Federal Court of Australia

Cooper v Nine Entertainment Co Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 726

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | NINE ENTERTAINMENT CO PTY LTD ACN 122 205 065 First Respondent MR JAKE NIALL Second Respondent MR PETER RYAN Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The Age Company Pty Ltd is joined as a respondent to the proceeding.

2. The applicant has leave to file an amended originating application substantially in the form of the document annexed to the applicant’s amended interlocutory accepted for filing on 3 July 2023.

3. The applicant has leave to file an amended statement of claim substantially in the form of the document annexed to the applicant’s amended interlocutory application accepted for filing on 3 July 2023.

4. Submissions as to consequential orders, including costs, are to be provided in writing within five business days of the publication of these reasons and with a right of reply three business days thereafter. The submissions must not in any case exceed five pages.

5. Subject to any further order of the Court, the determination of consequential orders and costs will be made on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MCELWAINE J:

1 The applicant Dr Russell Cooper is a general medical practitioner who consults in Queensland and Tasmania. He is aggrieved by what he claims was the publication of defamatory matter in The Age newspaper and online in February 2022 that, inter alia, described him as a Tasmanian doctor who assisted AFL players to circumvent COVID-19 vaccination rules in order to play football. He claims that the sting of the articles published imputed to him incompetence as a medical practitioner, that he is a conspiracy theorist and is otherwise an unprincipled and unethical medical practitioner.

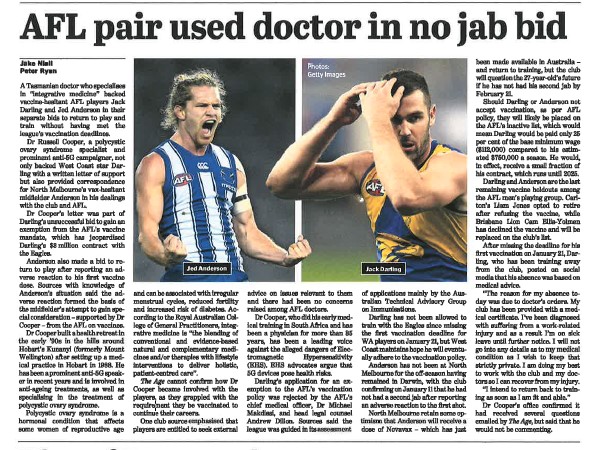

2 The print version of the publications of which he complains in The Age newspaper of 18 February 2022 is:

3 It is not in dispute that the publisher of The Age newspaper and its affiliated websites is The Age Company Pty Ltd, a body corporate ultimately related to Nine Co Holdings Ltd (Nine Holdings). Despite that, perhaps notorious fact, Dr Cooper in his originating application lodged with this Court on 15 February 2023 did not name The Age Company as respondent. Rather, it names Nine Entertainment Co Pty Ltd as the first respondent and two journalists, Jake Niall and Peter Ryan as the second and third respondents. That is not the only preliminary difficulty faced by Dr Cooper. His originating application seeks relief on the grounds stated in the accompanying statement of claim, which document is somewhat unusual in drafting style. Not only does it assert that the first respondent “owns and publishes” The Age newspaper together with its website, but the pleading does not mention the print copy of the newspaper, asserts that the respondents “did not take reasonable care to ensure the publication was true and further they knew the publication was not true”, asserts negligence with malice and continues that Dr Cooper “will provide an affidavit evidencing the publication identifying him and containing defamatory statements against him published or caused to be published by the Respondents”. Sixteen defamatory imputations are pleaded, when the respondents contend that only one defamatory imputation is mentioned in correspondence from Dr Cooper’s solicitor to the managing editor of The Age newspaper dated 23 December 2022. The respondents accept that this letter is a concerns notice within the meaning of s 12A of the Defamation Act 2005 (Tas).

4 Arising from a considerable amount of correspondence engaged in between the solicitors and following the commencement of this proceeding, Dr Cooper on 22 May 2023 filed an interlocutory application for leave to amend his originating application and statement of claim. The amendments then sought involved the following steps:

(1) A correction to the name of the first respondent, wrongly referred to as a proprietary company;

(2) Add The Age Company as a joint first respondent;

(3) Insert a pleading that each of the “First Respondents” are the “owners, proprietors or operators of (and thereby liable as publishers or participants in publications on and in) the masthead known as ‘The Age’, a newspaper having a wide and extensive circulation in all States and Territories of Australia, including by way of the internet and in particular the website located at the internet address https://www.theage.com.au”;

(4) Insert a pleading that on and from 17 February 2022 “and continuing thereafter, the Respondents published matter, of and concerning Dr Cooper, in hard copy editions of ‘The Age’ newspaper and also upon ‘The Age’s’ website by way of an article, in its internet version entitled ‘AFL players Darling, Anderson, used Tassie doctor for vaccine exemption bids’”, and which “text was published in the same or substantially the same form, save for the headline of “AFL pair use doctor in no jab bid” in the hardcopy newspaper version of ‘The Age’, in the Australian Capital Territory, the Northern Territory, Tasmania and the other States of Australia”;

(5) Substitute, and substantially amend, the defamatory imputations that are alleged;

(6) Include a plea that Dr Cooper by reason of the publication of the defamatory matter had suffered and was likely to suffer serious harm to his reputation;

(7) Include a plea of republication; and

(8) Make numerous additional amendments by way of additions and deletions to the extant statement of claim.

5 Upon the hearing on 16 June 2023, various amendments to the application were foreshadowed in the form of an unfiled draft amended application that was emailed to my chambers. In substance, Dr Cooper did not press the amendment to the name of the first respondent but maintained his application to join The Age Company. For reasons that were not satisfactorily explained, Dr Cooper failed to file the amended interlocutory application until 30 June 2023, after I had published my reasons and made orders. His error then became apparent. I vacated my orders, published my reasons to the parties, required Dr Cooper to file his amended application and requested further supplementary submissions. As now published, these reasons incorporate the necessary alterations and form of orders.

6 Dr Cooper seeks to make his amendments pursuant to rules 8.21 and or 9.05(3) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (Rules). The application is opposed by the respondents. At a hearing on 16 June 2023, I received affidavit evidence in support of and in opposition to the interlocutory application and I received submissions from Mr J Maclaurin SC and Mr R Broomhall, counsel for Dr Cooper and from Ms L Alick, solicitor and who holds the position of Executive Counsel in the Nine Group of companies.

7 For the following reasons I have decided to allow Dr Cooper’s application.

The discretions in issue

8 Rule 8.21(1) of the Rules confers discretionary power to grant leave to an applicant to amend an originating application “for any reason” including:

(g) to add or substitute a new claim for relief, or a new foundation in law for a claim for relief, that arises:

(i) out of the same facts or substantially the same facts as those already pleaded to support an existing claim for relief by the applicant; or

(ii) in whole or in part, out of facts or matters that have occurred or arisen since the start of the proceeding.

9 The rule in Weldon v Neale (1887) 19 QBD 394 which generally precluded amendments to a pleading to introduce a statute-barred cause of action is no longer applicable to a proceeding in this Court: s 59(2B) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act), save for amendments that engage r 8.21(1)(g)(ii) “after the time within which any statute that limits the time within which a proceeding may be started has expired”: r 8.21(3). A pleading may be amended once without leave before the close of pleadings and thereafter upon an application for leave: rr 16.51 and 16.53 of the Rules. Curiously, Dr Cooper confines his amendment application to r 8.21 of the Rules but no submission was put on behalf of the respondents that the application ought to be dismissed on that technical basis.

10 Dr Cooper also relies on r 9.05 of the Rules which confers power to order that a person be joined as a party to a proceeding if, inter alia, the person “ought to have been joined as a party to the proceeding”. This rule is directly relevant to the application to join The Age Company.

