FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

M House Pty Ltd v Secretary, Department of Health and Aged Care [2023] FCA 768

Table of Corrections | |

In paragraph 63(3), the expression “no reason person” has been amended to “no reasonable person”. |

ORDERS

M HOUSE PTY LTD (ACN 615 797 567) Applicant | ||

AND: | SECRETARY, DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND AGED CARE Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within seven days, the parties confer and file proposed agreed orders giving effect to the reasons of the Court.

2. If the parties are unable to agree proposed orders, each party is to file separate orders and written submissions in support of their proposed orders of no more than two pages within seven days.

3. The final orders of the Court will be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ANDERSON J

INTRODUCTION

1 The Applicant has applied for review of the decision (Decision) of the Respondent’s delegate (Delegate) to release certain information (Information) under s 61(5C) of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) (Act), on the grounds that the Decision was not authorised by s 61(5C). The Information comprises purported results of sampling and testing of two batches of a surgical face mask product (Mask), being batch LX202010 (First Batch) and N/B-BTWT260031 (Second Batch). The content of the Information is that:

(a) the First Batch was non-compliant with a “visual inspection”;

(b) the Second Batch was non-compliant with a visual inspection and for “fluid resistance”. The reference to “fluid resistance” is a reference to the requirement for surgical masks to provide a barrier to fluid penetration in order to reduce infection risk in medical, surgical and other environments.

2 The Information was released by the Respondent on the Therapeutic Goods Administration website (TGA website) concerned with the Respondent’s post-market review of face masks.

3 Before this Court, the Applicant ultimately pressed two grounds for review of the Decision. The primary ground pressed by the Applicant was that the Delegate’s Decision was not authorised by s 61(5C) of the Act. If the Court determined that the Decision was authorised by s 61(5C) of the Act, the Applicant alternatively contended that the Decision was an unreasonable exercise of power under s 61(5C) of the Act.

4 On 12 April 2023, the Respondent filed a Notice of a Constitutional Matter pursuant to s 78B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) (Section 78B Notice). In an affidavit dated 26 April 2023, Shauna Leigh Roeger, solicitor for the Respondent, deposed that she had, on 12 April 2023, notified the Attorney General of each State and Territory and the Commonwealth Attorney-General of the Section 78B Notice and that she had received responses to that notice from each Attorney-General except the Attorney-General of the Northern Territory. Each Attorney-General who responded to the Section 78B Notice stated that they would not be intervening.

5 I am satisfied that notice of the cause, specifying the nature of the matter, has been given to the Attorney-General of the Northern Territory, and a reasonable time has elapsed since the giving of the Section 78B Notice for consideration by the Attorneys-General. In the circumstances, I am content to proceed to determine the Applicant’s application for review.

6 For the reasons that follow, the Applicant’s application for review must succeed.

EVIDENCE

7 The Applicant tendered in evidence the affidavits of Sergiy Tsimidanov affirmed 1 September 2022 (Exhibit A1) and 23 December 2022 (Exhibit A2) and the affidavit of Alexander William King affirmed 1 September 2022 (Exhibit A3). Mr Tsimidanov is the General Manager of Softmed Manufacturing Pty Ltd, an associated entity of the Applicant, and Mr King is a solicitor for the Applicant. Neither Mr Tsimidanov nor Mr King was cross-examined on the content of their affidavits.

8 The Respondent tendered an affidavit of Freya Anne Henfrey affirmed 18 April 2023 (Exhibit R1) and affidavits of Shauna Leigh Roeger affirmed 18 April 2023 (Exhibit R2) and 26 April 2023 (Exhibit R3) together with a Tender Bundle (Exhibit R4). Ms Henfrey is a lawyer in the Regulatory Legal Services Branch of the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Ms Roeger is a solicitor for the Respondent. Neither Ms Henfrey nor Ms Roeger was cross-examined on the content of their affidavits.

9 The evidence tendered by the Applicant and the Respondent provided a procedural chronology of the events leading up to the Delegate’s Decision on 4 August 2022 to release the Information under s 61(5C) of the Act. Those background facts were substantially not in dispute between the parties.

RELEVANT FACTS

10 COVID-19 caused a rapid rise in demand for the manufacturing, importation and sale of face masks. As a result, there was an associated increase in medical device inclusions in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (Register), the purpose of which is to compile information in relation to, and provide for the evaluation of, therapeutic goods for use in humans. There was also a growth in concerns regarding the quality and performance of these kinds of devices.

11 The TGA undertook a post-market review of all face masks included in the Register. The context for this review was the TGA’s receipt of complaints and identified concerns in relation to face masks.

12 The Mask is included on the Register. The Applicant is, amongst other things, the “sponsor” in relation to the Mask, being the person “who imports, or arranges the importation of,” the Mask into Australia: s 3(1) of the Act (definition of “sponsor”). The First Batch and the Second Batch were imported by the Applicant.

13 In his affidavit affirmed on 23 December 2022, Mr Tsimidanov deposed that the Applicant had imported over 5 million masks in the Second Batch. The Applicant’s records indicated that those masks were delivered to the National Medical Stockpile in July 2020.

Sampling and Testing

14 As part of the “post-market review”, officers of the Department obtained two different samples of the Mask:

(a) one purchased on 30 October 2020 from a retailer, RSEA Pty Ltd (Purchase Sample), which was from the First Batch; and

(b) one taken from the National Medical Stockpile on 31 March 2021 (NMS Sample), which was from the Second Batch.

15 Officers of the Department then conducted testing upon masks within each sample in June 2021. That testing was directed to assessing whether the Purchase Sample and NMS Sample (together, Samples) complied with the “essential principles”, being the principles set out in Sch 1 to the Therapeutic Goods (Medical Devices) Regulations 2002 (Cth) (Medical Devices Regulations). Two tests were undertaken:

(a) a “Visual Inspection” of design and quality;

(b) “Fluid Resistance” testing, which tested for resistance against penetration by synthetic blood.

16 The results of the testing were set out in a “Certificate of Analysis” for each sample (Certificates), both of which were issued on 10 January 2022. In a letter from the TGA to the Applicant on 18 May 2022, referred to at [22] below, an officer of the TGA informed the Applicant that, although testing was carried out in June 2021, the Certificates were “reissued in January 2022 using an updated template to improve clarity”.

17 The Certificates relevantly stated:

(1) In relation to the Purchase Sample, it did not comply with the visual inspection requirements (because of the existence of variance in the seams, nose-piece embossing and material), but did comply with the fluid resistance requirements.

(2) In relation to the NMS Sample, “3 visually different variants were identified and tested separately”. Because of the existence of those variants, the sample did not comply with the visual inspection requirements. One of the three variants did not comply with the fluid resistance requirements.

Dispute concerning adequacy of sampling process

18 A factual dispute initially arose on the parties’ submissions and evidence concerning the adequacy of the sampling process undertaken by the TGA. In its written submissions dated 31 March 2023, the Applicant contended that, on the material before the Delegate, particularly with respect to the NMS Sample, the sampling process was so riddled with errors and deficiencies that the Information was both unreliable and uncertain, such that it could not be released under s 61(5C) of the Act. In support of this contention, the Applicant principally relied on a file note describing the collection of the NMS Sample on 31 March 2023 (File Note) which, according to the Applicant, raised the real risk that the stock held in the National Medical Stockpile was stored in inappropriate conditions and was affected by intermingling with another product.

19 In response, the Respondent relied on the affidavit of Ms Henfrey which was said to demonstrate that the Applicant’s assertions about what was revealed by the File Note were inconsistent with the objective evidence.

20 On 21 April 2023, I directed the Applicant to file an amended outline of submissions which identified the submissions relied on in support of each ground of judicial review. On 26 April 2023, the Applicant filed amended written submissions (AWS) which appeared to abandon any contention that any alleged errors in the sampling process in and of themselves precluded the Information from being released under s 61(5C) of the Act. During the hearing, counsel for the Applicant confirmed that the Applicant’s case was focussed firstly, on the question of the Respondent’s statutory power to publish the Information under s 61(5C) of the Act where the Respondent accepted that it had not undertaken sampling and testing under Pt 5 of the Therapeutic Goods Regulations 1990 (Cth) (Regulations), and secondly, the reasonable constraints on the exercise of that power when extrapolating to batches of the Mask. It follows that it is now not necessary to determine whether in fact there were errors or deficiencies in the sampling process undertaken by the TGA.

Initial correspondence concerning test results

21 In an “advice” from the TGA to the Applicant dated 11 January 2022 (Non-Compliance Advice), the TGA purported to inform the Applicant that the test results indicated that the Mask “does not comply with applicable provisions of the essential principles”, noting, in particular, essential principles 1 to 3. Essential principles 1-3 are set out at [37] below. The TGA noted that the testing “was conducted for the purposes of verifying compliance with Australian regulatory requirements, and not for certification”.

22 By email from the TGA to the Applicant on 18 May 2022 (18 May 2022 Email), the TGA informed the Applicant that it had undertaken testing of the Mask and attached a covering letter from the TGA dated 18 May 2022 (Cover Letter), the Non-Compliance Advice, a request for information and documents pursuant to s 41JA of the Act relating to the Mask (Section 41JA Notice), and the Certificates. In his affidavit affirmed on 1 September 2022, Mr Tsimidanov deposed that he had not received any correspondence or notice from the TGA regarding the Samples prior to the 18 May 2022 Email.

23 The 18 May 2022 Email noted that, if the Applicant requested a review of the test results and analysis, the Applicant was required to do so no later than 21 days after receipt of the Certificates. The email went on to state:

In accordance with reg 30(4) of the Regulations, the written evidence accompanying your request for review must include a certificate from an analyst who has appropriate qualifications and experience setting out:

• a statement that the analyst has analysed a part of the same sample, or a similar sample from the same batch of the goods (refer to note in cover letter); and

• the results of that analysis; and

• details of the tests used in the analysis.

24 Regulation 30(4) forms part of the scheme for examination, testing and analysis of goods prescribed in Pt 5 of the Regulations.

25 Notwithstanding this, the Cover Letter attached to the 18 May 2022 Email stated:

As mentioned above, batch LX202010 and N/B-BTWT260031 were purchased by an Authorised Officer and not submitted to the TGA for testing by M House.

It is open to the TGA to undertake testing of samples outside of the procedures set out in Part 5 of the Regulations. In particular, the TGA may receive samples by test purchase in which case Part 5 of the Regulations may not apply to those samples. Where the TGA undertakes testing in this way, the TGA acknowledges that a responsible analyst cannot validly issue a certificate under reg 29(1), and the TGA is not able to rely on any such certificate as conclusive proof of the matters set out in the certificate in proceedings under the Act or Regulations (reg 29(5)).

However, such test results may, where appropriate, be relied upon for other regulatory action. For these results, the TGA will issue a Certificate of Analysis, issued by a TGA analyst.

26 In addition, the Cover Letter informed the Applicant that the Applicant could provide to the Respondent “further evidence, such as test results from an accredited third-party laboratory, conducted on the same sample, or a similar sample from the same batch”, which could then inform any further decision regarding the Mask. It was conveyed to the Applicant that any such information “would also need to address the issue of the high level of intra batch variability” and that, if that issue was not addressed, “other test results [would be] unlikely to be sufficient to satisfy the delegate as to the compliance of the [Mask] with the essential principles”.

27 The Section 41JA Notice noted that the TGA was undertaking a post-market review of all face masks included in the Register. The Section 41JA Notice further stated:

The purpose of the review is to assess the safety and performance of the devices for the purposes for which they are to be used, with respect to the legislative requirements specified within the Act and the Therapeutic Goods (Medical Devices) Regulations 2002 (the Regulations). The review will determine whether appropriate conformity assessment procedures were applied to the devices supplied under the above ARTG entries and whether the devices meet the requirements of the Essential Principles.

28 The Section 41JA Notice requested specific information about the Mask. A “key purpose” of the request was said to be to ascertain “whether the certifications … [given by the applicant] under section 41FD of the Act were correct”. The information requested included, among other things:

(a) “[a]ll test reports (other than those previously provided to the TGA) for all internal (pre-release) and external (independent testing facility) testing of the [Mask] for resistance to synthetic blood penetration”; and

(b) “[a]ll reports (other than those previously provided to the TGA) for all visual inspections undertaken by the manufacturer of the [Mask]”.

The Delegate’s Decision to release the Information

29 By letter to the TGA dated 17 June 2022, the Applicant’s representative responded to the matters raised in the Cover Letter, the Certificates and the Non-Compliance Advice. For present purposes, it is sufficient to note that, in this letter, the Applicant expressed its position that the sampling and testing conducted did not comply with Pt 5 of the Regulations and, as a consequence, the determinations in the Non-Compliance Advice about the First and Second Batches were unlawful.

30 On 25 July 2022, the Delegate gave notice to the Applicant that she proposed to publish the Information on the website of the TGA. The Delegate invited any submissions in relation to the publication of the Information.

31 Further submissions were subsequently provided by the Applicant’s representative on 28 July 2022.

32 On 4 August 2022, the Delegate made the Decision to release the relevant Information under s 61(5C) of the Act.

33 The Information, which is summarised at [1] above, was subsequently published on the TGA’s website page concerning the Respondent’s post-market review of medical face masks.

LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK

Objects of the Act

34 The objects of the Act are set out in s 4. One of the objects is to provide, so far as the Constitution permits, “for the establishment and maintenance of a national system of controls relating to the quality, safety, efficacy and timely availability of therapeutic goods that are”, relevantly, “used in Australia, whether produced in Australia or elsewhere”: s 4(1)(a)(i). The reference to “efficacy”, in the context of medical devices, is a reference to the “performance of the devices as the manufacturer intended”: s 4(1A).

Chapter 4 of the Act

35 Chapter 4 of the Act, which spans ss 41B to 41MR of the Act, concerns “medical devices”, which are expressly identified as a type of “therapeutic good” within the definition of the latter term: s 3. The definition of a medical device is set out in s 41BD. It is not in dispute that the Mask is a medical device.

36 Section 41B sets out the purpose of Ch 4 in the following terms:

The purpose of this Chapter is to ensure the safety and satisfactory performance of medical devices. It does this by:

(a) setting out particular requirements for medical devices; and

(b) establishing administrative processes principally aimed at ensuring those requirements are met; and

(c) providing for enforcement through a series of offences and civil penalty provisions.

37 Under Ch 4, a requirement for medical devices is the “essential principles (that are about the safety and performance characteristics of medical devices)”: s 41BA. Section 41C states that “[t]he essential principles set out the requirements relating to the safety and performance characteristics of medical devices”. Section 41CA(1)-(2) provides that “[t]he regulations may set out requirements for medical devices” and these requirements are the “essential principles”.

38 The “essential principles” for medical devices are set out in Sch 1 to the Regulations. Clauses 1-3 relevantly provide:

1 Use of medical devices not to compromise health and safety

A medical device is to be designed and produced in a way that ensures that:

(a) the device will not compromise the clinical condition or safety of a patient, or the safety and health of the user or any other person, when the device is used on a patient under the conditions and for the purposes for which the device was intended and, if applicable, by a user with appropriate technical knowledge, experience, education or training; and

(b) any risks associated with the use of the device are:

(i) acceptable risks when weighed against the intended benefit to the patient; and

(ii) compatible with a high level of protection of health and safety.

2 Design and construction of medical devices to conform with safety principles

(1) The solutions adopted by the manufacturer for the design and construction of a medical device must conform with safety principles, having regard to the generally acknowledged state of the art.

…

3 Medical devices to be suitable for intended purpose

A medical device must:

(a) perform in the way intended by the manufacturer; and

(b) be designed, produced and packaged in a way that ensures that it is suitable for one or more of the purposes mentioned in the definition of medical device in subsection 41BD(1) of the Act.

39 Section 41BH of the Act is headed “Meaning of compliance with essential principles”. Section 41BH(1) provides that “[a] medical device complies, for the purposes of this Chapter (including Part 4-11), with the essential principles if and only if it does not contravene any of the essential principles”. There are various criminal offences, and civil penalties, that relate to the importation and supply of medical devices that do not comply with the essential principles: ss 41MA, 41MAA. Further, if a medical device is supplied while it is included in the Register, but the Respondent is satisfied that medical devices of that kind do not comply with the essential principles, the Respondent may, amongst other things, require the medical devices to be recalled or for the public to be notified that the relevant medical devices do not comply with the essential principles: s 41KA.

40 The Respondent is required to maintain the Register for the purpose of compiling information in relation to, and providing for the evaluation of, therapeutic goods for use in humans: s 9A(1). One part of the Register is dedicated to “medical devices” that are included in the Register under Ch 4: s 9A(3)(c).

41 Part 4-5 deals with the inclusion of medical devices in the Register. Division 1 deals with the application process for inclusion. A person may make an application to the Respondent for a kind of medical device to be included in the Register: s 41FC(1).

42 Under s 41FD, the Applicant must certify, among other things, that:

(a) the device complies with the essential principles: s 41FD(1)(d); and

(b) the Applicant “has available sufficient information to substantiate that compliance with the essential principles” or “has procedures in place, including a written agreement with the manufacturer of the kind of devices setting out the matters required by the regulations, to ensure that such information can be obtained from the manufacturer within the period specified in the regulations”: s 41FD(1)(e).

43 The Act prescribes criminal offences and civil penalties for making false or misleading statements “in or in connection with” a certification or purported certification under s 41FD: ss 41FE, 41FEA.

44 Division 2 deals with conditions of the inclusion of a kind of medical device in the Register. It is an automatic condition of inclusion in the Register that the person will deliver a reasonable number of samples of the kind of device if the Respondent so requests: s 41FN(2). It is also an automatic condition of inclusion in the Register that the person, at all times while the inclusion in the Register has effect, “has available sufficient information to substantiate compliance with the essential principles” or “has procedures in place, including a written agreement with the manufacturer of the kind of devices setting out the matters required by the regulations, to ensure that such information can be obtained from the manufacturer within the period specifies in the regulations”: s 41FN(3)(a).

45 Part 4-6 deals with suspension and cancellation of inclusions in the Register. Division 1 deals with the suspension of inclusions in the Register. Under s 41GA(1)(b), the Respondent may suspend a kind of device from the Register if the Respondent is satisfied that it is likely that there are grounds for cancelling the entry of the kind of device from the Register under Div 2 of Part 4-6 (subject to certain exceptions which are not presently relevant).

46 Division 2 deals with cancellation of entries in the Register. Within Div 2, s 41GL sets out a range of circumstances in which the Respondent may, by written notice, cancel the entry of a kind of device from the Register. Under s 41GL(e), the Respondent may cancel the entry of a kind of a device from the Register if, among other things, the Respondent is satisfied that a statement made in or in connection with the application for including the kind of device in the Register, or the certification or purported certification under s 41FD relating to the application, was false or misleading in a material particular.

47 Also within Div 2, under s 41GN(1), the Respondent may cancel the entry of a device from the Register if, among other things:

(a) the person in relation to whom the kind of medical device is included in the Register refuses or fails to comply with a condition to which that inclusion is subject: s 41GN(1)(b);

(b) the Respondent is satisfied that the safety or performance of the kind of device is unacceptable: s 41GN(1)(e); or

(c) the Respondent is satisfied that any certification, or part of a certification, under s 41FD in relation to the application for inclusion of the kind of device in the Register is incorrect, or is no longer correct, in a material particular: s 41GN(1)(f).

48 The Act prescribes various criminal offences, and civil penalties, for importing, exporting, or supplying medical devices that are not included on the Register: ss 41MI, 41MIB.

Sections 61 and 61A of the Act and the Therapeutic Goods Information (Laboratory Testing) Specification 2017 (Cth)

49 Chapter 7 deals with miscellaneous matters. Within Ch 7, s 61 of the Act is headed “Release of information”. The section confers various powers on the Respondent to release “therapeutic goods information”.

50 Section 61(1) defines the expression “therapeutic goods information” for the purpose of s 61 to mean:

information in relation to therapeutic goods that is held by the Department and relates to the performance of the Department’s functions (including functions relating to the EC Mutual Recognition Agreement, the EFTA Mutual Recognition Agreement or the Australia-UK Mutual Recognition Agreement).

51 Relevantly, s 61(5C) states that “[t]he Secretary may release to the public therapeutic goods information of a kind specified under subsection (5D)”. Section 61(5D) provides that “[t]he Minister may, by legislative instrument, specify kinds of therapeutic goods information for the purpose of s 61(5C)”.

52 Section 61A(1) confers an immunity on, amongst others, the Respondent in respect of loss, damage or injury of any kind suffered by another person as a result of anything done, or omitted to be done, by the Respondent “in relation to the performance or purported performance, or in relation to the exercise or purported exercise, of [the Respondent’s] functions, duties or powers” under the Act. The release of information to the public pursuant to s 61(5C) of the Act would constitute the exercise of a power under the Act, and would ordinarily attract the immunity conferred by s 61A(1) of the Act.

53 Various specifications have been made pursuant to s 61(5D) of the Act. The specification on which the Respondent relied in this case is the Therapeutic Goods Information (Laboratory Testing) Specification 2017 (Cth) (Testing Specification).

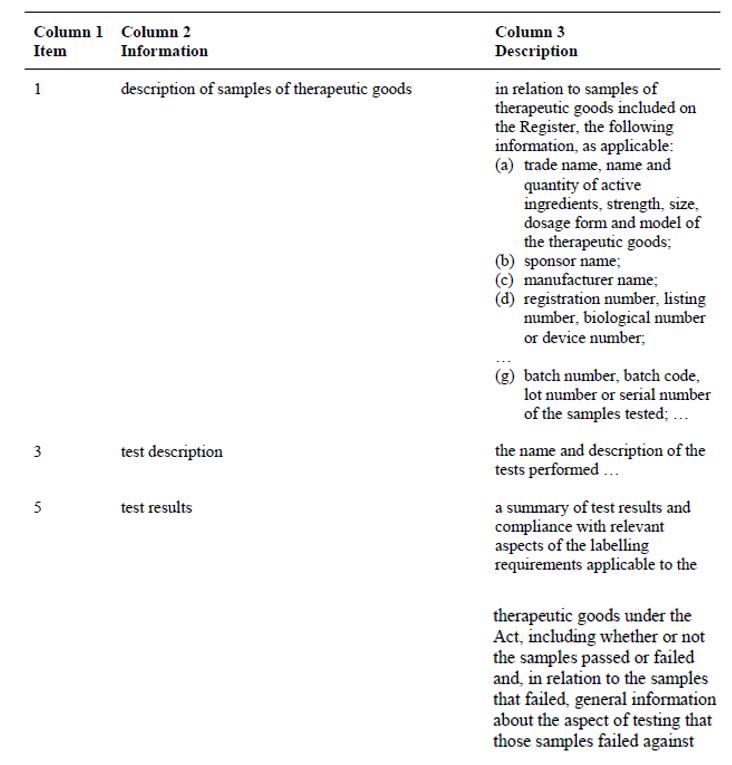

54 Schedule 1 to the Testing Specification sets out the kinds of therapeutic goods information that may be released to the public under s 61(5C) of the Act. The Respondent’s submissions provided a useful extract of the parts of the Testing Specification on which it relied. That extract is set out below:

55 The Testing Specification provides that the term “sample” has the same meaning as given in the Regulations: cl 4 (definition of “sample”). The Regulations state that a “sample includes a part of a sample”: reg 2 (definition of sample). The terms “test”, “test description” and “test results” are not defined in the Testing Specification.

56 The Explanatory Statement to the Testing Specification relevantly states:

The purpose of the Specification is to facilitate the publication of certain information relating to the laboratory testing activities of the TGA in its exercise of powers and functions under the Act. It is intended that the Specification will increase transparency and understanding of the regulation of therapeutic goods, promote consumer confidence in the quality, safety and efficacy of therapeutic goods, and encourage industry compliance with legislative requirements.

The publication of information specified in this instrument is not intended to replace any existing publications used by the TGA to inform consumers and health care professionals about serious safety issues. Safety information will continue to be published in existing publications on the TGA website, including early warnings, safety alerts, product recalls, adverse event notifications and general educational material about safety of medicines and medical devices. The publication of information specified in this instrument will not change the nature or extent of those publications.

The specified information is intended to be published on a half-yearly basis following a minimum period of six months between the completion of any testing and subsequent publication.

…

Responsive testing is conducted in response to a specific event or external trigger such as a complaint, seizure or adverse event investigation. This testing generally informs broader investigations conducted by other areas of the TGA. Any non-compliance detected by responsive testing may result in programmed testing or regulatory action including recalls. Depending on the associated risks, the outcomes of responsive testing may need to be published on the TGA website under existing publications for safety alerts and recalls, as appropriate. However, the publication of information pursuant to this Specification will also provide the TGA with the opportunity to publish more detailed information relating to its laboratory testing activities on the TGA website.

57 The Explanatory Statement makes no reference to the testing regime under the Regulations.

Section 63 of the Act and Pt 5 of the Regulations

58 Also within Ch 7 of the Act, s 63(1)(b) of the Act provides that the Governor-General may make regulations, not inconsistent with the Act, that are “necessary or convenient to be prescribed for carrying out or giving effect” to the Act. Under s 63(2)(d), the regulations may “provide for the procedures to be followed by the Department in the sampling and testing of therapeutic goods”. The Act does not define the meaning of “sampling” or “testing”.

59 The Regulations are made under s 63 of the Act. Part 5 of the Regulations is headed “Examination, testing and analysis of goods” and comprises regs 23-33.

60 Regulation 24 which is the first substantive provision in Pt 5 of the Regulations is titled “Authorised officer – powers and duties” and relevantly provides:

(1) An authorised officer may, during normal business hours:

(a) for the purpose of exercising the powers and performing the duties of an authorised officer under this regulation, enter the premises of a licence holder, manufacturer in respect of whom a conformity assessment certificate has been issued, or wholesaler on which therapeutic goods are kept for supply; and

(b) inspect the place at which those goods are kept; and

(c) take samples of those goods; and

(d) ask the owner of therapeutic goods, or the person apparently in charge of those goods, for information relevant to the manufacture and testing of those goods.

61 Part 5 sets out the following procedures applicable to testing:

(a) Pursuant to reg 25(3), an “official analyst” may: ask an authorised officer to take samples of therapeutic goods (reg 25(3)(a)); determine the tests that are to be performed on “a sample taken under paragraph (a) or delivered under paragraph [sic] 28(5)(h) or subsection 41FN(2) of the Act” (reg 25(3)(b)); or “nominate an analyst or official analyst to be the responsible analyst for a sample taken under paragraph (a) or delivered under paragraph [sic] 28(5)(h) or subsection 41FN(2) of the Act” (reg 25(3)(c)). The reference in reg 25(3)(b) to samples delivered under ss 28(5)(h) and 41FN(2) of the Act is a reference to the provision of samples upon request by the Respondent pursuant to a condition imposed at the point of the therapeutic good or medical device’s original registration. Section 28(5)(h) sets out the conditions applicable upon therapeutic goods that are not medical devices. Section 41FN(2), which is discussed above at [44], sets out the conditions applicable upon registration of medical devices.

(b) Regulations 25(4)-(5) provide:

(4) The tests determined under paragraph (3)(b), by an official analyst, for the following matters must be tests covered by regulation 28:

(a) determining whether particular therapeutic goods (other than medical devices) are goods that conform with a standard applicable to the goods;

(b) determining whether a particular kind of medical device complies with the applicable provisions of the essential principles.

(5) The tests determined under paragraph (3)(b), by an official analyst, for a matter not covered by subregulation (4), are the tests that the official analyst considers appropriate.

(c) The tests for determining whether a therapeutic good other than a medical device conforms with a standard applicable to the goods are set out in reg 28(1). The tests for determining whether a particular kind of medical device complies with the essential principles are set out in reg 28(2). Those tests are as follows:

(a) a test specified in a medical device standard or conformity assessment standard for the kind of device;

(b) a test accepted for the purpose of issuing a conformity assessment certificate in respect of the kind of device;

(c) a test required under paragraph 41FO(2)(d) of the Act as a condition of inclusion of the kind of device in the Register;

(d) any other suitable test that the Secretary requires to be carried out in respect of the kind of device for the purpose of demonstrating compliance with the applicable provisions of the essential principles.

(d) Where an authorised officer takes a sample, reg 26 prescribes a procedure for samples to be taken. Amongst other things, the authorised officer must:

(i) make the required notifications, including to the sponsor of the goods (regs 26(1)(a) and (b));

(ii) forward the sample to the relevant laboratory (reg 26(1)(c)); and

(iii) take various precautions – namely ensuring the samples are appropriately fastened and sealed and stored and transported in accordance with the instructions specified on the label of the goods (r 26(2)).

(e) When a sample of therapeutic goods is delivered under s 28(5)(h) or 41FN(2) of the Act, reg 26A prescribes procedures for ensuring the integrity of the sample has been maintained.

(f) On receiving a sample at a Departmental laboratory, a “samples officer” must determine whether the sample is appropriately fastened and sealed and, if so, store the sample under their control in conditions that are secure and appropriate to the goods: reg 27(1).

(g) The responsible analyst must, as soon as practicable, collect the sample from the samples officer and arrange for an analysis of the sample by performing the tests determined under reg 25(3)(b) to establish:

(i) the quantity and quality of goods comprising the sample (reg 27(2)(a)(i)); and

(ii) “any other matter relevant to determining whether […] the goods from which the sample was taken comply with the [essential principles]” (reg 27(2)(a)(ii)(B)).

(h) A responsible analyst “must” issue a certificate setting out the results of the reg 27(2) analysis and examination (reg 29(1)). If the certificate includes a compliance determination to the effect that the goods (from which the sample was taken) do not comply with the essential principles, then the certificate must be accompanied by the appropriate notice (regs 29(4), 29(4A)) which states, among other things, that the person may ask for a review of the results pursuant to reg 30. Reg 29(5) provides that in proceedings under the Act or Regulations, a certificate issued under reg 29(1) is, in the absence of contrary evidence, “conclusive proof” of the matters set out in the certificate.

(i) Regulation 30 prescribes a detailed regime for review of a compliance determination.

(j) Regulation 31 provides that “[i]f a sample of therapeutic goods is taken by an authorised officer, the Commonwealth is liable to pay the owner of the goods from which the sample was taken an amount equal to the value of any part of the sample removed by the authorised officer.”

(k) Regulation 32 prescribes various criminal offences in the case of interference with an authorised officer in the execution of his or her powers under the Regulations.

62 During the hearing, the Applicant also sought to rely on the Explanatory Statement to the Therapeutic Goods Legislation Amendment (2019 Measures No.1) Regulations 2019 (Cth) (Amendment Regulations), which made a number of amendments to Pt 5 of the Regulations. The Explanatory Statement for the Amendment Regulations relevantly stated:

Part 5 of the TG Regulations sets out requirements and arrangements relating to the handling and testing of samples of therapeutic goods by analysts at the TGA, including in particular samples of therapeutic goods that are provided by sponsors in compliance with statutory conditions of the entry of their goods in the Register to make such samples available.

These requirements and arrangements are principally designed to ensure the integrity of test results of samples tested by the TGA for the purpose of identifying whether the goods are safe for use and are complying with important elements of the regulatory scheme, such as applicable standards.

GROUNDS OF APPLICATION FOR JUDICIAL REVIEW

63 By originating application dated 1 September 2022, the Applicant sought to rely upon the following three grounds of judicial review:

(1) The Decision was ultra vires and not authorised by s 61(5C) of the Act as the Information was not therapeutic goods information of the kind specified in the Testing Specification.

(2) The Decision was ultra vires and an improper exercise of the power conferred by s 61(5C) of the Act because it was for a purpose other than a purpose for which the power was conferred.

(3) The Decision was ultra vires and an improper exercise of the power conferred by s 61(5C) of the Act because it was an exercise of a power that was so unreasonable that no reasonable person could have so exercised the power.

SUBMISSIONS

Applicant’s submissions

64 In its AWS at [2], the Applicant provided a summary of its contentions, the relevant aspects of which are set out below:

(a) Section 61 of the Act applies only to “therapeutic goods information” being “information in relation to therapeutic goods that is held by the Department and relates to the performance of the Department's functions”: s 61(1).

(b) Its purpose is to expressly permit release of information gathered in the exercise of a function conferred by the Act, in specific circumstances where there is obvious utility in doing so, such as for information-sharing with government agencies in other countries or Australian States or Territories.

(c) Pt 5 of the Regulations contains the procedures to be followed by the Department in the sampling and testing of therapeutic goods and is made under s 63(2)(d) of the Act, which authorises the Governor-General to make regulations that “provide for the procedures to be followed by the Department in the sampling and testing of therapeutic goods”.

(d) Sampling and testing of therapeutic goods may be conducted by officers of the Department in pursuit of various functions under the Act, including for the purpose of requiring public notification that the Respondent is satisfied that medical devices of a kind included on the Register do not comply with the “essential principles”: s 41KA(2)(b) of the Act. But on the proper construction of the Act, sampling and testing for that purpose must be done in accordance with Pt 5.

(e) The Information comprises the purported results of some kind of sampling and testing of medical devices that, by the Respondent's own admission, was not conducted in accordance with Pt 5.

(f) Section 61(5C) authorises release of information that the Department holds as the consequence of performing functions under the Act; it does not authorise the Department to conduct extra-statutory sampling, tests or investigations for the purpose of generating new information for release under that provision.

65 The Delegate’s Decision was made under s 61(5C) of the Act. It was therefore necessary for the Information to be: (1) “therapeutic goods information” as defined in s 61(1) of the Act; and (2) of a kind specified in the Testing Specification.

66 The AWS stated that the Applicant contended that the released information did not meet either requirement: AWS [50A(b)].

67 As to whether the Information constituted “therapeutic goods information”, the Applicant submitted in summary:

(a) In performing its functions by sampling and testing for the purpose of determining compliance with Essential Principles, the Department must follow the procedures in Pt 5 of the Regulations. In this case, the sampling and testing of the Samples was not undertaken under Pt 5. Consequently, the Information, which was derived from that sampling and testing, was not information that “relates to the performance of the Department’s functions” within the meaning of s 61(1).

(b) For the purposes of s 61(1) of the Act, the Department can only “hold” information obtained and stored lawfully in performance of its functions under the Act. The Information was not obtained or stored in the performance of any such function.

(c) For information to be “in relation to” therapeutic goods within the meaning of s 61(1) of the Act, there must be a verifiable connection between the information and the therapeutic goods. The Applicant submitted that the information must be relevant to, and directly connected with, the therapeutic goods, and the existence of a connection cannot be assumed or implied. The Applicant submitted that for the purposes of compliance testing, the Pt 5 integrity measures create the verifiable connection between the sample and the batch of therapeutic goods from which the sample was taken and satisfies the “in relation to” association or connection between the information and the therapeutic goods.

68 The Applicant’s submissions as to whether the Information constituted information of a kind specified in the Testing Specification were developed in its reply written submissions dated 21 April 2023 and during the hearing. In summary, the Applicant submitted that the Testing Specification must be construed as made within the power conferred by s 61(5D) of the Act. On the Applicant’s submissions, the Testing Specification had been carefully drafted by reference to the concepts and terms used in the Act, the Regulations and the Medical Devices Regulations. In particular, it specifies kinds of “therapeutic goods information”, as defined in s 61, by reference to “samples” and “tests”. The Applicant submitted that the Testing Specification should be construed as applying only to sampling and testing conducted: (1) in accordance with Pt 5 of the Regulations; and (2) for the purpose of performance by departmental officers of statutory functions under the Act

Respondent’s submissions

69 The Respondent contended in summary as follows:

(a) As to whether the Information constituted “therapeutic goods information”, the Respondent submitted that it was self-evident that the Information was held by the Department, and that it related to therapeutic goods. According to the Respondent, the real dispute concerned whether the Information related to the performance of the Department’s functions. The Respondent submitted that the correspondence between the parties and other evidence established that the testing of the Samples was conducted for the purpose of assessing whether the Mask complies with the essential principles. One of the Department’s functions is to ensure that medical devices on the Register, such as the Mask, comply with the essential principles: s 41BH of the Act. The provisions in Ch 4 of the Act confer powers upon officers of the Department to ensure that medical devices such as the Mask comply with the essential principles. On the Respondent’s submissions, this was sufficient to establish that the Information related to the performance of the Department’s functions within the meaning of s 61(1) of the Act.

(b) As to whether the Information constituted information of a kind specified in the Testing Specification, the Respondent submitted that the Testing Specification authorised the Respondent to release information relating to “samples” and “tests”. The Respondent observed that these terms were not limited to sampling and testing conducted under Pt 5 of the Regulations. In the absence of an express reference to the testing regime in Pt 5 of the Regulations, the Respondent submitted that the Court should give these expressions their ordinary meaning, which would clearly encompass the testing of the Samples undertaken by the Department.

(c) The Respondent’s position was that, so long as the Information constituted “therapeutic goods information” of a kind specified in the Testing Specification, the lawfulness of testing undertaken other than under Pt 5 of the Regulations was irrelevant.

(d) Nonetheless, the Respondent submitted that, in this case, the testing undertaken by the Department was lawful. There were two elements to the Respondent’s submissions:

(i) firstly, the Respondent submitted that testing of the Samples was carried out in the exercise of a non-statutory capacity, being an act involving nothing more than the utilisation of a bare capacity or permission. On the Respondent’s submissions, the sampling and testing of the Samples conducted by officers of the Department was, in effect, an information-gathering exercise, which is within the Department’s executive capacity as a power possessed by every individual citizen: Clough v Leahy (1904) 2 CLR 139 (Clough) at 156-157 (per Barton and O’Connor JJ concurring). The Respondent submitted that the only limitation on the Department’s power in that context is the same as any actor: it must comply with the general law (both common law and statute): Plaintiff M68/2015 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2016) 257 CLR 42 at [136] (Gageler J);

(ii) secondly, the Respondent accepted that a non-statutory capacity is “susceptible of control by statute” and a Commonwealth law may “limit or impose conditions” on the exercise of that capacity, such that “acts which would otherwise be supported by the executive power fall outside its scope”: Davis v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs [2023] HCA 10 (Davis 2023) at [23] (per Kiefel CJ, Gageler and Gleeson JJ), [65], [95] (per Gordon J), [290]-[291] (per Jagot J). The Respondent submitted that in this case, there are no express words in the Act or Regulations, nor is there any necessary implication arising from the Act or Regulations, that Pt 5 of the Regulations “covers the field” of sampling and testing. To the contrary, Pt 5 only applies in a limited set of circumstances, as the starting point of the sampling and testing process prescribed under Pt 5 was an exercise by an “authorised officer” of coercive powers under reg 24. Because Pt 5 was only engaged in these limited circumstances, the Respondent submitted that the consequence of the Applicant’s submission would be that the Respondent and officers of the Department could only sample and test medical devices for the purposes of assessing compliance with Ch 4 if coercive powers to acquire those samples were exercised under reg 24. According to the Respondent, this pointed strongly against the contention that Pt 5 exhausts the testing powers of the Department in the context of Ch 4 of the Act.

GROUND 1 – WAS THE RELEASE OF INFORMATION AUTHORISED?

Focus of the inquiry

70 As set out at [65] above, the Applicant has contended that s 61(5C) of the Act did not authorise the release of the Information because the Information was not (1) “therapeutic goods information” as defined in s 61(1) of the Act; and (2) of a kind specified in the Testing Specification.

71 In this case, it is not in dispute that the Respondent obtained the Samples and undertook testing of those Samples outside of the procedures set out in Pt 5 of the Regulations. That this is so is confirmed by the Cover Letter. Although the 18 May 2022 Email referred to the Applicant’s power of review under reg 30(4) – a provision within Pt 5 of the Regulations – counsel for the Respondent submitted, and I accept, that this was a mistake arising from the TGA’s use of a template email. It is also clear from the Advice and the Section 41JA Notice – and was a premise of the Respondent’s submissions – that the Respondent undertook testing of the Samples with a view to determining the Mask’s compliance with the essential principles as set out in Sch 1 to the Medical Devices Regulations.

72 Section 61(5C) of the Act provides that “[t]he Secretary may release to the public therapeutic goods information of a kind specified under subsection (5D)”. Section 61(5D) provides for the Minister to issue a legislative instrument specifying the kinds of therapeutic goods information for the purpose of s 61(5C)”. The Testing Specification is one such instrument, and the instrument relied on by the Respondent as empowering it to release the Information. Schedule 1 of the Testing Specification sets out the kinds of therapeutic goods information that may be released under s 61(5C) of the Act. Schedule 1 identifies “samples of therapeutic goods included on the Register”, “the name and description of the tests performed” and “a summary of test results” as kinds of therapeutic goods information that may be released under s 61(5C).

73 In my opinion, the critical question is whether the above references to “samples” and “tests” in Schedule 1 of the Testing Specification, when read in the context of ss 61(5C) and (5D) of the Act, are to be construed as encompassing sampling and testing which was expressly undertaken outside of the regime for sampling and testing prescribed in Pt 5 of the Regulations.

74 In my opinion, for the reasons that follow, they do not. It follows that, in my opinion, the Information was not of a kind specified in the Testing Specification, and s 61(5C) of the Act did not authorise the release of the Information.

Relevant principles

75 When interpreting a subordinate instrument such as the Testing Specification, the ordinary principles of statutory construction continue to apply: Collector of Customs v Agfa-Gevaert Ltd (1996) 186 CLR 389 at 398 (per Brennan CJ, Dawson, Toohey, Gaudron and McHugh JJ). The starting point for the ascertainment of the meaning of an instrument is the text of the instrument whilst, at the same time, regard is had to its context and purpose. Context should be regarded at this first stage and not at some later stage and it should be regarded in its widest sense: SZTAL v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2017) 262 CLR 362 at [14] (per Kiefel CJ, Nettle and Gordon JJ).

76 Any subordinate instrument must be placed in its statutory context – that is, the statute under which the instrument is enacted. It may be useful to read together the subordinate instrument and the Act pursuant to which the instrument was made in order to identify the nature of the legislative scheme which they comprise: Master Education Services Pty Ltd v Ketchell (2008) 236 CLR 101 at [19] (per Gummow ACJ, Kirby, Hayne, Crennan and Kiefel JJ).

77 In ADCO Constructions Pty Ltd v Goudappel (2014) 254 CLR 1, French CJ, Crennan, Kiefel, and Keane JJ stated (at [28]):

The appropriate inquiry in the construction of delegated legislation is directed to the text, context and purpose of the regulation, the discernment of relevant constructional choices, if they exist, and the determination of the construction that, according to established rules of interpretation, best serves the statutory purpose.

78 The Court may have regard to the fact that delegated instruments may be less carefully drafted and less keenly scrutinised than legislation: see generally Environment Protection Authority v Condon as liquidator for Orchard Holdings (NSW) Pty Ltd (in liq) (2014) 86 NSWLR 499 at [44] (per Leeming JA, Bathurst CJ and McColl JA agreeing). The Court must therefore bear in mind that subordinate instruments may exhibit minor inconsistencies, and it therefore may be necessary to construe them in light of practical considerations: Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v Anochie (2012) 209 FCR 497 at [25] (per Perram J). However, practical considerations do not empower the Court to embark on a wholesale rewriting of the instrument: Wingecarribee Shire Council v De Angelis [2016] NSWCA 189 at [20] (per Basten JA).

The sampling and testing regime in Pt 5 of the Regulations

79 The Applicant and the Respondent made competing submissions as to whether Pt 5 of the Regulations “covered the field” of all possible sampling and testing that may be undertaken for the purposes of determining compliance with the Act. The Applicant submitted that it did. The Respondent submitted that Pt 5 of the Regulations did not exclude the Department’s non-statutory capacity to conduct sampling and testing in the context of Ch 4 of the Act. The Respondent’s submissions as to the nature of the Department’s non-statutory capacity to conduct sampling and testing is discussed further at [95] and [105] below.

80 Before addressing those submissions, it is necessary to identify the following features of the sampling and testing regime in Pt 5 of the Regulations.

81 Firstly, s 63(2)(d) of the Act, pursuant to which Pt 5 was made, confers on the Governor-General the power to make regulations providing for “the” procedures to be followed by the Department in the sampling and testing of therapeutic goods.

82 Secondly, the provisions in Pt 5 of the Regulations, which are set out in detail at [61], reflect a detailed and precise series of integrity measures, which ensure the chain of custody of samples (regs 26-26A) and regularity of testing and examination applied (regs 25(4)-(5), 28). Part 5 also provides procedural protections to sponsors of goods and persons from whom goods are taken, including notice requirements at the time that goods are taken and when an adverse compliance determination is made (regs 26(1)(b) and 29(4A)) and a tailored regime for review of the results of any analysis (reg 30). The Explanatory Statement to the Amendment Regulations states that the procedures in Pt 5 of the Regulations “are principally designed to ensure the integrity of test results of samples tested by the TGA for the purpose of identifying whether the goods are safe for use and are complying with important elements of the regulatory scheme, such as applicable standards”. This statement as to the purpose of Pt 5 is consistent with the text of Pt 5.

83 Thirdly, within Pt 5 of the Regulations, reg 25(4)(a) empowers the official analyst to determine that tests covered by reg 28 are to be performed which determine whether particular therapeutic goods (other than medical devices) are goods that conform with a standard applicable to the goods. Regulation 25(4)(b) empowers the official analyst to determine that tests covered by reg 28 are to be performed which determine whether a particular kind of medical device complies with the essential principles. Regulation 25(5) provides that, in the case of tests for matters not covered by reg 25(4), the tests to be performed as determined by the official analyst “are the tests that the official analyst considers appropriate”. The effect of regs 25(4)-(5) when taken together is to confer on the official analyst a broad power to determine the tests to be performed on samples of therapeutic goods without any subject matter limitation.

84 Fourthly, reg 28(2) similarly sets out in a comprehensive manner the tests for determining whether a particular kind of medical device complies with the essential principles. After identifying particular tests for this purpose at regs 28(2)(a)-(c), reg 28(2)(d) authorises the use of “any other suitable test [other than the tests set out at regs 28(a)-(c)] that the Secretary requires to be carried out in respect of the kind of device for the purpose of demonstrating compliance with the applicable provisions of the essential principles.”

85 Fifthly, the parties were in dispute as to whether the sampling and testing regime in Pt 5 of the Regulations applied to any form of sampling and testing undertaken by the Department or had a more limited scope of operation. The Respondent submitted that the “starting point of the process” under Pt 5 was the exercise by an “authorised officer” of coercive powers under reg 24 of the Regulations, or by the delivery of goods pursuant to a request by the Respondent under ss 28(5)(h) and 41FN(2) of the Act. The Applicant submitted that Pt 5 was contemplated to be comprehensive in character, and there was no rationale for limiting the regime in Pt 5 to circumstances where sampling and testing was undertaken following the use of coercive powers under reg 24 of the Regulations, or ss 28(5)(h) and 41FN(2) of the Act.

86 I agree with the Respondent’s submissions for the following reasons:

(a) Nothing in the Regulations expressly and clearly identifies that Pt 5 is only engaged upon the exercise of coercive powers under reg 24 of the Regulations, or ss 28(5)(h) and 41FN(2) of the Act. However, it is appropriate to take a practical approach to the Regulations, because, in my opinion, it is evident that it has not been as closely scrutinised as would be the case for legislation: Environment Protection Authority v Condon as liquidator for Orchard Holdings (NSW) Pty Ltd (in liq) (2014) 86 NSWLR 499 at [44]; Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v Anochie (2012) 209 FCR 497 at [25] (per Perram J). This is evident from the various errors or omissions in cross-referencing in Pt 5 of the Regulations, such as at reg 23 (which alternates between referring to provisions in Pt 5 as regulations and paragraphs), reg 25(3)(b)-(c) (both of which erroneously cross-refer to “paragraph” 28(5)(h) of the Act) and reg 25(5) (which alternates between referring to provisions in reg 25 as “paragraph[s]” and “subregulation[s]”).

(b) In this case, the structure and the language of Pt 5 of the Regulations is instructive. Regulation 24 is the first substantive provision in Pt 5. It provides that an authorised officer may enter specified premises – namely, those of a licence holder, manufacturer in respect of whom a conformity assessment certificate has been issued, or a wholesaler – on which “therapeutic goods are kept for supply”, inspect the place at which the goods are kept, and “take samples of those goods” (emphasis added). The concept of “taking” goods by an authorised officer is subsequently adopted in:

(i) reg 25(3)(a) – referring to the power of an official analyst to ask an authorised officer to “take” a sample of therapeutic goods;

(ii) reg 25(3)(b)-(c) – referring to the powers of an official analyst to determine the tests to be performed on a “sample taken” under reg 25(3)(a), and nominate a responsible analyst for a “sample taken” under reg 25(3)(a);

(iii) reg 26 – which is titled ‘Taking of samples for testing” and is expressed to apply “when an authorised officer takes a sample of therapeutic goods”;

(iv) reg 29(2)(b) – which requires that, “if the sample was taken under paragraph 25(3)(a)”, the responsible analyst must notify “the person from whom the sample was taken”;

(v) reg 31 – which provides for payment of a “sample of therapeutic goods taken by an authorised officer”.

The consistent references to the “taking” of samples by an “authorised officer” in the above provisions points strongly to a conclusion that the concept of “taking” employed in those provisions is intended to cross-refer back to the power of an authorised officer to take samples of goods in reg 24(c).

(c) Regulation 31 provides that: “If a sample of therapeutic goods is taken by an authorised officer, the Commonwealth is liable to pay the owner of the goods from which the sample was taken an amount equal to the value of any part of the sample removed by the authorised officer”. The reference to “removal” of a sample in reg 31 assumes the exercise of coercive powers under reg 24. Further, the reference in reg 31 to the Commonwealth being “liable to pay the owner of the goods from which the sample was taken” an amount equal to the value of the goods again assumes the exercise of coercive powers under reg 24. Regulation 31 can have no sensible application to a case where, for example, the Department has bought goods from a pharmacy. Nor is it likely to apply in the case where the authorised officer obtains samples from the National Medical Stockpile, as it would necessitate an unnecessary transfer of funds from the Commonwealth to itself.

(d) Regulation 33 provides for the Respondent to issue authorised officers with an identity card, whose purpose (in reg 33(2)) is to enable an authorised officer to “enter premises in the course of his or her duties”. The provision of identity cards again assumes the exercise of coercive powers under reg 24.

(e) Pt 5 of the Regulations consistently identifies an alternative to “tak[ing]” samples under reg 25(3)(a) as delivery of samples in response to a request by the Respondent pursuant to ss 28(5)(h) and 41FN(2) of the Act: see regs 25(3)(b)-(c), 26A(1) and 31(1A)-(2). Relevantly, where goods are delivered pursuant to ss 28(5)(h) and 41FN(2) of the Act, they are being delivered in response to the exercise of the Respondent’s coercive power – that is, by reason of a condition applicable upon the registration of the relevant therapeutic good or medical device which requires samples to be delivered upon the request by the Respondent.

(f) Regulation 29(1) provides that a responsible analyst “must” issue a certificate setting out the results of any examination and analysis. Regulation 29(5) provides that this certificate will constitute, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, “conclusive proof” of the matters set out or stated in it. I accept the Respondent’s submissions that it could not be said that it was intended that every time the Department undertook any activity that might be classified as sampling and testing, this would result in a responsible analyst issuing such a certificate.

87 In my opinion, when the provisions within Pt 5 of the Regulations are read together, it is clear that Pt 5 was intended to only apply to sampling and testing undertaken following the exercise of coercive powers under reg 24 of the Regulations, or ss 28(5)(h) and 41FN(2) of the Act.

Non-statutory capacity to sample and test

88 The Respondent submitted that Pt 5 of the Regulations does not displace the Department’s non-statutory capacity to sample and test. To evaluate the Respondent’s contention, it is first necessary to set out the basis for the Department’s alleged non-statutory capacity to sample and test. It is then necessary to set out the authorities on which the Respondent relied to contend that such a capacity was not excluded by the Act and the Regulations.

Relevant principles concerning the Executive’s non-statutory capacity

89 The Department is a “department of State of the Commonwealth”, administered by the Minister: the Constitution, s 64; Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth), s 19. The Minister and officers of the Department, including the Respondent, are officers of the Executive Government of the Commonwealth: Davis 2023 at [24] (per Kiefel CJ, Gageler and Gleeson JJ; see also at [82] (per Gordon J)).

90 Section 61 of the Constitution vests the executive power of the Commonwealth in the Queen (now King), exercisable by the Governor-General, and “extends” that power to the execution and maintenance of the Constitution and of the laws of the Commonwealth. Section 61 of the Constitution is the ultimate source of all Commonwealth executive “power”, but s 61 neither defines the concept of executive power, nor explains the sources from which the content of that power can be identified: Davis 2023 at [118]-[119] (Edelman J). In their capacity as officers of the Executive, departmental officers may exercise the executive power of the Commonwealth.

91 In Davis v Commonwealth (1988) 166 CLR 79 at 108 (Davis 1988), Brennan J stated:

… executive power of the Commonwealth includes the mass of powers which the Executive Government possesses to act lawfully without statutory authority, together with statutory powers and capacities. It follows that an act done in execution of an executive power of the Commonwealth is done in execution of one of three categories of powers or capacities. A statutory non-prerogative power or capacity, a prerogative (non-statutory) power or capacity or a capacity which is neither a statutory nor a prerogative capacity. The relevant statute defines the scope of a power or capacity in the first category but there is no express criterion by which non-statutory powers and capacities may be classified as falling within the executive power of the Commonwealth.

92 Justice Gageler observed in Plaintiff M 68/2015 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2016) 257 CLR 42 (Plaintiff M 68) at [134]-[135]:

The tripartite categorisation posited by Brennan J has utility in highlighting, in relation to acts done in the exercise of a non-statutory power or capacity, the essential difference between an act done in the execution of a prerogative executive power and an act done in the execution of a non-prerogative executive capacity.

An act done in the execution of a prerogative executive power is an act which is capable of interfering with legal rights of others. An act done in the execution of a non-prerogative executive capacity, in contrast, involves nothing more than the utilisation of a bare capacity or permission, which can also be described as ability to act or as a “faculty”. Such effects as the act might have on legal rights or juridical relations result not from the act being uniquely that of the Executive Government but from the application to the act of the same substantive law as would be applicable in respect of the act had it been done by any other actor. In this respect, the Executive Government “is affected by the condition of the general law”. Subject to statute, and to the limited extent to which the operation of the common law accommodates to the continued existence of “those rights and capacities which the King enjoys alone” and which are therefore properly to be categorised as prerogative, the Executive Government must take the civil and criminal law as the Executive Government finds it, and must suffer the civil and criminal consequences of any breach.

93 In Clough, the High Court held that it was not unlawful for the Governor of New South Wales to establish a Royal Commission. Chief Justice Griffiths (Barton and O’Connor JJ concurring) held (at 156):

It is quite unnecessary, indeed, to call in aid what are called the ‘prerogative’ powers of the Crown. That term is generally used as an epithet to describe some special powers, greater than those possessed by individuals, which the Crown can exercise by virtue of the Royal authority. There are some such powers exercised under the law, but the power of inquiry is not a prerogative right. The power of inquiry, of asking questions, is a power which every individual citizen possesses, and, provided that in asking these questions he does not violate any law, what Court can prohibit him from asking them?...

We start, then, with the principle that every man is free to do any act that does not unlawfully interfere with the liberty or reputation of his neighbour or interfere with the course of justice. … The liberty of another can only be interfered with according to law, but, subject to that limitation, every person is free to make any inquiry he chooses; and that which is lawful to an individual can surely not be denied to the Crown, when the advisers of the Crown think it desirable in the public interest to get information on any topic.

94 The Executive’s capacity to establish a Royal Commission by reason of its “power of inquiry” has not been consistently endorsed by subsequent authorities. In McGuinness v Attorney-General (Vic) (1940) 63 CLR 73, Dixon J held (at 93-4) that the source of the power to establish a Royal Commission was the Executive’s prerogative power: see also Victoria v Australian Building Construction Employees’ and Builders Labourers’ Federation (1982) 152 CLR 25 (Victoria) at 155-6 (per Brennan J); Davis 2023 at [133]-[134] (per Edelman J).

95 In reliance on Clough, the Respondent submitted that the sampling and testing process undertaken in this case was, in effect, an information-gathering exercise, which was within the power of every citizen and, in turn, within the Executive’s non-statutory executive capacity under s 61 of the Constitution. The Respondent submitted that, as the Samples were obtained and tested without the exercise of coercive power, and did not interfere with the Applicant’s legal rights, the actions of the Respondent fell comfortably within the executive power.

Relevant principles concerning statutory exclusion of an executive non-statutory capacity

96 In submitting that the Respondent’s non-statutory capacity to undertake sampling and testing had not been abrogated by the Act or the Regulations, the Respondent placed emphasis on two cases: Ruddock v Vadarlis (2001) 110 FCR 491 (Ruddock) and Davis 2023.

97 In Ruddock, French J (Beaumont J agreeing) held that the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (Migration Act) did not deprive the Executive of its non-statutory power to prevent entry into Australia of unlawful non-citizens: at [202]. His Honour relevantly held (at [183]-[185]):

There is no place then for any doctrine that a law made on a particular subject matter is presumed to displace or regulate the operation of the Executive power in respect of that subject matter. The operation of the law upon the power is a matter of construction. …

That construction, while governed ultimately by the terms of the statute under consideration, is informed by a requirement for a clear intention to displace the power. …

The Executive power of the Commonwealth covers a wide range of matters, some of greater importance than others. Some are intimately connected to Australia's status as an independent, sovereign nation State. The relevance of the importance of the particular power to the question whether it has been displaced by a statute, appears to have been accepted by Jacobs J in Barton. The greater the significance of a particular Executive power to national sovereignty, the less likely it is that, absent clear words or inescapable implication, the parliament would have intended to extinguish the power.

98 Justice French went on to state (at [193]) that:

The power to determine who may come into Australia is so central to its sovereignty that it is not to be supposed that the Government of the nation would lack under the power conferred upon it directly by the Constitution, the ability to prevent people not part of the Australia community, from entering.

99 Justice French ultimately held that the Migration Act, by its creation of facultative provisions, could not be taken to deprive the Executive of the power necessary to prevent entry into Australia of unlawful non-citizens: at [202].

100 Davis 2023 concerned the operation of s 349 of the Migration Act. Section 351(1) of the Migration Act empowered the Minister to substitute for a decision of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal another decision more favourable to an applicant. Section 351(3) stated that the power “may only be exercised by the Minister personally”. The Minister issued instructions to his department providing that requests having unique or exceptional circumstances should be referred to the Minister, but other cases were to be “finalised” by the department. A majority of the High Court (Kiefel CJ, Gageler and Gleeson JJ; Gordon J agreeing; Edelman J agreeing; Jagot J agreeing; Steward J dissenting) held that, in issuing the instructions, the Minister exceeded the limit on executive power imposed by s 351(3) of the Migration Act.

101 The plurality (Kiefel CJ, Gageler and Gleeson JJ) noted that “[a] valid law of the Commonwealth may so limit or impose conditions on the exercise of the executive power that acts which would otherwise be supported by the executive power fall outside its scope”: Davis 2023 at [22], quoting Brown v West (1990) 169 CLR 195 at 202 (per Mason CJ, Brennan, Deane, Dawson and Toohey JJ). The plurality subsequently held (at [29]-[30]).

In enacting s 351 of the Act, the Parliament has seen fit to entrust to the Minister alone the evaluation of the public interest in substituting a more favourable decision for a decision of the Tribunal. A necessary implication of the exclusivity imposed by s 351(3) on the power which s 351(1) confers on the Minister is to deny the existence of executive power to entrust the dispositive evaluation of the public interest in substituting a more favourable decision to an executive officer other than the Minister.

Put another way, the extension by s 61 of the Constitution of the executive power of the Commonwealth to "the execution and maintenance ... of the laws of the Commonwealth" does not authorise a Minister or any other officer of the Executive Government of the Commonwealth to undertake any non-statutory action that is expressly or impliedly excluded by a law of the Commonwealth. By confining evaluation of the public interest for the purpose of s 351(1) to the Minister personally, s 351(3) of the Act effects such an exclusion.

102 In agreeing with the orders made by the plurality, and the plurality’s reasons for those orders, Gordon J relevantly stated (at [89]):

The function [that is, the execution and maintenance of the laws of the Commonwealth under s 61 of the Constitution] is characteristically performed by execution of statutory powers; however, it also extends to doing things which are necessary or incidental to the execution and maintenance of a valid law of the Commonwealth once that law has taken effect. The latter field does not require express statutory authority, nor is it necessary to find an implied power in the statute. In that sense, administrative action that is incidental to the execution of a law does not involve statutory power, but finds its source in – and is controlled by – the statute and s 61 of the Constitution. Incidental action is strictly ancillary; the Executive “cannot change or add to the law; it can only execute it”. In that respect, executive action is qualitatively different from legislative action. There is no executive power or capacity to dispense with the operation of the general law – whether statute or common law.

103 In agreeing with the orders made by the plurality, Edelman J provided a useful distillation of the state of the authorities concerning the Executive’s non-statutory prerogative and general powers and liberties: at [127]-[137]. Edelman J relevantly stated:

(a) The absence of a prohibition upon action provides no justification for the existence of a power of the Commonwealth Executive: at [131].

(b) “[A]n inquiry takes on a different complexion when it is undertaken by the Executive rather than a natural person”: at [133]. His Honour went on to state: “[w]hether a liberty of the Commonwealth Executive is properly characterised as one that is shared with a natural person generally or as a prerogative of the Commonwealth Executive might ultimately depend on the level of generality at which the liberty is described.”: at [134].

(c) The source of the non-statutory capacity or “liberty” is the reasonable necessity for actions by officers of the Executive arm of the Commonwealth polity to ensure the basic existence and functional operation of the polity: at [135]. The powers and liberties conferred on the Executive relate to “the ordinary course of administering a recognised part of the government”, and might include the power to hire and fire staff who perform the basic functions of administration, to enter contracts or dispose of property, in relation to matters that are a core part of the functioning of executive government. They might also include “powers and liberties that are necessarily incidental to the execution of a statutory provision”: at [136].

104 Edelman J subsequently held (at [194]):

It would have been a simple matter for the Commonwealth Parliament to have included an additional subsection, s 351(8), permitting departmental officials, as either delegates or agents, to exercise a liberty to decide whether to refer to the Minister an application for the exercise of the personal override power. … But the Commonwealth Parliament did not do so. The liberty to consider an application, like the power itself, was made personal to the Minister. The departmental officials could not lawfully exercise the Minister’s personal liberty to refuse to consider the [relevant requests]. In substance, that is what they did.

105 Jagot J also agreed with the orders made by the plurality. Jagot J relevantly expressed the limit on executive power in the following terms (at [290]):

The scope of executive power under s 61 of the Constitution in the present cases involves the fundamental concept of parliamentary supremacy. Parliamentary supremacy dictates that “it is of the very nature of executive power in a system of responsible government that it is susceptible to control by the exercise of legislative power by Parliament”. It follows that the “Executive cannot change or add to the law; it can only execute it”. In the words of Brennan J [in A v Hayden (1984) 156 CLR 532 at 580]:

“The incapacity of the executive government to dispense its servants from obedience to laws made by Parliament is the cornerstone of a parliamentary democracy.”

106 The Respondent contended that, in the context of executive power under s 61 of the Constitution, there is “no place for any doctrine that a law made on a particular subject matter is presumed to displace or regulate the operation of the executive power in respect of that subject matter”: Ruddock at [183] (per French J). To the contrary, the question of construction is “informed by a requirement for a clear intention to displace the power”: Ruddock at [184] (per French J). The Respondent contended that a clear intention may manifest through express words or by “necessary implication”: Davis 2023 at [23], [29] (per Kiefel CJ, Gageler and Gleeson JJ); Ruddock at [184]-[185] (per French J).

Consideration