Federal Court of Australia

Seven Network (Operations) Limited v 7-Eleven Inc [2023] FCA 608

ORDERS

| ||

SEVEN NETWORK (OPERATIONS) LIMITED Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 8 June 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer with a view to agreeing by 12:00pm on 14 June 2023: (a) orders to give effect to these reasons; and (b) appropriate orders with respect to costs.

2. The proceedings be listed at 9:00am on 15 June 2023 for resolution of any dispute as to appropriate orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THAWLEY J:

INTRODUCTION

1 By an originating application filed on 21 July 2021 the appellant, Seven Network (Operations) Limited, appeals to the Court in its original jurisdiction under s 104 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (TMA) from a decision of a delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks: Seven Network (Operations) Limited v 7 Eleven Inc [2021] ATMO 58; 164 IPR 370.

2 The delegate’s decision addressed a non-use application made by the respondent, 7-Eleven Inc, under s 92(1) of the TMA to remove Seven’s Australian Registered Trade Mark No 1540574 for the word “7NOW” in classes 9, 35, 38 and 41 (the 7NOW Mark). That application was made on the ground mentioned in s 92(4)(b) of the TMA, namely that Seven had not used the 7NOW Mark, or had not used it in good faith, during the three years between 10 June 2016 and 10 June 2019 (the non-use period). The delegate held that the 7NOW Mark should be removed from the register. The delegate was not satisfied that Seven had used the 7NOW Mark during the non-use period and was therefore satisfied that the ground on which 7-Eleven’s application had been made was established. The delegate did not exercise the discretion in s 101(3) of the TMA not to remove the mark.

3 Although s 104 of the TMA furnishes a statutory right of “appeal”, the proceeding is by way of a hearing de novo: Telstra Corporation Limited v Phone Directories Company Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 156; 237 FCR 388 at [192](2) (Besanko, Jagot and Edelman JJ). The Court stands in the shoes of the Registrar to consider the relevant issues afresh: Jafferjee v Scarlett [1937] HCA 36; 57 CLR 115 at 119 and 126; Kenman Kandy Australia Pty Ltd v Registrar of Trade Marks [2002] FCAFC 273; 122 FCR 494 at [21]; Woolworths Ltd v BP plc [2006] FCAFC 52; 150 FCR 134 at [30].

BACKGROUND FACTS

The Seven Group

4 Seven West Media Limited is the ultimate holding company of the Seven Group, a group of companies that together operate an integrated multi-media business, with a presence in broadcast television, publishing and online.

5 Seven is the major operating company for the Seven Group and operates the Seven Network, a major Australian commercial free-to-air television network broadcasting across Australia for many years. Seven’s core business operation is to generate revenue from the provision of advertising services and selling advertising space on its television channels. In order to generate that revenue, Seven makes content available for free and promotes that content with the aim of attracting audiences to whom advertisers can promote their goods and services. Seven has a dedicated team selling advertising to potential clients, currently providing its advertising services through two business units: 7RED and 7REDiQ.

6 Mr Coatsworth gave evidence for Seven. He is the company secretary and legal counsel of Seven West Media. He is a director, company secretary and legal counsel of Seven. He is also the company secretary of each of the companies in the Seven Group. Mr Coatsworth stated:

67. 7RED is a cross-media business that assists clients in developing and rolling out advertising campaigns, including creating advertising content and developing a programme for the screening that content across Seven’s channels and Seven West Media’s publications. The 7RED business includes the following business units:

(a) 7Fusion, which works closely with 7REDiQ (see paragraph 68 below) to combine data and information about content consumption and brand buying behaviours to give advertisers a detailed understanding of audiences.

(b) RED Engine TV is an internal production company that generates content that is funded by external brands. For example, Chemist Warehouse funds the production of House of Wellness, which includes a website at www.houseofwellness.com.au, a television programme and a radio station. …

(c) 7Creative is a team of producers, directors, designers, editors and writers who produce high quality creative, including television commercials, digital content plus in-program integrations, and billboard advertisements.

68. 7REDiQ gathers data from multiple sources including its own viewers and users of its websites, OzTAM, and through third party partnerships, and makes it available to advertisers to enable them to create targeted advertising campaigns and understand the impact of their advertising on audiences. In particular, Seven is able to gather and analyse data that allows segments of consumers with very specific characteristics to be identified, and to whom advertisers can roll out addressable (or targeted) advertising. For example, if a person is a registered user of the 7PLUS Website, Seven will know:

(a) the age of that person as that information is gathered as part of the

registration process;

(b) what content that person has accessed through the 7PLUS website;

(c) the devices they have used to access that content; and

(d) what other content that person has accessed on those devices.

69. Seven has recently introduced two additional products to further engagement with consumers, being 7Shop and 7Rewards. 7Shop is an integrated shopping experience that invites users of the 7PLUS Website to purchase the products they see on screen. This further drives revenue as commercial content is no longer limited to advertisement breaks, but embedded within the programmes.

70. 7Rewards is a unique reward program that uses data collated through 7REDiQ to provide customised advertising experiences for Seven’s audience. 7PLUS viewers will have access to personalised rewards, including dining, travel and activities for the family. Coupled with 7Shop, these products furthers Seven’s ability to generate and maximise revenue.

…

72. Seven promotes its advertising services through the website at https://www.inside7.com.au. Annexed to this affidavit … are screenshots I have caused to be taken of this website, relating to the services offered by both the 7RED and 7REDiQ business units.

7-Eleven

7 7-Eleven operates an international chain of convenience stores under its 7-ELEVEN brand, including in Australia since 1977. Overseas, 7-Eleven uses 7NOW in relation to a food and alcohol delivery and pick-up service. The service is promoted from a website at 7now.com, which is no longer accessible in Australia; and it is offered via an app called “The 7NOW App”, also not available in Australia. If 7-Eleven succeeds in having its marks registered, it proposes to use them to offer a similar service in Australia as is being offered overseas. The logo mark is as follows:

8 7-Eleven uses a variety of marks in jurisdictions outside of Australia, including 7-SELECT, 7REWARDS, 7-CONNECT, 7-FRESH, 7-EATS, 7-SIGNATURE, 7-SNACKS, 7-PREMIUM, 7-VENTURES, 7 NEXT, 7CAFE.

9 About three months after these proceedings were commenced, Seven commenced a proceeding against 7-Eleven seeking to cancel nine of its trademark registrations for non-use.

10 Although as Seven’s company secretary and legal counsel he had a general knowledge of Seven’s proceedings, and despite his detailed evidence in these proceedings concerning Seven’s marks, Mr Coatsworth was unable to confirm that the proceedings which Seven had commenced related to 7-Eleven’s 7-SELECT, 7-FRESH and 7-CONNECT marks.

Overview of relevant events

11 Seven requested registration of the domain name 7now.com.au on 27 July 2011.

12 Seven has been the registered owner of the 7NOW Mark since 7 August 2013. The specification for Seven’s 7NOW Mark is as follows (the underlining will be explained later):

Class 9: Computer software

Class 35: Advertising including advertising services provided by television and in the nature of dissemination of advertising for others via online global electronic communication networks; rental of advertising space including online; promotional services; the promotion and sale of goods and services for others including through the distribution of on-line promotional material and promotional contests; retail and wholesale services including retail trading via television programmes and by telephone and electronic means including the Internet; the bringing together, for the benefit of others, of a variety of goods enabling customers to conveniently view and purchase those goods including by mail order, telecommunications, website or television shopping channels; television commercials and production of television commercials; including the provision of all the aforesaid services via broadcasts, television, radio, cable, direct satellite, electronic communication networks, computer networks, global computer network related telecommunication and communication services, broadband access services, wireless application protocol, text message services, telephone and cellular telephone; information and advisory services relating to all the aforementioned

Class 38: Broadcasting services, including television broadcasting, interactive broadcasting services, broadcasting of electronic programming guides, free-to-air and subscription television broadcasting services and radio broadcasting services; datacasting; telecommunications and communication services, including interactive telecommunications and communication services; transmission of cable television and interactive audio and video services; personalised and interactive television transmission and programming services; streaming of audio and video material on the Internet; information and advisory services relating to all the aforementioned

Class 41: Entertainment services including those provided by, or in relation to, television, television broadcasting, television programmes and interactive television programmes, sporting events; pay and subscription television services in this class; entertainment services in the nature of producing, distributing and disseminating programs and information; online television entertainment and information services including digital recording of television programs for delayed, interactive and personalised viewing; online provision of television program listings and suggested viewing guides; personalised and interactive entertainment services in the nature of providing personalised television programming and interactive television programming and games; production of films, shows and television programs including interactive programs; news and news reporter services; providing on-line electronic publications; providing digital music, videos and television clips online; including the provision of all the aforesaid services via broadcasts, television, radio, cable, direct satellite and electronic communication networks, including computer networks, global computer network related telecommunication and communication services, broadband access services, wireless application protocol, text message services, telephones and cellular telephones; information and advisory services relating to all the aforementioned

13 Seven did not seek to argue that it used the 7NOW Mark as a trade mark at any time before around 24 July 2018.

14 From around 24 July 2018, the URL www.7now.com.au redirected users to the 7plus.com.au domain and users landed on the 7PLUS website. This was in place until 1 April 2019.

15 From 1 April 2019, the URL www.7now.com.au ceased redirecting to the 7plus.com.au domain. Users landed instead on a website created for 7NOW.

16 7-Eleven filed its non-use application on 10 July 2019.

