FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Blucher on behalf of the Gaangalu Nation People v State of Queensland (No 3) [2023] FCA 600

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The separate questions be answered as follows:

a. But for any question of extinguishment of native title, does native title exist in relation to any and, if so what, land and waters of the claim area?

Answer: No

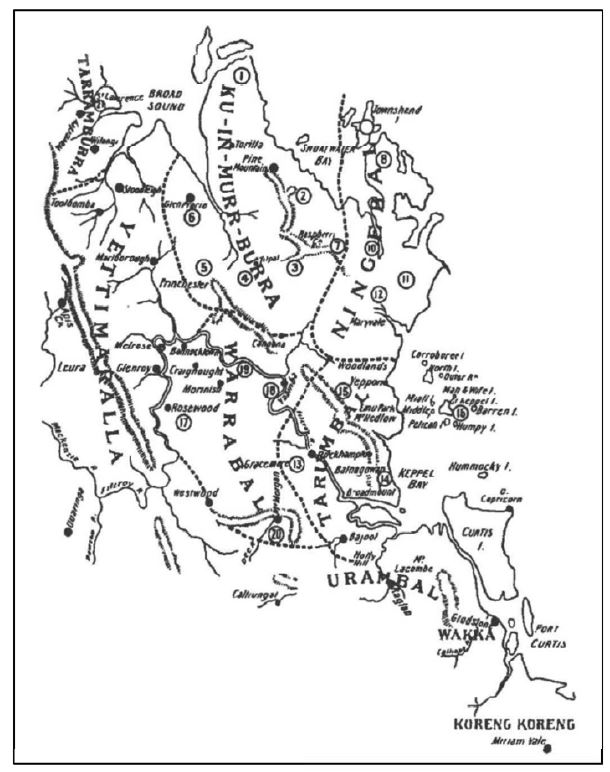

b. In relation to that part of the claim area where the answer to (a) above is in the affirmative:

i. Who are the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title?

ii. What is the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests?

Answer: Not applicable.

2. The parties are to confer as to appropriate orders and advise the Court within 28 days as to whether they have reached agreement.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

RANGIAH J:

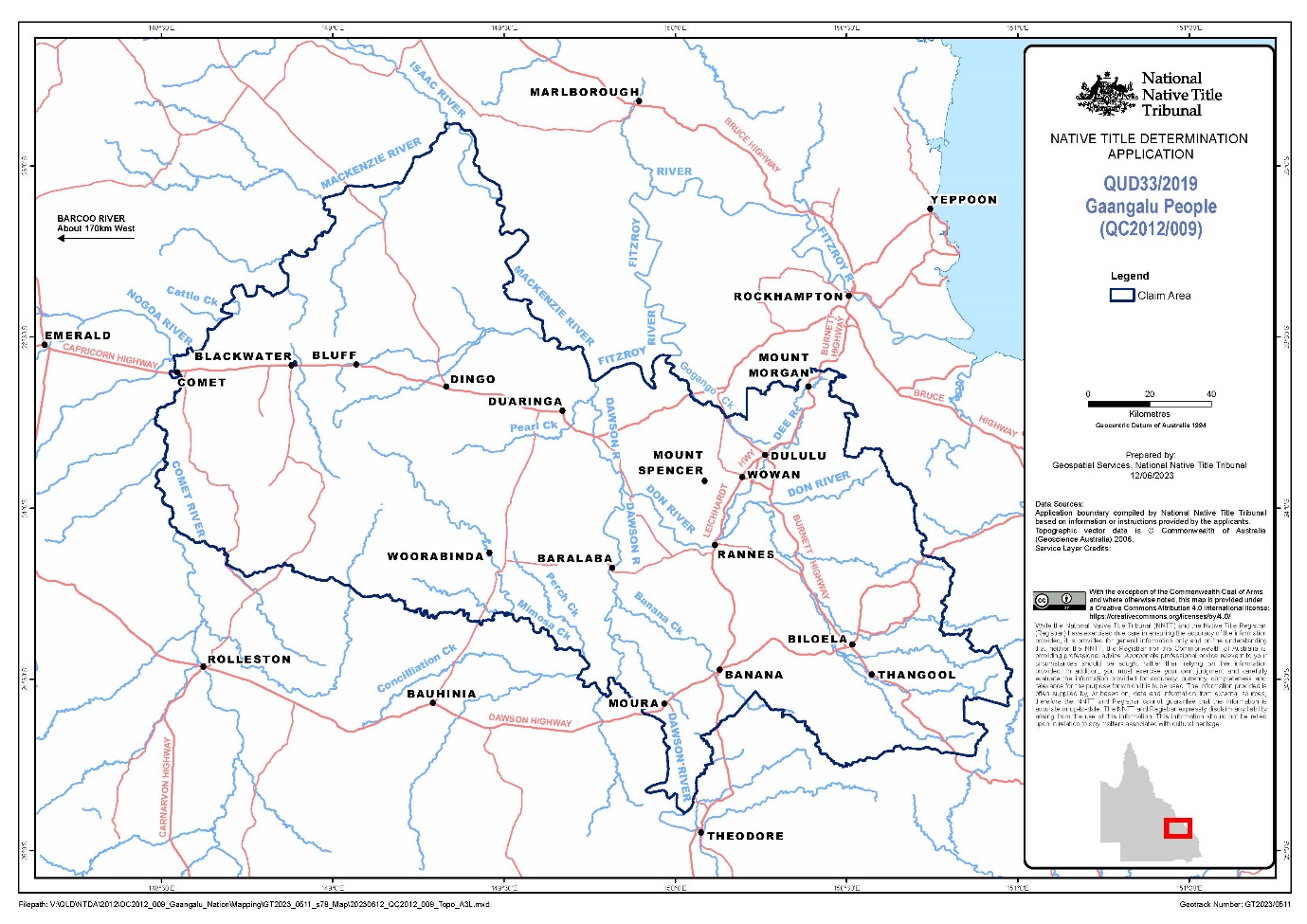

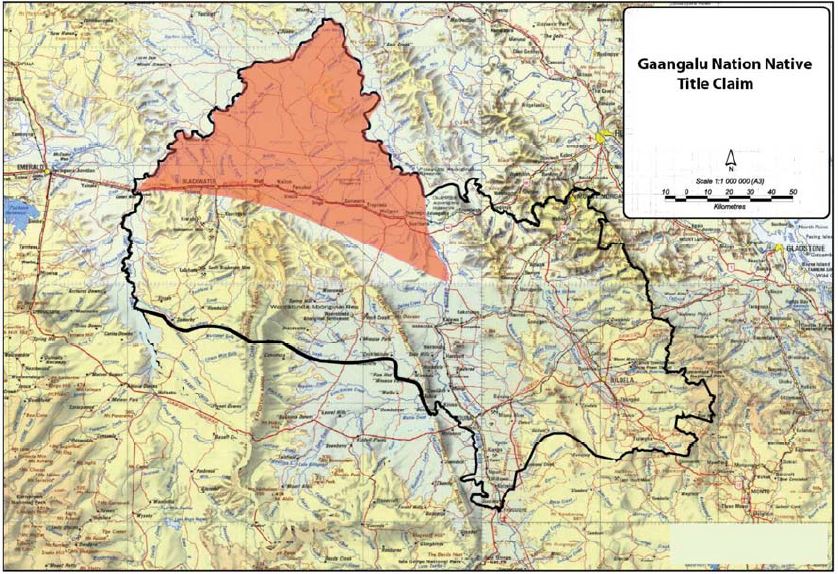

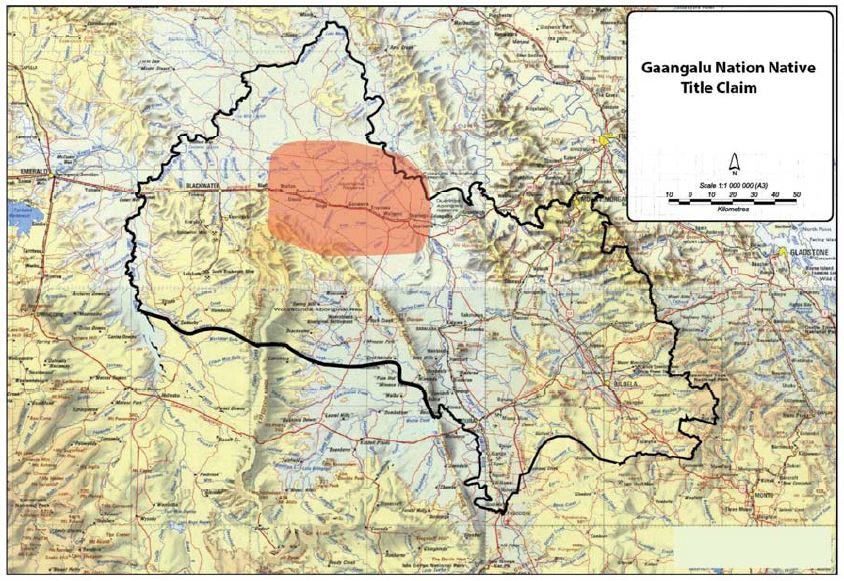

1 The applicant has applied under ss 13(1) and 61(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the NTA) for a determination of native title over approximately 25,506 km2 of land and waters in Central Queensland.

2 The area covered by the claim is to the west and south west of Rockhampton. It encompasses the towns of Banana, Baralaba, Biloela, Blackwater, Mount Morgan, Thangool and Woorabinda. The Dawson River, flowing generally south to north, bisects the claim area.

