Federal Court of Australia

Gadsden v MacKinnon (Liquidator), in the matter of Allibi Pty Ltd (in liq) [2023] FCA 647

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to ss 90-10, 90-15 and 90-20 of the Insolvency Practice Schedule (Corporations), Mr Hamish MacKinnon and Mr Nicholas Giasoumi cease to be external administrators of Allibi Pty Ltd (ACN 124 066 717) (in liquidation) (Allibi).

2. Mr Craig Crosbie and Mr Robert Ditrich each a registered liquidator be appointed liquidators of Allibi.

3. The parties file and exchange written submissions about costs not exceeding three pages within 7 days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

O’CALLAGHAN J:

Introduction

1 By Originating Application dated 7 October 2022, the first and second plaintiffs, Mr John Gadsden and Mr Daniel Paul Lindsay (collectively, the directors), and the third plaintiff, Aqueduct Nominees Pty Ltd (as trustee for the Gadsden Family Trust) (Aqueduct) seek, among other things, orders pursuant to ss 90-10, 90-15 and 90-20 of the Insolvency Practice Schedule (Corporations) (schedule 2 to the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)) (IPSC) replacing the first and second defendants, Mr Hamish Alan MacKinnon and Mr Nicholas Giasoumi as external administrators of the third defendant (the liquidators), Allibi Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (Allibi) with Mr Craig Crosbie and Mr Robert Ditrich of PricewaterhouseCoopers.

2 The directors brought the application in their capacity as directors of Allibi. Aqueduct brought the application on the basis that it is a creditor of Allibi.

3 The liquidators oppose the application.

4 The plaintiffs seeks those orders on the grounds set out in a document headed “Applicants’ particulars of grounds for replacement of the liquidators” filed at my request on 11 May 2023. The grounds are that the liquidators:

(a) have conducted the external administration of Allibi without the degree impartiality and objectivity required of a court appointed liquidator;

(b) have failed to pursue a chose in action available to Allibi;

(c) made, and maintain, serious allegations against the directors, demanded payment of $69m under threat of legal proceedings and an adverse report to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), and published the same on the public record, without first taking proper steps to satisfy themselves that there was any proper factual, legal or rational basis to make those allegations or the demand;

(d) failed to take adequate or timely steps to bring in property of Allibi, said to be an insurance claim in respect of legal fees incurred and settlement sum in a legal proceeding; and

(e) made extensive demands for documents from the directors without:

(i) considering or identifying how those documents could assist them to discharge their duty to take into their custody any property which is, or appears to be, property of Allibi;

(ii) taking account of the responsive information and documents provided to them by the directors and their solicitors.

5 The plaintiffs read affidavits of:

(1) Mr Lindsay affirmed 14 November 2022;

(2) Mr David John Markham, the plaintiffs’ solicitor, affirmed 7 October 2022 and 16 November 2022; and

(3) Mr Antonio Bellizia, a banking and finance expert, affirmed 20 February 2023.

6 The liquidators read affidavits of:

(1) Mr MacKinnon sworn 22 February 2023 and 5 May 2023;

(2) Mr Giasoumi sworn 10 May 2023.

7 None of the plaintiffs’ deponents was cross-examined. Both Mr MacKinnon and Mr Giasoumi were cross-examined, by Mr MD Wyles KC, who appeared with Mr L Currie of counsel for the plaintiffs. Ms CG Rome-Sievers of counsel appeared for the liquidators.

The facts

The background, relevant entities and the sale transaction

8 The Gadsden Trust was established in November 1997. In 2004, the trust bought a 45% share in the Billi Partnership which was later converted to a unit trust called the Billi Unit Trust. Around the same time, the Gadsden Trust also bought shares in various related corporate trustees of trusts related to the trust.

9 The Billi Unit Trust and related trusts operated and promoted the business of developing, marketing and controlling “under-the-sink” water filtration and dispensing systems, mainly in commercial premises (which the parties called the Billi business).

10 Allibi, then known as Billi Pty Ltd, was incorporated in 2007 and was appointed as the trustee of the Billi Unit Trust. Mr Gadsden and Lindsay were appointed as the directors of Allibi upon or shortly after its incorporation.

11 Aqueduct was incorporated in May 2012 and was appointed as trustee of the Gadsden Trust.

12 From early 2015, Allibi was approached by parties who expressed interest in purchasing the Billi business.

13 Around the middle of 2015, Ernst & Young was retained to act as professional advisors to Allibi with respect to selling the business and handling sale inquiries and a sale process if one eventuated.

14 Between 2016 and 2017, Allibi received offers from several interested parties, including from a UK corporation called Waterlogic Holdings Pty Ltd (Waterlogic).

15 In early 2017, Mr Gadsden instructed Ernst & Young to engage in commercial discussions with respect of a sale of the business to Waterlogic.

16 Mr Markham gave evidence that Waterlogic “would not countenance” any sale which involved the purchase of units in the Billi Unit Trust. It “insisted that the sale be structured as a sale of shares in a ‘clean’ company, which was to take ownership of the Billi business prior to completion of the sale to Waterlogic (or its nominee) of the shares in the owner of the Billi business”.

17 Billi Australia Pty Ltd (Billi Australia), which was referred to as “Newco” in certain documentation, was incorporated on 13 March 2018.

18 Pursuant to a Share Sale Agreement entered into on 13 March 2018 between Aqueduct, D&N Lindsay Pty Ltd, Officelink Project Management and Design Pty and Waterlogic Australia Holdings Pty Ltd, each of Aqueduct, D&N Lindsay and Officelink sold to Waterlogic Australia the whole of the issued shares in Billi Australia.

19 By Asset Sale Agreement dated 12 April 2018, Allibi (as trustee for the Billi Unit Trust) agreed to sell and Billi Australia agreed to purchase the Billi business and all assets owned, used or intended for use by Allibi (as trustee of the Billi Unit Trust) in connection with the Billi business, by no later than 27 April 2018.

20 That agreement provided that the consideration for the sale was to be issued to the unit holders of the Billi Unit Trust.

21 Clause 2.7 of the Asset Sale Agreement provided that “The Buyer [Billi Australia] is solely responsible for and indemnifies the Seller [Allibi] in respect of the Assumed Liabilities arising in connection with the Assets and the Business on or after Restriction Completion [27 April 2018], excluding the Excluded Liabilities”.

22 “Assumed Liabilities” was defined as: “all liabilities arising in connection with the Business including Employee Entitlements and the Leave Entitlements held by the Seller prior to the Restructure Completion Date, (including, for the avoidance of doubt, liabilities accrued and provided for in Annexure 1) excluding the Excluded Liabilities”.

23 “Excluded Liabilities” was defined as: “all liabilities of the Seller in connection with the Business that are not capable of legal transfer”.

24 “Business” was defined as: “the business carried on by the Seller as at the Agreement Date and as at the Restructure Completion Date, including the business of designing and manufacturing under-bench hot, cold and sparkling filtered water and washroom systems, using the Assets”.

25 Completion of the Asset Sale Agreement and the Share Sale Agreement occurred on 27 April 2018.

26 Thereafter, the Billi business was conducted as part of and by the Waterlogic Group.

27 When Allibi later received monies owing to the Billi business as at 27 April 2018, Allibi paid those monies to Billi Australia.

28 On 29 August 2018, the unit holders resolved to end the Billi Unit Trust and vest any remaining assets of it in the unit holders.

AEMS and the winding up order

29 Asian Electronics Manufacturing Services Pty Ltd (AEMS) was a supplier of tap dispensers and level sensors to the Billi business, until November 2017 when Allibi informed AEMS that it would no longer order tap dispensers from it.

30 On 12 January 2018, Allibi received a letter of demand from solicitors for AEMS, demanding payment of USD$140,576.37 from Allibi for “excess stock” held by AEMS. Allibi forwarded the letter of demand to its then solicitors.

