Federal Court of Australia

Yuanda Australia Pty Limited v Dawson [2023] FCA 551

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: | 31 May 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. By 4:00 pm, 31 May 2023, the parties are to confer and provide proposed short minutes by email to the Associate to Cheeseman J to give effect to these Reasons.

2. In the absence of agreement as to the proposed short minutes the subject of Order 1, the proceedings are to be listed at 11.15 am on 1 June 2023.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

CHEESEMAN J:

INTRODUCTION

1 These reasons address an interlocutory application by the respondents in the substantive proceedings seeking to strike out the Statement of Claim (SOC), or alternatively particular parts of it. The respondents are Paul Dawson, SRG Global Facades (Qld) Pty Limited (SRG Qld) and SRG Global Facades (Vic) Pty Limited (SRG Vic). The applicants, who are the respondents on the strike out application, are Yuanda Australia Pty Limited, Yuanda Queensland Pty Limited, and Yuanda Vic Pty Limited.

2 The respondents contend that the SOC, or parts of it, should be struck out because it is evasive or ambiguous; likely to cause prejudice or embarrassment in the proceeding; fails to disclose a reasonable cause of action; and / or is otherwise an abuse of process of the Court: r 16.21(1)(c), (d), (e) and / or (f) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth).

3 This proceeding was originally commenced by way of an Originating Application and Concise Statement. An Amended Originating Application (AOP) and SOC were filed after the Concise Statement was struck out and the matter was ordered to proceed on pleadings. The matter was ordered to proceed by pleadings in the context of the serious nature of the allegations made by the applicants against the respondents, which include allegations that, if proven, may give rise to liability for a civil penalty. The present application to strike out the SOC was initiated before the respondents put on their defences. The application is made on the express basis that if successful, the applicants should be given leave to re-plead.

BACKGROUND

4 The following outline is based on the allegations made in the AOP and SOC.

5 The applicant and respondent companies are competitors in specialist asset services, mining services and construction. Mr Dawson was an employee and director of Yuanda Australia during the period between 2007 and 2016 and was at various times a director of Yuanda Queensland and Yuanda Vic. In essence, the applicants allege that Mr Dawson covertly diverted commercial opportunities from the applicants toward both SRG Qld and SRG Vic, in circumstances where he owed statutory and fiduciary duties to each of the applicants, as well as duties under his employment contract with Yuanda Australia.

6 While employed by Yuanda Australia between July and November 2015, Mr Dawson was a director of SRG Vic, then named Yuanda Residential Pty Ltd. Despite the use of the name “Yuanda”, SRG Vic is not a company that is, or ever has been, associated with the Yuanda group of companies. Mr Dawson was appointed as a director of SRG Vic about 12 days after it was incorporated. Mr Dawson resigned from his employment with Yuanda Australia on 17 August 2016, after having resigned as a director of Yuanda Australia in June 2016. Following Mr Dawson’s resignation as a director in June 2016, he commenced employment with Global Construction Services Limited (GCS). SRG Qld and SRG Vic became part of the SRG Global group of companies in 2018 as part of a merger between SRG Limited and GCS. The two respondent companies were majority owned by GCS from October 2016 up until the time of the merger. Following the merger, Mr Dawson has been an employee of SRG Vic.

7 The allegations in the SOC centre on a series of guarantees alleged to have been entered into in respect of subcontracts on four construction projects: the 1 William Street Project, the Novartis Project, the Collins Street Project, and The Yards Project (collectively, the Projects). The operative allegations in the SOC are similar in respect of each of the Projects in that the headline allegation is, in substance, that commercial opportunities in respect of each of these Projects were diverted away from the applicants to the benefit of the respondents.

8 The respondents’ complaint is that the allegations concerning the Projects and the claims for relief are built upon a foundation of conclusory pleadings which are not substantiated by the material facts alleged. The respondents contend that the gaps in reasoning between the pleaded allegations and the material facts said to support them result in a pleading that is liable to be struck out and that it is appropriate for the applicants to re-plead.

9 The applicants submit in response that correspondence between the parties demonstrates that the respondents understand the case put against them and that the respondents’ real complaint is about whether the applicants can succeed on their substantive claim.