The grounds of opposition

11 On multiple grounds the respondents oppose the relief sought by Dr Cooper. From the submissions of Ms Alick the matters relied on are:

(1) No concerns notice was given for the online articles which is a fatal error in that s 12B of the Defamation Act sets as a mandatory pre-requisite to the commencement of a proceeding that an applicant must give a concerns notice in relation to each and every publication relied upon;

(2) The addition of a new claim in relation to the print article, for which a concerns notice was given, is statute barred and does not arise out of the same facts or substantially the same facts as those already pleaded within the meaning of r 8.21(1)(g) of the Rules;

(3) The Age Company should not be added as a party because the online publication asserted against it is not maintainable as no concerns notice was given about the claim and the claim is statute-barred. A further reason is that no satisfactory explanation has been given by Dr Cooper as to why The Age Company was not named as the publishing respondent from the outset; and

(4) It is not open to Dr Cooper to amend his proceeding in a way that relies on imputations that were not set out in his concerns notice.

12 In addition a miscellany of somewhat technical objections are relied upon relating to the purported naming of two corporations as the first respondent, that the particulars of identification are insufficient and no particulars of downloading of the online articles are pleaded. Overall a submission is put that I should not only dismiss the interlocutory application, but also the entirety of the proceedings pursuant to s 37P of the FCA Act or if not, that I should dispense with the necessity for the filing of a strikeout application and should determine the proceeding as if the respondents’ submissions constitute an application for summary judgment pursuant to s 31A of the FCA Act.

13 One answer that Dr Cooper raised in oral submissions is that if the statutory scheme operates such that any failure by him to give a concerns notice is fatal to his reliance on any publication not referred to in it, then the concerns notice provisions are not picked up by s 79 of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). Reliance is placed on part of the reasoning of O’Callaghan J in Selkirk v Hocking [2023] FCA 432. I granted leave to the respondents to provide a supplementary written submission in response to this new contention, which they did and thereafter Dr Cooper’s lawyers abandoned the point.

14 In due course it will be convenient to address the objections in that order. Before doing so, however, I turn to the statutory provisions. I observe that each party was content to proceed on the basis that the Defamation Act is the relevant statute and that there is no material variation between its provisions and those of, relevantly for jurisdictional purposes, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory.

15 Each statutory provision referenced in these reasons is, unless otherwise indicated, to the Defamation Act and each rule reference is to the Rules.

Statutory provisions

16 Lord Sumption JSC remarked in Lachaux v Independent Print Media Ltd [2020] AC 612 at [1] that coherence of the tort of defamation “has not been improved by attempts at statutory reform”. The provisions of the Defamation Act in issue upon this application are not straightforward and free of difficulty in meaning. Justice Rares made a similar point, describing the uniform provisions as “legislative morass”, in Barilaro v Shanks-Markovina (No 3) [2021] FCA 1100 at [12]. I commence with the statement of statutory objects at s 3 which includes:

(c) to provide effective and fair remedies for persons whose reputations are harmed by the publication of defamatory matter; and

(d) to promote speedy and non-litigious methods of resolving disputes about the publication of defamatory matter.

17 By s 6 the common law of defamation applies except to the extent that the Defamation Act provides otherwise, whether expressly or by necessary implication. As is well understood, three elements are necessary to make out the tort: publication, identification of the plaintiff and defamatory meaning. The distinction between libel and slander is abolished and the publication of defamatory matter of any kind is actionable without proof of special damage: s 7. Section 8 provides for a single cause of action for multiple defamatory imputations in the same matter. By s 10A it is a necessary element of a cause of action for defamation that the publication complained of has caused or is likely to cause serious harm to the reputation of the complainant.

18 Part 3 is concerned with the resolution of civil disputes without litigation. Section 12 provides:

Application of Division

(1) This Division applies if a person (the “publisher”) publishes matter (the “matter in question”) that is, or may be, defamatory of another person (the “aggrieved person”).

(2) The provisions of this Division may be used instead of the provisions of any rules of court or any other law in relation to payment into court or offers of compromise.

(3) Nothing in this Division prevents a publisher or aggrieved person from making or accepting a settlement offer in relation to the publication of the matter in question otherwise than in accordance with the provisions of this Division.

19 What is meant by “matter” is inclusively defined at s 4:

matter includes –

(a) an article, report, advertisement or other thing communicated by means of a newspaper, magazine or other periodical; and

(b) a program, report, advertisement or other thing communicated by means of television, radio, the internet or any other form of electronic communication; and

(c) a letter, note or other writing; and

(d) a picture, gesture or oral utterance; and

(e) any other thing by means of which something may be communicated to a person;

20 It will be necessary to return to this provision in some detail as a primary argument of the respondents is that this application provision applies to each separate publication of defamatory matter with the consequence that a concerns notice must separately identify each publication.

21 What is meant by, and the requirements for, a concerns notice is dealt with at s 12A:

Concerns notices

(1) For the purposes of this Act, a notice is a concerns notice if –

(a) the notice –

(i) is in writing; and

(ii) specifies the location where the matter in question can be accessed (for example, a webpage address); and

(iii) informs the publisher of the defamatory imputations that the aggrieved person considers are or may be carried about the aggrieved person by the matter in question (the imputations of concern); and

(iv) informs the publisher of the harm that the aggrieved person considers to be serious harm to the person’s reputation caused, or likely to be caused, by the publication of the matter in question; and

(v) for an aggrieved person that is an excluded corporation – also informs the publisher of the financial loss that the corporation considers to be serious financial loss caused, or likely to be caused, by the publication of the matter in question; and

(b) a copy of the matter in question is, if practicable, provided to the publisher together with the notice.

(2) For the avoidance of doubt, a document that is required to be filed or lodged to commence defamation proceedings cannot be used as a concerns notice.

(3) If a concerns notice fails to particularise adequately any of the information required by subsection (1)(a)(ii), (iii), (iv) or (v), the publisher may give the aggrieved person a written notice (a further particulars notice) requesting that the aggrieved person provide reasonable further particulars as specified in the further particulars notice about the information concerned.

(4) An aggrieved person to whom a further particulars notice is given must provide the reasonable further particulars specified in the notice within 14 days (or any further period agreed by the publisher and aggrieved person) after being given the notice.

(5) An aggrieved person who fails to provide the reasonable further particulars specified in a further particulars notice within the applicable period is taken not to have given the publisher a concerns notice under this section.

22 Section 12B erects a prohibition upon the commencement of proceedings:

Defamation proceedings cannot be commenced without concerns notice

(1) An aggrieved person cannot commence defamation proceedings unless –

(a) the person has given the proposed defendant a concerns notice in respect of the matter concerned; and

(b) the imputations to be relied on by the person in the proposed proceedings were particularised in the concerns notice; and

(c) the applicable period for an offer to make amends has elapsed.

(2) Subsection (1)(b) does not prevent reliance on –

(a) some, but not all, of the imputations particularised in a concerns notice; or

(b) imputations that are substantially the same as those particularised in a concerns notice.

(3) The court may grant leave for proceedings to be commenced despite non-compliance with subsection (1)(c) , but only if the proposed plaintiff satisfies the court that –

(a) the commencement of proceedings after the end of the applicable period for an offer to make amends contravenes the limitation law; or

(b) it is just and reasonable to grant leave.

(4) The commencement of proceedings contravenes the limitation law for the purposes of subsection (3)(a) if the proceedings could not be commenced after the end of the applicable period for an offer to make amends because the court will have ceased to have power to extend the limitation period.

(5) In this section –

limitation law, in relation to proceedings, means the provisions of Tasmanian law that apply in respect of the limitation periods in relation to the proceedings.

23 The balance of the provisions in Part 3 are concerned with the making of an offer to make amends by a publisher (s 13), the time period within which such an offer must be made (s 14), the content of an offer (s 15), withdrawal of an offer before acceptance (s 16), the effect of acceptance of an offer, or the failure to do so, (ss 17 and 18), and the general inadmissibility of any statement or admission made in connection with the making or acceptance of an offer to make amends (s 19).

