Federal Court of Australia

Aravanis (Trustee) v Kapp, in the matter of the Bankrupt Estate of Kapp [2023] FCA 702

ORDERS

ANDREW ARAVANIS & ANDREW CLARK AS TRUSTEES IN BANKRUPTCY OF THE BANKRUPT ESTATE OF PHILIP JAMES KAPP Applicants | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties provide a minute of order giving effect to these reasons within 14 days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 853 of 2019 | ||

IN THE MATTER OF THE BANKRUPT ESTATE OF PHILIP JAMES KAPP | ||

BETWEEN: | ANDREW ARAVANIS AND ALEXANDER CLARK AS TRUSTEES IN BANKRUPTCY OF THE BANKRUPT ESTATE OF PHILIP JAMES KAPP Applicants | |

AND: | TWIN INVESTORS PTY LTD ACN 608 534 505 AS TRUSTEE OF THE TWIN TRUST First Respondent MARYANN KAPP Second Respondent PHILIP JAMES KAPP, AS TRUSTEE OF THE TWIN TRUST Third Respondent | |

order made by: | PERRAM J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 28 June 2023 |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The Applicants are entitled to 35.94% of the proceeds of sale of the Swan Bay property.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. Mr Kapp, in his capacity as the trustee of the Twin Trust, pay to the Applicants out of the proceeds of sale of the Swan Bay property and, if necessary, the Main Beach property any shortfall between that 35.94% share and the sum of $151,250.01.

3. The Applicants’ entitlement under Order 2 be secured by a charge over the proceeds of sale of the Swan Bay and Main Beach properties.

4. The Applicants’ proceeding be otherwise dismissed.

5. Each party pay their own costs.

6. The First Respondent be removed as a party to the proceeding.

7. The name of the Third Respondent be changed to ‘Philip James Kapp, as trustee of the Twin Trust’.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRAM J:

1 These reasons deal with two different suits brought by the trustees in bankruptcy of Philip Kapp. The first suit Aravanis (Trustee) v Kapp, in the matter of the Bankrupt Estate of Kapp concerns the bankruptcy trustees’ claims on the sale proceeds of a home at Wahroonga held in the name of Mrs Maryann Kapp. The second suit concerns the same trustees’ claims on the sale proceeds of some properties held by a family trust associated with Philip Kapp. The second was argued sometime before the first. There are issues concerning issue estoppel arising from the existence of these two parallel proceedings which I resolve in these reasons. In order to avoid the prospect of two appeals and given that both cases arise out of the bankrupt’s insolvency and are interrelated, I have handed them down together.

Aravanis (Trustee) v Kapp, in the matter of the Bankrupt Estate of Kapp

NSD 928 of 2021

Introduction

2 Mr Philip James Kapp is married to Mrs Maryann Kapp although they are now separated. Without any disrespect intended, I will refer to Mr Kapp as Philip and Mrs Kapp as Maryann. On 4 March 2019 Philip became bankrupt on his own petition. The trustees in bankruptcy of Philip's bankrupt estate now sue Maryann. Their suit concerns the proceeds of sale of the former family home at Boundary Road in Wahroonga, a suburb of Sydney. That property was sold on 11 August 2021 for $4,150,088.00. Out of its proceeds of sale, and following the payment of some other debts, $616,819.00 is presently being held in the trust account of Maryann's solicitors. There are undertakings in place which limit further disbursal of these funds pending the outcome of this litigation.

3 The bankruptcy trustees' case has two limbs. The first relates to their claim on $232,433.60 of the sale proceeds. The manner in which they pursue this claim turns on their ability to trace that sum through a number of property transactions back to a disposition of Philip's property to Maryann in 2010. The bankruptcy trustees submit this disposition is void against them either pursuant to s 121 of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (‘Bankruptcy Act’) or s 37A of the Conveyancing Act 1919 (NSW) (‘Conveyancing Act’). In chronological order, the transactions are:

(a) Philip's transfer to Maryann of a 50% interest in a property in Leura in the Blue Mountains on 18 May 2010 (the impugned transaction);

(b) the purchase of a family home in Turramurra on 3 May 2011 in Maryann's name using funds which included a bridging loan in the amount of $230,700.00;

(c) the sale by Maryann of the Leura property on 12 September 2011 and the use of part of the proceeds of that sale to repay the bridging loan of $230,700.00 on the Turramurra home;

(d) the sale by Maryann of the home at Turramurra on 21 June 2013 and the realisation of net proceeds of that sale of $362,340.64;

(e) the purchase of another family home at Wahroonga in Maryann's name on 23 August 2013 for $2,400,000.00 funded, in part, from the proceeds of the sale of the Turramurra home; and

(f) the sale by Maryann of the home at Wahroonga on 11 August 2021 and the realisation of the proceeds of sale now subject to the bankruptcy trustees’ claims.

4 Both Turramurra and Wahroonga were registered in the sole name of Maryann. It is this fact which gives rise to the second limb of the bankruptcy trustees' case, which is that they are entitled to 50% of the net proceeds of sale of Wahroonga. The first reason advanced for this claim is that Maryann held her interest in Wahroonga subject to a constructive trust in favour of Philip. The constructive trust was itself pursued on two bases: (i) it was Philip and Maryann's common intention at the time she acquired Wahroonga (and, before it, Turramurra) that she would hold the property for their mutual benefit; or (ii) Philip and Maryann were engaged in a relationship, Philip provided the financial contributions which resulted in the property being in Maryann's name, the relationship had now ended and it would be unconscionable for Maryann thereafter to maintain that the property was entirely hers without recognising the role of Philip's contributions: Baumgartner v Baumgartner (1987) 164 CLR 137 (‘Baumgartner’).

5 The second reason for which the bankruptcy trustees claim a 50% interest in Wahroonga (and, if it be relevant, Turramurra) is that Philip's intention in arranging to put Turramurra, and then Wahroonga, into Maryann's name was to defeat the claims of his creditors. They submit that by doing so, Philip disposed of his property to her and that these dispositions are void against them by reason of s 121 of the Bankruptcy Act and s 37A of the Conveyancing Act. The bankruptcy trustees did not articulate in their written or oral submissions any claim against Maryann other than that the sale proceeds in her hands belong in equity to them. For example, they did not suggest that Maryann had breached her duties as constructive trustee by using the trust funds for her own benefit.

6 Whilst the bankruptcy trustees' claims have these two broad limbs, it is to be observed that as a matter of private law they may be seen to fall into two different categories. The first consists of claims that Philip has in equity against Maryann. These claims arise independently of his bankruptcy and only because Philip's rights against Maryann in relation to them happen now to have vested in the bankruptcy trustees in consequence of the sequestration of his estate. The second category consists of rights arising out of the administration of his bankrupt estate which relate not to pre-existing substantive rights of his but, rather, as an aspect of the bankruptcy itself; that is to say, as part of the mechanism for collective execution against the property of a debtor by creditors whose rights are admitted or established: Cambridge Gas Transport Corporation v Official Committee of Unsecured Creditors of Navigator Holdings plc [2007] 1 AC 508 at [14]-[15].

7 It is therefore useful to distinguish those claims which Philip has against Maryann in equity (now vested in the bankruptcy trustees) from those claims which the bankruptcy trustees have in their own right under s 121 of the Bankruptcy Act and s 37A of the Conveyancing Act. Another way of putting this is to distinguish between those claims the bankruptcy trustees have as a result of Philip's own rights devolving upon them and those they have which have not devolved in that fashion.

8 Maryann disputes the existence of Philip's claims in equity against her. In relation to the bankruptcy trustees’ statutory claims under s 121 and s 37A, Maryann submits that those provisions are not enlivened. Put in very general terms, the applicability of those provisions turns on the ability of the bankruptcy trustees to demonstrate that Philip either intended to defeat the claims of his creditors or was insolvent when the three dispositions of property which they attack – Leura, Turramurra and Wahroonga – occurred. The bankruptcy trustees submit that, at these times, Philip had significant current or prospective debts to the Commissioner of Taxation which make it more likely than not that Philip was seeking to defeat the claims of his creditors or that he had become insolvent.

9 For her part, Maryann submits that no property of Philip's may be traced into her hands. She says that previous family homes long before those at Turramurra and Wahroonga had been in her name and that this reflected an intention on the couple's part that the family home was for her and the children. There was evidence that an early decision was made to put the family home in her name to guard against unexpected partnership liabilities that might be incurred by Philip. Turramurra and Wahroonga were simply repetitions of that practice funded by Maryann's ownership of previous family homes. No property of Philip's was therefore disposed of when Turramurra and Wahroonga were purchased in her name. She notes that the bankruptcy trustees do not seek to attack her ownership of the family homes which preceded Turramurra and Wahroonga and that this means that the case against her in relation to Turramurra and Wahroonga makes no sense.