Applicable legal principles

10 The principles applicable to strike out applications are well-settled, and were broadly agreed between the parties.

11 The power to strike out in r 16.21 is a corollary of the requirements and function of pleadings in r 16.02. Both these rules must be interpreted and applied in light of s 37M of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), which provides that overarching purpose of the civil practice and procedure provisions is to resolve disputes according to law and as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible. The objectives served by the overarching purpose include facilitating the efficient use of judicial and administrative resources available for the purposes of the Court, efficient disposal of the Court’s overall caseload, and the disposal of all proceedings in a timely manner.

12 The requirements for pleadings are set out in r 16.02, which relevantly provides:

Content of pleadings — general

(1) A pleading must:

…

(b) be as brief as the nature of the case permits; and

(c) identify the issues that the party wants the Court to resolve; and

(d) state the material facts on which a party relies that are necessary to give the opposing party fair notice of the case to be made against that party at trial, but not the evidence by which the material facts are to be proved; and

(e) state the provisions of any statute relied on; and

(f) state the specific relief sought or claimed.

(2) A pleading must not:

(a) contain any scandalous material; or

(b) contain any frivolous or vexatious material; or

(c) be evasive or ambiguous; or

(d) be likely to cause prejudice, embarrassment or delay in the proceeding; or

(e) fail to disclose a reasonable cause of action or defence or other case appropriate to the nature of the pleading; or

(f) otherwise be an abuse of the process of the Court.

(3) A pleading may raise a point of law.

(4) A party is not entitled to seek any additional relief to the relief that is claimed in the originating application

(5) A party may plead a fact or matter that has occurred or arisen since the proceeding started.

13 I refer to my recent consideration of the purpose which pleadings serve in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Daly (Liability Hearing) [2023] FCA 290 at [254] to [262]. It is not necessary to repeat those observations here. It suffices to note that, where a case proceeds upon the pleadings, the pleadings serve three purposes: (1) to state with sufficient clarity the case that must be met; (2) to ensure that a party has an opportunity to meet that case; and (3) to define the issues for determination. As Moshinsky J observed in Sadie Ville Pty Ltd v Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu (A Firm) [2017] FCA 1202 at [17], proper pleading is of fundamental importance in assisting courts to achieve the overarching purpose of facilitating the just resolution of disputes according to law and as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible whether under ss 37M and 37N of the Act or under the “just, quick and cheap” rubric in s 56 of the Civil Procedure Act 2005 (NSW).

14 Allegations of civil penalty contraventions must be pleaded “clearly and strictly”: Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v BHP Coal Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 987 at [15]. Where fraud, or something analogous, is pleaded a rigorous approach to pleadings remains appropriate for the pleading to perform is basic function: KTC v David [2022] FCAFC 60 at [418(3)].

15 The strike out provisions in r 16.21(1)(c) to (f) are cognates of r 16.02(2)(c) to (f):

Application to strike out pleadings

(1) A party may apply to the Court for an order that all or part of a pleading be struck out on the ground that the pleading:

…

(c) is evasive or ambiguous; or

(d) is likely to cause prejudice, embarrassment or delay in the proceeding; or

(e) fails to disclose a reasonable cause of action or defence or other case appropriate to the nature of the pleading; or

(f) is otherwise an abuse of the process of the Court.

16 A pleading will be ambiguous or evasive where it does not, with sufficient clarity, state the case that must be met by the opposing party and does not define the issues for decision in a way that ensures the basic requirement of procedural fairness — that a party should have the opportunity of meeting the case against them — is met: Banque Commerciale S.A., en liquidation v Akhil Holdings Ltd [1990] HCA 11; 169 CLR 279 at 286, 296 and 302 to 303; Reilly v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (No 2) [2020] FCA 1502 at [17].

17 A pleading may be embarrassing for a variety of reasons. Relevantly for the purpose of the present application, a pleading will be embarrassing where it is conclusory and is either not supported by articulated material facts or based on inconsistent allegations that are not clearly framed in the alternative: Lock v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2016] FCA 31 at [10].

18 Also relevant on this application is the necessity for a pleading which relies on an inference being drawn to be supported by pleaded facts. In J & A Vaughan Super Pty Ltd (Trustee) v Becton Property Group Ltd [2014] FCA 581 at [19], Pagone J observed that “[i]nferences require facts from which an inference is capable of being drawn. That requires that the facts relied upon bear probatively upon those inferences which are sought to be drawn.”