24 A proceeding for defamation is subject to a one year limitation period by s 20A:

Proceedings generally to be commenced within one year

(1) Notwithstanding anything contained in any other Act, an action on a cause of action for defamation is not maintainable if brought after the end of a limitation period of one year running from the date of the publication of the matter complained of.

(2) The limitation period referred to in subsection (1) is taken to have been extended as provided by subsection (3) if a concerns notice is given to the proposed defendant on a day (the notice day) within the period of 56 days before the limitation period expires.

(3) The limitation period referred to in subsection (1) is extended for an additional period of 56 days, minus any days remaining after the notice day until the limitation period was to expire under subsection (1) .

(4) In this section –

date of the publication, in relation to the publication of a matter in electronic form, means the day on which the matter was first uploaded for access or sent electronically to a recipient.

25 There is provision for an extension of time, for a period of up to 3 years from the date of publication, if a plaintiff satisfies the court “that it is just and reasonable to allow an action to proceed”: s 20AC. Section 20AB enacts a single publication rule for publications to the public, although as I explain it is important to understand that its operation is confined to the limitation period:

Single publication rule

(1) This section applies if –

(a) a person (the first publisher) publishes matter to the public that is alleged to be defamatory (the first publication); and

(b) the first publisher, or an associate of the first publisher, subsequently publishes (whether or not to the public) matter that is substantially the same.

(2) Any cause of action for defamation against the first publisher, or an associate of the first publisher, in respect of the subsequent publication is to be treated as having accrued on the date of the first publication for the purposes of determining when –

(a) the limitation period applicable under section 20A begins; or

(b) the extended limitation period referred to in section 20AC(2) begins.

(3) Subsection (2) does not apply in relation to the subsequent publication if the manner of that publication is materially different from the manner of the first publication.

(4) In determining whether the manner of a subsequent publication is materially different from the manner of the first publication, the considerations to which the court may have regard include (but are not limited to) –

(a) the level of prominence that a matter is given; and

(b) the extent of the subsequent publication.

(5) For the avoidance of doubt, this section does not limit the power of a court under section 20AC to extend the limitation period applicable under section 20A .

(6) In this section –

associate of a first publisher means –

(a) an employee of the publisher; or

(b) a person publishing matter as a contractor of the publisher; or

(c) an associated entity (within the meaning of section 50AAA of the Corporations Act 2001 of the Commonwealth) of the publisher (or an employee or contractor of the associated entity);

date of the first publication, in relation to the publication of matter in electronic form, means the day on which the matter was first uploaded for access or sent electronically to a recipient;

public includes a section of the public.

26 This provision is to be read with s 20AD which is concerned with the date of publication of a matter in electronic form for limitation purposes:

Effect of limitation law concerning electronic publications on other laws

(1) This section applies in respect of any requirement under section 20A or 20AB for the date of the publication of a matter in electronic form to be determined by reference to the day on which the matter was first uploaded for access or sent electronically to a recipient.

(2) A requirement to which this section applies is relevant only for the purpose of determining when a limitation period begins and for no other purpose.

(3) Without limiting subsection (2) , a requirement to which this section applies is not relevant for –

(a) establishing whether there is a cause of action for defamation; or

(b) subject to section 20BA , the choice of law to be applied for cause of action for defamation.

27 I turn next to the respondents’ arguments in opposition to the relief sought in the interlocutory application.

The concerns notice point

28 The respondents’ first argument is that the meaning of s 12B(1)(a) is clear. A concerns notice is a statutory prerequisite to the commencement of a proceeding in defamation for each and every publication that is relied upon. In this case the concerns notice only referenced the print article which is not relied on as a publication in the originating application or statement of claim. Accordingly, Dr Cooper breached the statutory prohibition when he commenced the proceeding in reliance upon the online publication of the defamatory matter.

29 It is not in dispute that the article complained of was first published on the website of The Age newspaper on 17 February 2022 and was later published in the print edition on 18 February 2022. Although there was earlier correspondence between Dr Cooper and the Editor of The Age, the document that is accepted by the respondents as amounting to a concerns notice is a letter from the solicitor of Dr Cooper, Mr Peter Kimpton, addressed to the Editor of The Age newspaper dated 23 December 2022. It was not said on behalf of Dr Cooper that any of the preceding correspondence takes the matter any further. Omitting formal parts, the letter reads (without correcting for spelling or grammar):

…I refer to the defamatory article on page thee of your newspaper 17th February 2022 titled ‘AFL pair used doctor in no jab bid’. The article was written by Jake Niall and Peter Ryan. I have cc'd the journalists who will be included in the action.

The article made false allegations, was misleading and imputes to the reader that my client was complicit in helping high profile AFL footballers avoid being vaccinated and in doing so imputed that he had contravened medical directives, committed misconduct as a medical practitioner and practiced outside medical convention.

As a direct result of the publication, the peak medical regulator namely the Australian Practitioners Regulatory Authority (AHPRA) at its own behest, initiated a thorough investigation into my client’s practice. Based solely on the defamatory article my client was put through an extremely rigorous and enormously distressing investigation. To address the issues raised by AHPRA and the time frame required by the regulatory body my client had no choice but to suspend the majority of his consultations with patients during that process.

My client was at a real risk of being disbarred from practice. Despite my client being found not to be guilty of misconduct by AHPRA. The damage to my client’s reputation has been irreparable and he has suffered damage as a result.

His referrals as a specialist GP by both medical and legal practitioners for his specialist advice and patient consultancy dropped drastically as a direct result of the publication and the subsequent AHPRA investigation.

The AHPRA complaint and its contents on its own is direct evidence of the imputations the article has made against my client's reputation.

Despite the pleas and letters from my client you did not publish a detraction nor apologise to my client. My client has suffered considerable damage as a result and the evidence is clear that his practice has suffered a downturn of at least 40% and still dropping, directly attributable to the date of the defamatory publication.

As a result of your failure to address this issue appropriately, we are instructed to commence defamation proceedings in the Federal Court of Australia.

Counsel is currently settling documents to commence litigation. We will provide a copy of the settled draft as soon as practicable.

To avoid costs escalating and the potential for my client to seek indemnity for costs, my client invites an amicable resolution of this matter outside of court and invites your involvement to negotiate a suitable settlement to compensate my client for the damage caused.

Counsel is currently in the process of assessing my client's expected quantum of damages. We expect that an assessment of quantum will exceed $3 million in reputational damage alone. Readership for The Age is 5.321 million, which on its own will form part of assessing quantum separately from reputational damage. Further, there is the issue of follow-on effect of publications by others in either print and digital and their subsequent circulation.

We will continue to monitor media reporting and the flow on effect of the article with other publishers concerning of our client, if there is any further defamatory publications, we would add such to our client's claim and reassess our client's quantum accordingly.

30 In support of their construction of the legislative scheme, reliance is placed on the second reading speech of the Defamation Amendment Bill 2021 (Tas) given in the House of Assembly of the Tasmanian Parliament by the Attorney-General, Ms Archer on 2 September 2021 where in part she said:

The Bill also proposes to modify pre-litigation processes to encourage early resolution of defamation disputes. The Bill will make it mandatory for an aggrieved person to issue a written concerns notice, with adequate particulars of the complaint, to the publisher before commencing defamation proceedings. The enhanced concerns notice process provided for by these new sections will encourage the aggrieved person to turn their mind to the serious harm threshold at the time of preparing the concerns notice, and will also provide the publisher with sufficient information on which to make a reasonable offer of amends.

The “offer to make amends” procedure will be refined. The bill modifies the timing and content of offers to make amends, including that the offer must be made as soon as reasonably practicable after receipt of the concerns notice and that the offer must remain open for at least 28 days from the date it is made. These reforms will help and encourage parties to resolve disputes without resorting to litigation, easing the burden on courts and reducing the cost and time taken for individuals to resolve defamation disputes.