3 On 5 November 2019, I ordered that the following questions be determined separately:

a. But for any question of extinguishment of native title, does native title exist in relation to any and, if so what, land and waters of the claim area?

b. In relation to that part of the claim area where the answer to (a) above is in the affirmative:

i. Who are the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title?

ii. What is the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests?

4 The hearing of the separate questions took place over 12 days, including in Biloela, Blackwater and the Blackdown Tablelands. While there are 74 respondents, only the State of Queensland (the State) and the applicant participated in the hearing. The State contends that native title does not exist in relation to any part of the claim area.

5 This judgment answers the separate questions. For the reasons that follow, the first question will be answered, “No”; and the second, “Not applicable”.

6 The applicants’ Originating Application was filed on 11 January 2019 and its current version, the Fourth Amended Originating Application, was filed on 30 October 2019.

7 The application is made on behalf of “The Gaangalu Nation People” (the Gaangalu or Gangaalu people). The native title claim group is described as the biological descendants of 29 named ancestors.

8 Although the applicant has spelt the name of the claim group as “Gaangalu” in the Originating Application, a variety of spellings appear in material before the Court, including Gangulu, Ganulu, Kanoloo, Kong-oo-loo, Kong-ool-lo, Kanalloo, Kongulu, Khangalu, Kangalu, Kangalu, Kangooloo, Khangalu, Kongulu, Kongalu, Konguli. The differences in spelling arise partly from the first syllable beginning with a sound apparently pronounced somewhere between “G” and “K” in the English language. While the expert anthropologist engaged by the applicant, Dr Kim de Rijke, has preferred the spelling “Gangulu”, I will adopt the spelling used by the applicant.

9 The area of land and waters the subject of the application (the claim area) is broadly defined by the Great Dividing Range in the east, the lower Dawson River in the centre, the Comet River in the west, and the Mackenzie River in the north. The southern boundary follows a number of creeks, from Lonesome Creek in the southeast to Humboldt Creek in the southwest.

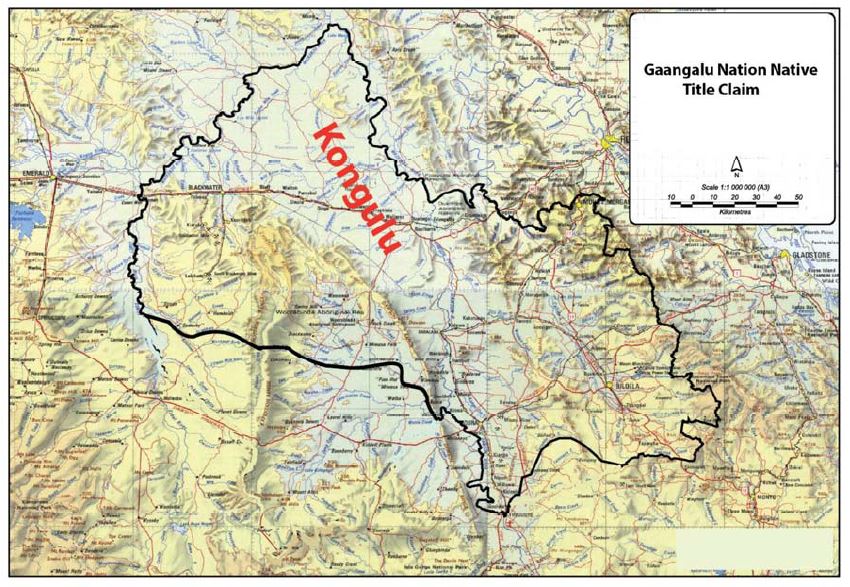

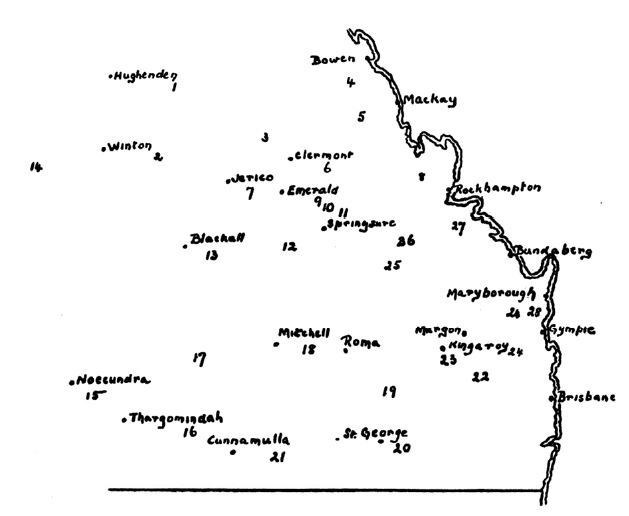

10 The following map produced by the National Native Title Tribunal depicts the claim area and some of the significant towns and geographical features:

11 The application claims exclusive and non-exclusive native title rights and interests in some areas, and non-exclusive rights and interests in the remainder.

12 The exclusive rights claimed in relation to land areas are possession, occupation, use and enjoyment to the exclusion of all others.

13 In the remaining areas, the non-exclusive rights and interests claimed are to:

(a) access, be present on, move about on and travel over the area;

(b) occupy, use and camp on the area, but not to reside permanently, and for that purpose to construct non-permanent structures;

(c) hunt, fish and gather on the land and waters of the area for personal, domestic, and non-commercial communal purposes;

(d) take, use, share and exchange natural resources from the land and waters of the area for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes;

(e) take and use the water of the area for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes;

(f) conduct ceremonies on the area;

(g) maintain places of importance and areas of significance to the native title holders under their traditional laws and customs and protect those places and areas from physical harm;

(h) teach on the area the physical and spiritual attributes of the area;

(i) light fires on the area for domestic purposes including cooking, but not for the purpose of hunting or clearing vegetation; and

(j) be buried and bury native title holders within the area.

14 These rights are asserted by the applicant to be held communally or as a group by the claim group.

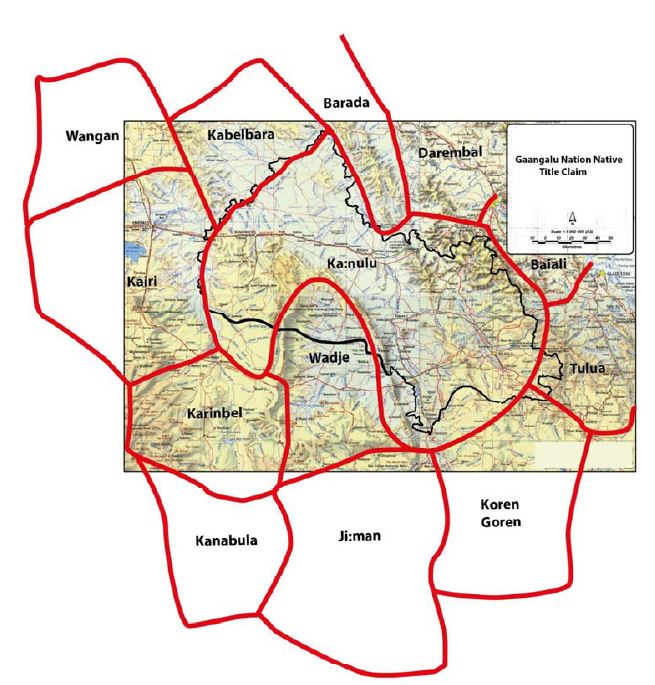

15 The claim area is surrounded by areas covered by a number of native title claims or determinations. It is bordered:

to the south-east by the Wakka Wakka People #4 Native Title Application (QUD91/2012) and the Port Curtis Coral Coast Native Title Determination: see Blackman on behalf of the Bailai, Gurang, Gooreng Gooreng, Taribelang Bunda People v State of Queensland (No 3) [2017] FCA 1637;

to the south-west by the Wadja People Native Title Application (QUD422/2012);

to the west by the Western Kangoulu People Application (QUD229/2013);

to the north by the Barada Kabalbara Yetimarala People Native Title Application (QUD383/2013);

to the east by the Darrambul People Native Title Determination: see Hatfield on behalf of Darrambul People v State of Queensland (No 3) [2016] FCA 723 (Collier J).

16 An application for a determination of native title over an area to the south-west of the claim area was dismissed in Wyman on behalf of the Bidjara People v Queensland (No 2) [2013] FCA 1229 (Jagot J) (Wyman). An application over an area to the north-west was dismissed in Malone v State of Queensland (Clermont-Belyando Area Native Title Claim) (No 5) (2021) 397 ALR 397; [2021] FCA 1639 (Reeves J) (Malone (No 5)).

17 Until 2014, the claim area was overlapped by Wadja People Native Title Application and the Kanoulu People #2 Native Title Application (QUD421/2012). In 2017, the Wulli Wulli People #3 (QUD619/2017) and the Warrabal People (QUD580/2017) applications were filed with an overlapping the claim area, but the former has since been amended to remove the overlap and the latter has been discontinued. There are no longer any overlapping claims. None of the neighbouring groups have appeared in opposition to the Gaangalu claim.

18 The current pleadings are the applicant’s Amended Statement of Claim and the State’s Defence. The Amended Statement of Claim is somewhat ambiguous and unclear, and the parties have made little reference to it.

19 The pleadings have largely been overtaken by the parties’ document entitled, Amended Statement of Agreed Facts and Substantive Issues in Dispute. In that document, the applicant and the State agree, relevantly for present purposes, upon the following facts and matters:

4. British sovereignty was asserted in respect of the claim area on or about 26 January 1788.

5. The first significant European incursions and European settlement in the claim area occurred between about 1845 and the mid-1850s.

6. At sovereignty and effective sovereignty, Aboriginal persons were present in, used and occupied the claim area.

7. The Aboriginal people present in, using and occupying the claim area at sovereignty and effective sovereignty were uninfluenced by laws, customs, traditions, practices or patterns of behaviour of non-Aboriginal origin.