31 On 19 January 2018, Allibi emailed the solicitors for AEMS denying any indebtedness.

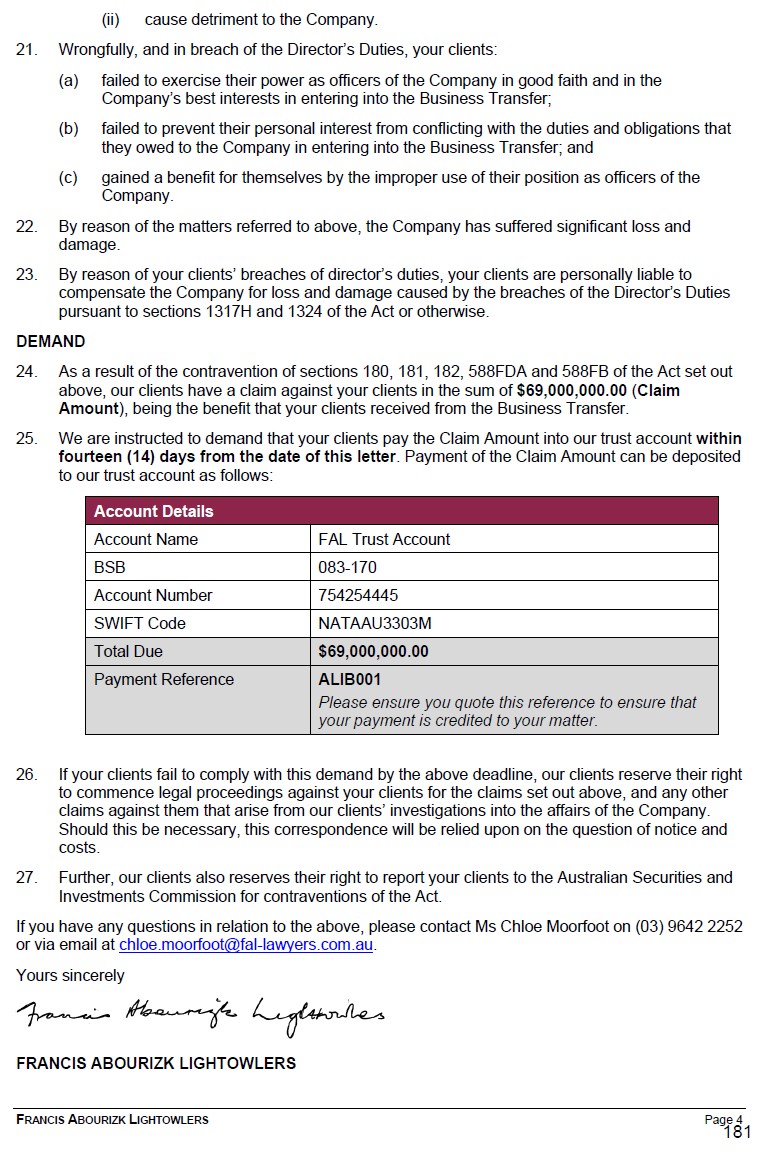

32 On 13 July 2018, AEMS served on Allibi a statutory demand claiming payment of US$344,490.84.

33 Allibi’s solicitors responded to the statutory demand and on 26 July 2018 its solicitors sent a letter to AEMS’ solicitors explaining why Allibi disputed the demand. The next day, AEMS withdrew it.

34 The directors asserted, and maintain today, that AEMS has no valid claim against Allibi.

35 On 13 November 2020, AEMS’ new solicitors (Madgwicks) made a further demand on Allibi, this time for US$344,490.84.

36 Allibi’s solicitors denied that Allibi was indebted to AEMS and confirming that they held instructions to accept service if proceedings were issued by AEMS.

37 Although Allibi’s solicitors told Mr Conti of Madgwicks that they had instructions to accept service of any documents initiating proceedings, on 31 January 2022 AEMS obtained default judgment against Allibi in the County Court of Victoria. The default relied on was the failure to file an appearance. It seems that the default occurred because the responsible partner at Madgwicks did not cause the proceedings to be served on Allibi’s solicitors, instead causing them to be delivered to Allibi’s registered office, which since 27 April 2018 had been under the control of and occupied by the Waterlogic Group. (Waterlogic Group did not pass on the documents to Allibi).

38 AEMS then issued a winding up application against Allibi in the Supreme Court of Victoria in respect of the default judgment.

39 That application also was not served on Allibi’s solicitors.

40 On 1 June 2022, and in the absence of an appearance by Allibi, a judicial registrar of the Supreme Court made orders winding up Allibi.

41 The documents were not provided to the directors until 2 June 2022, when the directors were first notified that Allibi had been wound up.

Waterlogic v Aquaduct proceeding

42 On 1 February 2019, Waterlogic commenced a proceeding in this court against the plaintiffs and two related entities in relation to the Share Sale Agreement and alleged misleading or deceptive conduct.

43 Allibi was not a party to the proceeding, which was subsequently settled on a basis that included a payment by the Aqueduct as trustee of the Gadsden Family Trust to Waterlogic of $3m.

44 The settlement deed provided that “[o]n payment of the settlement sum, the parties fully release and discharge each other from all actions, proceedings, claims, demands, liabilities, costs and expenses, wherever and however arising, known or unknown at the date of execution of this deed, arising out of or in connection with, or incidental to, or relating to the matters the subject of dispute in the Proceeding”.

45 The Company was made a party to the settlement deed by the directors.

46 Subsequently the directors submitted a claim to Allibi’s insurer in respect of the Waterlogic defence costs and settlement sum.

47 On 20 July 2022, the solicitor for the liquidators gave the following advice to the liquidators about AEMS’ claim and the right of indemnity contained in cl 2.7 of the Asset Sale Agreement:

AEMS Debt

Have you received any further correspondence from Madgwicks/AEMS regarding the petitioning creditor’s debt?

We note that clause 2.7 of the Asset Sale Agreement provides that the Buyer (New Billi) is liable for the Assumed Liabilities and has indemnified the Company for these liabilities. The Assumed Liabilities includes all liabilities arising from and in connection with the business, save for those liabilities that were not capable of being assigned. To this end, we note that Annexure 1 includes Trade Creditors of c. $3.178M. It is not clear if this amount includes the AEMS debt. We assume the answer is no based on your instructions that the directors had “forgotten” about the AEMS deb[t], but we should confirm.

If it includes the AEMSE debt, arguably, the petitioning creditor’s debt was assigned to New Billi as part of the sale agreement and the Company may be entitled to call upon that indemnity to seek payment. However, it is likely this claim has been released as part of the Settlement Agreement executed between the parties on 10 February 2022.

Do you have access to any of the books and records at the time of the sale so that you can look at the creditors ledgers?

48 On 13 October 2022 the liquidator’s solicitors wrote to Waterlogic’s solicitors inviting them to “confirm if Billi Australia accepts that it is liable for the AEMS debt in accordance with clauses 2.7 and 5.3 of the Asset Sale Agreement”. They declined to do so.

Correspondence between the parties

49 Both sides tendered through their witnesses a considerable body of correspondence that has passed between their legal representatives.

50 The correspondence relied on by the plaintiffs is set out in Mr Markham’s first affidavit at [33]-[48] and in exhibit DJM-1.

51 The plaintiffs also relied on the fact that have provided various documents to the liquidators, described in Schedule 1 to Mr Markham’s second affidavit.

52 The liquidators also adduced yet more correspondence in the defence of the application in Mr MacKinnon’s two affidavits.

53 I have attached to these reasons as annexure 1 a list of the correspondence relied on by all parties and a brief description of it.

54 Because of the view I have taken about the application, it is unnecessary, and I do not propose, to burden these reasons by setting out the correspondence, or to conduct an examination of the rights and wrongs of it all.

55 It is sufficient to say that the correspondence reflects a continuing disagreement between the plaintiffs and the liquidators about whether the liquidators have discharged their duties, obtained books and records, properly investigate the affairs of the company, evaluated the veracity of claims, and identified potential assets of Allibi, and whether the directors in turn have complied with their obligations, including to provide relevant books and records to the liquidators.

56 For reasons explained later, I accept the liquidators’ submissions that differences of opinion revealed in the correspondence do not found any proper basis for a removal order.

The $69m demand

57 On 30 August 2022, the liquidators’ solicitors wrote to Hall & Wilcox demanding that the directors pay the liquidators within 14 days “the sum of $69,000,000.00…being the benefit [they] received from the Business Transfer”; asserting that the directors had breached their duties as directors of Allibi; and expressly reserving the liquidators’ “right to report [the directors] to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission for contraventions of the [Corporations] Act”. The full letter was in these terms:

58 In his first affidavit at [51], Mr MacKinnon gave the following explanation for sending that letter:

It is my usual practice, and to my knowledge that of the fellow Registered Liquidators at my office, and common practice in the industry, for liquidators to identify potential claims at an early stage in a liquidation, and issue letters of demand in respect of them. These claims represent potential assets of a company in liquidation, and it is important and usual practice to identify and commence demand of them, as an early priority in the liquidation process. Often this may occur a year or more before recovery proceedings are eventually issued, especially claims against directors. In my experience it is not uncommon for the scope and even the nature of the claims to alter between the time of demand and the time that proceedings (if any) are issued, due to discussions with and information and documents received from the directors or other potential defendants, and the development of investigations in the liquidation.

59 The next day, the liquidators sent a circular including a statutory report to creditors (which was lodged with ASIC) listing the $69m claim against the directors as an asset of Allibi.

60 On 13 September 2022, Hall & Wilcox provided to FAL Lawyers a detailed written response denying liability and requesting further information from the liquidators with respect to their demand. The full letter was in these terms:

61 On 16 September 2022, Hall & Wilcox again wrote to FAL Lawyers, on behalf of Aqueduct, requiring explanation of the 30 August 2022 letter of demand.

62 On 27 September 2022, FAL Lawyers wrote to Hall & Wilcox, responding to Hall & Wilcox’s 13 and 16 September 2022 letters. That letter concluded:

In the interests in minimising the costs of the parties and narrowing the issues in dispute, we are instructed that our client is willing to attend a meeting with your office and your clients. The purpose of the meeting will be to identify the key issues in dispute and explore a pathway to resolving matters in the most commercial and efficient manner in the interests of creditors of the Company.

63 On 17 October 2022, FAL Lawyers wrote to Hall & Wilcox stating, among other things, “[w]hile the Liquidators have initially made a claim against Mr Gadsden and Mr Lindsay for the sum of $69 million, it would have been quite obvious to you that the claim would be limited to the quantum of proven debts at the time of the transfer of the Billi Business”. The letter continued:

You have advised the only unrelated claim is the AEMS undefended judgement debt of $497,723.20, which your clients deny liability. Your clients have failed to provide any documents to substantiate the reasons as to why they dispute the debt. Further, if your clients allege that there was no AEMS debt or if there was a debt it was assigned to Billi Australia, we reiterate our clients’ previous requests to produce evidence of such.

Until the liquidators have received the books and records of the Company and completed investigations, the liquidators cannot confirm if there were other creditors. Again, your clients have not been able to produce any meaningful books and records to assist the liquidators.

In the end if your clients are correct and there is no debt to AEMS and there are no other creditors then they should not be concerned about the liquidators claim, it should be a simple matter of providing documentation to support their claims.

The Liquidators have not commenced legal proceedings against Mr Gadsden and Mr Lindsay in respect of the claim, but rather afforded Mr Gadsden and Mr Lindsay an opportunity to respond to our clients’ investigations to date. Your clients were afforded an opportunity to provide sensible explanation of their defences to the claim for the Liquidators to consider or, alternatively, reach a settlement offer to avoid further costs and delays. To date, this has not been forthcoming.

To this end, we ask that your clients please confirm whether or not they have notified Allibi’s D&O Insurer of the Liquidators’ demand.

(Emphasis added).

64 The directors also complain that the liquidators have not corrected the content of the statutory report to creditors they filed with ASIC pursuant to s 70-40 of the Insolvency Practice Rules (Corporations) 2016 (Cth) (Insolvency Practice Rules or IPR) on 31 August 2011 which refers to a “potential legal recovery” of $69m, being “a claim we have made against the directors …”.

65 Section 70-40 of those rules relevantly provides:

70‑40 Report about dividends to be given in certain external administrations

(1) This section:

(a) is made for the purposes of section 70‑50 of the Insolvency Practice Schedule (Corporations); and

(b) applies if a liquidator has been appointed in relation to a company.

…

(3) If the company is not following the simplified liquidation process, or has ceased to follow the simplified liquidation process:

(a) the liquidator must provide to the creditors of the company a report containing information on the following:

(i) the estimated amounts of assets and liabilities of the company;

…

(vi) possible recovery actions; and

(b) the report must be provided before:

(i) the end of the period of 3 months after the date of the liquidator’s appointment; or

(ii) the end of the period of 1 month after the date on which the company ceased to follow the simplified liquidation process;

whichever occurs later; and

(c) a copy of the report must be lodged with ASIC in the approved form at the same time as it is provided to the creditors.

66 The liquidators say that they are powerless to correct the record. I should immediately deal with that assertion. Although there is no provision that provides in terms that ASIC may amend any report it lodges with ASIC under s 70-40(3)(c), it must be the case that if a report may be lodged, another report may also be lodged which has the effect of setting the record straight. To construe the section otherwise would be absurd.

67 I return to the facts.

68 On 16 September 2022, Aqueduct issued a request in writing to the liquidators pursuant to s 70‑45 of the IPSC seeking various information and documents relating to the liquidators’ $69m demand, and a proof of debt.

69 Section 70-45 of the IPSC provides:

70‑45 Right of individual creditor to request information etc. from external administrator

(1) A creditor may request the external administrator of a company to:

(a) give information; or

(b) provide a report; or

(c) produce a document;

to the creditor.

(2) The external administrator must comply with the request unless:

(a) the information, report or document is not relevant to the external administration of the company; or

(b) the external administrator would breach his or her duties in relation to the external administration of the company if the external administrator complied with the request; or

(c) it is otherwise not reasonable for the external administrator to comply with the request.

(3) The Insolvency Practice Rules may prescribe circumstances in which it is, or is not, reasonable for an external administrator of a company to comply with a request of a kind mentioned in subsection (1).

70 The information sought in the s 70-45 request was documents, reports or information that the liquidators sought to rely on:

(1) to substantiate their claim that Allibi “had creditors at the time of Transfer”;

(2) to found the conclusion that the mere transfer of assets from the Company to Billi Australia satisfied the requirements of s 588FDA(1)(a)(ii) of the Corporations Act;

(3) as evidence that Billi Australia took the assets of Allibi on behalf of the directors or for the benefit of the directors;

(4) to conclude that as at April 2018 the company was unable to pay all its debts as and when they became due and payable;

(5) to form the view that the directors, in breach of their duties, caused “significant loss and damage” to the company;

(6) to form the view that they can fund the prosecution of the claims made in the demand letter; and

(7) to decide that they will not seek to resolve the insurance claim in the best interests of the creditors until “all information is obtained in relation to the Company.

71 The liquidators subsequently admitted Aqueduct for $1 for voting purposes.

72 The liquidators did not respond to the s 70-45 request, nor did they give any reason for not doing so, as s 70-45(2) contemplates is possible in certain circumstances.

73 On 14 April 2023, FAL Lawyers wrote to Hall & Wilcox, relevantly as follows:

We wish to reiterate that our clients remain open to considering your clients’ position, (both in respect of Aqueduct’s Proof of Debt and the liquidators’ demand [for $69m]) and remain open to considering any further records that your clients have to support their contentions before making a decision in their capacity as liquidators of Allibi Pty Ltd …

The applicable law

74 Sections 90-15(1) and (3)(b) of the IPSC provide that “[t]he Court may make such orders as it thinks fit in relation to the external administration of a company”, including “an order that a person cease to be the external administrator of the company”.

75 Under s 90-15(4), the matters that the court may take into account include, but are not limited to:

(a) whether the liquidator has faithfully performed, or is faithfully performing, the liquidator’s duties;

(b) whether an action or failure to act by the liquidator is in compliance with the Act and the Insolvency Practice Rules;

(c) whether an action or failure to act by the liquidator is in compliance with an order of the Court;

(d) whether the company or any other person has suffered, or is likely to suffer, loss or damage because of an action or failure to act by the liquidator;

(e) the seriousness of the consequences of any action or failure to act by the liquidator, including the effect of that action or failure to act on public confidence in registered liquidators as a group.

76 In In the matter of Columbia Private Holdings Pty Ltd [2017] NSWSC 1859, Brereton J observed at [3]-[6] that:

… IPS s 90-15 provides a plenary power, by which “the Court may make such orders as it thinks fit in relation to the external administration of a company”. Such orders can be made on application under IPS s 90-20, which provides that those who may apply for such an order include “an officer of the company”, which encompasses a liquidator of the company. The types of orders that can be made are described in IPS sub-s 90-15(3) as including, without limitation, an order that a person ceases to be the external administrator of the company, and an order that another registered liquidator be appointed as the external administrator of the company.