31 I was not referred to any relevant authority in support of the respondents’ construction of ss 12, 12A or 12B. In the course of oral argument I mentioned to counsel to Teh v Woodworth [2022] NSWDC 411 (Teh), Gibson DCJ; Hoser v Herald and Weekly Times Pty Ltd [2022] VCC 2213 (Hoser), Judge Clayton and Newman v Whittington [2022] NSWSC 1725 (Newman), Rothman J as cases in which assistance may be found. Other than by reference to generalities, I did not receive detailed submissions from either counsel by reference to these cases.

32 I reject the construction submission of the respondents. The starting point is that at common law each publication of defamatory matter gives rise to a separate cause of action: Duke of Brunswick v Harmer (1849) 14 QB 185; Dow Jones & Company Inc v Gutnick (2002) 210 CLR 575; [2002] HCA 56 (Dow Jones) at [27], (Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow and Hayne JJ). At one point in her oral submissions, Ms Alick said that the effect of s 20AB of the Act is to abolish the multiple publication rule. That is not so. The provision is concerned with the problem of multiple publication of the same, or substantially the same, matter in which case any cause of action for defamation is taken to accrue on the date of first publication for the purposes of calculating the limitation period under s 20A or its extension under s 20AC(2). Where the publication complained of is in electronic form, the date of first publication is the date on which the matter was first uploaded for access or sent electronically to a recipient: s 20AB(6).

33 The focus of application of the concerns notice provisions is upon the publication of matter, which either is or may be defamatory of another person: s 12(1). A matter is only defamatory where it does or may damage reputation: Dow Jones at [25]; Radio 2UE Sydney Pty Ltd v Chesterton (2009) 238 CLR 460; [2009] HCA 16 (Radio 2UE) at [1], French CJ, Gummow, Kiefel and Bell JJ. Compensation is awarded for injury to reputation caused by the publication of defamatory matter. The centrality of injury to reputation was emphasised by the plurality in Radio 2UE at [2]-[4]:

Spencer Bower recognised the breadth of the term “reputation” as it applies to natural persons and gave as its meaning:

“[T]he esteem in which he is held, or the goodwill entertained towards him, or the confidence reposed in him by other persons, whether in respect of his personal character, his private or domestic life, his public, social, professional, or business qualifications, qualities, competence, dealings, conduct, or status, or his financial credit ...”.

A person’s reputation may therefore be said to be injured when the esteem in which that person is held by the community is diminished in some respect.

Lord Atkin proposed such a general test in Sim v Stretch, namely that statements might be defamatory if “the words tend to lower the plaintiff in the estimation of right-thinking members of society generally”. An earlier test asked whether the words were likely to injure the reputation of a plaintiff by exposing him (or her) to hatred, contempt or ridicule but it had come to be considered as too narrow. It was also accepted, as something of an exception to the requirement that there be damage to a plaintiff’s reputation, that matter might be defamatory if it caused a plaintiff to be shunned or avoided, which is to say excluded from society.

(Footnotes omitted.)

34 On its face s 12(1) draws no distinction between multiple publication of the same or substantially the same matter where each separate publication is treated differently for the purposes of injury to reputation in a concerns notice. Rather, it is concerned with the publication of an identified matter that conveys a meaning defamatory of the aggrieved person. Although the “sting”, being the injury to the reputation of the aggrieved person, is not the cause of action it is an essential component of it and the provision is drafted to operate at a preliminary stage where the purpose is to encourage early resolution of complaints about injury to reputation without resort to litigation. In my view it is contrary to this purpose to draw rigid distinctions that turn on how many causes of action exist and which must be identified in a concerns notice.

35 The content of a concerns notice is spelled out at s 12A. There are formal requirements, such that the notice must be in writing and must address the content requirements of subparagraphs (1)(a)(i)-(v). However, these subparagraphs do not set forth inflexible prescriptive criteria. The requirement to specify the location where the matter in question can be accessed, is plainly able to be addressed by referring for example to a particular edition of a newspaper published by the person to whom the notice is addressed or, in the case of a webpage, by stating its address. In this case: www.theage.com.au.

36 The requirement to inform the publisher “of the defamatory imputations that the aggrieved person considers are or may be carried about the aggrieved person by the matter in question” is concerned with the defamatory stings and not with multiple causes of action which the aggrieved person may have based on separate publication of material complained about. Similarly, the requirement to inform the “publisher of the harm that the aggrieved person considers to be serious harm to the person’s reputation caused, or likely to be caused, by the publication of the matter in question” is concerned with the harm to the reputation of the individual which at the preliminary stage must be the matter of concern to the individual and which may be satisfactorily resolved by the making and acceptance of an offer to make amends.

37 Supporting contextual meaning is found when one turns to the prohibition at s 12B. The bar operates on the commencement of defamation proceedings and not the content of the proceeding, which as is well-understood is likely to evolve over time through amendment and further particularisation. The respondents’ submission, if correct, confines the aggrieved person to the specific known publications identified in a concerns notice where others, perhaps unknown to the complainant, will likely be within the peculiar knowledge of the publisher; more so in the case of large media corporations. The submission harkens back to the forms of action at common law where an accidental slip and irrevocable choice in the method of procedure was usually fatal to success: see generally, Maitland FW, The Forms of Action at Common Law (1910) at 298-299.

38 Further, s 12B(1)(a) speaks to giving a concerns notice “in respect of the matter concerned”. These are wide words which generally only require a connexion or association between the notice and the matter: Fitness First Australia Pty Ltd v Fenshaw Pty Ltd (2017) 341 ALR 607; [2016] NSWCA 207 at [39]-[41], Leeming JA. Here the “matter concerned” in my view must be understood as a reference to the “matter in question” at ss 12(1) and 12A(1)(a)(ii), (iii), (iv) and (v) which is the publication that the aggrieved person is aware of and which carries the sting that is complained about. In the case of multiple publication of the same or substantially the same defamatory matter the connexion that s 12B(1)(a) requires is in my view satisfied where the aggrieved person in a concerns notice identifies a publication, or some of many, and which the person contends is or may be defamatory. Having satisfied that requirement, a proceeding subsequently commenced is in respect of the matter so identified because of the factual connexion between the publication and the sting complained of. The statutory bar operates at the level of commencement of a proceeding, not with multiple causes of action that may be asserted and which rely on multiple publication of the same or substantially the same material which is claimed to be injurious to the plaintiff’s reputation.

39 My views are consistent with part of the analysis of Rothman J in Newman. His Honour was concerned with a pleading dispute in a defamation claim in which the plaintiff sought leave to amend her statement of claim. Various objections were pressed by the defendant, including that two matters sought to be included by amendment (11 and 12) were not the subject of a concerns notice with the consequence that s 12B of the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) precluded a grant of leave to amend. The New South Wales provision is in identical terms to the Tasmanian provision. Matters 11 and 12 were published after the plaintiff commenced her proceeding. In granting leave to amend to include the additional publications (which raised the same imputations as the publications referenced in the concerns notice), his Honour noted the purpose of the provisions together with the serious harm element: “was to ensure that proceedings commenced for defamation related to reputational damage that caused serious harm and, to the extent possible, to bring forward and to encourage the early resolution and settlement of the issues between the parties” at [27] and continued at [28]-[31]:

The prohibition in s 12B of the Defamation Act is to the commencement of proceedings. Prior to the promulgation of s 64(2) of the Civil Procedure Act 2005 (NSW) and its predecessors, there was a common law prohibition on amending pleadings to include a cause of action that arose after the commencement of the proceedings. That common law prohibition no longer operates.