8. The Aboriginal people present in, using and occupying the claim area at effective sovereignty included descendants of the Aboriginal people present in, using and occupying the claim area at sovereignty.

9. At sovereignty and effective sovereignty, the presence in and use and occupation of the claim area by Aboriginal people was, (apart from the case of any casual entrant, trespasser or visitor), not coincidental only, truly random or merely opportunistic.

10. At sovereignty and effective sovereignty, Aboriginal people in the claim area (apart from the case of any casual entrant, trespasser or visitor) used and occupied the area in the exercise of a right or interests held by them under their traditional laws and customs.

11. At sovereignty and effective sovereignty:

(a) the Aboriginal people present in, using and occupying the claim area included persons who were part of a regional society or societies;

(b) the traditional laws and customs acknowledged and observed by the Aboriginal people referred to in sub-paragraph (a) above, conferred rights and interests in relation to the land and waters of the claim area, including land holding rights; and

(c) some of the traditional laws and customs referred to in sub-paragraph (b) above were normative.

12. At sovereignty and effective sovereignty any relevant regional society in the claim area acknowledged and observed laws and customs concerning the following, or with the following attributes (traditional laws and customs):

(a) a classificatory kinship system;

(b) a form of social organisation encompassing two named moieties and four named sections (though it is not agreed that this indicates the existence of any particular society);

(c) inalienability of rights in land and waters;

(d) an understanding of mythology, including spiritual forces inhering in land and waters;

(e) an understanding of totemism, including an association between totemism and kinship as well as personal totems;

(f) an understanding of spirits in the landscape including appropriate ways of managing spiritual presence;

(g) male and female rituals and initiation ceremonies (though the nature and content of any such laws and customs is not agreed);

(h) various funerary practices;

(i) a system of authority emphasising the role of senior people (though whether that indicates anything as to existence of any particular society is not agreed);

(j) responsibilities to manage and protect land and waters;

(k) the presence of landholding units which were small local groups (capable of description as hordes or clans) who recruited members mainly by patrilineal descent, (although whether such groups were identifiable, and if so, the identity of those groups, is not agreed);

(l) local groups which formed clusters or aggregations at a higher level of identification;

(m) customary use of natural resources; and

(n) recognition of gender specific and other significant sites (though whether access protocols applied, or their nature, is not agreed).

20 One of the uncertain aspects of the applicant’s Amended Statement of Claim concerns the allegation that:

The Gaangalu ancestors were also part of a broader regional society which encompassed a number of constituent groups comprised substantially of one or several extended family groupings with affiliations and particular rights to particular areas within the region which included, in addition to Gaangalu, included the Gangalu (Kangulu), Wadja and Garingbal peoples all of whom shared a regional identity label of “Gangalu” (variously spelled) and acknowledged and observed substantially the same traditional normative system.

21 It is unclear from the pleading whether the claimed native title rights and interests are asserted to be possessed under the traditional laws and customs of the Gaangalu people, or of the regional society, or both. To add to the uncertainty, the pleading asserts that the regional society is known under label “Gaangalu”. The parties’ Agreed Facts and Issues in Dispute and the applicant’s written submissions do not remove those uncertainties.

22 However, in oral submissions, the applicant’s counsel clarified that:

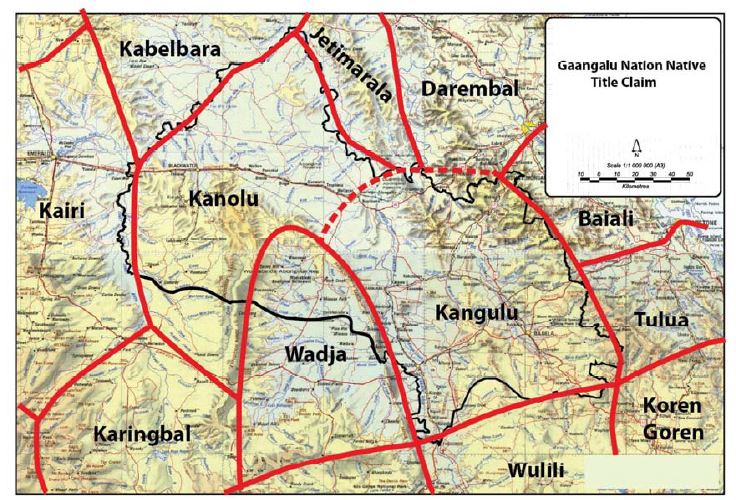

(1) The applicant alleges the existence of a pre-sovereignty regional society of which Gaangalu people was a constituent part.

(2) The applicant does not seek to demonstrate that there was and remains a society consisting of Gaangalu people.

(3) The applicants’ case, in substance, is that:

(a) the Gaangalu people possess their claimed rights and interests under the traditional laws and customs of the regional society;

(b) the Gaangalu people have a connection with the land and waters in the claim area by the traditional laws and customs of the regional society;

(c) the Gaangalu People are a “landholding group” which is a subgroup of the regional society.

23 Although the Amended Statement of Claim asserts that the pre-sovereignty regional society, “included the Gangalu (Kangulu), Wadja and Garingbal”, it is not apparent that any people other than the named groups are asserted to be part of the regional society. As I will discuss, this aspect of the applicant’s case is substantially based on the expert anthropological reports of Dr de Rijke, who identifies the pre-sovereignty regional society as consisting of the Gaangalu, Wadja and Garingbal. I will refer to that depiction of the relevant society as the “Regional Society”.

24 In the Amended Statement of Agreed Facts and Substantive Issues in Dispute, the State identifies the following matters which remain in dispute:

47. The composition, membership requirements and extent of any relevant regional society.

48. What groups, whether identifying as Gaangalu or otherwise, were constituent groups of the regional society.

49. Whether, at effective sovereignty, traditional laws and customs of the following nature were acknowledged and observed by members of any relevant regional society:

(a) laws and customs concerning inheritance of identity and rights in land and water of the claim group in relation to the claim area or parts thereof, and of any relevant regional society in respect of the region its members inhabited, including identification of how other agreed or asserted categories of laws and customs provide for or intersect with matters of identity and rights in land and waters; and

(b) intermarriage and trade across the across the area of the regional society and beyond;

(c) an embodied relationship between people and their land and waters; and

(d) an understanding of sorcery and healing.

50. The nature and content of the normative body of laws and customs of any relevant regional society, pursuant to which rights and interests were held at the time of effective sovereignty.

51. The nature and content of the rights and interests held by members of any relevant regional society at the time of effective sovereignty pursuant to the traditional laws and customs.

52. Whether, at effective sovereignty, the claim group and their ancestors or any relevant regional society were “a body of persons united in and by its acknowledgment and observance of a body of laws and custom” within the regional society (the pre-sovereignty society).

53. Whether, at effective sovereignty:

(a) by the traditional laws and customs observed by them at the time of effective sovereignty, the ancestors of the claim group had a connection with part or all of the land and waters of the claim area, and if so what parts; and

(b) the ancestors of the claim group were present in, occupied, used and enjoyed, part or parts of the land and waters of the claim area, and if so what parts.

54. Whether the pre-sovereignty society has substantially maintained its identity and existence from generation to generation in accordance with the traditional laws and customs through to the present time.

55. Whether the traditional laws and customs have been acknowledged and observed by the pre-sovereignty society and their successors, and whether such acknowledgement and observance has continued substantially uninterrupted since effective sovereignty.

56. Whether since effective sovereignty the pre-sovereignty society and their successors have maintained a connection with the claim area and have transmitted rights and interests in relation to the claim area by and in accordance with the traditional laws and customs.

57. Whether the claim group (as a whole), acknowledge and observe the traditional laws and customs.

58. The nature and content of the traditional laws and customs observed by members of the claim group.

59. Whether by the traditional laws and customs that are still observed by them, the claim group has a connection with the claim area.

60. Whether by the traditional laws and customs that are still observed by them, the claim group has rights and interests in the claim area and the nature and extent of the extant rights and interests.

61. As identified in paragraphs 6, 9, 10 and 11 herein (and in the context of the agreements in those referenced paragraphs), what part or parts of the claim area persons were present in, what part or parts of the claim area were used and occupied, that the presence in, use and occupation was substantially uninterrupted, or that it continues to the present day, is in issue.

25 It may be seen that the issues that remain in dispute include:

which parts of the claim area were occupied by Gaangalu people at sovereignty;

the existence of the Regional Society at sovereignty and its continued existence;

the nature and content of the Regional Society’s traditional laws and customs;

whether the claim group’s observance of the traditional laws and customs has continued substantially uninterrupted; and

whether by those traditional laws and customs, they continue to have a connection to the claim area.

26 It is necessary to say something about the applicant’s approach to its written submissions. Their written submissions consist largely of chunks of evidence extricated verbatim from the anthropological reports, statements or transcript, followed by the statement of one or more general propositions. To give one example, the section of their submissions dealing with continuity of traditional understanding of mythology starts with extensive extracts from the transcript and statements, and then segues to broad statements to the effect that those extracts demonstrate, “clear continuity in relation to the knowledge and content of the stories”. However, there is no analysis of the evidence concerning traditional mythology and how and why the contemporary evidence demonstrates continuity of that aspect of law and custom. It has been necessary for me to, in effect, construct the argument that the applicant may be putting and then address that putative argument. That kind of issue was repeated throughout the applicant’s lengthy written submissions. One important issue, the continuity of a traditional law and custom described as, “the presence of landholding units which were small local groups (capable of description as hordes or clans) who recruited members mainly by patrilineal descent”, was not addressed at all. The applicant’s approach has made the task of understanding and addressing some parts of the applicant’s case problematic.