17 On 23 March 2020, 7-Eleven applied in Australia to register 7NOW (2077255) and a figurative mark containing the words 7 NOW (2077257), both in respect of:

Class 35: Retail convenience stores; online retail convenience store services for a wide variety of consumer goods featuring home delivery service and in-store pickup

18 When 7-Eleven’s applications came to be examined by a delegate of the Registrar, Seven’s 7NOW Mark was cited as a basis to refuse registration.

19 The delegate made his decision on 30 June 2021, finding that Seven had not used the 7NOW Mark as a trade mark in respect of any of the specified goods or services during the relevant non-use period. The delegate was also not satisfied that the discretion in s 101 should be exercised in Seven’s favour in respect of any goods or services.

20 In this appeal (and as it had before the delegate), 7-Eleven seeks to defend the delegate’s decision only in respect of particular goods and services (the Defended Goods and Services) and consents to Seven’s appeal being allowed in relation to all other goods and services (the Undefended Goods and Services). The underlining in [12] above identifies the Defended Goods and Services, namely those which 7-Eleven maintains should be removed on the basis that its non-use application has been made out.

21 The Defended Goods and Services are as follows:

Category 1: computer software (in class 9);

Category 2: the promotion and sale of goods and services for others including through the distribution of online promotional material and promotional contests (in class 35);

Category 3: retail and wholesale services including retail trading via television programmes and by telephone and electronic means including the Internet (in class 35); and

Category 4: the bringing together, for the benefit of others, of a variety of goods enabling customers to conveniently view and purchase those goods including by mail order, telecommunications, website or television shopping channels (in class 35).

PART OF THE APPEAL ALLOWED BY CONSENT

22 As mentioned, the parties accepted that Seven’s appeal should be allowed in so far as it concerned the Undefended Goods and Services and that this should be done without a hearing on the merits concerning whether there had in fact been use of the 7NOW Mark during the non-use period in respect of those goods and services. The Registrar does not oppose that occurring.

23 Like in the present case, in Hungry Spirit Pty Limited ATF The Hungry Spirt Trust v Fit n Fast Australia Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 883, the parties asked the Court to make an order by consent allowing an appeal pursuant to s 104 of the TMA. The parties provided to the Court a letter from IP Australia stating that the Registrar did not object in principle to the orders sought by the parties.

24 Justice Burley summarised the operation of the statutory scheme from the filing of such an application in the following way (emphasis in original):

[8] The Registrar is obliged to give notice of an application under [s] 92, including by advertising the application in the Official Journal: s 95. The application for removal may be referred by the Registrar to a prescribed court for determination: s 94. That step was not taken in this case. Any person may oppose an application for removal by filing a notice of opposition with the Registrar in accordance with the regulations and within the prescribed period: s 96. If the application for removal is unopposed, or the opposition has been dismissed, the Registrar (or the court, if the application is referred to it) must remove the trade mark from the Register in respect of the goods and/or services specified in the application: s 97. If the application is opposed, the registrar must deal with the opposition in accordance with the regulations: s 99. The Trade Marks Regulations 1995 (Cth) provide that the applicant must file a notice of intention to defend the application, if a notice of intention to oppose the application is filed: reg 9.15. If a notice of intention to defend is not filed within the period required, the Registrar may decide to take the opposition to have succeeded, and refuse to remove the trade mark from the Register: reg 9.15(3).

[9] Section 100(1) provides that it is for the trade mark owner (as the opponent to the non-use application) to rebut any allegation that the trade mark has not been used or was not intended to be used.

[10] Section 101(1) provides that if the proceedings have not been discontinued or dismissed, and the Registrar is satisfied that the ground on which the application was made have been established the Registrar may decide to remove the trade mark from the Register in respect of any or all of the goods and/or services to which the application relates. Section 101(2) similarly provides that if, at the end of the proceedings relating to the opposed application the court is satisfied that the grounds on which the application was made have been established the court may order the Registrar to remove the trade mark from the register in respect of all or some of the goods or services to which the application relates. However, the Registrar (or the court) may elect not to effect any removal if she (or the court) is satisfied that it is reasonable to decline to do so: s 101(3), (4).

[11] If the application is determined by the Registrar (or her delegate) an appeal lies to this Court or the Federal Circuit Court from the decision: s 104. It is by that route that the present appeal is before the Court. As a hearing de novo, the Court stands in the shoes of the Registrar to consider afresh whether or not the non-use application should be allowed. Accordingly, although in its submissions Hungry Spirit drew specific attention to s 101(2), it is the language of s 101(1) that is directly applicable.

25 Justice Burley explained the nature of the appeal to the Court as being a hearing de novo in which the Court approaches the matter for the first time exercising the judicial power of the Commonwealth, not in order to correct error in an executive decision, but to deal with a controversy for the first time: at [13].

26 His Honour continued:

[14] The [TMA] and Regulations make clear that it is the applicant for removal that remains the moving party, despite the fact the appeal was initiated by Hungry Spirit and despite the reversal of onus effected by s 100. In this regard it is significant that the applicant is obliged to file a notice of intention to defend. If it does not do so, then the opposition may be taken to have succeeded and the removal application will fail. Whilst Hungry Spirit was obliged to file a notice of appeal in this Court, because it did not succeed before the delegate, the substantive moving party in the proceeding remained Fit n Fast, as the applicant for removal.

[15] Further, s 101(1) requires the Registrar to be satisfied that the grounds upon which the non-use application was made have been established. Accordingly, despite the reversal of onus, ultimately it is for the applicant for removal to persuade the Registrar of the appropriateness of any order made.

[16] In these circumstances, it is apparent that despite the different scheme set out in the Act and Regulations, the application for non-use must be initiated and prosecuted by the non-use applicant. The position is analogous to that which I considered in Hungry Spirit 1 [Hungry Spirit Pty Ltd ATF The Hungry Spirit Trust v Fit n Fast Australia Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 1277].

[17] In the present case, Fit n Fast and Hungry Spirit have reached a compromise, with the consequence that Fit n Fast no longer wishes to prosecute its application for non-use. Hungry Spirit maintains its opposition to the non-use application. Were that to have been the position before the delegate of the Registrar, she could pursuant to reg 9.15 have moved, in effect, to dismiss the application for non-use. Having been notified of the parties’ position, the Registrar does not oppose the orders sought, which will remove the limitation placed on the designation of goods and services. Furthermore, having regard to my consideration of the reasons given by the delegate, I can see no self-evident reason why, in these circumstances, the orders should not be made.

27 I followed the same approach in similar (but distinguishable) circumstances in Freshfood Holdings Pte Limited v Pablo Enterprise Pte Limited (No 2) [2021] FCA 1404; 164 IPR 5. The same approach is also followed here. It is relevant to observe, however, that accepting that the appeal should be allowed by consent is not equivalent to finding or accepting that there was use by Seven of the 7NOW Mark as a trade mark during the non-use period in relation to any of the Undefended Goods or Services.

THE ISSUES

28 The remaining issues to be resolved are:

(1) whether Seven has discharged its onus of proving that it has used the 7NOW Mark in respect of the Defended Goods and Services during the non-use period;

(2) if not, whether the Court should exercise the discretion under s 101 of the TMA to remove the 7NOW Mark in respect of the Defended Goods and Services.

29 As to the first issue, Seven does not assert any use of the 7NOW Mark as a trade mark before 24 July 2018. From then, the question of use is conveniently divided into two periods:

From 24 July 2018 to 1 April 2019 (the redirect period): the 7now.com.au domain redirected users to the 7plus.com.au domain. Seven contends that it used the 7NOW Mark during this period in relation to Categories 2, 3 and 4.

From 1 April 2019 to the end of the non-use period on 10 June 2019 (the 7NOW website period): the 7now.com.au domain ceased redirecting to 7plus.com.au and, instead, users landed on the 7NOW website. Seven contends that it used the 7NOW Mark during this period in relation to Categories 1, 2, 3 and 4.

30 Seven does not assert any use of the 7NOW Mark beyond the use of it in the domain name and on the 7NOW website during the non-use period.

31 As to the second issue – the exercise of discretion under s 101 – one of the issues raised by Seven is the contended use of the 7NOW Mark after the non-use period.

LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK

32 Section 92(1), (2) and (4)(b) of the TMA provide:

92 Application for removal of trade mark from Register etc.

(1) Subject to subsection (3), a person may apply to the Registrar to have a trade mark that is or may be registered removed from the Register.

(2) The application:

(a) must be in accordance with the regulations; and

(b) may be made in respect of any or all of the goods and/or services in respect of which the trade mark may be, or is, registered.

…

(4) An application under subsection (1) or (3) (non-use application) may be made on either or both of the following grounds, and on no other grounds:

(a) …

(b) that the trade mark has remained registered for a continuous period of 3 years ending one month before the day on which the non-use application is filed, and, at no time during that period, the person who was then the registered owner:

(i) used the trade mark in Australia; or

(ii) used the trade mark in good faith in Australia;

in relation to the goods and/or services to which the application relates.

33 The “use” about which s 92(4)(b) speaks is “use as a trade mark”: E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd [2010] HCA 15; 241 CLR 144 at [32]-[33], [43] (French CJ, Gummow, Crennan and Bell JJ; with whom Heydon J agreed at [87]); Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd [2023] HCA 8 at [7]. Use as a trade mark is discussed further below.