19 A pleading fails to disclose a reasonable cause of action where it is “so obviously untenable that it cannot possibly succeed”, “manifestly groundless” or “so manifestly faulty that it does not admit of argument”: General Steel Industries Inc v Commissioner for Railways (NSW) [1964] HCA 69; 112 CLR 125 at 129 (Barwick CJ).

20 An abuse of the process of the Court will generally exhibit at least one of three characteristics: (1) the Court’s process is invoked for an illegitimate or collateral purpose; (2) the use of the Court’s procedures would be unjustifiably oppressive to a party; or (3) the use of the Court’s procedures would bring the administration of justice into disrepute: PNJ v The Queen [2009] HCA 6; 252 ALR 612 at [3]. The respondents eschew reliance on illegitimate or collateral purpose. Instead, they submit that the abuse of process ground is relevant where, by the other criteria in r 16.21, the pleading is so defective that to require a party to answer it may have the potential to bring the administration into disrepute or be unjustifiably oppressive to the respondents.

21 If substantial parts of a pleading are struck out, the Court may strike out the entire pleading on the basis that the “residue would be confusing”: KTC v David at [124], citing Trade Practices Commission v Australian Iron & Steel Pty Ltd (1990) 22 FCR 305 at 323.

22 The Court has discretion to decline to strike out a defective pleading and ““great caution” should be exercised before striking out a party’s pleaded case and thereby potentially placing an impediment in the path to the vindication of a claim for relief”: Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v BHP Coal Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 50 at [44]. An application to strike out a pleading that is made on the basis that the pleader has liberty to re-plead ameliorates the prospect that a party will be unfairly denied access to the courts. Granting leave to re-plead may, in an appropriate case, strike the right balance between the public and private interests served by proper pleading.

THE RESPONDENTS’ APPLICATION

23 The respondents seek an order that the SOC be struck out because it is evasive or ambiguous; likely to cause prejudice or embarrassment in the proceeding; fails to disclose a reasonable cause of action; and / or is otherwise an abuse of process of the Court: r 16.21(1)(c), (d), (e) and / or (f) of the Rules. Alternatively, the respondents seek an order that paragraphs 31, 32, 34 to 37, 52 to 56, 70 to 72, 94 to 98 and 102 to 116 of the SOC be struck out on the same grounds. The respondents further seek orders that the applicants be given leave to re-plead and that the applicants pay their costs of and incidental to the application.

CONSIDERATION

24 It is convenient to first address the particular paragraphs of the SOC about which the respondents complain, before considering whether such deficiencies as are established warrant the entire pleading being struck out.

25 By way of preface, I note that the applicants, in seeking to resist the strike out, repeatedly submitted that the respondents know the case they have to meet because of what has passed between the parties in various communications about the pleadings and that, if the respondents do not know the case put against them, it is open to the respondents to request particulars. I am not persuaded, in the context of the serious allegations made in this case, that there is any merit in the applicants’ approach. To accede to it would undermine one of the core purposes that pleadings are intended to serve — namely, the identification and delineation of the real issues for determination. It would likely cause delay, prolong the hearing time, increase the prospect of arid pleading debates, and waste costs. The respondents have, consistently with their duty to the Court, resisted the temptation to put on a defence comprised of a series of bare denials to improperly pleaded allegations. Instead, by bringing this application, they have delivered, in effect, an advice on pleading to the applicants. The written submissions provided by the respondents are comprehensive in identifying the problems in the pleadings. The respondents expressly bring the application on the basis that the applicants should be given leave to re-plead. In circumstances where a consent position was not able to be reached, the respondents’ approach is to be commended. I reject the applicants’ repeated suggestion that any defect in the pleading, which they do not concede, may be cured by the respondents denying and thereafter pleading a fulsome positive defence on the basis of what the respondents suspect to be the allegations against them based on inter partes communications, which refer to matters not pleaded, or alternatively, by embarking on a particulars campaign. Such an approach would reverse the obligation imposed on the applicants to plead in accordance with r 16.02.