Overview of the Gaangalu witnesses

27 It has been recognised that the evidence provided by Aboriginal people is of the utmost importance in native title proceedings: Sampi v Western Australia [2005] FCA 777 (Sampi) at [48] (French J).

28 The evidence-in-chief of lay witnesses was, in accordance with the Court’s programming orders, provided in the form of statements, affidavits or outlines of evidence. The applicant called the following 20 witnesses, each of whom was cross-examined:

(a) Lynette Gail Blucher;

(b) Rosemary Hoffman;

(c) Dale Martin Toby;

(d) James Robert Waterton;

(e) Deborah Maree Tull;

(f) William Phillip Toby;

(g) Margaret Kemp;

(h) Patricia Leisha;

(i) Lynette Ann Anderson;

(j) Paul Hegarty;

(k) Priscilla Iles;

(l) Steven Raymond Kemp;

(m) Cedric James White;

(n) Desmond Allan Hamilton;

(o) Rodney John Jarro;

(p) Colin Toby;

(q) Samantha Neilsen;

(r) Lillian May Harrison;

(s) Elizabeth May Jacobs;

(t) Peter Mickelo.

29 The applicant also tendered the written statements or affidavits of the following persons who had passed away prior to the commencement of the hearing:

(a) Robert Toby;

(b) Mona Barry;

(c) Valerie Grace Hayes.

30 The evidence presented by the Gaangalu witnesses is of relevance to a number of the disputed issues, including continuity of observance of traditional laws and customs.

31 Each of the lay witnesses identified themselves as Gaangalu by reason of their biological descent from one or more Gaangalu ancestors and that self-identification was not challenged by the State.

32 The Gaangalu witnesses were cross-examined over a period totalling 7 days, between 12 April 2021 and 27 April 2021 at one of three locations within the claim area, Biloela, Blackwater or the Blackdown Tablelands.

33 The evidence of the Gaangalu witnesses seemed to me to be given candidly and to reflect their genuinely held beliefs. However, their evidence cannot simply be accepted uncritically. The extent of their knowledge of traditional laws and customs was, in some respects, limited, and often given at a level of generality and without significant detail. Their evidence on a number of issues was broadly consistent, but there were also some inconsistencies and differing levels of knowledge or understanding between the witnesses. For example, there are widely varying understandings of which places are special or sacred and why. In a number of instances, spiritual beliefs and experiences of witnesses appear idiosyncratic and are not apparently shared by other witnesses. In circumstances where the Gaangalu were removed from their land and subjected to policies of forced assimilation designed to remove all traces of their culture, substantial depletion of their knowledge of traditional laws and customs is understandable and unsurprising.

34 I will discuss the evidence of the Gaangalu witnesses in detail later in these reasons.

Overview of the expert evidence

35 The primacy of the evidence of Aboriginal witnesses does not mean that expert anthropological evidence is unimportant to the determination of issues in native title claims: see Wyman at [474].

36 In Alyawarr, Kaytetye, Warumungu, Wakay Native Title Claim Group v Northern Territory of Australia (2003) 207 ALR 539; [2004] FCA 472 at [89], Mansfield J observed that anthropological evidence may, amongst other things, provide a framework for understanding the primary evidence of Aboriginal witnesses in respect of the acknowledgment and observance of traditional laws, customs and practices; and make use of historical literature and anthropological material to compare traditional laws and traditional customs and interpret the similarities or differences.

37 In Jango v Northern Territory of Australia (2006) 152 FCR 150; [2006] FCA 318 (Jango) at [462], Sackville J noted that in the ordinary course, Aboriginal claimants adduce anthropological evidence to establish the link between current laws and customs and the laws and customs acknowledged and observed by the claimants’ ancestors at the time of sovereignty.

38 The Court is not, however, bound by the opinions of expert anthropologists even where that evidence is uncontradicted: Malone on behalf of the Western Kangoulu People v State of Queensland [2021] FCAFC 176 at [124] and [218]. That is particularly so where the evidence is upon an ultimate issue: Brodie v Singleton Shire Council (2001) 206 CLR 512; [2001] HCA 29 at [355] (Callinan J).

39 The applicant adduced evidence from an anthropologist, Dr Kim de Rijke, and a historian, Dr Hilda Maclean. The State called an anthropologist, Dr Anna Kenny. Their expertise is not in dispute.

40 Dr de Rijke has been engaged by the applicant since 2011 to investigate the Gaangalu claim.

41 In September 2018, Dr de Rijke prepared a report entitled, Gaangulu Nation People Native Title Determination Application (QUD400/2012), Expert Anthropological Report (first report). Dr de Rijke relied upon published works and documents specific to the region and of more general relevance to Aboriginal life and culture, interviews with 68 Aboriginal people of region and personal observations, as well as his own specialised knowledge based on training study and experience. The 68 Aboriginal people included 19 of the 23 Gaangalu witnesses who gave evidence.

42 Following the hearing of the lay evidence, Dr de Rijke produced a further report entitled, Gaangulu Nation People QUD33/19: Supplementary Expert Report (supplementary report) addressing the question of whether he continued to adhere to the opinions expressed in his first report. Dr de Rijke’s two reports were admitted into evidence.

43 Dr de Rijke and Dr Kenny gave concurrent oral evidence in Brisbane on 28 and 29 June and 14 July 2021. Dr de Rijke was called by the applicant and Dr Kenny was called by the State.

44 Dr Maclean was engaged by the applicant in 2013 to undertake a genealogical investigation for use in the claim.

45 Dr Maclean prepared an initial report entitled, Gaangalu Nation People Native Title Determination Application (QUD 400/2012): Review of the Genealogical Data – Gaangalu Nation People Apical Ancestors. She prepared a second report entitled, Review of the genealogical data concerning Myra Freeman, Sarah Dodd and Mary Ann Crook.

46 Dr Maclean’s two reports were admitted into evidence. She was not required for cross-examination.

47 Dr Kenny was engaged by the State in 2017 in respect of the Gaangalu application, as well as neighbouring claims made on behalf of the Western Kangoulu People and Wadja People Dr Kenny’s brief was expanded in 2018 to include Part A of the Wulli Wulli #3 People claim.

48 This group of proceedings has become known as the “GNP cluster”. I case-managed these proceedings together as they involved competing claims to apical ancestors and land.

49 Following orders made by Robertson J on 29 October 2018, materials filed or provided to the State in the Gaangalu, Wadja, Western Kangalou and Wulli Wulli #3 proceedings were permitted to be used for the purposes of each other proceeding. Dr Kenny produced a report dated 9 November 2018, entitled, Anthropology Overview Report: Assessment of Expert and Lay Evidence filed for the GNP Cluster Native Title Claims (QUD 400/2012, QUD 229/2013, QUD 422/2012, QUD 619/2017).

50 The report states that it, “only addresses the main issues that emerge from the expert reports and lay evidence relating to the GNP cluster applications and is not intended as a comprehensive anthropological report on the GNP cluster”. In her report, Dr Kenny indicates that she reviewed the relevant ethnography, the lay evidence and the expert evidence filed in the applications. Dr Kenny’s report was admitted into evidence and, as I have said, she gave concurrent oral evidence with Dr de Rijke.

Conferences of experts and joint reports

51 Following the exchange of expert reports, conferences of the expert anthropologists in this claim and in the Western Kangalou, Wadja and Wulli Wulli #3 proceedings were convened. The Court’s order of 5 November 2018 required that:

…the experts in like disciplines shall produce for the use of the parties and the Court a document(s) identifying with respect to matters and issues within their expertise:

(a) the matters and issues about which their opinions are in agreement;

(b) the matters and issues about which their opinions differ; and

(c) where their opinions differ, the reasons for their difference.

52 The relevant expert witnesses produced a joint report entitled Report of Conference of Experts held 20 February 2019 in Brisbane concerning this proceeding. There was substantial agreement between Dr de Rijke and Dr Kenny, except that Dr Kenny was unable to form a concluded view in relation to some claimed Gaangalu ancestors. In particular, Dr de Rijke and Dr Kenny agreed as follows:

a) There were Aboriginal people in occupation of the Gaangulu claim area at sovereignty and there were common laws and customs acknowledged and observed across the region.

b) Those people were part of a larger regional society extending beyond the claim area.

c) The traditional laws and customs of the identified society included those specified in the report.

d) At effective sovereignty: (i) land holding units were clans, whose members held proprietary rights and interests as a clan group at a local level, (i.e. in a local clan estate); (ii) other, secondary rights were held by clan members in a broader area; (iii) the local land owning clans formed clusters or aggregations at another level of identification which may have been a regional and/or linguistic identity and was not a land holding unit.

e) The members of the Gaangalu claim group are part of a broader regional society.

f) A number of the traditional laws and customs are no longer observed by the Gaangalu, but others are still observed in adapted form.

g) The Gaangalu claim group continues to hold rights and interests under traditional laws and customs as a group.

h) The Gaangalu no longer hold land on a clan estate level. Today, there is a broader cognatically constituted group that holds rights in land. Adaptation has occurred due to population loss (removals, massacres and disease), managing the impact of non-Aboriginal paternity, internment at reserves and loss of knowledge and refocusing from the very local estate to a broader concept of country usually under a language name. Traditional succession processes ensured that there was no “orphaned” country.

i) Members of the same society continue to observe traditional laws and customs. These laws and customs have adapted to the changing circumstances in which the ancestors of the claimants found themselves but continue to be rooted in tradition.

j) The Gaangalu claim group has a connection with the claim area by their acknowledgment and observance of traditional laws and customs throughout the claim area. This connection includes cognatically traced Gaangalu ancestry, as well as forms of physical and spiritual connection.