34 Seven bears the onus of rebutting the allegation made by 7-Eleven under s 92(4)(b), which it does by establishing on the balance of probabilities (Telstra at [132]-[133]) that the 7NOW Mark was used in good faith in Australia during the non-use period. The use as a trade mark be “real commercial use” or “ordinary and genuine use” and not “some fictitious or colourable use”: Lodestar Anstalt v Campari America LLC [2016] FCAFC 92; 244 FCR 557 at [120] per Nicholas J. Sections 100(1)(c) and 100(3)(a) of the TMA provide:

100 Burden on opponent to establish use of trade mark etc.

(1) In any proceedings relating to an opposed application, it is for the opponent to rebut:

…

(c) any allegation made under paragraph 92(4)(b) that the trade mark has not, at any time during the period of 3 years ending one month before the day on which the opposed application was filed, been used, or been used in good faith, by its registered owner in relation to the relevant goods and/or services.

…

(3) For the purposes of paragraph 1(c), the opponent is taken to have rebutted the allegation that the trade mark has not, at any time during the period referred to in that paragraph, been used, or been used in good faith, by its registered owner in relation to the relevant goods and/or services if:

(a) the opponent has established that the trade mark, or the trade mark with additions or alterations not substantially affecting its identity, was used in good faith by its registered owner in relation to those goods or services during that period …

35 In E & J Gallo at [62] (Heydon J agreeing at [87]), French CJ, Gummow, Crennan and Bell JJ confirmed the following about the meaning of “use in good faith” in s 92(4)(b):

(a) bona fide use must be “ordinary and genuine use” judged by commercial standards: Electrolux Ltd v Electrix Ltd (1953) 71 RPC 23 at 36 per Sir Raymond Evershed MR;

(b) bona fide use must be “perfectly genuine”, “substantial in amount”, and “a real commercial use on a substantial scale”: Electrolux at 41 per Jenkins LJ;

(c) bona fide use is not “some fictitious or colourable use but a real or genuine use”: Electrolux at 42 per Morris LJ;

(d) use of a trade mark for a purpose other than deriving profit and establishing goodwill is not use as required by the legislation: Imperial Group Ltd v Philip Morris & Co Ltd [1982] FSR 72 at 83 per Shaw LJ;

(e) contriving use for the purpose of defeating a trade rival’s plans will lack the necessary quality of genuineness: Re Concord Trade Mark [1987] FSR 209 at 226 per Falconer J;

(f) however, a use does not cease to be genuine even if it only occurs after an appreciation that a registration was vulnerable to an attack on the grounds of non-use: New South Wales Dairy Corporation v Murray Goulburn Co-operative Co Ltd (1989) 86 ALR 549 at 567 per Gummow J;

(g) in deciding that a use is not genuine, a court may be influenced by the quantum of sales: Imperial Group at 79 per Lawton LJ, and at 83 per Shaw LJ; Concord at 226 per Falconer J;

(h) whilst a single act of sale may not be sufficient to prevent removal: Re Nodoz Trade Mark [1962] RPC 1 per Wilberforce J, in the case of genuine use, a relatively small amount of use may be sufficient to constitute “ordinary and genuine” use judged by commercial standards: Electrolux at 36 per Sir Raymond Evershed MR.

36 Section 101 includes:

101 Determination of opposed application--general

…

(2) Subject to subsection (3) and to section 102, if, at the end of the proceedings relating to an opposed application, the court is satisfied that the grounds on which the application was made have been established, the court may order the Registrar to remove the trade mark from the Register in respect of any or all of the goods and/or services to which the application relates.

(3) If satisfied that it is reasonable to do so, the Registrar or the court may decide that the trade mark should not be removed from the Register even if the grounds on which the application was made have been established.

37 Under s 101(2), the Court may order the Registrar to remove Seven’s 7NOW Mark from the register in respect of some or all of the goods or services to which the removal application relates.

38 Even where the ground for removal under s 92(4)(b) exists, s 101(3) gives the Court the discretion to decide not to remove Seven’s 7NOW Mark if the Court is satisfied that it is reasonable not to do so. It might be observed that s 101(2), by its use of the word “may”, also contains a discretion, albeit one which is “subject to” s 101(3) and s 102, the latter of which is not presently relevant. The relevant principles will be discussed later.

USE AS A TRADE MARK

General principles

39 The TMA defines a trade mark at s 17 as follows:

A trade mark is a sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person.

40 The TMA defines a “sign” as inclusive of words, numerals and a combination of both: s 6(1).

41 A trade mark indicates the origin of the goods to which the mark is applied and aims to distinguish a connection between the goods or services of the “registered owner” of the mark from the goods or services of others in the course of trade: E & J Gallo at [42]; Self Care at [23]. Thus, a trade mark is a sign used as a “badge of origin” to draw a connection between the “goods and the user of the [trade] mark”: Self Care at [23]; E & J Gallo at [33]; Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect Distributors Ltd [1999] FCA 1721; 96 FCR 107 at [19].

42 The question whether a sign has been used as a trade mark is assessed objectively from the perspective of the consumer, taking into account the context of the use of the mark: Shell Company of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd [1963] HCA 66; 109 CLR 407 at 425; Johnson & Johnson Australia Pty Ltd v Sterling Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd [1991] FCA 402; 30 FCR 326 at 339-340; Self Care at [24]. It is to be assessed without reference to the subjective trading intentions of the user: E & J Gallo at [33]; Self Care at [24]. The context includes “the relevant trade, the way in which the words have been displayed, and how the words would present themselves to persons who read them and form a view about what they connote”: Self Care at [24]. It may be assessed with resort to common sense: Wellness Pty Ltd v Pro Bio Living Waters Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 438; 61 IPR 242 at [25].

43 In Nature’s Blend Pty Ltd v Nestlé Australia Ltd [2010] FCAFC 117; 272 ALR 487 at [19], the Full Court stated:

[19] In considering the reasons of the primary judge and the arguments put on appeal, it is necessary to bear in mind the principles governing whether Nestlé used “luscious Lips” as a trade mark. They may be summarised as follows:

1. Use as a trade mark is use of the mark as a “badge of origin”, a sign used to distinguish goods dealt with in the course of trade by a person from goods so dealt with by someone else: Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect Distributors Ltd (1999) 96 FCR 107 at [19]; E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Limited (2010) 265 ALR 645 at [43].

2. A mark may contain descriptive elements but still be a “badge of origin”: Johnson & Johnson Australia Pty Ltd v Sterling Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd (1991) 30 FCR 326 at 347- 348; Pepsico Australia Pty Ltd v Kettle Chip Co Pty Ltd (1996) 135 ALR 192; Aldi Stores Ltd Partnership v Frito-Lay Trading GmbH (2001) 54 IPR 344 at [60].

3. The appropriate question to ask is whether the impugned words would appear to consumers as possessing the character of the brand: Shell Company of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407 at 422.

4. The purpose and nature of the impugned use is the relevant inquiry in answering the question whether the use complained of is use “as a trade mark”: Johnson & Johnson at 347 per Gummow J; Shell Company at 422.

5. Consideration of the totality of the packaging, including the way in which the words are displayed in relation to the goods and the existence of a label of a clear and dominant brand, are relevant in determining the purpose and nature (or “context”) of the impugned words: Johnson & Johnson at 347; Anheuser-Busch, Inc v Budejovický Budvar, Národní Podnik (2002) 56 IPR 182.

6. In determining the nature and purpose of the impugned words, the Court must ask what a person looking at the label would see and take from it: Anheuser-Busch at [186] and the authorities there cited.

Use in the redirect period

Facts

44 From about 24 July 2018 to 1 April 2019, the URL www.7now.com.au redirected users to the 7PLUS website at www.7plus.com.au, which has operated since about December 2017. The 7PLUS website is a broadcaster video on-demand (BVOD) platform. Users of the 7PLUS website can access live streaming of Channel 7, 7two, 7mate, and 7flix and a range of other digital channels and on-demand television programmes.

45 Since December 2017, Seven has also provided the 7PLUS mobile device application on both Android and Apple devices (7PLUS App). The 7PLUS App provides the same BVOD service and offers the same content as the 7PLUS website.

46 During the redirect period, the 7PLUS website allowed users to stream Seven’s digital channels live. Seven sold advertising space on these channels, and screened advertisements for its clients.

Seven’s Case

47 Seven submitted that the selling of advertising space on the channels accessible on the 7PLUS website and 7PLUS App was conduct within Category 2.

48 In relation to Categories 2, 3 and 4, Seven referred to Seven’s television programs available for streaming through the 7PLUS website and the 7PLUS App, which included:

home shopping programs that promoted goods and services on behalf of third parties, and allowed users to buy those goods and services by using website and telephone details displayed on the screen; and

programs that incorporated advertorials that promoted goods and services on behalf of third parties.

49 Seven submitted that “[b]ecause the above categories of the Defended Goods and Services were offered or advertised on the 7PLUS website while the 7NOW domain name was redirecting there, it follows that the 7NOW domain name was used in respect of those goods and services during the redirect period”.

50 Seven relied in this respect on the decision of Perram J in Solahart Industries Pty Ltd v Solar Shop Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 700; 281 ALR 544. Seven relied, in particular, upon what his Honour stated at [61]:

One has, therefore, this position: the use of the word SOLARHUT [7NOW] as part of the domain name www.solarhut.com.au [www.7now.com.au]; access to that address taking consumers to what appeared to be a different website – www.sunsavers.com.au [www.7plus.com.au] – at which identical goods were sold; and an intention by Solar Hut to exploit the goodwill in the mark SOLARHUT [7NOW] to attract business to its website conducted from www.sunsavers.com.au [www.7plus.com.au]. The effect of the use of SOLARHUT [7NOW] in the mark was to increase the traffic to Solar Hut’s www.sunsavers.com.au [www.7plus.com.au] website. It was not used on a whim but as a sign whose only purpose was to increase sales of photovoltaic systems. This, within the principles I have outlined above, was trade mark use.