Bank Guarantee Summary Document (paragraphs 32, 34 to 37)

26 The first relevant section of the pleading on the strike out application relates to a Bank Guarantee Summary Document. The relevant pleading is as follows (emphasis in original):

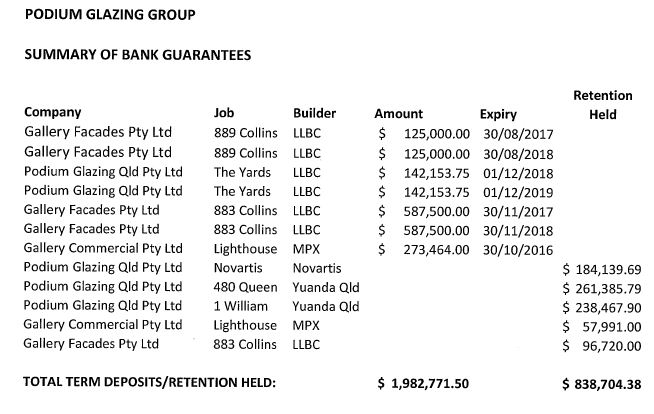

31. On 12 May 2016, the First Respondent sent an email from his Yuanda email account to his own personal email account, enclosing a document entitled ‘summary of bank guarantees’ (Bank Guarantee Summary Document).

Particulars

Email from Paul Dawson’s work email address [*] to his personal email address [*] dated 12 May 2016. The content of the document is set out below.

32. The Bank Guarantee Summary Document stated that:

(a) specified deposits had been paid to specified ‘builders’ for specified ‘jobs’ and for specified amounts with respect to 'Podium Glazing' entities and Yuanda Residential (Gallery Facades Pty Ltd), as referred to at paragraphs 21 to 24 and 30 above; and

(b) specified amounts had been paid to specified builders which were retained by the builders as security for specified ‘jobs’ with respect to ‘Podium Glazing’ entities and Yuanda Residential (Gallery Facades Pty Ltd), as referred to at paragraphs 21 to 24 and 30 above.

33. The Bank Guarantee Summary Document did not state the entity that had supplied the deposits or amounts retained as security.

34. By virtue of the First Respondent sending the Bank Guarantee Summary Document from his work email account to his personal email address on 12 May 2016, his position as General Manager of the First Applicant, and his position as director of each of the Applicants at the times pleaded in paragraph 11 above, it is to be inferred that:

(a) the First Respondent was aware of the contents of the Bank Guarantee Summary Document;

(b) one of the Applicants had given bank guarantees in the amounts specified in the Bank Guarantee Summary Document on behalf of each of the ‘Podium Glazing’ and Yuanda Residential (Gallery Facades Pty Ltd) entities to secure the performance of each of those entities’ obligations to each builder to assure performance of construction and defects obligations with respect to each specified ‘job’ (the Bank Guarantees);

(c) the First Respondent was involved in and/or executed the Bank Guarantees.

Particulars

The Applicants do not have a copy of all the Bank Guarantees other than bank guarantees provided to Novartis and 889 Collins, as set out later in the pleading. Further particulars will be provided after discovery and issuing subpoenas and notices to produce.

35. At all material times, the First Respondent did not inform Yuanda China:

(a) about the Bank Guarantee Summary Document; or

(b) that any of the Applicants had provided any Bank Guarantees.

36. At all material times, Yuanda China was not aware of:

(a) the Bank Guarantee Summary Document; or

(b) the fact of any of the Applicants providing any Bank Guarantees.

37. The First Respondent did not seek or obtain approval from, and was not otherwise authorised by, Yuanda China to provide the Bank Guarantees on behalf of any of the Applicants.

27 Paragraph 31 of the SOC provides the necessary context but is not challenged by the respondents. The particulars given in paragraph 31 include the entire content of the Bank Guarantee Summary Document.

28 Paragraph 32 then alleges that the Bank Guarantee Summary Document “stated” the matters alleged in paragraph 32(a) and (b).

29 The matters alleged to be “stated” in the document do not correspond to any part of the Bank Guarantee Summary Document. I am satisfied that the allegations in paragraph 32 are embarrassing and should be struck out. The paragraph positively asserts allegations that are incorrect. If the paragraph is intended to allege that the stated matters may be inferred from the Bank Guarantee Summary Document, then the applicants must plead the matters on which they rely to support the inferences for which they contend, including by reference to allegations concerning matters that occurred earlier in time but which are pleaded later in the SOC, if it be the case that those later allegations are relied on as the basis for the matters said to be inferred from the Bank Guarantee Summary Document.