As a consequence, even though the date of the commencement of proceedings for the purposes of limitation is on the date on which the amendment is filed, the proceedings are the same and the proceedings had already commenced prior to the publication of matters 11 and 12. On its face, the prohibition in s 12B of the Defamation Act does not apply to the amendment to the cause of action to raise matters 11 and 12.

As a matter of discretion, where additional matters are raised, the Court may, in defamation proceedings, refuse to allow the amendment unless a concerns notice has been served. However, in the present proceedings, the imputations said to arise from matters 11 and 12 are the same imputations — or so similar as not to be distinguishable — as the imputations raised in relation to the matters previously published and in respect of which a concerns notice has been already served. The effect of the foregoing circumstance is that the purpose of the legislature has been achieved by the initial service of the concerns notice and the identification of that which is said to be the serious harm caused by the alleged defamation.

In those circumstances, the prohibition in s 12B of the Defamation Act does not apply, and there is no discretionary reason why the Court should, because of the failure to serve a further concerns notice, not permit an amendment.

40 Although I am not concerned in this proceeding with an amendment that seeks to put in issue publications made after its commencement, that difference is of no importance. In each case the amendments relate to separate publications for which there is no concerns notice. As his Honour’s reasons demonstrate an application to amend a pleading to include additional publications of the same or substantially the same defamatory matter engages the discretion to grant leave to amend an existing proceeding. It is not the commencement of a proceeding without first giving a concerns notice. The prohibition at s 12B does not therefore apply though it is relevant to the exercise of the discretion.

41 A contrary view was reached by Gibson DCJ in Teh, where the plaintiff’s defamation claim was struck out for various reasons, including in relation to the publication of matter on 16 June 2022 because of non-compliance with the concerns notice procedure. A concerns notice was given to the publisher on 19 June 2022 in relation to publications made on 27 August 2019 and 20 February 2020. Her Honour reasoned at [21]-[26], first to the effect that a concerns notice is a mandatory requirement, second that s 12B(1) requires a notice “for the specific publication sued on” and third that a proceeding commenced in spite of it is “invalidate[d]”.

42 With respect to her Honour, classification of the concerns notice procedure as mandatory does not address the issue of why it is not open to a plaintiff who, having given a concerns notice that identifies at least one publication and the defamatory imputations to be relied on in a proposed proceeding, later discovers that there were other publications with the same or substantially the same imputations, cannot plead each publication in a proceeding when commenced or subsequently amended.

43 As I have sought to explain, the legislative scheme does not operate to rigidly confine a plaintiff to the publications that were known when the notice was given, provided that other publications were the same or substantially the same. That outcome is in my view consistent with the statutory object at s 3(d), the extract from the Second Reading Speech of the Attorney-General and s 8A of the Acts Interpretation Act 1931 (Tas) which requires as the preferred interpretation one that promotes that object, rather than one that does not. It is neither effective nor fair to strictly confine aggrieved persons to a remedy for publications that are specified in a concerns notice if there were other publications to the same or substantially the same effect, more so where the extent of publication is a matter within the knowledge of the publisher. Similarly disputation once a proceeding is commenced about the inability of an aggrieved person to seek redress for each publication is hardly conducive to the provision of efficient and fair redress for injury to reputation.

The limitation points

44 The second and fourth objections overlap and may be dealt with together. Dr Cooper did not name The Age Company as a respondent when he commenced the proceeding by lodgement for filing on 15 February 2023, that being generally accepted as the relevant date for limitation purposes: see McGee A, Limitation Periods (Sweet and Maxwell 7th ed 2014) at 2.009. No submission to the contrary was made to me. He now contends (and there is no dispute) that it is the publisher (or at least one of) of The Age newspaper and the associated website. The first publication occurred on the website on 17 February 2022, and the print edition issued the next day.

45 The limitation period is one year from the date of first publication: ss 20A(1), 20AB and 20AD. Dr Cooper has not made an application to extend time as provided for at s 20AC. On his submission an extension application is not necessary because this Court may join a party under r 9.05 and permit amendments to be made under r 8.21 even where a limitation period for the commencement of a proceeding has expired.

46 The respondents submit that leave to join and to amend should properly be refused for several reasons: the claims are out of time, the new claims for relief do not arise out of the same facts within the meaning of r 8.21(g), there is no existing claim for relief which may be joined, delay in making the application is unexplained and the proposed pleading is either embarrassing, confusing or is otherwise liable to be struck out pursuant to r 16.21.

47 A party may be joined pursuant to r 9.05 if, inter alia, the party ought to have been joined in the first place. An applicant may apply for leave to amend an originating application pursuant to r 8.21(g), which I have set out earlier. Sub-rules (2) and (3) provide:

(2) An applicant may apply to the Court for leave to amend an originating application in accordance with paragraph (1)(c), (d), (e) or subparagraph (g)(i) even if the application is made after the end of any relevant period of limitation applying at the date the proceeding was started.

(3) However, an applicant must not apply to amend an originating application in accordance with subparagraph (1)(g)(ii) after the time within which any statute that limits the time within which a proceeding may be started has expired.

48 Rule 9.05 is silent about whether a respondent may be added where it is claimed that the applicant is out of time. When a proceeding is amended to add a party the amendment operates prospectively: r 9.05(3). Futility is a reason to refuse amendment applications: Allstate Life Insurance Company v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd (1995) 58 FCR 26 at 36, Lindgren J. It is likely futile to permit an amendment which will obviously be defeated by a limitation defence, which explains the general rule of practice that a defendant will not be added where the cause of action is statute-barred: Bridge Shipping Pty Ltd v Grand Shipping SA (1991) 173 CLR 231 at 236, Dawson J. When a statement of claim is amended the relation back rule applies, unless it is otherwise ordered: Air Link Pty Ltd v Paterson (No 2) (2003) 58 NSWLR 388; [2003] NSWCA 251 (Airlink) at [47], Mason P. Rule 16.54 displaces the relation back rule but is limited in application to amendments made without leave under r 16.51. Similarly an amendment to an originating application made under r 8.21 relates back, save in the case of substitution of a party where r 8.22 applies and the proceeding is taken to have commenced for that party on the date of amendment: Environinvest Ltd (in liq) v Former Partnership of Webster, White, Gridley, Nairn, Newman, Peters and Miller (2012) 208 FCR 376; [2012] FCA 1307 at [29], Gordon J.

49 It should not be overlooked that Lord Esher MR in Weldon v Neal at 395 did not state a mandatory principle: Airlink at [56], Mason P. Rather his Lordship expressed in a summary way “the settled rule of practice” that amendments will not be allowed “when they prejudice the rights of the opposite party as existing at the date of such amendments.” The focus of the inquiry is whether it would be unjust to allow an amendment by introducing “a new matter of controversy at a time when it is already barred by statute”: Horton v Jones (No 2) (1939) 39 SR (NSW) 305 at 315, Jordan CJ; Airlink at [57]-[59], Mason P.

50 A curious aspect of the drafting of the Rules is that although Division 9.1 is concerned with multiple causes of action and the joinder of parties, an originating application may be amended under Division 8.3 for amendment generally “including” the matters enumerated at r 8.1(a)-(g) and r 8.22 expressly provides that where an originating application is amended to substitute a party, then the proceeding is taken to have started for that person on the day of the amendment unless otherwise ordered. Thus Division 9.1 is not a code for the joinder of parties.