51 Seven submitted that this case fit equally within those words.

Consideration

52 In Solahart, the applicant owned three trade marks for SOLAHART. The respondent commenced a business in May 2009 called Solar Hut which it launched from a website with the URL www.solarhut.com.au: at [2]-[3].

53 The respondent also advertised its solar panel products by reference to the trade mark SOLARHUT, including in television, radio and newspaper advertisements and invited consumers to visit its website at solarhut.com.au: at [43]-[44], [51].

54 All of this displeased Solahart. Solahart was concerned about the similarity of its name with the name SOLARHUT, particularly the aural similarity: at [4].

55 After correspondence from Solahart, the respondent decided in October 2009 to abandon its use of the word SOLARHUT in favour of SUNSAVERS. It created a new website with the URL www.sunsavers.com.au. However, it did not wholly abandon use of the word SOLARHUT, because it maintained the URL www.solarhut.com.au. If this URL was accessed, the user would be redirected to the new business website at www.sunsavers.com.au: at [5]. That is, despite rebranding, the respondent maintained its solarhut.com.au domain name and used it to redirect consumers to its Sunsavers website. Consumers searching for the words “Solar Hut” using a search engine and clicking on the results were taken to the Sunsavers website, and so the domain name solarhart.com.au “continued to funnel consumers to the website at www.sunsavers.com.au”: at [7], [53]. Solar Hut intended to have the solarhut.com.au domain name redirect consumers to the sunsavers.com.au website “for as long as possible to take advantage of whatever the benefits of its continued existence might be”: at [59]-[60].

56 Solahart alleged that the respondent infringed the trade marks in three ways: first, by Solar Hut’s sale of its photovoltaic systems using the word SOLARHUT; second, by keeping the website www.solarhut.com.au; and, third, by maintaining the website www.solarhut.com.au after the switch to the SUNSAVERS brand as a redirect to www.sunsavers.com.au: at [6]. It is the third aspect of the case upon which Seven relies in the present case.

57 Justice Perram stated the relevant principles in the following way at [50]:

The issue of whether use of a domain name is trade mark use is more difficult. The questions which arise in this area were usefully considered, and the authorities collected, by Kenny J in Sports Warehouse Inc v Fry Consulting Pty Ltd (2010) 186 FCR 519 at 552-556 [141]-[156] and I acknowledge the value and considerable advantage I have derived from her Honour’s reasons in what follows. A number of propositions should be accepted: first, mere registration of a domain name does not establish the infringement of a trade mark; secondly, where a cybersquatter does not seek to attract consumers to the occupied domain name but merely seeks to treat with the owner of the mark it is unlikely that trade mark infringement will be shown for there will be no goods or services being proffered to consumers to which the impugned sign, contained within the domain name, may be reasonably be seen as relating (‘[t]here could be a threatened infringement if one were to take seriously the suggestion that [the cyber squatter] intended to engage in the sugar trade’: CSR Ltd v Resource Capital Australia Pty Ltd (2003) 128 FCR 408 at 416 [412] per Hill J); thirdly, where a person uses a domain name to attract consumers to a website which promises connexions with goods or services relating to the registered mark infringement may be established even if the owner of the domain name does not sell the goods or services and instead merely benefits from a flow of traffic over the website (Nissan Motor Co v Nissan Computer Corp 378 F.3d 1002 (2004) (9th Cir. 2004)); fourthly, where a domain name is used to conduct a website from which goods or services are sold the same kinds of questions which arise in ordinary trade mark litigation will arise, for in such cases the analogy between the sign on the front of a shop and the goods sold within will be established; fifthly, explicit advertising of the website in that context is obviously relevant for it will show more clearly the connexion between the sign and the service.

58 Justice Perram’s conclusion that the domain name was still being used “as a trade mark” was reached in a context where: (a) before the time of the impugned use, there had been promotion of the SOLARHUT trade mark in conjunction with the solarhut.com.au domain name as indicating the trade origin of the solar panels that were for sale; and (b) the ongoing use of the domain name was to transfer customers who were looking for solar panels by reference to the SOLARHUT name, including by internet searches, to a business selling solar panels. It was in that specific factual context that the Court found that the domain name continued to function as a trade mark.

59 These facts bear no resemblance to the present facts.

60 The 7NOW Mark was in the domain name which had been registered in 2011. This was not a trade mark use: Sports Warehouse Inc v Fry Consulting Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 664; 186 FCR 519 at [153]; Solahart at [50]. All that had happened on around 24 July 2018 was that Seven caused a redirection to be put in place. There was no evidence of any promotion of 7NOW or the 7now.com.au website. Leaving aside the use of “7now” in the domain name, the 7NOW Mark was not apparently being used in any connection with any business or commercial activity. There was no evidence of anyone searching for 7NOW or in fact being redirected to the 7Plus website. There was no direct evidence about what a person who might have searched for 7NOW, or otherwise happened upon the www.7now.com.au website, might have been looking for or expecting to find or even if they expected goods or services to be available there.

61 In this context, Seven observed that “[i]t would be erroneous to require Seven to prove that the goods and services it offered under the mark were taken up by consumers” and that “[a]n offer of goods or services under a trade mark is use of that mark as a trade mark, regardless of whether that offer was taken up by a consumer”, referring to Moorgate Tobacco Co Ltd v Philip Morris Ltd (No 2) [1984] HCA 73; 156 CLR 414 at 443. This misses the point. The point is that “use as a trade mark” must be assessed having regard to the facts and context. There was no offer of goods or services in connection with the 7NOW Mark when it was used in the domain name during the redirect period from 24 July 2018 to 1 April 2019. There is no basis to conclude that a consumer attempting to access a webpage associated with www.7now.com.au would have identified the 7NOW Mark with any goods or services at all, including any of those which might happen to have been associated with the webpage www.7plus.com.au, to which the consumer was most likely unwittingly redirected.

62 Further, Seven argued that its use of “7now” in the domain name fell within the third proposition contained in Perram J’s summary in Solarhart at [50], namely: “where a person uses a domain name to attract consumers to a website which promises connexions with goods or services relating to the registered mark infringement may be established even if the owner of the domain name does not sell the goods or services and instead merely benefits from a flow of traffic over the website”.

63 Justice Perram’s third proposition was drawn from what Kenny J had stated in Sports Warehouse at [152] and from Nissan Motor Company v Nissan Computer Corporation 378 F (3d) 1002 (9th Cir. 2004). In Sports Warehouse at [152], Kenny J stated:

In the United States too, the appearance of a trade mark in a domain name may constitute use of the trade mark. For example, in Nissan Motor Company v Nissan Computer Corporation 378 F (3d) 1002 (9th Cir 2004), Nissan Motor Company sued Nissan Computer Corporation for using the internet websites www.Nissan.com and www.Nissan.net. The US Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit, held that the trade mark “NISSAN” used in connection with the sale of automobiles was infringed by these websites which, though not containing material regarding automobiles, provided links to other automobile-related websites, from which Nissan Computer Corporation profited: 378 F.3d at 1019.

64 In Nissan Motor, Mr Uzi Nissan used his last name for several business enterprises from 1980, including “Nissan Computer Corporation”. Nissan Computer used the domain names “nissan.com” and “nissan.net” for websites advertising various products, including for a period in 1999, automobile related products and services. The websites did not contain any material concerning automobiles, but would direct consumers to other automobile-related websites.

65 Nissan Motor, a Japanese automobile manufacturer that registered the trade mark NISSAN in 1959 in connection with the sale of automobiles, sued Nissan Computer, alleging that the use of “nissan.com” and “nissan.net” to direct users to automobile-related websites diluted and infringed the NISSAN mark.

66 On the main issues in the case, the Court held at 1007:

Initial interest confusion exists as a matter of law as to Nissan Computer’s automobile-related use of “nissan.com” because use of the mark for automobiles captures the attention of consumers interested in Nissan vehicles. To this extent “nissan.com” trades on Nissan Motor’s goodwill in the NISSAN mark and infringes it, but other uses do not because there is no possibility of confusion as to them.

67 Initial interest confusion is not a concept used in Australian law. It occurs when the defendant uses the plaintiff’s trade mark “in a manner calculated to capture initial consumer attention, even though no actual sale is finally completed as a result of the confusion”: at 1018.

68 The Court reasoned at 1019 (references omitted):

Nissan Computer’s use of nissan.com to sell non-automobile-related goods does not infringe because Nissan is a last name, a month in the Hebrew and Arabic calendars, a name used by many companies, and “the goods offered by these two companies differ significantly”. However, Nissan Computer traded on the goodwill of Nissan Motor by offering links to automobile-related websites. Although Nissan Computer was not directly selling automobiles, it was offering information about automobiles and this capitalized on consumers’ initial interest. An internet user interested in purchasing, or gaining information about Nissan automobiles would be likely to enter nissan.com. When the item on that website was computers, the auto-seeking consumer “would realize in one hot second that she was in the wrong place and either guess again or resort to a search engine to locate” Nissan Motor’s site. A consumer might initially be incorrect about the website, but Nissan Computer would not capitalize on the misdirected consumer. However, once nissan.com offered links to auto-related websites, then the auto-seeking consumer might logically be expected to follow those links to obtain information about automobiles. Nissan Computer financially benefitted because it received money for every click. Although nissan.com itself did not provide the information about automobiles, it provided direct links to such information. Due to the ease of clicking on a link, the required extra click does not rebut the conclusion that Nissan Computer traded on the goodwill of Nissan Motor’s mark.

