Federal Court of Australia

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Insurance Australia Limited, in the matter of Insurance Australia Limited [2023] FCA 724

ORDERS

IN THE MATTER OF INSURANCE AUSTRALIA LIMITED ACN 000 016 722 | ||

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | ||

AND: | INSURANCE AUSTRALIA LIMITED ACN 000 016 722 Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

BY CONSENT, THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

Note to orders: Capitalised terms are defined at the end of the orders.

1. Between 16 March 2014 and 25 September 2019, on each occasion that IAL made a Renewal Offer to an Affected Customer in respect of an Affected Policy:

(a) IAL applied a Cupping Mechanism which operated such that after loyalty discounts and/or no claim bonuses (“Discounts”) were applied to a renewing customer’s proposed renewal premium, a process was triggered if the calculation resulted in a decrease of that premium greater than the percentage limit set in the algorithm when compared to the customer’s premium for the previous year and if that occurred, the customer’s premium before discounts were applied (the “Base Premium”) was recalculated and increased, so that when the customer’s applicable Discounts were applied, the final premium would fall within the cupping limit. The recalculated final premium amount was the renewal premium proposed to the customer in the customer’s Certificate of Insurance;

(b) IAL represented by the terms of the Premium, Excess and Discounts guide applicable to the Relevant Policies, and by implication from the terms of the proposed Certificate of Insurance, that the Affected Premium payable by the customer on renewal of the policy had been calculated consistently with the information and process set out in the Premium, Excess and Discounts guide regarding calculation of the premium; that the Affected Premium payable included the full value of the Discounts which the customer would reasonably have expected to receive; and that the Discounts had been applied to the premium that would otherwise have been payable by the Affected Customer had the Discounts not been applied (the “Premium and Discounts Representation”);

(c) by reason of the application of the Cupping Mechanism as set out in paragraph (a) above, IAL:

(i) limited the extent to which the Discounts (set out in the Premium, Excess and Discounts guide and purported to be provided to Affected Customers in their Certificate of Insurance) were actually provided to customers such that the Affected Customers did not receive the full value of the Discounts they would reasonably have expected to receive;

(ii) increased the Base Premium offered to the Affected Customers and then applied the Discounts to that Base Premium;

(iii) by increasing the Base Premium before Discounts were applied, charged Affected Customers higher premiums upon renewal than if the Cupping Mechanism had not applied;

(iv) did not calculate the premium payable on renewal for Affected Customers consistently with the information and process set out in the applicable Premium, Excess and Discounts guide;

(v) failed to disclose to customers the existence, application and/or consequences of the Cupping Mechanism; and

(d) the conduct of IAL described above was in trade or commerce and in connection with the supply or possible supply of financial services.

2. IAL engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct or conduct that was likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 12DA(1) of the ASIC Act in making the Premium and Discounts Representation on each occasion between 16 March 2014 and 25 September 2019 when it sent a Renewal Offer in respect of Affected Policies to Affected Customers, in the circumstances referred to in paragraph 1 above.

3. IAL contravened s 12DB(1)(g) of the ASIC Act by making a false and/or misleading representation in connection with the price of the Affected Policies on each occasion that IAL made the Premium and Discounts Representation to an Affected Customer between 16 March 2014 and 25 September 2019, in the circumstances referred to in paragraph 1 above.

4. IAL contravened s 12DB(1)(i) of the ASIC Act by making a false and/or misleading representation in connection with the existence or effect of a condition, right or remedy on each occasion that IAL made the Premium and Discounts Representation to an Affected Customer between 16 March 2014 and 25 September 2019, in the circumstances referred to in paragraph 1 above.

5. By its conduct in paragraphs 1 to 4 above, IAL breached its general obligation to comply with financial services laws in contravention of s 912A(1)(c) of the Corporations Act between 16 March 2014 and 25 September 2019.

6. Between 16 March 2014 and 25 September 2019 IAL breached its obligation to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its financial services licence were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly, and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act by:

(a) its conduct in paragraphs 1 to 4 above, by making the Premium and Discounts Representation when sending Renewal Offers to Affected Customers in respect of the Affected Policies; and

(b) introducing and applying the Cupping Mechanism, which had the effect that Affected Customers were charged a higher premium on renewal than they would have been charged if the Cupping Mechanism had not applied.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Penalties and costs

7. Pursuant to s 12GBA(1) of the ASIC Act (as in force before 13 March 2019), within 30 days of this order, IAL pay to the Commonwealth of Australia $40 million in respect of IAL’s conduct declared to be contraventions of s 12DB(1) of the ASIC Act occurring during the period from 15 October 2015 and 25 September 2019.

8. Pursuant to s 43 of the FCA Act, IAL pay ASIC’s costs of and incidental to the proceeding, as assessed or agreed, within 28 days of such assessment or agreement.

Adverse publicity notice

9. IAL is to cause to be published, at its own expense, a notice in the terms set out at Schedule 2 to these orders (“Written Notice”) in the following manner:

(a) Within 30 days of the date of this Order, for a period of 90 days, by displaying a link in no less than 11 point font and no smaller than 50% of the size of the homepage banner, identified by the following crawlable text: “Notice ordered by Federal Court in ASIC case against IAL for failures to honour discount promises made to some consumers who held NRMA Insurance policies issued by IAL” to a PDF and/or webpage copy of the Written Notice in an immediately visible area of NRMA Insurance’s website homepage (https://www.nrma.com.au/);

(b) Commencing within 90 days of the date of this order, and for a period of no more than 6 months from commencement, include the following words, within the body of an email to customers (at least once per customer) who:

(i) held a Relevant Policy between 28 April 2014 and 3 November 2019; and

(ii) who continue to hold one or more of those policies (who have a preference for being communicated with by email),

stating “Please find attached for your information a Notice ordered by the Federal Court in ASIC case against IAL for failures to honour discount promises made to some consumers who held NRMA Insurance policies issued by IAL” and attach a pdf copy of the Written Notice to such correspondence; and

(c) Commencing within 90 days of the date of this order, and for a period of no more than 6 months from commencement, include the following words, within the body of a covering letter to customers (at least once per customer) who:

(i) held a Relevant Policy between 28 April 2014 and 3 November 2019; and

(ii) who continue to hold one or more of those policies (who have a preference for being communicated with by post, or otherwise have not nominated a preference),

stating “Please find enclosed for your information a Notice ordered by the Federal Court in ASIC case against IAL for failures to honour discount promises made to some consumers who held NRMA Insurance policies issued by IAL” and enclose a printed copy of the Written Notice to such correspondence.

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

10. In these Declarations and orders, the following terms have the following meanings:

(a) Affected Customer means a customer who held a Relevant Policy in the period from 16 March 2014 to 25 September 2019 (of which there were 611,000 groups of customers) where: a Renewal Offer was made in that period in relation to that Relevant Policy; the Certificate of Insurance sent to the customer as part of that Renewal Offer provided for a Discount; and, the premium offered in the Certificate of Insurance was an Affected Premium with the effect that the full value of the Discounts to which the customer was eligible, and described in the Certificate of Insurance, was not passed onto that customer.

(b) Affected Premium means the renewal premium amount set out in the Certificate of Insurance, where the Cupping Mechanism applied in the calculation of that amount.

(c) Affected Policy means a Relevant Policy held by an Affected Customer.

(d) ASIC means the Australian Securities and Investment Commission.

(e) ASIC Act means the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth).

(f) Corporations Act means the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

(g) Cupping Mechanism means the mechanism described at paragraph [38] of the Statement of Agreed Facts filed by the parties on 23 September 2022.

(h) FCA Act means the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

(i) IAL means Insurance Australia Limited.

(j) Relevant Policy means any one of the 13 insurance policy products offered by IAL under the NRMA Insurance brand as identified in Schedule 1 to these orders.

(k) Renewal Offer means, in the period between 16 March 2014 and 25 September 2019, a renewal letter or offer of renewal sent by IAL prior to the expiry of each existing Relevant Policy of an existing customer, offering a renewal of the customer’s existing insurance policy on the terms set out in the offer.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

SCHEDULE 1 – Relevant Policies

Product Category and Code | Description |

Home | |

BLDG | Home Buildings |

CONT | Home Contents |

HPAC | Home Package Buildings (BLDG) and/or Contents (GNCT) |

LAND | Landlords – Buildings (BLDG) and/or Contents (GNCT) |

Motor | |

CRCP | Comprehensive Motor |

CRFT | Car Fire, Theft (Third Party) |

CRTP | Car Third Party Property Damage |

BKCP | Bike Comprehensive |

BKTP | Bike Third Party Property Damage |

Boat | |

BOT | Boat Contents (CONT) and Boat Hull (HULL), or standalone Boat Hull, with layup cover applied to boat hull |

Caravan | |

ONS | Onsite Caravan (ONST CARA) and/or Onsite Caravan Contents (ONST CONT) |

CVT | Caravan Touring (CVT CARA) and/or Caravan Touring Contents (CVT CONT) |

TRLR | Trailer |

SCHEDULE 2 – Written Notice

Adverse Publicity Notice ordered by the Federal Court of Australia

The Federal Court of Australia finds that Insurance Australia Limited (IAL) made false or misleading representations to some consumers about applicable discounts for policy renewals.

On 30 June 2023, the Federal Court of Australia ordered IAL (the issuer of products under the NRMA insurance brand) to pay a penalty of $40 million to the Commonwealth for making false and misleading representations to certain customers about certain loyalty and no claims bonus discounts they would receive, but failing to deliver the full value of those discounts.

This affected about 466,000 NRMA branded Motor, Home, Boat and Caravan insurance policies between 15 October 2015 and 25 September 2019. Customers did not receive $35,393,000 of discounts they should have received. An additional 239,000 policies were also impacted in an earlier period from March 2014; however, the Court was unable to impose a penalty in relation to those policies due to limitations periods (but affected customers have been remediated by IAL, and have already been contacted and refunded as part of that process).

IAL sent renewal offer documents to affected customers representing that the discounts IAL promised had been passed on to them, but those discounts were actually applied to a higher base premium than those customers would otherwise have been charged.