51 In McGrath v HNSW Pty Ltd (2014) 219 FCR 489; [2014] FCA 165 (McGrath), Cowdroy J gave detailed consideration to Weldon v Neal and the evolution of this Court’s rules to ameliorate its consequences. Although his Honour’s reasons focus on the power to permit an amendment to introduce a new cause of action, where r 16.53 (like r 9.05) is silent on the point, his Honour concluded that it was open to do so and followed the reasoning of Murphy J in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Australian Property Custodian Holdings Ltd (No2) (2013) 213 FCR 289; [2013] FCA 409 (Custodian Holdings). In part, Cowdroy J reasoned at [50]-[51]:

I agree that r 16.53 of the Rules should not be understood to prevent amendments to statements of claim that would have the effect of adding a new cause of action that would otherwise be time barred. To suggest otherwise overlooks not only the changing philosophy and approach of the Court and of the legislature to ensuring that justice is done between the parties on all disputed issues, but also the structure and approach of the current Rules. That approach is to ensure flexibility. Rule 16.53, together with the power provided by s 59(2B) of the Federal Court Act, ensures that the Court will be able to do justice between the parties where amendment to pleadings is sought irrespective of the nature of the amendment or the circumstances in which it has arisen. The only limitation is the discretion of the Court to grant leave. Further, it would be a most unusual result if leave could be granted to amend an originating application to include an otherwise time barred claim, as is contained in r 8 of the Rules, if there were no power to allow consequential amendments to be made to the pleadings. An amendment to the originating application in those circumstances would be a futility.

It is not strictly necessary to revert to the broad discretionary powers contained in the Rules given my finding that r 16.53 is sufficient to grant the type of relief sought. If the interpretation of r 16.53 that I have adopted is incorrect though, rr 1.32, 1.33 and 1.35 may plainly be relied upon to produce the same result. Rule 1.32 permits the Court to ‘make any order that the Court considers appropriate in the interests of justice’. Rule 1.33 permits the Court to ‘make an order subject to any conditions the Court considers appropriate’. Rule 1.35 permits the Court to ‘make an order that is inconsistent with these Rules and in that event the order will prevail’. The breadth of such provisions allows the Court to exercise the power explicitly afforded to it following the decision of Wardley in 1994.

52 The Full Court in McGraw-Hill Financial, Inc v Clurname Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 211 (McGraw-Hill), Allsop CJ, Jagot and Yates JJ, dismissed an application for leave to appeal from the decision of a primary judge to grant leave to amend a statement of claim to include a claim for deceit and who further ordered that the amendments be taken to have effect from the date of commencement of the proceedings. The respondent conceded, and the Full Court accepted, that the primary judge erred in ordering that the amendment be back dated and substituted for it an order that the date of effect of the amendments to the originating application and statement of claim be determined at the trial. Otherwise, the application for leave to appeal was dismissed.

53 Relevantly for present purposes, the Full Court held that the Rules did not constrain the power of the Court to grant leave to amend an originating process and a statement of claim so as to add a statute-barred cause of action limited to the circumstances set out at r 8.21(2). Why was explained at [23]-[26]:

The primary judge also expressed doubt about the correctness of Voxson Pty Ltd v Telstra Corporation Ltd (No 7) [2017] FCA 267; 343 ALR 681 at 686 [21] in which it was said that “the Court has the power to grant leave to amend both an originating process and a pleading to add a statute-barred cause of action but only in the circumstances referred to in r 8.21(2) of the FCR”. The primary judge noted that Clurname had not submitted that Voxson was wrong to this extent, let alone plainly wrong, and thus proceeded assuming it to be correct, as he was required to do. We are not subject to the same constraints as the primary judge. We do not consider that Voxson is correct in this respect. The language of r 8.21(1) is clear: an applicant may apply to the Court for leave to amend an originating application for any reason “including” any of the reasons in r 8.21(1)(a)-(g). Subrules (a) to (g) are examples of amendments that may be the subject of application. They are not a code. Thus, the interaction of r 8.21(1)(g) and (2) does not mean that the Court’s power to permit an amendment asserted to involve a statute-barred claim is confined to the circumstances in r 8.21(1)(g)(i). We leave to one side for further argument the proper approach to an amendment introducing an unarguably statute-barred claim. Nevertheless, the following considerations undermine any rigid or bright-line approach exclusively based on r 8.21(1)(g) and r 8.21(2).

The Federal Court Rules must also be construed as a whole. Apart from the fact that the power to apply to amend is expressed inclusively in the opening words of r 8.21(1), other rules disclose the true position. Thus, the rules include

R 1.32

The Court may make any order that the Court considers appropriate in the interests of justice.

R 1.33

The Court may make an order subject to any conditions the Court considers appropriate.

R 1.34

The Court may dispense with compliance with any of these Rules, either before or after the occasion for compliance arises.

R 1.35

The Court may make an order that is inconsistent with these Rules and in that event the order will prevail.

R 16.51

(1) A party may amend a pleading once, at any time before the pleadings close, without the leave of the Court.

(2) However, a party may not amend a pleading if the pleading has previously been amended in accordance with the leave of the Court.

(3) A party may further amend a pleading at any time before the pleadings close if each other party consents to the amendment.

(4) An amendment may be made to plead a fact or matter that has occurred or arisen since the proceeding started.

Rules 1.32 to 1.35 are important weapons in the Court’s armoury to enable the overarching purpose of the “civil practice and procedure provisions” (defined in s 37M(4) of the Court Act to comprise the Rules and “any other provision made by or under this Act or any other Act with respect to the practice and procedure of the Court”) to be achieved as identified in s 37M(1) of the Court Act. The overarching purpose is to facilitate the just resolution of disputes according to law, as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible. Faced with these provisions to construe r 8.21(1)(g) as an exclusive power to permit a statute-barred amendment let alone a merely arguably statute-barred amendment (as in the present case) only in the circumstances permitted by r 8.21(2), is inconsistent with the language of the Rules and inimical to the overarching purpose in s 37M of the Court Act. As the present case demonstrates, given the competing arguments about when the cause of action first accrued and the potential operation of s 55(1) of the Limitation Act, if there is a reasonable argument the claim is not statute-barred, there is no reason in principle that an amendment should not be permitted, particularly if all rights are preserved by the date on which the amendment takes effect being determined as part of the final judgment rather than on an interlocutory basis.

To the extent it has any remaining operation in this Court, the rule in Weldon v Neal (1887) 19 QBD 394 at 395 to the effect that a party is not permitted to amend a pleading to add a cause of action which is statute-barred, depends on the new claim being statute-barred. As Wardley at 533-534 makes plain, that matter should not ordinarily be determined at an interlocutory stage.

54 Justice Jackson in Revill v John Holland Group Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1633 (Revill) refused an application for leave to join respondents under r 9.05 and to plead a statutory claim that was prima facie time-barred. The proceeding involved a claim by a former employee who contended that his terms of employment incorporated an employee financial support plan and a consequential obligation on the part of his employer to effect income protection insurance for his benefit. The employee suffered a non-work related injury in June 2013. His claim was refused, he asserted, in breach of contract. He did not commence a proceeding until August 2019. In defence the respondent denied that it was the employer and then named two employing entities. The employee then made an application to join the named entities as respondents. He did not prepare the form of a draft amended statement of claim. His Honour discerned from the content of the applicant’s written submissions that he intended to rely upon the statutory right of the third-party beneficiary pursuant to s48 of the Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Cth).

55 The respondents submitted the claim under any contract of insurance was time barred pursuant to the six year period at s 13 of the Limitation Act 2005 (WA) and accordingly the joinder application should be refused. His Honour accepted that the applicant had an arguable claim against the respondents as proposed to be joined, but dismissed the application on the basis that the claim did not have reasonable prospects of success because it was time barred. In reasoning in that way, his Honour correctly recognised that the standard of inquiry is whether the claim has “no reasonable prospect of success”: [21]-[22].

56 His Honour refused the joinder application for two reasons. One, the failure to articulate a coherent claim founding a liability in the parties proposed to be joined: [38]. The other that the limitation point was decisive at [37]:

It is true that if JHPL and JHG Mutual were to be joined, they would have the burden of establishing the limitation defence. But that makes little difference in circumstances where there can be no factual controversy about the application of the defence, and Mr Revill has failed to raise any cogent legal argument as to why it does not apply. In my view, the availability of the limitation defence means that Mr Revill’s proposed claim against JHPL or JHG Mutual would not have reasonable prospects of success, so that the court should exercise its discretion against joining those companies to this proceeding.

57 What is apparent from the decision is that counsel failed to draw to the attention of Jackson J the decisions in McGrath, Custodian Holdings and McGraw-Hill. Nor was any argument put to his Honour that a party may be joined and a claim amended in the exercise of this Court’s discretion by reference to any of the principles identified in those cases.

58 Whilst it is clear in this case that Dr Cooper did not commence a proceeding against The Age Company within one year from the date of first publication of the article complained of, he did commence a proceeding against Nine Entertainment as the asserted publisher and Mr Niall and Mr Ryan as the responsible journalists. In seeking to join The Age Company as a respondent and to allege that it is responsible for publication of the online article on 17 February 2022 and the print edition on 18 February 2022, he does not assert a new head of claim or materially different facts and the amendments as proposed plainly arise out of the same facts or substantially the same facts pleaded in relation to the online publication within the meaning of r 8.21(g)(i). I reject the contrary submission of Ms Alick to the effect that publication of the articles on different days and in different formats, each of which gives rise to a separate cause of action, steps this case outside of that rule. The submission is in my view, and with respect, pedantic and artificial. The issue is one of degree, requiring consideration of the extant pleaded facts and the proposed facts, which in this case includes consideration of the extent to which adding a respondent alters, if at all, the basis of the claim: Re Spec FS NSW Pty Ltd (in liq) (2013) 225 FCR 79; [2013] FCA 1027 at [39], Wigney J.

59 The pleading amendments so far as relevant to the limitation point are anodyne in content. Dr Cooper seeks to plead that The Age Company together with Nine Entertainment is part of a media group which owns, is the proprietor of and is the publisher of The Age newspaper and its associated websites. The amendments extend to pleading the fact of publication of the print edition of the newspaper on or about the date of first publication of the article on the website. Extensive deletions are proposed for a number of paragraphs that, on the face of it, have nothing to do with a claim in defamation, such as the plea that negligence is relevant to the plaintiff’s cause of action: Dow Jones at [25]. A more extensive series of amendments are proposed to plead new imputations, which is a matter the subject of separate objection by the respondents and which I address below. Dr Cooper then proposes to plead the serious harm element arising from the imputations contained in each publication of the articles complained of. There is a further proposed plea of republication as the natural and probable consequence of publication of each article in the first place.

60 It should not be overlooked that when Dr Cooper complained about publication of the article, in his email correspondence of 26 July 2022, 31 August 2022, 25 October 2022, 31 October 2022 and 2 November 2022, he addressed his emails to the Editor of The Age newspaper and referenced the print version of the article. The concerns notice was similarly addressed and referenced. Thus, there can be no doubt that The Age Company was on notice for a considerable period in 2022 that Dr Cooper considered that he had been defamed.

61 In oral submissions, I enquired of Ms Alick what prejudice, if any, might be suffered by The Age Company if it were to be joined to the proceeding which included a claim based on the print article. Apart from the obvious submission that a grant of leave would deprive The Age Company of the benefit of the statutory bar, no other prejudice was identified. A submission was however put to the effect that despite it being open to Dr Cooper to apply for an extension of the limitation period pursuant to s 20AC, he has not done so and that I should further find that his delay in providing a concerns notice and in ultimately commencing this proceeding is a reason to refuse the leave application. Dr Cooper did not provide an affidavit which explained his delay. In an affidavit made by his solicitor Mr Kimpton on 19 May 2023, there is some material that explains why Dr Cooper did not proceed sooner related to a notification received by him in April 2022 from the Australian Health Practitioner Regulatory Authority, which took time to deal with. In a further affidavit made on 9 June 2023, Mr Kimpton gives evidence about certain searches that he undertook in order to ascertain the publisher of The Age newspaper on that day. There is no evidence as to what searches, if any, were undertaken prior to the commencement of the proceeding in order to identify the publisher of The Age newspaper.

62 Balanced against these matters, I observe that what is presently sought by Dr Cooper is an amendment to his proceeding that was commenced within time, albeit one presently limited to the online publication. If the Rules of this Court permit the amendments to be made, then there is no reason for Dr Cooper to make a separate application for an extension of time for the commencement of his proceeding. Delay per se, if not satisfactorily explained, may be a reason to refuse the amendments. However, what is clear is that Dr Cooper was not silent throughout 2022 and, in the case of some of his correspondence, it was not responded to by the Editor of The Age newspaper for some months: as an example it took the Editor until 1 September 2022 to respond to the initial email from Dr Cooper of 26 July 2022. What is more significant in my view is that The Age Company as a proposed respondent does not contend that prejudice has been suffered by reason of delay, save for the limitation point.

63 Plainly I have a discretion pursuant to r 8.21(1)(g) to permit amendments to be made to the originating application to add or substitute a new claim for relief or a new foundation in law for a claim for relief that arises out of the same or substantially the same facts as those already pleaded. For the reasons I have given, the amendments to that extent are within this power. And further, I may do so even if the limitation period, in this case in relation to publication of the print article, has expired: r 8.21(2). The question in this case which informs the exercise of that discretion is whether the respondents will suffer prejudice. Apart from being deprived of what is, in my view, quite technical reliance upon the fact that in a defamation proceeding each publication is a separate cause of action, and therefore pleading the print article is out of time, there is simply no merit in the arguments relied upon to oppose the amendments so as to insert a claim based on the print article.

64 The next issue is whether I have a discretion to join The Age Company as a respondent where on the face of it, the proposed claim is out of time both as to the online and print publications. In my view, the correct lens to approach the resolution of that issue begins with acknowledgement that the so-called rule in Weldon v Neal is one of practice and procedure. Although the Full Court in McGraw-Hill left to one side the “proper approach to an amendment introducing an unarguably statute-barred claim” (at [23]), r 8.21 applies to amendments generally to an originating application and is expressly inclusive as to when leave may be granted. If it is open to amend the originating application to include a new claim for relief despite expiry of a relevant period of limitation, it is difficult to understand why the scheme of the Rules does not also permit the joinder of a party so as to make that claim against it pursuant to r 9.05.

65 As further explained by the Full Court in McGraw-Hill, the rules must be construed as a whole with the overall intent of achieving an harmonious operation. I accept as correct the reasoning of Murphy J in Custodian Holdings and of Cowdroy J in McGrath that, despite the absence of any reference to statute-barred claims at r 16.53, leave may be granted to amend a pleading even where the effect of doing so is to deprive a respondent of a limitation defence. That conclusion is consistent with the reasoning of the Full Court in McGraw-Hill, particularly the interaction of rr 1.32, 1.33 and 1.34 in order to achieve the overarching purpose of civil practice and procedure in this Court: ss 37M and 37N of the FCA Act. I do not approach resolution of the joinder and amendment applications in this case in the same way that Jackson J did in Revill. Ultimately decisions on matters of practice and procedure in this Court turn on evaluative assessment of individual facts. It should not be overlooked that the Rules are concerned with the practice and procedure of the court, may be dispensed with pursuant to r 1.34 and ultimately form a component of the tools available to best promote the overarching purpose: s 37M(3) of the FCA Act.

66 In my view the correct question in this case is whether the orders sought by Dr Cooper should be made in the interests of justice, in furtherance of the overarching purpose and in the context of the operation of rr 8.21 and 9.05 to the particular facts. There is no identifiable prejudice that is likely to be suffered by The Age Company beyond an inability to rely on a limitation defence. Prejudice of that type is common to all respondents who have a limitation defence and who unsuccessfully oppose amendment or joinder applications. Dr Cooper commenced a proceeding in time between a related corporate respondent and two journalists. There is no material difference in the online and print articles. When Dr Cooper complained, he corresponded with the Editor of The Age newspaper. The joinder and amendment applications arise out of the same factual substrate as pleaded in the proceeding as commenced. The delay of Dr Cooper in complaining and in commencing his proceeding is partly explained and in any event the Editor was tardy in his responses. Prima facie, Dr Cooper claims to have suffered significant damage by reason of each form of publication. On balance, I am satisfied that the interests of justice in permitting the joinder and amendments outweigh the prejudice to The Age Company in refusing it.

67 That brings me to the separate question whether in the interests of justice the amendment to plead reliance upon the print article against the original respondent should be allowed. In my view the case is stronger that they do. The material consideration is that each article complained of is in very similar form and the objection is technical and without merit.

The imputations

68 The fourth objection requires that I return to s 12B and in particular subsections (1)(b) and (2). Ms Alick submits that only one imputation was particularised in the concerns notice at paragraph 2. Her written submission partially quotes from it. It is well to repeat it. The entire paragraph reads:

The article made false allegations, was misleading and imputes to the reader that my client was complicit in helping high profile AFL footballers avoid being vaccinated and in doing so imputed that he had contravened medical directives, committed misconduct as a medical practitioner and practiced outside medical convention.

69 Ms Alick submits that this is a single imputation, whilst the statement of claim pleads 16 imputations that are “entirely different from it” contrary to s 12B. It is further submitted that when she raised objection to the 16 imputations in correspondence, the lawyers for Dr Cooper proposed a second set of 13 imputations, to which further objection was raised. As now resolved in the proposed amended statement of claim the imputations are set out at paragraph 6. Very helpfully, Ms Alick has provided a table of those imputations together with the objections of the respondents to which counsel for Dr Cooper has responded in a combined table. It provides:

Summary of Dr Cooper’s response to the respondents’ objections to imputations

Proposed Imputation | Respondents’ Objections | Dr Cooper’s Response |

(a) provided unprofessionally contrived COVID-19 medical exemption certificates for his AFL player patients, as part of a dishonest plan to assist his AFL player patients evade the AFL’s reasonable vaccination requirements. | • Not substantially the same, in breach of section 12(1)(b) of the Act. • “Unprofessionally contrived” is unclear and imprecise, which is defective in form. • Multiple meanings of “unprofessional” and/or “contrived” and/or “dishonest”, which is defective in the form | The December Concerns Notice (DCN) referred to the notion of complicity in helping high profile AFL footballers avoid being vaccinated and the notion of contraventions of medical directives and also of medical misconduct. The imputation also has to be viewed in the context of the publication as a whole. The imputation is clear in its import and it refers not to “unprofessional” but to “unprofessionally contrived”. “Dishonest” is not used in isolation, rather “as a dishonest plan.” The respondents extract and isolate words and phrases out of context to seek complain of multiple meanings or weasel words. When read as a whole, it does not bear those defects. |

(b) with unprofessional recklessness, provided COVID-19 medical exemptions certificates for his AFL player patients to the AFL that were not in accordance with ATAGI Guidelines and were therefore rightly rejected by the AFL, exposing his AFL player clients to sanctions and threats to their careers and livelihood. | • Not substantially the same, in breach of section 12(1)(b) of the Act. • “Unprofessional recklessness” is unclear and imprecise, which is defective in form. • “Unprofessional recklessness” combines two meanings, which is defective in form. | As with the above, falls within the ambit of complicity, the contravention of medical directives and misconduct. There is nothing unclear or imprecise about “unprofessional recklessness.” It is not two different meanings. The phrase marks and characterizes the recklessness. |

(d) is an incompetent medical practitioner as he did not follow the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisations (ATAGI) guidelines. | • Not substantially the same, in breach of section 12(1)(b) of the Act. | The concept of contravention of medical directives is identified in the DCN. The implications of that (incompetence) is something that is not different in substance to what is identified in the DCN. |

(e) purported to specialise in “integrative medicine” and Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) which are such eccentric and outlier areas of practice that male AFL Players should not be consulting with a doctor who purports to specialise in them and that he deserves to be shunned, ridiculed and mocked for offering his services to such players. | • Not substantially the same, in breach of section 12(1)(b) of the Act. • Eccentric” and “outlier” are unclear and imprecise, which is defective in form. • “Shunned, ridiculed and mocked” are alleged consequences, not part of the meaning of the publication. | Falls within concept of practicing outside medical convention, especially when considered in the context of the article itself. The term “eccentric,” “outlier” are not unclear and imprecise in the context of the imputation as a whole. “Shunned, ridiculed and mocked” is a proper part of the imputation when read as a whole |

f) is an incompetent medical practitioner. | • Not substantially the same, in breach of section 12(1)(b) of the Act. • Does not differ in substance from imputation (d). | Falls within the ambit of what is defamatory of a medical practitioner, from allegations of contravening medical directives, committing misconduct and practicing outside medical convention. Imputation (d) is a precise form of incompetence relating to guidelines. Without admission or concessions, the applicant will give consideration as to whether there could be a single imputation from (d) and (f) or imputation (d) might be modified. |

(g) is dangerously unprofessional as a medical practitioner because he conducts his medical practice and treatments based on unreliable conspiracy theories. | • Not substantially the same, in breach of section 12(1)(b) of the Act. • “Dangerously unprofessional” is unclear and imprecise, which is defective in form. • “Dangerously unprofessional” combines two meanings, which is defective in form. • The “medical practice”, the “treatments” and the “conspiracy theories” are not specified. | his flows from the notion of, at the least, practicing outside medical convention. The imputation as a whole is clear in its import. Once again, the objection extracts and parses words out of context. “Dangerously unprofessional” is not two meanings but one phrase/concept. It is not necessary to individually specify the medical practice, the treatments or the conspiracy theories, and no embarrassment or prejudice is caused because they are set out in the article itself. Inclusion of all such details might itself be seen as objectionable in an imputation. |

(h) is an unethical medical practitioner in that he does not follow acceptable rules or code of conduct and has breached (and caused his AFL player patients to breach) applicable codes of conduct. | • Not substantially the same, in breach of section 12(1)(b) of the Act. • “Rules” and “code of conduct” for medical practitioners, and “codes of conduct” for AFL players are not specified. • Multiple meanings of ‘does not follow rules/code for medical practitioners’ and/or ‘breached AFL codes of conduct’ and/or ‘caused his patients to breach AFL codes of conduct’, which is defective in form. | The matters in this imputation are contemplated and identified in the DCN, taken in the context of the article complained of and its subject matter. The rules and codes do not need to be specified or set out in the imputation itself. The extraction of separate phrases and (false) characterization of there being “multiple meanings,” belies the reading of the imputation as a whole. |

(i) is pushing a baseless conspiracy and falsehood that electromagnetic energy levels used in 5G technology is harmful to humans. | • Not substantially the same, in breach of section 12(1)(b) of the Act. • “Baseless conspiracy” is unclear and imprecise, which is defective in form. • Multiple meanings of “baseless conspiracy” and/or “falsehood” which is defective in form. | The above is repeated. The aspect of practice outside medical convention is identified in the DCN. The objections otherwise extract and parse parts of the imputation in an unrealistic way, and fail to have regard to the imputation as a whole. |

(j) should be ridiculed, mocked shunned, to be thought less of and despised by the readers of the article because he pushes falsehoods that electromagnetic energy levels used in 5G technology were harmful to humans | • Not substantially the same, in breach of section 12(1)(b) of the Act. • “Ridiculed, mocked shunned, to be thought less of and despised” are alleged consequences, not part of the meaning of the publication. • Does not differ in substance from imputation (i). | These concepts are contained in and contemplated in the DCN. However, without admission or concessions consideration might be given to whether (i) and (j) can be merged into one imputation to avoid any dispute. |

(k) is a quack doctor. | • Not substantially the same, in breach of section 12(1)(b) of the Act. | The concept is embraced within the practicing outside medical convention point. |