69 Seven emphasised that it was not relying on Nissan Motor, but rather on Perram J’s expression of the third principle in Solarhart at [50]. That may be so, but Perram J’s expression of principle was drawn from Nissan Motor and can only be so understood. The present case is nothing like Nissan Motor and, even if one were to read the principle expressed by Perram J divorced from its context, it is inapplicable to the present case.

70 Seven also relied on the decision in Edgetec International Pty Ltd v Zippykerb (NSW) Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 281; 98 IPR 1. The applicant, Edgetec, owned the trade mark Kwik Kerb. The respondents were Zippykerb and Mr May, who appears to have been the de facto controller of Zippykerb. Mr May registered a number of domain names including:

www.kwikkerbing.com;

www.kwikkerber.com.au;

www.kwikkerber.com;

www.zippykerb.com;

www.kwikcurb.net; and

www.zippykerb.com.au.

71 These domain names were used to redirect users to a single website: www.zippyker.com. The respondents’ case involved a submission that the “use of the website www.kwikkerbing.com is only for the purpose of redirecting users” to the respondent’s website where the user was unlikely to be misled because, on that website, the respondent distinguished its goods and services from those of Kwik Kerb in a comparative manner: Edgetec at [13](v).

72 Justice Reeves stated at [24]:

… If, as it says it did (see at [13](v) above), Zippykerb used the substantially identical signs or words in a domain name to redirect internet users to its website and that website displays, as it plainly does (see at [5] above), the goods and service being offered by Zippykerb, I consider this is trade mark use of those signs or words. That is so because this use of a domain name to redirect potential customers to a website displaying one’s goods and services is analogous to using those words as a sign on the front of a shop to indicate the goods or services that are sold within: see Solarhart Industries Pty Ltd v Solar Shop Pty Ltd (2011) 281 ALR 544; [2011] FCA 700 at [50] per Perram J; Sports Warehouse Inc v Fry Consulting Pty Ltd (2010) 186 FCR 519, [2010] FCA 664 at [153] per Kenny J and Mantra Group at [53]. Furthermore, once this trade mark use has been made of those words, it is immaterial, in my view, whether there are statements on the website (or inside the shop in the analogy above) stating that the goods and services offered are not those of the holder of the registered trade mark. If anything, this confirms the original trade mark use of those words in the domain name.

73 It may be accepted that the use of a domain name to redirect potential customers to a website displaying one’s goods and services may be analogous to using those words as a sign on the front of a shop to indicate the goods or services that are sold within. The question is whether that is so in the present case.

74 In Taxiprop Pty Ltd v Neutron Holdings Inc [2020] FCA 1565; 156 IPR 1, the website at the URL www.limetaxis.com.au ceased to operate and thereafter users navigating to that URL were taken to the 13CABS website, but still saw the limetaxis.com.au domain name in the browser. O’Callaghan J stated at [145]:

… Taking the process as a whole, where a user has navigated to the Lime domain name and been instantaneously repointed or redirected to the 13CABS website, it seems to me that the conclusion that a reasonable member of the public would draw is that the mark LIME is no longer in use, because, upon arriving at the 13CABS website, it is readily apparent that the Lime domain name is not a sign for online services identified by the LIME mark. On the contrary, those services are identified by the 13CABS mark.

75 O’Callaghan J concluded that Taxiprop had not established that the redirection of the Lime domain name to the 13CABS website constituted use of the mark during the non-use period.

76 This reasoning applies a fortiori to the present case. During the redirect period, the user would be instantaneously redirected to the 7PLUS website. Unlike in Taxiprop, the 7now.com.au domain name would not continue to be visible in the browser after the user was redirected. The 7NOW Mark did not appear on the 7PLUS website. At no time was a user taken to a 7NOW website. If anything, the user would assume that the 7NOW Mark was not in use at all.

77 The 7NOW Mark used in the URL www.7now.com.au was not being used as a trade mark during the period 24 July 2018 to 1 April 2019.

Use during the 7NOW website period

Facts

78 The essential facts were not in dispute.

79 From 1 April 2019, www.7now.com.au stopped redirecting to the 7PLUS website. Instead, it resolved to a standalone website that displayed its own content: the 7NOW website. That website is still operating. In the period 1 April 2019 to 10 June 2019, the “user traffic” to the website totalled 157. The first occasion on which there was any traffic was 16 May 2019 when 8 users visited the site. Traffic on the website during the non-use period peaked on 8 June 2019 with 11 users. The evidence did not indicate whether or not the majority of traffic was generated by Seven itself, for example, staff checking the content of the website.

80 The 7NOW website promotes television content that is available to users through Seven’s online platforms, and allows users to access that content directly from the 7NOW website. Specifically, at the time of its launch on 1 April 2019, the 7NOW website promoted and provided links to various websites, including the 7PLUS website; online streaming portals for Seven’s channels 7, 7MATE, 7TWO and 7Flix; the website for Seven’s news service, 7NEWS; and the webpages (within the 7PLUS website) of some of Seven’s most popular television programs, such as Home and Away, House Rules, My Kitchen Rules, Sunrise, Sunday Night, Andrew Denton’s Interview, and The Morning Show.

81 No full screenshot of the 7NOW website during the period 1 April 2019 to 10 June 2019 was in evidence. However, there were in evidence full screenshots of the 7NOW website as at 22 August 2019, 25 February 2020, 8 March 2020, 9 December 2021 and 7 July 2022. All of those screenshots show that the 7NOW Website featured the following 7NOW banner across the top of the web page:

82 Ms Monique Thompson gave unchallenged evidence that the 7NOW website as at 1 April 2019 also included a banner across the top of the page which was “similar” to this banner.

83 The evidence included two screenshots of the main body of the 7NOW webpage as at 1 April 2019. The first – showing the upper part of the screen – was as follows:

84 The second – showing the lower part of the screen – was as follows:

85 The red markings in the screenshots reflect amendments (deletions) which Ms Monique Thompson was asked to make to the 7NOW website and which she made on 2 April 2019.

Category 1

86 As mentioned, Category 1 of the Defended Goods and Services is “computer software” in class 9.

Summary of principal submissions

87 Seven submitted that the 7NOW website promoted the 7PLUS App by displaying the 7PLUS logo and providing links which stated “Get iOS App” and “Get the Android App”. The 7PLUS App is computer software that is designed to provide specific functionality to the user through the user’s device.

88 According to Seven, the 7PLUS App is promoted and offered on the 7NOW website. Seven noted that it is well established that more than one trade mark may be used in relation to the same product.

89 7-Eleven emphasised that, by clicking on the relevant link, the consumer is taken to a page on Apple’s App Store (for iOS) or Google Play (for android) and that the 7NOW Mark is not displayed on either of those pages.

90 Seven submitted that it was not necessary to establish that the 7NOW Mark was used at all times up to and including the point at which a consumer downloaded the 7PLUS App – an anterior promotion of a product by way of a trade mark still amounts to use of that trade mark in relation to that product. Seven referred in this respect to Moorgate at 443.

91 According to Seven, the impression of a connection between 7NOW and the 7PLUS App would be further strengthened by the clear overlap between the 7NOW and 7PLUS marks themselves, both featuring the prefix “7” (in Seven’s distinctive logo form) and appearing in the context of a website with numerous other references to Seven and its “7” logo.

92 According to Seven, the open and indeed obvious inference was that consumers viewing the 7PLUS App, promoted and offered via a 7NOW branded website, would perceive each of those marks as a brand identifying a commercial connection with the provider of that app. Seven observed that that inference would be correct: Seven is in fact the trader that operates the 7NOW website and makes the 7PLUS App available to consumers.

93 7-Eleven submitted that the 7NOW Mark was not being used in relation to the supply of the 7PLUS App, which was clearly “branded” with 7PLUS.

Consideration

94 The whole context must be taken into account.

95 The viewer of the 7NOW website would see the banner at the top of the page in which 7NOW appears. The viewer would also understand that the viewer was on a website the address of which included “7now”. The viewer would see the various tiles on the website and would not fail to notice that many of the them were associated with Seven.

96 At the bottom of the page, after the tiles, the viewer would see the 7PLUS mark in the following part of the screen:

97 The viewer would see a number of links provided under the 7PLUS mark in the first column: first, to the “7plus Website”, then to “Shows A-Z”, then to “Live TV” then to the “Get iOS App” and “Get the Android App”. The viewer would understand that there was a “7plus Website”, at which one was likely to be able to access 7PLUS’s “Shows A-Z” and “Live TV”. The viewer would understand that there was an iOS and Android App associated with 7PLUS which was likely to facilitate access to these things.

98 The viewer would see the various links provided in the other columns. Thus, in the second column, under the heading “7PLUS”, the viewer would see links to the official websites of “My Kitchen Rules”, “Home and Away” and “House Rules” and consider that these were offerings of 7PLUS. The viewer would understand the matters at the bottom of the screen as being trade offerings of 7PLUS.

99 The viewer would not also consider that the 7NOW Mark was being used to indicate a connection in the course of trade between the 7PLUS App and 7NOW. Of course, although the submissions tended to overlook this, the words “7PLUS App” do not appear at all on the 7NOW website. Rather, there is a reference to getting an app under the 7PLUS logo in the first column. I accept that the typical consumer would think that there was a commercial connection between the businesses of 7NOW and 7PLUS, but the typical consumer would: (a) presume the businesses to be separate and distinct; and (b) not understand that the 7NOW Mark was being used to distinguish the 7PLUS App (which is not directly named on the page) as an offering of 7NOW or as being co-offered by 7NOW together with 7PLUS. Nor would the consumer understand that the 7NOW Mark was being used to indicate the origin of the service of the supply of the 7PLUS App as opposed to the origin of the 7PLUS App itself.

