FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Equity Financial Planners Pty Ltd v AMP Financial Planning Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 741

ORDERS

EQUITY FINANCIAL PLANNERS PTY LTD Applicant | ||

AND: | AMP FINANCIAL PLANNING PTY LTD Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 21 days, the applicant file a minute of proposed orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons, together with a short outline of submissions (of not more than five pages) in support of those orders.

2. Within a further 14 days, the respondent file a minute of proposed orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons, together with a short outline of submissions (of not more than five pages) in support of those orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

MOSHINSKY J:

1 The applicant, Equity Financial Planners Pty Ltd (Equity), is and was at all relevant times a financial planning practice in the network of financial planning practices established by the respondent, AMP Financial Planning Pty Ltd (AMPFP).

2 Equity brings this proceeding, which is a representative proceeding under Pt IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), on its own behalf and on behalf of all persons who, as at 8 August 2019:

(a) were a party to an authorised representative agreement with AMPFP and were named as the Practice in that authorised representative agreement; and

(b) had not received a confirmed exercise date (for the purpose of AMPFP’s Buyer of Last Resort Policy (BOLR Policy)) of 8 August 2019 or earlier,

(group members).

3 The proceeding relates to changes made (or purportedly made) by AMPFP to the valuation methodology under its BOLR Policy on 8 August 2019. The BOLR Policy formed part of the contractual relationship between AMPFP and each financial planning practice in its network. As at August 2019, there were approximately 542 practices in the AMPFP network (described below). The BOLR Policy gave practices in the AMPFP network that wanted to exit the network the ability to sell back their register rights (defined below, but broadly the contractual relationships with customers including the right to commissions) to AMPFP on 12 months’ notice (or less in some cases). Under the BOLR Policy as it stood before the 8 August 2019 changes, subject to certain exceptions and qualifications, the register rights were to be valued on the basis of a multiple of 4x ongoing revenue (i.e. ongoing revenue received by the practice in the prior 12 months) and the practice would be paid that amount by AMPFP.

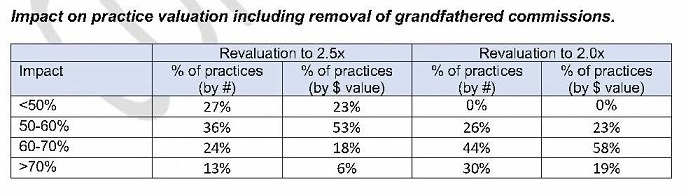

4 On 8 August 2019, AMPFP amended (or purported to amend) the valuation methodology under the BOLR Policy (the 8 August 2019 Changes) with immediate effect. The changes were broadly as follows:

(a) changing the multiple for the purposes of the BOLR Policy from 4x to 2.5x in respect of ongoing revenue other than grandfathered commission revenue; and

(b) changing the multiple for grandfathered commission revenue:

(i) initially, from 4x to 1.42x; and

(ii) then, reducing by 0.8333 per month (referred to as a “glide path”) from 1 September 2019, such that the multiple would be zero by 1 January 2021.

5 The changes to the multiples were applied by AMPFP not only to practices that submitted a BOLR application after 8 August 2019, but also to practices that had submitted a BOLR application before 8 August 2019 with an exercise date after 8 August 2019. Under the terms of the BOLR Policy, those practices could not withdraw their application once it had been submitted unless AMPFP consented.

6 The central issue in this proceeding is whether the 8 August 2019 Changes were effective. The BOLR Policy had been in place for many years, and had been revised from time to time. The latest version of the policy as at 8 August 2019 was the version of the policy that commenced on 1 June 2017 (the 2017 BOLR Policy). That version of the policy contained a term relating to amendments that had been agreed between AMPFP and the AMP Financial Planners Association Ltd (ampfpa), which was an organisation representing financial planning practices in the AMPFP network (described below). The amendment term (on page 5 of the policy) was as follows:

Changes to this policy

The AMP Financial Planners Association Ltd Board (ampfpa) and AMPFP have agreed in writing to the terms of this policy effective 1 June 2017.

– Unless a shorter period of notice is agreed to by the ampfpa, AMPFP will give 13 months’ notice of a change to the valuation methodology for registers and to any other change having a materially adverse financial or other significant effect on a practice.

– Subject to the above, AMPFP may make any other changes to this policy following consultation with the ampfpa.

– AMPFP has the right to make any change to this policy should legislation, economic or product changes render any part of this policy inappropriate following consultation with the ampfpa. In particular, where AMPFP believes that any provision contained in this policy will, or may, cause it to breach or be subject to a penalty under any laws.

– The Buyer of last resort terms that apply are those terms in force on the Buyer of last resort exercise date or the date the practice surrenders its AR [Authorised Representative] Agreement, whichever is the later.

(Emphasis added.)

7 I will refer to the third indented paragraph, which refers to “legislation, economic or product” changes, as the LEP Provision. (The paragraph was referred to as the “LEP Exception” in Equity’s submissions and as the “LEP Provision” in AMPFP’s submissions. Whether the paragraph constitutes an exception forms part of an issue in the proceeding, namely the issue of onus. I will therefore adopt the neutral expression, “LEP Provision”.)

8 Equity contends that the 8 August 2019 Changes were not authorised by the LEP Provision (or otherwise authorised by the amendment term). In summary, Equity contends that:

(a) AMPFP did not consult with ampfpa in relation to the changes as required by the LEP Provision and the Master Terms (referred to below);

(b) AMPFP did not identify the economic or legislation changes it was relying on in making the changes, and did not state how these rendered the policy inappropriate;

(c) there was no “economic change” or “legislation change” within the meaning of the LEP Provision;

(d) if (contrary to the above) there was an economic or legislation change, it did not render any part of the policy “inappropriate” within the meaning of the LEP Provision; and

(e) if (contrary to the above) there was an economic or legislation change that rendered a part of the policy inappropriate, the changes to the multiples were not reasonably necessary to address that circumstance (Equity contends that this is a requirement of the LEP Provision, properly interpreted).

9 Accordingly, Equity contends that the 8 August 2019 Changes were ineffective and that AMPFP acted in breach of contract in putting forward BOLR valuations based on those changes. Equity seeks a declaration that the changes were ineffective and claims damages for loss and damage. In the alternative, Equity claims that AMPFP acted in breach of a contractual obligation of good faith in relation to the changes. In the further alternative, Equity contends that AMPFP engaged in unconscionable conduct within the meaning of s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law, being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the Australian Consumer Law), in relation to the changes. Further, Equity contends that AMPFP engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in connection with the changes in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law.

10 In response, AMPFP contends that the 8 August 2019 Changes were authorised by the LEP Provision (and were effective immediately). In summary, AMPFP contends that:

(a) while there was a contractual obligation upon AMPFP to consult (within the meaning of cl 1.4 of the Master Terms) with ampfpa, the obligation was not “jurisdictional”; that is, a breach of the obligation does not have the effect that the changes are ineffective; the breach merely sounds in damages for the loss of opportunity to consult, but this results in an award of only nominal damages;

(b) in any event, on the facts, AMPFP did consult (within the meaning of cl 1.4 of the Master Terms) with ampfpa in relation to the changes;

(c) it is not a requirement of the LEP Provision that AMPFP identify the economic or legislation change that it relies on; nor is it a requirement that it state how these render the policy inappropriate;