53 Dr de Rijke and Dr Kenny produced another report entitled Report of Conference of Experts held 8 March 2019 in Brisbane. The report explained the reasons for their agreement that all but three of the ancestors then named in the application (Mary Ann Crook was not included at that time) had held rights and interests in the claim area. In relation to the three (Rose Ann Tyson, Biddy (wife of Jumbo) and Polly Doctor), Dr de Rijke considered their inclusion to be appropriate, whereas Dr Kenny explained she was not in a position to adopt a certain position because she had not conducted primary research.

54 The conference of Drs de Rijke and Kenny on 8 March 2019 also included consideration of whether the Gaangalu ancestors held rights and interests in immediately neighbouring claim areas and, if so, the nature of those rights and interests. Drs de Rijke and Kenny concluded that there was no evidence that would allow them to form an opinion about the rights and interest of any of the apical ancestors outside the claim area.

The evidence of Gaangalu witnesses

55 The evidence given by the Gaangalu witnesses is largely directed to continuity of the traditional laws and customs accepted by the parties to have existed in the claim area at sovereignty and connection with that area by those laws and customs.

56 In the summary of evidence that follows, it is convenient to describe the evidence by reference to aspects of traditional laws and customs agreed by the parties, while recognising that the evidence may in fact be relevant to several laws and customs.

57 Ms Lynette Blucher is 65 years old and was born at, and resides in, Mount Morgan within the claim area.

A classificatory kinship system, a system of authority, an understanding of totemism and funerary practices

58 Ms Blucher is a Gaangalu person through her apical ancestor William Toby I, who was her great grandfather, and her father, Gordon Toby, both Gaangalu men. Her father’s father, William Toby II, was also a Gaangalu man. Ms Blucher’s mother, Heather Elizabeth Toby, had Wadja, Gaangalu and Gurigbal connections, but she claimed her country was near the New South Wales border. Heather Toby’s father, Harold Tyson, was Gaangalu, Wadja and Guringbul, and his father, Peter Tyson, had Gaangalu ancestors. Ms Blucher’s parents had 12 children, 11 of whom were born at Mount Morgan, and Ms Blucher has four children of her own, all born at Mount Morgan.

59 Ms Blucher considers that everyone who has a Gaangalu ancestor is Gaangalu, regardless of whether it comes from the mother or father. A non-Gaangalu person does not become Gaangalu by marriage, but their children do. A Gaangalu person may choose between the different groups in their family history or choose more than one group. Ms Blucher had bloodlines connecting her to different groups but has always claimed she was Gaangalu, mostly because of her father’s influence, but also because she does not know the country and people of the other groups. She learnt about her mother’s background but due to her father’s influence and her residence at Mount Morgan for almost her entire life, she knows more about that area and Gaangalu people than she does about her mother’s side. Although she most strongly identifies with Gaangalu country and is mainly a Gaangalu person, Ms Blucher may mention her other connections when meeting new people. This way of introducing herself, and finding out who another person is, is something she learned and noticed other Gaangalu people doing.

60 Ms Blucher learnt about her family’s history and connections from older people in her family mostly from her mother and her father but also from other older Gaangalu people. She now passes on this information to her children, grandchildren and other Gaangalu people.

61 Gaangalu people get their rights in country at birth, through their ancestors. Ms Blucher got her rights as a Gaangalu person from her father and her great grandfather, and her children and grandchildren get their rights from her. This includes Ms Blucher’s right to be included in and to make decisions about country for the east side of Gaangalu. She acquired this right from her father and this right will be handed down to her children who will hand it down to their children. Ms Blucher’s adult children can be involved in decisions about country, as they have learnt Gaangalu ways from her. Ms Blucher intends to teach her grandchildren about country and customs so they can make decisions about country when they are old enough.

62 Ms Blucher was brought up understanding that her family should always find or make room for someone if they need a place to stay and that their home, food and other things are to be shared with both family and others. She claims that most Gaangalu people she knows have always done the same. Ms Blucher gave examples of having both family and non-family members staying at her house or staying for meals, ensuring that there was enough to go around. She also recalls her father taking her sibling and her to different family members when traveling to visit family, and a “big mob” of family and friends going camping and fishing together.

63 Ms Blucher explained other kinship practices, including families, marriage, elders, language and other laws and customs.

(1) It is common for Gaangalu people to look after nephews, nieces, grandchildren, distant cousins and others for long periods of time, and treat them as their own. This includes disciplining children and looking after elders. Responsibilities are shared across more than just the immediate family. Ms Blucher calls her nieces and nephews her kids, and her cousins her brothers and sisters. The people Ms Blucher and her siblings knew as their aunties and uncles, who may not have been family, would treat them as their own children.

(2) A Gaangalu person should not marry another Gaangalu person with the same yuri. A yuri is a totem, which signifies a meat and a plant. The descendants of William Toby I have the carpet snake as their meat and the cabbage palm tree as their plant. Accordingly, William Toby I’s descendants cannot marry another carpet snake or cabbage palm tree. To avoid this, older Gaangalu people get to know possible partners and discover who they are connected to and how. Gaangalu people also do not eat their yuri because it is their family.

(3) There is a system of authority emphasising the role of senior people. Senior people have authority and showing respect to elders is very important. Elders are consulted first when making decisions, such as bringing native title claims, and Gaangalu people must take into account what the elders say. When the older people meet, young Gaangalu people are not allowed to stay. Older people speak for the mob and the family.

(4) The language has been largely lost. Ms Blucher’s father only learnt a few words and Ms Blucher cannot speak in Gaangalu language or understand it.

(5) Other relevant Gaangalu laws and customs include the existence of spirit ancestors, using sandalwood smoke for ceremonial cleaning and protection, and various funerary practices. Examples of funerary practices include Ms Blucher’s father being buried, as he wanted, on country at Mount Morgan, Gaangalu peoples’ ashes being spread on property on the Don River and the requirement that Gaangalu people attend all funerals of a Gaangalu person, particularly to represent their family. Smoking ceremonies are performed at burials to cleanse the spirit and allow the deceased’s spirit to go to the spirit world.

Inalienability of rights in land and waters

64 Ms Blucher gave evidence that Gaangalu people cannot sell or give away Gaangalu country or stop the country from being Gaangalu country for future generations.

An understanding of mythology and of spirits in the landscape, and the recognition of gender specific sites

65 Ms Blucher gave evidence that these are special places on country, plants and spirit ancestors and children. There are special places, including Mount Murchison which is sacred ground, Wandoo Mountain, Lake Victoria, Cattle Creek, Mount Morgan, Lake Charlotte, Axe Factory, Newman Park, Mount Scoria, and Banana and Banana Creek. For example, Mount Murchison was used by Gaangalu people for gatherings and as a look out place. It looks out over Lake Victoria in Callide Valley, where a massacre of Gaangalu people occurred. There is a men’s site at Wandoo, which is a very special place where men’s business happens. Both Mount Morgan and Lake Charlotte have a bora ring, where gatherings and initiation ceremonies took place. They are men’s business sites and women do not go to those places. On the other hand, Mount Scoria is a special woman’s place.

66 Ms Blucher was taught that the cabbage palm tree was the “Gaangalu Palm Tree”. Ms Blucher sees the Palm Trees as her ancestors. They look after her and protect artefacts.

67 There are spirit ancestors and stories told to Gaangalu People. Examples include the Djandjaarris story told to children to prevent them from wandering off, the story of the Tall Man and the Yuinji ghost or scary man that tries to coax you away to follow him. Smoking ceremonies are used at burials to allow the deceased to go to the spirit world, or for protection to remove evil spirits hanging around.

Responsibilities to manage and protect land and waters and an embodied relationship between people and their land and waters

68 Ms Blucher’s father told her where Gaangalu country is, that it is their country, and that “Gaangalu country belongs to all Gaangalu people and it is their responsibility to look after it”. Uncle Bill taught Ms Blucher that the boundaries of their country were the Dawson River, Castle Creek, the Callide Range, the Mount Morgan Range, Sandy Creek, and then Gogango Creek into the Fitzroy. Uncle Bill and Ms Blucher’s father were clear to her and others that Mount Morgan was their country. Different Gaangalu people and families know about and must look after different parts of Gaangalu country, for example, on the east or west side of the claim area. People are still Gaangalu people even if they only refer to the other side of the Dawson River as their country. There was a lot of contact and connection between Gaangalu people in different areas.

69 Gaangalu people look after their country by taking responsibility for how they use it or let it be used. Accordingly, they cannot take too much or disturb the country, or let others do these things. Ms Blucher was brought up to understand that they could take what they needed from country but not more than they needed. Gaangalu people should acknowledge when they are going into other country, including across the Dawson River into the western part of Gaangalu country. Permission is required to cut down a tree when on other country to ensure the right Gaangalu people were looking after their country. Ms Blucher obtained her rights in country from, and can be involved in decision making for the east side of the claim area through, her descent from William Toby I.

70 To look after the country, Gaangalu people live on the country, visit places often, and listen to and take notice of what other people are doing and planning. Ms Blucher claims that the best way to protect their country is to leave it alone most of the time, without moving anything. She claims that a lot of recent activity, especially mining, has affected many areas. Items of importance have had to be moved to avoid them being lost or destroyed. There are five shipping containers on Gaangalu country which store artefacts as a temporary keeping place. They are located close to a cabbage palm tree to protect those artefacts until they are put back on country. However, Ms Blucher claims that these artefacts should be where they were found and it feels like they are taking life out of the land when these artefacts are removed from country. As the artefacts are not on the country where they were found, the Gaangalu people want to display them to teach people about Gaangalu culture and country, particularly so the younger generations can learn about how their ancestors used to live. It is also open to tourists so they can learn about the Gaangalu people, their culture and the land they are visiting. Ms Blucher describes this as part of their responsibility to look after and protect their land. She states that the Gaangalu people have looked after country this way for as long as she can remember. They have to look after the country so they can pass it down to their kids. Her father taught about and showed her siblings and her around country for that reason, and Ms Blucher does the same with her children.