100 It follows that I do not consider that there was use as a trade mark in relation to this category.

Category 2

101 As mentioned earlier, Category 2 is “the promotion and sale of goods and services for others including through the distribution of on-line promotional material and promotional contests” in class 35.

Summary of principal submissions

102 Seven submitted that the 7NOW website promotes and advertises other publications and businesses in which Seven West Media holds a commercial interest, being businesses which are nevertheless independent from Seven. It noted, for example, that the 7NOW website promotes:

the publications: The West Australian and Perth Now; and

the websites: 60 Starts at 60; Society One and HealthEngine.

103 Seven submitted that the advertising of these other businesses on the 7NOW website is Category 2 of the Defended Goods and Services. Seven also referred to The Morning Show for the purposes of Categories 2, 3 and 4.

104 7-Eleven characterised Category 2 as involving “a service that is being provided to third parties (to ‘others’), namely that the trade mark owner will provide to such third parties the service of promoting and selling their goods or services”. 7-Eleven submitted, taking The West Australian as an example, that Seven may be providing a promotional service to whichever company operates The West Australian. 7-Eleven submitted that no evidence was adduced as to how that service is offered and it was unlikely that any trade mark was used. 7-Eleven submitted it was “not sensible to describe a visitor to the 7now.com.au website as being provided with a promotional service within the meaning of Category 2”.

105 Seven submitted that 7-Eleven’s characterisation of Category 2 involved a mischaracterisation, because Category 2 comprised providing the relevant promotional services “for others”, not “to others”. Seven submitted that a correct reading of Category 2 makes clear that trade mark use may be demonstrated by use of the 7NOW Mark to promote goods and services “for others”. It submitted that the 7NOW website provided promotion “for” other parties of those parties’ services – for example, the businesses: 60 Starts at 60; Society One; Health Engine and AirTasker. According to Seven, such “public use is the epitome of trade mark use: that is, a use visible to consumers”. Seven submitted that the use of Seven’s 7NOW Mark for advertising the goods and services of others may be demonstrated by showing that mark being used in the actual promotion of the goods and services of others, in a manner visible to consumers.

Consideration

106 A viewer who clicked on the tiles 60 Starts at 60, Society One, Health Engine or AirTasker would be taken to the respective websites operated by each of those businesses. Each of those websites contained material which promoted the various goods and services of the businesses and allowed purchases of various goods and services.

107 The typical viewer of the 7NOW website would not understand that the 7NOW Mark was being used in the promotion of any of those goods or services.

108 The typical viewer would understand that the 7NOW website contained links to various businesses, accessible by clicking on the relevant tile. The typical viewer would understand that many of the businesses represented by a tile were commercially related to Seven; in particular, they would assume that every tile with the number “7” in it was commercially related in some way to Seven.

109 The present case is different to the position of an obviously unrelated entity including advertisements, such as a newspaper providing advertisements for goods and services of third parties. It is different because, at least in relation to most tiles, a commercial affiliation is likely to be inferred. Nevertheless, the typical viewer would not consider that the 7NOW Mark was used to indicate a trading connection between 7NOW and the goods and services offered by those other businesses.

110 Further, the typical viewer would not consider on the basis of what the consumer observed on the website that 7NOW was engaged in the business of “the promotion and sale of goods and services for others including through the distribution of on-line promotional material and promotional contests”. Promotional and advertising services are services in which one party promotes or advertises the goods or services of another party. The consumer is not the recipient of promotional or advertising services. The typical consumer would assume that 7NOW was affiliated in some way with other Seven entities and that Seven was promoting its own business interests. This is not and would not have been understood as 7NOW being engaged in promotional or advertising activities.

Category 3 and 4

111 The parties addressed Categories 3 and 4 together. I adopt the same approach, recognising that they are distinct. As mentioned, Categories 3 and 4 (in class 35) were:

retail and wholesale services including retail trading via television programmes and by telephone and electronic means including the Internet

the bringing together, for the benefit of others, of a variety of goods enabling customers to conveniently view and purchase those goods including by mail order, telecommunications, website or television shopping channels

Further factual background

112 As at 1 April 2019 (and 22 August 2019 – addressed below), the 7NOW website included click-through tiles for “7travel” and “Better Homes and Garden Shop”. As at 20 February 2020, the tile for “7travel” that appeared on the 7NOW website linked to a website at the URL www.7travel.com.au (7TRAVEL website). 7TRAVEL was an e-commerce platform operated by Seven from 2017 until early 2020, offering consumers access to a range of travel products supplied by companies with whom Seven entered into marketing partnerships.