10 Leura was not a family home and was in their joint names until Philip transferred his half interest to her. Maryann says that Philip already held his half for her so his transfer of it was not a disposition of his property. Alternatively, she submits that she paid consideration for that transfer.

11 If any of the three transactions involved dispositions of Philip's property which, if void, can be traced into her hands, Maryann then submits that they are not void. This she does on the basis that Philip was not insolvent at the relevant times and that it was his intention to provide for his family rather than to defeat his creditors. The determination of Philip's intentions is complicated by the fact that at the time when some of the transactions occurred he was living with a diagnosis of a terminal condition from which he was not expected to recover. As it happens, he did recover. The determination of his intentions is also complicated by the fact that Philip did not give evidence in these proceedings.

12 The bankruptcy trustees submit that Philip was in Maryann's camp for the purposes of these proceedings and that her failure to call him to give evidence about what his intentions had been should redound to her disadvantage in the Court's assessment of his intentions. Maryann, on the other hand, says that her relationship with Philip has broken down and that it is not reasonable to expect her to have called him.

13 If any of the bankruptcy trustees' claims on the Wahroonga sale proceeds should find their mark, Maryann pursues two freestanding defences. First, she says that she is entitled to have brought to account for her benefit the fact that, as Philip's surety, she paid some of his tax debts and legal fees out of her interest in Wahroonga and if, contrary to her primary case, Philip (and now the bankruptcy trustees) owned some part of Wahroonga, then she is entitled to be repaid those expenses by Philip (now the bankruptcy trustees) out of his share in Wahroonga. As such, she asserts that she is entitled to a charge on any interest the bankruptcy trustees establish in the sale proceeds to secure Philip's obligation to indemnify her; that is to say, she claims an equity of exoneration in the proceeds of sale. She also claims a right of exoneration out of the Wahroonga proceeds because, as surety, she paid some legal expenses of Philip’s which his solicitors had secured against Wahroonga.

14 Second, she submits that the bankruptcy trustees have already sued her once in separate proceedings they brought against a family trust (known as the Twin Trust) without at that time raising these claims. She contends that it was unreasonable for the bankruptcy trustees not to have raised their present claims in the Twin Trust proceedings so that they are now estopped from bringing them in this proceeding: Port of Melbourne Authority v Anshun Pty Ltd (1981) 147 CLR 589 (‘Anshun’). In response, amongst other matters, the bankruptcy trustees submit that at the time of the Twin Trust proceedings it was not known that there would be any equity in the Wahroonga property after the claims of the mortgagees were met and it was therefore not unreasonable for them not to bring claims which, at that time, appeared pointless.

15 In their written submissions, the bankruptcy trustees pursued personal claims against Maryann for sums which exceed the remaining proceeds of sale for Wahroonga. The rights asserted on Philip's behalf against Maryann give rise only to proprietary remedies; in this case, the property is the proceeds of sale for Wahroonga. Likewise, the attempt by the bankruptcy trustees to void particular transactions of Philip's may have the result that some property of Maryann's should belong to them. But on no view do either set of claims give the bankruptcy trustees in personam rights against Maryann extending beyond her rights to the proceeds of sale for Wahroonga. This aspect of the bankruptcy trustees' claims is misconceived and need not be mentioned again.

16 A useful order in which to consider the issues which arise is as follows:

(1) First, to give an account of the history of Philip and Maryann's relationship including the property transactions into which they entered and to consider the issues of tracing which underpin the bankruptcy trustees' claims relating to Leura.

(2) Second, to examine Philip's (and subsequently Maryann's) relationship with Philip's principal creditor, the Commissioner of Taxation. These events conclude with the settlement of some litigation between Maryann and the Commissioner at the time at which Philip and Maryann separated. The litigation concerned the Commissioner's attempts to obtain possession of the Wahroonga property under a second mortgage in his favour which secured, as against Maryann, a large part of Philip's very considerable tax debt. It was the settlement of this litigation in June 2021 on terms largely favourable to Maryann that gave rise to surplus funds in Maryann's hands upon the sale of Wahroonga.

(3) Third, to make findings about the reasonableness of the bankruptcy trustees' decision to commence their current proceeding against Maryann in relation to the surplus only after the sale of Wahroonga.

(4) Fourth, to make findings about Philip's intention in alienating to Maryann his half interest in Leura on 18 May 2010 and Philip and Maryann's intentions in placing Turramurra and Wahroonga in her sole name.

(5) Fifth, to determine the bankruptcy trustees' claims for a constructive trust over the sale proceeds of Wahroonga.

(6) Sixth, to determine the bankruptcy trustees' claims under s 121 of the Bankruptcy Act and s 37A of the Conveyancing Act in relation to each of Leura, Turramurra and Wahroonga.

(7) Seventh, to assess the extent to which Maryann is entitled to an equity of exoneration out of the sale proceeds for the sum of $480,000.00 which she says was contributed by her to the payment of Philip's tax debt, and $110,000.00 which she contends was paid by her for his legal fees in the Twin Trust litigation.

(8) Lastly, to examine Maryann's submissions concerning Anshun estoppel.

The history of Philip and Maryann's household

17 In what follows, I sketch the important features of their relationship from its commencement to its end. Although an important part of the case turns on Philip's relationship with the Commissioner of Taxation, it is convenient, at least at this stage, to leave the Commissioner out of the picture and only to overlay his role once a complete account of Philip and Maryann's transactions has been given.

18 Maryann first met Philip in 1995 when she worked as his secretary at Anderson Legal where he was then the managing partner. In 1999, Philip moved to Minter Ellison as the senior partner of their private equity group and Maryann went with him. At this time, Maryann was in a de facto relationship with another man and, in around 2000, she resigned from Minter Ellison to move to Western Australia with that man. There she began working in temporary secretarial roles. She returned to Sydney in about 2001 where she continued to work in temporary secretarial roles.

19 She and Philip then began to see each other in 2001. Philip had previously been married to Ms Shelley Kapp (who, with no disrespect, I will refer to as Shelley) but I infer that that marriage had ended by this time. During her formal examination by the bankruptcy trustees, Maryann gave evidence that she and Philip had begun to cohabit in January 2002. At that time, she did not have any assets of significance of her own.

20 In 2002 Andersen Legal closed following the collapse of Arthur Andersen in the wake of the Enron scandal. At this time Philip did not work there, having moved to Minter Ellison some years before in 1999. The significance of the closure of Arthur Andersen relates to evidence which I later discuss about protecting Philip's assets from partnership liabilities such as those generated by the Enron scandal.

21 Early in 2003, Maryann ceased working.

22 In September 2004, prior to the purchase of any properties by Philip and Maryann, Philip purchased a property at Belrose for his former wife, Shelley, and agreed with Shelley that he would make all the repayments on the loan for that property.

23 The first property purchased by Philip and Maryann was a property in Leura which they purchased as joint tenants. This occurred on around 22 November 2004 for a purchase price of $585,000.00. Of that purchase price, some $525,000.00 was provided by the Commonwealth Bank of Australia by way of a loan secured by a registered first mortgage.

24 Maryann gave evidence that her principal reason for wanting to purchase a property in Leura was that her brother and mother lived there. Her father had died in July 2004 and she said that she wanted to be able to spend as much time as she could with her family and, I would infer, to be near her mother following the death of her father. I accept this evidence. It is unclear to me the complete extent to which Philip and Maryann lived at this property. Philip's work would not have permitted him to commute from Leura and I incline to the view that it was a property used on an intermittent basis, possibly on the weekends or during vacations. This conclusion is consistent with Maryann's evidence that between September 2006 and March 2007, her brother and his family lived in the Leura property whilst renovation work was done at their own property.

25 On 18 February 2005 Maryann and Philip were married. By this time, Philip had left Minter Ellison to join Clayton Utz as a senior partner and was in receipt of substantial remuneration. Whilst it is unclear on the evidence where Philip and Maryann were living from early 2002, it appears that from 31 October 2005 until their separation in April 2021 they lived in a succession of properties each of which served as their home. Two of these homes do not appear to have been owned by them and I infer were rental properties. Although only Leura, Turramurra and Wahroonga are directly relevant to these proceedings, these other homes are significant for they throw light on the way in which the couple went about owning property.

