Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Kaur [2023] FCA 599

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

A. For the purposes of these orders, 'the Scheme' means the unregistered managed investment scheme operated by the first and second defendants, whereby between at least 1 March 2017 and 16 December 2020:

(a) the first and second defendants obtained monies from investors;

(b) the first and second defendants pooled that money in bank accounts, including the following accounts:

(i) Bendigo & Adelaide Bank account [redacted];

(ii) Bendigo & Adelaide Bank account [redacted];

(iii) Commonwealth Bank of Australia account [redacted]; and

(iv) Commonwealth Bank of Australia account [redacted];

(c) the first and second defendants represented and/or agreed with investors that the monies were to be invested into real property projects managed by the second defendant;

(d) the investors did not have day to day control over the use of the monies;

(e) the first and second defendants represented and/or agreed with investors that in return for advancing monies, investors would receive a right to interest payments;

(f) the second defendant was to use the monies to purchase, develop and sell real property, with a view to generating a profit, out of which interest payments were to be paid to investors; and

(g) the first defendant distributed the monies to:

(i) the second defendant for the purchase, development and sale of real property;

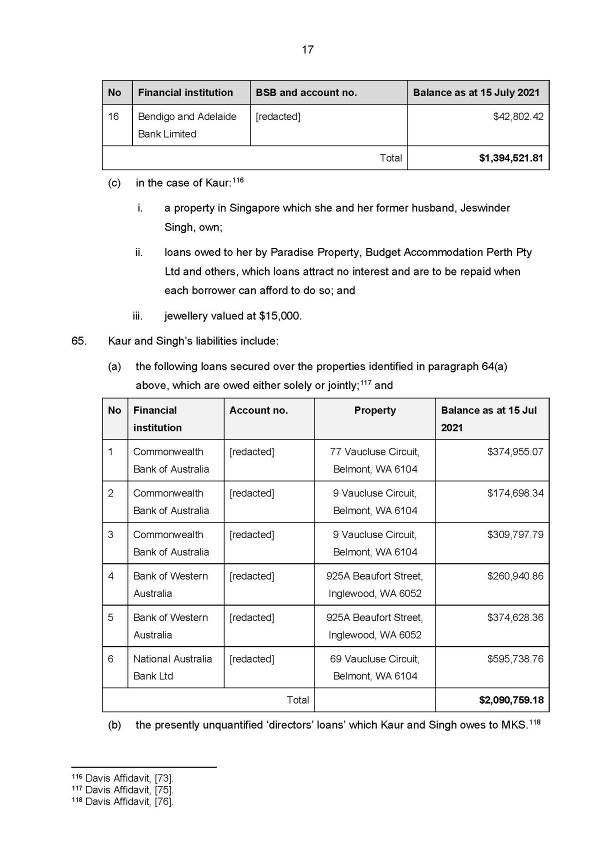

(ii) related parties, including the third, fifth and sixth defendants; and

(iii) herself and the fourth defendant for personal use.

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The first and second defendants, by operating the Scheme, contravened the provisions of s 911A(1) and s 911A(5B) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) in that each carried on a financial services business without holding an Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL) in the period between at least 1 March 2017 and 16 December 2020.

2. The first and second defendants operated the Scheme in contravention of s 601ED(5) and s 601ED(8) of the Corporations Act, in circumstances where the Scheme was required to be registered under s 601EB of the Corporations Act in the period between at least 1 March 2017 and 16 December 2020.

3. The first defendant, by advising clients to set up self-managed superannuation funds (SMSF) with the view of the SMSF investing monies with the second defendant and earning a fee for that advice, contravened the provisions of s 911A(1) and s 911A(5B) of the Corporations Act in that she carried on a financial services business without holding an AFSL in the period between at least 1 March 2017 and 16 December 2020.

4. The fourth defendant, by deferring all matters regarding the affairs of the second defendant to the first defendant, contravened the provisions of s 180(1) of the Corporations Act in the period between at least 1 March 2017 and 16 December 2020.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Receivership

5. Pursuant to s 1101B(1) and s 1323(1)(h) of the Corporations Act, David Hodgson and Andrew Hewitt, of Grant Thornton, be appointed as joint and several receivers and managers (Receivers), without security, of all property (as defined in the Corporations Act), whether within or outside the State of Western Australia, of:

(a) the first and fourth defendants; and

(b) the Scheme;

including, for the avoidance of doubt, the Commonwealth Bank account held in the name of the fifth defendant the account number for which ends in #1240 (Account #1240), the Commonwealth Bank account held in the name of the sixth defendant the account number for which ends in #4312 (Account #4312), and the property located at 4 Karimba Street Wanneroo in the name of the fifth defendant (Karimba St) (together, the Property).

6. Each of the first and fourth defendants are to immediately give over possession of all their property (as defined in the Corporations Act), whether within or outside the State of Western Australia, together with all books and records relating to that property, to the Receivers.

7. Each of the fifth and sixth defendants are to immediately give all books and records relating to Account #4312 and Account #1240 to the Receivers.

8. The fifth defendant is to, on request of the Receivers, do all things necessary to effect the transfer to, and the taking of possession by, the Receivers of Karimba St, together with all books and records relating to Karimba St.

9. The Receivers have the following powers:

(a) the power to do all things necessary or convenient to be done, in Australia and elsewhere, for or in connection with, or as incidental to the attainment of the objectives for which the Receivers are appointed including, without limitation, for the identification, preservation and securing of all of the Property for the benefit of creditors;

(b) the powers under s 1101B(8) of the Corporations Act provided that wherever in that section the word 'financial services licensee' appears, it shall be taken to refer to the first defendant, the fourth defendant and the Scheme;

(c) the powers set out in s 420 of the Corporations Act provided that wherever in that section the word 'corporation' appears, it shall be taken to refer to the first defendant, the fourth defendant and the Scheme;

(d) the power to require, by request in writing, the first defendant and fourth defendant and any employee, agent, banker, solicitor, stockbroker, accountant, consultant or other professionally qualified person who has provided services or advice to the first defendant or the fourth defendant to provide such reasonable assistance (including access to any documents, books or records to which the first and fourth defendants have a right of access or control) to the Receivers as may be required from time to time.

10. Upon being called upon to do so, the Receivers must deliver up that part of the Property that is property of the Scheme to the liquidators appointed pursuant to paragraph 19 below.

Receivership remuneration and indemnity

11. The Receivers shall be entitled to reasonable remuneration properly incurred in the performance of their duties arising in connection with their appointment and in the exercise of their powers as may be approved by the Court on the application of the Receivers, together with all costs, expenses and disbursements.

12. The Receivers' remuneration is to be calculated on the basis of time reasonably spent by the Receivers and any partner or employee of the firm to which the Receivers are attached, at the standard rates of the Receivers' firm from time to time for work of that nature.