30 The applicants’ submissions on this issue, rather than rebutting the respondents’ complaint, lay bare the problem. The applicants contend that the repeated reference to “states” in paragraph 32 is intended to mean “based on a proper interpretation of the document, read in context”. The applicants do not identify the context on which they rely to establish that the matters they say are “stated” in the document are in fact matters which may be properly inferred from the document when read in context. They have not pleaded the material facts on which they rely to establish the inferences which they contend should be drawn, or the basis on which the “proper interpretation” of the document is as they contend. In inter partes correspondence and in their submissions on this application, the applicants contended that a relevant part of the context is that Mr Dawson authored the Bank Guarantee Summary Document. That allegation is not pleaded in the SOC. If it is a material fact on which the applicants rely for the purpose of construing the Bank Guarantee Summary Document, it should be pleaded in a way that is capable of response in the defence(s) of the respondents. To do so would not only facilitate procedural fairness, but also the overarching purpose of conducting the proceedings in accordance with law as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible.

31 If the applicants do not have a basis to allege that Mr Dawson authored the Bank Guarantee Summary Document, then it does not advance their position on this application to make submissions based upon it. Paragraph 32 appears to be key to the allegations which follow. It is part of the foundation for what follows in terms of the allegations specific to each of the Projects: see paragraphs 52 to 56, 94 to 96, 102 to 106. Although paragraphs 52, 94 and 102 refer to paragraph 31 rather than paragraph 32, the particulars given for each of these paragraphs simply state “to be inferred from the Bank Guarantee Summary Document”, which in turn can only be understood by reference to paragraph 32. As presently framed, paragraph 32 establishes a false premise for the allegations which follow that rely on the Bank Guarantee Summary Document.

32 It is no answer to the defective pleading of paragraph 32 to assert, as the applicants do, that it would be open to the respondents (or, at least, to Mr Dawson) to deny the paragraph and then to further plead such matters as may be necessary to the proper interpretation of the Bank Guarantee Summary Document. That is not what procedural fairness requires, particularly in a case such as this where serious allegations are made. The respondents should not be left to guess. It may well be that once the applicants have themselves adequately exposed the material facts upon which they rely to contend that the Bank Guarantee Summary Document establishes the allegations in paragraphs 32(a) and (b) of the SOC, the respondents may then plead a fulsome responsive defence(s), but they should not be forced to do so in response to a defective pleading.

33 Paragraph 32 must be struck out with leave to re-plead.

34 No challenge is made to paragraph 33 or to paragraphs 34(a), 35(a) and 36(a).

35 It is convenient to consider paragraphs 34(b) to (c) and 35(b), 36(b) and 37 together. These paragraphs are each premised on the allegations that one of the applicants had in fact provided bank guarantees in the amounts specified in the Bank Guarantee Summary Document on behalf of each of the “ ‘Podium Glazing’ and Yuanda Residential (Gallery Facades Pty Ltd) entities to secure the performance of each of those entities’ obligations to each builder to assure performance of construction and defects obligations with respect to each specified ‘job’ (the Bank Guarantees)” and that Mr Dawson was involved in and / or executed the Bank Guarantees. Those allegations are said to be matters that can be inferred “[b]y virtue of [Mr Dawson] sending the Bank Guarantee Summary Document from his work email account to his personal email address on 12 May 2016, his position as General Manager of [Yuanda Australia], and his position as director of each of the Applicants at the times pleaded in paragraph 11 above”. The inferences which the applicants seek to have drawn are not supported by pleaded facts from which the inference is capable of being drawn. Even if one assumes the allegations in the chapeau of paragraph 34 of the SOC are true, they do not, without more, give rise to the matters sought to be inferred in paragraph 34(b) and (c). That is plain on the face of the pleading. It is also reinforced by the inter partes correspondence and the submissions made by the applicant, which seek to defend the pleading of the relevant inferences on the basis of allegations of fact that are not pleaded. Having regard to the nature of the allegations in this case, the respondents are entitled to have the case against them pleaded clearly, fully and with particularity. Paragraphs 35(b), 36(b) and 37 are premised on paragraphs 34(b) and (c). Accordingly, paragraphs 34(b) and (c) and 35(b), 36(b) and 37 must be struck out with liberty to re-plead.