26 The first of these homes was in Shadforth Street, Mosman, which was acquired by the couple on 31 October 2005 as tenants in common in equal shares. Philip and Maryann stayed there for just over a year, selling it for slightly more than they had purchased it on 23 November 2006. Five days later on 28 November 2006, Maryann purchased a new home at Harnett Avenue, Mosman for $1,425,000.00 in which I infer they lived. Unlike Shadforth Street, which had been equally owned by them both as tenants in common, Harnett Avenue was in Maryann's sole name. The date of 28 November 2006 is therefore significant in this litigation for it marks the time at which the family home ceased to be owned by them in equal shares and became owned by Maryann in her sole name.

27 The bankruptcy trustees do not claim in this proceeding that the purchase by Maryann in her sole name of Harnett Avenue was an alienation of Philip's property to her and therefore void against them under s 121 of the Bankruptcy Act or s 37A of the Conveyancing Act. Whilst the bankruptcy trustees suggest that Maryann did own these properties for Philip’s and her mutual benefit and that they are hence subject to a constructive trust in his favour, they do not claim that Maryann's subsequent disposal of Harnett Avenue and purchase of the next family home in her name involved a disposition by her of Philip's property.

28 Not very long after the move to Harnett Avenue, Maryann gave birth to their twin sons on 27 April 2007. The children are presently 16 years old. The family was not destined to stay put for long. On 23 October 2007, when the boys were only 6 months old, Harnett Avenue was sold for $1,700,000.00 for a tidy profit. At this time, it is apparent that there were several loans in existence. They are referred to in an email from the Commonwealth Bank to Philip explaining the manner in which the sale proceeds had been disbursed. It is explained there that the net sale proceeds from Shadforth Street, which had been solely in Maryann's name, had been $1,670,642.46 (which included the deposit released from the agent). These proceeds were then used to pay off a small amount which still remained owing under the loan in relation to Shadforth Street ($76,068.04), a large amount of $500,000.00 under a loan called the Mosman portfolio loan and $454,574.42 to reduce the loan on the Leura property. This last repayment resulted in the loan on Leura having available in it the sum of $429,666.42 by way of redraw.

29 At this point, it appears the family moved to premises at Sharland Avenue, Chatswood, which they did not own. They did not stay long at Sharland Avenue either. On 22 September 2008, Maryann purchased, again in her sole name, an apartment at Badham Avenue, Mosman, in which they then lived. The purchase price was $912,000.00. Again, the bankruptcy trustees do not contend that placing Badham Avenue in Maryann's name was void against them.

30 In about 2009, according to Maryann, Philip was diagnosed with a tumour in his right mandible and had to undergo a course of chemotherapy and radiation therapy. There is evidence which suggests that the diagnosis may have been in October 2008, just after the purchase of Badham Avenue. This evidence consists of records kept by officials within the Australian Taxation Office (‘ATO’) of conversations which Philip had with them. On 17 November 2009 there is an entry which records 'Taxpayer was diagnosed with cancer in Oct 2008 and was undergoing treatment which saw him falling behind with all his personal affairs'. Another entry in these notes for 30 August 2010 records 'Client has been ill and endured cancer battle since late 2008'. Similar references may be found in the entries for 24 November 2011 including that Philip 'was sick and recovering for most of 2009'.

31 I conclude that Philip was diagnosed with cancer in his jaw in October 2008. The ATO notes also suggest that a large tumour was removed from his jaw which I would infer occurred in late 2008. I find that Philip was sick for most of 2009 as a result of chemotherapy and radiation therapy but was beginning to recover by the beginning of 2010.

32 On 12 February 2010, Badham Avenue was sold for $1,112,000.00.

33 At this stage, Philip suffered a serious setback when, in April 2010, he was diagnosed with stage 3 multiple myeloma, an incurable form of blood cancer. His doctor told him that he only had a few months to live. The ATO notes record that at this time Philip told the tax authorities that he had been given a 50/50 chance of surviving for four months. I accept that, at this time, Philip expected to die.

34 Maryann gave evidence that around this time Philip told her that he had to get his affairs in order and that as part of that he was going to transfer his half interest in the Leura property to her. She also said that Philip said that the reason he was doing this was so that she and the boys would have somewhere to live when he died.

35 On its face, this evidence is plausible. The imminence of death has a clarifying effect on many people and a desire to put one's affairs in order seems understandable. However, there are problems with this evidence. The Leura property was owned by Philip and Maryann as joint tenants. The effect of Philip's death would be that the property would become fully vested in Maryann by reason of the right of survivorship attaching to her as a joint tenant. The possibilities are:

(a) Philip thought that he owned Leura with Maryann as tenants in common as to 50%;

(b) Philip did not know that on the death of one joint tenant, an estate in fee simple vests in the survivor and that he genuinely thought he had to transfer his half to her to provide a home for the family;

(c) Philip did know about the right of survivorship but in the midst of chemotherapy, radiation therapy and a terminal diagnosis became confused about it and thought that his family's best interests required him to transfer his half interest to Maryann notwithstanding that this was wrong;

(d) Philip did know about the right of survivorship but decided to lie about it to Maryann; or

(e) Philip did not say the words attributed to him by Maryann.

36 Proposition (b) may be dismissed as implausible given Philip was a lawyer of some aptitude. Proposition (a) is possible in light of his situation and receives some support from the fact that Shadforth Street had been owned as tenants in common. Proposition (c) is plausible. Proposition (d) is possible but it is difficult to identify any motive for Philip to lie about this. The evidence does not support (e).

37 Maryann gave evidence before me and I accept her as a witness of truth. As such, to embrace (e) I would need to find that she was mistaken. Whilst the lapse of time is significant, so also is the significance of the conversation from her perspective. I therefore accept the words were said. I also accept the bankruptcy trustees' submission that what Philip was saying did not make any sense because the transfer was unnecessary to achieve what Philip sought to do. If he died, the property would become hers by operation of law. I therefore conclude that (a) or (c) is the case but I do not choose between them.

38 In any event, regardless of what Philip's intentions were in making the transfer, there is no debate that by a transfer instrument dated 18 May 2010 Philip transferred to Maryann a one half share in the estate in fee simple in Leura. The effect of that transfer was to sever the joint tenancy which had existed, to vest in both a 50% interest as tenants in common and simultaneously to transfer Philip's 50% interest to Maryann. The result was that Maryann became the owner of Leura in her own right. The instrument of transfer does not appear to have been lodged for registration until 16 June 2010 but is expressed to be for consideration of $300,000.00. One of the bankruptcy trustees, Mr Aravanis, gives evidence which I accept that the sum of $300,000.00 does not appear to have been either paid by Maryann or received by Philip.

39 Maryann submitted that she had provided consideration for this transaction in two ways. First, she reminded me that on the sale of Harnett Avenue in October 2007 (which had been in her sole name), a sum of $454,574.42 had been used from its proceeds of sale to reduce the loan on Leura. This led to a submission that this sum represented the price paid by her for Philip's half of Leura.

40 I do not accept this submission for three reasons. First, the sale of Harnett Avenue occurred two and a half years before the transfer. Second, it is not referred to in the Commonwealth Bank's email dated 30 November 2007 (or the emails from Philip preceding that email) explaining the flow of funds following the sale of Harnett Avenue. A review of those emails suggests that Philip was moving funds between various loans to allow for the purchase of a property in Queensland. Whilst these emails are to some extent difficult to follow, they provide no support for the proposition that Maryann was purchasing Philip's half of Leura. Third, it is not consistent with Maryann's evidence that Philip told her in May 2010 that he wanted to give her his half of Leura to provide for her and the boys. If he had sold his half to her in October 2007 for $454,574.42, as she now contends, he would not have said this to her. I do not therefore accept that Maryann purchased Philip's half of Leura for $454,574.42.

41 The second submission from Maryann, in her amended defence at [26], was that Philip had held his interest in Leura at all times on a constructive trust in her favour. This was said to be a common intention constructive trust arising because Leura had been purchased using Maryann's funds. If this constructive trust arose then it would entail that the transfer of his half to her was no more than an adjustment of the title to reflect her true beneficial interest in the whole property. If this were correct it would imply that the transfer had not involved any disposition of Philip's property at all so that the bankruptcy trustees' claims under s 121 of the Bankruptcy Act and s 37A of the Conveyancing Act would have no disposition upon which to attach.

42 I do not accept that Leura was acquired by the couple with such an intention for it is inconsistent with Philip's statement to Maryann in about April 2010.

43 In those circumstances, I do not accept either that Maryann provided consideration for the transfer of Philip's half of Leura in the form of $454,574.42 or that the transfer simply reflected the fact that the property had always been hers.

44 Shortly after the transfer, Maryann says that she took steps to look for day care facilities for the two boys with the intention of moving to Leura on Philip's death. I accept this evidence.

45 No doubt because of the mortal condition in which he found himself, Philip signed a letter dated 29 July 2010 entitled 'Letter of Wishes'. The letter of wishes was attached to a trust deed which established a discretionary trust known as the James Trust. One curiosity is that the deed is dated 12 July 2010 whereas the letter of wishes annexed to it is dated 29 July 2010. By cl 10, the trustees of the James Trust were to take into account the contents of the letter of wishes in the exercise of their discretionary powers. The letter of wishes revealed the existence of multiple life insurance policies. The proceeds of the policies were to be contributed to the corpus of the James Trust. It was Philip's desire that the James Trust should use some of the proceeds to pay off the outstanding loan on Leura which the letter indicates Philip then understood to be in the order of $400,000.00. The letter contained this statement: 'I note that this is in effect a repayment of a loan of $400,000.00, which I borrowed from Maryann to settle a debt to the Australian Taxation Office.' It is not in dispute that $400,000.00 of the proceeds of sale for Harnett Avenue was, indeed, used to pay off some of Philip's tax debt. Maryann submits, but the bankruptcy trustees deny, that the existence of a loan of $400,000.00 demonstrates that Harnett Avenue was not only in her sole name but was treated by the couple as having been owned by her since a loan out of the sale proceeds is only consistent with her owning the funds in question. I return to this issue later in these reasons.

46 The letter of wishes also reveals that Philip made provision for his three daughters, Lauren, Kirsty and Michelle, from his first marriage to Shelley.

47 At some point, most likely in the second half of 2010, Philip undertook an experimental therapy for his multiple myeloma which included a stem cell bone marrow transplant. According to the ATO notes, Philip told the tax authorities that this treatment consisted of expensive chemotherapy and a cocktail of steroids and was accompanied by serious side effects including nerve damage, loss of memory, inability to think or concentrate, loss of the use of his limbs and damage to his immune system. There is evidence in the ATO's notes of conversations its officials had with Philip that this treatment included travelling to the United States for a period. Despite its asperity, the therapy was successful and, according to Maryann, Philip went into remission in the first few months of 2011. The cancer, however, remains incurable and Philip has to undertake blood tests every three months and an annual bone scan but, subject to these and other inconveniences, remains alive.

48 I saw Philip on more than one occasion during the Twin Trust litigation and was addressed by him when, from time to time, he sought to appear in that proceeding. It was obvious from these encounters that he has undergone a scarifying health experience which has left him very much diminished and, to an extent, has impacted on the soundness of his judgment. However, I accept that from early 2011 Philip has been in remission. I conclude that between October 2008 and early 2011 Philip was in a grave state of health which impaired his ability to administer his affairs as he would have liked.

49 On 4 February 2011, Maryann exchanged contracts to purchase a property at Fairlawn Avenue, Turramurra for $1,550,000.00 for the family to live in which was to settle on 3 May 2011. A deposit of $77,500.00 was paid, leaving a balance due on settlement of $1,472,500.00. There is, to my mind, a question about where the family lived between Badham Avenue being sold on 12 February 2010 and Turramurra being acquired on 3 May 2011. In her evidence, Maryann said that the family lived between Badham Avenue and Leura until the property at Turramurra was acquired. This would entail that they lived at Leura between 12 February 2010 and 3 May 2011. Corporate records of entities associated with Philip suggest that, during this time, he recorded his residential address as being 26 Wyalong Street, Willoughby, a property that does not appear to have been owned by either Philip or Maryann. There is other evidence to this effect: in the loan application for the Turramurra property (dealt with in more detail shortly), Philip and Maryann's residential address is listed as that address and in the ATO's notes dated 30 August 2010 the same address is recorded.

50 If it were necessary to decide, I would prefer this contemporaneous documentary evidence to Maryann's evidence. This was, no doubt, a stressful time in her life. Her husband had terminal cancer, her family's future was in doubt, she was moving house and she had to look after two young children. Further, as will be apparent from these reasons so far, the Kapp family was always on the move so that a precise recall of which home they lived in at a particular time might easily involve error.

51 Philip and Maryann completed a loan application with the Commonwealth Bank for the purchase of the Turramurra house. The proposed loan was to be for $1,470,900.00 and was to comprise three separate loan accounts in Philip’s name guaranteed by Maryann, with her guarantee secured by mortgage. The documentation appears to have been completed and submitted by Philip and Maryann sometime in March 2011 although, as will be seen, the loan was only extended on 3 May 2011.

52 One of these accounts was for a loan of $230,700.00. The consumer credit contract schedule in relation to this loan account provided by the bank to Philip dated 3 March 2011 indicates that it was to be serviced with 11 monthly interest-only payments and a bullet repayment of the principal and, I surmise, a small amount of interest by a twelfth and final payment in the sum of $232,003.23.

53 The consumer credit contract schedule states that ‘the amount of [$230,700.00] includes bridging finance’. The same document indicated that the loan was initially to be secured by mortgages over the Turramurra and Leura properties and a guarantee by Maryann. However, this security was to be replaced on the repayment of 'the bridging finance content of the Loan'. The bankruptcy trustees invited me to infer that the bridging finance was the interest-only one-year facility of $230,700.00. In my view, so much is plain from the terms of the consumer credit contract schedule in relation to this loan account.

54 Whereas during the pendency of the bridging loan the security consisted of mortgages over the Turramurra and Leura properties and a guarantee by Maryann, the new security was to consist only of a mortgage over the Turramurra property and a guarantee by Maryann. So once the bridging loan had been repaid, the bank’s mortgage over the Leura property would be discharged.

55 However, that conclusion must be considered in light of another matter. The consumer credit contract schedule also imposed a condition in relation to the bridging facility to the effect that the Leura property was to be sold within 12 months of its advance. The likely intent of this arrangement was that the proceeds of sale of the Leura property would be used to repay or reduce the bridging loan. If that occurred, and the sale proceeds proved sufficient, then the mortgage on the Leura property would necessarily be discharged. If, on the other hand, the sale proceeds were insufficient then Maryann would remain liable for the unpaid balance of the bridging facility under her guarantee.

56 Thus, the evidence supports the drawing of an inference that, probably in March 2011 and certainly by 3 May 2011, a decision had been made that in order to purchase Turramurra, the Leura property would need to be sold to pay down the bridging loan of $230,700.00.

57 The purchase of the Turramurra property settled on 3 May 2011 at which time I infer the bridging loan was advanced. Consequently, Maryann was obliged under the terms of the bridging loan to sell the Leura property by no later than 3 May 2012. The bankruptcy trustees submitted that as at March 2011 Philip and Maryann had already borrowed about $214,000.00 against the Leura property. The evidence for this was p 7 of the loan application. It is unclear to me what to make of this page. It records that Leura was subject to a 'prior charge' to the bank with a 'balance' of $153,883.35 and a 'subsequent charge' to the bank of $60,005.00. What exactly this means is unclear but I do accept that if these entries are to be read as recording the existence of loans then those loans do total $213,888.35. The significance of these loans, if they existed, to the issues in this case is not apparent to me and I do not mention them again.

58 Consistently with her obligation under the bridging facility, on 7 September 2011 Maryann sold the Leura property for $690,000 which sale price is broadly consistent with the valuation obtained in January of that year of $725,000. The bankruptcy trustees submit, and Maryann accepts, that 'all of the net proceeds of $620,463.08 were paid to the [Commonwealth Bank]'. The bankruptcy trustees also submitted that on that day the mortgage over Leura was discharged. This may be inferred from the fact that the property could not be sold without a discharge being tendered and I accept that this must be so.

59 The bankruptcy trustees then submitted that $232,433.60 of the sale proceeds was used to repay the bridging facility. This submission requires clarification. The bridging facility was only for $230,700.00. Whilst there were monthly interest payments due under it together with some other minor fees and charges, payment of these did not result, indeed could not result, in any reduction of the principal due under the facility there being no suggestion that interest or any other charge was to be capitalised. Thus whilst $232,433.60 may finally have been paid into the loan account constituting the bridging facility when Leura was sold, the principal debt has only ever been $230,700.00 and only that amount of principal can possibly have been repaid. This matters because on the bankruptcy trustees' case, only the repayment of the principal debt can serve to have increased the net proceeds of sale subsequently realised on the disposal of the Turramurra property; that is to say, the payment of interest and bank charges on the bridging facility are irrelevant to the tracing exercise that the bankruptcy trustees must undertake.

60 Further, the bankruptcy trustees’ submission does not constitute an accurate statement of what the single bank statement for the bridging loan actually shows. Prior to September 2011 Philip had been making monthly interest repayments on around the 15th of each month. Immediately prior to its repayment on 7 September 2011 the facility was in debit by an amount of $230,700.00. On 7 September 2011 there was a credit in the sum of $76,655.19 and a second credit in the sum of $232,433.60 (the figure now claimed by the bankruptcy trustees) which I infer came from the sale proceeds of the Leura property. This placed the account in credit by an amount of $78,388.79. However, the deposit of $76,655.19 was immediately reversed on 8 September 2011 for reasons which neither party explored. It appears appropriate to proceed on the basis that the credit for $76,655.19 should be treated as not having been made. Making that assumption, the reversal left the loan account in credit to the amount of $1,733.60 which was then consumed by a deferred establishment fee and some interest on 9 September 2011. As such $1,733.60 of the $232,433.60 was not used to repay the principal on the loan and the amount of principal repaid is the difference between these two sums which is $230,700.00, which, as might be expected, is the principal originally extended under the bridging facility.

61 I therefore find that the proceeds of the sale of Leura were used, in part, to repay the whole of the bridging loan of $230,700.00 to reduce Philip's debt which was secured by Maryann's guarantee and the mortgage she had given over Turramurra. I will treat the bankruptcy trustees’ submissions about the sum of $232,433.60 as being submissions about the sum of $230,700.00.

62 The family had moved to the Turramurra property on, or shortly after, 3 May 2011 when its purchase had been completed. I accept that during this time it was Philip who met the payments due under the loan facilities and that it was he who paid for the maintenance of the property. Whilst the bankruptcy trustees have demonstrated that the sale of Leura resulted in a repayment of principal on the bridging loan they did not seek to prove the extent of any of Philip's principal repayments under the other two loans extended to him in respect of Turramurra. They did submit that Philip had, in effect, paid for everything to do with Turramurra. But their tracing case is not concerned with Philip's payment of everything but rather with his payments of principal. Apart from the sale proceeds of Leura, no attempt was made to prove what elements of his repayments under the bank loans had been interest and what had been principal. In the absence of such an exercise, I do not find the submission that Philip paid for everything very helpful.

63 They remained in the Turramurra home until about 21 June 2013 when it was sold. The sale price was $1,650,000.00. Between 21 June 2013 and 24 June 2013 two amounts were paid into Maryann's account with the National Australia Bank (‘NAB’) which totalled $362,340.64 ($238,567.15 on 21 June 2013 and a further $123,773.49 on 24 June 2013). Maryann says that this sum was paid into her account with the Commonwealth Bank but, in this, she is in error (although she subsequently did pay these funds into her account with that bank, as will be seen). Those credits brought her account with the NAB to a credit balance of $371,051.32.

64 The bankruptcy trustees seek to trace the $230,700.00 from the proceeds of sale of Leura through the sale of Turramurra and into the purchase of the next property to be considered, Wahroonga. That purchase was completed on 23 August 2013 for $2,400,000.00. The thesis of the bankruptcy trustees' claim is that the net proceeds of sale of Turramurra were $362,340.64 and that the sale proceeds of Leura had contributed $230,700.00 to that sum. This is true inasmuch as the repayment of the bridging facility with a payment of that amount had extinguished that loan leaving only the two-year fixed loan and the variable home loan to be repaid. I therefore accept that the sale of Leura increased the net proceeds of Turramurra by $230,700.00. I therefore also accept that of the $362,340.64 that was deposited into Maryann's account with the NAB on 21 and 24 June 2013, some $230,700.00 of this represented the proceeds of sale of Leura.

65 The exercise in tracing, however, perhaps calls for more attention to detail than was necessarily implied in the bankruptcy trustees' submissions. Maryann's account with the NAB had been in credit immediately prior to the deposit of the Turramurra proceeds in the sum of $9,060.68 and the deposit brought the account to a credit balance of $371,051.32 (noting that this also included a debit of $350.00 as a settlement fee). As at 24 June 2013, therefore, the sale proceeds of Turramurra represented 97.65% of the contents of the account. On 19 August 2013, the sum of $380,000.00 was transferred out of the account and, as I will shortly explain, used to fund the purchase of the Wahroonga property. Between 24 June 2013 and 5 July 2013 Maryann's account balance drifted downwards as it was debited with the cost of various household living expenses which totalled $497.02. These expenses stopped after 5 July 2013. The balance was then increased by the deposit of a cheque for $1,444.85 on 11 July 2013 and a transfer from Philip of $10,000.00 on 5 August 2013 at which point the account stood in credit in the sum of $382,001.59. It remained in credit at that balance until a debit of $380,000 on 19 August 2013.

66 The sum of $382,001.59 therefore represented a blend of different funds. These were Maryann's initial credit balance of $9,060.68, the credit of $362,340.64 from the sale of Turramurra and the deposits of $1,444.85 and $10,000.00. The household expenses were debited immediately prior to the two deposits but after the crediting of the sale proceeds. The question at hand then is what amount of the $380,000.00 is to be seen as representing the sale proceeds of Turramurra.

67 Although where a fund is insufficient the application of the rule in Devaynes v Noble (1816) 1 Mer 529; 35 ER 767 is often displaced, I do not think that should happen in the case of the household expenses: Caron v Jahani (No 2) [2020] NSWCA 117; 102 NSWLR 537 at [78]-[84] per Bell P. I therefore conclude that the sale proceeds of Turramurra were reduced by the debiting of the household expenses because they immediately followed it. On this view, by 5 July 2013 the sale proceeds had been reduced to $361,843.62. Immediately prior to the transfer of the $380,000.00 on 19 August 2013 the account stood in credit in the amount of $382,001.59 and what was left of the sale proceeds after the household expenses – $361,843.62 – therefore represented 94.723% of the contents of the account. I would therefore conclude that of the $380,000.00 transferred from Maryann's NAB account on 19 August 2013, 94.723% of that figure ($359,947.65) should be apportioned to the sale proceeds of Turramurra.

68 The figure of $380,000.00 was deposited in Maryann's account with the Commonwealth Bank on 20 August 2013. At the time it was deposited, this account was in credit in the amount of $3,763.49. Immediately after the deposit it stood in credit in the amount of $383,763.49. Three days later, on 23 August 2013, the sum of $330,784.72 was debited from the account. The bank statement records that this was for 'SHORTFALL'. As will shortly be seen, this amount was contributed to the purchase of Wahroonga.

69 The next question is whether the whole of the $230,700.00 derived from the sale of Leura is to be treated as a fixed portion of the sum of $359,947.65 or whether it is to be treated as a proportion. In my view, it should be treated as a proportion. The net sale proceeds of Turramurra were $362,340.64 of which $230,700.00 represented the sums derived from the sale of Leura. This is 63.67%. That figure should be applied to the funds of $359,947.65 which I am satisfied found their way into the Wahroonga property. This is $229,176.40.

70 As I have said, the Wahroonga property was purchased on 23 August 2013 for $2,400,000.00. The conveyancer's file records that a deposit of $120,000.00 was paid.

71 The source of funds for the purchase were, according to the bankruptcy trustees, as follows:

(a) a part payment of the deposit by means of a cheque drawn on Philip’s account with the NAB in the sum of $70,000.00;

(b) a part payment of the deposit by means of a cheque drawn on Maryann's account with the Commonwealth Bank in the sum of $50,000;

(c) $330,784.72 from Maryann's account with the Commonwealth Bank; and

(d) $1,980,000.00 borrowed from the Commonwealth Bank.

72 These figures are not quite correct. The Commonwealth Bank extended three loans on 23 August 2013 which totalled $1,920,000.00, not $1,980,000.00. A cheque was drawn by Philip on 8 March 2013 for $70,000.00. I have not sighted the corresponding bank statement but Maryann accepted in her submissions that Philip had paid this sum. There was a debit on Maryann's account with the Commonwealth Bank on 11 March 2013 of $50,000.00. There was also a debit of $117,510.00 on her NAB account on 6 June 2013 which Mr Aravanis says, and I accept, was for stamp duty. Recourse to the conveyancer's file confirms this and demonstrates that on settlement the bank provided an amount of $2,250,784.72 to the vendors.

73 I am therefore satisfied of the following matters:

(a) a full deposit of $120,000.00 was paid consisting of $70,000.00 from Philip and $50,000.00 from Maryann;

(b) $330,784.72 was transferred from Maryann's account with the Commonwealth Bank on 23 August 2013;

(c) $1,920,000.00 was borrowed from the Commonwealth Bank on 23 August 2013; and

(d) the Commonwealth Bank provided the vendors with $2,250,784.72 on 23 August 2013 which consisted of Maryann's funds and its loan funds.

74 With the deposit, the total amount paid to the vendors was $2,370,784.72 which is less than the purchase price of $2,400,000.00. The difference is $29,215.28. This appears to be accounted for by adjustments on the day of the usual kind together with a large adjustment for a licence arrangement with the vendors, and some other adjustments for curtains and a swimming pool pump. As a side note, the bankruptcy trustees do not claim that Philip's payment of the deposit gave rise to a resulting trust in his favour. They do submit that Philip met the loan repayments but, as with Turramurra, they do not seek to identify any subsequent payments of principal made by him.

75 What does matter is that of the $2,400,000.00 purchase price, $380,784.72 was contributed with funds provided by Maryann. As I have explained above, $229,176.40 of that sum should be treated as having been derived from the sale proceeds of Leura. I therefore accept that 9.55% of the value of Wahroonga should be regarded as being derived from Leura being the proportion that $229,176.40 bears to $2,400,000.00.

76 From sometime in September 2013, the family resided at the Wahroonga property. Leaving aside Philip's (and subsequently, Maryann's) entanglements with the Commissioner, the picture from Maryann's perspective is nearly complete save for five matters. The first of these is Philip's bankruptcy which occurred on 4 March 2019 on his own petition.

77 The second is the commencement of a proceeding by the bankruptcy trustees against Maryann and the trustee of the Twin Trust on 31 May 2019. The third event is the separation of Philip and Maryann in April 2021 while remaining under the same roof and their complete separation in November 2021 when she locked him out of the house.

78 The fourth event is the sale of Wahroonga on 11 August 2021 for $4,151,252.81. The net sale proceeds following the discharge of two mortgages and other expenses were $1,233,639.07. In the result, half of that sum, $616,819.00, is being held by her solicitors in a trust account. The fund in dispute is therefore the amount of $616,819.00.

79 It will follow from the above that if the bankruptcy trustees are entitled to treat Philip's transfer to Maryann of his half share in Leura as void then I accept that 9.55% of the Wahroonga sale proceeds should be regarded as being derived from the sale of Leura and half of that, 4.775%, may be traced to Philip's interest in Leura.

80 The fifth event is the commencement of the current proceeding on 8 September 2021.

Philip's relationship with the Commissioner of Taxation

81 The bankruptcy trustees seek to establish three propositions. The first is that Philip intended not to pay his tax debts from at least April 2010. It was at this time that he understood himself only to have a few months to live and it was in May 2010 that he transferred his half interest in Leura to Maryann. The second is that everything Philip did after April 2010 was coloured by an ambition to ensure that his property did not fall into the hands of the Commissioner. This motive explained the transfer of his half share in Leura to Maryann and it provided the explanation for why the legal title to first Turramurra and then Wahroonga were placed in her sole name. The third is that Philip was insolvent from at least April 2010 (just before the transfer of his half interest in Leura).

82 It would be fair to say that Philip has lived for a long time under significant financial stress. The sources of this stress appear to be four in number. The first is his ambition to own properties on Sydney's north shore for his family. This was achieved using increasingly large amounts of bank debt which required servicing. In addition to the family homes, as I explain in my other reasons for judgment, the family owned two other properties at Swan Bay and Main Beach through the Twin Trust which were also encumbered with bank loans at various times. Leaving aside the question of who precisely owned these properties, there is no doubt that the person who was servicing the associated debt was always Philip. The same was also true of Shelley's home at Belrose. Thus, at all times, Philip has been obliged to meet the repayments on several substantial loans. I do not think, in principle, that this would have been beyond his means given the income he was earning as a lawyer.

83 The second concerns Philip's unresolved financial issues arising from his first marriage to Shelley. These were not finally resolved until 11 June 2015. The terms of Philip's property settlement with Shelley dealt with a number of matters. However, the bottom line of them was that Philip transferred to Shelley his interests in the property at Belrose and was to pay her $135,000.00.

84 The third concerns Philip's habit of not paying his tax debts in full. The bankruptcy trustees produced a table of Philip's unpaid tax debts and a graph which illustrated what it showed. The table was in these terms:

Date | Bankrupt’s Taxable Income ($) | Maryann’s Taxable Income ($) | Bankrupt’s Tax Liabilities ($) |

30/06/2001 | $292,823 | ||

30/06/2002 | $467,138 | ||

30/06/2003 | $704,347 | ||

30/06/2004 | $403,451 | ||

30/06/2005 | $474,808 | ||

30/06/2006 | $788,193 | $180,383 | |

30/06/2007 | $1,046,895 | $419,862 | |

30/06/2008 | $1,034,211 | $66,079 | $347,092 |

30/06/2009 | $1,354,831 | $15,450 | $487,836 |

30/06/2010 | $1,126,227 | $55,175 | $569,295 |

30/06/2011 | $1,375,817 | $65,148 | $1,166,793 |

30/06/2012 | $985,964 | $36,775 | $1,775,577 |

30/06/2013 | $1,342,313 | $15,037 | $1,903,471 |

30/06/2014 | $849,642 | $85,828 | $2,203,450 |

30/06/2015 | $1,259,034 | $47,409 | $2,801,804 |

30/06/2016 | $309,477 | $50,006 | $3,775,800 |

30/06/2017 | $721,572 | $30,000 | $3,903,559 |

30/06/2018 | $32,000 | $4,450,778 | |

4/03/2019 | $4,728,486 |

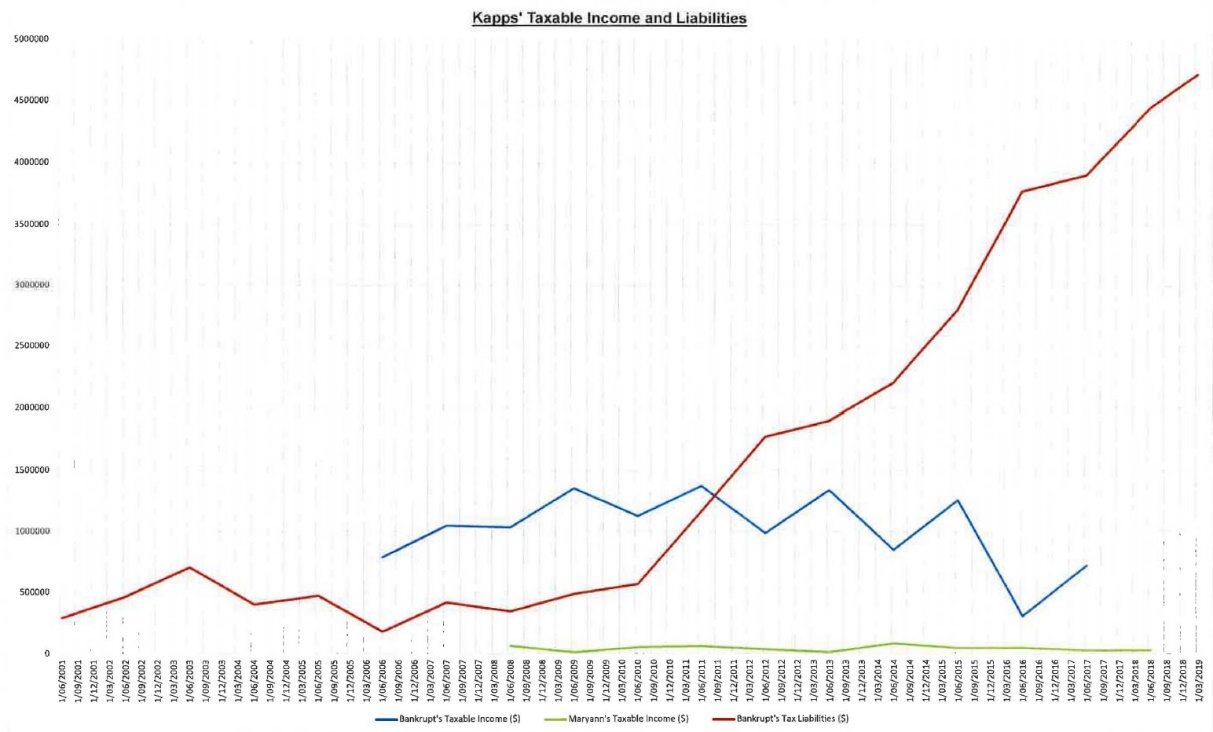

85 The graph depicting these figures is thus:

86 The fourth relates to the third (and the graph which embodies it) and concerns Philip's diagnosis with cancer in October 2008, his year of chemotherapy and radiation therapy in 2009, his diagnosis with terminal cancer in early 2010, his experimental treatment in the second half of 2010 and the remission of that cancer in early 2011. As can be seen from the graph, until 2010 Philip's accumulated tax debt was about half of his income. In itself, this is not an ideal position in which to find oneself although by no means is it necessarily irretrievable.

87 However, from the commencement of his health travails Philip's tax debt began to soar. The decision to borrow heavily to purchase the Wahroonga property on 23 August 2013 when his accumulated tax debt exceeded his income set him on the course to bankruptcy. It was not ultimately possible to service his secured debts and to pay his tax. Ultimately, Philip chose to prioritise the servicing of his secured debt and the consequences can be seen in the graph above.

88 The final stressor is the fact that Philip retired as a law firm partner on 30 June 2016 and took up employment as a consultant and businessman. As the graph shows, this was not as remunerative for him. I do not think that this drop in income was material to the final outcome although it may have accelerated it to some extent. I return later to the question of when Philip became insolvent.

89 Philip's decision to prioritise the servicing of his secured debts over the payment of his tax debt generated predictable friction with the tax authorities. The bankruptcy trustees submitted that Philip was unwilling to pay his tax debt. I think the position is more nuanced. Until his diagnosis with cancer in October 2008, a better description of the situation would be to say that Philip prioritised the servicing of his secured debts over the payment of his unsecured tax debt. But throughout the period from 30 June 2005 to October 2008 he made intermittent, although insufficient, payments to the ATO in service of his income tax debt. These included the payment of $400,000.00 out of the Harnett Avenue proceeds.

90 I do not by any means intend to suggest by this that Philip was tax compliant or that his approach to tax obligations was other than inappropriate. Two competing hypotheses explain his behaviour up until October 2008. The first is that Philip was careless in his personal affairs and that he moved money and his family around largely to meet the exigencies of events over which he could have had, but largely did not have, control. Under this hypothesis, which is the hypothesis of chaos, the family's ownership of increasingly expensive houses and Philip's steadily growing tax debt generated a series of financial spot fires for Philip which he was constantly putting out. There was no time for planning of any kind and Philip was reacting to events of which, it is true, he was the author but in which there was no clear narrative except that he was living beyond his means.

91 The second hypothesis is that Philip was in fact very careful in his affairs and appreciated that the fact that a tax debt could be accrued at interest meant that his income tax liability could, in effect, be borrowed from the Commissioner. Since the interest paid on tax debt was deductible against income, the nature of the credit arrangement thus extended made it attractive from Philip's perspective. All that was necessary to maintain this facility was that he should, from time to time, make sufficient payments of tax to ensure that neither recovery nor criminal proceedings were commenced against him. Under this hypothesis, which is the hypothesis of the agile juggler, Philip gave just enough to the Commissioner to keep him at bay but no more so that he could continue his family's adventures in the rich (and capital gains tax free) bounty of family home ownership in Sydney.

92 The evidence concerning Philip's tax affairs until October 2008 is consistent with both of these hypotheses. If it were necessary, I would prefer the hypothesis of chaos because the moving of his wife and two young children through a succession of seven houses (with five payments of stamp duty) signals turmoil rather than cunning. In the event, I do not think it is necessary to choose between them. Neither is consistent with an intention on Philip's part not to pay his tax. The latter involves an intention to utilise the ATO as a source of deductible debt which he otherwise would have had to borrow but certainly no intention not to pay the debt well before the falls, if not the rapids.

93 The former involves no intention on Philip's part at all beyond a wish somehow to keep it all together until present circumstances – admittedly alarming – improved. Regardless of which is the correct hypothesis, until his diagnosis with cancer in October 2008, I do not think that Philip expected or intended that he would not ultimately pay his tax debt.

94 In any event, whatever Philip's motivations were in being behind in his income tax payments prior to October 2008, between October 2008 and early 2011 Philip lost control of his tax situation as his health dramatically deteriorated. It is clear that from 17 November 2009, the ATO understood that Philip was facing a grave health crisis. It appears that at that time there were two case officers involved. One was minded to defer Philip's immediate tax payments given his health situation but his case had already been referred by this time to another official for 'firmer action'. This firmer action consisted of a formal demand for $434,271.65 issued on 14 April 2010 which required a response by 27 April 2010. The timing of this was unfortunate since it was around the same time that Philip was told that he had a terminal illness and had only a 50% chance of surviving for four months. This demand was the first such demand that the ATO had issued.

95 It was only a month after this mensis horribilis that Philip transferred his half interest in Leura to Maryann on 18 May 2010. Throughout his illness, Philip continued to be in receipt of his partnership income and reported substantial amounts of income when he filed returns. At the time of the transfer of his half interest to Maryann, Philip had not filed his tax returns for 2008 and 2009. Whilst the ATO had just demanded payment of $434,271.65 he would have appreciated, even through the fog of his treatments, that he was going to have a tax liability for those two years and also, when, 30 June 2010 arrived, a liability for the 2010 financial year. These liabilities did not exist yet because no notice of assessment had been issued in respect of them but Philip would have been aware of their impendency. It is also likely that he would have been aware that his tax liability would for each year be for hundreds of thousands of dollars since he knew what his drawings as a partner had been.

96 Given what he was going through at this time, these matters would not have been at the forefront of his mind and it may be accepted that the gruelling treatment he endured would have made these matters seem distant concerns. Nevertheless, even allowing for that, I am satisfied that Philip knew in broad terms what was happening with his relationship with the Commissioner.

97 That he was aware of the gravity of the situation is borne out by the fact that he did attempt to deal with it. On 23 July 2010, he entered into a payment agreement with the ATO under which he would pay certain sums and a lump sum on 23 January 2011. By 30 August 2010, however, Philip had defaulted on this arrangement. At this point, he was subject to a demand for $434,271.65 which he had not met, had defaulted on a payment agreement and must have been aware that further income tax assessments, likely to be in the vicinity of $750,000.00, were imminent for the years 2008, 2009 and 2010. He was also desperately unwell and for a time undergoing experimental treatment in the United States as the ATO notes reveal.

98 At this point, Philip and Maryann were living at Wyalong Street, Willoughby. It was in the midst of the financial chaos in which Philip was then enmeshed that the decision was taken to purchase the property at Turramurra which I have described above. The purchase was settled on 3 May 2011. It involved Philip borrowing $1,470,900.00 from the Commonwealth Bank. At this time, his tax debt was around $293,116.31. He did not disclose this debt to the Commonwealth Bank as his loan application form shows. Further, as the bankruptcy trustees correctly submit, he had an unassessed liability for the 2008, 2009 and 2010 years. When his returns for those years were finally lodged they resulted in an income tax liability of $750,398.50.

99 The upshot of this was that after the purchase of Turramurra Philip was saddled with debts approaching $3 million, $1 million of which was being borrowed from the ATO at the general interest charge. This statement leaves out of account the debts on Belrose and in the Twin Trust. His debts would be reduced by the size of the bridging loan when Leura was subsequently sold but even the existence of that arrangement tells one that Philip was rather too leveraged for the bank's taste (and it did not know about his tax problem). I have included in this assessment Philip's tax liabilities for the 2008, 2009 and 2010 years. Of course, because these returns had not been filed no such tax debts existed. However, in the real world of Philip's finances, I do not think that one can treat substantial tax liabilities as not existing through the device of not filing the tax returns for the years in which the relevant income was earned. In any event, authority confirms that a taxpayer does have a liability to tax on the earning of income which does not crystallise and become payable until the issue of a notice of assessment: Binetter v Commissioner of Taxation [2016] FCAFC 163; 249 FCR 534 at [148] per Perram and Davies JJ (Siopsis J agreeing at [1]); Commissioner of Taxation v H [2010] FCAFC 128; 188 FCR 440 at [39]-[42] per Downes, Edmonds and Greenwood JJ. See also Trustees of the Property of Cummins v Cummins [2006] HCA 6; 227 CLR 278 (‘Cummins’) at [30].

100 Following the purchase of Turramurra on 3 May 2011 Philip's financial condition inevitably deteriorated. The Commissioner issued garnishee notices to third parties on 28 October 2011 without apparent success and, on 16 November 2011, Philip’s tax agent was told that if he did not resolve his tax situation by 21 November 2011, recovery action would be commenced against him. This request arrived 6 days after he had returned from the United States on 15 November 2011 where he had undergone the experimental treatment. Unless at this point Philip had decided that Turramurra should be sold, there was no prospect of his tax debt being paid. I do not think he was minded to sell Turramurra, however wise that might have been. In notes made by an ATO official on 24 November 2011, it is recorded that a letter from Philip's tax agent received around that time says that Philip 'did not have the capacity to pay the debt in full'. I am not sure this was necessarily correct. Had both properties in the Twin Trust and the Turramurra property been sold, I think it is likely that the debt could have been paid in full and, if not in full, sufficiently to reduce the intensity of the ATO's demands. Instead, by his tax agent’s letter, Philip sought the ATO's agreement to a payment plan. This suggestion was rejected. The case officer making that decision noted that whilst it would be ‘unfortunate’ if Philip ceased to be a solicitor by reason of his bankruptcy at the hands of the Commissioner, it was 'unacceptable to expect the ATO to wait until death to pursue the debt'. It is clear by this point that the ATO's patience had run out.