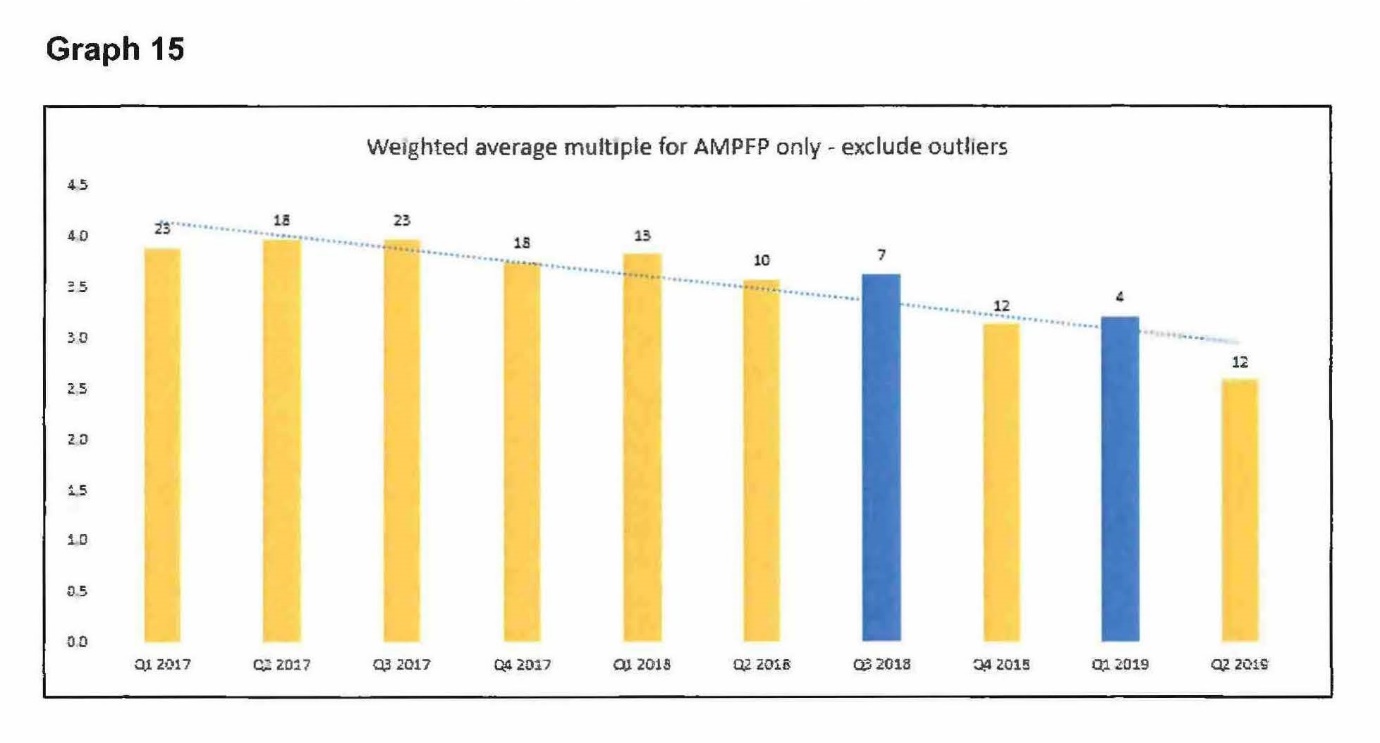

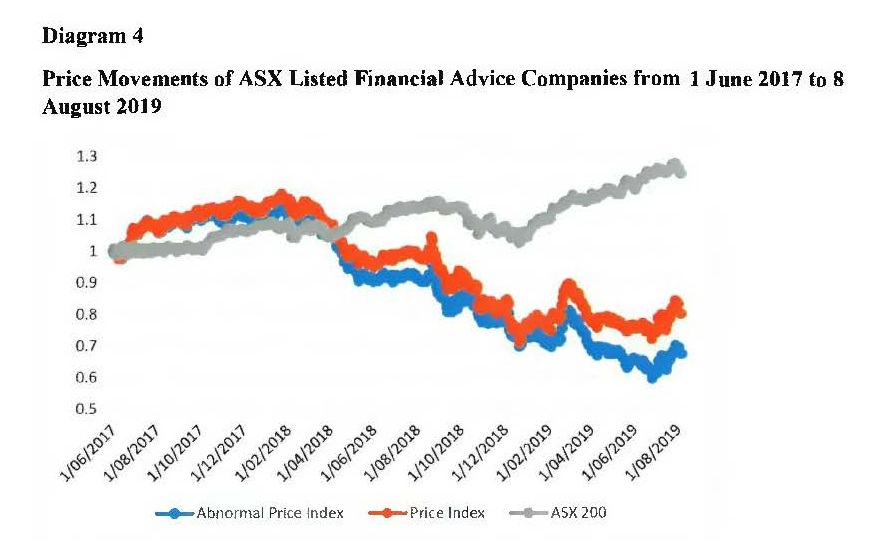

(d) there was an “economic change” that rendered the policy inappropriate, namely either:

(i) a sustained and quantifiable decrease in the market value of register rights linked to ongoing revenue; or

(ii) a material change in the supply of and demand for financial advice services and practices;

(e) further, in relation to the changes to grandfathered commission revenue, there was a “legislation change” that rendered the policy inappropriate; and

(f) the changes that were made were responsive to the economic and/or legislation changes (this being the relevant requirement, on AMPFP’s interpretation of the LEP Provision).

11 In the alternative, AMPFP contends that the 8 August 2019 Changes were effective 13 months later, that is, on 8 September 2020.

12 The hearing of this proceeding in October and November 2022 involved the trial of Equity’s claim against AMPFP on all issues of liability and the amount of any damages. Equity did not enter into a buy-back agreement with AMPFP and still holds its register rights.

13 The hearing also involved the trial of the claim of one sample group member, WealthStone Pty Ltd (WealthStone), on all issues of liability and the amount of any damages. Unlike Equity, WealthStone did enter into a buy-back agreement with AMPFP. That agreement contained a release in favour of AMPFP. AMPFP contends that the release defeats WealthStone’s claim against it. In response, the applicant contends that:

(a) the condition precedent to the operation of the release – the payment of the BOLR benefit (properly calculated) – has not been satisfied;

(b) the release is void under s 23 of the Australian Consumer Law, which applies to unfair terms of small business contracts; and

(c) AMPFP’s conduct in procuring the release was, in all the circumstances, unconscionable within the meaning of s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law.

14 I was informed by AMPFP that approximately 135 group members have signed buy-back agreements with AMPFP. About 120 of those agreements contain releases, but they are not all in the same form.

15 In summary, for the reasons that follow, I have concluded as follows:

(a) the 8 August 2019 Changes were not authorised by the LEP Provision on the basis of AMPFP’s first alternative economic change contention;

(b) the 8 August 2019 Changes were not authorised by the LEP Provision on the basis of AMPFP’s second alternative economic change contention;

(c) the changes to the multiple for grandfathered commission revenue (which were part of the 8 August 2019 Changes) cannot be supported on the basis of a “legislation change”;

(d) the requirement to consult (within the meaning of cl 1.4 of the Master Terms) is a precondition to the effectiveness of the change;

(e) AMPFP failed to consult within the meaning of cl 1.4 of the Master Terms in relation to the proposed changes; and

(f) it is unnecessary to determine whether AMPFP breached a contractual obligation of good faith.

16 It follows from the above that the 8 August 2019 Changes (with immediate effect) were not authorised by the LEP Provision and were ineffective.

17 Insofar as AMPFP contends, in the alternative, that the 8 August 2019 Changes were effective 13 months later (on 8 September 2020), I reject that contention.

18 In light of the above conclusions, it is unnecessary to determine whether AMPFP engaged in unconscionable conduct in relation to the 8 August 2019 Changes.

19 It is not necessary to resolve the misleading or deceptive conduct claim to determine the individual claims of Equity or WealthStone, and I therefore prefer not to do so at this stage.

20 In relation to Equity’s claim, I am satisfied that Equity has suffered loss and damage as a result of AMPFP’s breach of contract, and is entitled to damages in the sum of $813,560 (subject to the possible need to adjust this figure as discussed in [675] below).

21 In relation to WealthStone’s claim, I have concluded in summary that:

(a) the condition precedent to the operation of the release has been satisfied;

(b) the release is not void under s 23 of the Australian Consumer Law; and

(c) AMPFP’s conduct in procuring the release was, in all the circumstances, unconscionable.

22 WealthStone is entitled to an order declaring the release void to the extent that it would preclude its claims in this proceeding. Further, WealthStone is entitled to damages in the sum of $115,533.51 (subject to the possible need to adjust this figure as discussed in [719] below).

23 At the commencement of the hearing, Equity’s pleading was its second further amended statement of claim. On day 3 of the hearing, I granted leave (by consent) for Equity to amend its pleading and file its third further amended statement of claim (the statement of claim). Broadly, the amendments introduced additional causes of action (in particular, breach of an obligation of good faith and unconscionable conduct). The amendments were partly responsive to an application by AMPFP to amend its defence (see below) and partly so that the pleaded case aligned with the case as opened.

24 Shortly before trial, AMPFP provided a proposed second further amended defence. Some of the proposed amendments were opposed. AMPFP filed an interlocutory application dated 9 October 2022 seeking (inter alia) leave to amend. Most of the amendments were ultimately consented to. The only outstanding dispute was AMPFP’s application for leave to amend the defence to include paragraph 38(b), alleging that the applicant had failed to mitigate its loss. The issue was agitated on day 3, and I gave leave to AMPFP to amend to include this paragraph. AMPFP subsequently filed its third further amended defence to the third further amended statement of claim (the defence), which incorporates those amendments as well as pleadings in response to Equity’s amended pleading. I note for completeness that the particulars to paragraph 38(b) of the defence include three lines that are redacted. On day 19, senior counsel for AMPFP stated that AMPFP does not rely on the redacted portion of those particulars. In other words, the Court does not need to have access to the words that have been redacted and they can be put to one side.

25 In addition to the above pleadings, there is an amended reply. This was not amended during the hearing.

26 The parties prepared points of claim and points of defence in relation to WealthStone’s case. These documents were amended during the hearing. The latest versions of the documents are the further amended points of claim (the points of claim) and the further amended points of defence (the points of defence). There is also an amended reply to points of defence, which was not amended during the hearing.

27 Equity relied on lay evidence from the following witnesses:

(a) Kylie Braschey, a director of Equity;

(b) Leanne Scott, a director of Equity;

(c) Michael Finch, the sole director and majority shareholder of WealthStone;

(d) Neil Macdonald, the Chief Executive Officer and Company Secretary of ampfpa;

(e) Damien Jordan, a director and the Chair of ampfpa at the relevant times;

(f) Timothy Jones, a director of ampfpa at the relevant times (he was not required for cross-examination);

(g) Neill Brennan, the Managing Director of Augusta Ventures (Australia) Pty Ltd; the company is part of the Augusta group, which provides litigation funding (he was not required for cross-examination); and

(h) Louis Young, a director of Augusta Ventures Ltd and Augusta Pool 523 Limited (Augusta Pool 523), the litigation funder for the proceeding (he was not required for cross-examination).

28 Ms Braschey gave evidence in a clear, honest, helpful and straightforward manner. I accept her evidence.

29 Ms Scott’s evidence was largely corroborative of Ms Braschey’s evidence and the cross-examination of Ms Scott was brief. Apart from one factual error in her first affidavit (referred to below), which is of no consequence, I accept Ms Scott’s evidence.

30 Mr Finch displayed a clear recollection of the relevant events and a good grasp of the detail of the documents and other relevant matters. His answers to questions were careful and precise. I accept his evidence.

31 Mr Macdonald was a good, honest and careful witness. He has a deep and thorough knowledge of the industry. He gave precise answers to questions and sought to assist the Court. If and to the extent that it was suggested in cross-examination that Mr Macdonald lacked objectivity because of ampfpa’s role in bringing this proceeding about, I reject that suggestion. I accept his evidence, save where otherwise indicated below (in respect of certain minor matters).

32 Mr Jordan was not always responsive to questions put to him during cross-examination. His answers were on occasion unnecessarily discursive. That said, I am satisfied that he gave evidence honestly and accept him as a reliable witness. I accept his evidence, save where otherwise indicated below (in respect of certain minor matters).

33 Equity relied on expert evidence from the following witnesses:

(a) Mr George Siolis, a partner of RBB Economics, based in Melbourne;

(b) Mr Robert Neill, a financial services adviser; and

(c) Ms Dawna Wright, a forensic accountant (she was not required for cross-examination).

34 I will make observations about the expert witnesses who were cross-examined later in these reasons.

35 AMPFP relied on lay evidence from the following witnesses:

(a) Damian Byrne;

(b) David Akers;

(c) James Scott; and

(d) Natalie Tatasciore, a partner of King & Wood Mallesons (she was not required for cross-examination).

36 Mr Byrne was the Senior Manager, Value Exchange & Proposition, within the Advice business of the corporate group headed by AMP Limited (the AMP Group or AMP) from July 2017 to July 2021. The title of the position subsequently changed to Head of Commercial Offer. At the relevant times, within AMP’s Australian Wealth Management division, Mr Byrne was regarded as the custodian of the BOLR Policy, in the sense that he was regarded as the expert concerning, and the person responsible for, the terms of the BOLR Policy; queries about the BOLR Policy’s intended operation, necessary changes, or interpretation and clarifications came to him. Mr Byrne reported to Mr Akers for most of the relevant period.