Allegations in relation to the Projects (paragraphs 52 to 56, 70 to 72, 94 to 98 and 102 to 106)

36 The respondents contend that various paragraphs of the SOC which relate to the Projects should be struck out. As mentioned, the allegations in respect of each of the Projects are similar. The respondents submit, and I accept, that they each suffer from similar defects.

1 William Street Project (paragraphs 52 to 56)

37 The respondents identify a number of defects in this section of the SOC. It is sufficient to address only the more significant defects because I am satisfied that, having regard to those defects, it is appropriate to appropriate to strike out the paragraphs with leave to re-plead.

38 In paragraph 52, the matters pleaded in the chapeau by cross-reference to earlier paragraphs of the SOC do not support the propositions that a sum of money was withheld (and was withheld for a particular purpose) and that Mr Dawson was aware of those matters.

39 The pleading of paragraph 52 is also ambiguous in that the definition of “Brookfield Guarantee” introduced in paragraph 52(a) speaks in terms of an action — the withholding of money as security — whereas paragraph 52(b) then alleges that Mr Dawson “executed, or was at least aware of” the defined action but does not plead what he did to “execute” the defined action or clarify that an alternative contention is that the “Brookfield Guarantee” is a document that was executed. Further, it is not clear whether Mr Dawson is alleged to have been “at least aware of” the act of one of the applicants withholding money as security or of an instrument that comprised the “Brookfield Guarantee”. Further, in paragraph 52(a) the guarantee is defined as the “withholding” of money by the applicants, whereas in paragraph 53 the guarantee is said to be “provided” by Mr Dawson. The allegation changes in paragraph 54, which alleges that Mr Dawson entered into the guarantee.

40 Further ambiguity arises when the paragraph is read in the context of what is alleged in the earlier paragraphs of the SOC. Paragraph 52(a) refers to one of the applicants withholding a sum of money, whereas paragraph 32(b) alleges that deposits or amounts were paid to builders, whereas paragraph 34(b) alleges that bank guarantees were given. All three propositions are said to derive from what is alleged to be, but clearly is not, “stated” in the Bank Guarantee Summary Document.

41 Other significant defects in the pleading include the bare conclusory allegations that inform paragraphs 54 to 56. Take, for example, the allegation of conflict of interest in paragraph 54(a). The interests said to be in conflict are not pleaded. Moreover, the basis upon which Mr Dawson is alleged to have had a relevant interest in or involvement such as to give rise to the alleged conflict is not pleaded. Mr Dawson is not alleged have had any interest or involvement in Podium Glazing (Qld) Pty Ltd (PG(QLD)) (the name by which SRG Qld was previously known) at the relevant time. Similarly, the allegation that Mr Dawson did not act in good faith and for a proper purpose is rolled up in a conclusory form. The underlying premise for the allegations in paragraph 54(b), (d) and (e) is assumed but not clearly pleaded.

42 For these reasons, paragraphs 52 to 56 must be struck out. I will grant the applicants leave to re-plead.

Novartis Project (paragraphs 70 to 72)

43 Paragraphs 70 to 72 broadly replicate the defects in paragraphs 54 to 56 and will be struck out with leave to re-plead for the same reasons. I further note that the allegations in paragraph 70 are not tethered or connected to the allegations in paragraphs 67 and 68.

Collins St Project (paragraphs 94 to 98)

44 In paragraph 94, there is no reasonable link between the facts alleged in the chapeau (which refers back to paragraphs 31 and 73 to 93) and the allegations said to follow in sub-paragraphs (a) to (d). The particulars given in respect of paragraph 94 are limited to reliance on inferences to be drawn from the Bank Guarantee Summary Document, which is problematic for the reasons already given.

45 In relation to paragraph 94(a) and (b), the allegations at paragraphs 73 to 93 do not refer to any guarantee in relation to 883 Collins St. Its existence is not supported by the inference that I assume the applicants seek to have drawn from the Bank Guarantee Summary Document as pleaded in paragraphs 32 and 34. As presently pleaded, the Bank Guarantee Summary Document is not capable of supporting the allegation that a guarantee was obtained in relation to 883 Collins St, that it was provided by one of the applicants to guarantee Yuanda Residential’s performance, or that Mr Dawson executed or was aware of such a guarantee.