Although s 90-15 appears in Division 90 “Review of the external administration of a company”, Subdivision B “Court powers to inquire and make orders”, it is not confined to orders that can be made consequent upon an inquiry under s 90-5 or s 90-10. That that must be so follows from the circumstance that standing to apply or an inquiry under s 90-10 is conferred on the persons referred to in s 90-10(2), which list is not identical, though it is similar, to that which appears in s 90-20(1).

There is nothing – in the Explanatory Memorandum, the second reading Speech, or the legislation itself – to suggest that the Insolvency Law Reform Act 2016 and the enactment of the Insolvency Practice Schedule was intended to deprive the Court of any beneficial power that it had enjoyed under the preceding legislation. Rather, it seems that where those powers have not been directly replicated, the view has been taken that the general supervisory power contained in s 90-15 was ample to cover the situation. In the present context, that is fortified by the reference in sub-s (3) to the particular types of orders which I have mentioned.

I am satisfied therefore that what previously has been done under s 473, s 499 and s 503 can now be done under IPS s 90-15.

(Emphasis added).

77 Counsel for both the plaintiffs and the liquidators agreed with those emphasised observations. I too agree, and respectfully adopt them.

78 In Re FW Projects Pty Ltd (in liq) (2019) ACLC 19-034; [2019] NSWSC 892 at [86], [89], and [91], Black J observed:

The matters relevant to an application for removal of a liquidator include not only whether that course would be for the benefit of the liquidation, and the body of persons interested in it, but also the need for confidence in the integrity, objectivity and impartiality of the winding up. In Multi-Core Aerators Ltd v Dye [1999] VSC 205 at [48]; [1999] VSC 205; (1999) 17 ACLC 1172, which was quoted by Bergin CJ in Eq in SingTel Optus Pty Ltd v Weston [2012] NSWSC 674; (2012) 90 ACSR 225, although held not to be applicable in that case, Warren J (as her Honour then was) noted that “rancour” between the parties would not be sufficient to require removal of a liquidator, particularly if hostility had emanated from the party seeking the removal, rather than from the liquidator, where removal on that basis “would provide a creditor with an opportunity to manipulate the liquidation of the company.” Nonetheless, I proceed on the basis that a loss of confidence based on reasonable grounds by the creditors may, although it will not necessarily, justify removal of a liquidator: Re St Gregory’s Armenian School (in liq) [2012] NSWSC 1215; (2012) 92 ACSR 588 at [30].

…

It is also important that the Court should not overlook the professional consequences for a liquidator of an order for removal: SingTel Optus Pty Ltd v Weston above at [229]; Re St Gregory’s Armenian School (in liq) above at [26] …

…

The Liquidators point to authority that it should not been seen as easy to remove a liquidator, even if his or her conduct is less than ideal, and the onus to establish removal of a liquidator is not lightly discharged …

79 An order for removal may also appropriately be made where it is demonstrated that it would be for the better conduct of the liquidation or to the general advantage of persons interested in the winding up or in the best interests of the liquidation. See Re St Gregory’s Armenian School (in liq) (2012) 92 ACSR 588; [2012] NSWSC 1215 at [27] (Brereton J).

80 A loss of confidence in an insolvency practitioner based on reasonable grounds may be sufficient to justify the removal of a liquidator. See Re St Gregory’s Armenian School at [30].

81 As Neuberger J (as his Lordship then was) said in AMP Music Box Enterprises Ltd v Hoffman [2002] BCC 996; [2002] EWHC 1899 (Ch) at [21] and [27]:

The court’s power to remove and replace a liquidator is derived from s. 108(2) of the Insolvency Act 1986 which is pleasantly short: ‘The court may, on cause shown, remove a liquidator and appoint another.’ As a matter of ordinary principle and statutory interpretation, that seems to me to suggest as follows: (a) the court has a discretion whether or not to remove and replace the liquidator, (b) it will do so on good grounds, (c) it is up to the person seeking the order to establish those grounds, (d) whether good grounds are established will depend on the particular facts of a particular case, (e) in general it is inappropriate to lay down what facts will and what facts will not constitute sufficient grounds.

…

… if a liquidator has been generally effective and honest, the court must think carefully before deciding to remove him and replace him. It should not be seen to be easy to remove a liquidator merely because it can be shown that in one, or possibly more than one, respect his conduct has fallen short of ideal. So to hold would encourage applications … by creditors who have not had their preferred liquidator appointed, or who are for some other reason disgruntled. Once a liquidation has been conducted for a time, no doubt there can almost always be criticism of the conduct, in the sense that one can identify things that could have been done better, or things that could have been done earlier. It is all too easy for an insolvency practitioner, who has not been involved in a particular liquidation, to say, with the benefit of the wisdom of hindsight, how he could have done better. It would plainly be undesirable to encourage an application to remove a liquidator on such grounds. It would mean that any liquidator who was appointed, in circumstances where there was support for another possible liquidator, would spend much of his time looking over his shoulder, and there would be a risk of the court being flooded with applications of this sort. Further, the court has to bear in mind that in almost any case where it orders a liquidator to stand down, and replaces him with another liquidator, there will be undesirable consequences in terms of costs and in terms of delay.

82 The observations in the second of those paragraphs have been referred to with approval in a number of Australian cases.

83 Further, as Brereton J also said in Re St Gregory’s Armenian School at [25]:

The relevant “cause” to be shown is to be measured by reference to the “real, substantial, honest interest of the liquidation, and to the purpose for which the liquidator is appointed … the measure of due cause is the substantial and real interest of the liquidation” …”cause shown” is a broad concept concerned not so much with a search for particular instances of wrong or inappropriate conduct (although a particular event of that kind may suffice), but a more general inquiry into what is for the benefit of the administration and the body of persons interested in it, as well as the maintenance of confidence in the integrity, objectivity and impartiality of that administration, so that removal is warranted if, taken as a whole, the conduct of the liquidator can be seen to be such as to ground in the mind of a reasonable observer a perception of lack of impartiality as among the interests he is committed to serve and lack of objectivity in serving those interests. Before removing a liquidator from office, the court will normally need to be satisfied of “cause shown” going beyond a particular instance. If the complaint relates to a particular decision of the liquidator, the appropriate course is an appeal to the court under s 1321, even if the substance of the complaint is that the decision demonstrates incompetence or bias or other unfitness for office …

(Citations and internal quotations omitted).

84 And as Finkelstein J said in Independent Cement and Lime Pty Ltd v Brick and Block Co Ltd (in liq) (rec and mgs apptd) (2010) 267 ALR 613; [2010] FCA 352 at [49], administrators and deed administrators have “a duty to carry out reasonable investigations into potential claims so as to form an opinion as to what future course of action is in the creditors’ interests”. In doing so, they are “required to take into account the time, cost and uncertainty associated with litigating actions”, but a decision to litigate or not “should only be reached after careful consideration of the claims which can only be brought following a liquidation”.

85 Independent Cement and Lime was a case decided under s 503 of the Corporations Act to remove a liquidator for “cause shown”, and it concerned allegations held to found grounds for the removal of liquidators based on conduct the liquidators had engaged in while they were administrators and deed administrators before their appointment as liquidators. But his Honour’s description of the duty aptly describes the duty of a liquidator under the relevant provisions of the IPR applicable here.

86 It is also important to bear in mind that, as White J (with whom Jessup J and Robertson J agreed) said in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Franklin (2014) 223 FCR 204 at 217 [55] (a case also decided under s 503 of the Corporations Act):

The words “cause shown” are not to be construed narrowly. An applicant for removal may rely on any conduct or inactivity by a liquidator ranging from moral turpitude to bias, lack of independence, incompetence or other unfitness for office. The overall considerations are the interests of the liquidation and the purpose for which the liquidator was appointed.

(Citations omitted).

The competing submissions

The competing submissions about the $69m demand

87 The plaintiffs submitted that the evidence was “overwhelming” that when the liquidators made their $69 million demand, they were aware that:

• Allibi was the trustee of the Billi Unit Trust and only ever traded in that capacity;

• on 12 April 2018, Allibi (in its capacity as trustee of the Billi Unit Trust) entered into the Asset Sale Agreement, pursuant to which it agreed to sell all of its assets to Billi Australia;

• on 27 April 2018, the Asset Sale Agreement completed;

• on 27 April 2018 there was no extant AEMS demand that Allibi make payment to it;

• on 27 April 2018 Allibi had no interest in the proceeds of the sale of the Billi business to Waterlogic Group, other than as trustee of the Billi Unit Trust;

• on 18 May 2018, AEMS purported to issue the two disputed invoices to Allibi;

• on 13 July 2018, AEMS issued a statutory demand to Allibi claiming as a debt payable the two disputed invoices dated 18 May 2018;

• on 25 July 2018 MST Lawyers on behalf of Allibi responded to the AEMS statutory demand disputing the debt;

• on 26 July 2018, AEMS withdrew the statutory demand;

• on 29 August 2018, the Billi Unit Trust vested;

• as at 29 August 2018 the assets of the Billi Unit Trust equalled its liabilities;

• as at 29 August 2018 Allibi had no proper basis to seek indemnification from the beneficiaries of the Billi Unit Trust;

• on 13 November 2020 (i.e. more than two years after the Billi Unit Trust had vested), AEMS (using new solicitors, Madgwicks) issued a new demand for payment of the disputed 18 May 2018 invoices. This was the first time AEMS asserted its purported claim after withdrawing its statutory demand in July 2018;

• on 31 January 2022, AEMS obtained default judgment against Allibi because Allibi failed to enter an appearance and Madgwicks had failed to serve the proceeding on MST (who had instructions to accept service) in the County Court of Victoria, which amount was expressly based upon the two disputed invoices dated 18 May 2018; and

• on 1 June 2022, Allibi was wound up.

88 The plaintiffs were critical of the following evidence given by Mr MacKinnon in cross-examination concerning the $69m demand:

[MR WYLES]. Yes. Thank you. And when the letter of demand was written you were aware of only two claims. We see that from page 183 in your report to ASIC; that’s correct? Yes.

So there’s just no justification for demanding $69 million; is there? …

…

THE WITNESS: As I – I’ve already answered that question. I’ve said until I can work out what the creditors are – if I was to claim for a dollar, a creditor might have a go at me and say, “Well, hold on, why didn’t you claim for more. There’s – there’s $5 million of creditors that turn up”. If there’s $20 million of creditors turn up, and I only claim for 500,000 – being the AEMS’ debt – they could have criticised me as well.

89 The plaintiffs also relied on the evidence (italicised below) given by Mr MacKinnon in answer to a question from the court during the course of his re-examination:

MS ROME-SIEVERS: Perhaps if I ask it this way. As at 17 October, even at 30 August, you said that you didn’t know the full – you’ve said earlier that you didn’t know the full creditor position yet? Yes.

What did you know of it or what – were you aware of – what sorts of creditors were you expecting to see in this particular liquidation on the basis of what you knew then? I think I mentioned it before. This company had been trading for 15, 20 years.

Yes? And it had sold a huge amount of tapware.

Yes? And that would lead to a potential warranty claim from consumers.

Yes.

HIS HONOUR: Well, what has that got to do with $69 million? The 69 million?

What’s the correlation between ---?---Well---

---your---?---By – by the trust not receiving that money and those creditors coming to light, like the AEMS debtors come to light or was there originally, those consumers would not have any chance of recovery because at the time of the sale that asset, which was an asset of the trust, had gone effectively to the unitholders in the wind-up of the business or wind-up of the – after the sale and clearing the decks.

[Did] you have some idea in your mind that there might be these potential claims from tap users---?---Yes.

…

[HIS HONOUR]. So that’s why I ask the question what relevance does that thinking have to a demand made for---?---Well

---$69 million?---If there were taps sold and that led – prior to the sale, those consumers would have rights against the company, and at the time of the – the way the sale had been structured, the shares – the – the trust received no consideration apart from paying out the creditors.

90 The plaintiffs submitted that while Mr MacKinnon said he did not know if Allibi had traded since 27 April 2018, “that evidence was neither sensible nor factual and itself revealed a failure of the requisite impartiality and objectivity” because:

… the only unrelated creditor known to Mr MacKinnon as at 30 August 2022 was AEMS. The proposition that the liquidators had a genuine concern about inchoate warranty claims being made by customers, in circumstances where the business ceased trading more than four years earlier and none had been made, should be rejected as a retrospective attempt to justify their conduct. The notion of these potential warranty claims was raised by the liquidators for the first time in this proceeding, and never in any of the extensive correspondence that preceded it.

91 It was also submitted that “the liquidators have never clearly articulated the legal and factual basis upon which they have any claim against the directors. Specifically, they never explained in their evidence or their opening how their putative claim against the directors could be reconciled with the fact that Allibi sold its business as the trustee of the Billi Unit Trust and distributed the proceeds to the beneficiaries” (citing Carter Holt Harvey Woodproducts Australia Pty Ltd v Commonwealth (2019) 268 CLR 524 at 577-83 [128]-[145] (Gordon J).

92 The plaintiffs also submitted that there was “no legal or rational foundation to support” Mr MacKinnon’s evidence in response to the question from the court that “creditors coming to light … would not have any chance of recovery because at the time of the sale that asset, which was an asset of the trust, had gone effectively to the unitholders in the wind-up of the business … after the sale and clearing the decks” because the assets held by Allibi were at all times held by it as trustee of the Billi Unit Trust, and any alleged creditor of Allibi never possessed, and does not possess, a direct proprietary claim against the assets of the Billi Unit Trust.

93 The plaintiffs made the following submission in relation to the 30 August 2022 demand for $69m:

[In the 30 August 2022 letter of demand] the liquidators accused the directors in a formal written demand from their solicitors of wrongfully, and in breach of their directors’ duties …

….

The seriousness of these allegations was reinforced at the conclusion of the liquidators’ demand by the threat to report the directors to ASIC “for contraventions of the Act”. After the directors’ disputed their liability, the liquidators did not resile. By a further letter dated 27 September 2022 the liquidators stated, albeit in relation to the demand for documents, that they may report the directors to ASIC “which may result in your clients being criminally liable for their breaches”.

94 As to Mr MacKinnon’s evidence about his “usual practice”, the plaintiffs submitted that:

Mr MacKinnon gave evidence that it was his “usual practice” to issue demands in respect of “potential claims” and subsequently investigate whether such claims actually exist and in what amounts. This is a troubling admission in any winding up and even more so in the winding up of a trading trustee. It is a practice which is contrary to law. It is a practice which defies genuine steps. It is a practice not contemplated by s 474 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), which requires the identification of property of the company, and is a practice which falls outside of the power conferred by s 477(2)(a).

Liquidators pursuing the requisite impartiality and objectivity in the position of the liquidators here would have attended to their due diligence before instructing their solicitors to send the $69 million demand and accusing the directors of serious breaches of their statutory duties. There was no imminent limitation period about to expire nor was it alleged by the liquidators that interest would accrue if the amount demanded was unpaid by a specified date. There was also nothing preventing the liquidator from taking steps to verify the amount of any debts of Allibi that remained unpaid as at the date of the business transfer. The proof of this is that a matter of weeks later the liquidator conceded in correspondence to Hall & Wilcox (but not to ASIC) that its putative claim was something less than $500,000 and stated that “it would have been quite obvious to you that the claim would be limited to the quantum of proven debts at the time of the transfer of the Billi Business”. The liquidators’ conduct being further exacerbated by the publication to ASIC of a report which made the same allegations without qualification.

(Footnotes omitted).

95 The liquidators, on the other hand, submitted that “[t]he most that could be said against [them] is as to the full value cited for the potential claim, 3 months into the liquidation”. They agreed that “[i]t is a very large sum, but … the reasoned basis for the calculation of figure is that this was the net value of the diverted proceeds of sale of the business”.

96 The liquidators further submitted that although they “considered it too early to compromise the potential full value of the claim in the letter of demand until the full extent of unpaid creditors was known, and they were concerned as to how much that might be, and whilst it would hamper negotiations seeking recovery for creditors, they accept that an alternative approach they could fairly have taken would be to cite the interim value of the potential claim as the total of known unrelated creditors to date, with the caveat that that amount could increase if and when more unpaid creditors came to light”.

97 They contended, however, that “[e]ven if that criticism is made of them”, that is not a ground for removal.

98 The liquidators also reiterated in their written closing submissions that it is their “usual practice and common industry practice for liquidators to identify potential claims, as potential Company assets, as an early priority in a liquidation, and issue letters of demand in respect of them.”

99 It was also submitted that such “standard practice” is reflected in the Insolvency Practice Rules. In that regard they referred to s 70-40, which requires liquidators to prepare a report to creditors and file it with ASIC within three months of their appointment outlining, among other things, the “estimated amounts of assets and liabilities of the company” and “possible recovery actions”.

100 The submission continued:

The usual practice of liquidators writing letters of demand in the early months of a liquidation does not mean doing so without a reasonable basis. Investigations commence the day after appointment. Liquidators are given 3 months to commence investigations and identify possible recovery actions to be reported to creditors. Investigations continue, further evidence may come to light which may either put a different complexion on matters or reinforces the liquidators early view, proceedings may or may not be issued. But it is unrealistic and wrong to suggest that liquidators cannot properly write letters of demand, once possible claims are identified on evidence, and conduct negotiations until investigations are at a point where proceedings are about to be issued.

101 In their closing written submissions, the liquidators collated a litany of points, directed to the proposition that they were justified in forming the view that there was a “possible recovery action” in the sum of $69m. They included:

(1) when the letter of demand was sent, they knew of three potential groups of undisclosed creditors – AEMS, claimants as a result of detection of legionella in filtrations systems supplied by the Company and claims arising from the sale of the Billi Business, and/or consumer warranty claims;

(2) they were aware the directors “had already been sued for misleading and deceptive conduct, and misrepresentation, and had paid a multi-million dollar settlement” (it was $3m);

(3) they were aware the directors “were being selective and not forthcoming with information”;

(4) they “were aware that in the instance of AEMS, at best the directors had left a disputed claim behind in an assetless entity aware that it was still pressed but without resolving it” and they “did not know what other debts might have similarly been ignored by the them”;

(5) they “knew that the trustee Company’s financial records and tax returns did not show a distribution of trust assets” and that “[t]he diversion of the entire net proceeds of sale direct to the unit holders did not appear properly to have been accounted for by the trustee”;

(6) “this could all be legitimate” and their “concerns as to the asset sale could be satisfied, if the [p]laintiffs would clarify, with sufficient supporting documents to evidence assertions, what took place, how it was done, and why it was done in this way … [i]nstead …of issu[ing] this proceeding”;

The competing submissions about cl 2.7

102 The next ground concerned the alleged failure to pursue the cl 2.7 indemnity.

103 The plaintiffs submitted that the effect of the indemnity provided by cl 2.7 was to shift from Allibi to Billi Australia the risk of any liability arising in connection with the business which was not otherwise expressly captured in the Restructure Completion Balance Sheet annexed to the Asset Sale Agreement. They submitted that contrary to Mr MacKinnon’s assertion in cross-examination that the wording of the clause is “poor”, “on a plain reading it would appear to capture, or be capable of capturing, the claims asserted by AEMS”.

104 The plaintiffs were also critical of the legal advice received by the liquidators in July 2022 about the clause (see paragraph [47] above), and submitted that “the only legal advice apparently obtained by the liquidators in respect of cl 2.7 was the perfunctory and inconclusive half-page email from FAL Lawyers sent more than two months prior” and that their “failure to take any substantive action to pursue the chose in action against Billi Australia is to be contrasted to their dogged pursuit of the directors”, something it was said could “only be explained by an absence of the requisite impartiality and objectivity which the reasonable observer would expect and which the liquidators are duty bound to pursue”..

105 The liquidators submitted that in their “judgment, clause 2.7 properly construed does not appear to capture the AEMS claim and other debts such as legionnaires-related claims, customer warranty claims, claims arising from the sale to [Billi Australia].” The submission was put this way:

Obviously, on that view, the Liquidators cannot properly seek to recover a claim against a company which is not liable for it. The Liquidators holding an opinion which is contrary to that of the Directors demonstrates their objectivity. It is precisely because they are objective that they hold their own view and make up their own mind. The Plaintiffs’ real ‘beef’ here is that the Liquidators do not agree with their own opinion.

… This so-called ‘ground’ fails to address the release given in the Waterlogic proceeding in the settlement deed of February 2022, prior to the Liquidators’ appointment. Even if the Liquidators otherwise shared the Plaintiffs’ opinion as to the proper construction and operation of clause 2.7 meaning that it came within Newco’s indemnity, that indemnity no longer exists by virtue of the release in the settlement deed, and the Liquidators are barred thereby from any potential recovery against Newco.

… [E]ven if none of that were the case, the Liquidators could not pursue such an alleged chose in action against [Billi Australia] until it had formed a view on the AEMS claim. That is a prerequisite to any such chose in action. The liquidators have not yet formally adjudicated AEMS proof of debt … The AEMS claims are being investigated thoroughly by the Liquidators before a decision is made on its admission.

The competing submissions about the alleged failure to pursue the insurance claim with diligence

106 The plaintiffs submitted that upon the admission of the Aqueduct proof of debt, Allibi would obtain a corresponding asset in that amount, in the form of a chose in action against Allibi’s D&O insurer, and that any recovery would necessarily be dealt with by the liquidators in accordance with s 556 of the Corporations Act.

107 It was submitted that “the justification provided by Mr MacKinnon for not pursuing the insurance claim is not objectively reasonable or rational and would give rise to concerns about the liquidators’ conduct in the mind of the reasonable observer”.

108 The liquidators submitted that the directors “still have yet to provide adequate supporting documentation and information for the asserted claim, despite repeated and specific requests” and “[t]o be able to pursue the insurance claim for part of legal fees incurred by other parties and the settlement sum for litigation the Company was not involved in, [they] must be satisfied that the expense was indeed incurred by or on behalf of the Company, and that in turn necessitates the adjudication of the Aqueduct proof of debt”. They submit that it would be inappropriate and improper for them to pursue an insurance claim under Allibi’s insurance claim which is without proper foundation. They also say that had they pursued the insurance claim, they may open themselves to a personal exposure for pursuing a claim they did not understand and could not corroborate.

109 They also say that “[u]ntil the plaintiffs stop changing the quantum of the claim, and provide sufficient evidence supporting the claim, the insurance claim cannot properly be pursued”.

The competing submissions about the demands for documents

110 The plaintiffs submitted that the evidence establishes that the directors have performed their obligations to assist the liquidators.

111 They rely on the following:

a. on 15 June 2022 the liquidators were notified that Hall & Wilcox was acting for the directors;

b. on 20 June 2022, the liquidators were:

i. informed about the vesting of the BUT [Billi Unit Trust], the sale of the Billi business, the claim by Waterlogic, the insurance claim, the disputed AEMS debt;

ii. provided with a range of trust tax returns, financial statements, the BUT trust deed and constitution, the BUT vesting resolution and the completed ROCAP; and

iii. invited to meet with the directors’ solicitors to discuss the insurance claim further;

c. on 27 June 2022, the liquidators were provided with the Asset Sale Agreement and correspondence with respect to the notification of the insurer;

d. on 12 July 2022, the liquidators were provided with a bundle of additional insurance correspondence;

e. on 18 July 2022, the liquidators were provided with:

i. a further explanation for why the directors had concerns about providing the Share Sale Agreement (namely that it was confidential and Allibi was not a party to it);

ii. an explanation as to why the directors could not provide Allibi’s bank statements (namely that they were property of Waterlogic);

iii. a spreadsheet recording transactions undertaken by Allibi after the settlement of the sale to Waterlogic; and

iv. Allibi’s ANZ bank account number;

f. on 28 July 2022, the liquidators were provided with the Share Sale Agreement and informed that Hall & Wilcox expected to be in a position to respond further to the requests for the Ernst & Young and MST documents by 12 August 2022 (the email explained that Mr Kelcey, the partner with conduct of the matter was on leave until the following week);

g. on 16 August 2022, Hall & Wilcox sent FAL Lawyers two detailed letters, one in relation to the insurance claim and one in relation to the liquidators’ requests for documents;

h. on 13 September 2022, Hall & Wilcox provided a lengthy and detailed response as to why the directors rejected the liquidators’ $69 million demand;

i. on 27 September 2022, the liquidators received Aqueduct’s proof of debt;

j. on 3 October 2022, Hall & Wilcox sent the liquidators’ solicitors a detailed letter in relation to the liquidators’ document requests, Aqueduct’s request for information, the AEMS claim and Allibi’s bank account;

k. on 19 October 2022, the liquidators were provided with:

i. further details regarding Allibi’s bank statements and various transactions undertaken;

ii. details regarding advice provided in relation to the sale of the Billi business;

iii. details regarding advice provided in relation to the Waterlogic proceeding;

iv. confirmation that there was no correspondence between Billi Australia and Allibi leading up to the sale of the Billi business; and

v. further details regarding the AEMS claim;

l. on 20 October 2022, the liquidators were provided with a further detailed response to their demand for payment from the directors, as well as a detailed explanation for this proceeding, the directors’ response to various requests for books and records and the AEMS claim;

m. on 21 October 2022, Hall & Wilcox provided details and further supporting documents to support Allibi’s insurance claim;

n. on 30 January 2023, Hall & Wilcox invited the liquidators to inspect the entire Waterlogic Proceeding file; and

o. on 2 May 2023, Hall & Wilcox sent the liquidators’ solicitors a six-page letter providing further information on a range of topics, including a detailed description of the directors’ responses to the liquidators’ document requests.

112 The correspondence above is included in annexure 1 to these reasons.

113 In light of that it was submitted that “[a]ny contention that the directors have been uncooperative fails to pay proper regard to the evidence and is simply wrong. The correspondence demonstrates that the directors have acted reasonably and have gone to significant lengths to assist the liquidators to discharge their statutory duties. The liquidators have not sought to explain to the Court how any of the remaining documents they seek to obtain would assist them to bring in property of Allibi”.

114 The liquidators submitted that the directors “still have not provided” the following documents in relation to the insurance claim and Aqueduct’s proof of debt:

• The documents referred to in the pleadings filed in the Waterlogic proceeding,

• The affidavit of Ann Watson of Hall & Wilcox, wherein she is said to have deposed Hall & Wilcox acted for the Company, contrary to Hall & Wilcox’s repeated asserts to the Liquidators that they have never acted for the Company,

• Any written retainer between Hall & Wilcox and the Company,

• Any written indemnity agreements between Aqueduct and the Company,

• Any advice provided by any advisor or firm to the Company in relation to the settlement agreement,

• Any file notes, correspondence, memoranda of advice relating to the unsuccessful joinder application,

• Any record evidencing the basis upon which Aqueduct alleges that the Company shares liability for the legal fees incurred in the Waterlogic proceeding and the settlement sum. There were 5 defendants to the Waterlogic proceeding. The Company was not one of them. There were 6 parties to the settlement deed, not 3.

Competing submissions on prejudice

115 The plaintiffs’ banking and finance expert, Mr Bellizia, has worked in the banking industry for 44 years. He has held senior roles within credit risk at various banks. It is Mr Bellizia’s expert opinion that “[t]he Statutory Report to Creditors dated 31 August 2022 highlights numerous concerns for me/or any lender, in particular the Potential Legal Recoveries of $69m. I could not see how any lender/bank would advance/renew any facilities to the individuals/company based on the above”.

116 The plaintiffs submitted that Mr Bellizia’s evidence “must be accepted. Mr MacKinnon is not an expert in the areas in which Mr Bellizia has expertise, and any opinions expressed by Mr MacKinnon are subjugated to those of Mr Bellizia”.

117 They submitted that:

The conclusion the Court can and should draw on the evidence is that unless and until the liquidators’ erroneous and misconceived report to ASIC is corrected, the directors are exposed to real and substantial prejudice, namely the inability to refinance or obtain new finance. Given the current market conditions and interest rate volatility, there is a genuine possibility of this risk being realised in the near future.

In addition, the creditors of Allibi, including Aqueduct, continue to suffer the prejudice of the liquidators’ unnecessary work and wasted expenditure.

118 The liquidators submitted that although the directors feel aggrieved, there is no evidence of any prejudice (they have not sought and been denied credit, as a result of the report) and there is no evidence of a risk of potential prejudice because Mr Bellizia’s affidavit “is both hypothetical and irrelevant”.

Consideration

The $69m demand

119 I will turn first to the $69m demand, because in my view the contentions made by the plaintiffs about it are to be accepted, and are dispositive in their favour.

120 It is important to have regard to the specific terms of the liquidators’ 30 August 2022 letter of demand.

121 That letter asserted that “[i]n the course of our clients’ investigations into the Company’s affairs, our clients have identified a number of claims that the Company may have against your clients directly in relation to … [the Business Transfer] … including (without limitation): (a) entering into an unreasonable director-related transaction; (b) entering into an uncommercial transaction; and (c) breaches of directors duties”. Having touched on the only single “outstanding debt” that had been identified (the AEMS claim), the letter went on to plead a summary of a case against the directors pursuant to ss 180, 181, 182, 588FDA and 588FB of the Corporations Act.

122 In each case it was asserted that the constituent elements of each cause of action were established.

123 The letter asserted that:

(1) Each of the requirements under s 588FDA had been made out and that accordingly the Business Transfer was an unreasonable director-related transaction.

(2) The Business Transfer was an uncommercial transaction within the meaning of s 588FB and that it was “voidable as against your clients pursuant to [s] 588FE of the Act”.

(3) In breach of their duties under ss 180, 181, and 182 of the Act, the directors:

(a) failed to exercise their power as officers of the Company in good faith and in the Company’s best interests in entering into the Business Transfer;

(b) failed to prevent their personal interest from conflicting with the duties and obligations that they owed to the Company in entering into the Business Transfer; and

(c) gained a benefit for themselves by the improper use of their position as officers of the Company.

(4) By reason of those breaches, the directors were “personally liable to compensate the Company … pursuant to [ss] 1317H and 1324 of the Act …”

(5) As a result of those contraventions, the liquidators had a claim against the directors in the sum of $69m.

(6) The liquidators reserved their right to report the plaintiffs to ASIC “for contraventions of the Act”

124 As was submitted by the plaintiffs, they were allegations and claims – very serious ones – for which no proper foundation was, or has been, proffered.

125 It has long been the case that “court proceedings may not be used or threatened for the purpose of obtaining for the person so using or threatening them some collateral advantage to himself, and not for the purpose for which such proceedings are properly designed and exist; and a party so using or threatening proceedings will be liable to be held guilty of abusing the process of the court and therefore disqualified from invoking the powers of the court by proceedings he has abused”. See In re Majory [1955] Ch 600 at 623-24 (Lord Evershed), cited with approval by Mason CJ and Dawson, Toohey and McHugh JJ in Williams v Spautz (1992) 174 CLR 509 at 528.

126 Further, as Ward J (as her Honour then was) said in Accord Pacific Holdings v Accord Pacific Land Pty Ltd [2011] NSWSC 707 at [53] (a case concerning an application to set aside examination summonses):

There is general authority that the use of court process to secure a collateral advantage by way of a commercial settlement or compromise of a claim before trial, where it can be said that the proceedings are not instituted to vindicate a genuinely asserted right, may be an abuse of process (White Industries (Qld) Pty Ltd v Flower & Hart (1998) 156 ALR 169).

127 Re Sheahan & Lock (as liquidator of Valofo Pty Ltd (in liq)) [2010] NSWSC 1255 at [35] was another examination summons case. Justice Palmer observed that whether or not liquidators have abused the process of an examination summons “depends upon the same considerations as to whether they have abused any other litigious process which they might have commenced in the course of a liquidation: is the liquidator using the process, whatever it is, for a purpose for which it was not intended or designed or does the liquidator propose not to carry that process to its conclusion, but simply to use it as a means of coercion or to achieve a collateral purpose?”

128 His Honour also referred to the decision of Hetyey JR in Re KASO (2018) 133 ACSR 473; [2018] VSC 774 at [22] for the proposition that use of a court’s processes to inflict financial or other collateral harm will always be improper.

129 In that case, Hetyey JR also referred to the decision of Gardiner AsJ in Re DW Marketing Pty Ltd (in liq) [2009] VSC 663, where there was an unjustifiable demand for payment of an amount (comprising a specified sum, together with interest, costs and the expenses of the liquidation), coupled with the threat that if such demand was not met examinations would be resumed and directors would be examined about various matters including those going to possible criminal liability.

130 In this case, it seems to me a clear abuse of process to make what was, on any view, an unjustified demand for the payment of $69m, in circumstances where the liquidators insist, even now, that “it would have been quite obvious to [the plaintiffs] that the claim would be limited to the quantum of proven debts at the time of the transfer of the Billi Business” (which they said was $497,723.20). Quite how it is said that a formal demand for $69m, with an accompanying threat of legal proceedings and a reporting of the alleged contraventions to ASIC if the amount was not promptly paid, was supposed to be read as being a demand for $497,723 was not adequately explained.