101 Matters then took their course. On or after 29 May 2012, a Deputy Commissioner of Taxation issued a notice of intended recovery action. The tax debt nominated was $1,759,670.79. Philip had earlier sought hardship relief on 24 April 2012 but this was rejected. An objection to this decision was lodged and rejected and Philip then sought a review in the Administrative Appeals Tribunal but this was withdrawn. Throughout 2012 and 2013 Philip unsuccessfully sought to persuade the ATO to reach an agreement with him. Some of these efforts centred on persuading the ATO of the value, from its perspective, of his life insurance policies (thought by Philip to be worth around $7,000,000.00). But the ATO was unpersuaded since his death was not a near term certainty and the policies had no surrender value which could be borrowed against. Further, as the ATO notes in December 2013 show, it was concerned about the impact that Shelley's proceedings in the Family Court against Philip might have on his position including in relation to the proceeds of any life insurance policy.

102 It was against the backdrop of this tumult that the Turramurra property was sold in June 2013 and the Wahroonga property purchased in August 2013. This increased Philip's bank debt from around $1,240,000.00 (the size of the Turramurra loans less the repaid bridging facility) to $1,920,000.00. At this time, his accumulated tax debt was $1,930,284.68, the ATO was refusing all of his entreaties and, through his tax agent, he had told the ATO that he could not pay the tax debt even as it stood in November 2011. Philip's actions in taking on the burden of secured bank debt of $1,920,000.00 at this time show that he was living in two different worlds, only one of which was real. His separation from reality is borne out by the fact that in the application for the loan for Wahroonga he did not disclose the existence of his tax debt. Had he done so, I do not doubt that the bank would not have extended him the loan.

103 On 18 December 2013, an officer of the ATO suggested to Philip that bankruptcy might be his best option. But the night is darkest just before the dawn and, on 3 October 2014, there was a breakthrough in Philip's relationship with the Commissioner. On that day a deed was entered into between the Commissioner, Philip and Maryann. Philip and Maryann acknowledged that Philip's tax debt was $2,249,208.00 (cl 2(a)) and that whilst it remained unpaid it would continue to compound at the general interest charge (cl 2(b)). By cl 5.1 he agreed that he would pay the tax debt in full by 30 June 2019 or within nine months of his dying. This was subject to some minor relief of 30 days were he to be hospitalised for more than seven days. He also agreed to comply with his future obligations under taxation laws.

104 By cl 3.1 Maryann irrevocably and unconditionally assumed liability for the tax debt, guaranteed its full payment and agreed that if Philip did not pay any of it she would immediately pay the outstanding amount as if she was a principal obligor. By cl 3.10, Maryann agreed her guarantee was a principal obligation and was not to be treated as ancillary or collateral to Philip's obligations. Maryann's obligations were to be secured by a registered second mortgage in favour of the Commissioner over Wahroonga: cl 4. I mention these matters because they are relevant to Maryann's contention that she became entitled to an equity of exoneration against Philip when she subsequently paid part of this debt out of the proceeds of sale for Wahroonga.

105 In practical terms, the terms of the deed meant that if Philip failed to comply with a tax law before 30 June 2019, Maryann would become primarily liable for the whole of Philip's tax debt. Unfortunately, Philip failed to comply with his obligations under the taxation laws when, on 23 November 2015, he failed to file his income tax return for the year ended 30 June 2015. From this point the operation of the deed meant that Maryann had become liable for all of Philip's tax debt which was subject to the deed (there were, in fact, other tax debts owed by Philip but these are not material for present purposes).

106 On 19 May 2016, Philip attended a meeting with the ATO where it was noted that he was in default under the terms of the deed. Maryann did not attend this meeting. During its course Philip is recorded as having made three statements of significance:

(a) Maryann's equity in the Wahroonga property had been earned by her;

(b) the Wahroonga property came to be in her name 'under what is essentially an asset protection scheme'; and

(c) Maryann felt that she had been forced into providing the mortgage over Wahroonga.

107 The statements in (a) and (b) are relevant to an assessment of what Philip and Maryann intended by putting Harnett Avenue, Badham Avenue, Turramurra and Wahroonga in her name. I return to this issue below.

108 The next significant event is the commencement by the Commissioner of proceedings in the New South Wales Supreme Court against Philip for tax debts which were not covered by the deed of 3 October 2014 and which were, at that time, $1,610,831.28. This occurred on 10 May 2017. With his liabilities under the deed, his total debt to the Commissioner was now $4,480,367.77. Philip continued thereafter fruitless, one might say quixotic, negotiations with the Commissioner. On 12 July 2017, the Commissioner obtained default judgment against Philip in the sum of $1,452,918.89 (including costs). Further efforts by Philip to persuade the ATO to enter into yet another agreement yielded nothing. A bankruptcy notice was issued sometime before 2 April 2018 and served on Philip that day. On 23 April 2018, he failed to comply with the notice and thereby committed an act of bankruptcy. On 22 August 2018 the Commissioner issued a creditor's petition. Before that petition was determined Philip filed his own debtor's petition and became bankrupt on 4 March 2019.

109 Meanwhile, the Commissioner was pursuing Maryann under the terms of the deed. Although I have not sighted it, the parties agree that he served a notice of default on her on 26 March 2019. Shortly afterwards, on 10 April 2019, he appointed receivers under his second mortgage to the Wahroonga property and on 8 May 2019 those receivers issued a further notice to Maryann seeking payment of $3,376,941.20. On 22 July 2019, the Commissioner commenced proceedings against Maryann seeking payment of the amounts due under the deed and possession of the Wahroonga property. Maryann cross-claimed against the ATO seeking relief in relation to the deed and second mortgage granted under it on the basis that she had entered the deed under duress.

110 At around the same time, Philip and Maryann defaulted under the terms of the loan agreements with the Commonwealth Bank which were secured by a first mortgage over Wahroonga. This occurred on 28 April 2020. By October 2020, it had been determined that Wahroonga had to be sold and Maryann reached an agreement with the Commonwealth Bank to forbear on the enforcement of its rights until 30 August 2021 to permit this to occur.

111 On 1 April 2021, Maryann attended a mediation with the ATO. Maryann did not agree to Philip being present at this mediation other than on the end of the phone. As I have mentioned, Philip and Maryann became separated under the one roof during April 2021 and it may be inferred that the financial mayhem then besieging Maryann played its part in this. The mediation did not result in an agreement on the day. However, on 29 June 2021, Maryann entered into a contract to sell Wahroonga. The sale price was $4,150,088.00. The next day Maryann did reach an arrangement with the ATO which was reflected in a deed of that date. Under the deed, the Commissioner agreed to accept $480,000.00 from the net proceeds of sale of Wahroonga in full settlement of her obligations under the deed. The sale was completed on 11 August 2011. The net proceeds of sale in Maryann's hands after the discharge of the mortgages of the Commonwealth Bank and the Commissioner and the payment of other expenses was $1,233,639.07. Half of that balance is presently being held in the manner I have previously explained.

What the bankruptcy trustees knew in 2021 about the existence of net equity in Wahroonga

112 It was after it became clear that there was net equity in the Wahroonga property that the bankruptcy trustees say that it became apparent to them that they should commence the current proceeding. Wahroonga was purchased for $2,400,000.00 with bank debt of $1,920,000.00. From 21 November 2014, however, Wahroonga was also encumbered by a second mortgage which secured, by 8 May 2019, at least the sum of $3,376,941.20. The property was therefore encumbered by debts in excess of $5,000,000.00.

113 Unless Maryann was successful in escaping or reducing her liability under the deed, it was apparent that there would be no equity left in the Wahroonga property if it were sold. It is easy to understand that Maryann's defence to the Commissioner's possession proceeding was by no means without substance. This may be reflected in the Commissioner's settlement of the proceeding for the comparatively modest sum of $480,000.00. An alternative view is that the Commissioner was aware that the bankruptcy trustees' were going to claim on any sale proceeds left after its settlement with Maryann and, as the largest creditor, that it might obtain the benefit of any proceedings by them. Viewed that way, the actions of the ATO might seem a little disingenuous.