46 There are also defects with paragraph 94(c) to (d) in relation to the allegations based on the 883 Collins Subcontracting Agreement, as defined in paragraph 92. The latter paragraph defines the “883 Collins Subcontracting Agreement” as a proposed trade agency agreement, sent to Mr Dawson, and of which he was aware or ought to have been aware (paragraph 93)). The allegation in paragraph 94(c) that the 883 Collins Subcontracting Agreement was executed, and in 94(d) that it was executed by or with the awareness of Mr Dawson is a bare assertion rolled up with the allegation about the “889 Collins Subcontracting Agreement”. Paragraph 94 must be struck out. In so far as the paragraph relates to the 889 Collins Subcontracting Agreement, it is repetitive of paragraphs 90 and 91 of the SOC.

47 Paragraph 95 relies on the allegations in paragraph 94, as well as the existence of guarantees, and accordingly should also be struck out.

48 Paragraph 96 is premised on the same basis as paragraph 95. In addition, paragraph 96(a) to (c) are defective in the same way as paragraph 54(a) to (c). Further, no allegations of fact are made to support the allegation of conflict of interest at the relevant time.

49 Paragraphs 96(d) and (e) are defective in that the conclusions alleged are not supported by pleaded facts. The pleading does not contain an allegation that any work was performed pursuant to the 889 Collins Subcontracting Agreement or 883 Collins Subcontracting Agreement, or that Yuanda Residential obtained any income, profit or advantage in relation to those agreements. Further, paragraph 96(d) is framed in terms of “allowing Yuanda Residential to earn income and profit” in a way that is ambiguous. It is not clear whether the allegation is that Yuanda Residential was afforded a mere opportunity to earn income and profit, or whether it is alleged that Yuanda Residential availed itself of the alleged opportunity such that it in fact earned income and profit, or whether both are relied upon in the alternative. Finally, as already identified, the basis upon which it is alleged that the 883 Collins Subcontracting Agreement was executed is not exposed and the allegation that a commercial opportunity was therefore diverted is made without a factual basis.

50 Paragraphs 97 and 98 are premised on paragraphs 94 to 96, and should be struck out on the same basis.

The Yards Project (paragraphs 102 to 106)

51 For present purposes, paragraph 102 suffers from the same defect as paragraph 94 — it pleads no reasonable link between the pleaded facts in the chapeau (which again refers back to paragraph 31 and 99 to 101) and the conclusions drawn from those facts under sub-paragraphs (a) to (d). The alleged inference again relies entirely on the Bank Guarantee Summary Document.

52 The existence of the Bank Guarantee Summary Document and the facts alleged in relation to Lend Lease issuing an invitation to tender (paragraphs 99 and 100) and sending a proposed contract to Mr Dawson listing PG(QLD) as the proposed subcontractor (paragraph 101), do not demonstrate the further matters alleged in relation to the Yards Subcontracting Agreement and Yards Guarantee, as defined.

53 Paragraphs 103 and 104 are premised on the defective pleading in respect of the Yard Subcontracting Agreement and Yards Guarantee. Paragraph 104 also suffers from similar defects as identified in respect of paragraph 54(a) and (c). Paragraph 104(d) and (e) are not supported by an allegation that any work was performed pursuant to Yards Subcontracting Agreement, or that PG(QLD) obtained any income, profit or advantage in relation thereto.

54 Paragraphs 105 and 106 are premised on paragraphs 102 to 104 and must be struck out with liberty to re-plead.

Pleadings underpinning claims for relief (paragraphs 107 to 116)

55 Each of paragraphs 107 to 116 are premised on one or more paragraphs which have been addressed above. The respondents included in their submissions a table indicating the relevant paragraph, with the impugned paragraphs on which it is premised. It is not necessary to reproduce that table here. Suffice to say that to the extent the paragraphs which underpin the claims for relief are predicated on the paragraphs which are to be re-pleaded, leave is granted to amend those paragraphs to the extent it is necessary to do so.

CONCLUSION

56 For these reasons, I am satisfied that the respondents should succeed on their application to strike out the paragraphs I have identified and that the applicants should have leave to re-plead. Given the centrality of the impugned paragraphs, I will hear from the applicants as to whether the most efficient and cost effective course would be to strike out the entirety of the SOC and grant leave to re-plead in full. In the usual course, costs should follow the event. If any party seeks a different costs order, they are to notify my Associate by email copied to all parties’ representatives by 5.00 pm on 31 May 2023.

I certify that the preceding fifty-six (56) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Cheeseman. |

Associate: