockbroker.

88 It follows that the terms of the contract for the Facility between BT and Mr Holland comprised a suite of documents constituted by at least the “Borrower Details Form”, the “Risk Disclosure Statement”, the “Power of Attorney”, the “Declaration of Purpose” and the “Loan Agreement” as I have set out above. It is not clear to me whether the “Deed of Mortgage” was executed, however nothing turns on that.

89 There is no dispute between the parties that neither the Adelaide documents nor the London documents included a PDS in respect of the Facility.

90 In December 2003, Mr Bennett contacted Mr Holland and signed him up as a customer to his new brokerage firm, Centec. Subsequently, by letter dated 29 December 2003, Mr Holland advised BT that Mr Bennett was authorised to transact the Facility on Mr Holland’s behalf: Exhibit MWH-11, p 105. BT confirmed the change in details for Mr Bennett by its letter to Mr Holland on 12 January 2004.

91 Notwithstanding there is no issue that Barton and Centec acted only as stockbrokers and not as financial advisors to Mr Holland, in cross-examination Mr Holland accepted that Mr Bennett, then with Centec, was listed on Mr Holland’s Facility as Mr Holland’s “advisor” as at 1 November 2010: Exhibit D8. Mr Holland took no steps to correct that notation.

92 BT charged and collected interest at its published rates, known as the “headline rate”, monthly in arrears, in accordance with the terms of the Facility contract.

93 The Facility had a zero balance by 2 August 2021 (i.e. there were no monies owed to BT).

The Equities Distribution Agreement (EDA)

94 At all times whilst Mr Holland was using the Facility to transact shares with Centec as his stockbroker, BT (or Westpac) had an agreement with Centec regarding the payment of commission, referred to by the plaintiffs as a “remuneration agreement” but described by BT as an “Equities Distribution Agreement”. For the purposes of these reasons there is no difference between the two descriptions.

95 Annexed to the Morrissey affidavit at Annexures DMM-5 and DMM-6 respectively are an EDA between BT and Centec dated 26 June 2012 (2012 EDA) and an incomplete version of a previous EDA between BT and Centec dated 18 January 2011 (2011 EDA). Mr Morrissey has been unable to locate an earlier version of an EDA with Centec and unable to locate any EDA between Westpac or BT and Barton.

96 The 2012 EDA and the 2011 EDA refer to entities with whom BT contracted (albeit in the name of Westpac Group of which BT formed part) as the “Distributor”.

97 Mr Morrissey deposed that the general purpose of an EDA was that where a Distributor recommended a qualifying product to its client and it was sold to the client, the Distributor would receive a commission. The rate of that commission was, at least prior to the FoFA Act, a matter for negotiation between the financial institution and the Distributor. Mr Morrissey’s experience with BT is that the rate of commission negotiated for a new facility would apply to that new facility with the rate of commission payable on existing facilities that had been negotiated or fixed remaining unchanged.

98 Mr Morrissey is aware from the margin lending records of both BT and Westpac that prior to 2002 Westpac had a number of EDAs placed with different entities whereby those entities were authorised to recommend various Westpac products to their clients.

99 Mr Morrissey does not know whether BT had similar arrangements prior to 2002 when it became part of the Westpac Group. BT cannot now locate any EDA between itself and Barton that was operative at the time the Facility commenced in 1997 although it admits it was Westpac’s general practice and BT’s general practice at the time the Facility commenced to have EDAs in place with entities such as Barton.

100 Mr Morrissey has been unable to locate any record of the rate of commission payable prior to April 2013. He is not aware of leading commission ever having been paid in respect of the Facility or facilities of that nature. The plaintiffs have pleaded that leading commission was paid, however there is no evidence of that and in circumstances where Mr Morrissey has deposed that he is not aware of leading commission ever having been paid, I infer that leading commission was not paid on the Facility.

101 Clauses 6.1 and 6.2 of the 2012 EDA provide that the Distributor is entitled to receive commission at a rate no greater than the rate of the commission disclosed in the relevant PDS. That is consistent with the Act as it then stood. If the Distributor transfers any of its rights to receive commission to another person, commission will be paid to that other person.

102 The 2011 EDA also contains a commission clause in cl 6. It provides that Westpac will pay a commission to the Distributor for the issue or sale of a product by it as indicated by the application form bearing its (or one of its authorised representatives) identification details or as specified by notice in writing. Clause 6 is otherwise incomplete.

103 As I discuss below, there is no dispute that BT paid commission on the Facility to Centec between 1 April 2013 and 30 November 2020.

104 As to the terms of an EDA with Centec, on the basis of the 2012 EDA and Mr Morrissey’s evidence, I find that as at 1 April 2013:

(a) Centec (the Distributor) was authorised, at its discretion, to recommend to their clients specified products of the Westpac Group (which included BT);

(b) If Centec recommended to its client, and the client entered into, a margin loan facility (such as the Facility), BT would pay trailing commission to Centec calculated as a percentage of the client’s loan balance under that facility. Leading commission was not paid; and

(c) Where Centec assigned or otherwise transferred its rights to receive commission under the EDA to another person, BT would thereafter pay the commission to that person.

Did Barton and/or Centec receive commission?

105 The plaintiffs plead at [51] of the statement of claim that commission was paid by BT to the “stockbrokers” on a monthly basis from 1997 until December 2020. Those stockbrokers are not identified, however in all the circumstances it can only have been Mr Bennett, Barton and Centec. Although there is evidence that suggests EDA’s between BT and Barton may have existed, there is no evidence of whatever type that Mr Bennett or Barton received commission from BT or Westpac in relation to the Facility, nor is there any evidence of the rate of any commission, assuming commission was, in fact, paid. I find that neither received commission.

106 At [51] of its amended defence, amongst other things, BT admits that payments were made to Centec during the period 1 April 2013 - 30 November 2020 in the sum $1,059.80.

107 Annexure DMM-7 to the Morrissey affidavit is a record of commission paid by BT in respect of the Facility since April 2013. The record of commission reveals that commission was paid on the average monthly loan balance at a rate of 0.28% per annum and that BT paid commission to Centec in the sum of $1,059.80 over that period. BT is unable to locate documentation with Barton given the length of time that has passed such that it does not know the amount of commission, if any, paid to Barton prior to April 2013 and otherwise denies the allegations.

108 I accept Mr Morrissey’s evidence that trailing commission was paid to Centec on the average monthly loan balance of the Facility at a rate of 0.28% pa.

109 Apart from admitting payment of commission to Centec, in its amended defence at [51], BT cross-refers to [15] of its amended defence where it pleads that if Barton and/or Centec were not entitled to be paid commission under the EDAs in respect of the Facility then any commission paid to them by BT has been paid by mistake: [15 d iv]

110 BT also pleads:

(a) At [18b]: “pursuant to the EDA with Centec, between 1 April 2013 and 30 November 2020, any trailing commission payable was calculated monthly at the rate of 0.28% per annum on the previous months average loan balance”; and

(b) At [15db]: That by reason of the documents sent to Mr Holland prior to or in April 1997, “… [Mr Holland] knew or should have known that commission might be paid to a financial advisor or broker in respect of the Facility”.

111 As to Mr Holland’s knowledge pleaded in [15 db], I have found that the Risk Disclosure Form and the Borrower Details Form formed part of the contract between Mr Holland and BT and that Mr Holland did not have a stockbroker at the time he completed the forms in April 1997 to open the Facility. I find that knowledge proved.

112 In their amended reply, doing the best I can to understand the pleading, the plaintiffs plead, relevantly, that in answer to [51] of the amended defence:

(a) At [6], that if an EDA with Centec existed, the first trade made using Centec and settled through the Facility was on 9 January 2004 such that any payment of commission under the terms of the EDA was from January 2004; and

(b) At [11], that they do not know of the EDA but that trailing commission was paid to Barton and Centec at the rate of 0.28% per annum since the inception of the Facility in May 1997 until November 2020.

113 As to the pleading at [6], the pleading is based on an EDA with Centec and given the first trade made using Centec and settled through the Facility was on 9 January 2004 any payment of commission under the terms of the EDA was from that date. There is no evidence of the terms of any EDA with Centec and Westpac or BT as at 9 January 2004. So too, there is no evidence of any payment of commission to Centec of any type as from that date to 1 April 2013. It appears that I am once again being asked to draw an inference. Although there was evidence that it was likely there was an EDA between Centec and Westpac or BT as at January 2004, I am quite unable to determine what the terms of that EDA were nor am I able to infer whether the terms of that EDA authorised the payment of commission to Centec on the Facility, whether generally, or in the particular circumstances under which Mr Holland opened and operated the Facility nor the rate of any commission, assuming it was paid. Accordingly, I decline to do so.

114 As to the pleading at [11], it is not clear to me on what basis the pleading that trailing commission was paid from May 1997 until November 2020 is made. Again, there is no evidence of any type that payments of trailing commission commenced in 1997 and to the extent I am asked by the plaintiffs, at least implicitly, to infer payment of commission at 0.28% were made from the inception of the Facility in 1997 to 30 November 2020. I decline to do so.

115 I find that there was an EDA between Centec and BT as at 1 April 2013. I find that during the period from 1 April 2013 to 30 November 2020, trailing commission was paid to Centec calculated monthly at the rate of 0.28% per annum on the previous month’s average loan balance in the total sum of $1,059.80.

116 There is no evidence of any commission being paid to Centec by BT prior to 2013 and no evidence of Barton being paid any commission. Accordingly, the plaintiffs have failed to establish that prior to 2013 Centec and/or Barton were paid commission on the Facility.

How did Centec come to receive commission?

117 Mr Morrissey has reviewed BT’s electronic records and reproduces a screenshot of BT’s electronic records relating to the Facility. That screenshot reveals that from 1 April 2013 until 30 November 2020, Centec was noted as a “commission party” on the Facility such that it was recorded as being entitled to receive commission. Mr Morrissey does not know how or why it was recorded in that fashion and there is no evidence one way or the other. Mr Morrissey deposes that in circumstances where Centec did not recommend the Facility, it is likely that Centec was recorded as a commission party by mistake.

118 I have found that Mr Holland completed the forms to open the Facility on or about 28 April 1997 at which time he did not have a stockbroker, and that he completed Section F of the “Borrower Details Form” by indicating he had no stockbroker. Under those circumstances when BT updated its records following Mr Holland’s letter dated 27 May 1997: Morrissey affidavit, Exhibit D12, Annexure DMM-3, it recorded for the first time, the details of a stockbroker linked to Mr Holland and the Facility. The identity of the stockbroker changed on 29 December 2003 when Mr Holland wrote to BT advising that his stockbroker, Mr Bennett of Centec, was authorised to transact on the Facility: Fourth Holland affidavit, Exhibit P4, Annexure MWH-11, p 105, Exhibit P13, p 232.

119 The letter dated 29 December 2003 from Mr Holland to BT only advises that Mr Bennett is authorised to transact on the Facility and making or repaying advances in respect of which the Facility relates.

120 Exhibit D8 is a “BT Margin Loan Statement” for the Facility for the period 1 November 2010 to 30 November 2010. It records, “PETER BENNETT, CENTEC SECURITIES LTD”, as Mr Holland’s “adviser” as at 30 November 2010.

121 Mr Holland accepted that at no point after receiving Exhibit D8 did he contact BT and inform it that he had no advisor notwithstanding he had that opportunity.

122 Further, in about October 2014, BT sent to Mr Holland a “BT Margin Lending Nominated Financial Advisor” Form. The Form noted the existing financial advisor details as Kerry Clough/P Bennett of CENTEC SECURITIES LTD: Fourth Holland Affidavit, Exhibit P4 at [12], Annexure MWH-12. Notwithstanding that entry and the opportunity for Mr Holland to correct that entry, he took no action.

123 I deal with correspondence between BT and Mr Holland commencing on 9 November 2020 below, but relevant to the question of how an advisor came to be listed on Mr Holland’s account, is a statement in the letter from BT dated 25 May 2021 which records that:

We can confirm that BTML received a letter from yourself dated 29 December 2003 requesting Centec be listed as your stockbroker on your account. We responded to your request on 12 January 2004 confirm (sic) that this was processed correctly in accordance with the instructions received in your letter to BTML on 29 December 2003.

124 I find that BT entered onto Mr Holland’s Facility account the details of a stockbroker as provided by him, starting in 1997 (entered as “Bartpb” – Exhibit D12, Annexure DMM-3) and Peter Bennett, Centec Securities Ltd. That error was never corrected by Mr Holland.

125 I find that payments of commission were made to Centec from 30 April 2013 on the basis of the account details for the Facility held by BT and entered as a result of the instructions given by Mr Holland to BT.

126 In the light of Mr Morrissey’s evidence as to EDAs, of which the terms of the 2012 EDA between BT and Centec are a proximate example, I find that Centec was entitled to receive commission on loan accounts such as the Facility. Whereas I was not prepared to infer that the payment of commission to Centec on the average monthly balance of the Facility between 1997 and 1 April 2013 was made, about which there is no evidence of any type, there is no dispute that payment of commission was made by BT to Centec on this basis between 1 April 2013 and 30 November 2020.

127 The significance of an EDA such as the 2012 EDA, which in view of the payments of commission that were made I am prepared to infer represented the terms of any EDAs between BT/Westpac and Centec subsequent to 1 April 2013, is that there existed an obligation as between BT/Westpac and Centec for BT/Westpac to pay commission to Centec. To that extent, the absence of an agreement between BT/Westpac and Mr Holland for the payment of commission is irrelevant and does not impact on BT/Westpac’s obligation to pay commission in accordance with the terms of any EDA.

128 The only qualification to that obligation is whether there was an instruction to credit the amount of the commission to the Facility which, on the basis of the documents as I have found them, is to be found in Section F of the “Borrowers Details Form”. That was a provision to be completed by the relevant advisor/broker but clearly, it was not completed at the time the Facility commenced for the reasons I have set out. There is no evidence of any subsequent discussion between Centec and Mr Holland once commission started to be paid.

129 In circumstances where there were details of an advisor/broker on file entered subsequent to the opening of the Facility and no instructions given in Section F of the “Borrower’s Details Form” to remit any part or all of any commission payable to the Facility, I find that any payment of commission by BT to Centec was made in accordance with the terms of any EDA current at the time and in the absence of any instruction to the contrary, it was assumed that Centec was entitled to be paid commission. To the extent Mr Holland has an issue with the payment of commission by BT/Westpac to Centec, that is a matter between him and Centec, not BT/Westpac.

The effect of the payment of commission on the interest rate charged to Mr Holland

130 Mr Morrissey deposed that the payment of commission makes no difference to the headline interest rate, being the interest rate charged to the client on the Facility balance before any applicable discounts. In relation to the Facility, Mr Morrissey deposed that commission was paid by BT to the dealer group which in this case was Centec without that cost being passed on to the Facility or Mr Holland. So too, there is no fee payable or directly connected with commission paid to Distributors such as Barton or Centec and Mr Holland’s Facility was not the subject of any fee payable. I accept that evidence.

131 Further, Mr Morrissey deposes he is not aware of any premium being included in BT’s charges to Mr Holland for “advisory services”. Whether he is aware of it or not, there is no evidence of any premium being included in BT’s charges to Mr Holland for “advisory services” which is unsurprising given BT did not provide any services to Mr Holland other than the Facility.

132 Mr Holland accepted under cross-examination that he was paying the advertised rate of interest for a margin loan for the life of the Facility. He accepted that he was not charged, nor did he pay a rate of interest higher than the rate advertised. He accepted he was not charged a premium on account of the commission, or otherwise.

133 The rate of interest on the Facility was notified to Mr Holland by various means, including, in most recent years by notification on BT’s website: Morrissey affidavit [56]. BT charged interest on the Facility as amended from time-to-time with any change in interest rate in accordance with the terms of the Facility.

134 The fact that Mr Holland was not paying any kind of premium in respect of the Facility by reason of the payments of commission was confirmed to Mr Holland in writing on 25 May 2021: First Holland Affidavit, pp 27-28.

Grandfathered entitlements

135 The plaintiffs have referred to the commission paid to Centec as being conflicted remuneration. BT denies that commission paid was conflicted remuneration within the meaning of the Act because prior to 1 January 2021 the Act did not apply to benefits given under an arrangement entered into before 1 July 2013, and no commission was paid in respect of the Facility on or after 1 January 2021.

136 I find that the commission paid by BT to Centec was not conflicted remuneration.

137 Given that grandfathered entitlements or arrangements were banned as from 1 January 2021, Mr Morrissey deposed that BT did not pay commission on grandfathered arrangements after that date and discounted interest rates on all margin lending facilities on which it had, until that time, continued to pay commission to Distributors under grandfathered arrangements.

138 The consequence is that BT reduced the headline interest rate by the percentage commission being applied to the Facility such that the headline interest rate payable was reduced by 0.28%.

139 In cross-examination, Mr Holland conceded the payment of commission to Centec was not conflicted remuneration.

140 Mr Holland also submits any assertion by BT that the payments of commission under the EDA were eligible for grandfathering provisions of the Act, is a contravention of ss 964D, 965 and 936K of the Act. Once again, these sections are not pleaded but in any event, it is for the reasons I have set out that the payments of commission were grandfathered payments such that there is no such contravention.

Correspondence between 9 November 2020 and 21 July 2021

141 There was a series of correspondence between Mr Holland and BT between 9 November 2020 and 21 July 2021. That correspondence forms part of Mr Holland’s complaints about BT’s alleged conduct.

142 It was the change in legislation concerning grandfathered entitlements that caused BT to write to Mr Holland on 9 November 2020 informing him that BT currently made payments of commission to his financial advisor but that as from 1 January 2021 that was going to cease because of a change in legislation and that Mr Holland would receive a reduction on his variable interest rate equivalent to the payment previously made to his financial advisor: First Holland Affidavit, Exhibit P1, Annexure MWH-3; Exhibit P13, p 27.

143 BT’s letter prompted Mr Holland to write a letter to BT dated 24 February 2021 in which he requested the return of commission (which he refers to as “remuneration”) paid to Centec. That letter was returned to Mr Holland undelivered. Mr Holland wrote again to BT on 27 April 2021 complaining about remuneration paid to Centec and seeking a refund of $39,118 based on commission at 0.28% per annum on the average monthly balance of the Facility together with interest forgone at applicable margin lending rates: First Holland Affidavit, Exhibit P1, Annexure MWH-4 - MWH-6; Exhibit P13, pp 28-32.

144 By letter dated 25 May 2021, BT wrote to Mr Holland in response to his letter dated 27 April 2021: First Holland Affidavit, Exhibit P1, Annexure MWH-7; Exhibit P13, p 36. The letter refers to a subsequent telephone discussion, however there is no evidence about what was discussed nor with whom from BT Mr Holland had the telephone discussion. The letter summarises Mr Holland’s complaint as being that he never had a financial advice relationship with Centec and they were only his stockbroker for a period of time.

145 The author of BT’s letter advised that after having reviewed all the evidence, BT’s determination was that the product issuer had not made an error and the request for compensation was declined. It continued by acknowledging Mr Holland’s request in his letter dated 29 December 2003 for Centec to be listed as his stockbroker and that BT changed his advisor/broker to Mr Bennett in accordance with his instructions. The letter pointed out that if Mr Holland did not have a listed advisor on his account, he would not be entitled to the 0.28% discount being applied to the account after 30 November 2020.

146 In response to BT’s letter dated 25 May 2021, Mr Holland wrote to BT by letter dated 9 June 2021: First Holland Affidavit, Exhibit P1, Annexure MWH-9; Exhibit P13, pp 45-49. In that letter he increased his claim to $920,867; threatened to submit his complaint to the Australian Financial Complaints Authority (AFCA); sought to have the contract set aside (presumably the Facility contract); and his interest returned. He disputed BT’s assertion that it had not erred and accused it of making unlawful and unreasonable payments, misrepresentation in its communication and unconscionability in its conduct. In the alternative, Mr Holland sought $89,299 as comprising unlawful undisclosed conflicted remuneration. Mr Holland attached a document to the letter titled “Schedule of Deficiencies in Conduct”.

147 BT responded to Mr Holland’s letter dated 9 June 2021 by its letter which, although dated 6 June 2021 is likely to be 6 July 2021: First Holland Affidavit, Exhibit P1, Annexure MWH-10; Exhibit P13, p 54. I do not set out the contents of the letter, but it rejected the assertions made by Mr Holland in his letter dated 9 June 2021.

148 Mr Holland responded by letter dated 19 July 2021: First Holland Affidavit, Exhibit P1, Annexure MWH-12; Exhibit P13, p 61. Once again, I do not set out the contents of the letter but Mr Holland made a number of allegations against BT, including fraud, and demanded of BT the sum of $9,440,947. The letter included a number of attachments.

149 BT responded to Mr Holland’s letter dated 19 July 2021 by email sent 21 July 2021. Apart from acknowledging the complaints and stating that it had thoroughly investigated Mr Holland’s concerns, it provided contact details for AFCA: First Holland affidavit, Exhibit P1, Annexure MWH-13; Exhibit P13, p 78.

Allegation of fraudulent correspondence

150 I digress at this point to deal with the plaintiffs’ closing submissions at paragraph 6(g) where the plaintiffs submit that the letter written by BT on 9 November 2020: Exhibit P1, Annexure MWH-3, is fraudulent. It does so on grounds that the letter dated 9 November 2020 is false or misleading in a material particular with the intention of obtaining a financial advantage. The plaintiffs assert that the remuneration received by Centec was an asset based fee on borrowed amounts advanced after 1 July 2013 and were not eligible for grandfathering.

151 The same submission is made in the same section of the plaintiffs’ submissions in relation to BT’s correspondence dated 21 May 2021, 6 July 2021 and 21 July 2021 to which I have referred above: First Holland Affidavit, Exhibit P1, Annexures MWH-7, MWH-9 and MWH-13.

152 As to the letter dated 21 May 2021, the plaintiffs plead the letter is fraudulent: statement of claim [66], because it states BT had not made an error notwithstanding Mr Holland’s assertion in his letter dated 27 April 2021 that he had never had a financial advice relationship with Centec: Exhibit P4, Annexure MWH-6. In the letter, BT referred to Mr Holland’s letter dated 29 December 2003: Exhibit P4, Annexure MWH-11, in which Mr Holland requests Mr Bennett at Centec be listed as his stockbroker and BT’s response dated 12 January 2004, Exhibit P4, Annexure MWH-11, confirming it had changed his advisor/broker accordingly.

153 The plaintiffs also submit the letter dated 21 May 2021 is fraudulent because it said that:

(a) Payments were to a financial advisor and not a stockbroker;

(b) Mr Holland had agreed to pay interest by referring to BT’s website when the website did not exist at the time Mr Holland entered into the Facility;

(c) Mr Holland had a financial advisor listed on his account when it was not the case;

(d) BT had not made an error; and

(e) Mr Holland would not have been entitled to a discount had there been no financial advisor listed on the account.

154 BT’s letter dated 6 July 2021 is said to be fraudulent for the same reasons as the letter dated 21 May 2021 and BT’s email sent 21 July 2021 is said to be fraudulent because it asserts the other letters of response as being final.

155 Dealing first with the letter dated 9 November 2020, there is no evidence that the remuneration received by Centec was asset based. Indeed, the only evidence was that of Mr Morrissey, who explained that the commission was based on the average monthly loan balance. Further, the plaintiffs’ allegations of fraud in the statement of claim did not assert that the commission received by Centec was, in fact, asset based remuneration derived from the quantum of the borrowed amounts.

156 I find the commission received by Centec was not asset based remuneration.

157 The pleading of fraud by the plaintiffs is a bare pleading. No particulars of the type of fraud have been pleaded, only a conclusion is pleaded.

158 In Bell Group Ltd (in liq) v Westpac Banking Corp (No 9) [2008] WASC 239; (2008) 39 WAR 1 at [4849], Owen J cited with approval the following examples of equitable fraud taken from ‘Meagher, Gummow and Lehane’s, Equity, Doctrines & Remedies (4th ed, 2002)’:

(a) Misrepresentation by persons under an obligation to exercise skill and discharge reliance and trust, as in fiduciary relations, and inducements to contract or otherwise on which there is detrimental reliance by the representee upon the defendant.

(b) The use of power over another in the procurement of a bargain or gift disadvantageous to the other party.

(c) The pursuit of interest in conflict with duty arising from a fiduciary relation or the entrusting of a power by a donor. This gives rise, as noted above, to what may be regarded as ‘technical’ frauds in contrast to the more offensive conduct apt to be found in category (b).

(d) Improper reliance upon legal rights, with particular reference to the setting aside of judgments procured by fraud and to the use of statutory defences, where the relations and dealings between the parties make it unconscionable to press the statute.

(e) The constructive trust, viewed as a remedial device where it would be a fraud for the person on whom the court imposes the trust to assert beneficial ownership.

(f) Agreements which are bona fide between the parties but in fraud of third persons; this jurisdiction was described by Lord Harwicke LC as the fourth category of fraud in Earl of Chesterfield v Janssen.

(Citations omitted)

159 At a general level, fraud at common law is concerned primarily with representations which are fraudulent and which founds an action in deceit which involves conscious dishonestly.

160 There is, of course, also fraud which is the subject of the criminal law.

161 All of the correspondence to which I have referred in this section of the reasons and the matters raised in that correspondence, which are in some cases pleaded but which are all subject of submissions are, in the circumstances, quite incapable of amounting to fraud, of whatever type.

162 The pleading and submission of fraud is very serious. There is no evidence of whatever type to support the allegations of fraud and I have no hesitation in rejecting both the allegations and the submissions to that effect. The pleading and the submissions of fraud should not have been made.

Mrs Holland’s shares

163 There is no dispute that BT held a security interest in some shares belonging to Mrs Holland to secure Mr Holland’s performance of his obligations under the Facility and that Mrs Holland’s shares were sold by the plaintiffs (on 20 November 2008 and 9 August 2011) initially to Mr Holland and then to market with the proceeds totalling $315,586.54 paid to BT (at the time of each respective sale) to reduce the amount owed under the Facility.

164 Much of Mrs Holland’s second affidavit, Exhibit P7, centres around the formalities for witnessing documents in New Jersey in the United States of America, when she and Mr Holland were living there.

165 That evidence is irrelevant. It is not pleaded in any way nor do I consider there are any issues to which the matters Mrs Holland deposes to might relate in any meaningful way.

Alternative facilities, vulnerability, special disabilities

166 As to any alternative facility, Mr Holland agreed in cross-examination that he could have acquired identical or equivalent financial services from another financier if at any time he considered the interest rate applying to the Facility was too high for him. I find accordingly.

167 There is no dispute that Mr Holland was not operating under any special disability nor is there any suggestion that Mr Holland was vulnerable in any way.

168 There is no evidence Mr Holland has been treated differently by BT from other of its customers who had obtained a similar Facility to Mr Holland and I find accordingly.

169 Finally, there is an allegation at [58(f)] and [70(d)] of the statement of claim that BT assisted Mr Bennett in transitioning to a new employer. In cross-examination, Mr Holland accepted that he had no evidence of this fact and it was based on supposition or inference. This is a matter that should not have been pleaded and I have no hesitation in dismissing that allegation.

170 Against the background of these factual findings, I consider each of the causes of action.

Consideration of causes of action

1. Non-disclosure of the payment of Commission to Centec and the failure to provide a PDS to Mr Holland: Statement of Claim [23]-[27]

171 The pleading of the obligation to disclose is found in [24]-[27] of the statement of claim and [16] of the reply which pleads that various information should be included in a PDS including the EDA.

172 The following issues arise in considering this cause of action:

(a) Was BT obliged to provide Mr Holland with a PDS at the time the Facility was opened in April/May 1997?: [26], [27] of statement of claim;

(b) If so, was the PDS defective and if so, what flows from that?; and

(c) Was it a requirement of the Act that BT furnish clients with a supplementary PDS for products it issued?: [28], [29], [30] of statement of claim.

First issue - Was BT obliged to provide Mr Holland with a PDS when the Facility was opened?

173 Mr Holland alleges that:

(a) BT had an EDA with Barton (amongst other stockbrokers) at the time the Facility commenced under which both leading and trailing commission on the Facility was payable to Barton;

(b) The EDA was not included in any Product Disclosure Statement as required by the Corporations Act; and

(c) As a consequence, any commission paid was conflicted remuneration within the meaning of the Act.

174 The plaintiffs submit that there is no commission clause contained in the EDA documentation or the Facility application documents and neither Mr Bennett nor Barton disclosed commission receivable from BT. I have found that there is no evidence that Mr Bennett or Barton received commission from BT. I have also found that the Facility application documents disclosed that commission may be payable. Accordingly, I do not accept the plaintiffs’ submission.

175 Mr Holland submits that neither Mr Bennett nor Centec held a pre FSR or AFSL license permitting the provision of financial advice. There is no issue and I am satisfied that none of Mr Bennett, Barton and Centec provided financial advice to Mr Holland at any time. Further, it is clear that neither Mr Bennett nor Barton promoted the Facility to Mr Holland.

176 It is because BT recorded Mr Holland as a financial advisory client that Mr Holland submits BT was required to declare the commission payable to Centec. As I understand the argument, notwithstanding Mr Holland was not in receipt of financial advice, because he was recorded by BT as a recipient of financial advice, any commission had to be disclosed.

177 Taking the plaintiffs’ case at its highest, and accepting for the moment that there was no disclosure in the Facility documents as I have found them that payment of commission would occur as a matter of fact, (as opposed to that a commission “may” be payable), the issue centres around the non-provision of a PDS to Mr Holland as required by the Act.

178 This part of the cause of action may be disposed of quickly. There is no dispute that BT did not provide a PDS within the meaning of the Act to Mr Holland when the Facility commenced in 1997, however the Act was not in force at that time. Further, not only did the provisions Mr Holland appear to rely upon not come into effect until 11 March 2002, given the Facility is a margin lending facility, it was excluded from the operation of the Act until 1 January 2010.

179 In cross-examination, Mr Holland accepted that was the position and that he was not entitled to receive a PDS from BT at the time he entered into the Facility.

180 Although Mr Holland accepted that proposition, that does not bind the Court. Nonetheless, it is clearly correct and this part of the first cause of action fails.

181 Finally in this part, Mr Holland alleges the payment of commission is conflicted remuneration. It is for the reasons I have set out earlier above that the payment of commission that was made was not conflicted remuneration. As to the submission it was asset based remuneration. I have also found that was not the case earlier in these reasons. Further, there is no plea to that effect. I do not accept that submission.

Second issue - If there was an obligation to provide a PDS, was it defective and if so, what flows from that?

182 Given my finding as to the first issue, this issue does not arise.

Third issue - Was there a failure to provide a supplementary PDS (Ongoing Disclosure) - statement of claim [27]-[30]

183 Prior to dealing with this point, the plaintiffs submit that s 952B(1A) of the Act was introduced on 18 December 2003 and that reg 7.704 of the Corporation Regulations requires detailed disclosure in a “Financial Services Guide” when financial advice is provided.

184 The plaintiffs submit that BT was required to issue a financial services guide for the Facility disclosing the commission being paid by BT pursuant to the Reform Amendment Act and that pursuant to s 952C of the Act, non-compliance with that requirement is a strict liability offence.

185 They also submit that as a result, BT had a legal obligation to provide a supplementary financial services guide with additional disclosures and was therefore required to disclose the commission payable to Centec.

186 There is no pleading in the statement of claim to that effect.

187 There is a clear obligation in the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) at r 16.02(e) for a party to state the provisions of any statute relied on. That rule is observed by the plaintiffs more in the breach than anything else. In any event, in this case there being no reference to s 952B(1A) of the Act nor any reference to a “Financial Services Guide” allegedly required pursuant to that section, I do not consider the matter has been properly raised as part of this claim and I do not deal with the point any further.

188 As to the requirement that a supplementary PDS or ongoing disclosure was required pursuant to s 1017B of the Act, it is apparent from s 1017B(1)(d) as it existed on 11 March 2002, that it only applies if two preconditions are met. The first is that a PDS was or should have been produced and second, the financial product in question is a product to which the Act applies.