37 Mr Byrne was careful and precise in answering questions during cross-examination. He endeavoured to assist the Court. He made reasonable concessions. He was an excellent witness. I accept his evidence in relation to factual matters, save where otherwise indicated below (in relation to certain minor matters). Insofar as Mr Byrne expressed opinions (for example, as to whether there was an “economic change”), I accept that he held those opinions, but do not necessarily accept them.

38 Mr Akers was the Managing Director of Business Partnerships of the Australian Wealth Management division of the AMP Group between March 2019 and July 2021. Prior to that period, Mr Akers held the roles of Director of Channel Strategy and Services (between April 2017 and April 2018) and Acting Group Executive of Advice (between April 2018 and March 2019). He was also a director and the Chairperson of the AMPFP Board from March 2018 to July 2021.

39 Mr Akers was a good witness. He answered questions clearly and confidently. I accept his factual evidence, save for the matters discussed below. Insofar as Mr Akers expressed opinions (for example, as to whether sufficient time was allowed for consultation, and whether AMPFP had a right to amend the BOLR Policy under the LEP Provision), I accept that he held those opinions, but do not necessarily accept them.

40 Mr Scott was the National Manager of Transaction Strategy within Business Partnerships for the AMP Group from November 2018 to September 2021. In that role he was responsible for leading the Transaction Strategy team that supported AMP aligned practices, including those in the AMPFP network (described below), with merger and acquisition activity, including client register transfers. His role included supporting the Aligned Advice Licensees (described below), including AMPFP, in meeting their governance requirements around client register transfers. Mr Scott holds a Bachelor of Science from Loughborough University, England. He is a Chartered Management Accountant. From June 2012 to November 2017 (apart from a period of 12 weeks), he worked as a management accountant in a number of finance-related roles supporting Aligned Advice Licensees in the AMP Group. From November 2017 to November 2018 he was Transaction Strategy Manager in the Transaction Strategy team.

41 Mr Scott gave evidence in a precise and careful way. He made concessions where appropriate. I accept his evidence on all factual matters. Insofar as he expressed opinions, I do not necessarily reach the same opinions.

42 AMPFP filed an affidavit of Brian George, who was the Acting Managing Director of AMPFP from April 2019 to September 2020. However, AMPFP did not call Mr George to give evidence at the trial. The reasons were explained in an affidavit of Ms Tatasciore, parts of which are confidential.

43 AMPFP relied on expert evidence from the following witnesses:

(a) Professor Mark Brimble, Professor of Finance and Dean, Griffith Business School;

(b) Professor Alexandro Frino, Professor of Economics, Wollongong University; and

(c) Mr Warren Tappe, the Valuations & Technical Manager of the Valuations team, which forms part of the broader M&A Services team in the Advice division of the AMP Group, a position he has held since June 2018 (he was not required for cross-examination).

44 As noted above, I will make observations about the expert witnesses who were cross-examined later in these reasons.

45 In addition to the documents annexed to affidavits, the parties tendered a number of other documents.

46 The expert evidence was presented as part of each party’s case, rather than concurrently.

47 Following the hearing, the parties provided a Revised Court Book (Revised CB) containing the documents that went into evidence.

48 At the relevant times, AMPFP was a wholly-owned subsidiary of AMP Limited, and the holder of an Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL). AMPFP was one of three entities in the AMP Group that appointed representatives pursuant to authorised representative agreements. The other two entities were Charter Financial Planning Ltd (Charter) and Hillross Financial Services Ltd (Hillross). The effect of the authorised representative agreements was to authorise individuals and companies to provide financial services under the licensee’s AFSL. In Mr Akers’s first affidavit, AMPFP, Charter and Hillross are each referred to as an “Aligned Advice Licensee” and they are together referred to as the “Aligned Advice Business”. I will adopt these expressions.

49 At the relevant times, the majority of financial planners who provided advice under an AFSL held by a member of the AMP Group were not employed by the AMP Group; they either operated as a sole trader or were employed by a corporate entity or through a trust arrangement. The remainder of the financial planners who provided advice under an AFSL held by a member of the AMP Group were employed by an AMP service entity.

50 The Aligned Advice Business offered its advisers and advice practices various services, such as access to compliance and business systems including financial advice tools, education and learning opportunities, to assist with their businesses. Historically, each Aligned Advice Licensee had its own unique characteristics, including in relation to service offerings, brand options and commercial proposition.

51 At the relevant times, AMPFP was the largest of the three Aligned Advice Licensees. More than half of the advisers (that is, financial planners who provided advice under an AFSL held by a member of the AMP Group) were appointed as authorised representatives of AMPFP.

52 The expression “AMPFP network” refers to the network of financial planning practices providing services under an authorisation from AMPFP.

53 As noted above, ampfpa was an organisation representing financial planning practices in the AMPFP network. The members of ampfpa were current and former authorised representatives and/or accredited mortgage consultants of AMPFP.

54 At the relevant times, there was also a body called the Hillross Advisers Association, Inc (HAA). This was also a body representing financial planners. Subsequently, in January 2020, ampfpa and HAA merged. After that date, their combined activities were carried on by ampfpa. In February 2020, ampfpa changed its name to The Advisers Association.

55 At all relevant times, ampfpa’s membership included all of the authorised representatives of AMPFP. AMPFP notified ampfpa of new and departing authorised representatives, and ampfpa also checked the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) register about once a year to ensure that its list of AMPFP authorised representatives was up to date. Membership fees were paid to ampfpa by financial planning practices (on behalf of themselves and any authorised representatives and accredited mortgage consultants they employed). In 2019, practices paid an annual membership fee of $700 as well as a fee per authorised representative/accredited mortgage consultant of $450.

56 At all relevant times, ampfpa was governed by a Board of Directors, all of whom were members of ampfpa. Under ampfpa’s Constitution, the Board was solely responsible for the affairs of ampfpa (clause 9.1). The Board had power to exercise all powers of ampfpa, other than those required to be exercised by members under the Constitution or the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (clause 9.3(a)).

57 During 2019, the members of the Board were:

(a) Damien Jordan;

(b) Scott Weeks;

(c) Willem Beimers (from 16 September 2019);

(d) Mark Borg (21 May 2019 – 20 December 2019);

(e) Karen Grant (until 31 October 2019);

(f) Todd Jeffrey (until 21 May 2019);

(g) Timothy Jones;

(h) David Kelsey (until 19 August 2019); and

(i) Khoung Tang (from 22 January 2019).

58 Mr Macdonald was not a member of the Board, but he attended meetings of the Board in his capacity as CEO. The Board had a Chair and a Vice Chair. During 2019, the Chair was Mr Jordan and the Vice-Chair was Mr Weeks.

59 Aside from Mr Macdonald, ampfpa had three full-time staff and one contractor in 2019. Their roles were to deal with the day-to-day operations of ampfpa, manage member benefits that ampfpa arranged and provided, and address queries and complaints regarding ampfpa members’ relations with AMPFP.

60 At the relevant times, one of the subcommittees established by ampfpa Board was the Remuneration Committee (RemCo). During 2019, the members were:

(a) Mr Jordan (as Board Chair);

(b) Mr Weeks (as Board Vice-Chair);

(c) Mr Kelsey;

(d) Mr Jones (from 17 June 2019); and

(e) Mr Macdonald.

61 At the relevant times, RemCo was responsible for, among other things, engaging with ampfpa’s members and with AMPFP regarding proposed changes to the BOLR Policy. RemCo did not hold a delegation from ampfpa’s Board to conduct “consultation” with AMPFP for the purpose of the Master Terms and BOLR Policy.

Some key concepts – institutional ownership and register rights

62 At the relevant times, AMPFP maintained “institutional ownership” of each client register. The concept of “institutional ownership” is conveniently described in the 2017 BOLR Policy (in the definition of “Practice and client institutional ownership”):

Consistent with the terms of the AR [Authorised Representative] Agreement, AMPFP retains the relationship with those clients that were introduced to, and serviced by, the practice while an authorised representative of AMPFP. This is called “institutional client ownership”. If the AR Agreement is terminated, the clients that have been serviced by the practice principal (or by an adviser within the practice) will remain with AMPFP and continue to be serviced by AMPFP or by another authorised representative of AMP. Neither the practice nor the practice principal has any goodwill or other proprietary rights in relation to the clients. As per the Master Terms, for a period of 6 months after termination of the AR Agreements, the practice and the practice principal must not, either on their own account or in association with any other person approach, entice, induce, or encourage an existing client (as defined in the Master Terms) to transfer or remove custom from AMPFP. Subject to any other agreement reached with the practice, AMPFP does not claim institutional client ownership for those clients of the practice that were existing clients of the practice prior to the practice signing the AR Agreement with AMPFP (or a previous agency agreement with AMP Life).

(Footnotes omitted; emphasis added.)

63 The concept of “register rights” is also described in the 2017 BOLR Policy (in the definition of “Register and register rights”):

For each practice, AMPFP creates a client register.

The client register records the name and address of the client and the products held or services agreed by that client and for which AMPFP considers the practice to be the servicing practice of that client. The register includes, but is not limited to, those clients, products and services that have been allocated by AMPFP to the practice from the register of another practice or from an AMPFP register.

[I]f the practice holds an AR [Authorised Representative] Agreement with AMPFP and is recognised as the owner of the register rights, the practice has contractual register rights in relation to those clients and products on the register, namely:

– The right to contact and provide advice and other financial services to any client recorded on the register as authorised under the AR Agreement, subject to continued compliance with the obligations of the AR Agreement. This right does not prevent AMPFP contacting clients in line with any client protocols agreed from time to time between ampfpa and AMP and does not prevent the client approaching any other practice for advice and other financial services.

– The right to access the client’s files and records for the purpose of contacting and providing such advice and other financial services.

– The right to receive payments when they are made, e.g., permissible ongoing fee for service or commission, as agreed under the AR Agreement in return for providing financial advice and other services as long as the clients and policies remain on the register.

The practice is able to accumulate and build on the value attached to those register rights. The practice may realise the value in the manner noted below:

– Complete a practice-to-practice transfer, where the practice seeks AMPFP’s approval to surrender its register rights and transfer some or all of their clients on the register to another practice and for AMPFP to appoint the other practice as the servicing practice for those clients.

– Apply to AMPFP for a Buyer of last resort benefit.