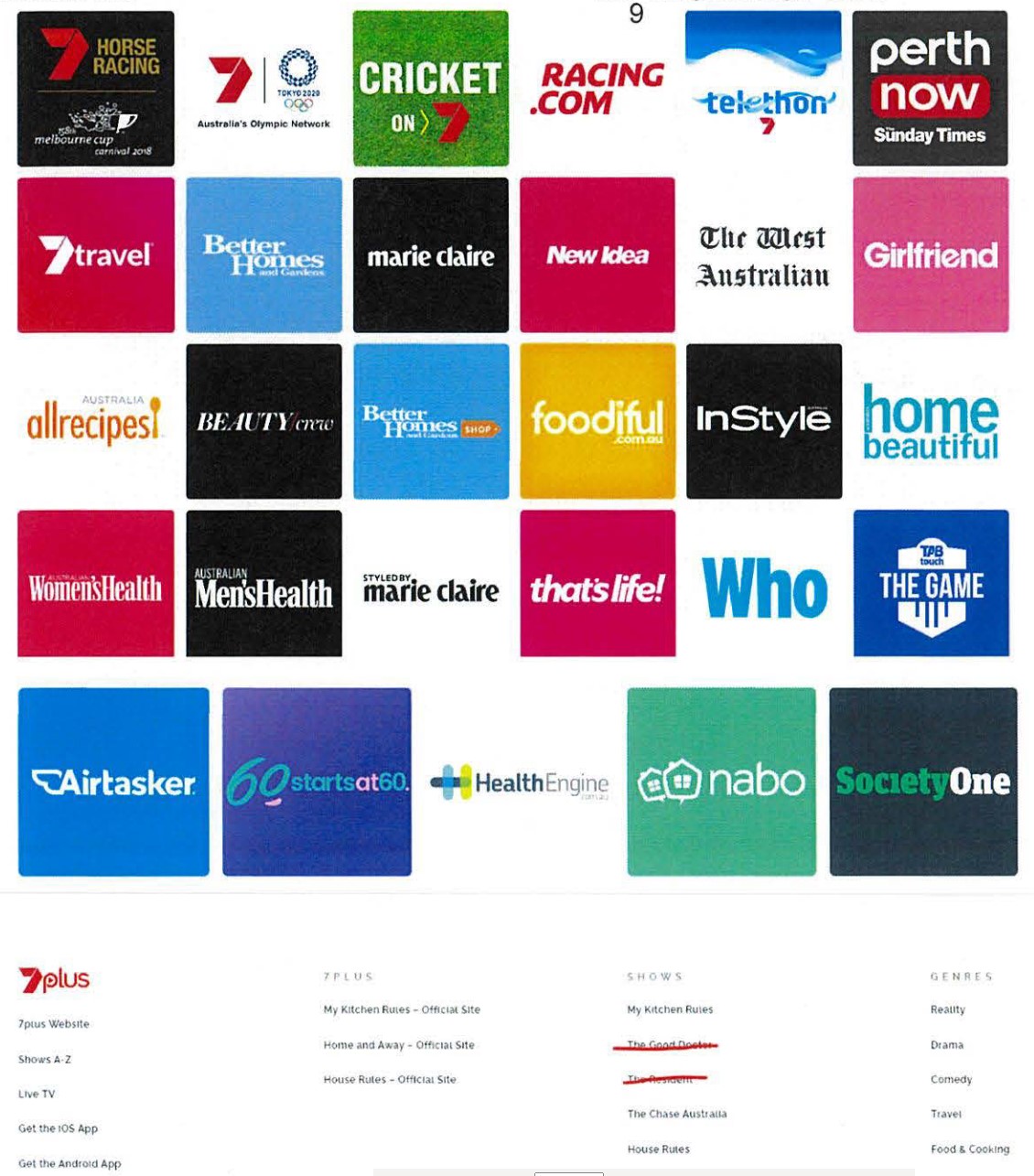

113 A screenshot of the 7TRAVEL website as at March 2019 is as follows:

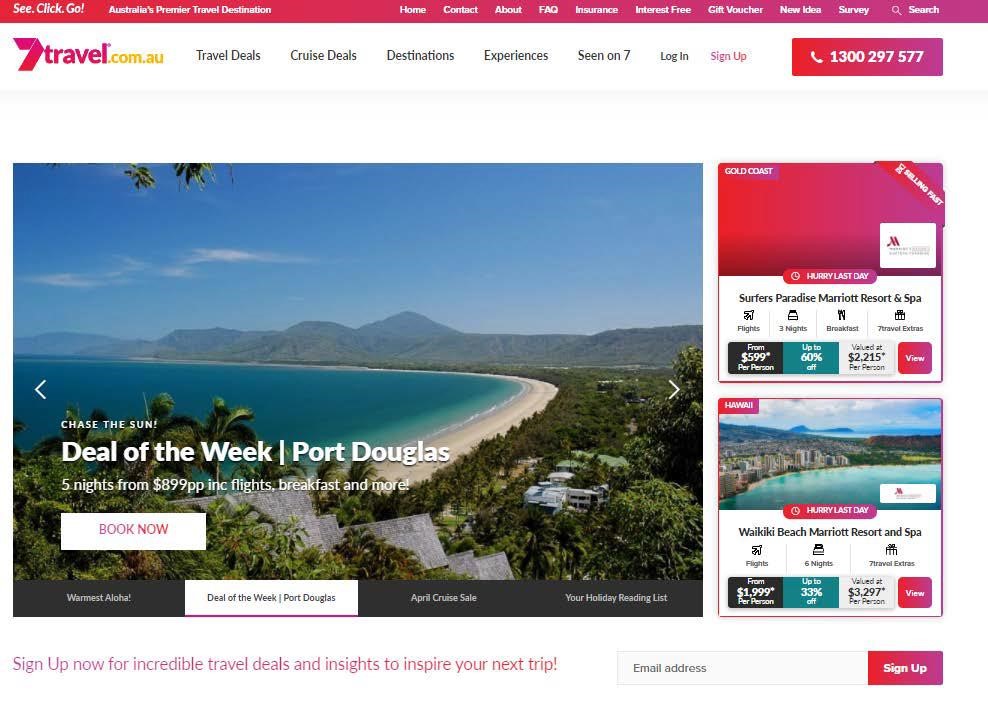

114 As at 28 February 2020, the tile for “Better Homes and Garden Shop” that appeared on the 7NOW website linked to a website at the URL www.bghshop.com.au. A screenshot from that website as at 28 February 2020 is as follows:

115 As at 1 April 2019 and 22 August 2019, the 7NOW website depicted a tile for “The Morning Show”. Clicking on this link directed the user to a page within the 7PLUS website at which the user could view The Morning Show program.

116 For more than 15 years, Seven has had product promotion segments or “advertorials” on its program, The Morning Show, which airs daily. During the course of the product promotion segments, there is a “call to action” for the viewer to call or visit a website and order the product. Contact details will appear on the screen. Examples of the products that have been promoted include products from Cancer Council, Health Partners, Finder, Sony Music, Pharmac 4 Less, iSelect, Brighte Finance, Brand Developers, and Chemist Warehouse.

Consideration

117 The 7TRAVEL website and the Better Homes and Gardens Shop website were characterised by Seven as “e-commerce platforms”. Each provide retail services. For example, if one were to access the 7TRAVEL website by clicking on the 7Travel icon on the 7NOW website, one would be able to book travel services like the “Deal of the Week” package to Port Douglas. The banner at the top of the page shows links to other goods and services, such as insurance and gift vouchers. Underneath the top banner is a series of further links to “Travel Deals”, “Cruise Deals”, “Destinations” and so on.

118 The services offered on the linked e-commerce platforms were not offered on the 7NOW website and the typical consumer would not have understood those services as being offered by reference to the 7NOW Mark. The 7NOW Mark was not used on the 7TRAVEL website or the Better Homes and Gardens Shop website. The connection or association must therefore derive from the use of the 7NOW Mark on the website which contains the relevant link. The typical consumer would not have understood the services offered on the websites to which they navigated from the 7NOW website as being services relevantly connected with and provided by 7NOW as opposed to services offered by businesses with some affiliation with 7NOW.

Conclusion on use during the contended non-use period

119 It follows from the foregoing, that the 7NOW Mark was not used as a trade mark in relation to Categories 1, 2, 3 or 4 during the non-use period.

DISCRETION UNDER SECTION 101

General principles

120 As noted earlier, s 101 of the TMA contains a discretion. Section 101(3) provides:

If satisfied that it is reasonable to do so, the Registrar or the court may decide that the trade mark should not be removed from the Register even if the grounds on which the application was made have been established.

121 The Full Court (Jagot, Nicholas and Burley JJ) in PDP Capital Pty Ltd v Grasshopper Ventures Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 128; 285 FCR 598 at [153], made a number of observations about the discretion, which may be summarised as follows:

(a) The discretion is broad and unfettered in the sense that there are no express limits on it. It is limited by the subject-matter, scope and purpose of the legislation and, in particular, by the subject-matter, scope and purpose of Part 9 of the TMA.

(b) The TMA strikes a balance between various interests, including:

• the interest of consumers in recognising a trade mark as a badge of origin and in avoiding confusion as to that origin;

• the interest of traders, both in protecting their goodwill through the creation of a statutory species of property protected by the action against infringement, and in turning the property to valuable account by licensing or assignment.

(c) Part 9 provides for the removal of unused trade marks from the register and is designed to protect the integrity of the register and in that way the interests of consumers. At the same time, it seeks to accommodate the interests of registered trade mark owners, where reasonable to do so.

(d) The Court must be positively satisfied that it is reasonable that the trade mark should not be removed. The onus in this respect lies on the trade mark owner to persuade the Court that it is reasonable to exercise the discretion in favour of the owner. Section 101(3) requires consideration of whether, at the time that the Court is called upon to make its decision, it is reasonable not to remove the mark.

(e) The range of factors considered in the exercise of the discretion has included whether or not:

• there has been abandonment of the mark;

• the registered proprietor of the mark still has a residual reputation in the mark;

• there have been sales by the registered owner of the mark of the goods for which removal was sought since the relevant period ended;

• the applicant for removal had entered the market in knowledge of the registered mark;

• the registered proprietors were aware of the applicant’s sales under the mark;

Summary of Seven’s submissions

122 Seven submitted that the discretion should be exercised to allow Seven’s 7NOW Mark to remain on the register, for the following reasons:

(1) First, Seven has been using Seven’s 7NOW Mark in Australia in relation to:

• the Defended Goods and Services, after the end of the non-use period; and

• goods and services which are similar or closely related to the Defended Goods and Services.

(2) Secondly, removal of Seven’s 7NOW Mark would “seriously prejudice” Seven’s private interests. Seven submitted that its 7NOW Mark is “part of Seven’s significant portfolio of 7-formative marks, in which it enjoys a very substantial and exclusive reputation”.

(3) Thirdly, removal of Seven’s 7NOW Mark would be against the public interest, because use of 7NOW by another trader (and particularly by 7-Eleven) in connection with any of the Defended Goods and Services, while Seven continues to use 7NOW in relation to the Undefended Goods and Services, is likely to give rise to confusion as to whether those goods and services are being offered, or are approved, by Seven.

123 In addition to these reasons, Seven submitted that “it is well established that the Court ought to avoid drawing ‘fine distinctions’ between goods and services resulting in ‘fragmented ownership’ of the same mark by different owners in respect of very similar goods or services”, referring to: McHattan v Australian Specialised Vehicle Systems Pty Ltd [1996] FCA 481; 34 IPR 537 at 544 per Drummond J; TiVo Inc v Vivo International Corporation Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 252 at [498] per Dodds-Streeton J; Sensis Pty Ltd v Senses Direct Mail and Fulfillment Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 719; 141 IPR 463 at [130] per Davies J. The fragmentation was said to be demonstrated by Annexure A to Seven’s written submissions which contained what is set out in [12] above.

Consideration

Use after the non-use period

124 Seven submitted that it has been using the 7NOW Mark in relation to the Defended Goods and Services after the end of the non-use period on 10 June 2019.

125 The 7NOW website continues to provide links to Seven’s digital television channels and television programs and third-party businesses.

126 In August 2021, Seven launched an “online retailing outlet” in the form of a merchandise store operated through a third-party platform, Liquid Promotions, available at seven.liquidpromotions.com.au. After the launch of the online merchandise store, the 7NOW website was updated to include a “7Merch” tile which provided a link to the merchandise store:

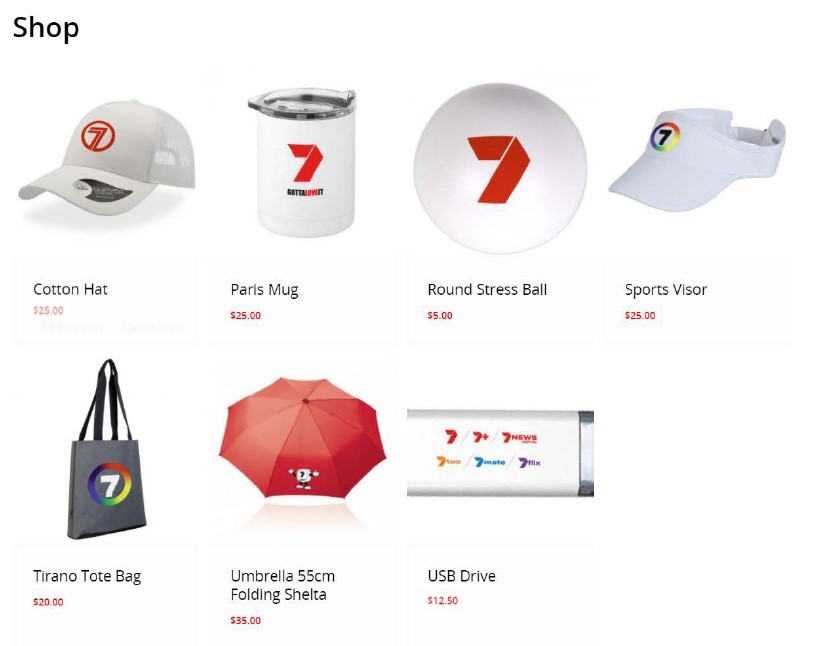

127 Clicking on the 7Merch tile on the 7NOW website directs the user to the merchandise store at seven.liquidpromotions.com.au. The 7NOW Mark is not depicted on any of the merchandise sold in the online store. Seven’s evidence includes screenshots of web pages at the URL https://seven.liquidpromotions.com.au as at 9 December 2021:

128 One of the products available in the merchandise store is a USB bearing a number of 7-formative marks, as depicted above and enlarged below. Seven emphasised that the USB contains firmware, which is a type of software.