IAL admitted that it had broken laws prohibiting it from making false, misleading or deceptive representations shortly after ASIC commenced proceedings against it and has apologised for its conduct.

IAL has completed issuing payments to all affected customers who are receiving payment as part of the remediation program.

Further information

The Court found that IAL made false or misleading representations to the affected customers that their renewal premiums:

• had been calculated as set out in IAL’s Premium, Excess and Discounts guide;

• included the full value of discounts that the customers expected to receive; and

• that the discounts were applied to the base premium that IAL would have otherwise charged them.

For more information, read ASIC’s media release and the Court’s judgment.

ABRAHAM J:

1 The defendant, Insurance Australian Limited (IAL) is an insurance company that issues products under a range of insurance brands including, relevantly, NRMA Insurance, which operates under an Australian financial services licence (AFSL).

2 IAL admits contraventions of ss 12DA(1) and 12DB(1) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act) and ss 912A(1)(a) and (c) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act).

3 The conduct occurred between 16 March 2014 and 25 September 2019 (the Relevant Period) when IAL offered renewals of NRMA Insurance branded policies to existing customers who held an NRMA Insurance Motor, Home, Boat or Caravan policy identified in Schedule 1 to the orders (each a Relevant Policy, and together, the Relevant Policies). The contraventions relate to the manner in which IAL calculated the renewing customer’s premium in relation to loyalty and no claim bonus discounts (Discounts), and the manner it represented to its customers the premium had been calculated and applicable Discounts had been applied. These reasons address the relief imposed for those contraventions.

4 The matter proceeded by way of a very detailed statement of agreed facts and admissions (SAFA) and two supplementary statements of agreed facts and admissions (Supplementary Statements). There was little by way of dispute between the parties in submission. IAL have agreed to the declarations sought by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), in the terms they propose. IAL agrees that the $40 million penalty sought by ASIC is appropriate and generally agrees with its submissions. The principle issue of contention is the appropriate form of an adverse publicity order.

5 For the reasons below, declarations are made in the terms sought, a pecuniary penalty of $40 million is imposed on IAL, and an adverse publicity order is made (to be given effect by a single post out to all customers who held a Relevant Policy between 28 April 2014 and 3 November 2019 and still hold at least one of those policies).

ASIC’s case

6 Given the level of agreement in this case, it is unnecessary to rehearse all the detail in the agreed statements, although that detail is important to understand the contraventions and the relief imposed. Accordingly, attached to these reasons as Annexures A - C are the SAFA and Supplementary Statements.

7 The following is an overview of the contraventions.

8 In summary, during the Relevant Period, upon offer to renew an existing Relevant Policy on terms set out in the offer (Renewal Offer), IAL sent a proposed certificate of insurance (COI) to existing customers, which set out details of the Discounts that had purportedly been provided to the customer and the renewal premium payable. On its face, the COI represented that the full value of the Discounts had been applied to the premium that would otherwise have been payable by the customer had the Discounts not been applied, supported by calculations purported to confirm this. In fact, as outlined below, for some customers this was not the case. The COI also referred the customer to the Premium Excess and Discounts guide (PED) applicable to the Relevant Policy, which set out how the premium payable had been determined and the process applied in calculating the premium with the Discounts applied.

9 During the Relevant Period, in calculating renewing customers’ annual premiums in respect of their Relevant Policy, IAL applied an algorithm (the Cupping Mechanism) which was triggered when a renewal premium (after applicable Discounts) fell by an amount greater than a set percentage limit (the Cup) compared to the customer’s prior year premium. When that occurred, the customer’s premium before the Discounts were applied (Base Premium) was recalculated and increased, so that when the customer’s applicable Discounts were applied, the final premium would fall within the cupping limit. The result was that for those customers (Affected Customers) whose policies had the Cup applied (the Affected Policies), the renewal premiums were increased and the full value of the Discounts were not passed on. Those customers were charged higher premiums on renewal than if the Cupping Mechanism had not been applied to their policies. Where the Cup was not triggered, the Cupping Mechanism would not affect a renewing customer’s premium.

10 Put another way, the Cupping Mechanism limited the extent to which promised Discounts were provided to customers in a manner that was not visible them. That was so, even if the customers checked the calculations provided to them in the COI for the very purpose of verifying their discounts. Further, once the Cup was triggered, even if it was not triggered again in subsequent years, some subsequent renewal premiums in respect of Affected Policies were higher than they otherwise would have been as a result of the Cup, as the way they were calculated included reference to the previous year’s inflated Base Premium. Neither the COI nor the PED identified that the previous year’s premium affected the renewal premium during the Relevant Period.

11 During the Relevant Period (or until late September 2020, a year after the Relevant Period ended when IAL commenced paying remediation to affected customers), IAL did not disclose to its customers the existence, application and consequences of the Cupping Mechanism used in the calculation of Affected Customers’ premiums. Instead, the terms of the COI implied to Affected Customers that the applicable Discounts had been applied to the premium that would otherwise have been payable by them.

12 The conduct occurred for the entirety of the Relevant Period, a significant period of time, exceeding 5½ years. It impacted approximately 611,000 groups of Affected Customers (where a group of Affected Customers may include one or more customers holding one or more policies), and approximately 705,000 separate Affected Policies. In total, cupping impacted those Affected Policies around 1,785,000 times. That is, each time an Affected Policy was impacted, the customer paid a renewal premium that was higher than they otherwise should have paid.

13 Over the course of the entire period of the conduct occurring during the Relevant Period, Affected Customers did not receive the Discounts to which they were entitled in an amount of $60,223,000 ($71,436,974 when including GST, Stamp Duty and FSL), where the total premiums paid by Affected Customers was $1,130,060,539.

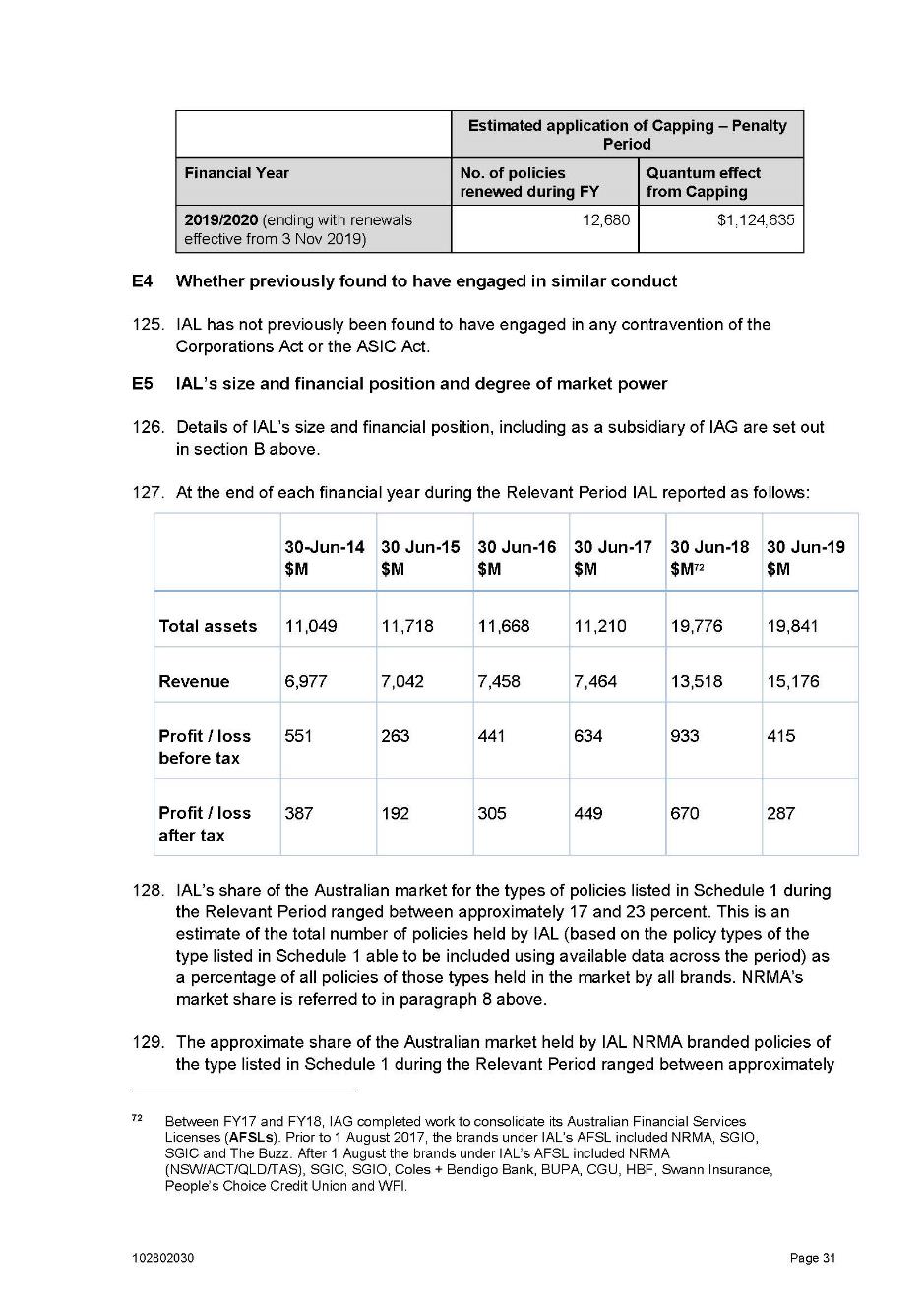

14 Although the Relevant Period commenced 16 March 2014, due to limitation periods a penalty was sought in respect of contraventions occurring from 15 October 2015. Accordingly, having regard to the period from 15 October 2015 to 25 September 2019 (Penalty Period):

(1) the Cupping Mechanism impacted:

(i) the Affected Policies around 1,098,000 times;

(ii) approximately 222,000 Affected Policies and 209,000 Affected Customer groups whose renewal was first impacted by the Cupping Mechanism in that period; and

(iii) approximately 466,000 Affected Policies and 419,000 Affected Customer groups, including where the application of the Cup occurred outside the Penalty Period but the Affected Policy or customer group experienced a subsequent year impact in that period; and

(iv) the Affected Customers suffered financial harm in the amount of $35,393,000 ($41,926,682 when including GST, Stamp Duty and FSL), where the total premiums paid by Affected Customers was $722,253,823.

15 The Cupping Mechanism was implemented by IAL in the context of it undertaking the Go Discounts project, which was directed to changing and simplifying the way the Discounts were offered to customers, and potentially providing significant discounts to some customers. These contraventions occurred in the context of IAL intentionally designing, approving and implementing the Cupping Mechanism, where one of the considerations for its approval and implementation was its potential loss of profit if the Cupping Mechanism was not implemented.

Contraventions

16 IAL admits to, and the parties agree, the contraventions set out in Section D of the SAFA (Admitted Contraventions). It is convenient to reproduce ASIC’s summary below.

17 In summary, the admitted contraventions are that:

(a) on each occasion that IAL issued an Renewal Offer to an Affected Customer, it made a representation (in the PED and COI) that:

(i) the Affected Premium payable by the customer on renewal of the policy had been calculated consistently with the information and process set out in the PED regarding calculation of the premium;

(ii) by implication from the terms in the COI, the applicable Discounts had been applied to the premium that would otherwise have been payable by the customer had the Discounts set out in the COI not been applied; and

(iii) the Affected Premium payable included the full value of the Discounts which the customer would reasonably have expected to receive (together, the Premium and Discounts Representation);

(b) the Premium and Discounts Representation was false, misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of ss 12DA(1) and 12DB(1)(g) and (i) because IAL:

(i) limited the extent to which the Discounts set out in the PEDs and purported to be provided to Affected Customers in their COIs were actually provided to customers such that the Affected Customers did not receive the full value of the Discounts they would reasonably have expected to receive;

(ii) increased the Base Premium calculated before discounts were applied offered to the Affected Customers and then applied the Discounts to that Base Premium;

(iii) by increasing the Base Premium before Discounts were applied, charged Affected Customers higher premiums upon renewal than if cupping had not applied;

(iv) did not calculate the premium payable on renewal consistently with the information and process set out in the PED; and

(v) failed to disclose to customers the existence, application and/or consequences of the Cupping Mechanism;

(c) to the extent that the Premium and Discounts Representation was a representation as to a future matter, by reason of the existence and application of the Cupping Mechanism during the Relevant Period, IAL did not have reasonable grounds for making the Premium and Discounts Representation (for the purposes of s 12BB of the ASIC Act);

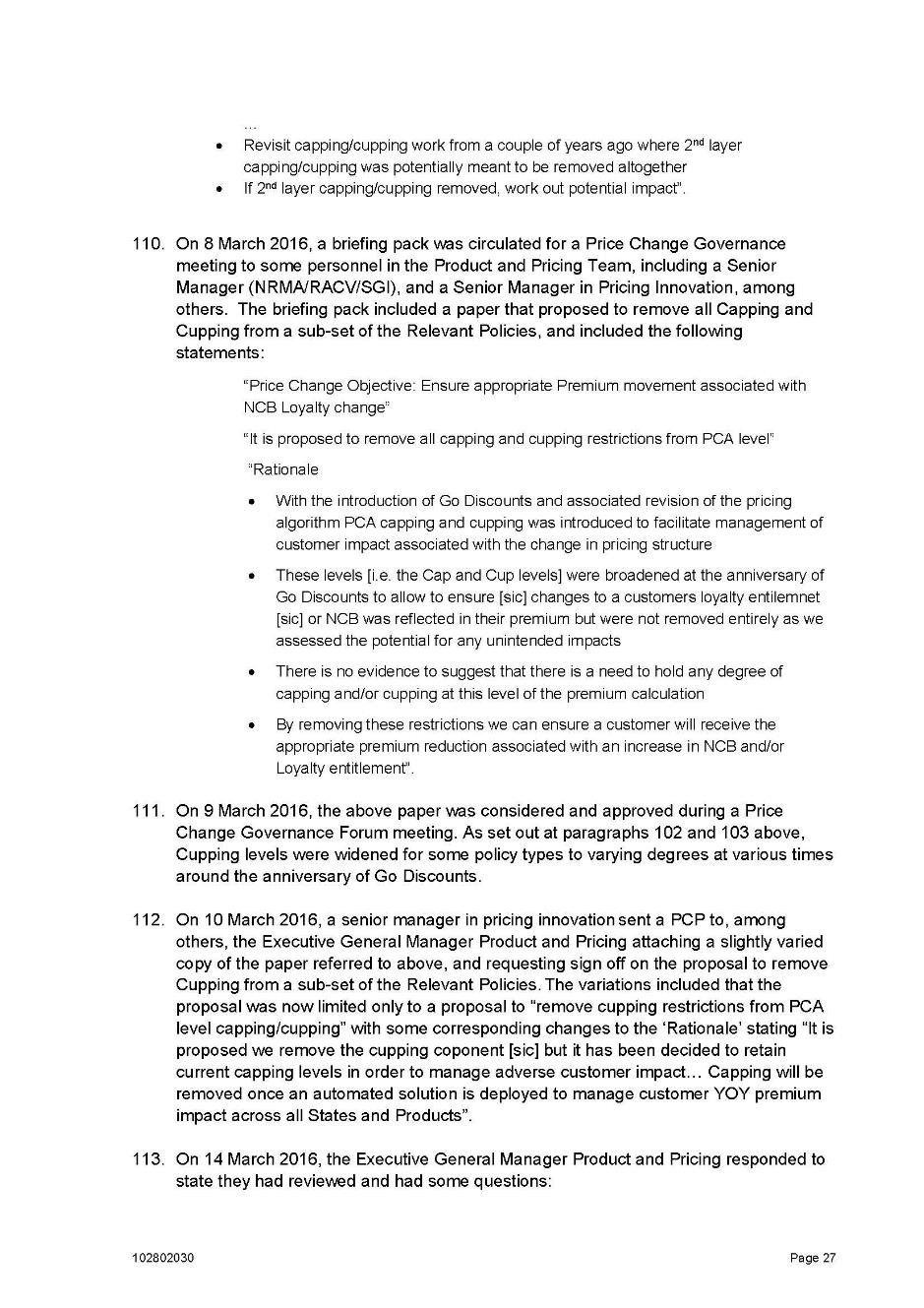

(d) there was a relationship between IAL and its customers as insurer and insured, and IAL accordingly owed its customers a duty of utmost good faith;

(e) by breaching ss 12DA(1) and 12DB(1)(g) and (i), IAL contravened s 912A(1)(c) of the Corporations Act;

(f) IAL contravened s 912A(1)(a) by:

(i) making the Premium and Discounts Representation and breaching ss 12DA(1) and 12DB(1)(g) and (i);

(ii) introducing the Cupping Mechanism with the effect of limiting the extent of reductions in premiums provided to Affected Customers; and

(iii) applying the Cupping Mechanism such that Affected Customers were charged a higher premium on renewal than if the Cupping Mechanism had not been triggered

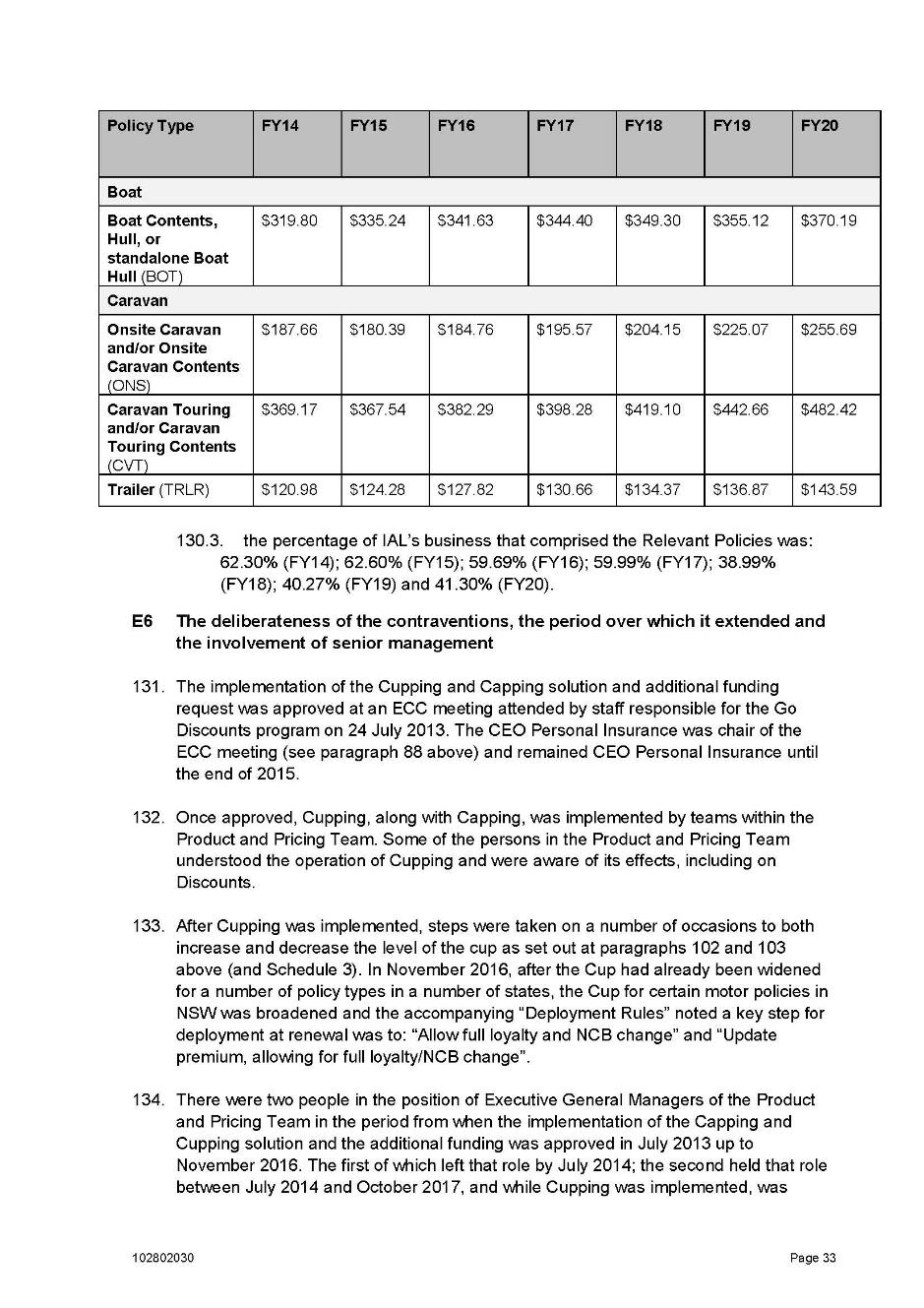

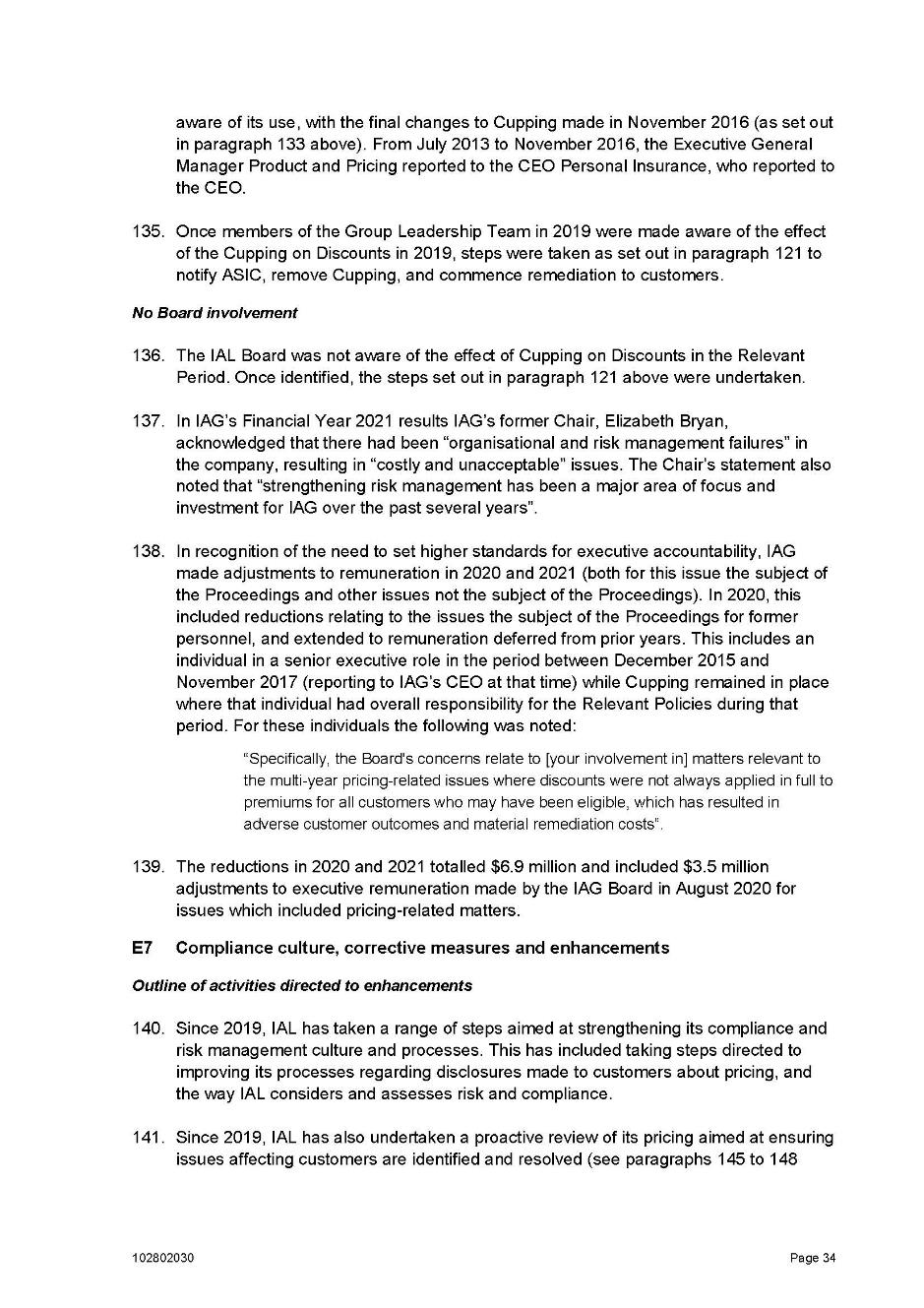

18 IAL also admits (and so, further, there is no issue between the parties) that:

(a) at all material times, each of the Relevant Policies was a financial product for the purposes of s 12BAA(1)(b), (5) and (7)(d) of the ASIC Act; and

(b) the conduct of IAL set out above was engaged in as part of IAL’s insurance business and thereby in trade or commerce. The conduct was in relation to and in connection with the supply or possible supply of financial services, being the issuing of and dealing in an insurance contract and policy, being a financial product.

Evidence

19 As explained above, this matter proceeded by the SAFA and the Supplementary Statements. In addition, IAL read three affidavits.

20 First, the affidavit of Ms Christa Marjoribanks, verified 20 December 2022, the Executive General Manager, Product, Pricing & Governance for the Intermediated Insurance Australia business within IAG group. Ms Marjoribanks also leads the Pricing Taskforce program at IAG that includes the remediation program in respect of the issue the subject of these proceedings. Ms Marjoribanks’ affidavit set out an explanation, based on her knowledge and experience, of how a number of concepts in insurance pricing are generally used. Ms Marjoribanks then outlined how IAG group’s data was analysed in order to provide a high-level estimate of the impact of capping (see [55] below) in comparison to cupping, and the results of that analysis.

21 Second, IAL read the affidavit of Ms Hope Prior, verified 30 March 2023, the Executive Manager, operational Design and Delivery at IAG. Ms Prior’s affidavit provided information regarding the number of policyholders presently holding NRMA Insurance policies, and certain cohorts of those customers, including those impacted by cupping, as well as estimates of the costs associated with, and impact of, sending communications to those cohorts of customers. Ms Prior’s affidavit also provided information regarding the impact to IAG’s call centres and associated costs arising from outbound communications to customers.

22 Third, IAL read a second affidavit of Ms Hope Prior, verified 8 May 2023. That affidavit provided supplementary information about certain matters referred to in Ms Prior’s first affidavit. This included estimates of the costs associated with, and impact of, sending communications to a cohort of customers presently holding NRMA Insurance policies.

Declarations

23 The power to grant declaratory relief pursuant to s 21 of Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act) "is a very wide one" and the court is "limited only by its discretion": Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd [2009] FCAFC 166; (2009) 182 FCR 160 at [1016], citing Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd [1972] HCA 61; (1972) 127 CLR 421 at 435. Three requirements need to be satisfied before making declarations: (1) the question must be a real and not a hypothetical or theoretical one; (2) the applicant must have a real interest in raising it; and (3) there must be a proper contradictor: Foster at 437-438. That a party has chosen not to oppose a grant of particular declaratory relief is not an impediment to such relief being granted by the Court: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd [2012] FCAFC 56; (2012) 201 FCR 378 at [14], [30]-[33]. Other factors relevant to the exercise of the discretion include: (a) whether the declaration will have any utility; (b) whether the proceeding involves a matter of public interest; and (c) whether the circumstances call for the marking of the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct: ASIC v Pegasus Leverages Options Group Pty Ltd [2002] NSWSC 310; (2002) 41 ACSR 561 at 571; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Monarch FX Group Pty Ltd, in the matter of Monarch FX Group Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1387; (2014) 103 ACSR 453 at [63]; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Stone Assets Management Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 630; (2012) 205 FCR 120 at [42].

24 For the contraventions of ss 12DA(1), 12DB(1)(g) and (i) of the ASIC Act and s 912A(1)(a) and (c) of the Corporations Act, the broad discretion under s 21 of the FCA Act and the power to make declarations of contraventions of laws relating to the provision of financial services under s 1101B(1)(a)(i) of the Corporations Act, empower the Court to make the declarations sought.

25 As indicated above at [4], ASIC seeks and IAL agrees to the making of declarations in a form set out by the parties regarding IAL’s contraventions for the whole of the Relevant Period.

26 Even where there is agreement between the parties in respect of proposed declarations, it remains for the Court to decide whether declaratory relief is appropriate: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v MLC Nominees; [2020] FCA 1306; (2020) 147 ACSR 266 (MLC Nominees) at [109].

27 I am satisfied that the declarations ought to be made in the terms sought. They set out the basis on which the Court determined IAL’s liability and on which the Court orders the pecuniary penalties imposed. There is a significant public interest in making the declarations sought, not only to record the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct, but as deterrence to IAL and others, from repeating such conduct. This in turn assists ASIC to fulfil its role. Consequently, the declarations sought have significant utility and I am satisfied that it is in the interests of justice that they be made.

Pecuniary penalty

28 ASIC seeks the imposition of a pecuniary penalty only in relation to the s 12DB(1) contraventions.

29 The balance of the contraventions either are not (and never were) civil penalty provisions (s 12DA(1) of the ASIC Act and s 912A(1)(c) of the Corporations Act), or were not civil penalty provisions during the Penalty Period (s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act). Noting that s 912A(1)(a) did become a civil penalty provision on and from 13 March 2019, it only operates where the conduct constituting the contravention of the provision occurred “wholly on or after” 13 March 2019. Accordingly, ASIC does not seek a civil penalty under s 912A(1)(a) in respect of IAL’s conduct. However, ASIC submitted the conduct constituting the contravention of s 912A(1)(a) is a serious contravention of the Corporations Act, and remains relevant to the consideration of penalty for the contraventions of s 12DB(1) of the ASIC Act.