131 Mr MacKinnon was asked in cross-examination what the justification for demanding $69m was. He replied: “… until I can work out what the creditors are – if I was to claim for a dollar, a creditor might have a go at me and say, ‘Well, hold on, why didn’t you claim for more. There’s – there’s $5 million of creditors that turn up’. If there’s $20 million of creditors turn up, and I only claim for 500,000 – being the AEMS’ debt – they could have criticised me as well.”

132 Mr MacKinnon was also asked “So your position was that the demand was the $500,000?” He answered: “No. My demand was for 69 million until I determined the creditors of the company”.

133 Those answers, and the submission advanced on behalf of the liquidators in closing submissions, suggest that the liquidators believed and still believe that it is appropriate to issue letters of demand by way of ambit claims. That is assuredly not so.

134 The collateral purpose of the demand is tolerably clear.

135 FAL Lawyers wrote to Hall & Wilcox on 27 September 2022 in response to letters written on behalf of each of the plaintiffs insisting on an explanation of the $69m demand, suggesting that “[i]n the interests [of] minimising the costs of the parties and narrowing the issues in dispute, we are instructed that our client is willing to attend a meeting with your office and your clients … [for] the purpose of … identify[ing] the key issues in dispute and explor[ing] a pathway to resolving matters in the most commercial and efficient manner in the interests of creditors of the Company”. That does rather suggest that at least one main purpose of the demand was to facilitate a commercial resolution.

136 Further, Mr MacKinnon deposed that it was his “usual practice” and “common practice in the industry, for liquidators to identify potential claims at an early stage in a liquidation, and issue letters of demand in respect of them” and that in his experience “it is not uncommon for the scope and even the nature of … claims [against directors] to alter between the time of demand and the time that proceedings (if any) are issued, due to discussions with and information and documents received from the directors or other potential defendants, and the development of investigations in the liquidation”.

137 The liquidators repeated this position in their counsel’s written closing submissions. See paragraph [98] above. They went so far as to contend that such “standard practice” is reflected in IPR s 70-40 (which provides that liquidators are to provide a report to creditors containing, among other things, the estimated amounts of assets and liabilities of the company and possible recovery actions).

138 In my view, the evidence given by Mr MacKinnon at paragraphs [88]-[89] above and the submissions by the liquidators’ counsel recorded at paragraph [101] above misconceive the nature of their obligations.

139 Liquidators are officers of the court. They are subject to its supervision. Like legal practitioners, they are bound by certain obligations. They also have special responsibilities under the Corporations Act.

140 Whether liquidators carry the obligations of a model litigant is not clear. In Viscariello v Macks (2014) 103 ASCR 542; [2014] SASC 189 at [641] Kourakis CJ said that they do. In Re St Gregory’s Armenian School at [32], Brereton J held that it “goes too far” to call them model litigants within the meaning of relevant Legal Services Directions, because:

Courts expect liquidators to make commercial judgments and to act commercially, and to pursue vigorously the interests of the company. Liquidators have a private interest apart from the public good — not their own personal interest, but that of the creditors or contributories. It adds an unnecessary layer to the inquiry into whether there is “cause shown” to superimpose an expectation that the liquidator be a model litigant.

141 Although his Honour went on to say, “[t]hat is not to say that a liquidator’s conduct in litigation may not be relevant to a judgment as to whether there is ‘cause shown’”.

142 It is not necessary to resolve that debate for the purposes of this application. The question of whether cause is shown is to be addressed by reference to the nature of the impugned conduct.

143 Because liquidators are officers of the court it is axiomatic that they should not make demands for the payment of large sums of monies, founded on asserted causes of action for which there is no proper basis. The litany of matters sought to be invoked now to justify the $69m demand listed at paragraph [101] above only make matters worse, because they do not, individually or collectively, form a proper or sufficient basis for the making of the demands in the 30 August 2022 letter. The obligation to identify “possible recovery actions” required by the IPSC does not, as the liquidators submissions seem to suggest, mean that they can make serious but purely speculative allegations (here, against directors under multiple provisions of the Corporations Act) in the hope that they may bear fruit or drive the directors to the bargaining table.

144 It is of course true, as McPherson and Pincus JJA, and Derrington J said in Re Qintex Group Management Services Pty Ltd (in liq) [1997] 2 Qd R 91 at 94-95, that liquidators “when they are appointed labour under the particular disability of not knowing as much about the affairs of the company as former directors and others, and that they often cannot obtain reliable information about suspicious transactions” and that they may be confronted with information in the books and records of the company that contain “contrived explanations” or “distortion[s] by persons not anxious to disclose what they really know about events that took place when they were in charge of the company’s affairs”. It is also sometimes the case that directors “are often unwilling and unco-operative witnesses especially in matters in which they are the target of proceedings brought by the liquidator”. And as the court also said in that case, “[f]ew other litigants suffer to that disadvantage, or to the same extent, as liquidators”. See also Grosvenor Hill (Qld) Pty Ltd v Barber (1994) 48 FCR 301 at 306 (Beaumont, Spender and Cooper JJ).

145 But the fact that liquidators are often placed in that difficult position is a reason that they are conferred with special powers, for example, to summons directors to give evidence. It does not mean that they are excused from compliance with rules applicable to all officers of the court, including rules and standards that govern the threat, initiation and conduct of legal proceedings. And it does not mean, as the cases make clear, that they can act oppressively or harshly, by seeking to exert pressure, with the spectre of legal costs, or causing undue embarrassment and the like (including here, by making a threat to “report” the contraventions to ASIC).

146 The liquidators conceded in counsel’s written closing submissions that “they accept that an alternative approach they could fairly have taken would be to cite the interim value of the potential claim as the total of known unrelated creditors to date, with the caveat that that amount could increase if and when more unpaid creditors came to light”. But that is not, with great respect, “an alternative approach”. If by “potential claim” the liquidators meant a claim which could reasonably and properly be made consistently with a liquidator’s duty as an officer of the court, then that is not an “alternative approach” to take. It is the only approach, for reasons which I trust I have adequately explained.

147 I should also say, if it matters, that I also accept the submission made on behalf of the directors that the liquidators did not, and have not, explained how the alleged claims against the directors can be reconciled with the fact that Allibi sold its business as the trustee of the Billi Unit Trust and distributed the proceeds to the beneficiaries of the trust.

148 The next question is whether the conduct by the liquidators identified above warrants their removal.

149 In my view, it does.

150 I have no doubt that Mr MacKinnon’s views about the $69m demand, and the “common industry practice” about what I have called “ambit claims” were honestly and sincerely held, and that he answered the questions put to him in the witness box honestly. But his views about the matter, for the reasons I have set out above, were plainly wrong and his actions (and those of Mr Giasoumi) in making and persisting (to this day) with the demand were inconsistent with their obligations as officers of the court.

151 As Neuberger J said in the passage quoted at paragraph [81] above that “… if a liquidator has been generally effective and honest, the court must think carefully before deciding to remove him and replace him” and that “[i]t should not be seen to be easy to remove a liquidator merely because it can be shown that in one, or possibly more than one, respect his conduct has fallen short of ideal”. And a judge does, of course, consider – and I have considered – the possible effect that an order for removal may have on the professional reputation of the liquidators.

152 In the circumstances of this case, however, I am satisfied that proper cause for removal has been shown, and that such an order should be made to maintain confidence in the integrity of the administration. I would also found the order on the basis that an order for removal is appropriate because the reasonable bystander would, on reasonable grounds, have lost confidence in the liquidators, in circumstances where their actions, in demanding damages in the sum of $69m founded on causes of action that were without a proper foundation, reveal that they lacked, and still lack, a sufficient understanding about a matter fundamental to their role.

153 The liquidators submitted that “[n]o ground for removal or any relief is shown with respect to the [$69m] demand”. They said that “[r]easonable minds can vary amongst professionals as to the course each would take in a particular situation”; that “[t]here is not one single reasonable path to take; that they “have brought an independent, experienced mind to bear in investigating the Company’s affairs and evaluating the evidence” and that “[i]t is clear they had a proper basis to form the views that they did, and they acted accordingly and in furtherance of their duties”.

154 It will be obvious from what I have said that I emphatically disagree.

The other grounds

155 It is therefore unnecessary to deal with the other grounds.

156 It is sufficient to say that I do not think that the other grounds provide any sufficient basis for removal, and that I accept the gist of the liquidators’ submissions in that regard.