129 Seven ran a social media and digital campaign aimed at directing more internet traffic to the online merchandise store from March 2022 to mid-May 2022. The campaign did not involve the 7NOW website.

130 Seven submitted that, although this online merchandise store was launched after the non-use period, it is nevertheless use of Seven’s 7NOW Mark in respect of the Defended Goods and Services in relation to Categories 1, 3 and 4.

131 Dealing first with the continued use of the 7NOW website absent the 7Merch tile, this does not establish use of the 7NOW Mark after the non-use period for the same reasons that it did not constitute use as a trade mark in relation to the particular categories during the non-use period.

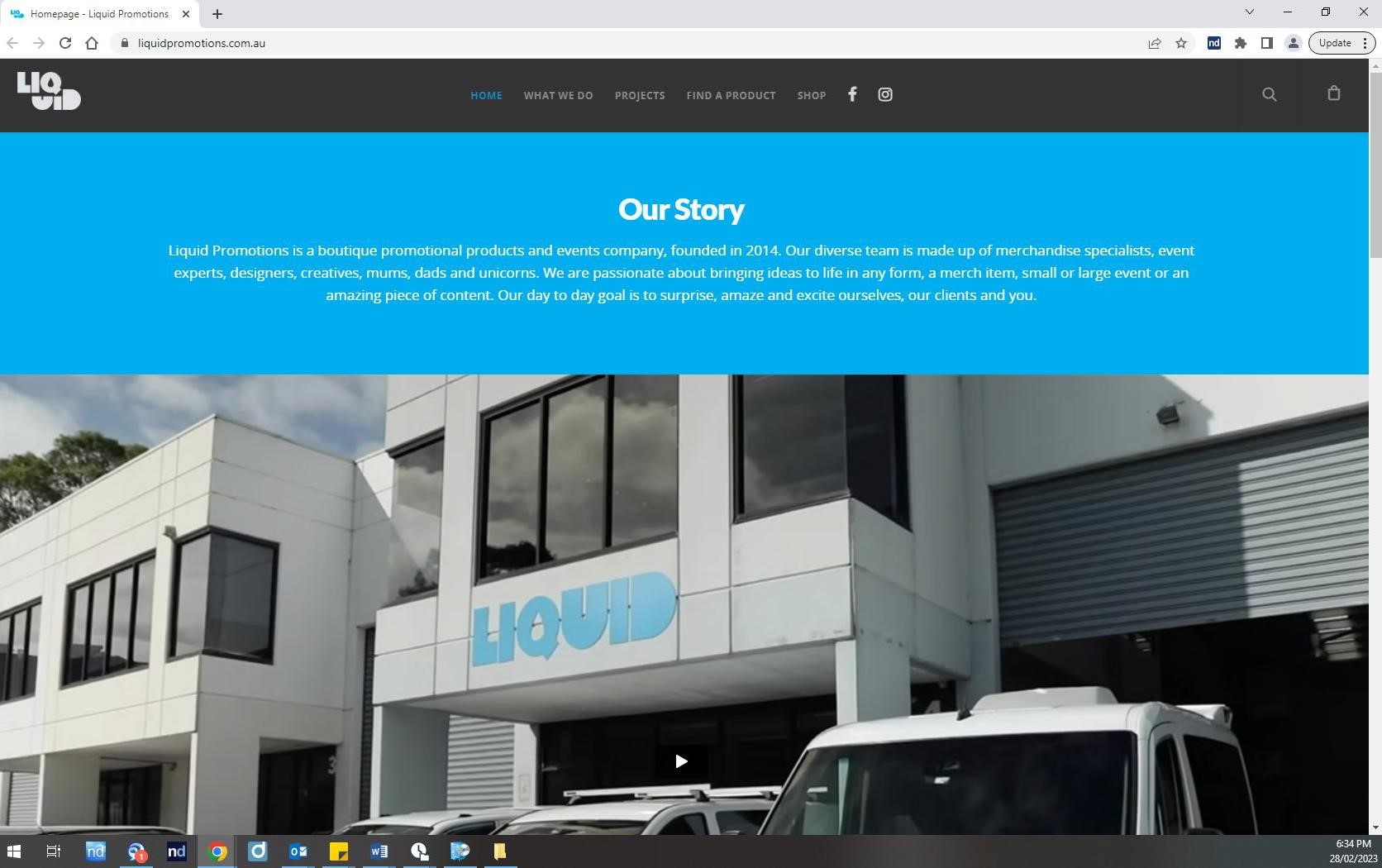

132 As to the 7Merch tile, this directs a user to a retail store operated through a third-party platform, Liquid Promotions, which sells merchandise bearing the marks “CHANNEL 7” and “7”. There is no apparent connection with the domain name liquidpromotions.com.au or the content of the webpage on which a user lands and 7NOW or any entity apart from Liquid Promotions. The webpage at the URL www.liquidpromotions.com.au is as follows:

133 A consumer purchasing goods through this platform would understand those goods to be sold by Liquid Promotions. It is true that there is a link on the 7NOW website to a website operated by a third party on which certain Seven merchandise is sold. However, a consumer would not understand those products were being sold by reference to the 7NOW Mark.

134 Seven also submitted that, if and to the extent the Court considered that Seven’s use of the 7NOW Mark during the non-use period was not use in relation to the Defended Goods and Services, it was at least use in relation to goods and services similar or closely related to the Defended Goods and Services. Seven relied on that use in the exercise of the discretion, as explicitly contemplated by s 101(4) of the TMA.

135 Seven has not demonstrated any use of the 7NOW Mark as a trade mark for any goods or services in the relevant categories so this issue does not arise.

136 7-Eleven submitted that Seven has not explained why it did not use the 7NOW Mark during the non-use period for each of the relevant goods and services, and it has not identified any other relevant intention to use the 7NOW Mark, noting also that more than three years have now passed since the non-use action was filed. Beyond contending that it had used the 7NOW Mark during the non-use period, Seven did not seek to explain any non-use.

Seven’s private interests and its portfolio of 7-formative marks

137 Seven submitted that the removal of Seven’s 7NOW Mark would “seriously prejudice Seven’s private interests”. It was submitted that the 7NOW Mark is part of Seven’s “significant portfolio of 7-formative marks, in which it enjoys a very substantial and exclusive reputation”, noting that it had consistently used 7-formative marks for many years.

138 In particular, Seven submitted that it had used its 7-formative marks in respect of the Defended Goods and Services, as follows (footnotes omitted):

(i) Categories 1 and 2 of the Defended Goods and Services

93. The flagship of Seven’s operation is broadcasting. Seven operates numerous digital television channels in Australia: 7HD, 7TWO, 7MATE, 7FLIX and 7BRAVO. Between 2018 and 2019, it also operated a digital channel called 7FOOD NETWORK. Seven also has regional affiliates that broadcast content generated by the Seven Group in regional markets. Examples are networks called PRIME7, GWN7, and Seven Regional, which operate in various regional parts of Australia.

94. Seven’s broadcasting under its various 7-formative marks reaches a very significant proportion of Australians. Since 2006, it has consistently been the highest rated television network in Australia (as determined by OzTAM and RegionalTAM) for every year except 2019 and 2020. Its average reach during the non-use period was in the many millions.

95. Over the years, Seven Group has produced and broadcast some of Australia’s best known programs and television shows, including 7NEWS, SUNRISE and WEEKEND SUNRISE, Better Homes and Gardens, Home and Away, and My Kitchen Rules. Seven has also broadcast many major sporting events, such as the AFL, International Test Cricket, the Olympics, and the Commonwealth Games. That broadcasting is done under the 7SPORT mark, among other 7-formative marks.

96. Since 2017, Seven has operated the 7PLUS Website, its BVOD platform, as well as the 7PLUS App. The 7PLUS App provides the same BVOD service and offers the same content as the 7PLUS Website. Seven has made the 7PLUS App available as a mobile App, Connected TV App, and web-based App, including for a number of different operating systems. The 7PLUS Website and the 7PLUS App bear the “7” mark prominently, in combination with “PLUS” or the “+” symbol. 7PLUS was the most popular commercial BVOD platform in Australia in 2020 and 2021, with 14.84 billion minutes streamed between 1 January and 27 November 2021. As set out above, there are currently 12.5 million unique registered users of 7PLUS.

97. In addition to the 7PLUS App, Seven is currently developing new Apps for release, and Seven has also developed a number of Apps which are no longer available to consumers including the 7Sport App, the 7CommGames App, the Plus7 App (a predecessor of the 7PLUS App), the 7Swimming App, the 7Golf App, the 7HorseRacing App and the 7Live App.

98. Of course, the ultimate commercial purpose of Seven’s broadcasting activities is advertising. It provides advertising services, and sells advertising space on its television channels. Seven Group has always had a dedicated team selling advertising to potential clients. In order to generate advertising revenue, Seven broadcasts its content to viewers for free, and promotes that content, which attracts audiences to whom advertisers can promote their goods and services.

99. Seven’s advertising services are sophisticated. It has a business unit called 7RED, which assists clients in developing and rolling out advertising campaigns, including creating advertising content and developing a program for screening that content across Seven’s channels and Seven West Media’s publications. Another business unit, 7REDiQ, gathers and analyses data to help advertising clients target their advertising and understand the impact of their advertising.