30 The purpose of a civil penalty is primarily protective, in promoting the public interest in compliance by deterring further contravening conduct: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; (2022) 399 ALR 599 at [15]-[16], [43] and [45] (Pattinson). A penalty of appropriate deterrent effect “must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not such as to be regarded by [the] offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business”: Pattinson at [17] citing Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; (2012) 287 ALR 249 at [62].

31 Section 12GBA(2) of the ASIC Act, which was replaced by 12GBB(5) following amendments taking effect in March 2019, provides that, in determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the Court must have regard to all relevant matters. Those matters include: the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and whether the person has previously been found by the court in proceedings under subdivision G (in which 12GBA is located), to have engaged in any similar conduct. The Court is to decide what penalty is “appropriate” in all the circumstances.

32 In addition, there are a number of factors identified in the authorities, relevant to this task. For example, the assessment of penalty of appropriate deterrent value will have regard to: (1) the nature and extent of the contravening conduct; (2) the amount of loss or damage caused; (3) the circumstances in which the conduct took place; (4) the size of the contravening company; (5) the degree of power it has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market; (6) the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended; (7) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level; (8) whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance, as evidenced by educational programs or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention; and (9) whether the company has shown a disposition to co-operate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to contravention: Pattinson at [18]. These are not to be considered to be a rigid list of factors to be ticked off: Pattinson at [19]. Rather, they are to inform a multifactorial investigation that leads to a result arrived at by a process of “instinctive synthesis” addressing the relevant considerations: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; (2016) 340 ALR 25 (Reckitt Benckiser) at [44].

33 ASIC submitted that conduct that occurred before the penalty period can reflect that there was a failure to take steps before the penalty period commenced, which continued throughout the penalty period. However, it also recognised that where an offending entity has remediated for the entire time period this may have a mitigating effect, showing that the offending entity did not confine its remediation to the penalty period. This is to be considered in the context of the entity’s obligations under s 912B of the Corporations Act to have compensation arrangements in place to compensate persons for loss or damage arising from breaches of obligations under Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act.

34 The maximum penalty is also one of the relevant factors. In this regard, in Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; (2005) 228 CLR 357, the majority observed at [31]:

…careful attention to maximum penalties will almost always be required, first because the legislature has legislated for them; secondly, because they invite comparison between the worst possible case and the case before the court at the time; and thirdly, because in that regard they do provide, taken and balanced with all of the other relevant factors, a yardstick.

35 In a civil penalty context, the relevance of a prescribed maximum penalty as a yardstick was explained by the Full Court of the Federal Court in Reckitt Benckiser at [155]-[156] as follows:

The reasoning in Markarian about the need to have regard to the maximum penalty when considering the quantum of a penalty has been accepted to apply to civil penalties in numerous decisions of this Court both at first instance and on appeal (Director of Consumer Affairs, Victoria v Alpha Flight Services Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 118 at [43]; Australian, Competition and Consumer Commission v BAJV Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 52; (2014) ATPR 42-470 at [50]-[52]; Setka v Gregor (No 2) [2011] FCAFC 90; (2011) 195 FCR 203 at [46]; McDonald v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner [2011] FCAFC 29; (2011) 202 IR 467 at [28]-[29]). As Markarian makes clear, the maximum penalty, while important, is but one yardstick that ordinarily must be applied.

Care must be taken to ensure that the maximum penalty is not applied mechanically, instead of it being treated as one of a number of relevant factors, albeit an important one. Put another way, a contravention that is objectively in the mid-range of objective seriousness may not, for that reason alone, transpose into a penalty range somewhere in the middle between zero and the maximum penalty. Similarly, just because a contravention is towards either end of the spectrum of contraventions of its kind does not mean that the penalty must be towards the bottom or top of the range respectively. However, ordinarily there must be some reasonable relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty imposed.

36 This passage was more recently cited with approval in Pattinson at [53].

37 ASIC relies on the ASIC Act before 13 March 2019. At that time, the Court’s power to order payment of a pecuniary penalty was located in s 12GBA of the ASIC Act. Pursuant to s 12GBA(1), if the Court is satisfied that a person has contravened a provision of Subdivision D (including s 12DB(1)(g) and (i)) of the ASIC Act), the Court has power to order a person pay a pecuniary penalty in respect of each act or omission by the person to which s 12GBA applies, as the Court determines to be appropriate. The value of a penalty unit, as fixed under s 4AA(1) of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth), and subject to indexation under s 4AA(3), was: $180 for the period 31 July 2015 to 30 June 2017; and $210 for the period 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2020.

38 A contravention of s 12DB(1) occurs each time the relevant false or misleading representation is made to a person: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Commonwealth Securities Limited [2022] FCA 1253 at [29].

39 Under 12GBA(3), the maximum pecuniary penalty payable for a contravention by a body corporate was 10,000 penalty units. Depending on when the contravention occurred during the Penalty Period, the maximum value of each contravention is $1.8m to $2.1m. I note that IAL admitted that it contravened s 12DB(1)(g) and (i) around 1,098,000 times: SAFA [61].

40 Where the theoretical maximum penalty is in the billions or trillions of dollars, the overall maximum penalty will not be a meaningful factor in the court’s assessment. In these circumstances, the appropriate range is best assessed by reference to factors other than where the conduct falls in the range of seriousness of offending in relation to the maximum penalty: Reckitt Benckiser at [157].

41 Ordinarily separate contraventions arising from separate acts should attract separate penalties. However, where separate acts give rise to separate contraventions which are inextricably interrelated, they may be regarded as a “course of conduct” for penalty purposes: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; (2018) 262 FCR 243 at [234]. This avoids double-punishment for those parts of the legally distinct contraventions that involve overlap in wrongdoing: see for example, Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; (2010) 269 ALR 1 at [39] and [41]. However, “[i]t is not appropriate or permissible to treat multiple contraventions as just one contravention for the purposes of determining the maximum limit dictated by the relevant legislation”: Yazaki at [227]. “It cannot in itself operate as a de facto limit on the penalty to be imposed for contraventions”: Reckitt Benckiser at [141] quoting Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Hillside (Australia New Media) Pty Ltd (t/as Bet365) (No 2) [2016] FCA 698 at [24] – [25].

42 The principle of totality requires the Court to make a “final check” of the penalties to be imposed on a wrongdoer, considered as a whole, to ensure that the total penalty does not exceed what is proper for the entire contravening conduct: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd [1997] FCA 450; (1997) 145 ALR 36 at 53, citing Mill v The Queen [1988] HCA 70; (1988) 166 CLR 59.

43 An appropriate penalty is therefore one that is fashioned by reference to the facts of the particular case before the Court, in order to arrive at a penalty that is sufficient to deter the conduct in question, without being overly oppressive: Pattinson at [46].

44 The principles to be applied in considering a jointly proposed penalty were considered in Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; (2015) 258 CLR 482 (DFWBII), where the majority observed at [46]:

[T]here is an important public policy involved in promoting predictability of outcome in civil penalty proceedings and that the practice of receiving and, if appropriate, accepting agreed penalty submissions increases the predictability of outcome for regulators and wrongdoers. As was recognised in Allied Mills and authoritatively determined in NW Frozen Foods, such predictability of outcome encourages corporations to acknowledge contraventions, which, in turn, assists in avoiding lengthy and complex litigation and thus tends to free the courts to deal with other matters and to free investigating officers to turn to other areas of investigation that await their attention.

45 Further, their Honours said at [58]:

... Subject to the court being sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the penalty which the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances thus revealed, it is consistent with principle and ... highly desirable in practice for the court to accept the parties’ proposal and therefore impose the proposed penalty.

(emphasis added)

46 Those observations about the desirability of acting upon agreed penalty submissions were made in the context of a broader recognition that as a civil litigant in civil proceedings, civil penalties are but one of numerous forms of relief which regulators can pursue, and it is entirely orthodox for regulators to make submissions as to that relief: see DFWBII at [24], [57]-[59], [63], [103], [107]. Those principles to be applied in considering a jointly proposed penalty were recently considered in Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2021] FCAFC 49; (2021) 284 FCR 24 (Volkswagen) at [124]-[131], referring to DFWBII, NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition Commission [1996] FCA 1134; (1996) 71 FCR 285 and Minister for Industry, Tourism and Resources v Mobil Oil Australia Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 72; (2004) ATPR 41-993. A number of points were highlighted, including: first, the Court must be satisfied that the penalty proposed by the parties is appropriate: at [125]; second, if persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and that the proposed penalty is an appropriate remedy, it is highly desirable for the Court to accept the proposal: at [126]; third, in considering whether the proposed penalty is appropriate, it is necessary to bear in mind that there is no single appropriate penalty, but rather a permissible range. The proposed penalty may be “an” appropriate penalty if it falls within that range: at [127]; fourth, the Court should generally recognise that the proposed penalty was most likely a result of compromise and pragmatism on the part of the regulator, and while the regulator must estimate the penalty necessary to achieve deterrence, the Court must assess the proposed penalty on its merits, being wary of the possibility that the regulator may have been too pragmatic: at [129]; fifth, the Court’s task is not limited to simply determining whether the jointly proposed penalty is within the permissible range, though that might be expected to be a highly relevant and perhaps determinative consideration. The overriding statutory directive is for the Court to impose a penalty that is determined to be appropriate having regard to all relevant matters: at [131].

Consideration

The nature and extent of the contraventions

47 It cannot be disputed that the contraventions of s 12DB(1)(g) and (i) are objectively very serious. So much is readily apparent from the SAFA.

48 I accept ASIC’s submission as to the characterisation of this conduct, and the reasons it advances.

49 First, the contraventions involved the making of false, misleading and deceptive representations in respect of common home and motor NRMA Insurance branded policies (amongst others) to consumers (ie, the Affected Customers) regarding the price of those policies, specifically the premiums and discounts those consumers would receive. Second, the consumers were at a relative disadvantage when compared with IAL, as they had no way of knowing whether the Discounts had been applied, and the way the information was provided to the consumers in the COI denoted that the full Discounts had been applied and that customers could verify this. Although Affected Customers’ personal circumstances would have varied greatly, many of the customers would have been low to middle income earners and more significantly affected by the conduct. Third, the significant length of time over which the contraventions occurred demonstrates one measure of the extent of the conduct. Fourth, the number of contraventions and number of Affected Policies and Affected Customers further demonstrate the extent of the conduct. Fifth, IAL is one the largest providers of these types of insurance policies in the market (those policies set out in Schedule 1 of the Orders), and NRMA Insurance is one of the most recognised and popular brands of such insurance in Australia. As a major insurer, who owes a duty of utmost good faith to its customers, customers would have relied on IAL to operate with integrity and in good faith. Customers would have expected that IAL would calculate and charge premiums to which they were entitled and consistently with its contractual arrangements.

The circumstances in which the conduct occurred

50 The nature and circumstances in which the contraventions occurred are detailed at SAFA [66]-[123].

51 The Cupping Mechanism was conceived, designed and implemented in the context of implementing the Go Discounts project: see SAFA [79]-[95].

52 ASIC highlights the following points. First, the very purpose and intended effect of the Cupping Mechanism was to reduce the actual discounts provided to customers whose premiums would have otherwise been reduced by more than the Cup. Second, the business need to introduce the Cupping Mechanism arose because IAL wanted to avoid the risk to revenue posed by the large discounts generated by the Go Discounts project. Third, IAL staff were aware before, during and after implementation of the Cupping Mechanism that the Cupping Mechanism would operate to reduce discounts. Fourth, it was also clear to some staff that because of the way the Cupping Mechanism worked that customers would not know that IAL had recalculated their premium unless IAL disclosed that fact. The team responsible for developing the Cupping Mechanism (the Rating Engine Enhancements project team) were aware of its effect on Affected Customers; other staff involved in the implementation of the Cupping Mechanism were aware of and raised concerns about its effect; and IAL was presented with several opportunities over the course of 2014 to 2016 to remove the Cupping Mechanism in the context of considering whether to adjust the level, or whether it should be removed in its entirety, to enable Affected Customers to more fully benefit from the Discounts offered by IAL. Fifth, despite all of the matters above, and despite that one of the very aims of the Go Discounts project was to improve transparency of premium and discounts provided, the issue of ensuring that the effect of the Cupping Mechanism on Discounts was apparent to customers was not directly addressed by any committee or forum responsible for initially approving the Cupping Mechanism. Sixth, it was not IAL who identified the issue of the effect of the Cupping Mechanism (initiating the chain of events that led to it being reported to ASIC and the conduct ceasing), but rather an external service provider. The Cupping Mechanism, or the non-disclosure of it, was not brought to the attention of anyone at Board level, despite the knowledge of others referred to above.

53 ASIC submitted that the above circumstances demonstrate an intention to develop, apply and maintain a process that reduced, and was intended to reduce, discounts to customers to the advantage of IAL, and without that reduction being visible to customers. ASIC submitted that the Cupping Mechanism was deliberately designed to reduce Discounts received by consumers (although accepted that the representations were not deliberately false). In those circumstances, having regard to the terms in which the COIs and PEDs were worded, it was incumbent on IAL to disclose these matters to consumers, so that they understood that in certain circumstances some consumers were not receiving the Discounts they would otherwise expect and were entitled to. ASIC submitted the seriousness of the failure to do so must be measured against the fact that various persons within IAL recognised the issue, knew how the Cupping Mechanism worked, and yet IAL failed to prevent the conduct from occurring.

54 I accept those submissions.

55 IAL submitted it was relevant to assessing the nature and circumstances of the contravention that the Cupping Mechanism was implemented in tandem with a second component of the automated process introduced into IAL’s pricing algorithm (the Capping Mechanism): SAFA [33]-[40]. IAL submitted that whereas the Cupping Mechanism imposed a limit on the maximum permitted decrease on a renewing customer’s premium, capping was the ‘flip side’ of that coin, being the maximum permitted increase on a renewing customer’s premium after a customer’s Discounts had been applied. The mechanisms operated in tandem to limit the extent to which renewal premiums could vary, up and down, year on year, designed to avoid ‘price shock’ for renewing customers. A renewing customer’s premium might be unaffected by either mechanism, or capping might reduce the premium payable by the customer, or (as was the case for the Affected Customers) cupping might cause the customer to pay a higher premium than they otherwise would have paid (including because the Discounts the customer was entitled to receive were not realised, either in full or in part).

56 IAL submitted that this was not a case where it contravened the law by charging fees for which it provided no services. The premiums charged were not suggested to be unreasonable or excessive by any objective measure, nor to be premiums that for any other reason could not properly be charged, provided the basis for them was properly represented and disclosed. The problem with IAL’s conduct, admittedly a very serious problem, was that it did not properly disclose the basis for the calculation of the premiums so that its conduct was misleading. Neither capping nor Cupping was disclosed. IAL submitted the failure to disclose capping and cupping was consistent with the position of both ASIC and IAL that there was no intent to mislead - the contraventions were not deliberate. IAL further submitted that to say that capping was implemented to further IAL’s financial interests to retain customers and increase or preserve revenue does not appropriately characterise the use or purpose of capping (and its interrelationship with cupping).

57 ASIC took issue with those submissions, given the nature of the contraventions in relation to cupping. It submitted that it was not possible for a policy held by an Affected Customer to be subject to the Cupping Mechanism and Capping Mechanism in any given year. Accordingly, no Affected Policy gained some benefit from capping in the same year. ASIC submitted that IAL had not quantified the extent to which customers affected by cupping were also affected by capping.. It also submitted that capping was implemented to further IAL’s financial interests to retain customers and increase (or, at the very least, preserve) revenue. This was said to be the same rationale for the introduction of the Cupping Mechanism, that is, that the absence of capping or the Cupping Mechanism would result in a loss of customers from increases or decreases in premiums of more than $100 and lower retention rates leading to revenue losses: SAFA [92], [95]. Each of cupping and capping were introduced by IAL to preserve revenue from a decline in gross written premiums if either (or both) were not introduced. Accordingly, ASIC submitted any comparison between the amounts by which premiums increased from cupping, against the amount by which premiums were reduced by capping during the same period, fails to measure the true financial position of IAL resulting from such conduct.

58 Although those submissions may be accepted, I accept IAL’s submission as to what the failure to disclose capping or cupping says of the state of mind of IAL in implementing cupping, namely, that there was no intent to mislead. That fact is not in issue.

The amount of loss or damage suffered and extent of profit from the contraventions

59 This loss is summarised above at [13]-[14], and relevant information detailed at SAFA [63]-[65] and [126]-[130] (which includes details of IAL’s revenue).

60 The total amount overcharged to customers in the Penalty Period was $35,393,000 (and $60,223,000 over the Relevant Period). It is plain from those figures that the number of Affected Customers and the size of the combined losses in the tens of millions of dollars is significant. It is also plain that when customers incurred losses because the Discounts were not passed on in full, the Cupping Mechanism was operating to increase or preserve IAL’s revenue, which was a key consideration for implementing the Cupping Mechanism: SAFA [90].

61 ASIC also submitted that not only did IAL obtain the benefit of the inflated premiums, but it retained a significant number of customers who, had they been properly informed that they were not in fact being given the full Discounts to which they had otherwise become entitled and which they were led to believe they were receiving, may well have chosen to leave IAL and seek an alternative provider of the relevant insurance policy. From IAL’s perspective, this is the potential loss of business from failing to retain customers. From the customers’ perspective, this is the unquantifiable potential harm of hundreds of thousands of consumers not being told of the true nature of the Discounts they were receiving. This is the lost opportunity of those consumers to consider changing insurers during the Relevant Period, had they known the true position. I accept ASIC’s submissions in this regard, and that the penalty to be imposed should account for IAL maintaining and profiting from the Cupping Mechanism over a lengthy period of time.

Size and financial position

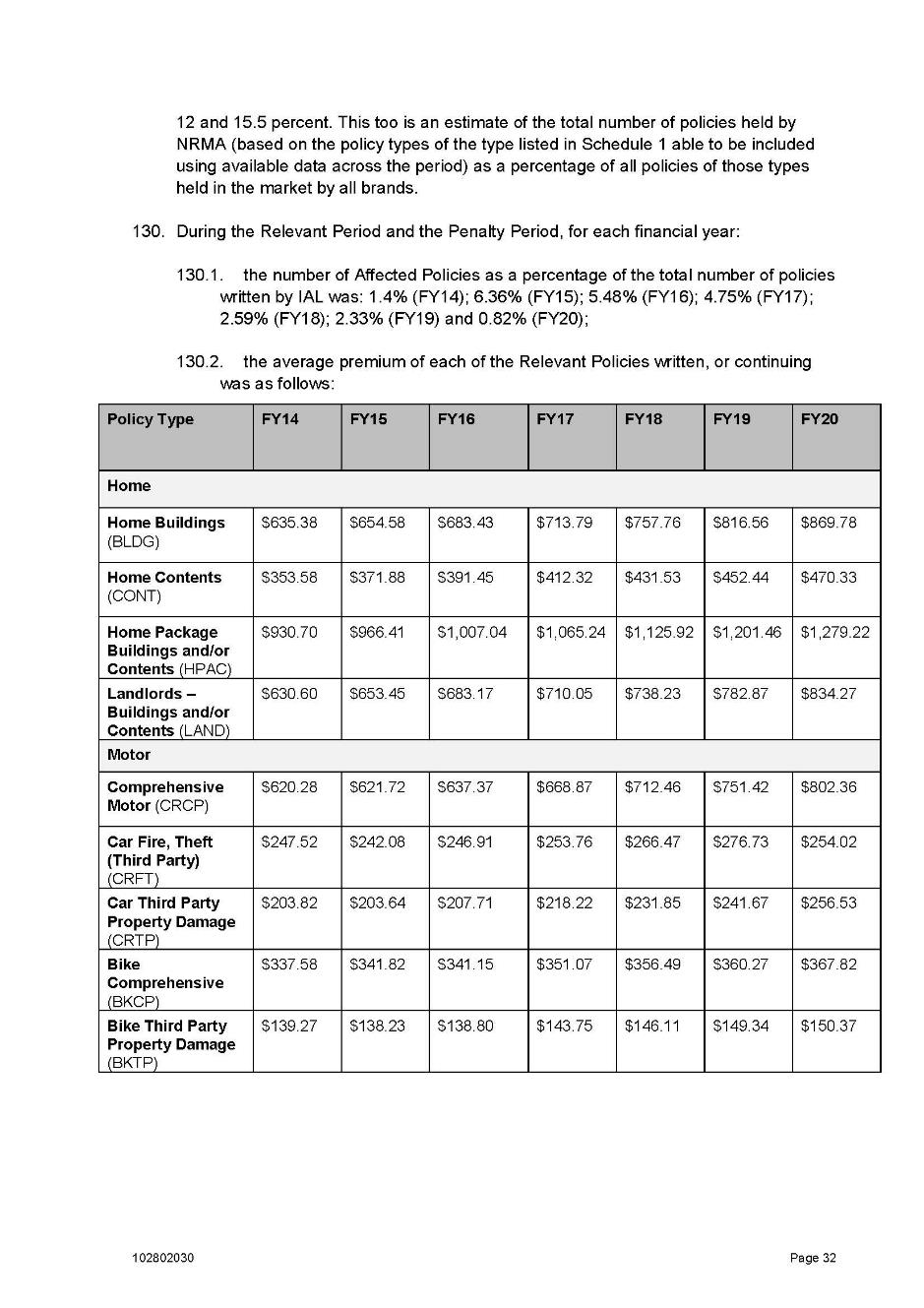

62 This is detailed at SAFA [8] and [126]-[130].

63 IAL is wholly owned by Insurance Australia Group Limited (IAG), which is a multinational insurance company and the largest general insurance company in Australia and New Zealand. During the Relevant Period, IAL held a significant part of the market share, being between around 17 – 23% of the Australian market for the types of policies represented by the Relevant Policies, and had significant assets and annual revenue: SAFA [127]-[128].

64 As submitted by ASIC, it is plain that IAL’s financial position and size are relevant to the issue of deterrence in determining an appropriate pecuniary penalty. I also accept that there is no evidence to suggest that IAL could not pay the penalty proposed by ASIC, despite recent losses, particularly having regard to the financial position of the group (ie, IAG).

Deliberateness of the conduct

65 ASIC does not submit that the representations made by IAL that were misleading and deceptive were deliberately or intentionally made in breach of the law, as IAL did not implement the Cupping Mechanism with the intention or purpose of misleading consumers. However, ASIC again noted the intended design, purpose and operation of the Cupping Mechanism, and the knowledge and concerns of staff within IAL, as addressed above at [53]. In those circumstances, it submitted that it can be inferred that it should have been obvious to IAL that if the COI only presented the figures that were said to be those with discounts applied, that consumers would be misled as to the discounts they were being provided. Accordingly, IAL ought to have known that it was likely to be misleading customers as to the way in which it was calculating customers’ premiums and applying discounts.

66 That is plainly correct, as is ASIC’s submission that this aspect of IAL’s conduct forms part of the circumstances relevant to the assessment of the relevant penalty.

The seniority of those involved

67 ASIC acknowledges that the Board was not aware of the Cupping Mechanism in the Relevant Period. That said, it submitted there were several senior staff members involved in the implementation of the Cupping Mechanism and the failure to remove it, including the CEO Personal Insurance between 2013 and 2015, and the Executive General Manager Product and Pricing, whom reported to the former, which is detailed at SAFA [131]-[139]. IAL accepts that some of the staff in the Product and Pricing Team understood the operation of cupping and were aware of its effects including on Discounts. However, it reiterated that IAL did not implement cupping with the intention or purpose of misleading consumers.

68 IAL queried the description of some of the persons as “senior” staff, when considering the structure of the organisation. It submitted that only the roles of CEO Personal Insurance and Executive General Manager Product and Pricing are accurately described as senior management roles. Roles below the rank of Executive General Manager Product and Pricing were not “senior management” roles in either IAL or IAG during the Relevant Period, even though some of them contain the word ‘senior’ in their title. Little turns on this. There were some senior staff and persons who ought to have known what was occurring. Persons in the position of implementing such schemes were given the responsibility to do so, including ultimate decision-making on the resolution of issues/risk and accountability for program outcomes. IAL also submitted that ASIC’s submission as to senior management must be read in light of the absence of evidence that the relevant senior managers were aware of IAL’s failure properly to inform customers of the effect of cupping on the value of the Discounts they would receive. That submission ignores that the senior staff that were involved in implementing the Cupping Mechanism ought to have known what was occurring.

Corporate culture

69 ASIC accepts that IAL has sought to strengthen its compliance and risk management culture and processes since reporting the conduct to ASIC in 2019: see SAFA [140]-[156]. I accept that the steps taken by IAL since removing the Cupping Mechanism are demonstrative of genuine steps to embed a culture of compliance.

Cooperation

70 These matters are detailed at SAFA [157]-[159].

71 ASIC accepts four mitigating factors relevant to the assessment of penalty in this case.

72 First, IAL has engaged constructively with ASIC since these proceedings commenced, including by making early admissions in relation to its conduct as set out at SAFA [158]. ASIC also noted that while IAL was also cooperative with ASIC before the commencement of the proceedings throughout the investigative process, consistent with its obligations as an AFSL holder, responding to compulsory notices is not cooperation of a kind that ought greatly to resonate in mitigation, as the law requires this: SAFA [157]. However, IAL is entitled to consideration for saving the community the costs of a lengthy trial. Second, IAL has undertaken a comprehensive remediation program to remediate customers for the application of the Cupping Mechanism, in accordance with the compensation arrangements is it legally required to have in place under s 912B of the Corporations Act: SAFA [149]-[152]. By at least 16 March 2023, payments to all Affected Customers had been issued, subject to limited exceptions: Further Supplementary Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions [2]; SAFA [154]. Third, IAL has apologised for its conduct to Affected Customers, to the public at large on the commencement of these proceedings and to its shareholders as part of its FY21 results: SAFA [159]. I note that IAL reiterated in this Court its deep regret for what had happened. Fourth, since identifying and reporting the conduct to ASIC in September 2019, IAL has taken steps to review its pricing promises and systems through the establishment of the Pricing Taskforce: SAFA [145]-[148].

73 IAL submitted that once members of IAG’s Group Leadership team were made aware of the effect of cupping on Discounts in 2019, IAL took steps to notify ASIC, remove cupping, commence remediating customers and undertake a structural program of pricing changes: SAFA [135], [121]. On 14 May 2019, an external service provider, who had encountered an issue with the operation of cupping at another insurer, alerted IAL: SAFA [119]. IAL subsequently undertook investigations to ascertain whether the same issue existed in its own brands and if so, in which brands and to what extent: SAFA [120]. Following that investigation, IAL reported the conduct to ASIC on 9 September 2019 pursuant to its obligations under s 912D of the Corporations Act: SAFA [121]. IAL removed the Cup (though not the cap) shortly afterwards from 26 September 2019: SAFA [121], [122].

74 Thereafter, IAL submitted, it promptly commenced work on a remediation response, starting with the establishment of a Pricing Taskforce, charged with reviewing and rectifying IAG’s pricing practices (including those of IAL) as necessary: SAFA [145]. That work was self-initiated by IAG and IAL: SAFA [157]. The SAFA details the steps taken by IAG and IAL since 2019 at [140]-[156]. The remediation program, as IAL submits, speak to IAL’s contrition and its determination to take responsibility for its contraventions in a timely and appropriate manner, citing Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation [2019] FCA 2147 at [285]. It submitted that on the filing of the Concise Statement, IAL immediately and publicly apologised for its failings, acknowledged that its conduct was significant and unacceptable, and stated that it was working to put things right for its customers as soon as possible. By its Concise Response, IAL promptly admitted contraventions. Those are all additional matters that evidence IAL’s contrition. I accept those submissions.

75 I also accept that IAL has undertaken extensive reform directed at ensuring that the contravening conduct is not repeated.

Previous similar conduct

76 IAL has not previously been found to have engaged in any contravention of the ASIC Act or the Corporations Act: SAFA [125].

77 That said, I accept ASIC’s submission it should be recognised that this conduct was not isolated, in the sense it continued for a significant period of time and across each of the Relevant Policies under the NRMA Insurance brand.

Course of conduct

78 ASIC submits IAL should be penalised for one course of conduct in the application of the Cupping Mechanism to the Relevant Policies throughout the Penalty Period. ASIC recognises that the factual substratum with respect to the representation is “unitary” and can be traced back to a single homogenous cause, citing MLC Nominees at [176].

79 Consequently, it is appropriate that a single penalty be imposed for the multiple contraventions involved in the proceeding.

Summary of submissions

80 ASIC submitted that, having regard to the circumstances outlined below, a very substantial penalty is required in order to fulfil the primary aim of deterrence. That IAL has undertaken and completed remediation of those Affected Customers, made changes to its corporate governance, and cooperated with ASIC in respect of these proceedings, does not alter the seriousness of the contraventions and the fact that corporations in IAL’s position must take better care to ensure such contraventions do not occur in the first place, rather than cleaning up afterwards. ASIC outlined that the circumstances included:

(a) the very serious nature of the contraventions involving the making of false, misleading and deceptive representations to over 600,000 Affected Customers over a significant period of 5½ years, with over 700,000 Affected Policies, and comprising about 1,785,000 individual contraventions (including the subsequent year impact described above);

(b) that the contraventions resulted in Affected Customers not receiving represented discounts in an amount of $60,223,000 (and when including GST, Stamp Duty and FSL, $71,436,974), where the total premiums paid by Affected Customers was $1,130,060,539;

(c) that while Affected Customers’ personal circumstances would have varied greatly, many of the customers would have been low to middle income earners and more significantly affected by the conduct;

(d) the position of trust held by IAL in society, in particular in respect of its brand NRMA Insurance, and all the more in circumstances where the law imposes an obligation of utmost good faith between the insurer and the insured;

(e) that those customers had no way of knowing about the false, misleading and deceptive conduct;

(f) that, from IAL’s perspective, if the fact of the implementation of the Cupping Mechanism had been disclosed, and its effect on premiums and discounts stated, over $1 billion in premium revenue might have been “in play”, ie some customers may have chosen to not renew those policies and sought insurance from another provider (as IAL indeed anticipated);

(g) that during the term of the Relevant Period, IAL earned between $260M and $930M per annum in profit, in circumstances where the business from the Relevant Policies comprised approximately 60% of IAL’s business;

(h) the fact that the contraventions came about in circumstances where the introduction of the Cupping Mechanism was intended to cause (and did cause) the reduction in Discounts which were then not disclosed to customers on renewal of premiums;

(i) the fact that the effect of the contravention was not just a one-off but would have repeat consequences in subsequent years;

(j) that one of the very aims of the Go Discounts project was to ensure transparency in disclosing the customers’ entitlements to Discounts, and to review the customer collateral documentation to be provided to renewing customers as part of the project;

(k) that having regard to the purpose and effect of the introduction and implementation of the Cupping Mechanism, and the goal of transparency in customer documentation, it ought to have been obvious to IAL (including its relevant senior management) that the process by which the Cupping Mechanism was being introduced and its effect would be hidden by the proposed documentation to be provided to renewing customers;

(l) the fact that, in those circumstances, persons within IAL recognised the very issue the subject of the contraventions, and other persons recognised that the application of the Cupping Mechanism would be hidden by the nature of the information and calculations shown to renewing customers via the proposed COI (i.e. “the numbers would add up”) but IAL still failed to have in place sufficient processes and governance as to ensure that the Cupping Mechanism was disclosed to customers or that consumers were not otherwise misled as to their premiums and Discounts; and

(m) the fact that the relevant failures included by persons who were within senior management of IAL, and IAL recognises the failures in the roles of relevant senior management in their “involvement in matters relevant to the multi-year pricing-related issues where discounts were not always applied in full to premiums for all customers who may have been eligible, which has resulted in adverse customer outcomes and material remediation costs”.

81 IAL submitted this is a case where the parties agree that a civil penalty of $40 million is appropriate. The Court should be satisfied that a penalty in that amount will be more than sufficient to achieve the object of deterrence for the reasons outlined in ASIC’s submissions and the matters referred to by IAL in its submissions. It submitted those reasons include the following:

(a) at the heart of the contravening conduct is IAL’s failure to disclose the effect of a particular pricing mechanism (cupping) on the Discounts customers would have reasonably expected to receive;

(b) the IAL board was not involved in approving or implementing cupping or the misleading conduct;

(c) although senior management was involved in approving the implementation of cupping, there is no evidence to suggest that those persons were aware of, or involved in, IAL’s failure to properly disclose the impact of cupping on the value of the Discounts received by customers whose premiums had been affected by the cup;

(d) it is accepted that there was no intention to mislead;

(e) once IAL was made aware of the potential issue in May 2019, IAL (and IAG) took action to investigate it, to report the issue to ASIC, cease the use of cupping, comprehensively remediate customers, impose sanctions via executive remuneration (a step taken by IAG’s Board), and implement substantive changes to pricing and disclosure practices and remuneration, risk and compliance systems, including IAG initiating a broader consideration of pricing through its Pricing Taskforce; and

(f) while the conduct was serious (and IAL has acknowledged it as such), Pattinson directs the Court to set a penalty at a level no greater than sufficient to deter future contraventions (rather than a penalty which is proportionate to the seriousness of the conduct). The evidence permits a finding that, even without a substantial penalty, IAL is deterred. A $40 million penalty will remove any doubt as to specific deterrence and secure the goal of general deterrence.

Further consideration

82 Having considered the facts as agreed, the submissions of the parties, the evidence relied on, the contraventions and relevant principles, I am satisfied that it is appropriate to order the pecuniary penalties in the amount agreed.

83 The detailed SAFA filed by ASIC and IAL reflect that they have given close and careful consideration to the relevant issues, to the appropriate declarations, orders and pecuniary penalties. Relevantly, ASIC is a specialist regulator. In that context, in DFWBII the High Court at [60]-[61] noted the relevance of a specialist regulator being able to offer “informed submissions as to the effects of contravention on the industry and the level of penalty necessary to achieve compliance”, albeit that such submissions will be considered on the merits in the ordinary way.

84 It is self-evident from the conduct described in the SAFA, as summarised above, that the seriousness of the contraventions warrants a significant penalty. The number of Affected Customers impacted by the conduct and the size of the combined losses in the tens of millions of dollars plainly reflect this. As to the circumstances of the contraventions, I refer in particular to, without repeating [8]-[15], [49]-[54].

85 It is important to recognise that deterrence is the primary consideration, and as such, it is necessary to impose a penalty of sufficient size to act as a strong deterrent to ensure IAL and others do not treat the risk of non-compliance as a mere cost of doing business.

86 In the circumstances of this case, the agreed penalty is appropriate to reflect the seriousness of the contravention, yet recognise the mitigating factors present, as described above. I am conscious that there is no one appropriate remedy, but a permissible range of penalties. The Court is to impose a penalty that is appropriate having regard to all relevant matters. I am satisfied of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the agreed penalty proposed is an appropriate remedy in all the circumstances. Having considered totality, I find the proposed penalty amount does not exceed what is proper for the entire contravening conduct. Accordingly, in this case it is highly desirable for the Court to accept the parties’ proposal and impose the proposed penalty: Volkswagen at [126]. I am satisfied that in the circumstances, the agreed penalty of $40 million satisfies the significant element of deterrence required. It carries a sufficient sting to ensure that the parties or others do not regard the penalty amount as an acceptable cost of doing business. Weighing all the relevant factors, bearing in mind the protective and deterrent purpose of a pecuniary penalty, as applied to the facts of this case, I am satisfied that agreed penalty is appropriate.

Adverse publicity order

87 The Court has power under s 12GLB(1)(a) of the ASIC Act (as in force prior to 13 March 2019) to make an adverse publicity order, as defined in s 12GLB(2), against a person who has been ordered to pay a pecuniary penalty under s 12GBA(1) (as in force prior to 13 March 2019).

88 The purposes of an order made under s 12GLB include: first, to alert affected persons to the fact that there has been misleading conduct; second, to protect the public interest by dispelling the incorrect or false impressions that were created; and third, to support the primary orders and assist in preventing repetition of the contravening conduct: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Commonwealth Bank of Australia (No 2) [2021] FCA 966 (ASIC v CBA (No 2)) at [12]-[15]; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Colonial First State Investments Ltd [2021] FCA 1268 at [84]; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd [2022] FCA 1251; (2022) 164 ACSR 428 at [238].

89 The particular audience of the information must be considered in determining the method and mode in which the communication required by the order is made: ASIC v CBA (No 2) at [16].

90 There is no dispute between the parties that: an order should be made under s 12GLB(1)(a) of the ASIC Act for the publication of a notice by IAL; the content and form of the notice to be published; that within 30 days from the date of the order, the notice should be published by displaying a link to a PDF or webpage copy of the notice in an immediately visible area on NRMA Insurance’s website homepage for a period of 90 days; and that IAL should also send the notice to (at least) the cohort of Affected Customers who remain customers of IAL, by post or email (depending on the selected preference of the customer to receive post or emails). For completeness, I also note the parties agreed the time period relevant to the cohort to receive any written notice differed slightly from the Relevant Period, being 28 April 2014 to 3 November 2019. This reflects that the first and last policy renewals to which the Cupping Mechanism applied occurred slightly after cupping commenced and ceased.

91 However, an issue remained as to the scope of the customer cohort receiving the notice, namely, whether the notice should be sent to all customers who were and who could have been directly affected by IAL’s conduct (ASIC’s position), or whether it should be sent to only those customers who were in fact affected (IAL’s position). Further the parties contested whether the notice should be distributed with the documents comprising the Renewal Offer (ASIC’s position), or whether it should be sent as a stand-alone communication (IAL’s position).

ASIC’s submissions

92 ASIC highlighted the purpose of such orders, as referred to above at [88]. Those purposes are both punitive and protective. In reflecting the punitive purpose, an order should not just serve the notion of deterrence, but should also represent “a condign curial response to what has occurred”: ASIC v CBA (No 2) at [13]. ASIC also focussed on the importance of the audience in fashioning the order to ensure the statutory purpose of the power is served. The way in which the audience will more readily digest and understand the information is relevant: ASIC v CBA (No 2) at [17].

93 In that context, ASIC submitted that those customers who held Relevant Policies during the Relevant Period should be notified of the contravening conduct as a proper matter to consider when deciding whether to renew their existing policies.

94 As to the cohort, ASIC submitted that it is appropriate that those who could have had (albeit did not have) the Cup applied be made aware of IAL’s contravening conduct, in order to achieve the punitive and protective aims of the order under s 12GLB(1)(a). First, the Cupping Mechanism was indiscriminate in its operation; if the Cup was triggered, it would apply to reduce Discounts. That is, IAL’s conduct is directly relevant to these people as it either did affect them, or could have affected them. Second, the reason for the introduction of cupping was to retain customers (or prevent customer churn). It is said that if IAL had not engaged in misleading conduct and instead had disclosed that the Cupping Mechanism was applied to all of the Relevant Policies during the Relevant Period, some of the customers who held such policies (whether ultimately affected or not) might have considered not renewing such policies and changing insurer. Those customers should be notified of the conduct engaged in by IAL. ASIC submitted, contrary to IAL’s submission, there was no evidence that distributing the notice to a wider cohort including customers who were not directly affected, would lead to any confusion for those recipients. In oral submissions responding to IAL, ASIC further submitted the letter that went to customers as part of the remediation process was deficient and that it was important people are properly told what happened.