71 Gaangalu people have knowledge of special places on country and living on and accessing country for fishing, camping, hunting and gathering. Uncle Bill and Ms Blucher’s father taught her that Mundagarra is important to Gaangalu people because he is the creator. He is like the rainbow serpent or carpet snake. He starts at the Dee River and comes up from the base of the river at Eulogie Crossing and out of the river at Piebald Mountain. Mundagarra created all the little creeks and streams that go into the Dawson River, and the Dawson River itself, up to Nathan Gorge. Ms Blucher has told her children about the Mundagarra and his places on Gaangalu country. Moreover, when old people pass away, they return to country to protect it and look after other Gaangalu people. Ms Blucher believes her father was at Tiamby when she lived there. She believes that old people look out for her when she is on country.

Customary use of natural resources and an understanding of sorcery and traditional healing

72 Ms Blucher has lived on and been doing traditional things on country for her entire life. Her father took her and her siblings camping on country and taught them how to hunt, fish and find bush tucker. For example, her father took them, often with relatives and other Gaangalu families, fishing and camping at different places on the Dee and the Don Rivers. When camping, they didn’t take a tent but instead would “rig up” a tarpaulin as shelter. They would stay on pastoral properties if her Dad knew the owner but as it was their country, they didn’t need to ask or tell anybody else. Ms Blucher continued this with her children, to get them out to country and to go fishing.

73 Other traditional activities included hunting, gathering, taking and using water and fire. Ms Blucher’s father hunted and went shooting, fishing and caught pigs and porcupines. They cooked the porcupines in the ground and used porcupine oil on their skin. They also went fishing and swimming at Kenny’s Waterhole and would catch yellow belly, catfish, jewfish, perch and eels using mussels or earth worms as bait. They gathered bush foods including, among others, bush apples, jew jews, blackberries, and wild plums. Ms Blucher grew up on freshwater country and used the water to drink, cook food and to boil gumbi gumbi leaves, which is a plant that grows in and around Gaangalu country and is like medicine. Fire was used for cooking and boiling water. When camping, fire was used to help them see at night and keep them warm. Smoking ceremonies were also performed for cleansing and protection.

Intermarriage and trade across the regional society

74 In the old days, the different mobs would meet to celebrate, trade and sometimes find marriage partners. For example, Ms Blucher’s mother married Gordon Toby, a Gaangalu man, and has Wadja, Gaangalu and Guringbal connections. However, Gaangalu people with the same yuri, or totem, cannot marry another Gaangalu person with the same yuri.

75 Ms Rosemary Hoffman is 71 years old and was born in Gladstone, but was raised in Mount Morgan. She still resides in Mount Morgan.

A classificatory kinship system, a system of authority emphasising the role of senior people, and various funerary practices

76 Ms Hoffmann is a Gaangalu woman and got her country from her father, Bill Toby, a Gaangalu man. Bill Toby’s father and grandfather were Gaangalu. Her father’s father is William Toby II. Ms Hoffman explained that food was shared with other family members and that Gaangalu people cannot marry into families who share the same totem.

77 Ms Hoffman stated that she welcomes any child that visits, whether they are her family or not. This includes disciplining them if they do not behave. This was the same when she was growing up with her aunties and uncles. She states that if a Gaangalu adult is called upon, they are there straight away. Her and other elders give advice to kids that are in trouble, and they respect the elders. Ms Hoffman stated that they have to respect elders and they instil that respect in their kids today. Ms Hoffman calls her cousins “sister” or “brother”.

78 If there is a funeral, they always go or someone will go in her place if she cannot attend. They also go to funerals in the west.

An understanding of mythology, an understanding of spirits in the landscape, an understanding of sorcery and traditional healing, and responsibilities to manage and protect land and waters

79 Ms Hoffman’s father would sing at night time around the fire and tell them tales about the wind and the dark, saying they should not be afraid of the dark. Old People, people who have gone, whistle and talk to you. Ms Hoffman’s father taught her that it was a healing thing. Djandjarri used to live at Cattle Creek. Ms Hoffman would see the min min lights there. Her father told them not to be frightened of the dead ones but to take spiritual care in those places.

80 Her father told her to never go on other country or take anything because it was not theirs to take. She also explained that if you took something from country, something bad would happen to you. For example, some people got really sick. Ms Hoffman was taught that if she goes out of her country, she needs to tell the ancestors. Her father taught her to talk to the ancestors.

An understanding of totemism

81 The Gaangalu people in the Mount Morgan area’s totem is a carpet snake. The snake comes into the Dee River. All Toby family members have the snake as their totem, including her father, uncles and aunties. Ms Hoffman identifies as the totem of her father, who was carpet snake, and her mother, who was freshwater turtle. This is passed down to her children and the younger generation. You never eat your totem or marry someone with the same totem.

Customary use of natural resources

82 Ms Hoffman’s father taught her how to dig in the ground for water. They also swam in the Mount Morgan dam and creeks, and hunted goannas. When they hunted food, they went through mountains and would get lemons, bush lemons, mangoes, prickly pears, wild cucumbers, jujus, bush apples and witchetty grubs. They used fire to cook the witchetty grubs and kangaroos that they hunted to eat and sold the kangaroo skins. Ms Hoffman also drank gumbi gumbi or made it into a paste to use for medicinal purposes. She used it on her kids when they were young.

Recognition of gender specific and other significant sites

83 Mount Morgan dam is a significant and spiritual-type place. One of Ms Hoffman’s sister’s children passed away and her ashes were spread there. Her other sister wants her ashes spread there when she passes too.

84 Cattle Creek is a significant place where Djandjarri lived. Ms Hoffman saw min min lights there at night. There is a bora ring at Box Flat, which is a sacred place because men’s business is conducted there.

85 Men’s business is different to women’s business. Women’s business was done down the road from Piebald Hill. Piebald Hill is a women’s meeting and birthing place. Razorback Mountain is significant because it is shaped like a carpet snake.

An embodied relationship between people and their land and waters

86 Ms Hoffman lives and was raised in Mount Morgan. She said that it has always been their country. Her father was born in Mount Morgan and Uncle Gordon Toby was born at Wura. Ms Hoffman’s father told her she was Gaangalu because her family is from Mount Morgan down to the Dawson Valley, Banana, Biloela, Wowan, and Kroombit Mountain, and that is their country. Her father would talk about places, rivers and mountains such as the Dee River, Wura and the Bald Mountain. She always remembered her father saying, “this is your country”.

87 They know that the Dawson River is the east side boundary of their country. People recognise that this is Gaangalu land and belongs to the Tobys. Woorabinda is not their country, but they go there for funeral services and relatives live there. There are many Gaangalu families, some from the west, and they all consider themselves as one Gaangalu. However, to go to the west, you need an invitation. They can come to meetings, but they cannot talk for country or cut down trees. If they did, spiritually bad things would happen.

88 Gaangalu people respect the country. Ms Hoffman’s father always told them not to go on other country and take anything because it was not theirs to take. If you did, something bad would happen like getting sick.

89 Ms Hoffman said they do “Welcome to Country” at Mount Morgan and take the kids for cultural heritage walks. The Old People taught them the names of the hills, Bald Hills and Box Flats. As kids, Ms Hoffman and her siblings would walk everywhere and discovered the creeks, rivers, dams and caves. They learnt how to swim in the Dee River and swam in the dams and creeks at Mount Morgan dam. When walking in the bush, her father taught them how to dig for water in the ground. They also hunted and gathered food, using fire to cook. Ms Hoffman was taught the traditional ways by her father, uncle and aunts. Her father would sing at night time around the fire and tell tales about the wind and the dark, saying that they should not be afraid of the dark. Other ways the embodied relationship manifests is through sacred places, such as Box Flat, and totems, whereby Gaangalu people cannot eat their totem.

90 When they pass away, Gaangalu people go back to their country. Ms Hoffman states that her father’s spirit is there. Some people are buried on country. Many Aboriginals were killed at Lake Victoria and their spirits are there.

91 Mr Dale Martin Toby is 63 years old and was born and resides in Mount Morgan.

A classificatory kinship system and an understanding of totemism and intermarriage

92 Mr Dale Toby gave evidence that he is a Gaangalu man through his great grandfather, William Toby I, who is an apical ancestor in the claim, and his father, Gordon Roy Toby Snr, who is a Gaangalu man. Gordon Toby Snr’s father was William Toby II, and Gordon Toby Snr’s grandfather was William Toby I. Both are Gaangalu men. Mr Dale Toby has rights in country because he is connected to a Gaangalu ancestor. Mr Dale Toby’s mother is an Iman woman, born and raised in Woorabinda.

93 Mr Dale Toby has two totems. On his father’s side it is the carpet snake, and on his mother’s side it is the emu. You cannot eat your totem and it is bad luck if you do. For example, you could pass away or things might happen to your children. Marriage may occur between east and west Gaangalu. Mr Dale Toby’s brother and his wife are married that way. However, Mr Dale Toby’s father told him that you cannot marry someone with the same totem or marry “too close”. If they did, they would be punished. To avoid this, they figure out who is who and ask, “who’s your mob?”.

94 Mr Dale Toby’s children are Gaangalu through him. A person is Gaangalu through their Gaangalu ancestors. It is passed down from generation to generation. Mr Dale Toby’s father told him he was a Gaangalu man and he tells his children that they are Gaangalu and where their country is. Mr Dale Toby says that is important for the next generation.