13. The Receivers' remuneration, costs, expenses and disbursements are to be paid from the Property.

14. The Receivers be indemnified from the Property against any claim, liability, proceeding, cost, charge or expense however arising and whether past, present or future, fixed or ascertained, actual or contingent, known (actually or contingently) or unknown which they may incur or be subject to as a result of or in connection with their appointment.

15. The above orders are not to affect the rights of any prior encumbrancer over the Property, including the rights of any secured creditor.

16. For the avoidance of doubt, the entitlement of the Receivers to be paid or indemnified from the Property pursuant to the orders above is not restricted or in any way limited by whether they are acting as receivers of property of the first defendant, the fourth defendant or the Scheme and they are entitled to treat the Property as a single combined pool of property for those purposes.

Winding up orders

17. Pursuant to s 601EE(2) of the Corporations Act, the Scheme be wound up.

18. Pursuant to s 461(1)(k) of the Corporations Act, the second defendant be wound up.

19. Pursuant to s 472(1) of the Corporations Act, the Receivers be appointed as joint and several liquidators (Liquidators) of:

(a) the Scheme; and

(b) the second defendant.

20. The asset preservation orders made on 16 December 2020 (as varied from time to time) in respect of the first, second and fourth defendants be vacated on the appointment of the Liquidators pursuant to paragraph 19 and the appointment of Receivers pursuant to paragraph 5.

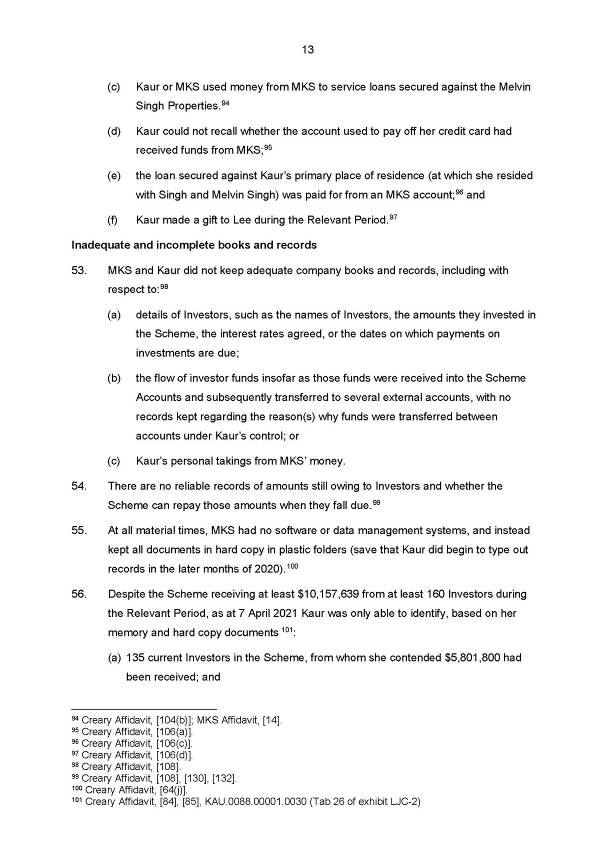

21. Pursuant to s 601EE(2) of the Corporations Act, and subject to any further orders of the Court:

(a) the winding up of the Scheme be conducted as if the Scheme were a 'company' or 'corporation' for the purposes of the Corporations Act and the provisions of Parts 5.4B, 5.6, 5.7B and 5.9 of the Corporations Act and Schedule 2 to the Corporations Act (Insolvency Practice Schedule (Corporations)) applied to the winding up (with such modifications as are reasonably necessary in the circumstances);

(b) the Liquidators of the Scheme have power to do, in Australia and elsewhere, all things necessary or convenient to be done for or in connection with the winding up of the Scheme, or incidental to the attainment of the winding up of the Scheme, including the functions and powers set out in Chapter 5 of the Corporations Act (as applicable) as if each reference there to a 'company' or 'corporation' was a reference to the Scheme (with such modifications as are reasonably necessary in the circumstances); and

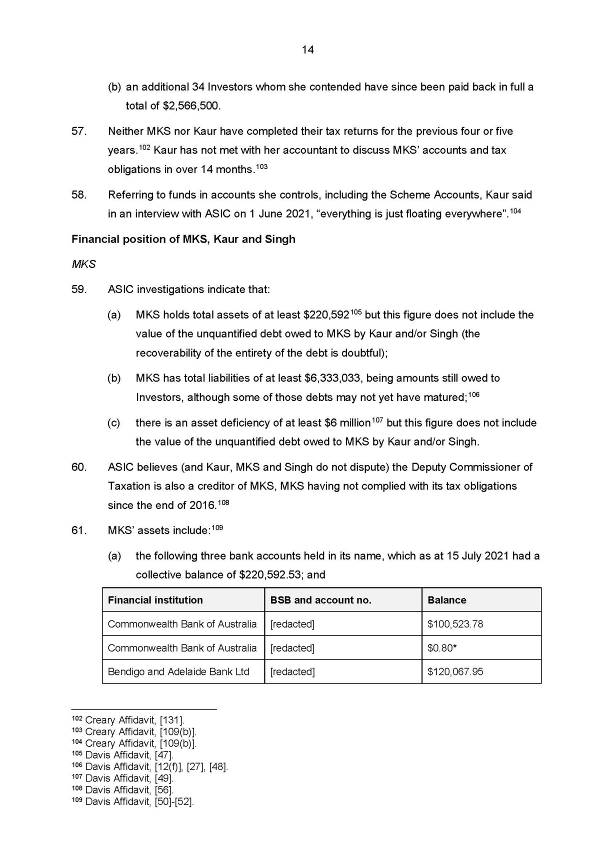

(c) without limiting the above, the Liquidators of the Scheme shall have the power to investigate or cause to be investigated any deficiency in the Scheme and to exercise the powers under Part 5.9 Division 1 of the Corporations Act as if the Scheme were a 'company' or 'corporation' being wound up.

Liquidation remuneration and indemnity orders

22. The Liquidators shall be entitled to reasonable remuneration properly incurred in the performance of their duties arising in connection with their appointment and in the exercise of their powers as may be approved by the Court on the application of the Liquidators, together with all costs, expenses and disbursements.

23. The Liquidators' remuneration is to be calculated on the basis of time reasonably spent by the Liquidators and any partner or employee of the firm to which the Liquidators are attached, at the standard rates of the Liquidators' firm from time to time for work of that nature.

24. The Liquidators' remuneration, costs, expenses and disbursements are to be paid out of the assets of the Scheme and/or the second defendant.

25. The Liquidators be indemnified from the assets of the Scheme (including the Property) and the second defendant against any claim, liability, proceeding, cost, charge or expense however arising and whether past, present or future, fixed or ascertained, actual or contingent, known (actually or contingently) or unknown which they may incur or be subject to as a result of or in connection with their appointment.

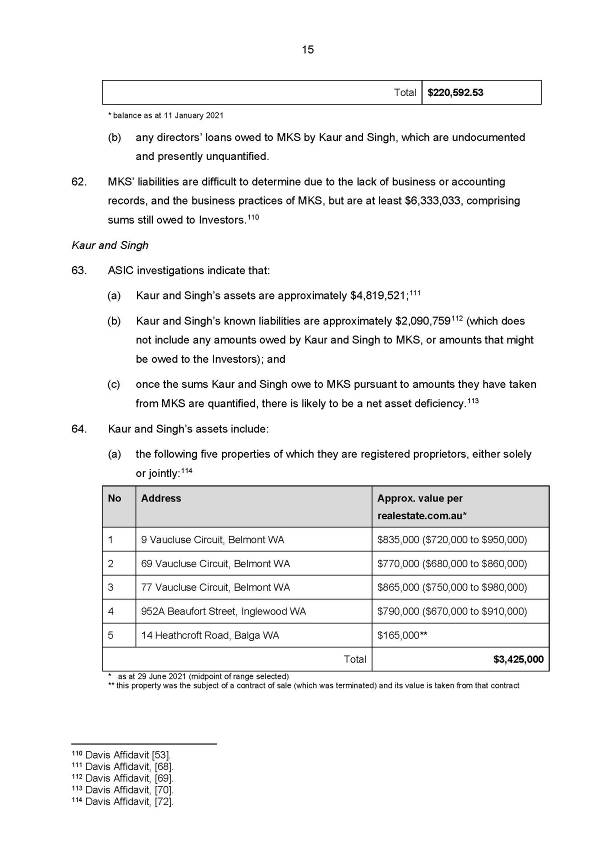

26. The above orders are not to affect the rights of any prior encumbrancer over the assets of the Scheme, including the rights of any secured creditor.

27. For the avoidance of doubt, the entitlement of the Liquidators to be paid or indemnified from the assets of the Scheme pursuant to the orders above is not restricted or in any way limited by whether they are acting as liquidators of the Scheme or the second defendant and they are entitled to treat the assets of the Scheme as a single combined pool of assets for those purposes.

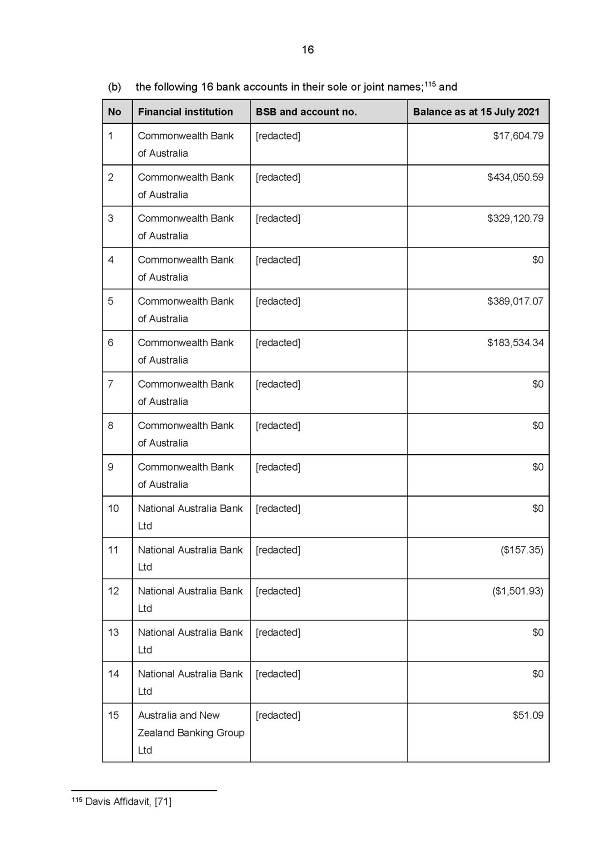

Injunctive relief

28. The first defendant be permanently restrained from:

(a) carrying on a financial services business in Australia; and

(b) operating an unregistered managed investment scheme in contravention of s 601ED(5) of the Corporations Act.

Disqualification order

29. Pursuant to s 206C of the Corporations Act:

(a) the first defendant be disqualified from managing corporations for life with effect from the date of this order.

(b) the fourth defendant be disqualified from managing corporations for 15 years from the date of this order.

Asset preservation orders

30. Paragraphs 6 and 7 made on 16 December 2020 (Principal Orders) (as varied from time to time) against the third, fifth and sixth defendant are vacated.

31. Until further order of the Court, pursuant to s 1323 of the Corporations Act and s 23 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth):

(a) the third defendant is to hold the amount of $80,000 in the ANZ Bank account held in its name, the account number for which ends in #3206, and is restrained from withdrawing, transferring or otherwise disposing of or dealing with those monies;

(b) subject to paragraph 32 below, the fifth defendant (by himself, his related entities or agent) is restrained from dealing in any property (as defined in the Corporations Act) in which he has any legal or equitable interest as at the date of this order, including, the property located at 3 Nelson Street, Inglewood and shares in Melvin Singh Super Pty Ltd and Auspicious Finance Pty Ltd (the Melvin Singh Property) by:

(i) removing, or causing or permitting the Melvin Singh Property to be removed from Australia;

(ii) selling, charging, mortgaging or otherwise dealing with, disposing of and/or diminishing the value of the Melvin Singh Property;

(iii) causing or permitting to be sold, charged, mortgaged or otherwise dealt with, disposed of, or diminish the value of the Melvin Singh Property;

(iv) without limiting the terms of sub-paragraphs (i) to (iii) above, incurring new liabilities after the date of this order that are secured against the Melvin Singh Property including, without limitation, liabilities incurred either directly or indirectly, through the use of a credit facility, a drawdown facility or a re-draw facility against the Melvin Singh Property; and

(v) without limiting the terms of sub-paragraphs (i) to (iv) above, withdrawing, transferring or otherwise disposing of or dealing with, any monies available in any account with any bank, building society or other financial institution (in Australia and elsewhere) as at the date of this order;

(c) the fifth defendant is to deposit the net proceeds of the sale of the business of Penguin (WA) Pty Ltd into a bank account in his name, which is subject to the above sub-paragraph (b); and

(d) the sixth defendant (by herself or her agent) is restrained from withdrawing, transferring or otherwise disposing of or dealing with, any monies available in any account with any bank, building society or financial institution in Australia, in which she has any legal or equitable interest as at the date of this order.

32. Paragraph 31(b) above does not:

(a) apply to property (as defined in the Corporations Act) purchased, secured or otherwise obtained by the fifth defendant after the date of this order;

(b) apply to any income, salary, bonus, dividends or interest or any other amount distributed to, or received or earned by the fifth defendant after the date of this order;

(c) prevent the fifth defendant from opening a new bank account;

(d) prevent the fifth defendant from causing Penguin (WA) Pty Ltd to complete the sale of its business;

(e) prevent any bank, building society or financial institution from exercising any right of set-off which it may have in respect of a facility afforded by it to each or any of the defendants prior to the date of this order;

(f) prevent the fifth defendant from incurring any liability after the date of this order;

(g) prevent the fifth defendant offering any property (as defined in the Corporations Act) purchased, secured or otherwise obtained by the fifth defendant after the date of this order as security for any liability;

(h) apply to any dealing in any property (as defined in the Corporations Act) of the third defendant or Futuristic Construction Pty Ltd (Company Property);

(i) prevent the third defendant or Futuristic Construction Pty Ltd from, or prevent the fifth defendant from causing or being involved in the third defendant or Futuristic Construction Pty Ltd:

(i) removing, or causing or permitting any Company Property to be removed from Australia;

(ii) selling, charging, mortgaging or otherwise dealing with, disposing of and/or diminishing the value of any Company Property;

(iii) causing or permitting to be sold, charged, mortgaged or otherwise dealt with, disposed of, or diminish the value of any Company Property;

(iv) incurring new liabilities including, without limitation, liabilities incurred either directly or indirectly, through the use of a credit facility, a drawdown facility or a re-draw facility against any Company Property;

(v) withdrawing, transferring or otherwise disposing of or dealing with, any monies available in any account with any bank, building society or other financial institution (in Australia and elsewhere); or

(vi) paying income, salaries, bonuses, dividends or interest to any person; or

(j) prevent MPS (WA) Pty Ltd as trustee for the MPS Trust from, or the fifth defendant from being involved in, distributing to any beneficiary of the MPS Trust any dividends or other amounts paid to MPS (WA) Pty Ltd as trustee for the MPS Trust by the third defendant or Futuristic Construction Pty Ltd.

Costs

33. The first, second and fourth defendants pay the plaintiff's costs of the proceedings, as taxed or agreed.

Other

34. The plaintiff must provide to the Receivers/Liquidators all documents obtained by the plaintiff during its investigations, including but not limited to:

(a) documents produced to the plaintiff in response to notices issued pursuant to s 19, s 30 and s 33 of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act);

(b) transcripts of examinations conducted by staff of the plaintiff pursuant to s 19 of the ASIC Act; and

(c) (to the extent permitted, reasonable and/or appropriate) documents otherwise produced voluntarily to the plaintiff during its investigations or obtained by the plaintiff through the exercise of some other power.

35. The Receivers, the Liquidators and the parties have liberty to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

JACKSON J:

1 In this case the first defendant, Monica Kaur, gave advice to potential investors which, in many cases, led them to do two things. The first was to set up their own self-managed superannuation funds (SMSFs) and to roll funds from existing superannuation accounts and other sources into those SMSFs. The second thing Ms Kaur advised investors to do was to use the funds so gathered to invest with a company she controlled, the second defendant, MKS Property Investments Developments Pty Ltd. Funds were to be pooled with the funds of other investors and invested in property development. The investors were to be paid a fixed return on the funds they invested, under instruments characterised as loan agreements, with the fixed return characterised as interest.

2 Over $10 million was invested in this way. Some investors have been repaid but many more have not. For those in the latter class, most of the capital invested is likely to have been lost. The chances of recovery of any funds have been significantly reduced by the failure of Ms Kaur and MKS to keep proper financial records. That is exacerbated by the fact that Ms Kaur used investor funds for her own benefit and for the benefit of members of her family. The retirement savings of hundreds of people are likely to have been impacted. All the while, Ms Kaur and MKS received over $1 million in fees for the advice and services they provided.

3 The plaintiff (ASIC) brought this proceeding alleging that in giving that advice and in operating the scheme that has been described (Scheme), Ms Kaur and MKS were carrying on a financial services business without the necessary Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL), and were operating an unregistered managed investment scheme in breach of s 601ED of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). The third defendant, Paradise Property Group Pty Ltd, is a company controlled by the fifth defendant, Ms Kaur's son Melvin Singh. Paradise Property Group and Melvin Singh are defendants because they appear to have received investor funds or property that was acquired with such funds. The fourth defendant, Sadu Singh, is Ms Kaur's husband and is presently the sole director of MKS. He holds 50% of the issued shares in MKS, with Ms Kaur holding the other 50%. ASIC claims that Sadu Singh left all of the affairs of MKS to Ms Kaur, and so breached s 180(1) of the Corporations Act, which imposes a duty of care and diligence on the directors of corporations. The sixth defendant, Stephanie Lee, is Ms Kaur's daughter and appears to have received a gift of investor funds.

4 ASIC and the defendants have agreed on the orders that are appropriate to be made to resolve the proceeding. With one exception, I have decided to make the orders largely in the terms sought. The orders appear at the beginning of these reasons. In summary, they include:

(a) declarations of contravention;

(b) the appointment of receivers and managers over the property of Ms Kaur, Sadu Singh and the Scheme;

(c) the winding up of the Scheme and of MKS, with the persons to be appointed as receivers also to be appointed as liquidators;

(d) disqualification of Ms Kaur for life and Sadu Singh for 15 years from managing corporations (this is the exception, in that ASIC seeks disqualification of Sadu Singh, effectively, for life);

(e) a permanent injunction restraining Ms Kaur from carrying on a financial services business in Australia and from operating an unregistered managed investment scheme in contravention of s 601ED(5) of the Corporations Act; and

(f) vacation or in some cases modification of asset preservation orders and travel restraint orders which the Court made at the outset of the proceeding.

5 The essential principles that govern the Court's approach to consent orders in these circumstances were conveniently summarised by Gordon J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1405 at [70]-[73]. Importantly, even though the parties may have reached agreement, the Court must still be satisfied that the orders are within its power and appropriate to make: Coles at [71]. But once so satisfied, the Court should exercise a degree of restraint when scrutinising the proposed settlement terms, particularly where (as here) all parties are legally represented: Coles at [72]. There is a well-recognised public interest in the settlement of cases in circumstances such as these: see Coles at [70]. The Court is also entitled to treat the consent of the defendants as an admission of all facts necessary or appropriate to the granting of the relief sought against them: Coles at [73]. The grant of declarations of contravention on the application of ASIC can serve an important law enforcement purpose: ASIC v McDougall [2006] FCA 427 at [55] (Young J).

6 In order to assist the Court to decide the matter in accordance with these principles, the parties have provided a statement of agreed facts under s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) and joint submissions and joint supplementary submissions. While the Court is not required to accept the statement of agreed facts uncritically, in this case I do accept it as proof of the facts it contains. It is credible and cogent and its effect is that evidence to prove those facts is not necessary: Evidence Act s 191(2); and see Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts v PGP Developments Pty Limited [2010] FCA 58; (2010) 183 FCR 10 at [35] (Stone J). The statement of agreed facts is annexed to these reasons and I will not describe the facts in detail save as necessary to resolve the particular issues addressed below. The overview given at the beginning of these reasons is sufficient to indicate the nature of the conduct which ASIC impugns and which the defendants accept breached the Corporations Act.

7 I turn now to consider a number of specific questions raised by the orders the parties seek.

Did Ms Kaur and MKS operate a managed investment scheme?

8 Section 601ED(1)(a) of the Corporations Act relevantly requires a managed investment scheme to be registered if it has more than 20 members. Section 601ED(5) prohibits a person from operating a managed investment scheme in a relevant jurisdiction unless it is registered. To do so is an offence, and contravention of s 601ED(5) is also a contravention of s 601ED(8), which is a civil penalty provision: s 1311(1); s 1317E. The statement of agreed facts establishes that neither Ms Kaur nor MKS registered any managed investment scheme. But were they operating one in the first place?

9 Section 9 of the Corporations Act relevantly defines 'managed investment scheme' (in paragraph (a) of the definition) as a scheme that has the following features:

(i) people contribute money or money's worth as consideration to acquire rights (interests) to benefits produced by the scheme (whether the rights are actual, prospective or contingent and whether they are enforceable or not);

(ii) any of the contributions are to be pooled, or used in a common enterprise, to produce financial benefits, or benefits consisting of rights or interests in property, for the people (the members) who hold interests in the scheme (whether as contributors to the scheme or as people who have acquired interests from holders);

(iii) the members do not have day-to-day control over the operation of the scheme (whether or not they have the right to be consulted or to give directions) …

10 On one view, the way in which investors contributed funds as summarised above does not give rise to a scheme with all of these features. That is because the advances they made can be characterised as individual loans to MKS rather than 'contributions': see ASIC v MyWealth Manager Financial Services Pty Ltd (No 3) [2020] FCA 1035 at [64] (Derrington J). A private loan by one person suggests an independent act as compared with where a contribution is made, suggesting a collective act: MyWealth at [64]. On this view, a managed investment scheme may not exist here if investors are perceived as having made independent, private loans.

11 Nevertheless, the legal form of the manner in which funds are provided is not determinative. In ASIC v Hutchings [2001] NSWSC 522, Windeyer J found that a managed investment scheme existed in a situation where the people operating it obtained funds by borrowing money from members of the public at very high interest rates. The features of the scheme that persuaded his Honour that it met the definition included that the investors were told that their contributions would be pooled and used in a common enterprise to provide financial benefits to them. The lenders had no control over the operation of the scheme. So the criteria in paragraphs (ii) and (iii) of the definition were met. The question, then, was whether the investors had contributed their money as consideration to acquire rights to benefits produced by the scheme, that is, whether the criterion in paragraph (i) was satisfied. Windeyer J was persuaded that they had because '[s]o far as the lenders were concerned the feature of the scheme was that they would receive rights to interest produced by the scheme of pooled borrowings, which borrowings were able to be invested so as to produce remarkable returns owing to the skill of Hutchings': Hutchings at [13]. In other words, there was a link between the returns to be produced by the use that was to be made of the pooled funds, and the interest that was to be payable to the individual investors: see also ASIC v Pegasus Leveraged Options Group Pty Ltd [2002] NSWSC 310 at [27]-[31] (Davies AJ).

12 I am satisfied that there was also such a link here. The statement of agreed facts establishes that the essence of the Scheme was that MKS pooled funds from investors, it then used the money to develop property, and the investors collected a guaranteed return, for example 20% paid at maturity. The purpose of the investors' advances of funds was to produce financial benefits from various property development projects which were used to pay those guaranteed returns. The link between the returns and the profits to be earned from the property developments was made explicit. For example, in 2017 Ms Kaur gave an interview published on the internet in which she said that (statement of agreed facts para 11(c)):

what she 'basically' did was 'pool in funds from investors, either cash or from their self-managed superannuation funds. I then use the money to do property developments. I do all the work and my investors just collect a guaranteed [return] of 12 per cent per annum'.

13 It does not matter that the investors did not have a legally enforceable right to a direct share in the benefits produced by the property developments; paragraph (i) of the definition of 'managed investment scheme' makes it clear that the 'right' in question need not be enforceable. I am satisfied that what was being promised to investors from the Scheme was, in substance, a right to participate at fixed rates of return in the profits to be earned from property developments that were conducted with investors' pooled funds. That is so even though the instrument the investors signed characterised their legally enforceable right to a return as a right to interest on a loan.

14 The Scheme therefore satisfies the definition of managed investment scheme. By operating the Scheme without being registered, Ms Kaur and MKS breached s 601ED(5). The parties seek a declaration of contravention of that subsection, but it is not a civil penalty provision (instead, contravention of it is an offence under s 1311(1)). Section 601ED(8) is the civil penalty provision in s 601ED, although (perhaps confusingly), it is contravened if a person contravenes s 601ED(5). That is, the substantive obligation appears in s 601ED(5), but a contravention of that is also a contravention of s 601ED(8), and only s 601ED(8) is a civil penalty provision. Section 1317E(1) and s 1317E(2) are quite specific in requiring the Court to make a declaration of contravention if it is satisfied that a civil penalty provision has been contravened, and in requiring the Court to specify the civil penalty provision that has been contravened. As a result, the declaration the parties seek will be modified, slightly, to declare that MKS and Ms Kaur contravened s 601ED(8) as well as s 601ED(5).

Did MKS and Ms Kaur carry on a financial services business?

15 A person who carries on a financial services business in the jurisdiction must hold an AFSL covering the provision of financial services: Corporations Act s 911A(1). Failure to comply is an offence (s 1311(1)) and a contravention of s 911A(1) is a contravention of s 911A(5B), which is a civil penalty provision: see s 1317E.

16 MKS and Ms Kaur did not have any AFSL. But the question of whether they carried on a financial services business requires consideration of a notoriously dense tangle of defined terms found in Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act.

17 A person provides a financial service if they, amongst other things, provide financial product advice or deal in a financial product: s 766A(1). Section 766B(1) provides that a person gives financial product advice if they recommend or state an opinion which is 'intended to influence a person … in making a decision in relation to a particular financial product' or could reasonably be regarded as intending to have such an influence. It can be personal or general advice: s 766B(2).

18 A financial product is a facility through which, or through the acquisition of which, a person, relevantly, makes a financial investment: s 763A(1)(a). Section 763B provides that a person makes a financial investment if:

(a) the investor gives money or money's worth (the contribution) to another person and any of the following apply:

(i) the other person uses the contribution to generate a financial return, or other benefit, for the investor;

(ii) the investor intends that the other person will use the contribution to generate a financial return, or other benefit, for the investor (even if no return or benefit is in fact generated);

(iii) the other person intends that the contribution will be used to generate a financial return, or other benefit, for the investor (even if no return or benefit is in fact generated); and

(b) the investor has no day-to-day control over the use of the contribution to generate the return or benefit.

19 Section 764A(1)(ba) specifically includes in the meaning of 'financial product' an interest in an unregistered managed investment scheme.

20 Section 764A(1)(g) also specifically includes a superannuation interest within the meaning of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (Cth) (SIS Act) as a financial product. A superannuation interest is a beneficial interest in a superannuation entity: s 10 SIS Act. A superannuation entity means, relevantly, a 'regulated superannuation fund' which has the meaning given by s 19: s 10 SIS Act.

21 A person deals in a financial product, amongst other things, if they issue a financial product: Corporations Act s 766C, s 761E.

22 The statement of agreed facts establishes that Ms Kaur advised hundreds of people to establish SMSFs and that nearly 300 people acted on that advice. It can be inferred that those SMSFs were regulated superannuation funds within the meaning of the SIS Act, so that what Ms Kaur was doing was recommending that people acquire a financial product, namely an interest in a superannuation entity. She was thereby carrying on a financial services business, without an AFSL. She also advised investors to acquire financial products comprised of interests in the Scheme.

23 Further, MKS carried on a financial services business because it dealt in financial products. It issued interests in the Scheme, which were facilities through which persons made financial investments as defined above, and were also financial products by reason of the specific inclusion of interests in unregistered managed investment schemes in the definitions of that term. As MKS's controlling mind, Ms Kaur carried on a financial services business in the same way.

24 The declarations sought by ASIC as to contraventions of s 911A of the Corporations Act are appropriate to be made. For reasons similar to those given in relation to s 601ED, the declarations sought by the parties will be modified slightly so that it is contraventions of s 911A(1) and s 911A(5B), the latter being the civil penalty provision, that are declared.

Should the Scheme be wound up?

25 Section 601EE of the Corporations Act provides that if a person operates a managed investment scheme in contravention of s 601ED(5), ASIC (among others) may apply to the Court to have the scheme wound up. ASIC has so applied here. On such an application, the Court may make any orders it considers appropriate for the winding up of the scheme.

26 It is appropriate to wind the Scheme up here. The statement of agreed facts establishes that:

(a) the Scheme has been operating unlawfully because it was not registered;

(b) the solvency of the Scheme is doubtful - MKS still owes investors over $6 million, where its only assets are approximately $220,000 in cash and any directors' loans owed by Ms Kaur and Sadu Singh which are undocumented and unquantified. Ms Kaur's and Sadu Singh's realisable assets may amount to about $1.3 million net of debts;

(c) Ms Kaur employed investor funds contributed to the Scheme for her own personal benefit and for the benefit of Sadu Singh, Melvin Singh and Ms Lee, and so (to put it mildly) she cannot be trusted to account properly for the remaining investor funds and property acquired with those funds;

(d) Ms Kaur and MKS did not keep adequate financial records; and

(e) ASIC seeks to wind up MKS, which (adopting a charitable approach to assessing the regularity of the legal underpinnings of the Scheme) can be called the 'responsible entity' of the Scheme.

27 In ASIC v Marco (No 6) [2020] FCA 1781 at [135], McKerracher J considered it was appropriate to make orders for the orderly cessation of a scheme and an associated company because of the persistence and seriousness of the contraventions; an evident shortfall in investor funds; the absence of any reasonably foreseeable prospect of a significant return to investors; evidence of related party and personal expenditure from investor funds; and deficiencies in record keeping as to investor entitlements. All of these matters are also evident in the Scheme here.

28 Largely for the reasons just given, it can readily be inferred that there is no prospect that the Scheme could be regularised and then carried on lawfully and profitably. The best prospect for any return to investors is to wind it up and so place it in the hands of the same persons who are to act as liquidators of MKS and receivers and managers of relevant property of the defendants. Orders to wind up the Scheme are appropriate and will be made.

Should MKS be wound up?

29 In circumstances in which ASIC is investigating, or has investigated the affairs of a company, under Division 1 of Part 3 of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth), ASIC may apply to the Court for the winding up of the company: s 464 Corporations Act. The precondition of an ASIC investigation is satisfied here. ASIC seeks the winding up of MKS pursuant to s 459B and s 461(1)(k). MKS consents to the making of such an order.

30 Section 459B provides that where, on application under s 464, the Court is satisfied that the company is insolvent, the Court may order that the company be wound up in insolvency. Section 461(1)(k) is the just and equitable ground.

31 In my view it is not necessary to reach any conclusions about whether MKS should be wound up in insolvency, as there is ample basis to wind it up on the just and equitable ground. The categories of circumstances that will justify such an order are not closed but it is well established that one such circumstance is where there is a justifiable lack of confidence in the conduct and management of the company's affairs and so a risk to the public interest that warrants protection. This can include a lack of confidence in the propensity of the controllers of the company to comply with obligations such as keeping proper books and records: see ASIC v ActiveSuper Pty Ltd (No 2) [2013] FCA 234 at [19]-[21] (Gordon J).

32 The facts set out in the statement of agreed facts lead inexorably to the conclusions that the Court lacks confidence in those who managed, or should have managed, MKS, namely Ms Kaur and Sadu Singh, and that the protection of the public interest requires that MKS be wound up. Subject to one further comment, I accept the parties' joint submission that this is because (para 74):

(a) MKS has been operating unlawfully, by conducting an unregistered managed investment scheme;

(b) MKS is more probably than not insolvent;

(c) its sole director, [Sadu] Singh, accepts he is not a fit and proper person to manage corporations (having effectively abdicated his role as director during the Period, while MKS contravened various statutory provisions);

(d) MKS' controlling mind, Kaur, and the only person genuinely familiar with its affairs, also accepts she is not a fit and proper person to manage corporations (given the various wrongful conduct outlined in the SOAF);

(e) if the Court is minded to make the orders otherwise contemplated by the proposed minute of order, MKS will be without a director, or any viable replacement director, upon [Sadu] Singh and Kaur's disqualification from managing corporations indefinitely;

(f) it is appropriate to have the affairs and true financial position of MKS investigated by an independent professional acting in the best interests of MKS' creditors, including the Investors;

(g) the liquidation of MKS may allow Investors (whose funds MKS might otherwise not be obliged to repay for a significant period of time) to secure the return of those Investor Funds which remain at the earliest opportunity by seeking to prove in MKS' liquidation.

33 The further comment is that the disqualification of the directors for any significant period of time will provide at least part of the basis for a just and equitable winding up where, as here, there are no candidates to replace them, and certainly no appropriate ones. The disqualification need not be 'indefinite'. Whether it is appropriate to order indefinite disqualification is addressed immediately below.

34 It will obviously be convenient to appoint as liquidators of MKS the same persons who are to be liquidators of the Scheme and receivers and managers of relevant property.

For what periods should Ms Kaur and Sadu Singh be disqualified?

35 ASIC applies for orders disqualifying Ms Kaur and Sadu Singh from managing corporations 'for an indefinite period'. Ms Kaur and Sadu Singh consent to this.

36 Section 206C of the Corporations Act provides that on application by ASIC, 'the Court may disqualify a person from managing corporations for a period that the Court considers appropriate' if, relevantly, a declaration is made under s 1317E that the person has contravened a corporations/scheme civil penalty provision, and the Court is satisfied that the disqualification is justified: s 206C.

37 Under s 1317E(3) of the Corporations Act, s 601ED(8) is a corporations/scheme civil penalty provision. Ms Kaur's contravention of s 601ED(8) means that the Court has power to disqualify her if it is satisfied that the disqualification is justified.

38 As for Sadu Singh, the joint submissions submit that he contravened s 180(1), which is also a corporations/scheme civil penalty provision. That provision obliged him, as a director and later as sole director of MKS, to exercise his powers and discharge his duties with the degree of care and diligence that a reasonable person would exercise in the circumstances. The statement of agreed facts establishes that Sadu Singh took no part in the management of MKS despite his role as director. He did not monitor or supervise Ms Kaur. Reliance on another to perform tasks is only reasonable where there are sufficient monitoring systems in place so as to be aware of possible internal irregularities: Daniels (formerly practising as Deloitte Haskins & Sells) v Anderson (1995) 37 NSWLR 438 at 500-501 (Clarke and Sheller JJA). It is never acceptable to blindly delegate responsibility: see Sheahan v Verco [2001] SASC 91; (2001) 79 SASR 109 at [101], [105] (Mullighan J). I am satisfied that Sadu Singh contravened s 180(1) of the Corporations Act. Under s 1317E, a declaration of that contravention must be made. The first precondition for disqualification of Sadu Singh under s 206C is satisfied; as in the case of Ms Kaur, the Court must consider whether the disqualification is justified.

39 The seriousness of Ms Kaur's and Sadu Singh's respective contraventions of the Corporations Act mean that some period of disqualification is justified. But I do not consider that it is appropriate to disqualify them for 'an indefinite period', that being the wording of the order sought. That is vague and ambiguous. There are several cases, however, in which persons have been disqualified permanently or for life, so I proceed on the basis that an order to that effect can be made: see ASIC v White [2006] VSC 239 at [17], [29]-[43]; ASIC v Maxwell [2006] NSWSC 1052; ASIC v Managed Investments Ltd (No 10) [2017] QSC 96; ASIC v Elm Financial Services Pty Ltd [2005] NSWSC 1065. Such an order would always be subject to the ability of the disqualified person to apply to the Court for leave to manage corporations or corporations of a particular class or particular corporations: s 206G.

40 The main factors that a court will take into account in determining the appropriate period of disqualification are itemised in Santow J's well-known judgment in ASIC v Adler [2002] NSWSC 483 at [56], and there is no need to set them out here. I will refer to them below to the extent that they are relevant when assessing the appropriate periods of disqualification. However two general observations of principle are worth making at the outset.

41 First, although it is often said that the purpose of the power to disqualify persons from managing corporations is to protect the public, that cannot be the only purpose behind it, in view of the way the courts have approached the power. If the purpose were purely protective, it would be difficult to explain why in most cases disqualification orders are made for fixed periods, not permanently: see Rich v ASIC [2004] HCA 42; (2004) 220 CLR 129 at [41]-[42] (McHugh J). If the public needs to be protected against the way that a person manages corporations now, it is difficult to see how that need, or the person, will change after 5, 10 or 15 years, say. In most cases of this kind, prospects of reform or rehabilitation are not considered. As Windeyer J observed in Hutchings at [20], while there remained a risk that the defendants in that case may use the corporate veil to engage in activities bringing harm to members of the public, there was no logical reason to think a disqualification period of say 5 or 10 years would be appropriate.

42 The second observation is that, when a law enforcement agency such as ASIC and defendants present agreed disqualification orders, the first function of the Court is not to decide what period is appropriate. It is to decide whether the periods proposed by the parties are within a range of appropriate outcomes. Only if the Court decides that they are not will it be necessary for it to decide what period is appropriate. In that sense, the approach to agreed disqualification orders is the same as the approach to agreed penalty orders as laid down in Commonwealth of Australia v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; (2015) 258 CLR 482 at [46]; see also ASIC v Woolridge [2019] FCAFC 172 at [18]-[22].

43 With those principles in mind, I am satisfied that the proposed period of disqualification of Ms Kaur, for an 'indefinite period' which I take to be equivalent to disqualification for life, is within the range of appropriate periods. Her conduct was very serious and very damaging to many members of the public. She advised hundreds of people, supposedly about what was in their best financial interests, but in fact she induced them to provide money to a venture she controlled and from which she benefitted. The benefit she gained was partly by reason of her unauthorised use of some of the money obtained, not for the venture but for her own personal benefit and that of members of her family. That fell well short of generally accepted standards of honesty and financial probity. All of this was done in complete disregard of important laws as to the licensing of persons giving financial advice and the registration of managed investment schemes. This disregard continued even after ASIC warned Ms Kaur in correspondence, twice, that she may have been breaching the law.

44 The venture into which Ms Kaur directed investor funds was risky and speculative as is shown by the likelihood that most if not all of the funds of many of the investors have been lost. Inadequate record keeping and a lack of controls over what was done with the funds are likely to exacerbate the losses and the difficulty of making any recovery on behalf of investors. The losses are going to be in the millions of dollars and are likely to impact on the retirement savings of many individuals. Ms Kaur's activities were thus activities undertaken in a field in which there was potential to do great financial damage. It is not clear whether Ms Kaur shows any contrition or remorse for all of this, although I do take into account the fact that she appears to have cooperated with ASIC at least since this proceeding was commenced. I also take into account that there is no evidence of any financial or corporate misfeasance on her part before she started to operate the Scheme.

45 These matters taken together show that disqualification of Ms Kaur for life from managing corporations is within the range of appropriate disqualification orders, and an order to that effect will be made.

46 Despite the agreed position of the parties that Sadu Singh should also be disqualified 'for an indefinite period', in my view his case is different. To be sure, his conduct, or the lack of any conduct, in leaving the management of MKS to Ms Kaur was a serious default of his duties of care and diligence as a director. His failure to prevent Ms Kaur from doing what she did has contributed to the serious damage to the retirement savings of many individuals which is mentioned above. A significant period of disqualification is appropriate. But there is a real difference between his neglect, as lamentable as it was, and the active misfeasance of Ms Kaur. The parties submit that she was the controlling mind of MKS at all times and the individual through whom it engaged in all wrongdoing. She is the one who dealt with all the investors and potential investors. There is no evidence of what Sadu Singh knew about what she was doing or evidence of the opportunity he had to prevent it. There is no evidence that Sadu Singh was knowingly involved in Ms Kaur's misfeasance. There is no evidence that he acted dishonestly.

47 Having regard to the objectives of general and specific deterrence in disqualification orders (see Adler at [56]) it is appropriate to mark the lesser seriousness of Sadu Singh's conduct when compared to that of Ms Kaur with a lesser period of disqualification. I do not consider that disqualification for life is within the range of appropriate penalties for Sadu Singh's breach of duties of care and diligence.

48 It is necessary, then, to decide what period of disqualification is justified. I take account of all the matters just mentioned, as well as the fact that, no doubt as a result of negotiation, the parties do not seek any pecuniary penalty against Sadu Singh, and the lack of any evidence that Sadu Singh will suffer hardship as a result of the disqualification. On the other hand, I also take account of his cooperation with ASIC since the proceeding was commenced, albeit in the absence of evidence of contrition or remorse. In my view, a period of disqualification of 15 years is justified. I have taken into account that, despite some contradictory evidence, it appears that Sadu Singh was born in 1961 and is almost 62 years old. A period of disqualification of 15 years means that he will be almost 77 years old when the disqualification order lifts. So while the disqualification is not for life, I have taken into account the fact that Sadu Singh may be of relatively advanced age by the time the disqualification expires.

Injunction against Ms Kaur

49 ASIC also seeks an order under s 1324 of the Corporations Act that Ms Kaur be permanently restrained from carrying on a financial services business in Australia, and from operating an unregistered managed investment scheme in contravention of s 601ED(5). In view of the seriousness of her misconduct it is appropriate to protect the public by making these orders on a permanent basis. While the latter part of the order will prohibit conduct that is already unlawful, it is appropriate to add the possible sanction of contempt of court. McKerracher J made similar orders in Marco (No 6): see at [122].

50 However there is one point of difference between the injunction in Marco (No 6) and the one in this case. The order McKerracher J made prohibited the carrying on of a financial services business in Australia without holding an AFSL - conduct that would be unlawful anyway - whereas here ASIC seeks an order restraining Ms Kaur from carrying on a financial services business in Australia in any circumstances. An order of that kind can be characterised as a financial services disqualification order; there is power to make it under s 1324 and the principles that apply to disqualification orders under s 206C can also be applied to orders of this kind: see Re Idylic Solutions Pty Ltd; ASIC v Hobbs [2013] NSWSC 106 at [91], [103] (Ward JA, as she then was).

51 The matters considered in relation to the disqualification of Ms Kaur from managing corporations apply equally in relation to the effective disqualification from carrying on a financial services business which ASIC seeks against her. The egregious nature of her conduct, the need to protect the public from such conduct and the other matters canvassed above justify a permanent restraint. An injunction in the terms proposed by the parties will be made.

Receivers

52 It is appropriate to appoint receivers to the property of Ms Kaur, Sadu Singh and the Scheme and to make ancillary delivery up orders against Melvin Singh and Ms Lee. The Court has power to appoint receivers under s 1101B of the Corporations Act, which provides that the Court may make such orders as it thinks fit if, among other things, on the application of ASIC it appears to the Court that a person has contravened a provision of Chapter 7 or any other law relating to dealing in financial products or providing financial services: s 1101B(1)(a)(i). The power to appoint receivers extends, at least, to the property of Ms Kaur and the Scheme since Ms Kaur has breached s 911A, which is in Chapter 7, and MKS, as the only possible other person operating the Scheme, has also breached that provision.

53 However, Sadu Singh has not been found to have breached any provision of Chapter 7, nor has there been any submission that the provision he has breached, s 180, is a law relating to dealing in financial products or providing financial services. It is not immediately apparent that s 1101B authorises the appointment of receivers over the property of a person who has not breached a provision or law of that kind. I have not received any submissions as to the application of s 1101B in relation to Sadu Singh, and in the absence of full submissions, I am not prepared to rely on it for the appointment of receivers over his property.

54 Nevertheless, s 1323(1)(h) empowers the Court to appoint receivers over Sadu Singh's property, he being a person against whom a civil proceeding has been commenced by ASIC: s 1323(1)(c). Section 1323 authorises the appointment of receivers (among other orders) to the property of such a person where the Court considers it necessary or desirable to do so for the purpose of protecting the interests of an aggrieved person, to whom the first person is liable or may be or may become liable to pay money, including by way of damages or compensation. MKS is such an aggrieved person in relation to Sadu Singh. His breach of s 180 has exposed the company to possible liabilities to investors and other persons, and therefore MKS may have a claim against him for compensation orders: s 1317H(1) and s 1317J(2). It is in the interests of MKS to preserve Sadu Singh's property by the appointment of receivers over it. As such, I will make orders for the appointment of receivers over Sadu Singh's property pursuant to s 1323(1)(h) of the Corporations Act.

55 It will be open to the receivers, consistently with the purpose of their appointment over Sadu Singh's property, to preserve and administer that property harmoniously with the duties and objectives attendant on the other appointments that will be effected by the orders to be made. But if, for any reason, the fact that the appointment is made under s 1323 rather than s 1101B prejudices the receivers' performance of their duties or, ultimately, the interests of the investors, it will be open to ASIC or the receivers to revisit the statutory basis of the appointment under the liberty to apply that will be conferred by the orders.

56 As mentioned above, the statement of agreed facts establishes a high degree of likelihood that the property to be covered by the receivership orders was acquired through the use of investor funds. It will be convenient and helpful in the overall task of dismantling the Scheme and attempting to recover investor funds to give the people who are to be appointed liquidators of MKS and the Scheme suitable powers over that property as well: see Marco (No 6) at [132].

Asset preservation orders

57 ASIC also seeks asset preservation orders under s 1323 of the Corporations Act in respect of property of Paradise Property Pty Ltd, Melvin Singh and Ms Lee. There is evidence that they may have received some investor funds. The asset preservation orders sought are less restrictive than those currently in place and the relevant defendants have consented to them. It is appropriate to make them in order to give the liquidators and receivers time to investigate what may have become of investor funds and whether recovery action should be taken.

Conclusion

58 Orders as set out at the beginning of this judgment will be made.

I certify that the preceding fifty-eight (58) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Jackson. |

Associate:

Annexure