(Footnotes omitted; emphasis added.)

64 As stated in the passage set out at [62] above, if an authorised representative agreement was terminated, the clients on the register would remain with AMPFP and continue to be serviced by AMPFP or another authorised representative of AMP.

65 Further, as the above passages record, the practice did not have proprietary rights in relation to the client register. The 2017 BOLR Policy allowed a practice to realise the value of its register rights by completing a practice-to-practice (P2P) transfer of some or all of its register rights (with AMPFP’s approval) or by applying to sell back its register rights to AMPFP under the BOLR Policy.

Authorised representative agreements

66 The evidence includes a number of examples of the template for the authorised representative agreements. There were two different versions: one for a corporate practice and one for a sole trader practice. It appears that the template for each version was updated from time to time.

67 By way of example, the Authorised Representative Deed of Agreement between AMPFP and Equity (which utilised the template for a corporate practice) stated in the “Background” section that: AMPFP had a “Licence” (defined as meaning an AFSL and an Australian credit licence); the Practice (i.e. Equity) had submitted an application to AMPFP to be given an “Authorisation” (defined as meaning an authorisation for the purposes of Ch 7 of the Corporations Act to provide the specified financial services on behalf of AMPFP and an authorisation for the purposes of the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth) to provide specified credit services on behalf of AMPFP); and AMPFP had agreed to give the Practice an Authorisation on the terms of the agreement.

68 Clause 2 (headed “Authorisation”) provided (inter alia) that AMPFP agreed to give the Practice an Authorisation as set out in Item 5 in the Schedule (which referred to a Financial Services Authorisation and a Credit Authorisation).

69 Clause 3.1 provided that the Master Terms formed part of the Agreement. The expression “Master Terms” was relevantly defined as meaning the “document (in electronic form) entitled ‘Authorised Representative – Master Terms’ which … sets out the additional terms applying to the Authorisation and includes reference to … the Practice Documents …”. The expression “Practice Documents” was not defined in the agreement, but clause 1.2(c) provided that words defined in the Master Terms “have the same meaning in this Agreement”.

70 The document titled the Authorised Representative Deed of Agreement – Master Terms (the Master Terms) went through a number of versions. The version to which the parties referred in their submissions is the third version, published in June 2015. I will refer to this version of the Master Terms in these reasons.

71 The Master Terms contained a number of definitions in clause 1.1. These included a definition of “Practice Documents” as follows:

Each of the following documents:

(a) the Register and Buyer of Last Resort (BOLR) Policy; and

(b) the Settlement and Recognition terms

as Published from time to time by AMP Financial Planning or otherwise Notified by AMP Financial Planning to the Representative from time to time.

72 It is clear from the above that the expression “Practice Documents” included the BOLR Policy.

73 The expression “Representative” was defined as meaning the person that had been given an Authorisation by AMPFP and had signed an authorised representative agreement and included the Practice.

74 Clause 1.4 of the Master Terms provided a definition of the word “Consult” for the purposes of clauses 3.2 and 10.2 of the Master Terms. Clause 1.4 provided:

1.4 Consultation process

The parties agree that a reference to Consult in clauses 3.2, and 10.2, means that there is no obligation on AMP Financial Planning to reach any agreement with the ampfpa but that AMP Financial Planning will:

(a) give the ampfpa reasonable prior notice about the proposed changes having regard to the urgency with which the changes must be made;

(b) advise the ampfpa about the proposed timetable for when those changes will come into effect;

(c) explain why AMP Financial Planning considers that those changes are required and their implications for Representatives as a whole; and

(d) consider, but not necessarily accept, any responses, options or alternatives offered by the ampfpa about those changes provided always that such responses, options or alternatives are provided to AMP Financial Planning promptly having regard to AMP Financial Planning’s timetable for when those changes will come into effect.

75 Clause 2 of the Master Terms dealt with matters relating to the authorisation of the Representative.

76 Clause 3 dealt with professional standards and Practice Documents. Clause 3.2 was in the following terms:

3.2 Practice Documents

(a) Without limiting the generality of any other obligations imposed on the Representative by this Agreement, the Representative agrees to comply with and be bound by the Practice Documents.

(b) From time to time, AMP Financial Planning may change, up-date or issue new provisions of the current Practice Documents or issue new Practice Documents dealing with other issues affecting the Representative. The Representative must comply with, and be bound by, the terms of any changed or up-dated Practice Documents or any new Practice Documents.

(c) Prior to any change to any Practice Documents or the issue of any new Practice Documents that, in the reasonable opinion of AMP Financial Planning, will have an adverse financial or other significant effect on the Representative, AMP Financial Planning will Consult with ampfpa about the changes or issue but there is no obligation on AMP Financial Planning to reach any agreement with ampfpa in connection with the changes or issue.

(d) Where the Representative is Working for the Practice, the Practice Documents only apply to the Practice.

(Emphasis added.)

77 It is common ground in this proceeding that, whether because of clause 3.2 of the Master Terms or otherwise, before making the 8 August 2019 Changes, AMPFP was required to consult with ampfpa within the meaning of clause 1.4 of the Master Terms.

78 As noted above, the version of the BOLR Policy in place at the time of the 8 August 2019 Changes was the 2017 BOLR Policy.

79 On pages 3-5 of the policy, a number of “principles and definitions are set out”. These include:

(a) The first of these is headed “Parties to the arrangement”. This states that the policy forms part of the authorised representative agreement between each practice and AMPFP, and that, “[w]hen exercising the [BOLR] facility, all parties will act in good faith”.

(b) The description of “Practice and client institutional ownership” has been set out above. Likewise, the description of “Register and register rights” has been set out earlier in these reasons.

(c) In the definition or description of “Control of entitlement” on page 4, it is stated that, if on termination of an authorised representative agreement a practice has not been an authorised representative for at least four years, it is not entitled to a BOLR benefit.

(d) The description of “Discretion to discount or pay on special conditions” states that “AMPFP retains the right to apply a discretionary discount to a practice’s Register Valuation (RV) at the time it is exercising [BOLR], if in AMPFP’s reasonable opinion it is prudent to do so”. The description includes:

The basic rationale behind BOLR is that AMPFP will pay a practice a BOLR benefit where the practice is closing down and that practice has been unable to find another AMPFP practice to take over all or part of the register. In exchange for the [BOLR] payment, however, AMPFP expects to receive clear title to the register without any undue threat that the practice, or those associated with the practice, will materially diminish the value of the client base or encourage clients to move away from AMPFP.

80 The amendment term, which is located on page 5 of the 2017 BOLR Policy, has been set out in the Introduction to these reasons (see [6] above).

81 The 2017 BOLR Policy states on page 6 that “AMPFP has agreed to provide a Buyer of last resort facility on terms outlined in this policy”.

82 In the section dealing with eligibility criteria, on pages 6-7, it is stated that the practice has the right to access BOLR only where (among other things) “the practice principal and all equity holders in the practice undertake not to compete”. This section also deals with the practice having made reasonable endeavours to transfer the register rights to another practice authorised by AMPFP prior to exercising the BOLR rights.

83 On page 8 of the policy, the valuation methodology is set out. It is stated that, under Buyer of Last Resort terms, “a practice’s client register will be valued at 4.0x annual ongoing revenue received by the practice in the prior 12 months”. It is then stated that “[o]ngoing revenue is defined as the recurrent revenue to which the practice is entitled in relation to the register rights being transferred, including permissible trail commission, renewal income and ongoing fees”. (I note that one type of ongoing revenue referred to in documents in evidence is ongoing fee arrangement (OFA) revenue.) Further details are then provided for the purposes of calculating ongoing revenue. There are also certain exclusions from ongoing revenue and register value. These include “[w]here AMPFP considers the revenue to be temporary and is expected to cease within 12 months of the exercise date” (page 9).

84 The 2017 BOLR Policy states (on page 9) that, once lodged, a BOLR application may not be withdrawn by the practice unless AMPFP agrees. This point is emphasised in Equity’s submissions in the proceeding. When AMPFP introduced the 8 August Changes, subject to certain exceptions, they applied to practices (such as Equity and WealthStone) that had submitted a BOLR application prior to 8 August 2019, and those practices were not entitled to withdraw their BOLR application unless AMPFP agreed.

85 The 2017 BOLR Policy also states that “[i]f the other parties to the BOLR Licensee Buy-Back Agreement refuse to sign that Agreement after AMPFP has given those parties at least 7 days to do so, the entitlement to a Buyer of last resort payment will lapse”.

86 The 2017 BOLR Policy contains terms relating to the notice period for exercise of the BOLR rights (at pages 10-11). The document states that the minimum notice period is “typically 12 months”. However, for practices with more than 15 years’ tenure at the exercise date, or practices willing to accept a register discount, the notice period is a minimum of 6 months. Further details are provided regarding the amount of the discount where a notice period less than 12 months is sought. For example, where the practice’s tenure is over 4 years and up to 10 years, the register value is to be discounted to 80%.

87 The 2017 BOLR Policy contains terms relating to “Buyback assessment” (at pages 11-15). This section describes a process of assessment of client files, with four discrete components: (1) client file assessment; (2) minimum client data requirements; (3) compliance concerns; and (4) ongoing fee arrangement assessment. The assessment of these matters could result in the discounting of a client register, or the reduction in the amount to be paid by AMPFP to the practice.

88 Payment terms are dealt with on pages 15-16 of the 2017 BOLR Policy. Various “exit scenarios” are outlined, and details are provided for a certain percentage of the total amount to be paid at the exercise date, with the balance to be deferred to 6 or 12 months later (depending on specified criteria).

89 A document that provides a useful overview of the BOLR Policy and its commercial context (before the 8 August 2019 Changes) is a memorandum dated 17 July 2018 from Mr Akers to the AMP Limited Board titled “Overview of Buyer of Last Resort (Bolr) Schemes” (the Akers July 2018 Memorandum). The purpose of the memorandum was stated to be “to update the Board on key features and risks of Buyer of last resort (Bolr) and other buyout programs within the Advice business”.

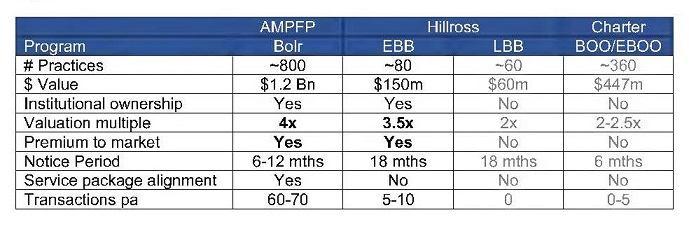

90 The section headed “AMP’s Buyout Programs” stated:

AMP has several buy-back models in place across its advice licensees, each with different terms and valuation methodologies. AMPFP’s Buyer-of-last-resort (Bolr) model represents the highest valuation, the largest exposure, and is the most commonly utilised of AMP’s buy-back models and this paper will focus primarily on the Bolr program. AMP’s exposure to Hillross’ EBB program is significantly smaller. The other programs (Hillross LBB and Charter) do not represent a premium to market, are infrequently [utilised] and are not considered to represent a material exposure.

91 As is apparent from the above extract, different buy-back models were in place in relation to AMPFP, Charter and Hillross. The buy-back model for the AMPFP network was referred to as the “BOLR” policy. The buy-back models in place for the Charter and Hillross networks were not referred to in this way. Consistently with this, when I refer in these reasons to the “BOLR Policy”, I am referring to the policy in place for the AMPFP network.

92 Despite the above table indicating there were 800 practices in the AMPFP network, Mr Akers gave evidence in his first affidavit, which I accept, that: at the start of 2018, AMPFP had approximately 640 practices in its network; and, as at 8 August 2019, AMPFP had approximately 542 practices in its network.

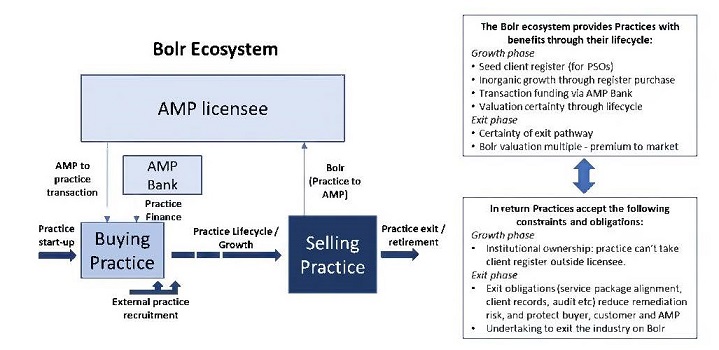

93 Under the heading “The Bolr Ecosystem”, the Akers July 2018 Memorandum stated:

AMPFP’s Bolr program is a buy-back arrangement under which practices may sell their client registers to the licensee and exit the industry, with AMP obliged to purchase based on a prescribed valuation methodology. All AMPFP practices with 4+ years tenure are eligible to exercise Bolr.

An “ecosystem” has developed to support the … transfer of client registers from practice-to-practice or between practices and AMP, and based on reciprocal benefits to AMP and practices as shown in the chart below.

AMPFP has several options to manage client books acquired from selling practices under Bolr, including (i) transfer/sell the client book to another servicing practice; (ii) maintain the practice as a “going concern” within AMP Advice’s employed adviser model; (iii) transfer high-touch clients to an existing AMP Advice practice; (iv) transfer low-touch clients to the AMP Assist direct servicing model.

Bolr has historically supported several objectives for AMP, practices and clients including:

• Support practice through life-cycle: through the transfer of client books to practices looking to grow inorganically, or to seed start up practices with initial client books.

• Provide continuity for clients when a practice exits: The client book of the exiting practice is transferred to another practice, with client servicing rights and obligations intact.

• Enhanced adviser value proposition: Bolr is highly valued by practices and historically has been a key component of AMPFP’s adviser value proposition. Practices principals that have successfully grown their business view Bolr as their nest-egg providing post-retirement security. Some practices also utilise Bolr as part of their internal business management activities, such as employee participation schemes and succession planning.

(Emphasis added.)

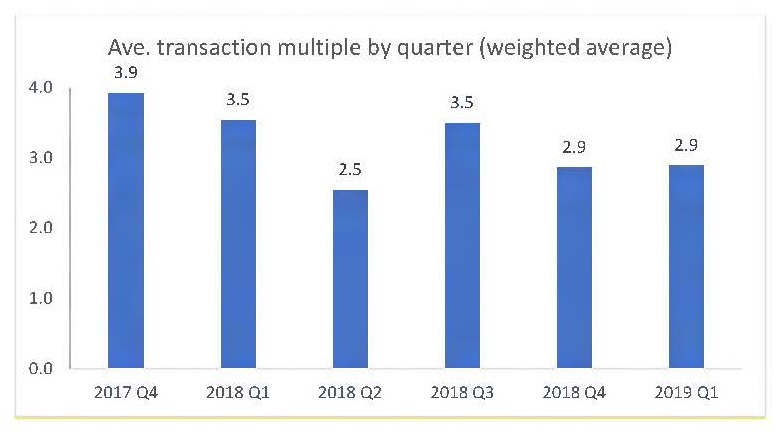

94 In the section headed “Bolr Valuation and Terms”, the memorandum stated:

Bolr valuation is based on a flat multiple of 4x ongoing income (both fee and commission income). One-off or upfront income is not included. Bolr is product-agnostic – income is valued whether linked to an AMP or non-AMP product. Bolr valuation is subject to discounting where an exit audit indicates that the practice has not maintained adequate client records or met servicing and compliance standards.

A review of recent transactions indicates an average discount of 20%, with most practices receiving discounts within the range of 10-25% (implying a valuation of 3.0-3.6x ongoing revenue). Deferred terms (12 months) also incentivise an adviser to provide effective handover to the next servicing adviser, and acts as downside protection should issues be found post settlement.

(Emphasis added.)

95 As indicated in the above extract, in many cases where a practice sold its client register to AMPFP under the BOLR Policy a discount was applied by AMPFP. This could arise, for example, where AMPFP’s audit of the client files revealed deficiencies in the records kept by the practice. In some documents (including the memorandum currently being discussed) this was said to imply a valuation of less than a 4x multiple of ongoing revenue. However, generally, including in Mr Scott’s evidence, the multiple for a transaction was a matter that was treated separately from the question whether any discounts applied to the transaction.

96 Appendix 1 to the Akers July 2018 Memorandum sets out key terms of the 2017 BOLR Policy. The appendix stated:

Eligibility | All AMPFP practices with 4+ years tenure. | |

Notice period | 12 months (reduced to 6 months for practices with 15+ years tenure). | |

Valuation | Bolr valuation is based on a flat multiple of 4x recurring income which applies to all ongoing fee and commission income irrespective of whether linked to an AMP or non-AMP product. One-off or upfront income is not included. | |

Bolr valuation is subject to discounting where: | ||

1. | The practice has not maintained adequate client data and contact details. | |

2. | The practice has not maintained adequate client files and records. | |

3. | The practice has compliance or remediation concerns. | |

4. | In the case of fee for service clients, where the practice does not have a service package in place with the client meeting AMP’s defined standards | |

Payment under Bolr is made in two instalments. In additional to the above discounts, an amount of 20% of the settlement price is deferred for 12 months and is “at risk”, and may be adjusted in the event that the quality of the client book has significantly decreased since the date of settlement. | ||

Institutional client ownership | AMPFP’s Bolr policy is linked with its “institutional ownership” framework, where AMPFP retains ultimate ownership of client relationships introduced to practices while licensed by AMPFP. If the practice exits, the clients that have been serviced by the practice will remain with AMPFP and continue to be serviced by another AR licensed by AMP. Institutional ownership has historically been viewed as the “quid pro quo” for AMPFP’s above-market Bolr multiple. | |

Pre-Bolr exit responsibilities | During their notice period, practices are required to: | |

1. | Notify clients of their departure | |

2. | Ensure client files and records are up-to-date. | |

3. | Obtain opt-ins in relation all existing servicing arrangements. | |

4. | Align their client servicing arrangements to meet AMP’s standard service packages (via a variation of the agreement, in cases where they don’t align). | |

Failure to undertake these activities may result in the relevant client policies not being valued under Bolr. | ||

Undertaking | As part of exercising Bolr, practice principals and equity-holders undertake not to approach former clients, and not to work in the finance industry for a period of 3 years from the exit date. This precludes them from continuing business under another non-AMP licensee during the undertaking period. | |

(Emphasis added.)

97 The emphasised passages in the above extract draw a link between the BOLR Policy and institutional ownership terms. As explained above, under institutional ownership terms, AMPFP retained the relationship with the clients and, if the authorised representative agreement was terminated, the clients remained with AMPFP rather than with the practice; neither the practice nor the practice principal had any goodwill or other proprietary rights in relation to the clients. While these terms placed restrictions on practices, practices were prepared to accept this in circumstances where the BOLR Policy existed and the multiple payable under the BOLR Policy was above that payable in the external market (that is, the market for the sale and purchase of financial planning practices not subject to institutional ownership terms with AMPFP or like terms with another AFSL holder) (the external market).

98 Another document that provides commercial context for the BOLR Policy (before the 8 August 2019 Changes) is a draft memorandum dated December 2018 from Mr Byrne to Mr Paff and Mr Symons titled “Buy back (BOLR) Strategy” (the Byrne December 2018 Memorandum). The evidence includes a number of versions of this draft memorandum, prepared during the period from March 2018 to January 2019. The Byrne December 2018 Memorandum included the following text under the heading “Real or notional benefits of existing [buy]back models”:

Maintain customer servicing via market creation: From a customer perspective, BOLR supports ongoing servicing when a practice exits the industry. This is achieved with a guaranteed valuation and service alignment approach that supports the transition of client servicing rights from exiting practices to new or existing practices or AMP (Appendix 3).

Practice value proposition: From a practice perspective, BOLR / EBB [a reference to one of the Hillross buy-back policies] represent a significant premium to market valuations and are therefore highly valued by incumbent practices. This practice value has encouraged practice recruitment and retention and provided an additional incentive for practice recurring revenue growth.

Practice, customer, and value retention: From AMPs perspective, the premium paid under BOLR and EBB is a key reason for practices accepting institutional ownership terms, which have restricted practices from exiting the licensee without exiting the industry. These terms have been effective at retaining clients within the network and have discouraged AMPFP and EBB practices from becoming self-licensed or joining competing licensees.

Support practice life cycle (start up, grow and exit): Historically AMP has resold acquired client registers to practices looking to grow inorganically, or to seed start up practices through PSO offers. This activity is more constrained now as AMP is actively acquiring registers and scaling internal servicing capabilities.

(Emphasis added.)

99 In the first emphasised passage in the above extract, it is stated that the BOLR Policy represents a “significant premium to market”. A large number of other documents in evidence also refer to the BOLR multiple representing a “premium” to market, being the external market. See, for example: the PowerPoint presentation dated April 2018 (AMP.5800.0116.0046 at _0001 and _0003); the draft memorandum dated May 2018 (AMP.5800.0093.0237, first page and _0002); the PowerPoint presentation of July 2019 (AMP.5800.0020.9035 at _0003). Further, Mr Byrne gave evidence in his affidavit that it was widely acknowledged within AMPFP and by practices that the valuation offered by the BOLR Policy was a premium to the external market value of the registers. In light of those documents and that evidence, I find that the BOLR multiple (prior to the 8 August 2019 Changes) represented a premium to the external market.

100 I note also that, in the second emphasised passage in the above extract, a link is drawn between the premium payable under the BOLR Policy and the acceptance by practices of institutional ownership terms. This is the same point as discussed at [97] above.

101 On 1 July 2013, the Future of Financial Advice (FOFA) reforms became mandatory. (The reforms were voluntary from 1 July 2012.) Relevantly for present purposes, the reforms banned conflicted remuneration, but commission arrangements that were already in place were “grandfathered”, meaning they could continue to be paid. These commissions were referred to by AMPFP as grandfathered advice revenue or “GAR”. In addition, certain other commissions remained permissible under FOFA (such as those relating to insurance and mortgages). Other than these commissions, conflicted commissions were prohibited by FOFA. As a result of these changes, where commission revenue was not available to subsidise advice, financial planning practices needed to charge clients an explicit advice fee; this could be a one-off fee paid by the client, but more often was a fee paid pursuant to an ongoing fee arrangement, with the fee deducted from the client’s product and remitted by the product issuer via the AFSL licensee.

The period May 2017 to August 2018

102 During this period, AMPFP made a strategic decision to keep (rather than on-sell) a portion of the client registers that it purchased under the BOLR Policy. (Historically, the large majority of client registers acquired by AMPFP under the BOLR Policy had been on-sold to an existing or a new practice in the AMPFP network.) Also during this period, early strategic thinking commenced within AMPFP as to a future “end state” in relation to the BOLR Policy.

103 The evidence includes a memorandum from Justin Morgan (Head of Licensee Value Management at AMP) and Mr Akers to AMP’s Advice Leadership Team dated 11 May 2017 on the subject “Buy Back and Planner to Planner Process Change”. Mr Akers was taken to this document during cross-examination and gave the following evidence, which I accept:

… what you were there identifying is a recommendation that AMP increase its ownership and ongoing servicing of customer registers purchased through licensee buyback policies?---Yes.

…

… But it did represent an intention to hold a greater proportion of registers than might have historically been the case in the past?---Yes.

Yes. And so rather than acting as a clearing house of all registers through the buyer of last resort policy what this reflected was a change in strategy to retaining a proportion of those registers?---That’s correct.

104 The evidence includes a memorandum dated 25 June 2017 from Mr Morgan to the AMP Life and NMLA Audit Committee on the subject “Customer Account Register Pool and Strategic BOLR review update”. The memorandum’s purpose was stated to be to provide an update on:

• Changes to AMP’s strategic approach to the purchase and onsell of client registers.

• The Strategic Review of BOLR including Project Derby phase 3

105 The executive summary of the memorandum stated:

• The establishment of a direct servicing capability through AMP Direct and AMP Advice has led to a change in our approach to managing business transactions across the network. Management is no longer actively working to minimize inventory levels.

• Under our revised approach, exiting businesses are assessed to determine the most appropriate transaction pathway, with options including (i) internal succession, (ii) install new ownership in a viable existing business, (iii) sell the client registers to another practice and (iv) acquire and develop a direct servicing relationship.

• This approach is being implemented and will be applied to the 75 business transactions scheduled to take place between July 2017 and June 2018. AMP expects to acquire a significant number of clients that will be serviced directly by AMP.

• Policies in Register Company (except for leased policies) will now be held as intangible assets, rather than as inventory. ~$45m was transferred from inventory to intangible on 30 June 2017.

• A program of work to update processes and systems relating to managing BOLR under changes to policy announced in 2016 is now almost complete.

(Emphasis added.)

106 “AMP Direct” and “AMP Advice” were explained in the “Background” section of the memorandum. That section included the following:

Under AMP’s historical approach to managing the buy-back ecoystem, management has actively worked to on-sell a high proportion of purchased client registers, and reduce AMP’s inventory level, to seed new business growth and to provide a growth channel for established practices.

At the AMP Investor Strategy day in May 2017, management highlighted our intention to enhance AMP’s operating margins through broader participation in the Advice value chain. One of the key opportunities to realise this objective is to implement a direct servicing capability that enables AMP to develop a service-based relationship for clients purchased through practice buy-back transactions.

The establishment of (i) AMP Direct as a remote servicing model for low-touch clients and (ii) AMP Advice as a face-to-face servicing model for high touch clients, provides the opportunity to increase AMP’s ownership of customer registers in a manner that would maximize AMP economic value, and offer a broader, deeper and more scalable servicing model to segments that are currently either non-serviced or else under-served. Under this approach, AMP can capture and maintain service fees attached to policies acquired by AMP (these fees are currently switched off).

This revised approach is currently being implemented. Consistent with this approach, management is no longer actively working to minimize inventory levels, and expects to acquire a significant number of clients that will be serviced directly by AMP.

Under our revised approach, exiting businesses are assessed to determine the most appropriate transaction pathway in the interests of our customers and the distribution network. Outcomes may include:

1. Internal succession within the business, where appropriate successor is identified.

2. Restructure and maintain the business as a viable going concern, owned by AMP, a new practice principal, or else under an equity partnership model.

3. Business to business transactions, which will continue to be supported where consistent with AMP’s strategic interests.

4. Buy back and service through AMP Direct and/or AMP Advice, with all commission and/or servicing revenue accruing to AMP.

(Emphasis added.)

107 “AMP Direct” was subsequently re-named “AMP Assist”. The name “AMP Advice” remained the same.

108 During cross-examination, Mr Byrne provided the following explanation of AMP Assist and AMP Advice. AMP Assist was a phone-based advice service. AMP Advice was a face-to-face advice service. AMP Advice involved both: (a) employed advisers providing advice in AMP offices; and (b) self-employed practices operating under the processes, technology and systems of AMP Advice.

109 During cross-examination, Mr Scott gave the following evidence, which I accept:

… at the time of the commencement of the buyer of last resort policy, in effect, from 1 July 2017, you were aware that AMP was changing its strategy with respect to on-selling registers by increasing the number of registers it would retain and have serviced by AMP Assist and AMP Advice?---Yes.

And that strategy involved not on-selling as many registers as had occurred historically?---Yes.

And concerned – rather than acting as a clearing house of registers through the buyer of last resort policy acting as a company which held a proportion of registers for direct servicing?---Yes.

110 The evidence includes a memorandum dated 4 July 2017 from Mr Scott to James Georgeson and John O’Farrell (of AMP) on the subject “Buyback update”. The “Purpose” section of the memorandum stated that the paper explained the change in accounting treatment for “buyback transactions resulting from the strategic decision to service more policies internally” and for “external policy write downs on purchase”. The executive summary included:

The Advice business are making changes to practice transaction processes based on a revised decision-making framework that will support a range of outcomes for business transactions across the network including buyback, on-sell and planner to planner.

Exiting businesses will be assessed, with a recommendation developed as to the most appropriate outcome in the interests of customers and the distribution network. Outcomes may include planner to planner transactions, internal succession within the business, and unbundling then allocating customers to an appropriate service channel. This will be aligned with a strategy to participate more in the Advice value chain and service policies internally.

The change in strategy by the Advice business requires a reclassification of buyback policies held on the balance sheet. AMP accounting policy is that client registers which are held for sale in the ordinary course of business are classified as inventory.

However, individual client policies will not be classified as inventory where either:

(a) a decision has been made by the business not to sell the policy; and/or

(b) the policy has an attribute that is been systematically excluded from sale

(Emphasis added.)

111 The evidence includes a memorandum dated 22 November 2017 from Mr Akers to the AMP Limited Board titled “Revised approach to acquire client registers”. The purpose of the memorandum was stated to be:

To provide the Board with an update on our strategy under which AMP will acquire client registers from aligned practices through buyout transactions and providing direct servicing to clients through AMP Assist and AMP Advice.

112 The executive summary of the memorandum stated:

AMP has implemented a revised approach to acquisition of customer registers, under which customers will be served through the channels most appropriate to meet their needs, including AMP Assist and AMP Advice.

Previously AMP has on-sold acquired client registers wherever feasible to other servicing practices or as part of Practice Start-up Offers. Our revised approach will retain a growing portion of these registers to be serviced through AMP-owned channels. This approach is expected to deliver returns to the Advice business through the in-housing of existing product commissions and fee-for-service client relationships, while also recognising the potential value to AMP Group of expanding our addressable customer base.

Over the next 5 years we expect to acquire ~$50m in customer registers per annum, with an aggregate capital investment of $250m. The financial impact is expected to approach hurdle excluding amortization and assuming lower cost to serve.

We are well positioned to execute on this strategy given the investment in underlying technology and infrastructure in recent years, enabling us to digital engage and serve clients in a more personalized yet scalable manner.

This strategy also enables us to take control of the inevitable increase in aligned businesses accessing buyer-of-last-resort terms over the coming years driven predominantly through the key deadlines for education standards; the trend of sub-scale businesses opting out and through more deliberate interventions by AMP on higher-risk and / or underperforming businesses.

(Emphasis added.)

113 On 14 December 2017, the Commonwealth Government established the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry (the Financial Services Royal Commission or the Royal Commission). The Honourable Kenneth Hayne AC QC was the sole commissioner.

114 In 2018, the Financial Adviser Standards and Ethics Authority (FASEA) announced educational requirements that advisers would need to meet. These changes placed pressure on advisers to consider their careers and their individual plans. This was particularly so for older advisers who were nearing retirement age and were concerned about taking educational courses and examinations for the first time in a long time.

115 During cross-examination, Mr Scott gave evidence, which I accept, that the strategy of AMPFP keeping (rather than on-selling) a portion of the registers acquired under the BOLR Policy was fully operational by early 2018. He gave evidence, which I accept, that from that point on (until August 2019), BOLR transaction registers (that is, registers acquired under the BOLR Policy) mainly went to AMP Advice and AMP Assist.

116 Further, Mr Scott gave evidence, which I accept, that AMP’s strategy in the period early 2018 to August 2019 involved placing as many clients as possible with AMP Advice and AMP Assist and then finding a home for remaining clients that did not meet the exceptions criteria and accreditation criteria for clients of AMP Advice/AMP Assist. Where clients could not be placed with AMP Advice/AMP Assist, or there were other reasons for not placing them with AMP Advice/AMP Assist, the clients were on-sold. This was referred to in the evidence as a “partial on-sell transaction”; in other words, it involved the on-sale of only part, rather than the whole, of a register.

117 The evidence includes a draft memorandum dated March 2018 from Mr Byrne, Chris Fernie (the Head of Channel Strategy at AMP) and Julian Cappe (a consultant engaged by AMP’s Australian Wealth Management division) to Mr Akers and Michael Paff (Managing Director of AMPFP and AMP Advice) titled “Buyback review”. The draft memorandum set out an “early hypothesis of end state”, which included a move away from the then current BOLR valuation methodology, and discussed an “early hypothesis of transition”. In relation to the latter topic, the draft memorandum discussed “tactical changes” (described as phase 1) and a “glide path” (described as phase 2). The draft memorandum stated in part:

Phase 2 – Glide path: As we move from the current BOLR valuation methodology to end state models it is recommended that an extended glide path be put in place. The concept of the extended glide path is to reduce the recurring revenue multiple very slowly so that growing practices are incentivised to remain in business and, over time, the new models become more attractive.

With an anticipated 13 month notice period and a minimum of 3 months of consultation with the ampfpa, (and need to have some key tactical changes such as run clause in place before any engagement) it is unlikely that the glide path would commence until early 2020 at the earliest. The rate at which the multiple reduces by and the time horizon of the glide path can be modelled, but an indicative approach may be a five year transition where the multiple decreases by 0.03x per month (0.36 or ~9% pa).

(Mark-up in original.)

118 During cross-examination, Mr Byrne gave the following evidence, which I accept, in relation to early 2018:

And your view in early 2018 was that AMPFP should change its model to remove institutional ownership and remove any premium payable under BOLR, wasn’t it?---Over an extended period of time, I saw that as, yes, something that the business should consider.

Let me be clear: my question was different to the question that you sought to answer. Your view in early 2018 was that AMPFP should change its model to entirely remove institutional ownership and remove any premium payable under the buyer of last resort policy, wasn’t it?---Over an extended period of time, yes.

And so when you say, “Over an extended period of time”, are you referring to the time at which your view was formed or the time at which those steps should be undertaken?---Time at which those steps should be undertaken.

119 Under the heading “Risks and challenges with hypothesis”, the draft memorandum dated March 2018 stated in part:

Timing risks: BOLR and institutional ownership are fundamental elements of the AMPFP and Hillross value propositions and the implications of change are far reaching. Practices and the adviser associations are highly sensitive to changes to these terms and there is an expectation that any reduction to practice value would be countered by an equal and opposite improvement in value elsewhere.

Changes introduced under Derby were designed internally for approximately 7 months with the assistance of three phases of engagement with AT Kearney. There was then a series of negotiations with the ampfpa over a 10 month period (to April 2016) when the changes were launched. Those changes did not take effect for a further 13 months. Although these changes were material, they were also designed to not materially impact the overall valuation of the network (therefore there were both winners and losers as a result of the changes). Despite the AMPFPA agreement to changes, the transition paths and held value terms put in place, there was still a large volume of BOLR exits following the changes. In recent discussions with the AMPFPA they have also noted that they would have preferred to have gone slower with the BOLR changes and not to have agreed to launch when we did. With this context, the aforementioned transition plan would be considered aspirational and unlikely to be realised unless a more aggressive approach to adviser association consultation is taken.

(Emphasis added.)

During cross-examination, in relation to a later memorandum (dated December 2018) with similar text to that set out above, Mr Byrne said that on reflection he would characterise BOLR and institutional ownership as important, rather than fundamental, elements of the value proposition.

120 In April 2018, the second round of hearings of the Financial Services Royal Commission (which dealt with financial advice) commenced. Mr Byrne accepted during cross-examination that, during the course of the Royal Commission hearings in early 2018, AMP suffered significant brand and reputational damage.

121 At about this time, Mr Byrne, as part of an AMP working group, started working on the implications for the AMP Advice Licensees if grandfathered commission revenue were to end.

122 The evidence includes a draft memorandum dated May 2018 from Mr Byrne, Mr Fernie and Mr Cappe to the Advice Leadership Team of AMP on the subject “Commercial Buyback terms – review”. The document was labelled “DRAFT for discussion”. The “discussion questions” were identified as:

1. Problem: Are the top three issues with AMP buy back models: (1) the liability risks and exposure of a ‘run’ on BOLR, (2) perception issues relating to institutional ownership for EBB and BOLR, and (3) the premium to market valuation offered under AMPFP BOLR and to a lesser extent Hillross EBB?

2. End state: Does the removal of BOLR/EBB terms and institutional ownership make sense as a response to these problems in an end state?

3. Transition: Is an initial phase of internal preparation in 2018/19 followed by an extended glide path reduction in values from 2020-2025 preferable to a more immediate change?

123 The section headed “BOLR and the Royal Commission into Financial Services” stated:

The Royal Commission into Banking and Financial Services has put AMP under intense media, customer and stakeholder scrutiny. A focus of that scrutiny has been AMPs charging of fees for no service when customers have been sold back to AMP and have remained in the ‘BOLR pool’. This issue was the result of system and process failures, but in some cases it was because of a business practice. Although this issue was resolved in November 2016, there is understandably a heightened awareness of all processes surrounding our buy back arrangements and an imperative to ensure customer servicing is maintained when practices exit the industry.

As a result of the negative stakeholder sentiment flowing from the Royal Commission, there has been a significant increase in practices asking about BOLR and also considerable media speculation on the potential for practice exits and AMPs liability. AMP is beginning to see a stepped increase in exit notices – with 5 received in the first week of May (last week), compared to an average of less than 1 week since the start of the year.

As a result of the Royal Commission, it is likely that practices within the network will have heightened sensitivity surrounding any changes to BOLR terms. This sensitivity is fuelled by speculation within the network surrounding; the future of grandfathered commissions, future changes to OFAs, the future of vertical integration, the future of licensee incentives, changes to AMP leadership, and the potential to make changes to BOLR terms outside the established notice period. In such an environment, it is likely that practices may submit their exit notices in an attempt to secure current terms, or act irrationally when changes are introduced.

124 I have referred to the Akers July 2018 Memorandum at [89] above. I now set out some additional extracts from that memorandum. In the section headed “Financial Impact”, the memorandum stated:

AMP’s total Bolr liability is $1.2Bn across ~800 practices (not including audit discounts). Since 2016, AMPFP has undertaken an average of 60 Bolr transactions a year, at average $1m each (ie. aggregate ~$60m transaction value pa). Prior to 2015, annual Bolr was ~$30-40m pa, with the recent uplift being linked to accelerating industry disruption. The strategic plan for Advice forecasts that Bolr volumes will remain at an elevated level over the next 5 years driven by adviser demographics and increasing industry professionalisation standards (est. $80m pa).

Since the Royal Commission hearings on financial advice, 22 Bolr notices for total $17m have been received, representing a moderate short-term increase in exits above normal levels (many of these practices were considered high propensity to exit even prior to the Royal Commission).

More recent propensity modelling (excluding Royal Commission fallout) suggests 2019 is likely to be the year we see the [largest] number of exits; linked to FASEA milestones.

125 After discussing “Risks and issues”, the memorandum contained a section headed “Changes to Bolr terms”. This stated in part:

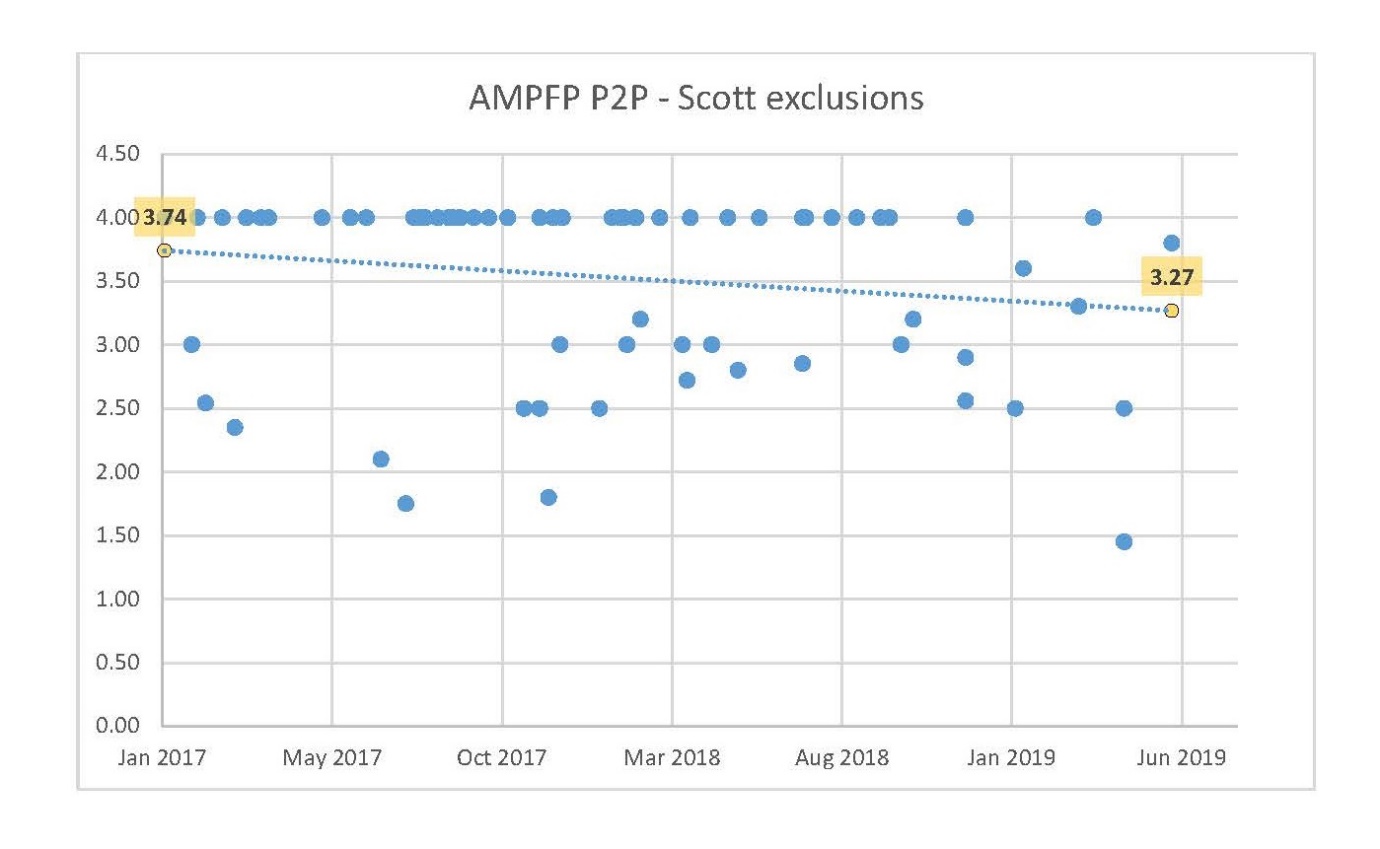

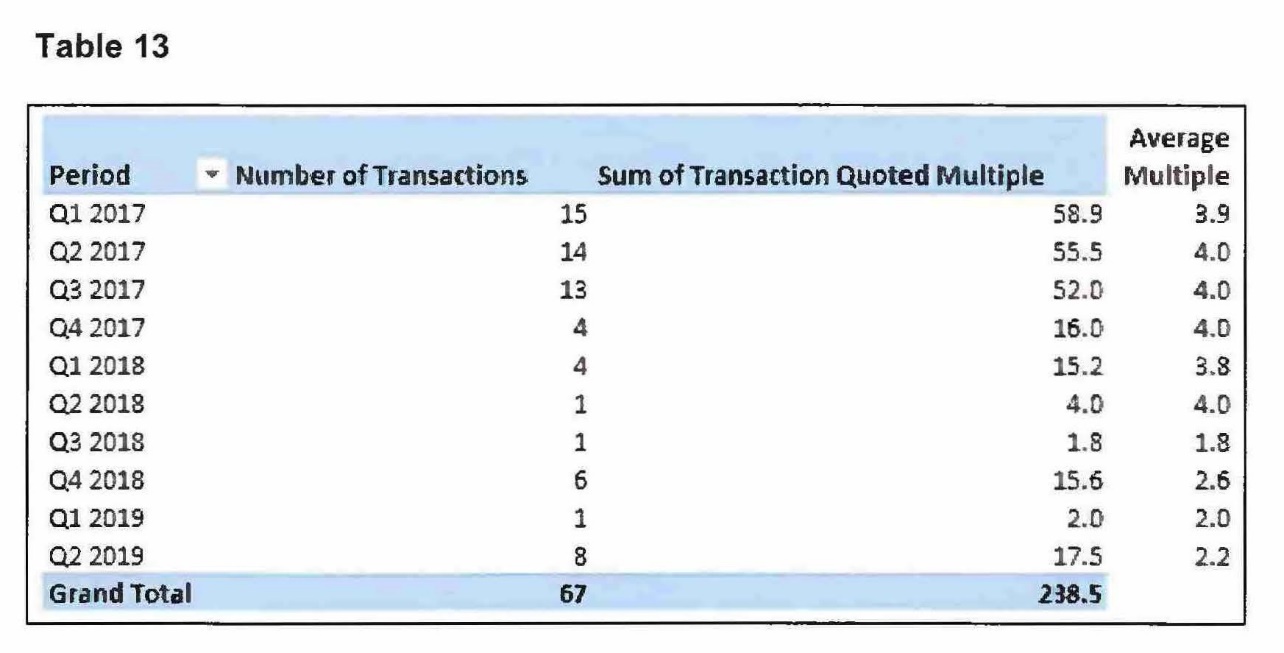

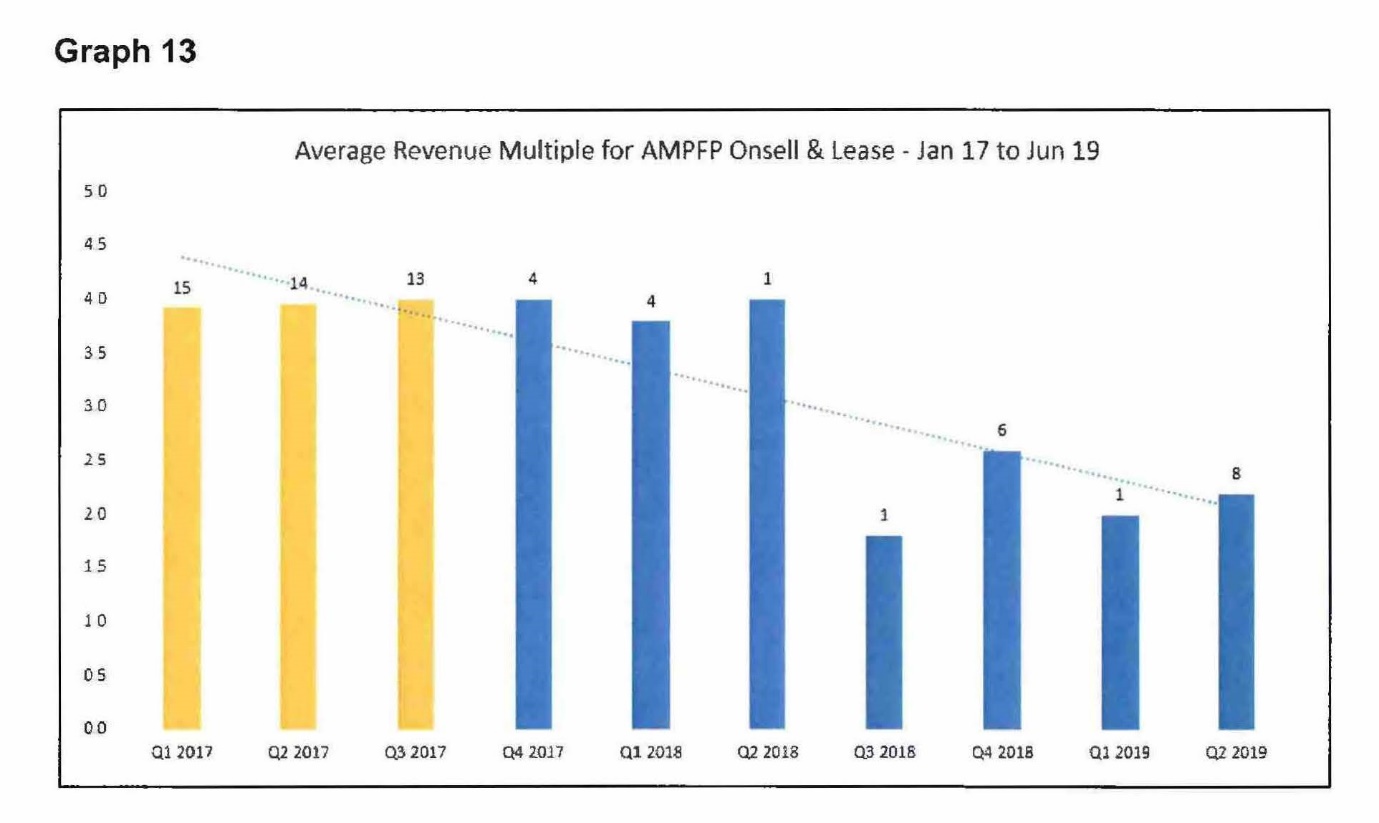

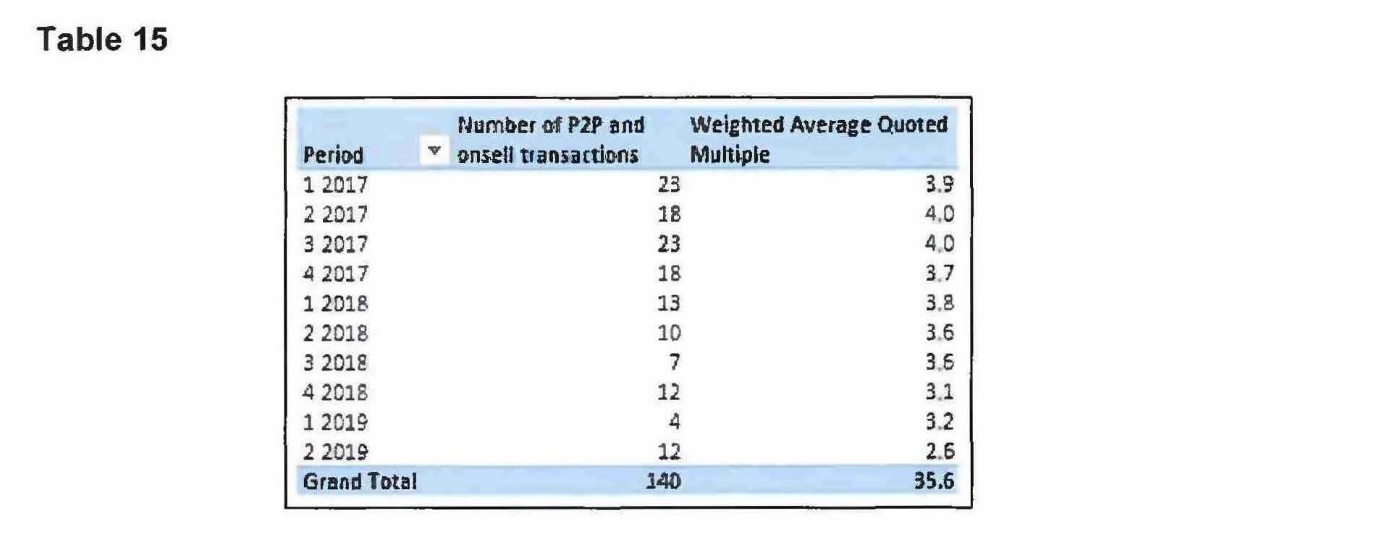

AMPFP periodically reviews its Bolr terms to ensure they meet the needs of AMP, advisers and customers, and comply with the evolving regulatory landscape. Changes to Bolr terms can be made with 13 months notice to advisers, or with a shorter notice period by agreement with the AMPFPA (adviser representative association).