95 Mr Dale Toby has lived most of his life in Mount Morgan. While in Mount Morgan, he had aunties and cousins visit, some from different tribes. Some cousins are Darumbal by marriage but they are still their blood cousins and continue to stay with them. He would visit cousins in Banana, Moura, Theodore and Mount Scoria near Thangool. They would go fishing in the Dawson River. When traveling to Theodore, they would go swimming, and Mr Dale Toby’s father would catch and cook turtles and eels.

96 Mr Dale Toby explained that one of the ways Gaangalu families stay together is that they “get together” and sometimes live together. Uncles, aunties and nephews can sometimes live in the one house, and you treat them like one of your own. They call cousins “brother” and “sister”. If you have young nieces and nephews, you take over the parental role if their parents are not around and treat them like they are your children. Grandparents look after the grandkids if parents are away or working. Sharing and helping are things that Mr Dale Toby’s family has done over his lifetime. It is really disrespectful to not help, and if you were busy, you would get someone else from the family to help. They also treat each other’s places as their own and will help themselves.

An understanding of mythology, spirits in the landscape and various funerary practices

97 Mr Dale Toby talks to country and talks to the ancestors of his country. His father told him to talk to the country and the spirit of the Elders because they will look after you. Mr Dale Toby has told this to his children so that they are safe on country. When he leave Gaangalu country, he introduces himself to country as a Gaangalu man and tells the ancestors where he is from. He states that you need permission to go on another tribe’s country.

98 If Mr Dale Toby finds an artefact, he will tell the ancestors what he has found. Bad things will happen if you take something from the country without the peoples’ or spirits’ knowledge. The best thing is to put things back where they were found or not to touch anything. A younger Aboriginal girl once took an artefact from Gaangalu country and got sick. A Gaangalu elder told her to return it and they did a smoking ceremony to heal her. Mr Dale Toby also explains that you can hunt but you have to talk to the land and spirits.

99 There are also some places on Gaangalu country that Mr Dale Toby will not go to, such as where women’s business is conducted. There are also some places that he might have to talk to elders before visiting, for example Lake Victoria, which is a sacred place. His father and uncles told him not to climb Wandoo Mountain because it has evil spirits. Stories have been told by Mr Dale Toby’s father and grandfather that bad things happened up there, such as two tribes having fought there.

100 Mr Dale Toby’s father told him about various mythological creatures, including:

(1) The Mundagadda which created the rivers and ranges in the dreamtime. It created all the creeks and ranges around the Callide Dawson Valley area, and the boundaries, which are the Dee, Don and Dawson Rivers.

(2) The min min lights on Piebald Mountain which are like spirits and draw you away from your tribunal area.

(3) The Djandjaddis which are small hairy men that take you away like the min min lights.

(4) The Kadartchi Man who is like a witch doctor. He does bad things like make people sick or catch you. In cross examination, Mr Dale Toby accepted that he called medicine men “witch doctors” who might point the bone at you and sing you to death but to his knowledge, they are no longer around.

(5) Featherfoot which is like a hitman and kills people.

(6) The Tall Man who is like the Kadartchi man.

101 Mr Dale Toby’s father and uncles told him about various mythological signs, including:

(1) A kookaburras laugh means someone is pregnant.

(2) A black cockatoo with a red tail means it is going to rain soon.

(3) Three or four black cockatoos flying around means it will rain in three or four day.

(4) A black crow means bad news is coming.

102 Smoking ceremonies are used for protection to get rid of bad spirits. For example, Mr Dale Toby’s father performed one when they were fishing at Riverslea because there was “something in the air”. He made smoke with some bark and did a complete circle around the fire and everyone who was there. Sandalwood twigs and leaves are usually used, which makes a thick, white smoke. Other examples of when smoking ceremonies are used is for protection from crocodiles in the river or to rid bad spirits in a house if someone died there or something bad happened. It is usually the men who do the big smoking ceremonies but women can too. A smoking ceremony was also performed when Aboriginal human remains were found in Theodore. They were taken to Biloela Police Station and ultimately reburied. The police told Phillip and Debbie that “funny things” were happening at the police station so Phillip did a smoking to rid any bad spirits.

103 Mr Dale Toby said that they go to funerals for Gaangalu people, including on the west side of the Dawson River. Someone from the family must represent the Tobys. They believe that when elders have passed, they go back to country. It is important that they are buried on country. This is also why they talk to country; they are talking to the old people.

A system of authority emphasising the role of senior people

104 Mr Dale Toby gave the evidence that elders are important in the Gaangalu community and you have to respect the elders. They teach the younger people about what it means to be Gaangalu and teach Gaangalu ways. Gaangalu people can then also hand down information and stories told by the elders to the next generation. Elders also discipline children, even if they are not their own children. Sometimes when the elders are talking, you shouldn’t go near them. When decisions are made, the whole family will get together and the elders have the last say in the decision. There are also some places that require talking to the elders before visiting. Mr Dale Toby was told by the elders not to climb Wandoo because of evil spirits.

Responsibilities to manage and protect land and waters

105 Mr Dale Toby gave the following evidence that it is their duty to look after their country. First, you need permission to go on another tribe’s country. This includes other tribes visiting Gaangalu country and visiting Gaangalu country on the west of the Dawson River. Second, you must respect and look after the land, otherwise it will not look after you. An important way they protect their country is by doing cultural heritage walks, where artefacts, caves, wall paintings and old campsites are shown to the next generation. These walks are important for the next generation so they know who the Gaangalu people are. Mr Dale Toby was told that if something is not in danger, they have to leave them there because it proves that their ancestors have been there before them. Mining disturbs the land and artefacts are moved to protect them. Before artefacts are removed and taken to a keeping place on country, an archaeologist will take a photo of it and use GPS to record where it was found. Artefacts are to be returned if possible. Third, you can only take resources from country as needed. When hunting, you have to talk to the land and the spirits to tell them that you are taking the animal for food. You cannot take more than is needed and waste food.

Customary use of natural resources and an understanding of sorcery and traditional healing

106 Mr Dale Toby has rights in country which means he has the right to take things from country, protect artefacts on country, talk to ancestors, and access country. He and his family used to visit Banana, Moura, Theodore and Mount Scoria near Thangool, and went fishing in the Dawson River outside of Moura and at Rannes. The Gaangalu people can take and use resources from country and exercise their rights and interests, including fishing, camping, using fire, hunting, gathering, taking and using water. For example, gumbi gumbi is used as medicine for colds, sores and your scalp. Mr Dale Toby’s father showed him how to make boomerangs from a U-shaped branch from a dead tree.

Recognition of gender specific and significant sites

107 Mr Dale Toby gave evidence that special places on country include:

(1) Wura, where Mr Dale Toby’s father was born.

(2) Piebald Mountain, where the min min lights are.

(3) Wandoo Mountain, which is not a good place because there are evil spirits.

(4) Axe Factory, where many axe heads carved by Gaangalu people can be found.

(5) Rannes, where they used to go fishing and where the native and normal police were.

(6) Lake Victoria, where a massacre happened.

(7) Wowan, where there is a Bora Ring.

(8) Theodore, where Aboriginal human remains were found.

An embodied relationship between people and their land and waters

108 Mr Dale Toby was born and grew up in Mount Morgan. He has lived most of his life there. His father was born at Wura and worked at Dululu and Mount Morgan.

109 His father told him that he is Gaangalu and that Gaangalu country is, “from the Mount Morgan range towards Riverslea, this side of Gogango Range, down to the Dawson River, down past Baralaba, down to Theodore, cutting back up to Callide Dawson Valley Range, around near Biloela, and back up to Mount Morgan”. The rivers, ranges, creeks and boundaries were made by the Mundagadda. Mr Dale Toby and his father travelled to various places on country. Mr Dale Toby tells his children that they are Gaangalu and where their country is.

110 The other side of the Dawson is not their country, but they are a related mob. When the east and west side come together as one tribe, they are stronger and “one big family”. However, they have different rights and responsibilities. His father would talk about other tribes. For example, Wadja on the other side of the Dawson, Darumbal on the other side of the Mount Morgan range and the Gooreng Gooreng near Gladstone. These groups are their neighbours and they have good relationships with them.

111 When Mr Dale Toby talks to country, he is talking to the ancestors of his country. He does so when he travels outside of Gaangalu country. Permission is also needed to enter another tribe’s country. Mr Dale Toby has rights in country and has the right to take things like dead wood from a fallen tree to make nulla nulla, spears or boomerangs and woomeras. He also has the right to access his country and protect artefacts on country from the environment, mining and vandalism.

112 When he is on country, Mr Dale Toby’s father told him to talk to the country and the spirit of the Elders because they look after him. Other facets of an embodied relationship between people and their land and waters are the existence of special places on country, the duty to respect, protect and manage country, performing smoking ceremonies for protection or to rid bad spirits, and the belief that a deceased person’s spirit goes back to country.

113 Mr James Robert Waterton is 42 years old and was born and resides in Rockhampton.

A classificatory kinship system, an understanding of totemism and intermarriage and a system of authority emphasising the role of senior people

114 Mr Waterton is a Gaangalu person though his great grandfather, William Toby I. Mr Waterton’s father is an Iman man. Mr Waterton’s mother, Elvina Waterton, nee Toby, was born at Mount Morgan. Elvina’s father was William Toby II who lived at Mount Morgan and her grandfather was William Toby I. Elvina had five brothers and seven sisters who all grew up at Mount Morgan and were around Mr Waterton as he was growing up. Mr Waterton has four sisters who are Gaangalu people too. Mr Waterton’s Uncle Philip was like a second father to him and taught Mr Waterton a lot about being Gaangalu.

115 Mr Waterton was taught by his parents and other Gaangalu people that to be Gaangalu, you must be a descendant of a Gaangalu person. If you are not related in this way, you cannot join or decide to become a Gaangalu person. You do not become Gaangalu through marriage, but any children will be Gaangalu because they will have the bloodline. Most of the time, children with a Gaangalu ancestor will also have ancestors from other groups. Children can follow the line of one of their ancestors, and are often brought up and grow up with a stronger attachment to one parent’s group. For example, Mr Waterton followed his mother to be Gaangalu, as opposed to being Iman like his father. Most children with Gaangalu ancestors who grow up in or near the Gaangalu area are brought up as Gaangalu people.

116 Mr Waterton’s totems are carpet snake and Cabbage Palm. His carpet snake totem comes from his mother’s Gaangalu totem and his father’s Iman totem. He also has the Cabbage Palm as his totem from his mother. The carpet snake is a special animal for Gaangalu people. Gaangalu people have respect for carpet snakes and they cannot kill or eat a carpet snake. Gaangalu people are told that the carpet snake is Mundagarra, who is special to them like a totem.

117 When Mr Waterton was growing up, a family was not just a mum, dad and the children. It included the uncles, aunties, cousins, nieces, nephews, grandparents and all other relatives. Words like “uncle”, “aunty”, “brother”, “sister” and “granny” described all people about the same age or generation. They were all part of the family. All of the older people looked after all of the children and all of the children obeyed and respected all of the older people in the same way that they would obey and respect their parents or other elders. It was common for children to live with uncles, aunties, grandparents and other relatives. They are a large group that looks after, shares and lives with each other.

118 Elders are important. Mr Waterton thinks of his Uncle Philip Toby as an elder. Auntie Lyn Blucher is an elder too. Mr Waterton says that elders like Uncle Philip and Auntie Lyn are old and wise Gaangalu people who are depended upon when important matters have to be decided or action has to be taken. They are the decision-makers and leaders. Elders are not elected or appointed. Instead they gradually develop a reputation and are respected.

An understanding of mythology and recognition of gender specific and other significant sites

119 Mr Waterton said that Mundagarra, the rainbow serpent, looks after Gaangalu people. Spirits reside in special places on country. Near Banana, there was a place that had been used for ceremonies which was where the old people gathered. Mr Waterton took this to mean the spirits of ancestors. Similarly, Mr Waterton’s mother told him to avoid a massacre and burial site near Banana and a women’s site near Woorabinda so he would not disturb the spirits there. He tells visitors not to go near these sites. Third, sandalwood grows in Gaangalu country and is used for smoking. The smoke from its branches and leaves cleanses and drives bad spirits away.

Responsibilities to manage and protect land and waters

120 Mr Waterton was taught that other people, including Gaangalu families from the west of the Dawson River, should not use their country unless they agree. He was taught the same with respect to using other peoples’ country. Doing this allows the country to be kept safe and makes sure that visitors coming onto country are kept safe. In particular, visitors can be told that they shouldn’t go to a particular place, or do things, out of respect for the ancestors and the future of Gaangalu people. This keeps the country and visitors safe. For example, there are sacred trees that should be preserved.

Customary use of natural resources and an understanding of sorcery and traditional healing

121 Growing up, Mr Waterton went camping around the Mackenzie, Comet and Dawson Rivers with his family. They did not ask or tell anyone before they went because they were taught that it was their country and they were free to go camping and take animals and plants. When he was on country, Mr Waterton was taught how to catch and cook animals, especially kangaroos, echidnas and yellow belly fish. They would gather timber to make a fire and cook. In addition to gathering and hunting plants and animals for food, Gaangalu people use other things found in Gaangalu country. For example, the gumbi gumbi tree grows on their country and its leaves can be boiled to make a drink that helps overcome sickness. Similarly, sandalwood grows on country and is used for smoking to cleanse and drive away bad spirits. Trees were used for firewood and to make implements, and they gathered bush honey from native bees.

An embodied relationship between people and their land and waters

122 Mr Waterton’s mother was born at Mount Morgan, and her father, William Toby II, lived at Mount Morgan. Mr Waterton was taught by his parents, uncles, aunties and old Gaangalu people that their country covers Theodore, Moura, Mount Morgan, Biloela and across to the Dawson River. Gaangalu people have lived, died and been buried on Gaangalu country. Mundagarra created Gaangalu country and looks after Gaangalu people. To Gaangalu people, he is a carpet snake and is special like a totem. He created their country, and lives where there is water, under the rivers and under the mountains. This country is Gaangalu country and Gaangalu people have the right to access country, camp, take resources, hunt, use timber, make fire, use gumbi gumbi and take bush honey.

123 The other side of the Dawson River is west side Gaangalu country, and they speak for themselves and their country. The families in east and west Gaangalu respect each other and would not do or say things relating to country that is not on their side without making sure the right families know and agree. These different families are not different mobs though. They get together, use the same language, follow the same rules and have the same stories. They are Gaangalu people and while it is all Gaangalu country, permission is still needed to enter country.

124 Mr Waterton was brought up with the understanding that his family’s country, the eastern part of Gaangalu country, is where he belongs. It has always been the country for his family’s ancestors and will always be the country for Gaangalu people in the future. To be Gaangalu, you must be a descendant from a Gaangalu ancestor.

125 Ms Deborah Maree Tull is 63 years old, was born at Mount Morgan and resides in Rockhampton.

A classificatory kinship system, intermarriage and a system of authority emphasising the role of senior people

126 Ms Tull is a Gaangalu woman through her great grandfather, William Toby I. Her father, Gordon Toby, was the son of William Toby II, who was a Gaangalu man. William Toby II was the son of Gaangalu man William Toby I.

127 Ms Tull’s mother, Heather Toby nee Tyson, was the daughter of Harold Tyson, who was a Gaangalu man from the west side. Harold Tyson descended from apical ancestor Pater Tyson and is the son of a Wadja woman, which gives Ms Tull her connection to Wadja. Ms Tull’s mother did not identify as Gaangalu, and told Ms Tull that she is Wadja Wadja through her father’s line but knows Gaangalu country and ways because of her marriage to Ms Tull’s father.

128 Ms Tull has connections to other groups but strongly identifies as Gaangalu through her father because her father and Uncle Bill told her that they are Gaangalu and that she is Gaangalu. To be Gaangalu, you must come from a Gaangalu ancestor.

129 Ms Tull and her husband, who is an Iman man, have five children together and 11 biological grandchildren. Two of her children were born in Mount Morgan before she moved to Rockhampton. Ms Tull’s oldest daughter, Jodi, and her partner, who is Darumbal, have six foster children who are Darumbal descendants. Ms Tull classes her foster grandchildren as her grandchildren but they are not Gaangalu because they do not come from a Gaangalu ancestor.

130 There is intermarriage between Gaangalu from the west and the east. For example, Ms Tull’s brother married a Gaangalu woman from the west. Their children have a connection to both the east and the west and have rights in both areas of country. Her brother takes his family to Blackdown Tableland once a year to meet and get together with other Gaangalu families. Ms Tull’s daughter, Shalee, was also in a relationship with a west Gaangalu man.

131 Ms Tull grew up on Gaangalu country and spent “a good part” of her life at Mountain Morgan. Her knowledge of Gaangalu country comes from her father, mother and her father’s brother, Uncle Bill Toby. Ms Tull has strong connections to Gaangalu country through her father and grandfather. You must come from a Gaangalu ancestor to inherit and be connected to Gaangalu country. Her rights to go on country and take her children and grandchildren on country come from her father and their ancestor William Toby I. All of her family has rights in country and the next generation will have those rights as well. Ms Tull’s foster grandchildren can use and access Gaangalu country, and can go camping and fishing, but they do not have rights to inherit or make decisions about Gaangalu country.

132 Ms Tull’s generation are becoming the next generation of Elders in the family because the Elders from her father’s generation are now deceased. When important decisions need to be made on country, Gaangalu families will have their own meetings. Although every person in Ms Tull’s family gets a say, Elders make the final decision. Ms Tull believes that that is what the other Gaangalu families do as well.

An understanding of mythology and an understanding of totemism and of spirits in the landscape, recognition of gender specific and other significant sites and male and female rituals and initiation ceremonies

133 Ms Tull talks to the ancestors when on country. She does this when she travels to Mount Morgan and gets close to the Mount Morgan Range and before going on cultural heritage surveys to let them know that it is her and that she is on country. If Ms Tull locates and identifies an artefact to be removed when doing a cultural heritage survey, she talks to the ancestors to let them know that she is looking after country. When Ms Tull visits the west side of the Dawson River, she announces herself and tells the ancestors that she is entering that area.

134 Ms Tull recounts various story places:

(1) When traveling from Rockhampton to Mount Morgan, you can see the shape of the Gaangalu serpent, Mundagadda. There are large boulders on the range which are the Mundagadda’s eggs.

(2) The top of Piebald Mountain is where the Mundagadda would rest and keep warm from the sun.

(3) Axe Factory is near Piebald Mountain and is where Gaangalu ancestors used to make axes and grinding stones. A lot of artefacts are there.

(4) Lake Victoria is a sacred place. They do not go there because their ancestors were massacred there and the deceased were drowned in the lake. Ms Tull once went to the lake and felt a bad spiritual presence. Uncle Bill later told Ms Tull that she should not go the lake.

(5) Wandoo Mountain is the face of an old Gaangalu man. It is a men’s place and only men can go there. Uncle Bill told Ms Tull that it is a place where the men used to fight.